User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Powered by CHEST Physician, Clinician Reviews, MDedge Family Medicine, Internal Medicine News, and The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management.

Antibiotic prescribing patterns for pediatric CAP vary widely

SAN DIEGO – Antibiotic prescribing patterns for pediatric community-acquired pneumonia vary substantially across both children’s hospitals and facilities that are not children’s hospitals, a large analysis found.

Specifically, children’s hospitals are far more likely to prescribe in accordance with national guidelines than are other hospitals.

“Moving forward, I think there’s a need for further study to understand these differences, so we can begin to narrow this gap between children’s and non–children’s hospitals,” lead study author Dr. Alison Tribble said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. “Across the board, we need to continue efforts to improve guideline adherence for all children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia.”

In 2012, community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) accounted for 120,000 known pneumonia admissions among children in the United States and about 7% of all pediatric hospitalizations, said Dr. Tribble, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital and the University of Michigan Medical Center, both in Ann Arbor. “We also know that pneumonia accounts for more days of antibiotic therapy than any other indication for admission to U.S. children’s hospitals,” she said.

In 2011, the Infectious Diseases Society of America and Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society released guidelines for pediatric CAP, which recommend a first-line therapy with penicillin, ampicillin, or amoxicillin for most children who are immunized and healthy. “Only in situations where there’s a significant concern for an atypical organism should we be adding coverage for that – even in older children,” Dr. Tribble said. Following the release of the guidelines, she continued, multiple studies have shown that the use of first-line therapy is increasing in children’s hospitals. “However, a substantial proportion of children with pneumonia are admitted to non–children’s hospitals,” she said. “Prior to release of the guidelines, one study showed that use of first-line therapy for pediatric CAP was low in non–children’s hospitals (J Pediatr. 2014 165[3]:585-91), but postguideline CAP therapy in non–children’s hospitals has not yet been evaluated.”

For the current study, Dr. Tribble and her associates set out to evaluate antibiotic prescribing patterns for pediatric CAP in non–children’s hospitals and to compare prescribing patterns between children’s and non–children’s hospitals. They conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study of children aged 1-17 years admitted for CAP in 2013 to 323 hospitals, captured via the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) and Premier Perspective databases. PHIS is an administrative database that includes billing data, diagnosis codes, and procedure codes for about 44 freestanding children’s hospitals nationwide, while Premier Perspective encompasses data from 522 hospitals nationwide. The researchers used a validated ICD-9 code-based algorithm to identify patients with CAP and excluded those with complicated pneumonia or complex chronic conditions, those who received intensive care, and those with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection or colonization.

Children’s hospitals were defined as those with pediatric admissions accounting for more than 75% of all admissions. “This was after excluding newborns and admission for childbirth, because many community hospitals will have a birthing center or a NICU, but otherwise would not be considered a children’s hospital,” Dr. Tribble explained. Any other hospital was considered a non–children’s hospital.

Three different outcomes for antibiotic use were examined: those who ever received penicillin, amoxicillin, or ampicillin (guideline therapy); those who ever received a macrolide, fluoroquinolone, or tetracycline (atypical therapy); and those who received anything other than penicillin, amoxicillin, or ampicillin (nonguideline therapy). The standardized probability of exposure to select antibiotics was compared between children’s and non–children’s hospitals, adjusted for age, sex, and insurance provider.

In all, 323 hospitals contributed 15,495 CAP cases. Of the 323 hospitals, 49 were identified as children’s hospitals (44 from the PHIS database and 5 from the Premier database). Dr. Tribble reported results from 9,224 subjects admitted to children’s hospitals and 6,271 subjects admitted to non–children’s hospitals. The demographics between the two groups were similar: The patients’ mean age was 3 years, and 66% were younger than age 5 years.

After adjustment of data, patients admitted to children’s hospitals were found to be more likely to receive guideline therapy, compared with those admitted to non–children’s hospitals (46% vs. 15%, respectively), were less likely to received atypical therapy (36% vs. 51%), and were less likely to receive nonguideline therapy (78% vs. 94%; P less than .001 for all comparisons).

Dr. Tribble acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the potential for misclassification of children’s hospitals in the Premier database, “although most likely I think we would have failed to identify a children’s hospital, and this would have biased us toward the null and made our difference less significant,” she said. “We are developing an absolute volume classification so we can look at this in another way.” Another limitation is that the study design did not account for the potential of combination therapy, “and you can’t account for change in therapy during hospitalization. Lastly, we compared data across different databases and across different hospital types.”

IDWeek marks the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. The study was supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Antibiotic prescribing patterns for pediatric community-acquired pneumonia vary substantially across both children’s hospitals and facilities that are not children’s hospitals, a large analysis found.

Specifically, children’s hospitals are far more likely to prescribe in accordance with national guidelines than are other hospitals.

“Moving forward, I think there’s a need for further study to understand these differences, so we can begin to narrow this gap between children’s and non–children’s hospitals,” lead study author Dr. Alison Tribble said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. “Across the board, we need to continue efforts to improve guideline adherence for all children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia.”

In 2012, community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) accounted for 120,000 known pneumonia admissions among children in the United States and about 7% of all pediatric hospitalizations, said Dr. Tribble, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital and the University of Michigan Medical Center, both in Ann Arbor. “We also know that pneumonia accounts for more days of antibiotic therapy than any other indication for admission to U.S. children’s hospitals,” she said.

In 2011, the Infectious Diseases Society of America and Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society released guidelines for pediatric CAP, which recommend a first-line therapy with penicillin, ampicillin, or amoxicillin for most children who are immunized and healthy. “Only in situations where there’s a significant concern for an atypical organism should we be adding coverage for that – even in older children,” Dr. Tribble said. Following the release of the guidelines, she continued, multiple studies have shown that the use of first-line therapy is increasing in children’s hospitals. “However, a substantial proportion of children with pneumonia are admitted to non–children’s hospitals,” she said. “Prior to release of the guidelines, one study showed that use of first-line therapy for pediatric CAP was low in non–children’s hospitals (J Pediatr. 2014 165[3]:585-91), but postguideline CAP therapy in non–children’s hospitals has not yet been evaluated.”

For the current study, Dr. Tribble and her associates set out to evaluate antibiotic prescribing patterns for pediatric CAP in non–children’s hospitals and to compare prescribing patterns between children’s and non–children’s hospitals. They conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study of children aged 1-17 years admitted for CAP in 2013 to 323 hospitals, captured via the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) and Premier Perspective databases. PHIS is an administrative database that includes billing data, diagnosis codes, and procedure codes for about 44 freestanding children’s hospitals nationwide, while Premier Perspective encompasses data from 522 hospitals nationwide. The researchers used a validated ICD-9 code-based algorithm to identify patients with CAP and excluded those with complicated pneumonia or complex chronic conditions, those who received intensive care, and those with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection or colonization.

Children’s hospitals were defined as those with pediatric admissions accounting for more than 75% of all admissions. “This was after excluding newborns and admission for childbirth, because many community hospitals will have a birthing center or a NICU, but otherwise would not be considered a children’s hospital,” Dr. Tribble explained. Any other hospital was considered a non–children’s hospital.

Three different outcomes for antibiotic use were examined: those who ever received penicillin, amoxicillin, or ampicillin (guideline therapy); those who ever received a macrolide, fluoroquinolone, or tetracycline (atypical therapy); and those who received anything other than penicillin, amoxicillin, or ampicillin (nonguideline therapy). The standardized probability of exposure to select antibiotics was compared between children’s and non–children’s hospitals, adjusted for age, sex, and insurance provider.

