User login

Microneedling With Bimatoprost to Treat Hypopigmented Skin Caused by Burn Scars

To the Editor:

Microneedling is a percutaneous collagen induction therapy frequently used in cosmetic dermatology to promote skin rejuvenation and hair growth and to treat scars by taking advantage of the body’s natural wound-healing cascade.1 The procedure works by generating thousands of microscopic wounds in the dermis with minimal damage to the epidermis, thus initiating the wound-healing cascade and subsequently promoting collagen production in a manner safe for all Fitzpatrick classification skin types.1-3 This therapy effectively treats scars by breaking down scarred collagen and replacing it with new healthy collagen. Microneedling also has application in drug delivery by increasing the permeability of the skin; the microwounds generated can serve as a portal for drug delivery.4

Bimatoprost is a prostaglandin analogue typically used to treat hypotrichosis and open-angle glaucoma.5-7 A known side effect of bimatoprost is hyperpigmentation of surrounding skin; the drug increases melanogenesis, melanocyte proliferation, and melanocyte dendricity, resulting in activation of the inflammatory response and subsequent prostaglandin release, which stimulates melanogenesis. This effect is similar to UV radiation–induced inflammation and hyperpigmentation.6,8

Capitalizing on this effect, a novel application of bimatoprost has been proposed—treating vitiligo, in which hypopigmentation results from destruction of melanocytes in certain areas of the skin. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% utilized as an off-label treatment for vitiligo has been shown to notably increase melanogenesis and return pigmentation to hypopigmented areas.8-10

A 32-year-old Black woman presented to our clinic with a 40×15-cm scar that was marked by postinflammatory hypopigmentation from a second-degree burn on the right proximal arm. The patient had been burned 5 months prior by boiling water that was spilled on the arm while cooking. She had immediately sought treatment at an emergency department and subsequently in a burn unit, where the burn was debrided twice; medication was not prescribed to continue treatment. The patient reported that the scarring and hypopigmentation had taken a psychologic toll; her hope was to have pigmentation restored to the affected area to boost her confidence.

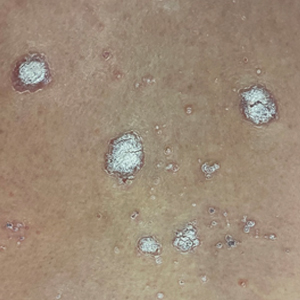

Physical examination revealed that the burn wound had healed but visible scarring and severe hypopigmentation due to destroyed melanocytes remained (Figure 1). To inhibit inflammation and stimulate repigmentation, we prescribed the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus ointment 0.1% to be applied daily to the affected area. The patient returned to the clinic 1 month later. Perifollicular hyperpigmentation was noted at the site of the scar.

Monthly microneedling sessions with bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% were started. To avoid damaging any potentially remaining unhealed hypodermis and vasculature, the first microneedling session was performed with 9 needles set at minimal needle depth and frequency. The number of needles and their depth and frequency gradually were increased with each subsequent treatment. The patient continued tacrolimus ointment 0.1% throughout the course of treatment.

For each microneedling procedure, a handheld motorized microneedling device was applied to the skin at a depth of 0.25 mm, which was gradually increased until pinpoint petechiae were achieved. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% was then painted on the skin and allowed to absorb. Microneedling was performed again, ensuring that bimatoprost entered the skin in the area of the burn scar.

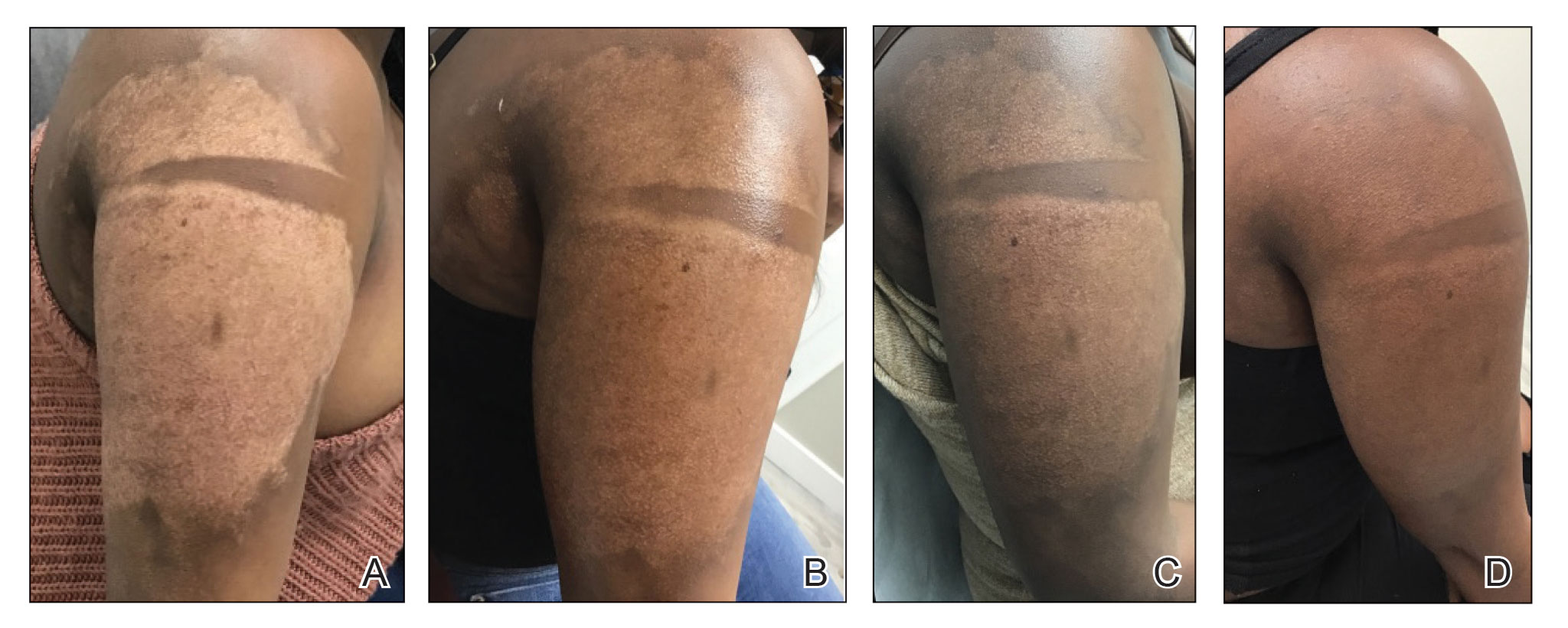

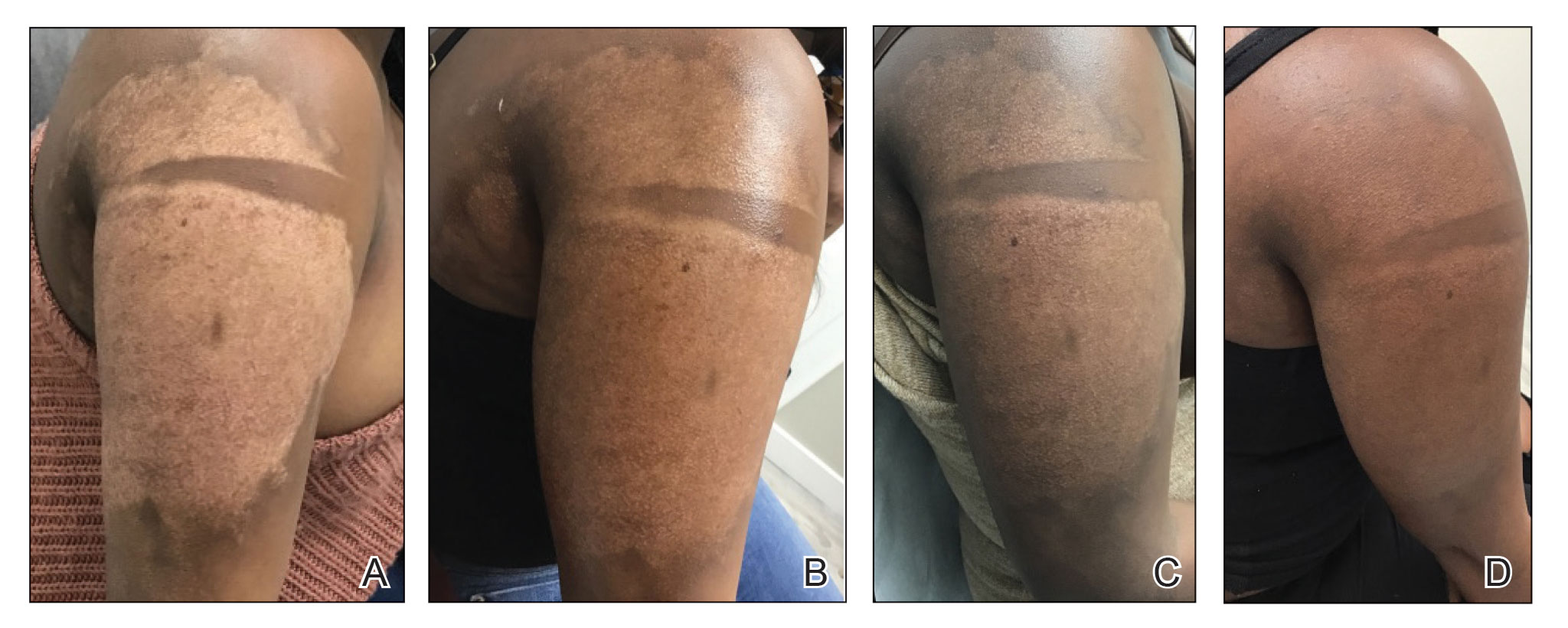

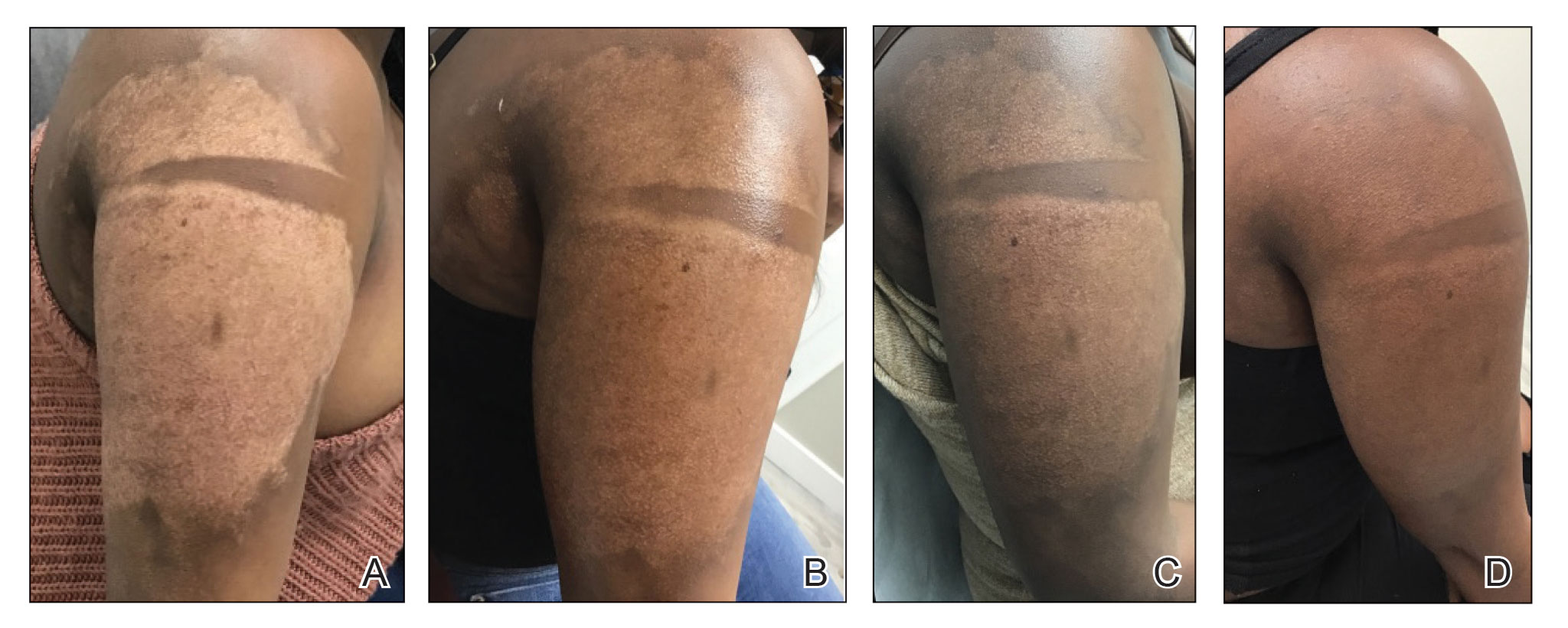

Microneedling procedures were performed monthly for 6 months, then once 3 months later, and once more 3 months later—8 treatments in total over the course of 1 year. Improvement in skin pigmentation was noted at each visit (Figure 2). Repigmentation was first noticed surrounding hair follicles; after later visits, it was observed that pigmentation began to spread from hair follicles to fill in remaining skin. The darkest areas of pigmentation were first noted around hair follicles; over time, melanocytes appeared to spontaneously regenerate and fill in surrounding areas as the scar continued to heal. The patient continued use of tacrolimus during the entire course of microneedling treatments and for the following 4 months. Sixteen months after initiation of treatment, the appearance of the skin was texturally smooth and returned to almost its original pigmentation (Figure 3).

We report a successful outcome in a patient with a hypopigmented burn scar who was treated with bimatoprost administered with traditional microneedling and alongside a tacrolimus regimen. Tacrolimus ointment inhibited the inflammatory response to allow melanocytes to heal and regenerate; bimatoprost and microneedling promoted hyperpigmentation of hair follicles in the affected area, eventually restoring pigmentation to the entire area. Our patient was extremely satisfied with the results of this combination treatment. She has reported feeling more confident going out and wearing short-sleeved clothing. Percutaneous drug delivery of bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% combined with topical tacrolimus may be an effective treatment for skin repigmentation. Further investigation of this regimen is needed to develop standardized treatment protocols.

- Juhasz MLW, Cohen JL. Micro-needling for the treatment of scars: an update for clinicians. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2020;13:997-1003. doi:10.2147/CCID.S267192

- Alster TS, Li MKY. Micro-needling of scars: a large prospective study with long-term follow-up. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145:358-364. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000006462

- Aust MC, Knobloch K, Reimers K, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction therapy: an alternative treatment for burn scars. Burns. 2010;36:836-843. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2009.11.014

- Kim Y-C, Park J-H, Prausnitz MR. Microneedles for drug and vaccine delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:1547-1568. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2012.04.005

- Doshi M, Edward DP, Osmanovic S. Clinical course of bimatoprost-induced periocular skin changes in Caucasians. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1961-1967. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.041

- Kapur R, Osmanovic S, Toyran S, et al. Bimatoprost-induced periocular skin hyperpigmentation: histopathological study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1541-1546. doi:10.1001/archopht.123.11.1541

- Priluck JC, Fu S. Latisse-induced periocular skin hyperpigmentation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:792-793. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.89

- Grimes PE. Bimatoprost 0.03% solution for the treatment of nonfacial vitiligo. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:703-710.

- Barbulescu C, Goldstein N, Roop D, et al. Harnessing the power of regenerative therapy for vitiligo and alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140: 29-37. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2019.03.1142

- Kanokrungsee S, Pruettivorawongse D, Rajatanavin N. Clinicaloutcomes of topical bimatoprost for nonsegmental facial vitiligo: a preliminary study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:812-818. doi.org/10.1111/jocd.13648

To the Editor:

Microneedling is a percutaneous collagen induction therapy frequently used in cosmetic dermatology to promote skin rejuvenation and hair growth and to treat scars by taking advantage of the body’s natural wound-healing cascade.1 The procedure works by generating thousands of microscopic wounds in the dermis with minimal damage to the epidermis, thus initiating the wound-healing cascade and subsequently promoting collagen production in a manner safe for all Fitzpatrick classification skin types.1-3 This therapy effectively treats scars by breaking down scarred collagen and replacing it with new healthy collagen. Microneedling also has application in drug delivery by increasing the permeability of the skin; the microwounds generated can serve as a portal for drug delivery.4

Bimatoprost is a prostaglandin analogue typically used to treat hypotrichosis and open-angle glaucoma.5-7 A known side effect of bimatoprost is hyperpigmentation of surrounding skin; the drug increases melanogenesis, melanocyte proliferation, and melanocyte dendricity, resulting in activation of the inflammatory response and subsequent prostaglandin release, which stimulates melanogenesis. This effect is similar to UV radiation–induced inflammation and hyperpigmentation.6,8

Capitalizing on this effect, a novel application of bimatoprost has been proposed—treating vitiligo, in which hypopigmentation results from destruction of melanocytes in certain areas of the skin. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% utilized as an off-label treatment for vitiligo has been shown to notably increase melanogenesis and return pigmentation to hypopigmented areas.8-10

A 32-year-old Black woman presented to our clinic with a 40×15-cm scar that was marked by postinflammatory hypopigmentation from a second-degree burn on the right proximal arm. The patient had been burned 5 months prior by boiling water that was spilled on the arm while cooking. She had immediately sought treatment at an emergency department and subsequently in a burn unit, where the burn was debrided twice; medication was not prescribed to continue treatment. The patient reported that the scarring and hypopigmentation had taken a psychologic toll; her hope was to have pigmentation restored to the affected area to boost her confidence.

Physical examination revealed that the burn wound had healed but visible scarring and severe hypopigmentation due to destroyed melanocytes remained (Figure 1). To inhibit inflammation and stimulate repigmentation, we prescribed the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus ointment 0.1% to be applied daily to the affected area. The patient returned to the clinic 1 month later. Perifollicular hyperpigmentation was noted at the site of the scar.

Monthly microneedling sessions with bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% were started. To avoid damaging any potentially remaining unhealed hypodermis and vasculature, the first microneedling session was performed with 9 needles set at minimal needle depth and frequency. The number of needles and their depth and frequency gradually were increased with each subsequent treatment. The patient continued tacrolimus ointment 0.1% throughout the course of treatment.

For each microneedling procedure, a handheld motorized microneedling device was applied to the skin at a depth of 0.25 mm, which was gradually increased until pinpoint petechiae were achieved. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% was then painted on the skin and allowed to absorb. Microneedling was performed again, ensuring that bimatoprost entered the skin in the area of the burn scar.

Microneedling procedures were performed monthly for 6 months, then once 3 months later, and once more 3 months later—8 treatments in total over the course of 1 year. Improvement in skin pigmentation was noted at each visit (Figure 2). Repigmentation was first noticed surrounding hair follicles; after later visits, it was observed that pigmentation began to spread from hair follicles to fill in remaining skin. The darkest areas of pigmentation were first noted around hair follicles; over time, melanocytes appeared to spontaneously regenerate and fill in surrounding areas as the scar continued to heal. The patient continued use of tacrolimus during the entire course of microneedling treatments and for the following 4 months. Sixteen months after initiation of treatment, the appearance of the skin was texturally smooth and returned to almost its original pigmentation (Figure 3).

We report a successful outcome in a patient with a hypopigmented burn scar who was treated with bimatoprost administered with traditional microneedling and alongside a tacrolimus regimen. Tacrolimus ointment inhibited the inflammatory response to allow melanocytes to heal and regenerate; bimatoprost and microneedling promoted hyperpigmentation of hair follicles in the affected area, eventually restoring pigmentation to the entire area. Our patient was extremely satisfied with the results of this combination treatment. She has reported feeling more confident going out and wearing short-sleeved clothing. Percutaneous drug delivery of bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% combined with topical tacrolimus may be an effective treatment for skin repigmentation. Further investigation of this regimen is needed to develop standardized treatment protocols.

To the Editor:

Microneedling is a percutaneous collagen induction therapy frequently used in cosmetic dermatology to promote skin rejuvenation and hair growth and to treat scars by taking advantage of the body’s natural wound-healing cascade.1 The procedure works by generating thousands of microscopic wounds in the dermis with minimal damage to the epidermis, thus initiating the wound-healing cascade and subsequently promoting collagen production in a manner safe for all Fitzpatrick classification skin types.1-3 This therapy effectively treats scars by breaking down scarred collagen and replacing it with new healthy collagen. Microneedling also has application in drug delivery by increasing the permeability of the skin; the microwounds generated can serve as a portal for drug delivery.4

Bimatoprost is a prostaglandin analogue typically used to treat hypotrichosis and open-angle glaucoma.5-7 A known side effect of bimatoprost is hyperpigmentation of surrounding skin; the drug increases melanogenesis, melanocyte proliferation, and melanocyte dendricity, resulting in activation of the inflammatory response and subsequent prostaglandin release, which stimulates melanogenesis. This effect is similar to UV radiation–induced inflammation and hyperpigmentation.6,8

Capitalizing on this effect, a novel application of bimatoprost has been proposed—treating vitiligo, in which hypopigmentation results from destruction of melanocytes in certain areas of the skin. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% utilized as an off-label treatment for vitiligo has been shown to notably increase melanogenesis and return pigmentation to hypopigmented areas.8-10

A 32-year-old Black woman presented to our clinic with a 40×15-cm scar that was marked by postinflammatory hypopigmentation from a second-degree burn on the right proximal arm. The patient had been burned 5 months prior by boiling water that was spilled on the arm while cooking. She had immediately sought treatment at an emergency department and subsequently in a burn unit, where the burn was debrided twice; medication was not prescribed to continue treatment. The patient reported that the scarring and hypopigmentation had taken a psychologic toll; her hope was to have pigmentation restored to the affected area to boost her confidence.

