User login

Vaginal hysterectomy: 6 challenges, an arsenal of solutions

Newer codes for vaginal hysterectomy capture the work of removing larger uteri without laparoscopy

True or false: When it comes to hysterectomy, surgeons tend to use the route that is safest, least invasive, and most economical.

Sadly, the statement is false. Although vaginal hysterectomy tops all 3 categories, it is the least utilized of surgical routes. The number of vaginal hysterectomies may have increased slightly over the past decade, likely due to the incorporation of laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy into the mainstream and increased practice with the vaginal component, but fewer than 30% of hysterectomies are performed vaginally.

This article addresses 6 common challenges at vaginal hysterectomy and offers strategies to overcome them.

Laparoscopic strategies ease vaginal hysterectomy, too

Laparoscopic hysterectomy became widely accepted when surgical instruments were developed to overcome the technical challenges inherent in operating with limited access. By incorporating some of the techniques we routinely use for laparoscopic surgery, we can overcome many of the challenges faced during difficult vaginal surgery.

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 1: Obesity

Unfortunately, our population is increasingly rotund. This is not only a significant risk factor for the patient’s health in general, but it poses some unique challenges for surgeons. I must say that, as tough as it may be to complete a hysterectomy vaginally in a morbidly obese woman, I would much rather approach her pelvic organs through the cul-de-sac, which contains no fat cells, than through the abdominal wall—either laparoscopically or abdominally! The trick is gaining access to the posterior cul-de-sac.

How to enter the cul-de-sac

It seems to be a perverse rule of nature, but a tight upper vaginal ring seems almost universal in obese women. Added to the redundant sidewalls and the large buttocks, this tightness makes entry into the anterior or posterior cul-de-sac problematic. Several tricks make peritoneal access possible:

Position the patient to increase access, with the buttocks well over the edge of the operating table. This brings the operative field a bit closer to the surgeon, and permits the use of long-handled retractors posteriorly.

Use candy-cane stirrups to allow assistants better access to the operative field. Adequate assistance is essential in attempting vaginal surgery in the morbidly obese.

Avoid the Trendelenburg position. Although it might seem that this position would facilitate visualization and placement of a posterior weighted speculum, all it does is allow the patient to slide up on the table, making placement of alternate retractors difficult.

Use the right tools. If the posterior weighted speculum will not stay in place or does not afford access to the cul-de-sac due to an upper vaginal ring, use a narrow Deaver retractor posteriorly (without sidewall or anterior retraction). Use a Jacob’s tenaculum on the posterior lip of the cervix and have your assistant pull straight up on the tenaculum while using the Deaver retractor to see the area between the uterosacral ligaments.

Use the uterosacral ligaments as a guide. Another perversity in morbidly obese women: Despite multiparity, they seem to have little or no apical prolapse but lots of vaginal wall redundancy. The cervix is often elongated, but the uterosacral ligaments are sky high.

I palpate these ligaments, injecting them with a combination of vasopressin diluted 1:5 with bupivacaine and epinephrine (for enhanced hemostasis and preemptive analgesia), then use a pencil electrosurgical electrode to rapidly open the vaginal epithelium between the ligaments.

I then use a long, toothed tissue forceps to tent the peritoneum at 90 degrees to the plane of the posterior cul-de-sac and use Mayo scissors to enter the peritoneal cavity. Usually there is a spurt of fluid to mark appropriate entry into the peritoneum.

I then use the blades of my scissors to stretch the peritoneum between the ligaments and place a moistened 4×4 sponge into the incision.

At the onset of the procedure, inject indigo carmine dye intravenously so that any injury to the bladder will be immediately recognized. I have the circulating nurse empty the bladder while she is prepping the patient, but do not leave an indwelling catheter in place during the operation. I find it cumbersome to work around the catheter.

Problematic entries

When entry into the posterior cul-de-sac is difficult, I stop dissection, place a 4×4 sponge into the incision to reduce bleeding from the vagina, and proceed to attempt anterior entry.

I place the Deaver retractor into the anterior space and move the tenaculum to the anterior lip of the cervix. This gives maximal space for downward traction on the cervix while anterior entry is attempted.

Once again, I inject the tissue with the bupivacaine solution before incising the vaginal epithelium at the level of the internal os. I use sharp dissection only when creating a plane between the lower uterine segment and the bladder.

Ensuring room to move and good visualization

If neither the anterior nor the posterior cul-de-sac can be accessed, it may be time to rethink the vaginal approach—but there is no harm in taking the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments extraperitoneally in an effort to gain some mobility. Hugging the uterus and leaving the anterior retractor in place to lift the bladder superiorly are essential steps to protect the ureters. The cervix can then be split in the midline (12 to 6 o’clock) to easily identify the peritoneal reflections.

Other tips

Sidewall retractors are rarely needed. They significantly impair placement of clamps and sutures by creating a long, narrow, parallel passageway. An alternative trick is to use the suction tip to retract the vaginal sidewall as the surgeon is working.

A disposable, fiberoptic, lighted suction irrigator is another option. The light can be directed precisely where it is needed, and the irrigation helps keep the field clean and tidy, simplifying identification of anatomy.

Skip the sutures whenever possible. Because it is difficult to place sutures with precision in a tight, poorly illuminated space, I use a vessel sealer for all pedicles above the uterosacral ligaments. Some of these instruments were designed specifically for vaginal hysterectomy in the same shape and size as Heaney clamps. They are remarkably efficient and permit the completion of a vaginal procedure when suture placement is difficult.

Use a Heaney needleholder, with the suture loaded precisely in the center of the needle curve, along with the lighted suction irrigator to retract redundant tissue away from the track of the needle, to facilitate suturing high in the pelvis.

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 2: Nulliparity

Many of us are reluctant to attempt vaginal hysterectomy in a woman who has never had children. Although this situation can be challenging at times, in my experience, the access issues tend to be more difficult in obese, multiparous women.

The same tricks and techniques addressed above will permit the vaginal approach in almost all nulliparous women.

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 3: Previous cesarean section

A prior cesarean delivery is sometimes considered an indication for laparoscopic hysterectomy. There are 2 concerns here: The patient may have a small pelvis, and there may be significant scar tissue and difficulty gaining access to the anterior cul-de-sac, as a result of repeated dissection between the lower uterine segment and the bladder. Several tricks may be useful:

Examine the patient under anesthesia to ensure that the fundus is not stuck to the anterior abdominal wall. This can occur if the peritoneum was not closed during the last cesarean section.

Empty the bladder before beginning the hysterectomy, and inject indigo carmine dye intravenously with the induction of anesthesia.

Use careful sharp dissection between the bladder and lower uterine segment using fine Metzenbaum scissors, with the tips pointed toward the uterus. Dissect only as far as you can easily see.

Secure the uterosacral, cardinal, and broad ligaments, if necessary, before pursuing entry into the anterior cul-de-sac. It is not essential to gain anterior access before taking these pedicles. The additional mobility and descensus enable safe sharp dissection.

If pedicles have been secured up to the fundus, and the anterior cul-de-sac remains difficult to assess, flip the fundus through the posterior cul-de-sac and reach your finger or an instrument around the top of the fundus to identify the peritoneum anteriorly, then incise it under direct vision.

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 4: Previous abdominal/pelvic surgery

This history is another often-cited rationale for avoiding the vaginal approach. In reality, the adhesions created from prior surgery tend to arise between the anterior abdominal wall and the omentum or small bowel. This situation makes laparoscopic or open abdominal entry riskier than vaginal peritoneal access through the cul-de-sac.

Two possible exceptions: a patient who has had surgery for deeply infiltrating endometriosis in the cul-de-sac or a woman who has undergone myomectomies with posterior incisions. These patients may have dense scarring in the cul-de-sac, which would preclude a vaginal approach. Whatever the surgical route, appropriate bowel preparation is necessary to permit simple closure of any intestinal injury at the time of hysterectomy. Why not begin vaginally if the exam under anesthesia demonstrates an accessible and reasonably free cul-de-sac?

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 5: Large myomatous uterus

A uterus of any size can be removed vaginally as long as there is mobility with access to the uterine arteries. The one exception: a patient with a small, normal uterus and a massive pedunculated myoma arising from the top of the fundus. If the fibroid cannot be pulled into the true pelvis for morcellation, it cannot be removed transvaginally. Fortunately, this situation is quite rare.

Keep the uterine serosa intact to maintain orientation.

