User login

Medication pricing: So this is how it works

This is the second part in a series on medication pricing.

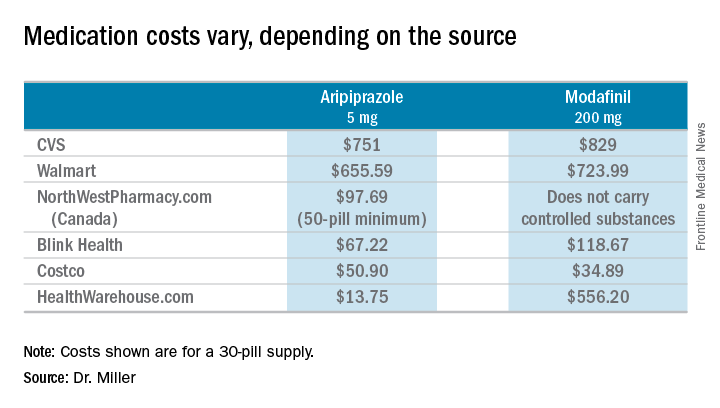

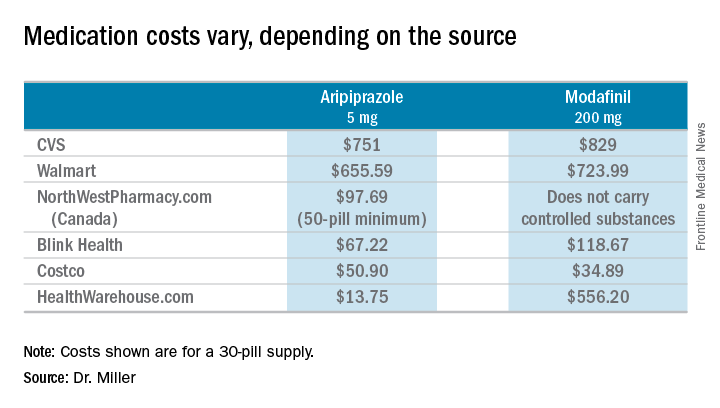

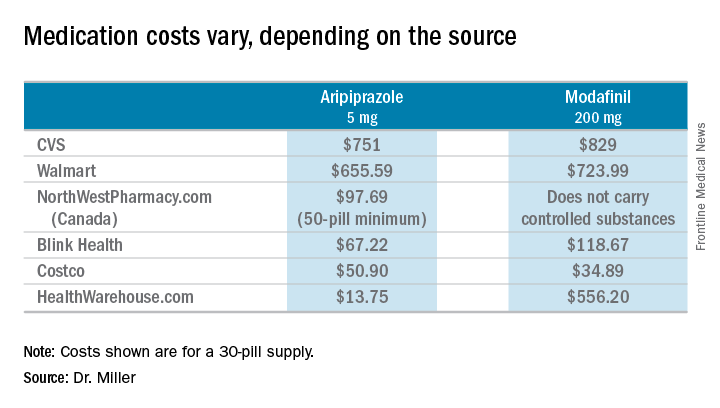

In my last column, I looked at the tremendous variation in prices among pharmacies for two psychotropic medications, aripiprazole and modafinil. The cash price variation could be as much as 45 times more from one pharmacy to the next, which I found to be both outrageous and incomprehensible.

To learn more about pharmaceutical pricing, I contacted Doug Hirsch, the cofounder of GoodRx, a firm based in Santa Monica, Calif., that offers deep discounts on some medications. The company sends discount cards to physicians’ offices – call me if you need some, I have many boxes of GoodRx cards – and has a website (www.GoodRx.com) and an app. It advertises that it is about transparency, and if you’ve ever tried the company’s site or app, the service it offers is remarkable and simple to use.

I approached Mr. Hirsch with two simple questions. The company offers “up to 90% discount” on the cash price of medications through its app, website, or discount card – all of which can be gotten for free. I wanted to know 1) Who pays for this difference in the medication cost, and 2) How does the company, with 95 employees, make any money? Mr. Hirsch was gracious enough (and patient enough!) to spend the next hour walking me through the steps of medication pricing. It was a lively conversation, so let me share with you what I have learned.

Medications are made by a pharmaceutical company or, for generics, there may be many manufacturers. The medications are sent to a pharmaceutical distributor, such as McKesson, and it, in turn, sells and delivers the products to pharmacy chains, as well as to smaller, independent pharmacies. The pharmacies pay an acquisition cost for medications then set a price for these medications that are considerably – or even astronomically – higher than the acquisition price. This is the cash retail price, or in medicine, what is called the Usual & Customary (U&C) cost of the medication. The price may be neither usual, customary, nor reasonable, and it’s not the price the pharmacy expects to recoup on sales.

Every major insurance company contracts with a pharmacy benefits manager (for example, Caremark, Express Scripts, and Optum) to negotiate the cost of medications with each major pharmacy chain. Physicians are familiar with PBMs, who intercede by requiring preauthorization procedures for certain medications or by instituting stepwise, fail-first, requirements before they will allow pharmacy benefits toward the purchase of medications. When the PBMs negotiate with the pharmacies, they will negotiate for a discount off the pharmacy’s U&C charge for medication, perhaps a discount as much as 75% or 80%. Mr. Hirsch noted, “The discount is not negotiated on a per-medication basis but as an across-the-board average, so for one medication, the insurance price may be 2% discount from the U&C cost, and on another medicine it may be 95%. There is a dramatic variation, more than you’d ever expect.”

GoodRx gathers prices from many places, including partnerships with a number of PBMs. In addition to providing discounted prices for insured customers, the PBMs also include in their negotiations a slightly less-discounted price for cash-paying patients who present with a GoodRx card or coupon. You might be surprised to learn that discounted prices can often be less than the typical patient copay. For patients with a high deductible, for medications that are not covered at all, or for times when the copay is higher than the cost of the medication, it will often be less expensive for patients to use a GoodRx discount instead of their insurance. And whether patients uses either their insurance or a GoodRx discount, part of the cost of the prescription includes an administrative fee that goes to the PBM. When GoodRx cards are used, the PBM pays GoodRx part of that fee. I hope you are still with me, because this is the part of the conversation where I started telling Mr. Hirsch that I was getting a headache.

I went back to the enormous cost discrepancy that I had discovered a couple of years ago with Provigil (modafinil). Thirty pills cost just under $35 at Costco, while all other pharmacies were charging close to $1,000. Mr. Hirsch explained, “From what I’ve been told, Costco bases their prices on their acquisition costs and then raises them a certain percent. It’s one way to provide a fair price, but that doesn’t mean they always have the lowest price. They are also the only major pharmacy that lists their drug prices on their website.”

I wanted to know what was in it for the PBMs. Why would Express Scripts be motivated to negotiate a discount in price for cash-paying customers outside of the insurance networks, and how did partnering with GoodRx benefit them? The answer, in part, lies with the fact that the website and app allow patients to comparison shop and go to pharmacies with lower prices. If patients use their insurance, the insurance company is paying less; if they don’t use their insurance because they learned the cash cost is less, then the cost burden has shifted from the insurance company entirely to the patient.

What’s in it for the pharmacies? Why would they be willing to accept less money from a patient bearing a discount card? Mr. Hirsch explained, “Pharmacies want to honor their contracts with PBMs, and the U&C prices are set high to enable negotiation so that they still make some profit. Most people couldn’t afford to pay the high U&C, but they can’t lower them for individual cash-pay customers because that would violate their agreements with PBMs, and Medicare and Medicaid, which is a felony. With the GoodRx price, they still make a profit, and people in drugstores buy other items as well.

GoodRx has 95 employees, and I was still left wondering how they generate income. Mr. Hirsch pinned it down to three sources: the portion of the administration fees the PBMs pay GoodRx, a small amount of advertising, and finally, GoodRx provides technology for the PBMs and charges for this service.

“We started asking how we could gather prices in this bizarre marketplace and address the pricing inefficiencies,” Mr. Hirsch said, “and now I get emails every day expressing gratitude.”

