User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

What ketamine and psilocybin can and cannot do in depression

Recent studies with hallucinogens have raised hopes for an effective drug-based therapy to treat chronic depression. At the German Congress of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, Torsten Passie, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry and psychotherapy at the Hannover (Germay) Medical School, gave a presentation on the current state of psilocybin and ketamine/esketamine research.

Dr. Passie, who also is head physician of the specialist unit for addiction and addiction prevention at the Diakonisches Werk in Hannover, has been investigating hallucinogenic substances and their application in psychotherapy for decades.

New therapies sought

In depression, gloom extends beyond the patient’s mood. For some time there has been little cause for joy with regard to chronic depression therapy. Established drug therapies hardly perform any better than placebo in meta-analyses, as a study recently confirmed. The pharmaceutical industry pulled out of psycho-pharmaceutical development more than 10 years ago. What’s more, the number of cases is rising, especially among young people, and there are long waiting times for psychotherapy appointments.

It is no wonder that some are welcoming new drug-based approaches with lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)–like hallucinogens. In 2016, a study on psilocybin was published in The Lancet Psychiatry, although the study was unblinded and included only 24 patients.

Evoking emotions

A range of substances can be classed as hallucinogens, including psilocybin, mescaline, LSD, 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA, also known as ecstasy), and ketamine.

Taking hallucinogens can cause a release of serotonin and dopamine, an increase in activity levels in the brain, a shift in stimulus filtering, an increase in the production of internal stimuli (inner experiences), and a change in sensory integration (for example, synesthesia).

Besides falling into a dreamlike state, patients can achieve an expansion or narrowing of consciousness if they focus on an inner experience. Internal perception increases. Perceptual routines are broken apart. Thought processes become more image-based and are more associative than normal.

Patients therefore are more capable of making new and unusual connections between different biographical or current situations. Previously unconscious ideas can become conscious. At higher doses, ego loss can occur, which can be associated with a mystical feeling of connectedness.

Hallucinogens mainly evoke and heighten emotions. Those effects may be experienced strongly as internal visions or in physical manifestations (for example, crying or laughing). In contrast, conventional antidepressants work by suppressing emotions (that is, emotional blunting).

These different mechanisms result in two contrasting management strategies. For example, SSRI antidepressants cause a patient to perceive workplace bullying as less severe and to do nothing to change the situation; the patient remains passive.

In contrast, a therapeutically guided, emotionally activating experience on hallucinogens can help the patient to try more actively to change the stressful situation.

Ketamine has a special place among hallucinogens. Unlike other hallucinogens, ketamine causes a strong clouding of consciousness, a reduction in physical sensory perception, and significant disruption in thinking and memory. It is therefore only suitable as a short-term intervention and is therapeutically impractical over the long term.

Ketamine’s effects

Ketamine, a racemic mixture of the enantiomers S-ketamine and R-ketamine, was originally used only as an analgesic and anesthetic. Owing to its rapid antidepressant effect, it has since also been used as an emergency medication for severe depression, sometimes in combination with SSRIs or serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors.

Approximately 60% of patients respond to the treatment. Whereas with conventional antidepressants, onset of action requires 10-14 days, ketamine is effective within a few hours. However, relapse always occurs, usually very quickly. After 2-3 days, the effect is usually approximately that of a placebo. An administration interval of about 2 days is optimal. However, “resistance” to the effect often develops after some time: the drug’s antidepressant effect diminishes.

Ketamine also has some unpleasant side effects, such as depersonalization, dissociation, impaired thinking, nystagmus, and psychotomimetic effects. Nausea and vomiting also occur. Interestingly, the latter does not bother the patient much, owing to the drug’s psychological effects, and it does not lead to treatment discontinuation, said Dr. Passie, who described his clinical experiences with ketamine.

Since ketamine causes a considerable clouding of consciousness, sensory disorders, and significant memory problems, it is not suitable for psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, unlike LSD or psilocybin, he emphasized.

Ketamine 2.0?

Esketamine, the pure S-enantiomer of ketamine, has been on the market since 2019 in the form of a nasal spray (Spravato). Esketamine has been approved in combination with oral antidepressant therapy for adults with a moderate to severe episode of major depression for acute treatment of a psychiatric emergency.

A meta-analysis from 2022 concluded that the original racemic ketamine is better than the new esketamine in reducing symptoms of depression.

In his own comprehensive study, Dr. Passie concluded that the mental impairments that occur during therapy did not differ significantly between substances. The patients even felt that the side effects from esketamine therapy were much more mentally unpleasant, said Dr. Passie. He concluded that the R-enantiomer may have a kind of protective effect against some of the psychopathological effects of the S-enantiomer (esketamine).

In addition, preclinical studies have indicated that the antidepressant effects of R-enantiomer, which is not contained in esketamine, are longer lasting and stronger.

Another problem is absorption, which can be inconsistent with a nasal spray. It may differ, for example, depending on the ambient humidity or whether the patient has recently had a cold. In addition, the spray is far more expensive than the ketamine injection, said Dr. Passie. Patients must also use the nasal spray under supervision at a medical practice (as with the intravenous application) and must receive follow-up care there. It therefore offers no advantage over the ketamine injection.

According to the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare, no additional benefit has been proven for esketamine over standard therapies for adults who have experienced a moderate to severe depressive episode when used as short-term treatment for the rapid reduction of depressive symptoms in a psychiatric emergency. The German Medical Association agreed with this evaluation in October 2021.

In the United Kingdom, the medication was never approved, owing to the fact that it was too expensive and that no studies comparing it with psychotherapy were available.

Add-on psilocybin?

What was experienced under the influence of psilocybin can also be subsequently processed and used in psychotherapy.

The acute effect of psilocybin begins after approximately 40 minutes and lasts for 4-6 hours. The antidepressant effect, if it occurs at all, is of immediate onset. Unlike ketamine/esketamine, psilocybin hardly has any physical side effects.

The neurologic mechanism of action has been investigated recently using fMRI and PET techniques. According to the investigations, the substance causes individual networks of activity in the patient’s brain to interconnect more strongly, said Dr. Passie. The thalamus, the filter station for sensory information, as well as the limbic and paralimbic structures, which generate emotions, and the cortex are all activated more strongly.

Two therapeutic settings

Psilocybin, at least in the context of studies, is used in two settings: psycholytic therapy and psychedelic therapy. Both settings originated in the 1950s and were also used with LSD as the active substance.

Psycholytic therapy with psilocybin entails multiple administrations at low doses (for example, 10-18 mg), incorporated into a longer, mostly psychodynamic therapy of around 50-100 hours (often on an inpatient basis at the beginning). It results in what is described as an extended encounter with oneself. The focus is on psychodynamic experiences, such as memories and internal conflicts. In addition, novel experiences with oneself and self-recognition are important.

Psychedelic therapy generally entails one or two sessions with a high dose (for example, 25-35 mg psilocybin). The preparation and follow-up are limited to a few sessions. These methods refer to so-called transpersonal psychology, which addresses extraordinary states of consciousness in line with religious experiences. It often leads to an intense self-confrontation as well as to new evaluations of self and world. The central element to this therapy is the experience of a mystical ego loss and the concomitant feeling of connectedness, which should help to expand one’s perspective.

Euphoria and disillusionment

The first promising studies with a few patients suffering from depression were followed by others in which the euphoria was allowed to fade away somewhat. In the first direct comparison in a methodically high-grade double-blind study, psilocybin was inferior to the SSRI antidepressant escitalopram.

“There is a great variation in response from person to person,” said Dr. Passie. “The better the study is methodically controlled, the worse the results,” he hypothesized.

“Since the method is up to 50 times more expensive in practice, compared to SSRI therapy over 6-12 weeks, the question clearly must be asked as to whether it really has any great future.”

Outlook for psilocybin

Nevertheless, Dr. Passie still sees potential in psilocybin. He considers an approach in which psilocybin therapy is more firmly incorporated into psychotherapy, with between four and 10 therapy sessions before and after administration of a lower therapeutic dose of the substance, to be more promising.

“With this kind of intensive preparation and follow-up, as well as the repeated psilocybin sessions, the patient can benefit much more than is possible with one or two high-dose sessions,” said Dr. Passie, who also is chair of the International Society for Substance-Assisted Psychotherapy. “The constant ‘in-depth work on the ego’ required for drastic therapeutic changes can be more effective and lead to permanent improvements. I have no doubt about this.”

In Dr. Passie’s opinion, the best approach would involve a dignified inpatient setting with a longer period of follow-up care and consistent posttreatment care, including group therapy. The shape of future psilocybin therapy depends on whether the rather abrupt change seen with high-dose psychedelic therapy is permanent. The answer to this question will be decisive for the method and manner of its future clinical use.

Because of the somewhat negative study results, however, the initial investors are pulling out. Dr. Passie is therefore skeptical about whether the necessary larger studies will take place and whether psilocybin will make it onto the market.

In Switzerland, which is not subject to EU restrictions, more than 30 physicians have been authorized to use psilocybin, LSD, and MDMA in psychotherapy sessions. Still, in some respects this is a special case that cannot be transferred easily to other countries, said Dr. Passie.

Possible psilocybin improvement?

Various chemical derivatives of psychoactive substances have been researched, including a psilocybin variant with the label CYB003. With CYB003, the length of the acute psychedelic experience is reduced from around 6 hours (such as with psilocybin) to 1 hour. The plasma concentration of the substance is less variable between different patients. It is assumed that its effects will also differ less from person to person.

In July, researchers began a study of the use of CYB003 in the treatment of major depression. In the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with 40 patients, multiple doses of the substance will be administered.

When asked, Dr. Passie was rather skeptical about the study. He considers the approaches with psilocybin derivatives to be the consequences of a “gold-rush atmosphere” and expects there will be no real additional benefit, especially not a reduction in the period of action.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Recent studies with hallucinogens have raised hopes for an effective drug-based therapy to treat chronic depression. At the German Congress of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, Torsten Passie, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry and psychotherapy at the Hannover (Germay) Medical School, gave a presentation on the current state of psilocybin and ketamine/esketamine research.

Dr. Passie, who also is head physician of the specialist unit for addiction and addiction prevention at the Diakonisches Werk in Hannover, has been investigating hallucinogenic substances and their application in psychotherapy for decades.

New therapies sought

In depression, gloom extends beyond the patient’s mood. For some time there has been little cause for joy with regard to chronic depression therapy. Established drug therapies hardly perform any better than placebo in meta-analyses, as a study recently confirmed. The pharmaceutical industry pulled out of psycho-pharmaceutical development more than 10 years ago. What’s more, the number of cases is rising, especially among young people, and there are long waiting times for psychotherapy appointments.

It is no wonder that some are welcoming new drug-based approaches with lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)–like hallucinogens. In 2016, a study on psilocybin was published in The Lancet Psychiatry, although the study was unblinded and included only 24 patients.

Evoking emotions

A range of substances can be classed as hallucinogens, including psilocybin, mescaline, LSD, 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA, also known as ecstasy), and ketamine.

Taking hallucinogens can cause a release of serotonin and dopamine, an increase in activity levels in the brain, a shift in stimulus filtering, an increase in the production of internal stimuli (inner experiences), and a change in sensory integration (for example, synesthesia).

Besides falling into a dreamlike state, patients can achieve an expansion or narrowing of consciousness if they focus on an inner experience. Internal perception increases. Perceptual routines are broken apart. Thought processes become more image-based and are more associative than normal.

Patients therefore are more capable of making new and unusual connections between different biographical or current situations. Previously unconscious ideas can become conscious. At higher doses, ego loss can occur, which can be associated with a mystical feeling of connectedness.

Hallucinogens mainly evoke and heighten emotions. Those effects may be experienced strongly as internal visions or in physical manifestations (for example, crying or laughing). In contrast, conventional antidepressants work by suppressing emotions (that is, emotional blunting).

These different mechanisms result in two contrasting management strategies. For example, SSRI antidepressants cause a patient to perceive workplace bullying as less severe and to do nothing to change the situation; the patient remains passive.

In contrast, a therapeutically guided, emotionally activating experience on hallucinogens can help the patient to try more actively to change the stressful situation.

Ketamine has a special place among hallucinogens. Unlike other hallucinogens, ketamine causes a strong clouding of consciousness, a reduction in physical sensory perception, and significant disruption in thinking and memory. It is therefore only suitable as a short-term intervention and is therapeutically impractical over the long term.

Ketamine’s effects

Ketamine, a racemic mixture of the enantiomers S-ketamine and R-ketamine, was originally used only as an analgesic and anesthetic. Owing to its rapid antidepressant effect, it has since also been used as an emergency medication for severe depression, sometimes in combination with SSRIs or serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors.

Approximately 60% of patients respond to the treatment. Whereas with conventional antidepressants, onset of action requires 10-14 days, ketamine is effective within a few hours. However, relapse always occurs, usually very quickly. After 2-3 days, the effect is usually approximately that of a placebo. An administration interval of about 2 days is optimal. However, “resistance” to the effect often develops after some time: the drug’s antidepressant effect diminishes.

Ketamine also has some unpleasant side effects, such as depersonalization, dissociation, impaired thinking, nystagmus, and psychotomimetic effects. Nausea and vomiting also occur. Interestingly, the latter does not bother the patient much, owing to the drug’s psychological effects, and it does not lead to treatment discontinuation, said Dr. Passie, who described his clinical experiences with ketamine.

Since ketamine causes a considerable clouding of consciousness, sensory disorders, and significant memory problems, it is not suitable for psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, unlike LSD or psilocybin, he emphasized.

Ketamine 2.0?

Esketamine, the pure S-enantiomer of ketamine, has been on the market since 2019 in the form of a nasal spray (Spravato). Esketamine has been approved in combination with oral antidepressant therapy for adults with a moderate to severe episode of major depression for acute treatment of a psychiatric emergency.

A meta-analysis from 2022 concluded that the original racemic ketamine is better than the new esketamine in reducing symptoms of depression.

In his own comprehensive study, Dr. Passie concluded that the mental impairments that occur during therapy did not differ significantly between substances. The patients even felt that the side effects from esketamine therapy were much more mentally unpleasant, said Dr. Passie. He concluded that the R-enantiomer may have a kind of protective effect against some of the psychopathological effects of the S-enantiomer (esketamine).

In addition, preclinical studies have indicated that the antidepressant effects of R-enantiomer, which is not contained in esketamine, are longer lasting and stronger.

Another problem is absorption, which can be inconsistent with a nasal spray. It may differ, for example, depending on the ambient humidity or whether the patient has recently had a cold. In addition, the spray is far more expensive than the ketamine injection, said Dr. Passie. Patients must also use the nasal spray under supervision at a medical practice (as with the intravenous application) and must receive follow-up care there. It therefore offers no advantage over the ketamine injection.

According to the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare, no additional benefit has been proven for esketamine over standard therapies for adults who have experienced a moderate to severe depressive episode when used as short-term treatment for the rapid reduction of depressive symptoms in a psychiatric emergency. The German Medical Association agreed with this evaluation in October 2021.

In the United Kingdom, the medication was never approved, owing to the fact that it was too expensive and that no studies comparing it with psychotherapy were available.

Add-on psilocybin?

What was experienced under the influence of psilocybin can also be subsequently processed and used in psychotherapy.

The acute effect of psilocybin begins after approximately 40 minutes and lasts for 4-6 hours. The antidepressant effect, if it occurs at all, is of immediate onset. Unlike ketamine/esketamine, psilocybin hardly has any physical side effects.

The neurologic mechanism of action has been investigated recently using fMRI and PET techniques. According to the investigations, the substance causes individual networks of activity in the patient’s brain to interconnect more strongly, said Dr. Passie. The thalamus, the filter station for sensory information, as well as the limbic and paralimbic structures, which generate emotions, and the cortex are all activated more strongly.

Two therapeutic settings

Psilocybin, at least in the context of studies, is used in two settings: psycholytic therapy and psychedelic therapy. Both settings originated in the 1950s and were also used with LSD as the active substance.

Psycholytic therapy with psilocybin entails multiple administrations at low doses (for example, 10-18 mg), incorporated into a longer, mostly psychodynamic therapy of around 50-100 hours (often on an inpatient basis at the beginning). It results in what is described as an extended encounter with oneself. The focus is on psychodynamic experiences, such as memories and internal conflicts. In addition, novel experiences with oneself and self-recognition are important.

Psychedelic therapy generally entails one or two sessions with a high dose (for example, 25-35 mg psilocybin). The preparation and follow-up are limited to a few sessions. These methods refer to so-called transpersonal psychology, which addresses extraordinary states of consciousness in line with religious experiences. It often leads to an intense self-confrontation as well as to new evaluations of self and world. The central element to this therapy is the experience of a mystical ego loss and the concomitant feeling of connectedness, which should help to expand one’s perspective.

Euphoria and disillusionment

The first promising studies with a few patients suffering from depression were followed by others in which the euphoria was allowed to fade away somewhat. In the first direct comparison in a methodically high-grade double-blind study, psilocybin was inferior to the SSRI antidepressant escitalopram.

“There is a great variation in response from person to person,” said Dr. Passie. “The better the study is methodically controlled, the worse the results,” he hypothesized.

“Since the method is up to 50 times more expensive in practice, compared to SSRI therapy over 6-12 weeks, the question clearly must be asked as to whether it really has any great future.”

Outlook for psilocybin

Nevertheless, Dr. Passie still sees potential in psilocybin. He considers an approach in which psilocybin therapy is more firmly incorporated into psychotherapy, with between four and 10 therapy sessions before and after administration of a lower therapeutic dose of the substance, to be more promising.

“With this kind of intensive preparation and follow-up, as well as the repeated psilocybin sessions, the patient can benefit much more than is possible with one or two high-dose sessions,” said Dr. Passie, who also is chair of the International Society for Substance-Assisted Psychotherapy. “The constant ‘in-depth work on the ego’ required for drastic therapeutic changes can be more effective and lead to permanent improvements. I have no doubt about this.”

In Dr. Passie’s opinion, the best approach would involve a dignified inpatient setting with a longer period of follow-up care and consistent posttreatment care, including group therapy. The shape of future psilocybin therapy depends on whether the rather abrupt change seen with high-dose psychedelic therapy is permanent. The answer to this question will be decisive for the method and manner of its future clinical use.

Because of the somewhat negative study results, however, the initial investors are pulling out. Dr. Passie is therefore skeptical about whether the necessary larger studies will take place and whether psilocybin will make it onto the market.

In Switzerland, which is not subject to EU restrictions, more than 30 physicians have been authorized to use psilocybin, LSD, and MDMA in psychotherapy sessions. Still, in some respects this is a special case that cannot be transferred easily to other countries, said Dr. Passie.

Possible psilocybin improvement?

Various chemical derivatives of psychoactive substances have been researched, including a psilocybin variant with the label CYB003. With CYB003, the length of the acute psychedelic experience is reduced from around 6 hours (such as with psilocybin) to 1 hour. The plasma concentration of the substance is less variable between different patients. It is assumed that its effects will also differ less from person to person.

In July, researchers began a study of the use of CYB003 in the treatment of major depression. In the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with 40 patients, multiple doses of the substance will be administered.

When asked, Dr. Passie was rather skeptical about the study. He considers the approaches with psilocybin derivatives to be the consequences of a “gold-rush atmosphere” and expects there will be no real additional benefit, especially not a reduction in the period of action.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Recent studies with hallucinogens have raised hopes for an effective drug-based therapy to treat chronic depression. At the German Congress of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, Torsten Passie, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry and psychotherapy at the Hannover (Germay) Medical School, gave a presentation on the current state of psilocybin and ketamine/esketamine research.

Dr. Passie, who also is head physician of the specialist unit for addiction and addiction prevention at the Diakonisches Werk in Hannover, has been investigating hallucinogenic substances and their application in psychotherapy for decades.

New therapies sought

In depression, gloom extends beyond the patient’s mood. For some time there has been little cause for joy with regard to chronic depression therapy. Established drug therapies hardly perform any better than placebo in meta-analyses, as a study recently confirmed. The pharmaceutical industry pulled out of psycho-pharmaceutical development more than 10 years ago. What’s more, the number of cases is rising, especially among young people, and there are long waiting times for psychotherapy appointments.

It is no wonder that some are welcoming new drug-based approaches with lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)–like hallucinogens. In 2016, a study on psilocybin was published in The Lancet Psychiatry, although the study was unblinded and included only 24 patients.

Evoking emotions

A range of substances can be classed as hallucinogens, including psilocybin, mescaline, LSD, 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA, also known as ecstasy), and ketamine.

Taking hallucinogens can cause a release of serotonin and dopamine, an increase in activity levels in the brain, a shift in stimulus filtering, an increase in the production of internal stimuli (inner experiences), and a change in sensory integration (for example, synesthesia).

Besides falling into a dreamlike state, patients can achieve an expansion or narrowing of consciousness if they focus on an inner experience. Internal perception increases. Perceptual routines are broken apart. Thought processes become more image-based and are more associative than normal.

Patients therefore are more capable of making new and unusual connections between different biographical or current situations. Previously unconscious ideas can become conscious. At higher doses, ego loss can occur, which can be associated with a mystical feeling of connectedness.

Hallucinogens mainly evoke and heighten emotions. Those effects may be experienced strongly as internal visions or in physical manifestations (for example, crying or laughing). In contrast, conventional antidepressants work by suppressing emotions (that is, emotional blunting).

These different mechanisms result in two contrasting management strategies. For example, SSRI antidepressants cause a patient to perceive workplace bullying as less severe and to do nothing to change the situation; the patient remains passive.

In contrast, a therapeutically guided, emotionally activating experience on hallucinogens can help the patient to try more actively to change the stressful situation.

Ketamine has a special place among hallucinogens. Unlike other hallucinogens, ketamine causes a strong clouding of consciousness, a reduction in physical sensory perception, and significant disruption in thinking and memory. It is therefore only suitable as a short-term intervention and is therapeutically impractical over the long term.

Ketamine’s effects

Ketamine, a racemic mixture of the enantiomers S-ketamine and R-ketamine, was originally used only as an analgesic and anesthetic. Owing to its rapid antidepressant effect, it has since also been used as an emergency medication for severe depression, sometimes in combination with SSRIs or serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors.

Approximately 60% of patients respond to the treatment. Whereas with conventional antidepressants, onset of action requires 10-14 days, ketamine is effective within a few hours. However, relapse always occurs, usually very quickly. After 2-3 days, the effect is usually approximately that of a placebo. An administration interval of about 2 days is optimal. However, “resistance” to the effect often develops after some time: the drug’s antidepressant effect diminishes.

Ketamine also has some unpleasant side effects, such as depersonalization, dissociation, impaired thinking, nystagmus, and psychotomimetic effects. Nausea and vomiting also occur. Interestingly, the latter does not bother the patient much, owing to the drug’s psychological effects, and it does not lead to treatment discontinuation, said Dr. Passie, who described his clinical experiences with ketamine.