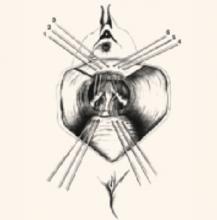

Split the uterus from 12 to 6 o’clock (bivalving). Protect the bladder with a Deaver retractor anteriorly, and protect the posterior vaginal epithelium with the weighted speculum posteriorly.

Remove chunks of tissue from the inside of the specimen. Orient your scalpel blade so that you are always cutting toward the center of the specimen. That way, if the blade slips, you will not accidentally injure tissue on the pelvic sidewall.

Use Lahey thyroid clamps to place the tissue you plan to remove under tension. Finding the capsule of each myoma and gently separating it from the surrounding myometrium facilitates delivery of larger fibroids into the endometrial cavity. Some myomas require morcellation themselves for removal.

Replace the scalpel blade periodically to keep it sharp. Calcified fibroids can dull the blade rapidly.

Work systematically to remove as much central tissue as possible. Try to keep a clean, sharp margin of tissue around the edges for easy grasping. Torn, irregular tissue is very difficult to grab and may cause significant frustration.

If access becomes limited, try clamping additional pedicles on each side of the specimen. A tiny amount of additional descensus can make a huge difference.

Do not administer GnRH agonists prior to surgery. The uterus may shrink, but the myomas tend to become quite soft and difficult to remove. If the patient is seriously anemic, give norethindrone acetate, 5 to 20 mg daily, to stop bleeding and allow the patient’s red blood cell volume to improve before elective surgery.

Use a vessel-sealing instrument to control the pedicles. This strategy produces optimal hemostasis to permit a dry field during morcellation. Moreover, the seals do not get disrupted when the large uterus is pulled past them. Placing suture around pedicles when there is a large, bulky uterus in the pelvis is challenging at best, and it is frustrating to see significant bleeding after removal of the specimen. This problem does not seem to occur with the sealing devices.

Know when to quit! We should not promise any patient a minimally invasive operation. If there is uncontrolled bleeding or no progress after 5 to 10 minutes, convert to a laparoscopic or abdominal approach.

I schedule cases I know will be challenging as “possible” laparoscopic or open hysterectomy. This alerts the OR staff to have additional equipment ready and nearby should we need it. It is not a surgical failure or complication to convert a minimally invasive hysterectomy to a more invasive technique when appropriate. Better to have tried and failed than never to have tried at all!

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 6: Avoiding complications

The most common complications of vaginal hysterectomy are bleeding, infection, and injury to the bladder. Ureteral injury is less common at vaginal hysterectomy than with the abdominal or laparoscopic approaches. Thus, I do not think routine cystoscopy is essential after uncomplicated vaginal hysterectomy, although I recommend intravenous administration of indigo carmine dye at the beginning of the procedure to enable rapid recognition of even a small bladder laceration. Sharp, careful dissection of the bladder off the lower uterine segment and the avoidance of finger dissection (especially with a gauze sponge) keep these injuries to a minimum.

Minimize bleeding by using newer vessel-sealing technologies rather than suture for most of the pedicles. I attach the uterosacral–cardinal ligament pedicles to the vaginal cuff at closure with suture. I suture the first pedicle once I have entered the posterior cul-de-sac and hold that suture to stay oriented.

Pay attention to patient positioning. Careful positioning will help you avoid neurological injuries. Avoid hyperflexion at the hips, which stretches the femoral nerve. Large nerves have comparatively little blood supply, so stretching them for prolonged periods can cause hypoxic injury. Although such injuries are almost always rapidly reversible, they are disconcerting for both the patient and her surgeon.

When operating on a very thin woman with a bony sacrum, I like to place egg-crate foam beneath the buttocks to provide some cushioning. I am also very careful with these women to keep their legs in a neutral position, and I watch my surgical assistants to be sure they are not leaning on the patient during the procedure.

Prophylactic antibiotics are a must to avoid postoperative vaginal cuff infections and pelvic abscess. Smokers and women with preexisting bacterial vaginosis are at highest risk for infection. I ask women to discontinue smoking at least 2 weeks prior to surgery and inform all smokers that their risk of infection is heightened. I treat anaerobic overgrowth in the vagina prior to surgery to help prevent infections in women with bacterial vaginosis.

The timing of prophylactic antibiotics is important. Intravenous first-generation cephalosporins must be administered within 60 minutes of the initial incision, but it is important to give them early enough for them to adequately disseminate to tissue before the colpotomy incision.

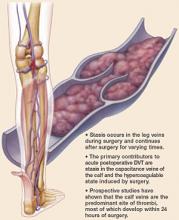

DVT prophylaxis is especially important for women with large uteri. Routine use of sequential compression stockings is both cost-effective and equivalent to the prophylactic use of subcutaneous heparin, so I use them for all patients undergoing vaginal hysterectomy. Early ambulation (usually within 2 hours of surgery) is also helpful in avoiding thromboses.

90% of hysterectomies can be performed vaginally

Using the techniques described in this article, I have been able to perform over 90% of the hysterectomies in my practice vaginally. More than 50% of my patients are either morbidly obese, nulliparous, or have had previous abdominal surgery of some type.

The instruments I find most useful are the lighted suction irrigator and the vessel-sealing Heaney-type clamp.

Establishing a routine and approaching technically challenging cases with a systematic and standardized set of techniques make the vaginal route possible for the vast majority of patients with benign disease.

Dr. Levy has served as a consultant to ValleyLab.

SUGGESTED READING

1. Abostini A, Vejux N, Colette E, et al. Risk of bladder injury during vaginal hysterectomy in women with a previous cesarean section. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:940-942.

2. Clave H, Barr H, Niccolai P. Painless vaginal hysterectomy with thermal hemostasis (results of a series of 152 cases). Gynecol Surg. 2005;2:101-105.

3. Isik-Akbay EF, Harmanli OH, Panganamamula UR, et al. Hysterectomy in obese women: a comparison of abdominal and vaginal routes. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:710-714.

4. Kovac SR. Clinical opinion: guidelines for hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:635-640.

5. O’Neal MG, Beste T, Shackelford DP. Utility of preemptive local analgesia in vaginal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1539-1542.

6. Johnson N, Barlow D, Lethaby A, Tavender E, Curr E, Garry R. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD003677.-

Newer codes for vaginal hysterectomy capture the work of removing larger uteri without laparoscopy

True or false: When it comes to hysterectomy, surgeons tend to use the route that is safest, least invasive, and most economical.

Sadly, the statement is false. Although vaginal hysterectomy tops all 3 categories, it is the least utilized of surgical routes. The number of vaginal hysterectomies may have increased slightly over the past decade, likely due to the incorporation of laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy into the mainstream and increased practice with the vaginal component, but fewer than 30% of hysterectomies are performed vaginally.

This article addresses 6 common challenges at vaginal hysterectomy and offers strategies to overcome them.

Laparoscopic strategies ease vaginal hysterectomy, too

Laparoscopic hysterectomy became widely accepted when surgical instruments were developed to overcome the technical challenges inherent in operating with limited access. By incorporating some of the techniques we routinely use for laparoscopic surgery, we can overcome many of the challenges faced during difficult vaginal surgery.

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 1: Obesity

Unfortunately, our population is increasingly rotund. This is not only a significant risk factor for the patient’s health in general, but it poses some unique challenges for surgeons. I must say that, as tough as it may be to complete a hysterectomy vaginally in a morbidly obese woman, I would much rather approach her pelvic organs through the cul-de-sac, which contains no fat cells, than through the abdominal wall—either laparoscopically or abdominally! The trick is gaining access to the posterior cul-de-sac.

How to enter the cul-de-sac

It seems to be a perverse rule of nature, but a tight upper vaginal ring seems almost universal in obese women. Added to the redundant sidewalls and the large buttocks, this tightness makes entry into the anterior or posterior cul-de-sac problematic. Several tricks make peritoneal access possible:

Position the patient to increase access, with the buttocks well over the edge of the operating table. This brings the operative field a bit closer to the surgeon, and permits the use of long-handled retractors posteriorly.

Use candy-cane stirrups to allow assistants better access to the operative field. Adequate assistance is essential in attempting vaginal surgery in the morbidly obese.

Avoid the Trendelenburg position. Although it might seem that this position would facilitate visualization and placement of a posterior weighted speculum, all it does is allow the patient to slide up on the table, making placement of alternate retractors difficult.

Use the right tools. If the posterior weighted speculum will not stay in place or does not afford access to the cul-de-sac due to an upper vaginal ring, use a narrow Deaver retractor posteriorly (without sidewall or anterior retraction). Use a Jacob’s tenaculum on the posterior lip of the cervix and have your assistant pull straight up on the tenaculum while using the Deaver retractor to see the area between the uterosacral ligaments.

