User login

Personalizing treatment plans for older patients with T2D

In the United States, type 2 diabetes (T2D) more commonly affects people older than 40 years, but it is most prevalent among adults over age 65, affecting more than 29% of this population. The heterogeneity in the health and functional status of older adults presents a challenge in the management and treatment of older patients with T2D. Moreover, there is an increased risk for health-related comorbidities and complications from diabetes treatment (for example, hypoglycemia) in older adults. Physiologic changes, such as decreased renal function, cognitive decline, and sarcopenia, may lead to an increased risk for adverse reactions to medications and require an individualized treatment approach. Although there have been a limited number of randomized controlled studies targeting older adults with multiple comorbidities and poor health status, subanalyses of diabetes trials with a subpopulation of older adults have provided additional evidence to better guide therapeutic approaches in caring for older patients with T2D.

Here’s a guide to developing personalized therapeutic regimens for older patients with T2D using lifestyle interventions, pharmacotherapy, and diabetes technology.

Determining an optimal glycemic target

An important first step in diabetes treatment is to determine the optimal glycemic target for patients. Although data support intensive glycemic control (hemoglobin A1c < 7%) to prevent complications from diabetes in younger patients with recently diagnosed disease, the data are less compelling in trials involving older populations with longer durations of T2D. One observational study with 71,092 older adults over age 60 reported a U-shaped correlation between A1c and mortality, with higher risks for mortality in those with A1c levels < 6% and ≥ 11%, compared with those with A1c levels of 6%-9%. Risks for any diabetes complications were higher at an A1c level ≥ 8%. Another observational study reported a U-shaped association between A1c and mortality, with the lowest hazard ratio for mortality at an A1c level of about 7.5%. Similarly, the ACCORD trial, which included older and middle-aged patients with T2D who had or were at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, found that mortality followed a U-shaped curve at the low (A1c < 7%) and high (A1c > 8%) ends in patients who were given standard glycemic therapy. Hence, there has been a general trend to recommend less strict glycemic control in older adults.

However, it is important to remember that older patients with T2D are a heterogeneous group. The spectrum includes adults with recent-onset diabetes with no or few complications, those with long-standing diabetes and many complications, and frail older adults with multiple comorbidities and complications. Determining the optimal glycemic target for an older patient with T2D requires assessment not only of the patient’s medical status and comorbidities but also functional status, cognitive and psychological health, social situation, individual preferences, and life expectancy. The American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes provides the following guidance in determining the optimal glycemic control for older adults:

- Healthy adults with few coexisting chronic illnesses and intact cognitive and functional status should have an A1c level < 7.0%-7.5%.

- Adults with complex or intermediate comorbidities (multiple coexisting chronic illnesses, or two or more instrumental activities of daily living impairments, or mild to moderate cognitive impairment) should have an A1c level < 8.0%.

- Patients with poor health (long-term care or end-stage chronic illnesses or moderate to severe cognitive impairment or two or more activities of daily living impairments) should avoid reliance on A1c, and the goal is to avoid hypoglycemia and symptomatic hyperglycemia.

Because older patients are at a higher risk for complications and adverse effects from polypharmacy, regular assessments are recommended and treatment plans should be routinely reviewed and modified to avoid overtreatment.

Lifestyle interventions and pharmacotherapy

Lifestyle interventions, such as exercise, optimal nutrition, and protein intake, are integral in treating older patients with T2D. Older adults should engage in regular exercise (that is, aerobic activity, weight-bearing exercise, or resistance training), and the activity should be customized to frailty status. Regular exercise improves insulin sensitivity and glucose control, enhances functional status, and provides cardiometabolic benefits. Optimal nutrition and adequate protein intake are also important to prevent the development or worsening of sarcopenia and frailty.

Several factors must be considered when choosing pharmacotherapy for T2D treatment in older adults. These patients are at higher risk for adverse reactions to medications that can trigger hypoglycemia and serious cardiovascular events, and worsen cognitive function. Therefore, side effects should always be reviewed when choosing antidiabetic drugs. The complexity of treatment plans needs to be matched with the patients’ self-management abilities and available social support. Medication costs and insurance coverage should be considered because many older adults live on a fixed income. Although limited, data exist on the safety and efficacy of some glucose-lowering agents in older adults, which can provide guidance for choosing the optimal therapy for these patients.

Among the insulin sensitizers, metformin is most commonly used because of its efficacy, low risk for hypoglycemia, and affordability. Metformin can be safely used in the setting of reduced renal function down to the estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥ 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2. However, metformin should be avoided in patients with more advanced renal disease, liver failure, or heart failure. In older patients with T2D, potential concerns of metformin include gastrointestinal side effects, leading to reduced appetite, mild weight loss, and risk for vitamin B12 deficiency.

Pioglitazone, an oral antidiabetic in the thiazolidinedione (TZD) class, also targets insulin resistance and may provide some cardiovascular benefits. However, these agents are not commonly used in treating older patients with T2D owing to associated risk for edema, heart failure, osteoporosis/fractures, and bladder cancer.

Sulfonylureas and meglitinides are insulin secretagogues, which can promote insulin release independent of glucose levels. Sulfonylureas are typically avoided in older patients because they are associated with high risk for hypoglycemia. Meglitinides have a lower hypoglycemia risk than sulfonylureas because of their short duration of action; however, they are more expensive and require multiple daily administration, which can lead to issues with adherence.

Since 2008, there have been numerous cardiovascular outcomes trials assessing the safety and efficacy of T2D therapies that included a subpopulation of older patients either with cardiovascular disease or at high risk for cardiovascular disease. Post hoc analysis of data from these trials and smaller studies dedicated to older adults demonstrated the safety and efficacy of most incretin-based therapies and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors in these patients. These newer medications have low hypoglycemia risk if not used in combination with insulin or insulin secretagogues.

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors have the mildest side effect profile. However, they can be expensive and not reduce major adverse cardiovascular outcomes, and one agent, saxagliptin, has been associated with increased risk for heart failure hospitalization. Some glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are effective in reducing major adverse cardiovascular events (cardiovascular deaths, stroke, and myocardial infarction) in patients older and younger than age 65. However, the gastrointestinal side effects and weight loss associated with this medication can be problematic for older patients. Most of the GLP-1 receptor agonists are injectables, which require good visual, motor, and cognitive skills for administration. SGLT2 inhibitors offer benefits for patients with T2D who have established cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease, with possible greater cardiovascular benefits in older adults. Adverse effects associated with SGLT2 inhibitors, such as weight loss, volume depletion, urinary incontinence, and genitourinary infections, may be a concern in older patients with T2D who are using these medications.

Because the insulin-secreting capacity of the pancreas declines with age, insulin therapy may be required for treatment of T2D in older patients. Insulin therapy can be complex and consideration must be given to patients’ social circumstances, as well as their physical and cognitive abilities. Older adults may need adaptive strategies, such as additional lighting, magnification glass, and premixed syringes. Simplification of complex insulin therapy (discontinuation of prandial insulin or sliding scale, changing timing of basal insulin) and use of insulin analogs with lower hypoglycemia risks should be considered. Weight gain as a result of insulin therapy may be beneficial in older adults with sarcopenia or frailty.

T2D technology for glycemic improvement

There have been major technological advancements in diabetes therapy. Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) and automated insulin delivery systems can improve glycemic control, decrease the rate of hypoglycemia, and enhance the quality of life of older patients. Most of the studies evaluating the use of automated insulin delivery systems in older patients have focused on those with type 1 diabetes and demonstrated improvement in glycemic control and/or reduced hypoglycemia. The DIAMOND trial demonstrated improved A1c and reduced glycemic variability with the use of CGM in adults older than 60 years with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes on multiple daily injections. Bluetooth-enabled “smart” insulin pens, which record the time and dose of insulin administrations, can also be a great asset in caring for older patients, especially those with cognitive impairment. With better insurance coverage, diabetes technologies may become more accessible and an asset in treating older patients with T2D.