Physical examination revealed that the burn wound had healed but visible scarring and severe hypopigmentation due to destroyed melanocytes remained (Figure 1). To inhibit inflammation and stimulate repigmentation, we prescribed the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus ointment 0.1% to be applied daily to the affected area. The patient returned to the clinic 1 month later. Perifollicular hyperpigmentation was noted at the site of the scar.

Monthly microneedling sessions with bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% were started. To avoid damaging any potentially remaining unhealed hypodermis and vasculature, the first microneedling session was performed with 9 needles set at minimal needle depth and frequency. The number of needles and their depth and frequency gradually were increased with each subsequent treatment. The patient continued tacrolimus ointment 0.1% throughout the course of treatment.

For each microneedling procedure, a handheld motorized microneedling device was applied to the skin at a depth of 0.25 mm, which was gradually increased until pinpoint petechiae were achieved. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% was then painted on the skin and allowed to absorb. Microneedling was performed again, ensuring that bimatoprost entered the skin in the area of the burn scar.

Microneedling procedures were performed monthly for 6 months, then once 3 months later, and once more 3 months later—8 treatments in total over the course of 1 year. Improvement in skin pigmentation was noted at each visit (Figure 2). Repigmentation was first noticed surrounding hair follicles; after later visits, it was observed that pigmentation began to spread from hair follicles to fill in remaining skin. The darkest areas of pigmentation were first noted around hair follicles; over time, melanocytes appeared to spontaneously regenerate and fill in surrounding areas as the scar continued to heal. The patient continued use of tacrolimus during the entire course of microneedling treatments and for the following 4 months. Sixteen months after initiation of treatment, the appearance of the skin was texturally smooth and returned to almost its original pigmentation (Figure 3).

We report a successful outcome in a patient with a hypopigmented burn scar who was treated with bimatoprost administered with traditional microneedling and alongside a tacrolimus regimen. Tacrolimus ointment inhibited the inflammatory response to allow melanocytes to heal and regenerate; bimatoprost and microneedling promoted hyperpigmentation of hair follicles in the affected area, eventually restoring pigmentation to the entire area. Our patient was extremely satisfied with the results of this combination treatment. She has reported feeling more confident going out and wearing short-sleeved clothing. Percutaneous drug delivery of bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% combined with topical tacrolimus may be an effective treatment for skin repigmentation. Further investigation of this regimen is needed to develop standardized treatment protocols.

- Juhasz MLW, Cohen JL. Micro-needling for the treatment of scars: an update for clinicians. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2020;13:997-1003. doi:10.2147/CCID.S267192

- Alster TS, Li MKY. Micro-needling of scars: a large prospective study with long-term follow-up. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145:358-364. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000006462

- Aust MC, Knobloch K, Reimers K, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction therapy: an alternative treatment for burn scars. Burns. 2010;36:836-843. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2009.11.014

- Kim Y-C, Park J-H, Prausnitz MR. Microneedles for drug and vaccine delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:1547-1568. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2012.04.005

- Doshi M, Edward DP, Osmanovic S. Clinical course of bimatoprost-induced periocular skin changes in Caucasians. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1961-1967. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.041

- Kapur R, Osmanovic S, Toyran S, et al. Bimatoprost-induced periocular skin hyperpigmentation: histopathological study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1541-1546. doi:10.1001/archopht.123.11.1541

- Priluck JC, Fu S. Latisse-induced periocular skin hyperpigmentation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:792-793. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.89

- Grimes PE. Bimatoprost 0.03% solution for the treatment of nonfacial vitiligo. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:703-710.

- Barbulescu C, Goldstein N, Roop D, et al. Harnessing the power of regenerative therapy for vitiligo and alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140: 29-37. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2019.03.1142

- Kanokrungsee S, Pruettivorawongse D, Rajatanavin N. Clinicaloutcomes of topical bimatoprost for nonsegmental facial vitiligo: a preliminary study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:812-818. doi.org/10.1111/jocd.13648

- Juhasz MLW, Cohen JL. Micro-needling for the treatment of scars: an update for clinicians. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2020;13:997-1003. doi:10.2147/CCID.S267192

- Alster TS, Li MKY. Micro-needling of scars: a large prospective study with long-term follow-up. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145:358-364. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000006462

- Aust MC, Knobloch K, Reimers K, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction therapy: an alternative treatment for burn scars. Burns. 2010;36:836-843. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2009.11.014

- Kim Y-C, Park J-H, Prausnitz MR. Microneedles for drug and vaccine delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:1547-1568. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2012.04.005

- Doshi M, Edward DP, Osmanovic S. Clinical course of bimatoprost-induced periocular skin changes in Caucasians. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1961-1967. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.041

- Kapur R, Osmanovic S, Toyran S, et al. Bimatoprost-induced periocular skin hyperpigmentation: histopathological study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1541-1546. doi:10.1001/archopht.123.11.1541

- Priluck JC, Fu S. Latisse-induced periocular skin hyperpigmentation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:792-793. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.89

- Grimes PE. Bimatoprost 0.03% solution for the treatment of nonfacial vitiligo. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:703-710.

- Barbulescu C, Goldstein N, Roop D, et al. Harnessing the power of regenerative therapy for vitiligo and alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140: 29-37. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2019.03.1142

- Kanokrungsee S, Pruettivorawongse D, Rajatanavin N. Clinicaloutcomes of topical bimatoprost for nonsegmental facial vitiligo: a preliminary study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:812-818. doi.org/10.1111/jocd.13648

PRACTICE POINTS

- Microneedling is a percutaneous collagen induction therapy that also may be used in drug delivery.

- Hypopigmentation can cause considerable distress for patients with skin of color.

- Percutaneous drug delivery of bimatoprost may be helpful in skin repigmentation.

Methacrylate Polymer Powder Dressing for a Lower Leg Surgical Defect

To the Editor:

Surgical wounds on the lower leg are challenging to manage because venous stasis, bacterial colonization, and high tension may contribute to protracted healing. Advances in technology led to the development of novel, polymer-based wound-healing modalities that hold promise for the management of these wounds.

A 75-year-old man presented with a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with a 3-mm depth of invasion on the left pretibial region. His comorbidities were notable for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, varicose veins, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, and a 32 pack-year cigarette smoking history. Current medications included clopidogrel bisulfate and warfarin sodium to manage a recently placed coronary artery stent.

