User login

An Algorithm to Identify PrEP-Potential Patients

Health care providers who do not have the time or tools to screen patients for HIV risk also may not be prescribing preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP). But help is on the way: NIH-funded researchers have come up with novel computerized methods to identify the patients PrEP could benefit.

In 2 separate studies, the researchers developed and validated algorithms that analyze electronic health records (EHR). In the first study, Harvard researchers used machine learning to create an HIV prediction algorithm using 2007 to 2015 data from > 1 million patients in Massachusetts. The model included variables such as diagnosis codes for HIV counseling or sexually transmitted infections (STIs), laboratory tests for HIV or STIs, and prescriptions for medications related to treating STIs.

The model was validated using data from nearly 600,000 other patients treated between 2011 and 2016. The prediction algorithm successfully distinguished with high precision between patients who did or did not acquire HIV and between those who did or did not receive a PrEP prescription.

The researchers found hundreds of potential missed opportunities. They point to > 9,500 people in the 2016 dataset with particularly high-risk scores who were not prescribed PrEP. A “striking outcome,” the researchers say, is that their analysis suggests that nearly 40% of new HIV cases might have been averted had clinicians received alerts to discuss and offer PrEP to patients with the highest 2% of risk scores.

In the second study, researchers used the EHRs of > 3.7 million patients who entered the Kaiser Permanente System Northern California between 2007 and 2014 to develop a model to predict HIV incidence, then validated the model with data from between 2015 and 2017. Of the original patient group, 784 developed HIV within 3 years of baseline. The study found that the model identified nearly half of the incident HIV cases among males by flagging only 2% of the general patient population.

Embedding the algorithm into the EHR, the lead investigator says, “could prompt providers to discuss PrEP with patients who are most likely to benefit.”

Health care providers who do not have the time or tools to screen patients for HIV risk also may not be prescribing preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP). But help is on the way: NIH-funded researchers have come up with novel computerized methods to identify the patients PrEP could benefit.

In 2 separate studies, the researchers developed and validated algorithms that analyze electronic health records (EHR). In the first study, Harvard researchers used machine learning to create an HIV prediction algorithm using 2007 to 2015 data from > 1 million patients in Massachusetts. The model included variables such as diagnosis codes for HIV counseling or sexually transmitted infections (STIs), laboratory tests for HIV or STIs, and prescriptions for medications related to treating STIs.

The model was validated using data from nearly 600,000 other patients treated between 2011 and 2016. The prediction algorithm successfully distinguished with high precision between patients who did or did not acquire HIV and between those who did or did not receive a PrEP prescription.

The researchers found hundreds of potential missed opportunities. They point to > 9,500 people in the 2016 dataset with particularly high-risk scores who were not prescribed PrEP. A “striking outcome,” the researchers say, is that their analysis suggests that nearly 40% of new HIV cases might have been averted had clinicians received alerts to discuss and offer PrEP to patients with the highest 2% of risk scores.

In the second study, researchers used the EHRs of > 3.7 million patients who entered the Kaiser Permanente System Northern California between 2007 and 2014 to develop a model to predict HIV incidence, then validated the model with data from between 2015 and 2017. Of the original patient group, 784 developed HIV within 3 years of baseline. The study found that the model identified nearly half of the incident HIV cases among males by flagging only 2% of the general patient population.

Embedding the algorithm into the EHR, the lead investigator says, “could prompt providers to discuss PrEP with patients who are most likely to benefit.”

Health care providers who do not have the time or tools to screen patients for HIV risk also may not be prescribing preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP). But help is on the way: NIH-funded researchers have come up with novel computerized methods to identify the patients PrEP could benefit.

In 2 separate studies, the researchers developed and validated algorithms that analyze electronic health records (EHR). In the first study, Harvard researchers used machine learning to create an HIV prediction algorithm using 2007 to 2015 data from > 1 million patients in Massachusetts. The model included variables such as diagnosis codes for HIV counseling or sexually transmitted infections (STIs), laboratory tests for HIV or STIs, and prescriptions for medications related to treating STIs.

The model was validated using data from nearly 600,000 other patients treated between 2011 and 2016. The prediction algorithm successfully distinguished with high precision between patients who did or did not acquire HIV and between those who did or did not receive a PrEP prescription.

The researchers found hundreds of potential missed opportunities. They point to > 9,500 people in the 2016 dataset with particularly high-risk scores who were not prescribed PrEP. A “striking outcome,” the researchers say, is that their analysis suggests that nearly 40% of new HIV cases might have been averted had clinicians received alerts to discuss and offer PrEP to patients with the highest 2% of risk scores.

In the second study, researchers used the EHRs of > 3.7 million patients who entered the Kaiser Permanente System Northern California between 2007 and 2014 to develop a model to predict HIV incidence, then validated the model with data from between 2015 and 2017. Of the original patient group, 784 developed HIV within 3 years of baseline. The study found that the model identified nearly half of the incident HIV cases among males by flagging only 2% of the general patient population.

Embedding the algorithm into the EHR, the lead investigator says, “could prompt providers to discuss PrEP with patients who are most likely to benefit.”

VA Urges All Veterans to Get Tested

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has a well-established National HIV Program, says Dr. Richard Stone, executive in charge of the VHA. In fact, he notes, the VA is the single largest provider of HIV care in America and has treated 31,000 veterans for HIV.

Thus, the VA plays a critical role in the effort to establish tools and resources to eradicate HIV in the US, Stone says, “one veteran at a time.” To realize this “ambitious but achievable target,” the VA is:

- Offering HIV testing at least once to every veteran and more often to those at risk;

- Rapidly linking those who are diagnosed to effective treatment;

- Deploying an HIV health force to hard-hit areas of the country, expanding timely access to high-quality HIV care and prevention across the VA’s integrated network, with both face-to-face encounters and telehealth; and

- Offering pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) when clinically appropriate.

The primary goal, Stone says, is for veterans with HIV or at risk for HIV to be able to access the best care “safely and free from stigma and discrimination.”

Resources and educational tools are available at www.hiv.va.gov, including recently updated fact sheets and videos for patients about PrEP

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has a well-established National HIV Program, says Dr. Richard Stone, executive in charge of the VHA. In fact, he notes, the VA is the single largest provider of HIV care in America and has treated 31,000 veterans for HIV.

Thus, the VA plays a critical role in the effort to establish tools and resources to eradicate HIV in the US, Stone says, “one veteran at a time.” To realize this “ambitious but achievable target,” the VA is:

- Offering HIV testing at least once to every veteran and more often to those at risk;

- Rapidly linking those who are diagnosed to effective treatment;

- Deploying an HIV health force to hard-hit areas of the country, expanding timely access to high-quality HIV care and prevention across the VA’s integrated network, with both face-to-face encounters and telehealth; and

- Offering pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) when clinically appropriate.

The primary goal, Stone says, is for veterans with HIV or at risk for HIV to be able to access the best care “safely and free from stigma and discrimination.”

Resources and educational tools are available at www.hiv.va.gov, including recently updated fact sheets and videos for patients about PrEP

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has a well-established National HIV Program, says Dr. Richard Stone, executive in charge of the VHA. In fact, he notes, the VA is the single largest provider of HIV care in America and has treated 31,000 veterans for HIV.

Thus, the VA plays a critical role in the effort to establish tools and resources to eradicate HIV in the US, Stone says, “one veteran at a time.” To realize this “ambitious but achievable target,” the VA is:

- Offering HIV testing at least once to every veteran and more often to those at risk;

- Rapidly linking those who are diagnosed to effective treatment;

- Deploying an HIV health force to hard-hit areas of the country, expanding timely access to high-quality HIV care and prevention across the VA’s integrated network, with both face-to-face encounters and telehealth; and

- Offering pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) when clinically appropriate.

