User login

When a drug is in short supply at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, a message goes out to the physicians on the hospital’s intranet system. When the shortage gets close to being critically short in supply, a message will be embedded into the physician order-entry system recommending that the physicians use an alternate drug—if there is an alternate.

It’s an alert system that has been put to frequent use lately, says Joseph Li, MD, SFHM, director of the hospital medicine program at Beth Israel Deaconess, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and president of SHM.

The rate of drug shortages has been rising steadily in recent years due to quality questions at manufacturers, consolidation in the drug-manufacturing industry, and other factors, according to data from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and other sources.

“It does seem like there’s more today than previous years,” says Dr. Li, who was a pharmacist before he trained in internal medicine.

Some of the recent shortages at Beth Israel Deaconess have involved the diuretic furosemide, the antiemetic Compazine, and the anticoagulant heparin. “More often than not, there’s a reasonable alternative that can be chosen,” he says. “Not necessarily exactly the same drug, but usually in the same therapeutic class.”

While actual cases of patient harm due to drug shortages appear to be relatively uncommon, having drugs in short supply can lead to a safety problem hovering over a medical center and its hospitalists. In addition to the potential of simply not having an alternate to give to a patient, hospitalists and their pharmacists sometimes have to adjust to a new dosage that comes with a replacement medication.

Plus, having to manage the problem when a drug shortage hits can be a headache, with time and resources spent trying to obtain updates from drug manufacturers and find other drugs that can be used in the meantime, experts say.

With hospitalists now treating so many patients, many of them complex and on multiple medications, it is an important issue for hospitalists to stay aware of and to be prepared for, Dr. Li says. More than 90% of all medical patients at Beth Israel Deaconess are now cared for by hospitalists, he says, and it’s a similar situation for many acute-care hospitals around the country.

If a drug is in short supply, balancing availability with patient needs can be especially tricky for a hospitalist caring for patients with a multitude of demands, Dr. Li says. “There is an effort to make sure that our most vulnerable population of patients receive these treatments before the general population of patients have access to it,” he adds.

However, the very existence of hospitalists makes it easier to navigate a shortage compared to the days when hundreds of providers would be caring for a pool of patients.

“If you’re trying to notify a group of providers about shortages and have an impact on their prescribing habits, I think it’s easier today,” he says.

Troubled Waters

The FDA says it confirmed a record 178 cases of drug shortages in 2010 (www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/drugshortages/default.htm). That was up from 55 shortages five years ago. And according to the University of Utah Drug Information Service, the problem is actually more pervasive than that, reporting 120 shortages in the U.S. in 2001, with a reported 211 in 2010. And through March of this year, there were 80 reported cases of shortages, on pace for another record year.

“In the past couple of years, it’s just been exponential,” says Diane Ginsburg, president of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and clinical professor and assistant dean for student affairs at the University of Texas’ College of Pharmacy in Austin.

According to the FDA, 77% of the shortages in 2010 involved sterile injectable drugs.

“There are fewer and fewer firms making these older sterile injectables, and they are often discontinued for newer, more profitable agents,” FDA spokeswoman Yolanda Fultz-Morris said in an email. “When one firm has a delay or a manufacturing problem, it is extremely difficult for the remaining firms to quickly increase production.”

The biggest cause for the shortages in those drugs has been product quality issues, namely microbial contamination and newly identified impurities, according to the FDA. From January to October of 2010, 42% of drug shortages were due to quality problems.

Eighteen percent were due to product discontinuation by the manufacturer and another 18% were due to delays and capacity problems. Nine percent were due to difficulties getting raw materials, and 4% of the sterile injectable shortages were due to increased demand because there was a shortage of another injectable medication. In other words, one shortage led directly to another.

Kevin Schweers, a spokesman for the National Community Pharmacists Association, says generic drugs, especially Schedule II substances, have been in short supply. But there can be problems even when one generic is available to replace another generic.

An example, he says, is when a “new generic substituted in place of the old one is made by a different manufacturer and may come in a different color or shape. That can leave patients”—including those just released from hospitals—“wondering and asking the pharmacist why their medication is different or if a mistake was made.”

Patient Safety and Communication Errors

Lalit Verma, MD, director of the hospital medicine program at Durham Regional Medical Center in North Carolina and assistant professor of medicine at the Duke University School of Medicine, is unaware of any situations in which a shortage put patients in jeopardy at his hospital. He says the pharmacy at Durham Regional, which has seen recent shortages in morphine and heparin, among other drugs, keeps doctors up to date and has adjusted doses appropriately when replacements are used.

“It’s probably been more than I’ve experienced in my 10 years as a hospitalist,” Dr. Verma says. “We have a very good pharmacy program that updates us regularly on drug shortages and offers alternatives.”

Dr. Li also says no patient’s safety has been jeopardized by a shortage.

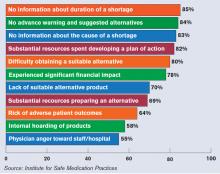

Others say patient safety has been affected, according to 1,800 healthcare practitioners who participated in a survey last year conducted by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), a nonprofit group. Twenty percent of the respondents said drug-shortage-related errors were made, while 32% said they had “near misses” related to drug shortages. Nineteen percent said there had been adverse patient outcomes as a result of drug shortages.

The study noted two instances in which patients died when they were switched to dilaudid because morphine was in short supply; both patients were given morphine doses instead of adjusted doses for dilaudid.

“It’s about six- or sevenfold more potent than morphine,” says Michael Cohen, ISMP president. “And so when that drug is prescribed in a morphine dose, that would be a massive overdose for some patients.”

He adds that hospitals have tried to stay on top of the drug shortage problem, but that “it’s very difficult.”

“A lot of this happens last-minute,” Cohen says. “Physicians aren’t given a chance to even realize that a certain drug isn’t available, so it causes an interruption in the whole flow of things in the hospital.” Some hospitals have had to hire staffers who handle just the inevitable daily drug shortages, he adds.

A law has been proposed in the U.S. Senate that would require drug manufacturers to notify the FDA when circumstances arise that might reasonably lead to a drug shortage (see “Senate Bill Would Require Advance Notice of Potential Shortages,” p. 41).

Cohen says another concern is that some hospitals, faced with shortages in electrolytes, such as potassium phosphate and sodium acetate, have been turning to less-regulated sterile compounding pharmacies for the products.

Dr. Verma, of Durham Regional, says perhaps the biggest challenge is staying on top of changing doses. “I think there was a learning curve for physicians in using dilaudid [rather than morphine] because the dosing is quite different, so that can cause challenges for patient care when you’re switching in and out of drug classes,” he says. “It’s not a perfect science. It doesn’t cripple us, but it does make it more challenging to fine-tune patient care.”

Ginsburg, of the ASHP, urges hospitalists to stay in close contact with the pharmacists at their hospitals and to be diligent about reporting shortages to the ASHP.

“Please work closely with the pharmacists, because we’re the ones that can really help,” she says. “We’re in it together with them, in terms of trying to provide care for their patients.” TH

Thomas R. Collins a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

When a drug is in short supply at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, a message goes out to the physicians on the hospital’s intranet system. When the shortage gets close to being critically short in supply, a message will be embedded into the physician order-entry system recommending that the physicians use an alternate drug—if there is an alternate.

It’s an alert system that has been put to frequent use lately, says Joseph Li, MD, SFHM, director of the hospital medicine program at Beth Israel Deaconess, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and president of SHM.

The rate of drug shortages has been rising steadily in recent years due to quality questions at manufacturers, consolidation in the drug-manufacturing industry, and other factors, according to data from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and other sources.

“It does seem like there’s more today than previous years,” says Dr. Li, who was a pharmacist before he trained in internal medicine.

Some of the recent shortages at Beth Israel Deaconess have involved the diuretic furosemide, the antiemetic Compazine, and the anticoagulant heparin. “More often than not, there’s a reasonable alternative that can be chosen,” he says. “Not necessarily exactly the same drug, but usually in the same therapeutic class.”

While actual cases of patient harm due to drug shortages appear to be relatively uncommon, having drugs in short supply can lead to a safety problem hovering over a medical center and its hospitalists. In addition to the potential of simply not having an alternate to give to a patient, hospitalists and their pharmacists sometimes have to adjust to a new dosage that comes with a replacement medication.

