User login

Treatment of delirium: A review of 3 studies

Delirium is defined as a disturbance in attention, awareness, and cognition that develops over hours to days as a direct physiological consequence of an underlying medical condition and is not better explained by another neurocognitive disorder.1 This condition is found in up to 31% of general medical patients and up to 87% of critically ill medical patients. Delirium is commonly seen in patients who have undergone surgery, those who are in palliative care, and patients with cancer.2 It is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Compared with those who do not develop delirium, patients who are hospitalized who develop delirium have a higher risk of longer hospital stays, post-hospitalization nursing facility placement, persistent cognitive dysfunction, and death.3

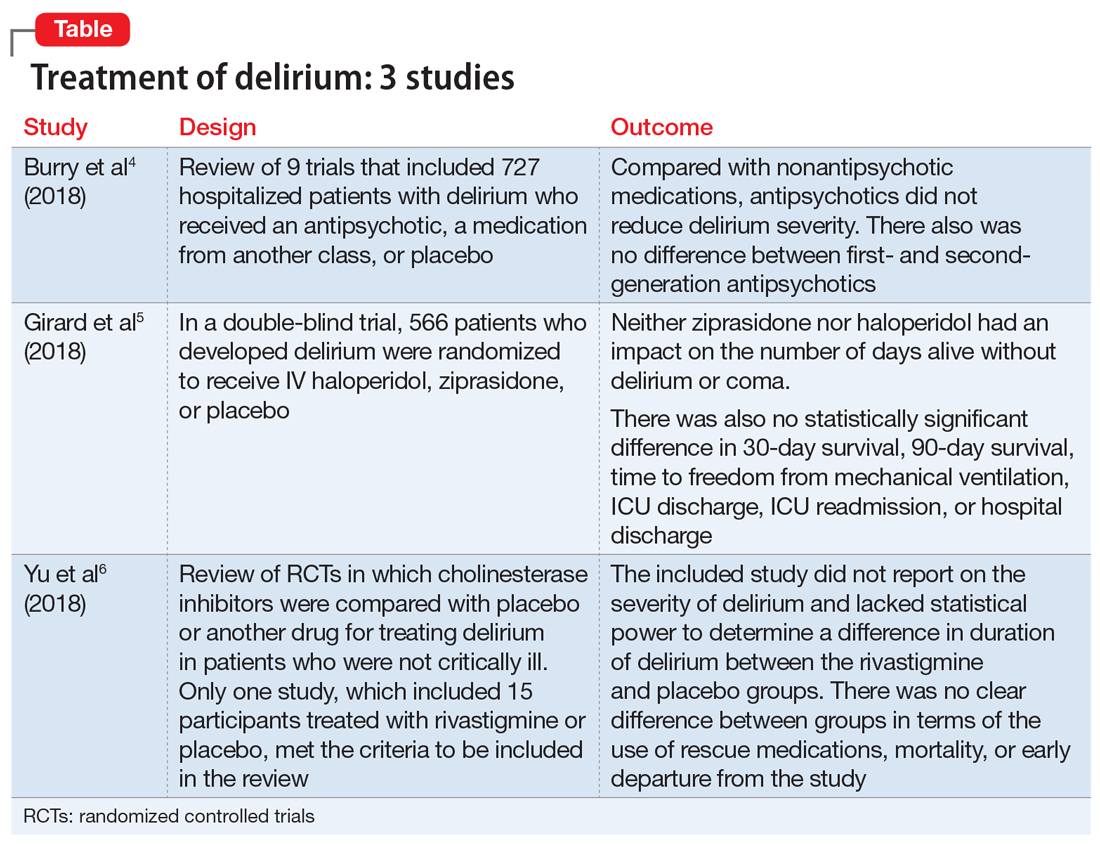

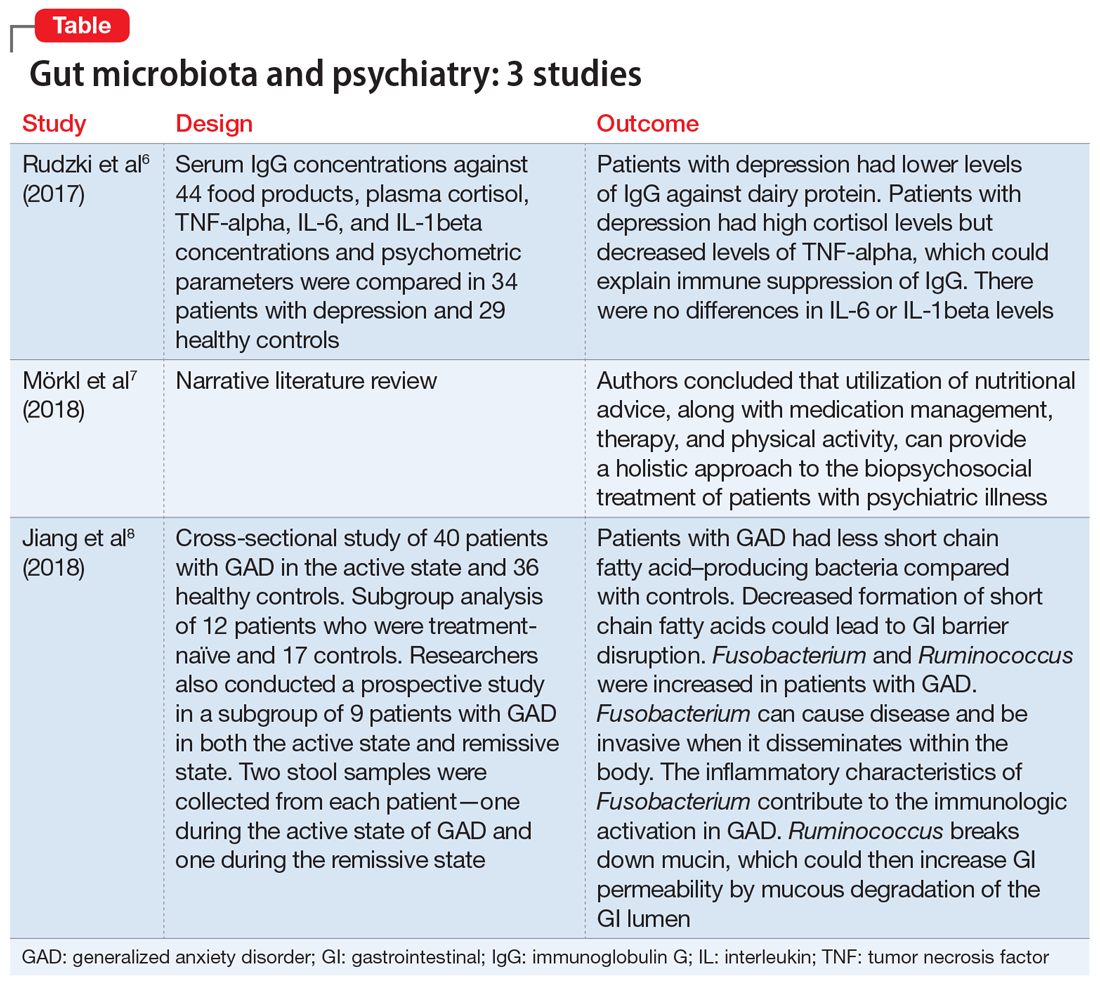

Thus far, the management and treatment of delirium have been complicated by an incomplete understanding of the pathophysiology of this condition. However, prevailing theories suggest a dysregulation of neurotransmitter synthesis, function, or availability.2 Recent literature reflects this theory; researchers have investigated agents that target dopamine or acetylcholine. Below we review some of this recent literature on treating delirium; these studies are summarized in the Table.4-6

1. Burry L, Mehta S, Perreault MM, et al. Antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in hospitalized non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD005594.

An extensive literature review identified randomized or quasi-randomized trials on the treatment of delirium among non-critically ill hospitalized patients in which antipsychotics were compared with nonantipsychotic medications or placebo, or in which a first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) was compared with a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA).4

Study design

- Researchers conducted a literature review of 9 trials that included 727 hospitalized but not critically ill patients (ie, they were not in an ICU) who developed delirium.

- Four trials compared an antipsychotic with a medication from another drug class or with placebo.

- Seven trials compared a FGA with an SGA.

Outcomes

- Although the intended primary outcome was the duration of delirium, none of the included studies reported on duration of delirium. Secondary outcomes were delirium severity and resolution, mortality, hospital length of stay, discharge disposition, health-related quality of life, and adverse effects.

- Among the secondary outcomes, no statistical difference was observed between delirium severity, delirium resolution, or mortality.

- None of the included studies reported on hospital length of stay, discharge disposition, or health-related quality of life.

- Evidence related to adverse effects was determined to be very low quality due to potential bias, inconsistency, and imprecision.

Conclusion

- A review of 9 randomized trials did not find any evidence supporting the use of antipsychotics for treating delirium. However, most of the studies included were of lower quality because they were single-center trials with insufficient sample sizes, heterogeneous study populations, and risk of bias.