The primary goal, Stone says, is for veterans with HIV or at risk for HIV to be able to access the best care “safely and free from stigma and discrimination.”

Resources and educational tools are available at www.hiv.va.gov, including recently updated fact sheets and videos for patients about PrEP

The FDA has revised its guidance on fish consumption

The revision touts the health benefits of fish and shellfish and promotes safer fish choices for those who should limit mercury exposure – including women who are or might become pregnant, women who are breastfeeding, and young children.

Those individuals should avoid commercial fish with the highest levels of mercury and should instead choose from “the many types of fish that are lower in mercury – including ones commonly found in grocery stores, such as salmon, shrimp, pollock, canned light tuna, tilapia, catfish, and cod,” according to an FDA press statement.

The potential health benefits of eating fish were highlighted in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Department of Agriculture 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and in 2017 the FDA and the Environmental Protection Agency released advice on fish consumption, including a user-friendly reference chart regarding mercury levels in various types of fish.

Although the information in the chart has not changed, the FDA revised its advice to expand on the “information about the benefits of fish as part of healthy eating patterns by promoting the science-based recommendations of the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.”

The advice calls for consumption of at least 8 ounces of seafood per week for adults (less for children) based on a 2,000 calorie diet, and for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, 8-12 ounces of a variety of seafood per week selected from choices lower in mercury.

“The FDA’s revised advice highlights the many nutrients found in fish, several of which have important roles in growth and development during pregnancy and early childhood. It also highlights the potential health benefits of eating fish as part of a healthy eating pattern, particularly for improving heart health and lowering the risk of obesity,” the press release states.

Despite these benefits – and the recommendations for intake – concerns about mercury in fish have led many pregnant women in the United States to consume far less than the recommended amount of seafood, according to Susan Mayne, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition.

“Our goal is to make sure Americans are equipped with this knowledge so that they can reap the benefits of eating fish, while choosing types of fish that are safe for them and their families to eat,” Dr. Mayne said in the FDA statement.

In response to the revised guidance, John S. Cullen, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said that all women should be counseled to eat a well-balanced and varied diet including meats, dairy products, fruits, vegetables, and grains, and pregnant women should limit their intake of fish and seafood products to 8-12 ounces, or about 2-3 fish meals, per week.

Pregnant women may eat salmon in moderation, but should avoid raw seafood of any type because of possible contamination with parasites and Norwalk-like viruses, he said, adding that seafood like shark, swordfish, king mackerel, tilefish, Bigeye (Ahi) tuna steaks, and other long-lived fish high on the food chain should be avoided completely because of high mercury levels.

“While the AAFP did not review the revised advice to the dietary guidelines, family physicians are on the front lines encouraging healthy nutrition for pregnant and breastfeeding women and young children. It’s an ongoing, important part of the patient-physician conversation that begins with the initial prenatal visit,” Dr. Cullen said in a statement.

Similarly, Christopher M. Zahn, MD, vice president of practice activities for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, said the FDA/EPA updated guidance is in line with ACOG recommendations.

“The guidance continues to underscore the value of eating seafood 2-3 times per week during pregnancy and the importance of avoiding fish products that are high in mercury. The additional emphasis on healthy eating patterns mirrors ACOG’s long-standing guidance on the importance of a well-balanced, varied, nutritional diet that is consistent with a woman’s access to food and food preferences,” he said in a statement, noting that “seafood is a nutrient-rich food that has proven beneficial to women and in aiding the development of a fetus throughout pregnancy.”

The revision touts the health benefits of fish and shellfish and promotes safer fish choices for those who should limit mercury exposure – including women who are or might become pregnant, women who are breastfeeding, and young children.

Those individuals should avoid commercial fish with the highest levels of mercury and should instead choose from “the many types of fish that are lower in mercury – including ones commonly found in grocery stores, such as salmon, shrimp, pollock, canned light tuna, tilapia, catfish, and cod,” according to an FDA press statement.

The potential health benefits of eating fish were highlighted in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Department of Agriculture 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and in 2017 the FDA and the Environmental Protection Agency released advice on fish consumption, including a user-friendly reference chart regarding mercury levels in various types of fish.

Although the information in the chart has not changed, the FDA revised its advice to expand on the “information about the benefits of fish as part of healthy eating patterns by promoting the science-based recommendations of the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.”

The advice calls for consumption of at least 8 ounces of seafood per week for adults (less for children) based on a 2,000 calorie diet, and for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, 8-12 ounces of a variety of seafood per week selected from choices lower in mercury.

“The FDA’s revised advice highlights the many nutrients found in fish, several of which have important roles in growth and development during pregnancy and early childhood. It also highlights the potential health benefits of eating fish as part of a healthy eating pattern, particularly for improving heart health and lowering the risk of obesity,” the press release states.

Despite these benefits – and the recommendations for intake – concerns about mercury in fish have led many pregnant women in the United States to consume far less than the recommended amount of seafood, according to Susan Mayne, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition.

“Our goal is to make sure Americans are equipped with this knowledge so that they can reap the benefits of eating fish, while choosing types of fish that are safe for them and their families to eat,” Dr. Mayne said in the FDA statement.

In response to the revised guidance, John S. Cullen, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said that all women should be counseled to eat a well-balanced and varied diet including meats, dairy products, fruits, vegetables, and grains, and pregnant women should limit their intake of fish and seafood products to 8-12 ounces, or about 2-3 fish meals, per week.

Pregnant women may eat salmon in moderation, but should avoid raw seafood of any type because of possible contamination with parasites and Norwalk-like viruses, he said, adding that seafood like shark, swordfish, king mackerel, tilefish, Bigeye (Ahi) tuna steaks, and other long-lived fish high on the food chain should be avoided completely because of high mercury levels.

“While the AAFP did not review the revised advice to the dietary guidelines, family physicians are on the front lines encouraging healthy nutrition for pregnant and breastfeeding women and young children. It’s an ongoing, important part of the patient-physician conversation that begins with the initial prenatal visit,” Dr. Cullen said in a statement.

Similarly, Christopher M. Zahn, MD, vice president of practice activities for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, said the FDA/EPA updated guidance is in line with ACOG recommendations.

“The guidance continues to underscore the value of eating seafood 2-3 times per week during pregnancy and the importance of avoiding fish products that are high in mercury. The additional emphasis on healthy eating patterns mirrors ACOG’s long-standing guidance on the importance of a well-balanced, varied, nutritional diet that is consistent with a woman’s access to food and food preferences,” he said in a statement, noting that “seafood is a nutrient-rich food that has proven beneficial to women and in aiding the development of a fetus throughout pregnancy.”

The revision touts the health benefits of fish and shellfish and promotes safer fish choices for those who should limit mercury exposure – including women who are or might become pregnant, women who are breastfeeding, and young children.

Those individuals should avoid commercial fish with the highest levels of mercury and should instead choose from “the many types of fish that are lower in mercury – including ones commonly found in grocery stores, such as salmon, shrimp, pollock, canned light tuna, tilapia, catfish, and cod,” according to an FDA press statement.

The potential health benefits of eating fish were highlighted in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Department of Agriculture 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and in 2017 the FDA and the Environmental Protection Agency released advice on fish consumption, including a user-friendly reference chart regarding mercury levels in various types of fish.

