User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Powered by CHEST Physician, Clinician Reviews, MDedge Family Medicine, Internal Medicine News, and The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management.

Hospital-acquired pneumonia threatens cervical spinal cord injury patients

SAN DIEGO – The overall rate of hospital-acquired pneumonia following cervical spinal cord injury is about 20%, results from a study of national data demonstrated.

“Cervical spinal cord injury patients are at an increased risk for the development of hospital-acquired pneumonia,” lead study author Dr. Pablo J. Diaz-Collado said in an interview after the annual meeting of the Cervical Spine Research Society.

“Complete cord injuries, longer length of stay, ICU stay and ventilation time lead to significantly increased risk of HAP, which then leads to poor inpatient outcomes,” he said. “It is of crucial importance to keep these risk factors in mind when treating patients with cervical spinal cord injuries. There is a need to optimize the management protocols for these patients to help prevent the development of HAPs.”

Dr. Diaz-Collado, an orthopedic surgery resident at Yale–New Haven (Conn.) Hospital, and his associates identified 5,198 cervical spinal cord injury patients in the 2011 and 2012 National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) to analyze risk factors for the development of HAP and inpatient outcomes in this population. They used multivariate logistic regression to identify independent associations of various risk factors with the occurrence of HAP.

The researchers found that the overall incidence of HAP among cervical spinal cord injury patients was 20.5%, which amounted to 1,065 patients. Factors independently associated with HAP were complete spinal cord injuries (compared to central cord injuries; OR 1.44; P = .009); longer inpatient length of stay (OR 3.08 for a stay that lasted 7-13 days, OR 10.21 for 21-27 days, and OR 14.89 for 35 days or more; P = .001 or less for all associations); longer ICU stay (OR 2.86 for a stay that lasted 9-11 days, OR 3.05 for 12-14 days, and OR 2.94 for 15 days or more; P less than .001 for all associations), and longer time on mechanical ventilation (OR 2.68 for ventilation that lasted 3-6 days, OR 3.76 for 7-13 days, OR 3.98 for 14-20 days, and OR 3.99 for 21 days or more; P less than .001 for all associations).

After the researchers controlled for all other risk factors, including patient comorbidities, Injury Severity Score, and other inpatient complications, HAP was associated with increased odds of death (OR 1.60; P = .005), inpatient adverse events (OR 1.65; P less than .001), discharge to an extended-care facility (OR 1.93; P = .001), and longer length of stay (a mean of an additional 10.93 days; P less than .001).

Dr. Diaz-Collado acknowledged that the study is “limited by the quality of the data entry. In addition, the database does not include classifications of fractures, and thus stratification of the analysis in terms of the different kinds of fractures in the cervical spine is not possible. Finally, procedural codes are less accurate and thus including whether or not patients underwent a surgical intervention is less reliable.”

Dr. Diaz-Collado reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The overall rate of hospital-acquired pneumonia following cervical spinal cord injury is about 20%, results from a study of national data demonstrated.

“Cervical spinal cord injury patients are at an increased risk for the development of hospital-acquired pneumonia,” lead study author Dr. Pablo J. Diaz-Collado said in an interview after the annual meeting of the Cervical Spine Research Society.

“Complete cord injuries, longer length of stay, ICU stay and ventilation time lead to significantly increased risk of HAP, which then leads to poor inpatient outcomes,” he said. “It is of crucial importance to keep these risk factors in mind when treating patients with cervical spinal cord injuries. There is a need to optimize the management protocols for these patients to help prevent the development of HAPs.”

Dr. Diaz-Collado, an orthopedic surgery resident at Yale–New Haven (Conn.) Hospital, and his associates identified 5,198 cervical spinal cord injury patients in the 2011 and 2012 National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) to analyze risk factors for the development of HAP and inpatient outcomes in this population. They used multivariate logistic regression to identify independent associations of various risk factors with the occurrence of HAP.

The researchers found that the overall incidence of HAP among cervical spinal cord injury patients was 20.5%, which amounted to 1,065 patients. Factors independently associated with HAP were complete spinal cord injuries (compared to central cord injuries; OR 1.44; P = .009); longer inpatient length of stay (OR 3.08 for a stay that lasted 7-13 days, OR 10.21 for 21-27 days, and OR 14.89 for 35 days or more; P = .001 or less for all associations); longer ICU stay (OR 2.86 for a stay that lasted 9-11 days, OR 3.05 for 12-14 days, and OR 2.94 for 15 days or more; P less than .001 for all associations), and longer time on mechanical ventilation (OR 2.68 for ventilation that lasted 3-6 days, OR 3.76 for 7-13 days, OR 3.98 for 14-20 days, and OR 3.99 for 21 days or more; P less than .001 for all associations).

After the researchers controlled for all other risk factors, including patient comorbidities, Injury Severity Score, and other inpatient complications, HAP was associated with increased odds of death (OR 1.60; P = .005), inpatient adverse events (OR 1.65; P less than .001), discharge to an extended-care facility (OR 1.93; P = .001), and longer length of stay (a mean of an additional 10.93 days; P less than .001).

Dr. Diaz-Collado acknowledged that the study is “limited by the quality of the data entry. In addition, the database does not include classifications of fractures, and thus stratification of the analysis in terms of the different kinds of fractures in the cervical spine is not possible. Finally, procedural codes are less accurate and thus including whether or not patients underwent a surgical intervention is less reliable.”

Dr. Diaz-Collado reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The overall rate of hospital-acquired pneumonia following cervical spinal cord injury is about 20%, results from a study of national data demonstrated.

“Cervical spinal cord injury patients are at an increased risk for the development of hospital-acquired pneumonia,” lead study author Dr. Pablo J. Diaz-Collado said in an interview after the annual meeting of the Cervical Spine Research Society.

“Complete cord injuries, longer length of stay, ICU stay and ventilation time lead to significantly increased risk of HAP, which then leads to poor inpatient outcomes,” he said. “It is of crucial importance to keep these risk factors in mind when treating patients with cervical spinal cord injuries. There is a need to optimize the management protocols for these patients to help prevent the development of HAPs.”

Dr. Diaz-Collado, an orthopedic surgery resident at Yale–New Haven (Conn.) Hospital, and his associates identified 5,198 cervical spinal cord injury patients in the 2011 and 2012 National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) to analyze risk factors for the development of HAP and inpatient outcomes in this population. They used multivariate logistic regression to identify independent associations of various risk factors with the occurrence of HAP.

The researchers found that the overall incidence of HAP among cervical spinal cord injury patients was 20.5%, which amounted to 1,065 patients. Factors independently associated with HAP were complete spinal cord injuries (compared to central cord injuries; OR 1.44; P = .009); longer inpatient length of stay (OR 3.08 for a stay that lasted 7-13 days, OR 10.21 for 21-27 days, and OR 14.89 for 35 days or more; P = .001 or less for all associations); longer ICU stay (OR 2.86 for a stay that lasted 9-11 days, OR 3.05 for 12-14 days, and OR 2.94 for 15 days or more; P less than .001 for all associations), and longer time on mechanical ventilation (OR 2.68 for ventilation that lasted 3-6 days, OR 3.76 for 7-13 days, OR 3.98 for 14-20 days, and OR 3.99 for 21 days or more; P less than .001 for all associations).

After the researchers controlled for all other risk factors, including patient comorbidities, Injury Severity Score, and other inpatient complications, HAP was associated with increased odds of death (OR 1.60; P = .005), inpatient adverse events (OR 1.65; P less than .001), discharge to an extended-care facility (OR 1.93; P = .001), and longer length of stay (a mean of an additional 10.93 days; P less than .001).

Dr. Diaz-Collado acknowledged that the study is “limited by the quality of the data entry. In addition, the database does not include classifications of fractures, and thus stratification of the analysis in terms of the different kinds of fractures in the cervical spine is not possible. Finally, procedural codes are less accurate and thus including whether or not patients underwent a surgical intervention is less reliable.”

Dr. Diaz-Collado reported having no financial disclosures.

