User login

Acute Painful Horner Syndrome as the First Presenting Sign of Carotid Artery Dissection

Horner syndrome is a rare condition that has no sex or race predilection and is characterized by the clinical triad of a miosis, anhidrosis, and small, unilateral ptosis. The prompt diagnosis and determination of the etiology of Horner syndrome are of utmost importance, as the condition can result from many life-threatening systemic complications. Horner syndrome is often asymptomatic but can have distinct, easily identified characteristics seen with an ophthalmic examination. This report describes a patient who presented with Horner syndrome resulting from an internal carotid artery dissection.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old woman presented with periorbital pain with onset 3 days prior. The patient described the pain as 7 of 10 that had been worsening and was localized around and behind the right eye. She reported new-onset headaches on the right side over the past week with associated intermittent vision blurriness in the right eye. She had a history of mobility issues and had fallen backward about 1 week before, hitting the back of her head on the floor without direct trauma to the eye. She was symptomatic for light sensitivity, syncope, and dizziness, with reports of a recent history of transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) of unknown etiology, which had occurred in the months preceding her examination. She reported no jaw claudication, scalp tenderness, and neck or shoulder pain. She was unaware of any changes in her perspiration pattern on the right side of her face but mentioned that she had noticed her right upper eyelid drooping while looking in the mirror.

This patient had a routine eye examination 2 months before, which was remarkable for stable, nonfoveal involving adult-onset vitelliform dystrophy in the left eye and nuclear sclerotic cataracts and mild refractive error in both eyes. No iris heterochromia was noted, and her pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light. Her history was remarkable for chest pain, obesity, bipolar disorder, vertigo, transient cerebral ischemia, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, alcohol use disorder, cocaine use disorder, and asthma. A carotid ultrasound had been performed 1 month before the onset of symptoms due to her history of TIAs, which showed no hemodynamically significant stenosis (> 50% stenosis) of either carotid artery. Her medications included oxybutynin chloride, amlodipine, acetaminophen, sertraline hydrochloride, lidocaine, albuterol, risperidone, hydroxyzine hydrochloride, lisinopril, omeprazole, once-daily baby aspirin, atorvastatin, and calcium.

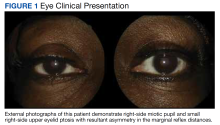

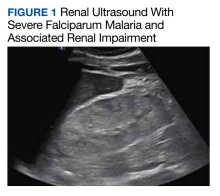

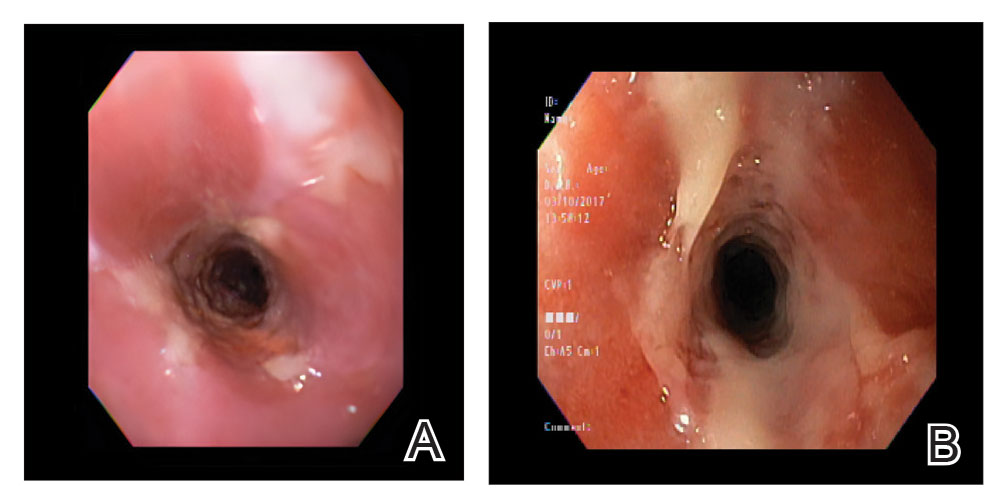

At the time of presentation, an ophthalmic examination revealed no decrease in visual acuity with a best-corrected visual acuity of 20/20 in the right and left eyes. The patient’s pupil sizes were unequal, with a smaller, more miotic right pupil with a greater difference between the pupil sizes in dim illumination (Figure 1).

As the patient had pathologic miosis, conditions causing pathologic mydriasis, such as Adie tonic pupil and cranial nerve III palsy, were ruled out. The presence of an acute, slight ptosis with pathologic miosis and pain in the ipsilateral eye with no reports of exposure to miotic pharmaceutical agents and no history of trauma to the globe or orbit eliminated other differentials, leading to a diagnosis of right-sided Horner syndrome. Due to concerns of acute onset periorbital and retrobulbar pain, she was referred to the emergency department with recommendations for computed tomography angiography (CTA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) of the head and neck to rule out a carotid artery dissection.

