User login

One versus two uterotonics: Which is better for minimizing postpartum blood loss?

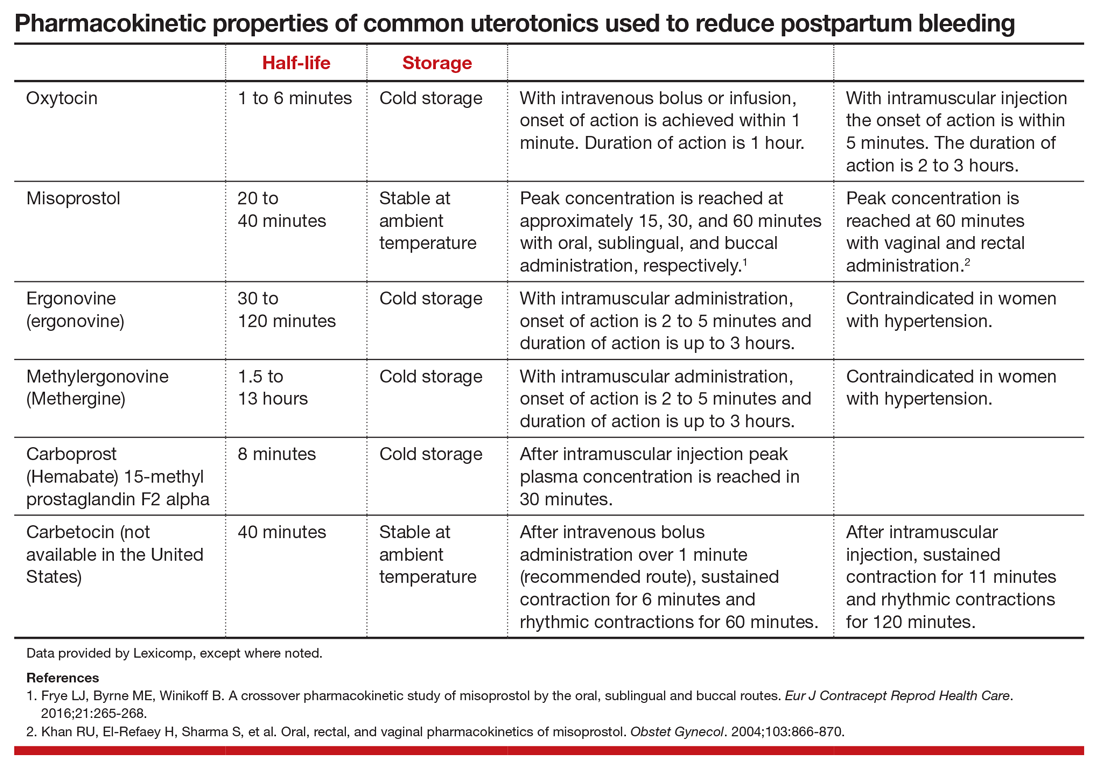

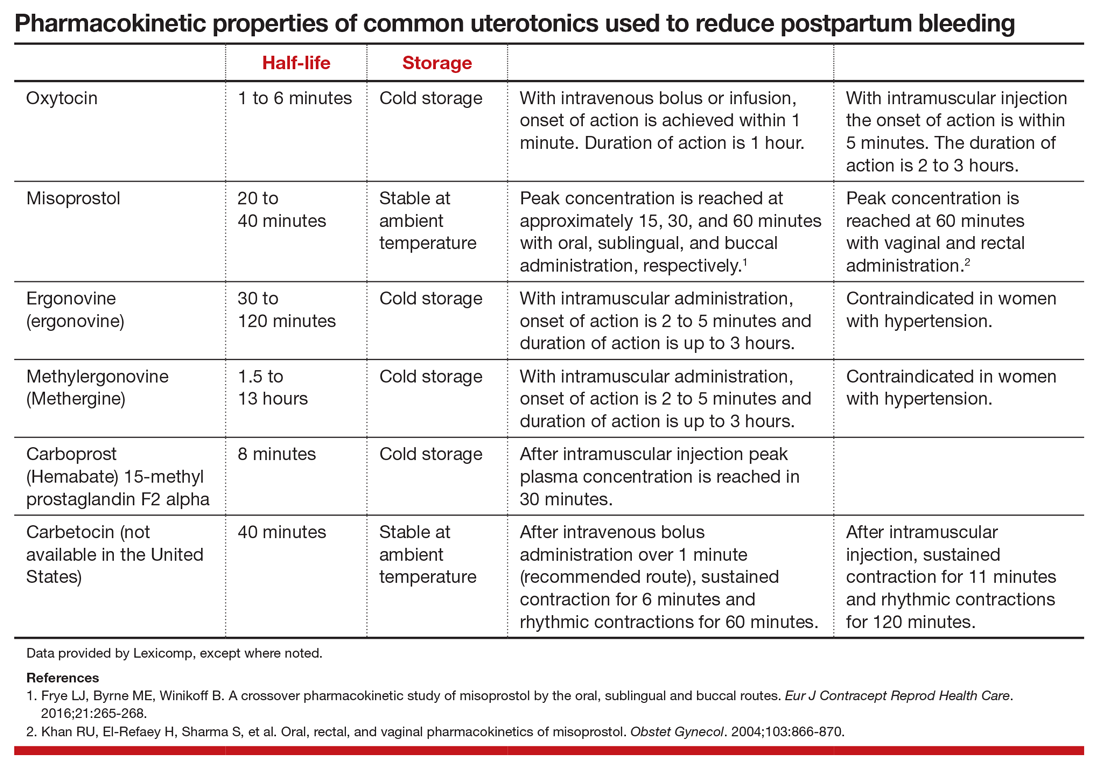

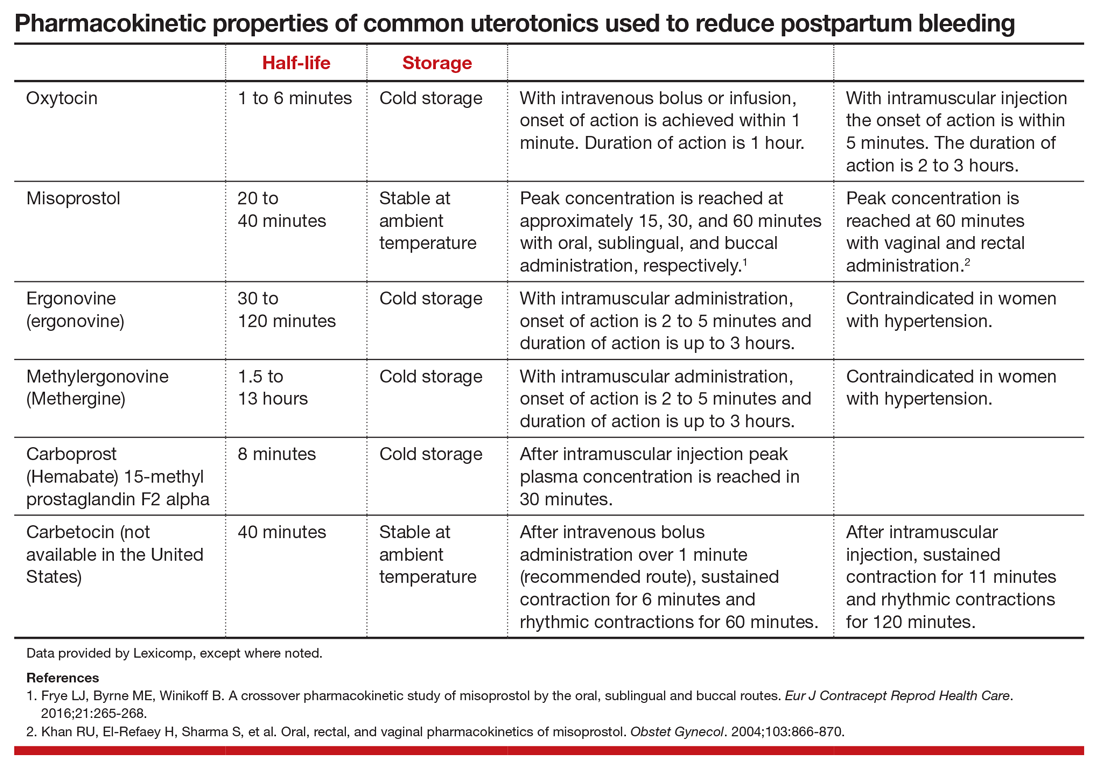

Excessive postpartum bleeding is a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Worldwide, obstetric hemorrhage is the most common cause of maternal death.1,2 Medications reported to reduce postpartum bleeding include oxytocin, misoprostol, ergonovine, methylergonovine, carboprost, and tranexamic acid. A recent Cochrane network meta-analysis of 196 trials, including 135,559 women, distilled in 1,361 pages of analysis, reported on the medications associated with the greatest reduction in postpartum bleeding.3 Surprisingly, for preventing blood loss ≥ 500 mL, misoprostol plus oxytocin and ergonovine plus oxytocin were the highest ranked interventions. This evidence is summarized here.

