User login

TB with Pott's Disease and Psoas Abscess

A 22‐year‐old man was referred from an outside hospital with 2 weeks of generalized weakness and difficulty ambulating. He also reported a 6‐month history of abdominal pain, right‐sided lumbar back pain, malaise, night sweats, cough, and weight loss of 30 kg. The patient was born in Mexico but had lived in the US for 10 years, working as a construction worker in northern California. He had had no prior medical care. On examination, the patient had a temperature of 40C, a heart rate of 109, and a respiratory rate of 20. His oxygen saturation was 97% on room air, and lung fields were clear bilaterally. Strength was slightly decreased in the right leg, with tenderness in the posterolateral aspect of the right thigh and thoracic lumbar spine.

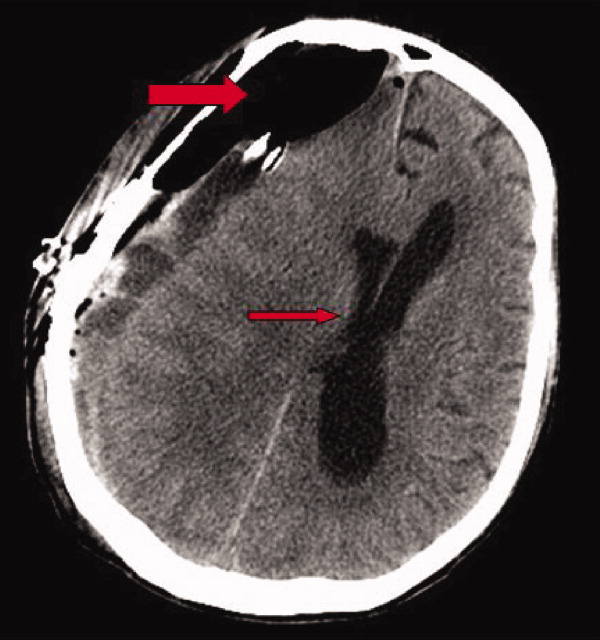

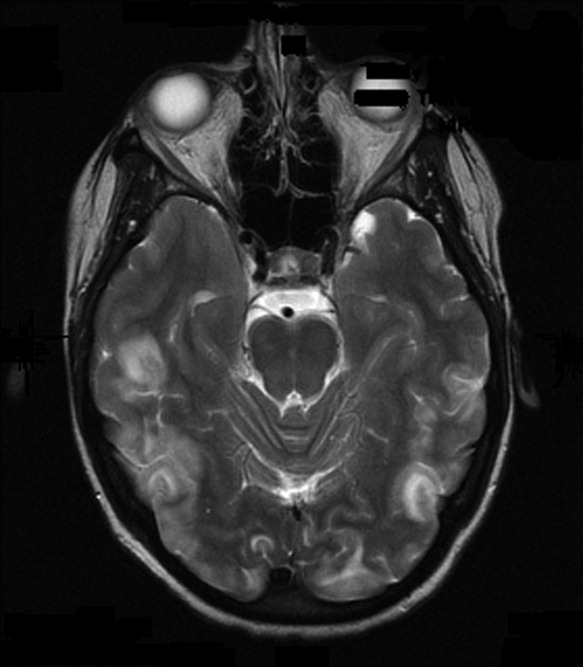

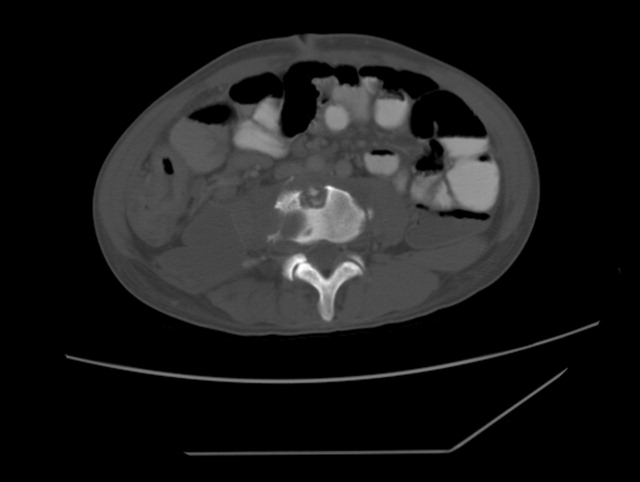

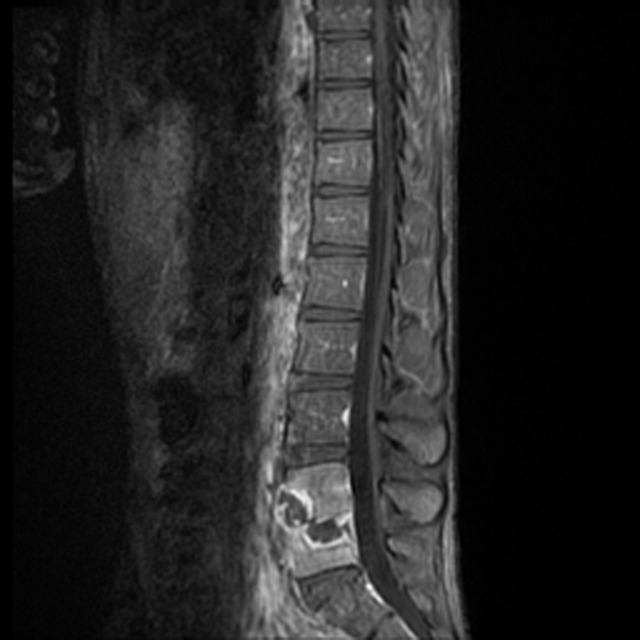

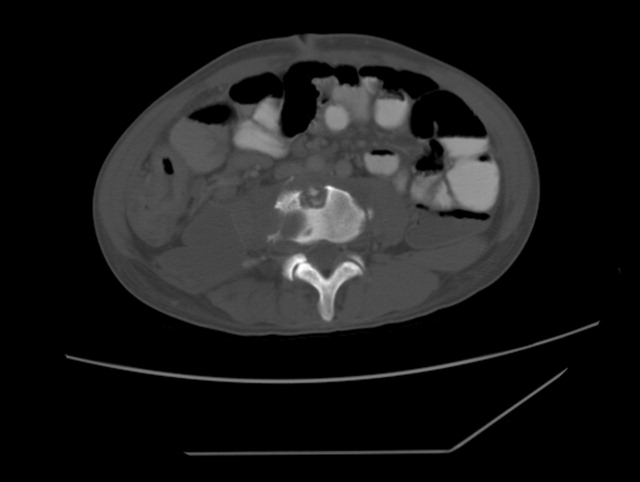

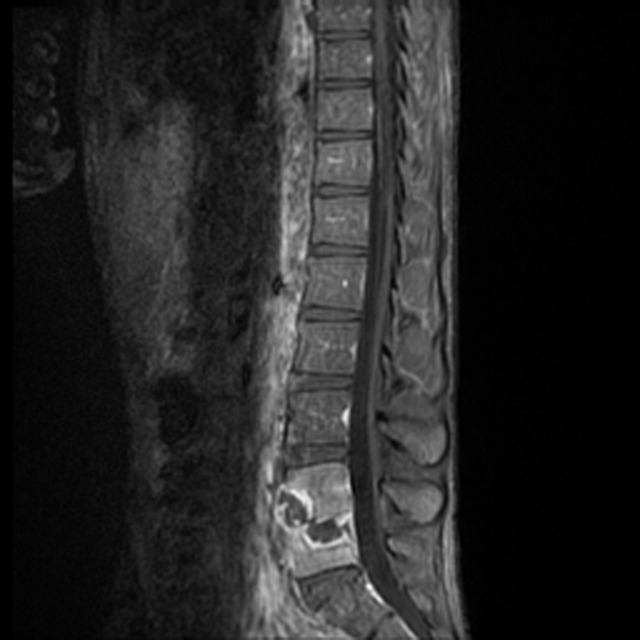

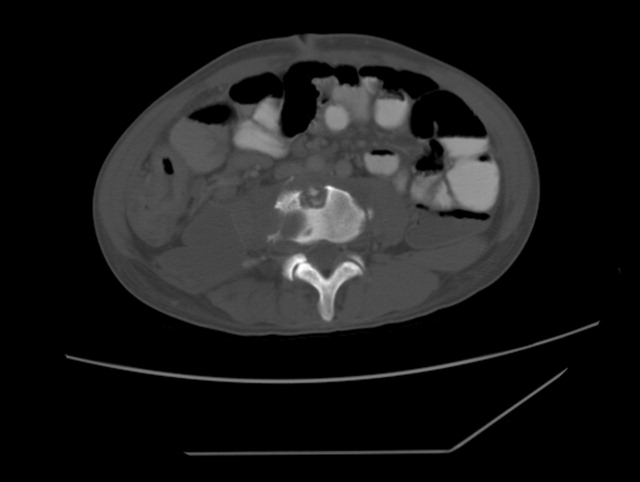

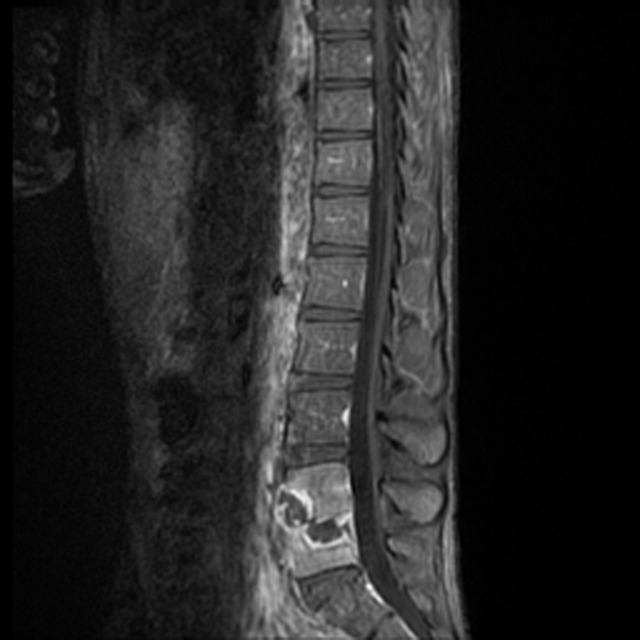

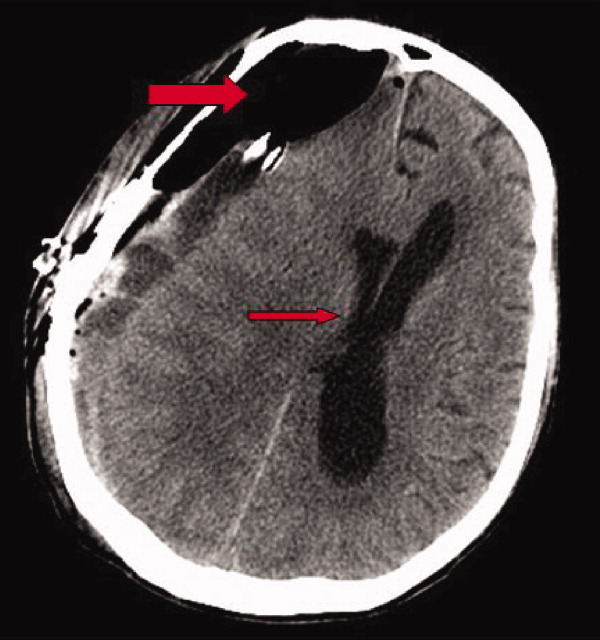

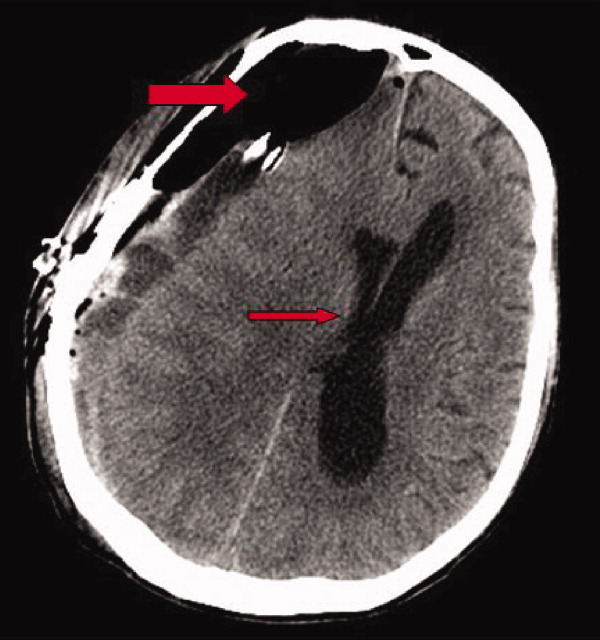

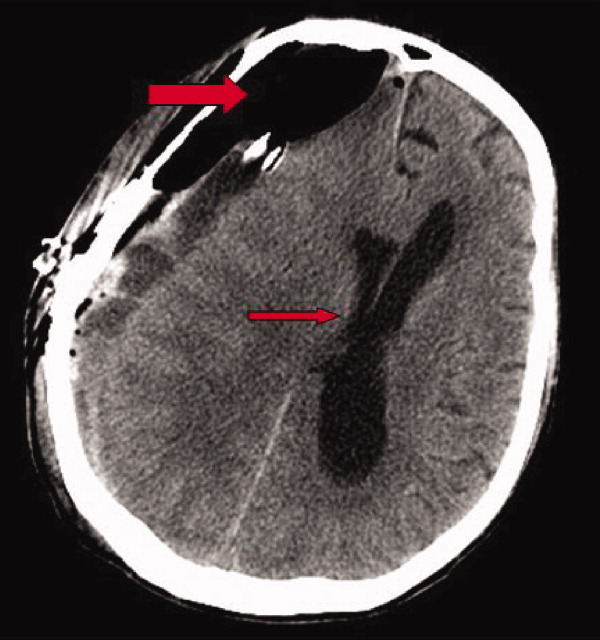

Radiograph of the chest showed bilateral upper lobe reticulonodular infiltrates, cavitation, and pleural thickening (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) showed innumerable pulmonary nodules throughout the mid and lower lungs, a loss of disc space between L4 and L5, and a large multiloculated abscess of the right iliacus and psoas muscles that extended into the right thigh (Figure 2). Longitudinal relaxation time (T1)‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine revealed vertebral destruction of L4 and L5 (Figure 3).

The patient underwent vertebrectomy of L4 and L5, anterior/posterior fixation and fusion from L4 to S1, and drainage of a large right‐sided psoas abscess. Acid‐fast bacilli were seen in abscess fluid and vertebral bone. Subsequently, the intraoperative cultures and 6 sequential sputum cultures all grew Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The patient was begun on rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol with a good clinical response, and subsequently transferred back to his referring hospital for continued medical care and rehabilitation.

Extrapulmonary manifestations of tuberculosis should be suspected in patients from a tuberculosis‐endemic country of origin. Bone and joint tuberculosis account for up to 35% of cases of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Spinal tuberculosis (Pott's disease) most commonly involves the anteroinferior aspect of vertebral bodies in the thoracic spine. Tuberculosis is a disease with diverse manifestations and can elude even the most astute physician if it is not considered as a diagnosis.

A 22‐year‐old man was referred from an outside hospital with 2 weeks of generalized weakness and difficulty ambulating. He also reported a 6‐month history of abdominal pain, right‐sided lumbar back pain, malaise, night sweats, cough, and weight loss of 30 kg. The patient was born in Mexico but had lived in the US for 10 years, working as a construction worker in northern California. He had had no prior medical care. On examination, the patient had a temperature of 40C, a heart rate of 109, and a respiratory rate of 20. His oxygen saturation was 97% on room air, and lung fields were clear bilaterally. Strength was slightly decreased in the right leg, with tenderness in the posterolateral aspect of the right thigh and thoracic lumbar spine.

Radiograph of the chest showed bilateral upper lobe reticulonodular infiltrates, cavitation, and pleural thickening (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) showed innumerable pulmonary nodules throughout the mid and lower lungs, a loss of disc space between L4 and L5, and a large multiloculated abscess of the right iliacus and psoas muscles that extended into the right thigh (Figure 2). Longitudinal relaxation time (T1)‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine revealed vertebral destruction of L4 and L5 (Figure 3).

The patient underwent vertebrectomy of L4 and L5, anterior/posterior fixation and fusion from L4 to S1, and drainage of a large right‐sided psoas abscess. Acid‐fast bacilli were seen in abscess fluid and vertebral bone. Subsequently, the intraoperative cultures and 6 sequential sputum cultures all grew Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The patient was begun on rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol with a good clinical response, and subsequently transferred back to his referring hospital for continued medical care and rehabilitation.

Extrapulmonary manifestations of tuberculosis should be suspected in patients from a tuberculosis‐endemic country of origin. Bone and joint tuberculosis account for up to 35% of cases of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Spinal tuberculosis (Pott's disease) most commonly involves the anteroinferior aspect of vertebral bodies in the thoracic spine. Tuberculosis is a disease with diverse manifestations and can elude even the most astute physician if it is not considered as a diagnosis.

A 22‐year‐old man was referred from an outside hospital with 2 weeks of generalized weakness and difficulty ambulating. He also reported a 6‐month history of abdominal pain, right‐sided lumbar back pain, malaise, night sweats, cough, and weight loss of 30 kg. The patient was born in Mexico but had lived in the US for 10 years, working as a construction worker in northern California. He had had no prior medical care. On examination, the patient had a temperature of 40C, a heart rate of 109, and a respiratory rate of 20. His oxygen saturation was 97% on room air, and lung fields were clear bilaterally. Strength was slightly decreased in the right leg, with tenderness in the posterolateral aspect of the right thigh and thoracic lumbar spine.

Radiograph of the chest showed bilateral upper lobe reticulonodular infiltrates, cavitation, and pleural thickening (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) showed innumerable pulmonary nodules throughout the mid and lower lungs, a loss of disc space between L4 and L5, and a large multiloculated abscess of the right iliacus and psoas muscles that extended into the right thigh (Figure 2). Longitudinal relaxation time (T1)‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine revealed vertebral destruction of L4 and L5 (Figure 3).

The patient underwent vertebrectomy of L4 and L5, anterior/posterior fixation and fusion from L4 to S1, and drainage of a large right‐sided psoas abscess. Acid‐fast bacilli were seen in abscess fluid and vertebral bone. Subsequently, the intraoperative cultures and 6 sequential sputum cultures all grew Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The patient was begun on rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol with a good clinical response, and subsequently transferred back to his referring hospital for continued medical care and rehabilitation.

Extrapulmonary manifestations of tuberculosis should be suspected in patients from a tuberculosis‐endemic country of origin. Bone and joint tuberculosis account for up to 35% of cases of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Spinal tuberculosis (Pott's disease) most commonly involves the anteroinferior aspect of vertebral bodies in the thoracic spine. Tuberculosis is a disease with diverse manifestations and can elude even the most astute physician if it is not considered as a diagnosis.

Evidence for Thromboembolism Prophylaxis

Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), collectively referred to as venous thromboembolism (VTE), are common events in hospitalized patients and result in significant morbidity and mortality. Often silent and frequently unexpected, VTE is preventable. Accordingly, the American College of Chest Physicians recommends that pharmacologic prophylaxis be given to acutely ill medical patients admitted to the hospital with congestive heart failure or severe respiratory disease, or to patients who are confined to bed who have additional risk factors, such as cancer or previous VTE.1 Three recent meta‐analyses24 demonstrated significant reductions in VTE in general medicine patients with pharmacologic prophylaxis. Recently the National Quality Forum advocated that hospitals evaluate each patient upon admission and regularly thereafter, for the risk of developing DVT/VTE and utilize clinically appropriate methods to prevent DVT/VTE.5

Despite recommendations for prophylaxis, multiple studies demonstrate utilization in <50% of at‐risk general medical patients.68 Physicians' lack of awareness may partially explain this underutilization, but other likely factors include physicians' questions about the clinical importance of the outcome (eg, some studies have shown reductions primarily in asymptomatic distal DVT), doubt regarding the best form of prophylaxis (ie, unfractionated heparin [UFH] vs. low molecular weight heparin [LMWH]), uncertainty regarding optimal dosing regimens, and comparable uncertainty regarding which patients have sufficiently high risk for VTE to outweigh the risks of anticoagulation.

We undertook the current meta‐analysis to address questions about thromboembolism prevention in general medicine patients. Does pharmacologic prophylaxis prevent clinically relevant events? Is LMWH or UFH preferable in terms of either efficacy or safety?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search Strategy

We conducted an extensive search that included reviewing electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL) through June 2008, reviewing conference proceedings, and contacting drug manufacturers. The MEDLINE search combined the key words deep venous thrombosis, thromboembolism, AND pulmonary embolism with the terms primary prevention, prophylaxis, OR prevention. We limited the search results using the filter for randomized controlled trials in PubMed. Similar strategies (available on request) were used to search EMBASE, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. We also searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews to identify previous reviews on the same topic. We obtained translations of eligible, non‐English‐language articles.

The proceedings of annual meetings from the American Thoracic Society, the American Society of Hematology, and the Society for General Internal Medicine from 1994 to 2008 were hand‐searched for reports on DVT or PE prevention published in abstract form only. (Note: the American Society of Hematology was only available through 2007). We contacted the 3 main manufacturers of LMWHPfizer (dalteparin), Aventis (enoxaparin), Glaxo Smith Kline (nadoparin)and requested information on unpublished pharmaceutical sponsored trials. First authors from the trials included in this meta‐analysis were also contacted to determine if they knew of additional published or unpublished trials.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were required to be prospective randomized controlled trials comparing UFH or LMWH to mechanical prophylaxis, placebo, or no intervention. We also included randomized head‐to‐head comparisons of UFH and LMWH. Eligible studies enrolled general medical patients. Trials including predominantly intensive care unit (ICU) patients; stroke, spinal cord, or acute myocardial infarction patients were excluded. We excluded trials focused on these populations because the risk for VTE may differ from that for general medical patients and because patients in these groups already commonly receive anticoagulants as a preventive measure or as active treatment (eg, for acute myocardial infarction [MI] care). Trials assessing thrombosis in patients with long‐term central venous access/catheters were also excluded. Articles focusing on long‐term rehabilitation patients were excluded.

Studies had to employ objective criteria for diagnosing VTE. For DVT these included duplex ultrasonography, venography, fibrinogen uptake scanning, impedance plethysmography, or autopsy as a primary or secondary outcome. Studies utilizing thermographic techniques were excluded.9 Eligible diagnostic modalities for PE consisted of pulmonary arteriogram, ventilation/perfusion scan, CT angiography, and autopsy.

After an initial review of article titles and abstracts, the full texts of all articles that potentially met our inclusion criteria were independently reviewed for eligibility by 2 authors (G.M.B., M.D.). In cases of disagreement, a third author (S.F.) independently reviewed the article and adjudicated decisions.

Quantitative Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

For all included articles, 2 reviewers independently abstracted data on key study features (including population size, trial design, modality of VTE diagnosis, and interventions delivered to treatment and control groups), results (including the rates of all DVT, proximal DVT, symptomatic DVT, PE, and death), as well as adverse events (such as bleeding and thrombocytopenia). We accepted the endpoint of DVT when assessed by duplex ultrasonography, venography, autopsy, or when diagnosed by fibrinogen uptake scanning or impedance plethysmography. For all endpoints we abstracted event rates as number of events based on intention to treat. Each study was assessed for quality using the Jadad scale.10 The Jadad scale is a validated tool for characterizing study quality that accounts for randomization, blinding, and description of withdrawals and dropouts in individual trials. The Jadad score ranges from 0 to 5 with higher numbers identifying trials of greater methodological rigor.

The trials were divided into 4 groups based on the prophylaxis agent used and the method of comparison (UFH vs. control, LMWH vs. control, LMWH vs. UFH, and LMWH/UFH combined vs. control). After combining trials for each group, we calculated a pooled relative risk (RR) and a 95% confidence interval (CI) based on both fixed and a random effects model using the DerSimonian and Laird method. Heterogeneity of the included studies was evaluated with a chi‐square statistic. The percentage of variation in the pooled RR attributable to heterogeneity was calculated and reported using the I‐squared statistic.11 Sensitivity analyses were performed and included repeating all analyses using high‐quality studies only (Jadad score 3 or higher). Publication bias was assessed using the methods developed by Egger et al.12 and Begg and Mazumdar.13 All analyses were performed using STATA SE version 9 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Study Identification and Selection

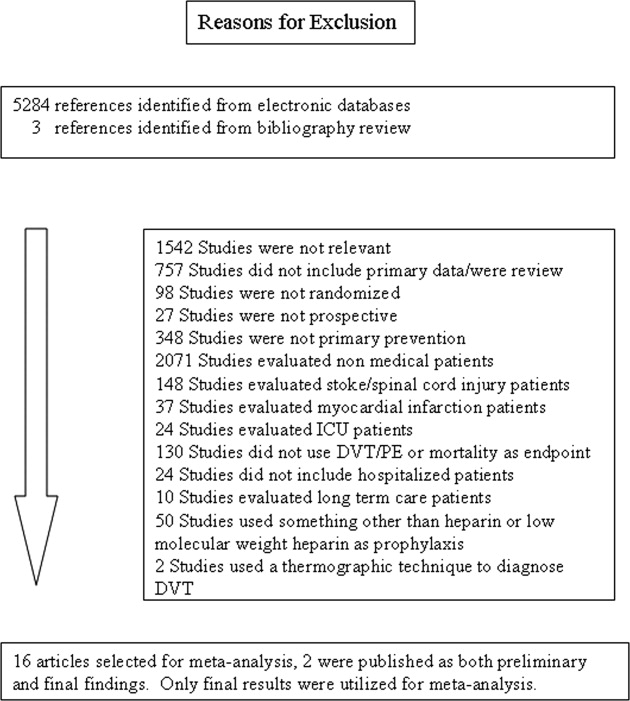

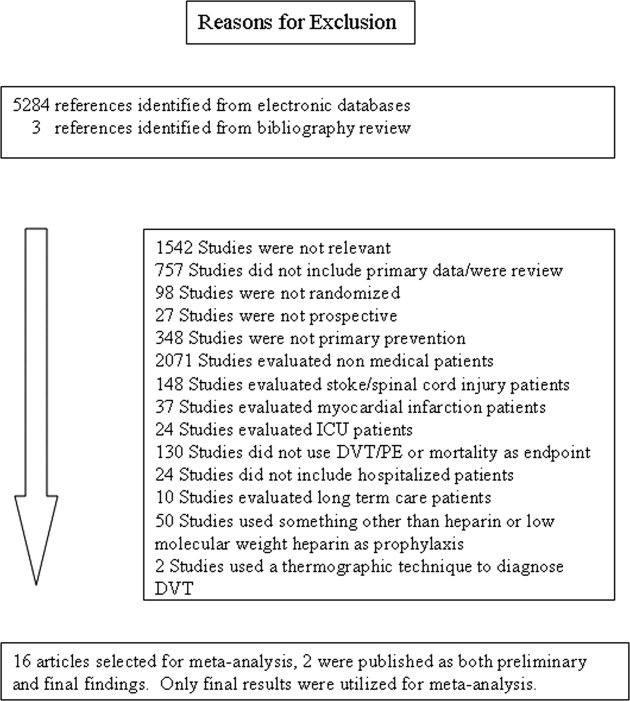

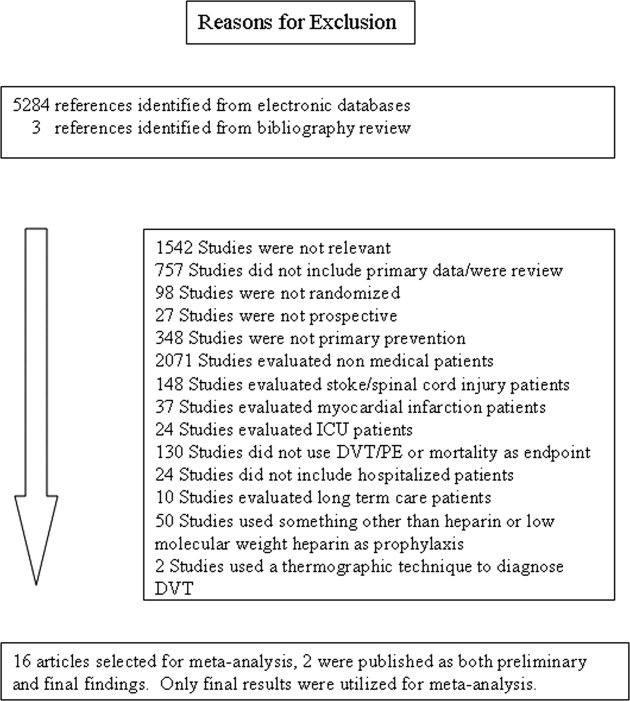

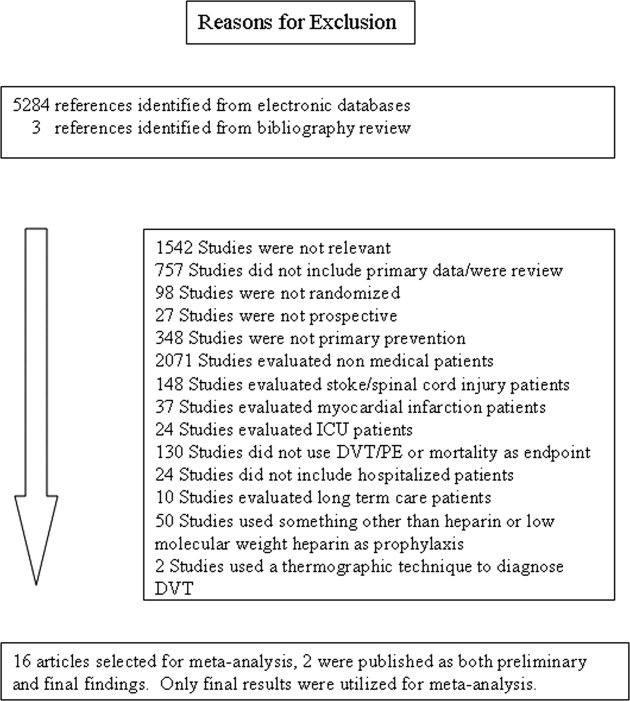

The computerized literature search resulted in 5284 articles. Three additional citations were found by review of bibliographies. No additional trials were identified from reviews of abstracts from national meetings. Representatives from the 3 pharmaceutical companies reported no knowledge of additional published or unpublished data. Of the 5287 studies identified by the search, 14 studies met all eligibility criteria (Figure 1).

Study Characteristics

The 14 trials eligible for inclusion in the analysis consisted of 8 comparisons of UFH or LMWH vs. control (Table 1) and 6 head‐to‐head comparisons of UFH and LMWH (Table 2). The 14 studies included 8 multicenter trials and enrolled a total of 24,515 patients: 20,594 in the 8 trials that compared UFH or LMWH with placebo and 3921 in the 6 trials that compared LMWH with UFH. Two trials exclusively enrolled patients with either congestive heart failure or severe respiratory disease,14, 15 while 12 trials enrolled mixed populations. In 8 trials a period of immobility was necessary for study entry,14, 1621 while in 2 trials immobility was not required.22, 23 In the 4 remaining trials immobility was not explicitly discussed.15, 2426 One‐half of the trials required a length of stay greater than 3 days.1719, 2225

| Study (Year)Reference | Patients (n) | Duration (days) | VTE Risk Factors | Drug Dose | Comparison | DVT Assessed | PE Assessed | Double Blind | Jadad Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Belch et al. (1981)15 | 100 | 8 | Age 40‐80 years; CHF; chest infection | UFH TID | None | FUS | VQ | No | 1 |

| Dahan et al. (1986)23 | 270 | 10* | Age >65 years | Enoxaparin 60 mg | Placebo | FUS | Autopsy | Yes | 3 |

| Halkin et al. (1982)20 | 1358 | Not reported | Age >40 years; immobile | UFH BID | None | No | No | No | 1 |

| Mahe et al. (2005)16 | 2474 | 13.08 | Age >40 years; immobile | Nadroparin 7500 IU | Placebo | Autopsy | Autopsy | Yes | 5 |

| Gardlund (1996)21 | 11693 | 8.2 | Age >55 years; immobile | UFH BID | None | Autopsy | Autopsy | No | 2 |

| Samama et al. (1999)24 | 738 | 7 | Age >40 years; length of stay 6 days; CHF; respiratory failure or 1 additional risk factor | Enoxaparin 40 mg | Placebo | Venography | Composite | Yes | 4 |

| Leizorovicz et al. (2004)25 | 3681 | 12.6 | Age >40 years; length of stay 4 days; CHF; respiratory failure or 1 additional risk factor | Dalteparin 5000 IU | Placebo | DUS | Composite | Yes | 4 |

| Lederle et al. (2006)22 | 280 | 13.4 | Age >60 years; length of stay 3 days | Enoxaparin 40 mg | Placebo | DUS | Composite | Yes | 5 |

| Study (Year)reference | Patients (n) | Duration (days) | VTE Risk Factors | Drug/Dose | Comparison | DVT Assessed | PE Assessed | Double Blind | Jadad Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Bergmann and Neuhart (1996)27 | 442 | 9.5 | Age >65 years; immobile | Enoxaparin 20 mg | UFH BID | FUS | Composite | Yes | 5 |

| Harenberg et al. (1990)19 | 166 | 10* | Age 40‐80 years; 1 week of bed rest | LMWH 1.500 aPTT units QD | UFH TID | IP | No | Yes | 3 |

| Kleber et al. (2003)14 | 665 | 9.8 | Age 18 years; severe CHF or respiratory disease; immobile | Enoxaparin 40 mg | UFH TID | Venography | Composite | No | 3 |

| Aquino et al. (1990)26 | 99 | Not reported | Age >70 years | Nadoparine 7500 IU | UFH BID | DUS | Composite | No | 1 |

| Harenberg et al. (1996)18 | 1590 | 10* | Age 50‐80 years; immobile + 1 additional risk factor | Nadoparine 36 mg | UFH TID | DUS | Composite | Yes | 4 |

| Lechler et al. (1996)17 | 959 | 7* | Age >18 years; immobile + 1 additional risk factor | Enoxaparin 40 mg | UFH TID | DUS | Composite | Yes | 3 |

While minimum age for study entry varied, the patient population predominantly ranged from 65 to 85 years of age. Many of the trials reported expected, not actual, treatment duration. The range of expected treatment was 7 to 21 days, with 10 days of treatment the most frequently mentioned. In the 8 trials1416, 21, 22, 24, 25, 27 that reported actual treatment duration, the range was 8 to 13.4 days. Most trials did not report number of VTE risk factors per patient, nor was there uniform acceptance of risk factors across trials.

UFH or LMWH vs. Control

DVT

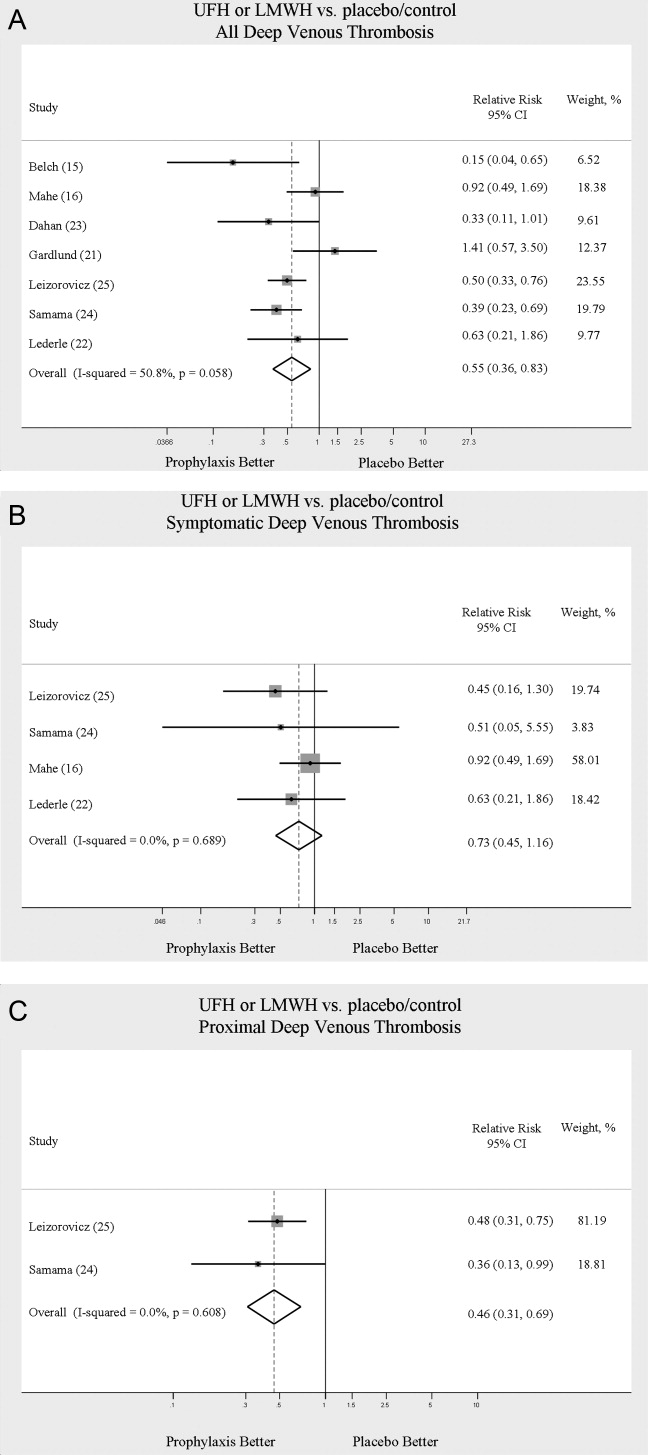

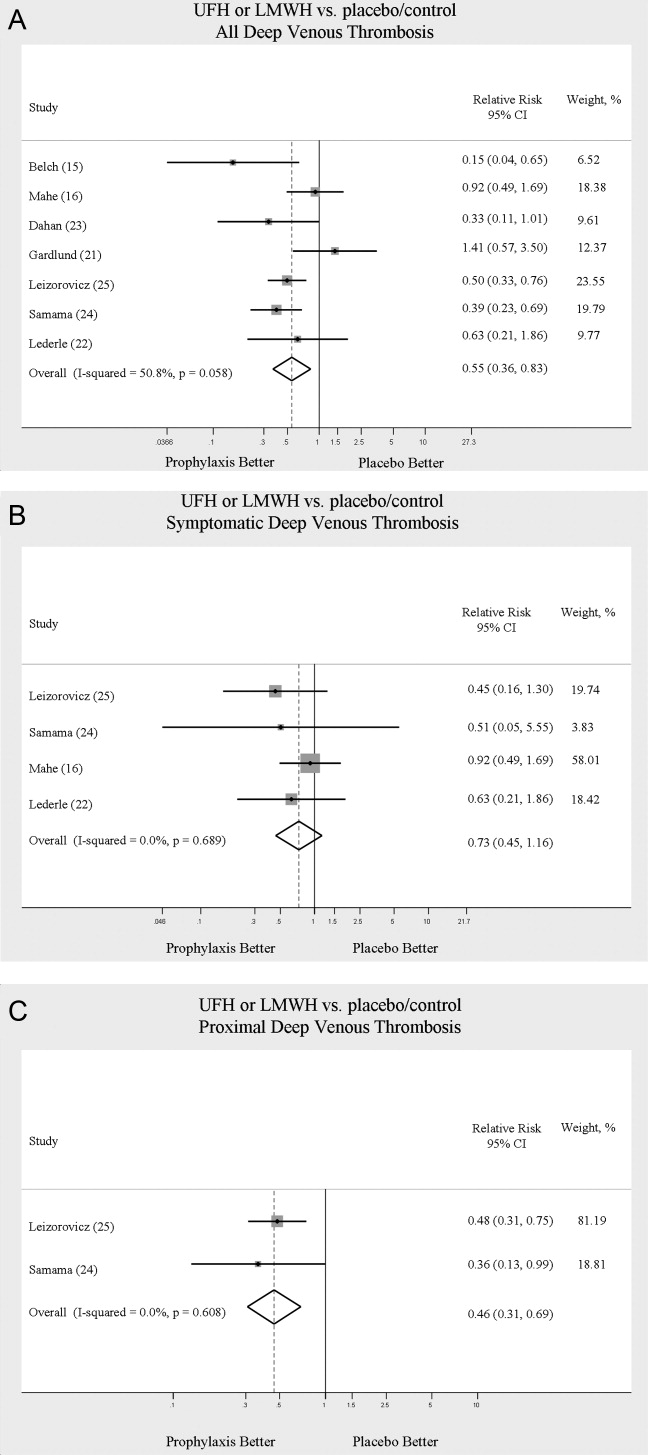

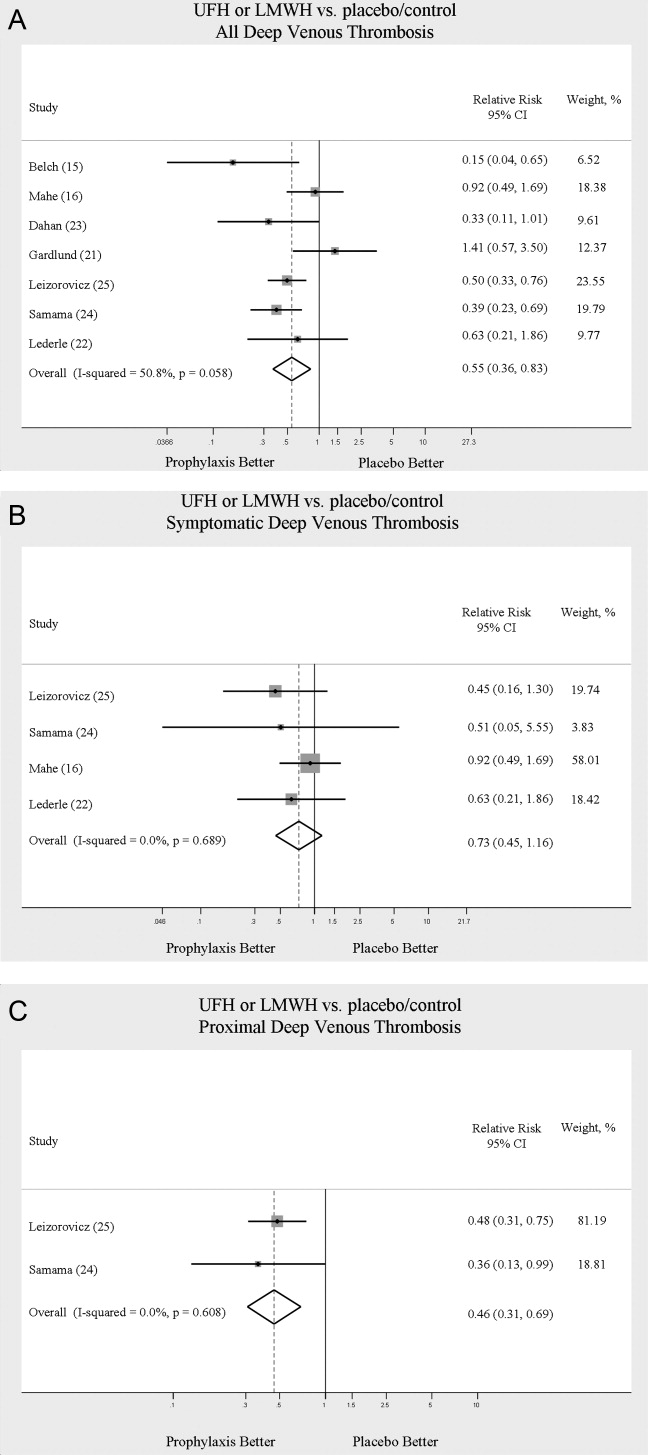

Across 7 trials comparing either UFH or LMWH to control, heparin products significantly decreased the risk of all DVT (RR = 0.55; 95% CI: 0.36‐0.83) (Figure 2A). When stratified by methodological quality, 5 trials16, 2225 with Jadad scores of 3 or higher showed an RR reduction of 0.53 (95% CI: 0.38‐0.72) in reducing all DVT. All of the higher‐quality trials compared LMWH to placebo. Across 4 trials that reported data for symptomatic DVT there was a nonsignificant reduction in RR compared with placebo (RR = 0.73; 95% CI: 0.45‐1.16) (Figure 2B). Only 2 trials24, 25 (both LMWH trials) reported results for proximal DVT and demonstrated significant benefit of prophylaxis with a pooled RR of 0.46 (95% CI: 0.31‐0.69) (Figure 2C).

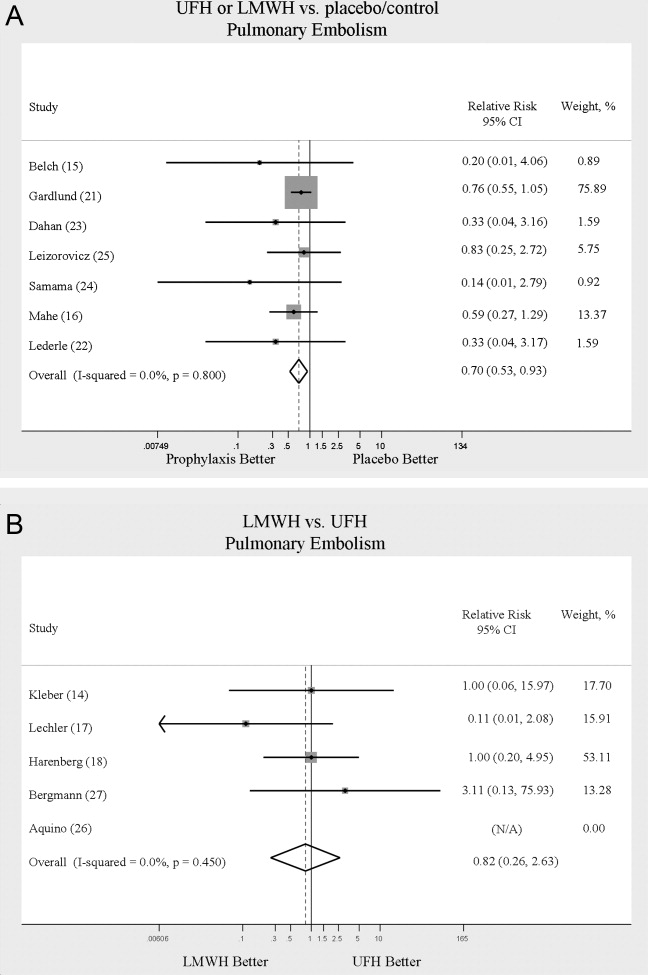

PE

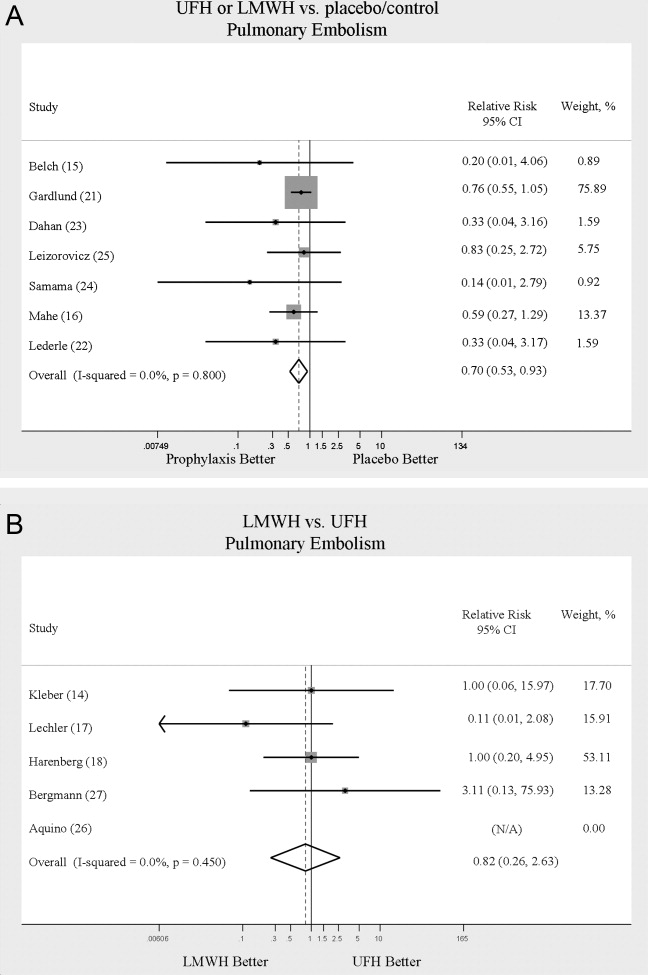

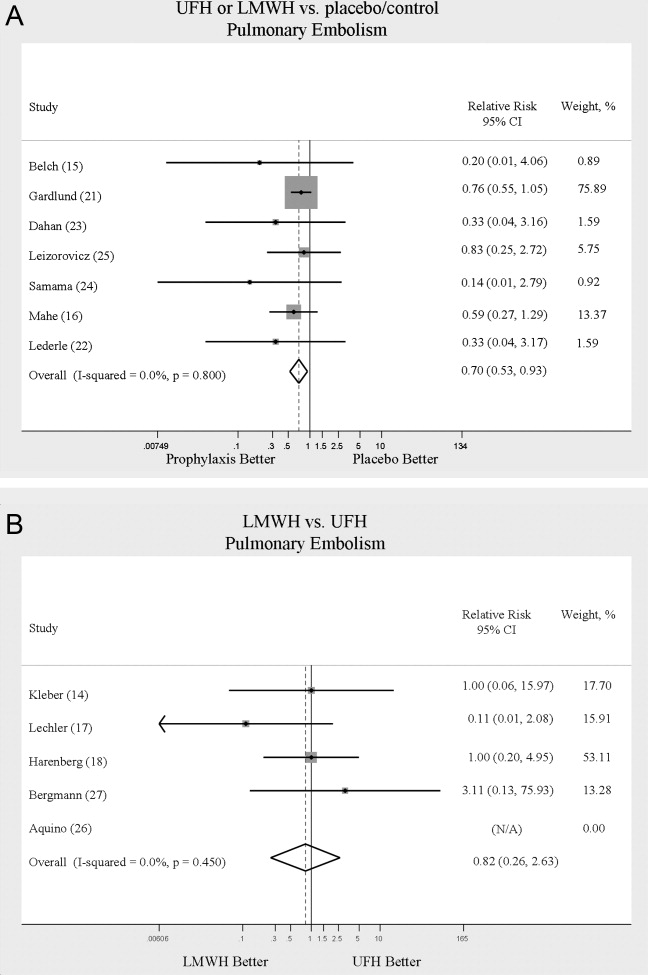

Across 7 trials comparing either UFH or LMWH to control, heparin products significantly decreased the risk of PE (RR = 0.70; 95% CI: 0.53‐0.93) (Figure 3A). The 5 trials16, 2225 with Jadad scores of 3 or greater showed a similar relative risk reduction, but the result was no longer statistically significant (RR = 0.56; 95% CI: 0.31‐1.02). Two of the trials16, 21 relied solely on the results of autopsy to diagnose PE, which may have given rise to chance differences in detection due to generally low autopsy rates. Eliminating these 2 studies from the analysis resulted in loss of statistical significance for the reduction in risk for PE (RR = 0.48; 95% CI: 0.20‐1.15).

Death

Seven trials16, 2025 comparing either UFH or LMWH to control examined the impact of pharmacologic prophylaxis on death and found no significant difference between treated and untreated patients across all trials (RR = 0.92; 95% CI: 0.82‐1.03) and those limited to studies with Jadad scores of 3 or higher (RR = 0.97; 95% CI: 0.80‐1.17).

LMWH vs. UFH

DVT

In 6 trials14, 1719, 26, 27 comparing LMWH to UFH given either twice a day (BID) or 3 times a day (TID), there was no statistically significant difference in all DVT (RR = 0.90; 95% CI: 0.57‐1.43). (For all analyses RRs <1 favor LMWH, while RRs >1 favor UFH.) A total of 2 trials14, 18 reported results separately for proximal DVT with no statistically significant difference noted between UFH and LMWH (RR = 1.60; 95% CI: 0.53‐4.88). One small trial26 reported findings comparing UFH to LMWH for prevention of symptomatic DVT with no difference noted.

PE

Pooled data from the 5 trials14, 17, 18, 26, 27 comparing UFH to LMWH in the prevention of PE showed no statistically significant difference in rates of pulmonary embolism (RR = 0.82; 95% CI: 0.26‐2.63) (Figure 3B). In sensitivity analysis this result was not impacted by Jadad score.

Death

When UFH was compared to LMWH no statistically significant difference in the rate of death was found (RR = 0.96; 95% CI: 0.50‐1.85). Here again, no difference was noted when limited to studies with Jadad scores of 3 or higher.

Complications

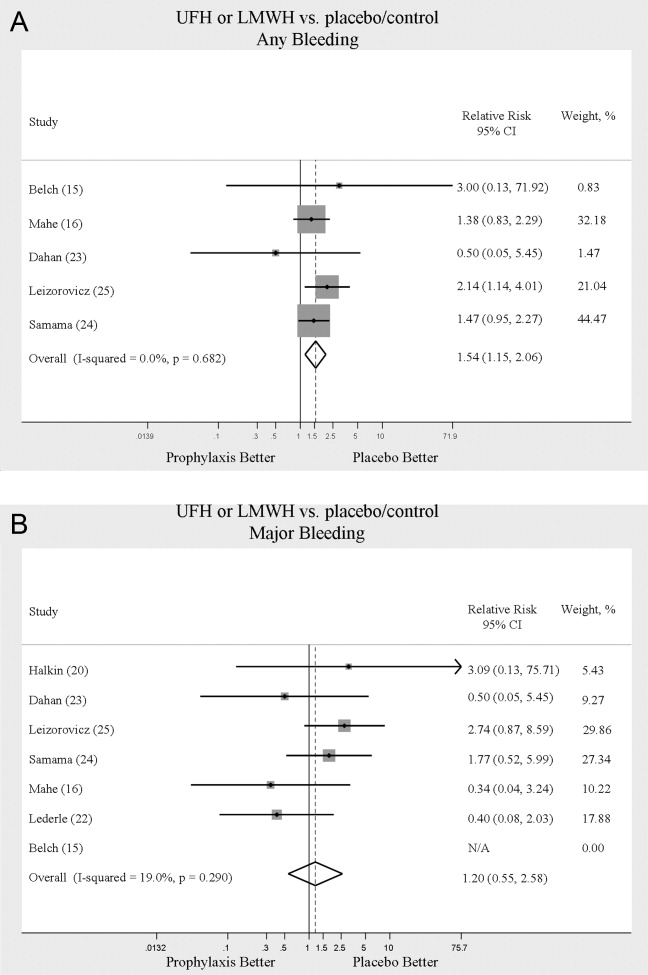

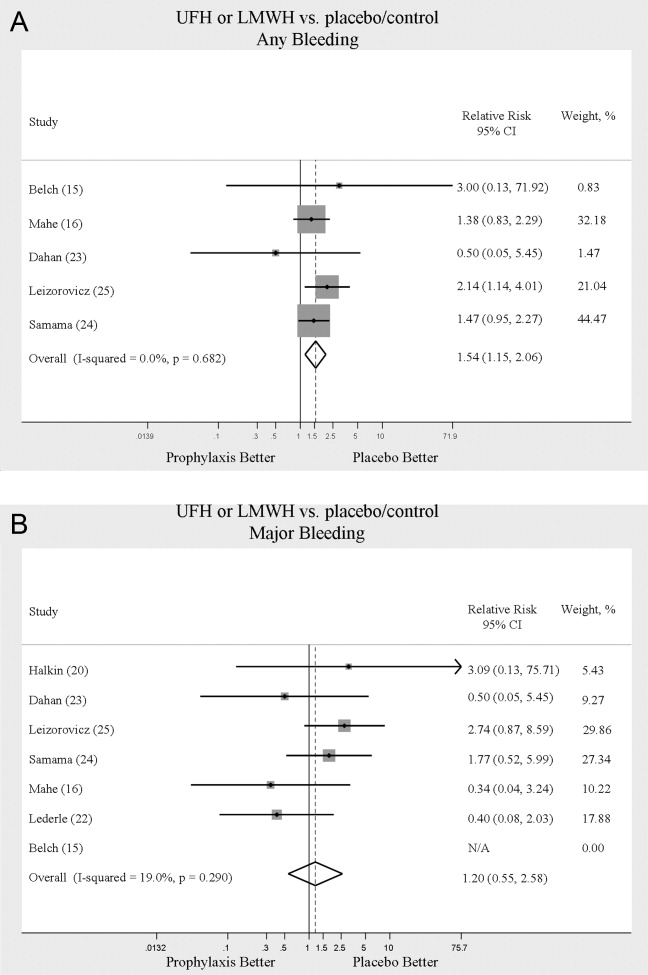

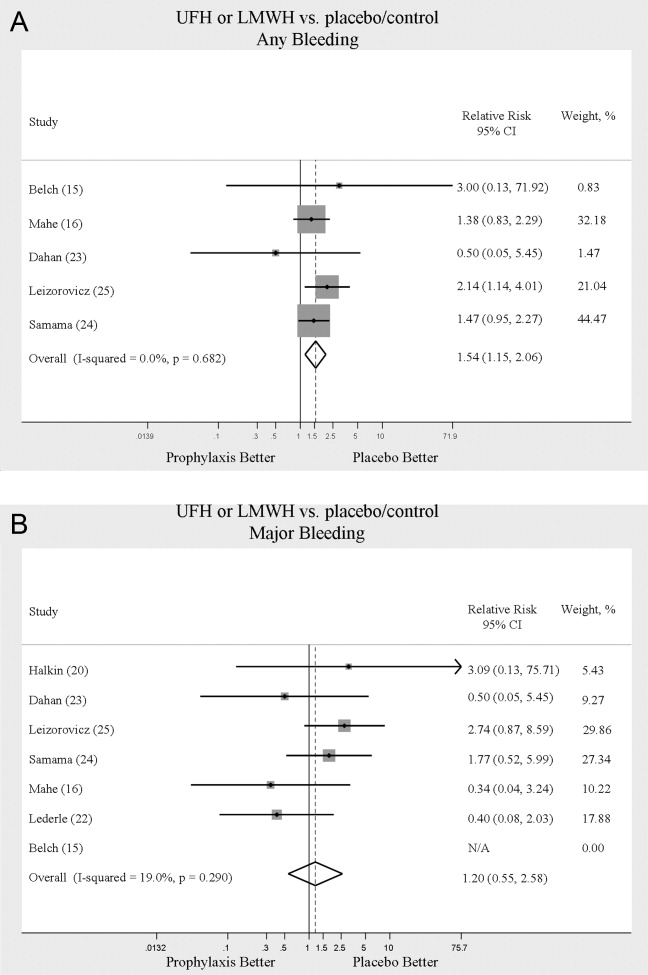

We evaluated adverse events of heparin products used for prophylaxis and whether there were differences between UFH and LMWH. Reporting of complications was not uniform from study to study, making pooling more difficult. However, we were able to abstract data on any bleeding, major bleeding, and thrombocytopenia from several studies. In 5 studies15, 16, 2325 of either UFH or LMWH vs. control, a significantly increased risk of any bleeding (RR = 1.54; 95% CI: 1.15‐2.06) (Figure 4A) was found. When only major bleeding was evaluated, no statistically significant difference was noted (RR = 1.20; 95% CI: 0.55‐2.58) (Figure 4B). In 4 trials16, 22, 24, 25 the occurrence of thrombocytopenia was not significantly different when comparing UFH or LMWH to control (RR = 0.92; 95% CI: 0.46‐1.86).

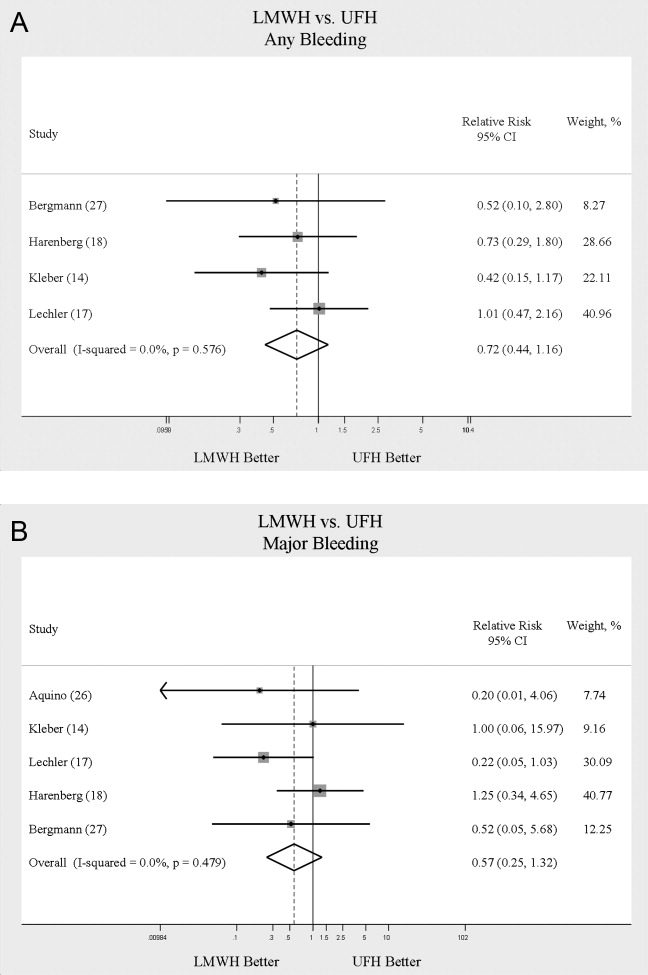

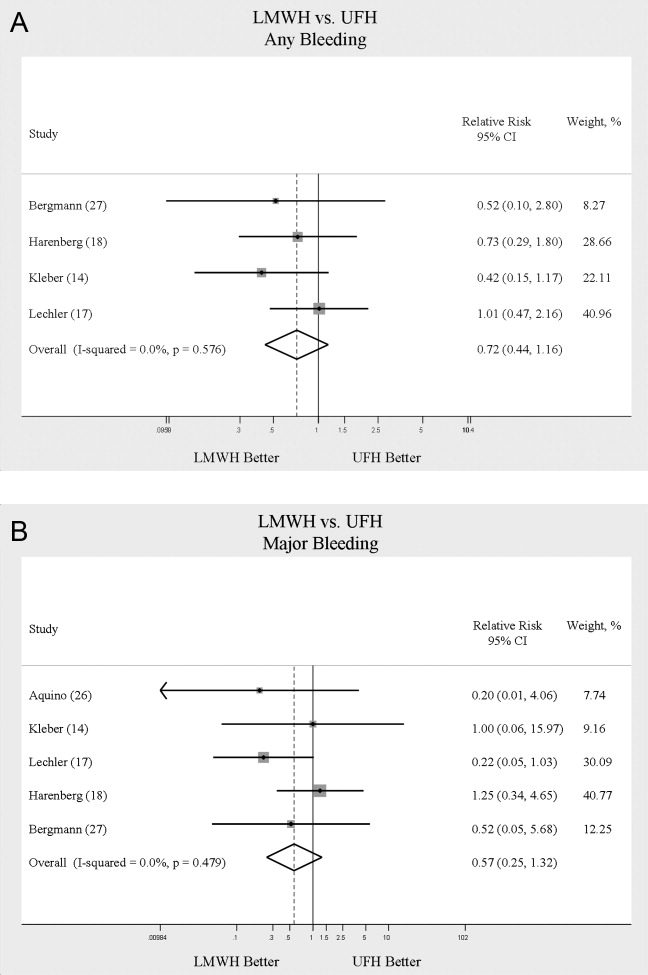

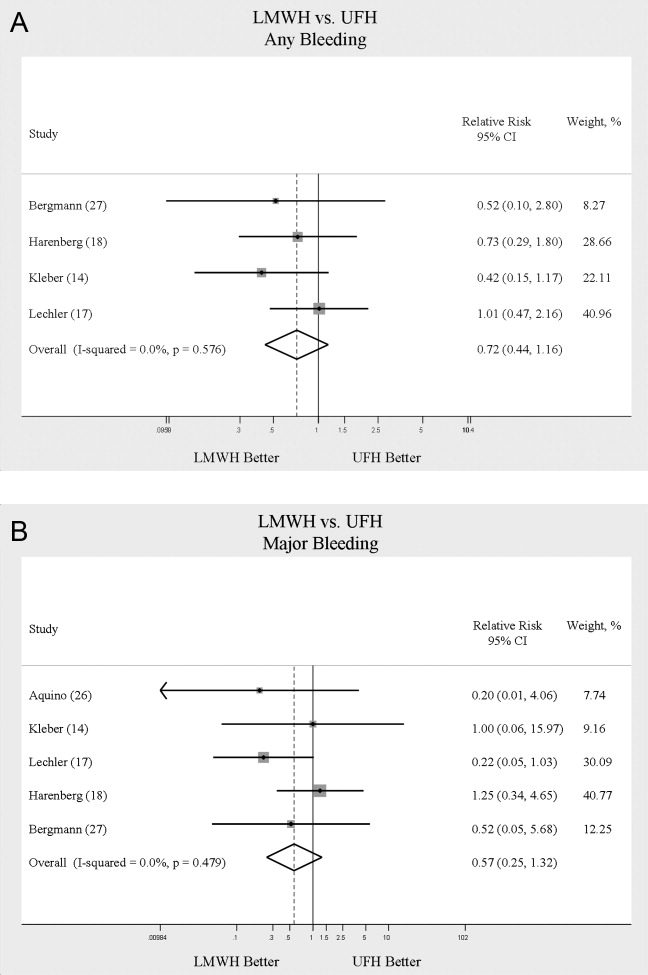

When LMWH was compared to UFH in 4 trials,14, 17, 18, 27 a nonsignificant trend toward a decrease in any bleeding was found in the LMWH group (RR = 0.72; 95% CI: 0.44‐1.16) (Figure 5A). A similar trend was seen favoring LMWH in rates of major bleeding (RR = 0.57; 95% CI: 0.25‐1.32) (Figure 5B). Neither trend was statistically significant. Three trials comparing LMWH to UFH reported on thrombocytopenia17, 18, 27 with no significant difference noted (RR = 0.52; 95% CI: 0.06‐4.18).

Heterogeneity and Publication Bias

No statistically significant heterogeneity was identified between trials for any outcomes. The highest I‐squared value was 54.5% (P = 0.14) for the endpoint of thrombocytopenia when UFH was compared to LMWH. In some cases, the nonsignificant results for tests of heterogeneity may have reflected small numbers of trials, but the values for I‐squared for all other endpoints were close to zero indicating that little nonrandom variation existed in the results across studies. All analyses were run using both random effects and fixed effects modeling. While we report results for random effects, no significant differences were observed using fixed effects.

We tested for publication bias using the methods developed by Egger et al.12 and Begg and Mazumdar.13 There was evidence of bias only for the outcome of PE when prophylaxis was compared to control, as the results for both tests were significant (Begg and Mazumdar:13 P = 0.035; Egger et al.:12 P = 0.010). For other outcomes tested, including all DVT (prophylaxis compared to control, and LMWH vs. UFH) as well as PE (LMWH vs. UFH), the P‐values were not significant.

DISCUSSION

When compared to control, LMWH or UFH decreased the risk of all DVT by 45% (RR = 0.55; 95% CI: 0.36‐0.83) and proximal DVT by 54% (RR = 0.46; 95% CI: 0.31‐0.69). PE was also decreased by 30% (RR = 0.70; 95% CI: 0.53‐0.93). Of note, when prophylaxis was compared with placebo all of the high‐quality studies showing a benefit were done using LMWH. The benefits of prophylaxis occurred at the cost of a 54% increased overall risk of bleeding (RR = 1.54; 95% CI 1.15‐2.06). However, the risk of major bleeding was not significantly increased. We did not find a mortality benefit to pharmacologic thromboembolism prophylaxis.

When comparing UFH to LMWH, we noted no difference in all DVT, symptomatic DVT, proximal DVT, PE, or death. While there was a trend toward less bleeding with LMWH, this was not statistically significant.

Taken in aggregate, our findings are in agreement with previous published meta‐analyses reporting net benefit for thromboembolism prophylaxis in medical patients.24, 22, 28, 29 Our meta‐analysis has several methodological strengths over the prior studies, including a comprehensive search of both the published and unpublished literature and assessment of the relationship between methodological quality of included trials and reported benefit. In contrast to previous reviews, our analysis highlights several limitations of the current evidence.

First, many of the studies are older, with predicted lengths of stay of greater than 1 week. The 8‐13‐day range of treatment duration we found in this study is longer than the average length of stay in today's hospitals. Second, there is variability in the diagnostic tests used to diagnose DVT, as well as variation in the definition of DVT among studies. Studies using fibrinogen uptake scanning reported rates of DVT as high as 26%15 while studies using venography reported DVT rates of almost 15% in the placebo arm.24 These rates are higher than most physicians' routine practice. One reason for this discrepancy is most studies did not distinguish below‐the‐knee DVT from more clinically relevant above‐the‐knee DVT. Systematic reviews of medical and surgical patients have found rates of proximal propagation from 0% to 29% in untreated patients.30, 31 Though controversial, below‐the‐knee DVT is believed less morbid than proximal DVT or symptomatic DVT. We addressed this by focusing specifically on clinically relevant endpoints of proximal and symptomatic DVT. When we restricted our analysis to proximal DVT we found a 54% RR reduction in 2 pooled trials of LMWH compared to placebo. In pooled analyses symptomatic DVT was not affected by prophylaxis. When compared head‐to‐head there were no differences between LMWH and UFH for proximal DVT or symptomatic DVT.

When considering PE, the utilization of autopsy as the sole diagnostic method in 2 large trials16, 21 is particularly problematic. In the trial by Garlund,21 the mortality rate was 5.4%, with an autopsy rate of 60.1%. Similarly, in the trial by Mahe et al.,16 the mortality rate was 10%, with an autopsy rate of 49%. Given the low absolute number of deaths and substantial proportion of decedents without autopsy, the potential for chance to produce an imbalance in detection of PE is high in these studies. When we excluded these 2 trials, we found that PE was no longer reduced to a statistically significant degree by prophylaxis. Loss of significance for PE in 2 sensitivity analyses (when excluding studies of lower quality, or using autopsy as a sole diagnostic study) is problematic and calls into question the true benefit of prophylaxis for prevention of PE.

Another limitation of the current literature centers on the variability of dosing used. We pooled trials of UFH whether given BID or TID. Given the small number of trials we did not do sensitivity analyses by dosage. A recent meta‐analysis3 found both doses are efficacious, while a recent review article32 suggested superiority of TID dosing. We believe the available literature does not clearly address this issue. Regarding comparisons of LMWH to UFH, dosing variability was also noted. The trial by Bergmann and Neuhart27 used enoxaparin 20 mg per day and found similar efficacy to UFH BID, while the Samama et al.24 trial found enoxaparin 20 mg per day no more efficacious than placebo. While the literature does not clearly define a best dose, we believe enoxaparin doses lower than 40 mg daily do not reflect the standard of care.

An additional limitation of the literature is publication bias. We assessed the possibility of publication bias by a variety of means. We did find statistical evidence of publication bias for the outcome of PE when prophylaxis was compared to control. Importantly, two meta‐analyses2, 4 on thromboembolism prophylaxis for general medicine patients suggested publication bias is present and our finding supports this conclusion. While no test for publication bias is foolproof, the best protection against publication bias, which we pursued in our study, consists of a thorough search for unpublished studies, including a search of conference proceedings, contact with experts in the field, and manufacturers of LMWH.

A final limitation of the current literature centers on risk assessment. All of the trials in this meta‐analysis included patients with an elevated level of risk. Unfortunately, risk was not clearly defined in many studies, and there was no minimum level of risk between trials. While immobility, age, and length of stay were reported for most studies, other risk factors such as personal history of thromboembolism and malignancy were not uniformly reported. Based on our analysis we are not confident our results can be extrapolated to all general medicine patients.

In conclusion, we found good evidence that pharmacologic prophylaxis significantly decreases the risk of all DVT and proximal DVT in at‐risk general medical patients. However, only LMWH was shown to prevent proximal DVT. We found inconclusive evidence that prophylaxis prevents PE. When compared directly we did not find clear superiority between UFH and LMWH, though several limitations of the current literature hamper decision‐making. Given the lower cost, it may seem justified to use UFH. However, there are other practical issues, such as the fact that LMWH is given once daily, and so potentially preferred by patients and more efficient for nurses. All of these results pertain to patients with elevated risk. While we did not find significant safety concerns with prophylaxis we do not know if these results can be extrapolated to lower‐risk patients. We believe that recommending widespread prophylaxis of all general medicine patients requires additional evidence about appropriate patient selection.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Emmanuelle Williams, MD, for translating articles from French; Claudia Figueroa, MS, for translating articles from Spanish; Vikas Gulani, MD, for translating articles from German; and Rebecca Lee, MS, for translating articles from German, Dutch, and Italian. In addition, the authors thank Dr. Dilzer from Pfizer Global Pharmaceuticals, Kathleen E. Moigis from Aventis, and Carol McCullen from Glaxo Smith Kline for their search for unpublished pharmaceutical trials of low molecular weight heparins. Finally, the authors thank the Veterans Administration/University of Michigan Patient Safety Enhancement Program for research support.

- ,,, et al.Prevention of venous thromboembolism: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy.Chest.2004;126(suppl):338S–400S.

- ,,,,.Pharmacological venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials.Arch Intern Med.2007;167(14):1476–1486.

- ,,,,.Twice vs three times daily heparin dosing for thromboembolism prophylaxis in the general medical population: a metaanalysis.Chest.2007;131(2):507–516.

- ,,,,.Meta‐analysis: anticoagulant prophylaxis to prevent symptomatic venous thromboembolism in hospitalized medical patients.Ann Intern Med.2007;146(4):278–288.

- National Quality Forum. National Consensus Standards for the Prevention and Care of Venous Thromboembolism (including Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism). Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/projects/completed/vte/index.asp. Accessed May2009.

- ,.A prospective registry of 5,451 patients with ultrasound‐confirmed deep vein thrombosis.Am J Cardiol.2004;93(2):259–262.

- ,,, et al.Venous thromboembolism risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE study): a multinational cross‐sectional study.Lancet.2008;371(9610):387–394.

- ,,,.Pharmacological thromboembolic prophylaxis in a medical ward: room for improvement.J Gen Intern Med.2002;17(10):788–791.

- ,,,.[Effectiveness of low molecular weight heparin (Fragmin) in the prevention of thromboembolism in internal medicine patients. A randomized double‐blind study].Med Klin (Munich).1988;83(7):241–245, 278.

- ,,, et al.Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary?Control Clin Trials.1996;17(1):1–12.

- ,.Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis.Stat Med.2002;21(11):1539–1558.

- ,,,.Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test.BMJ.1997;315(7109):629–634.

- ,.Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias.Biometrics.1994;50(4):1088–1101.

- ,,,,,.Randomized comparison of enoxaparin with unfractionated heparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in medical patients with heart failure or severe respiratory disease.Am Heart J.2003;145(4):614–621.

- ,,,,.Prevention of deep vein thrombosis in medical patients by low‐dose heparin.Scott Med J.1981;26(2):115–117.

- ,,,,.Lack of effect of a low‐molecular‐weight heparin (nadroparin) on mortality in bedridden medical in‐patients: a prospective randomised double‐blind study.Eur J Clin Pharmacol.2005;61(5‐6):347–351.

- ,,.The venous thrombotic risk in non‐surgical patients: epidemiological data and efficacy/safety profile of a low‐molecular‐weight heparin (enoxaparin). The Prime Study Group.Haemostasis.1996;26(suppl 2):49–56.

- ,,.Subcutaneous low‐molecular‐weight heparin versus standard heparin and the prevention of thromboembolism in medical inpatients. The Heparin Study in Internal Medicine Group.Haemostasis.1996;26(3):127–139.

- ,,, et al.Randomized controlled study of heparin and low molecular weight heparin for prevention of deep‐vein thrombosis in medical patients.Thromb Res.1990;59(3):639–650.

- ,,,.Reduction of mortality in general medical in‐patients by low‐dose heparin prophylaxis.Ann Intern Med.1982;96(5):561–565.

- .Randomised, controlled trial of low‐dose heparin for prevention of fatal pulmonary embolism in patients with infectious diseases. The Heparin Prophylaxis Study Group.Lancet.1996;347(9012):1357–1361.

- ,,, et al.The prophylaxis of medical patients for thromboembolism pilot study.Am J Med.2006;119(1):54–59.

- ,,, et al.Prevention of deep vein thrombosis in elderly medical in‐patients by a low molecular weight heparin: a randomized double‐blind trial.Haemostasis.1986;16(2):159–164.

- ,,, et al.A comparison of enoxaparin with placebo for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients. Prophylaxis in Medical Patients with Enoxaparin Study Group.N Engl J Med.1999;341(11):793–800.

- ,,,,,.Randomized, placebo‐controlled trial of dalteparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients.Circulation.2004;110(7):874–879.

- ,,.Prevention of thromboembolic accidents in elderly subjects with Fraxiparine. In: Bounameaux H, Samama MM, Ten Cate JW, eds.Fraxiaparine. 2nd International Symposium. Recent pharmacological and clinical data.New York:Schattauer;1990:51‐54.

- ,.A multicenter randomized double‐blind study of enoxaparin compared with unfractionated heparin in the prevention of venous thromboembolic disease in elderly in‐patients bedridden for an acute medical illness. The Enoxaparin in Medicine Study Group.Thromb Haemost.1996;76(4):529–534.

- ,,, et al.Prevention of venous thromboembolism in internal medicine with unfractionated or low‐molecular‐weight heparins: a meta‐analysis of randomised clinical trials.Thromb Haemost.2000;83(1):14–19.

- ,,,,.Meta‐analysis of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in medically Ill patients.Clin Ther.2007;29(11):2395–2405.

- ,,,,,.Clinical relevance of distal deep vein thrombosis. Review of literature data.Thromb Haemost.2006;95(1):56–64.

- .Natural history of venous thromboembolism.Circulation.2003;107(suppl 1):I22–I30.

- .Clinical practice. Prophylaxis for thromboembolism in hospitalized medical patients.N Engl J Med.2007;356(14):1438–1444.

Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), collectively referred to as venous thromboembolism (VTE), are common events in hospitalized patients and result in significant morbidity and mortality. Often silent and frequently unexpected, VTE is preventable. Accordingly, the American College of Chest Physicians recommends that pharmacologic prophylaxis be given to acutely ill medical patients admitted to the hospital with congestive heart failure or severe respiratory disease, or to patients who are confined to bed who have additional risk factors, such as cancer or previous VTE.1 Three recent meta‐analyses24 demonstrated significant reductions in VTE in general medicine patients with pharmacologic prophylaxis. Recently the National Quality Forum advocated that hospitals evaluate each patient upon admission and regularly thereafter, for the risk of developing DVT/VTE and utilize clinically appropriate methods to prevent DVT/VTE.5

Despite recommendations for prophylaxis, multiple studies demonstrate utilization in <50% of at‐risk general medical patients.68 Physicians' lack of awareness may partially explain this underutilization, but other likely factors include physicians' questions about the clinical importance of the outcome (eg, some studies have shown reductions primarily in asymptomatic distal DVT), doubt regarding the best form of prophylaxis (ie, unfractionated heparin [UFH] vs. low molecular weight heparin [LMWH]), uncertainty regarding optimal dosing regimens, and comparable uncertainty regarding which patients have sufficiently high risk for VTE to outweigh the risks of anticoagulation.

We undertook the current meta‐analysis to address questions about thromboembolism prevention in general medicine patients. Does pharmacologic prophylaxis prevent clinically relevant events? Is LMWH or UFH preferable in terms of either efficacy or safety?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search Strategy

We conducted an extensive search that included reviewing electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL) through June 2008, reviewing conference proceedings, and contacting drug manufacturers. The MEDLINE search combined the key words deep venous thrombosis, thromboembolism, AND pulmonary embolism with the terms primary prevention, prophylaxis, OR prevention. We limited the search results using the filter for randomized controlled trials in PubMed. Similar strategies (available on request) were used to search EMBASE, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. We also searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews to identify previous reviews on the same topic. We obtained translations of eligible, non‐English‐language articles.

The proceedings of annual meetings from the American Thoracic Society, the American Society of Hematology, and the Society for General Internal Medicine from 1994 to 2008 were hand‐searched for reports on DVT or PE prevention published in abstract form only. (Note: the American Society of Hematology was only available through 2007). We contacted the 3 main manufacturers of LMWHPfizer (dalteparin), Aventis (enoxaparin), Glaxo Smith Kline (nadoparin)and requested information on unpublished pharmaceutical sponsored trials. First authors from the trials included in this meta‐analysis were also contacted to determine if they knew of additional published or unpublished trials.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were required to be prospective randomized controlled trials comparing UFH or LMWH to mechanical prophylaxis, placebo, or no intervention. We also included randomized head‐to‐head comparisons of UFH and LMWH. Eligible studies enrolled general medical patients. Trials including predominantly intensive care unit (ICU) patients; stroke, spinal cord, or acute myocardial infarction patients were excluded. We excluded trials focused on these populations because the risk for VTE may differ from that for general medical patients and because patients in these groups already commonly receive anticoagulants as a preventive measure or as active treatment (eg, for acute myocardial infarction [MI] care). Trials assessing thrombosis in patients with long‐term central venous access/catheters were also excluded. Articles focusing on long‐term rehabilitation patients were excluded.

Studies had to employ objective criteria for diagnosing VTE. For DVT these included duplex ultrasonography, venography, fibrinogen uptake scanning, impedance plethysmography, or autopsy as a primary or secondary outcome. Studies utilizing thermographic techniques were excluded.9 Eligible diagnostic modalities for PE consisted of pulmonary arteriogram, ventilation/perfusion scan, CT angiography, and autopsy.

After an initial review of article titles and abstracts, the full texts of all articles that potentially met our inclusion criteria were independently reviewed for eligibility by 2 authors (G.M.B., M.D.). In cases of disagreement, a third author (S.F.) independently reviewed the article and adjudicated decisions.

Quantitative Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

For all included articles, 2 reviewers independently abstracted data on key study features (including population size, trial design, modality of VTE diagnosis, and interventions delivered to treatment and control groups), results (including the rates of all DVT, proximal DVT, symptomatic DVT, PE, and death), as well as adverse events (such as bleeding and thrombocytopenia). We accepted the endpoint of DVT when assessed by duplex ultrasonography, venography, autopsy, or when diagnosed by fibrinogen uptake scanning or impedance plethysmography. For all endpoints we abstracted event rates as number of events based on intention to treat. Each study was assessed for quality using the Jadad scale.10 The Jadad scale is a validated tool for characterizing study quality that accounts for randomization, blinding, and description of withdrawals and dropouts in individual trials. The Jadad score ranges from 0 to 5 with higher numbers identifying trials of greater methodological rigor.

The trials were divided into 4 groups based on the prophylaxis agent used and the method of comparison (UFH vs. control, LMWH vs. control, LMWH vs. UFH, and LMWH/UFH combined vs. control). After combining trials for each group, we calculated a pooled relative risk (RR) and a 95% confidence interval (CI) based on both fixed and a random effects model using the DerSimonian and Laird method. Heterogeneity of the included studies was evaluated with a chi‐square statistic. The percentage of variation in the pooled RR attributable to heterogeneity was calculated and reported using the I‐squared statistic.11 Sensitivity analyses were performed and included repeating all analyses using high‐quality studies only (Jadad score 3 or higher). Publication bias was assessed using the methods developed by Egger et al.12 and Begg and Mazumdar.13 All analyses were performed using STATA SE version 9 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Study Identification and Selection

The computerized literature search resulted in 5284 articles. Three additional citations were found by review of bibliographies. No additional trials were identified from reviews of abstracts from national meetings. Representatives from the 3 pharmaceutical companies reported no knowledge of additional published or unpublished data. Of the 5287 studies identified by the search, 14 studies met all eligibility criteria (Figure 1).

Study Characteristics

The 14 trials eligible for inclusion in the analysis consisted of 8 comparisons of UFH or LMWH vs. control (Table 1) and 6 head‐to‐head comparisons of UFH and LMWH (Table 2). The 14 studies included 8 multicenter trials and enrolled a total of 24,515 patients: 20,594 in the 8 trials that compared UFH or LMWH with placebo and 3921 in the 6 trials that compared LMWH with UFH. Two trials exclusively enrolled patients with either congestive heart failure or severe respiratory disease,14, 15 while 12 trials enrolled mixed populations. In 8 trials a period of immobility was necessary for study entry,14, 1621 while in 2 trials immobility was not required.22, 23 In the 4 remaining trials immobility was not explicitly discussed.15, 2426 One‐half of the trials required a length of stay greater than 3 days.1719, 2225

| Study (Year)Reference | Patients (n) | Duration (days) | VTE Risk Factors | Drug Dose | Comparison | DVT Assessed | PE Assessed | Double Blind | Jadad Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Belch et al. (1981)15 | 100 | 8 | Age 40‐80 years; CHF; chest infection | UFH TID | None | FUS | VQ | No | 1 |

| Dahan et al. (1986)23 | 270 | 10* | Age >65 years | Enoxaparin 60 mg | Placebo | FUS | Autopsy | Yes | 3 |

| Halkin et al. (1982)20 | 1358 | Not reported | Age >40 years; immobile | UFH BID | None | No | No | No | 1 |

| Mahe et al. (2005)16 | 2474 | 13.08 | Age >40 years; immobile | Nadroparin 7500 IU | Placebo | Autopsy | Autopsy | Yes | 5 |

| Gardlund (1996)21 | 11693 | 8.2 | Age >55 years; immobile | UFH BID | None | Autopsy | Autopsy | No | 2 |

| Samama et al. (1999)24 | 738 | 7 | Age >40 years; length of stay 6 days; CHF; respiratory failure or 1 additional risk factor | Enoxaparin 40 mg | Placebo | Venography | Composite | Yes | 4 |

| Leizorovicz et al. (2004)25 | 3681 | 12.6 | Age >40 years; length of stay 4 days; CHF; respiratory failure or 1 additional risk factor | Dalteparin 5000 IU | Placebo | DUS | Composite | Yes | 4 |

| Lederle et al. (2006)22 | 280 | 13.4 | Age >60 years; length of stay 3 days | Enoxaparin 40 mg | Placebo | DUS | Composite | Yes | 5 |

| Study (Year)reference | Patients (n) | Duration (days) | VTE Risk Factors | Drug/Dose | Comparison | DVT Assessed | PE Assessed | Double Blind | Jadad Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Bergmann and Neuhart (1996)27 | 442 | 9.5 | Age >65 years; immobile | Enoxaparin 20 mg | UFH BID | FUS | Composite | Yes | 5 |

| Harenberg et al. (1990)19 | 166 | 10* | Age 40‐80 years; 1 week of bed rest | LMWH 1.500 aPTT units QD | UFH TID | IP | No | Yes | 3 |

| Kleber et al. (2003)14 | 665 | 9.8 | Age 18 years; severe CHF or respiratory disease; immobile | Enoxaparin 40 mg | UFH TID | Venography | Composite | No | 3 |

| Aquino et al. (1990)26 | 99 | Not reported | Age >70 years | Nadoparine 7500 IU | UFH BID | DUS | Composite | No | 1 |

| Harenberg et al. (1996)18 | 1590 | 10* | Age 50‐80 years; immobile + 1 additional risk factor | Nadoparine 36 mg | UFH TID | DUS | Composite | Yes | 4 |

| Lechler et al. (1996)17 | 959 | 7* | Age >18 years; immobile + 1 additional risk factor | Enoxaparin 40 mg | UFH TID | DUS | Composite | Yes | 3 |

While minimum age for study entry varied, the patient population predominantly ranged from 65 to 85 years of age. Many of the trials reported expected, not actual, treatment duration. The range of expected treatment was 7 to 21 days, with 10 days of treatment the most frequently mentioned. In the 8 trials1416, 21, 22, 24, 25, 27 that reported actual treatment duration, the range was 8 to 13.4 days. Most trials did not report number of VTE risk factors per patient, nor was there uniform acceptance of risk factors across trials.

UFH or LMWH vs. Control

DVT

Across 7 trials comparing either UFH or LMWH to control, heparin products significantly decreased the risk of all DVT (RR = 0.55; 95% CI: 0.36‐0.83) (Figure 2A). When stratified by methodological quality, 5 trials16, 2225 with Jadad scores of 3 or higher showed an RR reduction of 0.53 (95% CI: 0.38‐0.72) in reducing all DVT. All of the higher‐quality trials compared LMWH to placebo. Across 4 trials that reported data for symptomatic DVT there was a nonsignificant reduction in RR compared with placebo (RR = 0.73; 95% CI: 0.45‐1.16) (Figure 2B). Only 2 trials24, 25 (both LMWH trials) reported results for proximal DVT and demonstrated significant benefit of prophylaxis with a pooled RR of 0.46 (95% CI: 0.31‐0.69) (Figure 2C).

PE

Across 7 trials comparing either UFH or LMWH to control, heparin products significantly decreased the risk of PE (RR = 0.70; 95% CI: 0.53‐0.93) (Figure 3A). The 5 trials16, 2225 with Jadad scores of 3 or greater showed a similar relative risk reduction, but the result was no longer statistically significant (RR = 0.56; 95% CI: 0.31‐1.02). Two of the trials16, 21 relied solely on the results of autopsy to diagnose PE, which may have given rise to chance differences in detection due to generally low autopsy rates. Eliminating these 2 studies from the analysis resulted in loss of statistical significance for the reduction in risk for PE (RR = 0.48; 95% CI: 0.20‐1.15).

Death

Seven trials16, 2025 comparing either UFH or LMWH to control examined the impact of pharmacologic prophylaxis on death and found no significant difference between treated and untreated patients across all trials (RR = 0.92; 95% CI: 0.82‐1.03) and those limited to studies with Jadad scores of 3 or higher (RR = 0.97; 95% CI: 0.80‐1.17).

LMWH vs. UFH

DVT

In 6 trials14, 1719, 26, 27 comparing LMWH to UFH given either twice a day (BID) or 3 times a day (TID), there was no statistically significant difference in all DVT (RR = 0.90; 95% CI: 0.57‐1.43). (For all analyses RRs <1 favor LMWH, while RRs >1 favor UFH.) A total of 2 trials14, 18 reported results separately for proximal DVT with no statistically significant difference noted between UFH and LMWH (RR = 1.60; 95% CI: 0.53‐4.88). One small trial26 reported findings comparing UFH to LMWH for prevention of symptomatic DVT with no difference noted.

PE

Pooled data from the 5 trials14, 17, 18, 26, 27 comparing UFH to LMWH in the prevention of PE showed no statistically significant difference in rates of pulmonary embolism (RR = 0.82; 95% CI: 0.26‐2.63) (Figure 3B). In sensitivity analysis this result was not impacted by Jadad score.

Death

When UFH was compared to LMWH no statistically significant difference in the rate of death was found (RR = 0.96; 95% CI: 0.50‐1.85). Here again, no difference was noted when limited to studies with Jadad scores of 3 or higher.

Complications

We evaluated adverse events of heparin products used for prophylaxis and whether there were differences between UFH and LMWH. Reporting of complications was not uniform from study to study, making pooling more difficult. However, we were able to abstract data on any bleeding, major bleeding, and thrombocytopenia from several studies. In 5 studies15, 16, 2325 of either UFH or LMWH vs. control, a significantly increased risk of any bleeding (RR = 1.54; 95% CI: 1.15‐2.06) (Figure 4A) was found. When only major bleeding was evaluated, no statistically significant difference was noted (RR = 1.20; 95% CI: 0.55‐2.58) (Figure 4B). In 4 trials16, 22, 24, 25 the occurrence of thrombocytopenia was not significantly different when comparing UFH or LMWH to control (RR = 0.92; 95% CI: 0.46‐1.86).

When LMWH was compared to UFH in 4 trials,14, 17, 18, 27 a nonsignificant trend toward a decrease in any bleeding was found in the LMWH group (RR = 0.72; 95% CI: 0.44‐1.16) (Figure 5A). A similar trend was seen favoring LMWH in rates of major bleeding (RR = 0.57; 95% CI: 0.25‐1.32) (Figure 5B). Neither trend was statistically significant. Three trials comparing LMWH to UFH reported on thrombocytopenia17, 18, 27 with no significant difference noted (RR = 0.52; 95% CI: 0.06‐4.18).

Heterogeneity and Publication Bias

No statistically significant heterogeneity was identified between trials for any outcomes. The highest I‐squared value was 54.5% (P = 0.14) for the endpoint of thrombocytopenia when UFH was compared to LMWH. In some cases, the nonsignificant results for tests of heterogeneity may have reflected small numbers of trials, but the values for I‐squared for all other endpoints were close to zero indicating that little nonrandom variation existed in the results across studies. All analyses were run using both random effects and fixed effects modeling. While we report results for random effects, no significant differences were observed using fixed effects.

We tested for publication bias using the methods developed by Egger et al.12 and Begg and Mazumdar.13 There was evidence of bias only for the outcome of PE when prophylaxis was compared to control, as the results for both tests were significant (Begg and Mazumdar:13 P = 0.035; Egger et al.:12 P = 0.010). For other outcomes tested, including all DVT (prophylaxis compared to control, and LMWH vs. UFH) as well as PE (LMWH vs. UFH), the P‐values were not significant.

DISCUSSION

When compared to control, LMWH or UFH decreased the risk of all DVT by 45% (RR = 0.55; 95% CI: 0.36‐0.83) and proximal DVT by 54% (RR = 0.46; 95% CI: 0.31‐0.69). PE was also decreased by 30% (RR = 0.70; 95% CI: 0.53‐0.93). Of note, when prophylaxis was compared with placebo all of the high‐quality studies showing a benefit were done using LMWH. The benefits of prophylaxis occurred at the cost of a 54% increased overall risk of bleeding (RR = 1.54; 95% CI 1.15‐2.06). However, the risk of major bleeding was not significantly increased. We did not find a mortality benefit to pharmacologic thromboembolism prophylaxis.

When comparing UFH to LMWH, we noted no difference in all DVT, symptomatic DVT, proximal DVT, PE, or death. While there was a trend toward less bleeding with LMWH, this was not statistically significant.

Taken in aggregate, our findings are in agreement with previous published meta‐analyses reporting net benefit for thromboembolism prophylaxis in medical patients.24, 22, 28, 29 Our meta‐analysis has several methodological strengths over the prior studies, including a comprehensive search of both the published and unpublished literature and assessment of the relationship between methodological quality of included trials and reported benefit. In contrast to previous reviews, our analysis highlights several limitations of the current evidence.

First, many of the studies are older, with predicted lengths of stay of greater than 1 week. The 8‐13‐day range of treatment duration we found in this study is longer than the average length of stay in today's hospitals. Second, there is variability in the diagnostic tests used to diagnose DVT, as well as variation in the definition of DVT among studies. Studies using fibrinogen uptake scanning reported rates of DVT as high as 26%15 while studies using venography reported DVT rates of almost 15% in the placebo arm.24 These rates are higher than most physicians' routine practice. One reason for this discrepancy is most studies did not distinguish below‐the‐knee DVT from more clinically relevant above‐the‐knee DVT. Systematic reviews of medical and surgical patients have found rates of proximal propagation from 0% to 29% in untreated patients.30, 31 Though controversial, below‐the‐knee DVT is believed less morbid than proximal DVT or symptomatic DVT. We addressed this by focusing specifically on clinically relevant endpoints of proximal and symptomatic DVT. When we restricted our analysis to proximal DVT we found a 54% RR reduction in 2 pooled trials of LMWH compared to placebo. In pooled analyses symptomatic DVT was not affected by prophylaxis. When compared head‐to‐head there were no differences between LMWH and UFH for proximal DVT or symptomatic DVT.

When considering PE, the utilization of autopsy as the sole diagnostic method in 2 large trials16, 21 is particularly problematic. In the trial by Garlund,21 the mortality rate was 5.4%, with an autopsy rate of 60.1%. Similarly, in the trial by Mahe et al.,16 the mortality rate was 10%, with an autopsy rate of 49%. Given the low absolute number of deaths and substantial proportion of decedents without autopsy, the potential for chance to produce an imbalance in detection of PE is high in these studies. When we excluded these 2 trials, we found that PE was no longer reduced to a statistically significant degree by prophylaxis. Loss of significance for PE in 2 sensitivity analyses (when excluding studies of lower quality, or using autopsy as a sole diagnostic study) is problematic and calls into question the true benefit of prophylaxis for prevention of PE.

Another limitation of the current literature centers on the variability of dosing used. We pooled trials of UFH whether given BID or TID. Given the small number of trials we did not do sensitivity analyses by dosage. A recent meta‐analysis3 found both doses are efficacious, while a recent review article32 suggested superiority of TID dosing. We believe the available literature does not clearly address this issue. Regarding comparisons of LMWH to UFH, dosing variability was also noted. The trial by Bergmann and Neuhart27 used enoxaparin 20 mg per day and found similar efficacy to UFH BID, while the Samama et al.24 trial found enoxaparin 20 mg per day no more efficacious than placebo. While the literature does not clearly define a best dose, we believe enoxaparin doses lower than 40 mg daily do not reflect the standard of care.

An additional limitation of the literature is publication bias. We assessed the possibility of publication bias by a variety of means. We did find statistical evidence of publication bias for the outcome of PE when prophylaxis was compared to control. Importantly, two meta‐analyses2, 4 on thromboembolism prophylaxis for general medicine patients suggested publication bias is present and our finding supports this conclusion. While no test for publication bias is foolproof, the best protection against publication bias, which we pursued in our study, consists of a thorough search for unpublished studies, including a search of conference proceedings, contact with experts in the field, and manufacturers of LMWH.

A final limitation of the current literature centers on risk assessment. All of the trials in this meta‐analysis included patients with an elevated level of risk. Unfortunately, risk was not clearly defined in many studies, and there was no minimum level of risk between trials. While immobility, age, and length of stay were reported for most studies, other risk factors such as personal history of thromboembolism and malignancy were not uniformly reported. Based on our analysis we are not confident our results can be extrapolated to all general medicine patients.

In conclusion, we found good evidence that pharmacologic prophylaxis significantly decreases the risk of all DVT and proximal DVT in at‐risk general medical patients. However, only LMWH was shown to prevent proximal DVT. We found inconclusive evidence that prophylaxis prevents PE. When compared directly we did not find clear superiority between UFH and LMWH, though several limitations of the current literature hamper decision‐making. Given the lower cost, it may seem justified to use UFH. However, there are other practical issues, such as the fact that LMWH is given once daily, and so potentially preferred by patients and more efficient for nurses. All of these results pertain to patients with elevated risk. While we did not find significant safety concerns with prophylaxis we do not know if these results can be extrapolated to lower‐risk patients. We believe that recommending widespread prophylaxis of all general medicine patients requires additional evidence about appropriate patient selection.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Emmanuelle Williams, MD, for translating articles from French; Claudia Figueroa, MS, for translating articles from Spanish; Vikas Gulani, MD, for translating articles from German; and Rebecca Lee, MS, for translating articles from German, Dutch, and Italian. In addition, the authors thank Dr. Dilzer from Pfizer Global Pharmaceuticals, Kathleen E. Moigis from Aventis, and Carol McCullen from Glaxo Smith Kline for their search for unpublished pharmaceutical trials of low molecular weight heparins. Finally, the authors thank the Veterans Administration/University of Michigan Patient Safety Enhancement Program for research support.

Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), collectively referred to as venous thromboembolism (VTE), are common events in hospitalized patients and result in significant morbidity and mortality. Often silent and frequently unexpected, VTE is preventable. Accordingly, the American College of Chest Physicians recommends that pharmacologic prophylaxis be given to acutely ill medical patients admitted to the hospital with congestive heart failure or severe respiratory disease, or to patients who are confined to bed who have additional risk factors, such as cancer or previous VTE.1 Three recent meta‐analyses24 demonstrated significant reductions in VTE in general medicine patients with pharmacologic prophylaxis. Recently the National Quality Forum advocated that hospitals evaluate each patient upon admission and regularly thereafter, for the risk of developing DVT/VTE and utilize clinically appropriate methods to prevent DVT/VTE.5

Despite recommendations for prophylaxis, multiple studies demonstrate utilization in <50% of at‐risk general medical patients.68 Physicians' lack of awareness may partially explain this underutilization, but other likely factors include physicians' questions about the clinical importance of the outcome (eg, some studies have shown reductions primarily in asymptomatic distal DVT), doubt regarding the best form of prophylaxis (ie, unfractionated heparin [UFH] vs. low molecular weight heparin [LMWH]), uncertainty regarding optimal dosing regimens, and comparable uncertainty regarding which patients have sufficiently high risk for VTE to outweigh the risks of anticoagulation.

We undertook the current meta‐analysis to address questions about thromboembolism prevention in general medicine patients. Does pharmacologic prophylaxis prevent clinically relevant events? Is LMWH or UFH preferable in terms of either efficacy or safety?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search Strategy

We conducted an extensive search that included reviewing electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL) through June 2008, reviewing conference proceedings, and contacting drug manufacturers. The MEDLINE search combined the key words deep venous thrombosis, thromboembolism, AND pulmonary embolism with the terms primary prevention, prophylaxis, OR prevention. We limited the search results using the filter for randomized controlled trials in PubMed. Similar strategies (available on request) were used to search EMBASE, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. We also searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews to identify previous reviews on the same topic. We obtained translations of eligible, non‐English‐language articles.

The proceedings of annual meetings from the American Thoracic Society, the American Society of Hematology, and the Society for General Internal Medicine from 1994 to 2008 were hand‐searched for reports on DVT or PE prevention published in abstract form only. (Note: the American Society of Hematology was only available through 2007). We contacted the 3 main manufacturers of LMWHPfizer (dalteparin), Aventis (enoxaparin), Glaxo Smith Kline (nadoparin)and requested information on unpublished pharmaceutical sponsored trials. First authors from the trials included in this meta‐analysis were also contacted to determine if they knew of additional published or unpublished trials.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were required to be prospective randomized controlled trials comparing UFH or LMWH to mechanical prophylaxis, placebo, or no intervention. We also included randomized head‐to‐head comparisons of UFH and LMWH. Eligible studies enrolled general medical patients. Trials including predominantly intensive care unit (ICU) patients; stroke, spinal cord, or acute myocardial infarction patients were excluded. We excluded trials focused on these populations because the risk for VTE may differ from that for general medical patients and because patients in these groups already commonly receive anticoagulants as a preventive measure or as active treatment (eg, for acute myocardial infarction [MI] care). Trials assessing thrombosis in patients with long‐term central venous access/catheters were also excluded. Articles focusing on long‐term rehabilitation patients were excluded.

Studies had to employ objective criteria for diagnosing VTE. For DVT these included duplex ultrasonography, venography, fibrinogen uptake scanning, impedance plethysmography, or autopsy as a primary or secondary outcome. Studies utilizing thermographic techniques were excluded.9 Eligible diagnostic modalities for PE consisted of pulmonary arteriogram, ventilation/perfusion scan, CT angiography, and autopsy.

After an initial review of article titles and abstracts, the full texts of all articles that potentially met our inclusion criteria were independently reviewed for eligibility by 2 authors (G.M.B., M.D.). In cases of disagreement, a third author (S.F.) independently reviewed the article and adjudicated decisions.

Quantitative Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

For all included articles, 2 reviewers independently abstracted data on key study features (including population size, trial design, modality of VTE diagnosis, and interventions delivered to treatment and control groups), results (including the rates of all DVT, proximal DVT, symptomatic DVT, PE, and death), as well as adverse events (such as bleeding and thrombocytopenia). We accepted the endpoint of DVT when assessed by duplex ultrasonography, venography, autopsy, or when diagnosed by fibrinogen uptake scanning or impedance plethysmography. For all endpoints we abstracted event rates as number of events based on intention to treat. Each study was assessed for quality using the Jadad scale.10 The Jadad scale is a validated tool for characterizing study quality that accounts for randomization, blinding, and description of withdrawals and dropouts in individual trials. The Jadad score ranges from 0 to 5 with higher numbers identifying trials of greater methodological rigor.

The trials were divided into 4 groups based on the prophylaxis agent used and the method of comparison (UFH vs. control, LMWH vs. control, LMWH vs. UFH, and LMWH/UFH combined vs. control). After combining trials for each group, we calculated a pooled relative risk (RR) and a 95% confidence interval (CI) based on both fixed and a random effects model using the DerSimonian and Laird method. Heterogeneity of the included studies was evaluated with a chi‐square statistic. The percentage of variation in the pooled RR attributable to heterogeneity was calculated and reported using the I‐squared statistic.11 Sensitivity analyses were performed and included repeating all analyses using high‐quality studies only (Jadad score 3 or higher). Publication bias was assessed using the methods developed by Egger et al.12 and Begg and Mazumdar.13 All analyses were performed using STATA SE version 9 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Study Identification and Selection

The computerized literature search resulted in 5284 articles. Three additional citations were found by review of bibliographies. No additional trials were identified from reviews of abstracts from national meetings. Representatives from the 3 pharmaceutical companies reported no knowledge of additional published or unpublished data. Of the 5287 studies identified by the search, 14 studies met all eligibility criteria (Figure 1).

Study Characteristics

The 14 trials eligible for inclusion in the analysis consisted of 8 comparisons of UFH or LMWH vs. control (Table 1) and 6 head‐to‐head comparisons of UFH and LMWH (Table 2). The 14 studies included 8 multicenter trials and enrolled a total of 24,515 patients: 20,594 in the 8 trials that compared UFH or LMWH with placebo and 3921 in the 6 trials that compared LMWH with UFH. Two trials exclusively enrolled patients with either congestive heart failure or severe respiratory disease,14, 15 while 12 trials enrolled mixed populations. In 8 trials a period of immobility was necessary for study entry,14, 1621 while in 2 trials immobility was not required.22, 23 In the 4 remaining trials immobility was not explicitly discussed.15, 2426 One‐half of the trials required a length of stay greater than 3 days.1719, 2225

| Study (Year)Reference | Patients (n) | Duration (days) | VTE Risk Factors | Drug Dose | Comparison | DVT Assessed | PE Assessed | Double Blind | Jadad Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Belch et al. (1981)15 | 100 | 8 | Age 40‐80 years; CHF; chest infection | UFH TID | None | FUS | VQ | No | 1 |

| Dahan et al. (1986)23 | 270 | 10* | Age >65 years | Enoxaparin 60 mg | Placebo | FUS | Autopsy | Yes | 3 |

| Halkin et al. (1982)20 | 1358 | Not reported | Age >40 years; immobile | UFH BID | None | No | No | No | 1 |

| Mahe et al. (2005)16 | 2474 | 13.08 | Age >40 years; immobile | Nadroparin 7500 IU | Placebo | Autopsy | Autopsy | Yes | 5 |

| Gardlund (1996)21 | 11693 | 8.2 | Age >55 years; immobile | UFH BID | None | Autopsy | Autopsy | No | 2 |

| Samama et al. (1999)24 | 738 | 7 | Age >40 years; length of stay 6 days; CHF; respiratory failure or 1 additional risk factor | Enoxaparin 40 mg | Placebo | Venography | Composite | Yes | 4 |

| Leizorovicz et al. (2004)25 | 3681 | 12.6 | Age >40 years; length of stay 4 days; CHF; respiratory failure or 1 additional risk factor | Dalteparin 5000 IU | Placebo | DUS | Composite | Yes | 4 |

| Lederle et al. (2006)22 | 280 | 13.4 | Age >60 years; length of stay 3 days | Enoxaparin 40 mg | Placebo | DUS | Composite | Yes | 5 |

| Study (Year)reference | Patients (n) | Duration (days) | VTE Risk Factors | Drug/Dose | Comparison | DVT Assessed | PE Assessed | Double Blind | Jadad Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Bergmann and Neuhart (1996)27 | 442 | 9.5 | Age >65 years; immobile | Enoxaparin 20 mg | UFH BID | FUS | Composite | Yes | 5 |

| Harenberg et al. (1990)19 | 166 | 10* | Age 40‐80 years; 1 week of bed rest | LMWH 1.500 aPTT units QD | UFH TID | IP | No | Yes | 3 |

| Kleber et al. (2003)14 | 665 | 9.8 | Age 18 years; severe CHF or respiratory disease; immobile | Enoxaparin 40 mg | UFH TID | Venography | Composite | No | 3 |

| Aquino et al. (1990)26 | 99 | Not reported | Age >70 years | Nadoparine 7500 IU | UFH BID | DUS | Composite | No | 1 |

| Harenberg et al. (1996)18 | 1590 | 10* | Age 50‐80 years; immobile + 1 additional risk factor | Nadoparine 36 mg | UFH TID | DUS | Composite | Yes | 4 |

| Lechler et al. (1996)17 | 959 | 7* | Age >18 years; immobile + 1 additional risk factor | Enoxaparin 40 mg | UFH TID | DUS | Composite | Yes | 3 |

While minimum age for study entry varied, the patient population predominantly ranged from 65 to 85 years of age. Many of the trials reported expected, not actual, treatment duration. The range of expected treatment was 7 to 21 days, with 10 days of treatment the most frequently mentioned. In the 8 trials1416, 21, 22, 24, 25, 27 that reported actual treatment duration, the range was 8 to 13.4 days. Most trials did not report number of VTE risk factors per patient, nor was there uniform acceptance of risk factors across trials.

UFH or LMWH vs. Control

DVT

Across 7 trials comparing either UFH or LMWH to control, heparin products significantly decreased the risk of all DVT (RR = 0.55; 95% CI: 0.36‐0.83) (Figure 2A). When stratified by methodological quality, 5 trials16, 2225 with Jadad scores of 3 or higher showed an RR reduction of 0.53 (95% CI: 0.38‐0.72) in reducing all DVT. All of the higher‐quality trials compared LMWH to placebo. Across 4 trials that reported data for symptomatic DVT there was a nonsignificant reduction in RR compared with placebo (RR = 0.73; 95% CI: 0.45‐1.16) (Figure 2B). Only 2 trials24, 25 (both LMWH trials) reported results for proximal DVT and demonstrated significant benefit of prophylaxis with a pooled RR of 0.46 (95% CI: 0.31‐0.69) (Figure 2C).

PE

Across 7 trials comparing either UFH or LMWH to control, heparin products significantly decreased the risk of PE (RR = 0.70; 95% CI: 0.53‐0.93) (Figure 3A). The 5 trials16, 2225 with Jadad scores of 3 or greater showed a similar relative risk reduction, but the result was no longer statistically significant (RR = 0.56; 95% CI: 0.31‐1.02). Two of the trials16, 21 relied solely on the results of autopsy to diagnose PE, which may have given rise to chance differences in detection due to generally low autopsy rates. Eliminating these 2 studies from the analysis resulted in loss of statistical significance for the reduction in risk for PE (RR = 0.48; 95% CI: 0.20‐1.15).

Death

Seven trials16, 2025 comparing either UFH or LMWH to control examined the impact of pharmacologic prophylaxis on death and found no significant difference between treated and untreated patients across all trials (RR = 0.92; 95% CI: 0.82‐1.03) and those limited to studies with Jadad scores of 3 or higher (RR = 0.97; 95% CI: 0.80‐1.17).

LMWH vs. UFH

DVT

In 6 trials14, 1719, 26, 27 comparing LMWH to UFH given either twice a day (BID) or 3 times a day (TID), there was no statistically significant difference in all DVT (RR = 0.90; 95% CI: 0.57‐1.43). (For all analyses RRs <1 favor LMWH, while RRs >1 favor UFH.) A total of 2 trials14, 18 reported results separately for proximal DVT with no statistically significant difference noted between UFH and LMWH (RR = 1.60; 95% CI: 0.53‐4.88). One small trial26 reported findings comparing UFH to LMWH for prevention of symptomatic DVT with no difference noted.

PE

Pooled data from the 5 trials14, 17, 18, 26, 27 comparing UFH to LMWH in the prevention of PE showed no statistically significant difference in rates of pulmonary embolism (RR = 0.82; 95% CI: 0.26‐2.63) (Figure 3B). In sensitivity analysis this result was not impacted by Jadad score.

Death

When UFH was compared to LMWH no statistically significant difference in the rate of death was found (RR = 0.96; 95% CI: 0.50‐1.85). Here again, no difference was noted when limited to studies with Jadad scores of 3 or higher.

Complications

We evaluated adverse events of heparin products used for prophylaxis and whether there were differences between UFH and LMWH. Reporting of complications was not uniform from study to study, making pooling more difficult. However, we were able to abstract data on any bleeding, major bleeding, and thrombocytopenia from several studies. In 5 studies15, 16, 2325 of either UFH or LMWH vs. control, a significantly increased risk of any bleeding (RR = 1.54; 95% CI: 1.15‐2.06) (Figure 4A) was found. When only major bleeding was evaluated, no statistically significant difference was noted (RR = 1.20; 95% CI: 0.55‐2.58) (Figure 4B). In 4 trials16, 22, 24, 25 the occurrence of thrombocytopenia was not significantly different when comparing UFH or LMWH to control (RR = 0.92; 95% CI: 0.46‐1.86).

When LMWH was compared to UFH in 4 trials,14, 17, 18, 27 a nonsignificant trend toward a decrease in any bleeding was found in the LMWH group (RR = 0.72; 95% CI: 0.44‐1.16) (Figure 5A). A similar trend was seen favoring LMWH in rates of major bleeding (RR = 0.57; 95% CI: 0.25‐1.32) (Figure 5B). Neither trend was statistically significant. Three trials comparing LMWH to UFH reported on thrombocytopenia17, 18, 27 with no significant difference noted (RR = 0.52; 95% CI: 0.06‐4.18).

Heterogeneity and Publication Bias

No statistically significant heterogeneity was identified between trials for any outcomes. The highest I‐squared value was 54.5% (P = 0.14) for the endpoint of thrombocytopenia when UFH was compared to LMWH. In some cases, the nonsignificant results for tests of heterogeneity may have reflected small numbers of trials, but the values for I‐squared for all other endpoints were close to zero indicating that little nonrandom variation existed in the results across studies. All analyses were run using both random effects and fixed effects modeling. While we report results for random effects, no significant differences were observed using fixed effects.

We tested for publication bias using the methods developed by Egger et al.12 and Begg and Mazumdar.13 There was evidence of bias only for the outcome of PE when prophylaxis was compared to control, as the results for both tests were significant (Begg and Mazumdar:13 P = 0.035; Egger et al.:12 P = 0.010). For other outcomes tested, including all DVT (prophylaxis compared to control, and LMWH vs. UFH) as well as PE (LMWH vs. UFH), the P‐values were not significant.

DISCUSSION

When compared to control, LMWH or UFH decreased the risk of all DVT by 45% (RR = 0.55; 95% CI: 0.36‐0.83) and proximal DVT by 54% (RR = 0.46; 95% CI: 0.31‐0.69). PE was also decreased by 30% (RR = 0.70; 95% CI: 0.53‐0.93). Of note, when prophylaxis was compared with placebo all of the high‐quality studies showing a benefit were done using LMWH. The benefits of prophylaxis occurred at the cost of a 54% increased overall risk of bleeding (RR = 1.54; 95% CI 1.15‐2.06). However, the risk of major bleeding was not significantly increased. We did not find a mortality benefit to pharmacologic thromboembolism prophylaxis.

When comparing UFH to LMWH, we noted no difference in all DVT, symptomatic DVT, proximal DVT, PE, or death. While there was a trend toward less bleeding with LMWH, this was not statistically significant.

Taken in aggregate, our findings are in agreement with previous published meta‐analyses reporting net benefit for thromboembolism prophylaxis in medical patients.24, 22, 28, 29 Our meta‐analysis has several methodological strengths over the prior studies, including a comprehensive search of both the published and unpublished literature and assessment of the relationship between methodological quality of included trials and reported benefit. In contrast to previous reviews, our analysis highlights several limitations of the current evidence.