User login

What Is the Appropriate Use of Antibiotics In Acute Exacerbations of COPD?

Case

A 58-year-old male smoker with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (FEV1 56% predicted) is admitted with an acute exacerbation of COPD for the second time this year. He presented to the ED with increased productive cough and shortness of breath, similar to prior exacerbations. He denies fevers, myalgias, or upper-respiratory symptoms. Physical exam is notable for bilateral inspiratory and expiratory wheezing. His sputum is purulent. He is given continuous nebulizer therapy and one dose of oral prednisone, but his dyspnea and wheezing persist. Chest X-ray does not reveal an infiltrate.

Should this patient be treated with antibiotics and, if so, what regimen is most appropriate?

Overview

Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) present a major health burden, accounting for more than 2.4% of all hospital admissions and causing significant morbidity, mortality, and costs.1 During 2006 and 2007, COPD mortality in the United States topped 39 deaths per 100,000 people, and more recently, hospital costs related to COPD were expected to exceed $13 billion annually.2 Patients with AECOPD also experience decreased quality of life and faster decline in pulmonary function, further highlighting the need for timely and appropriate treatment.1

Several guidelines have proposed treatment strategies now considered standard of care in AECOPD management.3,4,5,6 These include the use of corticosteroids, bronchodilator agents, and, in select cases, antibiotics. While there is well-established evidence for the use of steroids and bronchodilators in AECOPD, the debate continues over the appropriate use of antibiotics in the treatment of acute exacerbations. There are multiple potential factors leading to AECOPD, including viruses, bacteria, and common pollutants; as such, antibiotic treatment may not be indicated for all patients presenting with exacerbations. Further, the risks of antibiotic treatment—including adverse drug events, selection for drug-resistant bacteria, and associated costs—are not insignificant.

However, bacterial infections do play a role in approximately 50% of patients with AECOPD and, for this population, use of antibiotics may confer important benefits.7

Interestingly, a retrospective cohort study of 84,621 patients admitted for AECOPD demonstrated that 85% of patients received antibiotics at some point during hospitalization.8

Support for Antibiotics

Several randomized trials have compared clinical outcomes in patients with AECOPD who have received antibiotics versus those who received placebos. Most of these had small sample sizes and studied only ββ-lactam and tetracycline antibiotics in an outpatient setting; there are limited data involving inpatients and newer drugs. Nevertheless, antibiotic treatment has been associated with decreased risk of adverse outcomes in AECOPD.

One meta-analysis demonstrated that antibiotics reduced treatment failures by 66% and in-hospital mortality by 78% in the subset of trials involving hospitalized patients.8 Similarly, analysis of a large retrospective cohort of patients hospitalized for AECOPD found a significantly lower risk of treatment failure in antibiotic-treated versus untreated patients.9 Specifically, treated patients had lower rates of in-hospital mortality and readmission for AECOPD and a lower likelihood of requiring subsequent mechanical ventilation during the index hospitalization.

Data also suggest that antibiotic treatment during exacerbations might favorably impact subsequent exacerbations.10 A retrospective study of 18,928 Dutch patients with AECOPD compared outcomes among patients who had received antibiotics (most frequently doxycycline or a penicillin) as part of their therapy to those who did not. The authors demonstrated that the median time to the next exacerbation was significantly longer in the patients receiving antibiotics.10 Further, both mortality and overall risk of developing a subsequent exacerbation were significantly decreased in the antibiotic group, with median follow-up of approximately two years.

Indications for Antibiotics

Clinical symptoms. A landmark study by Anthonisen and colleagues set forth three clinical criteria that have formed the basis for treating AECOPD with antibiotics in subsequent studies and in clinical practice.11 Often referred to as the “cardinal symptoms” of AECOPD, these include increased dyspnea, sputum volume, and sputum purulence. In this study, 173 outpatients with COPD were randomized to a 10-day course of antibiotics or placebo at onset of an exacerbation and followed clinically. The authors found that antibiotic-treated patients were significantly more likely than the placebo group to achieve treatment success, defined as resolution of all exacerbated symptoms within 21 days (68.1% vs. 55.0%, P<0.01).

Importantly, treated patients were also significantly less likely to experience clinical deterioration after 72 hours (9.9% vs. 18.9%, P<0.05). Patients with Type I exacerbations, characterized by all three cardinal symptoms, were most likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, followed by patients with Type II exacerbations, in whom only two of the symptoms were present. Subsequent studies have suggested that sputum purulence correlates well with the presence of acute bacterial infection and therefore may be a reliable clinical indicator of patients who are likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy.12

Laboratory data. While sputum purulence is associated with bacterial infection, sputum culture is less reliable, as pathogenic bacteria are commonly isolated from patients with both AECOPD and stable COPD. In fact, the prevalence of bacterial colonization in moderate to severe COPD might be as high as 50%.13 Therefore, a positive bacterial sputum culture, in the absence of purulence or other signs of infection, is not recommended as the sole basis for which to prescribe antibiotics.

Serum biomarkers, most notably C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin, have been studied as a newer approach to identify patients who might benefit from antibiotic therapy for AECOPD. Studies have demonstrated increased CRP levels during AECOPD, particularly in patients with purulent sputum and positive bacterial sputum cultures.12 Procalcitonin is preferentially elevated in bacterial infections.

One randomized, placebo-controlled trial in hospitalized patients with AECOPD demonstrated a significant reduction in antibiotic usage based on low procalcitonin levels, without negatively impacting clinical success rate, hospital mortality, subsequent antibiotic needs, or time to next exacerbation.14 However, due to inconsistent evidence, use of these markers to guide antibiotic administration in AECOPD has not yet been definitively established.14,15 Additionally, these laboratory results are often not available at the point of care, potentially limiting their utility in the decision to initiate antibiotics.

Severity of illness. Severity of illness is an important factor in the decision to treat AECOPD with antibiotics. Patients with advanced, underlying airway obstruction, as measured by FEV1, are more likely to have a bacterial cause of AECOPD.16 Additionally, baseline clinical characteristics including advanced age and comorbid conditions, particularly cardiovascular disease and diabetes, increase the risk of severe exacerbations.17

One meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials found that patients with severe exacerbations were likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, while patients with mild or moderate exacerbations had no reduction in treatment failure or mortality rates.18 Patients presenting with acute respiratory failure necessitating intensive care and/or ventilator support (noninvasive or invasive) have also been shown to benefit from antibiotics.19

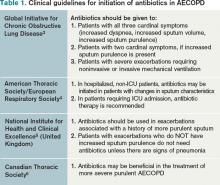

Current clinical guidelines vary slightly in their recommendations regarding when to give antibiotics in AECOPD (see Table 1). However, existing evidence favors antibiotic treatment for those patients presenting with two or three cardinal symptoms, specifically those with increased sputum purulence, and those with severe disease (i.e. pre-existing advanced airflow obstruction and/or exacerbations requiring mechanical ventilation). Conversely, studies have shown that many patients, particularly those with milder exacerbations, experience resolution of symptoms without antibiotic treatment.11,18

Antibiotic Choice in AECOPD

Risk stratification. In patients likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, an understanding of the relationship between severity of COPD, host risk factors for poor outcomes, and microbiology is paramount to guide clinical decision-making. Historically, such bacteria as Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AECOPD.3,7 In patients with simple exacerbations, antibiotics that target these pathogens should be used (see Table 2).

However, patients with more severe underlying airway obstruction (i.e. FEV1<50%) and risk factors for poor outcomes, specifically recent hospitalization (≥2 days during the previous 90 days), frequent antibiotics (>3 courses during the previous year), and severe exacerbations are more likely to be infected with resistant strains or gram-negative organisms.3,7 Pseudomonas aeruginosa, in particular, is of increasing concern in this population. In patients with complicated exacerbations, more broad-coverage, empiric antibiotics should be initiated (see Table 2).

