User login

How to say ‘no’ to inappropriate patient requests

Although we may want to say “yes” when our patients ask us for certain medications, work excuses, etc, often it is more appropriate to say “no” because the conditions do not support those requests. Saying no to a patient usually is not a comfortable experience, but we should not say yes to avoid hurting their feelings, damaging our rapport with them, or having them post potential negative reviews about us. For many of us, saying no is a skill that does not come naturally. For some, bluntly telling a patient no may work, but this approach is more likely to be ineffective. At the same time, saying no in an equivocal manner may weaken our patients’ confidence in us and could be displeasing for both our patients and us.1,2

We should say no in an “effective, professional manner that fosters good patient care and preserves the therapeutic relationship, while supporting physician well-being.”1 In this article, I provide practical tips for saying no to inappropriate patient requests in an emphatic manner so that we can feel more empowered and less uncomfortable.

Acknowledge and analyze your discomfort.

Before saying no, recognize that you are feeling uncomfortable with your patient’s inappropriate request. This uncomfortable feeling is a probable cue that there is likely no appropriate context for their request, ie, saying yes would be poor medical care, illegal, against policy, etc.1,3 In most cases, you should be able to identify the reason(s) your patient’s request feels inappropriate and uncomfortable.

Gather information and provide an explanation.

Ask your patient for more information about their request so you can determine if there are any underlying factors and if any additional information is needed.3 Once you decide to say no, explain why. Your explanation should be brief, because lengthy explanations might create room for debate (which could be exhausting and/or time-consuming), lead to giving in to their inappropriate request, and/or lead them to become more frustrated and misunderstood.1

Be empathetic, and re-establish rapport.

After declining a patient’s request, you may have to use empathy to re-establish rapport if it has been damaged. After being told no, your patient may feel frustrated or powerless. Acknowledge their feelings with statements such as “I know this is not want you wanted to hear” or “I can see you are irritated.”Accept your patient’s negative emotions, rather than minimizing them or trying to fix them.1,3

1. Kane M, Chambliss ML. Getting to no: how to respond to inappropriate patient requests. Fam Prac Manag. 2018;25(1):25-30.

2. Paterniti DA, Facher TL, Cipri CS, et al. Getting to “no”: strategies primary care physicians use to deny patient requests. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):381-388.

3. Huben-Kearney A. Just say no to certain patient requests—and here’s how. Psychiatric News. 2021;56(2):13.

Although we may want to say “yes” when our patients ask us for certain medications, work excuses, etc, often it is more appropriate to say “no” because the conditions do not support those requests. Saying no to a patient usually is not a comfortable experience, but we should not say yes to avoid hurting their feelings, damaging our rapport with them, or having them post potential negative reviews about us. For many of us, saying no is a skill that does not come naturally. For some, bluntly telling a patient no may work, but this approach is more likely to be ineffective. At the same time, saying no in an equivocal manner may weaken our patients’ confidence in us and could be displeasing for both our patients and us.1,2

We should say no in an “effective, professional manner that fosters good patient care and preserves the therapeutic relationship, while supporting physician well-being.”1 In this article, I provide practical tips for saying no to inappropriate patient requests in an emphatic manner so that we can feel more empowered and less uncomfortable.

Acknowledge and analyze your discomfort.

Before saying no, recognize that you are feeling uncomfortable with your patient’s inappropriate request. This uncomfortable feeling is a probable cue that there is likely no appropriate context for their request, ie, saying yes would be poor medical care, illegal, against policy, etc.1,3 In most cases, you should be able to identify the reason(s) your patient’s request feels inappropriate and uncomfortable.

Gather information and provide an explanation.

Ask your patient for more information about their request so you can determine if there are any underlying factors and if any additional information is needed.3 Once you decide to say no, explain why. Your explanation should be brief, because lengthy explanations might create room for debate (which could be exhausting and/or time-consuming), lead to giving in to their inappropriate request, and/or lead them to become more frustrated and misunderstood.1

Be empathetic, and re-establish rapport.

After declining a patient’s request, you may have to use empathy to re-establish rapport if it has been damaged. After being told no, your patient may feel frustrated or powerless. Acknowledge their feelings with statements such as “I know this is not want you wanted to hear” or “I can see you are irritated.”Accept your patient’s negative emotions, rather than minimizing them or trying to fix them.1,3

Although we may want to say “yes” when our patients ask us for certain medications, work excuses, etc, often it is more appropriate to say “no” because the conditions do not support those requests. Saying no to a patient usually is not a comfortable experience, but we should not say yes to avoid hurting their feelings, damaging our rapport with them, or having them post potential negative reviews about us. For many of us, saying no is a skill that does not come naturally. For some, bluntly telling a patient no may work, but this approach is more likely to be ineffective. At the same time, saying no in an equivocal manner may weaken our patients’ confidence in us and could be displeasing for both our patients and us.1,2

We should say no in an “effective, professional manner that fosters good patient care and preserves the therapeutic relationship, while supporting physician well-being.”1 In this article, I provide practical tips for saying no to inappropriate patient requests in an emphatic manner so that we can feel more empowered and less uncomfortable.

Acknowledge and analyze your discomfort.

Before saying no, recognize that you are feeling uncomfortable with your patient’s inappropriate request. This uncomfortable feeling is a probable cue that there is likely no appropriate context for their request, ie, saying yes would be poor medical care, illegal, against policy, etc.1,3 In most cases, you should be able to identify the reason(s) your patient’s request feels inappropriate and uncomfortable.

Gather information and provide an explanation.

Ask your patient for more information about their request so you can determine if there are any underlying factors and if any additional information is needed.3 Once you decide to say no, explain why. Your explanation should be brief, because lengthy explanations might create room for debate (which could be exhausting and/or time-consuming), lead to giving in to their inappropriate request, and/or lead them to become more frustrated and misunderstood.1

Be empathetic, and re-establish rapport.

After declining a patient’s request, you may have to use empathy to re-establish rapport if it has been damaged. After being told no, your patient may feel frustrated or powerless. Acknowledge their feelings with statements such as “I know this is not want you wanted to hear” or “I can see you are irritated.”Accept your patient’s negative emotions, rather than minimizing them or trying to fix them.1,3

1. Kane M, Chambliss ML. Getting to no: how to respond to inappropriate patient requests. Fam Prac Manag. 2018;25(1):25-30.

2. Paterniti DA, Facher TL, Cipri CS, et al. Getting to “no”: strategies primary care physicians use to deny patient requests. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):381-388.

3. Huben-Kearney A. Just say no to certain patient requests—and here’s how. Psychiatric News. 2021;56(2):13.

1. Kane M, Chambliss ML. Getting to no: how to respond to inappropriate patient requests. Fam Prac Manag. 2018;25(1):25-30.

2. Paterniti DA, Facher TL, Cipri CS, et al. Getting to “no”: strategies primary care physicians use to deny patient requests. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):381-388.

3. Huben-Kearney A. Just say no to certain patient requests—and here’s how. Psychiatric News. 2021;56(2):13.

Closing your practice: What to consider

Closing your practice can be a stressful experience, and it requires careful planning. The process requires numerous steps, such as informing your staff, notifying your patients, closing accounts with your vendors and suppliers, storing medical records, and following applicable federal and state laws for dissolving your practice.1,2 Many of these steps may require consulting with an attorney, an accountant, and your malpractice insurance carrier.1,2 Although the recommendations I provide in this article are not exhaustive, when faced with closing your practice, be sure to consider the following factors.

Notify staff and patients.

Select a date to close your practice that will allow you to stop taking new patients, provides adequate leeway for your staff to find new employment and for you to hire temporary staff if needed, ensures you meet your obligations to your staff, such as payroll, and gives you time to set up appropriate continuity of care for your patients. In addition to verbally notifying your patients of your practice’s closing, inform them in writing (whether hand-delivered or via certified mail with return receipt) of the date of the practice’s closure, reason for the closure, cancellation of scheduled appointments after the closure date, referral options, and how they can obtain a copy of their medical records.1,2 Make sure your patients have an adequate supply of their medications before the closure.

Notify other parties.

Inform all suppliers, vendors, contracted service providers, insurance broker(s) for your practice, and payers (including Medicare and Medicaid, if applicable) of your intent to close your practice.1,2 Provide payers with a forwarding address to send payments that resolve after your practice closes, and request final invoices from vendors and suppliers so you can close your accounts with them. If you don’t own the building in which your practice is located, notify the building management in accordance with the provisions of your lease.1,2 Give cancellation notices to utilities and ancillary services (eg, labs, imaging facilities) to which you refer your patients, and notify facilities where you are credentialed and have admitting privileges.1,2 Inform your state medical licensing board, your state’s controlled substance division, and the Drug Enforcement Administration, because these agencies have requirements regarding changing the status of your medical license (if you decide to retire), continuing or surrendering your state and federal controlled substance registration, and disposal of prescription medications and prescription pads.1,2 Contact your local post office and delivery services with your change of address.