Plus, having to manage the problem when a drug shortage hits can be a headache, with time and resources spent trying to obtain updates from drug manufacturers and find other drugs that can be used in the meantime, experts say.

With hospitalists now treating so many patients, many of them complex and on multiple medications, it is an important issue for hospitalists to stay aware of and to be prepared for, Dr. Li says. More than 90% of all medical patients at Beth Israel Deaconess are now cared for by hospitalists, he says, and it’s a similar situation for many acute-care hospitals around the country.

If a drug is in short supply, balancing availability with patient needs can be especially tricky for a hospitalist caring for patients with a multitude of demands, Dr. Li says. “There is an effort to make sure that our most vulnerable population of patients receive these treatments before the general population of patients have access to it,” he adds.

However, the very existence of hospitalists makes it easier to navigate a shortage compared to the days when hundreds of providers would be caring for a pool of patients.

“If you’re trying to notify a group of providers about shortages and have an impact on their prescribing habits, I think it’s easier today,” he says.

Troubled Waters

The FDA says it confirmed a record 178 cases of drug shortages in 2010 (www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/drugshortages/default.htm). That was up from 55 shortages five years ago. And according to the University of Utah Drug Information Service, the problem is actually more pervasive than that, reporting 120 shortages in the U.S. in 2001, with a reported 211 in 2010. And through March of this year, there were 80 reported cases of shortages, on pace for another record year.

“In the past couple of years, it’s just been exponential,” says Diane Ginsburg, president of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and clinical professor and assistant dean for student affairs at the University of Texas’ College of Pharmacy in Austin.

According to the FDA, 77% of the shortages in 2010 involved sterile injectable drugs.

“There are fewer and fewer firms making these older sterile injectables, and they are often discontinued for newer, more profitable agents,” FDA spokeswoman Yolanda Fultz-Morris said in an email. “When one firm has a delay or a manufacturing problem, it is extremely difficult for the remaining firms to quickly increase production.”

The biggest cause for the shortages in those drugs has been product quality issues, namely microbial contamination and newly identified impurities, according to the FDA. From January to October of 2010, 42% of drug shortages were due to quality problems.

Eighteen percent were due to product discontinuation by the manufacturer and another 18% were due to delays and capacity problems. Nine percent were due to difficulties getting raw materials, and 4% of the sterile injectable shortages were due to increased demand because there was a shortage of another injectable medication. In other words, one shortage led directly to another.

Kevin Schweers, a spokesman for the National Community Pharmacists Association, says generic drugs, especially Schedule II substances, have been in short supply. But there can be problems even when one generic is available to replace another generic.

An example, he says, is when a “new generic substituted in place of the old one is made by a different manufacturer and may come in a different color or shape. That can leave patients”—including those just released from hospitals—“wondering and asking the pharmacist why their medication is different or if a mistake was made.”

Patient Safety and Communication Errors

Lalit Verma, MD, director of the hospital medicine program at Durham Regional Medical Center in North Carolina and assistant professor of medicine at the Duke University School of Medicine, is unaware of any situations in which a shortage put patients in jeopardy at his hospital. He says the pharmacy at Durham Regional, which has seen recent shortages in morphine and heparin, among other drugs, keeps doctors up to date and has adjusted doses appropriately when replacements are used.

“It’s probably been more than I’ve experienced in my 10 years as a hospitalist,” Dr. Verma says. “We have a very good pharmacy program that updates us regularly on drug shortages and offers alternatives.”

Dr. Li also says no patient’s safety has been jeopardized by a shortage.

Others say patient safety has been affected, according to 1,800 healthcare practitioners who participated in a survey last year conducted by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), a nonprofit group. Twenty percent of the respondents said drug-shortage-related errors were made, while 32% said they had “near misses” related to drug shortages. Nineteen percent said there had been adverse patient outcomes as a result of drug shortages.

The study noted two instances in which patients died when they were switched to dilaudid because morphine was in short supply; both patients were given morphine doses instead of adjusted doses for dilaudid.

“It’s about six- or sevenfold more potent than morphine,” says Michael Cohen, ISMP president. “And so when that drug is prescribed in a morphine dose, that would be a massive overdose for some patients.”

He adds that hospitals have tried to stay on top of the drug shortage problem, but that “it’s very difficult.”