With this in mind, patients meeting criteria for treatment must first be stratified according to the severity of COPD and risk factors for poor outcomes before a decision regarding a specific antibiotic is reached. Figure 1 outlines a recommended approach for antibiotic administration in AECOPD. The optimal choice of antibiotics must consider cost-effectiveness, local patterns of antibiotic resistance, tissue penetration, patient adherence, and risk of such adverse drug events as diarrhea.

Comparative effectiveness. Current treatment guidelines do not favor the use of any particular antibiotic in simple AECOPD.3,4,5,6 However, as selective pressure has led to in vitro resistance to antibiotics traditionally considered first-line (e.g. doxycycline, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, amoxicillin), the use of second-line antibiotics (e.g. fluoroquinolones, macrolides, cephalosporins, β-lactam/ β-lactamase inhibitors) has increased. Consequently, several studies have compared the effectiveness of different antimicrobial regimens.

One meta-analysis found that second-line antibiotics, when compared with first-line agents, provided greater clinical improvement to patients with AECOPD, without significant differences in mortality, microbiologic eradication, or incidence of adverse drug events.20 Among the subgroup of trials enrolling hospitalized patients, the clinical effectiveness of second-line agents remained significantly greater than that of first-line agents.

Another meta-analysis compared trials that studied only macrolides, quinolones, and amoxicillin-clavulanate and found no difference in terms of short-term clinical effectiveness; however, there was weak evidence to suggest that quinolones were associated with better microbiological success and fewer recurrences of AECOPD.21 Fluoroquinolones are preferred in complicated cases of AECOPD in which there is a greater risk for enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas species.3,7

Antibiotic Duration

The duration of antibiotic therapy in AECOPD has been studied extensively, with randomized controlled trials consistently demonstrating no additional benefit to courses extending beyond five days. One meta-analysis of 21 studies found similar clinical and microbiologic cure rates among patients randomized to antibiotic treatment for ≤5 days versus >5 days.22 A subgroup analysis of the trials evaluating different durations of the same antibiotic also demonstrated no difference in clinical effectiveness, and this finding was confirmed in a separate meta-analysis.22,23

Advantages to shorter antibiotic courses include improved compliance and decreased rates of resistance. The usual duration of antibiotic therapy is three to seven days, depending upon the response to therapy.3

Back to the Case

As the patient has no significant comorbidities or risk factors, and meets criteria for a simple Anthonisen Type I exacerbation (increased dyspnea, sputum, and sputum purulence), antibiotic therapy with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is initiated on admission, in addition to the previously started steroid and bronchodilator treatments. The patient’s clinical status improves, and he is discharged on hospital Day 3 with a prescription to complete a five-day course of antibiotics.

Bottom Line

Antibiotic therapy is effective in select AECOPD patients, with maximal benefits obtained when the decision to treat is based on careful consideration of characteristic clinical symptoms and severity of illness. Choice and duration of antibiotics should follow likely bacterial causes and current guidelines.

Dr. Cunningham is an assistant professor of internal medicine and academic hospitalist in the section of hospital medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn. Dr. LaBrin is assistant professor of internal medicine and pediatrics and an academic hospitalist at Vanderbilt. Dr. Markley is a clinical instructor and academic hospitalist at Vanderbilt.

References

- Donaldson GC, Wedzicha JA. COPD exacerbations: 1. Epidemiology. Thorax. 2006;61:164-168.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. 2009 NHLBI Morbidity and Mortality Chartbook. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute website. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/cht-book.htm Accessed Oct. 10, 2011.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) website. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-resources.html Accessed Oct. 10, 2011.

- Celli BR, MacNee W, Agusti A, et al. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Resp J. 2004;23:932-946.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence website. Available at: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG101/Guidance/pdf/English. Accessed Oct. 10, 2011.

- O’Donnell DE, Aaron S, Bourbeau J, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—2007 update. Can Respir J. 2007;14(Suppl B):5B-32B.

- Sethi S, Murphy TF. Infection in the pathogenesis and course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2355-2565.

- Quon BS, Qi Gan W, Sin DD. Contemporary management of acute exacerbations of COPD: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest. 2008;133:756-766.

- Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, Lahti M, Brody O, Skiest DJ, Lindenauer PK. Antibiotic therapy and treatment failure in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2010;303:2035-2042.

- Roede BM, Bresser P, Bindels PJE, et al. Antibiotic treatment is associated with reduced risk of subsequent exacerbation in obstructive lung disease: a historical population based cohort study. Thorax. 2008;63:968-973.

- Anthonisen NR, Manfreda J, Warren CP, Hershfield ES, Harding GKM, Nelson NA. Antibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:196-204.

- Stockley RA, O’Brien C, Pye A, Hill SL. Relationship of sputum color to nature and outpatient management of acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2000;117:1638-1645.

- Rosell A, Monso E, Soler N, et al. Microbiologic determinants of exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165:891-897.

- Stolz D, Christ-Crain M, Bingisser R, et al. Antibiotic treatment of exacerbations of COPD: a randomized, controlled trial comparing procalcitonin-guidance with standard therapy. Chest. 2007;131:9-19.

- Daniels JMA, Schoorl M, Snijders D, et al. Procalcitonin vs C-reactive protein as predictive markers of response to antibiotic therapy in acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2010;138:1108-1015.

- Miravitlles M, Espinosa C, Fernandez-Laso E, Martos JA, Maldonado JA, Gallego M. Relationship between bacterial flora in sputum and functional impairment in patients with acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 1999;116:40-46.

- Patil SP, Krishnan JA, Lechtzin N, Diette GB. In-hospital mortality following acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1180-1186.

- Puhan MA, Vollenweider D, Latshang T, Steurer J, Steurer-Stey C. Exacerbations of chronic obstructive lung disease: when are antibiotics indicated? A systematic review. Resp Res. 2007;8:30-40.

- Nouira S, Marghli S, Belghith M, Besbes L, Elatrous S, Abroug F. Once daily ofloxacin in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation requiring mechanical ventilation: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358:2020-2025.

- Dimopoulos G, Siempos II, Korbila IP, Manta KG, Falagas ME. Comparison of first-line with second-line antibiotics for acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: a metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Chest. 2007;132:447-455.

- Siempos II, Dimopoulos G, Korbila IP, Manta KG, Falagas ME. Macrolides, quinolones and amoxicillin/clavulanate for chronic bronchitis: a meta-analysis. Eur Resp J. 2007;29:1127-1137.

- El-Moussaoui, Roede BM, Speelman P, Bresser P, Prins JM, Bossuyt PMM. Short-course antibiotic treatment in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and COPD: a meta-analysis of double-blind studies. Thorax. 2008;63:415-422.

- Falagas ME, Avgeri SG, Matthaiou DK, Dimopoulos G, Siempos II. Short- versus long-duration antimicrobial treatment for exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: a meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:442-450.

Case

A 58-year-old male smoker with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (FEV1 56% predicted) is admitted with an acute exacerbation of COPD for the second time this year. He presented to the ED with increased productive cough and shortness of breath, similar to prior exacerbations. He denies fevers, myalgias, or upper-respiratory symptoms. Physical exam is notable for bilateral inspiratory and expiratory wheezing. His sputum is purulent. He is given continuous nebulizer therapy and one dose of oral prednisone, but his dyspnea and wheezing persist. Chest X-ray does not reveal an infiltrate.

Should this patient be treated with antibiotics and, if so, what regimen is most appropriate?

