User login

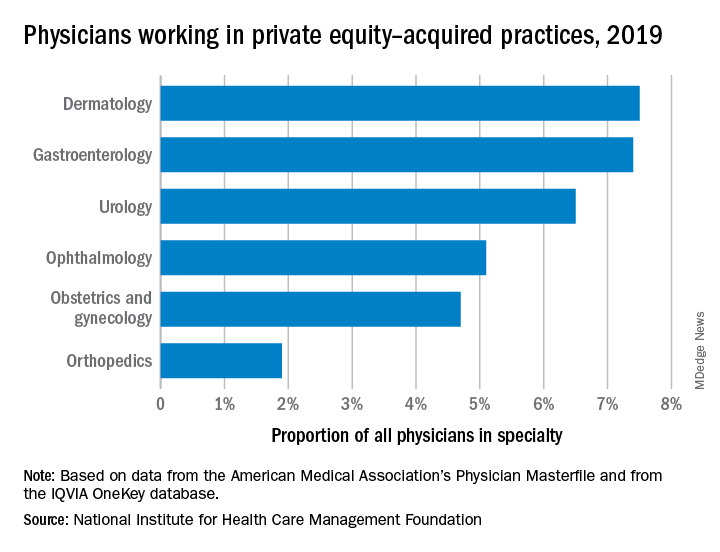

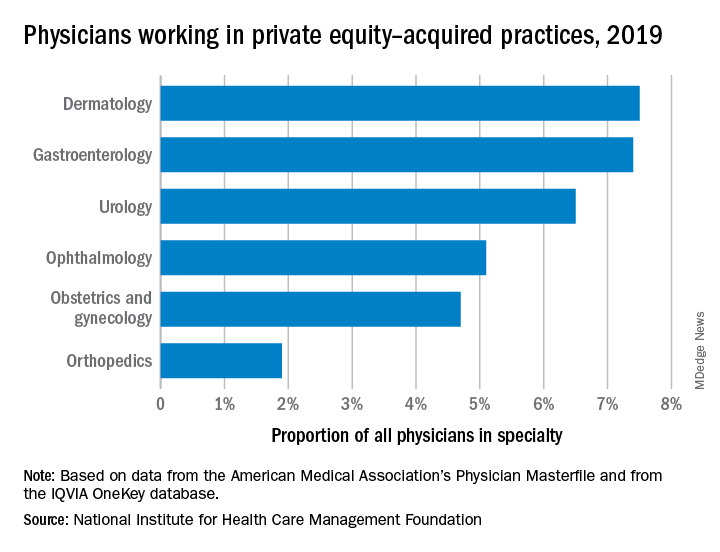

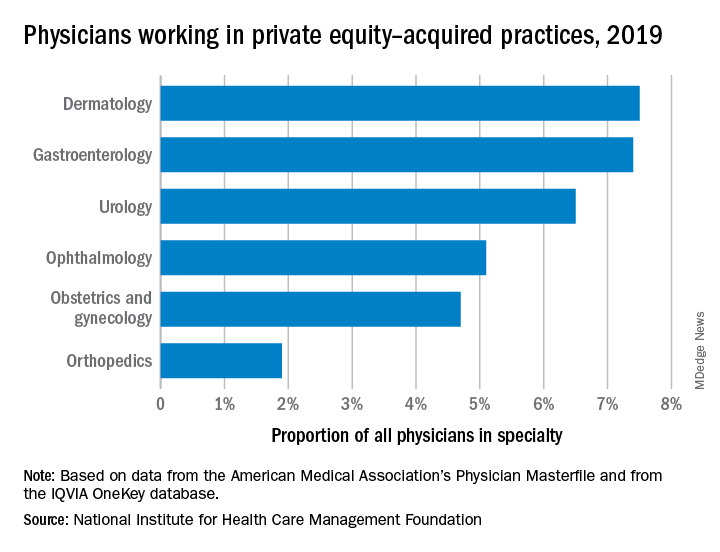

While tracking the extent of physician practice acquisition by private equity firms may be difficult, new research highlights what specialties and U.S. regions are most affected by such purchases.

The study, supported by the National Institute for Health Care Management (NIHCM), examined 97,094 physicians practicing in six specialties, 4,738 of whom worked in private equity–acquired practices. Of these specialties,

“These specialties offer private equity firms diverse revenue streams. You have a mix of commercially insured individuals with Medicare insurance and self-pay,” said Yashaswini Singh, MPA, a doctoral student at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and coauthor of the study, which was published in JAMA Health Forum as a research letter.

“In dermatology, you have a mix of surgical procedures that are covered under insurance, but also a lot of cosmetic procedures that are most likely to be self-pay procedures. This offers private equity several mechanisms to which they can increase their revenues.”

