User login

Adiposis Dolorosa Pain Management

Adiposis dolorosa (AD), or Dercum disease, is a rare disorder that was first described in 1888 and characterized by the National Organization of Rare Disorders (NORD) as a chronic pain condition of the adipose tissue generally found in patients who are overweight or obese.1,2 AD is more common in females aged 35 to 50 years and proposed to be a disease of postmenopausal women, though no prevalence studies exist.2 The etiology remains unclear.2 Several theories have been proposed, including endocrine and nervous system dysfunction, adipose tissue dysregulation, or pressure on peripheral nerves and chronic inflammation.2-4 Genetic, autoimmune, and trauma also have been proposed as a mechanism for developing the disease. Treatment modalities focusing on narcotic analgesics have been ineffective in long-term management.3

The objective of the case presentation is to report a variety of approaches for AD and their relative successes at pain control in order to assist other medical professionals who may come across patients with this rare condition.

Case Presentation

A 53-year-old male with a history of blast exposure-related traumatic brain injury, subsequent stroke with residual left hemiparesis, and seizure disorder presented with a 10-year history of nodule formation in his lower extremities causing restriction of motion and pain. The patient had previously undergone lower extremity fasciotomies for compartment syndrome with minimal pain relief. In addition, nodules over his abdomen and chest wall had been increasing over the past 5 years. He also experienced worsening fatigue, cramping, tightness, and paresthesias of the affected areas during this time. Erythema and temperature allodynia were noted in addition to an 80-pound weight gain. From the above symptoms and nodule excision showing histologic signs of lipomatous growth, a diagnosis of AD was made.

The following constitutes the approximate timetable of his treatments for 9 years. He was first diagnosed incidentally at the beginning of this period with AD during an electrodiagnostic examination. He had noticed the lipomas when he was in his 30s, but initially they were not painful. He was referred for treatment of pain to the physical medicine and rehabilitation department.

For the next 3 years, he was treated with prolotherapy. Five percent dextrose in water was injected around many of the painful lipomas in the upper extremities. He noted after the second round of neural prolotherapy that he had reduced swelling of his upper extremities and the lipomas decreased in size. He experienced mild improvement in pain and functional usage of his arms.

He continued to receive neural prolotherapy into the nodules in the arms, legs, abdomen, and chest wall. The number of painful nodules continued to increase, and the patient was started on hydrocodone 10 mg/acetaminophen 325 mg (1 tablet every 6 hours as needed) and methadone for pain relief. He was initially started on 5 mg per day of methadone and then was increased in a stepwise, gradual fashion to 10 mg in the morning and 15 mg in the evening. He transitioned to morphine sulfate, which was increased to a maximum dose of 45 mg twice daily. This medication was slowly tapered due to adverse effects (AEs), including sedation.

After weaning off morphine sulfate, the patient was started on lidocaine infusions every 3 months. Each infusion provided at least 50% pain reduction for 6 to 8 weeks. He was approved by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to have Vaser (Bausch Health, Laval, Canada) minimally invasive ultrasound liposuction treatment, performed at an outside facility. The patient was satisfied with the pain relief that he received and noted that the number of lipomas greatly diminished. However, due to funding issues, this treatment was discontinued after several months.

The patient had moderately good pain relief with methadone 5 mg in the morning, and 15 mg in the evening. However, the patient reported significant somnolence during the daytime with the regimen. Attempts to wean the patient off methadone was met with uncontrollable daytime pain. With suboptimal oral pain regimen, difficulty obtaining Vaser treatments, and limitation in frequency of neural prolotherapy, the decision was made to initiate 12 treatments of Calmare (Fairfield, CT) cutaneous electrostimulation.

During his first treatment, he had the electrodes placed on his lower extremities. The pre- and posttreatment 10-point visual analog scale (VAS) scores were 9 and 0, respectively, after the first visit. The position of the electrodes varied, depending on the location of his pain, including upper extremities and abdominal wall. During the treatment course, the patient experienced an improvement in subjective functional status. He was able to sleep in the same bed as his wife, shake hands without severe pain, and walk .25 mile, all of which he was unable to do before the electrostimulative treatment. He also reported overall improvement in emotional well-being, resumption of his hobbies (eg, playing the guitar), and social engagement. Methadone was successfully weaned off during this trial without breakthrough pain. This improvement in pain and functional status continued for several weeks; however, he had an exacerbation of his pain following a long plane flight. Due to uncertain reliability of pain relief with the procedure, the pain management service initiated a regimen of methadone 10 mg twice daily to be initiated when a procedure does not provide the desired duration of pain relief and gradually discontinued following the next interventional procedure.

The patient continued a regimen that included lidocaine infusions, neural prolotherapy, Calmare electrostimulative therapy, as well as lymphedema massage. Additionally, he began receiving weekly acupuncture treatments. He started with traditional full body acupuncture and then transitioned to battlefield acupuncture (BFA). Each acupuncture treatment provided about 50% improvement in pain on the VAS, and improved sleep for 3 days posttreatment.

However, after 18 months of the above treatment protocol, the patient experienced a general tonic-clonic seizure at home. Due to concern for the lowered seizure threshold, lidocaine infusions and methadone were discontinued. Long-acting oral morphine was initiated. The patient continued Calmare treatments and neural prolotherapy after a seizure-free interval. This regimen provided the patient with temporary pain relief but for a shorter duration than prior interventions.

Ketamine infusions were eventually initiated about 5 years after the diagnosis of AD was made, with postprocedure pain as 0/10 on the VAS. Pain relief was sustained for 3 months, with the notable AEs of hallucinations in the immediate postinfusion period. Administration consisted of the following: 500 mg of ketamine in a 500 mL bag of 0.9% NaCl. A 60-mg slow IV push was given followed by 60 mg/h increased every 15 min by 10 mg/h for a maximum dose of 150 mg/h. In a single visit the maximum total dose of ketamine administered was 500 mg. The protocol, which usually delivered 200 mg in a visit but was increased to 500 mg because the 200-mg dose was ineffective, was based on protocols at other institutions to accommodate the level of monitoring available in the Interventional Pain Clinic. The clinic also developed an infusion protocol with at least 1 month between treatments. The patient continues to undergo scheduled ketamine infusions every 14 weeks in addition to monthly BFA. The patient reported near total pain relief for about a month following ketamine infusion, with about 3 months of sustained pain relief. Each BFA session continues to provide 3 days of relief from insomnia. Calmare treatments and the neural prolotherapy regimen continue to provide effective but temporary relief from pain.

Discussion

Currently there is no curative treatment for AD. The majority of the literature is composed of case reports without summaries of potential interventions and their efficacies. AD therapies focus on symptom relief and mainly include pharmacologic and surgical intervention. In this case report several novel treatment modalities have been shown to be partially effective.

Surgical Intervention

Liposuction and lipoma resection have been described as effective only in the short term for AD.2,4-6 Hansson and colleagues suggested liposuction avulsion for sensory nerves and a portion of the proposed abnormal nerve connections between the peripheral nervous system and sensory nerves as a potential therapy for pain improvement.5 But the clinical significance of pain relief from liposuction is unclear and is contraindicated in recurrent lipomas.5

Pharmaceutical Approach

Although relief with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and narcotic analgesics have been unpredictable, Herbst and Asare-Bediako described significant pain relief in a subset of patients with AD with a variety of oral analgesics.7,8 However, the duration of this relief was not clearly stated, and the types or medications or combinations were not discussed. Other pharmacologic agents trialed in the treatment of AD include methotrexate, infliximab, Interferon α-2b, and calcium channel modulators (pregabalin and oxcarbazepine).2,9-11 However, the mechanism and significance of pain relief from these medications remain unclear.

Subanesthesia Therapy

Lidocaine has been used as both a topical agent and an IV infusion in the treatment of chronic pain due to AD for decades. Desai and colleagues described 60% sustained pain reduction in a patient using lidocaine 5% transdermal patches.4 IV infusion of lidocaine has been described in various dosages, though the mechanism of pain relief is ambiguous, and the duration of effect is longer than the biologic half-life.2-4,9 Kosseifi and colleagues describe a patient treated with local injections of lidocaine 1% and obtained symptomatic relief for 3 weeks.9 Animal studies suggest the action of lidocaine involves the sodium channels in peripheral nerves, while another study suggested there may be an increase in sympathetic nervous system activity after the infusion of lidocaine.2,9

Ketamine infusions not previously described in the treatment of AD have long been used to treat other chronic pain syndromes (chronic cancer pain, complex regional pain syndrome [CRPS], fibromyalgia, migraine, ischemic pain, and neuropathic pain).9,12,13 Ketamine has been shown to decrease pain intensity and reduce the amount of opioid analgesic necessary to achieve pain relief, likely through the antagonism of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors.12 A retrospective review by Patil and Anitescu described subanesthetic ketamine infusions used as a last-line therapy in refractory pain syndromes. They found ketamine reduced VAS scores from mean 8.5 prior to infusion to 0.8 after infusion in patients with CRPS and from 7.0 prior to infusion to 1.0 in patient with non-CRPS refractory pain syndromes.13 Hypertension and sedation were the most frequent AEs of ketamine infusion, though a higher incidence of hallucination and confusion were noted in non-CRPS patients. Hocking and Cousins suggest that psychotomimetic AEs of ketamine infusion may be more likely in patients with anxiety.14 However, it is important to note that ketamine infusion studies have been heterogeneous in their protocol, and only recently have standardization guidelines been proposed.

Physical Modalities

Manual lymphatic massage has been described in multiple reports for symptom relief in patients with cancer with malignant growth causing outflow lymphatic obstruction. This technique also has been used to treat the obstructive symptoms seen with the lipomatous growths of AD. Lange and colleagues described a case as providing reduction in pain and the diameter of extremities with twice weekly massage.14 Herbst and colleagues noted that patients had an equivocal response to massage, with some patients finding that it worsened the progression of lipomatous growths.7

Electrocutaneous Stimulation

In a case study by Martinenghi and colleagues, a patient with AD improved following transcutaneous frequency rhythmic electrical modulation system (FREMS) treatment.16 The treatment involved 4 cycles of 30 minutes each for 6 months. The patient had an improvement of pain on the VAS from 6.4 to 1.7 and an increase from 12 to 18 on the 100-point Barthel index scale for performance in activities of daily living, suggesting an improvement of functional independence as well.16

The MC5-A Calmare is another cutaneous electrostimulation modality that previously has been used for chronic cancer pain management. This FDA-cleared device is indicated for the treatment of various chronic pain syndromes. The device is proposed to stimulate 5 separate pain areas via cutaneous electrodes applied beyond and above the painful areas in order to “scramble” pain information and reduce perception of chronic pain intensity. Ricci and colleagues included cancer and noncancer subjects in their study and observed reduction in pain intensity by 74% (on numeric rating scale) in the entire subject group after 10 days of treatments. Further, no AEs were reported in either group, and most of the subjects were willing to continue treatment.17 However, this modality was limited by concerns with insurance coverage, access to a Calmare machine, operator training, and reproducibility of electrode placement to achieve “zero pain” as is the determinant of device treatment cycle output by the manufacturer.

Perineural Injection/Prolotherapy

Perineural injection therapy (PIT) involves the injection of dextrose solution into tissues surrounding an inflamed nerve to reduce neuropathic inflammation. The proposed source of this inflammation is the stimulation of the superficial branches of peptidergic peripheral nerves. Injections are SC and target the affected superficial nerve pathway. Pain relief is usually immediate but requires several treatments to ensure a lasting benefit. There have been no research studies or case reports on the use of PIT or prolotherapy and AD. Although there is a paucity of published literature on the efficacy of PIT, it remains an alternative modality for treatment of chronic pain syndromes. In a systematic review of prolotherapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain, Hauser and colleagues supported the use of dextrose prolotherapy to treat chronic tendinopathies, osteoarthritis of finger and knee joints, spinal and pelvic pain if conservative measures had failed. However, the efficacy on acute musculoskeletal pain was uncertain.18 In addition to the paucity of published literature, prolotherapy is not available to many patients due to lack of insurance coverage or lack of providers able to perform the procedure.

Hypobaric Pressure Therapy

Hypobaric pressure therapy has been offered as an alternative “touch-free” method for treatment of pain associated with edema. Herbst and Rutledge describe a pilot study focusing on hypobaric pressure therapy in patients with AD using a cyclic altitude conditioning system, which significantly decreased the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (tendency to catastrophize pain symptoms) in patients with AD after 5 days of therapy. VAS scores also demonstrated a linear decrease over 5 days.8

Acupuncture

There have been no research studies or case reports regarding the use of either traditional full body acupuncture or BFA in management of AD. However, prior studies have been performed that suggest that acupuncture can be beneficial in chronic pain relief. For examples, a Cochrane review by Manheimer and colleagues showed that acupuncture had a significant benefit in pain relief in subjects with peripheral joint arthritis.19 In another Cochrane review there was low-to-moderate level evidence compared with no treatment in pain relief, but moderate-level evidence that the effect of acupuncture does not differ from sham (placebo) acupuncture.20,21

Conclusion

Current therapeutic approaches to AD focus on invasive surgical intervention, chronic opiate and oral medication management. However, we have detailed several additional approaches to AD treatment. Ketamine infusions, which have long been a treatment in other chronic pain syndromes may present a viable alternative to lidocaine infusions in patients with AD. Electrocutaneous stimulation is a validated treatment of chronic pain syndromes, including chronic neuropathic pain and offers an alternative to surgical or pharmacologic management. Further, PIT offers another approach to neuropathic pain management, which has yet to be fully explored. As no standard treatment approach exists for patients with AD, multimodal therapies should be considered to optimize pain management and reduce dependency on opiate mediations.

Acknowledgments

Hunter Holmes McGuire Research Institute and the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Department provided the resources and facilities to make this work possible.

1. Dercum FX. A subcutaneous dystrophy. In: University of Pennsylvania. University of Pennsylvania Medical Bulletin. Vol 1. Philadelphia, PA; University of Pennsylvania Press; 1888:140-150. Accessed October 4, 2019.

2. Hansson E, Svensson H, Brorson H. Review of Dercum’s disease and proposal of diagnositc criteria, diagnositic methods, classification and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:1-15.

3. Amine B, Leguilchard F, Benhamou CL. Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa): a new case-report. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71(2):147-149.

4. Desai MJ, Siriki R, Wang D. Treatment of pain in Dercum’s disease with lidoderm (lidocaine 5% patch): a case report. Pain Med. 2008;9(8):1224-1226.

5. Hansson E, Svensson H, Brorson H. Liposuction may reduce pain in Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa). Pain Med. 2011;12:942-952.

