User login

Sweet Syndrome With Aseptic Splenic Abscesses and Multiple Myeloma

To the Editor:

An 84-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with 5 erythematous cutaneous nodules of several days’ duration on the legs ranging in size from 1.0 to 1.5 cm. Upon admission, the patient also had a chest radiograph suspicious for pneumonia. The patient had received sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim for a urinary tract infection as an outpatient 5 days prior to presentation, but he stopped the medication due to the appearance of the cutaneous nodules. Of note, the patient also reported unintentional weight loss of 15 pounds over the last few months.

New nodules had developed at a rate of 1 to 2 lesions daily in the 3 days prior to presentation and continued to develop after admission to the hospital. The nodules appeared as tender, erythematous lesions that evolved to form pustules and developed overlying crusts in later stages (Figure 1). They were limited to the arms and legs, primarily involving the lower legs. There was no evidence of oral or ocular involvement. A hemoglobin count of 10.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), white blood cell count of 8.8×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 69 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h) were noted on admission.

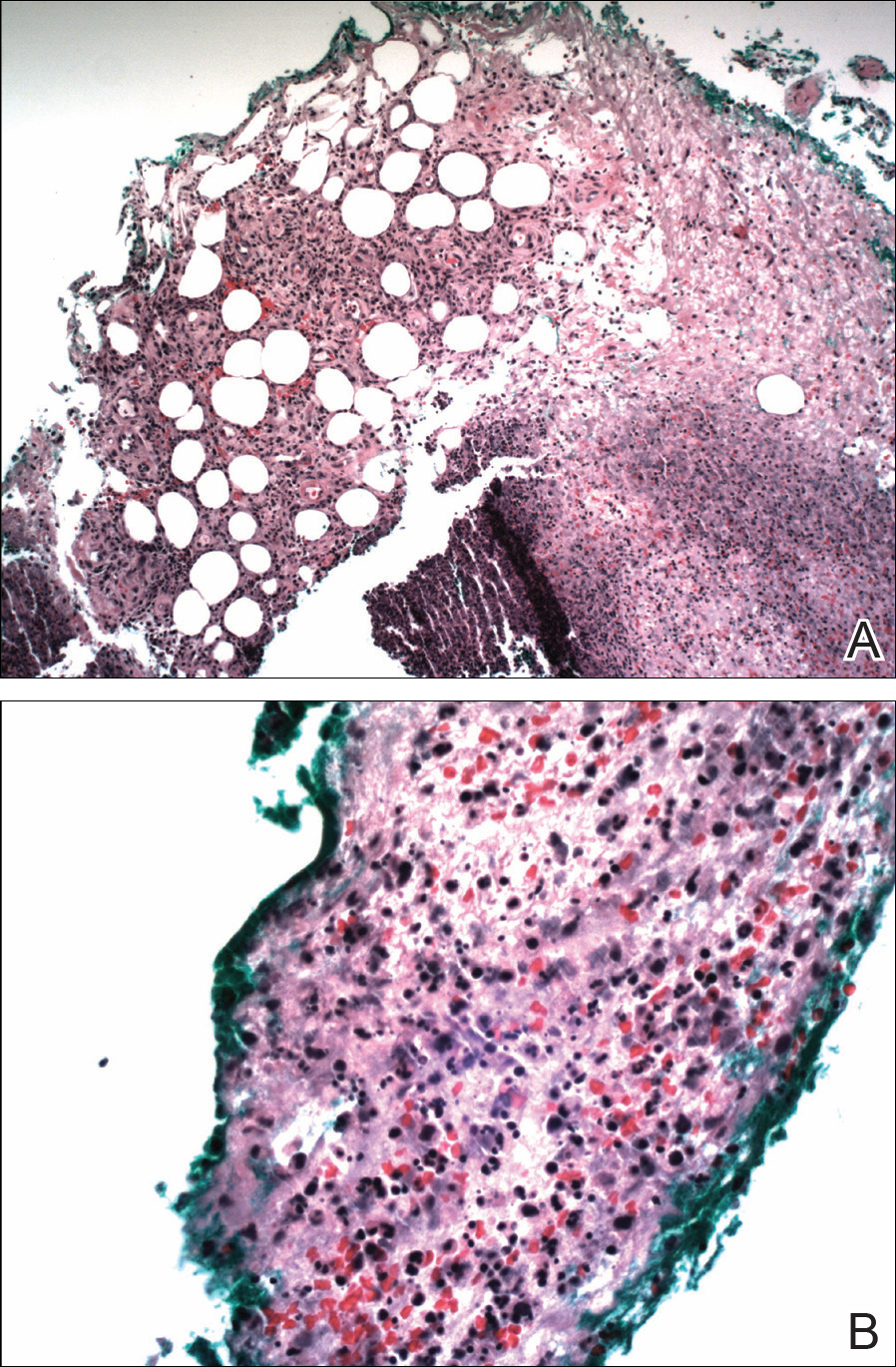

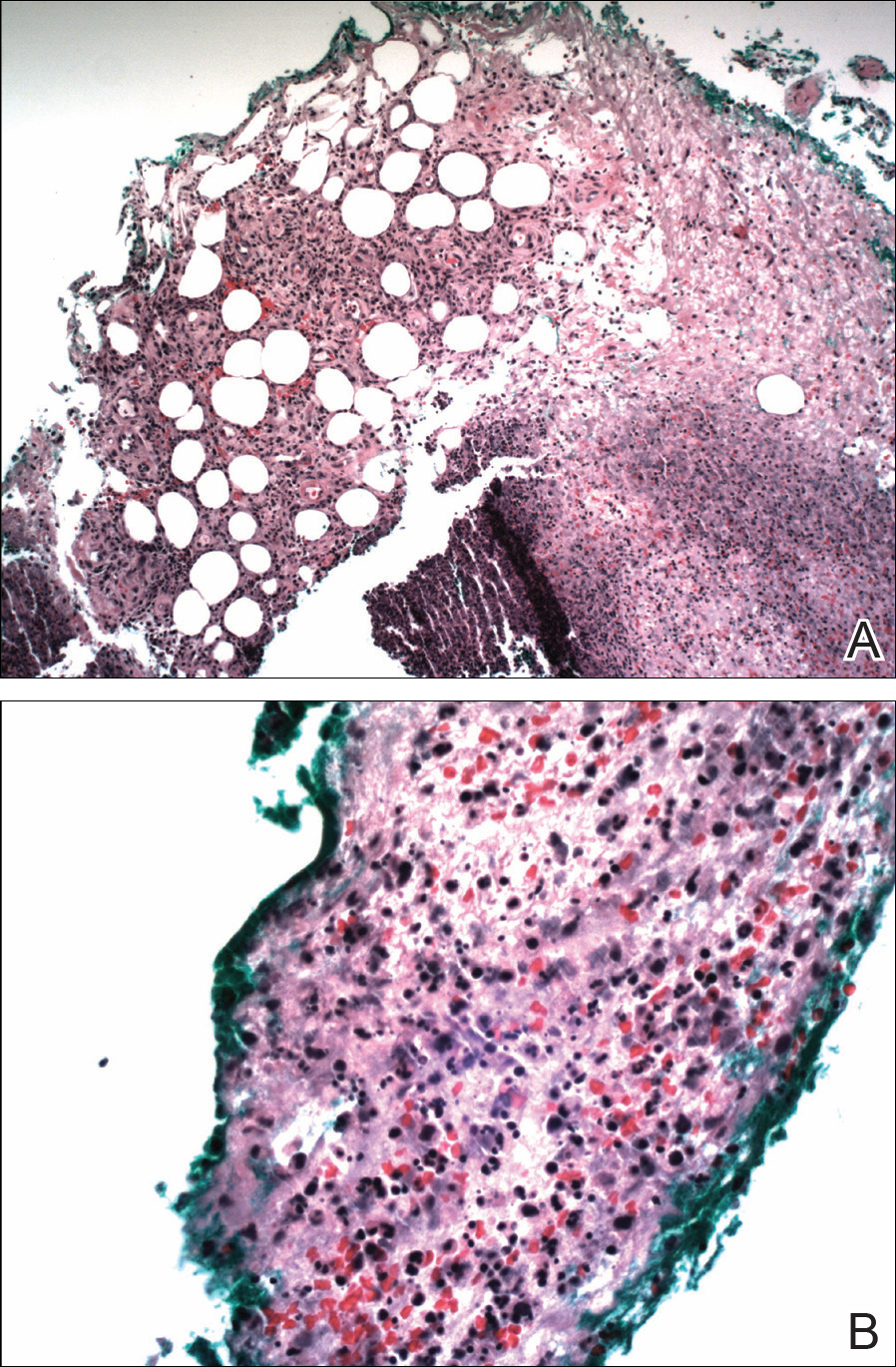

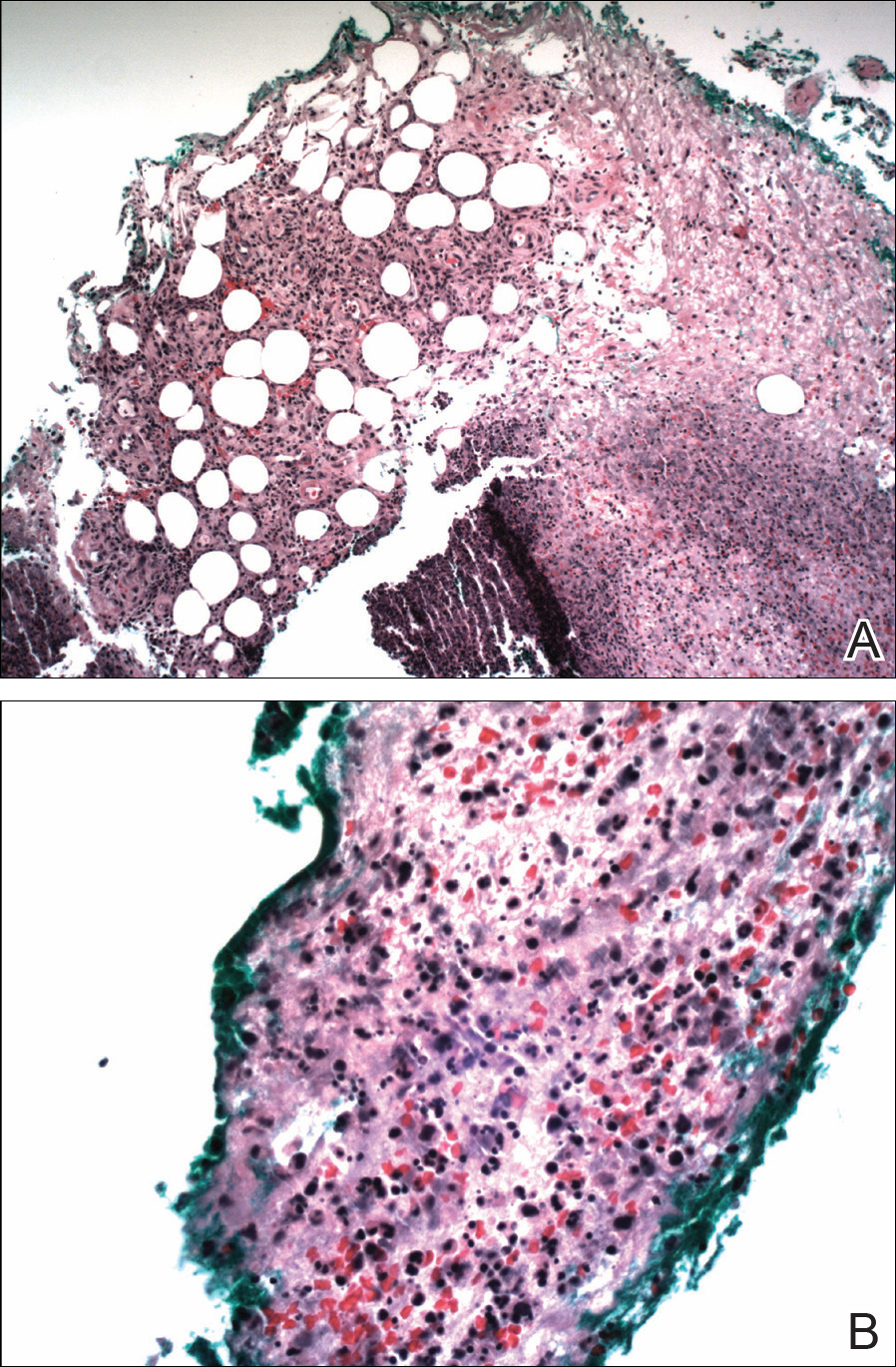

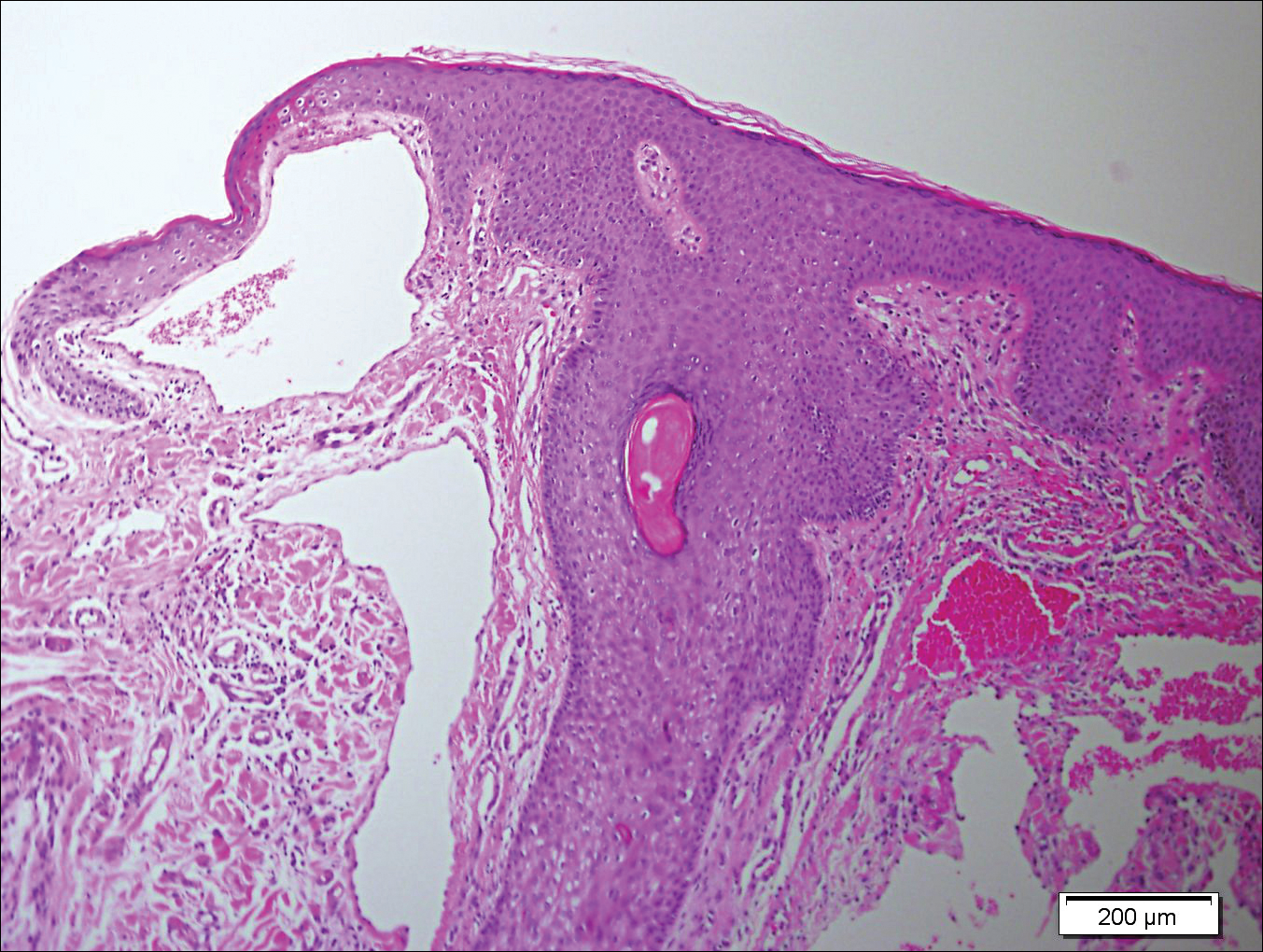

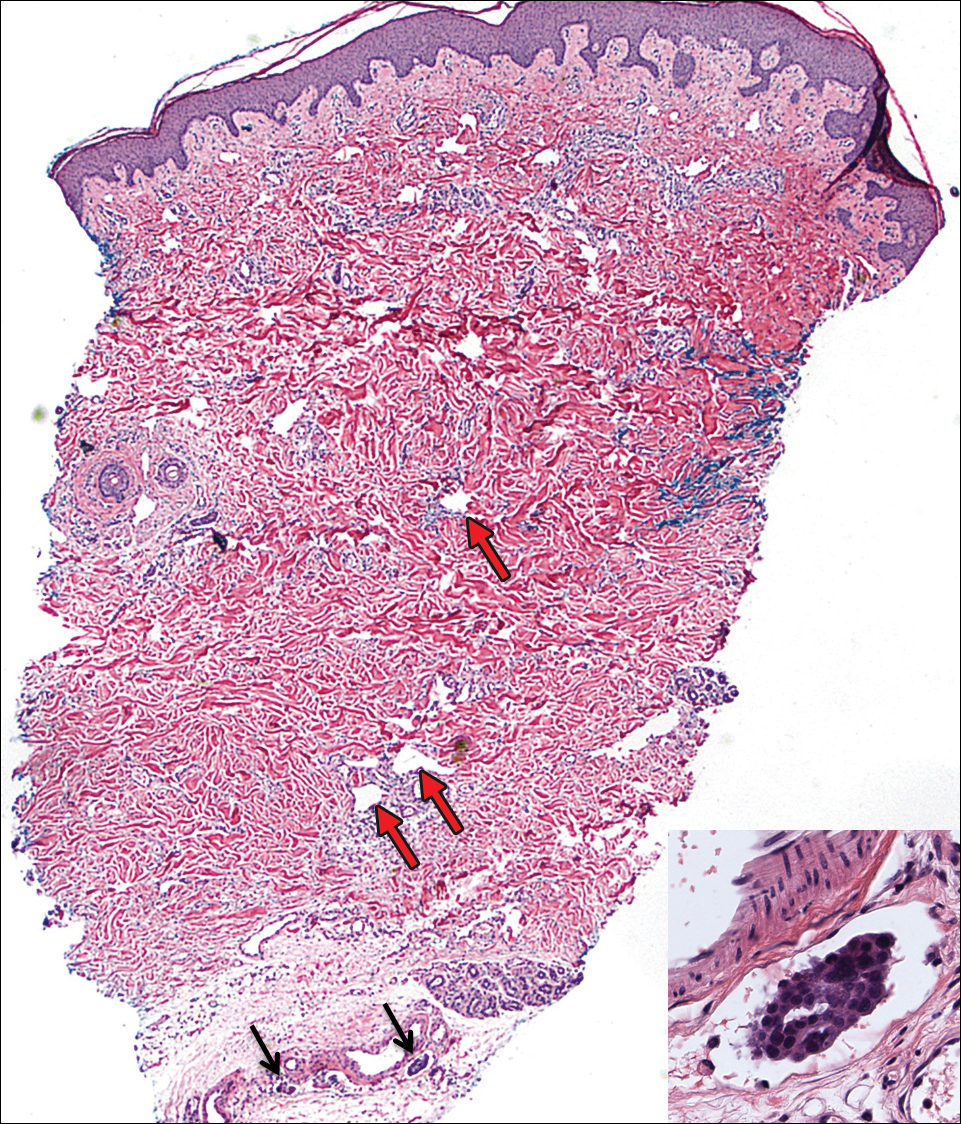

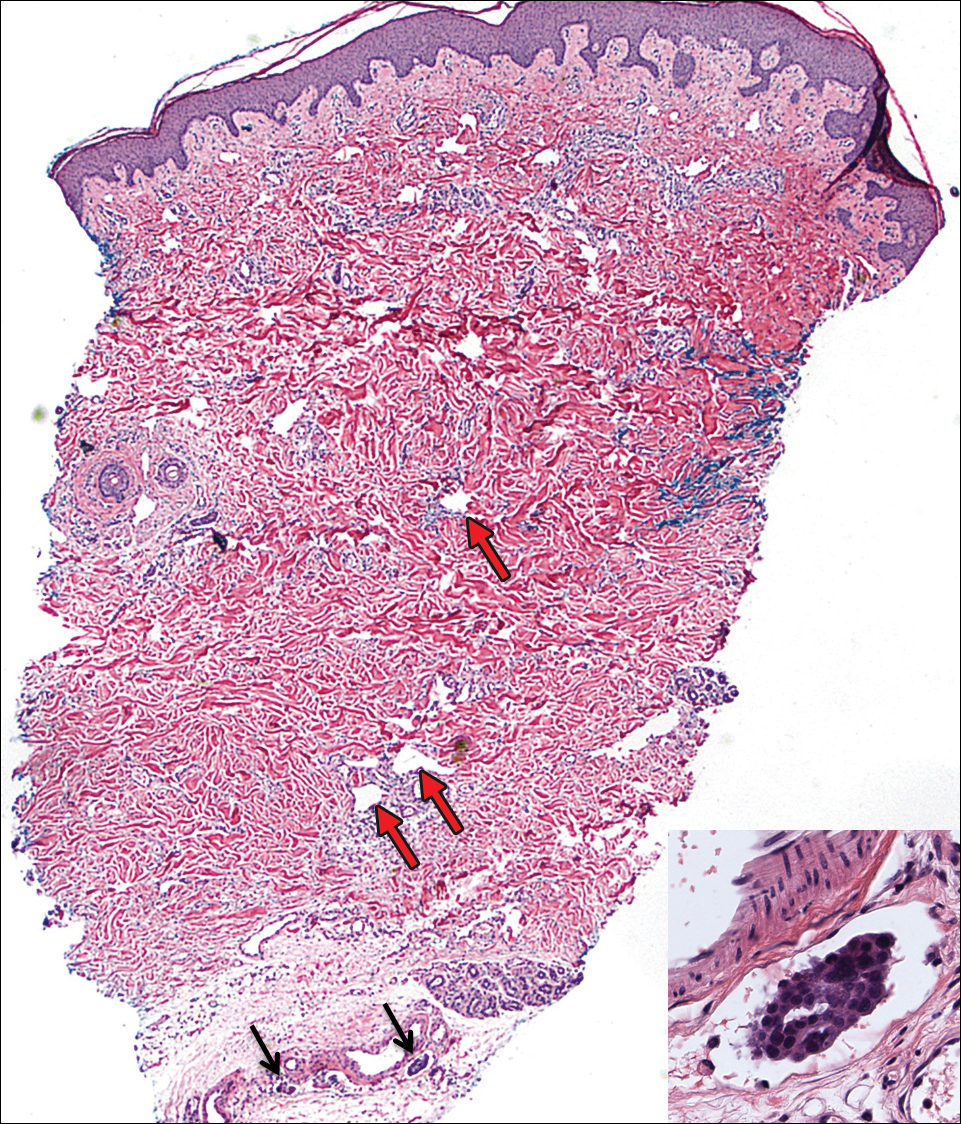

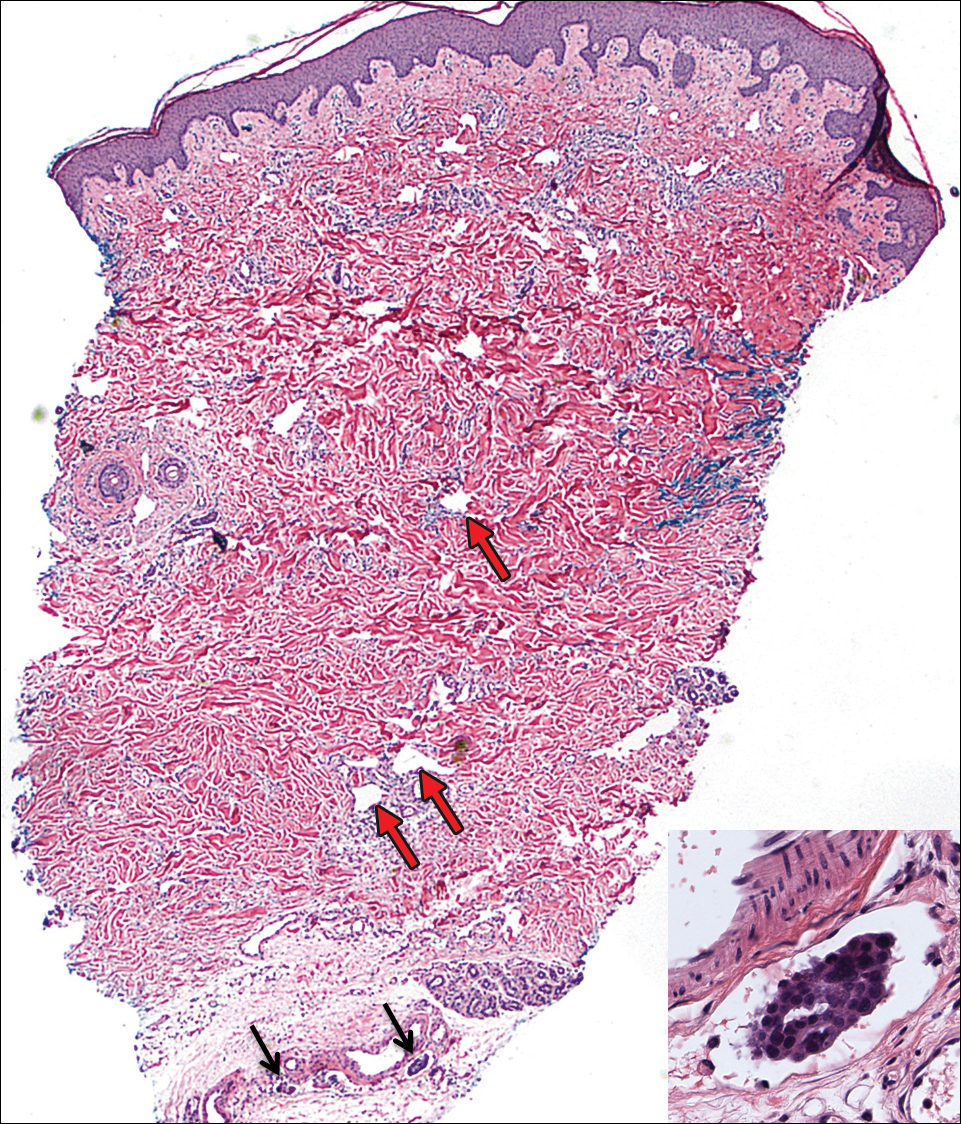

The patient was started on ceftriaxone and azithromycin for suspected pneumonia. The differential diagnosis for the cutaneous nodules included lymphoma, acid-fast bacilli (AFB) infection, deep fungal infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet syndrome (SS), panniculitis, erythema elevatum diutinum, and polyarteritis nodosa. A punch biopsy of a nodule on the left foot was performed. Histopathology demonstrated a neutrophilic panniculitis (Figure 2) with an epidermal abscess. No vasculitis was identified, and periodic acid–Schiff and AFB staining of the skin biopsy were negative. These findings were consistent with SS. Computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which were completed early in the course of hospitalization due to concern for underlying malignancy, revealed pericardial and pleural effusions as well as cystic lesions in the lungs, spleen, kidneys, and prostate, with the largest lesion on the spleen measuring 5.6×4.8 cm (Figure 3). Computed tomography scanning was negative for areas of consolidation in the lungs. A splenic biopsy was performed by an interventional radiologist during the patient's hospitalization that identified an aseptic, neutrophilic process. Fungal, bacterial, and AFB cultures of the splenic tissue and cystic contents were negative. Bilateral pleural effusions also were identified, and a thoracentesis was performed. The pleural fluid indicated rare mesothelial cells in the background of acute inflammation with no growth of the bacterial, fungal, or AFB cultures.

Due to the association of hematologic malignances with SS, a bone marrow biopsy was performed, which revealed multiple myeloma. Serum protein electrophoresis demonstrated monoclonal gammopathy of κ light chains. During the course of his hospitalization, new skin lesions continued to develop on the hands, face, and trunk. The patient was discharged from the hospital shortly after diagnosis to receive outpatient treatment for multiple myeloma with lenalidomide and dexamethasone. Upon follow-up with the patient’s family via telephone 3 weeks into treatment, his son confirmed that the nodules were resolving.

Our case could be consistent with either drug-induced or malignancy-associated SS. Sweet syndrome initially was described in 1964 in 8 female patients with leukocytosis and cutaneous plaques infiltrated by neutrophils.1 The skin lesions typically are red and painful, ranging in size from 0.5 cm to 12.0 cm, and can last weeks to years if not treated.2 Variations of skin lesions include bullous and pustular morphologies.3

Diagnostic criteria for SS have been established.4 Both of the major criteria must be met as well as 2 of 4 minor criteria. Major criteria include abrupt onset of tender erythematous plaques and nodules; secondly, a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis must be seen on histopathology. Minor criteria include pyrexia, association with underlying condition (malignancy, pregnancy, drug exposure, inflammatory disorder), responsiveness to systemic steroids, and abnormal laboratory values (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, neutrophilia).4

Sweet syndrome can be divided into 3 classifications: classical or idiopathic, drug-induced, or malignancy-associated.4 Classical SS most commonly is seen in middle-aged women after an upper respiratory or gastrointestinal infection. Drug-induced SS most often is associated with granulocyte-stimulating factor colony therapy4; however, it has been associated with use of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.5 Malignancy-associated SS most commonly is seen in individuals with hematologic malignancy, specifically acute myeloid leukemia. Although its association with multiple myeloma is not as frequent, cases of malignancy-associated SS identifying this association have been reported.6,7 Mucosal involvement in the form of aphthouslike lesions more frequently is seen in malignancy-associated SS.8 Differing from classical SS, which has a female predilection of around 4:1, the malignancy-associated disorder has a 1:1 female-to-male ratio.4

In the majority of cases of SS, the neutrophilic infiltrate is in the papillary and upper reticular dermis; however, if the neutrophilic infiltrate is predominately in the subcutaneous tissue (known as subcutaneous SS), there is a strong association with malignancy.9 The histopathology in our case demonstrated a neutrophilic infiltrate in the subcutaneous tissue.

Fever is the most common systemic manifestation of SS and is present in 54% to 65% of patients.8,10 Besides the skin, the most common site affected is the eye, with 13% to 75% of patients reporting ocular involvement, usually conjunctivitis.4,10 Although infrequent, extracutaneous SS has been identified in the bones, central nervous system, kidneys, heart, liver, spleen, lungs, ears, eyes, and intestines.4 A case of SS with splenic involvement in the form of sterile abscesses also was reported.11 This case was related to parvovirus B19.

Sweet syndrome is a condition characterized by tender, erythematous cutaneous lesions with histopathology demonstrating neutrophilic infiltrate in the absence of vasculitis. We report a case of suspected extracutaneous SS in the form of splenic cysts in a patient whose SS was associated with malignancy and/or drug ingestion.

- Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome and malignancy. Am J Med. 1987;82:1220-1226.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:182-184.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Walker DC, Cohen PR. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: case report and review of drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:918-923.

- Belhadjali H, Chaabane S, Njim L, et al. Sweet’s syndrome associated with multiple myeloma. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2008;17:31-33.

- Bayer-Garner IB, Cottler-Fox M, Smoller BR. Sweet syndrome in multiple myeloma: a series of six cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:261-264.

- Fett DL, Gibson LE, Su WP. Sweet’s syndrome: systemic signs and symptoms and associated disorders. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:234-240.

- von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556; quiz 557-560.

- Neoh CY, Tan AW, Ng SK. Sweet’s syndrome: a spectrum of unusual clinical presentation and associations. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:480-485.

- Fortna RR, Toporcer M, Elder DE, et al. A case of sweet syndrome with spleen and lymph node involvement preceded by parvovirus B19 infection, and review of the literature on extracutaneous Sweet syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:621-627.

To the Editor:

An 84-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with 5 erythematous cutaneous nodules of several days’ duration on the legs ranging in size from 1.0 to 1.5 cm. Upon admission, the patient also had a chest radiograph suspicious for pneumonia. The patient had received sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim for a urinary tract infection as an outpatient 5 days prior to presentation, but he stopped the medication due to the appearance of the cutaneous nodules. Of note, the patient also reported unintentional weight loss of 15 pounds over the last few months.

New nodules had developed at a rate of 1 to 2 lesions daily in the 3 days prior to presentation and continued to develop after admission to the hospital. The nodules appeared as tender, erythematous lesions that evolved to form pustules and developed overlying crusts in later stages (Figure 1). They were limited to the arms and legs, primarily involving the lower legs. There was no evidence of oral or ocular involvement. A hemoglobin count of 10.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), white blood cell count of 8.8×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 69 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h) were noted on admission.

The patient was started on ceftriaxone and azithromycin for suspected pneumonia. The differential diagnosis for the cutaneous nodules included lymphoma, acid-fast bacilli (AFB) infection, deep fungal infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet syndrome (SS), panniculitis, erythema elevatum diutinum, and polyarteritis nodosa. A punch biopsy of a nodule on the left foot was performed. Histopathology demonstrated a neutrophilic panniculitis (Figure 2) with an epidermal abscess. No vasculitis was identified, and periodic acid–Schiff and AFB staining of the skin biopsy were negative. These findings were consistent with SS. Computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which were completed early in the course of hospitalization due to concern for underlying malignancy, revealed pericardial and pleural effusions as well as cystic lesions in the lungs, spleen, kidneys, and prostate, with the largest lesion on the spleen measuring 5.6×4.8 cm (Figure 3). Computed tomography scanning was negative for areas of consolidation in the lungs. A splenic biopsy was performed by an interventional radiologist during the patient's hospitalization that identified an aseptic, neutrophilic process. Fungal, bacterial, and AFB cultures of the splenic tissue and cystic contents were negative. Bilateral pleural effusions also were identified, and a thoracentesis was performed. The pleural fluid indicated rare mesothelial cells in the background of acute inflammation with no growth of the bacterial, fungal, or AFB cultures.

Due to the association of hematologic malignances with SS, a bone marrow biopsy was performed, which revealed multiple myeloma. Serum protein electrophoresis demonstrated monoclonal gammopathy of κ light chains. During the course of his hospitalization, new skin lesions continued to develop on the hands, face, and trunk. The patient was discharged from the hospital shortly after diagnosis to receive outpatient treatment for multiple myeloma with lenalidomide and dexamethasone. Upon follow-up with the patient’s family via telephone 3 weeks into treatment, his son confirmed that the nodules were resolving.

Our case could be consistent with either drug-induced or malignancy-associated SS. Sweet syndrome initially was described in 1964 in 8 female patients with leukocytosis and cutaneous plaques infiltrated by neutrophils.1 The skin lesions typically are red and painful, ranging in size from 0.5 cm to 12.0 cm, and can last weeks to years if not treated.2 Variations of skin lesions include bullous and pustular morphologies.3

Diagnostic criteria for SS have been established.4 Both of the major criteria must be met as well as 2 of 4 minor criteria. Major criteria include abrupt onset of tender erythematous plaques and nodules; secondly, a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis must be seen on histopathology. Minor criteria include pyrexia, association with underlying condition (malignancy, pregnancy, drug exposure, inflammatory disorder), responsiveness to systemic steroids, and abnormal laboratory values (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, neutrophilia).4

Sweet syndrome can be divided into 3 classifications: classical or idiopathic, drug-induced, or malignancy-associated.4 Classical SS most commonly is seen in middle-aged women after an upper respiratory or gastrointestinal infection. Drug-induced SS most often is associated with granulocyte-stimulating factor colony therapy4; however, it has been associated with use of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.5 Malignancy-associated SS most commonly is seen in individuals with hematologic malignancy, specifically acute myeloid leukemia. Although its association with multiple myeloma is not as frequent, cases of malignancy-associated SS identifying this association have been reported.6,7 Mucosal involvement in the form of aphthouslike lesions more frequently is seen in malignancy-associated SS.8 Differing from classical SS, which has a female predilection of around 4:1, the malignancy-associated disorder has a 1:1 female-to-male ratio.4

In the majority of cases of SS, the neutrophilic infiltrate is in the papillary and upper reticular dermis; however, if the neutrophilic infiltrate is predominately in the subcutaneous tissue (known as subcutaneous SS), there is a strong association with malignancy.9 The histopathology in our case demonstrated a neutrophilic infiltrate in the subcutaneous tissue.

Fever is the most common systemic manifestation of SS and is present in 54% to 65% of patients.8,10 Besides the skin, the most common site affected is the eye, with 13% to 75% of patients reporting ocular involvement, usually conjunctivitis.4,10 Although infrequent, extracutaneous SS has been identified in the bones, central nervous system, kidneys, heart, liver, spleen, lungs, ears, eyes, and intestines.4 A case of SS with splenic involvement in the form of sterile abscesses also was reported.11 This case was related to parvovirus B19.

Sweet syndrome is a condition characterized by tender, erythematous cutaneous lesions with histopathology demonstrating neutrophilic infiltrate in the absence of vasculitis. We report a case of suspected extracutaneous SS in the form of splenic cysts in a patient whose SS was associated with malignancy and/or drug ingestion.

To the Editor:

An 84-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with 5 erythematous cutaneous nodules of several days’ duration on the legs ranging in size from 1.0 to 1.5 cm. Upon admission, the patient also had a chest radiograph suspicious for pneumonia. The patient had received sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim for a urinary tract infection as an outpatient 5 days prior to presentation, but he stopped the medication due to the appearance of the cutaneous nodules. Of note, the patient also reported unintentional weight loss of 15 pounds over the last few months.

New nodules had developed at a rate of 1 to 2 lesions daily in the 3 days prior to presentation and continued to develop after admission to the hospital. The nodules appeared as tender, erythematous lesions that evolved to form pustules and developed overlying crusts in later stages (Figure 1). They were limited to the arms and legs, primarily involving the lower legs. There was no evidence of oral or ocular involvement. A hemoglobin count of 10.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), white blood cell count of 8.8×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 69 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h) were noted on admission.

The patient was started on ceftriaxone and azithromycin for suspected pneumonia. The differential diagnosis for the cutaneous nodules included lymphoma, acid-fast bacilli (AFB) infection, deep fungal infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet syndrome (SS), panniculitis, erythema elevatum diutinum, and polyarteritis nodosa. A punch biopsy of a nodule on the left foot was performed. Histopathology demonstrated a neutrophilic panniculitis (Figure 2) with an epidermal abscess. No vasculitis was identified, and periodic acid–Schiff and AFB staining of the skin biopsy were negative. These findings were consistent with SS. Computed tomography scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which were completed early in the course of hospitalization due to concern for underlying malignancy, revealed pericardial and pleural effusions as well as cystic lesions in the lungs, spleen, kidneys, and prostate, with the largest lesion on the spleen measuring 5.6×4.8 cm (Figure 3). Computed tomography scanning was negative for areas of consolidation in the lungs. A splenic biopsy was performed by an interventional radiologist during the patient's hospitalization that identified an aseptic, neutrophilic process. Fungal, bacterial, and AFB cultures of the splenic tissue and cystic contents were negative. Bilateral pleural effusions also were identified, and a thoracentesis was performed. The pleural fluid indicated rare mesothelial cells in the background of acute inflammation with no growth of the bacterial, fungal, or AFB cultures.

Due to the association of hematologic malignances with SS, a bone marrow biopsy was performed, which revealed multiple myeloma. Serum protein electrophoresis demonstrated monoclonal gammopathy of κ light chains. During the course of his hospitalization, new skin lesions continued to develop on the hands, face, and trunk. The patient was discharged from the hospital shortly after diagnosis to receive outpatient treatment for multiple myeloma with lenalidomide and dexamethasone. Upon follow-up with the patient’s family via telephone 3 weeks into treatment, his son confirmed that the nodules were resolving.

Our case could be consistent with either drug-induced or malignancy-associated SS. Sweet syndrome initially was described in 1964 in 8 female patients with leukocytosis and cutaneous plaques infiltrated by neutrophils.1 The skin lesions typically are red and painful, ranging in size from 0.5 cm to 12.0 cm, and can last weeks to years if not treated.2 Variations of skin lesions include bullous and pustular morphologies.3

Diagnostic criteria for SS have been established.4 Both of the major criteria must be met as well as 2 of 4 minor criteria. Major criteria include abrupt onset of tender erythematous plaques and nodules; secondly, a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis must be seen on histopathology. Minor criteria include pyrexia, association with underlying condition (malignancy, pregnancy, drug exposure, inflammatory disorder), responsiveness to systemic steroids, and abnormal laboratory values (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, neutrophilia).4

Sweet syndrome can be divided into 3 classifications: classical or idiopathic, drug-induced, or malignancy-associated.4 Classical SS most commonly is seen in middle-aged women after an upper respiratory or gastrointestinal infection. Drug-induced SS most often is associated with granulocyte-stimulating factor colony therapy4; however, it has been associated with use of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.5 Malignancy-associated SS most commonly is seen in individuals with hematologic malignancy, specifically acute myeloid leukemia. Although its association with multiple myeloma is not as frequent, cases of malignancy-associated SS identifying this association have been reported.6,7 Mucosal involvement in the form of aphthouslike lesions more frequently is seen in malignancy-associated SS.8 Differing from classical SS, which has a female predilection of around 4:1, the malignancy-associated disorder has a 1:1 female-to-male ratio.4

In the majority of cases of SS, the neutrophilic infiltrate is in the papillary and upper reticular dermis; however, if the neutrophilic infiltrate is predominately in the subcutaneous tissue (known as subcutaneous SS), there is a strong association with malignancy.9 The histopathology in our case demonstrated a neutrophilic infiltrate in the subcutaneous tissue.

Fever is the most common systemic manifestation of SS and is present in 54% to 65% of patients.8,10 Besides the skin, the most common site affected is the eye, with 13% to 75% of patients reporting ocular involvement, usually conjunctivitis.4,10 Although infrequent, extracutaneous SS has been identified in the bones, central nervous system, kidneys, heart, liver, spleen, lungs, ears, eyes, and intestines.4 A case of SS with splenic involvement in the form of sterile abscesses also was reported.11 This case was related to parvovirus B19.

Sweet syndrome is a condition characterized by tender, erythematous cutaneous lesions with histopathology demonstrating neutrophilic infiltrate in the absence of vasculitis. We report a case of suspected extracutaneous SS in the form of splenic cysts in a patient whose SS was associated with malignancy and/or drug ingestion.

- Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome and malignancy. Am J Med. 1987;82:1220-1226.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:182-184.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Walker DC, Cohen PR. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: case report and review of drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:918-923.

- Belhadjali H, Chaabane S, Njim L, et al. Sweet’s syndrome associated with multiple myeloma. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2008;17:31-33.

- Bayer-Garner IB, Cottler-Fox M, Smoller BR. Sweet syndrome in multiple myeloma: a series of six cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:261-264.

- Fett DL, Gibson LE, Su WP. Sweet’s syndrome: systemic signs and symptoms and associated disorders. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:234-240.

- von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556; quiz 557-560.

- Neoh CY, Tan AW, Ng SK. Sweet’s syndrome: a spectrum of unusual clinical presentation and associations. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:480-485.

- Fortna RR, Toporcer M, Elder DE, et al. A case of sweet syndrome with spleen and lymph node involvement preceded by parvovirus B19 infection, and review of the literature on extracutaneous Sweet syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:621-627.

- Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome and malignancy. Am J Med. 1987;82:1220-1226.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:182-184.

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

- Walker DC, Cohen PR. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: case report and review of drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:918-923.

- Belhadjali H, Chaabane S, Njim L, et al. Sweet’s syndrome associated with multiple myeloma. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2008;17:31-33.

- Bayer-Garner IB, Cottler-Fox M, Smoller BR. Sweet syndrome in multiple myeloma: a series of six cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:261-264.

- Fett DL, Gibson LE, Su WP. Sweet’s syndrome: systemic signs and symptoms and associated disorders. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:234-240.

- von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556; quiz 557-560.

- Neoh CY, Tan AW, Ng SK. Sweet’s syndrome: a spectrum of unusual clinical presentation and associations. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:480-485.

- Fortna RR, Toporcer M, Elder DE, et al. A case of sweet syndrome with spleen and lymph node involvement preceded by parvovirus B19 infection, and review of the literature on extracutaneous Sweet syndrome. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:621-627.

Practice Points

- Sweet syndrome (SS), also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is an inflammatory process characterized by a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate in the absence of vasculitis.

- A diagnosis of SS warrants further investigation due to its association with malignancy, especially hematologic malignancy.

- Other organs in SS also may have aseptic involvement.

Beltlike Lichen Planus Pigmentosus Complicated With Focal Amyloidosis

To the Editor:

A 68-year-old man presented with slightly itchy macules on the waist and abdomen of approximately 2 years’ duration. He reported that the initial lesions were dark red and subsequently coalesced to form a beltlike pigmentation on the abdomen. He denied any prior treatment, and the lesions did not spontaneously resolve. The patient was taking escitalopram oxalate, telmisartan, and aspirin for depression and cardiovascular disease that was diagnosed 3 years prior. He reported no exposure to UV radiation or a heat source. He denied use of any cosmetics on the body as well as a family history of similar symptoms.

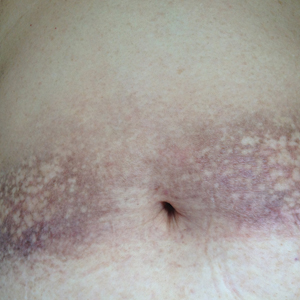

Physical examination showed reticulate brown-purple macules with slight scale on the surface that had become confluent, forming a beltlike pigmentation on the waist and abdomen (Figure 1). Wickham striae were not seen. The oral mucosa and nails were not affected. Microscopic examination for fungal infections was negative.

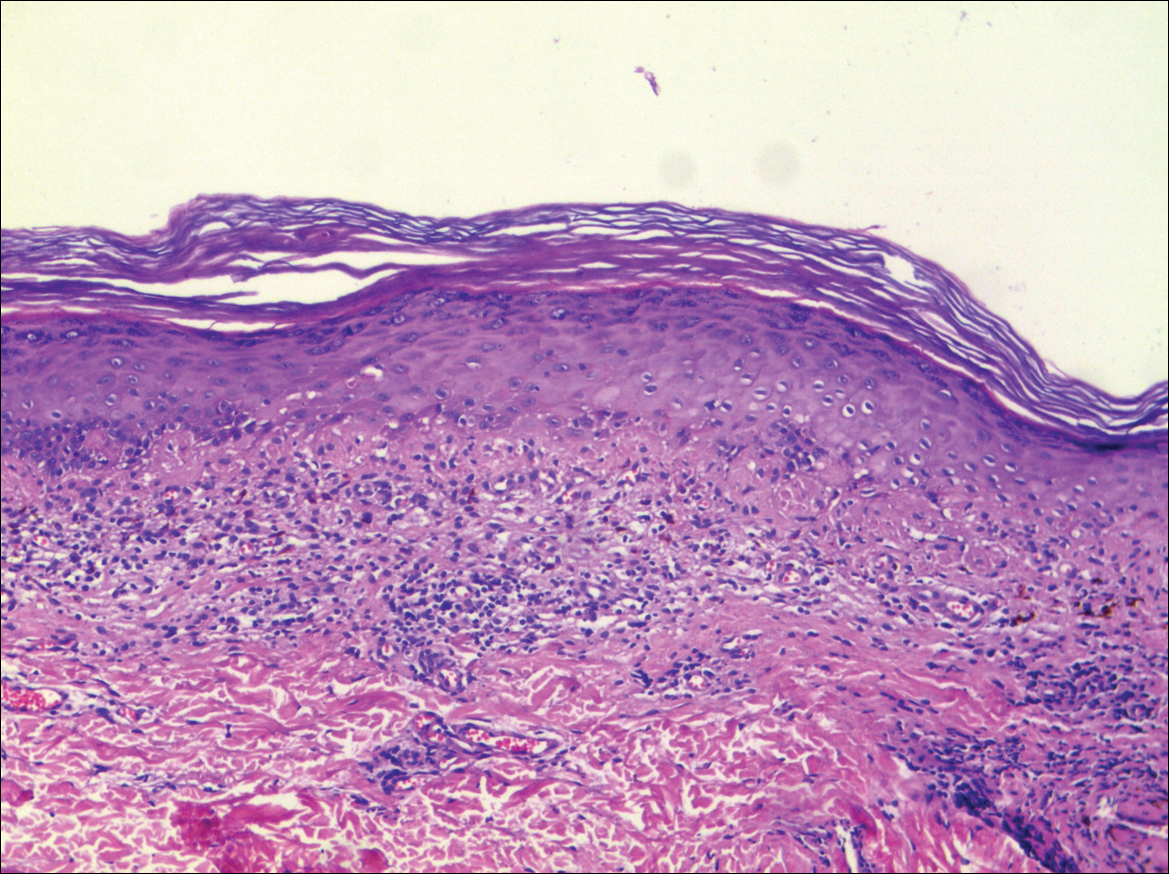

Systematic physical and laboratory examinations revealed no abnormalities. A skin biopsy from a macule on the abdomen showed hyperkeratosis, thinned out stratum spinosum with flattening of rete ridges, hypergranulosis with vacuolar alteration of the basal cell layer, and bandlike infiltration of lymphocytes and melanophages with incontinence of pigment (Figure 2). Focalized purplish homogeneous deposits were observed in the upper dermis (Figure 3), of which positive crystal violet staining indicated amyloidosis (Figure 4). Congo red stain revealed amyloid deposition (Figure 5). Thus, the diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) complicated with focal amyloidosis was made. The patient was treated with topical corticosteroids and tretinoin, and no notable therapeutic effects were observed at 3-month follow-up.

Lichen planus pigmentosus, a variant of lichen planus, is a condition of unknown etiology exhibiting dark brown macules and/or papules and a long clinical course. The face, neck, trunk, arms, and legs are the most common areas of presentation, whereas involvement of the scalp, nails, or oral mucosa is relatively rare.

The first clinicohistopathological study with a large sample size was documented by Bhutani et al1 in 1974 who termed the currently recognized entity lichen planus pigmentosus. Lichen planus pigmentosus is a frequently encountered hyperpigmentation disorder in Indians, whereas sporadic cases also are reported in other regions and ethnicities.2 In cases of LPP, the pigmentation is symmetrical, and its pattern most often is diffuse, then reticular, blotchy, and perifollicular.3 Two unique patterns of LPP have been documented, including linear/blaschkoid LPP and zosteriform LPP.4,5 Our patient showed a unique beltlike distribution pattern.

The pathogenesis of LPP still is unclear, and several inciting factors such as mustard oil, gold therapy,6 and hepatitis C virus infection have been cited.7 Mancuso and Berdondini8 reported a case of LPP flaring immediately after relapse of nephrotic syndrome. It also has been considered as a paraneoplastic phenomen.9 No exact cause was found in our patient after a series of relative examinations.

The histopathologic changes associated with LPP consist of atrophic epidermis; bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer in the epidermis; and prominent melanin incontinence in the upper dermis, which can be diverse depending on different sites of skin biopsy and the phase of LPP. Histopathologic findings in our patient were consistent with LPP. The differential diagnosis for the reticulate pattern of pigmentation seen in our patient included confluent and reticulated papillomatosis and poikilodermalike cutaneous amyloidosis, both easily excluded with histopathologic confirmation.

Local amyloidosis also was confirmed by crystal violet staining in our case and its etiology was uncertain. Generalized and local amyloidosis has been reported in association with lichen planus. The diagnosis of lichen planus was followed by the diagnosis of amyloidosis, and the typical skin lesions of these 2 conditions were able to be differentiated in these reported cases.10,11 However, beltlike pigmentation was the only manifestation for our patient and we could not separate the 2 conditions with the naked eye.

Chronic irritation to the skin resulting in excessive production of degenerate keratins and their subsequent conversion into amyloid deposits has been proposed to be an etiologic factor of amyloidosis.11 Because of the distribution pattern in our case, we believe focal amyloidosis could be attributed to chronic friction and scratching.

- Bhutani LK, Bedi TR, Pandhi RK, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus. Dermatologica. 1974;149:43-50.

- Kanwar AJ, Kaur S. Lichen planus pigmentosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(4, pt 1):815.

- Kanwar AJ, Dogra S, Handa S, et al. A study of 124 Indian patients with lichen planus pigmentosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:481-485.

- Akarsu S, Ilknur T, Özer E, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus distributed along the lines of Blaschko. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:253-254.

- Cho S, Whang KK. Lichen planus pigmentosus presenting in zosteriform pattern. J Dermatol. 1997;24:193-197.

- Ingber A, Weissmann-Katzenelson V, David M, et al. Lichen planus and lichen planus pigmentosus following gold therapy—case reports and review of the literature [in German]. Z Hautkr. 1986;61:315-319.

- Al-Mutairi N, El-Khalawany M. Clinicopathological characteristics of lichen planus pigmentosus and its response to tacrolimus ointment: an open label, non-randomized, prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:535-540.

- Mancuso G, Berdondini RM. Coexistence of lichen planus pigmentosus and minimal change nephrotic syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:389-390.

- Sassolas B, Zagnoli A, Leroy JP, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus associated with acrokeratosis of Bazex. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:70-73.

- Maeda H, Ohta S, Saito Y, et al. Epidermal origin of the amyloid in localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:345-351.

- Hongcharu W, Baldassano M, Gonzalez E. Generalized lichen amyloidosis associated with chronic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:346-348.

To the Editor:

A 68-year-old man presented with slightly itchy macules on the waist and abdomen of approximately 2 years’ duration. He reported that the initial lesions were dark red and subsequently coalesced to form a beltlike pigmentation on the abdomen. He denied any prior treatment, and the lesions did not spontaneously resolve. The patient was taking escitalopram oxalate, telmisartan, and aspirin for depression and cardiovascular disease that was diagnosed 3 years prior. He reported no exposure to UV radiation or a heat source. He denied use of any cosmetics on the body as well as a family history of similar symptoms.

Physical examination showed reticulate brown-purple macules with slight scale on the surface that had become confluent, forming a beltlike pigmentation on the waist and abdomen (Figure 1). Wickham striae were not seen. The oral mucosa and nails were not affected. Microscopic examination for fungal infections was negative.

Systematic physical and laboratory examinations revealed no abnormalities. A skin biopsy from a macule on the abdomen showed hyperkeratosis, thinned out stratum spinosum with flattening of rete ridges, hypergranulosis with vacuolar alteration of the basal cell layer, and bandlike infiltration of lymphocytes and melanophages with incontinence of pigment (Figure 2). Focalized purplish homogeneous deposits were observed in the upper dermis (Figure 3), of which positive crystal violet staining indicated amyloidosis (Figure 4). Congo red stain revealed amyloid deposition (Figure 5). Thus, the diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) complicated with focal amyloidosis was made. The patient was treated with topical corticosteroids and tretinoin, and no notable therapeutic effects were observed at 3-month follow-up.

Lichen planus pigmentosus, a variant of lichen planus, is a condition of unknown etiology exhibiting dark brown macules and/or papules and a long clinical course. The face, neck, trunk, arms, and legs are the most common areas of presentation, whereas involvement of the scalp, nails, or oral mucosa is relatively rare.

The first clinicohistopathological study with a large sample size was documented by Bhutani et al1 in 1974 who termed the currently recognized entity lichen planus pigmentosus. Lichen planus pigmentosus is a frequently encountered hyperpigmentation disorder in Indians, whereas sporadic cases also are reported in other regions and ethnicities.2 In cases of LPP, the pigmentation is symmetrical, and its pattern most often is diffuse, then reticular, blotchy, and perifollicular.3 Two unique patterns of LPP have been documented, including linear/blaschkoid LPP and zosteriform LPP.4,5 Our patient showed a unique beltlike distribution pattern.

The pathogenesis of LPP still is unclear, and several inciting factors such as mustard oil, gold therapy,6 and hepatitis C virus infection have been cited.7 Mancuso and Berdondini8 reported a case of LPP flaring immediately after relapse of nephrotic syndrome. It also has been considered as a paraneoplastic phenomen.9 No exact cause was found in our patient after a series of relative examinations.

The histopathologic changes associated with LPP consist of atrophic epidermis; bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer in the epidermis; and prominent melanin incontinence in the upper dermis, which can be diverse depending on different sites of skin biopsy and the phase of LPP. Histopathologic findings in our patient were consistent with LPP. The differential diagnosis for the reticulate pattern of pigmentation seen in our patient included confluent and reticulated papillomatosis and poikilodermalike cutaneous amyloidosis, both easily excluded with histopathologic confirmation.

Local amyloidosis also was confirmed by crystal violet staining in our case and its etiology was uncertain. Generalized and local amyloidosis has been reported in association with lichen planus. The diagnosis of lichen planus was followed by the diagnosis of amyloidosis, and the typical skin lesions of these 2 conditions were able to be differentiated in these reported cases.10,11 However, beltlike pigmentation was the only manifestation for our patient and we could not separate the 2 conditions with the naked eye.

Chronic irritation to the skin resulting in excessive production of degenerate keratins and their subsequent conversion into amyloid deposits has been proposed to be an etiologic factor of amyloidosis.11 Because of the distribution pattern in our case, we believe focal amyloidosis could be attributed to chronic friction and scratching.

To the Editor:

A 68-year-old man presented with slightly itchy macules on the waist and abdomen of approximately 2 years’ duration. He reported that the initial lesions were dark red and subsequently coalesced to form a beltlike pigmentation on the abdomen. He denied any prior treatment, and the lesions did not spontaneously resolve. The patient was taking escitalopram oxalate, telmisartan, and aspirin for depression and cardiovascular disease that was diagnosed 3 years prior. He reported no exposure to UV radiation or a heat source. He denied use of any cosmetics on the body as well as a family history of similar symptoms.

Physical examination showed reticulate brown-purple macules with slight scale on the surface that had become confluent, forming a beltlike pigmentation on the waist and abdomen (Figure 1). Wickham striae were not seen. The oral mucosa and nails were not affected. Microscopic examination for fungal infections was negative.

Systematic physical and laboratory examinations revealed no abnormalities. A skin biopsy from a macule on the abdomen showed hyperkeratosis, thinned out stratum spinosum with flattening of rete ridges, hypergranulosis with vacuolar alteration of the basal cell layer, and bandlike infiltration of lymphocytes and melanophages with incontinence of pigment (Figure 2). Focalized purplish homogeneous deposits were observed in the upper dermis (Figure 3), of which positive crystal violet staining indicated amyloidosis (Figure 4). Congo red stain revealed amyloid deposition (Figure 5). Thus, the diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) complicated with focal amyloidosis was made. The patient was treated with topical corticosteroids and tretinoin, and no notable therapeutic effects were observed at 3-month follow-up.

Lichen planus pigmentosus, a variant of lichen planus, is a condition of unknown etiology exhibiting dark brown macules and/or papules and a long clinical course. The face, neck, trunk, arms, and legs are the most common areas of presentation, whereas involvement of the scalp, nails, or oral mucosa is relatively rare.

The first clinicohistopathological study with a large sample size was documented by Bhutani et al1 in 1974 who termed the currently recognized entity lichen planus pigmentosus. Lichen planus pigmentosus is a frequently encountered hyperpigmentation disorder in Indians, whereas sporadic cases also are reported in other regions and ethnicities.2 In cases of LPP, the pigmentation is symmetrical, and its pattern most often is diffuse, then reticular, blotchy, and perifollicular.3 Two unique patterns of LPP have been documented, including linear/blaschkoid LPP and zosteriform LPP.4,5 Our patient showed a unique beltlike distribution pattern.

The pathogenesis of LPP still is unclear, and several inciting factors such as mustard oil, gold therapy,6 and hepatitis C virus infection have been cited.7 Mancuso and Berdondini8 reported a case of LPP flaring immediately after relapse of nephrotic syndrome. It also has been considered as a paraneoplastic phenomen.9 No exact cause was found in our patient after a series of relative examinations.

The histopathologic changes associated with LPP consist of atrophic epidermis; bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer in the epidermis; and prominent melanin incontinence in the upper dermis, which can be diverse depending on different sites of skin biopsy and the phase of LPP. Histopathologic findings in our patient were consistent with LPP. The differential diagnosis for the reticulate pattern of pigmentation seen in our patient included confluent and reticulated papillomatosis and poikilodermalike cutaneous amyloidosis, both easily excluded with histopathologic confirmation.

Local amyloidosis also was confirmed by crystal violet staining in our case and its etiology was uncertain. Generalized and local amyloidosis has been reported in association with lichen planus. The diagnosis of lichen planus was followed by the diagnosis of amyloidosis, and the typical skin lesions of these 2 conditions were able to be differentiated in these reported cases.10,11 However, beltlike pigmentation was the only manifestation for our patient and we could not separate the 2 conditions with the naked eye.

Chronic irritation to the skin resulting in excessive production of degenerate keratins and their subsequent conversion into amyloid deposits has been proposed to be an etiologic factor of amyloidosis.11 Because of the distribution pattern in our case, we believe focal amyloidosis could be attributed to chronic friction and scratching.

- Bhutani LK, Bedi TR, Pandhi RK, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus. Dermatologica. 1974;149:43-50.

- Kanwar AJ, Kaur S. Lichen planus pigmentosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(4, pt 1):815.

- Kanwar AJ, Dogra S, Handa S, et al. A study of 124 Indian patients with lichen planus pigmentosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:481-485.

- Akarsu S, Ilknur T, Özer E, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus distributed along the lines of Blaschko. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:253-254.

- Cho S, Whang KK. Lichen planus pigmentosus presenting in zosteriform pattern. J Dermatol. 1997;24:193-197.

- Ingber A, Weissmann-Katzenelson V, David M, et al. Lichen planus and lichen planus pigmentosus following gold therapy—case reports and review of the literature [in German]. Z Hautkr. 1986;61:315-319.

- Al-Mutairi N, El-Khalawany M. Clinicopathological characteristics of lichen planus pigmentosus and its response to tacrolimus ointment: an open label, non-randomized, prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:535-540.

- Mancuso G, Berdondini RM. Coexistence of lichen planus pigmentosus and minimal change nephrotic syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:389-390.

- Sassolas B, Zagnoli A, Leroy JP, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus associated with acrokeratosis of Bazex. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:70-73.

- Maeda H, Ohta S, Saito Y, et al. Epidermal origin of the amyloid in localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:345-351.

- Hongcharu W, Baldassano M, Gonzalez E. Generalized lichen amyloidosis associated with chronic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:346-348.

- Bhutani LK, Bedi TR, Pandhi RK, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus. Dermatologica. 1974;149:43-50.

- Kanwar AJ, Kaur S. Lichen planus pigmentosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(4, pt 1):815.

- Kanwar AJ, Dogra S, Handa S, et al. A study of 124 Indian patients with lichen planus pigmentosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:481-485.

- Akarsu S, Ilknur T, Özer E, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus distributed along the lines of Blaschko. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:253-254.

- Cho S, Whang KK. Lichen planus pigmentosus presenting in zosteriform pattern. J Dermatol. 1997;24:193-197.

- Ingber A, Weissmann-Katzenelson V, David M, et al. Lichen planus and lichen planus pigmentosus following gold therapy—case reports and review of the literature [in German]. Z Hautkr. 1986;61:315-319.

- Al-Mutairi N, El-Khalawany M. Clinicopathological characteristics of lichen planus pigmentosus and its response to tacrolimus ointment: an open label, non-randomized, prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:535-540.

- Mancuso G, Berdondini RM. Coexistence of lichen planus pigmentosus and minimal change nephrotic syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:389-390.

- Sassolas B, Zagnoli A, Leroy JP, et al. Lichen planus pigmentosus associated with acrokeratosis of Bazex. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:70-73.

- Maeda H, Ohta S, Saito Y, et al. Epidermal origin of the amyloid in localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:345-351.

- Hongcharu W, Baldassano M, Gonzalez E. Generalized lichen amyloidosis associated with chronic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:346-348.

Practice Points

- Lichen planus pigmentosus can present in a unique beltlike distribution pattern.

- Focal amyloidosis due to chronic friction and scratching cannot be excluded from the differential diagnosis.

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Caused by Pantoprazole

To the Editor:

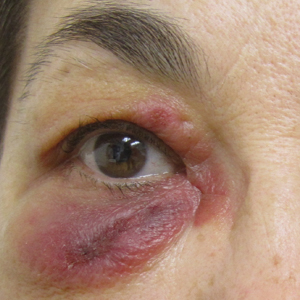

A 34-year-old woman presented with a generalized pustular eruption with subjective fevers, chills, night sweats, and light-headedness. Ten days prior to admission she developed a generalized erythematous and pruritic rash; she had started pantoprazole for reflux 4 days prior to the rash. On admission, skin examination revealed facial edema and diffuse erythema covering 80% of the total body surface area with multiple 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing into lakes of pus on the trunk as well as bilateral upper and lower arms and legs sparing the palms and soles. Desquamation and serous drainage with crust were observed on the skin of the head, upper trunk, and thighs (Figure 1). Vital signs were notable for hypotension. Laboratory tests on admission were remarkable for leukocytosis (white blood cell count: 22.5×103/μL [reference range, 4.5–11×103/μL]) with absolute eosinophilia but no neutrophilia. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated (237.9 mg/L [reference range, 5.0–9.9 mg/L]). Renal and hepatic functions were normal. Blood cultures grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Further infectious disease workup for viral and fungal pathogens was negative.

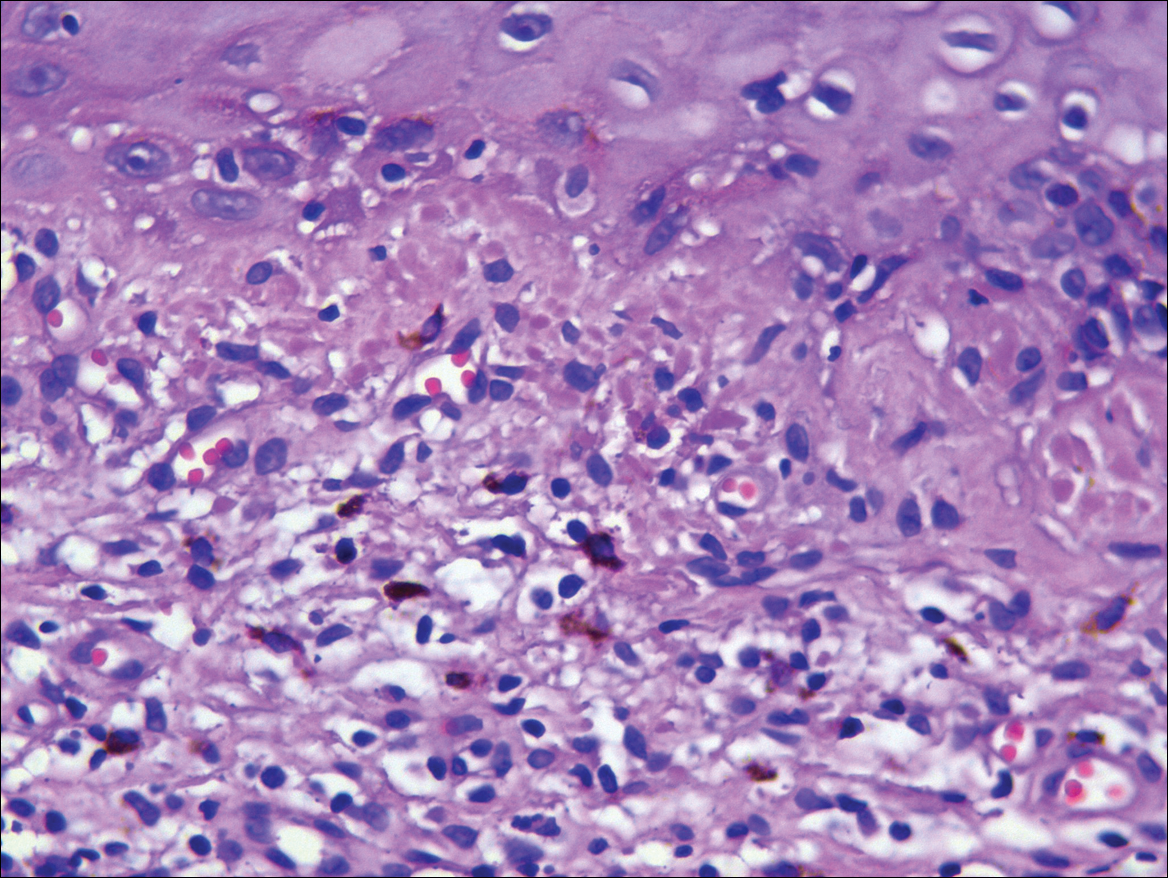

Skin biopsy from the left thigh revealed subcorneal, pustular, acute spongiotic dermatitis with marked intraepidermal spongiosis and papillary edema; exocytosis of eosinophils; and single cell necrosis of keratinocytes (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). Pantoprazole was discontinued, and cardiovascular support and antibiotic therapy for MSSA bacteremia were initiated. Respiratory, kidney, and liver functions remained normal throughout the 11-day hospitalization, and the pustular dermatitis, MSSA bacteremia, and cardiovascular symptoms resolved within 10 days.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon, self-limited, generalized sterile pustular eruption notable for the usual absence of systemic symptoms and extracutaneous organ involvement. Hotz et al1 found that mean peripheral neutrophil counts (mean, 21.5×103/μL) and CRP levels (mean, 241.6 mg/L) were notably elevated in patients with systemic (ie, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, bone marrow) involvement. In our patient, only the CRP approached the elevated value reported by Hotz et al.1 However, the patient exhibited only cardiovascular instability in the context of secondary bacteremia and no other systemic symptoms. The combination of highly elevated neutrophilia and CRP may be a better marker for AGEP-precipitated extracutaneous organ involvement.

Although infectious pathogens such as Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus have been implicated, the majority of AGEP cases are adverse reactions (ARs) to medications, such as β-lactam antibiotics. In our patient, the widely prescribed proton pump inhibitor (PPI) pantoprazole was the most likely cause. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis was reported in a patient taking another PPI, omeprazole.2 However, PPIs are recognized to cause many cutaneous and other organ ARs, though prevalence of ARs is still low. In Thailand, Chularojanamontri et al3 reported 13.8 per 100,000 individuals developed a cutaneous AR to PPIs, and the ARs most frequently were attributed to omeprazole. They found that drug exanthems were the most common cutaneous ARs.3 However, more severe hypersensitivity reactions have been reported, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and autoimmune eruptions such as cutaneous lupus erythematosus.3,4 Other systemic reactions to PPIs include increased risks for urticaria, pneumonia, Clostridium difficile infections, and acute interstitial nephritis.4,5

- Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

- Nantes Castillejo O, Zozaya Urmeneta JM, Valcayo Peñalba A, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by omeprazole [in Spanish]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;31:295-298.

- Chularojanamontri L, Jiamton S, Manapajon A, et al. Cutaneous reactions to proton pump inhibitors: a case-control study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E43-E47.

- Chang YS. Hypersensitivity reactions to proton pump inhibitors. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:348-353.

- Wilhelm SM, Rjater RG, Kale-Pradhan PB. Perils and pitfalls of long-term effects of proton pump inhibitors. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6:443-551.

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old woman presented with a generalized pustular eruption with subjective fevers, chills, night sweats, and light-headedness. Ten days prior to admission she developed a generalized erythematous and pruritic rash; she had started pantoprazole for reflux 4 days prior to the rash. On admission, skin examination revealed facial edema and diffuse erythema covering 80% of the total body surface area with multiple 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing into lakes of pus on the trunk as well as bilateral upper and lower arms and legs sparing the palms and soles. Desquamation and serous drainage with crust were observed on the skin of the head, upper trunk, and thighs (Figure 1). Vital signs were notable for hypotension. Laboratory tests on admission were remarkable for leukocytosis (white blood cell count: 22.5×103/μL [reference range, 4.5–11×103/μL]) with absolute eosinophilia but no neutrophilia. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated (237.9 mg/L [reference range, 5.0–9.9 mg/L]). Renal and hepatic functions were normal. Blood cultures grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Further infectious disease workup for viral and fungal pathogens was negative.

Skin biopsy from the left thigh revealed subcorneal, pustular, acute spongiotic dermatitis with marked intraepidermal spongiosis and papillary edema; exocytosis of eosinophils; and single cell necrosis of keratinocytes (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). Pantoprazole was discontinued, and cardiovascular support and antibiotic therapy for MSSA bacteremia were initiated. Respiratory, kidney, and liver functions remained normal throughout the 11-day hospitalization, and the pustular dermatitis, MSSA bacteremia, and cardiovascular symptoms resolved within 10 days.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon, self-limited, generalized sterile pustular eruption notable for the usual absence of systemic symptoms and extracutaneous organ involvement. Hotz et al1 found that mean peripheral neutrophil counts (mean, 21.5×103/μL) and CRP levels (mean, 241.6 mg/L) were notably elevated in patients with systemic (ie, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, bone marrow) involvement. In our patient, only the CRP approached the elevated value reported by Hotz et al.1 However, the patient exhibited only cardiovascular instability in the context of secondary bacteremia and no other systemic symptoms. The combination of highly elevated neutrophilia and CRP may be a better marker for AGEP-precipitated extracutaneous organ involvement.

