User login

Moroccan Health Care: A Link to Radicalization and Proposed Solution

The relationship between the Kingdom of Morocco and the US began just after the US declared its own independence. It is one of the oldest of US partnerships with a foreign country, and since the end of the First Barbary War in 1805 it has remained one of the most stable. The Utah National Guard (UTNG) has an active state partnership program (SPP) with Morocco, which helps maintain that stability and fosters the relationship. The SPP provides the Kingdom of Morocco assistance in the areas of disaster medicine, prehospital medicine, and rural access to health care.

The objective of this review is to highlight the role the SPP plays in ensuring Morocco’s continued stability, enhancing its role as a leader among African nations, aiding its medically vulnerable rural populations to prevent recruitment by terrorist organizations, and maintaining its long-term relationship with the US.

Background

The Kingdom of Morocco resides in a geologically and politically unstable part of the world, yet it has been a stable constitutional monarchy. Like California, Morocco has a long coastline of more than 1,000 miles. It sits along an active earthquake fault line with a disaster response program that is only in its infancy. The Kingdom has a high youth unemployment rate and lacks adequate public education opportunities, which exacerbate feelings of government indifference. Morocco’s medical system is highly centralized, and large parts of the rural population lack access to basic medical care—potentially alienating the population. The Moroccan current disaster plan ORSEC (plan d’ Organization des Secours) was established in 1966 and updated in 2005 but does not provide a comprehensive, unified disaster response. The ORSEC plan is of French derivation and is not a list of actions but a general plan of organization and supply. 1

When governments fail to provide basic services—health care being just one—those services may be filled by groups seeking to influence the government and population by threatening acts of violence to achieve political, religious, and ideologic gain; for example, the Taliban in Afghanistan, the Muslim brotherhood in Egypt and in the West Bank, and the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in Syria.2-5 These groups gain a foothold and legitimacy by providing mosques, youth groups, clinics, hospitals, and schools. 2-5

Identified Needs

Morocco is at risk of experiencing an earthquake and possible subsequent tsunami. In 1755, Morocco was impacted by the Great Lisbon earthquake and tsunami. Witnesses reported 15-meter waves with 24-meter crests.6 Building codes and architecture laws have changed little since the 1960 Agadir earthquake, which killed 12,000 people. The disaster response program—although improved since the 1960s—is still in the early stages of development, and another earthquake and possible subsequent tsunami would result in a disaster that could overwhelm the medical community of Morocco.

Perceived Government Indifference

The Moroccan constitutional monarchy is more stable than are the governments of its North African neighbors. King Mohammed VI presides over the government, and regular elections are held for members of Parliament, which names a prime minister. However, in August 2019, overall unemployment was at 8.5%, and youth unemployment was 22.3%.7 A United Nations report in August 2019 stated that literacy rates for Morocco were 71.7%. These data were from a 2015 census, the last year data were collected.8 These deficits in employment and education can foster anger toward the Moroccan government for not adequately providing these services and possibly introduce radicalization as a result of the population’s perceived government indifference and lack of economic mobility.

Access to Medical Care

Morocco has a 2-tiered medical system for providing services: urban and rural. In 2018 the Legatum Prosperity Index ranked Morocco 103 of 149 countries in health care. The prosperity index measures health variables, which include but were not limited to basic physical and mental health, health infrastructure, and preventive care.9 Outside the metropolitan areas, emergency medical care is nonexistent, primary care is sporadic, and there is little modern technology available.

Despite humanitarian efforts over many years, there is little to no medical care in the rural “medical desert.” A 2017 study from the University of Washington Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation compared the global burden of disease in similar countries. The study found that Morocco was significantly higher than the mean in the prevalence of ischemic heart disease and Alzheimer disease, lower than the mean in the areas of neonatal disorders, lower respiratory infections, and tuberculosis, and statistically indistinct from the mean in stroke, congenital defects, road injuries, diabetes mellitus, and hypertensive heart disease compared with the disease prevalence of other countries of similar size and economic measures.10 The study also found a particularly acute disparity in access to health care in rural areas. In 2016, the Oxford Business Group reported staff shortages and disproportionate distribution of resources in the Moroccan health care system.11

Additionally, the lack of trained health care personnel has added to an already overstressed health care system. A chief stressor in a health care system is an insufficient replacement rate. Health employees working for the Moroccan Ministry of Health retire at a rate of 1,500 per year.10,11 These shortages may serve to further the feelings of frustration and government indifference. This frustration is momentarily decreased by humanitarian efforts that have taken place in the African continent in the past decades, but this band-aid approach to assisting the population that is medically underserved has done little to alleviate the long-term problem of access to care. And feelings of government abandonment can sow the seeds of discontent in the rural population, creating fertile ground for recruitment by terrorist organizations.2,3

Lack of Health Care and Radicalism

It has been postulated that there is a link between radicalization and lack of medical care. Depression and perceived government indifference are considered contributors to radicalization.12-16 In 2005, Victoroff suggested that there are certain psychological traits characteristic of “typical" terrorists: these include high affective valence regarding an ideologic issue, a personal stake (perceived oppression, persecution or humiliation, need for identity, glory, or vengeance), low cognitive ability, low tolerance for ambiguity, and a capacity to suppress instinctive and learned moral constraints against harming innocents.15 In 2009, Lafree and Ackerman suggested that terrorism feeds on the ability of groups to portray governments and their agents as illegitimate.16 It is possible that part of the illegitimacy campaign of radicalization and terrorist recruitment may be identification of the lack of health care by the government thus magnifying feelings of government abandonment in a vulnerable population.

In 2011, the new Moroccan constitution identified access to basic health care as a right of the Moroccan people.17 Additionally, in 2013, a government white paper was produced outlining the need to increase access to health care, particularly in rural areas, including a focus on infant and maternal mortality, diabetes mellitus (DM), heart disease, and respiratory problems.17,18

Proposed Solutions, A Beginning

A health outreach program with a regional health professional training center in a relatively stable country within the African Union (AU) would be a step toward delivering health care to Morocco and interested AU members. Interested nations have been and will continue to be invited to train at the Moroccan center and return to their countries and start training programs. This idea was echoed by the World Bank in a 2015 loan proposal to Morocco, which suggested that addressing disparities in access to health care is a social justice issue, with other benefits such as increased productivity, employment, lower out-of-pocket expenditures, and promotion of good governance.17

In 2012, Buhi reported that a positive regard for authorities and healthier influences seemed to be a protective factor against radicalization. He also suggested a public health approach to understanding and preventing violent radicalization.19 The solutions are complex, especially in rural areas and in vulnerable nations common to Africa.

Medical training efforts by the US Department of Defense (DoD), Medical Readiness Training Institute (DMRT), and international health specialists working with the military and civilian entities in neighboring African countries have improved response to regional disasters. However, to address the broader issues, a more permanent, cooperative possible solution may begin with the establishment in Morocco of a regional education center for disaster preparedness and for health care providers (HCPs). This would serve as a training program for disaster first responders. Graduates of the program would receive additional training to become HCPs similar to physician assistant (PA) and nurse practitioner (NP) programs in the US. Morocco is uniquely positioned to accomplish this due to its location, political stability, and ties with other African nations.

The goal of the Moroccan regional education center (within the King Mohammed V Hospital) is to bring together global health experts and increase the intellectual infrastructure of not only Morocco, but also offer this training program to interested countries within the AU. Advancement of the regional education center will require legislative changes to expand prescriptive privileges and scope of practice within each country. The medical element of the SPP as presently constituted without the regional education center will continue its humanitarian goals, but the proposed creation of the regional education center will educate participants to serve the rural communities within each participating country. Eventually the entire educational program will be the responsibility of the Moroccan military and the AU participants. This will require reprioritizing resources from the provision of humanitarian health care services to an HCP education approach.

Disaster Response

Deficits in disaster response capabilities have been identified by members of the Moroccan military with the assistance of the UTNG. The most glaring deficit identified was the disparity in training between military and civilian first responders. Thus, a training program was initiated by the Moroccan military and the UTNG that combined internationally recognized, durable, robust emergency training programs. These programs consisted of, but were not limited to, parts or entire programs of the following: basic disaster life support, advanced disaster life support, disaster casualty care, and advanced trauma life support. The goal of this training was to improve communication, reduce mortality, and create strike teams, which can quickly provide health care independent of a hospital during a disaster.

Patients can overwhelm hospitals in a disaster when need exceeds resources. In 1996, Mallonee reported that at least 67% of the patients who sought care at a hospital during the Oklahoma City bombing disaster did not need advanced medical treatment.20 Such patients could be seen at an identified casualty collection point by a strike team and treated and released rather than traveling to the hospital and using staff and resources that could be used more judiciously for the more seriously injured.21 These teams consist of trained first responders with an experienced HCP (physician, PA, NP) and a nurse and are trained to operate for up to 72 hours in a predetermined location and serve as a “filter” for the hospital. Their role is to treat and release the less severely injured and refer only the more severely injured to the hospital after basic stabilization, thus preserving precious resources necessary for the more seriously injured.

This disaster response training program was offered to the Moroccan military, ministry of health and ministry of tourism, and quickly turned into an Africa-wide interest. A regional training center was proposed. This was assisted with the cooperation of Weber State University in Ogden Utah, Utah Valley University in Orem, and private interests in a public/private/military state partnership. Program supplies and didactic instruction were and will be provided by the UTNG and supplemented through the DoD Africa command. Instruction will be a cooperative effort agreed on between the UTNG and the Moroccan military medical specialists within their specific area of expertise.

Underserved Communities

Finally, from this pool of interested strike team members, a health care provider school will be formed to educate, certify, and service the needs of the underserved communities in Morocco and interested AU countries. This program will be similar to the PA and NP programs in the US and will be geared to those graduates from the previous programs with intense classroom instruction for one year followed by a year of one-on-one preceptorship with an experienced physician. The goal of the program is to prepare individuals with patient care experience to fulfill a bigger role in health care in an underserved (usually austere, rural) area that currently has minimal health care presence. This fills a need identified by the World Bank in 2015 that the Moroccan government needs to respond to the demand for improved access to and quality of health care services—particularly to the rural poor.17

The Moroccan military has a presence in many medically underserved areas. The logical fit for the HCP program will be drawn from a pool of active-duty military individuals who express an interest and qualify through attendance in all phases of the training.

Conclusion

This program of disaster medical education, strike teams, and HCPs is currently training more than 200 students a year throughout Morocco. The proposed direction of this cooperative program to produce HCPs in rural areas will increase access to health care for the Moroccan people who are now underserved. Morocco, as a health care training hub in Africa, will increase access to health care for interested African countries. The goal politically will be to reduce feelings of government indifference in vulnerable populations and reduce recruitment into radical ideologies.

1. Nahon M, Michaloux M. L’organisation de la réponse de la sécurité civile: le dispositif ORSEC Organisation of civilian emergency services: The ORSEC plan. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211423816300499#! Published July 2016. Accessed October 7, 2019.

2. Berman E. Hamas, Taliban and the Jewish underground: an economist's view of radical religious militias. NBER Working Paper No. w10004. https://ssrn.com/abstract=450885. Published September 2003. Accessed October 7, 2019.

3. Jordan J. Attacking the leader. Missing the mark; why terrorist groups survive decapitation strikes. Int Secur. 2014;38(4):7-38.

4. Grynkewich A. Welfare as warfare: how violent non-state groups use social services to attack the state. Stud Conflict Terrorism. 2008;31(4):350-370.

5. Marin M, Solomon H. Islamic State: understanding the nature of the beast and its funding. Contemp Rev Middle East. 2017;4(1):18-49.

6. Bressan D. November 1, 1755: the earthquake of Lisbon: wrath of god or natural disaster? Scientific American, History of Geology. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/history-of-geology/november-1-1755-the-earthquake-of-lisbon-wraith-of-god-or-natural-disaster. Published November 2011. Accessed October 7, 2019.

7. Trading Economics. Morocco unemployment rate. Second quarter statistics. August 2019. https://tradingeconomics.com/morocco/unemployment-rate. Accessed October 7, 2019.

8. Knoema World Data Atlas 2015. Morocco adult literacy rates. https://knoema.com/atlas/Morocco/topics/Education/Literacy/Adult-literacy-rate. Accessed October 4, 2019.

9. The Legatum Prosperity Index 2018. Morocco. https://www.prosperity.com/globe/morocco. Accessed October 7, 2019.

10. University of Washington, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Morocco. http://www.healthdata.org/morocco. Published 2018. Accessed October 7, 2019.

11. Oxford Business Group. Access to health care broadens in Morocco. https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/overview/forward-steps-access-care-has-broadened-and-infrastructure-improved-challenges-remain. Accessed September 12. 2019.

12. Wright NMJ, Hankins FM. Preventing radicalization and terrorism: Is there a GP response? Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(647):288-289.

13. Buhi K, Everitt K, Jones E. Might depression psychosocial adversity, and limited social assets explain vulnerability to and resistance against violent radicalization? PlosOne. 2014;9(9):e105918.

14. DeAngelis T. Understanding terrorism. apa.org/monitor/2009/11/terrorism. Published November 2009. Accessed October 14, 2019.

15. Victoroff J. The mind of the terrorist: a review and critique of psychological approaches. J Conflict Resolut. 2005;49(1):3-42.

16. Lafree G, Ackerman G. The empirical study of terrorism: social and legal research. Ann Rev Law Soc Sci. 2009;5:347-374.

17. World Bank. Morocco—improving primary health in rural areas program-for-results project (English). http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/716821468274482723/Morocco-Improving-Primary-Health-in-Rural-Areas-Program-for-Results-Project. Published 2015. Accessed September 16, 2019.

18. Royaume du Maroc, Ministère de la Santé. Livre blanc: pour une nouvelle gouvernance du secteur de la santé. Paper presented at: 2nd National Health Conference; July 1-3, 2013; Marrakesh, Morocco.

19. Buhi K, Hicks MH, Lashley M, Jones E. A public health approach to understanding and preventing violent radicalization. BMC Med. 2012;10:16.

20. Mallonee S, Sahriat S, Stennies G, Waxweiler R, Hogan D, Jordan F. Physical injuries and fatalities resulting from the Oklahoma City bombing. JAMA. 1996;276(5):382-387.

21. Ushizawa H, Foxwell AR, Bice S, et al. Needs for disaster medicine: lessons from the field of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Western Pac Surveil Response J. 2013;4(1):51-55.

The relationship between the Kingdom of Morocco and the US began just after the US declared its own independence. It is one of the oldest of US partnerships with a foreign country, and since the end of the First Barbary War in 1805 it has remained one of the most stable. The Utah National Guard (UTNG) has an active state partnership program (SPP) with Morocco, which helps maintain that stability and fosters the relationship. The SPP provides the Kingdom of Morocco assistance in the areas of disaster medicine, prehospital medicine, and rural access to health care.

The objective of this review is to highlight the role the SPP plays in ensuring Morocco’s continued stability, enhancing its role as a leader among African nations, aiding its medically vulnerable rural populations to prevent recruitment by terrorist organizations, and maintaining its long-term relationship with the US.

Background

The Kingdom of Morocco resides in a geologically and politically unstable part of the world, yet it has been a stable constitutional monarchy. Like California, Morocco has a long coastline of more than 1,000 miles. It sits along an active earthquake fault line with a disaster response program that is only in its infancy. The Kingdom has a high youth unemployment rate and lacks adequate public education opportunities, which exacerbate feelings of government indifference. Morocco’s medical system is highly centralized, and large parts of the rural population lack access to basic medical care—potentially alienating the population. The Moroccan current disaster plan ORSEC (plan d’ Organization des Secours) was established in 1966 and updated in 2005 but does not provide a comprehensive, unified disaster response. The ORSEC plan is of French derivation and is not a list of actions but a general plan of organization and supply. 1

When governments fail to provide basic services—health care being just one—those services may be filled by groups seeking to influence the government and population by threatening acts of violence to achieve political, religious, and ideologic gain; for example, the Taliban in Afghanistan, the Muslim brotherhood in Egypt and in the West Bank, and the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in Syria.2-5 These groups gain a foothold and legitimacy by providing mosques, youth groups, clinics, hospitals, and schools. 2-5

Identified Needs

Morocco is at risk of experiencing an earthquake and possible subsequent tsunami. In 1755, Morocco was impacted by the Great Lisbon earthquake and tsunami. Witnesses reported 15-meter waves with 24-meter crests.6 Building codes and architecture laws have changed little since the 1960 Agadir earthquake, which killed 12,000 people. The disaster response program—although improved since the 1960s—is still in the early stages of development, and another earthquake and possible subsequent tsunami would result in a disaster that could overwhelm the medical community of Morocco.

Perceived Government Indifference

The Moroccan constitutional monarchy is more stable than are the governments of its North African neighbors. King Mohammed VI presides over the government, and regular elections are held for members of Parliament, which names a prime minister. However, in August 2019, overall unemployment was at 8.5%, and youth unemployment was 22.3%.7 A United Nations report in August 2019 stated that literacy rates for Morocco were 71.7%. These data were from a 2015 census, the last year data were collected.8 These deficits in employment and education can foster anger toward the Moroccan government for not adequately providing these services and possibly introduce radicalization as a result of the population’s perceived government indifference and lack of economic mobility.

Access to Medical Care

Morocco has a 2-tiered medical system for providing services: urban and rural. In 2018 the Legatum Prosperity Index ranked Morocco 103 of 149 countries in health care. The prosperity index measures health variables, which include but were not limited to basic physical and mental health, health infrastructure, and preventive care.9 Outside the metropolitan areas, emergency medical care is nonexistent, primary care is sporadic, and there is little modern technology available.

Despite humanitarian efforts over many years, there is little to no medical care in the rural “medical desert.” A 2017 study from the University of Washington Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation compared the global burden of disease in similar countries. The study found that Morocco was significantly higher than the mean in the prevalence of ischemic heart disease and Alzheimer disease, lower than the mean in the areas of neonatal disorders, lower respiratory infections, and tuberculosis, and statistically indistinct from the mean in stroke, congenital defects, road injuries, diabetes mellitus, and hypertensive heart disease compared with the disease prevalence of other countries of similar size and economic measures.10 The study also found a particularly acute disparity in access to health care in rural areas. In 2016, the Oxford Business Group reported staff shortages and disproportionate distribution of resources in the Moroccan health care system.11

Additionally, the lack of trained health care personnel has added to an already overstressed health care system. A chief stressor in a health care system is an insufficient replacement rate. Health employees working for the Moroccan Ministry of Health retire at a rate of 1,500 per year.10,11 These shortages may serve to further the feelings of frustration and government indifference. This frustration is momentarily decreased by humanitarian efforts that have taken place in the African continent in the past decades, but this band-aid approach to assisting the population that is medically underserved has done little to alleviate the long-term problem of access to care. And feelings of government abandonment can sow the seeds of discontent in the rural population, creating fertile ground for recruitment by terrorist organizations.2,3

Lack of Health Care and Radicalism

It has been postulated that there is a link between radicalization and lack of medical care. Depression and perceived government indifference are considered contributors to radicalization.12-16 In 2005, Victoroff suggested that there are certain psychological traits characteristic of “typical" terrorists: these include high affective valence regarding an ideologic issue, a personal stake (perceived oppression, persecution or humiliation, need for identity, glory, or vengeance), low cognitive ability, low tolerance for ambiguity, and a capacity to suppress instinctive and learned moral constraints against harming innocents.15 In 2009, Lafree and Ackerman suggested that terrorism feeds on the ability of groups to portray governments and their agents as illegitimate.16 It is possible that part of the illegitimacy campaign of radicalization and terrorist recruitment may be identification of the lack of health care by the government thus magnifying feelings of government abandonment in a vulnerable population.

In 2011, the new Moroccan constitution identified access to basic health care as a right of the Moroccan people.17 Additionally, in 2013, a government white paper was produced outlining the need to increase access to health care, particularly in rural areas, including a focus on infant and maternal mortality, diabetes mellitus (DM), heart disease, and respiratory problems.17,18

Proposed Solutions, A Beginning

A health outreach program with a regional health professional training center in a relatively stable country within the African Union (AU) would be a step toward delivering health care to Morocco and interested AU members. Interested nations have been and will continue to be invited to train at the Moroccan center and return to their countries and start training programs. This idea was echoed by the World Bank in a 2015 loan proposal to Morocco, which suggested that addressing disparities in access to health care is a social justice issue, with other benefits such as increased productivity, employment, lower out-of-pocket expenditures, and promotion of good governance.17

In 2012, Buhi reported that a positive regard for authorities and healthier influences seemed to be a protective factor against radicalization. He also suggested a public health approach to understanding and preventing violent radicalization.19 The solutions are complex, especially in rural areas and in vulnerable nations common to Africa.

Medical training efforts by the US Department of Defense (DoD), Medical Readiness Training Institute (DMRT), and international health specialists working with the military and civilian entities in neighboring African countries have improved response to regional disasters. However, to address the broader issues, a more permanent, cooperative possible solution may begin with the establishment in Morocco of a regional education center for disaster preparedness and for health care providers (HCPs). This would serve as a training program for disaster first responders. Graduates of the program would receive additional training to become HCPs similar to physician assistant (PA) and nurse practitioner (NP) programs in the US. Morocco is uniquely positioned to accomplish this due to its location, political stability, and ties with other African nations.

The goal of the Moroccan regional education center (within the King Mohammed V Hospital) is to bring together global health experts and increase the intellectual infrastructure of not only Morocco, but also offer this training program to interested countries within the AU. Advancement of the regional education center will require legislative changes to expand prescriptive privileges and scope of practice within each country. The medical element of the SPP as presently constituted without the regional education center will continue its humanitarian goals, but the proposed creation of the regional education center will educate participants to serve the rural communities within each participating country. Eventually the entire educational program will be the responsibility of the Moroccan military and the AU participants. This will require reprioritizing resources from the provision of humanitarian health care services to an HCP education approach.

Disaster Response

Deficits in disaster response capabilities have been identified by members of the Moroccan military with the assistance of the UTNG. The most glaring deficit identified was the disparity in training between military and civilian first responders. Thus, a training program was initiated by the Moroccan military and the UTNG that combined internationally recognized, durable, robust emergency training programs. These programs consisted of, but were not limited to, parts or entire programs of the following: basic disaster life support, advanced disaster life support, disaster casualty care, and advanced trauma life support. The goal of this training was to improve communication, reduce mortality, and create strike teams, which can quickly provide health care independent of a hospital during a disaster.

Patients can overwhelm hospitals in a disaster when need exceeds resources. In 1996, Mallonee reported that at least 67% of the patients who sought care at a hospital during the Oklahoma City bombing disaster did not need advanced medical treatment.20 Such patients could be seen at an identified casualty collection point by a strike team and treated and released rather than traveling to the hospital and using staff and resources that could be used more judiciously for the more seriously injured.21 These teams consist of trained first responders with an experienced HCP (physician, PA, NP) and a nurse and are trained to operate for up to 72 hours in a predetermined location and serve as a “filter” for the hospital. Their role is to treat and release the less severely injured and refer only the more severely injured to the hospital after basic stabilization, thus preserving precious resources necessary for the more seriously injured.

This disaster response training program was offered to the Moroccan military, ministry of health and ministry of tourism, and quickly turned into an Africa-wide interest. A regional training center was proposed. This was assisted with the cooperation of Weber State University in Ogden Utah, Utah Valley University in Orem, and private interests in a public/private/military state partnership. Program supplies and didactic instruction were and will be provided by the UTNG and supplemented through the DoD Africa command. Instruction will be a cooperative effort agreed on between the UTNG and the Moroccan military medical specialists within their specific area of expertise.

Underserved Communities

Finally, from this pool of interested strike team members, a health care provider school will be formed to educate, certify, and service the needs of the underserved communities in Morocco and interested AU countries. This program will be similar to the PA and NP programs in the US and will be geared to those graduates from the previous programs with intense classroom instruction for one year followed by a year of one-on-one preceptorship with an experienced physician. The goal of the program is to prepare individuals with patient care experience to fulfill a bigger role in health care in an underserved (usually austere, rural) area that currently has minimal health care presence. This fills a need identified by the World Bank in 2015 that the Moroccan government needs to respond to the demand for improved access to and quality of health care services—particularly to the rural poor.17

The Moroccan military has a presence in many medically underserved areas. The logical fit for the HCP program will be drawn from a pool of active-duty military individuals who express an interest and qualify through attendance in all phases of the training.

