User login

Technology for primary care — terrific, terrifying, or both?

We have all been using technology in our primary care practices for a long time but newer formats have been emerging so fast that our minds, much less our staff’s minds, may be spinning.

Our old friend the telephone, a time-soaking nemesis for scheduling, checking coverage, questions calls, prescribing, quick consults, and follow-up is being replaced by EHR portals and SMS for messaging (e.g. DoctorConnect, SimplePractice), drop-in televisits and patient education links on our websites (e.g. Schmitt Pediatric Care, Remedy Connect), and chatbots for scheduling (e.g. CHEC-UP). While time is saved, what is lost may be hearing the subtext of anxiety or misperceptions in parents’ voices that would change our advice and the empathetic human connection in conversations with our patients. A hybrid approach may be better.

The paper appointment book has been replaced by scheduling systems sometimes lacking in flexibility for double booking, sibling visits, and variable length or extremely valuable multi-professional visits. Allowing patients to book their own visits may place complex problems in inappropriate slots, so only allowing online requests for visits is safer. On the other hand, many of us can now squeeze in “same day” televisits (e.g. Blueberry Pediatrics), sometimes from outside our practice (e.g., zocdoc), to increase payments and even entice new patients to enroll.

Amazing advances in technology are being made in specialty care such as genetic modifications (CRISPR), immunotherapies (mRNA vaccines and AI drug design), robot-assisted surgery, and 3-D printing of body parts and prosthetics. Technology as treatment such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and vagal stimulation are finding value in psychiatry.

But beside being aware of and able to order such specialty technologies, innovations are now extending our senses in primary care such as amplified or visual stethoscopes, bedside ultrasound (e.g. Butterfly), remote visualization (oto-, endo-)scopes, photographic vision screens (e.g. iScreen) for skin lesion (VisualDx) and genetic syndrome facial recognition. We need to be sure that technologies are tested and calibrated for children and different racial groups and genders to provide safe and equitable care. Early adoption may not always be the best approach. Costs of technology, as usual, may limit access to these advanced care aids especially, as usual, in practices serving low income and rural communities.

Patients, especially younger parents and youth, now expect to participate and can directly benefit from technology as part of their health care. Validated parent or self-report screens (e.g. EHRs, Phreesia) can detect important issues early for more effective intervention. Such questionnaires typically provide a pass/fail result or score, but other delivery systems (e.g. CHADIS) include interpretation, assist patients/parents in setting visit priorities and health goals, and even chain results of one questionnaire to secondary screens to hone in on problems, sometimes obviating a time-consuming second visit. Patient-completed comprehensive questionnaires (e.g. Well Visit Planner, CHADIS) allow us time to use our skills to focus on concerns, education, and management rather than asking myriad routine questions. Some (e.g. CHADIS) even create visit documentation reducing our “pajama time” write ups (and burnout); automate repeated online measures to track progress; and use questionnaire results to trigger related patient-specific education and resources rather than the often-ignored generic EHR handouts.

Digital therapeutics such as apps for anxiety (e.g. Calm), depression (e.g. SparkRx, Cass), weight control (e.g. Noom, Lose it), fitness, or sleep tracking (e.g. Whoop) help educate and, in some cases, provide real-time feedback to personalize discovery of contributing factors in order to maintain motivation for positive health behavior change. Some video games improve ADHD symptoms (e.g. EndeavorRX). Virtual reality scenarios have been shown to desensitize those with PTSD and social anxiety or teach social skills to children with autism.

Systems that trigger resource listings (including apps) from screen results can help, but now with over 10,000 apps for mental health, knowing what to recommend for what conditions is a challenge for which ratings (e.g. MINDapps.org) can help. With few product reps visiting to tell us what’s new, we need to read critically about innovations, search the web, subscribe to the AAP SOAPM LISTSERV, visit exhibitors at professional meetings, and talk with peers.

All the digital data collected from health care technology, if assembled with privacy constraints and analyzed with advanced statistical methods, have the possibility, with or without inclusion of genomic data, to allow for more accurate diagnostic and treatment decision support. While AI can search widely for patterns, it needs to be “trained” on appropriate data to make correct conclusions. We are all aware that the history determines 85% of both diagnosis and treatment decisions, particularly in primary care where x-rays or lab tests are not often needed.

But history in EHR notes is often idiosyncratic, entered hours after the visit by the clinician, and does not include the information needed to define diagnostic or guideline criteria, even if the clinician knows and considered those criteria. EHR templates are presented blank and are onerous and time consuming for clinicians. In addition, individual patient barriers to care, preferences, and environmental or subjective concerns are infrequently documented even though they may make the biggest difference to adherence and/or outcomes.

Notes made from voice to text digital AI translation of the encounter (e.g. Nuance DAX) are even less likely to include diagnostic criteria as it would be inappropriate to speak these. To use EHR history data to train AI and to test efficacy of care using variations of guidelines, guideline-related data is needed from online patient entries in questionnaires that are transformed to fill in templates along with some structured choices for clinician entries forming visit notes (e.g. CHADIS). New apps to facilitate clinician documentation of guidelines (e.g. AvoMD) could streamline visits as well as help document guideline criteria. The resulting combination of guideline-relevant patient histories and objective data to test and iteratively refine guidelines will allow a process known as a “Learning Health System.”

Technology to collect this kind of data can allow for the aspirational American Academy of Pediatrics CHILD Registry to approach this goal. Population-level data can provide surveillance for illness, toxins, effects of climate change, social drivers of health, and even effects of technologies themselves such as social media and remote learning so that we can attempt to make the best choices for the future.

Clinicians, staff, and patients will need to develop trust in technology as it infiltrates all aspects of health care. Professionals need both evidence and experience to trust a technology, which takes time and effort. Disinformation in the media may reduce trust or evoke unwarranted trust, as we have all seen regarding vaccines. Clear and coherent public health messaging can help but is no longer a panacea for developing trust in health care. Our nonjudgmental listening and informed opinions are needed more than ever.

The biggest issues for new technology are likely to be the need for workflow adjustments, changing our habit patterns, training, and cost/benefit analyses. With today’s high staff churn, confusion and even chaos can ensue when adopting new technology.

Staff need to be part of the selection process, if at all possible, and discuss how roles and flow will need to change. Having one staff member be a champion and expert for new tech can move adoption to a shared process rather than imposing “one more thing.” It is crucial to discuss the benefits for patients and staff even if the change is required. Sometimes cost savings can include a bonus for staff or free group lunches. Providing a certificate of achievement or title promotion for mastering new tech may be appropriate. Giving some time off from other tasks to learn new workflows can reduce resistance rather than just adding it on to a regular workload. Office “huddles” going forward can include examples of benefits staff have observed or heard about from the adoption. There are quality improvement processes that engage the team — some that earn MOC-4 or CEU credits — that apply to making workflow changes and measuring them iteratively.

If technology takes over important aspects of the work of medical professionals, even if it is faster and/or more accurate, it may degrade clinical observational, interactional, and decision-making skills through lack of use. It may also remove the sense of self-efficacy that motivates professionals to endure onerous training and desire to enter the field. Using technology may reduce empathetic interactions that are basic to humanistic motivation, work satisfaction, and even community respect. Moral injury is already rampant in medicine from restrictions on freedom to do what we see as important for our patients. Technology has great potential and already is enhancing our ability to provide the best care for patients but the risks need to be watched for and ameliorated.

When technology automates comprehensive visit documentation that highlights priority and risk areas from patient input and individualizes decision support, it can facilitate the personalized care that we and our patients want to experience. We must not be so awed, intrigued, or wary of new technology to miss its benefits nor give up our good clinical judgment about the technology or about our patients.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

We have all been using technology in our primary care practices for a long time but newer formats have been emerging so fast that our minds, much less our staff’s minds, may be spinning.

Our old friend the telephone, a time-soaking nemesis for scheduling, checking coverage, questions calls, prescribing, quick consults, and follow-up is being replaced by EHR portals and SMS for messaging (e.g. DoctorConnect, SimplePractice), drop-in televisits and patient education links on our websites (e.g. Schmitt Pediatric Care, Remedy Connect), and chatbots for scheduling (e.g. CHEC-UP). While time is saved, what is lost may be hearing the subtext of anxiety or misperceptions in parents’ voices that would change our advice and the empathetic human connection in conversations with our patients. A hybrid approach may be better.

The paper appointment book has been replaced by scheduling systems sometimes lacking in flexibility for double booking, sibling visits, and variable length or extremely valuable multi-professional visits. Allowing patients to book their own visits may place complex problems in inappropriate slots, so only allowing online requests for visits is safer. On the other hand, many of us can now squeeze in “same day” televisits (e.g. Blueberry Pediatrics), sometimes from outside our practice (e.g., zocdoc), to increase payments and even entice new patients to enroll.

Amazing advances in technology are being made in specialty care such as genetic modifications (CRISPR), immunotherapies (mRNA vaccines and AI drug design), robot-assisted surgery, and 3-D printing of body parts and prosthetics. Technology as treatment such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and vagal stimulation are finding value in psychiatry.

But beside being aware of and able to order such specialty technologies, innovations are now extending our senses in primary care such as amplified or visual stethoscopes, bedside ultrasound (e.g. Butterfly), remote visualization (oto-, endo-)scopes, photographic vision screens (e.g. iScreen) for skin lesion (VisualDx) and genetic syndrome facial recognition. We need to be sure that technologies are tested and calibrated for children and different racial groups and genders to provide safe and equitable care. Early adoption may not always be the best approach. Costs of technology, as usual, may limit access to these advanced care aids especially, as usual, in practices serving low income and rural communities.

Patients, especially younger parents and youth, now expect to participate and can directly benefit from technology as part of their health care. Validated parent or self-report screens (e.g. EHRs, Phreesia) can detect important issues early for more effective intervention. Such questionnaires typically provide a pass/fail result or score, but other delivery systems (e.g. CHADIS) include interpretation, assist patients/parents in setting visit priorities and health goals, and even chain results of one questionnaire to secondary screens to hone in on problems, sometimes obviating a time-consuming second visit. Patient-completed comprehensive questionnaires (e.g. Well Visit Planner, CHADIS) allow us time to use our skills to focus on concerns, education, and management rather than asking myriad routine questions. Some (e.g. CHADIS) even create visit documentation reducing our “pajama time” write ups (and burnout); automate repeated online measures to track progress; and use questionnaire results to trigger related patient-specific education and resources rather than the often-ignored generic EHR handouts.

Digital therapeutics such as apps for anxiety (e.g. Calm), depression (e.g. SparkRx, Cass), weight control (e.g. Noom, Lose it), fitness, or sleep tracking (e.g. Whoop) help educate and, in some cases, provide real-time feedback to personalize discovery of contributing factors in order to maintain motivation for positive health behavior change. Some video games improve ADHD symptoms (e.g. EndeavorRX). Virtual reality scenarios have been shown to desensitize those with PTSD and social anxiety or teach social skills to children with autism.

Systems that trigger resource listings (including apps) from screen results can help, but now with over 10,000 apps for mental health, knowing what to recommend for what conditions is a challenge for which ratings (e.g. MINDapps.org) can help. With few product reps visiting to tell us what’s new, we need to read critically about innovations, search the web, subscribe to the AAP SOAPM LISTSERV, visit exhibitors at professional meetings, and talk with peers.

All the digital data collected from health care technology, if assembled with privacy constraints and analyzed with advanced statistical methods, have the possibility, with or without inclusion of genomic data, to allow for more accurate diagnostic and treatment decision support. While AI can search widely for patterns, it needs to be “trained” on appropriate data to make correct conclusions. We are all aware that the history determines 85% of both diagnosis and treatment decisions, particularly in primary care where x-rays or lab tests are not often needed.

But history in EHR notes is often idiosyncratic, entered hours after the visit by the clinician, and does not include the information needed to define diagnostic or guideline criteria, even if the clinician knows and considered those criteria. EHR templates are presented blank and are onerous and time consuming for clinicians. In addition, individual patient barriers to care, preferences, and environmental or subjective concerns are infrequently documented even though they may make the biggest difference to adherence and/or outcomes.

Notes made from voice to text digital AI translation of the encounter (e.g. Nuance DAX) are even less likely to include diagnostic criteria as it would be inappropriate to speak these. To use EHR history data to train AI and to test efficacy of care using variations of guidelines, guideline-related data is needed from online patient entries in questionnaires that are transformed to fill in templates along with some structured choices for clinician entries forming visit notes (e.g. CHADIS). New apps to facilitate clinician documentation of guidelines (e.g. AvoMD) could streamline visits as well as help document guideline criteria. The resulting combination of guideline-relevant patient histories and objective data to test and iteratively refine guidelines will allow a process known as a “Learning Health System.”

Technology to collect this kind of data can allow for the aspirational American Academy of Pediatrics CHILD Registry to approach this goal. Population-level data can provide surveillance for illness, toxins, effects of climate change, social drivers of health, and even effects of technologies themselves such as social media and remote learning so that we can attempt to make the best choices for the future.

Clinicians, staff, and patients will need to develop trust in technology as it infiltrates all aspects of health care. Professionals need both evidence and experience to trust a technology, which takes time and effort. Disinformation in the media may reduce trust or evoke unwarranted trust, as we have all seen regarding vaccines. Clear and coherent public health messaging can help but is no longer a panacea for developing trust in health care. Our nonjudgmental listening and informed opinions are needed more than ever.

The biggest issues for new technology are likely to be the need for workflow adjustments, changing our habit patterns, training, and cost/benefit analyses. With today’s high staff churn, confusion and even chaos can ensue when adopting new technology.

Staff need to be part of the selection process, if at all possible, and discuss how roles and flow will need to change. Having one staff member be a champion and expert for new tech can move adoption to a shared process rather than imposing “one more thing.” It is crucial to discuss the benefits for patients and staff even if the change is required. Sometimes cost savings can include a bonus for staff or free group lunches. Providing a certificate of achievement or title promotion for mastering new tech may be appropriate. Giving some time off from other tasks to learn new workflows can reduce resistance rather than just adding it on to a regular workload. Office “huddles” going forward can include examples of benefits staff have observed or heard about from the adoption. There are quality improvement processes that engage the team — some that earn MOC-4 or CEU credits — that apply to making workflow changes and measuring them iteratively.

If technology takes over important aspects of the work of medical professionals, even if it is faster and/or more accurate, it may degrade clinical observational, interactional, and decision-making skills through lack of use. It may also remove the sense of self-efficacy that motivates professionals to endure onerous training and desire to enter the field. Using technology may reduce empathetic interactions that are basic to humanistic motivation, work satisfaction, and even community respect. Moral injury is already rampant in medicine from restrictions on freedom to do what we see as important for our patients. Technology has great potential and already is enhancing our ability to provide the best care for patients but the risks need to be watched for and ameliorated.

When technology automates comprehensive visit documentation that highlights priority and risk areas from patient input and individualizes decision support, it can facilitate the personalized care that we and our patients want to experience. We must not be so awed, intrigued, or wary of new technology to miss its benefits nor give up our good clinical judgment about the technology or about our patients.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

We have all been using technology in our primary care practices for a long time but newer formats have been emerging so fast that our minds, much less our staff’s minds, may be spinning.

Our old friend the telephone, a time-soaking nemesis for scheduling, checking coverage, questions calls, prescribing, quick consults, and follow-up is being replaced by EHR portals and SMS for messaging (e.g. DoctorConnect, SimplePractice), drop-in televisits and patient education links on our websites (e.g. Schmitt Pediatric Care, Remedy Connect), and chatbots for scheduling (e.g. CHEC-UP). While time is saved, what is lost may be hearing the subtext of anxiety or misperceptions in parents’ voices that would change our advice and the empathetic human connection in conversations with our patients. A hybrid approach may be better.

The paper appointment book has been replaced by scheduling systems sometimes lacking in flexibility for double booking, sibling visits, and variable length or extremely valuable multi-professional visits. Allowing patients to book their own visits may place complex problems in inappropriate slots, so only allowing online requests for visits is safer. On the other hand, many of us can now squeeze in “same day” televisits (e.g. Blueberry Pediatrics), sometimes from outside our practice (e.g., zocdoc), to increase payments and even entice new patients to enroll.

Amazing advances in technology are being made in specialty care such as genetic modifications (CRISPR), immunotherapies (mRNA vaccines and AI drug design), robot-assisted surgery, and 3-D printing of body parts and prosthetics. Technology as treatment such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and vagal stimulation are finding value in psychiatry.

But beside being aware of and able to order such specialty technologies, innovations are now extending our senses in primary care such as amplified or visual stethoscopes, bedside ultrasound (e.g. Butterfly), remote visualization (oto-, endo-)scopes, photographic vision screens (e.g. iScreen) for skin lesion (VisualDx) and genetic syndrome facial recognition. We need to be sure that technologies are tested and calibrated for children and different racial groups and genders to provide safe and equitable care. Early adoption may not always be the best approach. Costs of technology, as usual, may limit access to these advanced care aids especially, as usual, in practices serving low income and rural communities.

Patients, especially younger parents and youth, now expect to participate and can directly benefit from technology as part of their health care. Validated parent or self-report screens (e.g. EHRs, Phreesia) can detect important issues early for more effective intervention. Such questionnaires typically provide a pass/fail result or score, but other delivery systems (e.g. CHADIS) include interpretation, assist patients/parents in setting visit priorities and health goals, and even chain results of one questionnaire to secondary screens to hone in on problems, sometimes obviating a time-consuming second visit. Patient-completed comprehensive questionnaires (e.g. Well Visit Planner, CHADIS) allow us time to use our skills to focus on concerns, education, and management rather than asking myriad routine questions. Some (e.g. CHADIS) even create visit documentation reducing our “pajama time” write ups (and burnout); automate repeated online measures to track progress; and use questionnaire results to trigger related patient-specific education and resources rather than the often-ignored generic EHR handouts.

Digital therapeutics such as apps for anxiety (e.g. Calm), depression (e.g. SparkRx, Cass), weight control (e.g. Noom, Lose it), fitness, or sleep tracking (e.g. Whoop) help educate and, in some cases, provide real-time feedback to personalize discovery of contributing factors in order to maintain motivation for positive health behavior change. Some video games improve ADHD symptoms (e.g. EndeavorRX). Virtual reality scenarios have been shown to desensitize those with PTSD and social anxiety or teach social skills to children with autism.

Systems that trigger resource listings (including apps) from screen results can help, but now with over 10,000 apps for mental health, knowing what to recommend for what conditions is a challenge for which ratings (e.g. MINDapps.org) can help. With few product reps visiting to tell us what’s new, we need to read critically about innovations, search the web, subscribe to the AAP SOAPM LISTSERV, visit exhibitors at professional meetings, and talk with peers.

