User login

The Irritable Heart

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of morning report. Similar to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.

A30‐year‐old woman was referred for evaluation of chest pain, palpitations, and exercise intolerance. She had been previously healthy, active, and physically fit. Five months prior to our evaluation, she had an elective C5C6 cervical spine discectomy with interbody allograft fusion for a chronic neck injury that occurred 11 years ago during gymnastics. Two weeks after spine surgery, the patient developed numbness and tingling of her left thumb and palm that occurred with exertion or exposure to cold and subsided with rest. These episodes increased in frequency and intensity and after 1 week became associated with sharp, occasionally stabbing chest pain that radiated to the left arm. On one occasion, the patient had an episode of exertional chest pain with prolonged left arm cyanosis. Emergent left upper extremity angiography revealed normal great vessel anatomy with spasm of the radial artery and collateral ulnar flow. The patient was diagnosed with Raynaud's phenomenon and was started on nifedipine. A subsequent rheumatologic evaluation was unrevealing, and the patient was empirically switched to amlodipine with no improvement in symptoms.

This otherwise very healthy 30‐year‐old developed a multitude of symptoms. The patient's chest pain is atypical and in a young woman is unlikely to signify atherosclerotic coronary disease, but it should not be entirely disregarded. Vasospasm triggered by exposure to cold does raise suspicion for Raynaud's phenomenon, which is not uncommon in this demographic. However, this presentation is quite unusual because the vasospasm was limited to one vascular distribution of one extremity. Associated coronary vasospasm could explain the other symptoms, although coronary spasm is generally not associated with Raynaud's phenomenon. Vasculitis may also affect the pulmonary vasculature, leading to pulmonary hypertension and exercise intolerance. The temporal association with her spine surgery is intriguing but of unclear significance.

The patient continued to have frequent exertional episodes of sharp precordial chest pain radiating to her left arm that were accompanied by dyspnea and left upper extremity symptoms despite amlodipine therapy. These now occurred with limited activity when she walked 1 to 2 blocks uphill. Over the previous 2 months, she had also noticed palpitations occurring reliably with exercise that were relieved with 15 to 20 min of rest. With prolonged episodes, she reported dizziness, nausea, and blurry vision that improved with lying down. She twice had syncope with these symptoms. She noted lower extremity edema while taking calcium channel blockers, but this had resolved after discontinuation of the drugs.

The patient's past medical history included several high‐school orthopedic injuries. She had 2 kidney stones at ages 18 and 23 and had an appendectomy at age 28. Her only medication was an oral contraceptive, and she had discontinued the amlodipine. She denied the use of tobacco, alcohol, herbal medications, or illicit substances. There was no family history of sudden death or heart disease.

Palpitations in a 30‐year‐old woman may signify a cardiac arrhythmia. Paroxysmal supraventricular arrhythmias, such as atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, atrial tachycardia, and atrial fibrillation, are well described in the young. Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is another possible cause and could be idiopathic or related to occult structural heart disease. Young patients typically tolerate lone arrhythmias quite well, and her failure to do so raises suspicion for concomitant structural heart disease. Her palpitations may be from appropriate sinus tachycardia, which could be compensatory because of inadequate cardiac output reserve, which in turn could be caused by valvular disease, congenital heart disease, or ventricular dysfunction. The exertional chest pain is worrisome for ischemia. Pulmonary hypertension, severe ventricular hypertrophy, or congenital anomalies of the coronary circulation could lead to subendocardial myocardial ischemia with exertion, resulting in angina, dyspnea, and arrhythmias. However, the patient also experiences exertional palpitations without chest pain, which may signify an exertional tachyarrhythmia possibly mediated by catecholamines. Based solely on the history, the differential diagnosis remains broad.

On physical examination, the patient was a fit, thin, healthy woman. Her blood pressure was 120/70 mm Hg supine in both arms and 115/75 mm Hg standing; her pulse was 85 supine and 110 standing, Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. A cardiac exam revealed a normal jugular venous pressure, normal point of maximal impulse, regular rhythm with occasional ectopy, normal S1, and physiologically split S2 without extra heart sounds or murmurs. The right ventricular impulse was faintly palpable at the left sternal border. Head, neck, chest, abdominal, musculoskeletal, neurologic, extremity, and peripheral pulse examinations were normal.

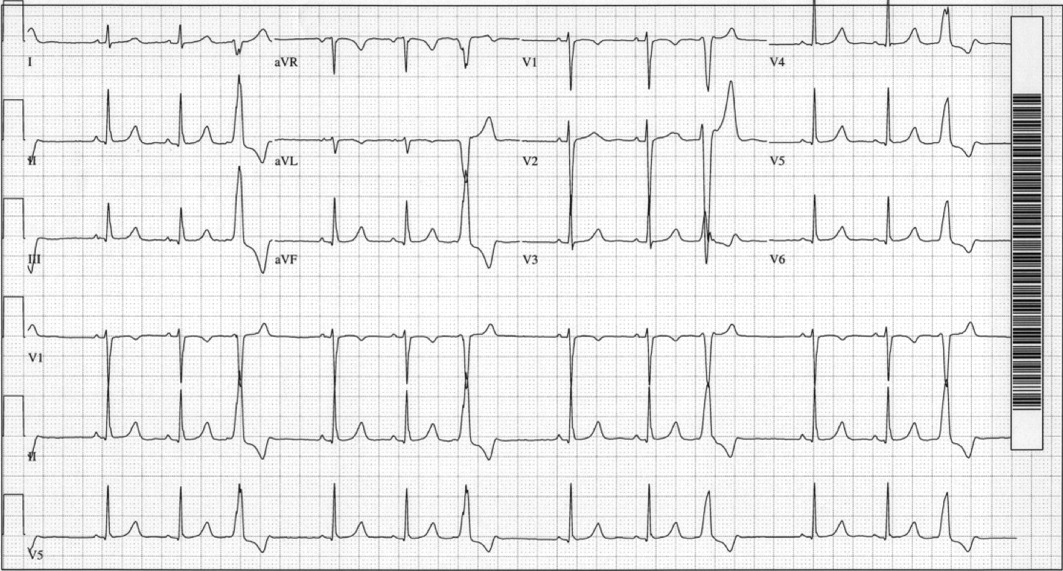

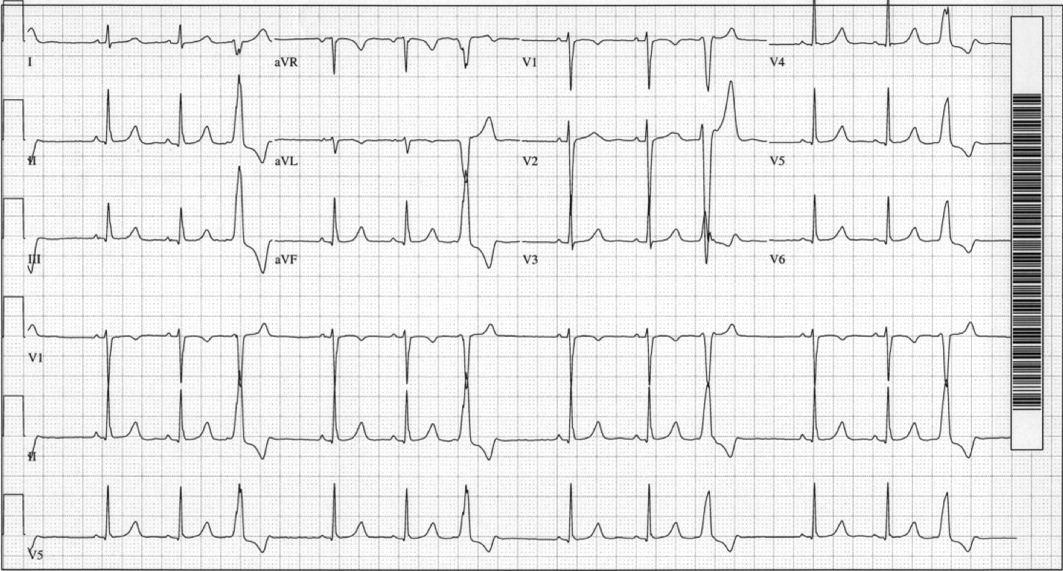

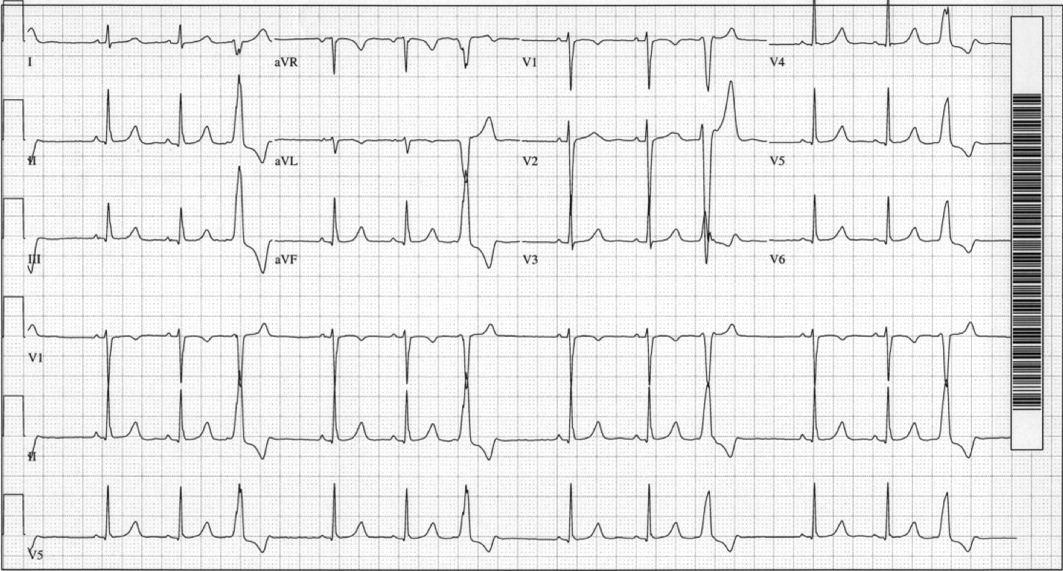

Laboratory data showed a normal complete blood count and normal chemistries. Serum tests for hepatitis C antibody, cardiolipin antibody, rheumatoid factor, cryoglobulins, and anti‐nuclear antibody were negative. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and thyroid stimulating hormone levels were within normal limits. An electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated a normal sinus rhythm with frequent premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) and normal axis and intervals. (Figure 1). The PR segment was normal and without preexcitation. A prior ECG from 3 months ago was similar with ventricular trigeminy.

Her unremarkable cardiac examination does not favor structural or valvular heart disease, and there are no obvious stigmata of vasculitis. She did become mildly tachycardic upon standing, and this raises the possibility of orthostatic tachycardia. A comprehensive rheumatologic panel revealed no evidence of autoimmune disease or vasculitis, and the clinical constellation is not consistent with primary or secondary Raynaud's disease. The ECG demonstrates frequent monomorphic PVCs complexes with a left bundle branch block pattern and an inferior axis. This pattern suggests that the PVCs arise from the right ventricular outflow tract. Idiopathic right ventricular outflow tract VT and arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia must be considered as a cause of exertional or catecholamine‐mediated tachycardia. The normal ECG argues against arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, in which patients typically have incomplete or complete right bundle branch block, right precordial T wave abnormalities, and occasionally epsilon waves. Her QT interval is normal, but excluding long‐QT syndrome with a single ECG has poor sensitivity. The next critical step is to document her cardiac rhythm during symptoms and to exclude malignant arrhythmias.

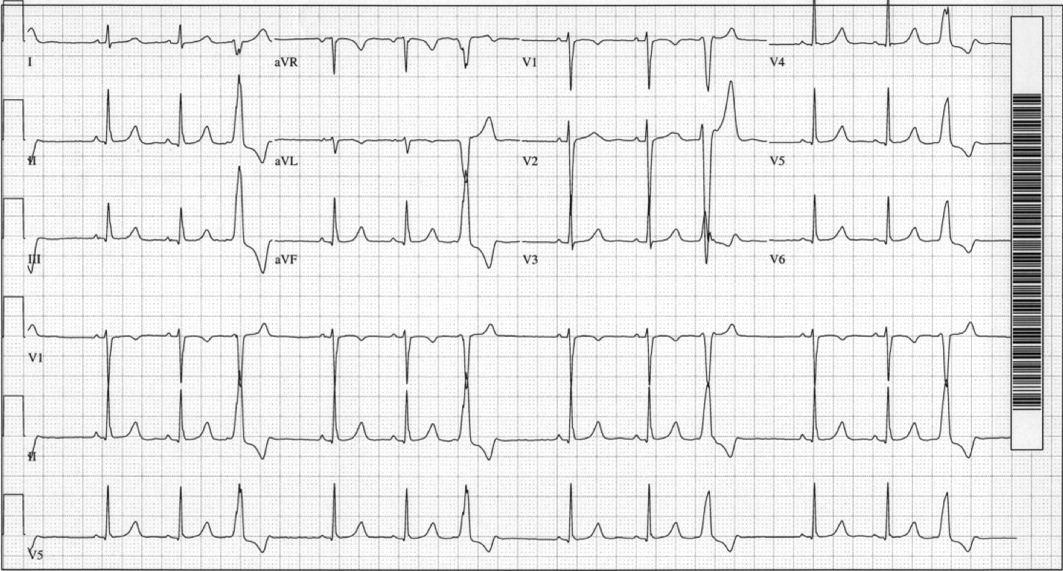

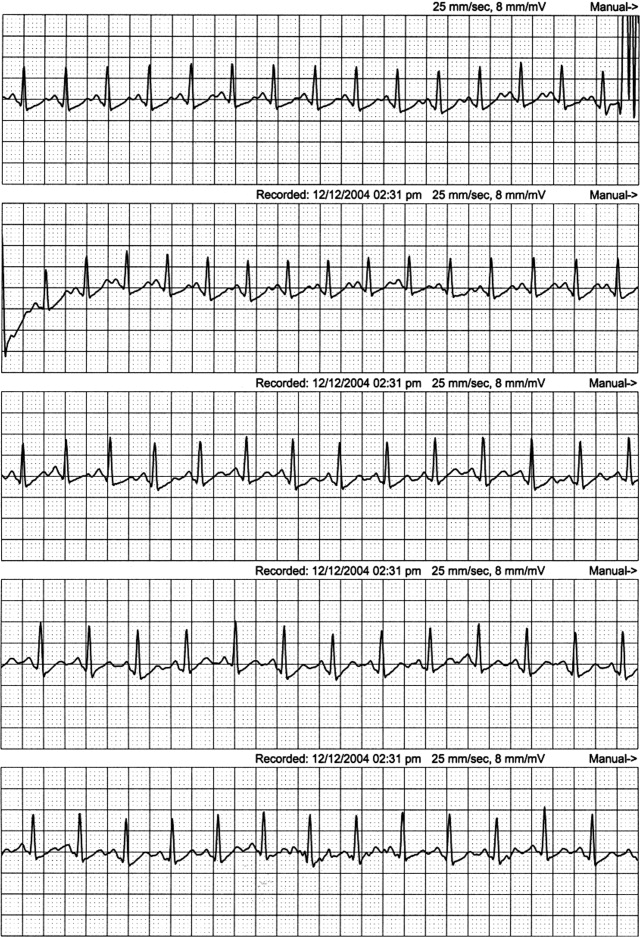

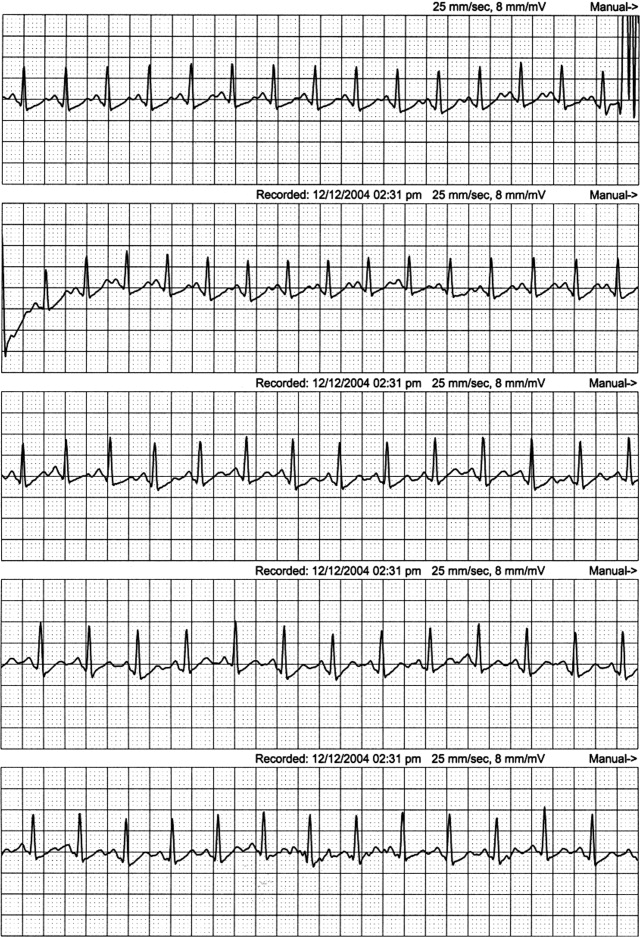

An event recorder and exercise echocardiogram were ordered. While the patient was wearing her event recorder, she had 4 episodes of exertional syncope while hiking and successfully triggered event recording before losing consciousness. She had chest pain and left arm pain after regaining consciousness. The patient came to the emergency room for evaluation. Her blood pressure was 116/80 mm Hg supine and 112/70 mm Hg seated. Her heart rate increased from 82 supine to 132 seated. The physical examination was unremarkable. ECG showed sinus rhythm with frequent PVCs. Troponin‐I measurements 10 hours apart were 0.7 and 0.3 g/L (normal < 1.1), with normal creatinine kinase and creatinine kinase MB fractions. Interrogation of the event recorder revealed multiple episodes of a narrow complex tachycardia with rates up to 180 bpm that correlated with symptoms (Figure 2). There were no episodes of wide complex tachycardia.

The patient was not hypotensive in the emergency room, but she had evidence of a marked orthostatic tachycardia. The minimal but significant troponin elevations are also troubling. Although her clinical picture is not consistent with an acute coronary syndrome, I am concerned about other mechanisms of myocardial ischemia or injury, such as a coronary anomaly or subendocardial ischemia from globally reduced myocardial perfusion. The presence of event recorder data from her syncopal events was fortuitous and revealed a supraventricular tachycardia. The arrhythmia was gradual in onset and resolution and had no triggers, such as premature atrial or ventricular complexes, which could suggest reentrant arrhythmias. The P wave morphology was also unchanged, and this argues against an atrial tachycardia. These findings are consistent with sinus tachycardia, which was notably out of proportion to her workload. This arrhythmia may be the primary cause of syncope, such as in inappropriate sinus tachycardia, or it may be a compensatory mechanism. Tachycardia from coronary vasospasm is often preceded by ST segment changes, which are not seen here. Although the event recorder had no episodes of VT, the patient's persistent frequent PVCs are still of concern. I would obtain an echocardiogram to exclude structural heart disease and an exercise test to exclude exertional VT. Finally, coronary angiography may be helpful in excluding congenital anomalies.

The patient was admitted for evaluation. An exercise treadmill test was performed, and the patient exercised 20 min on the standard Bruce protocol with a peak heart rate of 180 bpm. The test was notable for a premature rise in heart rate (in stage 1) without a rise in blood pressure. There were no symptoms or ST/T wave changes. Transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular size and function with normal anatomy, valves, and hemodynamics. Coronary angiography showed a right dominant system with normal anatomy and no atherosclerotic disease.

Ventricular arrhythmias could not be elicited with exercise. Her high exercise tolerance virtually excluded hemodynamically significant structural or valvular disease, and this was confirmed by the echocardiogram. Coronary angiography excluded coronary anomalies and myocardial bridging. The most intriguing finding is the rise in the patient's heart rate out of proportion to the workload. This, along with her orthostatic tachycardia, raises the issue of inappropriate sinus tachycardia or postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Carotid hypersensitivity is also a possibility. The patient was hiking when she fainted, and even light pressure on the patient's neck with head turning or from a camera strap, for example, could produce syncope. Although carotid hypersensitivity usually results in sinus bradycardia and AV block, it may be followed by reflex tachycardia, which was seen in this patient's event recordings. I would perform a tilt‐table test with carotid massage to make the diagnosis.

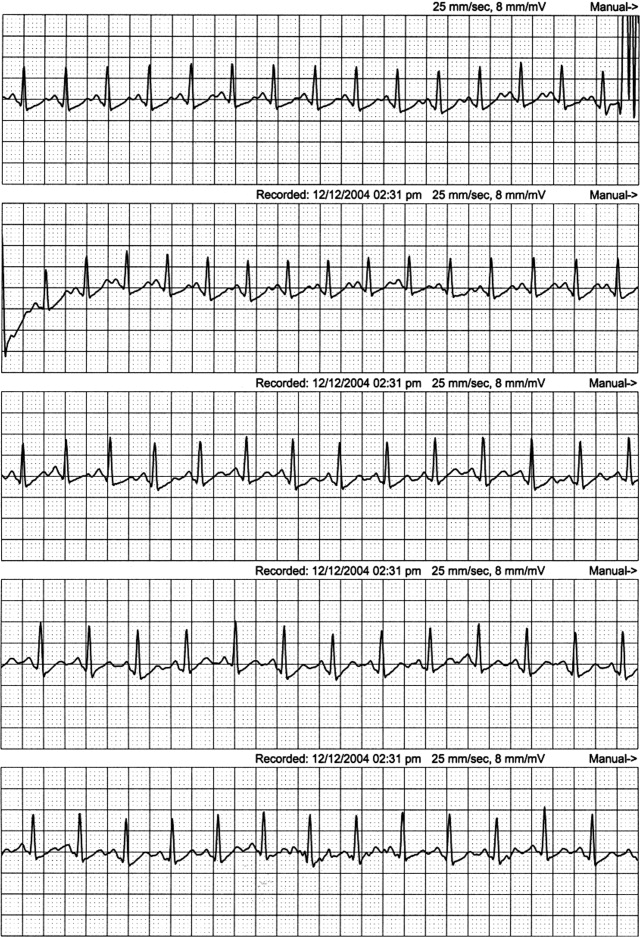

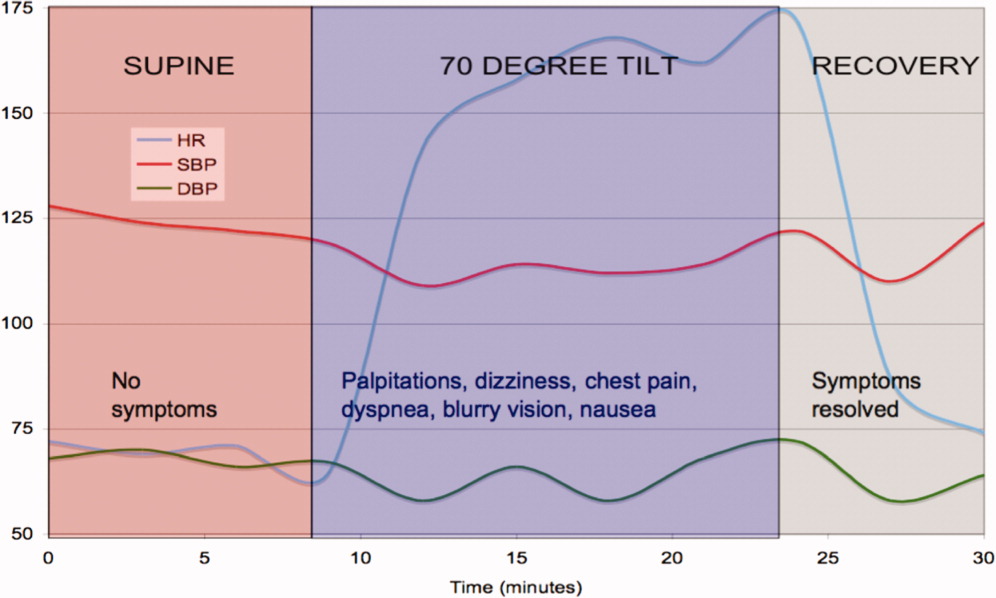

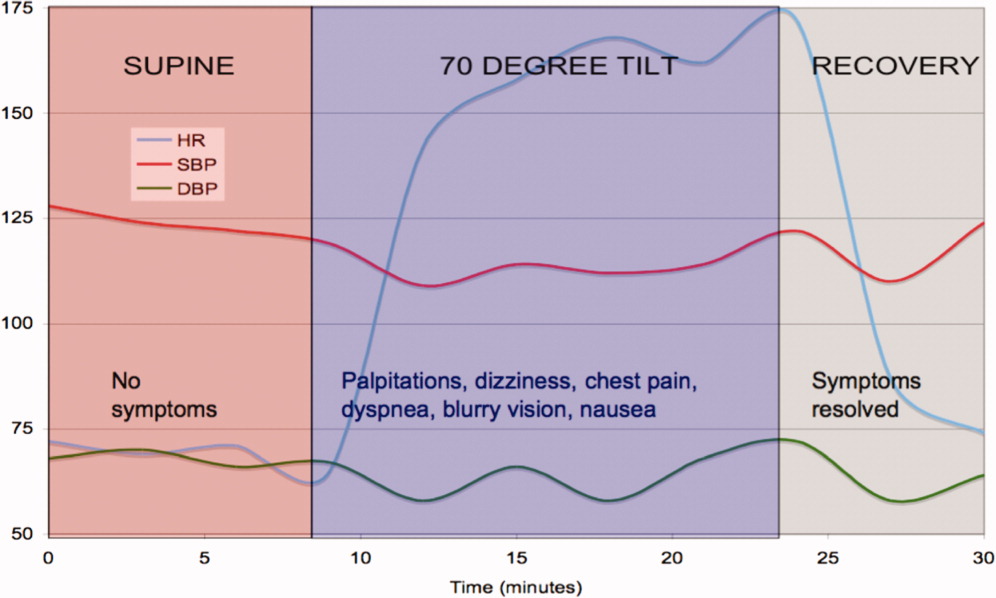

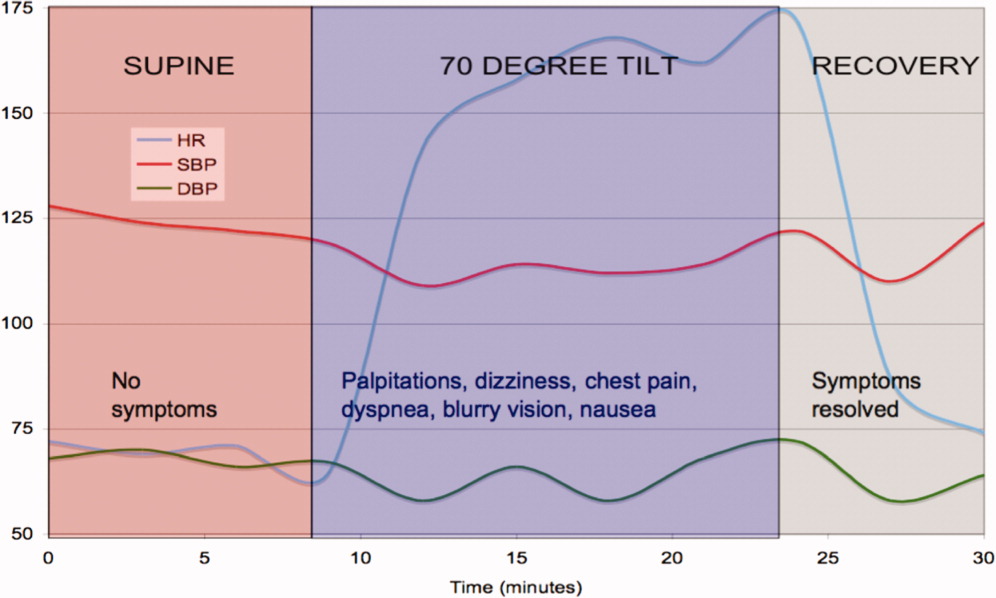

Tilt‐table testing was performed (Figure 3). Her supine blood pressure was 128/68 mm Hg, and her heart rate was 72 bpm with no change during the 10‐min supine period. Upon elevation to a 70‐degree tilt, the patient had an immediate increase in her heart rate to 160 bpm with a blood pressure nadir of 109/58 mm Hg and symptoms of palpitations, dizziness, dyspnea, chest pain, blurry vision, and nausea. Her peak heart rate was 172 bpm, and her peak blood pressure was 122/72 mm Hg. Vital signs did not change in response to carotid sinus massage in the supine or upright positions.

The tilt‐table test has 3 notable findings. First, her heart rate increased rapidly with tilt and decreased rapidly in supine recovery. Second, her usual symptoms started immediately after tilt and quickly resolved in recovery when vital signs returned to baseline. Finally, there was only a modest drop in blood pressure. These findings are classic for POTS. POTS is defined as symptomatic orthostasis with a heart rate increase of 30 bpm or a heart rate of 120 bpm. The physiologic lesions found in the syndrome are heterogeneous, but they all lead to a failure of orthostatic compensation. In POTS, the tachycardia is a reflex secondary to hypotension (baroreceptor reflex) or reduced preload (cardiac mechanoreceptors), in contrast to inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Interestingly, blood pressure is usually preserved until the final moments preceding syncope, when venous return further declines, tachycardia decreases the diastolic filling time and stroke volume, and mean arterial pressure sharply falls.

The patient was started on labetalol (200 mg 3 times daily), and her symptoms worsened. She also developed nausea and constipation. Midodrine and pindolol were also tried without success. She was then switched to fludrocortisone, salt supplementation, and leg support stockings with dramatic improvement.

COMMENTARY

In 1871, DeCosta1 published a report on the irritable heart, noting an affliction of extreme fatigue and exercise intolerance that occurred suddenly and without obvious cause. Subsequently, the terms vasoregulatory asthenia and neurocirculatory asthenia were used to link cardiovascular symptoms to impaired regulation of peripheral blood flow.2, 3 The term POTS was first used in 1982 to describe a single patient with postural tachycardia without hypotension and palpitations, weakness, abdominal pain, and presyncope.4

POTS is one of several disorders of autonomic control associated with orthostatic intolerance. The criteria for diagnosis are listed in Table 1. POTS typically occurs in women between the ages of 15 and 50 but tends to present during adolescence or young adulthood. The physiology has only recently been elucidated. When a person stands, 500 cc of the total blood volume is displaced to the dependent extremities and inferior mesenteric vessels.5 Normally, orthostatic stabilization occurs in less than 1 minute via 3 mechanisms: baroreceptor input, sympathetic reflex tachycardia and vasoconstriction, and enhanced venous return via the pumping action of skeletal muscles and venoconstriction. In POTS, there is a failure of at least one of these mechanisms, leading to decreased venous return, a 40% reduction in stroke volume, and cerebral hypoperfusion.6

| 1. Consistent symptoms of orthostatic intolerance [may include excessive fatigue, exercise intolerance, recurrent syncope or near syncope, dizziness, nausea, tachycardia, palpitations, visual disturbances, blurred vision, tunnel vision, tremulousness, weakness (most noticeable in the legs), chest discomfort, shortness of breath, mood swings, and gastrointestinal complaints] |

| 2. Heart rate increase 30 bpm or heart rate 120 bpm within 10 min of standing or head‐up tilt |

| 3. Absence of a known cause of autonomic neuropathy |

POTS is divided into 2 major subtypes on the basis of pathophysiology.5, 7 The partial dysautonomic form is the most common and the type that this patient most likely had. In this form, the development of an acquired peripheral autonomic neuropathy results in a failure of sympathetic venoconstriction, which leads to excessive venous pooling in the lower extremities and splanchnic circulation.8, 9 Failure to mobilize this venous reservoir upon standing leads to excessive orthostatic tachycardia secondary to a marked reduction in stroke volume. Peripheral arterial vasoconstriction is generally preserved, which is why midodrine, an arterial vasoconstrictor, did not improve symptoms. The labetalol may have further exacerbated peripheral pooling because of its alpha‐adrenergic blocking properties. Because total plasma volume is decreased and plasma renin activity is inappropriately low,10 volume expanders, including salt, low‐dose steroids, and fluids, can attenuate symptoms.11 The extrinsic venous compression from leg and abdominal support stockings may also dramatically reduce venous pooling.

In the less common hyperadrenergic form of POTS, patients may have orthostatic hypertension, tremulousness, cold, sweaty extremities, and anxiety due to an exaggerated response to beta‐adrenergic stimulation.7 The excessive sympathetic activity, which is poorly modulated by baroreflex activity, may be due to impaired mechanisms of norepinephrine reuptake by sympathetic ganglia.12 Consequently, serum norepinephrine levels are markedly elevated (>600 pg/mL).5

In adults, the presence of a POTS trigger is common and is usually an antecedent viral illness. Antibodies to the ganglionic acetylcholine receptor have been found in a subset of POTS patients,13 and this may suggest an idiopathic or postinflammatory autoimmune mechanism.14 This patient's presentation is unique because her symptoms developed after C5C6 spine surgery. The cervical spinal cord and sympathetic ganglia are dense with nerves involved in autonomic cardiovascular control, and damage to these fibers could explain the patient's physiology and symptoms. Among these, the descending vasomotor pathways traverse through the C5C8 area to innervate the splanchnic and leg venous circulation, receiving input from the heart along the way.15 The pattern of numbness and tingling fits the C5/C6 dermatomal distribution, as does the innervation of the radial artery. The frequent PVCs with a left bundle branch block pattern and inferior axis appear to arise from the right ventricular outflow tract and may be associated with regional sympathetic denervation, which has been described in idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias.16 POTS has been anecdotally reported after neck injury from motor vehicle accidents (whiplash), which is also thought to be related to cervical sympathetic nerve damage (B.P. Grubb, personal communication, 2005). Most cases of triggered POTS improve spontaneously after months to years, but this patient's prognosis remains uncertain because of the presumed mechanical disruption of the autonomic nerve fibers at the time of surgery.

This case demonstrates the complexities of arriving at a unifying diagnosis in the setting of a constellation of nonspecific symptoms and findings, some of which even suggest life‐threatening conditions. Because young women are primarily affected, symptoms of POTS can be mistakenly attributed to anxiety or other nonphysiological factors. A systematic approach excluded life‐threatening causes, including primary ventricular arrhythmias, coronary vasospasm, and coronary anomalies. The investigations narrowed the differential diagnosis, and the tilt‐table test confirmed POTS. Because the cardiac and circulatory dysautonomias encompass an array of distinct physiologic processes, understanding the patient's mechanism is critical to her management. The only effective therapies were those that counteracted venous pooling and improved venous return.

Teaching Points

-

The differential diagnosis of exertional syncope is extremely broad, ranging from benign to malignant conditions, and requires a systematic evaluation of the heart and circulatory system.

-

The diagnosis of POTS is elusive and frequently missed. Referral for tilt‐table testing is useful in identifying the mechanism of sinus tachycardia and syncope. Marked orthostatic tachycardia and symptoms of cerebral hypoperfusion out of proportion to the degree of hypotension strongly suggest POTS.

-

Cardiac and circulatory dysautonomias have distinct and varied mechanisms. Therapies, including beta‐blockers, vasoconstrictors, and volume expanders, must be directed at the underlying physiological defect.

- .An irritable heart.Am J Med Sci.1871;27:145–161.

- ,,,,,.Low physical working capacity in suspected heart cases due to inadequate adjustment of peripheral blood flow (vasoregulatory asthenia).Acta Med Scand.1957;158(6):413–436.

- ,,.Orthostatic tachycardia and orthostatic hypotension: defects in the return of venous blood to the heart.Am Heart J.1944;27:145–163.

- ,.Postural tachycardia syndrome. Reversal of sympathetic hyperresponsiveness and clinical improvement during sodium loading.Am J Med.1982;72(5):847–850.

- ,,.The postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: definitions, diagnosis, and management.Pacing Clin Electrophysiol.2003;26(8):1747– 1757.

- ,.Clinical disorders of the autonomic nervous system associated with orthostatic intolerance: an overview of classification, clinical evaluation, and management.Pacing Clin Electrophysiol.1999;22(5):798–810.

- ,.Idiopathic orthostatic intolerance and postural tachycardia syndromes.Am J Med Sci.1999;317(2):88–101.

- ,,, et al.Splanchnic‐mesenteric capacitance bed in the postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS).Auton Neurosci.2000;86(1–2):107–113.

- ,,,.Abnormal orthostatic changes in blood pressure and heart rate in subjects with intact sympathetic nervous function: evidence for excessive venous pooling.J Lab Clin Med.1988;111(3):326–335.

- ,,, et al.Renin‐aldosterone paradox and perturbed blood volume regulation underlying postural tachycardia syndrome.Circulation.2005;111(13):1574–1582.

- .Clinical practice. Neurocardiogenic syncope.N Engl J Med.2005;352(10):1004–1010.

- ,,, et al.Orthostatic intolerance and tachycardia associated with norepinephrine‐transporter deficiency.N Engl J Med.2000;342(8):541–549.

- ,,,,,.Autoantibodies to ganglionic acetylcholine receptors in autoimmune autonomic neuropathies.N Engl J Med.2000;343(12):847–855.

- ,,.The postural tachycardia syndrome: a concise guide to diagnosis and management.J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol.2006;17(1):108–112.

- ,,.Neurovegetative regulation of the vascular system. In:Lanzer P,Topol EJ, eds.Panvascular Medicine.Berlin, Germany:Springer‐Verlag;2002:175–187.

- ,,, et al.Regional cardiac sympathetic denervation in patients with ventricular tachycardia in the absence of coronary artery disease.J Am Coll Cardiol.1993;22(5):1344–1353.

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of morning report. Similar to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.

A30‐year‐old woman was referred for evaluation of chest pain, palpitations, and exercise intolerance. She had been previously healthy, active, and physically fit. Five months prior to our evaluation, she had an elective C5C6 cervical spine discectomy with interbody allograft fusion for a chronic neck injury that occurred 11 years ago during gymnastics. Two weeks after spine surgery, the patient developed numbness and tingling of her left thumb and palm that occurred with exertion or exposure to cold and subsided with rest. These episodes increased in frequency and intensity and after 1 week became associated with sharp, occasionally stabbing chest pain that radiated to the left arm. On one occasion, the patient had an episode of exertional chest pain with prolonged left arm cyanosis. Emergent left upper extremity angiography revealed normal great vessel anatomy with spasm of the radial artery and collateral ulnar flow. The patient was diagnosed with Raynaud's phenomenon and was started on nifedipine. A subsequent rheumatologic evaluation was unrevealing, and the patient was empirically switched to amlodipine with no improvement in symptoms.

This otherwise very healthy 30‐year‐old developed a multitude of symptoms. The patient's chest pain is atypical and in a young woman is unlikely to signify atherosclerotic coronary disease, but it should not be entirely disregarded. Vasospasm triggered by exposure to cold does raise suspicion for Raynaud's phenomenon, which is not uncommon in this demographic. However, this presentation is quite unusual because the vasospasm was limited to one vascular distribution of one extremity. Associated coronary vasospasm could explain the other symptoms, although coronary spasm is generally not associated with Raynaud's phenomenon. Vasculitis may also affect the pulmonary vasculature, leading to pulmonary hypertension and exercise intolerance. The temporal association with her spine surgery is intriguing but of unclear significance.

The patient continued to have frequent exertional episodes of sharp precordial chest pain radiating to her left arm that were accompanied by dyspnea and left upper extremity symptoms despite amlodipine therapy. These now occurred with limited activity when she walked 1 to 2 blocks uphill. Over the previous 2 months, she had also noticed palpitations occurring reliably with exercise that were relieved with 15 to 20 min of rest. With prolonged episodes, she reported dizziness, nausea, and blurry vision that improved with lying down. She twice had syncope with these symptoms. She noted lower extremity edema while taking calcium channel blockers, but this had resolved after discontinuation of the drugs.

The patient's past medical history included several high‐school orthopedic injuries. She had 2 kidney stones at ages 18 and 23 and had an appendectomy at age 28. Her only medication was an oral contraceptive, and she had discontinued the amlodipine. She denied the use of tobacco, alcohol, herbal medications, or illicit substances. There was no family history of sudden death or heart disease.

Palpitations in a 30‐year‐old woman may signify a cardiac arrhythmia. Paroxysmal supraventricular arrhythmias, such as atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, atrial tachycardia, and atrial fibrillation, are well described in the young. Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is another possible cause and could be idiopathic or related to occult structural heart disease. Young patients typically tolerate lone arrhythmias quite well, and her failure to do so raises suspicion for concomitant structural heart disease. Her palpitations may be from appropriate sinus tachycardia, which could be compensatory because of inadequate cardiac output reserve, which in turn could be caused by valvular disease, congenital heart disease, or ventricular dysfunction. The exertional chest pain is worrisome for ischemia. Pulmonary hypertension, severe ventricular hypertrophy, or congenital anomalies of the coronary circulation could lead to subendocardial myocardial ischemia with exertion, resulting in angina, dyspnea, and arrhythmias. However, the patient also experiences exertional palpitations without chest pain, which may signify an exertional tachyarrhythmia possibly mediated by catecholamines. Based solely on the history, the differential diagnosis remains broad.

On physical examination, the patient was a fit, thin, healthy woman. Her blood pressure was 120/70 mm Hg supine in both arms and 115/75 mm Hg standing; her pulse was 85 supine and 110 standing, Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. A cardiac exam revealed a normal jugular venous pressure, normal point of maximal impulse, regular rhythm with occasional ectopy, normal S1, and physiologically split S2 without extra heart sounds or murmurs. The right ventricular impulse was faintly palpable at the left sternal border. Head, neck, chest, abdominal, musculoskeletal, neurologic, extremity, and peripheral pulse examinations were normal.

Laboratory data showed a normal complete blood count and normal chemistries. Serum tests for hepatitis C antibody, cardiolipin antibody, rheumatoid factor, cryoglobulins, and anti‐nuclear antibody were negative. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and thyroid stimulating hormone levels were within normal limits. An electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated a normal sinus rhythm with frequent premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) and normal axis and intervals. (Figure 1). The PR segment was normal and without preexcitation. A prior ECG from 3 months ago was similar with ventricular trigeminy.

Her unremarkable cardiac examination does not favor structural or valvular heart disease, and there are no obvious stigmata of vasculitis. She did become mildly tachycardic upon standing, and this raises the possibility of orthostatic tachycardia. A comprehensive rheumatologic panel revealed no evidence of autoimmune disease or vasculitis, and the clinical constellation is not consistent with primary or secondary Raynaud's disease. The ECG demonstrates frequent monomorphic PVCs complexes with a left bundle branch block pattern and an inferior axis. This pattern suggests that the PVCs arise from the right ventricular outflow tract. Idiopathic right ventricular outflow tract VT and arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia must be considered as a cause of exertional or catecholamine‐mediated tachycardia. The normal ECG argues against arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, in which patients typically have incomplete or complete right bundle branch block, right precordial T wave abnormalities, and occasionally epsilon waves. Her QT interval is normal, but excluding long‐QT syndrome with a single ECG has poor sensitivity. The next critical step is to document her cardiac rhythm during symptoms and to exclude malignant arrhythmias.

An event recorder and exercise echocardiogram were ordered. While the patient was wearing her event recorder, she had 4 episodes of exertional syncope while hiking and successfully triggered event recording before losing consciousness. She had chest pain and left arm pain after regaining consciousness. The patient came to the emergency room for evaluation. Her blood pressure was 116/80 mm Hg supine and 112/70 mm Hg seated. Her heart rate increased from 82 supine to 132 seated. The physical examination was unremarkable. ECG showed sinus rhythm with frequent PVCs. Troponin‐I measurements 10 hours apart were 0.7 and 0.3 g/L (normal < 1.1), with normal creatinine kinase and creatinine kinase MB fractions. Interrogation of the event recorder revealed multiple episodes of a narrow complex tachycardia with rates up to 180 bpm that correlated with symptoms (Figure 2). There were no episodes of wide complex tachycardia.

The patient was not hypotensive in the emergency room, but she had evidence of a marked orthostatic tachycardia. The minimal but significant troponin elevations are also troubling. Although her clinical picture is not consistent with an acute coronary syndrome, I am concerned about other mechanisms of myocardial ischemia or injury, such as a coronary anomaly or subendocardial ischemia from globally reduced myocardial perfusion. The presence of event recorder data from her syncopal events was fortuitous and revealed a supraventricular tachycardia. The arrhythmia was gradual in onset and resolution and had no triggers, such as premature atrial or ventricular complexes, which could suggest reentrant arrhythmias. The P wave morphology was also unchanged, and this argues against an atrial tachycardia. These findings are consistent with sinus tachycardia, which was notably out of proportion to her workload. This arrhythmia may be the primary cause of syncope, such as in inappropriate sinus tachycardia, or it may be a compensatory mechanism. Tachycardia from coronary vasospasm is often preceded by ST segment changes, which are not seen here. Although the event recorder had no episodes of VT, the patient's persistent frequent PVCs are still of concern. I would obtain an echocardiogram to exclude structural heart disease and an exercise test to exclude exertional VT. Finally, coronary angiography may be helpful in excluding congenital anomalies.

The patient was admitted for evaluation. An exercise treadmill test was performed, and the patient exercised 20 min on the standard Bruce protocol with a peak heart rate of 180 bpm. The test was notable for a premature rise in heart rate (in stage 1) without a rise in blood pressure. There were no symptoms or ST/T wave changes. Transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular size and function with normal anatomy, valves, and hemodynamics. Coronary angiography showed a right dominant system with normal anatomy and no atherosclerotic disease.

Ventricular arrhythmias could not be elicited with exercise. Her high exercise tolerance virtually excluded hemodynamically significant structural or valvular disease, and this was confirmed by the echocardiogram. Coronary angiography excluded coronary anomalies and myocardial bridging. The most intriguing finding is the rise in the patient's heart rate out of proportion to the workload. This, along with her orthostatic tachycardia, raises the issue of inappropriate sinus tachycardia or postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Carotid hypersensitivity is also a possibility. The patient was hiking when she fainted, and even light pressure on the patient's neck with head turning or from a camera strap, for example, could produce syncope. Although carotid hypersensitivity usually results in sinus bradycardia and AV block, it may be followed by reflex tachycardia, which was seen in this patient's event recordings. I would perform a tilt‐table test with carotid massage to make the diagnosis.

Tilt‐table testing was performed (Figure 3). Her supine blood pressure was 128/68 mm Hg, and her heart rate was 72 bpm with no change during the 10‐min supine period. Upon elevation to a 70‐degree tilt, the patient had an immediate increase in her heart rate to 160 bpm with a blood pressure nadir of 109/58 mm Hg and symptoms of palpitations, dizziness, dyspnea, chest pain, blurry vision, and nausea. Her peak heart rate was 172 bpm, and her peak blood pressure was 122/72 mm Hg. Vital signs did not change in response to carotid sinus massage in the supine or upright positions.

The tilt‐table test has 3 notable findings. First, her heart rate increased rapidly with tilt and decreased rapidly in supine recovery. Second, her usual symptoms started immediately after tilt and quickly resolved in recovery when vital signs returned to baseline. Finally, there was only a modest drop in blood pressure. These findings are classic for POTS. POTS is defined as symptomatic orthostasis with a heart rate increase of 30 bpm or a heart rate of 120 bpm. The physiologic lesions found in the syndrome are heterogeneous, but they all lead to a failure of orthostatic compensation. In POTS, the tachycardia is a reflex secondary to hypotension (baroreceptor reflex) or reduced preload (cardiac mechanoreceptors), in contrast to inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Interestingly, blood pressure is usually preserved until the final moments preceding syncope, when venous return further declines, tachycardia decreases the diastolic filling time and stroke volume, and mean arterial pressure sharply falls.

The patient was started on labetalol (200 mg 3 times daily), and her symptoms worsened. She also developed nausea and constipation. Midodrine and pindolol were also tried without success. She was then switched to fludrocortisone, salt supplementation, and leg support stockings with dramatic improvement.

COMMENTARY

In 1871, DeCosta1 published a report on the irritable heart, noting an affliction of extreme fatigue and exercise intolerance that occurred suddenly and without obvious cause. Subsequently, the terms vasoregulatory asthenia and neurocirculatory asthenia were used to link cardiovascular symptoms to impaired regulation of peripheral blood flow.2, 3 The term POTS was first used in 1982 to describe a single patient with postural tachycardia without hypotension and palpitations, weakness, abdominal pain, and presyncope.4

POTS is one of several disorders of autonomic control associated with orthostatic intolerance. The criteria for diagnosis are listed in Table 1. POTS typically occurs in women between the ages of 15 and 50 but tends to present during adolescence or young adulthood. The physiology has only recently been elucidated. When a person stands, 500 cc of the total blood volume is displaced to the dependent extremities and inferior mesenteric vessels.5 Normally, orthostatic stabilization occurs in less than 1 minute via 3 mechanisms: baroreceptor input, sympathetic reflex tachycardia and vasoconstriction, and enhanced venous return via the pumping action of skeletal muscles and venoconstriction. In POTS, there is a failure of at least one of these mechanisms, leading to decreased venous return, a 40% reduction in stroke volume, and cerebral hypoperfusion.6

| 1. Consistent symptoms of orthostatic intolerance [may include excessive fatigue, exercise intolerance, recurrent syncope or near syncope, dizziness, nausea, tachycardia, palpitations, visual disturbances, blurred vision, tunnel vision, tremulousness, weakness (most noticeable in the legs), chest discomfort, shortness of breath, mood swings, and gastrointestinal complaints] |

| 2. Heart rate increase 30 bpm or heart rate 120 bpm within 10 min of standing or head‐up tilt |

| 3. Absence of a known cause of autonomic neuropathy |

POTS is divided into 2 major subtypes on the basis of pathophysiology.5, 7 The partial dysautonomic form is the most common and the type that this patient most likely had. In this form, the development of an acquired peripheral autonomic neuropathy results in a failure of sympathetic venoconstriction, which leads to excessive venous pooling in the lower extremities and splanchnic circulation.8, 9 Failure to mobilize this venous reservoir upon standing leads to excessive orthostatic tachycardia secondary to a marked reduction in stroke volume. Peripheral arterial vasoconstriction is generally preserved, which is why midodrine, an arterial vasoconstrictor, did not improve symptoms. The labetalol may have further exacerbated peripheral pooling because of its alpha‐adrenergic blocking properties. Because total plasma volume is decreased and plasma renin activity is inappropriately low,10 volume expanders, including salt, low‐dose steroids, and fluids, can attenuate symptoms.11 The extrinsic venous compression from leg and abdominal support stockings may also dramatically reduce venous pooling.

In the less common hyperadrenergic form of POTS, patients may have orthostatic hypertension, tremulousness, cold, sweaty extremities, and anxiety due to an exaggerated response to beta‐adrenergic stimulation.7 The excessive sympathetic activity, which is poorly modulated by baroreflex activity, may be due to impaired mechanisms of norepinephrine reuptake by sympathetic ganglia.12 Consequently, serum norepinephrine levels are markedly elevated (>600 pg/mL).5

In adults, the presence of a POTS trigger is common and is usually an antecedent viral illness. Antibodies to the ganglionic acetylcholine receptor have been found in a subset of POTS patients,13 and this may suggest an idiopathic or postinflammatory autoimmune mechanism.14 This patient's presentation is unique because her symptoms developed after C5C6 spine surgery. The cervical spinal cord and sympathetic ganglia are dense with nerves involved in autonomic cardiovascular control, and damage to these fibers could explain the patient's physiology and symptoms. Among these, the descending vasomotor pathways traverse through the C5C8 area to innervate the splanchnic and leg venous circulation, receiving input from the heart along the way.15 The pattern of numbness and tingling fits the C5/C6 dermatomal distribution, as does the innervation of the radial artery. The frequent PVCs with a left bundle branch block pattern and inferior axis appear to arise from the right ventricular outflow tract and may be associated with regional sympathetic denervation, which has been described in idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias.16 POTS has been anecdotally reported after neck injury from motor vehicle accidents (whiplash), which is also thought to be related to cervical sympathetic nerve damage (B.P. Grubb, personal communication, 2005). Most cases of triggered POTS improve spontaneously after months to years, but this patient's prognosis remains uncertain because of the presumed mechanical disruption of the autonomic nerve fibers at the time of surgery.

This case demonstrates the complexities of arriving at a unifying diagnosis in the setting of a constellation of nonspecific symptoms and findings, some of which even suggest life‐threatening conditions. Because young women are primarily affected, symptoms of POTS can be mistakenly attributed to anxiety or other nonphysiological factors. A systematic approach excluded life‐threatening causes, including primary ventricular arrhythmias, coronary vasospasm, and coronary anomalies. The investigations narrowed the differential diagnosis, and the tilt‐table test confirmed POTS. Because the cardiac and circulatory dysautonomias encompass an array of distinct physiologic processes, understanding the patient's mechanism is critical to her management. The only effective therapies were those that counteracted venous pooling and improved venous return.

Teaching Points

-

The differential diagnosis of exertional syncope is extremely broad, ranging from benign to malignant conditions, and requires a systematic evaluation of the heart and circulatory system.

-

The diagnosis of POTS is elusive and frequently missed. Referral for tilt‐table testing is useful in identifying the mechanism of sinus tachycardia and syncope. Marked orthostatic tachycardia and symptoms of cerebral hypoperfusion out of proportion to the degree of hypotension strongly suggest POTS.

-

Cardiac and circulatory dysautonomias have distinct and varied mechanisms. Therapies, including beta‐blockers, vasoconstrictors, and volume expanders, must be directed at the underlying physiological defect.

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of morning report. Similar to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.

A30‐year‐old woman was referred for evaluation of chest pain, palpitations, and exercise intolerance. She had been previously healthy, active, and physically fit. Five months prior to our evaluation, she had an elective C5C6 cervical spine discectomy with interbody allograft fusion for a chronic neck injury that occurred 11 years ago during gymnastics. Two weeks after spine surgery, the patient developed numbness and tingling of her left thumb and palm that occurred with exertion or exposure to cold and subsided with rest. These episodes increased in frequency and intensity and after 1 week became associated with sharp, occasionally stabbing chest pain that radiated to the left arm. On one occasion, the patient had an episode of exertional chest pain with prolonged left arm cyanosis. Emergent left upper extremity angiography revealed normal great vessel anatomy with spasm of the radial artery and collateral ulnar flow. The patient was diagnosed with Raynaud's phenomenon and was started on nifedipine. A subsequent rheumatologic evaluation was unrevealing, and the patient was empirically switched to amlodipine with no improvement in symptoms.

This otherwise very healthy 30‐year‐old developed a multitude of symptoms. The patient's chest pain is atypical and in a young woman is unlikely to signify atherosclerotic coronary disease, but it should not be entirely disregarded. Vasospasm triggered by exposure to cold does raise suspicion for Raynaud's phenomenon, which is not uncommon in this demographic. However, this presentation is quite unusual because the vasospasm was limited to one vascular distribution of one extremity. Associated coronary vasospasm could explain the other symptoms, although coronary spasm is generally not associated with Raynaud's phenomenon. Vasculitis may also affect the pulmonary vasculature, leading to pulmonary hypertension and exercise intolerance. The temporal association with her spine surgery is intriguing but of unclear significance.

The patient continued to have frequent exertional episodes of sharp precordial chest pain radiating to her left arm that were accompanied by dyspnea and left upper extremity symptoms despite amlodipine therapy. These now occurred with limited activity when she walked 1 to 2 blocks uphill. Over the previous 2 months, she had also noticed palpitations occurring reliably with exercise that were relieved with 15 to 20 min of rest. With prolonged episodes, she reported dizziness, nausea, and blurry vision that improved with lying down. She twice had syncope with these symptoms. She noted lower extremity edema while taking calcium channel blockers, but this had resolved after discontinuation of the drugs.

The patient's past medical history included several high‐school orthopedic injuries. She had 2 kidney stones at ages 18 and 23 and had an appendectomy at age 28. Her only medication was an oral contraceptive, and she had discontinued the amlodipine. She denied the use of tobacco, alcohol, herbal medications, or illicit substances. There was no family history of sudden death or heart disease.

Palpitations in a 30‐year‐old woman may signify a cardiac arrhythmia. Paroxysmal supraventricular arrhythmias, such as atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, atrial tachycardia, and atrial fibrillation, are well described in the young. Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is another possible cause and could be idiopathic or related to occult structural heart disease. Young patients typically tolerate lone arrhythmias quite well, and her failure to do so raises suspicion for concomitant structural heart disease. Her palpitations may be from appropriate sinus tachycardia, which could be compensatory because of inadequate cardiac output reserve, which in turn could be caused by valvular disease, congenital heart disease, or ventricular dysfunction. The exertional chest pain is worrisome for ischemia. Pulmonary hypertension, severe ventricular hypertrophy, or congenital anomalies of the coronary circulation could lead to subendocardial myocardial ischemia with exertion, resulting in angina, dyspnea, and arrhythmias. However, the patient also experiences exertional palpitations without chest pain, which may signify an exertional tachyarrhythmia possibly mediated by catecholamines. Based solely on the history, the differential diagnosis remains broad.

On physical examination, the patient was a fit, thin, healthy woman. Her blood pressure was 120/70 mm Hg supine in both arms and 115/75 mm Hg standing; her pulse was 85 supine and 110 standing, Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. A cardiac exam revealed a normal jugular venous pressure, normal point of maximal impulse, regular rhythm with occasional ectopy, normal S1, and physiologically split S2 without extra heart sounds or murmurs. The right ventricular impulse was faintly palpable at the left sternal border. Head, neck, chest, abdominal, musculoskeletal, neurologic, extremity, and peripheral pulse examinations were normal.

Laboratory data showed a normal complete blood count and normal chemistries. Serum tests for hepatitis C antibody, cardiolipin antibody, rheumatoid factor, cryoglobulins, and anti‐nuclear antibody were negative. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and thyroid stimulating hormone levels were within normal limits. An electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated a normal sinus rhythm with frequent premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) and normal axis and intervals. (Figure 1). The PR segment was normal and without preexcitation. A prior ECG from 3 months ago was similar with ventricular trigeminy.

Her unremarkable cardiac examination does not favor structural or valvular heart disease, and there are no obvious stigmata of vasculitis. She did become mildly tachycardic upon standing, and this raises the possibility of orthostatic tachycardia. A comprehensive rheumatologic panel revealed no evidence of autoimmune disease or vasculitis, and the clinical constellation is not consistent with primary or secondary Raynaud's disease. The ECG demonstrates frequent monomorphic PVCs complexes with a left bundle branch block pattern and an inferior axis. This pattern suggests that the PVCs arise from the right ventricular outflow tract. Idiopathic right ventricular outflow tract VT and arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia must be considered as a cause of exertional or catecholamine‐mediated tachycardia. The normal ECG argues against arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, in which patients typically have incomplete or complete right bundle branch block, right precordial T wave abnormalities, and occasionally epsilon waves. Her QT interval is normal, but excluding long‐QT syndrome with a single ECG has poor sensitivity. The next critical step is to document her cardiac rhythm during symptoms and to exclude malignant arrhythmias.

An event recorder and exercise echocardiogram were ordered. While the patient was wearing her event recorder, she had 4 episodes of exertional syncope while hiking and successfully triggered event recording before losing consciousness. She had chest pain and left arm pain after regaining consciousness. The patient came to the emergency room for evaluation. Her blood pressure was 116/80 mm Hg supine and 112/70 mm Hg seated. Her heart rate increased from 82 supine to 132 seated. The physical examination was unremarkable. ECG showed sinus rhythm with frequent PVCs. Troponin‐I measurements 10 hours apart were 0.7 and 0.3 g/L (normal < 1.1), with normal creatinine kinase and creatinine kinase MB fractions. Interrogation of the event recorder revealed multiple episodes of a narrow complex tachycardia with rates up to 180 bpm that correlated with symptoms (Figure 2). There were no episodes of wide complex tachycardia.

The patient was not hypotensive in the emergency room, but she had evidence of a marked orthostatic tachycardia. The minimal but significant troponin elevations are also troubling. Although her clinical picture is not consistent with an acute coronary syndrome, I am concerned about other mechanisms of myocardial ischemia or injury, such as a coronary anomaly or subendocardial ischemia from globally reduced myocardial perfusion. The presence of event recorder data from her syncopal events was fortuitous and revealed a supraventricular tachycardia. The arrhythmia was gradual in onset and resolution and had no triggers, such as premature atrial or ventricular complexes, which could suggest reentrant arrhythmias. The P wave morphology was also unchanged, and this argues against an atrial tachycardia. These findings are consistent with sinus tachycardia, which was notably out of proportion to her workload. This arrhythmia may be the primary cause of syncope, such as in inappropriate sinus tachycardia, or it may be a compensatory mechanism. Tachycardia from coronary vasospasm is often preceded by ST segment changes, which are not seen here. Although the event recorder had no episodes of VT, the patient's persistent frequent PVCs are still of concern. I would obtain an echocardiogram to exclude structural heart disease and an exercise test to exclude exertional VT. Finally, coronary angiography may be helpful in excluding congenital anomalies.

The patient was admitted for evaluation. An exercise treadmill test was performed, and the patient exercised 20 min on the standard Bruce protocol with a peak heart rate of 180 bpm. The test was notable for a premature rise in heart rate (in stage 1) without a rise in blood pressure. There were no symptoms or ST/T wave changes. Transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular size and function with normal anatomy, valves, and hemodynamics. Coronary angiography showed a right dominant system with normal anatomy and no atherosclerotic disease.

Ventricular arrhythmias could not be elicited with exercise. Her high exercise tolerance virtually excluded hemodynamically significant structural or valvular disease, and this was confirmed by the echocardiogram. Coronary angiography excluded coronary anomalies and myocardial bridging. The most intriguing finding is the rise in the patient's heart rate out of proportion to the workload. This, along with her orthostatic tachycardia, raises the issue of inappropriate sinus tachycardia or postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Carotid hypersensitivity is also a possibility. The patient was hiking when she fainted, and even light pressure on the patient's neck with head turning or from a camera strap, for example, could produce syncope. Although carotid hypersensitivity usually results in sinus bradycardia and AV block, it may be followed by reflex tachycardia, which was seen in this patient's event recordings. I would perform a tilt‐table test with carotid massage to make the diagnosis.

Tilt‐table testing was performed (Figure 3). Her supine blood pressure was 128/68 mm Hg, and her heart rate was 72 bpm with no change during the 10‐min supine period. Upon elevation to a 70‐degree tilt, the patient had an immediate increase in her heart rate to 160 bpm with a blood pressure nadir of 109/58 mm Hg and symptoms of palpitations, dizziness, dyspnea, chest pain, blurry vision, and nausea. Her peak heart rate was 172 bpm, and her peak blood pressure was 122/72 mm Hg. Vital signs did not change in response to carotid sinus massage in the supine or upright positions.

The tilt‐table test has 3 notable findings. First, her heart rate increased rapidly with tilt and decreased rapidly in supine recovery. Second, her usual symptoms started immediately after tilt and quickly resolved in recovery when vital signs returned to baseline. Finally, there was only a modest drop in blood pressure. These findings are classic for POTS. POTS is defined as symptomatic orthostasis with a heart rate increase of 30 bpm or a heart rate of 120 bpm. The physiologic lesions found in the syndrome are heterogeneous, but they all lead to a failure of orthostatic compensation. In POTS, the tachycardia is a reflex secondary to hypotension (baroreceptor reflex) or reduced preload (cardiac mechanoreceptors), in contrast to inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Interestingly, blood pressure is usually preserved until the final moments preceding syncope, when venous return further declines, tachycardia decreases the diastolic filling time and stroke volume, and mean arterial pressure sharply falls.

The patient was started on labetalol (200 mg 3 times daily), and her symptoms worsened. She also developed nausea and constipation. Midodrine and pindolol were also tried without success. She was then switched to fludrocortisone, salt supplementation, and leg support stockings with dramatic improvement.

COMMENTARY

In 1871, DeCosta1 published a report on the irritable heart, noting an affliction of extreme fatigue and exercise intolerance that occurred suddenly and without obvious cause. Subsequently, the terms vasoregulatory asthenia and neurocirculatory asthenia were used to link cardiovascular symptoms to impaired regulation of peripheral blood flow.2, 3 The term POTS was first used in 1982 to describe a single patient with postural tachycardia without hypotension and palpitations, weakness, abdominal pain, and presyncope.4

POTS is one of several disorders of autonomic control associated with orthostatic intolerance. The criteria for diagnosis are listed in Table 1. POTS typically occurs in women between the ages of 15 and 50 but tends to present during adolescence or young adulthood. The physiology has only recently been elucidated. When a person stands, 500 cc of the total blood volume is displaced to the dependent extremities and inferior mesenteric vessels.5 Normally, orthostatic stabilization occurs in less than 1 minute via 3 mechanisms: baroreceptor input, sympathetic reflex tachycardia and vasoconstriction, and enhanced venous return via the pumping action of skeletal muscles and venoconstriction. In POTS, there is a failure of at least one of these mechanisms, leading to decreased venous return, a 40% reduction in stroke volume, and cerebral hypoperfusion.6

| 1. Consistent symptoms of orthostatic intolerance [may include excessive fatigue, exercise intolerance, recurrent syncope or near syncope, dizziness, nausea, tachycardia, palpitations, visual disturbances, blurred vision, tunnel vision, tremulousness, weakness (most noticeable in the legs), chest discomfort, shortness of breath, mood swings, and gastrointestinal complaints] |

| 2. Heart rate increase 30 bpm or heart rate 120 bpm within 10 min of standing or head‐up tilt |

| 3. Absence of a known cause of autonomic neuropathy |

POTS is divided into 2 major subtypes on the basis of pathophysiology.5, 7 The partial dysautonomic form is the most common and the type that this patient most likely had. In this form, the development of an acquired peripheral autonomic neuropathy results in a failure of sympathetic venoconstriction, which leads to excessive venous pooling in the lower extremities and splanchnic circulation.8, 9 Failure to mobilize this venous reservoir upon standing leads to excessive orthostatic tachycardia secondary to a marked reduction in stroke volume. Peripheral arterial vasoconstriction is generally preserved, which is why midodrine, an arterial vasoconstrictor, did not improve symptoms. The labetalol may have further exacerbated peripheral pooling because of its alpha‐adrenergic blocking properties. Because total plasma volume is decreased and plasma renin activity is inappropriately low,10 volume expanders, including salt, low‐dose steroids, and fluids, can attenuate symptoms.11 The extrinsic venous compression from leg and abdominal support stockings may also dramatically reduce venous pooling.

In the less common hyperadrenergic form of POTS, patients may have orthostatic hypertension, tremulousness, cold, sweaty extremities, and anxiety due to an exaggerated response to beta‐adrenergic stimulation.7 The excessive sympathetic activity, which is poorly modulated by baroreflex activity, may be due to impaired mechanisms of norepinephrine reuptake by sympathetic ganglia.12 Consequently, serum norepinephrine levels are markedly elevated (>600 pg/mL).5

In adults, the presence of a POTS trigger is common and is usually an antecedent viral illness. Antibodies to the ganglionic acetylcholine receptor have been found in a subset of POTS patients,13 and this may suggest an idiopathic or postinflammatory autoimmune mechanism.14 This patient's presentation is unique because her symptoms developed after C5C6 spine surgery. The cervical spinal cord and sympathetic ganglia are dense with nerves involved in autonomic cardiovascular control, and damage to these fibers could explain the patient's physiology and symptoms. Among these, the descending vasomotor pathways traverse through the C5C8 area to innervate the splanchnic and leg venous circulation, receiving input from the heart along the way.15 The pattern of numbness and tingling fits the C5/C6 dermatomal distribution, as does the innervation of the radial artery. The frequent PVCs with a left bundle branch block pattern and inferior axis appear to arise from the right ventricular outflow tract and may be associated with regional sympathetic denervation, which has been described in idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias.16 POTS has been anecdotally reported after neck injury from motor vehicle accidents (whiplash), which is also thought to be related to cervical sympathetic nerve damage (B.P. Grubb, personal communication, 2005). Most cases of triggered POTS improve spontaneously after months to years, but this patient's prognosis remains uncertain because of the presumed mechanical disruption of the autonomic nerve fibers at the time of surgery.

This case demonstrates the complexities of arriving at a unifying diagnosis in the setting of a constellation of nonspecific symptoms and findings, some of which even suggest life‐threatening conditions. Because young women are primarily affected, symptoms of POTS can be mistakenly attributed to anxiety or other nonphysiological factors. A systematic approach excluded life‐threatening causes, including primary ventricular arrhythmias, coronary vasospasm, and coronary anomalies. The investigations narrowed the differential diagnosis, and the tilt‐table test confirmed POTS. Because the cardiac and circulatory dysautonomias encompass an array of distinct physiologic processes, understanding the patient's mechanism is critical to her management. The only effective therapies were those that counteracted venous pooling and improved venous return.

Teaching Points

-

The differential diagnosis of exertional syncope is extremely broad, ranging from benign to malignant conditions, and requires a systematic evaluation of the heart and circulatory system.

-

The diagnosis of POTS is elusive and frequently missed. Referral for tilt‐table testing is useful in identifying the mechanism of sinus tachycardia and syncope. Marked orthostatic tachycardia and symptoms of cerebral hypoperfusion out of proportion to the degree of hypotension strongly suggest POTS.

-

Cardiac and circulatory dysautonomias have distinct and varied mechanisms. Therapies, including beta‐blockers, vasoconstrictors, and volume expanders, must be directed at the underlying physiological defect.

- .An irritable heart.Am J Med Sci.1871;27:145–161.

- ,,,,,.Low physical working capacity in suspected heart cases due to inadequate adjustment of peripheral blood flow (vasoregulatory asthenia).Acta Med Scand.1957;158(6):413–436.

- ,,.Orthostatic tachycardia and orthostatic hypotension: defects in the return of venous blood to the heart.Am Heart J.1944;27:145–163.

- ,.Postural tachycardia syndrome. Reversal of sympathetic hyperresponsiveness and clinical improvement during sodium loading.Am J Med.1982;72(5):847–850.

- ,,.The postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: definitions, diagnosis, and management.Pacing Clin Electrophysiol.2003;26(8):1747– 1757.

- ,.Clinical disorders of the autonomic nervous system associated with orthostatic intolerance: an overview of classification, clinical evaluation, and management.Pacing Clin Electrophysiol.1999;22(5):798–810.

- ,.Idiopathic orthostatic intolerance and postural tachycardia syndromes.Am J Med Sci.1999;317(2):88–101.

- ,,, et al.Splanchnic‐mesenteric capacitance bed in the postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS).Auton Neurosci.2000;86(1–2):107–113.

- ,,,.Abnormal orthostatic changes in blood pressure and heart rate in subjects with intact sympathetic nervous function: evidence for excessive venous pooling.J Lab Clin Med.1988;111(3):326–335.

- ,,, et al.Renin‐aldosterone paradox and perturbed blood volume regulation underlying postural tachycardia syndrome.Circulation.2005;111(13):1574–1582.

- .Clinical practice. Neurocardiogenic syncope.N Engl J Med.2005;352(10):1004–1010.

- ,,, et al.Orthostatic intolerance and tachycardia associated with norepinephrine‐transporter deficiency.N Engl J Med.2000;342(8):541–549.

- ,,,,,.Autoantibodies to ganglionic acetylcholine receptors in autoimmune autonomic neuropathies.N Engl J Med.2000;343(12):847–855.

- ,,.The postural tachycardia syndrome: a concise guide to diagnosis and management.J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol.2006;17(1):108–112.

- ,,.Neurovegetative regulation of the vascular system. In:Lanzer P,Topol EJ, eds.Panvascular Medicine.Berlin, Germany:Springer‐Verlag;2002:175–187.

- ,,, et al.Regional cardiac sympathetic denervation in patients with ventricular tachycardia in the absence of coronary artery disease.J Am Coll Cardiol.1993;22(5):1344–1353.

- .An irritable heart.Am J Med Sci.1871;27:145–161.

- ,,,,,.Low physical working capacity in suspected heart cases due to inadequate adjustment of peripheral blood flow (vasoregulatory asthenia).Acta Med Scand.1957;158(6):413–436.

- ,,.Orthostatic tachycardia and orthostatic hypotension: defects in the return of venous blood to the heart.Am Heart J.1944;27:145–163.

- ,.Postural tachycardia syndrome. Reversal of sympathetic hyperresponsiveness and clinical improvement during sodium loading.Am J Med.1982;72(5):847–850.

- ,,.The postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: definitions, diagnosis, and management.Pacing Clin Electrophysiol.2003;26(8):1747– 1757.

- ,.Clinical disorders of the autonomic nervous system associated with orthostatic intolerance: an overview of classification, clinical evaluation, and management.Pacing Clin Electrophysiol.1999;22(5):798–810.

- ,.Idiopathic orthostatic intolerance and postural tachycardia syndromes.Am J Med Sci.1999;317(2):88–101.

- ,,, et al.Splanchnic‐mesenteric capacitance bed in the postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS).Auton Neurosci.2000;86(1–2):107–113.

- ,,,.Abnormal orthostatic changes in blood pressure and heart rate in subjects with intact sympathetic nervous function: evidence for excessive venous pooling.J Lab Clin Med.1988;111(3):326–335.

- ,,, et al.Renin‐aldosterone paradox and perturbed blood volume regulation underlying postural tachycardia syndrome.Circulation.2005;111(13):1574–1582.

- .Clinical practice. Neurocardiogenic syncope.N Engl J Med.2005;352(10):1004–1010.

- ,,, et al.Orthostatic intolerance and tachycardia associated with norepinephrine‐transporter deficiency.N Engl J Med.2000;342(8):541–549.

- ,,,,,.Autoantibodies to ganglionic acetylcholine receptors in autoimmune autonomic neuropathies.N Engl J Med.2000;343(12):847–855.

- ,,.The postural tachycardia syndrome: a concise guide to diagnosis and management.J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol.2006;17(1):108–112.

- ,,.Neurovegetative regulation of the vascular system. In:Lanzer P,Topol EJ, eds.Panvascular Medicine.Berlin, Germany:Springer‐Verlag;2002:175–187.

- ,,, et al.Regional cardiac sympathetic denervation in patients with ventricular tachycardia in the absence of coronary artery disease.J Am Coll Cardiol.1993;22(5):1344–1353.

Tobacco, Alcohol, and Drug Use Among Hospital Patients

Population‐based surveys of the adult US population estimate a prevalence of smoking of 25% and a prevalence of hazardous alcohol or illegal drug use of 23% and 8% respectively,1 with frequent concurrent use of these substances.2 The mortality associated with smoking and substance use is extremely high with tobacco first, alcohol third, and illicit drug use ninth as the leading causes of death in the US.3 Worldwide, the burden of disease from tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs accounts for almost 10% of all disability‐adjusted life years.4 Despite the availability of effective treatments,57 many patients do not receive professional intervention and few are offered comprehensive programs that address all of their harmful substance use.

Interventions have been successfully implemented for hospitalized smokers. Earlier work by Emmons8 and Orleans9 suggests that many smokers seek assistance to quit smoking during hospitalization. Over the past 15 years, hospital‐based smoking cessation interventions have been successfully implemented.10 Although mute on hospital‐based settings, the United States Preventive Service Task Force recommends screening and counseling interventions to reduce alcohol misuse among adults seen in primary care settings (B recommendation).6 Referral to specialized care is the accepted standard for most patients with substance dependence disorders7 regardless of the medical setting in which the diagnosis is made. Hospitalization provides a unique opportunity to initiate change in harmful substance use and smoking;11 however, interventions rarely are coordinated.

A high prevalence of smoking among substance users has been reported from population‐based surveys1215 and among patients in substance use treatment facilities.1618 Rates of concurrent smoking and substance use range from 35%44% in population‐based studies and may reach 80% in populations seeking substance use treatment.19 A recent hospital‐based study found at‐risk alcohol users were 3 times more likely to smoke.20 There are limited data describing concurrent smoking and substance use in the hospital population,15 and no reports describing the association between patients' willingness to quit smoking and readiness to change substance use behavior.

To better inform hospital‐based smoking and substance use intervention strategies, the epidemiology of smoking and substance use in the hospital population needs to be better described. Furthermore, there may be opportunities for synergy between these programs. In this study, we screened inpatients from multiple services at 2 hospitals for tobacco, alcohol, and illicit substance use. We report the prevalence and co‐occurrence of these behaviors and willingness to quit smoking among patients with and without at‐risk substance use.

METHODS

Data for this study were obtained for a 5‐year Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) grant to the Illinois Office of the Governor. The grant was awarded to implement screening, brief intervention, brief treatment, and referral to treatment programs for patients of the Cook County Bureau of Health Services who had alcohol or other drug use disorders. We analyzed data collected from nonIntensive Care Unit patients who had been hospitalized on the internal medicine, family practice, HIV, or surgery services at John H. Stroger Jr Hospital of Cook County (formerly Cook County Hospital, a 464‐bed public, tertiary‐care hospital) or Provident Hospital of Cook County (a 100‐bed public community hospital), in Chicago, Illinois. Because internal medicine and family practice patients were similar in demographic characteristics and interview responses, we considered these as a single service. There is an HIV service at Stroger Hospital; all HIV‐infected patients are admitted or transferred to this service. For each patient, we used data collected from their initial hospitalization during a 9‐month study period (April 1, 2006 through December 31, 2006). Using hospital admission data, we estimated that 65% of patients were interviewed by a counselor; only 5% of patients could not be interviewed due to patient refusal or mental status changes.

Patients were screened for alcohol use, drug use, and smoking history by bedside interview. We defined at‐risk substance use as any illicit drug use within the previous 3 months or alcohol use that exceeded the National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) guidelines for low‐risk drinking (no more than 5 drinks per day or 14 drinks per week for men up to age 65; no more than 3 drinks per day or 7 drinks per week for men over 65 and women). Based on their responses to questions about smoking history, patients were categorized into the following 4 groups: current smokers (ie, smoked within the previous 7 days), recent quitters (ie, quit within 8 days and 6 months), ex‐smokers (quit more than 6 months ago), or never smokers. Current smokers were also asked about their heaviness of smoking and willingness to quit. All smokers received a counseling session during hospitalization. All smokers who indicated a desire to quit were encouraged to call the Illinois Quitline after hospital discharge. Individuals who smoked between 10‐14 cigarettes per day and smoked their first cigarette within 30 minutes of waking or who smoked 15 or more cigarettes per day were classified as moderate or heavy smokers; all other smokers were classified as light smokers. We established these cut‐points by modifying the Public Health Service guideline and Heaviness of Smoking Index.5, 21, 22 The heaviness of smoking classification was used to guide recommendations to the primary service regarding the appropriateness of nicotine patch therapy during and after hospitalization. For moderate to heavy smokers who were willing to quit, the recommendation was to continue nicotine replacement after hospitalization.5

Patients were considered low health risk if their alcohol use did not exceed NIAAA guidelines and they reported no recent drug use. For all patients who reported alcohol use that exceeded the NIAAA guidelines or recent drug use, we administered the Texas Christian University Drug Screen II (TCU)23 to further characterize the severity of their use. Patients who had a TCU score of 3 were considered at‐risk substance users with substance dependence disorder; patients with scores of 2 or less were considered at‐risk substance users without dependence. Among all at‐risk substance users, we used a 10‐point visual analog scale to assess their readiness to change substance use. After evaluating the distribution and clustering of scores, we prespecified that a score 8 was indicative of a patient being ready to change their substance use behavior. This ruler has been successfully implemented as part of the Brief Negotiated Interview and Active Referral to Treatment Institute toolbox.24

Analysis

To facilitate comparison with other data sources, we used the same age categories as the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.1 Differences between proportions were evaluated by the chi‐squared test. We analyzed the trend in smoking behavior across the strata of substance use (ie, number of substances used and severity of use) using the Cochrane‐Armitage test for trend. To evaluate the association between substance use and smoking, multivariable models were constructed that included terms to adjust for age, race, gender, and hospital service; potential confounders (eg, age, race, gender, and service) were included in the final model if they significantly contributed to the outcome variable (P < 0.1). From these multivariable models, prevalence ratios were estimated using the binary log transformation in PROC GENMOD.25, 26 All data were analyzed using SAS version 9.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Of the 7,714 unique patients interviewed at the 2 hospitals, we had data on smoking status for 7,391 (96%) (Table 1). The mean age was 50 years, most were male, cared for by the internal medicine or family practice service, and the most common racial/ethnic category was non‐Hispanic Black, followed by Hispanic, non‐Hispanic White, and Asian (Table 1). More than one‐quarter of patients reported at‐risk substance use other than tobacco; the most common substance used was alcohol followed by cocaine, marijuana, and then heroin (Table 1). Most patients who were at‐risk substance users (52%) met criteria for substance dependence disorder.23

| Characteristic | N | (%) | Smoking prevalence* (%) | Prevalence ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Age category | |||||

| 18‐25 | 479 | (6) | 35 | 2.6 | (2.1 to 3.1) |

| 26‐34 | 664 | (9) | 38 | 2.8 | (2.4 to 3.4) |

| 35‐44 | 1306 | (18) | 46 | 3.4 | (2.9 to 4.0) |

| 45‐54 | 2182 | (30) | 46 | 3.4 | (2.9 to 4.0) |

| 55‐64 | 1563 | (21) | 31 | 2.3 | (2.0 to 2.7) |

| 65 and older | 1185 | (16) | 13 | ref | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Non Hispanic Black | 4990 | (68) | 45 | 3.0 | (2.2 to 4.0) |

| Non Hispanic White | 850 | (12) | 40 | 2.7 | (2.0 to 3.6) |

| Hispanic | 1222 | (17) | 19 | 1.3 | (0.9 to 1.7) |

| Asian | 253 | (3) | 15 | ref | |

| Other | 27 | (<1) | |||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 4279 | (58) | 42 | 1.5 | (1.4 to 1.6) |

| Female | 3099 | (42) | 29 | ref | |

| Service | |||||

| HIV | 227 | (3) | 52 | 1.7 | (1.5 to 2.0) |

| Internal medicine or | 6278 | (85) | 36 | 1.2 | (1.1 to 1.3) |

| family practice | |||||

| Surgery | 886 | (12) | 31 | ref | |

Tobacco Use

Many hospitalized patients were current smokers (36%) and 35% of current smokers were moderate to heavy smokers. The prevalence of smoking varied significantly by age category, race, gender, and service. By age category, the prevalence of smoking peaked at 3554 years with lower rates of smoking at either extreme of age (Table 1). Non‐Hispanic Blacks and Whites had a prevalence of smoking 3‐fold higher than Asians; Hispanics were less likely to smoke than non‐Hispanic Whites or Blacks. Men were more likely to smoke than women, and patients on the HIV or internal medicine/family practice services had a higher prevalence of smoking compared to patients on the surgery service (Table 1).

The proportion of current smokers who were moderate to heavy smokers was similar between patients with no‐risk or low‐risk substance use and those who had at‐risk substance use without dependence (32% versus 34%, respectively); however, current smokers who were substance‐dependent were 40% more likely to be moderate to heavy smokers (48%) (prevalence ratio [PR]: 1.4, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.1 to 1.9).

Concurrent Tobacco and Substance Use

Compared to patients who reported low‐risk substance use, patients with at‐risk substance use had a dramatically higher prevalence of smoking (Table 2). In addition, there was a significant increase in the likelihood of smoking across the 3 levels of substance use and the number of substances used (Table 2).

| N | (%) | Smoking prevalence (%) | Adjusted prevalence ratio (95% CI)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Risk Index | |||||

| Low Health Risk | 5419 | (73) | 24 | ref | |

| At‐Risk, not dependent | 945 | (13) | 64 | 2.2 | (2.0 to 2.3) |

| At‐Risk, dependent | 1027 | (14) | 75 | 2.5 | (2.3 to 2.6) |

| Specific substance use | |||||

| Low Health Risk | 5419 | (73) | 24 | ref | |

| At‐Risk Alcohol Use | 1171 | (16) | 68 | 2.2 | (2.1 to 2.4) |

| At‐ Risk Marijuana Use | 688 | (9) | 70 | 2.1 | (2.0 to 2.3) |

| At‐Risk Cocaine Use | 503 | (7) | 79 | 2.4 | (2.2 to 2.6) |

| At‐Risk Heroin Use | 448 | (6) | 82 | 2.4 | (2.2 to 2.6) |

| Number of drugs | |||||

| None | 5419 | (73) | 24 | ref | |

| One | 1284 | (17) | 64 | 2.2 | (2.0 to 2.3) |

| Two or more | 688 | (9) | 81 | 2.6 | (2.5 to 2.8) |

Willingness to Quit

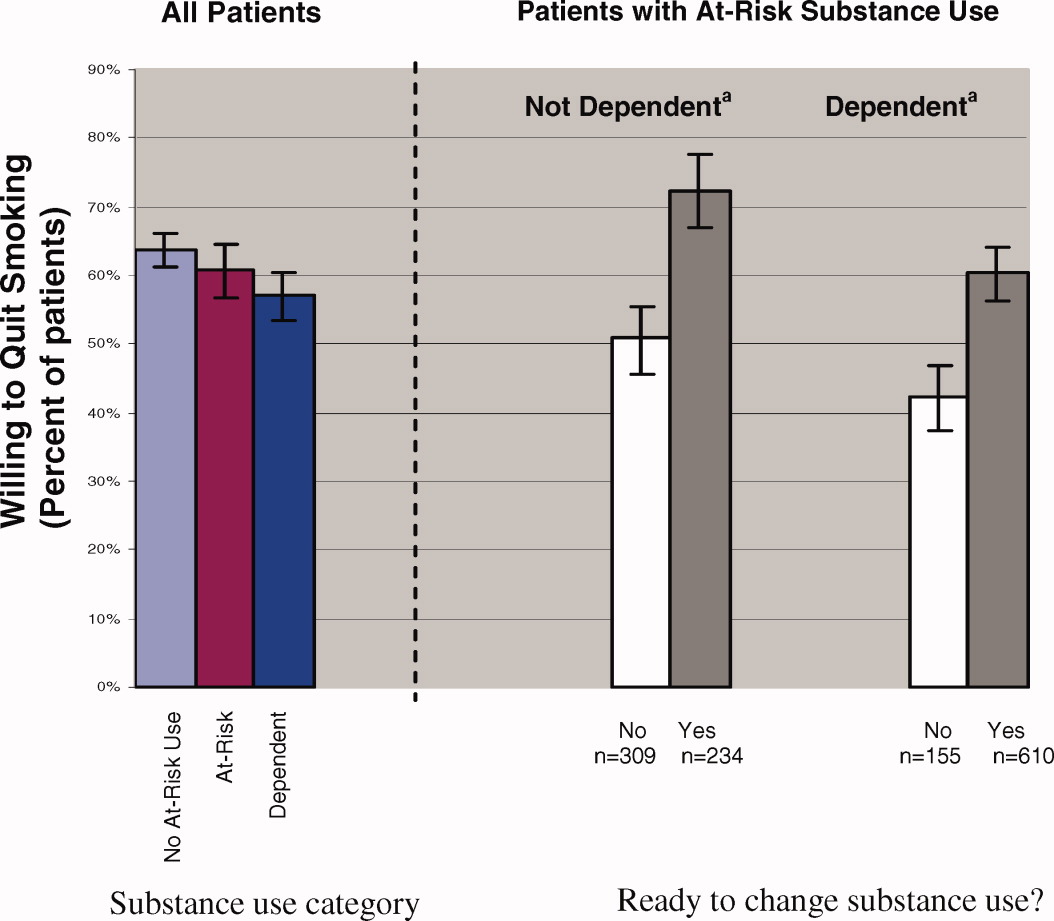

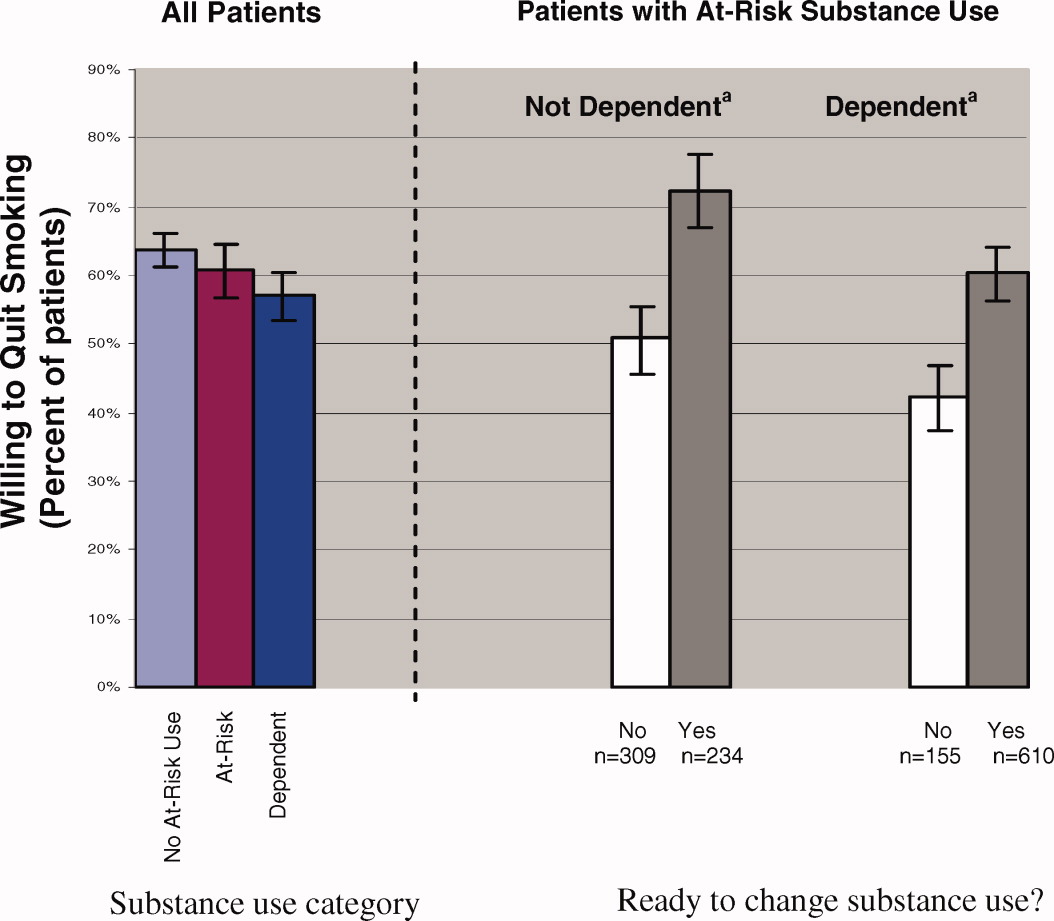

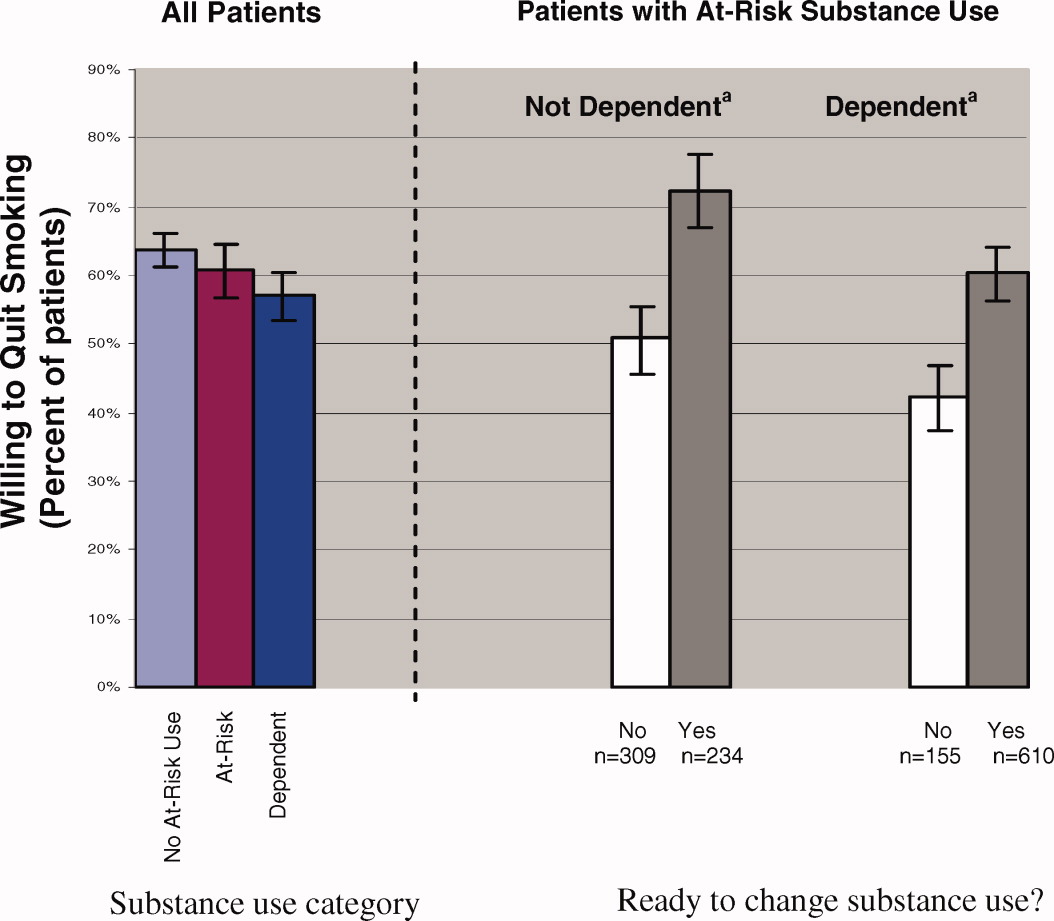

Most patients (61%) who smoked were willing to immediately quit smoking. After adjusting for other demographic confounders, non‐Hispanic Blacks and the elderly (age > 65) were more willing to quit (P < 0.05, data not shown). The substance use risk categories of low risk, at‐risk, and dependence were not associated with willingness to quit tobacco (Fig. 1, left panel).

Regardless of substance use category, most patients were ready to change their substance use behavior (Fig. 1). Those patients who were ready to change their substance use behavior, regardless of whether they were substance‐dependent, were significantly more likely to report a willingness to quit smoking than those who were not ready to change (Fig. 1, right panel). In fact, at‐risk substance users without dependence who were ready to change their substance use were more willing to quit smoking than patients without at‐risk substance use (72% versus 64%; P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION