User login

Intimate partner violence: Assessment in the era of telehealth

Intimate partner violence (IPV) includes “physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression (including coercive tactics) by a current or former intimate partner.”1

Ensure a safe environment

At the onset of a telehealth appointment, ask the patient “Who is in the room with you?” If an adult or child age >2 years is present, do not assess for IPV because it may be unsafe for the patient to answer such questions. Encourage the patient to use privacy-enhancing strategies (eg, wearing headphones, going outside, calling from a vehicle). Be flexible; someone may not be able to discuss IPV during an appointment but might be able to at a different time, such as when their partner goes to work. For patients who disclose IPV, identify a word, phrase, or gesture to quickly communicate their partner’s presence or need for immediate help.2 While the “Signal for Help” (ie, thumb first tucked into the palm, then covered with fingers to form a fist) has been developed,3 it is not universally familiar; until then, establish specific communications and preferences with each patient. Include a plan for the patient to abruptly disconnect (eg, “You have the wrong number”) with a pre-determined method of follow-up.

Obtain informed consent

Before asking a patient about IPV, provide psychoeducation about the purpose, including its relationship to one’s health. Acknowledge reasons it may not be safe to provide and/or document answers, and describe limits of confidentiality and local mandated reporting requirements.

Standardize the assessment

Intimate partner violence assessment should be normalized (eg, “Because violence is common, I ask everyone about their relationships”), direct, and well-integrated. Know whether your site uses a specific IPV screening tool, such as the Relationship Health and Safety Screen (RHSS), which is used at the VA; if so, learn and practice asking the specific questions aloud until it feels routine and you can maintain eye contact throughout. Examples of other IPV assessment instruments include the Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS); Hurt, Insult, Threaten, and Scream (HITS), Partner Violence Screen (PVS), and Women Abuse Screening Tool (WAST).4 Pay attention to the populations in which a tool has been studied, any associated copyright fees, and gender-neutral and non-heteronormative language. Avoid asking leading questions (eg, “You’re not being hurt, are you?”) or using charged/interpretable terms (eg, “Is someone abusing you?”).

Document with intention

Use person-centered, recovery-oriented language (eg, someone who experiences or uses IPV) rather than stigmatizing language (eg, victim, batterer, abuser). Describe what happened using the individual’s own words and clearly identify the source of information, witnesses, and any weapons used. Choose nonpejorative language (ie, “states” instead of “claims”). Do not document details of the safety plan in the chart because doing so can compromise safety.

Provide resources and referrals

Regardless of whether a patient consents to screening/documentation or discloses IPV, you should offer universal education, resources, and referrals. Review national contacts (National Domestic Violence Hotline: 1-800-799-7233), community agencies (available through www.domesticshelters.org), and suggested safety apps such as myPlan (www.myplanapp.org), but do not send a patient electronic or physical materials without first confirming it is safe to do so. Assess the patient’s interest in legal steps (eg, obtaining a protection order, pressing charges) while recognizing and respecting valid concerns about law enforcement involvement, particularly among the Black community and Black transgender women. Provide options instead of instructions, which will empower patients to choose what is best for their situation, and support their decisions.

1. Breiding MJ, Chen J, Black MC. Intimate partner violence in the United States – 2010. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published February 2014. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/cdc_nisvs_ipv_report_2013_v17_single_a.pdf

2. Evans ML, Lindauer JD, Farrell ME. A pandemic within a pandemic – intimate partner violence during Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(24):2302-2304. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2024046

3. Canadian Women’s Foundation. Signal for help. 2020. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://canadianwomen.org/signal-for-help/

4. Basile KC, Hertz MF, Back SE. Intimate partner violence and sexual violence victimization assessment instruments for use in healthcare settings: Version 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 2007. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv/ipvandsvscreening.pdf

Intimate partner violence (IPV) includes “physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression (including coercive tactics) by a current or former intimate partner.”1

Ensure a safe environment

At the onset of a telehealth appointment, ask the patient “Who is in the room with you?” If an adult or child age >2 years is present, do not assess for IPV because it may be unsafe for the patient to answer such questions. Encourage the patient to use privacy-enhancing strategies (eg, wearing headphones, going outside, calling from a vehicle). Be flexible; someone may not be able to discuss IPV during an appointment but might be able to at a different time, such as when their partner goes to work. For patients who disclose IPV, identify a word, phrase, or gesture to quickly communicate their partner’s presence or need for immediate help.2 While the “Signal for Help” (ie, thumb first tucked into the palm, then covered with fingers to form a fist) has been developed,3 it is not universally familiar; until then, establish specific communications and preferences with each patient. Include a plan for the patient to abruptly disconnect (eg, “You have the wrong number”) with a pre-determined method of follow-up.

Obtain informed consent

Before asking a patient about IPV, provide psychoeducation about the purpose, including its relationship to one’s health. Acknowledge reasons it may not be safe to provide and/or document answers, and describe limits of confidentiality and local mandated reporting requirements.

Standardize the assessment

Intimate partner violence assessment should be normalized (eg, “Because violence is common, I ask everyone about their relationships”), direct, and well-integrated. Know whether your site uses a specific IPV screening tool, such as the Relationship Health and Safety Screen (RHSS), which is used at the VA; if so, learn and practice asking the specific questions aloud until it feels routine and you can maintain eye contact throughout. Examples of other IPV assessment instruments include the Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS); Hurt, Insult, Threaten, and Scream (HITS), Partner Violence Screen (PVS), and Women Abuse Screening Tool (WAST).4 Pay attention to the populations in which a tool has been studied, any associated copyright fees, and gender-neutral and non-heteronormative language. Avoid asking leading questions (eg, “You’re not being hurt, are you?”) or using charged/interpretable terms (eg, “Is someone abusing you?”).

Document with intention

Use person-centered, recovery-oriented language (eg, someone who experiences or uses IPV) rather than stigmatizing language (eg, victim, batterer, abuser). Describe what happened using the individual’s own words and clearly identify the source of information, witnesses, and any weapons used. Choose nonpejorative language (ie, “states” instead of “claims”). Do not document details of the safety plan in the chart because doing so can compromise safety.

Provide resources and referrals

Regardless of whether a patient consents to screening/documentation or discloses IPV, you should offer universal education, resources, and referrals. Review national contacts (National Domestic Violence Hotline: 1-800-799-7233), community agencies (available through www.domesticshelters.org), and suggested safety apps such as myPlan (www.myplanapp.org), but do not send a patient electronic or physical materials without first confirming it is safe to do so. Assess the patient’s interest in legal steps (eg, obtaining a protection order, pressing charges) while recognizing and respecting valid concerns about law enforcement involvement, particularly among the Black community and Black transgender women. Provide options instead of instructions, which will empower patients to choose what is best for their situation, and support their decisions.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) includes “physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression (including coercive tactics) by a current or former intimate partner.”1

Ensure a safe environment

At the onset of a telehealth appointment, ask the patient “Who is in the room with you?” If an adult or child age >2 years is present, do not assess for IPV because it may be unsafe for the patient to answer such questions. Encourage the patient to use privacy-enhancing strategies (eg, wearing headphones, going outside, calling from a vehicle). Be flexible; someone may not be able to discuss IPV during an appointment but might be able to at a different time, such as when their partner goes to work. For patients who disclose IPV, identify a word, phrase, or gesture to quickly communicate their partner’s presence or need for immediate help.2 While the “Signal for Help” (ie, thumb first tucked into the palm, then covered with fingers to form a fist) has been developed,3 it is not universally familiar; until then, establish specific communications and preferences with each patient. Include a plan for the patient to abruptly disconnect (eg, “You have the wrong number”) with a pre-determined method of follow-up.

Obtain informed consent

Before asking a patient about IPV, provide psychoeducation about the purpose, including its relationship to one’s health. Acknowledge reasons it may not be safe to provide and/or document answers, and describe limits of confidentiality and local mandated reporting requirements.

Standardize the assessment

Intimate partner violence assessment should be normalized (eg, “Because violence is common, I ask everyone about their relationships”), direct, and well-integrated. Know whether your site uses a specific IPV screening tool, such as the Relationship Health and Safety Screen (RHSS), which is used at the VA; if so, learn and practice asking the specific questions aloud until it feels routine and you can maintain eye contact throughout. Examples of other IPV assessment instruments include the Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS); Hurt, Insult, Threaten, and Scream (HITS), Partner Violence Screen (PVS), and Women Abuse Screening Tool (WAST).4 Pay attention to the populations in which a tool has been studied, any associated copyright fees, and gender-neutral and non-heteronormative language. Avoid asking leading questions (eg, “You’re not being hurt, are you?”) or using charged/interpretable terms (eg, “Is someone abusing you?”).

Document with intention

Use person-centered, recovery-oriented language (eg, someone who experiences or uses IPV) rather than stigmatizing language (eg, victim, batterer, abuser). Describe what happened using the individual’s own words and clearly identify the source of information, witnesses, and any weapons used. Choose nonpejorative language (ie, “states” instead of “claims”). Do not document details of the safety plan in the chart because doing so can compromise safety.

Provide resources and referrals

Regardless of whether a patient consents to screening/documentation or discloses IPV, you should offer universal education, resources, and referrals. Review national contacts (National Domestic Violence Hotline: 1-800-799-7233), community agencies (available through www.domesticshelters.org), and suggested safety apps such as myPlan (www.myplanapp.org), but do not send a patient electronic or physical materials without first confirming it is safe to do so. Assess the patient’s interest in legal steps (eg, obtaining a protection order, pressing charges) while recognizing and respecting valid concerns about law enforcement involvement, particularly among the Black community and Black transgender women. Provide options instead of instructions, which will empower patients to choose what is best for their situation, and support their decisions.

1. Breiding MJ, Chen J, Black MC. Intimate partner violence in the United States – 2010. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published February 2014. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/cdc_nisvs_ipv_report_2013_v17_single_a.pdf

2. Evans ML, Lindauer JD, Farrell ME. A pandemic within a pandemic – intimate partner violence during Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(24):2302-2304. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2024046

3. Canadian Women’s Foundation. Signal for help. 2020. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://canadianwomen.org/signal-for-help/

4. Basile KC, Hertz MF, Back SE. Intimate partner violence and sexual violence victimization assessment instruments for use in healthcare settings: Version 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 2007. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv/ipvandsvscreening.pdf

1. Breiding MJ, Chen J, Black MC. Intimate partner violence in the United States – 2010. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published February 2014. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/cdc_nisvs_ipv_report_2013_v17_single_a.pdf

2. Evans ML, Lindauer JD, Farrell ME. A pandemic within a pandemic – intimate partner violence during Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(24):2302-2304. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2024046

3. Canadian Women’s Foundation. Signal for help. 2020. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://canadianwomen.org/signal-for-help/

4. Basile KC, Hertz MF, Back SE. Intimate partner violence and sexual violence victimization assessment instruments for use in healthcare settings: Version 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 2007. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv/ipvandsvscreening.pdf

Treating major depressive disorder after limited response to an initial agent

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are commonly used first-line agents for treating major depressive disorder. Less than one-half of patients with major depressive disorder experience remission after 1 acute trial of an antidepressant.1 After optimization of an initial agent’s dose and duration, potential next steps include switching agents or augmentation. Augmentation strategies may lead to clinical improvement but carry the risks of polypharmacy, including increased risk of adverse effects and drug interactions. Clinicians can consider the following evidence-based options for a patient with a limited response to an initial SSRI or SNRI.

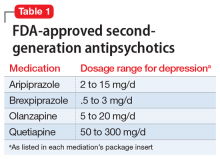

Second-generation antipsychotics, when used as augmentation agents to treat a patient with major depressive disorder, can lead to an approximately 10% improvement in remission rate compared with placebo.2 Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, olanzapine (in combination with fluoxetine only), and quetiapine are FDA-approved as adjunctive therapies with an antidepressant (Table 1). Second-generation antipsychotics should be started at lower doses than those used for schizophrenia, and these agents have an increased risk of metabolic adverse effects as well as extrapyramidal symptoms.

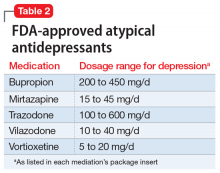

Atypical antidepressants are those that are not classified as an SSRI, SNRI, tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), or monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI). These include bupropion, mirtazapine, trazodone, vilazodone, and vortioxetine (Table 2). Bupropion is a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. When used for augmentation in clinical studies, it led to a 30% remission rate.3 Mirtazapine is an alpha-2 antagonist that can be used as monotherapy or in combination with another antidepressant.4 Trazodone is an antidepressant with activity at histamine and alpha-1-adrenergic receptors that is often used off-label for insomnia. Trazodone can be used safely and effectively in combination with other agents for treatment-resistant depression.5 Vilazodone is a 5-HT1A partial agonist, and vortioxetine is a 5-HT1A agonist and 5-HT3 antagonist; both are FDA-approved as alternative agents for monotherapy for major depressive disorder. Choosing among these agents for switching or augmenting can be guided by patient preference, adverse effect profile, and targeting specific symptoms, such as using mirtazapine to address poor sleep and appetite.

Lithium augmentation has been frequently investigated in placebo-controlled, double-blind studies. A meta-analysis showed that patients receiving lithium augmentation with a serum level of ≥0.5 mEq/L were >3 times more likely to respond than those receiving placebo.6 When lithium is used to treat bipolar disorder, the therapeutic serum range for lithium is 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L, with an increased risk of adverse effects (including toxicity) at higher levels.7

Triiodothyronine (T3) augmentation of antidepressants led to remission in approximately 1 in 4 patients who had not achieved remission or who were intolerant to an initial treatment with citalopram and a second switch or augmentation trial.8 In this study, the mean dose of T3 was 45.2 µg/d, with an average length of treatment of 9 weeks.

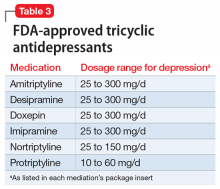

Tricyclic antidepressants are another option when considering switching agents (Table 3). TCAs are additionally effective for comorbid pain conditions.9 When TCAs are used in combination with SSRIs, drug interactions may occur that increase TCA plasma levels. There is also an increased risk of serotonin syndrome when used with serotonergic agents, though an SSRI/ TCA combination may be appropriate for a patient with treatment-resistant depression.10 Additionally, TCAs carry unique risks of cardiovascular effects, including cardiac arrhythmias. A meta-analysis comparing fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline to TCAs (amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine, doxepin, imipramine, and nortriptyline) concluded that both classes had similar efficacy in treating depression, though the drop-out rate was significantly higher among patients receiving TCAs.11

Buspirone is approved for generalized anxiety disorder. In studies where buspirone was used as an augmentation agent for major depressive disorder at a mean daily dose of 40.9 mg divided into 2 doses, it led to a remission rate >30%.3

Continue to: Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

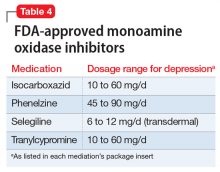

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors should typically be avoided in initial or early treatment of depression due to tolerability issues, drug interactions, and dietary restrictions to avoid hypertensive crisis. MAOIs are generally not recommended to be used with SSRIs, SNRIs, or TCAs, and typically require a “washout” period from other antidepressants (Table 4). One review found that MAOI treatment had advantage over TCA treatment for patients with early-stage treatment-resistant depression, though this advantage decreased as the number of failed antidepressant trials increased.12 One MAOI, selegiline, is available in a transdermal patch, and the 6-mg patch does not require dietary restriction.

Esketamine (intranasal) is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression (failure of response after at least 2 antidepressant trials with adequate dose and duration) in conjunction with an oral antidepressant. In clinical studies, a significant response was noted after 1 week of treatment.13 Esketamine requires an induction period of twice-weekly doses of 56 or 84 mg, with maintenance doses every 1 to 2 weeks. Each dosage administration requires monitoring for at least 2 hours by a health care professional at a certified treatment center. Esketamine’s indication was recently expanded to include treatment of patients with major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation or behavior.

Stimulants such as amphetamines, methylphenidate, or modafinil have been effective in open studies for augmentation in depression.14 However, no stimulant is FDA-approved for the treatment of depression. In addition to other adverse effects, these medications are controlled substances and carry risk of misuse, and their use may not be appropriate for all patients.

1. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40.

2. Kato M, Chang CM. Augmentation treatments with second-generation antipsychotics to antidepressants in treatment-resistant depression. CNS Drugs. 2013;27 Suppl 1:S11-S19.

3. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1243-1252.

4. Carpenter LL, Jocic Z, Hall JM, et al. Mirtazapine augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(1):45-49.

5. Maes M, Vandoolaeghe E, Desnyder R. Efficacy of treatment with trazodone in combination with pindolol or fluoxetine in major depression. J Affect Disord. 1996;41(3):201-210.

6. Bauer M, Dopfmer S. Lithium augmentation in treatment-resistant depression: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(5):427-434.

7. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170.

8. Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, et al. A comparison of lithium and T(3) augmentation following two failed medication treatments for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1519-1530; quiz 1665.

9. Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;17(4):CD005454.

10. Taylor D. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants in combination. Interactions and therapeutic uses. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(5):575-580.

11. Steffens DC, Krishnan KR, Helms MJ. Are SSRIs better than TCAs? Comparison of SSRIs and TCAs: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 1997;6(1):10-18.

12. Kim T, Xu C, Amsterdam JD. Relative effectiveness of tricyclic antidepressant versus monoamine oxidase inhibitor monotherapy for treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;250:199-203.

13. Daly EJ, Singh JB, Fedgchin M, et al. Efficacy and safety of intranasal esketamine adjunctive to oral antidepressant therapy in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):139-148.

14. DeBattista C. Augmentation and combination strategies for depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(3 Suppl):11-18.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are commonly used first-line agents for treating major depressive disorder. Less than one-half of patients with major depressive disorder experience remission after 1 acute trial of an antidepressant.1 After optimization of an initial agent’s dose and duration, potential next steps include switching agents or augmentation. Augmentation strategies may lead to clinical improvement but carry the risks of polypharmacy, including increased risk of adverse effects and drug interactions. Clinicians can consider the following evidence-based options for a patient with a limited response to an initial SSRI or SNRI.

Second-generation antipsychotics, when used as augmentation agents to treat a patient with major depressive disorder, can lead to an approximately 10% improvement in remission rate compared with placebo.2 Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, olanzapine (in combination with fluoxetine only), and quetiapine are FDA-approved as adjunctive therapies with an antidepressant (Table 1). Second-generation antipsychotics should be started at lower doses than those used for schizophrenia, and these agents have an increased risk of metabolic adverse effects as well as extrapyramidal symptoms.

Atypical antidepressants are those that are not classified as an SSRI, SNRI, tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), or monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI). These include bupropion, mirtazapine, trazodone, vilazodone, and vortioxetine (Table 2). Bupropion is a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. When used for augmentation in clinical studies, it led to a 30% remission rate.3 Mirtazapine is an alpha-2 antagonist that can be used as monotherapy or in combination with another antidepressant.4 Trazodone is an antidepressant with activity at histamine and alpha-1-adrenergic receptors that is often used off-label for insomnia. Trazodone can be used safely and effectively in combination with other agents for treatment-resistant depression.5 Vilazodone is a 5-HT1A partial agonist, and vortioxetine is a 5-HT1A agonist and 5-HT3 antagonist; both are FDA-approved as alternative agents for monotherapy for major depressive disorder. Choosing among these agents for switching or augmenting can be guided by patient preference, adverse effect profile, and targeting specific symptoms, such as using mirtazapine to address poor sleep and appetite.

Lithium augmentation has been frequently investigated in placebo-controlled, double-blind studies. A meta-analysis showed that patients receiving lithium augmentation with a serum level of ≥0.5 mEq/L were >3 times more likely to respond than those receiving placebo.6 When lithium is used to treat bipolar disorder, the therapeutic serum range for lithium is 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L, with an increased risk of adverse effects (including toxicity) at higher levels.7

Triiodothyronine (T3) augmentation of antidepressants led to remission in approximately 1 in 4 patients who had not achieved remission or who were intolerant to an initial treatment with citalopram and a second switch or augmentation trial.8 In this study, the mean dose of T3 was 45.2 µg/d, with an average length of treatment of 9 weeks.

Tricyclic antidepressants are another option when considering switching agents (Table 3). TCAs are additionally effective for comorbid pain conditions.9 When TCAs are used in combination with SSRIs, drug interactions may occur that increase TCA plasma levels. There is also an increased risk of serotonin syndrome when used with serotonergic agents, though an SSRI/ TCA combination may be appropriate for a patient with treatment-resistant depression.10 Additionally, TCAs carry unique risks of cardiovascular effects, including cardiac arrhythmias. A meta-analysis comparing fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline to TCAs (amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine, doxepin, imipramine, and nortriptyline) concluded that both classes had similar efficacy in treating depression, though the drop-out rate was significantly higher among patients receiving TCAs.11

Buspirone is approved for generalized anxiety disorder. In studies where buspirone was used as an augmentation agent for major depressive disorder at a mean daily dose of 40.9 mg divided into 2 doses, it led to a remission rate >30%.3

Continue to: Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors should typically be avoided in initial or early treatment of depression due to tolerability issues, drug interactions, and dietary restrictions to avoid hypertensive crisis. MAOIs are generally not recommended to be used with SSRIs, SNRIs, or TCAs, and typically require a “washout” period from other antidepressants (Table 4). One review found that MAOI treatment had advantage over TCA treatment for patients with early-stage treatment-resistant depression, though this advantage decreased as the number of failed antidepressant trials increased.12 One MAOI, selegiline, is available in a transdermal patch, and the 6-mg patch does not require dietary restriction.

Esketamine (intranasal) is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression (failure of response after at least 2 antidepressant trials with adequate dose and duration) in conjunction with an oral antidepressant. In clinical studies, a significant response was noted after 1 week of treatment.13 Esketamine requires an induction period of twice-weekly doses of 56 or 84 mg, with maintenance doses every 1 to 2 weeks. Each dosage administration requires monitoring for at least 2 hours by a health care professional at a certified treatment center. Esketamine’s indication was recently expanded to include treatment of patients with major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation or behavior.