Use the uterosacral ligaments as a guide. Another perversity in morbidly obese women: Despite multiparity, they seem to have little or no apical prolapse but lots of vaginal wall redundancy. The cervix is often elongated, but the uterosacral ligaments are sky high.

I palpate these ligaments, injecting them with a combination of vasopressin diluted 1:5 with bupivacaine and epinephrine (for enhanced hemostasis and preemptive analgesia), then use a pencil electrosurgical electrode to rapidly open the vaginal epithelium between the ligaments.

I then use a long, toothed tissue forceps to tent the peritoneum at 90 degrees to the plane of the posterior cul-de-sac and use Mayo scissors to enter the peritoneal cavity. Usually there is a spurt of fluid to mark appropriate entry into the peritoneum.

I then use the blades of my scissors to stretch the peritoneum between the ligaments and place a moistened 4×4 sponge into the incision.

At the onset of the procedure, inject indigo carmine dye intravenously so that any injury to the bladder will be immediately recognized. I have the circulating nurse empty the bladder while she is prepping the patient, but do not leave an indwelling catheter in place during the operation. I find it cumbersome to work around the catheter.

Problematic entries

When entry into the posterior cul-de-sac is difficult, I stop dissection, place a 4×4 sponge into the incision to reduce bleeding from the vagina, and proceed to attempt anterior entry.

I place the Deaver retractor into the anterior space and move the tenaculum to the anterior lip of the cervix. This gives maximal space for downward traction on the cervix while anterior entry is attempted.

Once again, I inject the tissue with the bupivacaine solution before incising the vaginal epithelium at the level of the internal os. I use sharp dissection only when creating a plane between the lower uterine segment and the bladder.

Ensuring room to move and good visualization

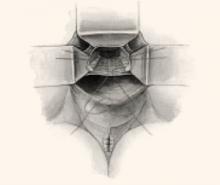

If neither the anterior nor the posterior cul-de-sac can be accessed, it may be time to rethink the vaginal approach—but there is no harm in taking the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments extraperitoneally in an effort to gain some mobility. Hugging the uterus and leaving the anterior retractor in place to lift the bladder superiorly are essential steps to protect the ureters. The cervix can then be split in the midline (12 to 6 o’clock) to easily identify the peritoneal reflections.

Other tips

Sidewall retractors are rarely needed. They significantly impair placement of clamps and sutures by creating a long, narrow, parallel passageway. An alternative trick is to use the suction tip to retract the vaginal sidewall as the surgeon is working.

A disposable, fiberoptic, lighted suction irrigator is another option. The light can be directed precisely where it is needed, and the irrigation helps keep the field clean and tidy, simplifying identification of anatomy.

Skip the sutures whenever possible. Because it is difficult to place sutures with precision in a tight, poorly illuminated space, I use a vessel sealer for all pedicles above the uterosacral ligaments. Some of these instruments were designed specifically for vaginal hysterectomy in the same shape and size as Heaney clamps. They are remarkably efficient and permit the completion of a vaginal procedure when suture placement is difficult.

Use a Heaney needleholder, with the suture loaded precisely in the center of the needle curve, along with the lighted suction irrigator to retract redundant tissue away from the track of the needle, to facilitate suturing high in the pelvis.

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 2: Nulliparity

Many of us are reluctant to attempt vaginal hysterectomy in a woman who has never had children. Although this situation can be challenging at times, in my experience, the access issues tend to be more difficult in obese, multiparous women.

The same tricks and techniques addressed above will permit the vaginal approach in almost all nulliparous women.

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 3: Previous cesarean section

A prior cesarean delivery is sometimes considered an indication for laparoscopic hysterectomy. There are 2 concerns here: The patient may have a small pelvis, and there may be significant scar tissue and difficulty gaining access to the anterior cul-de-sac, as a result of repeated dissection between the lower uterine segment and the bladder. Several tricks may be useful:

Examine the patient under anesthesia to ensure that the fundus is not stuck to the anterior abdominal wall. This can occur if the peritoneum was not closed during the last cesarean section.

Empty the bladder before beginning the hysterectomy, and inject indigo carmine dye intravenously with the induction of anesthesia.

Use careful sharp dissection between the bladder and lower uterine segment using fine Metzenbaum scissors, with the tips pointed toward the uterus. Dissect only as far as you can easily see.

Secure the uterosacral, cardinal, and broad ligaments, if necessary, before pursuing entry into the anterior cul-de-sac. It is not essential to gain anterior access before taking these pedicles. The additional mobility and descensus enable safe sharp dissection.

If pedicles have been secured up to the fundus, and the anterior cul-de-sac remains difficult to assess, flip the fundus through the posterior cul-de-sac and reach your finger or an instrument around the top of the fundus to identify the peritoneum anteriorly, then incise it under direct vision.

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 4: Previous abdominal/pelvic surgery

This history is another often-cited rationale for avoiding the vaginal approach. In reality, the adhesions created from prior surgery tend to arise between the anterior abdominal wall and the omentum or small bowel. This situation makes laparoscopic or open abdominal entry riskier than vaginal peritoneal access through the cul-de-sac.

Two possible exceptions: a patient who has had surgery for deeply infiltrating endometriosis in the cul-de-sac or a woman who has undergone myomectomies with posterior incisions. These patients may have dense scarring in the cul-de-sac, which would preclude a vaginal approach. Whatever the surgical route, appropriate bowel preparation is necessary to permit simple closure of any intestinal injury at the time of hysterectomy. Why not begin vaginally if the exam under anesthesia demonstrates an accessible and reasonably free cul-de-sac?

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 5: Large myomatous uterus

A uterus of any size can be removed vaginally as long as there is mobility with access to the uterine arteries. The one exception: a patient with a small, normal uterus and a massive pedunculated myoma arising from the top of the fundus. If the fibroid cannot be pulled into the true pelvis for morcellation, it cannot be removed transvaginally. Fortunately, this situation is quite rare.

Keep the uterine serosa intact to maintain orientation.

Split the uterus from 12 to 6 o’clock (bivalving). Protect the bladder with a Deaver retractor anteriorly, and protect the posterior vaginal epithelium with the weighted speculum posteriorly.

Remove chunks of tissue from the inside of the specimen. Orient your scalpel blade so that you are always cutting toward the center of the specimen. That way, if the blade slips, you will not accidentally injure tissue on the pelvic sidewall.

Use Lahey thyroid clamps to place the tissue you plan to remove under tension. Finding the capsule of each myoma and gently separating it from the surrounding myometrium facilitates delivery of larger fibroids into the endometrial cavity. Some myomas require morcellation themselves for removal.

Replace the scalpel blade periodically to keep it sharp. Calcified fibroids can dull the blade rapidly.

Work systematically to remove as much central tissue as possible. Try to keep a clean, sharp margin of tissue around the edges for easy grasping. Torn, irregular tissue is very difficult to grab and may cause significant frustration.

If access becomes limited, try clamping additional pedicles on each side of the specimen. A tiny amount of additional descensus can make a huge difference.

Do not administer GnRH agonists prior to surgery. The uterus may shrink, but the myomas tend to become quite soft and difficult to remove. If the patient is seriously anemic, give norethindrone acetate, 5 to 20 mg daily, to stop bleeding and allow the patient’s red blood cell volume to improve before elective surgery.

Use a vessel-sealing instrument to control the pedicles. This strategy produces optimal hemostasis to permit a dry field during morcellation. Moreover, the seals do not get disrupted when the large uterus is pulled past them. Placing suture around pedicles when there is a large, bulky uterus in the pelvis is challenging at best, and it is frustrating to see significant bleeding after removal of the specimen. This problem does not seem to occur with the sealing devices.

Know when to quit! We should not promise any patient a minimally invasive operation. If there is uncontrolled bleeding or no progress after 5 to 10 minutes, convert to a laparoscopic or abdominal approach.

I schedule cases I know will be challenging as “possible” laparoscopic or open hysterectomy. This alerts the OR staff to have additional equipment ready and nearby should we need it. It is not a surgical failure or complication to convert a minimally invasive hysterectomy to a more invasive technique when appropriate. Better to have tried and failed than never to have tried at all!

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 6: Avoiding complications

The most common complications of vaginal hysterectomy are bleeding, infection, and injury to the bladder. Ureteral injury is less common at vaginal hysterectomy than with the abdominal or laparoscopic approaches. Thus, I do not think routine cystoscopy is essential after uncomplicated vaginal hysterectomy, although I recommend intravenous administration of indigo carmine dye at the beginning of the procedure to enable rapid recognition of even a small bladder laceration. Sharp, careful dissection of the bladder off the lower uterine segment and the avoidance of finger dissection (especially with a gauze sponge) keep these injuries to a minimum.

Minimize bleeding by using newer vessel-sealing technologies rather than suture for most of the pedicles. I attach the uterosacral–cardinal ligament pedicles to the vaginal cuff at closure with suture. I suture the first pedicle once I have entered the posterior cul-de-sac and hold that suture to stay oriented.

Pay attention to patient positioning. Careful positioning will help you avoid neurological injuries. Avoid hyperflexion at the hips, which stretches the femoral nerve. Large nerves have comparatively little blood supply, so stretching them for prolonged periods can cause hypoxic injury. Although such injuries are almost always rapidly reversible, they are disconcerting for both the patient and her surgeon.

When operating on a very thin woman with a bony sacrum, I like to place egg-crate foam beneath the buttocks to provide some cushioning. I am also very careful with these women to keep their legs in a neutral position, and I watch my surgical assistants to be sure they are not leaning on the patient during the procedure.

Prophylactic antibiotics are a must to avoid postoperative vaginal cuff infections and pelvic abscess. Smokers and women with preexisting bacterial vaginosis are at highest risk for infection. I ask women to discontinue smoking at least 2 weeks prior to surgery and inform all smokers that their risk of infection is heightened. I treat anaerobic overgrowth in the vagina prior to surgery to help prevent infections in women with bacterial vaginosis.

The timing of prophylactic antibiotics is important. Intravenous first-generation cephalosporins must be administered within 60 minutes of the initial incision, but it is important to give them early enough for them to adequately disseminate to tissue before the colpotomy incision.

DVT prophylaxis is especially important for women with large uteri. Routine use of sequential compression stockings is both cost-effective and equivalent to the prophylactic use of subcutaneous heparin, so I use them for all patients undergoing vaginal hysterectomy. Early ambulation (usually within 2 hours of surgery) is also helpful in avoiding thromboses.

90% of hysterectomies can be performed vaginally

Using the techniques described in this article, I have been able to perform over 90% of the hysterectomies in my practice vaginally. More than 50% of my patients are either morbidly obese, nulliparous, or have had previous abdominal surgery of some type.

The instruments I find most useful are the lighted suction irrigator and the vessel-sealing Heaney-type clamp.

Establishing a routine and approaching technically challenging cases with a systematic and standardized set of techniques make the vaginal route possible for the vast majority of patients with benign disease.

Dr. Levy has served as a consultant to ValleyLab.

Newer codes for vaginal hysterectomy capture the work of removing larger uteri without laparoscopy

True or false: When it comes to hysterectomy, surgeons tend to use the route that is safest, least invasive, and most economical.

Sadly, the statement is false. Although vaginal hysterectomy tops all 3 categories, it is the least utilized of surgical routes. The number of vaginal hysterectomies may have increased slightly over the past decade, likely due to the incorporation of laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy into the mainstream and increased practice with the vaginal component, but fewer than 30% of hysterectomies are performed vaginally.

This article addresses 6 common challenges at vaginal hysterectomy and offers strategies to overcome them.

Laparoscopic strategies ease vaginal hysterectomy, too

Laparoscopic hysterectomy became widely accepted when surgical instruments were developed to overcome the technical challenges inherent in operating with limited access. By incorporating some of the techniques we routinely use for laparoscopic surgery, we can overcome many of the challenges faced during difficult vaginal surgery.

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 1: Obesity

Unfortunately, our population is increasingly rotund. This is not only a significant risk factor for the patient’s health in general, but it poses some unique challenges for surgeons. I must say that, as tough as it may be to complete a hysterectomy vaginally in a morbidly obese woman, I would much rather approach her pelvic organs through the cul-de-sac, which contains no fat cells, than through the abdominal wall—either laparoscopically or abdominally! The trick is gaining access to the posterior cul-de-sac.

How to enter the cul-de-sac

It seems to be a perverse rule of nature, but a tight upper vaginal ring seems almost universal in obese women. Added to the redundant sidewalls and the large buttocks, this tightness makes entry into the anterior or posterior cul-de-sac problematic. Several tricks make peritoneal access possible:

Position the patient to increase access, with the buttocks well over the edge of the operating table. This brings the operative field a bit closer to the surgeon, and permits the use of long-handled retractors posteriorly.

Use candy-cane stirrups to allow assistants better access to the operative field. Adequate assistance is essential in attempting vaginal surgery in the morbidly obese.

Avoid the Trendelenburg position. Although it might seem that this position would facilitate visualization and placement of a posterior weighted speculum, all it does is allow the patient to slide up on the table, making placement of alternate retractors difficult.

Use the right tools. If the posterior weighted speculum will not stay in place or does not afford access to the cul-de-sac due to an upper vaginal ring, use a narrow Deaver retractor posteriorly (without sidewall or anterior retraction). Use a Jacob’s tenaculum on the posterior lip of the cervix and have your assistant pull straight up on the tenaculum while using the Deaver retractor to see the area between the uterosacral ligaments.

Use the uterosacral ligaments as a guide. Another perversity in morbidly obese women: Despite multiparity, they seem to have little or no apical prolapse but lots of vaginal wall redundancy. The cervix is often elongated, but the uterosacral ligaments are sky high.

I palpate these ligaments, injecting them with a combination of vasopressin diluted 1:5 with bupivacaine and epinephrine (for enhanced hemostasis and preemptive analgesia), then use a pencil electrosurgical electrode to rapidly open the vaginal epithelium between the ligaments.

I then use a long, toothed tissue forceps to tent the peritoneum at 90 degrees to the plane of the posterior cul-de-sac and use Mayo scissors to enter the peritoneal cavity. Usually there is a spurt of fluid to mark appropriate entry into the peritoneum.

I then use the blades of my scissors to stretch the peritoneum between the ligaments and place a moistened 4×4 sponge into the incision.

At the onset of the procedure, inject indigo carmine dye intravenously so that any injury to the bladder will be immediately recognized. I have the circulating nurse empty the bladder while she is prepping the patient, but do not leave an indwelling catheter in place during the operation. I find it cumbersome to work around the catheter.

Problematic entries

When entry into the posterior cul-de-sac is difficult, I stop dissection, place a 4×4 sponge into the incision to reduce bleeding from the vagina, and proceed to attempt anterior entry.

I place the Deaver retractor into the anterior space and move the tenaculum to the anterior lip of the cervix. This gives maximal space for downward traction on the cervix while anterior entry is attempted.

Once again, I inject the tissue with the bupivacaine solution before incising the vaginal epithelium at the level of the internal os. I use sharp dissection only when creating a plane between the lower uterine segment and the bladder.

Ensuring room to move and good visualization

If neither the anterior nor the posterior cul-de-sac can be accessed, it may be time to rethink the vaginal approach—but there is no harm in taking the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments extraperitoneally in an effort to gain some mobility. Hugging the uterus and leaving the anterior retractor in place to lift the bladder superiorly are essential steps to protect the ureters. The cervix can then be split in the midline (12 to 6 o’clock) to easily identify the peritoneal reflections.

Other tips

Sidewall retractors are rarely needed. They significantly impair placement of clamps and sutures by creating a long, narrow, parallel passageway. An alternative trick is to use the suction tip to retract the vaginal sidewall as the surgeon is working.

A disposable, fiberoptic, lighted suction irrigator is another option. The light can be directed precisely where it is needed, and the irrigation helps keep the field clean and tidy, simplifying identification of anatomy.

Skip the sutures whenever possible. Because it is difficult to place sutures with precision in a tight, poorly illuminated space, I use a vessel sealer for all pedicles above the uterosacral ligaments. Some of these instruments were designed specifically for vaginal hysterectomy in the same shape and size as Heaney clamps. They are remarkably efficient and permit the completion of a vaginal procedure when suture placement is difficult.

Use a Heaney needleholder, with the suture loaded precisely in the center of the needle curve, along with the lighted suction irrigator to retract redundant tissue away from the track of the needle, to facilitate suturing high in the pelvis.

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 2: Nulliparity

Many of us are reluctant to attempt vaginal hysterectomy in a woman who has never had children. Although this situation can be challenging at times, in my experience, the access issues tend to be more difficult in obese, multiparous women.

