User login

Expanded hospital testing improves respiratory pathogen detection

SAN DIEGO – Systematic testing of acute respiratory illness patients can increase the likelihood of finding relevant pathogens, according to a study presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Currently, hospitals conduct either nonroutine assessments or rely heavily on clinical laboratory testing among severe acute respiratory illness patients, which can lead to missing clinically key viruses.

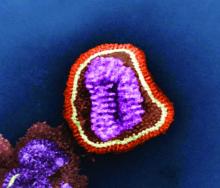

Systematic testing expands on tests ordered and carried out at hospitals, expanding on them by testing for influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus and enterovirus, adenovirus, coronavirus, and parainfluenza viruses 1-4. To test the efficacy of systematic testing, investigators studied 2,216 severe acute respiratory illness patients hospitalized in one of three hospitals in Minnesota during September 2015-August 2016. Patients were predominantly younger than 5 years old (57%) and had one or more chronic medical condition (63%).

Detection of at least one virus increased from 1,062 patients (48%) to 1,600 patients (72%) when comparing clinically ordered tests against expanded, systematic RT-PCR testing conducted through the Minnesota Health Department (MDH).

By patient age, viral detection increased by 27%, 24%, 18%, and 21% for patients aged younger than 5 years, 5-17 years, 18-64 years, and 65 years and older, respectively. Except for influenza viruses and RSV, the proportions of viruses identified, regardless of age, were all lower in hospital testing, compared with MDH testing.

“RSV targeting was almost systematic among children less than 5 years, but [accounted for] only 28% of RSV detection,” said Dr. Steffen in her presentation. “A smaller proportion of other respiratory viruses, including the human metapneumovirus, were detected at the hospital, and this was especially true for adults.”

Patients with rhinovirus and enterovirus saw a difference between hospital and expanded testing, increasing from a little over 300 patients detected, to nearly 800 patients.

“Patients admitted to the ICU were less likely to have a pathogen detection than those not admitted to the ICU, and those with one or more chronic medical condition had lower viral detection than those without,” Dr. Steffens said. “While testing at MDH did increase the percent of patients in each category, trends remained consistent and significant.”

Since testing information was only collected for patients with positive test results at the hospital, investigators were not able to compare testing practices between patients with and without viruses. This study may also have underrepresented pathogens detected through means other than the hospital laboratory, like rapid tests in emergency departments. The study was also limited by the short time frame of only 1 year.

The presenters reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Steffens A et al. Abstract 885.

SAN DIEGO – Systematic testing of acute respiratory illness patients can increase the likelihood of finding relevant pathogens, according to a study presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Currently, hospitals conduct either nonroutine assessments or rely heavily on clinical laboratory testing among severe acute respiratory illness patients, which can lead to missing clinically key viruses.

Systematic testing expands on tests ordered and carried out at hospitals, expanding on them by testing for influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus and enterovirus, adenovirus, coronavirus, and parainfluenza viruses 1-4. To test the efficacy of systematic testing, investigators studied 2,216 severe acute respiratory illness patients hospitalized in one of three hospitals in Minnesota during September 2015-August 2016. Patients were predominantly younger than 5 years old (57%) and had one or more chronic medical condition (63%).

Detection of at least one virus increased from 1,062 patients (48%) to 1,600 patients (72%) when comparing clinically ordered tests against expanded, systematic RT-PCR testing conducted through the Minnesota Health Department (MDH).

By patient age, viral detection increased by 27%, 24%, 18%, and 21% for patients aged younger than 5 years, 5-17 years, 18-64 years, and 65 years and older, respectively. Except for influenza viruses and RSV, the proportions of viruses identified, regardless of age, were all lower in hospital testing, compared with MDH testing.

“RSV targeting was almost systematic among children less than 5 years, but [accounted for] only 28% of RSV detection,” said Dr. Steffen in her presentation. “A smaller proportion of other respiratory viruses, including the human metapneumovirus, were detected at the hospital, and this was especially true for adults.”

Patients with rhinovirus and enterovirus saw a difference between hospital and expanded testing, increasing from a little over 300 patients detected, to nearly 800 patients.

“Patients admitted to the ICU were less likely to have a pathogen detection than those not admitted to the ICU, and those with one or more chronic medical condition had lower viral detection than those without,” Dr. Steffens said. “While testing at MDH did increase the percent of patients in each category, trends remained consistent and significant.”

Since testing information was only collected for patients with positive test results at the hospital, investigators were not able to compare testing practices between patients with and without viruses. This study may also have underrepresented pathogens detected through means other than the hospital laboratory, like rapid tests in emergency departments. The study was also limited by the short time frame of only 1 year.

The presenters reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Steffens A et al. Abstract 885.

SAN DIEGO – Systematic testing of acute respiratory illness patients can increase the likelihood of finding relevant pathogens, according to a study presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Currently, hospitals conduct either nonroutine assessments or rely heavily on clinical laboratory testing among severe acute respiratory illness patients, which can lead to missing clinically key viruses.

Systematic testing expands on tests ordered and carried out at hospitals, expanding on them by testing for influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus and enterovirus, adenovirus, coronavirus, and parainfluenza viruses 1-4. To test the efficacy of systematic testing, investigators studied 2,216 severe acute respiratory illness patients hospitalized in one of three hospitals in Minnesota during September 2015-August 2016. Patients were predominantly younger than 5 years old (57%) and had one or more chronic medical condition (63%).

Detection of at least one virus increased from 1,062 patients (48%) to 1,600 patients (72%) when comparing clinically ordered tests against expanded, systematic RT-PCR testing conducted through the Minnesota Health Department (MDH).

By patient age, viral detection increased by 27%, 24%, 18%, and 21% for patients aged younger than 5 years, 5-17 years, 18-64 years, and 65 years and older, respectively. Except for influenza viruses and RSV, the proportions of viruses identified, regardless of age, were all lower in hospital testing, compared with MDH testing.

“RSV targeting was almost systematic among children less than 5 years, but [accounted for] only 28% of RSV detection,” said Dr. Steffen in her presentation. “A smaller proportion of other respiratory viruses, including the human metapneumovirus, were detected at the hospital, and this was especially true for adults.”

Patients with rhinovirus and enterovirus saw a difference between hospital and expanded testing, increasing from a little over 300 patients detected, to nearly 800 patients.

“Patients admitted to the ICU were less likely to have a pathogen detection than those not admitted to the ICU, and those with one or more chronic medical condition had lower viral detection than those without,” Dr. Steffens said. “While testing at MDH did increase the percent of patients in each category, trends remained consistent and significant.”

Since testing information was only collected for patients with positive test results at the hospital, investigators were not able to compare testing practices between patients with and without viruses. This study may also have underrepresented pathogens detected through means other than the hospital laboratory, like rapid tests in emergency departments. The study was also limited by the short time frame of only 1 year.

The presenters reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Steffens A et al. Abstract 885.

REPORTING FROM ID WEEK 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among 2,216 patients studied, 1,600 (72%) were found to have at least one respiratory virus through expanded testing, compared with 1,062 (48%) patients tested through clincian-directed testing.

Study details: 2,351 severe acute respiratory illness patients hospitalized in one of three hospitals in Minnesota.

Disclosures: The presenter reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Steffens A et al. Abstract 885.

Managing mental health care at the hospital

The numbers tell a grim story. Nationwide, 43.7 million adult Americans experienced a mental health condition during 2016 – an increase of 1.2 million over the previous year. Mental health issues send almost 5.5 million people to emergency departments each year; nearly 60% of adults with a mental illness received no treatment at all.

