User login

Utilization, Cost, and Prescription Trends of Antipsychotics Prescribed by Dermatologists for Medicare Patients

To the Editor:

Patients with primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations often seek treatment from dermatologists instead of psychiatrists.1 For example, patients with delusions of parasitosis may lack insight into the underlying etiology of their disease and instead fixate on establishing an organic cause for their symptoms. As a result, it is an increasingly common practice for dermatologists to diagnose and treat psychiatric conditions.1 The goal of this study was to evaluate trends for the top 5 antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists in the Medicare Part D database.

In this retrospective analysis, we consulted the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data for January 2013 through December 2020, which is provided to the public by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.2 Only prescribing data from dermatologists were included in this study by using the built-in filter on the website to select “dermatology” as the prescriber type. All other provider types were excluded. We chose the top 5 most prescribed antipsychotics based on the number of supply days reported. Supply days—defined by Medicare as the number of days’ worth of medication that is prescribed—were used as a metric for utilization; therefore, each drug’s total supply days prescribed by dermatologists were calculated using this combined filter of drug name and total supply days using the database.

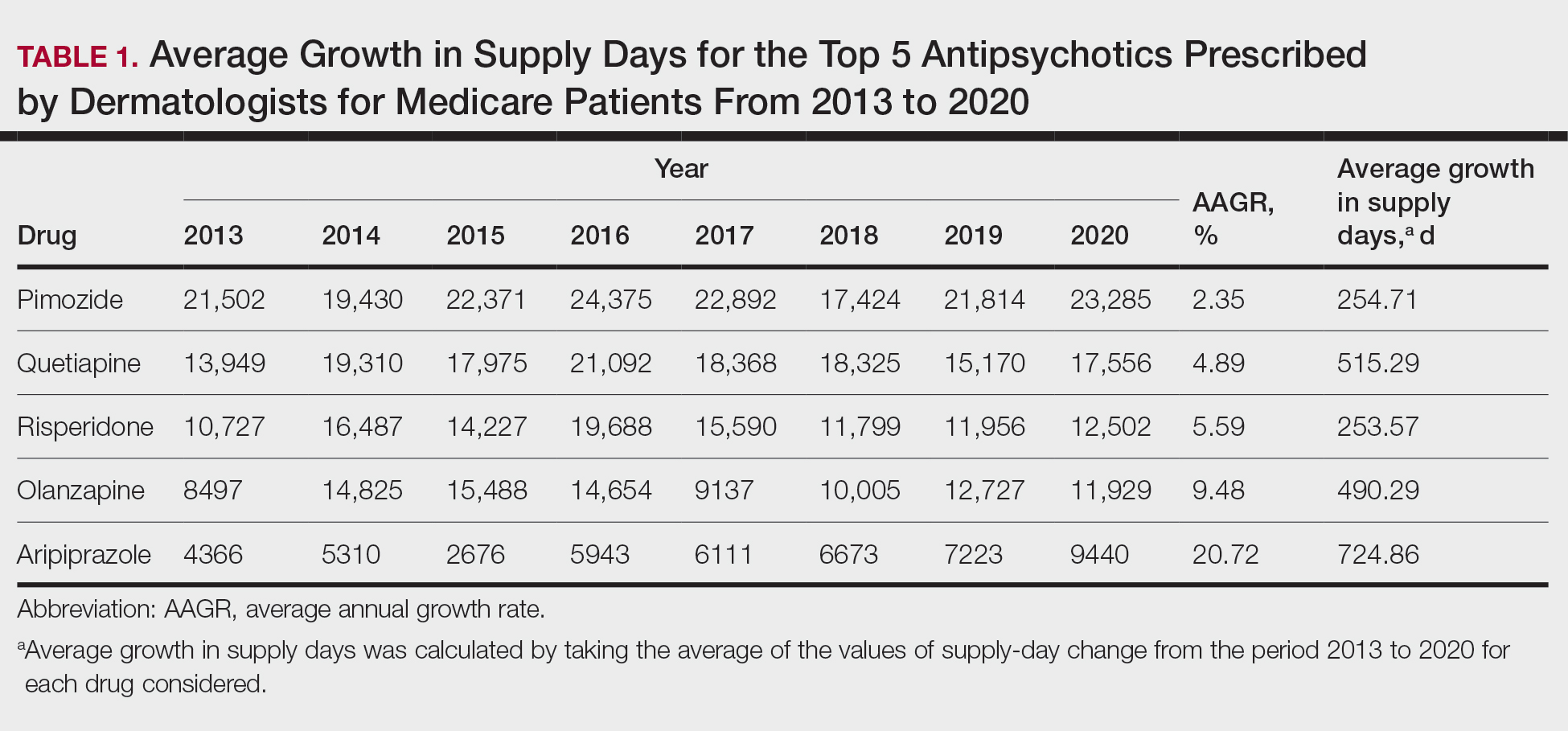

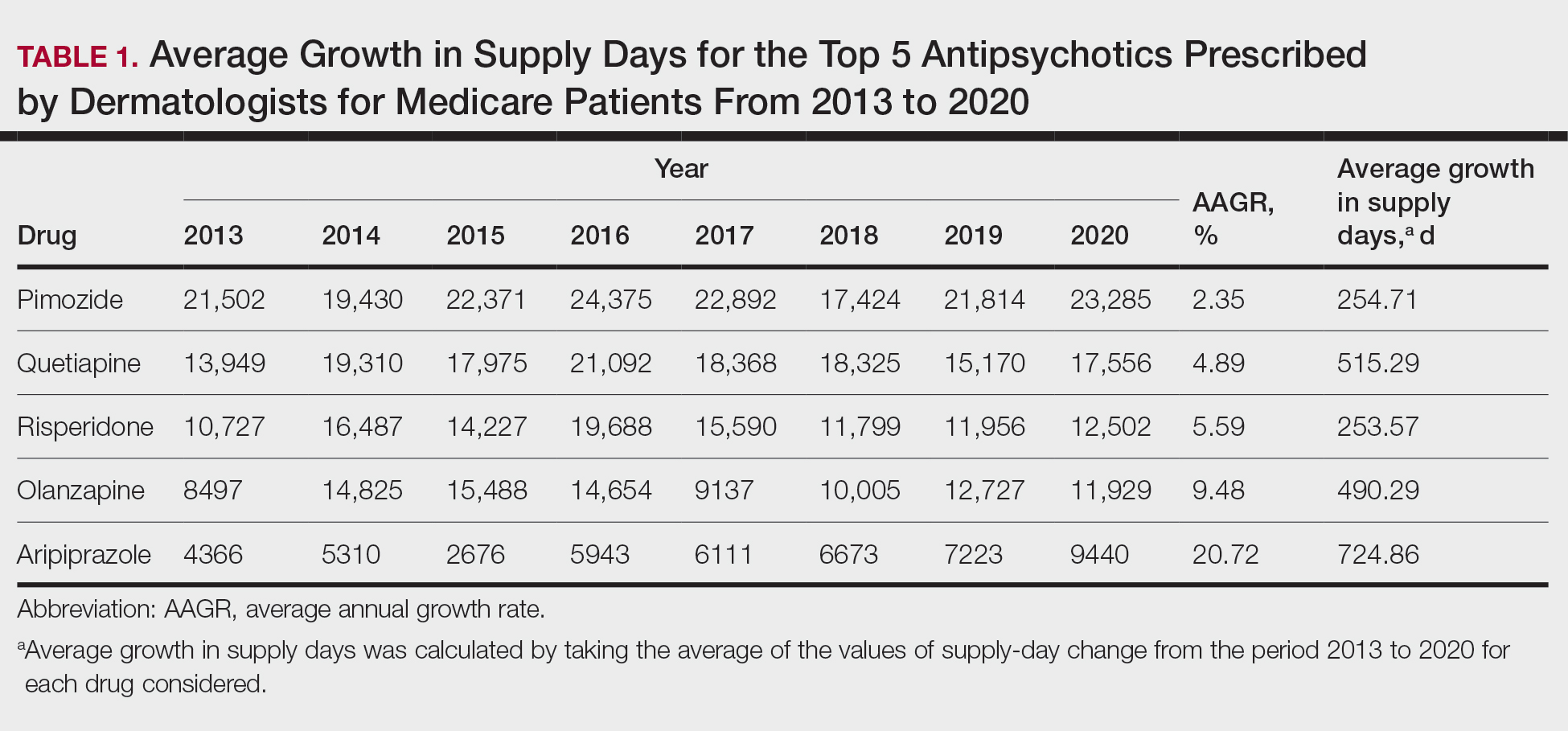

To analyze utilization over time, the annual average growth rate (AAGR) was calculated by determining the growth rate in total supply days annually from 2013 to 2020 and then averaging those rates to determine the overall AAGR. For greater clinical relevance, we calculated the average growth in supply days for the entire study period by determining the difference in the number of supply days for each year and then averaging these values. This was done to consider overall trends across dermatology rather than individual dermatologist prescribing patterns.