Overview

Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) present a major health burden, accounting for more than 2.4% of all hospital admissions and causing significant morbidity, mortality, and costs.1 During 2006 and 2007, COPD mortality in the United States topped 39 deaths per 100,000 people, and more recently, hospital costs related to COPD were expected to exceed $13 billion annually.2 Patients with AECOPD also experience decreased quality of life and faster decline in pulmonary function, further highlighting the need for timely and appropriate treatment.1

Several guidelines have proposed treatment strategies now considered standard of care in AECOPD management.3,4,5,6 These include the use of corticosteroids, bronchodilator agents, and, in select cases, antibiotics. While there is well-established evidence for the use of steroids and bronchodilators in AECOPD, the debate continues over the appropriate use of antibiotics in the treatment of acute exacerbations. There are multiple potential factors leading to AECOPD, including viruses, bacteria, and common pollutants; as such, antibiotic treatment may not be indicated for all patients presenting with exacerbations. Further, the risks of antibiotic treatment—including adverse drug events, selection for drug-resistant bacteria, and associated costs—are not insignificant.

However, bacterial infections do play a role in approximately 50% of patients with AECOPD and, for this population, use of antibiotics may confer important benefits.7

Interestingly, a retrospective cohort study of 84,621 patients admitted for AECOPD demonstrated that 85% of patients received antibiotics at some point during hospitalization.8

Support for Antibiotics

Several randomized trials have compared clinical outcomes in patients with AECOPD who have received antibiotics versus those who received placebos. Most of these had small sample sizes and studied only ββ-lactam and tetracycline antibiotics in an outpatient setting; there are limited data involving inpatients and newer drugs. Nevertheless, antibiotic treatment has been associated with decreased risk of adverse outcomes in AECOPD.

One meta-analysis demonstrated that antibiotics reduced treatment failures by 66% and in-hospital mortality by 78% in the subset of trials involving hospitalized patients.8 Similarly, analysis of a large retrospective cohort of patients hospitalized for AECOPD found a significantly lower risk of treatment failure in antibiotic-treated versus untreated patients.9 Specifically, treated patients had lower rates of in-hospital mortality and readmission for AECOPD and a lower likelihood of requiring subsequent mechanical ventilation during the index hospitalization.

Data also suggest that antibiotic treatment during exacerbations might favorably impact subsequent exacerbations.10 A retrospective study of 18,928 Dutch patients with AECOPD compared outcomes among patients who had received antibiotics (most frequently doxycycline or a penicillin) as part of their therapy to those who did not. The authors demonstrated that the median time to the next exacerbation was significantly longer in the patients receiving antibiotics.10 Further, both mortality and overall risk of developing a subsequent exacerbation were significantly decreased in the antibiotic group, with median follow-up of approximately two years.

Indications for Antibiotics

Clinical symptoms. A landmark study by Anthonisen and colleagues set forth three clinical criteria that have formed the basis for treating AECOPD with antibiotics in subsequent studies and in clinical practice.11 Often referred to as the “cardinal symptoms” of AECOPD, these include increased dyspnea, sputum volume, and sputum purulence. In this study, 173 outpatients with COPD were randomized to a 10-day course of antibiotics or placebo at onset of an exacerbation and followed clinically. The authors found that antibiotic-treated patients were significantly more likely than the placebo group to achieve treatment success, defined as resolution of all exacerbated symptoms within 21 days (68.1% vs. 55.0%, P<0.01).

Importantly, treated patients were also significantly less likely to experience clinical deterioration after 72 hours (9.9% vs. 18.9%, P<0.05). Patients with Type I exacerbations, characterized by all three cardinal symptoms, were most likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, followed by patients with Type II exacerbations, in whom only two of the symptoms were present. Subsequent studies have suggested that sputum purulence correlates well with the presence of acute bacterial infection and therefore may be a reliable clinical indicator of patients who are likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy.12

Laboratory data. While sputum purulence is associated with bacterial infection, sputum culture is less reliable, as pathogenic bacteria are commonly isolated from patients with both AECOPD and stable COPD. In fact, the prevalence of bacterial colonization in moderate to severe COPD might be as high as 50%.13 Therefore, a positive bacterial sputum culture, in the absence of purulence or other signs of infection, is not recommended as the sole basis for which to prescribe antibiotics.

Serum biomarkers, most notably C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin, have been studied as a newer approach to identify patients who might benefit from antibiotic therapy for AECOPD. Studies have demonstrated increased CRP levels during AECOPD, particularly in patients with purulent sputum and positive bacterial sputum cultures.12 Procalcitonin is preferentially elevated in bacterial infections.

One randomized, placebo-controlled trial in hospitalized patients with AECOPD demonstrated a significant reduction in antibiotic usage based on low procalcitonin levels, without negatively impacting clinical success rate, hospital mortality, subsequent antibiotic needs, or time to next exacerbation.14 However, due to inconsistent evidence, use of these markers to guide antibiotic administration in AECOPD has not yet been definitively established.14,15 Additionally, these laboratory results are often not available at the point of care, potentially limiting their utility in the decision to initiate antibiotics.

Severity of illness. Severity of illness is an important factor in the decision to treat AECOPD with antibiotics. Patients with advanced, underlying airway obstruction, as measured by FEV1, are more likely to have a bacterial cause of AECOPD.16 Additionally, baseline clinical characteristics including advanced age and comorbid conditions, particularly cardiovascular disease and diabetes, increase the risk of severe exacerbations.17

One meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials found that patients with severe exacerbations were likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, while patients with mild or moderate exacerbations had no reduction in treatment failure or mortality rates.18 Patients presenting with acute respiratory failure necessitating intensive care and/or ventilator support (noninvasive or invasive) have also been shown to benefit from antibiotics.19

Current clinical guidelines vary slightly in their recommendations regarding when to give antibiotics in AECOPD (see Table 1). However, existing evidence favors antibiotic treatment for those patients presenting with two or three cardinal symptoms, specifically those with increased sputum purulence, and those with severe disease (i.e. pre-existing advanced airflow obstruction and/or exacerbations requiring mechanical ventilation). Conversely, studies have shown that many patients, particularly those with milder exacerbations, experience resolution of symptoms without antibiotic treatment.11,18

Antibiotic Choice in AECOPD

Risk stratification. In patients likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, an understanding of the relationship between severity of COPD, host risk factors for poor outcomes, and microbiology is paramount to guide clinical decision-making. Historically, such bacteria as Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AECOPD.3,7 In patients with simple exacerbations, antibiotics that target these pathogens should be used (see Table 2).

However, patients with more severe underlying airway obstruction (i.e. FEV1<50%) and risk factors for poor outcomes, specifically recent hospitalization (≥2 days during the previous 90 days), frequent antibiotics (>3 courses during the previous year), and severe exacerbations are more likely to be infected with resistant strains or gram-negative organisms.3,7 Pseudomonas aeruginosa, in particular, is of increasing concern in this population. In patients with complicated exacerbations, more broad-coverage, empiric antibiotics should be initiated (see Table 2).

With this in mind, patients meeting criteria for treatment must first be stratified according to the severity of COPD and risk factors for poor outcomes before a decision regarding a specific antibiotic is reached. Figure 1 outlines a recommended approach for antibiotic administration in AECOPD. The optimal choice of antibiotics must consider cost-effectiveness, local patterns of antibiotic resistance, tissue penetration, patient adherence, and risk of such adverse drug events as diarrhea.

Comparative effectiveness. Current treatment guidelines do not favor the use of any particular antibiotic in simple AECOPD.3,4,5,6 However, as selective pressure has led to in vitro resistance to antibiotics traditionally considered first-line (e.g. doxycycline, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, amoxicillin), the use of second-line antibiotics (e.g. fluoroquinolones, macrolides, cephalosporins, β-lactam/ β-lactamase inhibitors) has increased. Consequently, several studies have compared the effectiveness of different antimicrobial regimens.

One meta-analysis found that second-line antibiotics, when compared with first-line agents, provided greater clinical improvement to patients with AECOPD, without significant differences in mortality, microbiologic eradication, or incidence of adverse drug events.20 Among the subgroup of trials enrolling hospitalized patients, the clinical effectiveness of second-line agents remained significantly greater than that of first-line agents.

