User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

New insight into the growing problem of gaming disorder

A team of international researchers led by Orsolya Király, PhD, of the Institute of Psychology, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, reviewed the characteristics and etiology of GD. They concluded that its genesis arises from the interaction of environmental factors, game-specific factors and individual factors, including personality traits, comorbid psychopathology, and genetic predisposition.

“The development of GD is a complex process and we identified three major factors involved,” study coauthor Mark Griffiths, PhD, distinguished professor of behavioral addiction and director of the international gaming research unit, psychology department, Nottingham (England) Trent University, said in an interview. Because of this complexity, “prevention and intervention in GD require multiprofessional action.”

The review was published in Comprehensive Psychiatry.

In a second paper, published online in Frontiers in Psychiatry, Chinese investigators reviewing randomized controlled trials (RCTs) presented “compelling evidence” to support four effective interventions for GD: group counseling, acceptance and cognitive restructuring intervention program (ACRIP), short-term cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and craving behavioral intervention (CBI).

A third paper, published online in the Journal of Behavioral Addictions, in which researchers analyzed close to 50 studies of GD, found that the concept of “recovery” is rarely mentioned in GD research. Lead author Belle Gavriel-Fried, PhD, senior professor, Bob Shapell School of Social Work, Tel Aviv University, said in an interview that recovery is a “holistic concept that taps into many aspects of life.”

Understanding the “differences in the impact and availability” of negative and positive human resources and their effect on recovery “can help clinicians to customize treatment,” she said.

Complex interplay

GD is garnering increasing attention in the clinical community, especially since 2019, when the World Health Organization included it in the ICD-11.

“Although for most individuals, gaming is a recreational activity or even a passion, a small group of gamers experiences negative symptoms which impact their mental and physical health and cause functional impairment,” wrote Dr. Király and colleagues.

Dr. Griffiths explained that his team wanted to provide an “up-to-date primer – a ‘one-stop shop’ – on all things etiologic concerning gaming disorder for academics and practitioners” as well as others, such as health policy makers, teachers, and individuals in the gaming industry.

The researchers identified three factors that increase the risk of developing GD, the first being gaming-related factors, which make video games “addictive in a way that vulnerable individuals may develop GD.”

For example, GD is more prevalent among online versus offline game players, possibly because online multiplayer games “provide safe environments in which players can fulfill their social needs while remaining invisible and anonymous.”

Game genre also matters, with massively multiplayer online role-playing games, first-person/third-person shooter games, real-time strategy games, and multiplayer online battle arena games most implicated in problematic gaming. Moreover, the “monetization techniques” of certain games also increase their addictive potential.

The researchers point to individual factors that increase the risk of developing GD, including male sex and younger age, personality traits like impulsivity and sensation-seeking, and comorbidities including ADHD, anxiety, and depression.

Poor self-esteem and lack of social competencies make gaming “an easy and efficient way to compensate for these deficiencies, which in turn, heightens the risk for developing GD,” they add. Neurobiological processes and genetic predisposition also play a role.

Lastly, the authors mentioned environmental factors, including family and peer-group issues, problems at work or school, and cultural factors.

“The take-home messages are that problematic gaming has had a long history of empirical research; that the psychiatric community now views GD as a legitimate mental health issue; and that the reasons for GD are complex, with many different factors involved in the acquisition, development, and maintenance of GD,” said Dr. Griffiths.

Beneficial behavioral therapies

Yuzhou Chen and colleagues, Southwest University, Chongqing, China, conducted a systematic review of RCTs investigating interventions for treating GD. Despite the “large number of intervention approaches developed over the past decade, as yet, there are no authoritative guidelines for what makes an effective GD intervention,” they wrote.

Few studies have focused specifically on GD but instead have focused on a combination of internet addiction and GD. But the interventions used to treat internet addiction may not apply to GD. And few studies have utilized an RCT design. The researchers therefore set out to review studies that specifically used an RCT design to investigate interventions for GD.

They searched six databases to identify RCTs that tested GD interventions from the inception of each database until the end of 2021. To be included, participants had to be diagnosed with GD and receive either a “complete and systematic intervention” or be in a comparator control group receiving no intervention or placebo.

Seven studies met the inclusion criteria (n = 332 participants). The studies tested five interventions:

- Group counseling with three different themes (interpersonal interaction, acceptance and commitment, cognition and behavior)

- CBI, which addresses cravings

- Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS)

- ACRIP with the main objectives of reducing GD symptoms and improving psychological well-being

- Short-term CBT, which addresses maladaptive cognitions

The mean duration of the interventions ranged from 3 to 15 weeks.

The primary outcome was GD severity, with secondary outcomes including depression, anxiety, cognition, game time, self-esteem, self-compassion, shyness, impulsivity, and psychological well-being.

Group counseling, CBI, ACRIP, and short-term CBT interventions had “a significant effect on decreasing the severity of GD,” while tDCS had “no significant effect.”

Behavioral therapy “exerts its effect on the behavioral mechanism of GD; for example, by reducing the association between game-related stimuli and the game player’s response to them,” the authors suggested.

Behavioral therapy “exerts its effect on the behavioral mechanism of GD; for example, by reducing the association between game-related stimuli and the game-player’s response to them,” the authors suggested.

Recovery vs. pathology

Recovery “traditionally represents the transition from trauma and illness to health,” Dr. Gavriel-Fried and colleagues noted.

Two paradigms of recovery are “deficit based” and “strength based.” The first assesses recovery in terms of abstinence, sobriety, and symptom reduction; and the second focuses on “growth, rather than a reduction in pathology.”

But although recovery is “embedded within mental health addiction policies and practice,” the concept has received “scant attention” in GD research.

The researchers therefore aimed to “map and summarize the state of the art on recovery from GD,” defining “recovery” as the “ability to handle conflicting feelings and emotions without external mediation.”

They conducted a scoping review of all literature regarding GD or internet GD published before February 2022 (47 studies, 2,924 participants with GD; mean age range, 13-26 years).

Most studies (n = 32) consisted of exclusively male subjects. Only 10 included both sexes, and female participants were in the minority.

Most studies (n = 42) did not address the concept of recovery, although all studies did report significant improvements in gaming-related pathology. Typical terminology used to describe changes in participants’ GD were “reduction” and/or “decrease” in symptom severity.

Although 18 studies mentioned the word “recovery,” only 5 actually discussed issues related to the notion of recovery, and only 5 used the term “abstinence.”

In addition, only 13 studies examined positive components of life in patients with GD, such as increased psychological well-being, life satisfaction, quality of life, improved emotional state, relational skills, and executive control, as well as improved self-care, hygiene, sleep, and interest in school studies.

“As a person and researcher who believes that words shape the way we perceive things, I think we should use the word ‘recovery’ rather than ‘pathology’ much more in research, therapy, and policy,” said Dr. Gavriel-Fried.

She noted that, because GD is a “relatively new behavioral addictive disorder, theories are still being developed and definitions of the symptoms are still being fine-tuned.”

“The field as a whole will benefit from future theoretical work that will lead to practical solutions for treating GD and ways to identify the risk factors,” Dr. Gavriel-Fried said.

Filling a research gap

In a comment, David Greenfield, MD, founder and medical director of the Connecticut-based Center for Internet and Technology Addiction, noted that 3 decades ago, there was almost no research into this area.

“The fact that we have these reviews and studies is good because all of the research adds to the science providing more data about an area we still don’t know that much about, where research is still in its infancy,” said Dr. Greenfield, who was not involved with the present study.

“Although we have definitions, there’s no complete agreement about the definitions of GD, and we do not yet have a unified approach,” continued Dr. Greenfield, who wrote the books Overcoming Internet Addiction for Dummies and Virtual Addiction.

He suggested that “recovery” is rarely used as a concept in GD research perhaps because there’s a “bifurcation in the field of addiction medicine in which behavioral addictions are not seen as equivalent to substance addictions,” and, particularly with GD, the principles of “recovery” have not yet matured.

“Recovery means meaningful life away from the screen, not just abstinence from the screen,” said Dr. Greenfield.