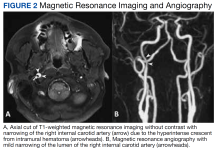

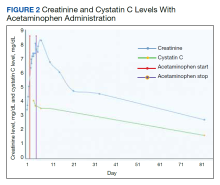

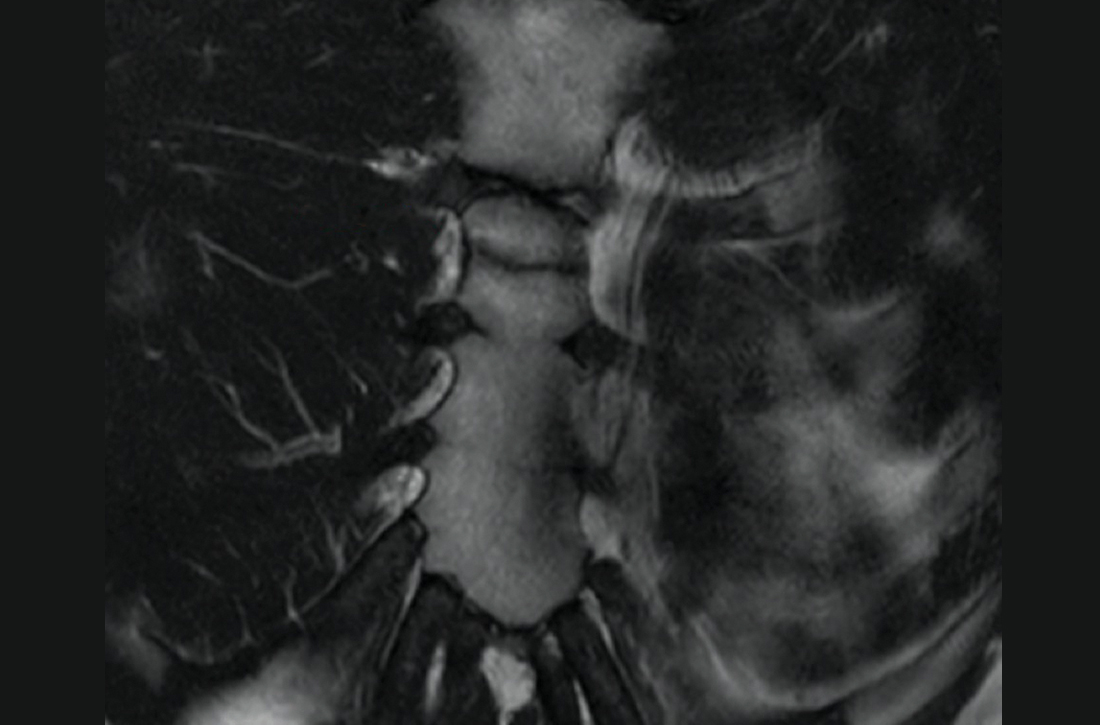

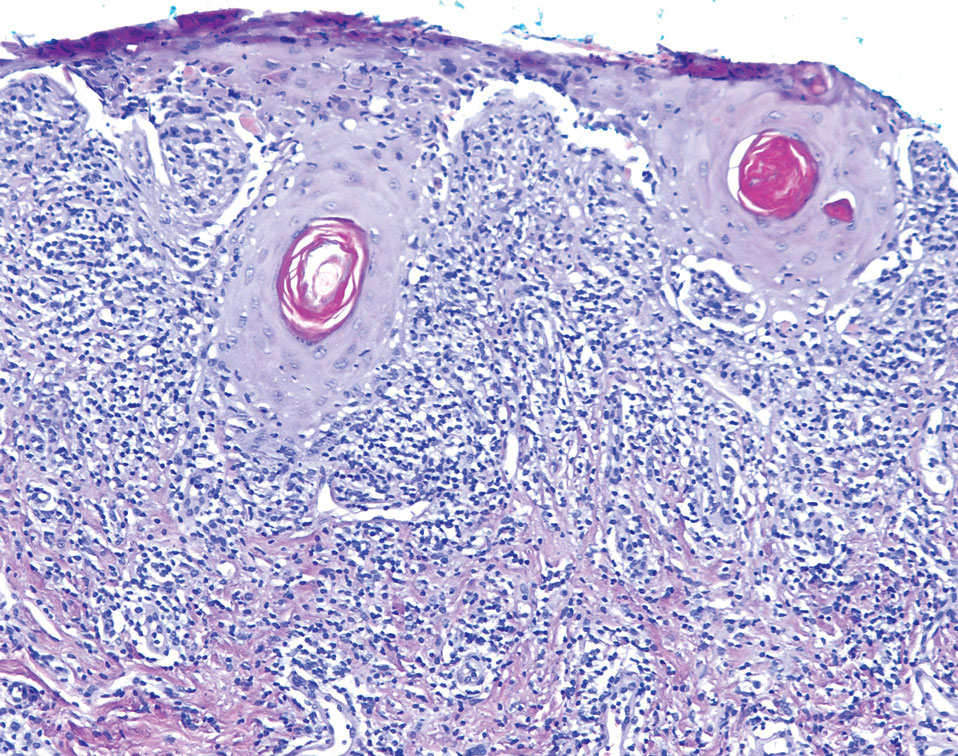

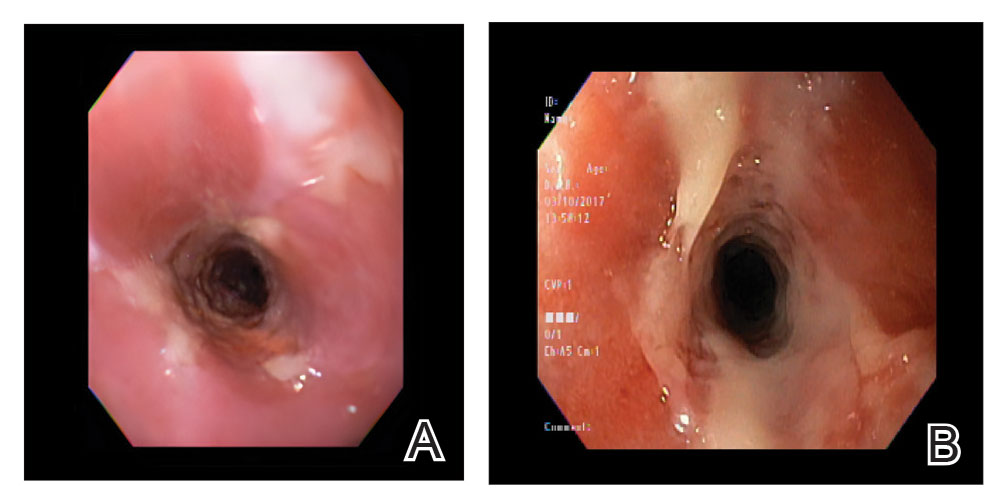

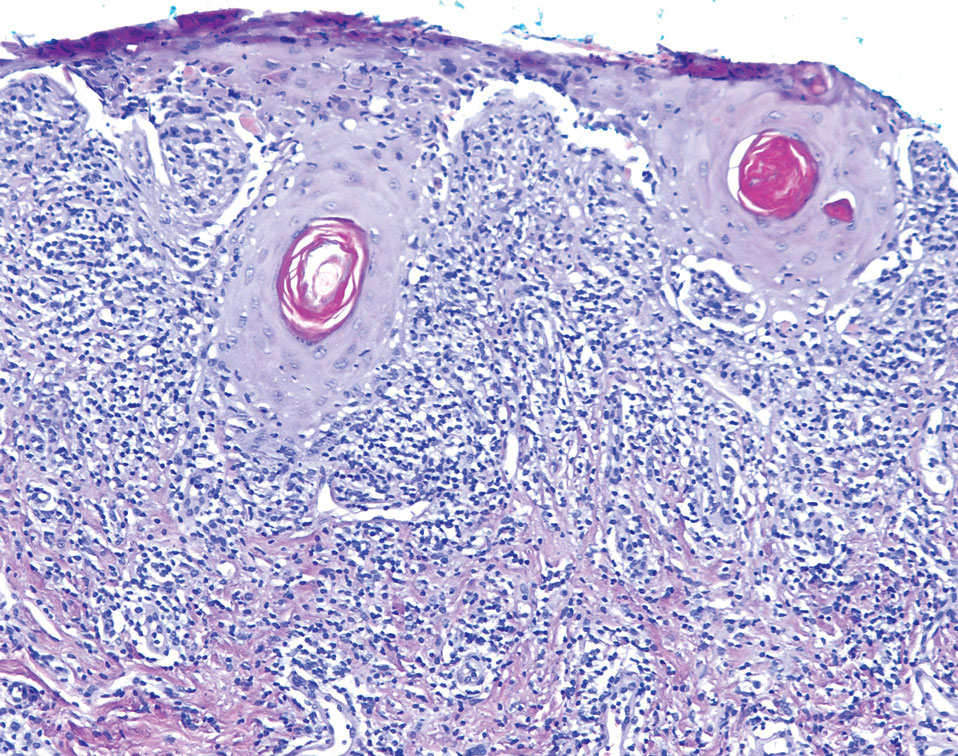

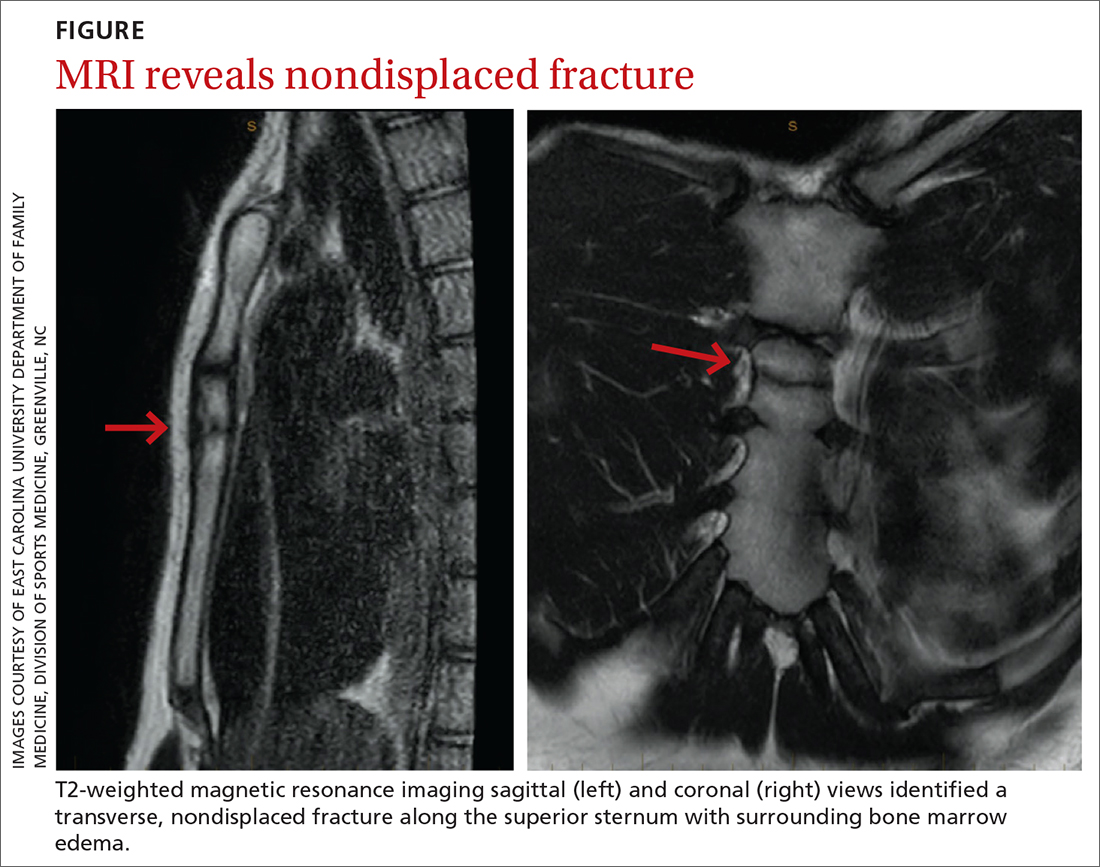

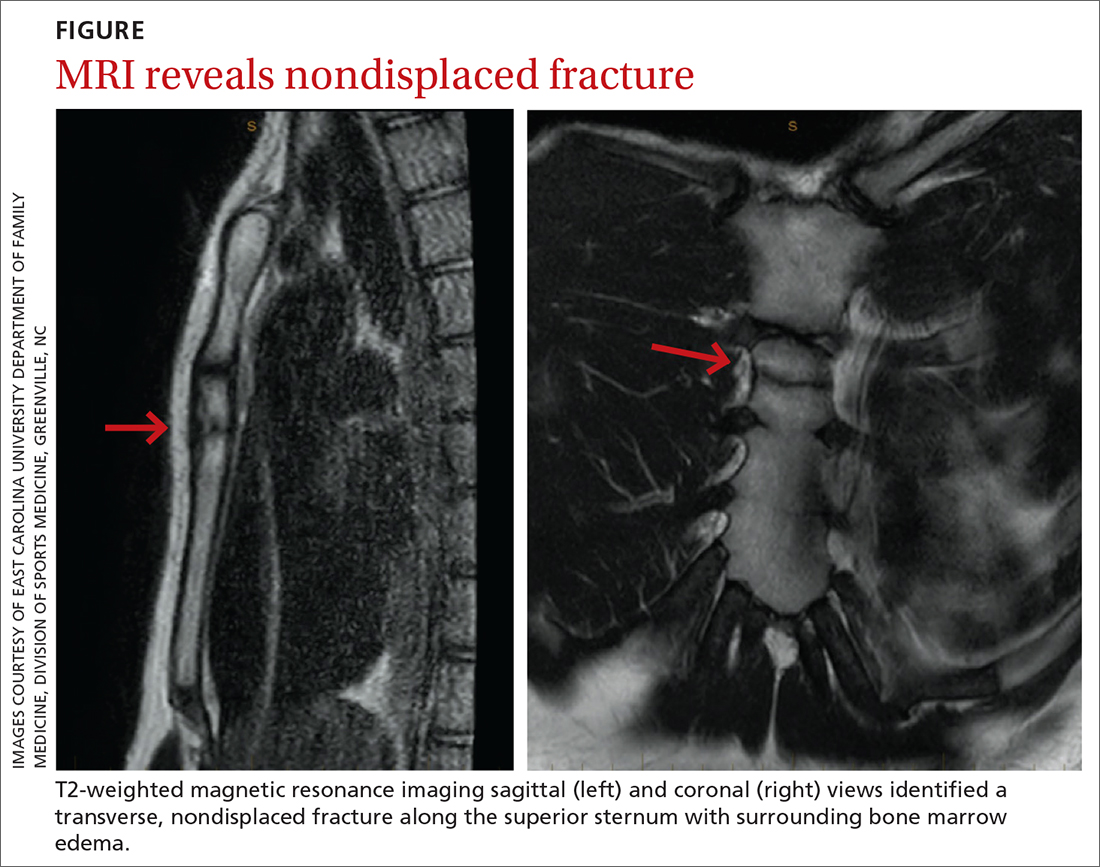

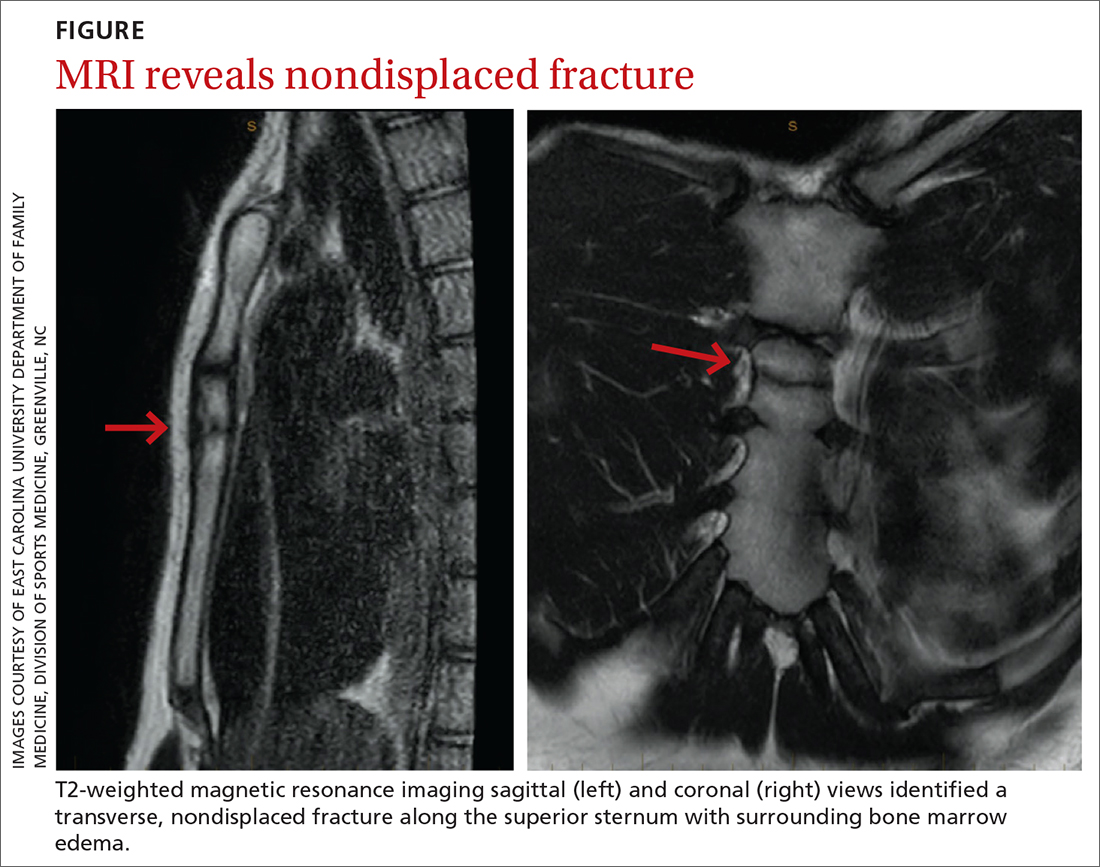

CTA revealed a focal linear filling defect in the right midinternal carotid artery, likely related to an internal carotid artery vascular flap. There was no evidence of proximal intracranial occlusive disease. MRI revealed a linear area of high-intensity signal projecting over the mid and distal right internal carotid artery lumen (Figure 2A).

Imaging suggested an internal carotid artery dissection, and the patient was admitted to the hospital for observation for 4 days. During this time, the patient was instructed to continue taking 81mg aspirin daily and to begin taking 75 mg clopidogrel bisulfate daily to prevent a cerebrovascular accident. Once stability was established, the patient was discharged with instructions to follow up with neurology and neuro-ophthalmology.

