User login

Collaboration Prevents Identification Band Errors

Clinical question: Can a quality-improvement (QI) collaborative decrease patient identification (ID) band errors?

Background: ID band errors often result in medication errors and unsafe care. Consequently, correct patient identification, through the use of at least two identifiers, has been an ongoing Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goal. Although individual sites have demonstrated improvement in accuracy of patient identification, there have not been reports of dissemination of successful practices.

Study design: Collaborative quality-improvement initiative.

Setting: Six hospitals.

Synopsis: ID band audits in 11,377 patients were performed in the learning collaborative’s six participating hospitals.

The audits were organized primarily around monthly conference calls. The hospital settings were diverse: community hospitals, hospitals within an academic medical center, and freestanding children’s hospitals. The aim of the collaborative was to reduce ID band errors by 50% within a one-year time frame across the collective sites.

Key interventions included transparent data collection and reporting; engagement of staff, families and leadership; voluntary event reporting; and auditing of failures. The mean combined ID band failure rate decreased to 4% from 22% within 13 months, representing a 77% relative reduction (P<0.001).

QI collaboratives are not designed to specifically result in generalizable knowledge, yet they might produce widespread improvement, as this effort demonstrates. The careful documentation of iterative factors implemented across sites in this initiative provides a blueprint for hospitals looking to replicate this success. Additionally, the interventions represent feasible and logical concepts within the basic constructs of improvement science methodology.

Bottom line: A QI collaborative might result in rapid and significant reductions in ID band errors.

Citation: Phillips SC, Saysana M, Worley S, Hain PD. Reduction in pediatric identification band errors: a quality collaborative. Pediatrics. 2012;129(6):e1587-e1593.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: Can a quality-improvement (QI) collaborative decrease patient identification (ID) band errors?

Background: ID band errors often result in medication errors and unsafe care. Consequently, correct patient identification, through the use of at least two identifiers, has been an ongoing Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goal. Although individual sites have demonstrated improvement in accuracy of patient identification, there have not been reports of dissemination of successful practices.

Study design: Collaborative quality-improvement initiative.

Setting: Six hospitals.

Synopsis: ID band audits in 11,377 patients were performed in the learning collaborative’s six participating hospitals.

The audits were organized primarily around monthly conference calls. The hospital settings were diverse: community hospitals, hospitals within an academic medical center, and freestanding children’s hospitals. The aim of the collaborative was to reduce ID band errors by 50% within a one-year time frame across the collective sites.

Key interventions included transparent data collection and reporting; engagement of staff, families and leadership; voluntary event reporting; and auditing of failures. The mean combined ID band failure rate decreased to 4% from 22% within 13 months, representing a 77% relative reduction (P<0.001).

QI collaboratives are not designed to specifically result in generalizable knowledge, yet they might produce widespread improvement, as this effort demonstrates. The careful documentation of iterative factors implemented across sites in this initiative provides a blueprint for hospitals looking to replicate this success. Additionally, the interventions represent feasible and logical concepts within the basic constructs of improvement science methodology.

Bottom line: A QI collaborative might result in rapid and significant reductions in ID band errors.

Citation: Phillips SC, Saysana M, Worley S, Hain PD. Reduction in pediatric identification band errors: a quality collaborative. Pediatrics. 2012;129(6):e1587-e1593.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: Can a quality-improvement (QI) collaborative decrease patient identification (ID) band errors?

Background: ID band errors often result in medication errors and unsafe care. Consequently, correct patient identification, through the use of at least two identifiers, has been an ongoing Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goal. Although individual sites have demonstrated improvement in accuracy of patient identification, there have not been reports of dissemination of successful practices.

Study design: Collaborative quality-improvement initiative.

Setting: Six hospitals.

Synopsis: ID band audits in 11,377 patients were performed in the learning collaborative’s six participating hospitals.

The audits were organized primarily around monthly conference calls. The hospital settings were diverse: community hospitals, hospitals within an academic medical center, and freestanding children’s hospitals. The aim of the collaborative was to reduce ID band errors by 50% within a one-year time frame across the collective sites.

Key interventions included transparent data collection and reporting; engagement of staff, families and leadership; voluntary event reporting; and auditing of failures. The mean combined ID band failure rate decreased to 4% from 22% within 13 months, representing a 77% relative reduction (P<0.001).

QI collaboratives are not designed to specifically result in generalizable knowledge, yet they might produce widespread improvement, as this effort demonstrates. The careful documentation of iterative factors implemented across sites in this initiative provides a blueprint for hospitals looking to replicate this success. Additionally, the interventions represent feasible and logical concepts within the basic constructs of improvement science methodology.

Bottom line: A QI collaborative might result in rapid and significant reductions in ID band errors.

Citation: Phillips SC, Saysana M, Worley S, Hain PD. Reduction in pediatric identification band errors: a quality collaborative. Pediatrics. 2012;129(6):e1587-e1593.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

The Academic Hospitalist Academy Helps Researchers Get Ahead

What’s the best way to get your research noticed—and make time for more research? How can academic hospitalists get involved in patient safety and quality-improvement (QI) work? For three years, the Academic Hospitalist Academy has helped hospitalist researchers answer these and other questions they face as they develop their careers.

Now in its fourth year, the popular three-and-a-half-day course—presented by the Society of General Internal Medicine, the Association of Chiefs and Leaders of General Internal Medicine, and SHM—focuses on the unique environment, challenges, and opportunities for academic hospitalists, led by national authorities in academic hospital medicine.