Another meta-analysis compared trials that studied only macrolides, quinolones, and amoxicillin-clavulanate and found no difference in terms of short-term clinical effectiveness; however, there was weak evidence to suggest that quinolones were associated with better microbiological success and fewer recurrences of AECOPD.21 Fluoroquinolones are preferred in complicated cases of AECOPD in which there is a greater risk for enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas species.3,7

Antibiotic Duration

The duration of antibiotic therapy in AECOPD has been studied extensively, with randomized controlled trials consistently demonstrating no additional benefit to courses extending beyond five days. One meta-analysis of 21 studies found similar clinical and microbiologic cure rates among patients randomized to antibiotic treatment for ≤5 days versus >5 days.22 A subgroup analysis of the trials evaluating different durations of the same antibiotic also demonstrated no difference in clinical effectiveness, and this finding was confirmed in a separate meta-analysis.22,23

Advantages to shorter antibiotic courses include improved compliance and decreased rates of resistance. The usual duration of antibiotic therapy is three to seven days, depending upon the response to therapy.3

Back to the Case

As the patient has no significant comorbidities or risk factors, and meets criteria for a simple Anthonisen Type I exacerbation (increased dyspnea, sputum, and sputum purulence), antibiotic therapy with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is initiated on admission, in addition to the previously started steroid and bronchodilator treatments. The patient’s clinical status improves, and he is discharged on hospital Day 3 with a prescription to complete a five-day course of antibiotics.

Bottom Line

Antibiotic therapy is effective in select AECOPD patients, with maximal benefits obtained when the decision to treat is based on careful consideration of characteristic clinical symptoms and severity of illness. Choice and duration of antibiotics should follow likely bacterial causes and current guidelines.

Dr. Cunningham is an assistant professor of internal medicine and academic hospitalist in the section of hospital medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn. Dr. LaBrin is assistant professor of internal medicine and pediatrics and an academic hospitalist at Vanderbilt. Dr. Markley is a clinical instructor and academic hospitalist at Vanderbilt.

References

- Donaldson GC, Wedzicha JA. COPD exacerbations: 1. Epidemiology. Thorax. 2006;61:164-168.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. 2009 NHLBI Morbidity and Mortality Chartbook. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute website. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/cht-book.htm Accessed Oct. 10, 2011.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) website. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-resources.html Accessed Oct. 10, 2011.

- Celli BR, MacNee W, Agusti A, et al. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Resp J. 2004;23:932-946.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence website. Available at: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG101/Guidance/pdf/English. Accessed Oct. 10, 2011.

- O’Donnell DE, Aaron S, Bourbeau J, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—2007 update. Can Respir J. 2007;14(Suppl B):5B-32B.

- Sethi S, Murphy TF. Infection in the pathogenesis and course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2355-2565.

- Quon BS, Qi Gan W, Sin DD. Contemporary management of acute exacerbations of COPD: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest. 2008;133:756-766.

- Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, Lahti M, Brody O, Skiest DJ, Lindenauer PK. Antibiotic therapy and treatment failure in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2010;303:2035-2042.

- Roede BM, Bresser P, Bindels PJE, et al. Antibiotic treatment is associated with reduced risk of subsequent exacerbation in obstructive lung disease: a historical population based cohort study. Thorax. 2008;63:968-973.

- Anthonisen NR, Manfreda J, Warren CP, Hershfield ES, Harding GKM, Nelson NA. Antibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:196-204.

- Stockley RA, O’Brien C, Pye A, Hill SL. Relationship of sputum color to nature and outpatient management of acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2000;117:1638-1645.

- Rosell A, Monso E, Soler N, et al. Microbiologic determinants of exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165:891-897.

- Stolz D, Christ-Crain M, Bingisser R, et al. Antibiotic treatment of exacerbations of COPD: a randomized, controlled trial comparing procalcitonin-guidance with standard therapy. Chest. 2007;131:9-19.

- Daniels JMA, Schoorl M, Snijders D, et al. Procalcitonin vs C-reactive protein as predictive markers of response to antibiotic therapy in acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2010;138:1108-1015.

- Miravitlles M, Espinosa C, Fernandez-Laso E, Martos JA, Maldonado JA, Gallego M. Relationship between bacterial flora in sputum and functional impairment in patients with acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 1999;116:40-46.

- Patil SP, Krishnan JA, Lechtzin N, Diette GB. In-hospital mortality following acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1180-1186.

- Puhan MA, Vollenweider D, Latshang T, Steurer J, Steurer-Stey C. Exacerbations of chronic obstructive lung disease: when are antibiotics indicated? A systematic review. Resp Res. 2007;8:30-40.

- Nouira S, Marghli S, Belghith M, Besbes L, Elatrous S, Abroug F. Once daily ofloxacin in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation requiring mechanical ventilation: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358:2020-2025.

- Dimopoulos G, Siempos II, Korbila IP, Manta KG, Falagas ME. Comparison of first-line with second-line antibiotics for acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: a metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Chest. 2007;132:447-455.

- Siempos II, Dimopoulos G, Korbila IP, Manta KG, Falagas ME. Macrolides, quinolones and amoxicillin/clavulanate for chronic bronchitis: a meta-analysis. Eur Resp J. 2007;29:1127-1137.

- El-Moussaoui, Roede BM, Speelman P, Bresser P, Prins JM, Bossuyt PMM. Short-course antibiotic treatment in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and COPD: a meta-analysis of double-blind studies. Thorax. 2008;63:415-422.

- Falagas ME, Avgeri SG, Matthaiou DK, Dimopoulos G, Siempos II. Short- versus long-duration antimicrobial treatment for exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: a meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:442-450.

Case

A 58-year-old male smoker with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (FEV1 56% predicted) is admitted with an acute exacerbation of COPD for the second time this year. He presented to the ED with increased productive cough and shortness of breath, similar to prior exacerbations. He denies fevers, myalgias, or upper-respiratory symptoms. Physical exam is notable for bilateral inspiratory and expiratory wheezing. His sputum is purulent. He is given continuous nebulizer therapy and one dose of oral prednisone, but his dyspnea and wheezing persist. Chest X-ray does not reveal an infiltrate.

Should this patient be treated with antibiotics and, if so, what regimen is most appropriate?

Overview

Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) present a major health burden, accounting for more than 2.4% of all hospital admissions and causing significant morbidity, mortality, and costs.1 During 2006 and 2007, COPD mortality in the United States topped 39 deaths per 100,000 people, and more recently, hospital costs related to COPD were expected to exceed $13 billion annually.2 Patients with AECOPD also experience decreased quality of life and faster decline in pulmonary function, further highlighting the need for timely and appropriate treatment.1

Several guidelines have proposed treatment strategies now considered standard of care in AECOPD management.3,4,5,6 These include the use of corticosteroids, bronchodilator agents, and, in select cases, antibiotics. While there is well-established evidence for the use of steroids and bronchodilators in AECOPD, the debate continues over the appropriate use of antibiotics in the treatment of acute exacerbations. There are multiple potential factors leading to AECOPD, including viruses, bacteria, and common pollutants; as such, antibiotic treatment may not be indicated for all patients presenting with exacerbations. Further, the risks of antibiotic treatment—including adverse drug events, selection for drug-resistant bacteria, and associated costs—are not insignificant.

However, bacterial infections do play a role in approximately 50% of patients with AECOPD and, for this population, use of antibiotics may confer important benefits.7

Interestingly, a retrospective cohort study of 84,621 patients admitted for AECOPD demonstrated that 85% of patients received antibiotics at some point during hospitalization.8

Support for Antibiotics

Several randomized trials have compared clinical outcomes in patients with AECOPD who have received antibiotics versus those who received placebos. Most of these had small sample sizes and studied only ββ-lactam and tetracycline antibiotics in an outpatient setting; there are limited data involving inpatients and newer drugs. Nevertheless, antibiotic treatment has been associated with decreased risk of adverse outcomes in AECOPD.

