User login

In the Literature: Research You Need to Know

In This Edition

Literature At A Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Screening for AAA

- Adverse events in atrial fibrillation

- Biological treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases

- Steroid treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases

- Levofloxacin for H. pylori

- Natural history of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy

- Predicting postoperative pulmonary complications

- Code status and goals of care in the ICU

New Screening Strategy To Identify Large Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

Clinical question: Can an effective scoring system be developed to better identify patients at risk for large abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA)?

Background: Screening reduces AAA-related mortality by about half in men aged >65. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended screening for AAA in men aged 65 to 75 with a history of smoking. However, more than 50% of AAA ruptures occur in individuals outside this patient cohort, and only some AAAs detected are large enough to warrant surgery.

Study design: Retrospective, observational cohort study.

Setting: More than 20,000 screening sites across the U.S.

Synopsis: Researchers collected demographics and risk factors from 3.1 million people undergoing ultrasound screening for AAA by Life Line Screening Inc. At the screening visit, subjects completed a questionnaire about their health status and medical history. Screening data also included diameter of the infrarenal abdominal aorta. To construct and test a risk model, the screened individuals were randomly allocated into two equal groups: a data set used for model development and one for validation.

Most of the AAAs greater than 5 cm in diameter discovered were in males (84.4%) and among subjects with a smoking history (83%). Other risk factors for large AAAs included advanced age, peripheral arterial disease, and obesity. The authors estimate that there are about 121,000 people with >5.0 cm aneurysms in the general population. Current guidelines would detect only 33.7% of the existing large AAAs. Study limitations include possible selection bias, as a majority of patients were self-referred. Also, the database did not include all comorbidities that could affect the risk of AAA. The self-reported nature of health data might cause misclassification of a patient’s true health status.

Bottom line: A screening strategy based on a newly developed scoring system is an effective way to identify patients at risk of large abdominal aortic aneurysms.

Citation: Greco G, Egorova NN, Gelijns AC, et al. Development of a novel scoring tool for the identification of large >5 cm abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann Surg. 2010;252(4):675-682.

Risk Factors for Adverse Events in Patients with Symptomatic Atrial Fibrillation

Clinical question: What are the predictors of 30-day adverse events in ED patients evaluated for symptomatic atrial fibrillation?

Background: Atrial fibrillation (AF) affects more than 2 million people in the U.S. and accounts for nearly 1% of ED visits. Physicians have little information to guide risk stratification, and they admit more than 65% of patients. A strategy to better define the ED management of patients presenting with atrial fibrillation is required.

Study design: Retrospective, observational cohort study.

Setting: Urban academic tertiary-care referral center with an adult ED.

Synopsis: A systematic review of the electronic medical records of all ED patients presenting with symptomatic atrial fibrillation over a three-year period was performed. Predefined adverse outcomes included 30-day ED return visits, unscheduled hospitalizations, cardiovascular complications, or death.

Of 832 eligible patients, 216 (25.9%) experienced at least one of the 30-day adverse events. Adverse events occurred in 181 of the 638 (28.4%) admitted patients and 35 of the 192 (18.2%) patients discharged from the ED. Increasing age, complaint of dyspnea, smoking history, inadequate ventricular rate control, and patients receiving beta-blockers were factors independently associated with higher risk for adverse events.

Study results were limited by a number of factors. This was a single-center, retrospective, observational study, with all of its inherent limitations. The predictor model did not include laboratory data, such as BNP or troponin. Patients might have experienced additional events within the 30 days that were treated at other hospitals and not recorded in the database. Patient disposition might have affected the results, as patients initially admitted from the ED had a higher rate of 30-day adverse events than patients who were discharged from the ED.

Bottom line: Patients with increased age, smoking history, complaints of dyspnea, inadequate ventricular rate control in the ED, and home beta-blocker therapy are more likely to experience an atrial-fibrillation-related adverse event within 30 days.

Citation: Barrett TW, Martin AR, Storrow AB, et al. A clinical prediction model to estimate risk for 30-day adverse events in emergency department patients with symptomatic atrial fibrillation. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57 (1):1-12.

Biological Therapies Are Effective in Inducing Remission in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Clinical question: Are biological therapies useful in the treatment of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD)?

Background: Patients with CD and UC often experience flares of disease activity, despite maintenance therapy with 5-aminosalicylic acid compounds. These flares are usually treated with corticosteroids, which carry numerous adverse side effects. The role of biological therapies in inducing remission is uncertain.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Twenty-seven randomized controlled trials involving 7,416 patients.

Synopsis: Anti-TNF α antibodies and natalizumab were both superior to placebo in inducing remission of luminal CD (RR of no remission 0.87 and 0.88, respectively). Anti-TNF antibodies also were superior to placebo in preventing relapse of luminal CD (RR of relapse=0.71). Infliximab was superior to placebo in inducing remission of moderate to severely active UC (RR=0.72; 95% CI, 0.57-0.91). There were no significantly increased adverse drug effects with anti-TNF α antibodies or with infliximab compared with placebo. Natalizumab caused significantly higher rates of headache.

Limitations include risk of publication bias inherent in meta-analyses. There also was evidence of moderate heterogeneity in the studies analyzed. Finally, not every study was consistent in reporting adverse drug effects.

Bottom line: Biological therapies are superior to placebo in inducing remission of active UC and CD, as well as preventing relapse of quiescent CD.

Citation: Ford AC, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, Hanauer SB, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011; 106(4):644-659.

Glucocorticosteroids Probably Effective in Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Primarily in Active Ulcerative Colitis

Clinical question: Is glucocorticosteroid therapy effective in the treatment of active IBD and in preventing relapses?

Background: Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are chronic inflammatory bowel diseases of unclear etiology. Use of standard glucocorticosteroids and budesonide is widespread in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) treatment. To date, there has been no large-scale meta-analysis to examine the effectiveness of both treatments in CD and UC.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Twenty randomized controlled trials totaling 2,398 patients.

Synopsis: Standard glucocorticosteroids were superior to placebo for UC remission (RR of no remission=0.65; 95% CI, 0.45-0.93). Both trials of standard glucocorticosteroids in CD remission reported a statistically significant effect, but the overall effect was not significant due to heterogeneity of the studies. Budesonide was superior to placebo for CD remission (RR=0.73; 95% CI, 0.63-0.84) but not in preventing CD relapse (RR=0.93; 95% CI, 0.83-1.04). Standard glucocorticosteroids were superior to budesonide for CD remission (RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.68-0.98) but with more adverse effects (RR=1.64; 95% CI, 1.34-2.00).

The limitations of the study include the poor overall quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis, with only one study judged as low risk of bias. There was intermediate to high heterogeneity between study results.

Bottom line: Standard glucocorticosteroids are likely effective in inducing remission in UC and, possibly, in CD. Budesonide probably is effective at inducing remission in active CD. Neither therapy was recommended in preventing relapse of UC and CD.

Citation: Ford AC, Bernstein CN, Khan KJ, et al. Glucocorticosteroid therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(4):590-599.

Levofloxacin Effective in Treatment of H. Pylori in Settings of High Clarithromycin Resistance

Clinical question: In areas with high H. pylori clarithromycin resistance rates, is levofloxacin more effective in eradicating H. pylori than standard clarithromycin, based treatment regimens?

Background: The rise in antimicrobial drug resistance is a major cause for the decreasing rate of H. pylori eradication. In areas with higher than 15% H. pyloriclarithromycin-resistant strains, quadruple therapy has been suggested as first-line therapy. The efficacy of a levofloxacin-based sequential therapy in eradicating H. pylori is undetermined.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter study with a parallel-group design.

Setting: Five gastroenterology clinics in Italy.

Synopsis: Researchers randomly assigned 375 patients who were infected with H. pylori and naive to treatment to one of three groups. All three treatment groups received an initial five days of omeprazole 20 mg BID and amoxicillin 1 gm BID, then five days of omeprazole 20 mg BID and tinidazole 500 mg BID. The groups also received either clarithromycin 500 mg BID, levofloxacin 250 mg BID, or levofloxacin 500 mg BID, respectively, during the second five days of treatment.

Eradication rates were 80.8% (95% CI, 72.8% to 87.3%) with clarithromycin sequential therapy, 96.0% (95% CI, 90.9% to 98.7%) with levofloxacin-250 sequential therapy, and 96.8% (95% CI, 92.0% to 99.1%) with levofloxacin-500 sequential therapy.

The clarithromycin-group eradication rate was significantly lower than both levofloxacin groups. No significant difference was observed between the levofloxacin-250 and levofloxacin-500 groups. No differences in prevalence of antimicrobial resistance or incidence of adverse events were observed between the groups. Levofloxacin-250 therapy does offer cost savings when compared with clarithromycin sequential therapy.

A potential limitation to the study is referral bias, as each of the patients first were sent by their primary physicians to a specialized GI clinic.

Bottom line: In areas with a high prevalence of clarithromycin-resistant strains of H. pylori levofloxacin-containing sequential therapy should be considered for a first-line eradication regimen.

Citation: Romano M, Cuomo A, Gravina AG, et al. Empirical levofloxacin-containing versus clarithromycin-containing sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomised trial. Gut. 2010;59(11):1465-1470.

Tako-Tsubo Cardiomyopathy Is Associated with Higher Hospital Readmission Rates and Long-Term Mortality

Clinical question: What is the natural history of patients who develop tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy?

Background: Stress-induced or tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC) is a rare acute cardiac syndrome, characterized by chest pain or dyspnea, ischemic electrocardiographic changes, transient left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, and limited release of cardiac injury markers, in the absence of epicardial coronary artery disease (CAD). The long-term outcome of this condition is unknown.

Study design: Prospective, case-control study.

Setting: Five urban-based hospitals in Italy.

Synopsis: One hundred-sixteen patients with TTC were included in the five-year study period. Patients were followed up at one and six months, then annually thereafter. Primary endpoints were death, TTC recurrence, and rehospitalization for any cause.

Mean initial LV ejection fraction (LVEF) was 36%. Two patients died of refractory heart failure during hospitalization. Of the patients who were discharged alive, all except one showed complete LV functional recovery.

At follow-up (mean two years), only 64 (55%) patients were asymptomatic. Rehospitalization rate was high (25%), with chest pain and dyspnea the most common causes. Only two patients had a recurrence of TTC. Eleven patients died (seven from cardiovascular causes). There was no significant difference in mortality or in other clinical events between patients with and without severe LV dysfunction at presentation. The standardized mortality ratio was 3.40 (95% CI, 1.83-6.34) in the TTC population, compared with the age- and sex-specific mortality of the general population.

The study is limited by a lack of patients with subclinical TTC disease and those who might have suffered from sudden cardiac death prior to enrollment, leading to a possible sampling bias, as well as the nonrandomized use of beta-blockers.

Bottom line: Tako-tsubo disease is associated with rare recurrence of the disease, common recurrence of chest pain and dyspnea, and three times the mortality rate of the general population.

Citation: Parodi G, Bellandi B, Del Pace S, et al. Natural history of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. Chest. 2011;139(4):887-892.

Seven Independent Risk Factors Predict Postoperative Pulmonary Complications

Clinical question: What are the clinical risk factors that predict higher rates of postoperative pulmonary complications?

Background: Postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) are a major cause of postoperative morbidity, mortality, and prolonged hospital stays. Previous studies looking at risk factors for PPCs were limited by sampling bias and small sample sizes.

Study design: Prospective, randomized-sample cohort study.

Setting: Fifty-nine participating Spanish hospitals (community, intermediate referral, or major tertiary-care facilities).

Synopsis: Patients undergoing surgical procedures with general, neuraxial, or regional anesthesia were selected randomly. The main outcome was the development of at least one of the following: respiratory infection, respiratory failure, bronchospasm, atelectasis, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, or aspiration pneumonitis. Of 2,464 patients enrolled, 252 events were observed in 123 patients (5%). The 30-day mortality rate was significantly higher in patients suffering a PPC than those who did not (19.5% vs. 0.5%). Additionally, regression modeling identified seven independent risk factors: low preoperative arterial oxygen saturation, acute respiratory infection within one month of surgery, advanced age, preoperative anemia, upper abdominal or intrathoracic surgery, surgical duration more than two hours, and emergency surgery.

The study was underpowered to assess the significance of all potential risk factors for PPCs. Also, given the number of centers involved in the study, variation in assessing development of PPCs is likely.

Bottom line: Postoperative pulmonary complications are a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Seven independent risk factors were identified for the development of PPCs, which could be useful in preoperative risk stratification.

Citation: Canet J, Gallart L, Gomar C, et al. Prediction of postoperative pulmonary complications in a population-based surgical cohort. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(6):1338-1350.

Code Status Orders and Goals of Medical ICU Care

Clinical question: How familiar are patients in the medical ICU (MICU) or their surrogates regarding code-status orders and goals of care, what are their preferences, and to what extent do they and their physicians differ?

Background: Discussions about code-status orders and goals of care carry great import in the MICU. However, little data exist on patients’ code-status preferences and goals of care. More knowledge of these issues can help physicians deliver more patient-centered care.

Study design: Prospective interviews.

Setting: Twenty-six-bed MICU at a large Midwestern academic medical center.

Synopsis: Data were collected from December 2008 to December 2009 on a random sample of patients—or their surrogates—admitted to the MICU. Of 135 eligible patients/surrogates, 100 completed interviews. Patients primarily were white (95%) and from the ages of 41 to 80 (79%).

Only 28% of participants recalled having a discussion about CPR and one goal of care, while 27% recalled no discussion at all; 83% preferred full code status but had limited knowledge of CPR and its outcomes in the hospital setting. Only 4% were able to identify all components of CPR, and they estimated the mean probability of survival following in-hospital arrest with CPR to be 71.8%, although data suggest survival is closer to 18%. There was a correlation between a higher estimation of survival following CPR and preference for it. After learning about the evidence-based likelihood of a good neurologic outcome following CPR, 8% of the participants became less interested.

Discrepancies between patients’ stated code status and that in the medical record was identified 16% of the time. Additionally, 67.7% of participants differed with their physicians regarding the most important goal of care.

Bottom line: Discussions about code status and goals of care in the MICU occur less frequently than recommended, leading to widespread discrepancies between patients/surrogates and their physicians regarding the most important goal of care. This is compounded by the fact that patients and their surrogates have limited knowledge about in-hospital CPR and its likelihood of success.

Citation: Gehlbach TG, Shinkunas LA, Forman-Hoffman VL, Thomas KW, Schmidt GA, Kaldjian LC. Code status orders and goals of care in the medical ICU. Chest. 2011;139:802-809. TH

In This Edition

Literature At A Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Screening for AAA

- Adverse events in atrial fibrillation

- Biological treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases

- Steroid treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases

- Levofloxacin for H. pylori

- Natural history of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy

- Predicting postoperative pulmonary complications

- Code status and goals of care in the ICU

New Screening Strategy To Identify Large Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

Clinical question: Can an effective scoring system be developed to better identify patients at risk for large abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA)?

Background: Screening reduces AAA-related mortality by about half in men aged >65. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended screening for AAA in men aged 65 to 75 with a history of smoking. However, more than 50% of AAA ruptures occur in individuals outside this patient cohort, and only some AAAs detected are large enough to warrant surgery.

Study design: Retrospective, observational cohort study.

Setting: More than 20,000 screening sites across the U.S.

Synopsis: Researchers collected demographics and risk factors from 3.1 million people undergoing ultrasound screening for AAA by Life Line Screening Inc. At the screening visit, subjects completed a questionnaire about their health status and medical history. Screening data also included diameter of the infrarenal abdominal aorta. To construct and test a risk model, the screened individuals were randomly allocated into two equal groups: a data set used for model development and one for validation.

Most of the AAAs greater than 5 cm in diameter discovered were in males (84.4%) and among subjects with a smoking history (83%). Other risk factors for large AAAs included advanced age, peripheral arterial disease, and obesity. The authors estimate that there are about 121,000 people with >5.0 cm aneurysms in the general population. Current guidelines would detect only 33.7% of the existing large AAAs. Study limitations include possible selection bias, as a majority of patients were self-referred. Also, the database did not include all comorbidities that could affect the risk of AAA. The self-reported nature of health data might cause misclassification of a patient’s true health status.

Bottom line: A screening strategy based on a newly developed scoring system is an effective way to identify patients at risk of large abdominal aortic aneurysms.

Citation: Greco G, Egorova NN, Gelijns AC, et al. Development of a novel scoring tool for the identification of large >5 cm abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann Surg. 2010;252(4):675-682.

Risk Factors for Adverse Events in Patients with Symptomatic Atrial Fibrillation

Clinical question: What are the predictors of 30-day adverse events in ED patients evaluated for symptomatic atrial fibrillation?

Background: Atrial fibrillation (AF) affects more than 2 million people in the U.S. and accounts for nearly 1% of ED visits. Physicians have little information to guide risk stratification, and they admit more than 65% of patients. A strategy to better define the ED management of patients presenting with atrial fibrillation is required.

Study design: Retrospective, observational cohort study.

Setting: Urban academic tertiary-care referral center with an adult ED.

Synopsis: A systematic review of the electronic medical records of all ED patients presenting with symptomatic atrial fibrillation over a three-year period was performed. Predefined adverse outcomes included 30-day ED return visits, unscheduled hospitalizations, cardiovascular complications, or death.

Of 832 eligible patients, 216 (25.9%) experienced at least one of the 30-day adverse events. Adverse events occurred in 181 of the 638 (28.4%) admitted patients and 35 of the 192 (18.2%) patients discharged from the ED. Increasing age, complaint of dyspnea, smoking history, inadequate ventricular rate control, and patients receiving beta-blockers were factors independently associated with higher risk for adverse events.

Study results were limited by a number of factors. This was a single-center, retrospective, observational study, with all of its inherent limitations. The predictor model did not include laboratory data, such as BNP or troponin. Patients might have experienced additional events within the 30 days that were treated at other hospitals and not recorded in the database. Patient disposition might have affected the results, as patients initially admitted from the ED had a higher rate of 30-day adverse events than patients who were discharged from the ED.

Bottom line: Patients with increased age, smoking history, complaints of dyspnea, inadequate ventricular rate control in the ED, and home beta-blocker therapy are more likely to experience an atrial-fibrillation-related adverse event within 30 days.

Citation: Barrett TW, Martin AR, Storrow AB, et al. A clinical prediction model to estimate risk for 30-day adverse events in emergency department patients with symptomatic atrial fibrillation. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57 (1):1-12.

Biological Therapies Are Effective in Inducing Remission in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Clinical question: Are biological therapies useful in the treatment of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD)?

Background: Patients with CD and UC often experience flares of disease activity, despite maintenance therapy with 5-aminosalicylic acid compounds. These flares are usually treated with corticosteroids, which carry numerous adverse side effects. The role of biological therapies in inducing remission is uncertain.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Twenty-seven randomized controlled trials involving 7,416 patients.

Synopsis: Anti-TNF α antibodies and natalizumab were both superior to placebo in inducing remission of luminal CD (RR of no remission 0.87 and 0.88, respectively). Anti-TNF antibodies also were superior to placebo in preventing relapse of luminal CD (RR of relapse=0.71). Infliximab was superior to placebo in inducing remission of moderate to severely active UC (RR=0.72; 95% CI, 0.57-0.91). There were no significantly increased adverse drug effects with anti-TNF α antibodies or with infliximab compared with placebo. Natalizumab caused significantly higher rates of headache.

Limitations include risk of publication bias inherent in meta-analyses. There also was evidence of moderate heterogeneity in the studies analyzed. Finally, not every study was consistent in reporting adverse drug effects.

Bottom line: Biological therapies are superior to placebo in inducing remission of active UC and CD, as well as preventing relapse of quiescent CD.

Citation: Ford AC, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, Hanauer SB, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011; 106(4):644-659.

Glucocorticosteroids Probably Effective in Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Primarily in Active Ulcerative Colitis

Clinical question: Is glucocorticosteroid therapy effective in the treatment of active IBD and in preventing relapses?

Background: Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are chronic inflammatory bowel diseases of unclear etiology. Use of standard glucocorticosteroids and budesonide is widespread in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) treatment. To date, there has been no large-scale meta-analysis to examine the effectiveness of both treatments in CD and UC.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Twenty randomized controlled trials totaling 2,398 patients.

Synopsis: Standard glucocorticosteroids were superior to placebo for UC remission (RR of no remission=0.65; 95% CI, 0.45-0.93). Both trials of standard glucocorticosteroids in CD remission reported a statistically significant effect, but the overall effect was not significant due to heterogeneity of the studies. Budesonide was superior to placebo for CD remission (RR=0.73; 95% CI, 0.63-0.84) but not in preventing CD relapse (RR=0.93; 95% CI, 0.83-1.04). Standard glucocorticosteroids were superior to budesonide for CD remission (RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.68-0.98) but with more adverse effects (RR=1.64; 95% CI, 1.34-2.00).

The limitations of the study include the poor overall quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis, with only one study judged as low risk of bias. There was intermediate to high heterogeneity between study results.

Bottom line: Standard glucocorticosteroids are likely effective in inducing remission in UC and, possibly, in CD. Budesonide probably is effective at inducing remission in active CD. Neither therapy was recommended in preventing relapse of UC and CD.

Citation: Ford AC, Bernstein CN, Khan KJ, et al. Glucocorticosteroid therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(4):590-599.

Levofloxacin Effective in Treatment of H. Pylori in Settings of High Clarithromycin Resistance

Clinical question: In areas with high H. pylori clarithromycin resistance rates, is levofloxacin more effective in eradicating H. pylori than standard clarithromycin, based treatment regimens?

Background: The rise in antimicrobial drug resistance is a major cause for the decreasing rate of H. pylori eradication. In areas with higher than 15% H. pyloriclarithromycin-resistant strains, quadruple therapy has been suggested as first-line therapy. The efficacy of a levofloxacin-based sequential therapy in eradicating H. pylori is undetermined.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter study with a parallel-group design.

Setting: Five gastroenterology clinics in Italy.

Synopsis: Researchers randomly assigned 375 patients who were infected with H. pylori and naive to treatment to one of three groups. All three treatment groups received an initial five days of omeprazole 20 mg BID and amoxicillin 1 gm BID, then five days of omeprazole 20 mg BID and tinidazole 500 mg BID. The groups also received either clarithromycin 500 mg BID, levofloxacin 250 mg BID, or levofloxacin 500 mg BID, respectively, during the second five days of treatment.

Eradication rates were 80.8% (95% CI, 72.8% to 87.3%) with clarithromycin sequential therapy, 96.0% (95% CI, 90.9% to 98.7%) with levofloxacin-250 sequential therapy, and 96.8% (95% CI, 92.0% to 99.1%) with levofloxacin-500 sequential therapy.

The clarithromycin-group eradication rate was significantly lower than both levofloxacin groups. No significant difference was observed between the levofloxacin-250 and levofloxacin-500 groups. No differences in prevalence of antimicrobial resistance or incidence of adverse events were observed between the groups. Levofloxacin-250 therapy does offer cost savings when compared with clarithromycin sequential therapy.

A potential limitation to the study is referral bias, as each of the patients first were sent by their primary physicians to a specialized GI clinic.

Bottom line: In areas with a high prevalence of clarithromycin-resistant strains of H. pylori levofloxacin-containing sequential therapy should be considered for a first-line eradication regimen.

Citation: Romano M, Cuomo A, Gravina AG, et al. Empirical levofloxacin-containing versus clarithromycin-containing sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomised trial. Gut. 2010;59(11):1465-1470.

Tako-Tsubo Cardiomyopathy Is Associated with Higher Hospital Readmission Rates and Long-Term Mortality

Clinical question: What is the natural history of patients who develop tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy?

Background: Stress-induced or tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC) is a rare acute cardiac syndrome, characterized by chest pain or dyspnea, ischemic electrocardiographic changes, transient left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, and limited release of cardiac injury markers, in the absence of epicardial coronary artery disease (CAD). The long-term outcome of this condition is unknown.

Study design: Prospective, case-control study.

Setting: Five urban-based hospitals in Italy.

Synopsis: One hundred-sixteen patients with TTC were included in the five-year study period. Patients were followed up at one and six months, then annually thereafter. Primary endpoints were death, TTC recurrence, and rehospitalization for any cause.

Mean initial LV ejection fraction (LVEF) was 36%. Two patients died of refractory heart failure during hospitalization. Of the patients who were discharged alive, all except one showed complete LV functional recovery.

At follow-up (mean two years), only 64 (55%) patients were asymptomatic. Rehospitalization rate was high (25%), with chest pain and dyspnea the most common causes. Only two patients had a recurrence of TTC. Eleven patients died (seven from cardiovascular causes). There was no significant difference in mortality or in other clinical events between patients with and without severe LV dysfunction at presentation. The standardized mortality ratio was 3.40 (95% CI, 1.83-6.34) in the TTC population, compared with the age- and sex-specific mortality of the general population.

The study is limited by a lack of patients with subclinical TTC disease and those who might have suffered from sudden cardiac death prior to enrollment, leading to a possible sampling bias, as well as the nonrandomized use of beta-blockers.

Bottom line: Tako-tsubo disease is associated with rare recurrence of the disease, common recurrence of chest pain and dyspnea, and three times the mortality rate of the general population.

Citation: Parodi G, Bellandi B, Del Pace S, et al. Natural history of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. Chest. 2011;139(4):887-892.

Seven Independent Risk Factors Predict Postoperative Pulmonary Complications

Clinical question: What are the clinical risk factors that predict higher rates of postoperative pulmonary complications?

Background: Postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) are a major cause of postoperative morbidity, mortality, and prolonged hospital stays. Previous studies looking at risk factors for PPCs were limited by sampling bias and small sample sizes.

Study design: Prospective, randomized-sample cohort study.

Setting: Fifty-nine participating Spanish hospitals (community, intermediate referral, or major tertiary-care facilities).

Synopsis: Patients undergoing surgical procedures with general, neuraxial, or regional anesthesia were selected randomly. The main outcome was the development of at least one of the following: respiratory infection, respiratory failure, bronchospasm, atelectasis, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, or aspiration pneumonitis. Of 2,464 patients enrolled, 252 events were observed in 123 patients (5%). The 30-day mortality rate was significantly higher in patients suffering a PPC than those who did not (19.5% vs. 0.5%). Additionally, regression modeling identified seven independent risk factors: low preoperative arterial oxygen saturation, acute respiratory infection within one month of surgery, advanced age, preoperative anemia, upper abdominal or intrathoracic surgery, surgical duration more than two hours, and emergency surgery.

The study was underpowered to assess the significance of all potential risk factors for PPCs. Also, given the number of centers involved in the study, variation in assessing development of PPCs is likely.

Bottom line: Postoperative pulmonary complications are a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Seven independent risk factors were identified for the development of PPCs, which could be useful in preoperative risk stratification.

Citation: Canet J, Gallart L, Gomar C, et al. Prediction of postoperative pulmonary complications in a population-based surgical cohort. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(6):1338-1350.

Code Status Orders and Goals of Medical ICU Care

Clinical question: How familiar are patients in the medical ICU (MICU) or their surrogates regarding code-status orders and goals of care, what are their preferences, and to what extent do they and their physicians differ?

Background: Discussions about code-status orders and goals of care carry great import in the MICU. However, little data exist on patients’ code-status preferences and goals of care. More knowledge of these issues can help physicians deliver more patient-centered care.

Study design: Prospective interviews.

Setting: Twenty-six-bed MICU at a large Midwestern academic medical center.

Synopsis: Data were collected from December 2008 to December 2009 on a random sample of patients—or their surrogates—admitted to the MICU. Of 135 eligible patients/surrogates, 100 completed interviews. Patients primarily were white (95%) and from the ages of 41 to 80 (79%).

Only 28% of participants recalled having a discussion about CPR and one goal of care, while 27% recalled no discussion at all; 83% preferred full code status but had limited knowledge of CPR and its outcomes in the hospital setting. Only 4% were able to identify all components of CPR, and they estimated the mean probability of survival following in-hospital arrest with CPR to be 71.8%, although data suggest survival is closer to 18%. There was a correlation between a higher estimation of survival following CPR and preference for it. After learning about the evidence-based likelihood of a good neurologic outcome following CPR, 8% of the participants became less interested.

Discrepancies between patients’ stated code status and that in the medical record was identified 16% of the time. Additionally, 67.7% of participants differed with their physicians regarding the most important goal of care.

Bottom line: Discussions about code status and goals of care in the MICU occur less frequently than recommended, leading to widespread discrepancies between patients/surrogates and their physicians regarding the most important goal of care. This is compounded by the fact that patients and their surrogates have limited knowledge about in-hospital CPR and its likelihood of success.

Citation: Gehlbach TG, Shinkunas LA, Forman-Hoffman VL, Thomas KW, Schmidt GA, Kaldjian LC. Code status orders and goals of care in the medical ICU. Chest. 2011;139:802-809. TH

In This Edition

Literature At A Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Screening for AAA

- Adverse events in atrial fibrillation

- Biological treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases

- Steroid treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases

- Levofloxacin for H. pylori

- Natural history of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy

- Predicting postoperative pulmonary complications

- Code status and goals of care in the ICU

New Screening Strategy To Identify Large Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

Clinical question: Can an effective scoring system be developed to better identify patients at risk for large abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA)?

Background: Screening reduces AAA-related mortality by about half in men aged >65. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended screening for AAA in men aged 65 to 75 with a history of smoking. However, more than 50% of AAA ruptures occur in individuals outside this patient cohort, and only some AAAs detected are large enough to warrant surgery.

Study design: Retrospective, observational cohort study.

Setting: More than 20,000 screening sites across the U.S.

Synopsis: Researchers collected demographics and risk factors from 3.1 million people undergoing ultrasound screening for AAA by Life Line Screening Inc. At the screening visit, subjects completed a questionnaire about their health status and medical history. Screening data also included diameter of the infrarenal abdominal aorta. To construct and test a risk model, the screened individuals were randomly allocated into two equal groups: a data set used for model development and one for validation.

Most of the AAAs greater than 5 cm in diameter discovered were in males (84.4%) and among subjects with a smoking history (83%). Other risk factors for large AAAs included advanced age, peripheral arterial disease, and obesity. The authors estimate that there are about 121,000 people with >5.0 cm aneurysms in the general population. Current guidelines would detect only 33.7% of the existing large AAAs. Study limitations include possible selection bias, as a majority of patients were self-referred. Also, the database did not include all comorbidities that could affect the risk of AAA. The self-reported nature of health data might cause misclassification of a patient’s true health status.

Bottom line: A screening strategy based on a newly developed scoring system is an effective way to identify patients at risk of large abdominal aortic aneurysms.

Citation: Greco G, Egorova NN, Gelijns AC, et al. Development of a novel scoring tool for the identification of large >5 cm abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann Surg. 2010;252(4):675-682.

Risk Factors for Adverse Events in Patients with Symptomatic Atrial Fibrillation

Clinical question: What are the predictors of 30-day adverse events in ED patients evaluated for symptomatic atrial fibrillation?

Background: Atrial fibrillation (AF) affects more than 2 million people in the U.S. and accounts for nearly 1% of ED visits. Physicians have little information to guide risk stratification, and they admit more than 65% of patients. A strategy to better define the ED management of patients presenting with atrial fibrillation is required.

Study design: Retrospective, observational cohort study.

Setting: Urban academic tertiary-care referral center with an adult ED.

Synopsis: A systematic review of the electronic medical records of all ED patients presenting with symptomatic atrial fibrillation over a three-year period was performed. Predefined adverse outcomes included 30-day ED return visits, unscheduled hospitalizations, cardiovascular complications, or death.

Of 832 eligible patients, 216 (25.9%) experienced at least one of the 30-day adverse events. Adverse events occurred in 181 of the 638 (28.4%) admitted patients and 35 of the 192 (18.2%) patients discharged from the ED. Increasing age, complaint of dyspnea, smoking history, inadequate ventricular rate control, and patients receiving beta-blockers were factors independently associated with higher risk for adverse events.

Study results were limited by a number of factors. This was a single-center, retrospective, observational study, with all of its inherent limitations. The predictor model did not include laboratory data, such as BNP or troponin. Patients might have experienced additional events within the 30 days that were treated at other hospitals and not recorded in the database. Patient disposition might have affected the results, as patients initially admitted from the ED had a higher rate of 30-day adverse events than patients who were discharged from the ED.

Bottom line: Patients with increased age, smoking history, complaints of dyspnea, inadequate ventricular rate control in the ED, and home beta-blocker therapy are more likely to experience an atrial-fibrillation-related adverse event within 30 days.

Citation: Barrett TW, Martin AR, Storrow AB, et al. A clinical prediction model to estimate risk for 30-day adverse events in emergency department patients with symptomatic atrial fibrillation. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57 (1):1-12.

Biological Therapies Are Effective in Inducing Remission in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Clinical question: Are biological therapies useful in the treatment of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD)?

Background: Patients with CD and UC often experience flares of disease activity, despite maintenance therapy with 5-aminosalicylic acid compounds. These flares are usually treated with corticosteroids, which carry numerous adverse side effects. The role of biological therapies in inducing remission is uncertain.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Twenty-seven randomized controlled trials involving 7,416 patients.

Synopsis: Anti-TNF α antibodies and natalizumab were both superior to placebo in inducing remission of luminal CD (RR of no remission 0.87 and 0.88, respectively). Anti-TNF antibodies also were superior to placebo in preventing relapse of luminal CD (RR of relapse=0.71). Infliximab was superior to placebo in inducing remission of moderate to severely active UC (RR=0.72; 95% CI, 0.57-0.91). There were no significantly increased adverse drug effects with anti-TNF α antibodies or with infliximab compared with placebo. Natalizumab caused significantly higher rates of headache.

Limitations include risk of publication bias inherent in meta-analyses. There also was evidence of moderate heterogeneity in the studies analyzed. Finally, not every study was consistent in reporting adverse drug effects.

Bottom line: Biological therapies are superior to placebo in inducing remission of active UC and CD, as well as preventing relapse of quiescent CD.

Citation: Ford AC, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, Hanauer SB, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011; 106(4):644-659.

Glucocorticosteroids Probably Effective in Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Primarily in Active Ulcerative Colitis

Clinical question: Is glucocorticosteroid therapy effective in the treatment of active IBD and in preventing relapses?

Background: Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are chronic inflammatory bowel diseases of unclear etiology. Use of standard glucocorticosteroids and budesonide is widespread in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) treatment. To date, there has been no large-scale meta-analysis to examine the effectiveness of both treatments in CD and UC.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Twenty randomized controlled trials totaling 2,398 patients.

Synopsis: Standard glucocorticosteroids were superior to placebo for UC remission (RR of no remission=0.65; 95% CI, 0.45-0.93). Both trials of standard glucocorticosteroids in CD remission reported a statistically significant effect, but the overall effect was not significant due to heterogeneity of the studies. Budesonide was superior to placebo for CD remission (RR=0.73; 95% CI, 0.63-0.84) but not in preventing CD relapse (RR=0.93; 95% CI, 0.83-1.04). Standard glucocorticosteroids were superior to budesonide for CD remission (RR=0.82; 95% CI, 0.68-0.98) but with more adverse effects (RR=1.64; 95% CI, 1.34-2.00).

The limitations of the study include the poor overall quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis, with only one study judged as low risk of bias. There was intermediate to high heterogeneity between study results.

Bottom line: Standard glucocorticosteroids are likely effective in inducing remission in UC and, possibly, in CD. Budesonide probably is effective at inducing remission in active CD. Neither therapy was recommended in preventing relapse of UC and CD.

Citation: Ford AC, Bernstein CN, Khan KJ, et al. Glucocorticosteroid therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(4):590-599.

Levofloxacin Effective in Treatment of H. Pylori in Settings of High Clarithromycin Resistance

Clinical question: In areas with high H. pylori clarithromycin resistance rates, is levofloxacin more effective in eradicating H. pylori than standard clarithromycin, based treatment regimens?

Background: The rise in antimicrobial drug resistance is a major cause for the decreasing rate of H. pylori eradication. In areas with higher than 15% H. pyloriclarithromycin-resistant strains, quadruple therapy has been suggested as first-line therapy. The efficacy of a levofloxacin-based sequential therapy in eradicating H. pylori is undetermined.

Study design: Prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter study with a parallel-group design.

Setting: Five gastroenterology clinics in Italy.

Synopsis: Researchers randomly assigned 375 patients who were infected with H. pylori and naive to treatment to one of three groups. All three treatment groups received an initial five days of omeprazole 20 mg BID and amoxicillin 1 gm BID, then five days of omeprazole 20 mg BID and tinidazole 500 mg BID. The groups also received either clarithromycin 500 mg BID, levofloxacin 250 mg BID, or levofloxacin 500 mg BID, respectively, during the second five days of treatment.

Eradication rates were 80.8% (95% CI, 72.8% to 87.3%) with clarithromycin sequential therapy, 96.0% (95% CI, 90.9% to 98.7%) with levofloxacin-250 sequential therapy, and 96.8% (95% CI, 92.0% to 99.1%) with levofloxacin-500 sequential therapy.

The clarithromycin-group eradication rate was significantly lower than both levofloxacin groups. No significant difference was observed between the levofloxacin-250 and levofloxacin-500 groups. No differences in prevalence of antimicrobial resistance or incidence of adverse events were observed between the groups. Levofloxacin-250 therapy does offer cost savings when compared with clarithromycin sequential therapy.

A potential limitation to the study is referral bias, as each of the patients first were sent by their primary physicians to a specialized GI clinic.

Bottom line: In areas with a high prevalence of clarithromycin-resistant strains of H. pylori levofloxacin-containing sequential therapy should be considered for a first-line eradication regimen.

Citation: Romano M, Cuomo A, Gravina AG, et al. Empirical levofloxacin-containing versus clarithromycin-containing sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomised trial. Gut. 2010;59(11):1465-1470.

Tako-Tsubo Cardiomyopathy Is Associated with Higher Hospital Readmission Rates and Long-Term Mortality

Clinical question: What is the natural history of patients who develop tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy?

Background: Stress-induced or tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC) is a rare acute cardiac syndrome, characterized by chest pain or dyspnea, ischemic electrocardiographic changes, transient left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, and limited release of cardiac injury markers, in the absence of epicardial coronary artery disease (CAD). The long-term outcome of this condition is unknown.

Study design: Prospective, case-control study.

Setting: Five urban-based hospitals in Italy.

Synopsis: One hundred-sixteen patients with TTC were included in the five-year study period. Patients were followed up at one and six months, then annually thereafter. Primary endpoints were death, TTC recurrence, and rehospitalization for any cause.

Mean initial LV ejection fraction (LVEF) was 36%. Two patients died of refractory heart failure during hospitalization. Of the patients who were discharged alive, all except one showed complete LV functional recovery.

At follow-up (mean two years), only 64 (55%) patients were asymptomatic. Rehospitalization rate was high (25%), with chest pain and dyspnea the most common causes. Only two patients had a recurrence of TTC. Eleven patients died (seven from cardiovascular causes). There was no significant difference in mortality or in other clinical events between patients with and without severe LV dysfunction at presentation. The standardized mortality ratio was 3.40 (95% CI, 1.83-6.34) in the TTC population, compared with the age- and sex-specific mortality of the general population.

The study is limited by a lack of patients with subclinical TTC disease and those who might have suffered from sudden cardiac death prior to enrollment, leading to a possible sampling bias, as well as the nonrandomized use of beta-blockers.

Bottom line: Tako-tsubo disease is associated with rare recurrence of the disease, common recurrence of chest pain and dyspnea, and three times the mortality rate of the general population.

Citation: Parodi G, Bellandi B, Del Pace S, et al. Natural history of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. Chest. 2011;139(4):887-892.

Seven Independent Risk Factors Predict Postoperative Pulmonary Complications

Clinical question: What are the clinical risk factors that predict higher rates of postoperative pulmonary complications?

Background: Postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) are a major cause of postoperative morbidity, mortality, and prolonged hospital stays. Previous studies looking at risk factors for PPCs were limited by sampling bias and small sample sizes.

Study design: Prospective, randomized-sample cohort study.

Setting: Fifty-nine participating Spanish hospitals (community, intermediate referral, or major tertiary-care facilities).

Synopsis: Patients undergoing surgical procedures with general, neuraxial, or regional anesthesia were selected randomly. The main outcome was the development of at least one of the following: respiratory infection, respiratory failure, bronchospasm, atelectasis, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, or aspiration pneumonitis. Of 2,464 patients enrolled, 252 events were observed in 123 patients (5%). The 30-day mortality rate was significantly higher in patients suffering a PPC than those who did not (19.5% vs. 0.5%). Additionally, regression modeling identified seven independent risk factors: low preoperative arterial oxygen saturation, acute respiratory infection within one month of surgery, advanced age, preoperative anemia, upper abdominal or intrathoracic surgery, surgical duration more than two hours, and emergency surgery.

The study was underpowered to assess the significance of all potential risk factors for PPCs. Also, given the number of centers involved in the study, variation in assessing development of PPCs is likely.

Bottom line: Postoperative pulmonary complications are a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Seven independent risk factors were identified for the development of PPCs, which could be useful in preoperative risk stratification.

Citation: Canet J, Gallart L, Gomar C, et al. Prediction of postoperative pulmonary complications in a population-based surgical cohort. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(6):1338-1350.

Code Status Orders and Goals of Medical ICU Care

Clinical question: How familiar are patients in the medical ICU (MICU) or their surrogates regarding code-status orders and goals of care, what are their preferences, and to what extent do they and their physicians differ?

Background: Discussions about code-status orders and goals of care carry great import in the MICU. However, little data exist on patients’ code-status preferences and goals of care. More knowledge of these issues can help physicians deliver more patient-centered care.

Study design: Prospective interviews.

Setting: Twenty-six-bed MICU at a large Midwestern academic medical center.

Synopsis: Data were collected from December 2008 to December 2009 on a random sample of patients—or their surrogates—admitted to the MICU. Of 135 eligible patients/surrogates, 100 completed interviews. Patients primarily were white (95%) and from the ages of 41 to 80 (79%).

Only 28% of participants recalled having a discussion about CPR and one goal of care, while 27% recalled no discussion at all; 83% preferred full code status but had limited knowledge of CPR and its outcomes in the hospital setting. Only 4% were able to identify all components of CPR, and they estimated the mean probability of survival following in-hospital arrest with CPR to be 71.8%, although data suggest survival is closer to 18%. There was a correlation between a higher estimation of survival following CPR and preference for it. After learning about the evidence-based likelihood of a good neurologic outcome following CPR, 8% of the participants became less interested.

Discrepancies between patients’ stated code status and that in the medical record was identified 16% of the time. Additionally, 67.7% of participants differed with their physicians regarding the most important goal of care.

Bottom line: Discussions about code status and goals of care in the MICU occur less frequently than recommended, leading to widespread discrepancies between patients/surrogates and their physicians regarding the most important goal of care. This is compounded by the fact that patients and their surrogates have limited knowledge about in-hospital CPR and its likelihood of success.

Citation: Gehlbach TG, Shinkunas LA, Forman-Hoffman VL, Thomas KW, Schmidt GA, Kaldjian LC. Code status orders and goals of care in the medical ICU. Chest. 2011;139:802-809. TH

SHM’S Leadership Academy Trains Next Generation of HM Leaders

As HM programs mature, seasoned leaders begin to evaluate the leadership potential of their staff, both clinical and administrative. Although the skills that brought each staff member to their current position often are well above average, the personal tools necessary to lead teams will ultimately come to the fore.

The need to develop and enhance leadership skills within hospitalist programs has attracted nearly 1,800 participants to SHM’s Leadership Academy courses.

Hundreds more are expected to attend the next academy, Sept. 12-15 at the historic Fontainebleau Miami Beach resort. Registration is available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership.

To encourage HM programs to strengthen entire teams, SHM offers a $100 discount per person for groups of three or more hospitalists. Group leaders who bring their administrators receive a 10% discount.

First-time Leadership Academy participants will participate in the "Foundations for Effective Leadership" course. Those who already have completed "Foundations" will take their leadership skills to the next level with "Advanced Leadership: Personal Leadership Excellence."

Another advanced leadership course, "Strengthening Your Organization," will be presented in February 2012 in New Orleans.

"I send every hospitalist to Leadership Academy because I believe it makes them better team members," said Eric Howell, section chief of hospital medicine and deputy director of hospital operations for the Department of Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, in a video presented at HM11. Dr. Howell, an academy faculty member, says the training makes hospitalists "better problem-solvers. I believe it makes them better doctors." TH

As HM programs mature, seasoned leaders begin to evaluate the leadership potential of their staff, both clinical and administrative. Although the skills that brought each staff member to their current position often are well above average, the personal tools necessary to lead teams will ultimately come to the fore.

The need to develop and enhance leadership skills within hospitalist programs has attracted nearly 1,800 participants to SHM’s Leadership Academy courses.

Hundreds more are expected to attend the next academy, Sept. 12-15 at the historic Fontainebleau Miami Beach resort. Registration is available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership.

To encourage HM programs to strengthen entire teams, SHM offers a $100 discount per person for groups of three or more hospitalists. Group leaders who bring their administrators receive a 10% discount.

First-time Leadership Academy participants will participate in the "Foundations for Effective Leadership" course. Those who already have completed "Foundations" will take their leadership skills to the next level with "Advanced Leadership: Personal Leadership Excellence."

Another advanced leadership course, "Strengthening Your Organization," will be presented in February 2012 in New Orleans.

"I send every hospitalist to Leadership Academy because I believe it makes them better team members," said Eric Howell, section chief of hospital medicine and deputy director of hospital operations for the Department of Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, in a video presented at HM11. Dr. Howell, an academy faculty member, says the training makes hospitalists "better problem-solvers. I believe it makes them better doctors." TH

As HM programs mature, seasoned leaders begin to evaluate the leadership potential of their staff, both clinical and administrative. Although the skills that brought each staff member to their current position often are well above average, the personal tools necessary to lead teams will ultimately come to the fore.

The need to develop and enhance leadership skills within hospitalist programs has attracted nearly 1,800 participants to SHM’s Leadership Academy courses.

Hundreds more are expected to attend the next academy, Sept. 12-15 at the historic Fontainebleau Miami Beach resort. Registration is available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership.

To encourage HM programs to strengthen entire teams, SHM offers a $100 discount per person for groups of three or more hospitalists. Group leaders who bring their administrators receive a 10% discount.

First-time Leadership Academy participants will participate in the "Foundations for Effective Leadership" course. Those who already have completed "Foundations" will take their leadership skills to the next level with "Advanced Leadership: Personal Leadership Excellence."

Another advanced leadership course, "Strengthening Your Organization," will be presented in February 2012 in New Orleans.

"I send every hospitalist to Leadership Academy because I believe it makes them better team members," said Eric Howell, section chief of hospital medicine and deputy director of hospital operations for the Department of Medicine at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, in a video presented at HM11. Dr. Howell, an academy faculty member, says the training makes hospitalists "better problem-solvers. I believe it makes them better doctors." TH

Policy Corner: Obama Suggests Eliminating Wasteful Regulations

The federal government is taking a hard look at many of its regulations, and hospitalists might have the chance to help identify those that no longer make sense.

On Jan. 18, President Obama issued Executive Order 13563, which calls, in part, for a comprehensive retrospective review of existing government regulations. The stated goal of this review is to improve or remove those rules that are out of date, unnecessary, excessively burdensome, or in conflict with other rules.

The Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), the executive-level department charged with overseeing the execution of this order, asked federal agencies to submit preliminary plans for how they will conduct their internal reviews. The agencies responded, and on May 26, the White House released 30 agency preliminary plans to the public, including those prepared by the Department of Commerce, the Department of Energy, and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

When reviewing some of these publicly available preliminary plans, the easy answer for some observers is to say that most rules should be eliminated. Rules requiring the use of such technologies as film X-rays instead of digital images are obvious culprits in the out-of date category; rules defining milk as "oil" (subjecting it to the same costly environmental safeguards as real oil) are just as absurd. Both of these regulations are being lifted as a result of the review.

In contrast, many rules actually do protect public health and safety and will not be subject to review. For example, as a result of federal rulemaking, highway deaths are at the lowest level in 60 years and the risk of contracting salmonella from eggs is relatively low.

As part of HHS, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) specifically stated that "the goal of the retrospective review will be to identify opportunities to improve patient care and outcomes and reduce system costs by removing obsolete or burdensome requirements." A major CMS concern will be to prevent the elimination or revision of a regulation only to find that the problem it sought to solve resurfaces, or that its removal or revision results in unanticipated and more serious outcomes.

This review could significantly impact HM in areas of quality measurement and reporting requirements:

- What quality measurements might not accomplish their intent?

- What measures might result in more harm than good?

- What reporting or process requirements could be changed to make for less duplication?

- If requirements cannot be eliminated, how can they be improved?

Due to hospitalist expertise in quality-improvement (QI) efforts and cost containment, these stated goals and the concerns that come with them are areas where hospitalists are likely to have some good answers. Hospitalists should not hesitate to provide their input to SHM Government Relations staff so that your ideas can be shared with CMS.

A complete list of agency proposals is available at www.whitehouse.gov/21stcentury gov/actions/21st-century-regulatory-system.

The federal government is taking a hard look at many of its regulations, and hospitalists might have the chance to help identify those that no longer make sense.

On Jan. 18, President Obama issued Executive Order 13563, which calls, in part, for a comprehensive retrospective review of existing government regulations. The stated goal of this review is to improve or remove those rules that are out of date, unnecessary, excessively burdensome, or in conflict with other rules.

The Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), the executive-level department charged with overseeing the execution of this order, asked federal agencies to submit preliminary plans for how they will conduct their internal reviews. The agencies responded, and on May 26, the White House released 30 agency preliminary plans to the public, including those prepared by the Department of Commerce, the Department of Energy, and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

When reviewing some of these publicly available preliminary plans, the easy answer for some observers is to say that most rules should be eliminated. Rules requiring the use of such technologies as film X-rays instead of digital images are obvious culprits in the out-of date category; rules defining milk as "oil" (subjecting it to the same costly environmental safeguards as real oil) are just as absurd. Both of these regulations are being lifted as a result of the review.

In contrast, many rules actually do protect public health and safety and will not be subject to review. For example, as a result of federal rulemaking, highway deaths are at the lowest level in 60 years and the risk of contracting salmonella from eggs is relatively low.

As part of HHS, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) specifically stated that "the goal of the retrospective review will be to identify opportunities to improve patient care and outcomes and reduce system costs by removing obsolete or burdensome requirements." A major CMS concern will be to prevent the elimination or revision of a regulation only to find that the problem it sought to solve resurfaces, or that its removal or revision results in unanticipated and more serious outcomes.

This review could significantly impact HM in areas of quality measurement and reporting requirements:

- What quality measurements might not accomplish their intent?

- What measures might result in more harm than good?

- What reporting or process requirements could be changed to make for less duplication?

- If requirements cannot be eliminated, how can they be improved?

Due to hospitalist expertise in quality-improvement (QI) efforts and cost containment, these stated goals and the concerns that come with them are areas where hospitalists are likely to have some good answers. Hospitalists should not hesitate to provide their input to SHM Government Relations staff so that your ideas can be shared with CMS.

A complete list of agency proposals is available at www.whitehouse.gov/21stcentury gov/actions/21st-century-regulatory-system.

The federal government is taking a hard look at many of its regulations, and hospitalists might have the chance to help identify those that no longer make sense.

On Jan. 18, President Obama issued Executive Order 13563, which calls, in part, for a comprehensive retrospective review of existing government regulations. The stated goal of this review is to improve or remove those rules that are out of date, unnecessary, excessively burdensome, or in conflict with other rules.

The Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), the executive-level department charged with overseeing the execution of this order, asked federal agencies to submit preliminary plans for how they will conduct their internal reviews. The agencies responded, and on May 26, the White House released 30 agency preliminary plans to the public, including those prepared by the Department of Commerce, the Department of Energy, and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

When reviewing some of these publicly available preliminary plans, the easy answer for some observers is to say that most rules should be eliminated. Rules requiring the use of such technologies as film X-rays instead of digital images are obvious culprits in the out-of date category; rules defining milk as "oil" (subjecting it to the same costly environmental safeguards as real oil) are just as absurd. Both of these regulations are being lifted as a result of the review.

In contrast, many rules actually do protect public health and safety and will not be subject to review. For example, as a result of federal rulemaking, highway deaths are at the lowest level in 60 years and the risk of contracting salmonella from eggs is relatively low.

As part of HHS, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) specifically stated that "the goal of the retrospective review will be to identify opportunities to improve patient care and outcomes and reduce system costs by removing obsolete or burdensome requirements." A major CMS concern will be to prevent the elimination or revision of a regulation only to find that the problem it sought to solve resurfaces, or that its removal or revision results in unanticipated and more serious outcomes.

This review could significantly impact HM in areas of quality measurement and reporting requirements:

- What quality measurements might not accomplish their intent?

- What measures might result in more harm than good?

- What reporting or process requirements could be changed to make for less duplication?

- If requirements cannot be eliminated, how can they be improved?

Due to hospitalist expertise in quality-improvement (QI) efforts and cost containment, these stated goals and the concerns that come with them are areas where hospitalists are likely to have some good answers. Hospitalists should not hesitate to provide their input to SHM Government Relations staff so that your ideas can be shared with CMS.

A complete list of agency proposals is available at www.whitehouse.gov/21stcentury gov/actions/21st-century-regulatory-system.

Master in HM profile

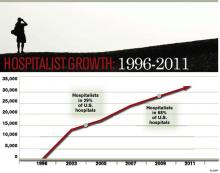

Fifteen years ago, Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, and Lee Goldman, MD, introduced hospital medicine and the term "hospitalist" to modern medicine in an article in the New England Journal of Medicine. In it, they wrote, "we anticipate the rapid growth of a new breed of physicians we call ‘hospitalists’—specialists in inpatient medicine—who will be responsible for managing the care of hospitalized patients in the same way that primary care physicians are responsible for managing the care of outpatients."

Since that introduction in 1996, the term "hospitalist" has gone from concept to cutting edge, and now to a title that describes more than 30,000 caregivers in hospitals around the world.

The evolution and growth of the hospitalist specialty owes much to Dr. Wachter. In addition to coining the term, he wrote the specialty’s first textbook, led SHM as president in 2000, and in 2010 was one of three HM pioneers honored by SHM as the first group of Masters in Hospital Medicine.

For each of the past three years, Modern Healthcare has listed him as one of healthcare’s most influential physician-executives.

Dr. Wachter used his recent presentation at HM11 to reflect on the growth of hospital medicine, where he showed how the specialty’s early focus on quality and safety puts hospitalists in positions of authority among physicians and hospitals.

Today, he is professor and associate chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco and chief of the division of hospital medicine, and chief of the medical service at UCSF Medical Center.

In July, Dr. Wachter was named chair-elect of the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) board of directors.

Fifteen years ago, Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, and Lee Goldman, MD, introduced hospital medicine and the term "hospitalist" to modern medicine in an article in the New England Journal of Medicine. In it, they wrote, "we anticipate the rapid growth of a new breed of physicians we call ‘hospitalists’—specialists in inpatient medicine—who will be responsible for managing the care of hospitalized patients in the same way that primary care physicians are responsible for managing the care of outpatients."

Since that introduction in 1996, the term "hospitalist" has gone from concept to cutting edge, and now to a title that describes more than 30,000 caregivers in hospitals around the world.

The evolution and growth of the hospitalist specialty owes much to Dr. Wachter. In addition to coining the term, he wrote the specialty’s first textbook, led SHM as president in 2000, and in 2010 was one of three HM pioneers honored by SHM as the first group of Masters in Hospital Medicine.

For each of the past three years, Modern Healthcare has listed him as one of healthcare’s most influential physician-executives.

Dr. Wachter used his recent presentation at HM11 to reflect on the growth of hospital medicine, where he showed how the specialty’s early focus on quality and safety puts hospitalists in positions of authority among physicians and hospitals.

Today, he is professor and associate chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco and chief of the division of hospital medicine, and chief of the medical service at UCSF Medical Center.

In July, Dr. Wachter was named chair-elect of the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) board of directors.

Fifteen years ago, Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, and Lee Goldman, MD, introduced hospital medicine and the term "hospitalist" to modern medicine in an article in the New England Journal of Medicine. In it, they wrote, "we anticipate the rapid growth of a new breed of physicians we call ‘hospitalists’—specialists in inpatient medicine—who will be responsible for managing the care of hospitalized patients in the same way that primary care physicians are responsible for managing the care of outpatients."

Since that introduction in 1996, the term "hospitalist" has gone from concept to cutting edge, and now to a title that describes more than 30,000 caregivers in hospitals around the world.

The evolution and growth of the hospitalist specialty owes much to Dr. Wachter. In addition to coining the term, he wrote the specialty’s first textbook, led SHM as president in 2000, and in 2010 was one of three HM pioneers honored by SHM as the first group of Masters in Hospital Medicine.

For each of the past three years, Modern Healthcare has listed him as one of healthcare’s most influential physician-executives.

Dr. Wachter used his recent presentation at HM11 to reflect on the growth of hospital medicine, where he showed how the specialty’s early focus on quality and safety puts hospitalists in positions of authority among physicians and hospitals.

Today, he is professor and associate chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco and chief of the division of hospital medicine, and chief of the medical service at UCSF Medical Center.

In July, Dr. Wachter was named chair-elect of the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) board of directors.

Hospitalists on the Move

Cogent HMG has announced its new executive team and outside directors following the merger of Cogent Healthcare and Hospitalists Management Group (HMG). Gene Fleming, formerly president and CEO of Cogent Healthcare, will serve as executive chairman, assisting CEO Stephen Houff, MD, founder and CEO of Hospitalists Management Group. Ron Greeno, MD, a founder of Cogent Healthcare, will serve as chief medical officer of Cogent HMG and will steer the consulting business and serve as an advisor to the board. Antoine Agassi will serve as president and oversee day-to-day business operations. Linda Ellis will serve as COO, directing all regional and site operations.

Other key executives: Rusty Holman, MD, chief clinical officer; Susan Brownie, chief financial officer; Doug Mefford, chief legal officer; Anna-Gene O’Neal, senior vice president of quality; and Cheryl Slack, senior vice president of human resources. In addition to Fleming and Houff, Cogent HMG board members include Gary Chartrand, executive chairman of Acosta Sales and Marketing; Mike Leavitt, founder and chairman of Leavitt Partners and former U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services; and Mark Neaman, president and CEO of NorthShore University HealthSystem.

The St. Anthony’s Hospital Foundation in St. Petersburg, Fla., has announced five new members of its board of directors: Emery Ellinger, CEO of the brokerage firm Aberdeen Advisors; Vitalis Unaeze, MD; Brian McNulty of USI Insurance Services; Angela Rouson, a St. Petersburg resident with a history of community service; and Dan Masi of Bright House Networks, a telecommunications company. Karim Godamunne, MD, has been promoted from medical director to vice president of clinical systems integration at Eagle Hospital Physicians in Atlanta.

Dr. Godamunne won primary stroke center designation within eight months of adding a teleneurology program to an existing Eagle hospitalist program at South Fulton Medical Center in East Point, Ga. Caitlin B. Foxley, MD, has been elected hospital medicine service chief for the Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha. Dr. Foxley is a member of Team Hospitalist.

Cynthia Roldan, MD, director of Westminster, Md.-based Carroll Hospital Center’s pediatric hospitalist program, has been selected as the hospital’s June Physician of the Month. A physician affiliated with Carroll Hospital Center for four years, Roldan was nominated for exceptional patient care and education of new and expecting mothers.

Dixon, Ill.-based Katherine Shaw Bethea Hospital has announced that hospitalist Tim Appenheimer, MD, has been promoted to vice president and CMO. The move is meant to address the growing focus on improving quality and patient safety across the country.

Cogent HMG has announced its new executive team and outside directors following the merger of Cogent Healthcare and Hospitalists Management Group (HMG). Gene Fleming, formerly president and CEO of Cogent Healthcare, will serve as executive chairman, assisting CEO Stephen Houff, MD, founder and CEO of Hospitalists Management Group. Ron Greeno, MD, a founder of Cogent Healthcare, will serve as chief medical officer of Cogent HMG and will steer the consulting business and serve as an advisor to the board. Antoine Agassi will serve as president and oversee day-to-day business operations. Linda Ellis will serve as COO, directing all regional and site operations.