Based on evaluations from the 2011 Academic Hospitalist Academy, 100% of attendees rated the meeting positively and felt the course was worth their time and money; 99% said they would recommend attending to their academic hospitalist colleagues. Check out www.academichospitalist.org testimonials to read what past attendees had to say about the academy.

What’s the best way to get your research noticed—and make time for more research? How can academic hospitalists get involved in patient safety and quality-improvement (QI) work? For three years, the Academic Hospitalist Academy has helped hospitalist researchers answer these and other questions they face as they develop their careers.

Now in its fourth year, the popular three-and-a-half-day course—presented by the Society of General Internal Medicine, the Association of Chiefs and Leaders of General Internal Medicine, and SHM—focuses on the unique environment, challenges, and opportunities for academic hospitalists, led by national authorities in academic hospital medicine.

Based on evaluations from the 2011 Academic Hospitalist Academy, 100% of attendees rated the meeting positively and felt the course was worth their time and money; 99% said they would recommend attending to their academic hospitalist colleagues. Check out www.academichospitalist.org testimonials to read what past attendees had to say about the academy.

What’s the best way to get your research noticed—and make time for more research? How can academic hospitalists get involved in patient safety and quality-improvement (QI) work? For three years, the Academic Hospitalist Academy has helped hospitalist researchers answer these and other questions they face as they develop their careers.

Now in its fourth year, the popular three-and-a-half-day course—presented by the Society of General Internal Medicine, the Association of Chiefs and Leaders of General Internal Medicine, and SHM—focuses on the unique environment, challenges, and opportunities for academic hospitalists, led by national authorities in academic hospital medicine.

Based on evaluations from the 2011 Academic Hospitalist Academy, 100% of attendees rated the meeting positively and felt the course was worth their time and money; 99% said they would recommend attending to their academic hospitalist colleagues. Check out www.academichospitalist.org testimonials to read what past attendees had to say about the academy.

Ready to Reduce Your Hospital's Readmissions?

More than 100 hospitals across the country have used Project BOOST to reduce readmissions and improve their discharge processes. You and your hospital can be next by applying for Project BOOST. The deadline for the next national cohort of Project BOOST is Sept. 1.

To improve your chances of acceptance, start soon. In addition to an online form, the application requires a letter of support from an executive sponsor from each institution.

In October, accepted Project BOOST sites will receive:

- A comprehensive intervention developed by a panel of nationally recognized experts based on the best available evidence;

- A comprehensive implementation guide that provides step-by-step instructions and project management tools, such as the “teachback” training curriculum, to help interdisciplinary teams redesign work flow and plan, implement, and evaluate the intervention;

- Longitudinal technical assistance that provides face-to-face training and a year of expert mentoring and coaching to implement BOOST interventions that build a culture that supports safe and complete transitions. The mentoring program provides a “train-the-trainer” DVD and curriculum for nurses and case managers on using the teachback process, and webinars targeting the educational needs of other team members, including administrators, data analysts, physicians, nurses; and others;

- A collaboration that allows sites to communicate with and learn from each other via the BOOST listserv, BOOST community site, and quarterly all-site teleconferences and webinars; and

- Access to the BOOST data center, an online resource center that allows sites to store and benchmark data against control units and other sites and generate reports.

To start the application process, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president for communications.

More than 100 hospitals across the country have used Project BOOST to reduce readmissions and improve their discharge processes. You and your hospital can be next by applying for Project BOOST. The deadline for the next national cohort of Project BOOST is Sept. 1.

To improve your chances of acceptance, start soon. In addition to an online form, the application requires a letter of support from an executive sponsor from each institution.

In October, accepted Project BOOST sites will receive:

- A comprehensive intervention developed by a panel of nationally recognized experts based on the best available evidence;

- A comprehensive implementation guide that provides step-by-step instructions and project management tools, such as the “teachback” training curriculum, to help interdisciplinary teams redesign work flow and plan, implement, and evaluate the intervention;

- Longitudinal technical assistance that provides face-to-face training and a year of expert mentoring and coaching to implement BOOST interventions that build a culture that supports safe and complete transitions. The mentoring program provides a “train-the-trainer” DVD and curriculum for nurses and case managers on using the teachback process, and webinars targeting the educational needs of other team members, including administrators, data analysts, physicians, nurses; and others;

- A collaboration that allows sites to communicate with and learn from each other via the BOOST listserv, BOOST community site, and quarterly all-site teleconferences and webinars; and

- Access to the BOOST data center, an online resource center that allows sites to store and benchmark data against control units and other sites and generate reports.

To start the application process, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president for communications.

More than 100 hospitals across the country have used Project BOOST to reduce readmissions and improve their discharge processes. You and your hospital can be next by applying for Project BOOST. The deadline for the next national cohort of Project BOOST is Sept. 1.

To improve your chances of acceptance, start soon. In addition to an online form, the application requires a letter of support from an executive sponsor from each institution.

In October, accepted Project BOOST sites will receive:

- A comprehensive intervention developed by a panel of nationally recognized experts based on the best available evidence;

- A comprehensive implementation guide that provides step-by-step instructions and project management tools, such as the “teachback” training curriculum, to help interdisciplinary teams redesign work flow and plan, implement, and evaluate the intervention;

- Longitudinal technical assistance that provides face-to-face training and a year of expert mentoring and coaching to implement BOOST interventions that build a culture that supports safe and complete transitions. The mentoring program provides a “train-the-trainer” DVD and curriculum for nurses and case managers on using the teachback process, and webinars targeting the educational needs of other team members, including administrators, data analysts, physicians, nurses; and others;

- A collaboration that allows sites to communicate with and learn from each other via the BOOST listserv, BOOST community site, and quarterly all-site teleconferences and webinars; and

- Access to the BOOST data center, an online resource center that allows sites to store and benchmark data against control units and other sites and generate reports.