All the digital data collected from health care technology, if assembled with privacy constraints and analyzed with advanced statistical methods, have the possibility, with or without inclusion of genomic data, to allow for more accurate diagnostic and treatment decision support. While AI can search widely for patterns, it needs to be “trained” on appropriate data to make correct conclusions. We are all aware that the history determines 85% of both diagnosis and treatment decisions, particularly in primary care where x-rays or lab tests are not often needed.

But history in EHR notes is often idiosyncratic, entered hours after the visit by the clinician, and does not include the information needed to define diagnostic or guideline criteria, even if the clinician knows and considered those criteria. EHR templates are presented blank and are onerous and time consuming for clinicians. In addition, individual patient barriers to care, preferences, and environmental or subjective concerns are infrequently documented even though they may make the biggest difference to adherence and/or outcomes.

Notes made from voice to text digital AI translation of the encounter (e.g. Nuance DAX) are even less likely to include diagnostic criteria as it would be inappropriate to speak these. To use EHR history data to train AI and to test efficacy of care using variations of guidelines, guideline-related data is needed from online patient entries in questionnaires that are transformed to fill in templates along with some structured choices for clinician entries forming visit notes (e.g. CHADIS). New apps to facilitate clinician documentation of guidelines (e.g. AvoMD) could streamline visits as well as help document guideline criteria. The resulting combination of guideline-relevant patient histories and objective data to test and iteratively refine guidelines will allow a process known as a “Learning Health System.”

Technology to collect this kind of data can allow for the aspirational American Academy of Pediatrics CHILD Registry to approach this goal. Population-level data can provide surveillance for illness, toxins, effects of climate change, social drivers of health, and even effects of technologies themselves such as social media and remote learning so that we can attempt to make the best choices for the future.

Clinicians, staff, and patients will need to develop trust in technology as it infiltrates all aspects of health care. Professionals need both evidence and experience to trust a technology, which takes time and effort. Disinformation in the media may reduce trust or evoke unwarranted trust, as we have all seen regarding vaccines. Clear and coherent public health messaging can help but is no longer a panacea for developing trust in health care. Our nonjudgmental listening and informed opinions are needed more than ever.

The biggest issues for new technology are likely to be the need for workflow adjustments, changing our habit patterns, training, and cost/benefit analyses. With today’s high staff churn, confusion and even chaos can ensue when adopting new technology.

Staff need to be part of the selection process, if at all possible, and discuss how roles and flow will need to change. Having one staff member be a champion and expert for new tech can move adoption to a shared process rather than imposing “one more thing.” It is crucial to discuss the benefits for patients and staff even if the change is required. Sometimes cost savings can include a bonus for staff or free group lunches. Providing a certificate of achievement or title promotion for mastering new tech may be appropriate. Giving some time off from other tasks to learn new workflows can reduce resistance rather than just adding it on to a regular workload. Office “huddles” going forward can include examples of benefits staff have observed or heard about from the adoption. There are quality improvement processes that engage the team — some that earn MOC-4 or CEU credits — that apply to making workflow changes and measuring them iteratively.

If technology takes over important aspects of the work of medical professionals, even if it is faster and/or more accurate, it may degrade clinical observational, interactional, and decision-making skills through lack of use. It may also remove the sense of self-efficacy that motivates professionals to endure onerous training and desire to enter the field. Using technology may reduce empathetic interactions that are basic to humanistic motivation, work satisfaction, and even community respect. Moral injury is already rampant in medicine from restrictions on freedom to do what we see as important for our patients. Technology has great potential and already is enhancing our ability to provide the best care for patients but the risks need to be watched for and ameliorated.

When technology automates comprehensive visit documentation that highlights priority and risk areas from patient input and individualizes decision support, it can facilitate the personalized care that we and our patients want to experience. We must not be so awed, intrigued, or wary of new technology to miss its benefits nor give up our good clinical judgment about the technology or about our patients.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. E-mail her at [email protected].

Why Are Prion Diseases on the Rise?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

In 1986, in Britain, cattle started dying.

The condition, quickly nicknamed “mad cow disease,” was clearly infectious, but the particular pathogen was difficult to identify. By 1993, 120,000 cattle in Britain were identified as being infected. As yet, no human cases had occurred and the UK government insisted that cattle were a dead-end host for the pathogen. By the mid-1990s, however, multiple human cases, attributable to ingestion of meat and organs from infected cattle, were discovered. In humans, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) was a media sensation — a nearly uniformly fatal, untreatable condition with a rapid onset of dementia, mobility issues characterized by jerky movements, and autopsy reports finding that the brain itself had turned into a spongy mess.

The United States banned UK beef imports in 1996 and only lifted the ban in 2020.

The disease was made all the more mysterious because the pathogen involved was not a bacterium, parasite, or virus, but a protein — or a proteinaceous infectious particle, shortened to “prion.”

Prions are misfolded proteins that aggregate in cells — in this case, in nerve cells. But what makes prions different from other misfolded proteins is that the misfolded protein catalyzes the conversion of its non-misfolded counterpart into the misfolded configuration. It creates a chain reaction, leading to rapid accumulation of misfolded proteins and cell death.

And, like a time bomb, we all have prion protein inside us. In its normally folded state, the function of prion protein remains unclear — knockout mice do okay without it — but it is also highly conserved across mammalian species, so it probably does something worthwhile, perhaps protecting nerve fibers.

Far more common than humans contracting mad cow disease is the condition known as sporadic CJD, responsible for 85% of all cases of prion-induced brain disease. The cause of sporadic CJD is unknown.

But one thing is known: Cases are increasing.

I don’t want you to freak out; we are not in the midst of a CJD epidemic. But it’s been a while since I’ve seen people discussing the condition — which remains as horrible as it was in the 1990s — and a new research letter appearing in JAMA Neurology brought it back to the top of my mind.

Researchers, led by Matthew Crane at Hopkins, used the CDC’s WONDER cause-of-death database, which pulls diagnoses from death certificates. Normally, I’m not a fan of using death certificates for cause-of-death analyses, but in this case I’ll give it a pass. Assuming that the diagnosis of CJD is made, it would be really unlikely for it not to appear on a death certificate.

