User login

When should I transfuse a patient who has anemia?

Clinical case

A 48-year-old man with cirrhosis and esophageal varices presents to the emergency department with hematochezia and hematemesis. Upon arrival to the floor, he has another bout of hematochezia and hematemesis. He appears pale. His pulse is 90 beats per minute, his blood pressure is 100/60 mmHg, and his respiratory rate is 14 breaths per minute. A complete blood count reveals a hemoglobin level of 7.8 g/dL and hematocrit of 23.5%. Should he receive a blood transfusion?

Introduction

Anemia is one of the most frequent conditions in hospitalized patients. Anemia is variably associated with morbidity and mortality depending on chronicity, etiology, and associated comorbidities. Before the 1980s, standard practice was to transfuse all patients to a hemoglobin level greater than 10 g/dL and/or a hematocrit greater than 30%. However, with concerns about the potential adverse effects and cost of transfusions, the safety and effectiveness of liberal versus restrictive transfusion thresholds became the subject of many studies.

The 2016 the AABB (formerly American Association of Blood Banks) guidelines focused on the evidence for hemodynamically stable and asymptomatic hospitalized patients. The guidelines are based on randomized controlled trials that measured mortality as the primary endpoint. Most trials and guidelines reinforce that if a patient is symptomatic or hemodynamically unstable from anemia or hemorrhage, RBC transfusion is appropriate irrespective of hemoglobin level.

Overview of the data

Critically ill patients

The Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care (TRICC) trial, published in 1999, was the first large clinical trial examining the safety of restrictive transfusion thresholds in critically ill patients.3

The subsequent Transfusion Requirements in Septic Shock (TRISS) study involved patients with septic shock and similarly found that patients assigned to a restrictive strategy (transfusion for hemoglobin less than 7 g/dL) had similar outcomes to patients assigned to a liberal strategy (transfusion for hemoglobin less than 9 g/dL). The patients in the restrictive group received fewer transfusions, but had similar rates of 90-day mortality, use of life support, and number of days alive and out of the hospital.4

These large randomized controlled trials in critically ill patients served as the basis for subsequent studies in patient populations outside of the ICU.

Acute upper GI bleed

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is one of the most common indications for RBC transfusion.

The TRIGGER trial, a cluster randomized multicenter study published in 2015, also found no difference in clinical outcomes, including mortality, between a restrictive strategy and liberal strategy for transfusion of patients with UGIB.6

Perioperative patients

Transfusion thresholds have been studied in large randomized trials for perioperative patients undergoing cardiac and orthopedic surgery.

The Transfusion Requirements after Cardiac Surgery (TRACS) trial, published in 2010, randomized patients undergoing cardiac surgery at a single center to a liberal strategy of blood transfusion (to maintain a hematocrit 30% or greater) or a restrictive strategy (hematocrit 24% or greater).7 Mortality and severe morbidity rates were noninferior in the restrictive strategy group. Mean hemoglobin concentrations were 10.5 g/dL in the liberal-strategy group and 9.1 g/dL in the restrictive-strategy group. Independent of transfusion strategy, the number of transfused red blood cell units was an independent risk factor for clinical complications and death at 30 days.

Based on these two trials, as well as other smaller randomized controlled trials and observational studies, the AABB guidelines recommend a restrictive RBC transfusion threshold of 8 g/dL for patients undergoing cardiac or orthopedic surgery.1

Acute coronary syndrome, stable coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure

Anemia is an independent predictor of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome.9 However, it remains controversial if transfusion has benefit or causes harm in patients with acute coronary syndrome. No randomized controlled trials have yet been published on this topic, and observational studies and subgroups from randomized controlled trials have yielded mixed results.

Similarly, there are no randomized controlled trials examining liberal versus restrictive transfusion goals for asymptomatic hospitalized patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD). However, patients with CAD were included in the TRICC and FOCUS trials.3,8 Of patients enrolled in the TRICC trial, 26% had a primary or secondary diagnosis of cardiac disease; subgroup analysis found no significant differences in 30-day mortality between treatment groups, similar to that of the entire study population.3 In a subgroup analysis of patients with “cardiovascular disease” the FOCUS trial found no difference in outcomes between a restrictive and liberal transfusion strategy, although there was a marginally higher incidence of myocardial infarction in the restrictive arm in the entire study population.8

Although some studies have included patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) as a subgroup, these subgroups are often not powered to show clinically meaningful differences. The risk of volume overload is one explanation for why transfusions may be harmful for patients with CHF.

Based on these limited available data, the AABB guidelines recommend a “restrictive RBC transfusion threshold (hemoglobin level of 8 g/dL)” for patients “with preexisting cardiovascular disease,” without distinguishing among patients with acute coronary syndrome, stable CAD, and CHF, but adds that the “threshold of 7 g/dL is likely comparable with 8 g/dL, but randomized controlled trial evidence is not available for all patient categories.”1

Of note, certain patient populations, such as those with end-stage renal disease, oncology patients (especially those undergoing active chemotherapy), and those with comorbid conditions such as thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy are specifically excluded from the AABB guidelines. The reader is referred to guidelines from respective specialty societies for further guidance.

Back to our case

This 48-year-old man with cirrhosis and esophageal varices presenting with ongoing blood loss due to hematochezia and hematemesis with a hemoglobin of 7.8 g/dL should be transfused due to his active bleeding; his hemoglobin level should not be a determining factor under such circumstances. This distinction is one of the most fundamental in interpreting the guidelines, that is, patients with hemodynamic insult, symptoms, and/or ongoing bleeding should be evaluated clinically, independent of their hemoglobin level.

Bottom line

Although recent guidelines generally favor a more restrictive hemoglobin goal threshold, in the presence of active blood loss or hemodynamic instability, blood transfusion should be considered independent of the initial hemoglobin level.

Key Points

- The AABB guidelines recommend transfusing stable general medical inpatients to a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL.

- For patients undergoing orthopedic surgery, cardiac surgery, and those with preexisting cardiovascular disease, a transfusion threshold of 8 g/dL is recommended.

- Patients with hemodynamic instability or active blood loss should be transfused based on clinical criteria, and not absolute hemoglobin levels.

- Patients with acute coronary syndrome, severe thrombocytopenia, and chronic transfusion–dependent anemia are excluded from these recommendations.

- Further studies are needed to further refine these recommendations to specific patient populations in maximizing the benefits and minimizing the risks of blood transfusions.

Quiz

In which of the following scenarios is RBC transfusion LEAST indicated?

- A. Active diverticular bleed, heart rate 125 beats/minute, blood pressure 85/65 mm HG, hemoglobin 10.5 g/dL

- B. Septic shock in the ICU, hemoglobin 6.7 g/dL

- C. Pulmonary embolism in the setting of stable coronary artery disease and hemoglobin 8.7 g/dL

- D. Lymphoma on chemotherapy, hemoglobin 7.5 g/d, patient becomes dizzy when standing

Answer: C – A hemoglobin transfusion goal of 8.0 g/dL is recommended for patients with cardiovascular disease. The patient in answer choice A has active blood loss, tachycardia, and hypotension, all pointing to the need for blood transfusion irrespective of an initial hemoglobin level greater than 8.0 g/dL. The patient in answer choice B has a hemoglobin level less than 7.0 g/dL, and the patient in choice D is symptomatic, possibly from anemia, as well as on chemotherapy, therefore making transfusion a reasonable option.

Dr. Sampat, Dr. Berger, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

References

1. Carson JL et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines From the AABB: Red Blood Cell Transfusion Thresholds and Storage. JAMA. 2016;316:2025-35.

2. Dwyre DM et al. Hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV transfusion-transmitted infections in the 21st century. Vox Sang. 2011;100:92-8.

3. Hébert PC et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-17.

4. Holst LB et al. Lower versus higher hemoglobin threshold for transfusion in septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1381-91.

5. Villanueva C et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:11-21.

6. Jairath V et al. Restrictive versus liberal blood transfusion for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (TRIGGER): a pragmatic, open-label, cluster randomised feasibility trial. Lancet. 2015;386:137-44.

