User login

Information Continuity on Outcomes

Hospitalists are common in North America.1, 2 Hospitalists have been associated with a range of beneficial outcomes including decreased length of stay.3, 4 A primary concern of the hospitalist model is its potential detrimental effect on continuity of care5 partly because patients are often not seen by their hospitalists after discharge.

Continuity of care6 is primarily composed of provider continuity (an ongoing relationship between a patient and a particular provider over time) and information continuity (availability of data from prior events for subsequent patient encounters).6 The association between continuity of care and patient outcomes has been quantified in many studies.720 However, the relationship of continuity and outcomes is especially relevant after discharge from the hospital since this is a time when patients have a high risk of poor patient outcomes21 and poor provider22 and information continuity.2325

The association between continuity and outcomes after hospital discharge has been directly quantified in 2 studies. One found that patients seen by a physician who treated them in the hospital had a significant adjusted relative risk reduction in 30‐day death or readmission of 5% and 3%, respectively.22 The other study found that patients discharged from a general medicine ward were less likely to be readmitted if they were seen by physicians who had access to their discharge summary.23 However, neither of these studies concurrently measured the influence of provider and information continuity on patient outcomes.

Determining whether and how continuity of care influences patient outcomes after hospital discharge is essential to improve health care in an evidence‐based fashion. In addition, the influence that hospital physician follow‐up has on patient outcomes can best be determined by measuring provider and information continuity in patients after hospital discharge. This study sought to measure the independent association of several provider and information continuity measures on death or urgent readmission after hospital discharge.

Methods

Study Design

This was a multicenter prospective cohort study of consecutive patients discharged to the community from the medical or surgical services of 11 Ontario hospitals (6 university‐affiliated hospitals and 5 community hospitals) in 5 cities after an elective or emergency hospitalization. Patients were invited to participate in the study if they were cognitively intact, had a telephone, and provided written informed consent. Patients were excluded if they were less than 18 years old, were discharged to nursing homes, or were not proficient in English and did not have someone to help communicate with study staff. Enrolled patients were excluded from the analysis if they had less than 2 physician visits prior to one of the study's outcomes or the end of patient observation (which was 6 months postdischarge). This final exclusion criterion was necessary since 2 continuity measures (including postdischarge physician continuity and postdischarge information continuity) were incalculable with less than 2 physician visits during follow‐up (Supporting information). The study was approved by the research ethics board of each participating hospital.

Data Collection

Prior to hospital discharge, patients were interviewed by study personnel to identify their baseline functional status, their living conditions, all physicians who regularly treated the patient prior to admission (including both family physicians and consultants), and chronic medical conditions. The latter were confirmed by a review of the patient's chart and hospital discharge summary, when available. Patients also provided principal contacts whom we could contact in the event patients could not be reached. The chart and discharge summary were also used to identify diagnoses in hospitalincluding complications (diagnoses arising in the hospital)and medications at discharge.

Patients or their designated contacts were telephoned 1, 3, and 6 months after hospital discharge to identify the date and the physician of all postdischarge physician visits. For each postdischarge physician visit, we determined whether the physician had access to a discharge summary for the index hospitalization. We also determined the availability of information from all previous postdischarge visits that the patient had with other physicians. The methods used to collect these data were previously detailed.26 Briefly, we used three complementary methods to elicit this information from each follow‐up physician. First, patients gave the physician a survey on which the physician listed all prior visits with other doctors for which they had information. If this survey was not returned, we faxed the survey to the physician. If the faxed survey was not returned, we telephoned the physician or their office staff and administered the survey over the telephone.

Continuity Measures

We measured components of both provider and information continuity. For the posthospitalization period, we measured provider continuity for physicians who had provided patient care during three distinct phases: the prehospital period; the hospital period; and the postdischarge period. Prehospital physicians were those classified by the patient as their regular physician(s) (defined as physiciansboth family physicians and consultantsthat they had seen in the past and were likely to see again in the future). Hospital provider continuity was divided into 2 components: hospital physician continuity (ie, the most responsible physician in the hospital); and hospital consultant continuity (ie, another physician who consulted on the patient during admission). Information continuity was divided into discharge summary continuity and postdischarge visit information continuity.

We quantified provider and information continuity using Breslau's Usual Provider of Continuity (UPC)27 measure. It is a widely used and validated continuity measure whose values are meaningful and interpretable.6 The UPC measures the proportion of visits with the physician of interest (for provider continuity) or the proportion of visits having the information of interest (for information continuity). The UPC was calculated as: $${\rm UPC} = {\rm n}_{\rm i} / {\rm N}$$

As the formulae in the supporting information suggest, all continuity measures were incalculable prior to the first postdischarge visit and all continuity measures changed value at each visit during patient observation. In addition, a particular physician visit could increase multiple continuity measures simultaneously. For example, a visit with a physician who was the hospital physician and who regularly treated the patient prior to the hospitalization would increase both hospital and prehospital provider continuity. If the patient had previously seen the physician after discharge, the visit would also increase postdischarge physician continuity.

Study Outcomes

Outcomes for the study included time to all‐cause death and time to all‐cause, urgent readmission. To be classified as urgent, readmissions could not be arranged when the patient was originally discharged from hospital or more than 4 weeks prior to the readmission. All hospital admissions meeting these criteria during the 6 month study period were labeled in this study as urgent readmissions even if they were unrelated to the index admission.

Principal contacts were called if we were unable to reach the patient to determine their outcomes. If the patient's vital status remained unclear, we contacted the Office of the Provincial Registrar to determine if and when the patient died during the 6 months after discharge from hospital.

Analysis

Outcome incidence densities and 95% confidence intervals [CIs] were calculated using PROC GENMOD in SAS to account for clustering of patients in hospitals. We used multivariate proportional hazards modeling to determine the independent association of provider and information continuity measures with time to death and time to urgent readmission. Patient observation started when patients were discharged from the hospital. Patient observation ended at the earliest of the following: death; urgent readmission to the hospital; end of follow‐up (which was 6 months after discharge from the hospital) or loss to follow‐up. Because hospital consultant continuity was very highly skewed (95.6% of patients had a value of 0; mean value of 0.016; skewness 6.9), it was not included in the primary regression models but was included in a sensitivity analysis.

To adjust for potential confounders in the association between continuity and the outcomes, our model included all factors that were independently associated with either the outcome or any continuity measure. Factors associated with death or urgent readmission were summarized using the LACE index.29 This index combines a patient's hospital length of stay, admission acuity, patient comorbidity (measured with the Charlson Score30 using updated disease category weights by Schneeweiss et al.),31 and emergency room utilization (measured as the number of visits in the 6 months prior to admission) into a single number ranging from 0 to 19. The LACE index was moderately discriminative and highly accurate at predicting 30‐day death or urgent readmission.29 In a separate study,28 we found that the following factors were independently associated with at least one of the continuity measures: patient age; patient sex; number of admissions in previous 6 months; number of regular treating physicians prior to admission; hospital service (medicine vs. surgery); and number of complications in the hospital (defined as new problems arising after admission to hospital). By including all factors that were independently associated with either the outcome or continuity, we controlled for all measured factors that could act as confounders in the association between continuity and outcomes. We accounted for the clustered study design by using conditional proportional hazards models that stratified by hospitals.32 Analytical details are given in the supporting information.

Results

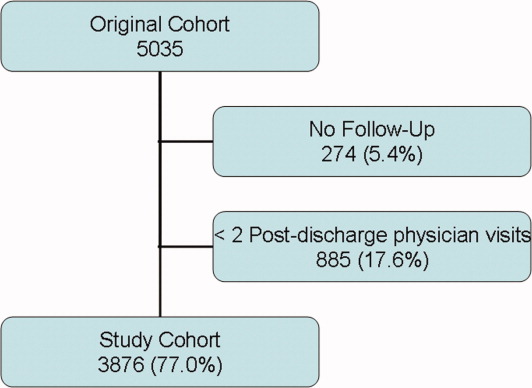

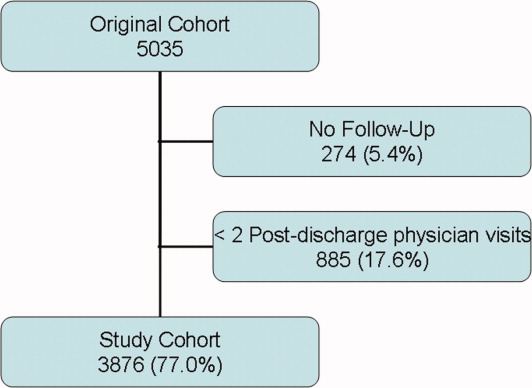

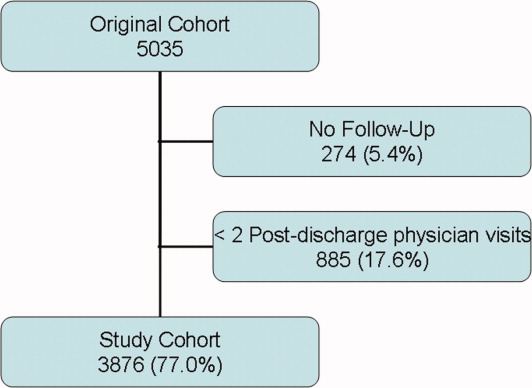

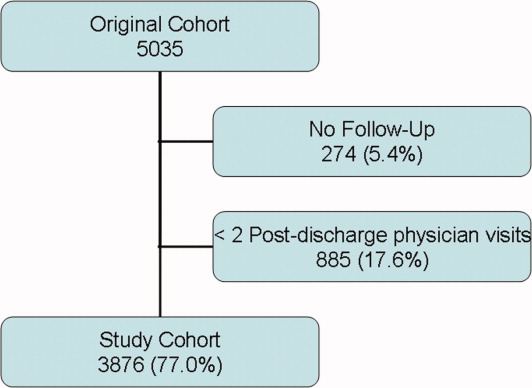

Between October 2002 and July 2006, we enrolled 5035 patients from 11 hospitals (Figure 1). Of the 5035 patients, 274 (5.4%) had no follow up interview with study personnel. A total of 885 (17.6%) had fewer than 2 post discharge physician visits and were not included in the continuity analyses. This left 3876 patients for this analysis (77.0% of the original cohort), of which 3727 had complete follow up (96.1% of the study cohort). A total of 531 patients (10.6% of the original cohort) had incomplete follow‐up because: 342 (6.8%) were lost to follow‐up; 172 (3.4%) refused participation; and 24 (0.5%) were transferred into a nursing home during the first month of observation.

The 3876 study patients are described in Table 1. Overall, these people had a mean age of 62 and most commonly had no physical limitations. Almost a third of patients had been admitted to the hospital in the previous 6 months. A total of 7.6% of patients had no regular prehospital physician while 5.8% had more than one regular prehospital physician. Patients were evenly split between acute and elective admissions and 12% had a complication during their admission. They were discharged after a median of 4 days on a median of 4 medications.

| Factor | Value | Death or Urgent Readmission | All (n = 3876) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 3491) | Yes (n = 385) | |||

| ||||

| Mean patient age, years (SD) | 61.59 16.16 | 67.70 15.53 | 62.19 16.20 | |

| Female (%) | 1838 (52.6) | 217 (56.4) | 2055 (53.0) | |

| Lives alone (%) | 791 (22.7) | 107 (27.8) | 898 (23.2) | |

| # activities of daily living requiring aids (%) | 0 | 3277 (93.9) | 354 (91.9) | 3631 (93.7) |

| 1 | 125 (3.6) | 20 (5.2) | 145 (3.7) | |

| >1 | 89 (2.5) | 11 (2.8) | 100 (2.8) | |

| # physicians who see patient regularly (%) | 0 | 241 (6.9) | 22 (5.7) | 263 (6.8) |

| 1 | 3060 (87.7) | 333 (86.5) | 3393 (87.5) | |

| 2 | 150 (4.3) | 21 (5.5) | 171 (4.4) | |

| >2 | 281 (8.0) | 31 (8.0) | 312 (8.0) | |

| # admissions in previous 6 months (%) | 0 | 2420 (69.3) | 222 (57.7) | 2642 (68.2) |

| 1 | 833 (23.9) | 103 (26.8) | 936 (24.1) | |

| >1 | 238 (6.8) | 60 (15.6) | 298 (7.7) | |

| Index hospitalization description | ||||

| Number of discharge medications (IQR) | 4 (2‐7) | 6 (3‐9) | 4 (2‐7) | |

| Admitted to medical service (%) | 1440 (41.2) | 231 (60.0) | 1671 (43.1) | |

| Acute diagnoses: | ||||

| CAD (%) | 238 (6.8) | 23 (6.0) | 261 (6.7) | |

| Neoplasm of unspecified nature (%) | 196 (5.6) | 35 (9.1) | 231 (6.0) | |

| Heart failure (%) | 127 (3.6) | 38 (9.9) | 165 (4.3) | |

| Acute procedures | ||||

| CABG (%) | 182 (5.2) | 14 (3.6) | 196 (5.1) | |

| Total knee arthoplasty (%) | 173 (5.0) | 10 (2.6) | 183 (4.7) | |

| Total hip arthroplasty (%) | 118 (3.4) | (0.5) | 120 (3.1) | |

| Complication during admission (%) | 403 (11.5) | 63 (16.4) | 466 (12.0) | |

| LACE index: mean (SD) | 8.0 (3.6) | 10.3 (3.8) | 8.2 (3.7) | |

| Length of stay in days: median (IQR) | 4 (2‐7) | 6 (3‐10) | 4 (2‐8) | |

| Acute/emergent admission (%) | 1851 (53.0) | 272 (70.6) | 2123 (54.8) | |

| Charlson score (%) | 0 | 2771 (79.4) | 241 (62.6) | 3012 (77.7) |

| 1 | 103 (3.0) | 17 (4.4) | 120 (3.1) | |

| 2 | 446 (12.8) | 86 (22.3) | 532 (13.7) | |

| >2 | 171 (4.9) | 41 (10.6) | 212 (5.5) | |

| Emergency room use (# visits/ year) (%) | 0 | 2342 (67.1) | 190 (49.4) | 2532 (65.3) |

| 1 | 761 (21.8) | 101 (26.2) | 862 (22.2) | |

| >1 | 388 (11.1) | 94 (24.4) | 482 (12.4) | |

Patients were observed in the study for a median of 175 days (interquartile range [IQR] 175‐178). During this time they had a median of 4 physician visits (IQR 3‐6). The first postdischarge physician visit occurred a median of 10 days (IQR 6‐18) after discharge from hospital.

Continuity Measures

Table 2 summarizes all continuity scores. Since continuity scores varied significantly over time,28 Table 2 provides continuity scores on the last day of patient observation. Preadmission provider, postdischarge provider, and discharge summary continuity all had similar values and distributions with median values ranging between 0.444 and 0.571. 1797 (46.4%) patients had a hospital physician provider continuity scorae of 0.

| Minimum | 25th Percentile | Median | 75th Percentile | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider continuity | |||||

| A: Pre‐admission physician | 0 | 0.143 | 0.444 | 0.667 | 1.000 |

| B: Hospital physician | 0 | 0 | 0.143 | 0.400 | 1.000 |

| C: Post‐discharge physician | 0 | 0.333 | 0.571 | 0.750 | 1.000 |

| Information continuity | |||||

| D: Discharge summary | 0 | 0.095 | 0.500 | 0.800 | 1.000 |

| E: Post‐discharge information | 0 | 0 | 0.182 | 0.500 | 1.000 |

Study Outcomes

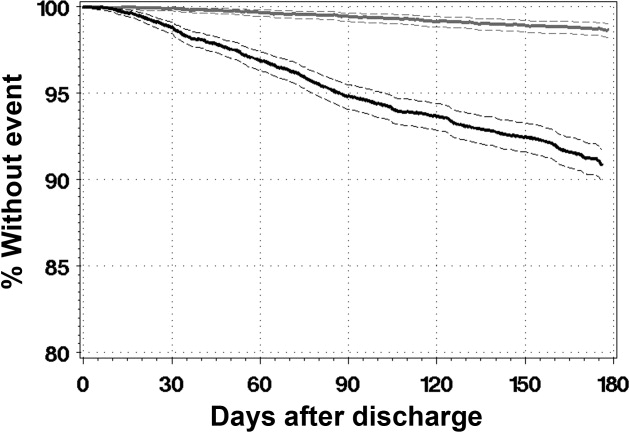

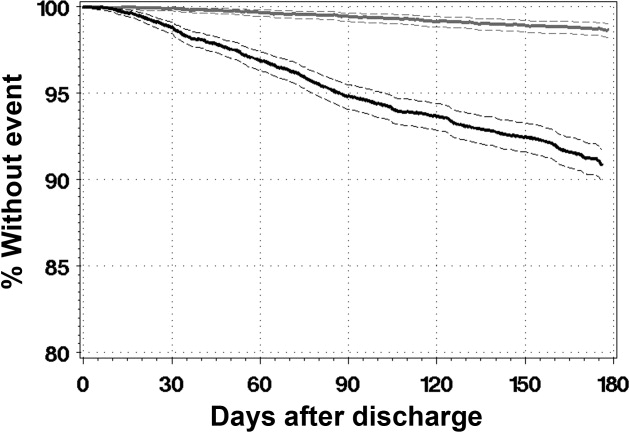

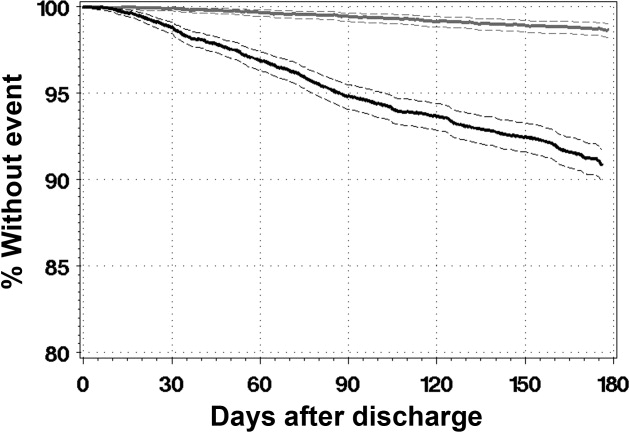

During a median of 175 days of observation, 45 patients died (event rate 2.6 events per 100 patient‐years observation [95% CI 2.0‐3.4]) and 340 patients were urgently readmitted (event rate 19.6 events per 100 patient‐years observation [95% CI 15.9‐24.3]). Figure 2 presents the survival curves for time to death and time to urgent readmission. The hazard of death was consistent through the observation period but the risk of urgent readmission decreased slightly after 90 days postdischarge.

Association Between Continuity and Outcomes

Table 3 summarizes the association between provider and information continuity with study outcomes. No continuity measure was associated with time to death by itself (Table 3, column A) or with the other continuity measures (Table 3, column B). Preadmission physician continuity was associated with a significantly decreased risk of urgent readmission. When the proportion of postdischarge visits with a prehospital physician increased by 10%, the adjusted risk of urgent readmission decreased by 6% (adjusted hazards ratio (adj‐HR)) of 0.94 (95% CI, 0.91‐0.98). None of the other continuity measuresincluding hospital physicianwere significantly associated with urgent readmission either by themselves (Table 3, column A) or after adjusting for other continuity measures (Table 3, column B).

| Outcome | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death (95% CI) | Urgent Readmission (95% CI) | |||||||

| A: Adjusted for Other Confounders Only | B: Adjusted for Other Confounders and Continuity Measures | A: Adjusted for Other Confounders Only | B: Adjusted for Other Confounders and Continuity Measures | |||||

| ||||||||

| Provider continuity | ||||||||

| A: Pre‐admission physician | 1.03 | (0.95, 1.12) | 1.06 | (0.95, 1.18) | 0.95 | (0.92, 0.98) | 0.94 | (0.91, 0.98) |

| B: Hospital physician | 0.87 | (0.74, 1.02) | 0.86 | (0.70, 1.03) | 0.98 | (0.94, 1.02) | 0.97 | (0.92, 1.01) |

| C: Post‐discharge physician | 0.97 | (0.89, 1.06) | 0.93 | (0.84, 1.04) | 0.98 | (0.95, 1.01) | 0.98 | (0.94, 1.02) |

| Information continuity | ||||||||

| D: Discharge Summary | 0.96 | (0.89, 1.04) | 0.94 | (0.87, 1.03) | 1.01 | (0.98, 1.04) | 1.02 | (0.99, 1.05) |

| E: Post‐discharge information | 1.01 | (0.94, 1.08) | 1.03 | (0.95, 1.11) | 1.00 | (0.97, 1.03) | 1.03 | (0.95, 1.11) |

| Other confounders | ||||||||

| Patient age in decades* | 1.43 | (1.13, 1.82) | 1.18 | (1.10, 1.28) | ||||

| Female | 1.50 | (0.81, 2.77) | 1.16 | (0.94, 1.44) | ||||

| # physicians who see patient regularly | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.46 | (0.92, 2.34) | ||||||

| 2 | 2.17 | (1.11, 4.26) | ||||||

| >2 | 3.71 | (1.55, 8.88) | ||||||

| Complications during admission | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.38 | (0.61, 3.10) | 0.81 | (0.55, 1.17) | ||||

| >1 | 1.01 | (0.28, 3.58) | 0.91 | (0.56, 1.48) | ||||

| # admissions in previous 6 months | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.27 | (0.59, 2.70) | 1.34 | (1.02, 1.76) | ||||

| >1 | 1.42 | (0.55, 3.67) | 1.78 | (1.26, 2.51) | ||||

| LACE index* | 1.16 | (1.06, 1.26) | 1.10 | (1.07, 1.14) | ||||

Increased patient age and increased LACE index score were both strongly associated with an increased risk of death (adj‐HR 1.43 [1.13‐1.82] and 1.16 [1.06‐1.26], respectively) and urgent readmission (adj‐HR 1.18 [1.10‐1.28] and 1.10 [1.07‐1.14], respectively). Hospitalization in the 6 months prior to admission significantly increased the risk of urgent readmission but not death. The risk of urgent readmission increased significantly as the number of regular prehospital physicians increased.

Sensitivity Analyses

Our study conclusions did not change in the sensitivity analyses. The number of postdischarge physician visits (expressed as a time‐dependent covariate) was not associated with either death or with urgent readmission and preadmission physician continuity remained significantly associated with time to urgent readmission (supporting information). Adding consultant continuity to the model also did not change our results (supporting information). In‐hospital consultant continuity was associated with an increased risk of urgent readmission (adj‐HR 1.10, 95% CI, 1.01‐1.20). The association between pre‐admission physician continuity and time to urgent readmission did not interact significantly with patient age, LACE index score, or number of previous admissions.

Discussion

This large, prospective cohort study measured the independent association of several provider and information continuity measures with important outcomes in patients discharged from hospital. After adjusting for potential confounders, we found that increased continuity with physicians who regularly cared for the patient prior to the admission was significantly and independently associated with a decreased risk of urgent readmission. Our data suggest that continuity with the hospital physician did not independently influence the risk of patient death or urgent readmission after discharge.

Although hospital physician continuity did not significantly change patient outcomes, we found that follow‐up with a physician who regularly treated the patient prior to their admission was associated with a significantly decreased risk of urgent readmission. This could reflect the important role that a patient's regular physician plays in their health care. Other studies have shown a positive association between continuity with a regular physician and improved outcomes including decreased emergency room utilization7, 8 and decreased hospitalization.10, 11

We were somewhat disappointed that information continuity was not independently associated with improved patient outcomes. Information continuity is likely more amenable to modification than is provider continuity. Of course, our study findings do not mean that information continuity does not improve patient outcomes, as in other studies.23, 33 Instead, our results could reflect that we solely measured the availability of information to physicians. Future studies that measure the quality, relevance, and actual utilization of patient information will be better able to discern the influence of information continuity on patient outcomes.

We believe that our study was methodologically strong and unique. We captured both provider and information continuity in a large group of representative patients using a broad range of measures that captured continuity's diverse components including both provider and information continuity. The continuity measures were expressed and properly analyzed as time‐dependent variables in a multivariate model.34 Our analysis controlled for important potential confounders. Our follow‐up and data collection was rigorous with 96.1% of our study group having complete follow‐up. Finally, the analysis used multiple imputation to appropriately handle missing data in the one incomplete variable (post‐discharge information continuity).3537

Several limitations of our study should be kept in mind. We are uncertain how our results might generalize to patients discharged from obstetrical or psychiatric services or people in other health systems. Our analysis had to exclude patients with less than two physician visits after discharge since this was the minimum required to calculate postdischarge physician and information continuity. Data collection for postdischarge information continuity was incomplete with data missing for 19.0% of all 15 401 visits in the original cohort.38 However, a response rate of 81.0% is very good39 when compared to other survey‐based studies40 and we accounted for the missing data using multiple imputation methods. The primary outcomes of our studytime to death or urgent readmissionmay be relatively insensitive to modification of quality of care, which is presumably improved by increased continuity.41 For example, Clarke found that the majority of readmissions in all patient groups were unavoidable with 94% of medical readmissions 1 month postdischarge judged to be unavoidable.42 Future studies regarding the effects of continuity could focus on its association with other outcomes that are more reflective of quality of care such as the risk of adverse events or medical error.21 Such outcomes would presumably be more sensitive to improved quality of care from increased continuity.

We believe that our study's major limitation was its inability to establish a causal association between continuity and patient outcomes. Our finding that increased consultant continuity was associated with an increased risk of poor outcomes highlights this concern. Presumably, patient follow‐up with a hospital consultant indicates a disease status with a high risk of bad patient outcomesa risk that is not entirely accounted for by the covariates used in this study. If we accept that unresolved confounding explains this association, the same could also apply to the association between preadmission physician continuity and improved outcomes. Perhaps patients who are doing well after discharge from hospital are able to return to their regular physician. Our analysis would therefore identify an association between increased preadmission physician continuity and improved patient outcomes. Analyses could also incorporate more discriminative measures of severity of hospital illness, such as those developed by Escobar et al.43 Since patients may experience health events after their discharge from hospital that could influence outcomes, recording these and expressing them in the study model as time‐dependent covariates will be important. Finally, similar to the classic study by Wasson et al.44 in 1984, a proper randomized trial that measures the effect of a continuity‐building intervention on both continuity of care and patient outcomes would help determine how continuity influences outcomes.

In conclusion, after discharge from hospital, increased continuity with physicians who routinely care for the patient is significantly and independently associated with a decreased risk of urgent readmission. Continuity with the hospital physician after discharge did not independently influence the risk of patient death or urgent readmission in our study. Further research is required to determine the causal association between preadmission physician continuity and improved outcomes. Until that time, clinicians should strive to optimize continuity with physicians their patients have seen prior to the hospitalization.

- Society of Hospital Medicine.2009.Ref Type: Internet Communication.

- ,,,.The status of hospital medicine groups in the United States.J Hosp Med.2006;1:75–80.

- ,.The hospitalist movement 5 years later. [see comment].JAMA.2002;287:487–494. [Review]

- ,,,.Hospitalists and the practice of inpatient medicine: results of a survey of the National Association of Inpatient Physicians. [see comment].Ann Intern Med.1999;130:343–349.

- ,,,.Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists.Am J Med.2001;111:15S–20S.

- ,,.Defusing the confusion: concepts and measures of continuity of healthcare.Ottawa,Canadian Health Services Research Foundation. Ref Type: Report.2002;1–50.

- ,,,,.Association between infant continuity of care and pediatric emergency department utilization.Pediatrics.2004;113:738–741.

- ,,,,.Is greater continuity of care associated with less emergency department utilization?Pediatrics.1999;103:738–742.

- ,,,,.Association of lower continuity of care with greater risk of emergency department use and hospitalization in children.Pediatrics.2001;107:524–529.

- ,,The role of provider continuity in preventing hospitalizations.Arch Fam Med.1998;7:352–357.

- ,.The importance of continuity of care in the likelihood of future hospitalization: is site of care equivalent to a primary clinician?Am J Public Health.1998;88:1539–1541.

- ,,,.Exploration of the relationship between continuity, trust in regular doctors and patient satisfaction with consultations with family doctors.Scand J Prim Health Care.2003;21:27–32.

- ,,,,.Longitudinal continuity of care is associated with high patient satisfaction with physical therapy.Phys Ther.2005;85:1046–1052.

- ,,,,.Provider continuity and outcomes of care for persons with schizophrenia.Ment Health Serv Res.2000;V2:201–211.

- ,,,,.Continuity of care is associated with well‐coordinated care.Ambul Pediatr.2003;3:82–86.

- ,,.The impact of insurance type and forced discontinuity on the delivery of primary care. [see comments.].J Fam Pract.1997;45:129–135.

- .Measuring attributes of primary care: development of a new instrument.J Fam Pract.1997;45:64–74.

- .Continuity of care during pregnancy: the effect of provider continuity on outcome.J Fam Pract.1985;21:375–380.

- ,,,,,.Physician‐patient relationship and medication compliance: a primary care investigation.Ann Fam Med.2004;2:455–461.

- ,,,.Continuity of care and cardiovascular risk factor management: does care by a single clinician add to informational continuity provided by electronic medical records?Am J Manag Care.2005;11:689–696.

- ,,,,.The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital.Ann Intern Med.2003;138:161–167.

- ,,,.Continuity of care and patient outcomes after hospital discharge.J Gen lntern Med.2004;19:624–645.

- ,,,.Effect of discharge summary availability during post‐discharge visits on hospital readmission.J Gen Intern Med.2002;17:186–192.

- ,,, et al.Association of communication between hospital‐based physicians and primary care providers with patient outcomes.[see comment].J Gen Intern Med2009;24(3):381–386.

- ,,,,,.Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care.JAMA.2007;297:831–841.

- ,,, et al.Information exchange among physicians caring for the same patient in the community.Can Med Assoc J.2008;179:1013–1018.

- ,.Continuity of care in a university‐based practice.J Med Educ.1975;965–969.

- ,,, et al.Provider and information continuity after discharge from hospital: a prospective cohort study.2009. Ref Type: Unpublished Work.

- ,,, et al.Derivation and validation of the LACE index to predict early death or unplanned readmission after discharge from hospital to the community.CMAJ. (In press)

- ,,,.A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation.J Chronic Dis.1987;40:373–383.

- ,,,.Improved comorbidity adjustment for predicting mortality in Medicare populations.Health Serv Res.2003;38(4):1103–1120.

- ,.Modelling clustered survival data from multicentre clinical trials.Stat Med.2004;23:369–388.

- ,,,.Prevalence of information gaps in the emergency department and the effect on patient outcomes.CMAJ.2003;169:1023–1028.

- ,,,.Time‐dependent bias due to improper analytical methodology is common in prominent medical journals.J Clin Epidemiol.2004;57:672–682.

- .What do we do with missing data? Some options for analysis of incomplete data.Annu Rev Public Health.2004;25:99–117.

- ,,,.Survival estimates of a prognostic classification depended more on year of treatment than on imputation of missing values.J Clin Epidemiol.2006;59:246–253. [Review]

- .Bias arising from missing data in predictive models.[see comment].J Clin Epidemiol.2006;59:1115–1123.

- ,,, et al.Information exchange among physicians caring for the same patient in the community.CMAJ.2008;179:1013–1018.

- .Survey Research Methods.2nd ed.,Beverly Hills:Sage;1993.

- ,,.Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals.J Clin Epidemiol.1997;50:1129–1136.

- .Readmission of patients to hospital: still ill defined and poorly understood.Int J Qual Health Care.2001;13:177–179.

- .Are readmissions avoidable?Br Med J.1990;301:1136–1138.

- ,,,,,.Risk‐adjusting hospital inpatient mortality using automated inpatient, outpatient, and laboratory databases.Med Care.2008;46:232–239.

- ,,, et al.Continuity of outpatient medical care in elderly men. A randomized trial.JAMA.1984;252:2413–2417.

Hospitalists are common in North America.1, 2 Hospitalists have been associated with a range of beneficial outcomes including decreased length of stay.3, 4 A primary concern of the hospitalist model is its potential detrimental effect on continuity of care5 partly because patients are often not seen by their hospitalists after discharge.

Continuity of care6 is primarily composed of provider continuity (an ongoing relationship between a patient and a particular provider over time) and information continuity (availability of data from prior events for subsequent patient encounters).6 The association between continuity of care and patient outcomes has been quantified in many studies.720 However, the relationship of continuity and outcomes is especially relevant after discharge from the hospital since this is a time when patients have a high risk of poor patient outcomes21 and poor provider22 and information continuity.2325

The association between continuity and outcomes after hospital discharge has been directly quantified in 2 studies. One found that patients seen by a physician who treated them in the hospital had a significant adjusted relative risk reduction in 30‐day death or readmission of 5% and 3%, respectively.22 The other study found that patients discharged from a general medicine ward were less likely to be readmitted if they were seen by physicians who had access to their discharge summary.23 However, neither of these studies concurrently measured the influence of provider and information continuity on patient outcomes.

Determining whether and how continuity of care influences patient outcomes after hospital discharge is essential to improve health care in an evidence‐based fashion. In addition, the influence that hospital physician follow‐up has on patient outcomes can best be determined by measuring provider and information continuity in patients after hospital discharge. This study sought to measure the independent association of several provider and information continuity measures on death or urgent readmission after hospital discharge.

Methods

Study Design

This was a multicenter prospective cohort study of consecutive patients discharged to the community from the medical or surgical services of 11 Ontario hospitals (6 university‐affiliated hospitals and 5 community hospitals) in 5 cities after an elective or emergency hospitalization. Patients were invited to participate in the study if they were cognitively intact, had a telephone, and provided written informed consent. Patients were excluded if they were less than 18 years old, were discharged to nursing homes, or were not proficient in English and did not have someone to help communicate with study staff. Enrolled patients were excluded from the analysis if they had less than 2 physician visits prior to one of the study's outcomes or the end of patient observation (which was 6 months postdischarge). This final exclusion criterion was necessary since 2 continuity measures (including postdischarge physician continuity and postdischarge information continuity) were incalculable with less than 2 physician visits during follow‐up (Supporting information). The study was approved by the research ethics board of each participating hospital.

Data Collection

Prior to hospital discharge, patients were interviewed by study personnel to identify their baseline functional status, their living conditions, all physicians who regularly treated the patient prior to admission (including both family physicians and consultants), and chronic medical conditions. The latter were confirmed by a review of the patient's chart and hospital discharge summary, when available. Patients also provided principal contacts whom we could contact in the event patients could not be reached. The chart and discharge summary were also used to identify diagnoses in hospitalincluding complications (diagnoses arising in the hospital)and medications at discharge.

Patients or their designated contacts were telephoned 1, 3, and 6 months after hospital discharge to identify the date and the physician of all postdischarge physician visits. For each postdischarge physician visit, we determined whether the physician had access to a discharge summary for the index hospitalization. We also determined the availability of information from all previous postdischarge visits that the patient had with other physicians. The methods used to collect these data were previously detailed.26 Briefly, we used three complementary methods to elicit this information from each follow‐up physician. First, patients gave the physician a survey on which the physician listed all prior visits with other doctors for which they had information. If this survey was not returned, we faxed the survey to the physician. If the faxed survey was not returned, we telephoned the physician or their office staff and administered the survey over the telephone.

Continuity Measures

We measured components of both provider and information continuity. For the posthospitalization period, we measured provider continuity for physicians who had provided patient care during three distinct phases: the prehospital period; the hospital period; and the postdischarge period. Prehospital physicians were those classified by the patient as their regular physician(s) (defined as physiciansboth family physicians and consultantsthat they had seen in the past and were likely to see again in the future). Hospital provider continuity was divided into 2 components: hospital physician continuity (ie, the most responsible physician in the hospital); and hospital consultant continuity (ie, another physician who consulted on the patient during admission). Information continuity was divided into discharge summary continuity and postdischarge visit information continuity.

We quantified provider and information continuity using Breslau's Usual Provider of Continuity (UPC)27 measure. It is a widely used and validated continuity measure whose values are meaningful and interpretable.6 The UPC measures the proportion of visits with the physician of interest (for provider continuity) or the proportion of visits having the information of interest (for information continuity). The UPC was calculated as: $${\rm UPC} = {\rm n}_{\rm i} / {\rm N}$$

As the formulae in the supporting information suggest, all continuity measures were incalculable prior to the first postdischarge visit and all continuity measures changed value at each visit during patient observation. In addition, a particular physician visit could increase multiple continuity measures simultaneously. For example, a visit with a physician who was the hospital physician and who regularly treated the patient prior to the hospitalization would increase both hospital and prehospital provider continuity. If the patient had previously seen the physician after discharge, the visit would also increase postdischarge physician continuity.

Study Outcomes

Outcomes for the study included time to all‐cause death and time to all‐cause, urgent readmission. To be classified as urgent, readmissions could not be arranged when the patient was originally discharged from hospital or more than 4 weeks prior to the readmission. All hospital admissions meeting these criteria during the 6 month study period were labeled in this study as urgent readmissions even if they were unrelated to the index admission.

Principal contacts were called if we were unable to reach the patient to determine their outcomes. If the patient's vital status remained unclear, we contacted the Office of the Provincial Registrar to determine if and when the patient died during the 6 months after discharge from hospital.

Analysis

Outcome incidence densities and 95% confidence intervals [CIs] were calculated using PROC GENMOD in SAS to account for clustering of patients in hospitals. We used multivariate proportional hazards modeling to determine the independent association of provider and information continuity measures with time to death and time to urgent readmission. Patient observation started when patients were discharged from the hospital. Patient observation ended at the earliest of the following: death; urgent readmission to the hospital; end of follow‐up (which was 6 months after discharge from the hospital) or loss to follow‐up. Because hospital consultant continuity was very highly skewed (95.6% of patients had a value of 0; mean value of 0.016; skewness 6.9), it was not included in the primary regression models but was included in a sensitivity analysis.

To adjust for potential confounders in the association between continuity and the outcomes, our model included all factors that were independently associated with either the outcome or any continuity measure. Factors associated with death or urgent readmission were summarized using the LACE index.29 This index combines a patient's hospital length of stay, admission acuity, patient comorbidity (measured with the Charlson Score30 using updated disease category weights by Schneeweiss et al.),31 and emergency room utilization (measured as the number of visits in the 6 months prior to admission) into a single number ranging from 0 to 19. The LACE index was moderately discriminative and highly accurate at predicting 30‐day death or urgent readmission.29 In a separate study,28 we found that the following factors were independently associated with at least one of the continuity measures: patient age; patient sex; number of admissions in previous 6 months; number of regular treating physicians prior to admission; hospital service (medicine vs. surgery); and number of complications in the hospital (defined as new problems arising after admission to hospital). By including all factors that were independently associated with either the outcome or continuity, we controlled for all measured factors that could act as confounders in the association between continuity and outcomes. We accounted for the clustered study design by using conditional proportional hazards models that stratified by hospitals.32 Analytical details are given in the supporting information.

Results

Between October 2002 and July 2006, we enrolled 5035 patients from 11 hospitals (Figure 1). Of the 5035 patients, 274 (5.4%) had no follow up interview with study personnel. A total of 885 (17.6%) had fewer than 2 post discharge physician visits and were not included in the continuity analyses. This left 3876 patients for this analysis (77.0% of the original cohort), of which 3727 had complete follow up (96.1% of the study cohort). A total of 531 patients (10.6% of the original cohort) had incomplete follow‐up because: 342 (6.8%) were lost to follow‐up; 172 (3.4%) refused participation; and 24 (0.5%) were transferred into a nursing home during the first month of observation.

The 3876 study patients are described in Table 1. Overall, these people had a mean age of 62 and most commonly had no physical limitations. Almost a third of patients had been admitted to the hospital in the previous 6 months. A total of 7.6% of patients had no regular prehospital physician while 5.8% had more than one regular prehospital physician. Patients were evenly split between acute and elective admissions and 12% had a complication during their admission. They were discharged after a median of 4 days on a median of 4 medications.

| Factor | Value | Death or Urgent Readmission | All (n = 3876) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 3491) | Yes (n = 385) | |||

| ||||

| Mean patient age, years (SD) | 61.59 16.16 | 67.70 15.53 | 62.19 16.20 | |

| Female (%) | 1838 (52.6) | 217 (56.4) | 2055 (53.0) | |

| Lives alone (%) | 791 (22.7) | 107 (27.8) | 898 (23.2) | |

| # activities of daily living requiring aids (%) | 0 | 3277 (93.9) | 354 (91.9) | 3631 (93.7) |

| 1 | 125 (3.6) | 20 (5.2) | 145 (3.7) | |

| >1 | 89 (2.5) | 11 (2.8) | 100 (2.8) | |

| # physicians who see patient regularly (%) | 0 | 241 (6.9) | 22 (5.7) | 263 (6.8) |

| 1 | 3060 (87.7) | 333 (86.5) | 3393 (87.5) | |

| 2 | 150 (4.3) | 21 (5.5) | 171 (4.4) | |

| >2 | 281 (8.0) | 31 (8.0) | 312 (8.0) | |

| # admissions in previous 6 months (%) | 0 | 2420 (69.3) | 222 (57.7) | 2642 (68.2) |

| 1 | 833 (23.9) | 103 (26.8) | 936 (24.1) | |

| >1 | 238 (6.8) | 60 (15.6) | 298 (7.7) | |

| Index hospitalization description | ||||

| Number of discharge medications (IQR) | 4 (2‐7) | 6 (3‐9) | 4 (2‐7) | |

| Admitted to medical service (%) | 1440 (41.2) | 231 (60.0) | 1671 (43.1) | |

| Acute diagnoses: | ||||

| CAD (%) | 238 (6.8) | 23 (6.0) | 261 (6.7) | |

| Neoplasm of unspecified nature (%) | 196 (5.6) | 35 (9.1) | 231 (6.0) | |

| Heart failure (%) | 127 (3.6) | 38 (9.9) | 165 (4.3) | |

| Acute procedures | ||||

| CABG (%) | 182 (5.2) | 14 (3.6) | 196 (5.1) | |

| Total knee arthoplasty (%) | 173 (5.0) | 10 (2.6) | 183 (4.7) | |

| Total hip arthroplasty (%) | 118 (3.4) | (0.5) | 120 (3.1) | |

| Complication during admission (%) | 403 (11.5) | 63 (16.4) | 466 (12.0) | |

| LACE index: mean (SD) | 8.0 (3.6) | 10.3 (3.8) | 8.2 (3.7) | |

| Length of stay in days: median (IQR) | 4 (2‐7) | 6 (3‐10) | 4 (2‐8) | |

| Acute/emergent admission (%) | 1851 (53.0) | 272 (70.6) | 2123 (54.8) | |

| Charlson score (%) | 0 | 2771 (79.4) | 241 (62.6) | 3012 (77.7) |

| 1 | 103 (3.0) | 17 (4.4) | 120 (3.1) | |

| 2 | 446 (12.8) | 86 (22.3) | 532 (13.7) | |

| >2 | 171 (4.9) | 41 (10.6) | 212 (5.5) | |

| Emergency room use (# visits/ year) (%) | 0 | 2342 (67.1) | 190 (49.4) | 2532 (65.3) |

| 1 | 761 (21.8) | 101 (26.2) | 862 (22.2) | |

| >1 | 388 (11.1) | 94 (24.4) | 482 (12.4) | |

Patients were observed in the study for a median of 175 days (interquartile range [IQR] 175‐178). During this time they had a median of 4 physician visits (IQR 3‐6). The first postdischarge physician visit occurred a median of 10 days (IQR 6‐18) after discharge from hospital.

Continuity Measures

Table 2 summarizes all continuity scores. Since continuity scores varied significantly over time,28 Table 2 provides continuity scores on the last day of patient observation. Preadmission provider, postdischarge provider, and discharge summary continuity all had similar values and distributions with median values ranging between 0.444 and 0.571. 1797 (46.4%) patients had a hospital physician provider continuity scorae of 0.

| Minimum | 25th Percentile | Median | 75th Percentile | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider continuity | |||||

| A: Pre‐admission physician | 0 | 0.143 | 0.444 | 0.667 | 1.000 |

| B: Hospital physician | 0 | 0 | 0.143 | 0.400 | 1.000 |

| C: Post‐discharge physician | 0 | 0.333 | 0.571 | 0.750 | 1.000 |

| Information continuity | |||||

| D: Discharge summary | 0 | 0.095 | 0.500 | 0.800 | 1.000 |

| E: Post‐discharge information | 0 | 0 | 0.182 | 0.500 | 1.000 |

Study Outcomes

During a median of 175 days of observation, 45 patients died (event rate 2.6 events per 100 patient‐years observation [95% CI 2.0‐3.4]) and 340 patients were urgently readmitted (event rate 19.6 events per 100 patient‐years observation [95% CI 15.9‐24.3]). Figure 2 presents the survival curves for time to death and time to urgent readmission. The hazard of death was consistent through the observation period but the risk of urgent readmission decreased slightly after 90 days postdischarge.

Association Between Continuity and Outcomes

Table 3 summarizes the association between provider and information continuity with study outcomes. No continuity measure was associated with time to death by itself (Table 3, column A) or with the other continuity measures (Table 3, column B). Preadmission physician continuity was associated with a significantly decreased risk of urgent readmission. When the proportion of postdischarge visits with a prehospital physician increased by 10%, the adjusted risk of urgent readmission decreased by 6% (adjusted hazards ratio (adj‐HR)) of 0.94 (95% CI, 0.91‐0.98). None of the other continuity measuresincluding hospital physicianwere significantly associated with urgent readmission either by themselves (Table 3, column A) or after adjusting for other continuity measures (Table 3, column B).

| Outcome | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death (95% CI) | Urgent Readmission (95% CI) | |||||||

| A: Adjusted for Other Confounders Only | B: Adjusted for Other Confounders and Continuity Measures | A: Adjusted for Other Confounders Only | B: Adjusted for Other Confounders and Continuity Measures | |||||

| ||||||||

| Provider continuity | ||||||||

| A: Pre‐admission physician | 1.03 | (0.95, 1.12) | 1.06 | (0.95, 1.18) | 0.95 | (0.92, 0.98) | 0.94 | (0.91, 0.98) |

| B: Hospital physician | 0.87 | (0.74, 1.02) | 0.86 | (0.70, 1.03) | 0.98 | (0.94, 1.02) | 0.97 | (0.92, 1.01) |

| C: Post‐discharge physician | 0.97 | (0.89, 1.06) | 0.93 | (0.84, 1.04) | 0.98 | (0.95, 1.01) | 0.98 | (0.94, 1.02) |

| Information continuity | ||||||||

| D: Discharge Summary | 0.96 | (0.89, 1.04) | 0.94 | (0.87, 1.03) | 1.01 | (0.98, 1.04) | 1.02 | (0.99, 1.05) |

| E: Post‐discharge information | 1.01 | (0.94, 1.08) | 1.03 | (0.95, 1.11) | 1.00 | (0.97, 1.03) | 1.03 | (0.95, 1.11) |

| Other confounders | ||||||||

| Patient age in decades* | 1.43 | (1.13, 1.82) | 1.18 | (1.10, 1.28) | ||||

| Female | 1.50 | (0.81, 2.77) | 1.16 | (0.94, 1.44) | ||||

| # physicians who see patient regularly | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.46 | (0.92, 2.34) | ||||||

| 2 | 2.17 | (1.11, 4.26) | ||||||

| >2 | 3.71 | (1.55, 8.88) | ||||||

| Complications during admission | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.38 | (0.61, 3.10) | 0.81 | (0.55, 1.17) | ||||

| >1 | 1.01 | (0.28, 3.58) | 0.91 | (0.56, 1.48) | ||||

| # admissions in previous 6 months | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.27 | (0.59, 2.70) | 1.34 | (1.02, 1.76) | ||||

| >1 | 1.42 | (0.55, 3.67) | 1.78 | (1.26, 2.51) | ||||

| LACE index* | 1.16 | (1.06, 1.26) | 1.10 | (1.07, 1.14) | ||||

Increased patient age and increased LACE index score were both strongly associated with an increased risk of death (adj‐HR 1.43 [1.13‐1.82] and 1.16 [1.06‐1.26], respectively) and urgent readmission (adj‐HR 1.18 [1.10‐1.28] and 1.10 [1.07‐1.14], respectively). Hospitalization in the 6 months prior to admission significantly increased the risk of urgent readmission but not death. The risk of urgent readmission increased significantly as the number of regular prehospital physicians increased.

Sensitivity Analyses

Our study conclusions did not change in the sensitivity analyses. The number of postdischarge physician visits (expressed as a time‐dependent covariate) was not associated with either death or with urgent readmission and preadmission physician continuity remained significantly associated with time to urgent readmission (supporting information). Adding consultant continuity to the model also did not change our results (supporting information). In‐hospital consultant continuity was associated with an increased risk of urgent readmission (adj‐HR 1.10, 95% CI, 1.01‐1.20). The association between pre‐admission physician continuity and time to urgent readmission did not interact significantly with patient age, LACE index score, or number of previous admissions.

Discussion

This large, prospective cohort study measured the independent association of several provider and information continuity measures with important outcomes in patients discharged from hospital. After adjusting for potential confounders, we found that increased continuity with physicians who regularly cared for the patient prior to the admission was significantly and independently associated with a decreased risk of urgent readmission. Our data suggest that continuity with the hospital physician did not independently influence the risk of patient death or urgent readmission after discharge.

Although hospital physician continuity did not significantly change patient outcomes, we found that follow‐up with a physician who regularly treated the patient prior to their admission was associated with a significantly decreased risk of urgent readmission. This could reflect the important role that a patient's regular physician plays in their health care. Other studies have shown a positive association between continuity with a regular physician and improved outcomes including decreased emergency room utilization7, 8 and decreased hospitalization.10, 11

We were somewhat disappointed that information continuity was not independently associated with improved patient outcomes. Information continuity is likely more amenable to modification than is provider continuity. Of course, our study findings do not mean that information continuity does not improve patient outcomes, as in other studies.23, 33 Instead, our results could reflect that we solely measured the availability of information to physicians. Future studies that measure the quality, relevance, and actual utilization of patient information will be better able to discern the influence of information continuity on patient outcomes.

We believe that our study was methodologically strong and unique. We captured both provider and information continuity in a large group of representative patients using a broad range of measures that captured continuity's diverse components including both provider and information continuity. The continuity measures were expressed and properly analyzed as time‐dependent variables in a multivariate model.34 Our analysis controlled for important potential confounders. Our follow‐up and data collection was rigorous with 96.1% of our study group having complete follow‐up. Finally, the analysis used multiple imputation to appropriately handle missing data in the one incomplete variable (post‐discharge information continuity).3537

Several limitations of our study should be kept in mind. We are uncertain how our results might generalize to patients discharged from obstetrical or psychiatric services or people in other health systems. Our analysis had to exclude patients with less than two physician visits after discharge since this was the minimum required to calculate postdischarge physician and information continuity. Data collection for postdischarge information continuity was incomplete with data missing for 19.0% of all 15 401 visits in the original cohort.38 However, a response rate of 81.0% is very good39 when compared to other survey‐based studies40 and we accounted for the missing data using multiple imputation methods. The primary outcomes of our studytime to death or urgent readmissionmay be relatively insensitive to modification of quality of care, which is presumably improved by increased continuity.41 For example, Clarke found that the majority of readmissions in all patient groups were unavoidable with 94% of medical readmissions 1 month postdischarge judged to be unavoidable.42 Future studies regarding the effects of continuity could focus on its association with other outcomes that are more reflective of quality of care such as the risk of adverse events or medical error.21 Such outcomes would presumably be more sensitive to improved quality of care from increased continuity.

We believe that our study's major limitation was its inability to establish a causal association between continuity and patient outcomes. Our finding that increased consultant continuity was associated with an increased risk of poor outcomes highlights this concern. Presumably, patient follow‐up with a hospital consultant indicates a disease status with a high risk of bad patient outcomesa risk that is not entirely accounted for by the covariates used in this study. If we accept that unresolved confounding explains this association, the same could also apply to the association between preadmission physician continuity and improved outcomes. Perhaps patients who are doing well after discharge from hospital are able to return to their regular physician. Our analysis would therefore identify an association between increased preadmission physician continuity and improved patient outcomes. Analyses could also incorporate more discriminative measures of severity of hospital illness, such as those developed by Escobar et al.43 Since patients may experience health events after their discharge from hospital that could influence outcomes, recording these and expressing them in the study model as time‐dependent covariates will be important. Finally, similar to the classic study by Wasson et al.44 in 1984, a proper randomized trial that measures the effect of a continuity‐building intervention on both continuity of care and patient outcomes would help determine how continuity influences outcomes.

In conclusion, after discharge from hospital, increased continuity with physicians who routinely care for the patient is significantly and independently associated with a decreased risk of urgent readmission. Continuity with the hospital physician after discharge did not independently influence the risk of patient death or urgent readmission in our study. Further research is required to determine the causal association between preadmission physician continuity and improved outcomes. Until that time, clinicians should strive to optimize continuity with physicians their patients have seen prior to the hospitalization.

Hospitalists are common in North America.1, 2 Hospitalists have been associated with a range of beneficial outcomes including decreased length of stay.3, 4 A primary concern of the hospitalist model is its potential detrimental effect on continuity of care5 partly because patients are often not seen by their hospitalists after discharge.

Continuity of care6 is primarily composed of provider continuity (an ongoing relationship between a patient and a particular provider over time) and information continuity (availability of data from prior events for subsequent patient encounters).6 The association between continuity of care and patient outcomes has been quantified in many studies.720 However, the relationship of continuity and outcomes is especially relevant after discharge from the hospital since this is a time when patients have a high risk of poor patient outcomes21 and poor provider22 and information continuity.2325

The association between continuity and outcomes after hospital discharge has been directly quantified in 2 studies. One found that patients seen by a physician who treated them in the hospital had a significant adjusted relative risk reduction in 30‐day death or readmission of 5% and 3%, respectively.22 The other study found that patients discharged from a general medicine ward were less likely to be readmitted if they were seen by physicians who had access to their discharge summary.23 However, neither of these studies concurrently measured the influence of provider and information continuity on patient outcomes.

Determining whether and how continuity of care influences patient outcomes after hospital discharge is essential to improve health care in an evidence‐based fashion. In addition, the influence that hospital physician follow‐up has on patient outcomes can best be determined by measuring provider and information continuity in patients after hospital discharge. This study sought to measure the independent association of several provider and information continuity measures on death or urgent readmission after hospital discharge.

Methods

Study Design

This was a multicenter prospective cohort study of consecutive patients discharged to the community from the medical or surgical services of 11 Ontario hospitals (6 university‐affiliated hospitals and 5 community hospitals) in 5 cities after an elective or emergency hospitalization. Patients were invited to participate in the study if they were cognitively intact, had a telephone, and provided written informed consent. Patients were excluded if they were less than 18 years old, were discharged to nursing homes, or were not proficient in English and did not have someone to help communicate with study staff. Enrolled patients were excluded from the analysis if they had less than 2 physician visits prior to one of the study's outcomes or the end of patient observation (which was 6 months postdischarge). This final exclusion criterion was necessary since 2 continuity measures (including postdischarge physician continuity and postdischarge information continuity) were incalculable with less than 2 physician visits during follow‐up (Supporting information). The study was approved by the research ethics board of each participating hospital.

Data Collection

Prior to hospital discharge, patients were interviewed by study personnel to identify their baseline functional status, their living conditions, all physicians who regularly treated the patient prior to admission (including both family physicians and consultants), and chronic medical conditions. The latter were confirmed by a review of the patient's chart and hospital discharge summary, when available. Patients also provided principal contacts whom we could contact in the event patients could not be reached. The chart and discharge summary were also used to identify diagnoses in hospitalincluding complications (diagnoses arising in the hospital)and medications at discharge.

Patients or their designated contacts were telephoned 1, 3, and 6 months after hospital discharge to identify the date and the physician of all postdischarge physician visits. For each postdischarge physician visit, we determined whether the physician had access to a discharge summary for the index hospitalization. We also determined the availability of information from all previous postdischarge visits that the patient had with other physicians. The methods used to collect these data were previously detailed.26 Briefly, we used three complementary methods to elicit this information from each follow‐up physician. First, patients gave the physician a survey on which the physician listed all prior visits with other doctors for which they had information. If this survey was not returned, we faxed the survey to the physician. If the faxed survey was not returned, we telephoned the physician or their office staff and administered the survey over the telephone.

Continuity Measures

We measured components of both provider and information continuity. For the posthospitalization period, we measured provider continuity for physicians who had provided patient care during three distinct phases: the prehospital period; the hospital period; and the postdischarge period. Prehospital physicians were those classified by the patient as their regular physician(s) (defined as physiciansboth family physicians and consultantsthat they had seen in the past and were likely to see again in the future). Hospital provider continuity was divided into 2 components: hospital physician continuity (ie, the most responsible physician in the hospital); and hospital consultant continuity (ie, another physician who consulted on the patient during admission). Information continuity was divided into discharge summary continuity and postdischarge visit information continuity.

We quantified provider and information continuity using Breslau's Usual Provider of Continuity (UPC)27 measure. It is a widely used and validated continuity measure whose values are meaningful and interpretable.6 The UPC measures the proportion of visits with the physician of interest (for provider continuity) or the proportion of visits having the information of interest (for information continuity). The UPC was calculated as: $${\rm UPC} = {\rm n}_{\rm i} / {\rm N}$$

As the formulae in the supporting information suggest, all continuity measures were incalculable prior to the first postdischarge visit and all continuity measures changed value at each visit during patient observation. In addition, a particular physician visit could increase multiple continuity measures simultaneously. For example, a visit with a physician who was the hospital physician and who regularly treated the patient prior to the hospitalization would increase both hospital and prehospital provider continuity. If the patient had previously seen the physician after discharge, the visit would also increase postdischarge physician continuity.

Study Outcomes

Outcomes for the study included time to all‐cause death and time to all‐cause, urgent readmission. To be classified as urgent, readmissions could not be arranged when the patient was originally discharged from hospital or more than 4 weeks prior to the readmission. All hospital admissions meeting these criteria during the 6 month study period were labeled in this study as urgent readmissions even if they were unrelated to the index admission.

Principal contacts were called if we were unable to reach the patient to determine their outcomes. If the patient's vital status remained unclear, we contacted the Office of the Provincial Registrar to determine if and when the patient died during the 6 months after discharge from hospital.

Analysis

Outcome incidence densities and 95% confidence intervals [CIs] were calculated using PROC GENMOD in SAS to account for clustering of patients in hospitals. We used multivariate proportional hazards modeling to determine the independent association of provider and information continuity measures with time to death and time to urgent readmission. Patient observation started when patients were discharged from the hospital. Patient observation ended at the earliest of the following: death; urgent readmission to the hospital; end of follow‐up (which was 6 months after discharge from the hospital) or loss to follow‐up. Because hospital consultant continuity was very highly skewed (95.6% of patients had a value of 0; mean value of 0.016; skewness 6.9), it was not included in the primary regression models but was included in a sensitivity analysis.

To adjust for potential confounders in the association between continuity and the outcomes, our model included all factors that were independently associated with either the outcome or any continuity measure. Factors associated with death or urgent readmission were summarized using the LACE index.29 This index combines a patient's hospital length of stay, admission acuity, patient comorbidity (measured with the Charlson Score30 using updated disease category weights by Schneeweiss et al.),31 and emergency room utilization (measured as the number of visits in the 6 months prior to admission) into a single number ranging from 0 to 19. The LACE index was moderately discriminative and highly accurate at predicting 30‐day death or urgent readmission.29 In a separate study,28 we found that the following factors were independently associated with at least one of the continuity measures: patient age; patient sex; number of admissions in previous 6 months; number of regular treating physicians prior to admission; hospital service (medicine vs. surgery); and number of complications in the hospital (defined as new problems arising after admission to hospital). By including all factors that were independently associated with either the outcome or continuity, we controlled for all measured factors that could act as confounders in the association between continuity and outcomes. We accounted for the clustered study design by using conditional proportional hazards models that stratified by hospitals.32 Analytical details are given in the supporting information.

Results

Between October 2002 and July 2006, we enrolled 5035 patients from 11 hospitals (Figure 1). Of the 5035 patients, 274 (5.4%) had no follow up interview with study personnel. A total of 885 (17.6%) had fewer than 2 post discharge physician visits and were not included in the continuity analyses. This left 3876 patients for this analysis (77.0% of the original cohort), of which 3727 had complete follow up (96.1% of the study cohort). A total of 531 patients (10.6% of the original cohort) had incomplete follow‐up because: 342 (6.8%) were lost to follow‐up; 172 (3.4%) refused participation; and 24 (0.5%) were transferred into a nursing home during the first month of observation.

The 3876 study patients are described in Table 1. Overall, these people had a mean age of 62 and most commonly had no physical limitations. Almost a third of patients had been admitted to the hospital in the previous 6 months. A total of 7.6% of patients had no regular prehospital physician while 5.8% had more than one regular prehospital physician. Patients were evenly split between acute and elective admissions and 12% had a complication during their admission. They were discharged after a median of 4 days on a median of 4 medications.

| Factor | Value | Death or Urgent Readmission | All (n = 3876) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 3491) | Yes (n = 385) | |||

| ||||

| Mean patient age, years (SD) | 61.59 16.16 | 67.70 15.53 | 62.19 16.20 | |

| Female (%) | 1838 (52.6) | 217 (56.4) | 2055 (53.0) | |

| Lives alone (%) | 791 (22.7) | 107 (27.8) | 898 (23.2) | |

| # activities of daily living requiring aids (%) | 0 | 3277 (93.9) | 354 (91.9) | 3631 (93.7) |

| 1 | 125 (3.6) | 20 (5.2) | 145 (3.7) | |

| >1 | 89 (2.5) | 11 (2.8) | 100 (2.8) | |

| # physicians who see patient regularly (%) | 0 | 241 (6.9) | 22 (5.7) | 263 (6.8) |

| 1 | 3060 (87.7) | 333 (86.5) | 3393 (87.5) | |

| 2 | 150 (4.3) | 21 (5.5) | 171 (4.4) | |

| >2 | 281 (8.0) | 31 (8.0) | 312 (8.0) | |

| # admissions in previous 6 months (%) | 0 | 2420 (69.3) | 222 (57.7) | 2642 (68.2) |

| 1 | 833 (23.9) | 103 (26.8) | 936 (24.1) | |

| >1 | 238 (6.8) | 60 (15.6) | 298 (7.7) | |

| Index hospitalization description | ||||

| Number of discharge medications (IQR) | 4 (2‐7) | 6 (3‐9) | 4 (2‐7) | |

| Admitted to medical service (%) | 1440 (41.2) | 231 (60.0) | 1671 (43.1) | |

| Acute diagnoses: | ||||

| CAD (%) | 238 (6.8) | 23 (6.0) | 261 (6.7) | |

| Neoplasm of unspecified nature (%) | 196 (5.6) | 35 (9.1) | 231 (6.0) | |

| Heart failure (%) | 127 (3.6) | 38 (9.9) | 165 (4.3) | |

| Acute procedures | ||||

| CABG (%) | 182 (5.2) | 14 (3.6) | 196 (5.1) | |

| Total knee arthoplasty (%) | 173 (5.0) | 10 (2.6) | 183 (4.7) | |

| Total hip arthroplasty (%) | 118 (3.4) | (0.5) | 120 (3.1) | |

| Complication during admission (%) | 403 (11.5) | 63 (16.4) | 466 (12.0) | |

| LACE index: mean (SD) | 8.0 (3.6) | 10.3 (3.8) | 8.2 (3.7) | |

| Length of stay in days: median (IQR) | 4 (2‐7) | 6 (3‐10) | 4 (2‐8) | |

| Acute/emergent admission (%) | 1851 (53.0) | 272 (70.6) | 2123 (54.8) | |

| Charlson score (%) | 0 | 2771 (79.4) | 241 (62.6) | 3012 (77.7) |

| 1 | 103 (3.0) | 17 (4.4) | 120 (3.1) | |

| 2 | 446 (12.8) | 86 (22.3) | 532 (13.7) | |

| >2 | 171 (4.9) | 41 (10.6) | 212 (5.5) | |

| Emergency room use (# visits/ year) (%) | 0 | 2342 (67.1) | 190 (49.4) | 2532 (65.3) |

| 1 | 761 (21.8) | 101 (26.2) | 862 (22.2) | |

| >1 | 388 (11.1) | 94 (24.4) | 482 (12.4) | |

Patients were observed in the study for a median of 175 days (interquartile range [IQR] 175‐178). During this time they had a median of 4 physician visits (IQR 3‐6). The first postdischarge physician visit occurred a median of 10 days (IQR 6‐18) after discharge from hospital.

Continuity Measures

Table 2 summarizes all continuity scores. Since continuity scores varied significantly over time,28 Table 2 provides continuity scores on the last day of patient observation. Preadmission provider, postdischarge provider, and discharge summary continuity all had similar values and distributions with median values ranging between 0.444 and 0.571. 1797 (46.4%) patients had a hospital physician provider continuity scorae of 0.

| Minimum | 25th Percentile | Median | 75th Percentile | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider continuity | |||||

| A: Pre‐admission physician | 0 | 0.143 | 0.444 | 0.667 | 1.000 |

| B: Hospital physician | 0 | 0 | 0.143 | 0.400 | 1.000 |

| C: Post‐discharge physician | 0 | 0.333 | 0.571 | 0.750 | 1.000 |

| Information continuity | |||||

| D: Discharge summary | 0 | 0.095 | 0.500 | 0.800 | 1.000 |

| E: Post‐discharge information | 0 | 0 | 0.182 | 0.500 | 1.000 |

Study Outcomes

During a median of 175 days of observation, 45 patients died (event rate 2.6 events per 100 patient‐years observation [95% CI 2.0‐3.4]) and 340 patients were urgently readmitted (event rate 19.6 events per 100 patient‐years observation [95% CI 15.9‐24.3]). Figure 2 presents the survival curves for time to death and time to urgent readmission. The hazard of death was consistent through the observation period but the risk of urgent readmission decreased slightly after 90 days postdischarge.

Association Between Continuity and Outcomes

Table 3 summarizes the association between provider and information continuity with study outcomes. No continuity measure was associated with time to death by itself (Table 3, column A) or with the other continuity measures (Table 3, column B). Preadmission physician continuity was associated with a significantly decreased risk of urgent readmission. When the proportion of postdischarge visits with a prehospital physician increased by 10%, the adjusted risk of urgent readmission decreased by 6% (adjusted hazards ratio (adj‐HR)) of 0.94 (95% CI, 0.91‐0.98). None of the other continuity measuresincluding hospital physicianwere significantly associated with urgent readmission either by themselves (Table 3, column A) or after adjusting for other continuity measures (Table 3, column B).

| Outcome | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death (95% CI) | Urgent Readmission (95% CI) | |||||||

| A: Adjusted for Other Confounders Only | B: Adjusted for Other Confounders and Continuity Measures | A: Adjusted for Other Confounders Only | B: Adjusted for Other Confounders and Continuity Measures | |||||

| ||||||||

| Provider continuity | ||||||||

| A: Pre‐admission physician | 1.03 | (0.95, 1.12) | 1.06 | (0.95, 1.18) | 0.95 | (0.92, 0.98) | 0.94 | (0.91, 0.98) |

| B: Hospital physician | 0.87 | (0.74, 1.02) | 0.86 | (0.70, 1.03) | 0.98 | (0.94, 1.02) | 0.97 | (0.92, 1.01) |

| C: Post‐discharge physician | 0.97 | (0.89, 1.06) | 0.93 | (0.84, 1.04) | 0.98 | (0.95, 1.01) | 0.98 | (0.94, 1.02) |

| Information continuity | ||||||||

| D: Discharge Summary | 0.96 | (0.89, 1.04) | 0.94 | (0.87, 1.03) | 1.01 | (0.98, 1.04) | 1.02 | (0.99, 1.05) |

| E: Post‐discharge information | 1.01 | (0.94, 1.08) | 1.03 | (0.95, 1.11) | 1.00 | (0.97, 1.03) | 1.03 | (0.95, 1.11) |

| Other confounders | ||||||||

| Patient age in decades* | 1.43 | (1.13, 1.82) | 1.18 | (1.10, 1.28) | ||||

| Female | 1.50 | (0.81, 2.77) | 1.16 | (0.94, 1.44) | ||||

| # physicians who see patient regularly | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.46 | (0.92, 2.34) | ||||||

| 2 | 2.17 | (1.11, 4.26) | ||||||

| >2 | 3.71 | (1.55, 8.88) | ||||||

| Complications during admission | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.38 | (0.61, 3.10) | 0.81 | (0.55, 1.17) | ||||

| >1 | 1.01 | (0.28, 3.58) | 0.91 | (0.56, 1.48) | ||||

| # admissions in previous 6 months | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.27 | (0.59, 2.70) | 1.34 | (1.02, 1.76) | ||||

| >1 | 1.42 | (0.55, 3.67) | 1.78 | (1.26, 2.51) | ||||

| LACE index* | 1.16 | (1.06, 1.26) | 1.10 | (1.07, 1.14) | ||||

Increased patient age and increased LACE index score were both strongly associated with an increased risk of death (adj‐HR 1.43 [1.13‐1.82] and 1.16 [1.06‐1.26], respectively) and urgent readmission (adj‐HR 1.18 [1.10‐1.28] and 1.10 [1.07‐1.14], respectively). Hospitalization in the 6 months prior to admission significantly increased the risk of urgent readmission but not death. The risk of urgent readmission increased significantly as the number of regular prehospital physicians increased.

Sensitivity Analyses

Our study conclusions did not change in the sensitivity analyses. The number of postdischarge physician visits (expressed as a time‐dependent covariate) was not associated with either death or with urgent readmission and preadmission physician continuity remained significantly associated with time to urgent readmission (supporting information). Adding consultant continuity to the model also did not change our results (supporting information). In‐hospital consultant continuity was associated with an increased risk of urgent readmission (adj‐HR 1.10, 95% CI, 1.01‐1.20). The association between pre‐admission physician continuity and time to urgent readmission did not interact significantly with patient age, LACE index score, or number of previous admissions.

Discussion

This large, prospective cohort study measured the independent association of several provider and information continuity measures with important outcomes in patients discharged from hospital. After adjusting for potential confounders, we found that increased continuity with physicians who regularly cared for the patient prior to the admission was significantly and independently associated with a decreased risk of urgent readmission. Our data suggest that continuity with the hospital physician did not independently influence the risk of patient death or urgent readmission after discharge.

Although hospital physician continuity did not significantly change patient outcomes, we found that follow‐up with a physician who regularly treated the patient prior to their admission was associated with a significantly decreased risk of urgent readmission. This could reflect the important role that a patient's regular physician plays in their health care. Other studies have shown a positive association between continuity with a regular physician and improved outcomes including decreased emergency room utilization7, 8 and decreased hospitalization.10, 11

We were somewhat disappointed that information continuity was not independently associated with improved patient outcomes. Information continuity is likely more amenable to modification than is provider continuity. Of course, our study findings do not mean that information continuity does not improve patient outcomes, as in other studies.23, 33 Instead, our results could reflect that we solely measured the availability of information to physicians. Future studies that measure the quality, relevance, and actual utilization of patient information will be better able to discern the influence of information continuity on patient outcomes.

We believe that our study was methodologically strong and unique. We captured both provider and information continuity in a large group of representative patients using a broad range of measures that captured continuity's diverse components including both provider and information continuity. The continuity measures were expressed and properly analyzed as time‐dependent variables in a multivariate model.34 Our analysis controlled for important potential confounders. Our follow‐up and data collection was rigorous with 96.1% of our study group having complete follow‐up. Finally, the analysis used multiple imputation to appropriately handle missing data in the one incomplete variable (post‐discharge information continuity).3537