In all, 323 hospitals contributed 15,495 CAP cases. Of the 323 hospitals, 49 were identified as children’s hospitals (44 from the PHIS database and 5 from the Premier database). Dr. Tribble reported results from 9,224 subjects admitted to children’s hospitals and 6,271 subjects admitted to non–children’s hospitals. The demographics between the two groups were similar: The patients’ mean age was 3 years, and 66% were younger than age 5 years.

After adjustment of data, patients admitted to children’s hospitals were found to be more likely to receive guideline therapy, compared with those admitted to non–children’s hospitals (46% vs. 15%, respectively), were less likely to received atypical therapy (36% vs. 51%), and were less likely to receive nonguideline therapy (78% vs. 94%; P less than .001 for all comparisons).

Dr. Tribble acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the potential for misclassification of children’s hospitals in the Premier database, “although most likely I think we would have failed to identify a children’s hospital, and this would have biased us toward the null and made our difference less significant,” she said. “We are developing an absolute volume classification so we can look at this in another way.” Another limitation is that the study design did not account for the potential of combination therapy, “and you can’t account for change in therapy during hospitalization. Lastly, we compared data across different databases and across different hospital types.”

IDWeek marks the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. The study was supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Antibiotic prescribing patterns for pediatric community-acquired pneumonia vary substantially across both children’s hospitals and facilities that are not children’s hospitals, a large analysis found.

Specifically, children’s hospitals are far more likely to prescribe in accordance with national guidelines than are other hospitals.

“Moving forward, I think there’s a need for further study to understand these differences, so we can begin to narrow this gap between children’s and non–children’s hospitals,” lead study author Dr. Alison Tribble said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. “Across the board, we need to continue efforts to improve guideline adherence for all children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia.”

In 2012, community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) accounted for 120,000 known pneumonia admissions among children in the United States and about 7% of all pediatric hospitalizations, said Dr. Tribble, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital and the University of Michigan Medical Center, both in Ann Arbor. “We also know that pneumonia accounts for more days of antibiotic therapy than any other indication for admission to U.S. children’s hospitals,” she said.

In 2011, the Infectious Diseases Society of America and Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society released guidelines for pediatric CAP, which recommend a first-line therapy with penicillin, ampicillin, or amoxicillin for most children who are immunized and healthy. “Only in situations where there’s a significant concern for an atypical organism should we be adding coverage for that – even in older children,” Dr. Tribble said. Following the release of the guidelines, she continued, multiple studies have shown that the use of first-line therapy is increasing in children’s hospitals. “However, a substantial proportion of children with pneumonia are admitted to non–children’s hospitals,” she said. “Prior to release of the guidelines, one study showed that use of first-line therapy for pediatric CAP was low in non–children’s hospitals (J Pediatr. 2014 165[3]:585-91), but postguideline CAP therapy in non–children’s hospitals has not yet been evaluated.”

For the current study, Dr. Tribble and her associates set out to evaluate antibiotic prescribing patterns for pediatric CAP in non–children’s hospitals and to compare prescribing patterns between children’s and non–children’s hospitals. They conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study of children aged 1-17 years admitted for CAP in 2013 to 323 hospitals, captured via the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) and Premier Perspective databases. PHIS is an administrative database that includes billing data, diagnosis codes, and procedure codes for about 44 freestanding children’s hospitals nationwide, while Premier Perspective encompasses data from 522 hospitals nationwide. The researchers used a validated ICD-9 code-based algorithm to identify patients with CAP and excluded those with complicated pneumonia or complex chronic conditions, those who received intensive care, and those with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection or colonization.

Children’s hospitals were defined as those with pediatric admissions accounting for more than 75% of all admissions. “This was after excluding newborns and admission for childbirth, because many community hospitals will have a birthing center or a NICU, but otherwise would not be considered a children’s hospital,” Dr. Tribble explained. Any other hospital was considered a non–children’s hospital.

Three different outcomes for antibiotic use were examined: those who ever received penicillin, amoxicillin, or ampicillin (guideline therapy); those who ever received a macrolide, fluoroquinolone, or tetracycline (atypical therapy); and those who received anything other than penicillin, amoxicillin, or ampicillin (nonguideline therapy). The standardized probability of exposure to select antibiotics was compared between children’s and non–children’s hospitals, adjusted for age, sex, and insurance provider.

In all, 323 hospitals contributed 15,495 CAP cases. Of the 323 hospitals, 49 were identified as children’s hospitals (44 from the PHIS database and 5 from the Premier database). Dr. Tribble reported results from 9,224 subjects admitted to children’s hospitals and 6,271 subjects admitted to non–children’s hospitals. The demographics between the two groups were similar: The patients’ mean age was 3 years, and 66% were younger than age 5 years.

After adjustment of data, patients admitted to children’s hospitals were found to be more likely to receive guideline therapy, compared with those admitted to non–children’s hospitals (46% vs. 15%, respectively), were less likely to received atypical therapy (36% vs. 51%), and were less likely to receive nonguideline therapy (78% vs. 94%; P less than .001 for all comparisons).

Dr. Tribble acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the potential for misclassification of children’s hospitals in the Premier database, “although most likely I think we would have failed to identify a children’s hospital, and this would have biased us toward the null and made our difference less significant,” she said. “We are developing an absolute volume classification so we can look at this in another way.” Another limitation is that the study design did not account for the potential of combination therapy, “and you can’t account for change in therapy during hospitalization. Lastly, we compared data across different databases and across different hospital types.”

IDWeek marks the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. The study was supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT IDWEEK 2015

Key clinical point: Significant disparities exist in antibiotic prescribing for pediatric community-acquired pneumonia between children’s and non–children’s hospitals.

Major finding: Patients with community-acquired pneumonia who were admitted to children’s hospitals were more likely to receive antibiotic therapy consistent with recent national guidelines, compared with those admitted to non–children’s hospitals (46% vs. 15%, respectively; P less than .001).

Data source: A retrospective cross-sectional study of children aged 1-17 years admitted for CAP in 2013 to 323 hospitals.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Early inhaled budesonide cuts bronchopulmonary dysplasia, but ups mortality

Inhaled budesonide delivered within 24 hours of birth decreases the incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely preterm neonates, but this benefit may be offset by a possible increase in mortality, according to a report published online Oct. 15 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Systemic glucocorticoids reduce the rate of bronchopulmonary dysplasia but appear to cause severe short- and long-term adverse effects including intestinal perforation and cerebral palsy. Administering the drugs by inhalation may avert these adverse systemic effects, but until now most studies of this mode of delivery have been small, haven’t initiated the treatment immediately after birth, and have produced inconclusive results. So researchers performed a large double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial in which inhaled budesonide or a matching placebo was administered within 24 hours of birth to 863 extremely preterm neonates.

The infants were treated at 40 medical centers in nine countries during a 3-year period, until they no longer needed supplemental oxygen and positive-pressure support or reached a postmenstrual age of 32 weeks, said Dr. Dirk Bassler of the department of neonatology, University Hospital Zurich, and his associates.

The primary outcome measure – a composite of death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks postmenstrual age – occurred in 40% of the budesonide group and 46% of the placebo group (relative risk, 0.86), indicating that the active drug produced a benefit of borderline significance, Dr. Bassler and his associates noted (N Engl J Med. 2015 Oct 14; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501917). However, when the two components of the composite outcome were examined separately, inhaled budesonide was significantly better than was placebo at reducing the rate of bronchopulmonary dysplasia but was associated with a nonsignificant excess in mortality. The lung disorder developed in 28% of neonates assigned to active treatment and in 38% of those assigned to placebo (RR, 0.74), while mortality was 17% for budesonide and 14% for placebo (RR, 1.24). Notably, the nonsignificant difference in mortality may have been due to chance, the investigators said.

