User login

Long-term Remission of Pyoderma Gangrenosum, Acne, and Hidradenitis Suppurativa Syndrome

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)(PASH) syndrome is a recently identified disease process within the spectrum of autoinflammatory diseases (AIDs), which are distinct from autoimmune, infectious, and allergic syndromes and are gaining increasing interest given their complex pathophysiology and therapeutic resistance.1 Autoinflammatory diseases are defined by a dysregulation of the innate immune system in the absence of typical autoimmune features, including autoantibodies and antigen-specific T lymphocytes.2 Mutations affecting proteins of the inflammasome or proteins involved in regulating inflammasome function have been associated with these AIDs.2

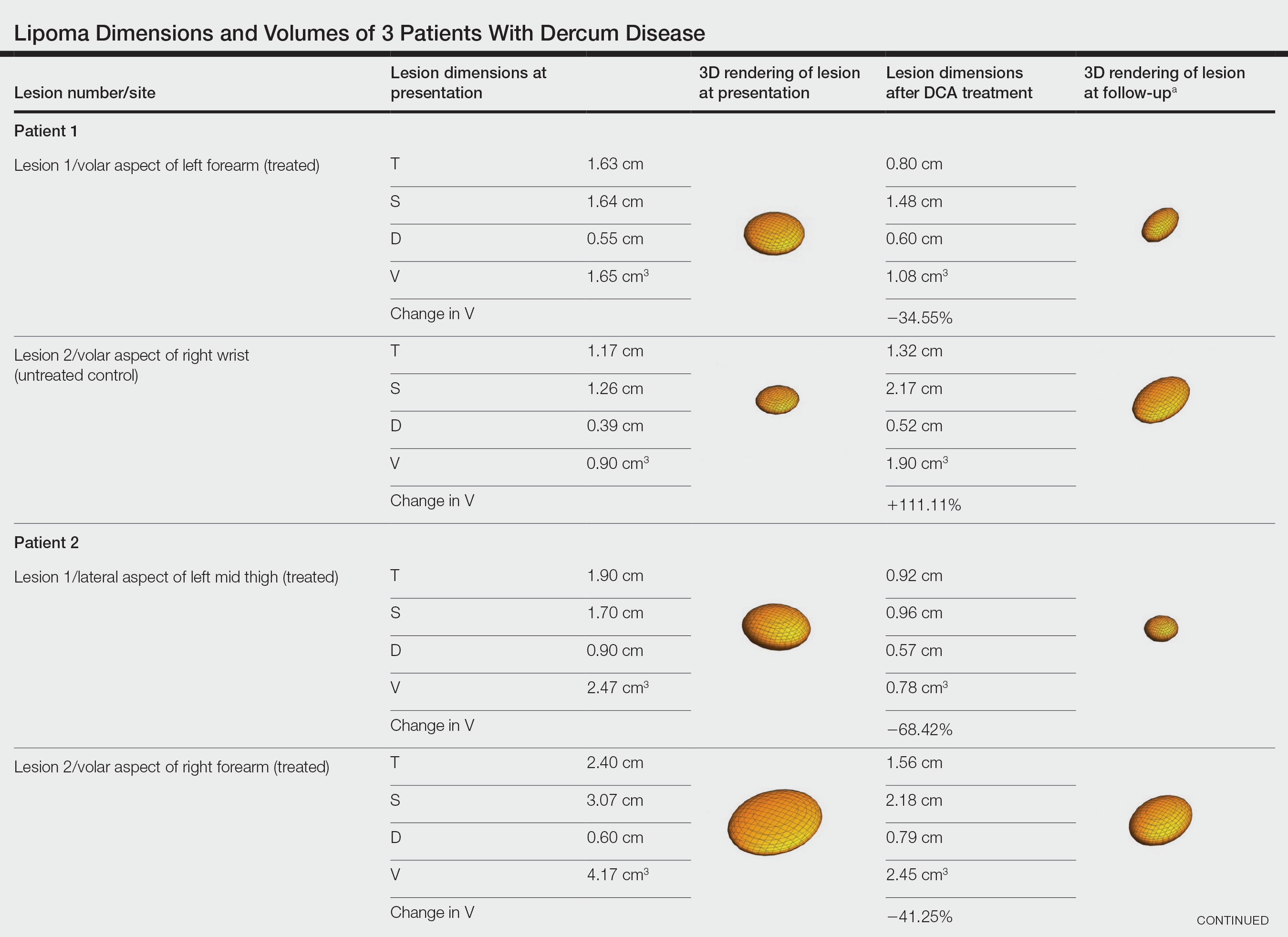

Many AIDs have cutaneous involvement, as seen in PASH syndrome. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis presenting as skin ulcers with undermined, erythematous, violaceous borders. It can be isolated, syndromic, or associated with inflammatory conditions (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatologic disorders, hematologic disorders).1 Acne vulgaris develops because of chronic obstruction of hair follicles as a result of disordered keratinization and abnormal sebaceous stem cell differentiation.2 Propionibacterium acnes can reside and replicate within the biofilm community of the hair follicle and activate the inflammasome.2,3 Hidradenitis suppurativa, a chronic relapsing neutrophilic dermatosis, is a debilitating inflammatory disease of the hair follicles involving apocrine gland–bearing skin (ie, the axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions).2 Onset often occurs between the ages of 20 and 40 years, with a 3-fold higher incidence in women compared to men.3 Patients experience painful, deep-seated nodules that drain into sinus tracts and abscesses. The condition can be isolated or associated with inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease.4

PASH syndrome has been described as a polygenic autoinflammatory condition that most commonly presents in young adults, with onset of acne beginning years prior to other manifestations. A study analyzing 5 patients with PASH syndrome reported an average age of 32.2 years at diagnosis with a disease duration of 3 to 7 years.5 Pathophysiology of this condition is not well understood, with many hypotheses calling upon dysregulation of the innate immune system, a commonality this syndrome may share with other AIDs. Given its poorly understood pathophysiology, treating PASH syndrome can be especially difficult. We report a novel case of disease remission lasting more than 4 years using adalimumab and cyclosporine. We also discuss prior treatment successes and hypotheses regarding etiologic factors in PASH syndrome.

Case Report

A 36-year-old woman presented for evaluation of open draining ulcerations on the back of 18 months’ duration. She had a 16-year history of scarring cystic acne of the face and HS of the groin. The patient’s family history was remarkable for severe cystic acne in her brother and son as well as HS in her mother and another brother. Her treatment history included isotretinoin, doxycycline, and topical steroids.