The same tricks and techniques addressed above will permit the vaginal approach in almost all nulliparous women.

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 3: Previous cesarean section

A prior cesarean delivery is sometimes considered an indication for laparoscopic hysterectomy. There are 2 concerns here: The patient may have a small pelvis, and there may be significant scar tissue and difficulty gaining access to the anterior cul-de-sac, as a result of repeated dissection between the lower uterine segment and the bladder. Several tricks may be useful:

Examine the patient under anesthesia to ensure that the fundus is not stuck to the anterior abdominal wall. This can occur if the peritoneum was not closed during the last cesarean section.

Empty the bladder before beginning the hysterectomy, and inject indigo carmine dye intravenously with the induction of anesthesia.

Use careful sharp dissection between the bladder and lower uterine segment using fine Metzenbaum scissors, with the tips pointed toward the uterus. Dissect only as far as you can easily see.

Secure the uterosacral, cardinal, and broad ligaments, if necessary, before pursuing entry into the anterior cul-de-sac. It is not essential to gain anterior access before taking these pedicles. The additional mobility and descensus enable safe sharp dissection.

If pedicles have been secured up to the fundus, and the anterior cul-de-sac remains difficult to assess, flip the fundus through the posterior cul-de-sac and reach your finger or an instrument around the top of the fundus to identify the peritoneum anteriorly, then incise it under direct vision.

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 4: Previous abdominal/pelvic surgery

This history is another often-cited rationale for avoiding the vaginal approach. In reality, the adhesions created from prior surgery tend to arise between the anterior abdominal wall and the omentum or small bowel. This situation makes laparoscopic or open abdominal entry riskier than vaginal peritoneal access through the cul-de-sac.

Two possible exceptions: a patient who has had surgery for deeply infiltrating endometriosis in the cul-de-sac or a woman who has undergone myomectomies with posterior incisions. These patients may have dense scarring in the cul-de-sac, which would preclude a vaginal approach. Whatever the surgical route, appropriate bowel preparation is necessary to permit simple closure of any intestinal injury at the time of hysterectomy. Why not begin vaginally if the exam under anesthesia demonstrates an accessible and reasonably free cul-de-sac?

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 5: Large myomatous uterus

A uterus of any size can be removed vaginally as long as there is mobility with access to the uterine arteries. The one exception: a patient with a small, normal uterus and a massive pedunculated myoma arising from the top of the fundus. If the fibroid cannot be pulled into the true pelvis for morcellation, it cannot be removed transvaginally. Fortunately, this situation is quite rare.

Keep the uterine serosa intact to maintain orientation.

Split the uterus from 12 to 6 o’clock (bivalving). Protect the bladder with a Deaver retractor anteriorly, and protect the posterior vaginal epithelium with the weighted speculum posteriorly.

Remove chunks of tissue from the inside of the specimen. Orient your scalpel blade so that you are always cutting toward the center of the specimen. That way, if the blade slips, you will not accidentally injure tissue on the pelvic sidewall.

Use Lahey thyroid clamps to place the tissue you plan to remove under tension. Finding the capsule of each myoma and gently separating it from the surrounding myometrium facilitates delivery of larger fibroids into the endometrial cavity. Some myomas require morcellation themselves for removal.

Replace the scalpel blade periodically to keep it sharp. Calcified fibroids can dull the blade rapidly.

Work systematically to remove as much central tissue as possible. Try to keep a clean, sharp margin of tissue around the edges for easy grasping. Torn, irregular tissue is very difficult to grab and may cause significant frustration.

If access becomes limited, try clamping additional pedicles on each side of the specimen. A tiny amount of additional descensus can make a huge difference.

Do not administer GnRH agonists prior to surgery. The uterus may shrink, but the myomas tend to become quite soft and difficult to remove. If the patient is seriously anemic, give norethindrone acetate, 5 to 20 mg daily, to stop bleeding and allow the patient’s red blood cell volume to improve before elective surgery.

Use a vessel-sealing instrument to control the pedicles. This strategy produces optimal hemostasis to permit a dry field during morcellation. Moreover, the seals do not get disrupted when the large uterus is pulled past them. Placing suture around pedicles when there is a large, bulky uterus in the pelvis is challenging at best, and it is frustrating to see significant bleeding after removal of the specimen. This problem does not seem to occur with the sealing devices.

Know when to quit! We should not promise any patient a minimally invasive operation. If there is uncontrolled bleeding or no progress after 5 to 10 minutes, convert to a laparoscopic or abdominal approach.

I schedule cases I know will be challenging as “possible” laparoscopic or open hysterectomy. This alerts the OR staff to have additional equipment ready and nearby should we need it. It is not a surgical failure or complication to convert a minimally invasive hysterectomy to a more invasive technique when appropriate. Better to have tried and failed than never to have tried at all!

VAGINAL HYSTERECTOMY CHALLENGE 6: Avoiding complications

The most common complications of vaginal hysterectomy are bleeding, infection, and injury to the bladder. Ureteral injury is less common at vaginal hysterectomy than with the abdominal or laparoscopic approaches. Thus, I do not think routine cystoscopy is essential after uncomplicated vaginal hysterectomy, although I recommend intravenous administration of indigo carmine dye at the beginning of the procedure to enable rapid recognition of even a small bladder laceration. Sharp, careful dissection of the bladder off the lower uterine segment and the avoidance of finger dissection (especially with a gauze sponge) keep these injuries to a minimum.

Minimize bleeding by using newer vessel-sealing technologies rather than suture for most of the pedicles. I attach the uterosacral–cardinal ligament pedicles to the vaginal cuff at closure with suture. I suture the first pedicle once I have entered the posterior cul-de-sac and hold that suture to stay oriented.

Pay attention to patient positioning. Careful positioning will help you avoid neurological injuries. Avoid hyperflexion at the hips, which stretches the femoral nerve. Large nerves have comparatively little blood supply, so stretching them for prolonged periods can cause hypoxic injury. Although such injuries are almost always rapidly reversible, they are disconcerting for both the patient and her surgeon.

When operating on a very thin woman with a bony sacrum, I like to place egg-crate foam beneath the buttocks to provide some cushioning. I am also very careful with these women to keep their legs in a neutral position, and I watch my surgical assistants to be sure they are not leaning on the patient during the procedure.

Prophylactic antibiotics are a must to avoid postoperative vaginal cuff infections and pelvic abscess. Smokers and women with preexisting bacterial vaginosis are at highest risk for infection. I ask women to discontinue smoking at least 2 weeks prior to surgery and inform all smokers that their risk of infection is heightened. I treat anaerobic overgrowth in the vagina prior to surgery to help prevent infections in women with bacterial vaginosis.

The timing of prophylactic antibiotics is important. Intravenous first-generation cephalosporins must be administered within 60 minutes of the initial incision, but it is important to give them early enough for them to adequately disseminate to tissue before the colpotomy incision.

DVT prophylaxis is especially important for women with large uteri. Routine use of sequential compression stockings is both cost-effective and equivalent to the prophylactic use of subcutaneous heparin, so I use them for all patients undergoing vaginal hysterectomy. Early ambulation (usually within 2 hours of surgery) is also helpful in avoiding thromboses.

90% of hysterectomies can be performed vaginally

Using the techniques described in this article, I have been able to perform over 90% of the hysterectomies in my practice vaginally. More than 50% of my patients are either morbidly obese, nulliparous, or have had previous abdominal surgery of some type.

The instruments I find most useful are the lighted suction irrigator and the vessel-sealing Heaney-type clamp.

Establishing a routine and approaching technically challenging cases with a systematic and standardized set of techniques make the vaginal route possible for the vast majority of patients with benign disease.

Dr. Levy has served as a consultant to ValleyLab.

SUGGESTED READING

1. Abostini A, Vejux N, Colette E, et al. Risk of bladder injury during vaginal hysterectomy in women with a previous cesarean section. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:940-942.

2. Clave H, Barr H, Niccolai P. Painless vaginal hysterectomy with thermal hemostasis (results of a series of 152 cases). Gynecol Surg. 2005;2:101-105.

3. Isik-Akbay EF, Harmanli OH, Panganamamula UR, et al. Hysterectomy in obese women: a comparison of abdominal and vaginal routes. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:710-714.

4. Kovac SR. Clinical opinion: guidelines for hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:635-640.

5. O’Neal MG, Beste T, Shackelford DP. Utility of preemptive local analgesia in vaginal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1539-1542.