7. Hajjar LA et al. Transfusion requirements after cardiac surgery: the TRACS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1559-67.

8. Carson JL et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2453-62.

9. Sabatine MS et al. Association of hemoglobin levels with clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2005;111:2042-9.

Clinical case

A 48-year-old man with cirrhosis and esophageal varices presents to the emergency department with hematochezia and hematemesis. Upon arrival to the floor, he has another bout of hematochezia and hematemesis. He appears pale. His pulse is 90 beats per minute, his blood pressure is 100/60 mmHg, and his respiratory rate is 14 breaths per minute. A complete blood count reveals a hemoglobin level of 7.8 g/dL and hematocrit of 23.5%. Should he receive a blood transfusion?

Introduction

Anemia is one of the most frequent conditions in hospitalized patients. Anemia is variably associated with morbidity and mortality depending on chronicity, etiology, and associated comorbidities. Before the 1980s, standard practice was to transfuse all patients to a hemoglobin level greater than 10 g/dL and/or a hematocrit greater than 30%. However, with concerns about the potential adverse effects and cost of transfusions, the safety and effectiveness of liberal versus restrictive transfusion thresholds became the subject of many studies.

The 2016 the AABB (formerly American Association of Blood Banks) guidelines focused on the evidence for hemodynamically stable and asymptomatic hospitalized patients. The guidelines are based on randomized controlled trials that measured mortality as the primary endpoint. Most trials and guidelines reinforce that if a patient is symptomatic or hemodynamically unstable from anemia or hemorrhage, RBC transfusion is appropriate irrespective of hemoglobin level.

Overview of the data

Critically ill patients

The Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care (TRICC) trial, published in 1999, was the first large clinical trial examining the safety of restrictive transfusion thresholds in critically ill patients.3

The subsequent Transfusion Requirements in Septic Shock (TRISS) study involved patients with septic shock and similarly found that patients assigned to a restrictive strategy (transfusion for hemoglobin less than 7 g/dL) had similar outcomes to patients assigned to a liberal strategy (transfusion for hemoglobin less than 9 g/dL). The patients in the restrictive group received fewer transfusions, but had similar rates of 90-day mortality, use of life support, and number of days alive and out of the hospital.4

These large randomized controlled trials in critically ill patients served as the basis for subsequent studies in patient populations outside of the ICU.

Acute upper GI bleed

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is one of the most common indications for RBC transfusion.

The TRIGGER trial, a cluster randomized multicenter study published in 2015, also found no difference in clinical outcomes, including mortality, between a restrictive strategy and liberal strategy for transfusion of patients with UGIB.6

Perioperative patients

Transfusion thresholds have been studied in large randomized trials for perioperative patients undergoing cardiac and orthopedic surgery.

The Transfusion Requirements after Cardiac Surgery (TRACS) trial, published in 2010, randomized patients undergoing cardiac surgery at a single center to a liberal strategy of blood transfusion (to maintain a hematocrit 30% or greater) or a restrictive strategy (hematocrit 24% or greater).7 Mortality and severe morbidity rates were noninferior in the restrictive strategy group. Mean hemoglobin concentrations were 10.5 g/dL in the liberal-strategy group and 9.1 g/dL in the restrictive-strategy group. Independent of transfusion strategy, the number of transfused red blood cell units was an independent risk factor for clinical complications and death at 30 days.

Based on these two trials, as well as other smaller randomized controlled trials and observational studies, the AABB guidelines recommend a restrictive RBC transfusion threshold of 8 g/dL for patients undergoing cardiac or orthopedic surgery.1

Acute coronary syndrome, stable coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure

Anemia is an independent predictor of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome.9 However, it remains controversial if transfusion has benefit or causes harm in patients with acute coronary syndrome. No randomized controlled trials have yet been published on this topic, and observational studies and subgroups from randomized controlled trials have yielded mixed results.

Similarly, there are no randomized controlled trials examining liberal versus restrictive transfusion goals for asymptomatic hospitalized patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD). However, patients with CAD were included in the TRICC and FOCUS trials.3,8 Of patients enrolled in the TRICC trial, 26% had a primary or secondary diagnosis of cardiac disease; subgroup analysis found no significant differences in 30-day mortality between treatment groups, similar to that of the entire study population.3 In a subgroup analysis of patients with “cardiovascular disease” the FOCUS trial found no difference in outcomes between a restrictive and liberal transfusion strategy, although there was a marginally higher incidence of myocardial infarction in the restrictive arm in the entire study population.8

Although some studies have included patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) as a subgroup, these subgroups are often not powered to show clinically meaningful differences. The risk of volume overload is one explanation for why transfusions may be harmful for patients with CHF.

Based on these limited available data, the AABB guidelines recommend a “restrictive RBC transfusion threshold (hemoglobin level of 8 g/dL)” for patients “with preexisting cardiovascular disease,” without distinguishing among patients with acute coronary syndrome, stable CAD, and CHF, but adds that the “threshold of 7 g/dL is likely comparable with 8 g/dL, but randomized controlled trial evidence is not available for all patient categories.”1

Of note, certain patient populations, such as those with end-stage renal disease, oncology patients (especially those undergoing active chemotherapy), and those with comorbid conditions such as thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy are specifically excluded from the AABB guidelines. The reader is referred to guidelines from respective specialty societies for further guidance.

Back to our case

This 48-year-old man with cirrhosis and esophageal varices presenting with ongoing blood loss due to hematochezia and hematemesis with a hemoglobin of 7.8 g/dL should be transfused due to his active bleeding; his hemoglobin level should not be a determining factor under such circumstances. This distinction is one of the most fundamental in interpreting the guidelines, that is, patients with hemodynamic insult, symptoms, and/or ongoing bleeding should be evaluated clinically, independent of their hemoglobin level.

Bottom line

Although recent guidelines generally favor a more restrictive hemoglobin goal threshold, in the presence of active blood loss or hemodynamic instability, blood transfusion should be considered independent of the initial hemoglobin level.

Key Points

- The AABB guidelines recommend transfusing stable general medical inpatients to a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL.

- For patients undergoing orthopedic surgery, cardiac surgery, and those with preexisting cardiovascular disease, a transfusion threshold of 8 g/dL is recommended.

- Patients with hemodynamic instability or active blood loss should be transfused based on clinical criteria, and not absolute hemoglobin levels.

- Patients with acute coronary syndrome, severe thrombocytopenia, and chronic transfusion–dependent anemia are excluded from these recommendations.

- Further studies are needed to further refine these recommendations to specific patient populations in maximizing the benefits and minimizing the risks of blood transfusions.

Quiz

In which of the following scenarios is RBC transfusion LEAST indicated?

- A. Active diverticular bleed, heart rate 125 beats/minute, blood pressure 85/65 mm HG, hemoglobin 10.5 g/dL

- B. Septic shock in the ICU, hemoglobin 6.7 g/dL

- C. Pulmonary embolism in the setting of stable coronary artery disease and hemoglobin 8.7 g/dL

- D. Lymphoma on chemotherapy, hemoglobin 7.5 g/d, patient becomes dizzy when standing

Answer: C – A hemoglobin transfusion goal of 8.0 g/dL is recommended for patients with cardiovascular disease. The patient in answer choice A has active blood loss, tachycardia, and hypotension, all pointing to the need for blood transfusion irrespective of an initial hemoglobin level greater than 8.0 g/dL. The patient in answer choice B has a hemoglobin level less than 7.0 g/dL, and the patient in choice D is symptomatic, possibly from anemia, as well as on chemotherapy, therefore making transfusion a reasonable option.

Dr. Sampat, Dr. Berger, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

References

1. Carson JL et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines From the AABB: Red Blood Cell Transfusion Thresholds and Storage. JAMA. 2016;316:2025-35.

2. Dwyre DM et al. Hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV transfusion-transmitted infections in the 21st century. Vox Sang. 2011;100:92-8.

3. Hébert PC et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-17.

4. Holst LB et al. Lower versus higher hemoglobin threshold for transfusion in septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1381-91.