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

This is the second part in a series on medication pricing.

In my last column, I looked at the tremendous variation in prices among pharmacies for two psychotropic medications, aripiprazole and modafinil. The cash price variation could be as much as 45 times more from one pharmacy to the next, which I found to be both outrageous and incomprehensible.

To learn more about pharmaceutical pricing, I contacted Doug Hirsch, the cofounder of GoodRx, a firm based in Santa Monica, Calif., that offers deep discounts on some medications. The company sends discount cards to physicians’ offices – call me if you need some, I have many boxes of GoodRx cards – and has a website (www.GoodRx.com) and an app. It advertises that it is about transparency, and if you’ve ever tried the company’s site or app, the service it offers is remarkable and simple to use.

I approached Mr. Hirsch with two simple questions. The company offers “up to 90% discount” on the cash price of medications through its app, website, or discount card – all of which can be gotten for free. I wanted to know 1) Who pays for this difference in the medication cost, and 2) How does the company, with 95 employees, make any money? Mr. Hirsch was gracious enough (and patient enough!) to spend the next hour walking me through the steps of medication pricing. It was a lively conversation, so let me share with you what I have learned.

Medications are made by a pharmaceutical company or, for generics, there may be many manufacturers. The medications are sent to a pharmaceutical distributor, such as McKesson, and it, in turn, sells and delivers the products to pharmacy chains, as well as to smaller, independent pharmacies. The pharmacies pay an acquisition cost for medications then set a price for these medications that are considerably – or even astronomically – higher than the acquisition price. This is the cash retail price, or in medicine, what is called the Usual & Customary (U&C) cost of the medication. The price may be neither usual, customary, nor reasonable, and it’s not the price the pharmacy expects to recoup on sales.

Every major insurance company contracts with a pharmacy benefits manager (for example, Caremark, Express Scripts, and Optum) to negotiate the cost of medications with each major pharmacy chain. Physicians are familiar with PBMs, who intercede by requiring preauthorization procedures for certain medications or by instituting stepwise, fail-first, requirements before they will allow pharmacy benefits toward the purchase of medications. When the PBMs negotiate with the pharmacies, they will negotiate for a discount off the pharmacy’s U&C charge for medication, perhaps a discount as much as 75% or 80%. Mr. Hirsch noted, “The discount is not negotiated on a per-medication basis but as an across-the-board average, so for one medication, the insurance price may be 2% discount from the U&C cost, and on another medicine it may be 95%. There is a dramatic variation, more than you’d ever expect.”

GoodRx gathers prices from many places, including partnerships with a number of PBMs. In addition to providing discounted prices for insured customers, the PBMs also include in their negotiations a slightly less-discounted price for cash-paying patients who present with a GoodRx card or coupon. You might be surprised to learn that discounted prices can often be less than the typical patient copay. For patients with a high deductible, for medications that are not covered at all, or for times when the copay is higher than the cost of the medication, it will often be less expensive for patients to use a GoodRx discount instead of their insurance. And whether patients uses either their insurance or a GoodRx discount, part of the cost of the prescription includes an administrative fee that goes to the PBM. When GoodRx cards are used, the PBM pays GoodRx part of that fee. I hope you are still with me, because this is the part of the conversation where I started telling Mr. Hirsch that I was getting a headache.

I went back to the enormous cost discrepancy that I had discovered a couple of years ago with Provigil (modafinil). Thirty pills cost just under $35 at Costco, while all other pharmacies were charging close to $1,000. Mr. Hirsch explained, “From what I’ve been told, Costco bases their prices on their acquisition costs and then raises them a certain percent. It’s one way to provide a fair price, but that doesn’t mean they always have the lowest price. They are also the only major pharmacy that lists their drug prices on their website.”

I wanted to know what was in it for the PBMs. Why would Express Scripts be motivated to negotiate a discount in price for cash-paying customers outside of the insurance networks, and how did partnering with GoodRx benefit them? The answer, in part, lies with the fact that the website and app allow patients to comparison shop and go to pharmacies with lower prices. If patients use their insurance, the insurance company is paying less; if they don’t use their insurance because they learned the cash cost is less, then the cost burden has shifted from the insurance company entirely to the patient.

What’s in it for the pharmacies? Why would they be willing to accept less money from a patient bearing a discount card? Mr. Hirsch explained, “Pharmacies want to honor their contracts with PBMs, and the U&C prices are set high to enable negotiation so that they still make some profit. Most people couldn’t afford to pay the high U&C, but they can’t lower them for individual cash-pay customers because that would violate their agreements with PBMs, and Medicare and Medicaid, which is a felony. With the GoodRx price, they still make a profit, and people in drugstores buy other items as well.

GoodRx has 95 employees, and I was still left wondering how they generate income. Mr. Hirsch pinned it down to three sources: the portion of the administration fees the PBMs pay GoodRx, a small amount of advertising, and finally, GoodRx provides technology for the PBMs and charges for this service.

“We started asking how we could gather prices in this bizarre marketplace and address the pricing inefficiencies,” Mr. Hirsch said, “and now I get emails every day expressing gratitude.”

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

This is the second part in a series on medication pricing.

In my last column, I looked at the tremendous variation in prices among pharmacies for two psychotropic medications, aripiprazole and modafinil. The cash price variation could be as much as 45 times more from one pharmacy to the next, which I found to be both outrageous and incomprehensible.

To learn more about pharmaceutical pricing, I contacted Doug Hirsch, the cofounder of GoodRx, a firm based in Santa Monica, Calif., that offers deep discounts on some medications. The company sends discount cards to physicians’ offices – call me if you need some, I have many boxes of GoodRx cards – and has a website (www.GoodRx.com) and an app. It advertises that it is about transparency, and if you’ve ever tried the company’s site or app, the service it offers is remarkable and simple to use.

I approached Mr. Hirsch with two simple questions. The company offers “up to 90% discount” on the cash price of medications through its app, website, or discount card – all of which can be gotten for free. I wanted to know 1) Who pays for this difference in the medication cost, and 2) How does the company, with 95 employees, make any money? Mr. Hirsch was gracious enough (and patient enough!) to spend the next hour walking me through the steps of medication pricing. It was a lively conversation, so let me share with you what I have learned.

Medications are made by a pharmaceutical company or, for generics, there may be many manufacturers. The medications are sent to a pharmaceutical distributor, such as McKesson, and it, in turn, sells and delivers the products to pharmacy chains, as well as to smaller, independent pharmacies. The pharmacies pay an acquisition cost for medications then set a price for these medications that are considerably – or even astronomically – higher than the acquisition price. This is the cash retail price, or in medicine, what is called the Usual & Customary (U&C) cost of the medication. The price may be neither usual, customary, nor reasonable, and it’s not the price the pharmacy expects to recoup on sales.

Every major insurance company contracts with a pharmacy benefits manager (for example, Caremark, Express Scripts, and Optum) to negotiate the cost of medications with each major pharmacy chain. Physicians are familiar with PBMs, who intercede by requiring preauthorization procedures for certain medications or by instituting stepwise, fail-first, requirements before they will allow pharmacy benefits toward the purchase of medications. When the PBMs negotiate with the pharmacies, they will negotiate for a discount off the pharmacy’s U&C charge for medication, perhaps a discount as much as 75% or 80%. Mr. Hirsch noted, “The discount is not negotiated on a per-medication basis but as an across-the-board average, so for one medication, the insurance price may be 2% discount from the U&C cost, and on another medicine it may be 95%. There is a dramatic variation, more than you’d ever expect.”

GoodRx gathers prices from many places, including partnerships with a number of PBMs. In addition to providing discounted prices for insured customers, the PBMs also include in their negotiations a slightly less-discounted price for cash-paying patients who present with a GoodRx card or coupon. You might be surprised to learn that discounted prices can often be less than the typical patient copay. For patients with a high deductible, for medications that are not covered at all, or for times when the copay is higher than the cost of the medication, it will often be less expensive for patients to use a GoodRx discount instead of their insurance. And whether patients uses either their insurance or a GoodRx discount, part of the cost of the prescription includes an administrative fee that goes to the PBM. When GoodRx cards are used, the PBM pays GoodRx part of that fee. I hope you are still with me, because this is the part of the conversation where I started telling Mr. Hirsch that I was getting a headache.

I went back to the enormous cost discrepancy that I had discovered a couple of years ago with Provigil (modafinil). Thirty pills cost just under $35 at Costco, while all other pharmacies were charging close to $1,000. Mr. Hirsch explained, “From what I’ve been told, Costco bases their prices on their acquisition costs and then raises them a certain percent. It’s one way to provide a fair price, but that doesn’t mean they always have the lowest price. They are also the only major pharmacy that lists their drug prices on their website.”

I wanted to know what was in it for the PBMs. Why would Express Scripts be motivated to negotiate a discount in price for cash-paying customers outside of the insurance networks, and how did partnering with GoodRx benefit them? The answer, in part, lies with the fact that the website and app allow patients to comparison shop and go to pharmacies with lower prices. If patients use their insurance, the insurance company is paying less; if they don’t use their insurance because they learned the cash cost is less, then the cost burden has shifted from the insurance company entirely to the patient.

What’s in it for the pharmacies? Why would they be willing to accept less money from a patient bearing a discount card? Mr. Hirsch explained, “Pharmacies want to honor their contracts with PBMs, and the U&C prices are set high to enable negotiation so that they still make some profit. Most people couldn’t afford to pay the high U&C, but they can’t lower them for individual cash-pay customers because that would violate their agreements with PBMs, and Medicare and Medicaid, which is a felony. With the GoodRx price, they still make a profit, and people in drugstores buy other items as well.

GoodRx has 95 employees, and I was still left wondering how they generate income. Mr. Hirsch pinned it down to three sources: the portion of the administration fees the PBMs pay GoodRx, a small amount of advertising, and finally, GoodRx provides technology for the PBMs and charges for this service.

“We started asking how we could gather prices in this bizarre marketplace and address the pricing inefficiencies,” Mr. Hirsch said, “and now I get emails every day expressing gratitude.”

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

The toxic zeitgeist of hyper-partisanship: A psychiatric perspective

It is always judicious to avoid discussing religious or political issues because inevitably someone will be offended. As a lifetime member of the American Psychiatric Association, I adhere to its "Goldwater Rule," which proscribes the gratuitous diagnosis of any president absent of a formal face-to-face psychiatric evaluation. But it is perfectly permissible to express a psychiatric opinion about the contemporary national political scene.

Frankly, the status of the political arena has become ugly. This should not be surprising, given that at its core, politics is an unquenchable thirst for power, and Machiavelli is its anointed godfather. The current political zeitgeist of the country is becoming downright grotesque and spiteful. Although fierce political rivalry is widely accepted as a tradition to achieve the national goals promulgated by each party, what we are witnessing today is a veritable blood sport fueled by “hyper-partisanship,” where drawing blood, not promoting the public good, has become an undisguised intent.

The intensity of hyper-partisanship has engulfed the collective national psyche and is bordering on the “religification” of politics. What used to be reasonable political views have been transformed into irrefutable articles of faith that do not lend themselves to rational debate or productive compromise. The metastasis of social media into our daily lives over the past decade is catalyzing the venomous crossfire across the political divide that used to be passionate and civil, but recently has degenerated into a raucous cacophony of hateful speech. Thoughtful debate of issues that promote the public good is becoming scarce. Instead of effectively defending the validity of their arguments, extremists focus on spewing accusations and ad hominem insults. It is worrisome that both fringe groups tenaciously uphold fixed and extreme political positions, the tenets of which can never be challenged.

Psychiatrically, those extreme ideological positions appear to be consistent with Jasper’s criteria for a delusion (a belief with an unparalleled degree of subjective feeling of certainty that cannot be influenced by experience or arguments) or McHugh’s definition of an overvalued idea, which resembles an egosyntonic obsession that is relished, amplified, and defended. Given that extremism is not just a “folie à deux” shared by 2 individuals but by many individuals, it may qualify as a “folie en masse.”

Having a political orientation is perfectly normal, a healthy evidence of absence of indolent apathy. However, the unconstrained fervor of political extremism can be as psychologically unhealthy as lethargic passivity. A significant segment of the population may see some merit on both sides of the gaping political chasm, but they are appalled by the intransigence of political extremism, which has become an impediment to the constructive compromise that is vital for progress in politics and in all human interactions.

Beliefs are a transcendent human trait. Homo sapiens represent the only animal species endowed by evolution with a large prefrontal cortex that enables each of its members to harbor a belief system. It prompts me to propose that Descartes’ famous dictum “I think, therefore I am” be revised to “I believe, therefore I am human.” But while many beliefs are reasonable and anchored in reality, irrational beliefs are odd and ambiguous, ranging from superstitions and overvalued ideas to conspiracy theories and cults, which I wrote about a decade ago.1 In fact, epidemiologic research studies have confirmed a high prevalence of subthreshold and pre-psychotic beliefs in the general population.2-5 Thus, radical political partisanship falls on the extreme end of that continuum.

The zeitgeist generated by extreme partisanship is intellectually stunting and emotionally numbing. Psychiatrists may wonder what consequences the intense anger and antipathy and scarcity of compromise between the opposing parties will have for the country’s citizens. Although psychiatrists cannot repair the dysfunctional political fragmentation at the national level, we can help patients who may be negatively affected by the conflicts permeating the national scene when we read or watch the daily news.

Just as it is disturbing for children to watch their parents undermine each other by arguing ferociously and hurling insults, so it is for a populace aghast at how frenzied and intolerant their leaders and their extremist followers have become, failing to work together for the common good and adversely impacting the mental health zeitgeist.

1. Nasrallah HA. Irrational beliefs: a ubiquitous human trait. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(2):15-16.

2. Kelleher I, Wigman JT, Harley M, et al. Psychotic experiences in the population: association with functioning and mental distress. Schizophr Res. 2015;165(1):9-14.

3. Landin-Romero R, McKenna PJ, Romaguera A, et al. Examining the continuum of psychosis: frequency and characteristics of psychotic-like symptoms in relatives and non-relatives of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016;178(1-3):6-11.

4. Hanssen M, Bak M, Bijl R, et al. The incidence and outcome of subclinical psychotic experiences in the general population. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005;44(pt 2):181-191.

5. Nelson B, Fusar-Poli P, Yung AR. Can we detect psychotic-like experiences in the general population? Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):376-385.

It is always judicious to avoid discussing religious or political issues because inevitably someone will be offended. As a lifetime member of the American Psychiatric Association, I adhere to its "Goldwater Rule," which proscribes the gratuitous diagnosis of any president absent of a formal face-to-face psychiatric evaluation. But it is perfectly permissible to express a psychiatric opinion about the contemporary national political scene.

Frankly, the status of the political arena has become ugly. This should not be surprising, given that at its core, politics is an unquenchable thirst for power, and Machiavelli is its anointed godfather. The current political zeitgeist of the country is becoming downright grotesque and spiteful. Although fierce political rivalry is widely accepted as a tradition to achieve the national goals promulgated by each party, what we are witnessing today is a veritable blood sport fueled by “hyper-partisanship,” where drawing blood, not promoting the public good, has become an undisguised intent.

The intensity of hyper-partisanship has engulfed the collective national psyche and is bordering on the “religification” of politics. What used to be reasonable political views have been transformed into irrefutable articles of faith that do not lend themselves to rational debate or productive compromise. The metastasis of social media into our daily lives over the past decade is catalyzing the venomous crossfire across the political divide that used to be passionate and civil, but recently has degenerated into a raucous cacophony of hateful speech. Thoughtful debate of issues that promote the public good is becoming scarce. Instead of effectively defending the validity of their arguments, extremists focus on spewing accusations and ad hominem insults. It is worrisome that both fringe groups tenaciously uphold fixed and extreme political positions, the tenets of which can never be challenged.

Psychiatrically, those extreme ideological positions appear to be consistent with Jasper’s criteria for a delusion (a belief with an unparalleled degree of subjective feeling of certainty that cannot be influenced by experience or arguments) or McHugh’s definition of an overvalued idea, which resembles an egosyntonic obsession that is relished, amplified, and defended. Given that extremism is not just a “folie à deux” shared by 2 individuals but by many individuals, it may qualify as a “folie en masse.”

Having a political orientation is perfectly normal, a healthy evidence of absence of indolent apathy. However, the unconstrained fervor of political extremism can be as psychologically unhealthy as lethargic passivity. A significant segment of the population may see some merit on both sides of the gaping political chasm, but they are appalled by the intransigence of political extremism, which has become an impediment to the constructive compromise that is vital for progress in politics and in all human interactions.

Beliefs are a transcendent human trait. Homo sapiens represent the only animal species endowed by evolution with a large prefrontal cortex that enables each of its members to harbor a belief system. It prompts me to propose that Descartes’ famous dictum “I think, therefore I am” be revised to “I believe, therefore I am human.” But while many beliefs are reasonable and anchored in reality, irrational beliefs are odd and ambiguous, ranging from superstitions and overvalued ideas to conspiracy theories and cults, which I wrote about a decade ago.1 In fact, epidemiologic research studies have confirmed a high prevalence of subthreshold and pre-psychotic beliefs in the general population.2-5 Thus, radical political partisanship falls on the extreme end of that continuum.

The zeitgeist generated by extreme partisanship is intellectually stunting and emotionally numbing. Psychiatrists may wonder what consequences the intense anger and antipathy and scarcity of compromise between the opposing parties will have for the country’s citizens. Although psychiatrists cannot repair the dysfunctional political fragmentation at the national level, we can help patients who may be negatively affected by the conflicts permeating the national scene when we read or watch the daily news.

Just as it is disturbing for children to watch their parents undermine each other by arguing ferociously and hurling insults, so it is for a populace aghast at how frenzied and intolerant their leaders and their extremist followers have become, failing to work together for the common good and adversely impacting the mental health zeitgeist.

It is always judicious to avoid discussing religious or political issues because inevitably someone will be offended. As a lifetime member of the American Psychiatric Association, I adhere to its "Goldwater Rule," which proscribes the gratuitous diagnosis of any president absent of a formal face-to-face psychiatric evaluation. But it is perfectly permissible to express a psychiatric opinion about the contemporary national political scene.

Frankly, the status of the political arena has become ugly. This should not be surprising, given that at its core, politics is an unquenchable thirst for power, and Machiavelli is its anointed godfather. The current political zeitgeist of the country is becoming downright grotesque and spiteful. Although fierce political rivalry is widely accepted as a tradition to achieve the national goals promulgated by each party, what we are witnessing today is a veritable blood sport fueled by “hyper-partisanship,” where drawing blood, not promoting the public good, has become an undisguised intent.

The intensity of hyper-partisanship has engulfed the collective national psyche and is bordering on the “religification” of politics. What used to be reasonable political views have been transformed into irrefutable articles of faith that do not lend themselves to rational debate or productive compromise. The metastasis of social media into our daily lives over the past decade is catalyzing the venomous crossfire across the political divide that used to be passionate and civil, but recently has degenerated into a raucous cacophony of hateful speech. Thoughtful debate of issues that promote the public good is becoming scarce. Instead of effectively defending the validity of their arguments, extremists focus on spewing accusations and ad hominem insults. It is worrisome that both fringe groups tenaciously uphold fixed and extreme political positions, the tenets of which can never be challenged.

Psychiatrically, those extreme ideological positions appear to be consistent with Jasper’s criteria for a delusion (a belief with an unparalleled degree of subjective feeling of certainty that cannot be influenced by experience or arguments) or McHugh’s definition of an overvalued idea, which resembles an egosyntonic obsession that is relished, amplified, and defended. Given that extremism is not just a “folie à deux” shared by 2 individuals but by many individuals, it may qualify as a “folie en masse.”

Having a political orientation is perfectly normal, a healthy evidence of absence of indolent apathy. However, the unconstrained fervor of political extremism can be as psychologically unhealthy as lethargic passivity. A significant segment of the population may see some merit on both sides of the gaping political chasm, but they are appalled by the intransigence of political extremism, which has become an impediment to the constructive compromise that is vital for progress in politics and in all human interactions.

Beliefs are a transcendent human trait. Homo sapiens represent the only animal species endowed by evolution with a large prefrontal cortex that enables each of its members to harbor a belief system. It prompts me to propose that Descartes’ famous dictum “I think, therefore I am” be revised to “I believe, therefore I am human.” But while many beliefs are reasonable and anchored in reality, irrational beliefs are odd and ambiguous, ranging from superstitions and overvalued ideas to conspiracy theories and cults, which I wrote about a decade ago.1 In fact, epidemiologic research studies have confirmed a high prevalence of subthreshold and pre-psychotic beliefs in the general population.2-5 Thus, radical political partisanship falls on the extreme end of that continuum.

The zeitgeist generated by extreme partisanship is intellectually stunting and emotionally numbing. Psychiatrists may wonder what consequences the intense anger and antipathy and scarcity of compromise between the opposing parties will have for the country’s citizens. Although psychiatrists cannot repair the dysfunctional political fragmentation at the national level, we can help patients who may be negatively affected by the conflicts permeating the national scene when we read or watch the daily news.

Just as it is disturbing for children to watch their parents undermine each other by arguing ferociously and hurling insults, so it is for a populace aghast at how frenzied and intolerant their leaders and their extremist followers have become, failing to work together for the common good and adversely impacting the mental health zeitgeist.

1. Nasrallah HA. Irrational beliefs: a ubiquitous human trait. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(2):15-16.

2. Kelleher I, Wigman JT, Harley M, et al. Psychotic experiences in the population: association with functioning and mental distress. Schizophr Res. 2015;165(1):9-14.

3. Landin-Romero R, McKenna PJ, Romaguera A, et al. Examining the continuum of psychosis: frequency and characteristics of psychotic-like symptoms in relatives and non-relatives of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016;178(1-3):6-11.

4. Hanssen M, Bak M, Bijl R, et al. The incidence and outcome of subclinical psychotic experiences in the general population. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005;44(pt 2):181-191.

5. Nelson B, Fusar-Poli P, Yung AR. Can we detect psychotic-like experiences in the general population? Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):376-385.

1. Nasrallah HA. Irrational beliefs: a ubiquitous human trait. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(2):15-16.

2. Kelleher I, Wigman JT, Harley M, et al. Psychotic experiences in the population: association with functioning and mental distress. Schizophr Res. 2015;165(1):9-14.

3. Landin-Romero R, McKenna PJ, Romaguera A, et al. Examining the continuum of psychosis: frequency and characteristics of psychotic-like symptoms in relatives and non-relatives of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016;178(1-3):6-11.

4. Hanssen M, Bak M, Bijl R, et al. The incidence and outcome of subclinical psychotic experiences in the general population. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005;44(pt 2):181-191.

5. Nelson B, Fusar-Poli P, Yung AR. Can we detect psychotic-like experiences in the general population? Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):376-385.

You paid how much for that medicine?

This is the first article in a series on the cost of medications.

While it’s not news that some pharmaceuticals are exorbitantly expensive and therefore unavailable to our patients, I have learned that there are ways around the obstacle of cost for at least some medications. I want to tell you what I’ve learned about the high cost of two medications: aripiprazole, the generic of Abilify, and modafinil, the generic of Provigil, but the lessons learned may apply to other psychotropics – and Smokey Robinson and the Miracles said it best in a line from their 1960 hit song, “You’d better shop around.”

Over the past few years, the price of aripiprazole has come down considerably, or so I believed. A patient recently complained that his copay after insurance for a 1-month supply of 2-mg tablets was hundreds of dollars, and he showed me a bill where the cost before insurance was more than $2,000! Another patient, also someone with commercial insurance, said he couldn’t afford aripiprazole and asked me to phone in a prescription to healthwarehouse.com. The medication was mailed to him for about $35 a month. Finally, a third patient with Medicare used an online service called Blink Health. He explained that he paid for the medicine online with a credit card – about $80, far less than the price quoted by the pharmacy. He was then given some type of code to present to the pharmacist, who then supplied the medications. In this case, the same pills, the same pharmacy, at a fraction of the cost. With that, I called several pharmacies and asked about the price of generic Abilify, 5 mg, 30 tablets.

I also wrote a column about the tremendous difficulty I had trying to get preauthorization for modafinil, in “Preauthorization of medications: Who oversees the placement of the hoops?” In that case, I spent weeks trying to get approval for the medication, and in the end, it was not approved, and the patient was not able to get it. Soon after, I learned on a Psychiatry Network Facebook discussion that generic Provigil is not expensive at all! Once again, I fired up my phone and called around. Those prices and those I found for Abilify are listed in the chart.

So these are cash prices; they do not take into account the cost with insurance. My patients have educated me after they could not afford the insurance copays. I wondered about my own coverage, and signed on to my pharmacy benefits manager account to look up the cost of both Abilify and Provigil. I’m sorry to say that I can’t report back: With my health insurance, Empire Blue Cross and Express Scripts, both medications require Coverage Review. It was also noted that Abilify requires Step treatment; I must first fail other medications. Should I ever need either of these medications, you’ll know where to find me: in line at the Costco pharmacy. I’ll be the one dancing to Smokey Robinson and the Miracles. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AQGXa3FiXKM

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

This is the first article in a series on the cost of medications.

While it’s not news that some pharmaceuticals are exorbitantly expensive and therefore unavailable to our patients, I have learned that there are ways around the obstacle of cost for at least some medications. I want to tell you what I’ve learned about the high cost of two medications: aripiprazole, the generic of Abilify, and modafinil, the generic of Provigil, but the lessons learned may apply to other psychotropics – and Smokey Robinson and the Miracles said it best in a line from their 1960 hit song, “You’d better shop around.”

Over the past few years, the price of aripiprazole has come down considerably, or so I believed. A patient recently complained that his copay after insurance for a 1-month supply of 2-mg tablets was hundreds of dollars, and he showed me a bill where the cost before insurance was more than $2,000! Another patient, also someone with commercial insurance, said he couldn’t afford aripiprazole and asked me to phone in a prescription to healthwarehouse.com. The medication was mailed to him for about $35 a month. Finally, a third patient with Medicare used an online service called Blink Health. He explained that he paid for the medicine online with a credit card – about $80, far less than the price quoted by the pharmacy. He was then given some type of code to present to the pharmacist, who then supplied the medications. In this case, the same pills, the same pharmacy, at a fraction of the cost. With that, I called several pharmacies and asked about the price of generic Abilify, 5 mg, 30 tablets.

I also wrote a column about the tremendous difficulty I had trying to get preauthorization for modafinil, in “Preauthorization of medications: Who oversees the placement of the hoops?” In that case, I spent weeks trying to get approval for the medication, and in the end, it was not approved, and the patient was not able to get it. Soon after, I learned on a Psychiatry Network Facebook discussion that generic Provigil is not expensive at all! Once again, I fired up my phone and called around. Those prices and those I found for Abilify are listed in the chart.

So these are cash prices; they do not take into account the cost with insurance. My patients have educated me after they could not afford the insurance copays. I wondered about my own coverage, and signed on to my pharmacy benefits manager account to look up the cost of both Abilify and Provigil. I’m sorry to say that I can’t report back: With my health insurance, Empire Blue Cross and Express Scripts, both medications require Coverage Review. It was also noted that Abilify requires Step treatment; I must first fail other medications. Should I ever need either of these medications, you’ll know where to find me: in line at the Costco pharmacy. I’ll be the one dancing to Smokey Robinson and the Miracles. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AQGXa3FiXKM

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

This is the first article in a series on the cost of medications.

While it’s not news that some pharmaceuticals are exorbitantly expensive and therefore unavailable to our patients, I have learned that there are ways around the obstacle of cost for at least some medications. I want to tell you what I’ve learned about the high cost of two medications: aripiprazole, the generic of Abilify, and modafinil, the generic of Provigil, but the lessons learned may apply to other psychotropics – and Smokey Robinson and the Miracles said it best in a line from their 1960 hit song, “You’d better shop around.”

Over the past few years, the price of aripiprazole has come down considerably, or so I believed. A patient recently complained that his copay after insurance for a 1-month supply of 2-mg tablets was hundreds of dollars, and he showed me a bill where the cost before insurance was more than $2,000! Another patient, also someone with commercial insurance, said he couldn’t afford aripiprazole and asked me to phone in a prescription to healthwarehouse.com. The medication was mailed to him for about $35 a month. Finally, a third patient with Medicare used an online service called Blink Health. He explained that he paid for the medicine online with a credit card – about $80, far less than the price quoted by the pharmacy. He was then given some type of code to present to the pharmacist, who then supplied the medications. In this case, the same pills, the same pharmacy, at a fraction of the cost. With that, I called several pharmacies and asked about the price of generic Abilify, 5 mg, 30 tablets.

I also wrote a column about the tremendous difficulty I had trying to get preauthorization for modafinil, in “Preauthorization of medications: Who oversees the placement of the hoops?” In that case, I spent weeks trying to get approval for the medication, and in the end, it was not approved, and the patient was not able to get it. Soon after, I learned on a Psychiatry Network Facebook discussion that generic Provigil is not expensive at all! Once again, I fired up my phone and called around. Those prices and those I found for Abilify are listed in the chart.

So these are cash prices; they do not take into account the cost with insurance. My patients have educated me after they could not afford the insurance copays. I wondered about my own coverage, and signed on to my pharmacy benefits manager account to look up the cost of both Abilify and Provigil. I’m sorry to say that I can’t report back: With my health insurance, Empire Blue Cross and Express Scripts, both medications require Coverage Review. It was also noted that Abilify requires Step treatment; I must first fail other medications. Should I ever need either of these medications, you’ll know where to find me: in line at the Costco pharmacy. I’ll be the one dancing to Smokey Robinson and the Miracles. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AQGXa3FiXKM

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

Approach to the asymptomatic adnexal mass: When to operate, refer, or observe

Adnexal masses are common findings in women. While the decision to operate on symptomatic adnexal masses is straightforward, the decision-making process for asymptomatic masses is more complicated. Here we address how to approach an asymptomatic adnexal mass, including how to decide when to operate, when to refer, or how to monitor.

It is important to minimize the number of surgeries for benign, asymptomatic adnexal masses because complications are reported in 2%-15% of surgeries for adnexal masses and these can range from minimal to devastating.1 In addition, unnecessary surgery is associated with a burden of cost to the health care system. Therefore, there is a paradigm shift in the management of asymptomatic adnexal masses trending toward surveillance of any masses that are likely to be benign. What becomes critical in this approach is the ability to accurately classify these masses preoperatively.

Determining the malignant potential of a mass

Guidance is provided by the ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 174, which was published in 2016: “Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses.”2 These guidelines remind clinicians that:

- Most adnexal masses are benign, even in postmenopausal patients.

- The recommended imaging modality is quality transvaginal ultrasonography with an ultrasonographer accredited through the American Registry of Diagnostic Medical Sonographers.

- Simple cysts up to 10 cm can be monitored using repeat imaging every 6 months without surgical intervention, even in postmenopausal patients. In prospective studies, no cases of malignancy were diagnosed over 6 years of surveillance and most resolved. Those that persist are likely to be serous cystadenomas.

- Many benign lesions such as endometriomas and cystic teratomas have characteristic radiologic features. Surgery for these lesions is warranted for large size, symptoms, or growth in size.

- Ultrasound characteristics of malignant masses include:

1. Cyst size greater than 10 cm

2. Papillary or solid components

3. Septations

4. Internal blood flow on color Doppler.

An alternative approach that has been proposed is an ultrasound scoring system devised by International Ovarian Tumor Analysis Group. The scoring system uses 10 ultrasound findings that are characteristic of malignant and benign and is designed to characterize masses as either benign or malignant.3 This approach is able to correctly classify 77% of masses. The remaining masses with features that do not fit the “simple rules” are considered potentially malignant and should be referred to an oncology specialist for further decision making.

Decision to operate

After referral to gynecologic oncologists, surgery is not always inevitable, particularly for women with indeterminate masses. The gynecologic oncologist uses a decision-making process that factors in the underlying surgical risks for that patient with the likelihood of malignancy based on the features of the mass. The threshold to operate is higher in women with underlying major comorbidities, such as morbid obesity, complex prior surgical history, or cardiopulmonary disease. Healthier surgical candidates are more likely to be considered for a surgery, even if the suspicion for malignancy is lower. However, low surgical risk does not equate to no surgical risk. Therefore, even in apparently “good” surgical candidates, the suspicion for underlying malignancy needs to be reasonably high in order to justify the cost and risk of surgery in an asymptomatic patient. Sometimes it is patient anxiety and a desire to avoid repeated surveillance that prompts a decision to operate.

How to monitor

The role of surveillance and monitoring is to establish a natural history of the lesion or to allow it to reveal itself to be stable or regressive. Surveillance with serial sonography has shown that most asymptomatic adnexal masses with low risk features will resolve over time. Lack of resolution in the setting of stable findings is not a worrisome feature and is not suggestive of malignancy. The mere persistence of an otherwise benign-appearing lesion is not a reason to intervene with surgery.

Unfortunately, there is no clear guidance on the surveillance intervals. Some experts recommend an initial repeat scan in 3 months. If at that point the morphologic features and size are stable or decreasing, ultrasounds can be repeated at annual intervals for 5 years. In one study, masses that became malignant demonstrated growth by 7 months. Other experts recommend limiting the period of surveillance of cystic lesions to 1 year and lesions with solid components to 2 years.

Conclusions

Many asymptomatic adnexal masses discovered on imaging can be monitored with serial sonography. Lesions with more worrisome morphology that’s suggestive of malignancy should prompt referral to a gynecologic oncologist. Surgery on benign masses can be avoided. Outcome data is needed to advise the optimal timing intervals and the limit of follow-up serial ultrasonography. A caveat of this watch-and-see approach is having to allay the patient’s fears of the malignant potential of the mass. This requires conversations with the patient informing them that the stability of the mass will be shown over time and that surgery can be safely avoided.

References

1. Glanc P et al. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:849-63.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins – Gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128(5):e210-26.

3. Timmerman D et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun;31(6):681-90.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is an associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Adnexal masses are common findings in women. While the decision to operate on symptomatic adnexal masses is straightforward, the decision-making process for asymptomatic masses is more complicated. Here we address how to approach an asymptomatic adnexal mass, including how to decide when to operate, when to refer, or how to monitor.

It is important to minimize the number of surgeries for benign, asymptomatic adnexal masses because complications are reported in 2%-15% of surgeries for adnexal masses and these can range from minimal to devastating.1 In addition, unnecessary surgery is associated with a burden of cost to the health care system. Therefore, there is a paradigm shift in the management of asymptomatic adnexal masses trending toward surveillance of any masses that are likely to be benign. What becomes critical in this approach is the ability to accurately classify these masses preoperatively.

Determining the malignant potential of a mass

Guidance is provided by the ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 174, which was published in 2016: “Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses.”2 These guidelines remind clinicians that:

- Most adnexal masses are benign, even in postmenopausal patients.

- The recommended imaging modality is quality transvaginal ultrasonography with an ultrasonographer accredited through the American Registry of Diagnostic Medical Sonographers.

- Simple cysts up to 10 cm can be monitored using repeat imaging every 6 months without surgical intervention, even in postmenopausal patients. In prospective studies, no cases of malignancy were diagnosed over 6 years of surveillance and most resolved. Those that persist are likely to be serous cystadenomas.

- Many benign lesions such as endometriomas and cystic teratomas have characteristic radiologic features. Surgery for these lesions is warranted for large size, symptoms, or growth in size.

- Ultrasound characteristics of malignant masses include:

1. Cyst size greater than 10 cm

2. Papillary or solid components

3. Septations

4. Internal blood flow on color Doppler.

An alternative approach that has been proposed is an ultrasound scoring system devised by International Ovarian Tumor Analysis Group. The scoring system uses 10 ultrasound findings that are characteristic of malignant and benign and is designed to characterize masses as either benign or malignant.3 This approach is able to correctly classify 77% of masses. The remaining masses with features that do not fit the “simple rules” are considered potentially malignant and should be referred to an oncology specialist for further decision making.

Decision to operate

After referral to gynecologic oncologists, surgery is not always inevitable, particularly for women with indeterminate masses. The gynecologic oncologist uses a decision-making process that factors in the underlying surgical risks for that patient with the likelihood of malignancy based on the features of the mass. The threshold to operate is higher in women with underlying major comorbidities, such as morbid obesity, complex prior surgical history, or cardiopulmonary disease. Healthier surgical candidates are more likely to be considered for a surgery, even if the suspicion for malignancy is lower. However, low surgical risk does not equate to no surgical risk. Therefore, even in apparently “good” surgical candidates, the suspicion for underlying malignancy needs to be reasonably high in order to justify the cost and risk of surgery in an asymptomatic patient. Sometimes it is patient anxiety and a desire to avoid repeated surveillance that prompts a decision to operate.

How to monitor

The role of surveillance and monitoring is to establish a natural history of the lesion or to allow it to reveal itself to be stable or regressive. Surveillance with serial sonography has shown that most asymptomatic adnexal masses with low risk features will resolve over time. Lack of resolution in the setting of stable findings is not a worrisome feature and is not suggestive of malignancy. The mere persistence of an otherwise benign-appearing lesion is not a reason to intervene with surgery.

Unfortunately, there is no clear guidance on the surveillance intervals. Some experts recommend an initial repeat scan in 3 months. If at that point the morphologic features and size are stable or decreasing, ultrasounds can be repeated at annual intervals for 5 years. In one study, masses that became malignant demonstrated growth by 7 months. Other experts recommend limiting the period of surveillance of cystic lesions to 1 year and lesions with solid components to 2 years.

Conclusions

Many asymptomatic adnexal masses discovered on imaging can be monitored with serial sonography. Lesions with more worrisome morphology that’s suggestive of malignancy should prompt referral to a gynecologic oncologist. Surgery on benign masses can be avoided. Outcome data is needed to advise the optimal timing intervals and the limit of follow-up serial ultrasonography. A caveat of this watch-and-see approach is having to allay the patient’s fears of the malignant potential of the mass. This requires conversations with the patient informing them that the stability of the mass will be shown over time and that surgery can be safely avoided.

References

1. Glanc P et al. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:849-63.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins – Gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128(5):e210-26.

3. Timmerman D et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun;31(6):681-90.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is an associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Adnexal masses are common findings in women. While the decision to operate on symptomatic adnexal masses is straightforward, the decision-making process for asymptomatic masses is more complicated. Here we address how to approach an asymptomatic adnexal mass, including how to decide when to operate, when to refer, or how to monitor.

It is important to minimize the number of surgeries for benign, asymptomatic adnexal masses because complications are reported in 2%-15% of surgeries for adnexal masses and these can range from minimal to devastating.1 In addition, unnecessary surgery is associated with a burden of cost to the health care system. Therefore, there is a paradigm shift in the management of asymptomatic adnexal masses trending toward surveillance of any masses that are likely to be benign. What becomes critical in this approach is the ability to accurately classify these masses preoperatively.

Determining the malignant potential of a mass

Guidance is provided by the ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 174, which was published in 2016: “Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses.”2 These guidelines remind clinicians that:

- Most adnexal masses are benign, even in postmenopausal patients.

- The recommended imaging modality is quality transvaginal ultrasonography with an ultrasonographer accredited through the American Registry of Diagnostic Medical Sonographers.

- Simple cysts up to 10 cm can be monitored using repeat imaging every 6 months without surgical intervention, even in postmenopausal patients. In prospective studies, no cases of malignancy were diagnosed over 6 years of surveillance and most resolved. Those that persist are likely to be serous cystadenomas.

- Many benign lesions such as endometriomas and cystic teratomas have characteristic radiologic features. Surgery for these lesions is warranted for large size, symptoms, or growth in size.

- Ultrasound characteristics of malignant masses include:

1. Cyst size greater than 10 cm

2. Papillary or solid components

3. Septations

4. Internal blood flow on color Doppler.

An alternative approach that has been proposed is an ultrasound scoring system devised by International Ovarian Tumor Analysis Group. The scoring system uses 10 ultrasound findings that are characteristic of malignant and benign and is designed to characterize masses as either benign or malignant.3 This approach is able to correctly classify 77% of masses. The remaining masses with features that do not fit the “simple rules” are considered potentially malignant and should be referred to an oncology specialist for further decision making.

Decision to operate

After referral to gynecologic oncologists, surgery is not always inevitable, particularly for women with indeterminate masses. The gynecologic oncologist uses a decision-making process that factors in the underlying surgical risks for that patient with the likelihood of malignancy based on the features of the mass. The threshold to operate is higher in women with underlying major comorbidities, such as morbid obesity, complex prior surgical history, or cardiopulmonary disease. Healthier surgical candidates are more likely to be considered for a surgery, even if the suspicion for malignancy is lower. However, low surgical risk does not equate to no surgical risk. Therefore, even in apparently “good” surgical candidates, the suspicion for underlying malignancy needs to be reasonably high in order to justify the cost and risk of surgery in an asymptomatic patient. Sometimes it is patient anxiety and a desire to avoid repeated surveillance that prompts a decision to operate.

How to monitor

The role of surveillance and monitoring is to establish a natural history of the lesion or to allow it to reveal itself to be stable or regressive. Surveillance with serial sonography has shown that most asymptomatic adnexal masses with low risk features will resolve over time. Lack of resolution in the setting of stable findings is not a worrisome feature and is not suggestive of malignancy. The mere persistence of an otherwise benign-appearing lesion is not a reason to intervene with surgery.

Unfortunately, there is no clear guidance on the surveillance intervals. Some experts recommend an initial repeat scan in 3 months. If at that point the morphologic features and size are stable or decreasing, ultrasounds can be repeated at annual intervals for 5 years. In one study, masses that became malignant demonstrated growth by 7 months. Other experts recommend limiting the period of surveillance of cystic lesions to 1 year and lesions with solid components to 2 years.

Conclusions

Many asymptomatic adnexal masses discovered on imaging can be monitored with serial sonography. Lesions with more worrisome morphology that’s suggestive of malignancy should prompt referral to a gynecologic oncologist. Surgery on benign masses can be avoided. Outcome data is needed to advise the optimal timing intervals and the limit of follow-up serial ultrasonography. A caveat of this watch-and-see approach is having to allay the patient’s fears of the malignant potential of the mass. This requires conversations with the patient informing them that the stability of the mass will be shown over time and that surgery can be safely avoided.

References

1. Glanc P et al. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:849-63.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins – Gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128(5):e210-26.

3. Timmerman D et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun;31(6):681-90.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is an associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Influenza vaccination of pregnant women needs surveillance

Seasonal influenza vaccine is specifically recommended for women who are or who might become pregnant in the flu season. This special population is targeted for vaccination because pregnant women are at increased risks of serious complications if infected with influenza virus. Despite this recommendation, recent evidence indicates that still fewer than 50% of women in the United States are vaccinated during pregnancy (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Dec 9;65[48]:1370-3).

Potential reasons for this lack of uptake are concerns about safety of the vaccine for mothers and fetuses (Vaccine. 2012 Dec 17;31[1]:213-8). This has highlighted the need for systematic safety surveillance for influenza vaccination with each subsequent seasonal formulation. To that end, season-specific studies of birth and infant outcomes since the 2009 season have been conducted; findings have been generally reassuring (Vaccine. 2016 Aug 17;34[37]:4443-9; Vaccine. 2016 Aug 17;34[37]:4450-9).

The authors found a doubling of risk for spontaneous abortion within that 28-day exposure window, but no association if the vaccination took place outside that period. This was in contrast to null findings for a similar analysis that the same group had conducted for vaccination in the 2005-2006 and 2006-2007 seasons. Of further interest, the authors noted even higher risks among women who had also been vaccinated for influenza in the previous season (adjusted odds ratio, 7.7; 95% confidence interval, 2.2-27.3). The highest odds ratios were among women who had been vaccinated in the 2010-2011 season and had also been vaccinated with monovalent pandemic H1N1 vaccine in the 2009-2010 season (aOR, 32.5; 95% CI, 2.9-359.0).

The VSD findings raise interesting questions about the biologic plausibility of strain-specific risks for spontaneous abortion, and risks of receiving a second vaccine containing the same strain in a subsequent season. However, this study should be interpreted with caution. With respect to the overall finding of a doubling of risk for spontaneous abortion, this is inconsistent with previous studies. A systematic review of 19 observational studies, 14 of which included exposure to the 2009 monovalent pandemic H1N1 strain, noted hazard ratios or odds ratios for spontaneous abortion ranging from 0.45 to 1.23 and 95% confidence intervals that crossed or were below the null (Vaccine. 2015 Apr 27;33[18]:2108-17). More recently, the Vaccines and Medications in Pregnancy Surveillance System investigators evaluated spontaneous abortion in pregnancies exposed to influenza vaccine over four seasons from 2010 to 2014 and found an overall hazard ratio of 1.09 (95% CI, 0.49-2.40).

However, there are a number of limitations that must be considered. Many previous studies, including the VSD analysis, could have had misclassification of exposure, especially in recent years when vaccines are often received in nontraditional settings. The VSD study findings could have been influenced by unmeasured confounding. For example, there could be differential vaccine uptake in women with comorbidities that are also associated with spontaneous abortion, such as subfertility and psychiatric disorders.

In summary, at present the data viewed as a whole do not support a change to the current recommendation that pregnant women be vaccinated for influenza regardless of trimester. However, these data do call for continued surveillance for the safety of each seasonal formulation of influenza vaccine, and for further exploration of the association between repeat vaccination and spontaneous abortion in other datasets.

Dr. Chambers is professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is also director of MotherToBaby California, a past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society. She has no direct conflicts of interest to disclose, but has received grant funding to study influenza vaccine from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) in the Department of Health and Human Services, and from Seqirus Corporation.

Seasonal influenza vaccine is specifically recommended for women who are or who might become pregnant in the flu season. This special population is targeted for vaccination because pregnant women are at increased risks of serious complications if infected with influenza virus. Despite this recommendation, recent evidence indicates that still fewer than 50% of women in the United States are vaccinated during pregnancy (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Dec 9;65[48]:1370-3).

Potential reasons for this lack of uptake are concerns about safety of the vaccine for mothers and fetuses (Vaccine. 2012 Dec 17;31[1]:213-8). This has highlighted the need for systematic safety surveillance for influenza vaccination with each subsequent seasonal formulation. To that end, season-specific studies of birth and infant outcomes since the 2009 season have been conducted; findings have been generally reassuring (Vaccine. 2016 Aug 17;34[37]:4443-9; Vaccine. 2016 Aug 17;34[37]:4450-9).