Although the information in the chart has not changed, the FDA revised its advice to expand on the “information about the benefits of fish as part of healthy eating patterns by promoting the science-based recommendations of the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.”

The advice calls for consumption of at least 8 ounces of seafood per week for adults (less for children) based on a 2,000 calorie diet, and for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, 8-12 ounces of a variety of seafood per week selected from choices lower in mercury.

“The FDA’s revised advice highlights the many nutrients found in fish, several of which have important roles in growth and development during pregnancy and early childhood. It also highlights the potential health benefits of eating fish as part of a healthy eating pattern, particularly for improving heart health and lowering the risk of obesity,” the press release states.

Despite these benefits – and the recommendations for intake – concerns about mercury in fish have led many pregnant women in the United States to consume far less than the recommended amount of seafood, according to Susan Mayne, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition.

“Our goal is to make sure Americans are equipped with this knowledge so that they can reap the benefits of eating fish, while choosing types of fish that are safe for them and their families to eat,” Dr. Mayne said in the FDA statement.

In response to the revised guidance, John S. Cullen, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said that all women should be counseled to eat a well-balanced and varied diet including meats, dairy products, fruits, vegetables, and grains, and pregnant women should limit their intake of fish and seafood products to 8-12 ounces, or about 2-3 fish meals, per week.

Pregnant women may eat salmon in moderation, but should avoid raw seafood of any type because of possible contamination with parasites and Norwalk-like viruses, he said, adding that seafood like shark, swordfish, king mackerel, tilefish, Bigeye (Ahi) tuna steaks, and other long-lived fish high on the food chain should be avoided completely because of high mercury levels.

“While the AAFP did not review the revised advice to the dietary guidelines, family physicians are on the front lines encouraging healthy nutrition for pregnant and breastfeeding women and young children. It’s an ongoing, important part of the patient-physician conversation that begins with the initial prenatal visit,” Dr. Cullen said in a statement.

Similarly, Christopher M. Zahn, MD, vice president of practice activities for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, said the FDA/EPA updated guidance is in line with ACOG recommendations.

“The guidance continues to underscore the value of eating seafood 2-3 times per week during pregnancy and the importance of avoiding fish products that are high in mercury. The additional emphasis on healthy eating patterns mirrors ACOG’s long-standing guidance on the importance of a well-balanced, varied, nutritional diet that is consistent with a woman’s access to food and food preferences,” he said in a statement, noting that “seafood is a nutrient-rich food that has proven beneficial to women and in aiding the development of a fetus throughout pregnancy.”

Bridging the “Digital Divide”

The “digital divide”: That is how the VA describes the situation of the 42% of veterans without reliable—or any—Internet access. The lack of access means they are effectively barred from participating in telehealth and other online services.

With the goal of “digital inclusion,” the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is partnering with a variety of nongovernmental businesses. VHA and T-Mobile, for instance, host the VA Video Connect application, which connects veterans to health care providers on a secure line on all devices with T-Mobile for free.

Walmart, Philips, and Veteran Service Organizations have set up remote clinics for veterans to access telehealth services closer to their home; with those partners, the VHA also lends Internet-connected iPads to veterans who do not have home computers.

Now, the VHA is working with Microsoft and Internet service providers to bring broadband access to rural areas with large populations of veterans.

The initiatives will not only improve access to health care, but also open other avenues. Dr. Kevin Galpin, executive director of VHA Telehealth Services, says, “We really want veterans to have the opportunities that come with being connected. There is lots of value in being able to maintain social relationships, conduct job searches online, and connect with VA. We know limited access is a problem and we’re exploring a multitude of options.”

The “digital divide”: That is how the VA describes the situation of the 42% of veterans without reliable—or any—Internet access. The lack of access means they are effectively barred from participating in telehealth and other online services.

With the goal of “digital inclusion,” the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is partnering with a variety of nongovernmental businesses. VHA and T-Mobile, for instance, host the VA Video Connect application, which connects veterans to health care providers on a secure line on all devices with T-Mobile for free.

Walmart, Philips, and Veteran Service Organizations have set up remote clinics for veterans to access telehealth services closer to their home; with those partners, the VHA also lends Internet-connected iPads to veterans who do not have home computers.

Now, the VHA is working with Microsoft and Internet service providers to bring broadband access to rural areas with large populations of veterans.

The initiatives will not only improve access to health care, but also open other avenues. Dr. Kevin Galpin, executive director of VHA Telehealth Services, says, “We really want veterans to have the opportunities that come with being connected. There is lots of value in being able to maintain social relationships, conduct job searches online, and connect with VA. We know limited access is a problem and we’re exploring a multitude of options.”

The “digital divide”: That is how the VA describes the situation of the 42% of veterans without reliable—or any—Internet access. The lack of access means they are effectively barred from participating in telehealth and other online services.

With the goal of “digital inclusion,” the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is partnering with a variety of nongovernmental businesses. VHA and T-Mobile, for instance, host the VA Video Connect application, which connects veterans to health care providers on a secure line on all devices with T-Mobile for free.

Walmart, Philips, and Veteran Service Organizations have set up remote clinics for veterans to access telehealth services closer to their home; with those partners, the VHA also lends Internet-connected iPads to veterans who do not have home computers.

Now, the VHA is working with Microsoft and Internet service providers to bring broadband access to rural areas with large populations of veterans.

The initiatives will not only improve access to health care, but also open other avenues. Dr. Kevin Galpin, executive director of VHA Telehealth Services, says, “We really want veterans to have the opportunities that come with being connected. There is lots of value in being able to maintain social relationships, conduct job searches online, and connect with VA. We know limited access is a problem and we’re exploring a multitude of options.”

CDC activates Emergency Operations Center for Congo Ebola outbreak

in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). With over 2,000 confirmed cases, the outbreak is the second largest ever recorded.

It recently spread to neighboring Uganda, by a family who crossed the border from the DRC.

As of June 11, 187 CDC staff have completed 278 deployments to the DRC, Uganda, and other neighboring countries, as well as to the World Health Organization in Geneva.

“We are activating the Emergency Operations Center at CDC headquarters to provide enhanced operational support to our” Ebola response team in the Congo. The level 3 activation – the lowest level – “allows the agency to provide increased operational support” and “logistics planning for a longer term, sustained effort,” CDC said in a press release.

Activation “does not mean that the threat of Ebola to the United States has increased.” The risk of global spread remains low, CDC said.

The outbreak is occurring in an area of armed conflict and other problems that complicate public health efforts and increase the risk of disease spread.

in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). With over 2,000 confirmed cases, the outbreak is the second largest ever recorded.

It recently spread to neighboring Uganda, by a family who crossed the border from the DRC.

As of June 11, 187 CDC staff have completed 278 deployments to the DRC, Uganda, and other neighboring countries, as well as to the World Health Organization in Geneva.

“We are activating the Emergency Operations Center at CDC headquarters to provide enhanced operational support to our” Ebola response team in the Congo. The level 3 activation – the lowest level – “allows the agency to provide increased operational support” and “logistics planning for a longer term, sustained effort,” CDC said in a press release.

Activation “does not mean that the threat of Ebola to the United States has increased.” The risk of global spread remains low, CDC said.

The outbreak is occurring in an area of armed conflict and other problems that complicate public health efforts and increase the risk of disease spread.

in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). With over 2,000 confirmed cases, the outbreak is the second largest ever recorded.

It recently spread to neighboring Uganda, by a family who crossed the border from the DRC.

As of June 11, 187 CDC staff have completed 278 deployments to the DRC, Uganda, and other neighboring countries, as well as to the World Health Organization in Geneva.

