User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Pediatrics group stresses benefits of vitamin K shots for infants

After the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) began recommending vitamin K shots for newborns in 1961, infant bleeding as a result of vitamin K deficiency plummeted. The life-threatening disorder is so rare that some parents now question the need for injections to safeguard against it.

The situation amounts to “a failure of our success,” Ivan Hand, MD, a coauthor of a new AAP statement on vitamin K, told this news organization. Much like diseases that can be prevented with vaccines, vitamin K deficiency bleeding isn’t top of mind for parents. “It’s not something they’re aware of or afraid of,” he said.

In 2019, however, the AAP listed public education about the importance of the shots in its 10 most important priorities.

The policy update urges clinicians to bone up on the benefits and perceived risks of vitamin K deficiency, which is essential for clotting, and to “strongly advocate” for the shot in discussions with parents who may get competing messages from their social circles, the internet, and other health care professionals.

Dr. Hand, director of neonatology at NYC Health + Hospitals Kings County, Brooklyn, said clinicians walk a line between educating and alienating parents who favor natural birth processes. “We’re hoping that by talking to the families and answering their questions and explaining the risks, parents will accept vitamin K as a necessary treatment for their babies,” he said.

Vitamin K does not easily pass through the placenta and is not plentiful in breast milk, the preferred nutrition source for newborns. It takes months for babies to build their stores through food and gut bacteria.

Infants who do not receive vitamin K at birth are 81 times more likely to develop late-onset vitamin K deficiency bleeding, which occurs a week to 6 months after birth, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One in five babies with the disorder dies, and about half have bleeding in the skull that can lead to brain damage.

New dosing for premature infants

The AAP’s new statement, published in the journal Pediatrics, reaffirms the administration of a 1-mg intramuscular dose for infants weighing more than 1,500 grams, or about 3 lb 5 oz, within 6 hours of birth. For premature infants who weigh less, the guidance recommends an intramuscular dose of 0.3 to 0.5 mg/kg.

The group notes that oral preparations of vitamin K have proven less effective because of malabsorption and challenges with adhering to dosing regimens.

The document also warns that breastfed babies can experience vitamin K deficiency bleeding even if they have received the shot, because concentration of vitamin K often wanes before a baby starts eating solid food. The disorder “should be considered when evaluating bleeding in the first 6 months of life, even in infants who received prophylaxis, and especially in exclusively breastfed infants,” it states.

Accounts of parental refusals date back to 2013, when the CDC reported four cases of deficiency bleeding in Tennessee. The infants’ parents said they declined vitamin K because they worried about increased risk of leukemia, thought the injection was unnecessary, or wanted to minimize the baby’s exposure to “toxins.” Leukemia concern stemmed from a 1992 report linking vitamin K to childhood cancer, an association that did not hold up in subsequent studies.

More recent research has documented parental concerns about preservatives and injection pain as well as distrust of medical and public health authorities. Some parents have been accused of neglect for refusing to allow their babies to receive the shots.

Phoebe Danziger, MD, a pediatrician and writer in rural Michigan who has studied parental refusal of standard-of-care interventions, called the document a “welcome update” to the AAP’s last statement on the topic, in 2003. She told this news organization that lower dosing for premature infants may reassure some vitamin K–hesitant parents who worry about one-size-fits-all dosing.

But Dr. Danziger added that “evidence is lacking to support the claim that pediatricians can really move the needle on parental hesitancy and refusal simply through better listening and more persuasive counseling.” She said the AAP should do more to address “the broader social climate of mistrust and misinformation” that fuels refusal.

Dr. Hand and Dr. Danziger have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) began recommending vitamin K shots for newborns in 1961, infant bleeding as a result of vitamin K deficiency plummeted. The life-threatening disorder is so rare that some parents now question the need for injections to safeguard against it.

The situation amounts to “a failure of our success,” Ivan Hand, MD, a coauthor of a new AAP statement on vitamin K, told this news organization. Much like diseases that can be prevented with vaccines, vitamin K deficiency bleeding isn’t top of mind for parents. “It’s not something they’re aware of or afraid of,” he said.

In 2019, however, the AAP listed public education about the importance of the shots in its 10 most important priorities.

The policy update urges clinicians to bone up on the benefits and perceived risks of vitamin K deficiency, which is essential for clotting, and to “strongly advocate” for the shot in discussions with parents who may get competing messages from their social circles, the internet, and other health care professionals.

Dr. Hand, director of neonatology at NYC Health + Hospitals Kings County, Brooklyn, said clinicians walk a line between educating and alienating parents who favor natural birth processes. “We’re hoping that by talking to the families and answering their questions and explaining the risks, parents will accept vitamin K as a necessary treatment for their babies,” he said.

Vitamin K does not easily pass through the placenta and is not plentiful in breast milk, the preferred nutrition source for newborns. It takes months for babies to build their stores through food and gut bacteria.

Infants who do not receive vitamin K at birth are 81 times more likely to develop late-onset vitamin K deficiency bleeding, which occurs a week to 6 months after birth, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One in five babies with the disorder dies, and about half have bleeding in the skull that can lead to brain damage.

New dosing for premature infants

The AAP’s new statement, published in the journal Pediatrics, reaffirms the administration of a 1-mg intramuscular dose for infants weighing more than 1,500 grams, or about 3 lb 5 oz, within 6 hours of birth. For premature infants who weigh less, the guidance recommends an intramuscular dose of 0.3 to 0.5 mg/kg.

The group notes that oral preparations of vitamin K have proven less effective because of malabsorption and challenges with adhering to dosing regimens.

The document also warns that breastfed babies can experience vitamin K deficiency bleeding even if they have received the shot, because concentration of vitamin K often wanes before a baby starts eating solid food. The disorder “should be considered when evaluating bleeding in the first 6 months of life, even in infants who received prophylaxis, and especially in exclusively breastfed infants,” it states.

Accounts of parental refusals date back to 2013, when the CDC reported four cases of deficiency bleeding in Tennessee. The infants’ parents said they declined vitamin K because they worried about increased risk of leukemia, thought the injection was unnecessary, or wanted to minimize the baby’s exposure to “toxins.” Leukemia concern stemmed from a 1992 report linking vitamin K to childhood cancer, an association that did not hold up in subsequent studies.

More recent research has documented parental concerns about preservatives and injection pain as well as distrust of medical and public health authorities. Some parents have been accused of neglect for refusing to allow their babies to receive the shots.

Phoebe Danziger, MD, a pediatrician and writer in rural Michigan who has studied parental refusal of standard-of-care interventions, called the document a “welcome update” to the AAP’s last statement on the topic, in 2003. She told this news organization that lower dosing for premature infants may reassure some vitamin K–hesitant parents who worry about one-size-fits-all dosing.

But Dr. Danziger added that “evidence is lacking to support the claim that pediatricians can really move the needle on parental hesitancy and refusal simply through better listening and more persuasive counseling.” She said the AAP should do more to address “the broader social climate of mistrust and misinformation” that fuels refusal.

Dr. Hand and Dr. Danziger have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) began recommending vitamin K shots for newborns in 1961, infant bleeding as a result of vitamin K deficiency plummeted. The life-threatening disorder is so rare that some parents now question the need for injections to safeguard against it.

The situation amounts to “a failure of our success,” Ivan Hand, MD, a coauthor of a new AAP statement on vitamin K, told this news organization. Much like diseases that can be prevented with vaccines, vitamin K deficiency bleeding isn’t top of mind for parents. “It’s not something they’re aware of or afraid of,” he said.

In 2019, however, the AAP listed public education about the importance of the shots in its 10 most important priorities.

The policy update urges clinicians to bone up on the benefits and perceived risks of vitamin K deficiency, which is essential for clotting, and to “strongly advocate” for the shot in discussions with parents who may get competing messages from their social circles, the internet, and other health care professionals.

Dr. Hand, director of neonatology at NYC Health + Hospitals Kings County, Brooklyn, said clinicians walk a line between educating and alienating parents who favor natural birth processes. “We’re hoping that by talking to the families and answering their questions and explaining the risks, parents will accept vitamin K as a necessary treatment for their babies,” he said.

