User login

US Preventive Services Task Force lowers diabetes screening age for overweight

The United States Preventive Services Task Force has updated its recommendation on the age of screening for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in the primary care setting – lowering the age from 40 to 35 years for asymptomatic patients who are overweight or obese and encouraging greater interventions when patients do show a risk.

“The USPSTF concludes with moderate certainty that screening for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes and offering or referring patients with prediabetes to effective preventive interventions has a moderate net benefit,” the task force concludes in its recommendation, published Aug. 24 in JAMA.

“Clinicians should offer or refer patients with prediabetes to effective preventive interventions,” they write.

Experts commenting on the issue strongly emphasize that it’s not just the screening, but the subsequent intervention that is needed to make a difference.

“If young adults newly identified with abnormal glucose metabolism do not receive the needed intensive behavioral change support, screening may provide no benefit,” write Richard W. Grant, MD, MPH, and colleagues in an editorial published with the recommendation.

“Given the role of our obesogenic and physically inactive society in the shift toward earlier onset of diabetes, efforts to increase screening and recognition of abnormal glucose metabolism must be coupled with robust public health measures to address the underlying contributors.”

BMI cutoff lower for at-risk ethnic populations

The recommendation, which updates the task force’s 2015 guideline, carries a “B” classification, meaning the USPSTF has high certainty that the net benefit is moderate. It now specifies screening from age 35to 70 for persons classified as overweight (body mass index at least 25) or obese (BMI at least 30) and recommends referral to preventive interventions when patients are found to have prediabetes.

In addition to recommendations of lifestyle changes, such as diet and physical activity, the task force also endorses the diabetes drug metformin as a beneficial intervention in the prevention or delay of diabetes, while noting fewer overall health benefits from metformin than from the lifestyle changes.

A lower BMI cutoff of at least 23 is recommended for diabetes screening of Asian Americans, and, importantly, screening for prediabetes and diabetes should be considered at an even earlier age if the patient is from a population with a disproportionately high prevalence of diabetes, including American Indian/Alaska Native, Black, Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic/Latino, the task force recommends.

Screening tests should include fasting plasma glucose, hemoglobin A1c, or an oral glucose tolerance test. Although screening every 3 years “may be a reasonable approach for adults with normal blood glucose levels,” the task force adds that “the optimal screening interval for adults with an initial normal glucose test result is uncertain.”

Data review: Few with prediabetes know they have it

The need for the update was prompted by troubling data showing increasing diabetes rates despite early signs that can and should be identified and acted upon in the primary care setting to prevent disease progression.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for instance, show that while 13% of all U.S. adults 18 years or older have diabetes and 35% meet criteria for prediabetes, as many as 21% of those with diabetes were not aware of or did not report having the disease. Furthermore, only a small fraction – 15% of those with prediabetes – said they had been told by a health professional that they had this condition, the task force notes.

The task force’s final recommendation was based on a systematic review of evidence regarding the screening of asymptomatic, nonpregnant adults and the harms and benefits of interventions, such as physical activity, behavioral counseling, or pharmacotherapy.

Among key evidence supporting the lower age was a 2014 study showing that the number of people necessary to obtain one positive test for diabetes with screening sharply drops from 80 among those aged 30-34 years to just 31 among those aged 36-39.

Opportunistic universal screening of eligible people aged 35 and older would yield a ratio of 1 out of just 15 to spot a positive test, the authors of that study reported.

In addition, a large cohort study in more than 77,000 people with prediabetes strongly links the risk of developing diabetes with increases in A1c level and with increasing BMI.

ADA recommendations differ

The new recommendations differ from American Diabetes Association guidelines, which call for diabetes screening at all ages for people who are overweight or obese and who have one or more risk factors, such as physical inactivity or a first-degree relative with diabetes. If results are normal, repeat screening at least every 3 years is recommended.

The ADA further recommends universal screening for all adults 45 years and older, regardless of their risk factors.

For the screening of adults over 45, the ADA recommends using a fasting plasma glucose level, 2-hour plasma glucose level during a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test, or A1c level, regardless of risk factors.

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinology also recommends universal screening for prediabetes and diabetes for all adults 45 years or older, regardless of risk factors, and also advises screening those who have risk factors for diabetes regardless of age.

Screening of little benefit without behavior change support

In an interview, Dr. Grant added that broad efforts are essential as those at the practice level have clearly not succeeded.

“The medical model of individual counseling and referral has not really been effective, and so we really need to think in terms of large-scale public health action,” said Dr. Grant, of the division of research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Oakland.

His editorial details the sweeping, multifactorial efforts that are needed.

“To turn this recommendation into action – that is, to translate screening activities into improved clinical outcomes – change is needed at the patient-clinician level (recognizing and encouraging eligible individuals to be screened), health care system level (reducing screening barriers and ensuring access to robust lifestyle programs), and societal level (applying effective public health interventions to reduce obesity and increase exercise),” they write.

A top priority has to be a focus on individuals of diverse backgrounds and issues such as access to healthy programs in minority communities, Dr. Grant noted.

“Newly diagnosed adults are more likely to be African-American and Latinx,” he said.

“We really need to invest in healthier communities for low-income, non-White communities to reverse the persistent health care disparities in these communities.”

While the challenges may appear daunting, history shows they are not necessarily insurmountable – as evidenced in the campaign to discourage tobacco smoking.

“National smoking cessation efforts are one example of a mostly successful public health campaign that has made a difference in health behaviors,” Grant noted.

The recommendation is also posted on the USPSTF web site .

Dr. Grant reports receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force has updated its recommendation on the age of screening for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in the primary care setting – lowering the age from 40 to 35 years for asymptomatic patients who are overweight or obese and encouraging greater interventions when patients do show a risk.

“The USPSTF concludes with moderate certainty that screening for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes and offering or referring patients with prediabetes to effective preventive interventions has a moderate net benefit,” the task force concludes in its recommendation, published Aug. 24 in JAMA.

“Clinicians should offer or refer patients with prediabetes to effective preventive interventions,” they write.

Experts commenting on the issue strongly emphasize that it’s not just the screening, but the subsequent intervention that is needed to make a difference.

“If young adults newly identified with abnormal glucose metabolism do not receive the needed intensive behavioral change support, screening may provide no benefit,” write Richard W. Grant, MD, MPH, and colleagues in an editorial published with the recommendation.

“Given the role of our obesogenic and physically inactive society in the shift toward earlier onset of diabetes, efforts to increase screening and recognition of abnormal glucose metabolism must be coupled with robust public health measures to address the underlying contributors.”

BMI cutoff lower for at-risk ethnic populations

The recommendation, which updates the task force’s 2015 guideline, carries a “B” classification, meaning the USPSTF has high certainty that the net benefit is moderate. It now specifies screening from age 35to 70 for persons classified as overweight (body mass index at least 25) or obese (BMI at least 30) and recommends referral to preventive interventions when patients are found to have prediabetes.

In addition to recommendations of lifestyle changes, such as diet and physical activity, the task force also endorses the diabetes drug metformin as a beneficial intervention in the prevention or delay of diabetes, while noting fewer overall health benefits from metformin than from the lifestyle changes.

A lower BMI cutoff of at least 23 is recommended for diabetes screening of Asian Americans, and, importantly, screening for prediabetes and diabetes should be considered at an even earlier age if the patient is from a population with a disproportionately high prevalence of diabetes, including American Indian/Alaska Native, Black, Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic/Latino, the task force recommends.

Screening tests should include fasting plasma glucose, hemoglobin A1c, or an oral glucose tolerance test. Although screening every 3 years “may be a reasonable approach for adults with normal blood glucose levels,” the task force adds that “the optimal screening interval for adults with an initial normal glucose test result is uncertain.”

Data review: Few with prediabetes know they have it

The need for the update was prompted by troubling data showing increasing diabetes rates despite early signs that can and should be identified and acted upon in the primary care setting to prevent disease progression.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for instance, show that while 13% of all U.S. adults 18 years or older have diabetes and 35% meet criteria for prediabetes, as many as 21% of those with diabetes were not aware of or did not report having the disease. Furthermore, only a small fraction – 15% of those with prediabetes – said they had been told by a health professional that they had this condition, the task force notes.

The task force’s final recommendation was based on a systematic review of evidence regarding the screening of asymptomatic, nonpregnant adults and the harms and benefits of interventions, such as physical activity, behavioral counseling, or pharmacotherapy.

Among key evidence supporting the lower age was a 2014 study showing that the number of people necessary to obtain one positive test for diabetes with screening sharply drops from 80 among those aged 30-34 years to just 31 among those aged 36-39.

Opportunistic universal screening of eligible people aged 35 and older would yield a ratio of 1 out of just 15 to spot a positive test, the authors of that study reported.

In addition, a large cohort study in more than 77,000 people with prediabetes strongly links the risk of developing diabetes with increases in A1c level and with increasing BMI.