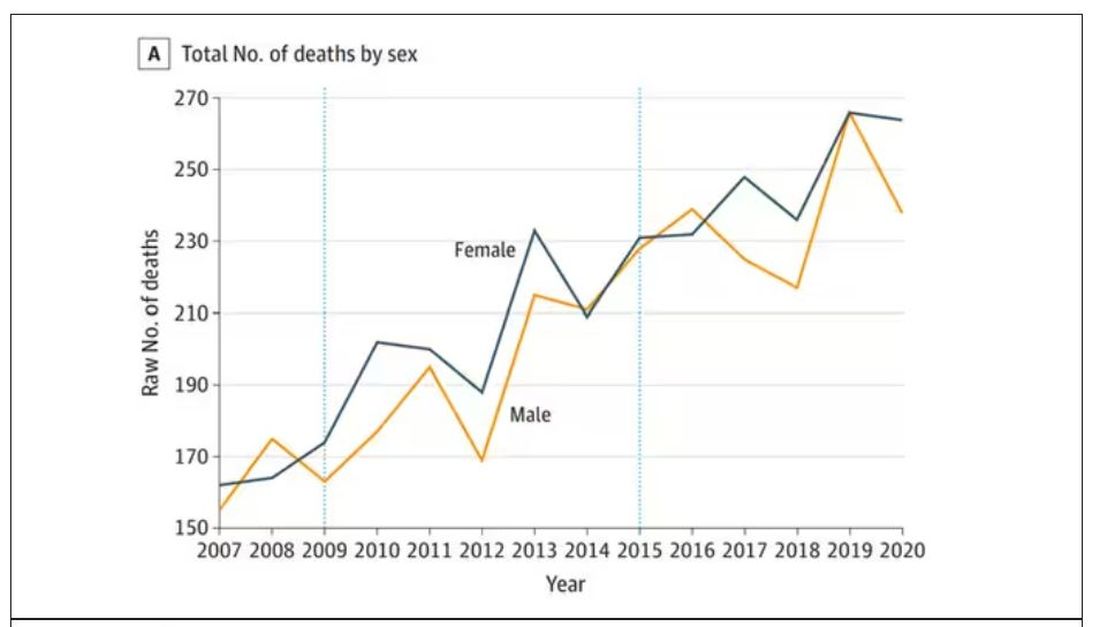

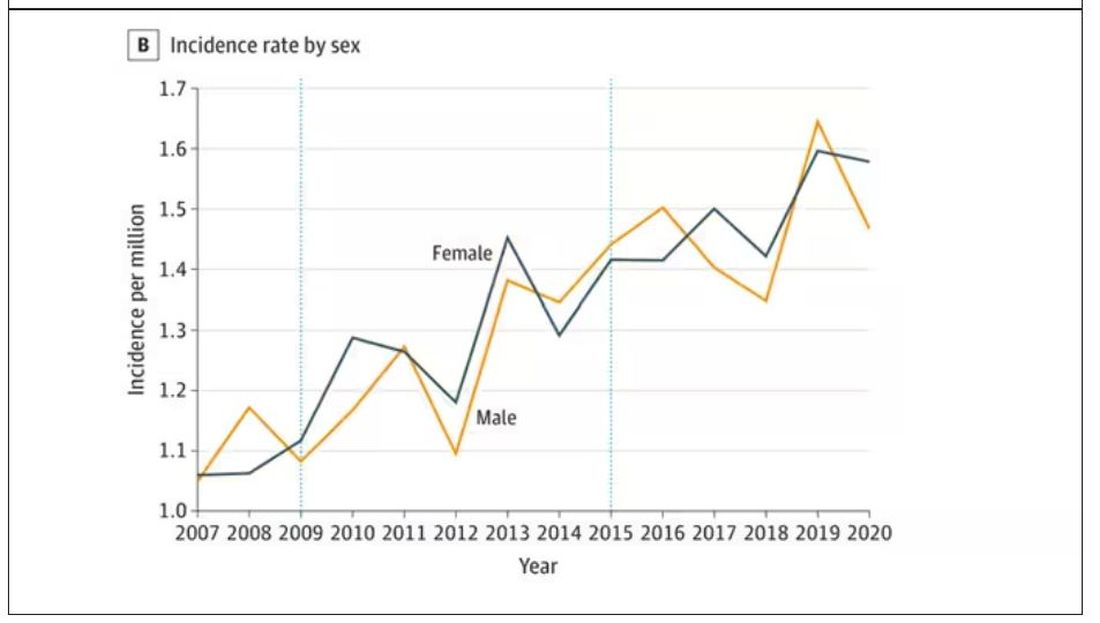

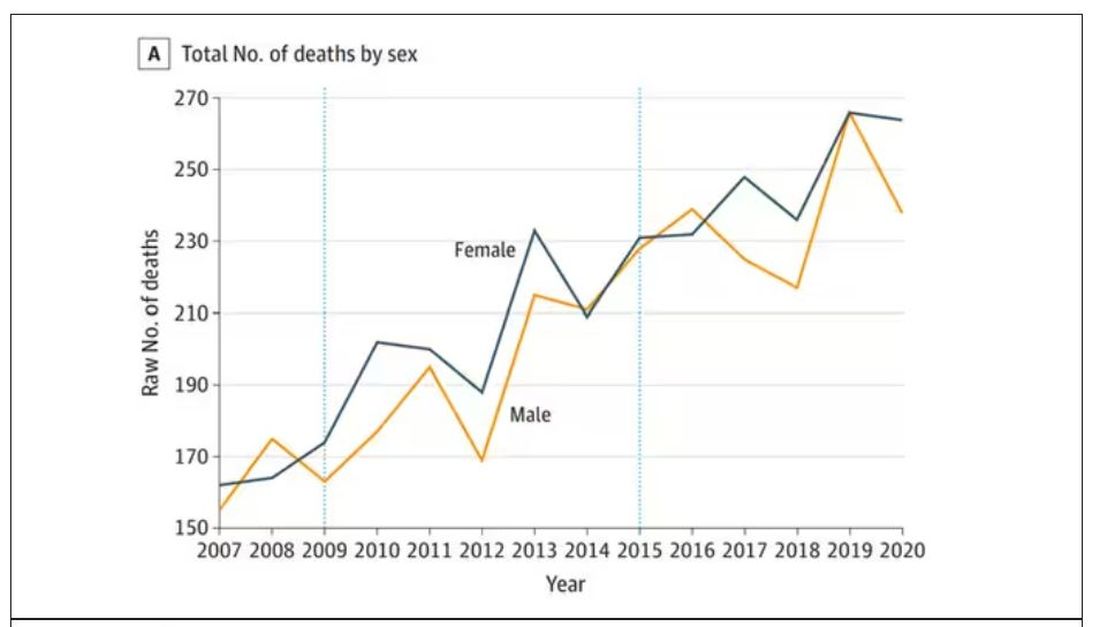

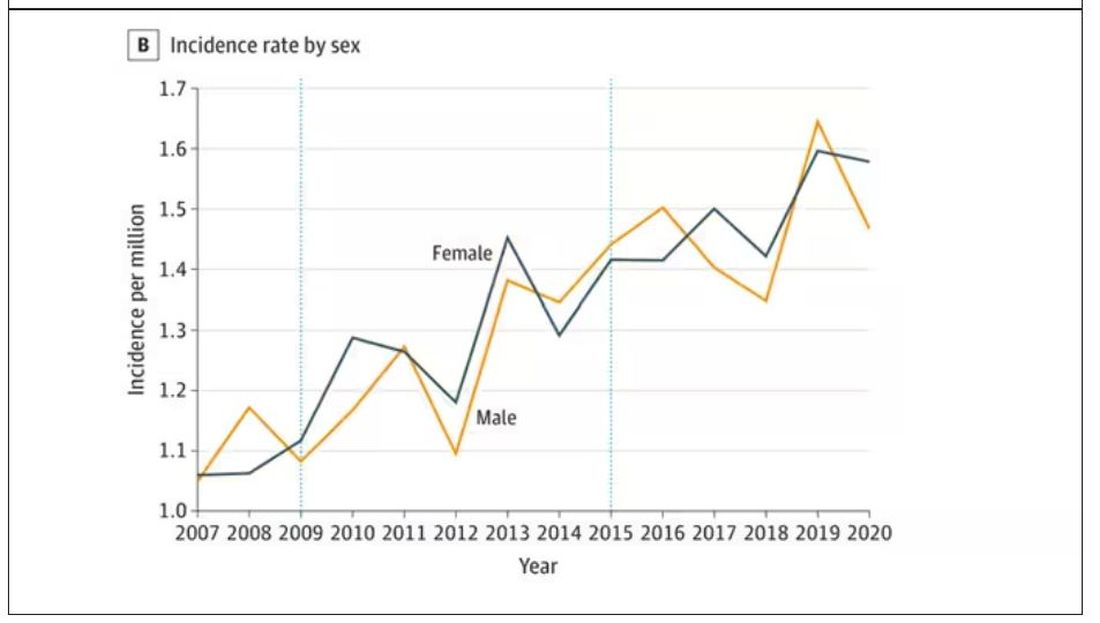

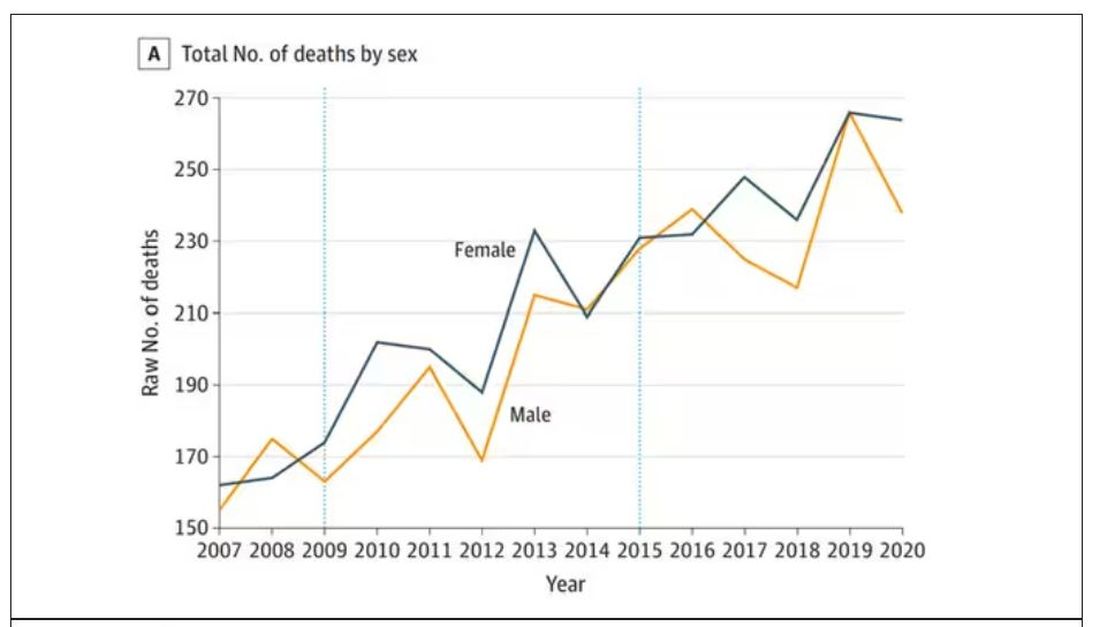

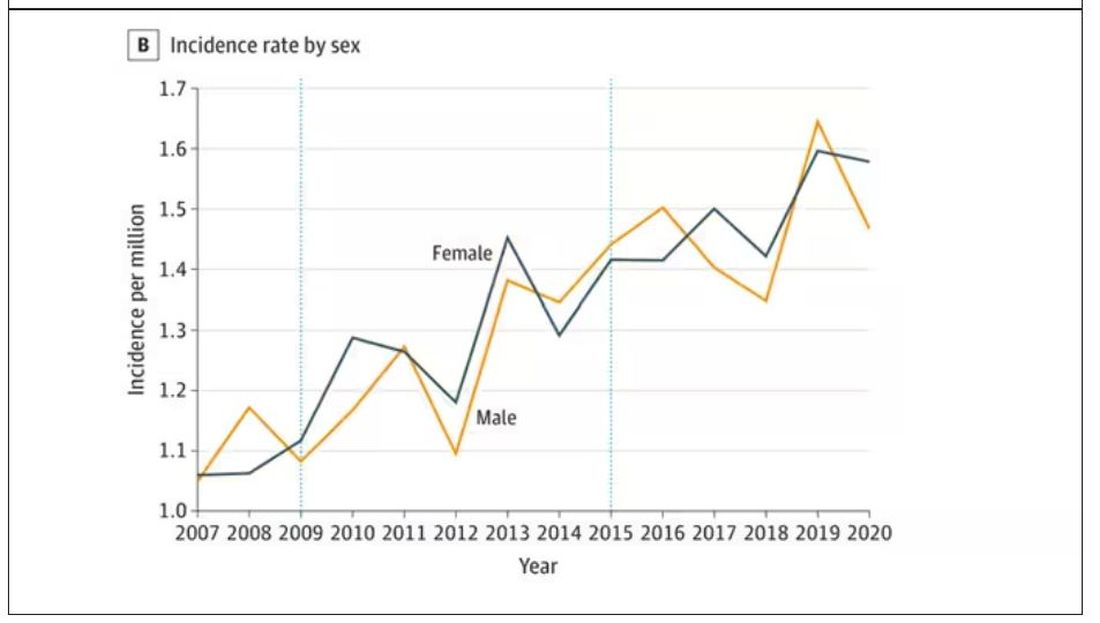

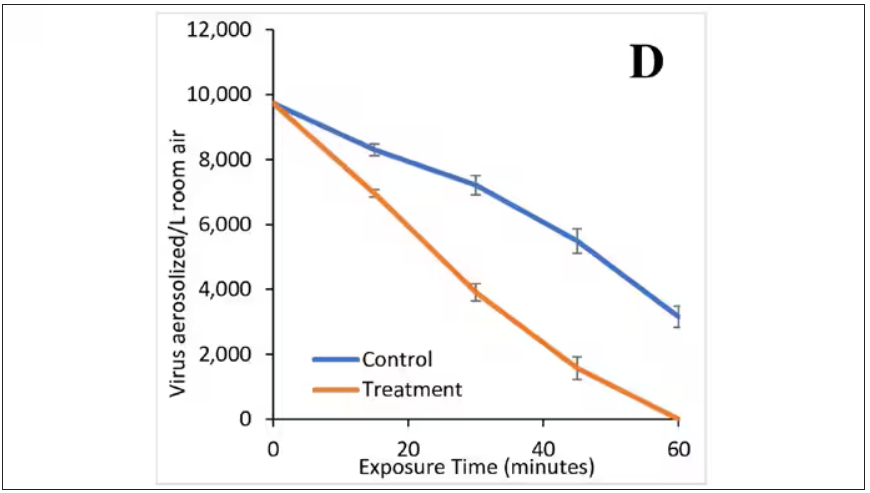

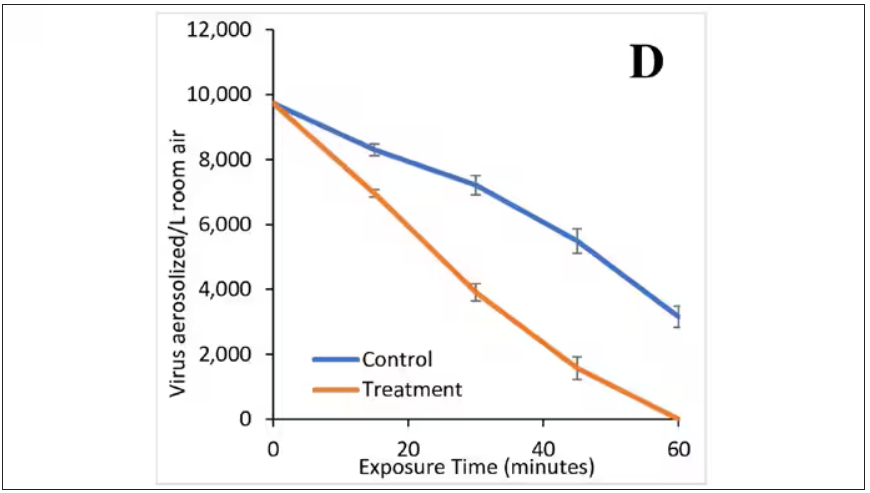

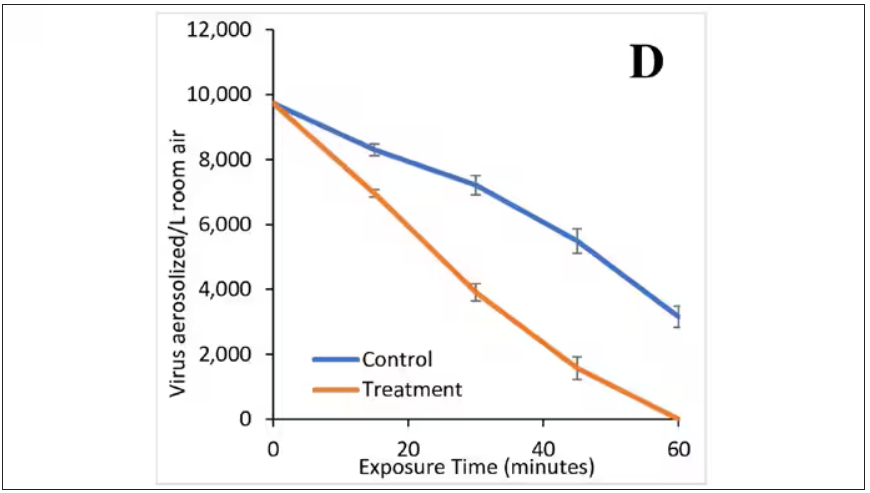

The main findings are seen here.

Note that we can’t tell whether these are sporadic CJD cases or variant CJD cases or even familial CJD cases; however, unless there has been a dramatic change in epidemiology, the vast majority of these will be sporadic.

The question is, why are there more cases?

Whenever this type of question comes up with any disease, there are basically three possibilities:

First, there may be an increase in the susceptible, or at-risk, population. In this case, we know that older people are at higher risk of developing sporadic CJD, and over time, the population has aged. To be fair, the authors adjusted for this and still saw an increase, though it was attenuated.

Second, we might be better at diagnosing the condition. A lot has happened since the mid-1990s, when the diagnosis was based more or less on symptoms. The advent of more sophisticated MRI protocols as well as a new diagnostic test called “real-time quaking-induced conversion testing” may mean we are just better at detecting people with this disease.

Third (and most concerning), a new exposure has occurred. What that exposure might be, where it might come from, is anyone’s guess. It’s hard to do broad-scale epidemiology on very rare diseases.

But given these findings, it seems that a bit more surveillance for this rare but devastating condition is well merited.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

In 1986, in Britain, cattle started dying.

The condition, quickly nicknamed “mad cow disease,” was clearly infectious, but the particular pathogen was difficult to identify. By 1993, 120,000 cattle in Britain were identified as being infected. As yet, no human cases had occurred and the UK government insisted that cattle were a dead-end host for the pathogen. By the mid-1990s, however, multiple human cases, attributable to ingestion of meat and organs from infected cattle, were discovered. In humans, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) was a media sensation — a nearly uniformly fatal, untreatable condition with a rapid onset of dementia, mobility issues characterized by jerky movements, and autopsy reports finding that the brain itself had turned into a spongy mess.

The United States banned UK beef imports in 1996 and only lifted the ban in 2020.

The disease was made all the more mysterious because the pathogen involved was not a bacterium, parasite, or virus, but a protein — or a proteinaceous infectious particle, shortened to “prion.”

Prions are misfolded proteins that aggregate in cells — in this case, in nerve cells. But what makes prions different from other misfolded proteins is that the misfolded protein catalyzes the conversion of its non-misfolded counterpart into the misfolded configuration. It creates a chain reaction, leading to rapid accumulation of misfolded proteins and cell death.

And, like a time bomb, we all have prion protein inside us. In its normally folded state, the function of prion protein remains unclear — knockout mice do okay without it — but it is also highly conserved across mammalian species, so it probably does something worthwhile, perhaps protecting nerve fibers.

Far more common than humans contracting mad cow disease is the condition known as sporadic CJD, responsible for 85% of all cases of prion-induced brain disease. The cause of sporadic CJD is unknown.

But one thing is known: Cases are increasing.

I don’t want you to freak out; we are not in the midst of a CJD epidemic. But it’s been a while since I’ve seen people discussing the condition — which remains as horrible as it was in the 1990s — and a new research letter appearing in JAMA Neurology brought it back to the top of my mind.

Researchers, led by Matthew Crane at Hopkins, used the CDC’s WONDER cause-of-death database, which pulls diagnoses from death certificates. Normally, I’m not a fan of using death certificates for cause-of-death analyses, but in this case I’ll give it a pass. Assuming that the diagnosis of CJD is made, it would be really unlikely for it not to appear on a death certificate.

The main findings are seen here.

Note that we can’t tell whether these are sporadic CJD cases or variant CJD cases or even familial CJD cases; however, unless there has been a dramatic change in epidemiology, the vast majority of these will be sporadic.

The question is, why are there more cases?

Whenever this type of question comes up with any disease, there are basically three possibilities:

First, there may be an increase in the susceptible, or at-risk, population. In this case, we know that older people are at higher risk of developing sporadic CJD, and over time, the population has aged. To be fair, the authors adjusted for this and still saw an increase, though it was attenuated.

Second, we might be better at diagnosing the condition. A lot has happened since the mid-1990s, when the diagnosis was based more or less on symptoms. The advent of more sophisticated MRI protocols as well as a new diagnostic test called “real-time quaking-induced conversion testing” may mean we are just better at detecting people with this disease.

Third (and most concerning), a new exposure has occurred. What that exposure might be, where it might come from, is anyone’s guess. It’s hard to do broad-scale epidemiology on very rare diseases.

But given these findings, it seems that a bit more surveillance for this rare but devastating condition is well merited.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

In 1986, in Britain, cattle started dying.

The condition, quickly nicknamed “mad cow disease,” was clearly infectious, but the particular pathogen was difficult to identify. By 1993, 120,000 cattle in Britain were identified as being infected. As yet, no human cases had occurred and the UK government insisted that cattle were a dead-end host for the pathogen. By the mid-1990s, however, multiple human cases, attributable to ingestion of meat and organs from infected cattle, were discovered. In humans, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) was a media sensation — a nearly uniformly fatal, untreatable condition with a rapid onset of dementia, mobility issues characterized by jerky movements, and autopsy reports finding that the brain itself had turned into a spongy mess.

The United States banned UK beef imports in 1996 and only lifted the ban in 2020.

The disease was made all the more mysterious because the pathogen involved was not a bacterium, parasite, or virus, but a protein — or a proteinaceous infectious particle, shortened to “prion.”

Prions are misfolded proteins that aggregate in cells — in this case, in nerve cells. But what makes prions different from other misfolded proteins is that the misfolded protein catalyzes the conversion of its non-misfolded counterpart into the misfolded configuration. It creates a chain reaction, leading to rapid accumulation of misfolded proteins and cell death.

And, like a time bomb, we all have prion protein inside us. In its normally folded state, the function of prion protein remains unclear — knockout mice do okay without it — but it is also highly conserved across mammalian species, so it probably does something worthwhile, perhaps protecting nerve fibers.

Far more common than humans contracting mad cow disease is the condition known as sporadic CJD, responsible for 85% of all cases of prion-induced brain disease. The cause of sporadic CJD is unknown.

But one thing is known: Cases are increasing.

I don’t want you to freak out; we are not in the midst of a CJD epidemic. But it’s been a while since I’ve seen people discussing the condition — which remains as horrible as it was in the 1990s — and a new research letter appearing in JAMA Neurology brought it back to the top of my mind.

Researchers, led by Matthew Crane at Hopkins, used the CDC’s WONDER cause-of-death database, which pulls diagnoses from death certificates. Normally, I’m not a fan of using death certificates for cause-of-death analyses, but in this case I’ll give it a pass. Assuming that the diagnosis of CJD is made, it would be really unlikely for it not to appear on a death certificate.

The main findings are seen here.

Note that we can’t tell whether these are sporadic CJD cases or variant CJD cases or even familial CJD cases; however, unless there has been a dramatic change in epidemiology, the vast majority of these will be sporadic.

The question is, why are there more cases?

Whenever this type of question comes up with any disease, there are basically three possibilities:

First, there may be an increase in the susceptible, or at-risk, population. In this case, we know that older people are at higher risk of developing sporadic CJD, and over time, the population has aged. To be fair, the authors adjusted for this and still saw an increase, though it was attenuated.

Second, we might be better at diagnosing the condition. A lot has happened since the mid-1990s, when the diagnosis was based more or less on symptoms. The advent of more sophisticated MRI protocols as well as a new diagnostic test called “real-time quaking-induced conversion testing” may mean we are just better at detecting people with this disease.

Third (and most concerning), a new exposure has occurred. What that exposure might be, where it might come from, is anyone’s guess. It’s hard to do broad-scale epidemiology on very rare diseases.

But given these findings, it seems that a bit more surveillance for this rare but devastating condition is well merited.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Can AI enhance mental health treatment?

Three questions for clinicians

Artificial intelligence (AI) is already impacting the mental health care space, with several new tools available to both clinicians and patients. While this technology could be a game-changer amid a mental health crisis and clinician shortage, there are important ethical and efficacy concerns clinicians should be aware of.

Current use cases illustrate both the potential and risks of AI. On one hand, AI has the potential to improve patient care with tools that can support diagnoses and inform treatment decisions at scale. The UK’s National Health Service is using an AI-powered diagnostic tool to help clinicians diagnose mental health disorders and determine the severity of a patient’s needs. Other tools leverage AI to analyze a patient’s voice for signs of depression or anxiety.

On the other hand, there are serious potential risks involving privacy, bias, and misinformation. One chatbot tool designed to counsel patients through disordered eating was shut down after giving problematic weight-loss advice.

The number of AI tools in the healthcare space is expected to increase fivefold by 2035. Keeping up with these advances is just as important for clinicians as keeping up with the latest medication and treatment options. That means being aware of both the limitations and the potential of AI. Here are three questions clinicians can ask as they explore ways to integrate these tools into their practice while navigating the risks.

• How can AI augment, not replace, the work of my staff?

For example, documentation and the use of electronic health records have consistently been linked to clinician burnout. Using AI to cut down on documentation would leave clinicians with more time and energy to focus on patient care.

One study from the National Library of Medicine found that physicians who did not have enough time to complete documentation were nearly three times more likely to report burnout. In some cases, clinic schedules were deliberately shortened to allow time for documentation.

New tools are emerging that use audio recording, transcription services, and large language models to generate clinical summaries and other documentation support. Amazon and 3M have partnered to solve documentation challenges using AI. This is an area I’ll definitely be keeping an eye on as it develops.

• Do I have patient consent to use this tool?

Since most AI tools remain relatively new, there is a gap in the legal and regulatory framework needed to ensure patient privacy and data protection. Clinicians should draw on existing guardrails and best practices to protect patient privacy and prioritize informed consent. The bottom line: Patients need to know how their data will be used and agree to it.

In the example above regarding documentation, a clinician should obtain patient consent before using technology that records or transcribes sessions. This extends to disclosing the use of AI chat tools and other touch points that occur between sessions. One mental health nonprofit has come under fire for using ChatGPT to provide mental health counseling to thousands of patients who weren’t aware the responses were generated by AI.

Beyond disclosing the use of these tools, clinicians should sufficiently explain how they work to ensure patients understand what they’re consenting to. Some technology companies offer guidance on how informed consent applies to their products and even offer template consent forms to support clinicians. Ultimately, accountability for maintaining patient privacy rests with the clinician, not the company behind the AI tool.

• Where is there a risk of bias?

There has been much discussion around the issue of bias within large language models in particular, since these programs will inherit any bias from the data points or text used to train them. However, there is often little to no visibility into how these models are trained, the algorithms they rely on, and how efficacy is measured.

This is especially concerning within the mental health care space, where bias can contribute to lower-quality care based on a patient’s race, gender or other characteristics. One systemic review published in JAMA Network Open found that most of the AI models used for psychiatric diagnoses that have been studied had a high overall risk of bias — which can lead to outputs that are misleading or incorrect, which can be dangerous in the healthcare field.

It’s important to keep the risk of bias top-of-mind when exploring AI tools and consider whether a tool would pose any direct harm to patients. Clinicians should have active oversight with any use of AI and, ultimately, consider an AI tool’s outputs alongside their own insights, expertise, and instincts.

Clinicians have the power to shape AI’s impact

While there is plenty to be excited about as these new tools develop, clinicians should explore AI with an eye toward the risks as well as the rewards. Practitioners have a significant opportunity to help shape how this technology develops by making informed decisions about which products to invest in and holding tech companies accountable. By educating patients, prioritizing informed consent, and seeking ways to augment their work that ultimately improve quality and scale of care, clinicians can help ensure positive outcomes while minimizing unintended consequences.

Dr. Patel-Dunn is a psychiatrist and chief medical officer at Lifestance Health, Scottsdale, Ariz.

Three questions for clinicians

Three questions for clinicians

Artificial intelligence (AI) is already impacting the mental health care space, with several new tools available to both clinicians and patients. While this technology could be a game-changer amid a mental health crisis and clinician shortage, there are important ethical and efficacy concerns clinicians should be aware of.

Current use cases illustrate both the potential and risks of AI. On one hand, AI has the potential to improve patient care with tools that can support diagnoses and inform treatment decisions at scale. The UK’s National Health Service is using an AI-powered diagnostic tool to help clinicians diagnose mental health disorders and determine the severity of a patient’s needs. Other tools leverage AI to analyze a patient’s voice for signs of depression or anxiety.

On the other hand, there are serious potential risks involving privacy, bias, and misinformation. One chatbot tool designed to counsel patients through disordered eating was shut down after giving problematic weight-loss advice.

The number of AI tools in the healthcare space is expected to increase fivefold by 2035. Keeping up with these advances is just as important for clinicians as keeping up with the latest medication and treatment options. That means being aware of both the limitations and the potential of AI. Here are three questions clinicians can ask as they explore ways to integrate these tools into their practice while navigating the risks.

• How can AI augment, not replace, the work of my staff?

For example, documentation and the use of electronic health records have consistently been linked to clinician burnout. Using AI to cut down on documentation would leave clinicians with more time and energy to focus on patient care.

One study from the National Library of Medicine found that physicians who did not have enough time to complete documentation were nearly three times more likely to report burnout. In some cases, clinic schedules were deliberately shortened to allow time for documentation.

New tools are emerging that use audio recording, transcription services, and large language models to generate clinical summaries and other documentation support. Amazon and 3M have partnered to solve documentation challenges using AI. This is an area I’ll definitely be keeping an eye on as it develops.

• Do I have patient consent to use this tool?

Since most AI tools remain relatively new, there is a gap in the legal and regulatory framework needed to ensure patient privacy and data protection. Clinicians should draw on existing guardrails and best practices to protect patient privacy and prioritize informed consent. The bottom line: Patients need to know how their data will be used and agree to it.

In the example above regarding documentation, a clinician should obtain patient consent before using technology that records or transcribes sessions. This extends to disclosing the use of AI chat tools and other touch points that occur between sessions. One mental health nonprofit has come under fire for using ChatGPT to provide mental health counseling to thousands of patients who weren’t aware the responses were generated by AI.

