User login

Accuracy of Endoscopic Ultrasound in Staging of Early Rectal Cancer (FULL)

Endoscopic ultrasound can be highly accurate for the staging of neoplasms in early rectal cancer.

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death in the US, with one-third of all colorectal cancers occurring within the rectum. Each year, an estimated 40000 Americans are diagnosed with rectal cancer (RC).1,2 The prognosis and treatment of RC depends on both T and N stage at the time of diagnosis.3-5 According to the most recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines from May 2019, patients with T1 to T2N0 tumors should undergo transanal or transabdominal surgery upfront, whereas patients with T3 to T4N0 or any TN1 to 2 should start with neoadjuvant therapy for better locoregional control, followed by surgery.6 Therefore, the appropriate management of RC requires adequate staging.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT) are the imaging techniques currently used to stage RC. In a meta-analysis of 90 articles published between 1985 and 2002 that compared the 3 radiologic modalities, Bipat and colleagues found that MRI and EUS had a similar sensitivity of 94%, whereas the specificity of EUS (86%) was significantly higher than that of MRI (69%) for muscularis propria invasion.7 CT was performed only in a limited number of trials because CT was considered inadequate to assess early T stage. For perirectal tissue invasion, the sensitivity of EUS was statistically higher than that of CT and MRI imaging: 90% compared with 79% and 82%, respectively. The specificity estimates for EUS, CT, and MRI were comparable: 75%, 78%, and 76%, respectively. The respective sensitivity and specificity of the 3 imaging modalities to evaluate lymph nodes were also comparable: EUS, 67% and 78%; CT, 55% and 74%; and MRI, 66% and 76%.

The role of EUS in the diagnosis and treatment of RC has long been validated.1,2-5 A meta-analysis of 42 studies involving 5039 patients found EUS to be highly accurate for differentiating various T stages.8 However, EUS cannot assess iliac and mesenteric lymph nodes or posterior tumor extension beyond endopelvic fascia in advanced RC. Notable heterogeneity was found among the studies in the meta-analyses with regard to the type of equipment used for staging, as well as the criteria used to assess the depth of penetration and nodal status. The recent introduction of phased-array coils and the development of T2-weighted fast spin sequences have improved the resolution of MRI. The MERCURY trial showed that extension of tumor to within 1 mm of the circumferential margin on high-resolution MRI correctly predicted margin involvement at the time of surgery in 92% of the patients.9 In the retrospective study by Balyasnikova and colleagues, MRI was found to correctly identify partial submucosal invasion and suitability for local excision in 89% of the cases.10

Therefore, both EUS and MRI are useful, more so than CT, in assessment of the depth of tumor invasion, nodal staging, and predicting the circumferential resection margin. The use of EUS, however, does not preclude the use of MRI, or vice versa. Rather, the 2 modalities can complement each other in staging and proper patient selection for treatment.11

Despite data supporting the value of EUS in staging RC, its use is limited by a high degree of operator dependence and a substantial learning curve,12-17 which may explain the low EUS accuracy observed in some reports.7,13,15 Given the presence of recognized alternatives such as MRI, we decided to reevaluate EUS accuracy for the staging of RC outside high-volume specialized centers and prospective clinical trials.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed that included all consecutive patients undergoing rectal ultrasound from January 2011 to August 2015 at the US Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Memphis, Tennessee. Sixty-five patients with short-stocked or sessile lesions < 15 cm from anal margin staged T2N0M0 or lower by endorectal ultrasound (ERUS) were included. The patients with neoplasms staged in excess of T2 or N0 were excluded from the study because treatment protocol dictates immediate neoadjuvant treatment, the administration of which would affect subsequent histopathology.

For the 37 patients included in the final analysis, ERUS results were compared with surgical pathology to ascertain accuracy. The resections were performed endoscopically or surgically with a goal of obtaining clear margins. The choice of procedure depended on size, shape, location, and depth of invasion. All patients underwent clinical and endoscopic surveillance with flexible sigmoidoscopy/EUS every 3 to 6 months for the first 2 years. We used 2 different gold standards for surveillance depending on the type of procedure performed to remove the lesion. A pathology report was the gold standard used for patients who underwent surgery. In patients who underwent endoscopic resection, we used the lack of recurrent disease, determined by normal endoscopic and endoscopic ultrasound examination, to signify complete endoscopic resection and therefore adequate staging as an early neoplasm.

Results

From January 2011 to August 2015, 65 rectal ultrasounds were performed. All EUS procedures were performed by 1 physician (C Ruben Tombazzi). All patients had previous endoscopic evaluation and tissue diagnoses. Twenty-eight patients were excluded: 18 had T3 or N1 disease, 2 had T2N0 but refused surgery, 2 had anal cancer, 3 patients with suspected cancer had benign nonneoplastic disease (2 radiation proctitis, 1 normal rectal wall), and 3 underwent EUS for benign tumors (1 ganglioneuroma and 2 lipomas).

Thirty-seven patients were included in the study, 3 of whom were staged as T2N0 and 34 as T1N0 or lower by EUS. All patients were men ranging in age from 43 to 73 years (mean, 59 years). All 37 patients underwent endoscopic or surgical resection of their early rectal neoplasm. The final pathologic evaluation of the specimens demonstrated 14 carcinoid tumors, 11 adenocarcinomas, 6 tubular adenomas with high-grade dysplasia, and 6 benign adenomas. The preoperative EUS staging was confirmed for all patients, with 100% sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. None of the patients who underwent endoscopic or surgical transanal resection had recurrence, determined by normal endoscopic and endoscopic ultrasound appearance, during a mean of 32.6 months surveillance.

Discussion

EUS has long been a recognized method for T and N staging of RC.1,3-5,7,8 Our data confirm that, in experienced hands, EUS is highly accurate in the staging of early rectal cancers.

The impact of EUS on the management of RC was demonstrated in a Mayo Clinic prospective blinded study.1 In that cohort of 80 consecutive patients who had previously had a CT for staging, EUS altered patient management in about 30% of cases. The most common change precipatated by EUS was the indication for additional neoadjuvant treatment.

However, the results have not been as encouraging when ERUS is performed outside of strict research protocol. A multicenter, prospective, country-wide quality assurance study from > 300 German hospitals was designed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of EUS in RC.13 Of 29206 patients, 7096 underwent surgery, without neoadjuvant treatment, and were included in the final analysis. The correspondence of tumor invasion with histopathology was 64.7%, with understaging of 18% and overstaging of 17.3%.13 These numbers were better in hospitals with greater experience performing ERUS: 73% accuracy in the centers with a case load of > 30 cases per year compared with 63.2% accuracy for the centers with < 10 cases a year. Marusch and colleagues had previously demonstrated an EUS accuracy of 63.3% in a study of 1463 patients with RC in Germany.14 Another study based out of the UK had similar findings. Ashraf and colleagues performed a database analyses from 20 UK centers and identified 165 patients with RC who underwent ERUS and endoscopic microsurgery.15 Compared with histopathology, EUS had 57.1% sensitivity, 73% specificity, and 42.9% accuracy for T1 cancers; EUS accuracy was 50% for T2 and 58% for T3 tumors. The authors concluded that the general accuracy of EUS in determining stage was around 50%, the statistical equivalent of flipping a coin.

The low accuracy of EUS observed by German and British multicenter studies13-15 was attributed to the difference that may exist in clinical trials at specialized centers compared with wider use of EUS in a community setting. As seen by our data, the Memphis VAMC is not a high-volume center for the treatment of RC. However, all our EUS procedures were performed and interpreted by a single operator (C. Ruben Tombazzi) with 18 years of EUS experience. We cannot conclude that no patient was overstaged, as patients receiving a stage of T3N0 or T > N0 received neoadjuvant treatment and were not included. However, we can conclude that no patient was understaged. All patients deemed to be T1 to T2N0 included in our study received accurate staging. Our results are consistent with the high accuracy of EUS reported from other centers with experience in diagnosis and treatment of RC.1,3-5,17,18

Although EUS is accurate in differentiating T1 from T2 tumors, it cannot reliably differentiate T1 from T0 lesions. In one study, 57.6% of adenomas and 30.7% of carcinomas in situ were staged as T1 on EUS, while almost half of T1 cancers were interpreted as T0.17 This drawback is a well-known limitation of EUS; although, the misinterpretation does not affect treatment, as both T0 and T1 lesions can be treated successfully by local excision alone, which was the algorithm used for our patients. The choice of the specific procedure for local excision was left to the clinicians and included transanal endoscopic or surgical resections. At a mean follow-up of 32.6 months, none of the 37 patients who underwent endoscopic or surgical transanal resection had evidence of recurrent disease.