Since ketamine causes a considerable clouding of consciousness, sensory disorders, and significant memory problems, it is not suitable for psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, unlike LSD or psilocybin, he emphasized.

Ketamine 2.0?

Esketamine, the pure S-enantiomer of ketamine, has been on the market since 2019 in the form of a nasal spray (Spravato). Esketamine has been approved in combination with oral antidepressant therapy for adults with a moderate to severe episode of major depression for acute treatment of a psychiatric emergency.

A meta-analysis from 2022 concluded that the original racemic ketamine is better than the new esketamine in reducing symptoms of depression.

In his own comprehensive study, Dr. Passie concluded that the mental impairments that occur during therapy did not differ significantly between substances. The patients even felt that the side effects from esketamine therapy were much more mentally unpleasant, said Dr. Passie. He concluded that the R-enantiomer may have a kind of protective effect against some of the psychopathological effects of the S-enantiomer (esketamine).

In addition, preclinical studies have indicated that the antidepressant effects of R-enantiomer, which is not contained in esketamine, are longer lasting and stronger.

Another problem is absorption, which can be inconsistent with a nasal spray. It may differ, for example, depending on the ambient humidity or whether the patient has recently had a cold. In addition, the spray is far more expensive than the ketamine injection, said Dr. Passie. Patients must also use the nasal spray under supervision at a medical practice (as with the intravenous application) and must receive follow-up care there. It therefore offers no advantage over the ketamine injection.

According to the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare, no additional benefit has been proven for esketamine over standard therapies for adults who have experienced a moderate to severe depressive episode when used as short-term treatment for the rapid reduction of depressive symptoms in a psychiatric emergency. The German Medical Association agreed with this evaluation in October 2021.

In the United Kingdom, the medication was never approved, owing to the fact that it was too expensive and that no studies comparing it with psychotherapy were available.

Add-on psilocybin?

What was experienced under the influence of psilocybin can also be subsequently processed and used in psychotherapy.

The acute effect of psilocybin begins after approximately 40 minutes and lasts for 4-6 hours. The antidepressant effect, if it occurs at all, is of immediate onset. Unlike ketamine/esketamine, psilocybin hardly has any physical side effects.

The neurologic mechanism of action has been investigated recently using fMRI and PET techniques. According to the investigations, the substance causes individual networks of activity in the patient’s brain to interconnect more strongly, said Dr. Passie. The thalamus, the filter station for sensory information, as well as the limbic and paralimbic structures, which generate emotions, and the cortex are all activated more strongly.

Two therapeutic settings

Psilocybin, at least in the context of studies, is used in two settings: psycholytic therapy and psychedelic therapy. Both settings originated in the 1950s and were also used with LSD as the active substance.

Psycholytic therapy with psilocybin entails multiple administrations at low doses (for example, 10-18 mg), incorporated into a longer, mostly psychodynamic therapy of around 50-100 hours (often on an inpatient basis at the beginning). It results in what is described as an extended encounter with oneself. The focus is on psychodynamic experiences, such as memories and internal conflicts. In addition, novel experiences with oneself and self-recognition are important.

Psychedelic therapy generally entails one or two sessions with a high dose (for example, 25-35 mg psilocybin). The preparation and follow-up are limited to a few sessions. These methods refer to so-called transpersonal psychology, which addresses extraordinary states of consciousness in line with religious experiences. It often leads to an intense self-confrontation as well as to new evaluations of self and world. The central element to this therapy is the experience of a mystical ego loss and the concomitant feeling of connectedness, which should help to expand one’s perspective.

Euphoria and disillusionment

The first promising studies with a few patients suffering from depression were followed by others in which the euphoria was allowed to fade away somewhat. In the first direct comparison in a methodically high-grade double-blind study, psilocybin was inferior to the SSRI antidepressant escitalopram.

“There is a great variation in response from person to person,” said Dr. Passie. “The better the study is methodically controlled, the worse the results,” he hypothesized.

“Since the method is up to 50 times more expensive in practice, compared to SSRI therapy over 6-12 weeks, the question clearly must be asked as to whether it really has any great future.”

Outlook for psilocybin

Nevertheless, Dr. Passie still sees potential in psilocybin. He considers an approach in which psilocybin therapy is more firmly incorporated into psychotherapy, with between four and 10 therapy sessions before and after administration of a lower therapeutic dose of the substance, to be more promising.

“With this kind of intensive preparation and follow-up, as well as the repeated psilocybin sessions, the patient can benefit much more than is possible with one or two high-dose sessions,” said Dr. Passie, who also is chair of the International Society for Substance-Assisted Psychotherapy. “The constant ‘in-depth work on the ego’ required for drastic therapeutic changes can be more effective and lead to permanent improvements. I have no doubt about this.”

In Dr. Passie’s opinion, the best approach would involve a dignified inpatient setting with a longer period of follow-up care and consistent posttreatment care, including group therapy. The shape of future psilocybin therapy depends on whether the rather abrupt change seen with high-dose psychedelic therapy is permanent. The answer to this question will be decisive for the method and manner of its future clinical use.

Because of the somewhat negative study results, however, the initial investors are pulling out. Dr. Passie is therefore skeptical about whether the necessary larger studies will take place and whether psilocybin will make it onto the market.

In Switzerland, which is not subject to EU restrictions, more than 30 physicians have been authorized to use psilocybin, LSD, and MDMA in psychotherapy sessions. Still, in some respects this is a special case that cannot be transferred easily to other countries, said Dr. Passie.

Possible psilocybin improvement?

Various chemical derivatives of psychoactive substances have been researched, including a psilocybin variant with the label CYB003. With CYB003, the length of the acute psychedelic experience is reduced from around 6 hours (such as with psilocybin) to 1 hour. The plasma concentration of the substance is less variable between different patients. It is assumed that its effects will also differ less from person to person.

In July, researchers began a study of the use of CYB003 in the treatment of major depression. In the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with 40 patients, multiple doses of the substance will be administered.

When asked, Dr. Passie was rather skeptical about the study. He considers the approaches with psilocybin derivatives to be the consequences of a “gold-rush atmosphere” and expects there will be no real additional benefit, especially not a reduction in the period of action.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Doctors using fake positive reviews to boost business

Five years ago, Kay Dean relied upon Yelp! and Google reviews in her search for a doctor in her area. After finding a physician with fairly high reviews, Ms. Dean was shocked when her personal experience was significantly worse than patients on the review platforms.

Following her experience, Ms. Dean, a former federal government investigator, became skeptical and used her skills to investigate the practice on all review platforms. She uncovered that the practice had a review from an individual who was involved in a review trading group on Facebook, where organizations openly barter their services in exchange for positive reviews fraud.

“I discovered that the online review world was just saturated with fake reviews, much more so than I think most people are aware ... and law enforcement regulators aren’t doing anything to address the problem,” said Ms. Dean. “In this online space, it’s the Wild West; cheating is rewarded.”

Ms. Dean decided to take matters into her own hands. She created a YouTube channel called Fake Review Watch, where she exposes real businesses and their attempts to dupe potential consumers with fake positive reviews.

For example, one video analyzes an orthopedic surgeon in Manhattan with an abundance of five-star reviews. Through her detailed analysis, Ms. Dean created a spreadsheet of the 26 alleged patients of the orthopedic surgeon that had submitted glowing reviews. She looked into other businesses that the individuals had left reviews for and found a significant amount of overlap.

According to the video, 19 of the doctor’s reviewers had left high reviews for the same moving company in Las Vegas, and 18 of them reviewed the same locksmith in Texas. Overall, eight of the patients reviewed the same mover, locksmith, and hotel in New Zealand.