In conclusion, management of T2D in older adults requires an individualized approach because of the heterogeneity in their health and functional status. Because cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of mortality in older patients with T2D, treatment plans should also address frequently coexisting cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Clinicians should consider patients’ overall health, comorbidities, cognitive and functional status, social support systems, preferences, and life expectancy when developing individualized therapeutic plans.

Dr. Gunawan is an assistant professor in the department of internal medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas. She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the United States, type 2 diabetes (T2D) more commonly affects people older than 40 years, but it is most prevalent among adults over age 65, affecting more than 29% of this population. The heterogeneity in the health and functional status of older adults presents a challenge in the management and treatment of older patients with T2D. Moreover, there is an increased risk for health-related comorbidities and complications from diabetes treatment (for example, hypoglycemia) in older adults. Physiologic changes, such as decreased renal function, cognitive decline, and sarcopenia, may lead to an increased risk for adverse reactions to medications and require an individualized treatment approach. Although there have been a limited number of randomized controlled studies targeting older adults with multiple comorbidities and poor health status, subanalyses of diabetes trials with a subpopulation of older adults have provided additional evidence to better guide therapeutic approaches in caring for older patients with T2D.

Here’s a guide to developing personalized therapeutic regimens for older patients with T2D using lifestyle interventions, pharmacotherapy, and diabetes technology.

Determining an optimal glycemic target

An important first step in diabetes treatment is to determine the optimal glycemic target for patients. Although data support intensive glycemic control (hemoglobin A1c < 7%) to prevent complications from diabetes in younger patients with recently diagnosed disease, the data are less compelling in trials involving older populations with longer durations of T2D. One observational study with 71,092 older adults over age 60 reported a U-shaped correlation between A1c and mortality, with higher risks for mortality in those with A1c levels < 6% and ≥ 11%, compared with those with A1c levels of 6%-9%. Risks for any diabetes complications were higher at an A1c level ≥ 8%. Another observational study reported a U-shaped association between A1c and mortality, with the lowest hazard ratio for mortality at an A1c level of about 7.5%. Similarly, the ACCORD trial, which included older and middle-aged patients with T2D who had or were at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, found that mortality followed a U-shaped curve at the low (A1c < 7%) and high (A1c > 8%) ends in patients who were given standard glycemic therapy. Hence, there has been a general trend to recommend less strict glycemic control in older adults.

However, it is important to remember that older patients with T2D are a heterogeneous group. The spectrum includes adults with recent-onset diabetes with no or few complications, those with long-standing diabetes and many complications, and frail older adults with multiple comorbidities and complications. Determining the optimal glycemic target for an older patient with T2D requires assessment not only of the patient’s medical status and comorbidities but also functional status, cognitive and psychological health, social situation, individual preferences, and life expectancy. The American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes provides the following guidance in determining the optimal glycemic control for older adults:

- Healthy adults with few coexisting chronic illnesses and intact cognitive and functional status should have an A1c level < 7.0%-7.5%.

- Adults with complex or intermediate comorbidities (multiple coexisting chronic illnesses, or two or more instrumental activities of daily living impairments, or mild to moderate cognitive impairment) should have an A1c level < 8.0%.

- Patients with poor health (long-term care or end-stage chronic illnesses or moderate to severe cognitive impairment or two or more activities of daily living impairments) should avoid reliance on A1c, and the goal is to avoid hypoglycemia and symptomatic hyperglycemia.

Because older patients are at a higher risk for complications and adverse effects from polypharmacy, regular assessments are recommended and treatment plans should be routinely reviewed and modified to avoid overtreatment.

Lifestyle interventions and pharmacotherapy

Lifestyle interventions, such as exercise, optimal nutrition, and protein intake, are integral in treating older patients with T2D. Older adults should engage in regular exercise (that is, aerobic activity, weight-bearing exercise, or resistance training), and the activity should be customized to frailty status. Regular exercise improves insulin sensitivity and glucose control, enhances functional status, and provides cardiometabolic benefits. Optimal nutrition and adequate protein intake are also important to prevent the development or worsening of sarcopenia and frailty.

Several factors must be considered when choosing pharmacotherapy for T2D treatment in older adults. These patients are at higher risk for adverse reactions to medications that can trigger hypoglycemia and serious cardiovascular events, and worsen cognitive function. Therefore, side effects should always be reviewed when choosing antidiabetic drugs. The complexity of treatment plans needs to be matched with the patients’ self-management abilities and available social support. Medication costs and insurance coverage should be considered because many older adults live on a fixed income. Although limited, data exist on the safety and efficacy of some glucose-lowering agents in older adults, which can provide guidance for choosing the optimal therapy for these patients.

Among the insulin sensitizers, metformin is most commonly used because of its efficacy, low risk for hypoglycemia, and affordability. Metformin can be safely used in the setting of reduced renal function down to the estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥ 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2. However, metformin should be avoided in patients with more advanced renal disease, liver failure, or heart failure. In older patients with T2D, potential concerns of metformin include gastrointestinal side effects, leading to reduced appetite, mild weight loss, and risk for vitamin B12 deficiency.

Pioglitazone, an oral antidiabetic in the thiazolidinedione (TZD) class, also targets insulin resistance and may provide some cardiovascular benefits. However, these agents are not commonly used in treating older patients with T2D owing to associated risk for edema, heart failure, osteoporosis/fractures, and bladder cancer.

Sulfonylureas and meglitinides are insulin secretagogues, which can promote insulin release independent of glucose levels. Sulfonylureas are typically avoided in older patients because they are associated with high risk for hypoglycemia. Meglitinides have a lower hypoglycemia risk than sulfonylureas because of their short duration of action; however, they are more expensive and require multiple daily administration, which can lead to issues with adherence.

Since 2008, there have been numerous cardiovascular outcomes trials assessing the safety and efficacy of T2D therapies that included a subpopulation of older patients either with cardiovascular disease or at high risk for cardiovascular disease. Post hoc analysis of data from these trials and smaller studies dedicated to older adults demonstrated the safety and efficacy of most incretin-based therapies and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors in these patients. These newer medications have low hypoglycemia risk if not used in combination with insulin or insulin secretagogues.

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors have the mildest side effect profile. However, they can be expensive and not reduce major adverse cardiovascular outcomes, and one agent, saxagliptin, has been associated with increased risk for heart failure hospitalization. Some glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are effective in reducing major adverse cardiovascular events (cardiovascular deaths, stroke, and myocardial infarction) in patients older and younger than age 65. However, the gastrointestinal side effects and weight loss associated with this medication can be problematic for older patients. Most of the GLP-1 receptor agonists are injectables, which require good visual, motor, and cognitive skills for administration. SGLT2 inhibitors offer benefits for patients with T2D who have established cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease, with possible greater cardiovascular benefits in older adults. Adverse effects associated with SGLT2 inhibitors, such as weight loss, volume depletion, urinary incontinence, and genitourinary infections, may be a concern in older patients with T2D who are using these medications.

Because the insulin-secreting capacity of the pancreas declines with age, insulin therapy may be required for treatment of T2D in older patients. Insulin therapy can be complex and consideration must be given to patients’ social circumstances, as well as their physical and cognitive abilities. Older adults may need adaptive strategies, such as additional lighting, magnification glass, and premixed syringes. Simplification of complex insulin therapy (discontinuation of prandial insulin or sliding scale, changing timing of basal insulin) and use of insulin analogs with lower hypoglycemia risks should be considered. Weight gain as a result of insulin therapy may be beneficial in older adults with sarcopenia or frailty.

T2D technology for glycemic improvement

There have been major technological advancements in diabetes therapy. Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) and automated insulin delivery systems can improve glycemic control, decrease the rate of hypoglycemia, and enhance the quality of life of older patients. Most of the studies evaluating the use of automated insulin delivery systems in older patients have focused on those with type 1 diabetes and demonstrated improvement in glycemic control and/or reduced hypoglycemia. The DIAMOND trial demonstrated improved A1c and reduced glycemic variability with the use of CGM in adults older than 60 years with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes on multiple daily injections. Bluetooth-enabled “smart” insulin pens, which record the time and dose of insulin administrations, can also be a great asset in caring for older patients, especially those with cognitive impairment. With better insurance coverage, diabetes technologies may become more accessible and an asset in treating older patients with T2D.