ADA recommendations differ

The new recommendations differ from American Diabetes Association guidelines, which call for diabetes screening at all ages for people who are overweight or obese and who have one or more risk factors, such as physical inactivity or a first-degree relative with diabetes. If results are normal, repeat screening at least every 3 years is recommended.

The ADA further recommends universal screening for all adults 45 years and older, regardless of their risk factors.

For the screening of adults over 45, the ADA recommends using a fasting plasma glucose level, 2-hour plasma glucose level during a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test, or A1c level, regardless of risk factors.

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinology also recommends universal screening for prediabetes and diabetes for all adults 45 years or older, regardless of risk factors, and also advises screening those who have risk factors for diabetes regardless of age.

Screening of little benefit without behavior change support

In an interview, Dr. Grant added that broad efforts are essential as those at the practice level have clearly not succeeded.

“The medical model of individual counseling and referral has not really been effective, and so we really need to think in terms of large-scale public health action,” said Dr. Grant, of the division of research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Oakland.

His editorial details the sweeping, multifactorial efforts that are needed.

“To turn this recommendation into action – that is, to translate screening activities into improved clinical outcomes – change is needed at the patient-clinician level (recognizing and encouraging eligible individuals to be screened), health care system level (reducing screening barriers and ensuring access to robust lifestyle programs), and societal level (applying effective public health interventions to reduce obesity and increase exercise),” they write.

A top priority has to be a focus on individuals of diverse backgrounds and issues such as access to healthy programs in minority communities, Dr. Grant noted.

“Newly diagnosed adults are more likely to be African-American and Latinx,” he said.

“We really need to invest in healthier communities for low-income, non-White communities to reverse the persistent health care disparities in these communities.”

While the challenges may appear daunting, history shows they are not necessarily insurmountable – as evidenced in the campaign to discourage tobacco smoking.

“National smoking cessation efforts are one example of a mostly successful public health campaign that has made a difference in health behaviors,” Grant noted.

The recommendation is also posted on the USPSTF web site .

Dr. Grant reports receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force has updated its recommendation on the age of screening for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in the primary care setting – lowering the age from 40 to 35 years for asymptomatic patients who are overweight or obese and encouraging greater interventions when patients do show a risk.

“The USPSTF concludes with moderate certainty that screening for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes and offering or referring patients with prediabetes to effective preventive interventions has a moderate net benefit,” the task force concludes in its recommendation, published Aug. 24 in JAMA.

“Clinicians should offer or refer patients with prediabetes to effective preventive interventions,” they write.

Experts commenting on the issue strongly emphasize that it’s not just the screening, but the subsequent intervention that is needed to make a difference.

“If young adults newly identified with abnormal glucose metabolism do not receive the needed intensive behavioral change support, screening may provide no benefit,” write Richard W. Grant, MD, MPH, and colleagues in an editorial published with the recommendation.

“Given the role of our obesogenic and physically inactive society in the shift toward earlier onset of diabetes, efforts to increase screening and recognition of abnormal glucose metabolism must be coupled with robust public health measures to address the underlying contributors.”

BMI cutoff lower for at-risk ethnic populations

The recommendation, which updates the task force’s 2015 guideline, carries a “B” classification, meaning the USPSTF has high certainty that the net benefit is moderate. It now specifies screening from age 35to 70 for persons classified as overweight (body mass index at least 25) or obese (BMI at least 30) and recommends referral to preventive interventions when patients are found to have prediabetes.

In addition to recommendations of lifestyle changes, such as diet and physical activity, the task force also endorses the diabetes drug metformin as a beneficial intervention in the prevention or delay of diabetes, while noting fewer overall health benefits from metformin than from the lifestyle changes.

A lower BMI cutoff of at least 23 is recommended for diabetes screening of Asian Americans, and, importantly, screening for prediabetes and diabetes should be considered at an even earlier age if the patient is from a population with a disproportionately high prevalence of diabetes, including American Indian/Alaska Native, Black, Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic/Latino, the task force recommends.

Screening tests should include fasting plasma glucose, hemoglobin A1c, or an oral glucose tolerance test. Although screening every 3 years “may be a reasonable approach for adults with normal blood glucose levels,” the task force adds that “the optimal screening interval for adults with an initial normal glucose test result is uncertain.”

Data review: Few with prediabetes know they have it

The need for the update was prompted by troubling data showing increasing diabetes rates despite early signs that can and should be identified and acted upon in the primary care setting to prevent disease progression.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for instance, show that while 13% of all U.S. adults 18 years or older have diabetes and 35% meet criteria for prediabetes, as many as 21% of those with diabetes were not aware of or did not report having the disease. Furthermore, only a small fraction – 15% of those with prediabetes – said they had been told by a health professional that they had this condition, the task force notes.

The task force’s final recommendation was based on a systematic review of evidence regarding the screening of asymptomatic, nonpregnant adults and the harms and benefits of interventions, such as physical activity, behavioral counseling, or pharmacotherapy.

Among key evidence supporting the lower age was a 2014 study showing that the number of people necessary to obtain one positive test for diabetes with screening sharply drops from 80 among those aged 30-34 years to just 31 among those aged 36-39.

Opportunistic universal screening of eligible people aged 35 and older would yield a ratio of 1 out of just 15 to spot a positive test, the authors of that study reported.

In addition, a large cohort study in more than 77,000 people with prediabetes strongly links the risk of developing diabetes with increases in A1c level and with increasing BMI.

ADA recommendations differ

The new recommendations differ from American Diabetes Association guidelines, which call for diabetes screening at all ages for people who are overweight or obese and who have one or more risk factors, such as physical inactivity or a first-degree relative with diabetes. If results are normal, repeat screening at least every 3 years is recommended.

The ADA further recommends universal screening for all adults 45 years and older, regardless of their risk factors.

For the screening of adults over 45, the ADA recommends using a fasting plasma glucose level, 2-hour plasma glucose level during a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test, or A1c level, regardless of risk factors.

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinology also recommends universal screening for prediabetes and diabetes for all adults 45 years or older, regardless of risk factors, and also advises screening those who have risk factors for diabetes regardless of age.

Screening of little benefit without behavior change support

In an interview, Dr. Grant added that broad efforts are essential as those at the practice level have clearly not succeeded.

“The medical model of individual counseling and referral has not really been effective, and so we really need to think in terms of large-scale public health action,” said Dr. Grant, of the division of research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Oakland.

His editorial details the sweeping, multifactorial efforts that are needed.

“To turn this recommendation into action – that is, to translate screening activities into improved clinical outcomes – change is needed at the patient-clinician level (recognizing and encouraging eligible individuals to be screened), health care system level (reducing screening barriers and ensuring access to robust lifestyle programs), and societal level (applying effective public health interventions to reduce obesity and increase exercise),” they write.

A top priority has to be a focus on individuals of diverse backgrounds and issues such as access to healthy programs in minority communities, Dr. Grant noted.

“Newly diagnosed adults are more likely to be African-American and Latinx,” he said.

“We really need to invest in healthier communities for low-income, non-White communities to reverse the persistent health care disparities in these communities.”

While the challenges may appear daunting, history shows they are not necessarily insurmountable – as evidenced in the campaign to discourage tobacco smoking.

“National smoking cessation efforts are one example of a mostly successful public health campaign that has made a difference in health behaviors,” Grant noted.

The recommendation is also posted on the USPSTF web site .

Dr. Grant reports receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

FROM JAMA

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Expert Review on colonoscopy quality improvement

The American Gastroenterological Association recently issued a clinical practice update expert review outlining tenets of high-quality colonoscopy screening and surveillance.

The update includes 15 best practice advice statements aimed at the endoscopist and/or endoscopy unit, reported lead author Rajesh N. Keswani, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues.

“The efficacy of colonoscopy varies widely among endoscopists, and lower-quality colonoscopies are associated with higher interval CRC [colorectal cancer] incidence and mortality,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology.

According to Dr. Keswani and colleagues, quality of colonoscopy screening and surveillance is shaped by three parameters: safety, effectiveness, and value. Some metrics may be best measured at a unit level, they noted, while others are more clinician specific.

“For uncommon outcomes (e.g., adverse events) or metrics that reflect system-based practice (e.g., bowel preparation quality), measurement of aggregate unit-level performance is best,” the investigators wrote. “In contrast, for metrics that primarily reflect colonoscopist skill (e.g., adenoma detection rate), endoscopist-level measurement is preferred to enable individual feedback.”

Endoscopy unit best practice advice

According to the update, endoscopy units should prepare patients for, and monitor, adverse events. Prior to the procedure, patients should be informed about possible adverse events and warning symptoms, and emergency contact information should be recorded. Following the procedure, systematic monitoring of delayed adverse events may be considered, including “postprocedure bleeding, perforation, hospital readmission, 30-day mortality, and/or interval colorectal cancer cases,” with rates reported at the unit level.

