User login

‘Not in our lane’: Physicians rebel at idea they should discuss gun safety with patients

The latest NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll shows that that the margin of public opinion in the United States is the widest that it has been during the past 10 years in favor of taking steps to control gun violence; 59% of U.S. adults said it’s more important to control gun violence than to protect gun rights, and 35% said the opposite.

Have physicians’ opinions about gun issues in our country shifted meaningfully during that period? That’s a complex question that can be informed with the basic snapshot provided by doctors› comments to New York University (and Medscape blogger) bioethicist Arthur L. Caplan’s four video blogs on whether physicians should discuss gun safety with their patients. Dr. Caplan’s video blogs appeared on the Medscape website in 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2022.

Hundreds of physicians have posted comments to Dr. Caplan’s arguments that doctors should bring up gun safety when talking to their patients. The great majority of comments opposed his position in 2014, and that remained the case through 2022, regardless of incidents of gun-related violence. Supportive comments have been a small minority that has grown only slightly over his four video blogs.

Physicians’ lack of qualifications

The most prevalent counterarguments expressed against Dr. Caplan’s position are that physicians lack the proper knowledge to discuss gun safety with patients; and the responsibility falls on family members, certified firearms instructors, teachers, and others – but not doctors – to educate people about firearm safety.

“Then there’s a third group that says, ‘I don’t want to do this because I am too busy trying to figure out what is wrong with the patient,’ ” Dr. Caplan says.

Here are a few on-point comments that were posted to his video blogs:

- “Unless physicians become certified firearms instructors like myself, they are not qualified to talk to patients on the subject and should advise patients to find a program and take a course.” – Dr. Ken Long, March 31, 2014

- “Gun safety should be taught in school, just like health and sex education.” – Patricia L., Feb. 11, 2016

- “None of my medical or surgical training or experience qualifies me as a policy expert on gun laws or regulations.” – Dr. Kelly Hyde, Dec. 23, 2018

- “I have the Constitution hanging in my office with an NRA plaque next to it. Most MDs can’t mow their own yard.” – Dr. Brian Anseeuw, June 21, 2022

Do mental health issues trump gun talks?

Another counterargument to discussing gun safety with patients involves mental health issues that many physicians may not be trained to address. Mental health entered comments to Dr. Caplan’s video blogs in 2016 and has shaped much of the discussion since.

- “First of all, two-thirds of gun deaths are suicides. It is foolish to talk about counseling patients about gun safety, etc, and ignore the mental health issues.” – Dr. Jeffrey Jennings, Jan. 25, 2016

- “Suicide victims and those committing mass shootings are mentally ill. ... Blame society, drugs, mental illness, easy access to illegal firearms, and poor recognition of SOS (signs of suicide).” – Dr. Alan DeCarlo, Dec. 24, 2018

- “Yes, we have gun violence, but what is the underlying problem? Bullying? Mental issues? Not enough parental supervision? These and others are the issues I feel need to be discussed.” – T. Deese, June 24, 2022

- “The causes of increased gun violence are mental health, problems with bullying, social media, and normalization of deviant behavior.” – Julie Johng, 2022

Added responsibility is too much

Another theme that has grown over time is that talks of gun safety just heap issues onto physicians’ treatment plates that are already too full.

- “Oh, for God’s sake, is there anything else I can do while I›m at it? Primary care has gotten to be more headache than it’s worth. Thanks for another reason to think about retiring.” – Dr. Kathleen Collins, March 31, 2014

- “THE JOB OF POLICE, COURTS, AND LAW-EDUCATED PROSECUTORS SHOULD NOT BE HANDLED BY PHYSICIANS.” – Dr. Sudarshan Singla, Jan. 25, 2016

- “This is a debate that only those at the academic/ivory tower–level of medicine even have time to lament. The frontline medical providers barely have enough time to adequately address the pertinent.” – Tobin Purslow, Jan. 15, 2016

Other ways to communicate

For his part, Dr. Caplan believes there is a variety of ways physicians can effectively discuss gun safety with patients to help minimize the potential of injury or death.

Acknowledging that other aspects of treatment are often more pressing, he suggested that the gun safety education could be done through educational videos that are shown in waiting rooms, through pamphlets available at the front desk, or throuigh a newsletter sent to patients.

“Everything doesn’t have to happen in conversation. The doctor’s office should become more of an educational site.

“I am 100% more passionate about this than when I first started down this road.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The latest NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll shows that that the margin of public opinion in the United States is the widest that it has been during the past 10 years in favor of taking steps to control gun violence; 59% of U.S. adults said it’s more important to control gun violence than to protect gun rights, and 35% said the opposite.

Have physicians’ opinions about gun issues in our country shifted meaningfully during that period? That’s a complex question that can be informed with the basic snapshot provided by doctors› comments to New York University (and Medscape blogger) bioethicist Arthur L. Caplan’s four video blogs on whether physicians should discuss gun safety with their patients. Dr. Caplan’s video blogs appeared on the Medscape website in 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2022.

Hundreds of physicians have posted comments to Dr. Caplan’s arguments that doctors should bring up gun safety when talking to their patients. The great majority of comments opposed his position in 2014, and that remained the case through 2022, regardless of incidents of gun-related violence. Supportive comments have been a small minority that has grown only slightly over his four video blogs.

Physicians’ lack of qualifications

The most prevalent counterarguments expressed against Dr. Caplan’s position are that physicians lack the proper knowledge to discuss gun safety with patients; and the responsibility falls on family members, certified firearms instructors, teachers, and others – but not doctors – to educate people about firearm safety.

“Then there’s a third group that says, ‘I don’t want to do this because I am too busy trying to figure out what is wrong with the patient,’ ” Dr. Caplan says.

Here are a few on-point comments that were posted to his video blogs:

- “Unless physicians become certified firearms instructors like myself, they are not qualified to talk to patients on the subject and should advise patients to find a program and take a course.” – Dr. Ken Long, March 31, 2014

- “Gun safety should be taught in school, just like health and sex education.” – Patricia L., Feb. 11, 2016

- “None of my medical or surgical training or experience qualifies me as a policy expert on gun laws or regulations.” – Dr. Kelly Hyde, Dec. 23, 2018

- “I have the Constitution hanging in my office with an NRA plaque next to it. Most MDs can’t mow their own yard.” – Dr. Brian Anseeuw, June 21, 2022

Do mental health issues trump gun talks?

Another counterargument to discussing gun safety with patients involves mental health issues that many physicians may not be trained to address. Mental health entered comments to Dr. Caplan’s video blogs in 2016 and has shaped much of the discussion since.

- “First of all, two-thirds of gun deaths are suicides. It is foolish to talk about counseling patients about gun safety, etc, and ignore the mental health issues.” – Dr. Jeffrey Jennings, Jan. 25, 2016

- “Suicide victims and those committing mass shootings are mentally ill. ... Blame society, drugs, mental illness, easy access to illegal firearms, and poor recognition of SOS (signs of suicide).” – Dr. Alan DeCarlo, Dec. 24, 2018

- “Yes, we have gun violence, but what is the underlying problem? Bullying? Mental issues? Not enough parental supervision? These and others are the issues I feel need to be discussed.” – T. Deese, June 24, 2022

- “The causes of increased gun violence are mental health, problems with bullying, social media, and normalization of deviant behavior.” – Julie Johng, 2022

Added responsibility is too much

Another theme that has grown over time is that talks of gun safety just heap issues onto physicians’ treatment plates that are already too full.

- “Oh, for God’s sake, is there anything else I can do while I›m at it? Primary care has gotten to be more headache than it’s worth. Thanks for another reason to think about retiring.” – Dr. Kathleen Collins, March 31, 2014

- “THE JOB OF POLICE, COURTS, AND LAW-EDUCATED PROSECUTORS SHOULD NOT BE HANDLED BY PHYSICIANS.” – Dr. Sudarshan Singla, Jan. 25, 2016

- “This is a debate that only those at the academic/ivory tower–level of medicine even have time to lament. The frontline medical providers barely have enough time to adequately address the pertinent.” – Tobin Purslow, Jan. 15, 2016

Other ways to communicate

For his part, Dr. Caplan believes there is a variety of ways physicians can effectively discuss gun safety with patients to help minimize the potential of injury or death.