Address other considerations.

Set up a medical record retention and destruction plan in accordance with state and federal regulations, arrange for the safe storage for both paper and electronic medical records, and make sure storage facilities have experience handling confidential, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-sensitive patient information.1,2 In addition, establish a process for permanently deleting all HIPAA-sensitive patient information from any equipment that you don’t intend to keep.1,2

1. Funicelli AM. Risk management checklist when closing your practice. Psychiatric News. 2020;55(23):11.

2. American Academy of Family Physicians. Closing your practice checklist. Accessed January 21, 2022. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/admin_staffing/ClosingPracticeChecklist.pdf

Closing your practice can be a stressful experience, and it requires careful planning. The process requires numerous steps, such as informing your staff, notifying your patients, closing accounts with your vendors and suppliers, storing medical records, and following applicable federal and state laws for dissolving your practice.1,2 Many of these steps may require consulting with an attorney, an accountant, and your malpractice insurance carrier.1,2 Although the recommendations I provide in this article are not exhaustive, when faced with closing your practice, be sure to consider the following factors.

Notify staff and patients.

Select a date to close your practice that will allow you to stop taking new patients, provides adequate leeway for your staff to find new employment and for you to hire temporary staff if needed, ensures you meet your obligations to your staff, such as payroll, and gives you time to set up appropriate continuity of care for your patients. In addition to verbally notifying your patients of your practice’s closing, inform them in writing (whether hand-delivered or via certified mail with return receipt) of the date of the practice’s closure, reason for the closure, cancellation of scheduled appointments after the closure date, referral options, and how they can obtain a copy of their medical records.1,2 Make sure your patients have an adequate supply of their medications before the closure.

Notify other parties.

Inform all suppliers, vendors, contracted service providers, insurance broker(s) for your practice, and payers (including Medicare and Medicaid, if applicable) of your intent to close your practice.1,2 Provide payers with a forwarding address to send payments that resolve after your practice closes, and request final invoices from vendors and suppliers so you can close your accounts with them. If you don’t own the building in which your practice is located, notify the building management in accordance with the provisions of your lease.1,2 Give cancellation notices to utilities and ancillary services (eg, labs, imaging facilities) to which you refer your patients, and notify facilities where you are credentialed and have admitting privileges.1,2 Inform your state medical licensing board, your state’s controlled substance division, and the Drug Enforcement Administration, because these agencies have requirements regarding changing the status of your medical license (if you decide to retire), continuing or surrendering your state and federal controlled substance registration, and disposal of prescription medications and prescription pads.1,2 Contact your local post office and delivery services with your change of address.

Address other considerations.

Set up a medical record retention and destruction plan in accordance with state and federal regulations, arrange for the safe storage for both paper and electronic medical records, and make sure storage facilities have experience handling confidential, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-sensitive patient information.1,2 In addition, establish a process for permanently deleting all HIPAA-sensitive patient information from any equipment that you don’t intend to keep.1,2

Closing your practice can be a stressful experience, and it requires careful planning. The process requires numerous steps, such as informing your staff, notifying your patients, closing accounts with your vendors and suppliers, storing medical records, and following applicable federal and state laws for dissolving your practice.1,2 Many of these steps may require consulting with an attorney, an accountant, and your malpractice insurance carrier.1,2 Although the recommendations I provide in this article are not exhaustive, when faced with closing your practice, be sure to consider the following factors.

Notify staff and patients.

Select a date to close your practice that will allow you to stop taking new patients, provides adequate leeway for your staff to find new employment and for you to hire temporary staff if needed, ensures you meet your obligations to your staff, such as payroll, and gives you time to set up appropriate continuity of care for your patients. In addition to verbally notifying your patients of your practice’s closing, inform them in writing (whether hand-delivered or via certified mail with return receipt) of the date of the practice’s closure, reason for the closure, cancellation of scheduled appointments after the closure date, referral options, and how they can obtain a copy of their medical records.1,2 Make sure your patients have an adequate supply of their medications before the closure.

Notify other parties.

Inform all suppliers, vendors, contracted service providers, insurance broker(s) for your practice, and payers (including Medicare and Medicaid, if applicable) of your intent to close your practice.1,2 Provide payers with a forwarding address to send payments that resolve after your practice closes, and request final invoices from vendors and suppliers so you can close your accounts with them. If you don’t own the building in which your practice is located, notify the building management in accordance with the provisions of your lease.1,2 Give cancellation notices to utilities and ancillary services (eg, labs, imaging facilities) to which you refer your patients, and notify facilities where you are credentialed and have admitting privileges.1,2 Inform your state medical licensing board, your state’s controlled substance division, and the Drug Enforcement Administration, because these agencies have requirements regarding changing the status of your medical license (if you decide to retire), continuing or surrendering your state and federal controlled substance registration, and disposal of prescription medications and prescription pads.1,2 Contact your local post office and delivery services with your change of address.

Address other considerations.

Set up a medical record retention and destruction plan in accordance with state and federal regulations, arrange for the safe storage for both paper and electronic medical records, and make sure storage facilities have experience handling confidential, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-sensitive patient information.1,2 In addition, establish a process for permanently deleting all HIPAA-sensitive patient information from any equipment that you don’t intend to keep.1,2

1. Funicelli AM. Risk management checklist when closing your practice. Psychiatric News. 2020;55(23):11.

2. American Academy of Family Physicians. Closing your practice checklist. Accessed January 21, 2022. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/admin_staffing/ClosingPracticeChecklist.pdf

1. Funicelli AM. Risk management checklist when closing your practice. Psychiatric News. 2020;55(23):11.

2. American Academy of Family Physicians. Closing your practice checklist. Accessed January 21, 2022. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/admin_staffing/ClosingPracticeChecklist.pdf

The skill of administering IM medications: 3 questions to consider

The intramuscular (IM) route is commonly used to administer medication in various clinical settings. Even when an IM medication is administered appropriately, patient factors such as high subcutaneous tissue, greater body mass index, and gender can lower the success rate of injections.1 A key but infrequently discussed issue is the skill of the individual administering the IM medication. Incorrectly administering an IM medication can lead to complications, such as abscesses, nerve injury, and skeletal muscle fibrosis.2 Poor IM injection technique can impact patient care and safety.1 For example, a poorly administered antipsychotic medication might lead to the patient receiving a subtherapeutic dose, and could prompt a clinician to ask, “Does this agitated patient need more emergent medication because the medication being given is not effective, or because the medication is not being administered properly?”

This article offers 3 questions to ask when clinicians are evaluating how IM medications are being administered in their clinical setting.

1. Who is administering the medication?

Is the person a registered nurse, licensed psychiatric technician, certified nursing assistant, licensed vocational nurse, or medical assistant? What a specific clinician is permitted to do in one state may not be permitted in another state. For example, in the state of Washington, under certain conditions a medical assistant is allowed to administer an IM medication.3

2. What is the individual’s training in administering IM medications?

Has the person been trained in the proper technique, depending on the body location? Is the injection being properly prepared? Is the correct needle gauge being used?

3. What is the individual’s comfort level with administering IM medications?

Is the person comfortable administering medication only when a patient is calm? Or are they comfortable administering medication when a patient is agitated and being physically held or in 4-point restraints, such as in inpatient psychiatric units or emergency departments?

1. Soliman E, Ranjan S, Xu T, et al. A narrative review of the success of intramuscular gluteal injections and its impact in psychiatry. Biodes Manuf. 2018;1(3):161-170.

2. Nicoll LH, Hesby A. Intramuscular injection: an integrative research review and guideline for evidence-based practice. Appl Nurs Res. 2002;15(3):149-162.

3. Washington State Legislature. WAC 246-827-0240. Medical assistant-certified—Administering medications and injections. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://apps.leg.wa.gov/wac/default.aspx?cite=246-827-0240

The intramuscular (IM) route is commonly used to administer medication in various clinical settings. Even when an IM medication is administered appropriately, patient factors such as high subcutaneous tissue, greater body mass index, and gender can lower the success rate of injections.1 A key but infrequently discussed issue is the skill of the individual administering the IM medication. Incorrectly administering an IM medication can lead to complications, such as abscesses, nerve injury, and skeletal muscle fibrosis.2 Poor IM injection technique can impact patient care and safety.1 For example, a poorly administered antipsychotic medication might lead to the patient receiving a subtherapeutic dose, and could prompt a clinician to ask, “Does this agitated patient need more emergent medication because the medication being given is not effective, or because the medication is not being administered properly?”