Budesonide also significantly reduced the incidence of two important secondary outcomes: patent ductus arteriosus requiring surgical ligation (RR, 0.55) and the need for reintubation after completion of the study drug (RR, 0.58). The therapy did not offer any benefit over placebo in the frequency of all other secondary outcomes, including retinopathy of prematurity, brain injury, necrotizing enterocolitis, patent ductus arteriosus requiring medical treatment, infections, oral candidiasis requiring treatment, hypertension requiring treatment, hyperglycemia requiring treatment, length of hospital stay, increase in weight or head circumference, and age at the last use of respiratory pressure support.

The rates of adverse events did not differ significantly between the two study groups.

The overall efficacy of early inhaled budesonide, as well as its associated risks, cannot be ascertained from these short-term outcomes alone. “Follow-up of our study cohort, including assessment of neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18-22 months of corrected age, is currently under way,” Dr. Bassler and his associates wrote.

This study was supported by the European Union and Chiesi Farmaceutici. Chiesi supplied the study drugs free of charge and Trudell Medical International supplied free spacers for the inhalers. Dr. Bassler and three of his associates reported receiving grant support and personal fees from Chiesi Farmaceutici. The other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

The risk/benefit profile of inhaled budesonide to prevent bronchopulmonary dysplasia remains uncertain, given that the treatment effects on the composite outcome in this study moved in opposite directions.

Inhaled budesonide’s ability to reduce rates of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, severe patent ductus arteriosus, and reintubation are probably real. But according to the available data, it is still uncertain whether the differential in mortality in favor of placebo represents truth or artifact.

Barbara Schmidt, M.D., is in the division of neonatology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. She reported receiving nonfinancial support from Chiesi Farmaceutici outside of this work. Dr. Schmidt made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Bassler’s report (N Engl J Med. 2015 Oct 14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1509243).

The risk/benefit profile of inhaled budesonide to prevent bronchopulmonary dysplasia remains uncertain, given that the treatment effects on the composite outcome in this study moved in opposite directions.

Inhaled budesonide’s ability to reduce rates of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, severe patent ductus arteriosus, and reintubation are probably real. But according to the available data, it is still uncertain whether the differential in mortality in favor of placebo represents truth or artifact.

Barbara Schmidt, M.D., is in the division of neonatology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. She reported receiving nonfinancial support from Chiesi Farmaceutici outside of this work. Dr. Schmidt made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Bassler’s report (N Engl J Med. 2015 Oct 14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1509243).

The risk/benefit profile of inhaled budesonide to prevent bronchopulmonary dysplasia remains uncertain, given that the treatment effects on the composite outcome in this study moved in opposite directions.

Inhaled budesonide’s ability to reduce rates of bronchopulmonary dysplasia, severe patent ductus arteriosus, and reintubation are probably real. But according to the available data, it is still uncertain whether the differential in mortality in favor of placebo represents truth or artifact.

Barbara Schmidt, M.D., is in the division of neonatology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. She reported receiving nonfinancial support from Chiesi Farmaceutici outside of this work. Dr. Schmidt made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Bassler’s report (N Engl J Med. 2015 Oct 14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1509243).

Inhaled budesonide delivered within 24 hours of birth decreases the incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely preterm neonates, but this benefit may be offset by a possible increase in mortality, according to a report published online Oct. 15 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Systemic glucocorticoids reduce the rate of bronchopulmonary dysplasia but appear to cause severe short- and long-term adverse effects including intestinal perforation and cerebral palsy. Administering the drugs by inhalation may avert these adverse systemic effects, but until now most studies of this mode of delivery have been small, haven’t initiated the treatment immediately after birth, and have produced inconclusive results. So researchers performed a large double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial in which inhaled budesonide or a matching placebo was administered within 24 hours of birth to 863 extremely preterm neonates.

The infants were treated at 40 medical centers in nine countries during a 3-year period, until they no longer needed supplemental oxygen and positive-pressure support or reached a postmenstrual age of 32 weeks, said Dr. Dirk Bassler of the department of neonatology, University Hospital Zurich, and his associates.

The primary outcome measure – a composite of death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks postmenstrual age – occurred in 40% of the budesonide group and 46% of the placebo group (relative risk, 0.86), indicating that the active drug produced a benefit of borderline significance, Dr. Bassler and his associates noted (N Engl J Med. 2015 Oct 14; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501917). However, when the two components of the composite outcome were examined separately, inhaled budesonide was significantly better than was placebo at reducing the rate of bronchopulmonary dysplasia but was associated with a nonsignificant excess in mortality. The lung disorder developed in 28% of neonates assigned to active treatment and in 38% of those assigned to placebo (RR, 0.74), while mortality was 17% for budesonide and 14% for placebo (RR, 1.24). Notably, the nonsignificant difference in mortality may have been due to chance, the investigators said.

Budesonide also significantly reduced the incidence of two important secondary outcomes: patent ductus arteriosus requiring surgical ligation (RR, 0.55) and the need for reintubation after completion of the study drug (RR, 0.58). The therapy did not offer any benefit over placebo in the frequency of all other secondary outcomes, including retinopathy of prematurity, brain injury, necrotizing enterocolitis, patent ductus arteriosus requiring medical treatment, infections, oral candidiasis requiring treatment, hypertension requiring treatment, hyperglycemia requiring treatment, length of hospital stay, increase in weight or head circumference, and age at the last use of respiratory pressure support.

The rates of adverse events did not differ significantly between the two study groups.

The overall efficacy of early inhaled budesonide, as well as its associated risks, cannot be ascertained from these short-term outcomes alone. “Follow-up of our study cohort, including assessment of neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18-22 months of corrected age, is currently under way,” Dr. Bassler and his associates wrote.

This study was supported by the European Union and Chiesi Farmaceutici. Chiesi supplied the study drugs free of charge and Trudell Medical International supplied free spacers for the inhalers. Dr. Bassler and three of his associates reported receiving grant support and personal fees from Chiesi Farmaceutici. The other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Inhaled budesonide delivered within 24 hours of birth decreases the incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely preterm neonates, but this benefit may be offset by a possible increase in mortality, according to a report published online Oct. 15 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Systemic glucocorticoids reduce the rate of bronchopulmonary dysplasia but appear to cause severe short- and long-term adverse effects including intestinal perforation and cerebral palsy. Administering the drugs by inhalation may avert these adverse systemic effects, but until now most studies of this mode of delivery have been small, haven’t initiated the treatment immediately after birth, and have produced inconclusive results. So researchers performed a large double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial in which inhaled budesonide or a matching placebo was administered within 24 hours of birth to 863 extremely preterm neonates.

The infants were treated at 40 medical centers in nine countries during a 3-year period, until they no longer needed supplemental oxygen and positive-pressure support or reached a postmenstrual age of 32 weeks, said Dr. Dirk Bassler of the department of neonatology, University Hospital Zurich, and his associates.