The study by Mr. Chen and colleagues was supported by grants from the National Social Science Foundation of China, the Chongqing Research Program of Basic Research and Frontier Technology, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities. Dr. Griffiths has reported receiving research funding from Norsk Tipping (the gambling operator owned by the Norwegian government). The study by Dr. Király and colleagues received support from the Hungarian National Research Development and Innovation Office and the Janos Bolyai Research Scholarship Academy of Sciences to individual investigators. The study by Dr. Gavriel-Fried and colleagues received support from the Hungarian National Research Development and Innovation Office and the Janos Bolyai Research Scholarship Academy of Sciences to individual investigators. Dr. Gavriel-Fried has reported receiving grants from the Israel National Insurance Institute and the Committee for Independent Studies of the Israel Lottery. Dr. Greenfield reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A team of international researchers led by Orsolya Király, PhD, of the Institute of Psychology, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, reviewed the characteristics and etiology of GD. They concluded that its genesis arises from the interaction of environmental factors, game-specific factors and individual factors, including personality traits, comorbid psychopathology, and genetic predisposition.

“The development of GD is a complex process and we identified three major factors involved,” study coauthor Mark Griffiths, PhD, distinguished professor of behavioral addiction and director of the international gaming research unit, psychology department, Nottingham (England) Trent University, said in an interview. Because of this complexity, “prevention and intervention in GD require multiprofessional action.”

The review was published in Comprehensive Psychiatry.

In a second paper, published online in Frontiers in Psychiatry, Chinese investigators reviewing randomized controlled trials (RCTs) presented “compelling evidence” to support four effective interventions for GD: group counseling, acceptance and cognitive restructuring intervention program (ACRIP), short-term cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and craving behavioral intervention (CBI).

A third paper, published online in the Journal of Behavioral Addictions, in which researchers analyzed close to 50 studies of GD, found that the concept of “recovery” is rarely mentioned in GD research. Lead author Belle Gavriel-Fried, PhD, senior professor, Bob Shapell School of Social Work, Tel Aviv University, said in an interview that recovery is a “holistic concept that taps into many aspects of life.”

Understanding the “differences in the impact and availability” of negative and positive human resources and their effect on recovery “can help clinicians to customize treatment,” she said.

Complex interplay

GD is garnering increasing attention in the clinical community, especially since 2019, when the World Health Organization included it in the ICD-11.

“Although for most individuals, gaming is a recreational activity or even a passion, a small group of gamers experiences negative symptoms which impact their mental and physical health and cause functional impairment,” wrote Dr. Király and colleagues.

Dr. Griffiths explained that his team wanted to provide an “up-to-date primer – a ‘one-stop shop’ – on all things etiologic concerning gaming disorder for academics and practitioners” as well as others, such as health policy makers, teachers, and individuals in the gaming industry.

The researchers identified three factors that increase the risk of developing GD, the first being gaming-related factors, which make video games “addictive in a way that vulnerable individuals may develop GD.”

For example, GD is more prevalent among online versus offline game players, possibly because online multiplayer games “provide safe environments in which players can fulfill their social needs while remaining invisible and anonymous.”

Game genre also matters, with massively multiplayer online role-playing games, first-person/third-person shooter games, real-time strategy games, and multiplayer online battle arena games most implicated in problematic gaming. Moreover, the “monetization techniques” of certain games also increase their addictive potential.

The researchers point to individual factors that increase the risk of developing GD, including male sex and younger age, personality traits like impulsivity and sensation-seeking, and comorbidities including ADHD, anxiety, and depression.

Poor self-esteem and lack of social competencies make gaming “an easy and efficient way to compensate for these deficiencies, which in turn, heightens the risk for developing GD,” they add. Neurobiological processes and genetic predisposition also play a role.

Lastly, the authors mentioned environmental factors, including family and peer-group issues, problems at work or school, and cultural factors.

“The take-home messages are that problematic gaming has had a long history of empirical research; that the psychiatric community now views GD as a legitimate mental health issue; and that the reasons for GD are complex, with many different factors involved in the acquisition, development, and maintenance of GD,” said Dr. Griffiths.

Beneficial behavioral therapies

Yuzhou Chen and colleagues, Southwest University, Chongqing, China, conducted a systematic review of RCTs investigating interventions for treating GD. Despite the “large number of intervention approaches developed over the past decade, as yet, there are no authoritative guidelines for what makes an effective GD intervention,” they wrote.

Few studies have focused specifically on GD but instead have focused on a combination of internet addiction and GD. But the interventions used to treat internet addiction may not apply to GD. And few studies have utilized an RCT design. The researchers therefore set out to review studies that specifically used an RCT design to investigate interventions for GD.

They searched six databases to identify RCTs that tested GD interventions from the inception of each database until the end of 2021. To be included, participants had to be diagnosed with GD and receive either a “complete and systematic intervention” or be in a comparator control group receiving no intervention or placebo.

Seven studies met the inclusion criteria (n = 332 participants). The studies tested five interventions:

- Group counseling with three different themes (interpersonal interaction, acceptance and commitment, cognition and behavior)

- CBI, which addresses cravings

- Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS)

- ACRIP with the main objectives of reducing GD symptoms and improving psychological well-being

- Short-term CBT, which addresses maladaptive cognitions

The mean duration of the interventions ranged from 3 to 15 weeks.

The primary outcome was GD severity, with secondary outcomes including depression, anxiety, cognition, game time, self-esteem, self-compassion, shyness, impulsivity, and psychological well-being.

Group counseling, CBI, ACRIP, and short-term CBT interventions had “a significant effect on decreasing the severity of GD,” while tDCS had “no significant effect.”

Behavioral therapy “exerts its effect on the behavioral mechanism of GD; for example, by reducing the association between game-related stimuli and the game player’s response to them,” the authors suggested.

Behavioral therapy “exerts its effect on the behavioral mechanism of GD; for example, by reducing the association between game-related stimuli and the game-player’s response to them,” the authors suggested.

Recovery vs. pathology

Recovery “traditionally represents the transition from trauma and illness to health,” Dr. Gavriel-Fried and colleagues noted.

Two paradigms of recovery are “deficit based” and “strength based.” The first assesses recovery in terms of abstinence, sobriety, and symptom reduction; and the second focuses on “growth, rather than a reduction in pathology.”

But although recovery is “embedded within mental health addiction policies and practice,” the concept has received “scant attention” in GD research.

The researchers therefore aimed to “map and summarize the state of the art on recovery from GD,” defining “recovery” as the “ability to handle conflicting feelings and emotions without external mediation.”

They conducted a scoping review of all literature regarding GD or internet GD published before February 2022 (47 studies, 2,924 participants with GD; mean age range, 13-26 years).

Most studies (n = 32) consisted of exclusively male subjects. Only 10 included both sexes, and female participants were in the minority.

Most studies (n = 42) did not address the concept of recovery, although all studies did report significant improvements in gaming-related pathology. Typical terminology used to describe changes in participants’ GD were “reduction” and/or “decrease” in symptom severity.

Although 18 studies mentioned the word “recovery,” only 5 actually discussed issues related to the notion of recovery, and only 5 used the term “abstinence.”

In addition, only 13 studies examined positive components of life in patients with GD, such as increased psychological well-being, life satisfaction, quality of life, improved emotional state, relational skills, and executive control, as well as improved self-care, hygiene, sleep, and interest in school studies.

“As a person and researcher who believes that words shape the way we perceive things, I think we should use the word ‘recovery’ rather than ‘pathology’ much more in research, therapy, and policy,” said Dr. Gavriel-Fried.

She noted that, because GD is a “relatively new behavioral addictive disorder, theories are still being developed and definitions of the symptoms are still being fine-tuned.”

“The field as a whole will benefit from future theoretical work that will lead to practical solutions for treating GD and ways to identify the risk factors,” Dr. Gavriel-Fried said.

Filling a research gap

In a comment, David Greenfield, MD, founder and medical director of the Connecticut-based Center for Internet and Technology Addiction, noted that 3 decades ago, there was almost no research into this area.