AT CSRS 2015

Key clinical point: About one in five cervical spinal cord injury patients develop hospital-acquired pneumonia.

Major finding: The overall incidence of HAP among cervical spinal cord injury patients was 20.5%.

Data source: A study of 5,198 cervical spinal cord injury patients in the 2011 and 2012 National Trauma Data Bank.

Disclosures: Dr. Diaz-Collado reported having no financial disclosures.

Novel treatments assessed in midst of Ebola crisis

Separate groups of researchers supported by nonprofit and government agencies have assessed two novel Ebola virus disease treatments in the midst of the recent outbreak in West Africa.

The first study was a “natural experiment” that occurred when one Liberian treatment center temporarily ran out of first-line antimalarial drugs. This allowed investigators to discover that a second-line regimen may actually be more effective in reducing mortality from Ebola infection. (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 7;374:23-32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504605).

The lack of effective therapies against the Ebola virus spurred the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to identify several potential candidate treatments among compounds that are already used to treat other diseases, including malaria. However, there is little or no evidence to date concerning the real-world efficacy of these agents that have shown in-vitro activity against Ebola, said Etienne Gignoux of Epicentre, an epidemiologic research group headquartered in Paris, and of Médecins sans Frontières in Paris and Geneva, and his associates.

At the treatment center in Foya, Liberia, infected patients were routinely prescribed prophylactic antibiotics and a 3-day course of the antimalarial combination therapy artemether-lumefantrine, along with supportive treatment such as intravenous fluids. A 2-week shortage of this first-line antimalarial occurred during a sudden surge in admissions, and patients were instead prescribed artesunate-amodiaquine. Mr. Gignoux and his associates assessed outcomes in 194 patients prescribed artemether-lumefantrine, 71 prescribed artesunate-amodiaquine, 63 prescribed no antimalarials, and 53 for whom prescription data were missing.

They found that mortality risk was 31% lower with artesunate-amodiaquine than with the first-line antimalarials (risk ratio, 0.69). This mortality benefit persisted across several subgroups of patients, as well as in an analysis that specifically adjusted for the effects of potential confounding factors.

The results suggest that artesunate-amodiaquine may be preferable for the treatment of Ebola infection, but more research is needed to confirm this and to establish the safest, most effective therapeutic dose in these patients, the investigators said.They noted that their study had several limitations. The patient records included only prescribing information, so it was impossible to assess whether patients completed the full course of treatment. And all the antimalarials were oral formulations, so severely ill patients may not have been able to swallow or to keep down all doses.

In addition, artesunate-amodiaquine is known to cause more gastrointestinal adverse effects than the other antimalarials, so it’s possible that patients in that group were less likely to complete the full course of treatment. And many patients were concomitantly given the antiemetic metoclopramide, but data on possible adverse effects of this drug or possible drug interactions were not recorded.

The Liberian study was largely supported by Médecins sans Frontières, and the researchers reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Efficacy of convalescent plasma

In the second study, researchers at an Ebola treatment center in Guinea examined whether transfusion of convalescent plasma – plasma derived from patients who recovered from Ebola infection, which presumably carries helpful antibodies to the virus – was safe and effective. Their 6-month nonrandomized study involved 84 patients given two consecutive transfusions of 200-250 mL ABO-compatible plasma plus routine supportive care and 418 historical control subjects who had been treated before the plasma transfusions became available (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 7;374:33-42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa15118212).

The primary outcome – the risk of death during the 3-16 days after diagnosis – was 31% in the intervention group and 38% in the control group, a nonsignificant difference. This indicates that convalescent plasma transfusions do not exert a marked survival effect, at least at this dosage, said Dr. Johan van Griensven of the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp (Belgium), and his associates.

There were no serious adverse effects from the transfusions, and the procedure was acceptable to donors, patients, and caregivers.

The main limitation of this study was that actual levels of neutralizing antibodies in the transfused plasma could not be assessed. Such assays require biosafety level-4 laboratories, which are not available in the affected countries. “It is possible that high-titer convalescent plasma or hyperimmune globulin might be more potent” than the plasma used in this study, or that more frequent administration and higher total volumes could be more effective, Dr. van Griensven and his associates said.

They added that they “cannot exclude the possibility that some patients will benefit more than others from treatment with convalescent plasma.” For example, children younger than 5 years are known to be at high risk of death from the Ebola virus and had the highest risk of death in this study’s control group. However, four of the five patients in this age group who received convalescent plasma survived. Similarly, pregnant women infected with Ebola virus also are at high risk of death, but six of the eight in this study who received convalescent plasma survived.

The Guinea study was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program, the Flemish Department of Economy, Science, and Innovation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research’s Unit on Emerging and Zoonotic Infections at the University of Liverpool, the Medical Research Council, and the Department for International Development. Dr. van Griensven and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Separate groups of researchers supported by nonprofit and government agencies have assessed two novel Ebola virus disease treatments in the midst of the recent outbreak in West Africa.

The first study was a “natural experiment” that occurred when one Liberian treatment center temporarily ran out of first-line antimalarial drugs. This allowed investigators to discover that a second-line regimen may actually be more effective in reducing mortality from Ebola infection. (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 7;374:23-32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504605).

The lack of effective therapies against the Ebola virus spurred the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to identify several potential candidate treatments among compounds that are already used to treat other diseases, including malaria. However, there is little or no evidence to date concerning the real-world efficacy of these agents that have shown in-vitro activity against Ebola, said Etienne Gignoux of Epicentre, an epidemiologic research group headquartered in Paris, and of Médecins sans Frontières in Paris and Geneva, and his associates.

At the treatment center in Foya, Liberia, infected patients were routinely prescribed prophylactic antibiotics and a 3-day course of the antimalarial combination therapy artemether-lumefantrine, along with supportive treatment such as intravenous fluids. A 2-week shortage of this first-line antimalarial occurred during a sudden surge in admissions, and patients were instead prescribed artesunate-amodiaquine. Mr. Gignoux and his associates assessed outcomes in 194 patients prescribed artemether-lumefantrine, 71 prescribed artesunate-amodiaquine, 63 prescribed no antimalarials, and 53 for whom prescription data were missing.

They found that mortality risk was 31% lower with artesunate-amodiaquine than with the first-line antimalarials (risk ratio, 0.69). This mortality benefit persisted across several subgroups of patients, as well as in an analysis that specifically adjusted for the effects of potential confounding factors.

The results suggest that artesunate-amodiaquine may be preferable for the treatment of Ebola infection, but more research is needed to confirm this and to establish the safest, most effective therapeutic dose in these patients, the investigators said.They noted that their study had several limitations. The patient records included only prescribing information, so it was impossible to assess whether patients completed the full course of treatment. And all the antimalarials were oral formulations, so severely ill patients may not have been able to swallow or to keep down all doses.

In addition, artesunate-amodiaquine is known to cause more gastrointestinal adverse effects than the other antimalarials, so it’s possible that patients in that group were less likely to complete the full course of treatment. And many patients were concomitantly given the antiemetic metoclopramide, but data on possible adverse effects of this drug or possible drug interactions were not recorded.

The Liberian study was largely supported by Médecins sans Frontières, and the researchers reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Efficacy of convalescent plasma

In the second study, researchers at an Ebola treatment center in Guinea examined whether transfusion of convalescent plasma – plasma derived from patients who recovered from Ebola infection, which presumably carries helpful antibodies to the virus – was safe and effective. Their 6-month nonrandomized study involved 84 patients given two consecutive transfusions of 200-250 mL ABO-compatible plasma plus routine supportive care and 418 historical control subjects who had been treated before the plasma transfusions became available (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 7;374:33-42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa15118212).

The primary outcome – the risk of death during the 3-16 days after diagnosis – was 31% in the intervention group and 38% in the control group, a nonsignificant difference. This indicates that convalescent plasma transfusions do not exert a marked survival effect, at least at this dosage, said Dr. Johan van Griensven of the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp (Belgium), and his associates.

There were no serious adverse effects from the transfusions, and the procedure was acceptable to donors, patients, and caregivers.