Ensuring high-quality bowel preparation is also the responsibility of the endoscopy unit, according to Dr. Keswani and colleagues, and should be measured at least annually. Units should aim for a Boston Bowel Preparation Scale score of at least 6, with each segment scoring at least 2, in at least 90% of colonoscopies. The update provides best practice advice on split-dose bowel prep, with patient instructions written at a sixth-grade level in their native language. If routine quality measurement reveals suboptimal bowel prep quality, instruction revision may be needed, as well as further patient education and support.

During the actual procedure, a high-definition colonoscope should be used, the expert panel wrote. They called for measurement of endoscopist performance via four parameters: cecal intubation rate, which should be at least 90%; mean withdrawal time, which should be at least 6 minutes (aspirational, ≥9 minutes); adenoma detection rate, measured annually or when a given endoscopist has accrued 250 screening colonoscopies; and serrated lesion detection rate.

Endoscopist best practice advice

Both adenoma detection rate and serrated lesion detection rate should also be measured at an endoscopist level, with rates of at least 30% for adenomas and at least 7% for serrated lesions (aspirational, ≥35% and ≥10%, respectively).

“If rates are low, improvement efforts should be oriented toward both colonoscopists and pathologists,” the investigators noted.

A variety of strategies are advised to improve outcomes at the endoscopist level, including a second look at the right colon to detect polyps, either in forward or retroflexed view; use of cold-snare polypectomy for nonpedunculated polyps 3-9 mm in size and avoidance of forceps in polyps greater than 2 mm in size; evaluation by an expert in polypectomy with attempted resection for patients with complex polyps lacking “overt malignant endoscopic features or pathology consistent with invasive adenocarcinoma”; and thorough documentation of all findings.

More broadly, the update advises endoscopists to follow guideline-recommended intervals for screening and surveillance, including repeat colonoscopy in 3 years for all patients with advanced adenomas versus a 10-year interval for patients with normal risk or “only distal hyperplastic polyps.”

Resource-limited institutions and a look ahead

Dr. Keswani and colleagues concluded the clinical practice update with a nod to the challenges of real-world practice, noting that some institutions may not have the resources to comply with all the best practice advice statements.

“If limited resources are available, measurement of cecal intubation rates, bowel preparation quality, and adenoma detection rate should be prioritized,” they wrote.

They also offered a succinct summary of outstanding research needs, saying “we anticipate future work to clarify optimal polyp resection techniques, refine surveillance intervals based on provider skill and patient risk, and highlight the benefits of artificial intelligence in improving colonoscopy quality.”

This clinical practice update was commissioned and approved by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee and the AGA Governing Board. Dr. Keswani consults for Boston Scientific. The other authors had no disclosures.

This article was updated Aug. 20, 2021.

The American Gastroenterological Association recently issued a clinical practice update expert review outlining tenets of high-quality colonoscopy screening and surveillance.

The update includes 15 best practice advice statements aimed at the endoscopist and/or endoscopy unit, reported lead author Rajesh N. Keswani, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues.

“The efficacy of colonoscopy varies widely among endoscopists, and lower-quality colonoscopies are associated with higher interval CRC [colorectal cancer] incidence and mortality,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology.

According to Dr. Keswani and colleagues, quality of colonoscopy screening and surveillance is shaped by three parameters: safety, effectiveness, and value. Some metrics may be best measured at a unit level, they noted, while others are more clinician specific.

“For uncommon outcomes (e.g., adverse events) or metrics that reflect system-based practice (e.g., bowel preparation quality), measurement of aggregate unit-level performance is best,” the investigators wrote. “In contrast, for metrics that primarily reflect colonoscopist skill (e.g., adenoma detection rate), endoscopist-level measurement is preferred to enable individual feedback.”

Endoscopy unit best practice advice

According to the update, endoscopy units should prepare patients for, and monitor, adverse events. Prior to the procedure, patients should be informed about possible adverse events and warning symptoms, and emergency contact information should be recorded. Following the procedure, systematic monitoring of delayed adverse events may be considered, including “postprocedure bleeding, perforation, hospital readmission, 30-day mortality, and/or interval colorectal cancer cases,” with rates reported at the unit level.

Ensuring high-quality bowel preparation is also the responsibility of the endoscopy unit, according to Dr. Keswani and colleagues, and should be measured at least annually. Units should aim for a Boston Bowel Preparation Scale score of at least 6, with each segment scoring at least 2, in at least 90% of colonoscopies. The update provides best practice advice on split-dose bowel prep, with patient instructions written at a sixth-grade level in their native language. If routine quality measurement reveals suboptimal bowel prep quality, instruction revision may be needed, as well as further patient education and support.

During the actual procedure, a high-definition colonoscope should be used, the expert panel wrote. They called for measurement of endoscopist performance via four parameters: cecal intubation rate, which should be at least 90%; mean withdrawal time, which should be at least 6 minutes (aspirational, ≥9 minutes); adenoma detection rate, measured annually or when a given endoscopist has accrued 250 screening colonoscopies; and serrated lesion detection rate.

Endoscopist best practice advice

Both adenoma detection rate and serrated lesion detection rate should also be measured at an endoscopist level, with rates of at least 30% for adenomas and at least 7% for serrated lesions (aspirational, ≥35% and ≥10%, respectively).

“If rates are low, improvement efforts should be oriented toward both colonoscopists and pathologists,” the investigators noted.

A variety of strategies are advised to improve outcomes at the endoscopist level, including a second look at the right colon to detect polyps, either in forward or retroflexed view; use of cold-snare polypectomy for nonpedunculated polyps 3-9 mm in size and avoidance of forceps in polyps greater than 2 mm in size; evaluation by an expert in polypectomy with attempted resection for patients with complex polyps lacking “overt malignant endoscopic features or pathology consistent with invasive adenocarcinoma”; and thorough documentation of all findings.

More broadly, the update advises endoscopists to follow guideline-recommended intervals for screening and surveillance, including repeat colonoscopy in 3 years for all patients with advanced adenomas versus a 10-year interval for patients with normal risk or “only distal hyperplastic polyps.”

Resource-limited institutions and a look ahead

Dr. Keswani and colleagues concluded the clinical practice update with a nod to the challenges of real-world practice, noting that some institutions may not have the resources to comply with all the best practice advice statements.

“If limited resources are available, measurement of cecal intubation rates, bowel preparation quality, and adenoma detection rate should be prioritized,” they wrote.

They also offered a succinct summary of outstanding research needs, saying “we anticipate future work to clarify optimal polyp resection techniques, refine surveillance intervals based on provider skill and patient risk, and highlight the benefits of artificial intelligence in improving colonoscopy quality.”

This clinical practice update was commissioned and approved by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee and the AGA Governing Board. Dr. Keswani consults for Boston Scientific. The other authors had no disclosures.

This article was updated Aug. 20, 2021.

The American Gastroenterological Association recently issued a clinical practice update expert review outlining tenets of high-quality colonoscopy screening and surveillance.

The update includes 15 best practice advice statements aimed at the endoscopist and/or endoscopy unit, reported lead author Rajesh N. Keswani, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues.

“The efficacy of colonoscopy varies widely among endoscopists, and lower-quality colonoscopies are associated with higher interval CRC [colorectal cancer] incidence and mortality,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology.

According to Dr. Keswani and colleagues, quality of colonoscopy screening and surveillance is shaped by three parameters: safety, effectiveness, and value. Some metrics may be best measured at a unit level, they noted, while others are more clinician specific.

“For uncommon outcomes (e.g., adverse events) or metrics that reflect system-based practice (e.g., bowel preparation quality), measurement of aggregate unit-level performance is best,” the investigators wrote. “In contrast, for metrics that primarily reflect colonoscopist skill (e.g., adenoma detection rate), endoscopist-level measurement is preferred to enable individual feedback.”

Endoscopy unit best practice advice

According to the update, endoscopy units should prepare patients for, and monitor, adverse events. Prior to the procedure, patients should be informed about possible adverse events and warning symptoms, and emergency contact information should be recorded. Following the procedure, systematic monitoring of delayed adverse events may be considered, including “postprocedure bleeding, perforation, hospital readmission, 30-day mortality, and/or interval colorectal cancer cases,” with rates reported at the unit level.

Ensuring high-quality bowel preparation is also the responsibility of the endoscopy unit, according to Dr. Keswani and colleagues, and should be measured at least annually. Units should aim for a Boston Bowel Preparation Scale score of at least 6, with each segment scoring at least 2, in at least 90% of colonoscopies. The update provides best practice advice on split-dose bowel prep, with patient instructions written at a sixth-grade level in their native language. If routine quality measurement reveals suboptimal bowel prep quality, instruction revision may be needed, as well as further patient education and support.

During the actual procedure, a high-definition colonoscope should be used, the expert panel wrote. They called for measurement of endoscopist performance via four parameters: cecal intubation rate, which should be at least 90%; mean withdrawal time, which should be at least 6 minutes (aspirational, ≥9 minutes); adenoma detection rate, measured annually or when a given endoscopist has accrued 250 screening colonoscopies; and serrated lesion detection rate.

Endoscopist best practice advice

Both adenoma detection rate and serrated lesion detection rate should also be measured at an endoscopist level, with rates of at least 30% for adenomas and at least 7% for serrated lesions (aspirational, ≥35% and ≥10%, respectively).

“If rates are low, improvement efforts should be oriented toward both colonoscopists and pathologists,” the investigators noted.

A variety of strategies are advised to improve outcomes at the endoscopist level, including a second look at the right colon to detect polyps, either in forward or retroflexed view; use of cold-snare polypectomy for nonpedunculated polyps 3-9 mm in size and avoidance of forceps in polyps greater than 2 mm in size; evaluation by an expert in polypectomy with attempted resection for patients with complex polyps lacking “overt malignant endoscopic features or pathology consistent with invasive adenocarcinoma”; and thorough documentation of all findings.

More broadly, the update advises endoscopists to follow guideline-recommended intervals for screening and surveillance, including repeat colonoscopy in 3 years for all patients with advanced adenomas versus a 10-year interval for patients with normal risk or “only distal hyperplastic polyps.”

Resource-limited institutions and a look ahead

Dr. Keswani and colleagues concluded the clinical practice update with a nod to the challenges of real-world practice, noting that some institutions may not have the resources to comply with all the best practice advice statements.

“If limited resources are available, measurement of cecal intubation rates, bowel preparation quality, and adenoma detection rate should be prioritized,” they wrote.

They also offered a succinct summary of outstanding research needs, saying “we anticipate future work to clarify optimal polyp resection techniques, refine surveillance intervals based on provider skill and patient risk, and highlight the benefits of artificial intelligence in improving colonoscopy quality.”

This clinical practice update was commissioned and approved by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee and the AGA Governing Board. Dr. Keswani consults for Boston Scientific. The other authors had no disclosures.

This article was updated Aug. 20, 2021.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Task force affirms routine gestational diabetes testing

Asymptomatic pregnant women with no previous diagnosis of type 1 or 2 diabetes should be screened for gestational diabetes at 24 weeks’ gestation or later, according to an updated recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Pregnant individuals who develop gestational diabetes are at increased risk for complications including preeclampsia, fetal macrosomia, and neonatal hypoglycemia, as well as negative long-term outcomes for themselves and their children, wrote lead author Karina W. Davidson, PhD, of Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, N.Y., and colleagues. The statement was published online in JAMA.

The B recommendation and I statement reflect “moderate certainty” that current evidence supports the recommendation in terms of harms versus benefits, and is consistent with the 2014 USPSTF recommendation.

The statement calls for a one-time screening using a glucose tolerance test at or after 24 weeks’ gestation. Although most screening in the United States takes place prior to 28 weeks’ gestation, it can be performed later in patients who begin prenatal care after 28 weeks’ gestation, according to the statement. Data on the harms and benefits of gestational diabetes screening prior to 24 weeks’ gestation are limited, the authors noted. Gestational diabetes was defined as diabetes that develops during pregnancy that is not clearly overt diabetes.

To update the 2014 recommendation, the USPSTF commissioned a systematic review. In 45 prospective studies on the accuracy of gestational diabetes screening, several tests, included oral glucose challenge test, oral glucose tolerance test, and fasting plasma glucose using either a one- or two-step approach were accurate detectors of gestational diabetes; therefore, the USPSTF does not recommend a specific test.

In 13 trials on the impact of treating gestational diabetes on intermediate and health outcomes, treatment was associated with a reduced risk of outcomes, including primary cesarean delivery (but not total cesarean delivery) and preterm delivery, but not with a reduced risk of outcomes including preeclampsia, emergency cesarean delivery, induction of labor, or maternal birth trauma.

The task force also reviewed seven studies of harms associated with screening for gestational diabetes, including three on psychosocial harms, three on hospital experiences, and one of the odds of cesarean delivery after a diagnosis of gestational diabetes. No increase in anxiety or depression occurred following a positive diagnosis or false-positive test result, but data suggested that a gestational diabetes diagnosis may be associated with higher rates of cesarean delivery.

A total of 13 trials evaluated the harms associated with treatment of gestational diabetes, and found no association between treatment and increased risk of several outcomes including severe maternal hypoglycemia, low birth weight, and small for gestational age, and no effect was noted on the number of cesarean deliveries.

Evidence gaps that require additional research include randomized, controlled trials on the effects of gestational diabetes screening on health outcomes, as well as benefits versus harms of screening for pregnant individuals prior to 24 weeks, and studies on the effects of screening in subpopulations of race/ethnicity, age, and socioeconomic factors, according to the task force. Additional research also is needed in areas of maternal health outcomes, long-term outcomes, and the effect on outcomes of one-step versus two-step screening, the USPSTF said.

However, “screening for and detecting gestational diabetes provides a potential opportunity to control blood glucose levels (through lifestyle changes, pharmacological interventions, or both) and reduce the risk of macrosomia and LGA [large for gestational age] infants,” the task force wrote. “In turn, this can prevent associated complications such as primary cesarean delivery, shoulder dystocia, and [neonatal] ICU admissions.”

Support screening with counseling on risk reduction

The USPSTF recommendation is important at this time because “the prevalence of gestational diabetes is increasing secondary to rising rates of obesity,” Iris Krishna, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview.

“In 2014, based on a systematic review of literature, the USPSTF recommended screening all asymptomatic pregnant women for gestational diabetes mellitus [GDM] starting at 24 weeks’ gestation. The recommended gestational age for screening coincides with increasing insulin resistance during pregnancy with advancing gestational age,” Dr. Krishna said.

“An updated systematic review by the USPSTF concluded that existing literature continues to affirm current recommendations of universal screening for GDM at 24 weeks gestation or later. There continues, however, to be no consensus on the optimal approach to screening,” she noted.

“Screening can be performed as a two-step or one-step approach,” said Dr. Krishna. “The two-step approach is commonly used in the United States, and all pregnant women are first screened with a 50-gram oral glucose solution followed by a diagnostic test if they have a positive initial screening.

“Women with risk factors for diabetes, such as prior GDM, obesity, strong family history of diabetes, or history of fetal macrosomia, should be screened early in pregnancy for GDM and have the GDM screen repeated at 24 weeks’ gestation or later if normal in early pregnancy,” Dr. Krishna said. “Pregnant women should be counseled on the importance of diet and exercise and appropriate weight gain in pregnancy to reduce the risk of GDM. Overall, timely diagnosis of gestational diabetes is crucial to improving maternal and fetal pregnancy outcomes.”

The full recommendation statement is also available on the USPSTF website. The research was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Krishna had no disclosures, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn News.

Asymptomatic pregnant women with no previous diagnosis of type 1 or 2 diabetes should be screened for gestational diabetes at 24 weeks’ gestation or later, according to an updated recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Pregnant individuals who develop gestational diabetes are at increased risk for complications including preeclampsia, fetal macrosomia, and neonatal hypoglycemia, as well as negative long-term outcomes for themselves and their children, wrote lead author Karina W. Davidson, PhD, of Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, N.Y., and colleagues. The statement was published online in JAMA.

The B recommendation and I statement reflect “moderate certainty” that current evidence supports the recommendation in terms of harms versus benefits, and is consistent with the 2014 USPSTF recommendation.

The statement calls for a one-time screening using a glucose tolerance test at or after 24 weeks’ gestation. Although most screening in the United States takes place prior to 28 weeks’ gestation, it can be performed later in patients who begin prenatal care after 28 weeks’ gestation, according to the statement. Data on the harms and benefits of gestational diabetes screening prior to 24 weeks’ gestation are limited, the authors noted. Gestational diabetes was defined as diabetes that develops during pregnancy that is not clearly overt diabetes.

To update the 2014 recommendation, the USPSTF commissioned a systematic review. In 45 prospective studies on the accuracy of gestational diabetes screening, several tests, included oral glucose challenge test, oral glucose tolerance test, and fasting plasma glucose using either a one- or two-step approach were accurate detectors of gestational diabetes; therefore, the USPSTF does not recommend a specific test.

In 13 trials on the impact of treating gestational diabetes on intermediate and health outcomes, treatment was associated with a reduced risk of outcomes, including primary cesarean delivery (but not total cesarean delivery) and preterm delivery, but not with a reduced risk of outcomes including preeclampsia, emergency cesarean delivery, induction of labor, or maternal birth trauma.

The task force also reviewed seven studies of harms associated with screening for gestational diabetes, including three on psychosocial harms, three on hospital experiences, and one of the odds of cesarean delivery after a diagnosis of gestational diabetes. No increase in anxiety or depression occurred following a positive diagnosis or false-positive test result, but data suggested that a gestational diabetes diagnosis may be associated with higher rates of cesarean delivery.

A total of 13 trials evaluated the harms associated with treatment of gestational diabetes, and found no association between treatment and increased risk of several outcomes including severe maternal hypoglycemia, low birth weight, and small for gestational age, and no effect was noted on the number of cesarean deliveries.

Evidence gaps that require additional research include randomized, controlled trials on the effects of gestational diabetes screening on health outcomes, as well as benefits versus harms of screening for pregnant individuals prior to 24 weeks, and studies on the effects of screening in subpopulations of race/ethnicity, age, and socioeconomic factors, according to the task force. Additional research also is needed in areas of maternal health outcomes, long-term outcomes, and the effect on outcomes of one-step versus two-step screening, the USPSTF said.

However, “screening for and detecting gestational diabetes provides a potential opportunity to control blood glucose levels (through lifestyle changes, pharmacological interventions, or both) and reduce the risk of macrosomia and LGA [large for gestational age] infants,” the task force wrote. “In turn, this can prevent associated complications such as primary cesarean delivery, shoulder dystocia, and [neonatal] ICU admissions.”

Support screening with counseling on risk reduction

The USPSTF recommendation is important at this time because “the prevalence of gestational diabetes is increasing secondary to rising rates of obesity,” Iris Krishna, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview.

“In 2014, based on a systematic review of literature, the USPSTF recommended screening all asymptomatic pregnant women for gestational diabetes mellitus [GDM] starting at 24 weeks’ gestation. The recommended gestational age for screening coincides with increasing insulin resistance during pregnancy with advancing gestational age,” Dr. Krishna said.

“An updated systematic review by the USPSTF concluded that existing literature continues to affirm current recommendations of universal screening for GDM at 24 weeks gestation or later. There continues, however, to be no consensus on the optimal approach to screening,” she noted.

“Screening can be performed as a two-step or one-step approach,” said Dr. Krishna. “The two-step approach is commonly used in the United States, and all pregnant women are first screened with a 50-gram oral glucose solution followed by a diagnostic test if they have a positive initial screening.

“Women with risk factors for diabetes, such as prior GDM, obesity, strong family history of diabetes, or history of fetal macrosomia, should be screened early in pregnancy for GDM and have the GDM screen repeated at 24 weeks’ gestation or later if normal in early pregnancy,” Dr. Krishna said. “Pregnant women should be counseled on the importance of diet and exercise and appropriate weight gain in pregnancy to reduce the risk of GDM. Overall, timely diagnosis of gestational diabetes is crucial to improving maternal and fetal pregnancy outcomes.”

The full recommendation statement is also available on the USPSTF website. The research was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Krishna had no disclosures, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn News.

Asymptomatic pregnant women with no previous diagnosis of type 1 or 2 diabetes should be screened for gestational diabetes at 24 weeks’ gestation or later, according to an updated recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Pregnant individuals who develop gestational diabetes are at increased risk for complications including preeclampsia, fetal macrosomia, and neonatal hypoglycemia, as well as negative long-term outcomes for themselves and their children, wrote lead author Karina W. Davidson, PhD, of Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, N.Y., and colleagues. The statement was published online in JAMA.

The B recommendation and I statement reflect “moderate certainty” that current evidence supports the recommendation in terms of harms versus benefits, and is consistent with the 2014 USPSTF recommendation.

The statement calls for a one-time screening using a glucose tolerance test at or after 24 weeks’ gestation. Although most screening in the United States takes place prior to 28 weeks’ gestation, it can be performed later in patients who begin prenatal care after 28 weeks’ gestation, according to the statement. Data on the harms and benefits of gestational diabetes screening prior to 24 weeks’ gestation are limited, the authors noted. Gestational diabetes was defined as diabetes that develops during pregnancy that is not clearly overt diabetes.

To update the 2014 recommendation, the USPSTF commissioned a systematic review. In 45 prospective studies on the accuracy of gestational diabetes screening, several tests, included oral glucose challenge test, oral glucose tolerance test, and fasting plasma glucose using either a one- or two-step approach were accurate detectors of gestational diabetes; therefore, the USPSTF does not recommend a specific test.

In 13 trials on the impact of treating gestational diabetes on intermediate and health outcomes, treatment was associated with a reduced risk of outcomes, including primary cesarean delivery (but not total cesarean delivery) and preterm delivery, but not with a reduced risk of outcomes including preeclampsia, emergency cesarean delivery, induction of labor, or maternal birth trauma.

The task force also reviewed seven studies of harms associated with screening for gestational diabetes, including three on psychosocial harms, three on hospital experiences, and one of the odds of cesarean delivery after a diagnosis of gestational diabetes. No increase in anxiety or depression occurred following a positive diagnosis or false-positive test result, but data suggested that a gestational diabetes diagnosis may be associated with higher rates of cesarean delivery.

A total of 13 trials evaluated the harms associated with treatment of gestational diabetes, and found no association between treatment and increased risk of several outcomes including severe maternal hypoglycemia, low birth weight, and small for gestational age, and no effect was noted on the number of cesarean deliveries.

Evidence gaps that require additional research include randomized, controlled trials on the effects of gestational diabetes screening on health outcomes, as well as benefits versus harms of screening for pregnant individuals prior to 24 weeks, and studies on the effects of screening in subpopulations of race/ethnicity, age, and socioeconomic factors, according to the task force. Additional research also is needed in areas of maternal health outcomes, long-term outcomes, and the effect on outcomes of one-step versus two-step screening, the USPSTF said.

However, “screening for and detecting gestational diabetes provides a potential opportunity to control blood glucose levels (through lifestyle changes, pharmacological interventions, or both) and reduce the risk of macrosomia and LGA [large for gestational age] infants,” the task force wrote. “In turn, this can prevent associated complications such as primary cesarean delivery, shoulder dystocia, and [neonatal] ICU admissions.”

Support screening with counseling on risk reduction

The USPSTF recommendation is important at this time because “the prevalence of gestational diabetes is increasing secondary to rising rates of obesity,” Iris Krishna, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview.

“In 2014, based on a systematic review of literature, the USPSTF recommended screening all asymptomatic pregnant women for gestational diabetes mellitus [GDM] starting at 24 weeks’ gestation. The recommended gestational age for screening coincides with increasing insulin resistance during pregnancy with advancing gestational age,” Dr. Krishna said.

“An updated systematic review by the USPSTF concluded that existing literature continues to affirm current recommendations of universal screening for GDM at 24 weeks gestation or later. There continues, however, to be no consensus on the optimal approach to screening,” she noted.

“Screening can be performed as a two-step or one-step approach,” said Dr. Krishna. “The two-step approach is commonly used in the United States, and all pregnant women are first screened with a 50-gram oral glucose solution followed by a diagnostic test if they have a positive initial screening.

“Women with risk factors for diabetes, such as prior GDM, obesity, strong family history of diabetes, or history of fetal macrosomia, should be screened early in pregnancy for GDM and have the GDM screen repeated at 24 weeks’ gestation or later if normal in early pregnancy,” Dr. Krishna said. “Pregnant women should be counseled on the importance of diet and exercise and appropriate weight gain in pregnancy to reduce the risk of GDM. Overall, timely diagnosis of gestational diabetes is crucial to improving maternal and fetal pregnancy outcomes.”

The full recommendation statement is also available on the USPSTF website. The research was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Krishna had no disclosures, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn News.

FROM JAMA

AGA Clinical Practice Update Expert Review: Management of malignant alimentary tract obstruction

The American Gastroenterological Association published a clinical practice update expert review for managing malignant alimentary tract obstructions (MATOs) that includes 14 best practice advice statements, ranging from general principles to specific clinical choices.

“There are many options available for the management of MATOs, with the addition of new modalities as interventional endoscopy continues to evolve,” Osman Ahmed, MD, of the University of Toronto and colleagues wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “The important concept to understand for any physician managing MATOs is that there is no longer a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach that can be applied to all patients.”

First, the investigators called for an individualized, multidisciplinary approach that includes oncologists, surgeons, and endoscopists. They advised physicians to “take into account the characteristics of the obstruction, patient’s expectations, prognosis, expected subsequent therapies, and functional status.”

The remaining advice statements are organized by site of obstruction, with various management approaches based on candidacy for resection and other patient factors.

Esophageal obstruction

For patients with esophageal obstruction who are candidates for resection or chemoradiation, Dr. Ahmed and colleagues advised against routine use of self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) due to “high rates of stent migration, higher morbidity and mortality, and potentially lower R0 (microscopically negative margins) resection rates.”

If such patients are at risk of malnutrition, an enteral feeding tube may be considered, although patients should be counseled about associated procedural risks, such as abdominal wall tumor seeding.

Among patients with esophageal obstruction who are not candidates for resection, SEMS insertion or brachytherapy may be used separately or in combination, according to the investigators.

“Clinicians should not consider the use of laser therapy or photodynamic therapy because of the lack of evidence of better outcomes and superior alternatives,” the investigators noted.