Continue to: 2...

2. Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS, et al; MIND-USA Investigators. Haloperidol and ziprasidone for treatment of delirium in critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2506-2516.

Study design

- Researchers used the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) to assess 1,183 patients with acute respiratory failure or shock in 16 medical centers in the United States.5

- Overall, 566 patients developed delirium and were randomized in a double-blind fashion to receive IV haloperidol, ziprasidone, or placebo.

- Haloperidol was started at 2.5 mg (age <70) or 1.25 mg (age ≥70) every 12 hours and titrated to a maximum dose of 20 mg/d as tolerated.

- Ziprasidone was started at 5 mg (age <70) or 2.5 mg (age ≥70) every 12 hours and titrated to a maximum dose of 40 mg/d as tolerated.

Outcomes

- The primary endpoint was days alive without delirium or coma. Secondary endpoints included duration of delirium, time to freedom from mechanical ventilation, time to final successful ICU discharge, time to ICU readmission, time to successful hospital discharge, 30-day survival, and 90-day survival.

- Neither ziprasidone nor haloperidol had an impact on number of days alive without delirium or coma.

- There was also no statistically significant difference in 30-day survival, 90-day survival, time to freedom from mechanical ventilation, ICU discharge, ICU readmission, or hospital discharge.

Conclusion

- This study found no evidence supporting haloperidol or ziprasidone for the treatment of delirium. Because all patients in this study were critically ill, it is unclear if these results would be generalizable to other hospitalized patient populations.

3. Yu A, Wu S, Zhang Z, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of delirium in non-ICU settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD012494.

Study design

- A literature review identified published and unpublished randomized controlled trials in English and Chinese in which cholinesterase inhibitors were compared with placebo or another drug for treating delirium in non-critically ill patients.6

- Only one study met the criteria to be included in the review. It included 15 participants treated with rivastigmine or placebo.

Outcomes

- The intended primary outcomes were severity of delirium and duration of delirium. However, the included study did not report on the severity of delirium. It also lacked statistical power to determine a difference in duration of delirium between the rivastigmine and placebo groups.

- Secondary outcomes included use of a rescue medication, persistent cognitive impairment, length of hospitalization, institutionalization, mortality, cost of intervention, early departure from the study, and quality of life.

- There was no clear difference between the rivastigmine group and the placebo group in terms of the use of rescue medications, mortality, or early departure from the study. The included study did not report on persistent cognitive impairment, length of hospitalization, institutionalization, cost of intervention, or quality of life.

Conclusion

- This literature review did not find any evidence to support the use of cholinesterase inhibitors for treating delirium. However, because this review included only a single small study, limited conclusions can be drawn from this research.

In summary, delirium is common, especially among patients who are acutely medically ill, and it is associated with poor physical and cognitive clinical outcomes. Because of these poor outcomes, it is important to identify delirium early and intervene aggressively. Clearly, there is a need for further research into short- and long-term treatments for delirium.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Maldonado JR. Acute brain failure: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management, and sequelae of delirium. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33(3):461-519.

3. Marcantonio ER. Delirium in hospitalized older adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(15):1456-1466.

4. Burry L, Mehta S, Perreault MM, et al. Antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in hospitalized non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD005594. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005594.pub3.

5. Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS, et al; MIND-USA Investigators. Haloperidol and ziprasidone for treatment of delirium in critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2506-2516.

6. Yu A, Wu S, Zhang Z, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of delirium in non-ICU settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD012494.

Delirium is defined as a disturbance in attention, awareness, and cognition that develops over hours to days as a direct physiological consequence of an underlying medical condition and is not better explained by another neurocognitive disorder.1 This condition is found in up to 31% of general medical patients and up to 87% of critically ill medical patients. Delirium is commonly seen in patients who have undergone surgery, those who are in palliative care, and patients with cancer.2 It is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Compared with those who do not develop delirium, patients who are hospitalized who develop delirium have a higher risk of longer hospital stays, post-hospitalization nursing facility placement, persistent cognitive dysfunction, and death.3

Thus far, the management and treatment of delirium have been complicated by an incomplete understanding of the pathophysiology of this condition. However, prevailing theories suggest a dysregulation of neurotransmitter synthesis, function, or availability.2 Recent literature reflects this theory; researchers have investigated agents that target dopamine or acetylcholine. Below we review some of this recent literature on treating delirium; these studies are summarized in the Table.4-6

1. Burry L, Mehta S, Perreault MM, et al. Antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in hospitalized non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD005594.

An extensive literature review identified randomized or quasi-randomized trials on the treatment of delirium among non-critically ill hospitalized patients in which antipsychotics were compared with nonantipsychotic medications or placebo, or in which a first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) was compared with a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA).4

Study design

- Researchers conducted a literature review of 9 trials that included 727 hospitalized but not critically ill patients (ie, they were not in an ICU) who developed delirium.

- Four trials compared an antipsychotic with a medication from another drug class or with placebo.

- Seven trials compared a FGA with an SGA.

Outcomes

- Although the intended primary outcome was the duration of delirium, none of the included studies reported on duration of delirium. Secondary outcomes were delirium severity and resolution, mortality, hospital length of stay, discharge disposition, health-related quality of life, and adverse effects.

- Among the secondary outcomes, no statistical difference was observed between delirium severity, delirium resolution, or mortality.

- None of the included studies reported on hospital length of stay, discharge disposition, or health-related quality of life.

- Evidence related to adverse effects was determined to be very low quality due to potential bias, inconsistency, and imprecision.

Conclusion

- A review of 9 randomized trials did not find any evidence supporting the use of antipsychotics for treating delirium. However, most of the studies included were of lower quality because they were single-center trials with insufficient sample sizes, heterogeneous study populations, and risk of bias.

Continue to: 2...

2. Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS, et al; MIND-USA Investigators. Haloperidol and ziprasidone for treatment of delirium in critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2506-2516.

Study design

- Researchers used the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) to assess 1,183 patients with acute respiratory failure or shock in 16 medical centers in the United States.5

- Overall, 566 patients developed delirium and were randomized in a double-blind fashion to receive IV haloperidol, ziprasidone, or placebo.

- Haloperidol was started at 2.5 mg (age <70) or 1.25 mg (age ≥70) every 12 hours and titrated to a maximum dose of 20 mg/d as tolerated.

- Ziprasidone was started at 5 mg (age <70) or 2.5 mg (age ≥70) every 12 hours and titrated to a maximum dose of 40 mg/d as tolerated.

Outcomes

- The primary endpoint was days alive without delirium or coma. Secondary endpoints included duration of delirium, time to freedom from mechanical ventilation, time to final successful ICU discharge, time to ICU readmission, time to successful hospital discharge, 30-day survival, and 90-day survival.

- Neither ziprasidone nor haloperidol had an impact on number of days alive without delirium or coma.

- There was also no statistically significant difference in 30-day survival, 90-day survival, time to freedom from mechanical ventilation, ICU discharge, ICU readmission, or hospital discharge.

Conclusion

- This study found no evidence supporting haloperidol or ziprasidone for the treatment of delirium. Because all patients in this study were critically ill, it is unclear if these results would be generalizable to other hospitalized patient populations.

3. Yu A, Wu S, Zhang Z, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of delirium in non-ICU settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD012494.

Study design

- A literature review identified published and unpublished randomized controlled trials in English and Chinese in which cholinesterase inhibitors were compared with placebo or another drug for treating delirium in non-critically ill patients.6

- Only one study met the criteria to be included in the review. It included 15 participants treated with rivastigmine or placebo.

Outcomes

- The intended primary outcomes were severity of delirium and duration of delirium. However, the included study did not report on the severity of delirium. It also lacked statistical power to determine a difference in duration of delirium between the rivastigmine and placebo groups.

- Secondary outcomes included use of a rescue medication, persistent cognitive impairment, length of hospitalization, institutionalization, mortality, cost of intervention, early departure from the study, and quality of life.

- There was no clear difference between the rivastigmine group and the placebo group in terms of the use of rescue medications, mortality, or early departure from the study. The included study did not report on persistent cognitive impairment, length of hospitalization, institutionalization, cost of intervention, or quality of life.

Conclusion

- This literature review did not find any evidence to support the use of cholinesterase inhibitors for treating delirium. However, because this review included only a single small study, limited conclusions can be drawn from this research.

In summary, delirium is common, especially among patients who are acutely medically ill, and it is associated with poor physical and cognitive clinical outcomes. Because of these poor outcomes, it is important to identify delirium early and intervene aggressively. Clearly, there is a need for further research into short- and long-term treatments for delirium.