Misoprostol plus oxytocin

After newborn delivery, active management of the third stage of labor, including uterotonic administration, is strongly recommended because it will reduce postpartum blood loss, decreasing the rate of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH).4 Both oxytocin and misoprostol are effective uterotonics. However, the combination of oxytocin plus misoprostol appears to be more effective than oxytocin alone in reducing the frequency of postpartum blood loss greater than 500 mL.3 To understand the clinical efficacy and adverse effects (AEs) of combined oxytocin plus misoprostol a meta-analysis was performed for both vaginal and cesarean deliveries (CDs).

Efficacy and AEs during vaginal delivery. In the meta-analysis, about 6,000 vaginal deliveries were analyzed, with no significant differences for misoprostol plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone found for the following outcomes: maternal death, intensive care unit admissions, and rate of blood loss ≥ 1,000 mL (1.7% for both uterotonics vs 2.2% for oxytocin alone).3 Misoprostol plus oxytocin was significantly superior to oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: reduced risk of blood transfusion (0.95% vs 2.5%), reduced risk of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (5.9% vs 8.0%), reduced risk of requiring an additional uterotonic (3.6% vs 5.8%), and a smaller decrease in hemoglobin concentration from pre- to postdelivery (-0.89 g/L).3

In my opinion, the difference in hemoglobin concentration, although statistically significant, is not of clinical significance. However, compared with oxytocin alone, misoprostol plus oxytocin caused significantly more nausea (2.4% vs 0.66%), vomiting (3.1% vs 0.86%), and fever (21% vs 3.9%).3 A weakness of this meta-analysis is that the trials used a wide range of misoprostol dosages (200 to 600 µg) and multiple routes of administration, including sublingual (under the tongue), buccal, and rectal. This makes it impossible to identify a best misoprostol dosage and administration route.

Efficacy and AEs during CD. In the same meta-analysis about 2,000 CDs were analyzed, with no significant difference for misoprostol plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: maternal death, intensive care unit admissions, and PPH ≥ 1,000 mL blood loss (6.2% vs 6.5%).3 Misoprostol plus oxytocin was significantly superior to oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: reduced risk of blood transfusion (2.6% vs 5.4%), reduced risk of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (32% vs 47%), reduced risk of requiring an additional uterotonic (14% vs 28%), and a smaller decrease in hemoglobin concentration from before to after delivery (-4.0 g/L).3 In my opinion, the statistically significant difference in hemoglobin concentration is not clinically significant. However, compared with oxytocin alone, misoprostol plus oxytocin caused significantly more nausea (12% vs 6.1%), vomiting (8.1% vs 5.4%), shivering (13% vs 7%), and fever (7.7% vs 4.0%).3

Continue to: Ergonovine plus oxytocin...

Ergonovine plus oxytocin

Ergonovine is an ergot derivative that causes uterine contractions and has been shown to effectively reduce blood loss at delivery. In the United States a methyl-derivative of ergonovine, methylergonovine, is widely available. In a meta-analysis with mostly vaginal deliveries, there were no significant differences for ergonovine plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: death, intensive care unit admission, rate of blood loss ≥ 1,000 mL(2.0% vs 2.7%), blood transfusion, administration of an additional uterotonic, change in hemoglobin from pre- to postdelivery, nausea, hypertension, shivering, and fever.3 However, ergonovine plus oxytocin, compared with oxytocin alone, resulted in a significantly reduced rate of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (8.3% vs 10.2%) and an increased rate of vomiting (8.1% vs 1.6%).3 In these trials women with a blood pressure ≥ 150/100 mm Hg were generally excluded from receiving ergonovine because of its hypertensive effect.

Clinical practice options

Given the Cochrane meta-analysis results, ObGyns have two approaches for optimizing PPH reduction.

Option 1: Use a single uterotonic to reduce postpartum blood loss. If excess bleeding occurs, rapidly administer a second uterotonic agent. Currently, monotherapy with intravenous or intramuscular oxytocin is the standard for reducing postpartum blood loss.5,6 Advantages of this approach compared with dual agent therapy include simplification of care and minimization of AEs. However, oxytocin monotherapy for minimizing postpartum bleeding may be suboptimal. In the largest trial ever performed (involving 29,645 women) when oxytocin was administered postpartum, the rates of estimated blood loss ≥ 500 mL and ≥ 1,000 mL were 9.1% and 1.45%, respectively.5 Is 9% an optimal rate for blood loss ≥ 500 mL following a vaginal delivery? Or should we try to achieve a lower rate?

Given the “high” rate of blood loss ≥ 500 mL with oxytocin alone, it is important for clinicians using the one-uterotonic approach to promptly recognize patients who have excessive bleeding and transition rapidly from prevention to treatment. When PPH cases are reviewed, a common finding is that the clinicians did not timely recognize excess bleeding, delaying transition to treatment with additional uterotonics and other interventions. When routinely using oxytocin monotherapy, lowering the threshold for administering a second uterotonic (methylergonovine, carboprost, misoprostol, or tranexamic acid) may help decrease the frequency of excess postpartum blood loss.

Option 2: Administer two uterotonics to reduce postpartum blood loss at all deliveries. Given the “high” rate of excess postpartum blood loss with oxytocin monotherapy, an alternative is to administer two uterotonics at all births or at births with a high risk of excess blood loss. As discussed, administering two uterotonics, oxytocin plus misoprostol or oxytocin plus ergonovine, has been reported to be more effective than oxytocin alone for reducing postpartum bleeding ≥ 500 mL.3 In the Cochrane meta-analysis, per 1,000 women given oxytocin following a vaginal birth, 122 would have blood loss ≥ 500 mL, compared with 85 given oxytocin plus misoprostol or oxytocin plus ergonovine.3

Misoprostol is administered sublingually, buccally, or rectally, and methylergonovine is administered by intramuscular injection. Although dual uterotonic therapy is more effective than monotherapy, dual therapy is associated with more AEs. As noted, compared with oxytocin monotherapy, the combination of oxytocin plus misoprostol is associated with more nausea, vomiting, shivering, and fever. Oxytocin plus ergonovine is associated with a higher rate of vomiting than oxytocin monotherapy. In my practice I prefer using intramuscular methylergonovine as the second agent to avoid the high rate of fever associated with misoprostol.

For dual agent therapy, one approach is to administer misoprostol 200 µg or 400 µg through the buccal7,8 or sublingual9,10 routes. Higher dosages of misoprostol (600 µg to 800 µg) have been used11,12 but are likely associated with higher rates of nausea, vomiting,shivering, and fever than the lower dosages. Methylergonovine 0.2 mg is administered intramuscularly.

Continue to: The bottom line...

The bottom line

PPH is a major cause of maternal morbidity, and in low-resource settings, mortality. Oxytocin is the standard for reducing postpartum blood loss, but rates of blood loss ≥ 500 mL are high following this monotherapy. To reduce postpartum blood loss beyond what is possible with oxytocin alone, clinicians can more rapidly transition to administering a second uterotonic when they suspect blood loss is becoming excessive or they can use two uterotonic agents with all births or in those at high risk for excess bleeding. If blood loss does become excessive, clinicians need to pivot rapidly from prevention with oxytocin to treatment with our entire therapeutic armamentarium.

- Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e323-e333.

- Slomski A. Why do hundreds of US women die annually in childbirth? JAMA. 2019;321:1239-1241.

- Gallos ID, Papadopoulou A, Man R, et al. Uterotonic agents for preventing postpartum haemorrhage: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD011689.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e168-e186.

- Widmer M, Piaggio G, Nguyen TM, et al; WHO Champion Trial Group. Heat-stable carbetocin versus oxytocin to prevent hemorrhage after vaginal birth. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:743-752.

- Adnan N, Conlan-Trant R, McCormick C, et al. Intramuscular versus intravenous oxytocin to prevent postpartum haemorrhage at vaginal delivery: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2018;362:k3546.

- Hamm J, Russell Z, Botha T, et al. Buccal misoprostol to prevent hemorrhage at cesarean delivery: a randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1404-1406.

- Bhullar A, Carlan SJ, Hamm J, et al. Buccal misoprostol to decrease blood loss after vaginal delivery: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1282-1288.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Fawole B, Mugerwa K, et al. Administration of 400 µg of misoprostol to augment routine active management of the third stage of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;112:98-102.

- Chaudhuri P, Majumdar A. A randomized trial of sublingual misoprostol to augment routine third-stage management among women at risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;132:191-195.

- Winikoff B, Dabash R, Durocher J, et al. Treatment of post-partum haemorrhage with sublingual misoprostol versus oxytocin in women not exposed to oxytocin during labor: a double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;375:210-216.