A matter of trust

Ms. Dean expressed the gravity of this phenomenon, especially in health care, as patients often head online first when searching for care options. Based on a survey by Software Advice, about 84% of patients use online reviews to assess a physician, and 77% use review sites as the first step in finding a doctor.

Patient trust has continued to diminish in recent years, particularly following the pandemic. In a 2021 global ranking of trust levels towards health care by country, the U.S. health care system ranked 19th, far below those of several developing countries.

Owing to the rise of fake patient reviews and their inscrutable nature, Ms. Dean advises staying away from online review platforms. Instead, she suggests sticking to the old-fashioned method of getting recommendations from friends and relatives, not virtual people.

Ms. Dean explained a few indicators that she looks for when trying to identify a fake review.

“The business has all five-star reviews, negative reviews are followed by five-star reviews, or the business has an abnormal number of positive reviews in a short period of time,” she noted. “Some businesses try to bury legitimate negative reviews by obtaining more recent, fake, positive ones. The recent reviews will contradict the specific criticisms in the negative review.”

She warned that consumers should not give credibility to reviews simply because the reviewer is dubbed “Elite” or a Google Local Guide, because she has seen plenty of these individuals posting fake reviews.

Unfortunately, review platforms haven’t been doing much self-policing. Google and Healthgrades have a series of policies against fake engagement, impersonation, misinformation, and misrepresentation, according to their websites. However, the only consequence of these violations is review removal.

Both Yelp! and Google say they have automated software that distinguishes real versus fake reviews. When Yelp! uncovers users engaging in compensation review activity, it removes their reviews, closes their account, and blocks those users from creating future Yelp! accounts.

Physicians’ basis

Moreover,

“I think there’s an erosion of business ethics because cheating is rewarded. You can’t compete in an environment where your competition is allowed to accumulate numerous fake reviews while you’re still trying to fill chairs in your business,” said Ms. Dean. “Your competition is then getting the business because the tech companies are allowing this fraud.”

Family physician and practice owner Mike Woo-Ming, MD, MPH, provides career coaching for physicians, including maintaining a good reputation – in-person and online. He has seen physicians bumping up their own five-star reviews personally as well as posting negative reviews for their competition.

“I’ve seen where they’re going to lose business, as many practices were affected through COVID,” he said. “Business owners can become desperate and may decide to start posting or buying reviews because they know people will choose certain services these days based upon reviews.”

Dr. Woo-Ming expressed his frustration with fellow physicians who give in to purchasing fake reviews, because the patients have no idea whether reviews are genuine or not.

To encourage genuine positive reviews, Dr. Woo-Ming’s practice uses a third-party app system that sends patients a follow-up email or text asking about their experience with a link to review sites.

“Honest reviews are a reflection of what I can do to improve my business. At the end of the day, if you’re truly providing great service and you’re helping people by providing great medical care, those are going to win out,” he said. “I would rather, as a responsible practice owner, improve the experience and outcome for the patient.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Five years ago, Kay Dean relied upon Yelp! and Google reviews in her search for a doctor in her area. After finding a physician with fairly high reviews, Ms. Dean was shocked when her personal experience was significantly worse than patients on the review platforms.

Following her experience, Ms. Dean, a former federal government investigator, became skeptical and used her skills to investigate the practice on all review platforms. She uncovered that the practice had a review from an individual who was involved in a review trading group on Facebook, where organizations openly barter their services in exchange for positive reviews fraud.

“I discovered that the online review world was just saturated with fake reviews, much more so than I think most people are aware ... and law enforcement regulators aren’t doing anything to address the problem,” said Ms. Dean. “In this online space, it’s the Wild West; cheating is rewarded.”

Ms. Dean decided to take matters into her own hands. She created a YouTube channel called Fake Review Watch, where she exposes real businesses and their attempts to dupe potential consumers with fake positive reviews.

For example, one video analyzes an orthopedic surgeon in Manhattan with an abundance of five-star reviews. Through her detailed analysis, Ms. Dean created a spreadsheet of the 26 alleged patients of the orthopedic surgeon that had submitted glowing reviews. She looked into other businesses that the individuals had left reviews for and found a significant amount of overlap.

According to the video, 19 of the doctor’s reviewers had left high reviews for the same moving company in Las Vegas, and 18 of them reviewed the same locksmith in Texas. Overall, eight of the patients reviewed the same mover, locksmith, and hotel in New Zealand.

A matter of trust

Ms. Dean expressed the gravity of this phenomenon, especially in health care, as patients often head online first when searching for care options. Based on a survey by Software Advice, about 84% of patients use online reviews to assess a physician, and 77% use review sites as the first step in finding a doctor.

Patient trust has continued to diminish in recent years, particularly following the pandemic. In a 2021 global ranking of trust levels towards health care by country, the U.S. health care system ranked 19th, far below those of several developing countries.

Owing to the rise of fake patient reviews and their inscrutable nature, Ms. Dean advises staying away from online review platforms. Instead, she suggests sticking to the old-fashioned method of getting recommendations from friends and relatives, not virtual people.

Ms. Dean explained a few indicators that she looks for when trying to identify a fake review.

“The business has all five-star reviews, negative reviews are followed by five-star reviews, or the business has an abnormal number of positive reviews in a short period of time,” she noted. “Some businesses try to bury legitimate negative reviews by obtaining more recent, fake, positive ones. The recent reviews will contradict the specific criticisms in the negative review.”

She warned that consumers should not give credibility to reviews simply because the reviewer is dubbed “Elite” or a Google Local Guide, because she has seen plenty of these individuals posting fake reviews.

Unfortunately, review platforms haven’t been doing much self-policing. Google and Healthgrades have a series of policies against fake engagement, impersonation, misinformation, and misrepresentation, according to their websites. However, the only consequence of these violations is review removal.

Both Yelp! and Google say they have automated software that distinguishes real versus fake reviews. When Yelp! uncovers users engaging in compensation review activity, it removes their reviews, closes their account, and blocks those users from creating future Yelp! accounts.

Physicians’ basis

Moreover,

“I think there’s an erosion of business ethics because cheating is rewarded. You can’t compete in an environment where your competition is allowed to accumulate numerous fake reviews while you’re still trying to fill chairs in your business,” said Ms. Dean. “Your competition is then getting the business because the tech companies are allowing this fraud.”

Family physician and practice owner Mike Woo-Ming, MD, MPH, provides career coaching for physicians, including maintaining a good reputation – in-person and online. He has seen physicians bumping up their own five-star reviews personally as well as posting negative reviews for their competition.

“I’ve seen where they’re going to lose business, as many practices were affected through COVID,” he said. “Business owners can become desperate and may decide to start posting or buying reviews because they know people will choose certain services these days based upon reviews.”

Dr. Woo-Ming expressed his frustration with fellow physicians who give in to purchasing fake reviews, because the patients have no idea whether reviews are genuine or not.

To encourage genuine positive reviews, Dr. Woo-Ming’s practice uses a third-party app system that sends patients a follow-up email or text asking about their experience with a link to review sites.

“Honest reviews are a reflection of what I can do to improve my business. At the end of the day, if you’re truly providing great service and you’re helping people by providing great medical care, those are going to win out,” he said. “I would rather, as a responsible practice owner, improve the experience and outcome for the patient.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Five years ago, Kay Dean relied upon Yelp! and Google reviews in her search for a doctor in her area. After finding a physician with fairly high reviews, Ms. Dean was shocked when her personal experience was significantly worse than patients on the review platforms.

Following her experience, Ms. Dean, a former federal government investigator, became skeptical and used her skills to investigate the practice on all review platforms. She uncovered that the practice had a review from an individual who was involved in a review trading group on Facebook, where organizations openly barter their services in exchange for positive reviews fraud.