One meta-analysis demonstrated that antibiotics reduced treatment failures by 66% and in-hospital mortality by 78% in the subset of trials involving hospitalized patients.8 Similarly, analysis of a large retrospective cohort of patients hospitalized for AECOPD found a significantly lower risk of treatment failure in antibiotic-treated versus untreated patients.9 Specifically, treated patients had lower rates of in-hospital mortality and readmission for AECOPD and a lower likelihood of requiring subsequent mechanical ventilation during the index hospitalization.

Data also suggest that antibiotic treatment during exacerbations might favorably impact subsequent exacerbations.10 A retrospective study of 18,928 Dutch patients with AECOPD compared outcomes among patients who had received antibiotics (most frequently doxycycline or a penicillin) as part of their therapy to those who did not. The authors demonstrated that the median time to the next exacerbation was significantly longer in the patients receiving antibiotics.10 Further, both mortality and overall risk of developing a subsequent exacerbation were significantly decreased in the antibiotic group, with median follow-up of approximately two years.

Indications for Antibiotics

Clinical symptoms. A landmark study by Anthonisen and colleagues set forth three clinical criteria that have formed the basis for treating AECOPD with antibiotics in subsequent studies and in clinical practice.11 Often referred to as the “cardinal symptoms” of AECOPD, these include increased dyspnea, sputum volume, and sputum purulence. In this study, 173 outpatients with COPD were randomized to a 10-day course of antibiotics or placebo at onset of an exacerbation and followed clinically. The authors found that antibiotic-treated patients were significantly more likely than the placebo group to achieve treatment success, defined as resolution of all exacerbated symptoms within 21 days (68.1% vs. 55.0%, P<0.01).

Importantly, treated patients were also significantly less likely to experience clinical deterioration after 72 hours (9.9% vs. 18.9%, P<0.05). Patients with Type I exacerbations, characterized by all three cardinal symptoms, were most likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, followed by patients with Type II exacerbations, in whom only two of the symptoms were present. Subsequent studies have suggested that sputum purulence correlates well with the presence of acute bacterial infection and therefore may be a reliable clinical indicator of patients who are likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy.12

Laboratory data. While sputum purulence is associated with bacterial infection, sputum culture is less reliable, as pathogenic bacteria are commonly isolated from patients with both AECOPD and stable COPD. In fact, the prevalence of bacterial colonization in moderate to severe COPD might be as high as 50%.13 Therefore, a positive bacterial sputum culture, in the absence of purulence or other signs of infection, is not recommended as the sole basis for which to prescribe antibiotics.

Serum biomarkers, most notably C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin, have been studied as a newer approach to identify patients who might benefit from antibiotic therapy for AECOPD. Studies have demonstrated increased CRP levels during AECOPD, particularly in patients with purulent sputum and positive bacterial sputum cultures.12 Procalcitonin is preferentially elevated in bacterial infections.

One randomized, placebo-controlled trial in hospitalized patients with AECOPD demonstrated a significant reduction in antibiotic usage based on low procalcitonin levels, without negatively impacting clinical success rate, hospital mortality, subsequent antibiotic needs, or time to next exacerbation.14 However, due to inconsistent evidence, use of these markers to guide antibiotic administration in AECOPD has not yet been definitively established.14,15 Additionally, these laboratory results are often not available at the point of care, potentially limiting their utility in the decision to initiate antibiotics.

Severity of illness. Severity of illness is an important factor in the decision to treat AECOPD with antibiotics. Patients with advanced, underlying airway obstruction, as measured by FEV1, are more likely to have a bacterial cause of AECOPD.16 Additionally, baseline clinical characteristics including advanced age and comorbid conditions, particularly cardiovascular disease and diabetes, increase the risk of severe exacerbations.17

One meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials found that patients with severe exacerbations were likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, while patients with mild or moderate exacerbations had no reduction in treatment failure or mortality rates.18 Patients presenting with acute respiratory failure necessitating intensive care and/or ventilator support (noninvasive or invasive) have also been shown to benefit from antibiotics.19

Current clinical guidelines vary slightly in their recommendations regarding when to give antibiotics in AECOPD (see Table 1). However, existing evidence favors antibiotic treatment for those patients presenting with two or three cardinal symptoms, specifically those with increased sputum purulence, and those with severe disease (i.e. pre-existing advanced airflow obstruction and/or exacerbations requiring mechanical ventilation). Conversely, studies have shown that many patients, particularly those with milder exacerbations, experience resolution of symptoms without antibiotic treatment.11,18

Antibiotic Choice in AECOPD

Risk stratification. In patients likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, an understanding of the relationship between severity of COPD, host risk factors for poor outcomes, and microbiology is paramount to guide clinical decision-making. Historically, such bacteria as Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AECOPD.3,7 In patients with simple exacerbations, antibiotics that target these pathogens should be used (see Table 2).

However, patients with more severe underlying airway obstruction (i.e. FEV1<50%) and risk factors for poor outcomes, specifically recent hospitalization (≥2 days during the previous 90 days), frequent antibiotics (>3 courses during the previous year), and severe exacerbations are more likely to be infected with resistant strains or gram-negative organisms.3,7 Pseudomonas aeruginosa, in particular, is of increasing concern in this population. In patients with complicated exacerbations, more broad-coverage, empiric antibiotics should be initiated (see Table 2).

With this in mind, patients meeting criteria for treatment must first be stratified according to the severity of COPD and risk factors for poor outcomes before a decision regarding a specific antibiotic is reached. Figure 1 outlines a recommended approach for antibiotic administration in AECOPD. The optimal choice of antibiotics must consider cost-effectiveness, local patterns of antibiotic resistance, tissue penetration, patient adherence, and risk of such adverse drug events as diarrhea.

Comparative effectiveness. Current treatment guidelines do not favor the use of any particular antibiotic in simple AECOPD.3,4,5,6 However, as selective pressure has led to in vitro resistance to antibiotics traditionally considered first-line (e.g. doxycycline, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, amoxicillin), the use of second-line antibiotics (e.g. fluoroquinolones, macrolides, cephalosporins, β-lactam/ β-lactamase inhibitors) has increased. Consequently, several studies have compared the effectiveness of different antimicrobial regimens.

One meta-analysis found that second-line antibiotics, when compared with first-line agents, provided greater clinical improvement to patients with AECOPD, without significant differences in mortality, microbiologic eradication, or incidence of adverse drug events.20 Among the subgroup of trials enrolling hospitalized patients, the clinical effectiveness of second-line agents remained significantly greater than that of first-line agents.

Another meta-analysis compared trials that studied only macrolides, quinolones, and amoxicillin-clavulanate and found no difference in terms of short-term clinical effectiveness; however, there was weak evidence to suggest that quinolones were associated with better microbiological success and fewer recurrences of AECOPD.21 Fluoroquinolones are preferred in complicated cases of AECOPD in which there is a greater risk for enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas species.3,7

Antibiotic Duration

The duration of antibiotic therapy in AECOPD has been studied extensively, with randomized controlled trials consistently demonstrating no additional benefit to courses extending beyond five days. One meta-analysis of 21 studies found similar clinical and microbiologic cure rates among patients randomized to antibiotic treatment for ≤5 days versus >5 days.22 A subgroup analysis of the trials evaluating different durations of the same antibiotic also demonstrated no difference in clinical effectiveness, and this finding was confirmed in a separate meta-analysis.22,23

Advantages to shorter antibiotic courses include improved compliance and decreased rates of resistance. The usual duration of antibiotic therapy is three to seven days, depending upon the response to therapy.3

Back to the Case

As the patient has no significant comorbidities or risk factors, and meets criteria for a simple Anthonisen Type I exacerbation (increased dyspnea, sputum, and sputum purulence), antibiotic therapy with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is initiated on admission, in addition to the previously started steroid and bronchodilator treatments. The patient’s clinical status improves, and he is discharged on hospital Day 3 with a prescription to complete a five-day course of antibiotics.