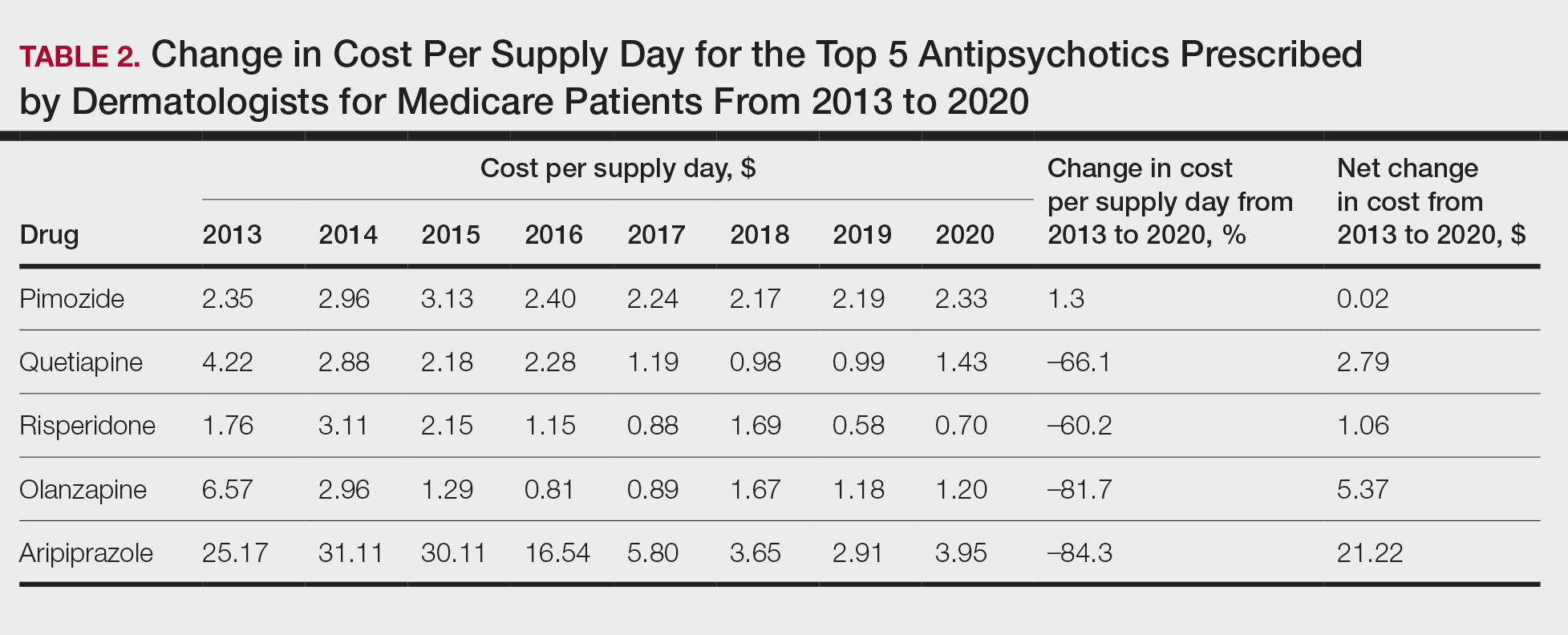

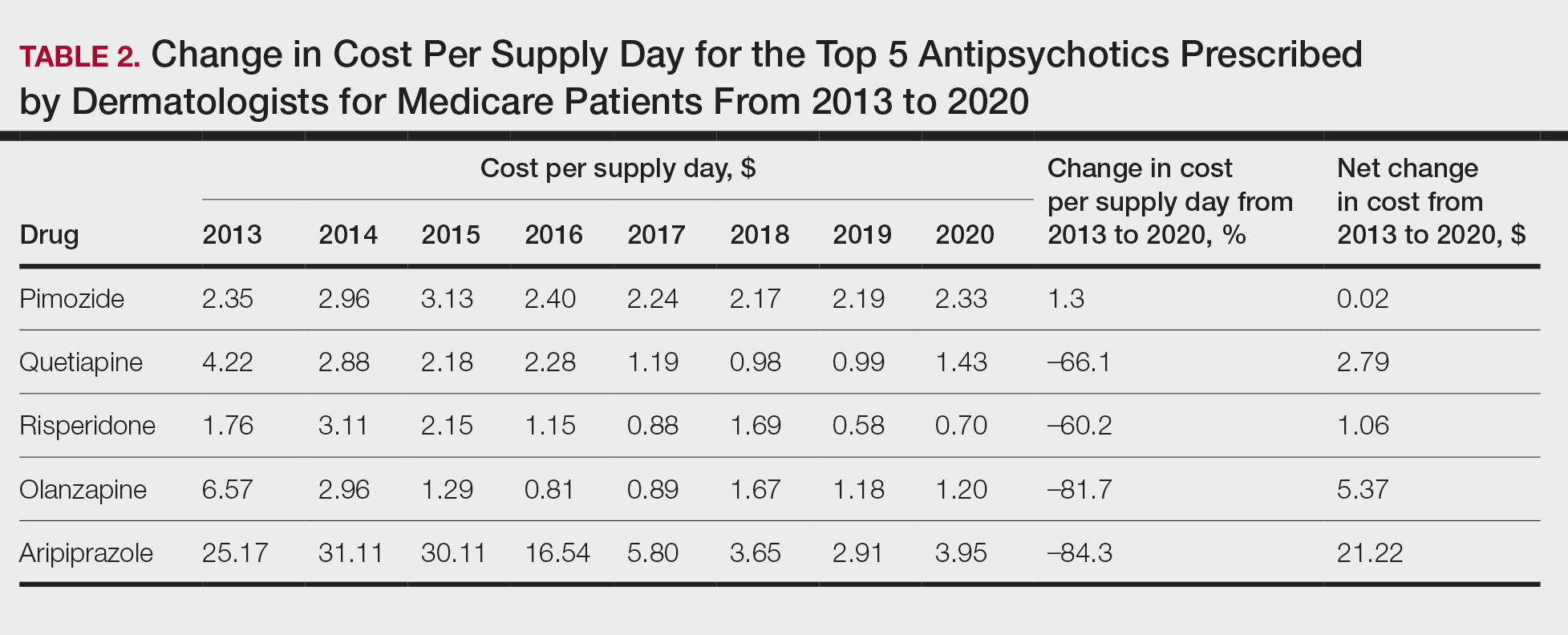

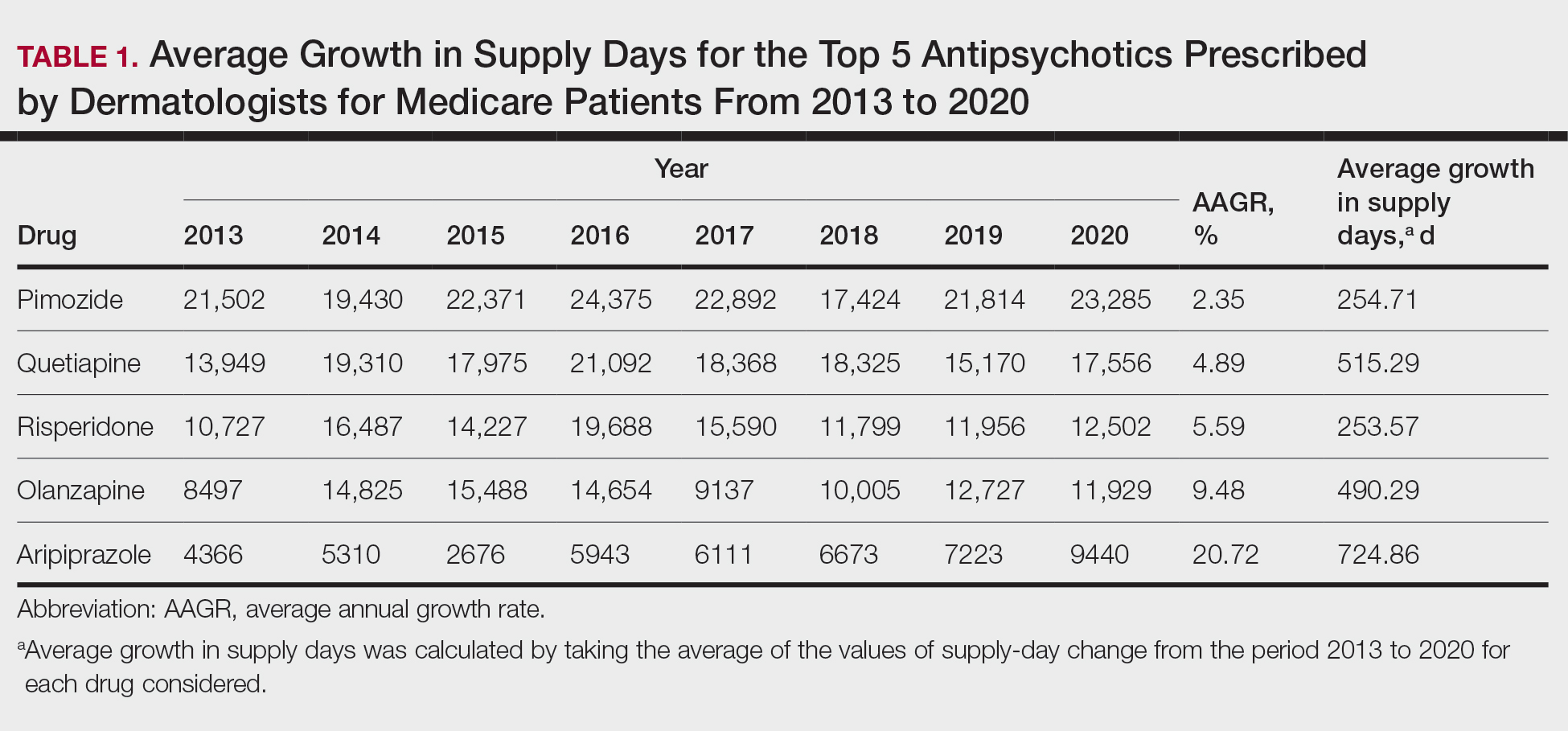

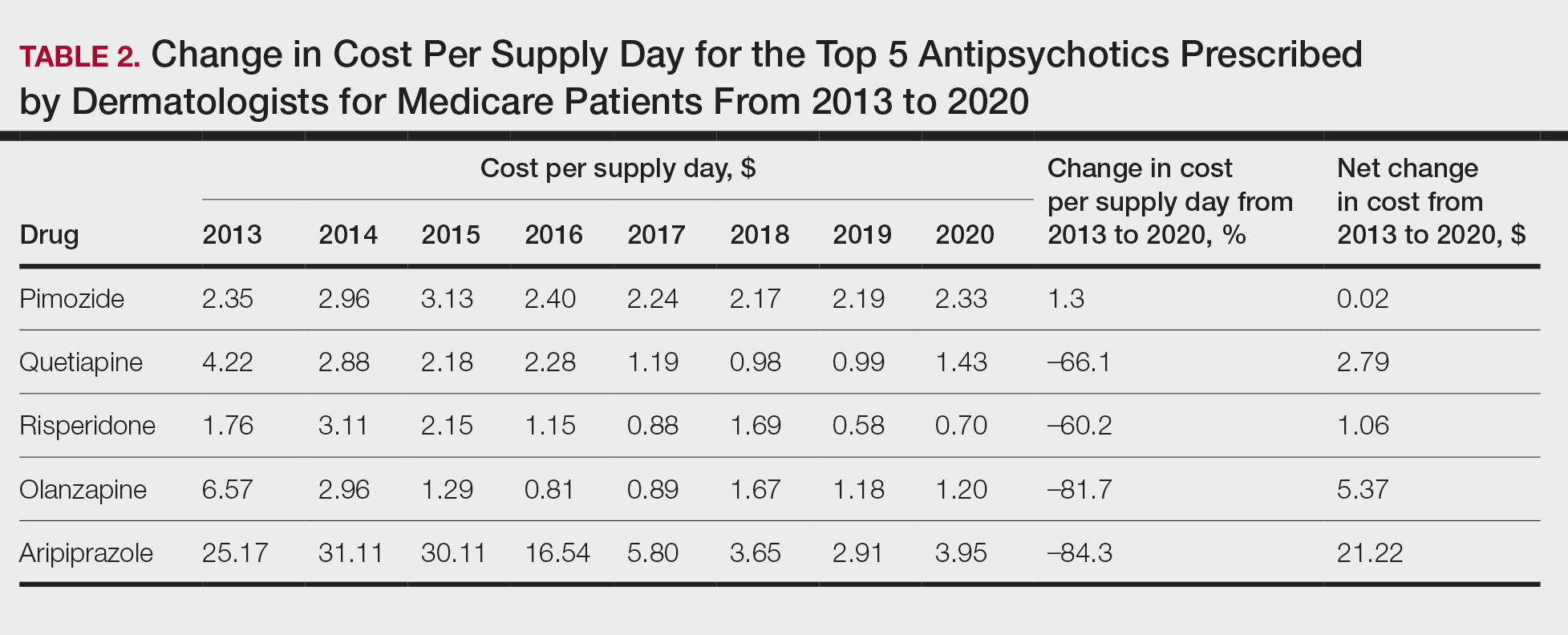

Based on our analysis, the antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists for Medicare patients from January 2013 to December 2020 were pimozide, quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole. The AAGR for each drug was 2.35%, 4.89%, 5.59%, 9.48%, and 20.72%, respectively, which is consistent with increased utilization over the study period for all 5 drugs (Table 1). The change in cost per supply day for the same period was 1.3%, –66.1%, –60.2%, –81.7%, and –84.3%, respectively. The net difference in cost per supply day over this entire period was $0.02, –$2.79, –$1.06, –$5.37, and –$21.22, respectively (Table 2).

There were several limitations to our study. Our analysis was limited to the Medicare population. Uninsured patients and those with Medicare Advantage or private health insurance plans were not included. In the Medicare database, only prescribers who prescribed a medication 10 times or more were recorded; therefore, some prescribers were not captured.

Although there was an increase in the dermatologic use of all 5 drugs in this study, perhaps the most marked growth was exhibited by aripiprazole, which had an AAGR of 20.72% (Table 1). Affordability may have been a factor, as the most marked reduction in price per supply day was noted for aripiprazole during the study period. Pimozide, which traditionally has been the first-line therapy for delusions of parasitosis, is the only first-generation antipsychotic drug among the 5 most frequently prescribed antipsychotics.3 Interestingly, pimozide had the lowest AAGR compared with the 4 second-generation antipsychotics. This finding also is corroborated by the average growth in supply days. While pimozide is a first-generation antipsychotic and had the lowest AAGR, pimozide still was the most prescribed antipsychotic in this study. Considering the average growth in Medicare beneficiaries during the study period was 2.70% per year,2 the AAGR of the 4 other drugs excluding pimozide shows that this growth was larger than what can be attributed to an increase in population size.

The most common conditions for which dermatologists prescribe antipsychotics are primary delusional infestation disorders as well as a range of self-inflicted dermatologic manifestations of dermatitis artefacta.4 Particularly, dermatologist-prescribed antipsychotics are first-line for these conditions in which perception of a persistent disease state is present.4 Importantly, dermatologists must differentiate between other dermatology-related psychiatric conditions such as trichotillomania and body dysmorphic disorder, which tend to respond better to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.4 Our data suggest that dermatologists are increasing their utilization of second-generation antipsychotics at a higher rate than first-generation antipsychotics, likely due to the lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms. Patients are more willing to initiate a trial of psychiatric medication when it is prescribed by a dermatologist vs a psychiatrist due to lack of perceived stigma, which can lead to greater treatment compliance rates.5 As mentioned previously, as part of the differential, dermatologists also can effectively prescribe medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for symptoms including anxiety, trichotillomania, body dysmorphic disorder, or secondary psychiatric disorders as a result of the burden of skin disease.5

In many cases, a dermatologist may be the first and only specialist to evaluate patients with conditions that overlap within the jurisdiction of dermatology and psychiatry. It is imperative that dermatologists feel comfortable treating this vulnerable patient population. As demonstrated by Medicare prescription data, the increasing utilization of antipsychotics in our specialty demands that dermatologists possess an adequate working knowledge of psychopharmacology, which may be accomplished during residency training through several directives, including focused didactic sessions, elective rotations in psychiatry, increased exposure to psychocutaneous lectures at national conferences, and finally through the establishment of joint dermatology-psychiatry clinics with interdepartmental collaboration.

- Weber MB, Recuero JK, Almeida CS. Use of psychiatric drugs in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95:133-143. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.12.002

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare provider utilization and payment data: part D prescriber. Updated September 10, 2024. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/data -research/statistics-trends-and-reports/medicare-provider-utilization-payment-data/part-d-prescriber

- Bolognia J, Schaffe JV, Lorenzo C. Dermatology. In: Duncan KO, Koo JYM, eds. Psychocutaneous Diseases. Elsevier; 2017:128-136.

- Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

- Jafferany M, Stamu-O’Brien C, Mkhoyan R, et al. Psychotropic drugs in dermatology: a dermatologist’s approach and choice of medications. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13385. doi:10.1111/dth.13385

To the Editor:

Patients with primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations often seek treatment from dermatologists instead of psychiatrists.1 For example, patients with delusions of parasitosis may lack insight into the underlying etiology of their disease and instead fixate on establishing an organic cause for their symptoms. As a result, it is an increasingly common practice for dermatologists to diagnose and treat psychiatric conditions.1 The goal of this study was to evaluate trends for the top 5 antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists in the Medicare Part D database.

In this retrospective analysis, we consulted the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data for January 2013 through December 2020, which is provided to the public by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.2 Only prescribing data from dermatologists were included in this study by using the built-in filter on the website to select “dermatology” as the prescriber type. All other provider types were excluded. We chose the top 5 most prescribed antipsychotics based on the number of supply days reported. Supply days—defined by Medicare as the number of days’ worth of medication that is prescribed—were used as a metric for utilization; therefore, each drug’s total supply days prescribed by dermatologists were calculated using this combined filter of drug name and total supply days using the database.

To analyze utilization over time, the annual average growth rate (AAGR) was calculated by determining the growth rate in total supply days annually from 2013 to 2020 and then averaging those rates to determine the overall AAGR. For greater clinical relevance, we calculated the average growth in supply days for the entire study period by determining the difference in the number of supply days for each year and then averaging these values. This was done to consider overall trends across dermatology rather than individual dermatologist prescribing patterns.