- Blum J, Winikoff B, Raghavan S, et al. Treatment of post-partum haemorrhage with sublingual misoprostol versus oxytocin in women receiving prophylactic oxytocin: a double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;375:217-223.

Excessive postpartum bleeding is a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Worldwide, obstetric hemorrhage is the most common cause of maternal death.1,2 Medications reported to reduce postpartum bleeding include oxytocin, misoprostol, ergonovine, methylergonovine, carboprost, and tranexamic acid. A recent Cochrane network meta-analysis of 196 trials, including 135,559 women, distilled in 1,361 pages of analysis, reported on the medications associated with the greatest reduction in postpartum bleeding.3 Surprisingly, for preventing blood loss ≥ 500 mL, misoprostol plus oxytocin and ergonovine plus oxytocin were the highest ranked interventions. This evidence is summarized here.

Misoprostol plus oxytocin

After newborn delivery, active management of the third stage of labor, including uterotonic administration, is strongly recommended because it will reduce postpartum blood loss, decreasing the rate of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH).4 Both oxytocin and misoprostol are effective uterotonics. However, the combination of oxytocin plus misoprostol appears to be more effective than oxytocin alone in reducing the frequency of postpartum blood loss greater than 500 mL.3 To understand the clinical efficacy and adverse effects (AEs) of combined oxytocin plus misoprostol a meta-analysis was performed for both vaginal and cesarean deliveries (CDs).

Efficacy and AEs during vaginal delivery. In the meta-analysis, about 6,000 vaginal deliveries were analyzed, with no significant differences for misoprostol plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone found for the following outcomes: maternal death, intensive care unit admissions, and rate of blood loss ≥ 1,000 mL (1.7% for both uterotonics vs 2.2% for oxytocin alone).3 Misoprostol plus oxytocin was significantly superior to oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: reduced risk of blood transfusion (0.95% vs 2.5%), reduced risk of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (5.9% vs 8.0%), reduced risk of requiring an additional uterotonic (3.6% vs 5.8%), and a smaller decrease in hemoglobin concentration from pre- to postdelivery (-0.89 g/L).3

In my opinion, the difference in hemoglobin concentration, although statistically significant, is not of clinical significance. However, compared with oxytocin alone, misoprostol plus oxytocin caused significantly more nausea (2.4% vs 0.66%), vomiting (3.1% vs 0.86%), and fever (21% vs 3.9%).3 A weakness of this meta-analysis is that the trials used a wide range of misoprostol dosages (200 to 600 µg) and multiple routes of administration, including sublingual (under the tongue), buccal, and rectal. This makes it impossible to identify a best misoprostol dosage and administration route.

Efficacy and AEs during CD. In the same meta-analysis about 2,000 CDs were analyzed, with no significant difference for misoprostol plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: maternal death, intensive care unit admissions, and PPH ≥ 1,000 mL blood loss (6.2% vs 6.5%).3 Misoprostol plus oxytocin was significantly superior to oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: reduced risk of blood transfusion (2.6% vs 5.4%), reduced risk of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (32% vs 47%), reduced risk of requiring an additional uterotonic (14% vs 28%), and a smaller decrease in hemoglobin concentration from before to after delivery (-4.0 g/L).3 In my opinion, the statistically significant difference in hemoglobin concentration is not clinically significant. However, compared with oxytocin alone, misoprostol plus oxytocin caused significantly more nausea (12% vs 6.1%), vomiting (8.1% vs 5.4%), shivering (13% vs 7%), and fever (7.7% vs 4.0%).3

Continue to: Ergonovine plus oxytocin...

Ergonovine plus oxytocin

Ergonovine is an ergot derivative that causes uterine contractions and has been shown to effectively reduce blood loss at delivery. In the United States a methyl-derivative of ergonovine, methylergonovine, is widely available. In a meta-analysis with mostly vaginal deliveries, there were no significant differences for ergonovine plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: death, intensive care unit admission, rate of blood loss ≥ 1,000 mL(2.0% vs 2.7%), blood transfusion, administration of an additional uterotonic, change in hemoglobin from pre- to postdelivery, nausea, hypertension, shivering, and fever.3 However, ergonovine plus oxytocin, compared with oxytocin alone, resulted in a significantly reduced rate of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (8.3% vs 10.2%) and an increased rate of vomiting (8.1% vs 1.6%).3 In these trials women with a blood pressure ≥ 150/100 mm Hg were generally excluded from receiving ergonovine because of its hypertensive effect.

Clinical practice options

Given the Cochrane meta-analysis results, ObGyns have two approaches for optimizing PPH reduction.

Option 1: Use a single uterotonic to reduce postpartum blood loss. If excess bleeding occurs, rapidly administer a second uterotonic agent. Currently, monotherapy with intravenous or intramuscular oxytocin is the standard for reducing postpartum blood loss.5,6 Advantages of this approach compared with dual agent therapy include simplification of care and minimization of AEs. However, oxytocin monotherapy for minimizing postpartum bleeding may be suboptimal. In the largest trial ever performed (involving 29,645 women) when oxytocin was administered postpartum, the rates of estimated blood loss ≥ 500 mL and ≥ 1,000 mL were 9.1% and 1.45%, respectively.5 Is 9% an optimal rate for blood loss ≥ 500 mL following a vaginal delivery? Or should we try to achieve a lower rate?

Given the “high” rate of blood loss ≥ 500 mL with oxytocin alone, it is important for clinicians using the one-uterotonic approach to promptly recognize patients who have excessive bleeding and transition rapidly from prevention to treatment. When PPH cases are reviewed, a common finding is that the clinicians did not timely recognize excess bleeding, delaying transition to treatment with additional uterotonics and other interventions. When routinely using oxytocin monotherapy, lowering the threshold for administering a second uterotonic (methylergonovine, carboprost, misoprostol, or tranexamic acid) may help decrease the frequency of excess postpartum blood loss.

Option 2: Administer two uterotonics to reduce postpartum blood loss at all deliveries. Given the “high” rate of excess postpartum blood loss with oxytocin monotherapy, an alternative is to administer two uterotonics at all births or at births with a high risk of excess blood loss. As discussed, administering two uterotonics, oxytocin plus misoprostol or oxytocin plus ergonovine, has been reported to be more effective than oxytocin alone for reducing postpartum bleeding ≥ 500 mL.3 In the Cochrane meta-analysis, per 1,000 women given oxytocin following a vaginal birth, 122 would have blood loss ≥ 500 mL, compared with 85 given oxytocin plus misoprostol or oxytocin plus ergonovine.3

Misoprostol is administered sublingually, buccally, or rectally, and methylergonovine is administered by intramuscular injection. Although dual uterotonic therapy is more effective than monotherapy, dual therapy is associated with more AEs. As noted, compared with oxytocin monotherapy, the combination of oxytocin plus misoprostol is associated with more nausea, vomiting, shivering, and fever. Oxytocin plus ergonovine is associated with a higher rate of vomiting than oxytocin monotherapy. In my practice I prefer using intramuscular methylergonovine as the second agent to avoid the high rate of fever associated with misoprostol.

For dual agent therapy, one approach is to administer misoprostol 200 µg or 400 µg through the buccal7,8 or sublingual9,10 routes. Higher dosages of misoprostol (600 µg to 800 µg) have been used11,12 but are likely associated with higher rates of nausea, vomiting,shivering, and fever than the lower dosages. Methylergonovine 0.2 mg is administered intramuscularly.

Continue to: The bottom line...

The bottom line

PPH is a major cause of maternal morbidity, and in low-resource settings, mortality. Oxytocin is the standard for reducing postpartum blood loss, but rates of blood loss ≥ 500 mL are high following this monotherapy. To reduce postpartum blood loss beyond what is possible with oxytocin alone, clinicians can more rapidly transition to administering a second uterotonic when they suspect blood loss is becoming excessive or they can use two uterotonic agents with all births or in those at high risk for excess bleeding. If blood loss does become excessive, clinicians need to pivot rapidly from prevention with oxytocin to treatment with our entire therapeutic armamentarium.

Excessive postpartum bleeding is a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Worldwide, obstetric hemorrhage is the most common cause of maternal death.1,2 Medications reported to reduce postpartum bleeding include oxytocin, misoprostol, ergonovine, methylergonovine, carboprost, and tranexamic acid. A recent Cochrane network meta-analysis of 196 trials, including 135,559 women, distilled in 1,361 pages of analysis, reported on the medications associated with the greatest reduction in postpartum bleeding.3 Surprisingly, for preventing blood loss ≥ 500 mL, misoprostol plus oxytocin and ergonovine plus oxytocin were the highest ranked interventions. This evidence is summarized here.