The authors found a doubling of risk for spontaneous abortion within that 28-day exposure window, but no association if the vaccination took place outside that period. This was in contrast to null findings for a similar analysis that the same group had conducted for vaccination in the 2005-2006 and 2006-2007 seasons. Of further interest, the authors noted even higher risks among women who had also been vaccinated for influenza in the previous season (adjusted odds ratio, 7.7; 95% confidence interval, 2.2-27.3). The highest odds ratios were among women who had been vaccinated in the 2010-2011 season and had also been vaccinated with monovalent pandemic H1N1 vaccine in the 2009-2010 season (aOR, 32.5; 95% CI, 2.9-359.0).

The VSD findings raise interesting questions about the biologic plausibility of strain-specific risks for spontaneous abortion, and risks of receiving a second vaccine containing the same strain in a subsequent season. However, this study should be interpreted with caution. With respect to the overall finding of a doubling of risk for spontaneous abortion, this is inconsistent with previous studies. A systematic review of 19 observational studies, 14 of which included exposure to the 2009 monovalent pandemic H1N1 strain, noted hazard ratios or odds ratios for spontaneous abortion ranging from 0.45 to 1.23 and 95% confidence intervals that crossed or were below the null (Vaccine. 2015 Apr 27;33[18]:2108-17). More recently, the Vaccines and Medications in Pregnancy Surveillance System investigators evaluated spontaneous abortion in pregnancies exposed to influenza vaccine over four seasons from 2010 to 2014 and found an overall hazard ratio of 1.09 (95% CI, 0.49-2.40).

However, there are a number of limitations that must be considered. Many previous studies, including the VSD analysis, could have had misclassification of exposure, especially in recent years when vaccines are often received in nontraditional settings. The VSD study findings could have been influenced by unmeasured confounding. For example, there could be differential vaccine uptake in women with comorbidities that are also associated with spontaneous abortion, such as subfertility and psychiatric disorders.

In summary, at present the data viewed as a whole do not support a change to the current recommendation that pregnant women be vaccinated for influenza regardless of trimester. However, these data do call for continued surveillance for the safety of each seasonal formulation of influenza vaccine, and for further exploration of the association between repeat vaccination and spontaneous abortion in other datasets.

Dr. Chambers is professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is also director of MotherToBaby California, a past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society. She has no direct conflicts of interest to disclose, but has received grant funding to study influenza vaccine from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) in the Department of Health and Human Services, and from Seqirus Corporation.

Seasonal influenza vaccine is specifically recommended for women who are or who might become pregnant in the flu season. This special population is targeted for vaccination because pregnant women are at increased risks of serious complications if infected with influenza virus. Despite this recommendation, recent evidence indicates that still fewer than 50% of women in the United States are vaccinated during pregnancy (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Dec 9;65[48]:1370-3).

Potential reasons for this lack of uptake are concerns about safety of the vaccine for mothers and fetuses (Vaccine. 2012 Dec 17;31[1]:213-8). This has highlighted the need for systematic safety surveillance for influenza vaccination with each subsequent seasonal formulation. To that end, season-specific studies of birth and infant outcomes since the 2009 season have been conducted; findings have been generally reassuring (Vaccine. 2016 Aug 17;34[37]:4443-9; Vaccine. 2016 Aug 17;34[37]:4450-9).

The authors found a doubling of risk for spontaneous abortion within that 28-day exposure window, but no association if the vaccination took place outside that period. This was in contrast to null findings for a similar analysis that the same group had conducted for vaccination in the 2005-2006 and 2006-2007 seasons. Of further interest, the authors noted even higher risks among women who had also been vaccinated for influenza in the previous season (adjusted odds ratio, 7.7; 95% confidence interval, 2.2-27.3). The highest odds ratios were among women who had been vaccinated in the 2010-2011 season and had also been vaccinated with monovalent pandemic H1N1 vaccine in the 2009-2010 season (aOR, 32.5; 95% CI, 2.9-359.0).

The VSD findings raise interesting questions about the biologic plausibility of strain-specific risks for spontaneous abortion, and risks of receiving a second vaccine containing the same strain in a subsequent season. However, this study should be interpreted with caution. With respect to the overall finding of a doubling of risk for spontaneous abortion, this is inconsistent with previous studies. A systematic review of 19 observational studies, 14 of which included exposure to the 2009 monovalent pandemic H1N1 strain, noted hazard ratios or odds ratios for spontaneous abortion ranging from 0.45 to 1.23 and 95% confidence intervals that crossed or were below the null (Vaccine. 2015 Apr 27;33[18]:2108-17). More recently, the Vaccines and Medications in Pregnancy Surveillance System investigators evaluated spontaneous abortion in pregnancies exposed to influenza vaccine over four seasons from 2010 to 2014 and found an overall hazard ratio of 1.09 (95% CI, 0.49-2.40).

However, there are a number of limitations that must be considered. Many previous studies, including the VSD analysis, could have had misclassification of exposure, especially in recent years when vaccines are often received in nontraditional settings. The VSD study findings could have been influenced by unmeasured confounding. For example, there could be differential vaccine uptake in women with comorbidities that are also associated with spontaneous abortion, such as subfertility and psychiatric disorders.

In summary, at present the data viewed as a whole do not support a change to the current recommendation that pregnant women be vaccinated for influenza regardless of trimester. However, these data do call for continued surveillance for the safety of each seasonal formulation of influenza vaccine, and for further exploration of the association between repeat vaccination and spontaneous abortion in other datasets.

Dr. Chambers is professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is also director of MotherToBaby California, a past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society. She has no direct conflicts of interest to disclose, but has received grant funding to study influenza vaccine from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) in the Department of Health and Human Services, and from Seqirus Corporation.

Families are essential partners in treating substance use disorders

Addiction used to be considered a moral failing, and the family was blamed for keeping the relative with addictions sick, through behaviors labeled “codependency” and “enabling.” The opioid epidemic can take credit for putting a serious dent in these destructive and stigmatizing notions. When psychiatrists actively include families as educated treatment partners, fatalities are less likely, and the havoc created by addiction on families is mitigated.

Genes and addiction

What causes addiction? Statistics show that Native Americans fare the worst of all minority groups, with death by opiates in whites and Native Americans double or triple the rates of African Americans and Latinos. Reasons put forward for Native American deaths are their vulnerability related to systemic racism, intergenerational trauma, and lack of access to health care. These “reasons” are well known to contribute to poor overall health status of impoverished communities.

Among impoverished white communities, the Monongahela Valley of Pennsylvania has been studied by Katherine McLean, PhD, as an example of postindustrial decay (Int J Drug Policy. 2016;[29]:19-26). Once a global center of steel production, the exodus of jobs, residents, and businesses since the early 1980s is thought to contribute to the high numbers of opioid deaths. A qualitative study of the people with addiction in the deteriorating mill city of McKeesport, Pa., characterized a risk environment hidden behind closed doors, and populated by unprepared, ambivalent overdose “assistants.” These people are “co-drug” users who themselves are reluctant to step forward because of fear of getting in trouble. The participants described the hopelessness and lack of opportunity as driving the use of heroin, with many stating that jobs and community reinvestment are needed to reduce fatalities. This certainly resonates with the Native American experience.

People with the AA variant of OXTR also have been shown to have less secure adult attachment and more social anxiety (World J Biol Psychiatry. 2016;17[1]:76-83). Comparing people with OXTR variants, the AA genotype was associated with a perceived negative social environment and significantly increased PTSD symptoms, whereas the GG genotype was protective.

However, for many decades, psychological theories about the defects of individuals and their moral failing have prevailed. In the family, aspersions have been cast on the family’s deficits in terms of setting limits and their enabling behaviors, mostly focusing on wives and mothers. The social mantra has been that since not all people get addicted, the strong resist and the weak succumb. Psychiatry has focused on providing psychotherapy to correct the personal deficits of the weak and addicted and, from a family perspective, on correcting negative personality traits in the caregivers, classified as codependency.

Roots of codependency