Based on our analysis, the antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists for Medicare patients from January 2013 to December 2020 were pimozide, quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole. The AAGR for each drug was 2.35%, 4.89%, 5.59%, 9.48%, and 20.72%, respectively, which is consistent with increased utilization over the study period for all 5 drugs (Table 1). The change in cost per supply day for the same period was 1.3%, –66.1%, –60.2%, –81.7%, and –84.3%, respectively. The net difference in cost per supply day over this entire period was $0.02, –$2.79, –$1.06, –$5.37, and –$21.22, respectively (Table 2).

There were several limitations to our study. Our analysis was limited to the Medicare population. Uninsured patients and those with Medicare Advantage or private health insurance plans were not included. In the Medicare database, only prescribers who prescribed a medication 10 times or more were recorded; therefore, some prescribers were not captured.

Although there was an increase in the dermatologic use of all 5 drugs in this study, perhaps the most marked growth was exhibited by aripiprazole, which had an AAGR of 20.72% (Table 1). Affordability may have been a factor, as the most marked reduction in price per supply day was noted for aripiprazole during the study period. Pimozide, which traditionally has been the first-line therapy for delusions of parasitosis, is the only first-generation antipsychotic drug among the 5 most frequently prescribed antipsychotics.3 Interestingly, pimozide had the lowest AAGR compared with the 4 second-generation antipsychotics. This finding also is corroborated by the average growth in supply days. While pimozide is a first-generation antipsychotic and had the lowest AAGR, pimozide still was the most prescribed antipsychotic in this study. Considering the average growth in Medicare beneficiaries during the study period was 2.70% per year,2 the AAGR of the 4 other drugs excluding pimozide shows that this growth was larger than what can be attributed to an increase in population size.

The most common conditions for which dermatologists prescribe antipsychotics are primary delusional infestation disorders as well as a range of self-inflicted dermatologic manifestations of dermatitis artefacta.4 Particularly, dermatologist-prescribed antipsychotics are first-line for these conditions in which perception of a persistent disease state is present.4 Importantly, dermatologists must differentiate between other dermatology-related psychiatric conditions such as trichotillomania and body dysmorphic disorder, which tend to respond better to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.4 Our data suggest that dermatologists are increasing their utilization of second-generation antipsychotics at a higher rate than first-generation antipsychotics, likely due to the lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms. Patients are more willing to initiate a trial of psychiatric medication when it is prescribed by a dermatologist vs a psychiatrist due to lack of perceived stigma, which can lead to greater treatment compliance rates.5 As mentioned previously, as part of the differential, dermatologists also can effectively prescribe medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for symptoms including anxiety, trichotillomania, body dysmorphic disorder, or secondary psychiatric disorders as a result of the burden of skin disease.5

In many cases, a dermatologist may be the first and only specialist to evaluate patients with conditions that overlap within the jurisdiction of dermatology and psychiatry. It is imperative that dermatologists feel comfortable treating this vulnerable patient population. As demonstrated by Medicare prescription data, the increasing utilization of antipsychotics in our specialty demands that dermatologists possess an adequate working knowledge of psychopharmacology, which may be accomplished during residency training through several directives, including focused didactic sessions, elective rotations in psychiatry, increased exposure to psychocutaneous lectures at national conferences, and finally through the establishment of joint dermatology-psychiatry clinics with interdepartmental collaboration.

To the Editor:

Patients with primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations often seek treatment from dermatologists instead of psychiatrists.1 For example, patients with delusions of parasitosis may lack insight into the underlying etiology of their disease and instead fixate on establishing an organic cause for their symptoms. As a result, it is an increasingly common practice for dermatologists to diagnose and treat psychiatric conditions.1 The goal of this study was to evaluate trends for the top 5 antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists in the Medicare Part D database.

In this retrospective analysis, we consulted the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data for January 2013 through December 2020, which is provided to the public by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.2 Only prescribing data from dermatologists were included in this study by using the built-in filter on the website to select “dermatology” as the prescriber type. All other provider types were excluded. We chose the top 5 most prescribed antipsychotics based on the number of supply days reported. Supply days—defined by Medicare as the number of days’ worth of medication that is prescribed—were used as a metric for utilization; therefore, each drug’s total supply days prescribed by dermatologists were calculated using this combined filter of drug name and total supply days using the database.

To analyze utilization over time, the annual average growth rate (AAGR) was calculated by determining the growth rate in total supply days annually from 2013 to 2020 and then averaging those rates to determine the overall AAGR. For greater clinical relevance, we calculated the average growth in supply days for the entire study period by determining the difference in the number of supply days for each year and then averaging these values. This was done to consider overall trends across dermatology rather than individual dermatologist prescribing patterns.

Based on our analysis, the antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists for Medicare patients from January 2013 to December 2020 were pimozide, quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole. The AAGR for each drug was 2.35%, 4.89%, 5.59%, 9.48%, and 20.72%, respectively, which is consistent with increased utilization over the study period for all 5 drugs (Table 1). The change in cost per supply day for the same period was 1.3%, –66.1%, –60.2%, –81.7%, and –84.3%, respectively. The net difference in cost per supply day over this entire period was $0.02, –$2.79, –$1.06, –$5.37, and –$21.22, respectively (Table 2).

There were several limitations to our study. Our analysis was limited to the Medicare population. Uninsured patients and those with Medicare Advantage or private health insurance plans were not included. In the Medicare database, only prescribers who prescribed a medication 10 times or more were recorded; therefore, some prescribers were not captured.

Although there was an increase in the dermatologic use of all 5 drugs in this study, perhaps the most marked growth was exhibited by aripiprazole, which had an AAGR of 20.72% (Table 1). Affordability may have been a factor, as the most marked reduction in price per supply day was noted for aripiprazole during the study period. Pimozide, which traditionally has been the first-line therapy for delusions of parasitosis, is the only first-generation antipsychotic drug among the 5 most frequently prescribed antipsychotics.3 Interestingly, pimozide had the lowest AAGR compared with the 4 second-generation antipsychotics. This finding also is corroborated by the average growth in supply days. While pimozide is a first-generation antipsychotic and had the lowest AAGR, pimozide still was the most prescribed antipsychotic in this study. Considering the average growth in Medicare beneficiaries during the study period was 2.70% per year,2 the AAGR of the 4 other drugs excluding pimozide shows that this growth was larger than what can be attributed to an increase in population size.

The most common conditions for which dermatologists prescribe antipsychotics are primary delusional infestation disorders as well as a range of self-inflicted dermatologic manifestations of dermatitis artefacta.4 Particularly, dermatologist-prescribed antipsychotics are first-line for these conditions in which perception of a persistent disease state is present.4 Importantly, dermatologists must differentiate between other dermatology-related psychiatric conditions such as trichotillomania and body dysmorphic disorder, which tend to respond better to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.4 Our data suggest that dermatologists are increasing their utilization of second-generation antipsychotics at a higher rate than first-generation antipsychotics, likely due to the lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms. Patients are more willing to initiate a trial of psychiatric medication when it is prescribed by a dermatologist vs a psychiatrist due to lack of perceived stigma, which can lead to greater treatment compliance rates.5 As mentioned previously, as part of the differential, dermatologists also can effectively prescribe medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for symptoms including anxiety, trichotillomania, body dysmorphic disorder, or secondary psychiatric disorders as a result of the burden of skin disease.5

In many cases, a dermatologist may be the first and only specialist to evaluate patients with conditions that overlap within the jurisdiction of dermatology and psychiatry. It is imperative that dermatologists feel comfortable treating this vulnerable patient population. As demonstrated by Medicare prescription data, the increasing utilization of antipsychotics in our specialty demands that dermatologists possess an adequate working knowledge of psychopharmacology, which may be accomplished during residency training through several directives, including focused didactic sessions, elective rotations in psychiatry, increased exposure to psychocutaneous lectures at national conferences, and finally through the establishment of joint dermatology-psychiatry clinics with interdepartmental collaboration.

- Weber MB, Recuero JK, Almeida CS. Use of psychiatric drugs in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95:133-143. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.12.002

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare provider utilization and payment data: part D prescriber. Updated September 10, 2024. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/data -research/statistics-trends-and-reports/medicare-provider-utilization-payment-data/part-d-prescriber

- Bolognia J, Schaffe JV, Lorenzo C. Dermatology. In: Duncan KO, Koo JYM, eds. Psychocutaneous Diseases. Elsevier; 2017:128-136.

- Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

- Jafferany M, Stamu-O’Brien C, Mkhoyan R, et al. Psychotropic drugs in dermatology: a dermatologist’s approach and choice of medications. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13385. doi:10.1111/dth.13385

- Weber MB, Recuero JK, Almeida CS. Use of psychiatric drugs in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95:133-143. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.12.002

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare provider utilization and payment data: part D prescriber. Updated September 10, 2024. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/data -research/statistics-trends-and-reports/medicare-provider-utilization-payment-data/part-d-prescriber

- Bolognia J, Schaffe JV, Lorenzo C. Dermatology. In: Duncan KO, Koo JYM, eds. Psychocutaneous Diseases. Elsevier; 2017:128-136.

- Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

- Jafferany M, Stamu-O’Brien C, Mkhoyan R, et al. Psychotropic drugs in dermatology: a dermatologist’s approach and choice of medications. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13385. doi:10.1111/dth.13385

Practice Points

- Dermatologists are frontline medical providers who can be useful in screening for primary psychiatric disorders in patients with dermatologic manifestations.

- Second-generation antipsychotics are effective for treating many psychiatric disorders.

Treat-to-Target Outcomes With Tapinarof Cream 1% in Phase 3 Trials for Plaque Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting approximately 8 million adults in the United States and 2% of the global population.1,2 Psoriasis causes pain, itching, and disfigurement and is associated with a physical, psychological, and economic burden that substantially affects health-related quality of life.3-5

Setting treatment goals and treating to target are evidence-based approaches that have been successfully applied to several chronic diseases to improve patient outcomes, including diabetes, hypertension, and rheumatoid arthritis.6-9 Treat-to-target strategies generally set low disease activity (or remission) as an overall goal and seek to achieve this using available therapeutic options as necessary. Introduced following the availability of biologics and targeted systemic therapies, treat-to-target strategies generally provide guidance on expectations of treatment but not specific treatments, as personalized treatment decisions depend on an assessment of individual patients and consider clinical and demographic features as well as preferences for available therapeutic options. If targets are not achieved in the assigned time span, adjustments can be made to the treatment approach in close consultation with the patient. If the target is reached, follow-up visits can be scheduled to ensure improvement is maintained or to establish if more aggressive goals could be selected.

Treat-to-target strategies for the management of psoriasis developed by the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) Medical Board include reducing the extent of psoriasis to 1% or lower total body surface area (BSA) after 3 months of treatment.10 Treatment targets endorsed by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) in guidelines on the use of systemic therapies in psoriasis include achieving a 75% or greater reduction in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score within 3 to 4 months of treatment.11

In clinical practice, many patients do not achieve these treatment targets, and topical treatments alone generally are insufficient in achieving treatment goals for psoriasis.12,13 Moreover, conventional topical treatments (eg, topical corticosteroids) used by most patients with psoriasis regardless of disease severity are associated with adverse events that can limit their use. Most topical corticosteroids have US Food and Drug Administration label restrictions relating to sites of application, duration and extent of use, and frequency of administration.14,15

Tapinarof cream 1% (VTAMA [Dermavant Sciences, Inc]) is a first-in-class topical nonsteroidal aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults16 and is being studied for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in children 2 years and older as well as for atopic dermatitis in adults and children 2 years and older. In PSOARING 1 (ClinicalTrials .gov identifier NCT03956355) and PSOARING 2 (NCT03983980)—identical 12-week pivotal phase 3 trials—monotherapy with tapinarof cream 1% once daily (QD) demonstrated statistically significant efficacy vs vehicle cream and was well tolerated in adults with mild to severe plaque psoriasis (Supplementary Figure S1).17 Lebwohl et al17 reported that significantly higher PASI75 responses were observed at week 12 with tapinarof cream vs vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 (36% and 48% vs 10% and 7%, respectively; both P<.0001). A significantly higher PASI90 response of 19% and 21% at week 12 also was observed with tapinarof cream vs 2% and 3% with vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2, respectively (P=.0005 and P<.0001).17

In PSOARING 3 (NCT04053387)—the long-term extension trial (Supplementary Figure S1)—efficacy continued to improve or was maintained beyond the two 12-week trials, with improvements in total BSA affected and PASI scores for up to 52 weeks.18 Tapinarof cream 1% QD demonstrated positive, rapid, and durable outcomes in PSOARING 3, including high rates of complete disease clearance (Physician Global Assessment [PGA] score=0 [clear])(40.9% [312/763]), durability of response on treatment with no evidence of tachyphylaxis, and a remittive effect of approximately 4 months when off therapy (defined as maintenance of a PGA score of 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear] after first achieving a PGA score of 0).18

Herein, we report absolute treatment targets for patients with plaque psoriasis who received tapinarof cream 1% QD in the PSOARING trials that are at least as stringent as the corresponding NPF and EADV targets of achieving a total BSA affected of 1% or lower or a PASI75 response within 3 to 4 months, respectively.

METHODS

Study Design

The pooled efficacy analyses included all patients with a baseline PGA score of 2 or higher (mild or worse) before treatment with tapinarof cream 1% QD in the PSOARING trials. This included patients who received tapinarof cream 1% in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 who may or may not have continued into PSOARING 3, as well as those who received the vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 who enrolled in PSOARING 3 and had a PGA score of 2 or higher before receiving tapinarof cream 1%.

Trial Participants

Full methods, including inclusion and exclusion criteria, for the PSOARING trials have been previously reported.17,18 Patients were aged 18 to 75 years and had chronic plaque psoriasis that was stable for at least 6 months before randomization; 3% to 20% total BSA affected (excluding the scalp, palms, fingernails, toenails, and soles); and a PGA score of 2 (mild), 3 (moderate), or 4 (severe) at baseline.

The clinical trials were conducted in compliance with the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was obtained from local ethics committees or institutional review boards at each center. All patients provided written informed consent.