Bottom Line

Antibiotic therapy is effective in select AECOPD patients, with maximal benefits obtained when the decision to treat is based on careful consideration of characteristic clinical symptoms and severity of illness. Choice and duration of antibiotics should follow likely bacterial causes and current guidelines.

Dr. Cunningham is an assistant professor of internal medicine and academic hospitalist in the section of hospital medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn. Dr. LaBrin is assistant professor of internal medicine and pediatrics and an academic hospitalist at Vanderbilt. Dr. Markley is a clinical instructor and academic hospitalist at Vanderbilt.

References

- Donaldson GC, Wedzicha JA. COPD exacerbations: 1. Epidemiology. Thorax. 2006;61:164-168.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. 2009 NHLBI Morbidity and Mortality Chartbook. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute website. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/cht-book.htm Accessed Oct. 10, 2011.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) website. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-resources.html Accessed Oct. 10, 2011.

- Celli BR, MacNee W, Agusti A, et al. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Resp J. 2004;23:932-946.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence website. Available at: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG101/Guidance/pdf/English. Accessed Oct. 10, 2011.

- O’Donnell DE, Aaron S, Bourbeau J, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—2007 update. Can Respir J. 2007;14(Suppl B):5B-32B.

- Sethi S, Murphy TF. Infection in the pathogenesis and course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2355-2565.

- Quon BS, Qi Gan W, Sin DD. Contemporary management of acute exacerbations of COPD: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest. 2008;133:756-766.

- Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, Lahti M, Brody O, Skiest DJ, Lindenauer PK. Antibiotic therapy and treatment failure in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2010;303:2035-2042.

- Roede BM, Bresser P, Bindels PJE, et al. Antibiotic treatment is associated with reduced risk of subsequent exacerbation in obstructive lung disease: a historical population based cohort study. Thorax. 2008;63:968-973.

- Anthonisen NR, Manfreda J, Warren CP, Hershfield ES, Harding GKM, Nelson NA. Antibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:196-204.

- Stockley RA, O’Brien C, Pye A, Hill SL. Relationship of sputum color to nature and outpatient management of acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2000;117:1638-1645.

- Rosell A, Monso E, Soler N, et al. Microbiologic determinants of exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165:891-897.

- Stolz D, Christ-Crain M, Bingisser R, et al. Antibiotic treatment of exacerbations of COPD: a randomized, controlled trial comparing procalcitonin-guidance with standard therapy. Chest. 2007;131:9-19.

- Daniels JMA, Schoorl M, Snijders D, et al. Procalcitonin vs C-reactive protein as predictive markers of response to antibiotic therapy in acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2010;138:1108-1015.

- Miravitlles M, Espinosa C, Fernandez-Laso E, Martos JA, Maldonado JA, Gallego M. Relationship between bacterial flora in sputum and functional impairment in patients with acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 1999;116:40-46.

- Patil SP, Krishnan JA, Lechtzin N, Diette GB. In-hospital mortality following acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1180-1186.

- Puhan MA, Vollenweider D, Latshang T, Steurer J, Steurer-Stey C. Exacerbations of chronic obstructive lung disease: when are antibiotics indicated? A systematic review. Resp Res. 2007;8:30-40.

- Nouira S, Marghli S, Belghith M, Besbes L, Elatrous S, Abroug F. Once daily ofloxacin in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation requiring mechanical ventilation: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358:2020-2025.

- Dimopoulos G, Siempos II, Korbila IP, Manta KG, Falagas ME. Comparison of first-line with second-line antibiotics for acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: a metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Chest. 2007;132:447-455.

- Siempos II, Dimopoulos G, Korbila IP, Manta KG, Falagas ME. Macrolides, quinolones and amoxicillin/clavulanate for chronic bronchitis: a meta-analysis. Eur Resp J. 2007;29:1127-1137.

- El-Moussaoui, Roede BM, Speelman P, Bresser P, Prins JM, Bossuyt PMM. Short-course antibiotic treatment in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and COPD: a meta-analysis of double-blind studies. Thorax. 2008;63:415-422.

- Falagas ME, Avgeri SG, Matthaiou DK, Dimopoulos G, Siempos II. Short- versus long-duration antimicrobial treatment for exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: a meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:442-450.

Hospitalist/Nurse Collaboration Drives Multidisciplinary Rounding

Aultidisciplinary patient rounding system implemented on a non-teaching hospitalist unit at the Ohio State University Medical Center (OSUMC) has been well received by unit staff, according to an HM11 abstract presentation. Key to its success, says lead author and OSUMC hospitalist Eric Schumacher, DO, MBA, was to involve nursing staff from the start and to work closely with the unit’s nurse manager and charge nurse.

“Once we got their buy-in, we proposed what we wanted to do and asked for their suggestions,” Dr. Schumacher says.

Hospitalists partner with the nurse leaders to establish a morning bedside rounding process on the unit, using a “Physician Nurse Rounding Sheet” for each hospitalist. The sheet is prepared daily by the charge nurse and unit clerks, listing the hospitalist’s patients, assigned nurses, and phone numbers. A short debriefing is performed outside the patient’s room before each encounter, and a daily feedback sheet is given to the patient and family with a picture of the hospitalist, a list of all care-team members, and such information as goals for the day, pending tests and consultations, and anticipated discharge date.

“Part of the challenge is to create a process that is efficient for both doctors and nurses, given multiple nurses caring for multiple patients,” Dr. Schumacher says.

Charge nurses or nursing managers provide backup when the bedside nurse is not available for bedside rounding. “Right now we’re rounding with hospitalists and nurses only, but a long-term goal is to expand it to include the social worker and other ancillary professionals,” he says.

Preliminary data on the project show the feasibility of multidisciplinary rounding, with elevated Press Ganey patient satisfaction scores on the unit in the first two months after rounding began. In the third month, compliance with rounding went down, and so did satisfaction scores, but with a renewed commitment the following month, scores went back up again. Subjective reports from hospitalists also suggest fewer interruptions during the day from nursing pages, Dr. Schumacher says.

Aultidisciplinary patient rounding system implemented on a non-teaching hospitalist unit at the Ohio State University Medical Center (OSUMC) has been well received by unit staff, according to an HM11 abstract presentation. Key to its success, says lead author and OSUMC hospitalist Eric Schumacher, DO, MBA, was to involve nursing staff from the start and to work closely with the unit’s nurse manager and charge nurse.

“Once we got their buy-in, we proposed what we wanted to do and asked for their suggestions,” Dr. Schumacher says.

Hospitalists partner with the nurse leaders to establish a morning bedside rounding process on the unit, using a “Physician Nurse Rounding Sheet” for each hospitalist. The sheet is prepared daily by the charge nurse and unit clerks, listing the hospitalist’s patients, assigned nurses, and phone numbers. A short debriefing is performed outside the patient’s room before each encounter, and a daily feedback sheet is given to the patient and family with a picture of the hospitalist, a list of all care-team members, and such information as goals for the day, pending tests and consultations, and anticipated discharge date.

“Part of the challenge is to create a process that is efficient for both doctors and nurses, given multiple nurses caring for multiple patients,” Dr. Schumacher says.

Charge nurses or nursing managers provide backup when the bedside nurse is not available for bedside rounding. “Right now we’re rounding with hospitalists and nurses only, but a long-term goal is to expand it to include the social worker and other ancillary professionals,” he says.

Preliminary data on the project show the feasibility of multidisciplinary rounding, with elevated Press Ganey patient satisfaction scores on the unit in the first two months after rounding began. In the third month, compliance with rounding went down, and so did satisfaction scores, but with a renewed commitment the following month, scores went back up again. Subjective reports from hospitalists also suggest fewer interruptions during the day from nursing pages, Dr. Schumacher says.