5. Villanueva C et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:11-21.

6. Jairath V et al. Restrictive versus liberal blood transfusion for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (TRIGGER): a pragmatic, open-label, cluster randomised feasibility trial. Lancet. 2015;386:137-44.

7. Hajjar LA et al. Transfusion requirements after cardiac surgery: the TRACS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1559-67.

8. Carson JL et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2453-62.

9. Sabatine MS et al. Association of hemoglobin levels with clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2005;111:2042-9.

Clinical case

A 48-year-old man with cirrhosis and esophageal varices presents to the emergency department with hematochezia and hematemesis. Upon arrival to the floor, he has another bout of hematochezia and hematemesis. He appears pale. His pulse is 90 beats per minute, his blood pressure is 100/60 mmHg, and his respiratory rate is 14 breaths per minute. A complete blood count reveals a hemoglobin level of 7.8 g/dL and hematocrit of 23.5%. Should he receive a blood transfusion?

Introduction

Anemia is one of the most frequent conditions in hospitalized patients. Anemia is variably associated with morbidity and mortality depending on chronicity, etiology, and associated comorbidities. Before the 1980s, standard practice was to transfuse all patients to a hemoglobin level greater than 10 g/dL and/or a hematocrit greater than 30%. However, with concerns about the potential adverse effects and cost of transfusions, the safety and effectiveness of liberal versus restrictive transfusion thresholds became the subject of many studies.

The 2016 the AABB (formerly American Association of Blood Banks) guidelines focused on the evidence for hemodynamically stable and asymptomatic hospitalized patients. The guidelines are based on randomized controlled trials that measured mortality as the primary endpoint. Most trials and guidelines reinforce that if a patient is symptomatic or hemodynamically unstable from anemia or hemorrhage, RBC transfusion is appropriate irrespective of hemoglobin level.

Overview of the data

Critically ill patients

The Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care (TRICC) trial, published in 1999, was the first large clinical trial examining the safety of restrictive transfusion thresholds in critically ill patients.3

The subsequent Transfusion Requirements in Septic Shock (TRISS) study involved patients with septic shock and similarly found that patients assigned to a restrictive strategy (transfusion for hemoglobin less than 7 g/dL) had similar outcomes to patients assigned to a liberal strategy (transfusion for hemoglobin less than 9 g/dL). The patients in the restrictive group received fewer transfusions, but had similar rates of 90-day mortality, use of life support, and number of days alive and out of the hospital.4

These large randomized controlled trials in critically ill patients served as the basis for subsequent studies in patient populations outside of the ICU.

Acute upper GI bleed

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is one of the most common indications for RBC transfusion.

The TRIGGER trial, a cluster randomized multicenter study published in 2015, also found no difference in clinical outcomes, including mortality, between a restrictive strategy and liberal strategy for transfusion of patients with UGIB.6

Perioperative patients

Transfusion thresholds have been studied in large randomized trials for perioperative patients undergoing cardiac and orthopedic surgery.

The Transfusion Requirements after Cardiac Surgery (TRACS) trial, published in 2010, randomized patients undergoing cardiac surgery at a single center to a liberal strategy of blood transfusion (to maintain a hematocrit 30% or greater) or a restrictive strategy (hematocrit 24% or greater).7 Mortality and severe morbidity rates were noninferior in the restrictive strategy group. Mean hemoglobin concentrations were 10.5 g/dL in the liberal-strategy group and 9.1 g/dL in the restrictive-strategy group. Independent of transfusion strategy, the number of transfused red blood cell units was an independent risk factor for clinical complications and death at 30 days.

Based on these two trials, as well as other smaller randomized controlled trials and observational studies, the AABB guidelines recommend a restrictive RBC transfusion threshold of 8 g/dL for patients undergoing cardiac or orthopedic surgery.1

Acute coronary syndrome, stable coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure

Anemia is an independent predictor of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome.9 However, it remains controversial if transfusion has benefit or causes harm in patients with acute coronary syndrome. No randomized controlled trials have yet been published on this topic, and observational studies and subgroups from randomized controlled trials have yielded mixed results.

Similarly, there are no randomized controlled trials examining liberal versus restrictive transfusion goals for asymptomatic hospitalized patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD). However, patients with CAD were included in the TRICC and FOCUS trials.3,8 Of patients enrolled in the TRICC trial, 26% had a primary or secondary diagnosis of cardiac disease; subgroup analysis found no significant differences in 30-day mortality between treatment groups, similar to that of the entire study population.3 In a subgroup analysis of patients with “cardiovascular disease” the FOCUS trial found no difference in outcomes between a restrictive and liberal transfusion strategy, although there was a marginally higher incidence of myocardial infarction in the restrictive arm in the entire study population.8

Although some studies have included patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) as a subgroup, these subgroups are often not powered to show clinically meaningful differences. The risk of volume overload is one explanation for why transfusions may be harmful for patients with CHF.

Based on these limited available data, the AABB guidelines recommend a “restrictive RBC transfusion threshold (hemoglobin level of 8 g/dL)” for patients “with preexisting cardiovascular disease,” without distinguishing among patients with acute coronary syndrome, stable CAD, and CHF, but adds that the “threshold of 7 g/dL is likely comparable with 8 g/dL, but randomized controlled trial evidence is not available for all patient categories.”1

Of note, certain patient populations, such as those with end-stage renal disease, oncology patients (especially those undergoing active chemotherapy), and those with comorbid conditions such as thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy are specifically excluded from the AABB guidelines. The reader is referred to guidelines from respective specialty societies for further guidance.

Back to our case

This 48-year-old man with cirrhosis and esophageal varices presenting with ongoing blood loss due to hematochezia and hematemesis with a hemoglobin of 7.8 g/dL should be transfused due to his active bleeding; his hemoglobin level should not be a determining factor under such circumstances. This distinction is one of the most fundamental in interpreting the guidelines, that is, patients with hemodynamic insult, symptoms, and/or ongoing bleeding should be evaluated clinically, independent of their hemoglobin level.

Bottom line

Although recent guidelines generally favor a more restrictive hemoglobin goal threshold, in the presence of active blood loss or hemodynamic instability, blood transfusion should be considered independent of the initial hemoglobin level.

Key Points

- The AABB guidelines recommend transfusing stable general medical inpatients to a hemoglobin level of 7 g/dL.

- For patients undergoing orthopedic surgery, cardiac surgery, and those with preexisting cardiovascular disease, a transfusion threshold of 8 g/dL is recommended.

- Patients with hemodynamic instability or active blood loss should be transfused based on clinical criteria, and not absolute hemoglobin levels.

- Patients with acute coronary syndrome, severe thrombocytopenia, and chronic transfusion–dependent anemia are excluded from these recommendations.

- Further studies are needed to further refine these recommendations to specific patient populations in maximizing the benefits and minimizing the risks of blood transfusions.

Quiz

In which of the following scenarios is RBC transfusion LEAST indicated?

- A. Active diverticular bleed, heart rate 125 beats/minute, blood pressure 85/65 mm HG, hemoglobin 10.5 g/dL

- B. Septic shock in the ICU, hemoglobin 6.7 g/dL

- C. Pulmonary embolism in the setting of stable coronary artery disease and hemoglobin 8.7 g/dL

- D. Lymphoma on chemotherapy, hemoglobin 7.5 g/d, patient becomes dizzy when standing

Answer: C – A hemoglobin transfusion goal of 8.0 g/dL is recommended for patients with cardiovascular disease. The patient in answer choice A has active blood loss, tachycardia, and hypotension, all pointing to the need for blood transfusion irrespective of an initial hemoglobin level greater than 8.0 g/dL. The patient in answer choice B has a hemoglobin level less than 7.0 g/dL, and the patient in choice D is symptomatic, possibly from anemia, as well as on chemotherapy, therefore making transfusion a reasonable option.

Dr. Sampat, Dr. Berger, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

References

1. Carson JL et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines From the AABB: Red Blood Cell Transfusion Thresholds and Storage. JAMA. 2016;316:2025-35.