The primary outcome measure – a composite of death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks postmenstrual age – occurred in 40% of the budesonide group and 46% of the placebo group (relative risk, 0.86), indicating that the active drug produced a benefit of borderline significance, Dr. Bassler and his associates noted (N Engl J Med. 2015 Oct 14; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501917). However, when the two components of the composite outcome were examined separately, inhaled budesonide was significantly better than was placebo at reducing the rate of bronchopulmonary dysplasia but was associated with a nonsignificant excess in mortality. The lung disorder developed in 28% of neonates assigned to active treatment and in 38% of those assigned to placebo (RR, 0.74), while mortality was 17% for budesonide and 14% for placebo (RR, 1.24). Notably, the nonsignificant difference in mortality may have been due to chance, the investigators said.

Budesonide also significantly reduced the incidence of two important secondary outcomes: patent ductus arteriosus requiring surgical ligation (RR, 0.55) and the need for reintubation after completion of the study drug (RR, 0.58). The therapy did not offer any benefit over placebo in the frequency of all other secondary outcomes, including retinopathy of prematurity, brain injury, necrotizing enterocolitis, patent ductus arteriosus requiring medical treatment, infections, oral candidiasis requiring treatment, hypertension requiring treatment, hyperglycemia requiring treatment, length of hospital stay, increase in weight or head circumference, and age at the last use of respiratory pressure support.

The rates of adverse events did not differ significantly between the two study groups.

The overall efficacy of early inhaled budesonide, as well as its associated risks, cannot be ascertained from these short-term outcomes alone. “Follow-up of our study cohort, including assessment of neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18-22 months of corrected age, is currently under way,” Dr. Bassler and his associates wrote.

This study was supported by the European Union and Chiesi Farmaceutici. Chiesi supplied the study drugs free of charge and Trudell Medical International supplied free spacers for the inhalers. Dr. Bassler and three of his associates reported receiving grant support and personal fees from Chiesi Farmaceutici. The other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Early inhaled budesonide decreases bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely preterm neonates, but may increase mortality.

Major finding: Bronchopulmonary dysplasia developed in 28% of neonates assigned to inhaled budesonide and in 38% of those assigned to placebo (RR, 0.74), while mortality was 17% with budesonide and 14% with placebo (RR, 1.24).

Data source: An international double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial involving 863 extremely preterm neonates treated at 40 medical centers and followed to a postmenstrual age of 36 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the European Union and Chiesi Farmaceutici. Chiesi supplied the study drugs free of charge and Trudell Medical International supplied free spacers for the inhalers. Dr. Bassler and three of his associates reported receiving grant support and personal fees from Chiesi Farmaceutici. The other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

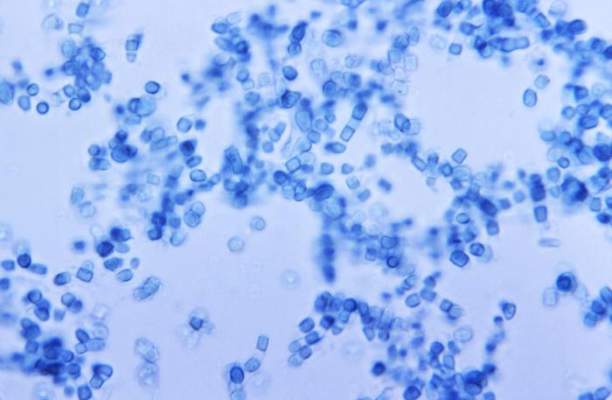

Coccidioidomycosis a respiratory threat to construction workers in Southwest

The expansion of the solar energy industry in Coccidioides-endemic areas of the southwestern United States is exposing more workers to the infection, say the authors of a study that found an attack rate of 1.2 cases per 100 workers.

A study among 3,572 workers at two solar power–generating facilities in California identified 44 individuals with the infection between October 2011 and April 2014, 9 of whom were hospitalized, according to a paper published in the Oct. 14 edition of Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The disease is acquired through inhalation of the soil-dwelling Coccidioides fungus spores and while the majority of the patients said they had received safety training about the risk of coccidioidomycosis, only six of those who regularly performed soil-disruptive work reported regularly using respiratory protection (Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Oct 14; doi: ).

“Large-scale construction, including solar farm construction, might involve substantial soil disturbance for months, and many employees, particularly from non–Coccidioides-endemic areas, probably lack immunity to Coccidioides,” wrote Jason A. Wilken, Ph.D., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and his coauthors.

“Medical providers should consider work-related coccidioidomycosis when evaluating construction workers with prolonged febrile respiratory illness, particularly after work in Central or Southern California or in Arizona, and medical providers should follow all statutory requirements for documenting and reporting occupational illness,” Dr. Wilken concluded.

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were declared.

The expansion of the solar energy industry in Coccidioides-endemic areas of the southwestern United States is exposing more workers to the infection, say the authors of a study that found an attack rate of 1.2 cases per 100 workers.

A study among 3,572 workers at two solar power–generating facilities in California identified 44 individuals with the infection between October 2011 and April 2014, 9 of whom were hospitalized, according to a paper published in the Oct. 14 edition of Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The disease is acquired through inhalation of the soil-dwelling Coccidioides fungus spores and while the majority of the patients said they had received safety training about the risk of coccidioidomycosis, only six of those who regularly performed soil-disruptive work reported regularly using respiratory protection (Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Oct 14; doi: ).

“Large-scale construction, including solar farm construction, might involve substantial soil disturbance for months, and many employees, particularly from non–Coccidioides-endemic areas, probably lack immunity to Coccidioides,” wrote Jason A. Wilken, Ph.D., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and his coauthors.

“Medical providers should consider work-related coccidioidomycosis when evaluating construction workers with prolonged febrile respiratory illness, particularly after work in Central or Southern California or in Arizona, and medical providers should follow all statutory requirements for documenting and reporting occupational illness,” Dr. Wilken concluded.

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were declared.

The expansion of the solar energy industry in Coccidioides-endemic areas of the southwestern United States is exposing more workers to the infection, say the authors of a study that found an attack rate of 1.2 cases per 100 workers.

A study among 3,572 workers at two solar power–generating facilities in California identified 44 individuals with the infection between October 2011 and April 2014, 9 of whom were hospitalized, according to a paper published in the Oct. 14 edition of Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The disease is acquired through inhalation of the soil-dwelling Coccidioides fungus spores and while the majority of the patients said they had received safety training about the risk of coccidioidomycosis, only six of those who regularly performed soil-disruptive work reported regularly using respiratory protection (Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Oct 14; doi: ).

“Large-scale construction, including solar farm construction, might involve substantial soil disturbance for months, and many employees, particularly from non–Coccidioides-endemic areas, probably lack immunity to Coccidioides,” wrote Jason A. Wilken, Ph.D., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and his coauthors.

“Medical providers should consider work-related coccidioidomycosis when evaluating construction workers with prolonged febrile respiratory illness, particularly after work in Central or Southern California or in Arizona, and medical providers should follow all statutory requirements for documenting and reporting occupational illness,” Dr. Wilken concluded.

The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM EMERGING INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point:Coccidioidomycosis is a significant risk in workers on solar power–generating facilities in Coccidioides-endemic areas of the Southwestern United States.

Major finding: The attack rate of Coccidioides could be as high 1.2 cases per 100 workers involved in constructing solar power–generating facilities.

Data source: A study among 3,572 workers at two solar power–generating facilities in California.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were declared.

VIDEO: Flu shot lowered hospitalization risk for influenza pneumonia

Getting a flu shot may be a highly effective method to prevent hospitalization for influenza-associated pneumonia.

That’s according to researchers who found that patients hospitalized with influenza-associated pneumonia were more likely to not have been vaccinated than patients whose pneumonia was due to other causes.

In video interviews, Dr. Kathryn M. Edwards and Dr. Carlos G. Grijalva of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, discussed their study of patients admitted through the emergency department for pneumonia and the benefits of flu vaccination in preventing hospitalization for influenza pneumonia.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Getting a flu shot may be a highly effective method to prevent hospitalization for influenza-associated pneumonia.

That’s according to researchers who found that patients hospitalized with influenza-associated pneumonia were more likely to not have been vaccinated than patients whose pneumonia was due to other causes.

In video interviews, Dr. Kathryn M. Edwards and Dr. Carlos G. Grijalva of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, discussed their study of patients admitted through the emergency department for pneumonia and the benefits of flu vaccination in preventing hospitalization for influenza pneumonia.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Getting a flu shot may be a highly effective method to prevent hospitalization for influenza-associated pneumonia.

That’s according to researchers who found that patients hospitalized with influenza-associated pneumonia were more likely to not have been vaccinated than patients whose pneumonia was due to other causes.

In video interviews, Dr. Kathryn M. Edwards and Dr. Carlos G. Grijalva of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, discussed their study of patients admitted through the emergency department for pneumonia and the benefits of flu vaccination in preventing hospitalization for influenza pneumonia.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

FROM JAMA

EADV: Novel topical crisaborole shines in atopic dermatitis

COPENHAGEN – The nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor crisaborole aced all Food and Drug Administration–required efficacy and safety endpoints as a topical treatment for atopic dermatitis, according to results from a pair of pivotal phase III randomized trials.

“This is a fairly rapidly effective treatment,” explained Dr. Mark G. Lebwohl, who presented the findings at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. “It has a favorable safety profile and has been studied in patients as young as 2 years of age. It may represent a new, safe, and efficacious treatment for patients 2 years of age and older with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis.”

Atopic dermatitis (AD) experts have long complained of a major unmet need for new, safe, and effective topical agents for AD, a condition that affects an estimated 18%-20% of children and 2%-10% of adults. Current treatment options all have drawbacks.

Topical steroids, long a treatment mainstay, are viewed by many parents with phobic mistrust of safety. And both FDA-approved topical calcineurin inhibitors carry black box warnings of possible cancer risk.

The two pivotal phase III studies, identical in design, included a total of 1,522 patients aged 2 years through adulthood with mild to moderate AD. Roughly 60% of patients had moderate disease, as defined by an Investigator’s Static Global Assessment (ISGA) score of 3 on a 0-4 scale; the other 40% had mild AD. The mean involved body surface area was 18%.

Participants were randomized two to one to crisaborole ointment 2% b.i.d. or vehicle for 28 days. Physicians assessed patients at baseline on day 1 of the study and again on days 8, 15, 22, 29, and 36. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients on day 29 who had an ISGA of 0 or 1 – clear or almost clear – as well as at least a 2-point improvement from baseline on that scale.

In one of the trials, that endpoint was achieved in 32.8% of the crisaborole group, compared with 25.4% of controls.

“That 25% placebo response is actually fairly typical for atopic dermatitis studies,” according to Dr. Lebwohl, professor and chairman of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York.

In the other study, 31.4% of the crisaborole group and 18% of controls achieved the primary endpoint. In both studies, the difference was statistically significant in favor of topical crisaborole.

There were two prespecified secondary endpoints. One was time to treatment success, as defined by clear or almost clear. A “striking” significant difference between the study arms appeared as early as the first assessment, just 1 week into the trial, Dr. Lebwohl observed.

The other secondary endpoint was the FDA’s former efficacy standard, which required being clear or almost clear without the additional need for at least a 2-point ISGA improvement. That endpoint was achieved by 51.7% and 48.5% of crisaborole-treated patients in the two studies, compared with 40.6% and 29.7% of controls. Again, both differences were statistically significant.

No treatment-related serious adverse events occurred in either study. Mild application-site pain was slightly more common in the crisaborole-treated patients. But the rate of study discontinuations because of adverse events was identical between the crisaborole and control groups, at 1.2%. No differences in laboratory values, ECGs, or vital signs were noted between the two groups.

Dr. Lebwohl explained that boron is an essential element in crisaborole. The boron stimulates an increase in cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels, which in turn results in a steep reduction in production of inflammatory cytokines, including interleukins-4, -2, and -31, as well as tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

One audience member asked if it’s possible that crisaborole acts systemically rather than topically, given that patients averaged 18% body surface area involvement, and such a large area of damaged skin could conceivably allow the topical agent ready access to the circulation.

Dr. Lebwohl replied that systemic absorption of the drug was minor. “If you break down the results into patients with very low body surface areas – the lowest was 5% – those patients improved as well. So, I think it would be unlikely that this was a systemic effect.”

Anacor, which is developing the drug as a treatment for AD and other skin diseases, plans to file for marketing approval during the first half of 2016.

Anacor sponsored the two pivotal phase III randomized trials. Dr. Lebwohl declared having no financial conflicts of interest, because all funds went directly to the medical center in which he practices.

COPENHAGEN – The nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor crisaborole aced all Food and Drug Administration–required efficacy and safety endpoints as a topical treatment for atopic dermatitis, according to results from a pair of pivotal phase III randomized trials.

“This is a fairly rapidly effective treatment,” explained Dr. Mark G. Lebwohl, who presented the findings at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. “It has a favorable safety profile and has been studied in patients as young as 2 years of age. It may represent a new, safe, and efficacious treatment for patients 2 years of age and older with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis.”

Atopic dermatitis (AD) experts have long complained of a major unmet need for new, safe, and effective topical agents for AD, a condition that affects an estimated 18%-20% of children and 2%-10% of adults. Current treatment options all have drawbacks.

Topical steroids, long a treatment mainstay, are viewed by many parents with phobic mistrust of safety. And both FDA-approved topical calcineurin inhibitors carry black box warnings of possible cancer risk.

The two pivotal phase III studies, identical in design, included a total of 1,522 patients aged 2 years through adulthood with mild to moderate AD. Roughly 60% of patients had moderate disease, as defined by an Investigator’s Static Global Assessment (ISGA) score of 3 on a 0-4 scale; the other 40% had mild AD. The mean involved body surface area was 18%.

Participants were randomized two to one to crisaborole ointment 2% b.i.d. or vehicle for 28 days. Physicians assessed patients at baseline on day 1 of the study and again on days 8, 15, 22, 29, and 36. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients on day 29 who had an ISGA of 0 or 1 – clear or almost clear – as well as at least a 2-point improvement from baseline on that scale.

In one of the trials, that endpoint was achieved in 32.8% of the crisaborole group, compared with 25.4% of controls.

“That 25% placebo response is actually fairly typical for atopic dermatitis studies,” according to Dr. Lebwohl, professor and chairman of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York.

In the other study, 31.4% of the crisaborole group and 18% of controls achieved the primary endpoint. In both studies, the difference was statistically significant in favor of topical crisaborole.

There were two prespecified secondary endpoints. One was time to treatment success, as defined by clear or almost clear. A “striking” significant difference between the study arms appeared as early as the first assessment, just 1 week into the trial, Dr. Lebwohl observed.

The other secondary endpoint was the FDA’s former efficacy standard, which required being clear or almost clear without the additional need for at least a 2-point ISGA improvement. That endpoint was achieved by 51.7% and 48.5% of crisaborole-treated patients in the two studies, compared with 40.6% and 29.7% of controls. Again, both differences were statistically significant.