“We are activating the Emergency Operations Center at CDC headquarters to provide enhanced operational support to our” Ebola response team in the Congo. The level 3 activation – the lowest level – “allows the agency to provide increased operational support” and “logistics planning for a longer term, sustained effort,” CDC said in a press release.

Activation “does not mean that the threat of Ebola to the United States has increased.” The risk of global spread remains low, CDC said.

The outbreak is occurring in an area of armed conflict and other problems that complicate public health efforts and increase the risk of disease spread.

FDA invites sample submission for FDA-ARGOS database

which seeks to support research and regulatory decisions regarding DNA testing for pathogens with quality-controlled and curated genomic sequence data. Such testing and devices could be used as medical countermeasures against biothreats such as Ebola and Zika.

Infectious disease next-generation sequencing could use DNA analysis to help identify pathogens – from viruses to parasites – faster and more efficiently by, in theory, accomplishing with one test what was only possible before with many, according to the FDA. In order to not only further development of such tests and devices but also aid regulatory and scientific review of them, the FDA has collaborated with the Department of Defense, the National Center for Biotechnology Information, and Institute for Genome Sciences at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, to create FDA-ARGOS.

However, the FDA and its collaborators need samples of pathogens to continue developing the database, so they’ve invited health care professionals to submit samples for that purpose. More information, including preferred organism list and submission guidelines, can be found on the FDA-ARGOS website.

which seeks to support research and regulatory decisions regarding DNA testing for pathogens with quality-controlled and curated genomic sequence data. Such testing and devices could be used as medical countermeasures against biothreats such as Ebola and Zika.

Infectious disease next-generation sequencing could use DNA analysis to help identify pathogens – from viruses to parasites – faster and more efficiently by, in theory, accomplishing with one test what was only possible before with many, according to the FDA. In order to not only further development of such tests and devices but also aid regulatory and scientific review of them, the FDA has collaborated with the Department of Defense, the National Center for Biotechnology Information, and Institute for Genome Sciences at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, to create FDA-ARGOS.

However, the FDA and its collaborators need samples of pathogens to continue developing the database, so they’ve invited health care professionals to submit samples for that purpose. More information, including preferred organism list and submission guidelines, can be found on the FDA-ARGOS website.

which seeks to support research and regulatory decisions regarding DNA testing for pathogens with quality-controlled and curated genomic sequence data. Such testing and devices could be used as medical countermeasures against biothreats such as Ebola and Zika.

Infectious disease next-generation sequencing could use DNA analysis to help identify pathogens – from viruses to parasites – faster and more efficiently by, in theory, accomplishing with one test what was only possible before with many, according to the FDA. In order to not only further development of such tests and devices but also aid regulatory and scientific review of them, the FDA has collaborated with the Department of Defense, the National Center for Biotechnology Information, and Institute for Genome Sciences at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, to create FDA-ARGOS.

However, the FDA and its collaborators need samples of pathogens to continue developing the database, so they’ve invited health care professionals to submit samples for that purpose. More information, including preferred organism list and submission guidelines, can be found on the FDA-ARGOS website.

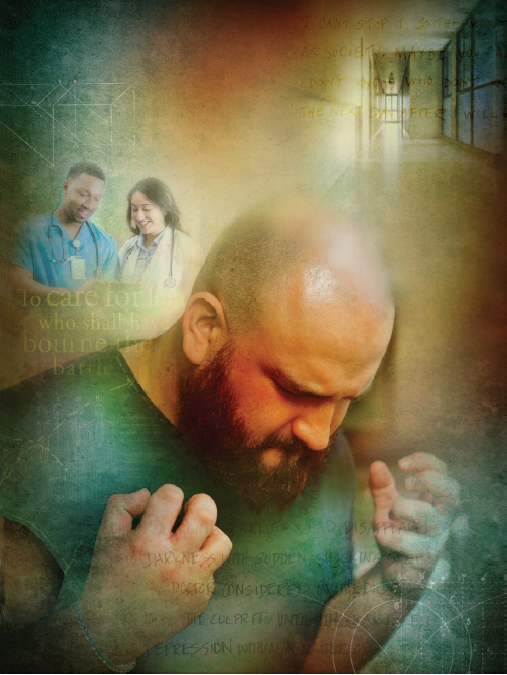

FDA overlooked red flags in esketamine testing

For some patients, it also has dwelled in the shadows of conventional medicine as a depression treatment – prescribed by their doctors, but not approved for that purpose by the federal agency responsible for determining which treatments are “safe and effective.”

That effectively changed in March, when the Food and Drug Administration approved a ketamine cousin called esketamine, taken as a nasal spray, for patients with intractable depression. With that, the esketamine nasal spray, under the brand name Spravato, was introduced as a miracle drug – announced in press releases, celebrated on the evening news, and embraced by major health care providers like the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The problem, critics say, is that the drug’s manufacturer, Janssen, provided the FDA with at best modest evidence it worked and then only in limited trials. It presented no information about the safety of Spravato for long-term use beyond 60 weeks. And three patients who received the drug died by suicide during clinical trials, compared with none in the control group, which raised red flags Janssen and the FDA dismissed.

The FDA, under political pressure to rapidly green-light drugs that treat life-threatening conditions, approved it anyway. And, though Spravato’s appearance on the market was greeted with public applause, some deep misgivings were expressed at its day-long review meeting and in the agency’s own briefing materials, according to public recordings, documents, and interviews with participants, KHN found.

Jess Fiedorowicz, MD, director of the Mood Disorders Center at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and a member of the FDA advisory committee that reviewed the drug, described its benefit as “almost certainly exaggerated” after hearing the evidence.

Dr. Fiedorowicz said he expected at least a split decision by the committee. “And then it went strongly in favor, which surprised me,” he said in an interview.

Esketamine’s trajectory to approval shows – step by step – how drugmakers can take advantage of shortcuts in the FDA process with the agency’s blessing and maneuver through safety and efficacy reviews to bring a lucrative drug to market.

Step 1: In late 2013, Janssen got the FDA to designate esketamine a “breakthrough therapy” because it showed the potential to reverse depression rapidly — a holy grail for suicidal patients, such as those in an emergency room. That potential was based on a 2-day study during which 30 patients were given esketamine intravenously.

“Breakthrough therapy” status puts drugs on a fast track to approval, with more frequent input from the FDA.

Step 2: But discussions between regulators and drug manufacturers can affect the amount and quality of evidence required by the agency. In the case of Spravato, they involved questions like “How many drugs must fail before a patient’s depression is considered intractable or ‘treatment resistant’?” and “How many successful clinical trials are necessary for FDA approval?”

Step 3: Any prior agreements can leave the FDA’s expert advisory committees hamstrung in reaching a verdict. Dr. Fiedorowicz abstained on Spravato because, though he considered Janssen’s study design flawed, the FDA had approved it.

The expert panel cleared the drug according to the evidence that the agency and Janssen had determined was sufficient. Matthew Rudorfer, MD, an associate director at the National Institute of Mental Health, concluded that the “benefits outweighed the risks.” Explaining his “yes” vote, he said, “I think we’re all agreeing on the very important, and sometimes life-or-death, risk of inadequately treated depression that factored into my equation.”

But others who also voted “yes” were more explicit in their qualms. “I don’t think that we really understand what happens when you take this week after week for weeks and months and years,” said Steven Meisel, PharmD, system director of medication safety for Fairview Health Services based in Minneapolis.

A Nasal Spray Offers A Path To A Patent

Spravato is available only under supervision at a certified facility where patients must be monitored for at least two hours after taking the drug to watch for side effects like dizziness, detachment from reality, and increased blood pressure, as well as to reduce the risk of abuse. Patients must take it with an oral antidepressant.

Despite those requirements, Janssen, part of Johnson & Johnson, defended its new offering. “Until the recent FDA approval of Spravato, health care providers haven’t had any new medication options,” Kristina Chang, a Janssen spokeswoman, wrote in an emailed statement.

Esketamine is the first new type of drug approved to treat severe depression in about three decades.

Although ketamine has been used off-label for years to treat depression and posttraumatic stress disorder, drugmakers saw little profit in doing the studies to prove to the FDA that it worked for that purpose. But a nasal spray of esketamine, which is derived from ketamine and is (in some studies) more potent, could be patented as a new drug.

Although Spravato costs more than $4,700 for the first month of treatment (not including the cost of monitoring or the oral antidepressant), insurers are more likely to reimburse for Spravato than for ketamine, since the latter is not approved for depression.

Shortly before the committee began voting, a study participant identifying herself only as “Patient 20015525” said, “I am offering real-world proof of efficacy, and that is I am both alive and here today.”

The drug did not work “for the majority of people who took it,” Dr. Meisel, the medication safety expert, said in an interview. “But for a subset of those for whom it did work, it was dramatic.”

Concerns About Testing Precedents

Those considerations apparently helped outweigh several scientific red flags that committee members called out during the hearing.

Although the drug had gotten breakthrough status because of its potential for results within 24 hours, the trials were not persuasive enough for the FDA to label it “rapid acting.”

The FDA typically requires that applicants provide at least two clinical trials demonstrating the drug’s efficacy, “each convincing on its own.” Janssen provided just one successful short-term, double-blind trial of esketamine. Two other trials it ran to test efficacy fell short.

To reach the two-trial threshold, the FDA broke its precedent for psychiatric drugs and allowed the company to count a trial conducted to study a different topic: relapse and remission trends. But, by definition, every patient in the trial had already taken and seen improvement from esketamine.

What’s more, that single positive efficacy trial showed just a 4-point improvement in depression symptoms, compared with the placebo treatment, on a 60-point scale some clinicians use to measure depression severity. Some committee members noted the trial wasn’t really blind since participants could recognize they were getting the drug from side effects like a temporary out-of-body sensation.

Finally, the FDA lowered the bar for “treatment-resistant depression.” Initially, for inclusion, trial participants would have had to have failed two classes of oral antidepressants.

Less than 2 years later, the FDA loosened that definition, saying a patient needed only to have taken two different pills, no matter the class.

Forty-nine of the 227 people who participated in Janssen’s only successful efficacy trial had failed just one class of oral antidepressants. “They weeded out the true treatment-resistant patients,” said Erick Turner, MD, a former FDA reviewer who serves on the committee but did not attend the meeting.

Six participants died during the studies, three by suicide. Janssen and the FDA dismissed the deaths as unrelated to the drug, noting the low number and lack of a pattern among hundreds of participants. They also pointed out that suicidal behavior is associated with severe depression – even though those who had suicidal ideation with some intent to act in the previous 6 months, or a history of suicidal behavior in the previous year, were excluded from the studies.

In a recent commentary in the American Journal of Psychiatry, Alan Schatzberg, MD, a Stanford (Calif.) University researcher who has studied ketamine, suggested there might be a link caused by “a protracted withdrawal reaction, as has been reported with opioids,” since ketamine appears to interact with the brain’s opioid receptors (Am J Psych. 2019. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19040423).

Kim Witczak, the committee’s consumer representative, found Janssen’s conclusion about the suicides unsatisfying. “I just feel like it was kind of a quick brush-over,” Ms. Witczak said in an interview. She voted against the drug.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

For some patients, it also has dwelled in the shadows of conventional medicine as a depression treatment – prescribed by their doctors, but not approved for that purpose by the federal agency responsible for determining which treatments are “safe and effective.”

That effectively changed in March, when the Food and Drug Administration approved a ketamine cousin called esketamine, taken as a nasal spray, for patients with intractable depression. With that, the esketamine nasal spray, under the brand name Spravato, was introduced as a miracle drug – announced in press releases, celebrated on the evening news, and embraced by major health care providers like the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The problem, critics say, is that the drug’s manufacturer, Janssen, provided the FDA with at best modest evidence it worked and then only in limited trials. It presented no information about the safety of Spravato for long-term use beyond 60 weeks. And three patients who received the drug died by suicide during clinical trials, compared with none in the control group, which raised red flags Janssen and the FDA dismissed.

The FDA, under political pressure to rapidly green-light drugs that treat life-threatening conditions, approved it anyway. And, though Spravato’s appearance on the market was greeted with public applause, some deep misgivings were expressed at its day-long review meeting and in the agency’s own briefing materials, according to public recordings, documents, and interviews with participants, KHN found.

Jess Fiedorowicz, MD, director of the Mood Disorders Center at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and a member of the FDA advisory committee that reviewed the drug, described its benefit as “almost certainly exaggerated” after hearing the evidence.

Dr. Fiedorowicz said he expected at least a split decision by the committee. “And then it went strongly in favor, which surprised me,” he said in an interview.

Esketamine’s trajectory to approval shows – step by step – how drugmakers can take advantage of shortcuts in the FDA process with the agency’s blessing and maneuver through safety and efficacy reviews to bring a lucrative drug to market.

Step 1: In late 2013, Janssen got the FDA to designate esketamine a “breakthrough therapy” because it showed the potential to reverse depression rapidly — a holy grail for suicidal patients, such as those in an emergency room. That potential was based on a 2-day study during which 30 patients were given esketamine intravenously.

“Breakthrough therapy” status puts drugs on a fast track to approval, with more frequent input from the FDA.

Step 2: But discussions between regulators and drug manufacturers can affect the amount and quality of evidence required by the agency. In the case of Spravato, they involved questions like “How many drugs must fail before a patient’s depression is considered intractable or ‘treatment resistant’?” and “How many successful clinical trials are necessary for FDA approval?”

Step 3: Any prior agreements can leave the FDA’s expert advisory committees hamstrung in reaching a verdict. Dr. Fiedorowicz abstained on Spravato because, though he considered Janssen’s study design flawed, the FDA had approved it.

The expert panel cleared the drug according to the evidence that the agency and Janssen had determined was sufficient. Matthew Rudorfer, MD, an associate director at the National Institute of Mental Health, concluded that the “benefits outweighed the risks.” Explaining his “yes” vote, he said, “I think we’re all agreeing on the very important, and sometimes life-or-death, risk of inadequately treated depression that factored into my equation.”

But others who also voted “yes” were more explicit in their qualms. “I don’t think that we really understand what happens when you take this week after week for weeks and months and years,” said Steven Meisel, PharmD, system director of medication safety for Fairview Health Services based in Minneapolis.

A Nasal Spray Offers A Path To A Patent

Spravato is available only under supervision at a certified facility where patients must be monitored for at least two hours after taking the drug to watch for side effects like dizziness, detachment from reality, and increased blood pressure, as well as to reduce the risk of abuse. Patients must take it with an oral antidepressant.

Despite those requirements, Janssen, part of Johnson & Johnson, defended its new offering. “Until the recent FDA approval of Spravato, health care providers haven’t had any new medication options,” Kristina Chang, a Janssen spokeswoman, wrote in an emailed statement.

Esketamine is the first new type of drug approved to treat severe depression in about three decades.