To start the application process, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president for communications.

Adult Hospital Medicine Boot Camp Offers PAs, NPs Advanced Training

The Adult Hospital Medicine Boot Camp is a great way for physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs) who practice as hospitalists to stay up to date on the latest in HM practice, and is the perfect opportunity to introduce new caregivers to the hospital setting.

Hosted by the American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) and SHM, Adult Hospital Medicine Boot Camp will be Oct. 17-21 at the JW Marriott in New Orleans. Registration is available at www.aapa.org/bootcamp.

The specialized, education-focused “boot camp” immerses clinicians who are already practicing in HM, or who are interested in it, an intensive internal-medicine review of commonly encountered diagnoses and diseases in hospitalized adult patients. The boot camp has been approved for a maximum of 29.5 AAPA Category I CME credits.

The Adult Hospital Medicine Boot Camp is a great way for physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs) who practice as hospitalists to stay up to date on the latest in HM practice, and is the perfect opportunity to introduce new caregivers to the hospital setting.

Hosted by the American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) and SHM, Adult Hospital Medicine Boot Camp will be Oct. 17-21 at the JW Marriott in New Orleans. Registration is available at www.aapa.org/bootcamp.

The specialized, education-focused “boot camp” immerses clinicians who are already practicing in HM, or who are interested in it, an intensive internal-medicine review of commonly encountered diagnoses and diseases in hospitalized adult patients. The boot camp has been approved for a maximum of 29.5 AAPA Category I CME credits.

The Adult Hospital Medicine Boot Camp is a great way for physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs) who practice as hospitalists to stay up to date on the latest in HM practice, and is the perfect opportunity to introduce new caregivers to the hospital setting.

Hosted by the American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) and SHM, Adult Hospital Medicine Boot Camp will be Oct. 17-21 at the JW Marriott in New Orleans. Registration is available at www.aapa.org/bootcamp.

The specialized, education-focused “boot camp” immerses clinicians who are already practicing in HM, or who are interested in it, an intensive internal-medicine review of commonly encountered diagnoses and diseases in hospitalized adult patients. The boot camp has been approved for a maximum of 29.5 AAPA Category I CME credits.

Recoding: SHM’s Popular Coding Series Returns

Coding is a challenging fact of life for most hospitalists, which explains the popularity of SHM’s educational resources for helping hospitalists stay on top of best practices in coding. Due to demand from hospitalists and hospital administrators who missed the first CODE-H series, SHM will present the series again.

CODE-H, which is eligible for CME or CEU credits, gathers the country’s foremost experts in hospital coding to help HM groups capture revenue and maintain compliance through six online courses:

- Basics of E&M Coding for Hospitalists, Part 1;

- Basics of E&M Coding for Hospitalists, Part 2;

- Coding for Hospitalists’ Expanding Scope of Services;

- Staying out of Trouble;

- Integrating Physician Billing & Hospital DRG Assurance; and

- Optimizing Performance and Compliance.

In addition to being presented in a highly interactive online community, each CODE-H series subscription enables as many as 10 individuals in an HM group to participate. Course materials include extensive reference

materials, pre-tests, and post-tests. For details and registration, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh.

Coding is a challenging fact of life for most hospitalists, which explains the popularity of SHM’s educational resources for helping hospitalists stay on top of best practices in coding. Due to demand from hospitalists and hospital administrators who missed the first CODE-H series, SHM will present the series again.

CODE-H, which is eligible for CME or CEU credits, gathers the country’s foremost experts in hospital coding to help HM groups capture revenue and maintain compliance through six online courses:

- Basics of E&M Coding for Hospitalists, Part 1;

- Basics of E&M Coding for Hospitalists, Part 2;

- Coding for Hospitalists’ Expanding Scope of Services;

- Staying out of Trouble;

- Integrating Physician Billing & Hospital DRG Assurance; and

- Optimizing Performance and Compliance.

In addition to being presented in a highly interactive online community, each CODE-H series subscription enables as many as 10 individuals in an HM group to participate. Course materials include extensive reference

materials, pre-tests, and post-tests. For details and registration, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh.

Coding is a challenging fact of life for most hospitalists, which explains the popularity of SHM’s educational resources for helping hospitalists stay on top of best practices in coding. Due to demand from hospitalists and hospital administrators who missed the first CODE-H series, SHM will present the series again.

CODE-H, which is eligible for CME or CEU credits, gathers the country’s foremost experts in hospital coding to help HM groups capture revenue and maintain compliance through six online courses:

- Basics of E&M Coding for Hospitalists, Part 1;

- Basics of E&M Coding for Hospitalists, Part 2;

- Coding for Hospitalists’ Expanding Scope of Services;

- Staying out of Trouble;

- Integrating Physician Billing & Hospital DRG Assurance; and

- Optimizing Performance and Compliance.

In addition to being presented in a highly interactive online community, each CODE-H series subscription enables as many as 10 individuals in an HM group to participate. Course materials include extensive reference

materials, pre-tests, and post-tests. For details and registration, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh.

Survey Insights: Better Understand CPT Coding Intensity

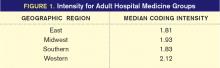

Many of the practice-management-related questions we field from members here at SHM are about documentation and coding issues; members are looking for ways to benchmark their group’s coding performance against other similar groups. One helpful metric reported in the SHM/MGMA State of Hospital Medicine report is the ratio of work-RVUs to total encounters, which I refer to as “coding intensity.”

Median coding intensity for adult medicine hospitalists in the 2011 report was 1.90, up slightly from 2010 levels.

The most obvious factor that influences coding intensity is the distribution of CPT codes within specific evaluation and management code sets, such as inpatient admissions (99221-99223) or follow-up visits (99231-99233). Other considerations include the degree to which hospitalists provide high-wRVU services, such as critical care or procedures, the ratio of inpatient vs. observation patients, and the group’s average length of stay.

One interesting finding was that coding intensity varies greatly by geographic region (see Figure 1, right).

What’s going on out there in the Western states? Are those folks receiving different training than the rest of us? Or are they just mavericks, more interested in generating professional fee revenues than hospitalists elsewhere are? It’s hard to say. One big factor is that length of stay (LOS) tends to be shorter in the West than in other parts of the country. That means the typical Western hospitalist will have a larger proportion of high-wRVU value admission and discharge codes relative to their proportion of low-wRVU value subsequent visit codes.

This isn’t the whole story, though. Hospitalists in the West actually did report a significantly more aggressive code distribution for all three CPT code sets for which data were collected (inpatient admissions, subsequent visits, and discharges). And hospitalists in the South, where LOS tends to be longer, also reported the least aggressive code distributions.

Unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of clues as to why these differences exist. We don’t know, for example, whether more hospitalists in the West work in the ICU or perform more procedures compared to other parts of the country. One possibility suggested by report data is that hospitalists in Western states have the highest average proportion of their total compensation allocated to productivity incentives. Hospitalists in the East have the lowest proportion of their compensation based on productivity. So productivity-based compensation might cause hospitalists to care a lot more about doing a good job with documentation and CPT coding.

Other interesting findings include the fact that hospitalists employed by multistate hospitalist-management companies had the lowest median coding intensity, while hospitalists employed by private hospitalist-only groups had the highest coding intensity. And, perhaps not surprisingly, the small proportion of practices that did not receive any financial support had a higher average coding intensity than practices receiving financial support.

While there are no clear answers about variations in CPT coding intensity among hospitalist practices, the State of Hospital Medicine report does offer some intriguing pointers, along with a variety of useful benchmarks about hospitalist CPT coding practices. And stay tuned: The new report, due out in August, will offer even more ways of looking at coding intensity and CPT code distribution.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor

Many of the practice-management-related questions we field from members here at SHM are about documentation and coding issues; members are looking for ways to benchmark their group’s coding performance against other similar groups. One helpful metric reported in the SHM/MGMA State of Hospital Medicine report is the ratio of work-RVUs to total encounters, which I refer to as “coding intensity.”

Median coding intensity for adult medicine hospitalists in the 2011 report was 1.90, up slightly from 2010 levels.

The most obvious factor that influences coding intensity is the distribution of CPT codes within specific evaluation and management code sets, such as inpatient admissions (99221-99223) or follow-up visits (99231-99233). Other considerations include the degree to which hospitalists provide high-wRVU services, such as critical care or procedures, the ratio of inpatient vs. observation patients, and the group’s average length of stay.

One interesting finding was that coding intensity varies greatly by geographic region (see Figure 1, right).

What’s going on out there in the Western states? Are those folks receiving different training than the rest of us? Or are they just mavericks, more interested in generating professional fee revenues than hospitalists elsewhere are? It’s hard to say. One big factor is that length of stay (LOS) tends to be shorter in the West than in other parts of the country. That means the typical Western hospitalist will have a larger proportion of high-wRVU value admission and discharge codes relative to their proportion of low-wRVU value subsequent visit codes.

This isn’t the whole story, though. Hospitalists in the West actually did report a significantly more aggressive code distribution for all three CPT code sets for which data were collected (inpatient admissions, subsequent visits, and discharges). And hospitalists in the South, where LOS tends to be longer, also reported the least aggressive code distributions.

Unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of clues as to why these differences exist. We don’t know, for example, whether more hospitalists in the West work in the ICU or perform more procedures compared to other parts of the country. One possibility suggested by report data is that hospitalists in Western states have the highest average proportion of their total compensation allocated to productivity incentives. Hospitalists in the East have the lowest proportion of their compensation based on productivity. So productivity-based compensation might cause hospitalists to care a lot more about doing a good job with documentation and CPT coding.

Other interesting findings include the fact that hospitalists employed by multistate hospitalist-management companies had the lowest median coding intensity, while hospitalists employed by private hospitalist-only groups had the highest coding intensity. And, perhaps not surprisingly, the small proportion of practices that did not receive any financial support had a higher average coding intensity than practices receiving financial support.

While there are no clear answers about variations in CPT coding intensity among hospitalist practices, the State of Hospital Medicine report does offer some intriguing pointers, along with a variety of useful benchmarks about hospitalist CPT coding practices. And stay tuned: The new report, due out in August, will offer even more ways of looking at coding intensity and CPT code distribution.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor

Many of the practice-management-related questions we field from members here at SHM are about documentation and coding issues; members are looking for ways to benchmark their group’s coding performance against other similar groups. One helpful metric reported in the SHM/MGMA State of Hospital Medicine report is the ratio of work-RVUs to total encounters, which I refer to as “coding intensity.”

Median coding intensity for adult medicine hospitalists in the 2011 report was 1.90, up slightly from 2010 levels.

The most obvious factor that influences coding intensity is the distribution of CPT codes within specific evaluation and management code sets, such as inpatient admissions (99221-99223) or follow-up visits (99231-99233). Other considerations include the degree to which hospitalists provide high-wRVU services, such as critical care or procedures, the ratio of inpatient vs. observation patients, and the group’s average length of stay.

