User login

Stress in medicine: Strategies for caregivers, patients, clinicians—The burdens of caregiver stress

The number of people in the United States who spend a significant part of each week working as unpaid caregivers is considerable, and the toll exacted for such work is high. Understanding the profi le of the caregiver, the nature of the duties performed, the stress imposed by such duties, and the consequences of the stress can assist the clinician in recognizing the caregiver in need of intervention.

A PROFILE OF THE CAREGIVER

A recent survey estimated that more than 65 million Americans provide unpaid assistance annually to older adults with disabilities.1 The value of that labor has been estimated at $306 billion annually, or nearly double the combined cost of home health care and nursing home care.2,3

The typical caregiver is a woman, about 48 years old, with some college education, who spends 20 hours or more each week providing unpaid care to someone aged 50 years or older.1 The recipients of care often have long-term physical disabilities; mental confusion or emotional problems frequently complicate care.

PSYCHOLOGIC AND PHYSICAL COSTS

Caregiving may take a toll on the caregiver in a variety of ways: behavioral, in the form of alcohol or substance use4; psychologic, in the form of depression or other mental health problems5; and physical, in the form of chronic health conditions and impaired immune response.6 About three-fifths of caregivers report fair or poor health, compared with one-third of noncaregivers, and caregivers have approximately twice as many chronic conditions, such as heart disease, cancer, arthritis, and diabetes, compared with noncaregivers.2,7 Caregiving also exacts a financial toll, as employees who are caregivers cost their employers $13.4 billion more per year in health care expenditures.8 In addition, absenteeism, workday interruptions, and shifts from full-time to part-time work by caregivers cost businesses between $17.1 and $33.6 billion per year.9

The cost of caregiving is higher for women, who exhibit higher levels of anxiety and depression and lower levels of subjective well-being, life satisfaction, and physical health.10,11 The stress of caregiving has also been identified as a risk factor for morbidity among older (66 to 96 years old) caregivers, who have a 63% greater mortality than noncaregivers of the same age.12

PSYCHOSOCIAL STRESS, UNHEALTHY BEHAVIORS, AND ILLNESS ARE LINKED

Psychosocial stress is a predictor of disease and can lead to unhealthy behaviors such as smoking, substance abuse, overeating, poor nutrition, and a sedentary lifestyle; these, in turn, can lead to physical and psychiatric illness. Behaviors adopted initially as coping skills may persist to become chronic, thereby promoting either continued wellness (in the case of healthy coping behaviors) or worsening levels of illness (in the case of unhealthy coping behaviors).

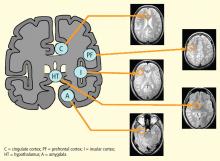

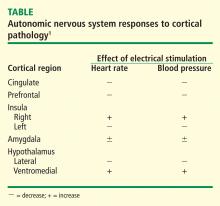

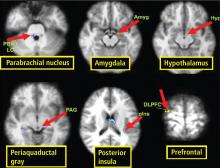

McEwen and Gianaros13 have suggested that these stress mechanisms arise from patterns of communication between the brain and the autonomic, cardiovascular, and immune systems, which mutually influenceone another. These so-called bidirectional stress processes affect cognition, experience, and behavior.

An integrated model of stress that maps the bidirectional causal pathways among psychosocial stressors, resulting unhealthy behaviors, and illness is needed. Although the steps from unhealthy behaviors to illness are fairly well understood, the links from psychosocial stress, such as those exhibited by caregivers, to unhealthy behaviors are not as clear. Several mediators are under study:

- Personality mediators can be either ameliorative (resilience, self-confi dence, self-control, optimism, high self-esteem, a sense of mastery, and finding meaning in life) or exacerbating (neuroticism and inhibition, which together form the so-called type D personality).

- Environmental mediators include social support, financial support, a history of a significant life change, and trauma early in life, which may increase one’s subsequent vulnerability to unhealthy behaviors.

- Biologic mediators may include prolonged sympathetic activation and enhanced platelet activation, caused by increased levels of depression and anxiety in chronically stressed caregivers.14

IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERVENTION

A significant percentage of caregivers do not need a clinician’s intervention to help them cope with stress or unhealthy coping skills. Among caregivers aged 50 years or older, 47% indicated in a recent study that the burden of caregiving is low (ie, 1 or 2 on a 5-point scale).1 Those who respond to stressors as challenges rather than threats tend to be resilient people who exert control over their lives, often through meditation or similar techniques, and have a strong social support network. Many report that caregiving provides them with an opportunity to act in accordance with their values and feel helpful rather than helpless.

Cognitive-behavioral interventions to alleviate stress-related symptoms appear to be more effective if offered as individual rather than group therapy. Teaching caregivers effective coping strategies, rather than merely providing social support, has been shown to improve caregiver psychologic health.15 Chief among the goals of intervention should be to alter brain function and instill optimism, a sense of control and self-esteem.13

- The National Alliance for Caregiving, in collaboration with the American Association of Retired Persons. Caregiving in the U.S. 2009. National Alliance for Caregiving Web site. http://www.caregiving.org/data/Caregiving_in_the_US_2009_full_report.pdf. Published November 2009. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Family Caregiver Alliance. Caregiver health. A population at risk. National Alliance for Caregiving Web site. http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content_node.jsp?nodeid=1822. Published 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Family Caregiver Alliance. Prevalence, hours, and economic value of family caregiving, updated state-by-state analysis of 2004 national estimates. National Alliance for Caregiving Web site. http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content/pdfs/State_Caregiving_Data_Amo_20061107.pdf. Published 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Evercare. Study of caregivers in decline: a close-up look at the health risks of caring for a loved one. National Alliance for Caregiving Web site. http://www.caregiving.org/data/Caregivers%20in%20Decline%20Study-FINAL-lowres.pdf. Published 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a metaanalysis. Psychol Aging 2003; 18:250–267.

- Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan JM. Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2003; 129:946–972.

- Ho A, Collins S, Davis K, Doty M. A look at working-age caregivers’ roles, health concerns, and need for support (issue brief). New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2005.

- MetLife study of working caregivers and employer health care costs. MetLife Web site. http://www.metlife.com/assets/cao/mmi/publications/studies/2010/mmi-working-caregivers-employers-health-carecosts.pdf. Published July 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- MetLife caregiving cost study: productivity losses to U.S. business. National Alliance for Caregiving Web site. http://www.caregiving. org/data/Caregiver%20Cost%20Study.pdf. Published July 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: an updated meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2006; 61:P33–P45.

- Johnson RW, Wiener JM. A profi le of frail older Americans and their caregivers. Urban Institute Web site. http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/311284_older_americans.pdf. Published February 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the caregiver health effects study. JAMA 1999; 282:2215–2219.

- McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Ann NY Acad Sci 2010; 1186:190–222.

- Aschbacher K, Mills PJ, von Känel R, et al. Effects of depressive and anxious symptoms on norepinephrine and platelet P-selectin responses to acute psychological stress among elderly caregivers. Brain Behav Immun 2008; 22:493–502.

- Selwood A, Johnston K, Katona C, Lyketsos C, Livingston G. Systematic review of the effect of psychological interventions on family caregivers of people with dementia. J Affect Disord 2007; 101:75–89.

The number of people in the United States who spend a significant part of each week working as unpaid caregivers is considerable, and the toll exacted for such work is high. Understanding the profi le of the caregiver, the nature of the duties performed, the stress imposed by such duties, and the consequences of the stress can assist the clinician in recognizing the caregiver in need of intervention.

A PROFILE OF THE CAREGIVER

A recent survey estimated that more than 65 million Americans provide unpaid assistance annually to older adults with disabilities.1 The value of that labor has been estimated at $306 billion annually, or nearly double the combined cost of home health care and nursing home care.2,3

The typical caregiver is a woman, about 48 years old, with some college education, who spends 20 hours or more each week providing unpaid care to someone aged 50 years or older.1 The recipients of care often have long-term physical disabilities; mental confusion or emotional problems frequently complicate care.

PSYCHOLOGIC AND PHYSICAL COSTS

Caregiving may take a toll on the caregiver in a variety of ways: behavioral, in the form of alcohol or substance use4; psychologic, in the form of depression or other mental health problems5; and physical, in the form of chronic health conditions and impaired immune response.6 About three-fifths of caregivers report fair or poor health, compared with one-third of noncaregivers, and caregivers have approximately twice as many chronic conditions, such as heart disease, cancer, arthritis, and diabetes, compared with noncaregivers.2,7 Caregiving also exacts a financial toll, as employees who are caregivers cost their employers $13.4 billion more per year in health care expenditures.8 In addition, absenteeism, workday interruptions, and shifts from full-time to part-time work by caregivers cost businesses between $17.1 and $33.6 billion per year.9

The cost of caregiving is higher for women, who exhibit higher levels of anxiety and depression and lower levels of subjective well-being, life satisfaction, and physical health.10,11 The stress of caregiving has also been identified as a risk factor for morbidity among older (66 to 96 years old) caregivers, who have a 63% greater mortality than noncaregivers of the same age.12

PSYCHOSOCIAL STRESS, UNHEALTHY BEHAVIORS, AND ILLNESS ARE LINKED

Psychosocial stress is a predictor of disease and can lead to unhealthy behaviors such as smoking, substance abuse, overeating, poor nutrition, and a sedentary lifestyle; these, in turn, can lead to physical and psychiatric illness. Behaviors adopted initially as coping skills may persist to become chronic, thereby promoting either continued wellness (in the case of healthy coping behaviors) or worsening levels of illness (in the case of unhealthy coping behaviors).

McEwen and Gianaros13 have suggested that these stress mechanisms arise from patterns of communication between the brain and the autonomic, cardiovascular, and immune systems, which mutually influenceone another. These so-called bidirectional stress processes affect cognition, experience, and behavior.

An integrated model of stress that maps the bidirectional causal pathways among psychosocial stressors, resulting unhealthy behaviors, and illness is needed. Although the steps from unhealthy behaviors to illness are fairly well understood, the links from psychosocial stress, such as those exhibited by caregivers, to unhealthy behaviors are not as clear. Several mediators are under study:

- Personality mediators can be either ameliorative (resilience, self-confi dence, self-control, optimism, high self-esteem, a sense of mastery, and finding meaning in life) or exacerbating (neuroticism and inhibition, which together form the so-called type D personality).

- Environmental mediators include social support, financial support, a history of a significant life change, and trauma early in life, which may increase one’s subsequent vulnerability to unhealthy behaviors.

- Biologic mediators may include prolonged sympathetic activation and enhanced platelet activation, caused by increased levels of depression and anxiety in chronically stressed caregivers.14

IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERVENTION

A significant percentage of caregivers do not need a clinician’s intervention to help them cope with stress or unhealthy coping skills. Among caregivers aged 50 years or older, 47% indicated in a recent study that the burden of caregiving is low (ie, 1 or 2 on a 5-point scale).1 Those who respond to stressors as challenges rather than threats tend to be resilient people who exert control over their lives, often through meditation or similar techniques, and have a strong social support network. Many report that caregiving provides them with an opportunity to act in accordance with their values and feel helpful rather than helpless.

Cognitive-behavioral interventions to alleviate stress-related symptoms appear to be more effective if offered as individual rather than group therapy. Teaching caregivers effective coping strategies, rather than merely providing social support, has been shown to improve caregiver psychologic health.15 Chief among the goals of intervention should be to alter brain function and instill optimism, a sense of control and self-esteem.13

The number of people in the United States who spend a significant part of each week working as unpaid caregivers is considerable, and the toll exacted for such work is high. Understanding the profi le of the caregiver, the nature of the duties performed, the stress imposed by such duties, and the consequences of the stress can assist the clinician in recognizing the caregiver in need of intervention.

A PROFILE OF THE CAREGIVER

A recent survey estimated that more than 65 million Americans provide unpaid assistance annually to older adults with disabilities.1 The value of that labor has been estimated at $306 billion annually, or nearly double the combined cost of home health care and nursing home care.2,3

The typical caregiver is a woman, about 48 years old, with some college education, who spends 20 hours or more each week providing unpaid care to someone aged 50 years or older.1 The recipients of care often have long-term physical disabilities; mental confusion or emotional problems frequently complicate care.

PSYCHOLOGIC AND PHYSICAL COSTS

Caregiving may take a toll on the caregiver in a variety of ways: behavioral, in the form of alcohol or substance use4; psychologic, in the form of depression or other mental health problems5; and physical, in the form of chronic health conditions and impaired immune response.6 About three-fifths of caregivers report fair or poor health, compared with one-third of noncaregivers, and caregivers have approximately twice as many chronic conditions, such as heart disease, cancer, arthritis, and diabetes, compared with noncaregivers.2,7 Caregiving also exacts a financial toll, as employees who are caregivers cost their employers $13.4 billion more per year in health care expenditures.8 In addition, absenteeism, workday interruptions, and shifts from full-time to part-time work by caregivers cost businesses between $17.1 and $33.6 billion per year.9

The cost of caregiving is higher for women, who exhibit higher levels of anxiety and depression and lower levels of subjective well-being, life satisfaction, and physical health.10,11 The stress of caregiving has also been identified as a risk factor for morbidity among older (66 to 96 years old) caregivers, who have a 63% greater mortality than noncaregivers of the same age.12

PSYCHOSOCIAL STRESS, UNHEALTHY BEHAVIORS, AND ILLNESS ARE LINKED

Psychosocial stress is a predictor of disease and can lead to unhealthy behaviors such as smoking, substance abuse, overeating, poor nutrition, and a sedentary lifestyle; these, in turn, can lead to physical and psychiatric illness. Behaviors adopted initially as coping skills may persist to become chronic, thereby promoting either continued wellness (in the case of healthy coping behaviors) or worsening levels of illness (in the case of unhealthy coping behaviors).

McEwen and Gianaros13 have suggested that these stress mechanisms arise from patterns of communication between the brain and the autonomic, cardiovascular, and immune systems, which mutually influenceone another. These so-called bidirectional stress processes affect cognition, experience, and behavior.

An integrated model of stress that maps the bidirectional causal pathways among psychosocial stressors, resulting unhealthy behaviors, and illness is needed. Although the steps from unhealthy behaviors to illness are fairly well understood, the links from psychosocial stress, such as those exhibited by caregivers, to unhealthy behaviors are not as clear. Several mediators are under study:

- Personality mediators can be either ameliorative (resilience, self-confi dence, self-control, optimism, high self-esteem, a sense of mastery, and finding meaning in life) or exacerbating (neuroticism and inhibition, which together form the so-called type D personality).

- Environmental mediators include social support, financial support, a history of a significant life change, and trauma early in life, which may increase one’s subsequent vulnerability to unhealthy behaviors.

- Biologic mediators may include prolonged sympathetic activation and enhanced platelet activation, caused by increased levels of depression and anxiety in chronically stressed caregivers.14

IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERVENTION

A significant percentage of caregivers do not need a clinician’s intervention to help them cope with stress or unhealthy coping skills. Among caregivers aged 50 years or older, 47% indicated in a recent study that the burden of caregiving is low (ie, 1 or 2 on a 5-point scale).1 Those who respond to stressors as challenges rather than threats tend to be resilient people who exert control over their lives, often through meditation or similar techniques, and have a strong social support network. Many report that caregiving provides them with an opportunity to act in accordance with their values and feel helpful rather than helpless.

Cognitive-behavioral interventions to alleviate stress-related symptoms appear to be more effective if offered as individual rather than group therapy. Teaching caregivers effective coping strategies, rather than merely providing social support, has been shown to improve caregiver psychologic health.15 Chief among the goals of intervention should be to alter brain function and instill optimism, a sense of control and self-esteem.13

- The National Alliance for Caregiving, in collaboration with the American Association of Retired Persons. Caregiving in the U.S. 2009. National Alliance for Caregiving Web site. http://www.caregiving.org/data/Caregiving_in_the_US_2009_full_report.pdf. Published November 2009. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Family Caregiver Alliance. Caregiver health. A population at risk. National Alliance for Caregiving Web site. http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content_node.jsp?nodeid=1822. Published 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Family Caregiver Alliance. Prevalence, hours, and economic value of family caregiving, updated state-by-state analysis of 2004 national estimates. National Alliance for Caregiving Web site. http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content/pdfs/State_Caregiving_Data_Amo_20061107.pdf. Published 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Evercare. Study of caregivers in decline: a close-up look at the health risks of caring for a loved one. National Alliance for Caregiving Web site. http://www.caregiving.org/data/Caregivers%20in%20Decline%20Study-FINAL-lowres.pdf. Published 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a metaanalysis. Psychol Aging 2003; 18:250–267.

- Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan JM. Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2003; 129:946–972.

- Ho A, Collins S, Davis K, Doty M. A look at working-age caregivers’ roles, health concerns, and need for support (issue brief). New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2005.

- MetLife study of working caregivers and employer health care costs. MetLife Web site. http://www.metlife.com/assets/cao/mmi/publications/studies/2010/mmi-working-caregivers-employers-health-carecosts.pdf. Published July 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- MetLife caregiving cost study: productivity losses to U.S. business. National Alliance for Caregiving Web site. http://www.caregiving. org/data/Caregiver%20Cost%20Study.pdf. Published July 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: an updated meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2006; 61:P33–P45.

- Johnson RW, Wiener JM. A profi le of frail older Americans and their caregivers. Urban Institute Web site. http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/311284_older_americans.pdf. Published February 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the caregiver health effects study. JAMA 1999; 282:2215–2219.

- McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Ann NY Acad Sci 2010; 1186:190–222.

- Aschbacher K, Mills PJ, von Känel R, et al. Effects of depressive and anxious symptoms on norepinephrine and platelet P-selectin responses to acute psychological stress among elderly caregivers. Brain Behav Immun 2008; 22:493–502.

- Selwood A, Johnston K, Katona C, Lyketsos C, Livingston G. Systematic review of the effect of psychological interventions on family caregivers of people with dementia. J Affect Disord 2007; 101:75–89.

- The National Alliance for Caregiving, in collaboration with the American Association of Retired Persons. Caregiving in the U.S. 2009. National Alliance for Caregiving Web site. http://www.caregiving.org/data/Caregiving_in_the_US_2009_full_report.pdf. Published November 2009. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Family Caregiver Alliance. Caregiver health. A population at risk. National Alliance for Caregiving Web site. http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content_node.jsp?nodeid=1822. Published 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Family Caregiver Alliance. Prevalence, hours, and economic value of family caregiving, updated state-by-state analysis of 2004 national estimates. National Alliance for Caregiving Web site. http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content/pdfs/State_Caregiving_Data_Amo_20061107.pdf. Published 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Evercare. Study of caregivers in decline: a close-up look at the health risks of caring for a loved one. National Alliance for Caregiving Web site. http://www.caregiving.org/data/Caregivers%20in%20Decline%20Study-FINAL-lowres.pdf. Published 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a metaanalysis. Psychol Aging 2003; 18:250–267.

- Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan JM. Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2003; 129:946–972.

- Ho A, Collins S, Davis K, Doty M. A look at working-age caregivers’ roles, health concerns, and need for support (issue brief). New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2005.

- MetLife study of working caregivers and employer health care costs. MetLife Web site. http://www.metlife.com/assets/cao/mmi/publications/studies/2010/mmi-working-caregivers-employers-health-carecosts.pdf. Published July 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- MetLife caregiving cost study: productivity losses to U.S. business. National Alliance for Caregiving Web site. http://www.caregiving. org/data/Caregiver%20Cost%20Study.pdf. Published July 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: an updated meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2006; 61:P33–P45.

- Johnson RW, Wiener JM. A profi le of frail older Americans and their caregivers. Urban Institute Web site. http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/311284_older_americans.pdf. Published February 2006. Accessed March 21, 2011.

- Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the caregiver health effects study. JAMA 1999; 282:2215–2219.

- McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Ann NY Acad Sci 2010; 1186:190–222.

- Aschbacher K, Mills PJ, von Känel R, et al. Effects of depressive and anxious symptoms on norepinephrine and platelet P-selectin responses to acute psychological stress among elderly caregivers. Brain Behav Immun 2008; 22:493–502.

- Selwood A, Johnston K, Katona C, Lyketsos C, Livingston G. Systematic review of the effect of psychological interventions on family caregivers of people with dementia. J Affect Disord 2007; 101:75–89.

Stress in medicine: Strategies for caregivers, patients, clinicians—Promoting better outcomes with stress and anxiety reduction

The traditional paradigm for cardiac care has emphasized the use of technology to treat disease. Our focus on technologies such as echocardiography, advanced imaging instrumentation, and cardiac catheterization mirrors the preoccupation of society as a whole with technologic advances.

Attention has only recently been given to the patient’s emotional experience and how this might relate to outcomes, recovery, and healing. An expanded paradigm of cardiac care incorporates pain relief, emotional support, spiritual healing, and a caring environment. These elements of patient-centered care aim to relieve stress and anxiety in order to achieve a better clinical outcome.

PATIENT-CENTERED CARE

The importance of patient-centered care is illustrated by the results of a 2007 survey in which 41% of patients cited elements of the patient experience as factors that most influenced their choice of hospital.1 Accepted wisdom on patient choice has historically centered on medical factors such as clinical reputation, physician recommendations, and hospital location, each of which was cited by 18% to 21% of the patients surveyed. Elements of the patient experience cited in the study include stress-reducing factors such as the appearance of the room, ease of scheduling, an environment that supports family needs, convenience and comfort of common areas, on-time performance, and simple registration procedures.

Székely et al2 found in a 4-year followup study that high levels of preoperative anxiety predicted greater mortality and cardiovascular morbidity following cardiac surgery. In a study by Tully et al,3 preoperative anxiety was also predictive of hospital readmission following cardiac surgery. Preoperative stress and anxiety are reliable predictors of postoperative distress.4

The variety and relative efficacy of interventions to reduce stress and anxiety are not well studied. Voss et al5 showed that cardiac surgery patients who were played soothing music experienced significantly reduced anxiety, pain, pain distress, and length of hospital stay. One Cleveland Clinic study of massage therapy, however, was unable to demonstrate a statistically significant therapeutic benefit, despite patient satisfaction with the therapy.6

THE ADVENT OF HEALING SERVICES

Identifying patients who exhibit significant preoperative stress and providing, as part of an expanded cardiac care paradigm, emotional care both pre- and postoperatively may ameliorate clinical outcomes. As such, the Heart and Vascular Institute at the Cleveland Clinic formed a healing services division, based on the concept that healing is more than simply physical recovery from a particular procedure. The division’s mission statement is: “To enhance the patient experience by promoting healing through a comprehensive set of coordinated services addressing the holistic needs of the patient.”

At the Cleveland Clinic, healing services are now integrated with standard services to enhance the cardiac care paradigm. Our standard medical services focus on areas of communication and pain control, both of which affect anxiety and stress. The need for enhanced communication is significant: 75% of patients admitted to a Chicago hospital were unable to name a single doctor assigned to their care, and of the remaining 25%, only 40% of responders were correct.7

It is worth noting that communicating more information to a patient is not necessarily better. Patients given detailed preoperative information about their disease and the potential complications of their cardiac surgery had levels of preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative stress, anxiety, and depression similar to those who received routine medical information.8,9 On the other hand, patients desire information about their postoperative plan of care while they are experiencing it, and value communication with physicians, nurses, healing services personnel, and other caregivers when it is presented in a calm and forthright manner. Communications should emphasize that the entire clinical team is there to help the patient get better.

THE FIFTH VITAL SIGN

Pain control is an aspect of care that was long ignored. The goal of the pain control task force at the Cleveland Clinic is the development of effective, efficient, and compassionate pain management.

The fifth vital sign, one that escapes the electronic medical record, can be addressed by this question: “How are you feeling?” Treating pain will reduce stress and anxiety. Before surgery, pain management priorities are discussed with patients, and at each daily encounter the goal is to set, refine, and exceed expectations for pain control through discussion and frequent pain assessments.

Reducing anxiety and stress is the goal of both standard care services and healing services, resulting in more satisfied patients with better clinical outcomes.

CASE: “YOU AND THE TEAM MADE ME GET OUTOF BED AND MOVE FORWARD”

Bobbi is a 78-year-old woman who was initially recovering well following cardiac surgery, including valve surgery, but had to return to the intensive care unit, which is difficult for patients. She was subsequently returned to the floor but was reluctant to walk and progressed slowly, despite normal electrocardiogram, radiographs, and blood panel results. We discovered that her husband was in hospice care in another state, causing Bobbi anxiety as she expressed concern over being her husband’s caregiver while being weakened physically herself. She was fearful of moving forward and her recovery stalled.

The primary care nurse referred her to the healing services team. The healing services team provided support for her anxiety and stress, and reviewed options for managing her husband’s care. She participated in Reiki, spiritual support, and social work services. During her admission her husband died, so the team provided appropriate support.

When asked about her experience upon leavingthe hospital, Bobbi did not mention her surgeon or the success of her heart valve procedure, but commented instead on the healing services team that enabled her to get through the experience.

- Grote KD, Newman JRS, Sutaria SS. A better hospital experience. The McKinsey Quarterly. November 2007.

- Székely A, Balog P, Benkö E, et al. Anxiety predicts mortality and morbidity after coronary artery and valve surgery—a 4-year followup study. Psychosom Med 2007; 69:625–631.

- Tully PJ, Baker RA, Turnbull D, Winefield H. The role of depression and anxiety symptoms in hospital readmissions after cardiac surgery. J Behav Med 2008; 31:281–290.

- Vingerhoets G. Perioperative anxiety and depression in open-heart surgery. Psychosomatics 1998; 39:30–37.

- Voss JA, Good M, Yates B, Baun MM, Thompson A, Hertzog M. Sedative music reduces anxiety and pain during chair rest after open-heart surgery. Pain 2004; 112:197–203.

- Albert NM, Gillinov AM, Lytle BW, Feng J, Cwynar R, Blackstone EH. A randomized trial of massage therapy after heart surgery. Heart Lung 2009; 38:480–490.

- Arora V, Gangireddy S, Mehrotra A, Ginde R, Tormey M, Meltzer D. Ability of hospitalized patients to identify their in-hospital physicians. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169:199–201.

- Ivarsson B, Larsson S, Lührs C, Sjöberg T. Extended written pre-operative information about possible complications at cardiac surgery—do the patients want to know? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2005; 28:407–414.

- Bergmann P, Huber S, Mächler H, et al. The influence of medical information on the perioperative course of stress in cardiac surgery patients. Anesth Analg 2001; 93:1093–1099.

The traditional paradigm for cardiac care has emphasized the use of technology to treat disease. Our focus on technologies such as echocardiography, advanced imaging instrumentation, and cardiac catheterization mirrors the preoccupation of society as a whole with technologic advances.

Attention has only recently been given to the patient’s emotional experience and how this might relate to outcomes, recovery, and healing. An expanded paradigm of cardiac care incorporates pain relief, emotional support, spiritual healing, and a caring environment. These elements of patient-centered care aim to relieve stress and anxiety in order to achieve a better clinical outcome.

PATIENT-CENTERED CARE

The importance of patient-centered care is illustrated by the results of a 2007 survey in which 41% of patients cited elements of the patient experience as factors that most influenced their choice of hospital.1 Accepted wisdom on patient choice has historically centered on medical factors such as clinical reputation, physician recommendations, and hospital location, each of which was cited by 18% to 21% of the patients surveyed. Elements of the patient experience cited in the study include stress-reducing factors such as the appearance of the room, ease of scheduling, an environment that supports family needs, convenience and comfort of common areas, on-time performance, and simple registration procedures.

Székely et al2 found in a 4-year followup study that high levels of preoperative anxiety predicted greater mortality and cardiovascular morbidity following cardiac surgery. In a study by Tully et al,3 preoperative anxiety was also predictive of hospital readmission following cardiac surgery. Preoperative stress and anxiety are reliable predictors of postoperative distress.4

The variety and relative efficacy of interventions to reduce stress and anxiety are not well studied. Voss et al5 showed that cardiac surgery patients who were played soothing music experienced significantly reduced anxiety, pain, pain distress, and length of hospital stay. One Cleveland Clinic study of massage therapy, however, was unable to demonstrate a statistically significant therapeutic benefit, despite patient satisfaction with the therapy.6

THE ADVENT OF HEALING SERVICES

Identifying patients who exhibit significant preoperative stress and providing, as part of an expanded cardiac care paradigm, emotional care both pre- and postoperatively may ameliorate clinical outcomes. As such, the Heart and Vascular Institute at the Cleveland Clinic formed a healing services division, based on the concept that healing is more than simply physical recovery from a particular procedure. The division’s mission statement is: “To enhance the patient experience by promoting healing through a comprehensive set of coordinated services addressing the holistic needs of the patient.”

At the Cleveland Clinic, healing services are now integrated with standard services to enhance the cardiac care paradigm. Our standard medical services focus on areas of communication and pain control, both of which affect anxiety and stress. The need for enhanced communication is significant: 75% of patients admitted to a Chicago hospital were unable to name a single doctor assigned to their care, and of the remaining 25%, only 40% of responders were correct.7

It is worth noting that communicating more information to a patient is not necessarily better. Patients given detailed preoperative information about their disease and the potential complications of their cardiac surgery had levels of preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative stress, anxiety, and depression similar to those who received routine medical information.8,9 On the other hand, patients desire information about their postoperative plan of care while they are experiencing it, and value communication with physicians, nurses, healing services personnel, and other caregivers when it is presented in a calm and forthright manner. Communications should emphasize that the entire clinical team is there to help the patient get better.

THE FIFTH VITAL SIGN

Pain control is an aspect of care that was long ignored. The goal of the pain control task force at the Cleveland Clinic is the development of effective, efficient, and compassionate pain management.

The fifth vital sign, one that escapes the electronic medical record, can be addressed by this question: “How are you feeling?” Treating pain will reduce stress and anxiety. Before surgery, pain management priorities are discussed with patients, and at each daily encounter the goal is to set, refine, and exceed expectations for pain control through discussion and frequent pain assessments.

Reducing anxiety and stress is the goal of both standard care services and healing services, resulting in more satisfied patients with better clinical outcomes.

CASE: “YOU AND THE TEAM MADE ME GET OUTOF BED AND MOVE FORWARD”

Bobbi is a 78-year-old woman who was initially recovering well following cardiac surgery, including valve surgery, but had to return to the intensive care unit, which is difficult for patients. She was subsequently returned to the floor but was reluctant to walk and progressed slowly, despite normal electrocardiogram, radiographs, and blood panel results. We discovered that her husband was in hospice care in another state, causing Bobbi anxiety as she expressed concern over being her husband’s caregiver while being weakened physically herself. She was fearful of moving forward and her recovery stalled.

The primary care nurse referred her to the healing services team. The healing services team provided support for her anxiety and stress, and reviewed options for managing her husband’s care. She participated in Reiki, spiritual support, and social work services. During her admission her husband died, so the team provided appropriate support.

When asked about her experience upon leavingthe hospital, Bobbi did not mention her surgeon or the success of her heart valve procedure, but commented instead on the healing services team that enabled her to get through the experience.

The traditional paradigm for cardiac care has emphasized the use of technology to treat disease. Our focus on technologies such as echocardiography, advanced imaging instrumentation, and cardiac catheterization mirrors the preoccupation of society as a whole with technologic advances.

Attention has only recently been given to the patient’s emotional experience and how this might relate to outcomes, recovery, and healing. An expanded paradigm of cardiac care incorporates pain relief, emotional support, spiritual healing, and a caring environment. These elements of patient-centered care aim to relieve stress and anxiety in order to achieve a better clinical outcome.

PATIENT-CENTERED CARE

The importance of patient-centered care is illustrated by the results of a 2007 survey in which 41% of patients cited elements of the patient experience as factors that most influenced their choice of hospital.1 Accepted wisdom on patient choice has historically centered on medical factors such as clinical reputation, physician recommendations, and hospital location, each of which was cited by 18% to 21% of the patients surveyed. Elements of the patient experience cited in the study include stress-reducing factors such as the appearance of the room, ease of scheduling, an environment that supports family needs, convenience and comfort of common areas, on-time performance, and simple registration procedures.

Székely et al2 found in a 4-year followup study that high levels of preoperative anxiety predicted greater mortality and cardiovascular morbidity following cardiac surgery. In a study by Tully et al,3 preoperative anxiety was also predictive of hospital readmission following cardiac surgery. Preoperative stress and anxiety are reliable predictors of postoperative distress.4

The variety and relative efficacy of interventions to reduce stress and anxiety are not well studied. Voss et al5 showed that cardiac surgery patients who were played soothing music experienced significantly reduced anxiety, pain, pain distress, and length of hospital stay. One Cleveland Clinic study of massage therapy, however, was unable to demonstrate a statistically significant therapeutic benefit, despite patient satisfaction with the therapy.6

THE ADVENT OF HEALING SERVICES

Identifying patients who exhibit significant preoperative stress and providing, as part of an expanded cardiac care paradigm, emotional care both pre- and postoperatively may ameliorate clinical outcomes. As such, the Heart and Vascular Institute at the Cleveland Clinic formed a healing services division, based on the concept that healing is more than simply physical recovery from a particular procedure. The division’s mission statement is: “To enhance the patient experience by promoting healing through a comprehensive set of coordinated services addressing the holistic needs of the patient.”

At the Cleveland Clinic, healing services are now integrated with standard services to enhance the cardiac care paradigm. Our standard medical services focus on areas of communication and pain control, both of which affect anxiety and stress. The need for enhanced communication is significant: 75% of patients admitted to a Chicago hospital were unable to name a single doctor assigned to their care, and of the remaining 25%, only 40% of responders were correct.7

It is worth noting that communicating more information to a patient is not necessarily better. Patients given detailed preoperative information about their disease and the potential complications of their cardiac surgery had levels of preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative stress, anxiety, and depression similar to those who received routine medical information.8,9 On the other hand, patients desire information about their postoperative plan of care while they are experiencing it, and value communication with physicians, nurses, healing services personnel, and other caregivers when it is presented in a calm and forthright manner. Communications should emphasize that the entire clinical team is there to help the patient get better.

THE FIFTH VITAL SIGN

Pain control is an aspect of care that was long ignored. The goal of the pain control task force at the Cleveland Clinic is the development of effective, efficient, and compassionate pain management.

The fifth vital sign, one that escapes the electronic medical record, can be addressed by this question: “How are you feeling?” Treating pain will reduce stress and anxiety. Before surgery, pain management priorities are discussed with patients, and at each daily encounter the goal is to set, refine, and exceed expectations for pain control through discussion and frequent pain assessments.

Reducing anxiety and stress is the goal of both standard care services and healing services, resulting in more satisfied patients with better clinical outcomes.

CASE: “YOU AND THE TEAM MADE ME GET OUTOF BED AND MOVE FORWARD”

Bobbi is a 78-year-old woman who was initially recovering well following cardiac surgery, including valve surgery, but had to return to the intensive care unit, which is difficult for patients. She was subsequently returned to the floor but was reluctant to walk and progressed slowly, despite normal electrocardiogram, radiographs, and blood panel results. We discovered that her husband was in hospice care in another state, causing Bobbi anxiety as she expressed concern over being her husband’s caregiver while being weakened physically herself. She was fearful of moving forward and her recovery stalled.

The primary care nurse referred her to the healing services team. The healing services team provided support for her anxiety and stress, and reviewed options for managing her husband’s care. She participated in Reiki, spiritual support, and social work services. During her admission her husband died, so the team provided appropriate support.

When asked about her experience upon leavingthe hospital, Bobbi did not mention her surgeon or the success of her heart valve procedure, but commented instead on the healing services team that enabled her to get through the experience.

- Grote KD, Newman JRS, Sutaria SS. A better hospital experience. The McKinsey Quarterly. November 2007.

- Székely A, Balog P, Benkö E, et al. Anxiety predicts mortality and morbidity after coronary artery and valve surgery—a 4-year followup study. Psychosom Med 2007; 69:625–631.

- Tully PJ, Baker RA, Turnbull D, Winefield H. The role of depression and anxiety symptoms in hospital readmissions after cardiac surgery. J Behav Med 2008; 31:281–290.

- Vingerhoets G. Perioperative anxiety and depression in open-heart surgery. Psychosomatics 1998; 39:30–37.

- Voss JA, Good M, Yates B, Baun MM, Thompson A, Hertzog M. Sedative music reduces anxiety and pain during chair rest after open-heart surgery. Pain 2004; 112:197–203.

- Albert NM, Gillinov AM, Lytle BW, Feng J, Cwynar R, Blackstone EH. A randomized trial of massage therapy after heart surgery. Heart Lung 2009; 38:480–490.

- Arora V, Gangireddy S, Mehrotra A, Ginde R, Tormey M, Meltzer D. Ability of hospitalized patients to identify their in-hospital physicians. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169:199–201.

- Ivarsson B, Larsson S, Lührs C, Sjöberg T. Extended written pre-operative information about possible complications at cardiac surgery—do the patients want to know? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2005; 28:407–414.

- Bergmann P, Huber S, Mächler H, et al. The influence of medical information on the perioperative course of stress in cardiac surgery patients. Anesth Analg 2001; 93:1093–1099.

- Grote KD, Newman JRS, Sutaria SS. A better hospital experience. The McKinsey Quarterly. November 2007.

- Székely A, Balog P, Benkö E, et al. Anxiety predicts mortality and morbidity after coronary artery and valve surgery—a 4-year followup study. Psychosom Med 2007; 69:625–631.

- Tully PJ, Baker RA, Turnbull D, Winefield H. The role of depression and anxiety symptoms in hospital readmissions after cardiac surgery. J Behav Med 2008; 31:281–290.

- Vingerhoets G. Perioperative anxiety and depression in open-heart surgery. Psychosomatics 1998; 39:30–37.

- Voss JA, Good M, Yates B, Baun MM, Thompson A, Hertzog M. Sedative music reduces anxiety and pain during chair rest after open-heart surgery. Pain 2004; 112:197–203.

- Albert NM, Gillinov AM, Lytle BW, Feng J, Cwynar R, Blackstone EH. A randomized trial of massage therapy after heart surgery. Heart Lung 2009; 38:480–490.

- Arora V, Gangireddy S, Mehrotra A, Ginde R, Tormey M, Meltzer D. Ability of hospitalized patients to identify their in-hospital physicians. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169:199–201.

- Ivarsson B, Larsson S, Lührs C, Sjöberg T. Extended written pre-operative information about possible complications at cardiac surgery—do the patients want to know? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2005; 28:407–414.

- Bergmann P, Huber S, Mächler H, et al. The influence of medical information on the perioperative course of stress in cardiac surgery patients. Anesth Analg 2001; 93:1093–1099.

Stress in medicine: Strategies for caregivers, patients, clinicians—Addressing the impact of clinician stress

The impact of clinician stress on the health care system is significant. It can adversely affect the patient experience, compromise patient safety, hinder the delivery of care in a manner that is inconsistent with producing quality outcomes, and increase the overall cost of care.

CLINICIAN STRESS IS PREVALENT

Models of health care that restore human interaction are desperately needed. Clinicians today are overwhelmed by performance assessments that are based on length of stay, use of evidence-based medication regimens, and morbidity and mortality outcomes. Yet clinicians have few opportunities to establish more than cursory relationships with their patients—relationships that would permit better understanding of patients’ emotional well-being and that would optimize the overall healing experience.

Shanafelt et al1 surveyed 7,905 surgeons and found that clinician stress is pervasive: 64% indicated that their work schedule left inadequate time for their personal or family life, 40% reported burnout, and 30% screened positive for symptoms of depression. Another survey of 763 practicing physicians in California found that 53% reported moderate to severe levels of stress.2 Nonphysician clinicians have significant levels of stress as well, with one survey of nurses finding that, of those who quit the profession, 26% cited stress as the cause.3

THE EFFECT OF CLINICIAN STRESSON QUALITY OF CARE

In the Shanafelt et al study, high levels of emotional exhaustion correlated positively with major medical errors over the previous 3 months.1 Nearly 9% of the surgeons surveyed reported making a stress-related major medical mistake in the past 3 months; among those surgeons with high levels of emotional exhaustion, that figure was nearly 15%. This study also found that every 1-point increase in the emotional exhaustion scale (range, 0 to 54) was associated with a 5% increase in the likelihood of reporting a medical error.1

In a study of internal medicine residents, fatigue and distress were associated with medical errors, which were reported by 39% of respondents.4

STRESS AND COMMUNICATION

Stress can damage the physician-nurse relationship, with a significant impact not only on clinicians, but also on delivery of care. The associated breakdowns in communication can negatively affect several areas, including critical care transitions and timely delivery of care. Stress also affects morale, job satisfaction, and job retention.5

ADDRESSING THE IMPACT OF CLINICIAN STRESS

The traditional response to complaints registered by patients has been behavioral coaching, disruptive-behavior programs, and the punitive use of satisfaction metrics, which are incorporated into the physician’s annual evaluation. These approaches do little to address the cause of the stress and can inculcate cynicism instead.

A more useful approach is to define and strive for an optimal working environment for clinicians, thereby promoting an enhanced patient experience. This approach attempts to restore balance to both the business and art of medicine and may incorporate biofeedback and other healing services to clinicians as tools to minimize and manage stress.

The business of medicine may be restored by enhancing the culture and climate of the hospital, improving communication and collaboration, reducing administrative tasks, restoring authority and autonomy, and eliminating punitive practices. The art of medicine may be restored by valuing the sacred relationship between clinician and patient, learning to listen more carefully to the patient, creating better healing environments, providing emotional support, and supporting caregivers.

- Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg 2010; 251:995–1000.

- Beck M. Checking up on the doctor. What patients can learn from the ways physicians take care of themselves. Wall Street Journal. May 25, 2010. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704113504575264364125574500.html?KEYWORDS=Checking+up+on+the+doctor. Accessed April 27, 2011.

- Reineck C, Furino A. Nursing career fulfillment: statistics and statements from registered nurses. Nursing Economics 2005; 23:25–30.

- West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA 2009; 302:1294–1300.

- Rosenstein AH. Nurse-physician relationships: Impact on nurses atisfaction and retention. Am J Nursing 2002; 102:26–34.

- Hickam DH, Severance S, Feldstein A, et al; Oregon Health & Science University Evidence-based Practice Center. The effect of health care working conditions on patient safety. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality publication 03-E031. http://www.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/evidence/pdf/work/work.pdf. Published May 2003. Accessed April 27, 2011.

The impact of clinician stress on the health care system is significant. It can adversely affect the patient experience, compromise patient safety, hinder the delivery of care in a manner that is inconsistent with producing quality outcomes, and increase the overall cost of care.

CLINICIAN STRESS IS PREVALENT

Models of health care that restore human interaction are desperately needed. Clinicians today are overwhelmed by performance assessments that are based on length of stay, use of evidence-based medication regimens, and morbidity and mortality outcomes. Yet clinicians have few opportunities to establish more than cursory relationships with their patients—relationships that would permit better understanding of patients’ emotional well-being and that would optimize the overall healing experience.

Shanafelt et al1 surveyed 7,905 surgeons and found that clinician stress is pervasive: 64% indicated that their work schedule left inadequate time for their personal or family life, 40% reported burnout, and 30% screened positive for symptoms of depression. Another survey of 763 practicing physicians in California found that 53% reported moderate to severe levels of stress.2 Nonphysician clinicians have significant levels of stress as well, with one survey of nurses finding that, of those who quit the profession, 26% cited stress as the cause.3

THE EFFECT OF CLINICIAN STRESSON QUALITY OF CARE

In the Shanafelt et al study, high levels of emotional exhaustion correlated positively with major medical errors over the previous 3 months.1 Nearly 9% of the surgeons surveyed reported making a stress-related major medical mistake in the past 3 months; among those surgeons with high levels of emotional exhaustion, that figure was nearly 15%. This study also found that every 1-point increase in the emotional exhaustion scale (range, 0 to 54) was associated with a 5% increase in the likelihood of reporting a medical error.1

In a study of internal medicine residents, fatigue and distress were associated with medical errors, which were reported by 39% of respondents.4

STRESS AND COMMUNICATION

Stress can damage the physician-nurse relationship, with a significant impact not only on clinicians, but also on delivery of care. The associated breakdowns in communication can negatively affect several areas, including critical care transitions and timely delivery of care. Stress also affects morale, job satisfaction, and job retention.5

ADDRESSING THE IMPACT OF CLINICIAN STRESS

The traditional response to complaints registered by patients has been behavioral coaching, disruptive-behavior programs, and the punitive use of satisfaction metrics, which are incorporated into the physician’s annual evaluation. These approaches do little to address the cause of the stress and can inculcate cynicism instead.

A more useful approach is to define and strive for an optimal working environment for clinicians, thereby promoting an enhanced patient experience. This approach attempts to restore balance to both the business and art of medicine and may incorporate biofeedback and other healing services to clinicians as tools to minimize and manage stress.

The business of medicine may be restored by enhancing the culture and climate of the hospital, improving communication and collaboration, reducing administrative tasks, restoring authority and autonomy, and eliminating punitive practices. The art of medicine may be restored by valuing the sacred relationship between clinician and patient, learning to listen more carefully to the patient, creating better healing environments, providing emotional support, and supporting caregivers.

The impact of clinician stress on the health care system is significant. It can adversely affect the patient experience, compromise patient safety, hinder the delivery of care in a manner that is inconsistent with producing quality outcomes, and increase the overall cost of care.

CLINICIAN STRESS IS PREVALENT

Models of health care that restore human interaction are desperately needed. Clinicians today are overwhelmed by performance assessments that are based on length of stay, use of evidence-based medication regimens, and morbidity and mortality outcomes. Yet clinicians have few opportunities to establish more than cursory relationships with their patients—relationships that would permit better understanding of patients’ emotional well-being and that would optimize the overall healing experience.

Shanafelt et al1 surveyed 7,905 surgeons and found that clinician stress is pervasive: 64% indicated that their work schedule left inadequate time for their personal or family life, 40% reported burnout, and 30% screened positive for symptoms of depression. Another survey of 763 practicing physicians in California found that 53% reported moderate to severe levels of stress.2 Nonphysician clinicians have significant levels of stress as well, with one survey of nurses finding that, of those who quit the profession, 26% cited stress as the cause.3

THE EFFECT OF CLINICIAN STRESSON QUALITY OF CARE

In the Shanafelt et al study, high levels of emotional exhaustion correlated positively with major medical errors over the previous 3 months.1 Nearly 9% of the surgeons surveyed reported making a stress-related major medical mistake in the past 3 months; among those surgeons with high levels of emotional exhaustion, that figure was nearly 15%. This study also found that every 1-point increase in the emotional exhaustion scale (range, 0 to 54) was associated with a 5% increase in the likelihood of reporting a medical error.1

In a study of internal medicine residents, fatigue and distress were associated with medical errors, which were reported by 39% of respondents.4

STRESS AND COMMUNICATION

Stress can damage the physician-nurse relationship, with a significant impact not only on clinicians, but also on delivery of care. The associated breakdowns in communication can negatively affect several areas, including critical care transitions and timely delivery of care. Stress also affects morale, job satisfaction, and job retention.5

ADDRESSING THE IMPACT OF CLINICIAN STRESS

The traditional response to complaints registered by patients has been behavioral coaching, disruptive-behavior programs, and the punitive use of satisfaction metrics, which are incorporated into the physician’s annual evaluation. These approaches do little to address the cause of the stress and can inculcate cynicism instead.

A more useful approach is to define and strive for an optimal working environment for clinicians, thereby promoting an enhanced patient experience. This approach attempts to restore balance to both the business and art of medicine and may incorporate biofeedback and other healing services to clinicians as tools to minimize and manage stress.

The business of medicine may be restored by enhancing the culture and climate of the hospital, improving communication and collaboration, reducing administrative tasks, restoring authority and autonomy, and eliminating punitive practices. The art of medicine may be restored by valuing the sacred relationship between clinician and patient, learning to listen more carefully to the patient, creating better healing environments, providing emotional support, and supporting caregivers.

- Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg 2010; 251:995–1000.

- Beck M. Checking up on the doctor. What patients can learn from the ways physicians take care of themselves. Wall Street Journal. May 25, 2010. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704113504575264364125574500.html?KEYWORDS=Checking+up+on+the+doctor. Accessed April 27, 2011.

- Reineck C, Furino A. Nursing career fulfillment: statistics and statements from registered nurses. Nursing Economics 2005; 23:25–30.

- West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA 2009; 302:1294–1300.

- Rosenstein AH. Nurse-physician relationships: Impact on nurses atisfaction and retention. Am J Nursing 2002; 102:26–34.

- Hickam DH, Severance S, Feldstein A, et al; Oregon Health & Science University Evidence-based Practice Center. The effect of health care working conditions on patient safety. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality publication 03-E031. http://www.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/evidence/pdf/work/work.pdf. Published May 2003. Accessed April 27, 2011.

- Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg 2010; 251:995–1000.

- Beck M. Checking up on the doctor. What patients can learn from the ways physicians take care of themselves. Wall Street Journal. May 25, 2010. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704113504575264364125574500.html?KEYWORDS=Checking+up+on+the+doctor. Accessed April 27, 2011.

- Reineck C, Furino A. Nursing career fulfillment: statistics and statements from registered nurses. Nursing Economics 2005; 23:25–30.

- West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA 2009; 302:1294–1300.

- Rosenstein AH. Nurse-physician relationships: Impact on nurses atisfaction and retention. Am J Nursing 2002; 102:26–34.

- Hickam DH, Severance S, Feldstein A, et al; Oregon Health & Science University Evidence-based Practice Center. The effect of health care working conditions on patient safety. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality publication 03-E031. http://www.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/evidence/pdf/work/work.pdf. Published May 2003. Accessed April 27, 2011.

Stress in medicine: Strategies for caregivers, patients, clinicians—Biofeedback in the treatment of stress

Traditionally, biofeedback was considered to be a stress management technique that targeted sympathetic nervous system (SNS) overdrive with an adrenal medullary system backup. Recent advances in autonomic physiology, however, have clarified that except in extreme situations, the SNS is not the key factor in day-to-day stress. Rather, the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system appears to be a more likely candidate for mediating routine stress because, unlike the SNS, which has slow-acting neurotransmitters (ie, catecholamines), the parasympathetic nervous system has the fast-acting transmitter acetylcholine.

VAGAL WITHDRAWAL: AN ALTERNATIVE TO SYMPATHETIC ACTIVATION

Porges1 first proposed the concept of vagal withdrawal as an indicator of stress and stress vulnerability; this contrasts with the idea that the stress response is a consequence of sympathetic activation and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response. In the vagal withdrawal model, the response to stress is stabilization of the sympathetic system followed by termination of parasympathetic activity, manifested as cardiac acceleration.

Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), or the variability in heart rate as it synchronizes with breathing, is considered an index of parasympathetic tone. In the laboratory, slow atropine infusion produces a transient paradoxical vagomimetic effect characterized by an initial increase in RSA, followed by a flattening and then a rise in the heart rate.2 This phenomenon has been measured in people during times of routine stress, such as when worrying about being late for an appointment. In such individuals, biofeedback training can result in recovery of normal RSA shortly after an episode of anxiety.

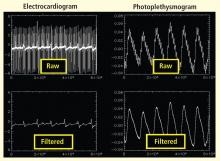

Historically, the focus of biofeedback was to cultivate low arousal, presumably reducing SNS activity, through the use of finger temperature, skin conductance training, and profound muscle relaxation. More sophisticated ways to look at both branches of the autonomic nervous system have since emerged that allow for sampling of the beat-by-beat changes in heart rate.

HEART RATE VARIABILITY BIOFEEDBACK

The concept of modifying the respiration rate (paced breathing) originated some 2,500 years ago as a component of meditation. It is being revisited today in the form of heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback training, which is being used as a stress-management tool and a method to correct disorders in which autonomic regulation is thought to be important. HRV biofeedback involves training to increase the amplitude of HRV rhythms and thus improve autonomic homeostasis.

Normal HRV has a pattern of overlapping oscillatory frequency components, including:

- a high-frequency rhythm, 0.15 to 0.4 Hz, which is the RSA;

- a low-frequency rhythm, 0.05 to 0.15 Hz, associated with blood pressure oscillations; and

- a very-low-frequency rhythm, 0.005 to 0.05 Hz, which may regulate vascular tone and body temperature.

The goal of HRV biofeedback is to achieve respiratory rates at which resonance occurs between cardiac rhythms associated with respiration (RSA, or high-frequency oscillations) and those caused by baroreflex activity (low-frequency oscillations).

Spectral analysis has demonstrated that nearly all of the activity with HRV biofeedback occurs at a low-frequency band. The reason is that activity in the low-frequency band is related more to baroreflex activity than to HRV compared with other ranges of frequency. Breathing rates that correspond to baroreflex effects, called resonance frequency breathing, represent resonance in the cardiovascular system. Several devices are available whose mechanisms are based on the concept of achieving resonance frequency breathing. One such device is a slow-breathing monitor (Resp-e-rate) that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the adjunctive treatment of hypertension.

Improved HRV may suggest an improved risk status: Kleiger et al4 found that the relative risk of mortality was 5.3 times greater for people with SDNN of less than 50 msec compared with those whose SDNN was greater than 100 msec. In Del Pozo’s study, eight of 30 patients in the intervention group achieved an SDNN of greater than 50 msec (vs 0 at pretreatment) compared with three of 31 controls (vs two at pretreatment).3 As an additional benefit of HRV biofeedback, patients in the intervention group who entered the study with hypertension all became normotensive.

In a meta-analysis, van Dixhoorn and White5 found fewer cardiac events, fewer episodes of angina, and less occurrence of arrhythmia and exercise-induced ischemia from intensive supervised relaxation therapy in patients with ischemic heart disease. Improvements in scales of depression and anxiety were also observed with relaxation therapy.

Other studies have shown biofeedback to have beneficial effects based on the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, and, in patients with mild to moderate heartfailure, the 6-minute walk test.6–8

The proposed mechanism for the beneficial effects of biofeedback found in clinical trials is improvement in baroreflex function, producing greater reflex efficiency and improved modulation of autonomic activity.

CONCLUSION

A shift in emphasis to vagal withdrawal has led to new forms of biofeedback that probably potentiate many of the same mechanisms thought to be present in Eastern practices such as yoga and tai chi. Results from small-scale trials have been promising for HRV biofeedback as a means of modifying responses to stress and promoting homeostatic processes that reduce the intensity of symptoms and improve surrogate markers associated with a number of disorders.

- Porges SW. Cardiac vagal tone: a physiological index of stress. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 1995; 19:225–233.

- Médigue C, Girard A, Laude D, Monti A, Wargon M, ElghoziJ-L. Relationship between pulse interval and respiratory sinusarrhythmia: a time- and frequency-domain analysis of the effects ofatropine. Eur J Physiol 2001; 441:650–655.

- Del Pozo JM, Gevirtz RN, Scher B, Guarneri E. Biofeedbacktreatment increases heart rate variability in patients withknown coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 2004; 147:e11. http://download.journals.elsevierhealth.com/pdfs/journals/0002-8703/PIIS0002870303007191.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2011.

- Kleiger RE, Miller JP, Bigger JT Jr, Moss AJ. Decreased heart ratevariability and its association with increased mortality after acutemyocardial infarciton. Am J Cardiol 1987; 59:256–262.

- van Dixhoorn JV, White A. Relaxation therapy for rehabilitationand prevention in ischaemic heart disease: a systematic review andmeta-analysis. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2005; 12:193–202.

- Karavidas MK, Lehrer PM, Vaschillo E, et al. Preliminary resultsof an open label study of heart rate variability biofeedback for thetreatment of major depression. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback2007; 32:19–30.

- Zucker TL, Samuelson KW, Muench F, Greenberg MA, GevirtzRN. The effects of respiratory sinus arrhythmia biofeedback onheart rate variability and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: apilot study. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 2009; 34:135–143.

- Swanson KS, Gevirtz RN, Brown M, Spira J, Guarneri E, StoletniyL. The effect of biofeedback on function in patients with heartfailure. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 2009; 34:71–91.

Traditionally, biofeedback was considered to be a stress management technique that targeted sympathetic nervous system (SNS) overdrive with an adrenal medullary system backup. Recent advances in autonomic physiology, however, have clarified that except in extreme situations, the SNS is not the key factor in day-to-day stress. Rather, the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system appears to be a more likely candidate for mediating routine stress because, unlike the SNS, which has slow-acting neurotransmitters (ie, catecholamines), the parasympathetic nervous system has the fast-acting transmitter acetylcholine.

VAGAL WITHDRAWAL: AN ALTERNATIVE TO SYMPATHETIC ACTIVATION

Porges1 first proposed the concept of vagal withdrawal as an indicator of stress and stress vulnerability; this contrasts with the idea that the stress response is a consequence of sympathetic activation and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response. In the vagal withdrawal model, the response to stress is stabilization of the sympathetic system followed by termination of parasympathetic activity, manifested as cardiac acceleration.

Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), or the variability in heart rate as it synchronizes with breathing, is considered an index of parasympathetic tone. In the laboratory, slow atropine infusion produces a transient paradoxical vagomimetic effect characterized by an initial increase in RSA, followed by a flattening and then a rise in the heart rate.2 This phenomenon has been measured in people during times of routine stress, such as when worrying about being late for an appointment. In such individuals, biofeedback training can result in recovery of normal RSA shortly after an episode of anxiety.

Historically, the focus of biofeedback was to cultivate low arousal, presumably reducing SNS activity, through the use of finger temperature, skin conductance training, and profound muscle relaxation. More sophisticated ways to look at both branches of the autonomic nervous system have since emerged that allow for sampling of the beat-by-beat changes in heart rate.

HEART RATE VARIABILITY BIOFEEDBACK

The concept of modifying the respiration rate (paced breathing) originated some 2,500 years ago as a component of meditation. It is being revisited today in the form of heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback training, which is being used as a stress-management tool and a method to correct disorders in which autonomic regulation is thought to be important. HRV biofeedback involves training to increase the amplitude of HRV rhythms and thus improve autonomic homeostasis.

Normal HRV has a pattern of overlapping oscillatory frequency components, including:

- a high-frequency rhythm, 0.15 to 0.4 Hz, which is the RSA;

- a low-frequency rhythm, 0.05 to 0.15 Hz, associated with blood pressure oscillations; and

- a very-low-frequency rhythm, 0.005 to 0.05 Hz, which may regulate vascular tone and body temperature.

The goal of HRV biofeedback is to achieve respiratory rates at which resonance occurs between cardiac rhythms associated with respiration (RSA, or high-frequency oscillations) and those caused by baroreflex activity (low-frequency oscillations).

Spectral analysis has demonstrated that nearly all of the activity with HRV biofeedback occurs at a low-frequency band. The reason is that activity in the low-frequency band is related more to baroreflex activity than to HRV compared with other ranges of frequency. Breathing rates that correspond to baroreflex effects, called resonance frequency breathing, represent resonance in the cardiovascular system. Several devices are available whose mechanisms are based on the concept of achieving resonance frequency breathing. One such device is a slow-breathing monitor (Resp-e-rate) that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the adjunctive treatment of hypertension.

Improved HRV may suggest an improved risk status: Kleiger et al4 found that the relative risk of mortality was 5.3 times greater for people with SDNN of less than 50 msec compared with those whose SDNN was greater than 100 msec. In Del Pozo’s study, eight of 30 patients in the intervention group achieved an SDNN of greater than 50 msec (vs 0 at pretreatment) compared with three of 31 controls (vs two at pretreatment).3 As an additional benefit of HRV biofeedback, patients in the intervention group who entered the study with hypertension all became normotensive.

In a meta-analysis, van Dixhoorn and White5 found fewer cardiac events, fewer episodes of angina, and less occurrence of arrhythmia and exercise-induced ischemia from intensive supervised relaxation therapy in patients with ischemic heart disease. Improvements in scales of depression and anxiety were also observed with relaxation therapy.

Other studies have shown biofeedback to have beneficial effects based on the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, and, in patients with mild to moderate heartfailure, the 6-minute walk test.6–8

The proposed mechanism for the beneficial effects of biofeedback found in clinical trials is improvement in baroreflex function, producing greater reflex efficiency and improved modulation of autonomic activity.

CONCLUSION

A shift in emphasis to vagal withdrawal has led to new forms of biofeedback that probably potentiate many of the same mechanisms thought to be present in Eastern practices such as yoga and tai chi. Results from small-scale trials have been promising for HRV biofeedback as a means of modifying responses to stress and promoting homeostatic processes that reduce the intensity of symptoms and improve surrogate markers associated with a number of disorders.

Traditionally, biofeedback was considered to be a stress management technique that targeted sympathetic nervous system (SNS) overdrive with an adrenal medullary system backup. Recent advances in autonomic physiology, however, have clarified that except in extreme situations, the SNS is not the key factor in day-to-day stress. Rather, the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system appears to be a more likely candidate for mediating routine stress because, unlike the SNS, which has slow-acting neurotransmitters (ie, catecholamines), the parasympathetic nervous system has the fast-acting transmitter acetylcholine.

VAGAL WITHDRAWAL: AN ALTERNATIVE TO SYMPATHETIC ACTIVATION

Porges1 first proposed the concept of vagal withdrawal as an indicator of stress and stress vulnerability; this contrasts with the idea that the stress response is a consequence of sympathetic activation and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response. In the vagal withdrawal model, the response to stress is stabilization of the sympathetic system followed by termination of parasympathetic activity, manifested as cardiac acceleration.

Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), or the variability in heart rate as it synchronizes with breathing, is considered an index of parasympathetic tone. In the laboratory, slow atropine infusion produces a transient paradoxical vagomimetic effect characterized by an initial increase in RSA, followed by a flattening and then a rise in the heart rate.2 This phenomenon has been measured in people during times of routine stress, such as when worrying about being late for an appointment. In such individuals, biofeedback training can result in recovery of normal RSA shortly after an episode of anxiety.

Historically, the focus of biofeedback was to cultivate low arousal, presumably reducing SNS activity, through the use of finger temperature, skin conductance training, and profound muscle relaxation. More sophisticated ways to look at both branches of the autonomic nervous system have since emerged that allow for sampling of the beat-by-beat changes in heart rate.