Although ketamine has been used off-label for years to treat depression and posttraumatic stress disorder, drugmakers saw little profit in doing the studies to prove to the FDA that it worked for that purpose. But a nasal spray of esketamine, which is derived from ketamine and is (in some studies) more potent, could be patented as a new drug.

Although Spravato costs more than $4,700 for the first month of treatment (not including the cost of monitoring or the oral antidepressant), insurers are more likely to reimburse for Spravato than for ketamine, since the latter is not approved for depression.

Shortly before the committee began voting, a study participant identifying herself only as “Patient 20015525” said, “I am offering real-world proof of efficacy, and that is I am both alive and here today.”

The drug did not work “for the majority of people who took it,” Dr. Meisel, the medication safety expert, said in an interview. “But for a subset of those for whom it did work, it was dramatic.”

Concerns About Testing Precedents

Those considerations apparently helped outweigh several scientific red flags that committee members called out during the hearing.

Although the drug had gotten breakthrough status because of its potential for results within 24 hours, the trials were not persuasive enough for the FDA to label it “rapid acting.”

The FDA typically requires that applicants provide at least two clinical trials demonstrating the drug’s efficacy, “each convincing on its own.” Janssen provided just one successful short-term, double-blind trial of esketamine. Two other trials it ran to test efficacy fell short.

To reach the two-trial threshold, the FDA broke its precedent for psychiatric drugs and allowed the company to count a trial conducted to study a different topic: relapse and remission trends. But, by definition, every patient in the trial had already taken and seen improvement from esketamine.

What’s more, that single positive efficacy trial showed just a 4-point improvement in depression symptoms, compared with the placebo treatment, on a 60-point scale some clinicians use to measure depression severity. Some committee members noted the trial wasn’t really blind since participants could recognize they were getting the drug from side effects like a temporary out-of-body sensation.

Finally, the FDA lowered the bar for “treatment-resistant depression.” Initially, for inclusion, trial participants would have had to have failed two classes of oral antidepressants.

Less than 2 years later, the FDA loosened that definition, saying a patient needed only to have taken two different pills, no matter the class.

Forty-nine of the 227 people who participated in Janssen’s only successful efficacy trial had failed just one class of oral antidepressants. “They weeded out the true treatment-resistant patients,” said Erick Turner, MD, a former FDA reviewer who serves on the committee but did not attend the meeting.

Six participants died during the studies, three by suicide. Janssen and the FDA dismissed the deaths as unrelated to the drug, noting the low number and lack of a pattern among hundreds of participants. They also pointed out that suicidal behavior is associated with severe depression – even though those who had suicidal ideation with some intent to act in the previous 6 months, or a history of suicidal behavior in the previous year, were excluded from the studies.

In a recent commentary in the American Journal of Psychiatry, Alan Schatzberg, MD, a Stanford (Calif.) University researcher who has studied ketamine, suggested there might be a link caused by “a protracted withdrawal reaction, as has been reported with opioids,” since ketamine appears to interact with the brain’s opioid receptors (Am J Psych. 2019. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19040423).

Kim Witczak, the committee’s consumer representative, found Janssen’s conclusion about the suicides unsatisfying. “I just feel like it was kind of a quick brush-over,” Ms. Witczak said in an interview. She voted against the drug.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

For some patients, it also has dwelled in the shadows of conventional medicine as a depression treatment – prescribed by their doctors, but not approved for that purpose by the federal agency responsible for determining which treatments are “safe and effective.”

That effectively changed in March, when the Food and Drug Administration approved a ketamine cousin called esketamine, taken as a nasal spray, for patients with intractable depression. With that, the esketamine nasal spray, under the brand name Spravato, was introduced as a miracle drug – announced in press releases, celebrated on the evening news, and embraced by major health care providers like the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The problem, critics say, is that the drug’s manufacturer, Janssen, provided the FDA with at best modest evidence it worked and then only in limited trials. It presented no information about the safety of Spravato for long-term use beyond 60 weeks. And three patients who received the drug died by suicide during clinical trials, compared with none in the control group, which raised red flags Janssen and the FDA dismissed.

The FDA, under political pressure to rapidly green-light drugs that treat life-threatening conditions, approved it anyway. And, though Spravato’s appearance on the market was greeted with public applause, some deep misgivings were expressed at its day-long review meeting and in the agency’s own briefing materials, according to public recordings, documents, and interviews with participants, KHN found.

Jess Fiedorowicz, MD, director of the Mood Disorders Center at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and a member of the FDA advisory committee that reviewed the drug, described its benefit as “almost certainly exaggerated” after hearing the evidence.

Dr. Fiedorowicz said he expected at least a split decision by the committee. “And then it went strongly in favor, which surprised me,” he said in an interview.

Esketamine’s trajectory to approval shows – step by step – how drugmakers can take advantage of shortcuts in the FDA process with the agency’s blessing and maneuver through safety and efficacy reviews to bring a lucrative drug to market.

Step 1: In late 2013, Janssen got the FDA to designate esketamine a “breakthrough therapy” because it showed the potential to reverse depression rapidly — a holy grail for suicidal patients, such as those in an emergency room. That potential was based on a 2-day study during which 30 patients were given esketamine intravenously.

“Breakthrough therapy” status puts drugs on a fast track to approval, with more frequent input from the FDA.

Step 2: But discussions between regulators and drug manufacturers can affect the amount and quality of evidence required by the agency. In the case of Spravato, they involved questions like “How many drugs must fail before a patient’s depression is considered intractable or ‘treatment resistant’?” and “How many successful clinical trials are necessary for FDA approval?”

Step 3: Any prior agreements can leave the FDA’s expert advisory committees hamstrung in reaching a verdict. Dr. Fiedorowicz abstained on Spravato because, though he considered Janssen’s study design flawed, the FDA had approved it.

The expert panel cleared the drug according to the evidence that the agency and Janssen had determined was sufficient. Matthew Rudorfer, MD, an associate director at the National Institute of Mental Health, concluded that the “benefits outweighed the risks.” Explaining his “yes” vote, he said, “I think we’re all agreeing on the very important, and sometimes life-or-death, risk of inadequately treated depression that factored into my equation.”

But others who also voted “yes” were more explicit in their qualms. “I don’t think that we really understand what happens when you take this week after week for weeks and months and years,” said Steven Meisel, PharmD, system director of medication safety for Fairview Health Services based in Minneapolis.

A Nasal Spray Offers A Path To A Patent

Spravato is available only under supervision at a certified facility where patients must be monitored for at least two hours after taking the drug to watch for side effects like dizziness, detachment from reality, and increased blood pressure, as well as to reduce the risk of abuse. Patients must take it with an oral antidepressant.

Despite those requirements, Janssen, part of Johnson & Johnson, defended its new offering. “Until the recent FDA approval of Spravato, health care providers haven’t had any new medication options,” Kristina Chang, a Janssen spokeswoman, wrote in an emailed statement.

Esketamine is the first new type of drug approved to treat severe depression in about three decades.

Although ketamine has been used off-label for years to treat depression and posttraumatic stress disorder, drugmakers saw little profit in doing the studies to prove to the FDA that it worked for that purpose. But a nasal spray of esketamine, which is derived from ketamine and is (in some studies) more potent, could be patented as a new drug.

Although Spravato costs more than $4,700 for the first month of treatment (not including the cost of monitoring or the oral antidepressant), insurers are more likely to reimburse for Spravato than for ketamine, since the latter is not approved for depression.

Shortly before the committee began voting, a study participant identifying herself only as “Patient 20015525” said, “I am offering real-world proof of efficacy, and that is I am both alive and here today.”

