User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Early or delayed menopause and irregular periods tied to new-onset atrial fibrillation

Takeaway

- Early or delayed menopause and a history of irregular menstrual cycles were significantly associated with a greater risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation (AF) in women.

- Women with nulliparity and multiparity had a greater risk of new-onset AF compared with those with one to two live births.

Why this matters

- Findings highlight the significance of considering the reproductive history of women while developing tailored screening and prevention strategies for AF.

Study design

- A population-based cohort study of 235,191 women (age, 40-69 years) without AF and a history of hysterectomy and/or bilateral oophorectomy, identified from the UK Biobank (2006-2010).

- Funding: Gender and Prevention Grant from ZonMw and other.

Key results

- During a median follow-up of 11.6 years, 4,629 (2.0%) women were diagnosed with new-onset AF.

- A history of irregular menstrual cycle was associated with higher risk of new-onset AF (adjusted HR, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.79; P = .04).

- Compared with women who experienced menarche at the age of 12 years, the risk of new-onset AF was significantly higher in those who experienced menarche:

- –Earlier between the ages of 7 and 11 years (aHR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.00-1.21; P = .04) and

- –Later between the ages of 13 and 18 years (aHR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.00-1.17; P = .05).

- The risk of new-onset AF was significantly higher in women who experienced menopause:

- –At the age of < 35 years (aHR, 2.25; 95% CI, 1.48-3.43; P < .001);

- –Between the ages of 35 and 44 years (aHR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.10-1.39; P < .001); and

- –At the age of ≥ 60 years (aHR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.10-1.78; P = .04).

- Women with no live births (aHR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.04-1.24; P < .01), four to six live births (aHR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.01-1.24; P = .04), and ≥ seven live births (aHR, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.03-2.70; P = .03) vs. those with one to two live births had a significantly higher risk of new-onset AF.

Limitations

- Observational design.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape UK.

Reference

Lu Z, Aribas E, Geurts S, Roeters van Lennep JE, Ikram MA, Bos MM, de Groot NMS, Kavousi M. Association Between Sex-Specific Risk Factors and Risk of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation Among Women. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(9):e2229716. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.29716. PMID: 36048441.

Takeaway

- Early or delayed menopause and a history of irregular menstrual cycles were significantly associated with a greater risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation (AF) in women.

- Women with nulliparity and multiparity had a greater risk of new-onset AF compared with those with one to two live births.

Why this matters

- Findings highlight the significance of considering the reproductive history of women while developing tailored screening and prevention strategies for AF.

Study design

- A population-based cohort study of 235,191 women (age, 40-69 years) without AF and a history of hysterectomy and/or bilateral oophorectomy, identified from the UK Biobank (2006-2010).

- Funding: Gender and Prevention Grant from ZonMw and other.

Key results

- During a median follow-up of 11.6 years, 4,629 (2.0%) women were diagnosed with new-onset AF.

- A history of irregular menstrual cycle was associated with higher risk of new-onset AF (adjusted HR, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.79; P = .04).

- Compared with women who experienced menarche at the age of 12 years, the risk of new-onset AF was significantly higher in those who experienced menarche:

- –Earlier between the ages of 7 and 11 years (aHR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.00-1.21; P = .04) and

- –Later between the ages of 13 and 18 years (aHR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.00-1.17; P = .05).

- The risk of new-onset AF was significantly higher in women who experienced menopause:

- –At the age of < 35 years (aHR, 2.25; 95% CI, 1.48-3.43; P < .001);

- –Between the ages of 35 and 44 years (aHR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.10-1.39; P < .001); and

- –At the age of ≥ 60 years (aHR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.10-1.78; P = .04).

- Women with no live births (aHR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.04-1.24; P < .01), four to six live births (aHR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.01-1.24; P = .04), and ≥ seven live births (aHR, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.03-2.70; P = .03) vs. those with one to two live births had a significantly higher risk of new-onset AF.

Limitations

- Observational design.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape UK.

Reference

Lu Z, Aribas E, Geurts S, Roeters van Lennep JE, Ikram MA, Bos MM, de Groot NMS, Kavousi M. Association Between Sex-Specific Risk Factors and Risk of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation Among Women. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(9):e2229716. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.29716. PMID: 36048441.

Takeaway

- Early or delayed menopause and a history of irregular menstrual cycles were significantly associated with a greater risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation (AF) in women.

- Women with nulliparity and multiparity had a greater risk of new-onset AF compared with those with one to two live births.

Why this matters

- Findings highlight the significance of considering the reproductive history of women while developing tailored screening and prevention strategies for AF.

Study design

- A population-based cohort study of 235,191 women (age, 40-69 years) without AF and a history of hysterectomy and/or bilateral oophorectomy, identified from the UK Biobank (2006-2010).

- Funding: Gender and Prevention Grant from ZonMw and other.

Key results

- During a median follow-up of 11.6 years, 4,629 (2.0%) women were diagnosed with new-onset AF.

- A history of irregular menstrual cycle was associated with higher risk of new-onset AF (adjusted HR, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.79; P = .04).

- Compared with women who experienced menarche at the age of 12 years, the risk of new-onset AF was significantly higher in those who experienced menarche:

- –Earlier between the ages of 7 and 11 years (aHR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.00-1.21; P = .04) and

- –Later between the ages of 13 and 18 years (aHR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.00-1.17; P = .05).

- The risk of new-onset AF was significantly higher in women who experienced menopause:

- –At the age of < 35 years (aHR, 2.25; 95% CI, 1.48-3.43; P < .001);

- –Between the ages of 35 and 44 years (aHR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.10-1.39; P < .001); and

- –At the age of ≥ 60 years (aHR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.10-1.78; P = .04).

- Women with no live births (aHR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.04-1.24; P < .01), four to six live births (aHR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.01-1.24; P = .04), and ≥ seven live births (aHR, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.03-2.70; P = .03) vs. those with one to two live births had a significantly higher risk of new-onset AF.

Limitations

- Observational design.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape UK.

Reference

Lu Z, Aribas E, Geurts S, Roeters van Lennep JE, Ikram MA, Bos MM, de Groot NMS, Kavousi M. Association Between Sex-Specific Risk Factors and Risk of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation Among Women. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(9):e2229716. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.29716. PMID: 36048441.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Nonsurgical treatments for patients with urinary incontinence

CASE Patient has urine leakage that worsens with exercise

At her annual preventative health visit, a 39-year-old woman reports that she has leakage of urine. She states that she drinks “a gallon of water daily” to help her lose the 20 lb she gained during the COVID-19 pandemic. She wants to resume Zumba fitness classes, but exercise makes her urine leakage worse. She started wearing protective pads because she finds herself often leaking urine on the way to the bathroom.

What nonsurgical treatment options are available for this patient?

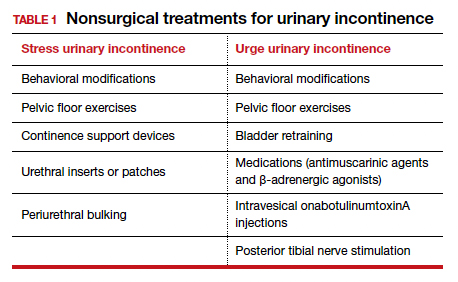

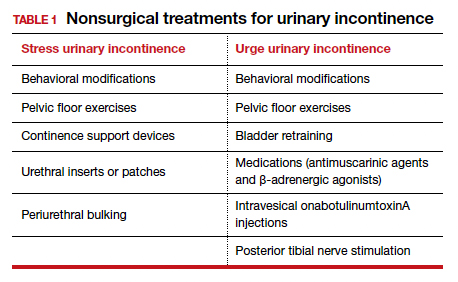

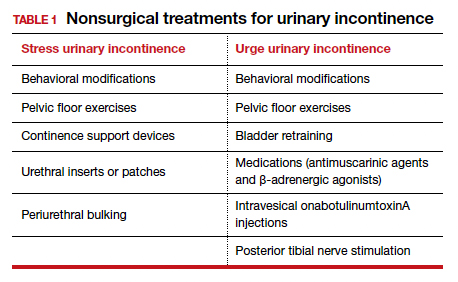

Nearly half of all women experience urinary incontinence (UI), the involuntary loss of urine, and the condition increases with age.1 This common condition negatively impacts physical and psychological health and has been associated with social isolation, sexual dysfunction, and reduced independence.2,3 Symptoms of UI are underreported, and therefore universal screening is recommended for women of all ages.4 The diversity of available treatments (TABLE 1) provides patients and clinicians an opportunity to develop a plan that aligns with their symptom severity, goals, preferences, and resources.

Types of UI

The most common types of UI are stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and urgency urinary incontinence (UUI). Mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) occurs when symptoms of both SUI and UUI are present. Although the mechanisms that lead to urine leakage vary by the type of incontinence, many primary interventions improve both types of leakage, so a clinical diagnosis is sufficient to initiate treatment.