One interesting finding was that coding intensity varies greatly by geographic region (see Figure 1, right).

What’s going on out there in the Western states? Are those folks receiving different training than the rest of us? Or are they just mavericks, more interested in generating professional fee revenues than hospitalists elsewhere are? It’s hard to say. One big factor is that length of stay (LOS) tends to be shorter in the West than in other parts of the country. That means the typical Western hospitalist will have a larger proportion of high-wRVU value admission and discharge codes relative to their proportion of low-wRVU value subsequent visit codes.

This isn’t the whole story, though. Hospitalists in the West actually did report a significantly more aggressive code distribution for all three CPT code sets for which data were collected (inpatient admissions, subsequent visits, and discharges). And hospitalists in the South, where LOS tends to be longer, also reported the least aggressive code distributions.

Unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of clues as to why these differences exist. We don’t know, for example, whether more hospitalists in the West work in the ICU or perform more procedures compared to other parts of the country. One possibility suggested by report data is that hospitalists in Western states have the highest average proportion of their total compensation allocated to productivity incentives. Hospitalists in the East have the lowest proportion of their compensation based on productivity. So productivity-based compensation might cause hospitalists to care a lot more about doing a good job with documentation and CPT coding.

Other interesting findings include the fact that hospitalists employed by multistate hospitalist-management companies had the lowest median coding intensity, while hospitalists employed by private hospitalist-only groups had the highest coding intensity. And, perhaps not surprisingly, the small proportion of practices that did not receive any financial support had a higher average coding intensity than practices receiving financial support.

While there are no clear answers about variations in CPT coding intensity among hospitalist practices, the State of Hospital Medicine report does offer some intriguing pointers, along with a variety of useful benchmarks about hospitalist CPT coding practices. And stay tuned: The new report, due out in August, will offer even more ways of looking at coding intensity and CPT code distribution.

Leslie Flores, SHM senior advisor

Hospitalists On the Move

Casa Grande Regional Medical Center in Arizona named hospitalist Ammar Saifo, MD, its Physician of the Year. The medical center’s nursing staff praised Dr. Saifo “for his leadership, compassion, dedication, and for ‘going the extra mile’” in caring for his patients.

Bob Adams, MD, former chief hospitalist at MedWest-Harris in North Carolina, has accepted a position at Angel Medical Center in Franklin, N.C. A veteran hospitalist, he began his new position July 1.

Syed Irfan Ali, MD, a hospitalist at MaineGeneral Medical Center’s Thayer Unit in Waterville, received the 2011 NASF Humanitarian of the Year award from the Nasreen & Alam Sher Foundation. Dr. Ali earned the honor after spending several days in Pakistan providing free care to patients at Aisha Bibi Memorial Hospital (see “Hospitalist Honored for Humanitarian Work in Pakistan,” the-hospitalist.org).

J.D. Fitz, MD, FACP, has joined Sound Physicians as senior vice president of physician development. Dr. Fitz comes from MultiCare Good Samaritan Hospital, where he worked as vice president of medical affairs for five years. In his new position, Dr. Fitz will direct professional development for Sound’s more than 500 physicians.

St. Luke’s The Woodlands Hospital in The Woodlands, Texas, recently awarded Seshasree Marupudi, MD, its 2012 Physician of the Year plaque. Dr. Marupudi is a hospitalist who has been at The Woodlands Hospital since 2008. According to her colleagues, she takes an active role in patient care, as well as in communication between staff, patients, and their families.

William Lamm, MD, was named Physician of the Year by the Western Maryland Health System (WMHS) at its annual recognition gala. Dr. Lamm joined the HM program at WMHS in 2004, and he serves as a clinical instructor at the University of Maryland Medical Center’s Department of Family Medicine, where he spent his residency.

Hospital executive Greg Ohe was recently appointed president of Health Central Hospital in Orlando, Fla. Ohe had served as senior vice president of the hospital since 2004, during which time he spearheaded several of the hospital’s successful programs, including its hospitalist program.

Blal Zafar, MD, hospitalist at River Park Hospital in McMinnville, Tenn., recently was awarded the 2012 Lathem Physician Leadership Award in Hand Hygiene. The award, sponsored by Proventix Systems Inc. of Birmingham, Ala., recognizes physicians who lead by example in their dedication to excellent hand hygiene.

Casa Grande Regional Medical Center in Arizona named hospitalist Ammar Saifo, MD, its Physician of the Year. The medical center’s nursing staff praised Dr. Saifo “for his leadership, compassion, dedication, and for ‘going the extra mile’” in caring for his patients.

Bob Adams, MD, former chief hospitalist at MedWest-Harris in North Carolina, has accepted a position at Angel Medical Center in Franklin, N.C. A veteran hospitalist, he began his new position July 1.

Syed Irfan Ali, MD, a hospitalist at MaineGeneral Medical Center’s Thayer Unit in Waterville, received the 2011 NASF Humanitarian of the Year award from the Nasreen & Alam Sher Foundation. Dr. Ali earned the honor after spending several days in Pakistan providing free care to patients at Aisha Bibi Memorial Hospital (see “Hospitalist Honored for Humanitarian Work in Pakistan,” the-hospitalist.org).

J.D. Fitz, MD, FACP, has joined Sound Physicians as senior vice president of physician development. Dr. Fitz comes from MultiCare Good Samaritan Hospital, where he worked as vice president of medical affairs for five years. In his new position, Dr. Fitz will direct professional development for Sound’s more than 500 physicians.