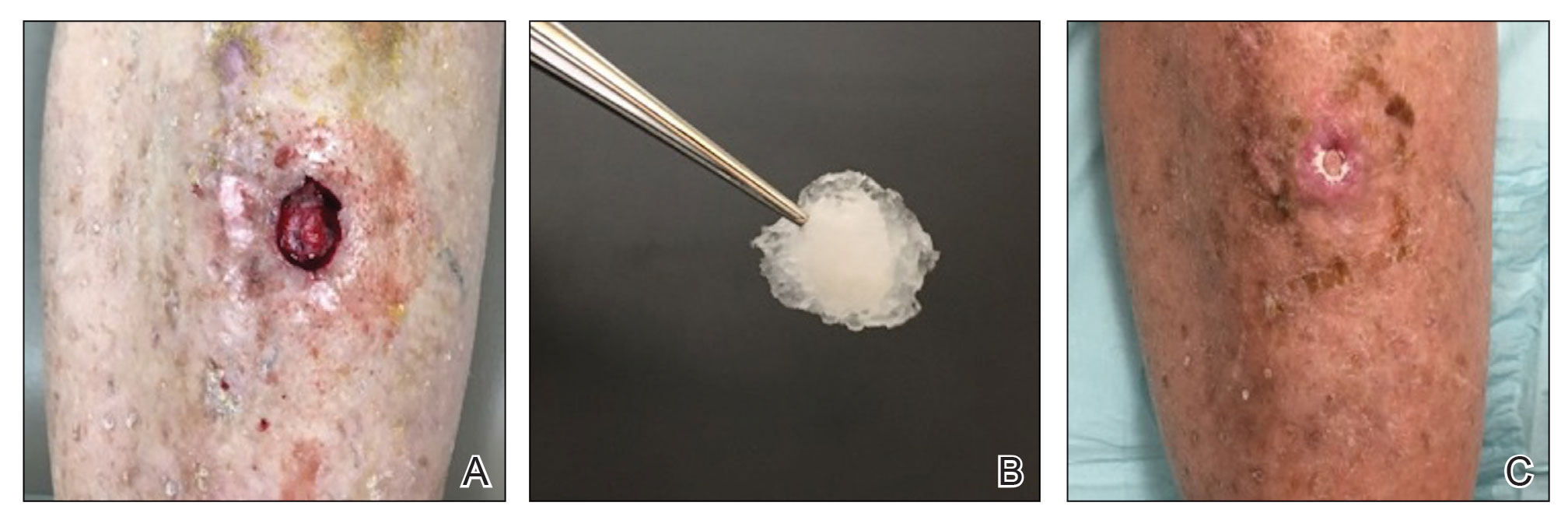

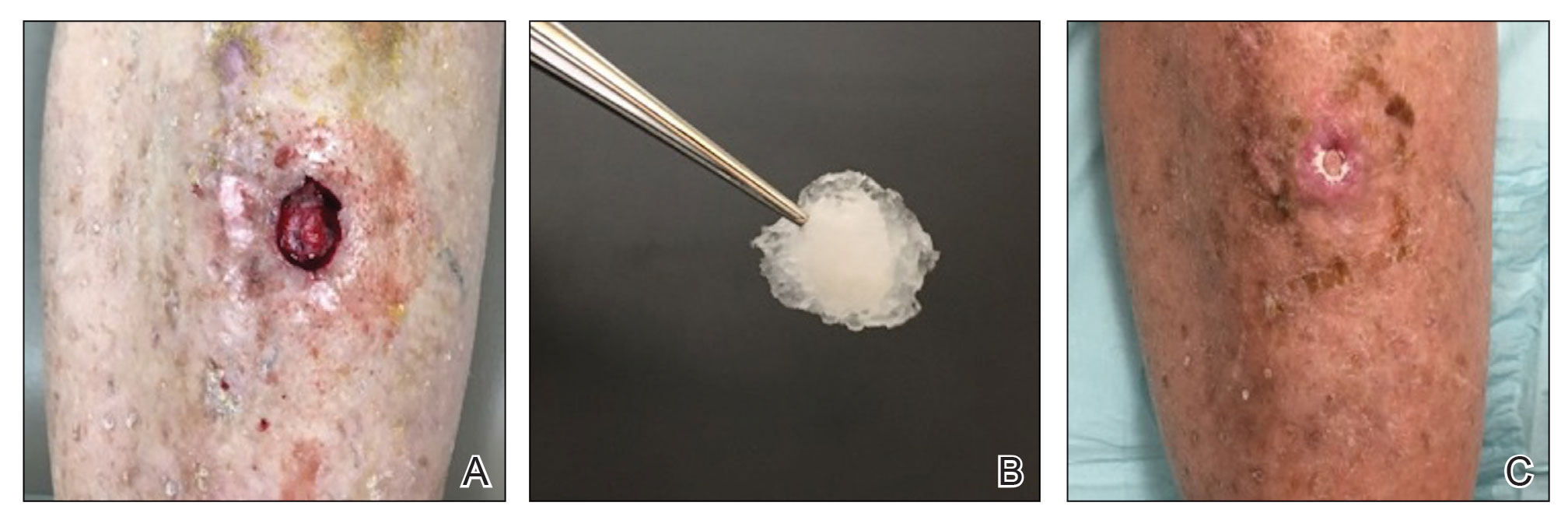

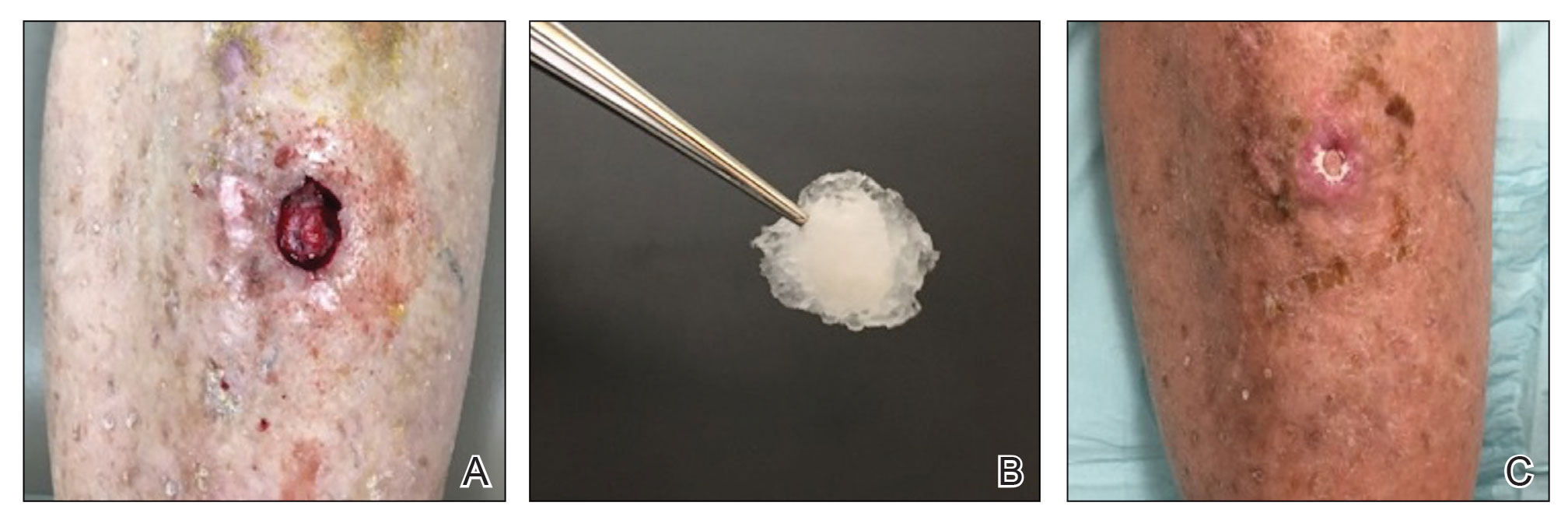

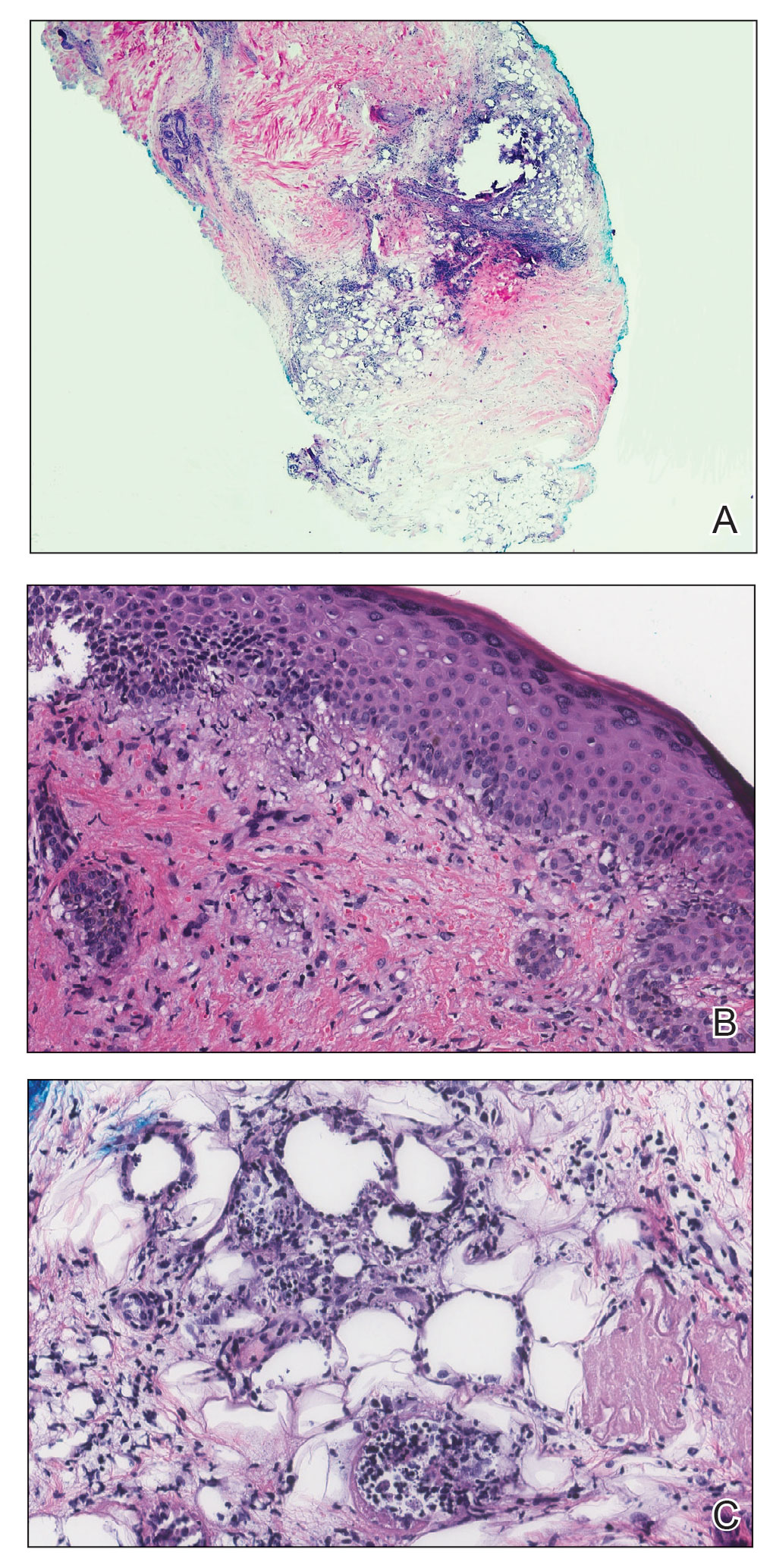

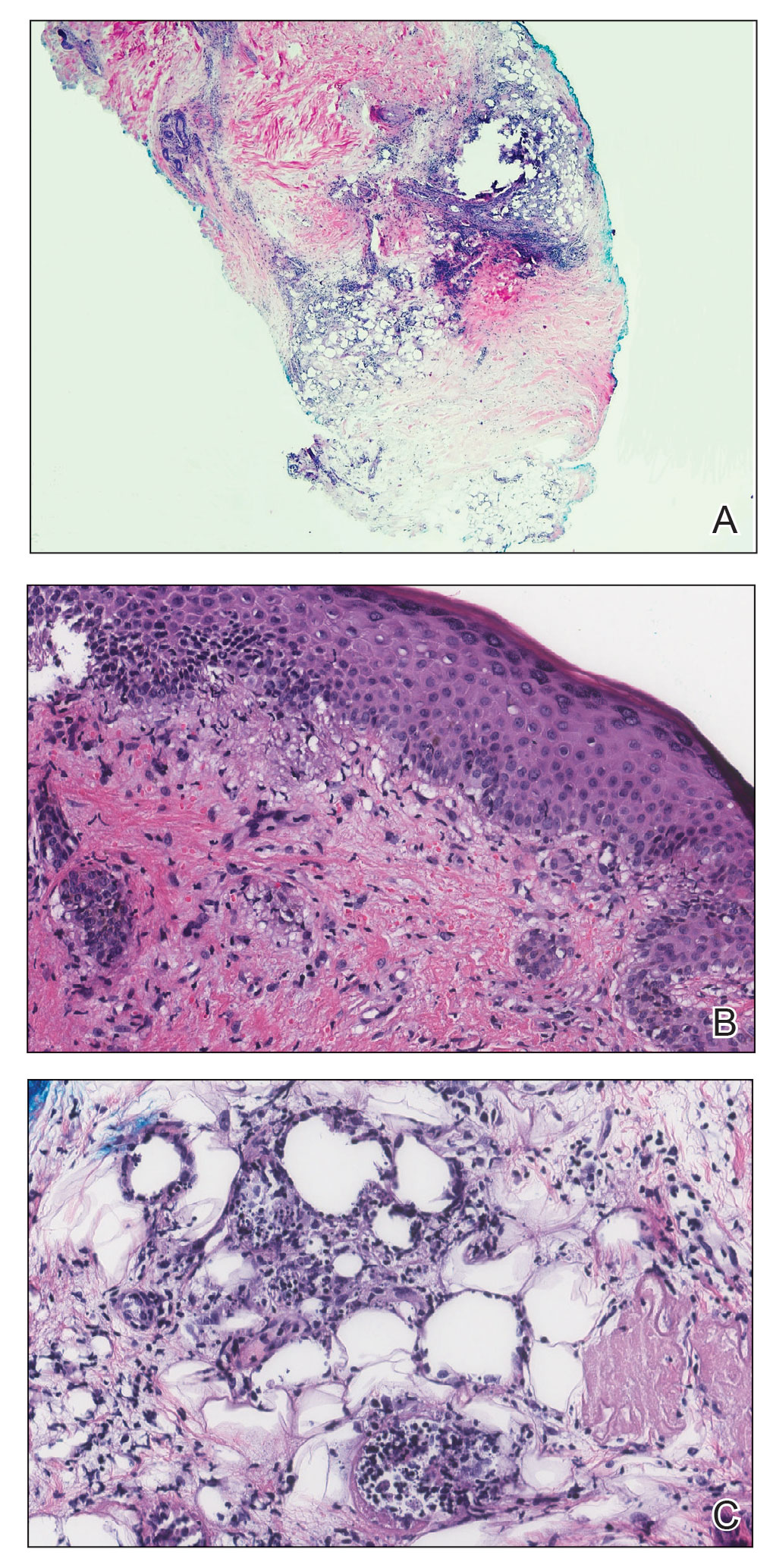

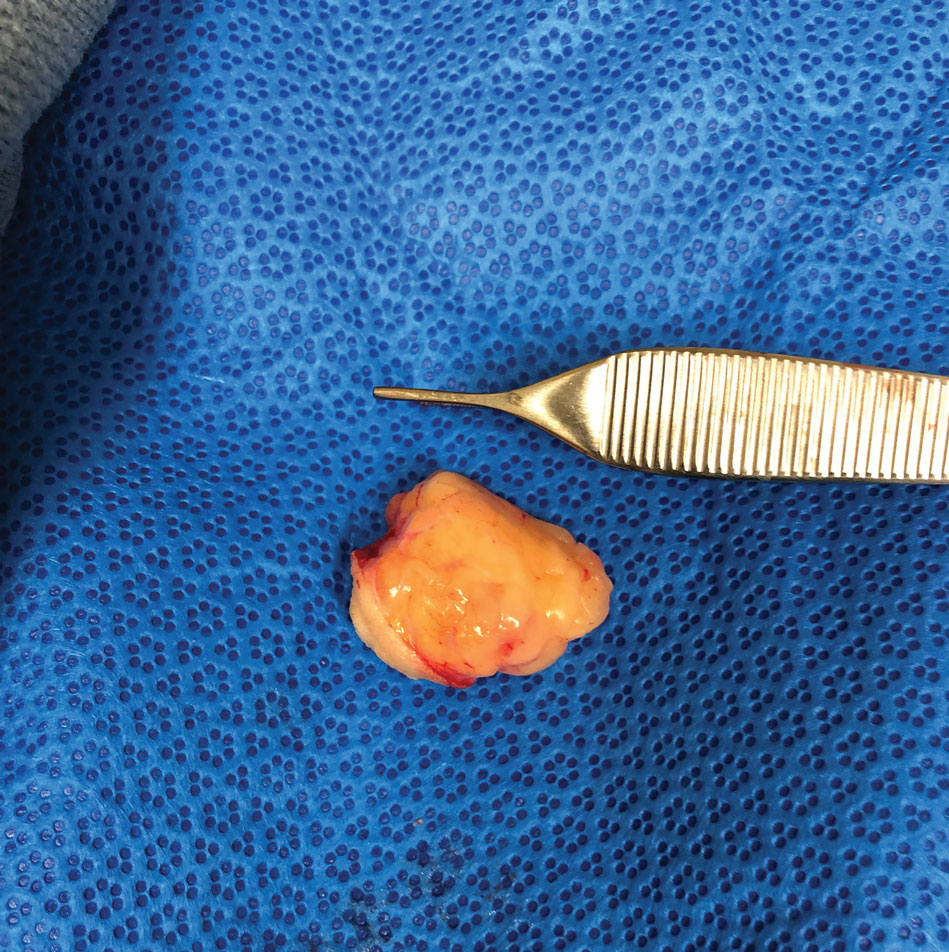

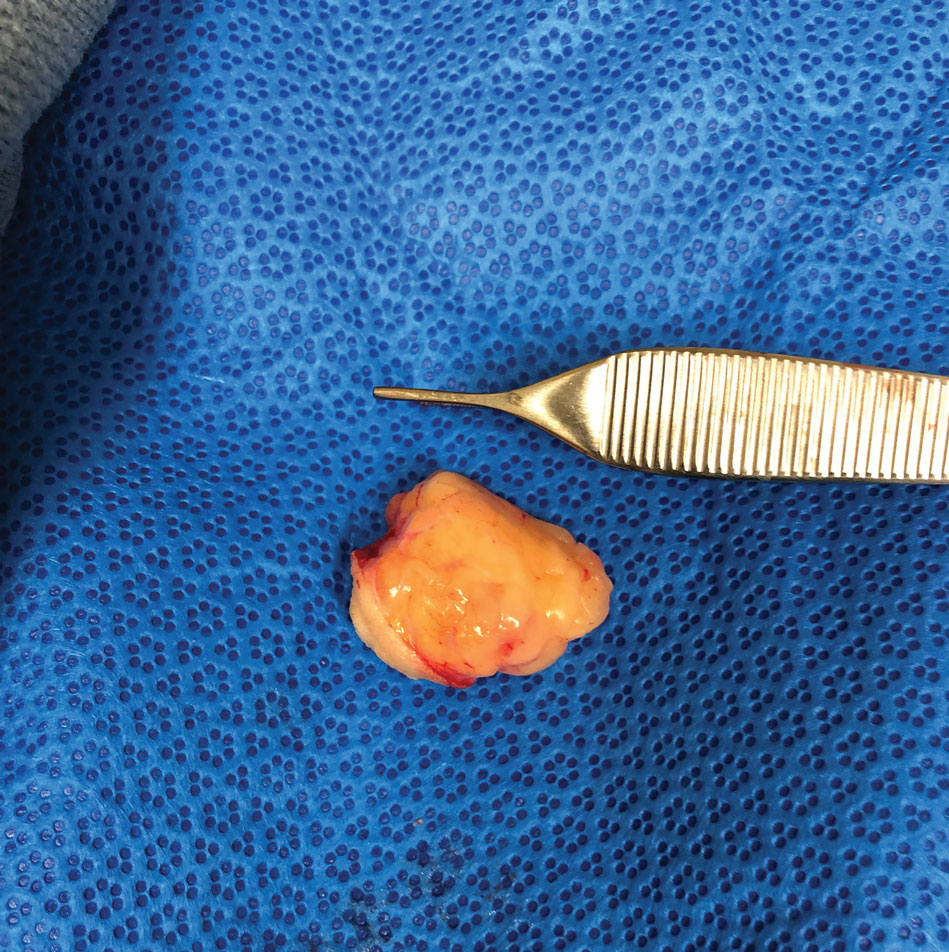

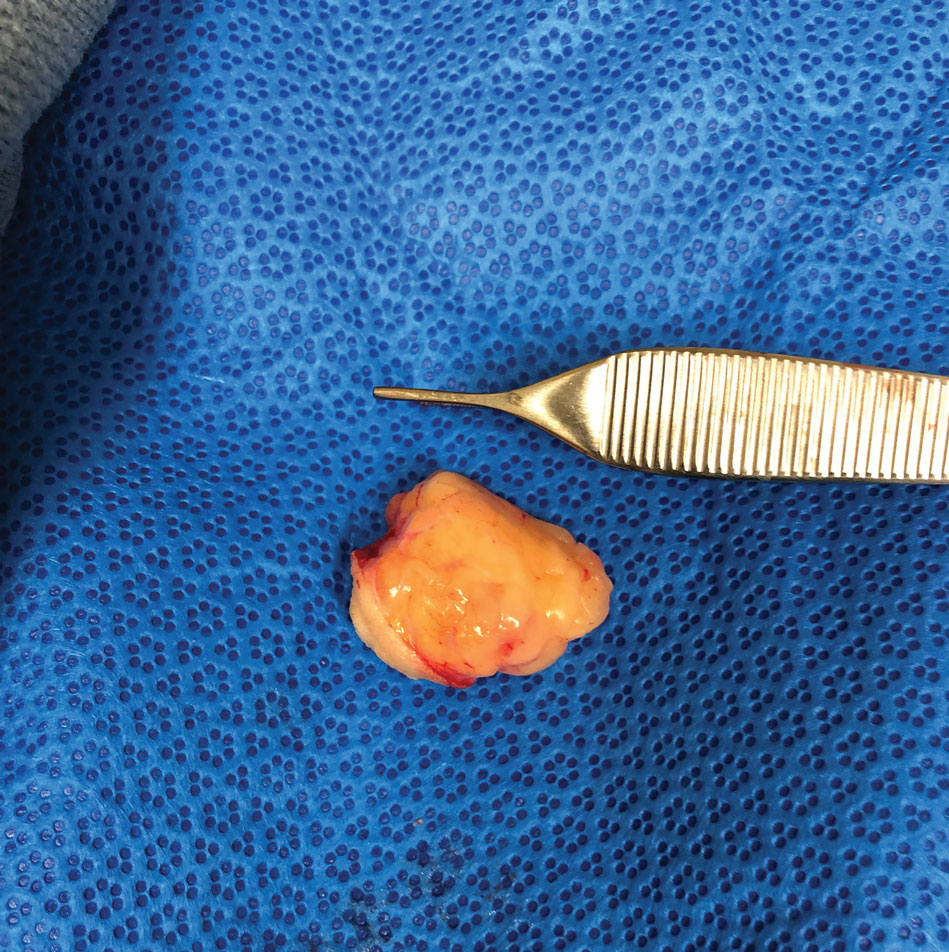

The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs micrographic surgery with excision down to tibialis anterior fascia (Figure 1A). The resultant defect measured 43×33 mm in area and 9 mm in depth (wound size, 12,771 mm3). Reconstructive options were discussed, including random-pattern flap repair and skin graft. Given the patient’s risk of bleeding, the decision was made to forego a flap repair. Additionally, the patient was a heavy smoker and could not comply with the wound care and elevation and ambulation restrictions required for optimal skin graft care. Therefore, a decision was made to proceed with secondary intention healing using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing.

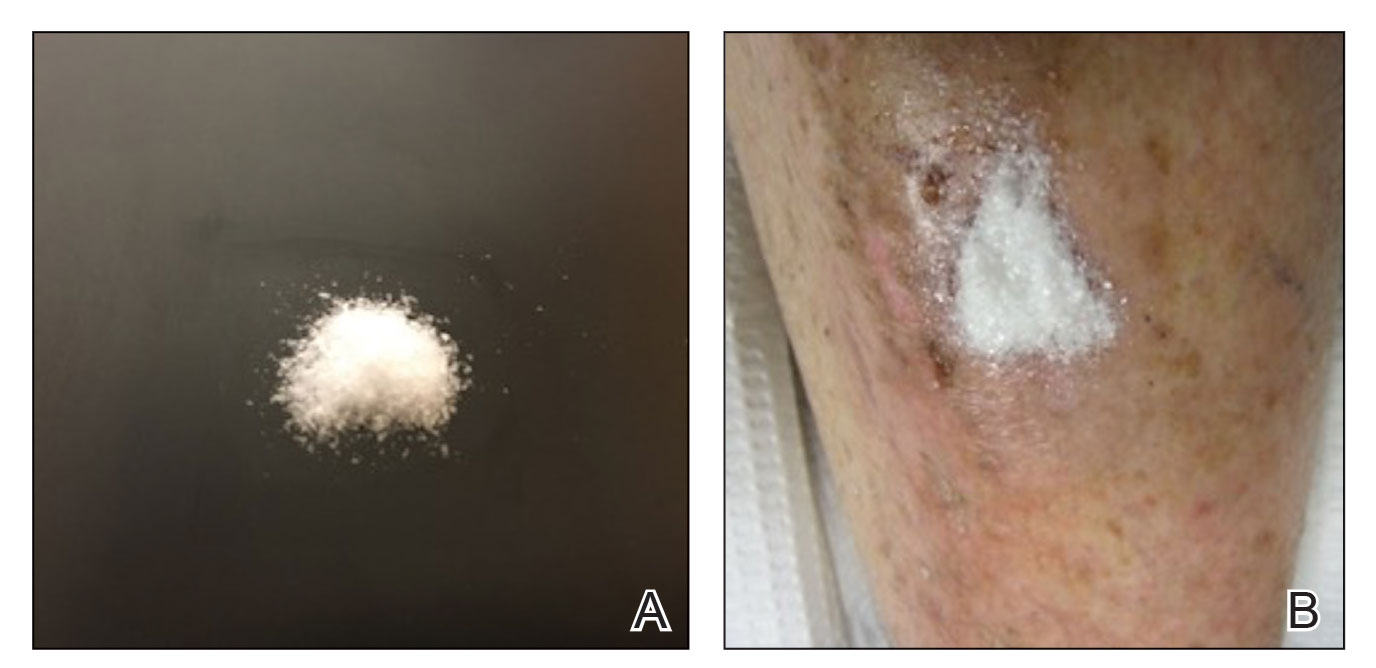

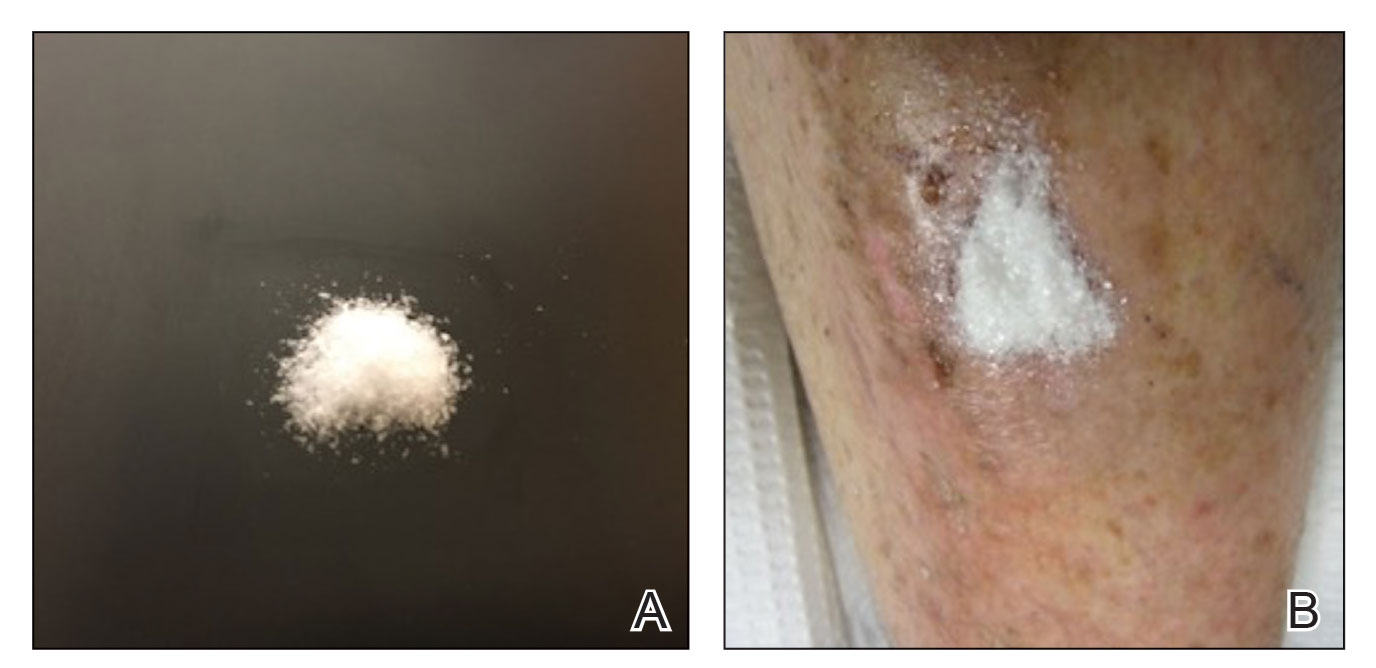

After achieving hemostasis, a novel 10-mg sterile, biologically inert methacrylate polymer powder dressing was poured over the wound in a uniform layer to fill and seal the entire wound surface (Figure 1B). Sterile normal saline 0.1 mL was sprayed onto the powder to activate particle aggregation. No secondary dressing was used, and the patient was permitted to get the dressing wet after 48 hours.

The dressing was changed in a similar fashion 4 weeks after application, following gentle debridement with gauze and normal saline. Eight weeks after surgery, the wound exhibited healthy granulation tissue and measured 5×6 mm in area and 2 mm in depth (wound size, 60 mm3), which represented a 99.5% reduction in wound size (Figure 1C). The dressing was not painful, and there were no reported adverse effects. The patient continued to smoke and ambulate fully throughout this period. No antibiotics were used.

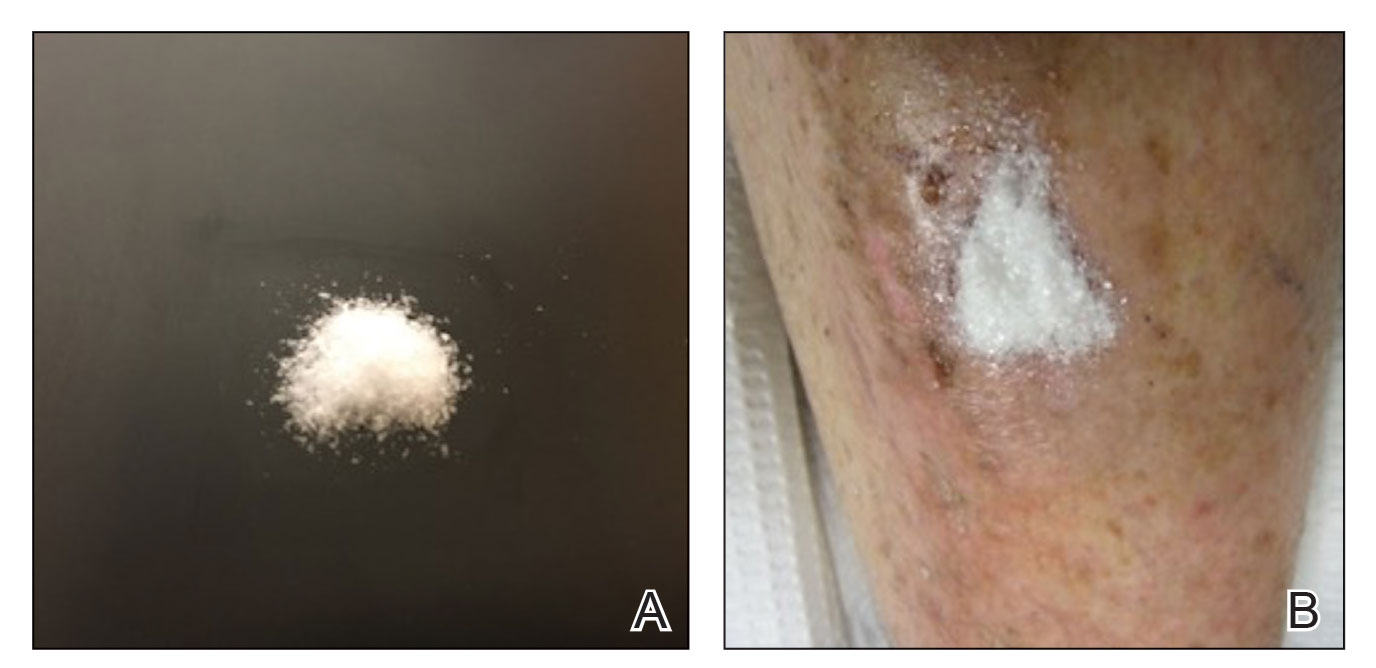

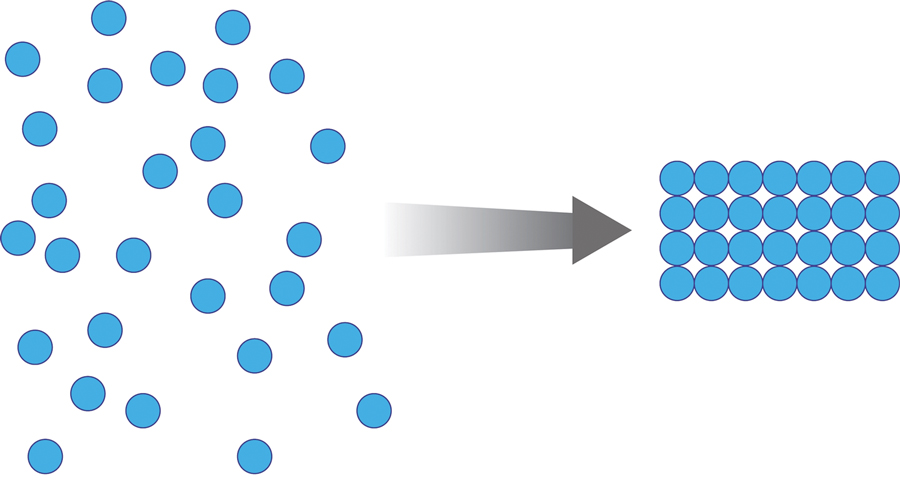

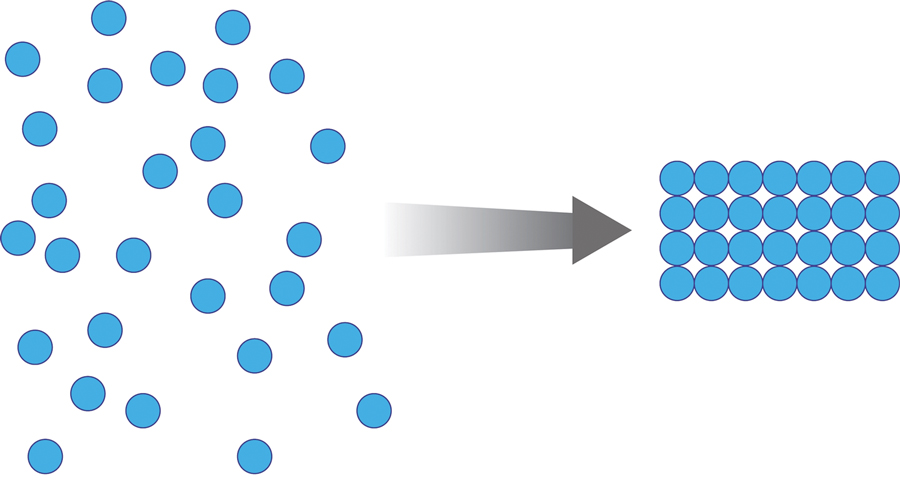

Methacrylate polymer powder dressings are a novel and sophisticated dressing modality with great promise for the management of surgical wounds on the lower limb. The dressing is a sterile powder consisting of 84.8% poly-2-hydroxyethylmethacrylate, 14.9% poly-2-hydroxypropylmethacrylate, and 0.3% sodium deoxycholate. These hydrophilic polymers have a covalent methacrylate backbone with a hydroxyl aliphatic side chain. When saline or wound exudate contacts the powder, the spheres hydrate and nonreversibly aggregate to form a moist, flexible dressing that conforms to the topography of the wound and seals it (Figure 2).1