2. Dwyre DM et al. Hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV transfusion-transmitted infections in the 21st century. Vox Sang. 2011;100:92-8.

3. Hébert PC et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-17.

4. Holst LB et al. Lower versus higher hemoglobin threshold for transfusion in septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1381-91.

5. Villanueva C et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:11-21.

6. Jairath V et al. Restrictive versus liberal blood transfusion for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (TRIGGER): a pragmatic, open-label, cluster randomised feasibility trial. Lancet. 2015;386:137-44.

7. Hajjar LA et al. Transfusion requirements after cardiac surgery: the TRACS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1559-67.

8. Carson JL et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2453-62.

9. Sabatine MS et al. Association of hemoglobin levels with clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2005;111:2042-9.

Treat sleep apnea with positive airway pressure, but don’t expect it to prevent heart attacks

Clinical question: In patients with sleep apnea, does using positive airway pressure (PAP) treatment prevent adverse cardiovascular events and death?

Background: Previous observational studies have suggested that untreated sleep apnea is a factor in cardiopulmonary morbidity as well as cerebrovascular events. Guidelines advise its use for prevention of cerebrovascular events. However, not enough is known from trials about its impact on prevention of cardiovascular events.

Synopsis: The authors analyzed 10 randomized-controlled trials encompassing 7,266 patients with sleep apnea. They examined instances of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE; acute coronary syndrome, stroke, cardiovascular death) as well as hospitalization for unstable angina and all-cause deaths, among others. They found no association between treatment with positive airway pressure and MACEs (169 events vs. 187 events, with a relative risk of 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.53-1.13) or all-cause death (324 events vs. 289 events, RR 1.13; 95% CI,0.99-1.29).

Bottom line: Positive airway pressure treatment for patients with sleep apnea is not an intervention to prevent cardiovascular morbidity.

Citation: Yu J et al. Association of positive airway pressure with cardiovascular events and death in adults with sleep apnea. JAMA. 2017 Jul 11;318(2):156-66.

Dr. Sata is a medical instructor, Duke University Hospital.

Clinical question: In patients with sleep apnea, does using positive airway pressure (PAP) treatment prevent adverse cardiovascular events and death?

Background: Previous observational studies have suggested that untreated sleep apnea is a factor in cardiopulmonary morbidity as well as cerebrovascular events. Guidelines advise its use for prevention of cerebrovascular events. However, not enough is known from trials about its impact on prevention of cardiovascular events.

Synopsis: The authors analyzed 10 randomized-controlled trials encompassing 7,266 patients with sleep apnea. They examined instances of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE; acute coronary syndrome, stroke, cardiovascular death) as well as hospitalization for unstable angina and all-cause deaths, among others. They found no association between treatment with positive airway pressure and MACEs (169 events vs. 187 events, with a relative risk of 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.53-1.13) or all-cause death (324 events vs. 289 events, RR 1.13; 95% CI,0.99-1.29).

Bottom line: Positive airway pressure treatment for patients with sleep apnea is not an intervention to prevent cardiovascular morbidity.

Citation: Yu J et al. Association of positive airway pressure with cardiovascular events and death in adults with sleep apnea. JAMA. 2017 Jul 11;318(2):156-66.

Dr. Sata is a medical instructor, Duke University Hospital.

Clinical question: In patients with sleep apnea, does using positive airway pressure (PAP) treatment prevent adverse cardiovascular events and death?

Background: Previous observational studies have suggested that untreated sleep apnea is a factor in cardiopulmonary morbidity as well as cerebrovascular events. Guidelines advise its use for prevention of cerebrovascular events. However, not enough is known from trials about its impact on prevention of cardiovascular events.

Synopsis: The authors analyzed 10 randomized-controlled trials encompassing 7,266 patients with sleep apnea. They examined instances of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE; acute coronary syndrome, stroke, cardiovascular death) as well as hospitalization for unstable angina and all-cause deaths, among others. They found no association between treatment with positive airway pressure and MACEs (169 events vs. 187 events, with a relative risk of 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.53-1.13) or all-cause death (324 events vs. 289 events, RR 1.13; 95% CI,0.99-1.29).

Bottom line: Positive airway pressure treatment for patients with sleep apnea is not an intervention to prevent cardiovascular morbidity.

Citation: Yu J et al. Association of positive airway pressure with cardiovascular events and death in adults with sleep apnea. JAMA. 2017 Jul 11;318(2):156-66.

Dr. Sata is a medical instructor, Duke University Hospital.

You aren’t (necessarily) a walking petri dish!

Clinical question: Does exposure to a patient with a multidrug-resistant organism result in colonization of a health care provider?

Background: Multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) are growing threats in our hospitals, particularly vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) and resistant gram-negative bacteria. The role of the health care team in preventing infection transmission is paramount. If a team member who is caring for a patient with an MDRO or handling lab specimens becomes colonized with these bacteria, he or she could potentially transmit them to the next patient.

Setting: Large academic research hospital.

Synopsis: Staff submitted self-collected rectal swabs, which were then cultured for MDROs. 379 health care personnel (which they defined as having had self-reported exposure to MDROs) were compared with 376 staff members in the control group, who reported no exposure to MDROs. There was a nonsignificant difference between growth of multidrug-resistant organisms between the groups (4.0% vs 3.2%).

Bottom line: This study suggests that occupational exposure to an MDRO does not result in subsequent colonization of the health care provider and may not be a major risk factor for nosocomial transmission.

Citation: Decker BK et al. Healthcare personnel intestinal colonization with multidrug-resistant organisms. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017 May 12. pii:S1198-743X(17)30270-7.

Dr. Sata is a medical instructor, Duke University Hospital.

Clinical question: Does exposure to a patient with a multidrug-resistant organism result in colonization of a health care provider?

Background: Multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) are growing threats in our hospitals, particularly vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) and resistant gram-negative bacteria. The role of the health care team in preventing infection transmission is paramount. If a team member who is caring for a patient with an MDRO or handling lab specimens becomes colonized with these bacteria, he or she could potentially transmit them to the next patient.

Setting: Large academic research hospital.

Synopsis: Staff submitted self-collected rectal swabs, which were then cultured for MDROs. 379 health care personnel (which they defined as having had self-reported exposure to MDROs) were compared with 376 staff members in the control group, who reported no exposure to MDROs. There was a nonsignificant difference between growth of multidrug-resistant organisms between the groups (4.0% vs 3.2%).

Bottom line: This study suggests that occupational exposure to an MDRO does not result in subsequent colonization of the health care provider and may not be a major risk factor for nosocomial transmission.

Citation: Decker BK et al. Healthcare personnel intestinal colonization with multidrug-resistant organisms. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017 May 12. pii:S1198-743X(17)30270-7.

Dr. Sata is a medical instructor, Duke University Hospital.

Clinical question: Does exposure to a patient with a multidrug-resistant organism result in colonization of a health care provider?

Background: Multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) are growing threats in our hospitals, particularly vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) and resistant gram-negative bacteria. The role of the health care team in preventing infection transmission is paramount. If a team member who is caring for a patient with an MDRO or handling lab specimens becomes colonized with these bacteria, he or she could potentially transmit them to the next patient.

Setting: Large academic research hospital.

Synopsis: Staff submitted self-collected rectal swabs, which were then cultured for MDROs. 379 health care personnel (which they defined as having had self-reported exposure to MDROs) were compared with 376 staff members in the control group, who reported no exposure to MDROs. There was a nonsignificant difference between growth of multidrug-resistant organisms between the groups (4.0% vs 3.2%).

Bottom line: This study suggests that occupational exposure to an MDRO does not result in subsequent colonization of the health care provider and may not be a major risk factor for nosocomial transmission.

Citation: Decker BK et al. Healthcare personnel intestinal colonization with multidrug-resistant organisms. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017 May 12. pii:S1198-743X(17)30270-7.

Dr. Sata is a medical instructor, Duke University Hospital.

Inpatient antiviral treatment reduces ICU admissions among influenza patients

SAN DIEGO – Administering inpatient antiviral influenza treatment may reduce admissions to the ICU among adults hospitalized with flu, according to a study presented at ID Week 2017, an infectious diseases meeting.