Misoprostol plus oxytocin

After newborn delivery, active management of the third stage of labor, including uterotonic administration, is strongly recommended because it will reduce postpartum blood loss, decreasing the rate of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH).4 Both oxytocin and misoprostol are effective uterotonics. However, the combination of oxytocin plus misoprostol appears to be more effective than oxytocin alone in reducing the frequency of postpartum blood loss greater than 500 mL.3 To understand the clinical efficacy and adverse effects (AEs) of combined oxytocin plus misoprostol a meta-analysis was performed for both vaginal and cesarean deliveries (CDs).

Efficacy and AEs during vaginal delivery. In the meta-analysis, about 6,000 vaginal deliveries were analyzed, with no significant differences for misoprostol plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone found for the following outcomes: maternal death, intensive care unit admissions, and rate of blood loss ≥ 1,000 mL (1.7% for both uterotonics vs 2.2% for oxytocin alone).3 Misoprostol plus oxytocin was significantly superior to oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: reduced risk of blood transfusion (0.95% vs 2.5%), reduced risk of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (5.9% vs 8.0%), reduced risk of requiring an additional uterotonic (3.6% vs 5.8%), and a smaller decrease in hemoglobin concentration from pre- to postdelivery (-0.89 g/L).3

In my opinion, the difference in hemoglobin concentration, although statistically significant, is not of clinical significance. However, compared with oxytocin alone, misoprostol plus oxytocin caused significantly more nausea (2.4% vs 0.66%), vomiting (3.1% vs 0.86%), and fever (21% vs 3.9%).3 A weakness of this meta-analysis is that the trials used a wide range of misoprostol dosages (200 to 600 µg) and multiple routes of administration, including sublingual (under the tongue), buccal, and rectal. This makes it impossible to identify a best misoprostol dosage and administration route.

Efficacy and AEs during CD. In the same meta-analysis about 2,000 CDs were analyzed, with no significant difference for misoprostol plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: maternal death, intensive care unit admissions, and PPH ≥ 1,000 mL blood loss (6.2% vs 6.5%).3 Misoprostol plus oxytocin was significantly superior to oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: reduced risk of blood transfusion (2.6% vs 5.4%), reduced risk of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (32% vs 47%), reduced risk of requiring an additional uterotonic (14% vs 28%), and a smaller decrease in hemoglobin concentration from before to after delivery (-4.0 g/L).3 In my opinion, the statistically significant difference in hemoglobin concentration is not clinically significant. However, compared with oxytocin alone, misoprostol plus oxytocin caused significantly more nausea (12% vs 6.1%), vomiting (8.1% vs 5.4%), shivering (13% vs 7%), and fever (7.7% vs 4.0%).3

Continue to: Ergonovine plus oxytocin...

Ergonovine plus oxytocin

Ergonovine is an ergot derivative that causes uterine contractions and has been shown to effectively reduce blood loss at delivery. In the United States a methyl-derivative of ergonovine, methylergonovine, is widely available. In a meta-analysis with mostly vaginal deliveries, there were no significant differences for ergonovine plus oxytocin versus oxytocin alone for the following outcomes: death, intensive care unit admission, rate of blood loss ≥ 1,000 mL(2.0% vs 2.7%), blood transfusion, administration of an additional uterotonic, change in hemoglobin from pre- to postdelivery, nausea, hypertension, shivering, and fever.3 However, ergonovine plus oxytocin, compared with oxytocin alone, resulted in a significantly reduced rate of blood loss ≥ 500 mL (8.3% vs 10.2%) and an increased rate of vomiting (8.1% vs 1.6%).3 In these trials women with a blood pressure ≥ 150/100 mm Hg were generally excluded from receiving ergonovine because of its hypertensive effect.

Clinical practice options

Given the Cochrane meta-analysis results, ObGyns have two approaches for optimizing PPH reduction.

Option 1: Use a single uterotonic to reduce postpartum blood loss. If excess bleeding occurs, rapidly administer a second uterotonic agent. Currently, monotherapy with intravenous or intramuscular oxytocin is the standard for reducing postpartum blood loss.5,6 Advantages of this approach compared with dual agent therapy include simplification of care and minimization of AEs. However, oxytocin monotherapy for minimizing postpartum bleeding may be suboptimal. In the largest trial ever performed (involving 29,645 women) when oxytocin was administered postpartum, the rates of estimated blood loss ≥ 500 mL and ≥ 1,000 mL were 9.1% and 1.45%, respectively.5 Is 9% an optimal rate for blood loss ≥ 500 mL following a vaginal delivery? Or should we try to achieve a lower rate?

Given the “high” rate of blood loss ≥ 500 mL with oxytocin alone, it is important for clinicians using the one-uterotonic approach to promptly recognize patients who have excessive bleeding and transition rapidly from prevention to treatment. When PPH cases are reviewed, a common finding is that the clinicians did not timely recognize excess bleeding, delaying transition to treatment with additional uterotonics and other interventions. When routinely using oxytocin monotherapy, lowering the threshold for administering a second uterotonic (methylergonovine, carboprost, misoprostol, or tranexamic acid) may help decrease the frequency of excess postpartum blood loss.

Option 2: Administer two uterotonics to reduce postpartum blood loss at all deliveries. Given the “high” rate of excess postpartum blood loss with oxytocin monotherapy, an alternative is to administer two uterotonics at all births or at births with a high risk of excess blood loss. As discussed, administering two uterotonics, oxytocin plus misoprostol or oxytocin plus ergonovine, has been reported to be more effective than oxytocin alone for reducing postpartum bleeding ≥ 500 mL.3 In the Cochrane meta-analysis, per 1,000 women given oxytocin following a vaginal birth, 122 would have blood loss ≥ 500 mL, compared with 85 given oxytocin plus misoprostol or oxytocin plus ergonovine.3

Misoprostol is administered sublingually, buccally, or rectally, and methylergonovine is administered by intramuscular injection. Although dual uterotonic therapy is more effective than monotherapy, dual therapy is associated with more AEs. As noted, compared with oxytocin monotherapy, the combination of oxytocin plus misoprostol is associated with more nausea, vomiting, shivering, and fever. Oxytocin plus ergonovine is associated with a higher rate of vomiting than oxytocin monotherapy. In my practice I prefer using intramuscular methylergonovine as the second agent to avoid the high rate of fever associated with misoprostol.

For dual agent therapy, one approach is to administer misoprostol 200 µg or 400 µg through the buccal7,8 or sublingual9,10 routes. Higher dosages of misoprostol (600 µg to 800 µg) have been used11,12 but are likely associated with higher rates of nausea, vomiting,shivering, and fever than the lower dosages. Methylergonovine 0.2 mg is administered intramuscularly.

Continue to: The bottom line...

The bottom line

PPH is a major cause of maternal morbidity, and in low-resource settings, mortality. Oxytocin is the standard for reducing postpartum blood loss, but rates of blood loss ≥ 500 mL are high following this monotherapy. To reduce postpartum blood loss beyond what is possible with oxytocin alone, clinicians can more rapidly transition to administering a second uterotonic when they suspect blood loss is becoming excessive or they can use two uterotonic agents with all births or in those at high risk for excess bleeding. If blood loss does become excessive, clinicians need to pivot rapidly from prevention with oxytocin to treatment with our entire therapeutic armamentarium.

- Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e323-e333.

- Slomski A. Why do hundreds of US women die annually in childbirth? JAMA. 2019;321:1239-1241.

- Gallos ID, Papadopoulou A, Man R, et al. Uterotonic agents for preventing postpartum haemorrhage: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD011689.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e168-e186.

- Widmer M, Piaggio G, Nguyen TM, et al; WHO Champion Trial Group. Heat-stable carbetocin versus oxytocin to prevent hemorrhage after vaginal birth. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:743-752.

- Adnan N, Conlan-Trant R, McCormick C, et al. Intramuscular versus intravenous oxytocin to prevent postpartum haemorrhage at vaginal delivery: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2018;362:k3546.

- Hamm J, Russell Z, Botha T, et al. Buccal misoprostol to prevent hemorrhage at cesarean delivery: a randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1404-1406.

- Bhullar A, Carlan SJ, Hamm J, et al. Buccal misoprostol to decrease blood loss after vaginal delivery: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1282-1288.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Fawole B, Mugerwa K, et al. Administration of 400 µg of misoprostol to augment routine active management of the third stage of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;112:98-102.

- Chaudhuri P, Majumdar A. A randomized trial of sublingual misoprostol to augment routine third-stage management among women at risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;132:191-195.

- Winikoff B, Dabash R, Durocher J, et al. Treatment of post-partum haemorrhage with sublingual misoprostol versus oxytocin in women not exposed to oxytocin during labor: a double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;375:210-216.

- Blum J, Winikoff B, Raghavan S, et al. Treatment of post-partum haemorrhage with sublingual misoprostol versus oxytocin in women receiving prophylactic oxytocin: a double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;375:217-223.

- Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e323-e333.

- Slomski A. Why do hundreds of US women die annually in childbirth? JAMA. 2019;321:1239-1241.

- Gallos ID, Papadopoulou A, Man R, et al. Uterotonic agents for preventing postpartum haemorrhage: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD011689.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 183: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e168-e186.