No treatment-related serious adverse events occurred in either study. Mild application-site pain was slightly more common in the crisaborole-treated patients. But the rate of study discontinuations because of adverse events was identical between the crisaborole and control groups, at 1.2%. No differences in laboratory values, ECGs, or vital signs were noted between the two groups.

Dr. Lebwohl explained that boron is an essential element in crisaborole. The boron stimulates an increase in cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels, which in turn results in a steep reduction in production of inflammatory cytokines, including interleukins-4, -2, and -31, as well as tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

One audience member asked if it’s possible that crisaborole acts systemically rather than topically, given that patients averaged 18% body surface area involvement, and such a large area of damaged skin could conceivably allow the topical agent ready access to the circulation.

Dr. Lebwohl replied that systemic absorption of the drug was minor. “If you break down the results into patients with very low body surface areas – the lowest was 5% – those patients improved as well. So, I think it would be unlikely that this was a systemic effect.”

Anacor, which is developing the drug as a treatment for AD and other skin diseases, plans to file for marketing approval during the first half of 2016.

Anacor sponsored the two pivotal phase III randomized trials. Dr. Lebwohl declared having no financial conflicts of interest, because all funds went directly to the medical center in which he practices.

COPENHAGEN – The nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor crisaborole aced all Food and Drug Administration–required efficacy and safety endpoints as a topical treatment for atopic dermatitis, according to results from a pair of pivotal phase III randomized trials.

“This is a fairly rapidly effective treatment,” explained Dr. Mark G. Lebwohl, who presented the findings at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. “It has a favorable safety profile and has been studied in patients as young as 2 years of age. It may represent a new, safe, and efficacious treatment for patients 2 years of age and older with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis.”

Atopic dermatitis (AD) experts have long complained of a major unmet need for new, safe, and effective topical agents for AD, a condition that affects an estimated 18%-20% of children and 2%-10% of adults. Current treatment options all have drawbacks.

Topical steroids, long a treatment mainstay, are viewed by many parents with phobic mistrust of safety. And both FDA-approved topical calcineurin inhibitors carry black box warnings of possible cancer risk.

The two pivotal phase III studies, identical in design, included a total of 1,522 patients aged 2 years through adulthood with mild to moderate AD. Roughly 60% of patients had moderate disease, as defined by an Investigator’s Static Global Assessment (ISGA) score of 3 on a 0-4 scale; the other 40% had mild AD. The mean involved body surface area was 18%.

Participants were randomized two to one to crisaborole ointment 2% b.i.d. or vehicle for 28 days. Physicians assessed patients at baseline on day 1 of the study and again on days 8, 15, 22, 29, and 36. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients on day 29 who had an ISGA of 0 or 1 – clear or almost clear – as well as at least a 2-point improvement from baseline on that scale.

In one of the trials, that endpoint was achieved in 32.8% of the crisaborole group, compared with 25.4% of controls.

“That 25% placebo response is actually fairly typical for atopic dermatitis studies,” according to Dr. Lebwohl, professor and chairman of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York.

In the other study, 31.4% of the crisaborole group and 18% of controls achieved the primary endpoint. In both studies, the difference was statistically significant in favor of topical crisaborole.

There were two prespecified secondary endpoints. One was time to treatment success, as defined by clear or almost clear. A “striking” significant difference between the study arms appeared as early as the first assessment, just 1 week into the trial, Dr. Lebwohl observed.

The other secondary endpoint was the FDA’s former efficacy standard, which required being clear or almost clear without the additional need for at least a 2-point ISGA improvement. That endpoint was achieved by 51.7% and 48.5% of crisaborole-treated patients in the two studies, compared with 40.6% and 29.7% of controls. Again, both differences were statistically significant.

No treatment-related serious adverse events occurred in either study. Mild application-site pain was slightly more common in the crisaborole-treated patients. But the rate of study discontinuations because of adverse events was identical between the crisaborole and control groups, at 1.2%. No differences in laboratory values, ECGs, or vital signs were noted between the two groups.

Dr. Lebwohl explained that boron is an essential element in crisaborole. The boron stimulates an increase in cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels, which in turn results in a steep reduction in production of inflammatory cytokines, including interleukins-4, -2, and -31, as well as tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

One audience member asked if it’s possible that crisaborole acts systemically rather than topically, given that patients averaged 18% body surface area involvement, and such a large area of damaged skin could conceivably allow the topical agent ready access to the circulation.

Dr. Lebwohl replied that systemic absorption of the drug was minor. “If you break down the results into patients with very low body surface areas – the lowest was 5% – those patients improved as well. So, I think it would be unlikely that this was a systemic effect.”

Anacor, which is developing the drug as a treatment for AD and other skin diseases, plans to file for marketing approval during the first half of 2016.

Anacor sponsored the two pivotal phase III randomized trials. Dr. Lebwohl declared having no financial conflicts of interest, because all funds went directly to the medical center in which he practices.

AT THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Crisaborole topical ointment 2% b.i.d. appeared to be a safe and effective treatment for mild to moderate atopic dermatitis in children and adults.

Major finding: The primary combined efficacy endpoint was met by 32.8% and 31.4% of crisaborole-treated patients in two randomized trials, compared with 25.4% and 18% of vehicle-treated patients.

Data source: The two identically designed pivotal phase III clinical trials included 759 patients and 763 patients aged 2 years through adulthood with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis.

Disclosures: Anacor sponsored the two pivotal phase III randomized trials. Dr. Lebwohl declared having no financial conflicts of interest, because all funds went directly to the medical center in which he practices.

Big declines seen in aspergillosis mortality

SAN DIEGO – In-hospital mortality in patients with aspergillosis plummeted nationally, according to data from 2001-2011, with the biggest improvement seen in immunocompromised patients traditionally considered at high mortality risk, Dr. Masako Mizusawa reported at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The decline in in-hospital mortality wasn’t linear. Rather, it followed a stepwise pattern, and those steps occurred in association with three major advances during the study years: Food and Drug Administration approval of voriconazole in 2002, the FDA’s 2003 approval of the galactomannan serologic assay allowing for speedier diagnosis of aspergillosis, and the 2008 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guidelines on the treatment of aspergillosis (Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Feb 1;46[3]:327-60).

“This was an observational study and we can’t actually say that these events are causative. But just looking at the time relationship, it certainly looks plausible,” Dr. Mizusawa said.

In addition, the median hospital length of stay decreased from 9 to 7 days in patients with this potentially life-threatening infection, noted Dr. Mizusawa of Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

She presented what she believes is the largest U.S. longitudinal study of hospital care for aspergillosis. The retrospective study used nationally representative data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Utilization and Cost Project–Nationwide Inpatient Sample.

Dr. Mizusawa and coinvestigators defined aspergillosis patients as being at high mortality risk if they had established risk factors indicative of immunocompromise, including hematologic malignancy, neutropenia, recent stem cell or solid organ transplantation, HIV, or rheumatologic disease. Patients at lower mortality risk included those with asthma, COPD, diabetes, malnutrition, pulmonary tuberculosis, or non-TB mycobacterial infection.

The proportion of patients who were high risk climbed over the years, from 41% among the 892 patients with aspergillosis-related hospitalization in the 2001 sample to 50% among 1,420 patients in 2011. Yet in-hospital mortality in high-risk patients fell from 26.4% in 2001 to 9.1% in 2011. Meanwhile, the mortality rate in lower-risk patients improved from 14.6% to 6.6%. The overall in-hospital mortality rate went from 18.8% to 7.7%.