This article offers 3 questions to ask when clinicians are evaluating how IM medications are being administered in their clinical setting.

1. Who is administering the medication?

Is the person a registered nurse, licensed psychiatric technician, certified nursing assistant, licensed vocational nurse, or medical assistant? What a specific clinician is permitted to do in one state may not be permitted in another state. For example, in the state of Washington, under certain conditions a medical assistant is allowed to administer an IM medication.3

2. What is the individual’s training in administering IM medications?

Has the person been trained in the proper technique, depending on the body location? Is the injection being properly prepared? Is the correct needle gauge being used?

3. What is the individual’s comfort level with administering IM medications?

Is the person comfortable administering medication only when a patient is calm? Or are they comfortable administering medication when a patient is agitated and being physically held or in 4-point restraints, such as in inpatient psychiatric units or emergency departments?

The intramuscular (IM) route is commonly used to administer medication in various clinical settings. Even when an IM medication is administered appropriately, patient factors such as high subcutaneous tissue, greater body mass index, and gender can lower the success rate of injections.1 A key but infrequently discussed issue is the skill of the individual administering the IM medication. Incorrectly administering an IM medication can lead to complications, such as abscesses, nerve injury, and skeletal muscle fibrosis.2 Poor IM injection technique can impact patient care and safety.1 For example, a poorly administered antipsychotic medication might lead to the patient receiving a subtherapeutic dose, and could prompt a clinician to ask, “Does this agitated patient need more emergent medication because the medication being given is not effective, or because the medication is not being administered properly?”

This article offers 3 questions to ask when clinicians are evaluating how IM medications are being administered in their clinical setting.

1. Who is administering the medication?

Is the person a registered nurse, licensed psychiatric technician, certified nursing assistant, licensed vocational nurse, or medical assistant? What a specific clinician is permitted to do in one state may not be permitted in another state. For example, in the state of Washington, under certain conditions a medical assistant is allowed to administer an IM medication.3

2. What is the individual’s training in administering IM medications?

Has the person been trained in the proper technique, depending on the body location? Is the injection being properly prepared? Is the correct needle gauge being used?

3. What is the individual’s comfort level with administering IM medications?

Is the person comfortable administering medication only when a patient is calm? Or are they comfortable administering medication when a patient is agitated and being physically held or in 4-point restraints, such as in inpatient psychiatric units or emergency departments?

1. Soliman E, Ranjan S, Xu T, et al. A narrative review of the success of intramuscular gluteal injections and its impact in psychiatry. Biodes Manuf. 2018;1(3):161-170.

2. Nicoll LH, Hesby A. Intramuscular injection: an integrative research review and guideline for evidence-based practice. Appl Nurs Res. 2002;15(3):149-162.

3. Washington State Legislature. WAC 246-827-0240. Medical assistant-certified—Administering medications and injections. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://apps.leg.wa.gov/wac/default.aspx?cite=246-827-0240

1. Soliman E, Ranjan S, Xu T, et al. A narrative review of the success of intramuscular gluteal injections and its impact in psychiatry. Biodes Manuf. 2018;1(3):161-170.

2. Nicoll LH, Hesby A. Intramuscular injection: an integrative research review and guideline for evidence-based practice. Appl Nurs Res. 2002;15(3):149-162.

3. Washington State Legislature. WAC 246-827-0240. Medical assistant-certified—Administering medications and injections. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://apps.leg.wa.gov/wac/default.aspx?cite=246-827-0240

Intermittent fasting: What to tell patients

Intermittent fasting is the purposeful, restricted intake of food (and sometimes water), usually for health or religious reasons. Common forms are alternative-day fasting or time-restricted fasting, with variable ratios of days or hours for fasting and eating/drinking.1 For example, fasting during Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, occurs from dawn to sunset, for a variable duration due to latitude and seasonal shifts.2 Clinicians are likely to care for a patient who occasionally fasts. While there are potential benefits of fasting, clinicians need to consider the implications for patients who fast, particularly those receiving psychotropic medications.

Potential benefits for weight loss, mood

Some research suggests fasting is popular and may have benefits for an individual’s physical and mental health. In a 2020 online poll (N = 1,241), 24% of respondents said they had tried intermittent fasting, and 87% said the practice was very effective (50%) or somewhat effective (37%) in helping them lose weight.3 While more randomized control trials are needed to examine the practice’s effectiveness in promoting and maintaining weight loss, fasting has been linked to better glucose control in both humans and animals, and patients may have better adherence with fasting compared to caloric restriction alone.1 Improved mood, alertness, tranquility, and sometimes euphoria have been documented among individuals who fast, but these benefits may not be sustained.4 A prospective study of 462 participants who fasted during Ramadan found the practice reduced depression in patients with diabetes, possibly due to mindfulness, decreased inflammation from improved insulin sensitivity, and/or social cohesion.5

Be aware of the potential risks

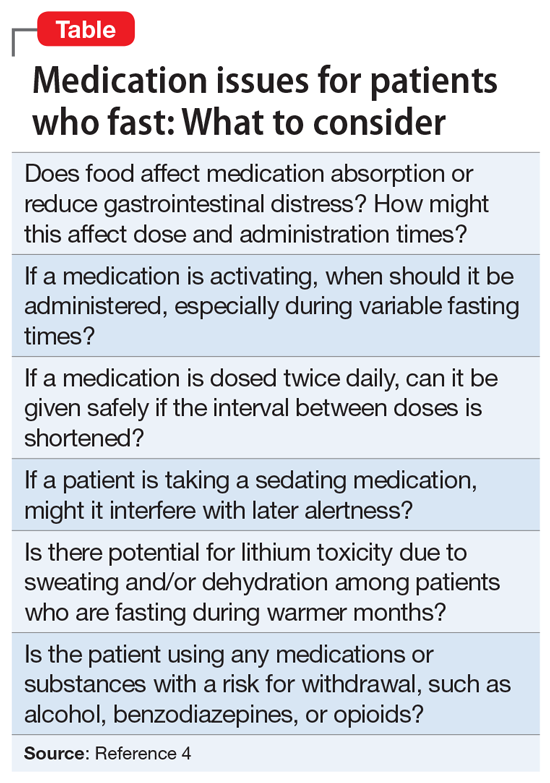

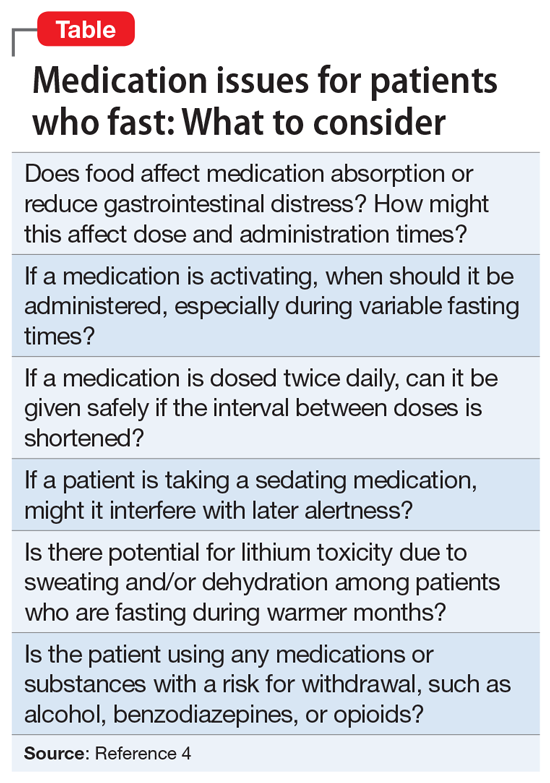

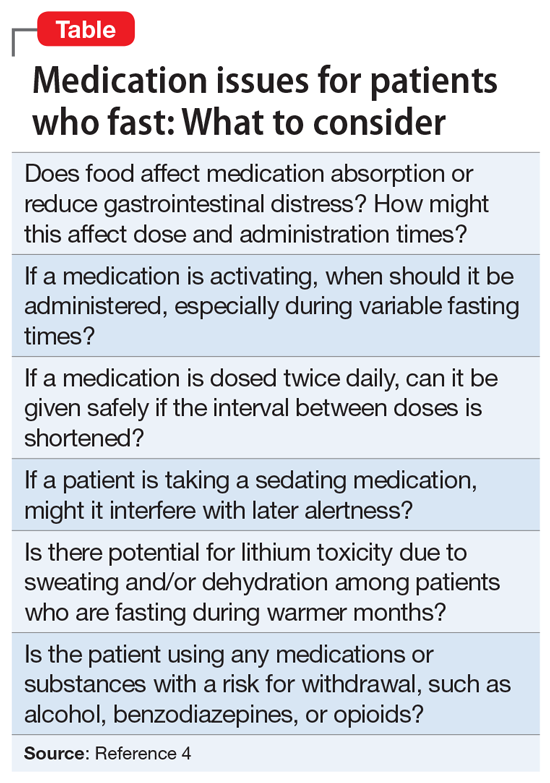

Fasting may either improve or destabilize mood in people with bipolar disorder by disrupting circadian rhythm and sleep.2 Fasting might exacerbate underlying eating disorders.2 Increased dehydration escalates the risk for orthostatic hypotension, which might require discontinuing clozapine.6 Hypotension and toxicity might arise during lithium pharmacotherapy. The Table4 summarizes things to consider when caring for a patient who fasts while receiving pharmacotherapy.

Provide patients with guidance

Advise patients not to fast if you believe it might exacerbate their mental illness, and encourage them to discuss with their primary care physicians any potential worsening of physical illnesses.2 When caring for a patient who fasts for religious reasons, consider consulting with the patient’s religious leaders.2 If patients choose to fast, monitor them for mood destabilization and/or medication adverse effects. If possible, avoid altering drug treatment regimens during fasting, and carefully monitor whenever a pharmaceutical change is necessary. When appropriate, the use of long-acting injectable medications may minimize adverse effects while maintaining mood stability. Encourage patients who fast to ensure they remain hydrated and practice sleep hygiene while they fast.7

1. Dong TA, Sandesara PB, Dhindsa DS, et al. Intermittent fasting: a heart healthy dietary pattern? Am J Med. 2020;133(8):901-907.

2. Fond G, Macgregor A, Leboyer M, et al. Fasting in mood disorders: neurobiology and effectiveness. A review of the literature. Psychiatry Res. 2013;209(3):253-258.

3. Ballard J. Americans say this popular diet is effective and inexpensive. YouGov. February 24, 2020. Accessed January 6, 2022. https://today.yougov.com/topics/food/articles-reports/2020/02/24/most-effective-diet-intermittent-fasting-poll

4. Furqan Z, Awaad R, Kurdyak P, et al. Considerations for clinicians treating Muslim patients with psychiatric disorders during Ramadan. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):556-557.

5. Al-Ozairi E, AlAwadhi MM, Al-Ozairi A, et al. A prospective study of the effect of fasting during the month of Ramadan on depression and diabetes distress in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2019;153:145-149.

6. Chehovich C, Demler TL, Leppien E. Impact of Ramadan fasting on medical and psychiatric health. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;34(6):317-322.

7. Farooq S, Nazar Z, Akhtar J, et al. Effect of fasting during Ramadan on serum lithium level and mental state in bipolar affective disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(6):323-327.

Intermittent fasting is the purposeful, restricted intake of food (and sometimes water), usually for health or religious reasons. Common forms are alternative-day fasting or time-restricted fasting, with variable ratios of days or hours for fasting and eating/drinking.1 For example, fasting during Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, occurs from dawn to sunset, for a variable duration due to latitude and seasonal shifts.2 Clinicians are likely to care for a patient who occasionally fasts. While there are potential benefits of fasting, clinicians need to consider the implications for patients who fast, particularly those receiving psychotropic medications.

Potential benefits for weight loss, mood

Some research suggests fasting is popular and may have benefits for an individual’s physical and mental health. In a 2020 online poll (N = 1,241), 24% of respondents said they had tried intermittent fasting, and 87% said the practice was very effective (50%) or somewhat effective (37%) in helping them lose weight.3 While more randomized control trials are needed to examine the practice’s effectiveness in promoting and maintaining weight loss, fasting has been linked to better glucose control in both humans and animals, and patients may have better adherence with fasting compared to caloric restriction alone.1 Improved mood, alertness, tranquility, and sometimes euphoria have been documented among individuals who fast, but these benefits may not be sustained.4 A prospective study of 462 participants who fasted during Ramadan found the practice reduced depression in patients with diabetes, possibly due to mindfulness, decreased inflammation from improved insulin sensitivity, and/or social cohesion.5

Be aware of the potential risks

Fasting may either improve or destabilize mood in people with bipolar disorder by disrupting circadian rhythm and sleep.2 Fasting might exacerbate underlying eating disorders.2 Increased dehydration escalates the risk for orthostatic hypotension, which might require discontinuing clozapine.6 Hypotension and toxicity might arise during lithium pharmacotherapy. The Table4 summarizes things to consider when caring for a patient who fasts while receiving pharmacotherapy.

Provide patients with guidance

Advise patients not to fast if you believe it might exacerbate their mental illness, and encourage them to discuss with their primary care physicians any potential worsening of physical illnesses.2 When caring for a patient who fasts for religious reasons, consider consulting with the patient’s religious leaders.2 If patients choose to fast, monitor them for mood destabilization and/or medication adverse effects. If possible, avoid altering drug treatment regimens during fasting, and carefully monitor whenever a pharmaceutical change is necessary. When appropriate, the use of long-acting injectable medications may minimize adverse effects while maintaining mood stability. Encourage patients who fast to ensure they remain hydrated and practice sleep hygiene while they fast.7

Intermittent fasting is the purposeful, restricted intake of food (and sometimes water), usually for health or religious reasons. Common forms are alternative-day fasting or time-restricted fasting, with variable ratios of days or hours for fasting and eating/drinking.1 For example, fasting during Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, occurs from dawn to sunset, for a variable duration due to latitude and seasonal shifts.2 Clinicians are likely to care for a patient who occasionally fasts. While there are potential benefits of fasting, clinicians need to consider the implications for patients who fast, particularly those receiving psychotropic medications.

Potential benefits for weight loss, mood

Some research suggests fasting is popular and may have benefits for an individual’s physical and mental health. In a 2020 online poll (N = 1,241), 24% of respondents said they had tried intermittent fasting, and 87% said the practice was very effective (50%) or somewhat effective (37%) in helping them lose weight.3 While more randomized control trials are needed to examine the practice’s effectiveness in promoting and maintaining weight loss, fasting has been linked to better glucose control in both humans and animals, and patients may have better adherence with fasting compared to caloric restriction alone.1 Improved mood, alertness, tranquility, and sometimes euphoria have been documented among individuals who fast, but these benefits may not be sustained.4 A prospective study of 462 participants who fasted during Ramadan found the practice reduced depression in patients with diabetes, possibly due to mindfulness, decreased inflammation from improved insulin sensitivity, and/or social cohesion.5

Be aware of the potential risks

Fasting may either improve or destabilize mood in people with bipolar disorder by disrupting circadian rhythm and sleep.2 Fasting might exacerbate underlying eating disorders.2 Increased dehydration escalates the risk for orthostatic hypotension, which might require discontinuing clozapine.6 Hypotension and toxicity might arise during lithium pharmacotherapy. The Table4 summarizes things to consider when caring for a patient who fasts while receiving pharmacotherapy.

Provide patients with guidance

Advise patients not to fast if you believe it might exacerbate their mental illness, and encourage them to discuss with their primary care physicians any potential worsening of physical illnesses.2 When caring for a patient who fasts for religious reasons, consider consulting with the patient’s religious leaders.2 If patients choose to fast, monitor them for mood destabilization and/or medication adverse effects. If possible, avoid altering drug treatment regimens during fasting, and carefully monitor whenever a pharmaceutical change is necessary. When appropriate, the use of long-acting injectable medications may minimize adverse effects while maintaining mood stability. Encourage patients who fast to ensure they remain hydrated and practice sleep hygiene while they fast.7

1. Dong TA, Sandesara PB, Dhindsa DS, et al. Intermittent fasting: a heart healthy dietary pattern? Am J Med. 2020;133(8):901-907.

2. Fond G, Macgregor A, Leboyer M, et al. Fasting in mood disorders: neurobiology and effectiveness. A review of the literature. Psychiatry Res. 2013;209(3):253-258.

3. Ballard J. Americans say this popular diet is effective and inexpensive. YouGov. February 24, 2020. Accessed January 6, 2022. https://today.yougov.com/topics/food/articles-reports/2020/02/24/most-effective-diet-intermittent-fasting-poll

4. Furqan Z, Awaad R, Kurdyak P, et al. Considerations for clinicians treating Muslim patients with psychiatric disorders during Ramadan. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):556-557.