A limitation of EUS, or any other imaging modality, is differentiating tumor invasion from peritumoral inflammation. The inflammation can render images of tumor borders ill-defined and irregular, which hinders precise staging. However, the accurate identification of tumors with deep involvement of the submucosa (T1sm3) is of importance, because these tumors are more advanced than the superficial and intermediate T1 lesions (T1sm1 and T1sm2, respectively).

Patients with RC whose lesions are considered T1sm3 are at higher risk of harboring lymph node metastases.18 Nascimbeni and colleagues had shown that the invasion into the lower third of the submucosa (sm3) was an independent risk factor for lower cancer-free survival among patients with T1 RC.19

Unlike rectal adenocarcinomas, the prognosis for carcinoid tumors correlates not only with the depth of invasion but also with the size of the tumor. The other adverse prognostic features include poor differentiation, high mitosis index, and lymphovascular invasion.20

EUS had been shown to be highly accurate in determining the precise carcinoid tumor size, depth of invasion, and lymph node metastases.20,21 In a study of 66 resected rectal carcinoid tumors by Ishii and colleagues, 57 lesions had a diameter of ≤ 10 mm and 9 lesions had a diameter of > 10 mm.21 All of the 57 carcinoid tumors with a diameter of ≤ 10 mm were confined to the submucosa. In contrast, 5 of the 9 lesions > 10 mm invaded the muscularis propria, 6 had a lymphovascular invasion, 4 were lymph node metastases, and 1 was a liver metastasis.

In our series, 4 of the 14 carcinoid tumors were > 10 mm but none were > 20 mm. None of the carcinoids with a diameter ≤ 10 mm invaded the muscularis propria. Of the 4 carcinoids > 10 mm, 1 was T2N0 and 3 were T1N0. All carcinoid tumors in our series were low grade and with low proliferation indexes, and all were treated successfully by local excision.

Conclusion

We believe our study shows that EUS can be highly accurate in staging rectal lesions, specifically lesions that are T1-T2N0, be they adenocarcinoma or carcinoid. Although we could not assess overstaging for lesions that were staged > T2 or > N0, we w

1. Harewood GC, Wiersema MJ, Nelson H, et al. A prospective, blinded assessment of the impact of preoperative staging on the management of rectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(1):24-32.

2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5-29.

3. Ahuja NK, Sauer BG, Wang AY, et al. Performance of endoscopic ultrasound in staging rectal adenocarcinoma appropriate for primary surgical resection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:339-44.

4. Doornebosch PG, Bronkhorst PJ, Hop WC, Bode WA, Sing AK, de Graaf EJ. The role of endorectal ultrasound in therapeutic decision-making for local vs. transabdominal resection of rectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(1):38-42.

5. Santoro GA, Gizzi G, Pellegrini L, Battistella G, Di Falco G. The value of high-resolution three-dimensional endorectal ultrasonography in the management of submucosal invasive rectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(11):1837-1843.

6. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: rectal cancer, version 2.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/rectal.pdf. Published May 15, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019.

7. Bipat S, Glas AS, Slors FJ, Zwinderman AH, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J. Rectal cancer: local staging and assessment of lymph node involvement with endoluminal US, CT, and MR imaging—a meta-analysis. Radiology. 2004;232(3):773-783.

8. Puli SR, Bechtold ML, Reddy JB, Choudhary A, Antillon MR, Brugge WR. How good is endoscopic ultrasound in differentiating various T stages of rectal cancer? Meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(2):254-265.

9. MERCURY Study Group. Diagnostic accuracy of preoperative magnetic resonance imaging in predicting curative resection of rectal cancer: prospective observational study. BMJ. 2006;333(7572):779.

10. Balyasnikova S, Read J, Wotherspoon A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of high-resolution MRI as a method to predict potentially safe endoscopic and surgical planes in patient with early rectal cancer. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2017;4(1):e000151.

11. Frasson M, Garcia-Granero E, Roda D, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation may not always be needed for patients with T3 and T2N+ rectal cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(14):3118-3125.

12. Rafaelsen SR, Sørensen T, Jakobsen A, Bisgaard C, Lindebjerg J. Transrectal ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the staging of rectal cancer. Effect of experience. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(4):440-446.

13. Marusch F, Ptok H, Sahm M, et al. Endorectal ultrasound in rectal carcinoma – do the literature results really correspond to the realities of routine clinical care? Endoscopy. 2011;43(5):425-431.

14. Marusch F, Koch A, Schmidt U, et al. Routine use of transrectal ultrasound in rectal carcinoma: results of a prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2002;34(5):385-390.

15. Ashraf S, Hompes R, Slater A, et al; Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery (TEM) Collaboration. A critical appraisal of endorectal ultrasound and transanal endoscopic microsurgery and decision-making in early rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(7):821-826.

16. Harewood GC. Assessment of clinical impact of endoscopic ultrasound on rectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(4):623-627.

17. Zorcolo L, Fantola G, Cabras F, Marongiu L, D’Alia G, Casula G. Preoperative staging of patients with rectal tumors suitable for transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM): comparison of endorectal ultrasound and histopathologic findings. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(6):1384-1389.

18. Akasu T, Kondo H, Moriya Y, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography and treatment of early stage rectal cancer. World J Surg. 2000;24(9):1061-1068.

19. Nascimbeni R, Nivatvongs S, Larson DR, Burgart LJ. Long-term survival after local excision for T1 carcinoma of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(11):1773-1779.

20. Park CH, Cheon JH, Kim JO, et al. Criteria for decision making after endoscopic resection of well-differentiated rectal carcinoids with regard to potential lymphatic spread. Endoscopy. 2011;43(9):790-795.

21. Ishii N, Horiki N, Itoh T, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection and preoperative assessment with endoscopic ultrasonography for the treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(6):1413-1419.

Endoscopic ultrasound can be highly accurate for the staging of neoplasms in early rectal cancer.

Endoscopic ultrasound can be highly accurate for the staging of neoplasms in early rectal cancer.

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death in the US, with one-third of all colorectal cancers occurring within the rectum. Each year, an estimated 40000 Americans are diagnosed with rectal cancer (RC).1,2 The prognosis and treatment of RC depends on both T and N stage at the time of diagnosis.3-5 According to the most recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines from May 2019, patients with T1 to T2N0 tumors should undergo transanal or transabdominal surgery upfront, whereas patients with T3 to T4N0 or any TN1 to 2 should start with neoadjuvant therapy for better locoregional control, followed by surgery.6 Therefore, the appropriate management of RC requires adequate staging.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT) are the imaging techniques currently used to stage RC. In a meta-analysis of 90 articles published between 1985 and 2002 that compared the 3 radiologic modalities, Bipat and colleagues found that MRI and EUS had a similar sensitivity of 94%, whereas the specificity of EUS (86%) was significantly higher than that of MRI (69%) for muscularis propria invasion.7 CT was performed only in a limited number of trials because CT was considered inadequate to assess early T stage. For perirectal tissue invasion, the sensitivity of EUS was statistically higher than that of CT and MRI imaging: 90% compared with 79% and 82%, respectively. The specificity estimates for EUS, CT, and MRI were comparable: 75%, 78%, and 76%, respectively. The respective sensitivity and specificity of the 3 imaging modalities to evaluate lymph nodes were also comparable: EUS, 67% and 78%; CT, 55% and 74%; and MRI, 66% and 76%.

The role of EUS in the diagnosis and treatment of RC has long been validated.1,2-5 A meta-analysis of 42 studies involving 5039 patients found EUS to be highly accurate for differentiating various T stages.8 However, EUS cannot assess iliac and mesenteric lymph nodes or posterior tumor extension beyond endopelvic fascia in advanced RC. Notable heterogeneity was found among the studies in the meta-analyses with regard to the type of equipment used for staging, as well as the criteria used to assess the depth of penetration and nodal status. The recent introduction of phased-array coils and the development of T2-weighted fast spin sequences have improved the resolution of MRI. The MERCURY trial showed that extension of tumor to within 1 mm of the circumferential margin on high-resolution MRI correctly predicted margin involvement at the time of surgery in 92% of the patients.9 In the retrospective study by Balyasnikova and colleagues, MRI was found to correctly identify partial submucosal invasion and suitability for local excision in 89% of the cases.10

Therefore, both EUS and MRI are useful, more so than CT, in assessment of the depth of tumor invasion, nodal staging, and predicting the circumferential resection margin. The use of EUS, however, does not preclude the use of MRI, or vice versa. Rather, the 2 modalities can complement each other in staging and proper patient selection for treatment.11

Despite data supporting the value of EUS in staging RC, its use is limited by a high degree of operator dependence and a substantial learning curve,12-17 which may explain the low EUS accuracy observed in some reports.7,13,15 Given the presence of recognized alternatives such as MRI, we decided to reevaluate EUS accuracy for the staging of RC outside high-volume specialized centers and prospective clinical trials.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed that included all consecutive patients undergoing rectal ultrasound from January 2011 to August 2015 at the US Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Memphis, Tennessee. Sixty-five patients with short-stocked or sessile lesions < 15 cm from anal margin staged T2N0M0 or lower by endorectal ultrasound (ERUS) were included. The patients with neoplasms staged in excess of T2 or N0 were excluded from the study because treatment protocol dictates immediate neoadjuvant treatment, the administration of which would affect subsequent histopathology.