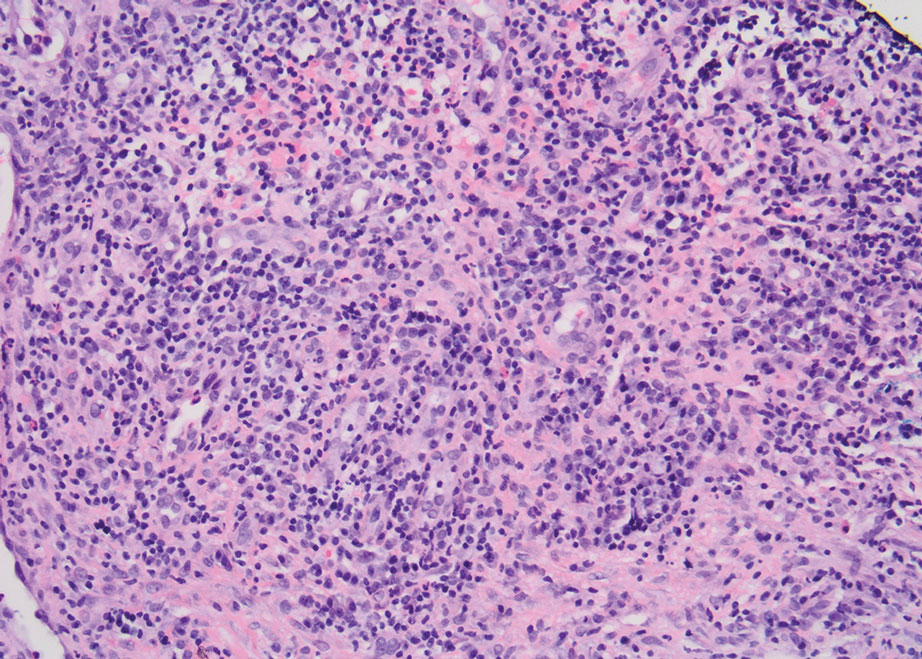

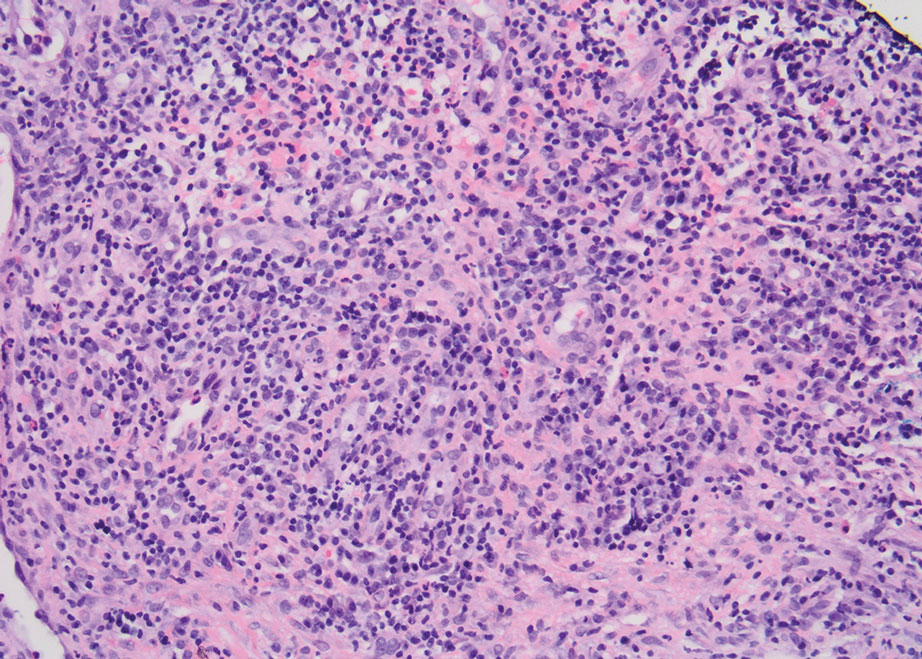

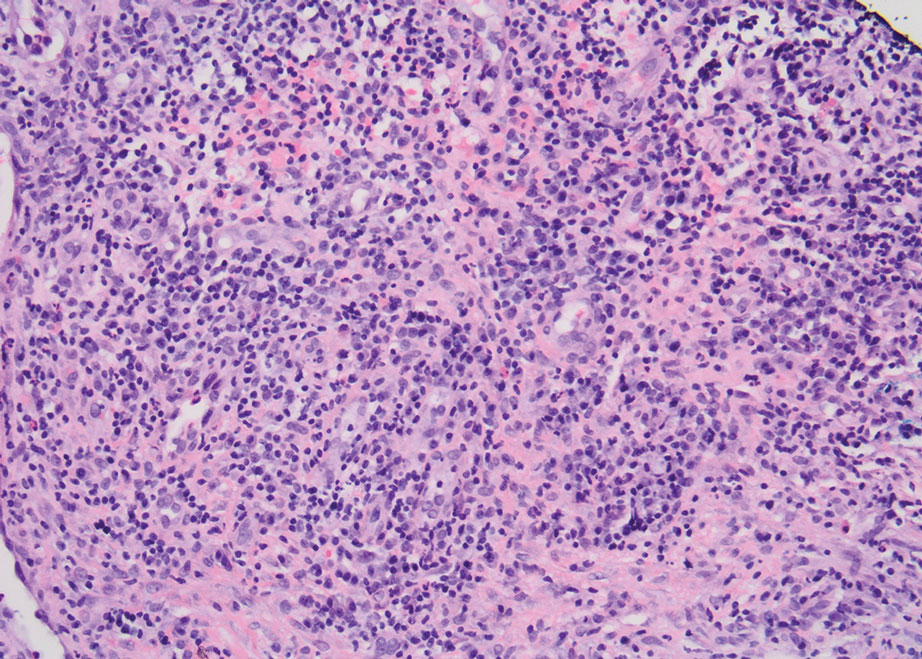

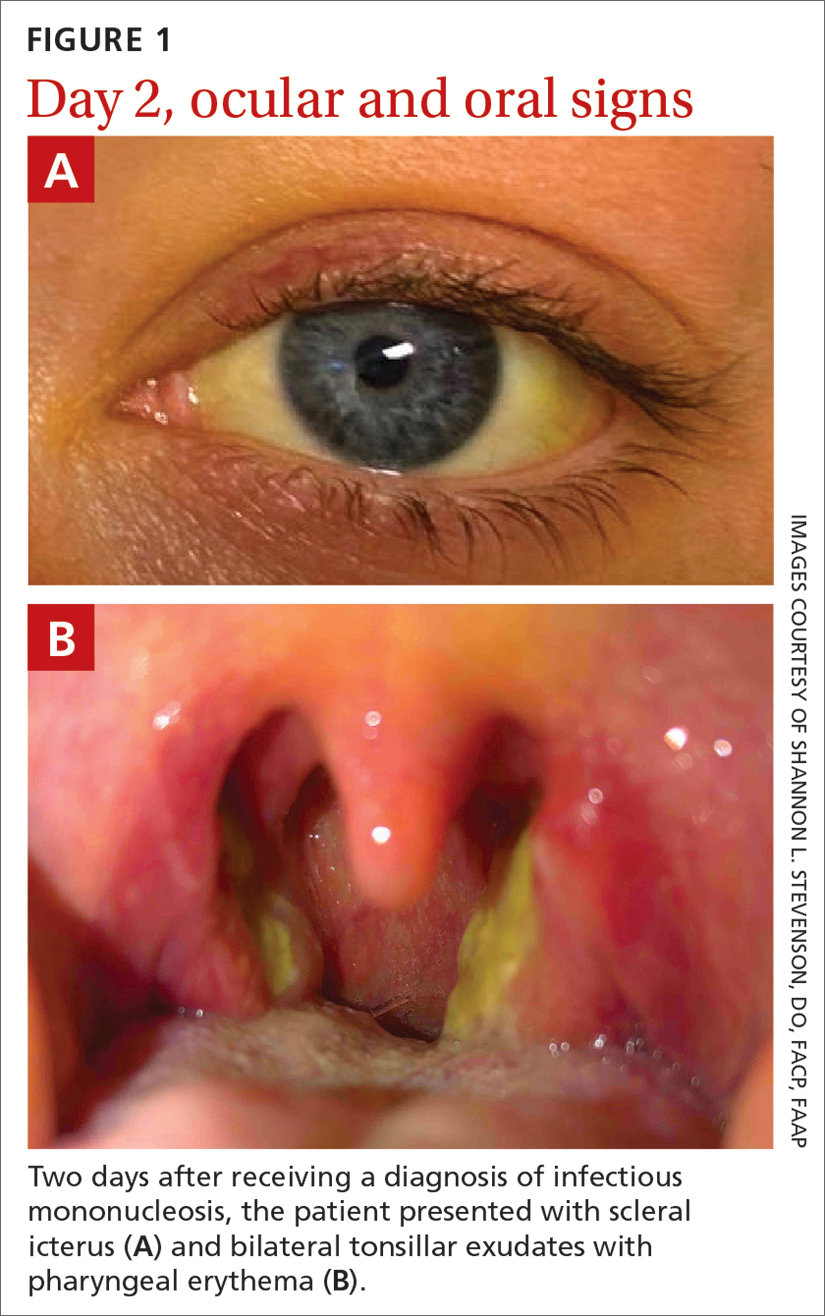

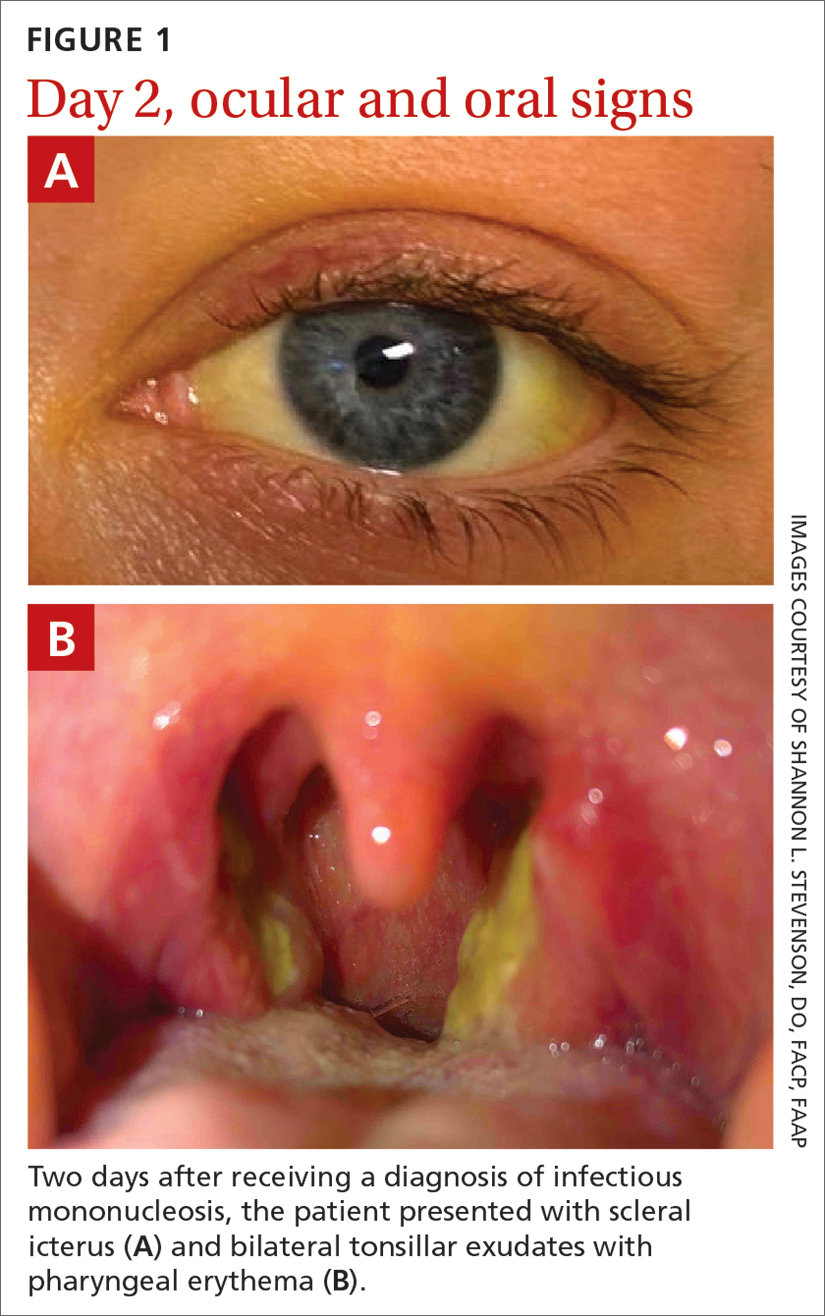

Physical examination revealed 2 ulcerations with violaceous borders involving the left upper back (greatest diameter, 5×7 cm)(Figure 1). Evidence of papular and cystic acne with residual scarring was noted on the cheeks. Scarring from HS was noted in the axillae and right groin. A biopsy from the edge of an ulceration on the back demonstrated epidermal spongiosis with acute and chronic inflammation and fibrosis (Figure 2). The clinicopathologic findings were most consistent with PG, and the patient was diagnosed with PASH syndrome, given the constellation of cutaneous lesions.

After treatment with topical and systemic antibiotics for acne and HS for more than 1 year failed, the patient was started on adalimumab. The initial dose was 160 mg subcutaneously, then 80 mg 2 weeks later, then 40 mg weekly thereafter. Doxycycline was continued for treatment of the acne and HS. After 6 weeks of adalimumab, the PG worsened and prednisone was added. She developed tender furuncles on the back, and cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus that responded to ciprofloxacin and cephalexin.

Due to progression of PG on adalimumab, switching to an infliximab infusion or anakinra was considered, but these options were not covered by the patient’s health insurance. Three months after the initial presentation, the patient was started on cyclosporine 100 mg 3 times daily (5 mg/kg/d) while adalimumab was continued; the ulcers started to improve within 2.5 weeks. After 3 months (Figure 3), the cyclosporine was reduced to 100 mg twice daily, and adalimumab was continued. She had a slight flare of PG after 8 months of treatment when adalimumab was unavailable to her for 2 months. After 8 months on cyclosporine, the dosage was tapered to 100 mg/d and then completely discontinued after 12 months.

The patient has continued on adalimumab 40 mg weekly with excellent control of the PG (Figure 4), although she did have one HS flare in the left axilla 11 months after the initial treatment. The patient’s cystic acne has intermittently flared and has been managed with spironolactone 100 mg/d for 3 years. After 4 years of management, the patient’s PG and HS remain well controlled on adalimumab.

Comment

Our case represents a major step in refining long-term treatment approaches for PASH syndrome due to the 4-year remission. Prior cases have reported use of anakinra, anakinra-cyclosporine combination, prednisone, azathioprine, topical tacrolimus, etanercept, and dapsone without sustainable success.1-6 The case studies discussed below have achieved remission via alternative drug combinations.

Staub et al4 found greatest success with a combination of infliximab, dapsone, and cyclosporine, and their patient had been in remission for 20 months at time of publication. Their hypothesis proposed that multiple inflammatory signaling pathways are involved in PASH syndrome, and this is why combination therapy is required for remission.4 In 2018, Lamiaux et al7 demonstrated successful treatment with rifampicin and clindamycin. Their patient had been in remission for 22 months at the time of publication—this time frame included 12 months of combination therapy and 10 months without medication. The authors hypothesized that, because of the autoinflammatory nature of these antibiotics, this pharmacologic combination could eradicate pathogenic bacteria from host microbiota while also inhibiting neutrophil function and synthesis of chemokines and cytokines.7

More recently, reports have been published regarding the success of tildrakizumab, an IL-23 antagonist, and ixekizumab, an IL-17 antagonist, in the treatment of PASH syndrome.6,8 Ixekizumab was used in combination with doxycycline, and remission was achieved in 12 months.8 However, tildrakizumab was used alone and achieved greater than 75% improvement in disease manifestations within 2 months.

Marzano et al5 conducted protein arrays and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to analyze the expression of cytokine, chemokine, and effector molecule profiles in PASH syndrome. It was determined that serum analysis displayed a normal cytokine/chemokine profile, with the only abnormalities being anemia and elevated C-reactive protein. There were no statistically significant differences in serum levels of IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, or IL-17 between PASH syndrome and healthy controls. However, cutaneous analysis revealed extensive cytokine and chemokine hyperactivity for IL-1β and IL-1β receptor; TNF-α; C-X-C motif ligands 1, 2, and 3; C-X-C motif ligand 16;

Ead et al3 presented a unique perspective focusing on cutaneous biofilm involvement in PASH syndrome. Microbes within these biofilms induce the migration and proliferation of inflammatory cells that consume factors normally utilized for tissue catabolism. These organisms deplete necessary biochemical cofactors used during healing. This lack of nutrients needed for healing not only slows the process but also promotes favorable conditions for the growth of anerobic species. In conjunction, biofilm formation restricts bacterial access to oxygen and nutrients, thus decreasing the bacterial metabolic rate and preventing the effects of antibiotic therapy. These features of biofilm communities contribute to inflammation and possibly the troubling resistance to many therapeutic options for PASH syndrome.

Each component of PASH syndrome has been associated with biofilm formation. As previously described, PG manifests in the skin as painful ulcerations, often with slough. This slough is hypothesized to be a consequence of increased vascular permeability and exudative byproducts that accompany the inflammatory nature of biofilms.3 Acne vulgaris has well-described associations with P acnes. Ead et al3 described P acnes as a component of the biofilm community within the microcomedone of hair follicles. This biofilm allows for antibiotic resistance occasionally seen in the treatment of acne and is potentially the pathogenic factor that both impedes healing and enhances the inflammatory state. Hidradenitis suppurativa has been associated with biofilm formation.3