Discussion

Anisocoria is defined as a difference in pupil sizes between the eyes.1 This difference can be physiologic with no underlying pathology as an etiology of the condition. If underlying pathology causes anisocoria, it can result in dysfunction with mydriasis, leading to a more miotic pupil, or it can result from issues with miosis, leading to a more mydriatic pupil.1

To determine whether anisocoria is physiologic or pathologic, one must assess the patient’s pupil sizes in dim and bright illumination. If the difference in the pupil size is the same in both room illuminations (ie, the anisocoria is 2 mm in both bright and dim illumination, pupillary constriction and dilation are functioning normally), then the patient has physiologic anisocoria.1 If anisocoria is different in bright and dim illumination (ie, the anisocoria is 1 mm in bright and 3 mm in dim settings or 3 mm in bright and 1 mm in dim settings), the condition is related to pathology. To determine the underlying pathology of anisocoria in cases that are not physiologic, it is important to first determine whether the anisocoria is related to miotic or mydriatic dysfunction.1

If the anisocoria is greater in dim illumination, this suggests mydriatic dysfunction and could be a result of damage to the sympathetic pupillary pathway.1 The smaller or more miotic pupil in this instance is the pathologic pupil. If the anisocoria is greater in bright illumination, this suggests miotic dysfunction and could be a result of damage to the parasympathetic pathway.1 The larger or more mydriatic pupil in this instance is the pathologic pupil. Congenital abnormalities, such as iris colobomas, aniridia, and ectopic pupils, can result in a wide range of pupil sizes and shapes, including miotic or mydriatic pupils.1

Pathologic Mydriasis

Pathologic mydriatic pupils can result from dysfunction in the parasympathetic nervous system, which results in a pupil that is not sufficiently able to dilate with the removal of a light stimulus. Mydriatic pupils can be related to Adie tonic pupil, Argyll-Robertson pupil, third nerve palsy, trauma, surgeries, or pharmacologic mydriasis.2 The conditions that cause mydriasis can be readily differentiated from one another based on clinical examination.

Adie tonic pupil results from damage to the ciliary ganglion.2 While pupillary constriction in response to light will be absent or sluggish in an Adie pupil, the patient will have an intact but sluggish accommodative pupillary response; therefore, the pupil will still constrict with accommodation and convergence to focus on near objects, although slowly. This is known as light-near dissociation.2

Argyll-Robertson pupils are caused by damage to the Edinger-Westphal nucleus in the rostral midbrain.3 Lesions to this area of the brain are typically associated with neurosyphilis but also can be a result of Lyme disease, multiple sclerosis, encephalitis, neurosarcoidosis, herpes zoster, diabetes mellitus, and chronic alcohol misuse.3 Argyll Robertson pupils can appear very similar to a tonic pupil in that this condition will also have a dilated pupil and light-near dissociation.3 These pupils will differ in that they also tend to have an irregular shape (dyscoria), and the pupils will constrict briskly when focusing on near objects and dilate briskly when focusing on distant objects, not sluggishly, as in Adie tonic pupil.3

Mydriasis due to a third nerve palsy will present with ptosis and extraocular muscle dysfunction (including deficits to the superior rectus, medial rectus, inferior oblique, and inferior rectus), with the classic presentation of a completed palsy with the eye positioned “down and out” or the patient’s inability to look medially and superiorly with the affected eye.2

As in cases of pathologic mydriasis, a thorough and in-depth history can help determine traumatic, surgical and pharmacologic etiologies of a mydriatic pupil. It should be determined whether the patient has had any previous trauma or surgeries to the eye or has been in contact with any of the following: acetylcholine receptor antagonists (atropine, scopolamine, homatropine, cyclopentolate, and tropicamide), motion sickness patches (scopolamine), nasal vasoconstrictors, glycopyrrolate deodorants, and/or various plants (Jimson weed or plants belonging to the digitalis family, such as foxglove).2

Pathologic Miosis

Pathologic miotic pupils can result from dysfunction in the sympathetic nervous system and can be related to blunt or penetrating trauma to the orbit, Horner syndrome, and pharmacologic miosis.2 Horner syndrome will be accompanied by a slight ptosis and sometimes anhidrosis on the ipsilateral side of the face. To differentiate between traumatic and pharmacologic miosis, a detailed history should be obtained, paying close attention to injuries to the eyes or head and/or possible exposure to chemical or pharmaceutical agents, including prostaglandins, pilocarpine, organophosphates, and opiates.2

Horner Syndrome

Horner syndrome is a neurologic condition that results from damage to the oculosympathetic pathway.4 The oculosympathetic pathway is a 3-neuron pathway that begins in the hypothalamus and follows a circuitous route to ultimately innervate the facial sweat glands, the smooth muscles of the blood vessels in the orbit and face, the iris dilator muscle, and the Müller muscles of the superior and inferior eyelids.1,5 Therefore, this pathway’s functions include vasoconstriction of facial blood vessels, facial diaphoresis (sweating), pupillary dilation, and maintaining an open position of the eyelids.1

Oculosympathetic pathway anatomy. To understand the findings associated with Horner syndrome, it is necessary to understand the anatomy of this 3-neuron pathway.5 First-order neurons, or central neurons, arise in the posterolateral aspect of the hypothalamus, where they then descend through the midbrain, pons, medulla, and cervical spinal cord via the intermediolateral gray column.6 The fibers then synapse in the ciliospinal center of Budge at the level of cervical vertebra C8 to thoracic vertebra T2, which give rise to the preganglionic, or second-order neurons.6

Second-order neurons begin at the ciliospinal center of Budge and exit the spinal cord via the central roots, most at the level of thoracic vertebra T1, with the remainder leaving at the levels of cervical vertebra C8 and thoracic vertebra T2.7 After exiting the spinal cord, the second-order neurons loop around the subclavian artery, where they then ascend close to the apex of the lung to synapse with the cell bodies of the third-order neurons at the superior cervical ganglion near cervical vertebrae C2 and C3.7

After arising at the superior cervical ganglion, third-order neurons diverge to follow 2 different courses.7 A portion of the neurons travels along the external carotid artery to ultimately innervate the facial sweat glands, while the other portion of the neurons combines with the carotid plexus and travels within the walls of the internal carotid artery and through the cavernous sinus.7 The fibers then briefly join the abducens nerve before anastomosing with the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve.7 After coursing through the superior orbital fissure, the fibers innervate the iris dilator and Müller muscles via the long ciliary nerves.7

Symptoms and signs. Patients with Horner syndrome can present with a variety of symptoms and signs. Patients may be largely asymptomatic or they may complain of a droopy eyelid and blurry vision. The full Horner syndrome triad consists of ipsilateral miosis, anhidrosis of the face, and mild ptosis of the upper eyelid with reverse ptosis of the lower eyelid.8 The difference in pupil size is greatest 4 to 5 seconds after switching from bright to dim room illumination due to dilation lag in the miotic pupil from poor innervation.1

Although the classical triad of ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis is emphasized in the literature, the full triad may not always be present.4 This variation is due to the anatomy of the oculosympathetic pathway with branches of the nerve system separating at the superior cervical ganglion and following different pathways along the internal and external carotid arteries, resulting in anhidrosis only in Horner syndrome caused by lesions to the first- or second-order neurons.4,5 Because of this deviation of the nerve fibers in the pathway, the presence of miosis and a slight ptosis in the absence of anhidrosis should still strongly suggest Horner syndrome.

In addition to the classic triad, Horner syndrome can present with other ophthalmic findings, including conjunctival injection, changes in accommodation, and a small decrease in intraocular pressure usually by no more than 1 to 2 mm Hg.4 Congenital Horner syndrome is unique in that it can result in iris heterochromia, with the lighter eye being the affected eye.4

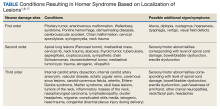

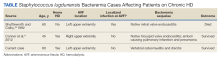

Due to the long and circuitous nature of the oculosympathetic pathway, damage can occur due to a wide variety of conditions (Table) and can present with many neurologic findings.7