“A lot of this happens last-minute,” Cohen says. “Physicians aren’t given a chance to even realize that a certain drug isn’t available, so it causes an interruption in the whole flow of things in the hospital.” Some hospitals have had to hire staffers who handle just the inevitable daily drug shortages, he adds.

A law has been proposed in the U.S. Senate that would require drug manufacturers to notify the FDA when circumstances arise that might reasonably lead to a drug shortage (see “Senate Bill Would Require Advance Notice of Potential Shortages,” p. 41).

Cohen says another concern is that some hospitals, faced with shortages in electrolytes, such as potassium phosphate and sodium acetate, have been turning to less-regulated sterile compounding pharmacies for the products.

Dr. Verma, of Durham Regional, says perhaps the biggest challenge is staying on top of changing doses. “I think there was a learning curve for physicians in using dilaudid [rather than morphine] because the dosing is quite different, so that can cause challenges for patient care when you’re switching in and out of drug classes,” he says. “It’s not a perfect science. It doesn’t cripple us, but it does make it more challenging to fine-tune patient care.”

Ginsburg, of the ASHP, urges hospitalists to stay in close contact with the pharmacists at their hospitals and to be diligent about reporting shortages to the ASHP.

“Please work closely with the pharmacists, because we’re the ones that can really help,” she says. “We’re in it together with them, in terms of trying to provide care for their patients.” TH

Thomas R. Collins a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

When a drug is in short supply at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, a message goes out to the physicians on the hospital’s intranet system. When the shortage gets close to being critically short in supply, a message will be embedded into the physician order-entry system recommending that the physicians use an alternate drug—if there is an alternate.

It’s an alert system that has been put to frequent use lately, says Joseph Li, MD, SFHM, director of the hospital medicine program at Beth Israel Deaconess, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and president of SHM.

The rate of drug shortages has been rising steadily in recent years due to quality questions at manufacturers, consolidation in the drug-manufacturing industry, and other factors, according to data from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and other sources.

“It does seem like there’s more today than previous years,” says Dr. Li, who was a pharmacist before he trained in internal medicine.

Some of the recent shortages at Beth Israel Deaconess have involved the diuretic furosemide, the antiemetic Compazine, and the anticoagulant heparin. “More often than not, there’s a reasonable alternative that can be chosen,” he says. “Not necessarily exactly the same drug, but usually in the same therapeutic class.”

While actual cases of patient harm due to drug shortages appear to be relatively uncommon, having drugs in short supply can lead to a safety problem hovering over a medical center and its hospitalists. In addition to the potential of simply not having an alternate to give to a patient, hospitalists and their pharmacists sometimes have to adjust to a new dosage that comes with a replacement medication.

Plus, having to manage the problem when a drug shortage hits can be a headache, with time and resources spent trying to obtain updates from drug manufacturers and find other drugs that can be used in the meantime, experts say.

With hospitalists now treating so many patients, many of them complex and on multiple medications, it is an important issue for hospitalists to stay aware of and to be prepared for, Dr. Li says. More than 90% of all medical patients at Beth Israel Deaconess are now cared for by hospitalists, he says, and it’s a similar situation for many acute-care hospitals around the country.

If a drug is in short supply, balancing availability with patient needs can be especially tricky for a hospitalist caring for patients with a multitude of demands, Dr. Li says. “There is an effort to make sure that our most vulnerable population of patients receive these treatments before the general population of patients have access to it,” he adds.

However, the very existence of hospitalists makes it easier to navigate a shortage compared to the days when hundreds of providers would be caring for a pool of patients.

“If you’re trying to notify a group of providers about shortages and have an impact on their prescribing habits, I think it’s easier today,” he says.

Troubled Waters

The FDA says it confirmed a record 178 cases of drug shortages in 2010 (www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/drugshortages/default.htm). That was up from 55 shortages five years ago. And according to the University of Utah Drug Information Service, the problem is actually more pervasive than that, reporting 120 shortages in the U.S. in 2001, with a reported 211 in 2010. And through March of this year, there were 80 reported cases of shortages, on pace for another record year.

“In the past couple of years, it’s just been exponential,” says Diane Ginsburg, president of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and clinical professor and assistant dean for student affairs at the University of Texas’ College of Pharmacy in Austin.