The drug did not work “for the majority of people who took it,” Dr. Meisel, the medication safety expert, said in an interview. “But for a subset of those for whom it did work, it was dramatic.”

Concerns About Testing Precedents

Those considerations apparently helped outweigh several scientific red flags that committee members called out during the hearing.

Although the drug had gotten breakthrough status because of its potential for results within 24 hours, the trials were not persuasive enough for the FDA to label it “rapid acting.”

The FDA typically requires that applicants provide at least two clinical trials demonstrating the drug’s efficacy, “each convincing on its own.” Janssen provided just one successful short-term, double-blind trial of esketamine. Two other trials it ran to test efficacy fell short.

To reach the two-trial threshold, the FDA broke its precedent for psychiatric drugs and allowed the company to count a trial conducted to study a different topic: relapse and remission trends. But, by definition, every patient in the trial had already taken and seen improvement from esketamine.

What’s more, that single positive efficacy trial showed just a 4-point improvement in depression symptoms, compared with the placebo treatment, on a 60-point scale some clinicians use to measure depression severity. Some committee members noted the trial wasn’t really blind since participants could recognize they were getting the drug from side effects like a temporary out-of-body sensation.

Finally, the FDA lowered the bar for “treatment-resistant depression.” Initially, for inclusion, trial participants would have had to have failed two classes of oral antidepressants.

Less than 2 years later, the FDA loosened that definition, saying a patient needed only to have taken two different pills, no matter the class.

Forty-nine of the 227 people who participated in Janssen’s only successful efficacy trial had failed just one class of oral antidepressants. “They weeded out the true treatment-resistant patients,” said Erick Turner, MD, a former FDA reviewer who serves on the committee but did not attend the meeting.

Six participants died during the studies, three by suicide. Janssen and the FDA dismissed the deaths as unrelated to the drug, noting the low number and lack of a pattern among hundreds of participants. They also pointed out that suicidal behavior is associated with severe depression – even though those who had suicidal ideation with some intent to act in the previous 6 months, or a history of suicidal behavior in the previous year, were excluded from the studies.

In a recent commentary in the American Journal of Psychiatry, Alan Schatzberg, MD, a Stanford (Calif.) University researcher who has studied ketamine, suggested there might be a link caused by “a protracted withdrawal reaction, as has been reported with opioids,” since ketamine appears to interact with the brain’s opioid receptors (Am J Psych. 2019. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19040423).

Kim Witczak, the committee’s consumer representative, found Janssen’s conclusion about the suicides unsatisfying. “I just feel like it was kind of a quick brush-over,” Ms. Witczak said in an interview. She voted against the drug.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

VA Rolls Out New and Improved Veterans Community Care Program

Calling it a landmark initiative, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has launched its “new and improved” Veterans Community Care Program, implementing portions of the Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act of 2018 (MISSION Act). The initiative both ends the Veterans Choice Program, which expired June 6, and establishes a new Veterans Community Care Program. Senior VA leaders will visit > 30 VA hospitals across the country to support the rollout.

The MISSION Act is intended to provide veterans with more health care options. It also strengthens the VA’s ability to recruit and retain clinicians, authorizes “Anywhere to Anywhere” telehealth across state lines, gives veterans better access to community care, and establishes a new urgent care benefit.

“The changes not only improve our ability to provide the health care veterans need, but also when and where they need it,” said VA Secretary Robert Wilkie. “It will also put veterans at the center of their care and offer options, including expanded telehealth and urgent care, so they can find the balance in the system that is right for them.”

Eligibility for community care does not require veterans to receive that care in the community; they can still choose to have VA care. A veteran may elect to receive care in the community if he or she:

- needs a service not available at any VA medical facility;

- lives in a US state or territory without a full-service VA medical facility (applies to veterans living in Alaska, Hawaii, New Hampshire, Guam, American Samoa, the Northern Mariana Islands and the US Virgin Islands);

- qualifies under the “grandfather” provision related to distance eligibility under the Veterans Choice Program; and/or

- meets specific access standards for average drive time or appointment wait times.

The veteran also is eligible if he or she and the referring clinician agree that it is in the best medical interest of the veteran to receive community care based on defined factors, or if the VA has determined that a VA medical service line is not providing care in a manner that complies with VA’s standards for quality based on specific conditions.

In addition to the new eligibility rules, the VA says it has made a variety of improvements that will “make community care work better for veterans.”

One is that existing programs will be combined into a single community care program, to reduce complexity and the “likelihood of errors and problems.” The VA also is streamlining internal processes and modernizing IT systems, aiming to “speed up all aspects of community care—eligibility, authorizations, appointments, care coordination, claims, payments—while improving overall communication between veterans, community providers, and VA staff members.”

The VA has announced, as well, that 2 final regulations of the Veterans Community Care Program have been published in the Federal Register. One concerns the new urgent care benefit that provides eligible veterans with greater choice and access to timely, high-quality care for minor injuries and illnesses. The second regulation governs how eligible veterans receive necessary hospital care, medical services, and extended-care services from non-VA entities or providers in the community.

The VA will purchase most community care for veterans through its contracted network with third-party administrators (currently TriWest Healthcare Alliance and Optum Public). When the new Community Care Network of community providers is implemented, VA staff will work directly with veterans to schedule appointments and support care coordination.

A complete rollout of all 6 regions of the Community Care Network is expected by 2020. More detailed information is available at www.missionact.va.gov.

Calling it a landmark initiative, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has launched its “new and improved” Veterans Community Care Program, implementing portions of the Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act of 2018 (MISSION Act). The initiative both ends the Veterans Choice Program, which expired June 6, and establishes a new Veterans Community Care Program. Senior VA leaders will visit > 30 VA hospitals across the country to support the rollout.

The MISSION Act is intended to provide veterans with more health care options. It also strengthens the VA’s ability to recruit and retain clinicians, authorizes “Anywhere to Anywhere” telehealth across state lines, gives veterans better access to community care, and establishes a new urgent care benefit.

“The changes not only improve our ability to provide the health care veterans need, but also when and where they need it,” said VA Secretary Robert Wilkie. “It will also put veterans at the center of their care and offer options, including expanded telehealth and urgent care, so they can find the balance in the system that is right for them.”

Eligibility for community care does not require veterans to receive that care in the community; they can still choose to have VA care. A veteran may elect to receive care in the community if he or she:

- needs a service not available at any VA medical facility;

- lives in a US state or territory without a full-service VA medical facility (applies to veterans living in Alaska, Hawaii, New Hampshire, Guam, American Samoa, the Northern Mariana Islands and the US Virgin Islands);

- qualifies under the “grandfather” provision related to distance eligibility under the Veterans Choice Program; and/or

- meets specific access standards for average drive time or appointment wait times.

The veteran also is eligible if he or she and the referring clinician agree that it is in the best medical interest of the veteran to receive community care based on defined factors, or if the VA has determined that a VA medical service line is not providing care in a manner that complies with VA’s standards for quality based on specific conditions.

In addition to the new eligibility rules, the VA says it has made a variety of improvements that will “make community care work better for veterans.”

One is that existing programs will be combined into a single community care program, to reduce complexity and the “likelihood of errors and problems.” The VA also is streamlining internal processes and modernizing IT systems, aiming to “speed up all aspects of community care—eligibility, authorizations, appointments, care coordination, claims, payments—while improving overall communication between veterans, community providers, and VA staff members.”

The VA has announced, as well, that 2 final regulations of the Veterans Community Care Program have been published in the Federal Register. One concerns the new urgent care benefit that provides eligible veterans with greater choice and access to timely, high-quality care for minor injuries and illnesses. The second regulation governs how eligible veterans receive necessary hospital care, medical services, and extended-care services from non-VA entities or providers in the community.