Beyond disclosing the use of these tools, clinicians should sufficiently explain how they work to ensure patients understand what they’re consenting to. Some technology companies offer guidance on how informed consent applies to their products and even offer template consent forms to support clinicians. Ultimately, accountability for maintaining patient privacy rests with the clinician, not the company behind the AI tool.

• Where is there a risk of bias?

There has been much discussion around the issue of bias within large language models in particular, since these programs will inherit any bias from the data points or text used to train them. However, there is often little to no visibility into how these models are trained, the algorithms they rely on, and how efficacy is measured.

This is especially concerning within the mental health care space, where bias can contribute to lower-quality care based on a patient’s race, gender or other characteristics. One systemic review published in JAMA Network Open found that most of the AI models used for psychiatric diagnoses that have been studied had a high overall risk of bias — which can lead to outputs that are misleading or incorrect, which can be dangerous in the healthcare field.

It’s important to keep the risk of bias top-of-mind when exploring AI tools and consider whether a tool would pose any direct harm to patients. Clinicians should have active oversight with any use of AI and, ultimately, consider an AI tool’s outputs alongside their own insights, expertise, and instincts.

Clinicians have the power to shape AI’s impact

While there is plenty to be excited about as these new tools develop, clinicians should explore AI with an eye toward the risks as well as the rewards. Practitioners have a significant opportunity to help shape how this technology develops by making informed decisions about which products to invest in and holding tech companies accountable. By educating patients, prioritizing informed consent, and seeking ways to augment their work that ultimately improve quality and scale of care, clinicians can help ensure positive outcomes while minimizing unintended consequences.

Dr. Patel-Dunn is a psychiatrist and chief medical officer at Lifestance Health, Scottsdale, Ariz.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is already impacting the mental health care space, with several new tools available to both clinicians and patients. While this technology could be a game-changer amid a mental health crisis and clinician shortage, there are important ethical and efficacy concerns clinicians should be aware of.

Current use cases illustrate both the potential and risks of AI. On one hand, AI has the potential to improve patient care with tools that can support diagnoses and inform treatment decisions at scale. The UK’s National Health Service is using an AI-powered diagnostic tool to help clinicians diagnose mental health disorders and determine the severity of a patient’s needs. Other tools leverage AI to analyze a patient’s voice for signs of depression or anxiety.

On the other hand, there are serious potential risks involving privacy, bias, and misinformation. One chatbot tool designed to counsel patients through disordered eating was shut down after giving problematic weight-loss advice.

The number of AI tools in the healthcare space is expected to increase fivefold by 2035. Keeping up with these advances is just as important for clinicians as keeping up with the latest medication and treatment options. That means being aware of both the limitations and the potential of AI. Here are three questions clinicians can ask as they explore ways to integrate these tools into their practice while navigating the risks.

• How can AI augment, not replace, the work of my staff?

For example, documentation and the use of electronic health records have consistently been linked to clinician burnout. Using AI to cut down on documentation would leave clinicians with more time and energy to focus on patient care.

One study from the National Library of Medicine found that physicians who did not have enough time to complete documentation were nearly three times more likely to report burnout. In some cases, clinic schedules were deliberately shortened to allow time for documentation.

New tools are emerging that use audio recording, transcription services, and large language models to generate clinical summaries and other documentation support. Amazon and 3M have partnered to solve documentation challenges using AI. This is an area I’ll definitely be keeping an eye on as it develops.

• Do I have patient consent to use this tool?

Since most AI tools remain relatively new, there is a gap in the legal and regulatory framework needed to ensure patient privacy and data protection. Clinicians should draw on existing guardrails and best practices to protect patient privacy and prioritize informed consent. The bottom line: Patients need to know how their data will be used and agree to it.

In the example above regarding documentation, a clinician should obtain patient consent before using technology that records or transcribes sessions. This extends to disclosing the use of AI chat tools and other touch points that occur between sessions. One mental health nonprofit has come under fire for using ChatGPT to provide mental health counseling to thousands of patients who weren’t aware the responses were generated by AI.

Beyond disclosing the use of these tools, clinicians should sufficiently explain how they work to ensure patients understand what they’re consenting to. Some technology companies offer guidance on how informed consent applies to their products and even offer template consent forms to support clinicians. Ultimately, accountability for maintaining patient privacy rests with the clinician, not the company behind the AI tool.

• Where is there a risk of bias?

There has been much discussion around the issue of bias within large language models in particular, since these programs will inherit any bias from the data points or text used to train them. However, there is often little to no visibility into how these models are trained, the algorithms they rely on, and how efficacy is measured.

This is especially concerning within the mental health care space, where bias can contribute to lower-quality care based on a patient’s race, gender or other characteristics. One systemic review published in JAMA Network Open found that most of the AI models used for psychiatric diagnoses that have been studied had a high overall risk of bias — which can lead to outputs that are misleading or incorrect, which can be dangerous in the healthcare field.

It’s important to keep the risk of bias top-of-mind when exploring AI tools and consider whether a tool would pose any direct harm to patients. Clinicians should have active oversight with any use of AI and, ultimately, consider an AI tool’s outputs alongside their own insights, expertise, and instincts.

Clinicians have the power to shape AI’s impact

While there is plenty to be excited about as these new tools develop, clinicians should explore AI with an eye toward the risks as well as the rewards. Practitioners have a significant opportunity to help shape how this technology develops by making informed decisions about which products to invest in and holding tech companies accountable. By educating patients, prioritizing informed consent, and seeking ways to augment their work that ultimately improve quality and scale of care, clinicians can help ensure positive outcomes while minimizing unintended consequences.

Dr. Patel-Dunn is a psychiatrist and chief medical officer at Lifestance Health, Scottsdale, Ariz.

Clinician responsibilities during times of geopolitical conflict

In the realm of clinical psychology and psychiatry, our primary duty and commitment is (and should be) to the well-being of our patients. Yet, as we find ourselves in an era marked by escalating geopolitical conflict, such as the Israel-Hamas war, probably more aptly titled the Israeli-Hamas-Hezbollah-Houthi war (a clarification that elucidates a later point), clinicians are increasingly confronted with ethical dilemmas that extend far beyond what is outlined in our code of ethics.

These challenges are not only impacting us on a personal level but are also spilling over into our professional lives, creating a divisive and non-collegial environment within the healthcare community. We commit to “do no harm” when delivering care and yet we are doing harm to one another as colleagues.

We are no strangers to the complexities of human behavior and the intricate tapestry of emotions that are involved with our professional work. However, the current geopolitical landscape has added an extra layer of difficulty to our already taxing professional lives. We are, after all, human first with unconscious drives that govern how we negotiate cognitive dissonance and our need for the illusion of absolute justice as Yuval Noah Harari explains in a recent podcast.

Humans are notoriously bad at holding the multiplicity of experience in mind and various (often competing narratives) that impede the capacity for nuanced thinking. We would like to believe we are better and more capable than the average person in doing so, but divisiveness in our profession has become disturbingly pronounced, making it essential for us to carve out reflective space, more than ever.

The personal and professional divide

Geopolitical conflicts like the current war have a unique capacity to ignite strong emotions and deeply held convictions. It’s not hard to quickly become embroiled in passionate and engaged debate.

While discussion and discourse are healthy, these are bleeding into professional spheres, creating rifts within our clinical communities and contributing to a culture where not everyone feels safe. Look at any professional listserv in medicine or psychology and you will find the evidence. It should be an immediate call to action that we need to be fostering a different type of environment.

The impact of divisiveness is profound, hindering opportunities for collaboration, mentorship, and the free exchange of ideas among clinicians. It may lead to misunderstandings, mistrust, and an erosion of the support systems we rely on, ultimately diverting energy away from the pursuit of providing quality patient-care.

Balancing obligations and limits

Because of the inherent power differential that accompanies being in a provider role (physician and psychologist alike), we have a social and moral responsibility to be mindful of what we share – for the sake of humanity. There is an implicit assumption that a provider’s guidance should be adhered to and respected. In other words, words carry tremendous weight and deeply matter, and people in the general public ascribe significant meaning to messages put out by professionals.

When providers steer from their lanes of professional expertise to provide the general public with opinions or recommendations on nonmedical topics, problematic precedents can be set. We may be doing people a disservice.

Unfortunately, I have heard several anecdotes about clinicians who spend their patient’s time in session pushing their own ideological agendas. The patient-provider relationship is founded on principles of trust, empathy, and collaboration, with the primary goal of improving overall well-being and addressing a specific presenting problem. Of course, issues emerge that need to be addressed outside of the initial scope of treatment, an inherent part of the process. However, a grave concern emerges when clinicians initiate dialogue that is not meaningful to a patient, disclose and discuss their personal ideologies, or put pressure on patients to explain their beliefs in an attempt to change the patients’ minds.

Clinicians pushing their own agenda during patient sessions is antithetical to the objectives of psychotherapy and compromises the therapeutic alliance by diverting the focus of care in a way that serves the clinician rather than the client. It is quite the opposite of the patient-centered care that we strive for in training and practice.

Even within one’s theoretical professional scope of competence, I have seen the impact of emotions running high during this conflict, and have witnessed trained professionals making light of, or even mocking, hostages and their behavior upon release. These are care providers who could elucidate the complexities of captor-captive dynamics and the impact of trauma for the general public, yet they are contributing to dangerous perceptions and divisiveness.

I have also seen providers justify sexual violence, diminishing survivor and witness testimony due to ideological differences and strong personal beliefs. This is harmful to those impacted and does a disservice to our profession at large. In a helping profession we should strive to support and advocate for anyone who has been maltreated or experienced any form of victimization, violence, or abuse. This should be a professional standard.

