User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Analysis boosts fluvoxamine for COVID, but what’s the evidence?

a new systematic review and meta-analysis has found. But outside experts differ over whether the evidence from just three studies is strong enough to warrant adding the drug to the COVID-19 armamentarium.

The report, published online in JAMA Network Open, looked at three studies and estimated that the drug could reduce the relative risk of hospitalization by around 25% (likelihood of moderate effect, 81.6%-91.8%), depending on the type of analysis used.

“This research might be valuable, but the jury remains out until several other adequately powered and designed trials are completed,” said infectious disease specialist Carl J. Fichtenbaum, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, who’s familiar with the findings. “I’m not sure how useful this is given we have several antiviral agents available. Why would we choose this over Paxlovid, remdesivir, or molnupiravir?”

According to Dr. Fichtenbaum, researchers began focusing on fluvoxamine after case reports about patients improving while on the medication. This led to further interest, he said, boosted by the drug’s known ability to dampen the immune system.

A Silicon Valley investor and antivaccine activist named Steve Kirsch has been pushing the drug along with the debunked treatment hydroxychloroquine. He’s accused the government of a cover-up of fluvoxamine’s worth, according to MIT Technology Review, and he wrote a commentary that referred to the drug as “the fast, easy, safe, simple, low-cost solution to COVID that works 100% of the time that nobody wants to talk about.”

For the new analysis, researchers examined three randomized clinical trials with a total of 2,196 participants. The most extensive trial, the TOGETHER study in Brazil (n = 1,497), focused on an unusual outcome: It linked the drug to a 32% reduction in relative risk of patients with COVID-19 being hospitalized in an ED for fewer than 6 hours or transferred to a tertiary hospital because of the disease.

Another study, the STOP COVID 2 trial in the United States and Canada (n = 547), was stopped because too few patients could be recruited to provide useful results. The initial phase of this trial, STOP COVID 1 (n = 152), was also included in the analysis.

All participants in the three studies were unvaccinated. Their median age was 46-50 years, 55%-72% were women, and 44%-56% were obese. Most were multiracial due to the high number of participants from Brazil.

“In the Bayesian analyses, the pooled risk ratio in favor of fluvoxamine was 0.78 (95% confidence interval, 0.58-1.08) for the weakly neutral prior and 0.73 (95% CI, 0.53-1.01) for the moderately optimistic prior,” the researchers reported, referring to a reduction in risk of hospitalization. “In the frequentist meta-analysis, the pooled risk ratio in favor of fluvoxamine was 0.75 (95% CI, 0.58-0.97; I2, 0.2%).”

Two of the authors of the new analysis were also coauthors of the TOGETHER trial and both STOP COVID trials.

Corresponding author Emily G. McDonald, MD, division of experimental medicine at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview that the findings show fluvoxamine “very likely reduces hospitalization in high-risk outpatient adults with COVID-19. This effect varies depending on your baseline risk of developing complications in the first place.”

Dr. McDonald added that “fluvoxamine is an option to reduce hospitalizations in high-risk adults. It is likely effective, is inexpensive, and has a long safety track record.” She also noted that “not all countries have access to Paxlovid, and some people have drug interactions that preclude its use. Existing monoclonals are not effective with newer variants.”

The drug’s apparent anti-inflammatory properties seem to be key, she said. According to her, the next steps should be “testing lower doses to see if they remain effective, following patients long term to see what impact there is on long COVID symptoms, testing related medications in the drug class to see if they also show an effect, and testing in vaccinated people and with newer variants.”

In an interview, biostatistician James Watson, PhD, of the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit, Bangkok, Thailand, and Nuffield department of medicine, University of Oxford, England, said the findings of the analysis are “not overwhelming data.”

He noted the TOGETHER study’s unusual focus on ED visits that latest fewer than 6 hours, which he described as “not a very objective endpoint.” The new meta-analysis focused instead on “outcome data on emergency department visits lasting more than 24 hours and used this as a more representative proxy for hospital admission than an ED visit alone.”

Dr. Fichtenbaum also highlighted the odd endpoint. “Most of us would have chosen something like use of oxygen, requirement for ventilation, or death,” he said. “There are many reasons why people go to the ED. This endpoint is not very strong.”

He also noted that the three studies “are very different in design and endpoints.”

Jeffrey S. Morris, PhD, a biostatistician at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, offered a different perspective about the findings in an interview. “There’s good evidence that it helps some,” he said, and may reduce hospitalizations by 10%. “If the pill is super cheap and toxicity is very acceptable, it’s not adding additional risk. Most clinicians would say that: ‘If I’m reducing risk by 10%, it’s worthwhile.’ ”

No funding was reported. Two authors report having a patent application filed by Washington University for methods of treating COVID-19 during the conduct of the study. Dr. Watson is an investigator for studies analyzing antiviral drugs and Prozac as COVID-19 treatments. Dr. Fichtenbaum and Dr. Morris disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a new systematic review and meta-analysis has found. But outside experts differ over whether the evidence from just three studies is strong enough to warrant adding the drug to the COVID-19 armamentarium.

The report, published online in JAMA Network Open, looked at three studies and estimated that the drug could reduce the relative risk of hospitalization by around 25% (likelihood of moderate effect, 81.6%-91.8%), depending on the type of analysis used.

“This research might be valuable, but the jury remains out until several other adequately powered and designed trials are completed,” said infectious disease specialist Carl J. Fichtenbaum, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, who’s familiar with the findings. “I’m not sure how useful this is given we have several antiviral agents available. Why would we choose this over Paxlovid, remdesivir, or molnupiravir?”

According to Dr. Fichtenbaum, researchers began focusing on fluvoxamine after case reports about patients improving while on the medication. This led to further interest, he said, boosted by the drug’s known ability to dampen the immune system.

A Silicon Valley investor and antivaccine activist named Steve Kirsch has been pushing the drug along with the debunked treatment hydroxychloroquine. He’s accused the government of a cover-up of fluvoxamine’s worth, according to MIT Technology Review, and he wrote a commentary that referred to the drug as “the fast, easy, safe, simple, low-cost solution to COVID that works 100% of the time that nobody wants to talk about.”

For the new analysis, researchers examined three randomized clinical trials with a total of 2,196 participants. The most extensive trial, the TOGETHER study in Brazil (n = 1,497), focused on an unusual outcome: It linked the drug to a 32% reduction in relative risk of patients with COVID-19 being hospitalized in an ED for fewer than 6 hours or transferred to a tertiary hospital because of the disease.

Another study, the STOP COVID 2 trial in the United States and Canada (n = 547), was stopped because too few patients could be recruited to provide useful results. The initial phase of this trial, STOP COVID 1 (n = 152), was also included in the analysis.

All participants in the three studies were unvaccinated. Their median age was 46-50 years, 55%-72% were women, and 44%-56% were obese. Most were multiracial due to the high number of participants from Brazil.

“In the Bayesian analyses, the pooled risk ratio in favor of fluvoxamine was 0.78 (95% confidence interval, 0.58-1.08) for the weakly neutral prior and 0.73 (95% CI, 0.53-1.01) for the moderately optimistic prior,” the researchers reported, referring to a reduction in risk of hospitalization. “In the frequentist meta-analysis, the pooled risk ratio in favor of fluvoxamine was 0.75 (95% CI, 0.58-0.97; I2, 0.2%).”

Two of the authors of the new analysis were also coauthors of the TOGETHER trial and both STOP COVID trials.

Corresponding author Emily G. McDonald, MD, division of experimental medicine at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview that the findings show fluvoxamine “very likely reduces hospitalization in high-risk outpatient adults with COVID-19. This effect varies depending on your baseline risk of developing complications in the first place.”

Dr. McDonald added that “fluvoxamine is an option to reduce hospitalizations in high-risk adults. It is likely effective, is inexpensive, and has a long safety track record.” She also noted that “not all countries have access to Paxlovid, and some people have drug interactions that preclude its use. Existing monoclonals are not effective with newer variants.”