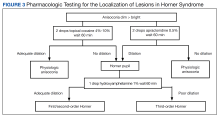

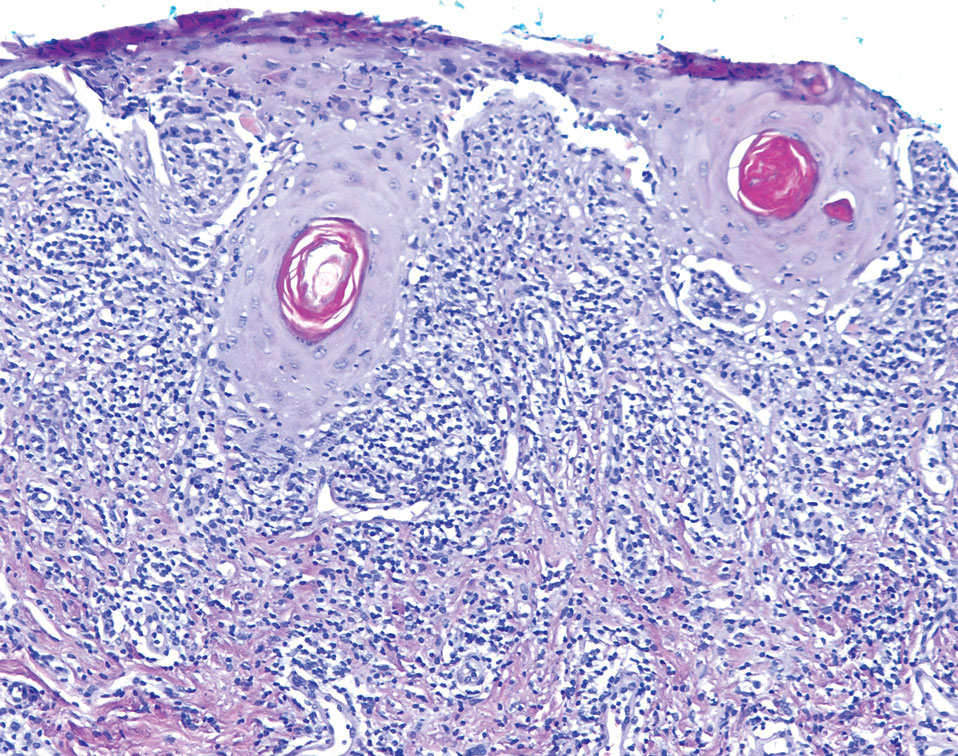

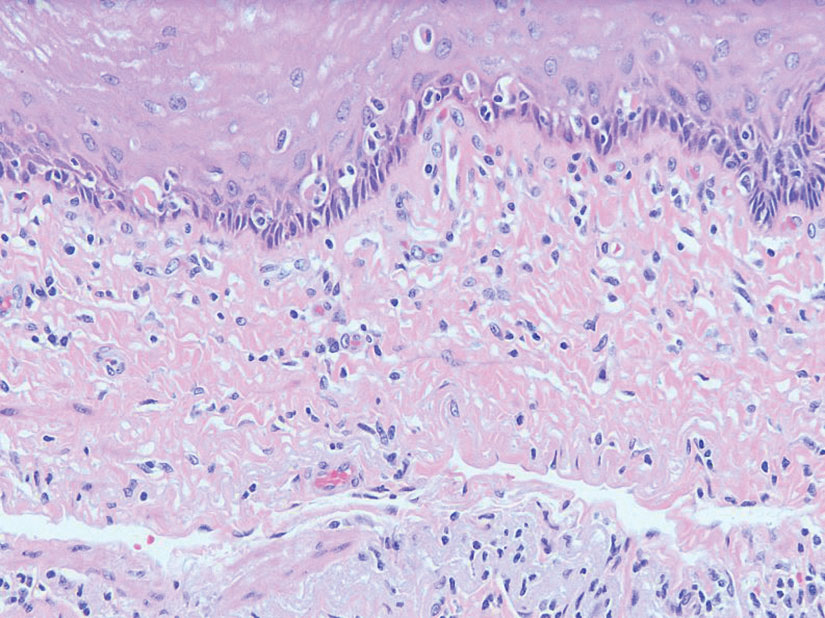

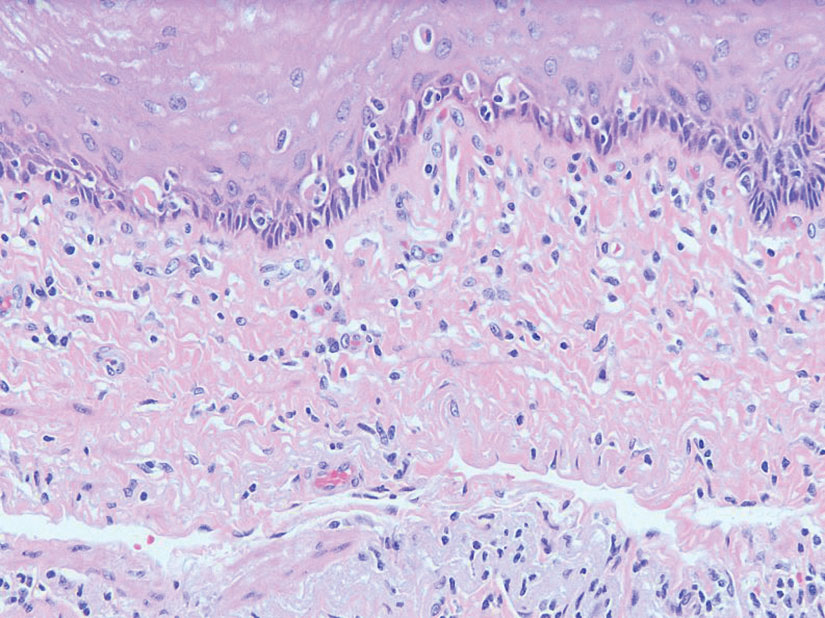

Localization of lesions. In Horner syndrome, 13% of lesions were present at first-order neurons, 44% at second-order neurons, and 43% at third-order neurons.7 While all these lesions have similar clinical presentations that can be difficult to differentiate, localization of the lesion within the oculosympathetic pathway is important to determine the underlying cause. This determination can be readily achieved in office with pharmacologic pupil testing (Figure 3).

Management. All acute Horner syndrome presentations should be referred for same-day evaluation to rule out potentially life-threatening conditions, such as a cerebrovascular accident, carotid artery dissection or aneurysm, and giant cell arteritis.10 The urgent evaluation should include CTA and MRI/MRA of the head and neck.5 If giant cell arteritis is suspected, it is also recommended to obtain urgent bloodwork, which should include complete blood count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein.5 Carotid angiography and CT of the chest also are indicated if the aforementioned tests are noncontributory, but these are less urgent and can be deferred for evaluation within 1 to 2 days after the initial diagnosis.10

In this patient’s case, an immediate neurologic evaluation was appropriate due to the acute and painful nature of her presentation. Ultimately, her Horner syndrome was determined to result from an internal carotid artery dissection. As indicated by Schievink, all acute Horner syndrome cases should be considered a result of a carotid artery dissection until proven otherwise, despite the presence or absence of any other signs or symptoms.11 This consideration is not only because of the potentially life-threatening sequelae associated with carotid dissections, but also because dissections have been shown to be the most common cause of ischemic strokes in young and middle-aged patients, accounting for 10% to 25% of all ischemic strokes.4,11

Carotid Artery Dissection

An artery dissection is typically the result of a tear of the

There are many causes of carotid artery dissections, such as structural defects of the arterial wall, fibromuscular dysplasia, cystic medial necrosis, and connective tissue disorders, including Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV, Marfan syndrome, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, and osteogenesis imperfecta type I.13 Many environmental factors also can induce a carotid artery dissection, such as a history of anesthesia use, resuscitation with classic cardiopulmonary resuscitation techniques, head or neck trauma, chiropractic manipulation of the neck, and hyperextension or rotation of the neck, which can occur in activities such as yoga, painting a ceiling, coughing, vomiting, or sneezing.11

Patients with an internal carotid artery dissection typically present with pain on one side of the neck, face, or head, which can be accompanied by a partial Horner syndrome that results from damage to the oculosympathetic neurons traveling with the carotid plexus in the internal carotid artery wall.9,10 Unilateral facial or orbital pain has been noted to be present in half of patients and is typically accompanied by an ipsilateral headache.9 These symptoms are typically followed by cerebral or retinal ischemia within hours or days of onset and other ophthalmic conditions that can cause blindness, such as ischemic optic neuropathy or retinal artery occlusions, although these are rare.9

Due to the potential complications that can arise, carotid artery dissections require prompt treatment with antithrombotic therapy for 3 to 6 months to prevent carotid artery occlusion, which can result in a hemispheric cerebrovascular accident or TIAs.15 The options for antithrombotic therapy include anticoagulants, such as warfarin, and antiplatelets, such as aspirin. Studies have found similar rates of recurrent ischemic strokes in treatment with anticoagulants compared with antiplatelets, so both are reasonable therapeutic options.15,16 Following a carotid artery dissection diagnosis, patients should be evaluated by neurology to minimize other cardiovascular risk factors and prevent other complications.

Conclusions

Due to the potential life-threatening complications that can arise from conditions resulting in Horner syndrome, it is imperative that clinicians have a thorough understanding of the condition and its appropriate treatment and management modalities. Understanding the need for immediate testing to determine the underlying etiology of Horner syndrome can help prevent a decrease in a patient’s vision or quality of life, and in some cases, prevent death.

Acknowledgments

The author recognizes and thanks Kyle Stuard for his invaluable assistance in the editing of this manuscript

1. Yanoff M, Duker J. Ophthalmology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2019.

2. Payne WN, Blair K, Barrett MJ. Anisocoria. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470384

3. Lee A, Bindiganavile SH, Fan J, Al-Zubidi N, Bhatti MT. Argyll Robertson pupils. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://eyewiki.aao.org/Argyll_Robertson_Pupils

4. Kedar S, Prakalapakorn G, Yen M, et al. Horner syndrome. American Academy of Optometry. 2021. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://eyewiki.aao.org/Horner_Syndrome

5. Daroff R, Bradley W, Jankovic J. Bradley and Daroff’s Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2022.

6. Kanagalingam S, Miller NR. Horner syndrome: clinical perspectives. Eye Brain. 2015;7:35-46. doi:10.2147/EB.S63633

7. Lykstad J, Reddy V, Hanna A. Neuroanatomy, Pupillary Dilation Pathway. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 11, 2021. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535421

8. Friedman N, Kaiser P, Pineda R. The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Illustrated Manual of Ophthalmology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

9. Silbert PL, Mokri B, Schievink WI. Headache and neck pain in spontaneous internal carotid and vertebral artery dissections. Neurology. 1995;45(8):1517-1522. doi:10.1212/wnl.45.8.1517

10. Gervasio K, Peck T. The Will’s Eye Manual. 8th ed. Walters Kluwer; 2022.

11. Schievink WI. Spontaneous dissection of the carotid and vertebral arteries. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(12):898-906. doi:10.1056/NEJM200103223441206

12. Hart RG, Easton JD. Dissections of cervical and cerebral arteries. Neurol Clin. 1983;1(1):155-182.

13. Goodfriend SD, Tadi P, Koury R. Carotid Artery Dissection. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated December 24, 2021. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430835

14. Blum CA, Yaghi S. Cervical artery dissection: a review of the epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and outcome. Arch Neurosci. 2015;2(4):e26670. doi:10.5812/archneurosci.26670

15. Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42(1):227-276. doi:10.1161/STR.0b013e3181f7d043

16. Mohr JP, Thompson JL, Lazar RM, et al; Warfarin-Aspirin Recurrent Stroke Study Group. A comparison of warfarin and aspirin for the prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(20):1444-1451. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa011258

17. Davagnanam I, Fraser CL, Miszkiel K, Daniel CS, Plant GT. Adult Horner’s syndrome: a combined clinical, pharmacological, and imaging algorithm. Eye (Lond). 2013;27(3):291-298. doi:10.1038/eye.2012.281

Horner syndrome is a rare condition that has no sex or race predilection and is characterized by the clinical triad of a miosis, anhidrosis, and small, unilateral ptosis. The prompt diagnosis and determination of the etiology of Horner syndrome are of utmost importance, as the condition can result from many life-threatening systemic complications. Horner syndrome is often asymptomatic but can have distinct, easily identified characteristics seen with an ophthalmic examination. This report describes a patient who presented with Horner syndrome resulting from an internal carotid artery dissection.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old woman presented with periorbital pain with onset 3 days prior. The patient described the pain as 7 of 10 that had been worsening and was localized around and behind the right eye. She reported new-onset headaches on the right side over the past week with associated intermittent vision blurriness in the right eye. She had a history of mobility issues and had fallen backward about 1 week before, hitting the back of her head on the floor without direct trauma to the eye. She was symptomatic for light sensitivity, syncope, and dizziness, with reports of a recent history of transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) of unknown etiology, which had occurred in the months preceding her examination. She reported no jaw claudication, scalp tenderness, and neck or shoulder pain. She was unaware of any changes in her perspiration pattern on the right side of her face but mentioned that she had noticed her right upper eyelid drooping while looking in the mirror.

This patient had a routine eye examination 2 months before, which was remarkable for stable, nonfoveal involving adult-onset vitelliform dystrophy in the left eye and nuclear sclerotic cataracts and mild refractive error in both eyes. No iris heterochromia was noted, and her pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light. Her history was remarkable for chest pain, obesity, bipolar disorder, vertigo, transient cerebral ischemia, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, alcohol use disorder, cocaine use disorder, and asthma. A carotid ultrasound had been performed 1 month before the onset of symptoms due to her history of TIAs, which showed no hemodynamically significant stenosis (> 50% stenosis) of either carotid artery. Her medications included oxybutynin chloride, amlodipine, acetaminophen, sertraline hydrochloride, lidocaine, albuterol, risperidone, hydroxyzine hydrochloride, lisinopril, omeprazole, once-daily baby aspirin, atorvastatin, and calcium.

At the time of presentation, an ophthalmic examination revealed no decrease in visual acuity with a best-corrected visual acuity of 20/20 in the right and left eyes. The patient’s pupil sizes were unequal, with a smaller, more miotic right pupil with a greater difference between the pupil sizes in dim illumination (Figure 1).

As the patient had pathologic miosis, conditions causing pathologic mydriasis, such as Adie tonic pupil and cranial nerve III palsy, were ruled out. The presence of an acute, slight ptosis with pathologic miosis and pain in the ipsilateral eye with no reports of exposure to miotic pharmaceutical agents and no history of trauma to the globe or orbit eliminated other differentials, leading to a diagnosis of right-sided Horner syndrome. Due to concerns of acute onset periorbital and retrobulbar pain, she was referred to the emergency department with recommendations for computed tomography angiography (CTA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) of the head and neck to rule out a carotid artery dissection.

CTA revealed a focal linear filling defect in the right midinternal carotid artery, likely related to an internal carotid artery vascular flap. There was no evidence of proximal intracranial occlusive disease. MRI revealed a linear area of high-intensity signal projecting over the mid and distal right internal carotid artery lumen (Figure 2A).

Imaging suggested an internal carotid artery dissection, and the patient was admitted to the hospital for observation for 4 days. During this time, the patient was instructed to continue taking 81mg aspirin daily and to begin taking 75 mg clopidogrel bisulfate daily to prevent a cerebrovascular accident. Once stability was established, the patient was discharged with instructions to follow up with neurology and neuro-ophthalmology.