The VA will purchase most community care for veterans through its contracted network with third-party administrators (currently TriWest Healthcare Alliance and Optum Public). When the new Community Care Network of community providers is implemented, VA staff will work directly with veterans to schedule appointments and support care coordination.

A complete rollout of all 6 regions of the Community Care Network is expected by 2020. More detailed information is available at www.missionact.va.gov.

Calling it a landmark initiative, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has launched its “new and improved” Veterans Community Care Program, implementing portions of the Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act of 2018 (MISSION Act). The initiative both ends the Veterans Choice Program, which expired June 6, and establishes a new Veterans Community Care Program. Senior VA leaders will visit > 30 VA hospitals across the country to support the rollout.

The MISSION Act is intended to provide veterans with more health care options. It also strengthens the VA’s ability to recruit and retain clinicians, authorizes “Anywhere to Anywhere” telehealth across state lines, gives veterans better access to community care, and establishes a new urgent care benefit.

“The changes not only improve our ability to provide the health care veterans need, but also when and where they need it,” said VA Secretary Robert Wilkie. “It will also put veterans at the center of their care and offer options, including expanded telehealth and urgent care, so they can find the balance in the system that is right for them.”

Eligibility for community care does not require veterans to receive that care in the community; they can still choose to have VA care. A veteran may elect to receive care in the community if he or she:

- needs a service not available at any VA medical facility;

- lives in a US state or territory without a full-service VA medical facility (applies to veterans living in Alaska, Hawaii, New Hampshire, Guam, American Samoa, the Northern Mariana Islands and the US Virgin Islands);

- qualifies under the “grandfather” provision related to distance eligibility under the Veterans Choice Program; and/or

- meets specific access standards for average drive time or appointment wait times.

The veteran also is eligible if he or she and the referring clinician agree that it is in the best medical interest of the veteran to receive community care based on defined factors, or if the VA has determined that a VA medical service line is not providing care in a manner that complies with VA’s standards for quality based on specific conditions.

In addition to the new eligibility rules, the VA says it has made a variety of improvements that will “make community care work better for veterans.”

One is that existing programs will be combined into a single community care program, to reduce complexity and the “likelihood of errors and problems.” The VA also is streamlining internal processes and modernizing IT systems, aiming to “speed up all aspects of community care—eligibility, authorizations, appointments, care coordination, claims, payments—while improving overall communication between veterans, community providers, and VA staff members.”

The VA has announced, as well, that 2 final regulations of the Veterans Community Care Program have been published in the Federal Register. One concerns the new urgent care benefit that provides eligible veterans with greater choice and access to timely, high-quality care for minor injuries and illnesses. The second regulation governs how eligible veterans receive necessary hospital care, medical services, and extended-care services from non-VA entities or providers in the community.

The VA will purchase most community care for veterans through its contracted network with third-party administrators (currently TriWest Healthcare Alliance and Optum Public). When the new Community Care Network of community providers is implemented, VA staff will work directly with veterans to schedule appointments and support care coordination.

A complete rollout of all 6 regions of the Community Care Network is expected by 2020. More detailed information is available at www.missionact.va.gov.

Occupational Hazard: Disruptive Behavior in Patients

While private or other public health care organizations can refuse to care for patients who have displayed disruptive behavior (DB), the VA Response to Disruptive Behavior of Patients law (38 CFR §17.107) prohibits the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) from refusing care to veterans who display DB.1 The VHA defines DB as any behavior that is intimidating, threatening, or dangerous or that has, or could, jeopardize the health or safety of patients, VHA staff, or others.2

VA Response to DB Law

The VA Response to Disruptive Behavior of Patients requires the VHA to provide alternative care options that minimize risk while ensuring services; for example, providing care at a different location and/or time when additional staff are available to assist and monitor the patient. This can provide a unique opportunity to capture data on DB and the results of alternative forms of caring for this population.

The reason public health care organizations refuse care to persons who display DB is clear: DBs hinder business operations, are financially taxing, and put health care workers at risk.3-10 “In 2009, the VHA spent close to $5.5 million on workers’ compensation and medical expenditures for 425 incidents–or about $130,000 per DB incident (Hodgson M, Drummond D, Van Male L. Unpublished data, 2010).” In another study, 106 of 762 nurses in 1 hospital system reported an assault by a patient, and 30 required medical attention, which resulted in a total cost of $94,156.8 From 2002 to 2013, incidents of serious workplace violence requiring days off for an injured worker to recover on average were 4 times more common in health care than in other industries.6-11 Incidents of patient violence and aggression toward staff transcend specialization; however, hospital nurses and staff from the emergency, rehabilitation and gerontology departments, psychiatric unit, and home-based services are more susceptible and vulnerable to DB incidents than are other types of employees.8,10-19

Data reported by health care staff suggest that patients rather than staff members or visitors initiate > 70% of serious physical attacks against health care workers.9,13,20-23 A 2015 study of VHA health care providers (HCPs) found that > 60% had experienced some form of DB, verbal abuse being the most prevalent, followed by sexual abuse and physical abuse.20 Of 72,000 VHA staff responding to a nationwide survey, 13% experienced, on average, ≥ 1 assault by a veteran (eg, something was thrown at them; they were pushed, kicked, slapped; or were threatened or injured by a weapon).8,21

To meet its legal obligations and deliver empathetic care, the VHA documents and analyzes data on all patients who exhibit DB. A local DB Committee (DBC) reviews the data, whether it occurs in an inpatient or outpatient setting, such as community-based outpatient clinics. Once a DB incident is reported, the DBC begins an evidence-based risk evaluation, including the option of contacting the persons who displayed or experienced the DB. Goals are to (1) prevent future DB incidents; (2) detect vulnerabilities in the environment; and (3) collaborate with HCPs and patients to provide optimal care while improving the patient/provider interactions.

Effects of Disruptive Behavior

DB has negative consequences for both patients and health care workers and results in poor evaluations of care from both groups.27-32 Aside from interfering with safe medical care, DB also impacts care for other patients by delaying access to care and increasing appointment wait times due to employee absenteeism and staff shortages.3,4,20,32,33 For HCPs, patient violence is associated with unwillingness to provide care, briefer treatment periods, and decreases in occupational satisfaction, performance, and commitment

Harmful health effects experienced by HCPs who have been victims of DB include fear, mood disorders, anxiety, all symptoms of psychological distress and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).10,22,30,34-36 In a study of the impact on productivity of PTSD triggered by job-related DB, PTSD symptoms were associated with withdrawal from or minimizing encounters with patients, job turnover, and troubles with thinking

Reporting Disruptive Behavior

The literature suggests that consistent and effective DB reporting is pivotal to improving the outcome and quality of care for those displaying DB.37-39 To provide high-quality health services to veterans who display DB, the VHA must promote the management and reporting of DB. Without knowledge of the full spectrum of DB events at VHA facilities, efforts to prevent or manage DB and ensure safety may have limited impact.7,37 Reports can be used for clinical decision making to optimize staff training in delivery of quality care while assuring staff safety. More than 80% of DB incidents occur during interactions with patients, thus this is a clinical issue that can affect the outcome of patient care.8,21

Documented DB reports are used to analyze the degree, frequency, and nature of incidents, which might reveal risk factors and develop preventive efforts and training for specific hazards.8,39 Some have argued that implementing a standardized DB reporting system is a crucial first step toward minimizing hazards and improving health care.38,40,41