User login

Permanent Alopecia in Breast Cancer Patients: Role of Taxanes and Endocrine Therapies

Anagen effluvium during chemotherapy is common, typically beginning within 1 month of treatment onset and resolving by 6 months after the final course.1 Permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia (PCIA), in which hair loss persists beyond 6 months after chemotherapy without recovery to original density, was first reported in patients following high-dose chemotherapy regimens for allogeneic bone marrow transplantation.2 There are now increasing reports of PCIA in patients with breast cancer; at least 400 such cases have been documented.3-16 In addition to chemotherapy, patients often receive adjuvant endocrine therapy with selective estrogen receptor modulators, aromatase inhibitors, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists.5-16 Endocrine therapies also can lead to alopecia, but their role in PCIA has not been well defined.15,16 We describe 3 patients with breast cancer who experienced PCIA following chemotherapy with taxanes with or without endocrine therapies. We also review the literature on non–bone marrow transplantation PCIA to better characterize this entity and explore the role of endocrine therapies in PCIA.

Case Reports

Patient 1

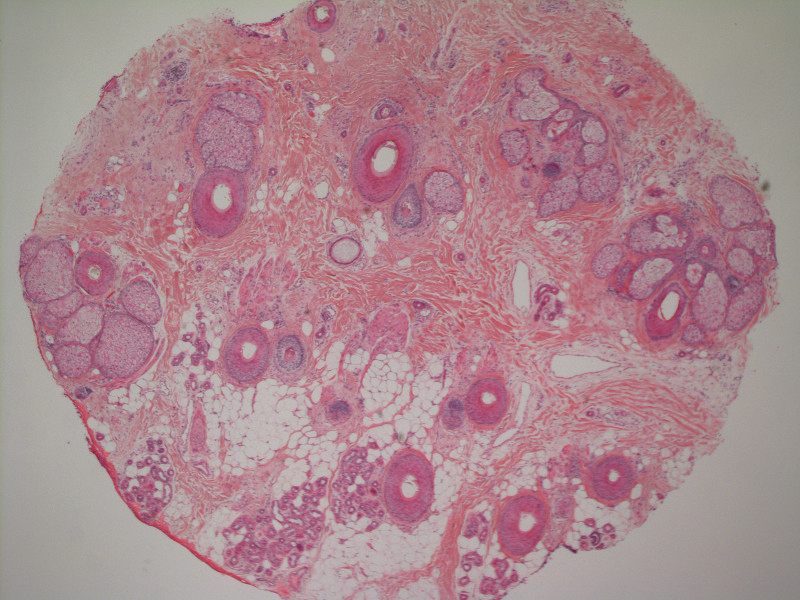

A 62-year-old woman with a history of stage II invasive ductal carcinoma presented with persistent hair loss 5 years after completing chemotherapy. She underwent 6 cycles of docetaxel and carboplatin along with radiation therapy as well as 1 year of trastuzumab and did not receive endocrine therapy. At the current presentation, she reported patchy hair regrowth that gradually filled in but failed to return to full density. Physical examination revealed the hair was diffusely thin, especially bitemporally (Figures 1A and 1B), and she did not experience any loss of body hair. She had no family history of hair loss. Her medical history was notable for hypertension, chronic obstructive bronchitis, osteopenia, and depression. Her thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level was within reference range. Medications included lisinopril, metoprolol, escitalopram, and trazodone. A biopsy from the occipital scalp showed nonscarring alopecia with variation of hair follicle size, a decreased number of hair follicles, and a decreased anagen to telogen ratio (Figure 1C). She was treated with clobetasol solution and minoxidil solution 5% for 1 year with mild improvement. She experienced no further hair loss but did not regain original hair density.

Patient 2

A 35-year-old woman with a history of stage II invasive ductal carcinoma presented with persistent hair loss 10 months after chemotherapy. She underwent 4 cycles of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by 4 cycles of paclitaxel and was started on trastuzumab. Tamoxifen was initiated 1 month after completing chemotherapy. She received radiation therapy the following month and continued trastuzumab for 1 year. At the current presentation, the patient noted that hair regrowth had started 1 month after the last course of chemotherapy but had progressed slowly. She denied body hair loss. Physical examination revealed diffuse thinning, especially over the crown, with scattered broken hairs throughout the scalp and several miniaturized hairs over the crown. She was evaluated as grade 3 on the Sinclair clinical grading scale used to evaluate female pattern hair loss (FPHL).17 Her family history was remarkable for FPHL in her maternal grandmother. She had no notable medical history, her TSH was normal, and she was taking tamoxifen and trastuzumab. Biopsy was not performed. The patient was started on minoxidil solution 2% and had mild improvement with no further broken-off hairs after 10 months. At that point, she was evaluated as grade 2 to 3 on the Sinclair scale.17

Patient 3

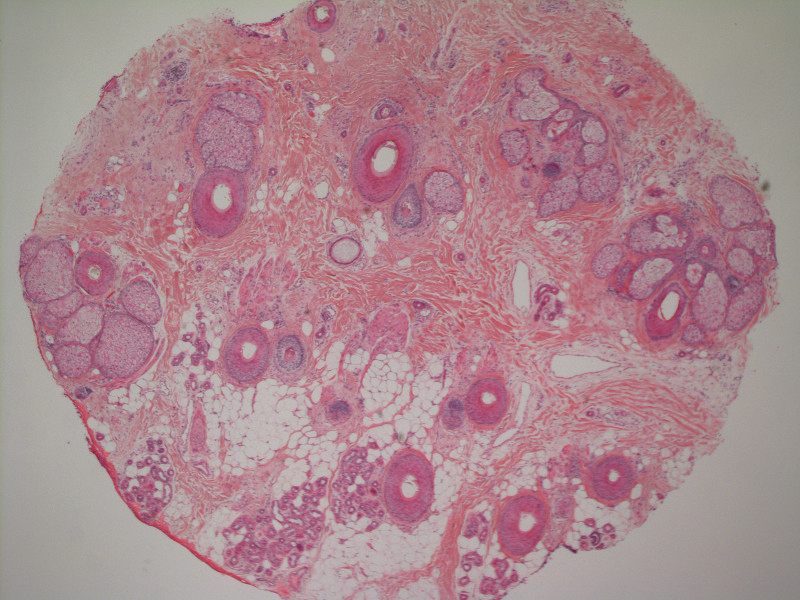

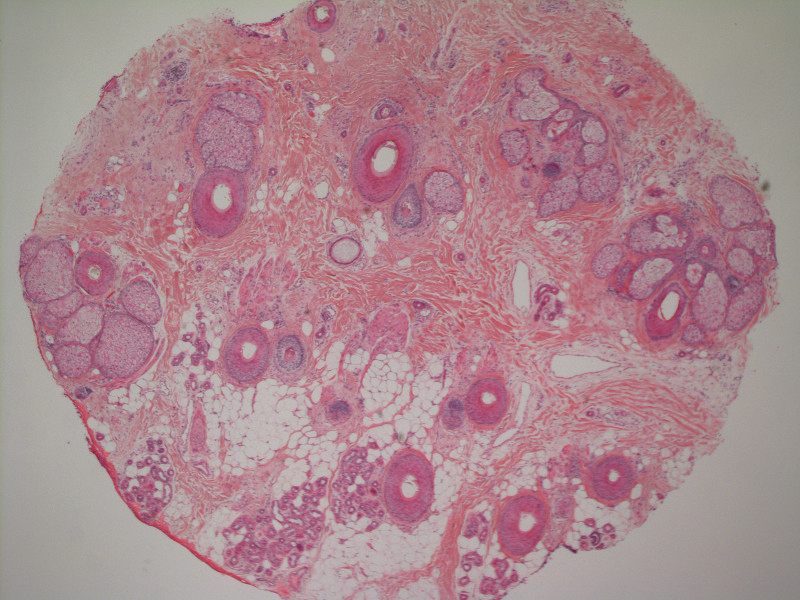

A 51-year-old woman with a history of papillary carcinoma and extensive ductal carcinoma in situ presented with persistent hair loss for 3.5 years following chemotherapy for recurrent breast cancer. After her initial diagnosis in the left breast, she received cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil but did not receive endocrine therapy. Her hair thinned during chemotherapy but returned to normal density within 1 year. She had a recurrence of the cancer in the right breast 14 years later and received 6 cycles of chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide and docetaxel followed by radiation therapy. After this course, her hair loss incompletely recovered. One year after chemotherapy, she underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and started anastrozole. Three months later, she noticed increased shedding and progressive thinning of the hair. Physical examination revealed diffuse thinning that was most pronounced over the crown. She also experienced lateral thinning of the eyebrows, decreased eyelashes, and dystrophic fingernails. Fluocinonide solution was discontinued by the patient due to scalp burning. She had a brother with bitemporal recession. Her medical history was notable for Hashimoto thyroiditis, vitamin D deficiency, and peripheral neuropathy. Her TSH occasionally was elevated, and she was intermittently on levothyroxine; however, her free T4 was maintained within reference range on all records. Her medications at the time of evaluation were anastrozole and gabapentin. Biopsies taken from the right and left temporal scalp revealed decreased follicle density with a majority of follicles in anagen, scattered miniaturized follicles, and a mild perivascular and perifollicular lymphoid infiltrate. Mild dermal fibrosis was present without evidence of frank scarring (Figure 2). She declined treatment, and there was no change in her condition over 3 years of follow-up.

Comment

Classification of Chemotherapy-Induced Hair Loss

Chemotherapy-induced alopecia is typically an anagen effluvium that is reversed within 6 months following the final course of chemotherapy. When incomplete regrowth persists, the patient is considered to have PCIA.1 The pathophysiology of PCIA is unclear.

