User login

Spotlight on Physicians' Safety in Hospitals

Hospitalists should take care to remember the potentially violent offenders and situations that surround them daily at work, says a member of SHM's Practice Management Committee.

Michael Radzienda, MD, SFHM, vice president of hospital medicine and clinical effectiveness at Vanguard Health System in Southborough, Mass., says the recent shooting of a doctor at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore serves as a stark reminder that violence in the hospital is a concern for providers more than ever. To Dr. Radzienda's mind, that includes patients attacking doctors or patients attacking other patients.

"It's a newer issue for hospitalists, but one that they need to pay attention to," Dr. Radzienda says. "The volume of high-risk interactions that a hospitalist might have is significant compared to what that volume might have looked like 10 years ago before the hospitalist (model) took off."

And while one might think the incident at Johns Hopkins is enough to shine a lasting spotlight on the issue, a report from The Joint Commission this summer on hospital violence faded relatively quickly after its issuance. The commission's Sentinel Event Database, in fact, includes a category of assault, rape, and homicide (combined) with 256 reports since 1995, a number the organization suggests is under-reported. The commission's latest report, published in June, found that since 2004, hospitals have reported "significant increases in reports of assault, rape, and homicide, with the greater number of reports in the last three years."

The report recommends physicians learn techniques to identify potentially violent patients, implement violence de-escalation approaches, and even conduct violence audits to help determine an institution’s safety protocols.

Dr. Radzienda understands that training time and resources are stretched thin, but he says more focus on violence would be helpful to institutions and individual physicians. "The problem is someone needs to recognize this type of thing," he says. "But how do you prioritize that?"

Hospitalists should take care to remember the potentially violent offenders and situations that surround them daily at work, says a member of SHM's Practice Management Committee.

Michael Radzienda, MD, SFHM, vice president of hospital medicine and clinical effectiveness at Vanguard Health System in Southborough, Mass., says the recent shooting of a doctor at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore serves as a stark reminder that violence in the hospital is a concern for providers more than ever. To Dr. Radzienda's mind, that includes patients attacking doctors or patients attacking other patients.

"It's a newer issue for hospitalists, but one that they need to pay attention to," Dr. Radzienda says. "The volume of high-risk interactions that a hospitalist might have is significant compared to what that volume might have looked like 10 years ago before the hospitalist (model) took off."

And while one might think the incident at Johns Hopkins is enough to shine a lasting spotlight on the issue, a report from The Joint Commission this summer on hospital violence faded relatively quickly after its issuance. The commission's Sentinel Event Database, in fact, includes a category of assault, rape, and homicide (combined) with 256 reports since 1995, a number the organization suggests is under-reported. The commission's latest report, published in June, found that since 2004, hospitals have reported "significant increases in reports of assault, rape, and homicide, with the greater number of reports in the last three years."

The report recommends physicians learn techniques to identify potentially violent patients, implement violence de-escalation approaches, and even conduct violence audits to help determine an institution’s safety protocols.

Dr. Radzienda understands that training time and resources are stretched thin, but he says more focus on violence would be helpful to institutions and individual physicians. "The problem is someone needs to recognize this type of thing," he says. "But how do you prioritize that?"

Hospitalists should take care to remember the potentially violent offenders and situations that surround them daily at work, says a member of SHM's Practice Management Committee.

Michael Radzienda, MD, SFHM, vice president of hospital medicine and clinical effectiveness at Vanguard Health System in Southborough, Mass., says the recent shooting of a doctor at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore serves as a stark reminder that violence in the hospital is a concern for providers more than ever. To Dr. Radzienda's mind, that includes patients attacking doctors or patients attacking other patients.

"It's a newer issue for hospitalists, but one that they need to pay attention to," Dr. Radzienda says. "The volume of high-risk interactions that a hospitalist might have is significant compared to what that volume might have looked like 10 years ago before the hospitalist (model) took off."

And while one might think the incident at Johns Hopkins is enough to shine a lasting spotlight on the issue, a report from The Joint Commission this summer on hospital violence faded relatively quickly after its issuance. The commission's Sentinel Event Database, in fact, includes a category of assault, rape, and homicide (combined) with 256 reports since 1995, a number the organization suggests is under-reported. The commission's latest report, published in June, found that since 2004, hospitals have reported "significant increases in reports of assault, rape, and homicide, with the greater number of reports in the last three years."

The report recommends physicians learn techniques to identify potentially violent patients, implement violence de-escalation approaches, and even conduct violence audits to help determine an institution’s safety protocols.

Dr. Radzienda understands that training time and resources are stretched thin, but he says more focus on violence would be helpful to institutions and individual physicians. "The problem is someone needs to recognize this type of thing," he says. "But how do you prioritize that?"

Operation Critical

There is going to be a healthcare crisis in Haiti in the next few years if things don’t markedly improve, says Jocelyn David, MD, chief hospitalist at the Miami VA Healthcare System in Miami, who has traveled to the island nation four times since the Jan. 12 earthquake.

Dr. David returned on Aug. 15 from a four-day trip she took with the Haitian Resource Development Foundation to assess the needs of smaller hospitals outside the capital of Port-au-Prince.

"People are traveling from the capital to these hospitals because the hospitals in the city are overwhelmed and struggling due to a lack of funds," Dr. David says.

Some city hospitals, such as CDTI du Sacre Coeur Hospital, one of the country’s more modern medical facilities, have outright closed, she says.

“I was surprised that I didn’t see any improvement,” says Mario A. Reyes, MD, FAAP, FHM, director of Pediatric Hospital Medicine at Miami Children’s Hospital, who volunteered in Haiti in January and went back in August to visit the Children’s Hospital of the Hopital de l’Universite d’Etat d’Haiti (HUEH), the largest academic public pediatric hospital in the capital.

The Children's Hospital is uninhabitable; medical staff are treating patients in makeshift wood houses provided by the United Nations, he says. Children sleep in hospital beds without mattresses, and oxygen tanks are shared by four or five children. There are no ultrasounds, and ventilators, IV lines, and antibiotics are in short supply, he says.

"There is a frustration among Haitian physicians that things aren't being done as quickly as they should," Dr. Reyes says. "The needs are immense."

Dr. David plans another trip to Haiti in October to train healthcare providers in BLS, ALS, and intubations in order to expand the limited emergency care. Meanwhile, Dr. Reyes and a group of physicians who work at Miami Children's Hospital are organizing professional and academic trips to HUEH so physicians can lend their expertise.

"That's what the Haitian providers want," he says. "They want us to teach and work with them."

The first trip is planned for December, and the group hopes the American Academy of Pediatrics will endorse their effort, which likely will include donating medical equipment and developing a telemedicine program.

Pediatric hospitalists who are interested in joining one of the trips to the Children’s Hospital of the Hopital de l’Universite d’Etat d’Haiti can contact Dr. Reyes at 305-668-5500 or at [email protected].

There is going to be a healthcare crisis in Haiti in the next few years if things don’t markedly improve, says Jocelyn David, MD, chief hospitalist at the Miami VA Healthcare System in Miami, who has traveled to the island nation four times since the Jan. 12 earthquake.

Dr. David returned on Aug. 15 from a four-day trip she took with the Haitian Resource Development Foundation to assess the needs of smaller hospitals outside the capital of Port-au-Prince.

"People are traveling from the capital to these hospitals because the hospitals in the city are overwhelmed and struggling due to a lack of funds," Dr. David says.

Some city hospitals, such as CDTI du Sacre Coeur Hospital, one of the country’s more modern medical facilities, have outright closed, she says.

“I was surprised that I didn’t see any improvement,” says Mario A. Reyes, MD, FAAP, FHM, director of Pediatric Hospital Medicine at Miami Children’s Hospital, who volunteered in Haiti in January and went back in August to visit the Children’s Hospital of the Hopital de l’Universite d’Etat d’Haiti (HUEH), the largest academic public pediatric hospital in the capital.

The Children's Hospital is uninhabitable; medical staff are treating patients in makeshift wood houses provided by the United Nations, he says. Children sleep in hospital beds without mattresses, and oxygen tanks are shared by four or five children. There are no ultrasounds, and ventilators, IV lines, and antibiotics are in short supply, he says.

"There is a frustration among Haitian physicians that things aren't being done as quickly as they should," Dr. Reyes says. "The needs are immense."

Dr. David plans another trip to Haiti in October to train healthcare providers in BLS, ALS, and intubations in order to expand the limited emergency care. Meanwhile, Dr. Reyes and a group of physicians who work at Miami Children's Hospital are organizing professional and academic trips to HUEH so physicians can lend their expertise.

"That's what the Haitian providers want," he says. "They want us to teach and work with them."

The first trip is planned for December, and the group hopes the American Academy of Pediatrics will endorse their effort, which likely will include donating medical equipment and developing a telemedicine program.

Pediatric hospitalists who are interested in joining one of the trips to the Children’s Hospital of the Hopital de l’Universite d’Etat d’Haiti can contact Dr. Reyes at 305-668-5500 or at [email protected].

There is going to be a healthcare crisis in Haiti in the next few years if things don’t markedly improve, says Jocelyn David, MD, chief hospitalist at the Miami VA Healthcare System in Miami, who has traveled to the island nation four times since the Jan. 12 earthquake.

Dr. David returned on Aug. 15 from a four-day trip she took with the Haitian Resource Development Foundation to assess the needs of smaller hospitals outside the capital of Port-au-Prince.

"People are traveling from the capital to these hospitals because the hospitals in the city are overwhelmed and struggling due to a lack of funds," Dr. David says.

Some city hospitals, such as CDTI du Sacre Coeur Hospital, one of the country’s more modern medical facilities, have outright closed, she says.

“I was surprised that I didn’t see any improvement,” says Mario A. Reyes, MD, FAAP, FHM, director of Pediatric Hospital Medicine at Miami Children’s Hospital, who volunteered in Haiti in January and went back in August to visit the Children’s Hospital of the Hopital de l’Universite d’Etat d’Haiti (HUEH), the largest academic public pediatric hospital in the capital.

The Children's Hospital is uninhabitable; medical staff are treating patients in makeshift wood houses provided by the United Nations, he says. Children sleep in hospital beds without mattresses, and oxygen tanks are shared by four or five children. There are no ultrasounds, and ventilators, IV lines, and antibiotics are in short supply, he says.

"There is a frustration among Haitian physicians that things aren't being done as quickly as they should," Dr. Reyes says. "The needs are immense."

Dr. David plans another trip to Haiti in October to train healthcare providers in BLS, ALS, and intubations in order to expand the limited emergency care. Meanwhile, Dr. Reyes and a group of physicians who work at Miami Children's Hospital are organizing professional and academic trips to HUEH so physicians can lend their expertise.

"That's what the Haitian providers want," he says. "They want us to teach and work with them."

The first trip is planned for December, and the group hopes the American Academy of Pediatrics will endorse their effort, which likely will include donating medical equipment and developing a telemedicine program.

Pediatric hospitalists who are interested in joining one of the trips to the Children’s Hospital of the Hopital de l’Universite d’Etat d’Haiti can contact Dr. Reyes at 305-668-5500 or at [email protected].

Hospitalist Compensation and Productivity Figures Released by MGMA

Enter text here

Enter text here

Enter text here

FDA panel recommends dabigatran: 9-0

The advisory panel for the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) voted unanimously on September 20 to recommend approval of dabigatran, an anticoagulant under investigation for the reduction of stroke risk and non-CNS systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation.

The advisory board only voted that dabigatran works at least as well as warfarin. But unlike warfarin, dabigatran does not require laboratory monitoring. Therefore, dabigatran is less difficult to use than the current standard of care.

The decision was based on the randomized, noninferiority RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy) trial of 18,000 patients. The trial compared unblinded warfarin administration with blinded doses of dabigatran at 110 mg and 150 mg.

The hazard ratio of dabigatran compared with warfarin was 0.66 (P<0.003) in the 150 mg dabigatran arm and 0.91 (P<0.0001) in the 110 mg dabigatran arm.

Bleeding risk remains the top safety concern. Receiving 150 mg of dabigatran seems to run the same risk as warfarin for bleeding complications, but in 110 mg doses of dabigatran, the risk was less than warfarin.

Conflict arose among committee members regarding whether or not to approve both doses. Some members disagreed, seeing that the 110 mg dose was only noninferior to warfarin, not superior. Other members believed that approving both doses would ensure wider use of the drug leading to the prevention of a greater number of strokes in atrial fibrillation patients.

There is one unexplained finding of the RE-LY study. Myocardial infarction rates were higher on dabigatran compared with warfarin. For every 1000 patients treated with dabigatran, there may be 2 more myocardial infarctions than in patients treated with warfarin.

The FDA often follows the advice of the panel of experts, although it is not required to. ![]()

The advisory panel for the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) voted unanimously on September 20 to recommend approval of dabigatran, an anticoagulant under investigation for the reduction of stroke risk and non-CNS systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation.

The advisory board only voted that dabigatran works at least as well as warfarin. But unlike warfarin, dabigatran does not require laboratory monitoring. Therefore, dabigatran is less difficult to use than the current standard of care.

The decision was based on the randomized, noninferiority RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy) trial of 18,000 patients. The trial compared unblinded warfarin administration with blinded doses of dabigatran at 110 mg and 150 mg.

The hazard ratio of dabigatran compared with warfarin was 0.66 (P<0.003) in the 150 mg dabigatran arm and 0.91 (P<0.0001) in the 110 mg dabigatran arm.

Bleeding risk remains the top safety concern. Receiving 150 mg of dabigatran seems to run the same risk as warfarin for bleeding complications, but in 110 mg doses of dabigatran, the risk was less than warfarin.

Conflict arose among committee members regarding whether or not to approve both doses. Some members disagreed, seeing that the 110 mg dose was only noninferior to warfarin, not superior. Other members believed that approving both doses would ensure wider use of the drug leading to the prevention of a greater number of strokes in atrial fibrillation patients.

There is one unexplained finding of the RE-LY study. Myocardial infarction rates were higher on dabigatran compared with warfarin. For every 1000 patients treated with dabigatran, there may be 2 more myocardial infarctions than in patients treated with warfarin.

The FDA often follows the advice of the panel of experts, although it is not required to. ![]()

The advisory panel for the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) voted unanimously on September 20 to recommend approval of dabigatran, an anticoagulant under investigation for the reduction of stroke risk and non-CNS systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation.

The advisory board only voted that dabigatran works at least as well as warfarin. But unlike warfarin, dabigatran does not require laboratory monitoring. Therefore, dabigatran is less difficult to use than the current standard of care.

The decision was based on the randomized, noninferiority RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy) trial of 18,000 patients. The trial compared unblinded warfarin administration with blinded doses of dabigatran at 110 mg and 150 mg.

The hazard ratio of dabigatran compared with warfarin was 0.66 (P<0.003) in the 150 mg dabigatran arm and 0.91 (P<0.0001) in the 110 mg dabigatran arm.

Bleeding risk remains the top safety concern. Receiving 150 mg of dabigatran seems to run the same risk as warfarin for bleeding complications, but in 110 mg doses of dabigatran, the risk was less than warfarin.

Conflict arose among committee members regarding whether or not to approve both doses. Some members disagreed, seeing that the 110 mg dose was only noninferior to warfarin, not superior. Other members believed that approving both doses would ensure wider use of the drug leading to the prevention of a greater number of strokes in atrial fibrillation patients.

There is one unexplained finding of the RE-LY study. Myocardial infarction rates were higher on dabigatran compared with warfarin. For every 1000 patients treated with dabigatran, there may be 2 more myocardial infarctions than in patients treated with warfarin.

The FDA often follows the advice of the panel of experts, although it is not required to. ![]()

Business Case for an Electronic Discharge Summary

Delivering the highest possible quality of care is among the top priorities of all medical centers. That said, any quality innovation must be seen as adding value from a variety of perspectives. Especially in the current economic climate, a sound business case is paramount to the advancement of any quality innovation. Given the nature of their work, hospitalists are ideally suited to undertake system improvement innovations. To assist hospitalists in successfully implementing quality and safety initiatives, we have designed a framework of elements required for a business case. We describe our experience developing and implementing an electronic discharge summary and utilize a structured framework to articulate the business case for its implementation.

Defining a Business Case Framework

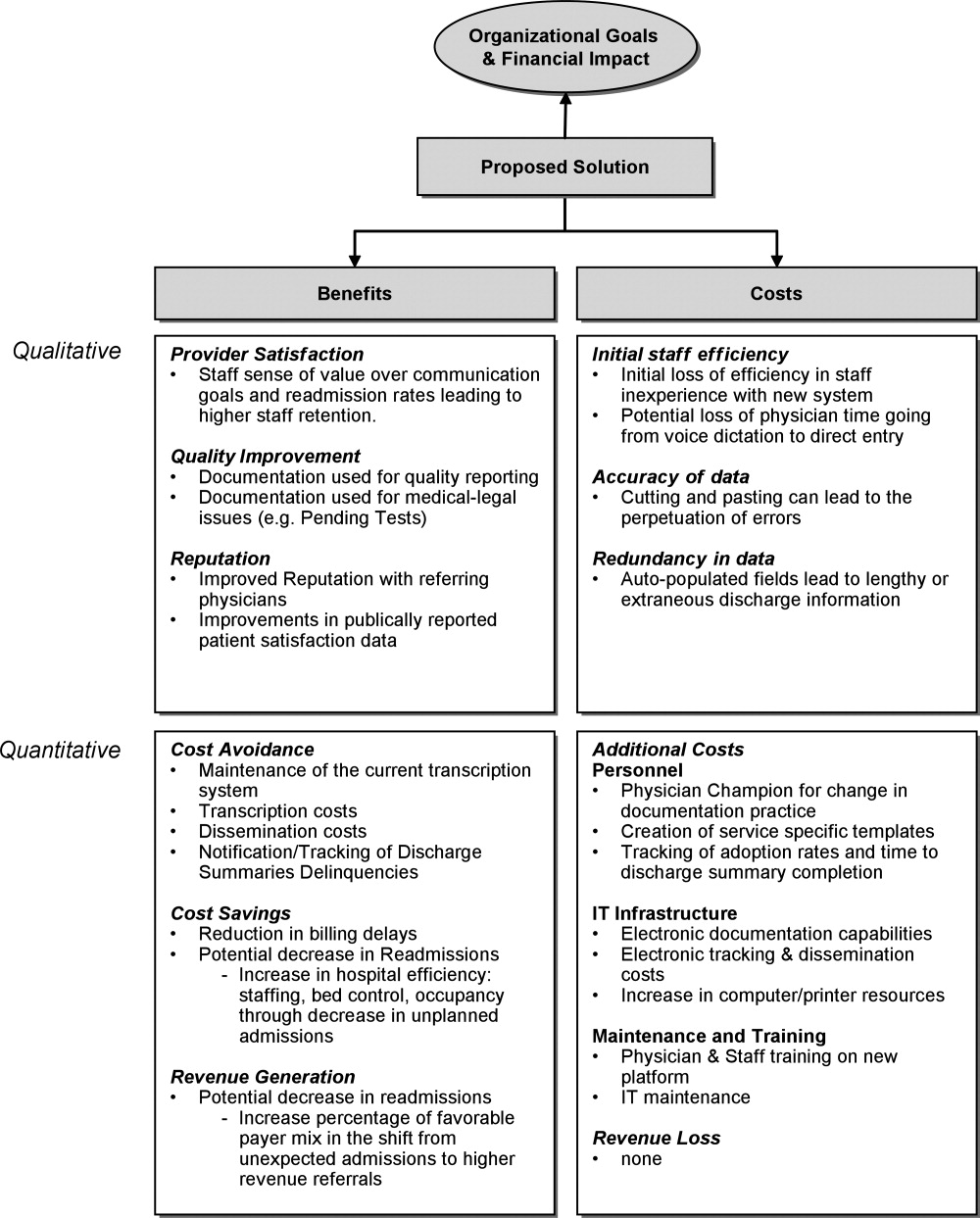

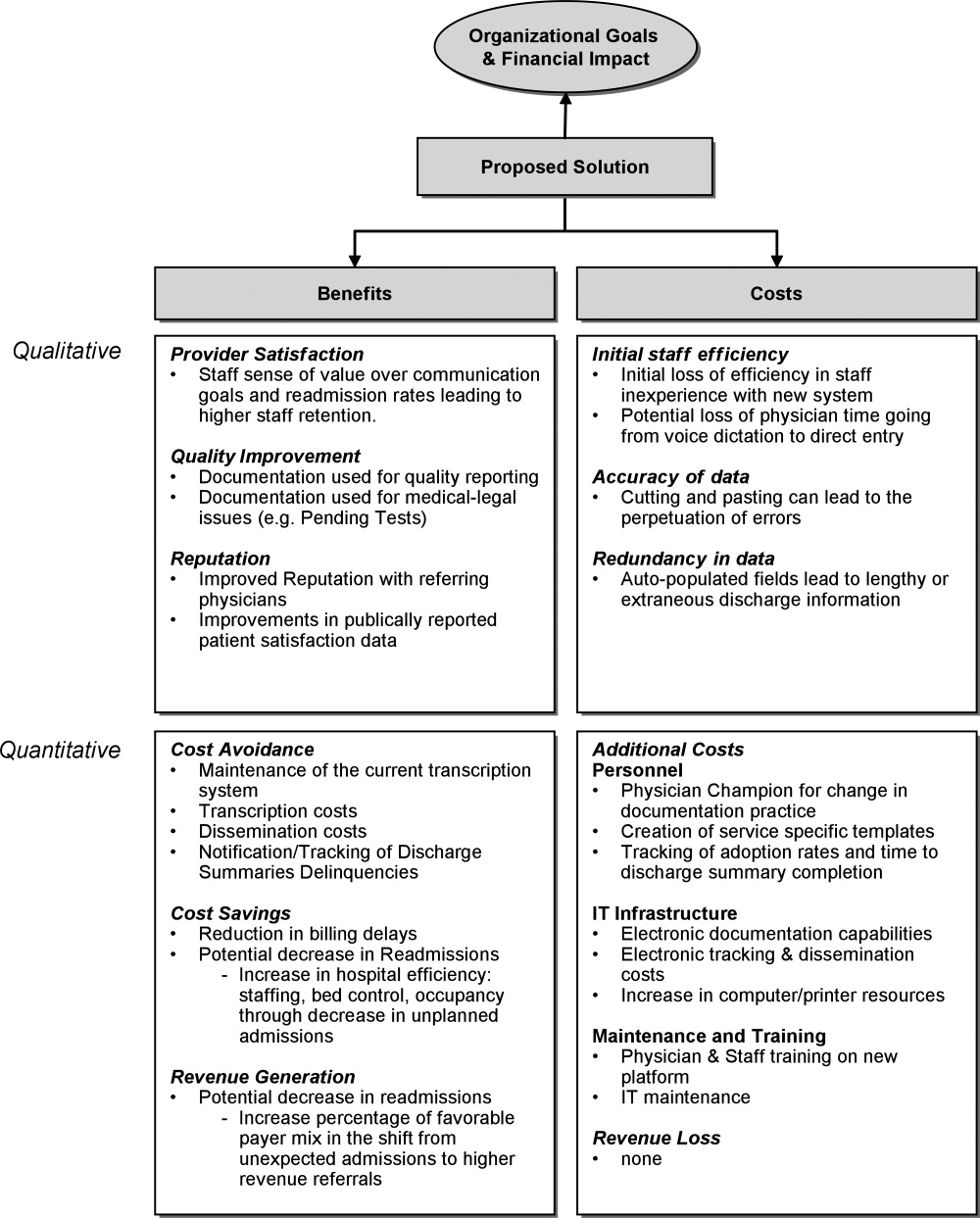

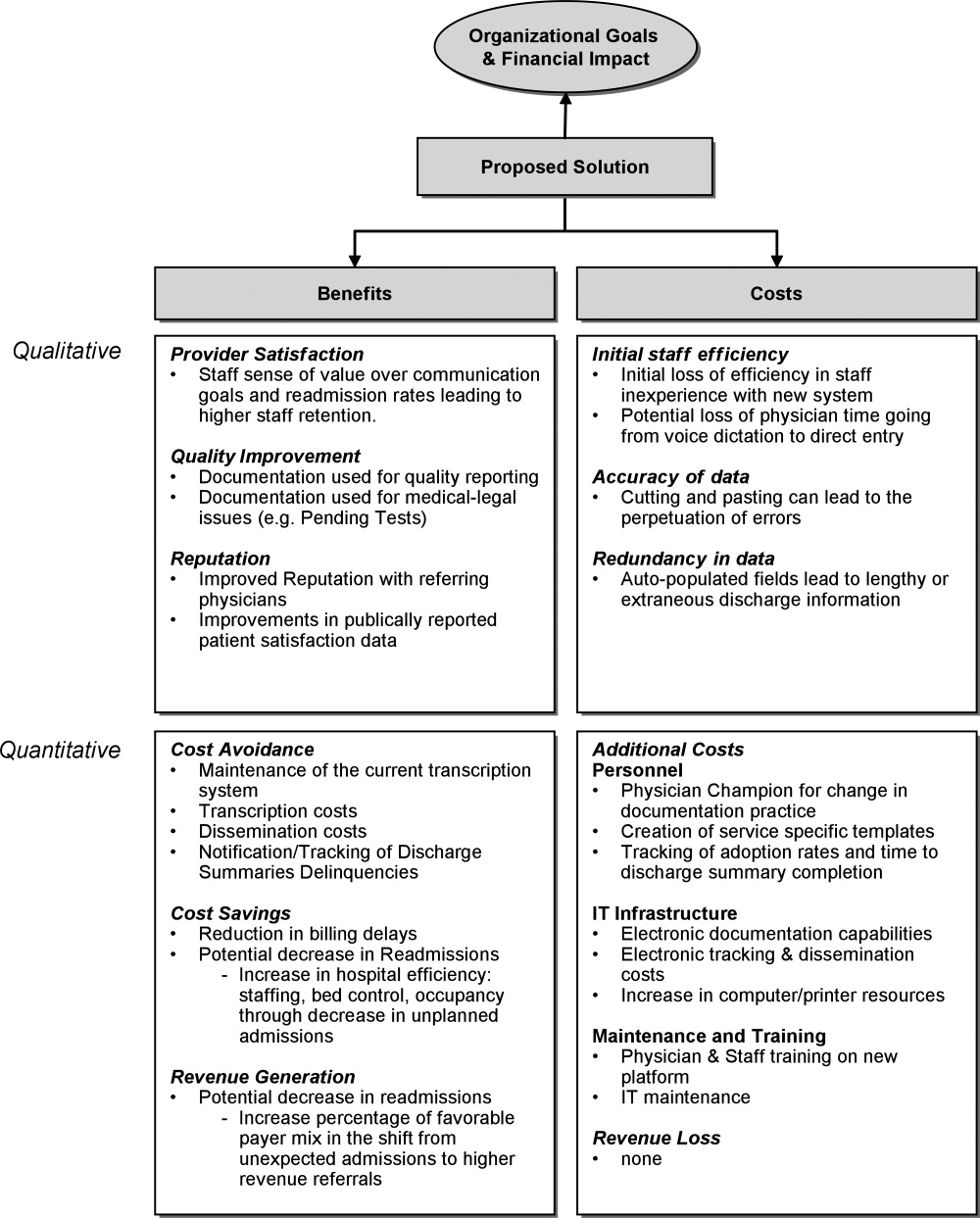

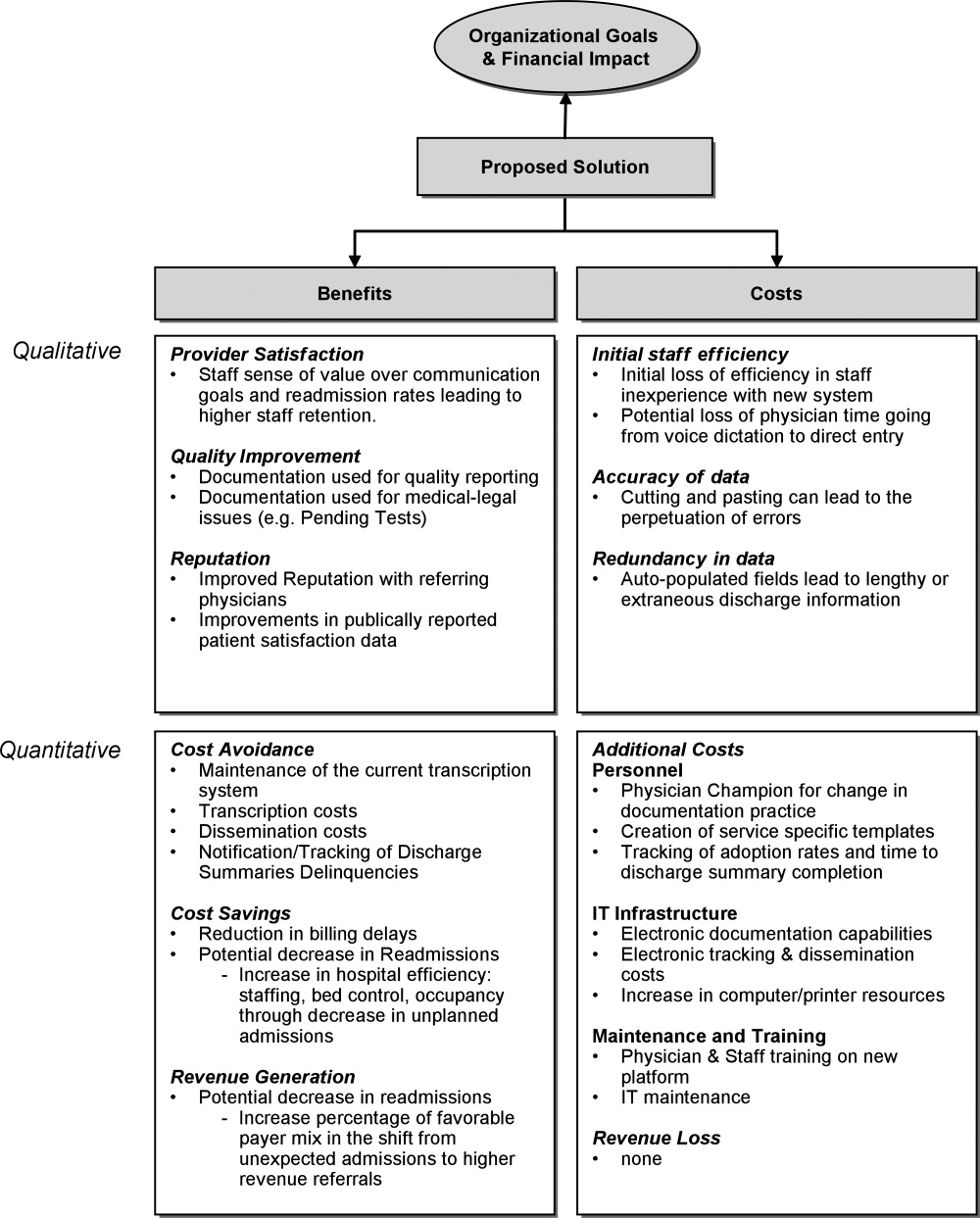

A business case is a structured proposal outlining the qualitative and quantitative factors that justify a course of action. An effective business case for a quality improvement initiative articulates how both factors are aligned with preexisting organizational goals. In modeling the business case framework for the electronic discharge summary, Figure 1 outlines the qualitative and quantitative costs and benefits that can affect institutional decision making.

Organizational Aims and Financial Impact: Determining Costs and Benefits

Organizational goals drive decision making and resource allocation at all levels. As priorities change with time, understanding which predominate in an organization will be essential to building a business case. Institutions may be more willing to adopt expensive innovations if they are justified by progress toward the qualitative organizational goals. Figure 1 demonstrates several institutional goals both qualitative (provider satisfaction, quality improvement, and institutional reputation) and quantitative (cost avoidance, cost savings, and revenue generation) that could drive the decision making for an electronic discharge summary. After examining how an initiative aligns with institutional aims, the next step is to weigh the benefits against the potential costs. Costs in our example include not only the quantitative financial investment in information technology (IT) infrastructure, personnel and maintenance, but also may include qualitative costs such as loss of staff efficiency and redundant documentation. Costs and savings will be geographically variable and depend on the institutional framework, eg, the existing system for medical records, institutional patient payer mix, type of payment structure (global vs. utilization based*), and reimbursement rates. While it may be impractical to account for every cost and savings resulting from the project implementation, every effort should be made to account for the key variables that make up the cost‐benefit calculation.

The Business Case for an Electronic Discharge Summary at University of California San Francisco (UCSF)

Current State of Discharge Documentation a UCSF

UCSF Medical Center is a 600‐bed quaternary care academic institution that discharges approximately 100 patients per day. Our hospital discharge summary is used to document a patient's hospital course and post discharge plan, information necessary for continued care in the outpatient setting. Literature supports the potential for timely and relevant discharge summaries to improve care transitions, clinician satisfaction, and resource use.1 In 2008, however, the majority of our discharge summaries were completed greater than 14 days post discharge, in accordance with national practice.2 Despite Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Joint Commission discharge summary standards regarding content,3, 4 most discharge summaries are composed using freeform dictation.2 Consequently, discharge summaries often lack critical information,57 and may not reach the correct outpatient provider in a timely manner.5, 811

Our Proposed Solution: E‐Discharge

As hospitals are increasingly implementing electronic medical records (EMR),12 there is a growing opportunity to efficiently and reliably incorporate information from the medical record into electronic or database assisted discharge materials. At UCSF the need to develop a system to document and communicate tests pending at discharge fueled the development of an electronic discharge summary. UCSF's vendor‐supplied EMR lacks the ability to integrate electronic patient data into a progress note or discharge summary in a manner usable for physicians. Instead physicians are required to use a telephone voice dictation system, which is subsequently transcribed to text within 1 to 3 days. A separate software platform tracks attending signature of the transcribed text and automatically triggers dissemination through computerized fax and campus mail. The turnaround time for a discharge summary can be as long as 3 weeks. With the time involved and high cost of implementing new or more sophisticated versions of EMR, we chose to design a solution that would improve care for our patients in a more immediate and cost neutral fashion. Our goal was to create an affordable, electronic, systematized solution to produce both timely and relevant discharge summaries, in the hopes of improving communications with providers and thus patient outcomes.

In earlier work, UCSF developed UCSF Note Writer, a template‐based documentation tool that uses web service to import data from the underlying database for provider documentation.13 As a standardized template has been shown to improve quality of communication to both patients and referring providers,1, 14, 15 we developed a template in UCSF Note Writer with both free text and auto‐populated fields for a discharge summary based on current guidelines.1619 We encouraged the documentation of medication changes, changes in functional status and pending tests.

The adoption of such an electronic format has also been shown to improve the efficiency of discharge documentation over conventional dictation and transcription.1, 2022 While this change may be institution dependent, we employed strategies such as allowing the discharge summary to be initiated and updated throughout the hospital admission and unifying the discharge summary with the last day's progress note to facilitate timeliness. To promote efficiency, we allowed providers to import pertinent labs, microbiology, and in the future, the importation of pending tests. While the electronic format in itself does not promote timeliness, it incorporates the discharge summary into physician daily workflow and enables efficiency in data gathering and transfer. For outpatient providers who can access the EMR, any delay or potential fault in the delivery of the discharge materials is eliminated, while outside providers can receive copies through other rapid and reliable modes of electronic delivery (eg, EMR inbox notification) with an appropriate infrastructure.

Application of the Business Framework to the Case for an Electronic Discharge

Considering the potential improvements in care delivery, the argument for an electronic discharge summary may seem self‐evident. To realize its implementation, however, it is necessary to consider other aspects of organizational decision making. We employed the following structure to articulate a robust and sound business case for e‐discharge.

Qualitative Benefits

Quality and Safety

Publically reported data are often derived from hospital chart abstraction and may impact accreditation, reputation, and pay for performance programs.18, 23, 24 The discharge summary is a readily available source of information regarding discharge medications, patient instruction, and communication regarding pending tests. As such, its quality should be a priority for hospital decision makers. Electronic discharge summaries have the potential to reduce adverse events in the high‐risk post‐hospitalization period.1, 25 As such they may improve outpatient physicians' ability to deliver relevant care, reduce preventable readmissions26 and reduce malpractice vulnerability27all key drivers in organizational decision making.

Patient Satisfaction

Patients want to feel prepared for discharge by understanding the continuity of their care from the hospital to the outpatient setting. Discharge preparedness, commonly queried and reported in national patient satisfaction surveys, is low.28 Many electronic discharge summary platforms allow for translation into tailored patient instructions available to the patient in real time, helping to ensure that patients receive quality discharge education.29

Referring Physician Satisfaction

Poor discharge communication reduces referring physicians' satisfaction, which may discourage them from referring patients to the hospital or organization, having broader financial implications.25, 30 Even for medical centers with a busy emergency department, outpatient physician referrals and recommendations make up over 50% of an institution's admissions.31 An electronic discharge summary available in the EMR at the time of discharge, electronically transmitted to referring providers can impact the referral patterns of community physicians.

Readmission

Now publicly reported, readmission rates are another benchmark by which to judge hospital care.32 Patients with discharge summaries that are unavailable to outpatient providers, a very common occurance,2 have a higher trend toward readmission.26 Improved quality of care at the time of discharge resulting in fewer readmissions will better position hospitals to contend with potential Medicare reforms.

Quantitative Benefits

IT Infrastructure: Transcription, Deficiency Tracking, Dissemination

Hospitals, including UCSF, use internal or external transcriptionists to transcribe dictated recordings into typed text at a substantial cost to large medical centers. Medical records staff also track both discharge summary completion and their dissemination to referring providers in compliance with regulatory mandates.4, 33 The use of electronic documentation that relies on physician‐direct entry and that automates dissemination and tracking of discharge documentation provides a potential cost savings to offset the costs of a new system. UCSF Medical Center discharges 100 patients per day and could conservatively avoid almost $500,000 in transcription costs annually (Text Box 1).34

Text Box 1

UCSF Transcription costs:

Average cost/line for transcribed text: $0.17

Average Lines in a discharge summary: 80

# pts discharged/day: 100

Yearly costs = $496,400

Billing

Delays in completion of discharge summaries result in billing delays when critical information required for coding is in the discharge summary. Deferred payment on long admissions can reach tens of thousands of dollars, representing a significant strain on medical center finances. Comprehensive electronic discharge materials may simplify coding through careful documentation and improve billing efficiency through rapid completion.

At our medical center, approximately 20% of billing is delayed due to incomplete discharge documentation. For a hospital that generates over $1.4 billion dollars in billing revenue per year, this can translate into significant financial losses. Hospitals may have to borrow money or draw from existing resources to cover operative deficits created by a delay in the receipt of large payment. Lenders charge approximately 1% to 2% annual interest rate, which translates into 0.2% to 0.4% in billed costs that the hospital gives away to their lenders. Hospitals would be well served by eliminating delays in billing to improve revenue flow (Text Box 2).

Text Box 2

UCSF Annual revenue: $1.4 Billion

Billing that requires discharge summary completion: 20%

Lender's interest rate: 12%

Lenders interest rate (12%) on delayed billing (20%) = 0.20.4% of total revenue

Assuming a 14 day delay in billing: 0.20.4% of total revenue ($1,400,000,000) for 14/365 days = $107,000$215,000

Qualitative Costs

Efficiency and Physician Time

Implementation of any new system is likely to result in initial diminished efficiency. If patient volume is stable, this may not translate into loss of revenue, but rather cause staff to change their workflow. For example, given the new inefficiency in charting, staff may spend less time on direct patient care tasks (Intravenous Catheter placement, FT placement, patient education, discharge instructions), thus increasing the qualitative costs to implementing the system.

To minimize these costs, we used a step wise phased role out starting with one pilot team, with a plan to expand to multiple teams prior to implementation on the entire medicine service. This allowed for the creation of one central and several ancillary physician champions to troubleshoot the new system to help minimize productivity losses. One of the largest concerns in the switch from voice dictation to physician‐direct entry into an electronic summary is the cost of physician time. System adjustments through several pilots helped ensure that the time investment of a novice user was not significantly greater than time previously spent dictating.

Quality of Documentation

Unanticipated consequences from a switch to an electronic platform must be considered, such as the possibility of longer more redundant discharge summaries. The amount of information available for automated import will vary by institutional preference, but the recipient's access to the EMR, primary physician preference, and technologic capabilities should be considered. At UCSF we made an effort to distill the information most important to subsequent care, disabling the importation of multiple days of radiology data and instead working to create a system for discharge medication importation. As with any electronic document, the medium also lends itself to cutting and pasting, which may lead to anachronistic information carried forward from hospital progress notes earlier in the stay.35, 36 The largest experience with this unintended consequence can be found in the Veteran's Affairs Health System EMR, which found that 9% of progress notes studied contained copied or duplicated text.37 The authors recommended that clear policies, programs to raise practitioner awareness, and the development of monitoring procedure be implemented coincident with electronic note‐writing capabilities.

Quantitative Costs

Quantitative Costs will be highly variable across institutions, geographical areas, and software platforms as the infrastructure of existing EMRs are highly variable. The cost of implementation depends heavily on whether inpatient documentation (and thus discharge documentation) is a feature of an institutional EMR, or whether a stand‐alone discharge documentation infrastructure is needed. An explanation of the differences between these types of EMRs and the importance to the cost of infrastructure implementation is further described in the following section. Rather than providing a direct accounting of costs, we have provided a tabular summary of costs that should be considered with the adoption of an electronic discharge summary based on the type of institutional EMR (Table 1).

| Voice Dictation | E‐Discharge in an EMR With Inpatient Documentation Abilities | E‐Discharge in an EMR Without Inpatient Documentation Abilities | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Infrastructure | |||

| Software | + | ||

| Hardware (sufficient computers and printers) | + | + | |

| Network connectivity | + | + | |

| Server capacity for system backup | + | + | |

| Interface with current EMR | + | ||

| Personnel | |||

| Physician champion | + | + | |

| Physician training | + | + | |

| Computer programmer | + | + | |

| Transcription | + | ||

| Deficiency tracking | + | ||

| Dissemination | + | ||

| Maintenance | |||

| Computer/printer maintenance | + | + | |

| Network maintenance | + | + | |

| Software add‐ons and updates | + | + | + |

Infrastructure

For most health care organizations, the transition to an EMR includes adoption of results reporting systems and computerized provider order entry; only a more select group of hospitals with a complete EMR electronically document inpatient care (eg, progress notes) through physician direct entry. While there is substantial literature regarding the benefits and pitfalls of adopting computerized order entry (CPOE),38, 39 there is less attention devoted to the costs of implementing large‐scale electronic documentation, including an electronic discharge summary, as opposed to paper notes or dictation.4042 Institutions using an EMR with electronic care documentation capability have already invested in the infrastructure to implement electronic discharge documentation, and can employ it at a modest cost. For these institutions, the infrastructure cost of the transition from paper charting or dictation to direct entry by physicians lies in ensuring sufficient computers and connectivity to handle the increased computer use. On the other hand, for those institutions where the EMR lacks this capability there are few freestanding documentation platforms available for purchase. The cost of implementing such a system is high, both for the purchase of additional software and the integration of that software in to the EMR supplied by the primary vendor. Other notable infrastructure costs to consider are ensuring sufficient network connectivity, computers and printers to accommodate increased use that will come with electronic note writing as well as server support for system backups.

Personnel

Engaging the right personnel will smooth the implementation of an electronic discharge summary. In addition to dedicated user training sessions, a physician champion who can promote and monitor user training on the new platform will facilitate prompt implementation. An IT support programmer should work with the physician champion to address concerns and troubleshoot problems. Additional personnel may also be needed to track progress in discharge summary adoption, quality and efficiency. Ideally these personnel can be funneled from those who work transcribing, disseminating and tracking completion of discharge summaries, positions that will be needed in a reduced capacity.

Maintenance

Increased IT infrastructure also means increased IT maintenance and upgrades of servers, network connectivity, computers and printers. Discussions with vendors regarding costs of maintenance, upgrades and add‐on features should be considered when adopting an electronic discharge summary platform.

Conclusion

While many QI initiatives have the potential to improve clinical care, resource limitations and competing priorities necessitate that hospital decision makers see the value of hospitalist driven improvements. A sound business case is the key to successfully influencing decision making and furthering necessary innovations. We have detailed the elements of a business case and applied them to a proposed innovationthe electronic discharge summary. While the cost of multifunctional EMR with full electronic care documentation may be impossible to implement given high initial costs and competing priorities, investing in an e‐discharge solution has real‐time benefits in the impact on patients, system improvements, qualitative benefits, and return on investment. Being able to articulate key qualitative and quantitative elements creates a sound business case that can be applied to QI initiatives in general, and assist hospitalists in garnering support and resources to continue to improve care.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Kathleen Kerr and the members of the BOOST collaborative for helping with background research and in creating the impetus for this work.

Global payments are fixed‐dollar payments for the care that patients may receive in a given time period, such as a month or year, whereas utilization based payments are payments based on the use of diagnostic and treatment modalities (eg, CT scans and blood cultures).

- ,,, et al.Creating a better discharge summary: Improvement in quality and timeliness using an electronic discharge summary.J Hosp Med.2009;4(4):219–225.

- ,,,,,.Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care.JAMA.2007;297(8):831–841.

- Standard IM.6.10Hospital Accredidation Standards. In: Oakbrook Terrace,IL:Joint Commission Resources;2006:338–340.

- .Medical Record Services, Section 482.24. In: MacDonald I, ed.The CMS Hospital Conditions of Participation.First edition.United States:Hc Pro Inc.;2005:24–25.

- .Hospital discharge and death communications.Br J Hosp Med.1989;42(1):59–61.

- ,,,.Hospital discharge reports: content and design.Br Med J.1975;4(5994):443–446.

- ,,, et al.Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge.Ann Intern Med.2005;143(2):121–128.

- .Delayed communication between hospitals and general practitioners: where does the problem lie?BMJ.1988;297(6640):28–29.

- .Study of “discharge communications” from hospital.Br Med J (Clin Res Ed).1986;293(6557):1283–1284.

- ,.Quality assessment of a discharge summary system.CMAJ.1995;152(9):1437–1442.

- ,,,.General practitioner‐hospital communications: a review of discharge summaries.J Qual Clin Pract.2001;21(4):104–108.

- .Stimulus bill spurs plans for rapid IT progress.Manag Care.2009;18(2):5–6.

- ,,, et al. UCSF Notewriter. Copyright Regents of the University of California.2006–year="2010"2010.

- ,,,,.Assessing quality and efficiency of discharge summaries.Am J Med Qual.2005;20(6):337–343.

- ,,,.Standardized or narrative discharge summaries. Which do family physicians prefer?Can Fam Physician.1998;44:62–69.

- ,,,.Standardized or narrative discharge summaries. Which do family physicians prefer?Can Fam Physician.1998;44:62–69.

- ,.What is necessary for high‐quality discharge summaries?Am J Med Qual.1999;14(4):160–169.

- ,,,,.Outpatient physicians' satisfaction with discharge summaries and perceived need for an electronic discharge summary.J Hosp Med.2006;1(5):317–320.

- ,.Are general practitioners satisfied with electronic discharge summaries?HIM J.2007;36(1):7–12.

- ,,,.Dictated versus database‐generated discharge summaries: a randomized clinical trial.CMAJ.1999;160(3):319–326.

- ,,,.Evaluation of computer generated neonatal discharge summaries.Arch Dis Child.1991;66(4 Spec No):433–436.

- ,,,,,.Evaluation of a computer‐generated discharge summary for patients with acute coronary syndromes.Br J Gen Pract.1998;48(429):1163–1164.

- The Common Wealth Fund. Why not the best org. Available at: http/www.whynotthebest.org. Updated 2009. Accessed May2010.

- ,.Pay for performance: an overview of the literature.Am J Med Qual.2009;24(2):140–163.

- ,,, et al.Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital.CMAJ.2004;170(3):345–349.

- ,,,.Effect of discharge summary availability during post‐discharge visits on hospital readmission.J Gen Intern Med.2002;17(3):186–192.

- ,,, et al.Missed and delayed diagnoses in the ambulatory setting: a study of closed malpractice claims.Ann Intern Med.2006;145(7):488–496.

- ,,.Assessing the quality of preparation for posthospital care from the patient's perspective: the care transitions measure.Med Care.2005;43(3):246–255.

- ,,, et al.A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial.Ann Intern Med.2009;150(3):178–187.

- ,,,,.Adverse drug events occurring following hospital discharge.J Gen Intern Med.2005;20(4):317–323.

- ,,.Referring physician satisfaction: toward a better understanding of hospital referrals.J Hosp Mark.1998;12(2):95–111.

- U.S. Department of Health 7(3):269–272.

- .IT vulnerabilities highlighted by errors, malfunctions at veterans' medical centers.JAMA.2009;301(9):919–920.

- ,.Copy and paste: a remediable hazard of electronic health records.Am J Med.2009;122(6):495–496.

- ,,,.Are electronic medical records trustworthy? Observations on copying, pasting and duplication.AMIA Annu Symp Proc.2003:269–273.

- ,,, et al.Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review.JAMA.2005;293(10):1223–1238.

- ,,, et al.Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors.JAMA.2005;293(10):1197–1203.

- ,,.The elements of electronic note style.J AHIMA.2003;74(2):68,70.

- ,,,,,.Impacts of computerized physician documentation in a teaching hospital: perceptions of faculty and resident physicians.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2004;11(4):300–309.

- ,,,.The transition to electronic documentation on a teaching hospital medical service.AMIA Annu Symp Proc.2006:629–633.

Delivering the highest possible quality of care is among the top priorities of all medical centers. That said, any quality innovation must be seen as adding value from a variety of perspectives. Especially in the current economic climate, a sound business case is paramount to the advancement of any quality innovation. Given the nature of their work, hospitalists are ideally suited to undertake system improvement innovations. To assist hospitalists in successfully implementing quality and safety initiatives, we have designed a framework of elements required for a business case. We describe our experience developing and implementing an electronic discharge summary and utilize a structured framework to articulate the business case for its implementation.

Defining a Business Case Framework

A business case is a structured proposal outlining the qualitative and quantitative factors that justify a course of action. An effective business case for a quality improvement initiative articulates how both factors are aligned with preexisting organizational goals. In modeling the business case framework for the electronic discharge summary, Figure 1 outlines the qualitative and quantitative costs and benefits that can affect institutional decision making.

Organizational Aims and Financial Impact: Determining Costs and Benefits

Organizational goals drive decision making and resource allocation at all levels. As priorities change with time, understanding which predominate in an organization will be essential to building a business case. Institutions may be more willing to adopt expensive innovations if they are justified by progress toward the qualitative organizational goals. Figure 1 demonstrates several institutional goals both qualitative (provider satisfaction, quality improvement, and institutional reputation) and quantitative (cost avoidance, cost savings, and revenue generation) that could drive the decision making for an electronic discharge summary. After examining how an initiative aligns with institutional aims, the next step is to weigh the benefits against the potential costs. Costs in our example include not only the quantitative financial investment in information technology (IT) infrastructure, personnel and maintenance, but also may include qualitative costs such as loss of staff efficiency and redundant documentation. Costs and savings will be geographically variable and depend on the institutional framework, eg, the existing system for medical records, institutional patient payer mix, type of payment structure (global vs. utilization based*), and reimbursement rates. While it may be impractical to account for every cost and savings resulting from the project implementation, every effort should be made to account for the key variables that make up the cost‐benefit calculation.

The Business Case for an Electronic Discharge Summary at University of California San Francisco (UCSF)

Current State of Discharge Documentation a UCSF

UCSF Medical Center is a 600‐bed quaternary care academic institution that discharges approximately 100 patients per day. Our hospital discharge summary is used to document a patient's hospital course and post discharge plan, information necessary for continued care in the outpatient setting. Literature supports the potential for timely and relevant discharge summaries to improve care transitions, clinician satisfaction, and resource use.1 In 2008, however, the majority of our discharge summaries were completed greater than 14 days post discharge, in accordance with national practice.2 Despite Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Joint Commission discharge summary standards regarding content,3, 4 most discharge summaries are composed using freeform dictation.2 Consequently, discharge summaries often lack critical information,57 and may not reach the correct outpatient provider in a timely manner.5, 811

Our Proposed Solution: E‐Discharge

As hospitals are increasingly implementing electronic medical records (EMR),12 there is a growing opportunity to efficiently and reliably incorporate information from the medical record into electronic or database assisted discharge materials. At UCSF the need to develop a system to document and communicate tests pending at discharge fueled the development of an electronic discharge summary. UCSF's vendor‐supplied EMR lacks the ability to integrate electronic patient data into a progress note or discharge summary in a manner usable for physicians. Instead physicians are required to use a telephone voice dictation system, which is subsequently transcribed to text within 1 to 3 days. A separate software platform tracks attending signature of the transcribed text and automatically triggers dissemination through computerized fax and campus mail. The turnaround time for a discharge summary can be as long as 3 weeks. With the time involved and high cost of implementing new or more sophisticated versions of EMR, we chose to design a solution that would improve care for our patients in a more immediate and cost neutral fashion. Our goal was to create an affordable, electronic, systematized solution to produce both timely and relevant discharge summaries, in the hopes of improving communications with providers and thus patient outcomes.

In earlier work, UCSF developed UCSF Note Writer, a template‐based documentation tool that uses web service to import data from the underlying database for provider documentation.13 As a standardized template has been shown to improve quality of communication to both patients and referring providers,1, 14, 15 we developed a template in UCSF Note Writer with both free text and auto‐populated fields for a discharge summary based on current guidelines.1619 We encouraged the documentation of medication changes, changes in functional status and pending tests.

The adoption of such an electronic format has also been shown to improve the efficiency of discharge documentation over conventional dictation and transcription.1, 2022 While this change may be institution dependent, we employed strategies such as allowing the discharge summary to be initiated and updated throughout the hospital admission and unifying the discharge summary with the last day's progress note to facilitate timeliness. To promote efficiency, we allowed providers to import pertinent labs, microbiology, and in the future, the importation of pending tests. While the electronic format in itself does not promote timeliness, it incorporates the discharge summary into physician daily workflow and enables efficiency in data gathering and transfer. For outpatient providers who can access the EMR, any delay or potential fault in the delivery of the discharge materials is eliminated, while outside providers can receive copies through other rapid and reliable modes of electronic delivery (eg, EMR inbox notification) with an appropriate infrastructure.

Application of the Business Framework to the Case for an Electronic Discharge

Considering the potential improvements in care delivery, the argument for an electronic discharge summary may seem self‐evident. To realize its implementation, however, it is necessary to consider other aspects of organizational decision making. We employed the following structure to articulate a robust and sound business case for e‐discharge.

Qualitative Benefits

Quality and Safety

Publically reported data are often derived from hospital chart abstraction and may impact accreditation, reputation, and pay for performance programs.18, 23, 24 The discharge summary is a readily available source of information regarding discharge medications, patient instruction, and communication regarding pending tests. As such, its quality should be a priority for hospital decision makers. Electronic discharge summaries have the potential to reduce adverse events in the high‐risk post‐hospitalization period.1, 25 As such they may improve outpatient physicians' ability to deliver relevant care, reduce preventable readmissions26 and reduce malpractice vulnerability27all key drivers in organizational decision making.

Patient Satisfaction

Patients want to feel prepared for discharge by understanding the continuity of their care from the hospital to the outpatient setting. Discharge preparedness, commonly queried and reported in national patient satisfaction surveys, is low.28 Many electronic discharge summary platforms allow for translation into tailored patient instructions available to the patient in real time, helping to ensure that patients receive quality discharge education.29

Referring Physician Satisfaction

Poor discharge communication reduces referring physicians' satisfaction, which may discourage them from referring patients to the hospital or organization, having broader financial implications.25, 30 Even for medical centers with a busy emergency department, outpatient physician referrals and recommendations make up over 50% of an institution's admissions.31 An electronic discharge summary available in the EMR at the time of discharge, electronically transmitted to referring providers can impact the referral patterns of community physicians.

Readmission

Now publicly reported, readmission rates are another benchmark by which to judge hospital care.32 Patients with discharge summaries that are unavailable to outpatient providers, a very common occurance,2 have a higher trend toward readmission.26 Improved quality of care at the time of discharge resulting in fewer readmissions will better position hospitals to contend with potential Medicare reforms.

Quantitative Benefits

IT Infrastructure: Transcription, Deficiency Tracking, Dissemination

Hospitals, including UCSF, use internal or external transcriptionists to transcribe dictated recordings into typed text at a substantial cost to large medical centers. Medical records staff also track both discharge summary completion and their dissemination to referring providers in compliance with regulatory mandates.4, 33 The use of electronic documentation that relies on physician‐direct entry and that automates dissemination and tracking of discharge documentation provides a potential cost savings to offset the costs of a new system. UCSF Medical Center discharges 100 patients per day and could conservatively avoid almost $500,000 in transcription costs annually (Text Box 1).34

Text Box 1

UCSF Transcription costs:

Average cost/line for transcribed text: $0.17

Average Lines in a discharge summary: 80

# pts discharged/day: 100

Yearly costs = $496,400

Billing

Delays in completion of discharge summaries result in billing delays when critical information required for coding is in the discharge summary. Deferred payment on long admissions can reach tens of thousands of dollars, representing a significant strain on medical center finances. Comprehensive electronic discharge materials may simplify coding through careful documentation and improve billing efficiency through rapid completion.

At our medical center, approximately 20% of billing is delayed due to incomplete discharge documentation. For a hospital that generates over $1.4 billion dollars in billing revenue per year, this can translate into significant financial losses. Hospitals may have to borrow money or draw from existing resources to cover operative deficits created by a delay in the receipt of large payment. Lenders charge approximately 1% to 2% annual interest rate, which translates into 0.2% to 0.4% in billed costs that the hospital gives away to their lenders. Hospitals would be well served by eliminating delays in billing to improve revenue flow (Text Box 2).

Text Box 2

UCSF Annual revenue: $1.4 Billion

Billing that requires discharge summary completion: 20%

Lender's interest rate: 12%

Lenders interest rate (12%) on delayed billing (20%) = 0.20.4% of total revenue

Assuming a 14 day delay in billing: 0.20.4% of total revenue ($1,400,000,000) for 14/365 days = $107,000$215,000

Qualitative Costs

Efficiency and Physician Time

Implementation of any new system is likely to result in initial diminished efficiency. If patient volume is stable, this may not translate into loss of revenue, but rather cause staff to change their workflow. For example, given the new inefficiency in charting, staff may spend less time on direct patient care tasks (Intravenous Catheter placement, FT placement, patient education, discharge instructions), thus increasing the qualitative costs to implementing the system.

To minimize these costs, we used a step wise phased role out starting with one pilot team, with a plan to expand to multiple teams prior to implementation on the entire medicine service. This allowed for the creation of one central and several ancillary physician champions to troubleshoot the new system to help minimize productivity losses. One of the largest concerns in the switch from voice dictation to physician‐direct entry into an electronic summary is the cost of physician time. System adjustments through several pilots helped ensure that the time investment of a novice user was not significantly greater than time previously spent dictating.

Quality of Documentation

Unanticipated consequences from a switch to an electronic platform must be considered, such as the possibility of longer more redundant discharge summaries. The amount of information available for automated import will vary by institutional preference, but the recipient's access to the EMR, primary physician preference, and technologic capabilities should be considered. At UCSF we made an effort to distill the information most important to subsequent care, disabling the importation of multiple days of radiology data and instead working to create a system for discharge medication importation. As with any electronic document, the medium also lends itself to cutting and pasting, which may lead to anachronistic information carried forward from hospital progress notes earlier in the stay.35, 36 The largest experience with this unintended consequence can be found in the Veteran's Affairs Health System EMR, which found that 9% of progress notes studied contained copied or duplicated text.37 The authors recommended that clear policies, programs to raise practitioner awareness, and the development of monitoring procedure be implemented coincident with electronic note‐writing capabilities.

Quantitative Costs

Quantitative Costs will be highly variable across institutions, geographical areas, and software platforms as the infrastructure of existing EMRs are highly variable. The cost of implementation depends heavily on whether inpatient documentation (and thus discharge documentation) is a feature of an institutional EMR, or whether a stand‐alone discharge documentation infrastructure is needed. An explanation of the differences between these types of EMRs and the importance to the cost of infrastructure implementation is further described in the following section. Rather than providing a direct accounting of costs, we have provided a tabular summary of costs that should be considered with the adoption of an electronic discharge summary based on the type of institutional EMR (Table 1).

| Voice Dictation | E‐Discharge in an EMR With Inpatient Documentation Abilities | E‐Discharge in an EMR Without Inpatient Documentation Abilities | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Infrastructure | |||

| Software | + | ||

| Hardware (sufficient computers and printers) | + | + | |

| Network connectivity | + | + | |

| Server capacity for system backup | + | + | |

| Interface with current EMR | + | ||

| Personnel | |||

| Physician champion | + | + | |

| Physician training | + | + | |

| Computer programmer | + | + | |

| Transcription | + | ||

| Deficiency tracking | + | ||

| Dissemination | + | ||

| Maintenance | |||

| Computer/printer maintenance | + | + | |

| Network maintenance | + | + | |

| Software add‐ons and updates | + | + | + |

Infrastructure

For most health care organizations, the transition to an EMR includes adoption of results reporting systems and computerized provider order entry; only a more select group of hospitals with a complete EMR electronically document inpatient care (eg, progress notes) through physician direct entry. While there is substantial literature regarding the benefits and pitfalls of adopting computerized order entry (CPOE),38, 39 there is less attention devoted to the costs of implementing large‐scale electronic documentation, including an electronic discharge summary, as opposed to paper notes or dictation.4042 Institutions using an EMR with electronic care documentation capability have already invested in the infrastructure to implement electronic discharge documentation, and can employ it at a modest cost. For these institutions, the infrastructure cost of the transition from paper charting or dictation to direct entry by physicians lies in ensuring sufficient computers and connectivity to handle the increased computer use. On the other hand, for those institutions where the EMR lacks this capability there are few freestanding documentation platforms available for purchase. The cost of implementing such a system is high, both for the purchase of additional software and the integration of that software in to the EMR supplied by the primary vendor. Other notable infrastructure costs to consider are ensuring sufficient network connectivity, computers and printers to accommodate increased use that will come with electronic note writing as well as server support for system backups.

Personnel

Engaging the right personnel will smooth the implementation of an electronic discharge summary. In addition to dedicated user training sessions, a physician champion who can promote and monitor user training on the new platform will facilitate prompt implementation. An IT support programmer should work with the physician champion to address concerns and troubleshoot problems. Additional personnel may also be needed to track progress in discharge summary adoption, quality and efficiency. Ideally these personnel can be funneled from those who work transcribing, disseminating and tracking completion of discharge summaries, positions that will be needed in a reduced capacity.

Maintenance

Increased IT infrastructure also means increased IT maintenance and upgrades of servers, network connectivity, computers and printers. Discussions with vendors regarding costs of maintenance, upgrades and add‐on features should be considered when adopting an electronic discharge summary platform.

Conclusion

While many QI initiatives have the potential to improve clinical care, resource limitations and competing priorities necessitate that hospital decision makers see the value of hospitalist driven improvements. A sound business case is the key to successfully influencing decision making and furthering necessary innovations. We have detailed the elements of a business case and applied them to a proposed innovationthe electronic discharge summary. While the cost of multifunctional EMR with full electronic care documentation may be impossible to implement given high initial costs and competing priorities, investing in an e‐discharge solution has real‐time benefits in the impact on patients, system improvements, qualitative benefits, and return on investment. Being able to articulate key qualitative and quantitative elements creates a sound business case that can be applied to QI initiatives in general, and assist hospitalists in garnering support and resources to continue to improve care.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Kathleen Kerr and the members of the BOOST collaborative for helping with background research and in creating the impetus for this work.

Global payments are fixed‐dollar payments for the care that patients may receive in a given time period, such as a month or year, whereas utilization based payments are payments based on the use of diagnostic and treatment modalities (eg, CT scans and blood cultures).

Delivering the highest possible quality of care is among the top priorities of all medical centers. That said, any quality innovation must be seen as adding value from a variety of perspectives. Especially in the current economic climate, a sound business case is paramount to the advancement of any quality innovation. Given the nature of their work, hospitalists are ideally suited to undertake system improvement innovations. To assist hospitalists in successfully implementing quality and safety initiatives, we have designed a framework of elements required for a business case. We describe our experience developing and implementing an electronic discharge summary and utilize a structured framework to articulate the business case for its implementation.

Defining a Business Case Framework

A business case is a structured proposal outlining the qualitative and quantitative factors that justify a course of action. An effective business case for a quality improvement initiative articulates how both factors are aligned with preexisting organizational goals. In modeling the business case framework for the electronic discharge summary, Figure 1 outlines the qualitative and quantitative costs and benefits that can affect institutional decision making.

Organizational Aims and Financial Impact: Determining Costs and Benefits

Organizational goals drive decision making and resource allocation at all levels. As priorities change with time, understanding which predominate in an organization will be essential to building a business case. Institutions may be more willing to adopt expensive innovations if they are justified by progress toward the qualitative organizational goals. Figure 1 demonstrates several institutional goals both qualitative (provider satisfaction, quality improvement, and institutional reputation) and quantitative (cost avoidance, cost savings, and revenue generation) that could drive the decision making for an electronic discharge summary. After examining how an initiative aligns with institutional aims, the next step is to weigh the benefits against the potential costs. Costs in our example include not only the quantitative financial investment in information technology (IT) infrastructure, personnel and maintenance, but also may include qualitative costs such as loss of staff efficiency and redundant documentation. Costs and savings will be geographically variable and depend on the institutional framework, eg, the existing system for medical records, institutional patient payer mix, type of payment structure (global vs. utilization based*), and reimbursement rates. While it may be impractical to account for every cost and savings resulting from the project implementation, every effort should be made to account for the key variables that make up the cost‐benefit calculation.

The Business Case for an Electronic Discharge Summary at University of California San Francisco (UCSF)

Current State of Discharge Documentation a UCSF

UCSF Medical Center is a 600‐bed quaternary care academic institution that discharges approximately 100 patients per day. Our hospital discharge summary is used to document a patient's hospital course and post discharge plan, information necessary for continued care in the outpatient setting. Literature supports the potential for timely and relevant discharge summaries to improve care transitions, clinician satisfaction, and resource use.1 In 2008, however, the majority of our discharge summaries were completed greater than 14 days post discharge, in accordance with national practice.2 Despite Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Joint Commission discharge summary standards regarding content,3, 4 most discharge summaries are composed using freeform dictation.2 Consequently, discharge summaries often lack critical information,57 and may not reach the correct outpatient provider in a timely manner.5, 811

Our Proposed Solution: E‐Discharge

As hospitals are increasingly implementing electronic medical records (EMR),12 there is a growing opportunity to efficiently and reliably incorporate information from the medical record into electronic or database assisted discharge materials. At UCSF the need to develop a system to document and communicate tests pending at discharge fueled the development of an electronic discharge summary. UCSF's vendor‐supplied EMR lacks the ability to integrate electronic patient data into a progress note or discharge summary in a manner usable for physicians. Instead physicians are required to use a telephone voice dictation system, which is subsequently transcribed to text within 1 to 3 days. A separate software platform tracks attending signature of the transcribed text and automatically triggers dissemination through computerized fax and campus mail. The turnaround time for a discharge summary can be as long as 3 weeks. With the time involved and high cost of implementing new or more sophisticated versions of EMR, we chose to design a solution that would improve care for our patients in a more immediate and cost neutral fashion. Our goal was to create an affordable, electronic, systematized solution to produce both timely and relevant discharge summaries, in the hopes of improving communications with providers and thus patient outcomes.

In earlier work, UCSF developed UCSF Note Writer, a template‐based documentation tool that uses web service to import data from the underlying database for provider documentation.13 As a standardized template has been shown to improve quality of communication to both patients and referring providers,1, 14, 15 we developed a template in UCSF Note Writer with both free text and auto‐populated fields for a discharge summary based on current guidelines.1619 We encouraged the documentation of medication changes, changes in functional status and pending tests.

The adoption of such an electronic format has also been shown to improve the efficiency of discharge documentation over conventional dictation and transcription.1, 2022 While this change may be institution dependent, we employed strategies such as allowing the discharge summary to be initiated and updated throughout the hospital admission and unifying the discharge summary with the last day's progress note to facilitate timeliness. To promote efficiency, we allowed providers to import pertinent labs, microbiology, and in the future, the importation of pending tests. While the electronic format in itself does not promote timeliness, it incorporates the discharge summary into physician daily workflow and enables efficiency in data gathering and transfer. For outpatient providers who can access the EMR, any delay or potential fault in the delivery of the discharge materials is eliminated, while outside providers can receive copies through other rapid and reliable modes of electronic delivery (eg, EMR inbox notification) with an appropriate infrastructure.

Application of the Business Framework to the Case for an Electronic Discharge

Considering the potential improvements in care delivery, the argument for an electronic discharge summary may seem self‐evident. To realize its implementation, however, it is necessary to consider other aspects of organizational decision making. We employed the following structure to articulate a robust and sound business case for e‐discharge.

Qualitative Benefits

Quality and Safety

Publically reported data are often derived from hospital chart abstraction and may impact accreditation, reputation, and pay for performance programs.18, 23, 24 The discharge summary is a readily available source of information regarding discharge medications, patient instruction, and communication regarding pending tests. As such, its quality should be a priority for hospital decision makers. Electronic discharge summaries have the potential to reduce adverse events in the high‐risk post‐hospitalization period.1, 25 As such they may improve outpatient physicians' ability to deliver relevant care, reduce preventable readmissions26 and reduce malpractice vulnerability27all key drivers in organizational decision making.

Patient Satisfaction

Patients want to feel prepared for discharge by understanding the continuity of their care from the hospital to the outpatient setting. Discharge preparedness, commonly queried and reported in national patient satisfaction surveys, is low.28 Many electronic discharge summary platforms allow for translation into tailored patient instructions available to the patient in real time, helping to ensure that patients receive quality discharge education.29

Referring Physician Satisfaction

Poor discharge communication reduces referring physicians' satisfaction, which may discourage them from referring patients to the hospital or organization, having broader financial implications.25, 30 Even for medical centers with a busy emergency department, outpatient physician referrals and recommendations make up over 50% of an institution's admissions.31 An electronic discharge summary available in the EMR at the time of discharge, electronically transmitted to referring providers can impact the referral patterns of community physicians.

Readmission

Now publicly reported, readmission rates are another benchmark by which to judge hospital care.32 Patients with discharge summaries that are unavailable to outpatient providers, a very common occurance,2 have a higher trend toward readmission.26 Improved quality of care at the time of discharge resulting in fewer readmissions will better position hospitals to contend with potential Medicare reforms.

Quantitative Benefits

IT Infrastructure: Transcription, Deficiency Tracking, Dissemination

Hospitals, including UCSF, use internal or external transcriptionists to transcribe dictated recordings into typed text at a substantial cost to large medical centers. Medical records staff also track both discharge summary completion and their dissemination to referring providers in compliance with regulatory mandates.4, 33 The use of electronic documentation that relies on physician‐direct entry and that automates dissemination and tracking of discharge documentation provides a potential cost savings to offset the costs of a new system. UCSF Medical Center discharges 100 patients per day and could conservatively avoid almost $500,000 in transcription costs annually (Text Box 1).34

Text Box 1

UCSF Transcription costs:

Average cost/line for transcribed text: $0.17

Average Lines in a discharge summary: 80

# pts discharged/day: 100

Yearly costs = $496,400

Billing

Delays in completion of discharge summaries result in billing delays when critical information required for coding is in the discharge summary. Deferred payment on long admissions can reach tens of thousands of dollars, representing a significant strain on medical center finances. Comprehensive electronic discharge materials may simplify coding through careful documentation and improve billing efficiency through rapid completion.

At our medical center, approximately 20% of billing is delayed due to incomplete discharge documentation. For a hospital that generates over $1.4 billion dollars in billing revenue per year, this can translate into significant financial losses. Hospitals may have to borrow money or draw from existing resources to cover operative deficits created by a delay in the receipt of large payment. Lenders charge approximately 1% to 2% annual interest rate, which translates into 0.2% to 0.4% in billed costs that the hospital gives away to their lenders. Hospitals would be well served by eliminating delays in billing to improve revenue flow (Text Box 2).

Text Box 2

UCSF Annual revenue: $1.4 Billion

Billing that requires discharge summary completion: 20%

Lender's interest rate: 12%

Lenders interest rate (12%) on delayed billing (20%) = 0.20.4% of total revenue

Assuming a 14 day delay in billing: 0.20.4% of total revenue ($1,400,000,000) for 14/365 days = $107,000$215,000

Qualitative Costs

Efficiency and Physician Time

Implementation of any new system is likely to result in initial diminished efficiency. If patient volume is stable, this may not translate into loss of revenue, but rather cause staff to change their workflow. For example, given the new inefficiency in charting, staff may spend less time on direct patient care tasks (Intravenous Catheter placement, FT placement, patient education, discharge instructions), thus increasing the qualitative costs to implementing the system.

To minimize these costs, we used a step wise phased role out starting with one pilot team, with a plan to expand to multiple teams prior to implementation on the entire medicine service. This allowed for the creation of one central and several ancillary physician champions to troubleshoot the new system to help minimize productivity losses. One of the largest concerns in the switch from voice dictation to physician‐direct entry into an electronic summary is the cost of physician time. System adjustments through several pilots helped ensure that the time investment of a novice user was not significantly greater than time previously spent dictating.

Quality of Documentation