“The fact that we have these reviews and studies is good because all of the research adds to the science providing more data about an area we still don’t know that much about, where research is still in its infancy,” said Dr. Greenfield, who was not involved with the present study.

“Although we have definitions, there’s no complete agreement about the definitions of GD, and we do not yet have a unified approach,” continued Dr. Greenfield, who wrote the books Overcoming Internet Addiction for Dummies and Virtual Addiction.

He suggested that “recovery” is rarely used as a concept in GD research perhaps because there’s a “bifurcation in the field of addiction medicine in which behavioral addictions are not seen as equivalent to substance addictions,” and, particularly with GD, the principles of “recovery” have not yet matured.

“Recovery means meaningful life away from the screen, not just abstinence from the screen,” said Dr. Greenfield.

The study by Mr. Chen and colleagues was supported by grants from the National Social Science Foundation of China, the Chongqing Research Program of Basic Research and Frontier Technology, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities. Dr. Griffiths has reported receiving research funding from Norsk Tipping (the gambling operator owned by the Norwegian government). The study by Dr. Király and colleagues received support from the Hungarian National Research Development and Innovation Office and the Janos Bolyai Research Scholarship Academy of Sciences to individual investigators. The study by Dr. Gavriel-Fried and colleagues received support from the Hungarian National Research Development and Innovation Office and the Janos Bolyai Research Scholarship Academy of Sciences to individual investigators. Dr. Gavriel-Fried has reported receiving grants from the Israel National Insurance Institute and the Committee for Independent Studies of the Israel Lottery. Dr. Greenfield reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A team of international researchers led by Orsolya Király, PhD, of the Institute of Psychology, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, reviewed the characteristics and etiology of GD. They concluded that its genesis arises from the interaction of environmental factors, game-specific factors and individual factors, including personality traits, comorbid psychopathology, and genetic predisposition.

“The development of GD is a complex process and we identified three major factors involved,” study coauthor Mark Griffiths, PhD, distinguished professor of behavioral addiction and director of the international gaming research unit, psychology department, Nottingham (England) Trent University, said in an interview. Because of this complexity, “prevention and intervention in GD require multiprofessional action.”

The review was published in Comprehensive Psychiatry.

In a second paper, published online in Frontiers in Psychiatry, Chinese investigators reviewing randomized controlled trials (RCTs) presented “compelling evidence” to support four effective interventions for GD: group counseling, acceptance and cognitive restructuring intervention program (ACRIP), short-term cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and craving behavioral intervention (CBI).

A third paper, published online in the Journal of Behavioral Addictions, in which researchers analyzed close to 50 studies of GD, found that the concept of “recovery” is rarely mentioned in GD research. Lead author Belle Gavriel-Fried, PhD, senior professor, Bob Shapell School of Social Work, Tel Aviv University, said in an interview that recovery is a “holistic concept that taps into many aspects of life.”

Understanding the “differences in the impact and availability” of negative and positive human resources and their effect on recovery “can help clinicians to customize treatment,” she said.

Complex interplay

GD is garnering increasing attention in the clinical community, especially since 2019, when the World Health Organization included it in the ICD-11.

“Although for most individuals, gaming is a recreational activity or even a passion, a small group of gamers experiences negative symptoms which impact their mental and physical health and cause functional impairment,” wrote Dr. Király and colleagues.

Dr. Griffiths explained that his team wanted to provide an “up-to-date primer – a ‘one-stop shop’ – on all things etiologic concerning gaming disorder for academics and practitioners” as well as others, such as health policy makers, teachers, and individuals in the gaming industry.

The researchers identified three factors that increase the risk of developing GD, the first being gaming-related factors, which make video games “addictive in a way that vulnerable individuals may develop GD.”

For example, GD is more prevalent among online versus offline game players, possibly because online multiplayer games “provide safe environments in which players can fulfill their social needs while remaining invisible and anonymous.”

Game genre also matters, with massively multiplayer online role-playing games, first-person/third-person shooter games, real-time strategy games, and multiplayer online battle arena games most implicated in problematic gaming. Moreover, the “monetization techniques” of certain games also increase their addictive potential.

The researchers point to individual factors that increase the risk of developing GD, including male sex and younger age, personality traits like impulsivity and sensation-seeking, and comorbidities including ADHD, anxiety, and depression.

Poor self-esteem and lack of social competencies make gaming “an easy and efficient way to compensate for these deficiencies, which in turn, heightens the risk for developing GD,” they add. Neurobiological processes and genetic predisposition also play a role.

Lastly, the authors mentioned environmental factors, including family and peer-group issues, problems at work or school, and cultural factors.

“The take-home messages are that problematic gaming has had a long history of empirical research; that the psychiatric community now views GD as a legitimate mental health issue; and that the reasons for GD are complex, with many different factors involved in the acquisition, development, and maintenance of GD,” said Dr. Griffiths.

Beneficial behavioral therapies

Yuzhou Chen and colleagues, Southwest University, Chongqing, China, conducted a systematic review of RCTs investigating interventions for treating GD. Despite the “large number of intervention approaches developed over the past decade, as yet, there are no authoritative guidelines for what makes an effective GD intervention,” they wrote.

Few studies have focused specifically on GD but instead have focused on a combination of internet addiction and GD. But the interventions used to treat internet addiction may not apply to GD. And few studies have utilized an RCT design. The researchers therefore set out to review studies that specifically used an RCT design to investigate interventions for GD.

They searched six databases to identify RCTs that tested GD interventions from the inception of each database until the end of 2021. To be included, participants had to be diagnosed with GD and receive either a “complete and systematic intervention” or be in a comparator control group receiving no intervention or placebo.

Seven studies met the inclusion criteria (n = 332 participants). The studies tested five interventions:

- Group counseling with three different themes (interpersonal interaction, acceptance and commitment, cognition and behavior)

- CBI, which addresses cravings

- Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS)

- ACRIP with the main objectives of reducing GD symptoms and improving psychological well-being

- Short-term CBT, which addresses maladaptive cognitions

The mean duration of the interventions ranged from 3 to 15 weeks.

The primary outcome was GD severity, with secondary outcomes including depression, anxiety, cognition, game time, self-esteem, self-compassion, shyness, impulsivity, and psychological well-being.

Group counseling, CBI, ACRIP, and short-term CBT interventions had “a significant effect on decreasing the severity of GD,” while tDCS had “no significant effect.”

Behavioral therapy “exerts its effect on the behavioral mechanism of GD; for example, by reducing the association between game-related stimuli and the game player’s response to them,” the authors suggested.

Behavioral therapy “exerts its effect on the behavioral mechanism of GD; for example, by reducing the association between game-related stimuli and the game-player’s response to them,” the authors suggested.

Recovery vs. pathology

Recovery “traditionally represents the transition from trauma and illness to health,” Dr. Gavriel-Fried and colleagues noted.

Two paradigms of recovery are “deficit based” and “strength based.” The first assesses recovery in terms of abstinence, sobriety, and symptom reduction; and the second focuses on “growth, rather than a reduction in pathology.”

But although recovery is “embedded within mental health addiction policies and practice,” the concept has received “scant attention” in GD research.

The researchers therefore aimed to “map and summarize the state of the art on recovery from GD,” defining “recovery” as the “ability to handle conflicting feelings and emotions without external mediation.”

They conducted a scoping review of all literature regarding GD or internet GD published before February 2022 (47 studies, 2,924 participants with GD; mean age range, 13-26 years).

Most studies (n = 32) consisted of exclusively male subjects. Only 10 included both sexes, and female participants were in the minority.

Most studies (n = 42) did not address the concept of recovery, although all studies did report significant improvements in gaming-related pathology. Typical terminology used to describe changes in participants’ GD were “reduction” and/or “decrease” in symptom severity.

Although 18 studies mentioned the word “recovery,” only 5 actually discussed issues related to the notion of recovery, and only 5 used the term “abstinence.”