“I discovered that the online review world was just saturated with fake reviews, much more so than I think most people are aware ... and law enforcement regulators aren’t doing anything to address the problem,” said Ms. Dean. “In this online space, it’s the Wild West; cheating is rewarded.”

Ms. Dean decided to take matters into her own hands. She created a YouTube channel called Fake Review Watch, where she exposes real businesses and their attempts to dupe potential consumers with fake positive reviews.

For example, one video analyzes an orthopedic surgeon in Manhattan with an abundance of five-star reviews. Through her detailed analysis, Ms. Dean created a spreadsheet of the 26 alleged patients of the orthopedic surgeon that had submitted glowing reviews. She looked into other businesses that the individuals had left reviews for and found a significant amount of overlap.

According to the video, 19 of the doctor’s reviewers had left high reviews for the same moving company in Las Vegas, and 18 of them reviewed the same locksmith in Texas. Overall, eight of the patients reviewed the same mover, locksmith, and hotel in New Zealand.

A matter of trust

Ms. Dean expressed the gravity of this phenomenon, especially in health care, as patients often head online first when searching for care options. Based on a survey by Software Advice, about 84% of patients use online reviews to assess a physician, and 77% use review sites as the first step in finding a doctor.

Patient trust has continued to diminish in recent years, particularly following the pandemic. In a 2021 global ranking of trust levels towards health care by country, the U.S. health care system ranked 19th, far below those of several developing countries.

Owing to the rise of fake patient reviews and their inscrutable nature, Ms. Dean advises staying away from online review platforms. Instead, she suggests sticking to the old-fashioned method of getting recommendations from friends and relatives, not virtual people.

Ms. Dean explained a few indicators that she looks for when trying to identify a fake review.

“The business has all five-star reviews, negative reviews are followed by five-star reviews, or the business has an abnormal number of positive reviews in a short period of time,” she noted. “Some businesses try to bury legitimate negative reviews by obtaining more recent, fake, positive ones. The recent reviews will contradict the specific criticisms in the negative review.”

She warned that consumers should not give credibility to reviews simply because the reviewer is dubbed “Elite” or a Google Local Guide, because she has seen plenty of these individuals posting fake reviews.

Unfortunately, review platforms haven’t been doing much self-policing. Google and Healthgrades have a series of policies against fake engagement, impersonation, misinformation, and misrepresentation, according to their websites. However, the only consequence of these violations is review removal.

Both Yelp! and Google say they have automated software that distinguishes real versus fake reviews. When Yelp! uncovers users engaging in compensation review activity, it removes their reviews, closes their account, and blocks those users from creating future Yelp! accounts.

Physicians’ basis

Moreover,

“I think there’s an erosion of business ethics because cheating is rewarded. You can’t compete in an environment where your competition is allowed to accumulate numerous fake reviews while you’re still trying to fill chairs in your business,” said Ms. Dean. “Your competition is then getting the business because the tech companies are allowing this fraud.”

Family physician and practice owner Mike Woo-Ming, MD, MPH, provides career coaching for physicians, including maintaining a good reputation – in-person and online. He has seen physicians bumping up their own five-star reviews personally as well as posting negative reviews for their competition.

“I’ve seen where they’re going to lose business, as many practices were affected through COVID,” he said. “Business owners can become desperate and may decide to start posting or buying reviews because they know people will choose certain services these days based upon reviews.”

Dr. Woo-Ming expressed his frustration with fellow physicians who give in to purchasing fake reviews, because the patients have no idea whether reviews are genuine or not.

To encourage genuine positive reviews, Dr. Woo-Ming’s practice uses a third-party app system that sends patients a follow-up email or text asking about their experience with a link to review sites.

“Honest reviews are a reflection of what I can do to improve my business. At the end of the day, if you’re truly providing great service and you’re helping people by providing great medical care, those are going to win out,” he said. “I would rather, as a responsible practice owner, improve the experience and outcome for the patient.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Why our brains wear out at the end of the day

The transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Once again, we’re doing an informal journal club to talk about a really interesting study, “A Neuro-metabolic Account of Why Daylong Cognitive Work Alters the Control of Economic Decisions,” that just came out. It tries to answer the question of why our brains wear out. I’m going to put myself in the corner here. Let’s walk through this study, which appears in Current Biology, by lead author Antonius Wiehler from Paris.

The big question is what’s going on with cognitive fatigue. If you look at chess players who are exerting a lot of cognitive effort, it’s well documented that over hours of play, they get worse and make more mistakes. It takes them longer to make decisions. The question is, why?

Why does your brain get tired?

To date, it’s been a little bit hard to tease that out. Now, there is some suggestion of what is responsible for this. The cognitive control center of the brain is probably somewhere in the left lateral prefrontal cortex (LLPC).

The prefrontal cortex is responsible for higher-level thinking. It’s what causes you to be inhibited. It gets shut off by alcohol and leads to impulsive behaviors. The LLPC, according to functional MRI studies, has reduced activity as people become more and more cognitively fatigued. The LLPC helps you think through choices. As you become more fatigued, this area of the brain isn’t working as well. But why would it not work as well? What is going on in that particular part of the brain? It doesn’t seem to be something simple, like glucose levels; that’s been investigated and glucose levels are pretty constant throughout the brain, regardless of cognitive task. This paper seeks to tease out what is actually going on in the LLPC when you are becoming cognitively tired.

They did an experiment where they induced cognitive fatigue, and it sounds like a painful experiment. For more than 6 hours, volunteers completed sessions during which they had to perform cognitive switching tasks. Investigators showed participants a letter, in either red or green, and the participant would respond with whether it was a vowel or a consonant or whether it was a capital or lowercase letter, based on the color. If it’s red, say whether it’s a consonant or vowel. If it’s green, say whether it’s upper- or lowercase.

It’s hard, and doing it for 6 hours is likely to induce a lot of cognitive fatigue. They had a control group as well, which is really important here. The control group also did a task like this for 6 hours, but for them, investigators didn’t change the color as often – perhaps only once per session. For the study group, they were switching colors back and forth quite a lot. They also incorporated a memory challenge that worked in a similar way.

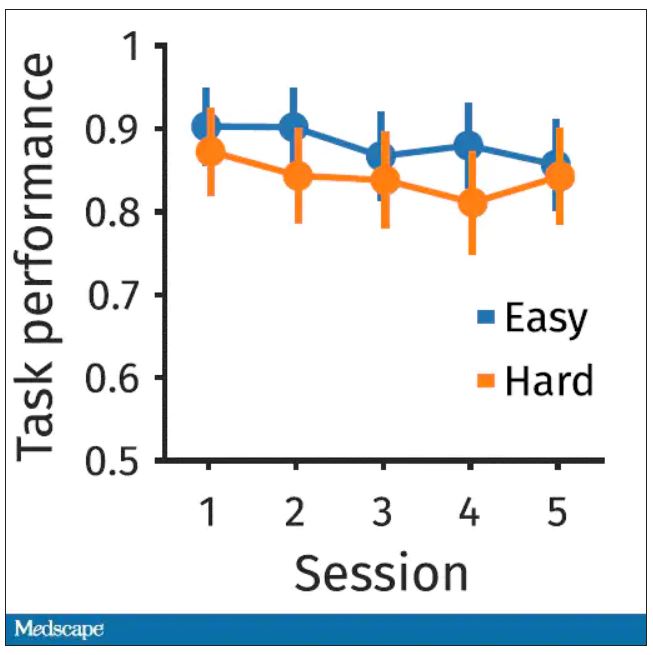

So, what are the readouts of this study? They had a group who went through the hard cognitive challenge and a group who went through the easy cognitive challenge. They looked at a variety of metrics. I’ll describe a few.

The first is performance decrement. Did they get it wrong? What percentage of the time did the participant say “consonant” when they should have said “lowercase?”

You can see here that the hard group did a little bit worse overall. It was harder, so they don’t do as well. That makes sense. But both groups kind of waned over time a little bit. It’s not as though the hard group declines much more. The slopes of those lines are pretty similar. So, not very robust findings there.

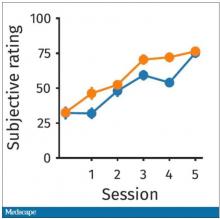

What about subjective fatigue? They asked the participants how exhausted they were from doing the tasks.

Both groups were worn out. It was a long day. There was a suggestion that the hard group became worn out a little bit sooner, but I don’t think this achieves statistical significance. Everyone was getting tired by hour 6 here.

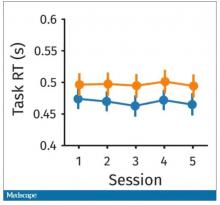

What about response time? How quickly could the participant say “consonant,” “vowel,” “lowercase,” or “uppercase?”

The hard group took longer to respond because it was a harder task. But over time, the response times were pretty flat.

So far there isn’t a robust readout that would make us say, oh, yeah, that is a good marker of cognitive fatigue. That’s how you measure cognitive fatigue. It’s not what people say. It’s not how quick they are. It’s not even how accurate they are.

But then the investigators got a little bit clever. Participants were asked to play a “would you rather” game, a reward game. Here are two examples.

Would you rather:

- Have a 25% chance of earning $50 OR a 95% chance of earning $17.30?

- Earn $50, but your next task session will be hard or earn $40 and your next task session will be easy?

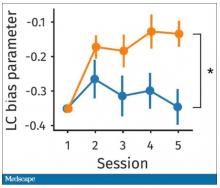

Participants had to figure out the better odds – what should they be choosing here? They had to tease out whether they preferred lower cost lower-risk choices – when they are cognitively fatigued, which has been shown in prior studies.

This showed a pretty dramatic difference between the groups in terms of the low-cost bias – how much more likely they were to pick the low-cost, easier choice as they became more and more cognitively fatigued. The hard group participants were more likely to pick the easy thing rather than the potentially more lucrative thing, which is really interesting when we think about how our own cognitive fatigue happens at the end of a difficult workday, how you may just be likely to go with the flow and do something easy because you just don’t have that much decision-making power left.

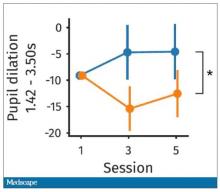

It would be nice to have some objective physiologic measurements for this, and they do. This is pupil dilation.

When you’re paying attention to something, your pupils dilate a little bit. They were able to show that as the hard group became more and more fatigued, pupil dilation sort of went away. In fact, if anything, their pupils constricted a little bit. But basically there was a significant difference here. The easy group’s pupils were still fine; they were still dilating. The hard group’s pupils got more sluggish. This is a physiologic correlate of what’s going on.

But again, these are all downstream of whatever is happening in the LLPC. So the real meat of this study is a functional MRI analysis, and the way they did this is pretty clever. They were looking for metabolites in the various parts of the brain using a labeled hydrogen MRI, which is even fancier than a functional MRI. It’s like MRI spectroscopy, and it can measure the levels of certain chemicals in the brain. They hypothesized that if there is a chemical that builds up when you are tired, it should build up preferentially in the LLPC.

Whereas in the rest of the brain, there shouldn’t be that much difference because we know the action is happening in the LLPC. The control part of the brain is a section called V1. They looked at a variety of metabolites, but the only one that behaved the way they expected was glutamate and glutamic acid (glutamate metabolites). In the hard group, the glutamate is building up over time, so there is a higher concentration of glutamate in the LLPC but not the rest of the brain. There is also a greater diffusion of glutamate from the intracellular to the extracellular space, which suggests that it’s kind of leaking out of the cells.

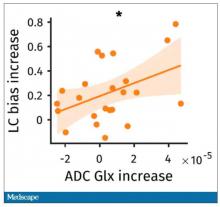

So the signal here is that the thing that’s impacting that part of the brain is this buildup of glutamate. To tie this together, they showed in the scatterplot the relationship between the increase in glutamate and the low-cost bias from the decision fatigue example.

It’s not the strongest correlation, but it is statistically significant that the more glutamate in your LLPC, the more likely you are to just take the easy decision as opposed to really thinking things through. That is pretty powerful. It’s telling us that your brain making you fatigued, and making you less likely to continue to use your LLPC, may be a self-defense mechanism against a buildup of glutamate, which may be neurotoxic. And that’s a fascinating bit of homeostasis.

Of course, it makes you wonder how we might adjust glutamate levels in the brain, although maybe we should let the brain be tired if the brain wants to be tired. It reminds me of that old Far Side cartoon where the guy is raising his hand and asking: “Can I be excused? My brain is full.” That is essentially what’s happening. This part of your brain is becoming taxed and building up glutamate. There’s some kind of negative feedback loop. The authors don’t know what the receptor pathway is that down-regulates that part of the brain based on the glutamate buildup, but some kind of negative feedback loop is saying, okay, give this part of the brain a rest. Things have gone on too far here.

It’s a fascinating study, although it’s not clear what we can do with this information. It’s not clear whether we can manipulate glutamate levels in this particular part of the brain or not. But it’s nice to see some biologic correlates of a psychological phenomenon that is incredibly well described – the phenomenon of decision fatigue. I think we all feel it at the end of a hard workday. If you’ve been doing a lot of cognitively intensive tasks, you just don’t have it in you anymore. And maybe the act of a good night’s sleep is clearing out some of that glutamate in the LLPC, which lets you start over and make some good decisions again. So I hope you all make some good decisions and keep your glutamate levels low. And I’ll see you next time.

For Medscape, I’m Perry Wilson.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Once again, we’re doing an informal journal club to talk about a really interesting study, “A Neuro-metabolic Account of Why Daylong Cognitive Work Alters the Control of Economic Decisions,” that just came out. It tries to answer the question of why our brains wear out. I’m going to put myself in the corner here. Let’s walk through this study, which appears in Current Biology, by lead author Antonius Wiehler from Paris.

The big question is what’s going on with cognitive fatigue. If you look at chess players who are exerting a lot of cognitive effort, it’s well documented that over hours of play, they get worse and make more mistakes. It takes them longer to make decisions. The question is, why?

Why does your brain get tired?

To date, it’s been a little bit hard to tease that out. Now, there is some suggestion of what is responsible for this. The cognitive control center of the brain is probably somewhere in the left lateral prefrontal cortex (LLPC).

The prefrontal cortex is responsible for higher-level thinking. It’s what causes you to be inhibited. It gets shut off by alcohol and leads to impulsive behaviors. The LLPC, according to functional MRI studies, has reduced activity as people become more and more cognitively fatigued. The LLPC helps you think through choices. As you become more fatigued, this area of the brain isn’t working as well. But why would it not work as well? What is going on in that particular part of the brain? It doesn’t seem to be something simple, like glucose levels; that’s been investigated and glucose levels are pretty constant throughout the brain, regardless of cognitive task. This paper seeks to tease out what is actually going on in the LLPC when you are becoming cognitively tired.

They did an experiment where they induced cognitive fatigue, and it sounds like a painful experiment. For more than 6 hours, volunteers completed sessions during which they had to perform cognitive switching tasks. Investigators showed participants a letter, in either red or green, and the participant would respond with whether it was a vowel or a consonant or whether it was a capital or lowercase letter, based on the color. If it’s red, say whether it’s a consonant or vowel. If it’s green, say whether it’s upper- or lowercase.