If that massive – and growing – need is one side of the story, shrinking resources are the other. Mental health resources had already been diminishing for decades before the recession hit – and hit them especially hard. Between 2009 and 2012, states cut $5 billion in mental health services; during that time, at least 4,500 public psychiatric hospital beds nationwide disappeared – nearly 10% of the total supply. The bulk of those resources have never been restored.

Provider numbers also are falling. “Psychiatry is probably the top manpower shortage among all specialties,” said Joe Parks, MD, medical director of the National Council for Behavioral Health. “We have about a third the number of psychiatrists that most estimates say we need, and the number per capita is decreasing.” A significant percentage of psychiatrists – more than 50% – only accept cash, bypassing the low reimbursement rates even private insurance typically offers.

Hospitals, of course, feel those financial disincentives too, which discourage them from investments of their own. “It’s a difficult population to manage, and it’s difficult to manage the financial realities of mental health as well,” said John McHugh, PhD, assistant professor of health policy at Columbia University, New York. “If you were a hospital administrator looking to invest your last dollar and you have the option of investing it in a new heart institute or in behavioral health service, more likely than not, you’re going to invest it in the more profitable cardiovascular service line.”

Providers of last resort

But much of the burden of caring for this population ends up falling on hospitals by default. At Denver Health, Melanie Rylander, MD, medical director of the inpatient psychiatric unit, reports seeing this manifest in three categories of patients. First, there is an influx of people coming into the emergency department with primary mental health issues.

“We’re also seeing an influx of people coming in with physical problems, and upon assessment it becomes very clear very quickly that the real issue is an underlying mental health issue,” she said. Then there are the people coming in for the same physical problems over and over – maybe decompensated heart failure or COPD exacerbations – because mental health issues are impeding their ability to take care of themselves.

Some hospitalists say they feel ill equipped to care for these patients. “We don’t have the facility or the resources many times to properly care for their psychiatric needs when they’re in the hospital. It’s not really part of an internist’s training to be familiar with a lot of the medications,” said Atashi Mandal, MD, a hospitalist and pediatrician in Los Angeles. “Sometimes they get improperly medicated because we don’t know what else to do and the patient’s behavioral issues are escalating, so it’s really a difficult position.”

It’s a dispiriting experience for a hospitalist. “It really bothers me when I am trying to care for a patient who has psychiatric needs, and I feel I’m not able to do it, and I can’t find resources, and I feel that this patient’s needs are being neglected – not because we don’t care, and not because of a lack of effort by the staff. It’s just set up to fail,” Dr. Mandal said.

Ending the silo mentality

Encouraging a more holistic view of health across health care would be an important step to begin to address the problem – after all, the mind and the body are not separate.

“We work in silos, and we really have to stop doing that because these are intertwined,” said Corey Karlin-Zysman, MD, FHM, FACP, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwell Health. “A schizophrenic will become worse when they’re medically ill. That illness will be harder to treat if their psychiatric illness is active.” This is starting to happen in the outpatient setting, evidenced by the expansion of the integrated care model, where a primary care doctor is the lead physician working in combination with psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers. Communication among providers becomes simpler, and patients don’t fall through the cracks as often while trying to navigate the system.

That idea of integration is also making its way into the hospital setting in various ways. In their efforts to bring the care to the patient, rather than the other way around, Dr. Karlin-Zysman’s hospital embedded two hospitalists in the neighboring inpatient psychiatric hospital; when patients need medical treatment, they can receive it without interrupting their behavioral health treatment. As a result, patients who used to end up in their emergency department don’t anymore, and their 30-day readmission rate has fallen by 50%.

But at its foundation, care integration is more of an attitude than a system; it begins with a mindset.

“We talk so much today about system reform, integrated systems, blah, blah,” said Lisa Rosenbaum, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. “I don’t want to make it seem like it’s not going to work, but what does it mean for the patient who is psychotic and has 10 problems, with whom you have 15 minutes? Taking good care of these patients means you have to take a deep breath and put in a lot of time and deal with all these things that have nothing to do with the health system under which you practice. There’s this ‘only so much you can do’ feeling that is a problem in itself, because there’s actually a lot we can do.”

Hospitals and communities

It’s axiomatic to say that a better approach to mental health would be based around prevention and early intervention, rather than the less crisis-oriented system we have now. Some efforts are being made in that direction, and they involve, and require, outreach outside the hospital.

“The best hospitals doing work in mental health are going beyond the hospital walls; they’re really looking at their community,” Dr. Nguyen said. “You have hospitals, like Accountable Care Organizations, who are trying to move earlier and think about mental health from a pediatric standpoint: How can we support parents and children during critical phases of brain growth? How can we provide prevention services?” Ultimately, those efforts should help lower future admission rates to EDs and hospitals.

That forward-looking approach may be necessary, but it’s also a challenge. “As a hospital administrator, I would think that you look out at the community and see this problem is not going away – in fact, it is likely going to get worse,” Dr. McHugh said. “A health system may look at themselves and say we have to take the lead on this.” The difficulty is that thinking of it in a sense of value to the community, and making the requisite investments, will have a very long period of payout; a health system that’s struggling may not be able to do it. “It’s the large [health systems] that tend to be more integrated … that are thinking about this much differently,” he said.

Still, the reality is that’s where the root of the problem lies, Dr. Rylander said – not in the hospital, but in the larger community. “In the absence of very basic needs – stable housing, food, heating – it’s really not reasonable to expect that people are going to take care of their physical needs,” she said. “It’s a much larger social issue: how to get resources so that these people can have stable places to live, they can get to and from appointments, that type of thing.”

Those needs are ongoing, of course. Many of these patients suffer from chronic conditions, meaning people will continue to need services and support, said Ron Honberg, JD, senior policy adviser for the National Alliance on Mental Illness. Often, people need services from different systems. “There are complexities in terms of navigating those systems and getting those systems to work well together. Until we make inroads in solving those things, or at least improving those things, the burdens are going to fall on the providers of last resort, and that includes hospitals,” he said.

A collaborative effort may be needed, but hospitals can still be active participants and even leaders.

“If hospitals really want to address these problems, they need to be part of the discussions taking place in communities among the various systems and providers and advocates,” Mr. Honberg said. “Ultimately, we need to develop a better community-based system of care, and a better way of handing people off from inpatient to community-based treatment, and some accountability in terms of requiring that people get services, so they don’t get rehospitalized quickly. You’re increasingly seeing accountability now with other health conditions; we’re measuring things in Medicare like rehospitalization rates and the like. We need to be doing that with mental health treatment as well.”

What a hospitalist can do

One thing hospitalists might consider is starting that practice at their own hospitals, measuring, recording, and sharing that kind of information.

“Hospitalists should measure systematically, and in a very neutral manner, the total burden and frequency of the problem and report it consistently to management, along with their assessment that this impairs the quality of care and creates patient risk,” Dr. Parks said. That information can help hospitalists lobby for access to psychiatric personnel, be that in person or through telemedicine. “We don’t have to lay hands on you. There’s no excuse for any hospital not having a contract in place for on-demand consultation in the ER and on the floors.”

Track outcomes, too, Dr. Mandal suggests. With access to the right personnel, are you getting patients out of the ED faster? Are you having fewer negative outcomes while these patients are in the hospital, such as having to use restraints or get security involved? “Hopefully you can get some data in terms of how much money you’ve saved by decreasing the length of stays and decreasing inadvertent adverse effects because the patients weren’t receiving the proper care,” he said.

As this challenge seems likely to continue to grow, hospitalists might consider finding more training in mental health issues themselves so they are more comfortable handling these issues, Dr. Parks said. “The average mini-psych rotation from medical school is only 4 weeks,” he noted. “The ob.gyn. is at least 8 weeks and often 12 weeks, and if you don’t go into ob.gyn., you’re going to see a lot more mentally ill people through the rest of your practice, no matter what you do, than you are going to see pregnant women.”

Just starting these conversations – with patients, with colleagues, with family and friends – might be the most important change of all. “Even though nobody is above these issues afflicting them, this is still something that is not part of an open dialogue, and this is something that affects our own colleagues,” Dr. Mandal said. “I don’t know how many more trainees jumping out of windows it will take, or colleagues going through depression and feeling that it’s a sign of weakness to even talk about it.

“We need to create safe harbors within our own medical communities and acknowledge that we ourselves can be prone to this,” he said. “Perhaps by doing that, we will develop more empathy and become more comfortable, not just with ourselves and our colleagues but also helping these patients. People get overwhelmed and throw their hands up because it is just such a difficult issue. I don’t want people to give up, both from the medical community and our society as a whole – we can’t give up.”

A med-psych unit pilot project

Med-psych units can be a good model to take on these challenges. At Long Island Jewish Medical Center, they launched a pilot project to see how one would work in their community and summarized the results in an SHM abstract.

The hospital shares a campus with a 200-bed inpatient psych hospital, and doctors were seeing a lot of back and forth between the two institutions, said Corey Karlin-Zysman, MD, FHM, FACP, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwell Health. “Patients would come into the hospital because they had an active medical issue, but because of their behavioral issues, they’d have to have continuous observation. It would not be uncommon for us to have sometimes close to 30 patients who needed 24-hour continuous observation to make sure they were not hurting themselves.” These PCAs or nurse’s assistants were doing 8-hour shifts, so each patient needed three. “The math is staggering – and with not any better outcomes.”

So the hospital created a 15-bed closed med-psych unit for medically ill patients with behavioral health disorders. They staffed it with a dedicated hospitalist, a nurse practitioner, a psychologist, and a nurse manager.

The number of patients requiring continuous observation fell to single digits. Once in their own unit, these patients caused less disruption and stress on the medical units. They had a lower length of stay compared to their previous admissions in other units, and this became one of the hospital’s highest performing units in terms of patient experience.

The biggest secret of their success, Dr. Karlin-Zysman said, is cohorting. “Instead of them going to the next open bed, wherever it may be, you get the patients all in one place geographically, with a team trained to manage those patients.” Another factor: it’s a hospitalist-run unit. “You can’t have 20 different doctors taking care of the patients; it’s one or two hospitalists running this unit.”

Care models like this can be a true win-win, and her hospital is using them more and more.

“I have a care model that’s a stroke unit; I have a care model that’s an onc unit and one that’s a pulmonary unit,” she said. “We’re creating these true teams, which I think hospitalists really like being part of. What’s that thing that makes them want to come to work every day? Things like this: running a care model, becoming specialized in something.” There are research and abstract opportunities for hospitalists on these units too, which also helps keep them engaged, she said. “I’ve used this care model and things like that to reduce burnout and keep people excited.”

The persistent mortality gap

Patients with mental illness tend to receive worse medical care than people without, studies have shown; they die an average of 25 years earlier, largely from preventable or treatable conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes. The World Health Organization has called the problem “a hidden human rights emergency.”

In one in a series of articles on mental health, Lisa Rosenbaum, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, raises the question: Might physician attitudes toward mentally ill people contribute to this mortality gap, and if so, can we change them?

She recognizes the many obstacles physicians face in treating these patients. “The medicines we have are good but not great and can cause obesity and diabetes, which contributes to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Rosenbaum said. “We have the adherence challenge for the psychiatric medications and for medications for chronic disease. It’s hard enough for anyone to take a medicine every day, and to do that if you’re homeless or you don’t have insight into the need for it, it’s really hard.”

Also, certain behaviors that are more common among people with serious mental illness – smoking, substance abuse, physical inactivity – increase their risk for chronic diseases.

These hurdles may foster a sense of helplessness among hospitalists who have just a small amount of time to spend with a patient, and attitudes may be hard to change.

“Negotiating more effectively about care refusals, more adeptly assessing capacity, and recognizing when our efforts to orchestrate care have been inadequate seem feasible,” Dr. Rosenbaum writes. “Far harder is overcoming any collective belief that what mentally ill people truly need is not something we can offer.” That’s why a truly honest examination of attitudes and biases is a necessary place to start.

She tells the story of one mentally ill patient she learned of in her research, who, after decades as the quintessential frequent flier in the ER, was living stably in the community. “No one could have known how many tries it would take to help him get there,” she writes. His doctor told her, “Let’s say 10 attempts are necessary. Someone needs to be number 2, 3 and 7. You just never know which number you are.”

Education for physicians

A course created by the National Alliance on Mental Illness addresses mental illness issues from a provider perspective.

“Although the description states that the course is intended for mental health professionals, it can be and has been used to educate and inform other healthcare professionals as well,” said Ron Honberg, JD, senior policy advisor for the National Alliance on Mental Illness. The standard course takes 15 hours; there is an abbreviated 4-hour alternative as well. More information can be found at http://www.nami.org/Find-Support/NAMI-Programs/NAMI-Provider-Education.

Sources

1. Szabo L. Cost of Not Caring: Nowhere to Go. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/05/12/mental-health-system-crisis/7746535/. Accessed March 10, 2017.

2. Mental Health America. The State of Mental Health in America. http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/issues/state-mental-health-america. Accessed March 30, 2017.

3. Karlin-Zysman C, Lerner K, Warner-Cohen J. Creating a Hybrid Medicine and Psychiatric Unit to Manage Medically Ill Patients with Behavioral Health Disorders [abstract]. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2015; 10 (suppl 2). http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/creating-a-hybrid-medicine-and-psychiatric-unit-to-manage-medically-ill-patients-with-behavioral-health-disorders/. Accessed March 19, 2017.

4. Garey J. When Doctors Discriminate. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/11/opinion/sunday/when-doctors-discriminate.html. August 10, 2013. Accessed March 15, 2017.

5. Rosenbaum L. Closing the Mortality Gap – Mental Illness and Medical Care. N Engl J Med. 2016; 375:1585-1589. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1610125.

6. Rosenbaum L. Unlearning Our Helplessness – Coexisting Serious Mental and Medical Illness. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1690-4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1610127.

The numbers tell a grim story. Nationwide, 43.7 million adult Americans experienced a mental health condition during 2016 – an increase of 1.2 million over the previous year. Mental health issues send almost 5.5 million people to emergency departments each year; nearly 60% of adults with a mental illness received no treatment at all.

If that massive – and growing – need is one side of the story, shrinking resources are the other. Mental health resources had already been diminishing for decades before the recession hit – and hit them especially hard. Between 2009 and 2012, states cut $5 billion in mental health services; during that time, at least 4,500 public psychiatric hospital beds nationwide disappeared – nearly 10% of the total supply. The bulk of those resources have never been restored.

Provider numbers also are falling. “Psychiatry is probably the top manpower shortage among all specialties,” said Joe Parks, MD, medical director of the National Council for Behavioral Health. “We have about a third the number of psychiatrists that most estimates say we need, and the number per capita is decreasing.” A significant percentage of psychiatrists – more than 50% – only accept cash, bypassing the low reimbursement rates even private insurance typically offers.

Hospitals, of course, feel those financial disincentives too, which discourage them from investments of their own. “It’s a difficult population to manage, and it’s difficult to manage the financial realities of mental health as well,” said John McHugh, PhD, assistant professor of health policy at Columbia University, New York. “If you were a hospital administrator looking to invest your last dollar and you have the option of investing it in a new heart institute or in behavioral health service, more likely than not, you’re going to invest it in the more profitable cardiovascular service line.”

