User login

Metastatic Melanoma and Prostatic Adenocarcinoma in the Same Sentinel Lymph Node

To the Editor:

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsies routinely are performed to detect regional metastases in a variety of malignancies, including breast cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Histologic examination of an SLN occasionally enables detection of other unsuspected underlying diseases that typically are inflammatory in nature. Although concomitant hematolymphoid malignancy, particularly chronic lymphocytic leukemia, has been reported in SLNs, collision of 2 different solid tumors in the same SLN is rare.1,2 We report a unique case documenting collision of both metastatic melanoma and prostatic adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN to raise awareness of the diagnostic challenges occurring in patients with coexisting malignancies.

A 71-year-old man with a history of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma to the bone presented for treatment of a melanoma that was newly diagnosed by an outside dermatologist. The patient’s medical history was notable for radical prostatectomy performed 15 years prior for treatment of a prostatic adenocarcinoma (Gleason score unknown) followed by bilateral orchiectomy performed 7 years later after his serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level began to rise, with no response to goserelin (a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist) therapy. Two years prior to the diagnosis of metastatic disease, his PSA level started to rise again and the patient received bicalutamide with little improvement, followed by 8 cycles of docetaxel. His PSA level improved and he most recently was being treated with abiraterone acetate. The patient’s latest computed tomography scan showed that the bony metastases secondary to prostatic adenocarcinoma had progressed. His serum PSA level was 105 ng/mL (reference range, <4.0 ng/mL) at the current presentation, elevated from 64 ng/mL one year prior.

Recently, the patient had noted a changing pigmented skin lesion on the left side of the flank. The patient described the lesion as a “black mole” first appearing 2 years prior, which had begun to ooze, change shape, and become darker and more nodular. A shave biopsy revealed a primary cutaneous malignant melanoma at least 3.4 mm in depth with ulceration and a mitotic rate of 15/mm2. No molecular studies were performed on the melanoma. Standard treatment via wide local excision and sentinel lymphadenectomy was planned.

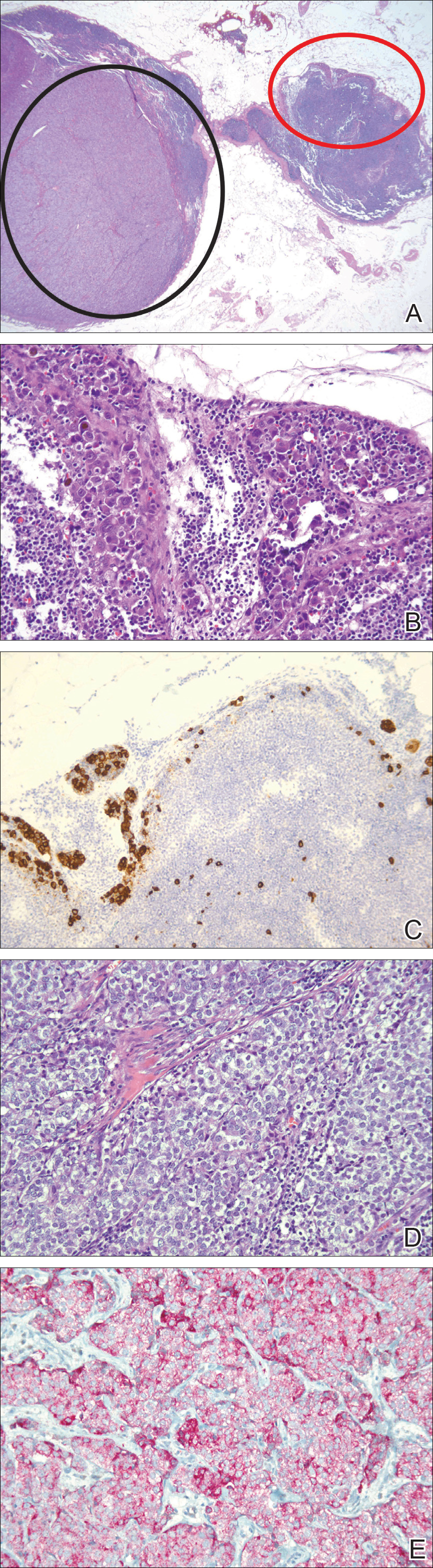

Lymphoscintigraphy revealed 3 left draining axillary lymph nodes. The patient was treated with wide local excision and left axillary SLN biopsy. Five SLNs and 3 non-SLNs were excised. Per protocol, all SLNs were examined pathologically with serial sections: 2 hematoxylin and eosin–stained levels, S-100, and melan-A immunohistochemical stains. No residual melanoma was identified in the wide-excision specimen. Examination of the left axillary SLNs revealed metastatic melanoma in 3 of 5 SLNs. Two SLNs demonstrated total replacement by metastatic melanoma. A third SLN revealed a metastatic malignant neoplasm occupying 75% of the nodal area (Figure, A). S-100 and melan-A immunohistochemical staining were negative in this nodule but revealed small aggregates and isolated tumor cells distinct from this nodule that were diagnostic of micrometastatic melanoma (Figures, B and C). The tumor cells in the large nodule were histologically distinct from the melanoma and were instead composed of nests of epithelioid cells with clear cytoplasm (Figure, D). Upon further immunohistochemical staining, this tumor was strongly positive for AE1/AE3 keratin and PIN4 cocktail (cytokeratin 5, cytokeratin 15, p63, and p504s/alpha-methylacyl-CoA-racemase)(Figure, E) with focal positivity for PSA and prostatic acid phosphatase, diagnostic of metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate origin.

A positron emission tomography scan performed a few days after the discovery of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma in the SLNs showed expected postoperative changes (eg, increased activity from procedure-related inflammation) in the left side of the flank and axilla as well as moderately hypermetabolic left supraclavicular lymph nodes suspicious for viable metastatic disease. Subsequent fine-needle aspiration of the aforementioned lymph nodes revealed metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. The preoperative lymphoscintigraphy at the time of SLN biopsy did not show drainage to the left supraclavicular nodal basin.

Based on a discussion of the patient’s case during a multidisciplinary tumor board consultation, the benefit of performing completion lymph node dissection for melanoma management did not outweigh the risks. Accordingly, the patient received adjuvant radiation therapy to the axillary nodal basin. He was started on ketoconazole and zoledronic acid therapy for metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma and was alive with disease at 6-month follow-up. The finding of both metastatic melanoma and prostate adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN after wide excision and SLN biopsy for cutaneous melanoma is a unique report of collision of these 2 tumors. Rare cases of collision between 2 solid tumors occurring in the same lymph node have involved prostate adenocarcinoma as one of the solid tumor components.1,3 Detection of tumor collision on lymph node biopsy between prostatic adenocarcinoma and urothelial carcinoma has been documented in 2 separate cases.1 Three additional cases of concurrent prostatic adenocarcinoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma identified on lymph node biopsy have been reported.1,3 Although never proven statistically, it is likely that these concurrent diagnoses are due to the high incidences of prostate and colorectal adenocarcinomas in the general US population; they are ranked first and third, respectively, for cancer incidence in US males.4

As demonstrated in the current case and the available literature, immunohistochemical stains play a vital role in the detection of tumor collision phenomena as well as identification of histologic source of the metastases. Furthermore, thorough histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens in the context of a patient’s clinical history remains paramount in obtaining an accurate diagnosis. Earlier identification of second malignancies in SLNs can alert the clinician to the presence of relapse of a known concurrent malignancy before it is clinically apparent, enhancing the possibility of more effective treatment of earlier disease. As has been demonstrated for lymphoma and melanoma, in rare cases awareness of the possibility of a second malignancy in the SLN can result in earlier initial diagnosis of undiscovered malignancy.2

- Sughayer MA, Zakarneh L, Abu-Shakra R. Collision metastasis of breast and ovarian adenocarcinoma in axillary lymph nodes: a case report and review of the literature. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:423-427.

- Farma JM, Zager JS, Barnica-Elvir V, et al. A collision of diseases: chronic lymphocytic leukemia discovered during lymph node biopsy for melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1360-1364.

- Wade ZK, Shippey JE, Hamon GA, et al. Collision metastasis of prostatic and colonic adenocarcinoma: report of 2 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:318-320.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11-30.

To the Editor:

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsies routinely are performed to detect regional metastases in a variety of malignancies, including breast cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Histologic examination of an SLN occasionally enables detection of other unsuspected underlying diseases that typically are inflammatory in nature. Although concomitant hematolymphoid malignancy, particularly chronic lymphocytic leukemia, has been reported in SLNs, collision of 2 different solid tumors in the same SLN is rare.1,2 We report a unique case documenting collision of both metastatic melanoma and prostatic adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN to raise awareness of the diagnostic challenges occurring in patients with coexisting malignancies.

A 71-year-old man with a history of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma to the bone presented for treatment of a melanoma that was newly diagnosed by an outside dermatologist. The patient’s medical history was notable for radical prostatectomy performed 15 years prior for treatment of a prostatic adenocarcinoma (Gleason score unknown) followed by bilateral orchiectomy performed 7 years later after his serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level began to rise, with no response to goserelin (a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist) therapy. Two years prior to the diagnosis of metastatic disease, his PSA level started to rise again and the patient received bicalutamide with little improvement, followed by 8 cycles of docetaxel. His PSA level improved and he most recently was being treated with abiraterone acetate. The patient’s latest computed tomography scan showed that the bony metastases secondary to prostatic adenocarcinoma had progressed. His serum PSA level was 105 ng/mL (reference range, <4.0 ng/mL) at the current presentation, elevated from 64 ng/mL one year prior.

Recently, the patient had noted a changing pigmented skin lesion on the left side of the flank. The patient described the lesion as a “black mole” first appearing 2 years prior, which had begun to ooze, change shape, and become darker and more nodular. A shave biopsy revealed a primary cutaneous malignant melanoma at least 3.4 mm in depth with ulceration and a mitotic rate of 15/mm2. No molecular studies were performed on the melanoma. Standard treatment via wide local excision and sentinel lymphadenectomy was planned.

Lymphoscintigraphy revealed 3 left draining axillary lymph nodes. The patient was treated with wide local excision and left axillary SLN biopsy. Five SLNs and 3 non-SLNs were excised. Per protocol, all SLNs were examined pathologically with serial sections: 2 hematoxylin and eosin–stained levels, S-100, and melan-A immunohistochemical stains. No residual melanoma was identified in the wide-excision specimen. Examination of the left axillary SLNs revealed metastatic melanoma in 3 of 5 SLNs. Two SLNs demonstrated total replacement by metastatic melanoma. A third SLN revealed a metastatic malignant neoplasm occupying 75% of the nodal area (Figure, A). S-100 and melan-A immunohistochemical staining were negative in this nodule but revealed small aggregates and isolated tumor cells distinct from this nodule that were diagnostic of micrometastatic melanoma (Figures, B and C). The tumor cells in the large nodule were histologically distinct from the melanoma and were instead composed of nests of epithelioid cells with clear cytoplasm (Figure, D). Upon further immunohistochemical staining, this tumor was strongly positive for AE1/AE3 keratin and PIN4 cocktail (cytokeratin 5, cytokeratin 15, p63, and p504s/alpha-methylacyl-CoA-racemase)(Figure, E) with focal positivity for PSA and prostatic acid phosphatase, diagnostic of metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate origin.

A positron emission tomography scan performed a few days after the discovery of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma in the SLNs showed expected postoperative changes (eg, increased activity from procedure-related inflammation) in the left side of the flank and axilla as well as moderately hypermetabolic left supraclavicular lymph nodes suspicious for viable metastatic disease. Subsequent fine-needle aspiration of the aforementioned lymph nodes revealed metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. The preoperative lymphoscintigraphy at the time of SLN biopsy did not show drainage to the left supraclavicular nodal basin.

Based on a discussion of the patient’s case during a multidisciplinary tumor board consultation, the benefit of performing completion lymph node dissection for melanoma management did not outweigh the risks. Accordingly, the patient received adjuvant radiation therapy to the axillary nodal basin. He was started on ketoconazole and zoledronic acid therapy for metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma and was alive with disease at 6-month follow-up. The finding of both metastatic melanoma and prostate adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN after wide excision and SLN biopsy for cutaneous melanoma is a unique report of collision of these 2 tumors. Rare cases of collision between 2 solid tumors occurring in the same lymph node have involved prostate adenocarcinoma as one of the solid tumor components.1,3 Detection of tumor collision on lymph node biopsy between prostatic adenocarcinoma and urothelial carcinoma has been documented in 2 separate cases.1 Three additional cases of concurrent prostatic adenocarcinoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma identified on lymph node biopsy have been reported.1,3 Although never proven statistically, it is likely that these concurrent diagnoses are due to the high incidences of prostate and colorectal adenocarcinomas in the general US population; they are ranked first and third, respectively, for cancer incidence in US males.4

As demonstrated in the current case and the available literature, immunohistochemical stains play a vital role in the detection of tumor collision phenomena as well as identification of histologic source of the metastases. Furthermore, thorough histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens in the context of a patient’s clinical history remains paramount in obtaining an accurate diagnosis. Earlier identification of second malignancies in SLNs can alert the clinician to the presence of relapse of a known concurrent malignancy before it is clinically apparent, enhancing the possibility of more effective treatment of earlier disease. As has been demonstrated for lymphoma and melanoma, in rare cases awareness of the possibility of a second malignancy in the SLN can result in earlier initial diagnosis of undiscovered malignancy.2

To the Editor:

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsies routinely are performed to detect regional metastases in a variety of malignancies, including breast cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Histologic examination of an SLN occasionally enables detection of other unsuspected underlying diseases that typically are inflammatory in nature. Although concomitant hematolymphoid malignancy, particularly chronic lymphocytic leukemia, has been reported in SLNs, collision of 2 different solid tumors in the same SLN is rare.1,2 We report a unique case documenting collision of both metastatic melanoma and prostatic adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN to raise awareness of the diagnostic challenges occurring in patients with coexisting malignancies.

A 71-year-old man with a history of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma to the bone presented for treatment of a melanoma that was newly diagnosed by an outside dermatologist. The patient’s medical history was notable for radical prostatectomy performed 15 years prior for treatment of a prostatic adenocarcinoma (Gleason score unknown) followed by bilateral orchiectomy performed 7 years later after his serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level began to rise, with no response to goserelin (a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist) therapy. Two years prior to the diagnosis of metastatic disease, his PSA level started to rise again and the patient received bicalutamide with little improvement, followed by 8 cycles of docetaxel. His PSA level improved and he most recently was being treated with abiraterone acetate. The patient’s latest computed tomography scan showed that the bony metastases secondary to prostatic adenocarcinoma had progressed. His serum PSA level was 105 ng/mL (reference range, <4.0 ng/mL) at the current presentation, elevated from 64 ng/mL one year prior.

Recently, the patient had noted a changing pigmented skin lesion on the left side of the flank. The patient described the lesion as a “black mole” first appearing 2 years prior, which had begun to ooze, change shape, and become darker and more nodular. A shave biopsy revealed a primary cutaneous malignant melanoma at least 3.4 mm in depth with ulceration and a mitotic rate of 15/mm2. No molecular studies were performed on the melanoma. Standard treatment via wide local excision and sentinel lymphadenectomy was planned.

Lymphoscintigraphy revealed 3 left draining axillary lymph nodes. The patient was treated with wide local excision and left axillary SLN biopsy. Five SLNs and 3 non-SLNs were excised. Per protocol, all SLNs were examined pathologically with serial sections: 2 hematoxylin and eosin–stained levels, S-100, and melan-A immunohistochemical stains. No residual melanoma was identified in the wide-excision specimen. Examination of the left axillary SLNs revealed metastatic melanoma in 3 of 5 SLNs. Two SLNs demonstrated total replacement by metastatic melanoma. A third SLN revealed a metastatic malignant neoplasm occupying 75% of the nodal area (Figure, A). S-100 and melan-A immunohistochemical staining were negative in this nodule but revealed small aggregates and isolated tumor cells distinct from this nodule that were diagnostic of micrometastatic melanoma (Figures, B and C). The tumor cells in the large nodule were histologically distinct from the melanoma and were instead composed of nests of epithelioid cells with clear cytoplasm (Figure, D). Upon further immunohistochemical staining, this tumor was strongly positive for AE1/AE3 keratin and PIN4 cocktail (cytokeratin 5, cytokeratin 15, p63, and p504s/alpha-methylacyl-CoA-racemase)(Figure, E) with focal positivity for PSA and prostatic acid phosphatase, diagnostic of metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate origin.

A positron emission tomography scan performed a few days after the discovery of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma in the SLNs showed expected postoperative changes (eg, increased activity from procedure-related inflammation) in the left side of the flank and axilla as well as moderately hypermetabolic left supraclavicular lymph nodes suspicious for viable metastatic disease. Subsequent fine-needle aspiration of the aforementioned lymph nodes revealed metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. The preoperative lymphoscintigraphy at the time of SLN biopsy did not show drainage to the left supraclavicular nodal basin.

Based on a discussion of the patient’s case during a multidisciplinary tumor board consultation, the benefit of performing completion lymph node dissection for melanoma management did not outweigh the risks. Accordingly, the patient received adjuvant radiation therapy to the axillary nodal basin. He was started on ketoconazole and zoledronic acid therapy for metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma and was alive with disease at 6-month follow-up. The finding of both metastatic melanoma and prostate adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN after wide excision and SLN biopsy for cutaneous melanoma is a unique report of collision of these 2 tumors. Rare cases of collision between 2 solid tumors occurring in the same lymph node have involved prostate adenocarcinoma as one of the solid tumor components.1,3 Detection of tumor collision on lymph node biopsy between prostatic adenocarcinoma and urothelial carcinoma has been documented in 2 separate cases.1 Three additional cases of concurrent prostatic adenocarcinoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma identified on lymph node biopsy have been reported.1,3 Although never proven statistically, it is likely that these concurrent diagnoses are due to the high incidences of prostate and colorectal adenocarcinomas in the general US population; they are ranked first and third, respectively, for cancer incidence in US males.4

As demonstrated in the current case and the available literature, immunohistochemical stains play a vital role in the detection of tumor collision phenomena as well as identification of histologic source of the metastases. Furthermore, thorough histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens in the context of a patient’s clinical history remains paramount in obtaining an accurate diagnosis. Earlier identification of second malignancies in SLNs can alert the clinician to the presence of relapse of a known concurrent malignancy before it is clinically apparent, enhancing the possibility of more effective treatment of earlier disease. As has been demonstrated for lymphoma and melanoma, in rare cases awareness of the possibility of a second malignancy in the SLN can result in earlier initial diagnosis of undiscovered malignancy.2

- Sughayer MA, Zakarneh L, Abu-Shakra R. Collision metastasis of breast and ovarian adenocarcinoma in axillary lymph nodes: a case report and review of the literature. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:423-427.

- Farma JM, Zager JS, Barnica-Elvir V, et al. A collision of diseases: chronic lymphocytic leukemia discovered during lymph node biopsy for melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1360-1364.

- Wade ZK, Shippey JE, Hamon GA, et al. Collision metastasis of prostatic and colonic adenocarcinoma: report of 2 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:318-320.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11-30.

- Sughayer MA, Zakarneh L, Abu-Shakra R. Collision metastasis of breast and ovarian adenocarcinoma in axillary lymph nodes: a case report and review of the literature. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:423-427.

- Farma JM, Zager JS, Barnica-Elvir V, et al. A collision of diseases: chronic lymphocytic leukemia discovered during lymph node biopsy for melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1360-1364.

- Wade ZK, Shippey JE, Hamon GA, et al. Collision metastasis of prostatic and colonic adenocarcinoma: report of 2 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:318-320.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11-30.

Practice Points

- Immunohistochemical stains play a vital role in the detection of tumor collision phenomena as well as identification of histologic sources of metastases.

- Thorough histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens in the context of a patient’s clinical history remains paramount in obtaining an accurate diagnosis, enhancing the possibility of more effective treatment of earlier disease.

Periorbital Lupuslike Presentation of Graft-versus-host Disease

To the Editor:

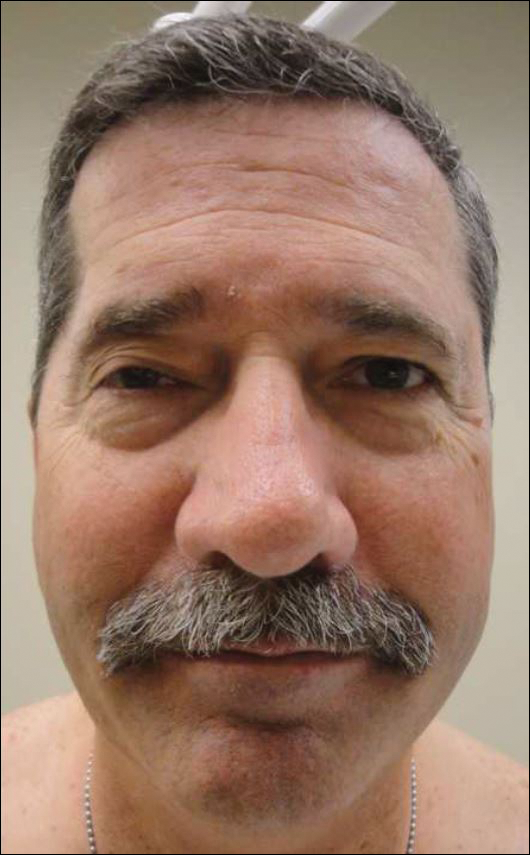

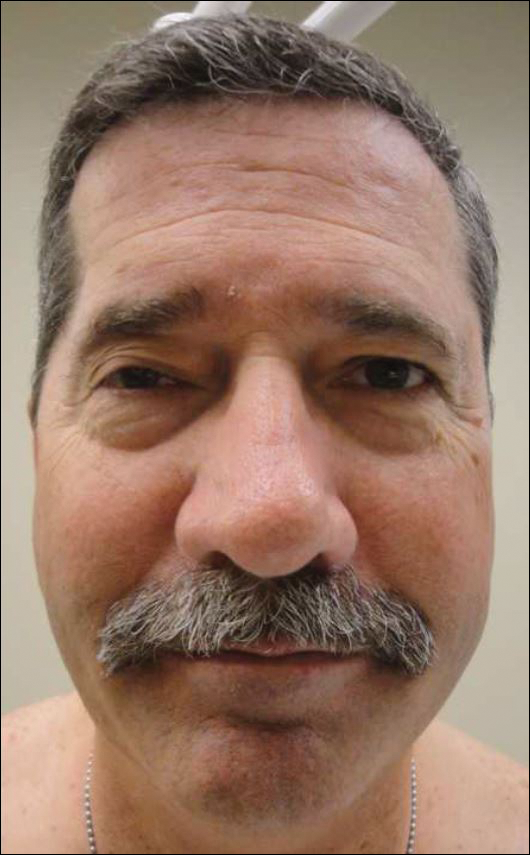

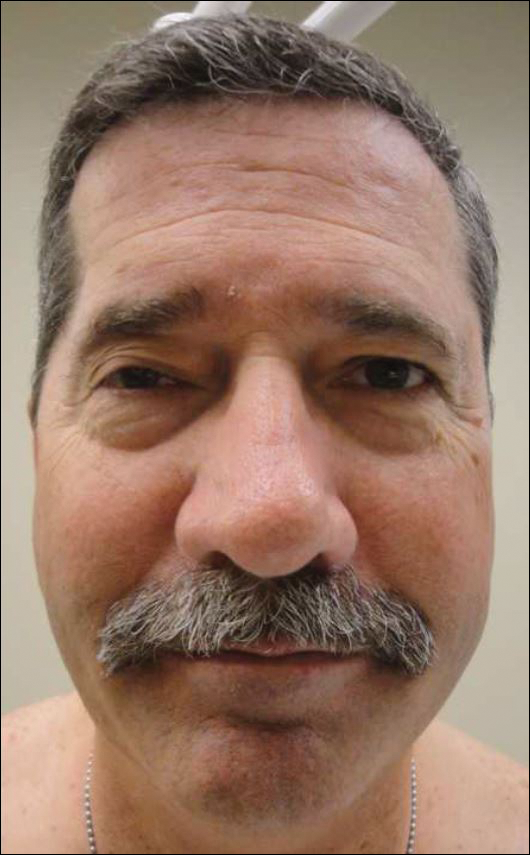

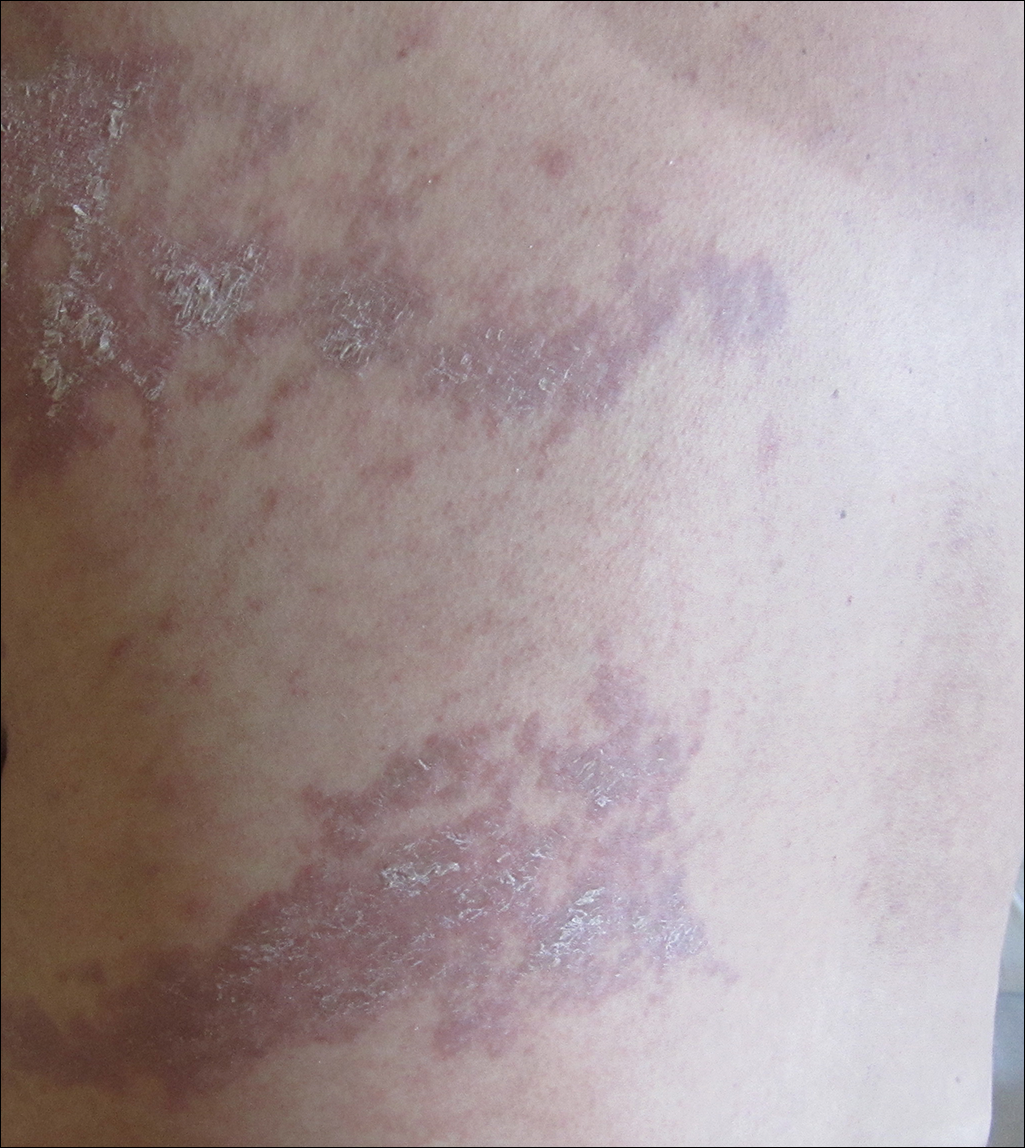

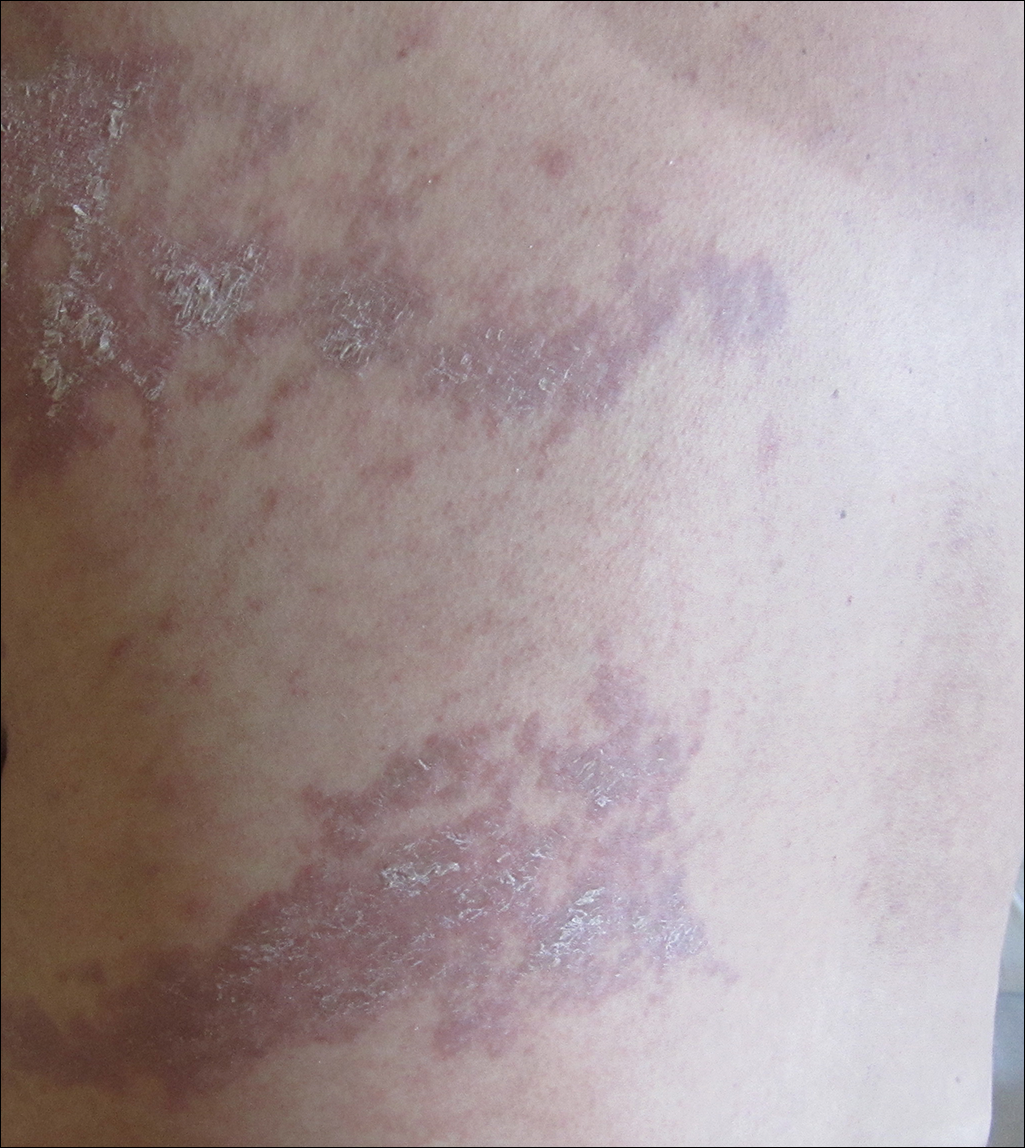

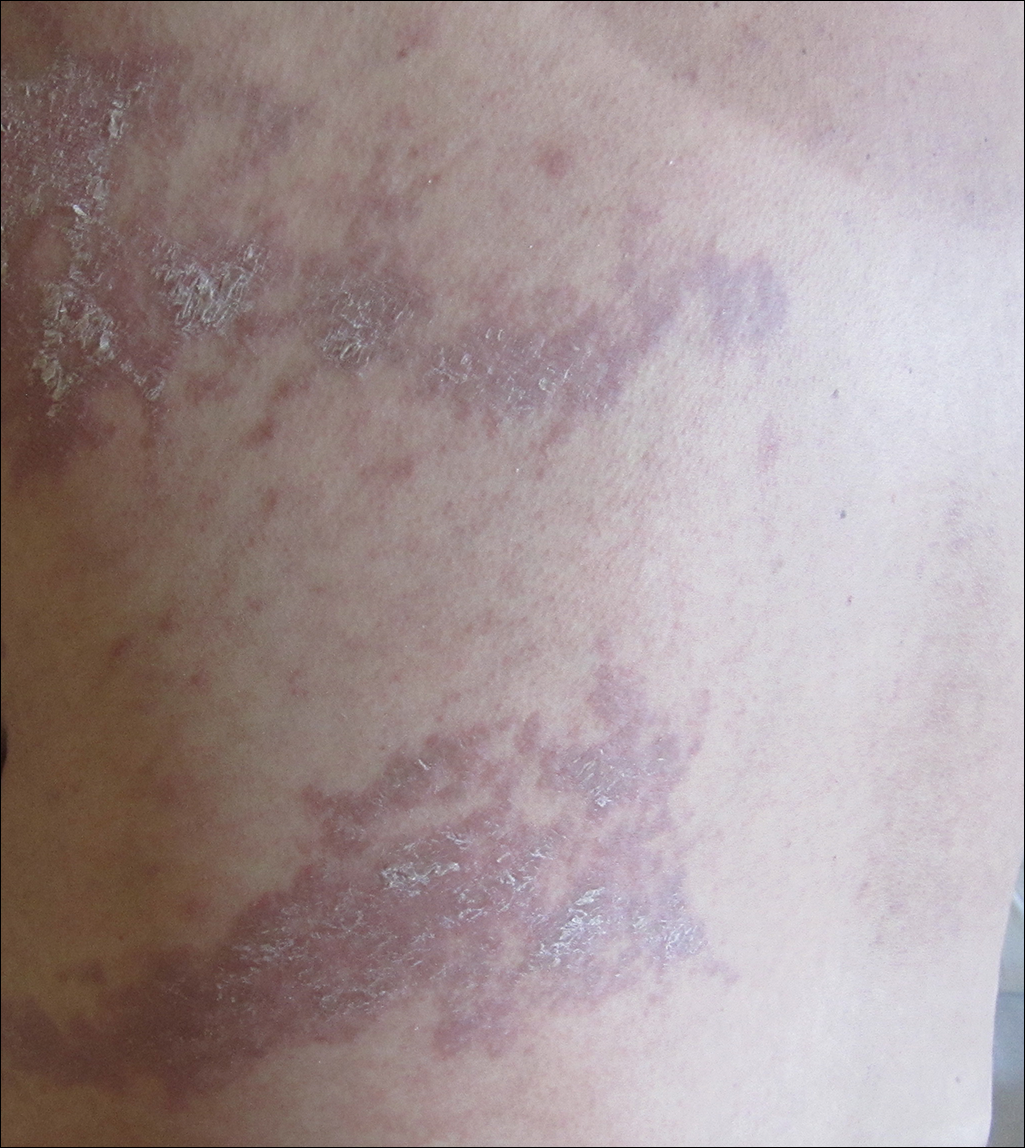

A 79-year-old man presented with a scaling eruption in the periorbital area, on the bilateral forearms, and on the chest of 4 weeks’ duration. The patient denied systemic symptoms including lethargy, muscle weakness, and fevers. His medical history was notable for blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, a form of acute myeloid leukemia, diagnosed 3 years prior to presentation. The patient received an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant 8 months later. His posttransplant course was complicated by gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD); progressive graft loss requiring a donor lymphocyte infusion after 1 month; and leukemia cutis, which spontaneously resolved after 1 month. The patient was taken off all immunosuppressive therapy 5 months after the transplant and had been doing well for 2 years with only mild mucosal GVHD affecting the oral mucosa and the head of the penis.

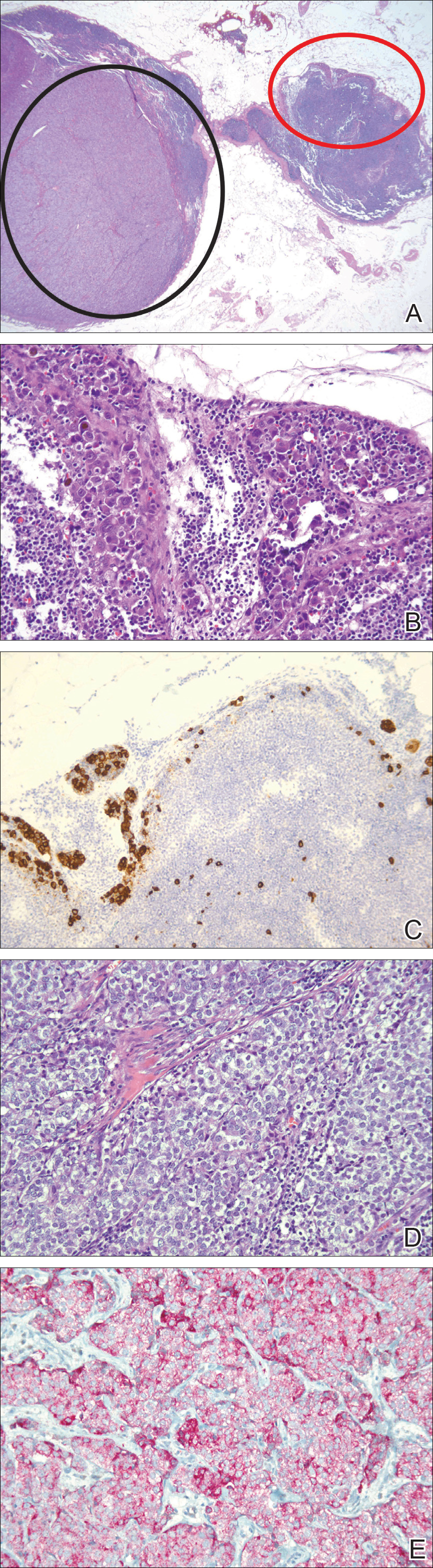

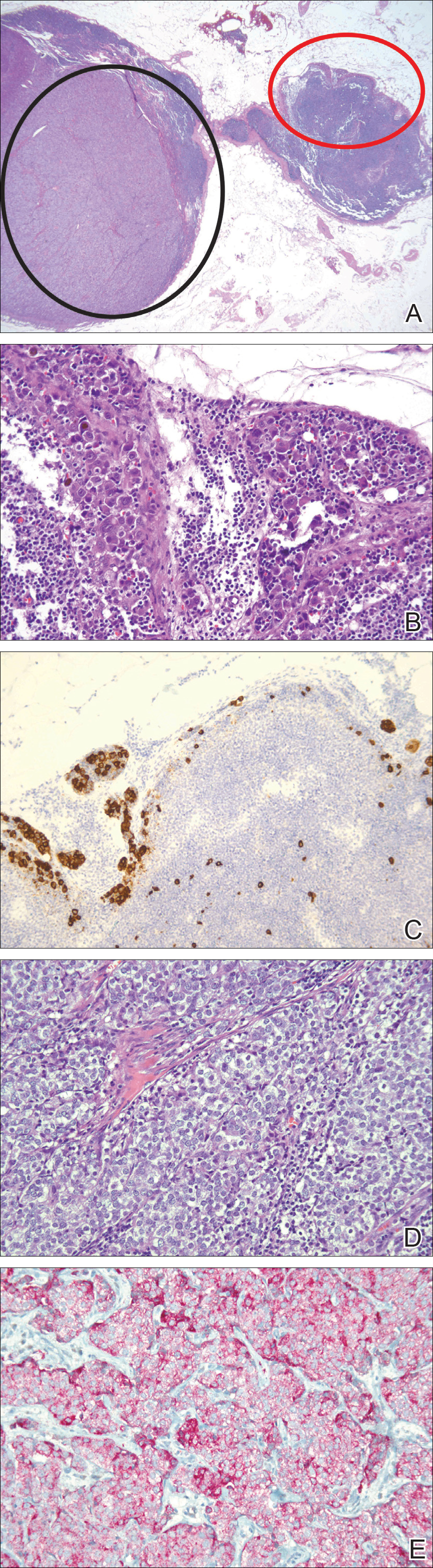

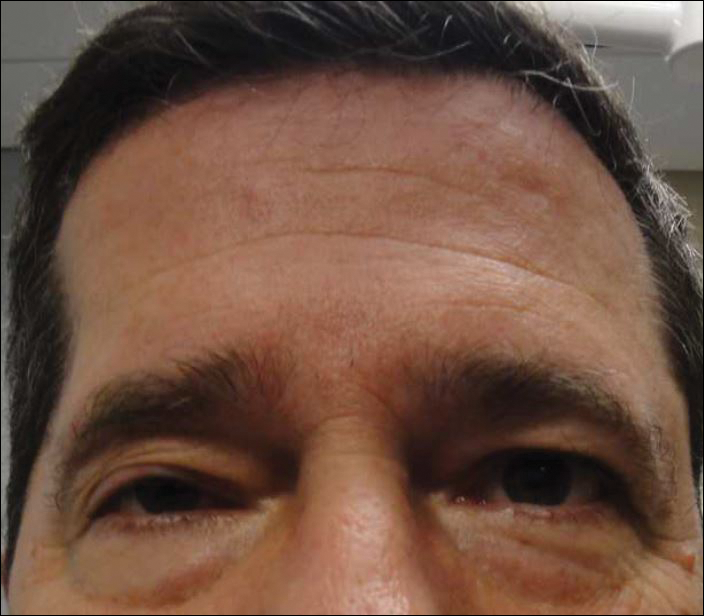

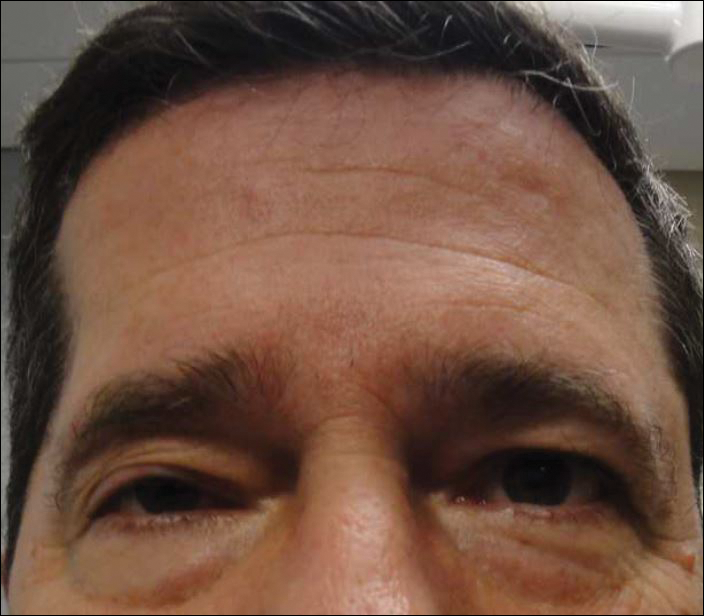

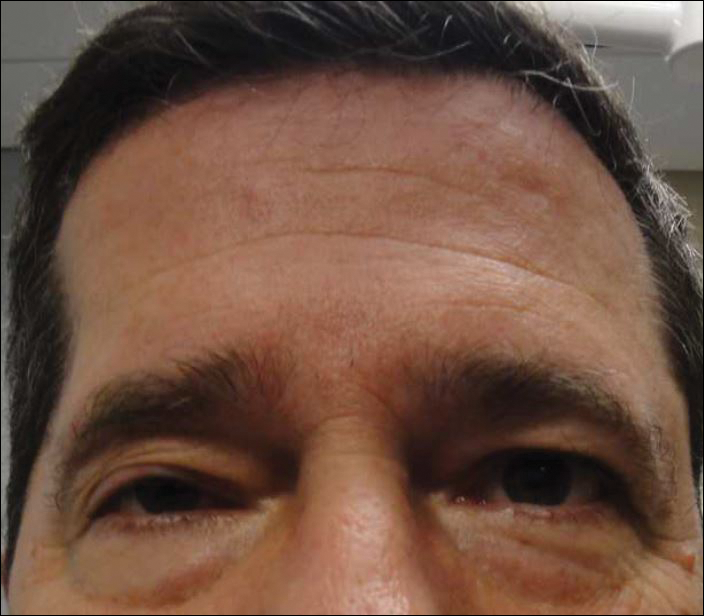

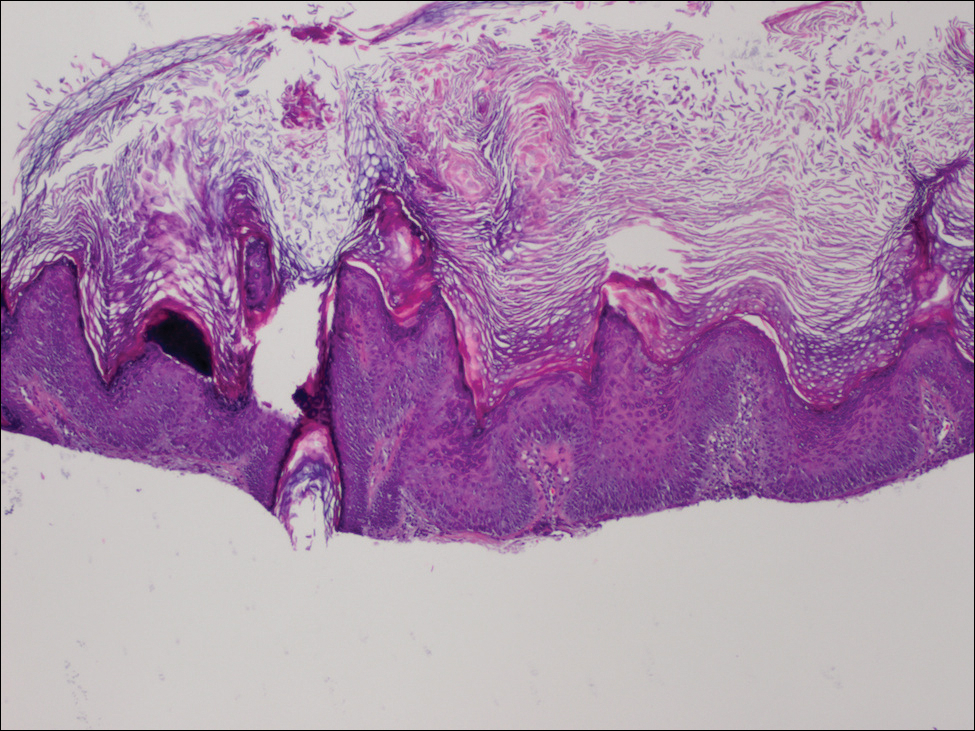

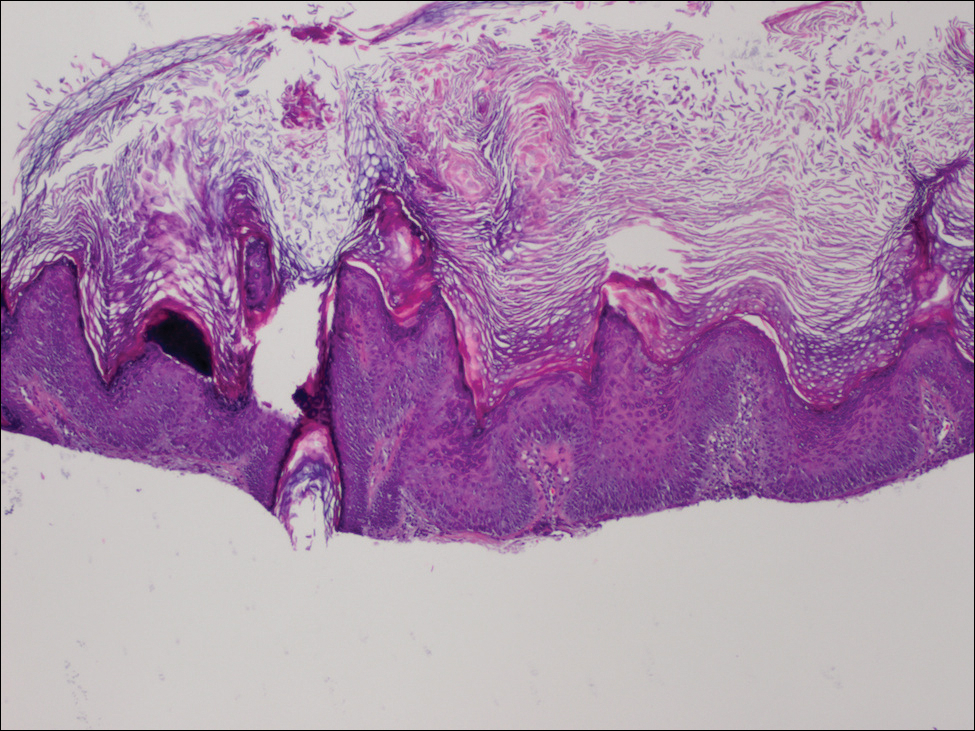

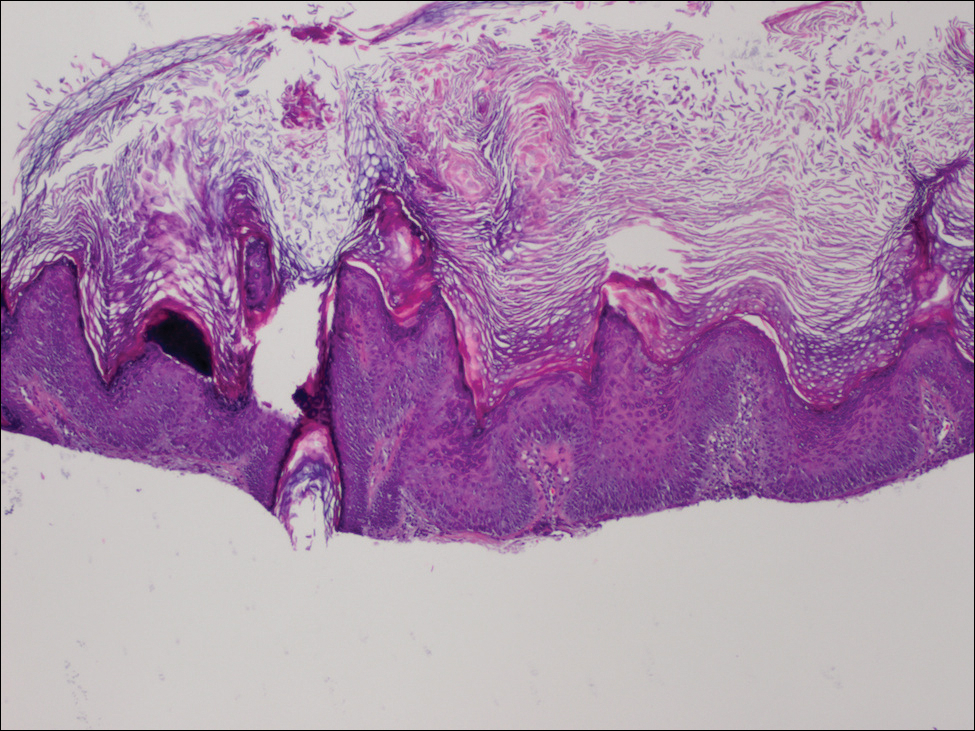

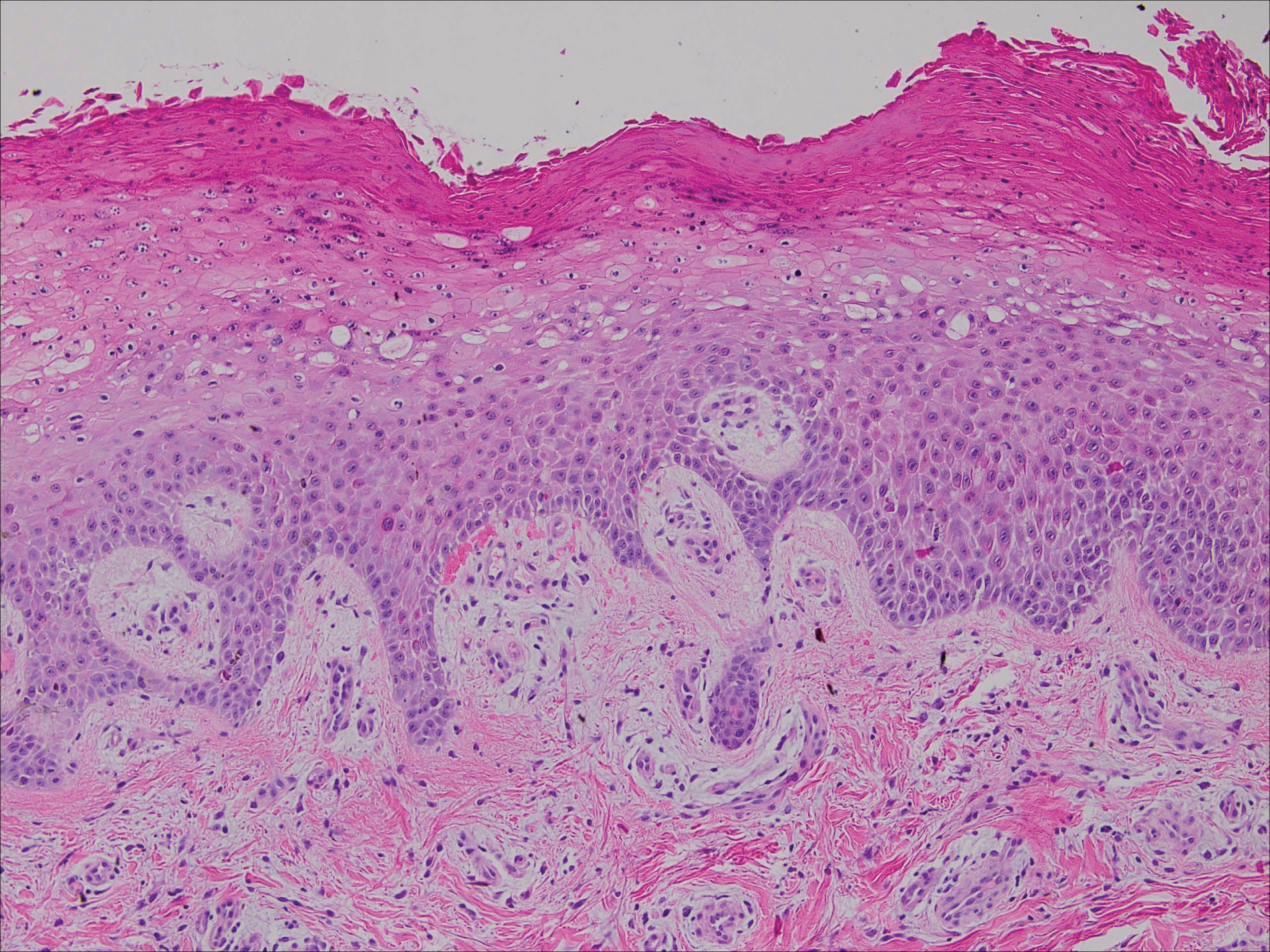

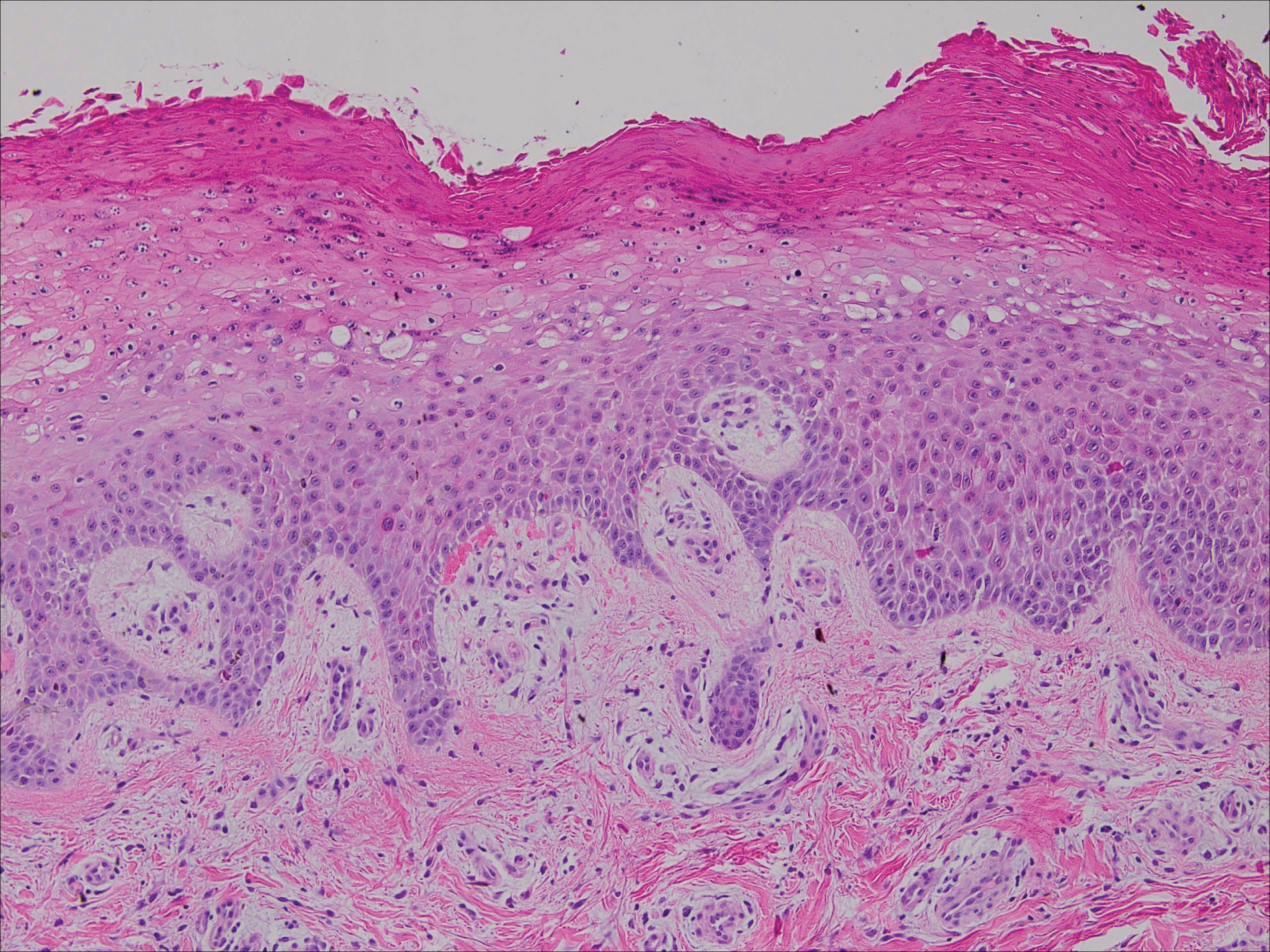

Physical examination at the current presentation revealed linear, atrophic, scaling, purplish plaques with adherent white scale on the upper and lower eyelids (Figure 1). The patient also had scattered purple scaling patches on the bilateral forearms and chest. Laboratory tests including complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lactate dehydrogenase demonstrated no gross abnormalities. Two shave biopsies of the right lower eyelid (Figure 2) and left arm (Figure 3) were performed for histologic examination and revealed basket weave hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, sawtooth rete ridges, and scattered dyskeratotic cells. Vacuolar changes and smudging of the basement membrane zone along with a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis also were noted in both biopsies. A diagnosis of lupuslike grade 1 GVHD was made.

Graft-versus-host disease remains a notable cause of morbidity and mortality in allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients.1 Skin manifestations represent the most common manifestation of GVHD and have been reclassified as acute or chronic disease based on clinical and histologic findings rather than time of onset. Although acute GVHD classically presents as diffuse morbilliform papules and macules, chronic GVHD has a large range of clinical presentations most commonly mimicking the skin findings of lichen planus, morphea, scleroderma, or lichen sclerosus.1

Lupuslike GVHD is a rarely reported manifestation of chronic GVHD that predominantly affects the lower eyelids and malar regions.2,3 Our case documents extensive involvement of both the upper and lower eyelids. A lupuslike manifestation of GVHD may portend a poor prognosis. In a case series of 5 patients with chronic GVHD presenting as facial lupuslike plaques, 1 patient died from a relapse of leukemia and 3 patients developed sclerodermatous GVHD. The fifth patient was lost to follow-up.2 In another case series, a retrospective analysis discovered that 3 of 7 patients with sclerodermatous GVHD initially presented with hyperpigmented periorbital plaques.4 Resolution of skin findings with topical steroids and oral tacrolimus was reported in a case of GVHD presenting with periorbital lupuslike plaques.3 Although further reports are needed to validate the relationship, a lupuslike presentation of chronic GVHD may be an important harbinger for the development of extensive sclerodermatous GVHD.

A diagnosis of lupuslike GVHD is made based on the correlation of a comprehensive medical history, clinical examination, and histopathologic findings. Although other cases of chronic GVHD resembling dermatomyositis presented with purple periorbital plaques, these patients demonstrated dermatomyositislike systemic symptoms including muscle weakness and fatigue, which were not present in our patient.5,6 Antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing is unlikely to be helpful in the diagnosis of this uncommon presentation, as 65% (41/63) of chronic GVHD patients developed ANA antibodies in one study.7 Also, other patients with lupuslike GVHD who progressed to sclerodermatous GVHD have had both positive and negative ANA serology.2 The histopathology of GVHD and lupus erythematosus can exhibit overlapping features, such as lymphocytic infiltrate with interface changes; however, in lupus erythematosus, mucin usually is present, the infiltrate usually is denser and deeper, and a thickened basement membrane zone may be present. Necrotic keratinocytes also usually are not seen in lupus erythematosus unless the patient’s photosensitivity has led to a sunburn reaction.

After his initial presentation, our patient’s mucosal GVHD flared in the mouth and on the penis, and he was started on prednisone 50 mg once daily and mycophenolate mofetil 1 g twice daily. With this treatment, our patient’s periorbital scaling plaques resolved to residual hyperpigmentation along with remarkable improvement of the mucosal GVHD. He has not manifested any signs of leukemia relapse or sclerodermatous GVHD; however, he remains under close clinical evaluation.

This case highlights an unusual presentation of GVHD with periorbital plaques mimicking hypertrophic lupus erythematous. A greater recognition of this rare entity is essential to further elucidate its prognosis and its relationship with sclerodermatous GVHD.

- Hymes SR, Alousi AM, Cowen EW. Graft-versus-host disease: part I. pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:515.e1-5.15e18; quiz 533-534.

- Goiriz R, Peñas PF, Delgado-Jiménez Y, et al. Cutaneous lichenoid graft-versus-host disease mimicking lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2008;17:591-595.

- Hu SW, Myskowski PL, Papadopoulos EB, et al. Chronic cutaneous graft-versus host disease simulating hypertrophic lupus erythematosus—a case report of a new morphologic variant of graft-versus-host disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:E81-E83.

- Chosidow O, Bagot M, Vernant JP, et al. Sclerodermatous chronic graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:49-55.

- Ollivier I, Wolkenstein P, Gherardi R, et al. Dermatomyositis-like graft-versus-host disease. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:558-559.

- Arin MJ, Scheid C, Hübel K, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease with skin signs suggestive of dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:141-143.

- Patriarca F, Skert C, Sperotto A, et al. The development of autoantibodies after allogeneic stem cell transplantation is related with chronic graft-vs-host disease and immune recovery. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:389-396.

To the Editor:

A 79-year-old man presented with a scaling eruption in the periorbital area, on the bilateral forearms, and on the chest of 4 weeks’ duration. The patient denied systemic symptoms including lethargy, muscle weakness, and fevers. His medical history was notable for blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, a form of acute myeloid leukemia, diagnosed 3 years prior to presentation. The patient received an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant 8 months later. His posttransplant course was complicated by gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD); progressive graft loss requiring a donor lymphocyte infusion after 1 month; and leukemia cutis, which spontaneously resolved after 1 month. The patient was taken off all immunosuppressive therapy 5 months after the transplant and had been doing well for 2 years with only mild mucosal GVHD affecting the oral mucosa and the head of the penis.

Physical examination at the current presentation revealed linear, atrophic, scaling, purplish plaques with adherent white scale on the upper and lower eyelids (Figure 1). The patient also had scattered purple scaling patches on the bilateral forearms and chest. Laboratory tests including complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lactate dehydrogenase demonstrated no gross abnormalities. Two shave biopsies of the right lower eyelid (Figure 2) and left arm (Figure 3) were performed for histologic examination and revealed basket weave hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, sawtooth rete ridges, and scattered dyskeratotic cells. Vacuolar changes and smudging of the basement membrane zone along with a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis also were noted in both biopsies. A diagnosis of lupuslike grade 1 GVHD was made.

Graft-versus-host disease remains a notable cause of morbidity and mortality in allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients.1 Skin manifestations represent the most common manifestation of GVHD and have been reclassified as acute or chronic disease based on clinical and histologic findings rather than time of onset. Although acute GVHD classically presents as diffuse morbilliform papules and macules, chronic GVHD has a large range of clinical presentations most commonly mimicking the skin findings of lichen planus, morphea, scleroderma, or lichen sclerosus.1

Lupuslike GVHD is a rarely reported manifestation of chronic GVHD that predominantly affects the lower eyelids and malar regions.2,3 Our case documents extensive involvement of both the upper and lower eyelids. A lupuslike manifestation of GVHD may portend a poor prognosis. In a case series of 5 patients with chronic GVHD presenting as facial lupuslike plaques, 1 patient died from a relapse of leukemia and 3 patients developed sclerodermatous GVHD. The fifth patient was lost to follow-up.2 In another case series, a retrospective analysis discovered that 3 of 7 patients with sclerodermatous GVHD initially presented with hyperpigmented periorbital plaques.4 Resolution of skin findings with topical steroids and oral tacrolimus was reported in a case of GVHD presenting with periorbital lupuslike plaques.3 Although further reports are needed to validate the relationship, a lupuslike presentation of chronic GVHD may be an important harbinger for the development of extensive sclerodermatous GVHD.

A diagnosis of lupuslike GVHD is made based on the correlation of a comprehensive medical history, clinical examination, and histopathologic findings. Although other cases of chronic GVHD resembling dermatomyositis presented with purple periorbital plaques, these patients demonstrated dermatomyositislike systemic symptoms including muscle weakness and fatigue, which were not present in our patient.5,6 Antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing is unlikely to be helpful in the diagnosis of this uncommon presentation, as 65% (41/63) of chronic GVHD patients developed ANA antibodies in one study.7 Also, other patients with lupuslike GVHD who progressed to sclerodermatous GVHD have had both positive and negative ANA serology.2 The histopathology of GVHD and lupus erythematosus can exhibit overlapping features, such as lymphocytic infiltrate with interface changes; however, in lupus erythematosus, mucin usually is present, the infiltrate usually is denser and deeper, and a thickened basement membrane zone may be present. Necrotic keratinocytes also usually are not seen in lupus erythematosus unless the patient’s photosensitivity has led to a sunburn reaction.

After his initial presentation, our patient’s mucosal GVHD flared in the mouth and on the penis, and he was started on prednisone 50 mg once daily and mycophenolate mofetil 1 g twice daily. With this treatment, our patient’s periorbital scaling plaques resolved to residual hyperpigmentation along with remarkable improvement of the mucosal GVHD. He has not manifested any signs of leukemia relapse or sclerodermatous GVHD; however, he remains under close clinical evaluation.

This case highlights an unusual presentation of GVHD with periorbital plaques mimicking hypertrophic lupus erythematous. A greater recognition of this rare entity is essential to further elucidate its prognosis and its relationship with sclerodermatous GVHD.

To the Editor:

A 79-year-old man presented with a scaling eruption in the periorbital area, on the bilateral forearms, and on the chest of 4 weeks’ duration. The patient denied systemic symptoms including lethargy, muscle weakness, and fevers. His medical history was notable for blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, a form of acute myeloid leukemia, diagnosed 3 years prior to presentation. The patient received an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant 8 months later. His posttransplant course was complicated by gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD); progressive graft loss requiring a donor lymphocyte infusion after 1 month; and leukemia cutis, which spontaneously resolved after 1 month. The patient was taken off all immunosuppressive therapy 5 months after the transplant and had been doing well for 2 years with only mild mucosal GVHD affecting the oral mucosa and the head of the penis.

Physical examination at the current presentation revealed linear, atrophic, scaling, purplish plaques with adherent white scale on the upper and lower eyelids (Figure 1). The patient also had scattered purple scaling patches on the bilateral forearms and chest. Laboratory tests including complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lactate dehydrogenase demonstrated no gross abnormalities. Two shave biopsies of the right lower eyelid (Figure 2) and left arm (Figure 3) were performed for histologic examination and revealed basket weave hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, sawtooth rete ridges, and scattered dyskeratotic cells. Vacuolar changes and smudging of the basement membrane zone along with a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis also were noted in both biopsies. A diagnosis of lupuslike grade 1 GVHD was made.

Graft-versus-host disease remains a notable cause of morbidity and mortality in allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients.1 Skin manifestations represent the most common manifestation of GVHD and have been reclassified as acute or chronic disease based on clinical and histologic findings rather than time of onset. Although acute GVHD classically presents as diffuse morbilliform papules and macules, chronic GVHD has a large range of clinical presentations most commonly mimicking the skin findings of lichen planus, morphea, scleroderma, or lichen sclerosus.1

Lupuslike GVHD is a rarely reported manifestation of chronic GVHD that predominantly affects the lower eyelids and malar regions.2,3 Our case documents extensive involvement of both the upper and lower eyelids. A lupuslike manifestation of GVHD may portend a poor prognosis. In a case series of 5 patients with chronic GVHD presenting as facial lupuslike plaques, 1 patient died from a relapse of leukemia and 3 patients developed sclerodermatous GVHD. The fifth patient was lost to follow-up.2 In another case series, a retrospective analysis discovered that 3 of 7 patients with sclerodermatous GVHD initially presented with hyperpigmented periorbital plaques.4 Resolution of skin findings with topical steroids and oral tacrolimus was reported in a case of GVHD presenting with periorbital lupuslike plaques.3 Although further reports are needed to validate the relationship, a lupuslike presentation of chronic GVHD may be an important harbinger for the development of extensive sclerodermatous GVHD.

A diagnosis of lupuslike GVHD is made based on the correlation of a comprehensive medical history, clinical examination, and histopathologic findings. Although other cases of chronic GVHD resembling dermatomyositis presented with purple periorbital plaques, these patients demonstrated dermatomyositislike systemic symptoms including muscle weakness and fatigue, which were not present in our patient.5,6 Antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing is unlikely to be helpful in the diagnosis of this uncommon presentation, as 65% (41/63) of chronic GVHD patients developed ANA antibodies in one study.7 Also, other patients with lupuslike GVHD who progressed to sclerodermatous GVHD have had both positive and negative ANA serology.2 The histopathology of GVHD and lupus erythematosus can exhibit overlapping features, such as lymphocytic infiltrate with interface changes; however, in lupus erythematosus, mucin usually is present, the infiltrate usually is denser and deeper, and a thickened basement membrane zone may be present. Necrotic keratinocytes also usually are not seen in lupus erythematosus unless the patient’s photosensitivity has led to a sunburn reaction.

After his initial presentation, our patient’s mucosal GVHD flared in the mouth and on the penis, and he was started on prednisone 50 mg once daily and mycophenolate mofetil 1 g twice daily. With this treatment, our patient’s periorbital scaling plaques resolved to residual hyperpigmentation along with remarkable improvement of the mucosal GVHD. He has not manifested any signs of leukemia relapse or sclerodermatous GVHD; however, he remains under close clinical evaluation.

This case highlights an unusual presentation of GVHD with periorbital plaques mimicking hypertrophic lupus erythematous. A greater recognition of this rare entity is essential to further elucidate its prognosis and its relationship with sclerodermatous GVHD.

- Hymes SR, Alousi AM, Cowen EW. Graft-versus-host disease: part I. pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:515.e1-5.15e18; quiz 533-534.

- Goiriz R, Peñas PF, Delgado-Jiménez Y, et al. Cutaneous lichenoid graft-versus-host disease mimicking lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2008;17:591-595.

- Hu SW, Myskowski PL, Papadopoulos EB, et al. Chronic cutaneous graft-versus host disease simulating hypertrophic lupus erythematosus—a case report of a new morphologic variant of graft-versus-host disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:E81-E83.

- Chosidow O, Bagot M, Vernant JP, et al. Sclerodermatous chronic graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:49-55.

- Ollivier I, Wolkenstein P, Gherardi R, et al. Dermatomyositis-like graft-versus-host disease. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:558-559.

- Arin MJ, Scheid C, Hübel K, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease with skin signs suggestive of dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:141-143.

- Patriarca F, Skert C, Sperotto A, et al. The development of autoantibodies after allogeneic stem cell transplantation is related with chronic graft-vs-host disease and immune recovery. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:389-396.

- Hymes SR, Alousi AM, Cowen EW. Graft-versus-host disease: part I. pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:515.e1-5.15e18; quiz 533-534.

- Goiriz R, Peñas PF, Delgado-Jiménez Y, et al. Cutaneous lichenoid graft-versus-host disease mimicking lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2008;17:591-595.

- Hu SW, Myskowski PL, Papadopoulos EB, et al. Chronic cutaneous graft-versus host disease simulating hypertrophic lupus erythematosus—a case report of a new morphologic variant of graft-versus-host disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:E81-E83.

- Chosidow O, Bagot M, Vernant JP, et al. Sclerodermatous chronic graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:49-55.

- Ollivier I, Wolkenstein P, Gherardi R, et al. Dermatomyositis-like graft-versus-host disease. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:558-559.

- Arin MJ, Scheid C, Hübel K, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease with skin signs suggestive of dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:141-143.

- Patriarca F, Skert C, Sperotto A, et al. The development of autoantibodies after allogeneic stem cell transplantation is related with chronic graft-vs-host disease and immune recovery. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:389-396.

Complete Remission of Metastatic Merkel Cell Carcinoma in a Patient With Severe Psoriasis

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old white man presented with a skin lesion on the back of 1 to 2 weeks’ duration. The patient stated he was unaware of it, but his wife had recently noticed the new spot. He denied any bleeding, pain, pruritus, or other associated symptoms with the lesion. He also denied any prior treatment to the area. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for severe psoriasis involving more than 80% body surface area, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, coronary artery disease, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic keratoses. He had been on multiple treatment regimens over the last 20 years for control of psoriasis including topical corticosteroids, psoralen plus UVA and UVB phototherapy, gold injections, acitretin, prednisone, efalizumab, ustekinumab, and alefacept upon evaluation of this new skin lesion. Utilization of immunosuppressive agents also provided an additional benefit of controlling the patient’s inflammatory arthritic disease.

On physical examination a 0.6×0.7-cm, pink to erythematous, pearly papule with superficial telangiectases was noted on the right side of the dorsal thorax (Figure 1). Multiple well-demarcated erythematous plaques with silvery scale and areas of secondary excoriation were noted on the trunk and both legs consistent with the patient’s history of psoriasis.

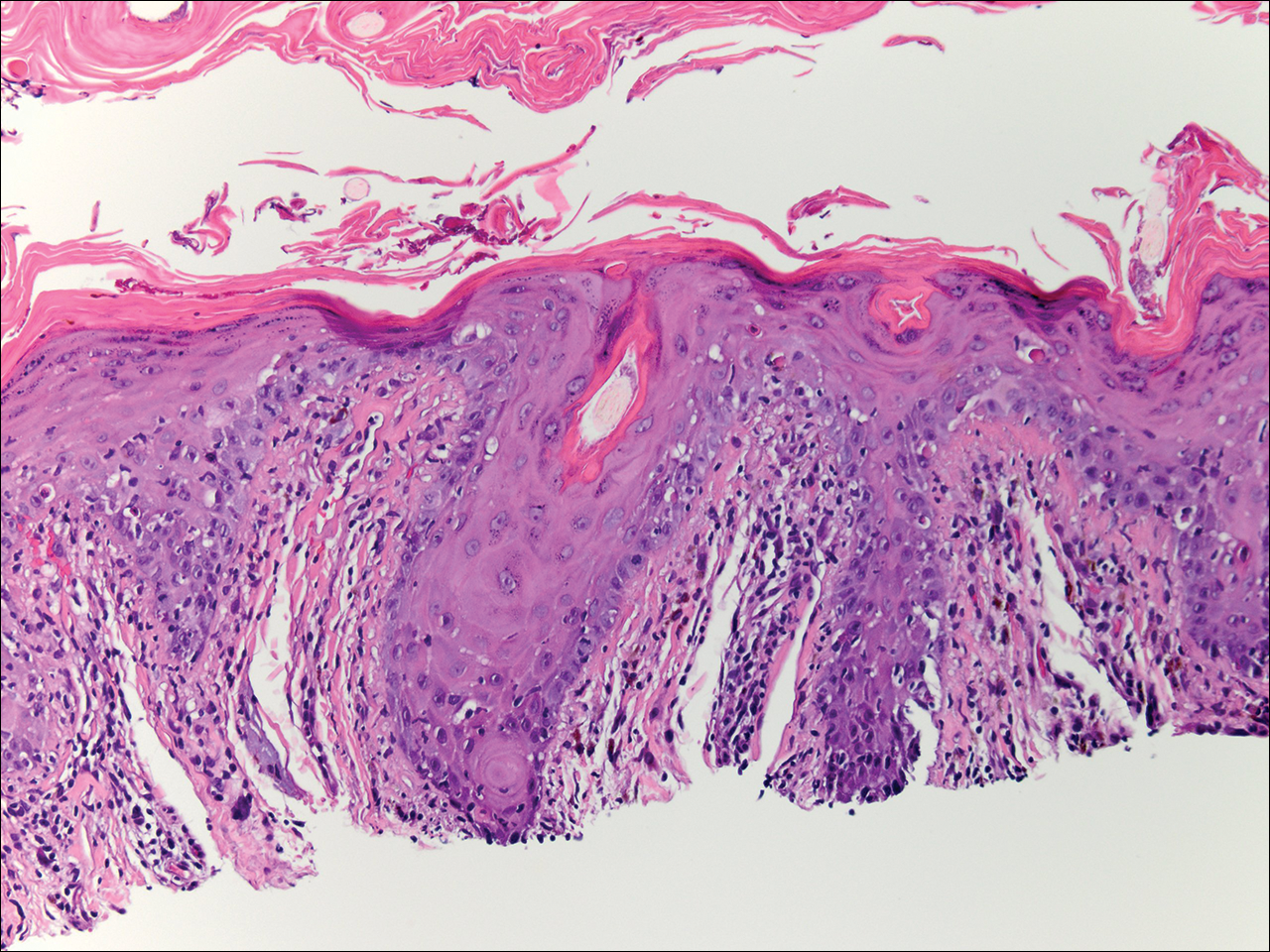

A shave biopsy was performed on the skin lesion on the right side of the dorsal thorax with a suspected clinical diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. Two weeks later the patient returned for a discussion of the pathology report, which revealed nodules of basaloid cells with tightly packed vesicular nuclei and scant cytoplasm in sheets within the superficial dermis, as well as areas of nuclear molding, numerous mitotic figures, and areas of focal necrosis (Figure 2). In addition, immunostaining was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 20 antibodies with a characteristic paranuclear dot uptake of the antibody. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). At that time, alefacept was discontinued and he was referred to a tertiary referral center for further evaluation and treatment.

The patient subsequently underwent wide excision with 1-cm margins of the MCC, with intraoperative lymphatic mapping/sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) of the right axillary nodal basin 1 month later, which he tolerated well without any associated complications. Further histopathologic examination revealed the deep, medial, and lateral surgical margins to be negative of residual neoplasm. However, one sentinel lymph node indicated positivity for micrometastatic MCC, consistent with stage IIIA disease progression.

He underwent a second procedure the following month for complete right axillary lymph node dissection. Histopathologic examination of the right axillary contents included 28 lymph nodes, which were negative for carcinoma. He continued to do well without any signs of clinical recurrence or distant metastasis at subsequent follow-up visits.

Approximately 2.5 years after the second procedure, the patient began to develop right upper quadrant abdominal pain of an unclear etiology. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, revealing areas of calcification and findings consistent with malignant lymphadenopathy. Multiple hepatic lesions also were noted including a 9-cm lesion in the posterior right hepatic lobe. Computed tomography–guided biopsy of the liver lesion was performed and the findings were consistent with metastatic MCC, indicating progression to stage IV disease.

The patient was subsequently started on combination chemotherapeutic treatment with carboplatin and VP-16, with a planned treatment course of 4 to 6 cycles. He was able to complete a total of 6 cycles over a 4-month period, tolerating the treatment regimen fairly well. Follow-up positron emission tomography–computed tomography was within normal limits with no evidence of any hypermetabolic activity noted, indicating a complete radiographic remission of MCC. He was seen approximately 1 month after completion of treatment for clinical follow-up and monthly thereafter.

While on chemotherapy, the patient experienced a notable improvement in the psoriasis and psoriatic joint disease. Upon completion of chemotherapy, he was restarted on the same treatment plan that was utilized prior to surgery including topical corticosteroids, calcitriol, intramuscular steroid injections, and UVB phototherapy, which provided substantial control of psoriasis and arthritic joint disease. The patient later died, likely due to his multiple comorbidities.

Merkel cells are slow-responding mechanoreceptors located within the basal layer of the epidermis and are the source of a rare aggressive cutaneous malignancy.1 Merkel cell carcinoma was first noted in 1972 and termed trabecular carcinoma of the skin, and it accounts for less than 1% of all nonmelanoma skin cancer.2,3 This primary neuroendocrine carcinoma has remarkable metastatic potential (34%–75%) and can invade regional lymph nodes, as well as distant metastasis most commonly to the liver, lungs, bones, and brain.2 Approximately 25% of patients present with palpable lymphadenopathy and 5% with distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis. This frequency of metastasis at diagnosis as well as the recurrence after treatment contributes to the poor prognosis of MCC. Local recurrence rates have been reported at 25% with lymph node involvement in 52% and metastasis in 34%, with most recurrences occurring within 2 years of diagnosis. Patient mortality is dependent on the aggressiveness of the tumor, with 5-year survival rates of 83.3% without lymph node involvement, 58.3% with lymph node involvement, and 31.3% in those with metastatic disease.4

The tumor classically presents as a red to violaceous, painless nodule with a smooth shiny surface most often on the head and neck region.4-6 Approximately 50% of MCC cases present in the head and neck region, 32% to 38% on the extremities, and 12% to 14% on the trunk.1 This nonspecific presentation may lead to diagnostic uncertainty and a consequent delay in treatment. Definitive diagnosis of MCC is achieved with a skin biopsy and allows for distinction from other clinically similar–appearing neoplasms. Merkel cell carcinoma presents histologically as small round basophilic cells penetrating through the dermis in 3 histologic patterns: the trabecular, intermediate (80% of cases), and small cell type.5 It may be differentiated immunohistochemically from other neoplasms, as it displays CK20 positivity (showing paranuclear dotlike depositions in the cytoplasm or cell membrane) and is negative for CK7. Chromagranin and synaptophysin positivity also may provide further histologic confirmation. In addition, absence of peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a fibromyxoid stroma allow for distinction from cutaneous basal cell carcinoma, which may display these features histologically. Other immunohistochemical markers that may be of value include thyroid transcription factor 1, which is typically positive in cutaneous metastasis of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung; S-100 and human melanoma black 45, which are positive in melanoma; and leukocyte common antigen (CD45), which can be positive in lymphoma. These stains are classically negative in MCC.3

Merkel cell carcinoma is commonly associated with the presence of Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) in tumor specimens, with a prevalence of 70% to 80% in all cases. Merkel cell polyomavirus is a class 2A carcinogen (ie, a probable carcinogen to humans) and is classified among a group of viruses that encode T antigens (ie, an antigen coded by a viral genome associated with transformation of infected cells by tumor viruses), which can lead to initiation of tumorigenesis through interference with cellular tumor suppressing proteins such as p53.5 In addition, several risk factors have been associated with the development of MCC including immunosuppression, older age (>50 years), and UV-exposed fair skin.7 One explanation for this phenomenon is the increase in MCPyV small T antigen transcripts induced by UV irradiation.5 In addition, as with other cancers induced by viruses, host immunity can impede tumor progression and development. Therefore, impairment of normal immune function likely creates a higher risk for MCC development and potential for a worse prognosis.3Although the exact incidence of MCC in immunosuppressed patients appears unclear, chronic immunosuppressive therapy may play a notable role in the pathogenesis of the tumor.3

Although each of these factors was observed in our patient, it also was possible that his associated comorbidities further contributed to disease presentation. In particular, rheumatoid arthritis has been shown to carry an increased risk for the development of MCC.8 In addition, inflammatory monocytes infected with MCPyV, as evidenced in a patient with a history of chronic psoriasis prior to diagnosis of MCC, also may contribute to the pathogenesis of MCC by traveling to inflammatory skin lesions, such as those seen in psoriasis, releasing MCPyV locally and infecting Merkel cells.9 Although MCPyV testing was never performed in our patient, it certainly would be prudent as well as further studies determining the correlation of MCC to these disease processes.

Although regression is rare, multiple cases have documented spontaneous regression of MCC after biopsy of these lesions.4,6,10 The exact mechanism is unclear, but apoptosis induced by T-cell immunity is suspected to play a role. Programmed cell death 1 protein (PD-1)–positive cells play a role. The PD-1 receptor is an inhibitory receptor expressed by T cells and in approximately half of tumor-infiltrating cells in MCC. It was found that in a regressed case of MCC there was a notably lower percentage of PD-1 positivity compared to cases with no apparent regression, suggesting that PD-1–positive cells suppress tumor immunity to MCC and that significant reduction in these cells may induce clinical regression.10 Additional investigation would be beneficial to examine the relationship of this phenomenon to tumor regression.

Initial evaluation of these patients should include a meticulous clinical examination with an emphasis on detection of cutaneous, lymph node, and distant metastasis. Due to the risk of metastatic potential, regional lymph node ultrasonography and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis typically are recommended at baseline. Other imaging modalities may be warranted based on clinical findings.3 Treatment modalities include various approaches, with surgical excision of the primary tumor with more than 1-cm margin to the fascial plane being the primary modality for uncomplicated cases.1,3,7 In addition, SLNB also should be performed at the time of the procedure. In the case of a positive SLNB or suspected regional lymph node involvement upon initial examination, radical regional lymph node dissection also is recommended.3 Although some authorities advocate postsurgical radiation therapy to minimize the risk of local recurrence, there does not appear to be a clear benefit in survival rate.3,5 However, radiation treatment as monotherapy has been advocated in certain instances, particularly in cases of unresectable tumors or patients who are poor surgical candidates.5,7 Cases of distant metastasis (stage IV disease) may include management with surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy. Although none of these modalities have consistently shown to improve survival, there appears to be up to a 60% response with chemotherapy in these patients.3

Because MCC tends to affect an older population, often with other notable comorbidities, important considerations involving a treatment plan include the cost, side effects, and convenience for patients. The combination of carboplatin and VP-16 (etoposide) was utilized and tolerated well in our patient, and it has been successful in achieving complete radiologic and clinical remission of his metastatic disease. This combination appears to prolong survival in patients with distant metastasis, as compared to those patients not receiving chemotherapy.1 Our patient has since died, but in these high-risk patients, close clinical monitoring is essential to help optimize their prognosis.

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare aggressive cutaneous neoplasm that most commonly affects the elderly, immunosuppressed, and those with chronic UV sun damage. An association between the oncogenesis of MCC and infection with MCPyV has been documented, but other underlying diseases also may play a role in this process including rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. Although these risk factors were associated with our patient, his history of chronic immunosuppressive therapy for treatment of his psoriasis and inflammatory joint disease likely played a role in the pathogenesis of the tumor and should be an important point of discussion with any patient requiring this type of long-term management for disease control. Our unique clinical case highlights a patient with substantial comorbidities who developed metastatic MCC and achieved complete clinical and radiologic remission after treatment with surgery and chemotherapy.

- Timmer FC, Klop WM, Relyveld GN, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: emphasizing the risk of undertreatment [published online March 11, 2015]. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:1243-1252.

- Açıkalın A, Paydas¸ S, Güleç ÜK, et al. A unique case of Merkel cell carcinoma with ovarian metastasis [published online December 1, 2014]. Balkan Med J. 2014;31:356-359.

- Samimi M, Gardair C, Nicol JT, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma: clinical and therapeutic perspectives [published online Dec 31, 2014]. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:347-358.

- Grandhaye M, Teixeira PG, Henrot P, et al. Focus on Merkel cell carcinoma: diagnosis and staging [published online January 30, 2015]. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44:777-786.

- Chatzinasiou F, Papadavid E, Korkolopoulou P, et al. An unusual case of diffuse Merkel cell carcinoma successfully treated with low dose radiotherapy [published online May 14, 2015]. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:282-286.

- Pang C, Sharma D, Sankar T. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature [published online November 13, 2014]. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7C:104-108.

- Kitamura N, Tomita R, Yamamoto M, et al. Complete remission of Merkel cell carcinoma on the upper lip treated with radiation monotherapy and a literature review of Japanese cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:152.

- Lanoy E, Engels EA. Skin cancers associated with autoimmune conditions among elderly adults [published online June 15, 2010]. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:112-114.

- Mertz KD, Junt T, Schmid M, et al. Inflammatory monocytes are a reservoir for Merkel cell polyomavirus [published online December 17, 2009]. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;130:1146-1151.

- Fujimoto N, Nakanishi G, Kabuto M, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma showing regression after biopsy: evaluation of programmed cell death 1-positive cells [published online February 24, 2015]. J Dermatol. 2015;42:496-499.

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old white man presented with a skin lesion on the back of 1 to 2 weeks’ duration. The patient stated he was unaware of it, but his wife had recently noticed the new spot. He denied any bleeding, pain, pruritus, or other associated symptoms with the lesion. He also denied any prior treatment to the area. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for severe psoriasis involving more than 80% body surface area, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, coronary artery disease, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic keratoses. He had been on multiple treatment regimens over the last 20 years for control of psoriasis including topical corticosteroids, psoralen plus UVA and UVB phototherapy, gold injections, acitretin, prednisone, efalizumab, ustekinumab, and alefacept upon evaluation of this new skin lesion. Utilization of immunosuppressive agents also provided an additional benefit of controlling the patient’s inflammatory arthritic disease.

On physical examination a 0.6×0.7-cm, pink to erythematous, pearly papule with superficial telangiectases was noted on the right side of the dorsal thorax (Figure 1). Multiple well-demarcated erythematous plaques with silvery scale and areas of secondary excoriation were noted on the trunk and both legs consistent with the patient’s history of psoriasis.

A shave biopsy was performed on the skin lesion on the right side of the dorsal thorax with a suspected clinical diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. Two weeks later the patient returned for a discussion of the pathology report, which revealed nodules of basaloid cells with tightly packed vesicular nuclei and scant cytoplasm in sheets within the superficial dermis, as well as areas of nuclear molding, numerous mitotic figures, and areas of focal necrosis (Figure 2). In addition, immunostaining was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 20 antibodies with a characteristic paranuclear dot uptake of the antibody. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). At that time, alefacept was discontinued and he was referred to a tertiary referral center for further evaluation and treatment.

The patient subsequently underwent wide excision with 1-cm margins of the MCC, with intraoperative lymphatic mapping/sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) of the right axillary nodal basin 1 month later, which he tolerated well without any associated complications. Further histopathologic examination revealed the deep, medial, and lateral surgical margins to be negative of residual neoplasm. However, one sentinel lymph node indicated positivity for micrometastatic MCC, consistent with stage IIIA disease progression.

He underwent a second procedure the following month for complete right axillary lymph node dissection. Histopathologic examination of the right axillary contents included 28 lymph nodes, which were negative for carcinoma. He continued to do well without any signs of clinical recurrence or distant metastasis at subsequent follow-up visits.

Approximately 2.5 years after the second procedure, the patient began to develop right upper quadrant abdominal pain of an unclear etiology. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, revealing areas of calcification and findings consistent with malignant lymphadenopathy. Multiple hepatic lesions also were noted including a 9-cm lesion in the posterior right hepatic lobe. Computed tomography–guided biopsy of the liver lesion was performed and the findings were consistent with metastatic MCC, indicating progression to stage IV disease.

The patient was subsequently started on combination chemotherapeutic treatment with carboplatin and VP-16, with a planned treatment course of 4 to 6 cycles. He was able to complete a total of 6 cycles over a 4-month period, tolerating the treatment regimen fairly well. Follow-up positron emission tomography–computed tomography was within normal limits with no evidence of any hypermetabolic activity noted, indicating a complete radiographic remission of MCC. He was seen approximately 1 month after completion of treatment for clinical follow-up and monthly thereafter.

While on chemotherapy, the patient experienced a notable improvement in the psoriasis and psoriatic joint disease. Upon completion of chemotherapy, he was restarted on the same treatment plan that was utilized prior to surgery including topical corticosteroids, calcitriol, intramuscular steroid injections, and UVB phototherapy, which provided substantial control of psoriasis and arthritic joint disease. The patient later died, likely due to his multiple comorbidities.