- Widmer M, Piaggio G, Nguyen TM, et al; WHO Champion Trial Group. Heat-stable carbetocin versus oxytocin to prevent hemorrhage after vaginal birth. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:743-752.

- Adnan N, Conlan-Trant R, McCormick C, et al. Intramuscular versus intravenous oxytocin to prevent postpartum haemorrhage at vaginal delivery: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2018;362:k3546.

- Hamm J, Russell Z, Botha T, et al. Buccal misoprostol to prevent hemorrhage at cesarean delivery: a randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1404-1406.

- Bhullar A, Carlan SJ, Hamm J, et al. Buccal misoprostol to decrease blood loss after vaginal delivery: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1282-1288.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Fawole B, Mugerwa K, et al. Administration of 400 µg of misoprostol to augment routine active management of the third stage of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;112:98-102.

- Chaudhuri P, Majumdar A. A randomized trial of sublingual misoprostol to augment routine third-stage management among women at risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;132:191-195.

- Winikoff B, Dabash R, Durocher J, et al. Treatment of post-partum haemorrhage with sublingual misoprostol versus oxytocin in women not exposed to oxytocin during labor: a double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;375:210-216.

- Blum J, Winikoff B, Raghavan S, et al. Treatment of post-partum haemorrhage with sublingual misoprostol versus oxytocin in women receiving prophylactic oxytocin: a double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;375:217-223.

The return of measles—an unnecessary sequel

So why are we, the trustworthy, having such a tough time convincing people to get routine vaccines for themselves and for their kids? In a sea of truthopenia, we need to do more.

Not everyone refuses vaccines. It is the rare patient in my examination room who, after a discussion, still steadfastly refuses to get a flu shot or pneumonia vaccine. But our dialogue has changed somewhat. Patients still tell me that they or someone they know got the flu from the flu shot or got sick from the pneumonia vaccine (explainable by discussing the immune system’s systemic anamnestic response to a vaccine in the setting of partial immunity—“It’s a good thing”). But more often, I’m hearing detailed stories from the Internet or social media. We heard a less-than-endorsing reflection on the value of vaccines from 2 potential presidential candidates, 1 being a physician, during a televised presidential primary debate. Then there are the tabloid stories, and, of course, there are the celebrity authors and TV talk show doctors touting the unsubstantiated or incompletely substantiated virtues of “anti-inflammatory” and “immune-boosting” diets and supplements as obvious and total truth, while I’m recommending vaccinations and traditional drug therapies. Who can the patient believe? In our limited office-visit time, we must somehow put this external noise into perspective and individualize our suggestions for the patient in front of us.

Certainly the major news media research teams and the on-screen physician consultants to the major news networks have offered up evidence-based discussions on vaccination, the impact of preventable infections on the unvaccinated, and the limitations and reasonable potential benefits of specific dietary interventions and supplements. Unfortunately, their message is being contaminated by the untrusting aura that surrounds mainstream written and TV media.

Despite physicians’ continued high professional rating in the 2018 Gallup poll, some patients, families, and communities are swayed by arguments offered outside of our offices. And when it comes to our summarizing large studies published in major medical journals, the rolling echo of possible fake news and alternative facts comes to the fore. Can they really trust the establishment? There remains doubt in some patients’ minds.

The problem with measles, as Porter and Goldfarb discuss in this issue of the Journal, is that it is extremely contagious. For “herd immunity” to provide protection and prevent outbreaks, nearly everyone must be vaccinated or have natural immunity from childhood infection. Those who are at special risk from infection include the very young, who have an underdeveloped immune system, and adults who were not appropriately vaccinated (eg, those who may only have gotten a single measles vaccination as a child or whose immune system is weakened by disease or immunosuppressive drugs).

What can we do? We need, as a united front, to know the evidence that supports the relative value of vaccination of our child and adult patients and pass it on. We need to confront, accept, and explain to patients that all vaccines are not 100% successful (measles seems to be pretty close, based on the near-eradication of the disease in vaccinated communities up until now), but that even partial immunity is probably beneficial with all vaccines. We need to have a united front when discussing the bulk of evidence that debunks the vaccination-autism connection. We need to support federal and state funding so that all children can get their routine medical exams and vaccinations. We need to support sufficient financial protection for those companies who in good faith continue to develop and test new and improved vaccines for use in this country and around the world; infections can be introduced by travelers who have passed through areas endemic for infections rarely seen in the United States and who may not be aware of their own infection.

We need to live up to our Gallup poll ranking as highly trusted professionals. And we need to partner with our even more highly trusted nursing colleagues to take every opportunity to inform our patients and fight the spread of disinformation.

The morbilliform rash attributed to measles—and not to a sulfa allergy—should have been a phenomenon of the past. We didn’t need to see it again.

So why are we, the trustworthy, having such a tough time convincing people to get routine vaccines for themselves and for their kids? In a sea of truthopenia, we need to do more.

Not everyone refuses vaccines. It is the rare patient in my examination room who, after a discussion, still steadfastly refuses to get a flu shot or pneumonia vaccine. But our dialogue has changed somewhat. Patients still tell me that they or someone they know got the flu from the flu shot or got sick from the pneumonia vaccine (explainable by discussing the immune system’s systemic anamnestic response to a vaccine in the setting of partial immunity—“It’s a good thing”). But more often, I’m hearing detailed stories from the Internet or social media. We heard a less-than-endorsing reflection on the value of vaccines from 2 potential presidential candidates, 1 being a physician, during a televised presidential primary debate. Then there are the tabloid stories, and, of course, there are the celebrity authors and TV talk show doctors touting the unsubstantiated or incompletely substantiated virtues of “anti-inflammatory” and “immune-boosting” diets and supplements as obvious and total truth, while I’m recommending vaccinations and traditional drug therapies. Who can the patient believe? In our limited office-visit time, we must somehow put this external noise into perspective and individualize our suggestions for the patient in front of us.

Certainly the major news media research teams and the on-screen physician consultants to the major news networks have offered up evidence-based discussions on vaccination, the impact of preventable infections on the unvaccinated, and the limitations and reasonable potential benefits of specific dietary interventions and supplements. Unfortunately, their message is being contaminated by the untrusting aura that surrounds mainstream written and TV media.

Despite physicians’ continued high professional rating in the 2018 Gallup poll, some patients, families, and communities are swayed by arguments offered outside of our offices. And when it comes to our summarizing large studies published in major medical journals, the rolling echo of possible fake news and alternative facts comes to the fore. Can they really trust the establishment? There remains doubt in some patients’ minds.

The problem with measles, as Porter and Goldfarb discuss in this issue of the Journal, is that it is extremely contagious. For “herd immunity” to provide protection and prevent outbreaks, nearly everyone must be vaccinated or have natural immunity from childhood infection. Those who are at special risk from infection include the very young, who have an underdeveloped immune system, and adults who were not appropriately vaccinated (eg, those who may only have gotten a single measles vaccination as a child or whose immune system is weakened by disease or immunosuppressive drugs).

What can we do? We need, as a united front, to know the evidence that supports the relative value of vaccination of our child and adult patients and pass it on. We need to confront, accept, and explain to patients that all vaccines are not 100% successful (measles seems to be pretty close, based on the near-eradication of the disease in vaccinated communities up until now), but that even partial immunity is probably beneficial with all vaccines. We need to have a united front when discussing the bulk of evidence that debunks the vaccination-autism connection. We need to support federal and state funding so that all children can get their routine medical exams and vaccinations. We need to support sufficient financial protection for those companies who in good faith continue to develop and test new and improved vaccines for use in this country and around the world; infections can be introduced by travelers who have passed through areas endemic for infections rarely seen in the United States and who may not be aware of their own infection.

We need to live up to our Gallup poll ranking as highly trusted professionals. And we need to partner with our even more highly trusted nursing colleagues to take every opportunity to inform our patients and fight the spread of disinformation.

The morbilliform rash attributed to measles—and not to a sulfa allergy—should have been a phenomenon of the past. We didn’t need to see it again.

So why are we, the trustworthy, having such a tough time convincing people to get routine vaccines for themselves and for their kids? In a sea of truthopenia, we need to do more.

Not everyone refuses vaccines. It is the rare patient in my examination room who, after a discussion, still steadfastly refuses to get a flu shot or pneumonia vaccine. But our dialogue has changed somewhat. Patients still tell me that they or someone they know got the flu from the flu shot or got sick from the pneumonia vaccine (explainable by discussing the immune system’s systemic anamnestic response to a vaccine in the setting of partial immunity—“It’s a good thing”). But more often, I’m hearing detailed stories from the Internet or social media. We heard a less-than-endorsing reflection on the value of vaccines from 2 potential presidential candidates, 1 being a physician, during a televised presidential primary debate. Then there are the tabloid stories, and, of course, there are the celebrity authors and TV talk show doctors touting the unsubstantiated or incompletely substantiated virtues of “anti-inflammatory” and “immune-boosting” diets and supplements as obvious and total truth, while I’m recommending vaccinations and traditional drug therapies. Who can the patient believe? In our limited office-visit time, we must somehow put this external noise into perspective and individualize our suggestions for the patient in front of us.