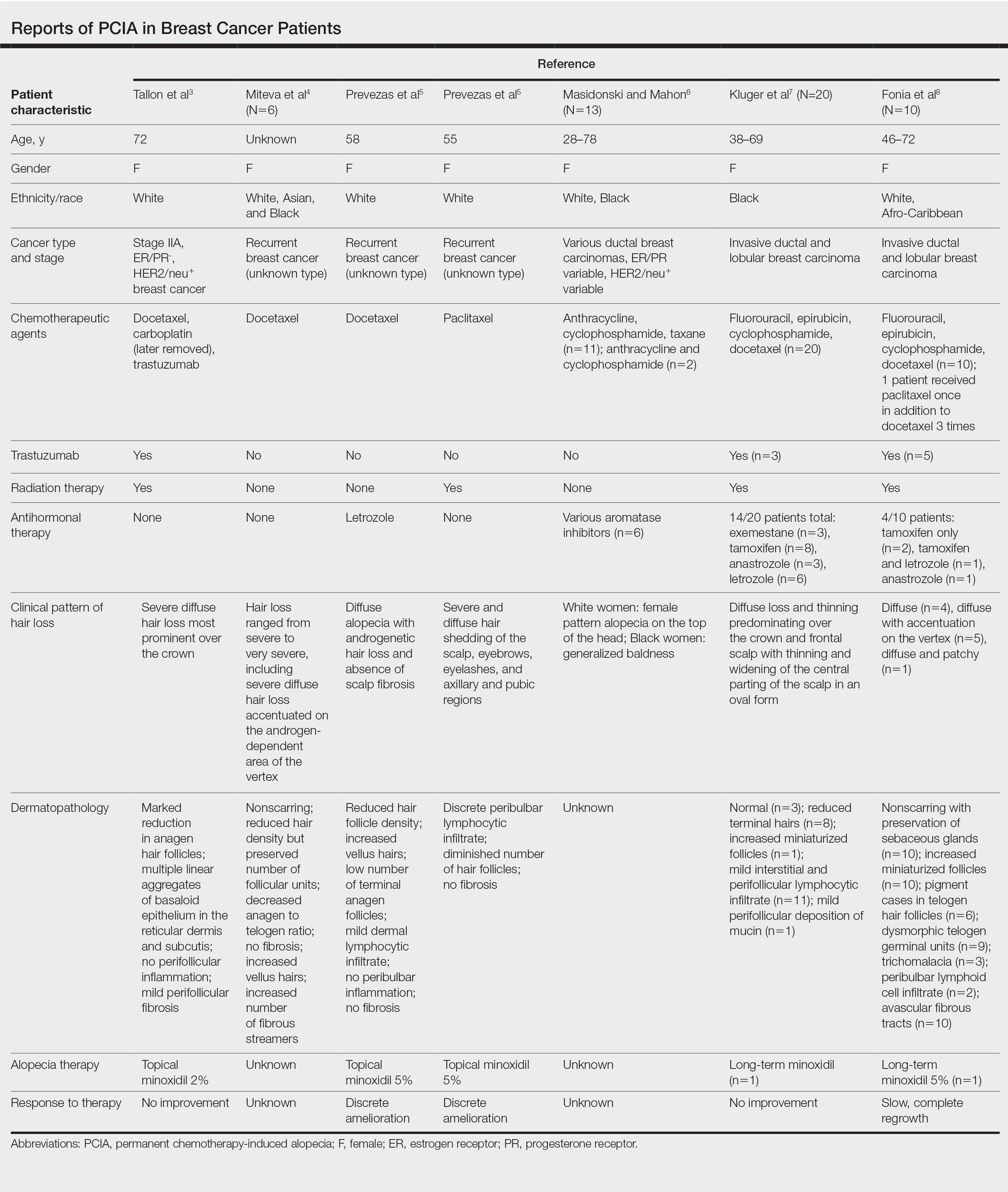

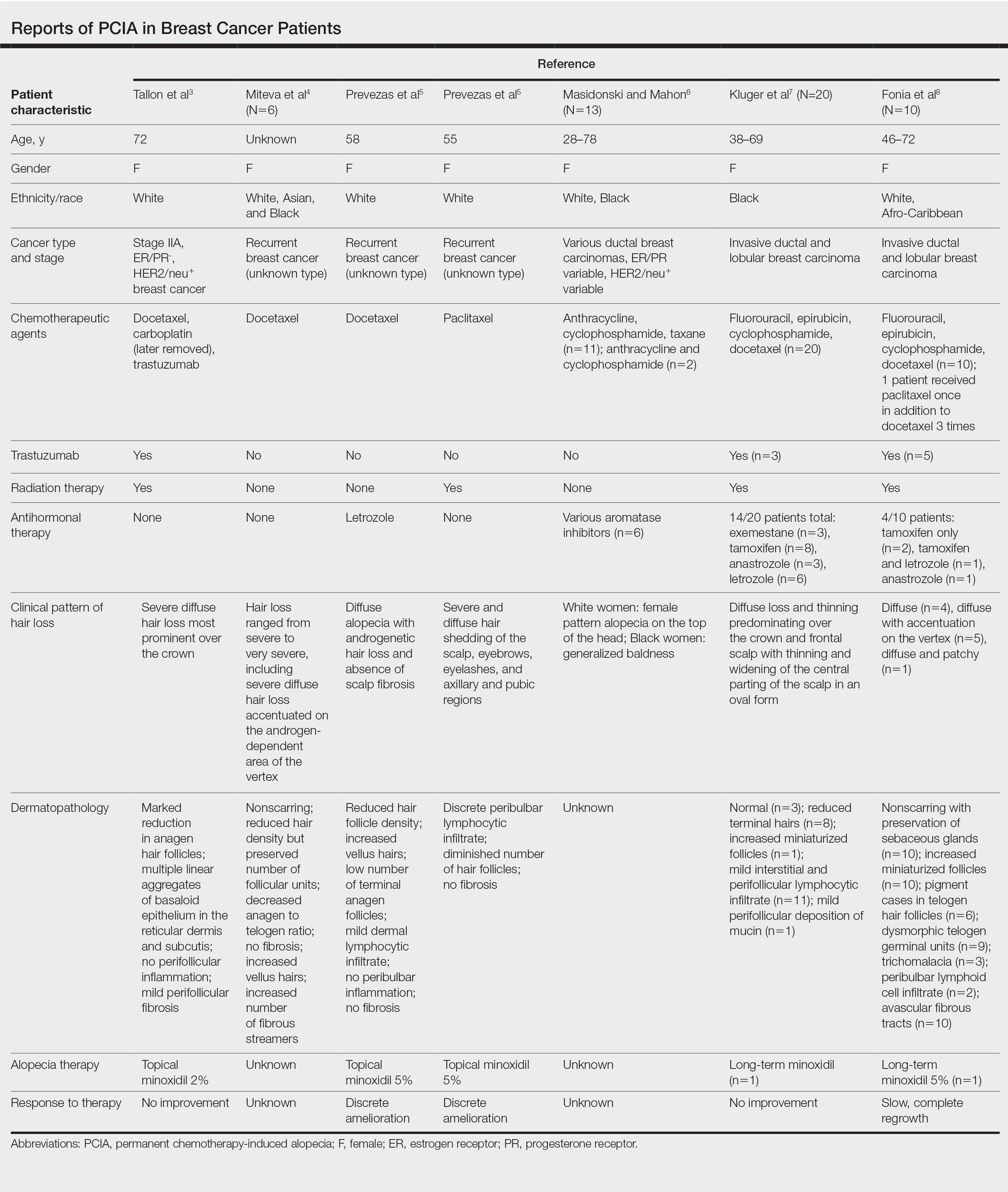

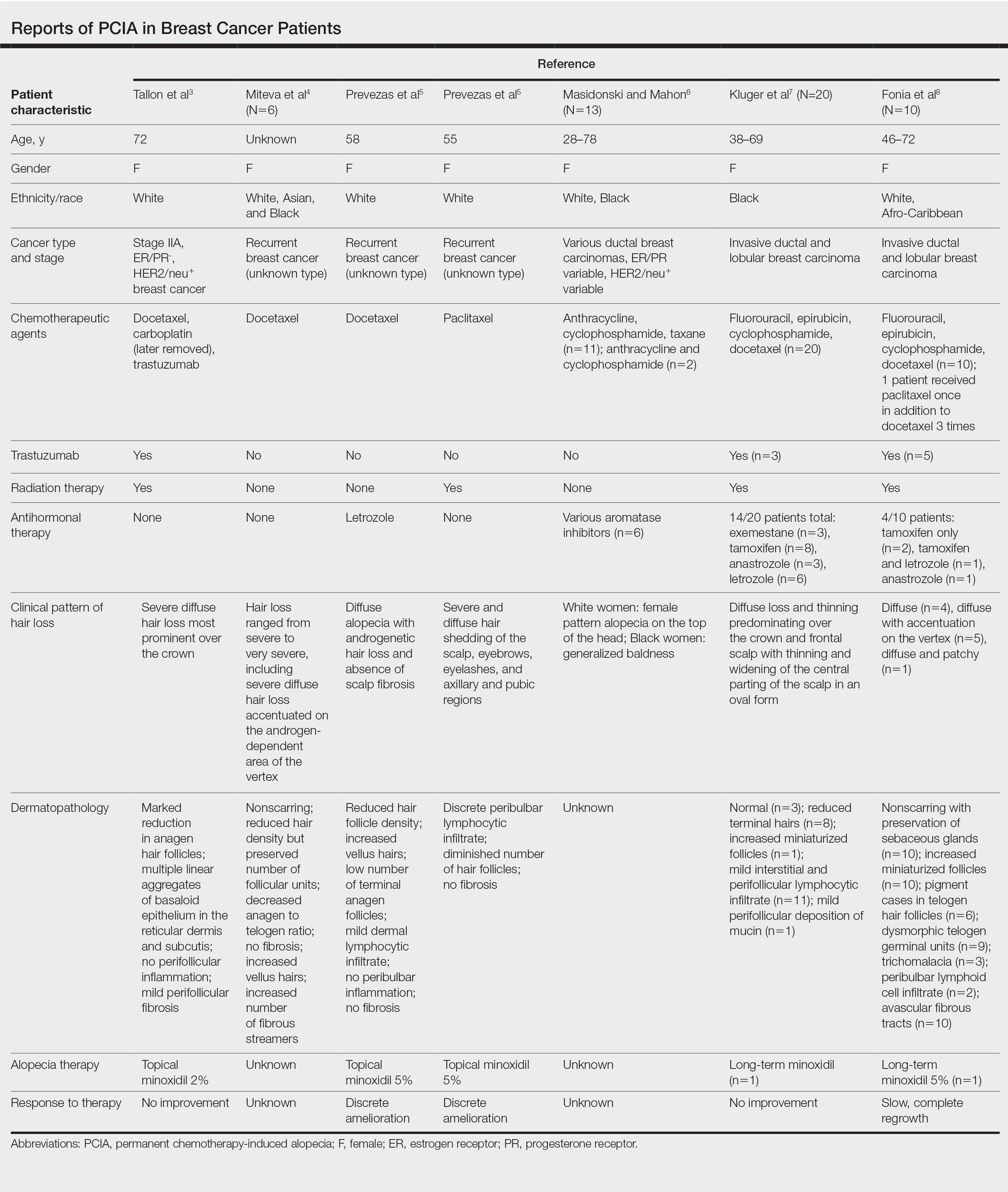

Traditional grading for chemotherapy-induced alopecia does not account for the patterns of loss seen in PCIA, of which the most common appears to be a female pattern with accentuated hair loss in androgen-dependent regions of the scalp.18 Other patterns include a diffuse type with body hair loss, patchy alopecia, and complete alopecia with or without body hair loss (Table).3-8 Whether these patterns all can be attributed to chemotherapy remains to be explored.