5. Al-Ozairi E, AlAwadhi MM, Al-Ozairi A, et al. A prospective study of the effect of fasting during the month of Ramadan on depression and diabetes distress in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2019;153:145-149.

6. Chehovich C, Demler TL, Leppien E. Impact of Ramadan fasting on medical and psychiatric health. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;34(6):317-322.

7. Farooq S, Nazar Z, Akhtar J, et al. Effect of fasting during Ramadan on serum lithium level and mental state in bipolar affective disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(6):323-327.

1. Dong TA, Sandesara PB, Dhindsa DS, et al. Intermittent fasting: a heart healthy dietary pattern? Am J Med. 2020;133(8):901-907.

2. Fond G, Macgregor A, Leboyer M, et al. Fasting in mood disorders: neurobiology and effectiveness. A review of the literature. Psychiatry Res. 2013;209(3):253-258.

3. Ballard J. Americans say this popular diet is effective and inexpensive. YouGov. February 24, 2020. Accessed January 6, 2022. https://today.yougov.com/topics/food/articles-reports/2020/02/24/most-effective-diet-intermittent-fasting-poll

4. Furqan Z, Awaad R, Kurdyak P, et al. Considerations for clinicians treating Muslim patients with psychiatric disorders during Ramadan. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):556-557.

5. Al-Ozairi E, AlAwadhi MM, Al-Ozairi A, et al. A prospective study of the effect of fasting during the month of Ramadan on depression and diabetes distress in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2019;153:145-149.

6. Chehovich C, Demler TL, Leppien E. Impact of Ramadan fasting on medical and psychiatric health. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;34(6):317-322.

7. Farooq S, Nazar Z, Akhtar J, et al. Effect of fasting during Ramadan on serum lithium level and mental state in bipolar affective disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(6):323-327.

Inpatient violence: Take steps to reduce your risk

Inpatient violence is a significant problem for psychiatric facilities because it can have serious physical and psychological consequences for both staff and patients.1 Victimized staff can experience decreased productivity and emotional distress, while victimized patients can experience disrupted treatment and delayed discharge.1 Twenty-five to 35% of psychiatric inpatients display violent behavior during their hospitalization.1 A subset are extreme offenders.1,2 This small group of violent patients accounts for the majority of inpatient violence and the most serious injuries.1,2

Reducing inpatient violence starts with conducting a targeted violence risk assessment to identify patients who are at elevated risk of being violent. Although conducting a targeted violence risk assessment is beyond the scope of this article, here I outline practical steps that clinicians can take to reduce the risk of inpatient violence. These steps complement and overlap with those I described in “Workplace violence: Enhance your safety in outpatient settings” (Pearls,

Identify underlying motives. Inpatient violence is often a result of 3 primary psychiatric etiologies: difficulty with impulse control, symptoms of psychosis, or predatory traits.1 Impulsivity drives most of the violence on inpatient units, followed by predatory violence and symptoms of psychosis.1 Once you identify the psychiatric motive, you can develop an individualized, tailored treatment plan to reduce the risk of violence. The treatment plan can include using de-escalation techniques, administering scheduled and as-needed medications to target underlying symptoms, having patients assume responsibility for their behaviors, holding patients accountable for their behaviors, and other psychosocial interventions.1 Use seclusion and restraint only when it is the least restrictive means of providing safety.1,4

Develop plans and policies. As you would do in an outpatient setting, assess for hazards within the inpatient unit. Plan for the possible types of violence that may occur on the unit (eg, physical violence against hospital personnel and/or other patients, verbal harassment, etc).3 Develop policies and procedures to identify, communicate, track, and document patients’ concerning behaviors (eg, posting a safety board where staff can record aggressive behaviors and other safety issues).3,4 When developing these plans and policies, include patients by creating patient/staff workgroups to develop expectations for civil behavior that apply to both patients and staff, as well as training patients to co-lead groups dealing with accepting responsibility for their own recovery.5 These plans and policies should include informing patients that threats and violence will not be tolerated. Frequently review these plans and policies with patients and staff.

Provide communication and education. Maintain strong psychiatric leadership on the unit that encourages open lines of communication. Encourage staff to promptly report incidents. Frequently ask staff if they have any safety concerns, and solicit their opinions on how to reduce risks.4 Include discussions about safety during staff and community meetings. Communicate patients’ behaviors that are distressing or undesired (eg, threats, harassment, etc) to all unit personnel.3 Notify staff when you plan to interact with a patient who is at risk for violence or is acutely agitated.4 Teach staff how to recognize the nonverbal warning signs of behavior escalation and provide training on proper de-escalation and response.3,4 Also train staff on how to develop strong therapeutic alliances with patients.1 After a violent incident, use the postincident debriefing session to gather information that can be used to develop additional interventions and reduce the risk of subsequent violence.1

Implement common-sense strategies. Ensure that there are adequate numbers of nursing staff during each shift.1 Avoid overcrowded units, hallways, and common areas. Consider additional monitoring during unit transition times, such as during shift changes, meals, and medication administration.1 Avoid excessive noise.1 Employ one-to-one staff observation as clinically indicated.1 Avoid taking an authoritarian stance when explaining to patients why their requests have been denied4; if possible, when you are unable to meet a patient’s demands, offer them choices.1,4 If feasible, accompany patients to a calmer space where they can de-escalate.1 Install video surveillance cameras at entrances, exits, and other strategic locations and post signs signaling their presence.3 Install panic buttons at the nursing station and other areas (eg, restrooms).3

Ensure your personal safety. As mentioned previously, do not interact with a patient who has recently been aggressive or has voiced threats without adequate staff support.4 During the patient encounter, leave space between you and the patient.1 Avoid having your back to the exit of the room,3,4 and make sure the patient is not blocking the exit and that you can leave the room quickly if needed. Don’t wear anything that could be used as a weapon against you (eg, ties or necklaces) or could impede your escape.4 Avoid wearing valuables that might be damaged during a “take down.”4 If feasible, wear an audible alarm.3

1. Fisher K. Inpatient violence. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(4):567-577.

2. Kraus JE, Sheitman BB. Characteristics of violent behavior in a large state psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(2):183-185.

3. Neal D. Seven actions to ensure safety in psychiatric office settings. Psychiatric News. 2020;55(7):15.

4. Xiong GL, Newman WJ. Take CAUTION in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(7):9-10.

5. Hardy DW, Patel M. Reduce inpatient violence: 6 strategies. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(5):80-81.

Inpatient violence is a significant problem for psychiatric facilities because it can have serious physical and psychological consequences for both staff and patients.1 Victimized staff can experience decreased productivity and emotional distress, while victimized patients can experience disrupted treatment and delayed discharge.1 Twenty-five to 35% of psychiatric inpatients display violent behavior during their hospitalization.1 A subset are extreme offenders.1,2 This small group of violent patients accounts for the majority of inpatient violence and the most serious injuries.1,2

Reducing inpatient violence starts with conducting a targeted violence risk assessment to identify patients who are at elevated risk of being violent. Although conducting a targeted violence risk assessment is beyond the scope of this article, here I outline practical steps that clinicians can take to reduce the risk of inpatient violence. These steps complement and overlap with those I described in “Workplace violence: Enhance your safety in outpatient settings” (Pearls,

Identify underlying motives. Inpatient violence is often a result of 3 primary psychiatric etiologies: difficulty with impulse control, symptoms of psychosis, or predatory traits.1 Impulsivity drives most of the violence on inpatient units, followed by predatory violence and symptoms of psychosis.1 Once you identify the psychiatric motive, you can develop an individualized, tailored treatment plan to reduce the risk of violence. The treatment plan can include using de-escalation techniques, administering scheduled and as-needed medications to target underlying symptoms, having patients assume responsibility for their behaviors, holding patients accountable for their behaviors, and other psychosocial interventions.1 Use seclusion and restraint only when it is the least restrictive means of providing safety.1,4

Develop plans and policies. As you would do in an outpatient setting, assess for hazards within the inpatient unit. Plan for the possible types of violence that may occur on the unit (eg, physical violence against hospital personnel and/or other patients, verbal harassment, etc).3 Develop policies and procedures to identify, communicate, track, and document patients’ concerning behaviors (eg, posting a safety board where staff can record aggressive behaviors and other safety issues).3,4 When developing these plans and policies, include patients by creating patient/staff workgroups to develop expectations for civil behavior that apply to both patients and staff, as well as training patients to co-lead groups dealing with accepting responsibility for their own recovery.5 These plans and policies should include informing patients that threats and violence will not be tolerated. Frequently review these plans and policies with patients and staff.