6. Johnson N, Barlow D, Lethaby A, Tavender E, Curr E, Garry R. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD003677.-

SUGGESTED READING

1. Abostini A, Vejux N, Colette E, et al. Risk of bladder injury during vaginal hysterectomy in women with a previous cesarean section. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:940-942.

2. Clave H, Barr H, Niccolai P. Painless vaginal hysterectomy with thermal hemostasis (results of a series of 152 cases). Gynecol Surg. 2005;2:101-105.

3. Isik-Akbay EF, Harmanli OH, Panganamamula UR, et al. Hysterectomy in obese women: a comparison of abdominal and vaginal routes. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:710-714.

4. Kovac SR. Clinical opinion: guidelines for hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:635-640.

5. O’Neal MG, Beste T, Shackelford DP. Utility of preemptive local analgesia in vaginal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1539-1542.

6. Johnson N, Barlow D, Lethaby A, Tavender E, Curr E, Garry R. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD003677.-

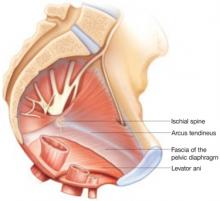

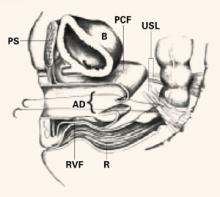

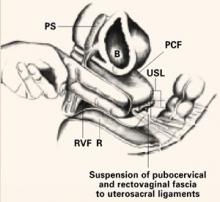

The Retroperitoneal Space: Keeping vital structures out of harm’s way

The accomplished gynecologic surgeon must know the anatomy of the retroperitoneal space in order to avoid damage to normal structures, as well as remove pathology. Many disease processes involve the pelvic peritoneum, uterosacral ligaments, rectosigmoid or ovarian pedicles, and require the surgeon to enter the retroperitoneal space to identify the ureters and blood vessels and keep them out of harm’s way. The challenges are complex:

- Badly distorted anatomy and the anterior and posterior cul-de-sac necessitate mobilization of the rectosigmoid and bladder.

- Intraligamentous fibroids require knowledge of the blood supply in the retroperitoneal space. Malignant disorders mandate that the lymph nodes be dissected to determine extent of disease and as part of treatment.

Is training adequate?

Every training program should teach the surgical anatomy of the retroperitoneal space, since every surgeon needs to be comfortable exposing the anatomy, both to prevent injury and to accomplish the needed surgery. Videotapes and cadaver courses can prepare the resident for the operating room.

The “landmark” umbilical ligament

The umbilical ligament was the umbilical artery in fetal life and courses along the edge of the bladder to the anterior abdominal wall up to the umbilicus. It is a useful guide into the perivesicle space. Lateral to it are the iliac vessels, and medial is the bladder. It is also a good marker for finding the right spot to open the round ligament.

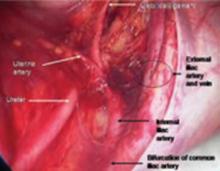

FIGURE 1 Opening the round ligament over the umbilical ligament

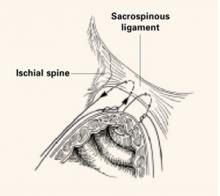

The round ligament is the key to exposing the retroperitoneal space. It should be open at the pelvic sidewall, just medial to the external iliac vessels. The umbilical ligament can be used as a landmark.

FIGURE 2 Opening lateral to the ovarian vessels

The divided round ligament is retracted ventrally and medially to place the ovarian vessels under traction. The peritoneum lateral to the ovarian vessels is divided up to the pelvic brim.

FIGURE 3 Right pelvic sidewall anatomy

Medial traction of the peritoneum around the ovarian vessels at the pelvic brim will expose the ureter coming over the iliac vessels at their bifurcation into external and internal branches.

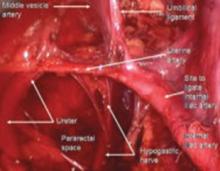

FIGURE 4 Relationship of ureter to the umbilical ligament

The ureter comes off medial with the fold of peritoneum. Once the space is developed, the operator’s finger or the laparoscopic probe can be introduced along the medial side of the internal iliac artery and ventral to the curve of the sacrum. This will open the pararectal space. The ureter and the anterior branch of the internal iliac artery are nearly parallel as they course through the pelvis.

FIGURE 5 Hypogastric nerve

The anterior branch of the internal iliac artery gives off the uterine artery and the middle and superior vesicle arteries before continuing on as the umbilical ligament.

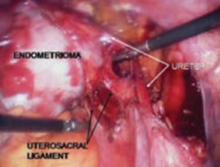

Endometriosis may imperil the ureter

Endometriomas and peritoneal implants are among the most common reasons for accessing the retroperitoneal space. Frequently the peritoneum between the ovarian vessels and the uterosacral ligaments (ovarian fossa) is thickened and retracted within the endometriosis implants. This alters the pelvic anatomy and puts the ureter at risk for injury.

Definitive surgical treatment for endometriosis includes removal of this diseased peritoneum. The ureter is best identified using the technique described, and then dissected off the peritoneum down to the uterine artery.

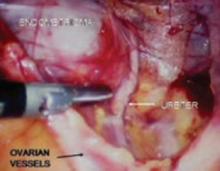

FIGURE 6 Finding the ureter lateral to an endometrioma

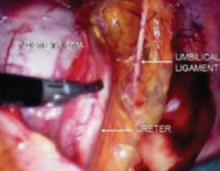

FIGURE 7 Relationship of ureter to the umbilical ligament

FIGURE 8 Dissecting the ureter out of the uterosacral ligament

The ureter may be placed on a Penrose drain to better isolate it and keep it under direct visualization. The cul-de-sac of Douglas is another site of endometrial implants. The fundus of the uterus is often adhesed to the rectosigmoid reflection and even the sigmoid colon. Nodules of endometriosis may infiltrate the uterosacral ligaments and extend into the rectovaginal space. To manage these implants, isolate the ureter to the point where it passes under the uterine artery.

FIGURE 9 Divide uterine artery lateral to endometrioma

Here, the uterine artery is taken lateral to the mass, enabling the surgeon to remove all of the uterosacral implants. The bladder flap will be developed and the bladder advanced caudad. By dissecting medial to the ureter as it courses under the uterine artery, it will be retracted laterally and provide the space necessary to resect the uterosacral implants.

FIGURE 10 Rectosigmoid reflection with endometrioma nodule

FIGURE 11 Postoperative appearance of endometriosis resection

As dissection proceeds medially, use the perirectal fatty plane to remove implants between the uterosacral area and rectum. In the midline, remove implants below the rectosigmoid peritoneal reflexion, taking care not to injure the rectum.

Implants above the peritoneal reflexion are often attached to the sigmoid tinea coli and cannot be removed without taking a portion of the bowel. Thus, patients with extensive endometriosis should have a bowel prep with two 10-ounce bottles of magnesium citrate the day before surgery.

If bowel resection is necessary, consult a general surgeon or gynecologic oncologist. A history of painful defecation or a finding of nodules in the cul-de-sac with rectal dimpling warrants preoperative consultation with a specialist skilled at bowel resection.

Ureteral injuries occur in 0.5% to 2.5% of women undergoing gynecologic surgery.1 The most common predisposing condition is previous pelvic surgery.2,3 The usual sites of injury are at the pelvic rim close to the ovarian vessels, at the level of the uterine artery, and lateral to the vaginal cuff. Neither preoperative excretory urograms nor placement of ureteral catheters preoperatively have been found to be effective prevention measures.2,4-6 Using the steps described above, the ureter can be identified and mobilized.

Blood supply to the ureter comes from the plexus of vessels that form a network along the length of the ureter. This plexus is fed by arteries from the renal pelvis, common iliac, internal iliac, uterine artery, and the base of the bladder. Complete mobilization of the ureter away from its peritoneal attachments and these lateral blood supply sources can be accomplished as long as the vascular plexus is not disrupted by cautery, crushing, or tearing. A clean transection can be re-anastomosed or reimplanted with the expectation of normal healing. Innervation of the ureter is from the inferior mesenteric plexus superiorly and the inferior hypogastric plexus in the pelvis. Ureteral peristalsis will continue, even if the ureter is completely divided or ligated.

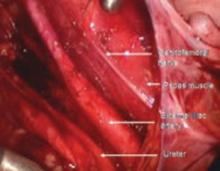

Protecting pelvic blood vessels

The majority of gynecologic operations involve the ovarian vessels and the uterine vessels. The operator rarely needs to explore the lateral pelvis to identify the rest of the vessels. When faced with a large endometrioma or cancer, knowledge of the anatomy of the lateral blood vessels is vital.