6. Kosseifi S, Anaya E, Dronovalli G, Leicht S. Dercum’s disease: an unusual presentation. Pain Med. 2010;11(9):1430-1434.

7. Herbst KL, Asare-Bediako S. Adiposis dolorasa is more than painful fat. Endocrinologist. 2007;17(6):326-334.

8. Herbst KL, Rutledge T. Pilot study: rapidly cycling hypobaric pressure improves pain after 5 days in adiposis dolorosa. J Pain Res. 2010;3:147-153.

9. Lange U, Oelzner P, Uhlemann C. Dercum’s disease (lipomatosis dolorosa): successful therapy with pregabalin and manual lymphatic drainage and a current overview. Rheumatol Int. 2008;29(1):17-22

10. Schaffer PR, Hale CS, Meehan SA, Shupack JL, Ramachandran S. Adoposis dolorosa. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20(12):1-3.

11. Singal A, Janiga JJ, Bossenbroek NM, Lim HW. Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa): a report of improvement with infliximab and methotrexate. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2007;21(5):717.

12. Loftus RW, Yeager MP, Clark JA, et al. Intraoperative ketamine reduces perioperative opiate consumption in opiate-dependent patients with chronic back pain undergoing back surgery. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(3):639-646.

13. Patil S, Anitescu M. Efficacy of outpatient ketamine infusions in refractory chronic pain syndromes: a 5-year retrospective analysis. Pain Med. 2012;13(2):263-269.

14. Hocking G, Cousins MJ. Ketamine in chronic pain management: an evidence-based review. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(6):1730-1739.

15. Cohen SP, Bhatia A, Buvanendran A, et al. Consensus guidelines on the use of intravenous ketamine infusions for chronic pain from the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(5):521-546.

16. Martinenghi S, Caretto A, Losio C, Scavini M, Bosi E. Successful treatment of Dercum’s disease by transcutaneous electrical stimulation: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(24):e950.

17. Ricci M, Pirotti S, Scarpi E, et al. Managing chronic pain: results from an open-label study using MC5-A Calmare device. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(2):405-412.

18. Hauser RA, Lackner JB, Steilen-Matias D, Harris DK. A systematic review of dextrose prolotherapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;9:139-159.

19. Manheimer E, Cheng K, Linde K, et al. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD001977.

20. Deare JC, Zheng Z, Xue CC, et al. Acupuncture for treating fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5):CD007070.

21. Chan MWC, Wu XY, Wu JCY, Wong SYS, Chung VCH. Safety of acupuncture: overview of systematic reviews. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3369.

Adiposis dolorosa (AD), or Dercum disease, is a rare disorder that was first described in 1888 and characterized by the National Organization of Rare Disorders (NORD) as a chronic pain condition of the adipose tissue generally found in patients who are overweight or obese.1,2 AD is more common in females aged 35 to 50 years and proposed to be a disease of postmenopausal women, though no prevalence studies exist.2 The etiology remains unclear.2 Several theories have been proposed, including endocrine and nervous system dysfunction, adipose tissue dysregulation, or pressure on peripheral nerves and chronic inflammation.2-4 Genetic, autoimmune, and trauma also have been proposed as a mechanism for developing the disease. Treatment modalities focusing on narcotic analgesics have been ineffective in long-term management.3

The objective of the case presentation is to report a variety of approaches for AD and their relative successes at pain control in order to assist other medical professionals who may come across patients with this rare condition.

Case Presentation

A 53-year-old male with a history of blast exposure-related traumatic brain injury, subsequent stroke with residual left hemiparesis, and seizure disorder presented with a 10-year history of nodule formation in his lower extremities causing restriction of motion and pain. The patient had previously undergone lower extremity fasciotomies for compartment syndrome with minimal pain relief. In addition, nodules over his abdomen and chest wall had been increasing over the past 5 years. He also experienced worsening fatigue, cramping, tightness, and paresthesias of the affected areas during this time. Erythema and temperature allodynia were noted in addition to an 80-pound weight gain. From the above symptoms and nodule excision showing histologic signs of lipomatous growth, a diagnosis of AD was made.

The following constitutes the approximate timetable of his treatments for 9 years. He was first diagnosed incidentally at the beginning of this period with AD during an electrodiagnostic examination. He had noticed the lipomas when he was in his 30s, but initially they were not painful. He was referred for treatment of pain to the physical medicine and rehabilitation department.

For the next 3 years, he was treated with prolotherapy. Five percent dextrose in water was injected around many of the painful lipomas in the upper extremities. He noted after the second round of neural prolotherapy that he had reduced swelling of his upper extremities and the lipomas decreased in size. He experienced mild improvement in pain and functional usage of his arms.

He continued to receive neural prolotherapy into the nodules in the arms, legs, abdomen, and chest wall. The number of painful nodules continued to increase, and the patient was started on hydrocodone 10 mg/acetaminophen 325 mg (1 tablet every 6 hours as needed) and methadone for pain relief. He was initially started on 5 mg per day of methadone and then was increased in a stepwise, gradual fashion to 10 mg in the morning and 15 mg in the evening. He transitioned to morphine sulfate, which was increased to a maximum dose of 45 mg twice daily. This medication was slowly tapered due to adverse effects (AEs), including sedation.

After weaning off morphine sulfate, the patient was started on lidocaine infusions every 3 months. Each infusion provided at least 50% pain reduction for 6 to 8 weeks. He was approved by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to have Vaser (Bausch Health, Laval, Canada) minimally invasive ultrasound liposuction treatment, performed at an outside facility. The patient was satisfied with the pain relief that he received and noted that the number of lipomas greatly diminished. However, due to funding issues, this treatment was discontinued after several months.

The patient had moderately good pain relief with methadone 5 mg in the morning, and 15 mg in the evening. However, the patient reported significant somnolence during the daytime with the regimen. Attempts to wean the patient off methadone was met with uncontrollable daytime pain. With suboptimal oral pain regimen, difficulty obtaining Vaser treatments, and limitation in frequency of neural prolotherapy, the decision was made to initiate 12 treatments of Calmare (Fairfield, CT) cutaneous electrostimulation.

During his first treatment, he had the electrodes placed on his lower extremities. The pre- and posttreatment 10-point visual analog scale (VAS) scores were 9 and 0, respectively, after the first visit. The position of the electrodes varied, depending on the location of his pain, including upper extremities and abdominal wall. During the treatment course, the patient experienced an improvement in subjective functional status. He was able to sleep in the same bed as his wife, shake hands without severe pain, and walk .25 mile, all of which he was unable to do before the electrostimulative treatment. He also reported overall improvement in emotional well-being, resumption of his hobbies (eg, playing the guitar), and social engagement. Methadone was successfully weaned off during this trial without breakthrough pain. This improvement in pain and functional status continued for several weeks; however, he had an exacerbation of his pain following a long plane flight. Due to uncertain reliability of pain relief with the procedure, the pain management service initiated a regimen of methadone 10 mg twice daily to be initiated when a procedure does not provide the desired duration of pain relief and gradually discontinued following the next interventional procedure.

The patient continued a regimen that included lidocaine infusions, neural prolotherapy, Calmare electrostimulative therapy, as well as lymphedema massage. Additionally, he began receiving weekly acupuncture treatments. He started with traditional full body acupuncture and then transitioned to battlefield acupuncture (BFA). Each acupuncture treatment provided about 50% improvement in pain on the VAS, and improved sleep for 3 days posttreatment.

However, after 18 months of the above treatment protocol, the patient experienced a general tonic-clonic seizure at home. Due to concern for the lowered seizure threshold, lidocaine infusions and methadone were discontinued. Long-acting oral morphine was initiated. The patient continued Calmare treatments and neural prolotherapy after a seizure-free interval. This regimen provided the patient with temporary pain relief but for a shorter duration than prior interventions.

Ketamine infusions were eventually initiated about 5 years after the diagnosis of AD was made, with postprocedure pain as 0/10 on the VAS. Pain relief was sustained for 3 months, with the notable AEs of hallucinations in the immediate postinfusion period. Administration consisted of the following: 500 mg of ketamine in a 500 mL bag of 0.9% NaCl. A 60-mg slow IV push was given followed by 60 mg/h increased every 15 min by 10 mg/h for a maximum dose of 150 mg/h. In a single visit the maximum total dose of ketamine administered was 500 mg. The protocol, which usually delivered 200 mg in a visit but was increased to 500 mg because the 200-mg dose was ineffective, was based on protocols at other institutions to accommodate the level of monitoring available in the Interventional Pain Clinic. The clinic also developed an infusion protocol with at least 1 month between treatments. The patient continues to undergo scheduled ketamine infusions every 14 weeks in addition to monthly BFA. The patient reported near total pain relief for about a month following ketamine infusion, with about 3 months of sustained pain relief. Each BFA session continues to provide 3 days of relief from insomnia. Calmare treatments and the neural prolotherapy regimen continue to provide effective but temporary relief from pain.

Discussion

Currently there is no curative treatment for AD. The majority of the literature is composed of case reports without summaries of potential interventions and their efficacies. AD therapies focus on symptom relief and mainly include pharmacologic and surgical intervention. In this case report several novel treatment modalities have been shown to be partially effective.

Surgical Intervention

Liposuction and lipoma resection have been described as effective only in the short term for AD.2,4-6 Hansson and colleagues suggested liposuction avulsion for sensory nerves and a portion of the proposed abnormal nerve connections between the peripheral nervous system and sensory nerves as a potential therapy for pain improvement.5 But the clinical significance of pain relief from liposuction is unclear and is contraindicated in recurrent lipomas.5

Pharmaceutical Approach

Although relief with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and narcotic analgesics have been unpredictable, Herbst and Asare-Bediako described significant pain relief in a subset of patients with AD with a variety of oral analgesics.7,8 However, the duration of this relief was not clearly stated, and the types or medications or combinations were not discussed. Other pharmacologic agents trialed in the treatment of AD include methotrexate, infliximab, Interferon α-2b, and calcium channel modulators (pregabalin and oxcarbazepine).2,9-11 However, the mechanism and significance of pain relief from these medications remain unclear.

Subanesthesia Therapy

Lidocaine has been used as both a topical agent and an IV infusion in the treatment of chronic pain due to AD for decades. Desai and colleagues described 60% sustained pain reduction in a patient using lidocaine 5% transdermal patches.4 IV infusion of lidocaine has been described in various dosages, though the mechanism of pain relief is ambiguous, and the duration of effect is longer than the biologic half-life.2-4,9 Kosseifi and colleagues describe a patient treated with local injections of lidocaine 1% and obtained symptomatic relief for 3 weeks.9 Animal studies suggest the action of lidocaine involves the sodium channels in peripheral nerves, while another study suggested there may be an increase in sympathetic nervous system activity after the infusion of lidocaine.2,9

Ketamine infusions not previously described in the treatment of AD have long been used to treat other chronic pain syndromes (chronic cancer pain, complex regional pain syndrome [CRPS], fibromyalgia, migraine, ischemic pain, and neuropathic pain).9,12,13 Ketamine has been shown to decrease pain intensity and reduce the amount of opioid analgesic necessary to achieve pain relief, likely through the antagonism of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors.12 A retrospective review by Patil and Anitescu described subanesthetic ketamine infusions used as a last-line therapy in refractory pain syndromes. They found ketamine reduced VAS scores from mean 8.5 prior to infusion to 0.8 after infusion in patients with CRPS and from 7.0 prior to infusion to 1.0 in patient with non-CRPS refractory pain syndromes.13 Hypertension and sedation were the most frequent AEs of ketamine infusion, though a higher incidence of hallucination and confusion were noted in non-CRPS patients. Hocking and Cousins suggest that psychotomimetic AEs of ketamine infusion may be more likely in patients with anxiety.14 However, it is important to note that ketamine infusion studies have been heterogeneous in their protocol, and only recently have standardization guidelines been proposed.

Physical Modalities

Manual lymphatic massage has been described in multiple reports for symptom relief in patients with cancer with malignant growth causing outflow lymphatic obstruction. This technique also has been used to treat the obstructive symptoms seen with the lipomatous growths of AD. Lange and colleagues described a case as providing reduction in pain and the diameter of extremities with twice weekly massage.14 Herbst and colleagues noted that patients had an equivocal response to massage, with some patients finding that it worsened the progression of lipomatous growths.7

Electrocutaneous Stimulation

In a case study by Martinenghi and colleagues, a patient with AD improved following transcutaneous frequency rhythmic electrical modulation system (FREMS) treatment.16 The treatment involved 4 cycles of 30 minutes each for 6 months. The patient had an improvement of pain on the VAS from 6.4 to 1.7 and an increase from 12 to 18 on the 100-point Barthel index scale for performance in activities of daily living, suggesting an improvement of functional independence as well.16

The MC5-A Calmare is another cutaneous electrostimulation modality that previously has been used for chronic cancer pain management. This FDA-cleared device is indicated for the treatment of various chronic pain syndromes. The device is proposed to stimulate 5 separate pain areas via cutaneous electrodes applied beyond and above the painful areas in order to “scramble” pain information and reduce perception of chronic pain intensity. Ricci and colleagues included cancer and noncancer subjects in their study and observed reduction in pain intensity by 74% (on numeric rating scale) in the entire subject group after 10 days of treatments. Further, no AEs were reported in either group, and most of the subjects were willing to continue treatment.17 However, this modality was limited by concerns with insurance coverage, access to a Calmare machine, operator training, and reproducibility of electrode placement to achieve “zero pain” as is the determinant of device treatment cycle output by the manufacturer.

Perineural Injection/Prolotherapy

Perineural injection therapy (PIT) involves the injection of dextrose solution into tissues surrounding an inflamed nerve to reduce neuropathic inflammation. The proposed source of this inflammation is the stimulation of the superficial branches of peptidergic peripheral nerves. Injections are SC and target the affected superficial nerve pathway. Pain relief is usually immediate but requires several treatments to ensure a lasting benefit. There have been no research studies or case reports on the use of PIT or prolotherapy and AD. Although there is a paucity of published literature on the efficacy of PIT, it remains an alternative modality for treatment of chronic pain syndromes. In a systematic review of prolotherapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain, Hauser and colleagues supported the use of dextrose prolotherapy to treat chronic tendinopathies, osteoarthritis of finger and knee joints, spinal and pelvic pain if conservative measures had failed. However, the efficacy on acute musculoskeletal pain was uncertain.18 In addition to the paucity of published literature, prolotherapy is not available to many patients due to lack of insurance coverage or lack of providers able to perform the procedure.