Delirium is defined as a disturbance in attention, awareness, and cognition that develops over hours to days as a direct physiological consequence of an underlying medical condition and is not better explained by another neurocognitive disorder.1 This condition is found in up to 31% of general medical patients and up to 87% of critically ill medical patients. Delirium is commonly seen in patients who have undergone surgery, those who are in palliative care, and patients with cancer.2 It is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Compared with those who do not develop delirium, patients who are hospitalized who develop delirium have a higher risk of longer hospital stays, post-hospitalization nursing facility placement, persistent cognitive dysfunction, and death.3

Thus far, the management and treatment of delirium have been complicated by an incomplete understanding of the pathophysiology of this condition. However, prevailing theories suggest a dysregulation of neurotransmitter synthesis, function, or availability.2 Recent literature reflects this theory; researchers have investigated agents that target dopamine or acetylcholine. Below we review some of this recent literature on treating delirium; these studies are summarized in the Table.4-6

1. Burry L, Mehta S, Perreault MM, et al. Antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in hospitalized non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD005594.

An extensive literature review identified randomized or quasi-randomized trials on the treatment of delirium among non-critically ill hospitalized patients in which antipsychotics were compared with nonantipsychotic medications or placebo, or in which a first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) was compared with a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA).4

Study design

- Researchers conducted a literature review of 9 trials that included 727 hospitalized but not critically ill patients (ie, they were not in an ICU) who developed delirium.

- Four trials compared an antipsychotic with a medication from another drug class or with placebo.

- Seven trials compared a FGA with an SGA.

Outcomes

- Although the intended primary outcome was the duration of delirium, none of the included studies reported on duration of delirium. Secondary outcomes were delirium severity and resolution, mortality, hospital length of stay, discharge disposition, health-related quality of life, and adverse effects.

- Among the secondary outcomes, no statistical difference was observed between delirium severity, delirium resolution, or mortality.

- None of the included studies reported on hospital length of stay, discharge disposition, or health-related quality of life.

- Evidence related to adverse effects was determined to be very low quality due to potential bias, inconsistency, and imprecision.

Conclusion

- A review of 9 randomized trials did not find any evidence supporting the use of antipsychotics for treating delirium. However, most of the studies included were of lower quality because they were single-center trials with insufficient sample sizes, heterogeneous study populations, and risk of bias.

Continue to: 2...

2. Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS, et al; MIND-USA Investigators. Haloperidol and ziprasidone for treatment of delirium in critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2506-2516.

Study design

- Researchers used the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) to assess 1,183 patients with acute respiratory failure or shock in 16 medical centers in the United States.5

- Overall, 566 patients developed delirium and were randomized in a double-blind fashion to receive IV haloperidol, ziprasidone, or placebo.

- Haloperidol was started at 2.5 mg (age <70) or 1.25 mg (age ≥70) every 12 hours and titrated to a maximum dose of 20 mg/d as tolerated.

- Ziprasidone was started at 5 mg (age <70) or 2.5 mg (age ≥70) every 12 hours and titrated to a maximum dose of 40 mg/d as tolerated.

Outcomes

- The primary endpoint was days alive without delirium or coma. Secondary endpoints included duration of delirium, time to freedom from mechanical ventilation, time to final successful ICU discharge, time to ICU readmission, time to successful hospital discharge, 30-day survival, and 90-day survival.

- Neither ziprasidone nor haloperidol had an impact on number of days alive without delirium or coma.

- There was also no statistically significant difference in 30-day survival, 90-day survival, time to freedom from mechanical ventilation, ICU discharge, ICU readmission, or hospital discharge.

Conclusion

- This study found no evidence supporting haloperidol or ziprasidone for the treatment of delirium. Because all patients in this study were critically ill, it is unclear if these results would be generalizable to other hospitalized patient populations.

3. Yu A, Wu S, Zhang Z, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of delirium in non-ICU settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD012494.

Study design

- A literature review identified published and unpublished randomized controlled trials in English and Chinese in which cholinesterase inhibitors were compared with placebo or another drug for treating delirium in non-critically ill patients.6

- Only one study met the criteria to be included in the review. It included 15 participants treated with rivastigmine or placebo.

Outcomes

- The intended primary outcomes were severity of delirium and duration of delirium. However, the included study did not report on the severity of delirium. It also lacked statistical power to determine a difference in duration of delirium between the rivastigmine and placebo groups.

- Secondary outcomes included use of a rescue medication, persistent cognitive impairment, length of hospitalization, institutionalization, mortality, cost of intervention, early departure from the study, and quality of life.

- There was no clear difference between the rivastigmine group and the placebo group in terms of the use of rescue medications, mortality, or early departure from the study. The included study did not report on persistent cognitive impairment, length of hospitalization, institutionalization, cost of intervention, or quality of life.

Conclusion

- This literature review did not find any evidence to support the use of cholinesterase inhibitors for treating delirium. However, because this review included only a single small study, limited conclusions can be drawn from this research.

In summary, delirium is common, especially among patients who are acutely medically ill, and it is associated with poor physical and cognitive clinical outcomes. Because of these poor outcomes, it is important to identify delirium early and intervene aggressively. Clearly, there is a need for further research into short- and long-term treatments for delirium.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Maldonado JR. Acute brain failure: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management, and sequelae of delirium. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33(3):461-519.

3. Marcantonio ER. Delirium in hospitalized older adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(15):1456-1466.

4. Burry L, Mehta S, Perreault MM, et al. Antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in hospitalized non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD005594. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005594.pub3.

5. Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS, et al; MIND-USA Investigators. Haloperidol and ziprasidone for treatment of delirium in critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2506-2516.

6. Yu A, Wu S, Zhang Z, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of delirium in non-ICU settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD012494.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Maldonado JR. Acute brain failure: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management, and sequelae of delirium. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33(3):461-519.

3. Marcantonio ER. Delirium in hospitalized older adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(15):1456-1466.

4. Burry L, Mehta S, Perreault MM, et al. Antipsychotics for treatment of delirium in hospitalized non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD005594. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005594.pub3.

5. Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS, et al; MIND-USA Investigators. Haloperidol and ziprasidone for treatment of delirium in critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2506-2516.

6. Yu A, Wu S, Zhang Z, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of delirium in non-ICU settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD012494.

Nothing to sneeze at: Upper respiratory infections and mood disorders

Acute upper respiratory infections (URIs) often lead to mild illnesses, but they can be severely destabilizing for individuals with mood disorders. Additionally, the medications patients often take to target symptoms of the common cold or influenza can interact with psychiatric medications to produce dangerous adverse events or induce further mood symptoms. In this article, we describe the relationship between URIs and mood disorders, the psychiatric diagnostic challenges that arise when evaluating a patient with a URI, and treatment approaches that emphasize psychoeducation and watchful waiting, when appropriate.

A bidirectional relationship

Acute upper respiratory infections are the most common human illnesses, affecting almost 25 million people annually in the United States.1 The common cold is caused by >200 different viruses; rhinovirus and coronavirus are the most common. Influenza, which also attacks the upper respiratory tract, is caused by strains of influenza A, B, or C virus.2 The common cold may present initially with mild symptoms of headache, sneezing, chills, and sore throat, and then progress to nasal discharge, congestion, cough, and malaise. When influenza strikes, patients may have a sudden onset of fever, headache, cough, sore throat, myalgia, congestion, weakness, anorexia, and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Production of URI symptoms results from viral cytopathic activity along with immune activation of inflammatory pathways.2,3 The incidence of colds is inversely correlated with age; adults average 2 to 4 colds per year.4,5 Cold symptoms peak at 1 to 3 days and typically last 7 to 10 days, but can persist up to 3 weeks.6 With influenza, fever and other systemic symptoms last for 3 days but can persist up to 8 days, while cough and lethargy can persist for another 2 weeks.7

Upper respiratory infections have the potential to disrupt mood. Large studies of psychiatrically-healthy undergraduate students have found that compared with healthy controls, participants with URIs endorsed a negative affect within the first week of viral illness,8 and that the number and intensity of URI symptoms caused by cold viruses were correlated with the degree of their negative affect.9 A few case reports have documented instances of individuals with no previous personal or family psychiatric history developing full manic episodes in the setting of influenza.10-12 One case report described an influenza-induced manic episode in a patient with pre-existing psychiatric illness.13 There are no published case reports of common cold viruses inducing a full depressive or manic episode. If cold symptom severity correlates with negative affect among individuals with no psychiatric illness, and if influenza can induce manic episodes, then it is reasonable to expect that patients with pre-existing mood disorders could have an elevated risk for mood disturbances when they experience a URI (Box).