In conclusion, management of T2D in older adults requires an individualized approach because of the heterogeneity in their health and functional status. Because cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of mortality in older patients with T2D, treatment plans should also address frequently coexisting cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Clinicians should consider patients’ overall health, comorbidities, cognitive and functional status, social support systems, preferences, and life expectancy when developing individualized therapeutic plans.

Dr. Gunawan is an assistant professor in the department of internal medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas. She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the United States, type 2 diabetes (T2D) more commonly affects people older than 40 years, but it is most prevalent among adults over age 65, affecting more than 29% of this population. The heterogeneity in the health and functional status of older adults presents a challenge in the management and treatment of older patients with T2D. Moreover, there is an increased risk for health-related comorbidities and complications from diabetes treatment (for example, hypoglycemia) in older adults. Physiologic changes, such as decreased renal function, cognitive decline, and sarcopenia, may lead to an increased risk for adverse reactions to medications and require an individualized treatment approach. Although there have been a limited number of randomized controlled studies targeting older adults with multiple comorbidities and poor health status, subanalyses of diabetes trials with a subpopulation of older adults have provided additional evidence to better guide therapeutic approaches in caring for older patients with T2D.

Here’s a guide to developing personalized therapeutic regimens for older patients with T2D using lifestyle interventions, pharmacotherapy, and diabetes technology.

Determining an optimal glycemic target

An important first step in diabetes treatment is to determine the optimal glycemic target for patients. Although data support intensive glycemic control (hemoglobin A1c < 7%) to prevent complications from diabetes in younger patients with recently diagnosed disease, the data are less compelling in trials involving older populations with longer durations of T2D. One observational study with 71,092 older adults over age 60 reported a U-shaped correlation between A1c and mortality, with higher risks for mortality in those with A1c levels < 6% and ≥ 11%, compared with those with A1c levels of 6%-9%. Risks for any diabetes complications were higher at an A1c level ≥ 8%. Another observational study reported a U-shaped association between A1c and mortality, with the lowest hazard ratio for mortality at an A1c level of about 7.5%. Similarly, the ACCORD trial, which included older and middle-aged patients with T2D who had or were at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, found that mortality followed a U-shaped curve at the low (A1c < 7%) and high (A1c > 8%) ends in patients who were given standard glycemic therapy. Hence, there has been a general trend to recommend less strict glycemic control in older adults.

However, it is important to remember that older patients with T2D are a heterogeneous group. The spectrum includes adults with recent-onset diabetes with no or few complications, those with long-standing diabetes and many complications, and frail older adults with multiple comorbidities and complications. Determining the optimal glycemic target for an older patient with T2D requires assessment not only of the patient’s medical status and comorbidities but also functional status, cognitive and psychological health, social situation, individual preferences, and life expectancy. The American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes provides the following guidance in determining the optimal glycemic control for older adults:

- Healthy adults with few coexisting chronic illnesses and intact cognitive and functional status should have an A1c level < 7.0%-7.5%.

- Adults with complex or intermediate comorbidities (multiple coexisting chronic illnesses, or two or more instrumental activities of daily living impairments, or mild to moderate cognitive impairment) should have an A1c level < 8.0%.

- Patients with poor health (long-term care or end-stage chronic illnesses or moderate to severe cognitive impairment or two or more activities of daily living impairments) should avoid reliance on A1c, and the goal is to avoid hypoglycemia and symptomatic hyperglycemia.

Because older patients are at a higher risk for complications and adverse effects from polypharmacy, regular assessments are recommended and treatment plans should be routinely reviewed and modified to avoid overtreatment.

Lifestyle interventions and pharmacotherapy

Lifestyle interventions, such as exercise, optimal nutrition, and protein intake, are integral in treating older patients with T2D. Older adults should engage in regular exercise (that is, aerobic activity, weight-bearing exercise, or resistance training), and the activity should be customized to frailty status. Regular exercise improves insulin sensitivity and glucose control, enhances functional status, and provides cardiometabolic benefits. Optimal nutrition and adequate protein intake are also important to prevent the development or worsening of sarcopenia and frailty.

Several factors must be considered when choosing pharmacotherapy for T2D treatment in older adults. These patients are at higher risk for adverse reactions to medications that can trigger hypoglycemia and serious cardiovascular events, and worsen cognitive function. Therefore, side effects should always be reviewed when choosing antidiabetic drugs. The complexity of treatment plans needs to be matched with the patients’ self-management abilities and available social support. Medication costs and insurance coverage should be considered because many older adults live on a fixed income. Although limited, data exist on the safety and efficacy of some glucose-lowering agents in older adults, which can provide guidance for choosing the optimal therapy for these patients.

Among the insulin sensitizers, metformin is most commonly used because of its efficacy, low risk for hypoglycemia, and affordability. Metformin can be safely used in the setting of reduced renal function down to the estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥ 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2. However, metformin should be avoided in patients with more advanced renal disease, liver failure, or heart failure. In older patients with T2D, potential concerns of metformin include gastrointestinal side effects, leading to reduced appetite, mild weight loss, and risk for vitamin B12 deficiency.

Pioglitazone, an oral antidiabetic in the thiazolidinedione (TZD) class, also targets insulin resistance and may provide some cardiovascular benefits. However, these agents are not commonly used in treating older patients with T2D owing to associated risk for edema, heart failure, osteoporosis/fractures, and bladder cancer.

Sulfonylureas and meglitinides are insulin secretagogues, which can promote insulin release independent of glucose levels. Sulfonylureas are typically avoided in older patients because they are associated with high risk for hypoglycemia. Meglitinides have a lower hypoglycemia risk than sulfonylureas because of their short duration of action; however, they are more expensive and require multiple daily administration, which can lead to issues with adherence.

Since 2008, there have been numerous cardiovascular outcomes trials assessing the safety and efficacy of T2D therapies that included a subpopulation of older patients either with cardiovascular disease or at high risk for cardiovascular disease. Post hoc analysis of data from these trials and smaller studies dedicated to older adults demonstrated the safety and efficacy of most incretin-based therapies and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors in these patients. These newer medications have low hypoglycemia risk if not used in combination with insulin or insulin secretagogues.

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors have the mildest side effect profile. However, they can be expensive and not reduce major adverse cardiovascular outcomes, and one agent, saxagliptin, has been associated with increased risk for heart failure hospitalization. Some glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are effective in reducing major adverse cardiovascular events (cardiovascular deaths, stroke, and myocardial infarction) in patients older and younger than age 65. However, the gastrointestinal side effects and weight loss associated with this medication can be problematic for older patients. Most of the GLP-1 receptor agonists are injectables, which require good visual, motor, and cognitive skills for administration. SGLT2 inhibitors offer benefits for patients with T2D who have established cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease, with possible greater cardiovascular benefits in older adults. Adverse effects associated with SGLT2 inhibitors, such as weight loss, volume depletion, urinary incontinence, and genitourinary infections, may be a concern in older patients with T2D who are using these medications.

Because the insulin-secreting capacity of the pancreas declines with age, insulin therapy may be required for treatment of T2D in older patients. Insulin therapy can be complex and consideration must be given to patients’ social circumstances, as well as their physical and cognitive abilities. Older adults may need adaptive strategies, such as additional lighting, magnification glass, and premixed syringes. Simplification of complex insulin therapy (discontinuation of prandial insulin or sliding scale, changing timing of basal insulin) and use of insulin analogs with lower hypoglycemia risks should be considered. Weight gain as a result of insulin therapy may be beneficial in older adults with sarcopenia or frailty.