Stimulants such as amphetamines, methylphenidate, or modafinil have been effective in open studies for augmentation in depression.14 However, no stimulant is FDA-approved for the treatment of depression. In addition to other adverse effects, these medications are controlled substances and carry risk of misuse, and their use may not be appropriate for all patients.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are commonly used first-line agents for treating major depressive disorder. Less than one-half of patients with major depressive disorder experience remission after 1 acute trial of an antidepressant.1 After optimization of an initial agent’s dose and duration, potential next steps include switching agents or augmentation. Augmentation strategies may lead to clinical improvement but carry the risks of polypharmacy, including increased risk of adverse effects and drug interactions. Clinicians can consider the following evidence-based options for a patient with a limited response to an initial SSRI or SNRI.

Second-generation antipsychotics, when used as augmentation agents to treat a patient with major depressive disorder, can lead to an approximately 10% improvement in remission rate compared with placebo.2 Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, olanzapine (in combination with fluoxetine only), and quetiapine are FDA-approved as adjunctive therapies with an antidepressant (Table 1). Second-generation antipsychotics should be started at lower doses than those used for schizophrenia, and these agents have an increased risk of metabolic adverse effects as well as extrapyramidal symptoms.

Atypical antidepressants are those that are not classified as an SSRI, SNRI, tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), or monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI). These include bupropion, mirtazapine, trazodone, vilazodone, and vortioxetine (Table 2). Bupropion is a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. When used for augmentation in clinical studies, it led to a 30% remission rate.3 Mirtazapine is an alpha-2 antagonist that can be used as monotherapy or in combination with another antidepressant.4 Trazodone is an antidepressant with activity at histamine and alpha-1-adrenergic receptors that is often used off-label for insomnia. Trazodone can be used safely and effectively in combination with other agents for treatment-resistant depression.5 Vilazodone is a 5-HT1A partial agonist, and vortioxetine is a 5-HT1A agonist and 5-HT3 antagonist; both are FDA-approved as alternative agents for monotherapy for major depressive disorder. Choosing among these agents for switching or augmenting can be guided by patient preference, adverse effect profile, and targeting specific symptoms, such as using mirtazapine to address poor sleep and appetite.

Lithium augmentation has been frequently investigated in placebo-controlled, double-blind studies. A meta-analysis showed that patients receiving lithium augmentation with a serum level of ≥0.5 mEq/L were >3 times more likely to respond than those receiving placebo.6 When lithium is used to treat bipolar disorder, the therapeutic serum range for lithium is 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L, with an increased risk of adverse effects (including toxicity) at higher levels.7

Triiodothyronine (T3) augmentation of antidepressants led to remission in approximately 1 in 4 patients who had not achieved remission or who were intolerant to an initial treatment with citalopram and a second switch or augmentation trial.8 In this study, the mean dose of T3 was 45.2 µg/d, with an average length of treatment of 9 weeks.

Tricyclic antidepressants are another option when considering switching agents (Table 3). TCAs are additionally effective for comorbid pain conditions.9 When TCAs are used in combination with SSRIs, drug interactions may occur that increase TCA plasma levels. There is also an increased risk of serotonin syndrome when used with serotonergic agents, though an SSRI/ TCA combination may be appropriate for a patient with treatment-resistant depression.10 Additionally, TCAs carry unique risks of cardiovascular effects, including cardiac arrhythmias. A meta-analysis comparing fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline to TCAs (amitriptyline, clomipramine, desipramine, doxepin, imipramine, and nortriptyline) concluded that both classes had similar efficacy in treating depression, though the drop-out rate was significantly higher among patients receiving TCAs.11

Buspirone is approved for generalized anxiety disorder. In studies where buspirone was used as an augmentation agent for major depressive disorder at a mean daily dose of 40.9 mg divided into 2 doses, it led to a remission rate >30%.3

Continue to: Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors should typically be avoided in initial or early treatment of depression due to tolerability issues, drug interactions, and dietary restrictions to avoid hypertensive crisis. MAOIs are generally not recommended to be used with SSRIs, SNRIs, or TCAs, and typically require a “washout” period from other antidepressants (Table 4). One review found that MAOI treatment had advantage over TCA treatment for patients with early-stage treatment-resistant depression, though this advantage decreased as the number of failed antidepressant trials increased.12 One MAOI, selegiline, is available in a transdermal patch, and the 6-mg patch does not require dietary restriction.

Esketamine (intranasal) is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression (failure of response after at least 2 antidepressant trials with adequate dose and duration) in conjunction with an oral antidepressant. In clinical studies, a significant response was noted after 1 week of treatment.13 Esketamine requires an induction period of twice-weekly doses of 56 or 84 mg, with maintenance doses every 1 to 2 weeks. Each dosage administration requires monitoring for at least 2 hours by a health care professional at a certified treatment center. Esketamine’s indication was recently expanded to include treatment of patients with major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation or behavior.

Stimulants such as amphetamines, methylphenidate, or modafinil have been effective in open studies for augmentation in depression.14 However, no stimulant is FDA-approved for the treatment of depression. In addition to other adverse effects, these medications are controlled substances and carry risk of misuse, and their use may not be appropriate for all patients.

1. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40.

2. Kato M, Chang CM. Augmentation treatments with second-generation antipsychotics to antidepressants in treatment-resistant depression. CNS Drugs. 2013;27 Suppl 1:S11-S19.

3. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1243-1252.

4. Carpenter LL, Jocic Z, Hall JM, et al. Mirtazapine augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(1):45-49.

5. Maes M, Vandoolaeghe E, Desnyder R. Efficacy of treatment with trazodone in combination with pindolol or fluoxetine in major depression. J Affect Disord. 1996;41(3):201-210.

6. Bauer M, Dopfmer S. Lithium augmentation in treatment-resistant depression: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(5):427-434.

7. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170.

8. Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, et al. A comparison of lithium and T(3) augmentation following two failed medication treatments for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1519-1530; quiz 1665.

9. Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;17(4):CD005454.

10. Taylor D. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants in combination. Interactions and therapeutic uses. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(5):575-580.

11. Steffens DC, Krishnan KR, Helms MJ. Are SSRIs better than TCAs? Comparison of SSRIs and TCAs: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 1997;6(1):10-18.

12. Kim T, Xu C, Amsterdam JD. Relative effectiveness of tricyclic antidepressant versus monoamine oxidase inhibitor monotherapy for treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;250:199-203.

13. Daly EJ, Singh JB, Fedgchin M, et al. Efficacy and safety of intranasal esketamine adjunctive to oral antidepressant therapy in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):139-148.

14. DeBattista C. Augmentation and combination strategies for depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(3 Suppl):11-18.

1. Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):28-40.

2. Kato M, Chang CM. Augmentation treatments with second-generation antipsychotics to antidepressants in treatment-resistant depression. CNS Drugs. 2013;27 Suppl 1:S11-S19.

3. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1243-1252.

4. Carpenter LL, Jocic Z, Hall JM, et al. Mirtazapine augmentation in the treatment of refractory depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(1):45-49.

5. Maes M, Vandoolaeghe E, Desnyder R. Efficacy of treatment with trazodone in combination with pindolol or fluoxetine in major depression. J Affect Disord. 1996;41(3):201-210.

6. Bauer M, Dopfmer S. Lithium augmentation in treatment-resistant depression: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(5):427-434.

7. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170.

8. Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, et al. A comparison of lithium and T(3) augmentation following two failed medication treatments for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1519-1530; quiz 1665.

9. Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;17(4):CD005454.

10. Taylor D. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants in combination. Interactions and therapeutic uses. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(5):575-580.

11. Steffens DC, Krishnan KR, Helms MJ. Are SSRIs better than TCAs? Comparison of SSRIs and TCAs: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 1997;6(1):10-18.

12. Kim T, Xu C, Amsterdam JD. Relative effectiveness of tricyclic antidepressant versus monoamine oxidase inhibitor monotherapy for treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;250:199-203.