Box

Ms. E is a 35-year-old financial analyst with bipolar disorder type I and alcohol use disorder in sustained remission. She had been euthymic for the last 3 years, receiving weekly psychotherapy and taking lamotrigine, 350 mg/d, lithium ER, 900 mg/d (lithium level: 1.0 mmol/L), lurasidone, 60 mg/d, and clonazepam, 1 mg/d. At her most recent quarterly outpatient psychiatrist visit, she says her depression had returned. She reports 1 week of crying spells, initial and middle insomnia, anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness, fatigue, poor concentration, and poor appetite. She denies having suicidal ideation or manic or psychotic symptoms, and she continues to abstain from alcohol, illicit drugs, and tobacco. She has been fully adherent to her medication regimen and has not added any new medications or made any dietary changes since her last visit. She is puzzled as to what brought on this depression recurrence and says she feels defeated by the bipolar illness, a condition she had worked tirelessly to manage. When asked about changes in her health, she reports that about 1.5 weeks ago she developed a cough, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and fatigue. Because of her annual goal to run a marathon, she continues to train, albeit at a slower pace, and has not had much time to rest because of her demanding job.

The psychiatrist explains to Ms. E that an upper respiratory infection (URI) can sometimes induce depressive symptoms. Given the patient’s lengthy period of euthymia and the absence of new medicines, dietary changes, or drug/alcohol intake, the psychiatrist suspects that the cause of her mood episode recurrence is related to the URI. Hearing this is a relief for Ms. E. She and the psychiatrist decide to refrain from making any medication changes with the expectation that the URI would soon resolve because it had already persisted for 1.5 weeks. The psychiatrist tells Ms. E that if it does not and her symptoms worsen, she should call him to discuss treatment options. The psychiatrist also encourages Ms. E to take a temporary break from training and allow her body to rest.

Three weeks later, Ms. E returns and reports that both the URI symptoms and the depressive symptoms lifted a few days after her last visit.

Mood disorders may also be a risk factor for contracting URIs. Patients with mood disorders are more likely than healthy controls to be seropositive for markers of influenza A, influenza B, and coronavirus, and those with a history of suicide attempts are more likely to be seropositive for markers of influenza B.14 In a community sample of German adults age 18 to 65, those with mood disorders had a 35% higher likelihood of having had a cold within the last 12 months compared with those without a mood disorder.15 A survey of Korean employees found the odds of having had a cold in the last 4 months were up to 2.5 times greater for individuals with elevated scores on a depression symptom severity scale compared with those with lower scores.16 Because these studies were retrospective, recall bias may have impacted the results, as patients who are depressed are more likely to recall negative recent events.17

Proposed mechanisms

Researchers have proposed several mechanisms to explain the association of URIs with mood episodes. Mood disorders, such as bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD), are associated with chronic dysregulation of the innate immune system, which leads to elevated levels of cortisol and pro-inflammatory cytokines.18,19 Men with chronic low-grade inflammation are more vulnerable to all types of infection, including those that cause respiratory illnesses.20 High levels of stress,21 a negative affective style,22 and depression23 have all been associated with reduced antibody response and/or cellular-mediated immunity following vaccination, which suggests a possible mechanism for the vulnerability to infection found in individuals with mood disorders. On the other hand, after influenza vaccination, patients with depression produce a greater and more prolonged release of the cytokine interleukin 6, which perpetuates the state of chronic low-grade inflammation.24 Additionally, patients with mood disorders may engage in behaviors that reduce immune functioning, such as using illicit substances, drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes, consuming an unhealthy diet, or living a sedentary lifestyle.

Conversely, there are several mechanisms by which a URI could induce a mood episode in a patient with a mood disorder. Animal studies have shown that a non-CNS viral infection can lead to depressive behavior by inducing peripheral interferon-beta release. This signaling protein binds to a receptor on the endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier, inducing the release of additional cytokines that affect neuronal functioning.25 Among patients receiving interferon treatments for hepatitis C, a history of depression increased their likelihood of becoming depressed during their treatment course, which suggests people with mood disorders have a sensitivity to peripheral cytokines.26

Sleep interruptions from nighttime coughing or nasal congestion can increase the risk of a recurrence of hypomania or mania in patients with bipolar disorder,27 or a recurrence of depression in a patient with MDD.28 The stress that comes with missed work days or the inability to take care of other personal responsibilities due to a URI may increase the risk of becoming depressed in a patient with bipolar disorder or MDD. When present, GI symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea can reduce the absorption of psychotropic medications and increase the risk of a mood recurrence. Finally, the treatments used for URIs may also contribute to mood instability. Case reports have described instances where patients with URIs developed mania or depression when exposed to medications such as intranasal corticosteroids,29 nasal decongestants,30,31 and anti-influenza treatments.32,33

Continue to: A diagnostic challenge

A diagnostic challenge

Making the diagnosis of a major depressive episode can be challenging in patients who present with a URI, particularly in those who are highly vigilant for relapse and seek care soon after mood symptoms emerge. Many symptoms overlap between the conditions, including insomnia, hypersomnia, reduced interest, anhedonia, fatigue, impaired concentration, and anorexia. Symptoms that are more specific for a major depressive episode include depressed mood, pathologic guilt, worthlessness, and suicidal ideation. Of course, a major depressive episode and a URI are not mutually exclusive and can occur simultaneously. However, incorrectly diagnosing recurrence of a major depressive episode in a euthymic patient who has a URI could lead to unnecessary changes to psychiatric treatment.

Psychoeducation is key

Teach patients about the bidirectional relationship between URIs and mood symptoms to reduce anxiety and confusion about the cause of the return of mood symptoms. Telling patients that they can expect their mood symptoms to be of short duration and self-limiting due to the URI can provide helpful reassurance.

Because it is possible that the mood symptoms will be transient, increasing psychotropic doses or adding a new psychotropic medication may not be necessary. The decision to initiate such changes should be made collaboratively with patients and should be based on the severity and duration of the patient’s mood symptoms. Symptoms that may warrant a medication change include psychosis, suicidal ideation, or mania. If a patient taking lithium becomes dehydrated because of excessive vomiting, diarrhea, or anorexia, temporarily reducing the dose or stopping the medication until the patient is hydrated may be appropriate.