Vitamin K does not easily pass through the placenta and is not plentiful in breast milk, the preferred nutrition source for newborns. It takes months for babies to build their stores through food and gut bacteria.

Infants who do not receive vitamin K at birth are 81 times more likely to develop late-onset vitamin K deficiency bleeding, which occurs a week to 6 months after birth, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One in five babies with the disorder dies, and about half have bleeding in the skull that can lead to brain damage.

New dosing for premature infants

The AAP’s new statement, published in the journal Pediatrics, reaffirms the administration of a 1-mg intramuscular dose for infants weighing more than 1,500 grams, or about 3 lb 5 oz, within 6 hours of birth. For premature infants who weigh less, the guidance recommends an intramuscular dose of 0.3 to 0.5 mg/kg.

The group notes that oral preparations of vitamin K have proven less effective because of malabsorption and challenges with adhering to dosing regimens.

The document also warns that breastfed babies can experience vitamin K deficiency bleeding even if they have received the shot, because concentration of vitamin K often wanes before a baby starts eating solid food. The disorder “should be considered when evaluating bleeding in the first 6 months of life, even in infants who received prophylaxis, and especially in exclusively breastfed infants,” it states.

Accounts of parental refusals date back to 2013, when the CDC reported four cases of deficiency bleeding in Tennessee. The infants’ parents said they declined vitamin K because they worried about increased risk of leukemia, thought the injection was unnecessary, or wanted to minimize the baby’s exposure to “toxins.” Leukemia concern stemmed from a 1992 report linking vitamin K to childhood cancer, an association that did not hold up in subsequent studies.

More recent research has documented parental concerns about preservatives and injection pain as well as distrust of medical and public health authorities. Some parents have been accused of neglect for refusing to allow their babies to receive the shots.

Phoebe Danziger, MD, a pediatrician and writer in rural Michigan who has studied parental refusal of standard-of-care interventions, called the document a “welcome update” to the AAP’s last statement on the topic, in 2003. She told this news organization that lower dosing for premature infants may reassure some vitamin K–hesitant parents who worry about one-size-fits-all dosing.

But Dr. Danziger added that “evidence is lacking to support the claim that pediatricians can really move the needle on parental hesitancy and refusal simply through better listening and more persuasive counseling.” She said the AAP should do more to address “the broader social climate of mistrust and misinformation” that fuels refusal.

Dr. Hand and Dr. Danziger have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children and COVID: The Omicron surge has become a retreat

The Omicron decline continued for a fourth consecutive week as new cases of COVID-19 in children fell by 42% from the week before, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That 42% represents a drop from the 299,000 new cases reported for Feb. 4-10 down to 174,000 for the most recent week, Feb. 11-17.

The overall count of COVID-19 cases in children is 12.5 million over the course of the pandemic, and that represents 19% of cases reported among all ages, the AAP and CHA said based on data collected from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Hospital admissions also continued to fall, with the rate for children aged 0-17 at 0.43 per 100,000 population as of Feb. 20, down by almost 66% from the peak of 1.25 per 100,000 reached on Jan. 16, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

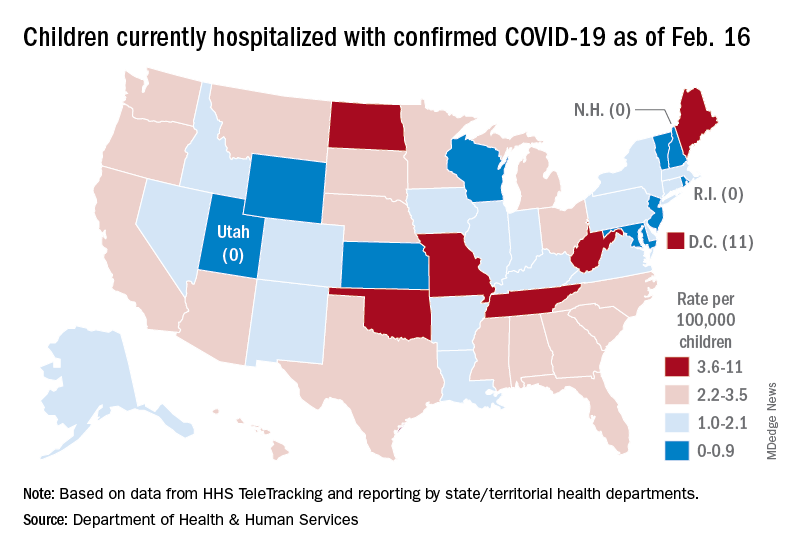

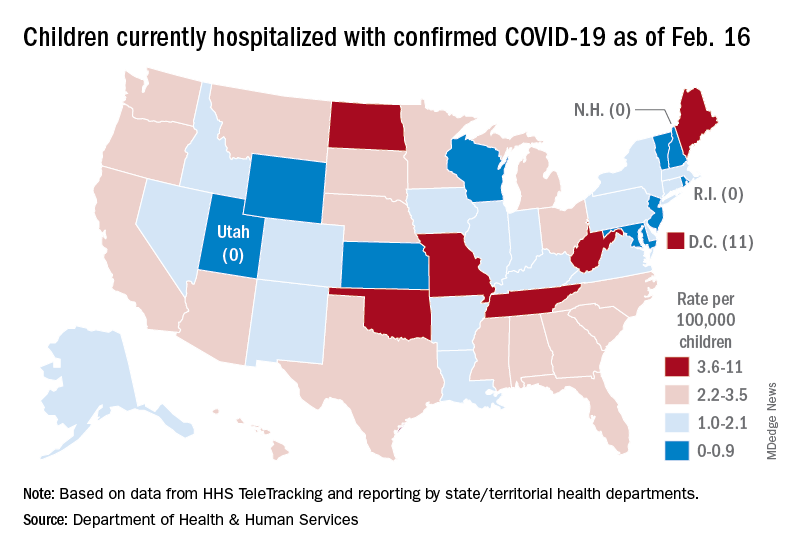

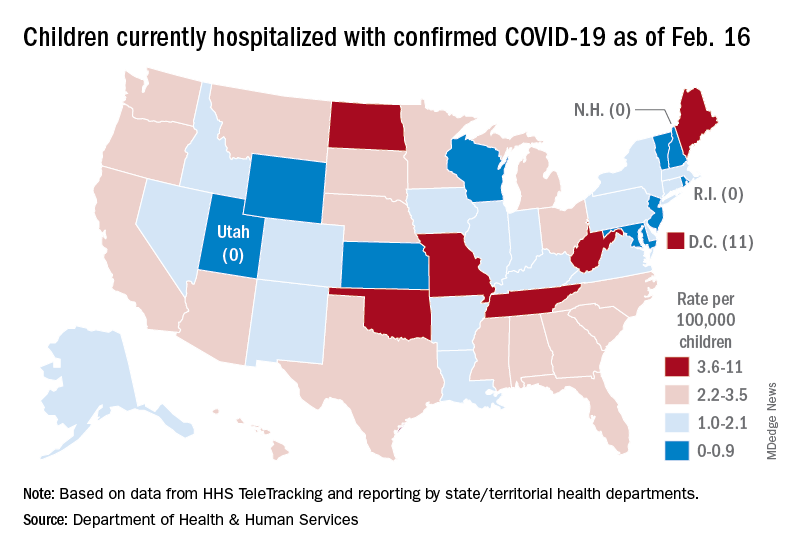

A snapshot of the hospitalization situation shows that 1,687 children were occupying inpatient beds on Feb. 16, compared with 4,070 on Jan. 19, which appears to be the peak of the Omicron surge, according to data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

The state with the highest rate – 5.6 per 100,000 children – on Feb. 16 was North Dakota, although the District of Columbia came in at 11.0 per 100,000. They were followed by Oklahoma (5.3), Missouri (5.2), and West Virginia (4.1). There were three states – New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Utah – with no children in the hospital on that date, the HHS said.

New vaccinations in children aged 5-11 years, which declined in mid- and late January, even as Omicron surged, continued to decline, as did vaccine completions. Vaccinations also fell among children aged 12-17 for the latest reporting week, Feb. 10-16, the AAP said in a separate report.

As more states and school districts drop mask mandates, data from the CDC indicate that 32.5% of 5- to 11-year olds and 67.4% of 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and that 25.1% and 57.3%, respectively, are fully vaccinated. Meanwhile, 20.5% of those fully vaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten a booster dose, the CDC said.

The Omicron decline continued for a fourth consecutive week as new cases of COVID-19 in children fell by 42% from the week before, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That 42% represents a drop from the 299,000 new cases reported for Feb. 4-10 down to 174,000 for the most recent week, Feb. 11-17.

The overall count of COVID-19 cases in children is 12.5 million over the course of the pandemic, and that represents 19% of cases reported among all ages, the AAP and CHA said based on data collected from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Hospital admissions also continued to fall, with the rate for children aged 0-17 at 0.43 per 100,000 population as of Feb. 20, down by almost 66% from the peak of 1.25 per 100,000 reached on Jan. 16, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

A snapshot of the hospitalization situation shows that 1,687 children were occupying inpatient beds on Feb. 16, compared with 4,070 on Jan. 19, which appears to be the peak of the Omicron surge, according to data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

The state with the highest rate – 5.6 per 100,000 children – on Feb. 16 was North Dakota, although the District of Columbia came in at 11.0 per 100,000. They were followed by Oklahoma (5.3), Missouri (5.2), and West Virginia (4.1). There were three states – New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Utah – with no children in the hospital on that date, the HHS said.

New vaccinations in children aged 5-11 years, which declined in mid- and late January, even as Omicron surged, continued to decline, as did vaccine completions. Vaccinations also fell among children aged 12-17 for the latest reporting week, Feb. 10-16, the AAP said in a separate report.

As more states and school districts drop mask mandates, data from the CDC indicate that 32.5% of 5- to 11-year olds and 67.4% of 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and that 25.1% and 57.3%, respectively, are fully vaccinated. Meanwhile, 20.5% of those fully vaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten a booster dose, the CDC said.

The Omicron decline continued for a fourth consecutive week as new cases of COVID-19 in children fell by 42% from the week before, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That 42% represents a drop from the 299,000 new cases reported for Feb. 4-10 down to 174,000 for the most recent week, Feb. 11-17.

The overall count of COVID-19 cases in children is 12.5 million over the course of the pandemic, and that represents 19% of cases reported among all ages, the AAP and CHA said based on data collected from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Hospital admissions also continued to fall, with the rate for children aged 0-17 at 0.43 per 100,000 population as of Feb. 20, down by almost 66% from the peak of 1.25 per 100,000 reached on Jan. 16, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

A snapshot of the hospitalization situation shows that 1,687 children were occupying inpatient beds on Feb. 16, compared with 4,070 on Jan. 19, which appears to be the peak of the Omicron surge, according to data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

The state with the highest rate – 5.6 per 100,000 children – on Feb. 16 was North Dakota, although the District of Columbia came in at 11.0 per 100,000. They were followed by Oklahoma (5.3), Missouri (5.2), and West Virginia (4.1). There were three states – New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Utah – with no children in the hospital on that date, the HHS said.

New vaccinations in children aged 5-11 years, which declined in mid- and late January, even as Omicron surged, continued to decline, as did vaccine completions. Vaccinations also fell among children aged 12-17 for the latest reporting week, Feb. 10-16, the AAP said in a separate report.

As more states and school districts drop mask mandates, data from the CDC indicate that 32.5% of 5- to 11-year olds and 67.4% of 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and that 25.1% and 57.3%, respectively, are fully vaccinated. Meanwhile, 20.5% of those fully vaccinated 12- to 17-year-olds have gotten a booster dose, the CDC said.

New MIS-C guidance addresses diagnostic challenges, cardiac care

Updated guidance for health care providers on multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) recognizes the evolving nature of the disease and offers strategies for pediatric rheumatologists, who also may be asked to recommend treatment for hyperinflammation in children with acute COVID-19.

Guidance is needed for many reasons, including the variable case definitions for MIS-C, the presence of MIS-C features in other infections and childhood rheumatic diseases, the extrapolation of treatment strategies from other conditions with similar presentations, and the issue of myocardial dysfunction, wrote Lauren A. Henderson, MD, MMSC, of Boston Children’s Hospital, and members of the American College of Rheumatology MIS-C and COVID-19–Related Hyperinflammation Task Force.

However, “modifications to treatment plans, particularly in patients with complex conditions, are highly disease, patient, geography, and time specific, and therefore must be individualized as part of a shared decision-making process,” the authors said. The updated guidance was published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Update needed in wake of Omicron

“We continue to see cases of MIS-C across the United States due to the spike in SARS-CoV-2 infections from the Omicron variant,” and therefore updated guidance is important at this time, Dr. Henderson told this news organization.

“MIS-C remains a serious complication of COVID-19 in children and the ACR wanted to continue to provide pediatricians with up-to-date recommendations for the management of MIS-C,” she said.

“Children began to present with MIS-C in April 2020. At that time, little was known about this entity. Most of the recommendations in the first version of the MIS-C guidance were based on expert opinion,” she explained. However, “over the last 2 years, pediatricians have worked very hard to conduct high-quality research studies to better understand MIS-C, so we now have more scientific evidence to guide our recommendations.

“In version three of the MIS-C guidance, there are new recommendations on treatment. Previously, it was unclear what medications should be used for first-line treatment in patients with MIS-C. Some children were given intravenous immunoglobulin while others were given IVIg and steroids together. Several new studies show that children with MIS-C who are treated with a combination of IVIg and steroids have better outcomes. Accordingly, the MIS-C guidance now recommends dual therapy with IVIg and steroids in children with MIS-C.”

Diagnostic evaluation

The guidance calls for maintaining a broad differential diagnosis of MIS-C, given that the condition remains rare, and that most children with COVID-19 present with mild symptoms and have excellent outcomes, the authors noted. The range of clinical features associated with MIS-C include fever, mucocutaneous findings, myocardial dysfunction, cardiac conduction abnormalities, shock, gastrointestinal symptoms, and lymphadenopathy.

Some patients also experience neurologic involvement in the form of severe headache, altered mental status, seizures, cranial nerve palsies, meningismus, cerebral edema, and ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Given the nonspecific nature of these symptoms, “it is imperative that a diagnostic evaluation for MIS-C include investigation for other possible causes, as deemed appropriate by the treating provider,” the authors emphasized. Other diagnostic considerations include the prevalence and chronology of COVID-19 in the community, which may change over time.

MIS-C and Kawasaki disease phenotypes

Earlier in the pandemic, when MIS-C first emerged, it was compared with Kawasaki disease (KD). “However, a closer examination of the literature shows that only about one-quarter to half of patients with a reported diagnosis of MIS-C meet the full diagnostic criteria for KD,” the authors wrote. Key features that separate MIS-C from KD include the greater incidence of KD among children in Japan and East Asia versus the higher incidence of MIS-C among non-Hispanic Black children. In addition, children with MIS-C have shown a wider age range, more prominent gastrointestinal and neurologic symptoms, and more frequent cardiac dysfunction, compared with those with KD.

Cardiac management

Close follow-up with cardiology is essential for children with MIS-C, according to the authors. The recommendations call for repeat echocardiograms for all children with MIS-C at a minimum of 7-14 days, then again at 4-6 weeks after the initial presentation. The authors also recommended additional echocardiograms for children with left ventricular dysfunction and cardiac aortic aneurysms.

MIS-C treatment

Current treatment recommendations emphasize that patients under investigation for MIS-C with life-threatening manifestations may need immunomodulatory therapy before a full diagnostic evaluation is complete, the authors said. However, patients without life-threatening manifestations should be evaluated before starting immunomodulatory treatment to avoid potentially harmful therapies for pediatric patients who don’t need them.

When MIS-C is refractory to initial immunomodulatory treatment, a second dose of IVIg is not recommended, but intensification therapy is advised with either high-dose (10-30 mg/kg per day) glucocorticoids, anakinra, or infliximab. However, there is little evidence available for selecting a specific agent for intensification therapy.