13. Daly EJ, Singh JB, Fedgchin M, et al. Efficacy and safety of intranasal esketamine adjunctive to oral antidepressant therapy in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):139-148.

14. DeBattista C. Augmentation and combination strategies for depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(3 Suppl):11-18.

Conspiracy theory or delusion? 3 questions to tell them apart

Many psychiatrists conceptualize mental illnesses, including psychotic disorders, across a continuum where their borders can be ambiguous.1 The same can be said of individual symptoms such as delusions, where the line separating clear-cut pathology from nonpathological or subclinical “delusion-like beliefs” is often blurred.2,3 However, the categorical distinction between mental illness and normality is fundamental to diagnostic reliability and crucial to clinical decisions about whether and how to intervene.

Conspiracy theory beliefs are delusion-like beliefs that are commonly encountered within today’s political landscape. Surveys have consistently revealed that approximately one-half of the population believes in at least 1 conspiracy theory, highlighting the normality of such beliefs despite their potential outlandishness.4 Here are 3 questions you can ask to help differentiate conspiracy theory beliefs from delusions.

1. What is the evidence for the belief?

Drawing from Karl Jaspers’ conceptualization of delusions as “impossible” and “unshareable,” the DSM-5 distinguishes delusions from culturally-sanctioned shared beliefs such as religious creeds.3 Whereas delusions often arise out of anomalous subjective experiences, individuals who come to believe in conspiracytheories have typically sought explanations and found them from secondary sources, often on the internet.5 Despite the familiar term “conspiracy theorist,” most who believe in conspiracy theories aren’t so much theorizing as they are adopting counter-narratives based on assimilated information. Unlike delusions, conspiracy theory beliefs are learned, with the “evidence” to support them easily located online.

2. Is the belief self-referential?

The stereotypical unshareability of delusions often hinges upon their self-referential content. For example, while it is easy to find others who believe in the Second Coming, it would be much harder to convince others that you are the Second Coming. Unlike delusions, conspiracy theories are beliefs about the world and explanations of real-life events; their content is rarely, if ever, directly related to the believer.

Conspiracy theory beliefs involve a negation of authoritative accounts that is rooted in “epistemic mistrust” of authoritative sources of information.5 While conspiratorial mistrust has been compared with paranoia, with paranoia found to be associated with belief in conspiracy theories,6 epistemic mistrust encompasses a range of justified cultural mistrust, unwarranted mistrust based on racial prejudice, and subclinical paranoia typical of schizotypy. The more self-referential the underlying paranoia, the more likely an associated belief is to cross the boundary from conspiracy theory to delusion.7

3. Is there overlap?

Conspiracy theory beliefs and delusions are not mutually exclusive. “Gang stalking” offers a vexing example of paranoia that is part shared conspiracy theory, part idiosyncratic delusion.8 Reliably disentangling these components requires identifying the conspiracy theory component as a widely-shared belief about government surveillance, while carefully analyzing the self-referential component to determine credibility and potential delusionality.

1. Pierre JM. The borders of mental disorder in psychiatry and the DSM: past, present, and future. J Psychiatric Practice. 2010;16(6):375-386.

2. Pierre JM. Faith or delusion? At the crossroads of religion and psychosis. J Psychiatr Practice. 2001;7(3):163-172.

3. Pierre JM. Forensic psychiatry versus the varieties of delusion-like belief. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2020;48(3):327-334.

4. Oliver JE, Wood, TJ. Conspiracy theories and the paranoid style(s) of mass opinion. Am J Pol Sci. 2014;58(5);952-966.

5. Pierre JM. Mistrust and misinformation: a two-component, socio-epistemic model of belief in conspiracy theories. J Soc Polit Psychol. 2020;8(2):617-641.

6. Dagnall N, Drinkwater K, Parker A, et al. Conspiracy theory and cognitive style: a worldview. Front Psychol. 2015;6:206.

7. Imhoff R, Lamberty P. How paranoid are conspiracy believers? Toward a more fine-grained understanding of the connect and disconnect between paranoia and belief in conspiracy theories. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2018;48(7):909-926.

8. Sheridan LP, James DV. Complaints of group-stalking (‘gang-stalking’): an exploratory study of their natures and impact on complainants. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2015;26(5):601-623.

Many psychiatrists conceptualize mental illnesses, including psychotic disorders, across a continuum where their borders can be ambiguous.1 The same can be said of individual symptoms such as delusions, where the line separating clear-cut pathology from nonpathological or subclinical “delusion-like beliefs” is often blurred.2,3 However, the categorical distinction between mental illness and normality is fundamental to diagnostic reliability and crucial to clinical decisions about whether and how to intervene.

Conspiracy theory beliefs are delusion-like beliefs that are commonly encountered within today’s political landscape. Surveys have consistently revealed that approximately one-half of the population believes in at least 1 conspiracy theory, highlighting the normality of such beliefs despite their potential outlandishness.4 Here are 3 questions you can ask to help differentiate conspiracy theory beliefs from delusions.

1. What is the evidence for the belief?

Drawing from Karl Jaspers’ conceptualization of delusions as “impossible” and “unshareable,” the DSM-5 distinguishes delusions from culturally-sanctioned shared beliefs such as religious creeds.3 Whereas delusions often arise out of anomalous subjective experiences, individuals who come to believe in conspiracytheories have typically sought explanations and found them from secondary sources, often on the internet.5 Despite the familiar term “conspiracy theorist,” most who believe in conspiracy theories aren’t so much theorizing as they are adopting counter-narratives based on assimilated information. Unlike delusions, conspiracy theory beliefs are learned, with the “evidence” to support them easily located online.

2. Is the belief self-referential?

The stereotypical unshareability of delusions often hinges upon their self-referential content. For example, while it is easy to find others who believe in the Second Coming, it would be much harder to convince others that you are the Second Coming. Unlike delusions, conspiracy theories are beliefs about the world and explanations of real-life events; their content is rarely, if ever, directly related to the believer.

Conspiracy theory beliefs involve a negation of authoritative accounts that is rooted in “epistemic mistrust” of authoritative sources of information.5 While conspiratorial mistrust has been compared with paranoia, with paranoia found to be associated with belief in conspiracy theories,6 epistemic mistrust encompasses a range of justified cultural mistrust, unwarranted mistrust based on racial prejudice, and subclinical paranoia typical of schizotypy. The more self-referential the underlying paranoia, the more likely an associated belief is to cross the boundary from conspiracy theory to delusion.7

3. Is there overlap?

Conspiracy theory beliefs and delusions are not mutually exclusive. “Gang stalking” offers a vexing example of paranoia that is part shared conspiracy theory, part idiosyncratic delusion.8 Reliably disentangling these components requires identifying the conspiracy theory component as a widely-shared belief about government surveillance, while carefully analyzing the self-referential component to determine credibility and potential delusionality.

Many psychiatrists conceptualize mental illnesses, including psychotic disorders, across a continuum where their borders can be ambiguous.1 The same can be said of individual symptoms such as delusions, where the line separating clear-cut pathology from nonpathological or subclinical “delusion-like beliefs” is often blurred.2,3 However, the categorical distinction between mental illness and normality is fundamental to diagnostic reliability and crucial to clinical decisions about whether and how to intervene.

Conspiracy theory beliefs are delusion-like beliefs that are commonly encountered within today’s political landscape. Surveys have consistently revealed that approximately one-half of the population believes in at least 1 conspiracy theory, highlighting the normality of such beliefs despite their potential outlandishness.4 Here are 3 questions you can ask to help differentiate conspiracy theory beliefs from delusions.