St. Luke’s The Woodlands Hospital in The Woodlands, Texas, recently awarded Seshasree Marupudi, MD, its 2012 Physician of the Year plaque. Dr. Marupudi is a hospitalist who has been at The Woodlands Hospital since 2008. According to her colleagues, she takes an active role in patient care, as well as in communication between staff, patients, and their families.

William Lamm, MD, was named Physician of the Year by the Western Maryland Health System (WMHS) at its annual recognition gala. Dr. Lamm joined the HM program at WMHS in 2004, and he serves as a clinical instructor at the University of Maryland Medical Center’s Department of Family Medicine, where he spent his residency.

Hospital executive Greg Ohe was recently appointed president of Health Central Hospital in Orlando, Fla. Ohe had served as senior vice president of the hospital since 2004, during which time he spearheaded several of the hospital’s successful programs, including its hospitalist program.

Blal Zafar, MD, hospitalist at River Park Hospital in McMinnville, Tenn., recently was awarded the 2012 Lathem Physician Leadership Award in Hand Hygiene. The award, sponsored by Proventix Systems Inc. of Birmingham, Ala., recognizes physicians who lead by example in their dedication to excellent hand hygiene.

Casa Grande Regional Medical Center in Arizona named hospitalist Ammar Saifo, MD, its Physician of the Year. The medical center’s nursing staff praised Dr. Saifo “for his leadership, compassion, dedication, and for ‘going the extra mile’” in caring for his patients.

Bob Adams, MD, former chief hospitalist at MedWest-Harris in North Carolina, has accepted a position at Angel Medical Center in Franklin, N.C. A veteran hospitalist, he began his new position July 1.

Syed Irfan Ali, MD, a hospitalist at MaineGeneral Medical Center’s Thayer Unit in Waterville, received the 2011 NASF Humanitarian of the Year award from the Nasreen & Alam Sher Foundation. Dr. Ali earned the honor after spending several days in Pakistan providing free care to patients at Aisha Bibi Memorial Hospital (see “Hospitalist Honored for Humanitarian Work in Pakistan,” the-hospitalist.org).

J.D. Fitz, MD, FACP, has joined Sound Physicians as senior vice president of physician development. Dr. Fitz comes from MultiCare Good Samaritan Hospital, where he worked as vice president of medical affairs for five years. In his new position, Dr. Fitz will direct professional development for Sound’s more than 500 physicians.

St. Luke’s The Woodlands Hospital in The Woodlands, Texas, recently awarded Seshasree Marupudi, MD, its 2012 Physician of the Year plaque. Dr. Marupudi is a hospitalist who has been at The Woodlands Hospital since 2008. According to her colleagues, she takes an active role in patient care, as well as in communication between staff, patients, and their families.

William Lamm, MD, was named Physician of the Year by the Western Maryland Health System (WMHS) at its annual recognition gala. Dr. Lamm joined the HM program at WMHS in 2004, and he serves as a clinical instructor at the University of Maryland Medical Center’s Department of Family Medicine, where he spent his residency.

Hospital executive Greg Ohe was recently appointed president of Health Central Hospital in Orlando, Fla. Ohe had served as senior vice president of the hospital since 2004, during which time he spearheaded several of the hospital’s successful programs, including its hospitalist program.

Blal Zafar, MD, hospitalist at River Park Hospital in McMinnville, Tenn., recently was awarded the 2012 Lathem Physician Leadership Award in Hand Hygiene. The award, sponsored by Proventix Systems Inc. of Birmingham, Ala., recognizes physicians who lead by example in their dedication to excellent hand hygiene.

Established Performance Metrics Help CMS Expand Its Value-Based Purchasing Program

—Thomas B. Valuck, MD, JD, senior vice president of strategic partnerships, National Quality Forum, former CMS adviser

No longer content to be a passive purchaser of healthcare services, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is becoming a savvier shopper, holding providers increasingly accountable for the quality and efficiency of the care they deliver. With its value-based purchasing (VPB) program for hospitals already in place, now it’s the physicians’ turn.

CMS is marching toward a value-based payment modifier program that will adjust physician reimbursement based on the relative quality and efficiency of care that physicians provide to Medicare fee-for-service patients. The program will begin January 2015 and will extend to all physicians in 2017. Like the hospital VBP program, it will be budget-neutral—meaning that payment will increase for some physicians but decrease for others.

The coming months mark a pivotal period for physicians as CMS tweaks its accountability apparatus in ways that will determine how reimbursement will rise and fall, for whom, and for what.

Menu of Metrics

In crafting the payment modifier program, CMS can tap performance metrics from several of its existing programs, including the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the soon-to-be-expanded Physician Compare website (www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx), and the Physician Feedback Program.

“These agendas are part of a continuum, and of equal importance, in the evolution toward physician value-based purchasing,” says Patrick J. Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Performance Measurement and Reporting Committee, and director of hospital medicine at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La.

PQRS began as a voluntary “pay for reporting” system that gave physicians a modest financial bonus (currently 0.5% of allowable Medicare charges) for submitting quality data (left). The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has since authorized CMS to penalize physicians who do not participate—1.5% of allowable Medicare charges beginning in 2015, and 2% in 2016.

The Physician Compare website, launched at the end of 2010, currently contains such rudimentary information as education, gender, and whether a physician is enrolled in Medicare and satisfactorily reports data to the PQRS. But as of January, the site will begin reporting some PQRS data, as well as other metrics.