Providers of last resort

But much of the burden of caring for this population ends up falling on hospitals by default. At Denver Health, Melanie Rylander, MD, medical director of the inpatient psychiatric unit, reports seeing this manifest in three categories of patients. First, there is an influx of people coming into the emergency department with primary mental health issues.

“We’re also seeing an influx of people coming in with physical problems, and upon assessment it becomes very clear very quickly that the real issue is an underlying mental health issue,” she said. Then there are the people coming in for the same physical problems over and over – maybe decompensated heart failure or COPD exacerbations – because mental health issues are impeding their ability to take care of themselves.

Some hospitalists say they feel ill equipped to care for these patients. “We don’t have the facility or the resources many times to properly care for their psychiatric needs when they’re in the hospital. It’s not really part of an internist’s training to be familiar with a lot of the medications,” said Atashi Mandal, MD, a hospitalist and pediatrician in Los Angeles. “Sometimes they get improperly medicated because we don’t know what else to do and the patient’s behavioral issues are escalating, so it’s really a difficult position.”

It’s a dispiriting experience for a hospitalist. “It really bothers me when I am trying to care for a patient who has psychiatric needs, and I feel I’m not able to do it, and I can’t find resources, and I feel that this patient’s needs are being neglected – not because we don’t care, and not because of a lack of effort by the staff. It’s just set up to fail,” Dr. Mandal said.

Ending the silo mentality

Encouraging a more holistic view of health across health care would be an important step to begin to address the problem – after all, the mind and the body are not separate.

“We work in silos, and we really have to stop doing that because these are intertwined,” said Corey Karlin-Zysman, MD, FHM, FACP, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwell Health. “A schizophrenic will become worse when they’re medically ill. That illness will be harder to treat if their psychiatric illness is active.” This is starting to happen in the outpatient setting, evidenced by the expansion of the integrated care model, where a primary care doctor is the lead physician working in combination with psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers. Communication among providers becomes simpler, and patients don’t fall through the cracks as often while trying to navigate the system.

That idea of integration is also making its way into the hospital setting in various ways. In their efforts to bring the care to the patient, rather than the other way around, Dr. Karlin-Zysman’s hospital embedded two hospitalists in the neighboring inpatient psychiatric hospital; when patients need medical treatment, they can receive it without interrupting their behavioral health treatment. As a result, patients who used to end up in their emergency department don’t anymore, and their 30-day readmission rate has fallen by 50%.

But at its foundation, care integration is more of an attitude than a system; it begins with a mindset.

“We talk so much today about system reform, integrated systems, blah, blah,” said Lisa Rosenbaum, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. “I don’t want to make it seem like it’s not going to work, but what does it mean for the patient who is psychotic and has 10 problems, with whom you have 15 minutes? Taking good care of these patients means you have to take a deep breath and put in a lot of time and deal with all these things that have nothing to do with the health system under which you practice. There’s this ‘only so much you can do’ feeling that is a problem in itself, because there’s actually a lot we can do.”

Hospitals and communities

It’s axiomatic to say that a better approach to mental health would be based around prevention and early intervention, rather than the less crisis-oriented system we have now. Some efforts are being made in that direction, and they involve, and require, outreach outside the hospital.

“The best hospitals doing work in mental health are going beyond the hospital walls; they’re really looking at their community,” Dr. Nguyen said. “You have hospitals, like Accountable Care Organizations, who are trying to move earlier and think about mental health from a pediatric standpoint: How can we support parents and children during critical phases of brain growth? How can we provide prevention services?” Ultimately, those efforts should help lower future admission rates to EDs and hospitals.

That forward-looking approach may be necessary, but it’s also a challenge. “As a hospital administrator, I would think that you look out at the community and see this problem is not going away – in fact, it is likely going to get worse,” Dr. McHugh said. “A health system may look at themselves and say we have to take the lead on this.” The difficulty is that thinking of it in a sense of value to the community, and making the requisite investments, will have a very long period of payout; a health system that’s struggling may not be able to do it. “It’s the large [health systems] that tend to be more integrated … that are thinking about this much differently,” he said.

Still, the reality is that’s where the root of the problem lies, Dr. Rylander said – not in the hospital, but in the larger community. “In the absence of very basic needs – stable housing, food, heating – it’s really not reasonable to expect that people are going to take care of their physical needs,” she said. “It’s a much larger social issue: how to get resources so that these people can have stable places to live, they can get to and from appointments, that type of thing.”

Those needs are ongoing, of course. Many of these patients suffer from chronic conditions, meaning people will continue to need services and support, said Ron Honberg, JD, senior policy adviser for the National Alliance on Mental Illness. Often, people need services from different systems. “There are complexities in terms of navigating those systems and getting those systems to work well together. Until we make inroads in solving those things, or at least improving those things, the burdens are going to fall on the providers of last resort, and that includes hospitals,” he said.

A collaborative effort may be needed, but hospitals can still be active participants and even leaders.

“If hospitals really want to address these problems, they need to be part of the discussions taking place in communities among the various systems and providers and advocates,” Mr. Honberg said. “Ultimately, we need to develop a better community-based system of care, and a better way of handing people off from inpatient to community-based treatment, and some accountability in terms of requiring that people get services, so they don’t get rehospitalized quickly. You’re increasingly seeing accountability now with other health conditions; we’re measuring things in Medicare like rehospitalization rates and the like. We need to be doing that with mental health treatment as well.”

What a hospitalist can do

One thing hospitalists might consider is starting that practice at their own hospitals, measuring, recording, and sharing that kind of information.

“Hospitalists should measure systematically, and in a very neutral manner, the total burden and frequency of the problem and report it consistently to management, along with their assessment that this impairs the quality of care and creates patient risk,” Dr. Parks said. That information can help hospitalists lobby for access to psychiatric personnel, be that in person or through telemedicine. “We don’t have to lay hands on you. There’s no excuse for any hospital not having a contract in place for on-demand consultation in the ER and on the floors.”

Track outcomes, too, Dr. Mandal suggests. With access to the right personnel, are you getting patients out of the ED faster? Are you having fewer negative outcomes while these patients are in the hospital, such as having to use restraints or get security involved? “Hopefully you can get some data in terms of how much money you’ve saved by decreasing the length of stays and decreasing inadvertent adverse effects because the patients weren’t receiving the proper care,” he said.

As this challenge seems likely to continue to grow, hospitalists might consider finding more training in mental health issues themselves so they are more comfortable handling these issues, Dr. Parks said. “The average mini-psych rotation from medical school is only 4 weeks,” he noted. “The ob.gyn. is at least 8 weeks and often 12 weeks, and if you don’t go into ob.gyn., you’re going to see a lot more mentally ill people through the rest of your practice, no matter what you do, than you are going to see pregnant women.”

Just starting these conversations – with patients, with colleagues, with family and friends – might be the most important change of all. “Even though nobody is above these issues afflicting them, this is still something that is not part of an open dialogue, and this is something that affects our own colleagues,” Dr. Mandal said. “I don’t know how many more trainees jumping out of windows it will take, or colleagues going through depression and feeling that it’s a sign of weakness to even talk about it.

“We need to create safe harbors within our own medical communities and acknowledge that we ourselves can be prone to this,” he said. “Perhaps by doing that, we will develop more empathy and become more comfortable, not just with ourselves and our colleagues but also helping these patients. People get overwhelmed and throw their hands up because it is just such a difficult issue. I don’t want people to give up, both from the medical community and our society as a whole – we can’t give up.”

