User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Boys may carry the weight, or overweight, of adults’ infertility

Overweight boy, infertile man?

When it comes to causes of infertility, history and science have generally focused on women. A lot of the research overlooks men, but some previous studies have suggested that male infertility contributes to about half of the cases of couple infertility. The reason for much of that male infertility, however, has been a mystery. Until now.

A group of Italian investigators looked at the declining trend in sperm counts over the past 40 years and the increase of childhood obesity. Is there a correlation? The researchers think so. Childhood obesity can be linked to multiple causes, but the researchers zeroed in on the effect that obesity has on metabolic rates and, therefore, testicular growth.

Collecting data on testicular volume, body mass index (BMI), and insulin resistance from 268 boys aged 2-18 years, the researchers discovered that those with normal weight and normal insulin levels had testicular volumes 1.5 times higher than their overweight counterparts and 1.5-2 times higher than those with hyperinsulinemia, building a case for obesity being a factor for infertility later in life.

Since low testicular volume is associated with lower sperm count and production as an adult, putting two and two together makes a compelling argument for childhood obesity being a major male infertility culprit. It also creates even more urgency for the health care industry and community decision makers to focus on childhood obesity.

It sure would be nice to be able to take one of the many risk factors for future human survival off the table. Maybe by taking something, like cake, off the table.

Fecal transplantation moves to the kitchen

Fecal microbiota transplantation is an effective way to treat Clostridioides difficile infection, but, in the end, it’s still a transplantation procedure involving a nasogastric or colorectal tube or rather large oral capsules with a demanding (30-40 capsules over 2 days) dosage. Please, Science, tell us there’s a better way.

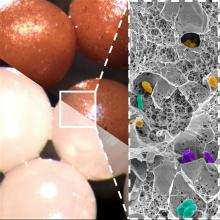

Science, in the form of investigators at the University of Geneva and Lausanne University Hospital in Switzerland, has spoken, and there may be a better way. Presenting fecal beads: All the bacterial goodness of donor stool without the tubal insertions or massive quantities of giant capsules.

We know you’re scoffing out there, but it’s true. All you need is a little alginate, which is a “biocompatible polysaccharide isolated from brown algae” of the Phaeophyceae family. The donor feces is microencapsulated by mixing it with the alginate, dropping that mixture into water containing calcium chloride, turning it into a gel, and then freeze-drying the gel into small (just 2 mm), solid beads.

Sounds plausible enough, but what do you do with them? “These brownish beads can be easily dispersed in a liquid or food that is pleasant to eat. They also have no taste,” senior author Eric Allémann, PhD, said in a statement released by the University of Geneva.

Pleasant to eat? No taste? So which is it? If you really want to know, watch fecal beads week on the new season of “The Great British Baking Show,” when Paul and Prue judge poop baked into crumpets, crepes, and crostatas. Yum.

We’re on the low-oxygen diet

Nine out of ten doctors agree: Oxygen is more important to your continued well-being than food. After all, a human can go weeks without food, but just minutes without oxygen. However, ten out of ten doctors agree that the United States has an obesity problem. They all also agree that previous research has shown soldiers who train at high altitudes lose more weight than those training at lower altitudes.

So, on the one hand, we have a country full of overweight people, and on the other, we have low oxygen levels causing weight loss. The solution, then, is obvious: Stop breathing.

More specifically (and somewhat less facetiously), researchers from Louisiana have launched the Low Oxygen and Weight Status trial and are currently recruiting individuals with BMIs of 30-40 to, uh, suffocate themselves. No, no, it’s okay, it’s just when they’re sleeping.

Fine, straight face. Participants in the LOWS trial will undergo an 8-week period when they will consume a controlled weight-loss diet and spend their nights in a hypoxic sealed tent, where they will sleep in an environment with an oxygen level equivalent to 8,500 feet above sea level (roughly equivalent to Aspen, Colo.). They will be compared with people on the same diet who sleep in a normal, sea-level oxygen environment.

The study’s goal is to determine whether or not spending time in a low-oxygen environment will suppress appetite, increase energy expenditure, and improve weight loss and insulin sensitivity. Excessive weight loss in high-altitude environments isn’t a good thing for soldiers – they kind of need their muscles and body weight to do the whole soldiering thing – but it could be great for people struggling to lose those last few pounds. And it also may prove LOTME’s previous thesis: Air is not good.

Overweight boy, infertile man?

When it comes to causes of infertility, history and science have generally focused on women. A lot of the research overlooks men, but some previous studies have suggested that male infertility contributes to about half of the cases of couple infertility. The reason for much of that male infertility, however, has been a mystery. Until now.

A group of Italian investigators looked at the declining trend in sperm counts over the past 40 years and the increase of childhood obesity. Is there a correlation? The researchers think so. Childhood obesity can be linked to multiple causes, but the researchers zeroed in on the effect that obesity has on metabolic rates and, therefore, testicular growth.

Collecting data on testicular volume, body mass index (BMI), and insulin resistance from 268 boys aged 2-18 years, the researchers discovered that those with normal weight and normal insulin levels had testicular volumes 1.5 times higher than their overweight counterparts and 1.5-2 times higher than those with hyperinsulinemia, building a case for obesity being a factor for infertility later in life.

Since low testicular volume is associated with lower sperm count and production as an adult, putting two and two together makes a compelling argument for childhood obesity being a major male infertility culprit. It also creates even more urgency for the health care industry and community decision makers to focus on childhood obesity.

It sure would be nice to be able to take one of the many risk factors for future human survival off the table. Maybe by taking something, like cake, off the table.

Fecal transplantation moves to the kitchen

Fecal microbiota transplantation is an effective way to treat Clostridioides difficile infection, but, in the end, it’s still a transplantation procedure involving a nasogastric or colorectal tube or rather large oral capsules with a demanding (30-40 capsules over 2 days) dosage. Please, Science, tell us there’s a better way.

Science, in the form of investigators at the University of Geneva and Lausanne University Hospital in Switzerland, has spoken, and there may be a better way. Presenting fecal beads: All the bacterial goodness of donor stool without the tubal insertions or massive quantities of giant capsules.

We know you’re scoffing out there, but it’s true. All you need is a little alginate, which is a “biocompatible polysaccharide isolated from brown algae” of the Phaeophyceae family. The donor feces is microencapsulated by mixing it with the alginate, dropping that mixture into water containing calcium chloride, turning it into a gel, and then freeze-drying the gel into small (just 2 mm), solid beads.

Sounds plausible enough, but what do you do with them? “These brownish beads can be easily dispersed in a liquid or food that is pleasant to eat. They also have no taste,” senior author Eric Allémann, PhD, said in a statement released by the University of Geneva.

Pleasant to eat? No taste? So which is it? If you really want to know, watch fecal beads week on the new season of “The Great British Baking Show,” when Paul and Prue judge poop baked into crumpets, crepes, and crostatas. Yum.

We’re on the low-oxygen diet

Nine out of ten doctors agree: Oxygen is more important to your continued well-being than food. After all, a human can go weeks without food, but just minutes without oxygen. However, ten out of ten doctors agree that the United States has an obesity problem. They all also agree that previous research has shown soldiers who train at high altitudes lose more weight than those training at lower altitudes.

So, on the one hand, we have a country full of overweight people, and on the other, we have low oxygen levels causing weight loss. The solution, then, is obvious: Stop breathing.

More specifically (and somewhat less facetiously), researchers from Louisiana have launched the Low Oxygen and Weight Status trial and are currently recruiting individuals with BMIs of 30-40 to, uh, suffocate themselves. No, no, it’s okay, it’s just when they’re sleeping.