Conclusion

This program of disaster medical education, strike teams, and HCPs is currently training more than 200 students a year throughout Morocco. The proposed direction of this cooperative program to produce HCPs in rural areas will increase access to health care for the Moroccan people who are now underserved. Morocco, as a health care training hub in Africa, will increase access to health care for interested African countries. The goal politically will be to reduce feelings of government indifference in vulnerable populations and reduce recruitment into radical ideologies.

The relationship between the Kingdom of Morocco and the US began just after the US declared its own independence. It is one of the oldest of US partnerships with a foreign country, and since the end of the First Barbary War in 1805 it has remained one of the most stable. The Utah National Guard (UTNG) has an active state partnership program (SPP) with Morocco, which helps maintain that stability and fosters the relationship. The SPP provides the Kingdom of Morocco assistance in the areas of disaster medicine, prehospital medicine, and rural access to health care.

The objective of this review is to highlight the role the SPP plays in ensuring Morocco’s continued stability, enhancing its role as a leader among African nations, aiding its medically vulnerable rural populations to prevent recruitment by terrorist organizations, and maintaining its long-term relationship with the US.

Background

The Kingdom of Morocco resides in a geologically and politically unstable part of the world, yet it has been a stable constitutional monarchy. Like California, Morocco has a long coastline of more than 1,000 miles. It sits along an active earthquake fault line with a disaster response program that is only in its infancy. The Kingdom has a high youth unemployment rate and lacks adequate public education opportunities, which exacerbate feelings of government indifference. Morocco’s medical system is highly centralized, and large parts of the rural population lack access to basic medical care—potentially alienating the population. The Moroccan current disaster plan ORSEC (plan d’ Organization des Secours) was established in 1966 and updated in 2005 but does not provide a comprehensive, unified disaster response. The ORSEC plan is of French derivation and is not a list of actions but a general plan of organization and supply. 1

When governments fail to provide basic services—health care being just one—those services may be filled by groups seeking to influence the government and population by threatening acts of violence to achieve political, religious, and ideologic gain; for example, the Taliban in Afghanistan, the Muslim brotherhood in Egypt and in the West Bank, and the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in Syria.2-5 These groups gain a foothold and legitimacy by providing mosques, youth groups, clinics, hospitals, and schools. 2-5

Identified Needs

Morocco is at risk of experiencing an earthquake and possible subsequent tsunami. In 1755, Morocco was impacted by the Great Lisbon earthquake and tsunami. Witnesses reported 15-meter waves with 24-meter crests.6 Building codes and architecture laws have changed little since the 1960 Agadir earthquake, which killed 12,000 people. The disaster response program—although improved since the 1960s—is still in the early stages of development, and another earthquake and possible subsequent tsunami would result in a disaster that could overwhelm the medical community of Morocco.

Perceived Government Indifference

The Moroccan constitutional monarchy is more stable than are the governments of its North African neighbors. King Mohammed VI presides over the government, and regular elections are held for members of Parliament, which names a prime minister. However, in August 2019, overall unemployment was at 8.5%, and youth unemployment was 22.3%.7 A United Nations report in August 2019 stated that literacy rates for Morocco were 71.7%. These data were from a 2015 census, the last year data were collected.8 These deficits in employment and education can foster anger toward the Moroccan government for not adequately providing these services and possibly introduce radicalization as a result of the population’s perceived government indifference and lack of economic mobility.

Access to Medical Care

Morocco has a 2-tiered medical system for providing services: urban and rural. In 2018 the Legatum Prosperity Index ranked Morocco 103 of 149 countries in health care. The prosperity index measures health variables, which include but were not limited to basic physical and mental health, health infrastructure, and preventive care.9 Outside the metropolitan areas, emergency medical care is nonexistent, primary care is sporadic, and there is little modern technology available.

Despite humanitarian efforts over many years, there is little to no medical care in the rural “medical desert.” A 2017 study from the University of Washington Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation compared the global burden of disease in similar countries. The study found that Morocco was significantly higher than the mean in the prevalence of ischemic heart disease and Alzheimer disease, lower than the mean in the areas of neonatal disorders, lower respiratory infections, and tuberculosis, and statistically indistinct from the mean in stroke, congenital defects, road injuries, diabetes mellitus, and hypertensive heart disease compared with the disease prevalence of other countries of similar size and economic measures.10 The study also found a particularly acute disparity in access to health care in rural areas. In 2016, the Oxford Business Group reported staff shortages and disproportionate distribution of resources in the Moroccan health care system.11

Additionally, the lack of trained health care personnel has added to an already overstressed health care system. A chief stressor in a health care system is an insufficient replacement rate. Health employees working for the Moroccan Ministry of Health retire at a rate of 1,500 per year.10,11 These shortages may serve to further the feelings of frustration and government indifference. This frustration is momentarily decreased by humanitarian efforts that have taken place in the African continent in the past decades, but this band-aid approach to assisting the population that is medically underserved has done little to alleviate the long-term problem of access to care. And feelings of government abandonment can sow the seeds of discontent in the rural population, creating fertile ground for recruitment by terrorist organizations.2,3

Lack of Health Care and Radicalism

It has been postulated that there is a link between radicalization and lack of medical care. Depression and perceived government indifference are considered contributors to radicalization.12-16 In 2005, Victoroff suggested that there are certain psychological traits characteristic of “typical" terrorists: these include high affective valence regarding an ideologic issue, a personal stake (perceived oppression, persecution or humiliation, need for identity, glory, or vengeance), low cognitive ability, low tolerance for ambiguity, and a capacity to suppress instinctive and learned moral constraints against harming innocents.15 In 2009, Lafree and Ackerman suggested that terrorism feeds on the ability of groups to portray governments and their agents as illegitimate.16 It is possible that part of the illegitimacy campaign of radicalization and terrorist recruitment may be identification of the lack of health care by the government thus magnifying feelings of government abandonment in a vulnerable population.

In 2011, the new Moroccan constitution identified access to basic health care as a right of the Moroccan people.17 Additionally, in 2013, a government white paper was produced outlining the need to increase access to health care, particularly in rural areas, including a focus on infant and maternal mortality, diabetes mellitus (DM), heart disease, and respiratory problems.17,18

Proposed Solutions, A Beginning

A health outreach program with a regional health professional training center in a relatively stable country within the African Union (AU) would be a step toward delivering health care to Morocco and interested AU members. Interested nations have been and will continue to be invited to train at the Moroccan center and return to their countries and start training programs. This idea was echoed by the World Bank in a 2015 loan proposal to Morocco, which suggested that addressing disparities in access to health care is a social justice issue, with other benefits such as increased productivity, employment, lower out-of-pocket expenditures, and promotion of good governance.17

In 2012, Buhi reported that a positive regard for authorities and healthier influences seemed to be a protective factor against radicalization. He also suggested a public health approach to understanding and preventing violent radicalization.19 The solutions are complex, especially in rural areas and in vulnerable nations common to Africa.

Medical training efforts by the US Department of Defense (DoD), Medical Readiness Training Institute (DMRT), and international health specialists working with the military and civilian entities in neighboring African countries have improved response to regional disasters. However, to address the broader issues, a more permanent, cooperative possible solution may begin with the establishment in Morocco of a regional education center for disaster preparedness and for health care providers (HCPs). This would serve as a training program for disaster first responders. Graduates of the program would receive additional training to become HCPs similar to physician assistant (PA) and nurse practitioner (NP) programs in the US. Morocco is uniquely positioned to accomplish this due to its location, political stability, and ties with other African nations.

The goal of the Moroccan regional education center (within the King Mohammed V Hospital) is to bring together global health experts and increase the intellectual infrastructure of not only Morocco, but also offer this training program to interested countries within the AU. Advancement of the regional education center will require legislative changes to expand prescriptive privileges and scope of practice within each country. The medical element of the SPP as presently constituted without the regional education center will continue its humanitarian goals, but the proposed creation of the regional education center will educate participants to serve the rural communities within each participating country. Eventually the entire educational program will be the responsibility of the Moroccan military and the AU participants. This will require reprioritizing resources from the provision of humanitarian health care services to an HCP education approach.

