User login

Physician health programs: ‘Diagnosing for dollars’?

As medicine struggles with rising rates of physician burnout, dissatisfaction, depression, and suicide, one solution comes in the form of Physician Health Programs, or PHPs. These organizations were originally started by volunteer physicians, often doctors in recovery, and funded by medical societies, as a way of providing help while maintaining confidentiality. Now, they are run by independent corporations, by medical societies in some states, and sometimes by hospitals or health systems. The services they offer vary by PHP, and they may have relationships with state licensing boards. While they can provide a gateway to help for a troubled doctor, there has also been concern about the services that are being provided.

Louise Andrew, MD, JD, served as the liaison from the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) to the the Federation of State Medical Boards from 2006 to 2014. In an online forum called Collective Wisdom, Andrew talked about the benefits of Physician Health Programs as entities that are helpful to stuggling doctors and urged her colleagues to use them as a safe alternative to suffering in silence.

More recently, Dr. Andrew has become concerned that PHPs may have taken on the role of what is more akin to “diagnosing for dollars.” In her May, 2016 column in Emergency Physician’s Monthly, Andrew noted, “A decade later, and my convictions have changed dramatically. Horror stories that colleagues related to me while I chaired ACEP’s Personal and Professional WellBeing Committee cannot all be isolated events. For example, physicians who self-referred to the PHP for management of stress and depression were reportedly railroaded into incredibly expensive and inconvenient out-of-state drug and alcohol treatment programs, even when there was no coexisting drug or alcohol problem.”

Dr. Andrew is not the only one voicing concerns about PHPs. In “Physician Health Programs: More harm than good?” (Medscape, Aug. 19, 2015), Pauline Anderson wrote about a several problems that have surfaced. In North Carolina, the state audited the PHPs after complaints that they were mandating physicians to lengthy and expensive inpatient programs. The complaints asserted that the physicians had no recourse and were not able to see their records. “The state auditor’s report found no abuse by North Carolina’s PHP. However, there was a caveat – the report determined that abuse could occur and potentially go undetected.

“It also found that the North Carolina PHP created the appearance of conflicts of interest by allowing the centers to provide both patient evaluation and treatments and that procedures did not ensure that physicians receive quality evaluations and treatment because the PHP had no documented criteria for selecting treatment centers and did not adequately monitor them.”

Finally, in a Florida Fox4News story, “Are FL doctors and nurses being sent to rehab unnecessarily? Accusations: Overdiagnosing; overcharging” (Nov. 16, 2017), reporters Katie Lagrone and Matthew Apthorp wrote about financial incentives for evaluators to refer doctors to inpatient substance abuse facilities.

The American Psychiatric Association has made it a priority to address physician burnout and mental health. Richard F. Summers, MD, APA Trustee-at-Large noted: “State PHPs are an essential resource for physicians, but there is a tremendous diversity in quality and approach. It is critical that these programs include attention to mental health problems as well as addiction, and that they support individual physicians’ treatment and journey toward well-being. They need to be accessible, private, and high quality, and they should be staffed by excellent psychiatrists and other mental health professionals.”

PHPs provide a much-needed and wanted service. But if the goal is to provide mental health and substance abuse services to physicians who are struggling – to prevent physicians from burning out, leaving medicine, and dying of suicide – then any whiff of corruption and any fear of professional repercussions become a reason not to use these services. If they are to be helpful, physicians must feel safe using them.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

As medicine struggles with rising rates of physician burnout, dissatisfaction, depression, and suicide, one solution comes in the form of Physician Health Programs, or PHPs. These organizations were originally started by volunteer physicians, often doctors in recovery, and funded by medical societies, as a way of providing help while maintaining confidentiality. Now, they are run by independent corporations, by medical societies in some states, and sometimes by hospitals or health systems. The services they offer vary by PHP, and they may have relationships with state licensing boards. While they can provide a gateway to help for a troubled doctor, there has also been concern about the services that are being provided.

Louise Andrew, MD, JD, served as the liaison from the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) to the the Federation of State Medical Boards from 2006 to 2014. In an online forum called Collective Wisdom, Andrew talked about the benefits of Physician Health Programs as entities that are helpful to stuggling doctors and urged her colleagues to use them as a safe alternative to suffering in silence.

More recently, Dr. Andrew has become concerned that PHPs may have taken on the role of what is more akin to “diagnosing for dollars.” In her May, 2016 column in Emergency Physician’s Monthly, Andrew noted, “A decade later, and my convictions have changed dramatically. Horror stories that colleagues related to me while I chaired ACEP’s Personal and Professional WellBeing Committee cannot all be isolated events. For example, physicians who self-referred to the PHP for management of stress and depression were reportedly railroaded into incredibly expensive and inconvenient out-of-state drug and alcohol treatment programs, even when there was no coexisting drug or alcohol problem.”

Dr. Andrew is not the only one voicing concerns about PHPs. In “Physician Health Programs: More harm than good?” (Medscape, Aug. 19, 2015), Pauline Anderson wrote about a several problems that have surfaced. In North Carolina, the state audited the PHPs after complaints that they were mandating physicians to lengthy and expensive inpatient programs. The complaints asserted that the physicians had no recourse and were not able to see their records. “The state auditor’s report found no abuse by North Carolina’s PHP. However, there was a caveat – the report determined that abuse could occur and potentially go undetected.

“It also found that the North Carolina PHP created the appearance of conflicts of interest by allowing the centers to provide both patient evaluation and treatments and that procedures did not ensure that physicians receive quality evaluations and treatment because the PHP had no documented criteria for selecting treatment centers and did not adequately monitor them.”

Finally, in a Florida Fox4News story, “Are FL doctors and nurses being sent to rehab unnecessarily? Accusations: Overdiagnosing; overcharging” (Nov. 16, 2017), reporters Katie Lagrone and Matthew Apthorp wrote about financial incentives for evaluators to refer doctors to inpatient substance abuse facilities.

The American Psychiatric Association has made it a priority to address physician burnout and mental health. Richard F. Summers, MD, APA Trustee-at-Large noted: “State PHPs are an essential resource for physicians, but there is a tremendous diversity in quality and approach. It is critical that these programs include attention to mental health problems as well as addiction, and that they support individual physicians’ treatment and journey toward well-being. They need to be accessible, private, and high quality, and they should be staffed by excellent psychiatrists and other mental health professionals.”

PHPs provide a much-needed and wanted service. But if the goal is to provide mental health and substance abuse services to physicians who are struggling – to prevent physicians from burning out, leaving medicine, and dying of suicide – then any whiff of corruption and any fear of professional repercussions become a reason not to use these services. If they are to be helpful, physicians must feel safe using them.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

As medicine struggles with rising rates of physician burnout, dissatisfaction, depression, and suicide, one solution comes in the form of Physician Health Programs, or PHPs. These organizations were originally started by volunteer physicians, often doctors in recovery, and funded by medical societies, as a way of providing help while maintaining confidentiality. Now, they are run by independent corporations, by medical societies in some states, and sometimes by hospitals or health systems. The services they offer vary by PHP, and they may have relationships with state licensing boards. While they can provide a gateway to help for a troubled doctor, there has also been concern about the services that are being provided.

Louise Andrew, MD, JD, served as the liaison from the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) to the the Federation of State Medical Boards from 2006 to 2014. In an online forum called Collective Wisdom, Andrew talked about the benefits of Physician Health Programs as entities that are helpful to stuggling doctors and urged her colleagues to use them as a safe alternative to suffering in silence.

More recently, Dr. Andrew has become concerned that PHPs may have taken on the role of what is more akin to “diagnosing for dollars.” In her May, 2016 column in Emergency Physician’s Monthly, Andrew noted, “A decade later, and my convictions have changed dramatically. Horror stories that colleagues related to me while I chaired ACEP’s Personal and Professional WellBeing Committee cannot all be isolated events. For example, physicians who self-referred to the PHP for management of stress and depression were reportedly railroaded into incredibly expensive and inconvenient out-of-state drug and alcohol treatment programs, even when there was no coexisting drug or alcohol problem.”