A med-psych unit pilot project

Med-psych units can be a good model to take on these challenges. At Long Island Jewish Medical Center, they launched a pilot project to see how one would work in their community and summarized the results in an SHM abstract.

The hospital shares a campus with a 200-bed inpatient psych hospital, and doctors were seeing a lot of back and forth between the two institutions, said Corey Karlin-Zysman, MD, FHM, FACP, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwell Health. “Patients would come into the hospital because they had an active medical issue, but because of their behavioral issues, they’d have to have continuous observation. It would not be uncommon for us to have sometimes close to 30 patients who needed 24-hour continuous observation to make sure they were not hurting themselves.” These PCAs or nurse’s assistants were doing 8-hour shifts, so each patient needed three. “The math is staggering – and with not any better outcomes.”

So the hospital created a 15-bed closed med-psych unit for medically ill patients with behavioral health disorders. They staffed it with a dedicated hospitalist, a nurse practitioner, a psychologist, and a nurse manager.

The number of patients requiring continuous observation fell to single digits. Once in their own unit, these patients caused less disruption and stress on the medical units. They had a lower length of stay compared to their previous admissions in other units, and this became one of the hospital’s highest performing units in terms of patient experience.

The biggest secret of their success, Dr. Karlin-Zysman said, is cohorting. “Instead of them going to the next open bed, wherever it may be, you get the patients all in one place geographically, with a team trained to manage those patients.” Another factor: it’s a hospitalist-run unit. “You can’t have 20 different doctors taking care of the patients; it’s one or two hospitalists running this unit.”

Care models like this can be a true win-win, and her hospital is using them more and more.

“I have a care model that’s a stroke unit; I have a care model that’s an onc unit and one that’s a pulmonary unit,” she said. “We’re creating these true teams, which I think hospitalists really like being part of. What’s that thing that makes them want to come to work every day? Things like this: running a care model, becoming specialized in something.” There are research and abstract opportunities for hospitalists on these units too, which also helps keep them engaged, she said. “I’ve used this care model and things like that to reduce burnout and keep people excited.”

The persistent mortality gap

Patients with mental illness tend to receive worse medical care than people without, studies have shown; they die an average of 25 years earlier, largely from preventable or treatable conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes. The World Health Organization has called the problem “a hidden human rights emergency.”

In one in a series of articles on mental health, Lisa Rosenbaum, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, raises the question: Might physician attitudes toward mentally ill people contribute to this mortality gap, and if so, can we change them?

She recognizes the many obstacles physicians face in treating these patients. “The medicines we have are good but not great and can cause obesity and diabetes, which contributes to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Rosenbaum said. “We have the adherence challenge for the psychiatric medications and for medications for chronic disease. It’s hard enough for anyone to take a medicine every day, and to do that if you’re homeless or you don’t have insight into the need for it, it’s really hard.”

Also, certain behaviors that are more common among people with serious mental illness – smoking, substance abuse, physical inactivity – increase their risk for chronic diseases.

These hurdles may foster a sense of helplessness among hospitalists who have just a small amount of time to spend with a patient, and attitudes may be hard to change.

“Negotiating more effectively about care refusals, more adeptly assessing capacity, and recognizing when our efforts to orchestrate care have been inadequate seem feasible,” Dr. Rosenbaum writes. “Far harder is overcoming any collective belief that what mentally ill people truly need is not something we can offer.” That’s why a truly honest examination of attitudes and biases is a necessary place to start.

She tells the story of one mentally ill patient she learned of in her research, who, after decades as the quintessential frequent flier in the ER, was living stably in the community. “No one could have known how many tries it would take to help him get there,” she writes. His doctor told her, “Let’s say 10 attempts are necessary. Someone needs to be number 2, 3 and 7. You just never know which number you are.”

Education for physicians

A course created by the National Alliance on Mental Illness addresses mental illness issues from a provider perspective.

“Although the description states that the course is intended for mental health professionals, it can be and has been used to educate and inform other healthcare professionals as well,” said Ron Honberg, JD, senior policy advisor for the National Alliance on Mental Illness. The standard course takes 15 hours; there is an abbreviated 4-hour alternative as well. More information can be found at http://www.nami.org/Find-Support/NAMI-Programs/NAMI-Provider-Education.

Sources

1. Szabo L. Cost of Not Caring: Nowhere to Go. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/05/12/mental-health-system-crisis/7746535/. Accessed March 10, 2017.

2. Mental Health America. The State of Mental Health in America. http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/issues/state-mental-health-america. Accessed March 30, 2017.

3. Karlin-Zysman C, Lerner K, Warner-Cohen J. Creating a Hybrid Medicine and Psychiatric Unit to Manage Medically Ill Patients with Behavioral Health Disorders [abstract]. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2015; 10 (suppl 2). http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/creating-a-hybrid-medicine-and-psychiatric-unit-to-manage-medically-ill-patients-with-behavioral-health-disorders/. Accessed March 19, 2017.

4. Garey J. When Doctors Discriminate. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/11/opinion/sunday/when-doctors-discriminate.html. August 10, 2013. Accessed March 15, 2017.

5. Rosenbaum L. Closing the Mortality Gap – Mental Illness and Medical Care. N Engl J Med. 2016; 375:1585-1589. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1610125.

6. Rosenbaum L. Unlearning Our Helplessness – Coexisting Serious Mental and Medical Illness. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1690-4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1610127.

The numbers tell a grim story. Nationwide, 43.7 million adult Americans experienced a mental health condition during 2016 – an increase of 1.2 million over the previous year. Mental health issues send almost 5.5 million people to emergency departments each year; nearly 60% of adults with a mental illness received no treatment at all.

If that massive – and growing – need is one side of the story, shrinking resources are the other. Mental health resources had already been diminishing for decades before the recession hit – and hit them especially hard. Between 2009 and 2012, states cut $5 billion in mental health services; during that time, at least 4,500 public psychiatric hospital beds nationwide disappeared – nearly 10% of the total supply. The bulk of those resources have never been restored.

Provider numbers also are falling. “Psychiatry is probably the top manpower shortage among all specialties,” said Joe Parks, MD, medical director of the National Council for Behavioral Health. “We have about a third the number of psychiatrists that most estimates say we need, and the number per capita is decreasing.” A significant percentage of psychiatrists – more than 50% – only accept cash, bypassing the low reimbursement rates even private insurance typically offers.

Hospitals, of course, feel those financial disincentives too, which discourage them from investments of their own. “It’s a difficult population to manage, and it’s difficult to manage the financial realities of mental health as well,” said John McHugh, PhD, assistant professor of health policy at Columbia University, New York. “If you were a hospital administrator looking to invest your last dollar and you have the option of investing it in a new heart institute or in behavioral health service, more likely than not, you’re going to invest it in the more profitable cardiovascular service line.”

Providers of last resort

But much of the burden of caring for this population ends up falling on hospitals by default. At Denver Health, Melanie Rylander, MD, medical director of the inpatient psychiatric unit, reports seeing this manifest in three categories of patients. First, there is an influx of people coming into the emergency department with primary mental health issues.

“We’re also seeing an influx of people coming in with physical problems, and upon assessment it becomes very clear very quickly that the real issue is an underlying mental health issue,” she said. Then there are the people coming in for the same physical problems over and over – maybe decompensated heart failure or COPD exacerbations – because mental health issues are impeding their ability to take care of themselves.

Some hospitalists say they feel ill equipped to care for these patients. “We don’t have the facility or the resources many times to properly care for their psychiatric needs when they’re in the hospital. It’s not really part of an internist’s training to be familiar with a lot of the medications,” said Atashi Mandal, MD, a hospitalist and pediatrician in Los Angeles. “Sometimes they get improperly medicated because we don’t know what else to do and the patient’s behavioral issues are escalating, so it’s really a difficult position.”