Hypobaric Pressure Therapy

Hypobaric pressure therapy has been offered as an alternative “touch-free” method for treatment of pain associated with edema. Herbst and Rutledge describe a pilot study focusing on hypobaric pressure therapy in patients with AD using a cyclic altitude conditioning system, which significantly decreased the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (tendency to catastrophize pain symptoms) in patients with AD after 5 days of therapy. VAS scores also demonstrated a linear decrease over 5 days.8

Acupuncture

There have been no research studies or case reports regarding the use of either traditional full body acupuncture or BFA in management of AD. However, prior studies have been performed that suggest that acupuncture can be beneficial in chronic pain relief. For examples, a Cochrane review by Manheimer and colleagues showed that acupuncture had a significant benefit in pain relief in subjects with peripheral joint arthritis.19 In another Cochrane review there was low-to-moderate level evidence compared with no treatment in pain relief, but moderate-level evidence that the effect of acupuncture does not differ from sham (placebo) acupuncture.20,21

Conclusion

Current therapeutic approaches to AD focus on invasive surgical intervention, chronic opiate and oral medication management. However, we have detailed several additional approaches to AD treatment. Ketamine infusions, which have long been a treatment in other chronic pain syndromes may present a viable alternative to lidocaine infusions in patients with AD. Electrocutaneous stimulation is a validated treatment of chronic pain syndromes, including chronic neuropathic pain and offers an alternative to surgical or pharmacologic management. Further, PIT offers another approach to neuropathic pain management, which has yet to be fully explored. As no standard treatment approach exists for patients with AD, multimodal therapies should be considered to optimize pain management and reduce dependency on opiate mediations.

Acknowledgments

Hunter Holmes McGuire Research Institute and the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Department provided the resources and facilities to make this work possible.

Adiposis dolorosa (AD), or Dercum disease, is a rare disorder that was first described in 1888 and characterized by the National Organization of Rare Disorders (NORD) as a chronic pain condition of the adipose tissue generally found in patients who are overweight or obese.1,2 AD is more common in females aged 35 to 50 years and proposed to be a disease of postmenopausal women, though no prevalence studies exist.2 The etiology remains unclear.2 Several theories have been proposed, including endocrine and nervous system dysfunction, adipose tissue dysregulation, or pressure on peripheral nerves and chronic inflammation.2-4 Genetic, autoimmune, and trauma also have been proposed as a mechanism for developing the disease. Treatment modalities focusing on narcotic analgesics have been ineffective in long-term management.3

The objective of the case presentation is to report a variety of approaches for AD and their relative successes at pain control in order to assist other medical professionals who may come across patients with this rare condition.

Case Presentation

A 53-year-old male with a history of blast exposure-related traumatic brain injury, subsequent stroke with residual left hemiparesis, and seizure disorder presented with a 10-year history of nodule formation in his lower extremities causing restriction of motion and pain. The patient had previously undergone lower extremity fasciotomies for compartment syndrome with minimal pain relief. In addition, nodules over his abdomen and chest wall had been increasing over the past 5 years. He also experienced worsening fatigue, cramping, tightness, and paresthesias of the affected areas during this time. Erythema and temperature allodynia were noted in addition to an 80-pound weight gain. From the above symptoms and nodule excision showing histologic signs of lipomatous growth, a diagnosis of AD was made.

The following constitutes the approximate timetable of his treatments for 9 years. He was first diagnosed incidentally at the beginning of this period with AD during an electrodiagnostic examination. He had noticed the lipomas when he was in his 30s, but initially they were not painful. He was referred for treatment of pain to the physical medicine and rehabilitation department.

For the next 3 years, he was treated with prolotherapy. Five percent dextrose in water was injected around many of the painful lipomas in the upper extremities. He noted after the second round of neural prolotherapy that he had reduced swelling of his upper extremities and the lipomas decreased in size. He experienced mild improvement in pain and functional usage of his arms.

He continued to receive neural prolotherapy into the nodules in the arms, legs, abdomen, and chest wall. The number of painful nodules continued to increase, and the patient was started on hydrocodone 10 mg/acetaminophen 325 mg (1 tablet every 6 hours as needed) and methadone for pain relief. He was initially started on 5 mg per day of methadone and then was increased in a stepwise, gradual fashion to 10 mg in the morning and 15 mg in the evening. He transitioned to morphine sulfate, which was increased to a maximum dose of 45 mg twice daily. This medication was slowly tapered due to adverse effects (AEs), including sedation.

After weaning off morphine sulfate, the patient was started on lidocaine infusions every 3 months. Each infusion provided at least 50% pain reduction for 6 to 8 weeks. He was approved by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to have Vaser (Bausch Health, Laval, Canada) minimally invasive ultrasound liposuction treatment, performed at an outside facility. The patient was satisfied with the pain relief that he received and noted that the number of lipomas greatly diminished. However, due to funding issues, this treatment was discontinued after several months.

The patient had moderately good pain relief with methadone 5 mg in the morning, and 15 mg in the evening. However, the patient reported significant somnolence during the daytime with the regimen. Attempts to wean the patient off methadone was met with uncontrollable daytime pain. With suboptimal oral pain regimen, difficulty obtaining Vaser treatments, and limitation in frequency of neural prolotherapy, the decision was made to initiate 12 treatments of Calmare (Fairfield, CT) cutaneous electrostimulation.

During his first treatment, he had the electrodes placed on his lower extremities. The pre- and posttreatment 10-point visual analog scale (VAS) scores were 9 and 0, respectively, after the first visit. The position of the electrodes varied, depending on the location of his pain, including upper extremities and abdominal wall. During the treatment course, the patient experienced an improvement in subjective functional status. He was able to sleep in the same bed as his wife, shake hands without severe pain, and walk .25 mile, all of which he was unable to do before the electrostimulative treatment. He also reported overall improvement in emotional well-being, resumption of his hobbies (eg, playing the guitar), and social engagement. Methadone was successfully weaned off during this trial without breakthrough pain. This improvement in pain and functional status continued for several weeks; however, he had an exacerbation of his pain following a long plane flight. Due to uncertain reliability of pain relief with the procedure, the pain management service initiated a regimen of methadone 10 mg twice daily to be initiated when a procedure does not provide the desired duration of pain relief and gradually discontinued following the next interventional procedure.

The patient continued a regimen that included lidocaine infusions, neural prolotherapy, Calmare electrostimulative therapy, as well as lymphedema massage. Additionally, he began receiving weekly acupuncture treatments. He started with traditional full body acupuncture and then transitioned to battlefield acupuncture (BFA). Each acupuncture treatment provided about 50% improvement in pain on the VAS, and improved sleep for 3 days posttreatment.

However, after 18 months of the above treatment protocol, the patient experienced a general tonic-clonic seizure at home. Due to concern for the lowered seizure threshold, lidocaine infusions and methadone were discontinued. Long-acting oral morphine was initiated. The patient continued Calmare treatments and neural prolotherapy after a seizure-free interval. This regimen provided the patient with temporary pain relief but for a shorter duration than prior interventions.

Ketamine infusions were eventually initiated about 5 years after the diagnosis of AD was made, with postprocedure pain as 0/10 on the VAS. Pain relief was sustained for 3 months, with the notable AEs of hallucinations in the immediate postinfusion period. Administration consisted of the following: 500 mg of ketamine in a 500 mL bag of 0.9% NaCl. A 60-mg slow IV push was given followed by 60 mg/h increased every 15 min by 10 mg/h for a maximum dose of 150 mg/h. In a single visit the maximum total dose of ketamine administered was 500 mg. The protocol, which usually delivered 200 mg in a visit but was increased to 500 mg because the 200-mg dose was ineffective, was based on protocols at other institutions to accommodate the level of monitoring available in the Interventional Pain Clinic. The clinic also developed an infusion protocol with at least 1 month between treatments. The patient continues to undergo scheduled ketamine infusions every 14 weeks in addition to monthly BFA. The patient reported near total pain relief for about a month following ketamine infusion, with about 3 months of sustained pain relief. Each BFA session continues to provide 3 days of relief from insomnia. Calmare treatments and the neural prolotherapy regimen continue to provide effective but temporary relief from pain.

Discussion

Currently there is no curative treatment for AD. The majority of the literature is composed of case reports without summaries of potential interventions and their efficacies. AD therapies focus on symptom relief and mainly include pharmacologic and surgical intervention. In this case report several novel treatment modalities have been shown to be partially effective.

Surgical Intervention

Liposuction and lipoma resection have been described as effective only in the short term for AD.2,4-6 Hansson and colleagues suggested liposuction avulsion for sensory nerves and a portion of the proposed abnormal nerve connections between the peripheral nervous system and sensory nerves as a potential therapy for pain improvement.5 But the clinical significance of pain relief from liposuction is unclear and is contraindicated in recurrent lipomas.5

Pharmaceutical Approach

Although relief with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and narcotic analgesics have been unpredictable, Herbst and Asare-Bediako described significant pain relief in a subset of patients with AD with a variety of oral analgesics.7,8 However, the duration of this relief was not clearly stated, and the types or medications or combinations were not discussed. Other pharmacologic agents trialed in the treatment of AD include methotrexate, infliximab, Interferon α-2b, and calcium channel modulators (pregabalin and oxcarbazepine).2,9-11 However, the mechanism and significance of pain relief from these medications remain unclear.

Subanesthesia Therapy

Lidocaine has been used as both a topical agent and an IV infusion in the treatment of chronic pain due to AD for decades. Desai and colleagues described 60% sustained pain reduction in a patient using lidocaine 5% transdermal patches.4 IV infusion of lidocaine has been described in various dosages, though the mechanism of pain relief is ambiguous, and the duration of effect is longer than the biologic half-life.2-4,9 Kosseifi and colleagues describe a patient treated with local injections of lidocaine 1% and obtained symptomatic relief for 3 weeks.9 Animal studies suggest the action of lidocaine involves the sodium channels in peripheral nerves, while another study suggested there may be an increase in sympathetic nervous system activity after the infusion of lidocaine.2,9

Ketamine infusions not previously described in the treatment of AD have long been used to treat other chronic pain syndromes (chronic cancer pain, complex regional pain syndrome [CRPS], fibromyalgia, migraine, ischemic pain, and neuropathic pain).9,12,13 Ketamine has been shown to decrease pain intensity and reduce the amount of opioid analgesic necessary to achieve pain relief, likely through the antagonism of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors.12 A retrospective review by Patil and Anitescu described subanesthetic ketamine infusions used as a last-line therapy in refractory pain syndromes. They found ketamine reduced VAS scores from mean 8.5 prior to infusion to 0.8 after infusion in patients with CRPS and from 7.0 prior to infusion to 1.0 in patient with non-CRPS refractory pain syndromes.13 Hypertension and sedation were the most frequent AEs of ketamine infusion, though a higher incidence of hallucination and confusion were noted in non-CRPS patients. Hocking and Cousins suggest that psychotomimetic AEs of ketamine infusion may be more likely in patients with anxiety.14 However, it is important to note that ketamine infusion studies have been heterogeneous in their protocol, and only recently have standardization guidelines been proposed.

Physical Modalities

Manual lymphatic massage has been described in multiple reports for symptom relief in patients with cancer with malignant growth causing outflow lymphatic obstruction. This technique also has been used to treat the obstructive symptoms seen with the lipomatous growths of AD. Lange and colleagues described a case as providing reduction in pain and the diameter of extremities with twice weekly massage.14 Herbst and colleagues noted that patients had an equivocal response to massage, with some patients finding that it worsened the progression of lipomatous growths.7

Electrocutaneous Stimulation

In a case study by Martinenghi and colleagues, a patient with AD improved following transcutaneous frequency rhythmic electrical modulation system (FREMS) treatment.16 The treatment involved 4 cycles of 30 minutes each for 6 months. The patient had an improvement of pain on the VAS from 6.4 to 1.7 and an increase from 12 to 18 on the 100-point Barthel index scale for performance in activities of daily living, suggesting an improvement of functional independence as well.16

The MC5-A Calmare is another cutaneous electrostimulation modality that previously has been used for chronic cancer pain management. This FDA-cleared device is indicated for the treatment of various chronic pain syndromes. The device is proposed to stimulate 5 separate pain areas via cutaneous electrodes applied beyond and above the painful areas in order to “scramble” pain information and reduce perception of chronic pain intensity. Ricci and colleagues included cancer and noncancer subjects in their study and observed reduction in pain intensity by 74% (on numeric rating scale) in the entire subject group after 10 days of treatments. Further, no AEs were reported in either group, and most of the subjects were willing to continue treatment.17 However, this modality was limited by concerns with insurance coverage, access to a Calmare machine, operator training, and reproducibility of electrode placement to achieve “zero pain” as is the determinant of device treatment cycle output by the manufacturer.

Perineural Injection/Prolotherapy

Perineural injection therapy (PIT) involves the injection of dextrose solution into tissues surrounding an inflamed nerve to reduce neuropathic inflammation. The proposed source of this inflammation is the stimulation of the superficial branches of peptidergic peripheral nerves. Injections are SC and target the affected superficial nerve pathway. Pain relief is usually immediate but requires several treatments to ensure a lasting benefit. There have been no research studies or case reports on the use of PIT or prolotherapy and AD. Although there is a paucity of published literature on the efficacy of PIT, it remains an alternative modality for treatment of chronic pain syndromes. In a systematic review of prolotherapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain, Hauser and colleagues supported the use of dextrose prolotherapy to treat chronic tendinopathies, osteoarthritis of finger and knee joints, spinal and pelvic pain if conservative measures had failed. However, the efficacy on acute musculoskeletal pain was uncertain.18 In addition to the paucity of published literature, prolotherapy is not available to many patients due to lack of insurance coverage or lack of providers able to perform the procedure.

Hypobaric Pressure Therapy

Hypobaric pressure therapy has been offered as an alternative “touch-free” method for treatment of pain associated with edema. Herbst and Rutledge describe a pilot study focusing on hypobaric pressure therapy in patients with AD using a cyclic altitude conditioning system, which significantly decreased the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (tendency to catastrophize pain symptoms) in patients with AD after 5 days of therapy. VAS scores also demonstrated a linear decrease over 5 days.8

Acupuncture

There have been no research studies or case reports regarding the use of either traditional full body acupuncture or BFA in management of AD. However, prior studies have been performed that suggest that acupuncture can be beneficial in chronic pain relief. For examples, a Cochrane review by Manheimer and colleagues showed that acupuncture had a significant benefit in pain relief in subjects with peripheral joint arthritis.19 In another Cochrane review there was low-to-moderate level evidence compared with no treatment in pain relief, but moderate-level evidence that the effect of acupuncture does not differ from sham (placebo) acupuncture.20,21

Conclusion

Current therapeutic approaches to AD focus on invasive surgical intervention, chronic opiate and oral medication management. However, we have detailed several additional approaches to AD treatment. Ketamine infusions, which have long been a treatment in other chronic pain syndromes may present a viable alternative to lidocaine infusions in patients with AD. Electrocutaneous stimulation is a validated treatment of chronic pain syndromes, including chronic neuropathic pain and offers an alternative to surgical or pharmacologic management. Further, PIT offers another approach to neuropathic pain management, which has yet to be fully explored. As no standard treatment approach exists for patients with AD, multimodal therapies should be considered to optimize pain management and reduce dependency on opiate mediations.