Of note, the proportion of aspergillosis patients with renal failure jumped from 9.8% in 2001 to 21.5% in 2011, even though the treatments for aspergillosis are relatively non-nephrotoxic, with the exception of amphotericin B. The outlook for these patients has improved greatly: In-hospital mortality for aspergillosis patients in renal failure went from 40.2% in 2001 to 16.1% in 2011.

While in-hospital mortality and length of stay were decreasing during the study years, total hospital charges for patients with aspergillosis were going up: from a median of $29,998 in 2001 to $44,888 in 2001 dollars a decade later. This cost-of-care increase was confined to patients at lower baseline risk or with no risk factors. Somewhat surprisingly, the high-risk group didn’t have a significant increase in hospital charges over the 10-year period.

“Maybe we’re just doing a better job of treating them, so they may not necessarily have to use a lot of resources,” Dr. Mizusawa offered as explanation.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this unfunded study.

SAN DIEGO – In-hospital mortality in patients with aspergillosis plummeted nationally, according to data from 2001-2011, with the biggest improvement seen in immunocompromised patients traditionally considered at high mortality risk, Dr. Masako Mizusawa reported at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The decline in in-hospital mortality wasn’t linear. Rather, it followed a stepwise pattern, and those steps occurred in association with three major advances during the study years: Food and Drug Administration approval of voriconazole in 2002, the FDA’s 2003 approval of the galactomannan serologic assay allowing for speedier diagnosis of aspergillosis, and the 2008 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guidelines on the treatment of aspergillosis (Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Feb 1;46[3]:327-60).

“This was an observational study and we can’t actually say that these events are causative. But just looking at the time relationship, it certainly looks plausible,” Dr. Mizusawa said.

In addition, the median hospital length of stay decreased from 9 to 7 days in patients with this potentially life-threatening infection, noted Dr. Mizusawa of Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

She presented what she believes is the largest U.S. longitudinal study of hospital care for aspergillosis. The retrospective study used nationally representative data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Utilization and Cost Project–Nationwide Inpatient Sample.

Dr. Mizusawa and coinvestigators defined aspergillosis patients as being at high mortality risk if they had established risk factors indicative of immunocompromise, including hematologic malignancy, neutropenia, recent stem cell or solid organ transplantation, HIV, or rheumatologic disease. Patients at lower mortality risk included those with asthma, COPD, diabetes, malnutrition, pulmonary tuberculosis, or non-TB mycobacterial infection.

The proportion of patients who were high risk climbed over the years, from 41% among the 892 patients with aspergillosis-related hospitalization in the 2001 sample to 50% among 1,420 patients in 2011. Yet in-hospital mortality in high-risk patients fell from 26.4% in 2001 to 9.1% in 2011. Meanwhile, the mortality rate in lower-risk patients improved from 14.6% to 6.6%. The overall in-hospital mortality rate went from 18.8% to 7.7%.

Of note, the proportion of aspergillosis patients with renal failure jumped from 9.8% in 2001 to 21.5% in 2011, even though the treatments for aspergillosis are relatively non-nephrotoxic, with the exception of amphotericin B. The outlook for these patients has improved greatly: In-hospital mortality for aspergillosis patients in renal failure went from 40.2% in 2001 to 16.1% in 2011.

While in-hospital mortality and length of stay were decreasing during the study years, total hospital charges for patients with aspergillosis were going up: from a median of $29,998 in 2001 to $44,888 in 2001 dollars a decade later. This cost-of-care increase was confined to patients at lower baseline risk or with no risk factors. Somewhat surprisingly, the high-risk group didn’t have a significant increase in hospital charges over the 10-year period.

“Maybe we’re just doing a better job of treating them, so they may not necessarily have to use a lot of resources,” Dr. Mizusawa offered as explanation.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this unfunded study.

SAN DIEGO – In-hospital mortality in patients with aspergillosis plummeted nationally, according to data from 2001-2011, with the biggest improvement seen in immunocompromised patients traditionally considered at high mortality risk, Dr. Masako Mizusawa reported at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The decline in in-hospital mortality wasn’t linear. Rather, it followed a stepwise pattern, and those steps occurred in association with three major advances during the study years: Food and Drug Administration approval of voriconazole in 2002, the FDA’s 2003 approval of the galactomannan serologic assay allowing for speedier diagnosis of aspergillosis, and the 2008 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guidelines on the treatment of aspergillosis (Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Feb 1;46[3]:327-60).

“This was an observational study and we can’t actually say that these events are causative. But just looking at the time relationship, it certainly looks plausible,” Dr. Mizusawa said.

In addition, the median hospital length of stay decreased from 9 to 7 days in patients with this potentially life-threatening infection, noted Dr. Mizusawa of Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

She presented what she believes is the largest U.S. longitudinal study of hospital care for aspergillosis. The retrospective study used nationally representative data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Utilization and Cost Project–Nationwide Inpatient Sample.

Dr. Mizusawa and coinvestigators defined aspergillosis patients as being at high mortality risk if they had established risk factors indicative of immunocompromise, including hematologic malignancy, neutropenia, recent stem cell or solid organ transplantation, HIV, or rheumatologic disease. Patients at lower mortality risk included those with asthma, COPD, diabetes, malnutrition, pulmonary tuberculosis, or non-TB mycobacterial infection.

The proportion of patients who were high risk climbed over the years, from 41% among the 892 patients with aspergillosis-related hospitalization in the 2001 sample to 50% among 1,420 patients in 2011. Yet in-hospital mortality in high-risk patients fell from 26.4% in 2001 to 9.1% in 2011. Meanwhile, the mortality rate in lower-risk patients improved from 14.6% to 6.6%. The overall in-hospital mortality rate went from 18.8% to 7.7%.

Of note, the proportion of aspergillosis patients with renal failure jumped from 9.8% in 2001 to 21.5% in 2011, even though the treatments for aspergillosis are relatively non-nephrotoxic, with the exception of amphotericin B. The outlook for these patients has improved greatly: In-hospital mortality for aspergillosis patients in renal failure went from 40.2% in 2001 to 16.1% in 2011.

While in-hospital mortality and length of stay were decreasing during the study years, total hospital charges for patients with aspergillosis were going up: from a median of $29,998 in 2001 to $44,888 in 2001 dollars a decade later. This cost-of-care increase was confined to patients at lower baseline risk or with no risk factors. Somewhat surprisingly, the high-risk group didn’t have a significant increase in hospital charges over the 10-year period.

“Maybe we’re just doing a better job of treating them, so they may not necessarily have to use a lot of resources,” Dr. Mizusawa offered as explanation.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding this unfunded study.

AT ICAAC 2015

Key clinical point: In-hospital mortality has more than halved for patients with aspergillosis-related hospitalization during a recent 10-year period.

Major finding: In-hospital mortality among patients with an aspergillosis-related hospitalization fell nationally from 18.8% in 2001 to 7.7% in 2011, with the biggest drop occurring in those at high risk.

Data source: A retrospective study of nationally representative data from the Healthcare Utilization and Cost Project–Nationwide Inpatient Sample for 2001-2011.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this unfunded study.

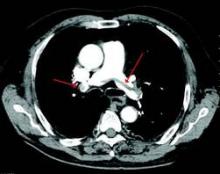

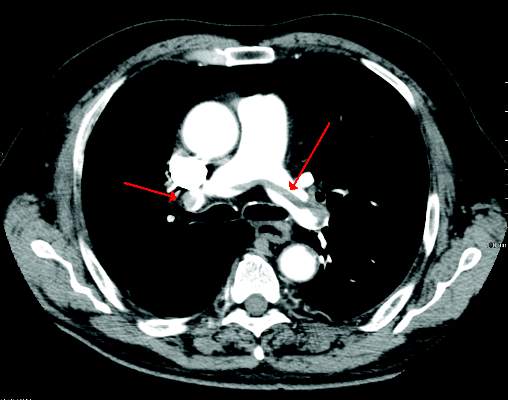

ESC model predicts recurrent VTE risk

Recurrent venous thromboembolism was significantly associated with a higher European Society of Cardiology (ESC) pulmonary embolism score. This association was independent of other factors such as age, sex, and body mass index, according to a long-term, prospective follow-up study of 627 patients with a first episode of pulmonary embolism.