Breast Cancer Therapies Causing PCIA

The main agents thought to be responsible for PCIA in breast cancer patients are taxanes. The role of endocrine therapies has not been well explored. Trastuzumab lacks several of the common side effects of chemotherapy due to its specificity for the HER2/neu receptor and has not been found to increase the rate of hair loss when combined with standard chemotherapy.19,20 Although radiation therapy has the potential to damage hair follicles, and a dose-dependent relationship has been described for temporary and permanent alopecia at irradiated sites, permanent alopecia predominantly has been reported with cranial radiation used in the treatment of intracranial malignancies.21 The role of radiation therapy of the breasts in PCIA is unclear, as its inclusion in therapy has not been consistently reported in the literature.

Docetaxel is known to cause chemotherapy-induced alopecia, with an 83.4% incidence in phase 2 trials; however, it also appears to be related to PCIA.20 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was performed using the terms permanent chemotherapy induced alopecia, chemotherapy, docetaxel, endocrine therapies, hair loss, alopecia, and breast cancer. More than 400 cases of PCIA related to chemotherapy in breast cancer patients have been reported in the literature from a combination of case reports/series, retrospective surveys, and at least one prospective study. Data from some of the more detailed reports (n=52) are summarized in the Table. In the single-center, 3-year prospective study of women given adjuvant taxane-based or non–taxane-based chemotherapy, those who received taxane therapy were more likely to develop PCIA (odds ratio, 8.01).9

All 3 of our patients received taxanes. Interestingly, patient 3 underwent 2 rounds of chemotherapy 14 years apart and experienced full regrowth of the hair after the first course of taxane-free chemotherapy but experienced persistent hair loss following docetaxel treatment. Adjuvant endocrine therapies also may contribute to PCIA. A review of the side effects of endocrine therapies revealed an incidence of alopecia that was higher than expected; tamoxifen was the greatest offender. Additionally, using endocrine treatments in combination was found to have a synergistic effect on alopecia.18 Adjuvant endocrine therapy was used in patients 2 and 3. Although endocrine therapies appear to have a milder effect on hair loss compared to chemotherapy, these medications are continued for a longer duration, potentially contributing to the severity of hair loss and prolonging the time to regrowth.

Furthermore, endocrine therapies used in breast cancer treatment decrease estrogen levels or antagonize estrogen receptors, creating an environment of relative hyperandrogenism that may contribute to FPHL in genetically susceptible women.18 Although taxanes may cause irreversible hair loss in these patients, the action of endocrine therapies on the remaining hair follicles may affect the typical female pattern seen clinically. Patients 2 and 3 who presented with FPHL received adjuvant endocrine therapies and had positive family history, while patient 1 did not. Of note, patient 3 experienced worsening hair loss following the addition of anastrozole, which suggests a contribution of endocrine therapy to her PCIA. Our limited cases do not allow for evaluation of a worsened outcome with the combination of taxanes and endocrine therapies; however, we suggest further evaluation for a synergistic effect that may be contributing to PCIA.

Conclusion

Permanent alopecia in breast cancer patients appears to be a true potential adverse effect of taxanes and endocrine therapies, and it is important to characterize it appropriately so that its mechanism can be understood and appropriate treatment and counseling can take place. Although it may not influence clinical decision-making, patients should be informed that hair loss with chemotherapy can be permanent. Treatment with scalp cooling can reduce the risk for severe chemotherapy-induced alopecia, but it is unclear if it reduces risk for PCIA.12,15 Topical or oral minoxidil may be helpful in the treatment of PCIA once it has developed.7,8,15,22 Better characterization of these cases may elucidate risk factors for developing permanent alopecia, allowing for more appropriate risk stratification, counseling, and treatment.

- Dorr VJ. A practitioner’s guide to cancer-related alopecia. Semin Oncol. 1998;25:562-570.

- Machado M, Moreb JS, Khan SA. Six cases of permanent alopecia after various conditioning regimens commonly used in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:979-982.

- Tallon B, Blanchard E, Goldberg LJ. Permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia: case report and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:333-336.

- Miteva M, Misciali C, Fanti PA, et al. Permanent alopecia after systemic chemotherapy: a clinicopathological study of 10 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:345-350.

- Prevezas C, Matard B, Pinquier L, et al. Irreversible and severe alopecia following docetaxel or paclitaxel cytotoxic therapy for breast cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:883-885.

- Masidonski P, Mahon SM. Permanent alopecia in women being treated for breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13:13-14.

- Kluger N, Jacot W, Frouin E, et al. Permanent scalp alopecia related to breast cancer chemotherapy by sequential fluorouracil/epirubicin/cyclophosphamide (FEC) and docetaxel: a prospective study of 20 patients. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2879-2884.

- Fonia A, Cota C, Setterfield JF, et al. Permanent alopecia in patients with breast cancer after taxane chemotherapy and adjuvant hormonal therapy: clinicopathologic findings in a cohort of 10 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:948-957.

- Kang D, Kim IR, Choi EK, et al. Permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia in patients with breast cancer: a 3-year prospective cohort study [published online August 17, 2018]. Oncologist. 2019;24:414-420.

- Chan J, Adderley H, Alameddine M, et al. Permanent hair loss associated with taxane chemotherapy use in breast cancer: a retrospective survey at two tertiary UK cancer centres [published online December 22, 2020]. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). doi:10.1111/ecc.13395

- Bourgeois H, Denis F, Kerbrat P, et al. Long term persistent alopecia and suboptimal hair regrowth after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: alert for an emerging side effect: ALOPERS Observatory. Cancer Res. 2009;69(24 suppl). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.SABCS-09-3174

- Bertrand M, Mailliez A, Vercambre S, et al. Permanent chemotherapy induced alopecia in early breast cancer patients after (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy: long term follow up. Cancer Res. 2013;73(24 suppl). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.SABCS13-P3-09-15

- Kim S, Park HS, Kim JY, et al. Irreversible chemotherapy-induced alopecia in breast cancer patient. Cancer Res. 2016;76(4 suppl). doi:10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS15-P1-15-04

- Thorp NJ, Swift F, Arundell D, et al. Long term hair loss in patients with early breast cancer receiving docetaxel chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2015;75(9 suppl). doi:10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS14-P5-17-04

- Freites-Martinez A, Shapiro J, van den Hurk C, et al. Hair disorders in cancer survivors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1199-1213.

- Freites-Martinez A, Chan D, Sibaud V, et al. Assessment of quality of life and treatment outcomes of patients with persistent postchemotherapy alopecia. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:724-728.

- Sinclair R, Jolley D, Mallari R, et al. The reliability of horizontally sectioned scalp biopsies in the diagnosis of chronic diffuse telogen hair loss in women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:189-199.

- Saggar V, Wu S, Dickler MN, et al. Alopecia with endocrine therapies in patients with cancer. Oncologist. 2013;18:1126-1134.

- Yeager CE, Olsen EA. Treatment of chemotherapy-induced alopecia. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:432-442.

- Baselga J. Clinical trials of single-agent trastuzumab (Herceptin). Semin Oncol. 2000;27(5 suppl 9):20-26.

- Lawenda BD, Gagne HM, Gierga DP, et al. Permanent alopecia after cranial irradiation: dose-response relationship. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:879-887.

- Yang X, Thai KE. Treatment of permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia with low dose oral minoxidil [published online May 13, 2015]. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:E130-E132.

Anagen effluvium during chemotherapy is common, typically beginning within 1 month of treatment onset and resolving by 6 months after the final course.1 Permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia (PCIA), in which hair loss persists beyond 6 months after chemotherapy without recovery to original density, was first reported in patients following high-dose chemotherapy regimens for allogeneic bone marrow transplantation.2 There are now increasing reports of PCIA in patients with breast cancer; at least 400 such cases have been documented.3-16 In addition to chemotherapy, patients often receive adjuvant endocrine therapy with selective estrogen receptor modulators, aromatase inhibitors, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists.5-16 Endocrine therapies also can lead to alopecia, but their role in PCIA has not been well defined.15,16 We describe 3 patients with breast cancer who experienced PCIA following chemotherapy with taxanes with or without endocrine therapies. We also review the literature on non–bone marrow transplantation PCIA to better characterize this entity and explore the role of endocrine therapies in PCIA.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 62-year-old woman with a history of stage II invasive ductal carcinoma presented with persistent hair loss 5 years after completing chemotherapy. She underwent 6 cycles of docetaxel and carboplatin along with radiation therapy as well as 1 year of trastuzumab and did not receive endocrine therapy. At the current presentation, she reported patchy hair regrowth that gradually filled in but failed to return to full density. Physical examination revealed the hair was diffusely thin, especially bitemporally (Figures 1A and 1B), and she did not experience any loss of body hair. She had no family history of hair loss. Her medical history was notable for hypertension, chronic obstructive bronchitis, osteopenia, and depression. Her thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level was within reference range. Medications included lisinopril, metoprolol, escitalopram, and trazodone. A biopsy from the occipital scalp showed nonscarring alopecia with variation of hair follicle size, a decreased number of hair follicles, and a decreased anagen to telogen ratio (Figure 1C). She was treated with clobetasol solution and minoxidil solution 5% for 1 year with mild improvement. She experienced no further hair loss but did not regain original hair density.