Acknowledgments

Hunter Holmes McGuire Research Institute and the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Department provided the resources and facilities to make this work possible.

1. Dercum FX. A subcutaneous dystrophy. In: University of Pennsylvania. University of Pennsylvania Medical Bulletin. Vol 1. Philadelphia, PA; University of Pennsylvania Press; 1888:140-150. Accessed October 4, 2019.

2. Hansson E, Svensson H, Brorson H. Review of Dercum’s disease and proposal of diagnositc criteria, diagnositic methods, classification and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:1-15.

3. Amine B, Leguilchard F, Benhamou CL. Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa): a new case-report. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71(2):147-149.

4. Desai MJ, Siriki R, Wang D. Treatment of pain in Dercum’s disease with lidoderm (lidocaine 5% patch): a case report. Pain Med. 2008;9(8):1224-1226.

5. Hansson E, Svensson H, Brorson H. Liposuction may reduce pain in Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa). Pain Med. 2011;12:942-952.

6. Kosseifi S, Anaya E, Dronovalli G, Leicht S. Dercum’s disease: an unusual presentation. Pain Med. 2010;11(9):1430-1434.

7. Herbst KL, Asare-Bediako S. Adiposis dolorasa is more than painful fat. Endocrinologist. 2007;17(6):326-334.

8. Herbst KL, Rutledge T. Pilot study: rapidly cycling hypobaric pressure improves pain after 5 days in adiposis dolorosa. J Pain Res. 2010;3:147-153.

9. Lange U, Oelzner P, Uhlemann C. Dercum’s disease (lipomatosis dolorosa): successful therapy with pregabalin and manual lymphatic drainage and a current overview. Rheumatol Int. 2008;29(1):17-22

10. Schaffer PR, Hale CS, Meehan SA, Shupack JL, Ramachandran S. Adoposis dolorosa. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20(12):1-3.

11. Singal A, Janiga JJ, Bossenbroek NM, Lim HW. Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa): a report of improvement with infliximab and methotrexate. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2007;21(5):717.

12. Loftus RW, Yeager MP, Clark JA, et al. Intraoperative ketamine reduces perioperative opiate consumption in opiate-dependent patients with chronic back pain undergoing back surgery. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(3):639-646.

13. Patil S, Anitescu M. Efficacy of outpatient ketamine infusions in refractory chronic pain syndromes: a 5-year retrospective analysis. Pain Med. 2012;13(2):263-269.

14. Hocking G, Cousins MJ. Ketamine in chronic pain management: an evidence-based review. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(6):1730-1739.

15. Cohen SP, Bhatia A, Buvanendran A, et al. Consensus guidelines on the use of intravenous ketamine infusions for chronic pain from the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(5):521-546.

16. Martinenghi S, Caretto A, Losio C, Scavini M, Bosi E. Successful treatment of Dercum’s disease by transcutaneous electrical stimulation: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(24):e950.

17. Ricci M, Pirotti S, Scarpi E, et al. Managing chronic pain: results from an open-label study using MC5-A Calmare device. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(2):405-412.

18. Hauser RA, Lackner JB, Steilen-Matias D, Harris DK. A systematic review of dextrose prolotherapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;9:139-159.

19. Manheimer E, Cheng K, Linde K, et al. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD001977.

20. Deare JC, Zheng Z, Xue CC, et al. Acupuncture for treating fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5):CD007070.

21. Chan MWC, Wu XY, Wu JCY, Wong SYS, Chung VCH. Safety of acupuncture: overview of systematic reviews. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3369.

1. Dercum FX. A subcutaneous dystrophy. In: University of Pennsylvania. University of Pennsylvania Medical Bulletin. Vol 1. Philadelphia, PA; University of Pennsylvania Press; 1888:140-150. Accessed October 4, 2019.

2. Hansson E, Svensson H, Brorson H. Review of Dercum’s disease and proposal of diagnositc criteria, diagnositic methods, classification and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:1-15.

3. Amine B, Leguilchard F, Benhamou CL. Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa): a new case-report. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71(2):147-149.

4. Desai MJ, Siriki R, Wang D. Treatment of pain in Dercum’s disease with lidoderm (lidocaine 5% patch): a case report. Pain Med. 2008;9(8):1224-1226.

5. Hansson E, Svensson H, Brorson H. Liposuction may reduce pain in Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa). Pain Med. 2011;12:942-952.

6. Kosseifi S, Anaya E, Dronovalli G, Leicht S. Dercum’s disease: an unusual presentation. Pain Med. 2010;11(9):1430-1434.

7. Herbst KL, Asare-Bediako S. Adiposis dolorasa is more than painful fat. Endocrinologist. 2007;17(6):326-334.

8. Herbst KL, Rutledge T. Pilot study: rapidly cycling hypobaric pressure improves pain after 5 days in adiposis dolorosa. J Pain Res. 2010;3:147-153.

9. Lange U, Oelzner P, Uhlemann C. Dercum’s disease (lipomatosis dolorosa): successful therapy with pregabalin and manual lymphatic drainage and a current overview. Rheumatol Int. 2008;29(1):17-22

10. Schaffer PR, Hale CS, Meehan SA, Shupack JL, Ramachandran S. Adoposis dolorosa. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20(12):1-3.

11. Singal A, Janiga JJ, Bossenbroek NM, Lim HW. Dercum’s disease (adiposis dolorosa): a report of improvement with infliximab and methotrexate. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2007;21(5):717.

12. Loftus RW, Yeager MP, Clark JA, et al. Intraoperative ketamine reduces perioperative opiate consumption in opiate-dependent patients with chronic back pain undergoing back surgery. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(3):639-646.

13. Patil S, Anitescu M. Efficacy of outpatient ketamine infusions in refractory chronic pain syndromes: a 5-year retrospective analysis. Pain Med. 2012;13(2):263-269.

14. Hocking G, Cousins MJ. Ketamine in chronic pain management: an evidence-based review. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(6):1730-1739.

15. Cohen SP, Bhatia A, Buvanendran A, et al. Consensus guidelines on the use of intravenous ketamine infusions for chronic pain from the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(5):521-546.

16. Martinenghi S, Caretto A, Losio C, Scavini M, Bosi E. Successful treatment of Dercum’s disease by transcutaneous electrical stimulation: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(24):e950.

17. Ricci M, Pirotti S, Scarpi E, et al. Managing chronic pain: results from an open-label study using MC5-A Calmare device. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(2):405-412.

18. Hauser RA, Lackner JB, Steilen-Matias D, Harris DK. A systematic review of dextrose prolotherapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;9:139-159.

19. Manheimer E, Cheng K, Linde K, et al. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD001977.

20. Deare JC, Zheng Z, Xue CC, et al. Acupuncture for treating fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5):CD007070.

21. Chan MWC, Wu XY, Wu JCY, Wong SYS, Chung VCH. Safety of acupuncture: overview of systematic reviews. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3369.

Systemic Epstein-Barr Virus–Positive T-cell Lymphoma of Childhood

Case Report

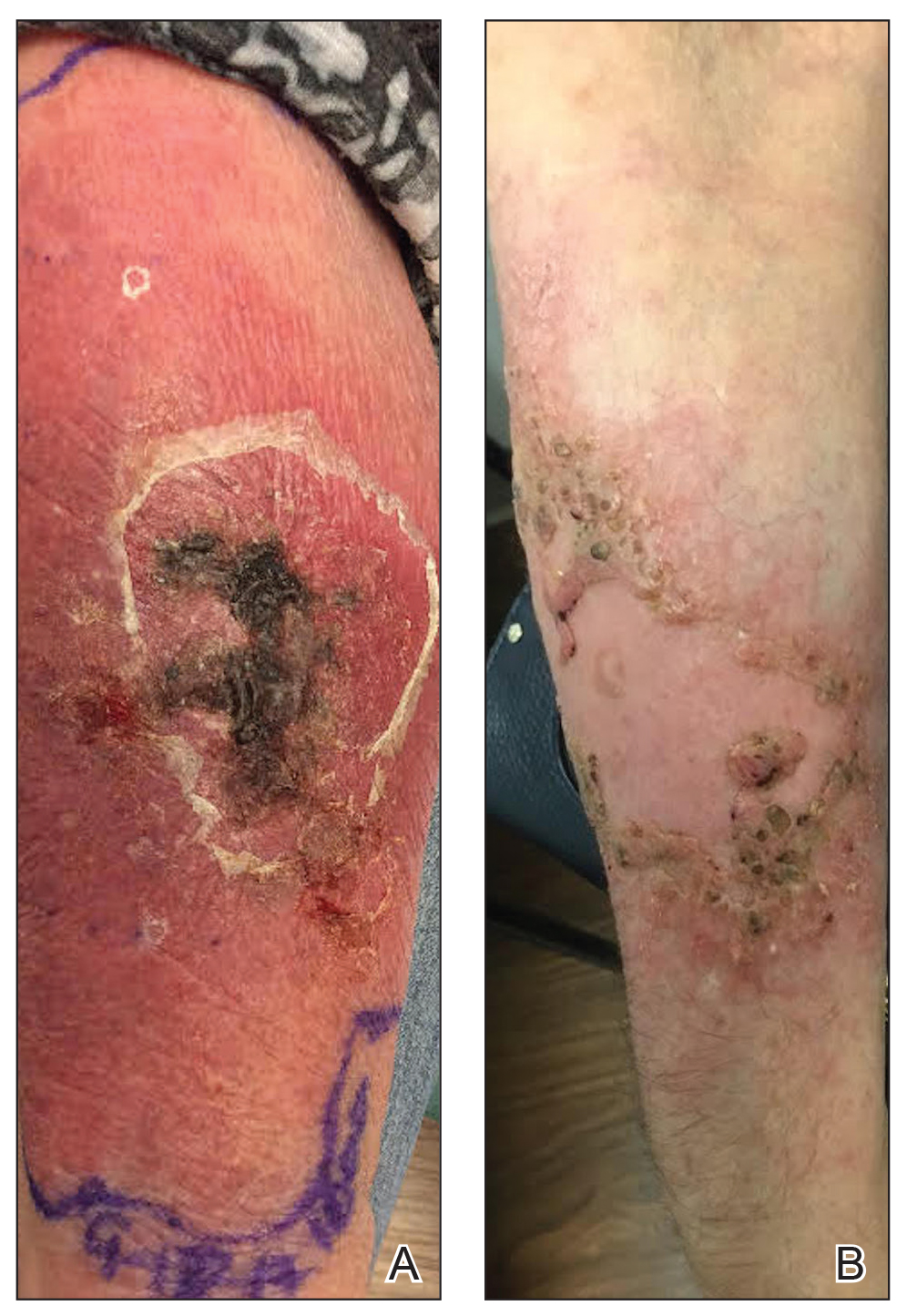

A 7-year-old Chinese boy presented with multiple painful oral and tongue ulcers of 2 weeks’ duration as well as acute onset of moderate to high fever (highest temperature, 39.3°C) for 5 days. The fever was reported to have run a relapsing course, accompanied by rigors but without convulsions or cognitive changes. At times, the patient had nasal congestion, nasal discharge, and cough. He also had a transient eruption on the back and hands as well as an indurated red nodule on the left forearm.

Before the patient was hospitalized, antibiotic therapy was administered by other physicians, but the condition of fever and oral ulcers did not improve. After the patient was hospitalized, new tender nodules emerged on the scalp, buttocks, and lower extremities. New ulcers also appeared on the palate.

History

Two months earlier, the patient had presented with a painful perioral skin ulcer that resolved after being treated as contagious eczema. Another dermatologist previously had considered a diagnosis of hand-foot-and-mouth disease.

The patient was born by normal spontaneous vaginal delivery, without abnormality. He was breastfed; feeding, growth, and the developmental history showed no abnormality. He was the family’s eldest child, with a healthy brother and sister. There was no history of familial illness. He received bacillus Calmette-Guérin and poliomyelitis vaccines after birth; the rest of the vaccine history was unclear. There was no history of immunologic abnormality.