If SEMS placement is elected, Dr. Ahmed and colleagues noted there remains ongoing debate. For this expert review, the authors advised using a fully covered stent, based on potentially higher risk for tumor ingrowth and reinterventions with uncovered SEMS.

Gastric outlet obstruction

According to the update, patients with gastric outlet obstruction who have good functional status and a life expectancy greater than 2 months should undergo surgical gastrojejunostomy, ideally via a laparoscopic approach instead of an open approach because of shorter hospital stays and less blood loss. If a sufficiently experienced endoscopist is available, an endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastrojejunostomy may be performed, although Dr. Ahmed and colleagues noted that no devices have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this technique.

For patients who are not candidates for gastrojejunostomy, enteral stent insertion should be considered; however, they should not be used in patients with severely impaired gastric motility or multiple luminal obstructions “because of limited benefit in these scenarios.” Instead, a venting gastrostomy may be elected.

Colonic obstruction

For patients with malignant colonic obstruction, SEMS may be considered as a “bridge to surgery,” wrote Dr. Ahmed and colleagues, and in the case of proximal or right-sided malignant obstruction, as a bridge to surgery or a palliative measure, keeping in mind “the technical challenges of SEMS insertion in those areas.”

Extracolonic obstruction

Finally, the expert panel suggested that SEMS may be appropriate for selective extracolonic malignancy if patients are not surgical candidates, noting that SEMS placement in this scenario “is more technically challenging, clinical success rates are more variable, and complications (including stent migration) are more frequent.”

The investigators concluded by advising clinicians to remain within the realm of their abilities when managing MATOs, and to refer when needed.

“[I]t is important for physicians to understand their limits and expertise and recognize when cases are best managed at experienced high-volume centers,” they wrote.

The clinical practice update expert review was commissioned and approved by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee and the AGA Governing Board. Dr. Lee disclosed a relationship with Boston Scientific.

The American Gastroenterological Association published a clinical practice update expert review for managing malignant alimentary tract obstructions (MATOs) that includes 14 best practice advice statements, ranging from general principles to specific clinical choices.

“There are many options available for the management of MATOs, with the addition of new modalities as interventional endoscopy continues to evolve,” Osman Ahmed, MD, of the University of Toronto and colleagues wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “The important concept to understand for any physician managing MATOs is that there is no longer a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach that can be applied to all patients.”

First, the investigators called for an individualized, multidisciplinary approach that includes oncologists, surgeons, and endoscopists. They advised physicians to “take into account the characteristics of the obstruction, patient’s expectations, prognosis, expected subsequent therapies, and functional status.”

The remaining advice statements are organized by site of obstruction, with various management approaches based on candidacy for resection and other patient factors.

Esophageal obstruction

For patients with esophageal obstruction who are candidates for resection or chemoradiation, Dr. Ahmed and colleagues advised against routine use of self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) due to “high rates of stent migration, higher morbidity and mortality, and potentially lower R0 (microscopically negative margins) resection rates.”

If such patients are at risk of malnutrition, an enteral feeding tube may be considered, although patients should be counseled about associated procedural risks, such as abdominal wall tumor seeding.

Among patients with esophageal obstruction who are not candidates for resection, SEMS insertion or brachytherapy may be used separately or in combination, according to the investigators.

“Clinicians should not consider the use of laser therapy or photodynamic therapy because of the lack of evidence of better outcomes and superior alternatives,” the investigators noted.

If SEMS placement is elected, Dr. Ahmed and colleagues noted there remains ongoing debate. For this expert review, the authors advised using a fully covered stent, based on potentially higher risk for tumor ingrowth and reinterventions with uncovered SEMS.

Gastric outlet obstruction

According to the update, patients with gastric outlet obstruction who have good functional status and a life expectancy greater than 2 months should undergo surgical gastrojejunostomy, ideally via a laparoscopic approach instead of an open approach because of shorter hospital stays and less blood loss. If a sufficiently experienced endoscopist is available, an endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastrojejunostomy may be performed, although Dr. Ahmed and colleagues noted that no devices have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this technique.

For patients who are not candidates for gastrojejunostomy, enteral stent insertion should be considered; however, they should not be used in patients with severely impaired gastric motility or multiple luminal obstructions “because of limited benefit in these scenarios.” Instead, a venting gastrostomy may be elected.

Colonic obstruction

For patients with malignant colonic obstruction, SEMS may be considered as a “bridge to surgery,” wrote Dr. Ahmed and colleagues, and in the case of proximal or right-sided malignant obstruction, as a bridge to surgery or a palliative measure, keeping in mind “the technical challenges of SEMS insertion in those areas.”

Extracolonic obstruction

Finally, the expert panel suggested that SEMS may be appropriate for selective extracolonic malignancy if patients are not surgical candidates, noting that SEMS placement in this scenario “is more technically challenging, clinical success rates are more variable, and complications (including stent migration) are more frequent.”

The investigators concluded by advising clinicians to remain within the realm of their abilities when managing MATOs, and to refer when needed.

“[I]t is important for physicians to understand their limits and expertise and recognize when cases are best managed at experienced high-volume centers,” they wrote.

The clinical practice update expert review was commissioned and approved by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee and the AGA Governing Board. Dr. Lee disclosed a relationship with Boston Scientific.

The American Gastroenterological Association published a clinical practice update expert review for managing malignant alimentary tract obstructions (MATOs) that includes 14 best practice advice statements, ranging from general principles to specific clinical choices.

“There are many options available for the management of MATOs, with the addition of new modalities as interventional endoscopy continues to evolve,” Osman Ahmed, MD, of the University of Toronto and colleagues wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “The important concept to understand for any physician managing MATOs is that there is no longer a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach that can be applied to all patients.”

First, the investigators called for an individualized, multidisciplinary approach that includes oncologists, surgeons, and endoscopists. They advised physicians to “take into account the characteristics of the obstruction, patient’s expectations, prognosis, expected subsequent therapies, and functional status.”

The remaining advice statements are organized by site of obstruction, with various management approaches based on candidacy for resection and other patient factors.

Esophageal obstruction

For patients with esophageal obstruction who are candidates for resection or chemoradiation, Dr. Ahmed and colleagues advised against routine use of self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) due to “high rates of stent migration, higher morbidity and mortality, and potentially lower R0 (microscopically negative margins) resection rates.”

If such patients are at risk of malnutrition, an enteral feeding tube may be considered, although patients should be counseled about associated procedural risks, such as abdominal wall tumor seeding.

Among patients with esophageal obstruction who are not candidates for resection, SEMS insertion or brachytherapy may be used separately or in combination, according to the investigators.

“Clinicians should not consider the use of laser therapy or photodynamic therapy because of the lack of evidence of better outcomes and superior alternatives,” the investigators noted.

If SEMS placement is elected, Dr. Ahmed and colleagues noted there remains ongoing debate. For this expert review, the authors advised using a fully covered stent, based on potentially higher risk for tumor ingrowth and reinterventions with uncovered SEMS.

Gastric outlet obstruction

According to the update, patients with gastric outlet obstruction who have good functional status and a life expectancy greater than 2 months should undergo surgical gastrojejunostomy, ideally via a laparoscopic approach instead of an open approach because of shorter hospital stays and less blood loss. If a sufficiently experienced endoscopist is available, an endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastrojejunostomy may be performed, although Dr. Ahmed and colleagues noted that no devices have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this technique.

For patients who are not candidates for gastrojejunostomy, enteral stent insertion should be considered; however, they should not be used in patients with severely impaired gastric motility or multiple luminal obstructions “because of limited benefit in these scenarios.” Instead, a venting gastrostomy may be elected.

Colonic obstruction

For patients with malignant colonic obstruction, SEMS may be considered as a “bridge to surgery,” wrote Dr. Ahmed and colleagues, and in the case of proximal or right-sided malignant obstruction, as a bridge to surgery or a palliative measure, keeping in mind “the technical challenges of SEMS insertion in those areas.”

Extracolonic obstruction

Finally, the expert panel suggested that SEMS may be appropriate for selective extracolonic malignancy if patients are not surgical candidates, noting that SEMS placement in this scenario “is more technically challenging, clinical success rates are more variable, and complications (including stent migration) are more frequent.”

The investigators concluded by advising clinicians to remain within the realm of their abilities when managing MATOs, and to refer when needed.

“[I]t is important for physicians to understand their limits and expertise and recognize when cases are best managed at experienced high-volume centers,” they wrote.

The clinical practice update expert review was commissioned and approved by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee and the AGA Governing Board. Dr. Lee disclosed a relationship with Boston Scientific.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

ESC heart failure guideline to integrate bounty of new meds

Today there are so many evidence-based drug therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) that physicians treating HF patients almost don’t know what to do them.

It’s an exciting new age that way, but to many vexingly unclear how best to merge the shiny new options with mainstay regimens based on time-honored renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors and beta-blockers.