It’s a dispiriting experience for a hospitalist. “It really bothers me when I am trying to care for a patient who has psychiatric needs, and I feel I’m not able to do it, and I can’t find resources, and I feel that this patient’s needs are being neglected – not because we don’t care, and not because of a lack of effort by the staff. It’s just set up to fail,” Dr. Mandal said.

Ending the silo mentality

Encouraging a more holistic view of health across health care would be an important step to begin to address the problem – after all, the mind and the body are not separate.

“We work in silos, and we really have to stop doing that because these are intertwined,” said Corey Karlin-Zysman, MD, FHM, FACP, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwell Health. “A schizophrenic will become worse when they’re medically ill. That illness will be harder to treat if their psychiatric illness is active.” This is starting to happen in the outpatient setting, evidenced by the expansion of the integrated care model, where a primary care doctor is the lead physician working in combination with psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers. Communication among providers becomes simpler, and patients don’t fall through the cracks as often while trying to navigate the system.

That idea of integration is also making its way into the hospital setting in various ways. In their efforts to bring the care to the patient, rather than the other way around, Dr. Karlin-Zysman’s hospital embedded two hospitalists in the neighboring inpatient psychiatric hospital; when patients need medical treatment, they can receive it without interrupting their behavioral health treatment. As a result, patients who used to end up in their emergency department don’t anymore, and their 30-day readmission rate has fallen by 50%.

But at its foundation, care integration is more of an attitude than a system; it begins with a mindset.

“We talk so much today about system reform, integrated systems, blah, blah,” said Lisa Rosenbaum, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. “I don’t want to make it seem like it’s not going to work, but what does it mean for the patient who is psychotic and has 10 problems, with whom you have 15 minutes? Taking good care of these patients means you have to take a deep breath and put in a lot of time and deal with all these things that have nothing to do with the health system under which you practice. There’s this ‘only so much you can do’ feeling that is a problem in itself, because there’s actually a lot we can do.”

Hospitals and communities

It’s axiomatic to say that a better approach to mental health would be based around prevention and early intervention, rather than the less crisis-oriented system we have now. Some efforts are being made in that direction, and they involve, and require, outreach outside the hospital.

“The best hospitals doing work in mental health are going beyond the hospital walls; they’re really looking at their community,” Dr. Nguyen said. “You have hospitals, like Accountable Care Organizations, who are trying to move earlier and think about mental health from a pediatric standpoint: How can we support parents and children during critical phases of brain growth? How can we provide prevention services?” Ultimately, those efforts should help lower future admission rates to EDs and hospitals.

That forward-looking approach may be necessary, but it’s also a challenge. “As a hospital administrator, I would think that you look out at the community and see this problem is not going away – in fact, it is likely going to get worse,” Dr. McHugh said. “A health system may look at themselves and say we have to take the lead on this.” The difficulty is that thinking of it in a sense of value to the community, and making the requisite investments, will have a very long period of payout; a health system that’s struggling may not be able to do it. “It’s the large [health systems] that tend to be more integrated … that are thinking about this much differently,” he said.

Still, the reality is that’s where the root of the problem lies, Dr. Rylander said – not in the hospital, but in the larger community. “In the absence of very basic needs – stable housing, food, heating – it’s really not reasonable to expect that people are going to take care of their physical needs,” she said. “It’s a much larger social issue: how to get resources so that these people can have stable places to live, they can get to and from appointments, that type of thing.”

Those needs are ongoing, of course. Many of these patients suffer from chronic conditions, meaning people will continue to need services and support, said Ron Honberg, JD, senior policy adviser for the National Alliance on Mental Illness. Often, people need services from different systems. “There are complexities in terms of navigating those systems and getting those systems to work well together. Until we make inroads in solving those things, or at least improving those things, the burdens are going to fall on the providers of last resort, and that includes hospitals,” he said.

A collaborative effort may be needed, but hospitals can still be active participants and even leaders.

“If hospitals really want to address these problems, they need to be part of the discussions taking place in communities among the various systems and providers and advocates,” Mr. Honberg said. “Ultimately, we need to develop a better community-based system of care, and a better way of handing people off from inpatient to community-based treatment, and some accountability in terms of requiring that people get services, so they don’t get rehospitalized quickly. You’re increasingly seeing accountability now with other health conditions; we’re measuring things in Medicare like rehospitalization rates and the like. We need to be doing that with mental health treatment as well.”

What a hospitalist can do

One thing hospitalists might consider is starting that practice at their own hospitals, measuring, recording, and sharing that kind of information.

“Hospitalists should measure systematically, and in a very neutral manner, the total burden and frequency of the problem and report it consistently to management, along with their assessment that this impairs the quality of care and creates patient risk,” Dr. Parks said. That information can help hospitalists lobby for access to psychiatric personnel, be that in person or through telemedicine. “We don’t have to lay hands on you. There’s no excuse for any hospital not having a contract in place for on-demand consultation in the ER and on the floors.”

Track outcomes, too, Dr. Mandal suggests. With access to the right personnel, are you getting patients out of the ED faster? Are you having fewer negative outcomes while these patients are in the hospital, such as having to use restraints or get security involved? “Hopefully you can get some data in terms of how much money you’ve saved by decreasing the length of stays and decreasing inadvertent adverse effects because the patients weren’t receiving the proper care,” he said.

As this challenge seems likely to continue to grow, hospitalists might consider finding more training in mental health issues themselves so they are more comfortable handling these issues, Dr. Parks said. “The average mini-psych rotation from medical school is only 4 weeks,” he noted. “The ob.gyn. is at least 8 weeks and often 12 weeks, and if you don’t go into ob.gyn., you’re going to see a lot more mentally ill people through the rest of your practice, no matter what you do, than you are going to see pregnant women.”

Just starting these conversations – with patients, with colleagues, with family and friends – might be the most important change of all. “Even though nobody is above these issues afflicting them, this is still something that is not part of an open dialogue, and this is something that affects our own colleagues,” Dr. Mandal said. “I don’t know how many more trainees jumping out of windows it will take, or colleagues going through depression and feeling that it’s a sign of weakness to even talk about it.

“We need to create safe harbors within our own medical communities and acknowledge that we ourselves can be prone to this,” he said. “Perhaps by doing that, we will develop more empathy and become more comfortable, not just with ourselves and our colleagues but also helping these patients. People get overwhelmed and throw their hands up because it is just such a difficult issue. I don’t want people to give up, both from the medical community and our society as a whole – we can’t give up.”

A med-psych unit pilot project

Med-psych units can be a good model to take on these challenges. At Long Island Jewish Medical Center, they launched a pilot project to see how one would work in their community and summarized the results in an SHM abstract.

The hospital shares a campus with a 200-bed inpatient psych hospital, and doctors were seeing a lot of back and forth between the two institutions, said Corey Karlin-Zysman, MD, FHM, FACP, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwell Health. “Patients would come into the hospital because they had an active medical issue, but because of their behavioral issues, they’d have to have continuous observation. It would not be uncommon for us to have sometimes close to 30 patients who needed 24-hour continuous observation to make sure they were not hurting themselves.” These PCAs or nurse’s assistants were doing 8-hour shifts, so each patient needed three. “The math is staggering – and with not any better outcomes.”

So the hospital created a 15-bed closed med-psych unit for medically ill patients with behavioral health disorders. They staffed it with a dedicated hospitalist, a nurse practitioner, a psychologist, and a nurse manager.