Trial Treatment

In PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2, patients were randomized (2:1) to receive tapinarof cream 1% or vehicle QD for 12 weeks. In PSOARING 3 (the long-term extension trial), patients received up to 40 weeks of open-label tapinarof, followed by 4 weeks of follow-up off treatment. Patients received intermittent or continuous treatment with tapinarof cream 1% in PSOARING 3 based on PGA score: those entering the trial with a PGA score of 1 or higher received tapinarof cream 1% until complete disease clearance was achieved (defined as a PGA score of 0 [clear]). Those entering PSOARING 3 with or achieving a PGA score of 0 (clear) discontinued treatment and were observed for the duration of maintenance of a PGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) while off therapy (the protocol-defined “duration of remittive effect”). If disease worsening (defined as a PGA score 2 or higher) occurred, tapinarof cream 1% was restarted and continued until a PGA score of 0 (clear) was achieved. This pattern of treatment, discontinuation on achieving a PGA score of 0 (clear), and retreatment on disease worsening continued until the end of the trial. As a result, patients in PSOARING 3 could receive tapinarof cream 1% continuously or intermittently for 40 weeks.

Outcome Measures and Statistical Analyses

The assessment of total BSA affected by plaque psoriasis is an estimate of the total extent of disease as a percentage of total skin area. In the PSOARING trials, the skin surface of one hand (palm and digits) was assumed to be approximately equivalent to 1% BSA. The total BSA affected by psoriasis was evaluated from 0% to 100%, with greater total BSA affected being an indication of more extensive disease. The BSA efficacy outcomes used in these analyses were based post hoc on the proportion of patients who achieved a 1% or lower or 0.5% or lower total BSA affected.

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index scores assess both the severity and extent of psoriasis. A PASI score lower than 5 often is considered indicative of mild psoriasis, a score of 5 to 10 indicates moderate disease, and a score higher than 10 indicates severe disease.19 The maximum PASI score is 72. The PASI efficacy outcomes used in these analyses were based post hoc on the proportion of patients who achieved an absolute total PASI score of 3 or lower, 2 or lower, and 1 or lower.

Efficacy analyses were based on pooled data for all patients in the PSOARING trials who had a PGA score of 2 to 4 (mild to severe) before treatment with tapinarof cream 1% in the intention-to-treat population using observed cases. Time-to-target analyses were based on Kaplan-Meier (KM) estimates using observed cases.

Safety analyses included the incidence and frequency of adverse events and were based on all patients who received tapinarof cream 1% in the PSOARING trials.

RESULTS

Baseline Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics

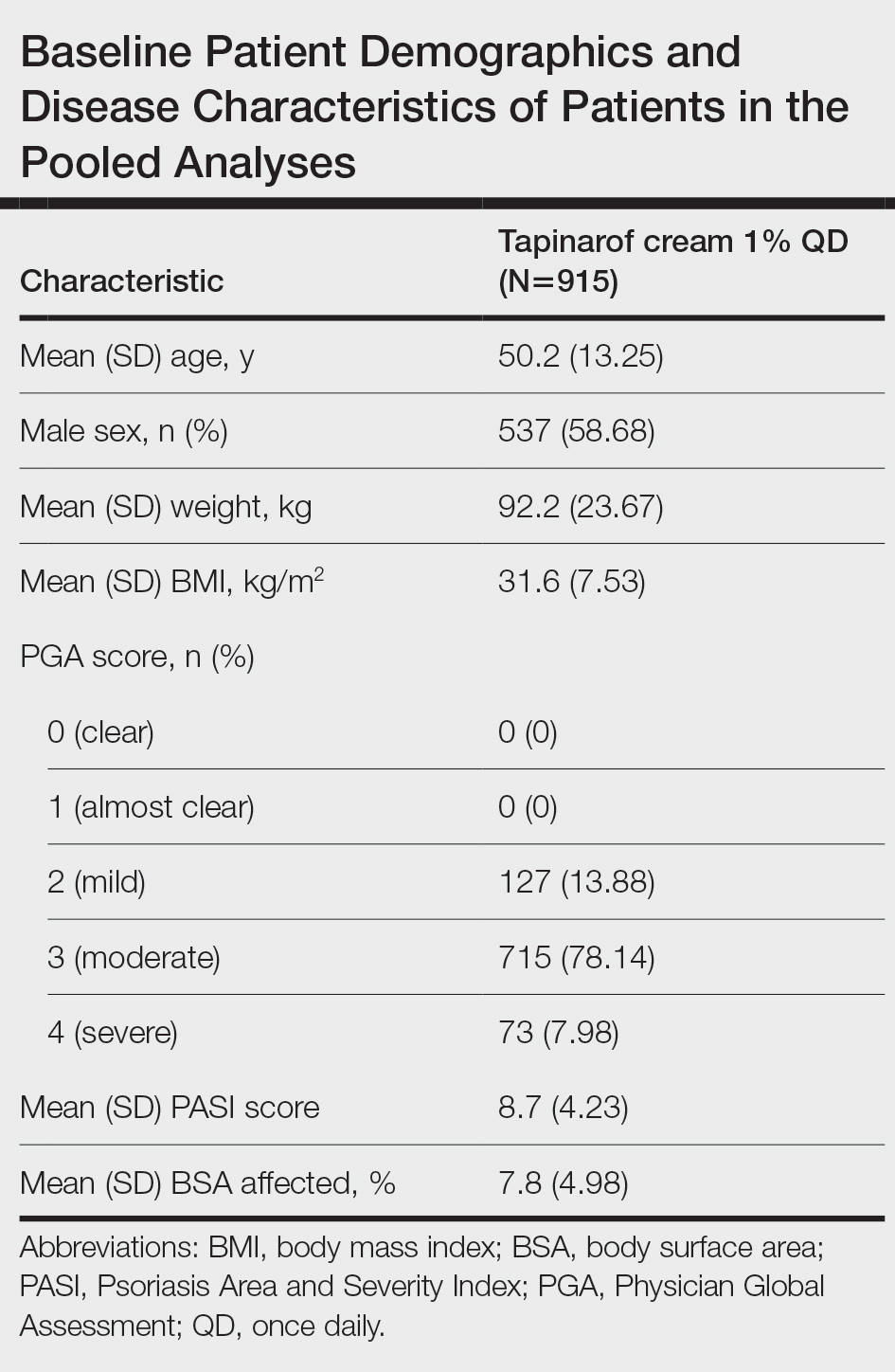

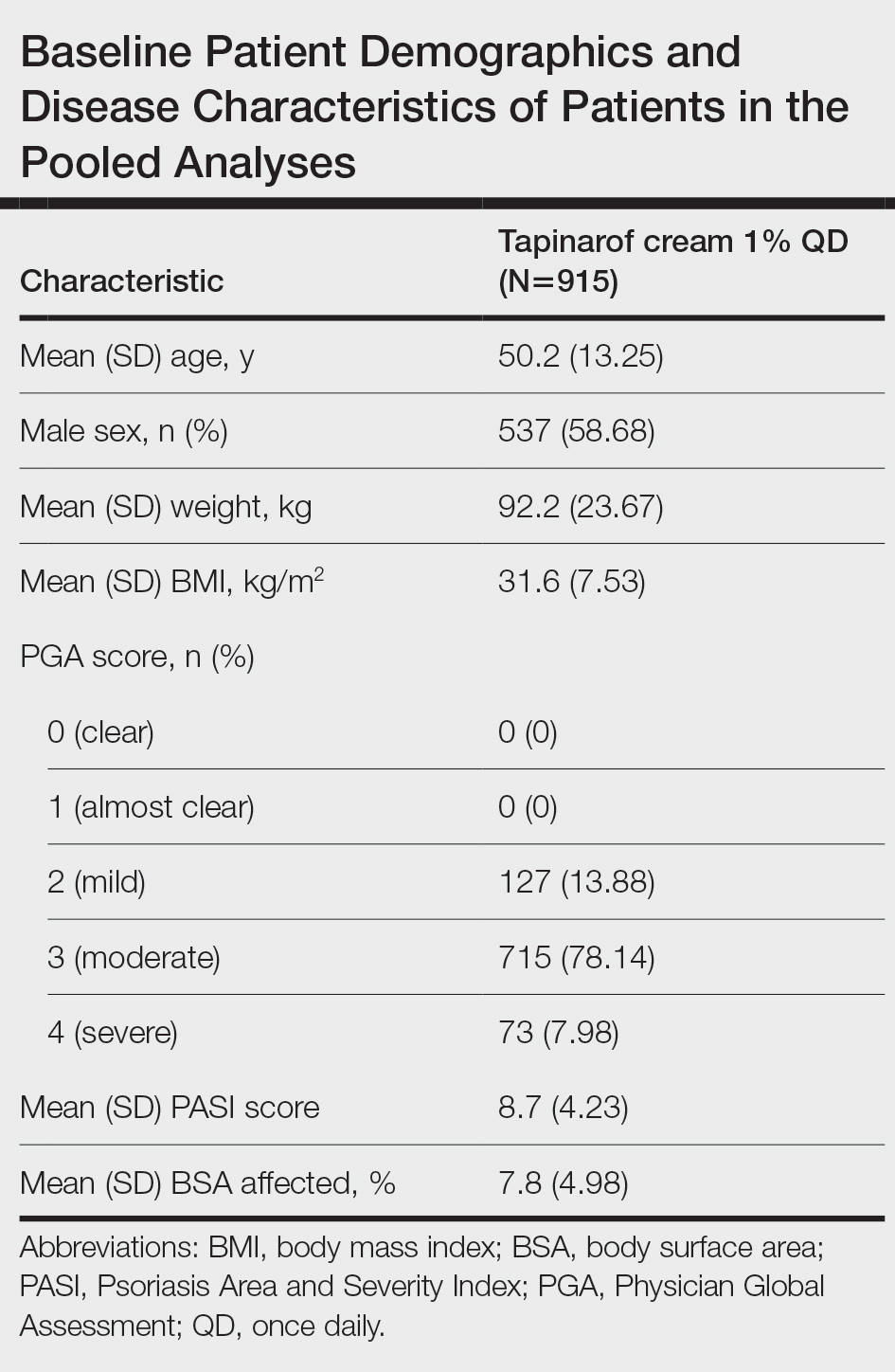

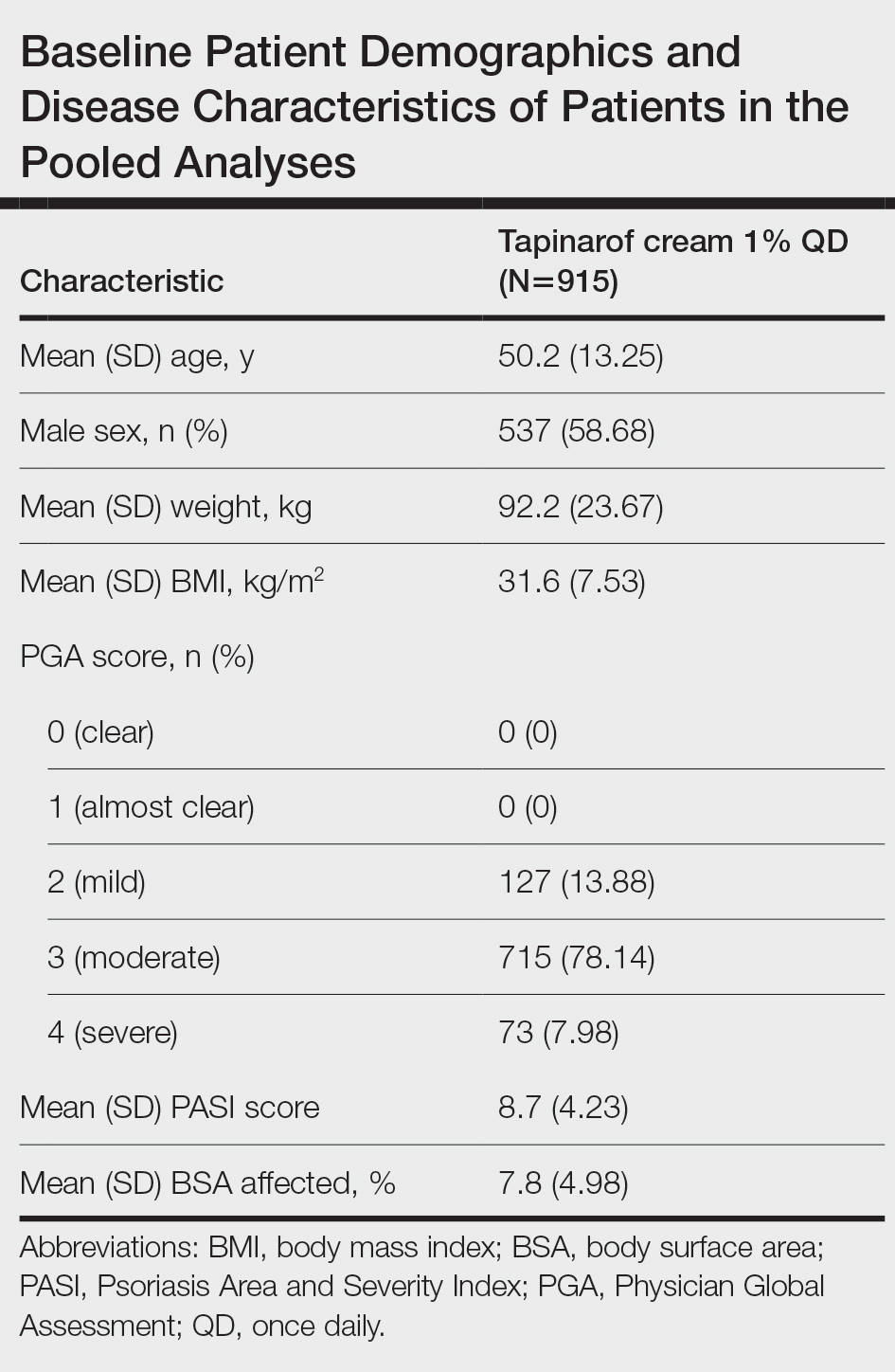

The pooled efficacy analyses included 915 eligible patients (Table). At baseline, the mean (SD) age was 50.2 (13.25) years, 58.7% were male, the mean (SD) weight was 92.2 (23.67) kg, and the mean (SD) body mass index was 31.6 (7.53) kg/m2. The percentage of patients with a PGA score of 2 (mild), 3 (moderate), or 4 (severe) was 13.9%, 78.1%, and 8.0%, respectively. The mean (SD) PASI score was 8.7 (4.23) and mean (SD) total BSA affected was 7.8% (4.98).