Merkel cells are slow-responding mechanoreceptors located within the basal layer of the epidermis and are the source of a rare aggressive cutaneous malignancy.1 Merkel cell carcinoma was first noted in 1972 and termed trabecular carcinoma of the skin, and it accounts for less than 1% of all nonmelanoma skin cancer.2,3 This primary neuroendocrine carcinoma has remarkable metastatic potential (34%–75%) and can invade regional lymph nodes, as well as distant metastasis most commonly to the liver, lungs, bones, and brain.2 Approximately 25% of patients present with palpable lymphadenopathy and 5% with distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis. This frequency of metastasis at diagnosis as well as the recurrence after treatment contributes to the poor prognosis of MCC. Local recurrence rates have been reported at 25% with lymph node involvement in 52% and metastasis in 34%, with most recurrences occurring within 2 years of diagnosis. Patient mortality is dependent on the aggressiveness of the tumor, with 5-year survival rates of 83.3% without lymph node involvement, 58.3% with lymph node involvement, and 31.3% in those with metastatic disease.4

The tumor classically presents as a red to violaceous, painless nodule with a smooth shiny surface most often on the head and neck region.4-6 Approximately 50% of MCC cases present in the head and neck region, 32% to 38% on the extremities, and 12% to 14% on the trunk.1 This nonspecific presentation may lead to diagnostic uncertainty and a consequent delay in treatment. Definitive diagnosis of MCC is achieved with a skin biopsy and allows for distinction from other clinically similar–appearing neoplasms. Merkel cell carcinoma presents histologically as small round basophilic cells penetrating through the dermis in 3 histologic patterns: the trabecular, intermediate (80% of cases), and small cell type.5 It may be differentiated immunohistochemically from other neoplasms, as it displays CK20 positivity (showing paranuclear dotlike depositions in the cytoplasm or cell membrane) and is negative for CK7. Chromagranin and synaptophysin positivity also may provide further histologic confirmation. In addition, absence of peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a fibromyxoid stroma allow for distinction from cutaneous basal cell carcinoma, which may display these features histologically. Other immunohistochemical markers that may be of value include thyroid transcription factor 1, which is typically positive in cutaneous metastasis of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung; S-100 and human melanoma black 45, which are positive in melanoma; and leukocyte common antigen (CD45), which can be positive in lymphoma. These stains are classically negative in MCC.3

Merkel cell carcinoma is commonly associated with the presence of Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) in tumor specimens, with a prevalence of 70% to 80% in all cases. Merkel cell polyomavirus is a class 2A carcinogen (ie, a probable carcinogen to humans) and is classified among a group of viruses that encode T antigens (ie, an antigen coded by a viral genome associated with transformation of infected cells by tumor viruses), which can lead to initiation of tumorigenesis through interference with cellular tumor suppressing proteins such as p53.5 In addition, several risk factors have been associated with the development of MCC including immunosuppression, older age (>50 years), and UV-exposed fair skin.7 One explanation for this phenomenon is the increase in MCPyV small T antigen transcripts induced by UV irradiation.5 In addition, as with other cancers induced by viruses, host immunity can impede tumor progression and development. Therefore, impairment of normal immune function likely creates a higher risk for MCC development and potential for a worse prognosis.3Although the exact incidence of MCC in immunosuppressed patients appears unclear, chronic immunosuppressive therapy may play a notable role in the pathogenesis of the tumor.3

Although each of these factors was observed in our patient, it also was possible that his associated comorbidities further contributed to disease presentation. In particular, rheumatoid arthritis has been shown to carry an increased risk for the development of MCC.8 In addition, inflammatory monocytes infected with MCPyV, as evidenced in a patient with a history of chronic psoriasis prior to diagnosis of MCC, also may contribute to the pathogenesis of MCC by traveling to inflammatory skin lesions, such as those seen in psoriasis, releasing MCPyV locally and infecting Merkel cells.9 Although MCPyV testing was never performed in our patient, it certainly would be prudent as well as further studies determining the correlation of MCC to these disease processes.

Although regression is rare, multiple cases have documented spontaneous regression of MCC after biopsy of these lesions.4,6,10 The exact mechanism is unclear, but apoptosis induced by T-cell immunity is suspected to play a role. Programmed cell death 1 protein (PD-1)–positive cells play a role. The PD-1 receptor is an inhibitory receptor expressed by T cells and in approximately half of tumor-infiltrating cells in MCC. It was found that in a regressed case of MCC there was a notably lower percentage of PD-1 positivity compared to cases with no apparent regression, suggesting that PD-1–positive cells suppress tumor immunity to MCC and that significant reduction in these cells may induce clinical regression.10 Additional investigation would be beneficial to examine the relationship of this phenomenon to tumor regression.

Initial evaluation of these patients should include a meticulous clinical examination with an emphasis on detection of cutaneous, lymph node, and distant metastasis. Due to the risk of metastatic potential, regional lymph node ultrasonography and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis typically are recommended at baseline. Other imaging modalities may be warranted based on clinical findings.3 Treatment modalities include various approaches, with surgical excision of the primary tumor with more than 1-cm margin to the fascial plane being the primary modality for uncomplicated cases.1,3,7 In addition, SLNB also should be performed at the time of the procedure. In the case of a positive SLNB or suspected regional lymph node involvement upon initial examination, radical regional lymph node dissection also is recommended.3 Although some authorities advocate postsurgical radiation therapy to minimize the risk of local recurrence, there does not appear to be a clear benefit in survival rate.3,5 However, radiation treatment as monotherapy has been advocated in certain instances, particularly in cases of unresectable tumors or patients who are poor surgical candidates.5,7 Cases of distant metastasis (stage IV disease) may include management with surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy. Although none of these modalities have consistently shown to improve survival, there appears to be up to a 60% response with chemotherapy in these patients.3

Because MCC tends to affect an older population, often with other notable comorbidities, important considerations involving a treatment plan include the cost, side effects, and convenience for patients. The combination of carboplatin and VP-16 (etoposide) was utilized and tolerated well in our patient, and it has been successful in achieving complete radiologic and clinical remission of his metastatic disease. This combination appears to prolong survival in patients with distant metastasis, as compared to those patients not receiving chemotherapy.1 Our patient has since died, but in these high-risk patients, close clinical monitoring is essential to help optimize their prognosis.

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare aggressive cutaneous neoplasm that most commonly affects the elderly, immunosuppressed, and those with chronic UV sun damage. An association between the oncogenesis of MCC and infection with MCPyV has been documented, but other underlying diseases also may play a role in this process including rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. Although these risk factors were associated with our patient, his history of chronic immunosuppressive therapy for treatment of his psoriasis and inflammatory joint disease likely played a role in the pathogenesis of the tumor and should be an important point of discussion with any patient requiring this type of long-term management for disease control. Our unique clinical case highlights a patient with substantial comorbidities who developed metastatic MCC and achieved complete clinical and radiologic remission after treatment with surgery and chemotherapy.

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old white man presented with a skin lesion on the back of 1 to 2 weeks’ duration. The patient stated he was unaware of it, but his wife had recently noticed the new spot. He denied any bleeding, pain, pruritus, or other associated symptoms with the lesion. He also denied any prior treatment to the area. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for severe psoriasis involving more than 80% body surface area, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, coronary artery disease, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic keratoses. He had been on multiple treatment regimens over the last 20 years for control of psoriasis including topical corticosteroids, psoralen plus UVA and UVB phototherapy, gold injections, acitretin, prednisone, efalizumab, ustekinumab, and alefacept upon evaluation of this new skin lesion. Utilization of immunosuppressive agents also provided an additional benefit of controlling the patient’s inflammatory arthritic disease.

On physical examination a 0.6×0.7-cm, pink to erythematous, pearly papule with superficial telangiectases was noted on the right side of the dorsal thorax (Figure 1). Multiple well-demarcated erythematous plaques with silvery scale and areas of secondary excoriation were noted on the trunk and both legs consistent with the patient’s history of psoriasis.

A shave biopsy was performed on the skin lesion on the right side of the dorsal thorax with a suspected clinical diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. Two weeks later the patient returned for a discussion of the pathology report, which revealed nodules of basaloid cells with tightly packed vesicular nuclei and scant cytoplasm in sheets within the superficial dermis, as well as areas of nuclear molding, numerous mitotic figures, and areas of focal necrosis (Figure 2). In addition, immunostaining was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 20 antibodies with a characteristic paranuclear dot uptake of the antibody. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). At that time, alefacept was discontinued and he was referred to a tertiary referral center for further evaluation and treatment.

The patient subsequently underwent wide excision with 1-cm margins of the MCC, with intraoperative lymphatic mapping/sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) of the right axillary nodal basin 1 month later, which he tolerated well without any associated complications. Further histopathologic examination revealed the deep, medial, and lateral surgical margins to be negative of residual neoplasm. However, one sentinel lymph node indicated positivity for micrometastatic MCC, consistent with stage IIIA disease progression.

He underwent a second procedure the following month for complete right axillary lymph node dissection. Histopathologic examination of the right axillary contents included 28 lymph nodes, which were negative for carcinoma. He continued to do well without any signs of clinical recurrence or distant metastasis at subsequent follow-up visits.

Approximately 2.5 years after the second procedure, the patient began to develop right upper quadrant abdominal pain of an unclear etiology. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, revealing areas of calcification and findings consistent with malignant lymphadenopathy. Multiple hepatic lesions also were noted including a 9-cm lesion in the posterior right hepatic lobe. Computed tomography–guided biopsy of the liver lesion was performed and the findings were consistent with metastatic MCC, indicating progression to stage IV disease.

The patient was subsequently started on combination chemotherapeutic treatment with carboplatin and VP-16, with a planned treatment course of 4 to 6 cycles. He was able to complete a total of 6 cycles over a 4-month period, tolerating the treatment regimen fairly well. Follow-up positron emission tomography–computed tomography was within normal limits with no evidence of any hypermetabolic activity noted, indicating a complete radiographic remission of MCC. He was seen approximately 1 month after completion of treatment for clinical follow-up and monthly thereafter.

While on chemotherapy, the patient experienced a notable improvement in the psoriasis and psoriatic joint disease. Upon completion of chemotherapy, he was restarted on the same treatment plan that was utilized prior to surgery including topical corticosteroids, calcitriol, intramuscular steroid injections, and UVB phototherapy, which provided substantial control of psoriasis and arthritic joint disease. The patient later died, likely due to his multiple comorbidities.

Merkel cells are slow-responding mechanoreceptors located within the basal layer of the epidermis and are the source of a rare aggressive cutaneous malignancy.1 Merkel cell carcinoma was first noted in 1972 and termed trabecular carcinoma of the skin, and it accounts for less than 1% of all nonmelanoma skin cancer.2,3 This primary neuroendocrine carcinoma has remarkable metastatic potential (34%–75%) and can invade regional lymph nodes, as well as distant metastasis most commonly to the liver, lungs, bones, and brain.2 Approximately 25% of patients present with palpable lymphadenopathy and 5% with distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis. This frequency of metastasis at diagnosis as well as the recurrence after treatment contributes to the poor prognosis of MCC. Local recurrence rates have been reported at 25% with lymph node involvement in 52% and metastasis in 34%, with most recurrences occurring within 2 years of diagnosis. Patient mortality is dependent on the aggressiveness of the tumor, with 5-year survival rates of 83.3% without lymph node involvement, 58.3% with lymph node involvement, and 31.3% in those with metastatic disease.4

The tumor classically presents as a red to violaceous, painless nodule with a smooth shiny surface most often on the head and neck region.4-6 Approximately 50% of MCC cases present in the head and neck region, 32% to 38% on the extremities, and 12% to 14% on the trunk.1 This nonspecific presentation may lead to diagnostic uncertainty and a consequent delay in treatment. Definitive diagnosis of MCC is achieved with a skin biopsy and allows for distinction from other clinically similar–appearing neoplasms. Merkel cell carcinoma presents histologically as small round basophilic cells penetrating through the dermis in 3 histologic patterns: the trabecular, intermediate (80% of cases), and small cell type.5 It may be differentiated immunohistochemically from other neoplasms, as it displays CK20 positivity (showing paranuclear dotlike depositions in the cytoplasm or cell membrane) and is negative for CK7. Chromagranin and synaptophysin positivity also may provide further histologic confirmation. In addition, absence of peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a fibromyxoid stroma allow for distinction from cutaneous basal cell carcinoma, which may display these features histologically. Other immunohistochemical markers that may be of value include thyroid transcription factor 1, which is typically positive in cutaneous metastasis of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung; S-100 and human melanoma black 45, which are positive in melanoma; and leukocyte common antigen (CD45), which can be positive in lymphoma. These stains are classically negative in MCC.3

Merkel cell carcinoma is commonly associated with the presence of Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) in tumor specimens, with a prevalence of 70% to 80% in all cases. Merkel cell polyomavirus is a class 2A carcinogen (ie, a probable carcinogen to humans) and is classified among a group of viruses that encode T antigens (ie, an antigen coded by a viral genome associated with transformation of infected cells by tumor viruses), which can lead to initiation of tumorigenesis through interference with cellular tumor suppressing proteins such as p53.5 In addition, several risk factors have been associated with the development of MCC including immunosuppression, older age (>50 years), and UV-exposed fair skin.7 One explanation for this phenomenon is the increase in MCPyV small T antigen transcripts induced by UV irradiation.5 In addition, as with other cancers induced by viruses, host immunity can impede tumor progression and development. Therefore, impairment of normal immune function likely creates a higher risk for MCC development and potential for a worse prognosis.3Although the exact incidence of MCC in immunosuppressed patients appears unclear, chronic immunosuppressive therapy may play a notable role in the pathogenesis of the tumor.3