In addition, only 13 studies examined positive components of life in patients with GD, such as increased psychological well-being, life satisfaction, quality of life, improved emotional state, relational skills, and executive control, as well as improved self-care, hygiene, sleep, and interest in school studies.

“As a person and researcher who believes that words shape the way we perceive things, I think we should use the word ‘recovery’ rather than ‘pathology’ much more in research, therapy, and policy,” said Dr. Gavriel-Fried.

She noted that, because GD is a “relatively new behavioral addictive disorder, theories are still being developed and definitions of the symptoms are still being fine-tuned.”

“The field as a whole will benefit from future theoretical work that will lead to practical solutions for treating GD and ways to identify the risk factors,” Dr. Gavriel-Fried said.

Filling a research gap

In a comment, David Greenfield, MD, founder and medical director of the Connecticut-based Center for Internet and Technology Addiction, noted that 3 decades ago, there was almost no research into this area.

“The fact that we have these reviews and studies is good because all of the research adds to the science providing more data about an area we still don’t know that much about, where research is still in its infancy,” said Dr. Greenfield, who was not involved with the present study.

“Although we have definitions, there’s no complete agreement about the definitions of GD, and we do not yet have a unified approach,” continued Dr. Greenfield, who wrote the books Overcoming Internet Addiction for Dummies and Virtual Addiction.

He suggested that “recovery” is rarely used as a concept in GD research perhaps because there’s a “bifurcation in the field of addiction medicine in which behavioral addictions are not seen as equivalent to substance addictions,” and, particularly with GD, the principles of “recovery” have not yet matured.

“Recovery means meaningful life away from the screen, not just abstinence from the screen,” said Dr. Greenfield.

The study by Mr. Chen and colleagues was supported by grants from the National Social Science Foundation of China, the Chongqing Research Program of Basic Research and Frontier Technology, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities. Dr. Griffiths has reported receiving research funding from Norsk Tipping (the gambling operator owned by the Norwegian government). The study by Dr. Király and colleagues received support from the Hungarian National Research Development and Innovation Office and the Janos Bolyai Research Scholarship Academy of Sciences to individual investigators. The study by Dr. Gavriel-Fried and colleagues received support from the Hungarian National Research Development and Innovation Office and the Janos Bolyai Research Scholarship Academy of Sciences to individual investigators. Dr. Gavriel-Fried has reported receiving grants from the Israel National Insurance Institute and the Committee for Independent Studies of the Israel Lottery. Dr. Greenfield reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New guidelines for cannabis in chronic pain management released

New clinical practice guidelines for cannabis in chronic pain management have been released.

Developed by a group of Canadian researchers, clinicians, and patients, the guidelines note that cannabinoid-based medicines (CBM) may help clinicians offer an effective, less addictive, alternative to opioids in patients with chronic noncancer pain and comorbid conditions.

“We don’t recommend using CBM first line for anything pretty much because there are other alternatives that may be more effective and also offer fewer side effects,” lead guideline author Alan Bell, MD, assistant professor of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto, told this news organization.

“But I would strongly argue that I would use cannabis-based medicine over opioids every time. Why would you use a high potency-high toxicity agent when there’s a low potency-low toxicity alternative?” he said.

The guidelines were published online in the journal Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research.

Examining the evidence

A consistent criticism of CBM has been the lack of quality research supporting its therapeutic utility. To develop the current recommendations, the task force reviewed 47 pain management studies enrolling more than 11,000 patients. Almost half of the studies (n = 22) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 12 of the 19 included systematic reviews focused solely on RCTs.

Overall, 38 of the 47 included studies demonstrated that CBM provided at least moderate benefits for chronic pain, resulting in a “strong” recommendation – mostly as an adjunct or replacement treatment in individuals living with chronic pain.

Overall, the guidelines place a high value on improving chronic pain and functionality, and addressing co-occurring conditions such as insomnia, anxiety and depression, mobility, and inflammation. They also provide practical dosing and formulation tips to support the use of CBM in the clinical setting.

When it comes to chronic pain, CBM is not a panacea. However, prior research suggests cannabinoids and opioids share several pharmacologic properties, including independent but possibly related mechanisms for antinociception, making them an intriguing combination.

In the current guidelines, all of the four studies specifically addressing combined opioids and vaporized cannabis flower demonstrated further pain reduction, reinforcing the conclusion that the benefits of CBM for improving pain control in patients taking opioids outweigh the risk of nonserious adverse events (AEs), such as dry mouth, dizziness, increased appetite, sedation, and concentration difficulties.

The recommendations also highlighted evidence demonstrating that a majority of participants were able to reduce use of routine pain medications with concomitant CBM/opioid administration, while simultaneously offering secondary benefits such as improved sleep, anxiety, and mood, as well as prevention of opioid tolerance and dose escalation.

Importantly, the guidelines offer an evidence-based algorithm with a clear framework for tapering patients off opioids, especially those who are on > 50 mg MED, which places them with a twofold greater risk for fatal overdose.

An effective alternative

Commenting on the new guidelines, Mark Wallace, MD, who has extensive experience researching and treating pain patients with medical cannabis, said the genesis of his interest in medical cannabis mirrors the guidelines’ focus.

“What got me interested in medical cannabis was trying to get patients off of opioids,” said Dr. Wallace, professor of anesthesiology and chief of the division of pain medicine in the department of anesthesiology at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Wallace, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development study, said that he’s “titrated hundreds of patients off of opioids using cannabis.”

Dr. Wallace said he found the guidelines’ dosing recommendations helpful.

“If you stay within the 1- to 5-mg dosing range, the risks are so incredibly low, you’re not going to harm the patient.”

While there are patients who abuse cannabis and CBMs, Dr. Wallace noted that he has seen only one patient in the past 20 years who was overusing the medical cannabis. He added that his patient population does not use medical cannabis to get high and, in fact, wants to avoid doses that produce that effect at all costs.

Also commenting on the guidelines, Christopher Gilligan, MD, MBA, associate chief medical officer and a pain medicine physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development, points to the risks.

“When we have an opportunity to use cannabinoids in place of opioids for our patients, I think that that’s a positive thing ... and a wise choice in terms of risk benefit,” Dr. Gilligan said.

On the other hand, he cautioned that “freely prescribing” cannabinoids for chronic pain in patients who aren’t on opioids is not good practice.

“We have to take seriously the potential adverse effects of [cannabis], including marijuana use disorder, interference with learning, memory impairment, and psychotic breakthroughs,” said Dr. Gilligan.

Given the current climate, it would appear that CBM is a long way from being endorsed by the Food and Drug Administration, but for clinicians interested in trying CBM for chronic pain patients, the guidelines may offer a roadmap for initiation and an alternative to prescribing opioids.

Dr. Bell, Dr. Gilligan, and Dr. Wallace report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New clinical practice guidelines for cannabis in chronic pain management have been released.

Developed by a group of Canadian researchers, clinicians, and patients, the guidelines note that cannabinoid-based medicines (CBM) may help clinicians offer an effective, less addictive, alternative to opioids in patients with chronic noncancer pain and comorbid conditions.

“We don’t recommend using CBM first line for anything pretty much because there are other alternatives that may be more effective and also offer fewer side effects,” lead guideline author Alan Bell, MD, assistant professor of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto, told this news organization.

“But I would strongly argue that I would use cannabis-based medicine over opioids every time. Why would you use a high potency-high toxicity agent when there’s a low potency-low toxicity alternative?” he said.

The guidelines were published online in the journal Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research.

Examining the evidence

A consistent criticism of CBM has been the lack of quality research supporting its therapeutic utility. To develop the current recommendations, the task force reviewed 47 pain management studies enrolling more than 11,000 patients. Almost half of the studies (n = 22) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 12 of the 19 included systematic reviews focused solely on RCTs.

Overall, 38 of the 47 included studies demonstrated that CBM provided at least moderate benefits for chronic pain, resulting in a “strong” recommendation – mostly as an adjunct or replacement treatment in individuals living with chronic pain.