Efficacy

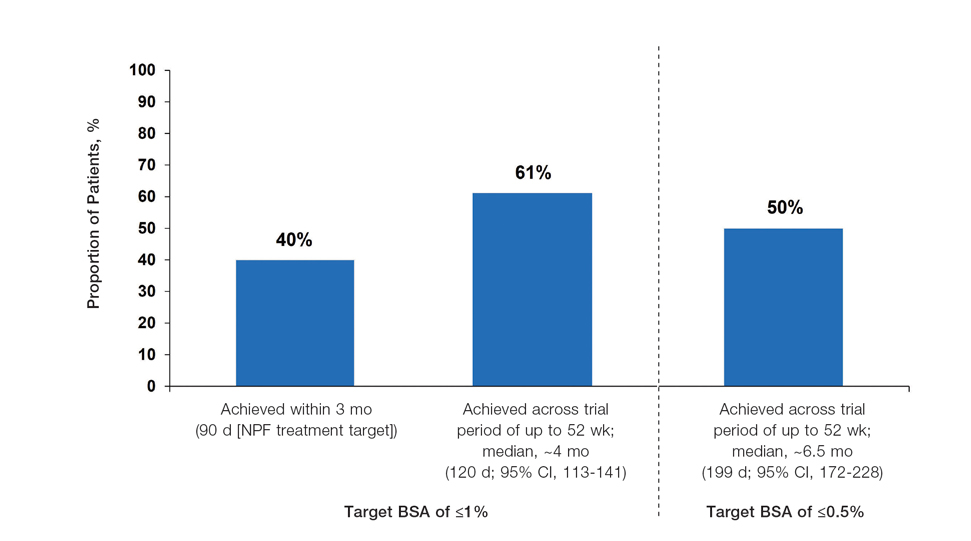

Achievement of BSA-Affected Targets—

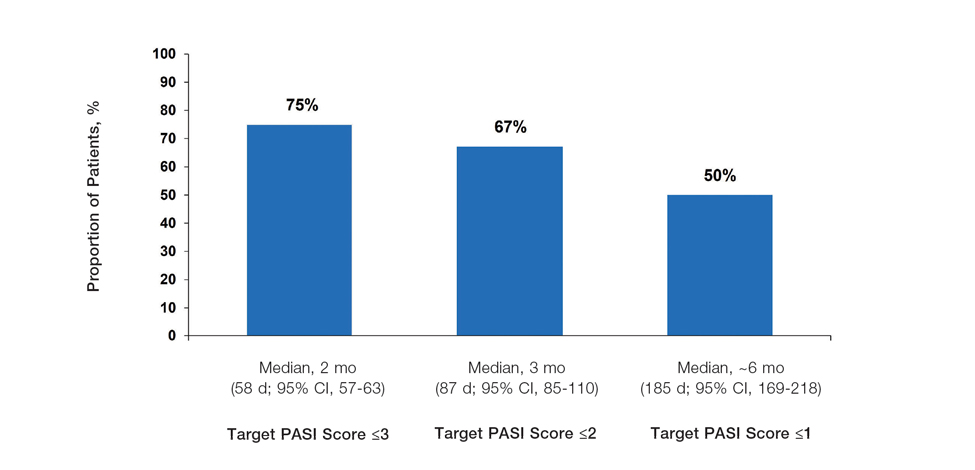

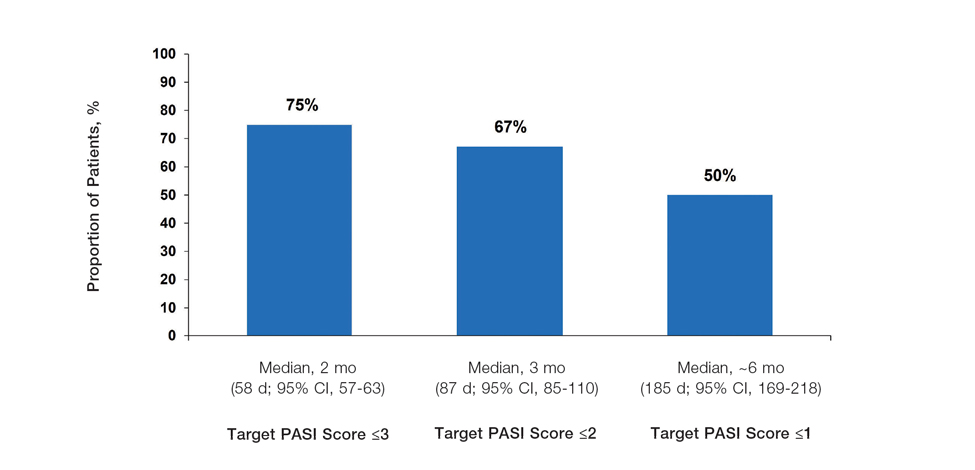

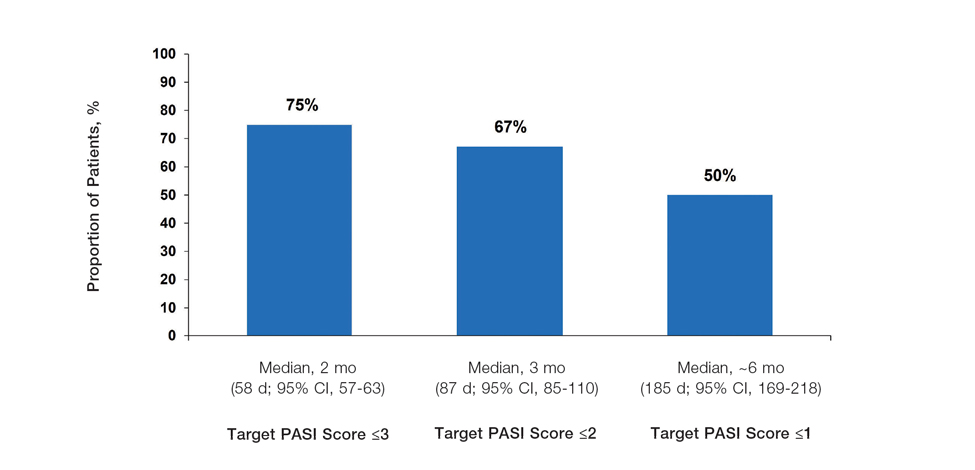

Achievement of Absolute PASI Targets—Across the total trial period (up to 52 weeks), an absolute total PASI score of 3 or lower was achieved by 75% of patients (686/915), with a median time to achieve this of 2 months (KM estimate: 58 days [95% CI, 57-63]); approximately 67% of patients (612/915) achieved a total PASI score of 2 or lower, with a median time to achieve of 3 months (KM estimate: 87 days [95% CI, 85-110])(Figure 2; Supplementary Figures S3a and S3b). A PASI score of 1 or lower was achieved by approximately 50% of patients (460/915), with a median time to achieve of approximately 6 months (KM estimate: 185 days [95% CI, 169-218])(Figure 2, Supplementary Figure S3c).