Physical Examination

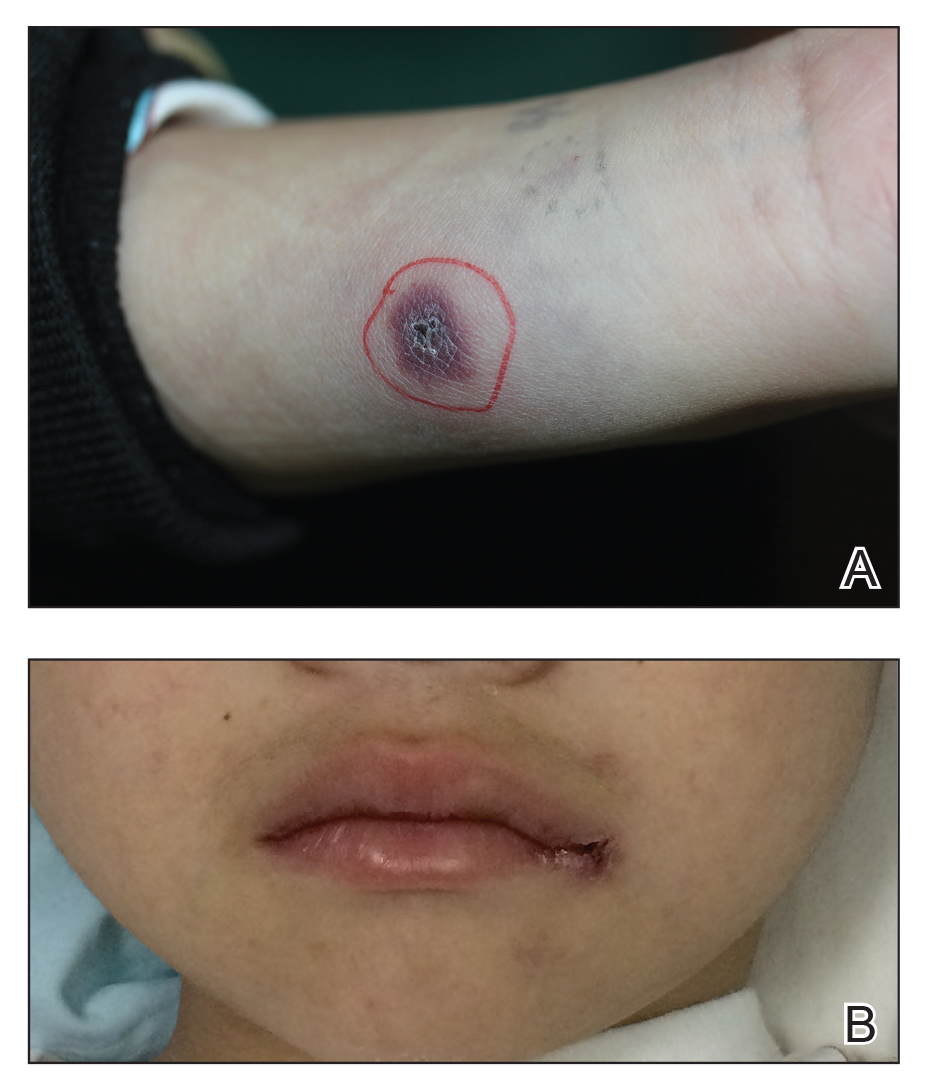

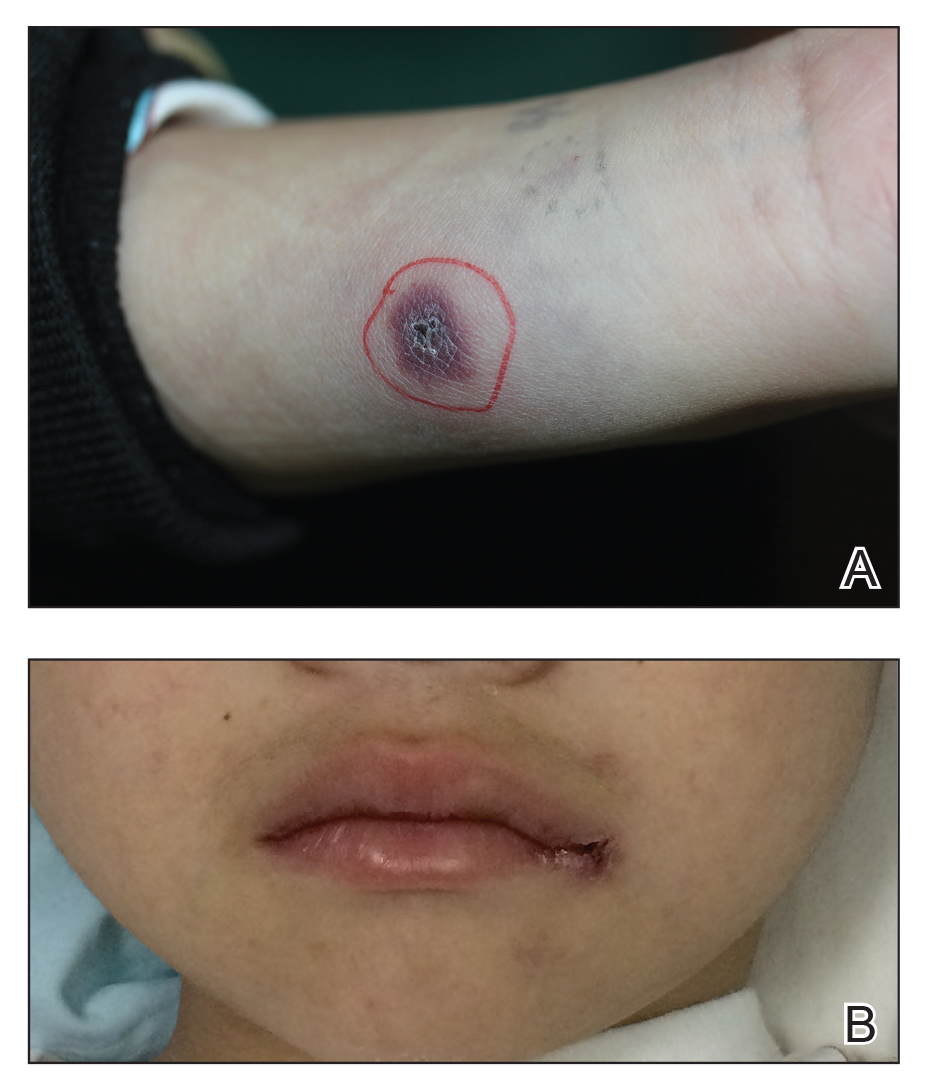

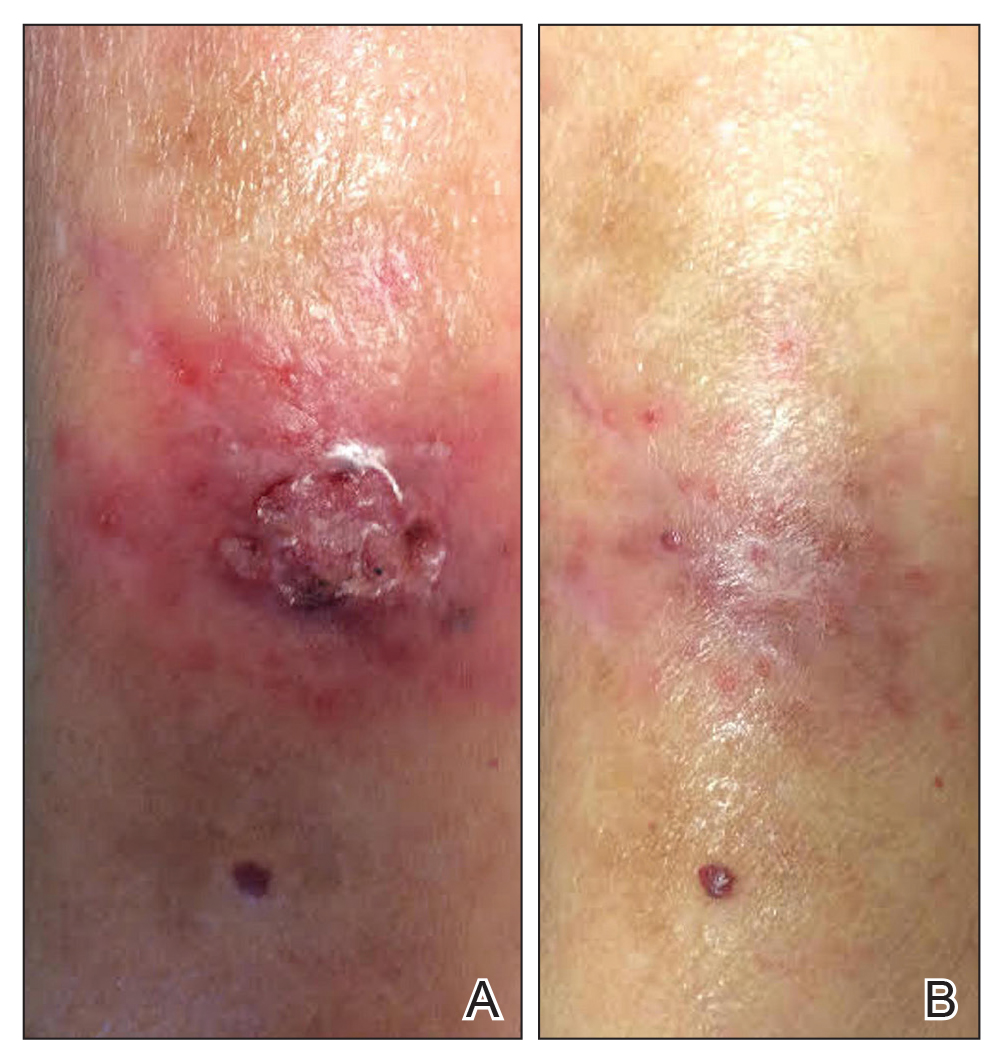

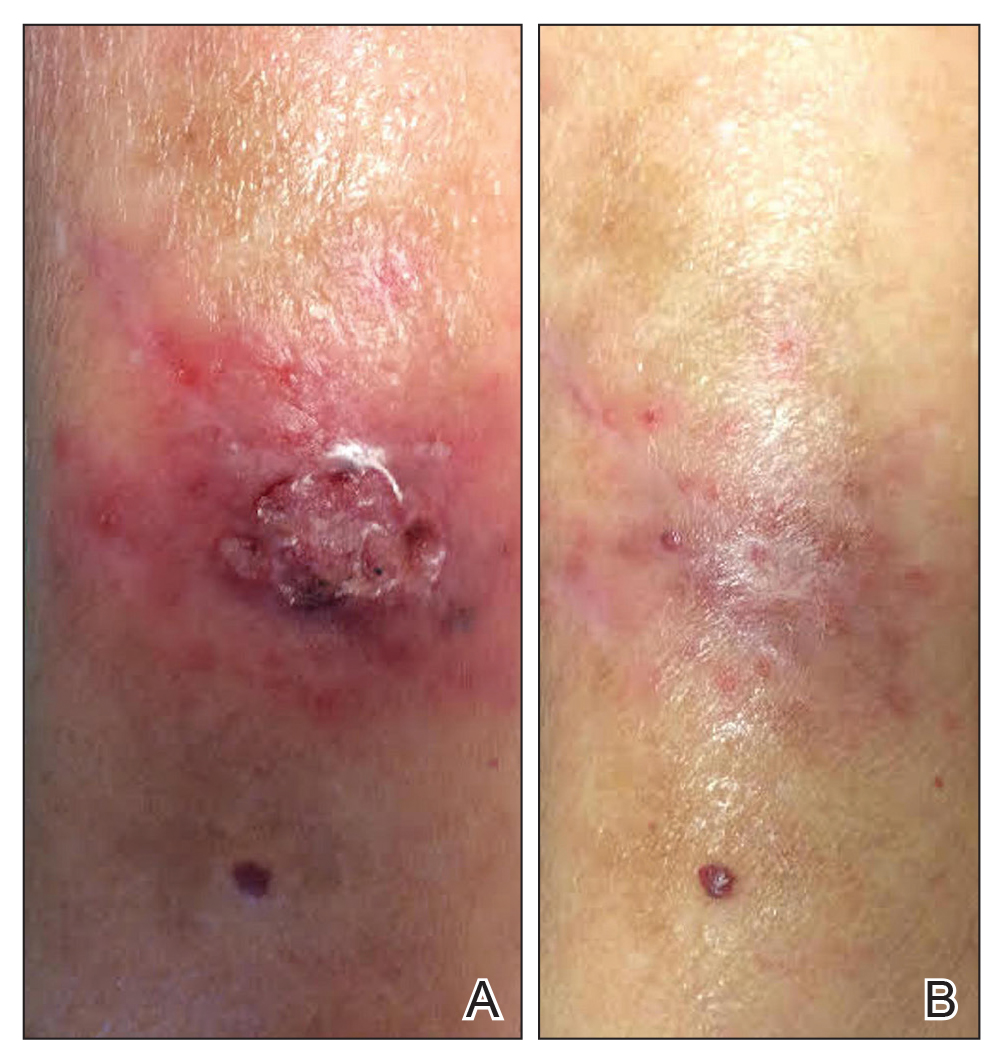

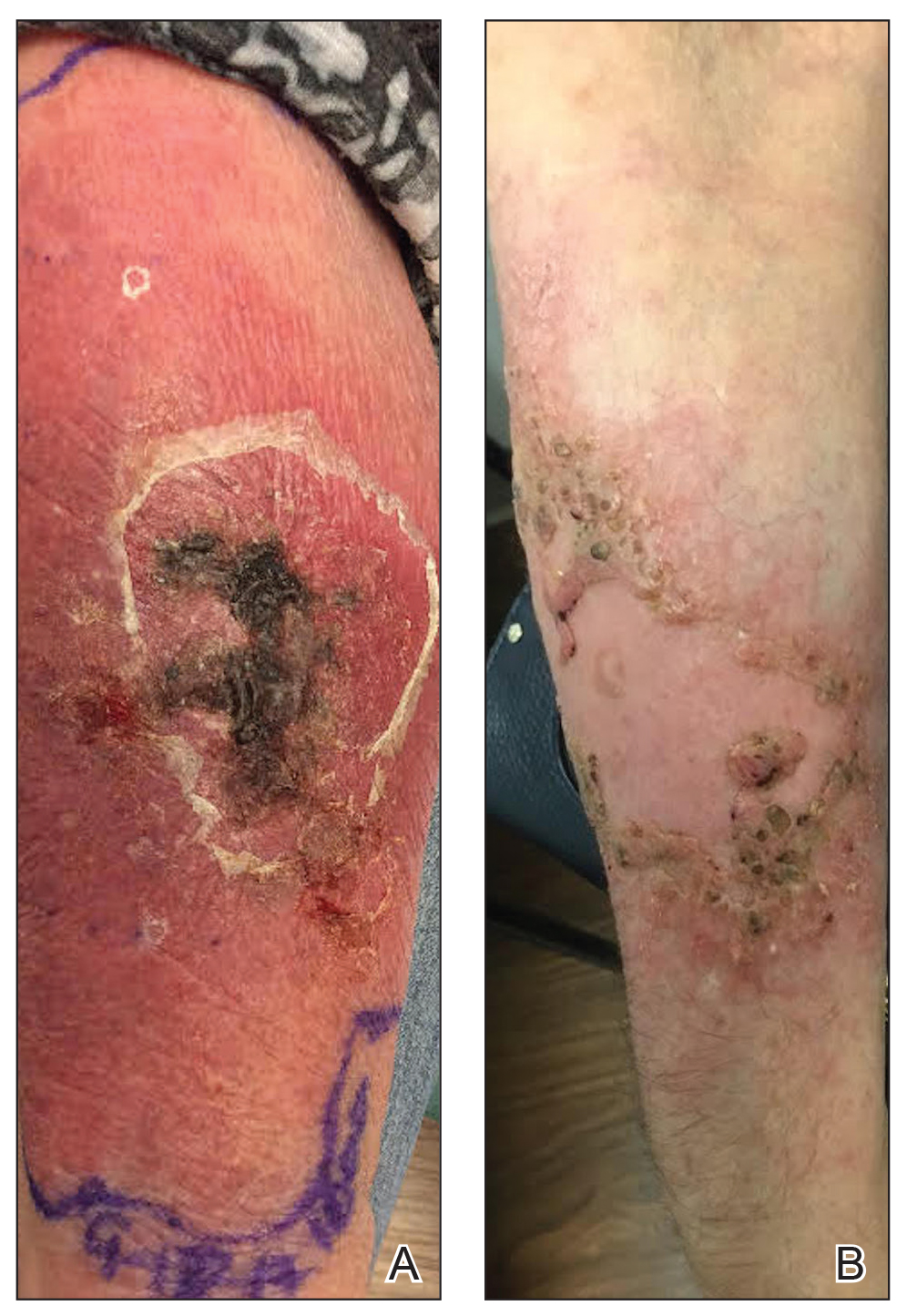

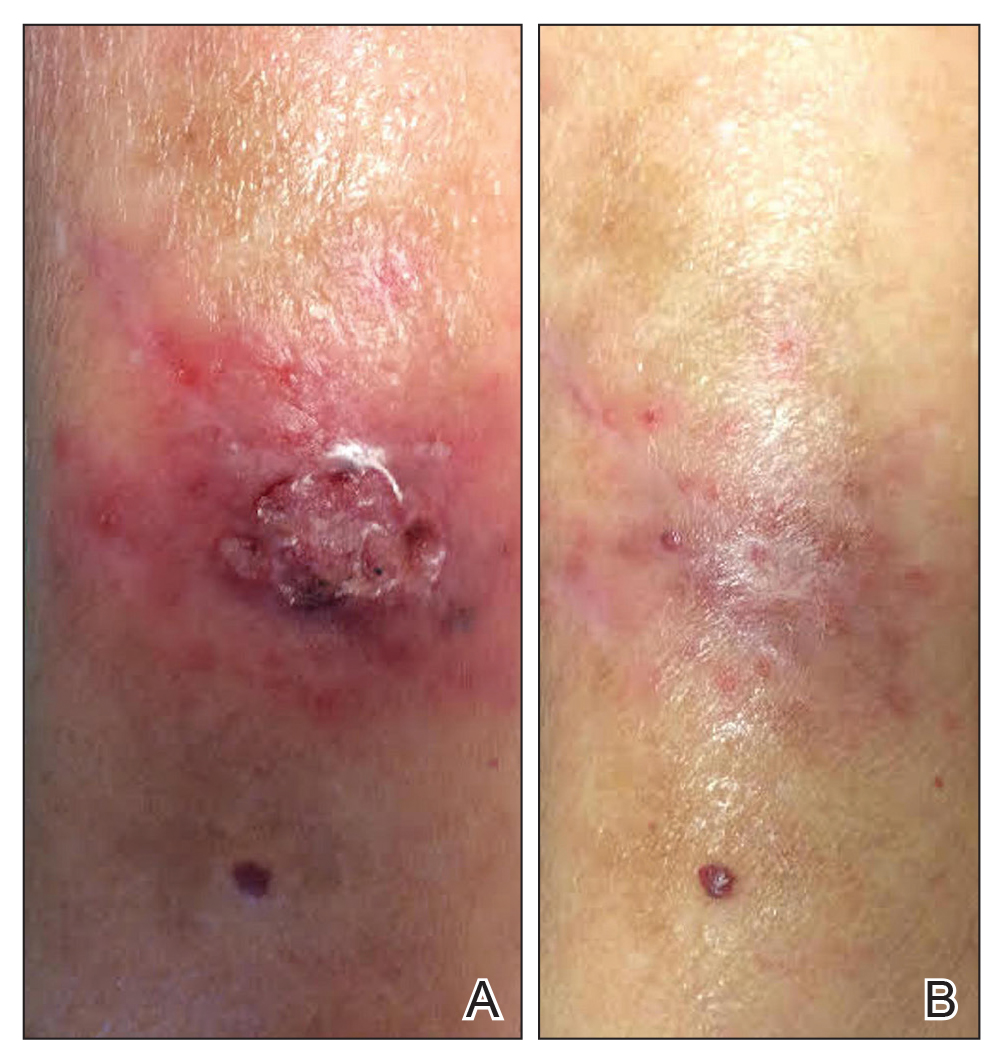

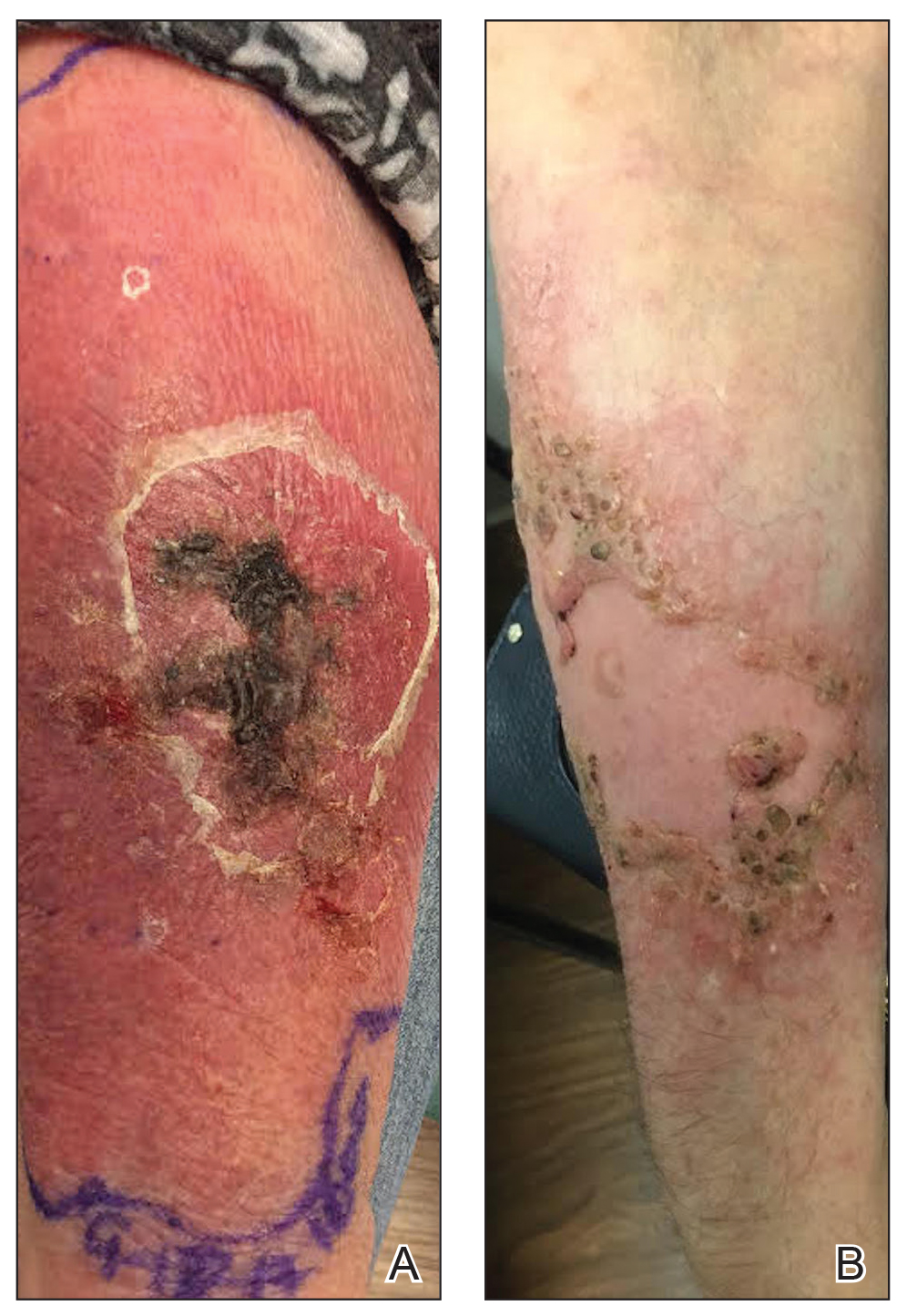

A 1.5×1.5-cm, warm, red nodule with a central black crust was noted on the left forearm (Figure 1A). Several similar lesions were noted on the buttocks, scalp, and lower extremities. Multiple ulcers, as large as 1 cm, were present on the tongue, palate, and left angle of the mouth (Figure 1B). The pharynx was congested, and the tonsils were mildly enlarged. Multiple enlarged, movable, nontender lymph nodes could be palpated in the cervical basins, axillae, and groin. No purpura or ecchymosis was detected.

Laboratory Results

Laboratory testing revealed a normal total white blood cell count (4.26×109/L [reference range, 4.0–12.0×109/L]), with normal neutrophils (1.36×109/L [reference range, 1.32–7.90×109/L]), lymphocytes (2.77×109/L [reference range, 1.20–6.00×109/L]), and monocytes (0.13×109/L [reference range, 0.08–0.80×109/L]); a mildly decreased hemoglobin level (115 g/L [reference range, 120–160 g/L]); a normal platelet count (102×109/L [reference range, 100–380×109/L]); an elevated lactate dehydrogenase level (614 U/L [reference range, 110–330 U/L]); an elevated α-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase level (483 U/L [reference range, 120–270 U/L]); elevated prothrombin time (15.3 s [reference range, 9–14 s]); elevated activated partial thromboplastin time (59.8 s [reference