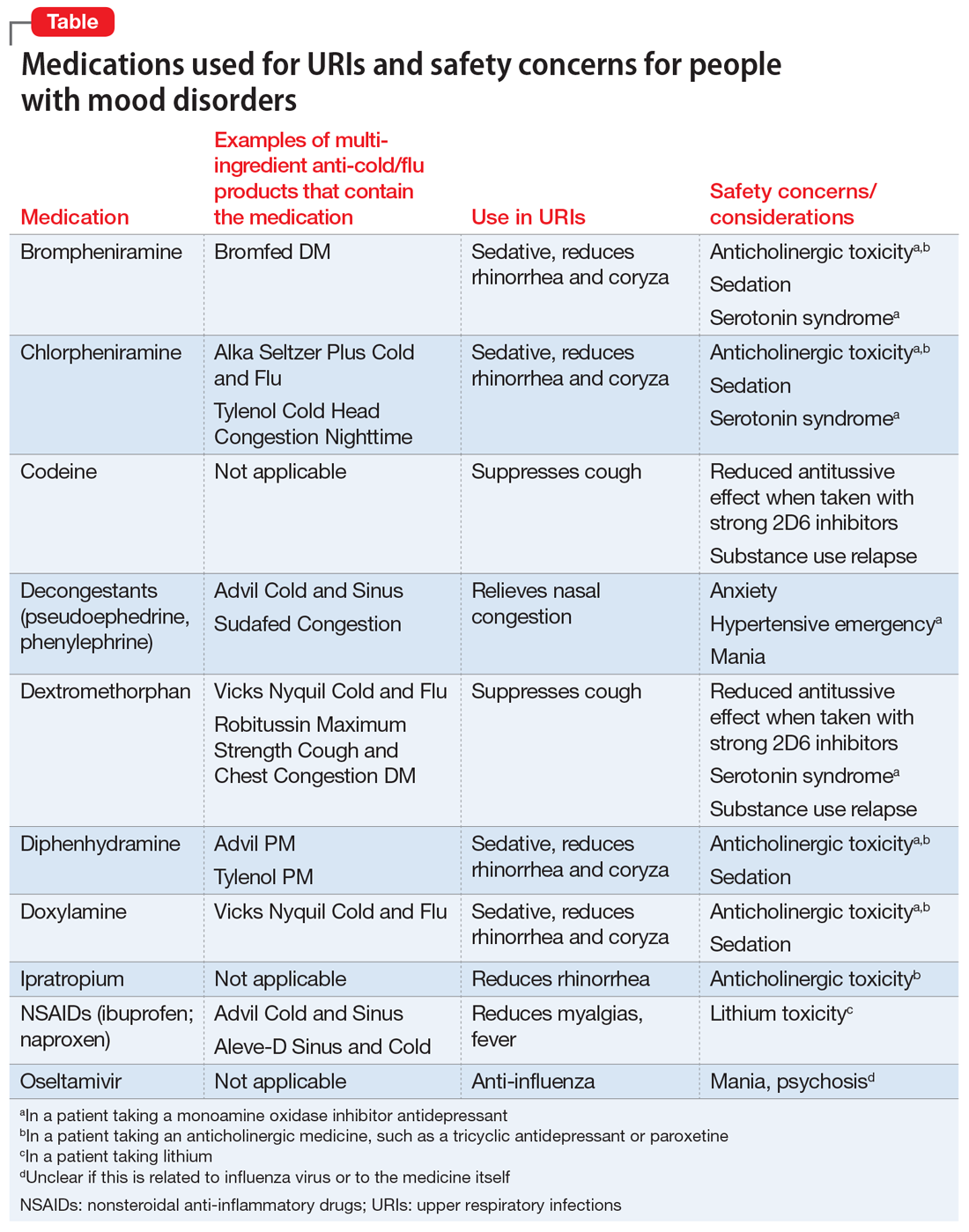

When a patient presents with a URI, make basic URI treatment recommendations, including rest, hydration, and the use of over-the-counter (OTC) anti-cold medications and zinc.34 Encourage patients with suspected influenza to visit their primary care physician so that they may receive an anti-influenza medication. However, also remind patients about the psychiatric risks associated with some of these treatments and their potential interactions with psychotropics (Table). For example, many OTC cold formulations contain dextromethorphan or chlorpheniramine, both of which have weak serotonin reuptake properties and should not be combined with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Such cold formulations may also contain non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, which could elevate lithium levels. Codeine, which is often prescribed to suppress the coughing reflex, can lead a patient with a history of substance use to relapse on their drug of choice.

Also recommend lifestyle modifications to help patients reduce their risk of infection. These includes frequent hand washing, avoiding or limiting alcohol use, avoiding cigarettes, exercising regularly, consuming a Mediterranean diet, and receiving scheduled immunizations. To avoid contracting a URI and infecting patients, wash your hands or use an alcohol-based cleanser after shaking hands with patients. Finally, if a patient does not have a primary care physician, encourage him/her to find one to help manage subsequent infections.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Patients with mood disorders may have an increased risk of developing an upper respiratory infection (URI), which can worsen their mood. Clinicians must make psychotropic treatment changes cautiously and guide patients to select safe over-the-counter medications for relief of URI symptoms.

Related Resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cold versus flu. www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/coldflu.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection. www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/materials-references/print-materials/hcp/adult-tract-infection.pdf.

Drug Brand Names

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Ipratropium • Atrovent

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Oseltamivir • Tamiflu

Paroxetine • Paxil

1. Gonzales R, Malone DC, Maselli JH, et al. Excessive antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(6):757-762.

2. Eccles R. Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(11):718-725.

3. Passioti M, Maggina P, Megremis S, et al. The common cold: potential for future prevention or cure. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14(2):413.

4. Monto AS, Ullman BM. Acute respiratory illness in an American community. The Tecumseh study. JAMA. 1974;227(2):164-169.

5. Monto AS. Studies of the community and family: acute respiratory illness and infection. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16(2):351-373.

6. Heikkinen T, Jarvinen A. The common cold. Lancet. 2003;361(9351):51-59.

7. Paules C, Subbarao K. Influenza. Lancet. 2017;390(10095):697-708.

8. Hall S, Smith A. Investigation of the effects and aftereffects of naturally occurring upper respiratory tract illnesses on mood and performance. Physiol Behav. 1996;59(3):569-577.

9. Smith A, Thomas M, Kent J, et al. Effects of the common cold on mood and performance. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23(7):733-739.

10. Ayub S, Kanner J, Riddle M, et al. Influenza-induced mania. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;28(1):e17-e18.

11. Maurizi CP. Influenza and mania: a possible connection with the locus ceruleus. South Med J. 1985;78(2):207-209.

12. Steinberg D, Hirsch SR, Marston SD, et al. Influenza infection causing manic psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1972;120(558):531-535.

13. Ishitobi M, Shukunami K, Murata T, et al. Hypomanic switching during influenza infection without intracranial infection in an adolescent patient with bipolar disorder. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(7):652-653.

14. Okusaga O, Yolken RH, Langenberg P, et al. Association of seropositivity for influenza and coronaviruses with history of mood disorders and suicide attempts. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1-2):220-225.

15. Adam Y, Meinlschmidt G, Lieb R. Associations between mental disorders and the common cold in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(1):69-73.

16. Kim HC, Park SG, Leem JH, et al. Depressive symptoms as a risk factor for the common cold among employees: a 4-month follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(3):194-196.

17. Dalgleish T, Werner-Seidler A. Disruptions in autobiographical memory processing in depression and the emergence of memory therapeutics. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18(11):596-604.

18. Rosenblat JD, McIntyre RS. Bipolar disorder and inflammation. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(1):125-137.

19. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM, Fagundes CP. Inflammation: depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(11):1075-1091.

20. Kaspersen KA, Dinh KM, Erikstrup LT, et al. Low-grade inflammation is associated with susceptibility to infection in healthy men: results from the Danish Blood Donor Study (DBDS). PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164220.

21. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, et al. Chronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(7):3043-3047.

22. Rosenkranz MA, Jackson DC, Dalton KM, et al. Affective style and in vivo immune response: neurobehavioral mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(19):11148-1152.

23. Irwin MR, Levin MJ, Laudenslager ML, et al. Varicella zoster virus-specific immune responses to a herpes zoster vaccine in elderly recipients with major depression and the impact of antidepressant medications. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1085-1093.

24. Glaser R, Robles TF, Sheridan J, et al. Mild depressive symptoms are associated with amplified and prolonged inflammatory responses after influenza virus vaccination in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(10):1009-1014.

25. Blank T, Detje CN, Spiess A, et al. Brain endothelial- and epithelial-specific interferon receptor chain 1 drives virus-induced sickness behavior and cognitive impairment. Immunity. 2016;44(4):901-912.

26. Smith KJ, Norris S, O’Farrelly C, et al. Risk factors for the development of depression in patients with hepatitis C taking interferon-α. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:275-292.

27. Plante DT, Winkelman JW. Sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder: therapeutic implications. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):830-843.

28. Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, et al. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1543-1550.

29. Saraga M. A manic episode in a patient with stable bipolar disorder triggered by intranasal mometasone furoate. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):48-49.

30. Kandeger A, Tekdemir R, Sen B, et al. A case report of patient who had two manic episodes with psychotic features induced by nasal decongestant. European Psychiatry. 2017;41(Suppl):S428.

31. Waters BG, Lapierre YD. Secondary mania associated with sympathomimetic drug use. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138(6):837-838.

32. Ho LN, Chung JP, Choy KL. Oseltamivir-induced mania in a patient with H1N1. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):350.

33. Jeon SW, Han C. Psychiatric symptoms in a patient with influenza A (H1N1) treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu): a case report. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):209-211.

34. Allan GM, Arroll B. Prevention and treatment of the common cold: making sense of the evidence. CMAJ. 2014;186(3):190-199.

Acute upper respiratory infections (URIs) often lead to mild illnesses, but they can be severely destabilizing for individuals with mood disorders. Additionally, the medications patients often take to target symptoms of the common cold or influenza can interact with psychiatric medications to produce dangerous adverse events or induce further mood symptoms. In this article, we describe the relationship between URIs and mood disorders, the psychiatric diagnostic challenges that arise when evaluating a patient with a URI, and treatment approaches that emphasize psychoeducation and watchful waiting, when appropriate.

A bidirectional relationship

Acute upper respiratory infections are the most common human illnesses, affecting almost 25 million people annually in the United States.1 The common cold is caused by >200 different viruses; rhinovirus and coronavirus are the most common. Influenza, which also attacks the upper respiratory tract, is caused by strains of influenza A, B, or C virus.2 The common cold may present initially with mild symptoms of headache, sneezing, chills, and sore throat, and then progress to nasal discharge, congestion, cough, and malaise. When influenza strikes, patients may have a sudden onset of fever, headache, cough, sore throat, myalgia, congestion, weakness, anorexia, and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Production of URI symptoms results from viral cytopathic activity along with immune activation of inflammatory pathways.2,3 The incidence of colds is inversely correlated with age; adults average 2 to 4 colds per year.4,5 Cold symptoms peak at 1 to 3 days and typically last 7 to 10 days, but can persist up to 3 weeks.6 With influenza, fever and other systemic symptoms last for 3 days but can persist up to 8 days, while cough and lethargy can persist for another 2 weeks.7

Upper respiratory infections have the potential to disrupt mood. Large studies of psychiatrically-healthy undergraduate students have found that compared with healthy controls, participants with URIs endorsed a negative affect within the first week of viral illness,8 and that the number and intensity of URI symptoms caused by cold viruses were correlated with the degree of their negative affect.9 A few case reports have documented instances of individuals with no previous personal or family psychiatric history developing full manic episodes in the setting of influenza.10-12 One case report described an influenza-induced manic episode in a patient with pre-existing psychiatric illness.13 There are no published case reports of common cold viruses inducing a full depressive or manic episode. If cold symptom severity correlates with negative affect among individuals with no psychiatric illness, and if influenza can induce manic episodes, then it is reasonable to expect that patients with pre-existing mood disorders could have an elevated risk for mood disturbances when they experience a URI (Box).