Aultidisciplinary patient rounding system implemented on a non-teaching hospitalist unit at the Ohio State University Medical Center (OSUMC) has been well received by unit staff, according to an HM11 abstract presentation. Key to its success, says lead author and OSUMC hospitalist Eric Schumacher, DO, MBA, was to involve nursing staff from the start and to work closely with the unit’s nurse manager and charge nurse.

“Once we got their buy-in, we proposed what we wanted to do and asked for their suggestions,” Dr. Schumacher says.

Hospitalists partner with the nurse leaders to establish a morning bedside rounding process on the unit, using a “Physician Nurse Rounding Sheet” for each hospitalist. The sheet is prepared daily by the charge nurse and unit clerks, listing the hospitalist’s patients, assigned nurses, and phone numbers. A short debriefing is performed outside the patient’s room before each encounter, and a daily feedback sheet is given to the patient and family with a picture of the hospitalist, a list of all care-team members, and such information as goals for the day, pending tests and consultations, and anticipated discharge date.

“Part of the challenge is to create a process that is efficient for both doctors and nurses, given multiple nurses caring for multiple patients,” Dr. Schumacher says.

Charge nurses or nursing managers provide backup when the bedside nurse is not available for bedside rounding. “Right now we’re rounding with hospitalists and nurses only, but a long-term goal is to expand it to include the social worker and other ancillary professionals,” he says.

Preliminary data on the project show the feasibility of multidisciplinary rounding, with elevated Press Ganey patient satisfaction scores on the unit in the first two months after rounding began. In the third month, compliance with rounding went down, and so did satisfaction scores, but with a renewed commitment the following month, scores went back up again. Subjective reports from hospitalists also suggest fewer interruptions during the day from nursing pages, Dr. Schumacher says.

Adverse Events and Rural Discharges

The Center on Patient Safety at Florida State University College of Medicine in Tallahassee has been awarded a two-year, $908,000 grant from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to study adverse events during the three weeks following hospital discharge, both for urban patients and, for the first time, those returning to rural settings.

Center director Dennis Tsilimingras, MD, MPH, says the project will enroll 600 patients, half urban and half rural, discharged by the Tallahassee Memorial Hospitalist Group, and track injuries resulting from medical errors, including medication errors, procedure-related injuries, nosocomial infections, and pressure ulcers.

Errors or injuries to patients may occur in the hospital but not be identified until after the patient goes home, he says, and such errors could contribute to rehospitalizations. “Our hypothesis is that the rate of adverse events post-discharge may be greater among rural patients because they have less access to follow-up care,” he adds.

Dr. Tsilimingras will be working closely with hospitalists, and Phase 2 of the research will use the hospital’s post-discharge transitional care clinic (see “Is a Post-Discharge Clinic in Your Hospital’s Future?,” December 2011) as an intervention strategy.

The eventual goal is to develop a screening tool to flag risk for post-discharge adverse events and develop strategies to reduce post-discharge problems, including readmissions, a quarter of which may be related to post-discharge adverse events, Dr. Tsilimingras says. He encourages hospitalists to reevaluate their patients and review their charts at the time of discharge, to see if post-discharge problems loom, and to reach out to primary care physicians by telephone, rather than just sending discharge summaries.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Armellino D, Hussain E, Schilling ME, et al. Using high-technology to enforce low-technology safety measures: the use of third-party remote video auditing and real-time feedback in healthcare [published online ahead of print Nov. 21, 2011. Clin Infect Dis. doi;10.1093/cid/cir773.

- Fuller C, Savage J, Besser S, et al. “The dirty handin the latex glove”: a study of hand hygiene compliance when gloves are worn. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(12):1194-1199.

The Center on Patient Safety at Florida State University College of Medicine in Tallahassee has been awarded a two-year, $908,000 grant from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to study adverse events during the three weeks following hospital discharge, both for urban patients and, for the first time, those returning to rural settings.

Center director Dennis Tsilimingras, MD, MPH, says the project will enroll 600 patients, half urban and half rural, discharged by the Tallahassee Memorial Hospitalist Group, and track injuries resulting from medical errors, including medication errors, procedure-related injuries, nosocomial infections, and pressure ulcers.

Errors or injuries to patients may occur in the hospital but not be identified until after the patient goes home, he says, and such errors could contribute to rehospitalizations. “Our hypothesis is that the rate of adverse events post-discharge may be greater among rural patients because they have less access to follow-up care,” he adds.

Dr. Tsilimingras will be working closely with hospitalists, and Phase 2 of the research will use the hospital’s post-discharge transitional care clinic (see “Is a Post-Discharge Clinic in Your Hospital’s Future?,” December 2011) as an intervention strategy.

The eventual goal is to develop a screening tool to flag risk for post-discharge adverse events and develop strategies to reduce post-discharge problems, including readmissions, a quarter of which may be related to post-discharge adverse events, Dr. Tsilimingras says. He encourages hospitalists to reevaluate their patients and review their charts at the time of discharge, to see if post-discharge problems loom, and to reach out to primary care physicians by telephone, rather than just sending discharge summaries.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Armellino D, Hussain E, Schilling ME, et al. Using high-technology to enforce low-technology safety measures: the use of third-party remote video auditing and real-time feedback in healthcare [published online ahead of print Nov. 21, 2011. Clin Infect Dis. doi;10.1093/cid/cir773.

- Fuller C, Savage J, Besser S, et al. “The dirty handin the latex glove”: a study of hand hygiene compliance when gloves are worn. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(12):1194-1199.

The Center on Patient Safety at Florida State University College of Medicine in Tallahassee has been awarded a two-year, $908,000 grant from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to study adverse events during the three weeks following hospital discharge, both for urban patients and, for the first time, those returning to rural settings.

Center director Dennis Tsilimingras, MD, MPH, says the project will enroll 600 patients, half urban and half rural, discharged by the Tallahassee Memorial Hospitalist Group, and track injuries resulting from medical errors, including medication errors, procedure-related injuries, nosocomial infections, and pressure ulcers.

Errors or injuries to patients may occur in the hospital but not be identified until after the patient goes home, he says, and such errors could contribute to rehospitalizations. “Our hypothesis is that the rate of adverse events post-discharge may be greater among rural patients because they have less access to follow-up care,” he adds.

Dr. Tsilimingras will be working closely with hospitalists, and Phase 2 of the research will use the hospital’s post-discharge transitional care clinic (see “Is a Post-Discharge Clinic in Your Hospital’s Future?,” December 2011) as an intervention strategy.

The eventual goal is to develop a screening tool to flag risk for post-discharge adverse events and develop strategies to reduce post-discharge problems, including readmissions, a quarter of which may be related to post-discharge adverse events, Dr. Tsilimingras says. He encourages hospitalists to reevaluate their patients and review their charts at the time of discharge, to see if post-discharge problems loom, and to reach out to primary care physicians by telephone, rather than just sending discharge summaries.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Armellino D, Hussain E, Schilling ME, et al. Using high-technology to enforce low-technology safety measures: the use of third-party remote video auditing and real-time feedback in healthcare [published online ahead of print Nov. 21, 2011. Clin Infect Dis. doi;10.1093/cid/cir773.

- Fuller C, Savage J, Besser S, et al. “The dirty handin the latex glove”: a study of hand hygiene compliance when gloves are worn. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(12):1194-1199.

Hand Hygiene Makes Headlines

Recent efforts to raise awareness about proper hand hygiene in health facilities in order to prevent disease transmission, range from the ScrubUp! campaign in Ohio to the World Health Organization’s global Clean Care is Safer Care campaign (www.who.int/gpsc/en/), which advocates for improving hand hygiene practices of health care workers around the world.

Twenty hospitals in Central Ohio staged ScrubUp! rallies on Dec. 5, 2011, during National Handwashing Awareness Week, not only to raise awareness of the hospitals’ commitment to hand hygiene, but also to encourage hospital visitors to wash their hands. The Ohio Hospital Association estimates that 50,000 people were exposed to these messages via a full-page ad in the Columbus Dispatch, overhead announcements and distribution tables in each hospital, handing out hand sanitizers to visitors, and engaging staff with humor, food, and prizes.