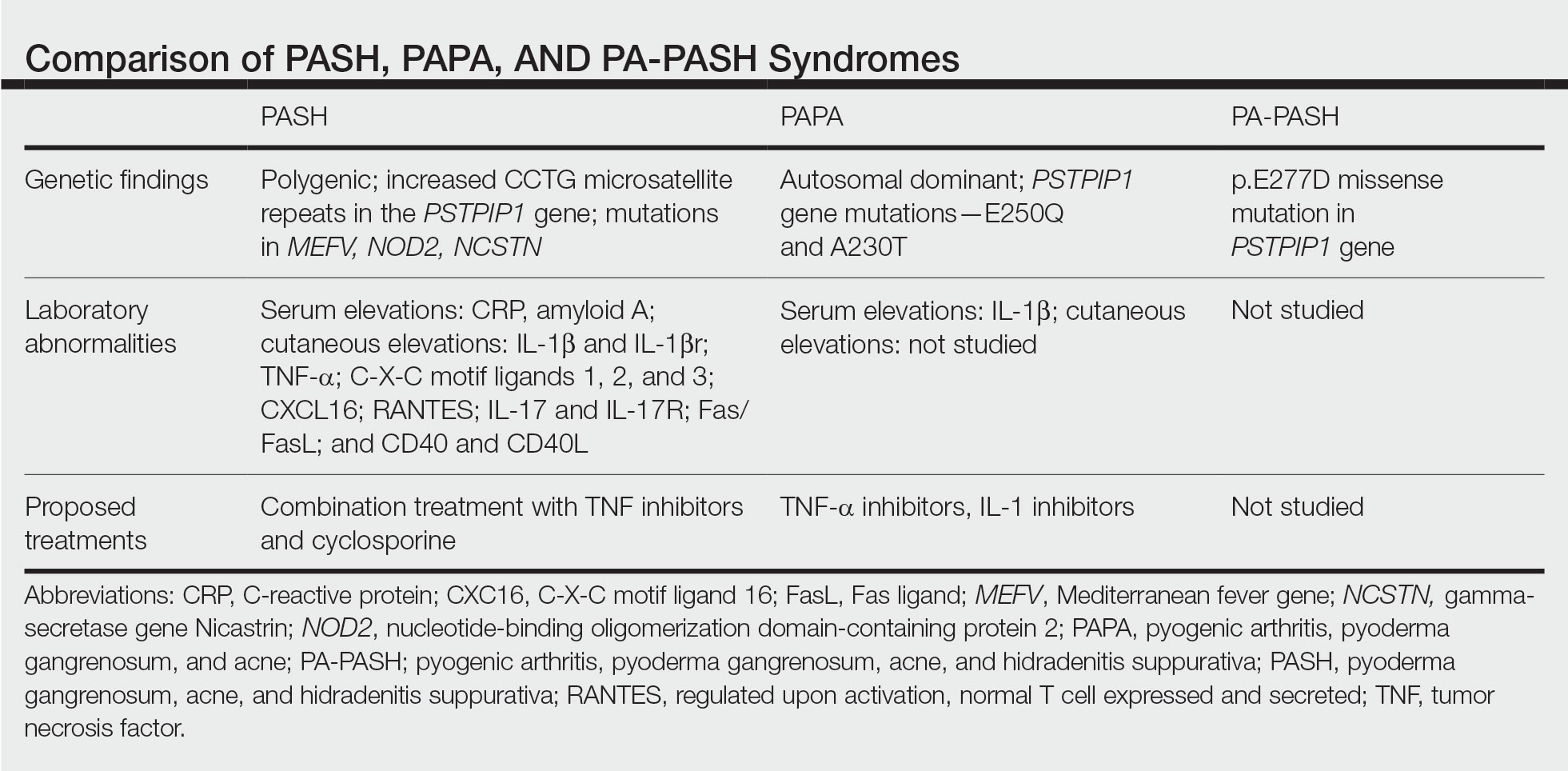

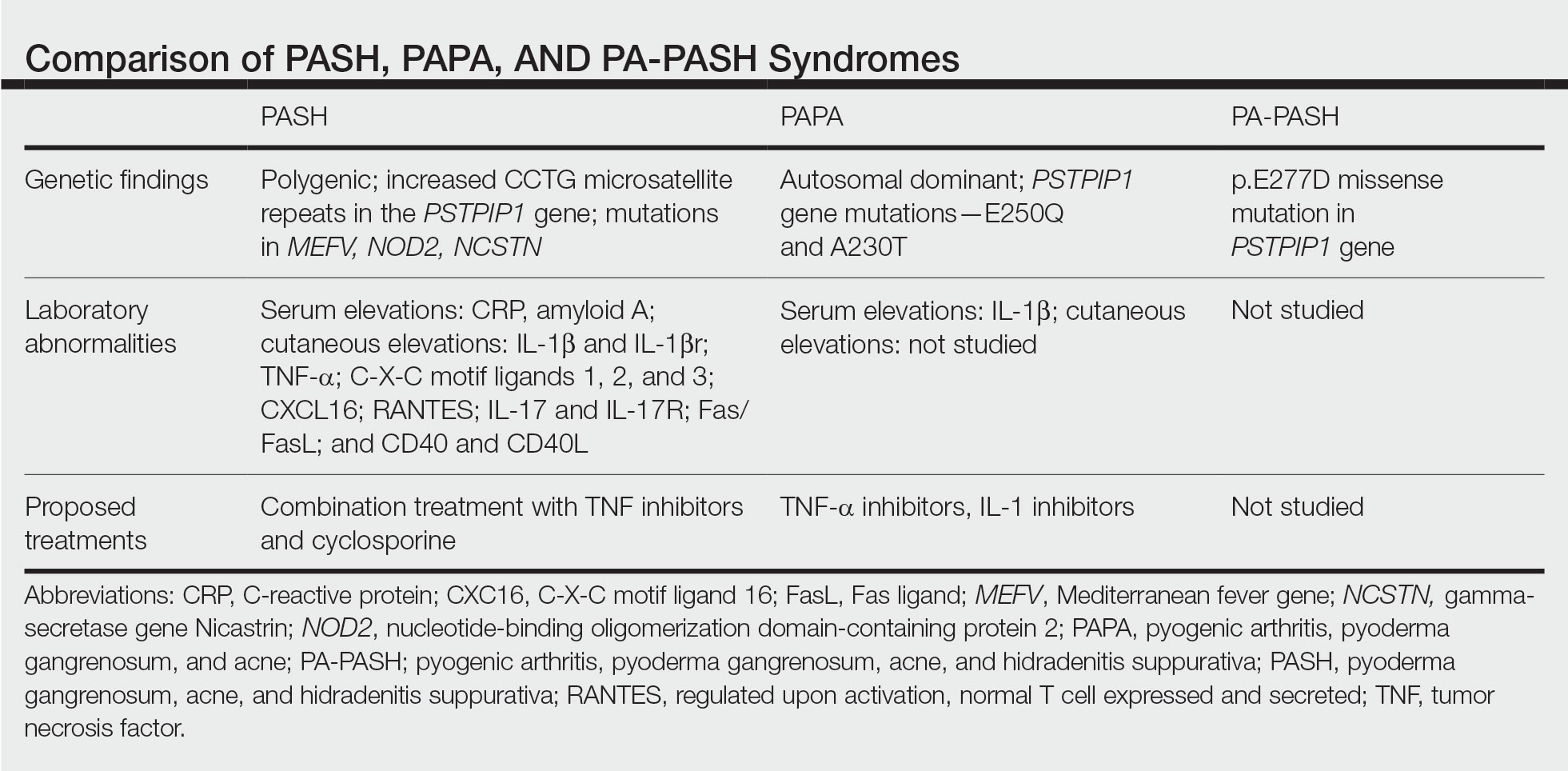

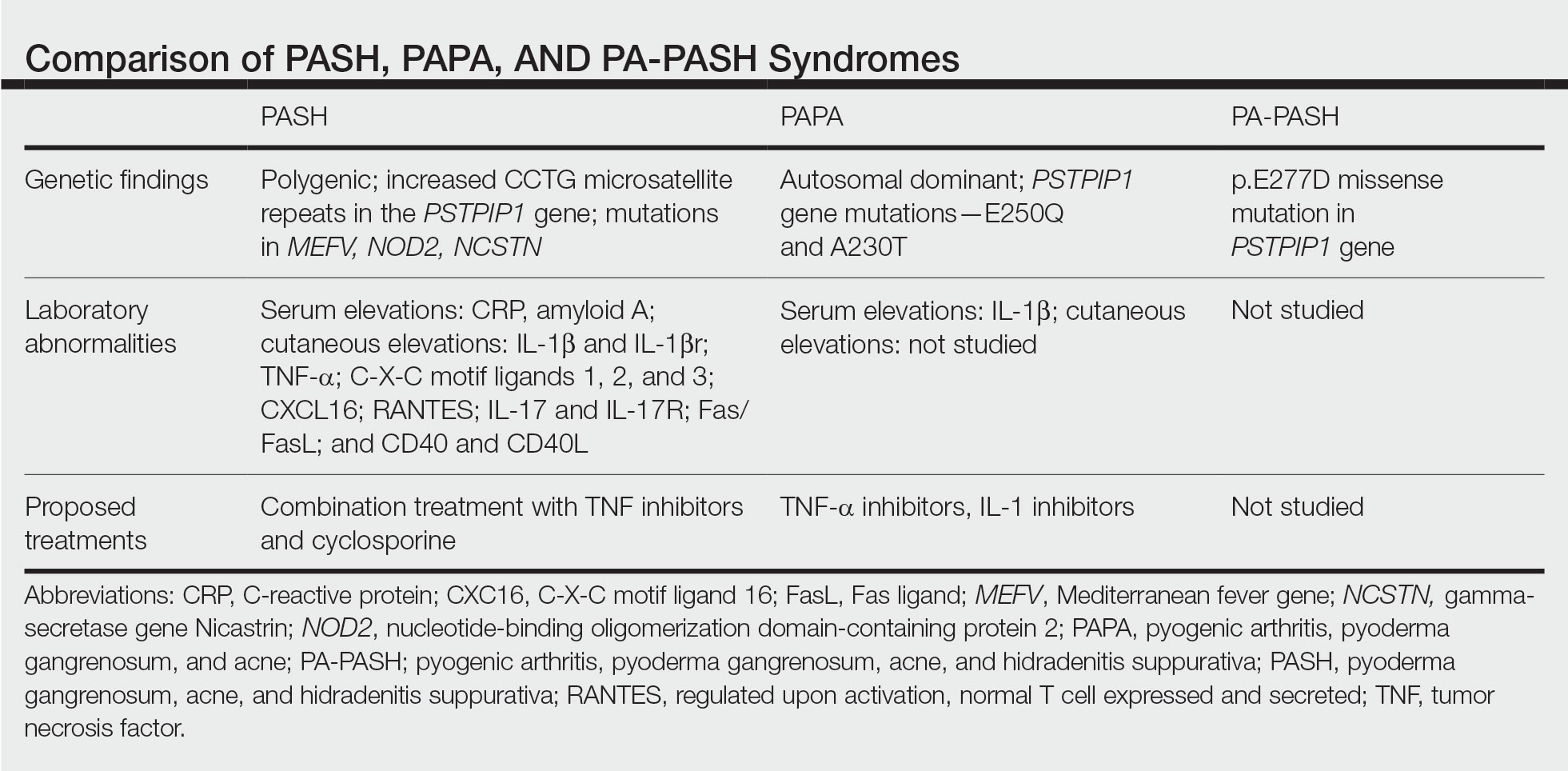

In further pursuit of PASH syndrome pathophysiology, many experts have sought to uncover the relationship between PASH syndrome and the previously described pyogenic arthritis, PG, and acne (PAPA) syndrome, another entity within the AIDs spectrum (Table). This condition was first recognized in 1997 in a 3-generation family with 10 affected members.1 It is characterized by PG and acne, similar to PASH; however, PAPA syndrome includes PG arthritis and lacks HS. Pyogenic arthritis manifests as recurrent aseptic inflammation of the joints, mainly the elbows, knees, and ankles. Pyogenic arthritis commonly is the presenting symptom of PAPA syndrome, with onset in childhood.2 As patients age, the arthritic symptoms decrease, and skin manifestations become more prominent.

PAPA syndrome has autosomal-dominant inheritance with mutations on chromosome 15 in the proline-serine-threonine phosphatase interacting protein 1 (PSTPIP1) gene.1 This mutation induces hyperphosphorylation of PSTPIP1, allowing for increased binding affinity to pyrin. Both PSTPIP1 and pyrin are co-expressed as parts of the NLRP3 inflammasome in granulocytes and monocytes.1 As a result, pyrin is more highly bound and loses its inhibitory effect on the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. This lack of inhibition allows for uninhibited cleavage of pro–IL-1β to active IL-1β by the inflammasome.1

Elevated concentrations of IL-1β in patients with PAPA syndrome result in a dysregulation of the innate immune system. IL-1β induces the release of proinflammatory cytokines, namely TNF-α; interferon γ; IL-8; and regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), all of which activate neutrophils and induce neutrophilic inflammation.2 IL-1β not only initiates this entire cascade but also acts as an antiapoptotic signal for neutrophils.2 When IL-1β reaches a critical threshold, it induces enough inflammation to cause severe tissue damage, thus causing joint and cutaneous disease in PAPA syndrome. IL-1 inhibitors (anakinra) or TNF-α inhibitors (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab) have been used many times to successfully treat PAPA syndrome, with TNF-α inhibitors providing the most consistent results.

Another AIDs entity with similarities to both PAPA syndrome and PASH syndrome is pyogenic arthritis, PG, acne, and HS (PA-PASH) syndrome. First identified in 2012 by Bruzzese,9 genetic analyses revealed a p.E277D missense mutation in PSTPIP1 in PA-PASH syndrome. Research has suggested that the key molecular feature is neutrophil activation by TH17 cells and the TNF-α axis.9 This syndrome has not been further characterized, and little is known regarding adequate treatment for PA-PASH syndrome.

Although it is similar in phenotype to aspects of PAPA and PA-PASH syndromes, PASH syndrome has distinct genotypic and immunologic abnormalities. Genetic analysis of this condition has shown an increased number of CCTG repeats in proximity to the PSTPIP1 promoter. It is hypothesized that these additional repeats predispose patients to neutrophilic inflammation in a similar manner to a condition described in France, termed aseptic abscess syndrome.1,5 Other mutations have been identified, including those in IL-1N, PSMB8, MEFV, NOD2, NCSTN, and more.2,7 However, it has been determined that the majority of these variants have already been filed in the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database or in the Registry of Hereditary Auto-inflammatory Disorders Mutations.2 The question remains regarding the origin of inflammation seen in PASH syndrome; the potential role of biofilms; and the relationship between PASH, PAPA, and PA-PASH syndromes. Much work remains to be done in refining therapeutic options for PASH syndrome. Continued biochemical research is necessary, as well as collaboration among dermatologists worldwide who find success in treating this condition.

Conclusion

There are genotypic and phenotypic similarities between PASH, PAPA, and PA-PASH syndromes, with various mutations within or near the PSTPIP1 gene; however, their genetic discrepancies seem to play a major role in the pathophysiology of each syndrome. Much work remains to be done in PA-PASH syndrome, which has not yet been well described. Meanwhile, PAPA syndrome has been well characterized with mutations affecting proteins of the NLRP3 inflammasome, resulting in elevated IL-1β and excess neutrophilic inflammation. In PASH syndrome, the importance of increased repeats near the PSTPIP1 promoter is yet to be elucidated. It has been shown that these abnormalities predispose individuals to neutrophilic inflammation, but the mechanism by which they do so is unknown. In addition, consideration of biofilms and their predisposition to inflammation within the pathophysiology of PASH syndrome is a possibility that must be considered when discussing therapeutic options. Based on our case study and previous successes in treating PASH syndrome, it is clear that a multidrug approach is necessary for remission. It is likely that the etiology of PASH syndrome is multifaceted and involves hyperactivity in multiple arms of the innate immune system.

Patients with PASH syndrome have severely impaired quality of life and often experience social withdrawal due to the disfiguring sequelae and limited treatment options available. To improve patient outcomes, it is essential for physicians and scientists to report on successful treatment strategies and advances in immunologic understanding. Improved understanding of PASH syndrome calls for further genetic exploration into the role of additional genomic repeats and how these affect the PSTPIP1 gene and inflammasome activity. As medical advances improve understanding of the pathophysiology of this disease entity, it will likely become clear which mechanisms are most important in disease progression and how clinicians can best optimize treatment.

- Braun-Falco M, Kovnerystyy O, Lohse P, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH)—a new autoinflammatory syndrome distinct from PAPA syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:409-415.

- Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV. PAPA, PASH and PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, presentation and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:555-562.

- Ead JK, Snyder RJ, Wise J, et al. Is PASH syndrome a biofilm disease?: a case series and review of the literature. Wounds. 2018;30:216-223.

- Staub J, Pfannschmidt N, Strohal R, et al. Successful treatment of PASH syndrome with infliximab, cyclosporine and dapsone. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2243-2247.

- Marzano AV, Ceccherini I, Gattorno M, et al. Association of pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) shares genetic and cytokine profiles with other autoinflammatory diseases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:E187.

- Kok Y, Nicolopoulos J, Varigos G, et al. Tildrakizumab in the treatment of PASH syndrome: a potential novel therapeutic target. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:E373-E374.

- Lamiaux M, Dabouz F, Wantz M, et al. Successful combined antibiotic therapy with oral clindamycin and oral rifampicin for pyoderma gangrenosum in patient with PASH syndrome. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:17-21.

- Gul MI, Singam V, Hanson C, et al. Remission of refractory PASH syndrome using ixekizumab and doxycycline. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:1123.

- Bruzzese V. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne conglobata, suppurative hidradenitis, and axial spondyloarthritis: efficacy of anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2012;18:413-415.

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)(PASH) syndrome is a recently identified disease process within the spectrum of autoinflammatory diseases (AIDs), which are distinct from autoimmune, infectious, and allergic syndromes and are gaining increasing interest given their complex pathophysiology and therapeutic resistance.1 Autoinflammatory diseases are defined by a dysregulation of the innate immune system in the absence of typical autoimmune features, including autoantibodies and antigen-specific T lymphocytes.2 Mutations affecting proteins of the inflammasome or proteins involved in regulating inflammasome function have been associated with these AIDs.2

Many AIDs have cutaneous involvement, as seen in PASH syndrome. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis presenting as skin ulcers with undermined, erythematous, violaceous borders. It can be isolated, syndromic, or associated with inflammatory conditions (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatologic disorders, hematologic disorders).1 Acne vulgaris develops because of chronic obstruction of hair follicles as a result of disordered keratinization and abnormal sebaceous stem cell differentiation.2 Propionibacterium acnes can reside and replicate within the biofilm community of the hair follicle and activate the inflammasome.2,3 Hidradenitis suppurativa, a chronic relapsing neutrophilic dermatosis, is a debilitating inflammatory disease of the hair follicles involving apocrine gland–bearing skin (ie, the axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions).2 Onset often occurs between the ages of 20 and 40 years, with a 3-fold higher incidence in women compared to men.3 Patients experience painful, deep-seated nodules that drain into sinus tracts and abscesses. The condition can be isolated or associated with inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease.4

PASH syndrome has been described as a polygenic autoinflammatory condition that most commonly presents in young adults, with onset of acne beginning years prior to other manifestations. A study analyzing 5 patients with PASH syndrome reported an average age of 32.2 years at diagnosis with a disease duration of 3 to 7 years.5 Pathophysiology of this condition is not well understood, with many hypotheses calling upon dysregulation of the innate immune system, a commonality this syndrome may share with other AIDs. Given its poorly understood pathophysiology, treating PASH syndrome can be especially difficult. We report a novel case of disease remission lasting more than 4 years using adalimumab and cyclosporine. We also discuss prior treatment successes and hypotheses regarding etiologic factors in PASH syndrome.

Case Report

A 36-year-old woman presented for evaluation of open draining ulcerations on the back of 18 months’ duration. She had a 16-year history of scarring cystic acne of the face and HS of the groin. The patient’s family history was remarkable for severe cystic acne in her brother and son as well as HS in her mother and another brother. Her treatment history included isotretinoin, doxycycline, and topical steroids.

Physical examination revealed 2 ulcerations with violaceous borders involving the left upper back (greatest diameter, 5×7 cm)(Figure 1). Evidence of papular and cystic acne with residual scarring was noted on the cheeks. Scarring from HS was noted in the axillae and right groin. A biopsy from the edge of an ulceration on the back demonstrated epidermal spongiosis with acute and chronic inflammation and fibrosis (Figure 2). The clinicopathologic findings were most consistent with PG, and the patient was diagnosed with PASH syndrome, given the constellation of cutaneous lesions.

After treatment with topical and systemic antibiotics for acne and HS for more than 1 year failed, the patient was started on adalimumab. The initial dose was 160 mg subcutaneously, then 80 mg 2 weeks later, then 40 mg weekly thereafter. Doxycycline was continued for treatment of the acne and HS. After 6 weeks of adalimumab, the PG worsened and prednisone was added. She developed tender furuncles on the back, and cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus that responded to ciprofloxacin and cephalexin.

Due to progression of PG on adalimumab, switching to an infliximab infusion or anakinra was considered, but these options were not covered by the patient’s health insurance. Three months after the initial presentation, the patient was started on cyclosporine 100 mg 3 times daily (5 mg/kg/d) while adalimumab was continued; the ulcers started to improve within 2.5 weeks. After 3 months (Figure 3), the cyclosporine was reduced to 100 mg twice daily, and adalimumab was continued. She had a slight flare of PG after 8 months of treatment when adalimumab was unavailable to her for 2 months. After 8 months on cyclosporine, the dosage was tapered to 100 mg/d and then completely discontinued after 12 months.

The patient has continued on adalimumab 40 mg weekly with excellent control of the PG (Figure 4), although she did have one HS flare in the left axilla 11 months after the initial treatment. The patient’s cystic acne has intermittently flared and has been managed with spironolactone 100 mg/d for 3 years. After 4 years of management, the patient’s PG and HS remain well controlled on adalimumab.

Comment

Our case represents a major step in refining long-term treatment approaches for PASH syndrome due to the 4-year remission. Prior cases have reported use of anakinra, anakinra-cyclosporine combination, prednisone, azathioprine, topical tacrolimus, etanercept, and dapsone without sustainable success.1-6 The case studies discussed below have achieved remission via alternative drug combinations.

Staub et al4 found greatest success with a combination of infliximab, dapsone, and cyclosporine, and their patient had been in remission for 20 months at time of publication. Their hypothesis proposed that multiple inflammatory signaling pathways are involved in PASH syndrome, and this is why combination therapy is required for remission.4 In 2018, Lamiaux et al7 demonstrated successful treatment with rifampicin and clindamycin. Their patient had been in remission for 22 months at the time of publication—this time frame included 12 months of combination therapy and 10 months without medication. The authors hypothesized that, because of the autoinflammatory nature of these antibiotics, this pharmacologic combination could eradicate pathogenic bacteria from host microbiota while also inhibiting neutrophil function and synthesis of chemokines and cytokines.7

More recently, reports have been published regarding the success of tildrakizumab, an IL-23 antagonist, and ixekizumab, an IL-17 antagonist, in the treatment of PASH syndrome.6,8 Ixekizumab was used in combination with doxycycline, and remission was achieved in 12 months.8 However, tildrakizumab was used alone and achieved greater than 75% improvement in disease manifestations within 2 months.

Marzano et al5 conducted protein arrays and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to analyze the expression of cytokine, chemokine, and effector molecule profiles in PASH syndrome. It was determined that serum analysis displayed a normal cytokine/chemokine profile, with the only abnormalities being anemia and elevated C-reactive protein. There were no statistically significant differences in serum levels of IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, or IL-17 between PASH syndrome and healthy controls. However, cutaneous analysis revealed extensive cytokine and chemokine hyperactivity for IL-1β and IL-1β receptor; TNF-α; C-X-C motif ligands 1, 2, and 3; C-X-C motif ligand 16;

Ead et al3 presented a unique perspective focusing on cutaneous biofilm involvement in PASH syndrome. Microbes within these biofilms induce the migration and proliferation of inflammatory cells that consume factors normally utilized for tissue catabolism. These organisms deplete necessary biochemical cofactors used during healing. This lack of nutrients needed for healing not only slows the process but also promotes favorable conditions for the growth of anerobic species. In conjunction, biofilm formation restricts bacterial access to oxygen and nutrients, thus decreasing the bacterial metabolic rate and preventing the effects of antibiotic therapy. These features of biofilm communities contribute to inflammation and possibly the troubling resistance to many therapeutic options for PASH syndrome.

Each component of PASH syndrome has been associated with biofilm formation. As previously described, PG manifests in the skin as painful ulcerations, often with slough. This slough is hypothesized to be a consequence of increased vascular permeability and exudative byproducts that accompany the inflammatory nature of biofilms.3 Acne vulgaris has well-described associations with P acnes. Ead et al3 described P acnes as a component of the biofilm community within the microcomedone of hair follicles. This biofilm allows for antibiotic resistance occasionally seen in the treatment of acne and is potentially the pathogenic factor that both impedes healing and enhances the inflammatory state. Hidradenitis suppurativa has been associated with biofilm formation.3

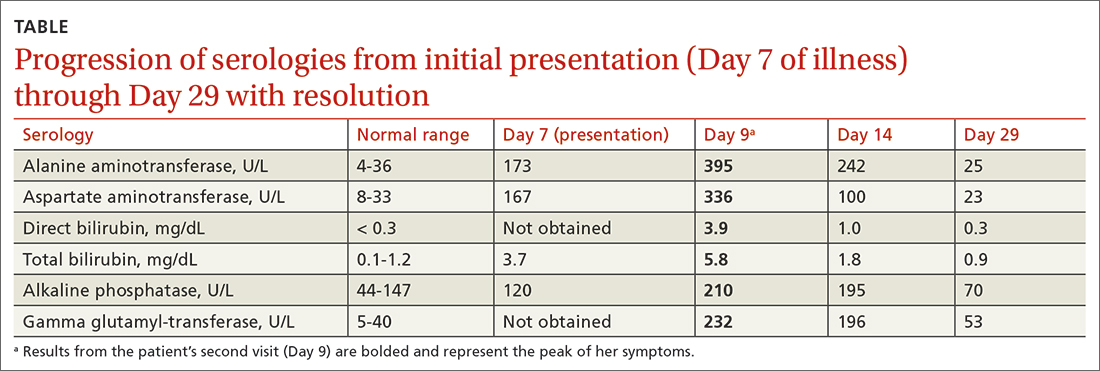

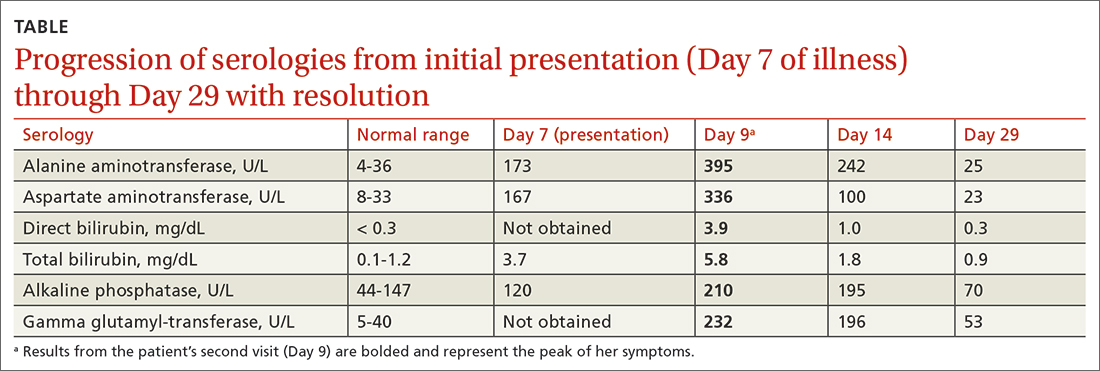

In further pursuit of PASH syndrome pathophysiology, many experts have sought to uncover the relationship between PASH syndrome and the previously described pyogenic arthritis, PG, and acne (PAPA) syndrome, another entity within the AIDs spectrum (Table). This condition was first recognized in 1997 in a 3-generation family with 10 affected members.1 It is characterized by PG and acne, similar to PASH; however, PAPA syndrome includes PG arthritis and lacks HS. Pyogenic arthritis manifests as recurrent aseptic inflammation of the joints, mainly the elbows, knees, and ankles. Pyogenic arthritis commonly is the presenting symptom of PAPA syndrome, with onset in childhood.2 As patients age, the arthritic symptoms decrease, and skin manifestations become more prominent.

PAPA syndrome has autosomal-dominant inheritance with mutations on chromosome 15 in the proline-serine-threonine phosphatase interacting protein 1 (PSTPIP1) gene.1 This mutation induces hyperphosphorylation of PSTPIP1, allowing for increased binding affinity to pyrin. Both PSTPIP1 and pyrin are co-expressed as parts of the NLRP3 inflammasome in granulocytes and monocytes.1 As a result, pyrin is more highly bound and loses its inhibitory effect on the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. This lack of inhibition allows for uninhibited cleavage of pro–IL-1β to active IL-1β by the inflammasome.1

Elevated concentrations of IL-1β in patients with PAPA syndrome result in a dysregulation of the innate immune system. IL-1β induces the release of proinflammatory cytokines, namely TNF-α; interferon γ; IL-8; and regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), all of which activate neutrophils and induce neutrophilic inflammation.2 IL-1β not only initiates this entire cascade but also acts as an antiapoptotic signal for neutrophils.2 When IL-1β reaches a critical threshold, it induces enough inflammation to cause severe tissue damage, thus causing joint and cutaneous disease in PAPA syndrome. IL-1 inhibitors (anakinra) or TNF-α inhibitors (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab) have been used many times to successfully treat PAPA syndrome, with TNF-α inhibitors providing the most consistent results.

Another AIDs entity with similarities to both PAPA syndrome and PASH syndrome is pyogenic arthritis, PG, acne, and HS (PA-PASH) syndrome. First identified in 2012 by Bruzzese,9 genetic analyses revealed a p.E277D missense mutation in PSTPIP1 in PA-PASH syndrome. Research has suggested that the key molecular feature is neutrophil activation by TH17 cells and the TNF-α axis.9 This syndrome has not been further characterized, and little is known regarding adequate treatment for PA-PASH syndrome.

Although it is similar in phenotype to aspects of PAPA and PA-PASH syndromes, PASH syndrome has distinct genotypic and immunologic abnormalities. Genetic analysis of this condition has shown an increased number of CCTG repeats in proximity to the PSTPIP1 promoter. It is hypothesized that these additional repeats predispose patients to neutrophilic inflammation in a similar manner to a condition described in France, termed aseptic abscess syndrome.1,5 Other mutations have been identified, including those in IL-1N, PSMB8, MEFV, NOD2, NCSTN, and more.2,7 However, it has been determined that the majority of these variants have already been filed in the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database or in the Registry of Hereditary Auto-inflammatory Disorders Mutations.2 The question remains regarding the origin of inflammation seen in PASH syndrome; the potential role of biofilms; and the relationship between PASH, PAPA, and PA-PASH syndromes. Much work remains to be done in refining therapeutic options for PASH syndrome. Continued biochemical research is necessary, as well as collaboration among dermatologists worldwide who find success in treating this condition.

Conclusion

There are genotypic and phenotypic similarities between PASH, PAPA, and PA-PASH syndromes, with various mutations within or near the PSTPIP1 gene; however, their genetic discrepancies seem to play a major role in the pathophysiology of each syndrome. Much work remains to be done in PA-PASH syndrome, which has not yet been well described. Meanwhile, PAPA syndrome has been well characterized with mutations affecting proteins of the NLRP3 inflammasome, resulting in elevated IL-1β and excess neutrophilic inflammation. In PASH syndrome, the importance of increased repeats near the PSTPIP1 promoter is yet to be elucidated. It has been shown that these abnormalities predispose individuals to neutrophilic inflammation, but the mechanism by which they do so is unknown. In addition, consideration of biofilms and their predisposition to inflammation within the pathophysiology of PASH syndrome is a possibility that must be considered when discussing therapeutic options. Based on our case study and previous successes in treating PASH syndrome, it is clear that a multidrug approach is necessary for remission. It is likely that the etiology of PASH syndrome is multifaceted and involves hyperactivity in multiple arms of the innate immune system.

Patients with PASH syndrome have severely impaired quality of life and often experience social withdrawal due to the disfiguring sequelae and limited treatment options available. To improve patient outcomes, it is essential for physicians and scientists to report on successful treatment strategies and advances in immunologic understanding. Improved understanding of PASH syndrome calls for further genetic exploration into the role of additional genomic repeats and how these affect the PSTPIP1 gene and inflammasome activity. As medical advances improve understanding of the pathophysiology of this disease entity, it will likely become clear which mechanisms are most important in disease progression and how clinicians can best optimize treatment.

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)(PASH) syndrome is a recently identified disease process within the spectrum of autoinflammatory diseases (AIDs), which are distinct from autoimmune, infectious, and allergic syndromes and are gaining increasing interest given their complex pathophysiology and therapeutic resistance.1 Autoinflammatory diseases are defined by a dysregulation of the innate immune system in the absence of typical autoimmune features, including autoantibodies and antigen-specific T lymphocytes.2 Mutations affecting proteins of the inflammasome or proteins involved in regulating inflammasome function have been associated with these AIDs.2

Many AIDs have cutaneous involvement, as seen in PASH syndrome. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis presenting as skin ulcers with undermined, erythematous, violaceous borders. It can be isolated, syndromic, or associated with inflammatory conditions (eg, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatologic disorders, hematologic disorders).1 Acne vulgaris develops because of chronic obstruction of hair follicles as a result of disordered keratinization and abnormal sebaceous stem cell differentiation.2 Propionibacterium acnes can reside and replicate within the biofilm community of the hair follicle and activate the inflammasome.2,3 Hidradenitis suppurativa, a chronic relapsing neutrophilic dermatosis, is a debilitating inflammatory disease of the hair follicles involving apocrine gland–bearing skin (ie, the axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions).2 Onset often occurs between the ages of 20 and 40 years, with a 3-fold higher incidence in women compared to men.3 Patients experience painful, deep-seated nodules that drain into sinus tracts and abscesses. The condition can be isolated or associated with inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease.4

PASH syndrome has been described as a polygenic autoinflammatory condition that most commonly presents in young adults, with onset of acne beginning years prior to other manifestations. A study analyzing 5 patients with PASH syndrome reported an average age of 32.2 years at diagnosis with a disease duration of 3 to 7 years.5 Pathophysiology of this condition is not well understood, with many hypotheses calling upon dysregulation of the innate immune system, a commonality this syndrome may share with other AIDs. Given its poorly understood pathophysiology, treating PASH syndrome can be especially difficult. We report a novel case of disease remission lasting more than 4 years using adalimumab and cyclosporine. We also discuss prior treatment successes and hypotheses regarding etiologic factors in PASH syndrome.

Case Report

A 36-year-old woman presented for evaluation of open draining ulcerations on the back of 18 months’ duration. She had a 16-year history of scarring cystic acne of the face and HS of the groin. The patient’s family history was remarkable for severe cystic acne in her brother and son as well as HS in her mother and another brother. Her treatment history included isotretinoin, doxycycline, and topical steroids.

Physical examination revealed 2 ulcerations with violaceous borders involving the left upper back (greatest diameter, 5×7 cm)(Figure 1). Evidence of papular and cystic acne with residual scarring was noted on the cheeks. Scarring from HS was noted in the axillae and right groin. A biopsy from the edge of an ulceration on the back demonstrated epidermal spongiosis with acute and chronic inflammation and fibrosis (Figure 2). The clinicopathologic findings were most consistent with PG, and the patient was diagnosed with PASH syndrome, given the constellation of cutaneous lesions.

After treatment with topical and systemic antibiotics for acne and HS for more than 1 year failed, the patient was started on adalimumab. The initial dose was 160 mg subcutaneously, then 80 mg 2 weeks later, then 40 mg weekly thereafter. Doxycycline was continued for treatment of the acne and HS. After 6 weeks of adalimumab, the PG worsened and prednisone was added. She developed tender furuncles on the back, and cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus that responded to ciprofloxacin and cephalexin.

Due to progression of PG on adalimumab, switching to an infliximab infusion or anakinra was considered, but these options were not covered by the patient’s health insurance. Three months after the initial presentation, the patient was started on cyclosporine 100 mg 3 times daily (5 mg/kg/d) while adalimumab was continued; the ulcers started to improve within 2.5 weeks. After 3 months (Figure 3), the cyclosporine was reduced to 100 mg twice daily, and adalimumab was continued. She had a slight flare of PG after 8 months of treatment when adalimumab was unavailable to her for 2 months. After 8 months on cyclosporine, the dosage was tapered to 100 mg/d and then completely discontinued after 12 months.

The patient has continued on adalimumab 40 mg weekly with excellent control of the PG (Figure 4), although she did have one HS flare in the left axilla 11 months after the initial treatment. The patient’s cystic acne has intermittently flared and has been managed with spironolactone 100 mg/d for 3 years. After 4 years of management, the patient’s PG and HS remain well controlled on adalimumab.

Comment

Our case represents a major step in refining long-term treatment approaches for PASH syndrome due to the 4-year remission. Prior cases have reported use of anakinra, anakinra-cyclosporine combination, prednisone, azathioprine, topical tacrolimus, etanercept, and dapsone without sustainable success.1-6 The case studies discussed below have achieved remission via alternative drug combinations.

Staub et al4 found greatest success with a combination of infliximab, dapsone, and cyclosporine, and their patient had been in remission for 20 months at time of publication. Their hypothesis proposed that multiple inflammatory signaling pathways are involved in PASH syndrome, and this is why combination therapy is required for remission.4 In 2018, Lamiaux et al7 demonstrated successful treatment with rifampicin and clindamycin. Their patient had been in remission for 22 months at the time of publication—this time frame included 12 months of combination therapy and 10 months without medication. The authors hypothesized that, because of the autoinflammatory nature of these antibiotics, this pharmacologic combination could eradicate pathogenic bacteria from host microbiota while also inhibiting neutrophil function and synthesis of chemokines and cytokines.7

More recently, reports have been published regarding the success of tildrakizumab, an IL-23 antagonist, and ixekizumab, an IL-17 antagonist, in the treatment of PASH syndrome.6,8 Ixekizumab was used in combination with doxycycline, and remission was achieved in 12 months.8 However, tildrakizumab was used alone and achieved greater than 75% improvement in disease manifestations within 2 months.

Marzano et al5 conducted protein arrays and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to analyze the expression of cytokine, chemokine, and effector molecule profiles in PASH syndrome. It was determined that serum analysis displayed a normal cytokine/chemokine profile, with the only abnormalities being anemia and elevated C-reactive protein. There were no statistically significant differences in serum levels of IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, or IL-17 between PASH syndrome and healthy controls. However, cutaneous analysis revealed extensive cytokine and chemokine hyperactivity for IL-1β and IL-1β receptor; TNF-α; C-X-C motif ligands 1, 2, and 3; C-X-C motif ligand 16;

Ead et al3 presented a unique perspective focusing on cutaneous biofilm involvement in PASH syndrome. Microbes within these biofilms induce the migration and proliferation of inflammatory cells that consume factors normally utilized for tissue catabolism. These organisms deplete necessary biochemical cofactors used during healing. This lack of nutrients needed for healing not only slows the process but also promotes favorable conditions for the growth of anerobic species. In conjunction, biofilm formation restricts bacterial access to oxygen and nutrients, thus decreasing the bacterial metabolic rate and preventing the effects of antibiotic therapy. These features of biofilm communities contribute to inflammation and possibly the troubling resistance to many therapeutic options for PASH syndrome.

Each component of PASH syndrome has been associated with biofilm formation. As previously described, PG manifests in the skin as painful ulcerations, often with slough. This slough is hypothesized to be a consequence of increased vascular permeability and exudative byproducts that accompany the inflammatory nature of biofilms.3 Acne vulgaris has well-described associations with P acnes. Ead et al3 described P acnes as a component of the biofilm community within the microcomedone of hair follicles. This biofilm allows for antibiotic resistance occasionally seen in the treatment of acne and is potentially the pathogenic factor that both impedes healing and enhances the inflammatory state. Hidradenitis suppurativa has been associated with biofilm formation.3

In further pursuit of PASH syndrome pathophysiology, many experts have sought to uncover the relationship between PASH syndrome and the previously described pyogenic arthritis, PG, and acne (PAPA) syndrome, another entity within the AIDs spectrum (Table). This condition was first recognized in 1997 in a 3-generation family with 10 affected members.1 It is characterized by PG and acne, similar to PASH; however, PAPA syndrome includes PG arthritis and lacks HS. Pyogenic arthritis manifests as recurrent aseptic inflammation of the joints, mainly the elbows, knees, and ankles. Pyogenic arthritis commonly is the presenting symptom of PAPA syndrome, with onset in childhood.2 As patients age, the arthritic symptoms decrease, and skin manifestations become more prominent.

PAPA syndrome has autosomal-dominant inheritance with mutations on chromosome 15 in the proline-serine-threonine phosphatase interacting protein 1 (PSTPIP1) gene.1 This mutation induces hyperphosphorylation of PSTPIP1, allowing for increased binding affinity to pyrin. Both PSTPIP1 and pyrin are co-expressed as parts of the NLRP3 inflammasome in granulocytes and monocytes.1 As a result, pyrin is more highly bound and loses its inhibitory effect on the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. This lack of inhibition allows for uninhibited cleavage of pro–IL-1β to active IL-1β by the inflammasome.1

Elevated concentrations of IL-1β in patients with PAPA syndrome result in a dysregulation of the innate immune system. IL-1β induces the release of proinflammatory cytokines, namely TNF-α; interferon γ; IL-8; and regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), all of which activate neutrophils and induce neutrophilic inflammation.2 IL-1β not only initiates this entire cascade but also acts as an antiapoptotic signal for neutrophils.2 When IL-1β reaches a critical threshold, it induces enough inflammation to cause severe tissue damage, thus causing joint and cutaneous disease in PAPA syndrome. IL-1 inhibitors (anakinra) or TNF-α inhibitors (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab) have been used many times to successfully treat PAPA syndrome, with TNF-α inhibitors providing the most consistent results.

Another AIDs entity with similarities to both PAPA syndrome and PASH syndrome is pyogenic arthritis, PG, acne, and HS (PA-PASH) syndrome. First identified in 2012 by Bruzzese,9 genetic analyses revealed a p.E277D missense mutation in PSTPIP1 in PA-PASH syndrome. Research has suggested that the key molecular feature is neutrophil activation by TH17 cells and the TNF-α axis.9 This syndrome has not been further characterized, and little is known regarding adequate treatment for PA-PASH syndrome.

Although it is similar in phenotype to aspects of PAPA and PA-PASH syndromes, PASH syndrome has distinct genotypic and immunologic abnormalities. Genetic analysis of this condition has shown an increased number of CCTG repeats in proximity to the PSTPIP1 promoter. It is hypothesized that these additional repeats predispose patients to neutrophilic inflammation in a similar manner to a condition described in France, termed aseptic abscess syndrome.1,5 Other mutations have been identified, including those in IL-1N, PSMB8, MEFV, NOD2, NCSTN, and more.2,7 However, it has been determined that the majority of these variants have already been filed in the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database or in the Registry of Hereditary Auto-inflammatory Disorders Mutations.2 The question remains regarding the origin of inflammation seen in PASH syndrome; the potential role of biofilms; and the relationship between PASH, PAPA, and PA-PASH syndromes. Much work remains to be done in refining therapeutic options for PASH syndrome. Continued biochemical research is necessary, as well as collaboration among dermatologists worldwide who find success in treating this condition.

Conclusion

There are genotypic and phenotypic similarities between PASH, PAPA, and PA-PASH syndromes, with various mutations within or near the PSTPIP1 gene; however, their genetic discrepancies seem to play a major role in the pathophysiology of each syndrome. Much work remains to be done in PA-PASH syndrome, which has not yet been well described. Meanwhile, PAPA syndrome has been well characterized with mutations affecting proteins of the NLRP3 inflammasome, resulting in elevated IL-1β and excess neutrophilic inflammation. In PASH syndrome, the importance of increased repeats near the PSTPIP1 promoter is yet to be elucidated. It has been shown that these abnormalities predispose individuals to neutrophilic inflammation, but the mechanism by which they do so is unknown. In addition, consideration of biofilms and their predisposition to inflammation within the pathophysiology of PASH syndrome is a possibility that must be considered when discussing therapeutic options. Based on our case study and previous successes in treating PASH syndrome, it is clear that a multidrug approach is necessary for remission. It is likely that the etiology of PASH syndrome is multifaceted and involves hyperactivity in multiple arms of the innate immune system.

Patients with PASH syndrome have severely impaired quality of life and often experience social withdrawal due to the disfiguring sequelae and limited treatment options available. To improve patient outcomes, it is essential for physicians and scientists to report on successful treatment strategies and advances in immunologic understanding. Improved understanding of PASH syndrome calls for further genetic exploration into the role of additional genomic repeats and how these affect the PSTPIP1 gene and inflammasome activity. As medical advances improve understanding of the pathophysiology of this disease entity, it will likely become clear which mechanisms are most important in disease progression and how clinicians can best optimize treatment.

- Braun-Falco M, Kovnerystyy O, Lohse P, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH)—a new autoinflammatory syndrome distinct from PAPA syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:409-415.

- Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV. PAPA, PASH and PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, presentation and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:555-562.

- Ead JK, Snyder RJ, Wise J, et al. Is PASH syndrome a biofilm disease?: a case series and review of the literature. Wounds. 2018;30:216-223.

- Staub J, Pfannschmidt N, Strohal R, et al. Successful treatment of PASH syndrome with infliximab, cyclosporine and dapsone. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2243-2247.

- Marzano AV, Ceccherini I, Gattorno M, et al. Association of pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) shares genetic and cytokine profiles with other autoinflammatory diseases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:E187.

- Kok Y, Nicolopoulos J, Varigos G, et al. Tildrakizumab in the treatment of PASH syndrome: a potential novel therapeutic target. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:E373-E374.

- Lamiaux M, Dabouz F, Wantz M, et al. Successful combined antibiotic therapy with oral clindamycin and oral rifampicin for pyoderma gangrenosum in patient with PASH syndrome. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:17-21.

- Gul MI, Singam V, Hanson C, et al. Remission of refractory PASH syndrome using ixekizumab and doxycycline. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:1123.

- Bruzzese V. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne conglobata, suppurative hidradenitis, and axial spondyloarthritis: efficacy of anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2012;18:413-415.

- Braun-Falco M, Kovnerystyy O, Lohse P, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH)—a new autoinflammatory syndrome distinct from PAPA syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:409-415.

- Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV. PAPA, PASH and PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, presentation and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:555-562.

- Ead JK, Snyder RJ, Wise J, et al. Is PASH syndrome a biofilm disease?: a case series and review of the literature. Wounds. 2018;30:216-223.

- Staub J, Pfannschmidt N, Strohal R, et al. Successful treatment of PASH syndrome with infliximab, cyclosporine and dapsone. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2243-2247.

- Marzano AV, Ceccherini I, Gattorno M, et al. Association of pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) shares genetic and cytokine profiles with other autoinflammatory diseases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:E187.

- Kok Y, Nicolopoulos J, Varigos G, et al. Tildrakizumab in the treatment of PASH syndrome: a potential novel therapeutic target. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:E373-E374.

- Lamiaux M, Dabouz F, Wantz M, et al. Successful combined antibiotic therapy with oral clindamycin and oral rifampicin for pyoderma gangrenosum in patient with PASH syndrome. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:17-21.

- Gul MI, Singam V, Hanson C, et al. Remission of refractory PASH syndrome using ixekizumab and doxycycline. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:1123.

- Bruzzese V. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne conglobata, suppurative hidradenitis, and axial spondyloarthritis: efficacy of anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2012;18:413-415.

Practice Points

- Despite phenotypic similarities among pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa (PASH) syndrome; pyogenic arthritis, PG, and acne syndrome; and pyogenic arthritis–PASH syndrome, there are genotypic differences that contribute to unique inflammatory cytokine patterns and the need for distinct pharmacologic considerations within each entity.

- When formulating therapeutic regimens for patients with PASH syndrome, it is essential for dermatologists to consider the likelihood of hyperactivity in multiple pathways of the innate immune system and utilize a combination of multimodal antiinflammatory therapies.

55-year-old woman • unilateral nasal drainage • salty taste • nasal redness • recent COVID-19 nasal swabs • Dx?

THE CASE

A 55-year-old woman was evaluated in a family medicine clinic for clear, right-side nasal drainage. She stated that the drainage began 5 months earlier after 2 hospitalizations for severe anxiety leading to emesis and hypokalemia. She reported 3 different COVID-19 nasal swab tests performed on the right nare. Chart review showed 2 negative COVID-19 tests, 6 days apart. Since the hospitalizations, the patient had been given antihistamines for rhinorrhea at an urgent care visit. Despite this treatment, the patient reported a constant drip from the right nare with a salty taste. She also reported experiencing occasional headaches but denied nausea/vomiting.

The patient’s history included uncontrolled hypertension, treatment-resistant anxiety and depression, obstructive sleep apnea, chronic sinus disease (observed on computed tomography [CT] scans), and type 2 diabetes. She was on amlodipine 10 mg/d for hypertension and was not taking any medication for diabetes.

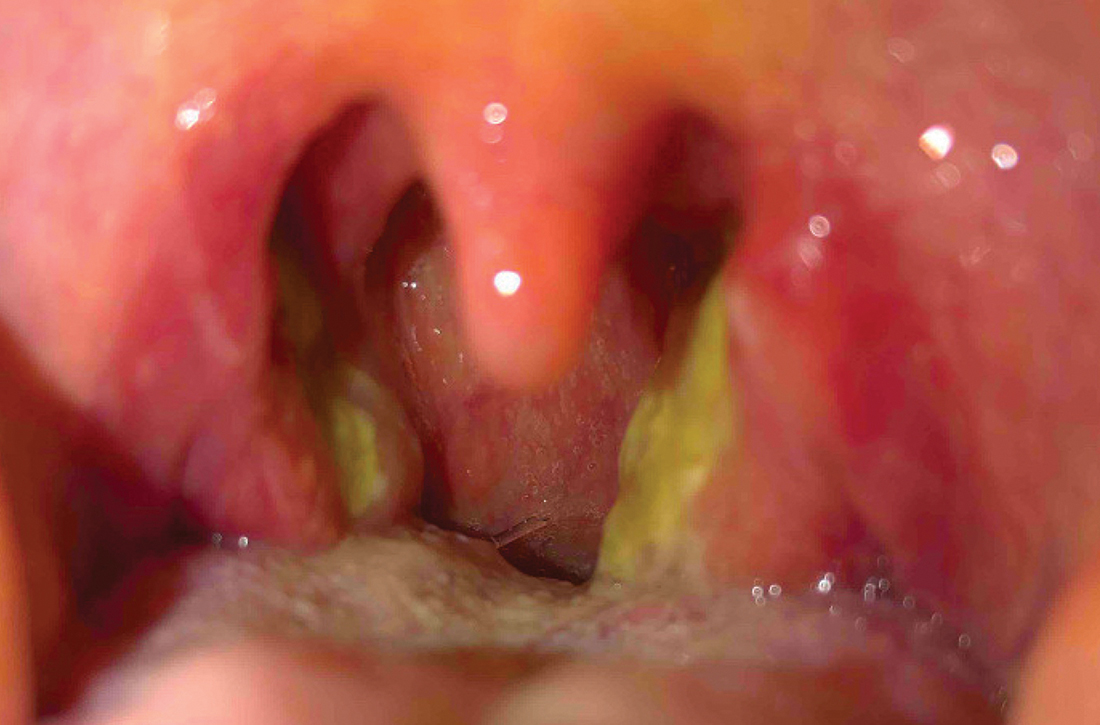

On examination, the patient’s vital signs were within normal limits except for an elevated blood pressure of 158/88 mm Hg. The patient had persistent clear rhinorrhea fluid draining from the right nostril that was exacerbated when she looked down. Right nasal erythema was present.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s negative COVID-19 tests, lack of improvement on antihistamines, and description of the nasal fluid as salty tasting prompted us to suspect a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. The clinical work-up included a halo (“double-ring”) sign test, a β-2 transferrin test, and a sinus x-ray.

The halo sign test was negative for CSF fluid. Sinus/skull x-ray did not show a cribriform or other fracture. However, a sample of the nasal fluid collected in a sterile container was positive for β-2 transferrin, the gold-standard laboratory test to confirm a CSF leak.

The patient was sent for a maxillofacial CT scan without contrast. Results showed a 3-mm defect over the right ethmoid roof associated with a 10 × 16–mm low-attenuation structure in the right ethmoid labyrinth, suspicious for encephalocele. This defect, in the setting of the patient’s history of chronic sinus disease, furthered our suspicion of a CSF leak secondary to COVID-19 testing. Radiology confirmed the diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

CSF rhinorrhea is CSF leakage through the nasal cavity due to abnormal communication between the arachnoid membrane and nasal mucosa.1 The most commonly reported risk factors for this include female sex, middle age (fourth to fifth decade), obesity (body mass index > 40), intracranial hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea.1,2

Continue to: Clear, unilateral rhinorrhea...

Clear, unilateral rhinorrhea drainage that increases at times of relatively increased intracranial pressure and has a metallic or salty taste is suspicious for CSF rhinorrhea.3 It can occur following skull‐base trauma (eg, cribriform plate, temporal bone), endoscopic sinus surgery, or neurosurgical procedures, or have a spontaneous etiology.3,4

Modalities to confirm CSF rhinorrhea include radionuclide cisternography and testing of fluid for the halo sign, glucose, and the CSF-specific proteins β‐2 transferrin and β-trace protein.3,4 High‐resolution CT is the imaging method most commonly used for localizing a CSF leak.4

Treatment is provided in the hospital

Patients with CSF rhinorrhea typically require inpatient management with bed rest, head-of-bed elevation, and frequent neurologic evaluation, as persistent CSF rhinorrhea increases the risk for meningitis, thus necessitating surgical intervention.3,5 Some cases resolve with bed rest alone. Endonasal endoscopic repair of CSF leaks has become the standard of care because of its high success rate and lower morbidity profile.4

The preferred treatment method for encephalocele is surgical removal after diagnosis is confirmed with CT or magnetic resonance imaging.6

Our patient underwent surgery to remove the encephalocele. The surgeons reported no evidence of fracture.

The final cause of her CSF leak is still uncertain. The surgeons felt confident it was due to ethmoidal encephalocele, a form of neural tube defect in which brain tissue herniates through structural weaknesses of the skull.6-8 While more common in infants, encephalocele can manifest in adulthood due to traumatic or iatrogenic causes.7,8

There is a previous report of encephalocele with CSF leak after COVID-19 testing.9 This case report suggests the possibility of a nasal swab causing trauma to a patient’s pre‐existing encephalocele—a probability in our patient’s case. It is unlikely, however, that the nasal swab itself violated the bony skull base.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case exemplifies how unexplained local symptoms, a high index of suspicion, and adequate work-up can lead to a rare diagnosis. Diagnostic strategies employed for cases of CSF rhinorrhea vary widely due to limited evidence-based guidance.4 Unilateral rhinorrhea with clear fluid that increases at times of increased intracranial pressure, such as bending over, should prompt suspicion for CSF rhinorrhea. With millions of people getting nasal swabs daily during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is even more important to keep CSF leak in our differential diagnosis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eliana Lizeth Garcia, MD, BS, BA, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, 1209 University Boulevard NE, Albuquerque, NM 87131-5001; [email protected]

1. Keshri A, Jain R, Manogaran RS, et al. Management of spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea: an institutional experience. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2019;80:493-499. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676334

2. Lobo BC, Baumanis MM, Nelson RF. Surgical repair of spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks: a systematic review. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2017;2:215-224. doi: 10.1002/lio2.75

3. Van Zele T, Dewaele F. Traumatic CSF leaks of the anterior skull base. B-ENT. 2016;suppl 26:19-27.

4. Oakley GM, Alt JA, Schlosser RJ, et al. Diagnosis of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: an evidence-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:8-16. doi: 10.1002/alr.21637

5. Friedman JA, Ebersold MJ, Quast LM. Post-traumatic cerebrospinal fluid leakage. World J Surg. 2001;25:1062-1066. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0059-7

6. Tirumandas M, Sharma A, Gbenimacho I, et al. Nasal encephaloceles: a review of etiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentations, diagnosis, treatment, and complications. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29:739-744. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1998-z

7. Junaid M, Sobani ZU, Shamim AA, et al. Nasal encephaloceles presenting at later ages: experience of otorhinolaryngology department at a tertiary care center in Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2012;62:74-76.

8. Dhirawani RB, Gupta R, Pathak S, et al. Frontoethmoidal encephalocele: case report and review on management. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2014;4:195-197. doi: 10.4103/2231-0746.147140

9. Paquin R, Ryan L, Vale FL, et al. CSF leak after COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab: a case report. Laryngoscope. 2021;131:1927-1929. doi: 10.1002/lary.29462

THE CASE

A 55-year-old woman was evaluated in a family medicine clinic for clear, right-side nasal drainage. She stated that the drainage began 5 months earlier after 2 hospitalizations for severe anxiety leading to emesis and hypokalemia. She reported 3 different COVID-19 nasal swab tests performed on the right nare. Chart review showed 2 negative COVID-19 tests, 6 days apart. Since the hospitalizations, the patient had been given antihistamines for rhinorrhea at an urgent care visit. Despite this treatment, the patient reported a constant drip from the right nare with a salty taste. She also reported experiencing occasional headaches but denied nausea/vomiting.

The patient’s history included uncontrolled hypertension, treatment-resistant anxiety and depression, obstructive sleep apnea, chronic sinus disease (observed on computed tomography [CT] scans), and type 2 diabetes. She was on amlodipine 10 mg/d for hypertension and was not taking any medication for diabetes.

On examination, the patient’s vital signs were within normal limits except for an elevated blood pressure of 158/88 mm Hg. The patient had persistent clear rhinorrhea fluid draining from the right nostril that was exacerbated when she looked down. Right nasal erythema was present.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s negative COVID-19 tests, lack of improvement on antihistamines, and description of the nasal fluid as salty tasting prompted us to suspect a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. The clinical work-up included a halo (“double-ring”) sign test, a β-2 transferrin test, and a sinus x-ray.

The halo sign test was negative for CSF fluid. Sinus/skull x-ray did not show a cribriform or other fracture. However, a sample of the nasal fluid collected in a sterile container was positive for β-2 transferrin, the gold-standard laboratory test to confirm a CSF leak.

The patient was sent for a maxillofacial CT scan without contrast. Results showed a 3-mm defect over the right ethmoid roof associated with a 10 × 16–mm low-attenuation structure in the right ethmoid labyrinth, suspicious for encephalocele. This defect, in the setting of the patient’s history of chronic sinus disease, furthered our suspicion of a CSF leak secondary to COVID-19 testing. Radiology confirmed the diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

CSF rhinorrhea is CSF leakage through the nasal cavity due to abnormal communication between the arachnoid membrane and nasal mucosa.1 The most commonly reported risk factors for this include female sex, middle age (fourth to fifth decade), obesity (body mass index > 40), intracranial hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea.1,2

Continue to: Clear, unilateral rhinorrhea...

Clear, unilateral rhinorrhea drainage that increases at times of relatively increased intracranial pressure and has a metallic or salty taste is suspicious for CSF rhinorrhea.3 It can occur following skull‐base trauma (eg, cribriform plate, temporal bone), endoscopic sinus surgery, or neurosurgical procedures, or have a spontaneous etiology.3,4

Modalities to confirm CSF rhinorrhea include radionuclide cisternography and testing of fluid for the halo sign, glucose, and the CSF-specific proteins β‐2 transferrin and β-trace protein.3,4 High‐resolution CT is the imaging method most commonly used for localizing a CSF leak.4

Treatment is provided in the hospital

Patients with CSF rhinorrhea typically require inpatient management with bed rest, head-of-bed elevation, and frequent neurologic evaluation, as persistent CSF rhinorrhea increases the risk for meningitis, thus necessitating surgical intervention.3,5 Some cases resolve with bed rest alone. Endonasal endoscopic repair of CSF leaks has become the standard of care because of its high success rate and lower morbidity profile.4

The preferred treatment method for encephalocele is surgical removal after diagnosis is confirmed with CT or magnetic resonance imaging.6

Our patient underwent surgery to remove the encephalocele. The surgeons reported no evidence of fracture.

The final cause of her CSF leak is still uncertain. The surgeons felt confident it was due to ethmoidal encephalocele, a form of neural tube defect in which brain tissue herniates through structural weaknesses of the skull.6-8 While more common in infants, encephalocele can manifest in adulthood due to traumatic or iatrogenic causes.7,8

There is a previous report of encephalocele with CSF leak after COVID-19 testing.9 This case report suggests the possibility of a nasal swab causing trauma to a patient’s pre‐existing encephalocele—a probability in our patient’s case. It is unlikely, however, that the nasal swab itself violated the bony skull base.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case exemplifies how unexplained local symptoms, a high index of suspicion, and adequate work-up can lead to a rare diagnosis. Diagnostic strategies employed for cases of CSF rhinorrhea vary widely due to limited evidence-based guidance.4 Unilateral rhinorrhea with clear fluid that increases at times of increased intracranial pressure, such as bending over, should prompt suspicion for CSF rhinorrhea. With millions of people getting nasal swabs daily during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is even more important to keep CSF leak in our differential diagnosis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eliana Lizeth Garcia, MD, BS, BA, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, 1209 University Boulevard NE, Albuquerque, NM 87131-5001; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 55-year-old woman was evaluated in a family medicine clinic for clear, right-side nasal drainage. She stated that the drainage began 5 months earlier after 2 hospitalizations for severe anxiety leading to emesis and hypokalemia. She reported 3 different COVID-19 nasal swab tests performed on the right nare. Chart review showed 2 negative COVID-19 tests, 6 days apart. Since the hospitalizations, the patient had been given antihistamines for rhinorrhea at an urgent care visit. Despite this treatment, the patient reported a constant drip from the right nare with a salty taste. She also reported experiencing occasional headaches but denied nausea/vomiting.

The patient’s history included uncontrolled hypertension, treatment-resistant anxiety and depression, obstructive sleep apnea, chronic sinus disease (observed on computed tomography [CT] scans), and type 2 diabetes. She was on amlodipine 10 mg/d for hypertension and was not taking any medication for diabetes.

On examination, the patient’s vital signs were within normal limits except for an elevated blood pressure of 158/88 mm Hg. The patient had persistent clear rhinorrhea fluid draining from the right nostril that was exacerbated when she looked down. Right nasal erythema was present.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s negative COVID-19 tests, lack of improvement on antihistamines, and description of the nasal fluid as salty tasting prompted us to suspect a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. The clinical work-up included a halo (“double-ring”) sign test, a β-2 transferrin test, and a sinus x-ray.

The halo sign test was negative for CSF fluid. Sinus/skull x-ray did not show a cribriform or other fracture. However, a sample of the nasal fluid collected in a sterile container was positive for β-2 transferrin, the gold-standard laboratory test to confirm a CSF leak.

The patient was sent for a maxillofacial CT scan without contrast. Results showed a 3-mm defect over the right ethmoid roof associated with a 10 × 16–mm low-attenuation structure in the right ethmoid labyrinth, suspicious for encephalocele. This defect, in the setting of the patient’s history of chronic sinus disease, furthered our suspicion of a CSF leak secondary to COVID-19 testing. Radiology confirmed the diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

CSF rhinorrhea is CSF leakage through the nasal cavity due to abnormal communication between the arachnoid membrane and nasal mucosa.1 The most commonly reported risk factors for this include female sex, middle age (fourth to fifth decade), obesity (body mass index > 40), intracranial hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea.1,2

Continue to: Clear, unilateral rhinorrhea...

Clear, unilateral rhinorrhea drainage that increases at times of relatively increased intracranial pressure and has a metallic or salty taste is suspicious for CSF rhinorrhea.3 It can occur following skull‐base trauma (eg, cribriform plate, temporal bone), endoscopic sinus surgery, or neurosurgical procedures, or have a spontaneous etiology.3,4

Modalities to confirm CSF rhinorrhea include radionuclide cisternography and testing of fluid for the halo sign, glucose, and the CSF-specific proteins β‐2 transferrin and β-trace protein.3,4 High‐resolution CT is the imaging method most commonly used for localizing a CSF leak.4

Treatment is provided in the hospital

Patients with CSF rhinorrhea typically require inpatient management with bed rest, head-of-bed elevation, and frequent neurologic evaluation, as persistent CSF rhinorrhea increases the risk for meningitis, thus necessitating surgical intervention.3,5 Some cases resolve with bed rest alone. Endonasal endoscopic repair of CSF leaks has become the standard of care because of its high success rate and lower morbidity profile.4

The preferred treatment method for encephalocele is surgical removal after diagnosis is confirmed with CT or magnetic resonance imaging.6

Our patient underwent surgery to remove the encephalocele. The surgeons reported no evidence of fracture.

The final cause of her CSF leak is still uncertain. The surgeons felt confident it was due to ethmoidal encephalocele, a form of neural tube defect in which brain tissue herniates through structural weaknesses of the skull.6-8 While more common in infants, encephalocele can manifest in adulthood due to traumatic or iatrogenic causes.7,8

There is a previous report of encephalocele with CSF leak after COVID-19 testing.9 This case report suggests the possibility of a nasal swab causing trauma to a patient’s pre‐existing encephalocele—a probability in our patient’s case. It is unlikely, however, that the nasal swab itself violated the bony skull base.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case exemplifies how unexplained local symptoms, a high index of suspicion, and adequate work-up can lead to a rare diagnosis. Diagnostic strategies employed for cases of CSF rhinorrhea vary widely due to limited evidence-based guidance.4 Unilateral rhinorrhea with clear fluid that increases at times of increased intracranial pressure, such as bending over, should prompt suspicion for CSF rhinorrhea. With millions of people getting nasal swabs daily during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is even more important to keep CSF leak in our differential diagnosis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Eliana Lizeth Garcia, MD, BS, BA, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, 1209 University Boulevard NE, Albuquerque, NM 87131-5001; [email protected]

1. Keshri A, Jain R, Manogaran RS, et al. Management of spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea: an institutional experience. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2019;80:493-499. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676334

2. Lobo BC, Baumanis MM, Nelson RF. Surgical repair of spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks: a systematic review. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2017;2:215-224. doi: 10.1002/lio2.75

3. Van Zele T, Dewaele F. Traumatic CSF leaks of the anterior skull base. B-ENT. 2016;suppl 26:19-27.

4. Oakley GM, Alt JA, Schlosser RJ, et al. Diagnosis of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: an evidence-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:8-16. doi: 10.1002/alr.21637

5. Friedman JA, Ebersold MJ, Quast LM. Post-traumatic cerebrospinal fluid leakage. World J Surg. 2001;25:1062-1066. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0059-7

6. Tirumandas M, Sharma A, Gbenimacho I, et al. Nasal encephaloceles: a review of etiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentations, diagnosis, treatment, and complications. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29:739-744. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1998-z

7. Junaid M, Sobani ZU, Shamim AA, et al. Nasal encephaloceles presenting at later ages: experience of otorhinolaryngology department at a tertiary care center in Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2012;62:74-76.

8. Dhirawani RB, Gupta R, Pathak S, et al. Frontoethmoidal encephalocele: case report and review on management. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2014;4:195-197. doi: 10.4103/2231-0746.147140

9. Paquin R, Ryan L, Vale FL, et al. CSF leak after COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab: a case report. Laryngoscope. 2021;131:1927-1929. doi: 10.1002/lary.29462

1. Keshri A, Jain R, Manogaran RS, et al. Management of spontaneous CSF rhinorrhea: an institutional experience. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2019;80:493-499. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676334

2. Lobo BC, Baumanis MM, Nelson RF. Surgical repair of spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks: a systematic review. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2017;2:215-224. doi: 10.1002/lio2.75

3. Van Zele T, Dewaele F. Traumatic CSF leaks of the anterior skull base. B-ENT. 2016;suppl 26:19-27.

4. Oakley GM, Alt JA, Schlosser RJ, et al. Diagnosis of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: an evidence-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:8-16. doi: 10.1002/alr.21637

5. Friedman JA, Ebersold MJ, Quast LM. Post-traumatic cerebrospinal fluid leakage. World J Surg. 2001;25:1062-1066. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0059-7

6. Tirumandas M, Sharma A, Gbenimacho I, et al. Nasal encephaloceles: a review of etiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentations, diagnosis, treatment, and complications. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29:739-744. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1998-z

7. Junaid M, Sobani ZU, Shamim AA, et al. Nasal encephaloceles presenting at later ages: experience of otorhinolaryngology department at a tertiary care center in Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2012;62:74-76.