Discussion

Anisocoria is defined as a difference in pupil sizes between the eyes.1 This difference can be physiologic with no underlying pathology as an etiology of the condition. If underlying pathology causes anisocoria, it can result in dysfunction with mydriasis, leading to a more miotic pupil, or it can result from issues with miosis, leading to a more mydriatic pupil.1

To determine whether anisocoria is physiologic or pathologic, one must assess the patient’s pupil sizes in dim and bright illumination. If the difference in the pupil size is the same in both room illuminations (ie, the anisocoria is 2 mm in both bright and dim illumination, pupillary constriction and dilation are functioning normally), then the patient has physiologic anisocoria.1 If anisocoria is different in bright and dim illumination (ie, the anisocoria is 1 mm in bright and 3 mm in dim settings or 3 mm in bright and 1 mm in dim settings), the condition is related to pathology. To determine the underlying pathology of anisocoria in cases that are not physiologic, it is important to first determine whether the anisocoria is related to miotic or mydriatic dysfunction.1

If the anisocoria is greater in dim illumination, this suggests mydriatic dysfunction and could be a result of damage to the sympathetic pupillary pathway.1 The smaller or more miotic pupil in this instance is the pathologic pupil. If the anisocoria is greater in bright illumination, this suggests miotic dysfunction and could be a result of damage to the parasympathetic pathway.1 The larger or more mydriatic pupil in this instance is the pathologic pupil. Congenital abnormalities, such as iris colobomas, aniridia, and ectopic pupils, can result in a wide range of pupil sizes and shapes, including miotic or mydriatic pupils.1

Pathologic Mydriasis

Pathologic mydriatic pupils can result from dysfunction in the parasympathetic nervous system, which results in a pupil that is not sufficiently able to dilate with the removal of a light stimulus. Mydriatic pupils can be related to Adie tonic pupil, Argyll-Robertson pupil, third nerve palsy, trauma, surgeries, or pharmacologic mydriasis.2 The conditions that cause mydriasis can be readily differentiated from one another based on clinical examination.

Adie tonic pupil results from damage to the ciliary ganglion.2 While pupillary constriction in response to light will be absent or sluggish in an Adie pupil, the patient will have an intact but sluggish accommodative pupillary response; therefore, the pupil will still constrict with accommodation and convergence to focus on near objects, although slowly. This is known as light-near dissociation.2

Argyll-Robertson pupils are caused by damage to the Edinger-Westphal nucleus in the rostral midbrain.3 Lesions to this area of the brain are typically associated with neurosyphilis but also can be a result of Lyme disease, multiple sclerosis, encephalitis, neurosarcoidosis, herpes zoster, diabetes mellitus, and chronic alcohol misuse.3 Argyll Robertson pupils can appear very similar to a tonic pupil in that this condition will also have a dilated pupil and light-near dissociation.3 These pupils will differ in that they also tend to have an irregular shape (dyscoria), and the pupils will constrict briskly when focusing on near objects and dilate briskly when focusing on distant objects, not sluggishly, as in Adie tonic pupil.3

Mydriasis due to a third nerve palsy will present with ptosis and extraocular muscle dysfunction (including deficits to the superior rectus, medial rectus, inferior oblique, and inferior rectus), with the classic presentation of a completed palsy with the eye positioned “down and out” or the patient’s inability to look medially and superiorly with the affected eye.2

As in cases of pathologic mydriasis, a thorough and in-depth history can help determine traumatic, surgical and pharmacologic etiologies of a mydriatic pupil. It should be determined whether the patient has had any previous trauma or surgeries to the eye or has been in contact with any of the following: acetylcholine receptor antagonists (atropine, scopolamine, homatropine, cyclopentolate, and tropicamide), motion sickness patches (scopolamine), nasal vasoconstrictors, glycopyrrolate deodorants, and/or various plants (Jimson weed or plants belonging to the digitalis family, such as foxglove).2

Pathologic Miosis

Pathologic miotic pupils can result from dysfunction in the sympathetic nervous system and can be related to blunt or penetrating trauma to the orbit, Horner syndrome, and pharmacologic miosis.2 Horner syndrome will be accompanied by a slight ptosis and sometimes anhidrosis on the ipsilateral side of the face. To differentiate between traumatic and pharmacologic miosis, a detailed history should be obtained, paying close attention to injuries to the eyes or head and/or possible exposure to chemical or pharmaceutical agents, including prostaglandins, pilocarpine, organophosphates, and opiates.2

Horner Syndrome

Horner syndrome is a neurologic condition that results from damage to the oculosympathetic pathway.4 The oculosympathetic pathway is a 3-neuron pathway that begins in the hypothalamus and follows a circuitous route to ultimately innervate the facial sweat glands, the smooth muscles of the blood vessels in the orbit and face, the iris dilator muscle, and the Müller muscles of the superior and inferior eyelids.1,5 Therefore, this pathway’s functions include vasoconstriction of facial blood vessels, facial diaphoresis (sweating), pupillary dilation, and maintaining an open position of the eyelids.1

Oculosympathetic pathway anatomy. To understand the findings associated with Horner syndrome, it is necessary to understand the anatomy of this 3-neuron pathway.5 First-order neurons, or central neurons, arise in the posterolateral aspect of the hypothalamus, where they then descend through the midbrain, pons, medulla, and cervical spinal cord via the intermediolateral gray column.6 The fibers then synapse in the ciliospinal center of Budge at the level of cervical vertebra C8 to thoracic vertebra T2, which give rise to the preganglionic, or second-order neurons.6

Second-order neurons begin at the ciliospinal center of Budge and exit the spinal cord via the central roots, most at the level of thoracic vertebra T1, with the remainder leaving at the levels of cervical vertebra C8 and thoracic vertebra T2.7 After exiting the spinal cord, the second-order neurons loop around the subclavian artery, where they then ascend close to the apex of the lung to synapse with the cell bodies of the third-order neurons at the superior cervical ganglion near cervical vertebrae C2 and C3.7

After arising at the superior cervical ganglion, third-order neurons diverge to follow 2 different courses.7 A portion of the neurons travels along the external carotid artery to ultimately innervate the facial sweat glands, while the other portion of the neurons combines with the carotid plexus and travels within the walls of the internal carotid artery and through the cavernous sinus.7 The fibers then briefly join the abducens nerve before anastomosing with the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve.7 After coursing through the superior orbital fissure, the fibers innervate the iris dilator and Müller muscles via the long ciliary nerves.7

Symptoms and signs. Patients with Horner syndrome can present with a variety of symptoms and signs. Patients may be largely asymptomatic or they may complain of a droopy eyelid and blurry vision. The full Horner syndrome triad consists of ipsilateral miosis, anhidrosis of the face, and mild ptosis of the upper eyelid with reverse ptosis of the lower eyelid.8 The difference in pupil size is greatest 4 to 5 seconds after switching from bright to dim room illumination due to dilation lag in the miotic pupil from poor innervation.1

Although the classical triad of ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis is emphasized in the literature, the full triad may not always be present.4 This variation is due to the anatomy of the oculosympathetic pathway with branches of the nerve system separating at the superior cervical ganglion and following different pathways along the internal and external carotid arteries, resulting in anhidrosis only in Horner syndrome caused by lesions to the first- or second-order neurons.4,5 Because of this deviation of the nerve fibers in the pathway, the presence of miosis and a slight ptosis in the absence of anhidrosis should still strongly suggest Horner syndrome.

In addition to the classic triad, Horner syndrome can present with other ophthalmic findings, including conjunctival injection, changes in accommodation, and a small decrease in intraocular pressure usually by no more than 1 to 2 mm Hg.4 Congenital Horner syndrome is unique in that it can result in iris heterochromia, with the lighter eye being the affected eye.4

Due to the long and circuitous nature of the oculosympathetic pathway, damage can occur due to a wide variety of conditions (Table) and can present with many neurologic findings.7

Localization of lesions. In Horner syndrome, 13% of lesions were present at first-order neurons, 44% at second-order neurons, and 43% at third-order neurons.7 While all these lesions have similar clinical presentations that can be difficult to differentiate, localization of the lesion within the oculosympathetic pathway is important to determine the underlying cause. This determination can be readily achieved in office with pharmacologic pupil testing (Figure 3).

Management. All acute Horner syndrome presentations should be referred for same-day evaluation to rule out potentially life-threatening conditions, such as a cerebrovascular accident, carotid artery dissection or aneurysm, and giant cell arteritis.10 The urgent evaluation should include CTA and MRI/MRA of the head and neck.5 If giant cell arteritis is suspected, it is also recommended to obtain urgent bloodwork, which should include complete blood count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein.5 Carotid angiography and CT of the chest also are indicated if the aforementioned tests are noncontributory, but these are less urgent and can be deferred for evaluation within 1 to 2 days after the initial diagnosis.10

In this patient’s case, an immediate neurologic evaluation was appropriate due to the acute and painful nature of her presentation. Ultimately, her Horner syndrome was determined to result from an internal carotid artery dissection. As indicated by Schievink, all acute Horner syndrome cases should be considered a result of a carotid artery dissection until proven otherwise, despite the presence or absence of any other signs or symptoms.11 This consideration is not only because of the potentially life-threatening sequelae associated with carotid dissections, but also because dissections have been shown to be the most common cause of ischemic strokes in young and middle-aged patients, accounting for 10% to 25% of all ischemic strokes.4,11

Carotid Artery Dissection

An artery dissection is typically the result of a tear of the

There are many causes of carotid artery dissections, such as structural defects of the arterial wall, fibromuscular dysplasia, cystic medial necrosis, and connective tissue disorders, including Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV, Marfan syndrome, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, and osteogenesis imperfecta type I.13 Many environmental factors also can induce a carotid artery dissection, such as a history of anesthesia use, resuscitation with classic cardiopulmonary resuscitation techniques, head or neck trauma, chiropractic manipulation of the neck, and hyperextension or rotation of the neck, which can occur in activities such as yoga, painting a ceiling, coughing, vomiting, or sneezing.11

Patients with an internal carotid artery dissection typically present with pain on one side of the neck, face, or head, which can be accompanied by a partial Horner syndrome that results from damage to the oculosympathetic neurons traveling with the carotid plexus in the internal carotid artery wall.9,10 Unilateral facial or orbital pain has been noted to be present in half of patients and is typically accompanied by an ipsilateral headache.9 These symptoms are typically followed by cerebral or retinal ischemia within hours or days of onset and other ophthalmic conditions that can cause blindness, such as ischemic optic neuropathy or retinal artery occlusions, although these are rare.9

Due to the potential complications that can arise, carotid artery dissections require prompt treatment with antithrombotic therapy for 3 to 6 months to prevent carotid artery occlusion, which can result in a hemispheric cerebrovascular accident or TIAs.15 The options for antithrombotic therapy include anticoagulants, such as warfarin, and antiplatelets, such as aspirin. Studies have found similar rates of recurrent ischemic strokes in treatment with anticoagulants compared with antiplatelets, so both are reasonable therapeutic options.15,16 Following a carotid artery dissection diagnosis, patients should be evaluated by neurology to minimize other cardiovascular risk factors and prevent other complications.

Conclusions

Due to the potential life-threatening complications that can arise from conditions resulting in Horner syndrome, it is imperative that clinicians have a thorough understanding of the condition and its appropriate treatment and management modalities. Understanding the need for immediate testing to determine the underlying etiology of Horner syndrome can help prevent a decrease in a patient’s vision or quality of life, and in some cases, prevent death.

Acknowledgments

The author recognizes and thanks Kyle Stuard for his invaluable assistance in the editing of this manuscript

Horner syndrome is a rare condition that has no sex or race predilection and is characterized by the clinical triad of a miosis, anhidrosis, and small, unilateral ptosis. The prompt diagnosis and determination of the etiology of Horner syndrome are of utmost importance, as the condition can result from many life-threatening systemic complications. Horner syndrome is often asymptomatic but can have distinct, easily identified characteristics seen with an ophthalmic examination. This report describes a patient who presented with Horner syndrome resulting from an internal carotid artery dissection.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old woman presented with periorbital pain with onset 3 days prior. The patient described the pain as 7 of 10 that had been worsening and was localized around and behind the right eye. She reported new-onset headaches on the right side over the past week with associated intermittent vision blurriness in the right eye. She had a history of mobility issues and had fallen backward about 1 week before, hitting the back of her head on the floor without direct trauma to the eye. She was symptomatic for light sensitivity, syncope, and dizziness, with reports of a recent history of transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) of unknown etiology, which had occurred in the months preceding her examination. She reported no jaw claudication, scalp tenderness, and neck or shoulder pain. She was unaware of any changes in her perspiration pattern on the right side of her face but mentioned that she had noticed her right upper eyelid drooping while looking in the mirror.

