User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Check biases when caring for children with obesity

Counting calories should not be the focus of weight-loss strategies for children with obesity, according to an expert who said pediatricians need to change the way they discuss weight with their patients.

During a plenary session of the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference, Joseph A. Skelton, MD, professor of pediatrics at Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, N.C., said pediatricians should recognize the behavioral, physical, environmental, and genetic factors that contribute to obesity. For instance, food deserts are on the rise, and they undermine the ability of parents to feed their children healthy meals. In addition, more children are less physically active.

“Obesity is a lot more complex than calories in, calories out,” Dr. Skelton said. “We choose to treat issues of obesity as personal responsibility – ‘you did this to yourself’ – but when you look at how we move around and live our lives, our food systems, our policies, the social and environmental changes have caused shifts in our behavior.”

According to Dr. Skelton, bias against children with obesity can harm their self-image and weaken their motivations for losing weight. In addition, doctors may change how they deliver care on the basis of stereotypes regarding obese children. These stereotypes are often reinforced in media portrayals, Dr. Skelton said.

“When children or when adults who have excess weight or obesity are portrayed, they are portrayed typically in a negative fashion,” Dr. Skelton said. “There’s increasing evidence that weight bias and weight discrimination are increasing the morbidity we see in patients who develop obesity.”

For many children with obesity, visits to the pediatrician often center on weight, regardless of the reason for the appointment. Weight stigma and bias on the part of health care providers can increase stress, as well as adverse health outcomes in children, according to a 2019 study (Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2019 Feb 1. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000453). Dr. Skelton recommended that pediatricians listen to their patients’ concerns and make a personalized care plan.

Dr. Skelton said doctors can pull from projects such as Health at Every Size, which offers templates for personalized health plans for children with obesity. It has a heavy focus on a weight-neutral approach to pediatric health.

“There are various ways to manage weight in a healthy and safe way,” Dr. Skelton said.

Evidence-based methods of treating obesity include focusing on health and healthy behaviors rather than weight and using the body mass index as a screening tool for further conversations about overall health, rather than as an indicator of health based on weight.

Dr. Skelton also encouraged pediatricians to be on the alert for indicators of disordered eating, which can include dieting, teasing, or talking excessively about weight at home and can involve reading misinformation about dieting online.

“Your job is to educate people on the dangers of following unscientific information online,” Dr. Skelton said. “We can address issues of weight health in a way that is patient centered and is very safe, without unintended consequences.” Brooke Sweeney, MD, professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at University of Missouri–Kansas City, said problems with weight bias in society and in clinical practice can lead to false assumptions about people who have obesity.

“It’s normal to gain adipose, or fat tissue, at different times in life, during puberty or pregnancy, and some people normally gain more weight than others,” Dr. Sweeney said.

The body will try to maintain a weight set point. That set point is influenced by many factors, such as genetics, environment, and lifestyle.

“When you lose weight, your body tries to get you back to the set point, decreasing energy expenditure and increasing hunger and reward pathways,” she said. “We have gained so much knowledge through research to better understand the pathophysiology of obesity, and we are making good progress on improving advanced treatments for increased weight in children.”

Dr. Skelton reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Counting calories should not be the focus of weight-loss strategies for children with obesity, according to an expert who said pediatricians need to change the way they discuss weight with their patients.

During a plenary session of the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference, Joseph A. Skelton, MD, professor of pediatrics at Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, N.C., said pediatricians should recognize the behavioral, physical, environmental, and genetic factors that contribute to obesity. For instance, food deserts are on the rise, and they undermine the ability of parents to feed their children healthy meals. In addition, more children are less physically active.

“Obesity is a lot more complex than calories in, calories out,” Dr. Skelton said. “We choose to treat issues of obesity as personal responsibility – ‘you did this to yourself’ – but when you look at how we move around and live our lives, our food systems, our policies, the social and environmental changes have caused shifts in our behavior.”

According to Dr. Skelton, bias against children with obesity can harm their self-image and weaken their motivations for losing weight. In addition, doctors may change how they deliver care on the basis of stereotypes regarding obese children. These stereotypes are often reinforced in media portrayals, Dr. Skelton said.

“When children or when adults who have excess weight or obesity are portrayed, they are portrayed typically in a negative fashion,” Dr. Skelton said. “There’s increasing evidence that weight bias and weight discrimination are increasing the morbidity we see in patients who develop obesity.”

For many children with obesity, visits to the pediatrician often center on weight, regardless of the reason for the appointment. Weight stigma and bias on the part of health care providers can increase stress, as well as adverse health outcomes in children, according to a 2019 study (Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2019 Feb 1. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000453). Dr. Skelton recommended that pediatricians listen to their patients’ concerns and make a personalized care plan.

Dr. Skelton said doctors can pull from projects such as Health at Every Size, which offers templates for personalized health plans for children with obesity. It has a heavy focus on a weight-neutral approach to pediatric health.

“There are various ways to manage weight in a healthy and safe way,” Dr. Skelton said.

Evidence-based methods of treating obesity include focusing on health and healthy behaviors rather than weight and using the body mass index as a screening tool for further conversations about overall health, rather than as an indicator of health based on weight.

Dr. Skelton also encouraged pediatricians to be on the alert for indicators of disordered eating, which can include dieting, teasing, or talking excessively about weight at home and can involve reading misinformation about dieting online.

“Your job is to educate people on the dangers of following unscientific information online,” Dr. Skelton said. “We can address issues of weight health in a way that is patient centered and is very safe, without unintended consequences.” Brooke Sweeney, MD, professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at University of Missouri–Kansas City, said problems with weight bias in society and in clinical practice can lead to false assumptions about people who have obesity.

“It’s normal to gain adipose, or fat tissue, at different times in life, during puberty or pregnancy, and some people normally gain more weight than others,” Dr. Sweeney said.

The body will try to maintain a weight set point. That set point is influenced by many factors, such as genetics, environment, and lifestyle.

“When you lose weight, your body tries to get you back to the set point, decreasing energy expenditure and increasing hunger and reward pathways,” she said. “We have gained so much knowledge through research to better understand the pathophysiology of obesity, and we are making good progress on improving advanced treatments for increased weight in children.”

Dr. Skelton reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Counting calories should not be the focus of weight-loss strategies for children with obesity, according to an expert who said pediatricians need to change the way they discuss weight with their patients.

During a plenary session of the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference, Joseph A. Skelton, MD, professor of pediatrics at Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, N.C., said pediatricians should recognize the behavioral, physical, environmental, and genetic factors that contribute to obesity. For instance, food deserts are on the rise, and they undermine the ability of parents to feed their children healthy meals. In addition, more children are less physically active.

“Obesity is a lot more complex than calories in, calories out,” Dr. Skelton said. “We choose to treat issues of obesity as personal responsibility – ‘you did this to yourself’ – but when you look at how we move around and live our lives, our food systems, our policies, the social and environmental changes have caused shifts in our behavior.”

According to Dr. Skelton, bias against children with obesity can harm their self-image and weaken their motivations for losing weight. In addition, doctors may change how they deliver care on the basis of stereotypes regarding obese children. These stereotypes are often reinforced in media portrayals, Dr. Skelton said.

“When children or when adults who have excess weight or obesity are portrayed, they are portrayed typically in a negative fashion,” Dr. Skelton said. “There’s increasing evidence that weight bias and weight discrimination are increasing the morbidity we see in patients who develop obesity.”