To impart some clarity, the authors of a new HF guideline document recently took center stage at the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC-HFA) annual meeting to preview their updated recommendations, with novel twists based on recent major trials, for the new age of HF pharmacotherapeutics.

The guideline committee considered the evidence base that existed “up until the end of March of this year,” Theresa A. McDonagh, MD, King’s College London, said during the presentation. The document “is now finalized, it’s with the publishers, and it will be presented in full with simultaneous publication at the ESC meeting” that starts August 27.

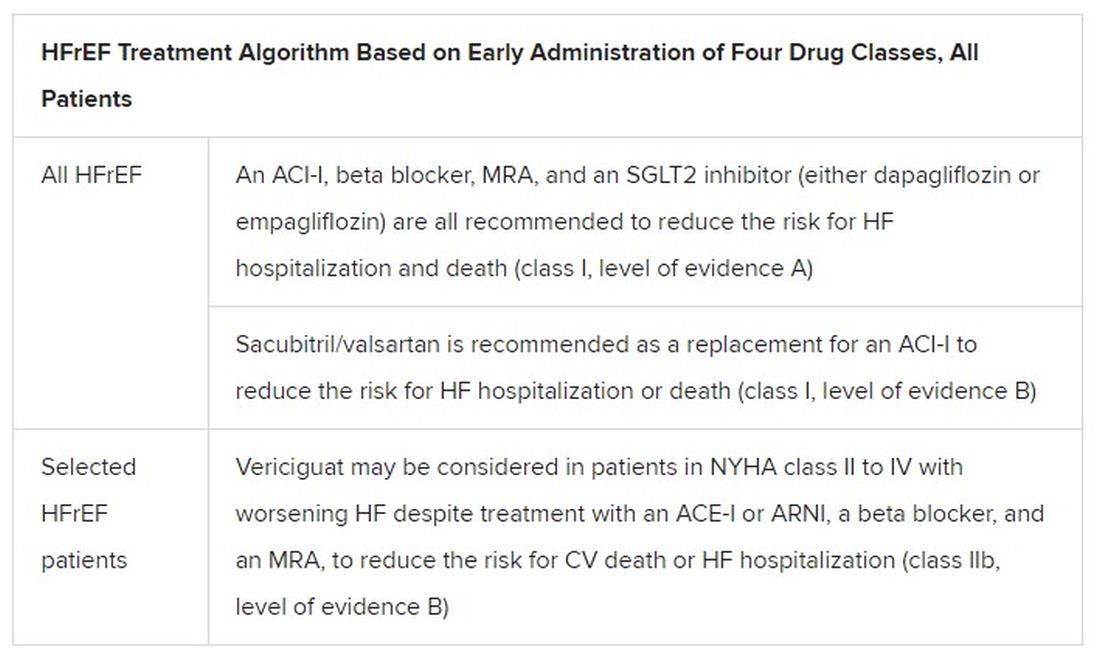

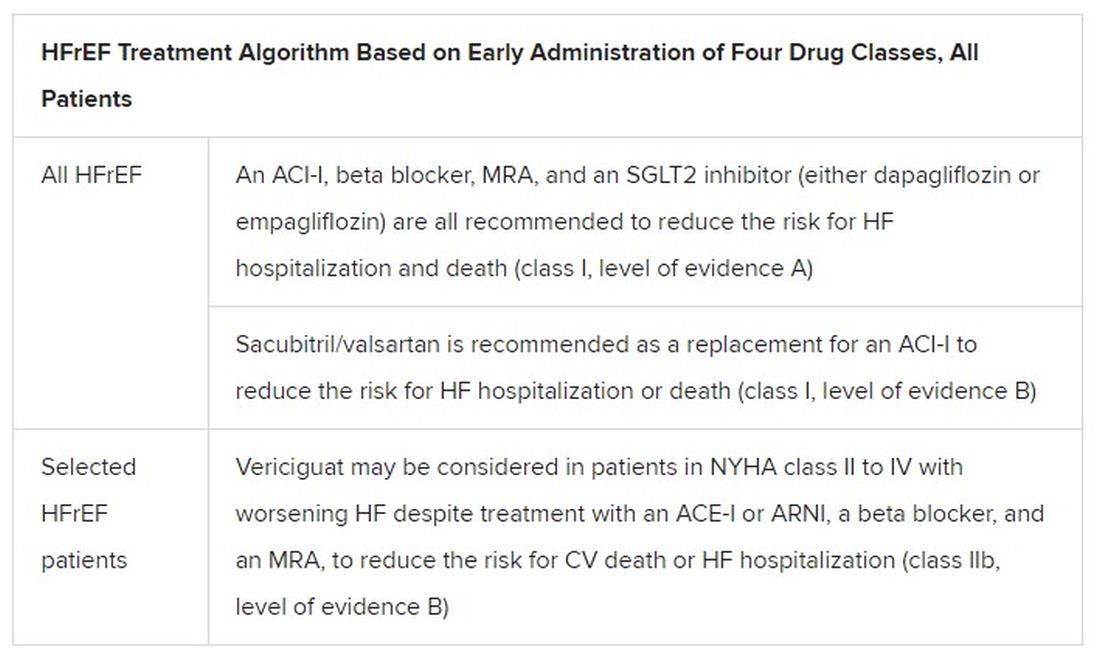

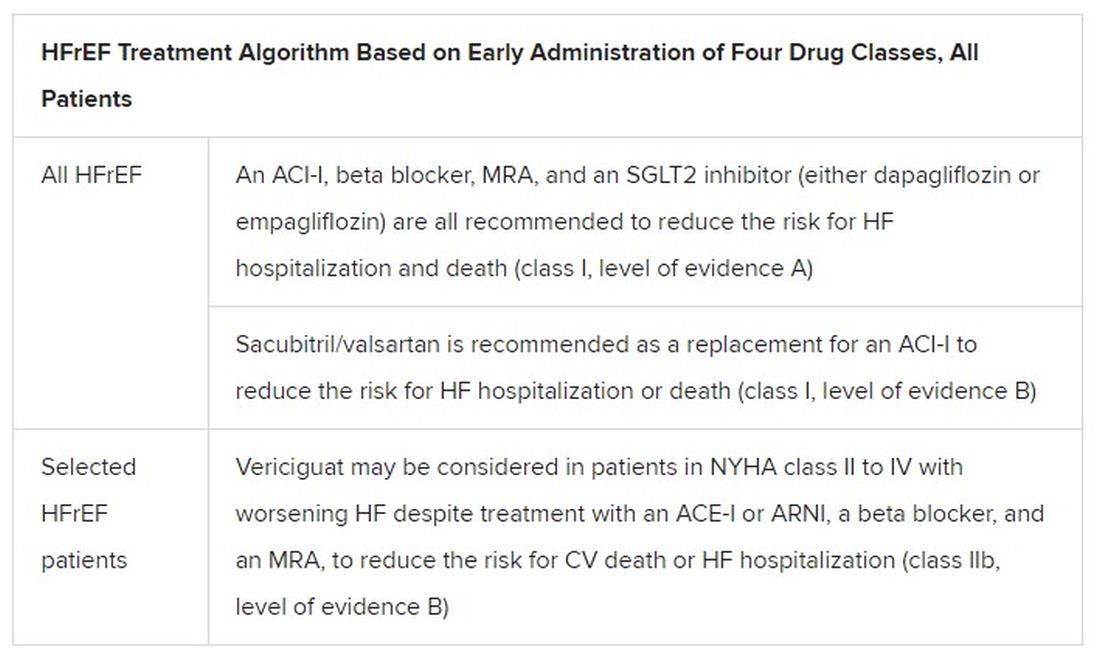

It describes a game plan, already followed by some clinicians in practice without official guidance, for initiating drugs from each of four classes in virtually all patients with HFrEF.

New indicated drugs, new perspective for HFrEF

Three of the drug categories are old acquaintances. Among them are the RAS inhibitors, which include angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitors, beta-blockers, and the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. The latter drugs are gaining new respect after having been underplayed in HF prescribing despite longstanding evidence of efficacy.

Completing the quartet of first-line HFrEF drug classes is a recent arrival to the HF arena, the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

“We now have new data and a simplified treatment algorithm for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction based on the early administration of the four major classes of drugs,” said Marco Metra, MD, University of Brescia (Italy), previewing the medical-therapy portions of the new guideline at the ESC-HFA sessions, which launched virtually and live in Florence, Italy, on July 29.

The new game plan offers a simple answer to a once-common but complex question: How and in what order are the different drug classes initiated in patients with HFrEF? In the new document, the stated goal is to get them all on board expeditiously and safely, by any means possible.

The guideline writers did not specify a sequence, preferring to leave that decision to physicians, said Dr. Metra, who stated only two guiding principles. The first is to consider the patient’s unique circumstances. The order in which the drugs are introduced might vary, depending on, for example, whether the patient has low or high blood pressure or renal dysfunction.

