User login

August 2008 Instant Poll Results

MARCH 2008

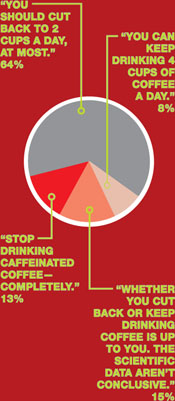

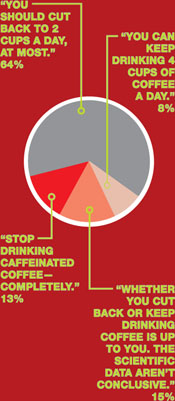

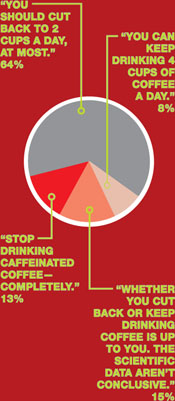

Coffee and conception—what’s your counsel?

A woman drinks 4 cups of caffeinated coffee daily but reports no other source of caffeine, which means that she consumes about 500 mg of caffeine a day. She tells you that she’s concerned about the impact of caffeine on a future pregnancy.

What would you say to this patient about her consumption of caffeine when she begins to try to conceive and, later, while she is pregnant?

APRIL 2008

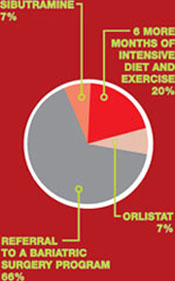

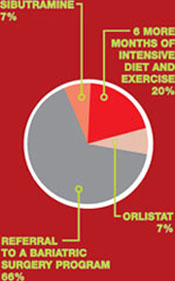

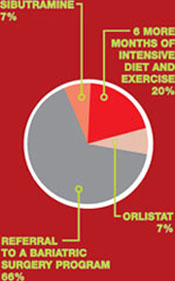

Failed weight loss: Take the next step

Your patient is a 27-year-old woman who has a body mass index of 41 and polycystic ovary syndrome. Her medications are an estrogen–progestin oral contraceptive and metformin, 1,500 mg/day.

She has tried to lose weight many times, without lasting success. She has consulted with nutritionists, personal trainers, and endocrinologists. The next step is yours:

MARCH 2008

Coffee and conception—what’s your counsel?

A woman drinks 4 cups of caffeinated coffee daily but reports no other source of caffeine, which means that she consumes about 500 mg of caffeine a day. She tells you that she’s concerned about the impact of caffeine on a future pregnancy.

What would you say to this patient about her consumption of caffeine when she begins to try to conceive and, later, while she is pregnant?

APRIL 2008

Failed weight loss: Take the next step

Your patient is a 27-year-old woman who has a body mass index of 41 and polycystic ovary syndrome. Her medications are an estrogen–progestin oral contraceptive and metformin, 1,500 mg/day.

She has tried to lose weight many times, without lasting success. She has consulted with nutritionists, personal trainers, and endocrinologists. The next step is yours:

MARCH 2008

Coffee and conception—what’s your counsel?

A woman drinks 4 cups of caffeinated coffee daily but reports no other source of caffeine, which means that she consumes about 500 mg of caffeine a day. She tells you that she’s concerned about the impact of caffeine on a future pregnancy.

What would you say to this patient about her consumption of caffeine when she begins to try to conceive and, later, while she is pregnant?

APRIL 2008

Failed weight loss: Take the next step

Your patient is a 27-year-old woman who has a body mass index of 41 and polycystic ovary syndrome. Her medications are an estrogen–progestin oral contraceptive and metformin, 1,500 mg/day.

She has tried to lose weight many times, without lasting success. She has consulted with nutritionists, personal trainers, and endocrinologists. The next step is yours:

Malpractice minute: June POLL RESULTS

Could a patient’s violent act have been prevented?

A man under outpatient care of the state’s regional behavioral health authority was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type. He killed his developmentally disabled niece, age 26. The niece’s family claimed the death could have been prevented if the man was civilly committed or heavily medicated. Was the behavioral health authority liable?

⋥ LIABLE: 11% ⋥ NOT LIABLE: 89%

What did the court decide?

The mother was found to be 39% at fault, the patient 11% at fault, and the behavioral health authority 50% at fault for the woman’s death and paid half of the verdict amount to the parents. A $101,740 verdict was returned for the niece’s mother and a $100,625 verdict was returned for the father.

Cases are selected by Current Psychiatry from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of its editor, Lewis Laska of Nashville, TN (www.verdictslaska.com). Information may be incomplete in some instances, but these cases represent clinical situations that typically result in litigation.

Could a patient’s violent act have been prevented?

A man under outpatient care of the state’s regional behavioral health authority was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type. He killed his developmentally disabled niece, age 26. The niece’s family claimed the death could have been prevented if the man was civilly committed or heavily medicated. Was the behavioral health authority liable?

⋥ LIABLE: 11% ⋥ NOT LIABLE: 89%

What did the court decide?

The mother was found to be 39% at fault, the patient 11% at fault, and the behavioral health authority 50% at fault for the woman’s death and paid half of the verdict amount to the parents. A $101,740 verdict was returned for the niece’s mother and a $100,625 verdict was returned for the father.

Could a patient’s violent act have been prevented?

A man under outpatient care of the state’s regional behavioral health authority was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid type. He killed his developmentally disabled niece, age 26. The niece’s family claimed the death could have been prevented if the man was civilly committed or heavily medicated. Was the behavioral health authority liable?

⋥ LIABLE: 11% ⋥ NOT LIABLE: 89%

What did the court decide?

The mother was found to be 39% at fault, the patient 11% at fault, and the behavioral health authority 50% at fault for the woman’s death and paid half of the verdict amount to the parents. A $101,740 verdict was returned for the niece’s mother and a $100,625 verdict was returned for the father.

Cases are selected by Current Psychiatry from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of its editor, Lewis Laska of Nashville, TN (www.verdictslaska.com). Information may be incomplete in some instances, but these cases represent clinical situations that typically result in litigation.

Cases are selected by Current Psychiatry from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of its editor, Lewis Laska of Nashville, TN (www.verdictslaska.com). Information may be incomplete in some instances, but these cases represent clinical situations that typically result in litigation.

Divorce, custody, and parental consent for psychiatric treatment

Dear Dr. Mossman:

I treat children and adolescents in an acute inpatient setting. Sometimes a child of divorced parents—call him “Johnny”—is admitted to the hospital by one parent—for example the mother—but she doesn’t inform the father. Although the parents have joint custody, Mom doesn’t want me to contact Dad.

I tell Mom that I’d like to get clinical information and consent from Dad, but she refuses, saying, “This will make me look bad, and my ex-husband will try to take emergency custody of Johnny.” My hospital’s legal department says consent from both parents isn’t needed.

These scenarios always leave me feeling upset and confused. I’d appreciate clarification on how to handle these matters.—Submitted by “Dr. K”

Knowing the correct legal answer to a question often doesn’t supply the best clinical solution for your patient. Dr. K received a legally sound response from hospital administrators: a parent who has legal custody may authorize medical treatment for a minor child without first asking or informing the other parent. But Dr. K feels unsatisfied because the hospital didn’t provide what Dr. K sought: a clinically sound answer.

This article reviews custody arrangements and the legal rights they give divorced parents. Also, we will discuss the mother’s concerns and explain why—despite her fears—notifying and involving Johnny’s father can be important, even when it’s not legally required.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at [email protected].

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

- All readers who submit questions will be included in quarterly drawings for a $50 gift certificate for Professional Risk Management Services, Inc’s online market-place of risk management publications and resources (www.prms.com).

Custody and urgent treatment

A minor—defined in most states as a person younger than age 18—legally cannot give consent for medical care except in limited circumstances, such as contraceptive care.1,2 When a minor undergoes psychiatric hospitalization, physicians usually must obtain consent from the minor’s legal custodian.

Married parents both have legal custody of their children. They also have equal rights to spend time with their children and make major decisions about their welfare, such as authorizing medical care. When parents divorce, these rights must be reassigned in a court-approved divorce decree. Table 1 explains some key terms used to describe custody arrangements after divorce.2,3

Several decades ago, children—especially those younger age 10—usually remained with their mothers, who received sole legal custody; fathers typically had visitation privileges.4 Now, however, most states’ statutes presume that divorced mothers and fathers will have joint legal custody.3

Joint legal custody lets both parents retain their individual legal authority to make decisions on behalf of minor children, although the children may spend most of their time in the physical custody of 1 parent. This means that when urgent medical care is needed—such as a psychiatric hospitalization—1 parent’s consent is sufficient legal authorization for treatment.1,2

What if a child’s parent claims to have legal custody, but the doctor isn’t sure? A doctor who in good faith relies on a parent’s statement can properly provide urgent treatment without delving into custody arrangements.2 In many states, noncustodial parents may authorize treatment in urgent situations—and even some nonurgent ones—if they happen to have physical control of the child when care is needed, such as during a visit.1

Table 1

Child custody: Key legal terms

| Term | Refers to |

|---|---|

| Custody arrangement | The specified times each parent will spend with a minor child and which parent(s) can make major decisions about a child’s welfare |

| Legal custody | A parent’s right to make major decisions about a child’s welfare, including medical care |

| Visitation | The child’s means of maintaining contact with a noncustodial parent |

| Physical custody | Who has physical possession of the child at a particular time, such as during visitation |

| Sole legal custody | A custody arrangement in which only one parent retains the right to make major decisions for the child |

| Joint legal custody | A custody arrangement in which both parents retain the right to make major decisions affecting the child |

| Modification of custody | A legal process in which a court changes a previous custody order |

| Source: Adapted from references 2,3 | |

Nonurgent treatment

After receiving urgent treatment, psychiatric patients typically need continuing, nonurgent care. Dr. K’s inquiry may be anticipating this scenario. In general, parents with joint custody have an equal right to authorize nonurgent care for their children, and Johnny’s treatment could proceed with only Mom’s consent.1 However, if Dr. K knows or has reason to think that Johnny’s father would refuse to give consent for ongoing, nonurgent psychiatric care, providing treatment over the father’s objection may be legally questionable. Under some joint legal custody agreements, both parents need to give consent for medical care and receive clinical information about their children.2

Moreover, trying to treat Johnny in the face of Dad’s explicit objection may be clinically unwise. Unfortunately, many couples’ conflicts are not resolved by divorce, and children can become pawns in ongoing postmarital battles. Such situations can exacerbate children’s emotional problems, which is the opposite of what Dr. K hopes to do for Johnny.

What can Dr. K do?

Address a parent’s fears. Few parents are at their levelheaded best when their children need psychiatric hospitalization. To help Mom and Johnny, Dr. K can point out these things:

- Many states, such as Ohio,5 give Dad the right to learn about Johnny’s treatment and access to treatment records.

- Sooner or later, Dad will find out about the hospitalization. The next time Johnny visits his father, he’ll probably tell Dad what happened. In a few weeks, Dad may receive insurance paperwork or a bill from the hospital.

- Dad may be far more upset and prone to retaliate if he finds out later and is excluded from Johnny’s treatment than if he is notified immediately and gets to participate in his son’s care.

- Realistically, Dad cannot take Johnny away because Mom has arranged for appropriate medical care. If hospitalization is indicated, Mom’s failure to get treatment for Johnny could be grounds for Dad to claim she’s an unfit parent.

Why both parents are needed

Johnny’s hospital care probably will benefit from Dad’s involvement for several reasons (Table 2).

More information. Child and adolescent psychiatrists agree that in most clinical situations it helps to obtain information from as many sources as possible.6-9 Johnny’s father might have crucial information relevant to diagnosis or treatment, such as family history details that Mom doesn’t know.

Debiasing. If Johnny spends time living with both parents, Dr. K should know how often symptoms appear in both environments. Dad’s perspective may be vital, but when postdivorce relationships are strained, what parents convey about each other can be biased. Getting information directly from both parents will give Dr. K a more realistic picture of the child’s environment and psychosocial stressors.7

Treatment planning. After a psychiatric hospitalization, both parents should be aware of Johnny’s diagnosis and treatment. Johnny may need careful supervision for recurrence of symptoms, such as suicidal or homicidal ideation, that can have life-threatening implications.

Medication management. If Johnny is taking medication, he’ll need to receive it regularly. Missing medication when Johnny is with Dad would reduce effectiveness and in some cases could be dangerous. Both parents also should know about possible side effects so they can provide good monitoring.

Psychotherapy. Often, family therapy is an important element of a child’s recovery and will achieve optimum results only if all family members participate. Also, children need consistency. If a behavioral plan is part of Johnny’s treatment, Mom and Dad will need to agree on the rules and implement them consistently at both homes.

Table 2

Why both parents’ input is valuable

| More information from different perspectives concerning behavior in a variety of contexts and settings |

| Less biased information |

| Better treatment planning |

| Better medication management |

| More effective therapy |

Work with parents

When one divorced parent is reluctant to inform the other about their child’s hospitalization, you can respond empathically to fears and concerns. Despite mental health professionals’ best efforts, psychiatric illness still generates feelings of stigma and shame. Divorced parents often feel guilty about the stress the divorce has brought to their children, and they may consciously or unconsciously blame themselves for their child’s illness. In the midst of an ongoing custody dispute, the parent initiating a psychiatric hospitalization may feel especially vulnerable and reluctant to inform the other parent about what’s happening.

Being attuned to these issues will help you address and normalize a parent’s fears. Parents should know that a court could support their seeking treatment for their children’s illness, and they could be contributing to medical neglect if they do not seek this treatment.

In rare instances, not informing the other parent may be the best clinical decision. In situations involving child abuse or extreme domestic violence, a parent’s learning about the hospitalization could create safety issues. In most instances, however, both Mom and Dad will see their child soon after hospitalization, so one parent cannot hope to conceal a hospitalization for very long. Involving both parents from the outset usually will give the child and his family the best shot at a positive outcome.

1. Berger JE. Consent by proxy for nonurgent pediatric care. Pediatrics 2003;112:1186-95.

2. Quinn KM, Weiner BA. Legal rights of children. In: Weiner BA, Wettstein RM, eds. Legal issues in mental health care. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1993:309-47.

3. Kelly JB. The determination of child custody. Future Child 1994;4:121-242.

4. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, Slobogin C. Psychological evaluations for the courts: a handbook for mental health professionals and lawyers. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007.

5. Ohio Rev Code § 3109. 051(H).

6. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the psychiatric assessment of children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(10 suppl):4S-20S.

7. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for the assessment of the family. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;46:922-37.

8. Bostic JQ, King RA. Clinical assessment of children and adolescents: content and structure. In: Martin A, Volkmar FR, eds. Lewis’s child and adolescent psychiatry: a comprehensive textbook. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:323-44.

9. Weston CG, Klykylo WM. The initial psychiatric evaluation of children and adolescents. In: Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman J, eds. Psychiatry. 3rd ed. London, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2008:546-54.

Dear Dr. Mossman:

I treat children and adolescents in an acute inpatient setting. Sometimes a child of divorced parents—call him “Johnny”—is admitted to the hospital by one parent—for example the mother—but she doesn’t inform the father. Although the parents have joint custody, Mom doesn’t want me to contact Dad.

I tell Mom that I’d like to get clinical information and consent from Dad, but she refuses, saying, “This will make me look bad, and my ex-husband will try to take emergency custody of Johnny.” My hospital’s legal department says consent from both parents isn’t needed.

These scenarios always leave me feeling upset and confused. I’d appreciate clarification on how to handle these matters.—Submitted by “Dr. K”

Knowing the correct legal answer to a question often doesn’t supply the best clinical solution for your patient. Dr. K received a legally sound response from hospital administrators: a parent who has legal custody may authorize medical treatment for a minor child without first asking or informing the other parent. But Dr. K feels unsatisfied because the hospital didn’t provide what Dr. K sought: a clinically sound answer.

This article reviews custody arrangements and the legal rights they give divorced parents. Also, we will discuss the mother’s concerns and explain why—despite her fears—notifying and involving Johnny’s father can be important, even when it’s not legally required.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at [email protected].

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

- All readers who submit questions will be included in quarterly drawings for a $50 gift certificate for Professional Risk Management Services, Inc’s online market-place of risk management publications and resources (www.prms.com).

Custody and urgent treatment

A minor—defined in most states as a person younger than age 18—legally cannot give consent for medical care except in limited circumstances, such as contraceptive care.1,2 When a minor undergoes psychiatric hospitalization, physicians usually must obtain consent from the minor’s legal custodian.

Married parents both have legal custody of their children. They also have equal rights to spend time with their children and make major decisions about their welfare, such as authorizing medical care. When parents divorce, these rights must be reassigned in a court-approved divorce decree. Table 1 explains some key terms used to describe custody arrangements after divorce.2,3

Several decades ago, children—especially those younger age 10—usually remained with their mothers, who received sole legal custody; fathers typically had visitation privileges.4 Now, however, most states’ statutes presume that divorced mothers and fathers will have joint legal custody.3

Joint legal custody lets both parents retain their individual legal authority to make decisions on behalf of minor children, although the children may spend most of their time in the physical custody of 1 parent. This means that when urgent medical care is needed—such as a psychiatric hospitalization—1 parent’s consent is sufficient legal authorization for treatment.1,2

What if a child’s parent claims to have legal custody, but the doctor isn’t sure? A doctor who in good faith relies on a parent’s statement can properly provide urgent treatment without delving into custody arrangements.2 In many states, noncustodial parents may authorize treatment in urgent situations—and even some nonurgent ones—if they happen to have physical control of the child when care is needed, such as during a visit.1

Table 1

Child custody: Key legal terms

| Term | Refers to |

|---|---|

| Custody arrangement | The specified times each parent will spend with a minor child and which parent(s) can make major decisions about a child’s welfare |

| Legal custody | A parent’s right to make major decisions about a child’s welfare, including medical care |

| Visitation | The child’s means of maintaining contact with a noncustodial parent |

| Physical custody | Who has physical possession of the child at a particular time, such as during visitation |

| Sole legal custody | A custody arrangement in which only one parent retains the right to make major decisions for the child |

| Joint legal custody | A custody arrangement in which both parents retain the right to make major decisions affecting the child |

| Modification of custody | A legal process in which a court changes a previous custody order |

| Source: Adapted from references 2,3 | |

Nonurgent treatment

After receiving urgent treatment, psychiatric patients typically need continuing, nonurgent care. Dr. K’s inquiry may be anticipating this scenario. In general, parents with joint custody have an equal right to authorize nonurgent care for their children, and Johnny’s treatment could proceed with only Mom’s consent.1 However, if Dr. K knows or has reason to think that Johnny’s father would refuse to give consent for ongoing, nonurgent psychiatric care, providing treatment over the father’s objection may be legally questionable. Under some joint legal custody agreements, both parents need to give consent for medical care and receive clinical information about their children.2

Moreover, trying to treat Johnny in the face of Dad’s explicit objection may be clinically unwise. Unfortunately, many couples’ conflicts are not resolved by divorce, and children can become pawns in ongoing postmarital battles. Such situations can exacerbate children’s emotional problems, which is the opposite of what Dr. K hopes to do for Johnny.

What can Dr. K do?

Address a parent’s fears. Few parents are at their levelheaded best when their children need psychiatric hospitalization. To help Mom and Johnny, Dr. K can point out these things:

- Many states, such as Ohio,5 give Dad the right to learn about Johnny’s treatment and access to treatment records.

- Sooner or later, Dad will find out about the hospitalization. The next time Johnny visits his father, he’ll probably tell Dad what happened. In a few weeks, Dad may receive insurance paperwork or a bill from the hospital.

- Dad may be far more upset and prone to retaliate if he finds out later and is excluded from Johnny’s treatment than if he is notified immediately and gets to participate in his son’s care.

- Realistically, Dad cannot take Johnny away because Mom has arranged for appropriate medical care. If hospitalization is indicated, Mom’s failure to get treatment for Johnny could be grounds for Dad to claim she’s an unfit parent.

Why both parents are needed

Johnny’s hospital care probably will benefit from Dad’s involvement for several reasons (Table 2).

More information. Child and adolescent psychiatrists agree that in most clinical situations it helps to obtain information from as many sources as possible.6-9 Johnny’s father might have crucial information relevant to diagnosis or treatment, such as family history details that Mom doesn’t know.

Debiasing. If Johnny spends time living with both parents, Dr. K should know how often symptoms appear in both environments. Dad’s perspective may be vital, but when postdivorce relationships are strained, what parents convey about each other can be biased. Getting information directly from both parents will give Dr. K a more realistic picture of the child’s environment and psychosocial stressors.7

Treatment planning. After a psychiatric hospitalization, both parents should be aware of Johnny’s diagnosis and treatment. Johnny may need careful supervision for recurrence of symptoms, such as suicidal or homicidal ideation, that can have life-threatening implications.

Medication management. If Johnny is taking medication, he’ll need to receive it regularly. Missing medication when Johnny is with Dad would reduce effectiveness and in some cases could be dangerous. Both parents also should know about possible side effects so they can provide good monitoring.

Psychotherapy. Often, family therapy is an important element of a child’s recovery and will achieve optimum results only if all family members participate. Also, children need consistency. If a behavioral plan is part of Johnny’s treatment, Mom and Dad will need to agree on the rules and implement them consistently at both homes.

Table 2

Why both parents’ input is valuable

| More information from different perspectives concerning behavior in a variety of contexts and settings |

| Less biased information |

| Better treatment planning |

| Better medication management |

| More effective therapy |

Work with parents

When one divorced parent is reluctant to inform the other about their child’s hospitalization, you can respond empathically to fears and concerns. Despite mental health professionals’ best efforts, psychiatric illness still generates feelings of stigma and shame. Divorced parents often feel guilty about the stress the divorce has brought to their children, and they may consciously or unconsciously blame themselves for their child’s illness. In the midst of an ongoing custody dispute, the parent initiating a psychiatric hospitalization may feel especially vulnerable and reluctant to inform the other parent about what’s happening.

Being attuned to these issues will help you address and normalize a parent’s fears. Parents should know that a court could support their seeking treatment for their children’s illness, and they could be contributing to medical neglect if they do not seek this treatment.

In rare instances, not informing the other parent may be the best clinical decision. In situations involving child abuse or extreme domestic violence, a parent’s learning about the hospitalization could create safety issues. In most instances, however, both Mom and Dad will see their child soon after hospitalization, so one parent cannot hope to conceal a hospitalization for very long. Involving both parents from the outset usually will give the child and his family the best shot at a positive outcome.

Dear Dr. Mossman:

I treat children and adolescents in an acute inpatient setting. Sometimes a child of divorced parents—call him “Johnny”—is admitted to the hospital by one parent—for example the mother—but she doesn’t inform the father. Although the parents have joint custody, Mom doesn’t want me to contact Dad.

I tell Mom that I’d like to get clinical information and consent from Dad, but she refuses, saying, “This will make me look bad, and my ex-husband will try to take emergency custody of Johnny.” My hospital’s legal department says consent from both parents isn’t needed.

These scenarios always leave me feeling upset and confused. I’d appreciate clarification on how to handle these matters.—Submitted by “Dr. K”

Knowing the correct legal answer to a question often doesn’t supply the best clinical solution for your patient. Dr. K received a legally sound response from hospital administrators: a parent who has legal custody may authorize medical treatment for a minor child without first asking or informing the other parent. But Dr. K feels unsatisfied because the hospital didn’t provide what Dr. K sought: a clinically sound answer.

This article reviews custody arrangements and the legal rights they give divorced parents. Also, we will discuss the mother’s concerns and explain why—despite her fears—notifying and involving Johnny’s father can be important, even when it’s not legally required.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at [email protected].

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

- All readers who submit questions will be included in quarterly drawings for a $50 gift certificate for Professional Risk Management Services, Inc’s online market-place of risk management publications and resources (www.prms.com).

Custody and urgent treatment

A minor—defined in most states as a person younger than age 18—legally cannot give consent for medical care except in limited circumstances, such as contraceptive care.1,2 When a minor undergoes psychiatric hospitalization, physicians usually must obtain consent from the minor’s legal custodian.

Married parents both have legal custody of their children. They also have equal rights to spend time with their children and make major decisions about their welfare, such as authorizing medical care. When parents divorce, these rights must be reassigned in a court-approved divorce decree. Table 1 explains some key terms used to describe custody arrangements after divorce.2,3

Several decades ago, children—especially those younger age 10—usually remained with their mothers, who received sole legal custody; fathers typically had visitation privileges.4 Now, however, most states’ statutes presume that divorced mothers and fathers will have joint legal custody.3

Joint legal custody lets both parents retain their individual legal authority to make decisions on behalf of minor children, although the children may spend most of their time in the physical custody of 1 parent. This means that when urgent medical care is needed—such as a psychiatric hospitalization—1 parent’s consent is sufficient legal authorization for treatment.1,2

What if a child’s parent claims to have legal custody, but the doctor isn’t sure? A doctor who in good faith relies on a parent’s statement can properly provide urgent treatment without delving into custody arrangements.2 In many states, noncustodial parents may authorize treatment in urgent situations—and even some nonurgent ones—if they happen to have physical control of the child when care is needed, such as during a visit.1

Table 1

Child custody: Key legal terms

| Term | Refers to |

|---|---|

| Custody arrangement | The specified times each parent will spend with a minor child and which parent(s) can make major decisions about a child’s welfare |

| Legal custody | A parent’s right to make major decisions about a child’s welfare, including medical care |

| Visitation | The child’s means of maintaining contact with a noncustodial parent |

| Physical custody | Who has physical possession of the child at a particular time, such as during visitation |

| Sole legal custody | A custody arrangement in which only one parent retains the right to make major decisions for the child |

| Joint legal custody | A custody arrangement in which both parents retain the right to make major decisions affecting the child |

| Modification of custody | A legal process in which a court changes a previous custody order |

| Source: Adapted from references 2,3 | |

Nonurgent treatment

After receiving urgent treatment, psychiatric patients typically need continuing, nonurgent care. Dr. K’s inquiry may be anticipating this scenario. In general, parents with joint custody have an equal right to authorize nonurgent care for their children, and Johnny’s treatment could proceed with only Mom’s consent.1 However, if Dr. K knows or has reason to think that Johnny’s father would refuse to give consent for ongoing, nonurgent psychiatric care, providing treatment over the father’s objection may be legally questionable. Under some joint legal custody agreements, both parents need to give consent for medical care and receive clinical information about their children.2

Moreover, trying to treat Johnny in the face of Dad’s explicit objection may be clinically unwise. Unfortunately, many couples’ conflicts are not resolved by divorce, and children can become pawns in ongoing postmarital battles. Such situations can exacerbate children’s emotional problems, which is the opposite of what Dr. K hopes to do for Johnny.

What can Dr. K do?

Address a parent’s fears. Few parents are at their levelheaded best when their children need psychiatric hospitalization. To help Mom and Johnny, Dr. K can point out these things:

- Many states, such as Ohio,5 give Dad the right to learn about Johnny’s treatment and access to treatment records.

- Sooner or later, Dad will find out about the hospitalization. The next time Johnny visits his father, he’ll probably tell Dad what happened. In a few weeks, Dad may receive insurance paperwork or a bill from the hospital.

- Dad may be far more upset and prone to retaliate if he finds out later and is excluded from Johnny’s treatment than if he is notified immediately and gets to participate in his son’s care.

- Realistically, Dad cannot take Johnny away because Mom has arranged for appropriate medical care. If hospitalization is indicated, Mom’s failure to get treatment for Johnny could be grounds for Dad to claim she’s an unfit parent.

Why both parents are needed

Johnny’s hospital care probably will benefit from Dad’s involvement for several reasons (Table 2).

More information. Child and adolescent psychiatrists agree that in most clinical situations it helps to obtain information from as many sources as possible.6-9 Johnny’s father might have crucial information relevant to diagnosis or treatment, such as family history details that Mom doesn’t know.

Debiasing. If Johnny spends time living with both parents, Dr. K should know how often symptoms appear in both environments. Dad’s perspective may be vital, but when postdivorce relationships are strained, what parents convey about each other can be biased. Getting information directly from both parents will give Dr. K a more realistic picture of the child’s environment and psychosocial stressors.7

Treatment planning. After a psychiatric hospitalization, both parents should be aware of Johnny’s diagnosis and treatment. Johnny may need careful supervision for recurrence of symptoms, such as suicidal or homicidal ideation, that can have life-threatening implications.

Medication management. If Johnny is taking medication, he’ll need to receive it regularly. Missing medication when Johnny is with Dad would reduce effectiveness and in some cases could be dangerous. Both parents also should know about possible side effects so they can provide good monitoring.

Psychotherapy. Often, family therapy is an important element of a child’s recovery and will achieve optimum results only if all family members participate. Also, children need consistency. If a behavioral plan is part of Johnny’s treatment, Mom and Dad will need to agree on the rules and implement them consistently at both homes.

Table 2

Why both parents’ input is valuable

| More information from different perspectives concerning behavior in a variety of contexts and settings |

| Less biased information |

| Better treatment planning |

| Better medication management |

| More effective therapy |

Work with parents

When one divorced parent is reluctant to inform the other about their child’s hospitalization, you can respond empathically to fears and concerns. Despite mental health professionals’ best efforts, psychiatric illness still generates feelings of stigma and shame. Divorced parents often feel guilty about the stress the divorce has brought to their children, and they may consciously or unconsciously blame themselves for their child’s illness. In the midst of an ongoing custody dispute, the parent initiating a psychiatric hospitalization may feel especially vulnerable and reluctant to inform the other parent about what’s happening.

Being attuned to these issues will help you address and normalize a parent’s fears. Parents should know that a court could support their seeking treatment for their children’s illness, and they could be contributing to medical neglect if they do not seek this treatment.

In rare instances, not informing the other parent may be the best clinical decision. In situations involving child abuse or extreme domestic violence, a parent’s learning about the hospitalization could create safety issues. In most instances, however, both Mom and Dad will see their child soon after hospitalization, so one parent cannot hope to conceal a hospitalization for very long. Involving both parents from the outset usually will give the child and his family the best shot at a positive outcome.

1. Berger JE. Consent by proxy for nonurgent pediatric care. Pediatrics 2003;112:1186-95.

2. Quinn KM, Weiner BA. Legal rights of children. In: Weiner BA, Wettstein RM, eds. Legal issues in mental health care. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1993:309-47.

3. Kelly JB. The determination of child custody. Future Child 1994;4:121-242.

4. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, Slobogin C. Psychological evaluations for the courts: a handbook for mental health professionals and lawyers. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007.

5. Ohio Rev Code § 3109. 051(H).

6. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the psychiatric assessment of children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(10 suppl):4S-20S.

7. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for the assessment of the family. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;46:922-37.

8. Bostic JQ, King RA. Clinical assessment of children and adolescents: content and structure. In: Martin A, Volkmar FR, eds. Lewis’s child and adolescent psychiatry: a comprehensive textbook. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:323-44.

9. Weston CG, Klykylo WM. The initial psychiatric evaluation of children and adolescents. In: Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman J, eds. Psychiatry. 3rd ed. London, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2008:546-54.

1. Berger JE. Consent by proxy for nonurgent pediatric care. Pediatrics 2003;112:1186-95.

2. Quinn KM, Weiner BA. Legal rights of children. In: Weiner BA, Wettstein RM, eds. Legal issues in mental health care. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1993:309-47.

3. Kelly JB. The determination of child custody. Future Child 1994;4:121-242.

4. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, Slobogin C. Psychological evaluations for the courts: a handbook for mental health professionals and lawyers. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007.

5. Ohio Rev Code § 3109. 051(H).

6. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the psychiatric assessment of children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(10 suppl):4S-20S.

7. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for the assessment of the family. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;46:922-37.

8. Bostic JQ, King RA. Clinical assessment of children and adolescents: content and structure. In: Martin A, Volkmar FR, eds. Lewis’s child and adolescent psychiatry: a comprehensive textbook. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:323-44.

9. Weston CG, Klykylo WM. The initial psychiatric evaluation of children and adolescents. In: Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman J, eds. Psychiatry. 3rd ed. London, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2008:546-54.

Listen to the Patient

As the healthcare system struggles with the definition of quality and the implementation of patient-centered care, renewed attention is being given to patient satisfaction.

Now, this performance measure has moved from the hospital’s marketing department into the C-suite, where senior administrators at some hospitals have patient satisfaction scores tied to their compensation.

Pressure is being applied to nudge key hospital care providers, including hospitalists, to keep their patients happy while giving them the care they deserve.

With the recent publishing of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare providers and Systems (HCAHPS) scorecards for each hospital on the Hospital Compare Web site (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov), patients can see and compare local hospitals.

Because hospitalists are managing an ever-increasing portion of the hospital census, we can count on being right in the middle of all this. Coupled with the fact that 40% of hospitalists are directly employed by their hospital and a significant portion of other hospitalist groups have contracts with hospitals tied to quality improvement, we can expect a lot of pressure to not only improve patient satisfaction, but to make the “numbers” look better.

What Survey Measures

An important starting point for hospitalists and especially their leaders, who will be engaged in conversations with the C-suite about patient satisfaction data, is to better understand what the data indicate.

First, you need to know that the patient questionnaires were designed by several large vendors, the largest being Press Ganey.

While it is possible to segment the patients by those treated by a hospitalist and those not, the questions were not meant to describe, define, or compare the performance of different physicians. Remember, non-hospitalists for this purpose includes not only internists, but also surgeons, obstetricians, and other specialists.

Some questions on the survey about physicians include:

- During this hospital stay, how often did doctors treat you with respect? (never, sometimes, usually, always);

- During this hospital stay, how often did doctors explain things in a way you could understand? and

- During this hospital stay, how often did doctors listen carefully to you?

Other questions that might pertain to care directed by hospitalists but also relate to the entire care team include:

- How often was your pain controlled?

- Before giving you a new medicine, how often did staff tell you what it was for? and

- Before giving you a new medicine, how often did staff describe possible side effects in a way you could understand?

While you might aggregate all the replies specifically about the doctors’ performance and grade all the doctors separately, the all-important questions to the C-suite are the last two sections:

- How do patients rate the hospital? and

- Would patients recommend the hospital to friends and family?

Patients Are Different

It is important to understand the unique characteristics of the patients admitted and managed by hospitalists and to understand how these patients may respond differently to the standard patient satisfaction surveys than others in the patient population.

More often than not, hospitalists admit patients who are acutely ill, presenting through the emergency department (ED) with medical problems. Some studies have estimated that more than 70% of hospitalists’ patients come through the ED, while for the rest of the staff it is closer to 30% to 40%.

It is well known that patients admitted electively are more satisfied than those with an acute illness who come through the ED. In addition, patients admitted for medical problems have lower satisfaction ratings than those admitted for general surgery, subspecialty surgery, or obstetrics.

Therefore, if your hospital administration has pulled together statistics that purport to compare patient satisfaction for your hospitalist group versus all other admissions, you need to make sure that comparisons are made to a similar population, i.e., acutely ill patients admitted through the ED with medical diagnoses. The survey companies should be able to produce just such a comparison.

It is equally as important to make sure you focus on the total experience at the hospital and not just the questions specifically concerning only the doctors. Since hospitalists not only do front-line, face-to-face patient care, but also work with the team and attempt to improve the system to provide better overall quality, make sure to focus on questions like “How do patients rate the hospital?” and “Would patients recommend the hospital to friends and family?”

The other consideration is to understand how close the top quartile is to the bottom quartile, when comparisons are made with this data. In many of these surveys the patients are giving ratings on a scale of one to four, with many of the responses at three or four. Therefore, the top score might be a 3.6 and the bottom score average 3.2. It is important to understand if you are just minor adjustments away from being in a good range or if you are either so far above or below the standard of care that a real situation exists.

HM’s Role

Does the hospitalist model lead to better patient satisfaction? Like most things in hospital medicine, the answer is yes, no, and maybe. There are certain aspects of hospital medicine that should lead to happier patients:

- Present and easily available;

- Expert in hospital care;

- Improved coordination of care by specialists;

- Availability for multiple visits if patient condition changes;

- Availability to visit with loved-ones at their convenience; and

- Rapid response to nurse’s concerns.

There are aspects of getting your care from a hospitalist that may initially make the patient more concerned:

- They may be unfamiliar with the hospitalist and the hospitalist model;

- The hospitalist may demonstrate little or no knowledge of the patient’s history;

- The referring physician may not introduce the patient to the hospitalist; and

- The hospitalist may not explain the relationship with the referring physician.

How to Be Proactive

With all we have to do every day (and the list seems to get longer by the minute), it is easy to get perplexed by having to be responsible for the patients’ satisfaction with their hospital experience. That being said, hospitalists perform well when we step up to the plate and take action in these ways:

- Proactively meet with the person in the C-suite who oversees the patient satisfaction survey process or relates to the hospitalist group (e.g., vice president of medical affairs or chief medical officer) to better understand the survey results;

- Make sure if the data are being used to compare hospitalist care with non-hospitalist care that the comparison group of patients is equivalent (i.e., acutely ill medical patients admitted through the ED, not surgical or obstetrical patients);

- Make sure to focus not only on the “doctor-related” questions, but on patients’ overall satisfaction with the hospital; and

- Offer to help the C-suite improve patient satisfaction, but don’t attempt to “own” this performance measure for the entire hospital. Hospitalists can be helpful, but this is broader than any one group of physicians.

Further, make improving patient satisfaction a core goal for your group. Some strategies that may work include:

- Have a script for each patient encounter (“Hi, I’m Dr. Smith, I take care of Dr. Jones’ patients in the hospital. The way we communicate about your care is … The advantages to our partnership are …”);

- Hand out a brochure with your group’s hospitalists’ pictures, answers to frequently asked questions, and how to contact the hospitalist; and

- Sit down and shut up (i.e., patients will perceive you are taking time with them and listening if you are seated and let them speak without interruption).

Hospitals have been doing patient surveys for some time now. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and other payers are placing more emphasis on this quality measure. Now that the results easily are available to the public, major newspapers and broadcast media are calling attention to patient perspectives on their hospital care.

Once hospitalist groups understand the data, there is an opportunity to partner with their hospitals to better understand how our patients see their hospital care and allow for hospitalists to have an appropriate role in working with the other health professionals to improve patients’ experience with their care. TH

Dr. Wellikson is the CEO of SHM.

Note to readers: I would like to acknowledge SHM co-founder Win Whitcomb, MD, and SHM Senior Vice President Joe Miller for their assistance with this column.

As the healthcare system struggles with the definition of quality and the implementation of patient-centered care, renewed attention is being given to patient satisfaction.

Now, this performance measure has moved from the hospital’s marketing department into the C-suite, where senior administrators at some hospitals have patient satisfaction scores tied to their compensation.

Pressure is being applied to nudge key hospital care providers, including hospitalists, to keep their patients happy while giving them the care they deserve.

With the recent publishing of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare providers and Systems (HCAHPS) scorecards for each hospital on the Hospital Compare Web site (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov), patients can see and compare local hospitals.

Because hospitalists are managing an ever-increasing portion of the hospital census, we can count on being right in the middle of all this. Coupled with the fact that 40% of hospitalists are directly employed by their hospital and a significant portion of other hospitalist groups have contracts with hospitals tied to quality improvement, we can expect a lot of pressure to not only improve patient satisfaction, but to make the “numbers” look better.

What Survey Measures

An important starting point for hospitalists and especially their leaders, who will be engaged in conversations with the C-suite about patient satisfaction data, is to better understand what the data indicate.

First, you need to know that the patient questionnaires were designed by several large vendors, the largest being Press Ganey.

While it is possible to segment the patients by those treated by a hospitalist and those not, the questions were not meant to describe, define, or compare the performance of different physicians. Remember, non-hospitalists for this purpose includes not only internists, but also surgeons, obstetricians, and other specialists.

Some questions on the survey about physicians include:

- During this hospital stay, how often did doctors treat you with respect? (never, sometimes, usually, always);

- During this hospital stay, how often did doctors explain things in a way you could understand? and

- During this hospital stay, how often did doctors listen carefully to you?

Other questions that might pertain to care directed by hospitalists but also relate to the entire care team include:

- How often was your pain controlled?

- Before giving you a new medicine, how often did staff tell you what it was for? and

- Before giving you a new medicine, how often did staff describe possible side effects in a way you could understand?

While you might aggregate all the replies specifically about the doctors’ performance and grade all the doctors separately, the all-important questions to the C-suite are the last two sections:

- How do patients rate the hospital? and

- Would patients recommend the hospital to friends and family?

Patients Are Different

It is important to understand the unique characteristics of the patients admitted and managed by hospitalists and to understand how these patients may respond differently to the standard patient satisfaction surveys than others in the patient population.

More often than not, hospitalists admit patients who are acutely ill, presenting through the emergency department (ED) with medical problems. Some studies have estimated that more than 70% of hospitalists’ patients come through the ED, while for the rest of the staff it is closer to 30% to 40%.

It is well known that patients admitted electively are more satisfied than those with an acute illness who come through the ED. In addition, patients admitted for medical problems have lower satisfaction ratings than those admitted for general surgery, subspecialty surgery, or obstetrics.

Therefore, if your hospital administration has pulled together statistics that purport to compare patient satisfaction for your hospitalist group versus all other admissions, you need to make sure that comparisons are made to a similar population, i.e., acutely ill patients admitted through the ED with medical diagnoses. The survey companies should be able to produce just such a comparison.

It is equally as important to make sure you focus on the total experience at the hospital and not just the questions specifically concerning only the doctors. Since hospitalists not only do front-line, face-to-face patient care, but also work with the team and attempt to improve the system to provide better overall quality, make sure to focus on questions like “How do patients rate the hospital?” and “Would patients recommend the hospital to friends and family?”

The other consideration is to understand how close the top quartile is to the bottom quartile, when comparisons are made with this data. In many of these surveys the patients are giving ratings on a scale of one to four, with many of the responses at three or four. Therefore, the top score might be a 3.6 and the bottom score average 3.2. It is important to understand if you are just minor adjustments away from being in a good range or if you are either so far above or below the standard of care that a real situation exists.

HM’s Role

Does the hospitalist model lead to better patient satisfaction? Like most things in hospital medicine, the answer is yes, no, and maybe. There are certain aspects of hospital medicine that should lead to happier patients:

- Present and easily available;

- Expert in hospital care;

- Improved coordination of care by specialists;

- Availability for multiple visits if patient condition changes;

- Availability to visit with loved-ones at their convenience; and

- Rapid response to nurse’s concerns.

There are aspects of getting your care from a hospitalist that may initially make the patient more concerned:

- They may be unfamiliar with the hospitalist and the hospitalist model;

- The hospitalist may demonstrate little or no knowledge of the patient’s history;

- The referring physician may not introduce the patient to the hospitalist; and

- The hospitalist may not explain the relationship with the referring physician.

How to Be Proactive

With all we have to do every day (and the list seems to get longer by the minute), it is easy to get perplexed by having to be responsible for the patients’ satisfaction with their hospital experience. That being said, hospitalists perform well when we step up to the plate and take action in these ways:

- Proactively meet with the person in the C-suite who oversees the patient satisfaction survey process or relates to the hospitalist group (e.g., vice president of medical affairs or chief medical officer) to better understand the survey results;

- Make sure if the data are being used to compare hospitalist care with non-hospitalist care that the comparison group of patients is equivalent (i.e., acutely ill medical patients admitted through the ED, not surgical or obstetrical patients);

- Make sure to focus not only on the “doctor-related” questions, but on patients’ overall satisfaction with the hospital; and

- Offer to help the C-suite improve patient satisfaction, but don’t attempt to “own” this performance measure for the entire hospital. Hospitalists can be helpful, but this is broader than any one group of physicians.

Further, make improving patient satisfaction a core goal for your group. Some strategies that may work include:

- Have a script for each patient encounter (“Hi, I’m Dr. Smith, I take care of Dr. Jones’ patients in the hospital. The way we communicate about your care is … The advantages to our partnership are …”);

- Hand out a brochure with your group’s hospitalists’ pictures, answers to frequently asked questions, and how to contact the hospitalist; and

- Sit down and shut up (i.e., patients will perceive you are taking time with them and listening if you are seated and let them speak without interruption).

Hospitals have been doing patient surveys for some time now. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and other payers are placing more emphasis on this quality measure. Now that the results easily are available to the public, major newspapers and broadcast media are calling attention to patient perspectives on their hospital care.

Once hospitalist groups understand the data, there is an opportunity to partner with their hospitals to better understand how our patients see their hospital care and allow for hospitalists to have an appropriate role in working with the other health professionals to improve patients’ experience with their care. TH

Dr. Wellikson is the CEO of SHM.

Note to readers: I would like to acknowledge SHM co-founder Win Whitcomb, MD, and SHM Senior Vice President Joe Miller for their assistance with this column.

As the healthcare system struggles with the definition of quality and the implementation of patient-centered care, renewed attention is being given to patient satisfaction.

Now, this performance measure has moved from the hospital’s marketing department into the C-suite, where senior administrators at some hospitals have patient satisfaction scores tied to their compensation.

Pressure is being applied to nudge key hospital care providers, including hospitalists, to keep their patients happy while giving them the care they deserve.

With the recent publishing of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare providers and Systems (HCAHPS) scorecards for each hospital on the Hospital Compare Web site (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov), patients can see and compare local hospitals.

Because hospitalists are managing an ever-increasing portion of the hospital census, we can count on being right in the middle of all this. Coupled with the fact that 40% of hospitalists are directly employed by their hospital and a significant portion of other hospitalist groups have contracts with hospitals tied to quality improvement, we can expect a lot of pressure to not only improve patient satisfaction, but to make the “numbers” look better.

What Survey Measures

An important starting point for hospitalists and especially their leaders, who will be engaged in conversations with the C-suite about patient satisfaction data, is to better understand what the data indicate.

First, you need to know that the patient questionnaires were designed by several large vendors, the largest being Press Ganey.

While it is possible to segment the patients by those treated by a hospitalist and those not, the questions were not meant to describe, define, or compare the performance of different physicians. Remember, non-hospitalists for this purpose includes not only internists, but also surgeons, obstetricians, and other specialists.

Some questions on the survey about physicians include:

- During this hospital stay, how often did doctors treat you with respect? (never, sometimes, usually, always);

- During this hospital stay, how often did doctors explain things in a way you could understand? and

- During this hospital stay, how often did doctors listen carefully to you?

Other questions that might pertain to care directed by hospitalists but also relate to the entire care team include:

- How often was your pain controlled?

- Before giving you a new medicine, how often did staff tell you what it was for? and

- Before giving you a new medicine, how often did staff describe possible side effects in a way you could understand?

While you might aggregate all the replies specifically about the doctors’ performance and grade all the doctors separately, the all-important questions to the C-suite are the last two sections:

- How do patients rate the hospital? and

- Would patients recommend the hospital to friends and family?

Patients Are Different

It is important to understand the unique characteristics of the patients admitted and managed by hospitalists and to understand how these patients may respond differently to the standard patient satisfaction surveys than others in the patient population.

More often than not, hospitalists admit patients who are acutely ill, presenting through the emergency department (ED) with medical problems. Some studies have estimated that more than 70% of hospitalists’ patients come through the ED, while for the rest of the staff it is closer to 30% to 40%.

It is well known that patients admitted electively are more satisfied than those with an acute illness who come through the ED. In addition, patients admitted for medical problems have lower satisfaction ratings than those admitted for general surgery, subspecialty surgery, or obstetrics.

Therefore, if your hospital administration has pulled together statistics that purport to compare patient satisfaction for your hospitalist group versus all other admissions, you need to make sure that comparisons are made to a similar population, i.e., acutely ill patients admitted through the ED with medical diagnoses. The survey companies should be able to produce just such a comparison.

It is equally as important to make sure you focus on the total experience at the hospital and not just the questions specifically concerning only the doctors. Since hospitalists not only do front-line, face-to-face patient care, but also work with the team and attempt to improve the system to provide better overall quality, make sure to focus on questions like “How do patients rate the hospital?” and “Would patients recommend the hospital to friends and family?”

The other consideration is to understand how close the top quartile is to the bottom quartile, when comparisons are made with this data. In many of these surveys the patients are giving ratings on a scale of one to four, with many of the responses at three or four. Therefore, the top score might be a 3.6 and the bottom score average 3.2. It is important to understand if you are just minor adjustments away from being in a good range or if you are either so far above or below the standard of care that a real situation exists.

HM’s Role

Does the hospitalist model lead to better patient satisfaction? Like most things in hospital medicine, the answer is yes, no, and maybe. There are certain aspects of hospital medicine that should lead to happier patients:

- Present and easily available;

- Expert in hospital care;

- Improved coordination of care by specialists;

- Availability for multiple visits if patient condition changes;

- Availability to visit with loved-ones at their convenience; and

- Rapid response to nurse’s concerns.

There are aspects of getting your care from a hospitalist that may initially make the patient more concerned:

- They may be unfamiliar with the hospitalist and the hospitalist model;

- The hospitalist may demonstrate little or no knowledge of the patient’s history;

- The referring physician may not introduce the patient to the hospitalist; and

- The hospitalist may not explain the relationship with the referring physician.

How to Be Proactive

With all we have to do every day (and the list seems to get longer by the minute), it is easy to get perplexed by having to be responsible for the patients’ satisfaction with their hospital experience. That being said, hospitalists perform well when we step up to the plate and take action in these ways:

- Proactively meet with the person in the C-suite who oversees the patient satisfaction survey process or relates to the hospitalist group (e.g., vice president of medical affairs or chief medical officer) to better understand the survey results;

- Make sure if the data are being used to compare hospitalist care with non-hospitalist care that the comparison group of patients is equivalent (i.e., acutely ill medical patients admitted through the ED, not surgical or obstetrical patients);

- Make sure to focus not only on the “doctor-related” questions, but on patients’ overall satisfaction with the hospital; and

- Offer to help the C-suite improve patient satisfaction, but don’t attempt to “own” this performance measure for the entire hospital. Hospitalists can be helpful, but this is broader than any one group of physicians.

Further, make improving patient satisfaction a core goal for your group. Some strategies that may work include:

- Have a script for each patient encounter (“Hi, I’m Dr. Smith, I take care of Dr. Jones’ patients in the hospital. The way we communicate about your care is … The advantages to our partnership are …”);

- Hand out a brochure with your group’s hospitalists’ pictures, answers to frequently asked questions, and how to contact the hospitalist; and

- Sit down and shut up (i.e., patients will perceive you are taking time with them and listening if you are seated and let them speak without interruption).

Hospitals have been doing patient surveys for some time now. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and other payers are placing more emphasis on this quality measure. Now that the results easily are available to the public, major newspapers and broadcast media are calling attention to patient perspectives on their hospital care.

Once hospitalist groups understand the data, there is an opportunity to partner with their hospitals to better understand how our patients see their hospital care and allow for hospitalists to have an appropriate role in working with the other health professionals to improve patients’ experience with their care. TH

Dr. Wellikson is the CEO of SHM.

Note to readers: I would like to acknowledge SHM co-founder Win Whitcomb, MD, and SHM Senior Vice President Joe Miller for their assistance with this column.

Maternity Maneuvers

Maternity Maneuvers

How do most hospitalist groups manage maternity leave? I recently took six weeks for maternity leave. My colleagues worked my shifts, and I have virtually paid them all back. To do so I often would end up working 18 to 20 days consecutively and numerous weekends. This was not ideal on many levels. I most likely will not [receive a] bonus this year as well. Is there a better way?

New Mom in Midwest

Dr. Hospitalist responds: Congratulations on the birth of your child. As you recognize, becoming a parent is a wonderful experience but also can be stressful. It is not easy to balance the competing demands of family and work.

Medical leave is not unique to hospitalists—but with the average age of hospitalists being 37, it is commonplace to have hospitalist staff start families at this stage of their lives. In fact, as a hospitalist director, it would be foolish for me not to expect and plan for maternity and paternity leaves.

Medical leaves often are stressful for hospitalist programs because of the need to find replacement staff to fill the work schedule. There is no “best” way to cover the schedule during medical leaves. One thing is certain: Not offering medical leave is not only unrealistic, it may be against the law.

Hospitalist directors and those contemplating medical leave from work should familiarize themselves with the federal government’s Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA). Of course, I’m not an attorney; anyone who is looking for accurate advice concerning FMLA and other legal matters should consult a lawyer.

Briefly stated, the FMLA requires that “covered employers must grant an eligible employee up to a total of 12 work weeks of unpaid leave during any 12-month period for one or more of the following reasons:

- Birth and care of the newborn child of the employee;

- Placement with the employee of a son or daughter for adoption or foster care;

- To care for an immediate family member (spouse, child, or parent) with a serious health condition; or

- To take medical leave when the employee is unable to work because of a serious health condition.

It is important to know that the FMLA strictly defines eligibility criteria. For example, a covered employer is one who “employs 50 or more employees for each working day during each of 20 or more calendar work weeks in the current or preceding calendar year.” There also are strict criteria that define whether one is an eligible employee. It is important to note that FMLA does not guarantee paid time off—it only requires unpaid leave. You can find additional information about the FMLA online at the government’s Web site: www.dol.gov/esa/whd/fmla.

Peer Pressure

I am an attorney who often represents physicians in hospital peer-review matters. I represent a hospitalist whom the medical staff has recommended be terminated. Two internists have been appointed to the peer-review committee; one has an office-based practice, and the other is a cardiologist. Neither is a hospitalist.

I am trying to convince the medical staff that there should be a hospitalist on the peer-review committee because I believe what a hospitalist does each day is fundamentally different in scope and patient mix than the other two internists. My argument will be much stronger if it is the case that a hospitalist’s practice is now its own medical specialty.

Can you point me to any information or articles that support my belief that hospital practice is now a separate specialty?

Anxious Attorney

Dr. Hospitalist responds: Is a hospitalist practice sufficiently different than that of an office-based internist or cardiologist, so much so that peer-review activities would necessitate at a minimum some involvement of other hospitalists? To answer this question, I think we need to understand the definition of a hospitalist.

I recently heard a doctor describe himself as a hospitalist despite working clinically in the hospital only one month annually. Is he correct in defining himself as a hospitalist? If so, how would we distinguish him from primary care doctors who spend one-twelfth of their work life caring for hospitalized patients?

SHM defines hospitalists as “physicians whose primary professional focus is the general medical care of hospitalized patients. Their activities include patient care, teaching, research, and leadership related to hospital medicine.” Based on this definition, the doctor who spends one month annually caring for inpatients could be a hospitalist if the remainder of his work involved teaching, research, and leadership related to hospital medicine.

In your example, you cite two physicians on the peer-review committee: an office based internist and a cardiologist. Is it reasonable to consider their work similar to or different from that of a hospitalist? In the case of the internist, I think the key point is the fact you described him as office-based. That suggests to me his primary professional focus does not involve hospitalized patients.

One could argue that since both the hospitalist and the office-based internist were trained in internal medicine and both have American Board of Internal Medicine certification, they should be considered peers. I would point out that one’s specialty training has nothing to do with the definition of a hospitalist.

Although the majority of hospitalists in this country are internists, many others are family physicians and pediatricians. Some have subspecialty training, some don’t. Even obstetricians and surgeons are defining themselves as hospitalists.

With all that in mind, would we consider the cardiologist a hospitalist? Again, I think it would depend on the nature of the cardiologist practice. If this cardiologist has a primarily outpatient practice, that would be quite different from a hospitalist practice.

What if this cardiologist’s practice primarily is inpatient? I think it is reasonable to think about the scope of these physicians’ practices. Assuming the cardiologist practice is limited to the care of patients with primary cardiac issues, this would be a much narrower scope than that of most hospitalists.

It also is important to consider the training of the hospitalist. Take geriatrics hospitalists, for instance. The scope of their practice may be quite similar to that of a geriatrician who spends the majority of time caring for hospitalized patients.

Does the hospitalist have additional cardiology training? Does the focus of discussion at peer-review committee involve care of patients with primarily cardiac needs? The issue of which physicians should serve on peer-review committees when evaluating hospitalists is a complicated one that demands further scrutiny. TH

Maternity Maneuvers

How do most hospitalist groups manage maternity leave? I recently took six weeks for maternity leave. My colleagues worked my shifts, and I have virtually paid them all back. To do so I often would end up working 18 to 20 days consecutively and numerous weekends. This was not ideal on many levels. I most likely will not [receive a] bonus this year as well. Is there a better way?

New Mom in Midwest

Dr. Hospitalist responds: Congratulations on the birth of your child. As you recognize, becoming a parent is a wonderful experience but also can be stressful. It is not easy to balance the competing demands of family and work.

Medical leave is not unique to hospitalists—but with the average age of hospitalists being 37, it is commonplace to have hospitalist staff start families at this stage of their lives. In fact, as a hospitalist director, it would be foolish for me not to expect and plan for maternity and paternity leaves.

Medical leaves often are stressful for hospitalist programs because of the need to find replacement staff to fill the work schedule. There is no “best” way to cover the schedule during medical leaves. One thing is certain: Not offering medical leave is not only unrealistic, it may be against the law.

Hospitalist directors and those contemplating medical leave from work should familiarize themselves with the federal government’s Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA). Of course, I’m not an attorney; anyone who is looking for accurate advice concerning FMLA and other legal matters should consult a lawyer.

Briefly stated, the FMLA requires that “covered employers must grant an eligible employee up to a total of 12 work weeks of unpaid leave during any 12-month period for one or more of the following reasons:

- Birth and care of the newborn child of the employee;

- Placement with the employee of a son or daughter for adoption or foster care;

- To care for an immediate family member (spouse, child, or parent) with a serious health condition; or

- To take medical leave when the employee is unable to work because of a serious health condition.

It is important to know that the FMLA strictly defines eligibility criteria. For example, a covered employer is one who “employs 50 or more employees for each working day during each of 20 or more calendar work weeks in the current or preceding calendar year.” There also are strict criteria that define whether one is an eligible employee. It is important to note that FMLA does not guarantee paid time off—it only requires unpaid leave. You can find additional information about the FMLA online at the government’s Web site: www.dol.gov/esa/whd/fmla.

Peer Pressure

I am an attorney who often represents physicians in hospital peer-review matters. I represent a hospitalist whom the medical staff has recommended be terminated. Two internists have been appointed to the peer-review committee; one has an office-based practice, and the other is a cardiologist. Neither is a hospitalist.

I am trying to convince the medical staff that there should be a hospitalist on the peer-review committee because I believe what a hospitalist does each day is fundamentally different in scope and patient mix than the other two internists. My argument will be much stronger if it is the case that a hospitalist’s practice is now its own medical specialty.

Can you point me to any information or articles that support my belief that hospital practice is now a separate specialty?

Anxious Attorney

Dr. Hospitalist responds: Is a hospitalist practice sufficiently different than that of an office-based internist or cardiologist, so much so that peer-review activities would necessitate at a minimum some involvement of other hospitalists? To answer this question, I think we need to understand the definition of a hospitalist.

I recently heard a doctor describe himself as a hospitalist despite working clinically in the hospital only one month annually. Is he correct in defining himself as a hospitalist? If so, how would we distinguish him from primary care doctors who spend one-twelfth of their work life caring for hospitalized patients?