Provide communication and education. Maintain strong psychiatric leadership on the unit that encourages open lines of communication. Encourage staff to promptly report incidents. Frequently ask staff if they have any safety concerns, and solicit their opinions on how to reduce risks.4 Include discussions about safety during staff and community meetings. Communicate patients’ behaviors that are distressing or undesired (eg, threats, harassment, etc) to all unit personnel.3 Notify staff when you plan to interact with a patient who is at risk for violence or is acutely agitated.4 Teach staff how to recognize the nonverbal warning signs of behavior escalation and provide training on proper de-escalation and response.3,4 Also train staff on how to develop strong therapeutic alliances with patients.1 After a violent incident, use the postincident debriefing session to gather information that can be used to develop additional interventions and reduce the risk of subsequent violence.1

Implement common-sense strategies. Ensure that there are adequate numbers of nursing staff during each shift.1 Avoid overcrowded units, hallways, and common areas. Consider additional monitoring during unit transition times, such as during shift changes, meals, and medication administration.1 Avoid excessive noise.1 Employ one-to-one staff observation as clinically indicated.1 Avoid taking an authoritarian stance when explaining to patients why their requests have been denied4; if possible, when you are unable to meet a patient’s demands, offer them choices.1,4 If feasible, accompany patients to a calmer space where they can de-escalate.1 Install video surveillance cameras at entrances, exits, and other strategic locations and post signs signaling their presence.3 Install panic buttons at the nursing station and other areas (eg, restrooms).3

Ensure your personal safety. As mentioned previously, do not interact with a patient who has recently been aggressive or has voiced threats without adequate staff support.4 During the patient encounter, leave space between you and the patient.1 Avoid having your back to the exit of the room,3,4 and make sure the patient is not blocking the exit and that you can leave the room quickly if needed. Don’t wear anything that could be used as a weapon against you (eg, ties or necklaces) or could impede your escape.4 Avoid wearing valuables that might be damaged during a “take down.”4 If feasible, wear an audible alarm.3

Inpatient violence is a significant problem for psychiatric facilities because it can have serious physical and psychological consequences for both staff and patients.1 Victimized staff can experience decreased productivity and emotional distress, while victimized patients can experience disrupted treatment and delayed discharge.1 Twenty-five to 35% of psychiatric inpatients display violent behavior during their hospitalization.1 A subset are extreme offenders.1,2 This small group of violent patients accounts for the majority of inpatient violence and the most serious injuries.1,2

Reducing inpatient violence starts with conducting a targeted violence risk assessment to identify patients who are at elevated risk of being violent. Although conducting a targeted violence risk assessment is beyond the scope of this article, here I outline practical steps that clinicians can take to reduce the risk of inpatient violence. These steps complement and overlap with those I described in “Workplace violence: Enhance your safety in outpatient settings” (Pearls,

Identify underlying motives. Inpatient violence is often a result of 3 primary psychiatric etiologies: difficulty with impulse control, symptoms of psychosis, or predatory traits.1 Impulsivity drives most of the violence on inpatient units, followed by predatory violence and symptoms of psychosis.1 Once you identify the psychiatric motive, you can develop an individualized, tailored treatment plan to reduce the risk of violence. The treatment plan can include using de-escalation techniques, administering scheduled and as-needed medications to target underlying symptoms, having patients assume responsibility for their behaviors, holding patients accountable for their behaviors, and other psychosocial interventions.1 Use seclusion and restraint only when it is the least restrictive means of providing safety.1,4

Develop plans and policies. As you would do in an outpatient setting, assess for hazards within the inpatient unit. Plan for the possible types of violence that may occur on the unit (eg, physical violence against hospital personnel and/or other patients, verbal harassment, etc).3 Develop policies and procedures to identify, communicate, track, and document patients’ concerning behaviors (eg, posting a safety board where staff can record aggressive behaviors and other safety issues).3,4 When developing these plans and policies, include patients by creating patient/staff workgroups to develop expectations for civil behavior that apply to both patients and staff, as well as training patients to co-lead groups dealing with accepting responsibility for their own recovery.5 These plans and policies should include informing patients that threats and violence will not be tolerated. Frequently review these plans and policies with patients and staff.

Provide communication and education. Maintain strong psychiatric leadership on the unit that encourages open lines of communication. Encourage staff to promptly report incidents. Frequently ask staff if they have any safety concerns, and solicit their opinions on how to reduce risks.4 Include discussions about safety during staff and community meetings. Communicate patients’ behaviors that are distressing or undesired (eg, threats, harassment, etc) to all unit personnel.3 Notify staff when you plan to interact with a patient who is at risk for violence or is acutely agitated.4 Teach staff how to recognize the nonverbal warning signs of behavior escalation and provide training on proper de-escalation and response.3,4 Also train staff on how to develop strong therapeutic alliances with patients.1 After a violent incident, use the postincident debriefing session to gather information that can be used to develop additional interventions and reduce the risk of subsequent violence.1

Implement common-sense strategies. Ensure that there are adequate numbers of nursing staff during each shift.1 Avoid overcrowded units, hallways, and common areas. Consider additional monitoring during unit transition times, such as during shift changes, meals, and medication administration.1 Avoid excessive noise.1 Employ one-to-one staff observation as clinically indicated.1 Avoid taking an authoritarian stance when explaining to patients why their requests have been denied4; if possible, when you are unable to meet a patient’s demands, offer them choices.1,4 If feasible, accompany patients to a calmer space where they can de-escalate.1 Install video surveillance cameras at entrances, exits, and other strategic locations and post signs signaling their presence.3 Install panic buttons at the nursing station and other areas (eg, restrooms).3

Ensure your personal safety. As mentioned previously, do not interact with a patient who has recently been aggressive or has voiced threats without adequate staff support.4 During the patient encounter, leave space between you and the patient.1 Avoid having your back to the exit of the room,3,4 and make sure the patient is not blocking the exit and that you can leave the room quickly if needed. Don’t wear anything that could be used as a weapon against you (eg, ties or necklaces) or could impede your escape.4 Avoid wearing valuables that might be damaged during a “take down.”4 If feasible, wear an audible alarm.3

1. Fisher K. Inpatient violence. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(4):567-577.

2. Kraus JE, Sheitman BB. Characteristics of violent behavior in a large state psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(2):183-185.

3. Neal D. Seven actions to ensure safety in psychiatric office settings. Psychiatric News. 2020;55(7):15.

4. Xiong GL, Newman WJ. Take CAUTION in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(7):9-10.

5. Hardy DW, Patel M. Reduce inpatient violence: 6 strategies. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(5):80-81.

1. Fisher K. Inpatient violence. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(4):567-577.

2. Kraus JE, Sheitman BB. Characteristics of violent behavior in a large state psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(2):183-185.

3. Neal D. Seven actions to ensure safety in psychiatric office settings. Psychiatric News. 2020;55(7):15.

4. Xiong GL, Newman WJ. Take CAUTION in emergency and inpatient psychiatric settings. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(7):9-10.

5. Hardy DW, Patel M. Reduce inpatient violence: 6 strategies. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(5):80-81.

SCAMP: Assessing body-focused repetitive behaviors

Repetitive behaviors towards the body, such as hair pulling and skin picking, are common. Approximately 5% of the general population may meet criteria for trichotillomania or excoriation disorder, in which the repetitive behaviors are excessive and impairing. The category of body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRBs) extends beyond these 2 disorders to include onychophagia (nail biting), onychotillomania (nail picking), and lip or cheek chewing, which in DSM-5 are categorized under Other Specified Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder—BFRB. Of particular concern are trichophagia or dermatophagia, the ritualizing and eating of skin or hair that can lead to gastrointestinal complications.1

The prevalence and associated distress from BFRBs have spurred increased research into psychotherapeutic interventions to remediate suffering and curb bodily damage. Under the broader umbrella of behavioral therapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy, the Expert Consensus Treatment Guidelines from the TLC Foundation2 describe habit reversal therapy, comprehensive behavioral treatment, and behavioral therapy that is enhanced by acceptance and commitment therapy or dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) skills. (Although these guidelines also summarize possible pharmacologic interventions, medication for patients with BFRBs is not discussed in this article.)