The main limitation of this study was that actual levels of neutralizing antibodies in the transfused plasma could not be assessed. Such assays require biosafety level-4 laboratories, which are not available in the affected countries. “It is possible that high-titer convalescent plasma or hyperimmune globulin might be more potent” than the plasma used in this study, or that more frequent administration and higher total volumes could be more effective, Dr. van Griensven and his associates said.

They added that they “cannot exclude the possibility that some patients will benefit more than others from treatment with convalescent plasma.” For example, children younger than 5 years are known to be at high risk of death from the Ebola virus and had the highest risk of death in this study’s control group. However, four of the five patients in this age group who received convalescent plasma survived. Similarly, pregnant women infected with Ebola virus also are at high risk of death, but six of the eight in this study who received convalescent plasma survived.

The Guinea study was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program, the Flemish Department of Economy, Science, and Innovation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research’s Unit on Emerging and Zoonotic Infections at the University of Liverpool, the Medical Research Council, and the Department for International Development. Dr. van Griensven and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Separate groups of researchers supported by nonprofit and government agencies have assessed two novel Ebola virus disease treatments in the midst of the recent outbreak in West Africa.

The first study was a “natural experiment” that occurred when one Liberian treatment center temporarily ran out of first-line antimalarial drugs. This allowed investigators to discover that a second-line regimen may actually be more effective in reducing mortality from Ebola infection. (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 7;374:23-32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504605).

The lack of effective therapies against the Ebola virus spurred the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to identify several potential candidate treatments among compounds that are already used to treat other diseases, including malaria. However, there is little or no evidence to date concerning the real-world efficacy of these agents that have shown in-vitro activity against Ebola, said Etienne Gignoux of Epicentre, an epidemiologic research group headquartered in Paris, and of Médecins sans Frontières in Paris and Geneva, and his associates.

At the treatment center in Foya, Liberia, infected patients were routinely prescribed prophylactic antibiotics and a 3-day course of the antimalarial combination therapy artemether-lumefantrine, along with supportive treatment such as intravenous fluids. A 2-week shortage of this first-line antimalarial occurred during a sudden surge in admissions, and patients were instead prescribed artesunate-amodiaquine. Mr. Gignoux and his associates assessed outcomes in 194 patients prescribed artemether-lumefantrine, 71 prescribed artesunate-amodiaquine, 63 prescribed no antimalarials, and 53 for whom prescription data were missing.

They found that mortality risk was 31% lower with artesunate-amodiaquine than with the first-line antimalarials (risk ratio, 0.69). This mortality benefit persisted across several subgroups of patients, as well as in an analysis that specifically adjusted for the effects of potential confounding factors.

The results suggest that artesunate-amodiaquine may be preferable for the treatment of Ebola infection, but more research is needed to confirm this and to establish the safest, most effective therapeutic dose in these patients, the investigators said.They noted that their study had several limitations. The patient records included only prescribing information, so it was impossible to assess whether patients completed the full course of treatment. And all the antimalarials were oral formulations, so severely ill patients may not have been able to swallow or to keep down all doses.

In addition, artesunate-amodiaquine is known to cause more gastrointestinal adverse effects than the other antimalarials, so it’s possible that patients in that group were less likely to complete the full course of treatment. And many patients were concomitantly given the antiemetic metoclopramide, but data on possible adverse effects of this drug or possible drug interactions were not recorded.

The Liberian study was largely supported by Médecins sans Frontières, and the researchers reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Efficacy of convalescent plasma

In the second study, researchers at an Ebola treatment center in Guinea examined whether transfusion of convalescent plasma – plasma derived from patients who recovered from Ebola infection, which presumably carries helpful antibodies to the virus – was safe and effective. Their 6-month nonrandomized study involved 84 patients given two consecutive transfusions of 200-250 mL ABO-compatible plasma plus routine supportive care and 418 historical control subjects who had been treated before the plasma transfusions became available (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jan 7;374:33-42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa15118212).

The primary outcome – the risk of death during the 3-16 days after diagnosis – was 31% in the intervention group and 38% in the control group, a nonsignificant difference. This indicates that convalescent plasma transfusions do not exert a marked survival effect, at least at this dosage, said Dr. Johan van Griensven of the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp (Belgium), and his associates.

There were no serious adverse effects from the transfusions, and the procedure was acceptable to donors, patients, and caregivers.

The main limitation of this study was that actual levels of neutralizing antibodies in the transfused plasma could not be assessed. Such assays require biosafety level-4 laboratories, which are not available in the affected countries. “It is possible that high-titer convalescent plasma or hyperimmune globulin might be more potent” than the plasma used in this study, or that more frequent administration and higher total volumes could be more effective, Dr. van Griensven and his associates said.

They added that they “cannot exclude the possibility that some patients will benefit more than others from treatment with convalescent plasma.” For example, children younger than 5 years are known to be at high risk of death from the Ebola virus and had the highest risk of death in this study’s control group. However, four of the five patients in this age group who received convalescent plasma survived. Similarly, pregnant women infected with Ebola virus also are at high risk of death, but six of the eight in this study who received convalescent plasma survived.

The Guinea study was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program, the Flemish Department of Economy, Science, and Innovation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research’s Unit on Emerging and Zoonotic Infections at the University of Liverpool, the Medical Research Council, and the Department for International Development. Dr. van Griensven and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Researchers were able to examine novel treatments in the midst of the recent Ebola crisis in West Africa.

Major finding: Mortality risk was 31% lower with artesunate-amodiaquine than with first-line antimalarials, suggesting that artesunate-amodiaquine may be preferable for the treatment of Ebola infection. Two consecutive transfusions of 200-250 mL ABO-compatible convalescent plasma do not exert a marked survival effect for Ebola virus disease patients.

Data source: A “natural experiment” comparing two different antimalarial regimens in 382 patients in Liberia, and a nonrandomized comparative study of plasma transfusions in 99 patients in Guinea.

Disclosures: The Liberian study was largely supported by Médecins sans Frontières; the Guinea study was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program, the Flemish Department of Economy, Science, and Innovation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research’s Unit on Emerging and Zoonotic Infections at the University of Liverpool, the Medical Research Council, and the Department for International Development. Mr. Gignoux, Dr. van Griensven, and their associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Statins might prevent vascular inflammation in sleep apnea

Statins reduced complement-related vascular inflammation in patients with obstructive sleep apnea, according to research published online Jan. 6 in Science Translational Medicine.

The “unexpected” finding suggests that statins might offer a targeted therapy for the significant vascular manifestations of OSA, wrote Dr. Memet Emin and Dr. Gang Wang of Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, together with their associates. “Statins also have antioxidant effects, which may be particularly beneficial in conditions associated with oxidative stress, such as OSA,” the investigators added.

Obstructive sleep apnea affects one in four Western adults and triples the risk of cardiovascular diseases. The disorder is uniquely characterized by intermittent hypoxia, which the researchers hypothesized might lead to a distinct pattern of endothelial cell (EC) activation. To test this theory, they used a phage display peptide library to analyze protein expression in vascular ECs from 76 patients with OSA and 52 OSA-free controls. They also modeled intermittent hypoxia by exposing cultured ECs to alternating periods of normal and low (2%) oxygen levels (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Jan 6. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad0634).

Patients with OSA who were receiving statins had EC surface levels of the CD59 complement inhibitor similar to those of controls, and significantly greater levels compared with patients with OSA who were not receiving statins (P = .05). The CD59 protein is a major complement regulator that inhibits the formation of the terminal membrane attack complex, and thereby protects cells from complement-mediated injury, the researchers noted. In addition, intermittent hypoxia induced the internalization of CD59 in cultured ECs, leading to MAC deposition and endothelial inflammation, they said.

Most notably, patients with OSA who were taking statins had normal EC surface levels of CD59, and cultured ECs that were treated with atorvastatin were better protected from complement activity in a cholesterol-dependent manner, the investigators reported. By reducing cholesterol biosynthesis, statins might decrease the formation of cholesterol-enriched plasma membrane and CD59 endocytosis, which would reduce its internalization and preserve its ability to protect cells against complement activity, they said.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health funded the study. The investigators had no disclosures.