Dr. Andrew is not the only one voicing concerns about PHPs. In “Physician Health Programs: More harm than good?” (Medscape, Aug. 19, 2015), Pauline Anderson wrote about a several problems that have surfaced. In North Carolina, the state audited the PHPs after complaints that they were mandating physicians to lengthy and expensive inpatient programs. The complaints asserted that the physicians had no recourse and were not able to see their records. “The state auditor’s report found no abuse by North Carolina’s PHP. However, there was a caveat – the report determined that abuse could occur and potentially go undetected.

“It also found that the North Carolina PHP created the appearance of conflicts of interest by allowing the centers to provide both patient evaluation and treatments and that procedures did not ensure that physicians receive quality evaluations and treatment because the PHP had no documented criteria for selecting treatment centers and did not adequately monitor them.”

Finally, in a Florida Fox4News story, “Are FL doctors and nurses being sent to rehab unnecessarily? Accusations: Overdiagnosing; overcharging” (Nov. 16, 2017), reporters Katie Lagrone and Matthew Apthorp wrote about financial incentives for evaluators to refer doctors to inpatient substance abuse facilities.

The American Psychiatric Association has made it a priority to address physician burnout and mental health. Richard F. Summers, MD, APA Trustee-at-Large noted: “State PHPs are an essential resource for physicians, but there is a tremendous diversity in quality and approach. It is critical that these programs include attention to mental health problems as well as addiction, and that they support individual physicians’ treatment and journey toward well-being. They need to be accessible, private, and high quality, and they should be staffed by excellent psychiatrists and other mental health professionals.”

PHPs provide a much-needed and wanted service. But if the goal is to provide mental health and substance abuse services to physicians who are struggling – to prevent physicians from burning out, leaving medicine, and dying of suicide – then any whiff of corruption and any fear of professional repercussions become a reason not to use these services. If they are to be helpful, physicians must feel safe using them.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

Introducing The Sarcoma Journal—The Official Journal of the Sarcoma Foundation of America ™ : An Exciting Initiative in Peer-Reviewed Professional Education and Patient Advocacy

The Sarcoma Journal — Official Journal of the Sarcoma Foundation of America™ represents a new and exciting initiative in professional education. We invite you to share in the excitement surrounding the launch of a medical journal designed to be your most authoritative and comprehensive source of scientific information on the diagnosis and treatment of sarcomas and sarcoma sub-types.

On behalf of myself, our editorial board, and editorial staff, I welcome you to this journal as we explore new treatment paradigms for this disease, translational research that bridges the bench and the clinic, and a broad range of science to encompass the many facets of sarcoma. In my opinion, the startup of this publication could not come at a better time.

As cancer specialists and allied health care professionals who attend regular meetings of your peers, including ASCO and CTOS, we have seen a dramatic shift in management within the last few years. In many ways we are at a threshold of a new era in sarcoma management, and the spectrum of treatment is expanding across subspecialties, promising more effective strategies for our patients that are based on an improved understanding of disease biology. We need a resource to maintain and clarify our focus on this disease as research opens new avenues for us to consider in the management of patients with sarcoma.

When I was approached to serve as Editor-in-Chief of The Sarcoma Journal by the Sarcoma Foundation of America, I began to recruit an esteemed group of colleagues whose knowledge, worldwide reputation as thought leaders, and dedicated work as researchers would reflect our commitment toward finding a cure for sarcoma. Many of the colleagues who will join me on the Editorial Advisory Board have long-standing affiliations with the Sarcoma Foundation of America and its comprehensive program of sarcoma research, patient support and education and advocacy. As you explore the first issue of the journal, you will discover how our editorial content is an extension of this three-tiered approach. The SFA program is characterized by a multi-dimensional and uniquely coordinated outreach program of videos and webinars, websites (a new journal website is launching as well) a sarcoma-specific clinical trials database, newsletters and related materials— all aimed ultimately at finding a cure for this disease. This professional journal complements and extends the SFA’s mission.

Although The Sarcoma Journal has a position within the SFA umbrella, my focus is foremost on ensuring that The Sarcoma Journal contains the most accurate, relevant and up to date information available. I urge you to explore our highly informative and relevant sarcoma-specific content—including original reports, review articles, a Journal Club, expert opinion, meeting reports, and patient advocacy that encapsulates the latest findings from the bench with implications for the bedside.

Whether it is discussing the latest findings in advanced sarcoma sub-types or implications of genetics as a prognostic factor, you will find the information in this journal, reliably analyzed by our team of experts who are leading sarcoma clinicians and investigators. All of the content we provide is presented in a thought-provoking, lively and peer-reviewed format; we welcome your comments and suggestions to keep us on the forefront of patient care as we cover a rapidly evolving landscape of new information in the treatment of sarcomas and frame it within a context directly applicable to enhancing the quality of patient care.

The Sarcoma Journal — Official Journal of the Sarcoma Foundation of America™ represents a new and exciting initiative in professional education. We invite you to share in the excitement surrounding the launch of a medical journal designed to be your most authoritative and comprehensive source of scientific information on the diagnosis and treatment of sarcomas and sarcoma sub-types.

On behalf of myself, our editorial board, and editorial staff, I welcome you to this journal as we explore new treatment paradigms for this disease, translational research that bridges the bench and the clinic, and a broad range of science to encompass the many facets of sarcoma. In my opinion, the startup of this publication could not come at a better time.

As cancer specialists and allied health care professionals who attend regular meetings of your peers, including ASCO and CTOS, we have seen a dramatic shift in management within the last few years. In many ways we are at a threshold of a new era in sarcoma management, and the spectrum of treatment is expanding across subspecialties, promising more effective strategies for our patients that are based on an improved understanding of disease biology. We need a resource to maintain and clarify our focus on this disease as research opens new avenues for us to consider in the management of patients with sarcoma.

When I was approached to serve as Editor-in-Chief of The Sarcoma Journal by the Sarcoma Foundation of America, I began to recruit an esteemed group of colleagues whose knowledge, worldwide reputation as thought leaders, and dedicated work as researchers would reflect our commitment toward finding a cure for sarcoma. Many of the colleagues who will join me on the Editorial Advisory Board have long-standing affiliations with the Sarcoma Foundation of America and its comprehensive program of sarcoma research, patient support and education and advocacy. As you explore the first issue of the journal, you will discover how our editorial content is an extension of this three-tiered approach. The SFA program is characterized by a multi-dimensional and uniquely coordinated outreach program of videos and webinars, websites (a new journal website is launching as well) a sarcoma-specific clinical trials database, newsletters and related materials— all aimed ultimately at finding a cure for this disease. This professional journal complements and extends the SFA’s mission.

Although The Sarcoma Journal has a position within the SFA umbrella, my focus is foremost on ensuring that The Sarcoma Journal contains the most accurate, relevant and up to date information available. I urge you to explore our highly informative and relevant sarcoma-specific content—including original reports, review articles, a Journal Club, expert opinion, meeting reports, and patient advocacy that encapsulates the latest findings from the bench with implications for the bedside.

Whether it is discussing the latest findings in advanced sarcoma sub-types or implications of genetics as a prognostic factor, you will find the information in this journal, reliably analyzed by our team of experts who are leading sarcoma clinicians and investigators. All of the content we provide is presented in a thought-provoking, lively and peer-reviewed format; we welcome your comments and suggestions to keep us on the forefront of patient care as we cover a rapidly evolving landscape of new information in the treatment of sarcomas and frame it within a context directly applicable to enhancing the quality of patient care.

The Sarcoma Journal — Official Journal of the Sarcoma Foundation of America™ represents a new and exciting initiative in professional education. We invite you to share in the excitement surrounding the launch of a medical journal designed to be your most authoritative and comprehensive source of scientific information on the diagnosis and treatment of sarcomas and sarcoma sub-types.