T2D technology for glycemic improvement

There have been major technological advancements in diabetes therapy. Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) and automated insulin delivery systems can improve glycemic control, decrease the rate of hypoglycemia, and enhance the quality of life of older patients. Most of the studies evaluating the use of automated insulin delivery systems in older patients have focused on those with type 1 diabetes and demonstrated improvement in glycemic control and/or reduced hypoglycemia. The DIAMOND trial demonstrated improved A1c and reduced glycemic variability with the use of CGM in adults older than 60 years with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes on multiple daily injections. Bluetooth-enabled “smart” insulin pens, which record the time and dose of insulin administrations, can also be a great asset in caring for older patients, especially those with cognitive impairment. With better insurance coverage, diabetes technologies may become more accessible and an asset in treating older patients with T2D.

In conclusion, management of T2D in older adults requires an individualized approach because of the heterogeneity in their health and functional status. Because cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of mortality in older patients with T2D, treatment plans should also address frequently coexisting cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Clinicians should consider patients’ overall health, comorbidities, cognitive and functional status, social support systems, preferences, and life expectancy when developing individualized therapeutic plans.

Dr. Gunawan is an assistant professor in the department of internal medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas. She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Should youth with type 1 diabetes use closed-loop systems?

Would closed-loop systems be a good option for young patients with type 1 diabetes?

International and French recommendations on closed-loop systems state that the use of an “artificial pancreas” should be reserved for adults who are fully engaged with their treatment. This means that young patients, especially adolescents, who are less likely to comply with treatment and are more likely to experience suboptimal blood glucose control, are often excluded from the use of such systems for managing their diabetes.

Several recent studies seem to call this approach into question.

One such study, which was presented at a Francophone Diabetes Society conference and was published in Nature Communications, showed that adolescents with poorly controlled diabetes who were equipped with closed-loop systems gained IQ points and reasoning capacity and experienced a reduction in edematous tissue in the brain cortex. Furthermore, with the closed-loop system, patients spent 13% more time in a target range, and there was a significant reduction in time spent in hyperglycemia.

In the same vein, a small prospective study published in Diabetes Care showed that the closed-loop system with the Minimed 780G pump improved glycemic control for 20 young patients with type 1 diabetes aged 13-25 years whose diabetes was poorly controlled (hemoglobin A1c ≥ 8.5%). At the end of the 3-month study period, the average A1c had decreased from 10.5% (±2.1%) to 7.6% (±1.1%), an average decrease of 2.9%. The time spent in target A1c, which was set from 0.70 g/L to 1.80 g/L, was increased by almost 40%.

With respect to very young children, a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine also showed a favorable risk-benefit ratio for closed-loop systems. The trial, which enrolled 102 children aged 2 years to less than 6 years who had type 1 diabetes, showed that the amount of time that the glucose level was within the target range during the 13-week study period was higher (+3 hours) for those who had been randomly assigned to receive the hybrid closed-loop system (n = 68) than for those who had received the standard treatment (n = 34), either with an insulin pump or multiple daily injections or a Dexcom G6 continuous glucose monitoring device.

A previous study carried out by the Paris Public Hospital System had already shown that the French Diabeloop system could reduce episodes of hypoglycemia and achieve good glycemic control for prepubescent children (n = 21; aged 6-12 years) with type 1 diabetes in real-life conditions.

Eric Renard, MD, PhD, head of the department of endocrinology and diabetes at Lapeyronie Hospital in Montpellier, France, was not surprised at the findings from the study, especially in adolescents with poorly controlled diabetes.

“We have already seen studies in which those patients who had the most poorly controlled diabetes at the start were the ones who improved the most with the closed-loop system, by at least 20% in terms of time in target. These findings resonate with what I see in my clinic,” said Dr. Renard in an interview.

“In my experience, these young adolescents, who neglected their diabetes when they had no devices to help control it, when they had to inject themselves, et cetera ... well, they’re just not the same people when they’re put on a closed-loop system,” he added. “They rise to the challenge, and for the first time, they succeed without making a huge effort, since the algorithm does what they weren’t doing. It’s astonishing to see near-total engagement in these young people when explaining the technology to them and saying, ‘Let’s give it a go.’ These are the very same youngsters who didn’t want to hear about their diabetes in the past. They are delighted and once again involved in managing their condition.”

That’s why Dr. Renard recommends keeping an open mind when considering treatment options for young patients with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes.

“When young people have very poorly controlled diabetes, they risk having cardiovascular complications and damaging their retinas and kidneys,” he said. “If we can get them from 25% to 45% time in target, even if that hasn’t been easy to achieve, this will help save their blood vessels! The only thing we have to be careful of is that we don’t set up a closed-loop system in someone who doesn’t want one. But, if it can manage to spark the interest of a young patient, in most cases, it’s beneficial.”

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

Would closed-loop systems be a good option for young patients with type 1 diabetes?

International and French recommendations on closed-loop systems state that the use of an “artificial pancreas” should be reserved for adults who are fully engaged with their treatment. This means that young patients, especially adolescents, who are less likely to comply with treatment and are more likely to experience suboptimal blood glucose control, are often excluded from the use of such systems for managing their diabetes.

Several recent studies seem to call this approach into question.

One such study, which was presented at a Francophone Diabetes Society conference and was published in Nature Communications, showed that adolescents with poorly controlled diabetes who were equipped with closed-loop systems gained IQ points and reasoning capacity and experienced a reduction in edematous tissue in the brain cortex. Furthermore, with the closed-loop system, patients spent 13% more time in a target range, and there was a significant reduction in time spent in hyperglycemia.

In the same vein, a small prospective study published in Diabetes Care showed that the closed-loop system with the Minimed 780G pump improved glycemic control for 20 young patients with type 1 diabetes aged 13-25 years whose diabetes was poorly controlled (hemoglobin A1c ≥ 8.5%). At the end of the 3-month study period, the average A1c had decreased from 10.5% (±2.1%) to 7.6% (±1.1%), an average decrease of 2.9%. The time spent in target A1c, which was set from 0.70 g/L to 1.80 g/L, was increased by almost 40%.

With respect to very young children, a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine also showed a favorable risk-benefit ratio for closed-loop systems. The trial, which enrolled 102 children aged 2 years to less than 6 years who had type 1 diabetes, showed that the amount of time that the glucose level was within the target range during the 13-week study period was higher (+3 hours) for those who had been randomly assigned to receive the hybrid closed-loop system (n = 68) than for those who had received the standard treatment (n = 34), either with an insulin pump or multiple daily injections or a Dexcom G6 continuous glucose monitoring device.

A previous study carried out by the Paris Public Hospital System had already shown that the French Diabeloop system could reduce episodes of hypoglycemia and achieve good glycemic control for prepubescent children (n = 21; aged 6-12 years) with type 1 diabetes in real-life conditions.

Eric Renard, MD, PhD, head of the department of endocrinology and diabetes at Lapeyronie Hospital in Montpellier, France, was not surprised at the findings from the study, especially in adolescents with poorly controlled diabetes.

“We have already seen studies in which those patients who had the most poorly controlled diabetes at the start were the ones who improved the most with the closed-loop system, by at least 20% in terms of time in target. These findings resonate with what I see in my clinic,” said Dr. Renard in an interview.

“In my experience, these young adolescents, who neglected their diabetes when they had no devices to help control it, when they had to inject themselves, et cetera ... well, they’re just not the same people when they’re put on a closed-loop system,” he added. “They rise to the challenge, and for the first time, they succeed without making a huge effort, since the algorithm does what they weren’t doing. It’s astonishing to see near-total engagement in these young people when explaining the technology to them and saying, ‘Let’s give it a go.’ These are the very same youngsters who didn’t want to hear about their diabetes in the past. They are delighted and once again involved in managing their condition.”

That’s why Dr. Renard recommends keeping an open mind when considering treatment options for young patients with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes.

“When young people have very poorly controlled diabetes, they risk having cardiovascular complications and damaging their retinas and kidneys,” he said. “If we can get them from 25% to 45% time in target, even if that hasn’t been easy to achieve, this will help save their blood vessels! The only thing we have to be careful of is that we don’t set up a closed-loop system in someone who doesn’t want one. But, if it can manage to spark the interest of a young patient, in most cases, it’s beneficial.”

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

Would closed-loop systems be a good option for young patients with type 1 diabetes?

International and French recommendations on closed-loop systems state that the use of an “artificial pancreas” should be reserved for adults who are fully engaged with their treatment. This means that young patients, especially adolescents, who are less likely to comply with treatment and are more likely to experience suboptimal blood glucose control, are often excluded from the use of such systems for managing their diabetes.

Several recent studies seem to call this approach into question.

One such study, which was presented at a Francophone Diabetes Society conference and was published in Nature Communications, showed that adolescents with poorly controlled diabetes who were equipped with closed-loop systems gained IQ points and reasoning capacity and experienced a reduction in edematous tissue in the brain cortex. Furthermore, with the closed-loop system, patients spent 13% more time in a target range, and there was a significant reduction in time spent in hyperglycemia.

In the same vein, a small prospective study published in Diabetes Care showed that the closed-loop system with the Minimed 780G pump improved glycemic control for 20 young patients with type 1 diabetes aged 13-25 years whose diabetes was poorly controlled (hemoglobin A1c ≥ 8.5%). At the end of the 3-month study period, the average A1c had decreased from 10.5% (±2.1%) to 7.6% (±1.1%), an average decrease of 2.9%. The time spent in target A1c, which was set from 0.70 g/L to 1.80 g/L, was increased by almost 40%.

With respect to very young children, a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine also showed a favorable risk-benefit ratio for closed-loop systems. The trial, which enrolled 102 children aged 2 years to less than 6 years who had type 1 diabetes, showed that the amount of time that the glucose level was within the target range during the 13-week study period was higher (+3 hours) for those who had been randomly assigned to receive the hybrid closed-loop system (n = 68) than for those who had received the standard treatment (n = 34), either with an insulin pump or multiple daily injections or a Dexcom G6 continuous glucose monitoring device.

A previous study carried out by the Paris Public Hospital System had already shown that the French Diabeloop system could reduce episodes of hypoglycemia and achieve good glycemic control for prepubescent children (n = 21; aged 6-12 years) with type 1 diabetes in real-life conditions.

Eric Renard, MD, PhD, head of the department of endocrinology and diabetes at Lapeyronie Hospital in Montpellier, France, was not surprised at the findings from the study, especially in adolescents with poorly controlled diabetes.

“We have already seen studies in which those patients who had the most poorly controlled diabetes at the start were the ones who improved the most with the closed-loop system, by at least 20% in terms of time in target. These findings resonate with what I see in my clinic,” said Dr. Renard in an interview.

“In my experience, these young adolescents, who neglected their diabetes when they had no devices to help control it, when they had to inject themselves, et cetera ... well, they’re just not the same people when they’re put on a closed-loop system,” he added. “They rise to the challenge, and for the first time, they succeed without making a huge effort, since the algorithm does what they weren’t doing. It’s astonishing to see near-total engagement in these young people when explaining the technology to them and saying, ‘Let’s give it a go.’ These are the very same youngsters who didn’t want to hear about their diabetes in the past. They are delighted and once again involved in managing their condition.”

That’s why Dr. Renard recommends keeping an open mind when considering treatment options for young patients with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes.

“When young people have very poorly controlled diabetes, they risk having cardiovascular complications and damaging their retinas and kidneys,” he said. “If we can get them from 25% to 45% time in target, even if that hasn’t been easy to achieve, this will help save their blood vessels! The only thing we have to be careful of is that we don’t set up a closed-loop system in someone who doesn’t want one. But, if it can manage to spark the interest of a young patient, in most cases, it’s beneficial.”

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

Obesity drugs overpriced, change needed to tackle issue

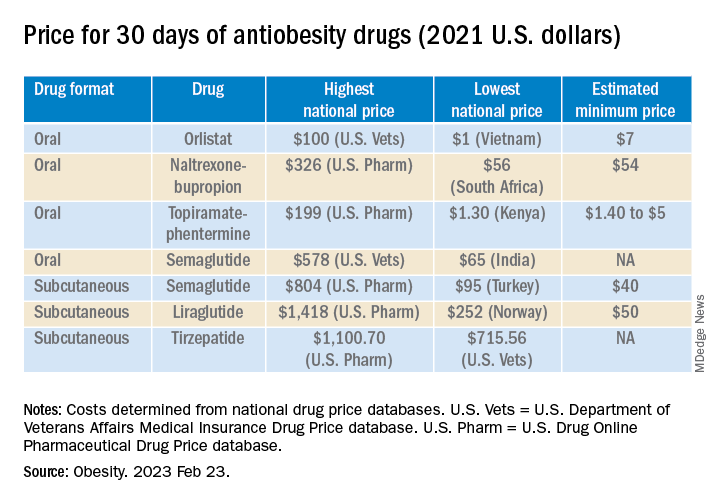

The lowest available national prices of drugs to treat obesity are up to 20 times higher than the estimated cost of profitable generic versions of the same agents, according to a new analysis.

The findings by Jacob Levi, MBBS, and colleagues were published in Obesity.

“Our study highlights the inequality in pricing that exists for effective antiobesity medications, which are largely unaffordable in most countries,” Dr. Levi, from Royal Free Hospital NHS Trust, London, said in a press release.

“We show that these drugs can actually be produced and sold profitably for low prices,” he summarized. “A public health approach that prioritizes improving access to medications should be adopted, instead of allowing companies to maximize profits,” Dr. Levi urged.

Dr. Levi and colleagues studied the oral agents orlistat, naltrexone/bupropion, topiramate/phentermine, and semaglutide, and subcutaneous liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide (all approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat obesity, except for oral semaglutide and subcutaneous tirzepatide, which are not yet approved to treat obesity in the absence of type 2 diabetes).

“Worldwide, more people are dying from diabetes and clinical obesity than HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria combined now,” senior author Andrew Hill, MD, department of pharmacology and therapeutics, University of Liverpool, England, pointed out.

We need to repeat the low-cost success story with obesity drugs

“Millions of lives have been saved by treating infectious diseases at low cost in poor countries,” Dr. Hill continued. “Now we need to repeat this medical success story, with mass treatment of diabetes and clinical obesity at low prices.”

However, in an accompanying editorial, Eric A. Finkelstein, MD, and Junxing Chay, PhD, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, maintain that “It would be great if everyone had affordable access to all medicines that might improve their health. Yet that is simply not possible, nor will it ever be.”

“What is truly needed is a better way to ration the health care dollars currently available in efforts to maximize population health. That is the challenge ahead not just for [antiobesity medications] but for all treatments,” they say.

“Greater use of cost-effectiveness analysis and direct negotiations, while maintaining the patent system, represents an appropriate approach for allocating scarce health care resources in the United States and beyond,” they continue.

Lowest current patented drug prices vs. estimated generic drug prices

New medications for obesity were highly effective in recent clinical trials, but high prices limit the ability of patients to get these medications, Dr. Levi and colleagues write.

They analyzed prices for obesity drugs in 16 low-, middle-, and high-income countries: Australia, Bangladesh, China, France, Germany, India, Kenya, Morocco, Norway, Peru, Pakistan, South Africa, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Vietnam.

The researchers assessed the price of a 30-day supply of each of the studied branded drugs based on the lowest available price (in 2021 U.S. dollars) from multiple online national price databases.

Then they calculated the estimated minimum price of a 30-day supply of a potential generic version of these drugs, which included the cost of the active medicinal ingredients, the excipients (nonactive ingredients), the prefilled injectable device plus needles (for subcutaneous drugs), transportation, 10% profit, and 27% tax on profit.

The national prices of the branded medications for obesity were significantly higher than the estimated minimum prices of potential generic drugs (see Table).

The highest national price for a branded oral drug for obesity vs. the estimated minimum price for a potential generic version was $100 vs. $7 for orlistat, $199 vs. $5 for phentermine/topiramate, and $326 vs. $54 for naltrexone/bupropion, for a 30-day supply.

There was an even greater difference between highest national branded drug price vs. estimated minimum generic drug price for the newer subcutaneously injectable drugs for obesity.