Acknowledging that other aspects of treatment are often more pressing, he suggested that the gun safety education could be done through educational videos that are shown in waiting rooms, through pamphlets available at the front desk, or throuigh a newsletter sent to patients.

“Everything doesn’t have to happen in conversation. The doctor’s office should become more of an educational site.

“I am 100% more passionate about this than when I first started down this road.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The latest NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll shows that that the margin of public opinion in the United States is the widest that it has been during the past 10 years in favor of taking steps to control gun violence; 59% of U.S. adults said it’s more important to control gun violence than to protect gun rights, and 35% said the opposite.

Have physicians’ opinions about gun issues in our country shifted meaningfully during that period? That’s a complex question that can be informed with the basic snapshot provided by doctors› comments to New York University (and Medscape blogger) bioethicist Arthur L. Caplan’s four video blogs on whether physicians should discuss gun safety with their patients. Dr. Caplan’s video blogs appeared on the Medscape website in 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2022.

Hundreds of physicians have posted comments to Dr. Caplan’s arguments that doctors should bring up gun safety when talking to their patients. The great majority of comments opposed his position in 2014, and that remained the case through 2022, regardless of incidents of gun-related violence. Supportive comments have been a small minority that has grown only slightly over his four video blogs.

Physicians’ lack of qualifications

The most prevalent counterarguments expressed against Dr. Caplan’s position are that physicians lack the proper knowledge to discuss gun safety with patients; and the responsibility falls on family members, certified firearms instructors, teachers, and others – but not doctors – to educate people about firearm safety.

“Then there’s a third group that says, ‘I don’t want to do this because I am too busy trying to figure out what is wrong with the patient,’ ” Dr. Caplan says.

Here are a few on-point comments that were posted to his video blogs:

- “Unless physicians become certified firearms instructors like myself, they are not qualified to talk to patients on the subject and should advise patients to find a program and take a course.” – Dr. Ken Long, March 31, 2014

- “Gun safety should be taught in school, just like health and sex education.” – Patricia L., Feb. 11, 2016

- “None of my medical or surgical training or experience qualifies me as a policy expert on gun laws or regulations.” – Dr. Kelly Hyde, Dec. 23, 2018

- “I have the Constitution hanging in my office with an NRA plaque next to it. Most MDs can’t mow their own yard.” – Dr. Brian Anseeuw, June 21, 2022

Do mental health issues trump gun talks?

Another counterargument to discussing gun safety with patients involves mental health issues that many physicians may not be trained to address. Mental health entered comments to Dr. Caplan’s video blogs in 2016 and has shaped much of the discussion since.

- “First of all, two-thirds of gun deaths are suicides. It is foolish to talk about counseling patients about gun safety, etc, and ignore the mental health issues.” – Dr. Jeffrey Jennings, Jan. 25, 2016

- “Suicide victims and those committing mass shootings are mentally ill. ... Blame society, drugs, mental illness, easy access to illegal firearms, and poor recognition of SOS (signs of suicide).” – Dr. Alan DeCarlo, Dec. 24, 2018

- “Yes, we have gun violence, but what is the underlying problem? Bullying? Mental issues? Not enough parental supervision? These and others are the issues I feel need to be discussed.” – T. Deese, June 24, 2022

- “The causes of increased gun violence are mental health, problems with bullying, social media, and normalization of deviant behavior.” – Julie Johng, 2022

Added responsibility is too much

Another theme that has grown over time is that talks of gun safety just heap issues onto physicians’ treatment plates that are already too full.

- “Oh, for God’s sake, is there anything else I can do while I›m at it? Primary care has gotten to be more headache than it’s worth. Thanks for another reason to think about retiring.” – Dr. Kathleen Collins, March 31, 2014

- “THE JOB OF POLICE, COURTS, AND LAW-EDUCATED PROSECUTORS SHOULD NOT BE HANDLED BY PHYSICIANS.” – Dr. Sudarshan Singla, Jan. 25, 2016

- “This is a debate that only those at the academic/ivory tower–level of medicine even have time to lament. The frontline medical providers barely have enough time to adequately address the pertinent.” – Tobin Purslow, Jan. 15, 2016

Other ways to communicate

For his part, Dr. Caplan believes there is a variety of ways physicians can effectively discuss gun safety with patients to help minimize the potential of injury or death.

Acknowledging that other aspects of treatment are often more pressing, he suggested that the gun safety education could be done through educational videos that are shown in waiting rooms, through pamphlets available at the front desk, or throuigh a newsletter sent to patients.

“Everything doesn’t have to happen in conversation. The doctor’s office should become more of an educational site.

“I am 100% more passionate about this than when I first started down this road.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Words, now actions: How medical associations try to fulfill pledges to combat racism in health care

– from health care outcomes, from the level and quality of patient treatment, from their own memberships. How have those pronouncements translated into programs that could have, or even have had, positive impacts?

For this article, this news organization asked several associations about tangible actions behind their vows to combat racism in health care. Meanwhile, a recent Medscape report focused on the degree to which physicians prioritize racial disparities as a leading social issue.

American Academy of Family Physicians

The American Academy of Family Physicians’ approach is to integrate diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts into all existing and new projects rather than tackle racial disparities as a discrete problem.

“Our policies, our advocacy efforts, everything our commissions and staff do ... is through a lens of diversity, equity, and inclusiveness,” said AAFP Board Chair Ada D. Stewart, MD, FAAP.

That lens is ground by a DEI center the AAFP created in 2017. Run by AAFP staff, members, and chapters, the center focuses on five areas: policy, education and training, practice, diversifying the workplace, and strategic partnerships.

The center has established a special project called EveryONE to provide AAFP members with relevant research, policy templates, and other resources to address patient needs. One example is the Neighborhood Navigator, an online tool that shows food, housing, transportation, and other needs in a patient’s neighborhood.

Meanwhile, the DEI center has created training programs for AAFP members on topics like unconscious and implicit racial biases. And the AAFP has implemented several relevant governing policies regarding pushes to improve childbirth conditions and limit race-based treatment, among other areas.

In January, the AAFP established a new DEI commission for family medicine to set the academy’s agenda on racial issues moving forward. “We only had 10 physician positions available on the commission, and over 100 individuals applied, which gave us comfort that we were going in the right direction,” Dr. Stewart said.

Association of American Medical Colleges

The Association of American Medical Colleges, which represents nearly 600 U.S. and Canadian medical schools and teaching hospitals, has a “longstanding” focus on racial equity, said Philip Alberti, founder of the AAMC Center for Health Justice. However, in 2020 that focus became more detailed and layered.

Those layers include:

- Encouraging self-reflection by members on how personal racial biases and stereotypes can lead to systemic racism in health care.

- Working on the AAMC organizational structure. Priorities range from hiring a consultant to help guide antiracism efforts, to establishing a DEI council and advisors, to regularly seeking input from staff. In 2021, the AAMC launched a Center for Health Justice to work more closely with communities.

- Ramping up collaboration with national and local academic medicine organizations and partners. As one example, the AAMC and American Medical Association released a guide for physicians and health care professionals on language that could be interpreted as racist or disrespectful.

- Continuing to be outspoken about racial disparities in health care in society generally.

Meanwhile, the AAMC is supporting more specific, localized health equity efforts in cities such as Cincinnati and Boston.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital research has found that children in poor neighborhoods are five times more likely to need hospital stays. AAMC members have helped identify “hot spots” for social needs among children and focused specifically on two neighborhoods in the city. The initiative has roped in partnerships with community and social service organizations as well as health care providers, and proponents say the number of child hospital stays in those neighborhoods has dropped by 20%.

Boston Medical Center researchers learned that Black and Latino patients experiencing problems with heart failure were less likely to be referred to a cardiologist. AAMC members assisted with a program to encourage physicians to make medically necessary referrals more often.

National Health Council

The National Health Council, an umbrella association of health organizations, similarly has made a “commitment, not just around policy work but anytime and anything the NHC is doing, to build around trying to identify and solve issues of health equity,” CEO Randall Rutta said.