Stress urinary incontinence results from an impaired or weakened sphincter, which leads to involuntary, yet predictable, urine loss during increased abdominal pressure, such as coughing, laughing, sneezing, lifting, or physical activity.5 In UUI, involuntary loss of urine often accompanies the sudden urge to void. UUI is associated with overactive bladder (OAB), defined as urinary urgency, with or without urinary incontinence, usually accompanied by urinary frequency and/or nocturia (urination that interrupts sleep).6

In OAB, the detrusor muscle contracts randomly, leading to a sudden urge to void. When bladder pressure exceeds urethral sphincter closure pressure, urine leakage occurs. Women describe the urgency episodes as unpredictable, the urine leakage as prolonged with large volumes, and often occurring as they seek the toilet. Risk factors include age, obesity, parity, history of vaginal delivery, family history, ethnicity/race, medical comorbidities, menopausal status, and tobacco use.5

Making a diagnosis

A basic office evaluation is the most key step for diagnostic accuracy that leads to treatment success. This includes a detailed history, assessment of symptom severity, physical exam, pelvic exam, urinalysis, postvoid residual (to rule out urinary retention), and a cough stress test (to demonstrate SUI). The goal is to assess symptom severity, determine the type of UI, and identify contributing and potentially reversible factors, such as a urinary tract infection, medications, pelvic organ prolapse, incomplete bladder emptying, or impaired neurologic status. In the absence of the latter, advanced diagnostic tests, such as urodynamics, contribute little toward discerning the type of incontinence or changing first-line treatment plans.7

During the COVID-19 pandemic, abbreviated, virtual assessments for urinary symptoms were associated with high degrees of satisfaction (91% for fulfillment of personal needs, 94% overall satisfaction).8 This highlights the value of validated symptom questionnaires that help establish a working diagnosis and treatment plan in the absence of a physical exam. Questionnaire-based diagnoses have acceptable accuracy for classifying UUI and SUI among women with uncomplicated medical and surgical histories and for initiating low-risk therapies for defined intervals.

The 3 incontinence questions (3IQ) screen is an example of a useful, quick diagnostic tool designed for the primary care setting (FIGURE 1).9 It has been used in pharmaceutical treatment trials for UUI, with low frequency of misdiagnosis (1%–4%), resulting in no harm by the drug treatment prescribed or by the delay in appropriate care.10 Due to the limitations of an abbreviated remote evaluation, however, clinicians should assess patient response to primary interventions in a timely window. Patients who fail to experience satisfactory symptom reduction within 6 to 12 weeks should complete their evaluation in person or through a referral to a urogynecology program.

Continue to: Primary therapies for UI...

Primary therapies for UI

Primary therapies for UUI and SUI target strength training of the pelvic floor muscles, moderation of fluid intake, and adjustment in voiding behaviors and medications. Any functional barriers to continence also should be identified and addressed. Simple interventions, including a daily bowel regimen to address constipation, a bedside commode, and scheduled voiding, may reduce incontinence episodes without incurring significant cost or risk. For women suspected of having MUI, the treatment plan should prioritize their most bothersome symptoms.

Lifestyle and behavioral modifications

Everyday habits, medical comorbidities, and medications may exacerbate the severity of both SUI and UUI. Behavioral therapy alone or in combination with other interventions effectively reduces both SUI and UUI symptoms and has been shown to improve the efficacy of continence surgery.11 Information gained from a 3-day bladder diary (FIGURE 2)12 can guide clinicians on personalized patient recommendations, such as reducing excessive consumption of fluids and bladder irritants, limiting late evening drinking in the setting of bothersome nocturia, and scheduling voids (every 2–3 hours) to preempt incontinence episodes.

Weight loss

Obesity is a strong, independent, modifiable risk factor for both SUI and UUI. Each 5 kg/m2 increase in body mass index (BMI) has been associated with a 20% to 70% increased risk of UI, while weight loss of 5% or greater in overweight or obese women can lead to at least a 50% decrease in UI frequency.13

Reducing fluid intake and bladder irritants

Overactive bladder symptoms often respond to moderation of excessive fluid intake and reduction of bladder irritants (caffeine, carbonated beverages, diet beverages, and alcohol). While there is no established definition of excess caffeine intake, one study categorized high caffeine intake as greater than 400 mg/day (approximately four 8-oz cups of coffee).14

Information provided in a bladder diary can guide individualized recommendations for reducing fluid intake, particularly when 24-hour urine production exceeds the normative range (> 50–60 oz or 1.5-1.8 L/day).15 Hydration needs vary by activity, environment, and food; some general guidelines suggest 48 to 64 oz/day.5,16

Continue to: Pelvic floor muscle training...

Pelvic floor muscle training

An effective treatment for both UUI and SUI symptoms, pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) leads to high degrees of patient satisfaction and improvement in quality of life.17 The presumed mechanisms of action of PFMT include improved urethral closure pressure and inhibition of detrusor muscle contractions.

Common exercise protocols recommend 3 sets of 10 contractions, held for 6 to 10 seconds per day, in varying positions of sitting, standing, and lying. While many women may be familiar with Kegel exercises, poor technique with straining and recruitment of gluteal and abdominal muscles can undermine the effect of PFMT. Clinicians can confirm successful pelvic muscle contractions by placing a finger in the vagina to appreciate contraction around and elevation of the finger toward the pubic symphysis in the absence of pushing.

Referral to supervised physical therapy and use of such teaching aid tools as booklets, mobile applications, and biofeedback can improve exercise adherence and outcomes.18,19 Systematic reviews report initial cure or improvement of incontinence symptoms as high as 74%, although little information is available about the long-term duration of effect.17