Disaster Response

Deficits in disaster response capabilities have been identified by members of the Moroccan military with the assistance of the UTNG. The most glaring deficit identified was the disparity in training between military and civilian first responders. Thus, a training program was initiated by the Moroccan military and the UTNG that combined internationally recognized, durable, robust emergency training programs. These programs consisted of, but were not limited to, parts or entire programs of the following: basic disaster life support, advanced disaster life support, disaster casualty care, and advanced trauma life support. The goal of this training was to improve communication, reduce mortality, and create strike teams, which can quickly provide health care independent of a hospital during a disaster.

Patients can overwhelm hospitals in a disaster when need exceeds resources. In 1996, Mallonee reported that at least 67% of the patients who sought care at a hospital during the Oklahoma City bombing disaster did not need advanced medical treatment.20 Such patients could be seen at an identified casualty collection point by a strike team and treated and released rather than traveling to the hospital and using staff and resources that could be used more judiciously for the more seriously injured.21 These teams consist of trained first responders with an experienced HCP (physician, PA, NP) and a nurse and are trained to operate for up to 72 hours in a predetermined location and serve as a “filter” for the hospital. Their role is to treat and release the less severely injured and refer only the more severely injured to the hospital after basic stabilization, thus preserving precious resources necessary for the more seriously injured.

This disaster response training program was offered to the Moroccan military, ministry of health and ministry of tourism, and quickly turned into an Africa-wide interest. A regional training center was proposed. This was assisted with the cooperation of Weber State University in Ogden Utah, Utah Valley University in Orem, and private interests in a public/private/military state partnership. Program supplies and didactic instruction were and will be provided by the UTNG and supplemented through the DoD Africa command. Instruction will be a cooperative effort agreed on between the UTNG and the Moroccan military medical specialists within their specific area of expertise.

Underserved Communities

Finally, from this pool of interested strike team members, a health care provider school will be formed to educate, certify, and service the needs of the underserved communities in Morocco and interested AU countries. This program will be similar to the PA and NP programs in the US and will be geared to those graduates from the previous programs with intense classroom instruction for one year followed by a year of one-on-one preceptorship with an experienced physician. The goal of the program is to prepare individuals with patient care experience to fulfill a bigger role in health care in an underserved (usually austere, rural) area that currently has minimal health care presence. This fills a need identified by the World Bank in 2015 that the Moroccan government needs to respond to the demand for improved access to and quality of health care services—particularly to the rural poor.17

The Moroccan military has a presence in many medically underserved areas. The logical fit for the HCP program will be drawn from a pool of active-duty military individuals who express an interest and qualify through attendance in all phases of the training.

Conclusion

This program of disaster medical education, strike teams, and HCPs is currently training more than 200 students a year throughout Morocco. The proposed direction of this cooperative program to produce HCPs in rural areas will increase access to health care for the Moroccan people who are now underserved. Morocco, as a health care training hub in Africa, will increase access to health care for interested African countries. The goal politically will be to reduce feelings of government indifference in vulnerable populations and reduce recruitment into radical ideologies.

1. Nahon M, Michaloux M. L’organisation de la réponse de la sécurité civile: le dispositif ORSEC Organisation of civilian emergency services: The ORSEC plan. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211423816300499#! Published July 2016. Accessed October 7, 2019.

2. Berman E. Hamas, Taliban and the Jewish underground: an economist's view of radical religious militias. NBER Working Paper No. w10004. https://ssrn.com/abstract=450885. Published September 2003. Accessed October 7, 2019.

3. Jordan J. Attacking the leader. Missing the mark; why terrorist groups survive decapitation strikes. Int Secur. 2014;38(4):7-38.

4. Grynkewich A. Welfare as warfare: how violent non-state groups use social services to attack the state. Stud Conflict Terrorism. 2008;31(4):350-370.

5. Marin M, Solomon H. Islamic State: understanding the nature of the beast and its funding. Contemp Rev Middle East. 2017;4(1):18-49.

6. Bressan D. November 1, 1755: the earthquake of Lisbon: wrath of god or natural disaster? Scientific American, History of Geology. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/history-of-geology/november-1-1755-the-earthquake-of-lisbon-wraith-of-god-or-natural-disaster. Published November 2011. Accessed October 7, 2019.

7. Trading Economics. Morocco unemployment rate. Second quarter statistics. August 2019. https://tradingeconomics.com/morocco/unemployment-rate. Accessed October 7, 2019.

8. Knoema World Data Atlas 2015. Morocco adult literacy rates. https://knoema.com/atlas/Morocco/topics/Education/Literacy/Adult-literacy-rate. Accessed October 4, 2019.

9. The Legatum Prosperity Index 2018. Morocco. https://www.prosperity.com/globe/morocco. Accessed October 7, 2019.

10. University of Washington, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Morocco. http://www.healthdata.org/morocco. Published 2018. Accessed October 7, 2019.

11. Oxford Business Group. Access to health care broadens in Morocco. https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/overview/forward-steps-access-care-has-broadened-and-infrastructure-improved-challenges-remain. Accessed September 12. 2019.

12. Wright NMJ, Hankins FM. Preventing radicalization and terrorism: Is there a GP response? Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(647):288-289.

13. Buhi K, Everitt K, Jones E. Might depression psychosocial adversity, and limited social assets explain vulnerability to and resistance against violent radicalization? PlosOne. 2014;9(9):e105918.

14. DeAngelis T. Understanding terrorism. apa.org/monitor/2009/11/terrorism. Published November 2009. Accessed October 14, 2019.

15. Victoroff J. The mind of the terrorist: a review and critique of psychological approaches. J Conflict Resolut. 2005;49(1):3-42.

16. Lafree G, Ackerman G. The empirical study of terrorism: social and legal research. Ann Rev Law Soc Sci. 2009;5:347-374.

17. World Bank. Morocco—improving primary health in rural areas program-for-results project (English). http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/716821468274482723/Morocco-Improving-Primary-Health-in-Rural-Areas-Program-for-Results-Project. Published 2015. Accessed September 16, 2019.

18. Royaume du Maroc, Ministère de la Santé. Livre blanc: pour une nouvelle gouvernance du secteur de la santé. Paper presented at: 2nd National Health Conference; July 1-3, 2013; Marrakesh, Morocco.

19. Buhi K, Hicks MH, Lashley M, Jones E. A public health approach to understanding and preventing violent radicalization. BMC Med. 2012;10:16.

20. Mallonee S, Sahriat S, Stennies G, Waxweiler R, Hogan D, Jordan F. Physical injuries and fatalities resulting from the Oklahoma City bombing. JAMA. 1996;276(5):382-387.

21. Ushizawa H, Foxwell AR, Bice S, et al. Needs for disaster medicine: lessons from the field of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Western Pac Surveil Response J. 2013;4(1):51-55.

1. Nahon M, Michaloux M. L’organisation de la réponse de la sécurité civile: le dispositif ORSEC Organisation of civilian emergency services: The ORSEC plan. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211423816300499#! Published July 2016. Accessed October 7, 2019.

2. Berman E. Hamas, Taliban and the Jewish underground: an economist's view of radical religious militias. NBER Working Paper No. w10004. https://ssrn.com/abstract=450885. Published September 2003. Accessed October 7, 2019.

3. Jordan J. Attacking the leader. Missing the mark; why terrorist groups survive decapitation strikes. Int Secur. 2014;38(4):7-38.

4. Grynkewich A. Welfare as warfare: how violent non-state groups use social services to attack the state. Stud Conflict Terrorism. 2008;31(4):350-370.

5. Marin M, Solomon H. Islamic State: understanding the nature of the beast and its funding. Contemp Rev Middle East. 2017;4(1):18-49.

6. Bressan D. November 1, 1755: the earthquake of Lisbon: wrath of god or natural disaster? Scientific American, History of Geology. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/history-of-geology/november-1-1755-the-earthquake-of-lisbon-wraith-of-god-or-natural-disaster. Published November 2011. Accessed October 7, 2019.