On behalf of myself, our editorial board, and editorial staff, I welcome you to this journal as we explore new treatment paradigms for this disease, translational research that bridges the bench and the clinic, and a broad range of science to encompass the many facets of sarcoma. In my opinion, the startup of this publication could not come at a better time.

As cancer specialists and allied health care professionals who attend regular meetings of your peers, including ASCO and CTOS, we have seen a dramatic shift in management within the last few years. In many ways we are at a threshold of a new era in sarcoma management, and the spectrum of treatment is expanding across subspecialties, promising more effective strategies for our patients that are based on an improved understanding of disease biology. We need a resource to maintain and clarify our focus on this disease as research opens new avenues for us to consider in the management of patients with sarcoma.

When I was approached to serve as Editor-in-Chief of The Sarcoma Journal by the Sarcoma Foundation of America, I began to recruit an esteemed group of colleagues whose knowledge, worldwide reputation as thought leaders, and dedicated work as researchers would reflect our commitment toward finding a cure for sarcoma. Many of the colleagues who will join me on the Editorial Advisory Board have long-standing affiliations with the Sarcoma Foundation of America and its comprehensive program of sarcoma research, patient support and education and advocacy. As you explore the first issue of the journal, you will discover how our editorial content is an extension of this three-tiered approach. The SFA program is characterized by a multi-dimensional and uniquely coordinated outreach program of videos and webinars, websites (a new journal website is launching as well) a sarcoma-specific clinical trials database, newsletters and related materials— all aimed ultimately at finding a cure for this disease. This professional journal complements and extends the SFA’s mission.

Although The Sarcoma Journal has a position within the SFA umbrella, my focus is foremost on ensuring that The Sarcoma Journal contains the most accurate, relevant and up to date information available. I urge you to explore our highly informative and relevant sarcoma-specific content—including original reports, review articles, a Journal Club, expert opinion, meeting reports, and patient advocacy that encapsulates the latest findings from the bench with implications for the bedside.

Whether it is discussing the latest findings in advanced sarcoma sub-types or implications of genetics as a prognostic factor, you will find the information in this journal, reliably analyzed by our team of experts who are leading sarcoma clinicians and investigators. All of the content we provide is presented in a thought-provoking, lively and peer-reviewed format; we welcome your comments and suggestions to keep us on the forefront of patient care as we cover a rapidly evolving landscape of new information in the treatment of sarcomas and frame it within a context directly applicable to enhancing the quality of patient care.

The dawn of precision psychiatry

Imagine being able to precisely select the medication with the optimal efficacy, safety, and tolerability at the outset of treatment for every psychiatric patient who needs pharmacotherapy. Imagine how much the patient would appreciate not receiving a series of drugs and suffering multiple adverse effects and unremitting symptoms until the “right medication” is identified. Imagine how gratifying it would be for you as a psychiatrist to watch every one of your patients improve rapidly with minimal complaints or adverse effects.

Precision psychiatry is the indispensable vehicle to achieve personalized medicine for psychiatric patients. Precision psychiatry is a cherished goal, but it remains an aspirational objective. Other medical specialties, especially oncology and cardiology, have made remarkable strides in precision medicine, but the journey to precision psychiatry is still in its early stages. Yet there is every reason to believe that we are making progress toward that cherished goal.

To implement precision psychiatry, we must be able to identify the biosignature of each patient’s psychiatric brain disorder. But there is a formidable challenge to overcome: the complex, extensive heterogeneity of psychiatric disorders, which requires intense and inspired neurobiology research. So, while clinicians go on with the mundane trial-and-error approach of contemporary psychopharmacology, psychiatric neuroscientists are diligently deconstructing major psychiatric disorders into specific biotypes with unique biosignatures that will one day guide accurate and prompt clinical management.

Psychiatric practitioners may be too busy to keep tabs on the progress being made in identifying various biomarkers that are the key ingredients to decoding the biosignature of each psychiatric patient. Take schizophrenia, for example. There are myriad clinical variations that comprise this heterogeneous brain syndrome, including level of premorbid functioning; acute vs gradual onset of psychosis; the type and severity of hallucinations or delusions; the dimensional spectrum of negative symptoms and cognitive impairments; the presence and intensity of suicidal or homicidal urges; and the type of medical and psychiatric comorbidities. No wonder every patient is a unique and fascinating clinical puzzle, and yet, patients with schizophrenia are still being homogenized under a single DSM diagnostic category.

There are hundreds of biomarkers in schizophrenia,1 but none can be used clinically until the biosignatures of the many diseases within the schizophrenia syndrome are identified. That grueling research quest will take time, given that so far >340 risk genes for schizophrenia have been discovered, along with countless copy number variants representing gene deletions or duplications, plus dozens of de novo mutations that preclude coding for any protein. Add to these the numerous prenatal pregnancy adverse events, delivery complications, and early childhood abuse—all of which are associated with neurodevelopmental disruptions that set up the brain for schizophrenia spectrum disorders in adulthood—and we have a perplexing conundrum to tackle.

Precision psychiatry will ultimately enable practitioners to recognize various psychotic diseases that are more specific than the current DSM psychosis categories. Further, precision psychiatry will provide guidance as to which member within a class of so-called “me-too” drugs is the optimal match for each patient. This will stand in stark contrast to the chaotic hit-or-miss approach.

Precision psychiatry also will reveal the absurdity of current FDA clinical trials design for drug development. How can a molecule with a putative mechanism of action relevant to a specific biotype be administered to a hodgepodge of heterogeneous biotypes that have been lumped in 1 clinical category, and yet be expected to exert efficacy in most biotypes? It is a small miracle that some new drugs beat placebo despite the extensive variability in both placebo responses and drug responses. But it is well known that in all FDA placebo-controlled trials, the therapeutic response across the patient population varies from extremely high to extremely low, and worsening may even occur in a subset of patients receiving either the active drug or placebo. Perhaps drug response should be used as 1 methodology to classify biotypes of patients encompassed within a heterogeneous syndrome such as schizophrenia.

Precision psychiatry will represent a huge paradigm shift in the science and practice of our specialty. In his landmark book, Thomas Kuhn defined a paradigm as “an entire worldview in which a theory exists and all the implications that come from that view.”2 Precision psychiatry will completely disrupt the current antiquated clinical paradigm, transforming psychiatry into the clinical neuroscience it is. Many “omics,” such as genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, lipidomics, and metagenomics, will inevitably find their way into the jargon of psychiatrists.3

A marriage of science and technology is essential for the emergence of precision psychiatry. To achieve this transformative amalgamation, we need to reconfigure our concepts, reengineer our methods, reinvent our models, and redesign our approaches to patient care.

As Peter Drucker said, “The best way to predict the future is to create it.”4 Precision psychiatry is our future. Let’s create it!

1. Nasrallah HA.

2. Kuhn TS. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1964.

3. Nasrallah HA. Advancing clinical neuroscience literacy among psychiatric practitioners. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9):17-18.

4. Cohen WA. Drucker on leadership: new lessons from the father of modern management. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2010.

Imagine being able to precisely select the medication with the optimal efficacy, safety, and tolerability at the outset of treatment for every psychiatric patient who needs pharmacotherapy. Imagine how much the patient would appreciate not receiving a series of drugs and suffering multiple adverse effects and unremitting symptoms until the “right medication” is identified. Imagine how gratifying it would be for you as a psychiatrist to watch every one of your patients improve rapidly with minimal complaints or adverse effects.

Precision psychiatry is the indispensable vehicle to achieve personalized medicine for psychiatric patients. Precision psychiatry is a cherished goal, but it remains an aspirational objective. Other medical specialties, especially oncology and cardiology, have made remarkable strides in precision medicine, but the journey to precision psychiatry is still in its early stages. Yet there is every reason to believe that we are making progress toward that cherished goal.

To implement precision psychiatry, we must be able to identify the biosignature of each patient’s psychiatric brain disorder. But there is a formidable challenge to overcome: the complex, extensive heterogeneity of psychiatric disorders, which requires intense and inspired neurobiology research. So, while clinicians go on with the mundane trial-and-error approach of contemporary psychopharmacology, psychiatric neuroscientists are diligently deconstructing major psychiatric disorders into specific biotypes with unique biosignatures that will one day guide accurate and prompt clinical management.

Psychiatric practitioners may be too busy to keep tabs on the progress being made in identifying various biomarkers that are the key ingredients to decoding the biosignature of each psychiatric patient. Take schizophrenia, for example. There are myriad clinical variations that comprise this heterogeneous brain syndrome, including level of premorbid functioning; acute vs gradual onset of psychosis; the type and severity of hallucinations or delusions; the dimensional spectrum of negative symptoms and cognitive impairments; the presence and intensity of suicidal or homicidal urges; and the type of medical and psychiatric comorbidities. No wonder every patient is a unique and fascinating clinical puzzle, and yet, patients with schizophrenia are still being homogenized under a single DSM diagnostic category.

There are hundreds of biomarkers in schizophrenia,1 but none can be used clinically until the biosignatures of the many diseases within the schizophrenia syndrome are identified. That grueling research quest will take time, given that so far >340 risk genes for schizophrenia have been discovered, along with countless copy number variants representing gene deletions or duplications, plus dozens of de novo mutations that preclude coding for any protein. Add to these the numerous prenatal pregnancy adverse events, delivery complications, and early childhood abuse—all of which are associated with neurodevelopmental disruptions that set up the brain for schizophrenia spectrum disorders in adulthood—and we have a perplexing conundrum to tackle.

Precision psychiatry will ultimately enable practitioners to recognize various psychotic diseases that are more specific than the current DSM psychosis categories. Further, precision psychiatry will provide guidance as to which member within a class of so-called “me-too” drugs is the optimal match for each patient. This will stand in stark contrast to the chaotic hit-or-miss approach.

Precision psychiatry also will reveal the absurdity of current FDA clinical trials design for drug development. How can a molecule with a putative mechanism of action relevant to a specific biotype be administered to a hodgepodge of heterogeneous biotypes that have been lumped in 1 clinical category, and yet be expected to exert efficacy in most biotypes? It is a small miracle that some new drugs beat placebo despite the extensive variability in both placebo responses and drug responses. But it is well known that in all FDA placebo-controlled trials, the therapeutic response across the patient population varies from extremely high to extremely low, and worsening may even occur in a subset of patients receiving either the active drug or placebo. Perhaps drug response should be used as 1 methodology to classify biotypes of patients encompassed within a heterogeneous syndrome such as schizophrenia.

Precision psychiatry will represent a huge paradigm shift in the science and practice of our specialty. In his landmark book, Thomas Kuhn defined a paradigm as “an entire worldview in which a theory exists and all the implications that come from that view.”2 Precision psychiatry will completely disrupt the current antiquated clinical paradigm, transforming psychiatry into the clinical neuroscience it is. Many “omics,” such as genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, lipidomics, and metagenomics, will inevitably find their way into the jargon of psychiatrists.3

A marriage of science and technology is essential for the emergence of precision psychiatry. To achieve this transformative amalgamation, we need to reconfigure our concepts, reengineer our methods, reinvent our models, and redesign our approaches to patient care.

As Peter Drucker said, “The best way to predict the future is to create it.”4 Precision psychiatry is our future. Let’s create it!

Imagine being able to precisely select the medication with the optimal efficacy, safety, and tolerability at the outset of treatment for every psychiatric patient who needs pharmacotherapy. Imagine how much the patient would appreciate not receiving a series of drugs and suffering multiple adverse effects and unremitting symptoms until the “right medication” is identified. Imagine how gratifying it would be for you as a psychiatrist to watch every one of your patients improve rapidly with minimal complaints or adverse effects.

Precision psychiatry is the indispensable vehicle to achieve personalized medicine for psychiatric patients. Precision psychiatry is a cherished goal, but it remains an aspirational objective. Other medical specialties, especially oncology and cardiology, have made remarkable strides in precision medicine, but the journey to precision psychiatry is still in its early stages. Yet there is every reason to believe that we are making progress toward that cherished goal.

To implement precision psychiatry, we must be able to identify the biosignature of each patient’s psychiatric brain disorder. But there is a formidable challenge to overcome: the complex, extensive heterogeneity of psychiatric disorders, which requires intense and inspired neurobiology research. So, while clinicians go on with the mundane trial-and-error approach of contemporary psychopharmacology, psychiatric neuroscientists are diligently deconstructing major psychiatric disorders into specific biotypes with unique biosignatures that will one day guide accurate and prompt clinical management.

Psychiatric practitioners may be too busy to keep tabs on the progress being made in identifying various biomarkers that are the key ingredients to decoding the biosignature of each psychiatric patient. Take schizophrenia, for example. There are myriad clinical variations that comprise this heterogeneous brain syndrome, including level of premorbid functioning; acute vs gradual onset of psychosis; the type and severity of hallucinations or delusions; the dimensional spectrum of negative symptoms and cognitive impairments; the presence and intensity of suicidal or homicidal urges; and the type of medical and psychiatric comorbidities. No wonder every patient is a unique and fascinating clinical puzzle, and yet, patients with schizophrenia are still being homogenized under a single DSM diagnostic category.

There are hundreds of biomarkers in schizophrenia,1 but none can be used clinically until the biosignatures of the many diseases within the schizophrenia syndrome are identified. That grueling research quest will take time, given that so far >340 risk genes for schizophrenia have been discovered, along with countless copy number variants representing gene deletions or duplications, plus dozens of de novo mutations that preclude coding for any protein. Add to these the numerous prenatal pregnancy adverse events, delivery complications, and early childhood abuse—all of which are associated with neurodevelopmental disruptions that set up the brain for schizophrenia spectrum disorders in adulthood—and we have a perplexing conundrum to tackle.

Precision psychiatry will ultimately enable practitioners to recognize various psychotic diseases that are more specific than the current DSM psychosis categories. Further, precision psychiatry will provide guidance as to which member within a class of so-called “me-too” drugs is the optimal match for each patient. This will stand in stark contrast to the chaotic hit-or-miss approach.

Precision psychiatry also will reveal the absurdity of current FDA clinical trials design for drug development. How can a molecule with a putative mechanism of action relevant to a specific biotype be administered to a hodgepodge of heterogeneous biotypes that have been lumped in 1 clinical category, and yet be expected to exert efficacy in most biotypes? It is a small miracle that some new drugs beat placebo despite the extensive variability in both placebo responses and drug responses. But it is well known that in all FDA placebo-controlled trials, the therapeutic response across the patient population varies from extremely high to extremely low, and worsening may even occur in a subset of patients receiving either the active drug or placebo. Perhaps drug response should be used as 1 methodology to classify biotypes of patients encompassed within a heterogeneous syndrome such as schizophrenia.

Precision psychiatry will represent a huge paradigm shift in the science and practice of our specialty. In his landmark book, Thomas Kuhn defined a paradigm as “an entire worldview in which a theory exists and all the implications that come from that view.”2 Precision psychiatry will completely disrupt the current antiquated clinical paradigm, transforming psychiatry into the clinical neuroscience it is. Many “omics,” such as genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, lipidomics, and metagenomics, will inevitably find their way into the jargon of psychiatrists.3

A marriage of science and technology is essential for the emergence of precision psychiatry. To achieve this transformative amalgamation, we need to reconfigure our concepts, reengineer our methods, reinvent our models, and redesign our approaches to patient care.

As Peter Drucker said, “The best way to predict the future is to create it.”4 Precision psychiatry is our future. Let’s create it!

1. Nasrallah HA.

2. Kuhn TS. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1964.

3. Nasrallah HA. Advancing clinical neuroscience literacy among psychiatric practitioners. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9):17-18.

4. Cohen WA. Drucker on leadership: new lessons from the father of modern management. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2010.

1. Nasrallah HA.

2. Kuhn TS. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1964.

3. Nasrallah HA. Advancing clinical neuroscience literacy among psychiatric practitioners. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(9):17-18.

4. Cohen WA. Drucker on leadership: new lessons from the father of modern management. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2010.

Times change, but children still come first

After decades of pediatric practice, Thomas K. McInerny, MD, still accentuates the positive. “I decided to become a pediatrician in my third year of medical school after my pediatrics rotation. I loved working with the children and their families so full of joy and hope,” he said. “I still feel that pediatrics is the greatest profession despite some frustrations with rules, regulations, and computer work.”

Many childhood diseases, including birth defects and forms of cancer that were fatal 50 years ago, now can be treated successfully, he noted. “However, there are more children with emotional, behavioral, and school problems, which pediatricians are now treating as there is a great shortage of mental health professionals for children.”

Although the dedication of pediatricians to their specialty has remained strong over the past 50 years, their work environment has evolved in many ways.

David T. Tayloe Jr., MD, also a past president of the AAP, currently practices in Goldsboro, N.C. When he established a solo community practice in 1977, he was one of a few pediatricians in the area, and he was busy. “I was the only pediatrician who could take care of really sick newborns and hospital patients, so I basically was available 24-7 for those first 2 years; there were two older pediatricians in town, and they took routine night call with me, giving me some time with my family,” he said. “With 1,500 deliveries a year at our hospital, there were always sick babies who needed my services. My office hours were 9 a.m. until 5 p.m. but often, in the cooler months, we saw patients until 8 p.m.” These days, Dr. Tayloe said he works 3-4 days in the office, and “my practice is largely behavioral health, school problems, obesity, asthma, and well-baby/child care.”

“In the last 20 years, my typical work day has changed in many ways,” said Julia Richerson, MD, who practices at the Family Health Center Iroquois office in South Louisville, Ky.

“I use electronic resources to find patient education, to look up current treatments, and research complicated diagnosis,” she noted.

“I feel that having the computer in the room isn’t a barrier to communication with my patients and families. Using the EHR doesn’t take me more time to see a patient,” she said. “However, the review of consult and ER records is harder and takes longer to complete. Consult, ER, and other outside records are much larger with the key clinical data more disorganized and harder to find among the pages and pages of nonrelevant content. This makes the workday much longer.”

The conditions that take up most of a pediatric office visit have changed as well, and include more complex medical, behavioral, and social issues, Dr. Richerson observed. “Obesity, ADHD, autism, complications of prematurity, behavioral health issues, developmental delays, and asthma are commonly seen in practice now. One in five children nationally have a chronic illness or special health care need. And we strive to help ease the challenges for families struggling with economic insecurity, and children growing up experiencing significant adversities.”

The office and the EHR

EHRs are a fact of life in all specialties today, but should not get in the way of interacting with patients, Dr. McInerny said. Many pediatricians complete their medical records after hours at home because they don’t have time to complete them in the office.

“I would advise the younger pediatricians to be sure to look at and interact with their families as much as possible while working on the computer, and showing the families entries and graphs from the computer. We were able to interact with families much more easily when writing out notes with pen and paper,” he said.

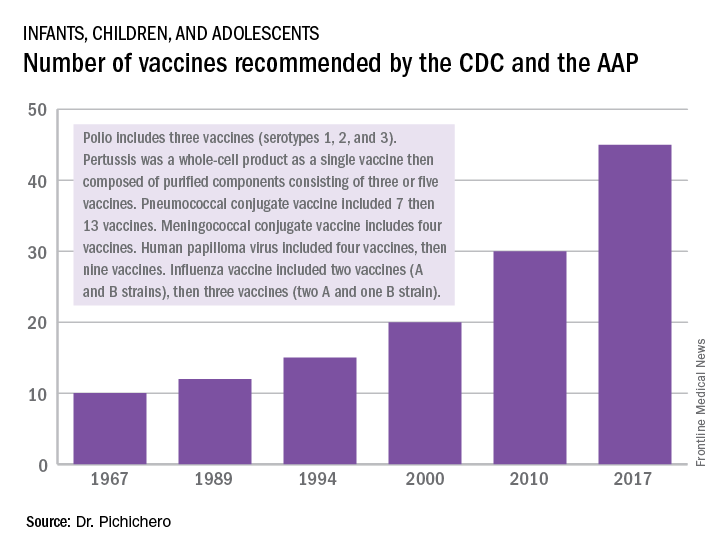

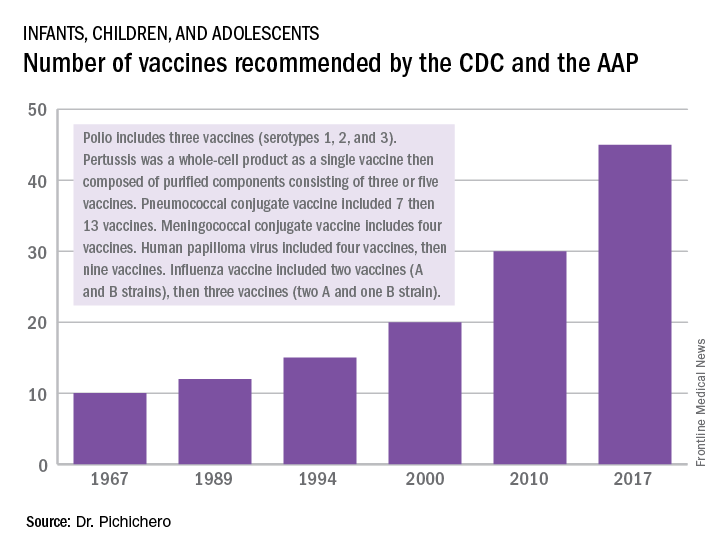

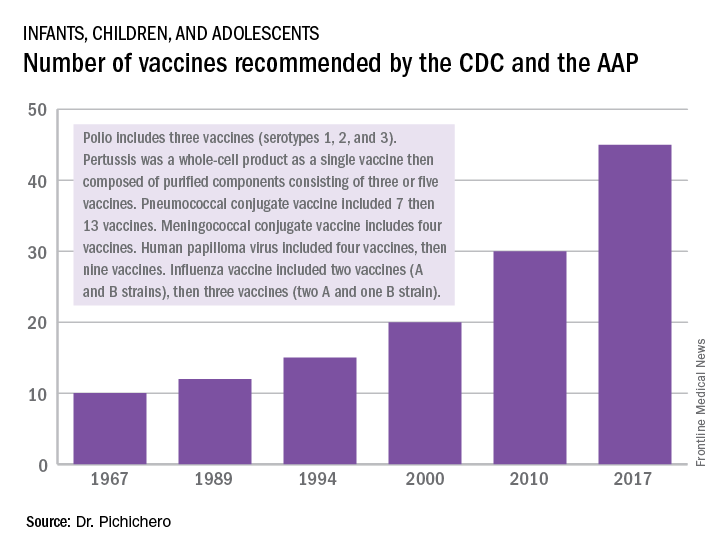

In his early years of practice, Dr. Tayloe recalled, “I spent less time with each patient; my focus was infectious disease, and I treated many patients with what today are vaccine-preventable diseases. I could see patients much faster with paper charts, but my documentation left much to be desired,” he said. “With the electronic record, I spend more time with each patient, but I type really fast and finish my charts in the exam rooms with the patients.”

“EHRs have made daily practice easier and more complicated for pediatricians,” said Dr. Richerson. “In the moment-to-moment use of EHRs while seeing patients, we can fairly quickly document the information we need to for patient care.” However, she said, “It takes some additional time to document all the data points required for quality- and value-based reimbursement programs, and it takes a significant amount of additional time in most EHRs to retrieve relevant information because you cannot query the system for clinical content on a patient. Also, reviewing incoming records is difficult because the information is voluminous and poorly organized,” she noted. “There are so many opportunities for improvement, and hopefully 20 years from now we will have EHRs that significantly improve quality and safety of patient care.”