For the 37 patients included in the final analysis, ERUS results were compared with surgical pathology to ascertain accuracy. The resections were performed endoscopically or surgically with a goal of obtaining clear margins. The choice of procedure depended on size, shape, location, and depth of invasion. All patients underwent clinical and endoscopic surveillance with flexible sigmoidoscopy/EUS every 3 to 6 months for the first 2 years. We used 2 different gold standards for surveillance depending on the type of procedure performed to remove the lesion. A pathology report was the gold standard used for patients who underwent surgery. In patients who underwent endoscopic resection, we used the lack of recurrent disease, determined by normal endoscopic and endoscopic ultrasound examination, to signify complete endoscopic resection and therefore adequate staging as an early neoplasm.

Results

From January 2011 to August 2015, 65 rectal ultrasounds were performed. All EUS procedures were performed by 1 physician (C Ruben Tombazzi). All patients had previous endoscopic evaluation and tissue diagnoses. Twenty-eight patients were excluded: 18 had T3 or N1 disease, 2 had T2N0 but refused surgery, 2 had anal cancer, 3 patients with suspected cancer had benign nonneoplastic disease (2 radiation proctitis, 1 normal rectal wall), and 3 underwent EUS for benign tumors (1 ganglioneuroma and 2 lipomas).

Thirty-seven patients were included in the study, 3 of whom were staged as T2N0 and 34 as T1N0 or lower by EUS. All patients were men ranging in age from 43 to 73 years (mean, 59 years). All 37 patients underwent endoscopic or surgical resection of their early rectal neoplasm. The final pathologic evaluation of the specimens demonstrated 14 carcinoid tumors, 11 adenocarcinomas, 6 tubular adenomas with high-grade dysplasia, and 6 benign adenomas. The preoperative EUS staging was confirmed for all patients, with 100% sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. None of the patients who underwent endoscopic or surgical transanal resection had recurrence, determined by normal endoscopic and endoscopic ultrasound appearance, during a mean of 32.6 months surveillance.

Discussion

EUS has long been a recognized method for T and N staging of RC.1,3-5,7,8 Our data confirm that, in experienced hands, EUS is highly accurate in the staging of early rectal cancers.

The impact of EUS on the management of RC was demonstrated in a Mayo Clinic prospective blinded study.1 In that cohort of 80 consecutive patients who had previously had a CT for staging, EUS altered patient management in about 30% of cases. The most common change precipatated by EUS was the indication for additional neoadjuvant treatment.

However, the results have not been as encouraging when ERUS is performed outside of strict research protocol. A multicenter, prospective, country-wide quality assurance study from > 300 German hospitals was designed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of EUS in RC.13 Of 29206 patients, 7096 underwent surgery, without neoadjuvant treatment, and were included in the final analysis. The correspondence of tumor invasion with histopathology was 64.7%, with understaging of 18% and overstaging of 17.3%.13 These numbers were better in hospitals with greater experience performing ERUS: 73% accuracy in the centers with a case load of > 30 cases per year compared with 63.2% accuracy for the centers with < 10 cases a year. Marusch and colleagues had previously demonstrated an EUS accuracy of 63.3% in a study of 1463 patients with RC in Germany.14 Another study based out of the UK had similar findings. Ashraf and colleagues performed a database analyses from 20 UK centers and identified 165 patients with RC who underwent ERUS and endoscopic microsurgery.15 Compared with histopathology, EUS had 57.1% sensitivity, 73% specificity, and 42.9% accuracy for T1 cancers; EUS accuracy was 50% for T2 and 58% for T3 tumors. The authors concluded that the general accuracy of EUS in determining stage was around 50%, the statistical equivalent of flipping a coin.

The low accuracy of EUS observed by German and British multicenter studies13-15 was attributed to the difference that may exist in clinical trials at specialized centers compared with wider use of EUS in a community setting. As seen by our data, the Memphis VAMC is not a high-volume center for the treatment of RC. However, all our EUS procedures were performed and interpreted by a single operator (C. Ruben Tombazzi) with 18 years of EUS experience. We cannot conclude that no patient was overstaged, as patients receiving a stage of T3N0 or T > N0 received neoadjuvant treatment and were not included. However, we can conclude that no patient was understaged. All patients deemed to be T1 to T2N0 included in our study received accurate staging. Our results are consistent with the high accuracy of EUS reported from other centers with experience in diagnosis and treatment of RC.1,3-5,17,18

Although EUS is accurate in differentiating T1 from T2 tumors, it cannot reliably differentiate T1 from T0 lesions. In one study, 57.6% of adenomas and 30.7% of carcinomas in situ were staged as T1 on EUS, while almost half of T1 cancers were interpreted as T0.17 This drawback is a well-known limitation of EUS; although, the misinterpretation does not affect treatment, as both T0 and T1 lesions can be treated successfully by local excision alone, which was the algorithm used for our patients. The choice of the specific procedure for local excision was left to the clinicians and included transanal endoscopic or surgical resections. At a mean follow-up of 32.6 months, none of the 37 patients who underwent endoscopic or surgical transanal resection had evidence of recurrent disease.

A limitation of EUS, or any other imaging modality, is differentiating tumor invasion from peritumoral inflammation. The inflammation can render images of tumor borders ill-defined and irregular, which hinders precise staging. However, the accurate identification of tumors with deep involvement of the submucosa (T1sm3) is of importance, because these tumors are more advanced than the superficial and intermediate T1 lesions (T1sm1 and T1sm2, respectively).

Patients with RC whose lesions are considered T1sm3 are at higher risk of harboring lymph node metastases.18 Nascimbeni and colleagues had shown that the invasion into the lower third of the submucosa (sm3) was an independent risk factor for lower cancer-free survival among patients with T1 RC.19

Unlike rectal adenocarcinomas, the prognosis for carcinoid tumors correlates not only with the depth of invasion but also with the size of the tumor. The other adverse prognostic features include poor differentiation, high mitosis index, and lymphovascular invasion.20

EUS had been shown to be highly accurate in determining the precise carcinoid tumor size, depth of invasion, and lymph node metastases.20,21 In a study of 66 resected rectal carcinoid tumors by Ishii and colleagues, 57 lesions had a diameter of ≤ 10 mm and 9 lesions had a diameter of > 10 mm.21 All of the 57 carcinoid tumors with a diameter of ≤ 10 mm were confined to the submucosa. In contrast, 5 of the 9 lesions > 10 mm invaded the muscularis propria, 6 had a lymphovascular invasion, 4 were lymph node metastases, and 1 was a liver metastasis.

In our series, 4 of the 14 carcinoid tumors were > 10 mm but none were > 20 mm. None of the carcinoids with a diameter ≤ 10 mm invaded the muscularis propria. Of the 4 carcinoids > 10 mm, 1 was T2N0 and 3 were T1N0. All carcinoid tumors in our series were low grade and with low proliferation indexes, and all were treated successfully by local excision.