Since the pathology is usually deeper in the pelvis, it is wise to identify the anatomy of the pelvis starting at the pelvic brim, where the common iliac bifurcates into the external and internal iliacs. There is a safe dissection plane medial to the internal iliac artery all the way to the uterine artery. This exposes the pararectal space, which can be opened without risk of major bleeding (FIGURE 5).

The obliterated umbilical vessel is the other friendly marker just distal to the uterine artery. It can be placed on traction and the uterine artery isolated. The inferior and superior vesical arteries are generally not dissected, as they are adjacent to the bladder and the surgery takes place medial to them in the prevesical fascial space.

Hypogastric artery ligations are rarely performed today, as interventional radiology is the standard of care for patients with postoperative and postpartum bleeding. When it becomes necessary, the hypogastric artery can be isolated and tied using the right-angle clamp to pass the tie. The superior gluteal artery branches so close to the bifurcation of the common iliac artery that it is not visualized. The inferior gluteal artery is the largest distal branch, which might be visualized during the ligation. It is not necessary to identify it.

FIGURE 12 Right genitofemoral nerve

The genitofemoral nerve runs along the medial aspect of the body of the psoas muscle. It is sometimes injured by the self-retaining retractors placed at the time of laparotomy. This leads to some numbness and burning of the skin of the anterior thigh.

FIGURE 13 Right pelvic sidewall anatomy

The obturator nerve is in the obturator space and typically far lateral to the usual dissection. Metastatic cancer to the obturator lymph nodes may entrap it, or it may be injured during a node dissection, causing loss of internal rotation of the anterior thigh.

The sciatic nerve is seen only during exenterative surgery. Pressure on the lateral pelvis by advanced pelvic tumors can lead to sciatic pain and motor weakness—even loss of motor function to the lower leg, which commonly leads to foot drop.

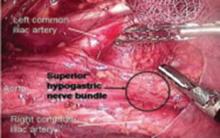

FIGURE 14 Superior hypogastric nerve bundle

The hypogastric plexus of nerves is sometimes damaged during surgery for endometriosis or for malignancy. The superior hypergastric plexus can be identified between the 2 common iliac arteries at the sacral promontory. The left common iliac vein runs underneath it.

FIGURE 15 Hypogastric nerve descending into the right pelvis

The right and left hypogastric nerves leave the hypogastric plexus and descend into the pelvis parallel to the ureter and 2 cm medial. It passes dorsal to the ureter as it goes through the cardinal ligament (FIGURE 5).

This plexus then supplies autonomic innervation of the bladder, rectum, uterus, and ureter. Complete disruption of the hypogastric nerve will lead to a hypertonic, noncontractile bladder and the necessity for self-catheterization to eliminate urine. Preservation of this nerve during radical hysterectomy or endometriosis resection is a high priority.

Laparoscopic uterosacral nerve ablation procedures divide the uterosacral ligament medial and caudad to the ureter and do not disrupt the main hypogastric nerve. Only the medial branches to the uterus are affected. Successful uterosacral nerve ablation has been reported in approximately 44% of women who have dysmenorrhea without visible endometriosis and approximately 62% of women who have visible endometriosis.7,8 The efficacy of this procedure is controversial, however. Removal of the superior hypogastric plexus (presacral neurectomy) has not proved to be more effective in controlling pelvic pain than conservative surgery that only destroys endometrial implants. Presacral neurectomy is no longer advised.9

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Educational Bulletin #238: Lower Urinary Tract Operative Injuries. Washington, DC: ACOG; 1985:1.

2. Daly JW, Higgins KA. Injury to the ureter during gynecologic surgical procedures. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1988;167:19-22.

3. Selzman AA, Spirnak JP. Iatrogenic ureteral injuries: a 20-year experience in treating 165 injuries. J Urol. 1996;155:878-881.

4. Symmonds RE. Ureteral injuries associated with gynecologic surgery: prevention and management. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 19676;19:623-644.

5. Higgins CC. Ureteral injuries during surgery: a review of 87 cases. JAMA 1967;199:82-88.

6. Fry DE, Milholen L, Harbrecht PJ. Iatrogenic ureteral injury. Options in management. Arch Surg. 1983;118:454-457.

7. Lichten EM, Bombard J. Surgical treatment of primary dysmenorrhea with laparoscopic uterine nerve ablation. J Reprod Med. 1987;32:37-41.

8. Sutton CJG, Ewen SP, Whitelaw N, Haines P. Prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of laser laparoscopy in the treatment of pelvic pain associated with minimal, mild, and moderate endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:696.-

9. Candiani GB, Fedele L, Vercellini P, Bianchi S, Di Nola G. Presacral neurectomy for the treatment of pelvic pain associated with endometriosis: a controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:100-103.

Dr. Hatch receives research/grant support from Merck; is a consultant to Ethicon, Merck, and Quest Laboratory; and is a speaker for Cytyc, Digene, Ethicon, and Merck.

The accomplished gynecologic surgeon must know the anatomy of the retroperitoneal space in order to avoid damage to normal structures, as well as remove pathology. Many disease processes involve the pelvic peritoneum, uterosacral ligaments, rectosigmoid or ovarian pedicles, and require the surgeon to enter the retroperitoneal space to identify the ureters and blood vessels and keep them out of harm’s way. The challenges are complex:

- Badly distorted anatomy and the anterior and posterior cul-de-sac necessitate mobilization of the rectosigmoid and bladder.

- Intraligamentous fibroids require knowledge of the blood supply in the retroperitoneal space. Malignant disorders mandate that the lymph nodes be dissected to determine extent of disease and as part of treatment.

Is training adequate?

Every training program should teach the surgical anatomy of the retroperitoneal space, since every surgeon needs to be comfortable exposing the anatomy, both to prevent injury and to accomplish the needed surgery. Videotapes and cadaver courses can prepare the resident for the operating room.

The “landmark” umbilical ligament

The umbilical ligament was the umbilical artery in fetal life and courses along the edge of the bladder to the anterior abdominal wall up to the umbilicus. It is a useful guide into the perivesicle space. Lateral to it are the iliac vessels, and medial is the bladder. It is also a good marker for finding the right spot to open the round ligament.

FIGURE 1 Opening the round ligament over the umbilical ligament

The round ligament is the key to exposing the retroperitoneal space. It should be open at the pelvic sidewall, just medial to the external iliac vessels. The umbilical ligament can be used as a landmark.

FIGURE 2 Opening lateral to the ovarian vessels

The divided round ligament is retracted ventrally and medially to place the ovarian vessels under traction. The peritoneum lateral to the ovarian vessels is divided up to the pelvic brim.

FIGURE 3 Right pelvic sidewall anatomy

Medial traction of the peritoneum around the ovarian vessels at the pelvic brim will expose the ureter coming over the iliac vessels at their bifurcation into external and internal branches.

FIGURE 4 Relationship of ureter to the umbilical ligament

The ureter comes off medial with the fold of peritoneum. Once the space is developed, the operator’s finger or the laparoscopic probe can be introduced along the medial side of the internal iliac artery and ventral to the curve of the sacrum. This will open the pararectal space. The ureter and the anterior branch of the internal iliac artery are nearly parallel as they course through the pelvis.

FIGURE 5 Hypogastric nerve

The anterior branch of the internal iliac artery gives off the uterine artery and the middle and superior vesicle arteries before continuing on as the umbilical ligament.

Endometriosis may imperil the ureter

Endometriomas and peritoneal implants are among the most common reasons for accessing the retroperitoneal space. Frequently the peritoneum between the ovarian vessels and the uterosacral ligaments (ovarian fossa) is thickened and retracted within the endometriosis implants. This alters the pelvic anatomy and puts the ureter at risk for injury.

Definitive surgical treatment for endometriosis includes removal of this diseased peritoneum. The ureter is best identified using the technique described, and then dissected off the peritoneum down to the uterine artery.

FIGURE 6 Finding the ureter lateral to an endometrioma

FIGURE 7 Relationship of ureter to the umbilical ligament

FIGURE 8 Dissecting the ureter out of the uterosacral ligament

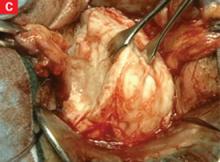

The ureter may be placed on a Penrose drain to better isolate it and keep it under direct visualization. The cul-de-sac of Douglas is another site of endometrial implants. The fundus of the uterus is often adhesed to the rectosigmoid reflection and even the sigmoid colon. Nodules of endometriosis may infiltrate the uterosacral ligaments and extend into the rectovaginal space. To manage these implants, isolate the ureter to the point where it passes under the uterine artery.