1. What is the evidence for the belief?

Drawing from Karl Jaspers’ conceptualization of delusions as “impossible” and “unshareable,” the DSM-5 distinguishes delusions from culturally-sanctioned shared beliefs such as religious creeds.3 Whereas delusions often arise out of anomalous subjective experiences, individuals who come to believe in conspiracytheories have typically sought explanations and found them from secondary sources, often on the internet.5 Despite the familiar term “conspiracy theorist,” most who believe in conspiracy theories aren’t so much theorizing as they are adopting counter-narratives based on assimilated information. Unlike delusions, conspiracy theory beliefs are learned, with the “evidence” to support them easily located online.

2. Is the belief self-referential?

The stereotypical unshareability of delusions often hinges upon their self-referential content. For example, while it is easy to find others who believe in the Second Coming, it would be much harder to convince others that you are the Second Coming. Unlike delusions, conspiracy theories are beliefs about the world and explanations of real-life events; their content is rarely, if ever, directly related to the believer.

Conspiracy theory beliefs involve a negation of authoritative accounts that is rooted in “epistemic mistrust” of authoritative sources of information.5 While conspiratorial mistrust has been compared with paranoia, with paranoia found to be associated with belief in conspiracy theories,6 epistemic mistrust encompasses a range of justified cultural mistrust, unwarranted mistrust based on racial prejudice, and subclinical paranoia typical of schizotypy. The more self-referential the underlying paranoia, the more likely an associated belief is to cross the boundary from conspiracy theory to delusion.7

3. Is there overlap?

Conspiracy theory beliefs and delusions are not mutually exclusive. “Gang stalking” offers a vexing example of paranoia that is part shared conspiracy theory, part idiosyncratic delusion.8 Reliably disentangling these components requires identifying the conspiracy theory component as a widely-shared belief about government surveillance, while carefully analyzing the self-referential component to determine credibility and potential delusionality.

1. Pierre JM. The borders of mental disorder in psychiatry and the DSM: past, present, and future. J Psychiatric Practice. 2010;16(6):375-386.

2. Pierre JM. Faith or delusion? At the crossroads of religion and psychosis. J Psychiatr Practice. 2001;7(3):163-172.

3. Pierre JM. Forensic psychiatry versus the varieties of delusion-like belief. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2020;48(3):327-334.

4. Oliver JE, Wood, TJ. Conspiracy theories and the paranoid style(s) of mass opinion. Am J Pol Sci. 2014;58(5);952-966.

5. Pierre JM. Mistrust and misinformation: a two-component, socio-epistemic model of belief in conspiracy theories. J Soc Polit Psychol. 2020;8(2):617-641.

6. Dagnall N, Drinkwater K, Parker A, et al. Conspiracy theory and cognitive style: a worldview. Front Psychol. 2015;6:206.

7. Imhoff R, Lamberty P. How paranoid are conspiracy believers? Toward a more fine-grained understanding of the connect and disconnect between paranoia and belief in conspiracy theories. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2018;48(7):909-926.

8. Sheridan LP, James DV. Complaints of group-stalking (‘gang-stalking’): an exploratory study of their natures and impact on complainants. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2015;26(5):601-623.

1. Pierre JM. The borders of mental disorder in psychiatry and the DSM: past, present, and future. J Psychiatric Practice. 2010;16(6):375-386.

2. Pierre JM. Faith or delusion? At the crossroads of religion and psychosis. J Psychiatr Practice. 2001;7(3):163-172.

3. Pierre JM. Forensic psychiatry versus the varieties of delusion-like belief. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2020;48(3):327-334.

4. Oliver JE, Wood, TJ. Conspiracy theories and the paranoid style(s) of mass opinion. Am J Pol Sci. 2014;58(5);952-966.

5. Pierre JM. Mistrust and misinformation: a two-component, socio-epistemic model of belief in conspiracy theories. J Soc Polit Psychol. 2020;8(2):617-641.

6. Dagnall N, Drinkwater K, Parker A, et al. Conspiracy theory and cognitive style: a worldview. Front Psychol. 2015;6:206.

7. Imhoff R, Lamberty P. How paranoid are conspiracy believers? Toward a more fine-grained understanding of the connect and disconnect between paranoia and belief in conspiracy theories. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2018;48(7):909-926.

8. Sheridan LP, James DV. Complaints of group-stalking (‘gang-stalking’): an exploratory study of their natures and impact on complainants. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2015;26(5):601-623.

Workplace violence: Enhance your safety in outpatient settings

In the health care setting, workplace violence directed by patients against clinicians or other staff (eg, verbal or physical assaults) is common.1-3 Factors that contribute to violent incidents within mental health settings include communication problems, substance use, patients’ noncompliance with medications, procedural failures (administrative and legal), and a lack of resources.4

Being verbally or physically assaulted, stalked, or threatened by a patient is a reality for mental health professionals, especially in outpatient settings with limited resources and a lack of onsite security.5 Addressing the concerns outlined in this article can enhance your safety in outpatient settings. These steps should be customized for your practice with the possible assistance of legal counsel, risk management, and/or law enforcement.5

Plans and policies to mitigate the risk of violence. Assess for hazards within and around the workplace.5 Learn to assess your patient’s violence risk level in pre-screening interviews before their first appointment. Create a violence prevention and response plan, which may involve calling law enforcement if you fear for your safety or the safety of others.5 The confidentiality clauses of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act make an exception to allow for disclosure to prevent or reduce a serious and substantial threat to the health or safety of an individual or society (you should limit your disclosure to pertinent nonclinical information).5,6 Develop policies and procedures to identify, communicate, track, and document patients’ concerning behaviors as well as policies and procedures to terminate care of patients who display these concerning behaviors.5 These plans and policies should include informing patients that neither violence nor threats of any kind will be tolerated. Frequently review these plans and policies with clinic personnel; these documents should be easily accessible to everyone (eg, posted on a board).

Communication and education. Keep open lines of communication with all clinic personnel, and encourage them to promptly report incidents and any concerning patient behaviors. Frequently check in with them about any safety concerns they have, and encourage them to suggest ways to reduce risks.7 Include discussions about safety during clinic meetings. Educate clinic personnel about the nonverbal warning signs of behavior escalation, and provide de-escalation and response training.5 Hold simulation drills so clinic personnel can become more familiar with the violence prevention and response plan.

Office safety. Install a security barrier between the waiting room and office spaces so that patients cannot easily barge into the office spaces. Ensure access to the office areas is restricted to clinic personnel using access card readers, electronic locks, locks with deadbolts, etc.5 Escort patients within the office and ensure that individuals who are not associated with the clinic are not permitted to enter any area of the office alone.5 Install video surveillance cameras at entrances, exits, and other strategic locations and post signs signaling their presence.5 Post signs stating that concealed weapons are not allowed on the premises. Install panic buttons in each office, at the reception desk, and other areas (eg, restrooms).5 Develop a code word or phrase that will allow front desk staff to know that you are in trouble when they call your office. Have a designated room in which staff can gather and lock themselves if they are not able to escape.5 Provide law enforcement with floor plans of the clinic to help expedite their response.2

Personal safety. During patient visits, position yourself so you can exit a room quickly if needed, and avoid having your back to the exit.5,7 Ensure the patient is not blocking the exit. Avoid wearing attire that can be used as a weapon against you, such as a tie or necklace, or can impede your escape, such as high heels.7 Avoid wearing valuable accessories that can be damaged or destroyed during a “take down.”7 Wear an audible alarm.5 Avoid posting personal information that is publicly accessible (eg, in the office or online) and may reveal your habits.5 Insist upon a “buddy system” in which no one works alone, including outside normal business hours, or goes to their car alone.5

1. Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(17):1661-1669.