range, 20.6–39.6 s]); and an elevated D-dimer level (1.51 mg/L [reference range, <0.73 mg/L]). In addition, autoantibody testing revealed a positive antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 and a strong positive anti–Ro-52 level.

The peripheral blood lymphocyte classification demonstrated a prominent elevated percentage of T lymphocytes, with predominantly CD8+ cells (CD3, 94.87%; CD8, 71.57%; CD4, 24.98%; CD4:CD8 ratio, 0.35) and a diminished percentage of B lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cells. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) antibody testing was positive for anti–viral capsid antigen (VCA) IgG and negative for anti-VCA IgM.

Smears of the ulcer on the tongue demonstrated gram-positive cocci, gram-negative bacilli, and diplococci. Culture of sputum showed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Inspection for acid-fast bacilli in sputum yielded negative results 3 times. A purified protein derivative skin test for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection was negative.

Imaging and Other Studies

Computed tomography of the chest and abdomen demonstrated 2 nodular opacities on the lower right lung; spotted opacities on the upper right lung; floccular opacities on the rest area of the lung; mild pleural effusion; enlargement of lymph nodes on the mediastinum, the bilateral hilum of the lung, and mesentery; and hepatosplenomegaly. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia. Nasal cavity endoscopy showed sinusitis. Fundus examination showed vasculopathy of the left retina. A colonoscopy showed normal mucosa.