This patient had a routine eye examination 2 months before, which was remarkable for stable, nonfoveal involving adult-onset vitelliform dystrophy in the left eye and nuclear sclerotic cataracts and mild refractive error in both eyes. No iris heterochromia was noted, and her pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light. Her history was remarkable for chest pain, obesity, bipolar disorder, vertigo, transient cerebral ischemia, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, alcohol use disorder, cocaine use disorder, and asthma. A carotid ultrasound had been performed 1 month before the onset of symptoms due to her history of TIAs, which showed no hemodynamically significant stenosis (> 50% stenosis) of either carotid artery. Her medications included oxybutynin chloride, amlodipine, acetaminophen, sertraline hydrochloride, lidocaine, albuterol, risperidone, hydroxyzine hydrochloride, lisinopril, omeprazole, once-daily baby aspirin, atorvastatin, and calcium.

At the time of presentation, an ophthalmic examination revealed no decrease in visual acuity with a best-corrected visual acuity of 20/20 in the right and left eyes. The patient’s pupil sizes were unequal, with a smaller, more miotic right pupil with a greater difference between the pupil sizes in dim illumination (Figure 1).

As the patient had pathologic miosis, conditions causing pathologic mydriasis, such as Adie tonic pupil and cranial nerve III palsy, were ruled out. The presence of an acute, slight ptosis with pathologic miosis and pain in the ipsilateral eye with no reports of exposure to miotic pharmaceutical agents and no history of trauma to the globe or orbit eliminated other differentials, leading to a diagnosis of right-sided Horner syndrome. Due to concerns of acute onset periorbital and retrobulbar pain, she was referred to the emergency department with recommendations for computed tomography angiography (CTA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) of the head and neck to rule out a carotid artery dissection.

CTA revealed a focal linear filling defect in the right midinternal carotid artery, likely related to an internal carotid artery vascular flap. There was no evidence of proximal intracranial occlusive disease. MRI revealed a linear area of high-intensity signal projecting over the mid and distal right internal carotid artery lumen (Figure 2A).

Imaging suggested an internal carotid artery dissection, and the patient was admitted to the hospital for observation for 4 days. During this time, the patient was instructed to continue taking 81mg aspirin daily and to begin taking 75 mg clopidogrel bisulfate daily to prevent a cerebrovascular accident. Once stability was established, the patient was discharged with instructions to follow up with neurology and neuro-ophthalmology.

Discussion

Anisocoria is defined as a difference in pupil sizes between the eyes.1 This difference can be physiologic with no underlying pathology as an etiology of the condition. If underlying pathology causes anisocoria, it can result in dysfunction with mydriasis, leading to a more miotic pupil, or it can result from issues with miosis, leading to a more mydriatic pupil.1

To determine whether anisocoria is physiologic or pathologic, one must assess the patient’s pupil sizes in dim and bright illumination. If the difference in the pupil size is the same in both room illuminations (ie, the anisocoria is 2 mm in both bright and dim illumination, pupillary constriction and dilation are functioning normally), then the patient has physiologic anisocoria.1 If anisocoria is different in bright and dim illumination (ie, the anisocoria is 1 mm in bright and 3 mm in dim settings or 3 mm in bright and 1 mm in dim settings), the condition is related to pathology. To determine the underlying pathology of anisocoria in cases that are not physiologic, it is important to first determine whether the anisocoria is related to miotic or mydriatic dysfunction.1

If the anisocoria is greater in dim illumination, this suggests mydriatic dysfunction and could be a result of damage to the sympathetic pupillary pathway.1 The smaller or more miotic pupil in this instance is the pathologic pupil. If the anisocoria is greater in bright illumination, this suggests miotic dysfunction and could be a result of damage to the parasympathetic pathway.1 The larger or more mydriatic pupil in this instance is the pathologic pupil. Congenital abnormalities, such as iris colobomas, aniridia, and ectopic pupils, can result in a wide range of pupil sizes and shapes, including miotic or mydriatic pupils.1

Pathologic Mydriasis

Pathologic mydriatic pupils can result from dysfunction in the parasympathetic nervous system, which results in a pupil that is not sufficiently able to dilate with the removal of a light stimulus. Mydriatic pupils can be related to Adie tonic pupil, Argyll-Robertson pupil, third nerve palsy, trauma, surgeries, or pharmacologic mydriasis.2 The conditions that cause mydriasis can be readily differentiated from one another based on clinical examination.

Adie tonic pupil results from damage to the ciliary ganglion.2 While pupillary constriction in response to light will be absent or sluggish in an Adie pupil, the patient will have an intact but sluggish accommodative pupillary response; therefore, the pupil will still constrict with accommodation and convergence to focus on near objects, although slowly. This is known as light-near dissociation.2

Argyll-Robertson pupils are caused by damage to the Edinger-Westphal nucleus in the rostral midbrain.3 Lesions to this area of the brain are typically associated with neurosyphilis but also can be a result of Lyme disease, multiple sclerosis, encephalitis, neurosarcoidosis, herpes zoster, diabetes mellitus, and chronic alcohol misuse.3 Argyll Robertson pupils can appear very similar to a tonic pupil in that this condition will also have a dilated pupil and light-near dissociation.3 These pupils will differ in that they also tend to have an irregular shape (dyscoria), and the pupils will constrict briskly when focusing on near objects and dilate briskly when focusing on distant objects, not sluggishly, as in Adie tonic pupil.3

Mydriasis due to a third nerve palsy will present with ptosis and extraocular muscle dysfunction (including deficits to the superior rectus, medial rectus, inferior oblique, and inferior rectus), with the classic presentation of a completed palsy with the eye positioned “down and out” or the patient’s inability to look medially and superiorly with the affected eye.2

As in cases of pathologic mydriasis, a thorough and in-depth history can help determine traumatic, surgical and pharmacologic etiologies of a mydriatic pupil. It should be determined whether the patient has had any previous trauma or surgeries to the eye or has been in contact with any of the following: acetylcholine receptor antagonists (atropine, scopolamine, homatropine, cyclopentolate, and tropicamide), motion sickness patches (scopolamine), nasal vasoconstrictors, glycopyrrolate deodorants, and/or various plants (Jimson weed or plants belonging to the digitalis family, such as foxglove).2

Pathologic Miosis

Pathologic miotic pupils can result from dysfunction in the sympathetic nervous system and can be related to blunt or penetrating trauma to the orbit, Horner syndrome, and pharmacologic miosis.2 Horner syndrome will be accompanied by a slight ptosis and sometimes anhidrosis on the ipsilateral side of the face. To differentiate between traumatic and pharmacologic miosis, a detailed history should be obtained, paying close attention to injuries to the eyes or head and/or possible exposure to chemical or pharmaceutical agents, including prostaglandins, pilocarpine, organophosphates, and opiates.2

Horner Syndrome

Horner syndrome is a neurologic condition that results from damage to the oculosympathetic pathway.4 The oculosympathetic pathway is a 3-neuron pathway that begins in the hypothalamus and follows a circuitous route to ultimately innervate the facial sweat glands, the smooth muscles of the blood vessels in the orbit and face, the iris dilator muscle, and the Müller muscles of the superior and inferior eyelids.1,5 Therefore, this pathway’s functions include vasoconstriction of facial blood vessels, facial diaphoresis (sweating), pupillary dilation, and maintaining an open position of the eyelids.1

Oculosympathetic pathway anatomy. To understand the findings associated with Horner syndrome, it is necessary to understand the anatomy of this 3-neuron pathway.5 First-order neurons, or central neurons, arise in the posterolateral aspect of the hypothalamus, where they then descend through the midbrain, pons, medulla, and cervical spinal cord via the intermediolateral gray column.6 The fibers then synapse in the ciliospinal center of Budge at the level of cervical vertebra C8 to thoracic vertebra T2, which give rise to the preganglionic, or second-order neurons.6

Second-order neurons begin at the ciliospinal center of Budge and exit the spinal cord via the central roots, most at the level of thoracic vertebra T1, with the remainder leaving at the levels of cervical vertebra C8 and thoracic vertebra T2.7 After exiting the spinal cord, the second-order neurons loop around the subclavian artery, where they then ascend close to the apex of the lung to synapse with the cell bodies of the third-order neurons at the superior cervical ganglion near cervical vertebrae C2 and C3.7

After arising at the superior cervical ganglion, third-order neurons diverge to follow 2 different courses.7 A portion of the neurons travels along the external carotid artery to ultimately innervate the facial sweat glands, while the other portion of the neurons combines with the carotid plexus and travels within the walls of the internal carotid artery and through the cavernous sinus.7 The fibers then briefly join the abducens nerve before anastomosing with the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve.7 After coursing through the superior orbital fissure, the fibers innervate the iris dilator and Müller muscles via the long ciliary nerves.7

Symptoms and signs. Patients with Horner syndrome can present with a variety of symptoms and signs. Patients may be largely asymptomatic or they may complain of a droopy eyelid and blurry vision. The full Horner syndrome triad consists of ipsilateral miosis, anhidrosis of the face, and mild ptosis of the upper eyelid with reverse ptosis of the lower eyelid.8 The difference in pupil size is greatest 4 to 5 seconds after switching from bright to dim room illumination due to dilation lag in the miotic pupil from poor innervation.1

Although the classical triad of ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis is emphasized in the literature, the full triad may not always be present.4 This variation is due to the anatomy of the oculosympathetic pathway with branches of the nerve system separating at the superior cervical ganglion and following different pathways along the internal and external carotid arteries, resulting in anhidrosis only in Horner syndrome caused by lesions to the first- or second-order neurons.4,5 Because of this deviation of the nerve fibers in the pathway, the presence of miosis and a slight ptosis in the absence of anhidrosis should still strongly suggest Horner syndrome.

In addition to the classic triad, Horner syndrome can present with other ophthalmic findings, including conjunctival injection, changes in accommodation, and a small decrease in intraocular pressure usually by no more than 1 to 2 mm Hg.4 Congenital Horner syndrome is unique in that it can result in iris heterochromia, with the lighter eye being the affected eye.4

Due to the long and circuitous nature of the oculosympathetic pathway, damage can occur due to a wide variety of conditions (Table) and can present with many neurologic findings.7

Localization of lesions. In Horner syndrome, 13% of lesions were present at first-order neurons, 44% at second-order neurons, and 43% at third-order neurons.7 While all these lesions have similar clinical presentations that can be difficult to differentiate, localization of the lesion within the oculosympathetic pathway is important to determine the underlying cause. This determination can be readily achieved in office with pharmacologic pupil testing (Figure 3).