7. Trading Economics. Morocco unemployment rate. Second quarter statistics. August 2019. https://tradingeconomics.com/morocco/unemployment-rate. Accessed October 7, 2019.

8. Knoema World Data Atlas 2015. Morocco adult literacy rates. https://knoema.com/atlas/Morocco/topics/Education/Literacy/Adult-literacy-rate. Accessed October 4, 2019.

9. The Legatum Prosperity Index 2018. Morocco. https://www.prosperity.com/globe/morocco. Accessed October 7, 2019.

10. University of Washington, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Morocco. http://www.healthdata.org/morocco. Published 2018. Accessed October 7, 2019.

11. Oxford Business Group. Access to health care broadens in Morocco. https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/overview/forward-steps-access-care-has-broadened-and-infrastructure-improved-challenges-remain. Accessed September 12. 2019.

12. Wright NMJ, Hankins FM. Preventing radicalization and terrorism: Is there a GP response? Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(647):288-289.

13. Buhi K, Everitt K, Jones E. Might depression psychosocial adversity, and limited social assets explain vulnerability to and resistance against violent radicalization? PlosOne. 2014;9(9):e105918.

14. DeAngelis T. Understanding terrorism. apa.org/monitor/2009/11/terrorism. Published November 2009. Accessed October 14, 2019.

15. Victoroff J. The mind of the terrorist: a review and critique of psychological approaches. J Conflict Resolut. 2005;49(1):3-42.

16. Lafree G, Ackerman G. The empirical study of terrorism: social and legal research. Ann Rev Law Soc Sci. 2009;5:347-374.

17. World Bank. Morocco—improving primary health in rural areas program-for-results project (English). http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/716821468274482723/Morocco-Improving-Primary-Health-in-Rural-Areas-Program-for-Results-Project. Published 2015. Accessed September 16, 2019.

18. Royaume du Maroc, Ministère de la Santé. Livre blanc: pour une nouvelle gouvernance du secteur de la santé. Paper presented at: 2nd National Health Conference; July 1-3, 2013; Marrakesh, Morocco.

19. Buhi K, Hicks MH, Lashley M, Jones E. A public health approach to understanding and preventing violent radicalization. BMC Med. 2012;10:16.

20. Mallonee S, Sahriat S, Stennies G, Waxweiler R, Hogan D, Jordan F. Physical injuries and fatalities resulting from the Oklahoma City bombing. JAMA. 1996;276(5):382-387.

21. Ushizawa H, Foxwell AR, Bice S, et al. Needs for disaster medicine: lessons from the field of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Western Pac Surveil Response J. 2013;4(1):51-55.

CDC, FDA in hot pursuit of source of vaping lung injuries

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is providing frequent updates of the wide-ranging and aggressive investigation of the cases and deaths linked to vaping, and although a definitive cause remains unknown, evidence is accumulating to implicate tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing devices. The investigation is being conducted in concert with the Food and Drug Administration, many state and local health departments, and public health and clinical partners.

The acronym EVALI has been developed by CDC to refer to e-cigarette, or vaping products use–associated lung injury. In a report summarizing data up to Oct. 22, CDC reported 1,604 EVALI cases and 34 deaths. These cases have occurred in all U.S. states (except Alaska), the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The CDC also published a report in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly report on characteristics of those patients who have died from EVALI-based symptoms as of Oct. 15, 2019.

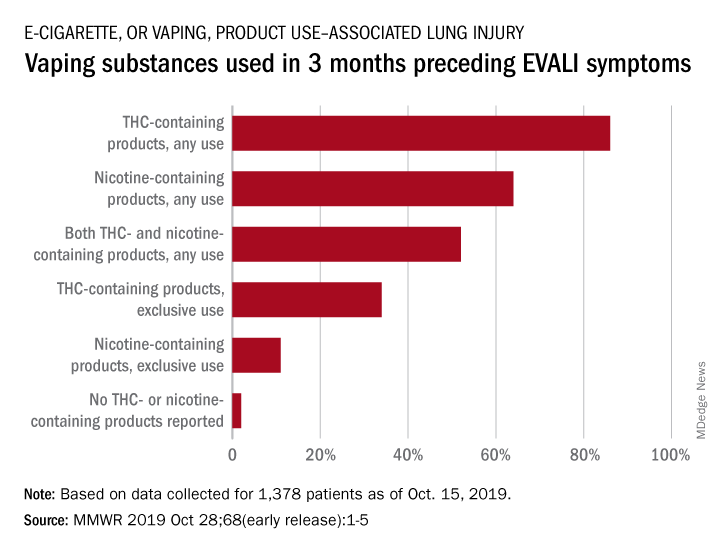

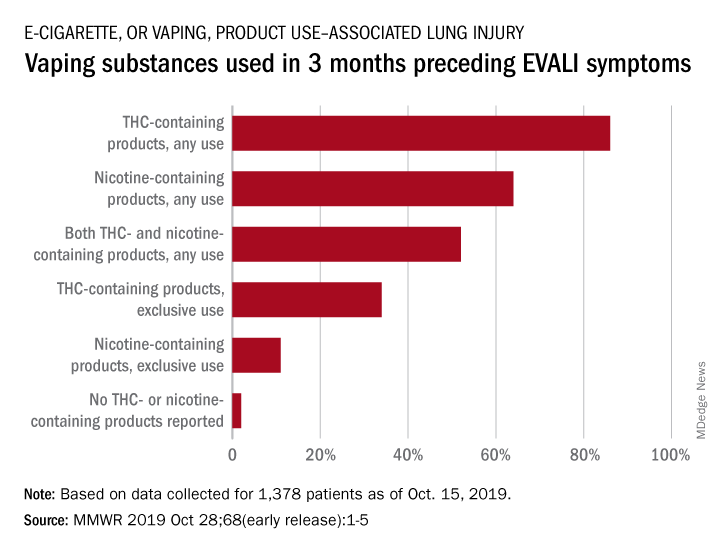

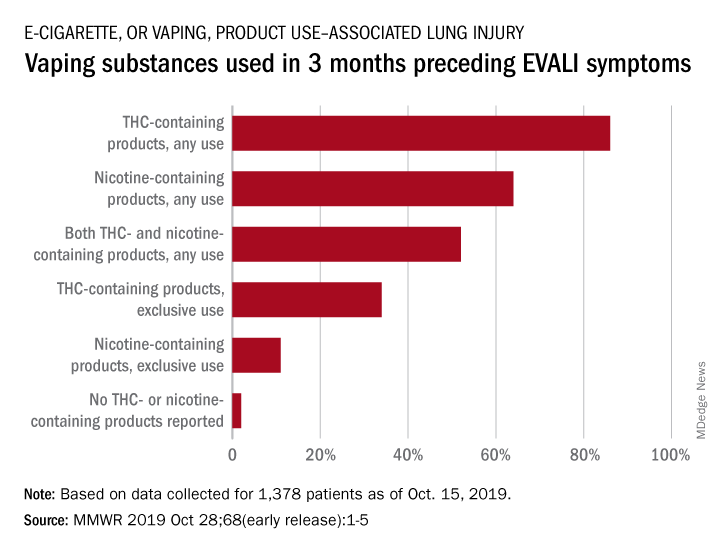

With data available for more than 867 patients with EVALI, about 86% had a history of using e-cigarette or vaping products that contained THC in the previous 90 days; 64% reported using nicotine-containing products; 34% reported exclusive use of THC-containing products, and 11% reported exclusive use of nicotine-containing products; 52% reported use of both.

In a telebriefing on Oct. 25, Anne Schuchat, MD, CDC principal deputy director, said, “The data do continue to point towards THC-containing products as the source of the vast majority of individuals’ lung injury. There are continuing cases that do not report that history. But I’d like to stress that we don’t know what the risky material or substance is. THC may be a marker for a way that cartridges were prepared or the way that the devices are producing harm. Whether there are similar activities going on with cartridges that don’t contain THC, for instance, remains to be seen. So, I think we are seeing the THC as a marker for products that are risky.”

EVALI deaths

Among the 29 deaths reported as of Oct. 15, 59% (17) were male; the median age was 45 years (range, 17-75 years), 55 years (range, 17-71 years) among males, and 43 years (range, 27-75 years) among females; the age difference between males and females was not statistically significant. Patients who died tended to be older than patients who survived. Among 19 EVALI patients who died and for whom data on substance use was available, the use of any THC-containing products was reported by patients or proxies for 84% (16), including 63% (12) who exclusively used THC-containing products. Use of any nicotine-containing products was reported for 37% (7), including 16% (3) who exclusively used nicotine-containing products. Use of both THC- and nicotine-containing products was reported in four of those who died.

Investigation update

Mitch Zeller, JD, director, Center for Tobacco Products at the Food and Drug Administration, participated in the telebriefing and provided an update on the ongoing investigation. “State of the art methods are being used to assess the presence of a broad range of chemicals including nicotine, THC, and other cannabinoids, opioids, additives, pesticides, poisons and toxins,” he said. “FDA has received or collected over 900 samples from 25 states to date. Those numbers continue to increase. The samples [were] collected directly from consumers, hospitals, and from state offices include vaping devices and products that contain liquid as well as packaging and some nearly empty containers.” He cautioned that identifying the substance is “but one piece of the puzzle and will not necessarily answer questions about causality.” He also noted that the self-reports of THC and/or nicotine could mean that there is misreported data, because reports in many cases are coming from teens and from jurisdictions in which THC is not legal.

The issue of whether EVALI has been seen in recent years but not recognized or whether EVALI is a new phenomenon was raised by a caller at the telebriefing. Dr. Schuchat responded, “We are aware of older cases that look similar to what we are seeing now. But we do not believe that this outbreak or surge in cases is due to better recognition.” She suggested that some evidence points to cutting agents being introduced to increase profits of e-cigarettes and that risky and unknown substances have been introduced into the supply chain.

A “handful” of cases of readmission have been reported, and the CDC is currently investigating whether these cases included patients who took up vaping again or had some other possible contributing factor. Dr. Schuchat cautioned recovering patients not to resume vaping because of the risk of readmission and the probability that their lungs will remain in a weakened state.

Clinical guidance update

The CDC provided detailed interim clinical guidance on evaluating and caring for patients with EVALI. The recommendations focus on patient history, lab testing, criteria for hospitalization, and follow-up for these patients.

Obtaining a detailed history of patients presenting with suspected EVALI is especially important for this patient population, given the many unknowns surrounding this condition, according to the CDC. The updated guidance states, “All health care providers evaluating patients for EVALI should ask about the use of e-cigarette or vaping products, and ideally should ask about types of substances used (e.g.,THC, cannabis [oil, dabs], nicotine, modified products or the addition of substances not intended by the manufacturer); product source, specific product brand and name; duration and frequency of use, time of last use; product delivery system and method of use (aerosolization, dabbing, or dripping).” The approach recommended for soliciting accurate information is “empathetic, nonjudgmental” and, the guidelines say, patients should be questioned in private regarding sensitive information to assure confidentiality.

A respiratory virus panel is recommended for all suspected EVALI patients, although at this time, these tests cannot be used to distinguish EVALI from infectious etiologies. All patients should be considered for urine toxicology testing, including testing for THC.

Imaging guidance for suspected EVALI patients includes chest x-ray, with additional CT scan when the x-ray result does not correlate with clinical findings or to evaluate severe or worsening disease.

Recommended criteria for hospitalization of patients with suspected EVALI are those patients with decreased O2 saturation (less than 95%) on room air, in respiratory distress, or with comorbidities that compromise pulmonary reserve. As of Oct. 8, 96% of patients with suspected EVALI reported to the CDC have been hospitalized.

As for medical treatment of these patients, corticosteroids have been found to be helpful. The statement noted, “Among 140 cases reported nationally to CDC that received corticosteroids, 82% of patients improved.”

The natural progression of this injury is not known, however, and it is possible that patients might recover without corticosteroids. Given the unknown etiology of the disease and “because the diagnosis remains one of exclusion, aggressive empiric therapy with corticosteroids, antimicrobial, and antiviral therapy might be warranted for patients with severe illness. A range of corticosteroid doses, durations, and taper plans might be considered on a case-by-case basis.”

The report concluded with a strong recommendation that patients hospitalized with EVALI are followed closely with a visit 1-2 weeks after discharge and again with additional testing 1-2 months later. Health care providers are also advised to consult medical specialists, in particular pulmonologists, who can offer further evaluation, recommend empiric treatment, and review indications for bronchoscopy.

CPT coding for EVALI

CDC has issued coding guidance to help track EVALI. The document was posted on the CDC website. The coding guidance is consistent with current clinical knowledge about EVALI-related disorders and is intended for use in conjunction with current ICD-10-CM classifications.

The following conditions associated with EVALI are covered in the new coding guidance:

- Bronchitis and pneumonitis caused by chemicals, gases, and fumes; including chemical pneumonitis; J68.0.

- Pneumonitis caused by inhalation of oils and essences; including lipoid pneumonia; J69.1.

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome; J80.

- Pulmonary eosinophilia, not elsewhere classified; J82.

- Acute interstitial pneumonitis; J84.114.

The document notes that the coding guidance has been approved by the National Center for Health Statistics, the American Health Information Management Association, the American Hospital Association, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Investigation continues

Mr. Zeller cautioned that this investigation will not be concluded in the near future. He noted, “We are committed to working to [solve the mystery] just as quickly as we can, but we also recognize that it will likely take some time. Importantly, the diversity of the patients and the products or substances they have reported using and the samples being tested may mean ultimately that there are multiple causes of these injuries.”

Richard Franki and Gregory Twachtman contributed to this story.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is providing frequent updates of the wide-ranging and aggressive investigation of the cases and deaths linked to vaping, and although a definitive cause remains unknown, evidence is accumulating to implicate tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing devices. The investigation is being conducted in concert with the Food and Drug Administration, many state and local health departments, and public health and clinical partners.

The acronym EVALI has been developed by CDC to refer to e-cigarette, or vaping products use–associated lung injury. In a report summarizing data up to Oct. 22, CDC reported 1,604 EVALI cases and 34 deaths. These cases have occurred in all U.S. states (except Alaska), the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The CDC also published a report in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly report on characteristics of those patients who have died from EVALI-based symptoms as of Oct. 15, 2019.

With data available for more than 867 patients with EVALI, about 86% had a history of using e-cigarette or vaping products that contained THC in the previous 90 days; 64% reported using nicotine-containing products; 34% reported exclusive use of THC-containing products, and 11% reported exclusive use of nicotine-containing products; 52% reported use of both.

In a telebriefing on Oct. 25, Anne Schuchat, MD, CDC principal deputy director, said, “The data do continue to point towards THC-containing products as the source of the vast majority of individuals’ lung injury. There are continuing cases that do not report that history. But I’d like to stress that we don’t know what the risky material or substance is. THC may be a marker for a way that cartridges were prepared or the way that the devices are producing harm. Whether there are similar activities going on with cartridges that don’t contain THC, for instance, remains to be seen. So, I think we are seeing the THC as a marker for products that are risky.”

EVALI deaths

Among the 29 deaths reported as of Oct. 15, 59% (17) were male; the median age was 45 years (range, 17-75 years), 55 years (range, 17-71 years) among males, and 43 years (range, 27-75 years) among females; the age difference between males and females was not statistically significant. Patients who died tended to be older than patients who survived. Among 19 EVALI patients who died and for whom data on substance use was available, the use of any THC-containing products was reported by patients or proxies for 84% (16), including 63% (12) who exclusively used THC-containing products. Use of any nicotine-containing products was reported for 37% (7), including 16% (3) who exclusively used nicotine-containing products. Use of both THC- and nicotine-containing products was reported in four of those who died.

Investigation update

Mitch Zeller, JD, director, Center for Tobacco Products at the Food and Drug Administration, participated in the telebriefing and provided an update on the ongoing investigation. “State of the art methods are being used to assess the presence of a broad range of chemicals including nicotine, THC, and other cannabinoids, opioids, additives, pesticides, poisons and toxins,” he said. “FDA has received or collected over 900 samples from 25 states to date. Those numbers continue to increase. The samples [were] collected directly from consumers, hospitals, and from state offices include vaping devices and products that contain liquid as well as packaging and some nearly empty containers.” He cautioned that identifying the substance is “but one piece of the puzzle and will not necessarily answer questions about causality.” He also noted that the self-reports of THC and/or nicotine could mean that there is misreported data, because reports in many cases are coming from teens and from jurisdictions in which THC is not legal.