Fine, straight face. Participants in the LOWS trial will undergo an 8-week period when they will consume a controlled weight-loss diet and spend their nights in a hypoxic sealed tent, where they will sleep in an environment with an oxygen level equivalent to 8,500 feet above sea level (roughly equivalent to Aspen, Colo.). They will be compared with people on the same diet who sleep in a normal, sea-level oxygen environment.

The study’s goal is to determine whether or not spending time in a low-oxygen environment will suppress appetite, increase energy expenditure, and improve weight loss and insulin sensitivity. Excessive weight loss in high-altitude environments isn’t a good thing for soldiers – they kind of need their muscles and body weight to do the whole soldiering thing – but it could be great for people struggling to lose those last few pounds. And it also may prove LOTME’s previous thesis: Air is not good.

Overweight boy, infertile man?

When it comes to causes of infertility, history and science have generally focused on women. A lot of the research overlooks men, but some previous studies have suggested that male infertility contributes to about half of the cases of couple infertility. The reason for much of that male infertility, however, has been a mystery. Until now.

A group of Italian investigators looked at the declining trend in sperm counts over the past 40 years and the increase of childhood obesity. Is there a correlation? The researchers think so. Childhood obesity can be linked to multiple causes, but the researchers zeroed in on the effect that obesity has on metabolic rates and, therefore, testicular growth.

Collecting data on testicular volume, body mass index (BMI), and insulin resistance from 268 boys aged 2-18 years, the researchers discovered that those with normal weight and normal insulin levels had testicular volumes 1.5 times higher than their overweight counterparts and 1.5-2 times higher than those with hyperinsulinemia, building a case for obesity being a factor for infertility later in life.

Since low testicular volume is associated with lower sperm count and production as an adult, putting two and two together makes a compelling argument for childhood obesity being a major male infertility culprit. It also creates even more urgency for the health care industry and community decision makers to focus on childhood obesity.

It sure would be nice to be able to take one of the many risk factors for future human survival off the table. Maybe by taking something, like cake, off the table.

Fecal transplantation moves to the kitchen

Fecal microbiota transplantation is an effective way to treat Clostridioides difficile infection, but, in the end, it’s still a transplantation procedure involving a nasogastric or colorectal tube or rather large oral capsules with a demanding (30-40 capsules over 2 days) dosage. Please, Science, tell us there’s a better way.

Science, in the form of investigators at the University of Geneva and Lausanne University Hospital in Switzerland, has spoken, and there may be a better way. Presenting fecal beads: All the bacterial goodness of donor stool without the tubal insertions or massive quantities of giant capsules.

We know you’re scoffing out there, but it’s true. All you need is a little alginate, which is a “biocompatible polysaccharide isolated from brown algae” of the Phaeophyceae family. The donor feces is microencapsulated by mixing it with the alginate, dropping that mixture into water containing calcium chloride, turning it into a gel, and then freeze-drying the gel into small (just 2 mm), solid beads.

Sounds plausible enough, but what do you do with them? “These brownish beads can be easily dispersed in a liquid or food that is pleasant to eat. They also have no taste,” senior author Eric Allémann, PhD, said in a statement released by the University of Geneva.

Pleasant to eat? No taste? So which is it? If you really want to know, watch fecal beads week on the new season of “The Great British Baking Show,” when Paul and Prue judge poop baked into crumpets, crepes, and crostatas. Yum.

We’re on the low-oxygen diet

Nine out of ten doctors agree: Oxygen is more important to your continued well-being than food. After all, a human can go weeks without food, but just minutes without oxygen. However, ten out of ten doctors agree that the United States has an obesity problem. They all also agree that previous research has shown soldiers who train at high altitudes lose more weight than those training at lower altitudes.

So, on the one hand, we have a country full of overweight people, and on the other, we have low oxygen levels causing weight loss. The solution, then, is obvious: Stop breathing.

More specifically (and somewhat less facetiously), researchers from Louisiana have launched the Low Oxygen and Weight Status trial and are currently recruiting individuals with BMIs of 30-40 to, uh, suffocate themselves. No, no, it’s okay, it’s just when they’re sleeping.

Fine, straight face. Participants in the LOWS trial will undergo an 8-week period when they will consume a controlled weight-loss diet and spend their nights in a hypoxic sealed tent, where they will sleep in an environment with an oxygen level equivalent to 8,500 feet above sea level (roughly equivalent to Aspen, Colo.). They will be compared with people on the same diet who sleep in a normal, sea-level oxygen environment.

The study’s goal is to determine whether or not spending time in a low-oxygen environment will suppress appetite, increase energy expenditure, and improve weight loss and insulin sensitivity. Excessive weight loss in high-altitude environments isn’t a good thing for soldiers – they kind of need their muscles and body weight to do the whole soldiering thing – but it could be great for people struggling to lose those last few pounds. And it also may prove LOTME’s previous thesis: Air is not good.

Part-time physician: Is it a viable career choice?

On average, physicians reported in the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2023 that they worked 50 hours per week. Five specialties, including critical care, cardiology, and general surgery reported working 55 or more hours weekly.

In 2011, The New England Journal of Medicine reported that part-time physician careers were rising. At the time, part-time doctors made up 21% of the physician workforce, up from 13% in 2005.

In a more recent survey from the California Health Care Foundation, only 12% of California physicians said they devoted 20-29 hours a week to patient care.

Amy Knoup, a senior recruitment adviser with Provider Solutions & Development), has been helping doctors find jobs for over a decade, and she’s noticed a trend.

“Not only are more physicians seeking part-time roles than they were 10 years ago, but more large health care systems are also offering part time or per diem as well,” said Ms. Knoup.

Who’s working part time, and why?

Ten years ago, the fastest growing segment of part-timers were men nearing retirement and early- to mid-career women.

Pediatricians led the part-time pack in 2002, according to an American Academy of Pediatrics study. At the time, 15% of pediatricians reported their hours as part time. However, the numbers may have increased over the years. For example, a 2021 study by the department of pediatrics, Boston Medical Center, and Boston University found that almost 30% of graduating pediatricians sought part-time work at the end of their training.

At PS&D, Ms. Knoup said she has noticed a trend toward part-timers among primary care, behavioral health, and outpatient specialties such as endocrinology. “We’re also seeing it with the inpatient side in roles that are more shift based like hospitalists, radiologists, and critical care and ER doctors.”

Another trend Ms. Knoup has noticed is with early-career doctors. “They have a different mindset,” she said. “Younger generations are acutely aware of burnout. They may have experienced it in residency or during the pandemic. They’ve had a taste of that and don’t want to go down that road again, so they’re seeking part-time roles. It’s an intentional choice.”

Tracey O’Connell, MD, a radiologist, always knew that she wanted to work part time. “I had a baby as a resident, and I was pregnant with my second child as a fellow,” she said. “I was already feeling overwhelmed with medical training and having a family.”

Dr. O’Connell worked in private practice for 16 years on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, with no nights or weekends.

“I still found it completely overwhelming,” she said. “Even though I had more days not working than working, I felt like the demands of medical life had advanced faster than human beings could adapt, and I still feel that way.”

Today she runs a part-time teleradiology practice from home but spends more time on her second career as a life coach. “Most of my clients are physicians looking for more fulfillment and sustainable ways of practicing medicine while maintaining their own identity as human beings, not just the all-consuming identity of ‘doctor,’ ” she said.

On the other end of the career spectrum is Lois Goodman, MD, an ob.gyn. in her late 70s. After 42 years in a group practice, she started her solo practice at 72, seeing patients 3 days per week. “I’m just happy to be working. That’s a tremendous payoff for me. I need to keep working for my mental health.”

How does part-time work affect physician shortages and care delivery?

Reducing clinical effort is one of the strategies physicians use to scale down overload. Still, it’s not viable as a long-term solution, said Christine Sinsky, MD, AMA’s vice president of professional satisfaction and a nationally regarded researcher on physician burnout.

“If all the physicians in a community went from working 100% FTE clinical to 50% FTE clinical, then the people in that community would have half the access to care that they had,” said Dr. Sinsky. “There’s less capacity in the system to care for patients.”

Some could argue, then, that part-time physician work may contribute to physician shortage predictions. An Association of American Medical Colleges report estimates there will be a shortage of 37,800 to 124,000 physicians by 2034.

But physicians working part-time express a contrasting point of view. “I don’t believe that part-time workers are responsible for the health care shortage but rather, a great solution,” said Dr. O’Connell. “Because in order to continue working for a long time rather than quitting when the demands exceed human capacity, working part time is a great compromise to offer a life of more sustainable well-being and longevity as a physician, and still live a wholehearted life.”

Pros and cons of being a part-time physician

Pros

Less burnout: The American Medical Association has tracked burnout rates for 22 years. By the end of 2021, nearly 63% of physicians reported burnout symptoms, compared with 38% the year before. Going part time appears to reduce burnout, suggests a study published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Better work-life balance: Rachel Miller, MD, an ob.gyn., worked 60-70 hours weekly for 9 years. In 2022, she went to work as an OB hospitalist for a health care system that welcomes part-time clinicians. Since then, she has achieved a better work-life balance, putting in 26-28 hours a week. Dr. Miller now spends more time with her kids and in her additional role as an executive coach to leaders in the medical field.

More focus: “When I’m at work, I’m 100% mentally in and focused,” said Dr. Miller. “My interactions with patients are different because I’m not burned out. My demeanor and my willingness to connect are stronger.”

Better health: Mehmet Cilingiroglu, MD, with CardioSolution, traded full-time work for part time when health issues and a kidney transplant sidelined his 30-year career in 2018. “Despite my significant health issues, I’ve been able to continue working at a pace that suits me rather than having to retire,” he said. “Part-time physicians can still enjoy patient care, research, innovation, education, and training while balancing that with other areas of life.”

Errin Weisman, a DO who gave up full-time work in 2016, said cutting back makes her feel healthier, happier, and more energized. “Part-time work helps me to bring my A game each day I work and deliver the best care.” She’s also a life coach encouraging other physicians to find balance in their professional and personal lives.

Cons

Cut in pay: Obviously, the No. 1 con is you’ll make less working part time, so adjusting to a salary decrease can be a huge issue, especially if you don’t have other sources of income. Physicians paying off student loans, those caring for children or elderly parents, or those in their prime earning years needing to save for retirement may not be able to go part time.

Diminished career: The chance for promotions or being well known in your field can be diminished, as well as a loss of proficiency if you’re only performing surgery or procedures part time. In some specialties, working part time and not keeping up with (or being able to practice) newer technology developments can harm your career or reputation in the long run.

Missing out: While working part time has many benefits, physicians also experience a wide range of drawbacks. Dr. Goodman, for example, said she misses delivering babies and doing surgeries. Dr. Miller said she gave up some aspects of her specialty, like performing hysterectomies, participating in complex cases, and no longer having an office like she did as a full-time ob.gyn.

Loss of fellowship: Dr. O’Connell said she missed the camaraderie and sense of belonging when she scaled back her hours. “I felt like a fish out of water, that my values didn’t align with the group’s values,” she said. This led to self-doubt, frustrated colleagues, and a reduction in benefits.

Lost esteem: Dr. O’Connell also felt she was expected to work overtime without additional pay and was no longer eligible for bonuses. “I was treated as a team player when I was needed, but not when it came to perks and benefits and insider privilege,” she said. There may be a loss of esteem among colleagues and supervisors.

Overcoming stigma: Because part-time physician work is still not prevalent among colleagues, some may resist the idea, have less respect for it, perceive it as not being serious about your career as a physician, or associate it with being lazy or entitled.

Summing it up

Every physician must weigh the value and drawbacks of part-time work, but the more physicians who go this route, the more part-time medicine gains traction and the more physicians can learn about its values versus its drawbacks.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On average, physicians reported in the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2023 that they worked 50 hours per week. Five specialties, including critical care, cardiology, and general surgery reported working 55 or more hours weekly.

In 2011, The New England Journal of Medicine reported that part-time physician careers were rising. At the time, part-time doctors made up 21% of the physician workforce, up from 13% in 2005.

In a more recent survey from the California Health Care Foundation, only 12% of California physicians said they devoted 20-29 hours a week to patient care.

Amy Knoup, a senior recruitment adviser with Provider Solutions & Development), has been helping doctors find jobs for over a decade, and she’s noticed a trend.

“Not only are more physicians seeking part-time roles than they were 10 years ago, but more large health care systems are also offering part time or per diem as well,” said Ms. Knoup.

Who’s working part time, and why?

Ten years ago, the fastest growing segment of part-timers were men nearing retirement and early- to mid-career women.

Pediatricians led the part-time pack in 2002, according to an American Academy of Pediatrics study. At the time, 15% of pediatricians reported their hours as part time. However, the numbers may have increased over the years. For example, a 2021 study by the department of pediatrics, Boston Medical Center, and Boston University found that almost 30% of graduating pediatricians sought part-time work at the end of their training.

At PS&D, Ms. Knoup said she has noticed a trend toward part-timers among primary care, behavioral health, and outpatient specialties such as endocrinology. “We’re also seeing it with the inpatient side in roles that are more shift based like hospitalists, radiologists, and critical care and ER doctors.”

Another trend Ms. Knoup has noticed is with early-career doctors. “They have a different mindset,” she said. “Younger generations are acutely aware of burnout. They may have experienced it in residency or during the pandemic. They’ve had a taste of that and don’t want to go down that road again, so they’re seeking part-time roles. It’s an intentional choice.”

Tracey O’Connell, MD, a radiologist, always knew that she wanted to work part time. “I had a baby as a resident, and I was pregnant with my second child as a fellow,” she said. “I was already feeling overwhelmed with medical training and having a family.”

Dr. O’Connell worked in private practice for 16 years on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, with no nights or weekends.

“I still found it completely overwhelming,” she said. “Even though I had more days not working than working, I felt like the demands of medical life had advanced faster than human beings could adapt, and I still feel that way.”

Today she runs a part-time teleradiology practice from home but spends more time on her second career as a life coach. “Most of my clients are physicians looking for more fulfillment and sustainable ways of practicing medicine while maintaining their own identity as human beings, not just the all-consuming identity of ‘doctor,’ ” she said.

On the other end of the career spectrum is Lois Goodman, MD, an ob.gyn. in her late 70s. After 42 years in a group practice, she started her solo practice at 72, seeing patients 3 days per week. “I’m just happy to be working. That’s a tremendous payoff for me. I need to keep working for my mental health.”

How does part-time work affect physician shortages and care delivery?

Reducing clinical effort is one of the strategies physicians use to scale down overload. Still, it’s not viable as a long-term solution, said Christine Sinsky, MD, AMA’s vice president of professional satisfaction and a nationally regarded researcher on physician burnout.

“If all the physicians in a community went from working 100% FTE clinical to 50% FTE clinical, then the people in that community would have half the access to care that they had,” said Dr. Sinsky. “There’s less capacity in the system to care for patients.”

