User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

The enemy of carcinogenic fumes is my friendly begonia

Sowing the seeds of cancer prevention

Are you looking to add to your quality of life, even though pets are not your speed? Might we suggest something with lower maintenance? Something a little greener?

Indoor plants can purify the air that comes from outside. Researchers at the University of Technology Sydney, in partnership with the plantscaping company Ambius, showed that a “green wall” made up of mixed indoor plants was able to suck up 97% of “the most toxic compounds” from the air in just 8 hours. We’re talking about lung-irritating, headache-inducing, cancer risk–boosting compounds from gasoline fumes, including benzene.

Public health initiatives often strive to reduce cardiovascular and obesity risks, but breathing seems pretty important too. According to the World Health Organization, household air pollution is responsible for about 2.5 million global premature deaths each year. And since 2020 we’ve become accustomed to spending more time inside and at home.

“This new research proves that plants should not just be seen as ‘nice to have,’ but rather a crucial part of every workplace wellness plan,” Ambius General Manager Johan Hodgson said in statement released by the university.

So don’t spend hundreds of dollars on a fancy air filtration system when a wall of plants can do that for next to nothing. Find what works for you and your space and become a plant parent today! Your lungs will thank you.

But officer, I had to swerve to miss the duodenal ampulla

Tiny video capsule endoscopes have been around for many years, but they have one big weakness: The ingestible cameras’ journey through the GI tract is passively driven by gravity and the natural movement of the body, so they often miss potential problem areas.

Not anymore. That flaw has been addressed by medical technology company AnX Robotica, which has taken endoscopy to the next level by adding that wondrous directional control device of the modern electronic age, a joystick.

The new system “uses an external magnet and hand-held video game style joysticks to move the capsule in three dimensions,” which allows physicians to “remotely drive a miniature video capsule to all regions of the stomach to visualize and photograph potential problem areas,” according to Andrew C. Meltzer, MD, of George Washington University and associates, who conducted a pilot study funded by AnX Robotica.

The video capsule provided a 95% rate of visualization in the stomachs of 40 patients who were examined at a medical office building by an emergency medicine physician who had no previous specialty training in endoscopy. “Capsules were driven by the ER physician and then the study reports were reviewed by an attending gastroenterologist who was physically off site,” the investigators said in a written statement.

The capsule operator did receive some additional training, and development of artificial intelligence to self-drive the capsule is in the works, but for now, we’re talking about a device controlled by a human using a joystick. And we all know that 50-year-olds are not especially known for their joystick skills. For that we need real experts. Yup, we need to put those joystick-controlled capsule endoscopes in the hands of teenage gamers. Who wants to go first?

Maybe AI isn’t ready for the big time after all

“How long before some intrepid stockholder says: ‘Hey, instead of paying doctors, why don’t we just use the free robot instead?’ ” Those words appeared on LOTME but a month ago. After all, the AI is supposed to be smarter and more empathetic than a doctor. And did we mention it’s free? Or at least extremely cheap. Cheaper than, say, a group of recently unionized health care workers.

In early May, the paid employees manning the National Eating Disorders Association emergency hotline voted to unionize, as they felt overwhelmed and underpaid. Apparently, paying six people an extra few thousand a year was too much for NEDA’s leadership, as they decided a few weeks later to fire those workers, fully closing down the hotline. Instead of talking to a real person, people “calling in” for support would be met with Tessa, a wellness chatbot that would hopefully guide them through their crisis. Key word, hopefully.

In perhaps the least surprising twist of the year, NEDA was forced to walk back its decision about a week after its initial announcement. It all started with a viral Instagram post from a woman who called in and received the following advice from Tessa: Lose 1-2 pounds a week, count calories and work for a 500- to 1,000-calorie deficit, weigh herself weekly, and restrict her diet. Unfortunately, all of these suggestions were things that led to the development of the woman’s eating disorder.

Naturally, NEDA responded in good grace, accusing the woman of lying. A NEDA vice president even left some nasty comments on the post, but hastily deleted them a day later when NEDA announced it was shutting down Tessa “until further notice for a complete investigation.” NEDA’s CEO insisted they hadn’t seen that behavior from Tessa before, calling it a “bug” and insisting the bot would only be down temporarily until the triggers causing the bug were fixed.

In the aftermath, several doctors and psychologists chimed in, terming the rush to automate human roles dangerous and risky. After all, much of what makes these hotlines effective is the volunteers speaking from their own experience. An unsupervised bot doesn’t seem to have what it takes to deal with a mental health crisis, but we’re betting that Tessa will be back. As a wise cephalopod once said: Nobody gives a care about the fate of labor as long as they can get their instant gratification.

You can’t spell existential without s-t-e-n-t

This week, we’re including a special “bonus” item that, to be honest, has nothing to do with stents. That’s why our editor is making us call this a “bonus” (and making us use quote marks, too): It doesn’t really have anything to do with stents or health care or those who practice health care. Actually, his exact words were, “You can’t just give the readers someone else’s ****ing list and expect to get paid for it.” Did we mention that he looks like Jack Nicklaus but acts like BoJack Horseman?

Anywaaay, we’re pretty sure that the list in question – “America’s Top 10 Most Googled Existential Questions” – says something about the human condition, just not about stents:

1. Why is the sky blue?

2. What do dreams mean?

3. What is the meaning of life?

4. Why am I so tired?

5. Who am I?

6. What is love?

7. Is a hot dog a sandwich?

8. What came first, the chicken or the egg?

9. What should I do?

10. Do animals have souls?

Sowing the seeds of cancer prevention

Are you looking to add to your quality of life, even though pets are not your speed? Might we suggest something with lower maintenance? Something a little greener?

Indoor plants can purify the air that comes from outside. Researchers at the University of Technology Sydney, in partnership with the plantscaping company Ambius, showed that a “green wall” made up of mixed indoor plants was able to suck up 97% of “the most toxic compounds” from the air in just 8 hours. We’re talking about lung-irritating, headache-inducing, cancer risk–boosting compounds from gasoline fumes, including benzene.

Public health initiatives often strive to reduce cardiovascular and obesity risks, but breathing seems pretty important too. According to the World Health Organization, household air pollution is responsible for about 2.5 million global premature deaths each year. And since 2020 we’ve become accustomed to spending more time inside and at home.

“This new research proves that plants should not just be seen as ‘nice to have,’ but rather a crucial part of every workplace wellness plan,” Ambius General Manager Johan Hodgson said in statement released by the university.

So don’t spend hundreds of dollars on a fancy air filtration system when a wall of plants can do that for next to nothing. Find what works for you and your space and become a plant parent today! Your lungs will thank you.

But officer, I had to swerve to miss the duodenal ampulla

Tiny video capsule endoscopes have been around for many years, but they have one big weakness: The ingestible cameras’ journey through the GI tract is passively driven by gravity and the natural movement of the body, so they often miss potential problem areas.

Not anymore. That flaw has been addressed by medical technology company AnX Robotica, which has taken endoscopy to the next level by adding that wondrous directional control device of the modern electronic age, a joystick.

The new system “uses an external magnet and hand-held video game style joysticks to move the capsule in three dimensions,” which allows physicians to “remotely drive a miniature video capsule to all regions of the stomach to visualize and photograph potential problem areas,” according to Andrew C. Meltzer, MD, of George Washington University and associates, who conducted a pilot study funded by AnX Robotica.

The video capsule provided a 95% rate of visualization in the stomachs of 40 patients who were examined at a medical office building by an emergency medicine physician who had no previous specialty training in endoscopy. “Capsules were driven by the ER physician and then the study reports were reviewed by an attending gastroenterologist who was physically off site,” the investigators said in a written statement.

The capsule operator did receive some additional training, and development of artificial intelligence to self-drive the capsule is in the works, but for now, we’re talking about a device controlled by a human using a joystick. And we all know that 50-year-olds are not especially known for their joystick skills. For that we need real experts. Yup, we need to put those joystick-controlled capsule endoscopes in the hands of teenage gamers. Who wants to go first?

Maybe AI isn’t ready for the big time after all

“How long before some intrepid stockholder says: ‘Hey, instead of paying doctors, why don’t we just use the free robot instead?’ ” Those words appeared on LOTME but a month ago. After all, the AI is supposed to be smarter and more empathetic than a doctor. And did we mention it’s free? Or at least extremely cheap. Cheaper than, say, a group of recently unionized health care workers.

In early May, the paid employees manning the National Eating Disorders Association emergency hotline voted to unionize, as they felt overwhelmed and underpaid. Apparently, paying six people an extra few thousand a year was too much for NEDA’s leadership, as they decided a few weeks later to fire those workers, fully closing down the hotline. Instead of talking to a real person, people “calling in” for support would be met with Tessa, a wellness chatbot that would hopefully guide them through their crisis. Key word, hopefully.

In perhaps the least surprising twist of the year, NEDA was forced to walk back its decision about a week after its initial announcement. It all started with a viral Instagram post from a woman who called in and received the following advice from Tessa: Lose 1-2 pounds a week, count calories and work for a 500- to 1,000-calorie deficit, weigh herself weekly, and restrict her diet. Unfortunately, all of these suggestions were things that led to the development of the woman’s eating disorder.

Naturally, NEDA responded in good grace, accusing the woman of lying. A NEDA vice president even left some nasty comments on the post, but hastily deleted them a day later when NEDA announced it was shutting down Tessa “until further notice for a complete investigation.” NEDA’s CEO insisted they hadn’t seen that behavior from Tessa before, calling it a “bug” and insisting the bot would only be down temporarily until the triggers causing the bug were fixed.

In the aftermath, several doctors and psychologists chimed in, terming the rush to automate human roles dangerous and risky. After all, much of what makes these hotlines effective is the volunteers speaking from their own experience. An unsupervised bot doesn’t seem to have what it takes to deal with a mental health crisis, but we’re betting that Tessa will be back. As a wise cephalopod once said: Nobody gives a care about the fate of labor as long as they can get their instant gratification.

You can’t spell existential without s-t-e-n-t

This week, we’re including a special “bonus” item that, to be honest, has nothing to do with stents. That’s why our editor is making us call this a “bonus” (and making us use quote marks, too): It doesn’t really have anything to do with stents or health care or those who practice health care. Actually, his exact words were, “You can’t just give the readers someone else’s ****ing list and expect to get paid for it.” Did we mention that he looks like Jack Nicklaus but acts like BoJack Horseman?

Anywaaay, we’re pretty sure that the list in question – “America’s Top 10 Most Googled Existential Questions” – says something about the human condition, just not about stents:

1. Why is the sky blue?

2. What do dreams mean?

3. What is the meaning of life?

4. Why am I so tired?

5. Who am I?

6. What is love?

7. Is a hot dog a sandwich?

8. What came first, the chicken or the egg?

9. What should I do?

10. Do animals have souls?

Sowing the seeds of cancer prevention

Are you looking to add to your quality of life, even though pets are not your speed? Might we suggest something with lower maintenance? Something a little greener?

Indoor plants can purify the air that comes from outside. Researchers at the University of Technology Sydney, in partnership with the plantscaping company Ambius, showed that a “green wall” made up of mixed indoor plants was able to suck up 97% of “the most toxic compounds” from the air in just 8 hours. We’re talking about lung-irritating, headache-inducing, cancer risk–boosting compounds from gasoline fumes, including benzene.

Public health initiatives often strive to reduce cardiovascular and obesity risks, but breathing seems pretty important too. According to the World Health Organization, household air pollution is responsible for about 2.5 million global premature deaths each year. And since 2020 we’ve become accustomed to spending more time inside and at home.

“This new research proves that plants should not just be seen as ‘nice to have,’ but rather a crucial part of every workplace wellness plan,” Ambius General Manager Johan Hodgson said in statement released by the university.

So don’t spend hundreds of dollars on a fancy air filtration system when a wall of plants can do that for next to nothing. Find what works for you and your space and become a plant parent today! Your lungs will thank you.

But officer, I had to swerve to miss the duodenal ampulla

Tiny video capsule endoscopes have been around for many years, but they have one big weakness: The ingestible cameras’ journey through the GI tract is passively driven by gravity and the natural movement of the body, so they often miss potential problem areas.

Not anymore. That flaw has been addressed by medical technology company AnX Robotica, which has taken endoscopy to the next level by adding that wondrous directional control device of the modern electronic age, a joystick.

The new system “uses an external magnet and hand-held video game style joysticks to move the capsule in three dimensions,” which allows physicians to “remotely drive a miniature video capsule to all regions of the stomach to visualize and photograph potential problem areas,” according to Andrew C. Meltzer, MD, of George Washington University and associates, who conducted a pilot study funded by AnX Robotica.

The video capsule provided a 95% rate of visualization in the stomachs of 40 patients who were examined at a medical office building by an emergency medicine physician who had no previous specialty training in endoscopy. “Capsules were driven by the ER physician and then the study reports were reviewed by an attending gastroenterologist who was physically off site,” the investigators said in a written statement.

The capsule operator did receive some additional training, and development of artificial intelligence to self-drive the capsule is in the works, but for now, we’re talking about a device controlled by a human using a joystick. And we all know that 50-year-olds are not especially known for their joystick skills. For that we need real experts. Yup, we need to put those joystick-controlled capsule endoscopes in the hands of teenage gamers. Who wants to go first?

Maybe AI isn’t ready for the big time after all

“How long before some intrepid stockholder says: ‘Hey, instead of paying doctors, why don’t we just use the free robot instead?’ ” Those words appeared on LOTME but a month ago. After all, the AI is supposed to be smarter and more empathetic than a doctor. And did we mention it’s free? Or at least extremely cheap. Cheaper than, say, a group of recently unionized health care workers.

In early May, the paid employees manning the National Eating Disorders Association emergency hotline voted to unionize, as they felt overwhelmed and underpaid. Apparently, paying six people an extra few thousand a year was too much for NEDA’s leadership, as they decided a few weeks later to fire those workers, fully closing down the hotline. Instead of talking to a real person, people “calling in” for support would be met with Tessa, a wellness chatbot that would hopefully guide them through their crisis. Key word, hopefully.

In perhaps the least surprising twist of the year, NEDA was forced to walk back its decision about a week after its initial announcement. It all started with a viral Instagram post from a woman who called in and received the following advice from Tessa: Lose 1-2 pounds a week, count calories and work for a 500- to 1,000-calorie deficit, weigh herself weekly, and restrict her diet. Unfortunately, all of these suggestions were things that led to the development of the woman’s eating disorder.

Naturally, NEDA responded in good grace, accusing the woman of lying. A NEDA vice president even left some nasty comments on the post, but hastily deleted them a day later when NEDA announced it was shutting down Tessa “until further notice for a complete investigation.” NEDA’s CEO insisted they hadn’t seen that behavior from Tessa before, calling it a “bug” and insisting the bot would only be down temporarily until the triggers causing the bug were fixed.

In the aftermath, several doctors and psychologists chimed in, terming the rush to automate human roles dangerous and risky. After all, much of what makes these hotlines effective is the volunteers speaking from their own experience. An unsupervised bot doesn’t seem to have what it takes to deal with a mental health crisis, but we’re betting that Tessa will be back. As a wise cephalopod once said: Nobody gives a care about the fate of labor as long as they can get their instant gratification.

You can’t spell existential without s-t-e-n-t

This week, we’re including a special “bonus” item that, to be honest, has nothing to do with stents. That’s why our editor is making us call this a “bonus” (and making us use quote marks, too): It doesn’t really have anything to do with stents or health care or those who practice health care. Actually, his exact words were, “You can’t just give the readers someone else’s ****ing list and expect to get paid for it.” Did we mention that he looks like Jack Nicklaus but acts like BoJack Horseman?

Anywaaay, we’re pretty sure that the list in question – “America’s Top 10 Most Googled Existential Questions” – says something about the human condition, just not about stents:

1. Why is the sky blue?

2. What do dreams mean?

3. What is the meaning of life?

4. Why am I so tired?

5. Who am I?

6. What is love?

7. Is a hot dog a sandwich?

8. What came first, the chicken or the egg?

9. What should I do?

10. Do animals have souls?

Therapeutic hypothermia to treat neonatal encephalopathy improves childhood outcomes

Therapeutic hypothermia (TH) for moderate and severe neonatal encephalopathy has been shown to reduce the risk of newborn death, major neurodevelopmental disability, developmental delay, and cerebral palsy.1 It is estimated that 8 newborns with moderate or severe neonatal encephalopathy need to be treated with TH to prevent 1 case of cerebral palsy.1 The key elements of TH include:

- initiate hypothermia within 6 hoursof birth

- cool the newborn to a core temperature of 33.5˚ C to 34.5˚ C (92.3˚ F to 94.1˚ F) for 72 hours

- obtain brain ultrasonography to assess for intracranial hemorrhage

- obtain sequential MRI studies to assess brain structure and function

- initiate EEG monitoring for seizure activity.

During hypothermia the newborn is sedated, and oral feedings are reduced. During TH, important physiological goals are to maintain normal oxygenation, blood pressure, fluid balance, and glucose levels.1,2

TH: The basics

Most of the major published randomized clinical trials used the following inclusion criteria to initiate TH2:

- gestational age at birth of ≥ 35 weeks

- neonate is within 6 hours of birth

- an Apgar score ≤ 5 at 10 minutes of life or prolonged resuscitation at birth or umbilical artery cord pH < 7.1 or neonatal blood gas within 60 minutes of life < 7.1

- moderate to severe encephalopathy or the presence of seizures

- absence of recognizable congenital abnormalities at birth.

However, in some institutions, expert neonatologists have developed more liberal criteria for the initiation of TH, to be considered on a case-by-case basis. These more inclusive criteria, which will result in more newborns being treated with TH, include3:

- gestational age at birth of ≥ 34 weeks

- neonate is within 12 hours of birth

- a sentinel event at birth or Apgar score ≤ 5 at 10 minutes of life or prolonged resuscitation or umbilical artery cord pH < 7.1 or neonatal blood gas within 60 minutes of life < 7.1 or postnatal cardiopulmonary failure

- moderate to severe encephalopathy or concern for the presence of seizures.

Birth at a gestational age ≤ 34 weeks is a contraindication to TH. Relative contraindications to initiation of TH include: birth weight < 1,750 g, severe congenital anomaly, major genetic disorders, known severe metabolic disorders, major intracranial hemorrhage, severe septicemia, and uncorrectable coagulopathy.3 Adverse outcomes of TH include thrombocytopenia, cardiac arrythmia, and fat necrosis.4

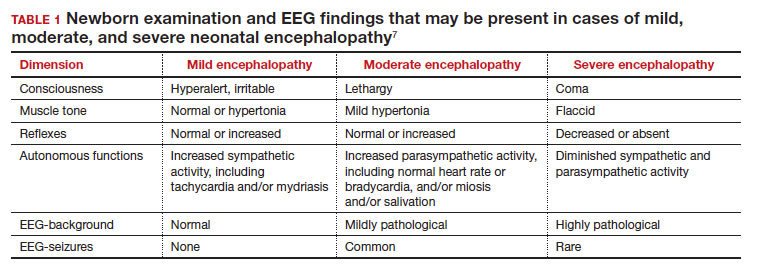

Diagnosing neonatal encephalopathy

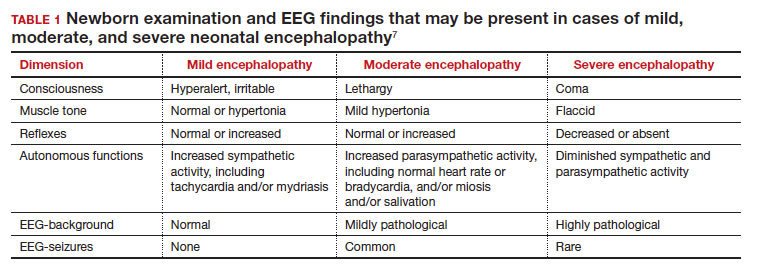

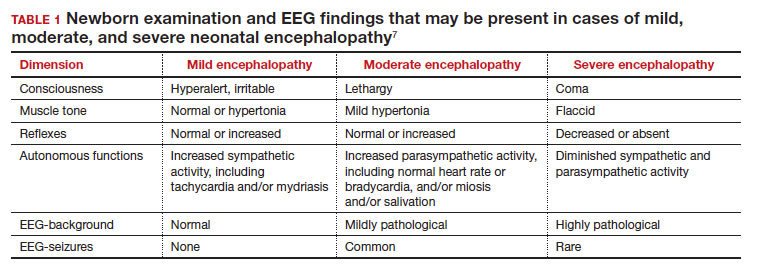

Neonatal encephalopathy is a clinical diagnosis, defined as abnormal neurologic function in the first few days of life in an infant born at ≥ 35 weeks’ gestation. It is divided into 3 categories: mild (Stage 1), moderate (Stage 2), and severe (Stage 3).5,6 Institutions vary in the criteria used to differentiate mild from moderate neonatal encephalopathy, the two most frequent forms of encephalopathy. Newborns with mild encephalopathy are not routinely treated with TH because TH has not been shown to be helpful in this setting. Institutions with liberal criteria for diagnosing moderate encephalopathy will initiate TH in more cases. Involvement of a pediatric neurologist in the diagnosis of moderate encephalopathy may help confirm the diagnosis made by the primary neonatologist and provide an independent, second opinion about whether the newborn should be diagnosed with mild or moderate encephalopathy, a clinically important distinction. Physical examination and EEG findings associated with cases of mild, moderate, and severe encephalopathy are presented in TABLE 1.7

Continue: Obstetric factors that may be associated with neonatal encephalopathy...

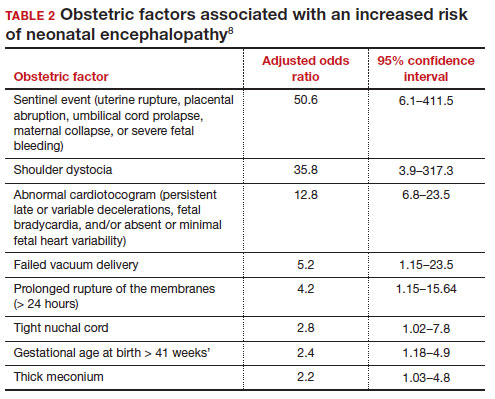

Obstetric factors that may be associated with neonatal encephalopathy

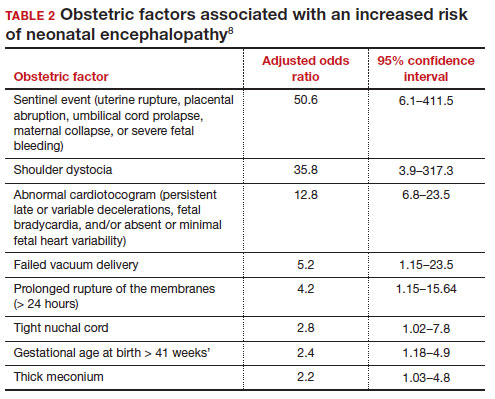

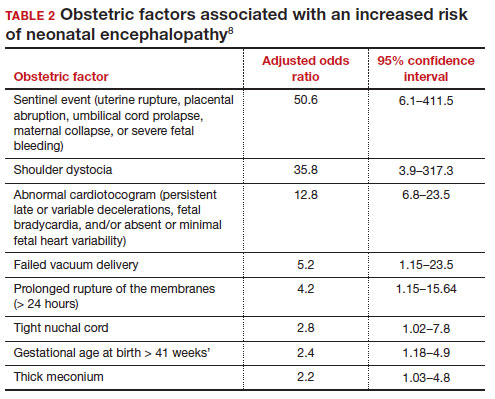

In a retrospective case-control study that included 405 newborns at ≥ 35 weeks’ gestational age with neonatal encephalopathy thought to be due to hypoxia, 8 obstetric factors were identified as being associated with an increased risk of neonatal encephalopathy, including (TABLE 2)8:

1. an obstetric sentinel event (uterine rupture, placental abruption, umbilical cord prolapse, maternal collapse, or severe fetal bleeding)

2. shoulder dystocia

3. abnormal cardiotocogram (persistent late or variable decelerations, fetal bradycardia, and/or absent or minimal fetal heart variability)

4. failed vacuum delivery

5. prolonged rupture of the membranes (> 24 hours)

6. tight nuchal cord

7. gestational age at birth > 41 weeks

8. thick meconium.

Similar findings have been reported by other investigators analyzing the obstetric risk factors for neonatal encephalopathy.7,9

Genetic causes of neonatal seizures and neonatal encephalopathy

Many neonatologists practice with the belief that for a newborn with encephalopathy in the setting of a sentinel labor event, a low Apgar score at 5 minutes, an umbilical cord artery pH < 7.00, and/or an elevated lactate level, the diagnosis of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy is warranted. However, there are many causes of neonatal encephalopathy not related to intrapartum events. For example, neonatal encephalopathy and seizures may be caused by infectious, vascular, metabolic, medications, or congenital problems.10

There are genetic disorders that can be associated with both neonatal seizures and encephalopathy, suggesting that in some cases the primary cause of the encephalopathy is a genetic problem, not management of labor. Mutations in the potassium channel and sodium channel genes are well recognized causes of neonatal seizures.11,12 Cerebral palsy, a childhood outcome that may follow neonatal encephalopathy, also has numerous etiologies, including genetic causes. Among 1,345 children with cerebral palsy referred for exome sequencing, investigators reported that a genetic abnormality was identified in 33% of the cases.13 Mutations in 86 genes were identified in multiple children. Similar results have been reported in other cohorts.14-16 Maintaining an open mind about the causes of a case of neonatal encephalopathy and not jumping to a conclusion before completing an evaluation is an optimal approach.

Parent’s evolving emotional and intellectual reaction to the initiation of TH

Initiation of TH for a newborn with encephalopathy catalyzes parents to wonder, “How did my baby develop an encephalopathy?”, “Did my obstetrician’s management of labor and delivery contribute to the outcome?” and “What is the prognosis for my baby?” These are difficult questions with high emotional valence for both patients and clinicians. Obstetricians and neonatologists should collaborate to provide consistent responses to these questions.

The presence of a low umbilical cord artery pH and high lactate in combination with a low Apgar score at 5 minutes may lead the neonatologist to diagnose hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in the medical record. The diagnosis of brain hypoxia and ischemia in a newborn may be interpreted by parents as meaning that labor events caused or contributed to the encephalopathy. During the 72 hours of TH, the newborn is sedated and separated from the parents, causing additional emotional stress and uncertainty. When a baby is transferred from a community hospital to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) at a tertiary center, the parents may be geographically separated from their baby during a critical period of time, adding to their anxiety. At some point during the care process most newborns treated with TH will have an EEG, brain ultrasound, and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These data will be discussed with the parent(s) and may cause confusion and additional stress.

The optimal approach to communicating with parents whose newborn is treated with TH continues to evolve. Best practices may include17-20:

- in-person, regular multidisciplinary family meetings with the parents, including neonatologists, obstetricians, social service specialists and mental health experts when possible

- providing emotional support to parents, recognizing the psychological trauma of the clinical events

- encouraging parents to have physical contact with the newborn during TH

- elevating the role of the parents in the care process by having them participate in care events such as diapering the newborn

- ensuring that clinicians do not blame other clinicians for the clinical outcome

- communicating the results and interpretation of advanced physiological monitoring and imaging studies, with an emphasis on clarity, recognizing the limitations of the studies

- providing educational materials for parents about TH, early intervention programs, and support resources.

Coordinated and consistent communication with the parents is often difficult to facilitate due to many factors, including the unique perspectives and vocabularies of clinicians from different specialties and the difficulty of coordinating communications with all those involved over multiple shifts and sites of care. In terms of vocabulary, neonatologists are comfortable with making a diagnosis of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in a newborn, but obstetricians would prefer that neonatologists use the more generic diagnosis of encephalopathy, holding judgment on the cause until additional data are available. In terms of coordinating communication over multiple shifts and sites of care, interactions between an obstetrician and their patient typically occurs in the postpartum unit, while interactions between neonatologists and parents occur in the NICU.

Parents of a baby with neonatal encephalopathy undergoing TH may have numerous traumatic experiences during the care process. For weeks or months after birth, they may recall or dream about the absence of sounds from their newborn at birth, the resuscitation events including chest compressions and intubation, the shivering of the baby during TH, and the jarring pivot from the expectation of holding and bonding with a healthy newborn to the reality of a sick newborn requiring intensive care. Obstetricians are also traumatized by these events and support from peers and mental health experts may help them recognize, explore, and adapt to the trauma. Neonatologists believe that TH can help improve the childhood outcomes of newborns with encephalopathy, a goal endorsed by all clinicians and family members. ●

- Jacobs SE, Berg M, Hunt R, et al. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;CD003311.

- Committee on Fetus and Newborn; Papile E, Baley JE, Benitz W, et al. Hypothermia and neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2014;133:1146-1150.

- Academic Medical Center Patient Safety Organization. Therapeutic hypothermia in neonates. Recommendations of the neonatal encephalopathy task force. 2016. https://www.rmf.harvard. edu/-/media/Files/_Global/KC/PDFs/Guide lines/crico_neonates.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2023.

- Zhang W, Ma J, Danzeng Q, et al. Safety of moderate hypothermia for perinatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Neurol. 2017;74:51-61.

- Sarnat HB, Sarnat MS. Neonatal encephalopathy following fetal distress: a clinical and electroencephalographic study. Arch Neurol. 1976;33:696-705.

- Thompson CM, Puterman AS, Linley LL, et al. The value of a scoring system for hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy in predicting neurodevelopmental outcome. Acta Pediatr. 1997;86:757-761.

- Lundgren C, Brudin L, Wanby AS, et al. Ante- and intrapartum risk factors for neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31:1595-1601.

- Martinez-Biarge M, Diez-Sebastian J, Wusthoff CJ, et al. Antepartum and intrapartum factors preceding neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e952-e959.

- Lorain P, Bower A, Gottardi E, et al. Risk factors for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in cases of severe acidosis: a case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022;101:471-478.

- Russ JB, Simmons R, Glass HC. Neonatal encephalopathy: beyond hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Neo Reviews. 2021;22:e148-e162.

- Allen NM, Mannion M, Conroy J, et al. The variable phenotypes of KCNQ-related epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55:e99-e105.

- Zibro J, Shellhaas RA. Neonatal seizures: diagnosis, etiologies and management. Semin Neurol. 2020;40:246-256.

- Moreno-De-Luca A, Millan F, Peacreta DR, et al. Molecular diagnostic yield of exome sequencing in patients with cerebral palsy. JAMA. 2021;325:467-475.

- Srivastava S, Lewis SA, Cohen JS, et al. Molecular diagnostic yield of exome sequencing and chromosomal microarray in cerebral palsy. A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurology. 2022;79:1287-1295.

- Gonzalez-Mantilla PJ, Hu Y, Myers SM, et al. Diagnostic yield of exome sequencing in cerebral palsy and implications for genetic testing guidelines. A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. Epub March 6, 2023.

- van Eyk C, MacLennon SC, MacLennan AH. All patients with cerebral palsy diagnosis merit genomic sequencing. JAMA Pediatr. Epub March 6, 2023.

- Craig AK, James C, Bainter J, et al. Parental perceptions of neonatal therapeutic hypothermia; emotional and healing experiences. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33:2889-2896. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1563592.

- Sagaser A, Pilon B, Goeller A, et al. Parent experience of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and hypothermia: a call for trauma informed care. Am J Perinatol. Epub March 4, 2022.

- Cascio A, Ferrand A, Racine E, et al. Discussing brain magnetic resonance imaging results for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy treated with hypothermia: a challenge for clinicians and parents. E Neurological Sci. 2022;29:100424.

- Thyagarajan B, Baral V, Gunda R, et al. Parental perceptions of hypothermia treatment for neonatal hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31:2527-2533.

Therapeutic hypothermia (TH) for moderate and severe neonatal encephalopathy has been shown to reduce the risk of newborn death, major neurodevelopmental disability, developmental delay, and cerebral palsy.1 It is estimated that 8 newborns with moderate or severe neonatal encephalopathy need to be treated with TH to prevent 1 case of cerebral palsy.1 The key elements of TH include:

- initiate hypothermia within 6 hoursof birth

- cool the newborn to a core temperature of 33.5˚ C to 34.5˚ C (92.3˚ F to 94.1˚ F) for 72 hours

- obtain brain ultrasonography to assess for intracranial hemorrhage

- obtain sequential MRI studies to assess brain structure and function

- initiate EEG monitoring for seizure activity.

During hypothermia the newborn is sedated, and oral feedings are reduced. During TH, important physiological goals are to maintain normal oxygenation, blood pressure, fluid balance, and glucose levels.1,2

TH: The basics

Most of the major published randomized clinical trials used the following inclusion criteria to initiate TH2:

- gestational age at birth of ≥ 35 weeks

- neonate is within 6 hours of birth

- an Apgar score ≤ 5 at 10 minutes of life or prolonged resuscitation at birth or umbilical artery cord pH < 7.1 or neonatal blood gas within 60 minutes of life < 7.1

- moderate to severe encephalopathy or the presence of seizures

- absence of recognizable congenital abnormalities at birth.

However, in some institutions, expert neonatologists have developed more liberal criteria for the initiation of TH, to be considered on a case-by-case basis. These more inclusive criteria, which will result in more newborns being treated with TH, include3:

- gestational age at birth of ≥ 34 weeks

- neonate is within 12 hours of birth

- a sentinel event at birth or Apgar score ≤ 5 at 10 minutes of life or prolonged resuscitation or umbilical artery cord pH < 7.1 or neonatal blood gas within 60 minutes of life < 7.1 or postnatal cardiopulmonary failure

- moderate to severe encephalopathy or concern for the presence of seizures.

Birth at a gestational age ≤ 34 weeks is a contraindication to TH. Relative contraindications to initiation of TH include: birth weight < 1,750 g, severe congenital anomaly, major genetic disorders, known severe metabolic disorders, major intracranial hemorrhage, severe septicemia, and uncorrectable coagulopathy.3 Adverse outcomes of TH include thrombocytopenia, cardiac arrythmia, and fat necrosis.4

Diagnosing neonatal encephalopathy

Neonatal encephalopathy is a clinical diagnosis, defined as abnormal neurologic function in the first few days of life in an infant born at ≥ 35 weeks’ gestation. It is divided into 3 categories: mild (Stage 1), moderate (Stage 2), and severe (Stage 3).5,6 Institutions vary in the criteria used to differentiate mild from moderate neonatal encephalopathy, the two most frequent forms of encephalopathy. Newborns with mild encephalopathy are not routinely treated with TH because TH has not been shown to be helpful in this setting. Institutions with liberal criteria for diagnosing moderate encephalopathy will initiate TH in more cases. Involvement of a pediatric neurologist in the diagnosis of moderate encephalopathy may help confirm the diagnosis made by the primary neonatologist and provide an independent, second opinion about whether the newborn should be diagnosed with mild or moderate encephalopathy, a clinically important distinction. Physical examination and EEG findings associated with cases of mild, moderate, and severe encephalopathy are presented in TABLE 1.7

Continue: Obstetric factors that may be associated with neonatal encephalopathy...

Obstetric factors that may be associated with neonatal encephalopathy

In a retrospective case-control study that included 405 newborns at ≥ 35 weeks’ gestational age with neonatal encephalopathy thought to be due to hypoxia, 8 obstetric factors were identified as being associated with an increased risk of neonatal encephalopathy, including (TABLE 2)8:

1. an obstetric sentinel event (uterine rupture, placental abruption, umbilical cord prolapse, maternal collapse, or severe fetal bleeding)

2. shoulder dystocia

3. abnormal cardiotocogram (persistent late or variable decelerations, fetal bradycardia, and/or absent or minimal fetal heart variability)

4. failed vacuum delivery

5. prolonged rupture of the membranes (> 24 hours)

6. tight nuchal cord

7. gestational age at birth > 41 weeks

8. thick meconium.

Similar findings have been reported by other investigators analyzing the obstetric risk factors for neonatal encephalopathy.7,9

Genetic causes of neonatal seizures and neonatal encephalopathy

Many neonatologists practice with the belief that for a newborn with encephalopathy in the setting of a sentinel labor event, a low Apgar score at 5 minutes, an umbilical cord artery pH < 7.00, and/or an elevated lactate level, the diagnosis of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy is warranted. However, there are many causes of neonatal encephalopathy not related to intrapartum events. For example, neonatal encephalopathy and seizures may be caused by infectious, vascular, metabolic, medications, or congenital problems.10

There are genetic disorders that can be associated with both neonatal seizures and encephalopathy, suggesting that in some cases the primary cause of the encephalopathy is a genetic problem, not management of labor. Mutations in the potassium channel and sodium channel genes are well recognized causes of neonatal seizures.11,12 Cerebral palsy, a childhood outcome that may follow neonatal encephalopathy, also has numerous etiologies, including genetic causes. Among 1,345 children with cerebral palsy referred for exome sequencing, investigators reported that a genetic abnormality was identified in 33% of the cases.13 Mutations in 86 genes were identified in multiple children. Similar results have been reported in other cohorts.14-16 Maintaining an open mind about the causes of a case of neonatal encephalopathy and not jumping to a conclusion before completing an evaluation is an optimal approach.

Parent’s evolving emotional and intellectual reaction to the initiation of TH

Initiation of TH for a newborn with encephalopathy catalyzes parents to wonder, “How did my baby develop an encephalopathy?”, “Did my obstetrician’s management of labor and delivery contribute to the outcome?” and “What is the prognosis for my baby?” These are difficult questions with high emotional valence for both patients and clinicians. Obstetricians and neonatologists should collaborate to provide consistent responses to these questions.

The presence of a low umbilical cord artery pH and high lactate in combination with a low Apgar score at 5 minutes may lead the neonatologist to diagnose hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in the medical record. The diagnosis of brain hypoxia and ischemia in a newborn may be interpreted by parents as meaning that labor events caused or contributed to the encephalopathy. During the 72 hours of TH, the newborn is sedated and separated from the parents, causing additional emotional stress and uncertainty. When a baby is transferred from a community hospital to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) at a tertiary center, the parents may be geographically separated from their baby during a critical period of time, adding to their anxiety. At some point during the care process most newborns treated with TH will have an EEG, brain ultrasound, and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These data will be discussed with the parent(s) and may cause confusion and additional stress.

The optimal approach to communicating with parents whose newborn is treated with TH continues to evolve. Best practices may include17-20:

- in-person, regular multidisciplinary family meetings with the parents, including neonatologists, obstetricians, social service specialists and mental health experts when possible

- providing emotional support to parents, recognizing the psychological trauma of the clinical events

- encouraging parents to have physical contact with the newborn during TH

- elevating the role of the parents in the care process by having them participate in care events such as diapering the newborn

- ensuring that clinicians do not blame other clinicians for the clinical outcome

- communicating the results and interpretation of advanced physiological monitoring and imaging studies, with an emphasis on clarity, recognizing the limitations of the studies

- providing educational materials for parents about TH, early intervention programs, and support resources.

Coordinated and consistent communication with the parents is often difficult to facilitate due to many factors, including the unique perspectives and vocabularies of clinicians from different specialties and the difficulty of coordinating communications with all those involved over multiple shifts and sites of care. In terms of vocabulary, neonatologists are comfortable with making a diagnosis of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in a newborn, but obstetricians would prefer that neonatologists use the more generic diagnosis of encephalopathy, holding judgment on the cause until additional data are available. In terms of coordinating communication over multiple shifts and sites of care, interactions between an obstetrician and their patient typically occurs in the postpartum unit, while interactions between neonatologists and parents occur in the NICU.

Parents of a baby with neonatal encephalopathy undergoing TH may have numerous traumatic experiences during the care process. For weeks or months after birth, they may recall or dream about the absence of sounds from their newborn at birth, the resuscitation events including chest compressions and intubation, the shivering of the baby during TH, and the jarring pivot from the expectation of holding and bonding with a healthy newborn to the reality of a sick newborn requiring intensive care. Obstetricians are also traumatized by these events and support from peers and mental health experts may help them recognize, explore, and adapt to the trauma. Neonatologists believe that TH can help improve the childhood outcomes of newborns with encephalopathy, a goal endorsed by all clinicians and family members. ●

Therapeutic hypothermia (TH) for moderate and severe neonatal encephalopathy has been shown to reduce the risk of newborn death, major neurodevelopmental disability, developmental delay, and cerebral palsy.1 It is estimated that 8 newborns with moderate or severe neonatal encephalopathy need to be treated with TH to prevent 1 case of cerebral palsy.1 The key elements of TH include:

- initiate hypothermia within 6 hoursof birth

- cool the newborn to a core temperature of 33.5˚ C to 34.5˚ C (92.3˚ F to 94.1˚ F) for 72 hours

- obtain brain ultrasonography to assess for intracranial hemorrhage

- obtain sequential MRI studies to assess brain structure and function

- initiate EEG monitoring for seizure activity.

During hypothermia the newborn is sedated, and oral feedings are reduced. During TH, important physiological goals are to maintain normal oxygenation, blood pressure, fluid balance, and glucose levels.1,2

TH: The basics

Most of the major published randomized clinical trials used the following inclusion criteria to initiate TH2:

- gestational age at birth of ≥ 35 weeks

- neonate is within 6 hours of birth

- an Apgar score ≤ 5 at 10 minutes of life or prolonged resuscitation at birth or umbilical artery cord pH < 7.1 or neonatal blood gas within 60 minutes of life < 7.1

- moderate to severe encephalopathy or the presence of seizures

- absence of recognizable congenital abnormalities at birth.

However, in some institutions, expert neonatologists have developed more liberal criteria for the initiation of TH, to be considered on a case-by-case basis. These more inclusive criteria, which will result in more newborns being treated with TH, include3:

- gestational age at birth of ≥ 34 weeks

- neonate is within 12 hours of birth

- a sentinel event at birth or Apgar score ≤ 5 at 10 minutes of life or prolonged resuscitation or umbilical artery cord pH < 7.1 or neonatal blood gas within 60 minutes of life < 7.1 or postnatal cardiopulmonary failure

- moderate to severe encephalopathy or concern for the presence of seizures.

Birth at a gestational age ≤ 34 weeks is a contraindication to TH. Relative contraindications to initiation of TH include: birth weight < 1,750 g, severe congenital anomaly, major genetic disorders, known severe metabolic disorders, major intracranial hemorrhage, severe septicemia, and uncorrectable coagulopathy.3 Adverse outcomes of TH include thrombocytopenia, cardiac arrythmia, and fat necrosis.4

Diagnosing neonatal encephalopathy

Neonatal encephalopathy is a clinical diagnosis, defined as abnormal neurologic function in the first few days of life in an infant born at ≥ 35 weeks’ gestation. It is divided into 3 categories: mild (Stage 1), moderate (Stage 2), and severe (Stage 3).5,6 Institutions vary in the criteria used to differentiate mild from moderate neonatal encephalopathy, the two most frequent forms of encephalopathy. Newborns with mild encephalopathy are not routinely treated with TH because TH has not been shown to be helpful in this setting. Institutions with liberal criteria for diagnosing moderate encephalopathy will initiate TH in more cases. Involvement of a pediatric neurologist in the diagnosis of moderate encephalopathy may help confirm the diagnosis made by the primary neonatologist and provide an independent, second opinion about whether the newborn should be diagnosed with mild or moderate encephalopathy, a clinically important distinction. Physical examination and EEG findings associated with cases of mild, moderate, and severe encephalopathy are presented in TABLE 1.7

Continue: Obstetric factors that may be associated with neonatal encephalopathy...

Obstetric factors that may be associated with neonatal encephalopathy

In a retrospective case-control study that included 405 newborns at ≥ 35 weeks’ gestational age with neonatal encephalopathy thought to be due to hypoxia, 8 obstetric factors were identified as being associated with an increased risk of neonatal encephalopathy, including (TABLE 2)8:

1. an obstetric sentinel event (uterine rupture, placental abruption, umbilical cord prolapse, maternal collapse, or severe fetal bleeding)

2. shoulder dystocia

3. abnormal cardiotocogram (persistent late or variable decelerations, fetal bradycardia, and/or absent or minimal fetal heart variability)

4. failed vacuum delivery

5. prolonged rupture of the membranes (> 24 hours)

6. tight nuchal cord

7. gestational age at birth > 41 weeks

8. thick meconium.

Similar findings have been reported by other investigators analyzing the obstetric risk factors for neonatal encephalopathy.7,9

Genetic causes of neonatal seizures and neonatal encephalopathy

Many neonatologists practice with the belief that for a newborn with encephalopathy in the setting of a sentinel labor event, a low Apgar score at 5 minutes, an umbilical cord artery pH < 7.00, and/or an elevated lactate level, the diagnosis of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy is warranted. However, there are many causes of neonatal encephalopathy not related to intrapartum events. For example, neonatal encephalopathy and seizures may be caused by infectious, vascular, metabolic, medications, or congenital problems.10

There are genetic disorders that can be associated with both neonatal seizures and encephalopathy, suggesting that in some cases the primary cause of the encephalopathy is a genetic problem, not management of labor. Mutations in the potassium channel and sodium channel genes are well recognized causes of neonatal seizures.11,12 Cerebral palsy, a childhood outcome that may follow neonatal encephalopathy, also has numerous etiologies, including genetic causes. Among 1,345 children with cerebral palsy referred for exome sequencing, investigators reported that a genetic abnormality was identified in 33% of the cases.13 Mutations in 86 genes were identified in multiple children. Similar results have been reported in other cohorts.14-16 Maintaining an open mind about the causes of a case of neonatal encephalopathy and not jumping to a conclusion before completing an evaluation is an optimal approach.

Parent’s evolving emotional and intellectual reaction to the initiation of TH

Initiation of TH for a newborn with encephalopathy catalyzes parents to wonder, “How did my baby develop an encephalopathy?”, “Did my obstetrician’s management of labor and delivery contribute to the outcome?” and “What is the prognosis for my baby?” These are difficult questions with high emotional valence for both patients and clinicians. Obstetricians and neonatologists should collaborate to provide consistent responses to these questions.

The presence of a low umbilical cord artery pH and high lactate in combination with a low Apgar score at 5 minutes may lead the neonatologist to diagnose hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in the medical record. The diagnosis of brain hypoxia and ischemia in a newborn may be interpreted by parents as meaning that labor events caused or contributed to the encephalopathy. During the 72 hours of TH, the newborn is sedated and separated from the parents, causing additional emotional stress and uncertainty. When a baby is transferred from a community hospital to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) at a tertiary center, the parents may be geographically separated from their baby during a critical period of time, adding to their anxiety. At some point during the care process most newborns treated with TH will have an EEG, brain ultrasound, and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These data will be discussed with the parent(s) and may cause confusion and additional stress.

The optimal approach to communicating with parents whose newborn is treated with TH continues to evolve. Best practices may include17-20:

- in-person, regular multidisciplinary family meetings with the parents, including neonatologists, obstetricians, social service specialists and mental health experts when possible

- providing emotional support to parents, recognizing the psychological trauma of the clinical events

- encouraging parents to have physical contact with the newborn during TH

- elevating the role of the parents in the care process by having them participate in care events such as diapering the newborn

- ensuring that clinicians do not blame other clinicians for the clinical outcome

- communicating the results and interpretation of advanced physiological monitoring and imaging studies, with an emphasis on clarity, recognizing the limitations of the studies

- providing educational materials for parents about TH, early intervention programs, and support resources.

Coordinated and consistent communication with the parents is often difficult to facilitate due to many factors, including the unique perspectives and vocabularies of clinicians from different specialties and the difficulty of coordinating communications with all those involved over multiple shifts and sites of care. In terms of vocabulary, neonatologists are comfortable with making a diagnosis of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in a newborn, but obstetricians would prefer that neonatologists use the more generic diagnosis of encephalopathy, holding judgment on the cause until additional data are available. In terms of coordinating communication over multiple shifts and sites of care, interactions between an obstetrician and their patient typically occurs in the postpartum unit, while interactions between neonatologists and parents occur in the NICU.

Parents of a baby with neonatal encephalopathy undergoing TH may have numerous traumatic experiences during the care process. For weeks or months after birth, they may recall or dream about the absence of sounds from their newborn at birth, the resuscitation events including chest compressions and intubation, the shivering of the baby during TH, and the jarring pivot from the expectation of holding and bonding with a healthy newborn to the reality of a sick newborn requiring intensive care. Obstetricians are also traumatized by these events and support from peers and mental health experts may help them recognize, explore, and adapt to the trauma. Neonatologists believe that TH can help improve the childhood outcomes of newborns with encephalopathy, a goal endorsed by all clinicians and family members. ●

- Jacobs SE, Berg M, Hunt R, et al. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;CD003311.

- Committee on Fetus and Newborn; Papile E, Baley JE, Benitz W, et al. Hypothermia and neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2014;133:1146-1150.

- Academic Medical Center Patient Safety Organization. Therapeutic hypothermia in neonates. Recommendations of the neonatal encephalopathy task force. 2016. https://www.rmf.harvard. edu/-/media/Files/_Global/KC/PDFs/Guide lines/crico_neonates.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2023.

- Zhang W, Ma J, Danzeng Q, et al. Safety of moderate hypothermia for perinatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Neurol. 2017;74:51-61.

- Sarnat HB, Sarnat MS. Neonatal encephalopathy following fetal distress: a clinical and electroencephalographic study. Arch Neurol. 1976;33:696-705.

- Thompson CM, Puterman AS, Linley LL, et al. The value of a scoring system for hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy in predicting neurodevelopmental outcome. Acta Pediatr. 1997;86:757-761.

- Lundgren C, Brudin L, Wanby AS, et al. Ante- and intrapartum risk factors for neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31:1595-1601.

- Martinez-Biarge M, Diez-Sebastian J, Wusthoff CJ, et al. Antepartum and intrapartum factors preceding neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e952-e959.

- Lorain P, Bower A, Gottardi E, et al. Risk factors for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in cases of severe acidosis: a case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022;101:471-478.

- Russ JB, Simmons R, Glass HC. Neonatal encephalopathy: beyond hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Neo Reviews. 2021;22:e148-e162.

- Allen NM, Mannion M, Conroy J, et al. The variable phenotypes of KCNQ-related epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55:e99-e105.

- Zibro J, Shellhaas RA. Neonatal seizures: diagnosis, etiologies and management. Semin Neurol. 2020;40:246-256.

- Moreno-De-Luca A, Millan F, Peacreta DR, et al. Molecular diagnostic yield of exome sequencing in patients with cerebral palsy. JAMA. 2021;325:467-475.

- Srivastava S, Lewis SA, Cohen JS, et al. Molecular diagnostic yield of exome sequencing and chromosomal microarray in cerebral palsy. A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurology. 2022;79:1287-1295.

- Gonzalez-Mantilla PJ, Hu Y, Myers SM, et al. Diagnostic yield of exome sequencing in cerebral palsy and implications for genetic testing guidelines. A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. Epub March 6, 2023.

- van Eyk C, MacLennon SC, MacLennan AH. All patients with cerebral palsy diagnosis merit genomic sequencing. JAMA Pediatr. Epub March 6, 2023.

- Craig AK, James C, Bainter J, et al. Parental perceptions of neonatal therapeutic hypothermia; emotional and healing experiences. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33:2889-2896. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1563592.

- Sagaser A, Pilon B, Goeller A, et al. Parent experience of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and hypothermia: a call for trauma informed care. Am J Perinatol. Epub March 4, 2022.

- Cascio A, Ferrand A, Racine E, et al. Discussing brain magnetic resonance imaging results for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy treated with hypothermia: a challenge for clinicians and parents. E Neurological Sci. 2022;29:100424.

- Thyagarajan B, Baral V, Gunda R, et al. Parental perceptions of hypothermia treatment for neonatal hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31:2527-2533.

- Jacobs SE, Berg M, Hunt R, et al. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;CD003311.

- Committee on Fetus and Newborn; Papile E, Baley JE, Benitz W, et al. Hypothermia and neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2014;133:1146-1150.

- Academic Medical Center Patient Safety Organization. Therapeutic hypothermia in neonates. Recommendations of the neonatal encephalopathy task force. 2016. https://www.rmf.harvard. edu/-/media/Files/_Global/KC/PDFs/Guide lines/crico_neonates.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2023.

- Zhang W, Ma J, Danzeng Q, et al. Safety of moderate hypothermia for perinatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Neurol. 2017;74:51-61.

- Sarnat HB, Sarnat MS. Neonatal encephalopathy following fetal distress: a clinical and electroencephalographic study. Arch Neurol. 1976;33:696-705.

- Thompson CM, Puterman AS, Linley LL, et al. The value of a scoring system for hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy in predicting neurodevelopmental outcome. Acta Pediatr. 1997;86:757-761.

- Lundgren C, Brudin L, Wanby AS, et al. Ante- and intrapartum risk factors for neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31:1595-1601.

- Martinez-Biarge M, Diez-Sebastian J, Wusthoff CJ, et al. Antepartum and intrapartum factors preceding neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e952-e959.

- Lorain P, Bower A, Gottardi E, et al. Risk factors for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in cases of severe acidosis: a case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022;101:471-478.

- Russ JB, Simmons R, Glass HC. Neonatal encephalopathy: beyond hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Neo Reviews. 2021;22:e148-e162.

- Allen NM, Mannion M, Conroy J, et al. The variable phenotypes of KCNQ-related epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55:e99-e105.

- Zibro J, Shellhaas RA. Neonatal seizures: diagnosis, etiologies and management. Semin Neurol. 2020;40:246-256.

- Moreno-De-Luca A, Millan F, Peacreta DR, et al. Molecular diagnostic yield of exome sequencing in patients with cerebral palsy. JAMA. 2021;325:467-475.

- Srivastava S, Lewis SA, Cohen JS, et al. Molecular diagnostic yield of exome sequencing and chromosomal microarray in cerebral palsy. A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurology. 2022;79:1287-1295.

- Gonzalez-Mantilla PJ, Hu Y, Myers SM, et al. Diagnostic yield of exome sequencing in cerebral palsy and implications for genetic testing guidelines. A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. Epub March 6, 2023.

- van Eyk C, MacLennon SC, MacLennan AH. All patients with cerebral palsy diagnosis merit genomic sequencing. JAMA Pediatr. Epub March 6, 2023.

- Craig AK, James C, Bainter J, et al. Parental perceptions of neonatal therapeutic hypothermia; emotional and healing experiences. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33:2889-2896. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1563592.

- Sagaser A, Pilon B, Goeller A, et al. Parent experience of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and hypothermia: a call for trauma informed care. Am J Perinatol. Epub March 4, 2022.

- Cascio A, Ferrand A, Racine E, et al. Discussing brain magnetic resonance imaging results for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy treated with hypothermia: a challenge for clinicians and parents. E Neurological Sci. 2022;29:100424.

- Thyagarajan B, Baral V, Gunda R, et al. Parental perceptions of hypothermia treatment for neonatal hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31:2527-2533.

Can cffDNA technology be used to determine the underlying cause of pregnancy loss to better inform future pregnancy planning?

Hartwig TJ, Ambye L, Gruhn JR, et al. Cell-free fetal DNA for genetic evaluation in Copenhagen Pregnancy Loss Study (COPL): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2023;401:762-771. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02610-1.

Expert Commentary

A devastating outcome for women, pregnancy loss is directly proportional to maternal age, estimated to occur in approximately 15% of clinically recognized pregnancies and 30% of preclinical pregnancies.1 Approximately 80% of pregnancy losses occur in the first trimester.2 The frequency of clinically recognized early pregnancy loss for women aged 20–30 years is 9% to 17%, and these rates increase sharply, from 20% at age 35 years to 40% at age 40 years, and 80% at age 45 years. Recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL), defined as the spontaneous loss of 2 or more clinically recognized pregnancies, affects less than 5% of women.3 Genetic testing using chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) has identified aneuploidy in about 55% of cases of miscarriage.4

Following ASRM guidelines for the evaluation of RPL, which consists of analyzing parental chromosomal abnormalities, congenital and acquired uterine anomalies, endocrine imbalances, and autoimmune factors (including antiphospholipid syndrome), no explainable cause is determined in 50% of cases.3 Recently, it has been shown that more than 90% of patients with RPL will have a probable or definitive cause identified when CMA testing on miscarriage tissue with the ASRM evaluation guidelines.5

Details of the study

In this prospective cohort study from Denmark, the authors analyzed maternal serum for cell-free fetal DNA (cffDNA) to determine the ploidy status of the pregnancy loss. One thousand women older than age 18 were included (those who demonstrated an ultrasound-confirmed intrauterine pregnancy loss prior to 22 weeks’ gestation). Maternal blood was obtained while pregnancy tissue was in situ or within 24 hours of passage of products of conception (POC), then analyzed by genome-wide sequencing of cffDNA.

For the first 333 recruited women (validation phase), direct sequencing of the POC was performed for sensitivity and specificity. Following the elimination of inconclusive samples, 302 of the 333 cases demonstrated a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 93%. In the subsequent evaluation of 667 women, researchers analyzed maternal serum from the gestational age of fetuses ranging from 35 days to 149 days.

Results. In total, nearly 90% of cases yielded conclusive results, with 50% euploid, 46% aneuploid, and 4% multiple aneuploidies. Earlier gestational ages (less than 7 weeks) had a no-call rate (ie, inconclusive) of approximately 50% (only based on 16 patients), with results typically obtained in maternal serum following passage of POC; in pregnancies at gestational ages past 7 weeks, the no-call rate was about 10%. In general, the longer the time after the pregnancy tissue passed, the higher likelihood of a no-call result.

Applying the technology of single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based CMA can improve identification of fetal and/or maternal sources as causes of pregnancy loss with accuracy, but it does require collection of POC. Of note, samples were deficient in this study, the authors cite, in one-third of the cases. Given this limitation of collection, the authors argue for use of the noninvasive method of cffDNA, obtained from maternal serum.

Study strengths and weaknesses

Several weaknesses of this study are highlighted. Of the validation cohort, one-third of pregnancy tissue could not be analyzed due to insufficient collection. Only 73% of cases allowed for DNA isolation from fetal tissue or chorionic villi; in 27% of cases samples were labeled “unknown tissue.” In those cases classified as unknown, 70% were further determined to be maternal. When all female and monosomy cases were excluded in an effort to assuredly reduce the risk of contamination with maternal DNA, sensitivity of the cffDNA testing process declined to 78%. Another limitation was the required short window for maternal blood sampling (within 24 hours) and its impact on the no-call rate.

The authors note an association with later-life morbidity in patients with a history of pregnancy loss and RPL (including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and mental health disorders), thereby arguing for cffDNA-based testing versus no causal testing; however, no treatment has been proven to be effective at reducing pregnancy loss. ●

The best management course for unexplained RPL is uncertain. Despite its use for a euploid miscarriage or parental chromosomal structural rearrangement, in vitro fertilization with preimplantation genetic testing remains an unproven modality.6,7 Given that approximately 70% of human conceptions never achieve viability, and 50% fail spontaneously before being detected,8 the authors’ findings demonstrate peripheral maternal blood can provide a reasonably high sensitivity and specificity for fetal ploidy status when compared with direct sequencing of pregnancy tissue. As fetal aneuploidy offers a higher percentage of subsequent successful pregnancy outcomes, cffDNA may offer reassurance, or direct further testing, following a pregnancy loss. As an application of their results, evaluation may be deferred for an aneuploid miscarriage.

—MARK P. TROLICE, MD, MBA

- Brown S. Miscarriage and its associations. Semin Reprod Med. 2008;26:391-400. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1087105.

- Wang X, Chen C , Wang L, et al. Conception, early pregnancy loss, and time to clinical pregnancy: a population-based prospective study. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:577-584.

- Evaluation and treatment of recurrent pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Fertil Steril. 2012;98: 1103-1111.

- Papas RS, Kutteh WH. Genetic testing for aneuploidy in patients who have had multiple miscarriages: a review of current literature. Appl Clin Genet. 2021;14:321-329. https://doi.org/10.2147/tacg.s320778.

- Popescu F, Jaslow FC, Kutteh WH. Recurrent pregnancy loss evaluation combined with 24-chromosome microarray of miscarriage tissue provides a probable or definite cause of pregnancy loss in over 90% of patients. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:579-587. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dey021.

- Dahdouh EM, Balayla J, Garcia-Velasco JA, et al. PGT-A for recurrent pregnancy loss: evidence is growing but the issue is not resolved. Hum Reprod. 2021;36:2805-2806. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deab194.

- Iews M, Tan J, Taskin O, et al. Does preimplantation genetic diagnosis improve reproductive outcome in couples with recurrent pregnancy loss owing to structural chromosomal rearrangement? A systematic review. Reproductive Bio Medicine Online. 2018;36:677-685. https://doi.org/10.1016 /j.rbmo.2018.03.005.

- Papas RS, Kutteh WH. Genetic testing for aneuploidy in patients who have had multiple miscarriages: a review of current literature. Appl Clin Genet. 2021;14:321-329. https://doi.org/10.2147/TACG.S320778.

Hartwig TJ, Ambye L, Gruhn JR, et al. Cell-free fetal DNA for genetic evaluation in Copenhagen Pregnancy Loss Study (COPL): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2023;401:762-771. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02610-1.

Expert Commentary

A devastating outcome for women, pregnancy loss is directly proportional to maternal age, estimated to occur in approximately 15% of clinically recognized pregnancies and 30% of preclinical pregnancies.1 Approximately 80% of pregnancy losses occur in the first trimester.2 The frequency of clinically recognized early pregnancy loss for women aged 20–30 years is 9% to 17%, and these rates increase sharply, from 20% at age 35 years to 40% at age 40 years, and 80% at age 45 years. Recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL), defined as the spontaneous loss of 2 or more clinically recognized pregnancies, affects less than 5% of women.3 Genetic testing using chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) has identified aneuploidy in about 55% of cases of miscarriage.4

Following ASRM guidelines for the evaluation of RPL, which consists of analyzing parental chromosomal abnormalities, congenital and acquired uterine anomalies, endocrine imbalances, and autoimmune factors (including antiphospholipid syndrome), no explainable cause is determined in 50% of cases.3 Recently, it has been shown that more than 90% of patients with RPL will have a probable or definitive cause identified when CMA testing on miscarriage tissue with the ASRM evaluation guidelines.5

Details of the study

In this prospective cohort study from Denmark, the authors analyzed maternal serum for cell-free fetal DNA (cffDNA) to determine the ploidy status of the pregnancy loss. One thousand women older than age 18 were included (those who demonstrated an ultrasound-confirmed intrauterine pregnancy loss prior to 22 weeks’ gestation). Maternal blood was obtained while pregnancy tissue was in situ or within 24 hours of passage of products of conception (POC), then analyzed by genome-wide sequencing of cffDNA.

For the first 333 recruited women (validation phase), direct sequencing of the POC was performed for sensitivity and specificity. Following the elimination of inconclusive samples, 302 of the 333 cases demonstrated a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 93%. In the subsequent evaluation of 667 women, researchers analyzed maternal serum from the gestational age of fetuses ranging from 35 days to 149 days.

Results. In total, nearly 90% of cases yielded conclusive results, with 50% euploid, 46% aneuploid, and 4% multiple aneuploidies. Earlier gestational ages (less than 7 weeks) had a no-call rate (ie, inconclusive) of approximately 50% (only based on 16 patients), with results typically obtained in maternal serum following passage of POC; in pregnancies at gestational ages past 7 weeks, the no-call rate was about 10%. In general, the longer the time after the pregnancy tissue passed, the higher likelihood of a no-call result.

Applying the technology of single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based CMA can improve identification of fetal and/or maternal sources as causes of pregnancy loss with accuracy, but it does require collection of POC. Of note, samples were deficient in this study, the authors cite, in one-third of the cases. Given this limitation of collection, the authors argue for use of the noninvasive method of cffDNA, obtained from maternal serum.

Study strengths and weaknesses

Several weaknesses of this study are highlighted. Of the validation cohort, one-third of pregnancy tissue could not be analyzed due to insufficient collection. Only 73% of cases allowed for DNA isolation from fetal tissue or chorionic villi; in 27% of cases samples were labeled “unknown tissue.” In those cases classified as unknown, 70% were further determined to be maternal. When all female and monosomy cases were excluded in an effort to assuredly reduce the risk of contamination with maternal DNA, sensitivity of the cffDNA testing process declined to 78%. Another limitation was the required short window for maternal blood sampling (within 24 hours) and its impact on the no-call rate.

The authors note an association with later-life morbidity in patients with a history of pregnancy loss and RPL (including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and mental health disorders), thereby arguing for cffDNA-based testing versus no causal testing; however, no treatment has been proven to be effective at reducing pregnancy loss. ●

The best management course for unexplained RPL is uncertain. Despite its use for a euploid miscarriage or parental chromosomal structural rearrangement, in vitro fertilization with preimplantation genetic testing remains an unproven modality.6,7 Given that approximately 70% of human conceptions never achieve viability, and 50% fail spontaneously before being detected,8 the authors’ findings demonstrate peripheral maternal blood can provide a reasonably high sensitivity and specificity for fetal ploidy status when compared with direct sequencing of pregnancy tissue. As fetal aneuploidy offers a higher percentage of subsequent successful pregnancy outcomes, cffDNA may offer reassurance, or direct further testing, following a pregnancy loss. As an application of their results, evaluation may be deferred for an aneuploid miscarriage.

—MARK P. TROLICE, MD, MBA

Hartwig TJ, Ambye L, Gruhn JR, et al. Cell-free fetal DNA for genetic evaluation in Copenhagen Pregnancy Loss Study (COPL): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2023;401:762-771. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02610-1.

Expert Commentary

A devastating outcome for women, pregnancy loss is directly proportional to maternal age, estimated to occur in approximately 15% of clinically recognized pregnancies and 30% of preclinical pregnancies.1 Approximately 80% of pregnancy losses occur in the first trimester.2 The frequency of clinically recognized early pregnancy loss for women aged 20–30 years is 9% to 17%, and these rates increase sharply, from 20% at age 35 years to 40% at age 40 years, and 80% at age 45 years. Recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL), defined as the spontaneous loss of 2 or more clinically recognized pregnancies, affects less than 5% of women.3 Genetic testing using chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) has identified aneuploidy in about 55% of cases of miscarriage.4

Following ASRM guidelines for the evaluation of RPL, which consists of analyzing parental chromosomal abnormalities, congenital and acquired uterine anomalies, endocrine imbalances, and autoimmune factors (including antiphospholipid syndrome), no explainable cause is determined in 50% of cases.3 Recently, it has been shown that more than 90% of patients with RPL will have a probable or definitive cause identified when CMA testing on miscarriage tissue with the ASRM evaluation guidelines.5

Details of the study

In this prospective cohort study from Denmark, the authors analyzed maternal serum for cell-free fetal DNA (cffDNA) to determine the ploidy status of the pregnancy loss. One thousand women older than age 18 were included (those who demonstrated an ultrasound-confirmed intrauterine pregnancy loss prior to 22 weeks’ gestation). Maternal blood was obtained while pregnancy tissue was in situ or within 24 hours of passage of products of conception (POC), then analyzed by genome-wide sequencing of cffDNA.

For the first 333 recruited women (validation phase), direct sequencing of the POC was performed for sensitivity and specificity. Following the elimination of inconclusive samples, 302 of the 333 cases demonstrated a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 93%. In the subsequent evaluation of 667 women, researchers analyzed maternal serum from the gestational age of fetuses ranging from 35 days to 149 days.

Results. In total, nearly 90% of cases yielded conclusive results, with 50% euploid, 46% aneuploid, and 4% multiple aneuploidies. Earlier gestational ages (less than 7 weeks) had a no-call rate (ie, inconclusive) of approximately 50% (only based on 16 patients), with results typically obtained in maternal serum following passage of POC; in pregnancies at gestational ages past 7 weeks, the no-call rate was about 10%. In general, the longer the time after the pregnancy tissue passed, the higher likelihood of a no-call result.