The drug’s apparent anti-inflammatory properties seem to be key, she said. According to her, the next steps should be “testing lower doses to see if they remain effective, following patients long term to see what impact there is on long COVID symptoms, testing related medications in the drug class to see if they also show an effect, and testing in vaccinated people and with newer variants.”

In an interview, biostatistician James Watson, PhD, of the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit, Bangkok, Thailand, and Nuffield department of medicine, University of Oxford, England, said the findings of the analysis are “not overwhelming data.”

He noted the TOGETHER study’s unusual focus on ED visits that latest fewer than 6 hours, which he described as “not a very objective endpoint.” The new meta-analysis focused instead on “outcome data on emergency department visits lasting more than 24 hours and used this as a more representative proxy for hospital admission than an ED visit alone.”

Dr. Fichtenbaum also highlighted the odd endpoint. “Most of us would have chosen something like use of oxygen, requirement for ventilation, or death,” he said. “There are many reasons why people go to the ED. This endpoint is not very strong.”

He also noted that the three studies “are very different in design and endpoints.”

Jeffrey S. Morris, PhD, a biostatistician at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, offered a different perspective about the findings in an interview. “There’s good evidence that it helps some,” he said, and may reduce hospitalizations by 10%. “If the pill is super cheap and toxicity is very acceptable, it’s not adding additional risk. Most clinicians would say that: ‘If I’m reducing risk by 10%, it’s worthwhile.’ ”

No funding was reported. Two authors report having a patent application filed by Washington University for methods of treating COVID-19 during the conduct of the study. Dr. Watson is an investigator for studies analyzing antiviral drugs and Prozac as COVID-19 treatments. Dr. Fichtenbaum and Dr. Morris disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a new systematic review and meta-analysis has found. But outside experts differ over whether the evidence from just three studies is strong enough to warrant adding the drug to the COVID-19 armamentarium.

The report, published online in JAMA Network Open, looked at three studies and estimated that the drug could reduce the relative risk of hospitalization by around 25% (likelihood of moderate effect, 81.6%-91.8%), depending on the type of analysis used.

“This research might be valuable, but the jury remains out until several other adequately powered and designed trials are completed,” said infectious disease specialist Carl J. Fichtenbaum, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, who’s familiar with the findings. “I’m not sure how useful this is given we have several antiviral agents available. Why would we choose this over Paxlovid, remdesivir, or molnupiravir?”

According to Dr. Fichtenbaum, researchers began focusing on fluvoxamine after case reports about patients improving while on the medication. This led to further interest, he said, boosted by the drug’s known ability to dampen the immune system.

A Silicon Valley investor and antivaccine activist named Steve Kirsch has been pushing the drug along with the debunked treatment hydroxychloroquine. He’s accused the government of a cover-up of fluvoxamine’s worth, according to MIT Technology Review, and he wrote a commentary that referred to the drug as “the fast, easy, safe, simple, low-cost solution to COVID that works 100% of the time that nobody wants to talk about.”

For the new analysis, researchers examined three randomized clinical trials with a total of 2,196 participants. The most extensive trial, the TOGETHER study in Brazil (n = 1,497), focused on an unusual outcome: It linked the drug to a 32% reduction in relative risk of patients with COVID-19 being hospitalized in an ED for fewer than 6 hours or transferred to a tertiary hospital because of the disease.

Another study, the STOP COVID 2 trial in the United States and Canada (n = 547), was stopped because too few patients could be recruited to provide useful results. The initial phase of this trial, STOP COVID 1 (n = 152), was also included in the analysis.

All participants in the three studies were unvaccinated. Their median age was 46-50 years, 55%-72% were women, and 44%-56% were obese. Most were multiracial due to the high number of participants from Brazil.

“In the Bayesian analyses, the pooled risk ratio in favor of fluvoxamine was 0.78 (95% confidence interval, 0.58-1.08) for the weakly neutral prior and 0.73 (95% CI, 0.53-1.01) for the moderately optimistic prior,” the researchers reported, referring to a reduction in risk of hospitalization. “In the frequentist meta-analysis, the pooled risk ratio in favor of fluvoxamine was 0.75 (95% CI, 0.58-0.97; I2, 0.2%).”

Two of the authors of the new analysis were also coauthors of the TOGETHER trial and both STOP COVID trials.

Corresponding author Emily G. McDonald, MD, division of experimental medicine at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview that the findings show fluvoxamine “very likely reduces hospitalization in high-risk outpatient adults with COVID-19. This effect varies depending on your baseline risk of developing complications in the first place.”

Dr. McDonald added that “fluvoxamine is an option to reduce hospitalizations in high-risk adults. It is likely effective, is inexpensive, and has a long safety track record.” She also noted that “not all countries have access to Paxlovid, and some people have drug interactions that preclude its use. Existing monoclonals are not effective with newer variants.”

The drug’s apparent anti-inflammatory properties seem to be key, she said. According to her, the next steps should be “testing lower doses to see if they remain effective, following patients long term to see what impact there is on long COVID symptoms, testing related medications in the drug class to see if they also show an effect, and testing in vaccinated people and with newer variants.”

In an interview, biostatistician James Watson, PhD, of the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit, Bangkok, Thailand, and Nuffield department of medicine, University of Oxford, England, said the findings of the analysis are “not overwhelming data.”

He noted the TOGETHER study’s unusual focus on ED visits that latest fewer than 6 hours, which he described as “not a very objective endpoint.” The new meta-analysis focused instead on “outcome data on emergency department visits lasting more than 24 hours and used this as a more representative proxy for hospital admission than an ED visit alone.”

Dr. Fichtenbaum also highlighted the odd endpoint. “Most of us would have chosen something like use of oxygen, requirement for ventilation, or death,” he said. “There are many reasons why people go to the ED. This endpoint is not very strong.”

He also noted that the three studies “are very different in design and endpoints.”

Jeffrey S. Morris, PhD, a biostatistician at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, offered a different perspective about the findings in an interview. “There’s good evidence that it helps some,” he said, and may reduce hospitalizations by 10%. “If the pill is super cheap and toxicity is very acceptable, it’s not adding additional risk. Most clinicians would say that: ‘If I’m reducing risk by 10%, it’s worthwhile.’ ”

No funding was reported. Two authors report having a patent application filed by Washington University for methods of treating COVID-19 during the conduct of the study. Dr. Watson is an investigator for studies analyzing antiviral drugs and Prozac as COVID-19 treatments. Dr. Fichtenbaum and Dr. Morris disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

COVID cases rising in about half of states

About half the states have reported increases in COVID cases fueled by the Omicron subvariant, Axios reported. Alaska, Vermont, and Rhode Island had the highest increases, with more than 20 new cases per 100,000 people.

Nationally, the statistics are encouraging, with the 7-day average of daily cases around 26,000 on April 6, down from around 41,000 on March 6, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The number of deaths has dropped to an average of around 600 a day, down 34% from 2 weeks ago.

National health officials have said some spots would have a lot of COVID cases.

“Looking across the country, we see that 95% of counties are reporting low COVID-19 community levels, which represent over 97% of the U.S. population,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said April 5 at a White House news briefing.

“If we look more closely at the local level, we find a handful of counties where we are seeing increases in both cases and markers of more severe disease, like hospitalizations and in-patient bed capacity, which have resulted in an increased COVID-19 community level in some areas.”

Meanwhile, the Commonwealth Fund issued a report April 8 saying the U.S. vaccine program had prevented an estimated 2.2 million deaths and 17 million hospitalizations.

If the vaccine program didn’t exist, the United States would have had another 66 million COVID infections and spent about $900 billion more on health care, the foundation said.

The United States has reported about 982,000 COVID-related deaths so far with about 80 million COVID cases, according to the CDC.

“Our findings highlight the profound and ongoing impact of the vaccination program in reducing infections, hospitalizations, and deaths,” the Commonwealth Fund said.

