User login

Evaluation of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Appropriate Use Criteria for the Nonarthroplasty Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis in Veterans

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) affects almost 9.3 million adults in the US and accounts for $27 billion in annual health care expenses.1,2 Due to the increasing cost of health care and an aging population, there has been renewed interest in establishing criteria for nonarthroplasty treatment of knee OA.

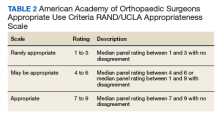

In 2013, using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness method, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) developed an appropriate use criteria (AUC) for nonarthroplasty management of primary OA of the knee, based on orthopaedic literature and expert opinion.3 Interventions such as activity modification, weight loss, prescribed physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tramadol, prescribed oral or transcutaneous opioids, acetaminophen, intra-articular corticosteroids, hinged or unloading knee braces, arthroscopic partial menisectomy or loose body removal, and realignment osteotomy were assessed. An algorithm was developed for 576 patients scenarios that incorporated patient-specific, prognostic/predictor variables to assign designations of “appropriate,” “may be appropriate,” or “rarely appropriate,” to treatment interventions.4,5 An online version of the algorithm (orthoguidelines.org) is available for physicians and surgeons to judge appropriateness of nonarthroplasty treatments; however, it is not intended to mandate candidacy for treatment or intervention.

Clinical evaluation of the AAOS AUC is necessary to determine how treatment recommendations correlate with current practice. A recent examination of the AAOS Appropriateness System for Surgical Management of Knee OA found that prognostic/predictor variables, such as patient age, OA severity, and pattern of knee OA involvement were more heavily weighted when determining arthroplasty appropriateness than was pain severity or functional loss.6 Furthermore, non-AAOS AUC prognostic/predictor variables, such as race and gender, have been linked to disparities in utilization of knee OA interventions.7-9 Such disparities can be costly not just from a patient perceptive, but also employer and societal perspectives.10

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system represents a model of equal-access-to care system in the US that is ideal for examination of issues about health care utilization and any disparities within the AAOS AUC model and has previously been used to assess utilization of total knee arthroplasty.9 The aim of this study was to characterize utilization of the AAOS AUC for nonarthroplasty treatment of knee OA in a VA patient population. We asked the following questions: (1) What variables are predictive of receiving a greater number of AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments? (2) What variables are predictive of receiving “rarely appropriate” AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatment? (3) What factors are predictive of duration of nonarthroplasty care until total knee arthroplasty (TKA)?

Methods

The institutional review board at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center in Ohio approved a retrospective chart review of nonarthroplasty treatments utilized by patients presenting to its orthopaedic section who subsequently underwent knee arthroplasty between 2013 and 2016. Eligibility criteria included patients aged ≥ 30 years with a diagnosis of unilateral or bilateral primary knee OA. Patients with posttraumatic OA, inflammatory arthritis, and a history of infectious arthritis or Charcot arthropathy of the knee were excluded. Patients with a body mass index (BMI) > 40 or a hemoglobin A1c > 8.0 at presentation were excluded as nonarthroplasty care was the recommended course of treatment above these thresholds.

Data collected included race, gender, duration of nonarthroplasty treatment, BMI, and Kellgren-Lawrence classification of knee OA at time of presentation for symptomatic knee OA.11 All AAOS AUC-evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments utilized prior to arthroplasty intervention also were recorded (Table 1).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was completed with GraphPad Software Prism 7.0a (La Jolla, CA) and Mathworks MatLab R2016b software (Natick, MA). Univariate analysis with Student t tests with Welch corrections in the setting of unequal variance, Mann-Whitney nonparametric tests, and Fisher exact test were generated in the appropriate setting. Multivariable analyses also were conducted. For continuous outcomes, stepwise multiple linear regression was used to generate predictive models; for binary outcomes, binomial logistic regression was used.

Factors analyzed in regression modeling for the total number of AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments utilized and the likelihood of receiving a rarely appropriate treatment included gender, race, function-limiting pain, range of motion (ROM), ligamentous instability, arthritis pattern, limb alignment, mechanical symptoms, BMI, age, and Kellgren-Lawrence grade. Factors analyzed in timing of TKA included the above variables plus the total number of AUC interventions, whether the patient received an inappropriate intervention, and average appropriateness of the interventions received. Residual analysis with Cook’s distance was used to identify outliers in regression. Observations with Cook’s distance > 3 times the mean Cook’s distance were identified as potential outliers, and models were adjusted accordingly. All statistical analyses were 2-tailed. Statistical significance was set to P ≤ .05 for all outputs.

Results

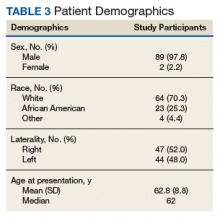

In the study, 97.8% of participants identified as male, and the mean age was 62.8 years (Table 3).

Appropriate Use Criteria Interventions

Patients received a mean of 5.2 AAOS AUC evaluated interventions before undergoing arthroplasty management at a mean of 32.3 months (range 2-181 months) from initial presentation. The majority of these interventions were classified as either appropriate or may be appropriate, according to the AUC definitions (95.1%). Self-management and physical therapy programs were widely utilized (100% and 90.1%, respectively), with all use of these interventions classified as appropriate.

Hinged or unloader knee braces were utilized in about half the study patients; this intervention was classified as rarely appropriate in 4.4% of these patients. Medical therapy was also widely used, with all use of NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and tramadol classified as appropriate or may be appropriate. Oral or transcutaneous opioid medications were prescribed in 14.3% of patients, with 92.3% of this use classified as rarely appropriate. Although the opioid medication prescribing provider was not specifically evaluated, there were no instances in which the orthopaedic service provided an oral or transcutaneous opioid prescriptions. Procedural interventions, with the exception of corticosteroid injections, were uncommon; no patient received realignment osteotomy, and only 12.1% of patients underwent arthroscopy. The use of arthroscopy was deemed rarely appropriate in 72.7% of these cases.

Factors Associated With AAOS AUC Intervention Use

There was no difference in the number of AAOS AUC evaluated interventions received based on BMI (mean [SD] BMI < 35, 5.2 [1.0] vs BMI ≥ 35, 5.3 [1.1], P = .49), age (mean [SD] aged < 60 years, 5.4 [1.0] vs aged ≥ 60 years, 5.1 [1.2], P = .23), or Kellgren-Lawrence arthritic grade (mean [SD] grade ≤ 2, 5.5 [1.0] vs grade > 2, 5.1 [1.1], P = .06). These variables also were not associated with receiving a rarely appropriate intervention (mean [SD] BMI < 35, 0.27 [0.5] vs BMI > 35, 0.2 [0.4], P = .81; aged > 60 years, 0.3 [0.5] vs aged < 60 years, 0.2 [0.4], P = .26; Kellgren-Lawrence grade < 2, 0.4 [0.6] vs grade > 2, 0.2 [0.4], P = .1).

Regression modeling to predict total number of AAOS AUC evaluated interventions received produced a significant model (R2 = 0.111, P = .006). The presence of ligamentous instability (β coefficient, -1.61) and the absence of mechanical symptoms (β coefficient, -0.67) were negative predictors of number of AUC interventions received. Variance inflation factors were 1.014 and 1.012, respectively. Likewise, regression modeling to identify factors predictive of receiving a rarely appropriate intervention also produced a significant model (pseudo R2= 0.06, P = .025), with lower Kellgren-Lawrence grade the only significant predictor of receiving a rarely appropriate intervention (odds ratio [OR] 0.54; 95% CI, 0.42 -0.72, per unit increase).

Timing from presentation to arthroplasty intervention was also evaluated. Age was a negative predictor (β coefficient -1.61), while positive predictors were reduced ROM (β coefficient 15.72) and having more AUC interventions (β coefficient 7.31) (model R2= 0.29, P = < .001). Age was the most significant predictor. Variance inflations factors were 1.02, 1.01, and 1.03, respectively. Receiving a rarely appropriate intervention was not associated with TKA timing.

Discussion

This single-center retrospective study examined the utilization of AAOS AUC-evaluated nonarthroplasty interventions for symptomatic knee OA prior to TKA. The aims of this study were to validate the AAOS AUC in a clinical setting and identify predictors of AAOS AUC utilization. In particular, this study focused on the number of interventions utilized prior to knee arthroplasty, whether interventions receiving a designation of rarely appropriate were used, and the duration of nonarthroplasty treatment.

Patients with knee instability used fewer total AAOS AUC evaluated interventions prior to TKA. Subjective instability has been reported as high as 27% in patients with OA and has been associated with fear of falling, poor balance confidence, activity limitations, and lower Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) physical function scores.12 However, it has not been found to correlate with knee laxity.13 Nevertheless, significant functional impairment with the risk of falling may reduce the number of nonarthroplasty interventions attempted. On the other hand, the presence of mechanical symptoms resulted in greater utilization of nonarthroplasty interventions. This is likely due to the greater utilization of arthroscopic partial menisectomy or loose body removal in this group of patients. Despite its inclusion as an AAOS AUC evaluated intervention, arthroscopy remains a contentious treatment for symptomatic knee pain in the setting of OA.14,15

For every unit decrease in Kellgren-Lawrence OA grade, patients were 54% more likely to receive a rarely appropriate intervention prior to knee arthroplasty. This is supported by the recent literature examining the AAOS AUC for surgical management of knee OA. Riddle and colleagues developed a classification tree to determine the contributions of various prognostic variables in final classifications of the 864 clinical vignettes used to develop the appropriateness algorithm and found that OA severity was strongly favored, with only 4 of the 432 vignettes with severe knee OA judged as rarely appropriate for surgical intervention.6

Our findings, too, may be explained by an AAOS AUC system that too heavily weighs radiographic severity of knee OA, resulting in more frequent rarely appropriate interventions in patients with less severe arthritis, including nonarthroplasty treatments. It is likely that rarely appropriate interventions were attempted in this subset of our study cohort based on patient’s subjective symptoms and functional status, both of which have been shown to be discordant with radiographic severity of knee OA.16

Oral or transcutaneous prescribed opioid medications were the most frequent intervention that received a rarely appropriate designation. Patients with preoperative opioid use undergoing TKA have been shown to have a greater risk for postoperative complications and longer hospital stay, particularly those patients aged < 75 years. Younger age, use of more interventions, and decreased knee ROM at presentation were predictive of longer duration of nonarthroplasty treatment. The use of more AAOS AUC evaluated interventions in these patients suggests that the AAOS AUC model may effectively be used to manage symptomatic OA, increasing the time from presentation to knee arthroplasty.

Interestingly, the use of rarely appropriate interventions did not affect TKA timing, as would be expected in a clinically effective nonarthroplasty treatment model. The reasons for rarely appropriate nonsurgical interventions are complex and require further investigation. One possible explanation is that decreased ROM was a marker for mechanical symptoms that necessitated additional intervention in the form of knee arthroscopy, delaying time to TKA.

Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. First, the small sample size (N = 90) requires acknowledgment; however, this limitation reflects the difficulty in following patients for years prior to an operative intervention. Second, the study population consists of veterans using the VA system and may not be reflective of the general population, differing with respect to gender, racial, and socioeconomic factors. Nevertheless, studies examining TKA utilization found, aside from racial and ethnic variability, patient gender and age do not affect arthroplasty utilization rate in the VA system.17

Additional limitations stem from the retrospective nature of this study. While the Computerized Patient Record System and centralized care of the VA system allows for review of all physical therapy consultations, orthotic consultations, and medications within the VA system, any treatments and intervention delivered by non-VA providers were not captured. Furthermore, the ability to assess for confounding variables limiting the prescription of certain medications, such as chronic kidney disease with NSAIDs or liver disease with acetaminophen, was limited by our study design.

Although our study suffers from selection bias with respect to examination of nonarthroplasty treatment in patients who have ultimately undergone TKA, we feel that this subset of patients with symptomatic knee OA represents the majority of patients evaluated for knee OA by orthopaedic surgeons in the clinic setting. It should be noted that although realignment osteotomies were sometimes indicated as appropriate by AAOS AUC model in our study population, this intervention was never performed due to patient and surgeon preference. Additionally, although it is not an AAOS AUC evaluated intervention, viscosupplementation was sporadically used during the study period; however, it is now off formulary at the investigation institution.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that patients without knee instability use more nonarthroplasty treatments over a longer period before TKA, and those patients with less severe knee OA are at risk of receiving an intervention judged to be rarely appropriate by the AAOS AUC. Such interventions do not affect timing of TKA. Nonarthroplasty care should be individualized to patients’ needs, and the decision to proceed with arthroplasty should be considered only after exhausting appropriate conservative measures. We recommend that providers use the AAOS AUC, especially when treating younger patients with less severe knee OA, particularly if considering opiate therapy or knee arthroscopy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Patrick Getty, MD, for his surgical care of some of the study patients. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center in Ohio.

1. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(7):1323-1330.

2. Losina E, Walensky RP, Kessler CL, et al. Cost-effectiveness of total knee arthroplasty in the United States: patient risk and hospital volume. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(12):1113-1121; discussion 1121-1122.

3. Members of the Writing, Review, and Voting Panels of the AUC on the Non-Arthroplasty Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee, Sanders JO, Heggeness MH, Murray J, Pezold R, Donnelly P. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Appropriate Use Criteria on the Non-Arthroplasty Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(14):1220-1221.

4. Sanders JO, Murray J, Gross L. Non-arthroplasty treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(4):256-260.

5. Yates AJ Jr, McGrory BJ, Starz TW, Vincent KR, McCardel B, Golightly YM. AAOS appropriate use criteria: optimizing the non-arthroplasty management of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(4):261-267.

6. Riddle DL, Perera RA. Appropriateness and total knee arthroplasty: an examination of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons appropriateness rating system. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(12):1994-1998.

7. Morgan RC Jr, Slover J. Breakout session: ethnic and racial disparities in joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1886-1890.

8. O’Connor MI, Hooten EG. Breakout session: gender disparities in knee osteoarthritis and TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1883-1885.

9. Ibrahim SA. Racial and ethnic disparities in hip and knee joint replacement: a review of research in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(suppl 1):S87-S94.

10. Karmarkar TD, Maurer A, Parks ML, et al. A fresh perspective on a familiar problem: examining disparities in knee osteoarthritis using a Markov model. Med Care. 2017;55(12):993-1000.

11. Kohn MD, Sassoon AA, Fernando ND. Classifications in brief: Kellgren-Lawrence Classification of Osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(8):1886-1893.

12. Nguyen U, Felson DT, Niu J, et al. The impact of knee instability with and without buckling on balance confidence, fear of falling and physical function: the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(4):527-534.

13. Schmitt LC, Fitzgerald GK, Reisman AS, Rudolph KS. Instability, laxity, and physical function in patients with medial knee osteoarthritis. Phys Ther. 2008;88(12):1506-1516.

14. Laupattarakasem W, Laopaiboon M, Laupattarakasem P, Sumananont C. Arthroscopic debridement for knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD005118.

15. Lamplot JD, Brophy RH. The role for arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in knees with degenerative changes: a systematic review. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(7):934-938.

16. Whittle R, Jordan KP, Thomas E, Peat G. Average symptom trajectories following incident radiographic knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. RMD Open. 2016;2(2):e000281.

17. Jones A, Kwoh CK, Kelley ME, Ibrahim SA. Racial disparity in knee arthroplasty utilization in the Veterans Health Administration. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(6):979-981.

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) affects almost 9.3 million adults in the US and accounts for $27 billion in annual health care expenses.1,2 Due to the increasing cost of health care and an aging population, there has been renewed interest in establishing criteria for nonarthroplasty treatment of knee OA.

In 2013, using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness method, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) developed an appropriate use criteria (AUC) for nonarthroplasty management of primary OA of the knee, based on orthopaedic literature and expert opinion.3 Interventions such as activity modification, weight loss, prescribed physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tramadol, prescribed oral or transcutaneous opioids, acetaminophen, intra-articular corticosteroids, hinged or unloading knee braces, arthroscopic partial menisectomy or loose body removal, and realignment osteotomy were assessed. An algorithm was developed for 576 patients scenarios that incorporated patient-specific, prognostic/predictor variables to assign designations of “appropriate,” “may be appropriate,” or “rarely appropriate,” to treatment interventions.4,5 An online version of the algorithm (orthoguidelines.org) is available for physicians and surgeons to judge appropriateness of nonarthroplasty treatments; however, it is not intended to mandate candidacy for treatment or intervention.

Clinical evaluation of the AAOS AUC is necessary to determine how treatment recommendations correlate with current practice. A recent examination of the AAOS Appropriateness System for Surgical Management of Knee OA found that prognostic/predictor variables, such as patient age, OA severity, and pattern of knee OA involvement were more heavily weighted when determining arthroplasty appropriateness than was pain severity or functional loss.6 Furthermore, non-AAOS AUC prognostic/predictor variables, such as race and gender, have been linked to disparities in utilization of knee OA interventions.7-9 Such disparities can be costly not just from a patient perceptive, but also employer and societal perspectives.10

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system represents a model of equal-access-to care system in the US that is ideal for examination of issues about health care utilization and any disparities within the AAOS AUC model and has previously been used to assess utilization of total knee arthroplasty.9 The aim of this study was to characterize utilization of the AAOS AUC for nonarthroplasty treatment of knee OA in a VA patient population. We asked the following questions: (1) What variables are predictive of receiving a greater number of AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments? (2) What variables are predictive of receiving “rarely appropriate” AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatment? (3) What factors are predictive of duration of nonarthroplasty care until total knee arthroplasty (TKA)?

Methods

The institutional review board at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center in Ohio approved a retrospective chart review of nonarthroplasty treatments utilized by patients presenting to its orthopaedic section who subsequently underwent knee arthroplasty between 2013 and 2016. Eligibility criteria included patients aged ≥ 30 years with a diagnosis of unilateral or bilateral primary knee OA. Patients with posttraumatic OA, inflammatory arthritis, and a history of infectious arthritis or Charcot arthropathy of the knee were excluded. Patients with a body mass index (BMI) > 40 or a hemoglobin A1c > 8.0 at presentation were excluded as nonarthroplasty care was the recommended course of treatment above these thresholds.

Data collected included race, gender, duration of nonarthroplasty treatment, BMI, and Kellgren-Lawrence classification of knee OA at time of presentation for symptomatic knee OA.11 All AAOS AUC-evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments utilized prior to arthroplasty intervention also were recorded (Table 1).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was completed with GraphPad Software Prism 7.0a (La Jolla, CA) and Mathworks MatLab R2016b software (Natick, MA). Univariate analysis with Student t tests with Welch corrections in the setting of unequal variance, Mann-Whitney nonparametric tests, and Fisher exact test were generated in the appropriate setting. Multivariable analyses also were conducted. For continuous outcomes, stepwise multiple linear regression was used to generate predictive models; for binary outcomes, binomial logistic regression was used.

Factors analyzed in regression modeling for the total number of AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments utilized and the likelihood of receiving a rarely appropriate treatment included gender, race, function-limiting pain, range of motion (ROM), ligamentous instability, arthritis pattern, limb alignment, mechanical symptoms, BMI, age, and Kellgren-Lawrence grade. Factors analyzed in timing of TKA included the above variables plus the total number of AUC interventions, whether the patient received an inappropriate intervention, and average appropriateness of the interventions received. Residual analysis with Cook’s distance was used to identify outliers in regression. Observations with Cook’s distance > 3 times the mean Cook’s distance were identified as potential outliers, and models were adjusted accordingly. All statistical analyses were 2-tailed. Statistical significance was set to P ≤ .05 for all outputs.

Results

In the study, 97.8% of participants identified as male, and the mean age was 62.8 years (Table 3).

Appropriate Use Criteria Interventions

Patients received a mean of 5.2 AAOS AUC evaluated interventions before undergoing arthroplasty management at a mean of 32.3 months (range 2-181 months) from initial presentation. The majority of these interventions were classified as either appropriate or may be appropriate, according to the AUC definitions (95.1%). Self-management and physical therapy programs were widely utilized (100% and 90.1%, respectively), with all use of these interventions classified as appropriate.

Hinged or unloader knee braces were utilized in about half the study patients; this intervention was classified as rarely appropriate in 4.4% of these patients. Medical therapy was also widely used, with all use of NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and tramadol classified as appropriate or may be appropriate. Oral or transcutaneous opioid medications were prescribed in 14.3% of patients, with 92.3% of this use classified as rarely appropriate. Although the opioid medication prescribing provider was not specifically evaluated, there were no instances in which the orthopaedic service provided an oral or transcutaneous opioid prescriptions. Procedural interventions, with the exception of corticosteroid injections, were uncommon; no patient received realignment osteotomy, and only 12.1% of patients underwent arthroscopy. The use of arthroscopy was deemed rarely appropriate in 72.7% of these cases.

Factors Associated With AAOS AUC Intervention Use

There was no difference in the number of AAOS AUC evaluated interventions received based on BMI (mean [SD] BMI < 35, 5.2 [1.0] vs BMI ≥ 35, 5.3 [1.1], P = .49), age (mean [SD] aged < 60 years, 5.4 [1.0] vs aged ≥ 60 years, 5.1 [1.2], P = .23), or Kellgren-Lawrence arthritic grade (mean [SD] grade ≤ 2, 5.5 [1.0] vs grade > 2, 5.1 [1.1], P = .06). These variables also were not associated with receiving a rarely appropriate intervention (mean [SD] BMI < 35, 0.27 [0.5] vs BMI > 35, 0.2 [0.4], P = .81; aged > 60 years, 0.3 [0.5] vs aged < 60 years, 0.2 [0.4], P = .26; Kellgren-Lawrence grade < 2, 0.4 [0.6] vs grade > 2, 0.2 [0.4], P = .1).

Regression modeling to predict total number of AAOS AUC evaluated interventions received produced a significant model (R2 = 0.111, P = .006). The presence of ligamentous instability (β coefficient, -1.61) and the absence of mechanical symptoms (β coefficient, -0.67) were negative predictors of number of AUC interventions received. Variance inflation factors were 1.014 and 1.012, respectively. Likewise, regression modeling to identify factors predictive of receiving a rarely appropriate intervention also produced a significant model (pseudo R2= 0.06, P = .025), with lower Kellgren-Lawrence grade the only significant predictor of receiving a rarely appropriate intervention (odds ratio [OR] 0.54; 95% CI, 0.42 -0.72, per unit increase).

Timing from presentation to arthroplasty intervention was also evaluated. Age was a negative predictor (β coefficient -1.61), while positive predictors were reduced ROM (β coefficient 15.72) and having more AUC interventions (β coefficient 7.31) (model R2= 0.29, P = < .001). Age was the most significant predictor. Variance inflations factors were 1.02, 1.01, and 1.03, respectively. Receiving a rarely appropriate intervention was not associated with TKA timing.

Discussion

This single-center retrospective study examined the utilization of AAOS AUC-evaluated nonarthroplasty interventions for symptomatic knee OA prior to TKA. The aims of this study were to validate the AAOS AUC in a clinical setting and identify predictors of AAOS AUC utilization. In particular, this study focused on the number of interventions utilized prior to knee arthroplasty, whether interventions receiving a designation of rarely appropriate were used, and the duration of nonarthroplasty treatment.

Patients with knee instability used fewer total AAOS AUC evaluated interventions prior to TKA. Subjective instability has been reported as high as 27% in patients with OA and has been associated with fear of falling, poor balance confidence, activity limitations, and lower Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) physical function scores.12 However, it has not been found to correlate with knee laxity.13 Nevertheless, significant functional impairment with the risk of falling may reduce the number of nonarthroplasty interventions attempted. On the other hand, the presence of mechanical symptoms resulted in greater utilization of nonarthroplasty interventions. This is likely due to the greater utilization of arthroscopic partial menisectomy or loose body removal in this group of patients. Despite its inclusion as an AAOS AUC evaluated intervention, arthroscopy remains a contentious treatment for symptomatic knee pain in the setting of OA.14,15

For every unit decrease in Kellgren-Lawrence OA grade, patients were 54% more likely to receive a rarely appropriate intervention prior to knee arthroplasty. This is supported by the recent literature examining the AAOS AUC for surgical management of knee OA. Riddle and colleagues developed a classification tree to determine the contributions of various prognostic variables in final classifications of the 864 clinical vignettes used to develop the appropriateness algorithm and found that OA severity was strongly favored, with only 4 of the 432 vignettes with severe knee OA judged as rarely appropriate for surgical intervention.6

Our findings, too, may be explained by an AAOS AUC system that too heavily weighs radiographic severity of knee OA, resulting in more frequent rarely appropriate interventions in patients with less severe arthritis, including nonarthroplasty treatments. It is likely that rarely appropriate interventions were attempted in this subset of our study cohort based on patient’s subjective symptoms and functional status, both of which have been shown to be discordant with radiographic severity of knee OA.16

Oral or transcutaneous prescribed opioid medications were the most frequent intervention that received a rarely appropriate designation. Patients with preoperative opioid use undergoing TKA have been shown to have a greater risk for postoperative complications and longer hospital stay, particularly those patients aged < 75 years. Younger age, use of more interventions, and decreased knee ROM at presentation were predictive of longer duration of nonarthroplasty treatment. The use of more AAOS AUC evaluated interventions in these patients suggests that the AAOS AUC model may effectively be used to manage symptomatic OA, increasing the time from presentation to knee arthroplasty.

Interestingly, the use of rarely appropriate interventions did not affect TKA timing, as would be expected in a clinically effective nonarthroplasty treatment model. The reasons for rarely appropriate nonsurgical interventions are complex and require further investigation. One possible explanation is that decreased ROM was a marker for mechanical symptoms that necessitated additional intervention in the form of knee arthroscopy, delaying time to TKA.

Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. First, the small sample size (N = 90) requires acknowledgment; however, this limitation reflects the difficulty in following patients for years prior to an operative intervention. Second, the study population consists of veterans using the VA system and may not be reflective of the general population, differing with respect to gender, racial, and socioeconomic factors. Nevertheless, studies examining TKA utilization found, aside from racial and ethnic variability, patient gender and age do not affect arthroplasty utilization rate in the VA system.17

Additional limitations stem from the retrospective nature of this study. While the Computerized Patient Record System and centralized care of the VA system allows for review of all physical therapy consultations, orthotic consultations, and medications within the VA system, any treatments and intervention delivered by non-VA providers were not captured. Furthermore, the ability to assess for confounding variables limiting the prescription of certain medications, such as chronic kidney disease with NSAIDs or liver disease with acetaminophen, was limited by our study design.

Although our study suffers from selection bias with respect to examination of nonarthroplasty treatment in patients who have ultimately undergone TKA, we feel that this subset of patients with symptomatic knee OA represents the majority of patients evaluated for knee OA by orthopaedic surgeons in the clinic setting. It should be noted that although realignment osteotomies were sometimes indicated as appropriate by AAOS AUC model in our study population, this intervention was never performed due to patient and surgeon preference. Additionally, although it is not an AAOS AUC evaluated intervention, viscosupplementation was sporadically used during the study period; however, it is now off formulary at the investigation institution.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that patients without knee instability use more nonarthroplasty treatments over a longer period before TKA, and those patients with less severe knee OA are at risk of receiving an intervention judged to be rarely appropriate by the AAOS AUC. Such interventions do not affect timing of TKA. Nonarthroplasty care should be individualized to patients’ needs, and the decision to proceed with arthroplasty should be considered only after exhausting appropriate conservative measures. We recommend that providers use the AAOS AUC, especially when treating younger patients with less severe knee OA, particularly if considering opiate therapy or knee arthroscopy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Patrick Getty, MD, for his surgical care of some of the study patients. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center in Ohio.

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) affects almost 9.3 million adults in the US and accounts for $27 billion in annual health care expenses.1,2 Due to the increasing cost of health care and an aging population, there has been renewed interest in establishing criteria for nonarthroplasty treatment of knee OA.

In 2013, using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness method, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) developed an appropriate use criteria (AUC) for nonarthroplasty management of primary OA of the knee, based on orthopaedic literature and expert opinion.3 Interventions such as activity modification, weight loss, prescribed physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tramadol, prescribed oral or transcutaneous opioids, acetaminophen, intra-articular corticosteroids, hinged or unloading knee braces, arthroscopic partial menisectomy or loose body removal, and realignment osteotomy were assessed. An algorithm was developed for 576 patients scenarios that incorporated patient-specific, prognostic/predictor variables to assign designations of “appropriate,” “may be appropriate,” or “rarely appropriate,” to treatment interventions.4,5 An online version of the algorithm (orthoguidelines.org) is available for physicians and surgeons to judge appropriateness of nonarthroplasty treatments; however, it is not intended to mandate candidacy for treatment or intervention.

Clinical evaluation of the AAOS AUC is necessary to determine how treatment recommendations correlate with current practice. A recent examination of the AAOS Appropriateness System for Surgical Management of Knee OA found that prognostic/predictor variables, such as patient age, OA severity, and pattern of knee OA involvement were more heavily weighted when determining arthroplasty appropriateness than was pain severity or functional loss.6 Furthermore, non-AAOS AUC prognostic/predictor variables, such as race and gender, have been linked to disparities in utilization of knee OA interventions.7-9 Such disparities can be costly not just from a patient perceptive, but also employer and societal perspectives.10

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system represents a model of equal-access-to care system in the US that is ideal for examination of issues about health care utilization and any disparities within the AAOS AUC model and has previously been used to assess utilization of total knee arthroplasty.9 The aim of this study was to characterize utilization of the AAOS AUC for nonarthroplasty treatment of knee OA in a VA patient population. We asked the following questions: (1) What variables are predictive of receiving a greater number of AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments? (2) What variables are predictive of receiving “rarely appropriate” AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatment? (3) What factors are predictive of duration of nonarthroplasty care until total knee arthroplasty (TKA)?

Methods

The institutional review board at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center in Ohio approved a retrospective chart review of nonarthroplasty treatments utilized by patients presenting to its orthopaedic section who subsequently underwent knee arthroplasty between 2013 and 2016. Eligibility criteria included patients aged ≥ 30 years with a diagnosis of unilateral or bilateral primary knee OA. Patients with posttraumatic OA, inflammatory arthritis, and a history of infectious arthritis or Charcot arthropathy of the knee were excluded. Patients with a body mass index (BMI) > 40 or a hemoglobin A1c > 8.0 at presentation were excluded as nonarthroplasty care was the recommended course of treatment above these thresholds.

Data collected included race, gender, duration of nonarthroplasty treatment, BMI, and Kellgren-Lawrence classification of knee OA at time of presentation for symptomatic knee OA.11 All AAOS AUC-evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments utilized prior to arthroplasty intervention also were recorded (Table 1).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was completed with GraphPad Software Prism 7.0a (La Jolla, CA) and Mathworks MatLab R2016b software (Natick, MA). Univariate analysis with Student t tests with Welch corrections in the setting of unequal variance, Mann-Whitney nonparametric tests, and Fisher exact test were generated in the appropriate setting. Multivariable analyses also were conducted. For continuous outcomes, stepwise multiple linear regression was used to generate predictive models; for binary outcomes, binomial logistic regression was used.

Factors analyzed in regression modeling for the total number of AAOS AUC evaluated nonarthroplasty treatments utilized and the likelihood of receiving a rarely appropriate treatment included gender, race, function-limiting pain, range of motion (ROM), ligamentous instability, arthritis pattern, limb alignment, mechanical symptoms, BMI, age, and Kellgren-Lawrence grade. Factors analyzed in timing of TKA included the above variables plus the total number of AUC interventions, whether the patient received an inappropriate intervention, and average appropriateness of the interventions received. Residual analysis with Cook’s distance was used to identify outliers in regression. Observations with Cook’s distance > 3 times the mean Cook’s distance were identified as potential outliers, and models were adjusted accordingly. All statistical analyses were 2-tailed. Statistical significance was set to P ≤ .05 for all outputs.

Results

In the study, 97.8% of participants identified as male, and the mean age was 62.8 years (Table 3).

Appropriate Use Criteria Interventions

Patients received a mean of 5.2 AAOS AUC evaluated interventions before undergoing arthroplasty management at a mean of 32.3 months (range 2-181 months) from initial presentation. The majority of these interventions were classified as either appropriate or may be appropriate, according to the AUC definitions (95.1%). Self-management and physical therapy programs were widely utilized (100% and 90.1%, respectively), with all use of these interventions classified as appropriate.

Hinged or unloader knee braces were utilized in about half the study patients; this intervention was classified as rarely appropriate in 4.4% of these patients. Medical therapy was also widely used, with all use of NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and tramadol classified as appropriate or may be appropriate. Oral or transcutaneous opioid medications were prescribed in 14.3% of patients, with 92.3% of this use classified as rarely appropriate. Although the opioid medication prescribing provider was not specifically evaluated, there were no instances in which the orthopaedic service provided an oral or transcutaneous opioid prescriptions. Procedural interventions, with the exception of corticosteroid injections, were uncommon; no patient received realignment osteotomy, and only 12.1% of patients underwent arthroscopy. The use of arthroscopy was deemed rarely appropriate in 72.7% of these cases.

Factors Associated With AAOS AUC Intervention Use

There was no difference in the number of AAOS AUC evaluated interventions received based on BMI (mean [SD] BMI < 35, 5.2 [1.0] vs BMI ≥ 35, 5.3 [1.1], P = .49), age (mean [SD] aged < 60 years, 5.4 [1.0] vs aged ≥ 60 years, 5.1 [1.2], P = .23), or Kellgren-Lawrence arthritic grade (mean [SD] grade ≤ 2, 5.5 [1.0] vs grade > 2, 5.1 [1.1], P = .06). These variables also were not associated with receiving a rarely appropriate intervention (mean [SD] BMI < 35, 0.27 [0.5] vs BMI > 35, 0.2 [0.4], P = .81; aged > 60 years, 0.3 [0.5] vs aged < 60 years, 0.2 [0.4], P = .26; Kellgren-Lawrence grade < 2, 0.4 [0.6] vs grade > 2, 0.2 [0.4], P = .1).

Regression modeling to predict total number of AAOS AUC evaluated interventions received produced a significant model (R2 = 0.111, P = .006). The presence of ligamentous instability (β coefficient, -1.61) and the absence of mechanical symptoms (β coefficient, -0.67) were negative predictors of number of AUC interventions received. Variance inflation factors were 1.014 and 1.012, respectively. Likewise, regression modeling to identify factors predictive of receiving a rarely appropriate intervention also produced a significant model (pseudo R2= 0.06, P = .025), with lower Kellgren-Lawrence grade the only significant predictor of receiving a rarely appropriate intervention (odds ratio [OR] 0.54; 95% CI, 0.42 -0.72, per unit increase).

Timing from presentation to arthroplasty intervention was also evaluated. Age was a negative predictor (β coefficient -1.61), while positive predictors were reduced ROM (β coefficient 15.72) and having more AUC interventions (β coefficient 7.31) (model R2= 0.29, P = < .001). Age was the most significant predictor. Variance inflations factors were 1.02, 1.01, and 1.03, respectively. Receiving a rarely appropriate intervention was not associated with TKA timing.

Discussion

This single-center retrospective study examined the utilization of AAOS AUC-evaluated nonarthroplasty interventions for symptomatic knee OA prior to TKA. The aims of this study were to validate the AAOS AUC in a clinical setting and identify predictors of AAOS AUC utilization. In particular, this study focused on the number of interventions utilized prior to knee arthroplasty, whether interventions receiving a designation of rarely appropriate were used, and the duration of nonarthroplasty treatment.

Patients with knee instability used fewer total AAOS AUC evaluated interventions prior to TKA. Subjective instability has been reported as high as 27% in patients with OA and has been associated with fear of falling, poor balance confidence, activity limitations, and lower Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) physical function scores.12 However, it has not been found to correlate with knee laxity.13 Nevertheless, significant functional impairment with the risk of falling may reduce the number of nonarthroplasty interventions attempted. On the other hand, the presence of mechanical symptoms resulted in greater utilization of nonarthroplasty interventions. This is likely due to the greater utilization of arthroscopic partial menisectomy or loose body removal in this group of patients. Despite its inclusion as an AAOS AUC evaluated intervention, arthroscopy remains a contentious treatment for symptomatic knee pain in the setting of OA.14,15

For every unit decrease in Kellgren-Lawrence OA grade, patients were 54% more likely to receive a rarely appropriate intervention prior to knee arthroplasty. This is supported by the recent literature examining the AAOS AUC for surgical management of knee OA. Riddle and colleagues developed a classification tree to determine the contributions of various prognostic variables in final classifications of the 864 clinical vignettes used to develop the appropriateness algorithm and found that OA severity was strongly favored, with only 4 of the 432 vignettes with severe knee OA judged as rarely appropriate for surgical intervention.6

Our findings, too, may be explained by an AAOS AUC system that too heavily weighs radiographic severity of knee OA, resulting in more frequent rarely appropriate interventions in patients with less severe arthritis, including nonarthroplasty treatments. It is likely that rarely appropriate interventions were attempted in this subset of our study cohort based on patient’s subjective symptoms and functional status, both of which have been shown to be discordant with radiographic severity of knee OA.16

Oral or transcutaneous prescribed opioid medications were the most frequent intervention that received a rarely appropriate designation. Patients with preoperative opioid use undergoing TKA have been shown to have a greater risk for postoperative complications and longer hospital stay, particularly those patients aged < 75 years. Younger age, use of more interventions, and decreased knee ROM at presentation were predictive of longer duration of nonarthroplasty treatment. The use of more AAOS AUC evaluated interventions in these patients suggests that the AAOS AUC model may effectively be used to manage symptomatic OA, increasing the time from presentation to knee arthroplasty.

Interestingly, the use of rarely appropriate interventions did not affect TKA timing, as would be expected in a clinically effective nonarthroplasty treatment model. The reasons for rarely appropriate nonsurgical interventions are complex and require further investigation. One possible explanation is that decreased ROM was a marker for mechanical symptoms that necessitated additional intervention in the form of knee arthroscopy, delaying time to TKA.

Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. First, the small sample size (N = 90) requires acknowledgment; however, this limitation reflects the difficulty in following patients for years prior to an operative intervention. Second, the study population consists of veterans using the VA system and may not be reflective of the general population, differing with respect to gender, racial, and socioeconomic factors. Nevertheless, studies examining TKA utilization found, aside from racial and ethnic variability, patient gender and age do not affect arthroplasty utilization rate in the VA system.17

Additional limitations stem from the retrospective nature of this study. While the Computerized Patient Record System and centralized care of the VA system allows for review of all physical therapy consultations, orthotic consultations, and medications within the VA system, any treatments and intervention delivered by non-VA providers were not captured. Furthermore, the ability to assess for confounding variables limiting the prescription of certain medications, such as chronic kidney disease with NSAIDs or liver disease with acetaminophen, was limited by our study design.

Although our study suffers from selection bias with respect to examination of nonarthroplasty treatment in patients who have ultimately undergone TKA, we feel that this subset of patients with symptomatic knee OA represents the majority of patients evaluated for knee OA by orthopaedic surgeons in the clinic setting. It should be noted that although realignment osteotomies were sometimes indicated as appropriate by AAOS AUC model in our study population, this intervention was never performed due to patient and surgeon preference. Additionally, although it is not an AAOS AUC evaluated intervention, viscosupplementation was sporadically used during the study period; however, it is now off formulary at the investigation institution.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that patients without knee instability use more nonarthroplasty treatments over a longer period before TKA, and those patients with less severe knee OA are at risk of receiving an intervention judged to be rarely appropriate by the AAOS AUC. Such interventions do not affect timing of TKA. Nonarthroplasty care should be individualized to patients’ needs, and the decision to proceed with arthroplasty should be considered only after exhausting appropriate conservative measures. We recommend that providers use the AAOS AUC, especially when treating younger patients with less severe knee OA, particularly if considering opiate therapy or knee arthroscopy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Patrick Getty, MD, for his surgical care of some of the study patients. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center in Ohio.

1. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(7):1323-1330.

2. Losina E, Walensky RP, Kessler CL, et al. Cost-effectiveness of total knee arthroplasty in the United States: patient risk and hospital volume. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(12):1113-1121; discussion 1121-1122.

3. Members of the Writing, Review, and Voting Panels of the AUC on the Non-Arthroplasty Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee, Sanders JO, Heggeness MH, Murray J, Pezold R, Donnelly P. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Appropriate Use Criteria on the Non-Arthroplasty Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(14):1220-1221.

4. Sanders JO, Murray J, Gross L. Non-arthroplasty treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(4):256-260.

5. Yates AJ Jr, McGrory BJ, Starz TW, Vincent KR, McCardel B, Golightly YM. AAOS appropriate use criteria: optimizing the non-arthroplasty management of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(4):261-267.

6. Riddle DL, Perera RA. Appropriateness and total knee arthroplasty: an examination of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons appropriateness rating system. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(12):1994-1998.

7. Morgan RC Jr, Slover J. Breakout session: ethnic and racial disparities in joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1886-1890.

8. O’Connor MI, Hooten EG. Breakout session: gender disparities in knee osteoarthritis and TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1883-1885.

9. Ibrahim SA. Racial and ethnic disparities in hip and knee joint replacement: a review of research in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(suppl 1):S87-S94.

10. Karmarkar TD, Maurer A, Parks ML, et al. A fresh perspective on a familiar problem: examining disparities in knee osteoarthritis using a Markov model. Med Care. 2017;55(12):993-1000.

11. Kohn MD, Sassoon AA, Fernando ND. Classifications in brief: Kellgren-Lawrence Classification of Osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(8):1886-1893.

12. Nguyen U, Felson DT, Niu J, et al. The impact of knee instability with and without buckling on balance confidence, fear of falling and physical function: the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(4):527-534.

13. Schmitt LC, Fitzgerald GK, Reisman AS, Rudolph KS. Instability, laxity, and physical function in patients with medial knee osteoarthritis. Phys Ther. 2008;88(12):1506-1516.

14. Laupattarakasem W, Laopaiboon M, Laupattarakasem P, Sumananont C. Arthroscopic debridement for knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD005118.

15. Lamplot JD, Brophy RH. The role for arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in knees with degenerative changes: a systematic review. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(7):934-938.

16. Whittle R, Jordan KP, Thomas E, Peat G. Average symptom trajectories following incident radiographic knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. RMD Open. 2016;2(2):e000281.

17. Jones A, Kwoh CK, Kelley ME, Ibrahim SA. Racial disparity in knee arthroplasty utilization in the Veterans Health Administration. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(6):979-981.

1. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(7):1323-1330.

2. Losina E, Walensky RP, Kessler CL, et al. Cost-effectiveness of total knee arthroplasty in the United States: patient risk and hospital volume. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(12):1113-1121; discussion 1121-1122.

3. Members of the Writing, Review, and Voting Panels of the AUC on the Non-Arthroplasty Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee, Sanders JO, Heggeness MH, Murray J, Pezold R, Donnelly P. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Appropriate Use Criteria on the Non-Arthroplasty Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(14):1220-1221.

4. Sanders JO, Murray J, Gross L. Non-arthroplasty treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(4):256-260.

5. Yates AJ Jr, McGrory BJ, Starz TW, Vincent KR, McCardel B, Golightly YM. AAOS appropriate use criteria: optimizing the non-arthroplasty management of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(4):261-267.

6. Riddle DL, Perera RA. Appropriateness and total knee arthroplasty: an examination of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons appropriateness rating system. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(12):1994-1998.

7. Morgan RC Jr, Slover J. Breakout session: ethnic and racial disparities in joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1886-1890.

8. O’Connor MI, Hooten EG. Breakout session: gender disparities in knee osteoarthritis and TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1883-1885.

9. Ibrahim SA. Racial and ethnic disparities in hip and knee joint replacement: a review of research in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(suppl 1):S87-S94.

10. Karmarkar TD, Maurer A, Parks ML, et al. A fresh perspective on a familiar problem: examining disparities in knee osteoarthritis using a Markov model. Med Care. 2017;55(12):993-1000.

11. Kohn MD, Sassoon AA, Fernando ND. Classifications in brief: Kellgren-Lawrence Classification of Osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(8):1886-1893.

12. Nguyen U, Felson DT, Niu J, et al. The impact of knee instability with and without buckling on balance confidence, fear of falling and physical function: the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(4):527-534.

13. Schmitt LC, Fitzgerald GK, Reisman AS, Rudolph KS. Instability, laxity, and physical function in patients with medial knee osteoarthritis. Phys Ther. 2008;88(12):1506-1516.

14. Laupattarakasem W, Laopaiboon M, Laupattarakasem P, Sumananont C. Arthroscopic debridement for knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD005118.

15. Lamplot JD, Brophy RH. The role for arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in knees with degenerative changes: a systematic review. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(7):934-938.

16. Whittle R, Jordan KP, Thomas E, Peat G. Average symptom trajectories following incident radiographic knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. RMD Open. 2016;2(2):e000281.

17. Jones A, Kwoh CK, Kelley ME, Ibrahim SA. Racial disparity in knee arthroplasty utilization in the Veterans Health Administration. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(6):979-981.

The Dyad Model for Interprofessional Academic Patient Aligned Care Teams

Background

In 2011, 5 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers were selected by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) to establish Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education (CoEPCE). As part of VA’s New Models of Care initiative, the 5 CoEPCEs are using VA primary care settings to develop and test innovative approaches to prepare physician residents and students, advanced practice nurses (APRNs), undergraduate nursing students, and other health professions trainees (such as pharmacy, social work, psychology, physician assistants) for primary care practice. The CoEPCE sites are developing, implementing, and evaluating curricula to prepare learners from relevant professions to practice in patientcentered, interprofessional team-based primary care settings. Patient aligned care teams (PACTs) that have 2 or more health professions trainees engaged in learning, working, and teaching are known as interprofessional academic PACTs (iAPACTs), which is the preferred model for the VA.

The Cleveland Transforming Outpatient Care (TOPC)-CoEPCE was designed for collaborative learning among nurse practitioner (NP) students and physician residents. Its robust curriculum consists of a dedicated half-day of didactics for all learners, interprofessional quality improvement projects, panel management sessions, and primary care clinical sessions for nursing and physician learners that include the dyad workplace learning model.

In 2015, the OAA lead evaluator observed the TOPC-CoEPCE dyad model process, reviewed background documents, and conducted 10 open-ended interviews with TOPC-CoEPCE staff, participating trainees, faculty, and affiliate leadership. Informants described their involvement, challenges encountered, and benefits of the TOPCCoEPC dyad model to participants, veterans, VA, and affiliates.

Lack of Interprofessional Learning Opportunities

Current health care professional education models typically do not have many workplace learning settings where physician and nursing trainees learn together and provide patient-centered care. Often in a shared clinical environment, trainees may engage in “parallel play,” which can result in physician trainees and NP students learning independently and being ill-prepared to practice effectively together.

Moreover, trainees from different professions have different learning needs. For example, less experienced NP students require greater time, supervision, and evaluation of their patient care skills. On the other hand, senior physician residents, who require less clinical instruction, need to be engaged in ways that provide opportunities to enhance their ambulatory teaching skills. Although enhancement of resident teaching skills occurs in the inpatient hospital setting, there have been limited teaching experiences for residents in a primary care setting where the instruction is traditionally faculty-based. The TOPCCoEPCE dyad model offers an opportunity to simultaneously provide trainees with a true interprofessional experience through advancement of skills in primary care, teamwork, and teaching, while addressing health care needs.

The Dyad Model

In 2011, the OAA directed COEPCE sites to develop innovative curriculum and workplace learning strategies to create more opportunities for physician and NP trainees to work as a team. There is evidence demonstrating that when students develop a shared understanding of each other’s skill set, care procedures, and values, patient care is improved.1 Further, training in pairs can be an effective strategy in education of preclerkship medical students.2 In April 2013, TOPC-CoEPCE staff asked representatives from the Student-Run Clinic at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) in Cleveland, Ohio, to present their approach to pairing nursing and medical students in clinic under supervision by volunteer faculty. However, formal structure and curricular objectives were lacking. To address diverse TOPCCoEPCE trainee needs and create a team approach to patient care, the staff formalized and developed a workplace curriculum called the dyad model. Specifically, the model pairs 1 NP student with a senior (PGY2 or PGY3) physician resident to care for ambulatory patients as a dyad teaching/learning team. The dyad model has 3 goals: improving clinical performance, learning team dynamics, and improving the physician resident’s teaching skills in an ambulatory setting.

Planning and Implementation

Planning the dyad model took 4 months. Initial conceptualization of the model was discussed at TOPC-CoEPCE infrastructure meetings. Workgroups with representatives from medicine, nursing, evaluation and medical center administration were formed to finalize the model. The workgroups met weekly or biweekly to develop protocols for scheduling, ongoing monitoring and assessment, microteaching session curriculum development, and logistics. A pilot program was initiated for 1 month with 2 dyads to monitor learner progress and improve components, such as adjusting the patient exam start times and curriculum. In maintaining the program, the workgroups continue to meet monthly to check for areas for further improvement and maintain dissemination activities.

Curriculum

The dyad model is a novel opportunity to have trainees from different professions not only collaborate in the care of the same patient at the same time, but also negotiate their respective responsibilities preand postvisit. The experience focuses on interprofessional relationships and open communication. TOPC-CoEPCE used a modified version of the RIME (Reporter-Interpreter-Manager-Educator) model called the O-RIME model (Table 1), which includes an observer (O) phase as the first component for clarification about a beginners’ role.3,4

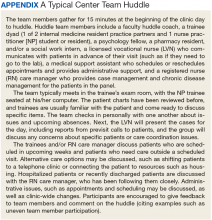

Four dyad pairs provide collaborative clinical care for veterans during one halfday session per week. The dyad conducts 4 hour-long patient visits per session. To be a dyad participant, the physician residents must be at least a PGY2, and their schedule must align with the NP student clinic schedule. Participation is mandatory for both NP students and physician residents. TOPC staff assemble the pairs.

The dyad model requires knowledge of the clinical and curricular interface and when to block the dyad team members’ schedules for 4 patients instead of 6. Physician residents are in the TOPC-CoEPCE for 12 weeks and then on inpatient for 12 weeks. Depending on the nursing school affiliate, NP student trainees are scheduled for either a 6- or 12-month TOPC-CoEPCE experience. For the 12-month NP students, they are paired with up to 4 internal medicine residents over the course of their dyad participation so they can experience different teaching styles of each resident while developing more varied interprofessional communication skills.

Faculty Roles and Development

The dyad model also seeks to address the paucity of deliberate interprofessional precepting in academic primary care settings. The TOPC-CoEPCE staff decided to use the existing primary care clinic faculty development series bimonthly for 1 hour each. The dyad model team members presented sessions covering foundational material in interprofessional teaching and precepting skills, which prepare faculty to precept for different professions and the dyad teams. It is important for preceptors to develop awareness of learners from different professions and the corresponding educational trajectories, so they can communicate with paired trainees of differing professions and academic levels who may require different levels of discussion.

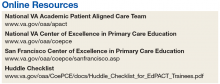

Resources

By utilizing advanced residents as teachers, faculty were able to increase the number of learners in the clinic without increasing the number preceptors. For example, precepting a student typically requires more preceptor time, especially when we consider that the preceptor must also see the patient. The TOPC-CoEPCE faculty run the microteaching sessions, and an evaluator monitors and evaluates the program. The microteaching sessions were derived from several teaching resources.

Monitoring and Assessment

The Cleveland TOPC administered 2 different surveys developed by the Dyad Model Infrastructure and Evaluation workgroup. A 7-item survey assesses dyad team communication and interprofessional team functioning, and an 8-item survey assesses the teaching/mentoring of the resident as teacher. Both were collected from all participants to evaluate the residents’ and students’ point of view. Surveys are collected in the first and last weeks of the dyad experience. Feedback from participants has been used to make improvements to the program (eg, monitoring how the dyad teams are functioning, coaching individual learners).

Partnerships

In addition to TOPC staff and faculty support and engagement, the initiative has benefited from partnerships with VA clinic staff and with the associated academic affiliates. In particular, the Associate Chief of General Internal Medicine at the Cleveland VA medical center and interim clinic director helped institute changes to the primary care clinic structure. Additionally, buy-in from the clinic nurse manager was needed to make adjustments with staff schedules and clinic resources. To implement the dyad model, the clinic director had to approve reductions in the residents’ clinic loads for the mornings when they participated.

The NP affiliates’ faculty at the schools of nursing are integral partners who assist with student recruitment and participate in the planning and refinement of TOPCCoEPCE components. The Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing at CWRU and the Breen School of Nursing of Ursuline College in Pepper Pike, Ohio, were involved in the planning stages and continue to receive monthly updates from TOPC-CoEPCE. Similarly, the CWRU School of Medicine and Cleveland Clinic Foundation affiliates contribute on an ongoing basis to the improvement and implementation process.

Discussion

One challenge has been advancing aspects of a nonhierarchical team approach while it is a teacher-student relationship. The dyad model is viewed as an opportunity to recognize nonhierarchical structures and teach negotiation and communication skills as well as increase interprofessional understanding of each other’s education, expertise, and scope of practice.

Another challenge is accommodating the diversity in NP training and clinical expertise. The NP student participants are in either the first or second year of their academic program. This is a challenge since both physician residents and physician faculty preceptors need to assess the NP students’ skills before providing opportunities to build on their skill level. Staff members have learned the value of checking in weekly on this issue.

Factors for Success

VA facility support and TOPC-CoEPCE leadership with the operations/academic partnership remain critical to integrating and sustaining the model into the Cleveland primary care clinic. The expertise of TOPC-CoEPCE dyad model faculty who serve as facilitators has been crucial, as they oversee team development concepts such as developing problem solving and negotiation skills. The workgroups ensured that faculty were skilled in understanding the different types of learners and provided guidance to dyad teams. Another success factor was the continual monitoring of the process and real-time evaluation of the program to adapt the model as needed.

Accomplishments and Benefits

There is evidence that the dyad model is achieving its goals: Trainees are using team skills during and outside formal dyad pairs; NP students report improvements in skill levels and comfort; and physician residents feel the teaching role in the dyad pair is an opportunity for them to improve their practice.