8. Dhirawani RB, Gupta R, Pathak S, et al. Frontoethmoidal encephalocele: case report and review on management. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2014;4:195-197. doi: 10.4103/2231-0746.147140

9. Paquin R, Ryan L, Vale FL, et al. CSF leak after COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab: a case report. Laryngoscope. 2021;131:1927-1929. doi: 10.1002/lary.29462

► Unilateral nasal drainage

► Salty taste

► Nasal redness

► Recent COVID-19 nasal swabs

64-year-old woman • hot flashes, facial flushing, excessive sweating, and palpitations • daily headaches • history of hypertension • Dx?

THE CASE

A 64-year-old woman sought care after having hot flashes, facial flushing, excessive sweating, palpitations, and daily headaches for 1 month. She had a history of hypertension that was well controlled with hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/d but over the previous month, it had become more difficult to control. Her blood pressure remained elevated to 150/100 mm Hg despite the addition of lisinopril 40 mg/d and amlodipine 10 mg/d, indicating resistant hypertension. She had no family history of hypertension, diabetes, or obesity or any other pertinent medical or surgical history. Physical examination was negative for weight gain, stretch marks, or muscle weakness.

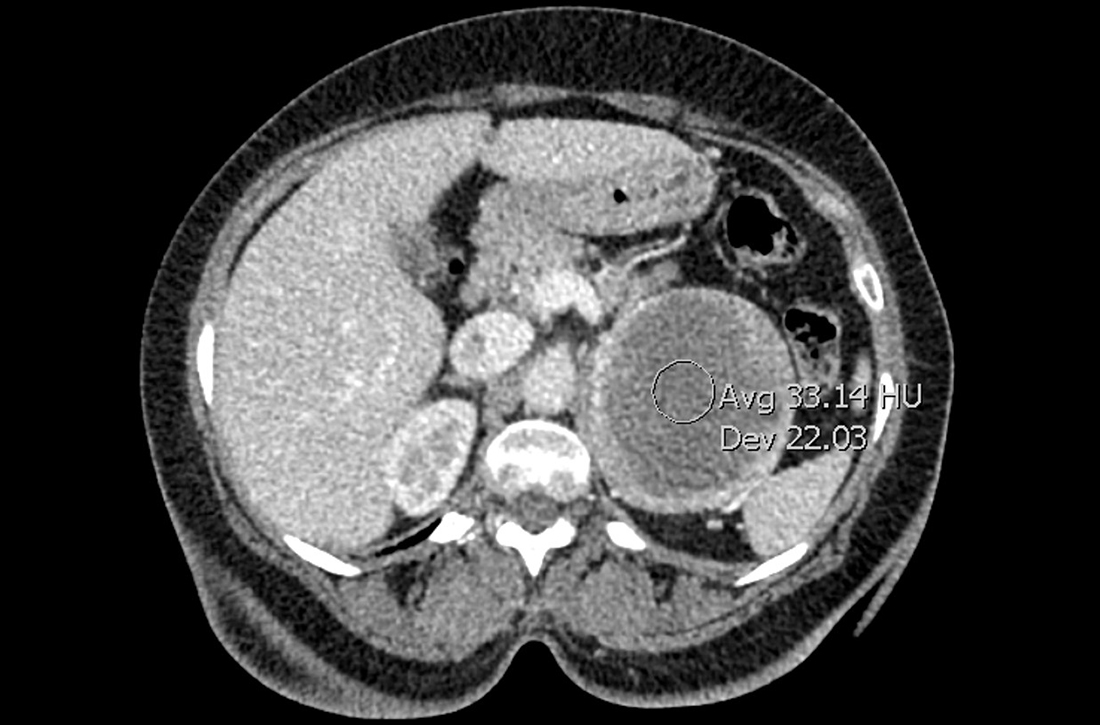

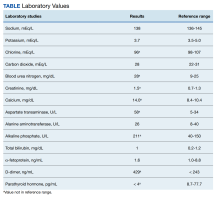

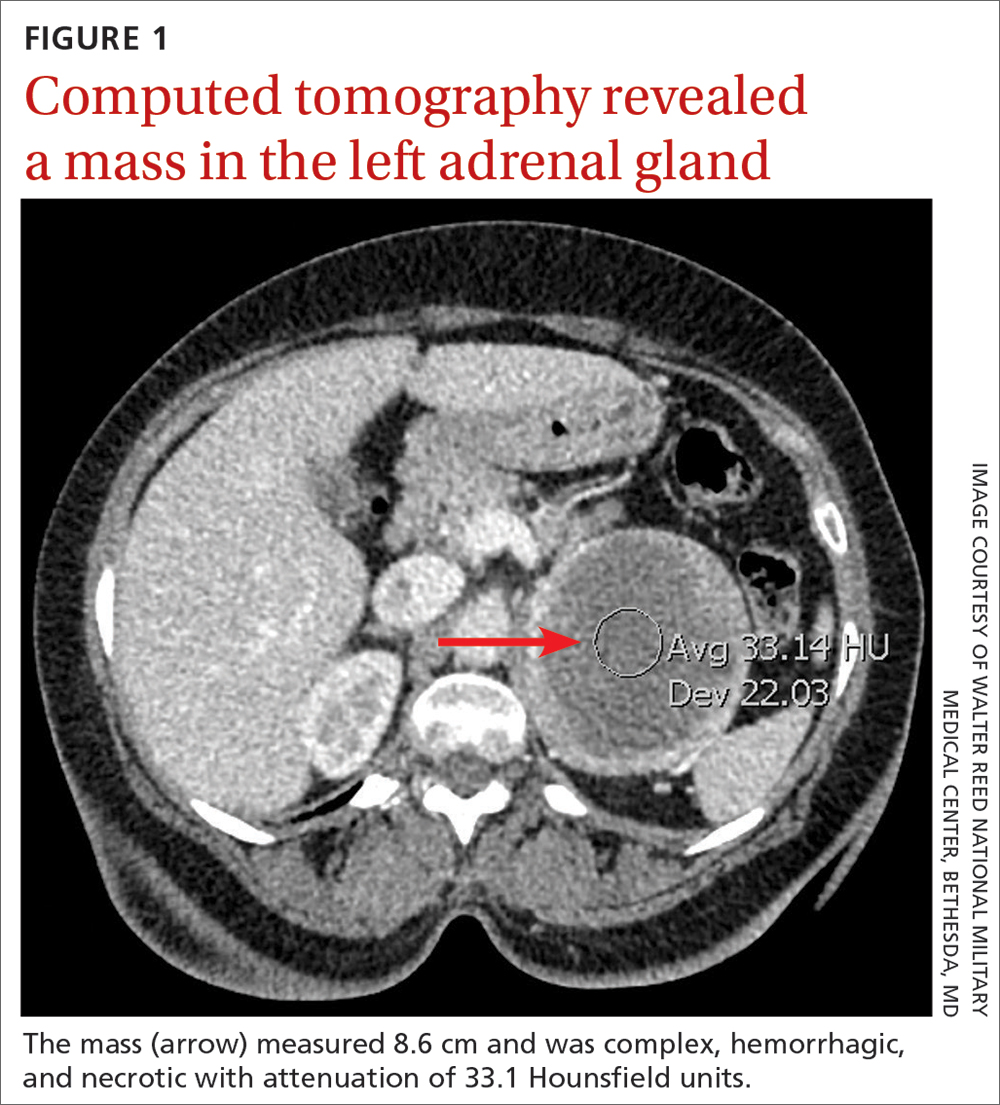

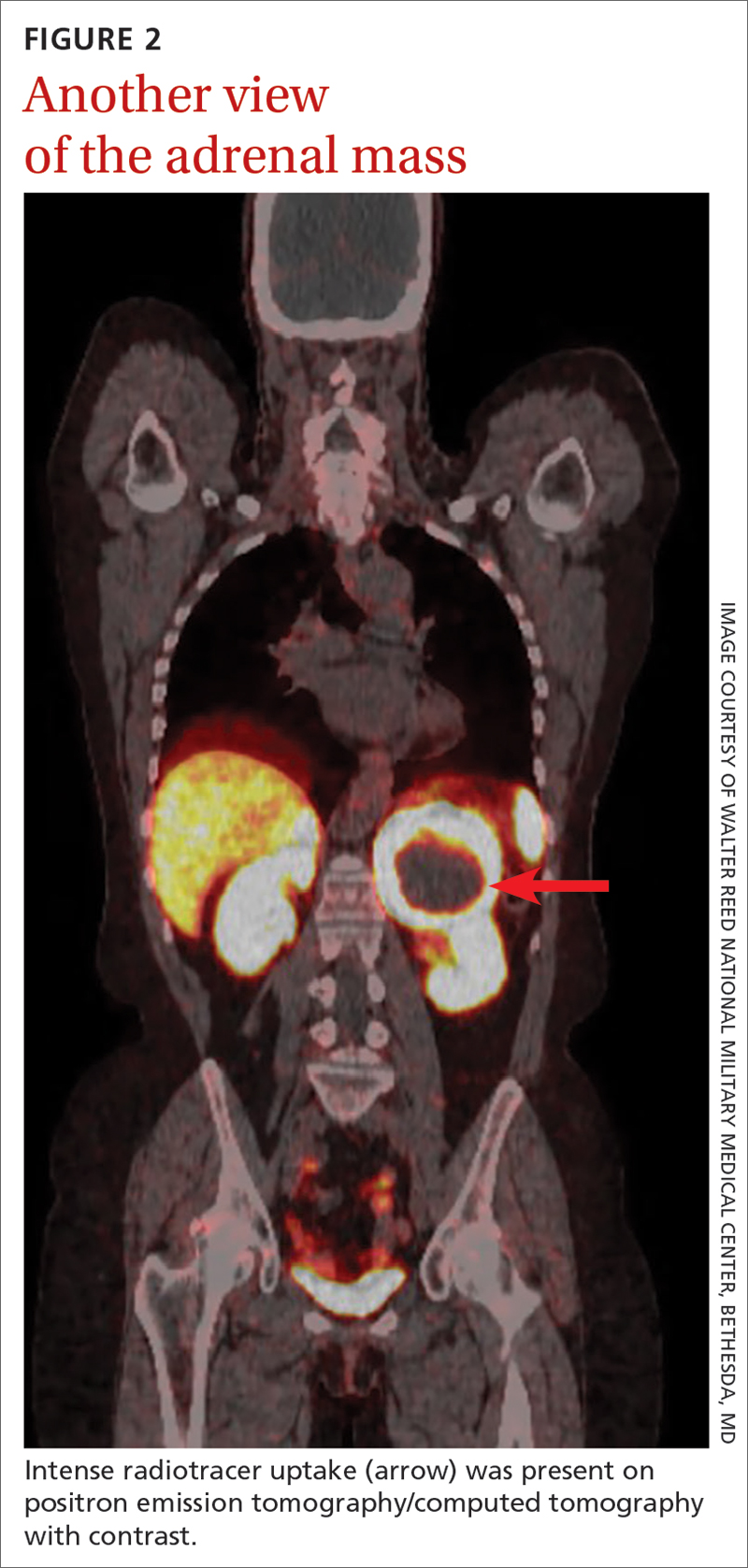

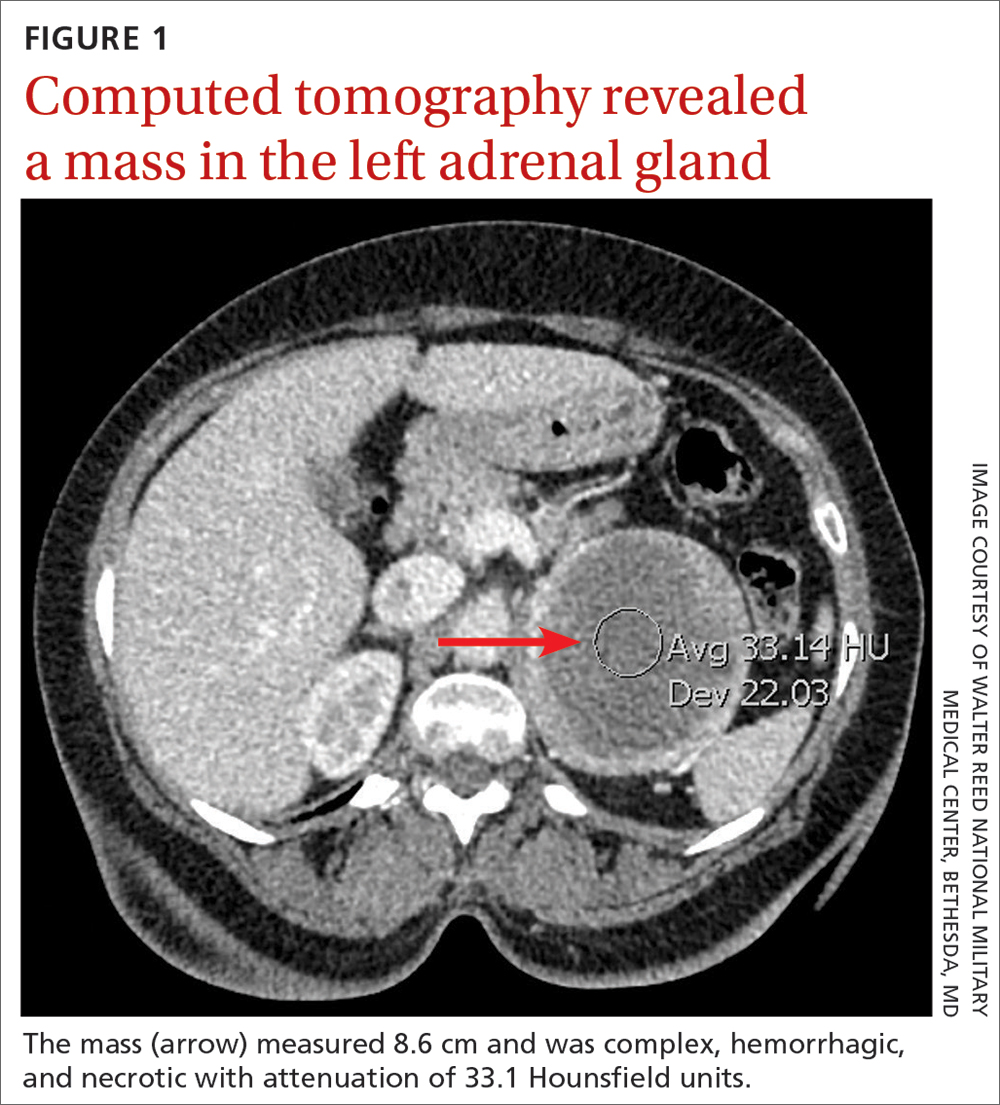

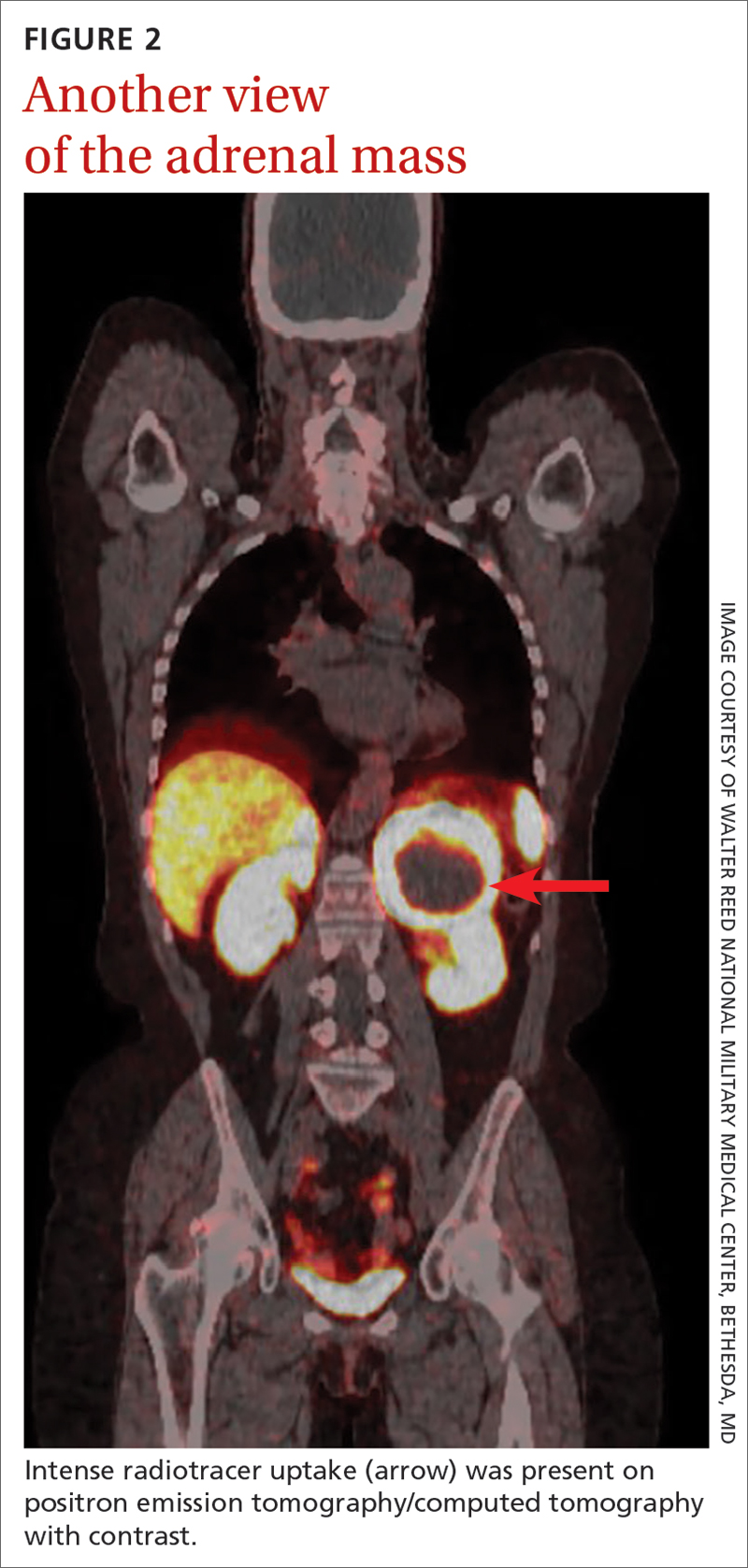

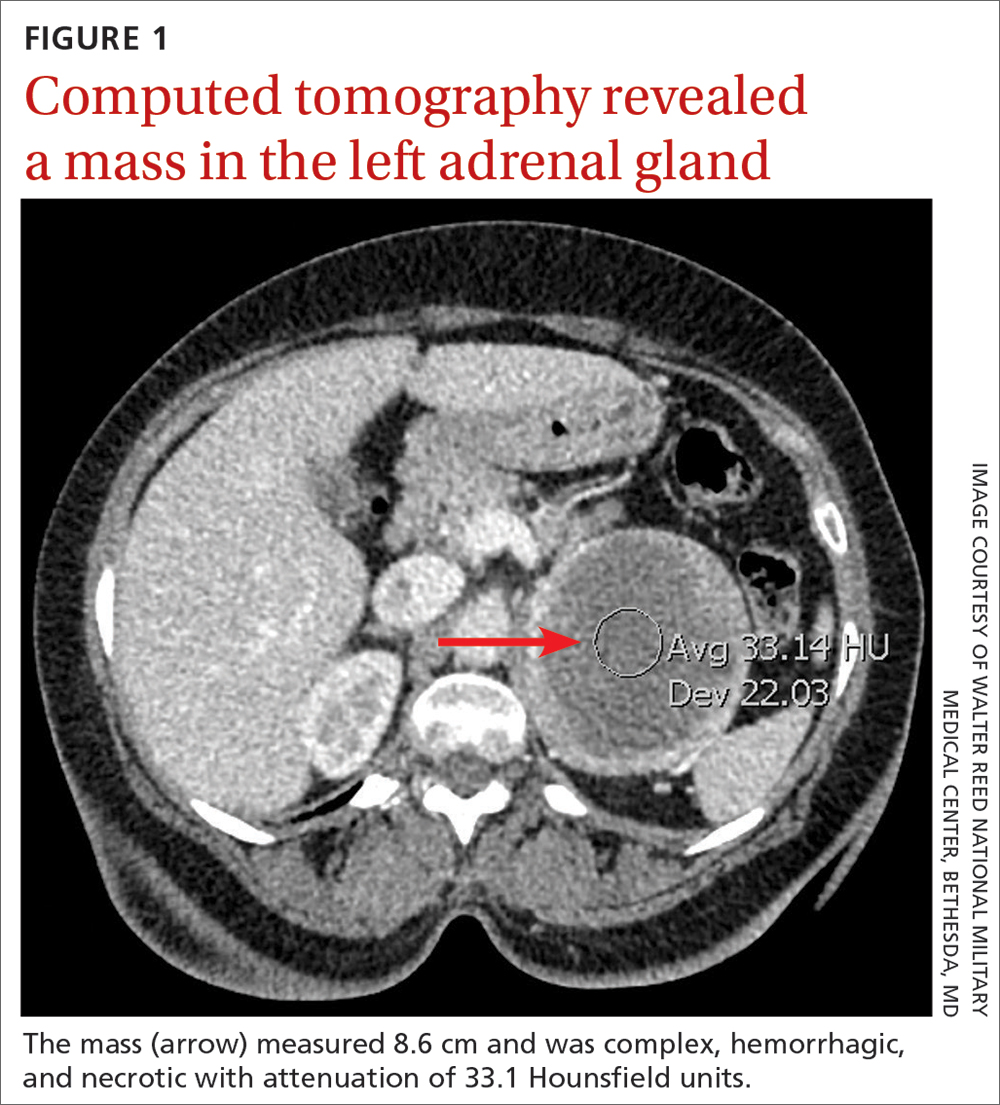

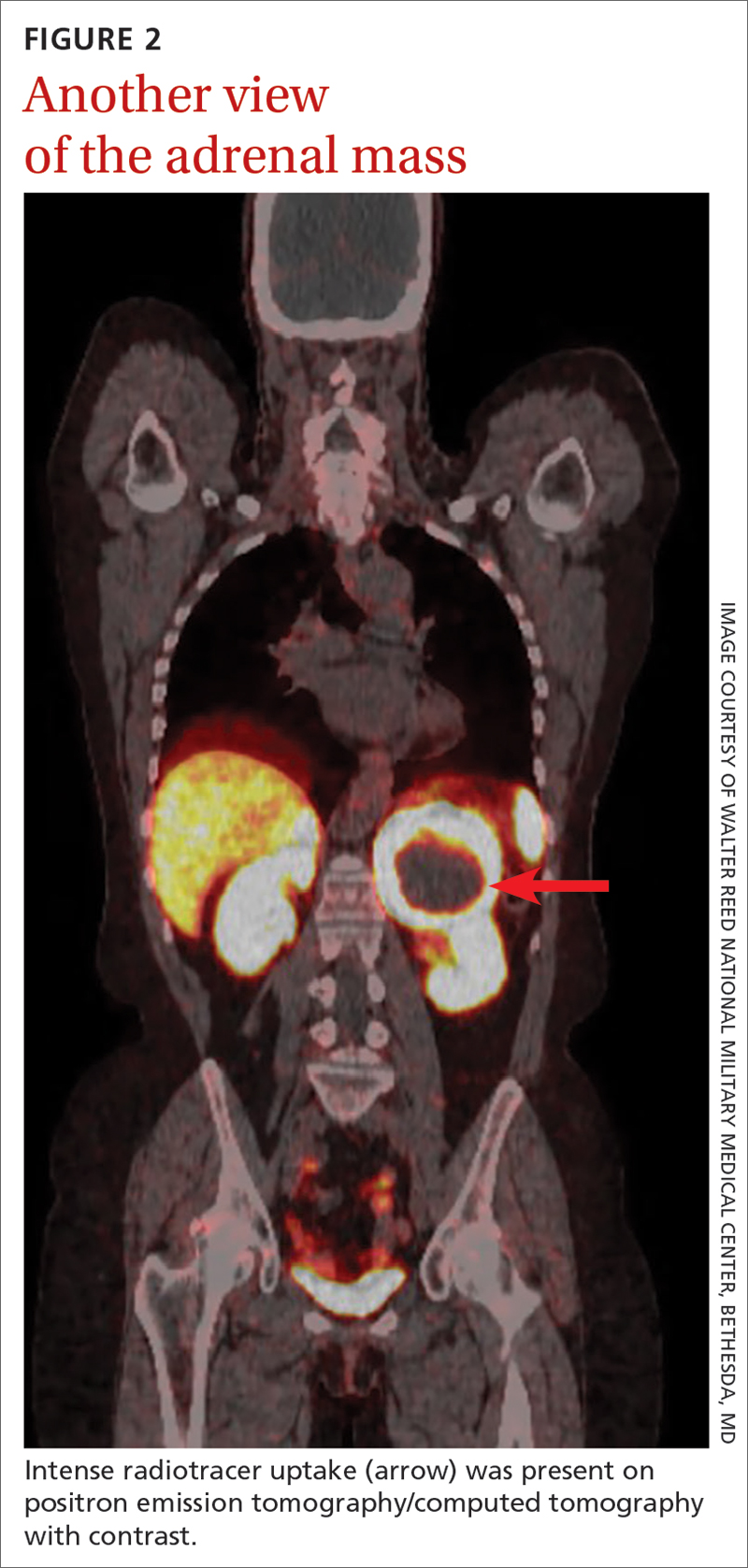

Laboratory tests revealed a normal serum aldosterone-renin ratio, renal function, and thyroid function; however, she had elevated levels of normetanephrine (2429 pg/mL; normal range, 0-145 pg/mL) and metanephrine (143 pg/mL; normal range, 0-62 pg/mL). Computed tomography (CT) revealed an 8.6-cm complex, hemorrhagic, necrotic left adrenal mass with attenuation of 33.1 Hounsfield units (HU) (FIGURE 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a T2 hyperintense left adrenal mass. An evaluation for Cushing syndrome was negative, and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT with gallium-68 dotatate was ordered. It showed intense radiotracer uptake in the left adrenal gland, with a maximum standardized uptake value of 70.1 (FIGURE 2).

THE DIAGNOSIS

After appropriate preparation with alpha blockade (phenoxybenzamine 20 mg twice daily for 7 days) and fluid resuscitation (normal saline run over 12 hours preoperatively), the patient underwent successful open surgical resection of the adrenal mass, during which her blood pressure was controlled with a nitroprusside infusion and boluses of esmolol and labetalol. Pathology results showed cells in a nested pattern with round to oval nuclei in a vascular background. There was no necrosis, increased mitotic figures, capsular invasion, or increased cellularity. Chromogranin immunohistochemical staining was positive. Given her resistant hypertension, clinical symptoms, and pathology results, the patient was given a diagnosis of pheochromocytoma.

DISCUSSION

Resistant hypertension is defined as blood pressure that is elevated above goal despite the use of 3 maximally titrated antihypertensive agents from different classes or that is well controlled with at least 4 antihypertensive medications.1 The prevalence of resistant hypertension is 12% to 18% in adults being treated for hypertension.1 Patients with resistant hypertension have a higher risk for cardiovascular events and death, are more likely to have a secondary cause of hypertension, and may benefit from special diagnostic testing or treatment approaches to control their blood pressure.1

There are many causes of resistant hypertension; primary aldosteronism is the most common cause (prevalence as high as 20%).2 Given the increased risk for cardiovascular/cerebrovascular disease, all patients with resistant hypertension should be screened for this condition.2 Other causes of resistant hypertension include renal parenchymal disease, renal artery stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, thyroid dysfunction, Cushing syndrome, paraganglioma, and as seen in our case, pheochromocytoma. Although pheochromocytoma is a rare cause of resistant hypertension (0.01%-4%),1 it is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality if left untreated and may be inherited, making it an essential diagnosis to consider in all patients with resistant hypertension.1,3

Common symptoms of pheochromocytoma are hypertension (paroxysmal or sustained), headaches, palpitations, pallor, and piloerection (or cold sweats).1 Patients with pheochromocytoma typically exhibit metanephrine levels that are more than 4 times the upper limit of normal.4 Therefore, measurement of plasma free metanephrines or urinary fractionated metanephrines is recommended.5 Elevated metanephrine levels also are caused by obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, and certain medications and should be ruled out.5

All pheochromocytomas are potentially malignant. Despite the existence of pathologic scoring systems6,7 and radiographic features that suggest malignancy,8,9 no single risk-stratification tool is recommended in the current literature.10 Ultimately, the only way to confirm malignancy is to see metastases where chromaffin tissue is not normally found on imaging.10

Continue to: Pathologic features to look for...

Pathologic features to look for include capsular/periadrenal adipose invasion, increased cellularity, necrosis, tumor cell spindling, increased/atypical mitotic figures, and nuclear pleomorphism. Radiographic features include larger size (≥ 4-6 cm),11 an irregular shape, necrosis, calcifications, attenuation of 10 HU or higher on noncontrast CT, absolute washout of 60% or lower, and relative washout of 40% or lower.8,12 On MRI, malignant lesions appear hypointense on T1-weighted imaging and hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging.9 Fluorodeoxyglucose avidity on PET scan also is indicative of malignancy.8,9

Treatment for pheochromocytoma is surgical resection. An experienced surgical team and proper preoperative preparation are necessary because the induction of anesthesia, endotracheal intubation, and tumor manipulation can lead to a release of catecholamines, potentially resulting in an intraoperative hypertensive crisis, cardiac arrhythmias, and multiorgan failure.

Proper preoperative preparation includes taking an alpha-adrenergic blocker, such as phenoxybenzamine, prazosin, terazosin, or doxazosin, for at least 7 days to normalize the patient’s blood pressure. Patients should be counseled that they may experience nasal congestion, orthostasis, and fatigue while taking these medications. Volume expansion with intravenous fluids also should be performed and a high-salt diet considered. Beta-adrenergic blockade can be initiated once appropriate alpha-adrenergic blockade is achieved to control the patient’s heart rate; beta-blockers should never be started first because of the risk for severe hypertension. Careful hemodynamic monitoring is vital intraoperatively and postoperatively.5,13 Because metastatic lesions can occur decades after resection, long-term follow-up is critical.5,10