Certainly the major news media research teams and the on-screen physician consultants to the major news networks have offered up evidence-based discussions on vaccination, the impact of preventable infections on the unvaccinated, and the limitations and reasonable potential benefits of specific dietary interventions and supplements. Unfortunately, their message is being contaminated by the untrusting aura that surrounds mainstream written and TV media.

Despite physicians’ continued high professional rating in the 2018 Gallup poll, some patients, families, and communities are swayed by arguments offered outside of our offices. And when it comes to our summarizing large studies published in major medical journals, the rolling echo of possible fake news and alternative facts comes to the fore. Can they really trust the establishment? There remains doubt in some patients’ minds.

The problem with measles, as Porter and Goldfarb discuss in this issue of the Journal, is that it is extremely contagious. For “herd immunity” to provide protection and prevent outbreaks, nearly everyone must be vaccinated or have natural immunity from childhood infection. Those who are at special risk from infection include the very young, who have an underdeveloped immune system, and adults who were not appropriately vaccinated (eg, those who may only have gotten a single measles vaccination as a child or whose immune system is weakened by disease or immunosuppressive drugs).

What can we do? We need, as a united front, to know the evidence that supports the relative value of vaccination of our child and adult patients and pass it on. We need to confront, accept, and explain to patients that all vaccines are not 100% successful (measles seems to be pretty close, based on the near-eradication of the disease in vaccinated communities up until now), but that even partial immunity is probably beneficial with all vaccines. We need to have a united front when discussing the bulk of evidence that debunks the vaccination-autism connection. We need to support federal and state funding so that all children can get their routine medical exams and vaccinations. We need to support sufficient financial protection for those companies who in good faith continue to develop and test new and improved vaccines for use in this country and around the world; infections can be introduced by travelers who have passed through areas endemic for infections rarely seen in the United States and who may not be aware of their own infection.

We need to live up to our Gallup poll ranking as highly trusted professionals. And we need to partner with our even more highly trusted nursing colleagues to take every opportunity to inform our patients and fight the spread of disinformation.

The morbilliform rash attributed to measles—and not to a sulfa allergy—should have been a phenomenon of the past. We didn’t need to see it again.

Timed perfectly

When I entered the examination room, I saw his alma mater’s logo on his wristwatch. He was a retired physician with a new diagnosis of leukemia who drove to see me, even though he lived closer to his beloved medical school where he had practiced his entire career.

As is frequently the case, he came to see me because he could not get the appointment he wanted in his university’s clinic for another 6 months. He called us on Friday, and 3 days later, he and I were meeting. He is still an ardent supporter of his institution, but I am now his hematologist.

As it turned out, his leukemia was asymptomatic, indolent, and required no treatment. He could have waited 6 months to be seen. But, no; he couldn’t.

This story repeats itself over and over again. A sick patient calls to be seen and is told there is no availability for weeks or months. I do not understand how health care facilities, my own included, find this acceptable.

My father was very proud of his policy to see every patient in his waiting room no matter how long his office needed to stay open. He felt that access was of primary importance to his patients and to his practice. If he didn’t see them, somebody else would. Those of us working in large academic centers do not always feel the financial consequences of patients lost because of poor service.

Luckily, I work in a large cancer center that values access as much as a small practice would. When a patient calls us with a hematologic problem, we see them in less than 7 days, unless the patient prefers a different time frame. We monitor the time it takes to see patients and proactively assess upcoming appointments to ensure insurance coverage and the availability of records. If an obstruction is identified, the case is escalated to administrative leadership to be addressed and resolved. We are very proud of this work.

However, our focus on access does not end there. Once seen, we expedite patient evaluation by assessing workflows to obtain all necessary testing as quickly as possible. By doing so, we accelerate the time it takes from diagnosis to the time we start treating (time to treat). We have always tried to reduce time to treat for acute leukemia and we have applied those lessons to patients with lymphoma and solid tumors, resulting in a 33% improvement over the last 5 years.

We not only lessen the anxiety that comes with a scary diagnosis, emerging data indicate outcomes are improved with faster treatment, too (PLoS One. 2019 Mar 1;14(3):e0213209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213209).

These efforts will be criticized by those who feel the delivery of medical care should be structured more around the physician than the patient. Certainly, the system has developed to support a mindset of “physician first.” Not only do patients have to make an appointment for the privilege of seeing us, they have to navigate significant geographic and financial hurdles for that privilege.

Once at the appointment, physicians have historically been the provider giving the “orders” while others correct them, carry them out, follow-up on the results, manage phone calls, and schedule follow-up. This hierarchy has served physicians very well, but the pyramidal structure of health care is on the verge of being upended.

Too few physicians for an increasing demand for medical attention has led to the rise of advanced practice providers (APPs), who often serve as the only provider a patient may have, particularly in rural areas. In our center, we evolved from thinking of APPs as similar to house-staff who saw patients with us and did most of the work, but could not bill, to independent providers who work with us, do most of the work, and bill for their efforts. This slow transformation of our practice will soon seem quaint as we face the rapid disruption coming to our current conception of the health care delivery system.

Technologically savvy patients already demand immediate access to unlimited supplies of consumer goods, video, audio, books, magazines, and just about anything else you can think of. Immediate access to health care at a time convenient to the patient also will become an expectation because plenty of health care delivery models already are providing it. The local pharmacy or retail store may have a physician or APP right there ready to see a patient at any time. Some physicians are already online ready for an electronic interaction. See MDLIVE and Teladoc as examples.

The nimble cancer center that embraces these trends to become more patient-centric will be the center that captures national – if not international – market share, as insurance companies and governments adjust their reimbursement models to include these services. With blood work obtained just about anywhere, what would keep a patient with immune thrombocytopenic purpura from consulting with any online hematologist she chooses, whenever she chooses?

If first impressions are important, then patient access is important. Refrains of “I don’t have clinic that day,” “the pathology has not yet been reviewed,” and “that is not a disease I take care of,” ring as hollow to me as I suspect they do to our patients. When someone in my family has a significant illness, I want them to be seen now, not later. I believe we all would want prompt, efficient service.

We should strive to provide the same level of care to our patients as we expect for our family. Patients do not know that chronic leukemia is not an emergency. Time may not be critical to us, but it is to them. The perfect time to meet their needs is now.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematology and medical oncology at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

When I entered the examination room, I saw his alma mater’s logo on his wristwatch. He was a retired physician with a new diagnosis of leukemia who drove to see me, even though he lived closer to his beloved medical school where he had practiced his entire career.

As is frequently the case, he came to see me because he could not get the appointment he wanted in his university’s clinic for another 6 months. He called us on Friday, and 3 days later, he and I were meeting. He is still an ardent supporter of his institution, but I am now his hematologist.

As it turned out, his leukemia was asymptomatic, indolent, and required no treatment. He could have waited 6 months to be seen. But, no; he couldn’t.

This story repeats itself over and over again. A sick patient calls to be seen and is told there is no availability for weeks or months. I do not understand how health care facilities, my own included, find this acceptable.

My father was very proud of his policy to see every patient in his waiting room no matter how long his office needed to stay open. He felt that access was of primary importance to his patients and to his practice. If he didn’t see them, somebody else would. Those of us working in large academic centers do not always feel the financial consequences of patients lost because of poor service.

Luckily, I work in a large cancer center that values access as much as a small practice would. When a patient calls us with a hematologic problem, we see them in less than 7 days, unless the patient prefers a different time frame. We monitor the time it takes to see patients and proactively assess upcoming appointments to ensure insurance coverage and the availability of records. If an obstruction is identified, the case is escalated to administrative leadership to be addressed and resolved. We are very proud of this work.

However, our focus on access does not end there. Once seen, we expedite patient evaluation by assessing workflows to obtain all necessary testing as quickly as possible. By doing so, we accelerate the time it takes from diagnosis to the time we start treating (time to treat). We have always tried to reduce time to treat for acute leukemia and we have applied those lessons to patients with lymphoma and solid tumors, resulting in a 33% improvement over the last 5 years.

We not only lessen the anxiety that comes with a scary diagnosis, emerging data indicate outcomes are improved with faster treatment, too (PLoS One. 2019 Mar 1;14(3):e0213209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213209).

These efforts will be criticized by those who feel the delivery of medical care should be structured more around the physician than the patient. Certainly, the system has developed to support a mindset of “physician first.” Not only do patients have to make an appointment for the privilege of seeing us, they have to navigate significant geographic and financial hurdles for that privilege.

Once at the appointment, physicians have historically been the provider giving the “orders” while others correct them, carry them out, follow-up on the results, manage phone calls, and schedule follow-up. This hierarchy has served physicians very well, but the pyramidal structure of health care is on the verge of being upended.

Too few physicians for an increasing demand for medical attention has led to the rise of advanced practice providers (APPs), who often serve as the only provider a patient may have, particularly in rural areas. In our center, we evolved from thinking of APPs as similar to house-staff who saw patients with us and did most of the work, but could not bill, to independent providers who work with us, do most of the work, and bill for their efforts. This slow transformation of our practice will soon seem quaint as we face the rapid disruption coming to our current conception of the health care delivery system.

Technologically savvy patients already demand immediate access to unlimited supplies of consumer goods, video, audio, books, magazines, and just about anything else you can think of. Immediate access to health care at a time convenient to the patient also will become an expectation because plenty of health care delivery models already are providing it. The local pharmacy or retail store may have a physician or APP right there ready to see a patient at any time. Some physicians are already online ready for an electronic interaction. See MDLIVE and Teladoc as examples.

The nimble cancer center that embraces these trends to become more patient-centric will be the center that captures national – if not international – market share, as insurance companies and governments adjust their reimbursement models to include these services. With blood work obtained just about anywhere, what would keep a patient with immune thrombocytopenic purpura from consulting with any online hematologist she chooses, whenever she chooses?

If first impressions are important, then patient access is important. Refrains of “I don’t have clinic that day,” “the pathology has not yet been reviewed,” and “that is not a disease I take care of,” ring as hollow to me as I suspect they do to our patients. When someone in my family has a significant illness, I want them to be seen now, not later. I believe we all would want prompt, efficient service.

We should strive to provide the same level of care to our patients as we expect for our family. Patients do not know that chronic leukemia is not an emergency. Time may not be critical to us, but it is to them. The perfect time to meet their needs is now.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematology and medical oncology at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

When I entered the examination room, I saw his alma mater’s logo on his wristwatch. He was a retired physician with a new diagnosis of leukemia who drove to see me, even though he lived closer to his beloved medical school where he had practiced his entire career.

As is frequently the case, he came to see me because he could not get the appointment he wanted in his university’s clinic for another 6 months. He called us on Friday, and 3 days later, he and I were meeting. He is still an ardent supporter of his institution, but I am now his hematologist.

As it turned out, his leukemia was asymptomatic, indolent, and required no treatment. He could have waited 6 months to be seen. But, no; he couldn’t.

This story repeats itself over and over again. A sick patient calls to be seen and is told there is no availability for weeks or months. I do not understand how health care facilities, my own included, find this acceptable.

My father was very proud of his policy to see every patient in his waiting room no matter how long his office needed to stay open. He felt that access was of primary importance to his patients and to his practice. If he didn’t see them, somebody else would. Those of us working in large academic centers do not always feel the financial consequences of patients lost because of poor service.

Luckily, I work in a large cancer center that values access as much as a small practice would. When a patient calls us with a hematologic problem, we see them in less than 7 days, unless the patient prefers a different time frame. We monitor the time it takes to see patients and proactively assess upcoming appointments to ensure insurance coverage and the availability of records. If an obstruction is identified, the case is escalated to administrative leadership to be addressed and resolved. We are very proud of this work.

However, our focus on access does not end there. Once seen, we expedite patient evaluation by assessing workflows to obtain all necessary testing as quickly as possible. By doing so, we accelerate the time it takes from diagnosis to the time we start treating (time to treat). We have always tried to reduce time to treat for acute leukemia and we have applied those lessons to patients with lymphoma and solid tumors, resulting in a 33% improvement over the last 5 years.

We not only lessen the anxiety that comes with a scary diagnosis, emerging data indicate outcomes are improved with faster treatment, too (PLoS One. 2019 Mar 1;14(3):e0213209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213209).

These efforts will be criticized by those who feel the delivery of medical care should be structured more around the physician than the patient. Certainly, the system has developed to support a mindset of “physician first.” Not only do patients have to make an appointment for the privilege of seeing us, they have to navigate significant geographic and financial hurdles for that privilege.

Once at the appointment, physicians have historically been the provider giving the “orders” while others correct them, carry them out, follow-up on the results, manage phone calls, and schedule follow-up. This hierarchy has served physicians very well, but the pyramidal structure of health care is on the verge of being upended.

Too few physicians for an increasing demand for medical attention has led to the rise of advanced practice providers (APPs), who often serve as the only provider a patient may have, particularly in rural areas. In our center, we evolved from thinking of APPs as similar to house-staff who saw patients with us and did most of the work, but could not bill, to independent providers who work with us, do most of the work, and bill for their efforts. This slow transformation of our practice will soon seem quaint as we face the rapid disruption coming to our current conception of the health care delivery system.

Technologically savvy patients already demand immediate access to unlimited supplies of consumer goods, video, audio, books, magazines, and just about anything else you can think of. Immediate access to health care at a time convenient to the patient also will become an expectation because plenty of health care delivery models already are providing it. The local pharmacy or retail store may have a physician or APP right there ready to see a patient at any time. Some physicians are already online ready for an electronic interaction. See MDLIVE and Teladoc as examples.

The nimble cancer center that embraces these trends to become more patient-centric will be the center that captures national – if not international – market share, as insurance companies and governments adjust their reimbursement models to include these services. With blood work obtained just about anywhere, what would keep a patient with immune thrombocytopenic purpura from consulting with any online hematologist she chooses, whenever she chooses?

If first impressions are important, then patient access is important. Refrains of “I don’t have clinic that day,” “the pathology has not yet been reviewed,” and “that is not a disease I take care of,” ring as hollow to me as I suspect they do to our patients. When someone in my family has a significant illness, I want them to be seen now, not later. I believe we all would want prompt, efficient service.

We should strive to provide the same level of care to our patients as we expect for our family. Patients do not know that chronic leukemia is not an emergency. Time may not be critical to us, but it is to them. The perfect time to meet their needs is now.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematology and medical oncology at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

It’s time to implement measurement-based care in psychiatric practice

In an editorial published in Current Psychiatry 10 years ago, I cited a stunning fact based on a readers’ survey: 98% of psychiatrists did not use any of the 4 clinical rating scales that are routinely used in the clinical trials required for FDA approval of medications for psychotic, mood, and anxiety disorders.1

As a follow-up, Ahmed Aboraya, MD, DrPH, and I would like to report on the state of measurement-based care (MBC), a term coined by Trivedi in 2006 and defined by Fortney as “the systematic administration of symptom rating scales and use of the results to drive clinical decision making at the level of the individual patient.”2

We will start with the creator of modern rating scales, Father Thomas Verner Moore (1877-1969), who is considered one of the most underrecognized legends in the history of modern psychiatry. Moore was a psychologist and psychiatrist who can lay claim to 3 major achievements in psychiatry: the creation of rating scales in psychiatry, the use of factor analysis to deconstruct psychosis, and the formulation of specific definitions for symptoms and signs of psychopathology. Moore’s 1933 book described the rating scales used in his research.3

Since that time, researchers have continued to invent clinician-rated scales, self-report scales, and other measures in psychiatry. The Handbook of Psychiatric Measures, which was published in 2000 by the American Psychiatric Association Task Force chaired by AJ Rush Jr., includes >240 measures covering adult and child psychiatric disorders.4

Recent research has shown the superiority of MBC compared with usual standard care (USC) in improving patient outcomes.2,5-7 A recent well-designed, blind-rater, randomized trial by Guo et al8 showed that MBC is more effective than USC both in achieving response and remission, and reducing the time to response and remission. Given the evidence of the benefits of MBC in improving patient outcomes, and the plethora of reliable and validated rating scales, an important question arises: Why has MBC not yet been established as the standard of care in psychiatric clinical practice? There are many barriers to implementing MBC,9 including:

- time constraints (most commonly cited reason by psychiatrists)

- mismatch between clinical needs and the content of the measure (ie, rating scales are designed for research and not for clinicians’ use)

- measurements produced by rating scales may not always be clinically relevant

- administering rating scales may interfere with establishing rapport with patients

- some measures, such as standardized diagnostic interviews, can be cumbersome, unwieldy, and complicated

- the lack of formal training for most clinicians (among the top barriers for residents and faculty)

- lack of availability of training manuals and protocols.