A recent study conducted at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, N.Y., found that hand hygiene compliance rates improve when remote video auditing platforms provide professionals with continuous feedback.1 During 16 weeks of real-time feedback on compliance with strict hand hygiene (i.e. within 10 seconds of entering/leaving patients’ rooms) via LED screens mounted on the walls of a MICU, compliance jumped to more than 80%.

A British study of 7,000 contacts in ICUs and geriatric units found that wearing latex gloves may discourage guideline-recommended hand washing, even though such failures to wash may contribute to spreading disease.2 Compliance was 47.7% without gloves, and 41% with gloves.

One of the study’s authors calls for further study of the behavioral reasons why healthcare workers are less likely to wash their hands when gloved, but urges that hand hygiene associated with gloving be part of educational campaigns.

Recent efforts to raise awareness about proper hand hygiene in health facilities in order to prevent disease transmission, range from the ScrubUp! campaign in Ohio to the World Health Organization’s global Clean Care is Safer Care campaign (www.who.int/gpsc/en/), which advocates for improving hand hygiene practices of health care workers around the world.

Twenty hospitals in Central Ohio staged ScrubUp! rallies on Dec. 5, 2011, during National Handwashing Awareness Week, not only to raise awareness of the hospitals’ commitment to hand hygiene, but also to encourage hospital visitors to wash their hands. The Ohio Hospital Association estimates that 50,000 people were exposed to these messages via a full-page ad in the Columbus Dispatch, overhead announcements and distribution tables in each hospital, handing out hand sanitizers to visitors, and engaging staff with humor, food, and prizes.

A recent study conducted at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, N.Y., found that hand hygiene compliance rates improve when remote video auditing platforms provide professionals with continuous feedback.1 During 16 weeks of real-time feedback on compliance with strict hand hygiene (i.e. within 10 seconds of entering/leaving patients’ rooms) via LED screens mounted on the walls of a MICU, compliance jumped to more than 80%.

A British study of 7,000 contacts in ICUs and geriatric units found that wearing latex gloves may discourage guideline-recommended hand washing, even though such failures to wash may contribute to spreading disease.2 Compliance was 47.7% without gloves, and 41% with gloves.

One of the study’s authors calls for further study of the behavioral reasons why healthcare workers are less likely to wash their hands when gloved, but urges that hand hygiene associated with gloving be part of educational campaigns.

Recent efforts to raise awareness about proper hand hygiene in health facilities in order to prevent disease transmission, range from the ScrubUp! campaign in Ohio to the World Health Organization’s global Clean Care is Safer Care campaign (www.who.int/gpsc/en/), which advocates for improving hand hygiene practices of health care workers around the world.

Twenty hospitals in Central Ohio staged ScrubUp! rallies on Dec. 5, 2011, during National Handwashing Awareness Week, not only to raise awareness of the hospitals’ commitment to hand hygiene, but also to encourage hospital visitors to wash their hands. The Ohio Hospital Association estimates that 50,000 people were exposed to these messages via a full-page ad in the Columbus Dispatch, overhead announcements and distribution tables in each hospital, handing out hand sanitizers to visitors, and engaging staff with humor, food, and prizes.

A recent study conducted at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, N.Y., found that hand hygiene compliance rates improve when remote video auditing platforms provide professionals with continuous feedback.1 During 16 weeks of real-time feedback on compliance with strict hand hygiene (i.e. within 10 seconds of entering/leaving patients’ rooms) via LED screens mounted on the walls of a MICU, compliance jumped to more than 80%.

A British study of 7,000 contacts in ICUs and geriatric units found that wearing latex gloves may discourage guideline-recommended hand washing, even though such failures to wash may contribute to spreading disease.2 Compliance was 47.7% without gloves, and 41% with gloves.

One of the study’s authors calls for further study of the behavioral reasons why healthcare workers are less likely to wash their hands when gloved, but urges that hand hygiene associated with gloving be part of educational campaigns.

By the Numbers: 57

Percentage of responding physicians who say they are using electronic health records (EHR), according to a survey of 10,000 office-based physicians by the National Center for Health Statistics, up from 51% usage in 2010. More than half say they intend to apply for meaningful use incentives offered by the government for implementing EHR, and 43% of those respondents report having computerized systems meeting Stage 1 Core Set criteria to qualify.

Percentage of responding physicians who say they are using electronic health records (EHR), according to a survey of 10,000 office-based physicians by the National Center for Health Statistics, up from 51% usage in 2010. More than half say they intend to apply for meaningful use incentives offered by the government for implementing EHR, and 43% of those respondents report having computerized systems meeting Stage 1 Core Set criteria to qualify.

Percentage of responding physicians who say they are using electronic health records (EHR), according to a survey of 10,000 office-based physicians by the National Center for Health Statistics, up from 51% usage in 2010. More than half say they intend to apply for meaningful use incentives offered by the government for implementing EHR, and 43% of those respondents report having computerized systems meeting Stage 1 Core Set criteria to qualify.

Resume Red Flags

Fifteen seconds: That’s approximately how long an employer looks at a CV. Recruiters and employers know what they want; they skim even the best resumes. They are on the lookout for applicants who meet their requirements; sometimes they’ll take a chance on a long shot whose pitch catches their eye.

So what happens when a resume stands out for the wrong reasons? Work histories aren’t always perfect, and recruiters and prospective employers will notice any blemishes.

“The thing about red flags is they’re just an indicator that the applicant is an outlier,” says Kim Bell, MD, FACP, SFHM, regional medical director of the Pacific West Region for EmCare, a Dallas-based company that provides outsourced physician services to more than 500 hospitals in 40 states. “It doesn’t necessarily rule them out.”

Preempt Suspicion

For hospitalists, resume imperfections that attract attention include:

- Gaps in employment;

- Frequent changes in employment;

- Changes in residency;

- Medical board sanctions or probation;

- Failures on the board exam; and

- Forced resignations or firings.

—Cheryl O’Malley, MD, FACP, program director, Department of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics, Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center, Phoenix

When recruiters or employers notice a red flag, they look for other problems to see if patterns emerge and to discern if the applicant exhibited bad judgment, has character flaws, or shows an inability to learn from a mistake, says Jeff Kaplan, PhD, MBA, MCC, a licensed psychologist and Philadelphia-based executive coach whose clients include healthcare industry executives. If such signs exist, the applicant is generally eliminated from consideration. Therefore, it’s critical that applicants explain clearly and succinctly the reason for any resume shortcoming.

“A good way is to actually write a cover letter to explain some uniqueness in their CV that they want [recruiters] to understand,” says Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, FACP, SFHM, professor and chairman of the Department of Medicine and executive director of the hospitalist program at the University of California at Irvine.

By explaining the situation, Dr. Bell says, the hospitalist doesn’t give the employer a chance to guess a reason for the red flag—and potentially guess wrong.

“There’s a big difference between there’s been some sort of serious censure and they’ve been driven out, versus they thought another setting might be more interesting or they just wanted to make a geographic move,” says Thomas E. Thorsheim, PhD, a licensed psychologist and physician leadership coach based in Greenville, S.C. “It’s important to preempt any concerns about how reliable or stable they’re going to be.”

Applicants with resume red flags should show that they’ve taken responsibility for what happened and grown from the experience, say Dr. Thorsheim and Cheryl O’Malley, MD, FACP, program director in the department of internal medicine and pediatrics at Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center in Phoenix.

“Everyone wants to know that you have learned from your mistakes. Try to have a demonstrated remediation of the concern and go above and beyond the minimum requirements,” Dr. O’Malley says. “For example, if the red flag is academic concerns or not passing your board exams, then bring in documentation of your schedule for reading daily and all of the CME and MKSAP you complete. If it is interpersonal issues, then give examples of recent successes that show how you have improved.”

Brand Recognition