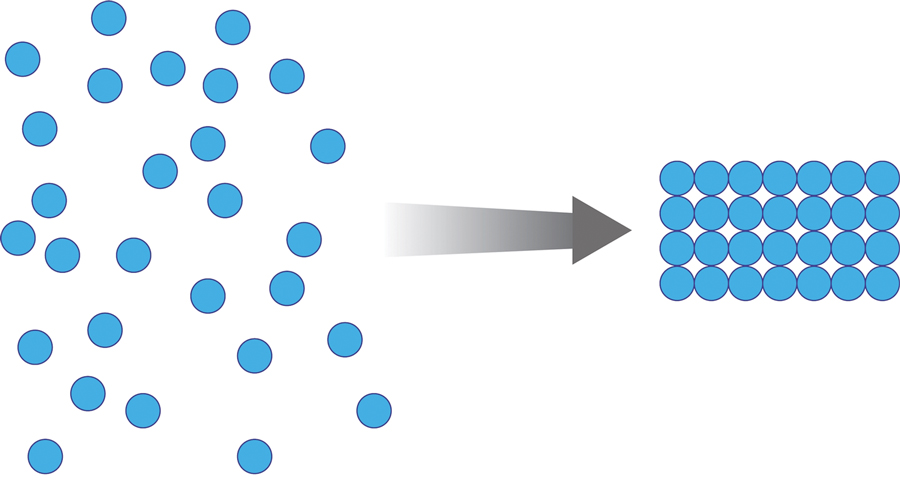

Once the spheres have aggregated, they are designed to orient in a honeycomb formation with 4- to 10-nm openings that serve as capillary channels (Figure 3). This porous architecture of the polymer is essential for adequate moisture management. It allows for vapor transpiration at a rate of 12 L/m2 per day, which ensures the capillary flow from the moist wound surface is evenly distributed through the dressing, contributing to its 68% water content. Notably, this approximately three-fifths water composition is similar to the water makeup of human skin. Optimized moisture management is theorized to enhance epithelial migration, stimulate angiogenesis, retain growth factors, promote autolytic debridement, and maintain ideal voltage and oxygen gradients for wound healing. The risk for infection is not increased by the existence of these pores, as their small size does not allow for bacterial migration.1

This case demonstrates the effectiveness of using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing to promote timely wound healing in a poorly vascularized lower leg surgical wound. The low maintenance, user-friendly dressing was changed at monthly intervals, which spared the patient the inconvenience and pain associated with the repeated application of more conventional primary and secondary dressings. The dressing was well tolerated and resulted in a 99.5% reduction in wound size. Further studies are needed to investigate the utility of this promising technology.

1. Fitzgerald RH, Bharara M, Mills JL, et al. Use of a nanoflex powder dressing for wound management following debridement for necrotising fasciitis in the diabetic foot. Int Wound J. 2009;6:133-139.

To the Editor:

Surgical wounds on the lower leg are challenging to manage because venous stasis, bacterial colonization, and high tension may contribute to protracted healing. Advances in technology led to the development of novel, polymer-based wound-healing modalities that hold promise for the management of these wounds.

A 75-year-old man presented with a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with a 3-mm depth of invasion on the left pretibial region. His comorbidities were notable for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, varicose veins, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, and a 32 pack-year cigarette smoking history. Current medications included clopidogrel bisulfate and warfarin sodium to manage a recently placed coronary artery stent.

The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs micrographic surgery with excision down to tibialis anterior fascia (Figure 1A). The resultant defect measured 43×33 mm in area and 9 mm in depth (wound size, 12,771 mm3). Reconstructive options were discussed, including random-pattern flap repair and skin graft. Given the patient’s risk of bleeding, the decision was made to forego a flap repair. Additionally, the patient was a heavy smoker and could not comply with the wound care and elevation and ambulation restrictions required for optimal skin graft care. Therefore, a decision was made to proceed with secondary intention healing using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing.

After achieving hemostasis, a novel 10-mg sterile, biologically inert methacrylate polymer powder dressing was poured over the wound in a uniform layer to fill and seal the entire wound surface (Figure 1B). Sterile normal saline 0.1 mL was sprayed onto the powder to activate particle aggregation. No secondary dressing was used, and the patient was permitted to get the dressing wet after 48 hours.

The dressing was changed in a similar fashion 4 weeks after application, following gentle debridement with gauze and normal saline. Eight weeks after surgery, the wound exhibited healthy granulation tissue and measured 5×6 mm in area and 2 mm in depth (wound size, 60 mm3), which represented a 99.5% reduction in wound size (Figure 1C). The dressing was not painful, and there were no reported adverse effects. The patient continued to smoke and ambulate fully throughout this period. No antibiotics were used.

Methacrylate polymer powder dressings are a novel and sophisticated dressing modality with great promise for the management of surgical wounds on the lower limb. The dressing is a sterile powder consisting of 84.8% poly-2-hydroxyethylmethacrylate, 14.9% poly-2-hydroxypropylmethacrylate, and 0.3% sodium deoxycholate. These hydrophilic polymers have a covalent methacrylate backbone with a hydroxyl aliphatic side chain. When saline or wound exudate contacts the powder, the spheres hydrate and nonreversibly aggregate to form a moist, flexible dressing that conforms to the topography of the wound and seals it (Figure 2).1

Once the spheres have aggregated, they are designed to orient in a honeycomb formation with 4- to 10-nm openings that serve as capillary channels (Figure 3). This porous architecture of the polymer is essential for adequate moisture management. It allows for vapor transpiration at a rate of 12 L/m2 per day, which ensures the capillary flow from the moist wound surface is evenly distributed through the dressing, contributing to its 68% water content. Notably, this approximately three-fifths water composition is similar to the water makeup of human skin. Optimized moisture management is theorized to enhance epithelial migration, stimulate angiogenesis, retain growth factors, promote autolytic debridement, and maintain ideal voltage and oxygen gradients for wound healing. The risk for infection is not increased by the existence of these pores, as their small size does not allow for bacterial migration.1

This case demonstrates the effectiveness of using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing to promote timely wound healing in a poorly vascularized lower leg surgical wound. The low maintenance, user-friendly dressing was changed at monthly intervals, which spared the patient the inconvenience and pain associated with the repeated application of more conventional primary and secondary dressings. The dressing was well tolerated and resulted in a 99.5% reduction in wound size. Further studies are needed to investigate the utility of this promising technology.

To the Editor:

Surgical wounds on the lower leg are challenging to manage because venous stasis, bacterial colonization, and high tension may contribute to protracted healing. Advances in technology led to the development of novel, polymer-based wound-healing modalities that hold promise for the management of these wounds.

A 75-year-old man presented with a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with a 3-mm depth of invasion on the left pretibial region. His comorbidities were notable for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, varicose veins, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, and a 32 pack-year cigarette smoking history. Current medications included clopidogrel bisulfate and warfarin sodium to manage a recently placed coronary artery stent.

The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs micrographic surgery with excision down to tibialis anterior fascia (Figure 1A). The resultant defect measured 43×33 mm in area and 9 mm in depth (wound size, 12,771 mm3). Reconstructive options were discussed, including random-pattern flap repair and skin graft. Given the patient’s risk of bleeding, the decision was made to forego a flap repair. Additionally, the patient was a heavy smoker and could not comply with the wound care and elevation and ambulation restrictions required for optimal skin graft care. Therefore, a decision was made to proceed with secondary intention healing using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing.

After achieving hemostasis, a novel 10-mg sterile, biologically inert methacrylate polymer powder dressing was poured over the wound in a uniform layer to fill and seal the entire wound surface (Figure 1B). Sterile normal saline 0.1 mL was sprayed onto the powder to activate particle aggregation. No secondary dressing was used, and the patient was permitted to get the dressing wet after 48 hours.

The dressing was changed in a similar fashion 4 weeks after application, following gentle debridement with gauze and normal saline. Eight weeks after surgery, the wound exhibited healthy granulation tissue and measured 5×6 mm in area and 2 mm in depth (wound size, 60 mm3), which represented a 99.5% reduction in wound size (Figure 1C). The dressing was not painful, and there were no reported adverse effects. The patient continued to smoke and ambulate fully throughout this period. No antibiotics were used.

Methacrylate polymer powder dressings are a novel and sophisticated dressing modality with great promise for the management of surgical wounds on the lower limb. The dressing is a sterile powder consisting of 84.8% poly-2-hydroxyethylmethacrylate, 14.9% poly-2-hydroxypropylmethacrylate, and 0.3% sodium deoxycholate. These hydrophilic polymers have a covalent methacrylate backbone with a hydroxyl aliphatic side chain. When saline or wound exudate contacts the powder, the spheres hydrate and nonreversibly aggregate to form a moist, flexible dressing that conforms to the topography of the wound and seals it (Figure 2).1

Once the spheres have aggregated, they are designed to orient in a honeycomb formation with 4- to 10-nm openings that serve as capillary channels (Figure 3). This porous architecture of the polymer is essential for adequate moisture management. It allows for vapor transpiration at a rate of 12 L/m2 per day, which ensures the capillary flow from the moist wound surface is evenly distributed through the dressing, contributing to its 68% water content. Notably, this approximately three-fifths water composition is similar to the water makeup of human skin. Optimized moisture management is theorized to enhance epithelial migration, stimulate angiogenesis, retain growth factors, promote autolytic debridement, and maintain ideal voltage and oxygen gradients for wound healing. The risk for infection is not increased by the existence of these pores, as their small size does not allow for bacterial migration.1

This case demonstrates the effectiveness of using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing to promote timely wound healing in a poorly vascularized lower leg surgical wound. The low maintenance, user-friendly dressing was changed at monthly intervals, which spared the patient the inconvenience and pain associated with the repeated application of more conventional primary and secondary dressings. The dressing was well tolerated and resulted in a 99.5% reduction in wound size. Further studies are needed to investigate the utility of this promising technology.

1. Fitzgerald RH, Bharara M, Mills JL, et al. Use of a nanoflex powder dressing for wound management following debridement for necrotising fasciitis in the diabetic foot. Int Wound J. 2009;6:133-139.

1. Fitzgerald RH, Bharara M, Mills JL, et al. Use of a nanoflex powder dressing for wound management following debridement for necrotising fasciitis in the diabetic foot. Int Wound J. 2009;6:133-139.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Lower leg surgical wounds are difficult to manage, as venous stasis, bacterial colonization, and high tension may contribute to protracted healing.

- A methacrylate polymer powder dressing is user friendly and facilitates granulation and reduction in size of difficult lower leg wounds.

Oral Propranolol Used as Adjunct Therapy in Cutaneous Angiosarcoma

To the Editor:

Angiosarcoma is a malignancy of the vascular endothelium that most commonly presents on the skin.1 Patients diagnosed with cutaneous angiosarcoma, which is a rare and aggressive malignancy, have a 5-year survival rate of approximately 30%.2,3 Angiosarcoma can be seen in the setting of chronic lymphedema; radiation therapy; and sporadically in elderly patients, where it is commonly seen on the head and neck. Presentation on the head and neck has been associated with worse outcomes, with a projected overall 10-year survival rate of 13.8%; the survival rate is lower if the tumor is surgically unresectable or larger in size. Metastasis can occur via both lymphatic and hematogenous routes, with pulmonary and hepatic metastases most frequently observed.1 Prognostications of poor outcomes for patients with head and neck cutaneous angiosarcoma via a 5-year survival rate were identified in a meta-analysis and included the following: patient age older than 70 years, larger tumors, tumor location of scalp vs face, nonsurgical treatments, and lack of clear margins on histology.2

Treatment of angiosarcoma historically has encompassed both surgical resection and adjuvant radiation therapy with suboptimal success. Evidence supporting various treatment regimens remains sparse due to the low incidence of the neoplasm. Although surgical resection is the only documented curative treatment, cutaneous angiosarcomas frequently are found to have positive surgical margins and require adjuvant radiation. Use of high-dose radiation (>50 Gy) with application over a wide treatment area such as total scalp irradiation is recommended.4 Although radiation has been found to diminish local recurrence rates, it has not substantially affected rates of distant disease recurrence.1 Cytotoxic chemotherapy has clinical utility in minimizing progression, but standard regimens afford a progression-free survival of only months.3 Adjuvant treatment with paclitaxel has been shown to have improved efficacy in scalp angiosarcoma vs other visceral sites, showing a nonprogression rate of 42% at 4 months after treatment.5 More recently, targeted chemotherapeutics, including the vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor bevacizumab and tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib, have shown some survival benefit, but it is unclear if these agents are superior to traditional cytotoxic agents.4,6-10 A phase 2 study of paclitaxel administered weekly with or without bevacizumab showed similar progression-free survival and overall survival, albeit at the expense of added toxicity experienced by participants in the combined group.10

The addition of the nonselective β-adrenergic blocker propranolol to the treatment armamentarium, which was pursued due to its utility in the treatment of benign infantile hemangioma and demonstrated ability to limit the expression of adrenergic receptors in angiosarcoma, has gained clinical attention for possible augmentation of cutaneous angiosarcoma therapy.11-14 Propranolol has been shown to reduce metastasis in other neoplasms—both vascular and nonvascular—and may play a role as an adjuvant treatment to current therapies in angiosarcoma.15-20 We report a patient with cutaneous angiosarcoma (T2 classification) with disease-free survival of nearly 6 years without evidence of recurrence in the setting of continuous propranolol use supplementary to chemotherapy and radiation.