Statins reduced complement-related vascular inflammation in patients with obstructive sleep apnea, according to research published online Jan. 6 in Science Translational Medicine.

The “unexpected” finding suggests that statins might offer a targeted therapy for the significant vascular manifestations of OSA, wrote Dr. Memet Emin and Dr. Gang Wang of Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, together with their associates. “Statins also have antioxidant effects, which may be particularly beneficial in conditions associated with oxidative stress, such as OSA,” the investigators added.

Obstructive sleep apnea affects one in four Western adults and triples the risk of cardiovascular diseases. The disorder is uniquely characterized by intermittent hypoxia, which the researchers hypothesized might lead to a distinct pattern of endothelial cell (EC) activation. To test this theory, they used a phage display peptide library to analyze protein expression in vascular ECs from 76 patients with OSA and 52 OSA-free controls. They also modeled intermittent hypoxia by exposing cultured ECs to alternating periods of normal and low (2%) oxygen levels (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Jan 6. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad0634).

Patients with OSA who were receiving statins had EC surface levels of the CD59 complement inhibitor similar to those of controls, and significantly greater levels compared with patients with OSA who were not receiving statins (P = .05). The CD59 protein is a major complement regulator that inhibits the formation of the terminal membrane attack complex, and thereby protects cells from complement-mediated injury, the researchers noted. In addition, intermittent hypoxia induced the internalization of CD59 in cultured ECs, leading to MAC deposition and endothelial inflammation, they said.

Most notably, patients with OSA who were taking statins had normal EC surface levels of CD59, and cultured ECs that were treated with atorvastatin were better protected from complement activity in a cholesterol-dependent manner, the investigators reported. By reducing cholesterol biosynthesis, statins might decrease the formation of cholesterol-enriched plasma membrane and CD59 endocytosis, which would reduce its internalization and preserve its ability to protect cells against complement activity, they said.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health funded the study. The investigators had no disclosures.

Statins reduced complement-related vascular inflammation in patients with obstructive sleep apnea, according to research published online Jan. 6 in Science Translational Medicine.

The “unexpected” finding suggests that statins might offer a targeted therapy for the significant vascular manifestations of OSA, wrote Dr. Memet Emin and Dr. Gang Wang of Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, together with their associates. “Statins also have antioxidant effects, which may be particularly beneficial in conditions associated with oxidative stress, such as OSA,” the investigators added.

Obstructive sleep apnea affects one in four Western adults and triples the risk of cardiovascular diseases. The disorder is uniquely characterized by intermittent hypoxia, which the researchers hypothesized might lead to a distinct pattern of endothelial cell (EC) activation. To test this theory, they used a phage display peptide library to analyze protein expression in vascular ECs from 76 patients with OSA and 52 OSA-free controls. They also modeled intermittent hypoxia by exposing cultured ECs to alternating periods of normal and low (2%) oxygen levels (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Jan 6. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad0634).

Patients with OSA who were receiving statins had EC surface levels of the CD59 complement inhibitor similar to those of controls, and significantly greater levels compared with patients with OSA who were not receiving statins (P = .05). The CD59 protein is a major complement regulator that inhibits the formation of the terminal membrane attack complex, and thereby protects cells from complement-mediated injury, the researchers noted. In addition, intermittent hypoxia induced the internalization of CD59 in cultured ECs, leading to MAC deposition and endothelial inflammation, they said.

Most notably, patients with OSA who were taking statins had normal EC surface levels of CD59, and cultured ECs that were treated with atorvastatin were better protected from complement activity in a cholesterol-dependent manner, the investigators reported. By reducing cholesterol biosynthesis, statins might decrease the formation of cholesterol-enriched plasma membrane and CD59 endocytosis, which would reduce its internalization and preserve its ability to protect cells against complement activity, they said.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health funded the study. The investigators had no disclosures.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Statin therapy might help prevent endothelial inflammation in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.

Major finding: Patients with OSA who were receiving statins had vascular endothelial cell surface levels of the CD59 complement inhibitor similar to those of controls, and greater cell surface levels compared with patients with OSA who were not receiving statins (P = .05).

Data source: A peptide library study of vascular endothelial cells from 76 patients with OSA and 52 OSA-free controls, plus an in vitro study of cultured endothelial cells.

Disclosures: The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health funded the study. The investigators had no disclosures.

Myth of the Month: Beta-blocker myths

A 59-year-old man is admitted to the ICU with a myocardial infarction. He is discharged after 5 days on enalapril, metoprolol, simvastatin, and aspirin. At a 3-month follow-up, he is noted to have marked anhedonia, complaints of insomnia, feelings of worthlessness, and psychomotor retardation.

What would you do?

A) Stop the enalapril.

B) Stop the metoprolol.

C) Stop the simvastatin.

D) Begin a tricyclic antidepressant.

E) Begin an SSRI.

When I was in medical school, the dogma was to never give beta-blockers to patients with systolic heart failure, because it would worsen the heart failure.1 As we all know, this dogma completely reversed, and beta-blocker therapy is a cornerstone of treatment of patients with systolic heart failure, with improvements in morbidity and mortality.2 Underutilization of beta-blockers for indicated conditions is likely due to fear of beta-blocker side effects.2

There has long been concern that beta-blockers can cause, or worsen, depression. As a result, beta-blockers are sometimes withheld from patients with a history of depression who may benefit, or beta-blockers are stopped in patients who develop depression.

Early reports of possible beta-blocker–induced depression surfaced soon after the beta-blocker propranolol became available in the 1960s. A frequently cited reference is a letter to the British Medical Journal in which H.J. Waal reported that 20 of 89 patients on propranolol volunteered or exhibited depressive symptoms.3 Almost half of those patients were diagnosed with grade I depression – symptoms of irritability, insomnia, nightmares, and fatigue. No control group of patients was evaluated to ascertain the prevalence of those symptoms in patients treated with other antihypertensives, or in nonhypertensive patients.

M. H. Pollack and colleagues reported on a series of three patients who developed symptoms of depression after starting propranolol, and the researchers concluded that depression following the administration of propranolol was a real phenomenon.4

Many subsequent studies have cast doubt on the association of beta-blockers and depression. Depression is common following myocardial infarction and in patients with coronary artery disease. Several studies have looked closely for association with beta-blocker use in this population.

Dr. Steven J. Schleifer and colleagues evaluated 190 patients who had sustained a myocardial infarction for evidence of depression. The patients were interviewed 8-10 days after the infarct and again at 3 months. No antianginal or antihypertensive medications, including beta-blockers, were associated with an increase in depression.5

Dr. Joost P. van Melle and colleagues participated in a multicenter study that looked at patients following myocardial infarction, assessing for depressive symptoms at baseline and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months using the Beck depression inventory.6 A total of 254 patients receiving beta-blockers were matched with 127 control patients post MI not receiving beta-blockers. No significant differences were found between non–beta-blocker users and beta-blocker users on the presence of depressive symptoms.

Robert Carney, Ph.D., and colleagues evaluated 75 patients undergoing elective cardiac catheterization with psychiatric interview and psychological assessments.7 Half of the patients in the study were receiving beta-blockers. Thirty-three percent of the patients who were not receiving beta-blockers met DSM-III criteria for depression, and 21% of the beta-blocker–treated patients met criteria for depression.

Dr. Linda Battes and colleagues reported that beta-blocker use actually decreased the risk of depression in patients who had undergone a percutaneous intervention, with a risk reduction of 49% for depression in beta-blocker–treated patients.8 In a study of elderly patients, Dr. Hendrika Luijendijk and colleagues followed 5,104 elderly persons for episodes of incident depression. They found that beta-blocker use did not increase the risk of developing depression.9

Beta-blockers often have been avoided in patients with obstructive pulmonary disease – both in patients with asthma and those with COPD – because of concern for worsening obstructive pulmonary disease. There is strong evidence now that beta-blocker use is not problematic in patients with COPD.