Box

Ms. E is a 35-year-old financial analyst with bipolar disorder type I and alcohol use disorder in sustained remission. She had been euthymic for the last 3 years, receiving weekly psychotherapy and taking lamotrigine, 350 mg/d, lithium ER, 900 mg/d (lithium level: 1.0 mmol/L), lurasidone, 60 mg/d, and clonazepam, 1 mg/d. At her most recent quarterly outpatient psychiatrist visit, she says her depression had returned. She reports 1 week of crying spells, initial and middle insomnia, anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness, fatigue, poor concentration, and poor appetite. She denies having suicidal ideation or manic or psychotic symptoms, and she continues to abstain from alcohol, illicit drugs, and tobacco. She has been fully adherent to her medication regimen and has not added any new medications or made any dietary changes since her last visit. She is puzzled as to what brought on this depression recurrence and says she feels defeated by the bipolar illness, a condition she had worked tirelessly to manage. When asked about changes in her health, she reports that about 1.5 weeks ago she developed a cough, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and fatigue. Because of her annual goal to run a marathon, she continues to train, albeit at a slower pace, and has not had much time to rest because of her demanding job.

The psychiatrist explains to Ms. E that an upper respiratory infection (URI) can sometimes induce depressive symptoms. Given the patient’s lengthy period of euthymia and the absence of new medicines, dietary changes, or drug/alcohol intake, the psychiatrist suspects that the cause of her mood episode recurrence is related to the URI. Hearing this is a relief for Ms. E. She and the psychiatrist decide to refrain from making any medication changes with the expectation that the URI would soon resolve because it had already persisted for 1.5 weeks. The psychiatrist tells Ms. E that if it does not and her symptoms worsen, she should call him to discuss treatment options. The psychiatrist also encourages Ms. E to take a temporary break from training and allow her body to rest.

Three weeks later, Ms. E returns and reports that both the URI symptoms and the depressive symptoms lifted a few days after her last visit.

Mood disorders may also be a risk factor for contracting URIs. Patients with mood disorders are more likely than healthy controls to be seropositive for markers of influenza A, influenza B, and coronavirus, and those with a history of suicide attempts are more likely to be seropositive for markers of influenza B.14 In a community sample of German adults age 18 to 65, those with mood disorders had a 35% higher likelihood of having had a cold within the last 12 months compared with those without a mood disorder.15 A survey of Korean employees found the odds of having had a cold in the last 4 months were up to 2.5 times greater for individuals with elevated scores on a depression symptom severity scale compared with those with lower scores.16 Because these studies were retrospective, recall bias may have impacted the results, as patients who are depressed are more likely to recall negative recent events.17

Proposed mechanisms

Researchers have proposed several mechanisms to explain the association of URIs with mood episodes. Mood disorders, such as bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD), are associated with chronic dysregulation of the innate immune system, which leads to elevated levels of cortisol and pro-inflammatory cytokines.18,19 Men with chronic low-grade inflammation are more vulnerable to all types of infection, including those that cause respiratory illnesses.20 High levels of stress,21 a negative affective style,22 and depression23 have all been associated with reduced antibody response and/or cellular-mediated immunity following vaccination, which suggests a possible mechanism for the vulnerability to infection found in individuals with mood disorders. On the other hand, after influenza vaccination, patients with depression produce a greater and more prolonged release of the cytokine interleukin 6, which perpetuates the state of chronic low-grade inflammation.24 Additionally, patients with mood disorders may engage in behaviors that reduce immune functioning, such as using illicit substances, drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes, consuming an unhealthy diet, or living a sedentary lifestyle.

Conversely, there are several mechanisms by which a URI could induce a mood episode in a patient with a mood disorder. Animal studies have shown that a non-CNS viral infection can lead to depressive behavior by inducing peripheral interferon-beta release. This signaling protein binds to a receptor on the endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier, inducing the release of additional cytokines that affect neuronal functioning.25 Among patients receiving interferon treatments for hepatitis C, a history of depression increased their likelihood of becoming depressed during their treatment course, which suggests people with mood disorders have a sensitivity to peripheral cytokines.26

Sleep interruptions from nighttime coughing or nasal congestion can increase the risk of a recurrence of hypomania or mania in patients with bipolar disorder,27 or a recurrence of depression in a patient with MDD.28 The stress that comes with missed work days or the inability to take care of other personal responsibilities due to a URI may increase the risk of becoming depressed in a patient with bipolar disorder or MDD. When present, GI symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea can reduce the absorption of psychotropic medications and increase the risk of a mood recurrence. Finally, the treatments used for URIs may also contribute to mood instability. Case reports have described instances where patients with URIs developed mania or depression when exposed to medications such as intranasal corticosteroids,29 nasal decongestants,30,31 and anti-influenza treatments.32,33

Continue to: A diagnostic challenge

A diagnostic challenge

Making the diagnosis of a major depressive episode can be challenging in patients who present with a URI, particularly in those who are highly vigilant for relapse and seek care soon after mood symptoms emerge. Many symptoms overlap between the conditions, including insomnia, hypersomnia, reduced interest, anhedonia, fatigue, impaired concentration, and anorexia. Symptoms that are more specific for a major depressive episode include depressed mood, pathologic guilt, worthlessness, and suicidal ideation. Of course, a major depressive episode and a URI are not mutually exclusive and can occur simultaneously. However, incorrectly diagnosing recurrence of a major depressive episode in a euthymic patient who has a URI could lead to unnecessary changes to psychiatric treatment.

Psychoeducation is key

Teach patients about the bidirectional relationship between URIs and mood symptoms to reduce anxiety and confusion about the cause of the return of mood symptoms. Telling patients that they can expect their mood symptoms to be of short duration and self-limiting due to the URI can provide helpful reassurance.

Because it is possible that the mood symptoms will be transient, increasing psychotropic doses or adding a new psychotropic medication may not be necessary. The decision to initiate such changes should be made collaboratively with patients and should be based on the severity and duration of the patient’s mood symptoms. Symptoms that may warrant a medication change include psychosis, suicidal ideation, or mania. If a patient taking lithium becomes dehydrated because of excessive vomiting, diarrhea, or anorexia, temporarily reducing the dose or stopping the medication until the patient is hydrated may be appropriate.

When a patient presents with a URI, make basic URI treatment recommendations, including rest, hydration, and the use of over-the-counter (OTC) anti-cold medications and zinc.34 Encourage patients with suspected influenza to visit their primary care physician so that they may receive an anti-influenza medication. However, also remind patients about the psychiatric risks associated with some of these treatments and their potential interactions with psychotropics (Table). For example, many OTC cold formulations contain dextromethorphan or chlorpheniramine, both of which have weak serotonin reuptake properties and should not be combined with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Such cold formulations may also contain non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, which could elevate lithium levels. Codeine, which is often prescribed to suppress the coughing reflex, can lead a patient with a history of substance use to relapse on their drug of choice.

Also recommend lifestyle modifications to help patients reduce their risk of infection. These includes frequent hand washing, avoiding or limiting alcohol use, avoiding cigarettes, exercising regularly, consuming a Mediterranean diet, and receiving scheduled immunizations. To avoid contracting a URI and infecting patients, wash your hands or use an alcohol-based cleanser after shaking hands with patients. Finally, if a patient does not have a primary care physician, encourage him/her to find one to help manage subsequent infections.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Patients with mood disorders may have an increased risk of developing an upper respiratory infection (URI), which can worsen their mood. Clinicians must make psychotropic treatment changes cautiously and guide patients to select safe over-the-counter medications for relief of URI symptoms.

Related Resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cold versus flu. www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/coldflu.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection. www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/materials-references/print-materials/hcp/adult-tract-infection.pdf.

Drug Brand Names

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Ipratropium • Atrovent

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Oseltamivir • Tamiflu

Paroxetine • Paxil

Acute upper respiratory infections (URIs) often lead to mild illnesses, but they can be severely destabilizing for individuals with mood disorders. Additionally, the medications patients often take to target symptoms of the common cold or influenza can interact with psychiatric medications to produce dangerous adverse events or induce further mood symptoms. In this article, we describe the relationship between URIs and mood disorders, the psychiatric diagnostic challenges that arise when evaluating a patient with a URI, and treatment approaches that emphasize psychoeducation and watchful waiting, when appropriate.