“Investing in vaccination programs also has produced substantial cost savings – approximately the size of one-fifth of annual national health expenditures – by dramatically reducing the amount spent on COVID-19 hospitalizations.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

About half the states have reported increases in COVID cases fueled by the Omicron subvariant, Axios reported. Alaska, Vermont, and Rhode Island had the highest increases, with more than 20 new cases per 100,000 people.

Nationally, the statistics are encouraging, with the 7-day average of daily cases around 26,000 on April 6, down from around 41,000 on March 6, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The number of deaths has dropped to an average of around 600 a day, down 34% from 2 weeks ago.

National health officials have said some spots would have a lot of COVID cases.

“Looking across the country, we see that 95% of counties are reporting low COVID-19 community levels, which represent over 97% of the U.S. population,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said April 5 at a White House news briefing.

“If we look more closely at the local level, we find a handful of counties where we are seeing increases in both cases and markers of more severe disease, like hospitalizations and in-patient bed capacity, which have resulted in an increased COVID-19 community level in some areas.”

Meanwhile, the Commonwealth Fund issued a report April 8 saying the U.S. vaccine program had prevented an estimated 2.2 million deaths and 17 million hospitalizations.

If the vaccine program didn’t exist, the United States would have had another 66 million COVID infections and spent about $900 billion more on health care, the foundation said.

The United States has reported about 982,000 COVID-related deaths so far with about 80 million COVID cases, according to the CDC.

“Our findings highlight the profound and ongoing impact of the vaccination program in reducing infections, hospitalizations, and deaths,” the Commonwealth Fund said.

“Investing in vaccination programs also has produced substantial cost savings – approximately the size of one-fifth of annual national health expenditures – by dramatically reducing the amount spent on COVID-19 hospitalizations.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

About half the states have reported increases in COVID cases fueled by the Omicron subvariant, Axios reported. Alaska, Vermont, and Rhode Island had the highest increases, with more than 20 new cases per 100,000 people.

Nationally, the statistics are encouraging, with the 7-day average of daily cases around 26,000 on April 6, down from around 41,000 on March 6, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The number of deaths has dropped to an average of around 600 a day, down 34% from 2 weeks ago.

National health officials have said some spots would have a lot of COVID cases.

“Looking across the country, we see that 95% of counties are reporting low COVID-19 community levels, which represent over 97% of the U.S. population,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said April 5 at a White House news briefing.

“If we look more closely at the local level, we find a handful of counties where we are seeing increases in both cases and markers of more severe disease, like hospitalizations and in-patient bed capacity, which have resulted in an increased COVID-19 community level in some areas.”

Meanwhile, the Commonwealth Fund issued a report April 8 saying the U.S. vaccine program had prevented an estimated 2.2 million deaths and 17 million hospitalizations.

If the vaccine program didn’t exist, the United States would have had another 66 million COVID infections and spent about $900 billion more on health care, the foundation said.

The United States has reported about 982,000 COVID-related deaths so far with about 80 million COVID cases, according to the CDC.

“Our findings highlight the profound and ongoing impact of the vaccination program in reducing infections, hospitalizations, and deaths,” the Commonwealth Fund said.

“Investing in vaccination programs also has produced substantial cost savings – approximately the size of one-fifth of annual national health expenditures – by dramatically reducing the amount spent on COVID-19 hospitalizations.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Transgender youth: Bringing evidence to the political debates

In 2021, state lawmakers introduced a record number of bills that would affect transgender and gender-diverse people. The vast majority were focused on transgender and gender-diverse youth in particular. We’ve seen bills that would take away gender-affirming medical care for minors, ones that would force trans kids to play on sports teams that don’t match their gender identity, and others that would ban trans kids from public facilities like bathrooms that match their gender identities.

These bills aren’t particularly new, but state lawmakers are putting more energy into them than ever. In response, some public figures have started pushing back. Ariana Grande just pledged to match up to 1.5 million dollars in donations to combat anti–trans youth legislative initiatives. However, doctors have been underrepresented in the political discourse.

Sadly, much of the discussion in this area has been driven by wild speculation and emotional rhetoric. It’s rare that we see actual data brought to the table. As clinicians and scientists, we have a responsibility to highlight the data relevant to these legislative debates, and to share them with our representatives. I’m going to break down what we know quantitatively about each of these issues, so that you’ll feel empowered to bring that information to these debates. My hope is that we can move toward evidence-based public policy instead of rhetoric-based public policy, so that we can ensure the best health possible for young people around the country.

Bathroom bills

Though they’ve been less of a focus recently, politicians for years have argued that trans people should be forced to use bathrooms and other public facilities that match their sex assigned at birth, not their gender identity. Their central argument is that trans-inclusive public facility policies will result in higher rates of assault. Published peer-review data show this isn’t true. A 2019 study in Sexuality Research and Social Policy examined the impacts of trans-inclusive public facility policies and found they resulted in no increase in assaults among the general (mostly cisgender) population. Another 2019 study in Pediatrics found that trans-inclusive facility policies were associated with lower odds of sexual assault victimization against transgender youth. The myth that trans-inclusive public facilities increase assault risk is simply that: a myth. All existing data indicate that trans-inclusive policies will improve public safety.

Sports bills

One of the hottest debates recently involves whether transgender girls should be allowed to participate in girls’ sports teams. Those in favor of these bills argue that transgender girls have an innate biological sports advantage over cisgender girls, and if allowed to compete in girls’ sports leagues, they will dominate the events, and cisgender girls will no longer win sports titles. The bills feed into longstanding assumptions – those who were assigned male at birth are strong, and those who were assigned female at birth are weak.

But evidence doesn’t show that trans women dominate female sports leagues. It turns out, there are shockingly few transgender athletes competing in sports leagues around the United States, and even fewer winning major titles. When the Associated Press conducted an investigation asking lawmakers introducing such sports bills to name trans athletes in their states, most couldn’t point to a single one. After Utah state legislators passed a trans sports ban, Governor Spencer Cox vetoed it, pointing out that, of 75,000 high school kids participating in sports in Utah, there was only a single transgender girl (the state legislature overrode the veto anyway).

California has explicitly protected the rights of trans athletes to compete on sports teams that match their gender identity since 2013. There’s still an underrepresentation of trans athletes in sports participation and titles. This is likely because the deck is stacked against these young people in so many other ways that are unrelated to testosterone levels. Trans youth suffer from high rates of harassment, discrimination, and subsequent anxiety and depression that make it difficult to compete in and excel in sports.

Medical bills

State legislators have introduced bills around the country that would criminalize the provision of gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth. Though such bills are opposed by all major medical organizations (including the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, and the American Psychiatric Association), misinformation continues to spread, and in some instances the bills have become law (though none are currently active due to legal challenges).

Clinicians should be aware that there have been sixteen studies to date, each with unique study designs, that have overall linked gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth to better mental health outcomes. While these interventions do (as with all medications) carry some risks (like delayed bone mineralization with pubertal suppression), the risks must be weighed against potential benefits. Unfortunately, these risks and benefits have not been accurately portrayed in state legislative debates. Politicians have spread a great deal of misinformation about gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth, including false assertions that puberty blockers cause infertility and that most transgender adolescents will grow up to identify as cisgender and regret gender-affirming medical interventions.

Minority stress

These bills have direct consequences for pediatric patients. For example, trans-inclusive bathroom policies are associated with lower rates of sexual assault. However, there are also important indirect effects to consider. The gender minority stress framework explains the ways in which stigmatizing national discourse drives higher rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidality among transgender youth. Under this model, so-called “distal factors” like the recent conversations at the national level that marginalize trans young people, are expected to drive higher rates of adverse mental health outcomes. As transgender youth hear high-profile politicians argue that they’re dangerous to their peers in bathrooms and on sports teams, it’s difficult to imagine their mental health would not worsen. Over time, such “distal factors” also lead to “proximal factors” like internalized transphobia in which youth begin to believe the negative things that are said about them. These dangerous processes can have dramatic negative impacts on self-esteem and emotional development. There is strong precedence that public policies have strong indirect mental health effects on LGBTQ youth.

We’ve entered a dangerous era in which politicians are legislating medical care and other aspects of public policy with the potential to hurt the mental health of our young patients. It’s imperative that clinicians and scientists contact their legislators to make sure they are voting for public policy based on data and fact, not misinformation and political rhetoric. The health of American children depends on it.

Dr. Turban (twitter.com/jack_turban) is a chief fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry at Stanford (Calif.) University.

In 2021, state lawmakers introduced a record number of bills that would affect transgender and gender-diverse people. The vast majority were focused on transgender and gender-diverse youth in particular. We’ve seen bills that would take away gender-affirming medical care for minors, ones that would force trans kids to play on sports teams that don’t match their gender identity, and others that would ban trans kids from public facilities like bathrooms that match their gender identities.

These bills aren’t particularly new, but state lawmakers are putting more energy into them than ever. In response, some public figures have started pushing back. Ariana Grande just pledged to match up to 1.5 million dollars in donations to combat anti–trans youth legislative initiatives. However, doctors have been underrepresented in the political discourse.

Sadly, much of the discussion in this area has been driven by wild speculation and emotional rhetoric. It’s rare that we see actual data brought to the table. As clinicians and scientists, we have a responsibility to highlight the data relevant to these legislative debates, and to share them with our representatives. I’m going to break down what we know quantitatively about each of these issues, so that you’ll feel empowered to bring that information to these debates. My hope is that we can move toward evidence-based public policy instead of rhetoric-based public policy, so that we can ensure the best health possible for young people around the country.

Bathroom bills

Though they’ve been less of a focus recently, politicians for years have argued that trans people should be forced to use bathrooms and other public facilities that match their sex assigned at birth, not their gender identity. Their central argument is that trans-inclusive public facility policies will result in higher rates of assault. Published peer-review data show this isn’t true. A 2019 study in Sexuality Research and Social Policy examined the impacts of trans-inclusive public facility policies and found they resulted in no increase in assaults among the general (mostly cisgender) population. Another 2019 study in Pediatrics found that trans-inclusive facility policies were associated with lower odds of sexual assault victimization against transgender youth. The myth that trans-inclusive public facilities increase assault risk is simply that: a myth. All existing data indicate that trans-inclusive policies will improve public safety.

Sports bills

One of the hottest debates recently involves whether transgender girls should be allowed to participate in girls’ sports teams. Those in favor of these bills argue that transgender girls have an innate biological sports advantage over cisgender girls, and if allowed to compete in girls’ sports leagues, they will dominate the events, and cisgender girls will no longer win sports titles. The bills feed into longstanding assumptions – those who were assigned male at birth are strong, and those who were assigned female at birth are weak.

But evidence doesn’t show that trans women dominate female sports leagues. It turns out, there are shockingly few transgender athletes competing in sports leagues around the United States, and even fewer winning major titles. When the Associated Press conducted an investigation asking lawmakers introducing such sports bills to name trans athletes in their states, most couldn’t point to a single one. After Utah state legislators passed a trans sports ban, Governor Spencer Cox vetoed it, pointing out that, of 75,000 high school kids participating in sports in Utah, there was only a single transgender girl (the state legislature overrode the veto anyway).

California has explicitly protected the rights of trans athletes to compete on sports teams that match their gender identity since 2013. There’s still an underrepresentation of trans athletes in sports participation and titles. This is likely because the deck is stacked against these young people in so many other ways that are unrelated to testosterone levels. Trans youth suffer from high rates of harassment, discrimination, and subsequent anxiety and depression that make it difficult to compete in and excel in sports.

Medical bills

State legislators have introduced bills around the country that would criminalize the provision of gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth. Though such bills are opposed by all major medical organizations (including the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, and the American Psychiatric Association), misinformation continues to spread, and in some instances the bills have become law (though none are currently active due to legal challenges).

Clinicians should be aware that there have been sixteen studies to date, each with unique study designs, that have overall linked gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth to better mental health outcomes. While these interventions do (as with all medications) carry some risks (like delayed bone mineralization with pubertal suppression), the risks must be weighed against potential benefits. Unfortunately, these risks and benefits have not been accurately portrayed in state legislative debates. Politicians have spread a great deal of misinformation about gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth, including false assertions that puberty blockers cause infertility and that most transgender adolescents will grow up to identify as cisgender and regret gender-affirming medical interventions.

Minority stress

These bills have direct consequences for pediatric patients. For example, trans-inclusive bathroom policies are associated with lower rates of sexual assault. However, there are also important indirect effects to consider. The gender minority stress framework explains the ways in which stigmatizing national discourse drives higher rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidality among transgender youth. Under this model, so-called “distal factors” like the recent conversations at the national level that marginalize trans young people, are expected to drive higher rates of adverse mental health outcomes. As transgender youth hear high-profile politicians argue that they’re dangerous to their peers in bathrooms and on sports teams, it’s difficult to imagine their mental health would not worsen. Over time, such “distal factors” also lead to “proximal factors” like internalized transphobia in which youth begin to believe the negative things that are said about them. These dangerous processes can have dramatic negative impacts on self-esteem and emotional development. There is strong precedence that public policies have strong indirect mental health effects on LGBTQ youth.

We’ve entered a dangerous era in which politicians are legislating medical care and other aspects of public policy with the potential to hurt the mental health of our young patients. It’s imperative that clinicians and scientists contact their legislators to make sure they are voting for public policy based on data and fact, not misinformation and political rhetoric. The health of American children depends on it.

Dr. Turban (twitter.com/jack_turban) is a chief fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry at Stanford (Calif.) University.

In 2021, state lawmakers introduced a record number of bills that would affect transgender and gender-diverse people. The vast majority were focused on transgender and gender-diverse youth in particular. We’ve seen bills that would take away gender-affirming medical care for minors, ones that would force trans kids to play on sports teams that don’t match their gender identity, and others that would ban trans kids from public facilities like bathrooms that match their gender identities.

These bills aren’t particularly new, but state lawmakers are putting more energy into them than ever. In response, some public figures have started pushing back. Ariana Grande just pledged to match up to 1.5 million dollars in donations to combat anti–trans youth legislative initiatives. However, doctors have been underrepresented in the political discourse.

Sadly, much of the discussion in this area has been driven by wild speculation and emotional rhetoric. It’s rare that we see actual data brought to the table. As clinicians and scientists, we have a responsibility to highlight the data relevant to these legislative debates, and to share them with our representatives. I’m going to break down what we know quantitatively about each of these issues, so that you’ll feel empowered to bring that information to these debates. My hope is that we can move toward evidence-based public policy instead of rhetoric-based public policy, so that we can ensure the best health possible for young people around the country.

Bathroom bills

Though they’ve been less of a focus recently, politicians for years have argued that trans people should be forced to use bathrooms and other public facilities that match their sex assigned at birth, not their gender identity. Their central argument is that trans-inclusive public facility policies will result in higher rates of assault. Published peer-review data show this isn’t true. A 2019 study in Sexuality Research and Social Policy examined the impacts of trans-inclusive public facility policies and found they resulted in no increase in assaults among the general (mostly cisgender) population. Another 2019 study in Pediatrics found that trans-inclusive facility policies were associated with lower odds of sexual assault victimization against transgender youth. The myth that trans-inclusive public facilities increase assault risk is simply that: a myth. All existing data indicate that trans-inclusive policies will improve public safety.

Sports bills

One of the hottest debates recently involves whether transgender girls should be allowed to participate in girls’ sports teams. Those in favor of these bills argue that transgender girls have an innate biological sports advantage over cisgender girls, and if allowed to compete in girls’ sports leagues, they will dominate the events, and cisgender girls will no longer win sports titles. The bills feed into longstanding assumptions – those who were assigned male at birth are strong, and those who were assigned female at birth are weak.

But evidence doesn’t show that trans women dominate female sports leagues. It turns out, there are shockingly few transgender athletes competing in sports leagues around the United States, and even fewer winning major titles. When the Associated Press conducted an investigation asking lawmakers introducing such sports bills to name trans athletes in their states, most couldn’t point to a single one. After Utah state legislators passed a trans sports ban, Governor Spencer Cox vetoed it, pointing out that, of 75,000 high school kids participating in sports in Utah, there was only a single transgender girl (the state legislature overrode the veto anyway).