Money and malpractice

The Vaccines for Children program led to an increase in incomes for pediatricians in the United States after 1994, according to Dr. Tayloe. “We began to be paid by insurance companies for most of what we do during the mid-90s and that boosted revenues,” he said. However, “On the flip side, we are now at the mercy of private payers, and must participate in all their very burdensome quality improvement/assurance programs if we are to be paid fairly. Our incomes were pretty flat over the last 5-10 years, especially for practices that participate fully in Medicaid/CHIP.”

Over the past 50 years, malpractice claims against pediatricians have remained consistently among the lowest for any medical specialty, according to Paul Greve, JD, a registered professional liability underwriter and executive vice president and senior consultant at Willis Towers Watson Health Care Practice.

The impact of EHRs on pediatric practice from a legal standpoint depends on the format of the EHR itself, Mr. Greve said. “Many of the EHRs that are designed for physicians, particularly the ones used in acute care settings, don’t allow the doctor to really highlight their thinking as they work through the diagnostic process, and that is very important in the defense of a malpractice case against a pediatrician,” he said.

“The pediatrician doesn’t have to be correct all the time, but it is important for the lawyers defending the case to see what the pediatrician’s thought process was. If the EHR allows for capturing the doctor’s thought process, that’s a well-designed EHR, and that’s critical,” he emphasized.

Diagnostic error is one of the most entrenched problems in medical malpractice, said Mr. Greve. Failure to diagnose and delay in diagnosis remain the most common allegations against pediatricians, he noted. Also, being aware of the environment is important to risk management in the office.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics has excellent publications on safety and risk management that all pediatricians should be aware of,” he said.

Inspiration and intangibles

“I think the changes that we are starting to see will continue to evolve over the next 50 years,” said Dr. Richerson. “Increased medical and social complexity of patients, changes in health technology, EHRs, personal health data monitoring, and continued changes in value based payment methods will be key.

“I hope that we gain, as a health delivery system, an appreciation of the impact of child health on adult health. Long-term adult health outcomes depend on improved child health outcomes. Investing in diseases like childhood obesity, mental health, and developmental issues, to name a few, will have a bigger impact on adult disease than any adult interventions,” she said. And really dealing with the impact of childhood adversity in health care and in the community and nationally in general is critical. This requires grassroots interventions to support families as well as local, state, and national policy. It also requires payment for health care services for the needed interventions in the office and hospital. Providing comprehensive medical care and addressing the medical and social complexities of child health in an effective, compassionate, and family-centered way takes time. It’s not easy, but it’s not impossible. But it requires more resources than are currently given to child health care. Adult medicine is accustomed to paying for disease managers for diabetes or care coordinators for heart failure. This is not the current state of delivery for children’s care and it should be. These are some of the major issues confronting pediatricians.

What has remained the same in pediatrics is the love the doctors have for their work, and the reflections of veteran clinicians on the intangible rewards of the practice may inspire the next generation.

Dr. Tayloe said that he chose pediatrics because “I was really intrigued by the skills necessary to care for sick newborns, including premature babies. I wanted to practice in a remote location where I could use all the skills I developed during residency, and be of significant value to the community.” Two of his four adult children were similarly inspired and followed in his footsteps.

“For pediatricians, helping families raise healthy children is a real privilege and very satisfying,” Dr. McInerny said.

After decades of pediatric practice, Thomas K. McInerny, MD, still accentuates the positive. “I decided to become a pediatrician in my third year of medical school after my pediatrics rotation. I loved working with the children and their families so full of joy and hope,” he said. “I still feel that pediatrics is the greatest profession despite some frustrations with rules, regulations, and computer work.”

Many childhood diseases, including birth defects and forms of cancer that were fatal 50 years ago, now can be treated successfully, he noted. “However, there are more children with emotional, behavioral, and school problems, which pediatricians are now treating as there is a great shortage of mental health professionals for children.”

Although the dedication of pediatricians to their specialty has remained strong over the past 50 years, their work environment has evolved in many ways.

David T. Tayloe Jr., MD, also a past president of the AAP, currently practices in Goldsboro, N.C. When he established a solo community practice in 1977, he was one of a few pediatricians in the area, and he was busy. “I was the only pediatrician who could take care of really sick newborns and hospital patients, so I basically was available 24-7 for those first 2 years; there were two older pediatricians in town, and they took routine night call with me, giving me some time with my family,” he said. “With 1,500 deliveries a year at our hospital, there were always sick babies who needed my services. My office hours were 9 a.m. until 5 p.m. but often, in the cooler months, we saw patients until 8 p.m.” These days, Dr. Tayloe said he works 3-4 days in the office, and “my practice is largely behavioral health, school problems, obesity, asthma, and well-baby/child care.”

“In the last 20 years, my typical work day has changed in many ways,” said Julia Richerson, MD, who practices at the Family Health Center Iroquois office in South Louisville, Ky.

“I use electronic resources to find patient education, to look up current treatments, and research complicated diagnosis,” she noted.

“I feel that having the computer in the room isn’t a barrier to communication with my patients and families. Using the EHR doesn’t take me more time to see a patient,” she said. “However, the review of consult and ER records is harder and takes longer to complete. Consult, ER, and other outside records are much larger with the key clinical data more disorganized and harder to find among the pages and pages of nonrelevant content. This makes the workday much longer.”

The conditions that take up most of a pediatric office visit have changed as well, and include more complex medical, behavioral, and social issues, Dr. Richerson observed. “Obesity, ADHD, autism, complications of prematurity, behavioral health issues, developmental delays, and asthma are commonly seen in practice now. One in five children nationally have a chronic illness or special health care need. And we strive to help ease the challenges for families struggling with economic insecurity, and children growing up experiencing significant adversities.”

The office and the EHR

EHRs are a fact of life in all specialties today, but should not get in the way of interacting with patients, Dr. McInerny said. Many pediatricians complete their medical records after hours at home because they don’t have time to complete them in the office.

“I would advise the younger pediatricians to be sure to look at and interact with their families as much as possible while working on the computer, and showing the families entries and graphs from the computer. We were able to interact with families much more easily when writing out notes with pen and paper,” he said.

In his early years of practice, Dr. Tayloe recalled, “I spent less time with each patient; my focus was infectious disease, and I treated many patients with what today are vaccine-preventable diseases. I could see patients much faster with paper charts, but my documentation left much to be desired,” he said. “With the electronic record, I spend more time with each patient, but I type really fast and finish my charts in the exam rooms with the patients.”

“EHRs have made daily practice easier and more complicated for pediatricians,” said Dr. Richerson. “In the moment-to-moment use of EHRs while seeing patients, we can fairly quickly document the information we need to for patient care.” However, she said, “It takes some additional time to document all the data points required for quality- and value-based reimbursement programs, and it takes a significant amount of additional time in most EHRs to retrieve relevant information because you cannot query the system for clinical content on a patient. Also, reviewing incoming records is difficult because the information is voluminous and poorly organized,” she noted. “There are so many opportunities for improvement, and hopefully 20 years from now we will have EHRs that significantly improve quality and safety of patient care.”

Money and malpractice

The Vaccines for Children program led to an increase in incomes for pediatricians in the United States after 1994, according to Dr. Tayloe. “We began to be paid by insurance companies for most of what we do during the mid-90s and that boosted revenues,” he said. However, “On the flip side, we are now at the mercy of private payers, and must participate in all their very burdensome quality improvement/assurance programs if we are to be paid fairly. Our incomes were pretty flat over the last 5-10 years, especially for practices that participate fully in Medicaid/CHIP.”

Over the past 50 years, malpractice claims against pediatricians have remained consistently among the lowest for any medical specialty, according to Paul Greve, JD, a registered professional liability underwriter and executive vice president and senior consultant at Willis Towers Watson Health Care Practice.

The impact of EHRs on pediatric practice from a legal standpoint depends on the format of the EHR itself, Mr. Greve said. “Many of the EHRs that are designed for physicians, particularly the ones used in acute care settings, don’t allow the doctor to really highlight their thinking as they work through the diagnostic process, and that is very important in the defense of a malpractice case against a pediatrician,” he said.