The NHC has identified four strategic policy areas including race and in 2021 issued a statement signed by 45 other health care organizations vowing to take on systemic racism and advance equity, through public policy and law.

In relation to policy, Mr. Rutta said his organization is lobbying Congress and federal agencies to diversify clinical trials.

“We want to make sure that clinical trials are inclusive of people from different racial and ethnic groups, in order to understand how [they are] affected by a particular condition,” he said. “As you would imagine, some conditions hit certain groups harder than others for genetic or other reasons, or it may just be a reflection of other disparities that occur across health care.”

The organization has issued suggestions for policy change in the Food and Drug Administration’s clinical trial policy and separately targeted telemedicine policy to promote equity and greater patient access. For example, one initiative aims to ensure patients’ privacy and civil rights as telemedicine’s popularity grows after the COVID-19 pandemic. The NHC presented the initiative in a congressional briefing last year.

American Public Health Association

The American Public Health Association says it started focusing on racial disparities in health care in 2015, following a series of racially fueled violent acts. The APHA started with a four-part webinar series on racism in health (more than 10,000 live participants and 40,000 replays to date).

Shortly afterward, then-APHA President Camara Jones, MD, MPH, PhD, launched a national campaign encouraging APHA members, affiliates, and partners to name and address racism as a determinant of health.

More recently in 2021, the APHA adopted a “Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation” guiding framework and “Healing Through Policy” initiative that offer local leaders policy templates and best practices.

“We have identified a suite of policies that have actually been implemented successfully and are advancing racial equity,” said Regina Davis Moss, APHA’s associate executive director of health policy and practice. “You can’t advance health without having a policy that supports it.”

Montgomery County, Md., is one community that has used the framework (for racial equity training of county employees). Leaders in Evanston, Ill., also used it in crafting a resolution to end structural racism in the city.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

– from health care outcomes, from the level and quality of patient treatment, from their own memberships. How have those pronouncements translated into programs that could have, or even have had, positive impacts?

For this article, this news organization asked several associations about tangible actions behind their vows to combat racism in health care. Meanwhile, a recent Medscape report focused on the degree to which physicians prioritize racial disparities as a leading social issue.

American Academy of Family Physicians

The American Academy of Family Physicians’ approach is to integrate diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts into all existing and new projects rather than tackle racial disparities as a discrete problem.

“Our policies, our advocacy efforts, everything our commissions and staff do ... is through a lens of diversity, equity, and inclusiveness,” said AAFP Board Chair Ada D. Stewart, MD, FAAP.

That lens is ground by a DEI center the AAFP created in 2017. Run by AAFP staff, members, and chapters, the center focuses on five areas: policy, education and training, practice, diversifying the workplace, and strategic partnerships.

The center has established a special project called EveryONE to provide AAFP members with relevant research, policy templates, and other resources to address patient needs. One example is the Neighborhood Navigator, an online tool that shows food, housing, transportation, and other needs in a patient’s neighborhood.

Meanwhile, the DEI center has created training programs for AAFP members on topics like unconscious and implicit racial biases. And the AAFP has implemented several relevant governing policies regarding pushes to improve childbirth conditions and limit race-based treatment, among other areas.

In January, the AAFP established a new DEI commission for family medicine to set the academy’s agenda on racial issues moving forward. “We only had 10 physician positions available on the commission, and over 100 individuals applied, which gave us comfort that we were going in the right direction,” Dr. Stewart said.

Association of American Medical Colleges

The Association of American Medical Colleges, which represents nearly 600 U.S. and Canadian medical schools and teaching hospitals, has a “longstanding” focus on racial equity, said Philip Alberti, founder of the AAMC Center for Health Justice. However, in 2020 that focus became more detailed and layered.

Those layers include:

- Encouraging self-reflection by members on how personal racial biases and stereotypes can lead to systemic racism in health care.

- Working on the AAMC organizational structure. Priorities range from hiring a consultant to help guide antiracism efforts, to establishing a DEI council and advisors, to regularly seeking input from staff. In 2021, the AAMC launched a Center for Health Justice to work more closely with communities.

- Ramping up collaboration with national and local academic medicine organizations and partners. As one example, the AAMC and American Medical Association released a guide for physicians and health care professionals on language that could be interpreted as racist or disrespectful.

- Continuing to be outspoken about racial disparities in health care in society generally.

Meanwhile, the AAMC is supporting more specific, localized health equity efforts in cities such as Cincinnati and Boston.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital research has found that children in poor neighborhoods are five times more likely to need hospital stays. AAMC members have helped identify “hot spots” for social needs among children and focused specifically on two neighborhoods in the city. The initiative has roped in partnerships with community and social service organizations as well as health care providers, and proponents say the number of child hospital stays in those neighborhoods has dropped by 20%.

Boston Medical Center researchers learned that Black and Latino patients experiencing problems with heart failure were less likely to be referred to a cardiologist. AAMC members assisted with a program to encourage physicians to make medically necessary referrals more often.

National Health Council

The National Health Council, an umbrella association of health organizations, similarly has made a “commitment, not just around policy work but anytime and anything the NHC is doing, to build around trying to identify and solve issues of health equity,” CEO Randall Rutta said.

The NHC has identified four strategic policy areas including race and in 2021 issued a statement signed by 45 other health care organizations vowing to take on systemic racism and advance equity, through public policy and law.

In relation to policy, Mr. Rutta said his organization is lobbying Congress and federal agencies to diversify clinical trials.

“We want to make sure that clinical trials are inclusive of people from different racial and ethnic groups, in order to understand how [they are] affected by a particular condition,” he said. “As you would imagine, some conditions hit certain groups harder than others for genetic or other reasons, or it may just be a reflection of other disparities that occur across health care.”

The organization has issued suggestions for policy change in the Food and Drug Administration’s clinical trial policy and separately targeted telemedicine policy to promote equity and greater patient access. For example, one initiative aims to ensure patients’ privacy and civil rights as telemedicine’s popularity grows after the COVID-19 pandemic. The NHC presented the initiative in a congressional briefing last year.

American Public Health Association

The American Public Health Association says it started focusing on racial disparities in health care in 2015, following a series of racially fueled violent acts. The APHA started with a four-part webinar series on racism in health (more than 10,000 live participants and 40,000 replays to date).

Shortly afterward, then-APHA President Camara Jones, MD, MPH, PhD, launched a national campaign encouraging APHA members, affiliates, and partners to name and address racism as a determinant of health.

More recently in 2021, the APHA adopted a “Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation” guiding framework and “Healing Through Policy” initiative that offer local leaders policy templates and best practices.

“We have identified a suite of policies that have actually been implemented successfully and are advancing racial equity,” said Regina Davis Moss, APHA’s associate executive director of health policy and practice. “You can’t advance health without having a policy that supports it.”

Montgomery County, Md., is one community that has used the framework (for racial equity training of county employees). Leaders in Evanston, Ill., also used it in crafting a resolution to end structural racism in the city.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

– from health care outcomes, from the level and quality of patient treatment, from their own memberships. How have those pronouncements translated into programs that could have, or even have had, positive impacts?

For this article, this news organization asked several associations about tangible actions behind their vows to combat racism in health care. Meanwhile, a recent Medscape report focused on the degree to which physicians prioritize racial disparities as a leading social issue.

American Academy of Family Physicians

The American Academy of Family Physicians’ approach is to integrate diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts into all existing and new projects rather than tackle racial disparities as a discrete problem.

“Our policies, our advocacy efforts, everything our commissions and staff do ... is through a lens of diversity, equity, and inclusiveness,” said AAFP Board Chair Ada D. Stewart, MD, FAAP.

That lens is ground by a DEI center the AAFP created in 2017. Run by AAFP staff, members, and chapters, the center focuses on five areas: policy, education and training, practice, diversifying the workplace, and strategic partnerships.

The center has established a special project called EveryONE to provide AAFP members with relevant research, policy templates, and other resources to address patient needs. One example is the Neighborhood Navigator, an online tool that shows food, housing, transportation, and other needs in a patient’s neighborhood.

Meanwhile, the DEI center has created training programs for AAFP members on topics like unconscious and implicit racial biases. And the AAFP has implemented several relevant governing policies regarding pushes to improve childbirth conditions and limit race-based treatment, among other areas.

In January, the AAFP established a new DEI commission for family medicine to set the academy’s agenda on racial issues moving forward. “We only had 10 physician positions available on the commission, and over 100 individuals applied, which gave us comfort that we were going in the right direction,” Dr. Stewart said.

Association of American Medical Colleges

The Association of American Medical Colleges, which represents nearly 600 U.S. and Canadian medical schools and teaching hospitals, has a “longstanding” focus on racial equity, said Philip Alberti, founder of the AAMC Center for Health Justice. However, in 2020 that focus became more detailed and layered.

Those layers include:

- Encouraging self-reflection by members on how personal racial biases and stereotypes can lead to systemic racism in health care.

- Working on the AAMC organizational structure. Priorities range from hiring a consultant to help guide antiracism efforts, to establishing a DEI council and advisors, to regularly seeking input from staff. In 2021, the AAMC launched a Center for Health Justice to work more closely with communities.

- Ramping up collaboration with national and local academic medicine organizations and partners. As one example, the AAMC and American Medical Association released a guide for physicians and health care professionals on language that could be interpreted as racist or disrespectful.

- Continuing to be outspoken about racial disparities in health care in society generally.

Meanwhile, the AAMC is supporting more specific, localized health equity efforts in cities such as Cincinnati and Boston.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital research has found that children in poor neighborhoods are five times more likely to need hospital stays. AAMC members have helped identify “hot spots” for social needs among children and focused specifically on two neighborhoods in the city. The initiative has roped in partnerships with community and social service organizations as well as health care providers, and proponents say the number of child hospital stays in those neighborhoods has dropped by 20%.

Boston Medical Center researchers learned that Black and Latino patients experiencing problems with heart failure were less likely to be referred to a cardiologist. AAMC members assisted with a program to encourage physicians to make medically necessary referrals more often.

National Health Council

The National Health Council, an umbrella association of health organizations, similarly has made a “commitment, not just around policy work but anytime and anything the NHC is doing, to build around trying to identify and solve issues of health equity,” CEO Randall Rutta said.

The NHC has identified four strategic policy areas including race and in 2021 issued a statement signed by 45 other health care organizations vowing to take on systemic racism and advance equity, through public policy and law.

In relation to policy, Mr. Rutta said his organization is lobbying Congress and federal agencies to diversify clinical trials.

“We want to make sure that clinical trials are inclusive of people from different racial and ethnic groups, in order to understand how [they are] affected by a particular condition,” he said. “As you would imagine, some conditions hit certain groups harder than others for genetic or other reasons, or it may just be a reflection of other disparities that occur across health care.”

The organization has issued suggestions for policy change in the Food and Drug Administration’s clinical trial policy and separately targeted telemedicine policy to promote equity and greater patient access. For example, one initiative aims to ensure patients’ privacy and civil rights as telemedicine’s popularity grows after the COVID-19 pandemic. The NHC presented the initiative in a congressional briefing last year.

American Public Health Association

The American Public Health Association says it started focusing on racial disparities in health care in 2015, following a series of racially fueled violent acts. The APHA started with a four-part webinar series on racism in health (more than 10,000 live participants and 40,000 replays to date).

Shortly afterward, then-APHA President Camara Jones, MD, MPH, PhD, launched a national campaign encouraging APHA members, affiliates, and partners to name and address racism as a determinant of health.

More recently in 2021, the APHA adopted a “Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation” guiding framework and “Healing Through Policy” initiative that offer local leaders policy templates and best practices.

“We have identified a suite of policies that have actually been implemented successfully and are advancing racial equity,” said Regina Davis Moss, APHA’s associate executive director of health policy and practice. “You can’t advance health without having a policy that supports it.”

Montgomery County, Md., is one community that has used the framework (for racial equity training of county employees). Leaders in Evanston, Ill., also used it in crafting a resolution to end structural racism in the city.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

At 100, Guinness’s oldest practicing doctor shows no signs of slowing down

In the same year that Howard Tucker, MD, began practicing neurology, the average loaf of bread cost 13 cents, the microwave oven became commercially available, and Jackie Robinson took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers as the first Black person to play Major League Baseball.

Since 1947, Dr. Tucker has witnessed major changes in health care, from President Harry S. Truman proposing a national health care plan to Congress to the current day, when patients carry their digital records around with them.

Dr. Tucker has been a resident of Cleveland Heights, Ohio, since 1922, the year he was born.

After graduating high school in 1940, Dr. Tucker attended Ohio State University, Columbus, where he received his undergraduate and medical degrees. During the Korean War, he served as chief neurologist for the Atlantic fleet at a U.S. Naval Hospital in Philadelphia. Following the war, he completed his residency at the Cleveland Clinic and trained at the Neurological Institute of New York.

Dr. Tucker chose to return to Cleveland, where he practiced at the University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center and Hillcrest Hospital for several decades.

Not content with just a medical degree, at the age of 67, Dr. Tucker attended Cleveland State University Cleveland Marshall College of Law. In 1989, he received his Juris Doctor degree and passed the Ohio bar examination.

And as if that weren’t enough career accomplishments, Guinness World Records dubbed him the world’s oldest practicing doctor at 98 years and 231 days. Dr. Tucker continues to practice into his 100th year. He celebrated his birthday in July.

Owing to the compelling and inspiring nature of his upbringing, Dr. Tucker has become the subject of a feature documentary film entitled “What’s Next?” The film is currently in production. It is being produced by his grandson, Austin Tucker, and is directed by Taylor Taglianetti.

This news organization recently spoke with Dr. Tucker about his life’s work in medicine.

Question: Why did you choose neurology?

Dr. Tucker: Well, I think I was just fascinated with medicine from about the seventh or eighth grade. I chose my specialty because it was a very cerebral one in those days. It was an intellectual pursuit. It was before the CAT scan, and you had to work hard to make a diagnosis. You even had to look at the spinal fluid. You had to look at EEGs, and it was a very detailed history taking.

Question: How has neurology changed since you started practicing?

Dr. Tucker: The MRI came in, so we don’t have to use spinal taps anymore. Lumbar puncture fluid and EEG aren’t needed as often either. Now we use EEG for convulsive disorders, but rarely when we suspect tumors like we used to. Also, when I was in med school, they said to use Dilaudid; don’t use morphine. And now, you can’t even find Dilaudin in emergency rooms anymore.

Question: How has medicine overall changed since you started practicing?

Dr. Tucker: Computers have made everything a different specialty.

In the old days, we would see a patient, call the referring doctor, and discuss [the case] with them in a very pleasant way. Now, when you call a doctor, he’ll say to you, “Let me read your note,” and that’s the end of it. He doesn’t want to talk to you. Medicine has changed dramatically.

It used to be a very warm relationship between you and your patients. You looked at your patient, you studied their expressions, and now you look at the screen and very rarely look at the patient.

Question: Why do you still enjoy practicing medicine?

Dr. Tucker: The challenge, the excitement of patients, and now I’m doing a lot of teaching, and I do love that part, too.

I teach neurology to residents and medical students that rotate through. When I retired from the Cleveland Clinic, 2 months of retirement was too much for me, so I went back to St. Vincent. It’s a smaller hospital but still has good residents and good teaching.

Question: What lessons do you teach to your residents?

Dr. Tucker: I ask my residents and physicians to think through a problem before they look at the CAT scan and imaging studies. Think through it, then you’ll know what questions you want to ask specifically before you even examine the patient, know exactly what you are going to find.

The complete neurological examination, aside from taking the history and checking mental status, is 5 minutes. You have them walk, check for excessive finger tapping, have them touch their nose, check their reflexes, check their strength – it’s over. That doesn’t take much time if you know what you’re looking for.

Residents say to me all the time, “55-year-old man, CAT scan shows ...” I have to say to them: “Slow down. Let’s talk about this first.”

Question: What advice do you have for physicians and medical students?