Management. All acute Horner syndrome presentations should be referred for same-day evaluation to rule out potentially life-threatening conditions, such as a cerebrovascular accident, carotid artery dissection or aneurysm, and giant cell arteritis.10 The urgent evaluation should include CTA and MRI/MRA of the head and neck.5 If giant cell arteritis is suspected, it is also recommended to obtain urgent bloodwork, which should include complete blood count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein.5 Carotid angiography and CT of the chest also are indicated if the aforementioned tests are noncontributory, but these are less urgent and can be deferred for evaluation within 1 to 2 days after the initial diagnosis.10

In this patient’s case, an immediate neurologic evaluation was appropriate due to the acute and painful nature of her presentation. Ultimately, her Horner syndrome was determined to result from an internal carotid artery dissection. As indicated by Schievink, all acute Horner syndrome cases should be considered a result of a carotid artery dissection until proven otherwise, despite the presence or absence of any other signs or symptoms.11 This consideration is not only because of the potentially life-threatening sequelae associated with carotid dissections, but also because dissections have been shown to be the most common cause of ischemic strokes in young and middle-aged patients, accounting for 10% to 25% of all ischemic strokes.4,11

Carotid Artery Dissection

An artery dissection is typically the result of a tear of the

There are many causes of carotid artery dissections, such as structural defects of the arterial wall, fibromuscular dysplasia, cystic medial necrosis, and connective tissue disorders, including Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV, Marfan syndrome, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, and osteogenesis imperfecta type I.13 Many environmental factors also can induce a carotid artery dissection, such as a history of anesthesia use, resuscitation with classic cardiopulmonary resuscitation techniques, head or neck trauma, chiropractic manipulation of the neck, and hyperextension or rotation of the neck, which can occur in activities such as yoga, painting a ceiling, coughing, vomiting, or sneezing.11

Patients with an internal carotid artery dissection typically present with pain on one side of the neck, face, or head, which can be accompanied by a partial Horner syndrome that results from damage to the oculosympathetic neurons traveling with the carotid plexus in the internal carotid artery wall.9,10 Unilateral facial or orbital pain has been noted to be present in half of patients and is typically accompanied by an ipsilateral headache.9 These symptoms are typically followed by cerebral or retinal ischemia within hours or days of onset and other ophthalmic conditions that can cause blindness, such as ischemic optic neuropathy or retinal artery occlusions, although these are rare.9

Due to the potential complications that can arise, carotid artery dissections require prompt treatment with antithrombotic therapy for 3 to 6 months to prevent carotid artery occlusion, which can result in a hemispheric cerebrovascular accident or TIAs.15 The options for antithrombotic therapy include anticoagulants, such as warfarin, and antiplatelets, such as aspirin. Studies have found similar rates of recurrent ischemic strokes in treatment with anticoagulants compared with antiplatelets, so both are reasonable therapeutic options.15,16 Following a carotid artery dissection diagnosis, patients should be evaluated by neurology to minimize other cardiovascular risk factors and prevent other complications.

Conclusions

Due to the potential life-threatening complications that can arise from conditions resulting in Horner syndrome, it is imperative that clinicians have a thorough understanding of the condition and its appropriate treatment and management modalities. Understanding the need for immediate testing to determine the underlying etiology of Horner syndrome can help prevent a decrease in a patient’s vision or quality of life, and in some cases, prevent death.

Acknowledgments

The author recognizes and thanks Kyle Stuard for his invaluable assistance in the editing of this manuscript

1. Yanoff M, Duker J. Ophthalmology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2019.

2. Payne WN, Blair K, Barrett MJ. Anisocoria. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470384

3. Lee A, Bindiganavile SH, Fan J, Al-Zubidi N, Bhatti MT. Argyll Robertson pupils. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://eyewiki.aao.org/Argyll_Robertson_Pupils

4. Kedar S, Prakalapakorn G, Yen M, et al. Horner syndrome. American Academy of Optometry. 2021. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://eyewiki.aao.org/Horner_Syndrome

5. Daroff R, Bradley W, Jankovic J. Bradley and Daroff’s Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2022.

6. Kanagalingam S, Miller NR. Horner syndrome: clinical perspectives. Eye Brain. 2015;7:35-46. doi:10.2147/EB.S63633

7. Lykstad J, Reddy V, Hanna A. Neuroanatomy, Pupillary Dilation Pathway. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 11, 2021. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535421

8. Friedman N, Kaiser P, Pineda R. The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Illustrated Manual of Ophthalmology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

9. Silbert PL, Mokri B, Schievink WI. Headache and neck pain in spontaneous internal carotid and vertebral artery dissections. Neurology. 1995;45(8):1517-1522. doi:10.1212/wnl.45.8.1517

10. Gervasio K, Peck T. The Will’s Eye Manual. 8th ed. Walters Kluwer; 2022.

11. Schievink WI. Spontaneous dissection of the carotid and vertebral arteries. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(12):898-906. doi:10.1056/NEJM200103223441206

12. Hart RG, Easton JD. Dissections of cervical and cerebral arteries. Neurol Clin. 1983;1(1):155-182.

13. Goodfriend SD, Tadi P, Koury R. Carotid Artery Dissection. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated December 24, 2021. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430835

14. Blum CA, Yaghi S. Cervical artery dissection: a review of the epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and outcome. Arch Neurosci. 2015;2(4):e26670. doi:10.5812/archneurosci.26670

15. Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42(1):227-276. doi:10.1161/STR.0b013e3181f7d043

16. Mohr JP, Thompson JL, Lazar RM, et al; Warfarin-Aspirin Recurrent Stroke Study Group. A comparison of warfarin and aspirin for the prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(20):1444-1451. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa011258

17. Davagnanam I, Fraser CL, Miszkiel K, Daniel CS, Plant GT. Adult Horner’s syndrome: a combined clinical, pharmacological, and imaging algorithm. Eye (Lond). 2013;27(3):291-298. doi:10.1038/eye.2012.281

1. Yanoff M, Duker J. Ophthalmology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2019.

2. Payne WN, Blair K, Barrett MJ. Anisocoria. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470384

3. Lee A, Bindiganavile SH, Fan J, Al-Zubidi N, Bhatti MT. Argyll Robertson pupils. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://eyewiki.aao.org/Argyll_Robertson_Pupils

4. Kedar S, Prakalapakorn G, Yen M, et al. Horner syndrome. American Academy of Optometry. 2021. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://eyewiki.aao.org/Horner_Syndrome

5. Daroff R, Bradley W, Jankovic J. Bradley and Daroff’s Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2022.

6. Kanagalingam S, Miller NR. Horner syndrome: clinical perspectives. Eye Brain. 2015;7:35-46. doi:10.2147/EB.S63633

7. Lykstad J, Reddy V, Hanna A. Neuroanatomy, Pupillary Dilation Pathway. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 11, 2021. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535421

8. Friedman N, Kaiser P, Pineda R. The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Illustrated Manual of Ophthalmology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

9. Silbert PL, Mokri B, Schievink WI. Headache and neck pain in spontaneous internal carotid and vertebral artery dissections. Neurology. 1995;45(8):1517-1522. doi:10.1212/wnl.45.8.1517

10. Gervasio K, Peck T. The Will’s Eye Manual. 8th ed. Walters Kluwer; 2022.

11. Schievink WI. Spontaneous dissection of the carotid and vertebral arteries. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(12):898-906. doi:10.1056/NEJM200103223441206

12. Hart RG, Easton JD. Dissections of cervical and cerebral arteries. Neurol Clin. 1983;1(1):155-182.

13. Goodfriend SD, Tadi P, Koury R. Carotid Artery Dissection. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated December 24, 2021. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430835

14. Blum CA, Yaghi S. Cervical artery dissection: a review of the epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and outcome. Arch Neurosci. 2015;2(4):e26670. doi:10.5812/archneurosci.26670

15. Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42(1):227-276. doi:10.1161/STR.0b013e3181f7d043

16. Mohr JP, Thompson JL, Lazar RM, et al; Warfarin-Aspirin Recurrent Stroke Study Group. A comparison of warfarin and aspirin for the prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(20):1444-1451. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa011258

17. Davagnanam I, Fraser CL, Miszkiel K, Daniel CS, Plant GT. Adult Horner’s syndrome: a combined clinical, pharmacological, and imaging algorithm. Eye (Lond). 2013;27(3):291-298. doi:10.1038/eye.2012.281

High-Grade Staphylococcus lugdunensis Bacteremia in a Patient on Home Hemodialysis

Staphylococcus lugdunensis (S lugdunensis) is a species of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS) and a constituent of human skin flora. Unlike other strains of CoNS, however, S lugdunensis has gained notoriety for virulence that resembles Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus). S lugdunensis is now recognized as an important nosocomial pathogen and cause of prosthetic device infections, including vascular catheter infections. We present a case of persistent S lugdunensis bacteremia occurring in a patient on hemodialysis (HD) without any implanted prosthetic materials.

Case Presentation

A 60-year-old man with a history of uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and end-stage renal disease on home HD via arteriovenous fistula (AVF) presented to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of subacute progressive low back pain. His symptoms began abruptly 2 weeks prior to presentation without any identifiable trigger or trauma. His pain localized to the lower thoracic spine, radiating anteriorly into his abdomen. He reported tactile fever for several days before presentation but no chills, night sweats, paresthesia, weakness, or bowel/bladder incontinence. He had no recent surgeries, implanted hardware, or invasive procedures involving the spine. HD was performed 5 times a week at home with a family member cannulating his AVF via buttonhole technique. He initially sought evaluation in a community hospital several days prior, where he underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the thoracic spine. He was discharged from the community ED with oral opioids prior to the MRI results. He presented to West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WLAVAMC) ED when MRI results came back indicating abnormalities and he reported recalcitrant pain.

On arrival at WLAVAMC, the patient was afebrile with a heart rate of 107 bpm and blood pressure of 152/97 mm Hg. The remainder of his vital signs were normal. The physical examination revealed midline tenderness on palpation of the distal thoracic and proximal lumbar spine. Muscle strength was 4 of 5 in the bilateral hip flexors, though this was limited by pain. The remainder of his neurologic examination was nonfocal. The cardiac examination was unremarkable with no murmurs auscultated. His left upper extremity AVF had an audible bruit and palpable thrill. The skin examination was notable for acanthosis nigricans but no areas of skin erythema or induration and no obvious stigmata of infective endocarditis.

The initial laboratory workup was remarkable for a white blood cell (WBC) count of 10.0 × 103/µL with left shift, blood urea nitrogen level of 59 mg/dL, and creatinine level of 9.3 mg/dL. The patient’s erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 45 mm/h (reference range, ≤ 20 mm/h) and C-reactive protein level was > 8.0 mg/L (reference range, ≤ 0.74 mg/L). Two months prior the hemoglobin A1c had been recorded at 9.9%.

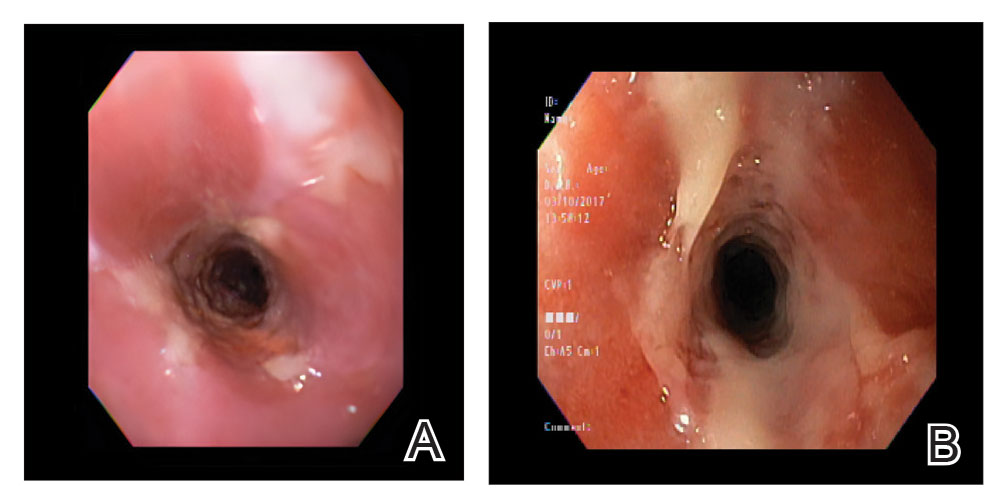

Given his intractable low back pain and elevated inflammatory markers, the patient underwent an MRI of the thoracic and lumbar spine with contrast while in the ED. This MRI revealed abnormal marrow edema in the T11-T12 vertebrae with abnormal fluid signal in the T11-T12 disc space. Subjacent paravertebral edema also was noted. There was no well-defined fluid collection or abnormal signal in the spinal cord. Taken together, these findings were concerning for T11-T12 discitis with osteomyelitis.

Two sets of blood cultures were obtained, and empiric IV vancomycin and ceftriaxone were started. Interventional radiology was consulted for consideration of vertebral biopsy but deferred while awaiting blood culture data. Neurosurgery also was consulted and recommended nonoperative management given his nonfocal neurologic examination and imaging without evidence of abscess. Both sets of blood cultures collected on admission later grew methicillin-sensitive S lugdunensis, a species of CoNS. A transthoracic and later transesophageal echocardiogram did not show any valvular vegetations. The patient’s antibiotic regimen was narrowed to IV oxacillin based on susceptibility data. It was later discovered that both blood cultures obtained during his outside ED encounter were also growing S lugdunensis.

The patient’s S lugdunensis bacteremia persisted for the first 8 days of his admission despite appropriate dosing of oxacillin. During this time, the patient remained afebrile with stable vital signs and a normal WBC count. Positron emission tomography was obtained to evaluate for potential sources of his persistent bacteremia. Aside from tracer uptake in the T11-T12 vertebral bodies and intervertebral disc space, no other areas showed suspicious uptake. Neurosurgery reevaluated the patient and again recommended nonoperative management. Blood cultures cleared and based on recommendations from an infectious disease specialist, the patient was transitioned to IV cefazolin dosed 3 times weekly after HD, which was transitioned to an outpatient dialysis center. The patient continued taking cefazolin for 6 weeks with subsequent improvement in back pain and normalization of inflammatory markers at outpatient follow-up.

Discussion

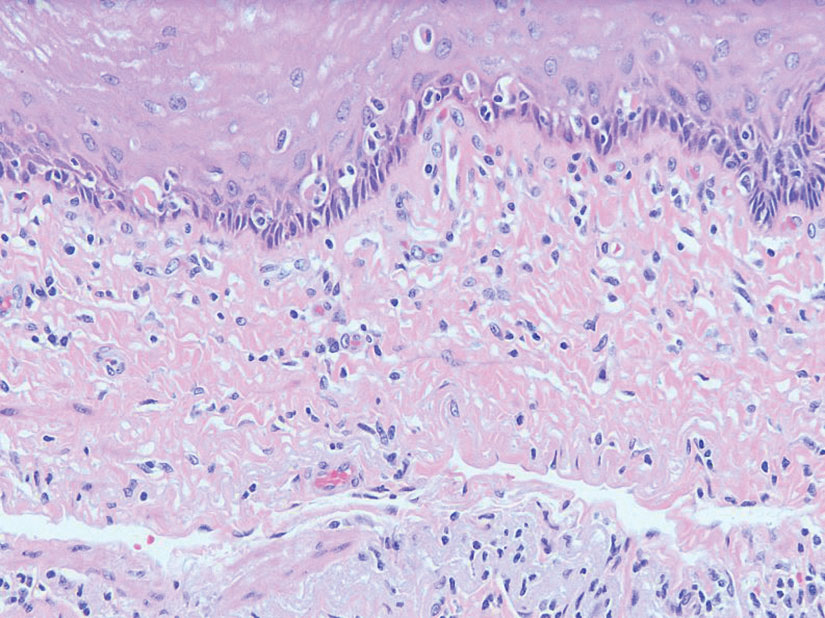

CoNS are a major contributor to human skin flora, a common contaminant of blood cultures, and an important cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections.1,2 These species have a predilection for forming biofilms, making CoNS a major cause of prosthetic device infections.3 S lugdunensis is a CoNS species that was first described in 1988.4 In addition to foreign body–related infections, S lugdunensis has been implicated in bone/joint infections, native valve endocarditis, toxic shock syndrome, and brain abscesses.5-8 Infections due to S lugdunensis are notorious for their aggressive and fulminant courses. With its increased virulence that is atypical of other CoNS, S lugdunensis has understandably been likened more to S aureus.

Prior cases have been reported of S lugdunensis bacteremia in patients using HD. However, the suspected source of bacteremia in these cases has generally been central venous catheters.9-12

Notably, our patient’s AVF was accessed using the buttonhole technique for his home HD sessions, which involves cannulating the same site along the fistula until an epithelialized track has formed from scar tissue. At later HD sessions, duller needles can then be used to cannulate this same track. In contrast, the rope-ladder technique involves cannulating a different site along the fistula until the entire length of the fistula has been used. Patients report higher levels of satisfaction with the buttonhole technique, citing decreased pain, decreased oozing, and the perception of easier cannulation by HD nurses.14 However, the buttonhole technique also appears to confer a higher risk of vascular access-related bloodstream infection when compared with the rope-ladder technique.13,15,16

The buttonhole technique is hypothesized to increase infection risk due to the repeated use of the same site for needle entry. Skin flora, including CoNS, may colonize the scab that forms after dialysis access. If proper sterilization techniques are not rigorously followed, the bacteria colonizing the scab and adjacent skin may be introduced into a patient’s bloodstream during needle puncture. Loss of skin integrity due to frequent cannulation of the same site may also contribute to this increased infection risk. It is relevant to recall that our patient received HD 5 times weekly using the buttonhole technique. The use of the buttonhole technique, frequency of his HD sessions, unclear sterilization methods, and immune dysfunction related to his uncontrolled T2DM and renal disease all likely contributed to our patient’s bacteremia.

Using topical mupirocin for prophylaxis at the intended buttonhole puncture site has shown promising results in decreasing rates of S aureus bacteremia.17 It is unclear whether this intervention also would be effective against S lugdunensis. Increasing rates of mupirocin resistance have been reported among S lugdunensis isolates in dialysis settings, but further research in this area is warranted.18

There are no established treatment guidelines for S lugdunensis infections. In vitro studies suggest that S lugdunensis is susceptible to a wide variety of antibiotics. The mecA gene is a major determinant of methicillin resistance that is commonly observed among CoNS but is uncommonly seen with S lugdunensis.5 In a study by Tan and colleagues of 106 S lugdunensis isolates, they found that only 5 (4.7%) were mecA positive.19

Vancomycin is generally reasonable for empiric antibiotic coverage of staphylococci while speciation is pending. However, if S lugdunensis is isolated, its favorable susceptibility pattern typically allows for de-escalation to an antistaphylococcal β-lactam, such as oxacillin or nafcillin. In cases of bloodstream infections caused by methicillin-sensitive S aureus, treatment with a β-lactam has demonstrated superiority over vancomycin due to the lower rates of treatment failure and mortality with β-lactams.20,21 It is unknown whether β-lactams is superior for treating bacteremia with methicillin-sensitive S lugdunensis.

Our patient’s isolate of S lugdunensis was pansensitive to all antibiotics tested, including penicillin. These susceptibility data were used to guide the de-escalation of his empiric vancomycin and ceftriaxone to oxacillin on hospital day 1.

Due to their virulence, bloodstream infections caused by S aureus and S lugdunensis often require more than timely antimicrobial treatment to ensure eradication. Consultation with an infectious disease specialist to manage patients with S aureus bacteremia has been proven to reduce mortality.25 A similar mortality benefit is seen when infectious disease specialists are consulted for S lugdunensis bacteremia.26 This mortality benefit is likely explained by S lugdunensis’ propensity to cause aggressive, metastatic infections. In such cases, infectious disease consultants may recommend additional imaging (eg, transthoracic echocardiogram) to evaluate for occult sources of infection, advocate for appropriate source control, and guide the selection of an appropriate antibiotic course to ensure resolution of the bacteremia.

Conclusions

S lugdunensis is an increasingly recognized cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections. Given the commonalities in virulence that S lugdunensis shares with S aureus, treatment of bacteremia caused by either species should follow similar management principles: prompt initiation of IV antistaphylococcal therapy, a thorough evaluation for the source(s) of bacteremia as well as metastatic complications, and consultation with an infectious disease specialist. This case report also highlights the importance of considering a patient’s AVF as a potential source for infection even in the absence of localized signs of infection. The buttonhole method of AVF cannulation was thought to be a major contributor to the development and persistence of our patient’s bacteremia. This risk should be discussed with patients using a shared decision-making approach when developing a dialysis treatment plan.

1. Huebner J, Goldmann DA. Coagulase-negative staphylococci: role as pathogens. Annu Rev Med. 1999;50(1):223-236. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.223

2. Beekmann SE, Diekema DJ, Doern GV. Determining the clinical significance of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from blood cultures. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26(6):559-566. doi:10.1086/502584

3. Arrecubieta C, Toba FA, von Bayern M, et al. SdrF, a Staphylococcus epidermidis surface protein, contributes to the initiation of ventricular assist device driveline–related infections. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(5):e1000411. doi.10.1371/journal.ppat.1000411

4. Freney J, Brun Y, Bes M, et al. Staphylococcus lugdunensis sp. nov. and Staphylococcus schleiferi sp. nov., two species from human clinical specimens. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1988;38(2):168-172. doi:10.1099/00207713-38-2-168

5. Frank KL, del Pozo JL, Patel R. From clinical microbiology to infection pathogenesis: how daring to be different works for Staphylococcus lugdunensis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(1):111-133. doi:10.1128/CMR.00036-07

6. Anguera I, Del Río A, Miró JM; Hospital Clinic Endocarditis Study Group. Staphylococcus lugdunensis infective endocarditis: description of 10 cases and analysis of native valve, prosthetic valve, and pacemaker lead endocarditis clinical profiles. Heart. 2005;91(2):e10. doi:10.1136/hrt.2004.040659

7. Pareja J, Gupta K, Koziel H. The toxic shock syndrome and Staphylococcus lugdunensis bacteremia. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(7):603-604. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-128-7-199804010-00029

8. Woznowski M, Quack I, Bölke E, et al. Fulminant Staphylococcus lugdunensis septicaemia following a pelvic varicella-zoster virus infection in an immune-deficient patient: a case report. Eur J Med Res. 201;15(9):410-414. doi:10.1186/2047-783x-15-9-410

9. Mallappallil M, Salifu M, Woredekal Y, et al. Staphylococcus lugdunensis bacteremia in hemodialysis patients. Int J Microbiol Res. 2012;4(2):178-181. doi:10.9735/0975-5276.4.2.178-181

10. Shuttleworth R, Colby W. Staphylococcus lugdunensis endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(8):5. doi:10.1128/jcm.30.8.1948-1952.1992

11. Conner RC, Byrnes TJ, Clough LA, Myers JP. Staphylococcus lugdunensis tricuspid valve endocarditis associated with home hemodialysis therapy: report of a case and review of the literature. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2012;20(3):182-183. doi:1097/IPC.0b013e318245d4f1

12. Kamaraju S, Nelson K, Williams D, Ayenew W, Modi K. Staphylococcus lugdunensis pulmonary valve endocarditis in a patient on chronic hemodialysis. Am J Nephrol. 1999;19(5):605-608. doi:1097/IPC.0b013e318245d4f1

13. Lok C, Sontrop J, Faratro R, Chan C, Zimmerman DL. Frequent hemodialysis fistula infectious complications. Nephron Extra. 2014;4(3):159-167. doi:10.1159/000366477

14. Hashmi A, Cheema MQ, Moss AH. Hemodialysis patients’ experience with and attitudes toward the buttonhole technique for arteriovenous fistula cannulation. Clin Nephrol. 2010;74(5):346-350. doi:10.5414/cnp74346

15. Lyman M, Nguyen DB, Shugart A, Gruhler H, Lines C, Patel PR. Risk of vascular access infection associated with buttonhole cannulation of fistulas: data from the National Healthcare Safety Network. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76(1):82-89. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.11.006

16. MacRae JM, Ahmed SB, Atkar R, Hemmelgarn BR. A randomized trial comparing buttonhole with rope ladder needling in conventional hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(10):1632-1638. doi:10.2215/CJN.02730312

17. Nesrallah GE, Cuerden M, Wong JHS, Pierratos A. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and buttonhole cannulation: long-term safety and efficacy of mupirocin prophylaxis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(6):1047-1053. doi:10.2215/CJN.00280110

18. Ho PL, Liu MCJ, Chow KH, et al. Emergence of ileS2 -carrying, multidrug-resistant plasmids in Staphylococcus lugdunensis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(10):6411-6414. doi:10.1128/AAC.00948-16

19. Tan TY, Ng SY, He J. Microbiological characteristics, presumptive identification, and antibiotic susceptibilities of Staphylococcus lugdunensis. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(7):2393-2395. doi:10.1128/JCM.00740-08

20. Chang FY, Peacock JE, Musher DM, et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: recurrence and the impact of antibiotic treatment in a prospective multicenter study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82(5):333-339. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000091184.93122.09