While interventions did not directly affect flu-related deaths, lower ICU admission rates could reduce morbidity as well as ease the financial burden felt during the influenza season.

Investigators retrospectively studied 4,679 influenza patients admitted to Canadian Immunization Research Network Serious Outcomes Surveillance (SOS) Network hospitals during 2011-2014. Of the 54% of patients given inpatient antiviral treatment, the risk of being admitted to the ICU was reduced by 90% (odds ratio, 0.10;95% confidence interval, 0.08-0.13; P less than .001).

Antiviral treatment was not protective against death outcomes in patients with either influenza A or influenza B (OR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7-1.2; P =.454).

The median age of patients was 70 years, with a majority older than 75 years(41%); the majority presented with one or more comorbidities (89%), and had influenza A (72%).

Researchers found that, of the 4,679 patients studied, 798 (16%) were admitted to the ICU, 511 (11%) required mechanical ventilation, and the average length of hospital stay was 11 days.

Of those studied, 444 (9%) died within 30 days of discharge.

Researchers also found that only 38% of those studied had received the current seasonal vaccine upon admittance. However, these numbers may be skewed from the general population, because patients who have not taken the vaccine are more likely to be hospitalized.

Along with the results of antivirals on hospitalized patients, researchers wanted to uncover how the effectiveness of inpatient vaccine administration would vary based on treatment timing, said presenter Zach Shaffelburg of the Canadian Center for Vaccinology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS.

Even when administered 4.28 days after symptom onset, antiviral treatments in patients proved to be associated with significant reductions in ICU admissions and the need for mechanical ventilation.

The investigators concluded that antivirals show a strong association with positive effects on serious, influenza-related outcomes in hospitalized patients and, while therapy remained effective with later treatment start, patients would benefit the most from initiation as soon as possible.

Currently, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) have guidelines instructing best practice for inpatient antiviral treatment, however the number of hospitalized patients given treatment has declined in Canada since 2009, according to Mr. Shaffelburg.

The reason more patients were not receiving inpatient antiviral treatment may be related to studies of different populations that failed to show significant impact, Mr. Shaffelburg suggested during a question and answer session following the presentation: “I think a lot of that comes from outpatient studies that involve patients who are younger and quite healthy [who received] antivirals, and it showed a very minimal impact,” Mr. Shaffelburg said. “So a lot of people saw that study and thought, ‘What’s that point of giving it if it’s not going to make an impact?’ ”

Mr. Shaffelburg and his colleagues are planning to continue their study of inpatient antiviral treatment, focusing more on the effectiveness of treatment in relation to time administered after onset.

Mr. Shaffelburg reported having no disclosures. The study was funded by the CIRN SOS network, Canadian Institutes for Health Research, and a partnership with GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. Some of the investigators were GSK employees or received grant funding from the company.

SOURCE: Shaffelburg Z et al. IDWeek 2017 Abstract 890.

SAN DIEGO – Administering inpatient antiviral influenza treatment may reduce admissions to the ICU among adults hospitalized with flu, according to a study presented at ID Week 2017, an infectious diseases meeting.

While interventions did not directly affect flu-related deaths, lower ICU admission rates could reduce morbidity as well as ease the financial burden felt during the influenza season.

Investigators retrospectively studied 4,679 influenza patients admitted to Canadian Immunization Research Network Serious Outcomes Surveillance (SOS) Network hospitals during 2011-2014. Of the 54% of patients given inpatient antiviral treatment, the risk of being admitted to the ICU was reduced by 90% (odds ratio, 0.10;95% confidence interval, 0.08-0.13; P less than .001).

Antiviral treatment was not protective against death outcomes in patients with either influenza A or influenza B (OR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7-1.2; P =.454).

The median age of patients was 70 years, with a majority older than 75 years(41%); the majority presented with one or more comorbidities (89%), and had influenza A (72%).

Researchers found that, of the 4,679 patients studied, 798 (16%) were admitted to the ICU, 511 (11%) required mechanical ventilation, and the average length of hospital stay was 11 days.

Of those studied, 444 (9%) died within 30 days of discharge.

Researchers also found that only 38% of those studied had received the current seasonal vaccine upon admittance. However, these numbers may be skewed from the general population, because patients who have not taken the vaccine are more likely to be hospitalized.

Along with the results of antivirals on hospitalized patients, researchers wanted to uncover how the effectiveness of inpatient vaccine administration would vary based on treatment timing, said presenter Zach Shaffelburg of the Canadian Center for Vaccinology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS.

Even when administered 4.28 days after symptom onset, antiviral treatments in patients proved to be associated with significant reductions in ICU admissions and the need for mechanical ventilation.

The investigators concluded that antivirals show a strong association with positive effects on serious, influenza-related outcomes in hospitalized patients and, while therapy remained effective with later treatment start, patients would benefit the most from initiation as soon as possible.

Currently, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) have guidelines instructing best practice for inpatient antiviral treatment, however the number of hospitalized patients given treatment has declined in Canada since 2009, according to Mr. Shaffelburg.

The reason more patients were not receiving inpatient antiviral treatment may be related to studies of different populations that failed to show significant impact, Mr. Shaffelburg suggested during a question and answer session following the presentation: “I think a lot of that comes from outpatient studies that involve patients who are younger and quite healthy [who received] antivirals, and it showed a very minimal impact,” Mr. Shaffelburg said. “So a lot of people saw that study and thought, ‘What’s that point of giving it if it’s not going to make an impact?’ ”

Mr. Shaffelburg and his colleagues are planning to continue their study of inpatient antiviral treatment, focusing more on the effectiveness of treatment in relation to time administered after onset.

Mr. Shaffelburg reported having no disclosures. The study was funded by the CIRN SOS network, Canadian Institutes for Health Research, and a partnership with GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. Some of the investigators were GSK employees or received grant funding from the company.

SOURCE: Shaffelburg Z et al. IDWeek 2017 Abstract 890.

SAN DIEGO – Administering inpatient antiviral influenza treatment may reduce admissions to the ICU among adults hospitalized with flu, according to a study presented at ID Week 2017, an infectious diseases meeting.

While interventions did not directly affect flu-related deaths, lower ICU admission rates could reduce morbidity as well as ease the financial burden felt during the influenza season.

Investigators retrospectively studied 4,679 influenza patients admitted to Canadian Immunization Research Network Serious Outcomes Surveillance (SOS) Network hospitals during 2011-2014. Of the 54% of patients given inpatient antiviral treatment, the risk of being admitted to the ICU was reduced by 90% (odds ratio, 0.10;95% confidence interval, 0.08-0.13; P less than .001).

Antiviral treatment was not protective against death outcomes in patients with either influenza A or influenza B (OR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.7-1.2; P =.454).

The median age of patients was 70 years, with a majority older than 75 years(41%); the majority presented with one or more comorbidities (89%), and had influenza A (72%).

Researchers found that, of the 4,679 patients studied, 798 (16%) were admitted to the ICU, 511 (11%) required mechanical ventilation, and the average length of hospital stay was 11 days.

Of those studied, 444 (9%) died within 30 days of discharge.

Researchers also found that only 38% of those studied had received the current seasonal vaccine upon admittance. However, these numbers may be skewed from the general population, because patients who have not taken the vaccine are more likely to be hospitalized.

Along with the results of antivirals on hospitalized patients, researchers wanted to uncover how the effectiveness of inpatient vaccine administration would vary based on treatment timing, said presenter Zach Shaffelburg of the Canadian Center for Vaccinology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS.

Even when administered 4.28 days after symptom onset, antiviral treatments in patients proved to be associated with significant reductions in ICU admissions and the need for mechanical ventilation.

The investigators concluded that antivirals show a strong association with positive effects on serious, influenza-related outcomes in hospitalized patients and, while therapy remained effective with later treatment start, patients would benefit the most from initiation as soon as possible.

Currently, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) have guidelines instructing best practice for inpatient antiviral treatment, however the number of hospitalized patients given treatment has declined in Canada since 2009, according to Mr. Shaffelburg.