As clinicians, we have an ethical obligation to uphold the well-being, autonomy, and dignity of our patients — and humanity. It is crucial to recognize the limits of our expertise and the ethical concerns that can arise in light of geopolitical conflict. How can we balance our duty to provide psychological support while also being cautious about delving into the realms of political analysis, foreign policy, or international relations?

The pitfalls of well-intentioned speaking out

In the age of social media and instant communication, a critical aspect to consider is the role of speaking out. The point I made above, in naming all partaking in the current conflict, speaks to this issue.

As providers and programs, we must be mindful of the inadvertent harm that can arise from making brief, underdeveloped, uninformed, or emotionally charged statements. Expressing opinions without a solid understanding of the historical, cultural, and political nuances of a conflict can contribute to misinformation and further polarization.

Anecdotally, there appears to be some significant degree of bias emerging within professional fields (e.g., psychology, medicine) and an innate calling for providers to “weigh in” as the war continues. Obviously, physicians and psychologists are trained to provide care and to be humanistic and empathic, but the majority do not have expertise in geopolitics or a nuanced awareness of the complexities of the conflict in the Middle East.

While hearts may be in the right place, issuing statements on complicated humanitarian/political situations can inadvertently have unintended and harmful consequences (in terms of antisemitism and islamophobia, increased incidence of hate crimes, and colleagues not feeling safe within professional societies or member organizations).

Unsophisticated, overly simplistic, and reductionistic statements that do not adequately convey nuance will not reflect the range of experience reflected by providers in the field (or the patients we treat). It is essential for clinicians and institutions putting out public statements to engage in deep reflection and utilize discernment. We must recognize that our words carry weight, given our position of influence as treatment providers. To minimize harm, we should seek to provide information that is fair, vetted, and balanced, and encourage open, respectful dialogue rather than asserting definitive positions.

Ultimately, as providers we must strive to seek unity and inclusivity amidst the current challenges. It is important for us to embody a spirit of collaboration during a time demarcated by deep fragmentation.

By acknowledging our limitations, promoting informed discussion, and avoiding the pitfalls of uninformed advocacy, we can contribute to a more compassionate and understanding world, even in the face of the most divisive geopolitical conflicts. We have an obligation to uphold when it comes to ourselves as professionals, and we need to foster healthy, respectful dialogue while maintaining an awareness of our blind spots.

Dr. Feldman is a licensed clinical psychologist in private practice in Miami. She is an adjunct professor in the College of Psychology at Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., where she teaches clinical psychology doctoral students. She is an affiliate of Baptist West Kendall Hospital/FIU Family Medicine Residency Program and serves as president on the board of directors of The Southeast Florida Association for Psychoanalytic Psychology. The opinions expressed by Dr. Feldman are her own and do not represent the institutions with which she is affiliated. She has no disclosures.

In the realm of clinical psychology and psychiatry, our primary duty and commitment is (and should be) to the well-being of our patients. Yet, as we find ourselves in an era marked by escalating geopolitical conflict, such as the Israel-Hamas war, probably more aptly titled the Israeli-Hamas-Hezbollah-Houthi war (a clarification that elucidates a later point), clinicians are increasingly confronted with ethical dilemmas that extend far beyond what is outlined in our code of ethics.

These challenges are not only impacting us on a personal level but are also spilling over into our professional lives, creating a divisive and non-collegial environment within the healthcare community. We commit to “do no harm” when delivering care and yet we are doing harm to one another as colleagues.

We are no strangers to the complexities of human behavior and the intricate tapestry of emotions that are involved with our professional work. However, the current geopolitical landscape has added an extra layer of difficulty to our already taxing professional lives. We are, after all, human first with unconscious drives that govern how we negotiate cognitive dissonance and our need for the illusion of absolute justice as Yuval Noah Harari explains in a recent podcast.

Humans are notoriously bad at holding the multiplicity of experience in mind and various (often competing narratives) that impede the capacity for nuanced thinking. We would like to believe we are better and more capable than the average person in doing so, but divisiveness in our profession has become disturbingly pronounced, making it essential for us to carve out reflective space, more than ever.

The personal and professional divide

Geopolitical conflicts like the current war have a unique capacity to ignite strong emotions and deeply held convictions. It’s not hard to quickly become embroiled in passionate and engaged debate.

While discussion and discourse are healthy, these are bleeding into professional spheres, creating rifts within our clinical communities and contributing to a culture where not everyone feels safe. Look at any professional listserv in medicine or psychology and you will find the evidence. It should be an immediate call to action that we need to be fostering a different type of environment.

The impact of divisiveness is profound, hindering opportunities for collaboration, mentorship, and the free exchange of ideas among clinicians. It may lead to misunderstandings, mistrust, and an erosion of the support systems we rely on, ultimately diverting energy away from the pursuit of providing quality patient-care.

Balancing obligations and limits

Because of the inherent power differential that accompanies being in a provider role (physician and psychologist alike), we have a social and moral responsibility to be mindful of what we share – for the sake of humanity. There is an implicit assumption that a provider’s guidance should be adhered to and respected. In other words, words carry tremendous weight and deeply matter, and people in the general public ascribe significant meaning to messages put out by professionals.

When providers steer from their lanes of professional expertise to provide the general public with opinions or recommendations on nonmedical topics, problematic precedents can be set. We may be doing people a disservice.

Unfortunately, I have heard several anecdotes about clinicians who spend their patient’s time in session pushing their own ideological agendas. The patient-provider relationship is founded on principles of trust, empathy, and collaboration, with the primary goal of improving overall well-being and addressing a specific presenting problem. Of course, issues emerge that need to be addressed outside of the initial scope of treatment, an inherent part of the process. However, a grave concern emerges when clinicians initiate dialogue that is not meaningful to a patient, disclose and discuss their personal ideologies, or put pressure on patients to explain their beliefs in an attempt to change the patients’ minds.

Clinicians pushing their own agenda during patient sessions is antithetical to the objectives of psychotherapy and compromises the therapeutic alliance by diverting the focus of care in a way that serves the clinician rather than the client. It is quite the opposite of the patient-centered care that we strive for in training and practice.

Even within one’s theoretical professional scope of competence, I have seen the impact of emotions running high during this conflict, and have witnessed trained professionals making light of, or even mocking, hostages and their behavior upon release. These are care providers who could elucidate the complexities of captor-captive dynamics and the impact of trauma for the general public, yet they are contributing to dangerous perceptions and divisiveness.

I have also seen providers justify sexual violence, diminishing survivor and witness testimony due to ideological differences and strong personal beliefs. This is harmful to those impacted and does a disservice to our profession at large. In a helping profession we should strive to support and advocate for anyone who has been maltreated or experienced any form of victimization, violence, or abuse. This should be a professional standard.

As clinicians, we have an ethical obligation to uphold the well-being, autonomy, and dignity of our patients — and humanity. It is crucial to recognize the limits of our expertise and the ethical concerns that can arise in light of geopolitical conflict. How can we balance our duty to provide psychological support while also being cautious about delving into the realms of political analysis, foreign policy, or international relations?

The pitfalls of well-intentioned speaking out

In the age of social media and instant communication, a critical aspect to consider is the role of speaking out. The point I made above, in naming all partaking in the current conflict, speaks to this issue.

As providers and programs, we must be mindful of the inadvertent harm that can arise from making brief, underdeveloped, uninformed, or emotionally charged statements. Expressing opinions without a solid understanding of the historical, cultural, and political nuances of a conflict can contribute to misinformation and further polarization.

Anecdotally, there appears to be some significant degree of bias emerging within professional fields (e.g., psychology, medicine) and an innate calling for providers to “weigh in” as the war continues. Obviously, physicians and psychologists are trained to provide care and to be humanistic and empathic, but the majority do not have expertise in geopolitics or a nuanced awareness of the complexities of the conflict in the Middle East.

While hearts may be in the right place, issuing statements on complicated humanitarian/political situations can inadvertently have unintended and harmful consequences (in terms of antisemitism and islamophobia, increased incidence of hate crimes, and colleagues not feeling safe within professional societies or member organizations).

Unsophisticated, overly simplistic, and reductionistic statements that do not adequately convey nuance will not reflect the range of experience reflected by providers in the field (or the patients we treat). It is essential for clinicians and institutions putting out public statements to engage in deep reflection and utilize discernment. We must recognize that our words carry weight, given our position of influence as treatment providers. To minimize harm, we should seek to provide information that is fair, vetted, and balanced, and encourage open, respectful dialogue rather than asserting definitive positions.

Ultimately, as providers we must strive to seek unity and inclusivity amidst the current challenges. It is important for us to embody a spirit of collaboration during a time demarcated by deep fragmentation.

By acknowledging our limitations, promoting informed discussion, and avoiding the pitfalls of uninformed advocacy, we can contribute to a more compassionate and understanding world, even in the face of the most divisive geopolitical conflicts. We have an obligation to uphold when it comes to ourselves as professionals, and we need to foster healthy, respectful dialogue while maintaining an awareness of our blind spots.

Dr. Feldman is a licensed clinical psychologist in private practice in Miami. She is an adjunct professor in the College of Psychology at Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., where she teaches clinical psychology doctoral students. She is an affiliate of Baptist West Kendall Hospital/FIU Family Medicine Residency Program and serves as president on the board of directors of The Southeast Florida Association for Psychoanalytic Psychology. The opinions expressed by Dr. Feldman are her own and do not represent the institutions with which she is affiliated. She has no disclosures.