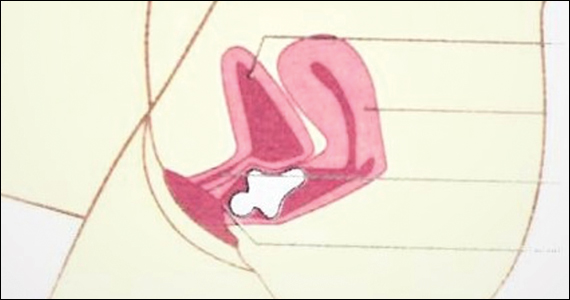

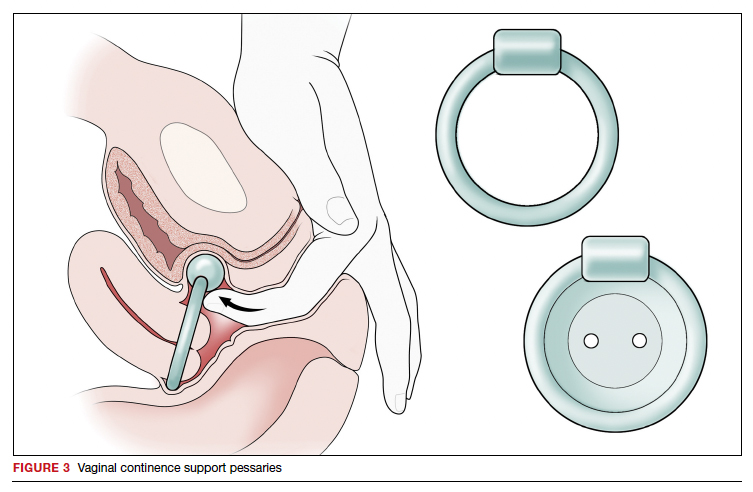

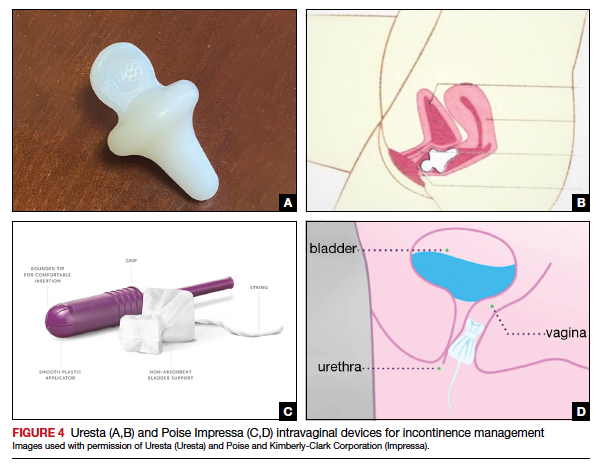

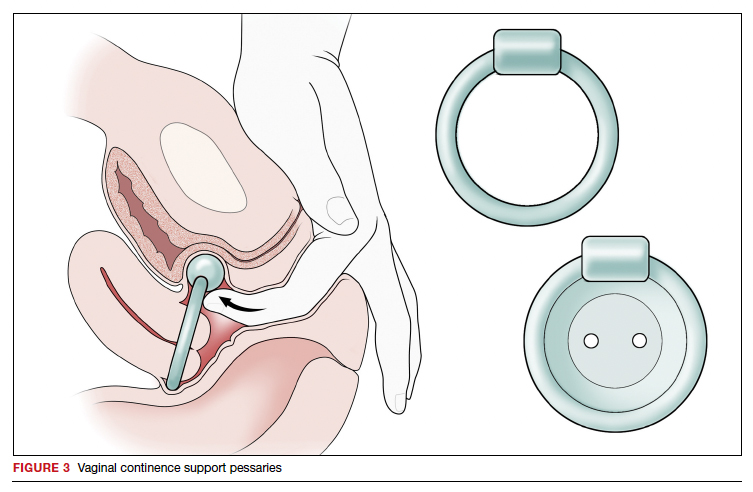

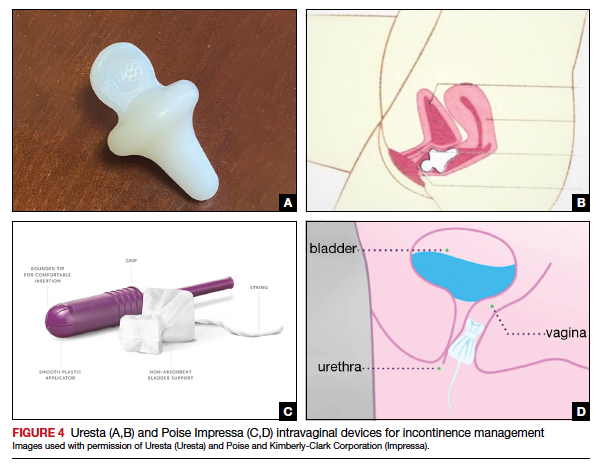

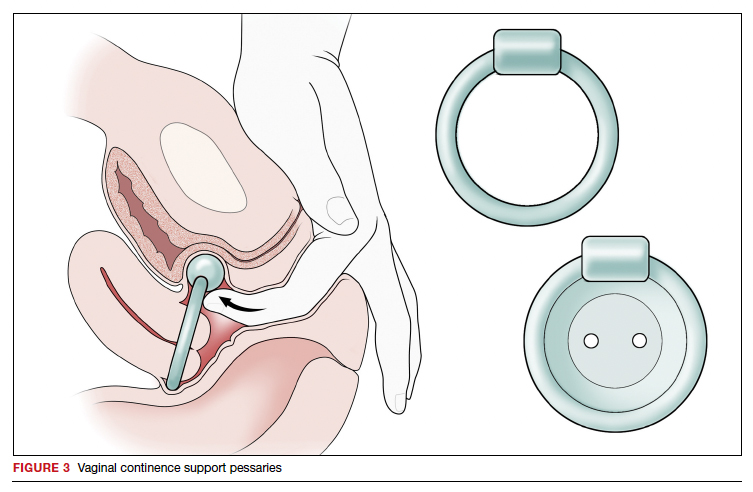

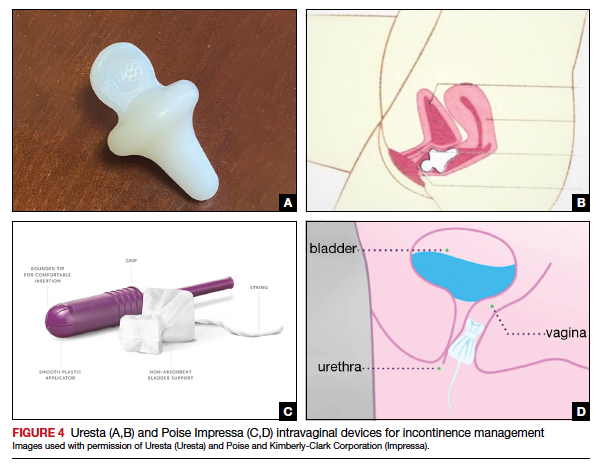

Vaginal pessaries

Vaginal continence support pessaries and devices work by stabilizing urethral mobility and compression of the bladder neck. Continence devices are particularly effective for situational SUI (such as during exercise).

The reusable medical grade silicone pessaries are available in numerous shapes and sizes and are fitted by a health care clinician (FIGURE 3). Uresta is a self-fitted intravaginal device that women can purchase online with a prescription. The Poise Impressa bladder support is a disposable intravaginal device marketed for incontinence and available over-the-counter, without a prescription (FIGURE 4). Anecdotally, many women find that menstrual tampons provide a similar effect, but outcome data are lacking.

In a comparative effectiveness trial of a continence pessary and behavior therapy, behavioral therapy was more likely to result in no bothersome incontinence symptoms (49% vs 33%, P = .006) and greater treatment satisfaction at 3 months.20 However, these short-term group differences did not persist at 12 months, presumably due to waning adherence.

UUI-specific nonsurgical treatments

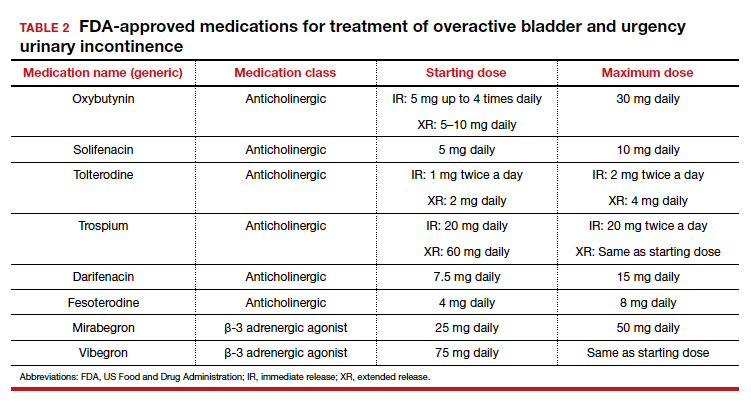

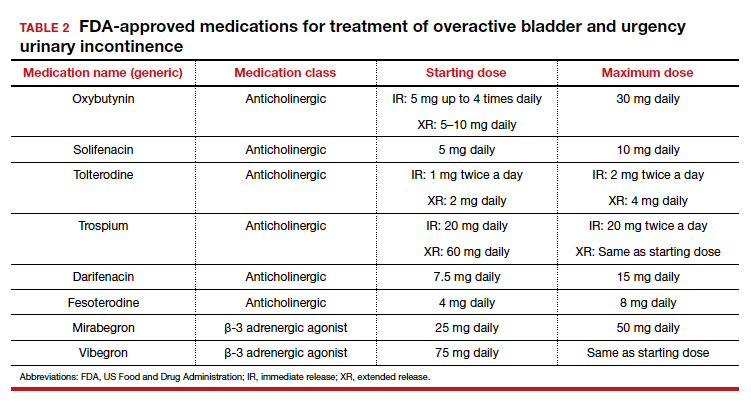

Drug therapy

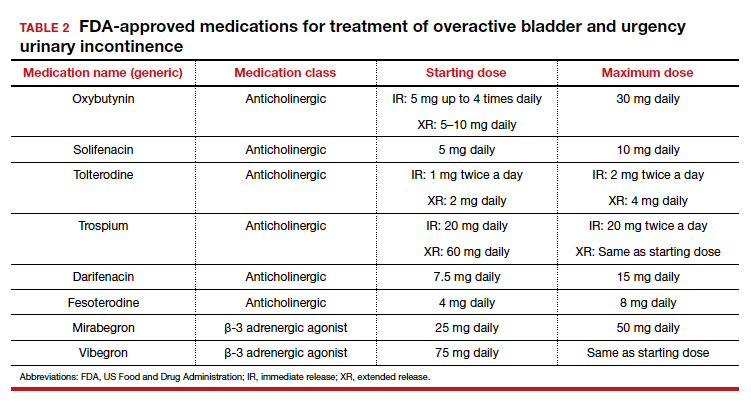

All medications approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for UI are for the indications of OAB or UUI. These second-line treatments are most effective as adjuncts to behavioral modifications and PFMT.

A multicenter randomized trial that evaluated the efficacy of drug therapy alone compared with drug therapy in combination with behavioral modification, PFMT, urge suppression strategies, timed voiding, and fluid management for UUI found that combined therapy was more successful in achieving greater than 70% reduction in incontinence episodes (58% for drug therapy vs 69% for combined therapy).21

Of the 8 medications currently marketed in the United States for OAB or UUI, 6 are anticholinergic agents that block muscarinic receptors in the smooth muscle of the bladder, leading to inhibition of detrusor contractions, and 2 are β-adrenergic receptor agonists that promote bladder storage capacity by relaxing the detrusor muscle (TABLE 2). Similar efficacies lead most clinicians to initiate drug therapy based on formulary coverage and tolerance for adverse effects. Patients can expect a 53% to 80% reduction in UUI episodes and a 12% to 32% reduction in urinary frequency.22

Extended-release formulations are associated with reduced anticholinergic side effects (dry mouth, constipation, somnolence, dry eyes), leading to improved adherence. Notably, the anticholinergic medications are contraindicated in patients with untreated narrow-angle glaucoma, gastric retention, and supraventricular tachycardia. Mirabegron should be used with caution in patients with poorly controlled hypertension. 5 Due to concerns regarding the association between cumulative anticholinergic burden and the development of dementia, clinicians may consider avoiding the anticholinergic medications in older and at-risk patients.23

Continue to: UUI office-based procedure treatments...

UUI office-based procedure treatments

If behavioral therapies and medications are ineffective, contraindicated, or not the patient’s preference, additional FDA-approved therapies for UUI are available, typically through referral to a urogynecologist, urologist, or continence center.

Posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) is a nondrug treatment that delivers electrical stimulation using an acupuncture needle for 12 weekly 30-minute sessions followed by monthly maintenance for responders. The time commitment for this treatment plan can be a barrier for some patients. However, patients who adhere to the recommended protocol can expect a 60% improvement in symptoms, with minimal adverse events. Treatment efficacy is comparable to that of anticholinergic medication.24

OnabotulinumtoxinA injections into the bladder muscle are performed cystoscopically under local anesthetic. The toxin blocks the presynaptic release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction, resulting in temporary muscle paralysis. This treatment is associated with high satisfaction. Efficacy varies by study population and outcome measure.

In one US comparative effectiveness trial, 67% of study participants with UUI symptoms refractory to oral medication reported a greater than 50% reduction in OAB symptoms at 6 months, 20% reported complete resolution of UUI, and 72% requested a second injection within 24 months.25 The interval between the first and second injection was nearly 1 year (350 days).Risks include urinary tract infection (12% within 1 month of the procedure and 35% through 6 months); urinary retention requiring catheterization has decreased to 6% with recognition that most moderate retention is tolerated by patients.

Some insurers limit onabotulinumtoxinA treatment coverage to patients who have failed to achieve symptom control with first- and second-line treatments.

SUI-specific nonsurgical treatments

Cystoscopic injection of urethral bulking agents into the urethral submucosa is designed to improve urethral coaptation. It is a minor procedure that can be performed in an ambulatory setting under local anesthetic with or without sedation.

Various bulking agents have been approved for use in the United States, some of which have been withdrawn due to complications of migration, erosion, and pseudoabscess formation. Cure or improvement after bulking agent injection was found to be superior to a home pelvic floor exercise program but inferior to a midurethral sling procedure for cure (9% vs 89%).26

The durability of currently available urethral bulking agents beyond 1 year is unknown. Complications are typically minor and transient and include pain at the injection site, urinary retention, de novo urgency, and implant leakage. The advantages include no postprocedure activity restrictions.

CASE Symptom presentation guides treatment plan

Our patient described symptoms of stress-predominant MUI. She was counseled to moderate her fluid intake to 2 L per day and to strategically time voids (before exercise, and at least every 4 hours). The patient was fitted with an incontinence pessary, and she elected to pursue a course of supervised physical therapy for pelvic floor muscle strengthening. Her follow-up visit is scheduled in 3 months to determine if other interventions are warranted. ●

1. Lee UJ, Feinstein L, Ward JB, et al. Prevalence of urinary incontinence among a nationally representative sample of women, 2005–2016: findings from the Urologic Diseases in America Project. J Urol. 2021;205:1718-1724. doi:10.1097 /JU.0000000000001634

2. Sims J, Browning C, Lundgren-Lindquist B, et al. Urinary incontinence in a community sample of older adults: prevalence and impact on quality of life. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:1389-1398. doi:10.3109/09638288.2010.532284

3. Sarikaya S, Yildiz FG, Senocak C, et al. Urinary incontinence as a cause of depression and sexual dysfunction: questionnaire-based study. Rev Int Androl. 2020:18:50-54. doi:10.1016 /j.androl.2018.08.003

4. O’Reilly N, Nelson HD, Conry JM, et al; Women’s Preventive Services Initiative. Screening for urinary incontinence in women: a recommendation from the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(5):320-328. doi:10.7326/M18-0595

5. Barber MD, Walters MD, Karram MM, et al. Walters & Karram Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. 5th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2021.

6. Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21: 5-26. doi:10.1007/s00192-009-0976-9

7. ACOG practice bulletin no. 155. Urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e66-e81. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000001148

8. Sansone S, Lu J, Drangsholt S, et al. No pelvic exam, no problem: patient satisfaction following the integration of comprehensive urogynecology telemedicine. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;1:3. doi:10.1007/s00192-022-05104-w

9. Brown JS, Bradley CS, Subak LL, et al; Diagnostic Aspects of Incontinence Study (DAISy) Research Group. The sensitivity and specificity of a simple test to distinguish between urge and stress urinary incontinence. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:715723. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00005

10. Hess R, Huang AJ, Richter HE, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of questionnaire-based initiation of urgency urinary incontinence treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:244. e1-9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.008

11. Sung VW, Borello-France D, Newman DK, et al; NICHD Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of behavioral and pelvic floor muscle therapy combined with surgery vs surgery alone on incontinence symptoms among women with mixed urinary incontinence. JAMA. 2019;322:1066-1076. doi:10.1001 /jama.2019.12467

12. American Urogynecologic Society. Voices for PFD: intake and voiding diary. Accessed August 11, 2022. https://www .voicesforpfd.org/assets/2/6/Voiding_Diary.pdf

13. Subak LL, Richter HE, Hunskaar S. Obesity and urinary incontinence: epidemiology and clinical research update. J Urol. 2009;182(6 suppl):S2-7. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.071

14. Arya LA, Myers DL, Jackson ND. Dietary caffeine intake and the risk for detrusor instability: a case-control study. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:85-89. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00808-5

15. Wyman JF, Zhou J, LaCoursiere DY, et al. Normative noninvasive bladder function measurements in healthy women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39:507-522. doi:10.1002/nau.24265

16. Hashim H, Al Mousa R. Management of fluid intake in patients with overactive bladder. Curr Urol Rep. 2009;10: 428-433. doi:10.1007/s11934-009-0068-x

17. Dumoulin C, Cacciari LP, Hay-Smith EJC. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10:CD005654. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005654.pub4

18. Araujo CC, de A Marques A, Juliato CRT. The adherence of home pelvic floor muscles training using a mobile device application for women with urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:697-703. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000670

19. Sjöström M, Umefjord G, Stenlund H, et al. Internet-based treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled study with focus on pelvic floor muscle training. BJU Int. 2013;112:362-372. doi:10.1111/j.1464 -410X.2012.11713.x

20. Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609617. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d055d4

21. Burgio KL, Kraus SR, Menefee S, et al. Behavioral therapy to enable women with urge incontinence to discontinue drug treatment: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(3): 161-169. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-149-3-200808050 -00005

22. Lukacz ES, Santiago-Lastra Y, Albo ME, et al. Urinary incontinence in women: a review. JAMA. 2017;318:1592-1604. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.12137

23. Welk B, Richardson K, Panicker JN. The cognitive effect of anticholinergics for patients with overactive bladder. Nat Rev Urol. 2021;18:686-700. doi:10.1038/s41585-021-00504-x

24. Burton C, Sajja A, Latthe PM. Effectiveness of percutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation for overactive bladder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:1206-1216. doi:10.1002/nau.22251

25. Amundsen CL, Richter HE, Menefee SA, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA vs sacral neuromodulation on refractory urgency urinary incontinence in women: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316:1366-1374. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.14617

26. Kirchin V, Page T, Keegan PE, et al. Urethral injection therapy for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD003881. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003881.pub4

CASE Patient has urine leakage that worsens with exercise

At her annual preventative health visit, a 39-year-old woman reports that she has leakage of urine. She states that she drinks “a gallon of water daily” to help her lose the 20 lb she gained during the COVID-19 pandemic. She wants to resume Zumba fitness classes, but exercise makes her urine leakage worse. She started wearing protective pads because she finds herself often leaking urine on the way to the bathroom.

What nonsurgical treatment options are available for this patient?

Nearly half of all women experience urinary incontinence (UI), the involuntary loss of urine, and the condition increases with age.1 This common condition negatively impacts physical and psychological health and has been associated with social isolation, sexual dysfunction, and reduced independence.2,3 Symptoms of UI are underreported, and therefore universal screening is recommended for women of all ages.4 The diversity of available treatments (TABLE 1) provides patients and clinicians an opportunity to develop a plan that aligns with their symptom severity, goals, preferences, and resources.

Types of UI

The most common types of UI are stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and urgency urinary incontinence (UUI). Mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) occurs when symptoms of both SUI and UUI are present. Although the mechanisms that lead to urine leakage vary by the type of incontinence, many primary interventions improve both types of leakage, so a clinical diagnosis is sufficient to initiate treatment.

Stress urinary incontinence results from an impaired or weakened sphincter, which leads to involuntary, yet predictable, urine loss during increased abdominal pressure, such as coughing, laughing, sneezing, lifting, or physical activity.5 In UUI, involuntary loss of urine often accompanies the sudden urge to void. UUI is associated with overactive bladder (OAB), defined as urinary urgency, with or without urinary incontinence, usually accompanied by urinary frequency and/or nocturia (urination that interrupts sleep).6

In OAB, the detrusor muscle contracts randomly, leading to a sudden urge to void. When bladder pressure exceeds urethral sphincter closure pressure, urine leakage occurs. Women describe the urgency episodes as unpredictable, the urine leakage as prolonged with large volumes, and often occurring as they seek the toilet. Risk factors include age, obesity, parity, history of vaginal delivery, family history, ethnicity/race, medical comorbidities, menopausal status, and tobacco use.5

Making a diagnosis

A basic office evaluation is the most key step for diagnostic accuracy that leads to treatment success. This includes a detailed history, assessment of symptom severity, physical exam, pelvic exam, urinalysis, postvoid residual (to rule out urinary retention), and a cough stress test (to demonstrate SUI). The goal is to assess symptom severity, determine the type of UI, and identify contributing and potentially reversible factors, such as a urinary tract infection, medications, pelvic organ prolapse, incomplete bladder emptying, or impaired neurologic status. In the absence of the latter, advanced diagnostic tests, such as urodynamics, contribute little toward discerning the type of incontinence or changing first-line treatment plans.7

During the COVID-19 pandemic, abbreviated, virtual assessments for urinary symptoms were associated with high degrees of satisfaction (91% for fulfillment of personal needs, 94% overall satisfaction).8 This highlights the value of validated symptom questionnaires that help establish a working diagnosis and treatment plan in the absence of a physical exam. Questionnaire-based diagnoses have acceptable accuracy for classifying UUI and SUI among women with uncomplicated medical and surgical histories and for initiating low-risk therapies for defined intervals.

The 3 incontinence questions (3IQ) screen is an example of a useful, quick diagnostic tool designed for the primary care setting (FIGURE 1).9 It has been used in pharmaceutical treatment trials for UUI, with low frequency of misdiagnosis (1%–4%), resulting in no harm by the drug treatment prescribed or by the delay in appropriate care.10 Due to the limitations of an abbreviated remote evaluation, however, clinicians should assess patient response to primary interventions in a timely window. Patients who fail to experience satisfactory symptom reduction within 6 to 12 weeks should complete their evaluation in person or through a referral to a urogynecology program.