The number of patients requiring continuous observation fell to single digits. Once in their own unit, these patients caused less disruption and stress on the medical units. They had a lower length of stay compared to their previous admissions in other units, and this became one of the hospital’s highest performing units in terms of patient experience.

The biggest secret of their success, Dr. Karlin-Zysman said, is cohorting. “Instead of them going to the next open bed, wherever it may be, you get the patients all in one place geographically, with a team trained to manage those patients.” Another factor: it’s a hospitalist-run unit. “You can’t have 20 different doctors taking care of the patients; it’s one or two hospitalists running this unit.”

Care models like this can be a true win-win, and her hospital is using them more and more.

“I have a care model that’s a stroke unit; I have a care model that’s an onc unit and one that’s a pulmonary unit,” she said. “We’re creating these true teams, which I think hospitalists really like being part of. What’s that thing that makes them want to come to work every day? Things like this: running a care model, becoming specialized in something.” There are research and abstract opportunities for hospitalists on these units too, which also helps keep them engaged, she said. “I’ve used this care model and things like that to reduce burnout and keep people excited.”

The persistent mortality gap

Patients with mental illness tend to receive worse medical care than people without, studies have shown; they die an average of 25 years earlier, largely from preventable or treatable conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes. The World Health Organization has called the problem “a hidden human rights emergency.”

In one in a series of articles on mental health, Lisa Rosenbaum, MD, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, raises the question: Might physician attitudes toward mentally ill people contribute to this mortality gap, and if so, can we change them?

She recognizes the many obstacles physicians face in treating these patients. “The medicines we have are good but not great and can cause obesity and diabetes, which contributes to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Rosenbaum said. “We have the adherence challenge for the psychiatric medications and for medications for chronic disease. It’s hard enough for anyone to take a medicine every day, and to do that if you’re homeless or you don’t have insight into the need for it, it’s really hard.”

Also, certain behaviors that are more common among people with serious mental illness – smoking, substance abuse, physical inactivity – increase their risk for chronic diseases.

These hurdles may foster a sense of helplessness among hospitalists who have just a small amount of time to spend with a patient, and attitudes may be hard to change.

“Negotiating more effectively about care refusals, more adeptly assessing capacity, and recognizing when our efforts to orchestrate care have been inadequate seem feasible,” Dr. Rosenbaum writes. “Far harder is overcoming any collective belief that what mentally ill people truly need is not something we can offer.” That’s why a truly honest examination of attitudes and biases is a necessary place to start.

She tells the story of one mentally ill patient she learned of in her research, who, after decades as the quintessential frequent flier in the ER, was living stably in the community. “No one could have known how many tries it would take to help him get there,” she writes. His doctor told her, “Let’s say 10 attempts are necessary. Someone needs to be number 2, 3 and 7. You just never know which number you are.”

Education for physicians

A course created by the National Alliance on Mental Illness addresses mental illness issues from a provider perspective.

“Although the description states that the course is intended for mental health professionals, it can be and has been used to educate and inform other healthcare professionals as well,” said Ron Honberg, JD, senior policy advisor for the National Alliance on Mental Illness. The standard course takes 15 hours; there is an abbreviated 4-hour alternative as well. More information can be found at http://www.nami.org/Find-Support/NAMI-Programs/NAMI-Provider-Education.

Sources

1. Szabo L. Cost of Not Caring: Nowhere to Go. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/05/12/mental-health-system-crisis/7746535/. Accessed March 10, 2017.

2. Mental Health America. The State of Mental Health in America. http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/issues/state-mental-health-america. Accessed March 30, 2017.

3. Karlin-Zysman C, Lerner K, Warner-Cohen J. Creating a Hybrid Medicine and Psychiatric Unit to Manage Medically Ill Patients with Behavioral Health Disorders [abstract]. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2015; 10 (suppl 2). http://www.shmabstracts.com/abstract/creating-a-hybrid-medicine-and-psychiatric-unit-to-manage-medically-ill-patients-with-behavioral-health-disorders/. Accessed March 19, 2017.

4. Garey J. When Doctors Discriminate. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/11/opinion/sunday/when-doctors-discriminate.html. August 10, 2013. Accessed March 15, 2017.

5. Rosenbaum L. Closing the Mortality Gap – Mental Illness and Medical Care. N Engl J Med. 2016; 375:1585-1589. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1610125.

6. Rosenbaum L. Unlearning Our Helplessness – Coexisting Serious Mental and Medical Illness. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1690-4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1610127.

Pharmacomechanical thrombolysis does not reduce post-thrombotic syndrome risk

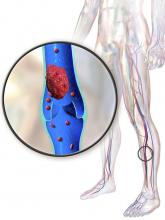

In patients with acute proximal deep vein thrombosis who were undergoing anticoagulation, adding pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis did not reduce risk of the post-thrombotic syndrome, according to results of a phase 3, randomized, controlled trial.

Moreover, addition of pharmacomechanical thrombolysis increased risk of major bleeding risk, investigators wrote in a report published online Dec. 6 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Our trial, for uncertain reasons, did not confirm these findings,” wrote Suresh Vedantham, MD of Washington University, St. Louis, and his coauthors.

Post-thrombotic syndrome is associated with chronic limb swelling and pain, and can lead to leg ulcers, impaired quality of life, and major disability. About half of patients with proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) will develop the post-thrombotic syndrome within 2 years, despite use of anticoagulation therapy, Dr. Vedantham and his colleagues noted.

Pharmacomechanical thrombosis is the catheter-directed delivery of a fibrinolytic agent into the thrombus, along with aspiration or maceration of the thrombus. The goal of the treatment is to reduce the burden of thrombus, which in turn might reduce risk of the post-thrombotic syndrome.

However, in their randomized trial known as ATTRACT, which included 692 patients with an acute proximal DVT, rates of post-thrombotic syndrome between 6 to 24 months after intervention were 47% in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group and 48% in the control group (risk ratio, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.82-1.11; P = .56), according to the report (N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2240-52). Control group patients received no procedural intervention.

Major bleeds within 10 days of the intervention were 1.7% and 0.3% for the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis and control groups, respectively (P = .049).

By contrast, in the CAVENT trial, catheter-directed thrombolysis reduced the risk of the post-thrombotic syndrome over 5 years of follow-up (Lancet Haematol. 2016;3[2]:e64-71). Dr. Vedantham and his coauthors suggested that factors potentially explaining the difference in outcomes include the number of patients enrolled (692 in ATTRACT, versus 209 in CAVENT), or the greater use of mechanical therapies in ATTRACT versus longer recombinant tissue plasminogen activator infusions in CAVENT.

The study was supported by multiple sources, including the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), Boston Scientific, Covidien (now Medtronic), Genentech, and others. Dr. Vedantham reported receiving grant support from Cook Medical and Volcano. Some of the other authors reported financial ties to Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and other pharmaceutical and device companies.

In patients with acute proximal deep vein thrombosis who were undergoing anticoagulation, adding pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis did not reduce risk of the post-thrombotic syndrome, according to results of a phase 3, randomized, controlled trial.

Moreover, addition of pharmacomechanical thrombolysis increased risk of major bleeding risk, investigators wrote in a report published online Dec. 6 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Our trial, for uncertain reasons, did not confirm these findings,” wrote Suresh Vedantham, MD of Washington University, St. Louis, and his coauthors.

Post-thrombotic syndrome is associated with chronic limb swelling and pain, and can lead to leg ulcers, impaired quality of life, and major disability. About half of patients with proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) will develop the post-thrombotic syndrome within 2 years, despite use of anticoagulation therapy, Dr. Vedantham and his colleagues noted.