It’s hard, and doing it for 6 hours is likely to induce a lot of cognitive fatigue. They had a control group as well, which is really important here. The control group also did a task like this for 6 hours, but for them, investigators didn’t change the color as often – perhaps only once per session. For the study group, they were switching colors back and forth quite a lot. They also incorporated a memory challenge that worked in a similar way.

So, what are the readouts of this study? They had a group who went through the hard cognitive challenge and a group who went through the easy cognitive challenge. They looked at a variety of metrics. I’ll describe a few.

The first is performance decrement. Did they get it wrong? What percentage of the time did the participant say “consonant” when they should have said “lowercase?”

You can see here that the hard group did a little bit worse overall. It was harder, so they don’t do as well. That makes sense. But both groups kind of waned over time a little bit. It’s not as though the hard group declines much more. The slopes of those lines are pretty similar. So, not very robust findings there.

What about subjective fatigue? They asked the participants how exhausted they were from doing the tasks.

Both groups were worn out. It was a long day. There was a suggestion that the hard group became worn out a little bit sooner, but I don’t think this achieves statistical significance. Everyone was getting tired by hour 6 here.

What about response time? How quickly could the participant say “consonant,” “vowel,” “lowercase,” or “uppercase?”

The hard group took longer to respond because it was a harder task. But over time, the response times were pretty flat.

So far there isn’t a robust readout that would make us say, oh, yeah, that is a good marker of cognitive fatigue. That’s how you measure cognitive fatigue. It’s not what people say. It’s not how quick they are. It’s not even how accurate they are.

But then the investigators got a little bit clever. Participants were asked to play a “would you rather” game, a reward game. Here are two examples.

Would you rather:

- Have a 25% chance of earning $50 OR a 95% chance of earning $17.30?

- Earn $50, but your next task session will be hard or earn $40 and your next task session will be easy?

Participants had to figure out the better odds – what should they be choosing here? They had to tease out whether they preferred lower cost lower-risk choices – when they are cognitively fatigued, which has been shown in prior studies.

This showed a pretty dramatic difference between the groups in terms of the low-cost bias – how much more likely they were to pick the low-cost, easier choice as they became more and more cognitively fatigued. The hard group participants were more likely to pick the easy thing rather than the potentially more lucrative thing, which is really interesting when we think about how our own cognitive fatigue happens at the end of a difficult workday, how you may just be likely to go with the flow and do something easy because you just don’t have that much decision-making power left.

It would be nice to have some objective physiologic measurements for this, and they do. This is pupil dilation.

When you’re paying attention to something, your pupils dilate a little bit. They were able to show that as the hard group became more and more fatigued, pupil dilation sort of went away. In fact, if anything, their pupils constricted a little bit. But basically there was a significant difference here. The easy group’s pupils were still fine; they were still dilating. The hard group’s pupils got more sluggish. This is a physiologic correlate of what’s going on.

But again, these are all downstream of whatever is happening in the LLPC. So the real meat of this study is a functional MRI analysis, and the way they did this is pretty clever. They were looking for metabolites in the various parts of the brain using a labeled hydrogen MRI, which is even fancier than a functional MRI. It’s like MRI spectroscopy, and it can measure the levels of certain chemicals in the brain. They hypothesized that if there is a chemical that builds up when you are tired, it should build up preferentially in the LLPC.

Whereas in the rest of the brain, there shouldn’t be that much difference because we know the action is happening in the LLPC. The control part of the brain is a section called V1. They looked at a variety of metabolites, but the only one that behaved the way they expected was glutamate and glutamic acid (glutamate metabolites). In the hard group, the glutamate is building up over time, so there is a higher concentration of glutamate in the LLPC but not the rest of the brain. There is also a greater diffusion of glutamate from the intracellular to the extracellular space, which suggests that it’s kind of leaking out of the cells.

So the signal here is that the thing that’s impacting that part of the brain is this buildup of glutamate. To tie this together, they showed in the scatterplot the relationship between the increase in glutamate and the low-cost bias from the decision fatigue example.

It’s not the strongest correlation, but it is statistically significant that the more glutamate in your LLPC, the more likely you are to just take the easy decision as opposed to really thinking things through. That is pretty powerful. It’s telling us that your brain making you fatigued, and making you less likely to continue to use your LLPC, may be a self-defense mechanism against a buildup of glutamate, which may be neurotoxic. And that’s a fascinating bit of homeostasis.

Of course, it makes you wonder how we might adjust glutamate levels in the brain, although maybe we should let the brain be tired if the brain wants to be tired. It reminds me of that old Far Side cartoon where the guy is raising his hand and asking: “Can I be excused? My brain is full.” That is essentially what’s happening. This part of your brain is becoming taxed and building up glutamate. There’s some kind of negative feedback loop. The authors don’t know what the receptor pathway is that down-regulates that part of the brain based on the glutamate buildup, but some kind of negative feedback loop is saying, okay, give this part of the brain a rest. Things have gone on too far here.

It’s a fascinating study, although it’s not clear what we can do with this information. It’s not clear whether we can manipulate glutamate levels in this particular part of the brain or not. But it’s nice to see some biologic correlates of a psychological phenomenon that is incredibly well described – the phenomenon of decision fatigue. I think we all feel it at the end of a hard workday. If you’ve been doing a lot of cognitively intensive tasks, you just don’t have it in you anymore. And maybe the act of a good night’s sleep is clearing out some of that glutamate in the LLPC, which lets you start over and make some good decisions again. So I hope you all make some good decisions and keep your glutamate levels low. And I’ll see you next time.

For Medscape, I’m Perry Wilson.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Once again, we’re doing an informal journal club to talk about a really interesting study, “A Neuro-metabolic Account of Why Daylong Cognitive Work Alters the Control of Economic Decisions,” that just came out. It tries to answer the question of why our brains wear out. I’m going to put myself in the corner here. Let’s walk through this study, which appears in Current Biology, by lead author Antonius Wiehler from Paris.

The big question is what’s going on with cognitive fatigue. If you look at chess players who are exerting a lot of cognitive effort, it’s well documented that over hours of play, they get worse and make more mistakes. It takes them longer to make decisions. The question is, why?

Why does your brain get tired?

To date, it’s been a little bit hard to tease that out. Now, there is some suggestion of what is responsible for this. The cognitive control center of the brain is probably somewhere in the left lateral prefrontal cortex (LLPC).

The prefrontal cortex is responsible for higher-level thinking. It’s what causes you to be inhibited. It gets shut off by alcohol and leads to impulsive behaviors. The LLPC, according to functional MRI studies, has reduced activity as people become more and more cognitively fatigued. The LLPC helps you think through choices. As you become more fatigued, this area of the brain isn’t working as well. But why would it not work as well? What is going on in that particular part of the brain? It doesn’t seem to be something simple, like glucose levels; that’s been investigated and glucose levels are pretty constant throughout the brain, regardless of cognitive task. This paper seeks to tease out what is actually going on in the LLPC when you are becoming cognitively tired.

They did an experiment where they induced cognitive fatigue, and it sounds like a painful experiment. For more than 6 hours, volunteers completed sessions during which they had to perform cognitive switching tasks. Investigators showed participants a letter, in either red or green, and the participant would respond with whether it was a vowel or a consonant or whether it was a capital or lowercase letter, based on the color. If it’s red, say whether it’s a consonant or vowel. If it’s green, say whether it’s upper- or lowercase.

It’s hard, and doing it for 6 hours is likely to induce a lot of cognitive fatigue. They had a control group as well, which is really important here. The control group also did a task like this for 6 hours, but for them, investigators didn’t change the color as often – perhaps only once per session. For the study group, they were switching colors back and forth quite a lot. They also incorporated a memory challenge that worked in a similar way.