The issue of whether EVALI has been seen in recent years but not recognized or whether EVALI is a new phenomenon was raised by a caller at the telebriefing. Dr. Schuchat responded, “We are aware of older cases that look similar to what we are seeing now. But we do not believe that this outbreak or surge in cases is due to better recognition.” She suggested that some evidence points to cutting agents being introduced to increase profits of e-cigarettes and that risky and unknown substances have been introduced into the supply chain.

A “handful” of cases of readmission have been reported, and the CDC is currently investigating whether these cases included patients who took up vaping again or had some other possible contributing factor. Dr. Schuchat cautioned recovering patients not to resume vaping because of the risk of readmission and the probability that their lungs will remain in a weakened state.

Clinical guidance update

The CDC provided detailed interim clinical guidance on evaluating and caring for patients with EVALI. The recommendations focus on patient history, lab testing, criteria for hospitalization, and follow-up for these patients.

Obtaining a detailed history of patients presenting with suspected EVALI is especially important for this patient population, given the many unknowns surrounding this condition, according to the CDC. The updated guidance states, “All health care providers evaluating patients for EVALI should ask about the use of e-cigarette or vaping products, and ideally should ask about types of substances used (e.g.,THC, cannabis [oil, dabs], nicotine, modified products or the addition of substances not intended by the manufacturer); product source, specific product brand and name; duration and frequency of use, time of last use; product delivery system and method of use (aerosolization, dabbing, or dripping).” The approach recommended for soliciting accurate information is “empathetic, nonjudgmental” and, the guidelines say, patients should be questioned in private regarding sensitive information to assure confidentiality.

A respiratory virus panel is recommended for all suspected EVALI patients, although at this time, these tests cannot be used to distinguish EVALI from infectious etiologies. All patients should be considered for urine toxicology testing, including testing for THC.

Imaging guidance for suspected EVALI patients includes chest x-ray, with additional CT scan when the x-ray result does not correlate with clinical findings or to evaluate severe or worsening disease.

Recommended criteria for hospitalization of patients with suspected EVALI are those patients with decreased O2 saturation (less than 95%) on room air, in respiratory distress, or with comorbidities that compromise pulmonary reserve. As of Oct. 8, 96% of patients with suspected EVALI reported to the CDC have been hospitalized.

As for medical treatment of these patients, corticosteroids have been found to be helpful. The statement noted, “Among 140 cases reported nationally to CDC that received corticosteroids, 82% of patients improved.”

The natural progression of this injury is not known, however, and it is possible that patients might recover without corticosteroids. Given the unknown etiology of the disease and “because the diagnosis remains one of exclusion, aggressive empiric therapy with corticosteroids, antimicrobial, and antiviral therapy might be warranted for patients with severe illness. A range of corticosteroid doses, durations, and taper plans might be considered on a case-by-case basis.”

The report concluded with a strong recommendation that patients hospitalized with EVALI are followed closely with a visit 1-2 weeks after discharge and again with additional testing 1-2 months later. Health care providers are also advised to consult medical specialists, in particular pulmonologists, who can offer further evaluation, recommend empiric treatment, and review indications for bronchoscopy.

CPT coding for EVALI

CDC has issued coding guidance to help track EVALI. The document was posted on the CDC website. The coding guidance is consistent with current clinical knowledge about EVALI-related disorders and is intended for use in conjunction with current ICD-10-CM classifications.

The following conditions associated with EVALI are covered in the new coding guidance:

- Bronchitis and pneumonitis caused by chemicals, gases, and fumes; including chemical pneumonitis; J68.0.

- Pneumonitis caused by inhalation of oils and essences; including lipoid pneumonia; J69.1.

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome; J80.

- Pulmonary eosinophilia, not elsewhere classified; J82.

- Acute interstitial pneumonitis; J84.114.

The document notes that the coding guidance has been approved by the National Center for Health Statistics, the American Health Information Management Association, the American Hospital Association, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Investigation continues

Mr. Zeller cautioned that this investigation will not be concluded in the near future. He noted, “We are committed to working to [solve the mystery] just as quickly as we can, but we also recognize that it will likely take some time. Importantly, the diversity of the patients and the products or substances they have reported using and the samples being tested may mean ultimately that there are multiple causes of these injuries.”

Richard Franki and Gregory Twachtman contributed to this story.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is providing frequent updates of the wide-ranging and aggressive investigation of the cases and deaths linked to vaping, and although a definitive cause remains unknown, evidence is accumulating to implicate tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing devices. The investigation is being conducted in concert with the Food and Drug Administration, many state and local health departments, and public health and clinical partners.

The acronym EVALI has been developed by CDC to refer to e-cigarette, or vaping products use–associated lung injury. In a report summarizing data up to Oct. 22, CDC reported 1,604 EVALI cases and 34 deaths. These cases have occurred in all U.S. states (except Alaska), the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The CDC also published a report in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly report on characteristics of those patients who have died from EVALI-based symptoms as of Oct. 15, 2019.

With data available for more than 867 patients with EVALI, about 86% had a history of using e-cigarette or vaping products that contained THC in the previous 90 days; 64% reported using nicotine-containing products; 34% reported exclusive use of THC-containing products, and 11% reported exclusive use of nicotine-containing products; 52% reported use of both.

In a telebriefing on Oct. 25, Anne Schuchat, MD, CDC principal deputy director, said, “The data do continue to point towards THC-containing products as the source of the vast majority of individuals’ lung injury. There are continuing cases that do not report that history. But I’d like to stress that we don’t know what the risky material or substance is. THC may be a marker for a way that cartridges were prepared or the way that the devices are producing harm. Whether there are similar activities going on with cartridges that don’t contain THC, for instance, remains to be seen. So, I think we are seeing the THC as a marker for products that are risky.”

EVALI deaths

Among the 29 deaths reported as of Oct. 15, 59% (17) were male; the median age was 45 years (range, 17-75 years), 55 years (range, 17-71 years) among males, and 43 years (range, 27-75 years) among females; the age difference between males and females was not statistically significant. Patients who died tended to be older than patients who survived. Among 19 EVALI patients who died and for whom data on substance use was available, the use of any THC-containing products was reported by patients or proxies for 84% (16), including 63% (12) who exclusively used THC-containing products. Use of any nicotine-containing products was reported for 37% (7), including 16% (3) who exclusively used nicotine-containing products. Use of both THC- and nicotine-containing products was reported in four of those who died.

Investigation update

Mitch Zeller, JD, director, Center for Tobacco Products at the Food and Drug Administration, participated in the telebriefing and provided an update on the ongoing investigation. “State of the art methods are being used to assess the presence of a broad range of chemicals including nicotine, THC, and other cannabinoids, opioids, additives, pesticides, poisons and toxins,” he said. “FDA has received or collected over 900 samples from 25 states to date. Those numbers continue to increase. The samples [were] collected directly from consumers, hospitals, and from state offices include vaping devices and products that contain liquid as well as packaging and some nearly empty containers.” He cautioned that identifying the substance is “but one piece of the puzzle and will not necessarily answer questions about causality.” He also noted that the self-reports of THC and/or nicotine could mean that there is misreported data, because reports in many cases are coming from teens and from jurisdictions in which THC is not legal.

The issue of whether EVALI has been seen in recent years but not recognized or whether EVALI is a new phenomenon was raised by a caller at the telebriefing. Dr. Schuchat responded, “We are aware of older cases that look similar to what we are seeing now. But we do not believe that this outbreak or surge in cases is due to better recognition.” She suggested that some evidence points to cutting agents being introduced to increase profits of e-cigarettes and that risky and unknown substances have been introduced into the supply chain.

A “handful” of cases of readmission have been reported, and the CDC is currently investigating whether these cases included patients who took up vaping again or had some other possible contributing factor. Dr. Schuchat cautioned recovering patients not to resume vaping because of the risk of readmission and the probability that their lungs will remain in a weakened state.