Clinician researchers have started to adapt and invent instruments that can be used in clinical settings. For more than 20 years, Mark Zimmerman, MD, has been the principal investigator of the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) Project, aimed at integrating the assessment methods of researchers into routine clinical practice.10 Zimmerman has developed self-report scales and outcome measures such as the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ), the Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale (CUDOS), the Standardized Clinical Outcome Rating for Depression (SCOR-D), the Clinically Useful Anxiety Outcome Scale (CUXOS), the Remission from Depression Questionnaire (RDQ), and the Clinically Useful Patient Satisfaction Scale (CUPSS).11-18

We have been critical of the utility of the existing diagnostic interviews and rating scales. I (AA) developed the Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP) as a MBC tool that addresses the most common barriers that clinicians face.9,19-23 The SCIP includes 18 clinician-rated scales for the following symptom domains: generalized anxiety, obsessions, compulsions, posttraumatic stress, depression, mania, delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thoughts, aggression, negative symptoms, alcohol use, drug use, attention deficit, hyperactivity, anorexia, binge-eating, and bulimia. The SCIP rating scales meet the criteria for MBC because they are efficient, reliable, and valid. They reflect how clinicians assess psychiatric disorders, and are relevant to decision-making. Both self-report and clinician-rated scales are important MBC tools and complementary to each other. The choice to use self-report scales, clinician-rated scales, or both depends on several factors, including the clinical setting (inpatient or outpatient), psychiatric diagnoses, and patient characteristics. No measure or scale will ever replace a seasoned and experienced clinician who has been evaluating and treating real-world patients for years. Just as thermometers, stethoscopes, and laboratories help other types of physicians to reach accurate diagnoses and provide appropriate management, the use of MBC by psychiatrists will enhance the accuracy of diagnoses and improve the outcomes of care.

Continue to: On a positive note...

On a positive note, I (AA) have completed a MBC curriculum for training psychiatry residents that includes 11 videotaped interviews with actual patients covering the major adult psychiatric disorders: generalized anxiety, panic, depressive, posttraumatic stress, bipolar, psychotic, eating, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity. The interviews show and teach how to rate psychopathology items, how to score the dimensions, and how to evaluate the severity of the disorder(s). All of the SCIP’s 18 scales have been uploaded into the Epic electronic health record (EHR) system at West Virginia University hospitals. A pilot project for implementing MBC in the treatment of adult psychiatric disorders at the West Virginia University residency program and other programs is underway. If we instruct residents in MBC during their psychiatric training, they will likely practice it for the rest of their clinical careers. Except for a minority of clinicians who are involved in clinical trials and who use rating scales in practice, most practicing clinicians were never trained to use scales. For more information about the MBC curriculum and videotapes, contact Dr. Aboraya at [email protected] or visit www.scip-psychiatry.com.

Today, some of the barriers that impede the implementation of MBC in psychiatric practice have been resolved, but much more work remains. Now is the time to implement MBC and provide an answer to AJ Rush, who asked, “Isn’t it about time to employ measurement-based care in practice?”24 The 3 main ingredients for MBC implementation—useful measures, integration of EHR, and health information technologies—exist today. We strongly encourage psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, and other mental health professionals to adopt MBC in their daily practice.

To comment on this editorial or other topics of interest: [email protected].

1. Nasrallah HA. Long overdue: measurement-based psychiatric practice. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(4):14-16.

2. Fortney JC, Unutzer J, Wrenn G, et al. A tipping point for measurement-based care. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;68(2):179-188.

3. Moore TV. The essential psychoses and their fundamental syndromes. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1933.

4. Rush AJ. Handbook of psychiatric measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

5. Scott K, Lewis CC. Using measurement-based care to enhance any treatment. Cogn Behav Pract. 2015;22(1):49-59.

6. Trivedi MH, Daly EJ. Measurement-based care for refractory depression: a clinical decision support model for clinical research and practice. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(Suppl 2):S61-S71.

7. Harding KJ, Rush AJ, Arbuckle M, et al. Measurement-based care in psychiatric practice: a policy framework for implementation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1136-1143.

8. Guo T, Xiang YT, Xiao L, et al. Measurement-based care versus standard care for major depression: a randomized controlled trial with blind raters. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(10):1004-1013.

9. Aboraya A, Nasrallah HA, Elswick D, et al. Measurement-based care in psychiatry: past, present and future. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2018;15(11-12):13-26.

10. Zimmerman M. A review of 20 years of research on overdiagnosis and underdiagnosis in the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) Project. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(2):71-79.

11. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. The reliability and validity of a screening questionnaire for 13 DSM-IV Axis I disorders (the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire) in psychiatric outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(10):677-683.

12. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. The Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire: development, reliability and validity. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42(3):175-189.

13. Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, McGlinchey JB, et al. A clinically useful depression outcome scale. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(2):131-140.

14. Zimmerman M, Posternak MA, Chelminski I, et al. Standardized clinical outcome rating scale for depression for use in clinical practice. Depress Anxiety. 2005;22(1):36-40.

15. Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, Young D, et al. A clinically useful anxiety outcome scale. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(5):534-542.

16. Zimmerman M, Galione JN, Attiullah N, et al. Depressed patients’ perspectives of 2 measures of outcome: the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS) and the Remission from Depression Questionnaire (RDQ). Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2011;23(3):208-212.

17. Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Attiullah N, et al. The remission from depression questionnaire as an outcome measure in the treatment of depression. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(6):533-538.

18. Zimmerman M, Gazarian D, Multach M, et al. A clinically useful self-report measure of psychiatric patients’ satisfaction with the initial evaluation. Psychiatry Res. 2017;252:38-44.

19. Aboraya A. The validity results of the Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP). Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2015;41(Suppl 1):S103-S104.

20. Aboraya A. Instruction manual for the Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP). http://innovationscns.com/wp-content/uploads/SCIP_Instruction_Manual.pdf. Accessed April 29, 2019.

21. Aboraya A, El-Missiry A, Barlowe J, et al. The reliability of the Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP): a clinician-administered tool with categorical, dimensional and numeric output. Schizophr Res. 2014;156(2-3):174-183.

22. Aboraya A, Nasrallah HA, Muvvala S, et al. The Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP): a clinician-administered tool with categorical, dimensional, and numeric output-conceptual development, design, and description of the SCIP. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2016;13(5-6):31-77.

23. Aboraya A, Nasrallah HA. Perspectives on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS): Use, misuse, drawbacks, and a new alternative for schizophrenia research. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2016;28(2):125-131.

24. Rush AJ. Isn’t it about time to employ measurement-based care in practice? Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(10):934-936.

In an editorial published in Current Psychiatry 10 years ago, I cited a stunning fact based on a readers’ survey: 98% of psychiatrists did not use any of the 4 clinical rating scales that are routinely used in the clinical trials required for FDA approval of medications for psychotic, mood, and anxiety disorders.1

As a follow-up, Ahmed Aboraya, MD, DrPH, and I would like to report on the state of measurement-based care (MBC), a term coined by Trivedi in 2006 and defined by Fortney as “the systematic administration of symptom rating scales and use of the results to drive clinical decision making at the level of the individual patient.”2

We will start with the creator of modern rating scales, Father Thomas Verner Moore (1877-1969), who is considered one of the most underrecognized legends in the history of modern psychiatry. Moore was a psychologist and psychiatrist who can lay claim to 3 major achievements in psychiatry: the creation of rating scales in psychiatry, the use of factor analysis to deconstruct psychosis, and the formulation of specific definitions for symptoms and signs of psychopathology. Moore’s 1933 book described the rating scales used in his research.3

Since that time, researchers have continued to invent clinician-rated scales, self-report scales, and other measures in psychiatry. The Handbook of Psychiatric Measures, which was published in 2000 by the American Psychiatric Association Task Force chaired by AJ Rush Jr., includes >240 measures covering adult and child psychiatric disorders.4

Recent research has shown the superiority of MBC compared with usual standard care (USC) in improving patient outcomes.2,5-7 A recent well-designed, blind-rater, randomized trial by Guo et al8 showed that MBC is more effective than USC both in achieving response and remission, and reducing the time to response and remission. Given the evidence of the benefits of MBC in improving patient outcomes, and the plethora of reliable and validated rating scales, an important question arises: Why has MBC not yet been established as the standard of care in psychiatric clinical practice? There are many barriers to implementing MBC,9 including:

- time constraints (most commonly cited reason by psychiatrists)

- mismatch between clinical needs and the content of the measure (ie, rating scales are designed for research and not for clinicians’ use)

- measurements produced by rating scales may not always be clinically relevant

- administering rating scales may interfere with establishing rapport with patients

- some measures, such as standardized diagnostic interviews, can be cumbersome, unwieldy, and complicated

- the lack of formal training for most clinicians (among the top barriers for residents and faculty)

- lack of availability of training manuals and protocols.

Clinician researchers have started to adapt and invent instruments that can be used in clinical settings. For more than 20 years, Mark Zimmerman, MD, has been the principal investigator of the Rhode Island Methods to Improve Diagnostic Assessment and Services (MIDAS) Project, aimed at integrating the assessment methods of researchers into routine clinical practice.10 Zimmerman has developed self-report scales and outcome measures such as the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ), the Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale (CUDOS), the Standardized Clinical Outcome Rating for Depression (SCOR-D), the Clinically Useful Anxiety Outcome Scale (CUXOS), the Remission from Depression Questionnaire (RDQ), and the Clinically Useful Patient Satisfaction Scale (CUPSS).11-18