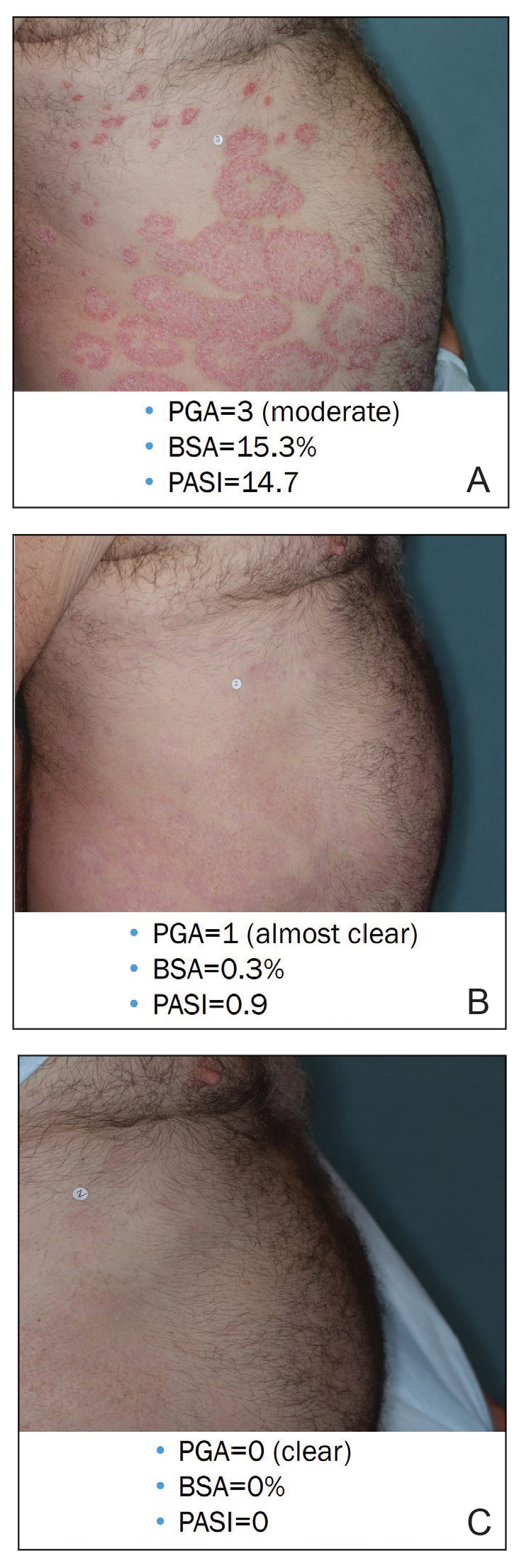

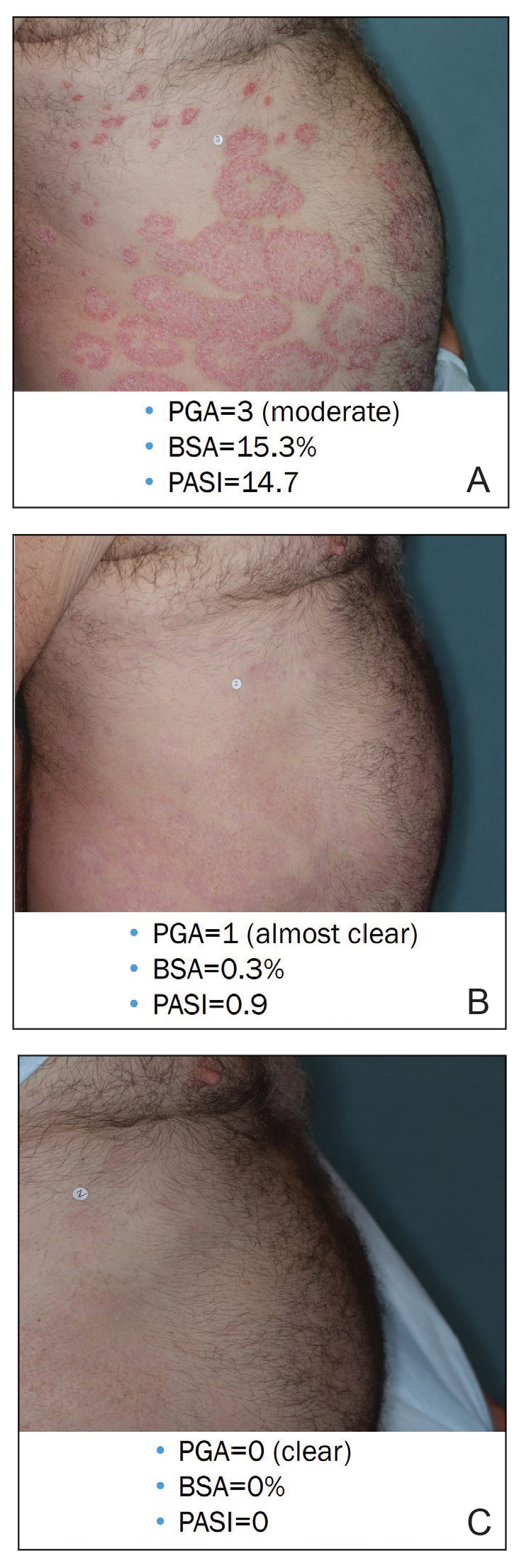

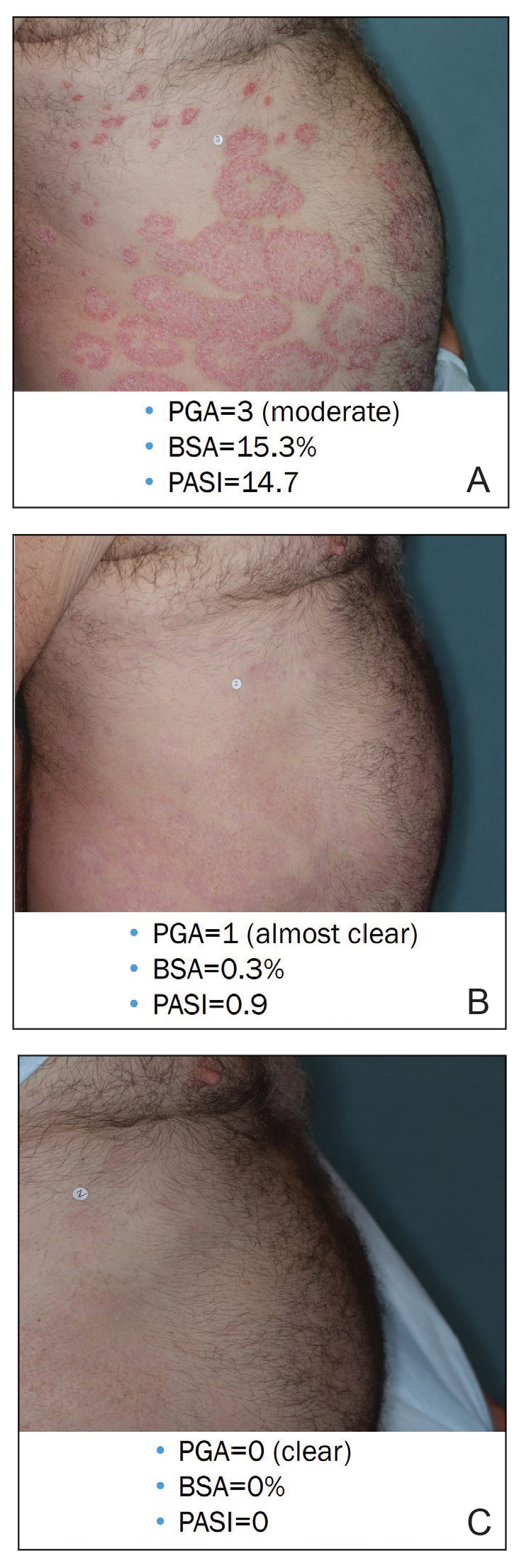

Illustrative Case—Case photography showing the clinical response in a 63-year-old man with moderate plaque psoriasis in PSOARING 2 is shown in Figure 3. After 12 weeks of treatment with tapinarof cream 1% QD, the patient achieved all primary and secondary efficacy end points. In addition to achieving the regulatory end point of a PGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) and a decrease from baseline of at least 2 points, achievement of 0% total BSA affected and a total PASI score of 0 at week 12 exceeded the NPF and EADV consensus treatment targets.10,11 Targets were achieved as early as week 4, with a total BSA affected of 0.5% or lower and a total PASI score of 1 or lower, illustrated by marked skin clearing and only faint residual erythema that completely resolved at week 12, with the absence of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Safety

Safety data for the PSOARING trials have been previously reported.17,18 The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were folliculitis, contact dermatitis, upper respiratory tract infection, and nasopharyngitis. Treatment-emergent adverse events generally were mild or moderate in severity and did not lead to trial discontinuation.17,18

COMMENT

Treat-to-target management approaches aim to improve patient outcomes by striving to achieve optimal goals. The treat-to-target approach supports shared decision-making between clinicians and patients based on common expectations of what constitutes treatment success.

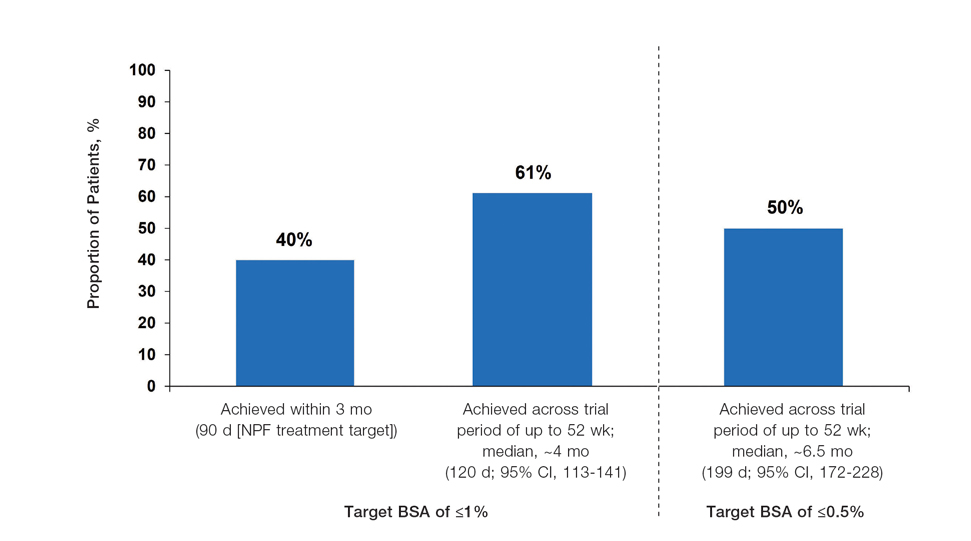

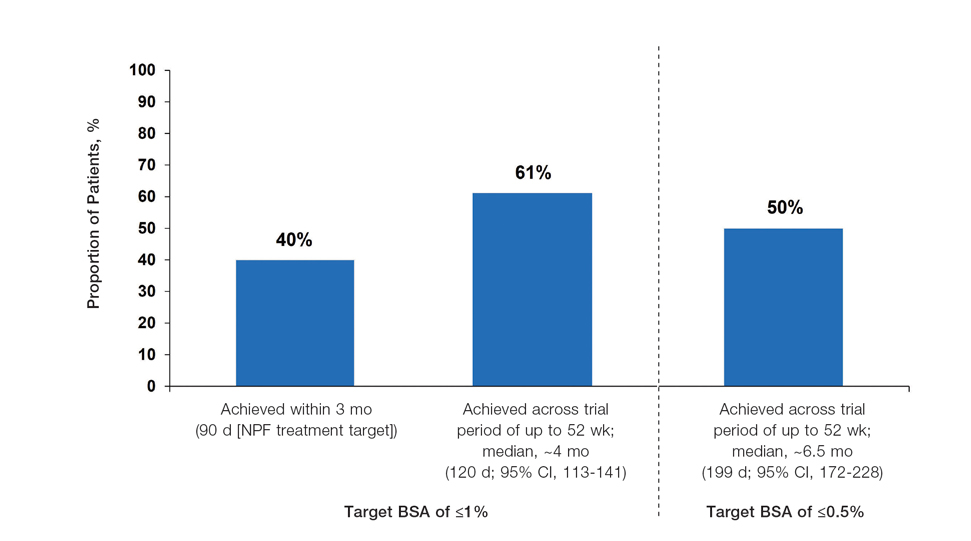

The findings of this analysis based on pooled data from a large cohort of patients demonstrate that a high proportion of patients can achieve or exceed recommended treatment targets with tapinarof cream 1% QD and maintain improvements long-term. The NPF-recommended treatment target of 1% or lower BSA affected within approximately 3 months (90 days) of treatment was achieved by 40% of tapinarof-treated patients. In addition, 1% or lower BSA affected at any time during the trials was achieved by 61% of patients (median, approximately 4 months). The analyses also indicated that PASI total scores of 3 or lower and 2 or lower were achieved by 75% and 67% of tapinarof-treated patients, respectively, within 2 to 3 months.

These findings support the previously reported efficacy of tapinarof cream, including high rates of complete disease clearance (40.9% [312/763]), durable response following treatment interruption, an off-therapy remittive effect of approximately 4 months, and good disease control on therapy with no evidence of tachyphylaxis.17,18

CONCLUSION

Taken together with previously reported tapinarof efficacy and safety results, our findings demonstrate that a high proportion of patients treated with tapinarof cream as monotherapy can achieve aggressive treatment targets set by both US and European guidelines developed for systemic and biologic therapies. Tapinarof cream 1% QD is an effective topical treatment option for patients with plaque psoriasis that has been approved without restrictions relating to severity or extent of disease treated, duration of use, or application sites, including application to sensitive and intertriginous skin.

Acknowledgments—Editorial and medical writing support under the guidance of the authors was provided by Melanie Govender, MSc (Med), ApotheCom (United Kingdom), and was funded by Dermavant Sciences, Inc, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP) guidelines.

- Armstrong AW, Mehta MD, Schupp CW, et al. Psoriasis prevalence in adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:940-946.

- Parisi R, Iskandar IYK, Kontopantelis E, et al. National, regional, and worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis: systematic analysis and modelling study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1590.

- Pilon D, Teeple A, Zhdanava M, et al. The economic burden of psoriasis with high comorbidity among privately insured patients in the United States. J Med Econ. 2019;22:196-203.

- Singh S, Taylor C, Kornmehl H, et al. Psoriasis and suicidality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:425-440.e2.

- Feldman SR, Goffe B, Rice G, et al. The challenge of managing psoriasis: unmet medical needs and stakeholder perspectives. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9:504-513.

- Ford JA, Solomon DH. Challenges in implementing treat-to-target strategies in rheumatology. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2019;45:101-112.

- Sitbon O, Galiè N. Treat-to-target strategies in pulmonary arterial hypertension: the importance of using multiple goals. Eur Respir Rev. 2010;19:272-278.

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:631-637.

- Wangnoo SK, Sethi B, Sahay RK, et al. Treat-to-target trials in diabetes. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18:166-174.

- Armstrong AW, Siegel MP, Bagel J, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: treatment targets for plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:290-298.

- Pathirana D, Ormerod AD, Saiag P, et al. European S3-guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(Suppl 2):1-70.

- Strober BE, van der Walt JM, Armstrong AW, et al. Clinical goals and barriers to effective psoriasis care. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019; 9:5-18.

- Bagel J, Gold LS. Combining topical psoriasis treatment to enhance systemic and phototherapy: a review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1209-1222.

- Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:432-470.

- Stein Gold LF. Topical therapies for psoriasis: improving management strategies and patient adherence. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2016;35 (2 Suppl 2):S36-S44; quiz S45.

- VTAMA® (tapinarof) cream. Prescribing information. Dermavant Sciences; 2022. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215272s000lbl.pdf

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229 and supplementary appendix.

- Strober B, Stein Gold L, Bissonnette R, et al. One-year safety and efficacy of tapinarof cream for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: results from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:800-806.

- Clinical Review Report: Guselkumab (Tremfya) [Internet]. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2018. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534047/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK534047.pdf

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting approximately 8 million adults in the United States and 2% of the global population.1,2 Psoriasis causes pain, itching, and disfigurement and is associated with a physical, psychological, and economic burden that substantially affects health-related quality of life.3-5

Setting treatment goals and treating to target are evidence-based approaches that have been successfully applied to several chronic diseases to improve patient outcomes, including diabetes, hypertension, and rheumatoid arthritis.6-9 Treat-to-target strategies generally set low disease activity (or remission) as an overall goal and seek to achieve this using available therapeutic options as necessary. Introduced following the availability of biologics and targeted systemic therapies, treat-to-target strategies generally provide guidance on expectations of treatment but not specific treatments, as personalized treatment decisions depend on an assessment of individual patients and consider clinical and demographic features as well as preferences for available therapeutic options. If targets are not achieved in the assigned time span, adjustments can be made to the treatment approach in close consultation with the patient. If the target is reached, follow-up visits can be scheduled to ensure improvement is maintained or to establish if more aggressive goals could be selected.

Treat-to-target strategies for the management of psoriasis developed by the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) Medical Board include reducing the extent of psoriasis to 1% or lower total body surface area (BSA) after 3 months of treatment.10 Treatment targets endorsed by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) in guidelines on the use of systemic therapies in psoriasis include achieving a 75% or greater reduction in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score within 3 to 4 months of treatment.11

In clinical practice, many patients do not achieve these treatment targets, and topical treatments alone generally are insufficient in achieving treatment goals for psoriasis.12,13 Moreover, conventional topical treatments (eg, topical corticosteroids) used by most patients with psoriasis regardless of disease severity are associated with adverse events that can limit their use. Most topical corticosteroids have US Food and Drug Administration label restrictions relating to sites of application, duration and extent of use, and frequency of administration.14,15

Tapinarof cream 1% (VTAMA [Dermavant Sciences, Inc]) is a first-in-class topical nonsteroidal aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults16 and is being studied for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in children 2 years and older as well as for atopic dermatitis in adults and children 2 years and older. In PSOARING 1 (ClinicalTrials .gov identifier NCT03956355) and PSOARING 2 (NCT03983980)—identical 12-week pivotal phase 3 trials—monotherapy with tapinarof cream 1% once daily (QD) demonstrated statistically significant efficacy vs vehicle cream and was well tolerated in adults with mild to severe plaque psoriasis (Supplementary Figure S1).17 Lebwohl et al17 reported that significantly higher PASI75 responses were observed at week 12 with tapinarof cream vs vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 (36% and 48% vs 10% and 7%, respectively; both P<.0001). A significantly higher PASI90 response of 19% and 21% at week 12 also was observed with tapinarof cream vs 2% and 3% with vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2, respectively (P=.0005 and P<.0001).17

In PSOARING 3 (NCT04053387)—the long-term extension trial (Supplementary Figure S1)—efficacy continued to improve or was maintained beyond the two 12-week trials, with improvements in total BSA affected and PASI scores for up to 52 weeks.18 Tapinarof cream 1% QD demonstrated positive, rapid, and durable outcomes in PSOARING 3, including high rates of complete disease clearance (Physician Global Assessment [PGA] score=0 [clear])(40.9% [312/763]), durability of response on treatment with no evidence of tachyphylaxis, and a remittive effect of approximately 4 months when off therapy (defined as maintenance of a PGA score of 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear] after first achieving a PGA score of 0).18

Herein, we report absolute treatment targets for patients with plaque psoriasis who received tapinarof cream 1% QD in the PSOARING trials that are at least as stringent as the corresponding NPF and EADV targets of achieving a total BSA affected of 1% or lower or a PASI75 response within 3 to 4 months, respectively.

METHODS

Study Design

The pooled efficacy analyses included all patients with a baseline PGA score of 2 or higher (mild or worse) before treatment with tapinarof cream 1% QD in the PSOARING trials. This included patients who received tapinarof cream 1% in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 who may or may not have continued into PSOARING 3, as well as those who received the vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 who enrolled in PSOARING 3 and had a PGA score of 2 or higher before receiving tapinarof cream 1%.