Although infectious pathogens such as Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus have been implicated, the majority of AGEP cases are adverse reactions (ARs) to medications, such as β-lactam antibiotics. In our patient, the widely prescribed proton pump inhibitor (PPI) pantoprazole was the most likely cause. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis was reported in a patient taking another PPI, omeprazole.2 However, PPIs are recognized to cause many cutaneous and other organ ARs, though prevalence of ARs is still low. In Thailand, Chularojanamontri et al3 reported 13.8 per 100,000 individuals developed a cutaneous AR to PPIs, and the ARs most frequently were attributed to omeprazole. They found that drug exanthems were the most common cutaneous ARs.3 However, more severe hypersensitivity reactions have been reported, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and autoimmune eruptions such as cutaneous lupus erythematosus.3,4 Other systemic reactions to PPIs include increased risks for urticaria, pneumonia, Clostridium difficile infections, and acute interstitial nephritis.4,5

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old woman presented with a generalized pustular eruption with subjective fevers, chills, night sweats, and light-headedness. Ten days prior to admission she developed a generalized erythematous and pruritic rash; she had started pantoprazole for reflux 4 days prior to the rash. On admission, skin examination revealed facial edema and diffuse erythema covering 80% of the total body surface area with multiple 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing into lakes of pus on the trunk as well as bilateral upper and lower arms and legs sparing the palms and soles. Desquamation and serous drainage with crust were observed on the skin of the head, upper trunk, and thighs (Figure 1). Vital signs were notable for hypotension. Laboratory tests on admission were remarkable for leukocytosis (white blood cell count: 22.5×103/μL [reference range, 4.5–11×103/μL]) with absolute eosinophilia but no neutrophilia. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated (237.9 mg/L [reference range, 5.0–9.9 mg/L]). Renal and hepatic functions were normal. Blood cultures grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Further infectious disease workup for viral and fungal pathogens was negative.

Skin biopsy from the left thigh revealed subcorneal, pustular, acute spongiotic dermatitis with marked intraepidermal spongiosis and papillary edema; exocytosis of eosinophils; and single cell necrosis of keratinocytes (Figure 2). These findings were consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). Pantoprazole was discontinued, and cardiovascular support and antibiotic therapy for MSSA bacteremia were initiated. Respiratory, kidney, and liver functions remained normal throughout the 11-day hospitalization, and the pustular dermatitis, MSSA bacteremia, and cardiovascular symptoms resolved within 10 days.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon, self-limited, generalized sterile pustular eruption notable for the usual absence of systemic symptoms and extracutaneous organ involvement. Hotz et al1 found that mean peripheral neutrophil counts (mean, 21.5×103/μL) and CRP levels (mean, 241.6 mg/L) were notably elevated in patients with systemic (ie, hepatic, pulmonary, renal, bone marrow) involvement. In our patient, only the CRP approached the elevated value reported by Hotz et al.1 However, the patient exhibited only cardiovascular instability in the context of secondary bacteremia and no other systemic symptoms. The combination of highly elevated neutrophilia and CRP may be a better marker for AGEP-precipitated extracutaneous organ involvement.

Although infectious pathogens such as Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus have been implicated, the majority of AGEP cases are adverse reactions (ARs) to medications, such as β-lactam antibiotics. In our patient, the widely prescribed proton pump inhibitor (PPI) pantoprazole was the most likely cause. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis was reported in a patient taking another PPI, omeprazole.2 However, PPIs are recognized to cause many cutaneous and other organ ARs, though prevalence of ARs is still low. In Thailand, Chularojanamontri et al3 reported 13.8 per 100,000 individuals developed a cutaneous AR to PPIs, and the ARs most frequently were attributed to omeprazole. They found that drug exanthems were the most common cutaneous ARs.3 However, more severe hypersensitivity reactions have been reported, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and autoimmune eruptions such as cutaneous lupus erythematosus.3,4 Other systemic reactions to PPIs include increased risks for urticaria, pneumonia, Clostridium difficile infections, and acute interstitial nephritis.4,5

- Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

- Nantes Castillejo O, Zozaya Urmeneta JM, Valcayo Peñalba A, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by omeprazole [in Spanish]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;31:295-298.

- Chularojanamontri L, Jiamton S, Manapajon A, et al. Cutaneous reactions to proton pump inhibitors: a case-control study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E43-E47.

- Chang YS. Hypersensitivity reactions to proton pump inhibitors. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:348-353.

- Wilhelm SM, Rjater RG, Kale-Pradhan PB. Perils and pitfalls of long-term effects of proton pump inhibitors. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6:443-551.

- Hotz C, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Haddad C, et al. Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1223-1232.

- Nantes Castillejo O, Zozaya Urmeneta JM, Valcayo Peñalba A, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by omeprazole [in Spanish]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;31:295-298.

- Chularojanamontri L, Jiamton S, Manapajon A, et al. Cutaneous reactions to proton pump inhibitors: a case-control study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E43-E47.

- Chang YS. Hypersensitivity reactions to proton pump inhibitors. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:348-353.

- Wilhelm SM, Rjater RG, Kale-Pradhan PB. Perils and pitfalls of long-term effects of proton pump inhibitors. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6:443-551.

Interstitial Granulomatous Dermatitis and Palisaded Neutrophilic Granulomatous Dermatitis

To the Editor:

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) is a rare disorder that often is associated with systemic disease. It has been shown to manifest in the presence of systemic lupus erythematosus; rheumatoid arthritis; Wegener granulomatosis; and other diseases, mainly autoimmune conditions. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) associated with arthritis was first described by Ackerman et al1 in 1993. In 1994, IGD was placed among the spectrum of PNGD by Chu et al.2 The disease entities included in the spectrum of PNGD of the immune complex disease are Churg-Strauss granuloma, cutaneous extravascular necrotizing granuloma, rheumatoid papules, superficial ulcerating rheumatoid necrobiosis, and IGD with arthritis.2 It has been suggested that IGD has a distinct clinical presentation with associated histopathology, while others suggest it still is part of the PNGD spectrum.2,3 We present 2 cases of granulomatous dermatitis and their findings related to IGD and PNGD.

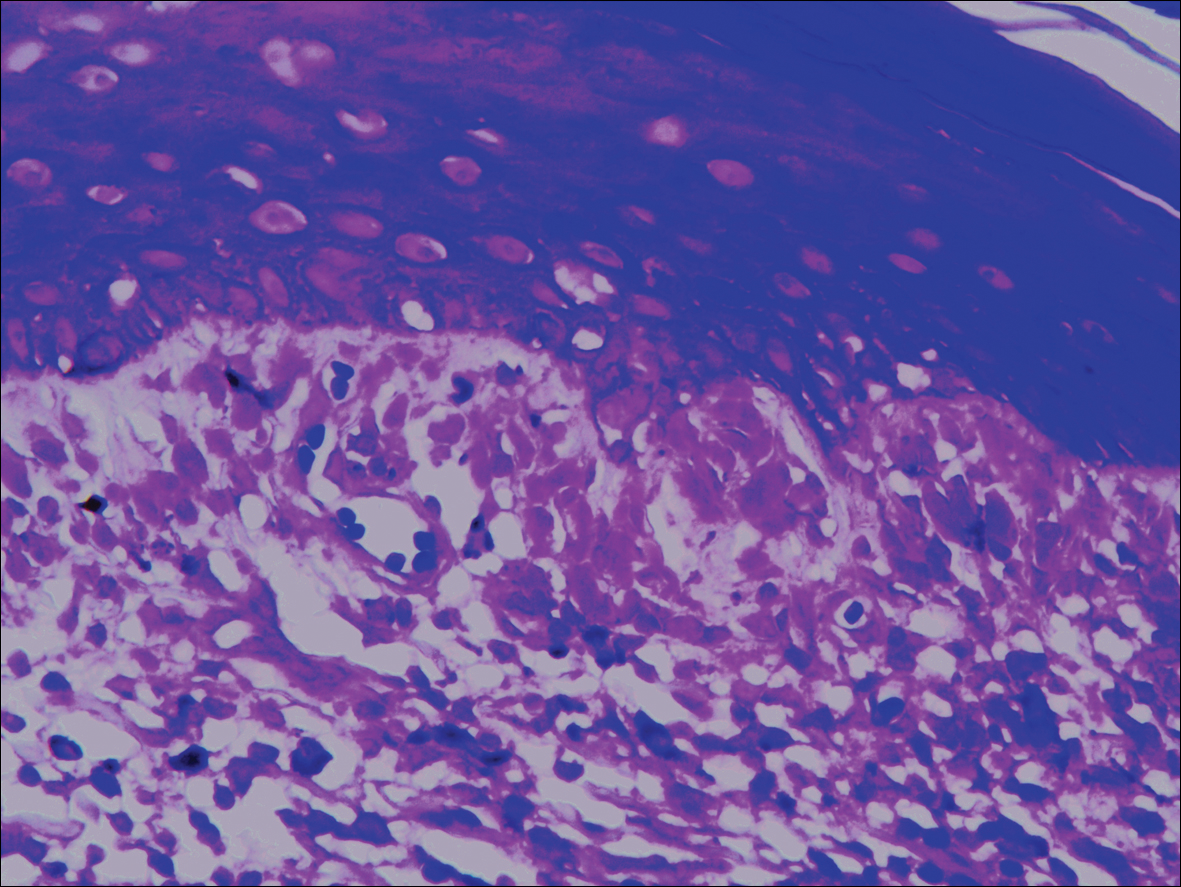

A 58-year-old woman presented with recurrent painful lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs of 2 years’ duration. The lesions spontaneously resolved without scarring or hyperpigmentation but would recur in different areas on the trunk. She was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis following a recent autoimmune workup. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender erythematous edematous plaques on the bilateral upper back (Figure 1) and erythematous nodules on the bilateral upper arms. The patient previously had an antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 with a speckled pattern. A repeat antinuclear antibody titer taken 1 year later was negative. Her rheumatoid factor initially was positive and remained positive upon repeat testing. Punch biopsies were performed for histologic evaluation of the lesions and immunofluorescence. Biopsies examined with hematoxylin and eosin stain revealed perivascular and interstitial mixed (lymphocytic, neutrophilic, eosinophilic) bottom-heavy inflammation with nuclear dust and basophilic degeneration of collagen (Figure 2). Immunofluorescence studies were negative. The patient deferred treatment.

A 74-year-old man presented with a rash on the flank and back with associated pruritus and occasional pain of 2 months’ duration. His primary care physician prescribed a course of cephalexin, but the rash did not improve. Review of systems was positive for intermittent swelling of the hands, feet, and lips, and negative for arthritis. His medical history included 2 episodes of rheumatic fever, one complicated by pneumonia. His medications included finasteride, simvastatin, bisoprolol-hydrochlorothiazide, aspirin, tiotropium, vitamin D, and fish oil. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender violaceous plaques with induration and central clearing distributed on the left side of the back, left side of the flank, and left axilla. The lesion on the axilla measured 30.0×3.5 cm and the lesions on the left side of the back measured 30.0×9.0 cm. The rims of the lesions were elevated and consistent with the rope sign (Figure 3). A punch biopsy of the lesion on the left axilla showed perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, histiocytes, and eosinophils. There was no evidence of fibrin deposition in the blood vessels. Small areas of necrobiotic collagen surrounded by multinucleated giant cells and lymphocytes were noted (Figure 4). The rash improved spontaneously at the time of suture removal. No treatment was initiated.

Granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder can present as IGD or PNGD. Both forms of granulomatous dermatitis are rare conditions and considered to be part of the same clinicopathological spectrum. These conditions can be difficult to distinguish clinically but are histologically unique.

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD can have a variable clinical expression. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis generally presents as flesh-colored to erythematous papules or plaques, most commonly located on the upper arms. The lesions may have a central umbilication with perforation and ulceration.4 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis most commonly presents as erythematous plaques and papules. The lesions are symmetric and asymptomatic. They most commonly appear on the trunk, axillae, buttocks, thighs, and groin. Subcutaneous linear cords (the rope sign) is a characteristic associated with IGD.3,5 However, the rope sign also has been reported in a patient with PNGD with systemic lupus,6 which further demonstrates the overlapping spectrum of clinical expression seen in these 2 forms of granulomatous dermatitis. Therefore, a diagnosis cannot be made by clinical expression alone; histologic findings are needed for confirmation.

When differentiating IGD and PNGD histologically, it is important to keep in mind that these features exist on a spectrum and depend on the age of the lesion. Deposition of the immune complex around the dermal blood vessel initiates the pathogenesis. Early lesions of PNGD show a neutrophilic infiltrate, focal leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and dense nuclear dust. Developed lesions show zones of basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris.2 The histologic pattern of IGD features smaller areas of palisading histiocytes surrounding foci of degenerated collagen. Neutrophils and eosinophils are seen among the degenerated collagen. There is no evidence of vasculitis and dermal mucin usually is absent.7

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis has been reported to improve with systemic steroids and dapsone.8 Th

Some authors have disputed the spectrum that Chu et al2 had determined in their study and proposed IGD is a separate entity from the PNGD spectrum. Verneuil et al9 stated that the clinical presentations in Chu et al’s2 study (symmetric papules of the extremities) had not been reported in a patient with IGD. However, in a study of IGD by Peroni et al,3 7 of 12 patients presented with symmetrical papules of the extremities. We believe that the spectrum proposed by Chu et al2 still holds true.

These 2 reports demonstrate the diverse presentation of IGD and PNGD. It is important for dermatologists to keep in mind the PNGD spectrum when a patient presents with granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder.

- Ackerman AB, Guo Y, Vitale P. Clues to diagnosis in dermatopathology. Am Society Clin Pathol. 1993;3:309-312.

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Hantash BM, Chiang D, Kohler S, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis associated with limited systemic sclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:661-664.

- Garcia-Rabasco A, Esteve-Martinez A, Zaragoza-Ninet V, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis in a patient with lupus erythematosus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:871-872.

- Gulati A, Paige D, Yaqoob M, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with the burning rope sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:711-714.

- Tomasini C, Pippione M. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with plaques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:892-899.

- Fett N, Kovarik C, Bennett D. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis without a definable underlying disorder treated with dapsone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E92-E93.

- Verneuil L, Dompmartin A, Comoz F, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with cutaneous cords and arthritis: a disorder associated with autoantibodies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:286-291.

To the Editor:

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) is a rare disorder that often is associated with systemic disease. It has been shown to manifest in the presence of systemic lupus erythematosus; rheumatoid arthritis; Wegener granulomatosis; and other diseases, mainly autoimmune conditions. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) associated with arthritis was first described by Ackerman et al1 in 1993. In 1994, IGD was placed among the spectrum of PNGD by Chu et al.2 The disease entities included in the spectrum of PNGD of the immune complex disease are Churg-Strauss granuloma, cutaneous extravascular necrotizing granuloma, rheumatoid papules, superficial ulcerating rheumatoid necrobiosis, and IGD with arthritis.2 It has been suggested that IGD has a distinct clinical presentation with associated histopathology, while others suggest it still is part of the PNGD spectrum.2,3 We present 2 cases of granulomatous dermatitis and their findings related to IGD and PNGD.

A 58-year-old woman presented with recurrent painful lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs of 2 years’ duration. The lesions spontaneously resolved without scarring or hyperpigmentation but would recur in different areas on the trunk. She was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis following a recent autoimmune workup. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender erythematous edematous plaques on the bilateral upper back (Figure 1) and erythematous nodules on the bilateral upper arms. The patient previously had an antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 with a speckled pattern. A repeat antinuclear antibody titer taken 1 year later was negative. Her rheumatoid factor initially was positive and remained positive upon repeat testing. Punch biopsies were performed for histologic evaluation of the lesions and immunofluorescence. Biopsies examined with hematoxylin and eosin stain revealed perivascular and interstitial mixed (lymphocytic, neutrophilic, eosinophilic) bottom-heavy inflammation with nuclear dust and basophilic degeneration of collagen (Figure 2). Immunofluorescence studies were negative. The patient deferred treatment.

A 74-year-old man presented with a rash on the flank and back with associated pruritus and occasional pain of 2 months’ duration. His primary care physician prescribed a course of cephalexin, but the rash did not improve. Review of systems was positive for intermittent swelling of the hands, feet, and lips, and negative for arthritis. His medical history included 2 episodes of rheumatic fever, one complicated by pneumonia. His medications included finasteride, simvastatin, bisoprolol-hydrochlorothiazide, aspirin, tiotropium, vitamin D, and fish oil. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender violaceous plaques with induration and central clearing distributed on the left side of the back, left side of the flank, and left axilla. The lesion on the axilla measured 30.0×3.5 cm and the lesions on the left side of the back measured 30.0×9.0 cm. The rims of the lesions were elevated and consistent with the rope sign (Figure 3). A punch biopsy of the lesion on the left axilla showed perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, histiocytes, and eosinophils. There was no evidence of fibrin deposition in the blood vessels. Small areas of necrobiotic collagen surrounded by multinucleated giant cells and lymphocytes were noted (Figure 4). The rash improved spontaneously at the time of suture removal. No treatment was initiated.

Granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder can present as IGD or PNGD. Both forms of granulomatous dermatitis are rare conditions and considered to be part of the same clinicopathological spectrum. These conditions can be difficult to distinguish clinically but are histologically unique.

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD can have a variable clinical expression. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis generally presents as flesh-colored to erythematous papules or plaques, most commonly located on the upper arms. The lesions may have a central umbilication with perforation and ulceration.4 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis most commonly presents as erythematous plaques and papules. The lesions are symmetric and asymptomatic. They most commonly appear on the trunk, axillae, buttocks, thighs, and groin. Subcutaneous linear cords (the rope sign) is a characteristic associated with IGD.3,5 However, the rope sign also has been reported in a patient with PNGD with systemic lupus,6 which further demonstrates the overlapping spectrum of clinical expression seen in these 2 forms of granulomatous dermatitis. Therefore, a diagnosis cannot be made by clinical expression alone; histologic findings are needed for confirmation.

When differentiating IGD and PNGD histologically, it is important to keep in mind that these features exist on a spectrum and depend on the age of the lesion. Deposition of the immune complex around the dermal blood vessel initiates the pathogenesis. Early lesions of PNGD show a neutrophilic infiltrate, focal leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and dense nuclear dust. Developed lesions show zones of basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris.2 The histologic pattern of IGD features smaller areas of palisading histiocytes surrounding foci of degenerated collagen. Neutrophils and eosinophils are seen among the degenerated collagen. There is no evidence of vasculitis and dermal mucin usually is absent.7

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis has been reported to improve with systemic steroids and dapsone.8 Th

Some authors have disputed the spectrum that Chu et al2 had determined in their study and proposed IGD is a separate entity from the PNGD spectrum. Verneuil et al9 stated that the clinical presentations in Chu et al’s2 study (symmetric papules of the extremities) had not been reported in a patient with IGD. However, in a study of IGD by Peroni et al,3 7 of 12 patients presented with symmetrical papules of the extremities. We believe that the spectrum proposed by Chu et al2 still holds true.

These 2 reports demonstrate the diverse presentation of IGD and PNGD. It is important for dermatologists to keep in mind the PNGD spectrum when a patient presents with granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder.

To the Editor:

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) is a rare disorder that often is associated with systemic disease. It has been shown to manifest in the presence of systemic lupus erythematosus; rheumatoid arthritis; Wegener granulomatosis; and other diseases, mainly autoimmune conditions. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (IGD) associated with arthritis was first described by Ackerman et al1 in 1993. In 1994, IGD was placed among the spectrum of PNGD by Chu et al.2 The disease entities included in the spectrum of PNGD of the immune complex disease are Churg-Strauss granuloma, cutaneous extravascular necrotizing granuloma, rheumatoid papules, superficial ulcerating rheumatoid necrobiosis, and IGD with arthritis.2 It has been suggested that IGD has a distinct clinical presentation with associated histopathology, while others suggest it still is part of the PNGD spectrum.2,3 We present 2 cases of granulomatous dermatitis and their findings related to IGD and PNGD.

A 58-year-old woman presented with recurrent painful lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs of 2 years’ duration. The lesions spontaneously resolved without scarring or hyperpigmentation but would recur in different areas on the trunk. She was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis following a recent autoimmune workup. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender erythematous edematous plaques on the bilateral upper back (Figure 1) and erythematous nodules on the bilateral upper arms. The patient previously had an antinuclear antibody titer of 1:320 with a speckled pattern. A repeat antinuclear antibody titer taken 1 year later was negative. Her rheumatoid factor initially was positive and remained positive upon repeat testing. Punch biopsies were performed for histologic evaluation of the lesions and immunofluorescence. Biopsies examined with hematoxylin and eosin stain revealed perivascular and interstitial mixed (lymphocytic, neutrophilic, eosinophilic) bottom-heavy inflammation with nuclear dust and basophilic degeneration of collagen (Figure 2). Immunofluorescence studies were negative. The patient deferred treatment.

A 74-year-old man presented with a rash on the flank and back with associated pruritus and occasional pain of 2 months’ duration. His primary care physician prescribed a course of cephalexin, but the rash did not improve. Review of systems was positive for intermittent swelling of the hands, feet, and lips, and negative for arthritis. His medical history included 2 episodes of rheumatic fever, one complicated by pneumonia. His medications included finasteride, simvastatin, bisoprolol-hydrochlorothiazide, aspirin, tiotropium, vitamin D, and fish oil. At presentation, physical examination revealed tender violaceous plaques with induration and central clearing distributed on the left side of the back, left side of the flank, and left axilla. The lesion on the axilla measured 30.0×3.5 cm and the lesions on the left side of the back measured 30.0×9.0 cm. The rims of the lesions were elevated and consistent with the rope sign (Figure 3). A punch biopsy of the lesion on the left axilla showed perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, histiocytes, and eosinophils. There was no evidence of fibrin deposition in the blood vessels. Small areas of necrobiotic collagen surrounded by multinucleated giant cells and lymphocytes were noted (Figure 4). The rash improved spontaneously at the time of suture removal. No treatment was initiated.

Granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder can present as IGD or PNGD. Both forms of granulomatous dermatitis are rare conditions and considered to be part of the same clinicopathological spectrum. These conditions can be difficult to distinguish clinically but are histologically unique.

Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and PNGD can have a variable clinical expression. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis generally presents as flesh-colored to erythematous papules or plaques, most commonly located on the upper arms. The lesions may have a central umbilication with perforation and ulceration.4 Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis most commonly presents as erythematous plaques and papules. The lesions are symmetric and asymptomatic. They most commonly appear on the trunk, axillae, buttocks, thighs, and groin. Subcutaneous linear cords (the rope sign) is a characteristic associated with IGD.3,5 However, the rope sign also has been reported in a patient with PNGD with systemic lupus,6 which further demonstrates the overlapping spectrum of clinical expression seen in these 2 forms of granulomatous dermatitis. Therefore, a diagnosis cannot be made by clinical expression alone; histologic findings are needed for confirmation.

When differentiating IGD and PNGD histologically, it is important to keep in mind that these features exist on a spectrum and depend on the age of the lesion. Deposition of the immune complex around the dermal blood vessel initiates the pathogenesis. Early lesions of PNGD show a neutrophilic infiltrate, focal leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and dense nuclear dust. Developed lesions show zones of basophilic degenerated collagen surrounded by palisades of histiocytes, neutrophils, and nuclear debris.2 The histologic pattern of IGD features smaller areas of palisading histiocytes surrounding foci of degenerated collagen. Neutrophils and eosinophils are seen among the degenerated collagen. There is no evidence of vasculitis and dermal mucin usually is absent.7

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis has been reported to improve with systemic steroids and dapsone.8 Th

Some authors have disputed the spectrum that Chu et al2 had determined in their study and proposed IGD is a separate entity from the PNGD spectrum. Verneuil et al9 stated that the clinical presentations in Chu et al’s2 study (symmetric papules of the extremities) had not been reported in a patient with IGD. However, in a study of IGD by Peroni et al,3 7 of 12 patients presented with symmetrical papules of the extremities. We believe that the spectrum proposed by Chu et al2 still holds true.

These 2 reports demonstrate the diverse presentation of IGD and PNGD. It is important for dermatologists to keep in mind the PNGD spectrum when a patient presents with granulomatous dermatitis in the presence of an autoimmune disorder.

- Ackerman AB, Guo Y, Vitale P. Clues to diagnosis in dermatopathology. Am Society Clin Pathol. 1993;3:309-312.

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.