Patient 2

A 35-year-old woman with a history of stage II invasive ductal carcinoma presented with persistent hair loss 10 months after chemotherapy. She underwent 4 cycles of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by 4 cycles of paclitaxel and was started on trastuzumab. Tamoxifen was initiated 1 month after completing chemotherapy. She received radiation therapy the following month and continued trastuzumab for 1 year. At the current presentation, the patient noted that hair regrowth had started 1 month after the last course of chemotherapy but had progressed slowly. She denied body hair loss. Physical examination revealed diffuse thinning, especially over the crown, with scattered broken hairs throughout the scalp and several miniaturized hairs over the crown. She was evaluated as grade 3 on the Sinclair clinical grading scale used to evaluate female pattern hair loss (FPHL).17 Her family history was remarkable for FPHL in her maternal grandmother. She had no notable medical history, her TSH was normal, and she was taking tamoxifen and trastuzumab. Biopsy was not performed. The patient was started on minoxidil solution 2% and had mild improvement with no further broken-off hairs after 10 months. At that point, she was evaluated as grade 2 to 3 on the Sinclair scale.17

Patient 3

A 51-year-old woman with a history of papillary carcinoma and extensive ductal carcinoma in situ presented with persistent hair loss for 3.5 years following chemotherapy for recurrent breast cancer. After her initial diagnosis in the left breast, she received cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil but did not receive endocrine therapy. Her hair thinned during chemotherapy but returned to normal density within 1 year. She had a recurrence of the cancer in the right breast 14 years later and received 6 cycles of chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide and docetaxel followed by radiation therapy. After this course, her hair loss incompletely recovered. One year after chemotherapy, she underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and started anastrozole. Three months later, she noticed increased shedding and progressive thinning of the hair. Physical examination revealed diffuse thinning that was most pronounced over the crown. She also experienced lateral thinning of the eyebrows, decreased eyelashes, and dystrophic fingernails. Fluocinonide solution was discontinued by the patient due to scalp burning. She had a brother with bitemporal recession. Her medical history was notable for Hashimoto thyroiditis, vitamin D deficiency, and peripheral neuropathy. Her TSH occasionally was elevated, and she was intermittently on levothyroxine; however, her free T4 was maintained within reference range on all records. Her medications at the time of evaluation were anastrozole and gabapentin. Biopsies taken from the right and left temporal scalp revealed decreased follicle density with a majority of follicles in anagen, scattered miniaturized follicles, and a mild perivascular and perifollicular lymphoid infiltrate. Mild dermal fibrosis was present without evidence of frank scarring (Figure 2). She declined treatment, and there was no change in her condition over 3 years of follow-up.

Comment

Classification of Chemotherapy-Induced Hair Loss

Chemotherapy-induced alopecia is typically an anagen effluvium that is reversed within 6 months following the final course of chemotherapy. When incomplete regrowth persists, the patient is considered to have PCIA.1 The pathophysiology of PCIA is unclear.

Traditional grading for chemotherapy-induced alopecia does not account for the patterns of loss seen in PCIA, of which the most common appears to be a female pattern with accentuated hair loss in androgen-dependent regions of the scalp.18 Other patterns include a diffuse type with body hair loss, patchy alopecia, and complete alopecia with or without body hair loss (Table).3-8 Whether these patterns all can be attributed to chemotherapy remains to be explored.

Breast Cancer Therapies Causing PCIA

The main agents thought to be responsible for PCIA in breast cancer patients are taxanes. The role of endocrine therapies has not been well explored. Trastuzumab lacks several of the common side effects of chemotherapy due to its specificity for the HER2/neu receptor and has not been found to increase the rate of hair loss when combined with standard chemotherapy.19,20 Although radiation therapy has the potential to damage hair follicles, and a dose-dependent relationship has been described for temporary and permanent alopecia at irradiated sites, permanent alopecia predominantly has been reported with cranial radiation used in the treatment of intracranial malignancies.21 The role of radiation therapy of the breasts in PCIA is unclear, as its inclusion in therapy has not been consistently reported in the literature.

Docetaxel is known to cause chemotherapy-induced alopecia, with an 83.4% incidence in phase 2 trials; however, it also appears to be related to PCIA.20 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was performed using the terms permanent chemotherapy induced alopecia, chemotherapy, docetaxel, endocrine therapies, hair loss, alopecia, and breast cancer. More than 400 cases of PCIA related to chemotherapy in breast cancer patients have been reported in the literature from a combination of case reports/series, retrospective surveys, and at least one prospective study. Data from some of the more detailed reports (n=52) are summarized in the Table. In the single-center, 3-year prospective study of women given adjuvant taxane-based or non–taxane-based chemotherapy, those who received taxane therapy were more likely to develop PCIA (odds ratio, 8.01).9

All 3 of our patients received taxanes. Interestingly, patient 3 underwent 2 rounds of chemotherapy 14 years apart and experienced full regrowth of the hair after the first course of taxane-free chemotherapy but experienced persistent hair loss following docetaxel treatment. Adjuvant endocrine therapies also may contribute to PCIA. A review of the side effects of endocrine therapies revealed an incidence of alopecia that was higher than expected; tamoxifen was the greatest offender. Additionally, using endocrine treatments in combination was found to have a synergistic effect on alopecia.18 Adjuvant endocrine therapy was used in patients 2 and 3. Although endocrine therapies appear to have a milder effect on hair loss compared to chemotherapy, these medications are continued for a longer duration, potentially contributing to the severity of hair loss and prolonging the time to regrowth.

Furthermore, endocrine therapies used in breast cancer treatment decrease estrogen levels or antagonize estrogen receptors, creating an environment of relative hyperandrogenism that may contribute to FPHL in genetically susceptible women.18 Although taxanes may cause irreversible hair loss in these patients, the action of endocrine therapies on the remaining hair follicles may affect the typical female pattern seen clinically. Patients 2 and 3 who presented with FPHL received adjuvant endocrine therapies and had positive family history, while patient 1 did not. Of note, patient 3 experienced worsening hair loss following the addition of anastrozole, which suggests a contribution of endocrine therapy to her PCIA. Our limited cases do not allow for evaluation of a worsened outcome with the combination of taxanes and endocrine therapies; however, we suggest further evaluation for a synergistic effect that may be contributing to PCIA.

Conclusion

Permanent alopecia in breast cancer patients appears to be a true potential adverse effect of taxanes and endocrine therapies, and it is important to characterize it appropriately so that its mechanism can be understood and appropriate treatment and counseling can take place. Although it may not influence clinical decision-making, patients should be informed that hair loss with chemotherapy can be permanent. Treatment with scalp cooling can reduce the risk for severe chemotherapy-induced alopecia, but it is unclear if it reduces risk for PCIA.12,15 Topical or oral minoxidil may be helpful in the treatment of PCIA once it has developed.7,8,15,22 Better characterization of these cases may elucidate risk factors for developing permanent alopecia, allowing for more appropriate risk stratification, counseling, and treatment.

Anagen effluvium during chemotherapy is common, typically beginning within 1 month of treatment onset and resolving by 6 months after the final course.1 Permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia (PCIA), in which hair loss persists beyond 6 months after chemotherapy without recovery to original density, was first reported in patients following high-dose chemotherapy regimens for allogeneic bone marrow transplantation.2 There are now increasing reports of PCIA in patients with breast cancer; at least 400 such cases have been documented.3-16 In addition to chemotherapy, patients often receive adjuvant endocrine therapy with selective estrogen receptor modulators, aromatase inhibitors, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists.5-16 Endocrine therapies also can lead to alopecia, but their role in PCIA has not been well defined.15,16 We describe 3 patients with breast cancer who experienced PCIA following chemotherapy with taxanes with or without endocrine therapies. We also review the literature on non–bone marrow transplantation PCIA to better characterize this entity and explore the role of endocrine therapies in PCIA.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 62-year-old woman with a history of stage II invasive ductal carcinoma presented with persistent hair loss 5 years after completing chemotherapy. She underwent 6 cycles of docetaxel and carboplatin along with radiation therapy as well as 1 year of trastuzumab and did not receive endocrine therapy. At the current presentation, she reported patchy hair regrowth that gradually filled in but failed to return to full density. Physical examination revealed the hair was diffusely thin, especially bitemporally (Figures 1A and 1B), and she did not experience any loss of body hair. She had no family history of hair loss. Her medical history was notable for hypertension, chronic obstructive bronchitis, osteopenia, and depression. Her thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level was within reference range. Medications included lisinopril, metoprolol, escitalopram, and trazodone. A biopsy from the occipital scalp showed nonscarring alopecia with variation of hair follicle size, a decreased number of hair follicles, and a decreased anagen to telogen ratio (Figure 1C). She was treated with clobetasol solution and minoxidil solution 5% for 1 year with mild improvement. She experienced no further hair loss but did not regain original hair density.