2. Workplace violence: issues in response. Rugala EA, Issacs AR (eds). Critical Incident Response Group, National Center for Analysis of Violent Crime, FBI Academy. 2003. Accessed November 27, 2020. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/stats-services-publications-workplace-violence-workplace-violence/view

3. Velani KH. 2019 Healthcare Crime Survey. International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety – Foundation (IAHSS – Foundation). Accessed November 27, 2020. https://iahssf.org/crime-surveys/2019-healthcare-crime-survey/3/

4. O’Rourke M, Wrigley C, Hammond S. Violence within mental health services: how to enhance risk management. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2018;11:159-167.

5. Neal D. Seven actions to ensure safety in psychiatric office settings. Psychiatric News. 2020;55(7):15.

6. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Public Law No. 104–191, 110 Stat. 1936 (1996).

7. Xiong GL, Newman WJ. Take CAUTION in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(7):9-10.

In the health care setting, workplace violence directed by patients against clinicians or other staff (eg, verbal or physical assaults) is common.1-3 Factors that contribute to violent incidents within mental health settings include communication problems, substance use, patients’ noncompliance with medications, procedural failures (administrative and legal), and a lack of resources.4

Being verbally or physically assaulted, stalked, or threatened by a patient is a reality for mental health professionals, especially in outpatient settings with limited resources and a lack of onsite security.5 Addressing the concerns outlined in this article can enhance your safety in outpatient settings. These steps should be customized for your practice with the possible assistance of legal counsel, risk management, and/or law enforcement.5

Plans and policies to mitigate the risk of violence. Assess for hazards within and around the workplace.5 Learn to assess your patient’s violence risk level in pre-screening interviews before their first appointment. Create a violence prevention and response plan, which may involve calling law enforcement if you fear for your safety or the safety of others.5 The confidentiality clauses of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act make an exception to allow for disclosure to prevent or reduce a serious and substantial threat to the health or safety of an individual or society (you should limit your disclosure to pertinent nonclinical information).5,6 Develop policies and procedures to identify, communicate, track, and document patients’ concerning behaviors as well as policies and procedures to terminate care of patients who display these concerning behaviors.5 These plans and policies should include informing patients that neither violence nor threats of any kind will be tolerated. Frequently review these plans and policies with clinic personnel; these documents should be easily accessible to everyone (eg, posted on a board).

Communication and education. Keep open lines of communication with all clinic personnel, and encourage them to promptly report incidents and any concerning patient behaviors. Frequently check in with them about any safety concerns they have, and encourage them to suggest ways to reduce risks.7 Include discussions about safety during clinic meetings. Educate clinic personnel about the nonverbal warning signs of behavior escalation, and provide de-escalation and response training.5 Hold simulation drills so clinic personnel can become more familiar with the violence prevention and response plan.

Office safety. Install a security barrier between the waiting room and office spaces so that patients cannot easily barge into the office spaces. Ensure access to the office areas is restricted to clinic personnel using access card readers, electronic locks, locks with deadbolts, etc.5 Escort patients within the office and ensure that individuals who are not associated with the clinic are not permitted to enter any area of the office alone.5 Install video surveillance cameras at entrances, exits, and other strategic locations and post signs signaling their presence.5 Post signs stating that concealed weapons are not allowed on the premises. Install panic buttons in each office, at the reception desk, and other areas (eg, restrooms).5 Develop a code word or phrase that will allow front desk staff to know that you are in trouble when they call your office. Have a designated room in which staff can gather and lock themselves if they are not able to escape.5 Provide law enforcement with floor plans of the clinic to help expedite their response.2

Personal safety. During patient visits, position yourself so you can exit a room quickly if needed, and avoid having your back to the exit.5,7 Ensure the patient is not blocking the exit. Avoid wearing attire that can be used as a weapon against you, such as a tie or necklace, or can impede your escape, such as high heels.7 Avoid wearing valuable accessories that can be damaged or destroyed during a “take down.”7 Wear an audible alarm.5 Avoid posting personal information that is publicly accessible (eg, in the office or online) and may reveal your habits.5 Insist upon a “buddy system” in which no one works alone, including outside normal business hours, or goes to their car alone.5

In the health care setting, workplace violence directed by patients against clinicians or other staff (eg, verbal or physical assaults) is common.1-3 Factors that contribute to violent incidents within mental health settings include communication problems, substance use, patients’ noncompliance with medications, procedural failures (administrative and legal), and a lack of resources.4

Being verbally or physically assaulted, stalked, or threatened by a patient is a reality for mental health professionals, especially in outpatient settings with limited resources and a lack of onsite security.5 Addressing the concerns outlined in this article can enhance your safety in outpatient settings. These steps should be customized for your practice with the possible assistance of legal counsel, risk management, and/or law enforcement.5

Plans and policies to mitigate the risk of violence. Assess for hazards within and around the workplace.5 Learn to assess your patient’s violence risk level in pre-screening interviews before their first appointment. Create a violence prevention and response plan, which may involve calling law enforcement if you fear for your safety or the safety of others.5 The confidentiality clauses of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act make an exception to allow for disclosure to prevent or reduce a serious and substantial threat to the health or safety of an individual or society (you should limit your disclosure to pertinent nonclinical information).5,6 Develop policies and procedures to identify, communicate, track, and document patients’ concerning behaviors as well as policies and procedures to terminate care of patients who display these concerning behaviors.5 These plans and policies should include informing patients that neither violence nor threats of any kind will be tolerated. Frequently review these plans and policies with clinic personnel; these documents should be easily accessible to everyone (eg, posted on a board).

Communication and education. Keep open lines of communication with all clinic personnel, and encourage them to promptly report incidents and any concerning patient behaviors. Frequently check in with them about any safety concerns they have, and encourage them to suggest ways to reduce risks.7 Include discussions about safety during clinic meetings. Educate clinic personnel about the nonverbal warning signs of behavior escalation, and provide de-escalation and response training.5 Hold simulation drills so clinic personnel can become more familiar with the violence prevention and response plan.

Office safety. Install a security barrier between the waiting room and office spaces so that patients cannot easily barge into the office spaces. Ensure access to the office areas is restricted to clinic personnel using access card readers, electronic locks, locks with deadbolts, etc.5 Escort patients within the office and ensure that individuals who are not associated with the clinic are not permitted to enter any area of the office alone.5 Install video surveillance cameras at entrances, exits, and other strategic locations and post signs signaling their presence.5 Post signs stating that concealed weapons are not allowed on the premises. Install panic buttons in each office, at the reception desk, and other areas (eg, restrooms).5 Develop a code word or phrase that will allow front desk staff to know that you are in trouble when they call your office. Have a designated room in which staff can gather and lock themselves if they are not able to escape.5 Provide law enforcement with floor plans of the clinic to help expedite their response.2

Personal safety. During patient visits, position yourself so you can exit a room quickly if needed, and avoid having your back to the exit.5,7 Ensure the patient is not blocking the exit. Avoid wearing attire that can be used as a weapon against you, such as a tie or necklace, or can impede your escape, such as high heels.7 Avoid wearing valuable accessories that can be damaged or destroyed during a “take down.”7 Wear an audible alarm.5 Avoid posting personal information that is publicly accessible (eg, in the office or online) and may reveal your habits.5 Insist upon a “buddy system” in which no one works alone, including outside normal business hours, or goes to their car alone.5

1. Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(17):1661-1669.