Dr. Surya Bhatt and colleagues found that beta-blocker use decreased COPD exacerbations.10 Almost 3,500 patients were included. During a median of 2.1 years of follow-up, beta-blocker use was associated with a significantly lower rate of total exacerbations (incidence risk ratio, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.90; P = .003) and severe exacerbations (IRR, 0.67, 95% CI, 0.48-0.93; P = .016).

Dr. Qingxia Du and colleagues found that beta-blocker use in patients with COPD both reduced exacerbations and reduced mortality.11 In another study, the use of beta-blockers in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbations of COPD reduced mortality.12 Most of the patients receiving beta-blockers in that study had severe cardiovascular disease.

There are far fewer data on beta-blocker use in patients with asthma. In general, beta-blockers are routinely avoided in patients with asthma. In one small study of asthmatic patients receiving propranolol, there was no effect on methacholine challenge response, histamine responsiveness, or asthma control questionnaire results.13 In a murine model of asthma, long-term administration of beta-blockers resulted in a decrease in airway hyperresponsiveness, suggesting an anti-inflammatory effect.14 This topic is an area of interest for further study in asthma control.

So much of what we thought we knew about beta-blockers has turned out to not be so. We keep our eyes open and welcome further enlightenment.

References

1. Circulation. 1983 Jun;67(6 Pt 2):I91.

2. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015 Dec;14(12):1855-63.

3. Br Med J. 1967 Apr 1;2(5543):50.

4. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985 Feb;173(2):118-9.

5. Am Heart J. 1991 May;121(5):1397-402.

6. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Dec 5;48(11):2209-14.

7. Am J Med. 1987 Aug;83(2):223-6.

8. J Affect Disord. 2012 Feb;136(3):751-7.

9. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011 Feb;31(1):45-50.

10. Thorax. 2016 Jan;71(1):8-14.

12. Thorax. 2008 Apr;63(4):301-5.

13. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013 Jun 15;187(12):1308-14.

14. Int J Gen Med. 2013 Jul 8;6:549-55.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

A 59-year-old man is admitted to the ICU with a myocardial infarction. He is discharged after 5 days on enalapril, metoprolol, simvastatin, and aspirin. At a 3-month follow-up, he is noted to have marked anhedonia, complaints of insomnia, feelings of worthlessness, and psychomotor retardation.

What would you do?

A) Stop the enalapril.

B) Stop the metoprolol.

C) Stop the simvastatin.

D) Begin a tricyclic antidepressant.

E) Begin an SSRI.

When I was in medical school, the dogma was to never give beta-blockers to patients with systolic heart failure, because it would worsen the heart failure.1 As we all know, this dogma completely reversed, and beta-blocker therapy is a cornerstone of treatment of patients with systolic heart failure, with improvements in morbidity and mortality.2 Underutilization of beta-blockers for indicated conditions is likely due to fear of beta-blocker side effects.2

There has long been concern that beta-blockers can cause, or worsen, depression. As a result, beta-blockers are sometimes withheld from patients with a history of depression who may benefit, or beta-blockers are stopped in patients who develop depression.

Early reports of possible beta-blocker–induced depression surfaced soon after the beta-blocker propranolol became available in the 1960s. A frequently cited reference is a letter to the British Medical Journal in which H.J. Waal reported that 20 of 89 patients on propranolol volunteered or exhibited depressive symptoms.3 Almost half of those patients were diagnosed with grade I depression – symptoms of irritability, insomnia, nightmares, and fatigue. No control group of patients was evaluated to ascertain the prevalence of those symptoms in patients treated with other antihypertensives, or in nonhypertensive patients.

M. H. Pollack and colleagues reported on a series of three patients who developed symptoms of depression after starting propranolol, and the researchers concluded that depression following the administration of propranolol was a real phenomenon.4

Many subsequent studies have cast doubt on the association of beta-blockers and depression. Depression is common following myocardial infarction and in patients with coronary artery disease. Several studies have looked closely for association with beta-blocker use in this population.

Dr. Steven J. Schleifer and colleagues evaluated 190 patients who had sustained a myocardial infarction for evidence of depression. The patients were interviewed 8-10 days after the infarct and again at 3 months. No antianginal or antihypertensive medications, including beta-blockers, were associated with an increase in depression.5

Dr. Joost P. van Melle and colleagues participated in a multicenter study that looked at patients following myocardial infarction, assessing for depressive symptoms at baseline and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months using the Beck depression inventory.6 A total of 254 patients receiving beta-blockers were matched with 127 control patients post MI not receiving beta-blockers. No significant differences were found between non–beta-blocker users and beta-blocker users on the presence of depressive symptoms.

Robert Carney, Ph.D., and colleagues evaluated 75 patients undergoing elective cardiac catheterization with psychiatric interview and psychological assessments.7 Half of the patients in the study were receiving beta-blockers. Thirty-three percent of the patients who were not receiving beta-blockers met DSM-III criteria for depression, and 21% of the beta-blocker–treated patients met criteria for depression.

Dr. Linda Battes and colleagues reported that beta-blocker use actually decreased the risk of depression in patients who had undergone a percutaneous intervention, with a risk reduction of 49% for depression in beta-blocker–treated patients.8 In a study of elderly patients, Dr. Hendrika Luijendijk and colleagues followed 5,104 elderly persons for episodes of incident depression. They found that beta-blocker use did not increase the risk of developing depression.9

Beta-blockers often have been avoided in patients with obstructive pulmonary disease – both in patients with asthma and those with COPD – because of concern for worsening obstructive pulmonary disease. There is strong evidence now that beta-blocker use is not problematic in patients with COPD.

Dr. Surya Bhatt and colleagues found that beta-blocker use decreased COPD exacerbations.10 Almost 3,500 patients were included. During a median of 2.1 years of follow-up, beta-blocker use was associated with a significantly lower rate of total exacerbations (incidence risk ratio, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.90; P = .003) and severe exacerbations (IRR, 0.67, 95% CI, 0.48-0.93; P = .016).

Dr. Qingxia Du and colleagues found that beta-blocker use in patients with COPD both reduced exacerbations and reduced mortality.11 In another study, the use of beta-blockers in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbations of COPD reduced mortality.12 Most of the patients receiving beta-blockers in that study had severe cardiovascular disease.

There are far fewer data on beta-blocker use in patients with asthma. In general, beta-blockers are routinely avoided in patients with asthma. In one small study of asthmatic patients receiving propranolol, there was no effect on methacholine challenge response, histamine responsiveness, or asthma control questionnaire results.13 In a murine model of asthma, long-term administration of beta-blockers resulted in a decrease in airway hyperresponsiveness, suggesting an anti-inflammatory effect.14 This topic is an area of interest for further study in asthma control.

So much of what we thought we knew about beta-blockers has turned out to not be so. We keep our eyes open and welcome further enlightenment.

References

1. Circulation. 1983 Jun;67(6 Pt 2):I91.

2. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015 Dec;14(12):1855-63.

3. Br Med J. 1967 Apr 1;2(5543):50.

4. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985 Feb;173(2):118-9.

5. Am Heart J. 1991 May;121(5):1397-402.

6. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Dec 5;48(11):2209-14.

7. Am J Med. 1987 Aug;83(2):223-6.

8. J Affect Disord. 2012 Feb;136(3):751-7.

9. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011 Feb;31(1):45-50.

10. Thorax. 2016 Jan;71(1):8-14.

12. Thorax. 2008 Apr;63(4):301-5.

13. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013 Jun 15;187(12):1308-14.

14. Int J Gen Med. 2013 Jul 8;6:549-55.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

A 59-year-old man is admitted to the ICU with a myocardial infarction. He is discharged after 5 days on enalapril, metoprolol, simvastatin, and aspirin. At a 3-month follow-up, he is noted to have marked anhedonia, complaints of insomnia, feelings of worthlessness, and psychomotor retardation.

What would you do?

A) Stop the enalapril.

B) Stop the metoprolol.

C) Stop the simvastatin.