Patient 2

A 35-year-old woman with a history of stage II invasive ductal carcinoma presented with persistent hair loss 10 months after chemotherapy. She underwent 4 cycles of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by 4 cycles of paclitaxel and was started on trastuzumab. Tamoxifen was initiated 1 month after completing chemotherapy. She received radiation therapy the following month and continued trastuzumab for 1 year. At the current presentation, the patient noted that hair regrowth had started 1 month after the last course of chemotherapy but had progressed slowly. She denied body hair loss. Physical examination revealed diffuse thinning, especially over the crown, with scattered broken hairs throughout the scalp and several miniaturized hairs over the crown. She was evaluated as grade 3 on the Sinclair clinical grading scale used to evaluate female pattern hair loss (FPHL).17 Her family history was remarkable for FPHL in her maternal grandmother. She had no notable medical history, her TSH was normal, and she was taking tamoxifen and trastuzumab. Biopsy was not performed. The patient was started on minoxidil solution 2% and had mild improvement with no further broken-off hairs after 10 months. At that point, she was evaluated as grade 2 to 3 on the Sinclair scale.17

Patient 3

A 51-year-old woman with a history of papillary carcinoma and extensive ductal carcinoma in situ presented with persistent hair loss for 3.5 years following chemotherapy for recurrent breast cancer. After her initial diagnosis in the left breast, she received cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil but did not receive endocrine therapy. Her hair thinned during chemotherapy but returned to normal density within 1 year. She had a recurrence of the cancer in the right breast 14 years later and received 6 cycles of chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide and docetaxel followed by radiation therapy. After this course, her hair loss incompletely recovered. One year after chemotherapy, she underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and started anastrozole. Three months later, she noticed increased shedding and progressive thinning of the hair. Physical examination revealed diffuse thinning that was most pronounced over the crown. She also experienced lateral thinning of the eyebrows, decreased eyelashes, and dystrophic fingernails. Fluocinonide solution was discontinued by the patient due to scalp burning. She had a brother with bitemporal recession. Her medical history was notable for Hashimoto thyroiditis, vitamin D deficiency, and peripheral neuropathy. Her TSH occasionally was elevated, and she was intermittently on levothyroxine; however, her free T4 was maintained within reference range on all records. Her medications at the time of evaluation were anastrozole and gabapentin. Biopsies taken from the right and left temporal scalp revealed decreased follicle density with a majority of follicles in anagen, scattered miniaturized follicles, and a mild perivascular and perifollicular lymphoid infiltrate. Mild dermal fibrosis was present without evidence of frank scarring (Figure 2). She declined treatment, and there was no change in her condition over 3 years of follow-up.

Comment

Classification of Chemotherapy-Induced Hair Loss

Chemotherapy-induced alopecia is typically an anagen effluvium that is reversed within 6 months following the final course of chemotherapy. When incomplete regrowth persists, the patient is considered to have PCIA.1 The pathophysiology of PCIA is unclear.

Traditional grading for chemotherapy-induced alopecia does not account for the patterns of loss seen in PCIA, of which the most common appears to be a female pattern with accentuated hair loss in androgen-dependent regions of the scalp.18 Other patterns include a diffuse type with body hair loss, patchy alopecia, and complete alopecia with or without body hair loss (Table).3-8 Whether these patterns all can be attributed to chemotherapy remains to be explored.

Breast Cancer Therapies Causing PCIA

The main agents thought to be responsible for PCIA in breast cancer patients are taxanes. The role of endocrine therapies has not been well explored. Trastuzumab lacks several of the common side effects of chemotherapy due to its specificity for the HER2/neu receptor and has not been found to increase the rate of hair loss when combined with standard chemotherapy.19,20 Although radiation therapy has the potential to damage hair follicles, and a dose-dependent relationship has been described for temporary and permanent alopecia at irradiated sites, permanent alopecia predominantly has been reported with cranial radiation used in the treatment of intracranial malignancies.21 The role of radiation therapy of the breasts in PCIA is unclear, as its inclusion in therapy has not been consistently reported in the literature.

Docetaxel is known to cause chemotherapy-induced alopecia, with an 83.4% incidence in phase 2 trials; however, it also appears to be related to PCIA.20 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was performed using the terms permanent chemotherapy induced alopecia, chemotherapy, docetaxel, endocrine therapies, hair loss, alopecia, and breast cancer. More than 400 cases of PCIA related to chemotherapy in breast cancer patients have been reported in the literature from a combination of case reports/series, retrospective surveys, and at least one prospective study. Data from some of the more detailed reports (n=52) are summarized in the Table. In the single-center, 3-year prospective study of women given adjuvant taxane-based or non–taxane-based chemotherapy, those who received taxane therapy were more likely to develop PCIA (odds ratio, 8.01).9

All 3 of our patients received taxanes. Interestingly, patient 3 underwent 2 rounds of chemotherapy 14 years apart and experienced full regrowth of the hair after the first course of taxane-free chemotherapy but experienced persistent hair loss following docetaxel treatment. Adjuvant endocrine therapies also may contribute to PCIA. A review of the side effects of endocrine therapies revealed an incidence of alopecia that was higher than expected; tamoxifen was the greatest offender. Additionally, using endocrine treatments in combination was found to have a synergistic effect on alopecia.18 Adjuvant endocrine therapy was used in patients 2 and 3. Although endocrine therapies appear to have a milder effect on hair loss compared to chemotherapy, these medications are continued for a longer duration, potentially contributing to the severity of hair loss and prolonging the time to regrowth.

Furthermore, endocrine therapies used in breast cancer treatment decrease estrogen levels or antagonize estrogen receptors, creating an environment of relative hyperandrogenism that may contribute to FPHL in genetically susceptible women.18 Although taxanes may cause irreversible hair loss in these patients, the action of endocrine therapies on the remaining hair follicles may affect the typical female pattern seen clinically. Patients 2 and 3 who presented with FPHL received adjuvant endocrine therapies and had positive family history, while patient 1 did not. Of note, patient 3 experienced worsening hair loss following the addition of anastrozole, which suggests a contribution of endocrine therapy to her PCIA. Our limited cases do not allow for evaluation of a worsened outcome with the combination of taxanes and endocrine therapies; however, we suggest further evaluation for a synergistic effect that may be contributing to PCIA.

Conclusion

Permanent alopecia in breast cancer patients appears to be a true potential adverse effect of taxanes and endocrine therapies, and it is important to characterize it appropriately so that its mechanism can be understood and appropriate treatment and counseling can take place. Although it may not influence clinical decision-making, patients should be informed that hair loss with chemotherapy can be permanent. Treatment with scalp cooling can reduce the risk for severe chemotherapy-induced alopecia, but it is unclear if it reduces risk for PCIA.12,15 Topical or oral minoxidil may be helpful in the treatment of PCIA once it has developed.7,8,15,22 Better characterization of these cases may elucidate risk factors for developing permanent alopecia, allowing for more appropriate risk stratification, counseling, and treatment.

- Dorr VJ. A practitioner’s guide to cancer-related alopecia. Semin Oncol. 1998;25:562-570.

- Machado M, Moreb JS, Khan SA. Six cases of permanent alopecia after various conditioning regimens commonly used in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:979-982.

- Tallon B, Blanchard E, Goldberg LJ. Permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia: case report and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:333-336.

- Miteva M, Misciali C, Fanti PA, et al. Permanent alopecia after systemic chemotherapy: a clinicopathological study of 10 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:345-350.

- Prevezas C, Matard B, Pinquier L, et al. Irreversible and severe alopecia following docetaxel or paclitaxel cytotoxic therapy for breast cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:883-885.

- Masidonski P, Mahon SM. Permanent alopecia in women being treated for breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13:13-14.

- Kluger N, Jacot W, Frouin E, et al. Permanent scalp alopecia related to breast cancer chemotherapy by sequential fluorouracil/epirubicin/cyclophosphamide (FEC) and docetaxel: a prospective study of 20 patients. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2879-2884.

- Fonia A, Cota C, Setterfield JF, et al. Permanent alopecia in patients with breast cancer after taxane chemotherapy and adjuvant hormonal therapy: clinicopathologic findings in a cohort of 10 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:948-957.

- Kang D, Kim IR, Choi EK, et al. Permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia in patients with breast cancer: a 3-year prospective cohort study [published online August 17, 2018]. Oncologist. 2019;24:414-420.

- Chan J, Adderley H, Alameddine M, et al. Permanent hair loss associated with taxane chemotherapy use in breast cancer: a retrospective survey at two tertiary UK cancer centres [published online December 22, 2020]. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). doi:10.1111/ecc.13395

- Bourgeois H, Denis F, Kerbrat P, et al. Long term persistent alopecia and suboptimal hair regrowth after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: alert for an emerging side effect: ALOPERS Observatory. Cancer Res. 2009;69(24 suppl). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.SABCS-09-3174

- Bertrand M, Mailliez A, Vercambre S, et al. Permanent chemotherapy induced alopecia in early breast cancer patients after (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy: long term follow up. Cancer Res. 2013;73(24 suppl). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.SABCS13-P3-09-15

- Kim S, Park HS, Kim JY, et al. Irreversible chemotherapy-induced alopecia in breast cancer patient. Cancer Res. 2016;76(4 suppl). doi:10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS15-P1-15-04

- Thorp NJ, Swift F, Arundell D, et al. Long term hair loss in patients with early breast cancer receiving docetaxel chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2015;75(9 suppl). doi:10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS14-P5-17-04

- Freites-Martinez A, Shapiro J, van den Hurk C, et al. Hair disorders in cancer survivors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1199-1213.

- Freites-Martinez A, Chan D, Sibaud V, et al. Assessment of quality of life and treatment outcomes of patients with persistent postchemotherapy alopecia. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:724-728.

- Sinclair R, Jolley D, Mallari R, et al. The reliability of horizontally sectioned scalp biopsies in the diagnosis of chronic diffuse telogen hair loss in women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:189-199.

- Saggar V, Wu S, Dickler MN, et al. Alopecia with endocrine therapies in patients with cancer. Oncologist. 2013;18:1126-1134.

- Yeager CE, Olsen EA. Treatment of chemotherapy-induced alopecia. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:432-442.

- Baselga J. Clinical trials of single-agent trastuzumab (Herceptin). Semin Oncol. 2000;27(5 suppl 9):20-26.

- Lawenda BD, Gagne HM, Gierga DP, et al. Permanent alopecia after cranial irradiation: dose-response relationship. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:879-887.

- Yang X, Thai KE. Treatment of permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia with low dose oral minoxidil [published online May 13, 2015]. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:E130-E132.