Histopathology

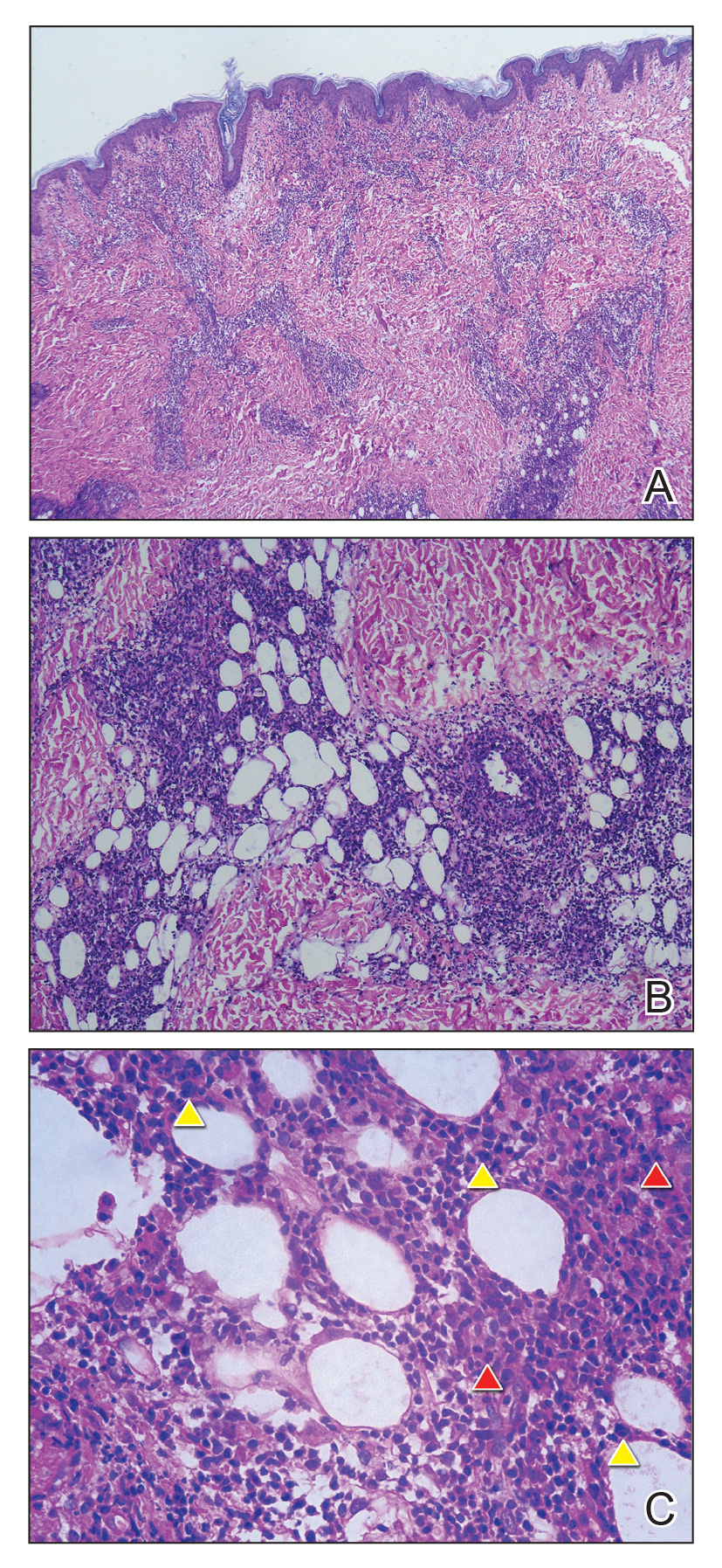

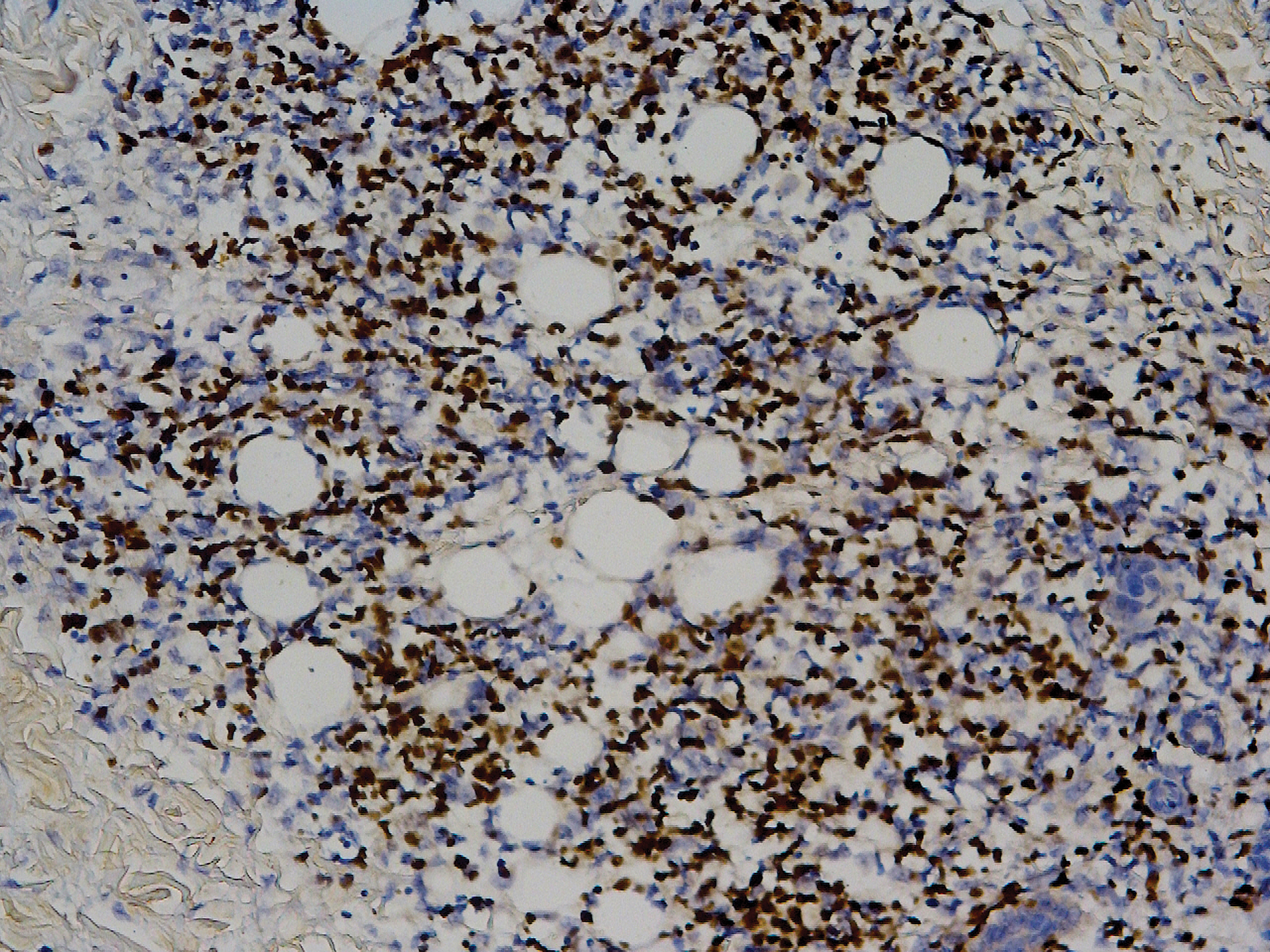

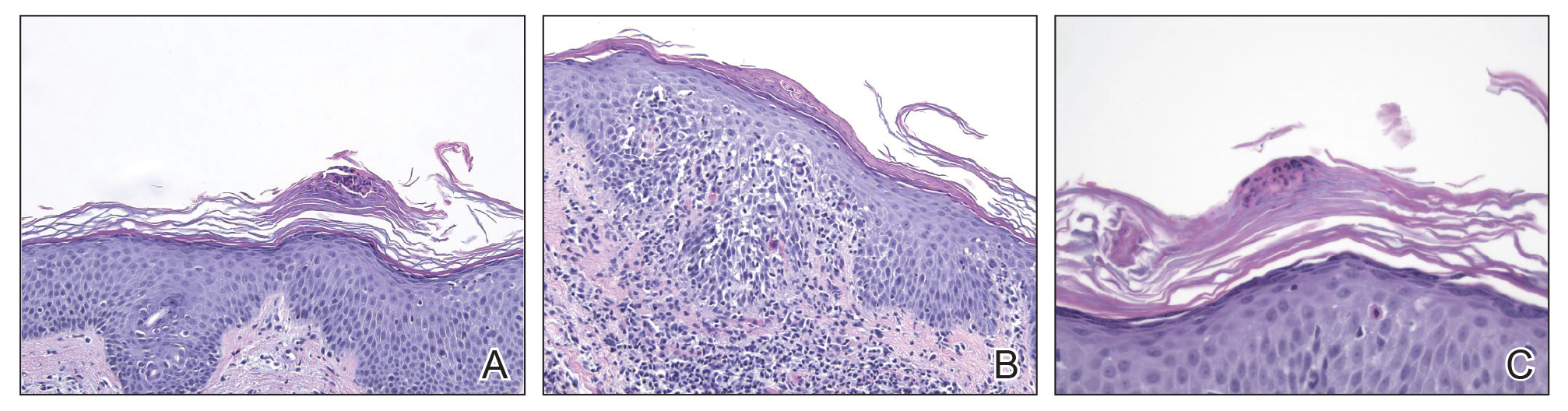

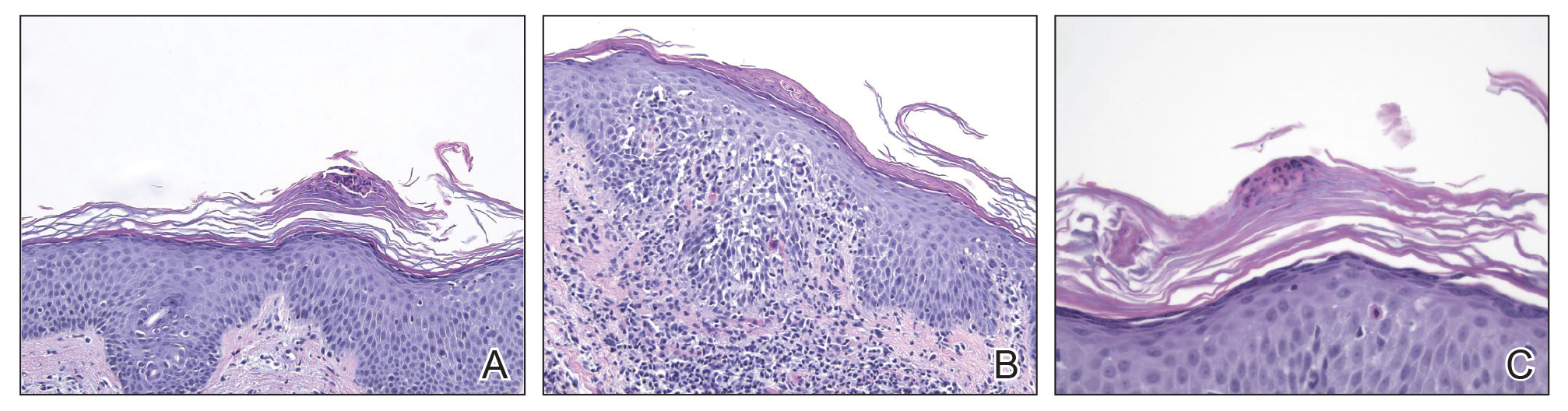

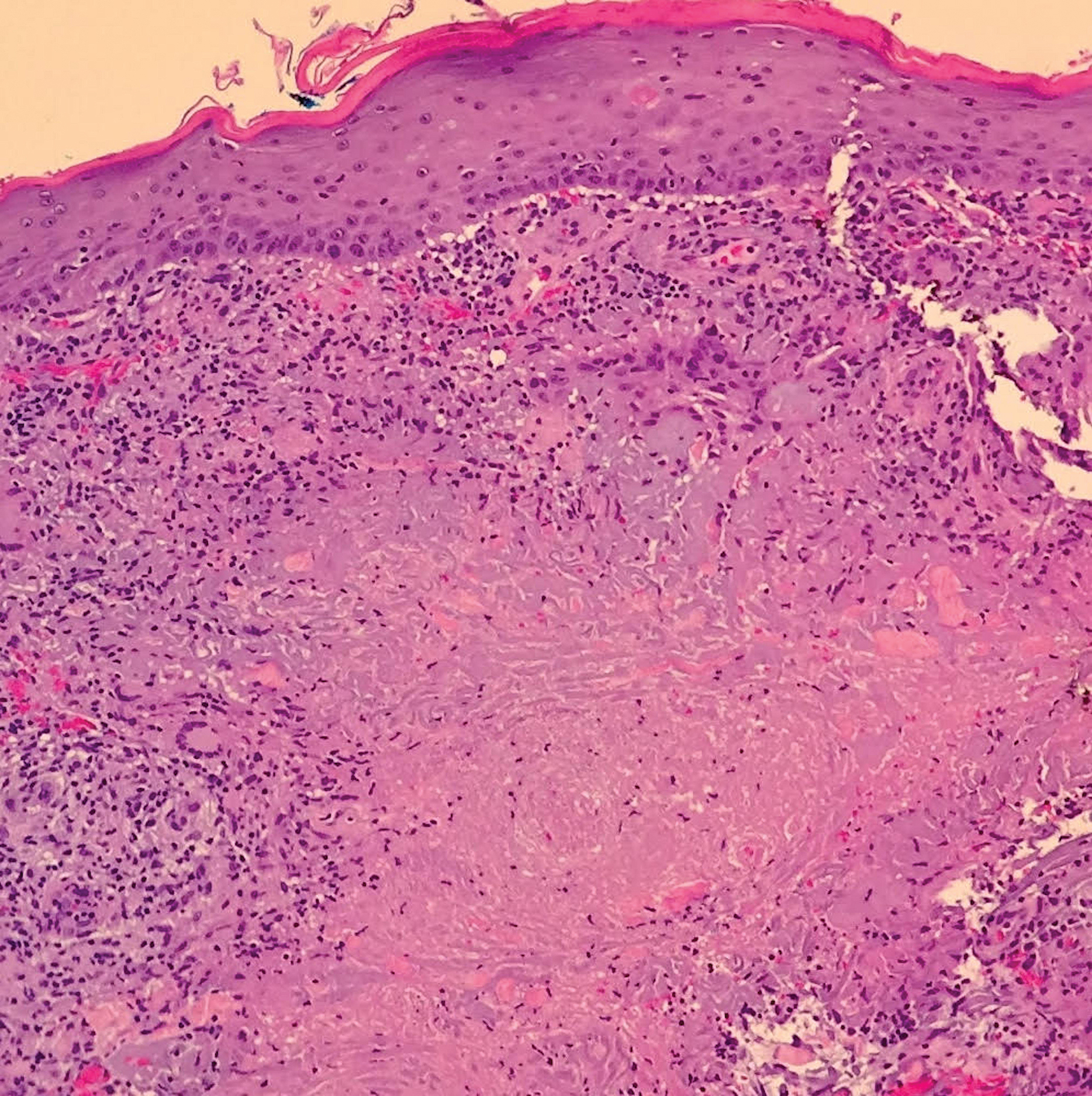

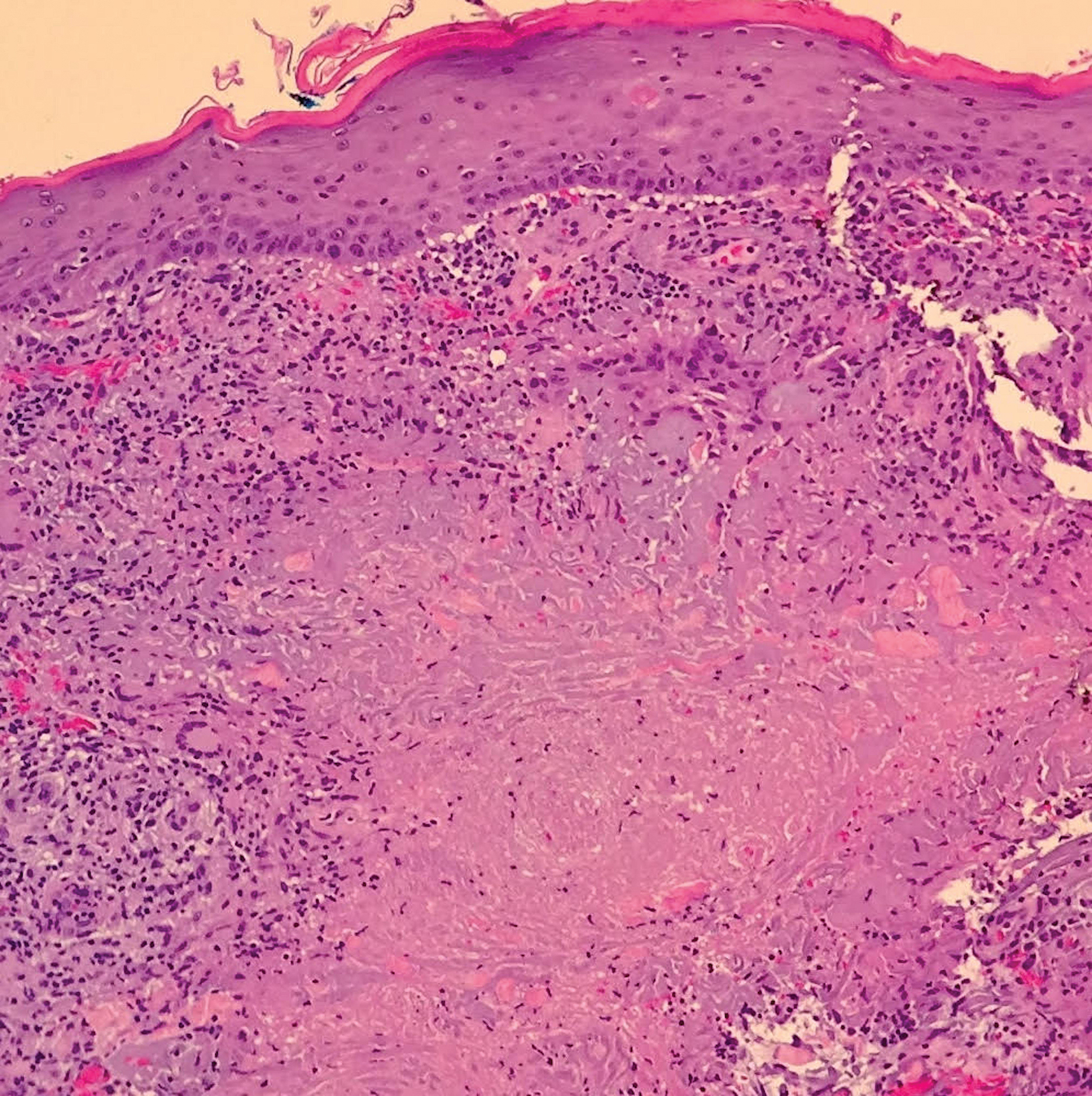

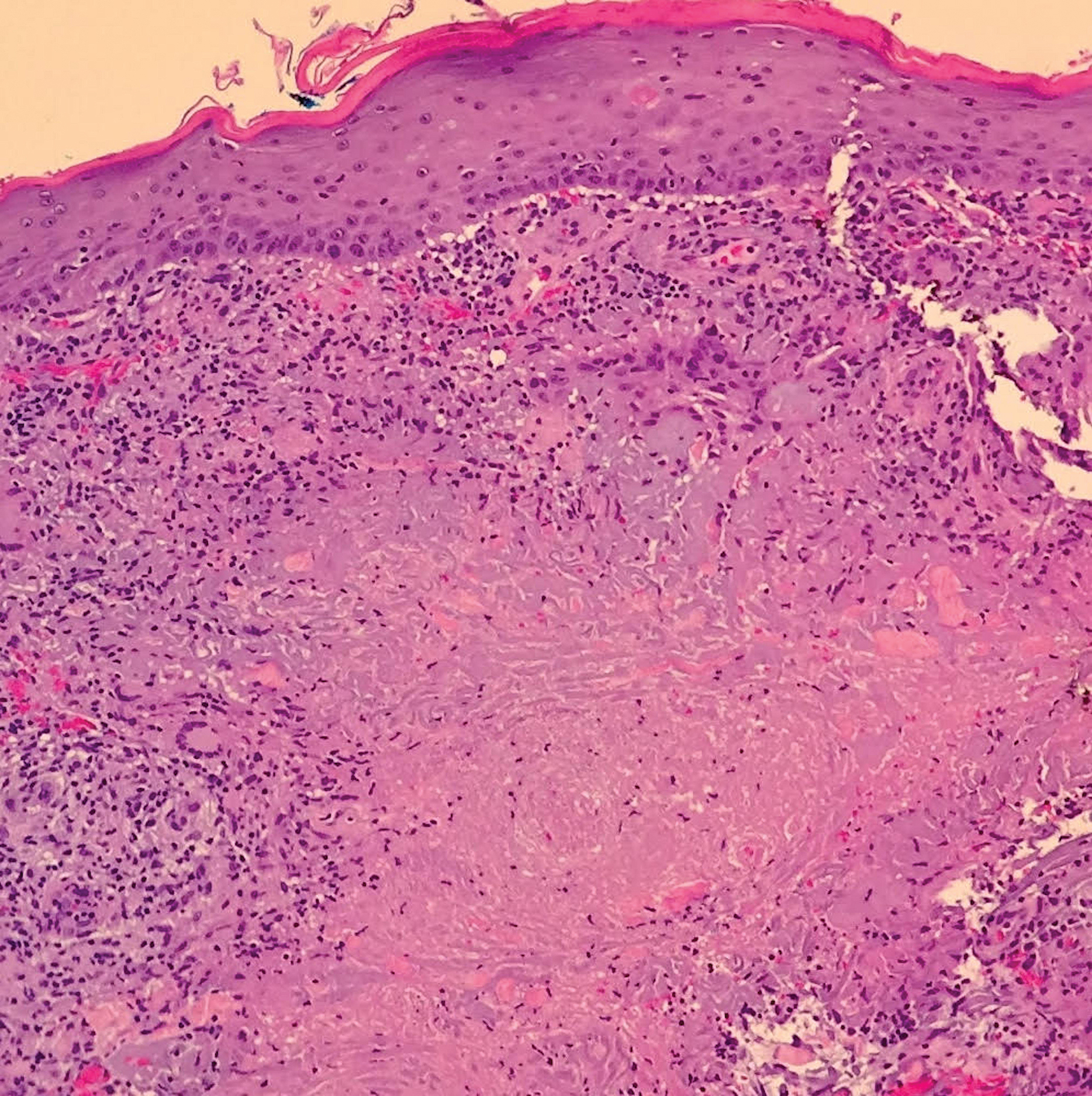

Biopsy of the nodule on the left arm showed dense, superficial to deep perivascular, periadnexal, perineural, and panniculitislike lymphoid infiltrates, as well as a sparse interstitial infiltrate with irregular and pleomorphic medium to large nuclei. Lymphoid cells showed mild epidermotropism, with tagging to the basal layer. Some vessel walls were infiltrated by similar cells (Figure 2). Infiltrative atypical lymphoid cells expressed CD3 and CD7 and were mostly CD8+, with a few CD4+ cells and most cells negative for CD5, CD20, CD30, CD56, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase. Cytotoxic markers granzyme B and T-cell intracellular antigen protein 1 were scattered positive. Immunostaining for Ki-67 protein highlighted an increased proliferative rate of 80% in malignant cells. In situ hybridization for EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) demonstrated EBV-positive atypical lymphoid cells (Figure 3). Analysis for T-cell receptor (TCR) γ gene rearrangement revealed a monoclonal pattern. Bone marrow aspirate showed proliferation of the 3 cell lines. The percentage of T lymphocytes was increased (20% of all nucleated cells). No hemophagocytic activity was found.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma was made. Before the final diagnosis was made, the patient was treated by rheumatologists with antibiotics, antiviral drugs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and other symptomatic treatments. Following antibiotic therapy, a sputum culture reverted to normal flora, the coagulation index (ie, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time) returned to normal, and the D-dimer level decreased to 1.19 mg/L.

The patient’s parents refused to accept chemotherapy for him. Instead, they chose herbal therapy only; 5 months later, they reported that all of his symptoms had resolved; however, the disease suddenly relapsed after another 7 months, with multiple skin nodules and fever. The patient died, even with chemotherapy in another hospital.

Comment

Prevalence and Presentation

Epstein-Barr virus is a ubiquitous γ-herpesvirus with tropism for B cells, affecting more than 90% of the adult population worldwide. In addition to infecting B cells, EBV is capable of infecting T and NK cells, leading to various EBV-related lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs). The frequency and clinical presentation of infection varies based on the type of EBV-infected cells and the state of host immunity.1-3

Primary infection usually is asymptomatic and occurs early in life; when symptomatic, the disease usually presents as infectious mononucleosis (IM), characterized by polyclonal expansion of infected B cells and subsequent cytotoxic T-cell response. A diagnosis of EBV infection can be made by testing for specific IgM and IgG antibodies against VCA, early antigens, and EBV nuclear antigen proteins.3,4

Associated LPDs

Although most symptoms associated with IM resolve within weeks or months, persistent or recurrent IM-like symptoms or even lasting disease occasionally occur, particularly in children and young adults. This complication is known as chronic active EBV infection (CAEBV), frequently associated with EBV-infected T-cell or NK-cell proliferation, especially in East Asian populations.3,5

Epstein-Barr virus–positive T-cell and NK-cell LPDs of childhood include CAEBV infection of T-cell and NK-cell types and systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood. The former includes hydroa vacciniforme–like LPD and severe mosquito bite allergy.3

Systemic EBV-Positive T-cell Lymphoma of Childhood

This entity occurs not only in children but also in adolescents and young adults. A fulminant illness characterized by clonal proliferation of EBV-infected cytotoxic T cells, it can develop shortly after primary EBV infection or is linked to CAEBV infection. The disorder is rare and has a racial predilection for Asian (ie, Japanese, Chinese, Korean) populations and indigenous populations of Mexico and Central and South America.6-8

Complications

Systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is often complicated by hemophagocytic syndrome, coagulopathy, sepsis, and multiorgan failure. Other signs and symptoms include high fever, rash, jaundice, diarrhea, pancytopenia, and hepatosplenomegaly. The liver, spleen, lymph nodes, and bone marrow are commonly involved, and the disease can involve skin, the heart, and the lungs.9,10

Diagnosis

When systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma occurs shortly after IM, serology shows low or absent anti-VCA IgM and positive anti-VCA IgG. Infiltrating T cells usually are small and lack cytologic atypia; however, cases with pleomorphic, medium to large lymphoid cells, irregular nuclei, and frequent mitoses have been described. Hemophagocytosis can be seen in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow.3,11

The most typical phenotype of systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma is CD2+CD3+CD8+CD20−CD56−, with expression of the cytotoxic granules known as T-cell intracellular antigen 1 and granzyme B. Rare cases of CD4+ and mixed CD4+/CD8+ phenotypes have been described, usually in the setting of CAEBV infection.3,12 Neoplastic cells have monoclonally rearranged TCR-γ genes and consistent EBER positivity with in situ hybridization.13 A final diagnosis is based on a comprehensive analysis of clinical, morphological, immunohistochemical, and molecular biological aspects.

Clinical Course and Prognosis

Most patients with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma have an aggressive clinical course with high mortality. In a few cases, patients were reported to respond to a regimen of etoposide and dexamethasone, followed by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.3

In recognition of the aggressive clinical behavior and desire to clearly distinguish systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma from CAEBV infection, the older term systemic EBV-positive T-cell LPD of childhood, which had been introduced in 2008 to the World Health Organization classification, was changed to systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood in the revised 2016 World Health Organization classification.6,12 However, Kim et al14 reported a case with excellent response to corticosteroid administration, suggesting that systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood may be more heterogeneous in terms of prognosis.