Continue to: Primary therapies for UI...

Primary therapies for UI

Primary therapies for UUI and SUI target strength training of the pelvic floor muscles, moderation of fluid intake, and adjustment in voiding behaviors and medications. Any functional barriers to continence also should be identified and addressed. Simple interventions, including a daily bowel regimen to address constipation, a bedside commode, and scheduled voiding, may reduce incontinence episodes without incurring significant cost or risk. For women suspected of having MUI, the treatment plan should prioritize their most bothersome symptoms.

Lifestyle and behavioral modifications

Everyday habits, medical comorbidities, and medications may exacerbate the severity of both SUI and UUI. Behavioral therapy alone or in combination with other interventions effectively reduces both SUI and UUI symptoms and has been shown to improve the efficacy of continence surgery.11 Information gained from a 3-day bladder diary (FIGURE 2)12 can guide clinicians on personalized patient recommendations, such as reducing excessive consumption of fluids and bladder irritants, limiting late evening drinking in the setting of bothersome nocturia, and scheduling voids (every 2–3 hours) to preempt incontinence episodes.

Weight loss

Obesity is a strong, independent, modifiable risk factor for both SUI and UUI. Each 5 kg/m2 increase in body mass index (BMI) has been associated with a 20% to 70% increased risk of UI, while weight loss of 5% or greater in overweight or obese women can lead to at least a 50% decrease in UI frequency.13

Reducing fluid intake and bladder irritants

Overactive bladder symptoms often respond to moderation of excessive fluid intake and reduction of bladder irritants (caffeine, carbonated beverages, diet beverages, and alcohol). While there is no established definition of excess caffeine intake, one study categorized high caffeine intake as greater than 400 mg/day (approximately four 8-oz cups of coffee).14

Information provided in a bladder diary can guide individualized recommendations for reducing fluid intake, particularly when 24-hour urine production exceeds the normative range (> 50–60 oz or 1.5-1.8 L/day).15 Hydration needs vary by activity, environment, and food; some general guidelines suggest 48 to 64 oz/day.5,16

Continue to: Pelvic floor muscle training...

Pelvic floor muscle training

An effective treatment for both UUI and SUI symptoms, pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) leads to high degrees of patient satisfaction and improvement in quality of life.17 The presumed mechanisms of action of PFMT include improved urethral closure pressure and inhibition of detrusor muscle contractions.

Common exercise protocols recommend 3 sets of 10 contractions, held for 6 to 10 seconds per day, in varying positions of sitting, standing, and lying. While many women may be familiar with Kegel exercises, poor technique with straining and recruitment of gluteal and abdominal muscles can undermine the effect of PFMT. Clinicians can confirm successful pelvic muscle contractions by placing a finger in the vagina to appreciate contraction around and elevation of the finger toward the pubic symphysis in the absence of pushing.

Referral to supervised physical therapy and use of such teaching aid tools as booklets, mobile applications, and biofeedback can improve exercise adherence and outcomes.18,19 Systematic reviews report initial cure or improvement of incontinence symptoms as high as 74%, although little information is available about the long-term duration of effect.17

Vaginal pessaries

Vaginal continence support pessaries and devices work by stabilizing urethral mobility and compression of the bladder neck. Continence devices are particularly effective for situational SUI (such as during exercise).

The reusable medical grade silicone pessaries are available in numerous shapes and sizes and are fitted by a health care clinician (FIGURE 3). Uresta is a self-fitted intravaginal device that women can purchase online with a prescription. The Poise Impressa bladder support is a disposable intravaginal device marketed for incontinence and available over-the-counter, without a prescription (FIGURE 4). Anecdotally, many women find that menstrual tampons provide a similar effect, but outcome data are lacking.

In a comparative effectiveness trial of a continence pessary and behavior therapy, behavioral therapy was more likely to result in no bothersome incontinence symptoms (49% vs 33%, P = .006) and greater treatment satisfaction at 3 months.20 However, these short-term group differences did not persist at 12 months, presumably due to waning adherence.

UUI-specific nonsurgical treatments

Drug therapy

All medications approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for UI are for the indications of OAB or UUI. These second-line treatments are most effective as adjuncts to behavioral modifications and PFMT.

A multicenter randomized trial that evaluated the efficacy of drug therapy alone compared with drug therapy in combination with behavioral modification, PFMT, urge suppression strategies, timed voiding, and fluid management for UUI found that combined therapy was more successful in achieving greater than 70% reduction in incontinence episodes (58% for drug therapy vs 69% for combined therapy).21

Of the 8 medications currently marketed in the United States for OAB or UUI, 6 are anticholinergic agents that block muscarinic receptors in the smooth muscle of the bladder, leading to inhibition of detrusor contractions, and 2 are β-adrenergic receptor agonists that promote bladder storage capacity by relaxing the detrusor muscle (TABLE 2). Similar efficacies lead most clinicians to initiate drug therapy based on formulary coverage and tolerance for adverse effects. Patients can expect a 53% to 80% reduction in UUI episodes and a 12% to 32% reduction in urinary frequency.22

Extended-release formulations are associated with reduced anticholinergic side effects (dry mouth, constipation, somnolence, dry eyes), leading to improved adherence. Notably, the anticholinergic medications are contraindicated in patients with untreated narrow-angle glaucoma, gastric retention, and supraventricular tachycardia. Mirabegron should be used with caution in patients with poorly controlled hypertension. 5 Due to concerns regarding the association between cumulative anticholinergic burden and the development of dementia, clinicians may consider avoiding the anticholinergic medications in older and at-risk patients.23

Continue to: UUI office-based procedure treatments...

UUI office-based procedure treatments

If behavioral therapies and medications are ineffective, contraindicated, or not the patient’s preference, additional FDA-approved therapies for UUI are available, typically through referral to a urogynecologist, urologist, or continence center.

Posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) is a nondrug treatment that delivers electrical stimulation using an acupuncture needle for 12 weekly 30-minute sessions followed by monthly maintenance for responders. The time commitment for this treatment plan can be a barrier for some patients. However, patients who adhere to the recommended protocol can expect a 60% improvement in symptoms, with minimal adverse events. Treatment efficacy is comparable to that of anticholinergic medication.24

OnabotulinumtoxinA injections into the bladder muscle are performed cystoscopically under local anesthetic. The toxin blocks the presynaptic release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction, resulting in temporary muscle paralysis. This treatment is associated with high satisfaction. Efficacy varies by study population and outcome measure.

In one US comparative effectiveness trial, 67% of study participants with UUI symptoms refractory to oral medication reported a greater than 50% reduction in OAB symptoms at 6 months, 20% reported complete resolution of UUI, and 72% requested a second injection within 24 months.25 The interval between the first and second injection was nearly 1 year (350 days).Risks include urinary tract infection (12% within 1 month of the procedure and 35% through 6 months); urinary retention requiring catheterization has decreased to 6% with recognition that most moderate retention is tolerated by patients.

Some insurers limit onabotulinumtoxinA treatment coverage to patients who have failed to achieve symptom control with first- and second-line treatments.

SUI-specific nonsurgical treatments

Cystoscopic injection of urethral bulking agents into the urethral submucosa is designed to improve urethral coaptation. It is a minor procedure that can be performed in an ambulatory setting under local anesthetic with or without sedation.

Various bulking agents have been approved for use in the United States, some of which have been withdrawn due to complications of migration, erosion, and pseudoabscess formation. Cure or improvement after bulking agent injection was found to be superior to a home pelvic floor exercise program but inferior to a midurethral sling procedure for cure (9% vs 89%).26

The durability of currently available urethral bulking agents beyond 1 year is unknown. Complications are typically minor and transient and include pain at the injection site, urinary retention, de novo urgency, and implant leakage. The advantages include no postprocedure activity restrictions.

CASE Symptom presentation guides treatment plan

Our patient described symptoms of stress-predominant MUI. She was counseled to moderate her fluid intake to 2 L per day and to strategically time voids (before exercise, and at least every 4 hours). The patient was fitted with an incontinence pessary, and she elected to pursue a course of supervised physical therapy for pelvic floor muscle strengthening. Her follow-up visit is scheduled in 3 months to determine if other interventions are warranted. ●

CASE Patient has urine leakage that worsens with exercise

At her annual preventative health visit, a 39-year-old woman reports that she has leakage of urine. She states that she drinks “a gallon of water daily” to help her lose the 20 lb she gained during the COVID-19 pandemic. She wants to resume Zumba fitness classes, but exercise makes her urine leakage worse. She started wearing protective pads because she finds herself often leaking urine on the way to the bathroom.

What nonsurgical treatment options are available for this patient?

Nearly half of all women experience urinary incontinence (UI), the involuntary loss of urine, and the condition increases with age.1 This common condition negatively impacts physical and psychological health and has been associated with social isolation, sexual dysfunction, and reduced independence.2,3 Symptoms of UI are underreported, and therefore universal screening is recommended for women of all ages.4 The diversity of available treatments (TABLE 1) provides patients and clinicians an opportunity to develop a plan that aligns with their symptom severity, goals, preferences, and resources.

Types of UI

The most common types of UI are stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and urgency urinary incontinence (UUI). Mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) occurs when symptoms of both SUI and UUI are present. Although the mechanisms that lead to urine leakage vary by the type of incontinence, many primary interventions improve both types of leakage, so a clinical diagnosis is sufficient to initiate treatment.