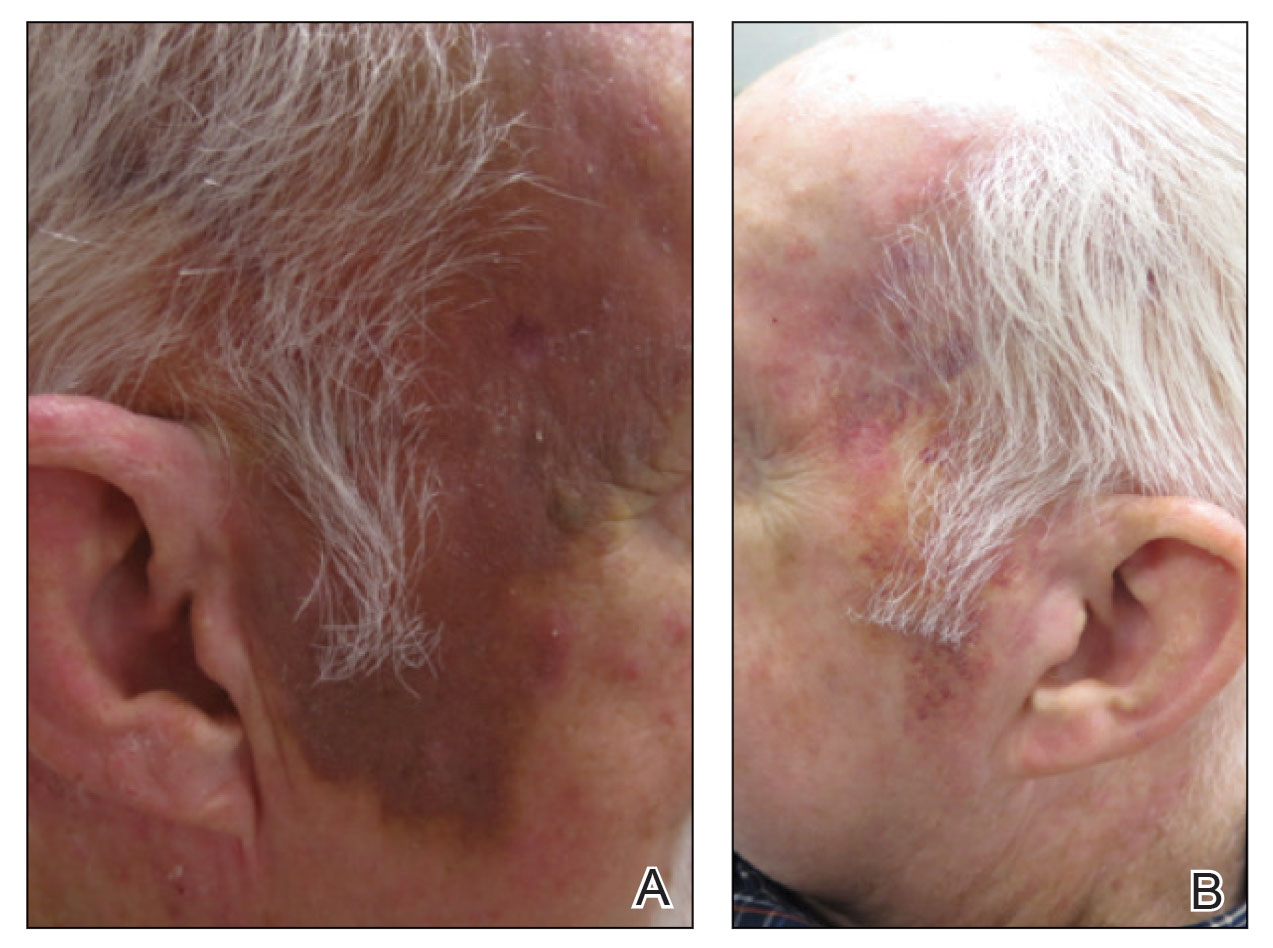

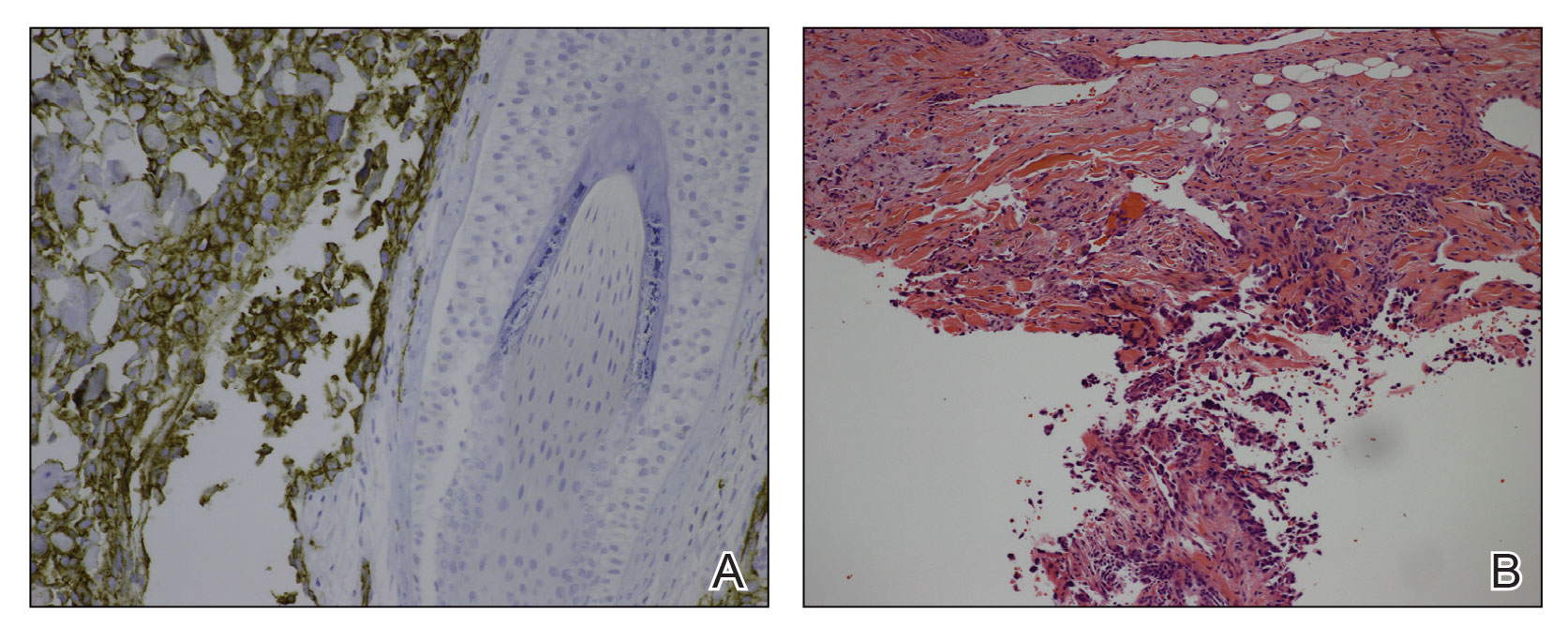

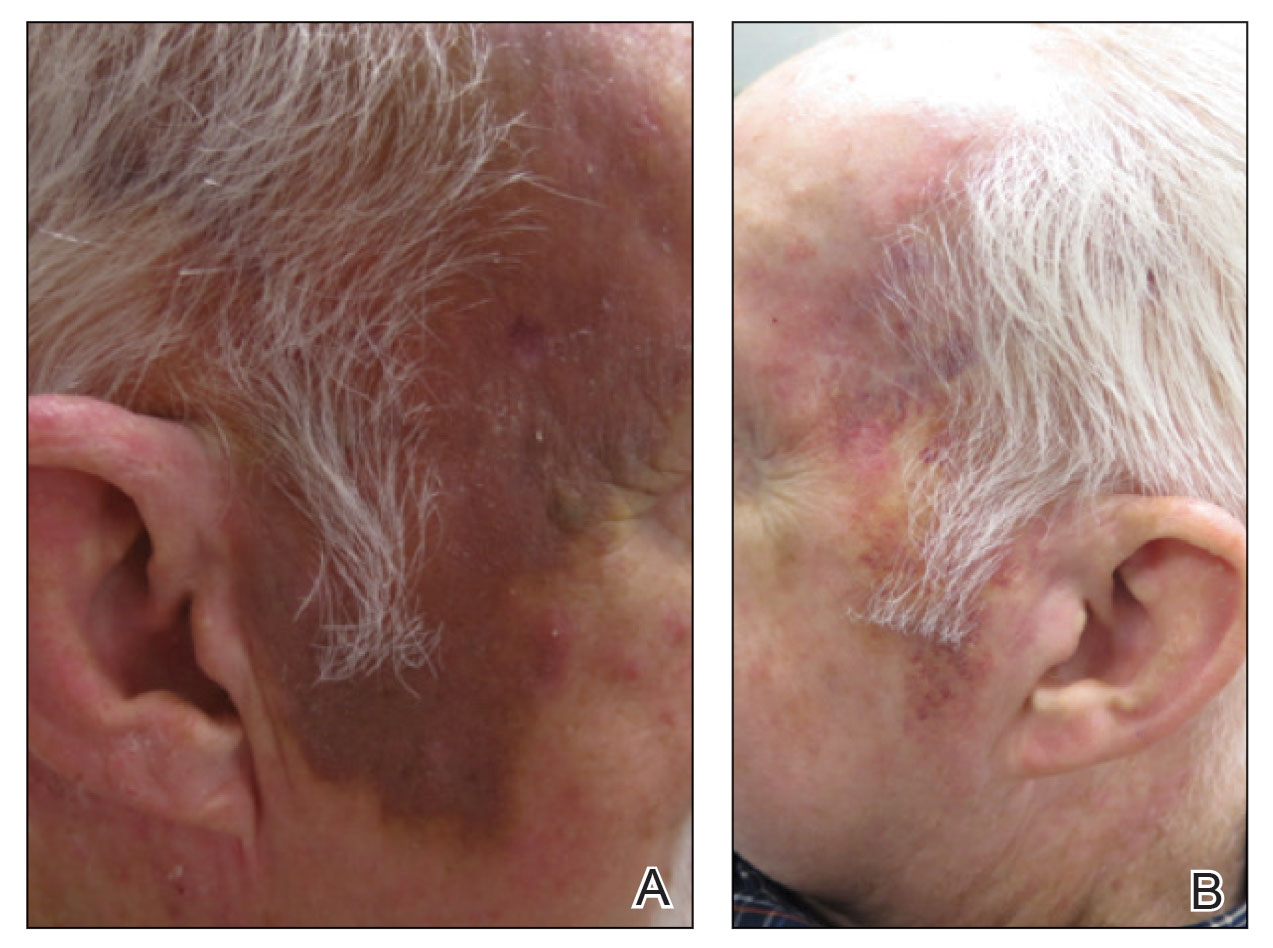

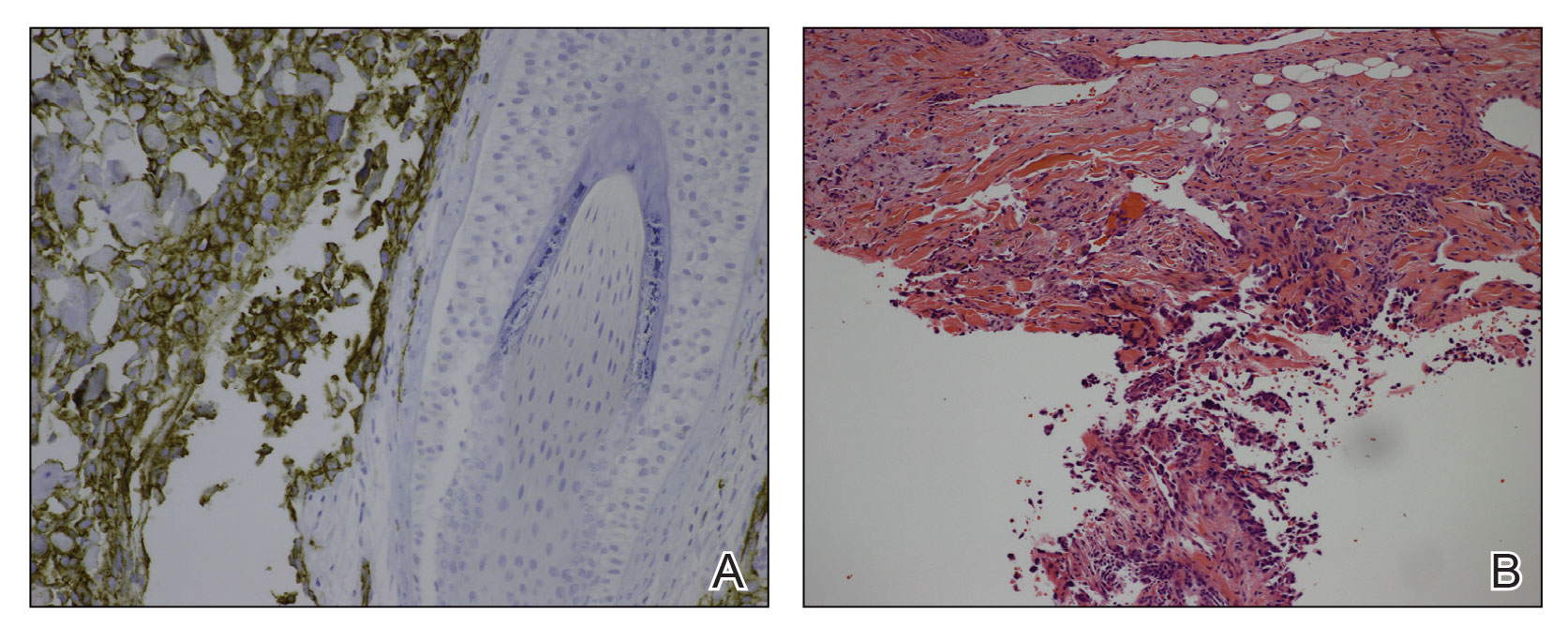

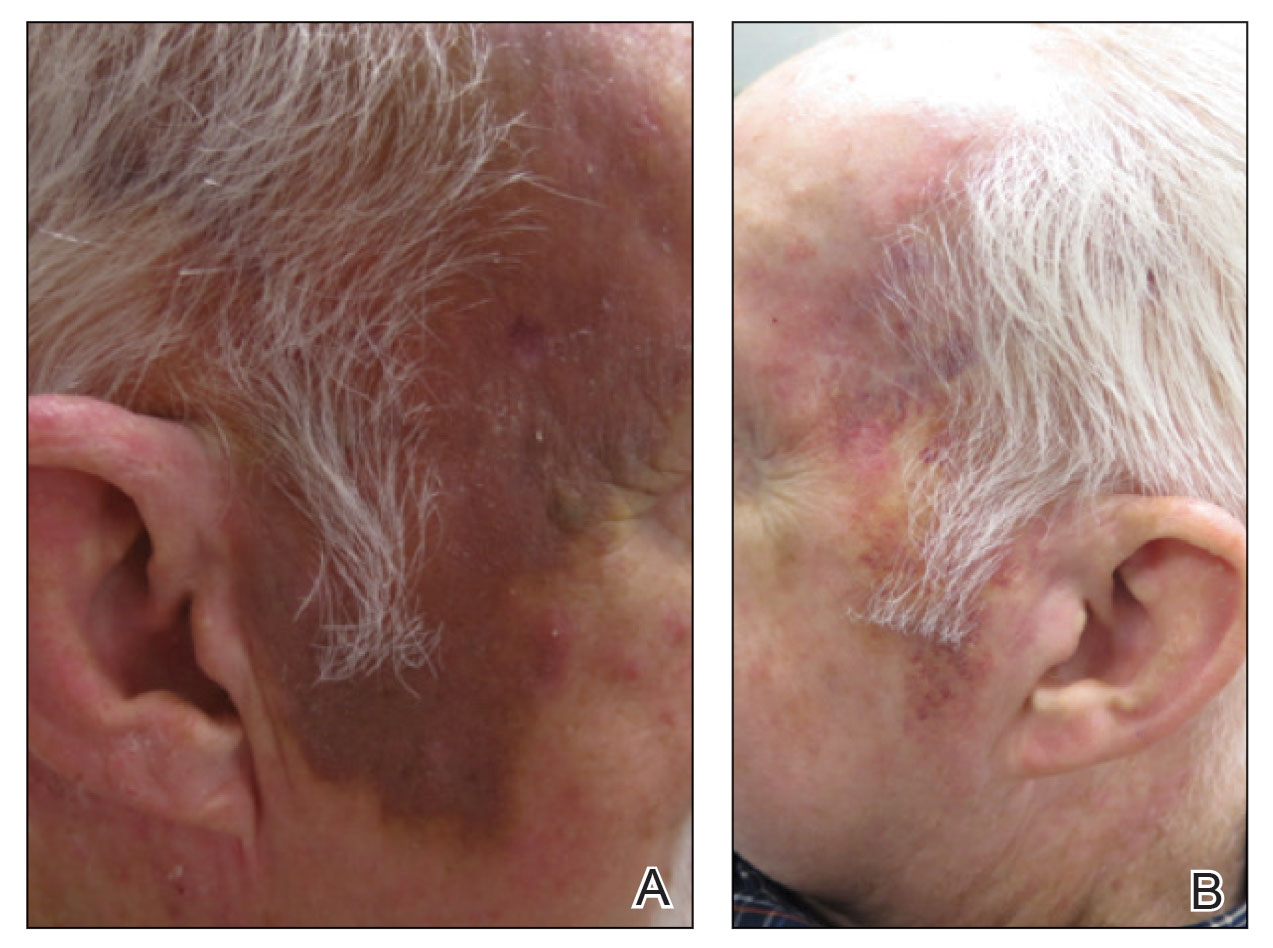

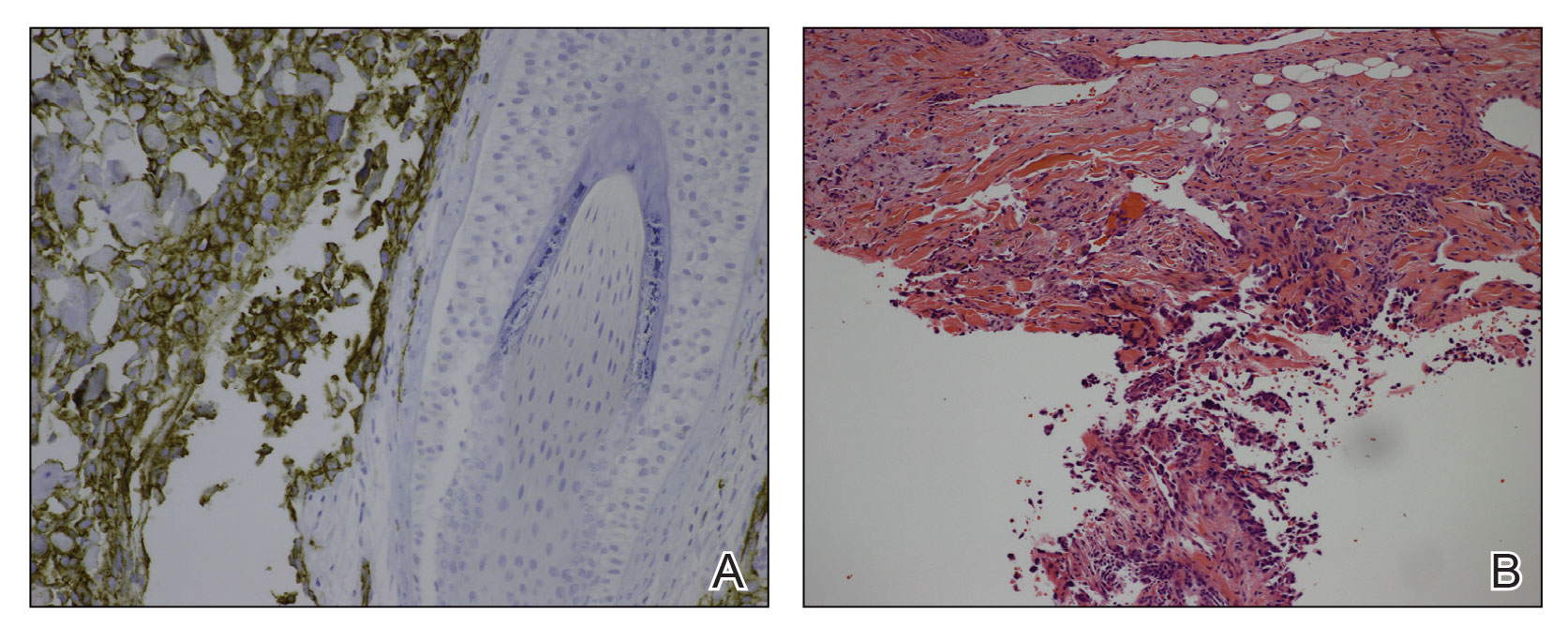

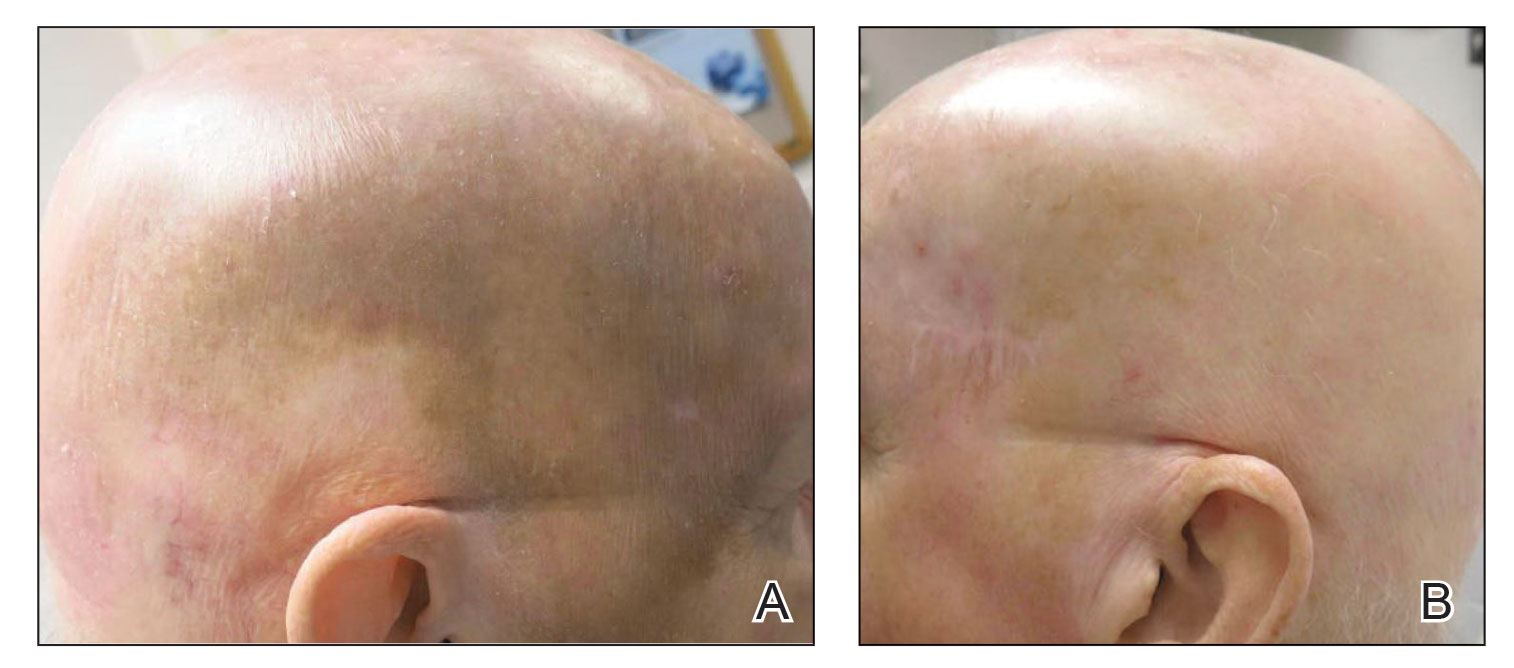

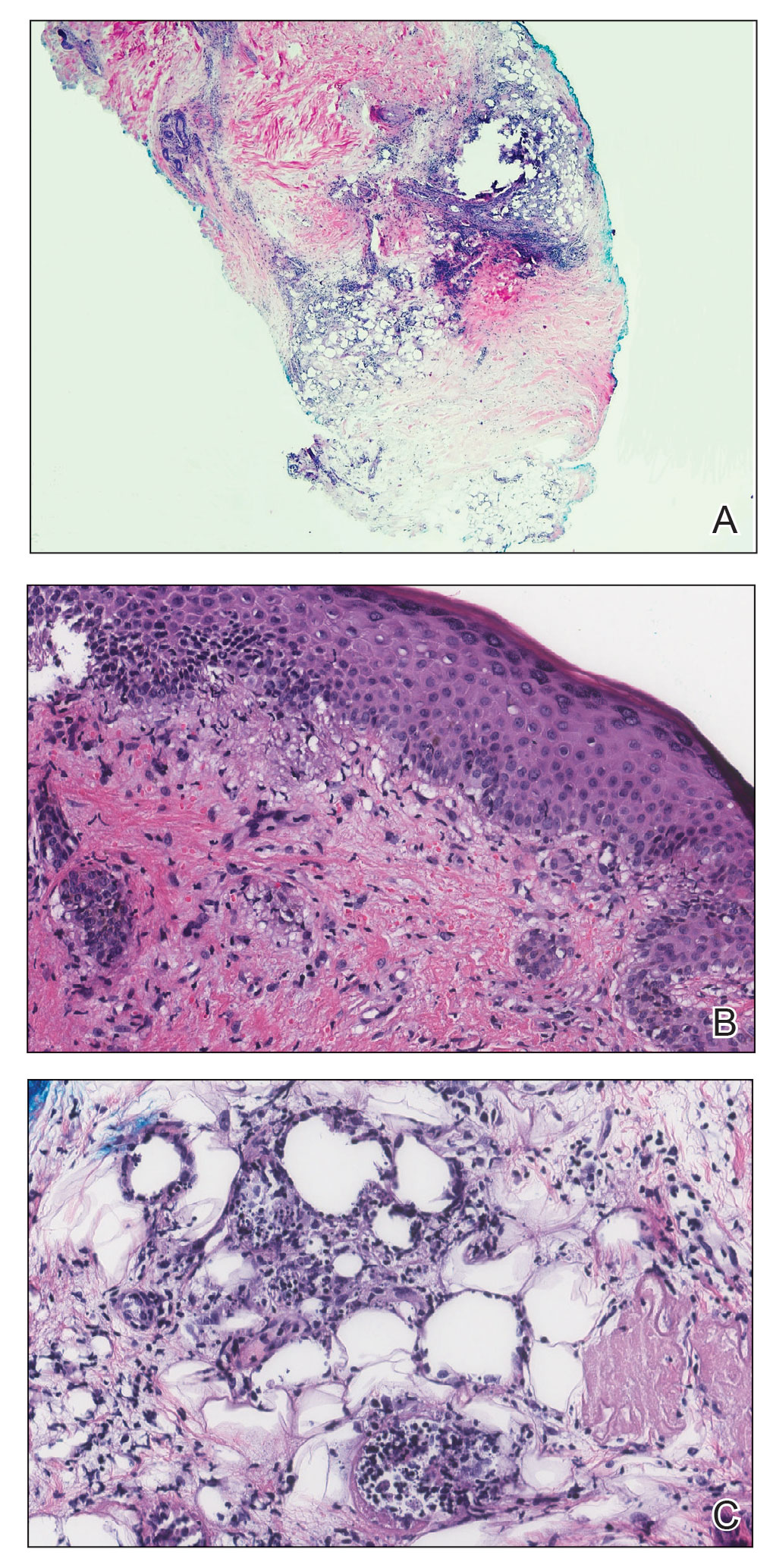

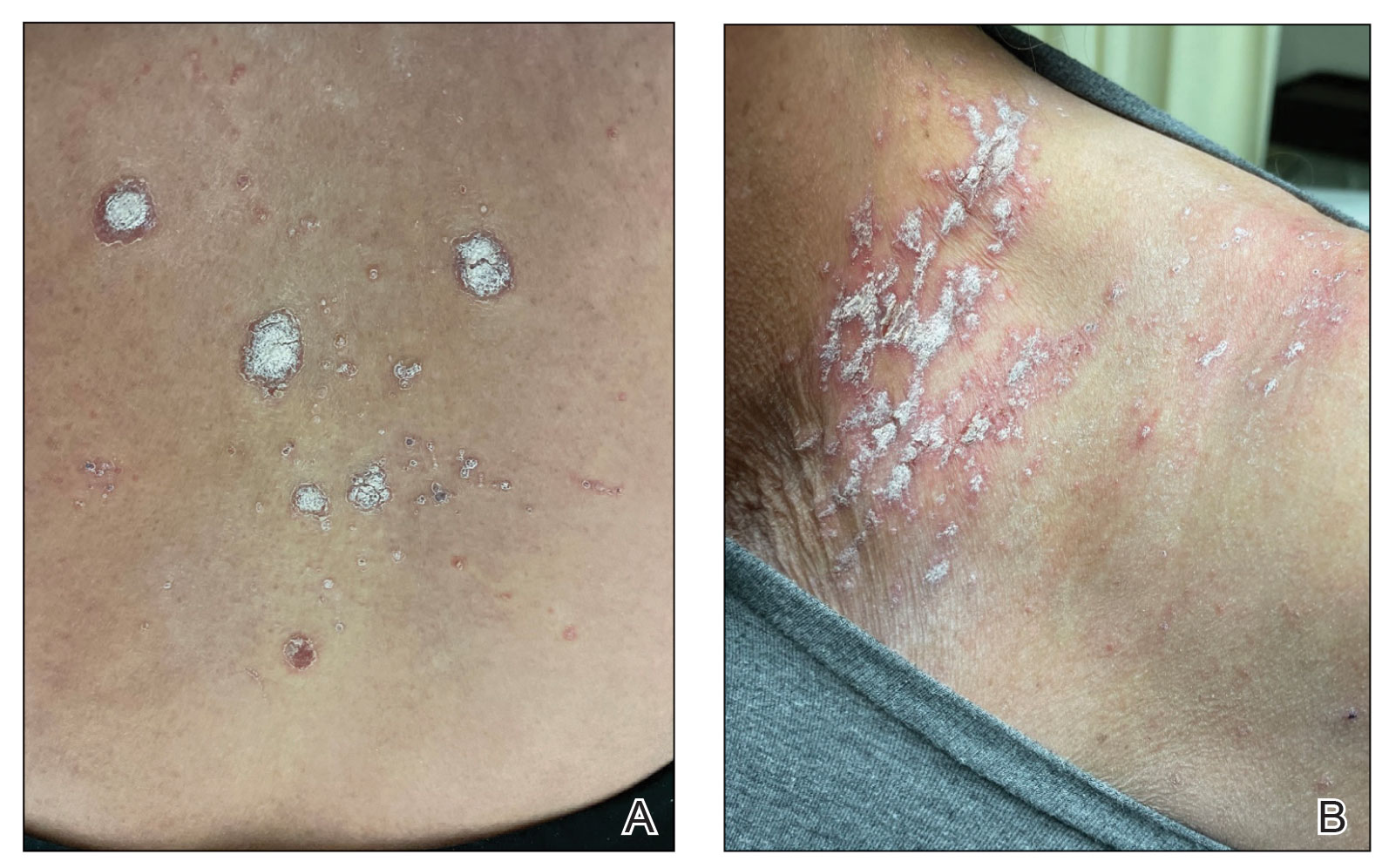

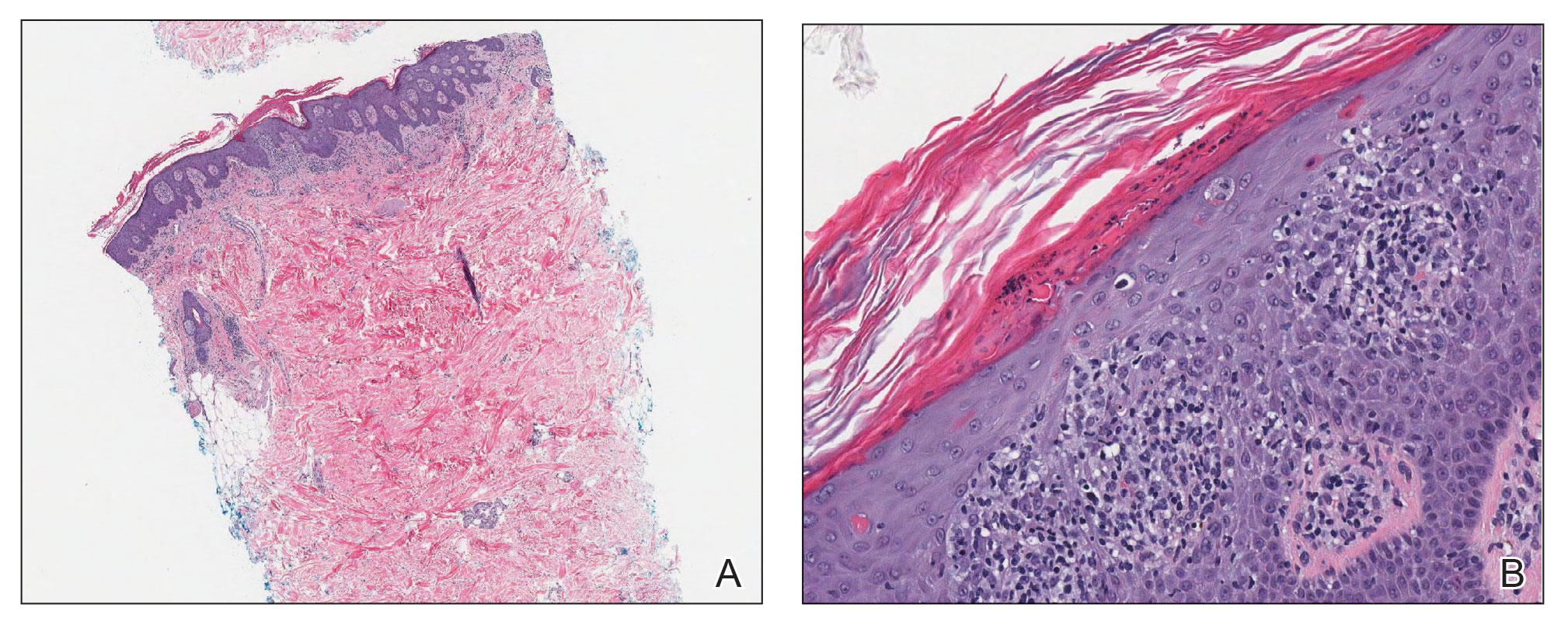

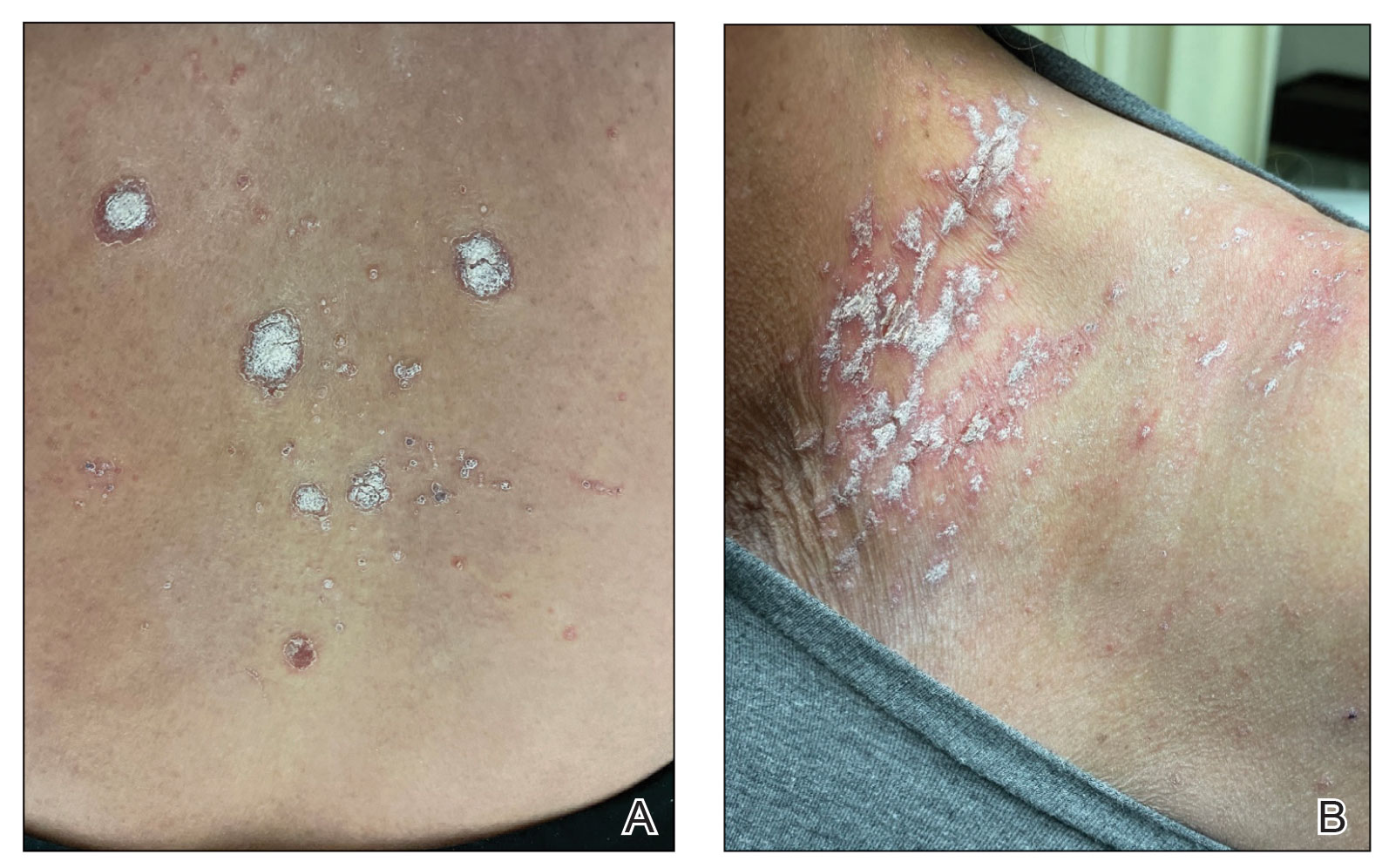

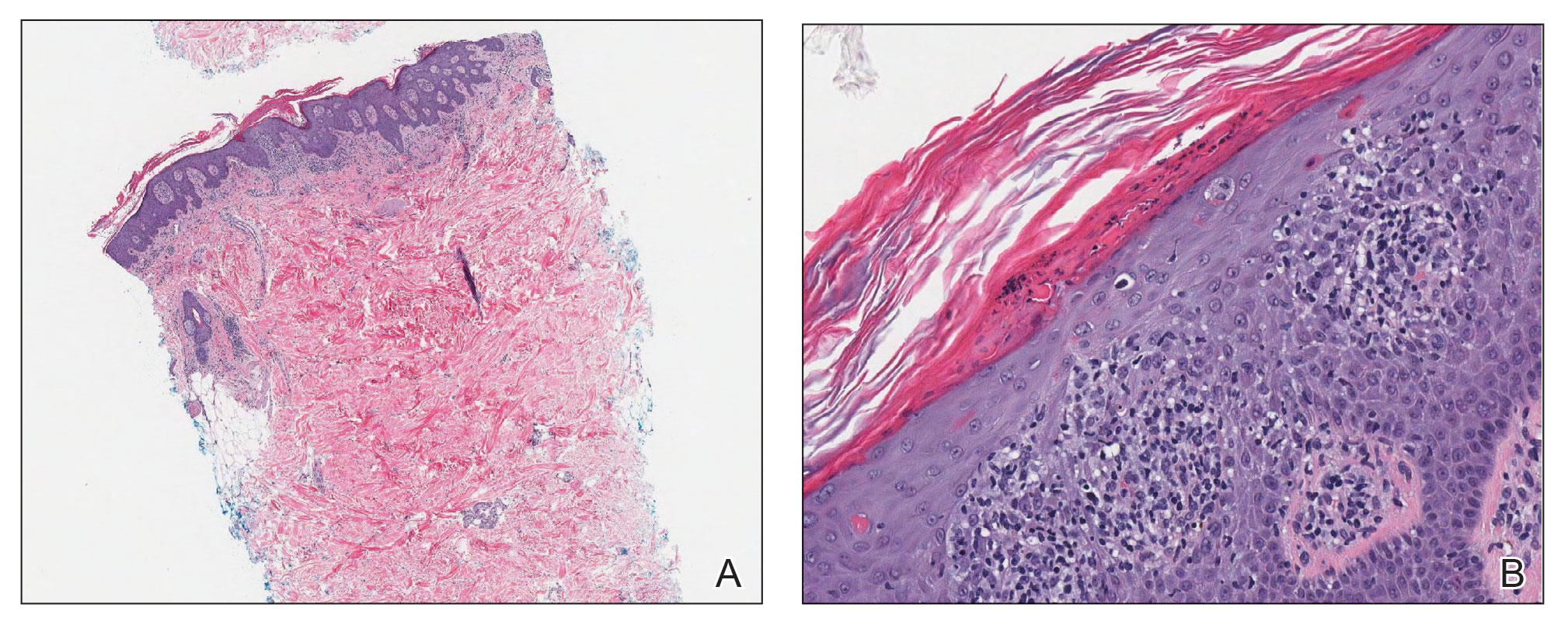

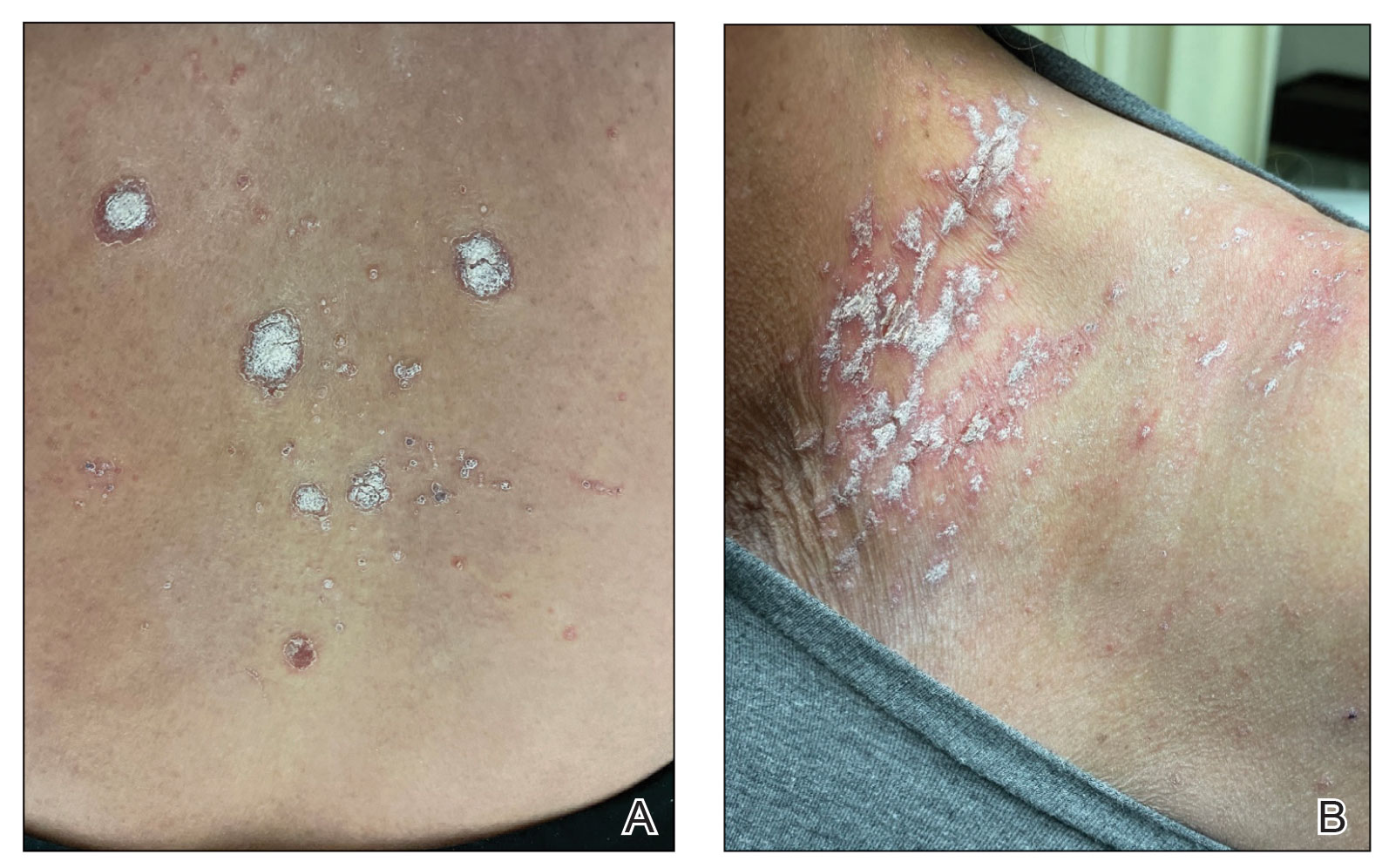

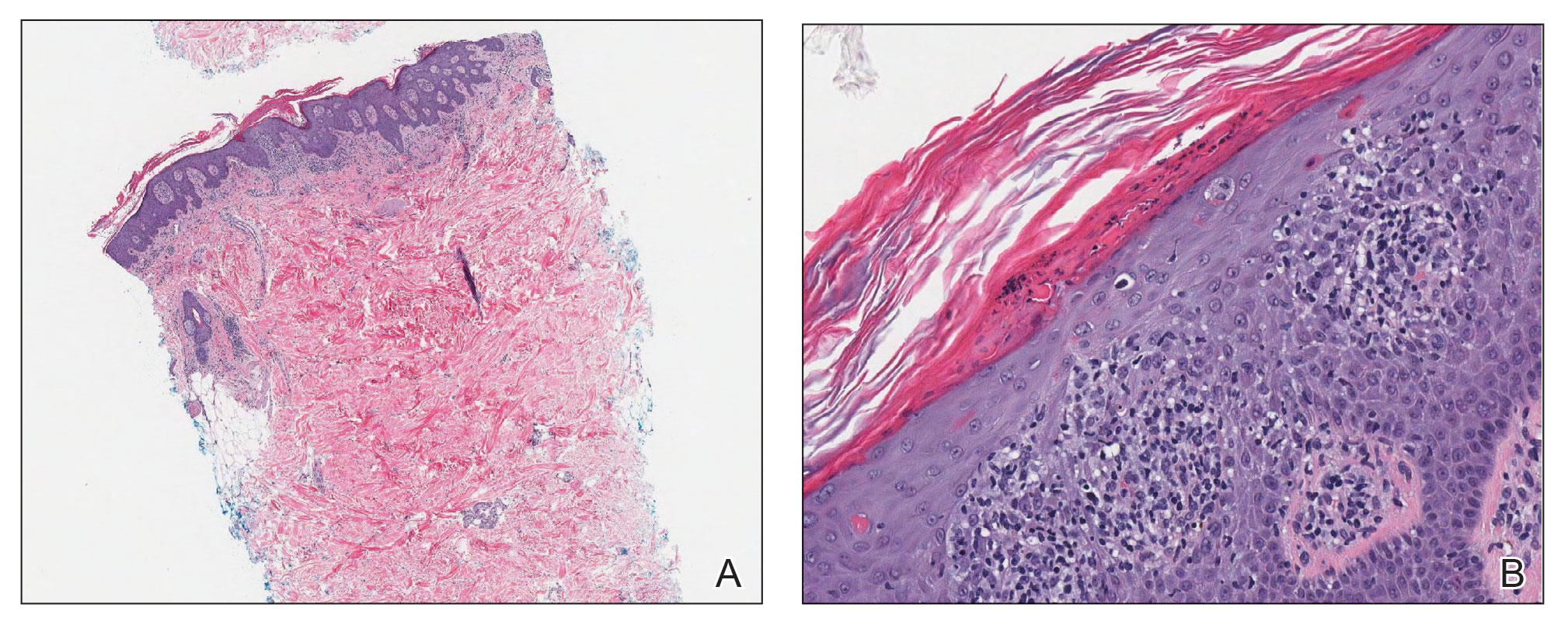

A 78-year-old man with a history of multiple basal cell carcinomas, hypertension, and remote smoking history presented to the dermatology clinic with an enlarging red-brown plaque on the scalp of 2 months’ duration. The lesion had grown rapidly to involve the forehead, right temple, preauricular region, and parietal scalp. At presentation, the tumor measured more than 20 cm in diameter at its greatest point (Figure 1). Physical examination revealed a 6-mm purple nodule within the lesion on the patient’s right parietal scalp. No clinical lymphadenopathy was appreciated at the time of diagnosis. Punch biopsies of the right parietal scalp nodule and right temple patch showed findings consistent with angiosarcoma with diffuse cytoplasmic staining of CD31 in atypical endothelial cells and no staining for human herpesvirus 8 (Figure 2). Concurrent computed tomography of the head showed thickening of the right epidermis, dermis, and deeper scalp tissues, but there was no evidence of skull involvement. Computed tomography of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis showed no evidence of metastatic disease. After a diagnostic workup, the patient was diagnosed with T2bN0M0 angiosarcoma.

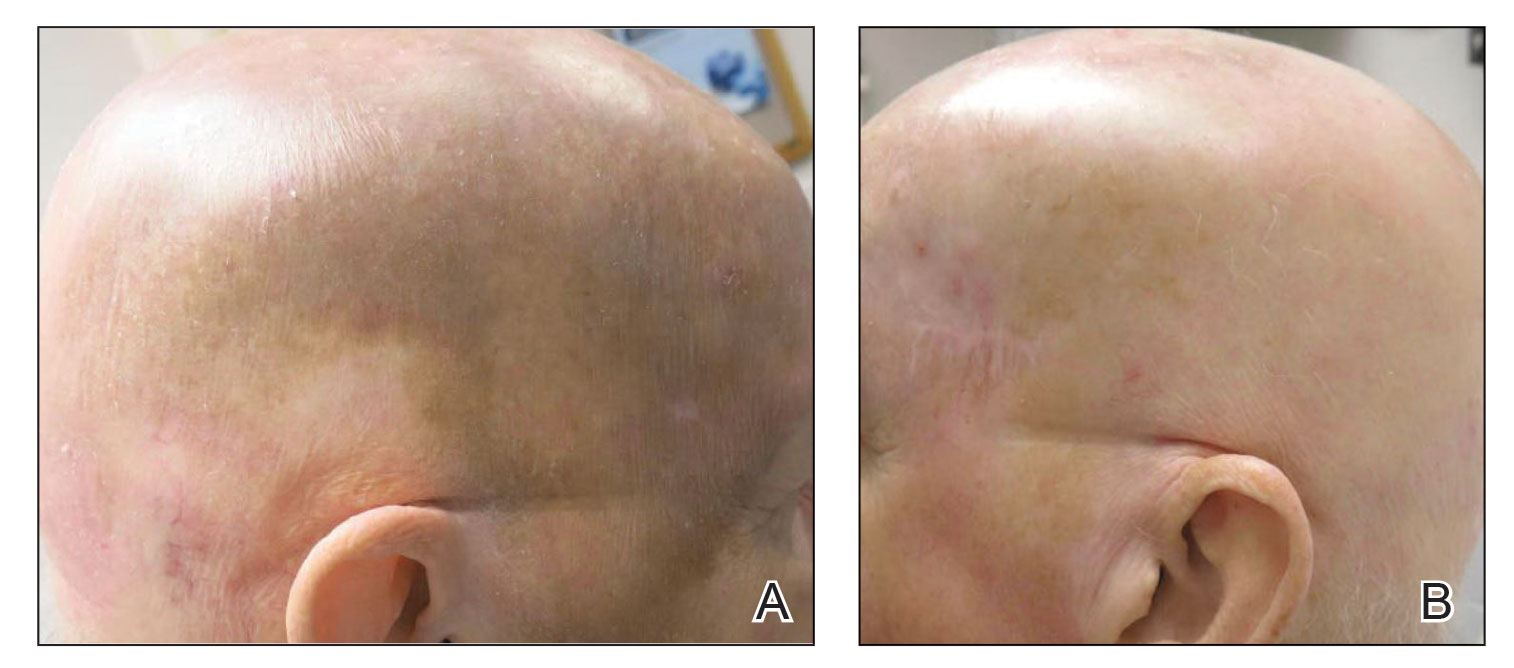

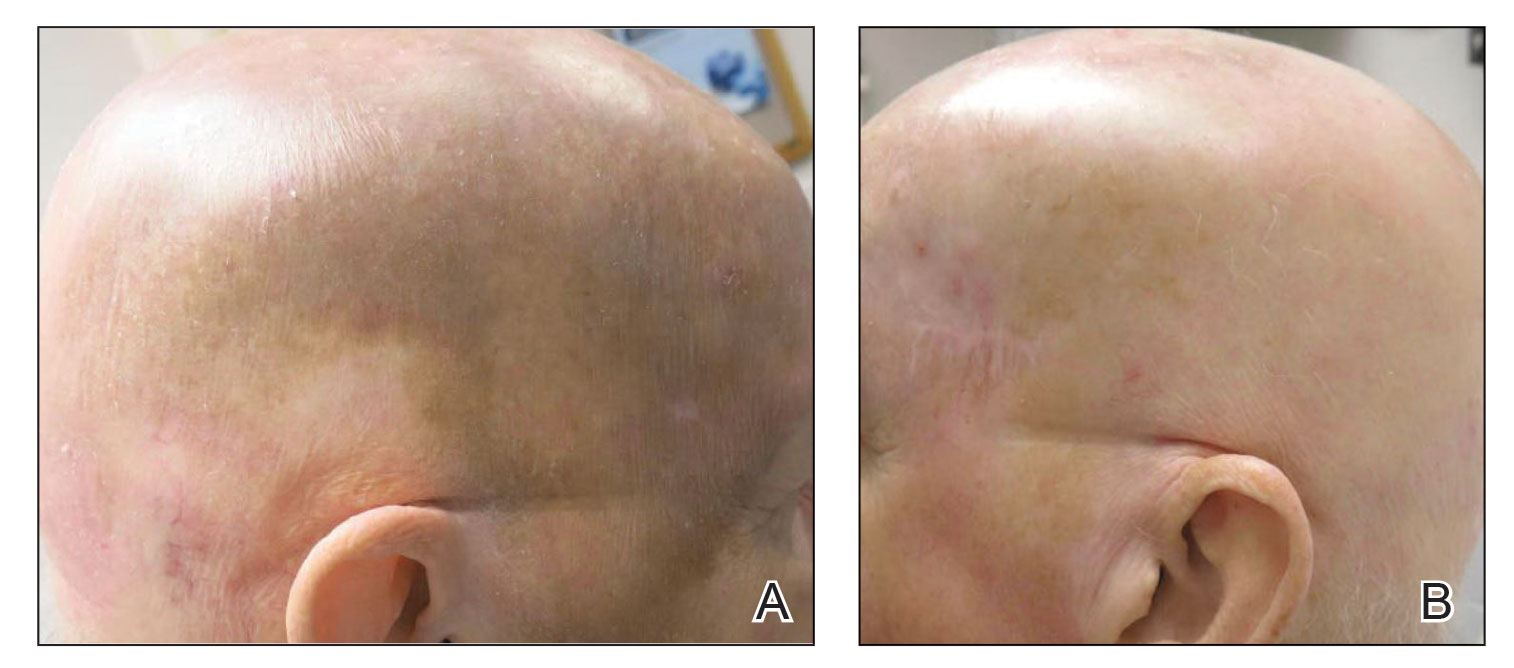

The lesion was determined to be nonresectable due to the extent of the patient’s cutaneous disease. The patient was started on a regimen of paclitaxel, scalp radiation, and oral propranolol. Propranolol 40 mg twice daily was initiated at the time of diagnosis with a plan to continue indefinitely. Starting 1 month after staging, the patient completed 10 weekly cycles of paclitaxel, and he was treated with 60 Gy of scalp radiation in 30 fractions, starting with the second cycle of paclitaxel. He tolerated both well with no reported adverse events. Repeat computed tomography performed 1 month after completion of chemotherapy and radiation showed no evidence of a mass or fluid collection in subcutaneous scalp tissues and no evidence of metastatic disease. This correlated with an observed clinical regression at 1 month and complete clinical response at 5 months with residual hemosiderin and radiation changes. The area of prior disease involvement subsequently evolved from violet to dusky gray in appearance to an eventual complete resolution 26 months after diagnosis, accompanied by atrophic radiation-induced sequelae (Figure 3).

The patient’s postchemotherapy course was complicated by hospitalization for a suspected malignant pleural effusion. Analysis revealed growing ground-glass opacities and nodules in the right lower lung lobe. A thoracentesis with cytology studies was negative for malignancy. Continued monitoring over 19 months demonstrated eventual resolution of those findings. He experienced notable complication from local radiation therapy to the scalp with chronic cutaneous ulceration refractory to wound care and surgical intervention. The patient did not exhibit additional signs or symptoms concerning for recurrence or metastasis and was followed by dermatology and oncology until he died nearly 5 years after initial diagnosis due to complications from acute hypoxic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19. The last imaging obtained showed no convincing evidence of metastasis, though spinal imaging within a month of his death showed lesions favored to represent benign angiomatous growths. His survival after diagnosis ultimately reached 57 months without confirmed disease recurrence and cause of death unrelated to malignancy history, which is a markedly long documented survival for this extent of disease.

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is an aggressive yet rare malignancy without effective treatments for prolonging survival or eradicating disease. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and neck has a reported 10-year survival rate of 13.8%.1 Although angiosarcoma in any location holds a bleak prognosis, cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp with a T2 classification has a 2-year survival rate of 0%. Moreover, even if remission is achieved, disease is highly recurrent, typically within months with the current standard of care.3,21,22