According to the FDA, 77% of the shortages in 2010 involved sterile injectable drugs.

“There are fewer and fewer firms making these older sterile injectables, and they are often discontinued for newer, more profitable agents,” FDA spokeswoman Yolanda Fultz-Morris said in an email. “When one firm has a delay or a manufacturing problem, it is extremely difficult for the remaining firms to quickly increase production.”

The biggest cause for the shortages in those drugs has been product quality issues, namely microbial contamination and newly identified impurities, according to the FDA. From January to October of 2010, 42% of drug shortages were due to quality problems.

Eighteen percent were due to product discontinuation by the manufacturer and another 18% were due to delays and capacity problems. Nine percent were due to difficulties getting raw materials, and 4% of the sterile injectable shortages were due to increased demand because there was a shortage of another injectable medication. In other words, one shortage led directly to another.

Kevin Schweers, a spokesman for the National Community Pharmacists Association, says generic drugs, especially Schedule II substances, have been in short supply. But there can be problems even when one generic is available to replace another generic.

An example, he says, is when a “new generic substituted in place of the old one is made by a different manufacturer and may come in a different color or shape. That can leave patients”—including those just released from hospitals—“wondering and asking the pharmacist why their medication is different or if a mistake was made.”

Patient Safety and Communication Errors

Lalit Verma, MD, director of the hospital medicine program at Durham Regional Medical Center in North Carolina and assistant professor of medicine at the Duke University School of Medicine, is unaware of any situations in which a shortage put patients in jeopardy at his hospital. He says the pharmacy at Durham Regional, which has seen recent shortages in morphine and heparin, among other drugs, keeps doctors up to date and has adjusted doses appropriately when replacements are used.

“It’s probably been more than I’ve experienced in my 10 years as a hospitalist,” Dr. Verma says. “We have a very good pharmacy program that updates us regularly on drug shortages and offers alternatives.”

Dr. Li also says no patient’s safety has been jeopardized by a shortage.

Others say patient safety has been affected, according to 1,800 healthcare practitioners who participated in a survey last year conducted by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), a nonprofit group. Twenty percent of the respondents said drug-shortage-related errors were made, while 32% said they had “near misses” related to drug shortages. Nineteen percent said there had been adverse patient outcomes as a result of drug shortages.

The study noted two instances in which patients died when they were switched to dilaudid because morphine was in short supply; both patients were given morphine doses instead of adjusted doses for dilaudid.

“It’s about six- or sevenfold more potent than morphine,” says Michael Cohen, ISMP president. “And so when that drug is prescribed in a morphine dose, that would be a massive overdose for some patients.”

He adds that hospitals have tried to stay on top of the drug shortage problem, but that “it’s very difficult.”

“A lot of this happens last-minute,” Cohen says. “Physicians aren’t given a chance to even realize that a certain drug isn’t available, so it causes an interruption in the whole flow of things in the hospital.” Some hospitals have had to hire staffers who handle just the inevitable daily drug shortages, he adds.

A law has been proposed in the U.S. Senate that would require drug manufacturers to notify the FDA when circumstances arise that might reasonably lead to a drug shortage (see “Senate Bill Would Require Advance Notice of Potential Shortages,” p. 41).

Cohen says another concern is that some hospitals, faced with shortages in electrolytes, such as potassium phosphate and sodium acetate, have been turning to less-regulated sterile compounding pharmacies for the products.

Dr. Verma, of Durham Regional, says perhaps the biggest challenge is staying on top of changing doses. “I think there was a learning curve for physicians in using dilaudid [rather than morphine] because the dosing is quite different, so that can cause challenges for patient care when you’re switching in and out of drug classes,” he says. “It’s not a perfect science. It doesn’t cripple us, but it does make it more challenging to fine-tune patient care.”

Ginsburg, of the ASHP, urges hospitalists to stay in close contact with the pharmacists at their hospitals and to be diligent about reporting shortages to the ASHP.

“Please work closely with the pharmacists, because we’re the ones that can really help,” she says. “We’re in it together with them, in terms of trying to provide care for their patients.” TH

Thomas R. Collins a freelance medical writer based in Florida.