Trial Participants

Full methods, including inclusion and exclusion criteria, for the PSOARING trials have been previously reported.17,18 Patients were aged 18 to 75 years and had chronic plaque psoriasis that was stable for at least 6 months before randomization; 3% to 20% total BSA affected (excluding the scalp, palms, fingernails, toenails, and soles); and a PGA score of 2 (mild), 3 (moderate), or 4 (severe) at baseline.

The clinical trials were conducted in compliance with the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was obtained from local ethics committees or institutional review boards at each center. All patients provided written informed consent.

Trial Treatment

In PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2, patients were randomized (2:1) to receive tapinarof cream 1% or vehicle QD for 12 weeks. In PSOARING 3 (the long-term extension trial), patients received up to 40 weeks of open-label tapinarof, followed by 4 weeks of follow-up off treatment. Patients received intermittent or continuous treatment with tapinarof cream 1% in PSOARING 3 based on PGA score: those entering the trial with a PGA score of 1 or higher received tapinarof cream 1% until complete disease clearance was achieved (defined as a PGA score of 0 [clear]). Those entering PSOARING 3 with or achieving a PGA score of 0 (clear) discontinued treatment and were observed for the duration of maintenance of a PGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) while off therapy (the protocol-defined “duration of remittive effect”). If disease worsening (defined as a PGA score 2 or higher) occurred, tapinarof cream 1% was restarted and continued until a PGA score of 0 (clear) was achieved. This pattern of treatment, discontinuation on achieving a PGA score of 0 (clear), and retreatment on disease worsening continued until the end of the trial. As a result, patients in PSOARING 3 could receive tapinarof cream 1% continuously or intermittently for 40 weeks.

Outcome Measures and Statistical Analyses

The assessment of total BSA affected by plaque psoriasis is an estimate of the total extent of disease as a percentage of total skin area. In the PSOARING trials, the skin surface of one hand (palm and digits) was assumed to be approximately equivalent to 1% BSA. The total BSA affected by psoriasis was evaluated from 0% to 100%, with greater total BSA affected being an indication of more extensive disease. The BSA efficacy outcomes used in these analyses were based post hoc on the proportion of patients who achieved a 1% or lower or 0.5% or lower total BSA affected.

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index scores assess both the severity and extent of psoriasis. A PASI score lower than 5 often is considered indicative of mild psoriasis, a score of 5 to 10 indicates moderate disease, and a score higher than 10 indicates severe disease.19 The maximum PASI score is 72. The PASI efficacy outcomes used in these analyses were based post hoc on the proportion of patients who achieved an absolute total PASI score of 3 or lower, 2 or lower, and 1 or lower.

Efficacy analyses were based on pooled data for all patients in the PSOARING trials who had a PGA score of 2 to 4 (mild to severe) before treatment with tapinarof cream 1% in the intention-to-treat population using observed cases. Time-to-target analyses were based on Kaplan-Meier (KM) estimates using observed cases.

Safety analyses included the incidence and frequency of adverse events and were based on all patients who received tapinarof cream 1% in the PSOARING trials.

RESULTS

Baseline Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics

The pooled efficacy analyses included 915 eligible patients (Table). At baseline, the mean (SD) age was 50.2 (13.25) years, 58.7% were male, the mean (SD) weight was 92.2 (23.67) kg, and the mean (SD) body mass index was 31.6 (7.53) kg/m2. The percentage of patients with a PGA score of 2 (mild), 3 (moderate), or 4 (severe) was 13.9%, 78.1%, and 8.0%, respectively. The mean (SD) PASI score was 8.7 (4.23) and mean (SD) total BSA affected was 7.8% (4.98).

Efficacy

Achievement of BSA-Affected Targets—

Achievement of Absolute PASI Targets—Across the total trial period (up to 52 weeks), an absolute total PASI score of 3 or lower was achieved by 75% of patients (686/915), with a median time to achieve this of 2 months (KM estimate: 58 days [95% CI, 57-63]); approximately 67% of patients (612/915) achieved a total PASI score of 2 or lower, with a median time to achieve of 3 months (KM estimate: 87 days [95% CI, 85-110])(Figure 2; Supplementary Figures S3a and S3b). A PASI score of 1 or lower was achieved by approximately 50% of patients (460/915), with a median time to achieve of approximately 6 months (KM estimate: 185 days [95% CI, 169-218])(Figure 2, Supplementary Figure S3c).

Illustrative Case—Case photography showing the clinical response in a 63-year-old man with moderate plaque psoriasis in PSOARING 2 is shown in Figure 3. After 12 weeks of treatment with tapinarof cream 1% QD, the patient achieved all primary and secondary efficacy end points. In addition to achieving the regulatory end point of a PGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) and a decrease from baseline of at least 2 points, achievement of 0% total BSA affected and a total PASI score of 0 at week 12 exceeded the NPF and EADV consensus treatment targets.10,11 Targets were achieved as early as week 4, with a total BSA affected of 0.5% or lower and a total PASI score of 1 or lower, illustrated by marked skin clearing and only faint residual erythema that completely resolved at week 12, with the absence of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Safety

Safety data for the PSOARING trials have been previously reported.17,18 The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were folliculitis, contact dermatitis, upper respiratory tract infection, and nasopharyngitis. Treatment-emergent adverse events generally were mild or moderate in severity and did not lead to trial discontinuation.17,18

COMMENT

Treat-to-target management approaches aim to improve patient outcomes by striving to achieve optimal goals. The treat-to-target approach supports shared decision-making between clinicians and patients based on common expectations of what constitutes treatment success.

The findings of this analysis based on pooled data from a large cohort of patients demonstrate that a high proportion of patients can achieve or exceed recommended treatment targets with tapinarof cream 1% QD and maintain improvements long-term. The NPF-recommended treatment target of 1% or lower BSA affected within approximately 3 months (90 days) of treatment was achieved by 40% of tapinarof-treated patients. In addition, 1% or lower BSA affected at any time during the trials was achieved by 61% of patients (median, approximately 4 months). The analyses also indicated that PASI total scores of 3 or lower and 2 or lower were achieved by 75% and 67% of tapinarof-treated patients, respectively, within 2 to 3 months.

These findings support the previously reported efficacy of tapinarof cream, including high rates of complete disease clearance (40.9% [312/763]), durable response following treatment interruption, an off-therapy remittive effect of approximately 4 months, and good disease control on therapy with no evidence of tachyphylaxis.17,18

CONCLUSION

Taken together with previously reported tapinarof efficacy and safety results, our findings demonstrate that a high proportion of patients treated with tapinarof cream as monotherapy can achieve aggressive treatment targets set by both US and European guidelines developed for systemic and biologic therapies. Tapinarof cream 1% QD is an effective topical treatment option for patients with plaque psoriasis that has been approved without restrictions relating to severity or extent of disease treated, duration of use, or application sites, including application to sensitive and intertriginous skin.

Acknowledgments—Editorial and medical writing support under the guidance of the authors was provided by Melanie Govender, MSc (Med), ApotheCom (United Kingdom), and was funded by Dermavant Sciences, Inc, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP) guidelines.

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting approximately 8 million adults in the United States and 2% of the global population.1,2 Psoriasis causes pain, itching, and disfigurement and is associated with a physical, psychological, and economic burden that substantially affects health-related quality of life.3-5

Setting treatment goals and treating to target are evidence-based approaches that have been successfully applied to several chronic diseases to improve patient outcomes, including diabetes, hypertension, and rheumatoid arthritis.6-9 Treat-to-target strategies generally set low disease activity (or remission) as an overall goal and seek to achieve this using available therapeutic options as necessary. Introduced following the availability of biologics and targeted systemic therapies, treat-to-target strategies generally provide guidance on expectations of treatment but not specific treatments, as personalized treatment decisions depend on an assessment of individual patients and consider clinical and demographic features as well as preferences for available therapeutic options. If targets are not achieved in the assigned time span, adjustments can be made to the treatment approach in close consultation with the patient. If the target is reached, follow-up visits can be scheduled to ensure improvement is maintained or to establish if more aggressive goals could be selected.

Treat-to-target strategies for the management of psoriasis developed by the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) Medical Board include reducing the extent of psoriasis to 1% or lower total body surface area (BSA) after 3 months of treatment.10 Treatment targets endorsed by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) in guidelines on the use of systemic therapies in psoriasis include achieving a 75% or greater reduction in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score within 3 to 4 months of treatment.11

In clinical practice, many patients do not achieve these treatment targets, and topical treatments alone generally are insufficient in achieving treatment goals for psoriasis.12,13 Moreover, conventional topical treatments (eg, topical corticosteroids) used by most patients with psoriasis regardless of disease severity are associated with adverse events that can limit their use. Most topical corticosteroids have US Food and Drug Administration label restrictions relating to sites of application, duration and extent of use, and frequency of administration.14,15

Tapinarof cream 1% (VTAMA [Dermavant Sciences, Inc]) is a first-in-class topical nonsteroidal aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults16 and is being studied for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in children 2 years and older as well as for atopic dermatitis in adults and children 2 years and older. In PSOARING 1 (ClinicalTrials .gov identifier NCT03956355) and PSOARING 2 (NCT03983980)—identical 12-week pivotal phase 3 trials—monotherapy with tapinarof cream 1% once daily (QD) demonstrated statistically significant efficacy vs vehicle cream and was well tolerated in adults with mild to severe plaque psoriasis (Supplementary Figure S1).17 Lebwohl et al17 reported that significantly higher PASI75 responses were observed at week 12 with tapinarof cream vs vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 (36% and 48% vs 10% and 7%, respectively; both P<.0001). A significantly higher PASI90 response of 19% and 21% at week 12 also was observed with tapinarof cream vs 2% and 3% with vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2, respectively (P=.0005 and P<.0001).17

In PSOARING 3 (NCT04053387)—the long-term extension trial (Supplementary Figure S1)—efficacy continued to improve or was maintained beyond the two 12-week trials, with improvements in total BSA affected and PASI scores for up to 52 weeks.18 Tapinarof cream 1% QD demonstrated positive, rapid, and durable outcomes in PSOARING 3, including high rates of complete disease clearance (Physician Global Assessment [PGA] score=0 [clear])(40.9% [312/763]), durability of response on treatment with no evidence of tachyphylaxis, and a remittive effect of approximately 4 months when off therapy (defined as maintenance of a PGA score of 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear] after first achieving a PGA score of 0).18

Herein, we report absolute treatment targets for patients with plaque psoriasis who received tapinarof cream 1% QD in the PSOARING trials that are at least as stringent as the corresponding NPF and EADV targets of achieving a total BSA affected of 1% or lower or a PASI75 response within 3 to 4 months, respectively.

METHODS

Study Design

The pooled efficacy analyses included all patients with a baseline PGA score of 2 or higher (mild or worse) before treatment with tapinarof cream 1% QD in the PSOARING trials. This included patients who received tapinarof cream 1% in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 who may or may not have continued into PSOARING 3, as well as those who received the vehicle in PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2 who enrolled in PSOARING 3 and had a PGA score of 2 or higher before receiving tapinarof cream 1%.

Trial Participants

Full methods, including inclusion and exclusion criteria, for the PSOARING trials have been previously reported.17,18 Patients were aged 18 to 75 years and had chronic plaque psoriasis that was stable for at least 6 months before randomization; 3% to 20% total BSA affected (excluding the scalp, palms, fingernails, toenails, and soles); and a PGA score of 2 (mild), 3 (moderate), or 4 (severe) at baseline.

The clinical trials were conducted in compliance with the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was obtained from local ethics committees or institutional review boards at each center. All patients provided written informed consent.

Trial Treatment

In PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2, patients were randomized (2:1) to receive tapinarof cream 1% or vehicle QD for 12 weeks. In PSOARING 3 (the long-term extension trial), patients received up to 40 weeks of open-label tapinarof, followed by 4 weeks of follow-up off treatment. Patients received intermittent or continuous treatment with tapinarof cream 1% in PSOARING 3 based on PGA score: those entering the trial with a PGA score of 1 or higher received tapinarof cream 1% until complete disease clearance was achieved (defined as a PGA score of 0 [clear]). Those entering PSOARING 3 with or achieving a PGA score of 0 (clear) discontinued treatment and were observed for the duration of maintenance of a PGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) while off therapy (the protocol-defined “duration of remittive effect”). If disease worsening (defined as a PGA score 2 or higher) occurred, tapinarof cream 1% was restarted and continued until a PGA score of 0 (clear) was achieved. This pattern of treatment, discontinuation on achieving a PGA score of 0 (clear), and retreatment on disease worsening continued until the end of the trial. As a result, patients in PSOARING 3 could receive tapinarof cream 1% continuously or intermittently for 40 weeks.

Outcome Measures and Statistical Analyses

The assessment of total BSA affected by plaque psoriasis is an estimate of the total extent of disease as a percentage of total skin area. In the PSOARING trials, the skin surface of one hand (palm and digits) was assumed to be approximately equivalent to 1% BSA. The total BSA affected by psoriasis was evaluated from 0% to 100%, with greater total BSA affected being an indication of more extensive disease. The BSA efficacy outcomes used in these analyses were based post hoc on the proportion of patients who achieved a 1% or lower or 0.5% or lower total BSA affected.

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index scores assess both the severity and extent of psoriasis. A PASI score lower than 5 often is considered indicative of mild psoriasis, a score of 5 to 10 indicates moderate disease, and a score higher than 10 indicates severe disease.19 The maximum PASI score is 72. The PASI efficacy outcomes used in these analyses were based post hoc on the proportion of patients who achieved an absolute total PASI score of 3 or lower, 2 or lower, and 1 or lower.