Emerging evidence for the possible role of β-adrenergic receptor blockade in the treatment of malignant vascular neoplasms is promising. Microarrays from a host of vascular growths have demonstrated expression of β-adrenergic receptors in 77% of sampled angiosarcoma specimens in addition to strong expression in infantile hemangiomas, hemangiomas, hemangioendotheliomas, and vascular malformations.19 Research findings have further verified the validity of this approach with the demonstration of b1-, b2-, and b3- adrenergic receptor expression by angiosarcoma cell lines. Propranolol subsequently was shown to effectively target proliferation of these cells and induce apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner and moreover be synergistic in effect with other chemotherapies.15 Several genes have exhibited differential expression between control tumor cells and propranolol-treated cells. Specifically, target genes including AXL (a receptor tyrosine kinase associated with cell adhesion, proliferation, and apoptosis and found to upregulated in melanoma and leukemia) and ERBB receptor feedback inhibitor 1 (receptor tyrosine kinase, with ERBB family members commonly overexpressed or mutated in the setting malignancy) have been posited as possible explanatory factors in the observed angiosarcoma response to propranolol.23

Several cases describing propranolol use as an adjunctive therapy for angiosarcoma suggest a beneficial role in clinical medicine. One case report described propranolol monotherapy for lesion to our patient, with a resultant reduction in Ki-67 as a measure of proliferative index within 1 week of initiating propranolol therapy.13 Propranolol also has been shown to halt or slow progression of metastatic disease in visceral and metastatic angiosarcomas.12-14 In combination with oral etoposide and cyclophosphamide, maintenance propranolol therapy in 7 cases of advanced cutaneous angiosarcoma resulted in 1 complete response and 3 very good partial responses, with a median progression-free survival of 11 months.11 Larger-scale studies have not been published, but the growing number of case reports and case series warrants further investigation of the utility of propranolol as an adjunct to current therapies in advanced angiosarcoma.

- Abraham JA, Hornicek FJ, Kaufman AM, et al. Treatment and outcome of 82 patients with angiosarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1953-1967.

- Shin JY, Roh SG, Lee NH, et al. Predisposing factors for poor prognosis of angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2017;39:380-386.

- Fury MG, Antonescu CR, Zee KJV, et al. A 14-year retrospective review of angiosarcoma: clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, and treatment outcomes with surgery and chemotherapy. Cancer. 2005;11:241-247.

- Dossett LA, Harrington M, Cruse CW, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2015;39:258-263.

- Penel N, Bui BN, Bay JO, et al. Phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel for unresectable angiosarcoma: the ANGIOTAX study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5269-5274.

- Agulnik M, Yarber JL, Okuno SH, et al. An open-label, multicenter, phase II study of bevacizumab for the treatment of angiosarcoma and epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:257-263.

- Maki RG, D’Adamo DR, Keohan ML, et al. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with metastatic or recurrent sarcomas. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3133-3140.

- Ishida Y, Otsuka A, Kabashima K. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: update on biology and latest treatment. Curr Opin Oncol. 2018;30:107-112.

- Ray-Coquard I, Italiano A, Bompas E, et al. Sorafenib for patients with advanced angiosarcoma: a phase II trial from the French Sarcoma Group (GSF/GETO). Oncologist. 2012;17:260-266.

- Ray-Coquard IL, Domont J, Tresch-Bruneel E, et al. Paclitaxel given once per week with or without bevacizumab in patients with advanced angiosarcoma: a randomized phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2797-2802.

- Pasquier E, Andre N, Street J, et al. Effective management of advanced angiosarcoma by the synergistic combination of propranolol and vinblastine-based metronomic chemotherapy: a bench to bedside study. EBioMedicine. 2016;6:87-95.

- Banavali S, Pasquier E, Andre N. Targeted therapy with propranolol and metronomic chemotherapy combination: sustained complete response of a relapsing metastatic angiosarcoma. Ecancermedicalscience. 2015;9:499.

- Chow W, Amaya CN, Rains S, et al. Growth attenuation of cutaneous angiosarcoma with propranolol-mediated beta-blockade. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1226-1229.

- Daguze J, Saint-Jean M, Peuvrel L, et al. Visceral metastatic angiosarcoma treated effectively with oral cyclophosphamide combined with propranolol. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:497-499.

- Stiles JM, Amaya C, Rains S, et al. Targeting of beta adrenergic receptors results in therapeutic efficacy against models of hemangioendothelioma and angiosarcoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60021.

- Chang PY, Chung CH, Chang WC, et al. The effect of propranolol on the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: a nationwide population-based study. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0216828.

- De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Benemei S, et al. Propranolol for off-label treatment of patients with melanoma: results from a cohort study. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:e172908.

- Rico M, Baglioni M, Bondarenko M, et al. Metformin and propranolol combination prevents cancer progression and metastasis in different breast cancer models. Oncotarget. 2017;8:2874-2889.

- Chisholm KM, Chang KW, Truong MT, et al. β-Adrenergic receptor expression in vascular tumors. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1446-1451.