Overall, the guidelines place a high value on improving chronic pain and functionality, and addressing co-occurring conditions such as insomnia, anxiety and depression, mobility, and inflammation. They also provide practical dosing and formulation tips to support the use of CBM in the clinical setting.

When it comes to chronic pain, CBM is not a panacea. However, prior research suggests cannabinoids and opioids share several pharmacologic properties, including independent but possibly related mechanisms for antinociception, making them an intriguing combination.

In the current guidelines, all of the four studies specifically addressing combined opioids and vaporized cannabis flower demonstrated further pain reduction, reinforcing the conclusion that the benefits of CBM for improving pain control in patients taking opioids outweigh the risk of nonserious adverse events (AEs), such as dry mouth, dizziness, increased appetite, sedation, and concentration difficulties.

The recommendations also highlighted evidence demonstrating that a majority of participants were able to reduce use of routine pain medications with concomitant CBM/opioid administration, while simultaneously offering secondary benefits such as improved sleep, anxiety, and mood, as well as prevention of opioid tolerance and dose escalation.

Importantly, the guidelines offer an evidence-based algorithm with a clear framework for tapering patients off opioids, especially those who are on > 50 mg MED, which places them with a twofold greater risk for fatal overdose.

An effective alternative

Commenting on the new guidelines, Mark Wallace, MD, who has extensive experience researching and treating pain patients with medical cannabis, said the genesis of his interest in medical cannabis mirrors the guidelines’ focus.

“What got me interested in medical cannabis was trying to get patients off of opioids,” said Dr. Wallace, professor of anesthesiology and chief of the division of pain medicine in the department of anesthesiology at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Wallace, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development study, said that he’s “titrated hundreds of patients off of opioids using cannabis.”

Dr. Wallace said he found the guidelines’ dosing recommendations helpful.

“If you stay within the 1- to 5-mg dosing range, the risks are so incredibly low, you’re not going to harm the patient.”

While there are patients who abuse cannabis and CBMs, Dr. Wallace noted that he has seen only one patient in the past 20 years who was overusing the medical cannabis. He added that his patient population does not use medical cannabis to get high and, in fact, wants to avoid doses that produce that effect at all costs.

Also commenting on the guidelines, Christopher Gilligan, MD, MBA, associate chief medical officer and a pain medicine physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development, points to the risks.

“When we have an opportunity to use cannabinoids in place of opioids for our patients, I think that that’s a positive thing ... and a wise choice in terms of risk benefit,” Dr. Gilligan said.

On the other hand, he cautioned that “freely prescribing” cannabinoids for chronic pain in patients who aren’t on opioids is not good practice.

“We have to take seriously the potential adverse effects of [cannabis], including marijuana use disorder, interference with learning, memory impairment, and psychotic breakthroughs,” said Dr. Gilligan.

Given the current climate, it would appear that CBM is a long way from being endorsed by the Food and Drug Administration, but for clinicians interested in trying CBM for chronic pain patients, the guidelines may offer a roadmap for initiation and an alternative to prescribing opioids.

Dr. Bell, Dr. Gilligan, and Dr. Wallace report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New clinical practice guidelines for cannabis in chronic pain management have been released.

Developed by a group of Canadian researchers, clinicians, and patients, the guidelines note that cannabinoid-based medicines (CBM) may help clinicians offer an effective, less addictive, alternative to opioids in patients with chronic noncancer pain and comorbid conditions.

“We don’t recommend using CBM first line for anything pretty much because there are other alternatives that may be more effective and also offer fewer side effects,” lead guideline author Alan Bell, MD, assistant professor of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto, told this news organization.

“But I would strongly argue that I would use cannabis-based medicine over opioids every time. Why would you use a high potency-high toxicity agent when there’s a low potency-low toxicity alternative?” he said.

The guidelines were published online in the journal Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research.

Examining the evidence

A consistent criticism of CBM has been the lack of quality research supporting its therapeutic utility. To develop the current recommendations, the task force reviewed 47 pain management studies enrolling more than 11,000 patients. Almost half of the studies (n = 22) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 12 of the 19 included systematic reviews focused solely on RCTs.

Overall, 38 of the 47 included studies demonstrated that CBM provided at least moderate benefits for chronic pain, resulting in a “strong” recommendation – mostly as an adjunct or replacement treatment in individuals living with chronic pain.

Overall, the guidelines place a high value on improving chronic pain and functionality, and addressing co-occurring conditions such as insomnia, anxiety and depression, mobility, and inflammation. They also provide practical dosing and formulation tips to support the use of CBM in the clinical setting.

When it comes to chronic pain, CBM is not a panacea. However, prior research suggests cannabinoids and opioids share several pharmacologic properties, including independent but possibly related mechanisms for antinociception, making them an intriguing combination.

In the current guidelines, all of the four studies specifically addressing combined opioids and vaporized cannabis flower demonstrated further pain reduction, reinforcing the conclusion that the benefits of CBM for improving pain control in patients taking opioids outweigh the risk of nonserious adverse events (AEs), such as dry mouth, dizziness, increased appetite, sedation, and concentration difficulties.

The recommendations also highlighted evidence demonstrating that a majority of participants were able to reduce use of routine pain medications with concomitant CBM/opioid administration, while simultaneously offering secondary benefits such as improved sleep, anxiety, and mood, as well as prevention of opioid tolerance and dose escalation.

Importantly, the guidelines offer an evidence-based algorithm with a clear framework for tapering patients off opioids, especially those who are on > 50 mg MED, which places them with a twofold greater risk for fatal overdose.

An effective alternative

Commenting on the new guidelines, Mark Wallace, MD, who has extensive experience researching and treating pain patients with medical cannabis, said the genesis of his interest in medical cannabis mirrors the guidelines’ focus.

“What got me interested in medical cannabis was trying to get patients off of opioids,” said Dr. Wallace, professor of anesthesiology and chief of the division of pain medicine in the department of anesthesiology at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Wallace, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development study, said that he’s “titrated hundreds of patients off of opioids using cannabis.”

Dr. Wallace said he found the guidelines’ dosing recommendations helpful.

“If you stay within the 1- to 5-mg dosing range, the risks are so incredibly low, you’re not going to harm the patient.”

While there are patients who abuse cannabis and CBMs, Dr. Wallace noted that he has seen only one patient in the past 20 years who was overusing the medical cannabis. He added that his patient population does not use medical cannabis to get high and, in fact, wants to avoid doses that produce that effect at all costs.

Also commenting on the guidelines, Christopher Gilligan, MD, MBA, associate chief medical officer and a pain medicine physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who was not involved in the guidelines’ development, points to the risks.

“When we have an opportunity to use cannabinoids in place of opioids for our patients, I think that that’s a positive thing ... and a wise choice in terms of risk benefit,” Dr. Gilligan said.

On the other hand, he cautioned that “freely prescribing” cannabinoids for chronic pain in patients who aren’t on opioids is not good practice.

“We have to take seriously the potential adverse effects of [cannabis], including marijuana use disorder, interference with learning, memory impairment, and psychotic breakthroughs,” said Dr. Gilligan.

Given the current climate, it would appear that CBM is a long way from being endorsed by the Food and Drug Administration, but for clinicians interested in trying CBM for chronic pain patients, the guidelines may offer a roadmap for initiation and an alternative to prescribing opioids.

Dr. Bell, Dr. Gilligan, and Dr. Wallace report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CANNABIS AND CANNABINOID RESEARCH

Four PTSD blood biomarkers identified

“More accurate means of predicting or screening for PTSD could help to overcome the disorder by identifying individuals at high risk of developing PTSD and providing them with early intervention or prevention strategies,” said study investigator Stacy-Ann Miller, MS.

She also noted that the biomarkers could be used to monitor treatment for PTSD, identify subtypes of PTSD, and lead to a new understanding of the mechanisms underlying PTSD.

The findings were presented at Discover BMB, the annual meeting of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

Toward better clinical assessment

The findings originated from research conducted by the Department of Defense–initiated PTSD Systems Biology Consortium. The consortium’s goals include developing a reproducible panel of blood-based biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity for PTSD diagnosis and is made up of about 45 researchers, led by Marti Jett, PhD, Charles Marmar, MD, and Francis J. Doyle III, PhD.

The researchers analyzed blood samples from 1,000 active-duty Army personnel from the 101st Airborne at Fort Campbell, Ky. Participants were assessed before and after deployment to Afghanistan in February 2014 and are referred to as the Fort Campbell Cohort (FCC). Participants’ age ranged from 25 to 30 and approximately 6% were female.

Investigators collected blood samples from the service members and looked for four biomarkers: glycolytic ratio, arginine, serotonin, and glutamate. The team then divided the participants into four groups – those with PTSD (PTSD Checklist score above 30), those who were subthreshold for PTSD (PTSD Checklist score 15-30), those who had high resilience, and those who had low levels of resilience.

The resilience groups were determined based on answers to the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire, Patient Health Questionnaire, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Intensive Combat Exposure (DRRI-D), the number of deployments, whether they had moderate or severe traumatic brain injury, and scores on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Those who scored in the high range at current or prior time points or who were PTSD/subthreshold at prior time points were placed in the low resilience group.

Ms. Miller noted that those in the PTSD group had more severe symptoms than those in the PTSD subthreshold group based on the longitudinal clinical assessment at 3-6 months, 5 years, and longer post deployment. The low resilience group had a much higher rate of PTSD post deployment than the high resilience group.

Investigators found participants with PTSD or subthreshold PTSD had significantly higher glycolic ratios and lower arginine than those with high resilience. They also found that those with PTSD had significantly lower serotonin and higher glutamate levels versus those with high resilience. These associations were independent of factors such as sex, age, body mass index, smoking, and caffeine consumption.

Ms. Miller said that the study results require further validation by the consortium’s labs and third-party labs.

“We are also interested in determining the most appropriate time to screen soldiers for PTSD, as it has been noted that the time period where we see the most psychological issues is around 2-3 months post return from deployment and when the soldier is preparing for their next assignment, perhaps a next deployment,” she said.

She added that previous studies have identified several promising biomarkers of PTSD. “However, like much of the research data, the study sample was comprised mainly of combat-exposed males. With more women serving on the front lines, the military faces new challenges in how combat affects females in the military,” including sex-specific biomarkers that will improve clinical assessment for female soldiers.

Eventually, the team would also like to be able to apply their research to the civilian population experiencing PTSD.

“Our research is anticipated to be useful in helping the medical provider select appropriate therapeutic interventions,” Ms. Miller said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“More accurate means of predicting or screening for PTSD could help to overcome the disorder by identifying individuals at high risk of developing PTSD and providing them with early intervention or prevention strategies,” said study investigator Stacy-Ann Miller, MS.

She also noted that the biomarkers could be used to monitor treatment for PTSD, identify subtypes of PTSD, and lead to a new understanding of the mechanisms underlying PTSD.

The findings were presented at Discover BMB, the annual meeting of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

Toward better clinical assessment

The findings originated from research conducted by the Department of Defense–initiated PTSD Systems Biology Consortium. The consortium’s goals include developing a reproducible panel of blood-based biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity for PTSD diagnosis and is made up of about 45 researchers, led by Marti Jett, PhD, Charles Marmar, MD, and Francis J. Doyle III, PhD.

The researchers analyzed blood samples from 1,000 active-duty Army personnel from the 101st Airborne at Fort Campbell, Ky. Participants were assessed before and after deployment to Afghanistan in February 2014 and are referred to as the Fort Campbell Cohort (FCC). Participants’ age ranged from 25 to 30 and approximately 6% were female.

Investigators collected blood samples from the service members and looked for four biomarkers: glycolytic ratio, arginine, serotonin, and glutamate. The team then divided the participants into four groups – those with PTSD (PTSD Checklist score above 30), those who were subthreshold for PTSD (PTSD Checklist score 15-30), those who had high resilience, and those who had low levels of resilience.

The resilience groups were determined based on answers to the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire, Patient Health Questionnaire, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Intensive Combat Exposure (DRRI-D), the number of deployments, whether they had moderate or severe traumatic brain injury, and scores on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Those who scored in the high range at current or prior time points or who were PTSD/subthreshold at prior time points were placed in the low resilience group.

Ms. Miller noted that those in the PTSD group had more severe symptoms than those in the PTSD subthreshold group based on the longitudinal clinical assessment at 3-6 months, 5 years, and longer post deployment. The low resilience group had a much higher rate of PTSD post deployment than the high resilience group.

Investigators found participants with PTSD or subthreshold PTSD had significantly higher glycolic ratios and lower arginine than those with high resilience. They also found that those with PTSD had significantly lower serotonin and higher glutamate levels versus those with high resilience. These associations were independent of factors such as sex, age, body mass index, smoking, and caffeine consumption.

Ms. Miller said that the study results require further validation by the consortium’s labs and third-party labs.

“We are also interested in determining the most appropriate time to screen soldiers for PTSD, as it has been noted that the time period where we see the most psychological issues is around 2-3 months post return from deployment and when the soldier is preparing for their next assignment, perhaps a next deployment,” she said.

She added that previous studies have identified several promising biomarkers of PTSD. “However, like much of the research data, the study sample was comprised mainly of combat-exposed males. With more women serving on the front lines, the military faces new challenges in how combat affects females in the military,” including sex-specific biomarkers that will improve clinical assessment for female soldiers.

Eventually, the team would also like to be able to apply their research to the civilian population experiencing PTSD.

“Our research is anticipated to be useful in helping the medical provider select appropriate therapeutic interventions,” Ms. Miller said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“More accurate means of predicting or screening for PTSD could help to overcome the disorder by identifying individuals at high risk of developing PTSD and providing them with early intervention or prevention strategies,” said study investigator Stacy-Ann Miller, MS.

She also noted that the biomarkers could be used to monitor treatment for PTSD, identify subtypes of PTSD, and lead to a new understanding of the mechanisms underlying PTSD.

The findings were presented at Discover BMB, the annual meeting of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

Toward better clinical assessment

The findings originated from research conducted by the Department of Defense–initiated PTSD Systems Biology Consortium. The consortium’s goals include developing a reproducible panel of blood-based biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity for PTSD diagnosis and is made up of about 45 researchers, led by Marti Jett, PhD, Charles Marmar, MD, and Francis J. Doyle III, PhD.

The researchers analyzed blood samples from 1,000 active-duty Army personnel from the 101st Airborne at Fort Campbell, Ky. Participants were assessed before and after deployment to Afghanistan in February 2014 and are referred to as the Fort Campbell Cohort (FCC). Participants’ age ranged from 25 to 30 and approximately 6% were female.

Investigators collected blood samples from the service members and looked for four biomarkers: glycolytic ratio, arginine, serotonin, and glutamate. The team then divided the participants into four groups – those with PTSD (PTSD Checklist score above 30), those who were subthreshold for PTSD (PTSD Checklist score 15-30), those who had high resilience, and those who had low levels of resilience.

The resilience groups were determined based on answers to the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire, Patient Health Questionnaire, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Intensive Combat Exposure (DRRI-D), the number of deployments, whether they had moderate or severe traumatic brain injury, and scores on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Those who scored in the high range at current or prior time points or who were PTSD/subthreshold at prior time points were placed in the low resilience group.

Ms. Miller noted that those in the PTSD group had more severe symptoms than those in the PTSD subthreshold group based on the longitudinal clinical assessment at 3-6 months, 5 years, and longer post deployment. The low resilience group had a much higher rate of PTSD post deployment than the high resilience group.

Investigators found participants with PTSD or subthreshold PTSD had significantly higher glycolic ratios and lower arginine than those with high resilience. They also found that those with PTSD had significantly lower serotonin and higher glutamate levels versus those with high resilience. These associations were independent of factors such as sex, age, body mass index, smoking, and caffeine consumption.

Ms. Miller said that the study results require further validation by the consortium’s labs and third-party labs.