D) Begin a tricyclic antidepressant.

E) Begin an SSRI.

When I was in medical school, the dogma was to never give beta-blockers to patients with systolic heart failure, because it would worsen the heart failure.1 As we all know, this dogma completely reversed, and beta-blocker therapy is a cornerstone of treatment of patients with systolic heart failure, with improvements in morbidity and mortality.2 Underutilization of beta-blockers for indicated conditions is likely due to fear of beta-blocker side effects.2

There has long been concern that beta-blockers can cause, or worsen, depression. As a result, beta-blockers are sometimes withheld from patients with a history of depression who may benefit, or beta-blockers are stopped in patients who develop depression.

Early reports of possible beta-blocker–induced depression surfaced soon after the beta-blocker propranolol became available in the 1960s. A frequently cited reference is a letter to the British Medical Journal in which H.J. Waal reported that 20 of 89 patients on propranolol volunteered or exhibited depressive symptoms.3 Almost half of those patients were diagnosed with grade I depression – symptoms of irritability, insomnia, nightmares, and fatigue. No control group of patients was evaluated to ascertain the prevalence of those symptoms in patients treated with other antihypertensives, or in nonhypertensive patients.

M. H. Pollack and colleagues reported on a series of three patients who developed symptoms of depression after starting propranolol, and the researchers concluded that depression following the administration of propranolol was a real phenomenon.4

Many subsequent studies have cast doubt on the association of beta-blockers and depression. Depression is common following myocardial infarction and in patients with coronary artery disease. Several studies have looked closely for association with beta-blocker use in this population.

Dr. Steven J. Schleifer and colleagues evaluated 190 patients who had sustained a myocardial infarction for evidence of depression. The patients were interviewed 8-10 days after the infarct and again at 3 months. No antianginal or antihypertensive medications, including beta-blockers, were associated with an increase in depression.5

Dr. Joost P. van Melle and colleagues participated in a multicenter study that looked at patients following myocardial infarction, assessing for depressive symptoms at baseline and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months using the Beck depression inventory.6 A total of 254 patients receiving beta-blockers were matched with 127 control patients post MI not receiving beta-blockers. No significant differences were found between non–beta-blocker users and beta-blocker users on the presence of depressive symptoms.

Robert Carney, Ph.D., and colleagues evaluated 75 patients undergoing elective cardiac catheterization with psychiatric interview and psychological assessments.7 Half of the patients in the study were receiving beta-blockers. Thirty-three percent of the patients who were not receiving beta-blockers met DSM-III criteria for depression, and 21% of the beta-blocker–treated patients met criteria for depression.

Dr. Linda Battes and colleagues reported that beta-blocker use actually decreased the risk of depression in patients who had undergone a percutaneous intervention, with a risk reduction of 49% for depression in beta-blocker–treated patients.8 In a study of elderly patients, Dr. Hendrika Luijendijk and colleagues followed 5,104 elderly persons for episodes of incident depression. They found that beta-blocker use did not increase the risk of developing depression.9

Beta-blockers often have been avoided in patients with obstructive pulmonary disease – both in patients with asthma and those with COPD – because of concern for worsening obstructive pulmonary disease. There is strong evidence now that beta-blocker use is not problematic in patients with COPD.

Dr. Surya Bhatt and colleagues found that beta-blocker use decreased COPD exacerbations.10 Almost 3,500 patients were included. During a median of 2.1 years of follow-up, beta-blocker use was associated with a significantly lower rate of total exacerbations (incidence risk ratio, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.90; P = .003) and severe exacerbations (IRR, 0.67, 95% CI, 0.48-0.93; P = .016).

Dr. Qingxia Du and colleagues found that beta-blocker use in patients with COPD both reduced exacerbations and reduced mortality.11 In another study, the use of beta-blockers in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbations of COPD reduced mortality.12 Most of the patients receiving beta-blockers in that study had severe cardiovascular disease.

There are far fewer data on beta-blocker use in patients with asthma. In general, beta-blockers are routinely avoided in patients with asthma. In one small study of asthmatic patients receiving propranolol, there was no effect on methacholine challenge response, histamine responsiveness, or asthma control questionnaire results.13 In a murine model of asthma, long-term administration of beta-blockers resulted in a decrease in airway hyperresponsiveness, suggesting an anti-inflammatory effect.14 This topic is an area of interest for further study in asthma control.

So much of what we thought we knew about beta-blockers has turned out to not be so. We keep our eyes open and welcome further enlightenment.

References

1. Circulation. 1983 Jun;67(6 Pt 2):I91.

2. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015 Dec;14(12):1855-63.

3. Br Med J. 1967 Apr 1;2(5543):50.

4. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985 Feb;173(2):118-9.

5. Am Heart J. 1991 May;121(5):1397-402.

6. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Dec 5;48(11):2209-14.

7. Am J Med. 1987 Aug;83(2):223-6.

8. J Affect Disord. 2012 Feb;136(3):751-7.

9. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011 Feb;31(1):45-50.

10. Thorax. 2016 Jan;71(1):8-14.

12. Thorax. 2008 Apr;63(4):301-5.

13. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013 Jun 15;187(12):1308-14.

14. Int J Gen Med. 2013 Jul 8;6:549-55.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

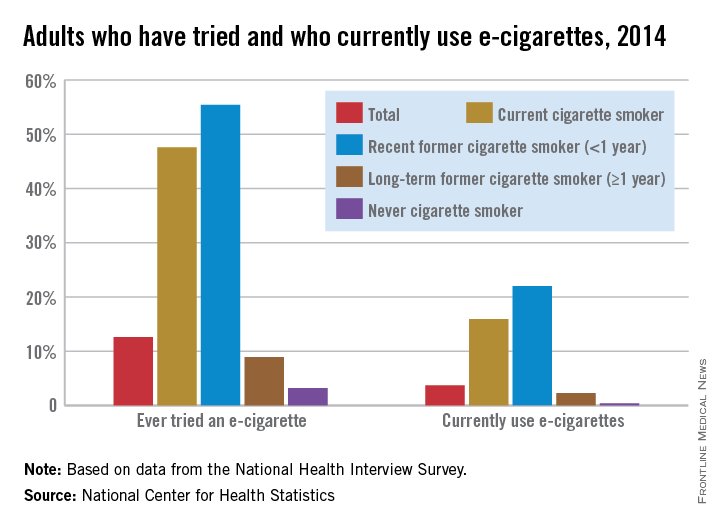

CDC sounds alarm over marketing of e-cigs to teens

Now that data indicate 7 out of 10 American youth are routinely exposed to electronic cigarette imagery, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are calling for restrictions on how e-cigarettes are marketed to teens.

“The same advertising tactics the tobacco industry used years ago to get kids addicted to nicotine are now being used to entice a new generation of young people to use e-cigarettes,” CDC director Dr. Thomas R. Frieden said in a media briefing. “I hope all can agree that kids should not use e-cigarettes.”

Data from the 2014 National Youth Tobacco Use Survey of 22,007 students in grades 6-12 indicated that 18.3 million youth take in imagery depicting e-cigarette use as desirable. Over half of all respondents reported retail establishments were responsible for their exposure to e-cigarette marketing. Nearly 40% said they were exposed to e-cigarette ads online, with more than a third saying they saw such advertising on television and in movies. A quarter reported seeing e-cigarette ads in print media (MMWR. 2016 Jan 5; 64[Early Release]:1-6).

E-cigarettes deliver nicotine and other additives to users in aerosol form by way of a battery-powered device. Tobacco use in teens has been implicated in thwarting healthy brain development, and to the development of lifelong addictions.

Marketing the electronic nicotine delivery devices to young Americans as expressions of “independence, rebellion, and sex” is no different from the tobacco industry’s past tactics for addicting youth to regular tobacco products, according to a CDC statement. In 2014, the CDC reported e-cigarettes had surpassed conventional cigarette use by U.S. teens, rising from 1.5% to 13.4% in high schoolers and from 0.6% to 3.9% in middle school-aged students between 2011 and 2014. Concurrently, industry spending on e-cigarette marketing exploded from $6.4 million to $115 million, according to a CDC statement.