Some could argue, then, that part-time physician work may contribute to physician shortage predictions. An Association of American Medical Colleges report estimates there will be a shortage of 37,800 to 124,000 physicians by 2034.

But physicians working part-time express a contrasting point of view. “I don’t believe that part-time workers are responsible for the health care shortage but rather, a great solution,” said Dr. O’Connell. “Because in order to continue working for a long time rather than quitting when the demands exceed human capacity, working part time is a great compromise to offer a life of more sustainable well-being and longevity as a physician, and still live a wholehearted life.”

Pros and cons of being a part-time physician

Pros

Less burnout: The American Medical Association has tracked burnout rates for 22 years. By the end of 2021, nearly 63% of physicians reported burnout symptoms, compared with 38% the year before. Going part time appears to reduce burnout, suggests a study published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Better work-life balance: Rachel Miller, MD, an ob.gyn., worked 60-70 hours weekly for 9 years. In 2022, she went to work as an OB hospitalist for a health care system that welcomes part-time clinicians. Since then, she has achieved a better work-life balance, putting in 26-28 hours a week. Dr. Miller now spends more time with her kids and in her additional role as an executive coach to leaders in the medical field.

More focus: “When I’m at work, I’m 100% mentally in and focused,” said Dr. Miller. “My interactions with patients are different because I’m not burned out. My demeanor and my willingness to connect are stronger.”

Better health: Mehmet Cilingiroglu, MD, with CardioSolution, traded full-time work for part time when health issues and a kidney transplant sidelined his 30-year career in 2018. “Despite my significant health issues, I’ve been able to continue working at a pace that suits me rather than having to retire,” he said. “Part-time physicians can still enjoy patient care, research, innovation, education, and training while balancing that with other areas of life.”

Errin Weisman, a DO who gave up full-time work in 2016, said cutting back makes her feel healthier, happier, and more energized. “Part-time work helps me to bring my A game each day I work and deliver the best care.” She’s also a life coach encouraging other physicians to find balance in their professional and personal lives.

Cons

Cut in pay: Obviously, the No. 1 con is you’ll make less working part time, so adjusting to a salary decrease can be a huge issue, especially if you don’t have other sources of income. Physicians paying off student loans, those caring for children or elderly parents, or those in their prime earning years needing to save for retirement may not be able to go part time.

Diminished career: The chance for promotions or being well known in your field can be diminished, as well as a loss of proficiency if you’re only performing surgery or procedures part time. In some specialties, working part time and not keeping up with (or being able to practice) newer technology developments can harm your career or reputation in the long run.

Missing out: While working part time has many benefits, physicians also experience a wide range of drawbacks. Dr. Goodman, for example, said she misses delivering babies and doing surgeries. Dr. Miller said she gave up some aspects of her specialty, like performing hysterectomies, participating in complex cases, and no longer having an office like she did as a full-time ob.gyn.

Loss of fellowship: Dr. O’Connell said she missed the camaraderie and sense of belonging when she scaled back her hours. “I felt like a fish out of water, that my values didn’t align with the group’s values,” she said. This led to self-doubt, frustrated colleagues, and a reduction in benefits.

Lost esteem: Dr. O’Connell also felt she was expected to work overtime without additional pay and was no longer eligible for bonuses. “I was treated as a team player when I was needed, but not when it came to perks and benefits and insider privilege,” she said. There may be a loss of esteem among colleagues and supervisors.

Overcoming stigma: Because part-time physician work is still not prevalent among colleagues, some may resist the idea, have less respect for it, perceive it as not being serious about your career as a physician, or associate it with being lazy or entitled.

Summing it up

Every physician must weigh the value and drawbacks of part-time work, but the more physicians who go this route, the more part-time medicine gains traction and the more physicians can learn about its values versus its drawbacks.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On average, physicians reported in the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2023 that they worked 50 hours per week. Five specialties, including critical care, cardiology, and general surgery reported working 55 or more hours weekly.

In 2011, The New England Journal of Medicine reported that part-time physician careers were rising. At the time, part-time doctors made up 21% of the physician workforce, up from 13% in 2005.

In a more recent survey from the California Health Care Foundation, only 12% of California physicians said they devoted 20-29 hours a week to patient care.

Amy Knoup, a senior recruitment adviser with Provider Solutions & Development), has been helping doctors find jobs for over a decade, and she’s noticed a trend.

“Not only are more physicians seeking part-time roles than they were 10 years ago, but more large health care systems are also offering part time or per diem as well,” said Ms. Knoup.

Who’s working part time, and why?

Ten years ago, the fastest growing segment of part-timers were men nearing retirement and early- to mid-career women.

Pediatricians led the part-time pack in 2002, according to an American Academy of Pediatrics study. At the time, 15% of pediatricians reported their hours as part time. However, the numbers may have increased over the years. For example, a 2021 study by the department of pediatrics, Boston Medical Center, and Boston University found that almost 30% of graduating pediatricians sought part-time work at the end of their training.

At PS&D, Ms. Knoup said she has noticed a trend toward part-timers among primary care, behavioral health, and outpatient specialties such as endocrinology. “We’re also seeing it with the inpatient side in roles that are more shift based like hospitalists, radiologists, and critical care and ER doctors.”

Another trend Ms. Knoup has noticed is with early-career doctors. “They have a different mindset,” she said. “Younger generations are acutely aware of burnout. They may have experienced it in residency or during the pandemic. They’ve had a taste of that and don’t want to go down that road again, so they’re seeking part-time roles. It’s an intentional choice.”

Tracey O’Connell, MD, a radiologist, always knew that she wanted to work part time. “I had a baby as a resident, and I was pregnant with my second child as a fellow,” she said. “I was already feeling overwhelmed with medical training and having a family.”

Dr. O’Connell worked in private practice for 16 years on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, with no nights or weekends.

“I still found it completely overwhelming,” she said. “Even though I had more days not working than working, I felt like the demands of medical life had advanced faster than human beings could adapt, and I still feel that way.”

Today she runs a part-time teleradiology practice from home but spends more time on her second career as a life coach. “Most of my clients are physicians looking for more fulfillment and sustainable ways of practicing medicine while maintaining their own identity as human beings, not just the all-consuming identity of ‘doctor,’ ” she said.

On the other end of the career spectrum is Lois Goodman, MD, an ob.gyn. in her late 70s. After 42 years in a group practice, she started her solo practice at 72, seeing patients 3 days per week. “I’m just happy to be working. That’s a tremendous payoff for me. I need to keep working for my mental health.”

How does part-time work affect physician shortages and care delivery?

Reducing clinical effort is one of the strategies physicians use to scale down overload. Still, it’s not viable as a long-term solution, said Christine Sinsky, MD, AMA’s vice president of professional satisfaction and a nationally regarded researcher on physician burnout.

“If all the physicians in a community went from working 100% FTE clinical to 50% FTE clinical, then the people in that community would have half the access to care that they had,” said Dr. Sinsky. “There’s less capacity in the system to care for patients.”

Some could argue, then, that part-time physician work may contribute to physician shortage predictions. An Association of American Medical Colleges report estimates there will be a shortage of 37,800 to 124,000 physicians by 2034.

But physicians working part-time express a contrasting point of view. “I don’t believe that part-time workers are responsible for the health care shortage but rather, a great solution,” said Dr. O’Connell. “Because in order to continue working for a long time rather than quitting when the demands exceed human capacity, working part time is a great compromise to offer a life of more sustainable well-being and longevity as a physician, and still live a wholehearted life.”

Pros and cons of being a part-time physician

Pros

Less burnout: The American Medical Association has tracked burnout rates for 22 years. By the end of 2021, nearly 63% of physicians reported burnout symptoms, compared with 38% the year before. Going part time appears to reduce burnout, suggests a study published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Better work-life balance: Rachel Miller, MD, an ob.gyn., worked 60-70 hours weekly for 9 years. In 2022, she went to work as an OB hospitalist for a health care system that welcomes part-time clinicians. Since then, she has achieved a better work-life balance, putting in 26-28 hours a week. Dr. Miller now spends more time with her kids and in her additional role as an executive coach to leaders in the medical field.

More focus: “When I’m at work, I’m 100% mentally in and focused,” said Dr. Miller. “My interactions with patients are different because I’m not burned out. My demeanor and my willingness to connect are stronger.”

Better health: Mehmet Cilingiroglu, MD, with CardioSolution, traded full-time work for part time when health issues and a kidney transplant sidelined his 30-year career in 2018. “Despite my significant health issues, I’ve been able to continue working at a pace that suits me rather than having to retire,” he said. “Part-time physicians can still enjoy patient care, research, innovation, education, and training while balancing that with other areas of life.”

Errin Weisman, a DO who gave up full-time work in 2016, said cutting back makes her feel healthier, happier, and more energized. “Part-time work helps me to bring my A game each day I work and deliver the best care.” She’s also a life coach encouraging other physicians to find balance in their professional and personal lives.

Cons

Cut in pay: Obviously, the No. 1 con is you’ll make less working part time, so adjusting to a salary decrease can be a huge issue, especially if you don’t have other sources of income. Physicians paying off student loans, those caring for children or elderly parents, or those in their prime earning years needing to save for retirement may not be able to go part time.

Diminished career: The chance for promotions or being well known in your field can be diminished, as well as a loss of proficiency if you’re only performing surgery or procedures part time. In some specialties, working part time and not keeping up with (or being able to practice) newer technology developments can harm your career or reputation in the long run.

Missing out: While working part time has many benefits, physicians also experience a wide range of drawbacks. Dr. Goodman, for example, said she misses delivering babies and doing surgeries. Dr. Miller said she gave up some aspects of her specialty, like performing hysterectomies, participating in complex cases, and no longer having an office like she did as a full-time ob.gyn.

Loss of fellowship: Dr. O’Connell said she missed the camaraderie and sense of belonging when she scaled back her hours. “I felt like a fish out of water, that my values didn’t align with the group’s values,” she said. This led to self-doubt, frustrated colleagues, and a reduction in benefits.

Lost esteem: Dr. O’Connell also felt she was expected to work overtime without additional pay and was no longer eligible for bonuses. “I was treated as a team player when I was needed, but not when it came to perks and benefits and insider privilege,” she said. There may be a loss of esteem among colleagues and supervisors.

Overcoming stigma: Because part-time physician work is still not prevalent among colleagues, some may resist the idea, have less respect for it, perceive it as not being serious about your career as a physician, or associate it with being lazy or entitled.

Summing it up

Every physician must weigh the value and drawbacks of part-time work, but the more physicians who go this route, the more part-time medicine gains traction and the more physicians can learn about its values versus its drawbacks.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New USPSTF draft suggests mammography start at 40, not 50

The major change: USPSTF proposed reducing the recommended start age for routine screening mammograms from age 50 to age 40. The latest recommendation, which carries a B grade, also calls for screening every other year and sets a cutoff age of 74.

The task force’s A and B ratings indicate strong confidence in the evidence for benefit, meaning that clinicians should encourage their patients to get these services as appropriate.

The influential federal advisory panel last updated these recommendations in 2016. At the time, USPSTF recommended routine screening mammograms starting at age 50, and gave a C grade to starting before that.

In the 2016 recommendations, “we felt a woman could start screening in her 40s depending on how she feels about the harms and benefits in an individualized personal decision,” USPSTF member John Wong, MD, chief of clinical decision making and a primary care physician at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, said in an interview. “In this draft recommendation, we now recommend that all women get screened starting at age 40.”

Two major factors prompted the change, explained Dr. Wong. One is that more women are being diagnosed with breast cancer in their 40s. The other is that a growing body of evidence showing that Black women get breast cancer younger, are more likely to die of breast cancer, and would benefit from earlier screening.

“It is now clear that screening every other year starting at age 40 has the potential to save about 20% more lives among all women and there is even greater potential benefit for Black women, who are much more likely to die from breast cancer,” Dr. Wong said.

The American Cancer Society (ACS) called the draft recommendations a “significant positive change,” while noting that the task force recommendations only apply to women at average risk for breast cancer.

The American College of Radiology (ACR) already recommends yearly mammograms for average risk women starting at age 40. Its latest guidelines on mammography call for women at higher-than-average risk for breast cancer to undergo a risk assessment by age 25 to determine if screening before age 40 is needed.

When asked about the differing views, Debra Monticciolo, MD, division chief for breast imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital, said annual screenings that follow ACR recommendations would save more lives than the every-other-year approach backed by the task force. Dr. Monticciolo also highlighted that the available scientific evidence supports earlier assessment as well as augmented and earlier-than-age-40 screening of many women – particularly Black women.

“These evidence-based updates should spur more-informed doctor–patient conversations and help providers save more lives,” Dr. Monticciolo said in a press release.

Insurance access

Typically, upgrading a USPSTF recommendation from C to B leads to better access and insurance coverage for patients. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 requires insurers to cover the cost of services that get A and B recommendations from the USPSTF without charging copays – a mandate intended to promote greater use for highly regarded services.

But Congress created a special workaround that effectively makes the ACA mandate apply to the 2002 task force recommendations on mammography. In those recommendations, the task force gave a B grade to screening mammograms every 1 or 2 years starting at age 40 without an age limit.

Federal lawmakers have sought to provide copay-free access to mammograms for this entire population even when the USPSTF recommendations in 2009 and 2016 gave a C grade to routine screening for women under 50.

Still, “it is important to note that our recommendation is based solely on the science of what works to prevent breast cancer and it is not a recommendation for or against insurance coverage,” the task force acknowledged when unveiling the new draft update. “Coverage decisions involve considerations beyond the evidence about clinical benefit, and in the end, these decisions are the responsibility of payors, regulators, and legislators.”

Uncertainties persist

The new draft recommendations also highlight the persistent gaps in knowledge about the uses of mammography, despite years of widespread use of this screening tool.

The updated draft recommendations emphasize the lack of sufficient evidence to address major areas of concern related to screening and treating Black women, older women, women with dense breasts, and those with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

The task force called for more research addressing the underlying causes of elevated breast cancer mortality rates among Black women.

The USPSTF also issued an ‘I’ statement for providing women with dense breasts additional screening with breast ultrasound or MRI and for screening women older than 75 for breast cancer. Such statements indicate that the available evidence is lacking, poor quality, or conflicting, and thus the USPSTF can’t assess the benefits and harms or make a recommendation for or against providing the preventive service.

“Nearly half of all women have dense breasts, which increases their risk for breast cancer and means that mammograms may not work as well for them. We need to know more about whether and how additional screening might help women with dense breasts stay healthy,” the task force explained.

The task force also called for more research on approaches to reduce the risk for overdiagnosis and overtreatment for breast lesions, such as DCIS, which are identified through screening.

One analysis – the COMET study – is currently underway to assess whether women could be spared surgery for DCIS and opt for watchful waiting instead.

“If we can find that monitoring them carefully, either with or without some sort of endocrine therapy, is just as effective in keeping patients free of invasive cancer as surgery, then I think we could help to de-escalate treatment for this very low-risk group of patients,” Shelley Hwang, MD, MPH, principal investigator of the COMET study, told this news organization in December.