Ms. Singh’s coauthors were part of a previous study looking at private practice penetration by private equity firms. That research found such deals surged from 59 deals in 2013 representing 843 physicians, to 136 private equity acquisition deals representing 1,882 physicians in 2016.

The most recent study notes limited data and use of nondisclosure agreements during early negotiations as part of the difficulty in truly pinpointing private equity’s presence in health care. Monitoring private equity activity has become necessary across all industries, noted the authors of the study. If continued at this rate, long-term private equity acquisition has a multitude of potential pros and cons.

Ms. Singh explained that such specialties are highly fragmented and they allow for economies of scale and scope. In particular, an aging population increases demand for dermatology, ophthalmology, and gastroenterology services such as skin biopsies, cataracts, and colonoscopies. This makes these specialties very attractive to private equity firms. The same can be said for obstetrics and gynecology, as fertility clinics have attracted many private equity investments.

“This is another area where understanding changes to physician practice patterns and patient outcomes is critical as women continue to delay motherhood,” said Ms. Singh.

Reducing competition, increasing focus on patient care

Researchers found significant geographical trends for private equity penetration, as it varies across the country. It is highest in the Northeast, Florida, and Arizona in hospital referral regions. Researchers are still analyzing the cause of this occurrence.

Geographic concentration of private equity penetration likely reflects strategic selection of investment opportunities by private equity funds as the decision to invest in a practice does not happen at random, Ms. Singh noted.

Ms. Singh said she hopes that by documenting a variation and geographic concentration that the NIHCM is providing the first foundational step to tackle questions related to incentives and regulations that facilitate investment.

“Understanding the regulatory and economic environments that facilitate private equity activity is an interesting and important question to explore further,” she said in an interview. “This can include supply-side factors that can shape the business environment, e.g., taxation environment, regulatory burden to complete acquisitions, as well as demand-side factors that facilitate growth.”

Researchers found that continued growth of private equity penetration may lead to consolidation among independent practices facing financial pressures, as well as reduced competition and increased prices within each local health care market.

“Localized consolidation in certain markets has the potential for competition to reduce, [and] reduced competition has been shown in a variety of settings to be associated with increases in prices and reduced access for patients,” said Ms. Singh.

Conversely, Ms. Singh addressed several benefits of growing private equity presence. Companies can exploit their full potential through the addition of private equity expertise and contacts. Specifically, health care development of technological infrastructure is likely, along with reduced patient wait times and the expansion of business hours. It could also be a way for practices to offload administrative responsibilities and for physicians to focus more on the care delivery process.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While tracking the extent of physician practice acquisition by private equity firms may be difficult, new research highlights what specialties and U.S. regions are most affected by such purchases.

The study, supported by the National Institute for Health Care Management (NIHCM), examined 97,094 physicians practicing in six specialties, 4,738 of whom worked in private equity–acquired practices. Of these specialties,

“These specialties offer private equity firms diverse revenue streams. You have a mix of commercially insured individuals with Medicare insurance and self-pay,” said Yashaswini Singh, MPA, a doctoral student at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and coauthor of the study, which was published in JAMA Health Forum as a research letter.

“In dermatology, you have a mix of surgical procedures that are covered under insurance, but also a lot of cosmetic procedures that are most likely to be self-pay procedures. This offers private equity several mechanisms to which they can increase their revenues.”

Ms. Singh’s coauthors were part of a previous study looking at private practice penetration by private equity firms. That research found such deals surged from 59 deals in 2013 representing 843 physicians, to 136 private equity acquisition deals representing 1,882 physicians in 2016.

The most recent study notes limited data and use of nondisclosure agreements during early negotiations as part of the difficulty in truly pinpointing private equity’s presence in health care. Monitoring private equity activity has become necessary across all industries, noted the authors of the study. If continued at this rate, long-term private equity acquisition has a multitude of potential pros and cons.

Ms. Singh explained that such specialties are highly fragmented and they allow for economies of scale and scope. In particular, an aging population increases demand for dermatology, ophthalmology, and gastroenterology services such as skin biopsies, cataracts, and colonoscopies. This makes these specialties very attractive to private equity firms. The same can be said for obstetrics and gynecology, as fertility clinics have attracted many private equity investments.

“This is another area where understanding changes to physician practice patterns and patient outcomes is critical as women continue to delay motherhood,” said Ms. Singh.

Reducing competition, increasing focus on patient care

Researchers found significant geographical trends for private equity penetration, as it varies across the country. It is highest in the Northeast, Florida, and Arizona in hospital referral regions. Researchers are still analyzing the cause of this occurrence.