California has explicitly protected the rights of trans athletes to compete on sports teams that match their gender identity since 2013. There’s still an underrepresentation of trans athletes in sports participation and titles. This is likely because the deck is stacked against these young people in so many other ways that are unrelated to testosterone levels. Trans youth suffer from high rates of harassment, discrimination, and subsequent anxiety and depression that make it difficult to compete in and excel in sports.

Medical bills

State legislators have introduced bills around the country that would criminalize the provision of gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth. Though such bills are opposed by all major medical organizations (including the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, and the American Psychiatric Association), misinformation continues to spread, and in some instances the bills have become law (though none are currently active due to legal challenges).

Clinicians should be aware that there have been sixteen studies to date, each with unique study designs, that have overall linked gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth to better mental health outcomes. While these interventions do (as with all medications) carry some risks (like delayed bone mineralization with pubertal suppression), the risks must be weighed against potential benefits. Unfortunately, these risks and benefits have not been accurately portrayed in state legislative debates. Politicians have spread a great deal of misinformation about gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth, including false assertions that puberty blockers cause infertility and that most transgender adolescents will grow up to identify as cisgender and regret gender-affirming medical interventions.

Minority stress

These bills have direct consequences for pediatric patients. For example, trans-inclusive bathroom policies are associated with lower rates of sexual assault. However, there are also important indirect effects to consider. The gender minority stress framework explains the ways in which stigmatizing national discourse drives higher rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidality among transgender youth. Under this model, so-called “distal factors” like the recent conversations at the national level that marginalize trans young people, are expected to drive higher rates of adverse mental health outcomes. As transgender youth hear high-profile politicians argue that they’re dangerous to their peers in bathrooms and on sports teams, it’s difficult to imagine their mental health would not worsen. Over time, such “distal factors” also lead to “proximal factors” like internalized transphobia in which youth begin to believe the negative things that are said about them. These dangerous processes can have dramatic negative impacts on self-esteem and emotional development. There is strong precedence that public policies have strong indirect mental health effects on LGBTQ youth.

We’ve entered a dangerous era in which politicians are legislating medical care and other aspects of public policy with the potential to hurt the mental health of our young patients. It’s imperative that clinicians and scientists contact their legislators to make sure they are voting for public policy based on data and fact, not misinformation and political rhetoric. The health of American children depends on it.

Dr. Turban (twitter.com/jack_turban) is a chief fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Metacognitive training an effective, durable treatment for schizophrenia

Metacognitive training (MCT) is effective in reducing positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, new research suggests.

MCT for psychosis is a brief intervention that “combines psychoeducation, cognitive bias modification, and strategy teaching but does not directly target psychosis symptoms.”

Additionally, MCT led to improvement in self-esteem and functioning, and all benefits were maintained up to 1 year post intervention.

“Our study demonstrates the effectiveness and durability of a brief, nonconfrontational intervention in the reduction of serious and debilitating symptoms of schizophrenia,” study investigator Danielle Penney, a doctoral candidate at the University of Montreal, told this news organization.

“Our results were observed in several treatment contexts and suggest that MCT can be successfully delivered by a variety of mental health practitioners [and] provide solid evidence to consider MCT in international treatment guidelines for schizophrenia spectrum disorders,” Ms. Penney said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Novel contribution’

MCT is a brief intervention consisting of eight to 16 modules that can be delivered in a group setting or on an individual basis. Instead of directly targeting psychotic symptoms, it uses an “indirect approach by promoting awareness of cognitive biases,” the investigators note.

Such biases include maladaptive thinking styles common to psychosis, such as jumping to conclusions, belief inflexibility, and overconfidence in judgments.

It is hypothesized that these biases “contribute to the formation and maintenance of positive symptoms, particularly delusions,” the researchers write.

MCT “aims to plant doubt in delusional beliefs through raising awareness of cognitive biases and aims to raise service engagement by proposing work on this less-confrontational objective first, which is likely to facilitate the therapeutic alliance and more direct work on psychotic symptoms,” they add.

Previous studies of MCT for psychosis yielded inconsistent results. Of the eight previous meta-analyses that analyzed MCT for psychosis, “none investigated the long-term effects of the intervention on directly targeted treatment outcomes,” such as delusions and cognitive biases, Ms. Penney said.

She added that “to our knowledge, no meta-analysis has examined the effectiveness of important indirectly targeted outcomes,” including self-esteem and functioning.

“These important gaps in the literature,” along with a large increase in recently conducted MCT efficacy trials, “provided the motivation for the current study,” said Ms. Penney.

To investigate, the researchers searched 11 databases, beginning with data from 2007, which was when the first report of MCT was published. Studies included participants with schizophrenia spectrum and related psychotic disorders.

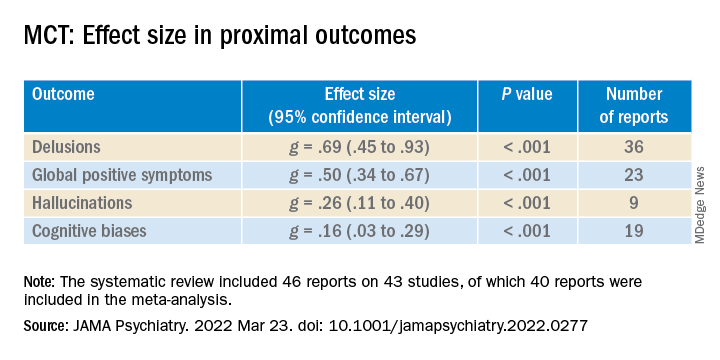

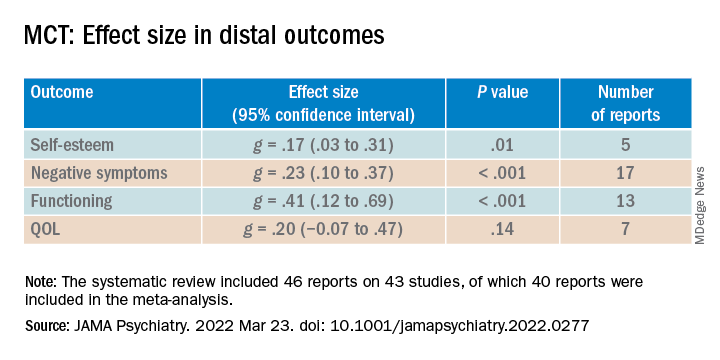

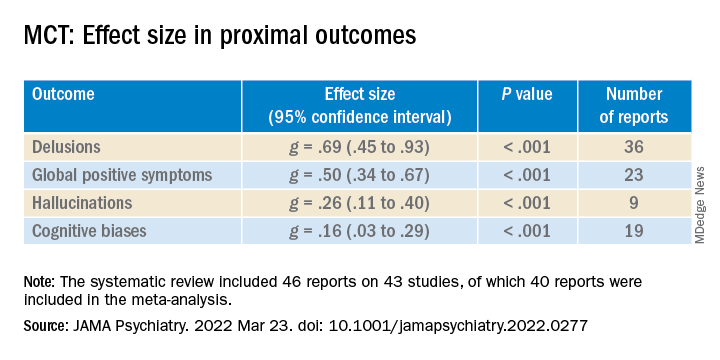

Outcomes for the current review and meta-analysis were organized according to a “proximal-distal framework.” Proximal outcomes were those directly targeted by MCT, while distal outcomes were those not directly targeted by MCT but that were associated with improvement in proximal outcomes, either directly or indirectly.

The investigators examined these outcomes quantitatively and qualitatively from preintervention to postintervention and follow-up, “which, to our knowledge, is a novel contribution,” they write.

The review included 43 studies, of which 30 (70%) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 11 (25%) were non-RCTs, and two (5%) were quantitative descriptive studies. Of these, 40 reports (n = 1,816 participants) were included in the meta-analysis, and six were included in the narrative review.

Transdiagnostic treatment?

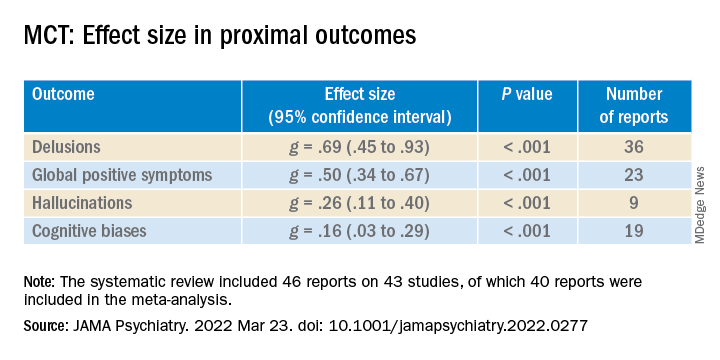

Results showed a “small to moderate” effect size (ES) in global proximal outcomes (g = .39; 95% confidence interval, .25-.53; P < .001; 38 reports).

When proximal outcomes were analyzed separately, the largest ES was found for delusions; smaller ES values were found for hallucinations and cognitive biases.

Newer studies reported higher ES values for hallucinations, compared with older studies (β = .04; 95% CI, .00-.07).

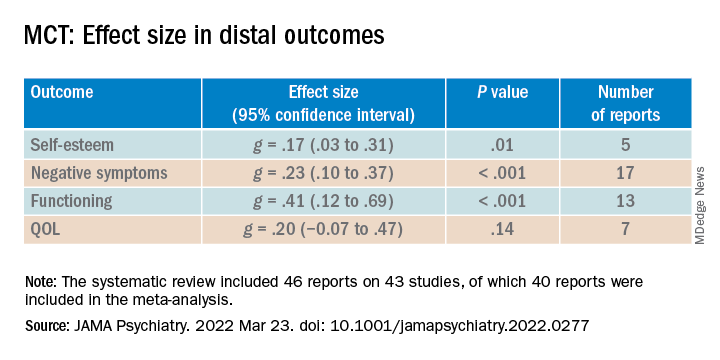

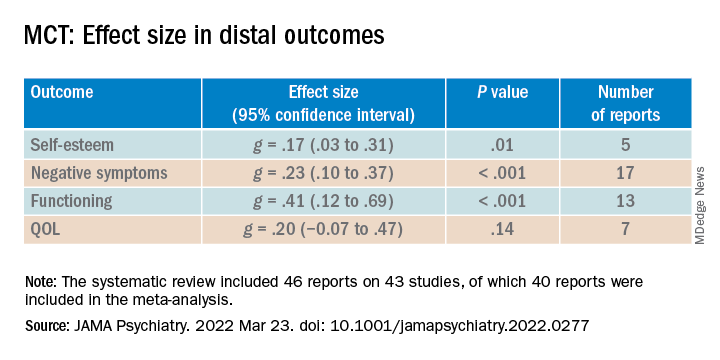

ES was small to moderate for distal outcomes (g = .31; 95% CI, .19-.44; P < .001; 26 reports). “Small but significant” ES values were shown for self-esteem and negative symptoms, small to moderate for functioning, and small but nonsignificant for quality of life (QOL).

The researchers also analyzed RCTs by comparing differences between the treatment and control groups in scores from follow-up to post-treatment. Although the therapeutic gains made by the experimental group were “steadily maintained, the ES values were “small” and nonsignificant.

When the difference in scores between follow-up and baseline were compared in both groups, small to moderate ES values were found for proximal as well as distal outcomes.

“These results further indicate that net therapeutic gains remain significant even 1 year following MCT,” the investigators note.

Lower-quality studies showed significantly lower ES values for distal (between-group comparison, P = .05) but not proximal outcomes.

Overall, the findings suggest that MCT is a “beneficial and durable low-threshold intervention that can be flexibly delivered at minimal cost in a variety of contexts to individuals with psychotic disorders,” the researchers write.

They note that MCT has also been associated with positive outcomes in other patient populations, including patients with borderline personality disorder, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Future research “might consider investigating MCT as a transdiagnostic treatment,” they add.

Consistent beneficial effects

Commenting on the study, Philip Harvey, PhD, Leonard M. Miller Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and director of the Division of Psychology, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, noted that self-awareness and self-assessment are critically important features in patients with serious mental illness.

Impairments in these areas “can actually have a greater impact on everyday functioning than cognitive deficits,” said Dr. Harvey, who is also the editor-in-chief of Schizophrenia Research: Cognition. He was not involved with the current meta-analysis.

He noted that the current results show that “MCT has consistent beneficial effects.”

“This is an intervention that should be considered for most people with serious mental illness, with a specific focus on those with specific types of delusions and more global challenges in self-assessment,” Dr. Harvey concluded.

Funding was provided by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, awarded through the Healthy Brains, Healthy Lives initiative at McGill University. Ms. Penney reported no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other investigators are listed in the original article. Dr. Harvey reported being a reviewer of the article but that he was not involved in its authorship.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Metacognitive training (MCT) is effective in reducing positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, new research suggests.

MCT for psychosis is a brief intervention that “combines psychoeducation, cognitive bias modification, and strategy teaching but does not directly target psychosis symptoms.”

Additionally, MCT led to improvement in self-esteem and functioning, and all benefits were maintained up to 1 year post intervention.

“Our study demonstrates the effectiveness and durability of a brief, nonconfrontational intervention in the reduction of serious and debilitating symptoms of schizophrenia,” study investigator Danielle Penney, a doctoral candidate at the University of Montreal, told this news organization.

“Our results were observed in several treatment contexts and suggest that MCT can be successfully delivered by a variety of mental health practitioners [and] provide solid evidence to consider MCT in international treatment guidelines for schizophrenia spectrum disorders,” Ms. Penney said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Novel contribution’

MCT is a brief intervention consisting of eight to 16 modules that can be delivered in a group setting or on an individual basis. Instead of directly targeting psychotic symptoms, it uses an “indirect approach by promoting awareness of cognitive biases,” the investigators note.

Such biases include maladaptive thinking styles common to psychosis, such as jumping to conclusions, belief inflexibility, and overconfidence in judgments.

It is hypothesized that these biases “contribute to the formation and maintenance of positive symptoms, particularly delusions,” the researchers write.

MCT “aims to plant doubt in delusional beliefs through raising awareness of cognitive biases and aims to raise service engagement by proposing work on this less-confrontational objective first, which is likely to facilitate the therapeutic alliance and more direct work on psychotic symptoms,” they add.

Previous studies of MCT for psychosis yielded inconsistent results. Of the eight previous meta-analyses that analyzed MCT for psychosis, “none investigated the long-term effects of the intervention on directly targeted treatment outcomes,” such as delusions and cognitive biases, Ms. Penney said.

She added that “to our knowledge, no meta-analysis has examined the effectiveness of important indirectly targeted outcomes,” including self-esteem and functioning.

“These important gaps in the literature,” along with a large increase in recently conducted MCT efficacy trials, “provided the motivation for the current study,” said Ms. Penney.

To investigate, the researchers searched 11 databases, beginning with data from 2007, which was when the first report of MCT was published. Studies included participants with schizophrenia spectrum and related psychotic disorders.

Outcomes for the current review and meta-analysis were organized according to a “proximal-distal framework.” Proximal outcomes were those directly targeted by MCT, while distal outcomes were those not directly targeted by MCT but that were associated with improvement in proximal outcomes, either directly or indirectly.

The investigators examined these outcomes quantitatively and qualitatively from preintervention to postintervention and follow-up, “which, to our knowledge, is a novel contribution,” they write.

The review included 43 studies, of which 30 (70%) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 11 (25%) were non-RCTs, and two (5%) were quantitative descriptive studies. Of these, 40 reports (n = 1,816 participants) were included in the meta-analysis, and six were included in the narrative review.

Transdiagnostic treatment?