Pharmacomechanical thrombosis is the catheter-directed delivery of a fibrinolytic agent into the thrombus, along with aspiration or maceration of the thrombus. The goal of the treatment is to reduce the burden of thrombus, which in turn might reduce risk of the post-thrombotic syndrome.

However, in their randomized trial known as ATTRACT, which included 692 patients with an acute proximal DVT, rates of post-thrombotic syndrome between 6 to 24 months after intervention were 47% in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group and 48% in the control group (risk ratio, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.82-1.11; P = .56), according to the report (N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2240-52). Control group patients received no procedural intervention.

Major bleeds within 10 days of the intervention were 1.7% and 0.3% for the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis and control groups, respectively (P = .049).

By contrast, in the CAVENT trial, catheter-directed thrombolysis reduced the risk of the post-thrombotic syndrome over 5 years of follow-up (Lancet Haematol. 2016;3[2]:e64-71). Dr. Vedantham and his coauthors suggested that factors potentially explaining the difference in outcomes include the number of patients enrolled (692 in ATTRACT, versus 209 in CAVENT), or the greater use of mechanical therapies in ATTRACT versus longer recombinant tissue plasminogen activator infusions in CAVENT.

The study was supported by multiple sources, including the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), Boston Scientific, Covidien (now Medtronic), Genentech, and others. Dr. Vedantham reported receiving grant support from Cook Medical and Volcano. Some of the other authors reported financial ties to Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and other pharmaceutical and device companies.

In patients with acute proximal deep vein thrombosis who were undergoing anticoagulation, adding pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis did not reduce risk of the post-thrombotic syndrome, according to results of a phase 3, randomized, controlled trial.

Moreover, addition of pharmacomechanical thrombolysis increased risk of major bleeding risk, investigators wrote in a report published online Dec. 6 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Our trial, for uncertain reasons, did not confirm these findings,” wrote Suresh Vedantham, MD of Washington University, St. Louis, and his coauthors.

Post-thrombotic syndrome is associated with chronic limb swelling and pain, and can lead to leg ulcers, impaired quality of life, and major disability. About half of patients with proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) will develop the post-thrombotic syndrome within 2 years, despite use of anticoagulation therapy, Dr. Vedantham and his colleagues noted.

Pharmacomechanical thrombosis is the catheter-directed delivery of a fibrinolytic agent into the thrombus, along with aspiration or maceration of the thrombus. The goal of the treatment is to reduce the burden of thrombus, which in turn might reduce risk of the post-thrombotic syndrome.

However, in their randomized trial known as ATTRACT, which included 692 patients with an acute proximal DVT, rates of post-thrombotic syndrome between 6 to 24 months after intervention were 47% in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group and 48% in the control group (risk ratio, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.82-1.11; P = .56), according to the report (N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2240-52). Control group patients received no procedural intervention.

Major bleeds within 10 days of the intervention were 1.7% and 0.3% for the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis and control groups, respectively (P = .049).

By contrast, in the CAVENT trial, catheter-directed thrombolysis reduced the risk of the post-thrombotic syndrome over 5 years of follow-up (Lancet Haematol. 2016;3[2]:e64-71). Dr. Vedantham and his coauthors suggested that factors potentially explaining the difference in outcomes include the number of patients enrolled (692 in ATTRACT, versus 209 in CAVENT), or the greater use of mechanical therapies in ATTRACT versus longer recombinant tissue plasminogen activator infusions in CAVENT.

The study was supported by multiple sources, including the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), Boston Scientific, Covidien (now Medtronic), Genentech, and others. Dr. Vedantham reported receiving grant support from Cook Medical and Volcano. Some of the other authors reported financial ties to Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and other pharmaceutical and device companies.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Rates of post-thrombotic syndrome were 47% in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group, and 48% in the control group (risk ratio, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.82-1.11; P = .56).

Data source: A phase 3, multicenter, randomized, open-label, assessor-blinded, controlled clinical trial, including 692 patients with acute proximal deep vein thrombosis.

Disclosures: The study was supported by multiple sources, including the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), Boston Scientific, Covidien (now Medtronic), Genentech, and others. First author Suresh Vedantham, MD, reported receiving grant support from Cook Medical and Volcano. Some of the other authors reported financial ties to Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and other pharmaceutical and device companies.

Alarm reductions don’t improve ICU response times

TORONTO – It will take more than a reduction in alarms to address the issue of alarm fatigue in the ICU; a change in the ICU staff culture is needed, suggests new research.

“It may take years to recondition clinicians [to realize] that alarms are actionable and must get a response,” Afua Kunadu, MD, said during her presentation on the study at the CHEST annual meeting. Results from prior studies had suggested that as many as 99% of clinical alarms do not result in clinical intervention, noted Dr. Kunadu, an internal medicine physician at Harlem Hospital Center in New York.

She described the program, which started in the 20-bed adult ICU of Harlem Hospital Center, following a 2014 National Patient Safety Goal issued by The Joint Commission to improve the safety of clinical alarm systems by reducing unneeded alarms and alarm fatigue. The Harlem Hospital task force that ran the program began with an audit of alarms that went off in the ICU and used the results to identify the three most common alarms: bedside cardiac monitors, infusion pumps, and mechanical ventilators. The task force arranged to reset the default settings on these devices to decrease alarm frequency and boost the clinical importance of each alarm that still sounded. Concurrently, they ran educational sessions about the new alarm thresholds, the anticipated drop in alarm number, and the increased urgency to respond to the remaining alarms very quickly for the ICU staff.

The raised thresholds effectively cut the number of alarms. The average number of alarms per patient per hour fell from 4.5 at baseline during September 2016 to about 2 after 1 month, during December 2016. Then the rate further declined to reach a steady nadir that stayed at about 1.3 alarms per patient per hour 4 months into the program.

But timely responses, measured as the percentage of alarm responses occurring within 60 seconds after the alarm went off, fell from 60% at 1 month into the program down to 12% after 4 months, Dr. Kunadu reported.

She had no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

TORONTO – It will take more than a reduction in alarms to address the issue of alarm fatigue in the ICU; a change in the ICU staff culture is needed, suggests new research.

“It may take years to recondition clinicians [to realize] that alarms are actionable and must get a response,” Afua Kunadu, MD, said during her presentation on the study at the CHEST annual meeting. Results from prior studies had suggested that as many as 99% of clinical alarms do not result in clinical intervention, noted Dr. Kunadu, an internal medicine physician at Harlem Hospital Center in New York.

She described the program, which started in the 20-bed adult ICU of Harlem Hospital Center, following a 2014 National Patient Safety Goal issued by The Joint Commission to improve the safety of clinical alarm systems by reducing unneeded alarms and alarm fatigue. The Harlem Hospital task force that ran the program began with an audit of alarms that went off in the ICU and used the results to identify the three most common alarms: bedside cardiac monitors, infusion pumps, and mechanical ventilators. The task force arranged to reset the default settings on these devices to decrease alarm frequency and boost the clinical importance of each alarm that still sounded. Concurrently, they ran educational sessions about the new alarm thresholds, the anticipated drop in alarm number, and the increased urgency to respond to the remaining alarms very quickly for the ICU staff.

The raised thresholds effectively cut the number of alarms. The average number of alarms per patient per hour fell from 4.5 at baseline during September 2016 to about 2 after 1 month, during December 2016. Then the rate further declined to reach a steady nadir that stayed at about 1.3 alarms per patient per hour 4 months into the program.

But timely responses, measured as the percentage of alarm responses occurring within 60 seconds after the alarm went off, fell from 60% at 1 month into the program down to 12% after 4 months, Dr. Kunadu reported.

She had no disclosures.