2. Workplace violence: issues in response. Rugala EA, Issacs AR (eds). Critical Incident Response Group, National Center for Analysis of Violent Crime, FBI Academy. 2003. Accessed November 27, 2020. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/stats-services-publications-workplace-violence-workplace-violence/view

3. Velani KH. 2019 Healthcare Crime Survey. International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety – Foundation (IAHSS – Foundation). Accessed November 27, 2020. https://iahssf.org/crime-surveys/2019-healthcare-crime-survey/3/

4. O’Rourke M, Wrigley C, Hammond S. Violence within mental health services: how to enhance risk management. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2018;11:159-167.

5. Neal D. Seven actions to ensure safety in psychiatric office settings. Psychiatric News. 2020;55(7):15.

6. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Public Law No. 104–191, 110 Stat. 1936 (1996).

7. Xiong GL, Newman WJ. Take CAUTION in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(7):9-10.

1. Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(17):1661-1669.

2. Workplace violence: issues in response. Rugala EA, Issacs AR (eds). Critical Incident Response Group, National Center for Analysis of Violent Crime, FBI Academy. 2003. Accessed November 27, 2020. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/stats-services-publications-workplace-violence-workplace-violence/view

3. Velani KH. 2019 Healthcare Crime Survey. International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety – Foundation (IAHSS – Foundation). Accessed November 27, 2020. https://iahssf.org/crime-surveys/2019-healthcare-crime-survey/3/

4. O’Rourke M, Wrigley C, Hammond S. Violence within mental health services: how to enhance risk management. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2018;11:159-167.

5. Neal D. Seven actions to ensure safety in psychiatric office settings. Psychiatric News. 2020;55(7):15.

6. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Public Law No. 104–191, 110 Stat. 1936 (1996).

7. Xiong GL, Newman WJ. Take CAUTION in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(7):9-10.

Writing letters for transgender patients undergoing medical transition

Transgender and nonconforming people are estimated to make up 0.3% to 1.4% of the population, and these estimates are likely undercounts.1 Knowingly or unknowingly, psychiatric and mental health clinicians are caring for transgender patients, and need to become familiar with ways to provide proper clinical care for this often-marginalized population. Being knowledgeable about the requirements for letter writing for patients who are transgender and desire to transition medically is one way that we can assist and affirm these individuals.

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) publishes standards of care (SOC) that discuss the role of mental health professionals during a patient’s gender transition.2 The initial mental health evaluation should establish if gender dysphoria exists, and not just assume that it does. It is also important to assess whether the patient has had past negative experiences in the treatment setting or a history of trauma, and to evaluate for stressors in social life. Some transgender people may present to mental health professionals solely for the purpose of pursuing gender-related services, and others do not. The transgender person may or may not choose to undergo hormone replacement therapy or surgical transition.

Within the United States, a small percentage of clinicians use the informed consent model and, instead of requiring letters for medical intervention, will conduct an assessment to determine if the patient can provide informed consent about the procedures. But because the WPATH SOC are considered the primary standards and insurance companies will not cover the surgeries without these letters, most surgeons will not accept a patient without this documentation.3

Letters for hormone therapy and upper body surgery

Adults need 1 letter of recommendation from a qualified mental health professional, and the following WPATH criteria must be met: 1) persistent, well-documented gender dysphoria, 2) capacity to make a fully informed decision to consent for treatment, 3) age of majority, and 4) if significant medical or mental health conditions are present, they must be reasonably well-controlled.4

The letter should contain identifying characteristics; diagnoses and psychosocial assessment; duration of clinical relationship; type of evaluation or therapy; an explanation that the criteria for hormone therapy have been met/clinical rationale (gender dysphoria, capacity to consent, age of majority, that other mental health conditions are reasonably well-controlled); a statement that informed consent had been obtained; and a statement that the referring clinician is available for coordination of care.

Letters for lower body surgery

WPATH recommends letters from 2 mental health clinicians who evaluated the patient. In addition to the criteria set for hormone therapy described above, the SOC recommend 12 months of continuous living in the gender role that is congruent with a patient’s gender identity before genital surgery. It is also suggested that the patient undergoes 12 months of hormone therapy before hysterectomy/oophorectomy in transgender men or before orchiectomy in transgender women.4

The letter should contain identifying characteristics; diagnoses and psychosocial assessment; duration of clinical relationship; type of evaluation or therapy; criteria for surgery/clinical rationale (gender dysphoria, capacity to consent, age of majority, other health concerns are well-controlled, hormone therapy, real-life experience), informed consent; and availability for coordination of care.

Transgender individuals need clinicians who can provide competent, sensitive health care, and gender affirmation can enhance psychological health.

1. Winter S, Diamond M, Green J, et al. Transgender people: health at the margins of society. Lancet. 2016;388(10042):390-400.

2. World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people. 7th version. Published 2012. Accessed July 14, 2021. https://www.wpath.org/publications/soc

3. Budge SL, Dickey LM. Barriers, challenges, and decision-making in the letter writing process for gender transition. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2016;40(1):65-78.

4. Coleman E, Bocking W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender and gender-nonconforming people. Version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism. 2011;13:165-232.

Transgender and nonconforming people are estimated to make up 0.3% to 1.4% of the population, and these estimates are likely undercounts.1 Knowingly or unknowingly, psychiatric and mental health clinicians are caring for transgender patients, and need to become familiar with ways to provide proper clinical care for this often-marginalized population. Being knowledgeable about the requirements for letter writing for patients who are transgender and desire to transition medically is one way that we can assist and affirm these individuals.

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) publishes standards of care (SOC) that discuss the role of mental health professionals during a patient’s gender transition.2 The initial mental health evaluation should establish if gender dysphoria exists, and not just assume that it does. It is also important to assess whether the patient has had past negative experiences in the treatment setting or a history of trauma, and to evaluate for stressors in social life. Some transgender people may present to mental health professionals solely for the purpose of pursuing gender-related services, and others do not. The transgender person may or may not choose to undergo hormone replacement therapy or surgical transition.

Within the United States, a small percentage of clinicians use the informed consent model and, instead of requiring letters for medical intervention, will conduct an assessment to determine if the patient can provide informed consent about the procedures. But because the WPATH SOC are considered the primary standards and insurance companies will not cover the surgeries without these letters, most surgeons will not accept a patient without this documentation.3

Letters for hormone therapy and upper body surgery

Adults need 1 letter of recommendation from a qualified mental health professional, and the following WPATH criteria must be met: 1) persistent, well-documented gender dysphoria, 2) capacity to make a fully informed decision to consent for treatment, 3) age of majority, and 4) if significant medical or mental health conditions are present, they must be reasonably well-controlled.4

The letter should contain identifying characteristics; diagnoses and psychosocial assessment; duration of clinical relationship; type of evaluation or therapy; an explanation that the criteria for hormone therapy have been met/clinical rationale (gender dysphoria, capacity to consent, age of majority, that other mental health conditions are reasonably well-controlled); a statement that informed consent had been obtained; and a statement that the referring clinician is available for coordination of care.

Letters for lower body surgery

WPATH recommends letters from 2 mental health clinicians who evaluated the patient. In addition to the criteria set for hormone therapy described above, the SOC recommend 12 months of continuous living in the gender role that is congruent with a patient’s gender identity before genital surgery. It is also suggested that the patient undergoes 12 months of hormone therapy before hysterectomy/oophorectomy in transgender men or before orchiectomy in transgender women.4

The letter should contain identifying characteristics; diagnoses and psychosocial assessment; duration of clinical relationship; type of evaluation or therapy; criteria for surgery/clinical rationale (gender dysphoria, capacity to consent, age of majority, other health concerns are well-controlled, hormone therapy, real-life experience), informed consent; and availability for coordination of care.