In addition, unprovoked PE and varicose veins of the lower limbs also increased recurrence risk, while longer anticoagulation treatment reduced it (Intnl J Cardiol. 2016;202:275-81).

Dr. Shuai Zhang of the Beijing Institute of Respiratory Medicine and coauthors categorized their patients into three groups according to the ESC risk stratification model (Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2276-315). These were low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups. Of the 627 patients, 84 had suspected VTE recurrence, 68 of whom had this confirmed by imaging diagnosis and were designated as the recurrent group. The 1-, 2-, and 5-year cumulative incidences of recurrent VTE were 4.5%. 7.3%, and 13.9%, respectively.

The researchers compared the 68 recurrent to the 559 nonrecurrent patients; all patients had had a first episode of PE.

Compared with nonrecurrent VTE patients, the recurrent group had significantly more high-risk and intermediate-risk patients, and the high-risk and intermediate-risk patients overall had significantly more cumulative recurrent events than the low-risk group. Multivariate analysis confirmed the association between higher risk in ESC stratification and VTE recurrence independent of age, sex, and body mass index.

Based on these results, the authors stated that, “The severity of disease should be considered in determining the initial treatment and duration of follow-up anticoagulation.”

“These finding support the notion that optimized therapy based on risk stratification is valuable while treating PE patients,” they concluded.

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Read the full study online in the International Journal of Cardiology.

Recurrent venous thromboembolism was significantly associated with a higher European Society of Cardiology (ESC) pulmonary embolism score. This association was independent of other factors such as age, sex, and body mass index, according to a long-term, prospective follow-up study of 627 patients with a first episode of pulmonary embolism.

In addition, unprovoked PE and varicose veins of the lower limbs also increased recurrence risk, while longer anticoagulation treatment reduced it (Intnl J Cardiol. 2016;202:275-81).

Dr. Shuai Zhang of the Beijing Institute of Respiratory Medicine and coauthors categorized their patients into three groups according to the ESC risk stratification model (Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2276-315). These were low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups. Of the 627 patients, 84 had suspected VTE recurrence, 68 of whom had this confirmed by imaging diagnosis and were designated as the recurrent group. The 1-, 2-, and 5-year cumulative incidences of recurrent VTE were 4.5%. 7.3%, and 13.9%, respectively.

The researchers compared the 68 recurrent to the 559 nonrecurrent patients; all patients had had a first episode of PE.

Compared with nonrecurrent VTE patients, the recurrent group had significantly more high-risk and intermediate-risk patients, and the high-risk and intermediate-risk patients overall had significantly more cumulative recurrent events than the low-risk group. Multivariate analysis confirmed the association between higher risk in ESC stratification and VTE recurrence independent of age, sex, and body mass index.

Based on these results, the authors stated that, “The severity of disease should be considered in determining the initial treatment and duration of follow-up anticoagulation.”

“These finding support the notion that optimized therapy based on risk stratification is valuable while treating PE patients,” they concluded.

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Read the full study online in the International Journal of Cardiology.

Recurrent venous thromboembolism was significantly associated with a higher European Society of Cardiology (ESC) pulmonary embolism score. This association was independent of other factors such as age, sex, and body mass index, according to a long-term, prospective follow-up study of 627 patients with a first episode of pulmonary embolism.

In addition, unprovoked PE and varicose veins of the lower limbs also increased recurrence risk, while longer anticoagulation treatment reduced it (Intnl J Cardiol. 2016;202:275-81).

Dr. Shuai Zhang of the Beijing Institute of Respiratory Medicine and coauthors categorized their patients into three groups according to the ESC risk stratification model (Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2276-315). These were low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups. Of the 627 patients, 84 had suspected VTE recurrence, 68 of whom had this confirmed by imaging diagnosis and were designated as the recurrent group. The 1-, 2-, and 5-year cumulative incidences of recurrent VTE were 4.5%. 7.3%, and 13.9%, respectively.

The researchers compared the 68 recurrent to the 559 nonrecurrent patients; all patients had had a first episode of PE.

Compared with nonrecurrent VTE patients, the recurrent group had significantly more high-risk and intermediate-risk patients, and the high-risk and intermediate-risk patients overall had significantly more cumulative recurrent events than the low-risk group. Multivariate analysis confirmed the association between higher risk in ESC stratification and VTE recurrence independent of age, sex, and body mass index.

Based on these results, the authors stated that, “The severity of disease should be considered in determining the initial treatment and duration of follow-up anticoagulation.”

“These finding support the notion that optimized therapy based on risk stratification is valuable while treating PE patients,” they concluded.

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Read the full study online in the International Journal of Cardiology.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CARDIOLOGY

VIDEO: Take steps now to keep gram-negative resistance at bay

CHICAGO – Gram-negative bacteria are the new frontier of antimicrobial resistance.

Resistant Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and other organisms are increasingly common in Asia, South America, and southern Europe, but haven’t quite established themselves yet in the United States.

In an interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, Dr. John Mazuski, a professor of surgery at Washington University in St. Louis, explained what’s known so far, and the steps to take now to keep the organisms in check.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

CHICAGO – Gram-negative bacteria are the new frontier of antimicrobial resistance.

Resistant Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and other organisms are increasingly common in Asia, South America, and southern Europe, but haven’t quite established themselves yet in the United States.

In an interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, Dr. John Mazuski, a professor of surgery at Washington University in St. Louis, explained what’s known so far, and the steps to take now to keep the organisms in check.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

CHICAGO – Gram-negative bacteria are the new frontier of antimicrobial resistance.

Resistant Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and other organisms are increasingly common in Asia, South America, and southern Europe, but haven’t quite established themselves yet in the United States.

In an interview at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, Dr. John Mazuski, a professor of surgery at Washington University in St. Louis, explained what’s known so far, and the steps to take now to keep the organisms in check.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Results mixed in hospital efforts to tackle antimicrobial resistance

SAN DIEGO – Canadian hospitals are making progress in reducing the rates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, but the rates of antimicrobial resistance in Canadian hospitals increased significantly for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, as well as vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

Those are among the key findings from a large national analysis known as CANWARD that were presented at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. “What it’s telling us is that some of the things that we’re doing on the antimicrobial resistance side are working,” lead study author George G. Zhanel, Pharm.D., professor of microbiology and infectious diseases at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, said in an interview. “But it also tells us that some of these pathogens like [vancomycin-resistant enterococci] and [extended-spectrum beta-lactamase]–producing E. coli continue to go up. So there is some good news and some bad news, but it tells us that it’s not all just doom and gloom. Some progress has been made, but there’s still a long way to go.”

Conducted annually, CANWARD is a national health surveillance study that assesses pathogens causing infections in Canadian hospitals and their patterns of antimicrobial resistance. For the current analysis, Dr. Zhanel and his associates collected 36,607 isolates from patients in tertiary care hospitals in Canada from January 2007 to December 2014. They used Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute broth microdilution methods to perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing on more than 45 marketed and investigational agents.