User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Who is my neighbor? The ethics of sharing medical resources in the world

India is in a crisis as the burden of COVID-19 has collapsed parts of the health care system. There are not enough beds, not enough oxygen, and not enough crematoria to handle the pandemic. India is also a major supplier of vaccines for itself and many other countries. That production capacity has also been affected by the local events, further worsening the response to the pandemic over the next few months.

This collapse is the specter that, in April 2020, placed a hospital ship next to Manhattan and rows of beds in its convention center. Fortunately, the lockdown in March 2020 sufficiently flattened the curve. The city avoided utilizing that disaster capacity, though many New Yorkers died out of sight in nursing homes. When the third and largest wave of cases in the United States peaked in January 2021, hospitals throughout California reached capacity but avoided bursting. In April 2021, localized outbreaks in Michigan, Arizona, and Ontario again tested the maximum capacity for providing modern medical treatments. Great Britain used a second lockdown in October 2020 and a third in January 2021 to control the pandemic, with Prime Minister Boris Johnson emphasizing that it was these social interventions, and not vaccines, which provided the mitigating effects. Other European Union nations adopted similar strategies. Prudent choices by government guided by science, combined with the cooperation of the public, have been and still are crucial to mollify the pandemic.

There is hope that soon vaccines will return daily life to a new normal. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has loosened restrictions on social gathering. An increase in daily new cases of COVID-19 in April 2021 has turned into just a blip before continuing to recede. Perhaps that is the first sign of vaccination working at the level of public health. However, the May 2021 lockdown in highly vaccinated Seychelles is a warning that the danger remains. A single match can start a huge forest fire. The first 150 million cases of COVID-19 worldwide have, through natural rates of mutation, produced several variants that might partially evade current vaccines. The danger of newer variants persists with the next 150 million cases as the pandemic continues to rage in many nations which are just one airplane ride away. All human inhabitants of this blue-covered third rock from the sun are interconnected.

The benefits of scientific advancement have been extolled for centuries. This includes both individual discoveries as well as a mindset that favors rationalism over fatalism. On the whole, the benefits of scientific progress outweigh the negatives. Negative environmental impacts include pollution and climate change. Economic impacts include raising the mean economic standard of living but with greater inequity. Historically, governmental and social institutions have attempted to mitigate these negative consequences. Those efforts have attempted to provide guidance and a moral compass to direct the progress of scientific advancement, particularly in fields like gene therapy. Those efforts have called upon developed nations to share the bounties of progress with other nations.

Modern medicine has provided the fruit of these scientific advancements to a limited fraction of the world’s population during the 20th century. The improvements in life expectancy and infant mortality have come primarily from civil engineers getting running water into cities and sewage out. A smaller portion of the benefits are from public health measures that reduced tuberculosis, smallpox, polio, and measles. Agriculture became more reliable, productive, and nutritious. In the 21st century, medical care (control of hypertension, diabetes, and clotting) aimed at reducing heart disease and strokes have added another 2-3 years to the life expectancy in the United States, with much of that benefit erased by the epidemics of obesity and opioid abuse.

Modern medical technology has created treatments that cost $10,000 a month to add a few extra months of life to geriatric patients with terminal cancer. Meanwhile, in more mundane care, efforts like Choosing Wisely seek to save money wasted on low-value, useless, and even harmful tests and therapies. There is no single person or agency managing this chaotic process of inventing expensive new technologies while inadequately addressing the widespread shortages of mental health care, disparities in education, and other social determinants of health. The pandemic has highlighted these preexisting weaknesses in the social fabric.

The cries from India have been accompanied by voices of anger from India and other nations accusing the United States of hoarding vaccines and the raw materials needed to produce them. This has been called vaccine apartheid. The United States is not alone in its political decision to prioritize domestic interests over international ones; India’s recent government is similarly nationalistic. Scientists warn that no one is safe locally as long as the pandemic rages in other countries. The Biden administration, in a delayed response to the crisis in India, finally announced plans to share some unused vaccines (of a brand not yet Food and Drug Administration approved) as well as some vaccine raw materials whose export was forbidden by a regulation under the Defense Production Act. Reading below the headlines, the promised response won’t be implemented for weeks or months. We must do better.

The logistics of sharing the benefits of advanced science are complicated. The ethics are not. Who is my neighbor? If you didn’t learn the answer to that in Sunday school, there isn’t much more I can say.

Dr. Powell is a retired pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He has no financial disclosures, Email him at [email protected]

India is in a crisis as the burden of COVID-19 has collapsed parts of the health care system. There are not enough beds, not enough oxygen, and not enough crematoria to handle the pandemic. India is also a major supplier of vaccines for itself and many other countries. That production capacity has also been affected by the local events, further worsening the response to the pandemic over the next few months.

This collapse is the specter that, in April 2020, placed a hospital ship next to Manhattan and rows of beds in its convention center. Fortunately, the lockdown in March 2020 sufficiently flattened the curve. The city avoided utilizing that disaster capacity, though many New Yorkers died out of sight in nursing homes. When the third and largest wave of cases in the United States peaked in January 2021, hospitals throughout California reached capacity but avoided bursting. In April 2021, localized outbreaks in Michigan, Arizona, and Ontario again tested the maximum capacity for providing modern medical treatments. Great Britain used a second lockdown in October 2020 and a third in January 2021 to control the pandemic, with Prime Minister Boris Johnson emphasizing that it was these social interventions, and not vaccines, which provided the mitigating effects. Other European Union nations adopted similar strategies. Prudent choices by government guided by science, combined with the cooperation of the public, have been and still are crucial to mollify the pandemic.

There is hope that soon vaccines will return daily life to a new normal. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has loosened restrictions on social gathering. An increase in daily new cases of COVID-19 in April 2021 has turned into just a blip before continuing to recede. Perhaps that is the first sign of vaccination working at the level of public health. However, the May 2021 lockdown in highly vaccinated Seychelles is a warning that the danger remains. A single match can start a huge forest fire. The first 150 million cases of COVID-19 worldwide have, through natural rates of mutation, produced several variants that might partially evade current vaccines. The danger of newer variants persists with the next 150 million cases as the pandemic continues to rage in many nations which are just one airplane ride away. All human inhabitants of this blue-covered third rock from the sun are interconnected.

The benefits of scientific advancement have been extolled for centuries. This includes both individual discoveries as well as a mindset that favors rationalism over fatalism. On the whole, the benefits of scientific progress outweigh the negatives. Negative environmental impacts include pollution and climate change. Economic impacts include raising the mean economic standard of living but with greater inequity. Historically, governmental and social institutions have attempted to mitigate these negative consequences. Those efforts have attempted to provide guidance and a moral compass to direct the progress of scientific advancement, particularly in fields like gene therapy. Those efforts have called upon developed nations to share the bounties of progress with other nations.

Modern medicine has provided the fruit of these scientific advancements to a limited fraction of the world’s population during the 20th century. The improvements in life expectancy and infant mortality have come primarily from civil engineers getting running water into cities and sewage out. A smaller portion of the benefits are from public health measures that reduced tuberculosis, smallpox, polio, and measles. Agriculture became more reliable, productive, and nutritious. In the 21st century, medical care (control of hypertension, diabetes, and clotting) aimed at reducing heart disease and strokes have added another 2-3 years to the life expectancy in the United States, with much of that benefit erased by the epidemics of obesity and opioid abuse.

Modern medical technology has created treatments that cost $10,000 a month to add a few extra months of life to geriatric patients with terminal cancer. Meanwhile, in more mundane care, efforts like Choosing Wisely seek to save money wasted on low-value, useless, and even harmful tests and therapies. There is no single person or agency managing this chaotic process of inventing expensive new technologies while inadequately addressing the widespread shortages of mental health care, disparities in education, and other social determinants of health. The pandemic has highlighted these preexisting weaknesses in the social fabric.

The cries from India have been accompanied by voices of anger from India and other nations accusing the United States of hoarding vaccines and the raw materials needed to produce them. This has been called vaccine apartheid. The United States is not alone in its political decision to prioritize domestic interests over international ones; India’s recent government is similarly nationalistic. Scientists warn that no one is safe locally as long as the pandemic rages in other countries. The Biden administration, in a delayed response to the crisis in India, finally announced plans to share some unused vaccines (of a brand not yet Food and Drug Administration approved) as well as some vaccine raw materials whose export was forbidden by a regulation under the Defense Production Act. Reading below the headlines, the promised response won’t be implemented for weeks or months. We must do better.

The logistics of sharing the benefits of advanced science are complicated. The ethics are not. Who is my neighbor? If you didn’t learn the answer to that in Sunday school, there isn’t much more I can say.

Dr. Powell is a retired pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He has no financial disclosures, Email him at [email protected]

India is in a crisis as the burden of COVID-19 has collapsed parts of the health care system. There are not enough beds, not enough oxygen, and not enough crematoria to handle the pandemic. India is also a major supplier of vaccines for itself and many other countries. That production capacity has also been affected by the local events, further worsening the response to the pandemic over the next few months.

This collapse is the specter that, in April 2020, placed a hospital ship next to Manhattan and rows of beds in its convention center. Fortunately, the lockdown in March 2020 sufficiently flattened the curve. The city avoided utilizing that disaster capacity, though many New Yorkers died out of sight in nursing homes. When the third and largest wave of cases in the United States peaked in January 2021, hospitals throughout California reached capacity but avoided bursting. In April 2021, localized outbreaks in Michigan, Arizona, and Ontario again tested the maximum capacity for providing modern medical treatments. Great Britain used a second lockdown in October 2020 and a third in January 2021 to control the pandemic, with Prime Minister Boris Johnson emphasizing that it was these social interventions, and not vaccines, which provided the mitigating effects. Other European Union nations adopted similar strategies. Prudent choices by government guided by science, combined with the cooperation of the public, have been and still are crucial to mollify the pandemic.

There is hope that soon vaccines will return daily life to a new normal. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has loosened restrictions on social gathering. An increase in daily new cases of COVID-19 in April 2021 has turned into just a blip before continuing to recede. Perhaps that is the first sign of vaccination working at the level of public health. However, the May 2021 lockdown in highly vaccinated Seychelles is a warning that the danger remains. A single match can start a huge forest fire. The first 150 million cases of COVID-19 worldwide have, through natural rates of mutation, produced several variants that might partially evade current vaccines. The danger of newer variants persists with the next 150 million cases as the pandemic continues to rage in many nations which are just one airplane ride away. All human inhabitants of this blue-covered third rock from the sun are interconnected.

The benefits of scientific advancement have been extolled for centuries. This includes both individual discoveries as well as a mindset that favors rationalism over fatalism. On the whole, the benefits of scientific progress outweigh the negatives. Negative environmental impacts include pollution and climate change. Economic impacts include raising the mean economic standard of living but with greater inequity. Historically, governmental and social institutions have attempted to mitigate these negative consequences. Those efforts have attempted to provide guidance and a moral compass to direct the progress of scientific advancement, particularly in fields like gene therapy. Those efforts have called upon developed nations to share the bounties of progress with other nations.

Modern medicine has provided the fruit of these scientific advancements to a limited fraction of the world’s population during the 20th century. The improvements in life expectancy and infant mortality have come primarily from civil engineers getting running water into cities and sewage out. A smaller portion of the benefits are from public health measures that reduced tuberculosis, smallpox, polio, and measles. Agriculture became more reliable, productive, and nutritious. In the 21st century, medical care (control of hypertension, diabetes, and clotting) aimed at reducing heart disease and strokes have added another 2-3 years to the life expectancy in the United States, with much of that benefit erased by the epidemics of obesity and opioid abuse.

Modern medical technology has created treatments that cost $10,000 a month to add a few extra months of life to geriatric patients with terminal cancer. Meanwhile, in more mundane care, efforts like Choosing Wisely seek to save money wasted on low-value, useless, and even harmful tests and therapies. There is no single person or agency managing this chaotic process of inventing expensive new technologies while inadequately addressing the widespread shortages of mental health care, disparities in education, and other social determinants of health. The pandemic has highlighted these preexisting weaknesses in the social fabric.

The cries from India have been accompanied by voices of anger from India and other nations accusing the United States of hoarding vaccines and the raw materials needed to produce them. This has been called vaccine apartheid. The United States is not alone in its political decision to prioritize domestic interests over international ones; India’s recent government is similarly nationalistic. Scientists warn that no one is safe locally as long as the pandemic rages in other countries. The Biden administration, in a delayed response to the crisis in India, finally announced plans to share some unused vaccines (of a brand not yet Food and Drug Administration approved) as well as some vaccine raw materials whose export was forbidden by a regulation under the Defense Production Act. Reading below the headlines, the promised response won’t be implemented for weeks or months. We must do better.

The logistics of sharing the benefits of advanced science are complicated. The ethics are not. Who is my neighbor? If you didn’t learn the answer to that in Sunday school, there isn’t much more I can say.

Dr. Powell is a retired pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He has no financial disclosures, Email him at [email protected]

Perinatal depression and the pediatrician’s role

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a common and treatable problem affecting over 10% of all pregnant women. Without routine use of a screening questionnaire, many women go undiagnosed and without treatment. The risks of untreated PPD in a new mother are the risks of depression tripled: to her health and to the health of her new infant and their whole family. Although pediatricians treat children, they take care of the whole family. They appreciate their role in offering support and guidance to new parents, and in the case of PPD, they are in a unique position. The American Academy of Pediatrics recognized this when they issued their policy statement, “Incorporating Recognition and Management of Perinatal Depression into Pediatric Practice,” in January 2019. By screening, tracking, and connecting affected mothers to care and services, you can truly provide “two-generational care” for your youngest patients.

PPD affects an estimated one in seven women (13%) globally. In one large retrospective study that looked at the 39 weeks before and after delivery, 15.4% of mothers received a diagnosis of PPD and a second study indicated that 22% of new mothers had depressive symptoms that were persistent for 6 months.1 The pathways to PPD include prior personal or family history of depression, stressors in the family (connected to social determinants of health), previous miscarriage or serious complications in a previous pregnancy, and sensitivity to hormonal changes. Indeed, PPD is the most common complication of childbirth.2 Although as many as half of all women eventually diagnosed with PPD had symptoms during their pregnancy, the misperception that PPD is only post partum leads to it being mistaken for the normal process of adjustment to parenthood. PPD is particularly insidious as new mothers are likely to be silent if they feel shame for not enjoying what they have been told will be a special and happy time, and those around them may mistake symptoms for the normal “baby blues” that will resolve quickly and with routine supports.

Untreated PPD, creates risks for mother, infant, and family as she manages needless suffering during a critical period for her new baby. While depression may remit over months without treatment, suicide is a real risk, and accounts for 20% of postpartum deaths.3 Infants face serious developmental consequences when their mothers are withdrawn and disconnected from them during the first months of life, including impaired social development, physical growth, and cognitive development. This impairment persists. Exposure to maternal depression during infancy is associated with lower IQ, attentional problems, and special educational needs by elementary school,4 and is a risk factor for psychiatric illnesses in childhood and adolescence.5,6 PPD has a broad range of severity, including psychosis that may include paranoia with the rare risk of infanticide. And maternal depression can add to the strains in a vulnerable caregiver relationship that can raise the risk for neglect or abuse of the mother, children, or both.

It is important to note that anxiety is often the presenting problem in perinatal mood disorders, with mothers experiencing intense morbid worries about their infant’s safety and health, and fear of inadequacy, criticism, and even infant removal. These fears may reinforce silence and isolation. But pediatricians are one group that these mothers are most likely to share their anxieties with as they look for reassurance. It can be challenging to distinguish PPD from obsessive-compulsive disorder or PTSD. The critical work of the pediatrician is not specific diagnosis and treatment. Instead, your task is to provide screening and support, to create a safe place to overcome silence and shame.

There are many reliable and valid screening instruments available for depression, but the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EDPS) has been specially developed for and tested in this population. It is a 10-item scale that is easy to complete and to score. Scores range from 0 to 30 and a score of 10 is considered a cutoff for depression. It can be used to track symptoms and is free and widely available online and in multiple languages. Ideally, this scale can be administered as part of a previsit, automatically entered into an electronic medical record and given at regular intervals during the infant’s first year of primary care. Some new mothers, especially if they are suffering from depression, may feel anxious about filling this out. It is important that your staff tell them that you screen all new mothers in your practice, and that PPD is common and treatable and the pediatrician’s office is committed to the health of the whole family.

If a new mother screens positive, you might consider yourself to have three tasks: Reassure her that she is a wonderful mother and this is a treatable illness, not a cause for guilt, shame, or alarm; expand her support and decrease her isolation by helping her to communicate with her family; and identify treatment resources for her. Start by being curious about some of her specific worries or feelings, her energy level, feelings of isolation or trouble with sleep. Offer compassion and validation around the pain of these experiences in the midst of so much transition. Only after hearing a little detail about her experience, then you may offer that such feelings are common, but when they are persistent or severe, they often indicate PPD, and that her screening test suggests they do for her. Offer that this form of depression is very treatable, with both pharmacologic and psychotherapy interventions. And if she is resistant, gently offer that treatment will be very protective of her new infant’s physical, social, and cognitive growth and development. Hearing this from a pediatrician is powerful for a new mother, even if depressed. Finally, ask if you might help her bring other important adults in her family into an understanding of this. Could she tell her spouse? Her sister? Her best friend? Perhaps she could bring one of them to the next weekly visit, so you can all speak together. This intervention greatly improves the likelihood of her engaging in treatment, and strong interpersonal connections are therapeutic in and of themselves.

For treatment, the easier your office can make it, the more likely she is to follow up. Identify local resources, perhaps through connected community organizations such as Jewish Family and Children’s Services or through a public program like California’s First Five. Connect with the local obstetric practice, which may already have a referral process in place. If you can connect with her primary care provider, they may take on the referral process or may even have integrated capacity for treatment. Identify strategies that may support her restful sleep, including realistic daily exercise, sharing infant care, and being cautious with caffeine and screen time. Identify ways for her to meet other new mothers or reconnect with friends. Reassure her that easy attachment activities, such as reading a book or singing to her baby can be good for both of them without requiring much energy. This may sound like a daunting task, but the conversation will only take a few minutes. Helping an isolated new parent recognize that their feelings of fear, inadequacy, and guilt are not facts, offering some simple immediate strategies and facilitating a referral can be lifesaving.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected]

References

1. Dietz PM et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1515-20.

2. Hanusa BH et al. J Women’s Health (Larchmt) 2008;17(4):585-96.

3. Lindahl V et al. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8(2):77-87.

4. Hay DF et al. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42(7):871-89.

5. Tully EC et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2008:165(9):1148-54.

6. Maternal depression and child development. Paediatr. Child Health 2004;9(8):575-98.

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a common and treatable problem affecting over 10% of all pregnant women. Without routine use of a screening questionnaire, many women go undiagnosed and without treatment. The risks of untreated PPD in a new mother are the risks of depression tripled: to her health and to the health of her new infant and their whole family. Although pediatricians treat children, they take care of the whole family. They appreciate their role in offering support and guidance to new parents, and in the case of PPD, they are in a unique position. The American Academy of Pediatrics recognized this when they issued their policy statement, “Incorporating Recognition and Management of Perinatal Depression into Pediatric Practice,” in January 2019. By screening, tracking, and connecting affected mothers to care and services, you can truly provide “two-generational care” for your youngest patients.

PPD affects an estimated one in seven women (13%) globally. In one large retrospective study that looked at the 39 weeks before and after delivery, 15.4% of mothers received a diagnosis of PPD and a second study indicated that 22% of new mothers had depressive symptoms that were persistent for 6 months.1 The pathways to PPD include prior personal or family history of depression, stressors in the family (connected to social determinants of health), previous miscarriage or serious complications in a previous pregnancy, and sensitivity to hormonal changes. Indeed, PPD is the most common complication of childbirth.2 Although as many as half of all women eventually diagnosed with PPD had symptoms during their pregnancy, the misperception that PPD is only post partum leads to it being mistaken for the normal process of adjustment to parenthood. PPD is particularly insidious as new mothers are likely to be silent if they feel shame for not enjoying what they have been told will be a special and happy time, and those around them may mistake symptoms for the normal “baby blues” that will resolve quickly and with routine supports.

Untreated PPD, creates risks for mother, infant, and family as she manages needless suffering during a critical period for her new baby. While depression may remit over months without treatment, suicide is a real risk, and accounts for 20% of postpartum deaths.3 Infants face serious developmental consequences when their mothers are withdrawn and disconnected from them during the first months of life, including impaired social development, physical growth, and cognitive development. This impairment persists. Exposure to maternal depression during infancy is associated with lower IQ, attentional problems, and special educational needs by elementary school,4 and is a risk factor for psychiatric illnesses in childhood and adolescence.5,6 PPD has a broad range of severity, including psychosis that may include paranoia with the rare risk of infanticide. And maternal depression can add to the strains in a vulnerable caregiver relationship that can raise the risk for neglect or abuse of the mother, children, or both.

It is important to note that anxiety is often the presenting problem in perinatal mood disorders, with mothers experiencing intense morbid worries about their infant’s safety and health, and fear of inadequacy, criticism, and even infant removal. These fears may reinforce silence and isolation. But pediatricians are one group that these mothers are most likely to share their anxieties with as they look for reassurance. It can be challenging to distinguish PPD from obsessive-compulsive disorder or PTSD. The critical work of the pediatrician is not specific diagnosis and treatment. Instead, your task is to provide screening and support, to create a safe place to overcome silence and shame.

There are many reliable and valid screening instruments available for depression, but the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EDPS) has been specially developed for and tested in this population. It is a 10-item scale that is easy to complete and to score. Scores range from 0 to 30 and a score of 10 is considered a cutoff for depression. It can be used to track symptoms and is free and widely available online and in multiple languages. Ideally, this scale can be administered as part of a previsit, automatically entered into an electronic medical record and given at regular intervals during the infant’s first year of primary care. Some new mothers, especially if they are suffering from depression, may feel anxious about filling this out. It is important that your staff tell them that you screen all new mothers in your practice, and that PPD is common and treatable and the pediatrician’s office is committed to the health of the whole family.

If a new mother screens positive, you might consider yourself to have three tasks: Reassure her that she is a wonderful mother and this is a treatable illness, not a cause for guilt, shame, or alarm; expand her support and decrease her isolation by helping her to communicate with her family; and identify treatment resources for her. Start by being curious about some of her specific worries or feelings, her energy level, feelings of isolation or trouble with sleep. Offer compassion and validation around the pain of these experiences in the midst of so much transition. Only after hearing a little detail about her experience, then you may offer that such feelings are common, but when they are persistent or severe, they often indicate PPD, and that her screening test suggests they do for her. Offer that this form of depression is very treatable, with both pharmacologic and psychotherapy interventions. And if she is resistant, gently offer that treatment will be very protective of her new infant’s physical, social, and cognitive growth and development. Hearing this from a pediatrician is powerful for a new mother, even if depressed. Finally, ask if you might help her bring other important adults in her family into an understanding of this. Could she tell her spouse? Her sister? Her best friend? Perhaps she could bring one of them to the next weekly visit, so you can all speak together. This intervention greatly improves the likelihood of her engaging in treatment, and strong interpersonal connections are therapeutic in and of themselves.

For treatment, the easier your office can make it, the more likely she is to follow up. Identify local resources, perhaps through connected community organizations such as Jewish Family and Children’s Services or through a public program like California’s First Five. Connect with the local obstetric practice, which may already have a referral process in place. If you can connect with her primary care provider, they may take on the referral process or may even have integrated capacity for treatment. Identify strategies that may support her restful sleep, including realistic daily exercise, sharing infant care, and being cautious with caffeine and screen time. Identify ways for her to meet other new mothers or reconnect with friends. Reassure her that easy attachment activities, such as reading a book or singing to her baby can be good for both of them without requiring much energy. This may sound like a daunting task, but the conversation will only take a few minutes. Helping an isolated new parent recognize that their feelings of fear, inadequacy, and guilt are not facts, offering some simple immediate strategies and facilitating a referral can be lifesaving.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected]

References

1. Dietz PM et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1515-20.

2. Hanusa BH et al. J Women’s Health (Larchmt) 2008;17(4):585-96.

3. Lindahl V et al. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8(2):77-87.

4. Hay DF et al. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42(7):871-89.

5. Tully EC et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2008:165(9):1148-54.

6. Maternal depression and child development. Paediatr. Child Health 2004;9(8):575-98.

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a common and treatable problem affecting over 10% of all pregnant women. Without routine use of a screening questionnaire, many women go undiagnosed and without treatment. The risks of untreated PPD in a new mother are the risks of depression tripled: to her health and to the health of her new infant and their whole family. Although pediatricians treat children, they take care of the whole family. They appreciate their role in offering support and guidance to new parents, and in the case of PPD, they are in a unique position. The American Academy of Pediatrics recognized this when they issued their policy statement, “Incorporating Recognition and Management of Perinatal Depression into Pediatric Practice,” in January 2019. By screening, tracking, and connecting affected mothers to care and services, you can truly provide “two-generational care” for your youngest patients.

PPD affects an estimated one in seven women (13%) globally. In one large retrospective study that looked at the 39 weeks before and after delivery, 15.4% of mothers received a diagnosis of PPD and a second study indicated that 22% of new mothers had depressive symptoms that were persistent for 6 months.1 The pathways to PPD include prior personal or family history of depression, stressors in the family (connected to social determinants of health), previous miscarriage or serious complications in a previous pregnancy, and sensitivity to hormonal changes. Indeed, PPD is the most common complication of childbirth.2 Although as many as half of all women eventually diagnosed with PPD had symptoms during their pregnancy, the misperception that PPD is only post partum leads to it being mistaken for the normal process of adjustment to parenthood. PPD is particularly insidious as new mothers are likely to be silent if they feel shame for not enjoying what they have been told will be a special and happy time, and those around them may mistake symptoms for the normal “baby blues” that will resolve quickly and with routine supports.

Untreated PPD, creates risks for mother, infant, and family as she manages needless suffering during a critical period for her new baby. While depression may remit over months without treatment, suicide is a real risk, and accounts for 20% of postpartum deaths.3 Infants face serious developmental consequences when their mothers are withdrawn and disconnected from them during the first months of life, including impaired social development, physical growth, and cognitive development. This impairment persists. Exposure to maternal depression during infancy is associated with lower IQ, attentional problems, and special educational needs by elementary school,4 and is a risk factor for psychiatric illnesses in childhood and adolescence.5,6 PPD has a broad range of severity, including psychosis that may include paranoia with the rare risk of infanticide. And maternal depression can add to the strains in a vulnerable caregiver relationship that can raise the risk for neglect or abuse of the mother, children, or both.

It is important to note that anxiety is often the presenting problem in perinatal mood disorders, with mothers experiencing intense morbid worries about their infant’s safety and health, and fear of inadequacy, criticism, and even infant removal. These fears may reinforce silence and isolation. But pediatricians are one group that these mothers are most likely to share their anxieties with as they look for reassurance. It can be challenging to distinguish PPD from obsessive-compulsive disorder or PTSD. The critical work of the pediatrician is not specific diagnosis and treatment. Instead, your task is to provide screening and support, to create a safe place to overcome silence and shame.

There are many reliable and valid screening instruments available for depression, but the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EDPS) has been specially developed for and tested in this population. It is a 10-item scale that is easy to complete and to score. Scores range from 0 to 30 and a score of 10 is considered a cutoff for depression. It can be used to track symptoms and is free and widely available online and in multiple languages. Ideally, this scale can be administered as part of a previsit, automatically entered into an electronic medical record and given at regular intervals during the infant’s first year of primary care. Some new mothers, especially if they are suffering from depression, may feel anxious about filling this out. It is important that your staff tell them that you screen all new mothers in your practice, and that PPD is common and treatable and the pediatrician’s office is committed to the health of the whole family.

If a new mother screens positive, you might consider yourself to have three tasks: Reassure her that she is a wonderful mother and this is a treatable illness, not a cause for guilt, shame, or alarm; expand her support and decrease her isolation by helping her to communicate with her family; and identify treatment resources for her. Start by being curious about some of her specific worries or feelings, her energy level, feelings of isolation or trouble with sleep. Offer compassion and validation around the pain of these experiences in the midst of so much transition. Only after hearing a little detail about her experience, then you may offer that such feelings are common, but when they are persistent or severe, they often indicate PPD, and that her screening test suggests they do for her. Offer that this form of depression is very treatable, with both pharmacologic and psychotherapy interventions. And if she is resistant, gently offer that treatment will be very protective of her new infant’s physical, social, and cognitive growth and development. Hearing this from a pediatrician is powerful for a new mother, even if depressed. Finally, ask if you might help her bring other important adults in her family into an understanding of this. Could she tell her spouse? Her sister? Her best friend? Perhaps she could bring one of them to the next weekly visit, so you can all speak together. This intervention greatly improves the likelihood of her engaging in treatment, and strong interpersonal connections are therapeutic in and of themselves.

For treatment, the easier your office can make it, the more likely she is to follow up. Identify local resources, perhaps through connected community organizations such as Jewish Family and Children’s Services or through a public program like California’s First Five. Connect with the local obstetric practice, which may already have a referral process in place. If you can connect with her primary care provider, they may take on the referral process or may even have integrated capacity for treatment. Identify strategies that may support her restful sleep, including realistic daily exercise, sharing infant care, and being cautious with caffeine and screen time. Identify ways for her to meet other new mothers or reconnect with friends. Reassure her that easy attachment activities, such as reading a book or singing to her baby can be good for both of them without requiring much energy. This may sound like a daunting task, but the conversation will only take a few minutes. Helping an isolated new parent recognize that their feelings of fear, inadequacy, and guilt are not facts, offering some simple immediate strategies and facilitating a referral can be lifesaving.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected]

References

1. Dietz PM et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1515-20.

2. Hanusa BH et al. J Women’s Health (Larchmt) 2008;17(4):585-96.

3. Lindahl V et al. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8(2):77-87.

4. Hay DF et al. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42(7):871-89.

5. Tully EC et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2008:165(9):1148-54.

6. Maternal depression and child development. Paediatr. Child Health 2004;9(8):575-98.

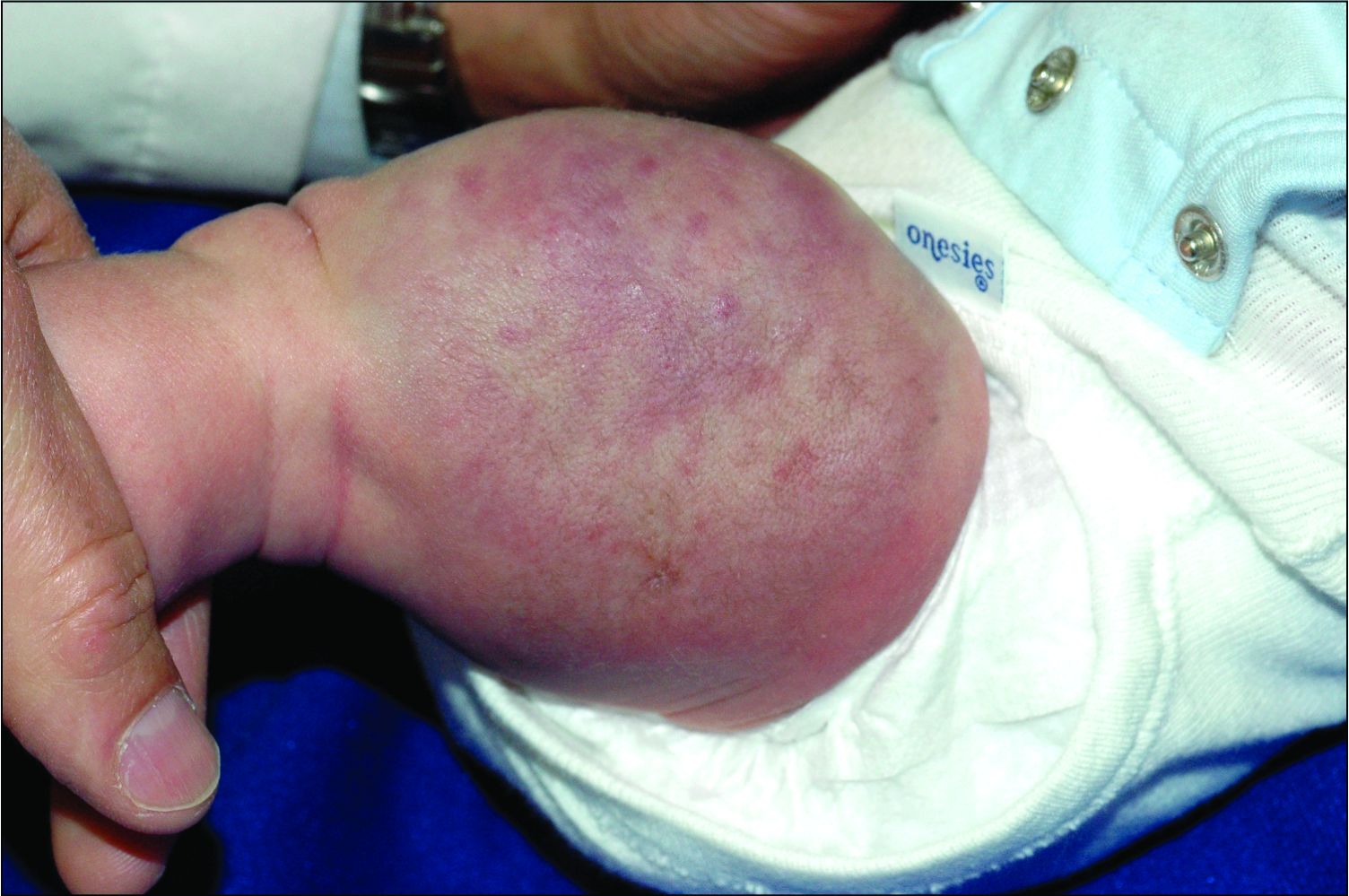

Ear tubes no better than antibiotics for otitis media in young kids

The debate over tympanostomy tubes versus antibiotics for recurrent acute otitis media (AOM) in young children is long-standing. Now, results of a randomized controlled trial show that tubes do not significantly lower the rate of episodes, compared with antibiotics, and medical management doesn’t increase antibiotic resistance.

“We found no evidence of microbial resistance from treating with antibiotics. If there’s not an impact on resistance, why take unnecessary chances on complications of surgery?” lead author Alejandro Hoberman, MD, from Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, said in an interview.

The study by Dr. Hoberman and colleagues was published May 13 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

AOM is the most frequent condition diagnosed in children in the United States after the common cold, affecting five of six children younger than 3 years. It is the leading indication for antimicrobial treatment, and tympanostomy tube insertion is the most frequently performed pediatric operation after the newborn period.

Randomized controlled clinical trials were conducted in the 1980s, but by the 1990s, questions of overuse arose. The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation published the first clinical practice guidelines in 2013.

Parents must weigh the pros and cons. The use of tubes may avoid or delay the next round of drugs, but tubes cost more and introduce small risks (anesthesia, refractory otorrhea, tube blockage, premature dislocation or extrusion, and mild conductive hearing loss).

“We addressed issues that plagued older studies – a longer-term follow-up of 2 years, validated diagnoses of infection to determine eligibility – and used rating scales to measure quality of life,” Dr. Hoberman said.

The researchers randomly assigned children to receive antibiotics or tubes. To be eligible, children had to be 6-35 months of age and have had at least three episodes of AOM within 6 months or at least four episodes within 12 months, including at least one within the preceding 6 months.

The primary outcome was the mean number of episodes of AOM per child-year. Children were assessed at 8-week intervals and within 48 hours of developing symptoms of ear infection. The medically treated children received oral amoxicillin or, if that was ineffective, intramuscular ceftriaxone.

Criteria for determining treatment failure included persistent otorrhea, tympanic membrane perforation, antibiotic-associated diarrhea, reaction to anesthesia, and recurrence of AOM at a frequency equal to the frequency before antibiotic treatment.

In comparing tympanostomy tubes with antibiotics, Dr. Hoberman said, “We were unable to show benefit in the rate of ear infections per child per year over a 2-year period.” As expected, the infection rate fell by about half from the first year to the second in all children.

Overall, the investigators found “no substantial differences between treatment groups” with regard to AOM frequency, percentage of severe episodes, extent of antimicrobial resistance, quality of life for the children, and parental stress.

In an intention-to-treat analysis, the rate of AOM episodes per child-year during the study was 1.48 ± 0.08 for tubes and 1.56 ± 0.08 for antibiotics (P = .66).

However, randomization was not maintained in the intention-to-treat arm. Ten percent (13 of 129) of the children slated to receive tubes didn’t get them because of parental request. Conversely, 16% (54 of 121) of children in the antibiotic group received tubes, 35 (29%) of them in accordance with the trial protocol because of frequent recurrences, and 19 (16%) at parental request.

In a per-protocol analysis, rates of AOM episodes per child-year were 1.47 ± 0.08 for tubes and 1.72 ± 0.11 for antibiotics.

Tubes were associated with longer time until the first ear infection post placement, at a median of 4.34 months, compared with 2.33 months for children who received antibiotics. A smaller percentage of children in the tube group had treatment failure than in the antibiotic group (45% vs. 62%). Children who received tubes also had fewer days per year with symptoms in comparison with the children in the antibiotic group (mean, 2.00 ± 0.29 days vs. 8.33 ± 0.59 days).

The frequency distribution of AOM episodes, the percentage of severe episodes, and antimicrobial resistance detected in respiratory specimens were the same for both groups.

“Hoberman and colleagues add to our knowledge of managing children with recurrent ear infections with a large and rigorous clinical trial showing comparable efficacy of tympanostomy tube insertion, with antibiotic eardrops for new infections versus watchful waiting, with intermittent oral antibiotics, if further ear infections occur,” said Richard M. Rosenfeld, MD, MPH, MBA, distinguished professor and chairman, department of otolaryngology, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, New York.

However, in an accompanying editorial, Ellen R. Wald, MD, from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, pointed out that the sample size was smaller than desired, owing to participants switching groups.

In addition, Dr. Rosenfeld, who was the lead author of the 2013 guidelines, said the study likely underestimates the impact of tubes “because about two-thirds of the children who received them did not have persistent middle-ear fluid at baseline and would not have been candidates for tubes based on the current national guideline on tube indications.”

“Both tubes and intermittent antibiotic therapy are effective for managing recurrent AOM, and parents of children with persistent middle-ear effusion should engage in shared decision-making with their physician to decide on the best management option,” said Dr. Rosenfeld. “When in doubt, watchful waiting is appropriate because many children with recurrent AOM do better over time.”

Dr. Hoberman owns stock in Kaizen Bioscience and holds patents on devices to diagnose and treat AOM. One coauthor consults for Merck. Dr. Wald and Dr. Rosenfeld report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The debate over tympanostomy tubes versus antibiotics for recurrent acute otitis media (AOM) in young children is long-standing. Now, results of a randomized controlled trial show that tubes do not significantly lower the rate of episodes, compared with antibiotics, and medical management doesn’t increase antibiotic resistance.

“We found no evidence of microbial resistance from treating with antibiotics. If there’s not an impact on resistance, why take unnecessary chances on complications of surgery?” lead author Alejandro Hoberman, MD, from Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, said in an interview.

The study by Dr. Hoberman and colleagues was published May 13 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

AOM is the most frequent condition diagnosed in children in the United States after the common cold, affecting five of six children younger than 3 years. It is the leading indication for antimicrobial treatment, and tympanostomy tube insertion is the most frequently performed pediatric operation after the newborn period.

Randomized controlled clinical trials were conducted in the 1980s, but by the 1990s, questions of overuse arose. The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation published the first clinical practice guidelines in 2013.

Parents must weigh the pros and cons. The use of tubes may avoid or delay the next round of drugs, but tubes cost more and introduce small risks (anesthesia, refractory otorrhea, tube blockage, premature dislocation or extrusion, and mild conductive hearing loss).

“We addressed issues that plagued older studies – a longer-term follow-up of 2 years, validated diagnoses of infection to determine eligibility – and used rating scales to measure quality of life,” Dr. Hoberman said.

The researchers randomly assigned children to receive antibiotics or tubes. To be eligible, children had to be 6-35 months of age and have had at least three episodes of AOM within 6 months or at least four episodes within 12 months, including at least one within the preceding 6 months.

The primary outcome was the mean number of episodes of AOM per child-year. Children were assessed at 8-week intervals and within 48 hours of developing symptoms of ear infection. The medically treated children received oral amoxicillin or, if that was ineffective, intramuscular ceftriaxone.

Criteria for determining treatment failure included persistent otorrhea, tympanic membrane perforation, antibiotic-associated diarrhea, reaction to anesthesia, and recurrence of AOM at a frequency equal to the frequency before antibiotic treatment.

In comparing tympanostomy tubes with antibiotics, Dr. Hoberman said, “We were unable to show benefit in the rate of ear infections per child per year over a 2-year period.” As expected, the infection rate fell by about half from the first year to the second in all children.

Overall, the investigators found “no substantial differences between treatment groups” with regard to AOM frequency, percentage of severe episodes, extent of antimicrobial resistance, quality of life for the children, and parental stress.

In an intention-to-treat analysis, the rate of AOM episodes per child-year during the study was 1.48 ± 0.08 for tubes and 1.56 ± 0.08 for antibiotics (P = .66).

However, randomization was not maintained in the intention-to-treat arm. Ten percent (13 of 129) of the children slated to receive tubes didn’t get them because of parental request. Conversely, 16% (54 of 121) of children in the antibiotic group received tubes, 35 (29%) of them in accordance with the trial protocol because of frequent recurrences, and 19 (16%) at parental request.

In a per-protocol analysis, rates of AOM episodes per child-year were 1.47 ± 0.08 for tubes and 1.72 ± 0.11 for antibiotics.

Tubes were associated with longer time until the first ear infection post placement, at a median of 4.34 months, compared with 2.33 months for children who received antibiotics. A smaller percentage of children in the tube group had treatment failure than in the antibiotic group (45% vs. 62%). Children who received tubes also had fewer days per year with symptoms in comparison with the children in the antibiotic group (mean, 2.00 ± 0.29 days vs. 8.33 ± 0.59 days).

The frequency distribution of AOM episodes, the percentage of severe episodes, and antimicrobial resistance detected in respiratory specimens were the same for both groups.

“Hoberman and colleagues add to our knowledge of managing children with recurrent ear infections with a large and rigorous clinical trial showing comparable efficacy of tympanostomy tube insertion, with antibiotic eardrops for new infections versus watchful waiting, with intermittent oral antibiotics, if further ear infections occur,” said Richard M. Rosenfeld, MD, MPH, MBA, distinguished professor and chairman, department of otolaryngology, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, New York.

However, in an accompanying editorial, Ellen R. Wald, MD, from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, pointed out that the sample size was smaller than desired, owing to participants switching groups.

In addition, Dr. Rosenfeld, who was the lead author of the 2013 guidelines, said the study likely underestimates the impact of tubes “because about two-thirds of the children who received them did not have persistent middle-ear fluid at baseline and would not have been candidates for tubes based on the current national guideline on tube indications.”

“Both tubes and intermittent antibiotic therapy are effective for managing recurrent AOM, and parents of children with persistent middle-ear effusion should engage in shared decision-making with their physician to decide on the best management option,” said Dr. Rosenfeld. “When in doubt, watchful waiting is appropriate because many children with recurrent AOM do better over time.”

Dr. Hoberman owns stock in Kaizen Bioscience and holds patents on devices to diagnose and treat AOM. One coauthor consults for Merck. Dr. Wald and Dr. Rosenfeld report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The debate over tympanostomy tubes versus antibiotics for recurrent acute otitis media (AOM) in young children is long-standing. Now, results of a randomized controlled trial show that tubes do not significantly lower the rate of episodes, compared with antibiotics, and medical management doesn’t increase antibiotic resistance.

“We found no evidence of microbial resistance from treating with antibiotics. If there’s not an impact on resistance, why take unnecessary chances on complications of surgery?” lead author Alejandro Hoberman, MD, from Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, said in an interview.

The study by Dr. Hoberman and colleagues was published May 13 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

AOM is the most frequent condition diagnosed in children in the United States after the common cold, affecting five of six children younger than 3 years. It is the leading indication for antimicrobial treatment, and tympanostomy tube insertion is the most frequently performed pediatric operation after the newborn period.

Randomized controlled clinical trials were conducted in the 1980s, but by the 1990s, questions of overuse arose. The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation published the first clinical practice guidelines in 2013.

Parents must weigh the pros and cons. The use of tubes may avoid or delay the next round of drugs, but tubes cost more and introduce small risks (anesthesia, refractory otorrhea, tube blockage, premature dislocation or extrusion, and mild conductive hearing loss).

“We addressed issues that plagued older studies – a longer-term follow-up of 2 years, validated diagnoses of infection to determine eligibility – and used rating scales to measure quality of life,” Dr. Hoberman said.

The researchers randomly assigned children to receive antibiotics or tubes. To be eligible, children had to be 6-35 months of age and have had at least three episodes of AOM within 6 months or at least four episodes within 12 months, including at least one within the preceding 6 months.

The primary outcome was the mean number of episodes of AOM per child-year. Children were assessed at 8-week intervals and within 48 hours of developing symptoms of ear infection. The medically treated children received oral amoxicillin or, if that was ineffective, intramuscular ceftriaxone.

Criteria for determining treatment failure included persistent otorrhea, tympanic membrane perforation, antibiotic-associated diarrhea, reaction to anesthesia, and recurrence of AOM at a frequency equal to the frequency before antibiotic treatment.

In comparing tympanostomy tubes with antibiotics, Dr. Hoberman said, “We were unable to show benefit in the rate of ear infections per child per year over a 2-year period.” As expected, the infection rate fell by about half from the first year to the second in all children.

Overall, the investigators found “no substantial differences between treatment groups” with regard to AOM frequency, percentage of severe episodes, extent of antimicrobial resistance, quality of life for the children, and parental stress.

In an intention-to-treat analysis, the rate of AOM episodes per child-year during the study was 1.48 ± 0.08 for tubes and 1.56 ± 0.08 for antibiotics (P = .66).

However, randomization was not maintained in the intention-to-treat arm. Ten percent (13 of 129) of the children slated to receive tubes didn’t get them because of parental request. Conversely, 16% (54 of 121) of children in the antibiotic group received tubes, 35 (29%) of them in accordance with the trial protocol because of frequent recurrences, and 19 (16%) at parental request.

In a per-protocol analysis, rates of AOM episodes per child-year were 1.47 ± 0.08 for tubes and 1.72 ± 0.11 for antibiotics.

Tubes were associated with longer time until the first ear infection post placement, at a median of 4.34 months, compared with 2.33 months for children who received antibiotics. A smaller percentage of children in the tube group had treatment failure than in the antibiotic group (45% vs. 62%). Children who received tubes also had fewer days per year with symptoms in comparison with the children in the antibiotic group (mean, 2.00 ± 0.29 days vs. 8.33 ± 0.59 days).

The frequency distribution of AOM episodes, the percentage of severe episodes, and antimicrobial resistance detected in respiratory specimens were the same for both groups.

“Hoberman and colleagues add to our knowledge of managing children with recurrent ear infections with a large and rigorous clinical trial showing comparable efficacy of tympanostomy tube insertion, with antibiotic eardrops for new infections versus watchful waiting, with intermittent oral antibiotics, if further ear infections occur,” said Richard M. Rosenfeld, MD, MPH, MBA, distinguished professor and chairman, department of otolaryngology, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, New York.

However, in an accompanying editorial, Ellen R. Wald, MD, from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, pointed out that the sample size was smaller than desired, owing to participants switching groups.

In addition, Dr. Rosenfeld, who was the lead author of the 2013 guidelines, said the study likely underestimates the impact of tubes “because about two-thirds of the children who received them did not have persistent middle-ear fluid at baseline and would not have been candidates for tubes based on the current national guideline on tube indications.”

“Both tubes and intermittent antibiotic therapy are effective for managing recurrent AOM, and parents of children with persistent middle-ear effusion should engage in shared decision-making with their physician to decide on the best management option,” said Dr. Rosenfeld. “When in doubt, watchful waiting is appropriate because many children with recurrent AOM do better over time.”

Dr. Hoberman owns stock in Kaizen Bioscience and holds patents on devices to diagnose and treat AOM. One coauthor consults for Merck. Dr. Wald and Dr. Rosenfeld report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Low-risk preterm infants may not need antibiotics

Selective use of antibiotics based on birth circumstances may reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure for preterm infants at risk of early-onset sepsis, based on data from 340 preterm infants at a single center.

Preterm infants born because of preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, and/or intraamniotic infection (IAI) are considered at increased risk for early-onset sepsis, and current management strategies include a blood culture and initiation of empirical antibiotics, said Kirtan Patel, MD, of Texas A&M University, Dallas, and colleagues in a poster (# 1720) presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

However, this blanket approach “may increase the unnecessary early antibiotic exposure in preterm infants possibly leading to future adverse health outcomes,” and physicians are advised to review the risks and benefits, Dr. Patel said.

Data from previous studies suggest that preterm infants born as a result of preterm labor and/or premature rupture of membranes with adequate Group B Streptococcus (GBS) intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis and no indication of IAI may be managed without empiric antibiotics because the early-onset sepsis risk in these infants is much lower than the ones born through IAI and inadequate GBS intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis.

To better identify preterm birth circumstances in which antibiotics might be avoided, the researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of preterm infants born at 28-34 weeks’ gestation during the period from Jan. 1, 2015, to Dec. 31, 2018. These infants were in the low-risk category of preterm birth because of preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes, with no IAI and adequate GBS intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, and no signs of cardiovascular or respiratory instability after birth. Of these, 157 (46.2%) received empiric antibiotics soon after birth and 183 infants (53.8%) did not receive empiric antibiotics.

The mean gestational age and birth weight were significantly lower in the empiric antibiotic group, but after correcting for these variables, the factors with the greatest influence on the initiation of antibiotics were maternal intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (odds ratio, 3.13); premature rupture of membranes (OR, 3.75); use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in the delivery room (OR, 1.84); CPAP on admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (OR, 1.94); drawing a blood culture (OR, 13.72); and a complete blood count with immature to total neutrophil ratio greater than 0.2 (OR, 3.84).

Three infants (2%) in the antibiotics group had culture-positive early-onset sepsis with Escherichia coli, compared with no infants in the no-antibiotics group. No differences in short-term hospital outcomes appeared between the two groups. The study was limited in part by the retrospective design and sample size, the researchers noted.

However, the results support a selective approach to antibiotics for preterm infants, taking various birth circumstances into account, they said.

Further risk factor identification could curb antibiotic use

In this study, empiric antibiotics were cast as a wide net to avoid missing serious infections in a few patients, said Tim Joos, MD, a Seattle-based clinician with a combination internal medicine/pediatrics practice, in an interview.

“It is interesting in this retrospective review of 340 preterm infants that the three newborns that did have serious bacterial infection were correctly given empiric antibiotics from the start,” Dr. Joos noted. “The authors were very effective at elucidating the possible factors that go into starting or not starting empiric antibiotics, although there may be other factors in the clinician’s judgment that are being missed. … More studies are needed on this topic,” Dr. Joos said. “Further research examining how the septic newborns differ from the nonseptic ones could help to even further narrow the use of empiric antibiotics,” he added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Joos had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves as a member of the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

Selective use of antibiotics based on birth circumstances may reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure for preterm infants at risk of early-onset sepsis, based on data from 340 preterm infants at a single center.

Preterm infants born because of preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, and/or intraamniotic infection (IAI) are considered at increased risk for early-onset sepsis, and current management strategies include a blood culture and initiation of empirical antibiotics, said Kirtan Patel, MD, of Texas A&M University, Dallas, and colleagues in a poster (# 1720) presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

However, this blanket approach “may increase the unnecessary early antibiotic exposure in preterm infants possibly leading to future adverse health outcomes,” and physicians are advised to review the risks and benefits, Dr. Patel said.

Data from previous studies suggest that preterm infants born as a result of preterm labor and/or premature rupture of membranes with adequate Group B Streptococcus (GBS) intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis and no indication of IAI may be managed without empiric antibiotics because the early-onset sepsis risk in these infants is much lower than the ones born through IAI and inadequate GBS intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis.

To better identify preterm birth circumstances in which antibiotics might be avoided, the researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of preterm infants born at 28-34 weeks’ gestation during the period from Jan. 1, 2015, to Dec. 31, 2018. These infants were in the low-risk category of preterm birth because of preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes, with no IAI and adequate GBS intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, and no signs of cardiovascular or respiratory instability after birth. Of these, 157 (46.2%) received empiric antibiotics soon after birth and 183 infants (53.8%) did not receive empiric antibiotics.

The mean gestational age and birth weight were significantly lower in the empiric antibiotic group, but after correcting for these variables, the factors with the greatest influence on the initiation of antibiotics were maternal intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (odds ratio, 3.13); premature rupture of membranes (OR, 3.75); use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in the delivery room (OR, 1.84); CPAP on admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (OR, 1.94); drawing a blood culture (OR, 13.72); and a complete blood count with immature to total neutrophil ratio greater than 0.2 (OR, 3.84).

Three infants (2%) in the antibiotics group had culture-positive early-onset sepsis with Escherichia coli, compared with no infants in the no-antibiotics group. No differences in short-term hospital outcomes appeared between the two groups. The study was limited in part by the retrospective design and sample size, the researchers noted.

However, the results support a selective approach to antibiotics for preterm infants, taking various birth circumstances into account, they said.

Further risk factor identification could curb antibiotic use

In this study, empiric antibiotics were cast as a wide net to avoid missing serious infections in a few patients, said Tim Joos, MD, a Seattle-based clinician with a combination internal medicine/pediatrics practice, in an interview.

“It is interesting in this retrospective review of 340 preterm infants that the three newborns that did have serious bacterial infection were correctly given empiric antibiotics from the start,” Dr. Joos noted. “The authors were very effective at elucidating the possible factors that go into starting or not starting empiric antibiotics, although there may be other factors in the clinician’s judgment that are being missed. … More studies are needed on this topic,” Dr. Joos said. “Further research examining how the septic newborns differ from the nonseptic ones could help to even further narrow the use of empiric antibiotics,” he added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Joos had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves as a member of the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

Selective use of antibiotics based on birth circumstances may reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure for preterm infants at risk of early-onset sepsis, based on data from 340 preterm infants at a single center.

Preterm infants born because of preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, and/or intraamniotic infection (IAI) are considered at increased risk for early-onset sepsis, and current management strategies include a blood culture and initiation of empirical antibiotics, said Kirtan Patel, MD, of Texas A&M University, Dallas, and colleagues in a poster (# 1720) presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

However, this blanket approach “may increase the unnecessary early antibiotic exposure in preterm infants possibly leading to future adverse health outcomes,” and physicians are advised to review the risks and benefits, Dr. Patel said.

Data from previous studies suggest that preterm infants born as a result of preterm labor and/or premature rupture of membranes with adequate Group B Streptococcus (GBS) intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis and no indication of IAI may be managed without empiric antibiotics because the early-onset sepsis risk in these infants is much lower than the ones born through IAI and inadequate GBS intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis.

To better identify preterm birth circumstances in which antibiotics might be avoided, the researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of preterm infants born at 28-34 weeks’ gestation during the period from Jan. 1, 2015, to Dec. 31, 2018. These infants were in the low-risk category of preterm birth because of preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes, with no IAI and adequate GBS intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, and no signs of cardiovascular or respiratory instability after birth. Of these, 157 (46.2%) received empiric antibiotics soon after birth and 183 infants (53.8%) did not receive empiric antibiotics.

The mean gestational age and birth weight were significantly lower in the empiric antibiotic group, but after correcting for these variables, the factors with the greatest influence on the initiation of antibiotics were maternal intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (odds ratio, 3.13); premature rupture of membranes (OR, 3.75); use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in the delivery room (OR, 1.84); CPAP on admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (OR, 1.94); drawing a blood culture (OR, 13.72); and a complete blood count with immature to total neutrophil ratio greater than 0.2 (OR, 3.84).

Three infants (2%) in the antibiotics group had culture-positive early-onset sepsis with Escherichia coli, compared with no infants in the no-antibiotics group. No differences in short-term hospital outcomes appeared between the two groups. The study was limited in part by the retrospective design and sample size, the researchers noted.

However, the results support a selective approach to antibiotics for preterm infants, taking various birth circumstances into account, they said.

Further risk factor identification could curb antibiotic use

In this study, empiric antibiotics were cast as a wide net to avoid missing serious infections in a few patients, said Tim Joos, MD, a Seattle-based clinician with a combination internal medicine/pediatrics practice, in an interview.

“It is interesting in this retrospective review of 340 preterm infants that the three newborns that did have serious bacterial infection were correctly given empiric antibiotics from the start,” Dr. Joos noted. “The authors were very effective at elucidating the possible factors that go into starting or not starting empiric antibiotics, although there may be other factors in the clinician’s judgment that are being missed. … More studies are needed on this topic,” Dr. Joos said. “Further research examining how the septic newborns differ from the nonseptic ones could help to even further narrow the use of empiric antibiotics,” he added.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Joos had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves as a member of the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

FROM PAS 2021

COVID-19 in children and adolescents: Disease burden and severity

My first thought on this column was maybe Pediatric News has written sufficiently about SARS-CoV-2 infection, and it is time to move on. However, the agenda for the May 12th Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice includes a review of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine safety and immunogenicity data for the 12- to 15-year-old age cohort that suggests the potential for vaccine availability and roll out for early adolescents in the near future and the need for up-to-date knowledge about the incidence, severity, and long-term outcome of COVID-19 in the pediatric population.

Updating and summarizing the pediatric experience for the pediatric community on what children and adolescents have experienced because of SARS-CoV-2 infection is critical to address the myriad of questions that will come from colleagues, parents, and adolescents themselves. A great resource, published weekly, is the joint report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.1 As of April 29, 2021, 3,782,724 total child COVID-19 cases have been reported from 49 states, New York City (NYC), the District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico. Children represent approximately 14% of cases in the United States and not surprisingly are an increasing proportion of total cases as vaccine impact reduces cases among older age groups. Nearly 5% of the pediatric population has already been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Fortunately, compared with adults, hospitalization, severe disease, and mortality remain far lower both in number and proportion than in the adult population. Cumulative hospitalizations from 24 states and NYC total 15,456 (0.8%) among those infected, with 303 deaths reported (from 43 states, NYC, Guam, and Puerto Rico). Case fatality rate approximates 0.01% in the most recent summary of state reports. One of the limitations of this report is that each state decides how to report the age distribution of COVID-19 cases resulting in variation in age range; another is the data are limited to those details individual states chose to make publicly available.

Although children do not commonly develop severe disease, and the case fatality is low, there are still insights to be learned from understanding risk features for severe disease. Preston et al. reviewed discharge data from 869 medical facilities to describe patients 18 years or younger who had an inpatient or emergency department encounter with a primary or secondary COVID-19 discharge diagnosis from March 1 through October 31, 2020.2 They reported that approximately 2,430 (11.7%) children were hospitalized and 746, nearly 31% of those hospitalized, had severe COVID disease. Those at greatest risk for severe disease were children with comorbid conditions and those less than 12 years, compared with the 12- to 18-year age group. They did not identify race as a risk for severe disease in this study. Moreira et al. described risk factors for morbidity and death from COVID in children less than 18 years of age3 using CDC COVID-NET, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19–associated hospitalization surveillance network. They reported a hospitalization rate of 4.7% among 27,045 cases. They identified three risk factors for hospitalization – age, race/ethnicity, and comorbid conditions. Thirty-nine children (0.19%) died; children who were black, non-Hispanic, and those with an underlying medical condition had a significantly increased risk of death. Thirty-three (85%) children who died had a comorbidity, and 27 (69%) were African American or Hispanic/Latino. The U.S. experience in children is also consistent with reports from the United Kingdom, Italy, Spain, Germany, France, and South Korea.4 Deaths from COVID-19 were uncommon but relatively more frequent in older children, compared with younger age groups among children less than 18 years of age in these countries.