Fearing a reversal of the progress made over the years in curbing tobacco use among teens, the CDC is calling for tighter controls on how e-cigarettes are sold. Among its suggested strategies are limiting the sale of nicotine-based products only to facilities where youth are not permitted; creating “tobacco-sales-free” zones around schools; banning online sales of e-cigarettes; and requiring age verification for the purchase and delivery acceptance of e-cigarettes or before customers can enter e-cigarette vendors’ websites.

The CDC also is calling upon health care providers to counsel younger patients about the dangers of tobacco use, including e-cigarettes, to encourage those who use such products to quit, and to offer assistance with quitting.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Now that data indicate 7 out of 10 American youth are routinely exposed to electronic cigarette imagery, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are calling for restrictions on how e-cigarettes are marketed to teens.

“The same advertising tactics the tobacco industry used years ago to get kids addicted to nicotine are now being used to entice a new generation of young people to use e-cigarettes,” CDC director Dr. Thomas R. Frieden said in a media briefing. “I hope all can agree that kids should not use e-cigarettes.”

Data from the 2014 National Youth Tobacco Use Survey of 22,007 students in grades 6-12 indicated that 18.3 million youth take in imagery depicting e-cigarette use as desirable. Over half of all respondents reported retail establishments were responsible for their exposure to e-cigarette marketing. Nearly 40% said they were exposed to e-cigarette ads online, with more than a third saying they saw such advertising on television and in movies. A quarter reported seeing e-cigarette ads in print media (MMWR. 2016 Jan 5; 64[Early Release]:1-6).

E-cigarettes deliver nicotine and other additives to users in aerosol form by way of a battery-powered device. Tobacco use in teens has been implicated in thwarting healthy brain development, and to the development of lifelong addictions.

Marketing the electronic nicotine delivery devices to young Americans as expressions of “independence, rebellion, and sex” is no different from the tobacco industry’s past tactics for addicting youth to regular tobacco products, according to a CDC statement. In 2014, the CDC reported e-cigarettes had surpassed conventional cigarette use by U.S. teens, rising from 1.5% to 13.4% in high schoolers and from 0.6% to 3.9% in middle school-aged students between 2011 and 2014. Concurrently, industry spending on e-cigarette marketing exploded from $6.4 million to $115 million, according to a CDC statement.

Fearing a reversal of the progress made over the years in curbing tobacco use among teens, the CDC is calling for tighter controls on how e-cigarettes are sold. Among its suggested strategies are limiting the sale of nicotine-based products only to facilities where youth are not permitted; creating “tobacco-sales-free” zones around schools; banning online sales of e-cigarettes; and requiring age verification for the purchase and delivery acceptance of e-cigarettes or before customers can enter e-cigarette vendors’ websites.

The CDC also is calling upon health care providers to counsel younger patients about the dangers of tobacco use, including e-cigarettes, to encourage those who use such products to quit, and to offer assistance with quitting.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Now that data indicate 7 out of 10 American youth are routinely exposed to electronic cigarette imagery, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are calling for restrictions on how e-cigarettes are marketed to teens.

“The same advertising tactics the tobacco industry used years ago to get kids addicted to nicotine are now being used to entice a new generation of young people to use e-cigarettes,” CDC director Dr. Thomas R. Frieden said in a media briefing. “I hope all can agree that kids should not use e-cigarettes.”

Data from the 2014 National Youth Tobacco Use Survey of 22,007 students in grades 6-12 indicated that 18.3 million youth take in imagery depicting e-cigarette use as desirable. Over half of all respondents reported retail establishments were responsible for their exposure to e-cigarette marketing. Nearly 40% said they were exposed to e-cigarette ads online, with more than a third saying they saw such advertising on television and in movies. A quarter reported seeing e-cigarette ads in print media (MMWR. 2016 Jan 5; 64[Early Release]:1-6).

E-cigarettes deliver nicotine and other additives to users in aerosol form by way of a battery-powered device. Tobacco use in teens has been implicated in thwarting healthy brain development, and to the development of lifelong addictions.

Marketing the electronic nicotine delivery devices to young Americans as expressions of “independence, rebellion, and sex” is no different from the tobacco industry’s past tactics for addicting youth to regular tobacco products, according to a CDC statement. In 2014, the CDC reported e-cigarettes had surpassed conventional cigarette use by U.S. teens, rising from 1.5% to 13.4% in high schoolers and from 0.6% to 3.9% in middle school-aged students between 2011 and 2014. Concurrently, industry spending on e-cigarette marketing exploded from $6.4 million to $115 million, according to a CDC statement.

Fearing a reversal of the progress made over the years in curbing tobacco use among teens, the CDC is calling for tighter controls on how e-cigarettes are sold. Among its suggested strategies are limiting the sale of nicotine-based products only to facilities where youth are not permitted; creating “tobacco-sales-free” zones around schools; banning online sales of e-cigarettes; and requiring age verification for the purchase and delivery acceptance of e-cigarettes or before customers can enter e-cigarette vendors’ websites.

The CDC also is calling upon health care providers to counsel younger patients about the dangers of tobacco use, including e-cigarettes, to encourage those who use such products to quit, and to offer assistance with quitting.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

FROM A CDC MEDIA BRIEFING

Late risks of breast cancer RT are higher for smokers

SAN ANTONIO – The late side effects of modern radiation therapy for breast cancer depend in part on a woman’s smoking status, suggests a meta-analysis of data from more than 40,000 women presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

For nonsmokers, radiation therapy had little impact on the absolute risks of lung cancer or cardiac death, the main risks identified, which combined totaled less than 1%, Dr. Carolyn Taylor reported on behalf of the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. But for women who had smoked throughout their adult life and continued to do so during and after treatment, it increased that absolute risk to roughly 2%.

“Smoking status can determine the net long-term effects of breast cancer radiotherapy on mortality. Stopping smoking at the time of radiotherapy may avoid much of the risk, and that’s because most of the risk of lung cancer starts more than 10 years after radiotherapy,” said Dr. Taylor, a radiation oncologist at the University of Oxford (England).

Radiation therapy remains an important tool in treating breast cancer, ultimately reducing the likelihood of death from the disease, she reminded symposium attendees. “The absolute benefit in women treated according to current guidelines is a few percent. Let’s remember the magnitude of that benefit as we think about the risks of radiotherapy.”

Attendee Dr. Steven Vogl of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, asked whether information was available on the location of the lung cancers that occurred in the trials.

“We didn’t have location of lung cancers. We didn’t even know if it was ipsilateral or contralateral to the previous breast cancer in this study,” Dr. Taylor replied. “But we’ve done other studies where we have known the location of the lung cancer, and there were similar findings in those studies.”

“In the last 4 years, we’ve had very good information that annual CT screening substantially and very quickly reduces the mortality from lung cancer,” Dr. Vogl added as a comment. “Any of us who care for patients who have been radiated where, really, any lung has been treated, who continue to smoke, should be screened – and screened and screened and screened again,” he recommended.

The investigators analyzed data from 40,781 women with breast cancer from 75 randomized trials conducted worldwide that compared outcomes with versus without radiation therapy. The median year of trial entry was 1983. On average, women in the trials received 10 Gy to both lungs combined and 6 Gy to the heart.

Comparing women who did and did not receive radiation therapy, the rate ratio for lung cancer was 2.10 at 10 or more years out, and the rate ratio for cardiac mortality was 1.30 overall. Given the mean radiation doses in the trials, the excess risk translated to 12% per Gray for lung cancer and 4% per Gray for cardiac mortality. “These rate ratios are likely to apply today,” Dr. Taylor maintained.

However, she noted, contemporary breast cancer radiation therapy techniques are much better at sparing normal tissues. To derive absolute risk estimates that are relevant today, she and her colleagues reviewed the literature for 2010-2015 and determined that women now receive an average of 5 Gy to both lungs combined and 4 Gy to the heart, with some centers achieving even lower values.