Interprofessional Educational Capacity

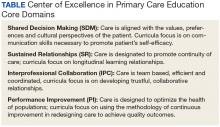

The dyad model complements the curriculum components and advances trainee understanding of 4 core domains: shared decision-making (SDM), sustained relationships (SR), interprofessional collaboration (IPC), and performance improvement (PI) (Table 2). The dyad model supports the other CoEPCE interprofessional education activities and is reinforced by these activities. The model is a learning laboratory for studying team dynamics and developing a curriculum that strengthens a team approach to patient-centered care.

Participants’ Knowledge, Attitudes, Skills, and Competencies

As of May 2015, 35 trainees (21 internal medicine physician residents and 14 NP students) have participated in dyads. Because physician residents participate over 2 years and may partner with more than 1 NP student, this has resulted in 27 dyad pairs in this time frame. Findings from an analysis of evaluations suggest that the dyad pair trainees learn from one another, and the model provides a safe space where trainees can practice and increase their confidence.1,6,7 The NP students seem to increase clinical skills quickly—expanding physical exam skills, building a differential diagnosis, and formulating therapeutic plans—and progressing to the Interpreter and Manager levels in the O-RIME model. The physician resident achieves the Educator level.

As of September 2015, the results from the pairs who completed beginning and end evaluations show that the physician residents increased the amount of feedback they provided about performance to the student, and likewise the student NPs also felt they received an increased amount of feedback about performance from the physician resident. In addition, physician residents reported improving the most in the following areas: allowing the student to make commitments in diagnoses and treatment plans and asking the student to provide supporting evidence for their commitment to the diagnoses. NP students reported the largest increases in receiving weekly feedback about their performance from the physician and their ability to listen to the patient.1,6,7

Interprofessional Collaboration

The TOPC-CoEPCE staff observed strengthened dyad pair relationships and mutual respect between the dyad partners. Trainees communicate with each other and work together to provide care of the patient. Second, dyad pair partners are learning about the other profession—their trajectory, their education model, and their differences. The physician resident develops an awareness of the partner NP student’s knowledge and expertise, such as their experience of social and psychological factors to become a more effective teacher, contributing to patient-centered care. The evaluation results illustrate increased ability of trainees to give and receive feedback and the change in roles for providing diagnosis and providing supporting evidence within the TOPCCoEPCE dyad team.6-8

The Future

The model has broad applicability for interprofessional education in the VA since it enhances skills that providers need to work in a PACT/PCMH model. Additionally, the TOPC-CoEPCE dyad model has proven to be an effective interprofessional training experience for its affiliates and may have applicability in other VA/affiliate training programs. The dyad model can be adapted to different trainee types in the ambulatory care setting. The TOPCCoEPCE is piloting a version of the dyad with NP residents (postgraduate) and first-year medical students. Additionally, the TOPCCoEPCE is paving the way for integrating improvement of physician resident teaching skills into the primary care setting and facilitating bidirectional teaching among different professions. TOPC-CoEPCE intends to develop additional resources to facilitate use of the model application in other settings such as the dyad implementation template.

1. Billett SR. Securing intersubjectivity through interprofessional workplace learning experiences. J Interprof Care. 2014;28(3):206-211.

2. Tolsgaard MG, Bjørck S, Rasmussen MB, Gustafsson A, Ringsted C. Improving efficiency of clinical skills training: a randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(8);1072-1077.

3. Pangaro L. A new vocabulary and other innovations for improving descriptive in-training evaluations. Acad Med. 1999;74(11):1203-1207.

4. Tham KY. Observer-Reporter-Interpreter-Manager-Educator (O-RIME) framework to guide formative assessment of medical students. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2013;42(11):603-607.

6. Clementz L, Dolansky MA, Lawrence RH, et al. Dyad teams: interprofessional collaboration and learning in ambulatory setting. Poster session presented: 38th Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine; April 2015:Toronto, Canada. www.pcori.org/sites/default/files /SGIM-Conference-Program-2015.pdf. Accessed August 29, 2018.

7. Singh M, Clementz L, Dolansky MA, et al. MD-NP learning dyad model: an innovative approach to interprofessional teaching and learning. Workshop presented at: Annual Meeting of the Midwest Society of General Internal Medicine; August 27, 2015: Cleveland, Ohio.

8. Lawrence RH, Dolansky MA, Clementz L, et al. Dyad teams: collaboration and learning in the ambulatory care setting. Poster session presented at: AAMC meeting, Innovations in Academic Medicine; November 7-11, 2014: Chicago, IL.

Background

In 2011, 5 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers were selected by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) to establish Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education (CoEPCE). As part of VA’s New Models of Care initiative, the 5 CoEPCEs are using VA primary care settings to develop and test innovative approaches to prepare physician residents and students, advanced practice nurses (APRNs), undergraduate nursing students, and other health professions trainees (such as pharmacy, social work, psychology, physician assistants) for primary care practice. The CoEPCE sites are developing, implementing, and evaluating curricula to prepare learners from relevant professions to practice in patientcentered, interprofessional team-based primary care settings. Patient aligned care teams (PACTs) that have 2 or more health professions trainees engaged in learning, working, and teaching are known as interprofessional academic PACTs (iAPACTs), which is the preferred model for the VA.

The Cleveland Transforming Outpatient Care (TOPC)-CoEPCE was designed for collaborative learning among nurse practitioner (NP) students and physician residents. Its robust curriculum consists of a dedicated half-day of didactics for all learners, interprofessional quality improvement projects, panel management sessions, and primary care clinical sessions for nursing and physician learners that include the dyad workplace learning model.

In 2015, the OAA lead evaluator observed the TOPC-CoEPCE dyad model process, reviewed background documents, and conducted 10 open-ended interviews with TOPC-CoEPCE staff, participating trainees, faculty, and affiliate leadership. Informants described their involvement, challenges encountered, and benefits of the TOPCCoEPC dyad model to participants, veterans, VA, and affiliates.

Lack of Interprofessional Learning Opportunities

Current health care professional education models typically do not have many workplace learning settings where physician and nursing trainees learn together and provide patient-centered care. Often in a shared clinical environment, trainees may engage in “parallel play,” which can result in physician trainees and NP students learning independently and being ill-prepared to practice effectively together.

Moreover, trainees from different professions have different learning needs. For example, less experienced NP students require greater time, supervision, and evaluation of their patient care skills. On the other hand, senior physician residents, who require less clinical instruction, need to be engaged in ways that provide opportunities to enhance their ambulatory teaching skills. Although enhancement of resident teaching skills occurs in the inpatient hospital setting, there have been limited teaching experiences for residents in a primary care setting where the instruction is traditionally faculty-based. The TOPCCoEPCE dyad model offers an opportunity to simultaneously provide trainees with a true interprofessional experience through advancement of skills in primary care, teamwork, and teaching, while addressing health care needs.

The Dyad Model

In 2011, the OAA directed COEPCE sites to develop innovative curriculum and workplace learning strategies to create more opportunities for physician and NP trainees to work as a team. There is evidence demonstrating that when students develop a shared understanding of each other’s skill set, care procedures, and values, patient care is improved.1 Further, training in pairs can be an effective strategy in education of preclerkship medical students.2 In April 2013, TOPC-CoEPCE staff asked representatives from the Student-Run Clinic at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) in Cleveland, Ohio, to present their approach to pairing nursing and medical students in clinic under supervision by volunteer faculty. However, formal structure and curricular objectives were lacking. To address diverse TOPCCoEPCE trainee needs and create a team approach to patient care, the staff formalized and developed a workplace curriculum called the dyad model. Specifically, the model pairs 1 NP student with a senior (PGY2 or PGY3) physician resident to care for ambulatory patients as a dyad teaching/learning team. The dyad model has 3 goals: improving clinical performance, learning team dynamics, and improving the physician resident’s teaching skills in an ambulatory setting.

Planning and Implementation