- Dorr VJ. A practitioner’s guide to cancer-related alopecia. Semin Oncol. 1998;25:562-570.

- Machado M, Moreb JS, Khan SA. Six cases of permanent alopecia after various conditioning regimens commonly used in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:979-982.

- Tallon B, Blanchard E, Goldberg LJ. Permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia: case report and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:333-336.

- Miteva M, Misciali C, Fanti PA, et al. Permanent alopecia after systemic chemotherapy: a clinicopathological study of 10 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:345-350.

- Prevezas C, Matard B, Pinquier L, et al. Irreversible and severe alopecia following docetaxel or paclitaxel cytotoxic therapy for breast cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:883-885.

- Masidonski P, Mahon SM. Permanent alopecia in women being treated for breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13:13-14.

- Kluger N, Jacot W, Frouin E, et al. Permanent scalp alopecia related to breast cancer chemotherapy by sequential fluorouracil/epirubicin/cyclophosphamide (FEC) and docetaxel: a prospective study of 20 patients. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2879-2884.

- Fonia A, Cota C, Setterfield JF, et al. Permanent alopecia in patients with breast cancer after taxane chemotherapy and adjuvant hormonal therapy: clinicopathologic findings in a cohort of 10 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:948-957.

- Kang D, Kim IR, Choi EK, et al. Permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia in patients with breast cancer: a 3-year prospective cohort study [published online August 17, 2018]. Oncologist. 2019;24:414-420.

- Chan J, Adderley H, Alameddine M, et al. Permanent hair loss associated with taxane chemotherapy use in breast cancer: a retrospective survey at two tertiary UK cancer centres [published online December 22, 2020]. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). doi:10.1111/ecc.13395

- Bourgeois H, Denis F, Kerbrat P, et al. Long term persistent alopecia and suboptimal hair regrowth after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: alert for an emerging side effect: ALOPERS Observatory. Cancer Res. 2009;69(24 suppl). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.SABCS-09-3174

- Bertrand M, Mailliez A, Vercambre S, et al. Permanent chemotherapy induced alopecia in early breast cancer patients after (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy: long term follow up. Cancer Res. 2013;73(24 suppl). doi:10.1158/0008-5472.SABCS13-P3-09-15

- Kim S, Park HS, Kim JY, et al. Irreversible chemotherapy-induced alopecia in breast cancer patient. Cancer Res. 2016;76(4 suppl). doi:10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS15-P1-15-04

- Thorp NJ, Swift F, Arundell D, et al. Long term hair loss in patients with early breast cancer receiving docetaxel chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2015;75(9 suppl). doi:10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS14-P5-17-04

- Freites-Martinez A, Shapiro J, van den Hurk C, et al. Hair disorders in cancer survivors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1199-1213.

- Freites-Martinez A, Chan D, Sibaud V, et al. Assessment of quality of life and treatment outcomes of patients with persistent postchemotherapy alopecia. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:724-728.

- Sinclair R, Jolley D, Mallari R, et al. The reliability of horizontally sectioned scalp biopsies in the diagnosis of chronic diffuse telogen hair loss in women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:189-199.

- Saggar V, Wu S, Dickler MN, et al. Alopecia with endocrine therapies in patients with cancer. Oncologist. 2013;18:1126-1134.

- Yeager CE, Olsen EA. Treatment of chemotherapy-induced alopecia. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:432-442.

- Baselga J. Clinical trials of single-agent trastuzumab (Herceptin). Semin Oncol. 2000;27(5 suppl 9):20-26.

- Lawenda BD, Gagne HM, Gierga DP, et al. Permanent alopecia after cranial irradiation: dose-response relationship. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:879-887.

- Yang X, Thai KE. Treatment of permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia with low dose oral minoxidil [published online May 13, 2015]. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:E130-E132.

Practice Points

- Permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia (PCIA) is defined as hair loss that persists beyond 6 months after treatment with chemotherapy. It may be complicated by the addition of endocrine therapies.

- Patients and clinicians should be aware that PCIA can occur and appears to be a higher risk with taxane therapy.

Treatment of Generalized Pustular Psoriasis of Pregnancy With Infliximab

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (GPPP), formerly known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a rare dermatosis that causes maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. It is characterized by widespread, circular, erythematous plaques with pustules at the periphery.1 Conventional first-line treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporine. The National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board also has included infliximab among the first-line treatment options for GPPP.2 Herein, we report a case of GPPP treated with infliximab at 30 weeks’ gestation and during the postpartum period.

Case Report

A 22-year-old woman was admitted to our inpatient clinic at 20 weeks’ gestation in her second pregnancy for evaluation of cutaneous eruptions covering the entire body. The lesions first appeared 3 to 4 days prior to her admission and dramatically progressed. She had a history of psoriasis vulgaris diagnosed during her first pregnancy 2 years prior that was treated with topical steroids throughout the pregnancy and methotrexate during lactation for a total of 11 months. She then was started on cyclosporine, which she used for 6 months due to ineffectiveness of the methotrexate, but she stopped treatment 4 months before the second pregnancy.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed erythroderma and widespread pustules on the chest, abdomen, arms, and legs, including the intertriginous regions, that tended to coalesce and form lakes of pus over an erythematous base (Figure 1). The mucosae were normal. She exhibited a low blood pressure (85/50 mmHg) and high body temperature (102 °F [38.9 °C]). Routine laboratory examination revealed anemia and a normal leukocyte count. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (57 mm/h [reference range, <20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (102 mg/L [reference range, <6 mg/L]) were elevated, whereas total calcium (8.11 mg/dL [reference range, 8.2–10.6 mg/dL]) and albumin (3.15 g/dL [reference range, >4.0 g/dL]) levels were low.

Empirical intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam was started due to hypotension, high fever, and elevated C-reactive protein levels; however, treatment was stopped after 4 days when microbiological cultures taken from blood and pustules revealed no bacterial growth, and therefore the fever was assumed to be caused by erythroderma. A skin biopsy before the start of topical and systemic treatment revealed changes consistent with GPPP.

Because her disease was extensive, systemic methylprednisolone 1.5 mg/kg once daily was started, and the dose was increased up to 2.5 mg/kg once daily on the tenth day of treatment to control new crops of eruptions. The dose was tapered to 2 mg/kg once daily when the lesions subsided 4 weeks into the treatment. The patient was discharged after 7 weeks at 27 weeks’ gestation.

Twelve days later, the patient was readmitted to the clinic in an erythrodermic state. The lesions were not controlled with increased doses of systemic corticosteroids. Treatment with cyclosporine was considered, but the patient refused; thus, infliximab treatment was planned. Isoniazid 300 mg once daily was started due to a risk of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection revealed by a tuberculosis blood test. Other evaluations revealed no contraindications, and an infusion of infliximab 300 mg (5 mg/kg) was administered at 30 weeks’ gestation. There was visible improvement in the erythroderma and pustular lesions within the same day of treatment, and the lesions were completely cleared within 2 days of the infusion. The methylprednisolone dose was reduced to 1.5 mg/kg once daily.

Three days after treatment with infliximab, lesions with yellow encrustation appeared in the perioral region and on the oral mucosa and left ear. She was diagnosed with an oral herpes infection. Oral valacyclovir 1 g twice daily and topical mupirocin were started and the lesions subsided within 1 week. Twelve days after the infliximab infusion, new pustular lesions appeared, and a second infusion of infliximab was administered 13 days after the first, which cleared all lesions within 48 hours.

The patient’s methylprednisolone dose was tapered and stopped prior to delivery at 34 weeks’ gestation—2 weeks after the second dose of infliximab—as she did not have any new skin eruptions. A third infliximab infusion that normally would have occurred 4 weeks after the second treatment was postponed for a Cesarean section scheduled at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation. The patient stayed at the hospital until delivery without any new skin lesions. The gross and histopathologic examination of the placenta was normal. The neonate weighed 4.8 lb at birth and had neonatal jaundice that resolved spontaneously within 10 days but was otherwise healthy.

The patient returned to the clinic 3 weeks postpartum with a few pustules on erythematous plaques on the chest, abdomen, and back. At this time, she received a third infusion of infliximab 8 weeks after the second dose. For the past 5 years, the patient has been undergoing infliximab maintenance treatment, which she receives at the hospital every 8 weeks with excellent response. She has had no further pregnancies to date.

Comment

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare condition that typically occurs in the third trimester but also can start in the first and second trimesters. It may result in maternal and fetal morbidity by causing fluid and electrolyte imbalance and/or placental insufficiency, resulting in an increased risk for fetal abnormalities, stillbirth, and neonatal death.3 In subsequent pregnancies, GPPP has been observed to recur at an earlier gestational age with a more severe presentation.1,3

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy usually involves an eruption that begins symmetrically in the intertriginous areas and spreads to the rest of the body. The lesions present as erythematous annular plaques with pustules on the periphery and desquamation in the center due to older pustules.1,3 The mucous membranes also may be involved with erosive and exfoliative plaques, and there may be nail involvement. Patients often present with systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, diarrhea, and vomiting.1 Laboratory investigations may reveal neutrophilic leukocytosis, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, hypocalcemia, and hypoalbuminemia.4 Cultures from blood and pustules show no bacterial growth. A skin biopsy is helpful in diagnosis, with features similar to generalized pustular psoriasis, demonstrating spongiform pustules containing neutrophils, lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates in the papillary dermis, and negative direct immunofluorescence.3