A bidirectional relationship

Acute upper respiratory infections are the most common human illnesses, affecting almost 25 million people annually in the United States.1 The common cold is caused by >200 different viruses; rhinovirus and coronavirus are the most common. Influenza, which also attacks the upper respiratory tract, is caused by strains of influenza A, B, or C virus.2 The common cold may present initially with mild symptoms of headache, sneezing, chills, and sore throat, and then progress to nasal discharge, congestion, cough, and malaise. When influenza strikes, patients may have a sudden onset of fever, headache, cough, sore throat, myalgia, congestion, weakness, anorexia, and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Production of URI symptoms results from viral cytopathic activity along with immune activation of inflammatory pathways.2,3 The incidence of colds is inversely correlated with age; adults average 2 to 4 colds per year.4,5 Cold symptoms peak at 1 to 3 days and typically last 7 to 10 days, but can persist up to 3 weeks.6 With influenza, fever and other systemic symptoms last for 3 days but can persist up to 8 days, while cough and lethargy can persist for another 2 weeks.7

Upper respiratory infections have the potential to disrupt mood. Large studies of psychiatrically-healthy undergraduate students have found that compared with healthy controls, participants with URIs endorsed a negative affect within the first week of viral illness,8 and that the number and intensity of URI symptoms caused by cold viruses were correlated with the degree of their negative affect.9 A few case reports have documented instances of individuals with no previous personal or family psychiatric history developing full manic episodes in the setting of influenza.10-12 One case report described an influenza-induced manic episode in a patient with pre-existing psychiatric illness.13 There are no published case reports of common cold viruses inducing a full depressive or manic episode. If cold symptom severity correlates with negative affect among individuals with no psychiatric illness, and if influenza can induce manic episodes, then it is reasonable to expect that patients with pre-existing mood disorders could have an elevated risk for mood disturbances when they experience a URI (Box).

Box

Ms. E is a 35-year-old financial analyst with bipolar disorder type I and alcohol use disorder in sustained remission. She had been euthymic for the last 3 years, receiving weekly psychotherapy and taking lamotrigine, 350 mg/d, lithium ER, 900 mg/d (lithium level: 1.0 mmol/L), lurasidone, 60 mg/d, and clonazepam, 1 mg/d. At her most recent quarterly outpatient psychiatrist visit, she says her depression had returned. She reports 1 week of crying spells, initial and middle insomnia, anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness, fatigue, poor concentration, and poor appetite. She denies having suicidal ideation or manic or psychotic symptoms, and she continues to abstain from alcohol, illicit drugs, and tobacco. She has been fully adherent to her medication regimen and has not added any new medications or made any dietary changes since her last visit. She is puzzled as to what brought on this depression recurrence and says she feels defeated by the bipolar illness, a condition she had worked tirelessly to manage. When asked about changes in her health, she reports that about 1.5 weeks ago she developed a cough, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and fatigue. Because of her annual goal to run a marathon, she continues to train, albeit at a slower pace, and has not had much time to rest because of her demanding job.

The psychiatrist explains to Ms. E that an upper respiratory infection (URI) can sometimes induce depressive symptoms. Given the patient’s lengthy period of euthymia and the absence of new medicines, dietary changes, or drug/alcohol intake, the psychiatrist suspects that the cause of her mood episode recurrence is related to the URI. Hearing this is a relief for Ms. E. She and the psychiatrist decide to refrain from making any medication changes with the expectation that the URI would soon resolve because it had already persisted for 1.5 weeks. The psychiatrist tells Ms. E that if it does not and her symptoms worsen, she should call him to discuss treatment options. The psychiatrist also encourages Ms. E to take a temporary break from training and allow her body to rest.

Three weeks later, Ms. E returns and reports that both the URI symptoms and the depressive symptoms lifted a few days after her last visit.

Mood disorders may also be a risk factor for contracting URIs. Patients with mood disorders are more likely than healthy controls to be seropositive for markers of influenza A, influenza B, and coronavirus, and those with a history of suicide attempts are more likely to be seropositive for markers of influenza B.14 In a community sample of German adults age 18 to 65, those with mood disorders had a 35% higher likelihood of having had a cold within the last 12 months compared with those without a mood disorder.15 A survey of Korean employees found the odds of having had a cold in the last 4 months were up to 2.5 times greater for individuals with elevated scores on a depression symptom severity scale compared with those with lower scores.16 Because these studies were retrospective, recall bias may have impacted the results, as patients who are depressed are more likely to recall negative recent events.17

Proposed mechanisms

Researchers have proposed several mechanisms to explain the association of URIs with mood episodes. Mood disorders, such as bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD), are associated with chronic dysregulation of the innate immune system, which leads to elevated levels of cortisol and pro-inflammatory cytokines.18,19 Men with chronic low-grade inflammation are more vulnerable to all types of infection, including those that cause respiratory illnesses.20 High levels of stress,21 a negative affective style,22 and depression23 have all been associated with reduced antibody response and/or cellular-mediated immunity following vaccination, which suggests a possible mechanism for the vulnerability to infection found in individuals with mood disorders. On the other hand, after influenza vaccination, patients with depression produce a greater and more prolonged release of the cytokine interleukin 6, which perpetuates the state of chronic low-grade inflammation.24 Additionally, patients with mood disorders may engage in behaviors that reduce immune functioning, such as using illicit substances, drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes, consuming an unhealthy diet, or living a sedentary lifestyle.

Conversely, there are several mechanisms by which a URI could induce a mood episode in a patient with a mood disorder. Animal studies have shown that a non-CNS viral infection can lead to depressive behavior by inducing peripheral interferon-beta release. This signaling protein binds to a receptor on the endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier, inducing the release of additional cytokines that affect neuronal functioning.25 Among patients receiving interferon treatments for hepatitis C, a history of depression increased their likelihood of becoming depressed during their treatment course, which suggests people with mood disorders have a sensitivity to peripheral cytokines.26

Sleep interruptions from nighttime coughing or nasal congestion can increase the risk of a recurrence of hypomania or mania in patients with bipolar disorder,27 or a recurrence of depression in a patient with MDD.28 The stress that comes with missed work days or the inability to take care of other personal responsibilities due to a URI may increase the risk of becoming depressed in a patient with bipolar disorder or MDD. When present, GI symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea can reduce the absorption of psychotropic medications and increase the risk of a mood recurrence. Finally, the treatments used for URIs may also contribute to mood instability. Case reports have described instances where patients with URIs developed mania or depression when exposed to medications such as intranasal corticosteroids,29 nasal decongestants,30,31 and anti-influenza treatments.32,33

Continue to: A diagnostic challenge

A diagnostic challenge

Making the diagnosis of a major depressive episode can be challenging in patients who present with a URI, particularly in those who are highly vigilant for relapse and seek care soon after mood symptoms emerge. Many symptoms overlap between the conditions, including insomnia, hypersomnia, reduced interest, anhedonia, fatigue, impaired concentration, and anorexia. Symptoms that are more specific for a major depressive episode include depressed mood, pathologic guilt, worthlessness, and suicidal ideation. Of course, a major depressive episode and a URI are not mutually exclusive and can occur simultaneously. However, incorrectly diagnosing recurrence of a major depressive episode in a euthymic patient who has a URI could lead to unnecessary changes to psychiatric treatment.

Psychoeducation is key

Teach patients about the bidirectional relationship between URIs and mood symptoms to reduce anxiety and confusion about the cause of the return of mood symptoms. Telling patients that they can expect their mood symptoms to be of short duration and self-limiting due to the URI can provide helpful reassurance.

Because it is possible that the mood symptoms will be transient, increasing psychotropic doses or adding a new psychotropic medication may not be necessary. The decision to initiate such changes should be made collaboratively with patients and should be based on the severity and duration of the patient’s mood symptoms. Symptoms that may warrant a medication change include psychosis, suicidal ideation, or mania. If a patient taking lithium becomes dehydrated because of excessive vomiting, diarrhea, or anorexia, temporarily reducing the dose or stopping the medication until the patient is hydrated may be appropriate.

When a patient presents with a URI, make basic URI treatment recommendations, including rest, hydration, and the use of over-the-counter (OTC) anti-cold medications and zinc.34 Encourage patients with suspected influenza to visit their primary care physician so that they may receive an anti-influenza medication. However, also remind patients about the psychiatric risks associated with some of these treatments and their potential interactions with psychotropics (Table). For example, many OTC cold formulations contain dextromethorphan or chlorpheniramine, both of which have weak serotonin reuptake properties and should not be combined with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Such cold formulations may also contain non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, which could elevate lithium levels. Codeine, which is often prescribed to suppress the coughing reflex, can lead a patient with a history of substance use to relapse on their drug of choice.

Also recommend lifestyle modifications to help patients reduce their risk of infection. These includes frequent hand washing, avoiding or limiting alcohol use, avoiding cigarettes, exercising regularly, consuming a Mediterranean diet, and receiving scheduled immunizations. To avoid contracting a URI and infecting patients, wash your hands or use an alcohol-based cleanser after shaking hands with patients. Finally, if a patient does not have a primary care physician, encourage him/her to find one to help manage subsequent infections.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Patients with mood disorders may have an increased risk of developing an upper respiratory infection (URI), which can worsen their mood. Clinicians must make psychotropic treatment changes cautiously and guide patients to select safe over-the-counter medications for relief of URI symptoms.

Related Resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cold versus flu. www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/coldflu.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection. www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/materials-references/print-materials/hcp/adult-tract-infection.pdf.

Drug Brand Names

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Ipratropium • Atrovent

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Oseltamivir • Tamiflu

Paroxetine • Paxil

1. Gonzales R, Malone DC, Maselli JH, et al. Excessive antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(6):757-762.

2. Eccles R. Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(11):718-725.

3. Passioti M, Maggina P, Megremis S, et al. The common cold: potential for future prevention or cure. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14(2):413.

4. Monto AS, Ullman BM. Acute respiratory illness in an American community. The Tecumseh study. JAMA. 1974;227(2):164-169.

5. Monto AS. Studies of the community and family: acute respiratory illness and infection. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16(2):351-373.

6. Heikkinen T, Jarvinen A. The common cold. Lancet. 2003;361(9351):51-59.

7. Paules C, Subbarao K. Influenza. Lancet. 2017;390(10095):697-708.

8. Hall S, Smith A. Investigation of the effects and aftereffects of naturally occurring upper respiratory tract illnesses on mood and performance. Physiol Behav. 1996;59(3):569-577.

9. Smith A, Thomas M, Kent J, et al. Effects of the common cold on mood and performance. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23(7):733-739.

10. Ayub S, Kanner J, Riddle M, et al. Influenza-induced mania. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;28(1):e17-e18.

11. Maurizi CP. Influenza and mania: a possible connection with the locus ceruleus. South Med J. 1985;78(2):207-209.

12. Steinberg D, Hirsch SR, Marston SD, et al. Influenza infection causing manic psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1972;120(558):531-535.

13. Ishitobi M, Shukunami K, Murata T, et al. Hypomanic switching during influenza infection without intracranial infection in an adolescent patient with bipolar disorder. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(7):652-653.

14. Okusaga O, Yolken RH, Langenberg P, et al. Association of seropositivity for influenza and coronaviruses with history of mood disorders and suicide attempts. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1-2):220-225.

15. Adam Y, Meinlschmidt G, Lieb R. Associations between mental disorders and the common cold in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(1):69-73.

16. Kim HC, Park SG, Leem JH, et al. Depressive symptoms as a risk factor for the common cold among employees: a 4-month follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(3):194-196.

17. Dalgleish T, Werner-Seidler A. Disruptions in autobiographical memory processing in depression and the emergence of memory therapeutics. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18(11):596-604.

18. Rosenblat JD, McIntyre RS. Bipolar disorder and inflammation. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(1):125-137.

19. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM, Fagundes CP. Inflammation: depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(11):1075-1091.

20. Kaspersen KA, Dinh KM, Erikstrup LT, et al. Low-grade inflammation is associated with susceptibility to infection in healthy men: results from the Danish Blood Donor Study (DBDS). PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164220.

21. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, et al. Chronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(7):3043-3047.

22. Rosenkranz MA, Jackson DC, Dalton KM, et al. Affective style and in vivo immune response: neurobehavioral mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(19):11148-1152.

23. Irwin MR, Levin MJ, Laudenslager ML, et al. Varicella zoster virus-specific immune responses to a herpes zoster vaccine in elderly recipients with major depression and the impact of antidepressant medications. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1085-1093.

24. Glaser R, Robles TF, Sheridan J, et al. Mild depressive symptoms are associated with amplified and prolonged inflammatory responses after influenza virus vaccination in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(10):1009-1014.

25. Blank T, Detje CN, Spiess A, et al. Brain endothelial- and epithelial-specific interferon receptor chain 1 drives virus-induced sickness behavior and cognitive impairment. Immunity. 2016;44(4):901-912.

26. Smith KJ, Norris S, O’Farrelly C, et al. Risk factors for the development of depression in patients with hepatitis C taking interferon-α. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:275-292.

27. Plante DT, Winkelman JW. Sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder: therapeutic implications. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):830-843.

28. Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, et al. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1543-1550.

29. Saraga M. A manic episode in a patient with stable bipolar disorder triggered by intranasal mometasone furoate. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):48-49.

30. Kandeger A, Tekdemir R, Sen B, et al. A case report of patient who had two manic episodes with psychotic features induced by nasal decongestant. European Psychiatry. 2017;41(Suppl):S428.

31. Waters BG, Lapierre YD. Secondary mania associated with sympathomimetic drug use. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138(6):837-838.

32. Ho LN, Chung JP, Choy KL. Oseltamivir-induced mania in a patient with H1N1. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):350.

33. Jeon SW, Han C. Psychiatric symptoms in a patient with influenza A (H1N1) treated with oseltamivir (Tamiflu): a case report. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):209-211.

34. Allan GM, Arroll B. Prevention and treatment of the common cold: making sense of the evidence. CMAJ. 2014;186(3):190-199.

1. Gonzales R, Malone DC, Maselli JH, et al. Excessive antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(6):757-762.

2. Eccles R. Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(11):718-725.

3. Passioti M, Maggina P, Megremis S, et al. The common cold: potential for future prevention or cure. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14(2):413.

4. Monto AS, Ullman BM. Acute respiratory illness in an American community. The Tecumseh study. JAMA. 1974;227(2):164-169.

5. Monto AS. Studies of the community and family: acute respiratory illness and infection. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16(2):351-373.

6. Heikkinen T, Jarvinen A. The common cold. Lancet. 2003;361(9351):51-59.

7. Paules C, Subbarao K. Influenza. Lancet. 2017;390(10095):697-708.

8. Hall S, Smith A. Investigation of the effects and aftereffects of naturally occurring upper respiratory tract illnesses on mood and performance. Physiol Behav. 1996;59(3):569-577.

9. Smith A, Thomas M, Kent J, et al. Effects of the common cold on mood and performance. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23(7):733-739.

10. Ayub S, Kanner J, Riddle M, et al. Influenza-induced mania. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;28(1):e17-e18.

11. Maurizi CP. Influenza and mania: a possible connection with the locus ceruleus. South Med J. 1985;78(2):207-209.

12. Steinberg D, Hirsch SR, Marston SD, et al. Influenza infection causing manic psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1972;120(558):531-535.

13. Ishitobi M, Shukunami K, Murata T, et al. Hypomanic switching during influenza infection without intracranial infection in an adolescent patient with bipolar disorder. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(7):652-653.

14. Okusaga O, Yolken RH, Langenberg P, et al. Association of seropositivity for influenza and coronaviruses with history of mood disorders and suicide attempts. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1-2):220-225.

15. Adam Y, Meinlschmidt G, Lieb R. Associations between mental disorders and the common cold in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(1):69-73.

16. Kim HC, Park SG, Leem JH, et al. Depressive symptoms as a risk factor for the common cold among employees: a 4-month follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(3):194-196.

17. Dalgleish T, Werner-Seidler A. Disruptions in autobiographical memory processing in depression and the emergence of memory therapeutics. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18(11):596-604.

18. Rosenblat JD, McIntyre RS. Bipolar disorder and inflammation. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(1):125-137.

19. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM, Fagundes CP. Inflammation: depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(11):1075-1091.

20. Kaspersen KA, Dinh KM, Erikstrup LT, et al. Low-grade inflammation is associated with susceptibility to infection in healthy men: results from the Danish Blood Donor Study (DBDS). PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164220.

21. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, et al. Chronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(7):3043-3047.

22. Rosenkranz MA, Jackson DC, Dalton KM, et al. Affective style and in vivo immune response: neurobehavioral mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(19):11148-1152.

23. Irwin MR, Levin MJ, Laudenslager ML, et al. Varicella zoster virus-specific immune responses to a herpes zoster vaccine in elderly recipients with major depression and the impact of antidepressant medications. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1085-1093.

24. Glaser R, Robles TF, Sheridan J, et al. Mild depressive symptoms are associated with amplified and prolonged inflammatory responses after influenza virus vaccination in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(10):1009-1014.

25. Blank T, Detje CN, Spiess A, et al. Brain endothelial- and epithelial-specific interferon receptor chain 1 drives virus-induced sickness behavior and cognitive impairment. Immunity. 2016;44(4):901-912.

26. Smith KJ, Norris S, O’Farrelly C, et al. Risk factors for the development of depression in patients with hepatitis C taking interferon-α. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:275-292.

27. Plante DT, Winkelman JW. Sleep disturbance in bipolar disorder: therapeutic implications. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):830-843.

28. Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, et al. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1543-1550.

29. Saraga M. A manic episode in a patient with stable bipolar disorder triggered by intranasal mometasone furoate. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):48-49.

30. Kandeger A, Tekdemir R, Sen B, et al. A case report of patient who had two manic episodes with psychotic features induced by nasal decongestant. European Psychiatry. 2017;41(Suppl):S428.

31. Waters BG, Lapierre YD. Secondary mania associated with sympathomimetic drug use. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138(6):837-838.