Dr. Tucker: Take a very careful history. Know the course of the illness. Make sure you have a diagnosis in your head and, specifically for medical residents, ask questions. You have to be smarter than the patients are, you have to know what to ask.

If someone hits their head on their steering wheel, they don’t know that they’ve lost their sense of smell. You have to ask that specifically, hence, why you have to be smarter than they are. Take a careful history before you do imaging studies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the same year that Howard Tucker, MD, began practicing neurology, the average loaf of bread cost 13 cents, the microwave oven became commercially available, and Jackie Robinson took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers as the first Black person to play Major League Baseball.

Since 1947, Dr. Tucker has witnessed major changes in health care, from President Harry S. Truman proposing a national health care plan to Congress to the current day, when patients carry their digital records around with them.

Dr. Tucker has been a resident of Cleveland Heights, Ohio, since 1922, the year he was born.

After graduating high school in 1940, Dr. Tucker attended Ohio State University, Columbus, where he received his undergraduate and medical degrees. During the Korean War, he served as chief neurologist for the Atlantic fleet at a U.S. Naval Hospital in Philadelphia. Following the war, he completed his residency at the Cleveland Clinic and trained at the Neurological Institute of New York.

Dr. Tucker chose to return to Cleveland, where he practiced at the University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center and Hillcrest Hospital for several decades.

Not content with just a medical degree, at the age of 67, Dr. Tucker attended Cleveland State University Cleveland Marshall College of Law. In 1989, he received his Juris Doctor degree and passed the Ohio bar examination.

And as if that weren’t enough career accomplishments, Guinness World Records dubbed him the world’s oldest practicing doctor at 98 years and 231 days. Dr. Tucker continues to practice into his 100th year. He celebrated his birthday in July.

Owing to the compelling and inspiring nature of his upbringing, Dr. Tucker has become the subject of a feature documentary film entitled “What’s Next?” The film is currently in production. It is being produced by his grandson, Austin Tucker, and is directed by Taylor Taglianetti.

This news organization recently spoke with Dr. Tucker about his life’s work in medicine.

Question: Why did you choose neurology?

Dr. Tucker: Well, I think I was just fascinated with medicine from about the seventh or eighth grade. I chose my specialty because it was a very cerebral one in those days. It was an intellectual pursuit. It was before the CAT scan, and you had to work hard to make a diagnosis. You even had to look at the spinal fluid. You had to look at EEGs, and it was a very detailed history taking.

Question: How has neurology changed since you started practicing?

Dr. Tucker: The MRI came in, so we don’t have to use spinal taps anymore. Lumbar puncture fluid and EEG aren’t needed as often either. Now we use EEG for convulsive disorders, but rarely when we suspect tumors like we used to. Also, when I was in med school, they said to use Dilaudid; don’t use morphine. And now, you can’t even find Dilaudin in emergency rooms anymore.

Question: How has medicine overall changed since you started practicing?

Dr. Tucker: Computers have made everything a different specialty.

In the old days, we would see a patient, call the referring doctor, and discuss [the case] with them in a very pleasant way. Now, when you call a doctor, he’ll say to you, “Let me read your note,” and that’s the end of it. He doesn’t want to talk to you. Medicine has changed dramatically.

It used to be a very warm relationship between you and your patients. You looked at your patient, you studied their expressions, and now you look at the screen and very rarely look at the patient.

Question: Why do you still enjoy practicing medicine?

Dr. Tucker: The challenge, the excitement of patients, and now I’m doing a lot of teaching, and I do love that part, too.

I teach neurology to residents and medical students that rotate through. When I retired from the Cleveland Clinic, 2 months of retirement was too much for me, so I went back to St. Vincent. It’s a smaller hospital but still has good residents and good teaching.

Question: What lessons do you teach to your residents?

Dr. Tucker: I ask my residents and physicians to think through a problem before they look at the CAT scan and imaging studies. Think through it, then you’ll know what questions you want to ask specifically before you even examine the patient, know exactly what you are going to find.

The complete neurological examination, aside from taking the history and checking mental status, is 5 minutes. You have them walk, check for excessive finger tapping, have them touch their nose, check their reflexes, check their strength – it’s over. That doesn’t take much time if you know what you’re looking for.

Residents say to me all the time, “55-year-old man, CAT scan shows ...” I have to say to them: “Slow down. Let’s talk about this first.”

Question: What advice do you have for physicians and medical students?

Dr. Tucker: Take a very careful history. Know the course of the illness. Make sure you have a diagnosis in your head and, specifically for medical residents, ask questions. You have to be smarter than the patients are, you have to know what to ask.

If someone hits their head on their steering wheel, they don’t know that they’ve lost their sense of smell. You have to ask that specifically, hence, why you have to be smarter than they are. Take a careful history before you do imaging studies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the same year that Howard Tucker, MD, began practicing neurology, the average loaf of bread cost 13 cents, the microwave oven became commercially available, and Jackie Robinson took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers as the first Black person to play Major League Baseball.

Since 1947, Dr. Tucker has witnessed major changes in health care, from President Harry S. Truman proposing a national health care plan to Congress to the current day, when patients carry their digital records around with them.

Dr. Tucker has been a resident of Cleveland Heights, Ohio, since 1922, the year he was born.

After graduating high school in 1940, Dr. Tucker attended Ohio State University, Columbus, where he received his undergraduate and medical degrees. During the Korean War, he served as chief neurologist for the Atlantic fleet at a U.S. Naval Hospital in Philadelphia. Following the war, he completed his residency at the Cleveland Clinic and trained at the Neurological Institute of New York.

Dr. Tucker chose to return to Cleveland, where he practiced at the University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center and Hillcrest Hospital for several decades.

Not content with just a medical degree, at the age of 67, Dr. Tucker attended Cleveland State University Cleveland Marshall College of Law. In 1989, he received his Juris Doctor degree and passed the Ohio bar examination.

And as if that weren’t enough career accomplishments, Guinness World Records dubbed him the world’s oldest practicing doctor at 98 years and 231 days. Dr. Tucker continues to practice into his 100th year. He celebrated his birthday in July.

Owing to the compelling and inspiring nature of his upbringing, Dr. Tucker has become the subject of a feature documentary film entitled “What’s Next?” The film is currently in production. It is being produced by his grandson, Austin Tucker, and is directed by Taylor Taglianetti.

This news organization recently spoke with Dr. Tucker about his life’s work in medicine.

Question: Why did you choose neurology?

Dr. Tucker: Well, I think I was just fascinated with medicine from about the seventh or eighth grade. I chose my specialty because it was a very cerebral one in those days. It was an intellectual pursuit. It was before the CAT scan, and you had to work hard to make a diagnosis. You even had to look at the spinal fluid. You had to look at EEGs, and it was a very detailed history taking.

Question: How has neurology changed since you started practicing?

Dr. Tucker: The MRI came in, so we don’t have to use spinal taps anymore. Lumbar puncture fluid and EEG aren’t needed as often either. Now we use EEG for convulsive disorders, but rarely when we suspect tumors like we used to. Also, when I was in med school, they said to use Dilaudid; don’t use morphine. And now, you can’t even find Dilaudin in emergency rooms anymore.

Question: How has medicine overall changed since you started practicing?

Dr. Tucker: Computers have made everything a different specialty.

In the old days, we would see a patient, call the referring doctor, and discuss [the case] with them in a very pleasant way. Now, when you call a doctor, he’ll say to you, “Let me read your note,” and that’s the end of it. He doesn’t want to talk to you. Medicine has changed dramatically.

It used to be a very warm relationship between you and your patients. You looked at your patient, you studied their expressions, and now you look at the screen and very rarely look at the patient.

Question: Why do you still enjoy practicing medicine?

Dr. Tucker: The challenge, the excitement of patients, and now I’m doing a lot of teaching, and I do love that part, too.

I teach neurology to residents and medical students that rotate through. When I retired from the Cleveland Clinic, 2 months of retirement was too much for me, so I went back to St. Vincent. It’s a smaller hospital but still has good residents and good teaching.

Question: What lessons do you teach to your residents?