Among nonsmokers, the estimated cumulative 30-year risk of lung cancer was 0.5% for women who did not receive radiation therapy and 0.8% for those who received radiation therapy with a mean dose of 5 Gy to both lungs combined, Dr. Taylor reported. However, among long-term smokers, it was 9.4% without radiation and a substantially higher 13.8% with it.

Similarly, among nonsmokers, the estimated cumulative 30-year risk of ischemic heart disease death was 1.8% for women who did not receive radiation therapy and 2.0% for women who received radiation therapy with a mean dose of 2 Gy to the heart. Among long-term smokers, it was 8.0% without radiation and a slightly higher 8.6% with it.

Additional analyses looking at other late side effects showed no radiation therapy–related excess risk of sarcomas, according to Dr. Taylor. The risk of leukemia was increased with radiation, but actual numbers of cases were very small, she cautioned.

Attendee Dr. Pamela Goodwin, University of Toronto, said, “I’m just wondering whether you considered if it was valid to assume that there was a linear relationship between radiation dose and the risk of lung cancer in the range of radiation doses that you looked at, so, from the higher range in the earlier studies to the much lower dose now.”

Numbers of heart disease events were sufficient to establish a linear relationship, according to Dr. Taylor. Numbers of lung cancers were not, but case-control studies in the literature with adequate numbers have identified a linear relationship there, too. “We use what we can, and we have got now several hundred events, if you combine all of the literature together. And they do suggest the dose-response relationship is linear, but we can’t know that for certain,” she said.

SAN ANTONIO – The late side effects of modern radiation therapy for breast cancer depend in part on a woman’s smoking status, suggests a meta-analysis of data from more than 40,000 women presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

For nonsmokers, radiation therapy had little impact on the absolute risks of lung cancer or cardiac death, the main risks identified, which combined totaled less than 1%, Dr. Carolyn Taylor reported on behalf of the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. But for women who had smoked throughout their adult life and continued to do so during and after treatment, it increased that absolute risk to roughly 2%.

“Smoking status can determine the net long-term effects of breast cancer radiotherapy on mortality. Stopping smoking at the time of radiotherapy may avoid much of the risk, and that’s because most of the risk of lung cancer starts more than 10 years after radiotherapy,” said Dr. Taylor, a radiation oncologist at the University of Oxford (England).

Radiation therapy remains an important tool in treating breast cancer, ultimately reducing the likelihood of death from the disease, she reminded symposium attendees. “The absolute benefit in women treated according to current guidelines is a few percent. Let’s remember the magnitude of that benefit as we think about the risks of radiotherapy.”

Attendee Dr. Steven Vogl of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, asked whether information was available on the location of the lung cancers that occurred in the trials.

“We didn’t have location of lung cancers. We didn’t even know if it was ipsilateral or contralateral to the previous breast cancer in this study,” Dr. Taylor replied. “But we’ve done other studies where we have known the location of the lung cancer, and there were similar findings in those studies.”

“In the last 4 years, we’ve had very good information that annual CT screening substantially and very quickly reduces the mortality from lung cancer,” Dr. Vogl added as a comment. “Any of us who care for patients who have been radiated where, really, any lung has been treated, who continue to smoke, should be screened – and screened and screened and screened again,” he recommended.

The investigators analyzed data from 40,781 women with breast cancer from 75 randomized trials conducted worldwide that compared outcomes with versus without radiation therapy. The median year of trial entry was 1983. On average, women in the trials received 10 Gy to both lungs combined and 6 Gy to the heart.

Comparing women who did and did not receive radiation therapy, the rate ratio for lung cancer was 2.10 at 10 or more years out, and the rate ratio for cardiac mortality was 1.30 overall. Given the mean radiation doses in the trials, the excess risk translated to 12% per Gray for lung cancer and 4% per Gray for cardiac mortality. “These rate ratios are likely to apply today,” Dr. Taylor maintained.

However, she noted, contemporary breast cancer radiation therapy techniques are much better at sparing normal tissues. To derive absolute risk estimates that are relevant today, she and her colleagues reviewed the literature for 2010-2015 and determined that women now receive an average of 5 Gy to both lungs combined and 4 Gy to the heart, with some centers achieving even lower values.

Among nonsmokers, the estimated cumulative 30-year risk of lung cancer was 0.5% for women who did not receive radiation therapy and 0.8% for those who received radiation therapy with a mean dose of 5 Gy to both lungs combined, Dr. Taylor reported. However, among long-term smokers, it was 9.4% without radiation and a substantially higher 13.8% with it.

Similarly, among nonsmokers, the estimated cumulative 30-year risk of ischemic heart disease death was 1.8% for women who did not receive radiation therapy and 2.0% for women who received radiation therapy with a mean dose of 2 Gy to the heart. Among long-term smokers, it was 8.0% without radiation and a slightly higher 8.6% with it.

Additional analyses looking at other late side effects showed no radiation therapy–related excess risk of sarcomas, according to Dr. Taylor. The risk of leukemia was increased with radiation, but actual numbers of cases were very small, she cautioned.

Attendee Dr. Pamela Goodwin, University of Toronto, said, “I’m just wondering whether you considered if it was valid to assume that there was a linear relationship between radiation dose and the risk of lung cancer in the range of radiation doses that you looked at, so, from the higher range in the earlier studies to the much lower dose now.”

Numbers of heart disease events were sufficient to establish a linear relationship, according to Dr. Taylor. Numbers of lung cancers were not, but case-control studies in the literature with adequate numbers have identified a linear relationship there, too. “We use what we can, and we have got now several hundred events, if you combine all of the literature together. And they do suggest the dose-response relationship is linear, but we can’t know that for certain,” she said.

SAN ANTONIO – The late side effects of modern radiation therapy for breast cancer depend in part on a woman’s smoking status, suggests a meta-analysis of data from more than 40,000 women presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

For nonsmokers, radiation therapy had little impact on the absolute risks of lung cancer or cardiac death, the main risks identified, which combined totaled less than 1%, Dr. Carolyn Taylor reported on behalf of the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. But for women who had smoked throughout their adult life and continued to do so during and after treatment, it increased that absolute risk to roughly 2%.

“Smoking status can determine the net long-term effects of breast cancer radiotherapy on mortality. Stopping smoking at the time of radiotherapy may avoid much of the risk, and that’s because most of the risk of lung cancer starts more than 10 years after radiotherapy,” said Dr. Taylor, a radiation oncologist at the University of Oxford (England).

Radiation therapy remains an important tool in treating breast cancer, ultimately reducing the likelihood of death from the disease, she reminded symposium attendees. “The absolute benefit in women treated according to current guidelines is a few percent. Let’s remember the magnitude of that benefit as we think about the risks of radiotherapy.”

Attendee Dr. Steven Vogl of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, asked whether information was available on the location of the lung cancers that occurred in the trials.

“We didn’t have location of lung cancers. We didn’t even know if it was ipsilateral or contralateral to the previous breast cancer in this study,” Dr. Taylor replied. “But we’ve done other studies where we have known the location of the lung cancer, and there were similar findings in those studies.”

“In the last 4 years, we’ve had very good information that annual CT screening substantially and very quickly reduces the mortality from lung cancer,” Dr. Vogl added as a comment. “Any of us who care for patients who have been radiated where, really, any lung has been treated, who continue to smoke, should be screened – and screened and screened and screened again,” he recommended.

The investigators analyzed data from 40,781 women with breast cancer from 75 randomized trials conducted worldwide that compared outcomes with versus without radiation therapy. The median year of trial entry was 1983. On average, women in the trials received 10 Gy to both lungs combined and 6 Gy to the heart.

Comparing women who did and did not receive radiation therapy, the rate ratio for lung cancer was 2.10 at 10 or more years out, and the rate ratio for cardiac mortality was 1.30 overall. Given the mean radiation doses in the trials, the excess risk translated to 12% per Gray for lung cancer and 4% per Gray for cardiac mortality. “These rate ratios are likely to apply today,” Dr. Taylor maintained.