The reason more patients were not receiving inpatient antiviral treatment may be related to studies of different populations that failed to show significant impact, Mr. Shaffelburg suggested during a question and answer session following the presentation: “I think a lot of that comes from outpatient studies that involve patients who are younger and quite healthy [who received] antivirals, and it showed a very minimal impact,” Mr. Shaffelburg said. “So a lot of people saw that study and thought, ‘What’s that point of giving it if it’s not going to make an impact?’ ”

Mr. Shaffelburg and his colleagues are planning to continue their study of inpatient antiviral treatment, focusing more on the effectiveness of treatment in relation to time administered after onset.

Mr. Shaffelburg reported having no disclosures. The study was funded by the CIRN SOS network, Canadian Institutes for Health Research, and a partnership with GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. Some of the investigators were GSK employees or received grant funding from the company.

SOURCE: Shaffelburg Z et al. IDWeek 2017 Abstract 890.

REPORTING FROM ID WEEK 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients who received antiviral treatment were significantly less likely to go to the ICU or need mechanical ventilation (OR, 0.10; 95% CI, 0.08-0.13; P less than .001).

Study details: Study of 4,679 hospitalized influenza patients admitted to the Canadian Immunization Research Network Serious Outcomes Surveillance (CIRN SOS) network hospitals between 2011 to 2014.

Disclosures: Mr. Shaffelburg reported having no disclosures. The study was funded by the CIRN SOS network, Canadian Institutes for Health Research, and a partnership with GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. Some of the investigators were GSK employees or received grant funding from the company.

Source: Shaffelburg Z et al. IDWeek 2017 Abstract 890.

Idarucizumab reverses anticoagulation effects of dabigatran

Clinical question: Can idarucizumab reverse anticoagulation effects of dabigatran in a timely manner for urgent surgery or in the event of bleeding?

Background: Reversing the anticoagulant properties of anticoagulants can be important in the event of a life-threatening bleed, or if patients taking these medications need urgent surgery or other interventions. Idarucizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody fragment, can reverse anticoagulant activity of dabigatran, increasing its acceptance for prescribing physicians as well as patients.

Study design: Multicenter prospective single cohort study.

Setting: 173 sites, 39 countries.

Synopsis: Among 503 patients (median age, 78 years, indication for dabigatran included stroke prophylaxis in setting of atrial fibrillation for most) who had either uncontrolled bleeding (n = 301) or needing emergent surgery (n = 202), a single 5-g dose of idarucizumab was able to reverse anticoagulation rapidly and completely in more than 98% of these patients independent of age, sex, renal function, and dabigatran concentration at baseline. Specifically in 68% of the patients in the bleeding group (excluding intracranial hemorrhage) median time to the cessation of bleeding was 2.5 hours and median time to the initiation of the procedure in the emergent surgery group was 1.6 hours. Study limited by lack of control group.

Bottom line: Idarucizumab can be effective for dabigatran reversal among patients who have uncontrolled bleeding or need to undergo urgent surgery.

Citation: Pollack CV Jr. et al. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal: Full cohort analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 3;377(5):431-41.

Dr. Kamath is a hospitalist and medical director of quality and patient safety, Duke Regional Hospital, Duke University Health System.

Clinical question: Can idarucizumab reverse anticoagulation effects of dabigatran in a timely manner for urgent surgery or in the event of bleeding?

Background: Reversing the anticoagulant properties of anticoagulants can be important in the event of a life-threatening bleed, or if patients taking these medications need urgent surgery or other interventions. Idarucizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody fragment, can reverse anticoagulant activity of dabigatran, increasing its acceptance for prescribing physicians as well as patients.

Study design: Multicenter prospective single cohort study.

Setting: 173 sites, 39 countries.

Synopsis: Among 503 patients (median age, 78 years, indication for dabigatran included stroke prophylaxis in setting of atrial fibrillation for most) who had either uncontrolled bleeding (n = 301) or needing emergent surgery (n = 202), a single 5-g dose of idarucizumab was able to reverse anticoagulation rapidly and completely in more than 98% of these patients independent of age, sex, renal function, and dabigatran concentration at baseline. Specifically in 68% of the patients in the bleeding group (excluding intracranial hemorrhage) median time to the cessation of bleeding was 2.5 hours and median time to the initiation of the procedure in the emergent surgery group was 1.6 hours. Study limited by lack of control group.

Bottom line: Idarucizumab can be effective for dabigatran reversal among patients who have uncontrolled bleeding or need to undergo urgent surgery.

Citation: Pollack CV Jr. et al. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal: Full cohort analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 3;377(5):431-41.

Dr. Kamath is a hospitalist and medical director of quality and patient safety, Duke Regional Hospital, Duke University Health System.

Clinical question: Can idarucizumab reverse anticoagulation effects of dabigatran in a timely manner for urgent surgery or in the event of bleeding?

Background: Reversing the anticoagulant properties of anticoagulants can be important in the event of a life-threatening bleed, or if patients taking these medications need urgent surgery or other interventions. Idarucizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody fragment, can reverse anticoagulant activity of dabigatran, increasing its acceptance for prescribing physicians as well as patients.

Study design: Multicenter prospective single cohort study.

Setting: 173 sites, 39 countries.

Synopsis: Among 503 patients (median age, 78 years, indication for dabigatran included stroke prophylaxis in setting of atrial fibrillation for most) who had either uncontrolled bleeding (n = 301) or needing emergent surgery (n = 202), a single 5-g dose of idarucizumab was able to reverse anticoagulation rapidly and completely in more than 98% of these patients independent of age, sex, renal function, and dabigatran concentration at baseline. Specifically in 68% of the patients in the bleeding group (excluding intracranial hemorrhage) median time to the cessation of bleeding was 2.5 hours and median time to the initiation of the procedure in the emergent surgery group was 1.6 hours. Study limited by lack of control group.

Bottom line: Idarucizumab can be effective for dabigatran reversal among patients who have uncontrolled bleeding or need to undergo urgent surgery.

Citation: Pollack CV Jr. et al. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal: Full cohort analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 3;377(5):431-41.

Dr. Kamath is a hospitalist and medical director of quality and patient safety, Duke Regional Hospital, Duke University Health System.

Helping patients with addictions get, stay clean

Roughly 6 months ago, a primary care physician referred a patient to our clinic for an assessment for opioid use disorder and a recommendation for treatment. The patient estimated, likely underestimated, his daily heroin use to five bags and dropped positive, in addition to heroin, for benzodiazepines, amphetamines, and cannabis. He was in a profession in which public safety was a critical concern, and he refused to notify his employer’s employee assistance program. He also declined to voluntarily admit himself for detox and treatment at the local, fully accredited addiction program, which was affiliated with a major university medical center. Instead, after an Internet search, the patient opted for an opioid treatment center featuring massage therapy, acupuncture, a stable, a sweat lodge – and a magnificent view of the Pacific Ocean.

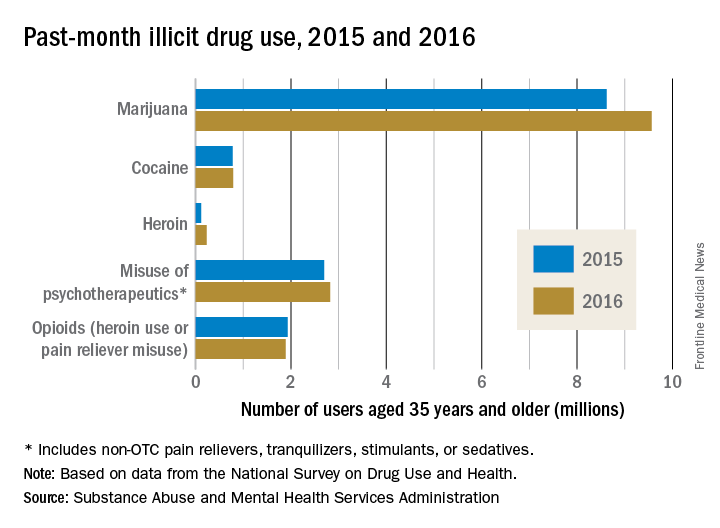

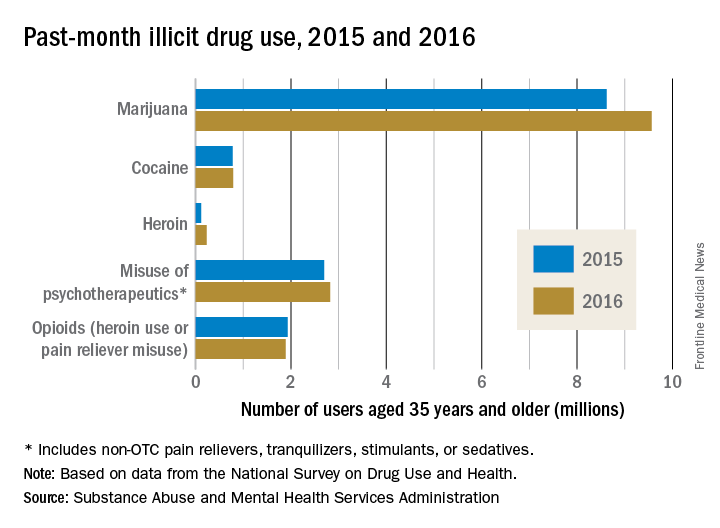

Mental health professionals and lay people alike are aware of the “opioid crisis” – the derailment of lives, the devastation to communities, the death toll. But despite proposals to increase research funding, policies aimed at tightening the prescribing of opioids, and pledges to ramp up interdiction of heroin traffic, there is often an ignorance and confusion regarding the best, evidence-based approaches to getting patients with substance use disorders clean and keeping them clean.

Unfortunately, as with any crisis, there will be opportunists preying on vulnerable patients and their families. And this travesty has reportedly escalated, as outpatient treatment centers take advantage of laws guaranteeing mental health parity and insurance companies paying out tens of thousands of dollars for residential and outpatient opioid treatment. The potential for significant profit is plainly illustrated by the influx of private equity firms, such as Bain Capital, that are investing heavily in treatment centers.

Reports of malfeasance and misconduct, by owners, operators, staff, and others connected with the industry are beginning to get the attention of authorities. There have been reports of outpatient treatment centers that spend lavishly on furnishing, on BMWs and signed art, yet are understaffed, leading to inadequate one-on-one counseling and even sexual transgressions between residents. There are centers that have been investigated for insurance fraud, such as illegally waiving a copay or a deductible or for charging up to $5,000 for a simple urine five drug screen, often multiple times a day. And there is evidence of “junkie hunters” who cruise for people with addictions and brokers who provide such people with fake addresses in order to qualify for insurance plans with excellent benefits for addiction treatment.

Probably the best means to find a suitable outpatient treatment center is by way of a local, experienced, and respected chemical dependency counselor or physician certified in addiction medicine. If people with substance use disorders and their families want to independently conduct a search, as a good rule of thumb, they should be advised to consider programs affiliated with major medical centers and hospitals or outpatient treatment centers that have been established in good standing for years, in contrast to the rash of pop-up, for-profit programs. Of equal, or even greater importance, is that the prospective center ought to be accredited by a national organization, for example, The Joint Commission, and its staff ought to be licensed and credentialed as well.

In addition, there is merit if the staff has been educated, trained, and supervised under the direction of a respected institution. Needless to add, an outpatient treatment center must use evidence-based practices as the bedrock of treatment; this includes pharmacotherapies such as Suboxone and naltrexone (Vivitrol), and behavioral therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, contingency management, and motivational enhancement. To date, massage and essential oils might be relaxing and pleasurable, but they are not considered accepted standard of care.

It is crucial, too, that an outpatient treatment center have both the resources to reliably handle acute medical detox, which can be a potentially life-threatening emergency, and the medical personnel who can assess and treat such medical conditions as hypertension as well as psychiatric illnesses such as bipolar and generalized anxiety disorders. A prospective patient also should inquire whether any of the staff has been the subject of disciplinary action by a licensing board or whether the center has been investigated by the state or a national accrediting organization.

Because addiction so often has facets rooted in the family system, and recovery so often depends on family support, an outpatient treatment center should provide a structured family program integrated into the patient’s treatment and emphasize the importance of continued family involvement after discharge.

Lastly, the best treatment centers often regularly update a patient’s local therapist and physician, spell out the elements of successful aftercare (12-step programs, and so on), and provide amenities, such as calls to a recently discharged patient and an alumni support network.

Dr. Marseille is a psychiatrist who works on the staff of a clinic in Wheaton, Ill. His special interests include adolescent and addiction medicine, eating disorders, trauma, bipolar disorder, and the psychiatric manifestations of acute and chronic medical conditions.

This article was updated 12/15/17.

Roughly 6 months ago, a primary care physician referred a patient to our clinic for an assessment for opioid use disorder and a recommendation for treatment. The patient estimated, likely underestimated, his daily heroin use to five bags and dropped positive, in addition to heroin, for benzodiazepines, amphetamines, and cannabis. He was in a profession in which public safety was a critical concern, and he refused to notify his employer’s employee assistance program. He also declined to voluntarily admit himself for detox and treatment at the local, fully accredited addiction program, which was affiliated with a major university medical center. Instead, after an Internet search, the patient opted for an opioid treatment center featuring massage therapy, acupuncture, a stable, a sweat lodge – and a magnificent view of the Pacific Ocean.

Mental health professionals and lay people alike are aware of the “opioid crisis” – the derailment of lives, the devastation to communities, the death toll. But despite proposals to increase research funding, policies aimed at tightening the prescribing of opioids, and pledges to ramp up interdiction of heroin traffic, there is often an ignorance and confusion regarding the best, evidence-based approaches to getting patients with substance use disorders clean and keeping them clean.

Unfortunately, as with any crisis, there will be opportunists preying on vulnerable patients and their families. And this travesty has reportedly escalated, as outpatient treatment centers take advantage of laws guaranteeing mental health parity and insurance companies paying out tens of thousands of dollars for residential and outpatient opioid treatment. The potential for significant profit is plainly illustrated by the influx of private equity firms, such as Bain Capital, that are investing heavily in treatment centers.

Reports of malfeasance and misconduct, by owners, operators, staff, and others connected with the industry are beginning to get the attention of authorities. There have been reports of outpatient treatment centers that spend lavishly on furnishing, on BMWs and signed art, yet are understaffed, leading to inadequate one-on-one counseling and even sexual transgressions between residents. There are centers that have been investigated for insurance fraud, such as illegally waiving a copay or a deductible or for charging up to $5,000 for a simple urine five drug screen, often multiple times a day. And there is evidence of “junkie hunters” who cruise for people with addictions and brokers who provide such people with fake addresses in order to qualify for insurance plans with excellent benefits for addiction treatment.

Probably the best means to find a suitable outpatient treatment center is by way of a local, experienced, and respected chemical dependency counselor or physician certified in addiction medicine. If people with substance use disorders and their families want to independently conduct a search, as a good rule of thumb, they should be advised to consider programs affiliated with major medical centers and hospitals or outpatient treatment centers that have been established in good standing for years, in contrast to the rash of pop-up, for-profit programs. Of equal, or even greater importance, is that the prospective center ought to be accredited by a national organization, for example, The Joint Commission, and its staff ought to be licensed and credentialed as well.

In addition, there is merit if the staff has been educated, trained, and supervised under the direction of a respected institution. Needless to add, an outpatient treatment center must use evidence-based practices as the bedrock of treatment; this includes pharmacotherapies such as Suboxone and naltrexone (Vivitrol), and behavioral therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, contingency management, and motivational enhancement. To date, massage and essential oils might be relaxing and pleasurable, but they are not considered accepted standard of care.

It is crucial, too, that an outpatient treatment center have both the resources to reliably handle acute medical detox, which can be a potentially life-threatening emergency, and the medical personnel who can assess and treat such medical conditions as hypertension as well as psychiatric illnesses such as bipolar and generalized anxiety disorders. A prospective patient also should inquire whether any of the staff has been the subject of disciplinary action by a licensing board or whether the center has been investigated by the state or a national accrediting organization.