Understanding the antecedents and consequences of these recurrent behaviors is a key aspect of psychotherapeutic treatments because diverse contingencies reinforce these repetitive behaviors. As with any comprehensive assessment, asking questions to understand the function of the behaviors guides personalized treatment recommendations or referrals. Mansueto et al3 described a systematic approach to assessing BFRBs. Asking questions based on these researchers’ SCAMP domains (Sensory, Cognitive, Affective, Motor, Place) can provide patients and clinicians with a clear picture of pulling, picking, or other repetitive behaviors.

Sensory. Start with an assessment of how sensory experiences might play into the cycle. Questions might include: Does the patient see a distinctive hair (eg, color, texture) or skin irregularity that draws them into the behavior? Do they visually inspect the hair or skin before, during, or after? Do they describe a premonitory sensation, such as an itch? Do they have a dermatologic condition that cues interoceptive hypervigilance? Do they taste or smell the scab, excoriate, or hair? Are they particularly attuned to the auditory experiences of the process (ie, hearing the pop or a pull)? Could any substances or medications be impacting the body’s restlessness?

Cognitive. Just as we assess common automatic thoughts associated with other psychopathologies, it is important to appreciate the cognitions that occur during this behavioral chain. Some thoughts involve an intolerance of imperfection: “That hair looks different. I have to remove it.” “It is important for pores to be completely clean.” Other thoughts may involve granting permission: “I’ll just pull one.” “It has been a long week so I deserve to do just this one.” Certainly, many patients may be thinking about other daily stressors, such as occupational or interpersonal difficulties. Knowing about the patient’s mental state throughout the BFRB can guide a clinician to recommend treatment focused on (for example) cognitive-behavioral therapy for perfectionism or approaches to address existing stressors.

Affective. One common assumption is that patients who engage in BFRBs are anxious. While it certainly may be the case, an array of affective states may accompany the repetitive behavior. Patients may describe feeling tense, bored, sad, anxious, excited, relieved, agitated, guilty, worried, or ashamed. It is typically helpful to inquire about affect before, during, and after. Knowing the emotional experiences during and outside of BFRBs can call attention to possible comorbidities that warrant treatment, such as a mood or anxiety disorder. Additionally, dysregulation in affective states during the BFRB may point to useful adjunctive skills, such as DBT.

Motor. Some patients describe being quite unaware of their BFRB (often called “automatic”), whereas for other patients pulling or picking may be directed and within awareness (often called “focused”). It is common for patients to have both automatic and focused behaviors. Questions to understand the motor experience include: Is the patient operating on autopilot when they are engaged in the behavior? Does the behavior occur more often in certain postures, such as when they are seated or lying in bed? Understanding the choreography of the BFRB can help in determining physical barriers to protect the skin or hair.

Place. Finally, ask the patient if they believe certain locations increase the occurrence of the BFRB. For instance, some patients may notice the behavior is more likely to occur in the bathroom or bedroom. Bathrooms often contain implements associated with these behaviors, including mirrors, tweezers, or bright lights. Knowing where the BFRB is most likely to occur can help the clinician develop planning strategies to minimize behavioral engagement. An example is a patient who is more likely to pull or pick on a long commute from work. Planning to have a hat and sweater in their vehicle for the drive home may serve as a deterrent and break the cycle. When considering the place, it may also be helpful to ask about the time of day and presence of others.

Gathering information from the SCAMP domains can lead to individualized approaches to care. Of course, nonsuicidal self-injury, delusional parasitosis, or body dysmorphic disorder are a few of the many differential diagnoses that should be considered during the assessment. After a detailed assessment, clinicians can proceed by collaboratively developing strategies with the patient, referring them to a clinician who specializes in treating BFRBs using a resource such as the TLC Foundation’s Find a Therapist directory (https://www.bfrb.org/find-help-support/find-a-therapist), or recommending a self-guided resource such as StopPulling.com or StopPicking.com.

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. The TLC Foundation for Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors (2016). Expert consensus treatment guidelines. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.bfrb.org/storage/documents/Expert_Consensus_Treatment_Guidelines_2016w.pdf

3. Mansueto CS, Vavricheck SM, Golomb RG. Overcoming Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors: A Comprehensive Behavioral Treatment for Hair Pulling and Skin Picking. New Harbinger Publications; 2019.

Repetitive behaviors towards the body, such as hair pulling and skin picking, are common. Approximately 5% of the general population may meet criteria for trichotillomania or excoriation disorder, in which the repetitive behaviors are excessive and impairing. The category of body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRBs) extends beyond these 2 disorders to include onychophagia (nail biting), onychotillomania (nail picking), and lip or cheek chewing, which in DSM-5 are categorized under Other Specified Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder—BFRB. Of particular concern are trichophagia or dermatophagia, the ritualizing and eating of skin or hair that can lead to gastrointestinal complications.1

The prevalence and associated distress from BFRBs have spurred increased research into psychotherapeutic interventions to remediate suffering and curb bodily damage. Under the broader umbrella of behavioral therapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy, the Expert Consensus Treatment Guidelines from the TLC Foundation2 describe habit reversal therapy, comprehensive behavioral treatment, and behavioral therapy that is enhanced by acceptance and commitment therapy or dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) skills. (Although these guidelines also summarize possible pharmacologic interventions, medication for patients with BFRBs is not discussed in this article.)

Understanding the antecedents and consequences of these recurrent behaviors is a key aspect of psychotherapeutic treatments because diverse contingencies reinforce these repetitive behaviors. As with any comprehensive assessment, asking questions to understand the function of the behaviors guides personalized treatment recommendations or referrals. Mansueto et al3 described a systematic approach to assessing BFRBs. Asking questions based on these researchers’ SCAMP domains (Sensory, Cognitive, Affective, Motor, Place) can provide patients and clinicians with a clear picture of pulling, picking, or other repetitive behaviors.

Sensory. Start with an assessment of how sensory experiences might play into the cycle. Questions might include: Does the patient see a distinctive hair (eg, color, texture) or skin irregularity that draws them into the behavior? Do they visually inspect the hair or skin before, during, or after? Do they describe a premonitory sensation, such as an itch? Do they have a dermatologic condition that cues interoceptive hypervigilance? Do they taste or smell the scab, excoriate, or hair? Are they particularly attuned to the auditory experiences of the process (ie, hearing the pop or a pull)? Could any substances or medications be impacting the body’s restlessness?

Cognitive. Just as we assess common automatic thoughts associated with other psychopathologies, it is important to appreciate the cognitions that occur during this behavioral chain. Some thoughts involve an intolerance of imperfection: “That hair looks different. I have to remove it.” “It is important for pores to be completely clean.” Other thoughts may involve granting permission: “I’ll just pull one.” “It has been a long week so I deserve to do just this one.” Certainly, many patients may be thinking about other daily stressors, such as occupational or interpersonal difficulties. Knowing about the patient’s mental state throughout the BFRB can guide a clinician to recommend treatment focused on (for example) cognitive-behavioral therapy for perfectionism or approaches to address existing stressors.

Affective. One common assumption is that patients who engage in BFRBs are anxious. While it certainly may be the case, an array of affective states may accompany the repetitive behavior. Patients may describe feeling tense, bored, sad, anxious, excited, relieved, agitated, guilty, worried, or ashamed. It is typically helpful to inquire about affect before, during, and after. Knowing the emotional experiences during and outside of BFRBs can call attention to possible comorbidities that warrant treatment, such as a mood or anxiety disorder. Additionally, dysregulation in affective states during the BFRB may point to useful adjunctive skills, such as DBT.

Motor. Some patients describe being quite unaware of their BFRB (often called “automatic”), whereas for other patients pulling or picking may be directed and within awareness (often called “focused”). It is common for patients to have both automatic and focused behaviors. Questions to understand the motor experience include: Is the patient operating on autopilot when they are engaged in the behavior? Does the behavior occur more often in certain postures, such as when they are seated or lying in bed? Understanding the choreography of the BFRB can help in determining physical barriers to protect the skin or hair.

Place. Finally, ask the patient if they believe certain locations increase the occurrence of the BFRB. For instance, some patients may notice the behavior is more likely to occur in the bathroom or bedroom. Bathrooms often contain implements associated with these behaviors, including mirrors, tweezers, or bright lights. Knowing where the BFRB is most likely to occur can help the clinician develop planning strategies to minimize behavioral engagement. An example is a patient who is more likely to pull or pick on a long commute from work. Planning to have a hat and sweater in their vehicle for the drive home may serve as a deterrent and break the cycle. When considering the place, it may also be helpful to ask about the time of day and presence of others.