Geographic concentration of private equity penetration likely reflects strategic selection of investment opportunities by private equity funds as the decision to invest in a practice does not happen at random, Ms. Singh noted.

Ms. Singh said she hopes that by documenting a variation and geographic concentration that the NIHCM is providing the first foundational step to tackle questions related to incentives and regulations that facilitate investment.

“Understanding the regulatory and economic environments that facilitate private equity activity is an interesting and important question to explore further,” she said in an interview. “This can include supply-side factors that can shape the business environment, e.g., taxation environment, regulatory burden to complete acquisitions, as well as demand-side factors that facilitate growth.”

Researchers found that continued growth of private equity penetration may lead to consolidation among independent practices facing financial pressures, as well as reduced competition and increased prices within each local health care market.

“Localized consolidation in certain markets has the potential for competition to reduce, [and] reduced competition has been shown in a variety of settings to be associated with increases in prices and reduced access for patients,” said Ms. Singh.

Conversely, Ms. Singh addressed several benefits of growing private equity presence. Companies can exploit their full potential through the addition of private equity expertise and contacts. Specifically, health care development of technological infrastructure is likely, along with reduced patient wait times and the expansion of business hours. It could also be a way for practices to offload administrative responsibilities and for physicians to focus more on the care delivery process.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While tracking the extent of physician practice acquisition by private equity firms may be difficult, new research highlights what specialties and U.S. regions are most affected by such purchases.

The study, supported by the National Institute for Health Care Management (NIHCM), examined 97,094 physicians practicing in six specialties, 4,738 of whom worked in private equity–acquired practices. Of these specialties,

“These specialties offer private equity firms diverse revenue streams. You have a mix of commercially insured individuals with Medicare insurance and self-pay,” said Yashaswini Singh, MPA, a doctoral student at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and coauthor of the study, which was published in JAMA Health Forum as a research letter.

“In dermatology, you have a mix of surgical procedures that are covered under insurance, but also a lot of cosmetic procedures that are most likely to be self-pay procedures. This offers private equity several mechanisms to which they can increase their revenues.”

Ms. Singh’s coauthors were part of a previous study looking at private practice penetration by private equity firms. That research found such deals surged from 59 deals in 2013 representing 843 physicians, to 136 private equity acquisition deals representing 1,882 physicians in 2016.

The most recent study notes limited data and use of nondisclosure agreements during early negotiations as part of the difficulty in truly pinpointing private equity’s presence in health care. Monitoring private equity activity has become necessary across all industries, noted the authors of the study. If continued at this rate, long-term private equity acquisition has a multitude of potential pros and cons.

Ms. Singh explained that such specialties are highly fragmented and they allow for economies of scale and scope. In particular, an aging population increases demand for dermatology, ophthalmology, and gastroenterology services such as skin biopsies, cataracts, and colonoscopies. This makes these specialties very attractive to private equity firms. The same can be said for obstetrics and gynecology, as fertility clinics have attracted many private equity investments.

“This is another area where understanding changes to physician practice patterns and patient outcomes is critical as women continue to delay motherhood,” said Ms. Singh.

Reducing competition, increasing focus on patient care

Researchers found significant geographical trends for private equity penetration, as it varies across the country. It is highest in the Northeast, Florida, and Arizona in hospital referral regions. Researchers are still analyzing the cause of this occurrence.

Geographic concentration of private equity penetration likely reflects strategic selection of investment opportunities by private equity funds as the decision to invest in a practice does not happen at random, Ms. Singh noted.

Ms. Singh said she hopes that by documenting a variation and geographic concentration that the NIHCM is providing the first foundational step to tackle questions related to incentives and regulations that facilitate investment.

“Understanding the regulatory and economic environments that facilitate private equity activity is an interesting and important question to explore further,” she said in an interview. “This can include supply-side factors that can shape the business environment, e.g., taxation environment, regulatory burden to complete acquisitions, as well as demand-side factors that facilitate growth.”

Researchers found that continued growth of private equity penetration may lead to consolidation among independent practices facing financial pressures, as well as reduced competition and increased prices within each local health care market.

“Localized consolidation in certain markets has the potential for competition to reduce, [and] reduced competition has been shown in a variety of settings to be associated with increases in prices and reduced access for patients,” said Ms. Singh.

Conversely, Ms. Singh addressed several benefits of growing private equity presence. Companies can exploit their full potential through the addition of private equity expertise and contacts. Specifically, health care development of technological infrastructure is likely, along with reduced patient wait times and the expansion of business hours. It could also be a way for practices to offload administrative responsibilities and for physicians to focus more on the care delivery process.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA HEALTH FORUM