“We are also interested in determining the most appropriate time to screen soldiers for PTSD, as it has been noted that the time period where we see the most psychological issues is around 2-3 months post return from deployment and when the soldier is preparing for their next assignment, perhaps a next deployment,” she said.

She added that previous studies have identified several promising biomarkers of PTSD. “However, like much of the research data, the study sample was comprised mainly of combat-exposed males. With more women serving on the front lines, the military faces new challenges in how combat affects females in the military,” including sex-specific biomarkers that will improve clinical assessment for female soldiers.

Eventually, the team would also like to be able to apply their research to the civilian population experiencing PTSD.

“Our research is anticipated to be useful in helping the medical provider select appropriate therapeutic interventions,” Ms. Miller said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DISCOVER BMB

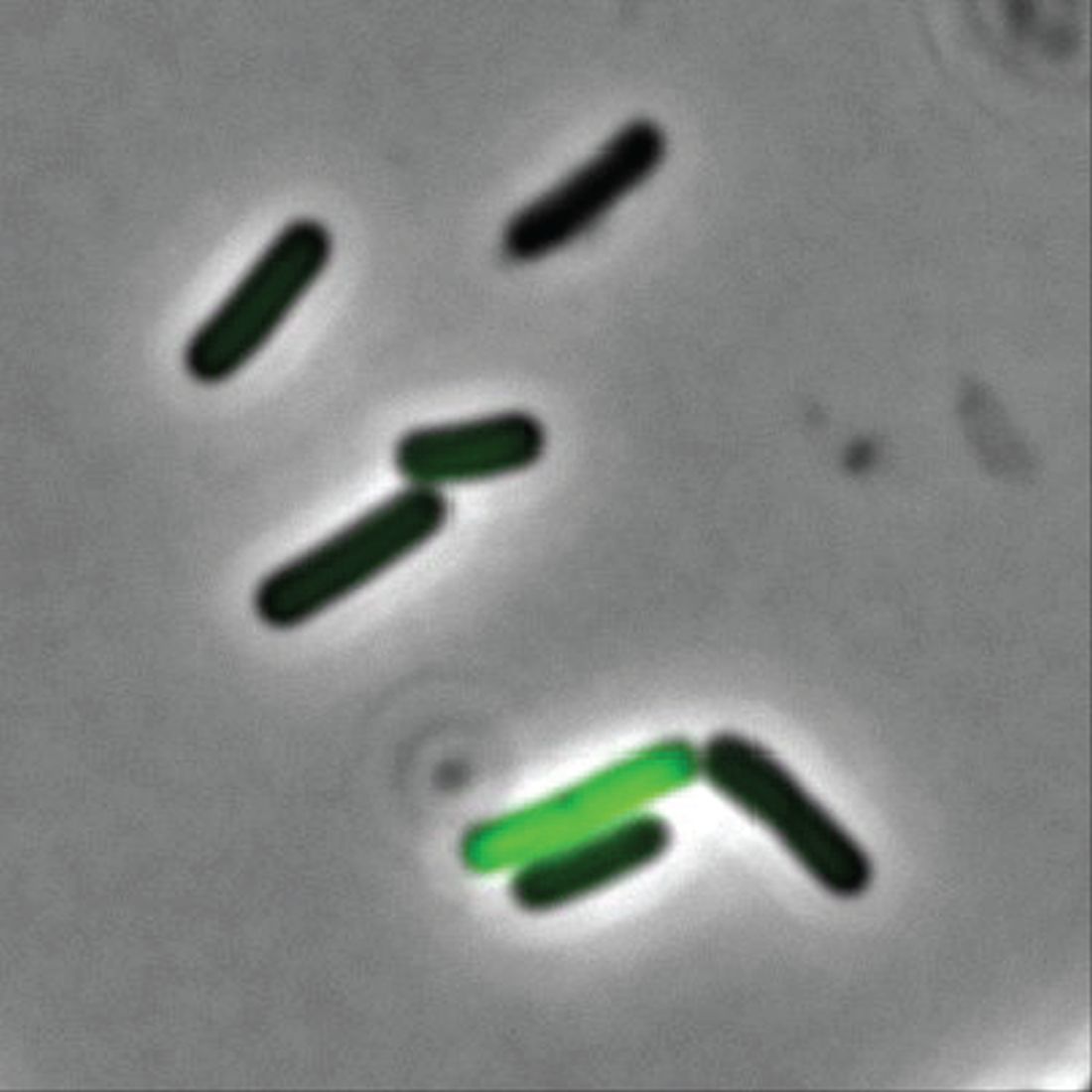

Lack of food for thought: Starve a bacterium, feed an infection

A whole new, tiny level of hangry

Ever been so hungry that everything just got on your nerves? Maybe you feel a little snappy right now? Like you’ll just lash out unless you get something to eat? Been there. And so have bacteria.

New research shows that some bacteria go into a full-on Hulk smash if they’re not getting the nutrients they need by releasing toxins into the body. Sounds like a bacterial temper tantrum.

Even though two cells may be genetically identical, they don’t always behave the same in a bacterial community. Some do their job and stay in line, but some evil twins rage out and make people sick by releasing toxins into the environment, Adam Rosenthal, PhD, of the University of North Carolina and his colleagues discovered.

To figure out why some cells were all business as usual while others were not, the investigators looked at Clostridium perfringens, a bacterium found in the intestines of humans and other vertebrates. When the C. perfringens cells were fed a little acetate to munch on, the hangry cells calmed down faster than a kid with a bag of fruit snacks, reducing toxin levels. Some cells even disappeared, falling in line with their model-citizen counterparts.

So what does this really mean? More research, duh. Now that we know nutrients play a role in toxicity, it may open the door to finding a way to fight against antibiotic resistance in humans and reduce antibiotic use in the food industry.

So think to yourself. Are you bothered for no reason? Getting a little testy with your friends and coworkers? Maybe you just haven’t eaten in a while. You’re literally not alone. Even a single-cell organism can behave based on its hunger levels.

Now go have a snack. Your bacteria are getting restless.

The very hangry iguana?

Imagine yourself on a warm, sunny tropical beach. You are enjoying a piece of cake as you take in the slow beat of the waves lapping against the shore. Life is as good as it could be.

Then you feel a presence nearby. Hostility. Hunger. A set of feral, covetous eyes in the nearby jungle. A reptilian beast stalks you, and its all-encompassing sweet tooth desires your cake.

Wait, hold on, what?

As an unfortunate 3-year-old on vacation in Costa Rica found out, there’s at least one iguana in the world out there with a taste for sugar (better than a taste for blood, we suppose).

While out on the beach, the lizard darted out of nowhere, bit the girl on the back of the hand, and stole her cake. Still not the worst party guest ever. The child was taken to a local clinic, where the wound was cleaned and a 5-day antibiotic treatment (lizards carry salmonella) was provided. Things seemed fine, and the girl returned home without incident.

But of course, that’s not the end of the story. Five months later, the girl’s parents noticed a red bump at the wound site. Over the next 3 months, the surrounding skin grew red and painful. A trip to the hospital in California revealed that she had a ganglion cyst and a discharge of pus. Turns out our cake-obsessed lizard friend did give the little girl a gift: the first known human case of Mycobacterium marinum infection following an iguana bite on record.

M. marinum, which causes a disease similar to tuberculosis, typically infects fish but can infect humans if skin wounds are exposed to contaminated water. It’s also resistant to most antibiotics, which is why the first round didn’t clear up the infection. A second round of more-potent antibiotics seems to be working well.

So, to sum up, this poor child got bitten by a lizard, had her cake stolen, and contracted a rare illness in exchange. For a 3-year-old, that’s gotta be in the top-10 worst days ever. Unless, of course, we’re actually living in the Marvel universe (sorry, multiverse at this point). Then we’re totally going to see the emergence of the new superhero Iguana Girl in 15 years or so. Keep your eyes open.

No allergies? Let them give up cake

Allergy season is already here – starting earlier every year, it seems – and many people are not happy about it. So unhappy, actually, that there’s a list of things they would be willing to give up for a year to get rid of their of allergies, according to a survey conducted by OnePoll on behalf of Flonase.

Nearly 40% of 2,000 respondents with allergies would go a year without eating cake or chocolate or playing video games in exchange for allergy-free status, the survey results show. Almost as many would forgo coffee (38%) or pizza (37%) for a year, while 36% would stay off social media and 31% would take a pay cut or give up their smartphones, the Independent reported.

More than half of the allergic Americans – 54%, to be exact – who were polled this past winter – Feb. 24 to March 1, to be exact – consider allergy symptoms to be the most frustrating part of the spring. Annoying things that were less frustrating to the group included mosquitoes (41%), filing tax returns (38%), and daylight savings time (37%).

The Trump arraignment circus, of course, occurred too late to make the list, as did the big “We’re going back to the office! No wait, we’re closing the office forever!” email extravaganza and emotional roller coaster. That second one, however, did not get nearly as much media coverage.

A whole new, tiny level of hangry

Ever been so hungry that everything just got on your nerves? Maybe you feel a little snappy right now? Like you’ll just lash out unless you get something to eat? Been there. And so have bacteria.

New research shows that some bacteria go into a full-on Hulk smash if they’re not getting the nutrients they need by releasing toxins into the body. Sounds like a bacterial temper tantrum.

Even though two cells may be genetically identical, they don’t always behave the same in a bacterial community. Some do their job and stay in line, but some evil twins rage out and make people sick by releasing toxins into the environment, Adam Rosenthal, PhD, of the University of North Carolina and his colleagues discovered.

To figure out why some cells were all business as usual while others were not, the investigators looked at Clostridium perfringens, a bacterium found in the intestines of humans and other vertebrates. When the C. perfringens cells were fed a little acetate to munch on, the hangry cells calmed down faster than a kid with a bag of fruit snacks, reducing toxin levels. Some cells even disappeared, falling in line with their model-citizen counterparts.

So what does this really mean? More research, duh. Now that we know nutrients play a role in toxicity, it may open the door to finding a way to fight against antibiotic resistance in humans and reduce antibiotic use in the food industry.

So think to yourself. Are you bothered for no reason? Getting a little testy with your friends and coworkers? Maybe you just haven’t eaten in a while. You’re literally not alone. Even a single-cell organism can behave based on its hunger levels.

Now go have a snack. Your bacteria are getting restless.

The very hangry iguana?

Imagine yourself on a warm, sunny tropical beach. You are enjoying a piece of cake as you take in the slow beat of the waves lapping against the shore. Life is as good as it could be.

Then you feel a presence nearby. Hostility. Hunger. A set of feral, covetous eyes in the nearby jungle. A reptilian beast stalks you, and its all-encompassing sweet tooth desires your cake.

Wait, hold on, what?

As an unfortunate 3-year-old on vacation in Costa Rica found out, there’s at least one iguana in the world out there with a taste for sugar (better than a taste for blood, we suppose).

While out on the beach, the lizard darted out of nowhere, bit the girl on the back of the hand, and stole her cake. Still not the worst party guest ever. The child was taken to a local clinic, where the wound was cleaned and a 5-day antibiotic treatment (lizards carry salmonella) was provided. Things seemed fine, and the girl returned home without incident.

But of course, that’s not the end of the story. Five months later, the girl’s parents noticed a red bump at the wound site. Over the next 3 months, the surrounding skin grew red and painful. A trip to the hospital in California revealed that she had a ganglion cyst and a discharge of pus. Turns out our cake-obsessed lizard friend did give the little girl a gift: the first known human case of Mycobacterium marinum infection following an iguana bite on record.

M. marinum, which causes a disease similar to tuberculosis, typically infects fish but can infect humans if skin wounds are exposed to contaminated water. It’s also resistant to most antibiotics, which is why the first round didn’t clear up the infection. A second round of more-potent antibiotics seems to be working well.

So, to sum up, this poor child got bitten by a lizard, had her cake stolen, and contracted a rare illness in exchange. For a 3-year-old, that’s gotta be in the top-10 worst days ever. Unless, of course, we’re actually living in the Marvel universe (sorry, multiverse at this point). Then we’re totally going to see the emergence of the new superhero Iguana Girl in 15 years or so. Keep your eyes open.

No allergies? Let them give up cake

Allergy season is already here – starting earlier every year, it seems – and many people are not happy about it. So unhappy, actually, that there’s a list of things they would be willing to give up for a year to get rid of their of allergies, according to a survey conducted by OnePoll on behalf of Flonase.

Nearly 40% of 2,000 respondents with allergies would go a year without eating cake or chocolate or playing video games in exchange for allergy-free status, the survey results show. Almost as many would forgo coffee (38%) or pizza (37%) for a year, while 36% would stay off social media and 31% would take a pay cut or give up their smartphones, the Independent reported.

More than half of the allergic Americans – 54%, to be exact – who were polled this past winter – Feb. 24 to March 1, to be exact – consider allergy symptoms to be the most frustrating part of the spring. Annoying things that were less frustrating to the group included mosquitoes (41%), filing tax returns (38%), and daylight savings time (37%).

The Trump arraignment circus, of course, occurred too late to make the list, as did the big “We’re going back to the office! No wait, we’re closing the office forever!” email extravaganza and emotional roller coaster. That second one, however, did not get nearly as much media coverage.

A whole new, tiny level of hangry

Ever been so hungry that everything just got on your nerves? Maybe you feel a little snappy right now? Like you’ll just lash out unless you get something to eat? Been there. And so have bacteria.

New research shows that some bacteria go into a full-on Hulk smash if they’re not getting the nutrients they need by releasing toxins into the body. Sounds like a bacterial temper tantrum.

Even though two cells may be genetically identical, they don’t always behave the same in a bacterial community. Some do their job and stay in line, but some evil twins rage out and make people sick by releasing toxins into the environment, Adam Rosenthal, PhD, of the University of North Carolina and his colleagues discovered.

To figure out why some cells were all business as usual while others were not, the investigators looked at Clostridium perfringens, a bacterium found in the intestines of humans and other vertebrates. When the C. perfringens cells were fed a little acetate to munch on, the hangry cells calmed down faster than a kid with a bag of fruit snacks, reducing toxin levels. Some cells even disappeared, falling in line with their model-citizen counterparts.

So what does this really mean? More research, duh. Now that we know nutrients play a role in toxicity, it may open the door to finding a way to fight against antibiotic resistance in humans and reduce antibiotic use in the food industry.

So think to yourself. Are you bothered for no reason? Getting a little testy with your friends and coworkers? Maybe you just haven’t eaten in a while. You’re literally not alone. Even a single-cell organism can behave based on its hunger levels.

Now go have a snack. Your bacteria are getting restless.

The very hangry iguana?

Imagine yourself on a warm, sunny tropical beach. You are enjoying a piece of cake as you take in the slow beat of the waves lapping against the shore. Life is as good as it could be.

Then you feel a presence nearby. Hostility. Hunger. A set of feral, covetous eyes in the nearby jungle. A reptilian beast stalks you, and its all-encompassing sweet tooth desires your cake.

Wait, hold on, what?

As an unfortunate 3-year-old on vacation in Costa Rica found out, there’s at least one iguana in the world out there with a taste for sugar (better than a taste for blood, we suppose).

While out on the beach, the lizard darted out of nowhere, bit the girl on the back of the hand, and stole her cake. Still not the worst party guest ever. The child was taken to a local clinic, where the wound was cleaned and a 5-day antibiotic treatment (lizards carry salmonella) was provided. Things seemed fine, and the girl returned home without incident.

But of course, that’s not the end of the story. Five months later, the girl’s parents noticed a red bump at the wound site. Over the next 3 months, the surrounding skin grew red and painful. A trip to the hospital in California revealed that she had a ganglion cyst and a discharge of pus. Turns out our cake-obsessed lizard friend did give the little girl a gift: the first known human case of Mycobacterium marinum infection following an iguana bite on record.