Our patient presented with acute IM-like symptoms, including high fever, tonsillar enlargement, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly, as well as uncommon oral ulcers and skin lesions, including indurated nodules. Histopathologic changes in the skin nodule, proliferation in bone marrow, immunohistochemical phenotype, and positivity of EBER and TCR-γ monoclonal rearrangement were all consistent with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood. The patient was positive for VCA IgG and negative for VCA IgM, compatible with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood occurring shortly after IM. Neither pancytopenia, hemophagocytic syndrome, nor multiorgan failure occurred during the course.

Differential Diagnosis

It is important to distinguish IM from systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood and CAEBV infection. Detection of anti–VCA IgM in the early stage, its disappearance during the clinical course, and appearance of anti-EBV–determined nuclear antigen is useful to distinguish IM from the neoplasms, as systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is negative for anti-EBV–determined nuclear antigen. Carefully following the clinical course also is important.3,15

Epstein-Barr virus–associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis can occur in association with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood and might represent a continuum of disease rather than distinct entities.14 The most useful marker for differentiating EBV-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is an abnormal karyotype rather than molecular clonality.16

Outcome

Mortality risk in EBV-associated T-cell and NK-cell LPD is not primarily dependent on whether the lesion has progressed to lymphoma but instead is related to associated complications.17

Conclusion

Although systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood is a rare disorder and has race predilection, dermatologists should be aware due to the aggressive clinical source and poor prognosis. Histopathology and in situ hybridization for EBER and TCR gene rearrangements are critical for final diagnosis. Although rare cases can show temporary resolution, the final outcome of this disease is not optimistic.

- Ameli F, Ghafourian F, Masir N. Systematic Epstein-Barr virus-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease presenting as a persistent fever and cough: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:288.

- Kim HJ, Ko YH, Kim JE, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lympho-proliferative disorders: review and update on 2016 WHO classification. J Pathol Transl Med. 2017;51:352-358.

- Dojcinov SD, Fend F, Quintanilla-Martinez L. EBV-positive lymphoproliferations of B- T- and NK-cell derivation in non-immunocompromised hosts [published online March 7, 2018]. Pathogens. doi:10.3390/pathogens7010028.

- Luzuriaga K, Sullivan JL. Infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1993-2000.

- Cohen JI, Kimura H, Nakamura S, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disease in non-immunocompromised hosts: a status report and summary of an international meeting, 8-9 September 2008. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1472-1482.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390.

- Kim WY, Montes-Mojarro IA, Fend F, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated T and NK-cell lymphoproliferative diseases. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:71.

- Hong M, Ko YH, Yoo KH, et al. EBV-positive T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childhood. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:137-147.

- Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kumar S, Fend F, et al. Fulminant EBV(+) T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder following acute/chronic EBV infection: a distinct clinicopathologic syndrome. Blood. 2000;96:443-451.

- Chen G, Chen L, Qin X, et al. Systemic Epstein-Barr virus positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childhood with hemophagocytic syndrome. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:7110-7113.

- Grywalska E, Rolinski J. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphomas. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:291-303.

- Huang W, Lv N, Ying J, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of four cases of EBV positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders of childhood in China. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:4991-4999.

- Tabanelli V, Agostinelli C, Sabattini E, et al. Systemic Epstein-Barr-virus-positive T cell lymphoproliferative childhood disease in a 22-year-old Caucasian man: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:218.

- Kim DH, Kim M, Kim Y, et al. Systemic Epstein-Barr virus-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disease of childhood with good response to steroid therapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017;39:e497-e500.

- Arai A, Yamaguchi T, Komatsu H, et al. Infectious mononucleosis accompanied by clonal proliferation of EBV-infected cells and infection of CD8-positive cells. Int J Hematol. 2014;99:671-675.

- Smith MC, Cohen DN, Greig B, et al. The ambiguous boundary between EBV-related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and systemic EBV-driven T cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5738-5749.

- Paik JH, Choe JY, Kim H, et al. Clinicopathological categorization of Epstein-Barr virus-positive T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative disease: an analysis of 42 cases with an emphasis on prognostic implications. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:53-63.

Case Report

A 7-year-old Chinese boy presented with multiple painful oral and tongue ulcers of 2 weeks’ duration as well as acute onset of moderate to high fever (highest temperature, 39.3°C) for 5 days. The fever was reported to have run a relapsing course, accompanied by rigors but without convulsions or cognitive changes. At times, the patient had nasal congestion, nasal discharge, and cough. He also had a transient eruption on the back and hands as well as an indurated red nodule on the left forearm.

Before the patient was hospitalized, antibiotic therapy was administered by other physicians, but the condition of fever and oral ulcers did not improve. After the patient was hospitalized, new tender nodules emerged on the scalp, buttocks, and lower extremities. New ulcers also appeared on the palate.

History