The task force also advises giving low-dose aspirin (3-5 mg/kg per day, up to 81 mg once daily) to all MIS-C patients without active bleeding or significant bleeding risk until normalization of the platelet count and confirmed normal coronary arteries at least 4 weeks after diagnosis.

COVID-19 and hyperinflammation

The task force also noted a distinction between MIS-C and severe COVID-19 in children. Although many children with MIS-C are previously healthy, most children who develop severe COVID-19 during an initial infection have complex conditions or comorbidities such as developmental delay or genetic anomaly, or chronic conditions such as congenital heart disease, type 1 diabetes, or asthma, the authors said. They recommend that “hospitalized children with COVID-19 requiring supplemental oxygen or respiratory support should be considered for immunomodulatory therapy in addition to supportive care and antiviral medications.”

The authors acknowledged the limitations and evolving nature of the recommendations, which will continue to change and do not replace clinical judgment for the management of individual patients. In the meantime, the ACR will support the task force in reviewing new evidence and providing revised versions of the current document.

Many questions about MIS-C remain, Dr. Henderson said in an interview. “It can be very hard to diagnose children with MIS-C because many of the symptoms are similar to those seen in other febrile illness of childhood. We need to identify better biomarkers to help us make the diagnosis of MIS-C. In addition, we need studies to provide information about what treatments should be used if children fail to respond to IVIg and steroids. Finally, it appears that vaccination [against SARS-CoV-2] protects against severe forms of MIS-C, and studies are needed to see how vaccination protects children from MIS-C.”

The development of the guidance was supported by the American College of Rheumatology. Dr. Henderson disclosed relationships with companies including Sobi, Pfizer, and Adaptive Biotechnologies (less than $10,000) and research support from the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance and research grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Updated guidance for health care providers on multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) recognizes the evolving nature of the disease and offers strategies for pediatric rheumatologists, who also may be asked to recommend treatment for hyperinflammation in children with acute COVID-19.

Guidance is needed for many reasons, including the variable case definitions for MIS-C, the presence of MIS-C features in other infections and childhood rheumatic diseases, the extrapolation of treatment strategies from other conditions with similar presentations, and the issue of myocardial dysfunction, wrote Lauren A. Henderson, MD, MMSC, of Boston Children’s Hospital, and members of the American College of Rheumatology MIS-C and COVID-19–Related Hyperinflammation Task Force.

However, “modifications to treatment plans, particularly in patients with complex conditions, are highly disease, patient, geography, and time specific, and therefore must be individualized as part of a shared decision-making process,” the authors said. The updated guidance was published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Update needed in wake of Omicron

“We continue to see cases of MIS-C across the United States due to the spike in SARS-CoV-2 infections from the Omicron variant,” and therefore updated guidance is important at this time, Dr. Henderson told this news organization.

“MIS-C remains a serious complication of COVID-19 in children and the ACR wanted to continue to provide pediatricians with up-to-date recommendations for the management of MIS-C,” she said.

“Children began to present with MIS-C in April 2020. At that time, little was known about this entity. Most of the recommendations in the first version of the MIS-C guidance were based on expert opinion,” she explained. However, “over the last 2 years, pediatricians have worked very hard to conduct high-quality research studies to better understand MIS-C, so we now have more scientific evidence to guide our recommendations.

“In version three of the MIS-C guidance, there are new recommendations on treatment. Previously, it was unclear what medications should be used for first-line treatment in patients with MIS-C. Some children were given intravenous immunoglobulin while others were given IVIg and steroids together. Several new studies show that children with MIS-C who are treated with a combination of IVIg and steroids have better outcomes. Accordingly, the MIS-C guidance now recommends dual therapy with IVIg and steroids in children with MIS-C.”

Diagnostic evaluation

The guidance calls for maintaining a broad differential diagnosis of MIS-C, given that the condition remains rare, and that most children with COVID-19 present with mild symptoms and have excellent outcomes, the authors noted. The range of clinical features associated with MIS-C include fever, mucocutaneous findings, myocardial dysfunction, cardiac conduction abnormalities, shock, gastrointestinal symptoms, and lymphadenopathy.

Some patients also experience neurologic involvement in the form of severe headache, altered mental status, seizures, cranial nerve palsies, meningismus, cerebral edema, and ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Given the nonspecific nature of these symptoms, “it is imperative that a diagnostic evaluation for MIS-C include investigation for other possible causes, as deemed appropriate by the treating provider,” the authors emphasized. Other diagnostic considerations include the prevalence and chronology of COVID-19 in the community, which may change over time.

MIS-C and Kawasaki disease phenotypes

Earlier in the pandemic, when MIS-C first emerged, it was compared with Kawasaki disease (KD). “However, a closer examination of the literature shows that only about one-quarter to half of patients with a reported diagnosis of MIS-C meet the full diagnostic criteria for KD,” the authors wrote. Key features that separate MIS-C from KD include the greater incidence of KD among children in Japan and East Asia versus the higher incidence of MIS-C among non-Hispanic Black children. In addition, children with MIS-C have shown a wider age range, more prominent gastrointestinal and neurologic symptoms, and more frequent cardiac dysfunction, compared with those with KD.

Cardiac management

Close follow-up with cardiology is essential for children with MIS-C, according to the authors. The recommendations call for repeat echocardiograms for all children with MIS-C at a minimum of 7-14 days, then again at 4-6 weeks after the initial presentation. The authors also recommended additional echocardiograms for children with left ventricular dysfunction and cardiac aortic aneurysms.

MIS-C treatment

Current treatment recommendations emphasize that patients under investigation for MIS-C with life-threatening manifestations may need immunomodulatory therapy before a full diagnostic evaluation is complete, the authors said. However, patients without life-threatening manifestations should be evaluated before starting immunomodulatory treatment to avoid potentially harmful therapies for pediatric patients who don’t need them.

When MIS-C is refractory to initial immunomodulatory treatment, a second dose of IVIg is not recommended, but intensification therapy is advised with either high-dose (10-30 mg/kg per day) glucocorticoids, anakinra, or infliximab. However, there is little evidence available for selecting a specific agent for intensification therapy.

The task force also advises giving low-dose aspirin (3-5 mg/kg per day, up to 81 mg once daily) to all MIS-C patients without active bleeding or significant bleeding risk until normalization of the platelet count and confirmed normal coronary arteries at least 4 weeks after diagnosis.

COVID-19 and hyperinflammation

The task force also noted a distinction between MIS-C and severe COVID-19 in children. Although many children with MIS-C are previously healthy, most children who develop severe COVID-19 during an initial infection have complex conditions or comorbidities such as developmental delay or genetic anomaly, or chronic conditions such as congenital heart disease, type 1 diabetes, or asthma, the authors said. They recommend that “hospitalized children with COVID-19 requiring supplemental oxygen or respiratory support should be considered for immunomodulatory therapy in addition to supportive care and antiviral medications.”

The authors acknowledged the limitations and evolving nature of the recommendations, which will continue to change and do not replace clinical judgment for the management of individual patients. In the meantime, the ACR will support the task force in reviewing new evidence and providing revised versions of the current document.

Many questions about MIS-C remain, Dr. Henderson said in an interview. “It can be very hard to diagnose children with MIS-C because many of the symptoms are similar to those seen in other febrile illness of childhood. We need to identify better biomarkers to help us make the diagnosis of MIS-C. In addition, we need studies to provide information about what treatments should be used if children fail to respond to IVIg and steroids. Finally, it appears that vaccination [against SARS-CoV-2] protects against severe forms of MIS-C, and studies are needed to see how vaccination protects children from MIS-C.”

The development of the guidance was supported by the American College of Rheumatology. Dr. Henderson disclosed relationships with companies including Sobi, Pfizer, and Adaptive Biotechnologies (less than $10,000) and research support from the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance and research grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Updated guidance for health care providers on multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) recognizes the evolving nature of the disease and offers strategies for pediatric rheumatologists, who also may be asked to recommend treatment for hyperinflammation in children with acute COVID-19.

Guidance is needed for many reasons, including the variable case definitions for MIS-C, the presence of MIS-C features in other infections and childhood rheumatic diseases, the extrapolation of treatment strategies from other conditions with similar presentations, and the issue of myocardial dysfunction, wrote Lauren A. Henderson, MD, MMSC, of Boston Children’s Hospital, and members of the American College of Rheumatology MIS-C and COVID-19–Related Hyperinflammation Task Force.

However, “modifications to treatment plans, particularly in patients with complex conditions, are highly disease, patient, geography, and time specific, and therefore must be individualized as part of a shared decision-making process,” the authors said. The updated guidance was published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Update needed in wake of Omicron

“We continue to see cases of MIS-C across the United States due to the spike in SARS-CoV-2 infections from the Omicron variant,” and therefore updated guidance is important at this time, Dr. Henderson told this news organization.

“MIS-C remains a serious complication of COVID-19 in children and the ACR wanted to continue to provide pediatricians with up-to-date recommendations for the management of MIS-C,” she said.

“Children began to present with MIS-C in April 2020. At that time, little was known about this entity. Most of the recommendations in the first version of the MIS-C guidance were based on expert opinion,” she explained. However, “over the last 2 years, pediatricians have worked very hard to conduct high-quality research studies to better understand MIS-C, so we now have more scientific evidence to guide our recommendations.

“In version three of the MIS-C guidance, there are new recommendations on treatment. Previously, it was unclear what medications should be used for first-line treatment in patients with MIS-C. Some children were given intravenous immunoglobulin while others were given IVIg and steroids together. Several new studies show that children with MIS-C who are treated with a combination of IVIg and steroids have better outcomes. Accordingly, the MIS-C guidance now recommends dual therapy with IVIg and steroids in children with MIS-C.”

Diagnostic evaluation

The guidance calls for maintaining a broad differential diagnosis of MIS-C, given that the condition remains rare, and that most children with COVID-19 present with mild symptoms and have excellent outcomes, the authors noted. The range of clinical features associated with MIS-C include fever, mucocutaneous findings, myocardial dysfunction, cardiac conduction abnormalities, shock, gastrointestinal symptoms, and lymphadenopathy.

Some patients also experience neurologic involvement in the form of severe headache, altered mental status, seizures, cranial nerve palsies, meningismus, cerebral edema, and ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Given the nonspecific nature of these symptoms, “it is imperative that a diagnostic evaluation for MIS-C include investigation for other possible causes, as deemed appropriate by the treating provider,” the authors emphasized. Other diagnostic considerations include the prevalence and chronology of COVID-19 in the community, which may change over time.

MIS-C and Kawasaki disease phenotypes

Earlier in the pandemic, when MIS-C first emerged, it was compared with Kawasaki disease (KD). “However, a closer examination of the literature shows that only about one-quarter to half of patients with a reported diagnosis of MIS-C meet the full diagnostic criteria for KD,” the authors wrote. Key features that separate MIS-C from KD include the greater incidence of KD among children in Japan and East Asia versus the higher incidence of MIS-C among non-Hispanic Black children. In addition, children with MIS-C have shown a wider age range, more prominent gastrointestinal and neurologic symptoms, and more frequent cardiac dysfunction, compared with those with KD.

Cardiac management

Close follow-up with cardiology is essential for children with MIS-C, according to the authors. The recommendations call for repeat echocardiograms for all children with MIS-C at a minimum of 7-14 days, then again at 4-6 weeks after the initial presentation. The authors also recommended additional echocardiograms for children with left ventricular dysfunction and cardiac aortic aneurysms.

MIS-C treatment

Current treatment recommendations emphasize that patients under investigation for MIS-C with life-threatening manifestations may need immunomodulatory therapy before a full diagnostic evaluation is complete, the authors said. However, patients without life-threatening manifestations should be evaluated before starting immunomodulatory treatment to avoid potentially harmful therapies for pediatric patients who don’t need them.

When MIS-C is refractory to initial immunomodulatory treatment, a second dose of IVIg is not recommended, but intensification therapy is advised with either high-dose (10-30 mg/kg per day) glucocorticoids, anakinra, or infliximab. However, there is little evidence available for selecting a specific agent for intensification therapy.

The task force also advises giving low-dose aspirin (3-5 mg/kg per day, up to 81 mg once daily) to all MIS-C patients without active bleeding or significant bleeding risk until normalization of the platelet count and confirmed normal coronary arteries at least 4 weeks after diagnosis.

COVID-19 and hyperinflammation

The task force also noted a distinction between MIS-C and severe COVID-19 in children. Although many children with MIS-C are previously healthy, most children who develop severe COVID-19 during an initial infection have complex conditions or comorbidities such as developmental delay or genetic anomaly, or chronic conditions such as congenital heart disease, type 1 diabetes, or asthma, the authors said. They recommend that “hospitalized children with COVID-19 requiring supplemental oxygen or respiratory support should be considered for immunomodulatory therapy in addition to supportive care and antiviral medications.”

The authors acknowledged the limitations and evolving nature of the recommendations, which will continue to change and do not replace clinical judgment for the management of individual patients. In the meantime, the ACR will support the task force in reviewing new evidence and providing revised versions of the current document.

Many questions about MIS-C remain, Dr. Henderson said in an interview. “It can be very hard to diagnose children with MIS-C because many of the symptoms are similar to those seen in other febrile illness of childhood. We need to identify better biomarkers to help us make the diagnosis of MIS-C. In addition, we need studies to provide information about what treatments should be used if children fail to respond to IVIg and steroids. Finally, it appears that vaccination [against SARS-CoV-2] protects against severe forms of MIS-C, and studies are needed to see how vaccination protects children from MIS-C.”

The development of the guidance was supported by the American College of Rheumatology. Dr. Henderson disclosed relationships with companies including Sobi, Pfizer, and Adaptive Biotechnologies (less than $10,000) and research support from the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance and research grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ARTHRITIS AND RHEUMATOLOGY

Subvariant may be more dangerous than original Omicron strain

, a lab study from Japan says.

“Our multiscale investigations suggest that the risk of BA.2 for global health is potentially higher than that of BA.1,” the researchers said in the study published on the preprint server bioRxiv. The study has not been peer-reviewed.

The researchers infected hamsters with BA.1 and BA.2. The hamsters infected with BA.2 got sicker, with more lung damage and loss of body weight. Results were similar when mice were infected with BA.1 and BA.2.

“Infection experiments using hamsters show that BA.2 is more pathogenic than BA.1,” the study said.

BA.1 and BA.2 both appear to evade immunity created by COVID-19 vaccines, the study said. But a booster shot makes illness after infection 74% less likely, CNN said.

What’s more, therapeutic monoclonal antibodies used to treat people infected with COVID didn’t have much effect on BA.2.

BA.2 was “almost completely resistant” to casirivimab and imdevimab and was 35 times more resistant to sotrovimab, compared to the original B.1.1 virus, the researchers wrote.

“In summary, our data suggest the possibility that BA.2 would be the most concerned variant to global health,” the researchers wrote. “Currently, both BA.2 and BA.1 are recognised together as Omicron and these are almost undistinguishable. Based on our findings, we propose that BA.2 should be recognised as a unique variant of concern, and this SARS-CoV-2 variant should be monitored in depth.”

If the World Health Organization recognized BA.2 as a “unique variant of concern,” it would be given its own Greek letter.

But some scientists noted that findings in the lab don’t always reflect what’s happening in the real world of people.

“I think it’s always hard to translate differences in animal and cell culture models to what’s going on with regards to human disease,” Jeremy Kamil, PhD, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, told Newsweek. “That said, the differences do look real.”

“It might be, from a human’s perspective, a worse virus than BA.1 and might be able to transmit better and cause worse disease,” Daniel Rhoads, MD, section head of microbiology at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, told CNN. He reviewed the Japanese study but was not involved in it.

Another scientist who reviewed the study but was not involved in the research noted that human immune systems are evolving along with the COVID variants.

“One of the caveats that we have to think about, as we get new variants that might seem more dangerous, is the fact that there’s two sides to the story,” Deborah Fuller, PhD, a virologist at the University of Washington School of Medicine, told CNN. “Our immune system is evolving as well. And so that’s pushing back on things.”

Scientists have already established that BA.2 is more transmissible than BA.1. The Omicron subvariant has been detected in 74 countries and 47 U.S. states, according to CNN. About 4% of Americans with COVID were infected with BA.2, the outlet reported, citing the CDC, but it’s now the dominant strain in other nations.

It’s not clear yet if BA.2 causes more severe illness in people. While BA.2 spreads faster than BA.1, there’s no evidence the subvariant makes people any sicker, an official with the World Health Organization said, according to CNBC.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, a lab study from Japan says.

“Our multiscale investigations suggest that the risk of BA.2 for global health is potentially higher than that of BA.1,” the researchers said in the study published on the preprint server bioRxiv. The study has not been peer-reviewed.

The researchers infected hamsters with BA.1 and BA.2. The hamsters infected with BA.2 got sicker, with more lung damage and loss of body weight. Results were similar when mice were infected with BA.1 and BA.2.

“Infection experiments using hamsters show that BA.2 is more pathogenic than BA.1,” the study said.

BA.1 and BA.2 both appear to evade immunity created by COVID-19 vaccines, the study said. But a booster shot makes illness after infection 74% less likely, CNN said.

What’s more, therapeutic monoclonal antibodies used to treat people infected with COVID didn’t have much effect on BA.2.

BA.2 was “almost completely resistant” to casirivimab and imdevimab and was 35 times more resistant to sotrovimab, compared to the original B.1.1 virus, the researchers wrote.

“In summary, our data suggest the possibility that BA.2 would be the most concerned variant to global health,” the researchers wrote. “Currently, both BA.2 and BA.1 are recognised together as Omicron and these are almost undistinguishable. Based on our findings, we propose that BA.2 should be recognised as a unique variant of concern, and this SARS-CoV-2 variant should be monitored in depth.”

If the World Health Organization recognized BA.2 as a “unique variant of concern,” it would be given its own Greek letter.

But some scientists noted that findings in the lab don’t always reflect what’s happening in the real world of people.

“I think it’s always hard to translate differences in animal and cell culture models to what’s going on with regards to human disease,” Jeremy Kamil, PhD, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, told Newsweek. “That said, the differences do look real.”

“It might be, from a human’s perspective, a worse virus than BA.1 and might be able to transmit better and cause worse disease,” Daniel Rhoads, MD, section head of microbiology at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, told CNN. He reviewed the Japanese study but was not involved in it.

Another scientist who reviewed the study but was not involved in the research noted that human immune systems are evolving along with the COVID variants.

“One of the caveats that we have to think about, as we get new variants that might seem more dangerous, is the fact that there’s two sides to the story,” Deborah Fuller, PhD, a virologist at the University of Washington School of Medicine, told CNN. “Our immune system is evolving as well. And so that’s pushing back on things.”

Scientists have already established that BA.2 is more transmissible than BA.1. The Omicron subvariant has been detected in 74 countries and 47 U.S. states, according to CNN. About 4% of Americans with COVID were infected with BA.2, the outlet reported, citing the CDC, but it’s now the dominant strain in other nations.

It’s not clear yet if BA.2 causes more severe illness in people. While BA.2 spreads faster than BA.1, there’s no evidence the subvariant makes people any sicker, an official with the World Health Organization said, according to CNBC.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, a lab study from Japan says.

“Our multiscale investigations suggest that the risk of BA.2 for global health is potentially higher than that of BA.1,” the researchers said in the study published on the preprint server bioRxiv. The study has not been peer-reviewed.

The researchers infected hamsters with BA.1 and BA.2. The hamsters infected with BA.2 got sicker, with more lung damage and loss of body weight. Results were similar when mice were infected with BA.1 and BA.2.

“Infection experiments using hamsters show that BA.2 is more pathogenic than BA.1,” the study said.

BA.1 and BA.2 both appear to evade immunity created by COVID-19 vaccines, the study said. But a booster shot makes illness after infection 74% less likely, CNN said.

What’s more, therapeutic monoclonal antibodies used to treat people infected with COVID didn’t have much effect on BA.2.

BA.2 was “almost completely resistant” to casirivimab and imdevimab and was 35 times more resistant to sotrovimab, compared to the original B.1.1 virus, the researchers wrote.

“In summary, our data suggest the possibility that BA.2 would be the most concerned variant to global health,” the researchers wrote. “Currently, both BA.2 and BA.1 are recognised together as Omicron and these are almost undistinguishable. Based on our findings, we propose that BA.2 should be recognised as a unique variant of concern, and this SARS-CoV-2 variant should be monitored in depth.”

If the World Health Organization recognized BA.2 as a “unique variant of concern,” it would be given its own Greek letter.

But some scientists noted that findings in the lab don’t always reflect what’s happening in the real world of people.

“I think it’s always hard to translate differences in animal and cell culture models to what’s going on with regards to human disease,” Jeremy Kamil, PhD, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, told Newsweek. “That said, the differences do look real.”

“It might be, from a human’s perspective, a worse virus than BA.1 and might be able to transmit better and cause worse disease,” Daniel Rhoads, MD, section head of microbiology at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, told CNN. He reviewed the Japanese study but was not involved in it.

Another scientist who reviewed the study but was not involved in the research noted that human immune systems are evolving along with the COVID variants.

“One of the caveats that we have to think about, as we get new variants that might seem more dangerous, is the fact that there’s two sides to the story,” Deborah Fuller, PhD, a virologist at the University of Washington School of Medicine, told CNN. “Our immune system is evolving as well. And so that’s pushing back on things.”

Scientists have already established that BA.2 is more transmissible than BA.1. The Omicron subvariant has been detected in 74 countries and 47 U.S. states, according to CNN. About 4% of Americans with COVID were infected with BA.2, the outlet reported, citing the CDC, but it’s now the dominant strain in other nations.

It’s not clear yet if BA.2 causes more severe illness in people. While BA.2 spreads faster than BA.1, there’s no evidence the subvariant makes people any sicker, an official with the World Health Organization said, according to CNBC.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Malawi declares polio outbreak after girl, 3, paralyzed

Health authorities in Malawi have declared an outbreak of wild poliovirus type 1 after a case was confirmed in a 3-year-old girl in the capital, Lilongwe. It was the first case in Africa in 5 years, according to the World Health Organization.

Globally, there were only five cases of wild poliovirus in 2021, the WHO states.

“As long as wild polio exists anywhere in the world all countries remain at risk of importation of the virus,” Matshidiso Moeti, MBBS, WHO regional director for Africa, said in the statement.

Girl paralyzed in November

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) said in a statement that the 3-year-old girl experienced paralysis in November, and stool specimens were collected. Sequencing of the virus was conducted in February, 2022, by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases in South Africa, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the case as WPV1.

According to the WHO announcement, laboratory analysis shows that the strain identified in Malawi is linked to one circulating in Sindh Province in Pakistan. Polio remains endemic only in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Kacey C. Ernst, PhD, MPH, professor and infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Arizona’s Zuckerman College of Public Health in Tucson, pointed out that what is not clear from the press release is whether the girl had traveled to Pakistan or was infected in Malawi.

“This is a very significant detail that would indicate whether or not transmission was actively occurring in Malawi. Until that information is released, it is hard to judge the extent of the possible outbreak,” she said in an interview. “The good news is that this case was in fact detected. The surveillance systems are in place and they were able to identify wild-type cases.”

Dr. Ernst said that although there is cause for concern, it is “not a reason to panic. Malawi has very high polio vaccination rates and it is quite possible that this will be a very small defined outbreak that will be well contained.”

She added that the medical community should be alerted that this case has been identified so travelers who have been to affected areas who have any symptoms can be appropriately screened.

The WHO said it is helping Malawi health authorities in the response, including increasing immunizations.

However, a vaccination campaign comes at a time of health system upheaval in Malawi.

“Malawi, like countries all over the world, has seen an interruption in services due to COVID,” Joia S. Mukherjee, MD, MPH, chief medical officer with Partners in Health and associate professor with the division of global health equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and in the department of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “In addition, Malawi is currently dealing with the aftermath of a cyclone – where nearly a million people were displaced. Vaccination campaigns work best if there is solid infrastructure. Both COVID and the impact of climate change have shaken the health system.”

UN health agencies warned last year that millions of children who have not received immunizations during the pandemic, especially in Africa, “are now at risk from life-threatening diseases such as measles, polio, yellow fever, and diphtheria,” Reuters reported.

Africa was certified as wild poliovirus free on Aug. 25, 2020. The CDC had served as the lead partner over 3 decades in helping Africa reach the milestone. Africa will retain that status, the WHO stated, because the strain originated in Pakistan.

Five of six WHO regions have been certified polio free. The Americas received eradication certification in 1994.

There is no cure for polio, which can cause irreversible paralysis within hours, but the disease has been largely eradicated globally with an effective vaccine.

GPEI sending teams

The GPEI is sending a team to Malawi to support emergency operations, communications, and surveillance. Partner organizations will also send teams to support operations and innovative vaccination campaign solutions.

GPEI was launched in 1988 with the combined efforts of national governments, WHO, Rotary International, the CDC, and UNICEF. The GPEI partnership has included the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and, in recent years, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

The CDC states, “[G]lobal incidence of polio has decreased by 99.9% since GPEI’s foundation. An estimated 16 million people today are walking who would otherwise have been paralyzed by the disease, and more than 1.5 million people are alive, whose lives would otherwise have been lost. Now the task remains to tackle polio in its last few strongholds and get rid of the final 0.1% of polio cases.”

Three wild poliovirus strains

There are three wild poliovirus strains: type 1 (WPV1), type 2 (WPV2), and type 3 (WPV3).

“Symptomatically, all three strains are identical, in that they cause irreversible paralysis or even death. But there are genetic and virologic differences which make these three strains three separate viruses that must each be eradicated individually,” according to WHO.

WPV3 is the second strain to be wiped out, following the certification of the eradication of WPV2 in 2015.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Health authorities in Malawi have declared an outbreak of wild poliovirus type 1 after a case was confirmed in a 3-year-old girl in the capital, Lilongwe. It was the first case in Africa in 5 years, according to the World Health Organization.

Globally, there were only five cases of wild poliovirus in 2021, the WHO states.

“As long as wild polio exists anywhere in the world all countries remain at risk of importation of the virus,” Matshidiso Moeti, MBBS, WHO regional director for Africa, said in the statement.

Girl paralyzed in November

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) said in a statement that the 3-year-old girl experienced paralysis in November, and stool specimens were collected. Sequencing of the virus was conducted in February, 2022, by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases in South Africa, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the case as WPV1.

According to the WHO announcement, laboratory analysis shows that the strain identified in Malawi is linked to one circulating in Sindh Province in Pakistan. Polio remains endemic only in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Kacey C. Ernst, PhD, MPH, professor and infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Arizona’s Zuckerman College of Public Health in Tucson, pointed out that what is not clear from the press release is whether the girl had traveled to Pakistan or was infected in Malawi.

“This is a very significant detail that would indicate whether or not transmission was actively occurring in Malawi. Until that information is released, it is hard to judge the extent of the possible outbreak,” she said in an interview. “The good news is that this case was in fact detected. The surveillance systems are in place and they were able to identify wild-type cases.”

Dr. Ernst said that although there is cause for concern, it is “not a reason to panic. Malawi has very high polio vaccination rates and it is quite possible that this will be a very small defined outbreak that will be well contained.”

She added that the medical community should be alerted that this case has been identified so travelers who have been to affected areas who have any symptoms can be appropriately screened.

The WHO said it is helping Malawi health authorities in the response, including increasing immunizations.

However, a vaccination campaign comes at a time of health system upheaval in Malawi.

“Malawi, like countries all over the world, has seen an interruption in services due to COVID,” Joia S. Mukherjee, MD, MPH, chief medical officer with Partners in Health and associate professor with the division of global health equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and in the department of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “In addition, Malawi is currently dealing with the aftermath of a cyclone – where nearly a million people were displaced. Vaccination campaigns work best if there is solid infrastructure. Both COVID and the impact of climate change have shaken the health system.”

UN health agencies warned last year that millions of children who have not received immunizations during the pandemic, especially in Africa, “are now at risk from life-threatening diseases such as measles, polio, yellow fever, and diphtheria,” Reuters reported.

Africa was certified as wild poliovirus free on Aug. 25, 2020. The CDC had served as the lead partner over 3 decades in helping Africa reach the milestone. Africa will retain that status, the WHO stated, because the strain originated in Pakistan.

Five of six WHO regions have been certified polio free. The Americas received eradication certification in 1994.

There is no cure for polio, which can cause irreversible paralysis within hours, but the disease has been largely eradicated globally with an effective vaccine.

GPEI sending teams

The GPEI is sending a team to Malawi to support emergency operations, communications, and surveillance. Partner organizations will also send teams to support operations and innovative vaccination campaign solutions.

GPEI was launched in 1988 with the combined efforts of national governments, WHO, Rotary International, the CDC, and UNICEF. The GPEI partnership has included the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and, in recent years, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

The CDC states, “[G]lobal incidence of polio has decreased by 99.9% since GPEI’s foundation. An estimated 16 million people today are walking who would otherwise have been paralyzed by the disease, and more than 1.5 million people are alive, whose lives would otherwise have been lost. Now the task remains to tackle polio in its last few strongholds and get rid of the final 0.1% of polio cases.”

Three wild poliovirus strains

There are three wild poliovirus strains: type 1 (WPV1), type 2 (WPV2), and type 3 (WPV3).

“Symptomatically, all three strains are identical, in that they cause irreversible paralysis or even death. But there are genetic and virologic differences which make these three strains three separate viruses that must each be eradicated individually,” according to WHO.

WPV3 is the second strain to be wiped out, following the certification of the eradication of WPV2 in 2015.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Health authorities in Malawi have declared an outbreak of wild poliovirus type 1 after a case was confirmed in a 3-year-old girl in the capital, Lilongwe. It was the first case in Africa in 5 years, according to the World Health Organization.

Globally, there were only five cases of wild poliovirus in 2021, the WHO states.

“As long as wild polio exists anywhere in the world all countries remain at risk of importation of the virus,” Matshidiso Moeti, MBBS, WHO regional director for Africa, said in the statement.

Girl paralyzed in November

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) said in a statement that the 3-year-old girl experienced paralysis in November, and stool specimens were collected. Sequencing of the virus was conducted in February, 2022, by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases in South Africa, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the case as WPV1.

According to the WHO announcement, laboratory analysis shows that the strain identified in Malawi is linked to one circulating in Sindh Province in Pakistan. Polio remains endemic only in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Kacey C. Ernst, PhD, MPH, professor and infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Arizona’s Zuckerman College of Public Health in Tucson, pointed out that what is not clear from the press release is whether the girl had traveled to Pakistan or was infected in Malawi.

“This is a very significant detail that would indicate whether or not transmission was actively occurring in Malawi. Until that information is released, it is hard to judge the extent of the possible outbreak,” she said in an interview. “The good news is that this case was in fact detected. The surveillance systems are in place and they were able to identify wild-type cases.”

Dr. Ernst said that although there is cause for concern, it is “not a reason to panic. Malawi has very high polio vaccination rates and it is quite possible that this will be a very small defined outbreak that will be well contained.”

She added that the medical community should be alerted that this case has been identified so travelers who have been to affected areas who have any symptoms can be appropriately screened.

The WHO said it is helping Malawi health authorities in the response, including increasing immunizations.

However, a vaccination campaign comes at a time of health system upheaval in Malawi.

“Malawi, like countries all over the world, has seen an interruption in services due to COVID,” Joia S. Mukherjee, MD, MPH, chief medical officer with Partners in Health and associate professor with the division of global health equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and in the department of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “In addition, Malawi is currently dealing with the aftermath of a cyclone – where nearly a million people were displaced. Vaccination campaigns work best if there is solid infrastructure. Both COVID and the impact of climate change have shaken the health system.”

UN health agencies warned last year that millions of children who have not received immunizations during the pandemic, especially in Africa, “are now at risk from life-threatening diseases such as measles, polio, yellow fever, and diphtheria,” Reuters reported.

Africa was certified as wild poliovirus free on Aug. 25, 2020. The CDC had served as the lead partner over 3 decades in helping Africa reach the milestone. Africa will retain that status, the WHO stated, because the strain originated in Pakistan.

Five of six WHO regions have been certified polio free. The Americas received eradication certification in 1994.

There is no cure for polio, which can cause irreversible paralysis within hours, but the disease has been largely eradicated globally with an effective vaccine.

GPEI sending teams

The GPEI is sending a team to Malawi to support emergency operations, communications, and surveillance. Partner organizations will also send teams to support operations and innovative vaccination campaign solutions.

GPEI was launched in 1988 with the combined efforts of national governments, WHO, Rotary International, the CDC, and UNICEF. The GPEI partnership has included the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and, in recent years, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

The CDC states, “[G]lobal incidence of polio has decreased by 99.9% since GPEI’s foundation. An estimated 16 million people today are walking who would otherwise have been paralyzed by the disease, and more than 1.5 million people are alive, whose lives would otherwise have been lost. Now the task remains to tackle polio in its last few strongholds and get rid of the final 0.1% of polio cases.”

Three wild poliovirus strains

There are three wild poliovirus strains: type 1 (WPV1), type 2 (WPV2), and type 3 (WPV3).

“Symptomatically, all three strains are identical, in that they cause irreversible paralysis or even death. But there are genetic and virologic differences which make these three strains three separate viruses that must each be eradicated individually,” according to WHO.

WPV3 is the second strain to be wiped out, following the certification of the eradication of WPV2 in 2015.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Spironolactone not linked to increased cancer risk in systematic review and meta-analysis

covering seven observational studies and a total population of over 4.5 million people.

The data, published in JAMA Dermatology, are “reassuring,” the authors reported, considering that the spironolactone label carries a Food and Drug Administration warning regarding possible tumorigenicity, which is based on animal studies of doses up to 150-fold greater than doses used for humans. The drug’s antiandrogenic properties have driven its off-label use as a treatment for acne, hidradenitis, androgenetic alopecia, and hirsutism.

Spironolactone, a synthetic 17-lactone steroid, is approved for the treatment of heart failure, edema and ascites, hypertension, and primary hyperaldosteronism. Off label, it is also frequently used in gender-affirming care and is included in Endocrine Society guidelines as part of hormonal regimens for transgender women, the authors noted.

The seven eligible studies looked at the occurrence of cancer in men and women who had any exposure to the drug, regardless of the primary indication. Sample sizes ranged from 18,035 to 2.3 million, and the mean age across all studies was 62.6-72 years.

The researchers synthesized the studies, mostly of European individuals, using random effects meta-analysis and found no statistically significant association between spironolactone use and risk of breast cancer (risk ratio, 1.04; 95% confidence interval, 0.86-1.22). Three of the seven studies investigated breast cancer.

There was also no significant association between spironolactone use and risk of ovarian cancer (two studies), bladder cancer (three studies), kidney cancer (two studies), gastric cancer (two studies), or esophageal cancer (two studies).

For prostate cancer, investigated in four studies, use of the drug was associated with decreased risk (RR, 0.79, 95% CI, 0.68-0.90).

Kanthi Bommareddy, MD, of the University of Miami and coauthors concluded that all studies were at low risk of bias after appraising each one using a scale that looks at selection bias, confounding bias, and detection and outcome bias.

In dermatology, the results should “help us to take a collective sigh of relief,” said Julie C. Harper, MD, of the Dermatology and Skin Care Center of Birmingham, Ala., who was asked to comment on the study. The drug has been “safe and effective in our clinics and it is affordable and accessible to our patients,” she said, but with the FDA’s warning and the drug’s antiandrogen capacity, “there has been concern that we might be putting our patients at increased risk of breast cancer [in particular].”

The pooling of seven large studies together and the finding of no substantive increased risk of cancer “gives us evidence and comfort that spironolactone does not increase the risk of cancer in our dermatology patients,” said Dr. Harper, a past president of the American Acne & Rosacea Society.

“With every passing year,” she noted, “dermatologists are prescribing more and more spironolactone for acne, hidradenitis, androgenetic alopecia, and hirsutism.”

Four of the seven studies stratified analyses by sex, and in those without stratification by sex, women accounted for 17.2%-54.4% of the samples.

The studies had long follow-up periods of 5-20 years, but certainty of the evidence was low and since many of the studies included mostly older individuals, “they may not generalize to younger populations, such as those treated with spironolactone for acne,” the investigators wrote.

The authors also noted they were unable to look for dose-dependent associations between spironolactone and cancer risk, and that confidence intervals for rarer cancers like ovarian cancer were wide. “We cannot entirely exclude the potential for a meaningful increase in cancer risk,” and future studies are needed, in populations that include younger patients and those with acne or hirsutism.

Dr. Bommareddy reported no disclosures. Other coauthors reported grants from the National Cancer Institute outside the submitted work, and personal fees as a Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas Scholar in Cancer Research. There was no funding reported for the study. Dr. Harper said she had no disclosures.

covering seven observational studies and a total population of over 4.5 million people.

The data, published in JAMA Dermatology, are “reassuring,” the authors reported, considering that the spironolactone label carries a Food and Drug Administration warning regarding possible tumorigenicity, which is based on animal studies of doses up to 150-fold greater than doses used for humans. The drug’s antiandrogenic properties have driven its off-label use as a treatment for acne, hidradenitis, androgenetic alopecia, and hirsutism.

Spironolactone, a synthetic 17-lactone steroid, is approved for the treatment of heart failure, edema and ascites, hypertension, and primary hyperaldosteronism. Off label, it is also frequently used in gender-affirming care and is included in Endocrine Society guidelines as part of hormonal regimens for transgender women, the authors noted.

The seven eligible studies looked at the occurrence of cancer in men and women who had any exposure to the drug, regardless of the primary indication. Sample sizes ranged from 18,035 to 2.3 million, and the mean age across all studies was 62.6-72 years.

The researchers synthesized the studies, mostly of European individuals, using random effects meta-analysis and found no statistically significant association between spironolactone use and risk of breast cancer (risk ratio, 1.04; 95% confidence interval, 0.86-1.22). Three of the seven studies investigated breast cancer.

There was also no significant association between spironolactone use and risk of ovarian cancer (two studies), bladder cancer (three studies), kidney cancer (two studies), gastric cancer (two studies), or esophageal cancer (two studies).

For prostate cancer, investigated in four studies, use of the drug was associated with decreased risk (RR, 0.79, 95% CI, 0.68-0.90).

Kanthi Bommareddy, MD, of the University of Miami and coauthors concluded that all studies were at low risk of bias after appraising each one using a scale that looks at selection bias, confounding bias, and detection and outcome bias.

In dermatology, the results should “help us to take a collective sigh of relief,” said Julie C. Harper, MD, of the Dermatology and Skin Care Center of Birmingham, Ala., who was asked to comment on the study. The drug has been “safe and effective in our clinics and it is affordable and accessible to our patients,” she said, but with the FDA’s warning and the drug’s antiandrogen capacity, “there has been concern that we might be putting our patients at increased risk of breast cancer [in particular].”

The pooling of seven large studies together and the finding of no substantive increased risk of cancer “gives us evidence and comfort that spironolactone does not increase the risk of cancer in our dermatology patients,” said Dr. Harper, a past president of the American Acne & Rosacea Society.

“With every passing year,” she noted, “dermatologists are prescribing more and more spironolactone for acne, hidradenitis, androgenetic alopecia, and hirsutism.”

Four of the seven studies stratified analyses by sex, and in those without stratification by sex, women accounted for 17.2%-54.4% of the samples.

The studies had long follow-up periods of 5-20 years, but certainty of the evidence was low and since many of the studies included mostly older individuals, “they may not generalize to younger populations, such as those treated with spironolactone for acne,” the investigators wrote.

The authors also noted they were unable to look for dose-dependent associations between spironolactone and cancer risk, and that confidence intervals for rarer cancers like ovarian cancer were wide. “We cannot entirely exclude the potential for a meaningful increase in cancer risk,” and future studies are needed, in populations that include younger patients and those with acne or hirsutism.