Efficacy analyses were based on pooled data for all patients in the PSOARING trials who had a PGA score of 2 to 4 (mild to severe) before treatment with tapinarof cream 1% in the intention-to-treat population using observed cases. Time-to-target analyses were based on Kaplan-Meier (KM) estimates using observed cases.

Safety analyses included the incidence and frequency of adverse events and were based on all patients who received tapinarof cream 1% in the PSOARING trials.

RESULTS

Baseline Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics

The pooled efficacy analyses included 915 eligible patients (Table). At baseline, the mean (SD) age was 50.2 (13.25) years, 58.7% were male, the mean (SD) weight was 92.2 (23.67) kg, and the mean (SD) body mass index was 31.6 (7.53) kg/m2. The percentage of patients with a PGA score of 2 (mild), 3 (moderate), or 4 (severe) was 13.9%, 78.1%, and 8.0%, respectively. The mean (SD) PASI score was 8.7 (4.23) and mean (SD) total BSA affected was 7.8% (4.98).

Efficacy

Achievement of BSA-Affected Targets—

Achievement of Absolute PASI Targets—Across the total trial period (up to 52 weeks), an absolute total PASI score of 3 or lower was achieved by 75% of patients (686/915), with a median time to achieve this of 2 months (KM estimate: 58 days [95% CI, 57-63]); approximately 67% of patients (612/915) achieved a total PASI score of 2 or lower, with a median time to achieve of 3 months (KM estimate: 87 days [95% CI, 85-110])(Figure 2; Supplementary Figures S3a and S3b). A PASI score of 1 or lower was achieved by approximately 50% of patients (460/915), with a median time to achieve of approximately 6 months (KM estimate: 185 days [95% CI, 169-218])(Figure 2, Supplementary Figure S3c).

Illustrative Case—Case photography showing the clinical response in a 63-year-old man with moderate plaque psoriasis in PSOARING 2 is shown in Figure 3. After 12 weeks of treatment with tapinarof cream 1% QD, the patient achieved all primary and secondary efficacy end points. In addition to achieving the regulatory end point of a PGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) and a decrease from baseline of at least 2 points, achievement of 0% total BSA affected and a total PASI score of 0 at week 12 exceeded the NPF and EADV consensus treatment targets.10,11 Targets were achieved as early as week 4, with a total BSA affected of 0.5% or lower and a total PASI score of 1 or lower, illustrated by marked skin clearing and only faint residual erythema that completely resolved at week 12, with the absence of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Safety

Safety data for the PSOARING trials have been previously reported.17,18 The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were folliculitis, contact dermatitis, upper respiratory tract infection, and nasopharyngitis. Treatment-emergent adverse events generally were mild or moderate in severity and did not lead to trial discontinuation.17,18

COMMENT

Treat-to-target management approaches aim to improve patient outcomes by striving to achieve optimal goals. The treat-to-target approach supports shared decision-making between clinicians and patients based on common expectations of what constitutes treatment success.

The findings of this analysis based on pooled data from a large cohort of patients demonstrate that a high proportion of patients can achieve or exceed recommended treatment targets with tapinarof cream 1% QD and maintain improvements long-term. The NPF-recommended treatment target of 1% or lower BSA affected within approximately 3 months (90 days) of treatment was achieved by 40% of tapinarof-treated patients. In addition, 1% or lower BSA affected at any time during the trials was achieved by 61% of patients (median, approximately 4 months). The analyses also indicated that PASI total scores of 3 or lower and 2 or lower were achieved by 75% and 67% of tapinarof-treated patients, respectively, within 2 to 3 months.

These findings support the previously reported efficacy of tapinarof cream, including high rates of complete disease clearance (40.9% [312/763]), durable response following treatment interruption, an off-therapy remittive effect of approximately 4 months, and good disease control on therapy with no evidence of tachyphylaxis.17,18

CONCLUSION

Taken together with previously reported tapinarof efficacy and safety results, our findings demonstrate that a high proportion of patients treated with tapinarof cream as monotherapy can achieve aggressive treatment targets set by both US and European guidelines developed for systemic and biologic therapies. Tapinarof cream 1% QD is an effective topical treatment option for patients with plaque psoriasis that has been approved without restrictions relating to severity or extent of disease treated, duration of use, or application sites, including application to sensitive and intertriginous skin.

Acknowledgments—Editorial and medical writing support under the guidance of the authors was provided by Melanie Govender, MSc (Med), ApotheCom (United Kingdom), and was funded by Dermavant Sciences, Inc, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP) guidelines.

- Armstrong AW, Mehta MD, Schupp CW, et al. Psoriasis prevalence in adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:940-946.

- Parisi R, Iskandar IYK, Kontopantelis E, et al. National, regional, and worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis: systematic analysis and modelling study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1590.

- Pilon D, Teeple A, Zhdanava M, et al. The economic burden of psoriasis with high comorbidity among privately insured patients in the United States. J Med Econ. 2019;22:196-203.

- Singh S, Taylor C, Kornmehl H, et al. Psoriasis and suicidality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:425-440.e2.

- Feldman SR, Goffe B, Rice G, et al. The challenge of managing psoriasis: unmet medical needs and stakeholder perspectives. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9:504-513.

- Ford JA, Solomon DH. Challenges in implementing treat-to-target strategies in rheumatology. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2019;45:101-112.

- Sitbon O, Galiè N. Treat-to-target strategies in pulmonary arterial hypertension: the importance of using multiple goals. Eur Respir Rev. 2010;19:272-278.

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:631-637.

- Wangnoo SK, Sethi B, Sahay RK, et al. Treat-to-target trials in diabetes. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18:166-174.

- Armstrong AW, Siegel MP, Bagel J, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: treatment targets for plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:290-298.

- Pathirana D, Ormerod AD, Saiag P, et al. European S3-guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(Suppl 2):1-70.

- Strober BE, van der Walt JM, Armstrong AW, et al. Clinical goals and barriers to effective psoriasis care. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019; 9:5-18.

- Bagel J, Gold LS. Combining topical psoriasis treatment to enhance systemic and phototherapy: a review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1209-1222.

- Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:432-470.

- Stein Gold LF. Topical therapies for psoriasis: improving management strategies and patient adherence. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2016;35 (2 Suppl 2):S36-S44; quiz S45.

- VTAMA® (tapinarof) cream. Prescribing information. Dermavant Sciences; 2022. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215272s000lbl.pdf

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229 and supplementary appendix.

- Strober B, Stein Gold L, Bissonnette R, et al. One-year safety and efficacy of tapinarof cream for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: results from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:800-806.

- Clinical Review Report: Guselkumab (Tremfya) [Internet]. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2018. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534047/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK534047.pdf

- Armstrong AW, Mehta MD, Schupp CW, et al. Psoriasis prevalence in adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:940-946.

- Parisi R, Iskandar IYK, Kontopantelis E, et al. National, regional, and worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis: systematic analysis and modelling study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1590.

- Pilon D, Teeple A, Zhdanava M, et al. The economic burden of psoriasis with high comorbidity among privately insured patients in the United States. J Med Econ. 2019;22:196-203.

- Singh S, Taylor C, Kornmehl H, et al. Psoriasis and suicidality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:425-440.e2.

- Feldman SR, Goffe B, Rice G, et al. The challenge of managing psoriasis: unmet medical needs and stakeholder perspectives. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9:504-513.

- Ford JA, Solomon DH. Challenges in implementing treat-to-target strategies in rheumatology. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2019;45:101-112.

- Sitbon O, Galiè N. Treat-to-target strategies in pulmonary arterial hypertension: the importance of using multiple goals. Eur Respir Rev. 2010;19:272-278.

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:631-637.

- Wangnoo SK, Sethi B, Sahay RK, et al. Treat-to-target trials in diabetes. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18:166-174.

- Armstrong AW, Siegel MP, Bagel J, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: treatment targets for plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:290-298.

- Pathirana D, Ormerod AD, Saiag P, et al. European S3-guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(Suppl 2):1-70.

- Strober BE, van der Walt JM, Armstrong AW, et al. Clinical goals and barriers to effective psoriasis care. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019; 9:5-18.

- Bagel J, Gold LS. Combining topical psoriasis treatment to enhance systemic and phototherapy: a review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1209-1222.

- Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:432-470.

- Stein Gold LF. Topical therapies for psoriasis: improving management strategies and patient adherence. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2016;35 (2 Suppl 2):S36-S44; quiz S45.

- VTAMA® (tapinarof) cream. Prescribing information. Dermavant Sciences; 2022. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215272s000lbl.pdf

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229 and supplementary appendix.

- Strober B, Stein Gold L, Bissonnette R, et al. One-year safety and efficacy of tapinarof cream for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: results from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:800-806.

- Clinical Review Report: Guselkumab (Tremfya) [Internet]. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2018. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534047/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK534047.pdf

Practice Points

- In clinical practice, many patients with psoriasis do not achieve treatment targets set forth by the National Psoriasis Foundation and the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, and topical treatments alone generally are insufficient in achieving treatment goals for psoriasis.

- Tapinarof cream 1% is a nonsteroidal aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults; it also is being studied for the treatment of plaque psoriasis in children 2 years and older.

- Tapinarof cream 1% is an effective topical treatment option for patients with plaque psoriasis of any severity, with no limitations on treatment duration, total extent of use, or application sites, including intertriginous skin and sensitive areas.

Pediatric Melanoma Outcomes by Race and Socioeconomic Factors

To the Editor:

Skin cancers are extremely common worldwide. Malignant melanomas comprise approximately 1 in 5 of these cancers. Exposure to UV radiation is postulated to be responsible for a global rise in melanoma cases over the past 50 years.1 Pediatric melanoma is a particularly rare condition that affects approximately 6 in every 1 million children.2 Melanoma incidence in children ranges by age, increasing by approximately 10-fold from age 1 to 4 years to age 15 to 19 years. Tumor ulceration is a feature more commonly seen among children younger than 10 years and is associated with worse outcomes. Tumor thickness and ulceration strongly predict sentinel lymph node metastases among children, which also is associated with a poor prognosis.3

A recent study evaluating stage IV melanoma survival rates in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) vs older adults found that survival is much worse among AYAs. Thicker tumors and public health insurance also were associated with worse survival rates for AYAs, while early detection was associated with better survival rates.4

Health disparities and their role in the prognosis of pediatric melanoma is another important factor. One study analyzed this relationship at the state level using Texas Cancer Registry data (1995-2009).5 Patients’ socioeconomic status (SES) and driving distance to the nearest pediatric cancer care center were included in the analysis. Hispanic children were found to be 3 times more likely to present with advanced disease than non-Hispanic White children. Although SES and distance to the nearest treatment center were not found to affect the melanoma stage at presentation, Hispanic ethnicity or being in the lowest SES quartile were correlated with a higher mortality risk.5

When considering specific subtypes of melanoma, acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM) is known to develop in patients with skin of color. A 2023 study by Holman et al6 reported that the percentage of melanomas that were ALMs ranged from 0.8% in non-Hispanic White individuals to 19.1% in Hispanic Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Asian/Pacific Islander individuals. However, ALM is rare in children. In a pooled cohort study with patient information retrieved from the nationwide Dutch Pathology Registry, only 1 child and 1 adolescent were found to have ALM across a total of 514 patients.7 We sought to analyze pediatric melanoma outcomes based on race and other barriers to appropriate care.

We conducted a search of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from January 1995 to December 2016 for patients aged 21 years and younger with a primary melanoma diagnosis. The primary outcome was the 5-year survival rate. County-level SES variables were used to calculate a prosperity index. Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazards model were used to compare 5-year survival rates among the different racial/ethnic groups.

A sample of 2742 patients was identified during the study period and followed for 5 years. Eighty-two percent were White, 6% Hispanic, 2% Asian, 1% Black, and 5% classified as other/unknown race (data were missing for 4%). The cohort was predominantly female (61%). White patients were more likely to present with localized disease than any other race/ethnicity (83% vs 65% in Hispanic, 60% in Asian/Pacific Islander, and 45% in Black patients [P<.05]).

Black and Hispanic patients had the worst 5-year survival rates on bivariate analysis. On multivariate analysis, this finding remained significant for Hispanic patients when compared with White patients (hazard ratio, 2.37 [P<.05]). Increasing age, male sex, advanced stage at diagnosis, and failure to receive surgery were associated with increased odds of mortality.

Patients with regionalized and disseminated disease had increased odds of mortality (6.16 and 64.45, respectively; P<.05) compared with patients with localized disease. Socioeconomic status and urbanization were not found to influence 5-year survival rates.

Pediatric melanoma often presents a clinical challenge with special considerations. Pediatric-specific predisposing risk factors for melanoma and an atypical clinical presentation are some of the major concerns that necessitate a tailored approach to this malignancy, especially among different age groups, skin types, and racial and socioeconomic groups.5

Standard ABCDE criteria often are inadequate for accurate detection of pediatric melanomas. Initial lesions often manifest as raised, red, amelanotic lesions mimicking pyogenic granulomas. Lesions tend to be very small (<6 mm in diameter) and can be uniform in color, thereby making the melanoma more difficult to detect compared to the characteristic findings in adults.5 Bleeding or ulceration often can be a warning sign during physical examination.

With regard to incidence, pediatric melanoma is relatively rare. Since the 1970s, the incidence of pediatric melanoma has been increasing; however, a recent analysis of the SEER database showed a decreasing trend from 2000 to 2010.4

Our analysis of the SEER data showed an increased risk for pediatric melanoma in older adolescents. In addition, the incidence of pediatric melanoma was higher in females of all racial groups except Asian/Pacific Islander individuals. However, SES was not found to significantly influence the 5-year survival rate in pediatric melanoma.

White pediatric patients were more likely to present with localized disease compared with other races. Pediatric melanoma patients with regional disease had a 6-fold increase in mortality rate vs those with localized disease; those with disseminated disease had a 65-fold higher risk. Consistent with this, Black and Hispanic patients had the worst 5-year survival rates on bivariate analysis.