Gathering information from the SCAMP domains can lead to individualized approaches to care. Of course, nonsuicidal self-injury, delusional parasitosis, or body dysmorphic disorder are a few of the many differential diagnoses that should be considered during the assessment. After a detailed assessment, clinicians can proceed by collaboratively developing strategies with the patient, referring them to a clinician who specializes in treating BFRBs using a resource such as the TLC Foundation’s Find a Therapist directory (https://www.bfrb.org/find-help-support/find-a-therapist), or recommending a self-guided resource such as StopPulling.com or StopPicking.com.

Repetitive behaviors towards the body, such as hair pulling and skin picking, are common. Approximately 5% of the general population may meet criteria for trichotillomania or excoriation disorder, in which the repetitive behaviors are excessive and impairing. The category of body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRBs) extends beyond these 2 disorders to include onychophagia (nail biting), onychotillomania (nail picking), and lip or cheek chewing, which in DSM-5 are categorized under Other Specified Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder—BFRB. Of particular concern are trichophagia or dermatophagia, the ritualizing and eating of skin or hair that can lead to gastrointestinal complications.1

The prevalence and associated distress from BFRBs have spurred increased research into psychotherapeutic interventions to remediate suffering and curb bodily damage. Under the broader umbrella of behavioral therapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy, the Expert Consensus Treatment Guidelines from the TLC Foundation2 describe habit reversal therapy, comprehensive behavioral treatment, and behavioral therapy that is enhanced by acceptance and commitment therapy or dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) skills. (Although these guidelines also summarize possible pharmacologic interventions, medication for patients with BFRBs is not discussed in this article.)

Understanding the antecedents and consequences of these recurrent behaviors is a key aspect of psychotherapeutic treatments because diverse contingencies reinforce these repetitive behaviors. As with any comprehensive assessment, asking questions to understand the function of the behaviors guides personalized treatment recommendations or referrals. Mansueto et al3 described a systematic approach to assessing BFRBs. Asking questions based on these researchers’ SCAMP domains (Sensory, Cognitive, Affective, Motor, Place) can provide patients and clinicians with a clear picture of pulling, picking, or other repetitive behaviors.

Sensory. Start with an assessment of how sensory experiences might play into the cycle. Questions might include: Does the patient see a distinctive hair (eg, color, texture) or skin irregularity that draws them into the behavior? Do they visually inspect the hair or skin before, during, or after? Do they describe a premonitory sensation, such as an itch? Do they have a dermatologic condition that cues interoceptive hypervigilance? Do they taste or smell the scab, excoriate, or hair? Are they particularly attuned to the auditory experiences of the process (ie, hearing the pop or a pull)? Could any substances or medications be impacting the body’s restlessness?

Cognitive. Just as we assess common automatic thoughts associated with other psychopathologies, it is important to appreciate the cognitions that occur during this behavioral chain. Some thoughts involve an intolerance of imperfection: “That hair looks different. I have to remove it.” “It is important for pores to be completely clean.” Other thoughts may involve granting permission: “I’ll just pull one.” “It has been a long week so I deserve to do just this one.” Certainly, many patients may be thinking about other daily stressors, such as occupational or interpersonal difficulties. Knowing about the patient’s mental state throughout the BFRB can guide a clinician to recommend treatment focused on (for example) cognitive-behavioral therapy for perfectionism or approaches to address existing stressors.

Affective. One common assumption is that patients who engage in BFRBs are anxious. While it certainly may be the case, an array of affective states may accompany the repetitive behavior. Patients may describe feeling tense, bored, sad, anxious, excited, relieved, agitated, guilty, worried, or ashamed. It is typically helpful to inquire about affect before, during, and after. Knowing the emotional experiences during and outside of BFRBs can call attention to possible comorbidities that warrant treatment, such as a mood or anxiety disorder. Additionally, dysregulation in affective states during the BFRB may point to useful adjunctive skills, such as DBT.

Motor. Some patients describe being quite unaware of their BFRB (often called “automatic”), whereas for other patients pulling or picking may be directed and within awareness (often called “focused”). It is common for patients to have both automatic and focused behaviors. Questions to understand the motor experience include: Is the patient operating on autopilot when they are engaged in the behavior? Does the behavior occur more often in certain postures, such as when they are seated or lying in bed? Understanding the choreography of the BFRB can help in determining physical barriers to protect the skin or hair.

Place. Finally, ask the patient if they believe certain locations increase the occurrence of the BFRB. For instance, some patients may notice the behavior is more likely to occur in the bathroom or bedroom. Bathrooms often contain implements associated with these behaviors, including mirrors, tweezers, or bright lights. Knowing where the BFRB is most likely to occur can help the clinician develop planning strategies to minimize behavioral engagement. An example is a patient who is more likely to pull or pick on a long commute from work. Planning to have a hat and sweater in their vehicle for the drive home may serve as a deterrent and break the cycle. When considering the place, it may also be helpful to ask about the time of day and presence of others.

Gathering information from the SCAMP domains can lead to individualized approaches to care. Of course, nonsuicidal self-injury, delusional parasitosis, or body dysmorphic disorder are a few of the many differential diagnoses that should be considered during the assessment. After a detailed assessment, clinicians can proceed by collaboratively developing strategies with the patient, referring them to a clinician who specializes in treating BFRBs using a resource such as the TLC Foundation’s Find a Therapist directory (https://www.bfrb.org/find-help-support/find-a-therapist), or recommending a self-guided resource such as StopPulling.com or StopPicking.com.

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. The TLC Foundation for Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors (2016). Expert consensus treatment guidelines. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.bfrb.org/storage/documents/Expert_Consensus_Treatment_Guidelines_2016w.pdf

3. Mansueto CS, Vavricheck SM, Golomb RG. Overcoming Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors: A Comprehensive Behavioral Treatment for Hair Pulling and Skin Picking. New Harbinger Publications; 2019.

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. The TLC Foundation for Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors (2016). Expert consensus treatment guidelines. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.bfrb.org/storage/documents/Expert_Consensus_Treatment_Guidelines_2016w.pdf

3. Mansueto CS, Vavricheck SM, Golomb RG. Overcoming Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors: A Comprehensive Behavioral Treatment for Hair Pulling and Skin Picking. New Harbinger Publications; 2019.

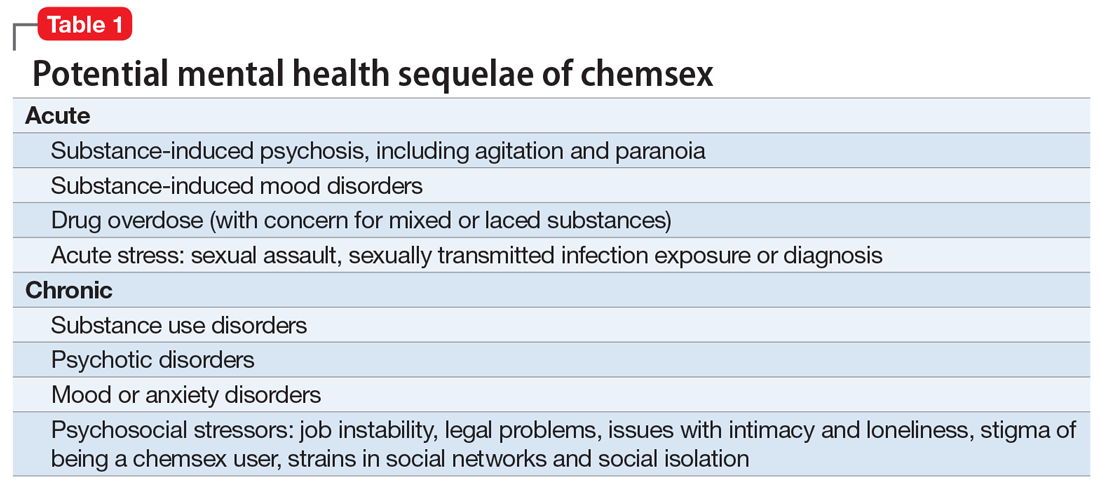

Let’s talk about ‘chemsex’: Sexualized drug use among men who have sex with men

Consider the following patients who have presented to our hospital system:

- A 27-year-old gay man is brought to the emergency department by police after bizarre behavior in a hotel. He is paranoid, disorganized, and responding to internal stimuli. He admits to using methamphetamine before a potential “hookup” at the hotel

- A 35-year-old bisexual man presents to the psychiatric emergency department, worried he will lose his job and relationship after downloading a dating app on his work phone to buy methamphetamine

- A 30-year-old gay man divulges to his psychiatrist that he is insecure about his sexual performance and intimacy with his partner because most of their sexual contact involves using gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB).