User login

Flu season’s almost here: Are you ready?

Influenza pandemics like the one we had last year are uncommon, and mounting an effective response was a difficult challenge. The pandemic hit early and hard. Physicians and the public health system responded well, administering a seasonal flu vaccine as well as a new H1N1 vaccine that was approved, produced, and distributed in record time. Before the end of the season, approximately 30% of the population had received an H1N1 vaccine and 40% a seasonal vaccine.1

What happened last year

The influenza attack rate in 2009-2010 exceeded that of a normal influenza season and the age groups most affected were also different, with those over the age of 65 largely spared.2 Virtually all the influenza last year was caused by the pandemic H1N1 strain.2 Fortuitously, the virus was not especially virulent and the death rates were below what was initially expected. TABLE 1 lists the population death rates that occurred for different age groups.2 Most of the more than 2000 deaths were among those with high-risk conditions.3 Those conditions are listed in TABLE 2.

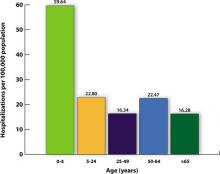

There were, however, 269 deaths by late March among children, which far exceeded the number of deaths in this age group for the previous 3 influenza seasons.2 For the most part, these higher mortality rates were due to higher attack rates, rather than higher case fatality rates. This is evident from hospitalization rates for children younger than age 5, which exceeded those of other age groups, as shown in FIGURE 1.

TABLE 1

2009-2010 Influenza death rates by age

| Age group, years | Death rate/100,000 |

|---|---|

| 0-4 | 0.43 |

| 5-18 | 0.36 |

| 19-24 | 0.54 |

| 25-49 | 0.87 |

| 50-64 | 1.56 |

| ≥65 | 0.95 |

| Source: CDC. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010.2 | |

TABLE 2

Individuals at higher risk for influenza complications (or who may spread infection to those at higher risk)

|

| Source: CDC. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010.4 |

FIGURE 1

Cumulative lab-confirmed hospitalization rate by age group, 2009 H1N1, April 2009-February 13, 2010*

*Based on 35 states reporting (n=49,516).

Source: Finelli L, et al. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/downloads/mtg-slides-feb10/05-2-flu-vac.pdf. 2010.3

The task will be simpler this year

While it’s not possible to predict what will happen in the upcoming season, 2 developments should simplify the family physician’s task of adhering to official recommendations:

- Only 1 vaccine formulation will be available, and

- For the first time, the recommendation is to vaccinate everyone who does not have a contraindication.4

The vaccine for the 2010-2011 season will contain 3 antigens: the pandemic H1N1 virus, an H3N2 A strain (A/Perth/16/2009), and a B virus (B/Brisbane/60/2008).2 The decision on which antigens to include is made 6 months in advance of the start of the next flu season and is based on information about the most common influenza antigens circulating worldwide at that time.

Immunization for all

This year’s recommendation to immunize everyone who does not have a contraindication is a major change from the age- and risk-based recommendations of past years. The universal recommendation is the culmination of the incremental expansions of recommendation categories that occurred over the past decade, which resulted in suboptimal immunization rates.1 In 2009, only 40% to 50% of adults for whom the seasonal vaccine was recommended received it.5 While the annual influenza vaccine recommendation is now universal, those who should be specially targeted include those in TABLE 2. Most public health authorities believe children should also receive special emphasis because of the high transmission rate among school-age children and their home contacts. Next, of course, come health care workers, who should be vaccinated to protect ourselves, our families, and our patients.4,6

Antivirals for treatment and prevention

There are 2 uses for antivirals to combat influenza: treatment of those infected and chemoprevention for those exposed to someone infected. Treatment is recommended for those with confirmed or suspected influenza who have severe, complicated, or progressive illness or who are hospitalized.7 Treatment should be strongly considered for anyone at higher risk for complications and death from influenza.7

Chemoprevention is now being deemphasized because of a concern for possible development of antiviral resistance. It should be considered for those in the high-risk categories (TABLE 2) with a documented exposure.7

Which antiviral to use will depend on which influenza strains are circulating and their resistance patterns. So far, H1N1 has remained largely sensitive to both neuraminidase inhibitors: oseltamivir and zanamivir. However, oseltamivir resistance has been documented in a few cases and will be monitored carefully.

Family physicians will need to stay informed by state and local health departments about circulating strains and resistance patterns. The latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidance on antiviral therapy can be consulted for dosage and other details on the 4 antiviral drugs licensed in the United States.7

What you must know about vaccine safety

Because of increasing public awareness of safety issues, family physicians will frequently need to address patients’ questions about the safety of this year’s vaccine. Last year, multiple reporting systems including the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) Project, the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS), and others, extensively monitored adverse events that could potentially be linked to the H1N1 vaccine.8 Three so-called weak signals—indications of a possible link to a rare, but statistically significant adverse event—were received.

The 3 signals were for Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), Bell’s palsy, and thrombocytopenia/idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. The status of the investigation of each potential link to the vaccine can be found on the National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC) safety Web site at http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/nvac/reports/index.html.

The GBS signal has been investigated the most aggressively because this adverse reaction has been linked to the so-called swine flu vaccine of 1976. One analysis has been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.9 Whether GBS has a causal link to the H1N1 vaccine remains in doubt. In the worst-case scenario, if causation is determined, it appears that the vaccine would account for no more than 1 excess case of GBS per million doses.9

In Western Australia, there has been a recent report of an excess of fever and febrile seizures in children 6 months to 5 years of age, and fever in children 5 to 9 years of age who received seasonal influenza vaccine. The rate of febrile seizures in children younger than age 3 was 7 per 1000, which is 7 times the rate normally expected. These adverse reactions were associated with only 1 vaccine product, Fluvax, and Fluvax Junior, manufactured by CSL Biotherapies.10 The CSL product is marketed in the United States by Merck & Co. under the brand name Afluria.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has issued the following recommendations:11

- Afluria should not be used in children ages 6 months through 8 years. The exception: children who are ages 5 through 8 years who are considered to be at high risk for influenza complications and for whom no other trivalent inactivated vaccine is available.

- Other age-appropriate, licensed seasonal influenza vaccine formulations should be used for prevention of influenza in children ages 6 months through 8 years.

High-dose vaccine for elderly patients

A new seasonal influenza vaccine (Fluzone High-Dose, manufactured by Sanofi Pasteur) is now available for use in people who are 65 years of age and older.12 Fluzone High-Dose contains 4 times the amount of influenza antigen as other inactivated seasonal influenza vaccines. Fluzone High-Dose vaccine produces higher antibody levels in the elderly but also a higher frequency of local reactions. Studies are being conducted to see if the vaccine results in better patient outcomes. ACIP does not state a preference for any of the available influenza vaccines for those who are 65 years of age and older.12

Children younger than age 9: One dose or two?

The new recommendations for deciding if a child under the age of 9 years should receive 1 or 2 doses of the vaccine run counter to the trend for simplification in influenza vaccine recommendations. The decision depends on the child’s past immunization history for both seasonal and H1N1 vaccines. To be fully vaccinated with only 1 dose this year, a child must have previously received at least 1 dose of H1N1 vaccine and 2 doses of seasonal vaccine. FIGURE 2 illustrates the process you need to go through to make the dosage choice. When the child’s immunization history is unknown or uncertain, give 2 doses, separated by 4 weeks.4

FIGURE 2

Children younger than 9: Ask 4 questions

Source: CDC. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010.4

1. Singleton JA. H1N1 vaccination coverage: updated interim results February 24, 2010. ACIP presentation slides, February 2010 meeting. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/downloads/mtg-slides-feb10/05-4-flu-vac.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2010.

2. CDC. Update: influenza activity—United States, August 30, 2009-March 27, 2010, and composition of the 2010-11 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:423-438.

3. Finelli L, Brammer L, Kniss K, et al. Influenza epidemiology and surveillance. ACIP Presentation slides, February 2010 meeting. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/downloads/mtg-slides-feb10/05-2-flu-vac.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2010.

4. CDC. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. July 29, 2010 (early release);1-62.

5. Harris KM, Maurer J, Uscher-Pines L. Seasonal influenza vaccine use by adults in the US: a snapshot as of mid-November 2009. Available at: http://www.rand.org/pubs/occasional_papers/OP289/. Accessed July 16, 2010.

6. Fiore A. Influenza vaccine workgroup discussions and recommendations, November 2009-February 2010. ACIP presentation slides, February 2010 meeting. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/downloads/mtg-slides-feb10/05-7-flu-vac.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2010.

7. CDC. Updated interim recommendations for the use of antiviral medications in the treatment and prevention of influenza for the 2009-2010 season. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/H1N1flu/recommendations.htm. Accessed July 16, 2010.

8. National Vaccine Advisory Committee Report on 2009 H1N1 Vaccine Safety Risk Assessment. June 2010. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/nvac/reports/vsrawg_repot_may2010.html. Accessed July 16, 2010.

9. CDC. Preliminary results: surveillance for Guillain-Barré syndrome after receipt of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccine—United States, 2009–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:657-661.

10. McNeil M. Febrile seizures in Australia and CDC monitoring plan for 2010-2011 seasonal influenza vaccine. Available at: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/downloads/mtg-slides-jun10/10-8-flu.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2010.

11. CDC. Media statement: ACIP recommendation for use of CSL influenza vaccine. August 6, 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/media/pressrel/2010/s100806.htm?s_cid=mediarel_s100806. Accessed August 6, 2010.

12. CDC. Licensure of a high-dose inactivated influenza vaccine for persons aged ≥65 years (Fluzone High-Dose) and guidance for use—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:485-486.

Influenza pandemics like the one we had last year are uncommon, and mounting an effective response was a difficult challenge. The pandemic hit early and hard. Physicians and the public health system responded well, administering a seasonal flu vaccine as well as a new H1N1 vaccine that was approved, produced, and distributed in record time. Before the end of the season, approximately 30% of the population had received an H1N1 vaccine and 40% a seasonal vaccine.1

What happened last year

The influenza attack rate in 2009-2010 exceeded that of a normal influenza season and the age groups most affected were also different, with those over the age of 65 largely spared.2 Virtually all the influenza last year was caused by the pandemic H1N1 strain.2 Fortuitously, the virus was not especially virulent and the death rates were below what was initially expected. TABLE 1 lists the population death rates that occurred for different age groups.2 Most of the more than 2000 deaths were among those with high-risk conditions.3 Those conditions are listed in TABLE 2.

There were, however, 269 deaths by late March among children, which far exceeded the number of deaths in this age group for the previous 3 influenza seasons.2 For the most part, these higher mortality rates were due to higher attack rates, rather than higher case fatality rates. This is evident from hospitalization rates for children younger than age 5, which exceeded those of other age groups, as shown in FIGURE 1.

TABLE 1

2009-2010 Influenza death rates by age

| Age group, years | Death rate/100,000 |

|---|---|

| 0-4 | 0.43 |

| 5-18 | 0.36 |

| 19-24 | 0.54 |

| 25-49 | 0.87 |

| 50-64 | 1.56 |

| ≥65 | 0.95 |

| Source: CDC. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010.2 | |

TABLE 2

Individuals at higher risk for influenza complications (or who may spread infection to those at higher risk)

|

| Source: CDC. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010.4 |

FIGURE 1

Cumulative lab-confirmed hospitalization rate by age group, 2009 H1N1, April 2009-February 13, 2010*

*Based on 35 states reporting (n=49,516).

Source: Finelli L, et al. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/downloads/mtg-slides-feb10/05-2-flu-vac.pdf. 2010.3

The task will be simpler this year

While it’s not possible to predict what will happen in the upcoming season, 2 developments should simplify the family physician’s task of adhering to official recommendations:

- Only 1 vaccine formulation will be available, and

- For the first time, the recommendation is to vaccinate everyone who does not have a contraindication.4

The vaccine for the 2010-2011 season will contain 3 antigens: the pandemic H1N1 virus, an H3N2 A strain (A/Perth/16/2009), and a B virus (B/Brisbane/60/2008).2 The decision on which antigens to include is made 6 months in advance of the start of the next flu season and is based on information about the most common influenza antigens circulating worldwide at that time.

Immunization for all

This year’s recommendation to immunize everyone who does not have a contraindication is a major change from the age- and risk-based recommendations of past years. The universal recommendation is the culmination of the incremental expansions of recommendation categories that occurred over the past decade, which resulted in suboptimal immunization rates.1 In 2009, only 40% to 50% of adults for whom the seasonal vaccine was recommended received it.5 While the annual influenza vaccine recommendation is now universal, those who should be specially targeted include those in TABLE 2. Most public health authorities believe children should also receive special emphasis because of the high transmission rate among school-age children and their home contacts. Next, of course, come health care workers, who should be vaccinated to protect ourselves, our families, and our patients.4,6

Antivirals for treatment and prevention

There are 2 uses for antivirals to combat influenza: treatment of those infected and chemoprevention for those exposed to someone infected. Treatment is recommended for those with confirmed or suspected influenza who have severe, complicated, or progressive illness or who are hospitalized.7 Treatment should be strongly considered for anyone at higher risk for complications and death from influenza.7

Chemoprevention is now being deemphasized because of a concern for possible development of antiviral resistance. It should be considered for those in the high-risk categories (TABLE 2) with a documented exposure.7

Which antiviral to use will depend on which influenza strains are circulating and their resistance patterns. So far, H1N1 has remained largely sensitive to both neuraminidase inhibitors: oseltamivir and zanamivir. However, oseltamivir resistance has been documented in a few cases and will be monitored carefully.

Family physicians will need to stay informed by state and local health departments about circulating strains and resistance patterns. The latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidance on antiviral therapy can be consulted for dosage and other details on the 4 antiviral drugs licensed in the United States.7

What you must know about vaccine safety

Because of increasing public awareness of safety issues, family physicians will frequently need to address patients’ questions about the safety of this year’s vaccine. Last year, multiple reporting systems including the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) Project, the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS), and others, extensively monitored adverse events that could potentially be linked to the H1N1 vaccine.8 Three so-called weak signals—indications of a possible link to a rare, but statistically significant adverse event—were received.

The 3 signals were for Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), Bell’s palsy, and thrombocytopenia/idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. The status of the investigation of each potential link to the vaccine can be found on the National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC) safety Web site at http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/nvac/reports/index.html.

The GBS signal has been investigated the most aggressively because this adverse reaction has been linked to the so-called swine flu vaccine of 1976. One analysis has been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.9 Whether GBS has a causal link to the H1N1 vaccine remains in doubt. In the worst-case scenario, if causation is determined, it appears that the vaccine would account for no more than 1 excess case of GBS per million doses.9

In Western Australia, there has been a recent report of an excess of fever and febrile seizures in children 6 months to 5 years of age, and fever in children 5 to 9 years of age who received seasonal influenza vaccine. The rate of febrile seizures in children younger than age 3 was 7 per 1000, which is 7 times the rate normally expected. These adverse reactions were associated with only 1 vaccine product, Fluvax, and Fluvax Junior, manufactured by CSL Biotherapies.10 The CSL product is marketed in the United States by Merck & Co. under the brand name Afluria.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has issued the following recommendations:11

- Afluria should not be used in children ages 6 months through 8 years. The exception: children who are ages 5 through 8 years who are considered to be at high risk for influenza complications and for whom no other trivalent inactivated vaccine is available.

- Other age-appropriate, licensed seasonal influenza vaccine formulations should be used for prevention of influenza in children ages 6 months through 8 years.

High-dose vaccine for elderly patients

A new seasonal influenza vaccine (Fluzone High-Dose, manufactured by Sanofi Pasteur) is now available for use in people who are 65 years of age and older.12 Fluzone High-Dose contains 4 times the amount of influenza antigen as other inactivated seasonal influenza vaccines. Fluzone High-Dose vaccine produces higher antibody levels in the elderly but also a higher frequency of local reactions. Studies are being conducted to see if the vaccine results in better patient outcomes. ACIP does not state a preference for any of the available influenza vaccines for those who are 65 years of age and older.12

Children younger than age 9: One dose or two?

The new recommendations for deciding if a child under the age of 9 years should receive 1 or 2 doses of the vaccine run counter to the trend for simplification in influenza vaccine recommendations. The decision depends on the child’s past immunization history for both seasonal and H1N1 vaccines. To be fully vaccinated with only 1 dose this year, a child must have previously received at least 1 dose of H1N1 vaccine and 2 doses of seasonal vaccine. FIGURE 2 illustrates the process you need to go through to make the dosage choice. When the child’s immunization history is unknown or uncertain, give 2 doses, separated by 4 weeks.4

FIGURE 2

Children younger than 9: Ask 4 questions

Source: CDC. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010.4

Influenza pandemics like the one we had last year are uncommon, and mounting an effective response was a difficult challenge. The pandemic hit early and hard. Physicians and the public health system responded well, administering a seasonal flu vaccine as well as a new H1N1 vaccine that was approved, produced, and distributed in record time. Before the end of the season, approximately 30% of the population had received an H1N1 vaccine and 40% a seasonal vaccine.1

What happened last year

The influenza attack rate in 2009-2010 exceeded that of a normal influenza season and the age groups most affected were also different, with those over the age of 65 largely spared.2 Virtually all the influenza last year was caused by the pandemic H1N1 strain.2 Fortuitously, the virus was not especially virulent and the death rates were below what was initially expected. TABLE 1 lists the population death rates that occurred for different age groups.2 Most of the more than 2000 deaths were among those with high-risk conditions.3 Those conditions are listed in TABLE 2.

There were, however, 269 deaths by late March among children, which far exceeded the number of deaths in this age group for the previous 3 influenza seasons.2 For the most part, these higher mortality rates were due to higher attack rates, rather than higher case fatality rates. This is evident from hospitalization rates for children younger than age 5, which exceeded those of other age groups, as shown in FIGURE 1.

TABLE 1

2009-2010 Influenza death rates by age

| Age group, years | Death rate/100,000 |

|---|---|

| 0-4 | 0.43 |

| 5-18 | 0.36 |

| 19-24 | 0.54 |

| 25-49 | 0.87 |

| 50-64 | 1.56 |

| ≥65 | 0.95 |

| Source: CDC. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010.2 | |

TABLE 2

Individuals at higher risk for influenza complications (or who may spread infection to those at higher risk)

|

| Source: CDC. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010.4 |

FIGURE 1

Cumulative lab-confirmed hospitalization rate by age group, 2009 H1N1, April 2009-February 13, 2010*

*Based on 35 states reporting (n=49,516).

Source: Finelli L, et al. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/downloads/mtg-slides-feb10/05-2-flu-vac.pdf. 2010.3

The task will be simpler this year

While it’s not possible to predict what will happen in the upcoming season, 2 developments should simplify the family physician’s task of adhering to official recommendations:

- Only 1 vaccine formulation will be available, and

- For the first time, the recommendation is to vaccinate everyone who does not have a contraindication.4

The vaccine for the 2010-2011 season will contain 3 antigens: the pandemic H1N1 virus, an H3N2 A strain (A/Perth/16/2009), and a B virus (B/Brisbane/60/2008).2 The decision on which antigens to include is made 6 months in advance of the start of the next flu season and is based on information about the most common influenza antigens circulating worldwide at that time.

Immunization for all

This year’s recommendation to immunize everyone who does not have a contraindication is a major change from the age- and risk-based recommendations of past years. The universal recommendation is the culmination of the incremental expansions of recommendation categories that occurred over the past decade, which resulted in suboptimal immunization rates.1 In 2009, only 40% to 50% of adults for whom the seasonal vaccine was recommended received it.5 While the annual influenza vaccine recommendation is now universal, those who should be specially targeted include those in TABLE 2. Most public health authorities believe children should also receive special emphasis because of the high transmission rate among school-age children and their home contacts. Next, of course, come health care workers, who should be vaccinated to protect ourselves, our families, and our patients.4,6

Antivirals for treatment and prevention

There are 2 uses for antivirals to combat influenza: treatment of those infected and chemoprevention for those exposed to someone infected. Treatment is recommended for those with confirmed or suspected influenza who have severe, complicated, or progressive illness or who are hospitalized.7 Treatment should be strongly considered for anyone at higher risk for complications and death from influenza.7

Chemoprevention is now being deemphasized because of a concern for possible development of antiviral resistance. It should be considered for those in the high-risk categories (TABLE 2) with a documented exposure.7

Which antiviral to use will depend on which influenza strains are circulating and their resistance patterns. So far, H1N1 has remained largely sensitive to both neuraminidase inhibitors: oseltamivir and zanamivir. However, oseltamivir resistance has been documented in a few cases and will be monitored carefully.

Family physicians will need to stay informed by state and local health departments about circulating strains and resistance patterns. The latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidance on antiviral therapy can be consulted for dosage and other details on the 4 antiviral drugs licensed in the United States.7

What you must know about vaccine safety

Because of increasing public awareness of safety issues, family physicians will frequently need to address patients’ questions about the safety of this year’s vaccine. Last year, multiple reporting systems including the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) Project, the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS), and others, extensively monitored adverse events that could potentially be linked to the H1N1 vaccine.8 Three so-called weak signals—indications of a possible link to a rare, but statistically significant adverse event—were received.

The 3 signals were for Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), Bell’s palsy, and thrombocytopenia/idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. The status of the investigation of each potential link to the vaccine can be found on the National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC) safety Web site at http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/nvac/reports/index.html.

The GBS signal has been investigated the most aggressively because this adverse reaction has been linked to the so-called swine flu vaccine of 1976. One analysis has been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.9 Whether GBS has a causal link to the H1N1 vaccine remains in doubt. In the worst-case scenario, if causation is determined, it appears that the vaccine would account for no more than 1 excess case of GBS per million doses.9

In Western Australia, there has been a recent report of an excess of fever and febrile seizures in children 6 months to 5 years of age, and fever in children 5 to 9 years of age who received seasonal influenza vaccine. The rate of febrile seizures in children younger than age 3 was 7 per 1000, which is 7 times the rate normally expected. These adverse reactions were associated with only 1 vaccine product, Fluvax, and Fluvax Junior, manufactured by CSL Biotherapies.10 The CSL product is marketed in the United States by Merck & Co. under the brand name Afluria.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has issued the following recommendations:11

- Afluria should not be used in children ages 6 months through 8 years. The exception: children who are ages 5 through 8 years who are considered to be at high risk for influenza complications and for whom no other trivalent inactivated vaccine is available.

- Other age-appropriate, licensed seasonal influenza vaccine formulations should be used for prevention of influenza in children ages 6 months through 8 years.

High-dose vaccine for elderly patients

A new seasonal influenza vaccine (Fluzone High-Dose, manufactured by Sanofi Pasteur) is now available for use in people who are 65 years of age and older.12 Fluzone High-Dose contains 4 times the amount of influenza antigen as other inactivated seasonal influenza vaccines. Fluzone High-Dose vaccine produces higher antibody levels in the elderly but also a higher frequency of local reactions. Studies are being conducted to see if the vaccine results in better patient outcomes. ACIP does not state a preference for any of the available influenza vaccines for those who are 65 years of age and older.12

Children younger than age 9: One dose or two?

The new recommendations for deciding if a child under the age of 9 years should receive 1 or 2 doses of the vaccine run counter to the trend for simplification in influenza vaccine recommendations. The decision depends on the child’s past immunization history for both seasonal and H1N1 vaccines. To be fully vaccinated with only 1 dose this year, a child must have previously received at least 1 dose of H1N1 vaccine and 2 doses of seasonal vaccine. FIGURE 2 illustrates the process you need to go through to make the dosage choice. When the child’s immunization history is unknown or uncertain, give 2 doses, separated by 4 weeks.4

FIGURE 2

Children younger than 9: Ask 4 questions

Source: CDC. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010.4

1. Singleton JA. H1N1 vaccination coverage: updated interim results February 24, 2010. ACIP presentation slides, February 2010 meeting. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/downloads/mtg-slides-feb10/05-4-flu-vac.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2010.

2. CDC. Update: influenza activity—United States, August 30, 2009-March 27, 2010, and composition of the 2010-11 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:423-438.

3. Finelli L, Brammer L, Kniss K, et al. Influenza epidemiology and surveillance. ACIP Presentation slides, February 2010 meeting. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/downloads/mtg-slides-feb10/05-2-flu-vac.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2010.

4. CDC. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. July 29, 2010 (early release);1-62.

5. Harris KM, Maurer J, Uscher-Pines L. Seasonal influenza vaccine use by adults in the US: a snapshot as of mid-November 2009. Available at: http://www.rand.org/pubs/occasional_papers/OP289/. Accessed July 16, 2010.

6. Fiore A. Influenza vaccine workgroup discussions and recommendations, November 2009-February 2010. ACIP presentation slides, February 2010 meeting. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/downloads/mtg-slides-feb10/05-7-flu-vac.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2010.

7. CDC. Updated interim recommendations for the use of antiviral medications in the treatment and prevention of influenza for the 2009-2010 season. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/H1N1flu/recommendations.htm. Accessed July 16, 2010.

8. National Vaccine Advisory Committee Report on 2009 H1N1 Vaccine Safety Risk Assessment. June 2010. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/nvac/reports/vsrawg_repot_may2010.html. Accessed July 16, 2010.

9. CDC. Preliminary results: surveillance for Guillain-Barré syndrome after receipt of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccine—United States, 2009–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:657-661.

10. McNeil M. Febrile seizures in Australia and CDC monitoring plan for 2010-2011 seasonal influenza vaccine. Available at: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/downloads/mtg-slides-jun10/10-8-flu.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2010.

11. CDC. Media statement: ACIP recommendation for use of CSL influenza vaccine. August 6, 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/media/pressrel/2010/s100806.htm?s_cid=mediarel_s100806. Accessed August 6, 2010.

12. CDC. Licensure of a high-dose inactivated influenza vaccine for persons aged ≥65 years (Fluzone High-Dose) and guidance for use—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:485-486.

1. Singleton JA. H1N1 vaccination coverage: updated interim results February 24, 2010. ACIP presentation slides, February 2010 meeting. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/downloads/mtg-slides-feb10/05-4-flu-vac.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2010.

2. CDC. Update: influenza activity—United States, August 30, 2009-March 27, 2010, and composition of the 2010-11 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:423-438.

3. Finelli L, Brammer L, Kniss K, et al. Influenza epidemiology and surveillance. ACIP Presentation slides, February 2010 meeting. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/downloads/mtg-slides-feb10/05-2-flu-vac.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2010.

4. CDC. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. July 29, 2010 (early release);1-62.

5. Harris KM, Maurer J, Uscher-Pines L. Seasonal influenza vaccine use by adults in the US: a snapshot as of mid-November 2009. Available at: http://www.rand.org/pubs/occasional_papers/OP289/. Accessed July 16, 2010.

6. Fiore A. Influenza vaccine workgroup discussions and recommendations, November 2009-February 2010. ACIP presentation slides, February 2010 meeting. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/downloads/mtg-slides-feb10/05-7-flu-vac.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2010.

7. CDC. Updated interim recommendations for the use of antiviral medications in the treatment and prevention of influenza for the 2009-2010 season. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/H1N1flu/recommendations.htm. Accessed July 16, 2010.

8. National Vaccine Advisory Committee Report on 2009 H1N1 Vaccine Safety Risk Assessment. June 2010. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/nvac/reports/vsrawg_repot_may2010.html. Accessed July 16, 2010.

9. CDC. Preliminary results: surveillance for Guillain-Barré syndrome after receipt of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccine—United States, 2009–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:657-661.

10. McNeil M. Febrile seizures in Australia and CDC monitoring plan for 2010-2011 seasonal influenza vaccine. Available at: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/downloads/mtg-slides-jun10/10-8-flu.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2010.

11. CDC. Media statement: ACIP recommendation for use of CSL influenza vaccine. August 6, 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/media/pressrel/2010/s100806.htm?s_cid=mediarel_s100806. Accessed August 6, 2010.

12. CDC. Licensure of a high-dose inactivated influenza vaccine for persons aged ≥65 years (Fluzone High-Dose) and guidance for use—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:485-486.

Should you restrain yourself from ordering restraints?

Dear Dr. Mossman:

We often have to administer sedating medications to aggressive patients who pose an immediate threat of harm to themselves or others. But I am unsure about whether these “chemical restraints” create more liability problems than “physical restraints”—or vice versa. Does one type of restraint carry more legal risk than the other?—Submitted by “Dr. L”

Mental health professionals view “mechanical” or “physical” restraints in a way that really differs from how they felt 2 decades ago. In the 1980s, physical restraint use was a common response when patients seemed to be immediately dangerous to themselves or others. But recent practice guidelines say physical restraints are a “last resort,” to be used only when other treatment measures to prevent aggression fail to work.

What should psychiatrists do? Is use of physical restraints malpractice? Are “chemical” restraints better?

This article looks at:

- definitions of restraint

- medical risks of restraint

- evolution and status of restraint policy

- what you can do about legal risks of restraint.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at [email protected].

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

Definitions

In medical contexts, restraint typically refers to “any device or medication used to restrict a patient’s movement.”1 The longer, official US regulatory definitions of physical and chemical restraints appear in Table 1.2 Two important notes:

- Neither regulatory definition of restraint is limited to psychiatric patients; both definitions and the accompanying regulations on restraint apply to any patient in a hospital eligible for federal reimbursement.

- The definition of physical restraint would include holding a patient still while administering an injection.

The detailed interpretive rules (“Conditions of Participation for Hospitals”)3 for these regulations require hospitals to document conditions surrounding and reasons related to restraint incidents and to make this documentation available to federal surveyors.

Table 1

Federal regulatory definitions of ‘restraint’

| Physical restraint | Any manual method, physical or mechanical device, material, or equipment that immobilizes or reduces the ability of a patient to move his or her arms, legs, body, or head freely |

| Chemical restraint | A drug or medication when it is used as a restriction to manage the patient’s behavior or restrict the patient’s freedom of movement and is not a standard treatment or dosage for the patient’s condition |

| Source: Reference 2 | |

Medical risks of restraint

In 1998, the Hartford Courant investigative series “Deadly restraint”4 reported on 142 deaths of psychiatric patients and alerted the public to the potentially fatal consequences of physical restraint. Often, restraint deaths result from asphyxia when patients try to free themselves and get caught in positions that restrict breathing.5 Other injuries—particularly those produced by falls—can result from well-intentioned efforts to protect confused patients by restraining them.6

Evolution of restraint policy

Although restraining patients might inadvertently cause harm, isn’t it better to restrain someone, which prevents harm from aggression and accidents? Mental health professionals once thought the answer to this question was, “Of course!” But scientific data say, “Often not.”

Studies conducted when physical restraint was more common found order-of-magnitude disparities in restraint rates at sites with similar patient populations. This suggested that institutional norms and practice styles—not patients’ problems or dangerousness—explained why much restraint occurred.7-9

Reacting to these kinds of findings, psychiatric hospitals in the United States and abroad implemented various methods and policy changes to reduce restraint. Follow-up studies typically showed that episodes of restraint and total time spent in restraints could decrease markedly without any increase in events that harmed patients or staff members.10 In addition, mental health professionals now recognize that being restrained is psychologically traumatic for patients, even when restraint causes no physical injury.11

Patients in psychiatric settings represent a minority of persons who get restrained. On inpatient medical/surgical units, patient confusion and wandering, fall prevention, and perceived medical necessity can lead to physical restraint use.12 Yet physical restraints as innocent-seeming as bed rails can lead to deaths and injuries.13

Nursing homes are another environment where restraints may be common but sometimes detrimental. A recent study found that in all aspects of nursing home patients’ health and functioning—behavior, cognitive performance, falls, walking, activities of daily living, pressure sores, and contractures—physical restraints lead to worse outcomes than leaving patients unrestrained.14

For all these reasons, restraining patients is often viewed as “poor practice”14 and a response of last resort for behavioral problems.15-17

Federal regulations

Publication of the Courant article spurred Congress to develop standards18 that, a decade later, permit restraint or seclusion only when less restrictive interventions will not prevent harm, only for limited periods, and only with careful medical monitoring. Restraint is permissible when no alternative exists, but facilities that use restraint must train staff members to recognize and avert situations that might lead to physical interventions and must generate proper documentation each time restraint is used.2

Federal regulations also apply to “chemical restraints” and aim to restrict their use. This doesn’t mean you can’t use drugs to treat patients, however. Regulations explicitly allow you to prescribe “standard treatment” (Table 2)3 to help your patients function or sleep better, to alleviate pain, or to reduce agitation—and such uses of medication are not “chemical restraint.” Rather, you’re using “chemical restraint” if you prescribe a drug to control bothersome behavior—for example, to “knock out” a patient with dementia whose “sundowning” bothers staff members.19 Psychiatrists should be familiar with the risks of medications used for behavioral control, particularly in elderly patients.20

Table 2

Federal criteria for ‘standard treatment‘

| Medication is used within FDA-approved pharmaceutical parameters and manufacturer indications |

| Medication use follows standards recognized by the medical community |

| Choice of medication is based on patient’s symptoms, overall clinical situation, and prescriber’s knowledge of the patient’s treatment response |

| Source: Reference 3 |

Avoiding legal risks

No study or systematic data will ever tell us whether physical or chemical restraints create a greater liability risk. Obviously, the best way to avoid legal liability for restraints is to minimize use of physical restraints and to avoid using medications as chemical restraints. Psychiatrists who work in hospitals or other institutional settings can politely but firmly decline to prescribe medications or to order physical restraints when staff members request these measures for non-therapeutic reasons—ie, for a patient who has calmed down but whom staff members believe “needs to learn a lesson” or “get some consequences” for throwing a chair. When restraints are necessary, psychiatrists (along with other staff members) should document the reasons why, including what other interventions were tried first.

Many psychiatric facilities and care systems have reduced incidence of restraint and time spent by patients in restraint through programs that broadly address institutional practices. Such programs usually involve a multi-disciplinary, multi-strategy commitment to alternatives—to helping staff members see that restraints represent a failure in treatment rather than a form of treatment, and to developing other mechanisms for averting or responding to patients’ aggression before restraint becomes the only option.10,21 Individual psychiatrists can play an important role in advocating and supporting institutional policies, practices, and training that help staff members minimize restraint use.

1. Agens JE. Chemical and physical restraint use in the older person. BJMP. 2010;3:302.-

2. Code of Federal Regulations. Conditions of participation for hospitals: Condition of participation: Patient’s rights. Title 42, Part 482, § 482.13. Available at: http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/cfr_2004/octqtr/pdf/42cfr482.13.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2010.

3. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Pub. 100-07 State Operations (Provider Certification, Transmittal 37). Available at: https://146.123.140.205/transmittals/downloads/R37SOMA.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2010.

4. Weiss EM. Deadly restraint: a Hartford Courant investigative report. Hartford Courant. October 11-15, 1998.

5. Karger B, Fracasso T, Pfeiffer H. Fatalities related to medical restraint devices—asphyxia is a common finding. Forensic Sci Int. 2008;178:178-184.

6. Inouye SK, Brown CJ, Tinetti ME. Medicare nonpayment, hospital falls, and unintended consequences. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2390-2393.

7. Betemps EJ, Somoza E, Buncher CR. Hospital characteristics, diagnoses, and staff reasons associated with use of seclusion and restraint. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44:367-371.

8. Crenshaw WB, Francis PS. A national survey on seclusion and restraint in state psychiatric hospitals. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:1026-1031.

9. Ray NK, Rappaport ME. Use of restraint and seclusion in psychiatric settings in New York State. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:1032-1037.

10. Smith GM, Davis RH, Bixler EO, et al. Pennsylvania State Hospital system’s seclusion and restraint reduction program. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1115-1122.

11. Frueh BC, Knapp RG, Cusack KJ, et al. Patients’ reports of traumatic or harmful experiences within the psychiatric setting. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1123-1133.

12. Forrester DA, McCabe-Bender J, Walsh N, et al. Physical restraint management of hospitalized adults and follow-up study. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2000;16:267-276.

13. The Joint Commission. Bed rail-related entrapment deaths. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/ sentinelevents/alert/sea_27.htm. Accessed July 20, 2010.

14. Castle NG, Engberg J. The health consequences of using physical restraints in nursing homes. Med Care. 2009;47:1164-1173.

15. Marder SR. A review of agitation in mental illness: treatment guidelines and current therapies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 10):13-21.

16. Borckardt JJ, Grubaugh AL, Pelic CG, et al. Enhancing patient safety in psychiatric settings. J Psychiatr Pract. 2007;13:355-361.

17. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. Position Statement on Seclusion and Restraint. Available at: http://www.nasmhpd.org/general_files/position_statement/posses1.htm. Accessed July 18, 2010.

18. Appelbaum P. Seclusion and restraint: Congress reacts to reports of abuse. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:881-882, 885.

19. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. State operations manual: appendix A—survey protocol, regulations and interpretive guidelines for hospitals. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/som107ap_a_hospitals.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2010.

20. Salzman C, Jeste DV, Meyer RE, et al. Elderly patients with dementia-related symptoms of severe agitation and aggression: consensus statement on treatment options, clinical trials methodology, and policy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:889-898.

21. Gaskin CJ, Elsom SJ, Happell B. Interventions for reducing the use of seclusion in psychiatric facilities: review of the literature. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:298-303.

Dear Dr. Mossman:

We often have to administer sedating medications to aggressive patients who pose an immediate threat of harm to themselves or others. But I am unsure about whether these “chemical restraints” create more liability problems than “physical restraints”—or vice versa. Does one type of restraint carry more legal risk than the other?—Submitted by “Dr. L”

Mental health professionals view “mechanical” or “physical” restraints in a way that really differs from how they felt 2 decades ago. In the 1980s, physical restraint use was a common response when patients seemed to be immediately dangerous to themselves or others. But recent practice guidelines say physical restraints are a “last resort,” to be used only when other treatment measures to prevent aggression fail to work.

What should psychiatrists do? Is use of physical restraints malpractice? Are “chemical” restraints better?

This article looks at:

- definitions of restraint

- medical risks of restraint

- evolution and status of restraint policy

- what you can do about legal risks of restraint.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at [email protected].

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

Definitions

In medical contexts, restraint typically refers to “any device or medication used to restrict a patient’s movement.”1 The longer, official US regulatory definitions of physical and chemical restraints appear in Table 1.2 Two important notes:

- Neither regulatory definition of restraint is limited to psychiatric patients; both definitions and the accompanying regulations on restraint apply to any patient in a hospital eligible for federal reimbursement.

- The definition of physical restraint would include holding a patient still while administering an injection.

The detailed interpretive rules (“Conditions of Participation for Hospitals”)3 for these regulations require hospitals to document conditions surrounding and reasons related to restraint incidents and to make this documentation available to federal surveyors.

Table 1

Federal regulatory definitions of ‘restraint’

| Physical restraint | Any manual method, physical or mechanical device, material, or equipment that immobilizes or reduces the ability of a patient to move his or her arms, legs, body, or head freely |

| Chemical restraint | A drug or medication when it is used as a restriction to manage the patient’s behavior or restrict the patient’s freedom of movement and is not a standard treatment or dosage for the patient’s condition |

| Source: Reference 2 | |

Medical risks of restraint

In 1998, the Hartford Courant investigative series “Deadly restraint”4 reported on 142 deaths of psychiatric patients and alerted the public to the potentially fatal consequences of physical restraint. Often, restraint deaths result from asphyxia when patients try to free themselves and get caught in positions that restrict breathing.5 Other injuries—particularly those produced by falls—can result from well-intentioned efforts to protect confused patients by restraining them.6

Evolution of restraint policy

Although restraining patients might inadvertently cause harm, isn’t it better to restrain someone, which prevents harm from aggression and accidents? Mental health professionals once thought the answer to this question was, “Of course!” But scientific data say, “Often not.”

Studies conducted when physical restraint was more common found order-of-magnitude disparities in restraint rates at sites with similar patient populations. This suggested that institutional norms and practice styles—not patients’ problems or dangerousness—explained why much restraint occurred.7-9

Reacting to these kinds of findings, psychiatric hospitals in the United States and abroad implemented various methods and policy changes to reduce restraint. Follow-up studies typically showed that episodes of restraint and total time spent in restraints could decrease markedly without any increase in events that harmed patients or staff members.10 In addition, mental health professionals now recognize that being restrained is psychologically traumatic for patients, even when restraint causes no physical injury.11

Patients in psychiatric settings represent a minority of persons who get restrained. On inpatient medical/surgical units, patient confusion and wandering, fall prevention, and perceived medical necessity can lead to physical restraint use.12 Yet physical restraints as innocent-seeming as bed rails can lead to deaths and injuries.13

Nursing homes are another environment where restraints may be common but sometimes detrimental. A recent study found that in all aspects of nursing home patients’ health and functioning—behavior, cognitive performance, falls, walking, activities of daily living, pressure sores, and contractures—physical restraints lead to worse outcomes than leaving patients unrestrained.14

For all these reasons, restraining patients is often viewed as “poor practice”14 and a response of last resort for behavioral problems.15-17

Federal regulations

Publication of the Courant article spurred Congress to develop standards18 that, a decade later, permit restraint or seclusion only when less restrictive interventions will not prevent harm, only for limited periods, and only with careful medical monitoring. Restraint is permissible when no alternative exists, but facilities that use restraint must train staff members to recognize and avert situations that might lead to physical interventions and must generate proper documentation each time restraint is used.2

Federal regulations also apply to “chemical restraints” and aim to restrict their use. This doesn’t mean you can’t use drugs to treat patients, however. Regulations explicitly allow you to prescribe “standard treatment” (Table 2)3 to help your patients function or sleep better, to alleviate pain, or to reduce agitation—and such uses of medication are not “chemical restraint.” Rather, you’re using “chemical restraint” if you prescribe a drug to control bothersome behavior—for example, to “knock out” a patient with dementia whose “sundowning” bothers staff members.19 Psychiatrists should be familiar with the risks of medications used for behavioral control, particularly in elderly patients.20

Table 2

Federal criteria for ‘standard treatment‘

| Medication is used within FDA-approved pharmaceutical parameters and manufacturer indications |

| Medication use follows standards recognized by the medical community |

| Choice of medication is based on patient’s symptoms, overall clinical situation, and prescriber’s knowledge of the patient’s treatment response |

| Source: Reference 3 |

Avoiding legal risks

No study or systematic data will ever tell us whether physical or chemical restraints create a greater liability risk. Obviously, the best way to avoid legal liability for restraints is to minimize use of physical restraints and to avoid using medications as chemical restraints. Psychiatrists who work in hospitals or other institutional settings can politely but firmly decline to prescribe medications or to order physical restraints when staff members request these measures for non-therapeutic reasons—ie, for a patient who has calmed down but whom staff members believe “needs to learn a lesson” or “get some consequences” for throwing a chair. When restraints are necessary, psychiatrists (along with other staff members) should document the reasons why, including what other interventions were tried first.

Many psychiatric facilities and care systems have reduced incidence of restraint and time spent by patients in restraint through programs that broadly address institutional practices. Such programs usually involve a multi-disciplinary, multi-strategy commitment to alternatives—to helping staff members see that restraints represent a failure in treatment rather than a form of treatment, and to developing other mechanisms for averting or responding to patients’ aggression before restraint becomes the only option.10,21 Individual psychiatrists can play an important role in advocating and supporting institutional policies, practices, and training that help staff members minimize restraint use.

Dear Dr. Mossman:

We often have to administer sedating medications to aggressive patients who pose an immediate threat of harm to themselves or others. But I am unsure about whether these “chemical restraints” create more liability problems than “physical restraints”—or vice versa. Does one type of restraint carry more legal risk than the other?—Submitted by “Dr. L”

Mental health professionals view “mechanical” or “physical” restraints in a way that really differs from how they felt 2 decades ago. In the 1980s, physical restraint use was a common response when patients seemed to be immediately dangerous to themselves or others. But recent practice guidelines say physical restraints are a “last resort,” to be used only when other treatment measures to prevent aggression fail to work.

What should psychiatrists do? Is use of physical restraints malpractice? Are “chemical” restraints better?

This article looks at:

- definitions of restraint

- medical risks of restraint

- evolution and status of restraint policy

- what you can do about legal risks of restraint.

- Submit your malpractice-related questions to Dr. Mossman at [email protected].

- Include your name, address, and practice location. If your question is chosen for publication, your name can be withheld by request.

Definitions

In medical contexts, restraint typically refers to “any device or medication used to restrict a patient’s movement.”1 The longer, official US regulatory definitions of physical and chemical restraints appear in Table 1.2 Two important notes:

- Neither regulatory definition of restraint is limited to psychiatric patients; both definitions and the accompanying regulations on restraint apply to any patient in a hospital eligible for federal reimbursement.

- The definition of physical restraint would include holding a patient still while administering an injection.

The detailed interpretive rules (“Conditions of Participation for Hospitals”)3 for these regulations require hospitals to document conditions surrounding and reasons related to restraint incidents and to make this documentation available to federal surveyors.

Table 1

Federal regulatory definitions of ‘restraint’

| Physical restraint | Any manual method, physical or mechanical device, material, or equipment that immobilizes or reduces the ability of a patient to move his or her arms, legs, body, or head freely |

| Chemical restraint | A drug or medication when it is used as a restriction to manage the patient’s behavior or restrict the patient’s freedom of movement and is not a standard treatment or dosage for the patient’s condition |

| Source: Reference 2 | |

Medical risks of restraint

In 1998, the Hartford Courant investigative series “Deadly restraint”4 reported on 142 deaths of psychiatric patients and alerted the public to the potentially fatal consequences of physical restraint. Often, restraint deaths result from asphyxia when patients try to free themselves and get caught in positions that restrict breathing.5 Other injuries—particularly those produced by falls—can result from well-intentioned efforts to protect confused patients by restraining them.6

Evolution of restraint policy

Although restraining patients might inadvertently cause harm, isn’t it better to restrain someone, which prevents harm from aggression and accidents? Mental health professionals once thought the answer to this question was, “Of course!” But scientific data say, “Often not.”

Studies conducted when physical restraint was more common found order-of-magnitude disparities in restraint rates at sites with similar patient populations. This suggested that institutional norms and practice styles—not patients’ problems or dangerousness—explained why much restraint occurred.7-9

Reacting to these kinds of findings, psychiatric hospitals in the United States and abroad implemented various methods and policy changes to reduce restraint. Follow-up studies typically showed that episodes of restraint and total time spent in restraints could decrease markedly without any increase in events that harmed patients or staff members.10 In addition, mental health professionals now recognize that being restrained is psychologically traumatic for patients, even when restraint causes no physical injury.11

Patients in psychiatric settings represent a minority of persons who get restrained. On inpatient medical/surgical units, patient confusion and wandering, fall prevention, and perceived medical necessity can lead to physical restraint use.12 Yet physical restraints as innocent-seeming as bed rails can lead to deaths and injuries.13

Nursing homes are another environment where restraints may be common but sometimes detrimental. A recent study found that in all aspects of nursing home patients’ health and functioning—behavior, cognitive performance, falls, walking, activities of daily living, pressure sores, and contractures—physical restraints lead to worse outcomes than leaving patients unrestrained.14

For all these reasons, restraining patients is often viewed as “poor practice”14 and a response of last resort for behavioral problems.15-17

Federal regulations

Publication of the Courant article spurred Congress to develop standards18 that, a decade later, permit restraint or seclusion only when less restrictive interventions will not prevent harm, only for limited periods, and only with careful medical monitoring. Restraint is permissible when no alternative exists, but facilities that use restraint must train staff members to recognize and avert situations that might lead to physical interventions and must generate proper documentation each time restraint is used.2

Federal regulations also apply to “chemical restraints” and aim to restrict their use. This doesn’t mean you can’t use drugs to treat patients, however. Regulations explicitly allow you to prescribe “standard treatment” (Table 2)3 to help your patients function or sleep better, to alleviate pain, or to reduce agitation—and such uses of medication are not “chemical restraint.” Rather, you’re using “chemical restraint” if you prescribe a drug to control bothersome behavior—for example, to “knock out” a patient with dementia whose “sundowning” bothers staff members.19 Psychiatrists should be familiar with the risks of medications used for behavioral control, particularly in elderly patients.20

Table 2

Federal criteria for ‘standard treatment‘

| Medication is used within FDA-approved pharmaceutical parameters and manufacturer indications |

| Medication use follows standards recognized by the medical community |

| Choice of medication is based on patient’s symptoms, overall clinical situation, and prescriber’s knowledge of the patient’s treatment response |

| Source: Reference 3 |

Avoiding legal risks

No study or systematic data will ever tell us whether physical or chemical restraints create a greater liability risk. Obviously, the best way to avoid legal liability for restraints is to minimize use of physical restraints and to avoid using medications as chemical restraints. Psychiatrists who work in hospitals or other institutional settings can politely but firmly decline to prescribe medications or to order physical restraints when staff members request these measures for non-therapeutic reasons—ie, for a patient who has calmed down but whom staff members believe “needs to learn a lesson” or “get some consequences” for throwing a chair. When restraints are necessary, psychiatrists (along with other staff members) should document the reasons why, including what other interventions were tried first.

Many psychiatric facilities and care systems have reduced incidence of restraint and time spent by patients in restraint through programs that broadly address institutional practices. Such programs usually involve a multi-disciplinary, multi-strategy commitment to alternatives—to helping staff members see that restraints represent a failure in treatment rather than a form of treatment, and to developing other mechanisms for averting or responding to patients’ aggression before restraint becomes the only option.10,21 Individual psychiatrists can play an important role in advocating and supporting institutional policies, practices, and training that help staff members minimize restraint use.

1. Agens JE. Chemical and physical restraint use in the older person. BJMP. 2010;3:302.-

2. Code of Federal Regulations. Conditions of participation for hospitals: Condition of participation: Patient’s rights. Title 42, Part 482, § 482.13. Available at: http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/cfr_2004/octqtr/pdf/42cfr482.13.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2010.

3. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Pub. 100-07 State Operations (Provider Certification, Transmittal 37). Available at: https://146.123.140.205/transmittals/downloads/R37SOMA.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2010.

4. Weiss EM. Deadly restraint: a Hartford Courant investigative report. Hartford Courant. October 11-15, 1998.

5. Karger B, Fracasso T, Pfeiffer H. Fatalities related to medical restraint devices—asphyxia is a common finding. Forensic Sci Int. 2008;178:178-184.

6. Inouye SK, Brown CJ, Tinetti ME. Medicare nonpayment, hospital falls, and unintended consequences. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2390-2393.

7. Betemps EJ, Somoza E, Buncher CR. Hospital characteristics, diagnoses, and staff reasons associated with use of seclusion and restraint. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44:367-371.

8. Crenshaw WB, Francis PS. A national survey on seclusion and restraint in state psychiatric hospitals. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:1026-1031.

9. Ray NK, Rappaport ME. Use of restraint and seclusion in psychiatric settings in New York State. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:1032-1037.

10. Smith GM, Davis RH, Bixler EO, et al. Pennsylvania State Hospital system’s seclusion and restraint reduction program. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1115-1122.

11. Frueh BC, Knapp RG, Cusack KJ, et al. Patients’ reports of traumatic or harmful experiences within the psychiatric setting. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1123-1133.

12. Forrester DA, McCabe-Bender J, Walsh N, et al. Physical restraint management of hospitalized adults and follow-up study. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2000;16:267-276.

13. The Joint Commission. Bed rail-related entrapment deaths. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/ sentinelevents/alert/sea_27.htm. Accessed July 20, 2010.

14. Castle NG, Engberg J. The health consequences of using physical restraints in nursing homes. Med Care. 2009;47:1164-1173.

15. Marder SR. A review of agitation in mental illness: treatment guidelines and current therapies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 10):13-21.

16. Borckardt JJ, Grubaugh AL, Pelic CG, et al. Enhancing patient safety in psychiatric settings. J Psychiatr Pract. 2007;13:355-361.

17. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. Position Statement on Seclusion and Restraint. Available at: http://www.nasmhpd.org/general_files/position_statement/posses1.htm. Accessed July 18, 2010.

18. Appelbaum P. Seclusion and restraint: Congress reacts to reports of abuse. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:881-882, 885.

19. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. State operations manual: appendix A—survey protocol, regulations and interpretive guidelines for hospitals. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/som107ap_a_hospitals.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2010.

20. Salzman C, Jeste DV, Meyer RE, et al. Elderly patients with dementia-related symptoms of severe agitation and aggression: consensus statement on treatment options, clinical trials methodology, and policy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:889-898.

21. Gaskin CJ, Elsom SJ, Happell B. Interventions for reducing the use of seclusion in psychiatric facilities: review of the literature. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:298-303.

1. Agens JE. Chemical and physical restraint use in the older person. BJMP. 2010;3:302.-

2. Code of Federal Regulations. Conditions of participation for hospitals: Condition of participation: Patient’s rights. Title 42, Part 482, § 482.13. Available at: http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/cfr_2004/octqtr/pdf/42cfr482.13.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2010.

3. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Pub. 100-07 State Operations (Provider Certification, Transmittal 37). Available at: https://146.123.140.205/transmittals/downloads/R37SOMA.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2010.

4. Weiss EM. Deadly restraint: a Hartford Courant investigative report. Hartford Courant. October 11-15, 1998.

5. Karger B, Fracasso T, Pfeiffer H. Fatalities related to medical restraint devices—asphyxia is a common finding. Forensic Sci Int. 2008;178:178-184.

6. Inouye SK, Brown CJ, Tinetti ME. Medicare nonpayment, hospital falls, and unintended consequences. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2390-2393.

7. Betemps EJ, Somoza E, Buncher CR. Hospital characteristics, diagnoses, and staff reasons associated with use of seclusion and restraint. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44:367-371.

8. Crenshaw WB, Francis PS. A national survey on seclusion and restraint in state psychiatric hospitals. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:1026-1031.

9. Ray NK, Rappaport ME. Use of restraint and seclusion in psychiatric settings in New York State. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:1032-1037.

10. Smith GM, Davis RH, Bixler EO, et al. Pennsylvania State Hospital system’s seclusion and restraint reduction program. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1115-1122.

11. Frueh BC, Knapp RG, Cusack KJ, et al. Patients’ reports of traumatic or harmful experiences within the psychiatric setting. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1123-1133.

12. Forrester DA, McCabe-Bender J, Walsh N, et al. Physical restraint management of hospitalized adults and follow-up study. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2000;16:267-276.

13. The Joint Commission. Bed rail-related entrapment deaths. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/ sentinelevents/alert/sea_27.htm. Accessed July 20, 2010.

14. Castle NG, Engberg J. The health consequences of using physical restraints in nursing homes. Med Care. 2009;47:1164-1173.

15. Marder SR. A review of agitation in mental illness: treatment guidelines and current therapies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 10):13-21.

16. Borckardt JJ, Grubaugh AL, Pelic CG, et al. Enhancing patient safety in psychiatric settings. J Psychiatr Pract. 2007;13:355-361.

17. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. Position Statement on Seclusion and Restraint. Available at: http://www.nasmhpd.org/general_files/position_statement/posses1.htm. Accessed July 18, 2010.

18. Appelbaum P. Seclusion and restraint: Congress reacts to reports of abuse. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:881-882, 885.

19. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. State operations manual: appendix A—survey protocol, regulations and interpretive guidelines for hospitals. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/som107ap_a_hospitals.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2010.

20. Salzman C, Jeste DV, Meyer RE, et al. Elderly patients with dementia-related symptoms of severe agitation and aggression: consensus statement on treatment options, clinical trials methodology, and policy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:889-898.

21. Gaskin CJ, Elsom SJ, Happell B. Interventions for reducing the use of seclusion in psychiatric facilities: review of the literature. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:298-303.

Hallucinogen sequelae

I appreciated “The woman who saw the light” (Current Psychiatry, July 2010, p. 44-48) in which Dr. R. Andrew Sewell et al describe a 30-year-old woman with schizoaffective disorder and a 7-year history of visual disturbances, including “flashing lights.” The authors’ differential diagnosis did not include the possibility of visual disturbance secondary to atypical anti-psychotic serotonergic antagonism. Photopsia and similar phenomena are not uncommon with 5HT antagonist antidepressants, such as nefazodone.1 They also are well-known sequelae of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), a complex serotonin antagonist/agonist, and would be included under the DSM-IV-TR diagnosis hallucinogen persisting perceptual disorder (HPPD).2 Risperidone, a 5HT2-blocking atypical, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may worsen HPPD effects.3,4 Visual disturbance with risperidone also has been reported in a patient with no LSD exposure.5 Dr. Sewell’s patient was treated sequentially with aripiprazole and olanzapine. Both have 5HT blocking properties.

I wonder if the patient has a history of hallucinogen or LSD exposure, or whether her visual symptoms might be related to the use of atypical anti-psychotics combined with sertraline. It would be interesting to see if her symptoms abated with use of a first-generation antipsychotic.

Charles Krasnow, MD

Adjunct clinical assistant professor of psychiatry

University of Michigan Medical School

Ann Arbor, MI

The authors respond

We agree with Dr. Krasnow that HPPD belongs within our differential diagnosis for photopsia and regret omitting it from our article. We consider this to be unlikely, however, because she had no prior LSD use, a history of well-formed visual hallucinations not characteristic of HPPD, and no other characteristic symptoms of HPPD (palinopsia, afterimages, illusory movement, etc.).

In addition, she tolerated olanzapine well, and there is anecdotal evidence and 1 case report to suggest that olanzapine exacerbates HPPD.1

HPPD typically is considered a rare sequela of LSD use, although even more rarely it may be caused by other drugs. Common visual disturbances attributed to HPPD are recurrent geometric hallucinations, perception of peripheral movement, colored flashes, intensified colors, palinopsia, positive afterimages, haloes around objects, macropsia, and micropsia occurring spontaneously in individuals with no prior psychopathology. These disturbances can be intermittent or continuous, slowly reversible or irreversible, but are severe, intrusive, and cause functional debility. Sufferers retain insight that these phenomena are the consequence of LSD use and usually seek psychiatric help.

HPPD may be diagnosed by the presence of an identifiable trigger, prodromal symptoms, and presentation onset; by the characteristics of the perceptual disturbances, their frequency, duration, intensity, and course; and by the accompanying negative affect and preserved insight.2

This LSD-induced persistence of visual imagery after the image is removed from the visual field is thought to result from dysfunction of serotonergic cortical inhibitory interneurons with GABAergic outputs that normally suppress visual processors.3 Clonazepam often is helpful.2

R. Andrew Sewell, MD

VA Connecticut Healthcare/Yale University

School of Medicine

New Haven, CT

David Kozin

McLean Hospital/Harvard Medical School

Belmont, MA

Miles G. Cunningham, MD, PhD

McLean Hospital/Harvard Medical School

Belmont, MA

1. Espiard ML, Lecardeur L, Abadie P, et al. Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder after psilocybin consumption: a case study. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:458-460.

2. Lerner AG, Gelkopf M, Skladman I, et al. Clonazepam treatment of lysergic acid diethylamide-induced hallucinogen persisting perception disorder with anxiety features. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:101-105.

3. Abraham HD, Aldridge AM. Adverse consequences of lysergic acid diethylamide. Addiction. 1993;88:1327-1334.

I appreciated “The woman who saw the light” (Current Psychiatry, July 2010, p. 44-48) in which Dr. R. Andrew Sewell et al describe a 30-year-old woman with schizoaffective disorder and a 7-year history of visual disturbances, including “flashing lights.” The authors’ differential diagnosis did not include the possibility of visual disturbance secondary to atypical anti-psychotic serotonergic antagonism. Photopsia and similar phenomena are not uncommon with 5HT antagonist antidepressants, such as nefazodone.1 They also are well-known sequelae of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), a complex serotonin antagonist/agonist, and would be included under the DSM-IV-TR diagnosis hallucinogen persisting perceptual disorder (HPPD).2 Risperidone, a 5HT2-blocking atypical, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may worsen HPPD effects.3,4 Visual disturbance with risperidone also has been reported in a patient with no LSD exposure.5 Dr. Sewell’s patient was treated sequentially with aripiprazole and olanzapine. Both have 5HT blocking properties.

I wonder if the patient has a history of hallucinogen or LSD exposure, or whether her visual symptoms might be related to the use of atypical anti-psychotics combined with sertraline. It would be interesting to see if her symptoms abated with use of a first-generation antipsychotic.

Charles Krasnow, MD

Adjunct clinical assistant professor of psychiatry

University of Michigan Medical School

Ann Arbor, MI

The authors respond

We agree with Dr. Krasnow that HPPD belongs within our differential diagnosis for photopsia and regret omitting it from our article. We consider this to be unlikely, however, because she had no prior LSD use, a history of well-formed visual hallucinations not characteristic of HPPD, and no other characteristic symptoms of HPPD (palinopsia, afterimages, illusory movement, etc.).

In addition, she tolerated olanzapine well, and there is anecdotal evidence and 1 case report to suggest that olanzapine exacerbates HPPD.1

HPPD typically is considered a rare sequela of LSD use, although even more rarely it may be caused by other drugs. Common visual disturbances attributed to HPPD are recurrent geometric hallucinations, perception of peripheral movement, colored flashes, intensified colors, palinopsia, positive afterimages, haloes around objects, macropsia, and micropsia occurring spontaneously in individuals with no prior psychopathology. These disturbances can be intermittent or continuous, slowly reversible or irreversible, but are severe, intrusive, and cause functional debility. Sufferers retain insight that these phenomena are the consequence of LSD use and usually seek psychiatric help.

HPPD may be diagnosed by the presence of an identifiable trigger, prodromal symptoms, and presentation onset; by the characteristics of the perceptual disturbances, their frequency, duration, intensity, and course; and by the accompanying negative affect and preserved insight.2