For example, the price of a 30-day course of subcutaneous semaglutide ranged from $804 (United States) to $95 (Turkey), while the estimated minimum potential generic drug price was $40 (which is 20 times lower).

The study was funded by grants from the Make Medicines Affordable/International Treatment Preparedness Coalition and from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. Coauthor Francois Venter has reported receiving support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, U.S. Agency for International Development, Unitaid, SA Medical Research Council, Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics, the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, Gilead, ViiV, Mylan, Merck, Adcock Ingram, Aspen, Abbott, Roche, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, Virology Education, SA HIV Clinicians Society, and Dira Sengwe. The other authors and Dr. Chay have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Finkelstein has reported receiving support for serving on the WW scientific advisory board and an educational grant unrelated to the present work from Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

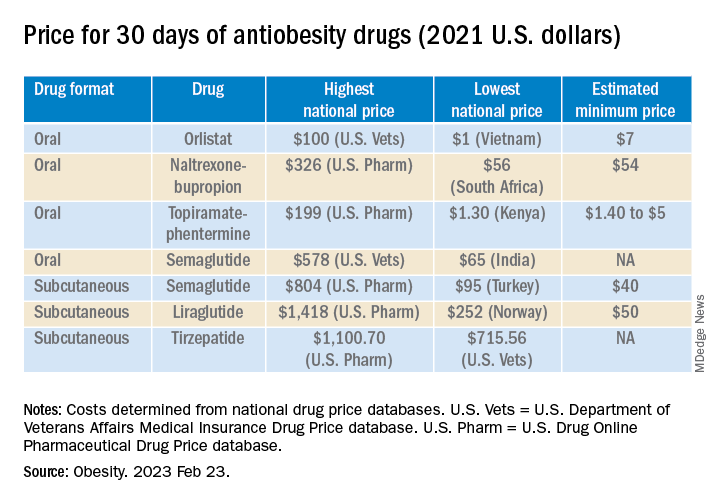

The lowest available national prices of drugs to treat obesity are up to 20 times higher than the estimated cost of profitable generic versions of the same agents, according to a new analysis.

The findings by Jacob Levi, MBBS, and colleagues were published in Obesity.

“Our study highlights the inequality in pricing that exists for effective antiobesity medications, which are largely unaffordable in most countries,” Dr. Levi, from Royal Free Hospital NHS Trust, London, said in a press release.

“We show that these drugs can actually be produced and sold profitably for low prices,” he summarized. “A public health approach that prioritizes improving access to medications should be adopted, instead of allowing companies to maximize profits,” Dr. Levi urged.

Dr. Levi and colleagues studied the oral agents orlistat, naltrexone/bupropion, topiramate/phentermine, and semaglutide, and subcutaneous liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide (all approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat obesity, except for oral semaglutide and subcutaneous tirzepatide, which are not yet approved to treat obesity in the absence of type 2 diabetes).

“Worldwide, more people are dying from diabetes and clinical obesity than HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria combined now,” senior author Andrew Hill, MD, department of pharmacology and therapeutics, University of Liverpool, England, pointed out.

We need to repeat the low-cost success story with obesity drugs

“Millions of lives have been saved by treating infectious diseases at low cost in poor countries,” Dr. Hill continued. “Now we need to repeat this medical success story, with mass treatment of diabetes and clinical obesity at low prices.”

However, in an accompanying editorial, Eric A. Finkelstein, MD, and Junxing Chay, PhD, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, maintain that “It would be great if everyone had affordable access to all medicines that might improve their health. Yet that is simply not possible, nor will it ever be.”

“What is truly needed is a better way to ration the health care dollars currently available in efforts to maximize population health. That is the challenge ahead not just for [antiobesity medications] but for all treatments,” they say.

“Greater use of cost-effectiveness analysis and direct negotiations, while maintaining the patent system, represents an appropriate approach for allocating scarce health care resources in the United States and beyond,” they continue.

Lowest current patented drug prices vs. estimated generic drug prices

New medications for obesity were highly effective in recent clinical trials, but high prices limit the ability of patients to get these medications, Dr. Levi and colleagues write.

They analyzed prices for obesity drugs in 16 low-, middle-, and high-income countries: Australia, Bangladesh, China, France, Germany, India, Kenya, Morocco, Norway, Peru, Pakistan, South Africa, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Vietnam.

The researchers assessed the price of a 30-day supply of each of the studied branded drugs based on the lowest available price (in 2021 U.S. dollars) from multiple online national price databases.

Then they calculated the estimated minimum price of a 30-day supply of a potential generic version of these drugs, which included the cost of the active medicinal ingredients, the excipients (nonactive ingredients), the prefilled injectable device plus needles (for subcutaneous drugs), transportation, 10% profit, and 27% tax on profit.

The national prices of the branded medications for obesity were significantly higher than the estimated minimum prices of potential generic drugs (see Table).

The highest national price for a branded oral drug for obesity vs. the estimated minimum price for a potential generic version was $100 vs. $7 for orlistat, $199 vs. $5 for phentermine/topiramate, and $326 vs. $54 for naltrexone/bupropion, for a 30-day supply.

There was an even greater difference between highest national branded drug price vs. estimated minimum generic drug price for the newer subcutaneously injectable drugs for obesity.

For example, the price of a 30-day course of subcutaneous semaglutide ranged from $804 (United States) to $95 (Turkey), while the estimated minimum potential generic drug price was $40 (which is 20 times lower).

The study was funded by grants from the Make Medicines Affordable/International Treatment Preparedness Coalition and from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. Coauthor Francois Venter has reported receiving support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, U.S. Agency for International Development, Unitaid, SA Medical Research Council, Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics, the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, Gilead, ViiV, Mylan, Merck, Adcock Ingram, Aspen, Abbott, Roche, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, Virology Education, SA HIV Clinicians Society, and Dira Sengwe. The other authors and Dr. Chay have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Finkelstein has reported receiving support for serving on the WW scientific advisory board and an educational grant unrelated to the present work from Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

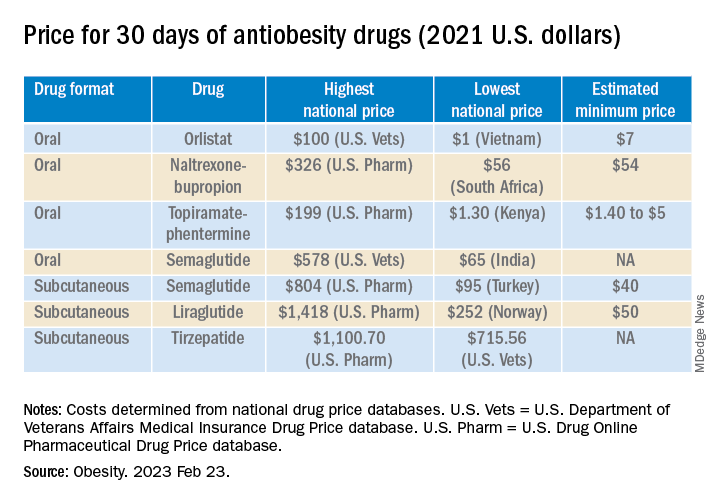

The lowest available national prices of drugs to treat obesity are up to 20 times higher than the estimated cost of profitable generic versions of the same agents, according to a new analysis.

The findings by Jacob Levi, MBBS, and colleagues were published in Obesity.

“Our study highlights the inequality in pricing that exists for effective antiobesity medications, which are largely unaffordable in most countries,” Dr. Levi, from Royal Free Hospital NHS Trust, London, said in a press release.

“We show that these drugs can actually be produced and sold profitably for low prices,” he summarized. “A public health approach that prioritizes improving access to medications should be adopted, instead of allowing companies to maximize profits,” Dr. Levi urged.

Dr. Levi and colleagues studied the oral agents orlistat, naltrexone/bupropion, topiramate/phentermine, and semaglutide, and subcutaneous liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide (all approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat obesity, except for oral semaglutide and subcutaneous tirzepatide, which are not yet approved to treat obesity in the absence of type 2 diabetes).