The task force will accept comments from the public on this draft update through June 5.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The major change: USPSTF proposed reducing the recommended start age for routine screening mammograms from age 50 to age 40. The latest recommendation, which carries a B grade, also calls for screening every other year and sets a cutoff age of 74.

The task force’s A and B ratings indicate strong confidence in the evidence for benefit, meaning that clinicians should encourage their patients to get these services as appropriate.

The influential federal advisory panel last updated these recommendations in 2016. At the time, USPSTF recommended routine screening mammograms starting at age 50, and gave a C grade to starting before that.

In the 2016 recommendations, “we felt a woman could start screening in her 40s depending on how she feels about the harms and benefits in an individualized personal decision,” USPSTF member John Wong, MD, chief of clinical decision making and a primary care physician at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, said in an interview. “In this draft recommendation, we now recommend that all women get screened starting at age 40.”

Two major factors prompted the change, explained Dr. Wong. One is that more women are being diagnosed with breast cancer in their 40s. The other is that a growing body of evidence showing that Black women get breast cancer younger, are more likely to die of breast cancer, and would benefit from earlier screening.

“It is now clear that screening every other year starting at age 40 has the potential to save about 20% more lives among all women and there is even greater potential benefit for Black women, who are much more likely to die from breast cancer,” Dr. Wong said.

The American Cancer Society (ACS) called the draft recommendations a “significant positive change,” while noting that the task force recommendations only apply to women at average risk for breast cancer.

The American College of Radiology (ACR) already recommends yearly mammograms for average risk women starting at age 40. Its latest guidelines on mammography call for women at higher-than-average risk for breast cancer to undergo a risk assessment by age 25 to determine if screening before age 40 is needed.

When asked about the differing views, Debra Monticciolo, MD, division chief for breast imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital, said annual screenings that follow ACR recommendations would save more lives than the every-other-year approach backed by the task force. Dr. Monticciolo also highlighted that the available scientific evidence supports earlier assessment as well as augmented and earlier-than-age-40 screening of many women – particularly Black women.

“These evidence-based updates should spur more-informed doctor–patient conversations and help providers save more lives,” Dr. Monticciolo said in a press release.

Insurance access

Typically, upgrading a USPSTF recommendation from C to B leads to better access and insurance coverage for patients. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 requires insurers to cover the cost of services that get A and B recommendations from the USPSTF without charging copays – a mandate intended to promote greater use for highly regarded services.

But Congress created a special workaround that effectively makes the ACA mandate apply to the 2002 task force recommendations on mammography. In those recommendations, the task force gave a B grade to screening mammograms every 1 or 2 years starting at age 40 without an age limit.

Federal lawmakers have sought to provide copay-free access to mammograms for this entire population even when the USPSTF recommendations in 2009 and 2016 gave a C grade to routine screening for women under 50.

Still, “it is important to note that our recommendation is based solely on the science of what works to prevent breast cancer and it is not a recommendation for or against insurance coverage,” the task force acknowledged when unveiling the new draft update. “Coverage decisions involve considerations beyond the evidence about clinical benefit, and in the end, these decisions are the responsibility of payors, regulators, and legislators.”

Uncertainties persist

The new draft recommendations also highlight the persistent gaps in knowledge about the uses of mammography, despite years of widespread use of this screening tool.

The updated draft recommendations emphasize the lack of sufficient evidence to address major areas of concern related to screening and treating Black women, older women, women with dense breasts, and those with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

The task force called for more research addressing the underlying causes of elevated breast cancer mortality rates among Black women.

The USPSTF also issued an ‘I’ statement for providing women with dense breasts additional screening with breast ultrasound or MRI and for screening women older than 75 for breast cancer. Such statements indicate that the available evidence is lacking, poor quality, or conflicting, and thus the USPSTF can’t assess the benefits and harms or make a recommendation for or against providing the preventive service.

“Nearly half of all women have dense breasts, which increases their risk for breast cancer and means that mammograms may not work as well for them. We need to know more about whether and how additional screening might help women with dense breasts stay healthy,” the task force explained.

The task force also called for more research on approaches to reduce the risk for overdiagnosis and overtreatment for breast lesions, such as DCIS, which are identified through screening.

One analysis – the COMET study – is currently underway to assess whether women could be spared surgery for DCIS and opt for watchful waiting instead.

“If we can find that monitoring them carefully, either with or without some sort of endocrine therapy, is just as effective in keeping patients free of invasive cancer as surgery, then I think we could help to de-escalate treatment for this very low-risk group of patients,” Shelley Hwang, MD, MPH, principal investigator of the COMET study, told this news organization in December.

The task force will accept comments from the public on this draft update through June 5.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The major change: USPSTF proposed reducing the recommended start age for routine screening mammograms from age 50 to age 40. The latest recommendation, which carries a B grade, also calls for screening every other year and sets a cutoff age of 74.

The task force’s A and B ratings indicate strong confidence in the evidence for benefit, meaning that clinicians should encourage their patients to get these services as appropriate.

The influential federal advisory panel last updated these recommendations in 2016. At the time, USPSTF recommended routine screening mammograms starting at age 50, and gave a C grade to starting before that.

In the 2016 recommendations, “we felt a woman could start screening in her 40s depending on how she feels about the harms and benefits in an individualized personal decision,” USPSTF member John Wong, MD, chief of clinical decision making and a primary care physician at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, said in an interview. “In this draft recommendation, we now recommend that all women get screened starting at age 40.”

Two major factors prompted the change, explained Dr. Wong. One is that more women are being diagnosed with breast cancer in their 40s. The other is that a growing body of evidence showing that Black women get breast cancer younger, are more likely to die of breast cancer, and would benefit from earlier screening.

“It is now clear that screening every other year starting at age 40 has the potential to save about 20% more lives among all women and there is even greater potential benefit for Black women, who are much more likely to die from breast cancer,” Dr. Wong said.

The American Cancer Society (ACS) called the draft recommendations a “significant positive change,” while noting that the task force recommendations only apply to women at average risk for breast cancer.

The American College of Radiology (ACR) already recommends yearly mammograms for average risk women starting at age 40. Its latest guidelines on mammography call for women at higher-than-average risk for breast cancer to undergo a risk assessment by age 25 to determine if screening before age 40 is needed.

When asked about the differing views, Debra Monticciolo, MD, division chief for breast imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital, said annual screenings that follow ACR recommendations would save more lives than the every-other-year approach backed by the task force. Dr. Monticciolo also highlighted that the available scientific evidence supports earlier assessment as well as augmented and earlier-than-age-40 screening of many women – particularly Black women.

“These evidence-based updates should spur more-informed doctor–patient conversations and help providers save more lives,” Dr. Monticciolo said in a press release.

Insurance access

Typically, upgrading a USPSTF recommendation from C to B leads to better access and insurance coverage for patients. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 requires insurers to cover the cost of services that get A and B recommendations from the USPSTF without charging copays – a mandate intended to promote greater use for highly regarded services.

But Congress created a special workaround that effectively makes the ACA mandate apply to the 2002 task force recommendations on mammography. In those recommendations, the task force gave a B grade to screening mammograms every 1 or 2 years starting at age 40 without an age limit.

Federal lawmakers have sought to provide copay-free access to mammograms for this entire population even when the USPSTF recommendations in 2009 and 2016 gave a C grade to routine screening for women under 50.

Still, “it is important to note that our recommendation is based solely on the science of what works to prevent breast cancer and it is not a recommendation for or against insurance coverage,” the task force acknowledged when unveiling the new draft update. “Coverage decisions involve considerations beyond the evidence about clinical benefit, and in the end, these decisions are the responsibility of payors, regulators, and legislators.”

Uncertainties persist

The new draft recommendations also highlight the persistent gaps in knowledge about the uses of mammography, despite years of widespread use of this screening tool.

The updated draft recommendations emphasize the lack of sufficient evidence to address major areas of concern related to screening and treating Black women, older women, women with dense breasts, and those with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

The task force called for more research addressing the underlying causes of elevated breast cancer mortality rates among Black women.

The USPSTF also issued an ‘I’ statement for providing women with dense breasts additional screening with breast ultrasound or MRI and for screening women older than 75 for breast cancer. Such statements indicate that the available evidence is lacking, poor quality, or conflicting, and thus the USPSTF can’t assess the benefits and harms or make a recommendation for or against providing the preventive service.

“Nearly half of all women have dense breasts, which increases their risk for breast cancer and means that mammograms may not work as well for them. We need to know more about whether and how additional screening might help women with dense breasts stay healthy,” the task force explained.

The task force also called for more research on approaches to reduce the risk for overdiagnosis and overtreatment for breast lesions, such as DCIS, which are identified through screening.

One analysis – the COMET study – is currently underway to assess whether women could be spared surgery for DCIS and opt for watchful waiting instead.

“If we can find that monitoring them carefully, either with or without some sort of endocrine therapy, is just as effective in keeping patients free of invasive cancer as surgery, then I think we could help to de-escalate treatment for this very low-risk group of patients,” Shelley Hwang, MD, MPH, principal investigator of the COMET study, told this news organization in December.

The task force will accept comments from the public on this draft update through June 5.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Familial cancer risk complex, not limited to same site

The researchers found, for instance, that children of breast cancer patients had a 27% higher risk of any discordant early-onset cancer, and patients’ siblings had a 7.6-fold higher risk of early pancreatic cancer. The analysis also indicated that children of patients’ siblings had a significantly increased risk of testicular and ovarian cancers.

“The findings suggest that the familial risk extends to discordant early-onset cancers, including ovarian, testicular, and pancreatic cancers, as well as beyond first-degree relatives,” the researchers, led by Janne M. Pitkäniemi, PhD, Finnish Cancer Registry, Institute for Statistical and Epidemiological Cancer Research, Helsinki, say. “Our findings are interesting but raise some questions about unknown [genetic] and environmental mechanisms that need to be further studied.”

Erin F. Cobain, MD, who was not involved in the research, said the findings are “not very surprising to me.”

Dr. Cobain said that at her institution, she has seen “many, many cases” of family members of early-onset breast cancer patients with discordant cancers “where we are unable to find a clear genetic cause.”

Not being able to find an identifiable cause for the clustering of early-onset cancers can be “very frustrating” for patients and their families, said Dr. Cobain, a medical oncologist at the University of Michigan Health, Ann Arbor.

The study was published online in the International Journal of Cancer.

Family members of patients with early-onset breast cancer are at elevated risk for early-onset breast cancer. However, it is “unclear whether the familial risk is limited to early-onset cancer of the same site,” the authors explained.

To investigate, the researchers studied data from the Finnish Cancer Registry and the Finnish Population System, which included 54,753 relatives from 5,562 families of females diagnosed with early-onset breast cancer, defined as probands. A proband was the first member of the family diagnosed with female breast cancer at age 40 years or younger in Finland between January 1970 and December 31, 2012. Cancers were considered familial if they occurred in a family with a previously diagnosed proband and were deemed early onset if diagnosed before age 41.

The researchers found that only 5.5% of probands’ families had a family member with a discordant early-onset cancer. The most common diagnoses were testicular cancer (0.6% of families) and cancer of the thyroid gland (also 0.6%), followed by melanoma (0.5%).

Overall, the risk of any nonbreast early-onset cancer among first-degree relatives of probands was comparable with the risk in the general population (standardized incidence ratio, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.84-1.16).

However, the risk was elevated for certain family members and certain cancers.

Specifically, the children of probands had an increased risk for any discordant cancer (SIR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05-1.55).

The siblings of probands had an elevated risk for early-onset pancreatic cancer (SIR, 7.61) but not overall for any discordant cancer (SIR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.68-1.25).

And siblings’ children faced an elevated risk for testicular (SIR, 1.74) and ovarian (SIR, 2.69) cancer, though not of any discordant cancer (SIR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.97-1.37).

The researchers also found that the fathers (SIR, 0.43), mothers (SIR, 0.48), and spouses (SIR, 0.58) of probands appeared to have a decreased risk of any discordant early-onset cancer.

A potential limitation to the study was that the authors could not identify individuals with hereditary cancer syndromes or concerning gene mutations, such as BRCA carriers, because “registry data do not include comprehensive information on the gene mutation carriage status.” But the authors note that the number of BRCA carriers is likely low because of the low number of ovarian cancers observed in first-degree relatives of probands.

Dr. Cobain noted as well that the current study is potentially limited by its “very homogeneous” cohort.

But, overall, the findings indicate that familial risk is often “a much more complicated problem, mathematically and statistically,” than were there a single genetic culprit, Dr. Cobain said. One possibility is that some shared environmental exposure may be increasing the cancer risk among members of the same family.

“Genetic diversity is so vast and understanding how the interplay of multiple genes can influence an individual’s cancer risk is so much more complicated than a single BRCA1 mutation that clearly influences your breast cancer risk,” she added. However, “we’re starting to get there.”

The study was funded by the Cancer Foundation Finland and Academy of Finland. The authors and Dr. Cobain had no relevant financial relationships to declare.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The researchers found, for instance, that children of breast cancer patients had a 27% higher risk of any discordant early-onset cancer, and patients’ siblings had a 7.6-fold higher risk of early pancreatic cancer. The analysis also indicated that children of patients’ siblings had a significantly increased risk of testicular and ovarian cancers.

“The findings suggest that the familial risk extends to discordant early-onset cancers, including ovarian, testicular, and pancreatic cancers, as well as beyond first-degree relatives,” the researchers, led by Janne M. Pitkäniemi, PhD, Finnish Cancer Registry, Institute for Statistical and Epidemiological Cancer Research, Helsinki, say. “Our findings are interesting but raise some questions about unknown [genetic] and environmental mechanisms that need to be further studied.”

Erin F. Cobain, MD, who was not involved in the research, said the findings are “not very surprising to me.”

Dr. Cobain said that at her institution, she has seen “many, many cases” of family members of early-onset breast cancer patients with discordant cancers “where we are unable to find a clear genetic cause.”

Not being able to find an identifiable cause for the clustering of early-onset cancers can be “very frustrating” for patients and their families, said Dr. Cobain, a medical oncologist at the University of Michigan Health, Ann Arbor.

The study was published online in the International Journal of Cancer.

Family members of patients with early-onset breast cancer are at elevated risk for early-onset breast cancer. However, it is “unclear whether the familial risk is limited to early-onset cancer of the same site,” the authors explained.

To investigate, the researchers studied data from the Finnish Cancer Registry and the Finnish Population System, which included 54,753 relatives from 5,562 families of females diagnosed with early-onset breast cancer, defined as probands. A proband was the first member of the family diagnosed with female breast cancer at age 40 years or younger in Finland between January 1970 and December 31, 2012. Cancers were considered familial if they occurred in a family with a previously diagnosed proband and were deemed early onset if diagnosed before age 41.

The researchers found that only 5.5% of probands’ families had a family member with a discordant early-onset cancer. The most common diagnoses were testicular cancer (0.6% of families) and cancer of the thyroid gland (also 0.6%), followed by melanoma (0.5%).

Overall, the risk of any nonbreast early-onset cancer among first-degree relatives of probands was comparable with the risk in the general population (standardized incidence ratio, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.84-1.16).

However, the risk was elevated for certain family members and certain cancers.

Specifically, the children of probands had an increased risk for any discordant cancer (SIR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05-1.55).

The siblings of probands had an elevated risk for early-onset pancreatic cancer (SIR, 7.61) but not overall for any discordant cancer (SIR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.68-1.25).

And siblings’ children faced an elevated risk for testicular (SIR, 1.74) and ovarian (SIR, 2.69) cancer, though not of any discordant cancer (SIR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.97-1.37).

The researchers also found that the fathers (SIR, 0.43), mothers (SIR, 0.48), and spouses (SIR, 0.58) of probands appeared to have a decreased risk of any discordant early-onset cancer.

A potential limitation to the study was that the authors could not identify individuals with hereditary cancer syndromes or concerning gene mutations, such as BRCA carriers, because “registry data do not include comprehensive information on the gene mutation carriage status.” But the authors note that the number of BRCA carriers is likely low because of the low number of ovarian cancers observed in first-degree relatives of probands.

Dr. Cobain noted as well that the current study is potentially limited by its “very homogeneous” cohort.

But, overall, the findings indicate that familial risk is often “a much more complicated problem, mathematically and statistically,” than were there a single genetic culprit, Dr. Cobain said. One possibility is that some shared environmental exposure may be increasing the cancer risk among members of the same family.

“Genetic diversity is so vast and understanding how the interplay of multiple genes can influence an individual’s cancer risk is so much more complicated than a single BRCA1 mutation that clearly influences your breast cancer risk,” she added. However, “we’re starting to get there.”

The study was funded by the Cancer Foundation Finland and Academy of Finland. The authors and Dr. Cobain had no relevant financial relationships to declare.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The researchers found, for instance, that children of breast cancer patients had a 27% higher risk of any discordant early-onset cancer, and patients’ siblings had a 7.6-fold higher risk of early pancreatic cancer. The analysis also indicated that children of patients’ siblings had a significantly increased risk of testicular and ovarian cancers.

“The findings suggest that the familial risk extends to discordant early-onset cancers, including ovarian, testicular, and pancreatic cancers, as well as beyond first-degree relatives,” the researchers, led by Janne M. Pitkäniemi, PhD, Finnish Cancer Registry, Institute for Statistical and Epidemiological Cancer Research, Helsinki, say. “Our findings are interesting but raise some questions about unknown [genetic] and environmental mechanisms that need to be further studied.”

Erin F. Cobain, MD, who was not involved in the research, said the findings are “not very surprising to me.”

Dr. Cobain said that at her institution, she has seen “many, many cases” of family members of early-onset breast cancer patients with discordant cancers “where we are unable to find a clear genetic cause.”

Not being able to find an identifiable cause for the clustering of early-onset cancers can be “very frustrating” for patients and their families, said Dr. Cobain, a medical oncologist at the University of Michigan Health, Ann Arbor.

The study was published online in the International Journal of Cancer.

Family members of patients with early-onset breast cancer are at elevated risk for early-onset breast cancer. However, it is “unclear whether the familial risk is limited to early-onset cancer of the same site,” the authors explained.

To investigate, the researchers studied data from the Finnish Cancer Registry and the Finnish Population System, which included 54,753 relatives from 5,562 families of females diagnosed with early-onset breast cancer, defined as probands. A proband was the first member of the family diagnosed with female breast cancer at age 40 years or younger in Finland between January 1970 and December 31, 2012. Cancers were considered familial if they occurred in a family with a previously diagnosed proband and were deemed early onset if diagnosed before age 41.

The researchers found that only 5.5% of probands’ families had a family member with a discordant early-onset cancer. The most common diagnoses were testicular cancer (0.6% of families) and cancer of the thyroid gland (also 0.6%), followed by melanoma (0.5%).

Overall, the risk of any nonbreast early-onset cancer among first-degree relatives of probands was comparable with the risk in the general population (standardized incidence ratio, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.84-1.16).

However, the risk was elevated for certain family members and certain cancers.

Specifically, the children of probands had an increased risk for any discordant cancer (SIR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.05-1.55).

The siblings of probands had an elevated risk for early-onset pancreatic cancer (SIR, 7.61) but not overall for any discordant cancer (SIR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.68-1.25).

And siblings’ children faced an elevated risk for testicular (SIR, 1.74) and ovarian (SIR, 2.69) cancer, though not of any discordant cancer (SIR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.97-1.37).

The researchers also found that the fathers (SIR, 0.43), mothers (SIR, 0.48), and spouses (SIR, 0.58) of probands appeared to have a decreased risk of any discordant early-onset cancer.

A potential limitation to the study was that the authors could not identify individuals with hereditary cancer syndromes or concerning gene mutations, such as BRCA carriers, because “registry data do not include comprehensive information on the gene mutation carriage status.” But the authors note that the number of BRCA carriers is likely low because of the low number of ovarian cancers observed in first-degree relatives of probands.

Dr. Cobain noted as well that the current study is potentially limited by its “very homogeneous” cohort.

But, overall, the findings indicate that familial risk is often “a much more complicated problem, mathematically and statistically,” than were there a single genetic culprit, Dr. Cobain said. One possibility is that some shared environmental exposure may be increasing the cancer risk among members of the same family.

“Genetic diversity is so vast and understanding how the interplay of multiple genes can influence an individual’s cancer risk is so much more complicated than a single BRCA1 mutation that clearly influences your breast cancer risk,” she added. However, “we’re starting to get there.”

The study was funded by the Cancer Foundation Finland and Academy of Finland. The authors and Dr. Cobain had no relevant financial relationships to declare.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CANCER

Pausing endocrine therapy to attempt pregnancy is safe

The results provide the “strongest evidence to date on the short-term safety of this choice,” Sharon Giordano, MD, MPH, with University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, wrote in an editorial accompanying the study.

“Physicians should now incorporate these positive data into their shared decision-making process with patients,” Dr. Giordano said.

The POSITIVE trial findings were published online in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Before the analysis, the risks associated with taking a break from endocrine therapy among young women with hormone receptor (HR)–positive breast cancer remained unclear.

In the current trial, Ann Partridge, MD, MPH, and colleagues sought prospective data on the safety associated with taking a temporary break from therapy to attempt pregnancy.

The single-group trial enrolled more than 500 premenopausal women who had received 18-30 months of endocrine therapy for mostly stage I or II HR-positive breast cancer. After a 3-month washout, the women were given 2 years to conceive, deliver, and breastfeed, if desired, before resuming treatment. Breast cancer events – the primary outcome – were defined as local, regional, or distant recurrence of invasive breast cancer or new contralateral invasive breast cancer.

The results, initially reported at San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS) 2022, showed that a temporary interruption of therapy to attempt pregnancy did not appear to lead to worse breast cancer outcomes.

Among 497 women who were followed for pregnancy status, 368 (74%) had at least one pregnancy, and 317 (64%) had at least one live birth.

After a median follow-up of 3.4 years, 44 women had had a breast cancer event – a result that was close to, but did not exceed, the safety threshold of 46 breast cancer events.

The 3-year incidence of breast cancer events was 8.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 6.3-11.6) in the treatment-interruption group compared with 9.2% (95% CI, 7.6-10.8) among historical controls, which included women who would have met the entry criteria for the trial.