Because addiction so often has facets rooted in the family system, and recovery so often depends on family support, an outpatient treatment center should provide a structured family program integrated into the patient’s treatment and emphasize the importance of continued family involvement after discharge.

Lastly, the best treatment centers often regularly update a patient’s local therapist and physician, spell out the elements of successful aftercare (12-step programs, and so on), and provide amenities, such as calls to a recently discharged patient and an alumni support network.

Dr. Marseille is a psychiatrist who works on the staff of a clinic in Wheaton, Ill. His special interests include adolescent and addiction medicine, eating disorders, trauma, bipolar disorder, and the psychiatric manifestations of acute and chronic medical conditions.

This article was updated 12/15/17.

Roughly 6 months ago, a primary care physician referred a patient to our clinic for an assessment for opioid use disorder and a recommendation for treatment. The patient estimated, likely underestimated, his daily heroin use to five bags and dropped positive, in addition to heroin, for benzodiazepines, amphetamines, and cannabis. He was in a profession in which public safety was a critical concern, and he refused to notify his employer’s employee assistance program. He also declined to voluntarily admit himself for detox and treatment at the local, fully accredited addiction program, which was affiliated with a major university medical center. Instead, after an Internet search, the patient opted for an opioid treatment center featuring massage therapy, acupuncture, a stable, a sweat lodge – and a magnificent view of the Pacific Ocean.

Mental health professionals and lay people alike are aware of the “opioid crisis” – the derailment of lives, the devastation to communities, the death toll. But despite proposals to increase research funding, policies aimed at tightening the prescribing of opioids, and pledges to ramp up interdiction of heroin traffic, there is often an ignorance and confusion regarding the best, evidence-based approaches to getting patients with substance use disorders clean and keeping them clean.

Unfortunately, as with any crisis, there will be opportunists preying on vulnerable patients and their families. And this travesty has reportedly escalated, as outpatient treatment centers take advantage of laws guaranteeing mental health parity and insurance companies paying out tens of thousands of dollars for residential and outpatient opioid treatment. The potential for significant profit is plainly illustrated by the influx of private equity firms, such as Bain Capital, that are investing heavily in treatment centers.

Reports of malfeasance and misconduct, by owners, operators, staff, and others connected with the industry are beginning to get the attention of authorities. There have been reports of outpatient treatment centers that spend lavishly on furnishing, on BMWs and signed art, yet are understaffed, leading to inadequate one-on-one counseling and even sexual transgressions between residents. There are centers that have been investigated for insurance fraud, such as illegally waiving a copay or a deductible or for charging up to $5,000 for a simple urine five drug screen, often multiple times a day. And there is evidence of “junkie hunters” who cruise for people with addictions and brokers who provide such people with fake addresses in order to qualify for insurance plans with excellent benefits for addiction treatment.

Probably the best means to find a suitable outpatient treatment center is by way of a local, experienced, and respected chemical dependency counselor or physician certified in addiction medicine. If people with substance use disorders and their families want to independently conduct a search, as a good rule of thumb, they should be advised to consider programs affiliated with major medical centers and hospitals or outpatient treatment centers that have been established in good standing for years, in contrast to the rash of pop-up, for-profit programs. Of equal, or even greater importance, is that the prospective center ought to be accredited by a national organization, for example, The Joint Commission, and its staff ought to be licensed and credentialed as well.

In addition, there is merit if the staff has been educated, trained, and supervised under the direction of a respected institution. Needless to add, an outpatient treatment center must use evidence-based practices as the bedrock of treatment; this includes pharmacotherapies such as Suboxone and naltrexone (Vivitrol), and behavioral therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, contingency management, and motivational enhancement. To date, massage and essential oils might be relaxing and pleasurable, but they are not considered accepted standard of care.

It is crucial, too, that an outpatient treatment center have both the resources to reliably handle acute medical detox, which can be a potentially life-threatening emergency, and the medical personnel who can assess and treat such medical conditions as hypertension as well as psychiatric illnesses such as bipolar and generalized anxiety disorders. A prospective patient also should inquire whether any of the staff has been the subject of disciplinary action by a licensing board or whether the center has been investigated by the state or a national accrediting organization.

Because addiction so often has facets rooted in the family system, and recovery so often depends on family support, an outpatient treatment center should provide a structured family program integrated into the patient’s treatment and emphasize the importance of continued family involvement after discharge.

Lastly, the best treatment centers often regularly update a patient’s local therapist and physician, spell out the elements of successful aftercare (12-step programs, and so on), and provide amenities, such as calls to a recently discharged patient and an alumni support network.

Dr. Marseille is a psychiatrist who works on the staff of a clinic in Wheaton, Ill. His special interests include adolescent and addiction medicine, eating disorders, trauma, bipolar disorder, and the psychiatric manifestations of acute and chronic medical conditions.

This article was updated 12/15/17.

FDA approves premixed, low-volume colon-cleansing solution

in adults preparing to undergo colonoscopy, according to Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

The sodium picosulfate, magnesium oxide, and anhydrous citric acid oral solution is a relatively low-volume, premixed, cranberry-flavored solution, making it easier to use and more palatable for patients.

The oral solution is approved with two dosing options: split dose, one dose the evening prior and one dose the morning of the procedure, or the day before dose, which involves taking both doses the day prior to the procedure. Day before dosing is an alternative and should be used when split dosing is not appropriate. After each dose of sodium picosulfate, magnesium oxide, and anhydrous citric acid oral solution, clear liquids should be consumed based on the dosing recommendation. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends the split-dose regimen because of its improved cleansing quality of the colon and better tolerability of the liquid volume by patients.

Patients with impaired renal function should exercise caution if using sodium picosulfate, magnesium oxide, and anhydrous citric acid oral solution as it may effect renal function. A more comprehensive list of safety information is available at www.clenpiq.com.

in adults preparing to undergo colonoscopy, according to Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

The sodium picosulfate, magnesium oxide, and anhydrous citric acid oral solution is a relatively low-volume, premixed, cranberry-flavored solution, making it easier to use and more palatable for patients.

The oral solution is approved with two dosing options: split dose, one dose the evening prior and one dose the morning of the procedure, or the day before dose, which involves taking both doses the day prior to the procedure. Day before dosing is an alternative and should be used when split dosing is not appropriate. After each dose of sodium picosulfate, magnesium oxide, and anhydrous citric acid oral solution, clear liquids should be consumed based on the dosing recommendation. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends the split-dose regimen because of its improved cleansing quality of the colon and better tolerability of the liquid volume by patients.

Patients with impaired renal function should exercise caution if using sodium picosulfate, magnesium oxide, and anhydrous citric acid oral solution as it may effect renal function. A more comprehensive list of safety information is available at www.clenpiq.com.

in adults preparing to undergo colonoscopy, according to Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

The sodium picosulfate, magnesium oxide, and anhydrous citric acid oral solution is a relatively low-volume, premixed, cranberry-flavored solution, making it easier to use and more palatable for patients.

The oral solution is approved with two dosing options: split dose, one dose the evening prior and one dose the morning of the procedure, or the day before dose, which involves taking both doses the day prior to the procedure. Day before dosing is an alternative and should be used when split dosing is not appropriate. After each dose of sodium picosulfate, magnesium oxide, and anhydrous citric acid oral solution, clear liquids should be consumed based on the dosing recommendation. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends the split-dose regimen because of its improved cleansing quality of the colon and better tolerability of the liquid volume by patients.

Patients with impaired renal function should exercise caution if using sodium picosulfate, magnesium oxide, and anhydrous citric acid oral solution as it may effect renal function. A more comprehensive list of safety information is available at www.clenpiq.com.

Consider ‘impactibility’ to prevent hospital readmissions

With the goal of reducing 28-day or 30-day readmissions, some health care teams are turning to predictive models to identify patients at high risk for readmission and to efficiently focus resource-intensive prevention strategies. Recently, there’s been a rapid multiplying of these models.