Dr. Tucker: I ask my residents and physicians to think through a problem before they look at the CAT scan and imaging studies. Think through it, then you’ll know what questions you want to ask specifically before you even examine the patient, know exactly what you are going to find.

The complete neurological examination, aside from taking the history and checking mental status, is 5 minutes. You have them walk, check for excessive finger tapping, have them touch their nose, check their reflexes, check their strength – it’s over. That doesn’t take much time if you know what you’re looking for.

Residents say to me all the time, “55-year-old man, CAT scan shows ...” I have to say to them: “Slow down. Let’s talk about this first.”

Question: What advice do you have for physicians and medical students?

Dr. Tucker: Take a very careful history. Know the course of the illness. Make sure you have a diagnosis in your head and, specifically for medical residents, ask questions. You have to be smarter than the patients are, you have to know what to ask.

If someone hits their head on their steering wheel, they don’t know that they’ve lost their sense of smell. You have to ask that specifically, hence, why you have to be smarter than they are. Take a careful history before you do imaging studies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Doctors using fake positive reviews to boost business

Five years ago, Kay Dean relied upon Yelp! and Google reviews in her search for a doctor in her area. After finding a physician with fairly high reviews, Ms. Dean was shocked when her personal experience was significantly worse than patients on the review platforms.

Following her experience, Ms. Dean, a former federal government investigator, became skeptical and used her skills to investigate the practice on all review platforms. She uncovered that the practice had a review from an individual who was involved in a review trading group on Facebook, where organizations openly barter their services in exchange for positive reviews fraud.

“I discovered that the online review world was just saturated with fake reviews, much more so than I think most people are aware ... and law enforcement regulators aren’t doing anything to address the problem,” said Ms. Dean. “In this online space, it’s the Wild West; cheating is rewarded.”

Ms. Dean decided to take matters into her own hands. She created a YouTube channel called Fake Review Watch, where she exposes real businesses and their attempts to dupe potential consumers with fake positive reviews.

For example, one video analyzes an orthopedic surgeon in Manhattan with an abundance of five-star reviews. Through her detailed analysis, Ms. Dean created a spreadsheet of the 26 alleged patients of the orthopedic surgeon that had submitted glowing reviews. She looked into other businesses that the individuals had left reviews for and found a significant amount of overlap.

According to the video, 19 of the doctor’s reviewers had left high reviews for the same moving company in Las Vegas, and 18 of them reviewed the same locksmith in Texas. Overall, eight of the patients reviewed the same mover, locksmith, and hotel in New Zealand.

A matter of trust

Ms. Dean expressed the gravity of this phenomenon, especially in health care, as patients often head online first when searching for care options. Based on a survey by Software Advice, about 84% of patients use online reviews to assess a physician, and 77% use review sites as the first step in finding a doctor.

Patient trust has continued to diminish in recent years, particularly following the pandemic. In a 2021 global ranking of trust levels towards health care by country, the U.S. health care system ranked 19th, far below those of several developing countries.

Owing to the rise of fake patient reviews and their inscrutable nature, Ms. Dean advises staying away from online review platforms. Instead, she suggests sticking to the old-fashioned method of getting recommendations from friends and relatives, not virtual people.

Ms. Dean explained a few indicators that she looks for when trying to identify a fake review.

“The business has all five-star reviews, negative reviews are followed by five-star reviews, or the business has an abnormal number of positive reviews in a short period of time,” she noted. “Some businesses try to bury legitimate negative reviews by obtaining more recent, fake, positive ones. The recent reviews will contradict the specific criticisms in the negative review.”

She warned that consumers should not give credibility to reviews simply because the reviewer is dubbed “Elite” or a Google Local Guide, because she has seen plenty of these individuals posting fake reviews.

Unfortunately, review platforms haven’t been doing much self-policing. Google and Healthgrades have a series of policies against fake engagement, impersonation, misinformation, and misrepresentation, according to their websites. However, the only consequence of these violations is review removal.

Both Yelp! and Google say they have automated software that distinguishes real versus fake reviews. When Yelp! uncovers users engaging in compensation review activity, it removes their reviews, closes their account, and blocks those users from creating future Yelp! accounts.

Physicians’ basis

Moreover,

“I think there’s an erosion of business ethics because cheating is rewarded. You can’t compete in an environment where your competition is allowed to accumulate numerous fake reviews while you’re still trying to fill chairs in your business,” said Ms. Dean. “Your competition is then getting the business because the tech companies are allowing this fraud.”

Family physician and practice owner Mike Woo-Ming, MD, MPH, provides career coaching for physicians, including maintaining a good reputation – in-person and online. He has seen physicians bumping up their own five-star reviews personally as well as posting negative reviews for their competition.

“I’ve seen where they’re going to lose business, as many practices were affected through COVID,” he said. “Business owners can become desperate and may decide to start posting or buying reviews because they know people will choose certain services these days based upon reviews.”

Dr. Woo-Ming expressed his frustration with fellow physicians who give in to purchasing fake reviews, because the patients have no idea whether reviews are genuine or not.

To encourage genuine positive reviews, Dr. Woo-Ming’s practice uses a third-party app system that sends patients a follow-up email or text asking about their experience with a link to review sites.

“Honest reviews are a reflection of what I can do to improve my business. At the end of the day, if you’re truly providing great service and you’re helping people by providing great medical care, those are going to win out,” he said. “I would rather, as a responsible practice owner, improve the experience and outcome for the patient.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Five years ago, Kay Dean relied upon Yelp! and Google reviews in her search for a doctor in her area. After finding a physician with fairly high reviews, Ms. Dean was shocked when her personal experience was significantly worse than patients on the review platforms.

Following her experience, Ms. Dean, a former federal government investigator, became skeptical and used her skills to investigate the practice on all review platforms. She uncovered that the practice had a review from an individual who was involved in a review trading group on Facebook, where organizations openly barter their services in exchange for positive reviews fraud.

“I discovered that the online review world was just saturated with fake reviews, much more so than I think most people are aware ... and law enforcement regulators aren’t doing anything to address the problem,” said Ms. Dean. “In this online space, it’s the Wild West; cheating is rewarded.”

Ms. Dean decided to take matters into her own hands. She created a YouTube channel called Fake Review Watch, where she exposes real businesses and their attempts to dupe potential consumers with fake positive reviews.

For example, one video analyzes an orthopedic surgeon in Manhattan with an abundance of five-star reviews. Through her detailed analysis, Ms. Dean created a spreadsheet of the 26 alleged patients of the orthopedic surgeon that had submitted glowing reviews. She looked into other businesses that the individuals had left reviews for and found a significant amount of overlap.

According to the video, 19 of the doctor’s reviewers had left high reviews for the same moving company in Las Vegas, and 18 of them reviewed the same locksmith in Texas. Overall, eight of the patients reviewed the same mover, locksmith, and hotel in New Zealand.

A matter of trust

Ms. Dean expressed the gravity of this phenomenon, especially in health care, as patients often head online first when searching for care options. Based on a survey by Software Advice, about 84% of patients use online reviews to assess a physician, and 77% use review sites as the first step in finding a doctor.

Patient trust has continued to diminish in recent years, particularly following the pandemic. In a 2021 global ranking of trust levels towards health care by country, the U.S. health care system ranked 19th, far below those of several developing countries.

Owing to the rise of fake patient reviews and their inscrutable nature, Ms. Dean advises staying away from online review platforms. Instead, she suggests sticking to the old-fashioned method of getting recommendations from friends and relatives, not virtual people.

Ms. Dean explained a few indicators that she looks for when trying to identify a fake review.

“The business has all five-star reviews, negative reviews are followed by five-star reviews, or the business has an abnormal number of positive reviews in a short period of time,” she noted. “Some businesses try to bury legitimate negative reviews by obtaining more recent, fake, positive ones. The recent reviews will contradict the specific criticisms in the negative review.”

She warned that consumers should not give credibility to reviews simply because the reviewer is dubbed “Elite” or a Google Local Guide, because she has seen plenty of these individuals posting fake reviews.