“Worldwide, more people are dying from diabetes and clinical obesity than HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria combined now,” senior author Andrew Hill, MD, department of pharmacology and therapeutics, University of Liverpool, England, pointed out.

We need to repeat the low-cost success story with obesity drugs

“Millions of lives have been saved by treating infectious diseases at low cost in poor countries,” Dr. Hill continued. “Now we need to repeat this medical success story, with mass treatment of diabetes and clinical obesity at low prices.”

However, in an accompanying editorial, Eric A. Finkelstein, MD, and Junxing Chay, PhD, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, maintain that “It would be great if everyone had affordable access to all medicines that might improve their health. Yet that is simply not possible, nor will it ever be.”

“What is truly needed is a better way to ration the health care dollars currently available in efforts to maximize population health. That is the challenge ahead not just for [antiobesity medications] but for all treatments,” they say.

“Greater use of cost-effectiveness analysis and direct negotiations, while maintaining the patent system, represents an appropriate approach for allocating scarce health care resources in the United States and beyond,” they continue.

Lowest current patented drug prices vs. estimated generic drug prices

New medications for obesity were highly effective in recent clinical trials, but high prices limit the ability of patients to get these medications, Dr. Levi and colleagues write.

They analyzed prices for obesity drugs in 16 low-, middle-, and high-income countries: Australia, Bangladesh, China, France, Germany, India, Kenya, Morocco, Norway, Peru, Pakistan, South Africa, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Vietnam.

The researchers assessed the price of a 30-day supply of each of the studied branded drugs based on the lowest available price (in 2021 U.S. dollars) from multiple online national price databases.

Then they calculated the estimated minimum price of a 30-day supply of a potential generic version of these drugs, which included the cost of the active medicinal ingredients, the excipients (nonactive ingredients), the prefilled injectable device plus needles (for subcutaneous drugs), transportation, 10% profit, and 27% tax on profit.

The national prices of the branded medications for obesity were significantly higher than the estimated minimum prices of potential generic drugs (see Table).

The highest national price for a branded oral drug for obesity vs. the estimated minimum price for a potential generic version was $100 vs. $7 for orlistat, $199 vs. $5 for phentermine/topiramate, and $326 vs. $54 for naltrexone/bupropion, for a 30-day supply.

There was an even greater difference between highest national branded drug price vs. estimated minimum generic drug price for the newer subcutaneously injectable drugs for obesity.

For example, the price of a 30-day course of subcutaneous semaglutide ranged from $804 (United States) to $95 (Turkey), while the estimated minimum potential generic drug price was $40 (which is 20 times lower).

The study was funded by grants from the Make Medicines Affordable/International Treatment Preparedness Coalition and from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. Coauthor Francois Venter has reported receiving support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, U.S. Agency for International Development, Unitaid, SA Medical Research Council, Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics, the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, Gilead, ViiV, Mylan, Merck, Adcock Ingram, Aspen, Abbott, Roche, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, Virology Education, SA HIV Clinicians Society, and Dira Sengwe. The other authors and Dr. Chay have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Finkelstein has reported receiving support for serving on the WW scientific advisory board and an educational grant unrelated to the present work from Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tirzepatide scores win in second obesity trial, SURMOUNT-2

The “twincretin” tirzepatide (Mounjaro) has proven successful in SURMOUNT-2, the second pivotal trial for the drug as an antiobesity agent, according to top-line results reported April 27 by tirzepatide’s manufacturer, Lilly, in a press release. The company reveals that tirzepatide achieved both of its primary endpoints in the trial, as well as all its key secondary endpoints.

The findings pave the way for tirzepatide to likely receive Food and Drug Administration approval as a treatment for obesity, perhaps before the end of 2023.

Tirzepatide received FDA approval in May 2022 for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in adults, under the brand name Mounjaro, and some people have already been using it off-label to treat obesity.

Tirzepatide is a dual glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonist and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide agonist. Several GLP-1 receptor agonists are already approved in the United States, including semaglutide, a once-weekly injection, which is approved as Wegovy for patients with obesity and as Ozempic for treatment of type 2 diabetes.

These agents have been incredibly popular among celebrity influencers, and with use of the #Ozempic hashtag and others on social media, this has led to unprecedented use of these products for weight loss, often among those who do not even have obesity or type 2 diabetes. Subsequently, patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity who need them have often struggled to obtain them, owing to shortages following this phenomenon.

SURMOUNT-2: Weight loss around 15%, less than seen in SURMOUNT-1

SURMOUNT-2 enrolled 938 adults with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes and had dual primary endpoints that both focused on weight loss, compared with placebo.

The first completed pivotal trial of tirzepatide for weight loss, SURMOUNT-1, enrolled people with overweight or obesity but no diabetes and had its main results reported in 2022. At the time, the weight loss achieved with tirzepatide, was described as “unprecedented,” with those given the highest dose in that trial (15 mg subcutaneously per week) losing an average of 20%-22% of body weight over 72 weeks, depending on the specific statistical analysis used.

For SURMOUNT-2’s first primary endpoint, 72 weeks of weekly subcutaneous injections with tirzepatide at dosages of 10 mg or 15 mg led to an average weight loss from baseline of 13.4% and 15.7%, respectively, compared with an average loss of 3.3% from baseline in the placebo-treated control arm.

For the second primary endpoint, 81.6% of people on the 10-mg dose and 86.4% on the 15-mg dose achieved at least 5% weight loss from baseline, compared with 30.5% of controls who had at least 5% weight loss from baseline.

In one key secondary endpoint, tirzepatide at dosages of 10 mg or 15 mg weekly produced at least a 15% cut in weight from baseline in 41.4% and 51.8% of participants, respectively, compared with a 2.6% rate of this endpoint in the placebo controls.

So the extent of weight loss seen in in SURMOUNT-2 was somewhat less than was reported in SURMOUNT-1, a finding consistent with many prior studies of incretin-based weight-loss agents, which seem to pack a more potent weight-loss punch in people without type 2 diabetes.

Lilly did not specifically report the treatment effect of tirzepatide on hemoglobin A1c in SURMOUNT-2, only saying that the effect was similar to what had been seen in the series of five SURPASS trials that led to the approval of tirzepatide for type 2 diabetes.

Lilly also reported that the safety profile of tirzepatide in SURMOUNT-2 generally matched what was seen in SURMOUNT-1 as well as in the SURPASS trials. The most common adverse events in SURMOUNT-2 involved gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting; these were generally mild to moderate in severity and clustered during the dose-escalation phase at the start of treatment. Treatment discontinuations caused by adverse effects were 3.8% on the 10-mg dosage, 7.4% on the 15-mg dosage, and 3.8% on placebo.

SURMOUNT-2 enrolled patients in the United States, Puerto Rico, and five other countries. All participants also received interventions designed to reduce their calorie intake and increase their physical activity.

More SURMOUNT-2 results at ADA in June

Lilly also announced that researchers would report more complete results from SURMOUNT-2 at the 2023 scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association, being held in San Diego in late June, and publish the findings in a major medical journal.

Results from two additional phase 3 trials of tirzepatide in people with overweight or obesity, SURMOUNT-3 and SURMOUNT-4, are expected later in 2023.

Lilly started an application to the FDA for an indication for weight loss in October 2022 under a fast track designation by the agency, and the data collected in SURMOUNT-2 are expected to complete this application, which would then be subject to an FDA decision within about 6 months. Lilly said in its April 27 press release that it anticipates an FDA decision on this application may occur before the end of 2023.

SURMOUNT-2 and all of the other tirzepatide trials were sponsored by Lilly.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The “twincretin” tirzepatide (Mounjaro) has proven successful in SURMOUNT-2, the second pivotal trial for the drug as an antiobesity agent, according to top-line results reported April 27 by tirzepatide’s manufacturer, Lilly, in a press release. The company reveals that tirzepatide achieved both of its primary endpoints in the trial, as well as all its key secondary endpoints.