FIGURE 9 Divide uterine artery lateral to endometrioma

Here, the uterine artery is taken lateral to the mass, enabling the surgeon to remove all of the uterosacral implants. The bladder flap will be developed and the bladder advanced caudad. By dissecting medial to the ureter as it courses under the uterine artery, it will be retracted laterally and provide the space necessary to resect the uterosacral implants.

FIGURE 10 Rectosigmoid reflection with endometrioma nodule

FIGURE 11 Postoperative appearance of endometriosis resection

As dissection proceeds medially, use the perirectal fatty plane to remove implants between the uterosacral area and rectum. In the midline, remove implants below the rectosigmoid peritoneal reflexion, taking care not to injure the rectum.

Implants above the peritoneal reflexion are often attached to the sigmoid tinea coli and cannot be removed without taking a portion of the bowel. Thus, patients with extensive endometriosis should have a bowel prep with two 10-ounce bottles of magnesium citrate the day before surgery.

If bowel resection is necessary, consult a general surgeon or gynecologic oncologist. A history of painful defecation or a finding of nodules in the cul-de-sac with rectal dimpling warrants preoperative consultation with a specialist skilled at bowel resection.

Ureteral injuries occur in 0.5% to 2.5% of women undergoing gynecologic surgery.1 The most common predisposing condition is previous pelvic surgery.2,3 The usual sites of injury are at the pelvic rim close to the ovarian vessels, at the level of the uterine artery, and lateral to the vaginal cuff. Neither preoperative excretory urograms nor placement of ureteral catheters preoperatively have been found to be effective prevention measures.2,4-6 Using the steps described above, the ureter can be identified and mobilized.

Blood supply to the ureter comes from the plexus of vessels that form a network along the length of the ureter. This plexus is fed by arteries from the renal pelvis, common iliac, internal iliac, uterine artery, and the base of the bladder. Complete mobilization of the ureter away from its peritoneal attachments and these lateral blood supply sources can be accomplished as long as the vascular plexus is not disrupted by cautery, crushing, or tearing. A clean transection can be re-anastomosed or reimplanted with the expectation of normal healing. Innervation of the ureter is from the inferior mesenteric plexus superiorly and the inferior hypogastric plexus in the pelvis. Ureteral peristalsis will continue, even if the ureter is completely divided or ligated.

Protecting pelvic blood vessels

The majority of gynecologic operations involve the ovarian vessels and the uterine vessels. The operator rarely needs to explore the lateral pelvis to identify the rest of the vessels. When faced with a large endometrioma or cancer, knowledge of the anatomy of the lateral blood vessels is vital.

Since the pathology is usually deeper in the pelvis, it is wise to identify the anatomy of the pelvis starting at the pelvic brim, where the common iliac bifurcates into the external and internal iliacs. There is a safe dissection plane medial to the internal iliac artery all the way to the uterine artery. This exposes the pararectal space, which can be opened without risk of major bleeding (FIGURE 5).

The obliterated umbilical vessel is the other friendly marker just distal to the uterine artery. It can be placed on traction and the uterine artery isolated. The inferior and superior vesical arteries are generally not dissected, as they are adjacent to the bladder and the surgery takes place medial to them in the prevesical fascial space.

Hypogastric artery ligations are rarely performed today, as interventional radiology is the standard of care for patients with postoperative and postpartum bleeding. When it becomes necessary, the hypogastric artery can be isolated and tied using the right-angle clamp to pass the tie. The superior gluteal artery branches so close to the bifurcation of the common iliac artery that it is not visualized. The inferior gluteal artery is the largest distal branch, which might be visualized during the ligation. It is not necessary to identify it.

FIGURE 12 Right genitofemoral nerve

The genitofemoral nerve runs along the medial aspect of the body of the psoas muscle. It is sometimes injured by the self-retaining retractors placed at the time of laparotomy. This leads to some numbness and burning of the skin of the anterior thigh.

FIGURE 13 Right pelvic sidewall anatomy

The obturator nerve is in the obturator space and typically far lateral to the usual dissection. Metastatic cancer to the obturator lymph nodes may entrap it, or it may be injured during a node dissection, causing loss of internal rotation of the anterior thigh.

The sciatic nerve is seen only during exenterative surgery. Pressure on the lateral pelvis by advanced pelvic tumors can lead to sciatic pain and motor weakness—even loss of motor function to the lower leg, which commonly leads to foot drop.

FIGURE 14 Superior hypogastric nerve bundle

The hypogastric plexus of nerves is sometimes damaged during surgery for endometriosis or for malignancy. The superior hypergastric plexus can be identified between the 2 common iliac arteries at the sacral promontory. The left common iliac vein runs underneath it.

FIGURE 15 Hypogastric nerve descending into the right pelvis

The right and left hypogastric nerves leave the hypogastric plexus and descend into the pelvis parallel to the ureter and 2 cm medial. It passes dorsal to the ureter as it goes through the cardinal ligament (FIGURE 5).

This plexus then supplies autonomic innervation of the bladder, rectum, uterus, and ureter. Complete disruption of the hypogastric nerve will lead to a hypertonic, noncontractile bladder and the necessity for self-catheterization to eliminate urine. Preservation of this nerve during radical hysterectomy or endometriosis resection is a high priority.

Laparoscopic uterosacral nerve ablation procedures divide the uterosacral ligament medial and caudad to the ureter and do not disrupt the main hypogastric nerve. Only the medial branches to the uterus are affected. Successful uterosacral nerve ablation has been reported in approximately 44% of women who have dysmenorrhea without visible endometriosis and approximately 62% of women who have visible endometriosis.7,8 The efficacy of this procedure is controversial, however. Removal of the superior hypogastric plexus (presacral neurectomy) has not proved to be more effective in controlling pelvic pain than conservative surgery that only destroys endometrial implants. Presacral neurectomy is no longer advised.9

The accomplished gynecologic surgeon must know the anatomy of the retroperitoneal space in order to avoid damage to normal structures, as well as remove pathology. Many disease processes involve the pelvic peritoneum, uterosacral ligaments, rectosigmoid or ovarian pedicles, and require the surgeon to enter the retroperitoneal space to identify the ureters and blood vessels and keep them out of harm’s way. The challenges are complex:

- Badly distorted anatomy and the anterior and posterior cul-de-sac necessitate mobilization of the rectosigmoid and bladder.

- Intraligamentous fibroids require knowledge of the blood supply in the retroperitoneal space. Malignant disorders mandate that the lymph nodes be dissected to determine extent of disease and as part of treatment.

Is training adequate?

Every training program should teach the surgical anatomy of the retroperitoneal space, since every surgeon needs to be comfortable exposing the anatomy, both to prevent injury and to accomplish the needed surgery. Videotapes and cadaver courses can prepare the resident for the operating room.

The “landmark” umbilical ligament

The umbilical ligament was the umbilical artery in fetal life and courses along the edge of the bladder to the anterior abdominal wall up to the umbilicus. It is a useful guide into the perivesicle space. Lateral to it are the iliac vessels, and medial is the bladder. It is also a good marker for finding the right spot to open the round ligament.

FIGURE 1 Opening the round ligament over the umbilical ligament

The round ligament is the key to exposing the retroperitoneal space. It should be open at the pelvic sidewall, just medial to the external iliac vessels. The umbilical ligament can be used as a landmark.

FIGURE 2 Opening lateral to the ovarian vessels

The divided round ligament is retracted ventrally and medially to place the ovarian vessels under traction. The peritoneum lateral to the ovarian vessels is divided up to the pelvic brim.

FIGURE 3 Right pelvic sidewall anatomy

Medial traction of the peritoneum around the ovarian vessels at the pelvic brim will expose the ureter coming over the iliac vessels at their bifurcation into external and internal branches.

FIGURE 4 Relationship of ureter to the umbilical ligament

The ureter comes off medial with the fold of peritoneum. Once the space is developed, the operator’s finger or the laparoscopic probe can be introduced along the medial side of the internal iliac artery and ventral to the curve of the sacrum. This will open the pararectal space. The ureter and the anterior branch of the internal iliac artery are nearly parallel as they course through the pelvis.

FIGURE 5 Hypogastric nerve

The anterior branch of the internal iliac artery gives off the uterine artery and the middle and superior vesicle arteries before continuing on as the umbilical ligament.

Endometriosis may imperil the ureter