Stress urinary incontinence results from an impaired or weakened sphincter, which leads to involuntary, yet predictable, urine loss during increased abdominal pressure, such as coughing, laughing, sneezing, lifting, or physical activity.5 In UUI, involuntary loss of urine often accompanies the sudden urge to void. UUI is associated with overactive bladder (OAB), defined as urinary urgency, with or without urinary incontinence, usually accompanied by urinary frequency and/or nocturia (urination that interrupts sleep).6

In OAB, the detrusor muscle contracts randomly, leading to a sudden urge to void. When bladder pressure exceeds urethral sphincter closure pressure, urine leakage occurs. Women describe the urgency episodes as unpredictable, the urine leakage as prolonged with large volumes, and often occurring as they seek the toilet. Risk factors include age, obesity, parity, history of vaginal delivery, family history, ethnicity/race, medical comorbidities, menopausal status, and tobacco use.5

Making a diagnosis

A basic office evaluation is the most key step for diagnostic accuracy that leads to treatment success. This includes a detailed history, assessment of symptom severity, physical exam, pelvic exam, urinalysis, postvoid residual (to rule out urinary retention), and a cough stress test (to demonstrate SUI). The goal is to assess symptom severity, determine the type of UI, and identify contributing and potentially reversible factors, such as a urinary tract infection, medications, pelvic organ prolapse, incomplete bladder emptying, or impaired neurologic status. In the absence of the latter, advanced diagnostic tests, such as urodynamics, contribute little toward discerning the type of incontinence or changing first-line treatment plans.7

During the COVID-19 pandemic, abbreviated, virtual assessments for urinary symptoms were associated with high degrees of satisfaction (91% for fulfillment of personal needs, 94% overall satisfaction).8 This highlights the value of validated symptom questionnaires that help establish a working diagnosis and treatment plan in the absence of a physical exam. Questionnaire-based diagnoses have acceptable accuracy for classifying UUI and SUI among women with uncomplicated medical and surgical histories and for initiating low-risk therapies for defined intervals.

The 3 incontinence questions (3IQ) screen is an example of a useful, quick diagnostic tool designed for the primary care setting (FIGURE 1).9 It has been used in pharmaceutical treatment trials for UUI, with low frequency of misdiagnosis (1%–4%), resulting in no harm by the drug treatment prescribed or by the delay in appropriate care.10 Due to the limitations of an abbreviated remote evaluation, however, clinicians should assess patient response to primary interventions in a timely window. Patients who fail to experience satisfactory symptom reduction within 6 to 12 weeks should complete their evaluation in person or through a referral to a urogynecology program.

Continue to: Primary therapies for UI...

Primary therapies for UI

Primary therapies for UUI and SUI target strength training of the pelvic floor muscles, moderation of fluid intake, and adjustment in voiding behaviors and medications. Any functional barriers to continence also should be identified and addressed. Simple interventions, including a daily bowel regimen to address constipation, a bedside commode, and scheduled voiding, may reduce incontinence episodes without incurring significant cost or risk. For women suspected of having MUI, the treatment plan should prioritize their most bothersome symptoms.

Lifestyle and behavioral modifications

Everyday habits, medical comorbidities, and medications may exacerbate the severity of both SUI and UUI. Behavioral therapy alone or in combination with other interventions effectively reduces both SUI and UUI symptoms and has been shown to improve the efficacy of continence surgery.11 Information gained from a 3-day bladder diary (FIGURE 2)12 can guide clinicians on personalized patient recommendations, such as reducing excessive consumption of fluids and bladder irritants, limiting late evening drinking in the setting of bothersome nocturia, and scheduling voids (every 2–3 hours) to preempt incontinence episodes.

Weight loss

Obesity is a strong, independent, modifiable risk factor for both SUI and UUI. Each 5 kg/m2 increase in body mass index (BMI) has been associated with a 20% to 70% increased risk of UI, while weight loss of 5% or greater in overweight or obese women can lead to at least a 50% decrease in UI frequency.13

Reducing fluid intake and bladder irritants

Overactive bladder symptoms often respond to moderation of excessive fluid intake and reduction of bladder irritants (caffeine, carbonated beverages, diet beverages, and alcohol). While there is no established definition of excess caffeine intake, one study categorized high caffeine intake as greater than 400 mg/day (approximately four 8-oz cups of coffee).14

Information provided in a bladder diary can guide individualized recommendations for reducing fluid intake, particularly when 24-hour urine production exceeds the normative range (> 50–60 oz or 1.5-1.8 L/day).15 Hydration needs vary by activity, environment, and food; some general guidelines suggest 48 to 64 oz/day.5,16

Continue to: Pelvic floor muscle training...

Pelvic floor muscle training

An effective treatment for both UUI and SUI symptoms, pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) leads to high degrees of patient satisfaction and improvement in quality of life.17 The presumed mechanisms of action of PFMT include improved urethral closure pressure and inhibition of detrusor muscle contractions.

Common exercise protocols recommend 3 sets of 10 contractions, held for 6 to 10 seconds per day, in varying positions of sitting, standing, and lying. While many women may be familiar with Kegel exercises, poor technique with straining and recruitment of gluteal and abdominal muscles can undermine the effect of PFMT. Clinicians can confirm successful pelvic muscle contractions by placing a finger in the vagina to appreciate contraction around and elevation of the finger toward the pubic symphysis in the absence of pushing.

Referral to supervised physical therapy and use of such teaching aid tools as booklets, mobile applications, and biofeedback can improve exercise adherence and outcomes.18,19 Systematic reviews report initial cure or improvement of incontinence symptoms as high as 74%, although little information is available about the long-term duration of effect.17

Vaginal pessaries

Vaginal continence support pessaries and devices work by stabilizing urethral mobility and compression of the bladder neck. Continence devices are particularly effective for situational SUI (such as during exercise).

The reusable medical grade silicone pessaries are available in numerous shapes and sizes and are fitted by a health care clinician (FIGURE 3). Uresta is a self-fitted intravaginal device that women can purchase online with a prescription. The Poise Impressa bladder support is a disposable intravaginal device marketed for incontinence and available over-the-counter, without a prescription (FIGURE 4). Anecdotally, many women find that menstrual tampons provide a similar effect, but outcome data are lacking.

In a comparative effectiveness trial of a continence pessary and behavior therapy, behavioral therapy was more likely to result in no bothersome incontinence symptoms (49% vs 33%, P = .006) and greater treatment satisfaction at 3 months.20 However, these short-term group differences did not persist at 12 months, presumably due to waning adherence.

UUI-specific nonsurgical treatments

Drug therapy

All medications approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for UI are for the indications of OAB or UUI. These second-line treatments are most effective as adjuncts to behavioral modifications and PFMT.

A multicenter randomized trial that evaluated the efficacy of drug therapy alone compared with drug therapy in combination with behavioral modification, PFMT, urge suppression strategies, timed voiding, and fluid management for UUI found that combined therapy was more successful in achieving greater than 70% reduction in incontinence episodes (58% for drug therapy vs 69% for combined therapy).21

Of the 8 medications currently marketed in the United States for OAB or UUI, 6 are anticholinergic agents that block muscarinic receptors in the smooth muscle of the bladder, leading to inhibition of detrusor contractions, and 2 are β-adrenergic receptor agonists that promote bladder storage capacity by relaxing the detrusor muscle (TABLE 2). Similar efficacies lead most clinicians to initiate drug therapy based on formulary coverage and tolerance for adverse effects. Patients can expect a 53% to 80% reduction in UUI episodes and a 12% to 32% reduction in urinary frequency.22

Extended-release formulations are associated with reduced anticholinergic side effects (dry mouth, constipation, somnolence, dry eyes), leading to improved adherence. Notably, the anticholinergic medications are contraindicated in patients with untreated narrow-angle glaucoma, gastric retention, and supraventricular tachycardia. Mirabegron should be used with caution in patients with poorly controlled hypertension. 5 Due to concerns regarding the association between cumulative anticholinergic burden and the development of dementia, clinicians may consider avoiding the anticholinergic medications in older and at-risk patients.23

Continue to: UUI office-based procedure treatments...

UUI office-based procedure treatments

If behavioral therapies and medications are ineffective, contraindicated, or not the patient’s preference, additional FDA-approved therapies for UUI are available, typically through referral to a urogynecologist, urologist, or continence center.

Posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) is a nondrug treatment that delivers electrical stimulation using an acupuncture needle for 12 weekly 30-minute sessions followed by monthly maintenance for responders. The time commitment for this treatment plan can be a barrier for some patients. However, patients who adhere to the recommended protocol can expect a 60% improvement in symptoms, with minimal adverse events. Treatment efficacy is comparable to that of anticholinergic medication.24

OnabotulinumtoxinA injections into the bladder muscle are performed cystoscopically under local anesthetic. The toxin blocks the presynaptic release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction, resulting in temporary muscle paralysis. This treatment is associated with high satisfaction. Efficacy varies by study population and outcome measure.

In one US comparative effectiveness trial, 67% of study participants with UUI symptoms refractory to oral medication reported a greater than 50% reduction in OAB symptoms at 6 months, 20% reported complete resolution of UUI, and 72% requested a second injection within 24 months.25 The interval between the first and second injection was nearly 1 year (350 days).Risks include urinary tract infection (12% within 1 month of the procedure and 35% through 6 months); urinary retention requiring catheterization has decreased to 6% with recognition that most moderate retention is tolerated by patients.

Some insurers limit onabotulinumtoxinA treatment coverage to patients who have failed to achieve symptom control with first- and second-line treatments.

SUI-specific nonsurgical treatments

Cystoscopic injection of urethral bulking agents into the urethral submucosa is designed to improve urethral coaptation. It is a minor procedure that can be performed in an ambulatory setting under local anesthetic with or without sedation.

Various bulking agents have been approved for use in the United States, some of which have been withdrawn due to complications of migration, erosion, and pseudoabscess formation. Cure or improvement after bulking agent injection was found to be superior to a home pelvic floor exercise program but inferior to a midurethral sling procedure for cure (9% vs 89%).26

The durability of currently available urethral bulking agents beyond 1 year is unknown. Complications are typically minor and transient and include pain at the injection site, urinary retention, de novo urgency, and implant leakage. The advantages include no postprocedure activity restrictions.

CASE Symptom presentation guides treatment plan

Our patient described symptoms of stress-predominant MUI. She was counseled to moderate her fluid intake to 2 L per day and to strategically time voids (before exercise, and at least every 4 hours). The patient was fitted with an incontinence pessary, and she elected to pursue a course of supervised physical therapy for pelvic floor muscle strengthening. Her follow-up visit is scheduled in 3 months to determine if other interventions are warranted. ●

1. Lee UJ, Feinstein L, Ward JB, et al. Prevalence of urinary incontinence among a nationally representative sample of women, 2005–2016: findings from the Urologic Diseases in America Project. J Urol. 2021;205:1718-1724. doi:10.1097 /JU.0000000000001634

2. Sims J, Browning C, Lundgren-Lindquist B, et al. Urinary incontinence in a community sample of older adults: prevalence and impact on quality of life. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:1389-1398. doi:10.3109/09638288.2010.532284

3. Sarikaya S, Yildiz FG, Senocak C, et al. Urinary incontinence as a cause of depression and sexual dysfunction: questionnaire-based study. Rev Int Androl. 2020:18:50-54. doi:10.1016 /j.androl.2018.08.003

4. O’Reilly N, Nelson HD, Conry JM, et al; Women’s Preventive Services Initiative. Screening for urinary incontinence in women: a recommendation from the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(5):320-328. doi:10.7326/M18-0595

5. Barber MD, Walters MD, Karram MM, et al. Walters & Karram Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. 5th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2021.

6. Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21: 5-26. doi:10.1007/s00192-009-0976-9

7. ACOG practice bulletin no. 155. Urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e66-e81. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000001148

8. Sansone S, Lu J, Drangsholt S, et al. No pelvic exam, no problem: patient satisfaction following the integration of comprehensive urogynecology telemedicine. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;1:3. doi:10.1007/s00192-022-05104-w

9. Brown JS, Bradley CS, Subak LL, et al; Diagnostic Aspects of Incontinence Study (DAISy) Research Group. The sensitivity and specificity of a simple test to distinguish between urge and stress urinary incontinence. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:715723. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00005

10. Hess R, Huang AJ, Richter HE, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of questionnaire-based initiation of urgency urinary incontinence treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:244. e1-9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.008

11. Sung VW, Borello-France D, Newman DK, et al; NICHD Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of behavioral and pelvic floor muscle therapy combined with surgery vs surgery alone on incontinence symptoms among women with mixed urinary incontinence. JAMA. 2019;322:1066-1076. doi:10.1001 /jama.2019.12467

12. American Urogynecologic Society. Voices for PFD: intake and voiding diary. Accessed August 11, 2022. https://www .voicesforpfd.org/assets/2/6/Voiding_Diary.pdf

13. Subak LL, Richter HE, Hunskaar S. Obesity and urinary incontinence: epidemiology and clinical research update. J Urol. 2009;182(6 suppl):S2-7. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.071

14. Arya LA, Myers DL, Jackson ND. Dietary caffeine intake and the risk for detrusor instability: a case-control study. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:85-89. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00808-5

15. Wyman JF, Zhou J, LaCoursiere DY, et al. Normative noninvasive bladder function measurements in healthy women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39:507-522. doi:10.1002/nau.24265

16. Hashim H, Al Mousa R. Management of fluid intake in patients with overactive bladder. Curr Urol Rep. 2009;10: 428-433. doi:10.1007/s11934-009-0068-x

17. Dumoulin C, Cacciari LP, Hay-Smith EJC. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10:CD005654. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005654.pub4

18. Araujo CC, de A Marques A, Juliato CRT. The adherence of home pelvic floor muscles training using a mobile device application for women with urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:697-703. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000670

19. Sjöström M, Umefjord G, Stenlund H, et al. Internet-based treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled study with focus on pelvic floor muscle training. BJU Int. 2013;112:362-372. doi:10.1111/j.1464 -410X.2012.11713.x

20. Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609617. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d055d4

21. Burgio KL, Kraus SR, Menefee S, et al. Behavioral therapy to enable women with urge incontinence to discontinue drug treatment: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(3): 161-169. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-149-3-200808050 -00005

22. Lukacz ES, Santiago-Lastra Y, Albo ME, et al. Urinary incontinence in women: a review. JAMA. 2017;318:1592-1604. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.12137

23. Welk B, Richardson K, Panicker JN. The cognitive effect of anticholinergics for patients with overactive bladder. Nat Rev Urol. 2021;18:686-700. doi:10.1038/s41585-021-00504-x

24. Burton C, Sajja A, Latthe PM. Effectiveness of percutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation for overactive bladder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:1206-1216. doi:10.1002/nau.22251

25. Amundsen CL, Richter HE, Menefee SA, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA vs sacral neuromodulation on refractory urgency urinary incontinence in women: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316:1366-1374. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.14617

26. Kirchin V, Page T, Keegan PE, et al. Urethral injection therapy for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD003881. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003881.pub4

1. Lee UJ, Feinstein L, Ward JB, et al. Prevalence of urinary incontinence among a nationally representative sample of women, 2005–2016: findings from the Urologic Diseases in America Project. J Urol. 2021;205:1718-1724. doi:10.1097 /JU.0000000000001634

2. Sims J, Browning C, Lundgren-Lindquist B, et al. Urinary incontinence in a community sample of older adults: prevalence and impact on quality of life. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:1389-1398. doi:10.3109/09638288.2010.532284

3. Sarikaya S, Yildiz FG, Senocak C, et al. Urinary incontinence as a cause of depression and sexual dysfunction: questionnaire-based study. Rev Int Androl. 2020:18:50-54. doi:10.1016 /j.androl.2018.08.003

4. O’Reilly N, Nelson HD, Conry JM, et al; Women’s Preventive Services Initiative. Screening for urinary incontinence in women: a recommendation from the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(5):320-328. doi:10.7326/M18-0595

5. Barber MD, Walters MD, Karram MM, et al. Walters & Karram Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. 5th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2021.

6. Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21: 5-26. doi:10.1007/s00192-009-0976-9

7. ACOG practice bulletin no. 155. Urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e66-e81. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000001148

8. Sansone S, Lu J, Drangsholt S, et al. No pelvic exam, no problem: patient satisfaction following the integration of comprehensive urogynecology telemedicine. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;1:3. doi:10.1007/s00192-022-05104-w

9. Brown JS, Bradley CS, Subak LL, et al; Diagnostic Aspects of Incontinence Study (DAISy) Research Group. The sensitivity and specificity of a simple test to distinguish between urge and stress urinary incontinence. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:715723. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00005

10. Hess R, Huang AJ, Richter HE, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of questionnaire-based initiation of urgency urinary incontinence treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:244. e1-9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.008

11. Sung VW, Borello-France D, Newman DK, et al; NICHD Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of behavioral and pelvic floor muscle therapy combined with surgery vs surgery alone on incontinence symptoms among women with mixed urinary incontinence. JAMA. 2019;322:1066-1076. doi:10.1001 /jama.2019.12467

12. American Urogynecologic Society. Voices for PFD: intake and voiding diary. Accessed August 11, 2022. https://www .voicesforpfd.org/assets/2/6/Voiding_Diary.pdf

13. Subak LL, Richter HE, Hunskaar S. Obesity and urinary incontinence: epidemiology and clinical research update. J Urol. 2009;182(6 suppl):S2-7. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.071

14. Arya LA, Myers DL, Jackson ND. Dietary caffeine intake and the risk for detrusor instability: a case-control study. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:85-89. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00808-5

15. Wyman JF, Zhou J, LaCoursiere DY, et al. Normative noninvasive bladder function measurements in healthy women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39:507-522. doi:10.1002/nau.24265

16. Hashim H, Al Mousa R. Management of fluid intake in patients with overactive bladder. Curr Urol Rep. 2009;10: 428-433. doi:10.1007/s11934-009-0068-x

17. Dumoulin C, Cacciari LP, Hay-Smith EJC. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10:CD005654. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005654.pub4

18. Araujo CC, de A Marques A, Juliato CRT. The adherence of home pelvic floor muscles training using a mobile device application for women with urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:697-703. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000670

19. Sjöström M, Umefjord G, Stenlund H, et al. Internet-based treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled study with focus on pelvic floor muscle training. BJU Int. 2013;112:362-372. doi:10.1111/j.1464 -410X.2012.11713.x

20. Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609617. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d055d4

21. Burgio KL, Kraus SR, Menefee S, et al. Behavioral therapy to enable women with urge incontinence to discontinue drug treatment: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(3): 161-169. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-149-3-200808050 -00005

22. Lukacz ES, Santiago-Lastra Y, Albo ME, et al. Urinary incontinence in women: a review. JAMA. 2017;318:1592-1604. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.12137

23. Welk B, Richardson K, Panicker JN. The cognitive effect of anticholinergics for patients with overactive bladder. Nat Rev Urol. 2021;18:686-700. doi:10.1038/s41585-021-00504-x

24. Burton C, Sajja A, Latthe PM. Effectiveness of percutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation for overactive bladder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:1206-1216. doi:10.1002/nau.22251

25. Amundsen CL, Richter HE, Menefee SA, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA vs sacral neuromodulation on refractory urgency urinary incontinence in women: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316:1366-1374. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.14617

26. Kirchin V, Page T, Keegan PE, et al. Urethral injection therapy for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD003881. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003881.pub4

2022 Update on abnormal uterine bleeding

In this Update, we focus on therapies for abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) that include a new formulation of a progesterone-only pill (POP), drospirenone 4 mg in a 24/4 regimen (24 days of drospirenone/4 days of inert tablets), which recently showed benefit over the use of desogestrel in a European randomized clinical trial (RCT). Two other commonly used treatments for AUB— the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG IUS) and endometrial ablation—were studied in terms of cost-effectiveness as well as whether they should be used in combination for added efficacy. In addition, although at times either COVID-19 disease or the COVID-19 vaccine has been blamed for societal and medical problems, one study showed that it is unlikely that significant changes in the menstrual cycle are a result of the COVID-19 vaccine.

COVID-19 vaccination had minimal effects on menstrual cycle length

Edelman A, Boniface ER, Benhar W, et al. Association between menstrual cycle length and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination: a US cohort. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:481-489.

Does receiving the COVID-19 vaccination result in abnormal menstrual cycles? Patients often ask this question, and it has been a topic of social media discussion (including NPR) and concerns about the possibility of vaccine hesitancy,1,2 as the menstrual cycle is often considered a sign of health and fertility.

To better understand this possible association, Edelman and colleagues conducted a study that prospectively tracked menstrual cycle data using the digital app Natural Cycles in US residents aged 18 to 45 years for 3 consecutive cycles in both a vaccinated and an unvaccinated cohort.3 Almost 4,000 individuals were studied; 2,403 were vaccinated and 1,556 were unvaccinated. The study vaccine types included the BioNTech (Pfizer), Moderna, Johnson & Johnson/Janssen, and unspecified vaccines.

The primary outcome was the within-individual change in cycle length in days, comparing a 3-cycle postvaccine average to a 3-cycle prevaccination average in the 2 groups. (For the unvaccinated group, cycles 1, 2, and 3 were considered the equivalent of prevaccination cycles; cycle 4 was designated as the artificial first vaccine dose-cycle and cycle 5 as the artificial second-dose cycle.)

Increase in cycle length clinically negligible

The investigators found that the vaccinated cohort had less than a 1-day unadjusted increase in the length of their menstrual cycle, which was essentially a 0.71-day increase (98.75% confidence interval [CI], 0.47–0.94). Although this is considered statistically significant, it is likely clinically insignificant in that the overlaid histograms comparing the distribution of change showed a cycle length distribution in vaccinated individuals that is essentially equivalent to that in unvaccinated individuals. After adjusting for confounders, the difference in cycle length was reduced to a 0.64 day (98.75% CI, 0.27–1.01).

An interesting finding was that a subset of individuals who received both vaccine doses in a single cycle had, on average, an adjusted 2-day increase in their menstrual cycle compared with unvaccinated individuals. To explain this slightly longer cycle length, the authors postulated that mRNA vaccines create an immune response, or stressor, which could temporarily affect the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis if timed correctly. It is certainly possible for an individual to receive 2 doses in a single cycle, which could have both been administered in the early follicular phase. Such cycle length variability can be caused by events, including stressors, that affect the recruitment and maturation of the dominant follicle.

Counseling takeaway

This study provides reassurance to most individuals who receive a COVID-19 vaccine that it likely will not affect their menstrual cycle in a clinically significant manner.

This robust study by Edelman and colleagues on COVID-19 vaccination effects on menstrual cycle length had more than 99% power to detect an unadjusted 1-day difference in cycle length. However, given that most of the study participants were White and had access to the Natural Cycles app, the results may not be generalizable to all individuals who receive the vaccine.

Continue to: Drospirenone improved bleeding profiles, lowered discontinuation rates compared with desogestrel...

Drospirenone improved bleeding profiles, lowered discontinuation rates compared with desogestrel

Regidor PA, Colli E, Palacios S. Overall and bleeding-related discontinuation rates of a new oral contraceptive containing 4 mg drospirenone only in a 24/4 regimen and comparison to 0.075 mg desogestrel. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2021;37:1121-1127.

A new POP, marketed under the name Slynd, recently came to market. It contains the progestin drospirenone (DRSP) 4 mg in a 24/4 regimen. This formulation has the advantage of being an antiandrogenic progestin, with a long enough half-life to allow for managing a missed pill in the same fashion as combined oral contraceptives (COCs).

Investigators in Europe conducted a double-blind, randomized trial to assess discontinuation rates due to adverse events (mainly bleeding disorders) in participants taking DRSP 4 mg in a 24/4 regimen compared with those taking the POP desogestrel (DSG) 0.075 mg, which is commonly used in Europe.4 Regidor and colleagues compared 858 women with 6,691 DRSP treatment cycles with 332 women with 2,487 DSG treatment cycles.

Top reasons for stopping a POP

The discontinuation rate for abnormal bleeding was 3.7% in the DRSP group versus 7.3% in the DSG group (55.7% lower). The most common reasons for stopping either POP formulation were vaginal bleeding and acne. Both of these adverse events were less common in the DRSP group. Pill discontinuation due to vaginal bleeding was 2.6% in the DRSP group versus 5.4% in the DSG group, while discontinuation due to acne occurred in 1% in the DRSP group versus 2.7% in the DSG group.

New oral contraception option

This study shows improved acceptability and bleeding profiles in women using this new DRSP contraception pill regimen.

Adherence to a contraceptive method is influenced by patient satisfaction, and this is particularly important in patients who cannot take COCs. It also should be noted that the discontinuation rate for DRSP as a POP used in this 24/4 regimen was similar to discontinuation rates for COCs containing 20 µg and 30 µg of ethinyl estradiol. Cost, however, may be an issue with DRSP, depending on a patient’s insurance coverage.

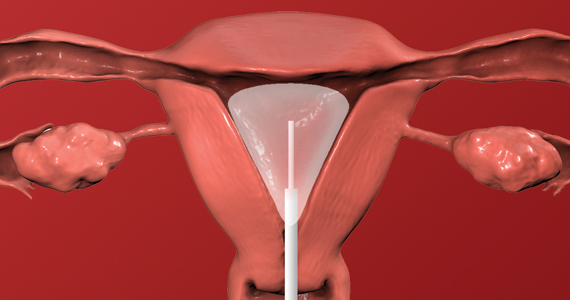

Continue to: Placing an LNG IUS after endometrial ablation for heavy menstrual bleeding reduced risk of hysterectomy...

Placing an LNG IUS after endometrial ablation for heavy menstrual bleeding reduced risk of hysterectomy

Oderkerk TJ, van de Kar MMA, van der Zanden CHM, et al. The combined use of endometrial ablation or resection and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in women with heavy menstrual bleeding: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:1779-1787.

Over the years, a smattering of articles have suggested that a reduction in uterine bleeding was associated with placement of an LNG IUS at the conclusion of endometrial ablation. We now have a systematic review of this surgical modification.

Oderkerk and colleagues sifted through 747 articles to find 7 publications that could provide meaningful data on the impact of combined use of endometrial ablation and LNG IUS insertion for women with heavy menstrual bleeding.5 These included 4 retrospective cohort studies with control groups, 2 retrospective studies without control groups, and 1 case series. The primary outcome was the hysterectomy rate after therapy.

Promising results for combined therapy

Although no statistically significant intergroup differences were seen in the combined treatment group versus the endometrial ablation alone group for the first 6 months of treatment, significant differences existed at the 12- and 24-month mark. Hysterectomy rates after combined treatment varied from 0% to 11% versus 9.4% to 24% after endometrial ablation alone. Complication rates for combined treatment did not appear higher than those for endometrial ablation alone.

The authors postulated that the failure of endometrial ablation is generally caused by either remaining or regenerating endometrial tissue and that the addition of an LNG IUS allows for suppression of endometrial tissue. Also encouraging was that, in general, the removal of the LNG IUS was relatively simple. A single difficult removal was described due to uterine synechiae, but hysteroscopic resection was not necessary. The authors acknowledged that the data from these 7 retrospective studies are limited and that high-quality research from prospective studies is needed.

Bottom line

The data available from this systematic review suggest that placement of an LNG IUS at the completion of an endometrial ablation may result in lower hysterectomy rates, without apparent risk, and without significantly difficult LNG IUS removal when needed.

The data provided by Oderkerk and colleagues’ systematic review are promising and, although not studied in the reviewed publications, the potential may exist to reduce the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer by adding an LNG IUS.

Continue to: LNG IUS is less expensive, and less effective, than endometrial ablation for heavy menstrual bleeding, cost analysis shows...