The differential diagnosis of GPPP includes subcorneal pustular dermatosis, dermatitis herpetiformis, herpes gestationis, impetigo, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.1,3 Due to concerns of fetal implications, treatment options in GPPP are somewhat limited; however, the condition requires treatment because it may result in unfavorable pregnancy outcomes. Topical corticosteroids may be an option for limited disease.5,6 Systemic corticosteroids (eg, prednisone 60–80 mg/d) were previously considered as first-line agents, although they have shown limited efficacy in our case as well as in other case reports.7 Their ineffectiveness and risk for flare-up after dose tapering should be kept in mind when starting GPPP patients on systemic corticosteroids. Systemic cyclosporine (2–3 mg/kg/d) may be added to increase the efficacy of systemic steroids, which was done in several cases in literature.1,6,8 Although cyclosporine has been classified as a pregnancy category C drug, an analysis of pregnancy outcomes of 629 renal transplant patients revealed no association with adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to the general population and no increase in fetal malformations.9 Therefore, cyclosporine is a safe treatment option and was classified as a first-line drug for GPPP in a 2012 review by the National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board.2 Narrowband UVB also has been reported to be used for the treatment of GPPP.10 Methotrexate and retinoids have been used in cases with lesions that persisted postpartum.1

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α agents are another effective option for treatment of GPPP. Anti-TNF agents are classified as pregnancy category B due to results showing that anti-mouse TNF-α monoclonal antibodies did not cause embryotoxicity or teratogenicity in pregnant mice.11 Although Carter et al12 published a review of US Food and Drug Administration data on pregnant women receiving anti-TNF treatment and concluded that these agents were associated with the VACTERL group of malformations (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defect, tracheoesophageal fistula with esophageal atresia, cardiac defects, renal and limb anomalies), no such association was found in further studies. A 2014 study showed no difference in the rate of major malformations in infants born to women who were treated with anti-TNF drugs compared to the disease-matched group not treated with these agents and pregnant women counselled for nonteratogenic exposure.13 The same study detected an increase in preterm and low-birth-weight deliveries and suggested this might be caused by the increased severity of disease in patients requiring anti-TNF medication. The British Society of Rheumatology Biologics Register published data on pregnancy outcomes in 130 rheumatoid arthritis patients who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents.14 The results suggested an increased rate of spontaneous abortions in women exposed to anti-TNF treatment around the time of conception, especially in those taking these medications together with methotrexate or leflunomide; however, results also indicated that disease activity may have had an impact on the rate of spontaneous abortions in these patients. In a 2013 review of 462 women with inflammatory bowel disease who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents during pregnancy, the investigators concluded that pregnancy outcomes and the rate of congenital anomalies did not significantly differ from other inflammatory bowel disease patients not receiving anti-TNF drugs or the general population.15

In 2012, the National Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation put infliximab amongst the first-line treatment modalities for GPPP.2 In one case of GPPP in which the eruption persisted after delivery, the patient was treated with infliximab 7 weeks postpartum due to failure to control the disease with prednisolone 60 mg daily and cyclosporine 7.5 mg/kg daily. Unlike our patient, this patient was only started on an infliximab regimen after delivery.16 In another case reported in 2010, the patient was started on infliximab during the postpartum period of her first pregnancy following a pustular flare of previously diagnosed plaque psoriasis (not a generalized pustular psoriasis, as in our case).17 As a good response was obtained, infliximab treatment was continued in the patient throughout her second pregnancy.

Our case is unique in that infliximab was started during pregnancy because of intractable disease leading to systemic symptoms. Our patient showed an excellent response to infliximab after a 10-week disease course with repeated flare-ups and impairment to her overall condition. Delivery occurred at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation; however, the neonate was born with a 5-minute APGAR score of 10 and required no special medical care, which suggests that the low birth weight was constitutional due to the patient’s small frame (her height was 4 ft 11 in). The breast milk of patients with inflammatory bowel disease has been detected to contain very small amounts of infliximab (101 ng/mL, about 1/200 of the therapeutic blood level).18 Considering the large molecular weight of this agent and possible proteolysis in the stomach and intestines, infliximab is unlikely to affect the neonate.15 Thus, we encouraged our patient to breastfeed her baby. A case of fatal disseminated Bacille-Calmette-Guérin infection in an infant whose mother received infliximab treatment during pregnancy has been reported.19 It has been suggested that live vaccines should be avoided in neonates exposed to anti-TNF agents at least for the first 6 months of life or until the agent is no longer detectable in their blood.15 We therefore informed our patient’s family practitioner about this data.

Conclusion

We report a case of infliximab treatment for GPPP that was continued during the postpartum period. Infliximab was an effective treatment option in our patient with no detected serious adverse events and may be considered in other cases of GPPP that are not responsive to systemic steroids. However, further studies are warranted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of infliximab treatment for GPPP and psoriasis in pregnancy.

- Lerhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101-104.

- Gao QQ, Xi MR, Yao Q. Impetigo herpetiformis during pregnancy: a case report and literature review. Dermatology. 2013;226:35-40.

- Bae YS, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Review of treatment options for psoriasis in pregnant or lactating women: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:459-477.

- Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine [published May 12, 2011]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr.02.2011.3915

- Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

- Luan L, Han S, Zhang Z, et al. Personal treatment experience for severe generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: two case reports. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:174-177.

- Lamarque V, Leleu MF, Monka C, et al. Analysis of 629 pregnancy outcomes in transplant recipients treated with Sandimmun. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:2480.

- Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrowband UVB. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

- Treacy G. Using an analogous monoclonal antibody to evaluate the reproductive and chronic toxicity potential for a humanized anti-TNF alpha monoclonal antibody. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2000;19:226-228.

- Carter JD, Ladhani A, Ricca LR, et al. A safety assessment of tumor necrosis factor antagonists during pregnancy: a review of the Food and Drug Administration database. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:635-641.

- Diav-Citrin O, Otcheretianski-Volodarsky A, Shechtman S, et al. Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to TNF-alpha-inhibitors: a prospective, comparative, observational study. Reprod Toxicol. 2014;43:78-84.

- Verstappen SM, King Y, Watson KD, et al. Anti-TNF therapies and pregnancy: outcome of 130 pregnancies in the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:823-826.

- Gisbert JP, Chaparro M. Safety of anti-TNF agents during pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1426-1438.

- Sheth N, Greenblatt DT, Acland K, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy treated with infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:521-522.

- Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

- Ben-Horin S, Yavzori M, Kopylov U, et al. Detection of infliximab in breast milk of nursing mothers with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:555-558.

- Cheent K, Nolan J, Shariq S, et al. Case report: fatal case of disseminated BCG infection in an infant born to a mother taking infliximab for Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:603-605.

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (GPPP), formerly known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a rare dermatosis that causes maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. It is characterized by widespread, circular, erythematous plaques with pustules at the periphery.1 Conventional first-line treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporine. The National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board also has included infliximab among the first-line treatment options for GPPP.2 Herein, we report a case of GPPP treated with infliximab at 30 weeks’ gestation and during the postpartum period.

Case Report

A 22-year-old woman was admitted to our inpatient clinic at 20 weeks’ gestation in her second pregnancy for evaluation of cutaneous eruptions covering the entire body. The lesions first appeared 3 to 4 days prior to her admission and dramatically progressed. She had a history of psoriasis vulgaris diagnosed during her first pregnancy 2 years prior that was treated with topical steroids throughout the pregnancy and methotrexate during lactation for a total of 11 months. She then was started on cyclosporine, which she used for 6 months due to ineffectiveness of the methotrexate, but she stopped treatment 4 months before the second pregnancy.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed erythroderma and widespread pustules on the chest, abdomen, arms, and legs, including the intertriginous regions, that tended to coalesce and form lakes of pus over an erythematous base (Figure 1). The mucosae were normal. She exhibited a low blood pressure (85/50 mmHg) and high body temperature (102 °F [38.9 °C]). Routine laboratory examination revealed anemia and a normal leukocyte count. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (57 mm/h [reference range, <20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (102 mg/L [reference range, <6 mg/L]) were elevated, whereas total calcium (8.11 mg/dL [reference range, 8.2–10.6 mg/dL]) and albumin (3.15 g/dL [reference range, >4.0 g/dL]) levels were low.

Empirical intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam was started due to hypotension, high fever, and elevated C-reactive protein levels; however, treatment was stopped after 4 days when microbiological cultures taken from blood and pustules revealed no bacterial growth, and therefore the fever was assumed to be caused by erythroderma. A skin biopsy before the start of topical and systemic treatment revealed changes consistent with GPPP.

Because her disease was extensive, systemic methylprednisolone 1.5 mg/kg once daily was started, and the dose was increased up to 2.5 mg/kg once daily on the tenth day of treatment to control new crops of eruptions. The dose was tapered to 2 mg/kg once daily when the lesions subsided 4 weeks into the treatment. The patient was discharged after 7 weeks at 27 weeks’ gestation.

Twelve days later, the patient was readmitted to the clinic in an erythrodermic state. The lesions were not controlled with increased doses of systemic corticosteroids. Treatment with cyclosporine was considered, but the patient refused; thus, infliximab treatment was planned. Isoniazid 300 mg once daily was started due to a risk of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection revealed by a tuberculosis blood test. Other evaluations revealed no contraindications, and an infusion of infliximab 300 mg (5 mg/kg) was administered at 30 weeks’ gestation. There was visible improvement in the erythroderma and pustular lesions within the same day of treatment, and the lesions were completely cleared within 2 days of the infusion. The methylprednisolone dose was reduced to 1.5 mg/kg once daily.

Three days after treatment with infliximab, lesions with yellow encrustation appeared in the perioral region and on the oral mucosa and left ear. She was diagnosed with an oral herpes infection. Oral valacyclovir 1 g twice daily and topical mupirocin were started and the lesions subsided within 1 week. Twelve days after the infliximab infusion, new pustular lesions appeared, and a second infusion of infliximab was administered 13 days after the first, which cleared all lesions within 48 hours.

The patient’s methylprednisolone dose was tapered and stopped prior to delivery at 34 weeks’ gestation—2 weeks after the second dose of infliximab—as she did not have any new skin eruptions. A third infliximab infusion that normally would have occurred 4 weeks after the second treatment was postponed for a Cesarean section scheduled at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation. The patient stayed at the hospital until delivery without any new skin lesions. The gross and histopathologic examination of the placenta was normal. The neonate weighed 4.8 lb at birth and had neonatal jaundice that resolved spontaneously within 10 days but was otherwise healthy.

The patient returned to the clinic 3 weeks postpartum with a few pustules on erythematous plaques on the chest, abdomen, and back. At this time, she received a third infusion of infliximab 8 weeks after the second dose. For the past 5 years, the patient has been undergoing infliximab maintenance treatment, which she receives at the hospital every 8 weeks with excellent response. She has had no further pregnancies to date.

Comment

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare condition that typically occurs in the third trimester but also can start in the first and second trimesters. It may result in maternal and fetal morbidity by causing fluid and electrolyte imbalance and/or placental insufficiency, resulting in an increased risk for fetal abnormalities, stillbirth, and neonatal death.3 In subsequent pregnancies, GPPP has been observed to recur at an earlier gestational age with a more severe presentation.1,3

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy usually involves an eruption that begins symmetrically in the intertriginous areas and spreads to the rest of the body. The lesions present as erythematous annular plaques with pustules on the periphery and desquamation in the center due to older pustules.1,3 The mucous membranes also may be involved with erosive and exfoliative plaques, and there may be nail involvement. Patients often present with systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, diarrhea, and vomiting.1 Laboratory investigations may reveal neutrophilic leukocytosis, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, hypocalcemia, and hypoalbuminemia.4 Cultures from blood and pustules show no bacterial growth. A skin biopsy is helpful in diagnosis, with features similar to generalized pustular psoriasis, demonstrating spongiform pustules containing neutrophils, lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates in the papillary dermis, and negative direct immunofluorescence.3

The differential diagnosis of GPPP includes subcorneal pustular dermatosis, dermatitis herpetiformis, herpes gestationis, impetigo, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.1,3 Due to concerns of fetal implications, treatment options in GPPP are somewhat limited; however, the condition requires treatment because it may result in unfavorable pregnancy outcomes. Topical corticosteroids may be an option for limited disease.5,6 Systemic corticosteroids (eg, prednisone 60–80 mg/d) were previously considered as first-line agents, although they have shown limited efficacy in our case as well as in other case reports.7 Their ineffectiveness and risk for flare-up after dose tapering should be kept in mind when starting GPPP patients on systemic corticosteroids. Systemic cyclosporine (2–3 mg/kg/d) may be added to increase the efficacy of systemic steroids, which was done in several cases in literature.1,6,8 Although cyclosporine has been classified as a pregnancy category C drug, an analysis of pregnancy outcomes of 629 renal transplant patients revealed no association with adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to the general population and no increase in fetal malformations.9 Therefore, cyclosporine is a safe treatment option and was classified as a first-line drug for GPPP in a 2012 review by the National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board.2 Narrowband UVB also has been reported to be used for the treatment of GPPP.10 Methotrexate and retinoids have been used in cases with lesions that persisted postpartum.1

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α agents are another effective option for treatment of GPPP. Anti-TNF agents are classified as pregnancy category B due to results showing that anti-mouse TNF-α monoclonal antibodies did not cause embryotoxicity or teratogenicity in pregnant mice.11 Although Carter et al12 published a review of US Food and Drug Administration data on pregnant women receiving anti-TNF treatment and concluded that these agents were associated with the VACTERL group of malformations (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defect, tracheoesophageal fistula with esophageal atresia, cardiac defects, renal and limb anomalies), no such association was found in further studies. A 2014 study showed no difference in the rate of major malformations in infants born to women who were treated with anti-TNF drugs compared to the disease-matched group not treated with these agents and pregnant women counselled for nonteratogenic exposure.13 The same study detected an increase in preterm and low-birth-weight deliveries and suggested this might be caused by the increased severity of disease in patients requiring anti-TNF medication. The British Society of Rheumatology Biologics Register published data on pregnancy outcomes in 130 rheumatoid arthritis patients who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents.14 The results suggested an increased rate of spontaneous abortions in women exposed to anti-TNF treatment around the time of conception, especially in those taking these medications together with methotrexate or leflunomide; however, results also indicated that disease activity may have had an impact on the rate of spontaneous abortions in these patients. In a 2013 review of 462 women with inflammatory bowel disease who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents during pregnancy, the investigators concluded that pregnancy outcomes and the rate of congenital anomalies did not significantly differ from other inflammatory bowel disease patients not receiving anti-TNF drugs or the general population.15

In 2012, the National Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation put infliximab amongst the first-line treatment modalities for GPPP.2 In one case of GPPP in which the eruption persisted after delivery, the patient was treated with infliximab 7 weeks postpartum due to failure to control the disease with prednisolone 60 mg daily and cyclosporine 7.5 mg/kg daily. Unlike our patient, this patient was only started on an infliximab regimen after delivery.16 In another case reported in 2010, the patient was started on infliximab during the postpartum period of her first pregnancy following a pustular flare of previously diagnosed plaque psoriasis (not a generalized pustular psoriasis, as in our case).17 As a good response was obtained, infliximab treatment was continued in the patient throughout her second pregnancy.

Our case is unique in that infliximab was started during pregnancy because of intractable disease leading to systemic symptoms. Our patient showed an excellent response to infliximab after a 10-week disease course with repeated flare-ups and impairment to her overall condition. Delivery occurred at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation; however, the neonate was born with a 5-minute APGAR score of 10 and required no special medical care, which suggests that the low birth weight was constitutional due to the patient’s small frame (her height was 4 ft 11 in). The breast milk of patients with inflammatory bowel disease has been detected to contain very small amounts of infliximab (101 ng/mL, about 1/200 of the therapeutic blood level).18 Considering the large molecular weight of this agent and possible proteolysis in the stomach and intestines, infliximab is unlikely to affect the neonate.15 Thus, we encouraged our patient to breastfeed her baby. A case of fatal disseminated Bacille-Calmette-Guérin infection in an infant whose mother received infliximab treatment during pregnancy has been reported.19 It has been suggested that live vaccines should be avoided in neonates exposed to anti-TNF agents at least for the first 6 months of life or until the agent is no longer detectable in their blood.15 We therefore informed our patient’s family practitioner about this data.

Conclusion

We report a case of infliximab treatment for GPPP that was continued during the postpartum period. Infliximab was an effective treatment option in our patient with no detected serious adverse events and may be considered in other cases of GPPP that are not responsive to systemic steroids. However, further studies are warranted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of infliximab treatment for GPPP and psoriasis in pregnancy.

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (GPPP), formerly known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a rare dermatosis that causes maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. It is characterized by widespread, circular, erythematous plaques with pustules at the periphery.1 Conventional first-line treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporine. The National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board also has included infliximab among the first-line treatment options for GPPP.2 Herein, we report a case of GPPP treated with infliximab at 30 weeks’ gestation and during the postpartum period.

Case Report

A 22-year-old woman was admitted to our inpatient clinic at 20 weeks’ gestation in her second pregnancy for evaluation of cutaneous eruptions covering the entire body. The lesions first appeared 3 to 4 days prior to her admission and dramatically progressed. She had a history of psoriasis vulgaris diagnosed during her first pregnancy 2 years prior that was treated with topical steroids throughout the pregnancy and methotrexate during lactation for a total of 11 months. She then was started on cyclosporine, which she used for 6 months due to ineffectiveness of the methotrexate, but she stopped treatment 4 months before the second pregnancy.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed erythroderma and widespread pustules on the chest, abdomen, arms, and legs, including the intertriginous regions, that tended to coalesce and form lakes of pus over an erythematous base (Figure 1). The mucosae were normal. She exhibited a low blood pressure (85/50 mmHg) and high body temperature (102 °F [38.9 °C]). Routine laboratory examination revealed anemia and a normal leukocyte count. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (57 mm/h [reference range, <20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (102 mg/L [reference range, <6 mg/L]) were elevated, whereas total calcium (8.11 mg/dL [reference range, 8.2–10.6 mg/dL]) and albumin (3.15 g/dL [reference range, >4.0 g/dL]) levels were low.

Empirical intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam was started due to hypotension, high fever, and elevated C-reactive protein levels; however, treatment was stopped after 4 days when microbiological cultures taken from blood and pustules revealed no bacterial growth, and therefore the fever was assumed to be caused by erythroderma. A skin biopsy before the start of topical and systemic treatment revealed changes consistent with GPPP.

Because her disease was extensive, systemic methylprednisolone 1.5 mg/kg once daily was started, and the dose was increased up to 2.5 mg/kg once daily on the tenth day of treatment to control new crops of eruptions. The dose was tapered to 2 mg/kg once daily when the lesions subsided 4 weeks into the treatment. The patient was discharged after 7 weeks at 27 weeks’ gestation.

Twelve days later, the patient was readmitted to the clinic in an erythrodermic state. The lesions were not controlled with increased doses of systemic corticosteroids. Treatment with cyclosporine was considered, but the patient refused; thus, infliximab treatment was planned. Isoniazid 300 mg once daily was started due to a risk of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection revealed by a tuberculosis blood test. Other evaluations revealed no contraindications, and an infusion of infliximab 300 mg (5 mg/kg) was administered at 30 weeks’ gestation. There was visible improvement in the erythroderma and pustular lesions within the same day of treatment, and the lesions were completely cleared within 2 days of the infusion. The methylprednisolone dose was reduced to 1.5 mg/kg once daily.

Three days after treatment with infliximab, lesions with yellow encrustation appeared in the perioral region and on the oral mucosa and left ear. She was diagnosed with an oral herpes infection. Oral valacyclovir 1 g twice daily and topical mupirocin were started and the lesions subsided within 1 week. Twelve days after the infliximab infusion, new pustular lesions appeared, and a second infusion of infliximab was administered 13 days after the first, which cleared all lesions within 48 hours.

The patient’s methylprednisolone dose was tapered and stopped prior to delivery at 34 weeks’ gestation—2 weeks after the second dose of infliximab—as she did not have any new skin eruptions. A third infliximab infusion that normally would have occurred 4 weeks after the second treatment was postponed for a Cesarean section scheduled at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation. The patient stayed at the hospital until delivery without any new skin lesions. The gross and histopathologic examination of the placenta was normal. The neonate weighed 4.8 lb at birth and had neonatal jaundice that resolved spontaneously within 10 days but was otherwise healthy.