- Leaute-Labreze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T, et al. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2649-2651.

- Maddox JC, Evans HL. Angiosarcoma of skin and soft tissue: a study of forty-four cases. Cancer. 1981;48:1907-1921.

- Morgan MB, Swann M, Somach S, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a case series with prognostic correlation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:867-874.

- Zhou S, Liu P, Jiang W, et al. Identification of potential target genes associated with the effect of propranolol on angiosarcoma via microarray analysis. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:4267-4275.

To the Editor:

Angiosarcoma is a malignancy of the vascular endothelium that most commonly presents on the skin.1 Patients diagnosed with cutaneous angiosarcoma, which is a rare and aggressive malignancy, have a 5-year survival rate of approximately 30%.2,3 Angiosarcoma can be seen in the setting of chronic lymphedema; radiation therapy; and sporadically in elderly patients, where it is commonly seen on the head and neck. Presentation on the head and neck has been associated with worse outcomes, with a projected overall 10-year survival rate of 13.8%; the survival rate is lower if the tumor is surgically unresectable or larger in size. Metastasis can occur via both lymphatic and hematogenous routes, with pulmonary and hepatic metastases most frequently observed.1 Prognostications of poor outcomes for patients with head and neck cutaneous angiosarcoma via a 5-year survival rate were identified in a meta-analysis and included the following: patient age older than 70 years, larger tumors, tumor location of scalp vs face, nonsurgical treatments, and lack of clear margins on histology.2

Treatment of angiosarcoma historically has encompassed both surgical resection and adjuvant radiation therapy with suboptimal success. Evidence supporting various treatment regimens remains sparse due to the low incidence of the neoplasm. Although surgical resection is the only documented curative treatment, cutaneous angiosarcomas frequently are found to have positive surgical margins and require adjuvant radiation. Use of high-dose radiation (>50 Gy) with application over a wide treatment area such as total scalp irradiation is recommended.4 Although radiation has been found to diminish local recurrence rates, it has not substantially affected rates of distant disease recurrence.1 Cytotoxic chemotherapy has clinical utility in minimizing progression, but standard regimens afford a progression-free survival of only months.3 Adjuvant treatment with paclitaxel has been shown to have improved efficacy in scalp angiosarcoma vs other visceral sites, showing a nonprogression rate of 42% at 4 months after treatment.5 More recently, targeted chemotherapeutics, including the vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor bevacizumab and tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib, have shown some survival benefit, but it is unclear if these agents are superior to traditional cytotoxic agents.4,6-10 A phase 2 study of paclitaxel administered weekly with or without bevacizumab showed similar progression-free survival and overall survival, albeit at the expense of added toxicity experienced by participants in the combined group.10

The addition of the nonselective β-adrenergic blocker propranolol to the treatment armamentarium, which was pursued due to its utility in the treatment of benign infantile hemangioma and demonstrated ability to limit the expression of adrenergic receptors in angiosarcoma, has gained clinical attention for possible augmentation of cutaneous angiosarcoma therapy.11-14 Propranolol has been shown to reduce metastasis in other neoplasms—both vascular and nonvascular—and may play a role as an adjuvant treatment to current therapies in angiosarcoma.15-20 We report a patient with cutaneous angiosarcoma (T2 classification) with disease-free survival of nearly 6 years without evidence of recurrence in the setting of continuous propranolol use supplementary to chemotherapy and radiation.

A 78-year-old man with a history of multiple basal cell carcinomas, hypertension, and remote smoking history presented to the dermatology clinic with an enlarging red-brown plaque on the scalp of 2 months’ duration. The lesion had grown rapidly to involve the forehead, right temple, preauricular region, and parietal scalp. At presentation, the tumor measured more than 20 cm in diameter at its greatest point (Figure 1). Physical examination revealed a 6-mm purple nodule within the lesion on the patient’s right parietal scalp. No clinical lymphadenopathy was appreciated at the time of diagnosis. Punch biopsies of the right parietal scalp nodule and right temple patch showed findings consistent with angiosarcoma with diffuse cytoplasmic staining of CD31 in atypical endothelial cells and no staining for human herpesvirus 8 (Figure 2). Concurrent computed tomography of the head showed thickening of the right epidermis, dermis, and deeper scalp tissues, but there was no evidence of skull involvement. Computed tomography of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis showed no evidence of metastatic disease. After a diagnostic workup, the patient was diagnosed with T2bN0M0 angiosarcoma.