Results showed a “small to moderate” effect size (ES) in global proximal outcomes (g = .39; 95% confidence interval, .25-.53; P < .001; 38 reports).

When proximal outcomes were analyzed separately, the largest ES was found for delusions; smaller ES values were found for hallucinations and cognitive biases.

Newer studies reported higher ES values for hallucinations, compared with older studies (β = .04; 95% CI, .00-.07).

ES was small to moderate for distal outcomes (g = .31; 95% CI, .19-.44; P < .001; 26 reports). “Small but significant” ES values were shown for self-esteem and negative symptoms, small to moderate for functioning, and small but nonsignificant for quality of life (QOL).

The researchers also analyzed RCTs by comparing differences between the treatment and control groups in scores from follow-up to post-treatment. Although the therapeutic gains made by the experimental group were “steadily maintained, the ES values were “small” and nonsignificant.

When the difference in scores between follow-up and baseline were compared in both groups, small to moderate ES values were found for proximal as well as distal outcomes.

“These results further indicate that net therapeutic gains remain significant even 1 year following MCT,” the investigators note.

Lower-quality studies showed significantly lower ES values for distal (between-group comparison, P = .05) but not proximal outcomes.

Overall, the findings suggest that MCT is a “beneficial and durable low-threshold intervention that can be flexibly delivered at minimal cost in a variety of contexts to individuals with psychotic disorders,” the researchers write.

They note that MCT has also been associated with positive outcomes in other patient populations, including patients with borderline personality disorder, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Future research “might consider investigating MCT as a transdiagnostic treatment,” they add.

Consistent beneficial effects

Commenting on the study, Philip Harvey, PhD, Leonard M. Miller Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and director of the Division of Psychology, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, noted that self-awareness and self-assessment are critically important features in patients with serious mental illness.

Impairments in these areas “can actually have a greater impact on everyday functioning than cognitive deficits,” said Dr. Harvey, who is also the editor-in-chief of Schizophrenia Research: Cognition. He was not involved with the current meta-analysis.

He noted that the current results show that “MCT has consistent beneficial effects.”

“This is an intervention that should be considered for most people with serious mental illness, with a specific focus on those with specific types of delusions and more global challenges in self-assessment,” Dr. Harvey concluded.

Funding was provided by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, awarded through the Healthy Brains, Healthy Lives initiative at McGill University. Ms. Penney reported no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other investigators are listed in the original article. Dr. Harvey reported being a reviewer of the article but that he was not involved in its authorship.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Metacognitive training (MCT) is effective in reducing positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, new research suggests.

MCT for psychosis is a brief intervention that “combines psychoeducation, cognitive bias modification, and strategy teaching but does not directly target psychosis symptoms.”

Additionally, MCT led to improvement in self-esteem and functioning, and all benefits were maintained up to 1 year post intervention.

“Our study demonstrates the effectiveness and durability of a brief, nonconfrontational intervention in the reduction of serious and debilitating symptoms of schizophrenia,” study investigator Danielle Penney, a doctoral candidate at the University of Montreal, told this news organization.

“Our results were observed in several treatment contexts and suggest that MCT can be successfully delivered by a variety of mental health practitioners [and] provide solid evidence to consider MCT in international treatment guidelines for schizophrenia spectrum disorders,” Ms. Penney said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Novel contribution’

MCT is a brief intervention consisting of eight to 16 modules that can be delivered in a group setting or on an individual basis. Instead of directly targeting psychotic symptoms, it uses an “indirect approach by promoting awareness of cognitive biases,” the investigators note.

Such biases include maladaptive thinking styles common to psychosis, such as jumping to conclusions, belief inflexibility, and overconfidence in judgments.

It is hypothesized that these biases “contribute to the formation and maintenance of positive symptoms, particularly delusions,” the researchers write.

MCT “aims to plant doubt in delusional beliefs through raising awareness of cognitive biases and aims to raise service engagement by proposing work on this less-confrontational objective first, which is likely to facilitate the therapeutic alliance and more direct work on psychotic symptoms,” they add.

Previous studies of MCT for psychosis yielded inconsistent results. Of the eight previous meta-analyses that analyzed MCT for psychosis, “none investigated the long-term effects of the intervention on directly targeted treatment outcomes,” such as delusions and cognitive biases, Ms. Penney said.

She added that “to our knowledge, no meta-analysis has examined the effectiveness of important indirectly targeted outcomes,” including self-esteem and functioning.

“These important gaps in the literature,” along with a large increase in recently conducted MCT efficacy trials, “provided the motivation for the current study,” said Ms. Penney.

To investigate, the researchers searched 11 databases, beginning with data from 2007, which was when the first report of MCT was published. Studies included participants with schizophrenia spectrum and related psychotic disorders.

Outcomes for the current review and meta-analysis were organized according to a “proximal-distal framework.” Proximal outcomes were those directly targeted by MCT, while distal outcomes were those not directly targeted by MCT but that were associated with improvement in proximal outcomes, either directly or indirectly.

The investigators examined these outcomes quantitatively and qualitatively from preintervention to postintervention and follow-up, “which, to our knowledge, is a novel contribution,” they write.

The review included 43 studies, of which 30 (70%) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 11 (25%) were non-RCTs, and two (5%) were quantitative descriptive studies. Of these, 40 reports (n = 1,816 participants) were included in the meta-analysis, and six were included in the narrative review.

Transdiagnostic treatment?

Results showed a “small to moderate” effect size (ES) in global proximal outcomes (g = .39; 95% confidence interval, .25-.53; P < .001; 38 reports).

When proximal outcomes were analyzed separately, the largest ES was found for delusions; smaller ES values were found for hallucinations and cognitive biases.

Newer studies reported higher ES values for hallucinations, compared with older studies (β = .04; 95% CI, .00-.07).

ES was small to moderate for distal outcomes (g = .31; 95% CI, .19-.44; P < .001; 26 reports). “Small but significant” ES values were shown for self-esteem and negative symptoms, small to moderate for functioning, and small but nonsignificant for quality of life (QOL).

The researchers also analyzed RCTs by comparing differences between the treatment and control groups in scores from follow-up to post-treatment. Although the therapeutic gains made by the experimental group were “steadily maintained, the ES values were “small” and nonsignificant.

When the difference in scores between follow-up and baseline were compared in both groups, small to moderate ES values were found for proximal as well as distal outcomes.

“These results further indicate that net therapeutic gains remain significant even 1 year following MCT,” the investigators note.

Lower-quality studies showed significantly lower ES values for distal (between-group comparison, P = .05) but not proximal outcomes.

Overall, the findings suggest that MCT is a “beneficial and durable low-threshold intervention that can be flexibly delivered at minimal cost in a variety of contexts to individuals with psychotic disorders,” the researchers write.

They note that MCT has also been associated with positive outcomes in other patient populations, including patients with borderline personality disorder, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Future research “might consider investigating MCT as a transdiagnostic treatment,” they add.

Consistent beneficial effects

Commenting on the study, Philip Harvey, PhD, Leonard M. Miller Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and director of the Division of Psychology, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, noted that self-awareness and self-assessment are critically important features in patients with serious mental illness.

Impairments in these areas “can actually have a greater impact on everyday functioning than cognitive deficits,” said Dr. Harvey, who is also the editor-in-chief of Schizophrenia Research: Cognition. He was not involved with the current meta-analysis.

He noted that the current results show that “MCT has consistent beneficial effects.”

“This is an intervention that should be considered for most people with serious mental illness, with a specific focus on those with specific types of delusions and more global challenges in self-assessment,” Dr. Harvey concluded.

Funding was provided by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, awarded through the Healthy Brains, Healthy Lives initiative at McGill University. Ms. Penney reported no relevant financial relationships. Disclosures for the other investigators are listed in the original article. Dr. Harvey reported being a reviewer of the article but that he was not involved in its authorship.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Study: Physical fitness in children linked with concentration, quality of life

The findings of the German study involving more than 6,500 kids emphasize the importance of cardiorespiratory health in childhood, and support physical fitness initiatives in schools, according to lead author Katharina Köble, MSc, of the Technical University of Munich (Germany), and colleagues.