Unfortunately, review platforms haven’t been doing much self-policing. Google and Healthgrades have a series of policies against fake engagement, impersonation, misinformation, and misrepresentation, according to their websites. However, the only consequence of these violations is review removal.

Both Yelp! and Google say they have automated software that distinguishes real versus fake reviews. When Yelp! uncovers users engaging in compensation review activity, it removes their reviews, closes their account, and blocks those users from creating future Yelp! accounts.

Physicians’ basis

Moreover,

“I think there’s an erosion of business ethics because cheating is rewarded. You can’t compete in an environment where your competition is allowed to accumulate numerous fake reviews while you’re still trying to fill chairs in your business,” said Ms. Dean. “Your competition is then getting the business because the tech companies are allowing this fraud.”

Family physician and practice owner Mike Woo-Ming, MD, MPH, provides career coaching for physicians, including maintaining a good reputation – in-person and online. He has seen physicians bumping up their own five-star reviews personally as well as posting negative reviews for their competition.

“I’ve seen where they’re going to lose business, as many practices were affected through COVID,” he said. “Business owners can become desperate and may decide to start posting or buying reviews because they know people will choose certain services these days based upon reviews.”

Dr. Woo-Ming expressed his frustration with fellow physicians who give in to purchasing fake reviews, because the patients have no idea whether reviews are genuine or not.

To encourage genuine positive reviews, Dr. Woo-Ming’s practice uses a third-party app system that sends patients a follow-up email or text asking about their experience with a link to review sites.

“Honest reviews are a reflection of what I can do to improve my business. At the end of the day, if you’re truly providing great service and you’re helping people by providing great medical care, those are going to win out,” he said. “I would rather, as a responsible practice owner, improve the experience and outcome for the patient.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Five years ago, Kay Dean relied upon Yelp! and Google reviews in her search for a doctor in her area. After finding a physician with fairly high reviews, Ms. Dean was shocked when her personal experience was significantly worse than patients on the review platforms.

Following her experience, Ms. Dean, a former federal government investigator, became skeptical and used her skills to investigate the practice on all review platforms. She uncovered that the practice had a review from an individual who was involved in a review trading group on Facebook, where organizations openly barter their services in exchange for positive reviews fraud.

“I discovered that the online review world was just saturated with fake reviews, much more so than I think most people are aware ... and law enforcement regulators aren’t doing anything to address the problem,” said Ms. Dean. “In this online space, it’s the Wild West; cheating is rewarded.”

Ms. Dean decided to take matters into her own hands. She created a YouTube channel called Fake Review Watch, where she exposes real businesses and their attempts to dupe potential consumers with fake positive reviews.

For example, one video analyzes an orthopedic surgeon in Manhattan with an abundance of five-star reviews. Through her detailed analysis, Ms. Dean created a spreadsheet of the 26 alleged patients of the orthopedic surgeon that had submitted glowing reviews. She looked into other businesses that the individuals had left reviews for and found a significant amount of overlap.

According to the video, 19 of the doctor’s reviewers had left high reviews for the same moving company in Las Vegas, and 18 of them reviewed the same locksmith in Texas. Overall, eight of the patients reviewed the same mover, locksmith, and hotel in New Zealand.

A matter of trust

Ms. Dean expressed the gravity of this phenomenon, especially in health care, as patients often head online first when searching for care options. Based on a survey by Software Advice, about 84% of patients use online reviews to assess a physician, and 77% use review sites as the first step in finding a doctor.

Patient trust has continued to diminish in recent years, particularly following the pandemic. In a 2021 global ranking of trust levels towards health care by country, the U.S. health care system ranked 19th, far below those of several developing countries.

Owing to the rise of fake patient reviews and their inscrutable nature, Ms. Dean advises staying away from online review platforms. Instead, she suggests sticking to the old-fashioned method of getting recommendations from friends and relatives, not virtual people.

Ms. Dean explained a few indicators that she looks for when trying to identify a fake review.

“The business has all five-star reviews, negative reviews are followed by five-star reviews, or the business has an abnormal number of positive reviews in a short period of time,” she noted. “Some businesses try to bury legitimate negative reviews by obtaining more recent, fake, positive ones. The recent reviews will contradict the specific criticisms in the negative review.”

She warned that consumers should not give credibility to reviews simply because the reviewer is dubbed “Elite” or a Google Local Guide, because she has seen plenty of these individuals posting fake reviews.

Unfortunately, review platforms haven’t been doing much self-policing. Google and Healthgrades have a series of policies against fake engagement, impersonation, misinformation, and misrepresentation, according to their websites. However, the only consequence of these violations is review removal.

Both Yelp! and Google say they have automated software that distinguishes real versus fake reviews. When Yelp! uncovers users engaging in compensation review activity, it removes their reviews, closes their account, and blocks those users from creating future Yelp! accounts.

Physicians’ basis

Moreover,

“I think there’s an erosion of business ethics because cheating is rewarded. You can’t compete in an environment where your competition is allowed to accumulate numerous fake reviews while you’re still trying to fill chairs in your business,” said Ms. Dean. “Your competition is then getting the business because the tech companies are allowing this fraud.”

Family physician and practice owner Mike Woo-Ming, MD, MPH, provides career coaching for physicians, including maintaining a good reputation – in-person and online. He has seen physicians bumping up their own five-star reviews personally as well as posting negative reviews for their competition.

“I’ve seen where they’re going to lose business, as many practices were affected through COVID,” he said. “Business owners can become desperate and may decide to start posting or buying reviews because they know people will choose certain services these days based upon reviews.”

Dr. Woo-Ming expressed his frustration with fellow physicians who give in to purchasing fake reviews, because the patients have no idea whether reviews are genuine or not.

To encourage genuine positive reviews, Dr. Woo-Ming’s practice uses a third-party app system that sends patients a follow-up email or text asking about their experience with a link to review sites.

“Honest reviews are a reflection of what I can do to improve my business. At the end of the day, if you’re truly providing great service and you’re helping people by providing great medical care, those are going to win out,” he said. “I would rather, as a responsible practice owner, improve the experience and outcome for the patient.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

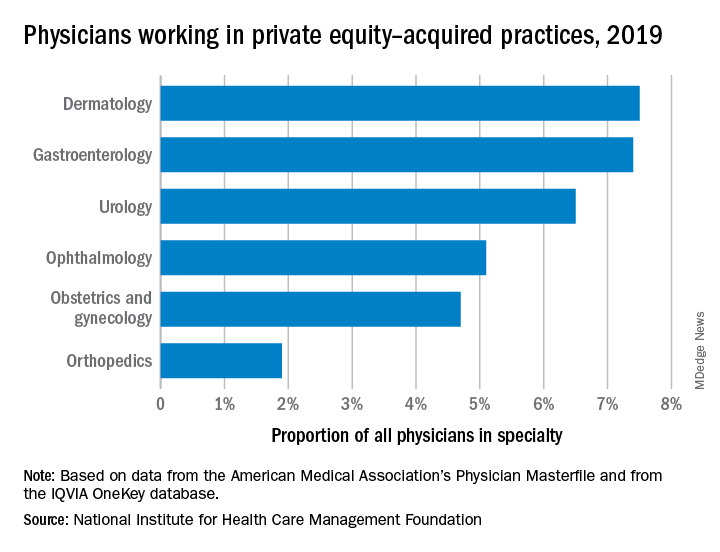

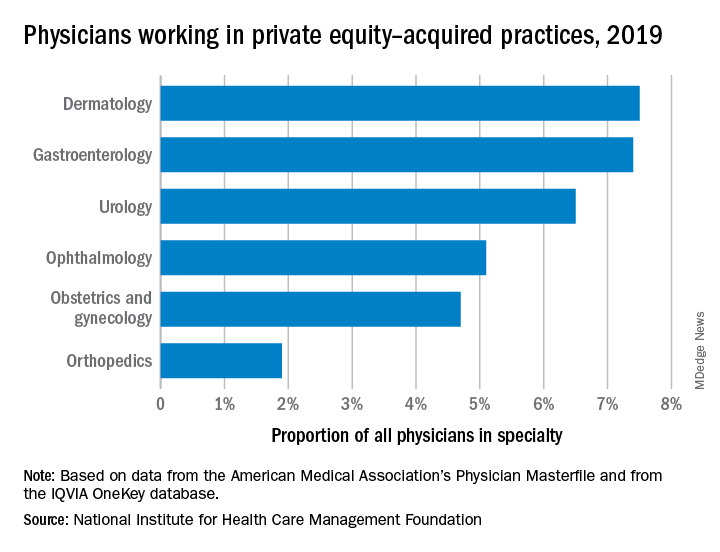

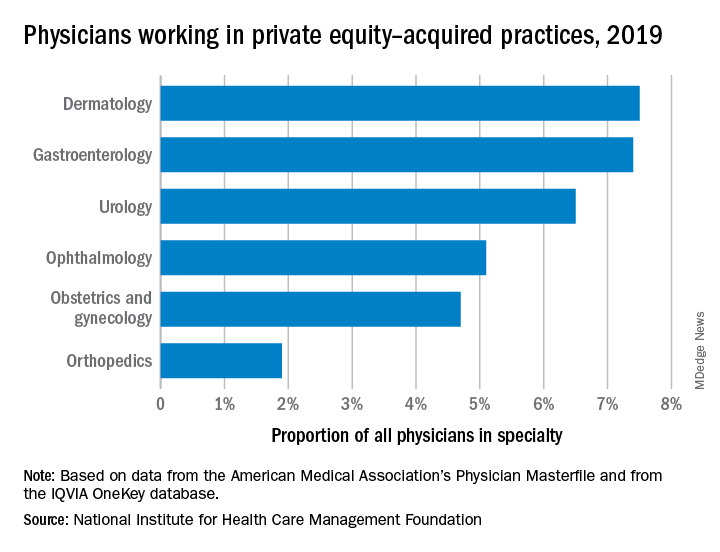

Six specialties attracting the highest private equity acquisitions

While tracking the extent of physician practice acquisition by private equity firms may be difficult, new research highlights what specialties and U.S. regions are most affected by such purchases.

The study, supported by the National Institute for Health Care Management (NIHCM), examined 97,094 physicians practicing in six specialties, 4,738 of whom worked in private equity–acquired practices. Of these specialties,

“These specialties offer private equity firms diverse revenue streams. You have a mix of commercially insured individuals with Medicare insurance and self-pay,” said Yashaswini Singh, MPA, a doctoral student at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and coauthor of the study, which was published in JAMA Health Forum as a research letter.

“In dermatology, you have a mix of surgical procedures that are covered under insurance, but also a lot of cosmetic procedures that are most likely to be self-pay procedures. This offers private equity several mechanisms to which they can increase their revenues.”

Ms. Singh’s coauthors were part of a previous study looking at private practice penetration by private equity firms. That research found such deals surged from 59 deals in 2013 representing 843 physicians, to 136 private equity acquisition deals representing 1,882 physicians in 2016.

The most recent study notes limited data and use of nondisclosure agreements during early negotiations as part of the difficulty in truly pinpointing private equity’s presence in health care. Monitoring private equity activity has become necessary across all industries, noted the authors of the study. If continued at this rate, long-term private equity acquisition has a multitude of potential pros and cons.

Ms. Singh explained that such specialties are highly fragmented and they allow for economies of scale and scope. In particular, an aging population increases demand for dermatology, ophthalmology, and gastroenterology services such as skin biopsies, cataracts, and colonoscopies. This makes these specialties very attractive to private equity firms. The same can be said for obstetrics and gynecology, as fertility clinics have attracted many private equity investments.

“This is another area where understanding changes to physician practice patterns and patient outcomes is critical as women continue to delay motherhood,” said Ms. Singh.

Reducing competition, increasing focus on patient care

Researchers found significant geographical trends for private equity penetration, as it varies across the country. It is highest in the Northeast, Florida, and Arizona in hospital referral regions. Researchers are still analyzing the cause of this occurrence.

Geographic concentration of private equity penetration likely reflects strategic selection of investment opportunities by private equity funds as the decision to invest in a practice does not happen at random, Ms. Singh noted.

Ms. Singh said she hopes that by documenting a variation and geographic concentration that the NIHCM is providing the first foundational step to tackle questions related to incentives and regulations that facilitate investment.

“Understanding the regulatory and economic environments that facilitate private equity activity is an interesting and important question to explore further,” she said in an interview. “This can include supply-side factors that can shape the business environment, e.g., taxation environment, regulatory burden to complete acquisitions, as well as demand-side factors that facilitate growth.”

Researchers found that continued growth of private equity penetration may lead to consolidation among independent practices facing financial pressures, as well as reduced competition and increased prices within each local health care market.

“Localized consolidation in certain markets has the potential for competition to reduce, [and] reduced competition has been shown in a variety of settings to be associated with increases in prices and reduced access for patients,” said Ms. Singh.

Conversely, Ms. Singh addressed several benefits of growing private equity presence. Companies can exploit their full potential through the addition of private equity expertise and contacts. Specifically, health care development of technological infrastructure is likely, along with reduced patient wait times and the expansion of business hours. It could also be a way for practices to offload administrative responsibilities and for physicians to focus more on the care delivery process.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While tracking the extent of physician practice acquisition by private equity firms may be difficult, new research highlights what specialties and U.S. regions are most affected by such purchases.

The study, supported by the National Institute for Health Care Management (NIHCM), examined 97,094 physicians practicing in six specialties, 4,738 of whom worked in private equity–acquired practices. Of these specialties,

“These specialties offer private equity firms diverse revenue streams. You have a mix of commercially insured individuals with Medicare insurance and self-pay,” said Yashaswini Singh, MPA, a doctoral student at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and coauthor of the study, which was published in JAMA Health Forum as a research letter.

“In dermatology, you have a mix of surgical procedures that are covered under insurance, but also a lot of cosmetic procedures that are most likely to be self-pay procedures. This offers private equity several mechanisms to which they can increase their revenues.”

Ms. Singh’s coauthors were part of a previous study looking at private practice penetration by private equity firms. That research found such deals surged from 59 deals in 2013 representing 843 physicians, to 136 private equity acquisition deals representing 1,882 physicians in 2016.

The most recent study notes limited data and use of nondisclosure agreements during early negotiations as part of the difficulty in truly pinpointing private equity’s presence in health care. Monitoring private equity activity has become necessary across all industries, noted the authors of the study. If continued at this rate, long-term private equity acquisition has a multitude of potential pros and cons.

Ms. Singh explained that such specialties are highly fragmented and they allow for economies of scale and scope. In particular, an aging population increases demand for dermatology, ophthalmology, and gastroenterology services such as skin biopsies, cataracts, and colonoscopies. This makes these specialties very attractive to private equity firms. The same can be said for obstetrics and gynecology, as fertility clinics have attracted many private equity investments.

“This is another area where understanding changes to physician practice patterns and patient outcomes is critical as women continue to delay motherhood,” said Ms. Singh.

Reducing competition, increasing focus on patient care

Researchers found significant geographical trends for private equity penetration, as it varies across the country. It is highest in the Northeast, Florida, and Arizona in hospital referral regions. Researchers are still analyzing the cause of this occurrence.

Geographic concentration of private equity penetration likely reflects strategic selection of investment opportunities by private equity funds as the decision to invest in a practice does not happen at random, Ms. Singh noted.

Ms. Singh said she hopes that by documenting a variation and geographic concentration that the NIHCM is providing the first foundational step to tackle questions related to incentives and regulations that facilitate investment.

“Understanding the regulatory and economic environments that facilitate private equity activity is an interesting and important question to explore further,” she said in an interview. “This can include supply-side factors that can shape the business environment, e.g., taxation environment, regulatory burden to complete acquisitions, as well as demand-side factors that facilitate growth.”

Researchers found that continued growth of private equity penetration may lead to consolidation among independent practices facing financial pressures, as well as reduced competition and increased prices within each local health care market.

“Localized consolidation in certain markets has the potential for competition to reduce, [and] reduced competition has been shown in a variety of settings to be associated with increases in prices and reduced access for patients,” said Ms. Singh.