The lesion was determined to be nonresectable due to the extent of the patient’s cutaneous disease. The patient was started on a regimen of paclitaxel, scalp radiation, and oral propranolol. Propranolol 40 mg twice daily was initiated at the time of diagnosis with a plan to continue indefinitely. Starting 1 month after staging, the patient completed 10 weekly cycles of paclitaxel, and he was treated with 60 Gy of scalp radiation in 30 fractions, starting with the second cycle of paclitaxel. He tolerated both well with no reported adverse events. Repeat computed tomography performed 1 month after completion of chemotherapy and radiation showed no evidence of a mass or fluid collection in subcutaneous scalp tissues and no evidence of metastatic disease. This correlated with an observed clinical regression at 1 month and complete clinical response at 5 months with residual hemosiderin and radiation changes. The area of prior disease involvement subsequently evolved from violet to dusky gray in appearance to an eventual complete resolution 26 months after diagnosis, accompanied by atrophic radiation-induced sequelae (Figure 3).

The patient’s postchemotherapy course was complicated by hospitalization for a suspected malignant pleural effusion. Analysis revealed growing ground-glass opacities and nodules in the right lower lung lobe. A thoracentesis with cytology studies was negative for malignancy. Continued monitoring over 19 months demonstrated eventual resolution of those findings. He experienced notable complication from local radiation therapy to the scalp with chronic cutaneous ulceration refractory to wound care and surgical intervention. The patient did not exhibit additional signs or symptoms concerning for recurrence or metastasis and was followed by dermatology and oncology until he died nearly 5 years after initial diagnosis due to complications from acute hypoxic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19. The last imaging obtained showed no convincing evidence of metastasis, though spinal imaging within a month of his death showed lesions favored to represent benign angiomatous growths. His survival after diagnosis ultimately reached 57 months without confirmed disease recurrence and cause of death unrelated to malignancy history, which is a markedly long documented survival for this extent of disease.

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is an aggressive yet rare malignancy without effective treatments for prolonging survival or eradicating disease. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and neck has a reported 10-year survival rate of 13.8%.1 Although angiosarcoma in any location holds a bleak prognosis, cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp with a T2 classification has a 2-year survival rate of 0%. Moreover, even if remission is achieved, disease is highly recurrent, typically within months with the current standard of care.3,21,22

Emerging evidence for the possible role of β-adrenergic receptor blockade in the treatment of malignant vascular neoplasms is promising. Microarrays from a host of vascular growths have demonstrated expression of β-adrenergic receptors in 77% of sampled angiosarcoma specimens in addition to strong expression in infantile hemangiomas, hemangiomas, hemangioendotheliomas, and vascular malformations.19 Research findings have further verified the validity of this approach with the demonstration of b1-, b2-, and b3- adrenergic receptor expression by angiosarcoma cell lines. Propranolol subsequently was shown to effectively target proliferation of these cells and induce apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner and moreover be synergistic in effect with other chemotherapies.15 Several genes have exhibited differential expression between control tumor cells and propranolol-treated cells. Specifically, target genes including AXL (a receptor tyrosine kinase associated with cell adhesion, proliferation, and apoptosis and found to upregulated in melanoma and leukemia) and ERBB receptor feedback inhibitor 1 (receptor tyrosine kinase, with ERBB family members commonly overexpressed or mutated in the setting malignancy) have been posited as possible explanatory factors in the observed angiosarcoma response to propranolol.23

Several cases describing propranolol use as an adjunctive therapy for angiosarcoma suggest a beneficial role in clinical medicine. One case report described propranolol monotherapy for lesion to our patient, with a resultant reduction in Ki-67 as a measure of proliferative index within 1 week of initiating propranolol therapy.13 Propranolol also has been shown to halt or slow progression of metastatic disease in visceral and metastatic angiosarcomas.12-14 In combination with oral etoposide and cyclophosphamide, maintenance propranolol therapy in 7 cases of advanced cutaneous angiosarcoma resulted in 1 complete response and 3 very good partial responses, with a median progression-free survival of 11 months.11 Larger-scale studies have not been published, but the growing number of case reports and case series warrants further investigation of the utility of propranolol as an adjunct to current therapies in advanced angiosarcoma.

To the Editor:

Angiosarcoma is a malignancy of the vascular endothelium that most commonly presents on the skin.1 Patients diagnosed with cutaneous angiosarcoma, which is a rare and aggressive malignancy, have a 5-year survival rate of approximately 30%.2,3 Angiosarcoma can be seen in the setting of chronic lymphedema; radiation therapy; and sporadically in elderly patients, where it is commonly seen on the head and neck. Presentation on the head and neck has been associated with worse outcomes, with a projected overall 10-year survival rate of 13.8%; the survival rate is lower if the tumor is surgically unresectable or larger in size. Metastasis can occur via both lymphatic and hematogenous routes, with pulmonary and hepatic metastases most frequently observed.1 Prognostications of poor outcomes for patients with head and neck cutaneous angiosarcoma via a 5-year survival rate were identified in a meta-analysis and included the following: patient age older than 70 years, larger tumors, tumor location of scalp vs face, nonsurgical treatments, and lack of clear margins on histology.2

Treatment of angiosarcoma historically has encompassed both surgical resection and adjuvant radiation therapy with suboptimal success. Evidence supporting various treatment regimens remains sparse due to the low incidence of the neoplasm. Although surgical resection is the only documented curative treatment, cutaneous angiosarcomas frequently are found to have positive surgical margins and require adjuvant radiation. Use of high-dose radiation (>50 Gy) with application over a wide treatment area such as total scalp irradiation is recommended.4 Although radiation has been found to diminish local recurrence rates, it has not substantially affected rates of distant disease recurrence.1 Cytotoxic chemotherapy has clinical utility in minimizing progression, but standard regimens afford a progression-free survival of only months.3 Adjuvant treatment with paclitaxel has been shown to have improved efficacy in scalp angiosarcoma vs other visceral sites, showing a nonprogression rate of 42% at 4 months after treatment.5 More recently, targeted chemotherapeutics, including the vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor bevacizumab and tyrosine kinase inhibitor sorafenib, have shown some survival benefit, but it is unclear if these agents are superior to traditional cytotoxic agents.4,6-10 A phase 2 study of paclitaxel administered weekly with or without bevacizumab showed similar progression-free survival and overall survival, albeit at the expense of added toxicity experienced by participants in the combined group.10

The addition of the nonselective β-adrenergic blocker propranolol to the treatment armamentarium, which was pursued due to its utility in the treatment of benign infantile hemangioma and demonstrated ability to limit the expression of adrenergic receptors in angiosarcoma, has gained clinical attention for possible augmentation of cutaneous angiosarcoma therapy.11-14 Propranolol has been shown to reduce metastasis in other neoplasms—both vascular and nonvascular—and may play a role as an adjuvant treatment to current therapies in angiosarcoma.15-20 We report a patient with cutaneous angiosarcoma (T2 classification) with disease-free survival of nearly 6 years without evidence of recurrence in the setting of continuous propranolol use supplementary to chemotherapy and radiation.

A 78-year-old man with a history of multiple basal cell carcinomas, hypertension, and remote smoking history presented to the dermatology clinic with an enlarging red-brown plaque on the scalp of 2 months’ duration. The lesion had grown rapidly to involve the forehead, right temple, preauricular region, and parietal scalp. At presentation, the tumor measured more than 20 cm in diameter at its greatest point (Figure 1). Physical examination revealed a 6-mm purple nodule within the lesion on the patient’s right parietal scalp. No clinical lymphadenopathy was appreciated at the time of diagnosis. Punch biopsies of the right parietal scalp nodule and right temple patch showed findings consistent with angiosarcoma with diffuse cytoplasmic staining of CD31 in atypical endothelial cells and no staining for human herpesvirus 8 (Figure 2). Concurrent computed tomography of the head showed thickening of the right epidermis, dermis, and deeper scalp tissues, but there was no evidence of skull involvement. Computed tomography of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis showed no evidence of metastatic disease. After a diagnostic workup, the patient was diagnosed with T2bN0M0 angiosarcoma.

The lesion was determined to be nonresectable due to the extent of the patient’s cutaneous disease. The patient was started on a regimen of paclitaxel, scalp radiation, and oral propranolol. Propranolol 40 mg twice daily was initiated at the time of diagnosis with a plan to continue indefinitely. Starting 1 month after staging, the patient completed 10 weekly cycles of paclitaxel, and he was treated with 60 Gy of scalp radiation in 30 fractions, starting with the second cycle of paclitaxel. He tolerated both well with no reported adverse events. Repeat computed tomography performed 1 month after completion of chemotherapy and radiation showed no evidence of a mass or fluid collection in subcutaneous scalp tissues and no evidence of metastatic disease. This correlated with an observed clinical regression at 1 month and complete clinical response at 5 months with residual hemosiderin and radiation changes. The area of prior disease involvement subsequently evolved from violet to dusky gray in appearance to an eventual complete resolution 26 months after diagnosis, accompanied by atrophic radiation-induced sequelae (Figure 3).

The patient’s postchemotherapy course was complicated by hospitalization for a suspected malignant pleural effusion. Analysis revealed growing ground-glass opacities and nodules in the right lower lung lobe. A thoracentesis with cytology studies was negative for malignancy. Continued monitoring over 19 months demonstrated eventual resolution of those findings. He experienced notable complication from local radiation therapy to the scalp with chronic cutaneous ulceration refractory to wound care and surgical intervention. The patient did not exhibit additional signs or symptoms concerning for recurrence or metastasis and was followed by dermatology and oncology until he died nearly 5 years after initial diagnosis due to complications from acute hypoxic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19. The last imaging obtained showed no convincing evidence of metastasis, though spinal imaging within a month of his death showed lesions favored to represent benign angiomatous growths. His survival after diagnosis ultimately reached 57 months without confirmed disease recurrence and cause of death unrelated to malignancy history, which is a markedly long documented survival for this extent of disease.

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is an aggressive yet rare malignancy without effective treatments for prolonging survival or eradicating disease. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head and neck has a reported 10-year survival rate of 13.8%.1 Although angiosarcoma in any location holds a bleak prognosis, cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp with a T2 classification has a 2-year survival rate of 0%. Moreover, even if remission is achieved, disease is highly recurrent, typically within months with the current standard of care.3,21,22

Emerging evidence for the possible role of β-adrenergic receptor blockade in the treatment of malignant vascular neoplasms is promising. Microarrays from a host of vascular growths have demonstrated expression of β-adrenergic receptors in 77% of sampled angiosarcoma specimens in addition to strong expression in infantile hemangiomas, hemangiomas, hemangioendotheliomas, and vascular malformations.19 Research findings have further verified the validity of this approach with the demonstration of b1-, b2-, and b3- adrenergic receptor expression by angiosarcoma cell lines. Propranolol subsequently was shown to effectively target proliferation of these cells and induce apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner and moreover be synergistic in effect with other chemotherapies.15 Several genes have exhibited differential expression between control tumor cells and propranolol-treated cells. Specifically, target genes including AXL (a receptor tyrosine kinase associated with cell adhesion, proliferation, and apoptosis and found to upregulated in melanoma and leukemia) and ERBB receptor feedback inhibitor 1 (receptor tyrosine kinase, with ERBB family members commonly overexpressed or mutated in the setting malignancy) have been posited as possible explanatory factors in the observed angiosarcoma response to propranolol.23

Several cases describing propranolol use as an adjunctive therapy for angiosarcoma suggest a beneficial role in clinical medicine. One case report described propranolol monotherapy for lesion to our patient, with a resultant reduction in Ki-67 as a measure of proliferative index within 1 week of initiating propranolol therapy.13 Propranolol also has been shown to halt or slow progression of metastatic disease in visceral and metastatic angiosarcomas.12-14 In combination with oral etoposide and cyclophosphamide, maintenance propranolol therapy in 7 cases of advanced cutaneous angiosarcoma resulted in 1 complete response and 3 very good partial responses, with a median progression-free survival of 11 months.11 Larger-scale studies have not been published, but the growing number of case reports and case series warrants further investigation of the utility of propranolol as an adjunct to current therapies in advanced angiosarcoma.

- Abraham JA, Hornicek FJ, Kaufman AM, et al. Treatment and outcome of 82 patients with angiosarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1953-1967.

- Shin JY, Roh SG, Lee NH, et al. Predisposing factors for poor prognosis of angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2017;39:380-386.

- Fury MG, Antonescu CR, Zee KJV, et al. A 14-year retrospective review of angiosarcoma: clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, and treatment outcomes with surgery and chemotherapy. Cancer. 2005;11:241-247.

- Dossett LA, Harrington M, Cruse CW, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2015;39:258-263.

- Penel N, Bui BN, Bay JO, et al. Phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel for unresectable angiosarcoma: the ANGIOTAX study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5269-5274.

- Agulnik M, Yarber JL, Okuno SH, et al. An open-label, multicenter, phase II study of bevacizumab for the treatment of angiosarcoma and epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:257-263.

- Maki RG, D’Adamo DR, Keohan ML, et al. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with metastatic or recurrent sarcomas. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3133-3140.

- Ishida Y, Otsuka A, Kabashima K. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: update on biology and latest treatment. Curr Opin Oncol. 2018;30:107-112.

- Ray-Coquard I, Italiano A, Bompas E, et al. Sorafenib for patients with advanced angiosarcoma: a phase II trial from the French Sarcoma Group (GSF/GETO). Oncologist. 2012;17:260-266.

- Ray-Coquard IL, Domont J, Tresch-Bruneel E, et al. Paclitaxel given once per week with or without bevacizumab in patients with advanced angiosarcoma: a randomized phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2797-2802.

- Pasquier E, Andre N, Street J, et al. Effective management of advanced angiosarcoma by the synergistic combination of propranolol and vinblastine-based metronomic chemotherapy: a bench to bedside study. EBioMedicine. 2016;6:87-95.

- Banavali S, Pasquier E, Andre N. Targeted therapy with propranolol and metronomic chemotherapy combination: sustained complete response of a relapsing metastatic angiosarcoma. Ecancermedicalscience. 2015;9:499.

- Chow W, Amaya CN, Rains S, et al. Growth attenuation of cutaneous angiosarcoma with propranolol-mediated beta-blockade. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1226-1229.

- Daguze J, Saint-Jean M, Peuvrel L, et al. Visceral metastatic angiosarcoma treated effectively with oral cyclophosphamide combined with propranolol. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:497-499.

- Stiles JM, Amaya C, Rains S, et al. Targeting of beta adrenergic receptors results in therapeutic efficacy against models of hemangioendothelioma and angiosarcoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60021.

- Chang PY, Chung CH, Chang WC, et al. The effect of propranolol on the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: a nationwide population-based study. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0216828.

- De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Benemei S, et al. Propranolol for off-label treatment of patients with melanoma: results from a cohort study. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:e172908.

- Rico M, Baglioni M, Bondarenko M, et al. Metformin and propranolol combination prevents cancer progression and metastasis in different breast cancer models. Oncotarget. 2017;8:2874-2889.

- Chisholm KM, Chang KW, Truong MT, et al. β-Adrenergic receptor expression in vascular tumors. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1446-1451.

- Leaute-Labreze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T, et al. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2649-2651.

- Maddox JC, Evans HL. Angiosarcoma of skin and soft tissue: a study of forty-four cases. Cancer. 1981;48:1907-1921.

- Morgan MB, Swann M, Somach S, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a case series with prognostic correlation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:867-874.

- Zhou S, Liu P, Jiang W, et al. Identification of potential target genes associated with the effect of propranolol on angiosarcoma via microarray analysis. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:4267-4275.

- Abraham JA, Hornicek FJ, Kaufman AM, et al. Treatment and outcome of 82 patients with angiosarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1953-1967.

- Shin JY, Roh SG, Lee NH, et al. Predisposing factors for poor prognosis of angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2017;39:380-386.

- Fury MG, Antonescu CR, Zee KJV, et al. A 14-year retrospective review of angiosarcoma: clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, and treatment outcomes with surgery and chemotherapy. Cancer. 2005;11:241-247.

- Dossett LA, Harrington M, Cruse CW, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2015;39:258-263.

- Penel N, Bui BN, Bay JO, et al. Phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel for unresectable angiosarcoma: the ANGIOTAX study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5269-5274.

- Agulnik M, Yarber JL, Okuno SH, et al. An open-label, multicenter, phase II study of bevacizumab for the treatment of angiosarcoma and epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:257-263.

- Maki RG, D’Adamo DR, Keohan ML, et al. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with metastatic or recurrent sarcomas. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3133-3140.

- Ishida Y, Otsuka A, Kabashima K. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: update on biology and latest treatment. Curr Opin Oncol. 2018;30:107-112.

- Ray-Coquard I, Italiano A, Bompas E, et al. Sorafenib for patients with advanced angiosarcoma: a phase II trial from the French Sarcoma Group (GSF/GETO). Oncologist. 2012;17:260-266.

- Ray-Coquard IL, Domont J, Tresch-Bruneel E, et al. Paclitaxel given once per week with or without bevacizumab in patients with advanced angiosarcoma: a randomized phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2797-2802.

- Pasquier E, Andre N, Street J, et al. Effective management of advanced angiosarcoma by the synergistic combination of propranolol and vinblastine-based metronomic chemotherapy: a bench to bedside study. EBioMedicine. 2016;6:87-95.

- Banavali S, Pasquier E, Andre N. Targeted therapy with propranolol and metronomic chemotherapy combination: sustained complete response of a relapsing metastatic angiosarcoma. Ecancermedicalscience. 2015;9:499.

- Chow W, Amaya CN, Rains S, et al. Growth attenuation of cutaneous angiosarcoma with propranolol-mediated beta-blockade. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1226-1229.

- Daguze J, Saint-Jean M, Peuvrel L, et al. Visceral metastatic angiosarcoma treated effectively with oral cyclophosphamide combined with propranolol. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:497-499.

- Stiles JM, Amaya C, Rains S, et al. Targeting of beta adrenergic receptors results in therapeutic efficacy against models of hemangioendothelioma and angiosarcoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60021.

- Chang PY, Chung CH, Chang WC, et al. The effect of propranolol on the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: a nationwide population-based study. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0216828.

- De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Benemei S, et al. Propranolol for off-label treatment of patients with melanoma: results from a cohort study. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:e172908.

- Rico M, Baglioni M, Bondarenko M, et al. Metformin and propranolol combination prevents cancer progression and metastasis in different breast cancer models. Oncotarget. 2017;8:2874-2889.

- Chisholm KM, Chang KW, Truong MT, et al. β-Adrenergic receptor expression in vascular tumors. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1446-1451.

- Leaute-Labreze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T, et al. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2649-2651.

- Maddox JC, Evans HL. Angiosarcoma of skin and soft tissue: a study of forty-four cases. Cancer. 1981;48:1907-1921.

- Morgan MB, Swann M, Somach S, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a case series with prognostic correlation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:867-874.

- Zhou S, Liu P, Jiang W, et al. Identification of potential target genes associated with the effect of propranolol on angiosarcoma via microarray analysis. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:4267-4275.

PRACTICE POINTS

- In one classic presentation, cutaneous angiosarcoma characteristically appears as a bruiselike patch on the head and neck of an elderly gentleman.

- Although cutaneous angiosarcoma typically portends a poor prognosis at the time of diagnosis, adjunctive oral propranolol may be a promising and relatively benign therapy, posited to afford benefit in a manner similar to its efficacy in the treatment of infantile hemangiomas.

Use of Dupilumab in Severe, Multifactorial, Chronic Itch for Geriatric Patients

To the Editor:

Today’s geriatric population is the fastest growing in history. The National Institutes of Health predicts there will be over 1.5 billion individuals aged 65 years and older by the year 2050: 17% of the world’s population.1 Pruritus—either acute or chronic (>6 weeks)—is defined as a sensory perception that leads to an intense desire to scratch.2 Chronic pruritus is an increasing health concern that impacts quality of life within the geriatric population. Elderly patients have various risk factors for developing chronic itch, including aging skin, polypharmacy, and increased systemic comorbidities.3-7

Although the therapeutic armamentarium for chronic itch continues to grow, health care providers often are hesitant to prescribe medications for geriatric patients because of comorbidities and potential drug-drug interactions. Novel biologic therapies now provide alternatives for this complex population. Dupilumab is a fully humanized, monoclonal antibody approved for treatment-resistant atopic dermatitis. This biologic prevents helper T-cell (TH2) signaling, IL-4 and IL-13 release, and subsequent effector cell (eg, mast cell, eosinophil) activity.8-10 The combined efficacy and safety of this medication has changed the treatment landscape of resistant atopic dermatitis. We present the use of dupilumab in a geriatric patient with severe and recalcitrant itch resistant to numerous topical and oral medications.