The findings pave the way for tirzepatide to likely receive Food and Drug Administration approval as a treatment for obesity, perhaps before the end of 2023.

Tirzepatide received FDA approval in May 2022 for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in adults, under the brand name Mounjaro, and some people have already been using it off-label to treat obesity.

Tirzepatide is a dual glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonist and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide agonist. Several GLP-1 receptor agonists are already approved in the United States, including semaglutide, a once-weekly injection, which is approved as Wegovy for patients with obesity and as Ozempic for treatment of type 2 diabetes.

These agents have been incredibly popular among celebrity influencers, and with use of the #Ozempic hashtag and others on social media, this has led to unprecedented use of these products for weight loss, often among those who do not even have obesity or type 2 diabetes. Subsequently, patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity who need them have often struggled to obtain them, owing to shortages following this phenomenon.

SURMOUNT-2: Weight loss around 15%, less than seen in SURMOUNT-1

SURMOUNT-2 enrolled 938 adults with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes and had dual primary endpoints that both focused on weight loss, compared with placebo.

The first completed pivotal trial of tirzepatide for weight loss, SURMOUNT-1, enrolled people with overweight or obesity but no diabetes and had its main results reported in 2022. At the time, the weight loss achieved with tirzepatide, was described as “unprecedented,” with those given the highest dose in that trial (15 mg subcutaneously per week) losing an average of 20%-22% of body weight over 72 weeks, depending on the specific statistical analysis used.

For SURMOUNT-2’s first primary endpoint, 72 weeks of weekly subcutaneous injections with tirzepatide at dosages of 10 mg or 15 mg led to an average weight loss from baseline of 13.4% and 15.7%, respectively, compared with an average loss of 3.3% from baseline in the placebo-treated control arm.

For the second primary endpoint, 81.6% of people on the 10-mg dose and 86.4% on the 15-mg dose achieved at least 5% weight loss from baseline, compared with 30.5% of controls who had at least 5% weight loss from baseline.

In one key secondary endpoint, tirzepatide at dosages of 10 mg or 15 mg weekly produced at least a 15% cut in weight from baseline in 41.4% and 51.8% of participants, respectively, compared with a 2.6% rate of this endpoint in the placebo controls.

So the extent of weight loss seen in in SURMOUNT-2 was somewhat less than was reported in SURMOUNT-1, a finding consistent with many prior studies of incretin-based weight-loss agents, which seem to pack a more potent weight-loss punch in people without type 2 diabetes.

Lilly did not specifically report the treatment effect of tirzepatide on hemoglobin A1c in SURMOUNT-2, only saying that the effect was similar to what had been seen in the series of five SURPASS trials that led to the approval of tirzepatide for type 2 diabetes.

Lilly also reported that the safety profile of tirzepatide in SURMOUNT-2 generally matched what was seen in SURMOUNT-1 as well as in the SURPASS trials. The most common adverse events in SURMOUNT-2 involved gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting; these were generally mild to moderate in severity and clustered during the dose-escalation phase at the start of treatment. Treatment discontinuations caused by adverse effects were 3.8% on the 10-mg dosage, 7.4% on the 15-mg dosage, and 3.8% on placebo.

SURMOUNT-2 enrolled patients in the United States, Puerto Rico, and five other countries. All participants also received interventions designed to reduce their calorie intake and increase their physical activity.

More SURMOUNT-2 results at ADA in June

Lilly also announced that researchers would report more complete results from SURMOUNT-2 at the 2023 scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association, being held in San Diego in late June, and publish the findings in a major medical journal.

Results from two additional phase 3 trials of tirzepatide in people with overweight or obesity, SURMOUNT-3 and SURMOUNT-4, are expected later in 2023.

Lilly started an application to the FDA for an indication for weight loss in October 2022 under a fast track designation by the agency, and the data collected in SURMOUNT-2 are expected to complete this application, which would then be subject to an FDA decision within about 6 months. Lilly said in its April 27 press release that it anticipates an FDA decision on this application may occur before the end of 2023.

SURMOUNT-2 and all of the other tirzepatide trials were sponsored by Lilly.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The “twincretin” tirzepatide (Mounjaro) has proven successful in SURMOUNT-2, the second pivotal trial for the drug as an antiobesity agent, according to top-line results reported April 27 by tirzepatide’s manufacturer, Lilly, in a press release. The company reveals that tirzepatide achieved both of its primary endpoints in the trial, as well as all its key secondary endpoints.

The findings pave the way for tirzepatide to likely receive Food and Drug Administration approval as a treatment for obesity, perhaps before the end of 2023.

Tirzepatide received FDA approval in May 2022 for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in adults, under the brand name Mounjaro, and some people have already been using it off-label to treat obesity.

Tirzepatide is a dual glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonist and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide agonist. Several GLP-1 receptor agonists are already approved in the United States, including semaglutide, a once-weekly injection, which is approved as Wegovy for patients with obesity and as Ozempic for treatment of type 2 diabetes.

These agents have been incredibly popular among celebrity influencers, and with use of the #Ozempic hashtag and others on social media, this has led to unprecedented use of these products for weight loss, often among those who do not even have obesity or type 2 diabetes. Subsequently, patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity who need them have often struggled to obtain them, owing to shortages following this phenomenon.

SURMOUNT-2: Weight loss around 15%, less than seen in SURMOUNT-1

SURMOUNT-2 enrolled 938 adults with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes and had dual primary endpoints that both focused on weight loss, compared with placebo.

The first completed pivotal trial of tirzepatide for weight loss, SURMOUNT-1, enrolled people with overweight or obesity but no diabetes and had its main results reported in 2022. At the time, the weight loss achieved with tirzepatide, was described as “unprecedented,” with those given the highest dose in that trial (15 mg subcutaneously per week) losing an average of 20%-22% of body weight over 72 weeks, depending on the specific statistical analysis used.

For SURMOUNT-2’s first primary endpoint, 72 weeks of weekly subcutaneous injections with tirzepatide at dosages of 10 mg or 15 mg led to an average weight loss from baseline of 13.4% and 15.7%, respectively, compared with an average loss of 3.3% from baseline in the placebo-treated control arm.

For the second primary endpoint, 81.6% of people on the 10-mg dose and 86.4% on the 15-mg dose achieved at least 5% weight loss from baseline, compared with 30.5% of controls who had at least 5% weight loss from baseline.

In one key secondary endpoint, tirzepatide at dosages of 10 mg or 15 mg weekly produced at least a 15% cut in weight from baseline in 41.4% and 51.8% of participants, respectively, compared with a 2.6% rate of this endpoint in the placebo controls.

So the extent of weight loss seen in in SURMOUNT-2 was somewhat less than was reported in SURMOUNT-1, a finding consistent with many prior studies of incretin-based weight-loss agents, which seem to pack a more potent weight-loss punch in people without type 2 diabetes.

Lilly did not specifically report the treatment effect of tirzepatide on hemoglobin A1c in SURMOUNT-2, only saying that the effect was similar to what had been seen in the series of five SURPASS trials that led to the approval of tirzepatide for type 2 diabetes.

Lilly also reported that the safety profile of tirzepatide in SURMOUNT-2 generally matched what was seen in SURMOUNT-1 as well as in the SURPASS trials. The most common adverse events in SURMOUNT-2 involved gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting; these were generally mild to moderate in severity and clustered during the dose-escalation phase at the start of treatment. Treatment discontinuations caused by adverse effects were 3.8% on the 10-mg dosage, 7.4% on the 15-mg dosage, and 3.8% on placebo.

SURMOUNT-2 enrolled patients in the United States, Puerto Rico, and five other countries. All participants also received interventions designed to reduce their calorie intake and increase their physical activity.

More SURMOUNT-2 results at ADA in June

Lilly also announced that researchers would report more complete results from SURMOUNT-2 at the 2023 scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association, being held in San Diego in late June, and publish the findings in a major medical journal.

Results from two additional phase 3 trials of tirzepatide in people with overweight or obesity, SURMOUNT-3 and SURMOUNT-4, are expected later in 2023.