For many children with obesity, visits to the pediatrician often center on weight, regardless of the reason for the appointment. Weight stigma and bias on the part of health care providers can increase stress, as well as adverse health outcomes in children, according to a 2019 study (Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2019 Feb 1. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000453). Dr. Skelton recommended that pediatricians listen to their patients’ concerns and make a personalized care plan.

Dr. Skelton said doctors can pull from projects such as Health at Every Size, which offers templates for personalized health plans for children with obesity. It has a heavy focus on a weight-neutral approach to pediatric health.

“There are various ways to manage weight in a healthy and safe way,” Dr. Skelton said.

Evidence-based methods of treating obesity include focusing on health and healthy behaviors rather than weight and using the body mass index as a screening tool for further conversations about overall health, rather than as an indicator of health based on weight.

Dr. Skelton also encouraged pediatricians to be on the alert for indicators of disordered eating, which can include dieting, teasing, or talking excessively about weight at home and can involve reading misinformation about dieting online.

“Your job is to educate people on the dangers of following unscientific information online,” Dr. Skelton said. “We can address issues of weight health in a way that is patient centered and is very safe, without unintended consequences.” Brooke Sweeney, MD, professor of internal medicine and pediatrics at University of Missouri–Kansas City, said problems with weight bias in society and in clinical practice can lead to false assumptions about people who have obesity.

“It’s normal to gain adipose, or fat tissue, at different times in life, during puberty or pregnancy, and some people normally gain more weight than others,” Dr. Sweeney said.

The body will try to maintain a weight set point. That set point is influenced by many factors, such as genetics, environment, and lifestyle.

“When you lose weight, your body tries to get you back to the set point, decreasing energy expenditure and increasing hunger and reward pathways,” she said. “We have gained so much knowledge through research to better understand the pathophysiology of obesity, and we are making good progress on improving advanced treatments for increased weight in children.”

Dr. Skelton reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAP 2022

Pediatricians urged to check for vision problems after concussion

Pediatricians should consider screening children suspected of having a concussion for resulting vision problems that are often overlooked, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Christina Master, MD, a pediatrician and sports medicine specialist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said many doctors don’t think of vision problems when examining children who’ve experienced a head injury. But the issues are common and can significantly affect a child’s performance in school and sports, and disrupt daily life.

Dr. Master led a team of sports medicine and vision specialists who wrote an AAP policy statement on vision and concussion. She summarized the new recommendations during a plenary session Oct. 9 at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference.

Dr. Master told this news organization that the vast majority of the estimated 1.4 million U.S. children and adolescents who have concussions annually are treated in pediatricians’ offices.

Up to 40% of young patients experience symptoms such as blurred vision, light sensitivity, and double vision following a concussion, the panel said. In addition, children with vision problems are more likely to have prolonged recoveries and delays in returning to school than children who have concussions but don’t have similar eyesight issues.

Concussions affect neurologic pathways of the visual system and disturb basic functions such as the ability of the eyes to change focus from a distant object to a near one.

Dr. Master said most pediatricians do not routinely check for vision problems following a concussion, and children themselves may not recognize that they have vision deficits “unless you ask them very specifically.”

In addition to asking children about their vision, the policy statement recommends pediatricians conduct a thorough exam to assess ocular alignment, the ability to track a moving object, and the ability to maintain focus on an image while moving.

Dr. Master said that an assessment of vision and balance, which is described in an accompanying clinical report, lasts about 5 minutes and is easy for pediatricians to learn.

Managing vision problems

Pediatricians can guide parents in talking to their child’s school about accommodations such as extra time on classroom tasks, creating materials with enlarged fonts, and using preprinted or audio notes, the statement said.

At school, vision deficits can interfere with reading by causing children to skip words, lose their place, become fatigued, or lose interest, according to the statement.

Children can also take breaks from visual stressors such as bright lights and screens, and use prescription glasses temporarily to correct blurred vision, the panel noted.

Although most children will recover from a concussion on their own within 4 weeks, up to one-third will have persistent symptoms and may benefit from seeing a specialist who can provide treatment such as rehabilitative exercises. While evidence suggests that referring some children to specialty care within a week of a concussion improves outcomes, the signs of who would benefit are not always clear, according to the panel.

Specialties such as sports medicine, neurology, physiatry, otorhinolaryngology, and occupational therapy may provide care for prolonged symptoms, Dr. Master said.

The panel noted that more study is needed on treatment options such as rehabilitation exercises, which have been shown to help with balance and dizziness.

Dr. Master said the panel did not recommend that pediatricians provide a home exercise program to treat concussion, as she does in her practice, explaining that “it’s not clear that it’s necessary for all kids.”

One author of the policy statement, Ankoor Shah, MD, PhD, reported an intellectual property relationship with Rebion involving a patent application for a pediatric vision screener. Others, including Dr. Master, reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pediatricians should consider screening children suspected of having a concussion for resulting vision problems that are often overlooked, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Christina Master, MD, a pediatrician and sports medicine specialist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said many doctors don’t think of vision problems when examining children who’ve experienced a head injury. But the issues are common and can significantly affect a child’s performance in school and sports, and disrupt daily life.

Dr. Master led a team of sports medicine and vision specialists who wrote an AAP policy statement on vision and concussion. She summarized the new recommendations during a plenary session Oct. 9 at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference.

Dr. Master told this news organization that the vast majority of the estimated 1.4 million U.S. children and adolescents who have concussions annually are treated in pediatricians’ offices.

Up to 40% of young patients experience symptoms such as blurred vision, light sensitivity, and double vision following a concussion, the panel said. In addition, children with vision problems are more likely to have prolonged recoveries and delays in returning to school than children who have concussions but don’t have similar eyesight issues.

Concussions affect neurologic pathways of the visual system and disturb basic functions such as the ability of the eyes to change focus from a distant object to a near one.

Dr. Master said most pediatricians do not routinely check for vision problems following a concussion, and children themselves may not recognize that they have vision deficits “unless you ask them very specifically.”

In addition to asking children about their vision, the policy statement recommends pediatricians conduct a thorough exam to assess ocular alignment, the ability to track a moving object, and the ability to maintain focus on an image while moving.

Dr. Master said that an assessment of vision and balance, which is described in an accompanying clinical report, lasts about 5 minutes and is easy for pediatricians to learn.

Managing vision problems

Pediatricians can guide parents in talking to their child’s school about accommodations such as extra time on classroom tasks, creating materials with enlarged fonts, and using preprinted or audio notes, the statement said.

At school, vision deficits can interfere with reading by causing children to skip words, lose their place, become fatigued, or lose interest, according to the statement.

Children can also take breaks from visual stressors such as bright lights and screens, and use prescription glasses temporarily to correct blurred vision, the panel noted.

Although most children will recover from a concussion on their own within 4 weeks, up to one-third will have persistent symptoms and may benefit from seeing a specialist who can provide treatment such as rehabilitative exercises. While evidence suggests that referring some children to specialty care within a week of a concussion improves outcomes, the signs of who would benefit are not always clear, according to the panel.

Specialties such as sports medicine, neurology, physiatry, otorhinolaryngology, and occupational therapy may provide care for prolonged symptoms, Dr. Master said.

The panel noted that more study is needed on treatment options such as rehabilitation exercises, which have been shown to help with balance and dizziness.

Dr. Master said the panel did not recommend that pediatricians provide a home exercise program to treat concussion, as she does in her practice, explaining that “it’s not clear that it’s necessary for all kids.”

One author of the policy statement, Ankoor Shah, MD, PhD, reported an intellectual property relationship with Rebion involving a patent application for a pediatric vision screener. Others, including Dr. Master, reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pediatricians should consider screening children suspected of having a concussion for resulting vision problems that are often overlooked, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Christina Master, MD, a pediatrician and sports medicine specialist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said many doctors don’t think of vision problems when examining children who’ve experienced a head injury. But the issues are common and can significantly affect a child’s performance in school and sports, and disrupt daily life.

Dr. Master led a team of sports medicine and vision specialists who wrote an AAP policy statement on vision and concussion. She summarized the new recommendations during a plenary session Oct. 9 at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference.

Dr. Master told this news organization that the vast majority of the estimated 1.4 million U.S. children and adolescents who have concussions annually are treated in pediatricians’ offices.

Up to 40% of young patients experience symptoms such as blurred vision, light sensitivity, and double vision following a concussion, the panel said. In addition, children with vision problems are more likely to have prolonged recoveries and delays in returning to school than children who have concussions but don’t have similar eyesight issues.

Concussions affect neurologic pathways of the visual system and disturb basic functions such as the ability of the eyes to change focus from a distant object to a near one.

Dr. Master said most pediatricians do not routinely check for vision problems following a concussion, and children themselves may not recognize that they have vision deficits “unless you ask them very specifically.”

In addition to asking children about their vision, the policy statement recommends pediatricians conduct a thorough exam to assess ocular alignment, the ability to track a moving object, and the ability to maintain focus on an image while moving.

Dr. Master said that an assessment of vision and balance, which is described in an accompanying clinical report, lasts about 5 minutes and is easy for pediatricians to learn.

Managing vision problems

Pediatricians can guide parents in talking to their child’s school about accommodations such as extra time on classroom tasks, creating materials with enlarged fonts, and using preprinted or audio notes, the statement said.

At school, vision deficits can interfere with reading by causing children to skip words, lose their place, become fatigued, or lose interest, according to the statement.

Children can also take breaks from visual stressors such as bright lights and screens, and use prescription glasses temporarily to correct blurred vision, the panel noted.

Although most children will recover from a concussion on their own within 4 weeks, up to one-third will have persistent symptoms and may benefit from seeing a specialist who can provide treatment such as rehabilitative exercises. While evidence suggests that referring some children to specialty care within a week of a concussion improves outcomes, the signs of who would benefit are not always clear, according to the panel.

Specialties such as sports medicine, neurology, physiatry, otorhinolaryngology, and occupational therapy may provide care for prolonged symptoms, Dr. Master said.

The panel noted that more study is needed on treatment options such as rehabilitation exercises, which have been shown to help with balance and dizziness.

Dr. Master said the panel did not recommend that pediatricians provide a home exercise program to treat concussion, as she does in her practice, explaining that “it’s not clear that it’s necessary for all kids.”

One author of the policy statement, Ankoor Shah, MD, PhD, reported an intellectual property relationship with Rebion involving a patent application for a pediatric vision screener. Others, including Dr. Master, reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAP 2022

With sleuth work, pediatricians can identify genetic disorders

Jennifer Kalish, MD, PhD, fields as many as 10 inquiries a month from pediatricians who spot an unusual feature during a clinical exam, and wonder if they should refer the family to a geneticist.

“There are hundreds of rare disorders, and for a pediatrician, they can be hard to recognize,” Dr. Kalish said. “That’s why we’re here as geneticists – to partner so that we can help.”

Pediatricians play a key role in spotting signs of rare genetic diseases, but may need guidance for recognizing the more subtle presentations of a disorder, according to Dr. Kalish, a geneticist and director of the Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome Clinic at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who spoke at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference.

Spectrums of disease

Pediatricians may struggle with deciding whether to make a referral, in part because genetic syndromes “do not always look like the textbook,” she said.

With many conditions, “we’re starting to understand that there’s really a spectrum of how affected versus less affected one can be,” by genetic and epigenetic changes, which have led to recognition that many cases are more subtle and harder to diagnose, she said.

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome is a prime example. The overgrowth disorder affects an estimated 1 in 10,340 infants, and is associated with a heightened risk of Wilms tumors, a form of kidney cancer, and hepatoblastomas. Children diagnosed with these conditions typically undergo frequent screenings to detect tumors to jumpstart treatment.

Some researchers believe Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome is underdiagnosed because it can present in many different ways because of variations in the distributions of affected cells in the body, known as mosaicism.

To address the complexity, Dr. Kalish guided development of a scoring system for determining whether molecular testing is warranted. Primary features such as an enlarged tongue and lateralized overgrowth carry more points, whereas suggestive features like ear creases or large birth weight carry fewer points.

Diagnostic advances have occurred for other syndromes, as well. For example, researchers have created a scoring system for Russell-Silver syndrome, a less common disorder characterized by slow growth before and after birth, in which mosaicism is also present.

Early diagnosis and intervention of Russell-Silver syndrome can ensure that patients grow to their maximum potential and address problems such as feeding issues.

Spotting a “compilation of features”

Although tools are available, Dr. Kalish said pediatricians don’t need to make a diagnosis, and instead can refer patients to a geneticist after recognizing clinical features that hint at a genetic etiology.

For pediatricians, the process of deciding whether to refer a patient to a geneticist may entail ruling out nongenetic causes, considering patient and family history, and ultimately deciding whether there is a “compilation of features” that falls outside the norm, she said. Unfortunately, she added, there’s “not a simple list I could just hand out saying, ‘If you see these things, call me.’ ”

Dr. Kalish said pediatricians should be aware that two children with similar features can have different syndromes. She presented case studies of two infants, who both had enlarged tongues and older mothers.

One child had hallmarks that pointed to Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome: conception with in vitro fertilization, length in the 98th percentile, a long umbilical cord, nevus simplex birthmarks, and labial and leg asymmetry.

The other baby had features aligned with Down syndrome: a heart murmur, upward slanting eyes, and a single crease on the palm.

In some cases, isolated features such as the shape, slant, or spacing of eyes, or the presence of creases on the ears, may simply be familial or inherited traits, Dr. Kalish said.

She noted that “there’s been a lot of work in genetics in the past few years to show what syndromes look like” in diverse populations. The American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A has published a series of reports on the topic.

Dr. Kalish reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Jennifer Kalish, MD, PhD, fields as many as 10 inquiries a month from pediatricians who spot an unusual feature during a clinical exam, and wonder if they should refer the family to a geneticist.

“There are hundreds of rare disorders, and for a pediatrician, they can be hard to recognize,” Dr. Kalish said. “That’s why we’re here as geneticists – to partner so that we can help.”

Pediatricians play a key role in spotting signs of rare genetic diseases, but may need guidance for recognizing the more subtle presentations of a disorder, according to Dr. Kalish, a geneticist and director of the Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome Clinic at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who spoke at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference.

Spectrums of disease

Pediatricians may struggle with deciding whether to make a referral, in part because genetic syndromes “do not always look like the textbook,” she said.

With many conditions, “we’re starting to understand that there’s really a spectrum of how affected versus less affected one can be,” by genetic and epigenetic changes, which have led to recognition that many cases are more subtle and harder to diagnose, she said.

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome is a prime example. The overgrowth disorder affects an estimated 1 in 10,340 infants, and is associated with a heightened risk of Wilms tumors, a form of kidney cancer, and hepatoblastomas. Children diagnosed with these conditions typically undergo frequent screenings to detect tumors to jumpstart treatment.

Some researchers believe Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome is underdiagnosed because it can present in many different ways because of variations in the distributions of affected cells in the body, known as mosaicism.

To address the complexity, Dr. Kalish guided development of a scoring system for determining whether molecular testing is warranted. Primary features such as an enlarged tongue and lateralized overgrowth carry more points, whereas suggestive features like ear creases or large birth weight carry fewer points.

Diagnostic advances have occurred for other syndromes, as well. For example, researchers have created a scoring system for Russell-Silver syndrome, a less common disorder characterized by slow growth before and after birth, in which mosaicism is also present.

Early diagnosis and intervention of Russell-Silver syndrome can ensure that patients grow to their maximum potential and address problems such as feeding issues.

Spotting a “compilation of features”

Although tools are available, Dr. Kalish said pediatricians don’t need to make a diagnosis, and instead can refer patients to a geneticist after recognizing clinical features that hint at a genetic etiology.

For pediatricians, the process of deciding whether to refer a patient to a geneticist may entail ruling out nongenetic causes, considering patient and family history, and ultimately deciding whether there is a “compilation of features” that falls outside the norm, she said. Unfortunately, she added, there’s “not a simple list I could just hand out saying, ‘If you see these things, call me.’ ”

Dr. Kalish said pediatricians should be aware that two children with similar features can have different syndromes. She presented case studies of two infants, who both had enlarged tongues and older mothers.

One child had hallmarks that pointed to Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome: conception with in vitro fertilization, length in the 98th percentile, a long umbilical cord, nevus simplex birthmarks, and labial and leg asymmetry.

The other baby had features aligned with Down syndrome: a heart murmur, upward slanting eyes, and a single crease on the palm.

In some cases, isolated features such as the shape, slant, or spacing of eyes, or the presence of creases on the ears, may simply be familial or inherited traits, Dr. Kalish said.

She noted that “there’s been a lot of work in genetics in the past few years to show what syndromes look like” in diverse populations. The American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A has published a series of reports on the topic.

Dr. Kalish reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Jennifer Kalish, MD, PhD, fields as many as 10 inquiries a month from pediatricians who spot an unusual feature during a clinical exam, and wonder if they should refer the family to a geneticist.

“There are hundreds of rare disorders, and for a pediatrician, they can be hard to recognize,” Dr. Kalish said. “That’s why we’re here as geneticists – to partner so that we can help.”

Pediatricians play a key role in spotting signs of rare genetic diseases, but may need guidance for recognizing the more subtle presentations of a disorder, according to Dr. Kalish, a geneticist and director of the Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome Clinic at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who spoke at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference.

Spectrums of disease

Pediatricians may struggle with deciding whether to make a referral, in part because genetic syndromes “do not always look like the textbook,” she said.

With many conditions, “we’re starting to understand that there’s really a spectrum of how affected versus less affected one can be,” by genetic and epigenetic changes, which have led to recognition that many cases are more subtle and harder to diagnose, she said.

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome is a prime example. The overgrowth disorder affects an estimated 1 in 10,340 infants, and is associated with a heightened risk of Wilms tumors, a form of kidney cancer, and hepatoblastomas. Children diagnosed with these conditions typically undergo frequent screenings to detect tumors to jumpstart treatment.

Some researchers believe Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome is underdiagnosed because it can present in many different ways because of variations in the distributions of affected cells in the body, known as mosaicism.

To address the complexity, Dr. Kalish guided development of a scoring system for determining whether molecular testing is warranted. Primary features such as an enlarged tongue and lateralized overgrowth carry more points, whereas suggestive features like ear creases or large birth weight carry fewer points.

Diagnostic advances have occurred for other syndromes, as well. For example, researchers have created a scoring system for Russell-Silver syndrome, a less common disorder characterized by slow growth before and after birth, in which mosaicism is also present.

Early diagnosis and intervention of Russell-Silver syndrome can ensure that patients grow to their maximum potential and address problems such as feeding issues.

Spotting a “compilation of features”

Although tools are available, Dr. Kalish said pediatricians don’t need to make a diagnosis, and instead can refer patients to a geneticist after recognizing clinical features that hint at a genetic etiology.

For pediatricians, the process of deciding whether to refer a patient to a geneticist may entail ruling out nongenetic causes, considering patient and family history, and ultimately deciding whether there is a “compilation of features” that falls outside the norm, she said. Unfortunately, she added, there’s “not a simple list I could just hand out saying, ‘If you see these things, call me.’ ”

Dr. Kalish said pediatricians should be aware that two children with similar features can have different syndromes. She presented case studies of two infants, who both had enlarged tongues and older mothers.

One child had hallmarks that pointed to Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome: conception with in vitro fertilization, length in the 98th percentile, a long umbilical cord, nevus simplex birthmarks, and labial and leg asymmetry.

The other baby had features aligned with Down syndrome: a heart murmur, upward slanting eyes, and a single crease on the palm.

In some cases, isolated features such as the shape, slant, or spacing of eyes, or the presence of creases on the ears, may simply be familial or inherited traits, Dr. Kalish said.

She noted that “there’s been a lot of work in genetics in the past few years to show what syndromes look like” in diverse populations. The American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A has published a series of reports on the topic.

Dr. Kalish reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAP 2022

Congenital syphilis: It’s still a significant public health problem

You’re rounding in the nursery and informed of the following about one of your new patients: He’s a 38-week-old infant delivered to a mother diagnosed with syphilis at 12 weeks’ gestation at her initial prenatal visit. Her rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was 1:64 and the fluorescent treponemal antibody–absorption (FTA-ABS) test was positive. By report she was appropriately treated. Maternal RPRs obtained at 18 and 28 weeks’ gestation were 1:16 and 1:4, respectively. Maternal RPR at delivery and the infant’s RPR obtained shortly after birth were both 1:4. The mother wants to know if her baby is infected.

One result of syphilis during pregnancy is intrauterine infection and resultant congenital disease in the infant. Before you answer this mother, let’s discuss syphilis.

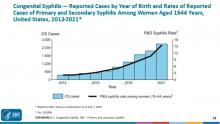

Congenital syphilis is a significant public health problem. In 2021, there were a total of 2,677 cases reported for a rate of 74.1 per 100,000 live births. Between 2020 and 2021, the number of cases of congenital syphilis increased 24.1% (2,158-2,677 cases), concurrent with a 45.8% increase (10.7-15.6 per 100,000) in the rate of primary and secondary syphilis in women aged 15-44 years. Between 2012 and 2021, the number of cases of congenital syphilis increased 701.5% (334-2,677 cases) and the increase in rates of primary and secondary syphilis in women aged 15-44 was 642.9% over the same period.

Why are the rates of congenital syphilis increasing? Most cases result from a lack of prenatal care and thus no testing for syphilis. The next most common cause is inadequate maternal treatment.

Congenital syphilis usually is acquired through transplacental transmission of spirochetes in the maternal bloodstream. Occasionally, it occurs at delivery via direct contact with maternal lesions. It is not transmitted in breast milk. Transmission of syphilis:

- Can occur any time during pregnancy.

- Is more likely to occur in women with untreated primary or secondary disease (60%-100%).

- Is approximately 40% in those with early latent syphilis and less than 8% in mothers with late latent syphilis.

- Is higher in women coinfected with HIV since they more frequently receive no prenatal care and their disease is inadequately treated.

Coinfection with syphilis may also increase the rate of mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

Untreated early syphilis during pregnancy results in spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, or perinatal death in up to 40% of cases. Infected newborns with early congenital syphilis can be asymptomatic or have evidence of hepatosplenomegaly, generalized lymphadenopathy, nasal discharge that is occasionally bloody, rash, and skeletal abnormalities (osteochondritis and periostitis). Other manifestations include edema, hemolytic anemia, jaundice, pneumonia, pseudoparalysis, and thrombocytopenia. Asymptomatic infants may have abnormal cerebrospinal fluid findings including elevated CSF white cell count, elevated protein, and a reactive venereal disease research laboratory test.

Late congenital syphilis, defined as the onset of symptoms after 2 years of age is secondary to scarring or persistent inflammation and gumma formation in a variety of tissues. It occurs in up to 40% of cases of untreated maternal disease. Most cases can be prevented by maternal treatment and treatment of the infant within the first 3 months of life. Common clinical manifestations include interstitial keratitis, sensorineural hearing loss, frontal bossing, saddle nose, Hutchinson teeth, mulberry molars, perforation of the hard palate, anterior bowing of the tibia (saber shins), and other skeletal abnormalities.

Diagnostic tests. Maternal diagnosis is dependent upon knowing the results of both a nontreponemal (RPR, VDRL) and a confirmatory treponemal test (TP-PA, TP-EIA, TP-CIA, FTA-ABS,) before or at delivery. TP-PA is the preferred test. When maternal disease is confirmed, the newborn should have the same quantitative nontreponemal test as the mother. A confirmatory treponemal test is not required

Evaluation and treatment. It’s imperative that children born to mothers with a reactive test, regardless of their treatment status, have a thorough exam performed before hospital discharge. The provider must determine what additional interventions should be performed.

The American Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/congenital-syphilis.htm) have developed standard algorithms for the diagnostic approach and treatment of infants born to mothers with reactive serologic tests for syphilis. It is available in the Red Book for AAP members (https://publications.aap.org/redbook). Recommendations based on various scenarios for neonates up to 1 month of age include proven or highly probable congenital syphilis, possible congenital syphilis, congenital syphilis less likely, and congenital syphilis unlikely. It is beyond the scope of this article to list the criteria and evaluation for each scenario. The reader is referred to the algorithm.

If syphilis is suspected in infants or children older than 1 month, the challenge is to determine if it is untreated congenital syphilis or acquired syphilis. Maternal syphilis status should be determined. Evaluation for congenital syphilis in this age group includes CSF analysis for VDRL, cell count and protein, CBC with differential and platelets, hepatic panel, abdominal ultrasound, long-bone radiographs, chest radiograph, neuroimaging, auditory brain stem response, and HIV testing.

Let’s go back to your patient. The mother was diagnosed with syphilis during pregnancy. You confirm that she was treated with benzathine penicillin G, and the course was completed at least 4 weeks before delivery. Treatment with any other drug during pregnancy is not appropriate. The RPR has declined, and the infant’s titer is equal to or less than four times the maternal titer. The exam is significant for generalized adenopathy and slightly bloody nasal discharge. This infant has two findings consistent with congenital syphilis regardless of RPR titer or treatment status. This places him in the proven or highly probable congenital syphilis group. Management includes CSF analysis (VDRL, cell count, and protein), CBC with differential and platelet count, and treatment with penicillin G for 10 days. Additional tests as clinically indicated include: long-bone radiograph, chest radiography, aspartate aminotranferase and alanine aminotransferase levels, neuroimaging, ophthalmologic exam, and auditory brain stem response. Despite maternal treatment, this newborn has congenital syphilis. The same nontreponemal test should be obtained every 2-3 months until it is nonreactive. It should be nonreactive by 6 months. If the infection persists to 6-12 months post treatment, reevaluation including CSF analysis and retreatment may be indicated.

Congenital syphilis can be prevented by maternal screening, diagnosis, and treatment. When that fails it is up to us to diagnosis and adequately treat our patients.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

You’re rounding in the nursery and informed of the following about one of your new patients: He’s a 38-week-old infant delivered to a mother diagnosed with syphilis at 12 weeks’ gestation at her initial prenatal visit. Her rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was 1:64 and the fluorescent treponemal antibody–absorption (FTA-ABS) test was positive. By report she was appropriately treated. Maternal RPRs obtained at 18 and 28 weeks’ gestation were 1:16 and 1:4, respectively. Maternal RPR at delivery and the infant’s RPR obtained shortly after birth were both 1:4. The mother wants to know if her baby is infected.

One result of syphilis during pregnancy is intrauterine infection and resultant congenital disease in the infant. Before you answer this mother, let’s discuss syphilis.

Congenital syphilis is a significant public health problem. In 2021, there were a total of 2,677 cases reported for a rate of 74.1 per 100,000 live births. Between 2020 and 2021, the number of cases of congenital syphilis increased 24.1% (2,158-2,677 cases), concurrent with a 45.8% increase (10.7-15.6 per 100,000) in the rate of primary and secondary syphilis in women aged 15-44 years. Between 2012 and 2021, the number of cases of congenital syphilis increased 701.5% (334-2,677 cases) and the increase in rates of primary and secondary syphilis in women aged 15-44 was 642.9% over the same period.

Why are the rates of congenital syphilis increasing? Most cases result from a lack of prenatal care and thus no testing for syphilis. The next most common cause is inadequate maternal treatment.

Congenital syphilis usually is acquired through transplacental transmission of spirochetes in the maternal bloodstream. Occasionally, it occurs at delivery via direct contact with maternal lesions. It is not transmitted in breast milk. Transmission of syphilis:

- Can occur any time during pregnancy.

- Is more likely to occur in women with untreated primary or secondary disease (60%-100%).

- Is approximately 40% in those with early latent syphilis and less than 8% in mothers with late latent syphilis.

- Is higher in women coinfected with HIV since they more frequently receive no prenatal care and their disease is inadequately treated.

Coinfection with syphilis may also increase the rate of mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

Untreated early syphilis during pregnancy results in spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, or perinatal death in up to 40% of cases. Infected newborns with early congenital syphilis can be asymptomatic or have evidence of hepatosplenomegaly, generalized lymphadenopathy, nasal discharge that is occasionally bloody, rash, and skeletal abnormalities (osteochondritis and periostitis). Other manifestations include edema, hemolytic anemia, jaundice, pneumonia, pseudoparalysis, and thrombocytopenia. Asymptomatic infants may have abnormal cerebrospinal fluid findings including elevated CSF white cell count, elevated protein, and a reactive venereal disease research laboratory test.

Late congenital syphilis, defined as the onset of symptoms after 2 years of age is secondary to scarring or persistent inflammation and gumma formation in a variety of tissues. It occurs in up to 40% of cases of untreated maternal disease. Most cases can be prevented by maternal treatment and treatment of the infant within the first 3 months of life. Common clinical manifestations include interstitial keratitis, sensorineural hearing loss, frontal bossing, saddle nose, Hutchinson teeth, mulberry molars, perforation of the hard palate, anterior bowing of the tibia (saber shins), and other skeletal abnormalities.

Diagnostic tests. Maternal diagnosis is dependent upon knowing the results of both a nontreponemal (RPR, VDRL) and a confirmatory treponemal test (TP-PA, TP-EIA, TP-CIA, FTA-ABS,) before or at delivery. TP-PA is the preferred test. When maternal disease is confirmed, the newborn should have the same quantitative nontreponemal test as the mother. A confirmatory treponemal test is not required

Evaluation and treatment. It’s imperative that children born to mothers with a reactive test, regardless of their treatment status, have a thorough exam performed before hospital discharge. The provider must determine what additional interventions should be performed.

The American Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/congenital-syphilis.htm) have developed standard algorithms for the diagnostic approach and treatment of infants born to mothers with reactive serologic tests for syphilis. It is available in the Red Book for AAP members (https://publications.aap.org/redbook). Recommendations based on various scenarios for neonates up to 1 month of age include proven or highly probable congenital syphilis, possible congenital syphilis, congenital syphilis less likely, and congenital syphilis unlikely. It is beyond the scope of this article to list the criteria and evaluation for each scenario. The reader is referred to the algorithm.

If syphilis is suspected in infants or children older than 1 month, the challenge is to determine if it is untreated congenital syphilis or acquired syphilis. Maternal syphilis status should be determined. Evaluation for congenital syphilis in this age group includes CSF analysis for VDRL, cell count and protein, CBC with differential and platelets, hepatic panel, abdominal ultrasound, long-bone radiographs, chest radiograph, neuroimaging, auditory brain stem response, and HIV testing.

Let’s go back to your patient. The mother was diagnosed with syphilis during pregnancy. You confirm that she was treated with benzathine penicillin G, and the course was completed at least 4 weeks before delivery. Treatment with any other drug during pregnancy is not appropriate. The RPR has declined, and the infant’s titer is equal to or less than four times the maternal titer. The exam is significant for generalized adenopathy and slightly bloody nasal discharge. This infant has two findings consistent with congenital syphilis regardless of RPR titer or treatment status. This places him in the proven or highly probable congenital syphilis group. Management includes CSF analysis (VDRL, cell count, and protein), CBC with differential and platelet count, and treatment with penicillin G for 10 days. Additional tests as clinically indicated include: long-bone radiograph, chest radiography, aspartate aminotranferase and alanine aminotransferase levels, neuroimaging, ophthalmologic exam, and auditory brain stem response. Despite maternal treatment, this newborn has congenital syphilis. The same nontreponemal test should be obtained every 2-3 months until it is nonreactive. It should be nonreactive by 6 months. If the infection persists to 6-12 months post treatment, reevaluation including CSF analysis and retreatment may be indicated.

Congenital syphilis can be prevented by maternal screening, diagnosis, and treatment. When that fails it is up to us to diagnosis and adequately treat our patients.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

You’re rounding in the nursery and informed of the following about one of your new patients: He’s a 38-week-old infant delivered to a mother diagnosed with syphilis at 12 weeks’ gestation at her initial prenatal visit. Her rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was 1:64 and the fluorescent treponemal antibody–absorption (FTA-ABS) test was positive. By report she was appropriately treated. Maternal RPRs obtained at 18 and 28 weeks’ gestation were 1:16 and 1:4, respectively. Maternal RPR at delivery and the infant’s RPR obtained shortly after birth were both 1:4. The mother wants to know if her baby is infected.

One result of syphilis during pregnancy is intrauterine infection and resultant congenital disease in the infant. Before you answer this mother, let’s discuss syphilis.

Congenital syphilis is a significant public health problem. In 2021, there were a total of 2,677 cases reported for a rate of 74.1 per 100,000 live births. Between 2020 and 2021, the number of cases of congenital syphilis increased 24.1% (2,158-2,677 cases), concurrent with a 45.8% increase (10.7-15.6 per 100,000) in the rate of primary and secondary syphilis in women aged 15-44 years. Between 2012 and 2021, the number of cases of congenital syphilis increased 701.5% (334-2,677 cases) and the increase in rates of primary and secondary syphilis in women aged 15-44 was 642.9% over the same period.

Why are the rates of congenital syphilis increasing? Most cases result from a lack of prenatal care and thus no testing for syphilis. The next most common cause is inadequate maternal treatment.

Congenital syphilis usually is acquired through transplacental transmission of spirochetes in the maternal bloodstream. Occasionally, it occurs at delivery via direct contact with maternal lesions. It is not transmitted in breast milk. Transmission of syphilis:

- Can occur any time during pregnancy.

- Is more likely to occur in women with untreated primary or secondary disease (60%-100%).

- Is approximately 40% in those with early latent syphilis and less than 8% in mothers with late latent syphilis.

- Is higher in women coinfected with HIV since they more frequently receive no prenatal care and their disease is inadequately treated.

Coinfection with syphilis may also increase the rate of mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

Untreated early syphilis during pregnancy results in spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, or perinatal death in up to 40% of cases. Infected newborns with early congenital syphilis can be asymptomatic or have evidence of hepatosplenomegaly, generalized lymphadenopathy, nasal discharge that is occasionally bloody, rash, and skeletal abnormalities (osteochondritis and periostitis). Other manifestations include edema, hemolytic anemia, jaundice, pneumonia, pseudoparalysis, and thrombocytopenia. Asymptomatic infants may have abnormal cerebrospinal fluid findings including elevated CSF white cell count, elevated protein, and a reactive venereal disease research laboratory test.

Late congenital syphilis, defined as the onset of symptoms after 2 years of age is secondary to scarring or persistent inflammation and gumma formation in a variety of tissues. It occurs in up to 40% of cases of untreated maternal disease. Most cases can be prevented by maternal treatment and treatment of the infant within the first 3 months of life. Common clinical manifestations include interstitial keratitis, sensorineural hearing loss, frontal bossing, saddle nose, Hutchinson teeth, mulberry molars, perforation of the hard palate, anterior bowing of the tibia (saber shins), and other skeletal abnormalities.

Diagnostic tests. Maternal diagnosis is dependent upon knowing the results of both a nontreponemal (RPR, VDRL) and a confirmatory treponemal test (TP-PA, TP-EIA, TP-CIA, FTA-ABS,) before or at delivery. TP-PA is the preferred test. When maternal disease is confirmed, the newborn should have the same quantitative nontreponemal test as the mother. A confirmatory treponemal test is not required

Evaluation and treatment. It’s imperative that children born to mothers with a reactive test, regardless of their treatment status, have a thorough exam performed before hospital discharge. The provider must determine what additional interventions should be performed.

The American Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/congenital-syphilis.htm) have developed standard algorithms for the diagnostic approach and treatment of infants born to mothers with reactive serologic tests for syphilis. It is available in the Red Book for AAP members (https://publications.aap.org/redbook). Recommendations based on various scenarios for neonates up to 1 month of age include proven or highly probable congenital syphilis, possible congenital syphilis, congenital syphilis less likely, and congenital syphilis unlikely. It is beyond the scope of this article to list the criteria and evaluation for each scenario. The reader is referred to the algorithm.

If syphilis is suspected in infants or children older than 1 month, the challenge is to determine if it is untreated congenital syphilis or acquired syphilis. Maternal syphilis status should be determined. Evaluation for congenital syphilis in this age group includes CSF analysis for VDRL, cell count and protein, CBC with differential and platelets, hepatic panel, abdominal ultrasound, long-bone radiographs, chest radiograph, neuroimaging, auditory brain stem response, and HIV testing.

Let’s go back to your patient. The mother was diagnosed with syphilis during pregnancy. You confirm that she was treated with benzathine penicillin G, and the course was completed at least 4 weeks before delivery. Treatment with any other drug during pregnancy is not appropriate. The RPR has declined, and the infant’s titer is equal to or less than four times the maternal titer. The exam is significant for generalized adenopathy and slightly bloody nasal discharge. This infant has two findings consistent with congenital syphilis regardless of RPR titer or treatment status. This places him in the proven or highly probable congenital syphilis group. Management includes CSF analysis (VDRL, cell count, and protein), CBC with differential and platelet count, and treatment with penicillin G for 10 days. Additional tests as clinically indicated include: long-bone radiograph, chest radiography, aspartate aminotranferase and alanine aminotransferase levels, neuroimaging, ophthalmologic exam, and auditory brain stem response. Despite maternal treatment, this newborn has congenital syphilis. The same nontreponemal test should be obtained every 2-3 months until it is nonreactive. It should be nonreactive by 6 months. If the infection persists to 6-12 months post treatment, reevaluation including CSF analysis and retreatment may be indicated.

Congenital syphilis can be prevented by maternal screening, diagnosis, and treatment. When that fails it is up to us to diagnosis and adequately treat our patients.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Digital mental health training acceptable to boarding teens

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – A modular digital intervention to teach mental health skills to youth awaiting transfer to psychiatric care appeared feasible to implement and acceptable to teens and their parents, according to a study presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference.

“This program has the potential to teach evidence-based mental health skills to youth during boarding, providing a head start on recovery prior to psychiatric hospitalization,” study coauthor Samantha House, DO, MPH, section chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H., told attendees.

Mental health boarding has become increasingly common as psychiatric care resources have been stretched by a crisis in pediatric mental health that began even before the COVID pandemic. Since youth often don’t receive evidence-based therapies while boarding, Dr. House and her coauthor, JoAnna K. Leyenaar, MD, PhD, MPH, developed a pilot program called I-CARE, which stands for Improving Care, Accelerating Recovery and Education.

I-CARE is a digital health intervention that combines videos on a tablet with workbook exercises that teach mental health skills. The seven modules include an introduction and one each on schedule-making, safety planning, psychoeducation, behavioral activation, relaxation skills, and mindfulness skills. Licensed nursing assistants who have received a 6-hour training from a clinical psychologist administer the program and provide safety supervision during boarding.

“I-CARE was designed to be largely self-directed, supported by ‘coaches’ who are not mental health professionals,” Dr. Leyenaar, vice chair of research in the department of pediatrics and an associate professor of pediatrics at Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., said in an interview. With this model, the program requires minimal additional resources beyond the tablets and workbooks, and is designed for implementation in settings with few or no mental health professionals, she said.

Cora Breuner, MD, MPH, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington, Seattle, and an attending physician at Seattle Children’s Hospital, was not involved in the study but was excited to see it.

“I think it’s a really good idea, and I like that it’s being studied,” Dr. Breuner said in an interview. She said the health care and public health system has let down an entire population who data had shown were experiencing mental health problems.

“We knew before the pandemic that behavioral health issues were creeping up slowly with anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, and, of course, substance use disorders and eating disorders, and not a lot was being done about it,” Dr. Breuner said, and the pandemic exacerbated those issues. ”I don’t know why no one realized that this was going to be the downstream effect of having no socialization for kids for 18 months and limited resources for those who we need desperately to provide care for,” especially BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and people of color] kids and underresourced kids.

That sentiment is exactly what inspired the creation of the program, according to Dr. Leyenaar.

The I-CARE program was implemented at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center in November 2021 for adolescents aged 12-17 who were boarding because of suicidality or self-harm. The program and study excluded youth with psychosis and other cognitive or behavioral conditions that didn’t fit with the skills taught by the module training.

The researchers qualitatively evaluated the I-CARE program in youth who were offered at least two I-CARE modules and with parents present during boarding.

Twenty-four youth, with a median age of 14, were offered the I-CARE program between November 2021 and April 2022 while boarding for a median 8 days. Most of the patients were female (79%), and a third were transgender or gender diverse. Most were White (83%), and about two-thirds had Medicaid (62.5%). The most common diagnoses among the participants were major depressive disorder (71%) and generalized anxiety disorder (46%). Others included PTSD (29%), restrictive eating disorder (21%), and bipolar disorder (12.5%).

All offered the program completed the first module, and 79% participated in additional modules. The main reason for discontinuation was transfer to another facility, but a few youth either refused to engage with the program or felt they knew the material well enough that they weren’t benefiting from it.

The evaluation involved 16 youth, seven parents, and 17 clinicians. On a Likert scale, the composite score for the program’s appropriateness – suitability, applicability, and meeting needs – was an average 3.7, with a higher rating from clinicians (4.3) and caregivers (3.5) than youth (2.8).

“Some youth felt the intervention was better suited for a younger audience or those with less familiarity with mental health skills, but they acknowledged that the intervention would be helpful and appropriate for others,” Dr. House, who is also an assistant professor of pediatrics at Geisel School of Medicine, said.

Youth rated the acceptability of the program more highly (3.6) and all three groups found it easy to use, with an average feasibility score of 4 across the board. The program’s acceptability received an average score of 4 from parents and clinicians.

”Teens seem to particularly value the psychoeducation module that explains the relationship between thoughts and feelings, as well as the opportunity to develop a personalized safety plan,” Dr. Leyenaar said.

Among the challenges expressed by the participating teens were that the loud sounds and beeping in the hospital made it difficult to practice mindfulness and that they often had to wait for staff to be available to do I-CARE.

“I feel like not many people have been trained yet,” one teen said, “so to have more nurses available to do I-CARE would be helpful.”

Another participant found the coaches helpful. “Sometimes they were my nurse, sometimes they were someone I never met before. … and also, they were all really, really nice,” the teen said.

Another teen regarded the material as “really surface-level mental health stuff” that they thought “could be helpful to other people who are here for the first time.” But others found the content more beneficial.

“The videos were helpful. … I was worried that they weren’t going to be very informative, but they did make sense to me,” one participant said. “They weren’t overcomplicating things. … They weren’t saying anything I didn’t understand, so that was good.”

The researchers next plan to conduct a multisite study to determine the program’s effectiveness in improving health outcomes and reducing suicidal ideation. Dr. House and Dr. Leyenaar are looking at ways to refine the program.

”We may narrow the age range for participants, with an upper age limit of 16, since some older teens said that the modules were best suited for a younger audience,” Dr. Leyenaar said. “We are also discussing how to best support youth who are readmitted to our hospital and have participated in I-CARE previously.”

Dr. Breuner said she would be interested to see, in future studies of the program, whether it reduced the likelihood of inpatient psychiatric stay, the length of psychiatric stay after admission, or the risk of readmission. She also wondered if the program might be offered in languages other than English, whether a version might be specifically designed for BIPOC youth, and whether the researchers had considered offering the intervention to caregivers as well.

The modules are teaching the kids but should they also be teaching the parents? Dr. Breuner wondered. A lot of times, she said, the parents are bringing these kids in because they don’t know what to do and can’t deal with them anymore. Offering modules on the same skills to caregivers would also enable the caregivers to reinforce and reteach the skills to their children, especially if the youth struggled to really take in what the modules were trying to teach.

Dr. Leyenaar said she expects buy-in for a program like this would be high at other institutions, but it’s premature to scale it up until they’ve conducted at least another clinical trial on its effectiveness. The biggest potential barrier to buy-in that Dr. Breuner perceived would be cost.

“It’s always difficult when it costs money” since the hospital needs to train the clinicians who provide the care, Dr. Breuner said, but it’s possible those costs could be offset if the program reduces the risk of readmission or return to the emergency department.

While the overall risk of harms from the intervention are low, Dr. Breuner said it is important to be conscious that the intervention may not necessarily be appropriate for all youth.

“There’s always risk when there’s a trauma background, and you have to be very careful, especially with mindfulness training,” Dr. Breuner said. For those with a history of abuse or other adverse childhood experiences “for someone to get into a very calm, still place can actually be counterproductive.”

Dr. Breuner especially appreciated that the researchers involved the youth and caregivers in the evaluation process. “That the parents expressed positive attitudes is really incredible,” she said.

Dr. House, Dr. Leyenaar, and Dr. Breuner had no disclosures. No external funding was noted for the study.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – A modular digital intervention to teach mental health skills to youth awaiting transfer to psychiatric care appeared feasible to implement and acceptable to teens and their parents, according to a study presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference.

“This program has the potential to teach evidence-based mental health skills to youth during boarding, providing a head start on recovery prior to psychiatric hospitalization,” study coauthor Samantha House, DO, MPH, section chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H., told attendees.

Mental health boarding has become increasingly common as psychiatric care resources have been stretched by a crisis in pediatric mental health that began even before the COVID pandemic. Since youth often don’t receive evidence-based therapies while boarding, Dr. House and her coauthor, JoAnna K. Leyenaar, MD, PhD, MPH, developed a pilot program called I-CARE, which stands for Improving Care, Accelerating Recovery and Education.

I-CARE is a digital health intervention that combines videos on a tablet with workbook exercises that teach mental health skills. The seven modules include an introduction and one each on schedule-making, safety planning, psychoeducation, behavioral activation, relaxation skills, and mindfulness skills. Licensed nursing assistants who have received a 6-hour training from a clinical psychologist administer the program and provide safety supervision during boarding.

“I-CARE was designed to be largely self-directed, supported by ‘coaches’ who are not mental health professionals,” Dr. Leyenaar, vice chair of research in the department of pediatrics and an associate professor of pediatrics at Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., said in an interview. With this model, the program requires minimal additional resources beyond the tablets and workbooks, and is designed for implementation in settings with few or no mental health professionals, she said.

Cora Breuner, MD, MPH, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington, Seattle, and an attending physician at Seattle Children’s Hospital, was not involved in the study but was excited to see it.

“I think it’s a really good idea, and I like that it’s being studied,” Dr. Breuner said in an interview. She said the health care and public health system has let down an entire population who data had shown were experiencing mental health problems.

“We knew before the pandemic that behavioral health issues were creeping up slowly with anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, and, of course, substance use disorders and eating disorders, and not a lot was being done about it,” Dr. Breuner said, and the pandemic exacerbated those issues. ”I don’t know why no one realized that this was going to be the downstream effect of having no socialization for kids for 18 months and limited resources for those who we need desperately to provide care for,” especially BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and people of color] kids and underresourced kids.

That sentiment is exactly what inspired the creation of the program, according to Dr. Leyenaar.

The I-CARE program was implemented at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center in November 2021 for adolescents aged 12-17 who were boarding because of suicidality or self-harm. The program and study excluded youth with psychosis and other cognitive or behavioral conditions that didn’t fit with the skills taught by the module training.

The researchers qualitatively evaluated the I-CARE program in youth who were offered at least two I-CARE modules and with parents present during boarding.

Twenty-four youth, with a median age of 14, were offered the I-CARE program between November 2021 and April 2022 while boarding for a median 8 days. Most of the patients were female (79%), and a third were transgender or gender diverse. Most were White (83%), and about two-thirds had Medicaid (62.5%). The most common diagnoses among the participants were major depressive disorder (71%) and generalized anxiety disorder (46%). Others included PTSD (29%), restrictive eating disorder (21%), and bipolar disorder (12.5%).

All offered the program completed the first module, and 79% participated in additional modules. The main reason for discontinuation was transfer to another facility, but a few youth either refused to engage with the program or felt they knew the material well enough that they weren’t benefiting from it.

The evaluation involved 16 youth, seven parents, and 17 clinicians. On a Likert scale, the composite score for the program’s appropriateness – suitability, applicability, and meeting needs – was an average 3.7, with a higher rating from clinicians (4.3) and caregivers (3.5) than youth (2.8).

“Some youth felt the intervention was better suited for a younger audience or those with less familiarity with mental health skills, but they acknowledged that the intervention would be helpful and appropriate for others,” Dr. House, who is also an assistant professor of pediatrics at Geisel School of Medicine, said.

Youth rated the acceptability of the program more highly (3.6) and all three groups found it easy to use, with an average feasibility score of 4 across the board. The program’s acceptability received an average score of 4 from parents and clinicians.

”Teens seem to particularly value the psychoeducation module that explains the relationship between thoughts and feelings, as well as the opportunity to develop a personalized safety plan,” Dr. Leyenaar said.

Among the challenges expressed by the participating teens were that the loud sounds and beeping in the hospital made it difficult to practice mindfulness and that they often had to wait for staff to be available to do I-CARE.

“I feel like not many people have been trained yet,” one teen said, “so to have more nurses available to do I-CARE would be helpful.”

Another participant found the coaches helpful. “Sometimes they were my nurse, sometimes they were someone I never met before. … and also, they were all really, really nice,” the teen said.

Another teen regarded the material as “really surface-level mental health stuff” that they thought “could be helpful to other people who are here for the first time.” But others found the content more beneficial.

“The videos were helpful. … I was worried that they weren’t going to be very informative, but they did make sense to me,” one participant said. “They weren’t overcomplicating things. … They weren’t saying anything I didn’t understand, so that was good.”

The researchers next plan to conduct a multisite study to determine the program’s effectiveness in improving health outcomes and reducing suicidal ideation. Dr. House and Dr. Leyenaar are looking at ways to refine the program.

”We may narrow the age range for participants, with an upper age limit of 16, since some older teens said that the modules were best suited for a younger audience,” Dr. Leyenaar said. “We are also discussing how to best support youth who are readmitted to our hospital and have participated in I-CARE previously.”

Dr. Breuner said she would be interested to see, in future studies of the program, whether it reduced the likelihood of inpatient psychiatric stay, the length of psychiatric stay after admission, or the risk of readmission. She also wondered if the program might be offered in languages other than English, whether a version might be specifically designed for BIPOC youth, and whether the researchers had considered offering the intervention to caregivers as well.

The modules are teaching the kids but should they also be teaching the parents? Dr. Breuner wondered. A lot of times, she said, the parents are bringing these kids in because they don’t know what to do and can’t deal with them anymore. Offering modules on the same skills to caregivers would also enable the caregivers to reinforce and reteach the skills to their children, especially if the youth struggled to really take in what the modules were trying to teach.

Dr. Leyenaar said she expects buy-in for a program like this would be high at other institutions, but it’s premature to scale it up until they’ve conducted at least another clinical trial on its effectiveness. The biggest potential barrier to buy-in that Dr. Breuner perceived would be cost.

“It’s always difficult when it costs money” since the hospital needs to train the clinicians who provide the care, Dr. Breuner said, but it’s possible those costs could be offset if the program reduces the risk of readmission or return to the emergency department.

While the overall risk of harms from the intervention are low, Dr. Breuner said it is important to be conscious that the intervention may not necessarily be appropriate for all youth.

“There’s always risk when there’s a trauma background, and you have to be very careful, especially with mindfulness training,” Dr. Breuner said. For those with a history of abuse or other adverse childhood experiences “for someone to get into a very calm, still place can actually be counterproductive.”