Conclusion

We believe our study shows that EUS can be highly accurate in staging rectal lesions, specifically lesions that are T1-T2N0, be they adenocarcinoma or carcinoid. Although we could not assess overstaging for lesions that were staged > T2 or > N0, we w

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death in the US, with one-third of all colorectal cancers occurring within the rectum. Each year, an estimated 40000 Americans are diagnosed with rectal cancer (RC).1,2 The prognosis and treatment of RC depends on both T and N stage at the time of diagnosis.3-5 According to the most recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines from May 2019, patients with T1 to T2N0 tumors should undergo transanal or transabdominal surgery upfront, whereas patients with T3 to T4N0 or any TN1 to 2 should start with neoadjuvant therapy for better locoregional control, followed by surgery.6 Therefore, the appropriate management of RC requires adequate staging.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT) are the imaging techniques currently used to stage RC. In a meta-analysis of 90 articles published between 1985 and 2002 that compared the 3 radiologic modalities, Bipat and colleagues found that MRI and EUS had a similar sensitivity of 94%, whereas the specificity of EUS (86%) was significantly higher than that of MRI (69%) for muscularis propria invasion.7 CT was performed only in a limited number of trials because CT was considered inadequate to assess early T stage. For perirectal tissue invasion, the sensitivity of EUS was statistically higher than that of CT and MRI imaging: 90% compared with 79% and 82%, respectively. The specificity estimates for EUS, CT, and MRI were comparable: 75%, 78%, and 76%, respectively. The respective sensitivity and specificity of the 3 imaging modalities to evaluate lymph nodes were also comparable: EUS, 67% and 78%; CT, 55% and 74%; and MRI, 66% and 76%.

The role of EUS in the diagnosis and treatment of RC has long been validated.1,2-5 A meta-analysis of 42 studies involving 5039 patients found EUS to be highly accurate for differentiating various T stages.8 However, EUS cannot assess iliac and mesenteric lymph nodes or posterior tumor extension beyond endopelvic fascia in advanced RC. Notable heterogeneity was found among the studies in the meta-analyses with regard to the type of equipment used for staging, as well as the criteria used to assess the depth of penetration and nodal status. The recent introduction of phased-array coils and the development of T2-weighted fast spin sequences have improved the resolution of MRI. The MERCURY trial showed that extension of tumor to within 1 mm of the circumferential margin on high-resolution MRI correctly predicted margin involvement at the time of surgery in 92% of the patients.9 In the retrospective study by Balyasnikova and colleagues, MRI was found to correctly identify partial submucosal invasion and suitability for local excision in 89% of the cases.10

Therefore, both EUS and MRI are useful, more so than CT, in assessment of the depth of tumor invasion, nodal staging, and predicting the circumferential resection margin. The use of EUS, however, does not preclude the use of MRI, or vice versa. Rather, the 2 modalities can complement each other in staging and proper patient selection for treatment.11

Despite data supporting the value of EUS in staging RC, its use is limited by a high degree of operator dependence and a substantial learning curve,12-17 which may explain the low EUS accuracy observed in some reports.7,13,15 Given the presence of recognized alternatives such as MRI, we decided to reevaluate EUS accuracy for the staging of RC outside high-volume specialized centers and prospective clinical trials.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed that included all consecutive patients undergoing rectal ultrasound from January 2011 to August 2015 at the US Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Memphis, Tennessee. Sixty-five patients with short-stocked or sessile lesions < 15 cm from anal margin staged T2N0M0 or lower by endorectal ultrasound (ERUS) were included. The patients with neoplasms staged in excess of T2 or N0 were excluded from the study because treatment protocol dictates immediate neoadjuvant treatment, the administration of which would affect subsequent histopathology.

For the 37 patients included in the final analysis, ERUS results were compared with surgical pathology to ascertain accuracy. The resections were performed endoscopically or surgically with a goal of obtaining clear margins. The choice of procedure depended on size, shape, location, and depth of invasion. All patients underwent clinical and endoscopic surveillance with flexible sigmoidoscopy/EUS every 3 to 6 months for the first 2 years. We used 2 different gold standards for surveillance depending on the type of procedure performed to remove the lesion. A pathology report was the gold standard used for patients who underwent surgery. In patients who underwent endoscopic resection, we used the lack of recurrent disease, determined by normal endoscopic and endoscopic ultrasound examination, to signify complete endoscopic resection and therefore adequate staging as an early neoplasm.

Results

From January 2011 to August 2015, 65 rectal ultrasounds were performed. All EUS procedures were performed by 1 physician (C Ruben Tombazzi). All patients had previous endoscopic evaluation and tissue diagnoses. Twenty-eight patients were excluded: 18 had T3 or N1 disease, 2 had T2N0 but refused surgery, 2 had anal cancer, 3 patients with suspected cancer had benign nonneoplastic disease (2 radiation proctitis, 1 normal rectal wall), and 3 underwent EUS for benign tumors (1 ganglioneuroma and 2 lipomas).

Thirty-seven patients were included in the study, 3 of whom were staged as T2N0 and 34 as T1N0 or lower by EUS. All patients were men ranging in age from 43 to 73 years (mean, 59 years). All 37 patients underwent endoscopic or surgical resection of their early rectal neoplasm. The final pathologic evaluation of the specimens demonstrated 14 carcinoid tumors, 11 adenocarcinomas, 6 tubular adenomas with high-grade dysplasia, and 6 benign adenomas. The preoperative EUS staging was confirmed for all patients, with 100% sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. None of the patients who underwent endoscopic or surgical transanal resection had recurrence, determined by normal endoscopic and endoscopic ultrasound appearance, during a mean of 32.6 months surveillance.

Discussion

EUS has long been a recognized method for T and N staging of RC.1,3-5,7,8 Our data confirm that, in experienced hands, EUS is highly accurate in the staging of early rectal cancers.

The impact of EUS on the management of RC was demonstrated in a Mayo Clinic prospective blinded study.1 In that cohort of 80 consecutive patients who had previously had a CT for staging, EUS altered patient management in about 30% of cases. The most common change precipatated by EUS was the indication for additional neoadjuvant treatment.

However, the results have not been as encouraging when ERUS is performed outside of strict research protocol. A multicenter, prospective, country-wide quality assurance study from > 300 German hospitals was designed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of EUS in RC.13 Of 29206 patients, 7096 underwent surgery, without neoadjuvant treatment, and were included in the final analysis. The correspondence of tumor invasion with histopathology was 64.7%, with understaging of 18% and overstaging of 17.3%.13 These numbers were better in hospitals with greater experience performing ERUS: 73% accuracy in the centers with a case load of > 30 cases per year compared with 63.2% accuracy for the centers with < 10 cases a year. Marusch and colleagues had previously demonstrated an EUS accuracy of 63.3% in a study of 1463 patients with RC in Germany.14 Another study based out of the UK had similar findings. Ashraf and colleagues performed a database analyses from 20 UK centers and identified 165 patients with RC who underwent ERUS and endoscopic microsurgery.15 Compared with histopathology, EUS had 57.1% sensitivity, 73% specificity, and 42.9% accuracy for T1 cancers; EUS accuracy was 50% for T2 and 58% for T3 tumors. The authors concluded that the general accuracy of EUS in determining stage was around 50%, the statistical equivalent of flipping a coin.

The low accuracy of EUS observed by German and British multicenter studies13-15 was attributed to the difference that may exist in clinical trials at specialized centers compared with wider use of EUS in a community setting. As seen by our data, the Memphis VAMC is not a high-volume center for the treatment of RC. However, all our EUS procedures were performed and interpreted by a single operator (C. Ruben Tombazzi) with 18 years of EUS experience. We cannot conclude that no patient was overstaged, as patients receiving a stage of T3N0 or T > N0 received neoadjuvant treatment and were not included. However, we can conclude that no patient was understaged. All patients deemed to be T1 to T2N0 included in our study received accurate staging. Our results are consistent with the high accuracy of EUS reported from other centers with experience in diagnosis and treatment of RC.1,3-5,17,18

Although EUS is accurate in differentiating T1 from T2 tumors, it cannot reliably differentiate T1 from T0 lesions. In one study, 57.6% of adenomas and 30.7% of carcinomas in situ were staged as T1 on EUS, while almost half of T1 cancers were interpreted as T0.17 This drawback is a well-known limitation of EUS; although, the misinterpretation does not affect treatment, as both T0 and T1 lesions can be treated successfully by local excision alone, which was the algorithm used for our patients. The choice of the specific procedure for local excision was left to the clinicians and included transanal endoscopic or surgical resections. At a mean follow-up of 32.6 months, none of the 37 patients who underwent endoscopic or surgical transanal resection had evidence of recurrent disease.

A limitation of EUS, or any other imaging modality, is differentiating tumor invasion from peritumoral inflammation. The inflammation can render images of tumor borders ill-defined and irregular, which hinders precise staging. However, the accurate identification of tumors with deep involvement of the submucosa (T1sm3) is of importance, because these tumors are more advanced than the superficial and intermediate T1 lesions (T1sm1 and T1sm2, respectively).

Patients with RC whose lesions are considered T1sm3 are at higher risk of harboring lymph node metastases.18 Nascimbeni and colleagues had shown that the invasion into the lower third of the submucosa (sm3) was an independent risk factor for lower cancer-free survival among patients with T1 RC.19

Unlike rectal adenocarcinomas, the prognosis for carcinoid tumors correlates not only with the depth of invasion but also with the size of the tumor. The other adverse prognostic features include poor differentiation, high mitosis index, and lymphovascular invasion.20

EUS had been shown to be highly accurate in determining the precise carcinoid tumor size, depth of invasion, and lymph node metastases.20,21 In a study of 66 resected rectal carcinoid tumors by Ishii and colleagues, 57 lesions had a diameter of ≤ 10 mm and 9 lesions had a diameter of > 10 mm.21 All of the 57 carcinoid tumors with a diameter of ≤ 10 mm were confined to the submucosa. In contrast, 5 of the 9 lesions > 10 mm invaded the muscularis propria, 6 had a lymphovascular invasion, 4 were lymph node metastases, and 1 was a liver metastasis.

In our series, 4 of the 14 carcinoid tumors were > 10 mm but none were > 20 mm. None of the carcinoids with a diameter ≤ 10 mm invaded the muscularis propria. Of the 4 carcinoids > 10 mm, 1 was T2N0 and 3 were T1N0. All carcinoid tumors in our series were low grade and with low proliferation indexes, and all were treated successfully by local excision.

Conclusion

We believe our study shows that EUS can be highly accurate in staging rectal lesions, specifically lesions that are T1-T2N0, be they adenocarcinoma or carcinoid. Although we could not assess overstaging for lesions that were staged > T2 or > N0, we w

1. Harewood GC, Wiersema MJ, Nelson H, et al. A prospective, blinded assessment of the impact of preoperative staging on the management of rectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(1):24-32.

2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5-29.

3. Ahuja NK, Sauer BG, Wang AY, et al. Performance of endoscopic ultrasound in staging rectal adenocarcinoma appropriate for primary surgical resection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:339-44.

4. Doornebosch PG, Bronkhorst PJ, Hop WC, Bode WA, Sing AK, de Graaf EJ. The role of endorectal ultrasound in therapeutic decision-making for local vs. transabdominal resection of rectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(1):38-42.

5. Santoro GA, Gizzi G, Pellegrini L, Battistella G, Di Falco G. The value of high-resolution three-dimensional endorectal ultrasonography in the management of submucosal invasive rectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(11):1837-1843.

6. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: rectal cancer, version 2.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/rectal.pdf. Published May 15, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019.

7. Bipat S, Glas AS, Slors FJ, Zwinderman AH, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J. Rectal cancer: local staging and assessment of lymph node involvement with endoluminal US, CT, and MR imaging—a meta-analysis. Radiology. 2004;232(3):773-783.

8. Puli SR, Bechtold ML, Reddy JB, Choudhary A, Antillon MR, Brugge WR. How good is endoscopic ultrasound in differentiating various T stages of rectal cancer? Meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(2):254-265.

9. MERCURY Study Group. Diagnostic accuracy of preoperative magnetic resonance imaging in predicting curative resection of rectal cancer: prospective observational study. BMJ. 2006;333(7572):779.

10. Balyasnikova S, Read J, Wotherspoon A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of high-resolution MRI as a method to predict potentially safe endoscopic and surgical planes in patient with early rectal cancer. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2017;4(1):e000151.

11. Frasson M, Garcia-Granero E, Roda D, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation may not always be needed for patients with T3 and T2N+ rectal cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(14):3118-3125.

12. Rafaelsen SR, Sørensen T, Jakobsen A, Bisgaard C, Lindebjerg J. Transrectal ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the staging of rectal cancer. Effect of experience. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(4):440-446.

13. Marusch F, Ptok H, Sahm M, et al. Endorectal ultrasound in rectal carcinoma – do the literature results really correspond to the realities of routine clinical care? Endoscopy. 2011;43(5):425-431.

14. Marusch F, Koch A, Schmidt U, et al. Routine use of transrectal ultrasound in rectal carcinoma: results of a prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2002;34(5):385-390.

15. Ashraf S, Hompes R, Slater A, et al; Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery (TEM) Collaboration. A critical appraisal of endorectal ultrasound and transanal endoscopic microsurgery and decision-making in early rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(7):821-826.

16. Harewood GC. Assessment of clinical impact of endoscopic ultrasound on rectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(4):623-627.

17. Zorcolo L, Fantola G, Cabras F, Marongiu L, D’Alia G, Casula G. Preoperative staging of patients with rectal tumors suitable for transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM): comparison of endorectal ultrasound and histopathologic findings. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(6):1384-1389.

18. Akasu T, Kondo H, Moriya Y, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography and treatment of early stage rectal cancer. World J Surg. 2000;24(9):1061-1068.

19. Nascimbeni R, Nivatvongs S, Larson DR, Burgart LJ. Long-term survival after local excision for T1 carcinoma of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(11):1773-1779.

20. Park CH, Cheon JH, Kim JO, et al. Criteria for decision making after endoscopic resection of well-differentiated rectal carcinoids with regard to potential lymphatic spread. Endoscopy. 2011;43(9):790-795.

21. Ishii N, Horiki N, Itoh T, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection and preoperative assessment with endoscopic ultrasonography for the treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(6):1413-1419.

1. Harewood GC, Wiersema MJ, Nelson H, et al. A prospective, blinded assessment of the impact of preoperative staging on the management of rectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(1):24-32.

2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5-29.

3. Ahuja NK, Sauer BG, Wang AY, et al. Performance of endoscopic ultrasound in staging rectal adenocarcinoma appropriate for primary surgical resection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:339-44.

4. Doornebosch PG, Bronkhorst PJ, Hop WC, Bode WA, Sing AK, de Graaf EJ. The role of endorectal ultrasound in therapeutic decision-making for local vs. transabdominal resection of rectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(1):38-42.

5. Santoro GA, Gizzi G, Pellegrini L, Battistella G, Di Falco G. The value of high-resolution three-dimensional endorectal ultrasonography in the management of submucosal invasive rectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(11):1837-1843.

6. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: rectal cancer, version 2.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/rectal.pdf. Published May 15, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019.

7. Bipat S, Glas AS, Slors FJ, Zwinderman AH, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J. Rectal cancer: local staging and assessment of lymph node involvement with endoluminal US, CT, and MR imaging—a meta-analysis. Radiology. 2004;232(3):773-783.

8. Puli SR, Bechtold ML, Reddy JB, Choudhary A, Antillon MR, Brugge WR. How good is endoscopic ultrasound in differentiating various T stages of rectal cancer? Meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(2):254-265.

9. MERCURY Study Group. Diagnostic accuracy of preoperative magnetic resonance imaging in predicting curative resection of rectal cancer: prospective observational study. BMJ. 2006;333(7572):779.

10. Balyasnikova S, Read J, Wotherspoon A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of high-resolution MRI as a method to predict potentially safe endoscopic and surgical planes in patient with early rectal cancer. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2017;4(1):e000151.

11. Frasson M, Garcia-Granero E, Roda D, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation may not always be needed for patients with T3 and T2N+ rectal cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(14):3118-3125.

12. Rafaelsen SR, Sørensen T, Jakobsen A, Bisgaard C, Lindebjerg J. Transrectal ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the staging of rectal cancer. Effect of experience. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(4):440-446.

13. Marusch F, Ptok H, Sahm M, et al. Endorectal ultrasound in rectal carcinoma – do the literature results really correspond to the realities of routine clinical care? Endoscopy. 2011;43(5):425-431.

14. Marusch F, Koch A, Schmidt U, et al. Routine use of transrectal ultrasound in rectal carcinoma: results of a prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2002;34(5):385-390.

15. Ashraf S, Hompes R, Slater A, et al; Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery (TEM) Collaboration. A critical appraisal of endorectal ultrasound and transanal endoscopic microsurgery and decision-making in early rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(7):821-826.

16. Harewood GC. Assessment of clinical impact of endoscopic ultrasound on rectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(4):623-627.

17. Zorcolo L, Fantola G, Cabras F, Marongiu L, D’Alia G, Casula G. Preoperative staging of patients with rectal tumors suitable for transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM): comparison of endorectal ultrasound and histopathologic findings. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(6):1384-1389.

18. Akasu T, Kondo H, Moriya Y, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography and treatment of early stage rectal cancer. World J Surg. 2000;24(9):1061-1068.

19. Nascimbeni R, Nivatvongs S, Larson DR, Burgart LJ. Long-term survival after local excision for T1 carcinoma of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(11):1773-1779.

20. Park CH, Cheon JH, Kim JO, et al. Criteria for decision making after endoscopic resection of well-differentiated rectal carcinoids with regard to potential lymphatic spread. Endoscopy. 2011;43(9):790-795.

21. Ishii N, Horiki N, Itoh T, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection and preoperative assessment with endoscopic ultrasonography for the treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(6):1413-1419.

Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction in Patients With Low Back Pain

Patients experiencing sacroiliac joint (SIJ) dysfunction might show symptoms that overlap with those seen in lumbar spine pathology. This article reviews diagnostic tools that assist practitioners to discern the true pain generator in patients with low back pain (LBP) and therapeutic approaches when the cause is SIJ dysfunction.

Prevalence

Most of the US population will experience LBP at some point in their lives. A 2002 National Health Interview survey found that more than one-quarter (26.4%) of 31 044 respondents had complained of LBP in the previous 3 months.1 About 74 million individuals in the US experienced LBP in the past 3 months.1 A full 10% of the US population is expected to suffer from chronic LBP, and it is estimated that 2.3% of all visits to physicians are related to LBP.1

The etiology of LBP often is unclear even after thorough clinical and radiographic evaluation because of the myriad possible mechanisms. Degenerative disc disease, facet arthropathy, ligamentous hypertrophy, muscle spasm, hip arthropathy, and SIJ dysfunction are potential pain generators and exact clinical and radiographic correlation is not always possible. Compounding this difficulty is the lack of specificity with current diagnostic techniques. For example, many patients will have disc desiccation or herniation without any LBP or radicular symptoms on radiographic studies, such as X-rays, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). As such, providers of patients with diffuse radiographic abnormalities often have to identify a specific pain generator, which might not have any role in the patient’s pain.

Other tests, such as electromyographic studies, positron emission tomography (PET) scans, discography, and epidural steroid injections, can help pinpoint a specific pain generator. These tests might help determine whether the patient has a surgically treatable condition and could help predict whether a patient’s symptoms will respond to surgery.

However, the standard spine surgery workup often fails to identify an obvious pain generator in many individuals. The significant number of patients that fall into this category has prompted spine surgeons to consider other potential etiologies for LBP, and SIJ dysfunction has become a rapidly developing field of research.

Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction

The SIJ is a bilateral, C-shaped synovial joint surrounded by a fibrous capsule and affixes the sacrum to the ilia. Several sacral ligaments and pelvic muscles support the SIJ. The L5 nerve ventral ramus and lumbosacral trunk pass anteriorly and the S1 nerve ventral ramus passes inferiorly to the joint capsule. The SIJ is innervated by the dorsal rami of L4-S3 nerve roots, transmitting nociception and temperature. Mechanisms of injury to the SIJ could arise from intra- and extra-articular etiologies, including capsular disruption, ligamentous tension, muscular inflammation, shearing, fractures, arthritis, and infection.2 Patients could develop SIJ pain spontaneously or after a traumatic event or repetitive shear.3 Risk factors for developing SIJ dysfunction include a history of lumbar fusion, scoliosis, leg length discrepancies, sustained athletic activity, pregnancy, seronegative HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathies, or gait abnormalities. Inflammation of the SIJ and surrounding structures secondary to an environmental insult in susceptible individuals is a common theme among these etiologies.2

Pain from the SIJ is localized to an area of approximately 3 cm × 10 cm that is inferior to the ipsilateral posterior superior iliac spine.4 Referred pain maps from SIJ dysfunction extend in the L5-S1 nerve distributions, commonly seen in the buttocks, groin, posterior thigh, and lower leg with radicular symptoms. However, this pain distribution demonstrates extensive variability among patients and bears strong similarities to discogenic or facet joint sources of LBP.5-7 Direct communication has been shown between the SIJ and adjacent neural structures, namely the L5 nerve, sacral foramina, and the lumbosacral plexus. These direct pathways could explain an inflammatory mechanism for lower extremity symptoms seen in SIJ dysfunction.8

The prevalence of SIJ dysfunction among patients with LBP is estimated to be 15% to 30%, an extraordinary number given the total number of patients presenting with LBP every year.9 These patients might represent a significant segment of patients with an unrevealing standard spine evaluation. Despite the large number of patients who experience SIJ dysfunction, there is disagreement about optimal methods for diagnosis and treatment.

Diagnosis

The International Association for the Study of Pain has proposed criteria for evaluating patients who have suspected SIJ dysfunction: Pain must be in the SIJ area, should be reproducible by performing specific provocative maneuvers, and must be relieved by injection of local anesthetic into the SIJ.10 These criteria provide a sound foundation, but in clinical practice, patients often defy categorization.

The presence of pain in the area inferior to the posterior superior iliac spine and lateral to the gluteal fold with pain referral patterns in the L5-S1 nerve distributions is highly sensitive for identifying patients with SIJ dysfunction. Furthermore, pain arising from the SIJ will not be above the level of the L5 nerve sensory distribution. However, this diagnostic finding alone is not specific and might represent other etiologies known to produce similar pain, such as intervertebral discs and facet joints. Patients with SIJ dysfunction often describe their pain as sciatica-like, recurrent, and triggered with bending or twisting motions. It is worsened with any activity loading the SIJ, such as walking, climbing stairs, standing, or sitting upright. SIJ pain might be accompanied by dyspareunia and changes in bladder function because of the nerves involved.11

The use of provocative maneuvers for testing SIJ dysfunction is controversial because of the high rate of false positives and the inability to distinguish whether the SIJ or an adjacent structure is affected. However, the diagnostic utility of specific stress tests has been studied, and clusters of tests are recommended if a health care provider (HCP) suspects SIJ dysfunction. A diagnostic algorithm should first focus on using the distraction test and the thigh thrust test. Distraction is done by applying vertically oriented pressure to the anterior superior iliac spine while aiming posteriorly, therefore distracting the SIJ. During the thigh thrust test the examiner fixates the patient’s sacrum against the table with the left hand and applies a vertical force through the line of the femur aiming posteriorly, producing a posterior shearing force at the SIJ. Studies show that the thigh thrust test is the most sensitive, and the distraction test is the most specific. If both tests are positive, there is reasonable evidence to suggest SIJ dysfunction as the source of LBP.

If there are not 2 positive results, the addition of the compression test, followed by the sacral thrust test also can point to the diagnosis. The compression test is performed with vertical downward force applied to the iliac crest with the patient lying on each side, compressing the SIJ by transverse pressure across the pelvis. The sacral thrust test is performed with vertical force applied to the midline posterior sacrum at its apex directed anteriorly with the patient lying prone, producing a shearing force at the SIJs. The Gaenslen test uses a torsion force by applying a superior and posterior force to the right knee and posteriorly directed force to the left knee. Omitting the Gaenslen test has not been shown to compromise diagnostic efficacy of the other tests and can be safely excluded.12

A HCP can rule out SIJ dysfunction if these provocation tests are negative. However, the diagnostic predictive value of these tests is subject to variability among HCPs, and their reliability is increased when used in clusters.9,13

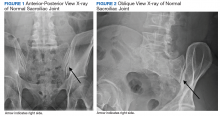

Imaging for the SIJ should begin with anterior/posterior, oblique, and lateral view plain X-rays of the pelvis (Figures 1 and 2), which will rule out other pathologies by identifying other sources of LBP, such as spondylolisthesis or hip osteoarthritis. HCPs should obtain lumbar and pelvis CT images to identify inflammatory or degenerative changes within the SIJ. CT images provide the high resolution that is needed to identify pathologies, such as fractures and tumors within the pelvic ring that could cause similar pain. MRI does not reliably depict a dysfunctional ligamentous apparatus within the SIJ; however, it can help identify inflammatory sacroiliitis, such as is seen in the spondyloarthropathies.11,14 Recent studies show combined single photon emission tomography and CT (SPECT-CT) might be the most promising imaging modality to reveal mechanical failure of load transfer with increased scintigraphic uptake in the posterior and superior SIJ ligamentous attachments. The joint loses its characteristic “dumbbell” shape in affected patients with about 50% higher uptake than unaffected joints. These findings were evident in patients who experienced pelvic trauma or during the peripartum period.15,16

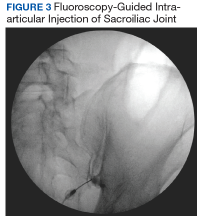

Fluoroscopy-guided intra-articular injection of a local anesthetic (lidocaine) and/or a corticosteroid (triamcinolone) has the dual functionality of diagnosis and treatment (Figure 3). It often is considered the most reliable method to diagnose SIJ dysfunction and has the benefit of pain relief for up to 1 year. However, intra-articular injections lack diagnostic validity because the solution often extravasates to extracapsular structures. This confounds the source of the pain and makes it difficult to interpret these diagnostic injections. In addition, the injection might not reach the entire SIJ capsule and could result in a false-negative diagnosis.17,18 Periarticular injections have been shown to result in better pain relief in patients diagnosed with SIJ dysfunction than intra-articular injections. Periarticular injections also are easier to perform and could be a first-step option for these patients.19

Treatment

Nonoperative management of SIJ dysfunction includes exercise programs, physical therapy, manual manipulation therapy, sacroiliac belts, and periodic articular injections. Efficacy of these methods is variable, and analgesics often do not significantly benefit this type of pain. Another nonoperative approach is radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of the lumbar dorsal rami and lateral sacral branches, which can vary based on the number of rami treated as well as the technique used. About two-thirds of patients report pain relief after RFA.2 When successful, pain is relieved for 6 to 12 months, which is a temporary yet effective option for patients experiencing SIJ dysfunction.14,20

Fusion Surgery

Cadaver studies show that biomechanical stabilization of the SIJ leads to decreased range of motion in flexion/extension, lateral bending, and axial rotation. This results in a decreased need for periarticular muscular and ligamentous support, therefore facilitating load transfer across the SIJ.21,22 Patients undergoing minimally invasive surgery report better pain relief compared with those receiving open surgery at 12 months postoperatively.23 The 2 main SIJ fusion approaches used are the lateral transarticular and the dorsal approaches. In the dorsal approach, the SIJ is distracted and allograft dowels or titanium cages with graft are inserted into the joint space posteriorly through the back. When approaching laterally, hollow screw implants filled with graft or triangular titanium implants are placed across the joint, accessing the SIJ through the iliac bones using imaging guidance. This lateral transiliac approach using porous titanium triangular rods currently is the most studied technique.24

A recent prospective, multicenter trial included 423 patients with SIJ dysfunction who were randomized to receive SIJ fusion with triangular titanium implants vs a control group who received nonoperative management. Patients in the SIJ fusion group showed substantially greater improvement in pain (81.4%) compared with that of the nonoperative group (26.1%) 6 months after surgery. Pain relief in the SIJ fusion group was maintained at > 80% at 1 and 2 year follow-up, while the nonoperative group’s pain relief decreased to < 10% at the follow-ups. Measures of quality of life and disability also improved for the SIJ fusion group compared with that of the nonoperative group. Patients who were crossed over from conservative management to SIJ fusion after 6 months demonstrated improvements that were similar to those in the SIJ fusion group by the end of the study. Only 3% of patients required surgical revision. The strongest predictor of pain relief after surgery was a diagnostic SIJ anesthetic block of 30 to 60 minutes, which resulted in > 75% pain reduction.21,25 Additional predictors of successful SIJ fusion include nonsmokers, nonopioid users, and older patients who have a longer time course of SIJ pain.26

Another study investigating the outcomes of SIJ fusion, RFA, and conservative management with a 6-year follow-up demonstrated similar results.27 This further confirms the durability of the surgical group’s outcome, which sustained significant improvement compared with RFA and conservative management group in pain relief, daily function, and opioid use.

HCPs should consider SIJ fusion for patients who have at least 6 months of unsuccessful nonoperative management, significant SIJ pain (> 5 in a 10-point scale), ≥ 3 positive provocation tests, and at least 50% pain relief (> 75% preferred) with diagnostic intra-articular anesthetic injection.14 It is reasonable for primary care providers to refer these patients to a neurosurgeon or orthopedic spine surgeon for possible fusion. Patients with earlier lumbar/lumbosacral spinal fusions and persistent LBP should be evaluated for potential SIJ dysfunction. SIJ dysfunction after lumbosacral fusion could be considered a form of distal pseudarthrosis resulting from increased motion at the joint. One study found its incidence correlated with the number of segments fused in the lumbar spine.28 Another study found that about one-third of patients with persistent LBP after lumbosacral fusion could be attributed to SIJ dysfunction.29

Case Presentation

A 27-year-old female army veteran presented with bilateral buttock pain, which she described as a dull, aching pain across her sacral region, 8 out of 10 in severity. The pain was in a L5-S1 pattern. The pain was bilateral, with the right side worse than the left, and worsened with lateral bending and load transferring. She reported no numbness, tingling, or weakness.

On physical examination, she had full strength in her lower extremities and intact sensation. She reported tenderness to palpation of the sacrum and SIJ. Her gait was normal. The patient had positive thigh thrust and distraction tests. Lumbar spine X-ray, CT, MRI, and electromyographic studies did not show any pathology. She described little or no relief with analgesics or physical therapy. Previous L4-L5 and L5-S1 facet anesthetic injections and transforaminal epidural steroid injections provided minimal pain relief immediately after the procedures. Bilateral SIJ anesthetic injections under fluoroscopic guidance decreased her pain severity from a 7 to 3 out of 10 for 2 to 3 months before returning to her baseline. Radiofrequency ablation of the right SIJ under fluoroscopy provided moderate relief for about 4 months.

After exhausting nonoperative management for SIJ dysfunction without adequate pain control, the patient was referred to neurosurgery for surgical fusion. The patient was deemed an appropriate surgical candidate and underwent a right-sided SIJ fusion (Figures 4 and 5). At her 6-month and 1-year follow-up appointments, she had lasting pain relief, 2 out of 10.

Conclusion

SIJ dysfunction is widely overlooked because of the difficulty in distinguishing it from other similarly presenting syndromes. However, with a detailed history, appropriate physical maneuvers, imaging, and adequate response to intra-articular anesthetic, providers can reach an accurate diagnosis that will inform subsequent treatments. After failure of nonsurgical methods, patients with SIJ dysfunction should be considered for minimally invasive fusion techniques, which have proven to be a safe, effective, and viable treatment option.

1. Zaidi HA, Montoure AJ, Dickman CA. Surgical and clinical efficacy of sacroiliac joint fusion: a systematic review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2015;23(1):59-66.

2. Cohen SP. Sacroiliac joint pain: a comprehensive review of anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Anesth Analg. 2005;101(5):1440-1453.

3. Chou LH, Slipman CW, Bhagia SM, et al. Inciting events initiating injection‐proven sacroiliac joint syndrome. Pain Med. 2004;5(1):26-32.

4. Dreyfuss P, Dreyer SJ, Cole A, Mayo K. Sacroiliac joint pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12(4):255-265.

5. Buijs E, Visser L, Groen G. Sciatica and the sacroiliac joint: a forgotten concept. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99(5):713-716.

6. Fortin JD, Dwyer AP, West S, Pier J. Sacroiliac joint: pain referral maps upon applying a new injection/arthrography technique. Part I: asymptomatic volunteers. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19(13):1475-1482.

7. Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Bogduk N. The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(1):31-37.

8. Fortin JD, Washington WJ, Falco FJ. Three pathways between the sacroiliac joint and neural structures. ANJR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20(8):1429-1434.

9. Szadek KM, van der Wurff P, van Tulder MW, Zuurmond WW, Perez RS. Diagnostic validity of criteria for sacroiliac joint pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2009;10(4):354-368.

10. Merskey H, Bogduk N, eds. Classification of Chronic Pain: Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. 2nd ed. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 1994.

11. Cusi MF. Paradigm for assessment and treatment of SIJ mechanical dysfunction. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2010;14(2):152-161.

12. Laslett M, Aprill CN, McDonald B, Young SB. Diagnosis of sacroiliac joint pain: validity of individual provocation tests and composites of tests. Man Ther. 2005;10(3):207-218.

13. Laslett M. Evidence-based diagnosis and treatment of the painful sacroiliac joint. J Man Manip Ther. 2008;16(3):142-152.

14. Polly DW Jr. The sacroiliac joint. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2017;28(3):301-312.

15. Cusi M, Van Der Wall H, Saunders J, Fogelman I. Metabolic disturbances identified by SPECT-CT in patients with a clinical diagnosis of sacroiliac joint incompetence. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(7):1674-1682.

16. Tofuku K, Koga H, Komiya S. The diagnostic value of single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography for severe sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(4):859-863.

17. Kennedy DJ, Engel A, Kreiner DS, Nampiaparampil D, Duszynski B, MacVicar J. Fluoroscopically guided diagnostic and therapeutic intra‐articular sacroiliac joint injections: a systematic review. Pain Med. 2015;16(8):1500-1518.

18. Schneider BJ, Huynh L, Levin J, Rinkaekan P, Kordi R, Kennedy DJ. Does immediate pain relief after an injection into the sacroiliac joint with anesthetic and corticosteroid predict subsequent pain relief? Pain Med. 2018;19(2):244-251.

19. Murakami E, Tanaka Y, Aizawa T, Ishizuka M, Kokubun S. Effect of periarticular and intraarticular lidocaine injections for sacroiliac joint pain: prospective comparative study. J Orthop Sci. 2007;12(3):274-280.

20. Cohen SP, Hurley RW, Buckenmaier CC 3rd, Kurihara C, Morlando B, Dragovich A. Randomized placebo-controlled study evaluating lateral branch radiofrequency denervation for sacroiliac joint pain. Anesthesiology. 2008;109(2):279-288.

21. Polly DW, Cher DJ, Wine KD, et al; INSITE Study Group. Randomized controlled trial of minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion using triangular titanium implants vs nonsurgical management for sacroiliac joint dysfunction: 12-month outcomes. Neurosurgery. 2015;77(5):674-690.

22. Soriano-Baron H, Lindsey DP, Rodriguez-Martinez N, et al. The effect of implant placement on sacroiliac joint range of motion: posterior versus transarticular. Spine. 2015;40(9):E525-E530.

23. Smith AG, Capobianco R, Cher D, et al. Open versus minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion: a multi-center comparison of perioperative measures and clinical outcomes. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2013;7(1):14.

24. Rashbaum RF, Ohnmeiss DD, Lindley EM, Kitchel SH, Patel VV. Sacroiliac joint pain and its treatment. Clin Spine Surg. 2016;29(2):42-48.

25. Polly DW, Swofford J, Whang PG, et al. Two-year outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion vs. non-surgical management for sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Int J Spine Surg. 2016;10:28.

26. Dengler J, Duhon B, Whang P, et al. Predictors of outcome in conservative and minimally invasive surgical management of pain originating from the sacroiliac joint: a pooled analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017;42(21):1664-1673.

27. Vanaclocha V, Herrera JM, Sáiz-Sapena N, Rivera-Paz M, Verdú-López F. Minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion, radiofrequency denervation, and conservative management for sacroiliac joint pain: 6-year comparative case series. Neurosurgery. 2018;82(1):48-55.

28. Unoki E, Abe E, Murai H, Kobayashi T, Abe T. Fusion of multiple segments can increase the incidence of sacroiliac joint pain after lumbar or lumbosacral fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2016;41(12):999-1005.

29. Katz V, Schofferman J, Reynolds J. The sacroiliac joint: a potential cause of pain after lumbar fusion to the sacrum. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16(1):96-99.

Patients experiencing sacroiliac joint (SIJ) dysfunction might show symptoms that overlap with those seen in lumbar spine pathology. This article reviews diagnostic tools that assist practitioners to discern the true pain generator in patients with low back pain (LBP) and therapeutic approaches when the cause is SIJ dysfunction.

Prevalence

Most of the US population will experience LBP at some point in their lives. A 2002 National Health Interview survey found that more than one-quarter (26.4%) of 31 044 respondents had complained of LBP in the previous 3 months.1 About 74 million individuals in the US experienced LBP in the past 3 months.1 A full 10% of the US population is expected to suffer from chronic LBP, and it is estimated that 2.3% of all visits to physicians are related to LBP.1

The etiology of LBP often is unclear even after thorough clinical and radiographic evaluation because of the myriad possible mechanisms. Degenerative disc disease, facet arthropathy, ligamentous hypertrophy, muscle spasm, hip arthropathy, and SIJ dysfunction are potential pain generators and exact clinical and radiographic correlation is not always possible. Compounding this difficulty is the lack of specificity with current diagnostic techniques. For example, many patients will have disc desiccation or herniation without any LBP or radicular symptoms on radiographic studies, such as X-rays, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). As such, providers of patients with diffuse radiographic abnormalities often have to identify a specific pain generator, which might not have any role in the patient’s pain.

Other tests, such as electromyographic studies, positron emission tomography (PET) scans, discography, and epidural steroid injections, can help pinpoint a specific pain generator. These tests might help determine whether the patient has a surgically treatable condition and could help predict whether a patient’s symptoms will respond to surgery.

However, the standard spine surgery workup often fails to identify an obvious pain generator in many individuals. The significant number of patients that fall into this category has prompted spine surgeons to consider other potential etiologies for LBP, and SIJ dysfunction has become a rapidly developing field of research.

Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction

The SIJ is a bilateral, C-shaped synovial joint surrounded by a fibrous capsule and affixes the sacrum to the ilia. Several sacral ligaments and pelvic muscles support the SIJ. The L5 nerve ventral ramus and lumbosacral trunk pass anteriorly and the S1 nerve ventral ramus passes inferiorly to the joint capsule. The SIJ is innervated by the dorsal rami of L4-S3 nerve roots, transmitting nociception and temperature. Mechanisms of injury to the SIJ could arise from intra- and extra-articular etiologies, including capsular disruption, ligamentous tension, muscular inflammation, shearing, fractures, arthritis, and infection.2 Patients could develop SIJ pain spontaneously or after a traumatic event or repetitive shear.3 Risk factors for developing SIJ dysfunction include a history of lumbar fusion, scoliosis, leg length discrepancies, sustained athletic activity, pregnancy, seronegative HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathies, or gait abnormalities. Inflammation of the SIJ and surrounding structures secondary to an environmental insult in susceptible individuals is a common theme among these etiologies.2

Pain from the SIJ is localized to an area of approximately 3 cm × 10 cm that is inferior to the ipsilateral posterior superior iliac spine.4 Referred pain maps from SIJ dysfunction extend in the L5-S1 nerve distributions, commonly seen in the buttocks, groin, posterior thigh, and lower leg with radicular symptoms. However, this pain distribution demonstrates extensive variability among patients and bears strong similarities to discogenic or facet joint sources of LBP.5-7 Direct communication has been shown between the SIJ and adjacent neural structures, namely the L5 nerve, sacral foramina, and the lumbosacral plexus. These direct pathways could explain an inflammatory mechanism for lower extremity symptoms seen in SIJ dysfunction.8

The prevalence of SIJ dysfunction among patients with LBP is estimated to be 15% to 30%, an extraordinary number given the total number of patients presenting with LBP every year.9 These patients might represent a significant segment of patients with an unrevealing standard spine evaluation. Despite the large number of patients who experience SIJ dysfunction, there is disagreement about optimal methods for diagnosis and treatment.

Diagnosis

The International Association for the Study of Pain has proposed criteria for evaluating patients who have suspected SIJ dysfunction: Pain must be in the SIJ area, should be reproducible by performing specific provocative maneuvers, and must be relieved by injection of local anesthetic into the SIJ.10 These criteria provide a sound foundation, but in clinical practice, patients often defy categorization.

The presence of pain in the area inferior to the posterior superior iliac spine and lateral to the gluteal fold with pain referral patterns in the L5-S1 nerve distributions is highly sensitive for identifying patients with SIJ dysfunction. Furthermore, pain arising from the SIJ will not be above the level of the L5 nerve sensory distribution. However, this diagnostic finding alone is not specific and might represent other etiologies known to produce similar pain, such as intervertebral discs and facet joints. Patients with SIJ dysfunction often describe their pain as sciatica-like, recurrent, and triggered with bending or twisting motions. It is worsened with any activity loading the SIJ, such as walking, climbing stairs, standing, or sitting upright. SIJ pain might be accompanied by dyspareunia and changes in bladder function because of the nerves involved.11

The use of provocative maneuvers for testing SIJ dysfunction is controversial because of the high rate of false positives and the inability to distinguish whether the SIJ or an adjacent structure is affected. However, the diagnostic utility of specific stress tests has been studied, and clusters of tests are recommended if a health care provider (HCP) suspects SIJ dysfunction. A diagnostic algorithm should first focus on using the distraction test and the thigh thrust test. Distraction is done by applying vertically oriented pressure to the anterior superior iliac spine while aiming posteriorly, therefore distracting the SIJ. During the thigh thrust test the examiner fixates the patient’s sacrum against the table with the left hand and applies a vertical force through the line of the femur aiming posteriorly, producing a posterior shearing force at the SIJ. Studies show that the thigh thrust test is the most sensitive, and the distraction test is the most specific. If both tests are positive, there is reasonable evidence to suggest SIJ dysfunction as the source of LBP.