Second, “it is very important that we try to give all four classes of drugs to the patient in the shortest time possible, because this saves lives,” he said.

That there is no recommendation on sequencing the drugs has led some to the wrong interpretation that all should be started at once, observed coauthor Javed Butler, MD, MPH, University of Mississippi, Jackson, as a panelist during the presentation. Far from it, he said. “The doctor with the patient in front of you can make the best decision. The idea here is to get all the therapies on as soon as possible, as safely as possible.”

“The order in which they are introduced is not really important,” agreed Vijay Chopra, MD, Max Super Specialty Hospital Saket, New Delhi, another coauthor on the panel. “The important thing is that at least some dose of all the four drugs needs to be introduced in the first 4-6 weeks, and then up-titrated.”

Other medical therapy can be more tailored, Dr. Metra noted, such as loop diuretics for patients with congestion, iron for those with iron deficiency, and other drugs depending on whether there is, for example, atrial fibrillation or coronary disease.

Adoption of emerging definitions

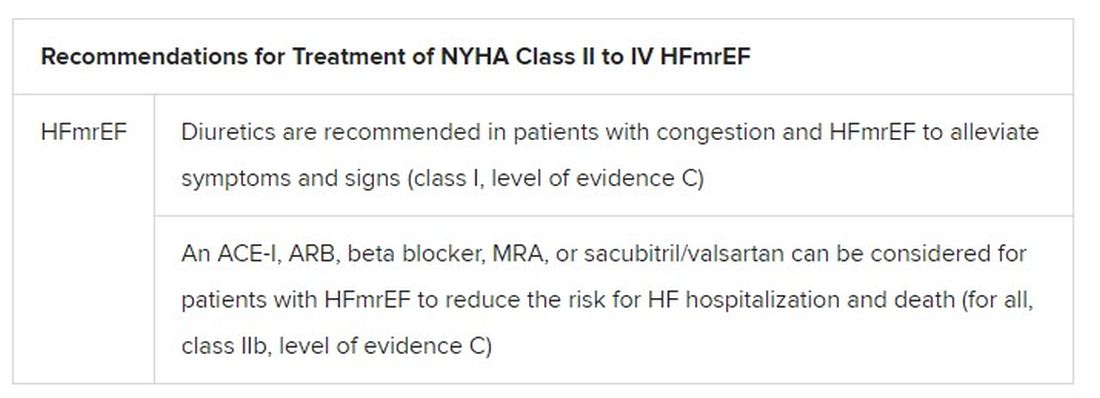

The document adopts the emerging characterization of HFrEF by a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) up to 40%.

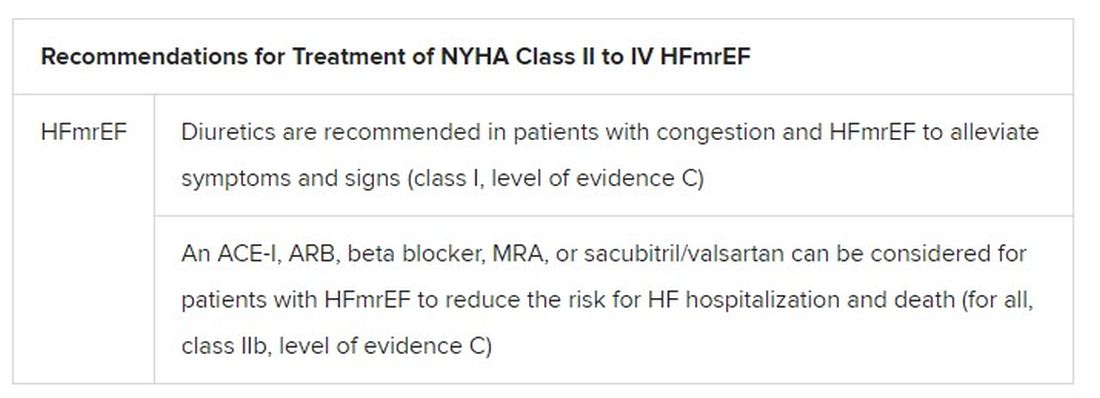

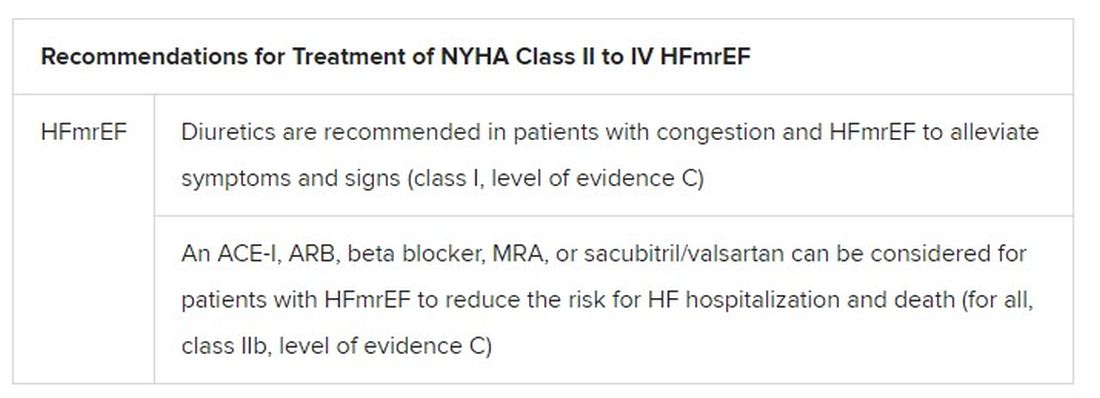

And it will leverage an expanding evidence base for medication in a segment of patients once said to have HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), who had therefore lacked specific, guideline-directed medical therapies. Now, patients with an LVEF of 41%-49% will be said to have HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), a tweak to the recently introduced HF with “mid-range” LVEF that is designed to assert its nature as something to treat. The new document’s HFmrEF recommendations come with various class and level-of-evidence ratings.

That leaves HFpEF to be characterized by an LVEF of 50% in combination with structural or functional abnormalities associated with LV diastolic dysfunction or raised LV filling pressures, including raised natriuretic peptide levels.

The definitions are consistent with those proposed internationally by the ESC-HFA, the Heart Failure Society of America, and other groups in a statement published in March.

Expanded HFrEF med landscape

Since the 2016 ESC guideline on HF therapy, Dr. McDonagh said, “there’s been no substantial change in the evidence for many of the classical drugs that we use in heart failure. However, we had a lot of new and exciting evidence to consider,” especially in support of the SGLT2 inhibitors as one of the core medications in HFrEF.

The new data came from two controlled trials in particular. In DAPA-HF, patients with HFrEF who were initially without diabetes and who went on dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) showed a 27% drop in cardiovascular (CV) death or worsening-HF events over a median of 18 months.

“That was followed up with very concordant results with empagliflozin [Jardiance, Boehringer Ingelheim/Eli Lilly] in HFrEF in the EMPEROR-Reduced trial,” Dr. McDonagh said. In that trial, comparable patients who took empagliflozin showed a 25% drop in a primary endpoint similar to that in DAPA-HF over the median 16-month follow-up.

Other HFrEF recommendations are for selected patients. They include ivabradine, already in the guidelines, for patients in sinus rhythm with an elevated resting heart rate who can’t take beta-blockers for whatever reason. But, Dr. McDonagh noted, “we had some new classes of drugs to consider as well.”

In particular, the oral soluble guanylate-cyclase receptor stimulator vericiguat (Verquvo) emerged about a year ago from the VICTORIA trial as a modest success for patients with HFrEF and a previous HF hospitalization. In the trial with more than 5,000 patients, treatment with vericiguat atop standard drug and device therapy was followed by a significant 10% drop in risk for CV death or HF hospitalization.

Available now or likely to be available in the United States, the European Union, Japan, and other countries, vericiguat is recommended in the new guideline for VICTORIA-like patients who don’t adequately respond to other indicated medications.

Little for HFpEF as newly defined

“Almost nothing is new” in the guidelines for HFpEF, Dr. Metra said. The document recommends screening for and treatment of any underlying disorder and comorbidities, plus diuretics for any congestion. “That’s what we have to date.”

But that evidence base might soon change. The new HFpEF recommendations could possibly be up-staged at the ESC sessions by the August 27 scheduled presentation of EMPEROR-Preserved, a randomized test of empagliflozin in HFpEF and – it could be said – HFmrEF. The trial entered patients with chronic HF and an LVEF greater than 40%.

Eli Lilly and Boehringer Ingelheim offered the world a peek at the results, which suggest the SGLT2 inhibitor had a positive impact on the primary endpoint of CV death or HF hospitalization. They announced the cursory top-line outcomes in early July as part of its regulatory obligations, noting that the trial had “met” its primary endpoint.

But many unknowns remain, including the degree of benefit and whether it varied among subgroups, and especially whether outcomes were different for HFmrEF than for HFpEF.

Upgrades for familiar agents