“Recent studies show that only a few children meet the recommendations of physical activity,” the investigators wrote in Journal of Clinical Medicine.

While the health benefits of physical activity are clearly documented, Ms. Köble and colleagues noted that typical measures of activity, such as accelerometers or self-reported questionnaires, are suboptimal research tools.

“Physical fitness is a more objective parameter to quantify when evaluating health promotion,” the investigators wrote. “Furthermore, cardiorespiratory fitness as part of physical fitness is more strongly related to risk factors of cardiovascular disease than physical activity.”

According to the investigators, physical fitness has also been linked with better concentration and HRQOL, but never in the same population of children.

The new study aimed to address this knowledge gap by assessing 6,533 healthy children aged 6-10 years, approximately half boys and half girls. Associations between physical fitness, concentration, and HRQOL were evaluated using multiple linear regression analysis in participants aged 9-10 years.

Physical fitness was measured using a series of challenges, including curl-ups (pull-ups with palms facing body), push-ups, standing long jump, handgrip strength measurement, and Progressive Aerobic Cardiovascular Endurance Run (PACER). Performing the multistage shuttle run, PACER, “requires participants to maintain the pace set by an audio signal, which progressively increases the intensity every minute.” Results of the PACER test were used to estimate VO2max.

Concentration was measured using the d2-R test, “a paper-pencil cancellation test, where subjects have to cross out all ‘d’ letters with two dashes under a time limit.”

HRQOL was evaluated with the KINDL questionnaire, which covers emotional well-being, physical well-being, everyday functioning (school), friends, family, and self-esteem.

Analysis showed that physical fitness improved with age (P < .001), except for VO2max in girls (P = .129). Concentration also improved with age (P < .001), while HRQOL did not (P = .179).

Among children aged 9-10 years, VO2max scores were strongly associated with both HRQOL (P < .001) and concentration (P < .001).

“VO2max was found to be one of the main factors influencing concentration levels and HRQOL dimensions in primary school children,” the investigators wrote. “Physical fitness, especially cardiorespiratory performance, should therefore be promoted more specifically in school settings to support the promotion of an overall healthy lifestyle in children and adolescents.”

Findings are having a real-word impact, according to researcher

In an interview, Ms. Köble noted that the findings are already having a real-world impact.

“We continued data assessment in the long-term and specifically adapted prevention programs in school to the needs of the school children we identified in our study,” she said. “Schools are partially offering specific movement and nutrition classes now.”

In addition, Ms. Köble and colleagues plan on educating teachers about the “urgent need for sufficient physical activity.”

“Academic performance should be considered as an additional health factor in future studies, as well as screen time and eating patterns, as all those variables showed interactions with physical fitness and concentration. In a subanalysis, we showed that children with better physical fitness and concentration values were those who usually went to higher education secondary schools,” they wrote.

VO2max did not correlate with BMI

Gregory Weaver, MD, a pediatrician at Cleveland Clinic Children’s, voiced some concerns about the reliability of the findings. He noted that VO2max did not correlate with body mass index or other measures of physical fitness, and that using the PACER test to estimate VO2max may have skewed the association between physical fitness and concentration.

“It is quite conceivable that children who can maintain the focus to perform maximally on this test will also do well on other tests of attention/concentration,” Dr. Weaver said. “Most children I know would have a very difficult time performing a physical fitness test which requires them to match a recorded pace that slowly increases overtime. I’m not an expert in the area, but it is my understanding that usually VO2max tests involve a treadmill which allows investigators to have complete control over pace.”

Dr. Weaver concluded that more work is needed to determine if physical fitness interventions can have a positive impact on HRQOL and concentration.

“I think the authors of this study attempted to ask an important question about the possible association between physical fitness and concentration among school aged children,” Dr. Weaver said in an interview. “But what is even more vital are studies demonstrating that a change in modifiable health factors like nutrition, physical fitness, or the built environment can improve quality of life. I was hoping the authors would show that an improvement in VO2max over time resulted in an improvement in concentration. Frustratingly, that is not what this article demonstrates.”

The investigators and Dr. Weaver reported no conflicts of interest.

The findings of the German study involving more than 6,500 kids emphasize the importance of cardiorespiratory health in childhood, and support physical fitness initiatives in schools, according to lead author Katharina Köble, MSc, of the Technical University of Munich (Germany), and colleagues.

“Recent studies show that only a few children meet the recommendations of physical activity,” the investigators wrote in Journal of Clinical Medicine.

While the health benefits of physical activity are clearly documented, Ms. Köble and colleagues noted that typical measures of activity, such as accelerometers or self-reported questionnaires, are suboptimal research tools.

“Physical fitness is a more objective parameter to quantify when evaluating health promotion,” the investigators wrote. “Furthermore, cardiorespiratory fitness as part of physical fitness is more strongly related to risk factors of cardiovascular disease than physical activity.”

According to the investigators, physical fitness has also been linked with better concentration and HRQOL, but never in the same population of children.

The new study aimed to address this knowledge gap by assessing 6,533 healthy children aged 6-10 years, approximately half boys and half girls. Associations between physical fitness, concentration, and HRQOL were evaluated using multiple linear regression analysis in participants aged 9-10 years.

Physical fitness was measured using a series of challenges, including curl-ups (pull-ups with palms facing body), push-ups, standing long jump, handgrip strength measurement, and Progressive Aerobic Cardiovascular Endurance Run (PACER). Performing the multistage shuttle run, PACER, “requires participants to maintain the pace set by an audio signal, which progressively increases the intensity every minute.” Results of the PACER test were used to estimate VO2max.

Concentration was measured using the d2-R test, “a paper-pencil cancellation test, where subjects have to cross out all ‘d’ letters with two dashes under a time limit.”

HRQOL was evaluated with the KINDL questionnaire, which covers emotional well-being, physical well-being, everyday functioning (school), friends, family, and self-esteem.

Analysis showed that physical fitness improved with age (P < .001), except for VO2max in girls (P = .129). Concentration also improved with age (P < .001), while HRQOL did not (P = .179).

Among children aged 9-10 years, VO2max scores were strongly associated with both HRQOL (P < .001) and concentration (P < .001).

“VO2max was found to be one of the main factors influencing concentration levels and HRQOL dimensions in primary school children,” the investigators wrote. “Physical fitness, especially cardiorespiratory performance, should therefore be promoted more specifically in school settings to support the promotion of an overall healthy lifestyle in children and adolescents.”

Findings are having a real-word impact, according to researcher

In an interview, Ms. Köble noted that the findings are already having a real-world impact.

“We continued data assessment in the long-term and specifically adapted prevention programs in school to the needs of the school children we identified in our study,” she said. “Schools are partially offering specific movement and nutrition classes now.”

In addition, Ms. Köble and colleagues plan on educating teachers about the “urgent need for sufficient physical activity.”

“Academic performance should be considered as an additional health factor in future studies, as well as screen time and eating patterns, as all those variables showed interactions with physical fitness and concentration. In a subanalysis, we showed that children with better physical fitness and concentration values were those who usually went to higher education secondary schools,” they wrote.

VO2max did not correlate with BMI

Gregory Weaver, MD, a pediatrician at Cleveland Clinic Children’s, voiced some concerns about the reliability of the findings. He noted that VO2max did not correlate with body mass index or other measures of physical fitness, and that using the PACER test to estimate VO2max may have skewed the association between physical fitness and concentration.

“It is quite conceivable that children who can maintain the focus to perform maximally on this test will also do well on other tests of attention/concentration,” Dr. Weaver said. “Most children I know would have a very difficult time performing a physical fitness test which requires them to match a recorded pace that slowly increases overtime. I’m not an expert in the area, but it is my understanding that usually VO2max tests involve a treadmill which allows investigators to have complete control over pace.”

Dr. Weaver concluded that more work is needed to determine if physical fitness interventions can have a positive impact on HRQOL and concentration.