“The pediatrician doesn’t have to be correct all the time, but it is important for the lawyers defending the case to see what the pediatrician’s thought process was. If the EHR allows for capturing the doctor’s thought process, that’s a well-designed EHR, and that’s critical,” he emphasized.

Diagnostic error is one of the most entrenched problems in medical malpractice, said Mr. Greve. Failure to diagnose and delay in diagnosis remain the most common allegations against pediatricians, he noted. Also, being aware of the environment is important to risk management in the office.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics has excellent publications on safety and risk management that all pediatricians should be aware of,” he said.

Inspiration and intangibles

“I think the changes that we are starting to see will continue to evolve over the next 50 years,” said Dr. Richerson. “Increased medical and social complexity of patients, changes in health technology, EHRs, personal health data monitoring, and continued changes in value based payment methods will be key.

“I hope that we gain, as a health delivery system, an appreciation of the impact of child health on adult health. Long-term adult health outcomes depend on improved child health outcomes. Investing in diseases like childhood obesity, mental health, and developmental issues, to name a few, will have a bigger impact on adult disease than any adult interventions,” she said. And really dealing with the impact of childhood adversity in health care and in the community and nationally in general is critical. This requires grassroots interventions to support families as well as local, state, and national policy. It also requires payment for health care services for the needed interventions in the office and hospital. Providing comprehensive medical care and addressing the medical and social complexities of child health in an effective, compassionate, and family-centered way takes time. It’s not easy, but it’s not impossible. But it requires more resources than are currently given to child health care. Adult medicine is accustomed to paying for disease managers for diabetes or care coordinators for heart failure. This is not the current state of delivery for children’s care and it should be. These are some of the major issues confronting pediatricians.

What has remained the same in pediatrics is the love the doctors have for their work, and the reflections of veteran clinicians on the intangible rewards of the practice may inspire the next generation.

Dr. Tayloe said that he chose pediatrics because “I was really intrigued by the skills necessary to care for sick newborns, including premature babies. I wanted to practice in a remote location where I could use all the skills I developed during residency, and be of significant value to the community.” Two of his four adult children were similarly inspired and followed in his footsteps.

“For pediatricians, helping families raise healthy children is a real privilege and very satisfying,” Dr. McInerny said.

After decades of pediatric practice, Thomas K. McInerny, MD, still accentuates the positive. “I decided to become a pediatrician in my third year of medical school after my pediatrics rotation. I loved working with the children and their families so full of joy and hope,” he said. “I still feel that pediatrics is the greatest profession despite some frustrations with rules, regulations, and computer work.”

Many childhood diseases, including birth defects and forms of cancer that were fatal 50 years ago, now can be treated successfully, he noted. “However, there are more children with emotional, behavioral, and school problems, which pediatricians are now treating as there is a great shortage of mental health professionals for children.”

Although the dedication of pediatricians to their specialty has remained strong over the past 50 years, their work environment has evolved in many ways.

David T. Tayloe Jr., MD, also a past president of the AAP, currently practices in Goldsboro, N.C. When he established a solo community practice in 1977, he was one of a few pediatricians in the area, and he was busy. “I was the only pediatrician who could take care of really sick newborns and hospital patients, so I basically was available 24-7 for those first 2 years; there were two older pediatricians in town, and they took routine night call with me, giving me some time with my family,” he said. “With 1,500 deliveries a year at our hospital, there were always sick babies who needed my services. My office hours were 9 a.m. until 5 p.m. but often, in the cooler months, we saw patients until 8 p.m.” These days, Dr. Tayloe said he works 3-4 days in the office, and “my practice is largely behavioral health, school problems, obesity, asthma, and well-baby/child care.”

“In the last 20 years, my typical work day has changed in many ways,” said Julia Richerson, MD, who practices at the Family Health Center Iroquois office in South Louisville, Ky.

“I use electronic resources to find patient education, to look up current treatments, and research complicated diagnosis,” she noted.

“I feel that having the computer in the room isn’t a barrier to communication with my patients and families. Using the EHR doesn’t take me more time to see a patient,” she said. “However, the review of consult and ER records is harder and takes longer to complete. Consult, ER, and other outside records are much larger with the key clinical data more disorganized and harder to find among the pages and pages of nonrelevant content. This makes the workday much longer.”

The conditions that take up most of a pediatric office visit have changed as well, and include more complex medical, behavioral, and social issues, Dr. Richerson observed. “Obesity, ADHD, autism, complications of prematurity, behavioral health issues, developmental delays, and asthma are commonly seen in practice now. One in five children nationally have a chronic illness or special health care need. And we strive to help ease the challenges for families struggling with economic insecurity, and children growing up experiencing significant adversities.”

The office and the EHR

EHRs are a fact of life in all specialties today, but should not get in the way of interacting with patients, Dr. McInerny said. Many pediatricians complete their medical records after hours at home because they don’t have time to complete them in the office.

“I would advise the younger pediatricians to be sure to look at and interact with their families as much as possible while working on the computer, and showing the families entries and graphs from the computer. We were able to interact with families much more easily when writing out notes with pen and paper,” he said.

In his early years of practice, Dr. Tayloe recalled, “I spent less time with each patient; my focus was infectious disease, and I treated many patients with what today are vaccine-preventable diseases. I could see patients much faster with paper charts, but my documentation left much to be desired,” he said. “With the electronic record, I spend more time with each patient, but I type really fast and finish my charts in the exam rooms with the patients.”

“EHRs have made daily practice easier and more complicated for pediatricians,” said Dr. Richerson. “In the moment-to-moment use of EHRs while seeing patients, we can fairly quickly document the information we need to for patient care.” However, she said, “It takes some additional time to document all the data points required for quality- and value-based reimbursement programs, and it takes a significant amount of additional time in most EHRs to retrieve relevant information because you cannot query the system for clinical content on a patient. Also, reviewing incoming records is difficult because the information is voluminous and poorly organized,” she noted. “There are so many opportunities for improvement, and hopefully 20 years from now we will have EHRs that significantly improve quality and safety of patient care.”

Money and malpractice

The Vaccines for Children program led to an increase in incomes for pediatricians in the United States after 1994, according to Dr. Tayloe. “We began to be paid by insurance companies for most of what we do during the mid-90s and that boosted revenues,” he said. However, “On the flip side, we are now at the mercy of private payers, and must participate in all their very burdensome quality improvement/assurance programs if we are to be paid fairly. Our incomes were pretty flat over the last 5-10 years, especially for practices that participate fully in Medicaid/CHIP.”

Over the past 50 years, malpractice claims against pediatricians have remained consistently among the lowest for any medical specialty, according to Paul Greve, JD, a registered professional liability underwriter and executive vice president and senior consultant at Willis Towers Watson Health Care Practice.

The impact of EHRs on pediatric practice from a legal standpoint depends on the format of the EHR itself, Mr. Greve said. “Many of the EHRs that are designed for physicians, particularly the ones used in acute care settings, don’t allow the doctor to really highlight their thinking as they work through the diagnostic process, and that is very important in the defense of a malpractice case against a pediatrician,” he said.

“The pediatrician doesn’t have to be correct all the time, but it is important for the lawyers defending the case to see what the pediatrician’s thought process was. If the EHR allows for capturing the doctor’s thought process, that’s a well-designed EHR, and that’s critical,” he emphasized.

Diagnostic error is one of the most entrenched problems in medical malpractice, said Mr. Greve. Failure to diagnose and delay in diagnosis remain the most common allegations against pediatricians, he noted. Also, being aware of the environment is important to risk management in the office.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics has excellent publications on safety and risk management that all pediatricians should be aware of,” he said.

Inspiration and intangibles

“I think the changes that we are starting to see will continue to evolve over the next 50 years,” said Dr. Richerson. “Increased medical and social complexity of patients, changes in health technology, EHRs, personal health data monitoring, and continued changes in value based payment methods will be key.

