User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

COVID-19: Peginterferon lambda may prevent clinical deterioration, shorten viral shedding

and shorten the duration of viral shedding, according to results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (NCT04354259).

Reductions in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) RNA were greater with peginterferon lambda than with placebo from day 3 onward in the phase 2 study led by Jordan J. Feld, MD, of the Toronto Centre for Liver Disease. The findings were reported in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

Fewer side effects

To date in randomized clinical trials, efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 has been shown only for remdesivir and dexamethasone in hospitalized patients, and in an interim analysis of accelerated viral clearance for a monoclonal antibody infusion in outpatients.

Activity against respiratory pathogens has been demonstrated for interferon lambda-1, a type III interferon shown to be involved in innate antiviral responses. Interferons, Dr. Feld and coauthors stated, drive induction of genes with antiviral, antiproliferative and immunoregulatory properties, and early treatment with interferons might halt clinical progression and shorten the duration of viral shedding with reduced onward transmission. In addition, interferon lambdas (type III) use a distinct receptor complex with high expression levels limited to epithelial cells in the lung, liver, and intestine, leading to fewer side effects than other interferons, including avoiding risk of promoting cytokine storm syndrome.

The researchers investigated peginterferon lambda safety and efficacy in treatment of patients with laboratory-confirmed, mild to moderate COVID-19. Sixty patients (median age 46 years, about 60% female, about 50% White) were recruited from outpatient testing centers at six institutions in Toronto, and referred to a single ambulatory site. Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to a single subcutaneous injection of peginterferon lambda 180 mcg or placebo within 7 days of symptom onset or, if asymptomatic, of their first positive swab. Mean time from symptom onset to injection was about 4.5 days, and about 18.5% were asymptomatic. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients negative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA on day 7 after the injection.

Greater benefit with higher baseline load

A higher baseline SARS-CoV-2 RNA concentration found in the peginterferon lambda group was found to be significantly associated with day 7 clearance (odds ratio [OR] 0.69 [95% confidence interval 0.51-0.87]; P = ·001). In the peginterferon lambda group, also, the mean decline in SARS-CoV-2 RNA was significantly larger than in the placebo group across all time points (days 3, 5, 7, and14). While viral load decline was 0.81 log greater in the treatment group (P = .14) by day 3, viral load decline increased to 1.67 log copies per mL by day 5 (P = .013) and 2.42 log copies per mL by day 7 (P = .0041). At day 14, the viral decline was 1.77 log copies per mL larger in the peginterferon lambda group (P = .048). The investigators pointed out that the difference in viral load decline between groups was greater in patients with high baseline viral load (at or above 106 copies per mL). In the peginterferon lambda high baseline viral load group, the reduction was 7.17 log copies per mL, versus 4.92 log copies per mL in the placebo group (P = .004).

More patients SARS-CoV-2 RNA negative

By day 7, 80% of patients in the peginterferon lambda group were negative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA, compared with 63% in the placebo group (P = .15). After baseline load adjustment, however, the peginterferon lambda treatment was significantly associated with day 7 clearance (OR 4·12 [95% CI 1·15-16·73]; P = .029).

Respiratory symptoms improved faster

Most symptoms in both groups were mild to moderate, without difference in frequency or severity. While symptom improvement was generally similar over time for both groups, respiratory symptoms improved faster with peginterferon lambda, with the effect more pronounced in the high baseline viral load group (OR 5·88 (0·81-42·46; P =. 079).

Laboratory adverse events, similar for both groups, were mild.

“Peginterferon lambda has potential to prevent clinical deterioration and shorten duration of viral shedding,” the investigators concluded.

“This clinical trial is important” because it suggests that a single intravenous dose of peginterferon lambda administered to outpatients with a positive SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swab speeds reduction of SARS-CoV-2 viral load, David L. Bowton, MD, FCCP, professor emeritus, Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C., said in an interview. He observed that the smaller viral load difference observed at day 14 likely reflects host immune responses.

Dr. Bowton also noted that two placebo group baseline characteristics (five placebo group patients with anti-SARS-CoV-2 S protein IgG antibodies; two times more undetectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA at baseline assessment) would tend to reduce differences between the peginterferon lambda and placebo groups. He added that the study findings were concordant with another phase 2 trial of hospitalized COVID-19 patients receiving inhaled interferon beta-1a.

“Thus, interferons may find a place in the treatment of COVID-19 and perhaps other severe viral illnesses,” Dr. Bowton said.

The study was funded by the Toronto COVID-19 Action Initiative, University of Toronto, and the Ontario First COVID-19 Rapid Research Fund, Toronto General & Western Hospital Foundation.

Dr. Bowton had no disclosures. Disclosures for Dr. Feld and coauthors are listed on the Lancet Respiratory Medicine website.

and shorten the duration of viral shedding, according to results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (NCT04354259).

Reductions in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) RNA were greater with peginterferon lambda than with placebo from day 3 onward in the phase 2 study led by Jordan J. Feld, MD, of the Toronto Centre for Liver Disease. The findings were reported in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

Fewer side effects

To date in randomized clinical trials, efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 has been shown only for remdesivir and dexamethasone in hospitalized patients, and in an interim analysis of accelerated viral clearance for a monoclonal antibody infusion in outpatients.

Activity against respiratory pathogens has been demonstrated for interferon lambda-1, a type III interferon shown to be involved in innate antiviral responses. Interferons, Dr. Feld and coauthors stated, drive induction of genes with antiviral, antiproliferative and immunoregulatory properties, and early treatment with interferons might halt clinical progression and shorten the duration of viral shedding with reduced onward transmission. In addition, interferon lambdas (type III) use a distinct receptor complex with high expression levels limited to epithelial cells in the lung, liver, and intestine, leading to fewer side effects than other interferons, including avoiding risk of promoting cytokine storm syndrome.

The researchers investigated peginterferon lambda safety and efficacy in treatment of patients with laboratory-confirmed, mild to moderate COVID-19. Sixty patients (median age 46 years, about 60% female, about 50% White) were recruited from outpatient testing centers at six institutions in Toronto, and referred to a single ambulatory site. Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to a single subcutaneous injection of peginterferon lambda 180 mcg or placebo within 7 days of symptom onset or, if asymptomatic, of their first positive swab. Mean time from symptom onset to injection was about 4.5 days, and about 18.5% were asymptomatic. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients negative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA on day 7 after the injection.

Greater benefit with higher baseline load

A higher baseline SARS-CoV-2 RNA concentration found in the peginterferon lambda group was found to be significantly associated with day 7 clearance (odds ratio [OR] 0.69 [95% confidence interval 0.51-0.87]; P = ·001). In the peginterferon lambda group, also, the mean decline in SARS-CoV-2 RNA was significantly larger than in the placebo group across all time points (days 3, 5, 7, and14). While viral load decline was 0.81 log greater in the treatment group (P = .14) by day 3, viral load decline increased to 1.67 log copies per mL by day 5 (P = .013) and 2.42 log copies per mL by day 7 (P = .0041). At day 14, the viral decline was 1.77 log copies per mL larger in the peginterferon lambda group (P = .048). The investigators pointed out that the difference in viral load decline between groups was greater in patients with high baseline viral load (at or above 106 copies per mL). In the peginterferon lambda high baseline viral load group, the reduction was 7.17 log copies per mL, versus 4.92 log copies per mL in the placebo group (P = .004).

More patients SARS-CoV-2 RNA negative

By day 7, 80% of patients in the peginterferon lambda group were negative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA, compared with 63% in the placebo group (P = .15). After baseline load adjustment, however, the peginterferon lambda treatment was significantly associated with day 7 clearance (OR 4·12 [95% CI 1·15-16·73]; P = .029).

Respiratory symptoms improved faster

Most symptoms in both groups were mild to moderate, without difference in frequency or severity. While symptom improvement was generally similar over time for both groups, respiratory symptoms improved faster with peginterferon lambda, with the effect more pronounced in the high baseline viral load group (OR 5·88 (0·81-42·46; P =. 079).

Laboratory adverse events, similar for both groups, were mild.

“Peginterferon lambda has potential to prevent clinical deterioration and shorten duration of viral shedding,” the investigators concluded.

“This clinical trial is important” because it suggests that a single intravenous dose of peginterferon lambda administered to outpatients with a positive SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swab speeds reduction of SARS-CoV-2 viral load, David L. Bowton, MD, FCCP, professor emeritus, Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C., said in an interview. He observed that the smaller viral load difference observed at day 14 likely reflects host immune responses.

Dr. Bowton also noted that two placebo group baseline characteristics (five placebo group patients with anti-SARS-CoV-2 S protein IgG antibodies; two times more undetectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA at baseline assessment) would tend to reduce differences between the peginterferon lambda and placebo groups. He added that the study findings were concordant with another phase 2 trial of hospitalized COVID-19 patients receiving inhaled interferon beta-1a.

“Thus, interferons may find a place in the treatment of COVID-19 and perhaps other severe viral illnesses,” Dr. Bowton said.

The study was funded by the Toronto COVID-19 Action Initiative, University of Toronto, and the Ontario First COVID-19 Rapid Research Fund, Toronto General & Western Hospital Foundation.

Dr. Bowton had no disclosures. Disclosures for Dr. Feld and coauthors are listed on the Lancet Respiratory Medicine website.

and shorten the duration of viral shedding, according to results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (NCT04354259).

Reductions in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) RNA were greater with peginterferon lambda than with placebo from day 3 onward in the phase 2 study led by Jordan J. Feld, MD, of the Toronto Centre for Liver Disease. The findings were reported in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

Fewer side effects

To date in randomized clinical trials, efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 has been shown only for remdesivir and dexamethasone in hospitalized patients, and in an interim analysis of accelerated viral clearance for a monoclonal antibody infusion in outpatients.

Activity against respiratory pathogens has been demonstrated for interferon lambda-1, a type III interferon shown to be involved in innate antiviral responses. Interferons, Dr. Feld and coauthors stated, drive induction of genes with antiviral, antiproliferative and immunoregulatory properties, and early treatment with interferons might halt clinical progression and shorten the duration of viral shedding with reduced onward transmission. In addition, interferon lambdas (type III) use a distinct receptor complex with high expression levels limited to epithelial cells in the lung, liver, and intestine, leading to fewer side effects than other interferons, including avoiding risk of promoting cytokine storm syndrome.

The researchers investigated peginterferon lambda safety and efficacy in treatment of patients with laboratory-confirmed, mild to moderate COVID-19. Sixty patients (median age 46 years, about 60% female, about 50% White) were recruited from outpatient testing centers at six institutions in Toronto, and referred to a single ambulatory site. Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to a single subcutaneous injection of peginterferon lambda 180 mcg or placebo within 7 days of symptom onset or, if asymptomatic, of their first positive swab. Mean time from symptom onset to injection was about 4.5 days, and about 18.5% were asymptomatic. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients negative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA on day 7 after the injection.

Greater benefit with higher baseline load

A higher baseline SARS-CoV-2 RNA concentration found in the peginterferon lambda group was found to be significantly associated with day 7 clearance (odds ratio [OR] 0.69 [95% confidence interval 0.51-0.87]; P = ·001). In the peginterferon lambda group, also, the mean decline in SARS-CoV-2 RNA was significantly larger than in the placebo group across all time points (days 3, 5, 7, and14). While viral load decline was 0.81 log greater in the treatment group (P = .14) by day 3, viral load decline increased to 1.67 log copies per mL by day 5 (P = .013) and 2.42 log copies per mL by day 7 (P = .0041). At day 14, the viral decline was 1.77 log copies per mL larger in the peginterferon lambda group (P = .048). The investigators pointed out that the difference in viral load decline between groups was greater in patients with high baseline viral load (at or above 106 copies per mL). In the peginterferon lambda high baseline viral load group, the reduction was 7.17 log copies per mL, versus 4.92 log copies per mL in the placebo group (P = .004).

More patients SARS-CoV-2 RNA negative

By day 7, 80% of patients in the peginterferon lambda group were negative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA, compared with 63% in the placebo group (P = .15). After baseline load adjustment, however, the peginterferon lambda treatment was significantly associated with day 7 clearance (OR 4·12 [95% CI 1·15-16·73]; P = .029).

Respiratory symptoms improved faster

Most symptoms in both groups were mild to moderate, without difference in frequency or severity. While symptom improvement was generally similar over time for both groups, respiratory symptoms improved faster with peginterferon lambda, with the effect more pronounced in the high baseline viral load group (OR 5·88 (0·81-42·46; P =. 079).

Laboratory adverse events, similar for both groups, were mild.

“Peginterferon lambda has potential to prevent clinical deterioration and shorten duration of viral shedding,” the investigators concluded.

“This clinical trial is important” because it suggests that a single intravenous dose of peginterferon lambda administered to outpatients with a positive SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swab speeds reduction of SARS-CoV-2 viral load, David L. Bowton, MD, FCCP, professor emeritus, Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C., said in an interview. He observed that the smaller viral load difference observed at day 14 likely reflects host immune responses.

Dr. Bowton also noted that two placebo group baseline characteristics (five placebo group patients with anti-SARS-CoV-2 S protein IgG antibodies; two times more undetectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA at baseline assessment) would tend to reduce differences between the peginterferon lambda and placebo groups. He added that the study findings were concordant with another phase 2 trial of hospitalized COVID-19 patients receiving inhaled interferon beta-1a.

“Thus, interferons may find a place in the treatment of COVID-19 and perhaps other severe viral illnesses,” Dr. Bowton said.

The study was funded by the Toronto COVID-19 Action Initiative, University of Toronto, and the Ontario First COVID-19 Rapid Research Fund, Toronto General & Western Hospital Foundation.

Dr. Bowton had no disclosures. Disclosures for Dr. Feld and coauthors are listed on the Lancet Respiratory Medicine website.

FROM THE LANCET RESPIRATORY MEDICINE

Teenagers get in the queue for COVID-19 vaccines

The vaccinations can’t come soon enough for parents like Stacy Hillenburg, a developmental therapist in Aurora, Ill., whose 9-year-old son takes immunosuppressants because he had a heart transplant when he was 7 weeks old. Although school-age children aren’t yet included in clinical trials, if her 12- and 13-year-old daughters could get vaccinated, along with both parents, then the family could relax some of the protocols they currently follow to prevent infection.

Whenever they are around other people, even masked and socially distanced, they come home and immediately shower and change their clothes. So far, no one in the family has been infected with COVID, but the anxiety is ever-present. “I can’t wait for it to come out,” Ms. Hillenburg said of a pediatric COVID vaccine. “It will ease my mind so much.”

She isn’t alone in that anticipation. In the fall, the American Academy of Pediatrics and other pediatric vaccine experts urged faster action on pediatric vaccine trials and worried that children would be left behind as adults gained protection from COVID. But recent developments have eased those concerns.

“Over the next couple of months, we will be doing trials in an age-deescalation manner,” with studies moving gradually to younger children, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, chief medical adviser on COVID-19 to the president, said in a coronavirus response team briefing on Jan. 29. “So that hopefully, as we get to the late spring and summer, we will have children being able to be vaccinated.”

Pfizer completed enrollment of 2,259 teens aged 12-15 years in late January and expects to move forward with a separate pediatric trial of children aged 5-11 years by this spring, Keanna Ghazvini, senior associate for global media relations at Pfizer, said in an interview.

Enrollment in Moderna’s TeenCove study of adolescents ages 12-17 years began slowly in late December, but the pace has since picked up, said company spokesperson Colleen Hussey. “We continue to bring clinical trial sites online, and we are on track to provide updated data around mid-year 2021.” A trial extension in children 11 years and younger is expected to begin later in 2021.

Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca said they expect to begin adolescent trials in early 2021, according to data shared by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. An interim analysis of J&J’s Janssen COVID-19 vaccine trial data, released on Jan. 29, showed it was 72% effective in US participants aged 18 years or older. AstraZeneca’s U.S. trial in adults is ongoing.

Easing the burden

Vaccination could lessen children’s risk of severe disease as well as the social and emotional burdens of the pandemic, says James Campbell, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Maryland’s Center for Vaccine Development in Baltimore, which was involved in the Moderna and early-phase Pfizer trials. He coauthored a September 2020 article in Clinical Infectious Diseases titled: “Warp Speed for COVID-19 vaccines: Why are children stuck in neutral?”

The adolescent trials are a vital step to ensure timely vaccine access for teens and younger children. “It is reasonable, when you have limited vaccine, that your rollout goes to the highest priority and then moves to lower and lower priorities. In adults, we’re just saying: ‘Wait your turn,’ ” he said of the current vaccination effort. “If we didn’t have the [vaccine trial] data in children, we’d be saying: ‘You don’t have a turn.’ ”

As the pandemic has worn on, the burden on children has grown. As of Tuesday, 269 children had died of COVID-19. That is well above the highest annual death toll recorded during a regular flu season – 188 flu deaths among children and adolescents under 18 in the 2019-2020 and 2017-2018 flu seasons.

Children are less likely to transmit COVID-19 in their household than adults, according to a meta-analysis of 54 studies published in JAMA Network Open. But that does not necessarily mean children are less infectious, the authors said, noting that unmeasured factors could have affected the spread of infection among adults.

Moreover, children and adolescents need protection from COVID infection – and from the potential for severe disease or lingering effects – and, given that there are 74 million children and teens in the United States, their vaccination is an important part of stopping the pandemic, said Grace Lee, MD, professor of pediatrics at Stanford (Calif.) University, and cochair of ACIP’s COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Technical Subgroup.

“In order to interrupt transmission, I don’t see how we’re going to do that without vaccinating children and adolescents,” she said.

Dr. Lee said her 16-year-old daughter misses the normal teenage social life and is excited about getting the vaccine when she is eligible. (Adolescents without high-risk conditions are in the lowest vaccination tier, according to ACIP recommendations.) “There is truly individual protection to be gained,” Dr. Lee said.

She noted that researchers continue to assess the immune responses to the adult vaccines – even looking at immune characteristics of the small percentage of people who aren’t protected from infection – and that information helps in the evaluation of the pediatric immune responses. As the trials expand to younger children and infants, dosing will be a major focus. “How many doses do they need they need to receive the same immunity? Safety considerations will be critically important,” she said.

Teen trials underway

Pfizer/BioNTech extended its adult trial to 16- and 17-year-olds in October, which enabled older teens to be included in its emergency-use authorization. They and younger teens, ages 12-15, receive the same dose as adults.

The ongoing trials with Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are immunobridging trials, designed to study safety and immunogenicity. Investigators will compare the teens’ immune response with the findings from the larger adult trials. When the trials expand to school-age children (6-12 years), protocols call for testing the safety and immunogenicity of a half-dose vaccine as well as the full dose.

Children ages 2-5 years and infants and toddlers will be enrolled in future trials, studying safety and immunogenicity of full, half, or even quarter dosages. The Pediatric Research Equity Act of 2003 requires licensed vaccines to be tested for safety and efficacy in children, unless they are not appropriate for a pediatric population.

Demand for the teen trials has been strong. At Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 259 teenagers joined the Pfizer/BioNTech trial, but some teenagers were turned away when the trial’s national enrollment closed in late January.

“Many of the children are having no side effects, and if they are, they’re having the same [effects] as the young adults – local redness or pain, fatigue, and headaches,” said Robert Frenck, MD, director of the Cincinnati Children’s Gamble Program for Clinical Studies.

Parents may share some of the vaccine hesitancy that has affected adult vaccination. But that is balanced by the hope that vaccines will end the pandemic and usher in a new normal. “If it looks like [vaccines] will increase the likelihood of children returning to school safely, that may be a motivating factor,” Dr. Frenck said.

Cody Meissner, MD, chief of the pediatric infectious disease service at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, was initially cautious about the extension of vaccination to adolescents. A member of the Vaccine and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, which evaluates data and makes recommendations to the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Meissner initially abstained in the vote on the Pfizer/BioNTech emergency-use authorization for people 16 and older.

He noted that, at the time the committee reviewed the Pfizer vaccine, the company had data available for just 134 teenagers, half of whom received a placebo. But the vaccination of 34 million adults has provided robust data about the vaccine’s safety, and the trial expansion into adolescents is important.

“I’m comfortable with the way these trials are going now,” he said. “This is the way I was hoping they would go.”

Ms. Hillenburg is on the parent advisory board of Voices for Vaccines, an organization of parents supporting vaccination that is affiliated with the Task Force for Global Health, an Atlanta-based independent public health organization. Dr. Campbell’s institution has received funds to conduct clinical trials from the National Institutes of Health and several companies, including Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Pfizer, and Moderna. He has served pro bono on many safety and data monitoring committees. Dr. Frenck’s institution is receiving funds to conduct the Pfizer trial. In the past 5 years, he has also participated in clinical trials for GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Meissa vaccines. Dr. Lee and Dr. Meissner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The vaccinations can’t come soon enough for parents like Stacy Hillenburg, a developmental therapist in Aurora, Ill., whose 9-year-old son takes immunosuppressants because he had a heart transplant when he was 7 weeks old. Although school-age children aren’t yet included in clinical trials, if her 12- and 13-year-old daughters could get vaccinated, along with both parents, then the family could relax some of the protocols they currently follow to prevent infection.

Whenever they are around other people, even masked and socially distanced, they come home and immediately shower and change their clothes. So far, no one in the family has been infected with COVID, but the anxiety is ever-present. “I can’t wait for it to come out,” Ms. Hillenburg said of a pediatric COVID vaccine. “It will ease my mind so much.”

She isn’t alone in that anticipation. In the fall, the American Academy of Pediatrics and other pediatric vaccine experts urged faster action on pediatric vaccine trials and worried that children would be left behind as adults gained protection from COVID. But recent developments have eased those concerns.

“Over the next couple of months, we will be doing trials in an age-deescalation manner,” with studies moving gradually to younger children, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, chief medical adviser on COVID-19 to the president, said in a coronavirus response team briefing on Jan. 29. “So that hopefully, as we get to the late spring and summer, we will have children being able to be vaccinated.”

Pfizer completed enrollment of 2,259 teens aged 12-15 years in late January and expects to move forward with a separate pediatric trial of children aged 5-11 years by this spring, Keanna Ghazvini, senior associate for global media relations at Pfizer, said in an interview.

Enrollment in Moderna’s TeenCove study of adolescents ages 12-17 years began slowly in late December, but the pace has since picked up, said company spokesperson Colleen Hussey. “We continue to bring clinical trial sites online, and we are on track to provide updated data around mid-year 2021.” A trial extension in children 11 years and younger is expected to begin later in 2021.

Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca said they expect to begin adolescent trials in early 2021, according to data shared by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. An interim analysis of J&J’s Janssen COVID-19 vaccine trial data, released on Jan. 29, showed it was 72% effective in US participants aged 18 years or older. AstraZeneca’s U.S. trial in adults is ongoing.

Easing the burden

Vaccination could lessen children’s risk of severe disease as well as the social and emotional burdens of the pandemic, says James Campbell, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Maryland’s Center for Vaccine Development in Baltimore, which was involved in the Moderna and early-phase Pfizer trials. He coauthored a September 2020 article in Clinical Infectious Diseases titled: “Warp Speed for COVID-19 vaccines: Why are children stuck in neutral?”

The adolescent trials are a vital step to ensure timely vaccine access for teens and younger children. “It is reasonable, when you have limited vaccine, that your rollout goes to the highest priority and then moves to lower and lower priorities. In adults, we’re just saying: ‘Wait your turn,’ ” he said of the current vaccination effort. “If we didn’t have the [vaccine trial] data in children, we’d be saying: ‘You don’t have a turn.’ ”

As the pandemic has worn on, the burden on children has grown. As of Tuesday, 269 children had died of COVID-19. That is well above the highest annual death toll recorded during a regular flu season – 188 flu deaths among children and adolescents under 18 in the 2019-2020 and 2017-2018 flu seasons.

Children are less likely to transmit COVID-19 in their household than adults, according to a meta-analysis of 54 studies published in JAMA Network Open. But that does not necessarily mean children are less infectious, the authors said, noting that unmeasured factors could have affected the spread of infection among adults.

Moreover, children and adolescents need protection from COVID infection – and from the potential for severe disease or lingering effects – and, given that there are 74 million children and teens in the United States, their vaccination is an important part of stopping the pandemic, said Grace Lee, MD, professor of pediatrics at Stanford (Calif.) University, and cochair of ACIP’s COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Technical Subgroup.

“In order to interrupt transmission, I don’t see how we’re going to do that without vaccinating children and adolescents,” she said.

Dr. Lee said her 16-year-old daughter misses the normal teenage social life and is excited about getting the vaccine when she is eligible. (Adolescents without high-risk conditions are in the lowest vaccination tier, according to ACIP recommendations.) “There is truly individual protection to be gained,” Dr. Lee said.

She noted that researchers continue to assess the immune responses to the adult vaccines – even looking at immune characteristics of the small percentage of people who aren’t protected from infection – and that information helps in the evaluation of the pediatric immune responses. As the trials expand to younger children and infants, dosing will be a major focus. “How many doses do they need they need to receive the same immunity? Safety considerations will be critically important,” she said.

Teen trials underway

Pfizer/BioNTech extended its adult trial to 16- and 17-year-olds in October, which enabled older teens to be included in its emergency-use authorization. They and younger teens, ages 12-15, receive the same dose as adults.

The ongoing trials with Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are immunobridging trials, designed to study safety and immunogenicity. Investigators will compare the teens’ immune response with the findings from the larger adult trials. When the trials expand to school-age children (6-12 years), protocols call for testing the safety and immunogenicity of a half-dose vaccine as well as the full dose.

Children ages 2-5 years and infants and toddlers will be enrolled in future trials, studying safety and immunogenicity of full, half, or even quarter dosages. The Pediatric Research Equity Act of 2003 requires licensed vaccines to be tested for safety and efficacy in children, unless they are not appropriate for a pediatric population.

Demand for the teen trials has been strong. At Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 259 teenagers joined the Pfizer/BioNTech trial, but some teenagers were turned away when the trial’s national enrollment closed in late January.

“Many of the children are having no side effects, and if they are, they’re having the same [effects] as the young adults – local redness or pain, fatigue, and headaches,” said Robert Frenck, MD, director of the Cincinnati Children’s Gamble Program for Clinical Studies.

Parents may share some of the vaccine hesitancy that has affected adult vaccination. But that is balanced by the hope that vaccines will end the pandemic and usher in a new normal. “If it looks like [vaccines] will increase the likelihood of children returning to school safely, that may be a motivating factor,” Dr. Frenck said.

Cody Meissner, MD, chief of the pediatric infectious disease service at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, was initially cautious about the extension of vaccination to adolescents. A member of the Vaccine and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, which evaluates data and makes recommendations to the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Meissner initially abstained in the vote on the Pfizer/BioNTech emergency-use authorization for people 16 and older.

He noted that, at the time the committee reviewed the Pfizer vaccine, the company had data available for just 134 teenagers, half of whom received a placebo. But the vaccination of 34 million adults has provided robust data about the vaccine’s safety, and the trial expansion into adolescents is important.

“I’m comfortable with the way these trials are going now,” he said. “This is the way I was hoping they would go.”

Ms. Hillenburg is on the parent advisory board of Voices for Vaccines, an organization of parents supporting vaccination that is affiliated with the Task Force for Global Health, an Atlanta-based independent public health organization. Dr. Campbell’s institution has received funds to conduct clinical trials from the National Institutes of Health and several companies, including Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Pfizer, and Moderna. He has served pro bono on many safety and data monitoring committees. Dr. Frenck’s institution is receiving funds to conduct the Pfizer trial. In the past 5 years, he has also participated in clinical trials for GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Meissa vaccines. Dr. Lee and Dr. Meissner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The vaccinations can’t come soon enough for parents like Stacy Hillenburg, a developmental therapist in Aurora, Ill., whose 9-year-old son takes immunosuppressants because he had a heart transplant when he was 7 weeks old. Although school-age children aren’t yet included in clinical trials, if her 12- and 13-year-old daughters could get vaccinated, along with both parents, then the family could relax some of the protocols they currently follow to prevent infection.

Whenever they are around other people, even masked and socially distanced, they come home and immediately shower and change their clothes. So far, no one in the family has been infected with COVID, but the anxiety is ever-present. “I can’t wait for it to come out,” Ms. Hillenburg said of a pediatric COVID vaccine. “It will ease my mind so much.”

She isn’t alone in that anticipation. In the fall, the American Academy of Pediatrics and other pediatric vaccine experts urged faster action on pediatric vaccine trials and worried that children would be left behind as adults gained protection from COVID. But recent developments have eased those concerns.

“Over the next couple of months, we will be doing trials in an age-deescalation manner,” with studies moving gradually to younger children, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, chief medical adviser on COVID-19 to the president, said in a coronavirus response team briefing on Jan. 29. “So that hopefully, as we get to the late spring and summer, we will have children being able to be vaccinated.”

Pfizer completed enrollment of 2,259 teens aged 12-15 years in late January and expects to move forward with a separate pediatric trial of children aged 5-11 years by this spring, Keanna Ghazvini, senior associate for global media relations at Pfizer, said in an interview.

Enrollment in Moderna’s TeenCove study of adolescents ages 12-17 years began slowly in late December, but the pace has since picked up, said company spokesperson Colleen Hussey. “We continue to bring clinical trial sites online, and we are on track to provide updated data around mid-year 2021.” A trial extension in children 11 years and younger is expected to begin later in 2021.

Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca said they expect to begin adolescent trials in early 2021, according to data shared by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. An interim analysis of J&J’s Janssen COVID-19 vaccine trial data, released on Jan. 29, showed it was 72% effective in US participants aged 18 years or older. AstraZeneca’s U.S. trial in adults is ongoing.

Easing the burden

Vaccination could lessen children’s risk of severe disease as well as the social and emotional burdens of the pandemic, says James Campbell, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Maryland’s Center for Vaccine Development in Baltimore, which was involved in the Moderna and early-phase Pfizer trials. He coauthored a September 2020 article in Clinical Infectious Diseases titled: “Warp Speed for COVID-19 vaccines: Why are children stuck in neutral?”

The adolescent trials are a vital step to ensure timely vaccine access for teens and younger children. “It is reasonable, when you have limited vaccine, that your rollout goes to the highest priority and then moves to lower and lower priorities. In adults, we’re just saying: ‘Wait your turn,’ ” he said of the current vaccination effort. “If we didn’t have the [vaccine trial] data in children, we’d be saying: ‘You don’t have a turn.’ ”

As the pandemic has worn on, the burden on children has grown. As of Tuesday, 269 children had died of COVID-19. That is well above the highest annual death toll recorded during a regular flu season – 188 flu deaths among children and adolescents under 18 in the 2019-2020 and 2017-2018 flu seasons.

Children are less likely to transmit COVID-19 in their household than adults, according to a meta-analysis of 54 studies published in JAMA Network Open. But that does not necessarily mean children are less infectious, the authors said, noting that unmeasured factors could have affected the spread of infection among adults.

Moreover, children and adolescents need protection from COVID infection – and from the potential for severe disease or lingering effects – and, given that there are 74 million children and teens in the United States, their vaccination is an important part of stopping the pandemic, said Grace Lee, MD, professor of pediatrics at Stanford (Calif.) University, and cochair of ACIP’s COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Technical Subgroup.

“In order to interrupt transmission, I don’t see how we’re going to do that without vaccinating children and adolescents,” she said.

Dr. Lee said her 16-year-old daughter misses the normal teenage social life and is excited about getting the vaccine when she is eligible. (Adolescents without high-risk conditions are in the lowest vaccination tier, according to ACIP recommendations.) “There is truly individual protection to be gained,” Dr. Lee said.

She noted that researchers continue to assess the immune responses to the adult vaccines – even looking at immune characteristics of the small percentage of people who aren’t protected from infection – and that information helps in the evaluation of the pediatric immune responses. As the trials expand to younger children and infants, dosing will be a major focus. “How many doses do they need they need to receive the same immunity? Safety considerations will be critically important,” she said.

Teen trials underway

Pfizer/BioNTech extended its adult trial to 16- and 17-year-olds in October, which enabled older teens to be included in its emergency-use authorization. They and younger teens, ages 12-15, receive the same dose as adults.

The ongoing trials with Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are immunobridging trials, designed to study safety and immunogenicity. Investigators will compare the teens’ immune response with the findings from the larger adult trials. When the trials expand to school-age children (6-12 years), protocols call for testing the safety and immunogenicity of a half-dose vaccine as well as the full dose.

Children ages 2-5 years and infants and toddlers will be enrolled in future trials, studying safety and immunogenicity of full, half, or even quarter dosages. The Pediatric Research Equity Act of 2003 requires licensed vaccines to be tested for safety and efficacy in children, unless they are not appropriate for a pediatric population.

Demand for the teen trials has been strong. At Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 259 teenagers joined the Pfizer/BioNTech trial, but some teenagers were turned away when the trial’s national enrollment closed in late January.

“Many of the children are having no side effects, and if they are, they’re having the same [effects] as the young adults – local redness or pain, fatigue, and headaches,” said Robert Frenck, MD, director of the Cincinnati Children’s Gamble Program for Clinical Studies.

Parents may share some of the vaccine hesitancy that has affected adult vaccination. But that is balanced by the hope that vaccines will end the pandemic and usher in a new normal. “If it looks like [vaccines] will increase the likelihood of children returning to school safely, that may be a motivating factor,” Dr. Frenck said.

Cody Meissner, MD, chief of the pediatric infectious disease service at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, was initially cautious about the extension of vaccination to adolescents. A member of the Vaccine and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, which evaluates data and makes recommendations to the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Meissner initially abstained in the vote on the Pfizer/BioNTech emergency-use authorization for people 16 and older.

He noted that, at the time the committee reviewed the Pfizer vaccine, the company had data available for just 134 teenagers, half of whom received a placebo. But the vaccination of 34 million adults has provided robust data about the vaccine’s safety, and the trial expansion into adolescents is important.

“I’m comfortable with the way these trials are going now,” he said. “This is the way I was hoping they would go.”

Ms. Hillenburg is on the parent advisory board of Voices for Vaccines, an organization of parents supporting vaccination that is affiliated with the Task Force for Global Health, an Atlanta-based independent public health organization. Dr. Campbell’s institution has received funds to conduct clinical trials from the National Institutes of Health and several companies, including Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Pfizer, and Moderna. He has served pro bono on many safety and data monitoring committees. Dr. Frenck’s institution is receiving funds to conduct the Pfizer trial. In the past 5 years, he has also participated in clinical trials for GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Meissa vaccines. Dr. Lee and Dr. Meissner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

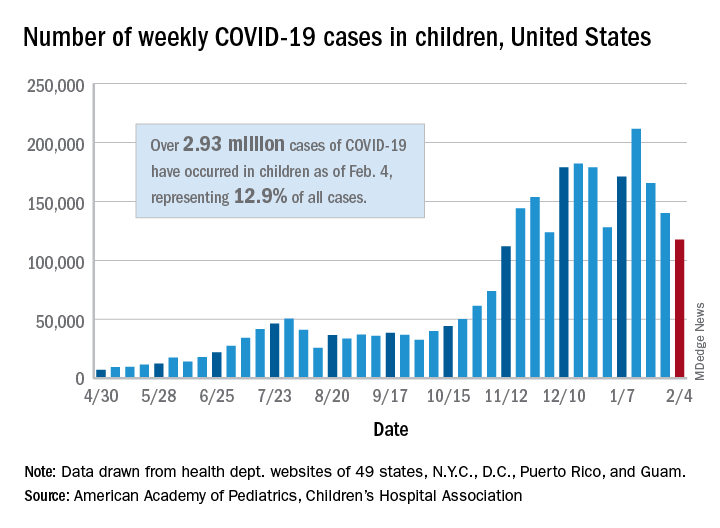

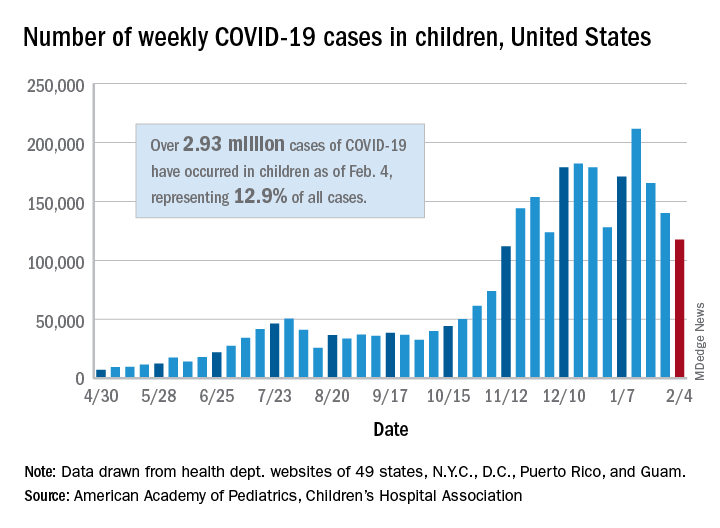

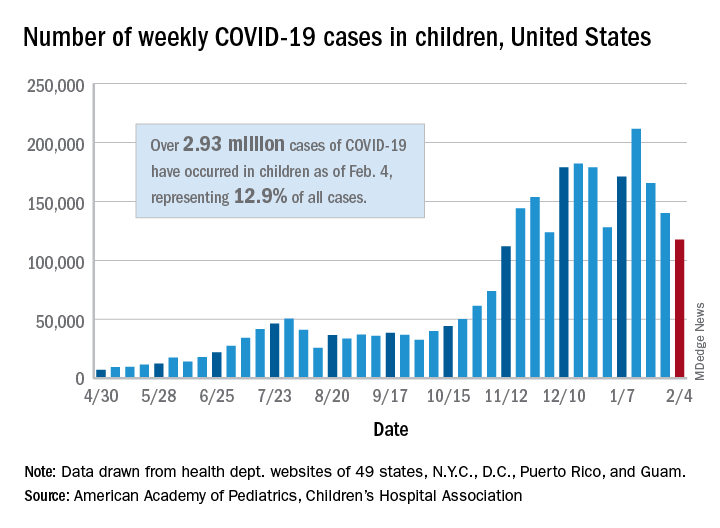

COVID-19 in children: New cases down for third straight week

New COVID-19 cases in children dropped for the third consecutive week, even as children continue to make up a larger share of all cases, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

New child cases totaled almost 118,000 for the week of Jan. 29-Feb. 4, continuing the decline that began right after the United States topped 200,000 cases for the only time Jan. 8-14, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

For the latest week, however, children represented 16.0% of all new COVID-19 cases, continuing a 5-week increase that began in early December 2020, after the proportion had dropped to 12.6%, based on data collected from the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. During the week of Sept. 11-17, children made up 16.9% of all cases, the highest level seen during the pandemic.

The 2.93 million cases that have been reported in children make up 12.9% of all cases since the pandemic began, and the overall rate of pediatric coronavirus infection is 3,899 cases per 100,000 children in the population. Taking a step down from the national level, 30 states are above that rate and 18 are below it, along with D.C., New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam (New York and Texas are excluded), the AAP and CHA reported.

There were 12 new COVID-19–related child deaths in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are reporting such data, bringing the total to 227. Nationally, 0.06% of all deaths have occurred in children, with rates ranging from 0.00% (11 states) to 0.26% (Nebraska) in the 45 jurisdictions, the AAP/CHA report shows.

Child hospitalizations rose to 1.9% of all hospitalizations after holding at 1.8% since mid-November in 25 reporting jurisdictions (24 states and New York City), but the hospitalization rate among children with COVID held at 0.8%, where it has been for the last 4 weeks. Hospitalization rates as high as 3.8% were recorded early in the pandemic, the AAP and CHA noted.

New COVID-19 cases in children dropped for the third consecutive week, even as children continue to make up a larger share of all cases, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

New child cases totaled almost 118,000 for the week of Jan. 29-Feb. 4, continuing the decline that began right after the United States topped 200,000 cases for the only time Jan. 8-14, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

For the latest week, however, children represented 16.0% of all new COVID-19 cases, continuing a 5-week increase that began in early December 2020, after the proportion had dropped to 12.6%, based on data collected from the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. During the week of Sept. 11-17, children made up 16.9% of all cases, the highest level seen during the pandemic.

The 2.93 million cases that have been reported in children make up 12.9% of all cases since the pandemic began, and the overall rate of pediatric coronavirus infection is 3,899 cases per 100,000 children in the population. Taking a step down from the national level, 30 states are above that rate and 18 are below it, along with D.C., New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam (New York and Texas are excluded), the AAP and CHA reported.

There were 12 new COVID-19–related child deaths in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are reporting such data, bringing the total to 227. Nationally, 0.06% of all deaths have occurred in children, with rates ranging from 0.00% (11 states) to 0.26% (Nebraska) in the 45 jurisdictions, the AAP/CHA report shows.

Child hospitalizations rose to 1.9% of all hospitalizations after holding at 1.8% since mid-November in 25 reporting jurisdictions (24 states and New York City), but the hospitalization rate among children with COVID held at 0.8%, where it has been for the last 4 weeks. Hospitalization rates as high as 3.8% were recorded early in the pandemic, the AAP and CHA noted.

New COVID-19 cases in children dropped for the third consecutive week, even as children continue to make up a larger share of all cases, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

New child cases totaled almost 118,000 for the week of Jan. 29-Feb. 4, continuing the decline that began right after the United States topped 200,000 cases for the only time Jan. 8-14, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

For the latest week, however, children represented 16.0% of all new COVID-19 cases, continuing a 5-week increase that began in early December 2020, after the proportion had dropped to 12.6%, based on data collected from the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. During the week of Sept. 11-17, children made up 16.9% of all cases, the highest level seen during the pandemic.

The 2.93 million cases that have been reported in children make up 12.9% of all cases since the pandemic began, and the overall rate of pediatric coronavirus infection is 3,899 cases per 100,000 children in the population. Taking a step down from the national level, 30 states are above that rate and 18 are below it, along with D.C., New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam (New York and Texas are excluded), the AAP and CHA reported.

There were 12 new COVID-19–related child deaths in the 43 states, along with New York City and Guam, that are reporting such data, bringing the total to 227. Nationally, 0.06% of all deaths have occurred in children, with rates ranging from 0.00% (11 states) to 0.26% (Nebraska) in the 45 jurisdictions, the AAP/CHA report shows.

Child hospitalizations rose to 1.9% of all hospitalizations after holding at 1.8% since mid-November in 25 reporting jurisdictions (24 states and New York City), but the hospitalization rate among children with COVID held at 0.8%, where it has been for the last 4 weeks. Hospitalization rates as high as 3.8% were recorded early in the pandemic, the AAP and CHA noted.

Study tests ways to increase autism screening and referrals

To improve autism screening rates, researchers in Utah tried a range of interventions.

They added automatic reminders to the electronic health record (EHR). They started using a shorter, more sensitive screening instrument. And they trained clinicians to perform autism-specific evaluations in a primary care clinic.

The researchers found that these interventions were associated with increased rates of autism screening and referrals.

At the same time, they looked at screening and referral rates at other community clinics in their health care system. These clinics incorporated EHR reminders but not all of the other changes.

“The community clinics had an increase in screening frequency with only automatic reminders,” the researchers reported. At the two intervention clinics, however, screening rates increased more than they did at the community clinics. Referrals did not significantly increase at the community clinics.

Kathleen Campbell, MD, MHSc, a pediatric resident at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, and colleagues described their research in a study published in Pediatrics.

Three phases

They examined more than 12,000 well-child visits for children aged 16-30 months between July 2017 and June 2019.

In all, 4,155 visits occurred at the 2 intervention clinics, and 8,078 visits occurred at the 27 community clinics in the University of Utah health care system.

From baseline through the interventions, the proportion of visits with screening increased by 51% in the intervention clinics (from 58.6% to 88.8%), and by 21% in the community clinics (from 43.4% to 52.4%). The proportion of referrals increased 1.5-fold in intervention clinics, from 1.3% to 3.3%, the authors said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) supports screening for autism in all children starting at age 18 months, but “only 44% of children with autism have had a comprehensive autism evaluation before age 36 months,” Dr. Campbell and colleagues wrote.

In their system, about half of the children were being screened for autism, and 0.5% had autism diagnosed.

In an effort to increase the proportion of visits with screening for autism and the proportion of visits with referrals for autism evaluation, Dr. Campbell and colleagues designed a quality improvement study.

Following a baseline period, they implemented interventions in three phases.

Initially, all clinics used the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised (M-CHAT-R) for autism screening. For the first phase starting in July 2018, the researchers changed the screening instrument at the two intervention clinics to the Parent’s Observation of Social Interaction (POSI). This instrument “is embedded in a broadband developmental screen, is shorter than the M-CHAT-R, and includes questions about the consistency of the child’s behavior,” the authors said. “The POSI has greater sensitivity than the M-CHAT-R ... and similar, although somewhat lower, specificity.”

In intervention phase 2 starting in November 2018, the researchers “added an automatic reminder for autism screening to the EHR health maintenance screen.” Both the intervention clinics and the community clinics received the automatic reminders.

In intervention phase 3 starting in February 2019, they “added a referral option that clinicians could use for rapid access to autism-specific evaluation ... for children who had a POSI result suggestive of autism and for whom the clinician had sufficient concerns about autism that would indicate the need for referral for autism evaluation,” the researchers said.

“Using an online tutorial, we trained three clinicians in the intervention clinics to administer an observational assessment known as the Screening Tool for Autism in Toddlers (STAT),” which requires a 30-minute visit, they said. “Children who had a STAT result suggestive of autism were referred for expedited autism diagnostic evaluation, which was performed by a multidisciplinary team in our university-based developmental assessment clinic. Children who had a STAT result that did not suggest autism did not receive further autism evaluations unless the clinician felt they still needed further evaluation at the developmental clinic.”

After the switch to POSI, the percentage of visits with a positive screen result increased from 4.7% to 13.5% in the intervention clinics.

Furthermore, referrals were 3.4 times more frequent for visits during phase 3 in the intervention clinics, relative to the baseline period.

Potential to overwhelm

“The change to a more sensitive screening instrument increased the frequency of screening results suggestive of autism and informed our improvement team of the need to implement autism evaluation in primary care to avoid overwhelming our referral system,” Dr. Campbell and coauthors reported.

Future studies may assess whether increased screening and referrals speed the time to diagnosis and treatment and improve long-term functional abilities of children with autism. Some children in the study have received an autism diagnosis, while others have not yet been evaluated.

The use of STAT in primary care may be limited by “the barriers of training providers and purchasing materials,” the authors noted. “However, the time-based billing for lengthier appointments and billing for developmental testing help to cover cost.”

The intervention clinics and community clinics were staffed by pediatric providers, including residents and attendings, said Dr. Campbell.

“The staffing is similar at the community and intervention clinics, with mostly pediatricians and some nurse practitioners,” Dr. Campbell said. “One difference is that there are a few family medicine physicians in the community clinics, but we did not study whether that made a difference in screening. At the beginning of the study the approach to screening was the same.”

From the start, the community clinics were screening for autism and referring for further autism evaluation less often than the intervention clinics. “I don’t know why they were screening less, but they did improve with the automatic reminders,” said Dr. Campbell. “We didn’t examine type of provider or type of practice in this study, but the literature suggests that family physicians do not screen for autism as often as pediatricians.”

Payment and referral challenges

In theory, the approach in the study is a great idea, but it may not be feasible to implement for many private practices, said Herschel Lessin, MD. Dr. Lessin is a senior partner of the Children’s Medical Group in New York.

“We desperately need autism screening in a primary care setting,” Dr. Lessin said. “These authors found that wasn’t being done as recommended by the AAP Bright Futures, which is a problem.”

However, the researchers incorporated the interventions in a health care system with “far more resources than most people in practice would ever have” and substituted a less familiar screening tool.

In addition, the ability to use confirmatory STAT for primary care evaluations may be limited. “Unless you can find pediatricians willing to commit 30 to 45 minutes on one of these evaluations ... few are going to do that,” he said.

“The whole problem is that there are no referrals available or very few referrals available, and that insurance payments so underpay for developmental screening and evaluation that it does not justify the time doing it, so a lot of doctors are unable to do it,” said Dr. Lessin. When a referral is warranted, developmental pediatricians may have 6- to 12-month waiting lists, he said.

“For people in clinical practice, this is not news,” Dr. Lessin said. “We know we should screen for autism. The problem is it’s time consuming. Nobody pays for it. We have no place to send them even when we are suspicious.”

From screening to diagnosis to treatment

“Autism screen approaches vary but with educational efforts on the part of the AAP, CDC, and family organizations the rates for autism screening have dramatically improved,” said Susan L. Hyman, MD, professor of pediatrics at the University of Rochester in New York. “I do not know if screening rates have been impacted by COVID.”

Dr. Hyman and coauthors wrote an AAP clinical report on the identification, evaluation, and management of children with autism spectrum disorder. The report was published in the January 2020 issue of Pediatrics.

After screening and diagnostic testing, patients most importantly need to be able to access “timely and equitable evidence-based intervention,” which should be available, said Dr. Hyman.

Although researchers have proposed training primary care providers in autism diagnostics, “older, more complex patients with co-occurring behavioral health or other developmental disorders may need more specialized diagnostic assessment than could be accomplished in a primary care setting,” Dr. Hyman added.

“However, it is very important to identify children with therapeutic needs as early as possible and move them through the continuum from screening to diagnosis to treatment in a timely fashion. It would be wonderful if symptoms could be addressed without the need for diagnosis in the very youngest children,” Dr. Hyman said. “Early symptoms, even if not autism, are likely to be appropriate for intervention – whether it is speech therapy, attention to food selectivity, sleep problems – things that impact quality of life and potential future symptoms.”

The research was supported by the Utah Stimulating Access to Research in Residency Transition Scholar award, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Campbell is an inventor on a patent related to screening for autism. The study authors otherwise had no disclosures. Dr. Lessin is on the editorial advisory board for Pediatric News and is on an advisory board for Cognoa, which is developing a medical device to diagnose autism and he is also the co-editor of the AAP's current ADHD Toolkit. Dr. Hyman had no relevant financial disclosures.

*This story was updated on Feb. 11, 2021.

To improve autism screening rates, researchers in Utah tried a range of interventions.

They added automatic reminders to the electronic health record (EHR). They started using a shorter, more sensitive screening instrument. And they trained clinicians to perform autism-specific evaluations in a primary care clinic.

The researchers found that these interventions were associated with increased rates of autism screening and referrals.

At the same time, they looked at screening and referral rates at other community clinics in their health care system. These clinics incorporated EHR reminders but not all of the other changes.

“The community clinics had an increase in screening frequency with only automatic reminders,” the researchers reported. At the two intervention clinics, however, screening rates increased more than they did at the community clinics. Referrals did not significantly increase at the community clinics.

Kathleen Campbell, MD, MHSc, a pediatric resident at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, and colleagues described their research in a study published in Pediatrics.

Three phases

They examined more than 12,000 well-child visits for children aged 16-30 months between July 2017 and June 2019.

In all, 4,155 visits occurred at the 2 intervention clinics, and 8,078 visits occurred at the 27 community clinics in the University of Utah health care system.

From baseline through the interventions, the proportion of visits with screening increased by 51% in the intervention clinics (from 58.6% to 88.8%), and by 21% in the community clinics (from 43.4% to 52.4%). The proportion of referrals increased 1.5-fold in intervention clinics, from 1.3% to 3.3%, the authors said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) supports screening for autism in all children starting at age 18 months, but “only 44% of children with autism have had a comprehensive autism evaluation before age 36 months,” Dr. Campbell and colleagues wrote.

In their system, about half of the children were being screened for autism, and 0.5% had autism diagnosed.

In an effort to increase the proportion of visits with screening for autism and the proportion of visits with referrals for autism evaluation, Dr. Campbell and colleagues designed a quality improvement study.

Following a baseline period, they implemented interventions in three phases.

Initially, all clinics used the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised (M-CHAT-R) for autism screening. For the first phase starting in July 2018, the researchers changed the screening instrument at the two intervention clinics to the Parent’s Observation of Social Interaction (POSI). This instrument “is embedded in a broadband developmental screen, is shorter than the M-CHAT-R, and includes questions about the consistency of the child’s behavior,” the authors said. “The POSI has greater sensitivity than the M-CHAT-R ... and similar, although somewhat lower, specificity.”

In intervention phase 2 starting in November 2018, the researchers “added an automatic reminder for autism screening to the EHR health maintenance screen.” Both the intervention clinics and the community clinics received the automatic reminders.

In intervention phase 3 starting in February 2019, they “added a referral option that clinicians could use for rapid access to autism-specific evaluation ... for children who had a POSI result suggestive of autism and for whom the clinician had sufficient concerns about autism that would indicate the need for referral for autism evaluation,” the researchers said.

“Using an online tutorial, we trained three clinicians in the intervention clinics to administer an observational assessment known as the Screening Tool for Autism in Toddlers (STAT),” which requires a 30-minute visit, they said. “Children who had a STAT result suggestive of autism were referred for expedited autism diagnostic evaluation, which was performed by a multidisciplinary team in our university-based developmental assessment clinic. Children who had a STAT result that did not suggest autism did not receive further autism evaluations unless the clinician felt they still needed further evaluation at the developmental clinic.”

After the switch to POSI, the percentage of visits with a positive screen result increased from 4.7% to 13.5% in the intervention clinics.

Furthermore, referrals were 3.4 times more frequent for visits during phase 3 in the intervention clinics, relative to the baseline period.

Potential to overwhelm

“The change to a more sensitive screening instrument increased the frequency of screening results suggestive of autism and informed our improvement team of the need to implement autism evaluation in primary care to avoid overwhelming our referral system,” Dr. Campbell and coauthors reported.

Future studies may assess whether increased screening and referrals speed the time to diagnosis and treatment and improve long-term functional abilities of children with autism. Some children in the study have received an autism diagnosis, while others have not yet been evaluated.

The use of STAT in primary care may be limited by “the barriers of training providers and purchasing materials,” the authors noted. “However, the time-based billing for lengthier appointments and billing for developmental testing help to cover cost.”

The intervention clinics and community clinics were staffed by pediatric providers, including residents and attendings, said Dr. Campbell.

“The staffing is similar at the community and intervention clinics, with mostly pediatricians and some nurse practitioners,” Dr. Campbell said. “One difference is that there are a few family medicine physicians in the community clinics, but we did not study whether that made a difference in screening. At the beginning of the study the approach to screening was the same.”

From the start, the community clinics were screening for autism and referring for further autism evaluation less often than the intervention clinics. “I don’t know why they were screening less, but they did improve with the automatic reminders,” said Dr. Campbell. “We didn’t examine type of provider or type of practice in this study, but the literature suggests that family physicians do not screen for autism as often as pediatricians.”

Payment and referral challenges

In theory, the approach in the study is a great idea, but it may not be feasible to implement for many private practices, said Herschel Lessin, MD. Dr. Lessin is a senior partner of the Children’s Medical Group in New York.

“We desperately need autism screening in a primary care setting,” Dr. Lessin said. “These authors found that wasn’t being done as recommended by the AAP Bright Futures, which is a problem.”

However, the researchers incorporated the interventions in a health care system with “far more resources than most people in practice would ever have” and substituted a less familiar screening tool.

In addition, the ability to use confirmatory STAT for primary care evaluations may be limited. “Unless you can find pediatricians willing to commit 30 to 45 minutes on one of these evaluations ... few are going to do that,” he said.

“The whole problem is that there are no referrals available or very few referrals available, and that insurance payments so underpay for developmental screening and evaluation that it does not justify the time doing it, so a lot of doctors are unable to do it,” said Dr. Lessin. When a referral is warranted, developmental pediatricians may have 6- to 12-month waiting lists, he said.

“For people in clinical practice, this is not news,” Dr. Lessin said. “We know we should screen for autism. The problem is it’s time consuming. Nobody pays for it. We have no place to send them even when we are suspicious.”

From screening to diagnosis to treatment

“Autism screen approaches vary but with educational efforts on the part of the AAP, CDC, and family organizations the rates for autism screening have dramatically improved,” said Susan L. Hyman, MD, professor of pediatrics at the University of Rochester in New York. “I do not know if screening rates have been impacted by COVID.”

Dr. Hyman and coauthors wrote an AAP clinical report on the identification, evaluation, and management of children with autism spectrum disorder. The report was published in the January 2020 issue of Pediatrics.

After screening and diagnostic testing, patients most importantly need to be able to access “timely and equitable evidence-based intervention,” which should be available, said Dr. Hyman.

Although researchers have proposed training primary care providers in autism diagnostics, “older, more complex patients with co-occurring behavioral health or other developmental disorders may need more specialized diagnostic assessment than could be accomplished in a primary care setting,” Dr. Hyman added.

“However, it is very important to identify children with therapeutic needs as early as possible and move them through the continuum from screening to diagnosis to treatment in a timely fashion. It would be wonderful if symptoms could be addressed without the need for diagnosis in the very youngest children,” Dr. Hyman said. “Early symptoms, even if not autism, are likely to be appropriate for intervention – whether it is speech therapy, attention to food selectivity, sleep problems – things that impact quality of life and potential future symptoms.”

The research was supported by the Utah Stimulating Access to Research in Residency Transition Scholar award, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Campbell is an inventor on a patent related to screening for autism. The study authors otherwise had no disclosures. Dr. Lessin is on the editorial advisory board for Pediatric News and is on an advisory board for Cognoa, which is developing a medical device to diagnose autism and he is also the co-editor of the AAP's current ADHD Toolkit. Dr. Hyman had no relevant financial disclosures.

*This story was updated on Feb. 11, 2021.

To improve autism screening rates, researchers in Utah tried a range of interventions.

They added automatic reminders to the electronic health record (EHR). They started using a shorter, more sensitive screening instrument. And they trained clinicians to perform autism-specific evaluations in a primary care clinic.

The researchers found that these interventions were associated with increased rates of autism screening and referrals.

At the same time, they looked at screening and referral rates at other community clinics in their health care system. These clinics incorporated EHR reminders but not all of the other changes.

“The community clinics had an increase in screening frequency with only automatic reminders,” the researchers reported. At the two intervention clinics, however, screening rates increased more than they did at the community clinics. Referrals did not significantly increase at the community clinics.

Kathleen Campbell, MD, MHSc, a pediatric resident at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, and colleagues described their research in a study published in Pediatrics.

Three phases

They examined more than 12,000 well-child visits for children aged 16-30 months between July 2017 and June 2019.

In all, 4,155 visits occurred at the 2 intervention clinics, and 8,078 visits occurred at the 27 community clinics in the University of Utah health care system.

From baseline through the interventions, the proportion of visits with screening increased by 51% in the intervention clinics (from 58.6% to 88.8%), and by 21% in the community clinics (from 43.4% to 52.4%). The proportion of referrals increased 1.5-fold in intervention clinics, from 1.3% to 3.3%, the authors said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) supports screening for autism in all children starting at age 18 months, but “only 44% of children with autism have had a comprehensive autism evaluation before age 36 months,” Dr. Campbell and colleagues wrote.

In their system, about half of the children were being screened for autism, and 0.5% had autism diagnosed.

In an effort to increase the proportion of visits with screening for autism and the proportion of visits with referrals for autism evaluation, Dr. Campbell and colleagues designed a quality improvement study.

Following a baseline period, they implemented interventions in three phases.

Initially, all clinics used the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised (M-CHAT-R) for autism screening. For the first phase starting in July 2018, the researchers changed the screening instrument at the two intervention clinics to the Parent’s Observation of Social Interaction (POSI). This instrument “is embedded in a broadband developmental screen, is shorter than the M-CHAT-R, and includes questions about the consistency of the child’s behavior,” the authors said. “The POSI has greater sensitivity than the M-CHAT-R ... and similar, although somewhat lower, specificity.”

In intervention phase 2 starting in November 2018, the researchers “added an automatic reminder for autism screening to the EHR health maintenance screen.” Both the intervention clinics and the community clinics received the automatic reminders.

In intervention phase 3 starting in February 2019, they “added a referral option that clinicians could use for rapid access to autism-specific evaluation ... for children who had a POSI result suggestive of autism and for whom the clinician had sufficient concerns about autism that would indicate the need for referral for autism evaluation,” the researchers said.

“Using an online tutorial, we trained three clinicians in the intervention clinics to administer an observational assessment known as the Screening Tool for Autism in Toddlers (STAT),” which requires a 30-minute visit, they said. “Children who had a STAT result suggestive of autism were referred for expedited autism diagnostic evaluation, which was performed by a multidisciplinary team in our university-based developmental assessment clinic. Children who had a STAT result that did not suggest autism did not receive further autism evaluations unless the clinician felt they still needed further evaluation at the developmental clinic.”

After the switch to POSI, the percentage of visits with a positive screen result increased from 4.7% to 13.5% in the intervention clinics.

Furthermore, referrals were 3.4 times more frequent for visits during phase 3 in the intervention clinics, relative to the baseline period.

Potential to overwhelm

“The change to a more sensitive screening instrument increased the frequency of screening results suggestive of autism and informed our improvement team of the need to implement autism evaluation in primary care to avoid overwhelming our referral system,” Dr. Campbell and coauthors reported.

Future studies may assess whether increased screening and referrals speed the time to diagnosis and treatment and improve long-term functional abilities of children with autism. Some children in the study have received an autism diagnosis, while others have not yet been evaluated.

The use of STAT in primary care may be limited by “the barriers of training providers and purchasing materials,” the authors noted. “However, the time-based billing for lengthier appointments and billing for developmental testing help to cover cost.”

The intervention clinics and community clinics were staffed by pediatric providers, including residents and attendings, said Dr. Campbell.

“The staffing is similar at the community and intervention clinics, with mostly pediatricians and some nurse practitioners,” Dr. Campbell said. “One difference is that there are a few family medicine physicians in the community clinics, but we did not study whether that made a difference in screening. At the beginning of the study the approach to screening was the same.”

From the start, the community clinics were screening for autism and referring for further autism evaluation less often than the intervention clinics. “I don’t know why they were screening less, but they did improve with the automatic reminders,” said Dr. Campbell. “We didn’t examine type of provider or type of practice in this study, but the literature suggests that family physicians do not screen for autism as often as pediatricians.”

Payment and referral challenges

In theory, the approach in the study is a great idea, but it may not be feasible to implement for many private practices, said Herschel Lessin, MD. Dr. Lessin is a senior partner of the Children’s Medical Group in New York.

“We desperately need autism screening in a primary care setting,” Dr. Lessin said. “These authors found that wasn’t being done as recommended by the AAP Bright Futures, which is a problem.”

However, the researchers incorporated the interventions in a health care system with “far more resources than most people in practice would ever have” and substituted a less familiar screening tool.

In addition, the ability to use confirmatory STAT for primary care evaluations may be limited. “Unless you can find pediatricians willing to commit 30 to 45 minutes on one of these evaluations ... few are going to do that,” he said.

“The whole problem is that there are no referrals available or very few referrals available, and that insurance payments so underpay for developmental screening and evaluation that it does not justify the time doing it, so a lot of doctors are unable to do it,” said Dr. Lessin. When a referral is warranted, developmental pediatricians may have 6- to 12-month waiting lists, he said.