User login

Annual Meeting Mariner

It’s been one of those days. It all started at 4:30 this morning, when my 3-year-old son crawled into our bed, naked except for the diarrhea dripping down his leg. Turns out, this was his way—quite effective, I might add—of telling my wife and me that he had had an “accident.” After an hour of carrying soiled sheets to the washer, child-bathing, and Weimaraner coat-scrubbing, we relaxed to the sound of our 1-year-old daughter’s blood-curdling screams.

Upon examination, we found that the night had mysteriously transformed our precious little button-nosed bundle of joy into a tangle-haired, snot-nosed bundle of melancholy. Where her face used to be, there now hung something approximating the mask from that Scream movie. Additionally, her throat was raw, olive-sized lymph nodes populated her neck, and her nose had taken to perpetual booger-manufacturing. A rapid strep swab would later reveal the culprit, but at the moment, our differential tilted toward demonic possession.

That Dripping Feeling

Moments later, my wife and I picked 6:15 a.m. as the time to discover that we both had 7 a.m. meetings and no time to drop the kids off at daycare, especially when factoring in the 10-minute “discussion” we had about who was going to drop the kids off at daycare. All of this preceded my 7:10 a.m. arrival time for the 7 o’clock meeting with a hospital executive team to discuss our HM group funding for the next year—an encounter that left me feeling as my son must have just prior to crawling into bed with us that morning.

Now 8 a.m., I had to meet with a surgeon eager to unveil his “great idea” for our hospitalists to admit all of his patients. “It solves our problem of no interns, and allows you to play a meaningful role in the hospital!” he exclaimed.

“The meaningful role of intern?” I replied. Again, I had that dripping feeling.

It was 8:30 a.m. and I was ready to round on my patients. The first patient, a lovely woman, was stricken with un-insure-ia and a deep-seated belief that the inequitable health system that rendered her unable to get her surgery was clearly the result of some moral failing on my part. Next up was a spectacularly intoxicated male who welcomed my caring touch by belching a bit of breakfast burrito onto my cheek. Then it was a floridly bipolar patient whose apparent life mission was to drop her pants to show me her new mesh thong.

Burnout, Respect, Satisfaction

And so it continued until 1 p.m., when I had a meeting with a resident mentee of mine. It turns out that he wanted to tell me that despite his desire to be a hospitalist since his fourth year of medical school, he instead was going to apply to a rheumatology fellowship. After talking to several practicing hospitalists, he’d decided it just wasn’t for him—discussions he summarized as too much burnout, too little respect, and not enough satisfaction. Again, that dripping feeling.

Stuffing my face with a vending-machine carb-load that doubled as both breakfast and lunch, I sat down for a few minutes of e-mail. First up, a journal rejection of a research paper we’d recently submitted. Oh, the fulfillment of academics. Next were two e-mails that enzymatically trebled my “to do” list for the day. Sandwiched between those e-mails and one from a friend reminding me not to be late for a dinner that night that I was clearly going to be late for was an e-mail from a nice-appearing Nigerian man wanting to give me millions of dollars; at last, my day was turning around.

Alas, this was not the case. Checking my voicemail, I found out that my uncle was in the hospital, my dog’s lab tests were abnormal, my mom was angry about something, and I had missed a dentist appointment that morning. Finally, our group assistant came with a message that our prized hospitalist recruit had accepted a job at another institution. Drip … drip … drip…

Self-Reflection

Now 2:30 p.m., I took stock of my day and reflected on what my resident mentee had said about hospitalists. Trying to balance the rigors of patient care, academic requirements, life, friends, family, and being a boss, I was most definitely feeling a bit downtrodden, unsated, and crispy around the edges. What, exactly, did I like about this job? Was this what I wanted professionally? Would I ever find balance? Perhaps, too, a rheumatology application could salve my problems.

It was at that point that the notice for the SHM annual meeting appeared, oracle-like, on my desk. Picking it up, I realized this, not a two-year sojourn through the world of creaky joints, was the tonic to my problems.

Meeting Hierarchy

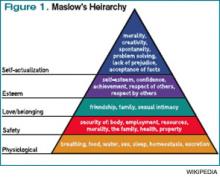

Every year since I began going to the SHM annual meeting in 2003, the meeting has helped me rejuvenate and grow. Much like Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which posits that humans develop in stages that build on each other, I’ve found stepwise growth in the annual meeting.

Before my first meeting, I had been wandering nomadically through a hospitalist job for three years, wondering what, exactly, I was doing. I was the only hospitalist in my group, had few days off, with no support system around me. I had just agreed to take a job at another institution to build a new 10-person hospitalist group and had no idea how to do this. In Maslow terms, I was trying to satisfy my “physiologic needs” to survive. I needed to find, metaphorically, “food, water, clothes, and shelter.”

I found them at the annual meeting. The practice-management pre-course taught me how to build a hospitalist group, the mentorship breakfast introduced me to a veteran I still turn to, and the educational offerings helped improve my patient-care skills. I had conquered the base of Maslow’s pyramid.

The next year, I became involved in an SHM committee, and our gathering at the annual meeting helped set the course for our group’s future endeavors. I also met up with many friends I hadn’t seen since medical school and even recruited a person to my new group. In Maslow-speak, the meeting was helping me achieve my “safety needs” by providing control, well-being, and predictability.

By the third year, I was beginning to look forward to meeting up with national colleagues I had met at prior annual meetings, fulfilling Maslow’s third-stage need of “belonging.” During the ensuing years, I presented research projects, gave talks, and helped develop and lead forums and summits, thus quenching Maslow’s “self-esteem” need.

I wonder, as I leave my office to go back to see my afternoon complement of new patients, what my ninth annual meeting will bring. I’m not sure if I’ll ever achieve Maslow’s final phase of “self-actualization,” mostly because I’m not entirely sure what that means. However, I do know this: This job can be tough. We all feel it regardless of our age, gender, or practice setting. It is easy to get knocked out of balance, to get beaten down, to lose our focus. It is at those times that we all need a mariner to right the course. To remind us why we do this, to allow us to recharge, to facilitate our growth, to fulfill our needs.

For me, that mariner is the annual meeting. I look forward to seeing you all in Dallas next month. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

It’s been one of those days. It all started at 4:30 this morning, when my 3-year-old son crawled into our bed, naked except for the diarrhea dripping down his leg. Turns out, this was his way—quite effective, I might add—of telling my wife and me that he had had an “accident.” After an hour of carrying soiled sheets to the washer, child-bathing, and Weimaraner coat-scrubbing, we relaxed to the sound of our 1-year-old daughter’s blood-curdling screams.

Upon examination, we found that the night had mysteriously transformed our precious little button-nosed bundle of joy into a tangle-haired, snot-nosed bundle of melancholy. Where her face used to be, there now hung something approximating the mask from that Scream movie. Additionally, her throat was raw, olive-sized lymph nodes populated her neck, and her nose had taken to perpetual booger-manufacturing. A rapid strep swab would later reveal the culprit, but at the moment, our differential tilted toward demonic possession.

That Dripping Feeling

Moments later, my wife and I picked 6:15 a.m. as the time to discover that we both had 7 a.m. meetings and no time to drop the kids off at daycare, especially when factoring in the 10-minute “discussion” we had about who was going to drop the kids off at daycare. All of this preceded my 7:10 a.m. arrival time for the 7 o’clock meeting with a hospital executive team to discuss our HM group funding for the next year—an encounter that left me feeling as my son must have just prior to crawling into bed with us that morning.

Now 8 a.m., I had to meet with a surgeon eager to unveil his “great idea” for our hospitalists to admit all of his patients. “It solves our problem of no interns, and allows you to play a meaningful role in the hospital!” he exclaimed.

“The meaningful role of intern?” I replied. Again, I had that dripping feeling.