“I hope that we gain, as a health delivery system, an appreciation of the impact of child health on adult health. Long-term adult health outcomes depend on improved child health outcomes. Investing in diseases like childhood obesity, mental health, and developmental issues, to name a few, will have a bigger impact on adult disease than any adult interventions,” she said. And really dealing with the impact of childhood adversity in health care and in the community and nationally in general is critical. This requires grassroots interventions to support families as well as local, state, and national policy. It also requires payment for health care services for the needed interventions in the office and hospital. Providing comprehensive medical care and addressing the medical and social complexities of child health in an effective, compassionate, and family-centered way takes time. It’s not easy, but it’s not impossible. But it requires more resources than are currently given to child health care. Adult medicine is accustomed to paying for disease managers for diabetes or care coordinators for heart failure. This is not the current state of delivery for children’s care and it should be. These are some of the major issues confronting pediatricians.

What has remained the same in pediatrics is the love the doctors have for their work, and the reflections of veteran clinicians on the intangible rewards of the practice may inspire the next generation.

Dr. Tayloe said that he chose pediatrics because “I was really intrigued by the skills necessary to care for sick newborns, including premature babies. I wanted to practice in a remote location where I could use all the skills I developed during residency, and be of significant value to the community.” Two of his four adult children were similarly inspired and followed in his footsteps.

“For pediatricians, helping families raise healthy children is a real privilege and very satisfying,” Dr. McInerny said.

More to psychiatry than just neuroscience; The impact of childhood trauma

More to psychiatry than just neuroscience

In his editorial “Advancing clinical neuroscience literacy among psychiatric practitioners” (From the Editor,

I find that many of my patients look for more or different drugs to fix their dysfunctional patterns in life—many of which stem from their dysfunctional and traumatic childhoods. Thus, it is more than just drugs and neurochemical pathways, more than just the “dysregulated neural circuitry,” that we need to focus on in our psychiatric practice.

I finished my psychiatric residency in 1972, before we knew much about neuroscience. Since then, we have learned so much about neuroscience and the specific neuroscience mechanisms involved in the brain and mind. Those advances have done much to aid our core understanding of psychiatric disorders. However, let us not forget that there is more to the mind than just neurochemistry, and more to our practice of psychiatry than just neuroscience.

Leonard Korn, MD

Psychiatrist

Portsmouth Regional Hospital

Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Dr. Nasrallah responds

It is now widely accepted in our field that all psychological phenomena and all human behaviors are associated with neurobiological components. All life events, especially traumatic experiences, are transduced into structural and chemical changes, often within minutes. The formation of dendritic spines to encode the memory of one’s experiences throughout waking hours is well established in neuroscience, and hundreds of studies have been published about this.

Psychotherapy is a neurobiological intervention that induces neuroplasticity and leads to structural brain repair, because talking, listening, triggering memories, inducing insight, and “connecting the dots” in one’s behavior are all biological events.1,2 There is no such thing as a purely psychological process independent of the brain. The mind is the product of ongoing complex, intricate activity of brain neurocircuits whose neurobiological activity is translated into thoughts, emotions, impulses, and behaviors. The mind is perpetually tethered to its neurological roots.

Thus, reductionism actually describes a scientific fact and is not a term with pejorative connotations used to shut down scientific discourse about the biological basis of human behavior. By advancing their clinical neuroscience literacy, psychiatric practitioners will understand that they deal with a specific brain pathology in every patient that they treat and that the medications and psychotherapeutic interventions they employ are synergistic biological treatments.3

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

References

1. Nasrallah HA. Repositioning psychotherapy as a neurobiological intervention. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):18-19.

2. Nasrallah HA. Out-of-the-box questions about psychotherapy. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(10):13-14.

3. Nasrallah HA. Medications with psychotherapy: a synergy to heal the brain. C urrent Psychiatry. 2006;5(10):11-12.

The impact of childhood trauma

I enjoyed Dr. Nasrallah’s article “Beyond DSM-5: Clinical and biologic features shared by major psychiatric syndromes” (From the Editor, Current Psychiatry. October 2017, p. 4,6-7), but there was only 1 mention of childhood trauma, which shares features with most of the commonalities he described, such as inflammation, smaller brain volumes, gene and environment interaction, shortened telomeres, and elevated cortisol levels. The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study1 taught us about the impact of childhood trauma on the entire organism. We need to focus on that commonality.

Susan Jones, MD

Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist

Virginia Treatment Center for Children

Assistant Professor

Virginia Commonwealth University

School of Medicine

Richmond, Virginia

Reference

1. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245-258

Dr. Nasrallah responds

It is worth pointing out that childhood trauma predominantly leads to psychotic and mood disorders in adulthood, and the criteria I mentioned would then hold true.

More to psychiatry than just neuroscience

In his editorial “Advancing clinical neuroscience literacy among psychiatric practitioners” (From the Editor,

I find that many of my patients look for more or different drugs to fix their dysfunctional patterns in life—many of which stem from their dysfunctional and traumatic childhoods. Thus, it is more than just drugs and neurochemical pathways, more than just the “dysregulated neural circuitry,” that we need to focus on in our psychiatric practice.

I finished my psychiatric residency in 1972, before we knew much about neuroscience. Since then, we have learned so much about neuroscience and the specific neuroscience mechanisms involved in the brain and mind. Those advances have done much to aid our core understanding of psychiatric disorders. However, let us not forget that there is more to the mind than just neurochemistry, and more to our practice of psychiatry than just neuroscience.

Leonard Korn, MD

Psychiatrist

Portsmouth Regional Hospital

Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Dr. Nasrallah responds

It is now widely accepted in our field that all psychological phenomena and all human behaviors are associated with neurobiological components. All life events, especially traumatic experiences, are transduced into structural and chemical changes, often within minutes. The formation of dendritic spines to encode the memory of one’s experiences throughout waking hours is well established in neuroscience, and hundreds of studies have been published about this.

Psychotherapy is a neurobiological intervention that induces neuroplasticity and leads to structural brain repair, because talking, listening, triggering memories, inducing insight, and “connecting the dots” in one’s behavior are all biological events.1,2 There is no such thing as a purely psychological process independent of the brain. The mind is the product of ongoing complex, intricate activity of brain neurocircuits whose neurobiological activity is translated into thoughts, emotions, impulses, and behaviors. The mind is perpetually tethered to its neurological roots.

Thus, reductionism actually describes a scientific fact and is not a term with pejorative connotations used to shut down scientific discourse about the biological basis of human behavior. By advancing their clinical neuroscience literacy, psychiatric practitioners will understand that they deal with a specific brain pathology in every patient that they treat and that the medications and psychotherapeutic interventions they employ are synergistic biological treatments.3

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

References

1. Nasrallah HA. Repositioning psychotherapy as a neurobiological intervention. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(12):18-19.

2. Nasrallah HA. Out-of-the-box questions about psychotherapy. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(10):13-14.

3. Nasrallah HA. Medications with psychotherapy: a synergy to heal the brain. C urrent Psychiatry. 2006;5(10):11-12.

The impact of childhood trauma

I enjoyed Dr. Nasrallah’s article “Beyond DSM-5: Clinical and biologic features shared by major psychiatric syndromes” (From the Editor, Current Psychiatry. October 2017, p. 4,6-7), but there was only 1 mention of childhood trauma, which shares features with most of the commonalities he described, such as inflammation, smaller brain volumes, gene and environment interaction, shortened telomeres, and elevated cortisol levels. The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study1 taught us about the impact of childhood trauma on the entire organism. We need to focus on that commonality.

Susan Jones, MD

Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist

Virginia Treatment Center for Children

Assistant Professor

Virginia Commonwealth University

School of Medicine

Richmond, Virginia

Reference

1. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245-258

Dr. Nasrallah responds

It is worth pointing out that childhood trauma predominantly leads to psychotic and mood disorders in adulthood, and the criteria I mentioned would then hold true.

More to psychiatry than just neuroscience

In his editorial “Advancing clinical neuroscience literacy among psychiatric practitioners” (From the Editor,