It was 8:30 a.m. and I was ready to round on my patients. The first patient, a lovely woman, was stricken with un-insure-ia and a deep-seated belief that the inequitable health system that rendered her unable to get her surgery was clearly the result of some moral failing on my part. Next up was a spectacularly intoxicated male who welcomed my caring touch by belching a bit of breakfast burrito onto my cheek. Then it was a floridly bipolar patient whose apparent life mission was to drop her pants to show me her new mesh thong.

Burnout, Respect, Satisfaction

And so it continued until 1 p.m., when I had a meeting with a resident mentee of mine. It turns out that he wanted to tell me that despite his desire to be a hospitalist since his fourth year of medical school, he instead was going to apply to a rheumatology fellowship. After talking to several practicing hospitalists, he’d decided it just wasn’t for him—discussions he summarized as too much burnout, too little respect, and not enough satisfaction. Again, that dripping feeling.

Stuffing my face with a vending-machine carb-load that doubled as both breakfast and lunch, I sat down for a few minutes of e-mail. First up, a journal rejection of a research paper we’d recently submitted. Oh, the fulfillment of academics. Next were two e-mails that enzymatically trebled my “to do” list for the day. Sandwiched between those e-mails and one from a friend reminding me not to be late for a dinner that night that I was clearly going to be late for was an e-mail from a nice-appearing Nigerian man wanting to give me millions of dollars; at last, my day was turning around.

Alas, this was not the case. Checking my voicemail, I found out that my uncle was in the hospital, my dog’s lab tests were abnormal, my mom was angry about something, and I had missed a dentist appointment that morning. Finally, our group assistant came with a message that our prized hospitalist recruit had accepted a job at another institution. Drip … drip … drip…

Self-Reflection

Now 2:30 p.m., I took stock of my day and reflected on what my resident mentee had said about hospitalists. Trying to balance the rigors of patient care, academic requirements, life, friends, family, and being a boss, I was most definitely feeling a bit downtrodden, unsated, and crispy around the edges. What, exactly, did I like about this job? Was this what I wanted professionally? Would I ever find balance? Perhaps, too, a rheumatology application could salve my problems.

It was at that point that the notice for the SHM annual meeting appeared, oracle-like, on my desk. Picking it up, I realized this, not a two-year sojourn through the world of creaky joints, was the tonic to my problems.

Meeting Hierarchy

Every year since I began going to the SHM annual meeting in 2003, the meeting has helped me rejuvenate and grow. Much like Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which posits that humans develop in stages that build on each other, I’ve found stepwise growth in the annual meeting.

Before my first meeting, I had been wandering nomadically through a hospitalist job for three years, wondering what, exactly, I was doing. I was the only hospitalist in my group, had few days off, with no support system around me. I had just agreed to take a job at another institution to build a new 10-person hospitalist group and had no idea how to do this. In Maslow terms, I was trying to satisfy my “physiologic needs” to survive. I needed to find, metaphorically, “food, water, clothes, and shelter.”

I found them at the annual meeting. The practice-management pre-course taught me how to build a hospitalist group, the mentorship breakfast introduced me to a veteran I still turn to, and the educational offerings helped improve my patient-care skills. I had conquered the base of Maslow’s pyramid.

The next year, I became involved in an SHM committee, and our gathering at the annual meeting helped set the course for our group’s future endeavors. I also met up with many friends I hadn’t seen since medical school and even recruited a person to my new group. In Maslow-speak, the meeting was helping me achieve my “safety needs” by providing control, well-being, and predictability.

By the third year, I was beginning to look forward to meeting up with national colleagues I had met at prior annual meetings, fulfilling Maslow’s third-stage need of “belonging.” During the ensuing years, I presented research projects, gave talks, and helped develop and lead forums and summits, thus quenching Maslow’s “self-esteem” need.

I wonder, as I leave my office to go back to see my afternoon complement of new patients, what my ninth annual meeting will bring. I’m not sure if I’ll ever achieve Maslow’s final phase of “self-actualization,” mostly because I’m not entirely sure what that means. However, I do know this: This job can be tough. We all feel it regardless of our age, gender, or practice setting. It is easy to get knocked out of balance, to get beaten down, to lose our focus. It is at those times that we all need a mariner to right the course. To remind us why we do this, to allow us to recharge, to facilitate our growth, to fulfill our needs.

For me, that mariner is the annual meeting. I look forward to seeing you all in Dallas next month. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

It’s been one of those days. It all started at 4:30 this morning, when my 3-year-old son crawled into our bed, naked except for the diarrhea dripping down his leg. Turns out, this was his way—quite effective, I might add—of telling my wife and me that he had had an “accident.” After an hour of carrying soiled sheets to the washer, child-bathing, and Weimaraner coat-scrubbing, we relaxed to the sound of our 1-year-old daughter’s blood-curdling screams.

Upon examination, we found that the night had mysteriously transformed our precious little button-nosed bundle of joy into a tangle-haired, snot-nosed bundle of melancholy. Where her face used to be, there now hung something approximating the mask from that Scream movie. Additionally, her throat was raw, olive-sized lymph nodes populated her neck, and her nose had taken to perpetual booger-manufacturing. A rapid strep swab would later reveal the culprit, but at the moment, our differential tilted toward demonic possession.

That Dripping Feeling

Moments later, my wife and I picked 6:15 a.m. as the time to discover that we both had 7 a.m. meetings and no time to drop the kids off at daycare, especially when factoring in the 10-minute “discussion” we had about who was going to drop the kids off at daycare. All of this preceded my 7:10 a.m. arrival time for the 7 o’clock meeting with a hospital executive team to discuss our HM group funding for the next year—an encounter that left me feeling as my son must have just prior to crawling into bed with us that morning.

Now 8 a.m., I had to meet with a surgeon eager to unveil his “great idea” for our hospitalists to admit all of his patients. “It solves our problem of no interns, and allows you to play a meaningful role in the hospital!” he exclaimed.

“The meaningful role of intern?” I replied. Again, I had that dripping feeling.

It was 8:30 a.m. and I was ready to round on my patients. The first patient, a lovely woman, was stricken with un-insure-ia and a deep-seated belief that the inequitable health system that rendered her unable to get her surgery was clearly the result of some moral failing on my part. Next up was a spectacularly intoxicated male who welcomed my caring touch by belching a bit of breakfast burrito onto my cheek. Then it was a floridly bipolar patient whose apparent life mission was to drop her pants to show me her new mesh thong.

Burnout, Respect, Satisfaction

And so it continued until 1 p.m., when I had a meeting with a resident mentee of mine. It turns out that he wanted to tell me that despite his desire to be a hospitalist since his fourth year of medical school, he instead was going to apply to a rheumatology fellowship. After talking to several practicing hospitalists, he’d decided it just wasn’t for him—discussions he summarized as too much burnout, too little respect, and not enough satisfaction. Again, that dripping feeling.

Stuffing my face with a vending-machine carb-load that doubled as both breakfast and lunch, I sat down for a few minutes of e-mail. First up, a journal rejection of a research paper we’d recently submitted. Oh, the fulfillment of academics. Next were two e-mails that enzymatically trebled my “to do” list for the day. Sandwiched between those e-mails and one from a friend reminding me not to be late for a dinner that night that I was clearly going to be late for was an e-mail from a nice-appearing Nigerian man wanting to give me millions of dollars; at last, my day was turning around.

Alas, this was not the case. Checking my voicemail, I found out that my uncle was in the hospital, my dog’s lab tests were abnormal, my mom was angry about something, and I had missed a dentist appointment that morning. Finally, our group assistant came with a message that our prized hospitalist recruit had accepted a job at another institution. Drip … drip … drip…

Self-Reflection

Now 2:30 p.m., I took stock of my day and reflected on what my resident mentee had said about hospitalists. Trying to balance the rigors of patient care, academic requirements, life, friends, family, and being a boss, I was most definitely feeling a bit downtrodden, unsated, and crispy around the edges. What, exactly, did I like about this job? Was this what I wanted professionally? Would I ever find balance? Perhaps, too, a rheumatology application could salve my problems.

It was at that point that the notice for the SHM annual meeting appeared, oracle-like, on my desk. Picking it up, I realized this, not a two-year sojourn through the world of creaky joints, was the tonic to my problems.

Meeting Hierarchy

Every year since I began going to the SHM annual meeting in 2003, the meeting has helped me rejuvenate and grow. Much like Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which posits that humans develop in stages that build on each other, I’ve found stepwise growth in the annual meeting.

Before my first meeting, I had been wandering nomadically through a hospitalist job for three years, wondering what, exactly, I was doing. I was the only hospitalist in my group, had few days off, with no support system around me. I had just agreed to take a job at another institution to build a new 10-person hospitalist group and had no idea how to do this. In Maslow terms, I was trying to satisfy my “physiologic needs” to survive. I needed to find, metaphorically, “food, water, clothes, and shelter.”

I found them at the annual meeting. The practice-management pre-course taught me how to build a hospitalist group, the mentorship breakfast introduced me to a veteran I still turn to, and the educational offerings helped improve my patient-care skills. I had conquered the base of Maslow’s pyramid.

The next year, I became involved in an SHM committee, and our gathering at the annual meeting helped set the course for our group’s future endeavors. I also met up with many friends I hadn’t seen since medical school and even recruited a person to my new group. In Maslow-speak, the meeting was helping me achieve my “safety needs” by providing control, well-being, and predictability.

By the third year, I was beginning to look forward to meeting up with national colleagues I had met at prior annual meetings, fulfilling Maslow’s third-stage need of “belonging.” During the ensuing years, I presented research projects, gave talks, and helped develop and lead forums and summits, thus quenching Maslow’s “self-esteem” need.

I wonder, as I leave my office to go back to see my afternoon complement of new patients, what my ninth annual meeting will bring. I’m not sure if I’ll ever achieve Maslow’s final phase of “self-actualization,” mostly because I’m not entirely sure what that means. However, I do know this: This job can be tough. We all feel it regardless of our age, gender, or practice setting. It is easy to get knocked out of balance, to get beaten down, to lose our focus. It is at those times that we all need a mariner to right the course. To remind us why we do this, to allow us to recharge, to facilitate our growth, to fulfill our needs.

For me, that mariner is the annual meeting. I look forward to seeing you all in Dallas next month. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

The To-Don’t List

Last month, I wrote about the attributes of hospitalist practices that I associate with success. This month, I’ll do the opposite. That is, I’ll write about strategies your practice could, or even should, do without. Of course, all of these things are open to debate, and some thoughtful people might (and in my experience, probably will) arrive at different conclusions.

So I offer my list as food for thought, and if your practice relies on some of these strategies, you shouldn’t feel threatened by my opinion. But you might want to think about whether they’ve been made part of your practice by design, or if things just evolved this way without careful consideration of alternatives. I’ve listed them in no particular order.

Fixed-duration day shifts. My sense is that the majority of practices have a day shift with a predetermined start and end. That is, the hospitalist is expected to arrive and depart at the same time each day.

This seems to make a lot of sense, but it ignores the dramatic variations in workload a practice will have. For example, a practice that is appropriately staffed with four daytime hospitalists, and schedules each of them to work a 12-hour shift, provides 48 hours of daytime hospitalist manpower each day. But that will turn out to be precisely the right level of staffing only a few days a year. On all other days, daytime staffing will be optimal with a different number of hours. So it would make sense for the doctors to work more or less on those days.

Telling doctors that their shift always starts at the same time has significant lifestyle advantages. But it can inhibit the doctors who would be happy to start earlier to address more discharges early in the day and potentially go home earlier. So, just like most other doctors at your hospital have, why not let the doctors have significant latitude in when they start and stop working each day? In most cases, it might be necessary to have a time by which every doctor must be available to respond to pages (and one who must be on-site before the night doctor leaves), but they should feel free to actually arrive and start working when they choose. Most will make good choices and will likely feel a little more empowered and happy with their work.

And, at the end of the day, it might be reasonable to allow some of the day-shift doctors to leave when their work is done, and allow the others to stay to handle admissions until the night shift takes over. Those who leave early might still be required to respond to pages until a specified time.

Shifts that don’t involve rounding on “continuity” patients, such as night and evening (“swing”) shifts, usually should be arranged with predetermined start. I wrote in more detail on this topic in January 2007 and October 2010.

Contractual vacation provisions. Hospitalists should have significant amounts of time off. We work a lot of evenings, nights, and weekends, and we must have liberal amounts of time away from work. But for many practices, there is no advantage in classifying this time as vacation (or CME, etc.) time. In most cases, it makes the most sense to simply specify how much work (e.g. number of shifts) a doctor is to do each year and not specify a number of days or hours of vacation time. For more detail, read “The Vacation Conundrum” from March 2007.

If your practice has a vacation system that works well, then stick with it. But if you or your administrators are going nuts trying to categorize nonworking days between vacation and days the doctor simply wasn’t scheduled, then it might be best to stop trying. Just settle on the number of shifts (or some other metric) that a doctor is to work each year.

Tenure-based salary increases. It makes a lot of sense to pay doctors in most specialties an increasing salary based on his or her tenure with the practice. As they build a patient population and a referral stream, they generate more revenue and should benefit accordingly. But a new hospitalist who joins an existing group almost never has to build the referrals. In most cases, the group hired the doctor because the referrals are already coming and the practice needs more help, or the new doctor is replacing a departing one. So paying a new hospitalist a lower salary that increases automatically every few years isn’t really a raise earned by the doctor’s improved financial performance. Usually it’s just a system of withholding money that could be available for compensation for the doctor’s first few years in the practice. This lower starting salary might adversely impact recruiting. For more, see “Compensation Conundrum” from December 2009.

Poor roles for nonphysician providers (NPPs). I’ve worked with a lot of practices that have NPs and PAs (and, in some cases, RNs) who are doing what amounts to clerical work. They’re faxing discharge summaries, making calls to schedule patient appointments, dividing up the overnight admissions for the day rounders, etc.

Don’t make this mistake. Hire a secretary for that sort of work. And be sure that the roles occupied by trained clinicians (PAs, NPs, RNs, etc.) are professionally satisfying and will position them to make an effective contribution to the practice.

For more on this topic, see “The 411 on NPPs” from September 2008 and “Role Refinement” from September 2009; the latter features the perspective of Ryan Genzink, a thoughtful PA-C from Michigan.

Blinded performance reporting. First, make sure your practice provides regular, meaningful reports on each doctor’s performance and the group as a whole. This usually takes the form of a dashboard or report card. In my experience, too few practices do this. Make sure your group isn’t in that category.

Groups that do provide performance data often allow each doctor to see only his or her data. If data about other individuals in the group are provided, the names have often been removed. With exception of certain human resources issues (e.g. counseling a doctor to prevent termination), I think all performance data in the group should be shared by name with the whole group. In most practices, everyone should know by name which doctors are the high and low producers, each doctor’s compensation, and CPT coding practices (e.g. the portion of discharges coded at the high level).

When clinical performance can be attributed to individual providers, report those metrics openly, too. This usually creates greater cohesion within the group and helps foster a mentality of practice ownership. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm (www.nelsonflores.com). He is course co-director and faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program.” This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Last month, I wrote about the attributes of hospitalist practices that I associate with success. This month, I’ll do the opposite. That is, I’ll write about strategies your practice could, or even should, do without. Of course, all of these things are open to debate, and some thoughtful people might (and in my experience, probably will) arrive at different conclusions.

So I offer my list as food for thought, and if your practice relies on some of these strategies, you shouldn’t feel threatened by my opinion. But you might want to think about whether they’ve been made part of your practice by design, or if things just evolved this way without careful consideration of alternatives. I’ve listed them in no particular order.

Fixed-duration day shifts. My sense is that the majority of practices have a day shift with a predetermined start and end. That is, the hospitalist is expected to arrive and depart at the same time each day.

This seems to make a lot of sense, but it ignores the dramatic variations in workload a practice will have. For example, a practice that is appropriately staffed with four daytime hospitalists, and schedules each of them to work a 12-hour shift, provides 48 hours of daytime hospitalist manpower each day. But that will turn out to be precisely the right level of staffing only a few days a year. On all other days, daytime staffing will be optimal with a different number of hours. So it would make sense for the doctors to work more or less on those days.

Telling doctors that their shift always starts at the same time has significant lifestyle advantages. But it can inhibit the doctors who would be happy to start earlier to address more discharges early in the day and potentially go home earlier. So, just like most other doctors at your hospital have, why not let the doctors have significant latitude in when they start and stop working each day? In most cases, it might be necessary to have a time by which every doctor must be available to respond to pages (and one who must be on-site before the night doctor leaves), but they should feel free to actually arrive and start working when they choose. Most will make good choices and will likely feel a little more empowered and happy with their work.

And, at the end of the day, it might be reasonable to allow some of the day-shift doctors to leave when their work is done, and allow the others to stay to handle admissions until the night shift takes over. Those who leave early might still be required to respond to pages until a specified time.

Shifts that don’t involve rounding on “continuity” patients, such as night and evening (“swing”) shifts, usually should be arranged with predetermined start. I wrote in more detail on this topic in January 2007 and October 2010.

Contractual vacation provisions. Hospitalists should have significant amounts of time off. We work a lot of evenings, nights, and weekends, and we must have liberal amounts of time away from work. But for many practices, there is no advantage in classifying this time as vacation (or CME, etc.) time. In most cases, it makes the most sense to simply specify how much work (e.g. number of shifts) a doctor is to do each year and not specify a number of days or hours of vacation time. For more detail, read “The Vacation Conundrum” from March 2007.

If your practice has a vacation system that works well, then stick with it. But if you or your administrators are going nuts trying to categorize nonworking days between vacation and days the doctor simply wasn’t scheduled, then it might be best to stop trying. Just settle on the number of shifts (or some other metric) that a doctor is to work each year.

Tenure-based salary increases. It makes a lot of sense to pay doctors in most specialties an increasing salary based on his or her tenure with the practice. As they build a patient population and a referral stream, they generate more revenue and should benefit accordingly. But a new hospitalist who joins an existing group almost never has to build the referrals. In most cases, the group hired the doctor because the referrals are already coming and the practice needs more help, or the new doctor is replacing a departing one. So paying a new hospitalist a lower salary that increases automatically every few years isn’t really a raise earned by the doctor’s improved financial performance. Usually it’s just a system of withholding money that could be available for compensation for the doctor’s first few years in the practice. This lower starting salary might adversely impact recruiting. For more, see “Compensation Conundrum” from December 2009.

Poor roles for nonphysician providers (NPPs). I’ve worked with a lot of practices that have NPs and PAs (and, in some cases, RNs) who are doing what amounts to clerical work. They’re faxing discharge summaries, making calls to schedule patient appointments, dividing up the overnight admissions for the day rounders, etc.

Don’t make this mistake. Hire a secretary for that sort of work. And be sure that the roles occupied by trained clinicians (PAs, NPs, RNs, etc.) are professionally satisfying and will position them to make an effective contribution to the practice.

For more on this topic, see “The 411 on NPPs” from September 2008 and “Role Refinement” from September 2009; the latter features the perspective of Ryan Genzink, a thoughtful PA-C from Michigan.

Blinded performance reporting. First, make sure your practice provides regular, meaningful reports on each doctor’s performance and the group as a whole. This usually takes the form of a dashboard or report card. In my experience, too few practices do this. Make sure your group isn’t in that category.

Groups that do provide performance data often allow each doctor to see only his or her data. If data about other individuals in the group are provided, the names have often been removed. With exception of certain human resources issues (e.g. counseling a doctor to prevent termination), I think all performance data in the group should be shared by name with the whole group. In most practices, everyone should know by name which doctors are the high and low producers, each doctor’s compensation, and CPT coding practices (e.g. the portion of discharges coded at the high level).

When clinical performance can be attributed to individual providers, report those metrics openly, too. This usually creates greater cohesion within the group and helps foster a mentality of practice ownership. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm (www.nelsonflores.com). He is course co-director and faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program.” This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Last month, I wrote about the attributes of hospitalist practices that I associate with success. This month, I’ll do the opposite. That is, I’ll write about strategies your practice could, or even should, do without. Of course, all of these things are open to debate, and some thoughtful people might (and in my experience, probably will) arrive at different conclusions.

So I offer my list as food for thought, and if your practice relies on some of these strategies, you shouldn’t feel threatened by my opinion. But you might want to think about whether they’ve been made part of your practice by design, or if things just evolved this way without careful consideration of alternatives. I’ve listed them in no particular order.

Fixed-duration day shifts. My sense is that the majority of practices have a day shift with a predetermined start and end. That is, the hospitalist is expected to arrive and depart at the same time each day.

This seems to make a lot of sense, but it ignores the dramatic variations in workload a practice will have. For example, a practice that is appropriately staffed with four daytime hospitalists, and schedules each of them to work a 12-hour shift, provides 48 hours of daytime hospitalist manpower each day. But that will turn out to be precisely the right level of staffing only a few days a year. On all other days, daytime staffing will be optimal with a different number of hours. So it would make sense for the doctors to work more or less on those days.

Telling doctors that their shift always starts at the same time has significant lifestyle advantages. But it can inhibit the doctors who would be happy to start earlier to address more discharges early in the day and potentially go home earlier. So, just like most other doctors at your hospital have, why not let the doctors have significant latitude in when they start and stop working each day? In most cases, it might be necessary to have a time by which every doctor must be available to respond to pages (and one who must be on-site before the night doctor leaves), but they should feel free to actually arrive and start working when they choose. Most will make good choices and will likely feel a little more empowered and happy with their work.

And, at the end of the day, it might be reasonable to allow some of the day-shift doctors to leave when their work is done, and allow the others to stay to handle admissions until the night shift takes over. Those who leave early might still be required to respond to pages until a specified time.

Shifts that don’t involve rounding on “continuity” patients, such as night and evening (“swing”) shifts, usually should be arranged with predetermined start. I wrote in more detail on this topic in January 2007 and October 2010.

Contractual vacation provisions. Hospitalists should have significant amounts of time off. We work a lot of evenings, nights, and weekends, and we must have liberal amounts of time away from work. But for many practices, there is no advantage in classifying this time as vacation (or CME, etc.) time. In most cases, it makes the most sense to simply specify how much work (e.g. number of shifts) a doctor is to do each year and not specify a number of days or hours of vacation time. For more detail, read “The Vacation Conundrum” from March 2007.

If your practice has a vacation system that works well, then stick with it. But if you or your administrators are going nuts trying to categorize nonworking days between vacation and days the doctor simply wasn’t scheduled, then it might be best to stop trying. Just settle on the number of shifts (or some other metric) that a doctor is to work each year.

Tenure-based salary increases. It makes a lot of sense to pay doctors in most specialties an increasing salary based on his or her tenure with the practice. As they build a patient population and a referral stream, they generate more revenue and should benefit accordingly. But a new hospitalist who joins an existing group almost never has to build the referrals. In most cases, the group hired the doctor because the referrals are already coming and the practice needs more help, or the new doctor is replacing a departing one. So paying a new hospitalist a lower salary that increases automatically every few years isn’t really a raise earned by the doctor’s improved financial performance. Usually it’s just a system of withholding money that could be available for compensation for the doctor’s first few years in the practice. This lower starting salary might adversely impact recruiting. For more, see “Compensation Conundrum” from December 2009.

Poor roles for nonphysician providers (NPPs). I’ve worked with a lot of practices that have NPs and PAs (and, in some cases, RNs) who are doing what amounts to clerical work. They’re faxing discharge summaries, making calls to schedule patient appointments, dividing up the overnight admissions for the day rounders, etc.

Don’t make this mistake. Hire a secretary for that sort of work. And be sure that the roles occupied by trained clinicians (PAs, NPs, RNs, etc.) are professionally satisfying and will position them to make an effective contribution to the practice.

For more on this topic, see “The 411 on NPPs” from September 2008 and “Role Refinement” from September 2009; the latter features the perspective of Ryan Genzink, a thoughtful PA-C from Michigan.

Blinded performance reporting. First, make sure your practice provides regular, meaningful reports on each doctor’s performance and the group as a whole. This usually takes the form of a dashboard or report card. In my experience, too few practices do this. Make sure your group isn’t in that category.

Groups that do provide performance data often allow each doctor to see only his or her data. If data about other individuals in the group are provided, the names have often been removed. With exception of certain human resources issues (e.g. counseling a doctor to prevent termination), I think all performance data in the group should be shared by name with the whole group. In most practices, everyone should know by name which doctors are the high and low producers, each doctor’s compensation, and CPT coding practices (e.g. the portion of discharges coded at the high level).

When clinical performance can be attributed to individual providers, report those metrics openly, too. This usually creates greater cohesion within the group and helps foster a mentality of practice ownership. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm (www.nelsonflores.com). He is course co-director and faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program.” This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

FDA Mandates Enrollment for Erythropoesis Stimulating Agents

I heard from my hospital’s pharmacist director that soon I will not be able to prescribe Epogen unless I get some additional certification. Is this true? Can you explain what is going on?

Ritesh Magge, MD,

Detroit

Dr. Hospitalist responds: Your pharmacist is referring to the new FDA-mandated requirements, which went into effect in February, that will affect who can prescribe erythropoesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), including epoetin (Epogen, Procrit) and darbepoetin (Aranesp). This is part of a broader FDA strategy to improve patient safety as it relates to medications.

According to the FDA website, “The Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 gave FDA the authority to require a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) from manufacturers to ensure that the benefits of a drug or biological product outweigh its risks.”

The ESAs are not the only class of drug that will require a REM. More than 150 drugs already have varying requirements. For a complete list of these medications, please visit the FDA website (www.fda.gov) and search “drug safety.” The FDA plans to create additional REMs for additional drugs and biologic agents.

If you are a provider who will prescribe a medication with a REM, you will be obligated to adhere to the FDA REM associated with that medication. The drug manufacturers are working with the FDA to set up REMs for their drugs. For example, if you plan to prescribe an ESA for a patient with cancer, you will first need to enroll in the ESA APPRISE (Assisting Providers and Cancer Patients with Risk Information for the Safe Use of ESAs) Oncology Program, which was established by ESA drug manufacturers. Once enrolled in the program, you will be assigned a unique ESA APPRISE ID number. ESA prescribers will be required to provide and review the ESA Medication Guide and counsel each patient on the risks and benefits of ESAs before each course of therapy. This counseling must be done no more than every 30 days after the first dose. (At the same time, prescribing ESAs to non-cancer patients basically only entails patient education.)

Providers also will be required to fill out the ESA APPRISE Oncology Program Patient and Healthcare Professional Acknowledgment form, which documents that the risk-benefit discussion occurred. This form is in triplicate and includes both the patient and the provider signature. One copy is given to the patient, another copy placed in the chart, and the third copy is stored for potential future audit.

For more information about the ESA APPRISE Oncology Program, please visit www.esaapprise.com/ESAAppriseUI/ESAAppriseUI/default.jsp. TH

I heard from my hospital’s pharmacist director that soon I will not be able to prescribe Epogen unless I get some additional certification. Is this true? Can you explain what is going on?

Ritesh Magge, MD,

Detroit

Dr. Hospitalist responds: Your pharmacist is referring to the new FDA-mandated requirements, which went into effect in February, that will affect who can prescribe erythropoesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), including epoetin (Epogen, Procrit) and darbepoetin (Aranesp). This is part of a broader FDA strategy to improve patient safety as it relates to medications.

According to the FDA website, “The Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 gave FDA the authority to require a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) from manufacturers to ensure that the benefits of a drug or biological product outweigh its risks.”

The ESAs are not the only class of drug that will require a REM. More than 150 drugs already have varying requirements. For a complete list of these medications, please visit the FDA website (www.fda.gov) and search “drug safety.” The FDA plans to create additional REMs for additional drugs and biologic agents.

If you are a provider who will prescribe a medication with a REM, you will be obligated to adhere to the FDA REM associated with that medication. The drug manufacturers are working with the FDA to set up REMs for their drugs. For example, if you plan to prescribe an ESA for a patient with cancer, you will first need to enroll in the ESA APPRISE (Assisting Providers and Cancer Patients with Risk Information for the Safe Use of ESAs) Oncology Program, which was established by ESA drug manufacturers. Once enrolled in the program, you will be assigned a unique ESA APPRISE ID number. ESA prescribers will be required to provide and review the ESA Medication Guide and counsel each patient on the risks and benefits of ESAs before each course of therapy. This counseling must be done no more than every 30 days after the first dose. (At the same time, prescribing ESAs to non-cancer patients basically only entails patient education.)

Providers also will be required to fill out the ESA APPRISE Oncology Program Patient and Healthcare Professional Acknowledgment form, which documents that the risk-benefit discussion occurred. This form is in triplicate and includes both the patient and the provider signature. One copy is given to the patient, another copy placed in the chart, and the third copy is stored for potential future audit.

For more information about the ESA APPRISE Oncology Program, please visit www.esaapprise.com/ESAAppriseUI/ESAAppriseUI/default.jsp. TH

I heard from my hospital’s pharmacist director that soon I will not be able to prescribe Epogen unless I get some additional certification. Is this true? Can you explain what is going on?

Ritesh Magge, MD,

Detroit

Dr. Hospitalist responds: Your pharmacist is referring to the new FDA-mandated requirements, which went into effect in February, that will affect who can prescribe erythropoesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), including epoetin (Epogen, Procrit) and darbepoetin (Aranesp). This is part of a broader FDA strategy to improve patient safety as it relates to medications.

According to the FDA website, “The Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 gave FDA the authority to require a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) from manufacturers to ensure that the benefits of a drug or biological product outweigh its risks.”

The ESAs are not the only class of drug that will require a REM. More than 150 drugs already have varying requirements. For a complete list of these medications, please visit the FDA website (www.fda.gov) and search “drug safety.” The FDA plans to create additional REMs for additional drugs and biologic agents.

If you are a provider who will prescribe a medication with a REM, you will be obligated to adhere to the FDA REM associated with that medication. The drug manufacturers are working with the FDA to set up REMs for their drugs. For example, if you plan to prescribe an ESA for a patient with cancer, you will first need to enroll in the ESA APPRISE (Assisting Providers and Cancer Patients with Risk Information for the Safe Use of ESAs) Oncology Program, which was established by ESA drug manufacturers. Once enrolled in the program, you will be assigned a unique ESA APPRISE ID number. ESA prescribers will be required to provide and review the ESA Medication Guide and counsel each patient on the risks and benefits of ESAs before each course of therapy. This counseling must be done no more than every 30 days after the first dose. (At the same time, prescribing ESAs to non-cancer patients basically only entails patient education.)

Providers also will be required to fill out the ESA APPRISE Oncology Program Patient and Healthcare Professional Acknowledgment form, which documents that the risk-benefit discussion occurred. This form is in triplicate and includes both the patient and the provider signature. One copy is given to the patient, another copy placed in the chart, and the third copy is stored for potential future audit.

For more information about the ESA APPRISE Oncology Program, please visit www.esaapprise.com/ESAAppriseUI/ESAAppriseUI/default.jsp. TH

Emerging research on biomarkers that may help clarify diagnosis

Improving Medication Adherence in Chronic Disease Management

The magnitude of medication nonadherence and the consequent negative health impact are great and should create a sense of urgency among clinicians to address this serious problem.

The magnitude of medication nonadherence and the consequent negative health impact are great and should create a sense of urgency among clinicians to address this serious problem.

The magnitude of medication nonadherence and the consequent negative health impact are great and should create a sense of urgency among clinicians to address this serious problem.

Giant cell arteritis: Suspect it, treat it promptly

Giant cell arteritis is the most common primary systemic vasculitis. The disease occurs almost exclusively in people over age 50, with an annual incidence of 15 to 25 per 100,000.1 Incidence rates vary significantly depending on ethnicity. The highest rates are in whites, particularly those of North European descent.2 Incidence rates progressively increase after age 50. The disease is more prevalent in women. Its cause is unknown; both genetic and environmental factors are thought to play a role.

INFLAMED ARTERIES

Giant cell arteritis is characterized by a granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate affecting large and medium-size arteries. Not all vessels are equally affected: the most susceptible are the cranial arteries, the aorta, and the aorta’s primary branches, particularly those in the upper extremities.

The disease is usually associated with an intense acute-phase response. Vessel wall inflammation results in intimal hyperplasia, luminal occlusion, and tissue ischemia. Typical histologic features include a mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate primarily composed of CD4+ T cells and activated macrophages. Multinucleated giant cells are seen in only about 50% of positive biopsies; therefore, their presence is not essential for the diagnosis.3

FOUR MAIN PHENOTYPES

Some of the possible symptoms of giant cell arteritis readily point to the correct diagnosis, eg, those due to cranial artery involvement, such as temporal headache, claudication of masticatory muscles, and visual changes. However, the clinical presentation can be quite varied.

There are four predominant clinical phenotypes, which may be present at the onset of disease or appear later as the disease progresses. Although they will be described separately in this review, these clinical presentations often overlap.

Cranial arteritis

Cranial arteritis is the clinical presentation most readily associated with giant cell arteritis. Clinical features result from involvement of branches of the external or internal carotid artery.

Headache, the most frequent symptom, is typically but not exclusively localized to the temporal areas.

Visual loss is due to involvement of the branches of the ophthalmic or posterior ciliary arteries, resulting in ischemia of the optic nerve or its tracts. It occurs in up to 20% of patients.4,5

Other symptoms and complications from cranial arteritis include tenderness of the scalp and temporal areas, claudication of the tongue or jaw muscles, stroke, and more rarely, tongue infarction.

Polymyalgia rheumatica

Polymyalgia rheumatica is a clinical syndrome that can occur by itself or in conjunction with giant cell arteritis. It may occur independently of giant cell arteritis, but also occurs in about 40% of patients with giant cell arteritis. It may precede, develop simultaneously with, or develop later during the course of the giant cell arteritis.6,7 It is a common clinical manifestation in relapses of giant cell arteritis, even in those who did not have symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica at the time giant cell arteritis was diagnosed.

Polymyalgia rheumatica is characterized by aching of the shoulder and hip girdle, with morning stiffness. Fatigue and malaise are often present and may be severe. Some patients with polymyalgia rheumatica may also present with peripheral joint synovitis, which may be mistakenly diagnosed as rheumatoid arthritis.8 Muscle weakness and elevated muscle enzymes are not associated with polymyalgia rheumatica.

Polymyalgia rheumatica is a clinical diagnosis. Approximately 80% of patients with polymyalgia rheumatica have an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate or an elevated C-reactive protein level.9 When it occurs in the absence of giant cell arteritis, it is treated differently, with less intense doses of corticosteroids. All patients with polymyalgia rheumatica should be routinely questioned regarding symptoms of giant cell arteritis.

Nonspecific systemic inflammatory disease

Some patients with giant cell arteritis may present with a nonspecific systemic inflammatory disease characterized by some combination of fever, night sweats, fatigue, malaise, and weight loss. In these patients, the diagnosis may be delayed by the lack of localizing symptoms.

Laboratory tests typically show anemia, leukocytosis, and thrombocytosis. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and the C-reactive protein level are usually very high.

Giant cell arteritis should be in the differential diagnosis when these signs and symptoms are found in patients over age 50.

Large-vessel vasculitis

Although thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection have been described as late complications of giant cell arteritis, large-vessel vasculitis may precede or occur concomitantly with cranial arteritis early in the disease.10,11

Population-based surveys have shown that large-vessel vasculitis is extremely frequent in patients with giant cell arteritis. In a postmortem study of 11 patients with giant cell arteritis, all of them had evidence of arteritis involving the subclavian artery, the carotid artery, and the aorta.12

Patients may have no symptoms or may present with symptoms or signs of tissue ischemia such as claudication of the extremities, carotid artery tenderness, decreased or absent pulses, and large-vessel bruits on physical examination.

CONSIDER THE DIAGNOSIS IN OLDER PATIENTS

Giant cell arteritis should always be considered in patients over age 50 who have any of the clinical features described above. It is therefore very important to be familiar with its symptoms and signs.

A complete and detailed history and a detailed but focused physical examination that includes a comprehensive vascular examination are the first and most important steps in establishing the diagnosis. The vascular examination includes measuring the blood pressure in all four extremities, palpating the peripheral pulses, listening for bruits, and palpating the temporal arteries.

Temporal artery biopsy: The gold standard

Confirming the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis requires histologic findings of inflammation in the temporal artery. Superficial temporal artery biopsy is recommended for diagnostic confirmation in patients who have cranial symptoms and other signs suggesting the disease.

The biopsy should be performed on the same side as the symptoms or abnormal findings on examination. Performing a biopsy in both temporal arteries may increase the diagnostic yield but may not need to be done routinely.13

Although some experts recommend temporal artery biopsy in all patients in whom giant cell arteritis is suspected, biopsy has a lower diagnostic yield in patients who have no cranial symptoms. Interestingly, 5% to 15% of temporal artery biopsies performed in patients who had isolated polymyalgia rheumatica were found to be positive.14,15 Patients with polymyalgia rheumatica and no clinical symptoms to suggest giant cell arteritis generally are not biopsied.

The segmental nature of the inflammation involving the temporal artery in giant cell arteritis may result in negative biopsy results in patients with giant cell arteritis. A temporal artery biopsy length of 5 mm or less has a very low (8%) rate of positive results, whereas a length longer than 20 mm exceeds a 50% rate of positive results. Although the optimal length of a temporal artery specimen is still debated, a longer biopsy specimen should be obtained to increase the chance of arterial specimens showing inflammatory changes.16,17

Laboratory studies: Acute-phase reactants may be elevated

High levels of acute-phase reactants should increase one’s suspicion of giant cell arteritis. Elevations in the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein and interleukin 6 levels reflect the inflammatory process in this disease.19 However, not all patients with giant cell arteritis have a high sedimentation rate, and as many as 20% of patients with biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis have a normal sedimentation rate before therapy.20 Therefore, a normal sedimentation rate does not exclude the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis and should not delay its diagnosis and treatment.

As a result of systemic inflammation, the patient may also present with normochromic normocytic anemia, leukocytosis, and thrombocytosis.

Imaging studies are controversial

Imaging studies are potentially useful diagnostic tools in large-vessel vasculitis but are still the subject of significant controversy.

Ultrasonography of the temporal artery has been a controversial subject in many studies.21,22 Color duplex ultrasonography of the temporal artery has been reported to be helpful in the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis (showing a “halo” around the arterial lumen), but further studies are needed to establish its clinical utility.

At this time, temporal artery biopsy remains the gold standard diagnostic test for giant cell arteritis, and ultrasonography is neither a substitute for biopsy nor a screening test for this disease.23 Some have suggested, however, that ultrasonography may help to identify the best site for biopsy of the temporal artery in some patients.

Arteriography is an accurate technique for evaluating the vessel lumen and allows for measuring central blood pressure and performing vascular interventions. However, because of potential complications, it has been largely replaced by noninvasive angiographic imaging to delineate vascular anatomy.

TREATMENT

Glucocorticoid therapy remains the standard of care

Once the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis is established, glucocorticoid treatment should be started. Glucocorticoids are the standard therapy, and they usually bring about a prompt clinical response. Although never evaluated in placebo-controlled trials, these drugs have been shown to prevent progression of visual loss in a retrospective study.26

In patients with visual symptoms or imminent visual loss, therapy should be started promptly once suspicion of giant cell arteritis is raised; ie, one should not wait until the diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy.

Ideally, a glucocorticoid should be started after a temporal artery biopsy is done, but treatment should not be delayed, as it rapidly suppresses the inflammatory response and may prevent complications from tissue ischemia, such as blindness. Visual loss is usually irreversible.

There is still a role for obtaining a temporal artery biopsy up to several weeks after glucocorticoid therapy is started, as the pathological abnormalities of arteritis do not rapidly resolve.27

Glucocorticoid therapy is highly effective in inducing disease remission in patients with giant cell arteritis. Nearly all patients respond to 1 mg/kg (40–60 mg) per day of prednisone or its equivalent.

The initial dosing is usually maintained for 4 weeks and then decreased slowly. The duration of therapy varies; most patients remain on therapy for at least 1 year, and some cannot stop it completely without recurrence of symptoms.

If a patient is about to lose his or her vision or has lost all or some vision in one eye, a higher initial dose of a glucocorticoid is usually used (ie, a pulse of 500 or 1,000 mg of intravenous methylprednisolone) and may be beneficial.28

Although a rapid clinical response to therapy is usually seen within 48 hours, some patients may have a more delayed clinical improvement.

Alternate-day therapy was compared with daily therapy and was found to be less effective, and as a result it is not recommended.29

Glucocorticoid therapy can cause significant toxicity in patients with giant cell arteritis, as they commonly must take these drugs for long periods. The rate of relapse in those who discontinue therapy is quite high—as high as 77% within 12 months.30

Given the concern about glucocorticoid toxicity, several studies have evaluated alternative strategies and other immunosuppressive drugs. However, no study has concluded that other medications are effective in the treatment of giant cell arteritis.

Mazlumzadeh et al31 evaluated the initial use of intravenous pulse methylprednisolone therapy (15 mg/kg ideal body weight on 3 consecutive days) in an attempt to decrease the glucocorticoid requirement. Although the group receiving this therapy had a lower relapse rate than in the placebo group, and their cumulative dose of glucocorticoid was lower (all patients also received oral prednisone), there was no reduction in the rate of glucocorticoid-associated toxicity.31 Care must be taken to prevent and monitor for corticosteroid complications such as osteoporosis, glaucoma, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension.

Methotrexate: Mixed results in clinical trials

Methotrexate has been evaluated in three prospective randomized trials,30,32,33 with mixed results.

Spiera et al32 enrolled 21 patients in a double-blind placebo-controlled trial: 12 patients received low-dose methotrexate (7.5 mg/week) and 9 received placebo. In addition, all 21 received a glucocorticoid. There was no significant difference between the methotrexate- and placebo-treated patients in the cumulative dose of glucocorticoid, duration of glucocorticoid therapy, time to taper off the glucocorticoid to less than 10 mg of prednisone per day, or glucocorticoidrelated adverse effects.

Jover et al,33 in another double-blind placebo-controlled trial, studied 42 patients with giant cell arteritis, half of whom were randomized to receive methotrexate 10 mg/week, while the other half received placebo. All patients received prednisone. Patients in the methotrexate group had fewer relapses and a 25% lower cumulative dose of prednisone during follow-up. However, the incidence of adverse events was similar in both groups. Methotrexate was discontinued in 3 patients who developed drug-related adverse events.

Hoffman et al30 randomized 98 patients to receive either methotrexate (up to 15 mg/week) or placebo in a double-blind fashion. All patients also received prednisone at an initial dose of 1 mg/kg/day (up to 60 mg/day). At completion of the study, no differences between the groups were noted in the rates of relapse or treatment-related morbidity or in the cumulative dose of glucocorticoid. However, treatment with methotrexate appeared to lower the rate of recurrence of isolated polymyalgia rheumatica in a small number of patients.30

Comment. Differences in the results of these trials may be attributed to several factors, including different definitions of relapses and different glucocorticoid doses and tapering regimens.

A meta-analysis of these three trials34 showed a reduction in the risk of relapse: 4 patients would have to be treated to prevent one first relapse, 5 would have to be treated to prevent one second relapse, and 11 would need to be treated to prevent one first relapse of cranial symptoms in the first 48 weeks. However, the main goal of methotrexate therapy is to decrease the frequency of adverse events from glucocorticoids, and this meta-analysis found no difference in rates of glucocorticoid-related adverse events in patients treated with methotrexate.

The study raises the question of whether methotrexate should be further evaluated in in different patient populations and at higher doses.34

Infliximab is not recommended

In a prospective study, patients with giant cell arteritis were randomly assigned to receive either infliximab (Remicade) 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks or placebo, in addition to standard glucocorticoid therapy. The study showed no significant difference in the relapse rate and a higher rate of infection in the infliximab group (71%) than in the placebo group (56%). Given the lack of any benefit observed in this study, infliximab is not recommended in the treatment of patients with giant cell arteritis.35

Aspirin is recommended

Daily low-dose aspirin therapy has been shown in several studies to be effective in preventing ischemic complications of giant cell arteritis, including stroke and visual loss. It is currently recommended that all patients with giant cell arteritis without a major contraindication take aspirin 81 mg daily.36–38

- Salvarani C, Gabriel SE, O’Fallon WM, Hunder GG. The incidence of giant cell arteritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota: apparent fluctuations in a cyclic pattern. Ann Intern Med 1995; 123:192–194.

- Baldursson O, Steinsson K, Björnsson J, Lie JT. Giant cell arteritis in Iceland. An epidemiologic and histopathologic analysis. Arthritis Rheum 1994; 37:1007–1012.

- Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Medium- and large-vessel vasculitis. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:160–169.

- Aiello PD, Trautmann JC, McPhee TJ, Kunselman AR, Hunder GG. Visual prognosis in giant cell arteritis. Ophthalmology 1993; 100:550–555.

- Salvarani C, Cimino L, Macchioni P, et al. Risk factors for visual loss in an Italian population-based cohort of patients with giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 53:293–297.

- Bahlas S, Ramos-Remus C, Davis P. Clinical outcome of 149 patients with polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis. J Rheumatol 1998; 25:99–104.

- Gonzalez-Gay MA, Barros S, Lopez-Diaz MJ, Garcia-Porrua C, Sanchez-Andrade A, Llorca J. Giant cell arteritis: disease patterns of clinical presentation in a series of 240 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2005; 84:269–276.

- Salvarani C, Cantini F, Macchioni P, et al. Distal musculoskeletal manifestations in polymyalgia rheumatica: a prospective followup study. Arthritis Rheum 1998; 41:1221–1226.

- Salvarani C, Cantini F, Boiardi L, Hunder GG. Polymyalgia rheumatica and giant-cell arteritis. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:261–271.

- Lie JT. Aortic and extracranial large vessel giant cell arteritis: a review of 72 cases with histopathologic documentation. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1995; 24:422–431.

- Evans JM, O’Fallon WM, Hunder GG. Increased incidence of aortic aneurysm and dissection in giant cell (temporal) arteritis. A population-based study. Ann Intern Med 1995; 122:502–507.

- Ostberg G. An arteritis with special reference to polymyalgia arteritica. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand Suppl 1973; 237(suppl 237):1–59.

- Boyev LR, Miller NR, Green WR. Efficacy of unilateral versus bilateral temporal artery biopsies for the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis. Am J Ophthalmol 1999; 128:211–215.

- González-Gay MA, Garcia-Porrua C, Rivas MJ, Rodriguez-Ledo P, Llorca J. Epidemiology of biopsy proven giant cell arteritis in northwestern Spain: trend over an 18 year period. Ann Rheum Dis 2001; 60:367–371.

- Rodriguez-Valverde V, Sarabia JM, González-Gay MA, et al. Risk factors and predictive models of giant cell arteritis in polymyalgia rheumatica. Am J Med 1997; 102:331–336.

- Mahr A, Saba M, Kambouchner M, et al. Temporal artery biopsy for diagnosing giant cell arteritis: the longer, the better? Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 65:826–828.

- Breuer GS, Nesher R, Nesher G. Effect of biopsy length on the rate of positive temporal artery biopsies. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2009; 27(1 suppl 52):S10–S13.

- Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Giant-cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139:505–515.

- Salvarani C, Cantini F, Boiardi L, Hunder GG. Laboratory investigations useful in giant cell arteritis and Takayasu’s arteritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2003; 21(6 suppl 32):S23–S28.

- Salvarani C, Hunder GG. Giant cell arteritis with low erythrocyte sedimentation rate: frequency of occurence in a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum 2001; 45:140–145.

- Schmidt WA, Kraft HE, Vorpahl K, Völker L, Gromnica-Ihle EJ. Color duplex ultrasonography in the diagnosis of temporal arteritis. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:1336–1342.

- Karassa FB, Matsagas MI, Schmidt WA, Ioannidis JP. Meta-analysis: test performance of ultrasonography for giant-cell arteritis. Ann Intern Med 2005; 142:359–369.

- Maldini C, Dépinay-Dhellemmes C, Tra TT, et al. Limited value of temporal artery ultrasonography examinations for diagnosis of giant cell arteritis: analysis of 77 subjects. J Rheumatol 2010; Epub ahead of print.

- Both M, Ahmadi-Simab K, Reuter M, et al. MRI and FDG-PET in the assessment of inflammatory aortic arch syndrome in complicated courses of giant cell arteritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67:1030–1033.

- Tso E, Flamm SD, White RD, Schvartzman PR, Mascha E, Hoffman GS. Takayasu arteritis: utility and limitations of magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosis and treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46:1634–1642.

- Birkhead NC, Wagener HP, Shick RM. Treatment of temporal arteritis with adrenal corticosteroids; results in fifty-five cases in which lesion was proved at biopsy. J Am Med Assoc 1957; 163:821–827.

- Ray-Chaudhuri N, Kiné DA, Tijani SO, et al. Effect of prior steroid treatment on temporal artery biopsy findings in giant cell arteritis. Br J Ophthalmol 2002; 86:530–532.

- Chan CC, Paine M, O’Day J. Steroid management in giant cell arteritis. Br J Ophthalmol 2001; 85:1061–1064.

- Hunder GG, Sheps SG, Allen GL, Joyce JW. Daily and alternate-day corticosteroid regimens in treatment of giant cell arteritis: comparison in a prospective study. Ann Intern Med 1975; 82:613–618.

- Hoffman GS, Cid MC, Hellmann DB, et al; International Network for the Study of Systemic Vasculitides. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of adjuvant methotrexate treatment for giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46:1309–1318.

- Mazlumzadeh M, Hunder GG, Easley KA, et al. Treatment of giant cell arteritis using induction therapy with high-dose glucocorticoids: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized prospective clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54:3310–3318.

- Spiera RF, Mitnick HJ, Kupersmith M, et al. A prospective, doubleblind, randomized, placebo controlled trial of methotrexate in the treatment of giant cell arteritis (GCA). Clin Exp Rheumatol 2001; 19:495–501.

- Jover JA, Hernández-García C, Morado IC, Vargas E, Bañares A, Fernández-Gutiérrez B. Combined treatment of giant-cell arteritis with methotrexate and prednisone. a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134:106–114.

- Mahr AD, Jover JA, Spiera RF, et al. Adjunctive methotrexate for treatment of giant cell arteritis: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2007; 56:2789–2797.

- Hoffman GS, Cid MC, Rendt-Zagar KE, et al; Infliximab-GCA Study Group. Infliximab for maintenance of glucocorticosteroid-induced remission of giant cell arteritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007; 146:621–630.

- Weyand CM, Kaiser M, Yang H, Younge B, Goronzy JJ. Therapeutic effects of acetylsalicylic acid in giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46:457–466.

- Nesher G, Berkun Y, Mates M, Baras M, Rubinow A, Sonnenblick M. Low-dose aspirin and prevention of cranial ischemic complications in giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50:1332–1337.

- Lee MS, Smith SD, Galor A, Hoffman GS. Antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy in patients with giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54:3306–3309.

Giant cell arteritis is the most common primary systemic vasculitis. The disease occurs almost exclusively in people over age 50, with an annual incidence of 15 to 25 per 100,000.1 Incidence rates vary significantly depending on ethnicity. The highest rates are in whites, particularly those of North European descent.2 Incidence rates progressively increase after age 50. The disease is more prevalent in women. Its cause is unknown; both genetic and environmental factors are thought to play a role.

INFLAMED ARTERIES

Giant cell arteritis is characterized by a granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate affecting large and medium-size arteries. Not all vessels are equally affected: the most susceptible are the cranial arteries, the aorta, and the aorta’s primary branches, particularly those in the upper extremities.

The disease is usually associated with an intense acute-phase response. Vessel wall inflammation results in intimal hyperplasia, luminal occlusion, and tissue ischemia. Typical histologic features include a mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate primarily composed of CD4+ T cells and activated macrophages. Multinucleated giant cells are seen in only about 50% of positive biopsies; therefore, their presence is not essential for the diagnosis.3

FOUR MAIN PHENOTYPES

Some of the possible symptoms of giant cell arteritis readily point to the correct diagnosis, eg, those due to cranial artery involvement, such as temporal headache, claudication of masticatory muscles, and visual changes. However, the clinical presentation can be quite varied.

There are four predominant clinical phenotypes, which may be present at the onset of disease or appear later as the disease progresses. Although they will be described separately in this review, these clinical presentations often overlap.

Cranial arteritis

Cranial arteritis is the clinical presentation most readily associated with giant cell arteritis. Clinical features result from involvement of branches of the external or internal carotid artery.

Headache, the most frequent symptom, is typically but not exclusively localized to the temporal areas.

Visual loss is due to involvement of the branches of the ophthalmic or posterior ciliary arteries, resulting in ischemia of the optic nerve or its tracts. It occurs in up to 20% of patients.4,5

Other symptoms and complications from cranial arteritis include tenderness of the scalp and temporal areas, claudication of the tongue or jaw muscles, stroke, and more rarely, tongue infarction.

Polymyalgia rheumatica

Polymyalgia rheumatica is a clinical syndrome that can occur by itself or in conjunction with giant cell arteritis. It may occur independently of giant cell arteritis, but also occurs in about 40% of patients with giant cell arteritis. It may precede, develop simultaneously with, or develop later during the course of the giant cell arteritis.6,7 It is a common clinical manifestation in relapses of giant cell arteritis, even in those who did not have symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica at the time giant cell arteritis was diagnosed.

Polymyalgia rheumatica is characterized by aching of the shoulder and hip girdle, with morning stiffness. Fatigue and malaise are often present and may be severe. Some patients with polymyalgia rheumatica may also present with peripheral joint synovitis, which may be mistakenly diagnosed as rheumatoid arthritis.8 Muscle weakness and elevated muscle enzymes are not associated with polymyalgia rheumatica.