CMS’ Physician Feedback Program provides quality and cost information to physicians in an effort to encourage them to improve the care they provide and its efficiency. CMS recently combined the program with its value-based payment modifier program as it moves toward physician reimbursement that it says will reward “value rather than volume.” The program, currently being piloted in Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas, and Missouri, issues to physicians confidential quality and resource use reports (QRURs) that compare their performance to peer groups in similar specialties by tracking PQRS results, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures, and per-capita cost data and preventable hospital admission rates for various medical conditions. CMS will roll out the program nationwide next year.

Metrics Lack Relevance

Developing performance measures that capture the most relevant activities of physicians across many different specialties with equal validity is notoriously difficult—something that CMS acknowledges.1

Assigning the right patient to the right physician (i.e. figuring out who contributed what care, in what proportion, to which patient) also is fraught with complications, especially in the inpatient care setting, where a patient is likely to see many different physicians during a hospitalization.

SHM president Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM, highlighted these challenges in a letter sent in May to acting CMS administrator Marilyn B. Tavenner in which he pointed to dramatic data deficiencies in the initial round of QRURs sent to Physician Feedback Program participants that included hospitalists in Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas and Missouri. Because hospitalists were categorized as general internal-medicine physicians in the reports, their per-capita cost of care was dramatically higher (73% higher, in one case study) than the average cost of all internal-medicine physicians. No allowance was made for distinguishing the outpatient-oriented practice of a general internist from the inherently more expensive inpatient-focused hospitalist practice.

In the case study reviewed by SHM, the hospitalist’s patients saw, on average, 28 different physicians over the course of a year, during which the hospitalist contributed to the care of many patients but did not direct the care of any one of them—facts that clearly highlight the difficulty of assigning responsibility and accountability for a patient’s care when comparing physician performance.

“Based on the measurement used in the QRUR, it seems likely that a hospitalist would be severely disadvantaged with the introduction of a value-based modifier based on the present QRUR methodology,” Dr. Frost wrote.

SHM is similarly critical of the PQRS measures, which Dr. Torcson says lack relevance to hospitalist practices. “We want to be defined as HM physicians with our own unique measures of quality and cost,” he says. “Our results will look very different from those of an internist with a primarily outpatient practice.”

Dr. Torcson notes that SHM is an active participant in providing feedback during CMS rule proposals and has offered to work with the CMS on further refining the measures. For example, SHM proposed adding additional measures related to care transitions, given their particular relevance to hospitalist practices.

Rule-Changing Reform

The disruptive innovation of CMS’ healthcare reform agenda might wind up being a game-changer that dramatically affects the contours of all provider performance reporting and incentive systems, redefining the issues of physician accountability and patient assignment.

“We’re going to need to figure out how to restructure our measurement systems to match our evolving healthcare delivery and payment systems,” says Thomas B. Valuck, MD, JD, senior vice president of strategic partnerships for the National Quality Forum and former CMS adviser to the VBP program. Healthcare quality reporting should focus more on measures that cut across care contexts and assess whether the care provided truly made a difference for patients—metrics such as health improvement, return to functional status, level of patient involvement in the management of their care, provider team coordination, and other patient needs and preferences, Dr. Valuck believes.

“We need to be focused more on measures that encourage joint responsibility and cooperation among providers, and are important to patients across hospital, post-acute, and ambulatory settings, rather than those that are compartmentalized to one setting or relevant only to specific diseases or subspecialties,” Dr. Valuck says.

Such measure sets, while still retaining some disease- and physician-specific metrics, ideally would be complementary with families of related measures at the community, state, and national levels, Dr. Valuck says. “Such a multidimensional framework can begin to tell a meaningful story about what’s happening to the patient, and how well our system is delivering the right care,” he adds.

Dr. Torcson says HM has a pioneering role to play in this evolution, and he notes that SHM has proposed that CMS harmonize measures that align hospital-based physician activities (e.g. hospital medicine, emergency medicine, anesthesia, radiology) with hospital-level performance agendas so that physicians practicing together in the hospital setting can report on measures that are relevant to both.

Christopher Guadagnino is a freelance medical writer in Philadelphia.

Reference

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Physician Quality Reporting System Town Hall Meeting. Available at: http://www.usqualitymeasures.org/shared/content/C4M_PQRS_transcript.pdf. Accessed July 3, 2012.

—Thomas B. Valuck, MD, JD, senior vice president of strategic partnerships, National Quality Forum, former CMS adviser

No longer content to be a passive purchaser of healthcare services, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is becoming a savvier shopper, holding providers increasingly accountable for the quality and efficiency of the care they deliver. With its value-based purchasing (VPB) program for hospitals already in place, now it’s the physicians’ turn.

CMS is marching toward a value-based payment modifier program that will adjust physician reimbursement based on the relative quality and efficiency of care that physicians provide to Medicare fee-for-service patients. The program will begin January 2015 and will extend to all physicians in 2017. Like the hospital VBP program, it will be budget-neutral—meaning that payment will increase for some physicians but decrease for others.

The coming months mark a pivotal period for physicians as CMS tweaks its accountability apparatus in ways that will determine how reimbursement will rise and fall, for whom, and for what.

Menu of Metrics

In crafting the payment modifier program, CMS can tap performance metrics from several of its existing programs, including the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the soon-to-be-expanded Physician Compare website (www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx), and the Physician Feedback Program.

“These agendas are part of a continuum, and of equal importance, in the evolution toward physician value-based purchasing,” says Patrick J. Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Performance Measurement and Reporting Committee, and director of hospital medicine at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La.

PQRS began as a voluntary “pay for reporting” system that gave physicians a modest financial bonus (currently 0.5% of allowable Medicare charges) for submitting quality data (left). The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has since authorized CMS to penalize physicians who do not participate—1.5% of allowable Medicare charges beginning in 2015, and 2% in 2016.

The Physician Compare website, launched at the end of 2010, currently contains such rudimentary information as education, gender, and whether a physician is enrolled in Medicare and satisfactorily reports data to the PQRS. But as of January, the site will begin reporting some PQRS data, as well as other metrics.

CMS’ Physician Feedback Program provides quality and cost information to physicians in an effort to encourage them to improve the care they provide and its efficiency. CMS recently combined the program with its value-based payment modifier program as it moves toward physician reimbursement that it says will reward “value rather than volume.” The program, currently being piloted in Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas, and Missouri, issues to physicians confidential quality and resource use reports (QRURs) that compare their performance to peer groups in similar specialties by tracking PQRS results, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures, and per-capita cost data and preventable hospital admission rates for various medical conditions. CMS will roll out the program nationwide next year.

Metrics Lack Relevance

Developing performance measures that capture the most relevant activities of physicians across many different specialties with equal validity is notoriously difficult—something that CMS acknowledges.1

Assigning the right patient to the right physician (i.e. figuring out who contributed what care, in what proportion, to which patient) also is fraught with complications, especially in the inpatient care setting, where a patient is likely to see many different physicians during a hospitalization.

SHM president Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM, highlighted these challenges in a letter sent in May to acting CMS administrator Marilyn B. Tavenner in which he pointed to dramatic data deficiencies in the initial round of QRURs sent to Physician Feedback Program participants that included hospitalists in Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas and Missouri. Because hospitalists were categorized as general internal-medicine physicians in the reports, their per-capita cost of care was dramatically higher (73% higher, in one case study) than the average cost of all internal-medicine physicians. No allowance was made for distinguishing the outpatient-oriented practice of a general internist from the inherently more expensive inpatient-focused hospitalist practice.

In the case study reviewed by SHM, the hospitalist’s patients saw, on average, 28 different physicians over the course of a year, during which the hospitalist contributed to the care of many patients but did not direct the care of any one of them—facts that clearly highlight the difficulty of assigning responsibility and accountability for a patient’s care when comparing physician performance.

“Based on the measurement used in the QRUR, it seems likely that a hospitalist would be severely disadvantaged with the introduction of a value-based modifier based on the present QRUR methodology,” Dr. Frost wrote.

SHM is similarly critical of the PQRS measures, which Dr. Torcson says lack relevance to hospitalist practices. “We want to be defined as HM physicians with our own unique measures of quality and cost,” he says. “Our results will look very different from those of an internist with a primarily outpatient practice.”

Dr. Torcson notes that SHM is an active participant in providing feedback during CMS rule proposals and has offered to work with the CMS on further refining the measures. For example, SHM proposed adding additional measures related to care transitions, given their particular relevance to hospitalist practices.

Rule-Changing Reform

The disruptive innovation of CMS’ healthcare reform agenda might wind up being a game-changer that dramatically affects the contours of all provider performance reporting and incentive systems, redefining the issues of physician accountability and patient assignment.

“We’re going to need to figure out how to restructure our measurement systems to match our evolving healthcare delivery and payment systems,” says Thomas B. Valuck, MD, JD, senior vice president of strategic partnerships for the National Quality Forum and former CMS adviser to the VBP program. Healthcare quality reporting should focus more on measures that cut across care contexts and assess whether the care provided truly made a difference for patients—metrics such as health improvement, return to functional status, level of patient involvement in the management of their care, provider team coordination, and other patient needs and preferences, Dr. Valuck believes.

“We need to be focused more on measures that encourage joint responsibility and cooperation among providers, and are important to patients across hospital, post-acute, and ambulatory settings, rather than those that are compartmentalized to one setting or relevant only to specific diseases or subspecialties,” Dr. Valuck says.

Such measure sets, while still retaining some disease- and physician-specific metrics, ideally would be complementary with families of related measures at the community, state, and national levels, Dr. Valuck says. “Such a multidimensional framework can begin to tell a meaningful story about what’s happening to the patient, and how well our system is delivering the right care,” he adds.

Dr. Torcson says HM has a pioneering role to play in this evolution, and he notes that SHM has proposed that CMS harmonize measures that align hospital-based physician activities (e.g. hospital medicine, emergency medicine, anesthesia, radiology) with hospital-level performance agendas so that physicians practicing together in the hospital setting can report on measures that are relevant to both.

Christopher Guadagnino is a freelance medical writer in Philadelphia.

Reference

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Physician Quality Reporting System Town Hall Meeting. Available at: http://www.usqualitymeasures.org/shared/content/C4M_PQRS_transcript.pdf. Accessed July 3, 2012.

—Thomas B. Valuck, MD, JD, senior vice president of strategic partnerships, National Quality Forum, former CMS adviser

No longer content to be a passive purchaser of healthcare services, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is becoming a savvier shopper, holding providers increasingly accountable for the quality and efficiency of the care they deliver. With its value-based purchasing (VPB) program for hospitals already in place, now it’s the physicians’ turn.

CMS is marching toward a value-based payment modifier program that will adjust physician reimbursement based on the relative quality and efficiency of care that physicians provide to Medicare fee-for-service patients. The program will begin January 2015 and will extend to all physicians in 2017. Like the hospital VBP program, it will be budget-neutral—meaning that payment will increase for some physicians but decrease for others.

The coming months mark a pivotal period for physicians as CMS tweaks its accountability apparatus in ways that will determine how reimbursement will rise and fall, for whom, and for what.

Menu of Metrics

In crafting the payment modifier program, CMS can tap performance metrics from several of its existing programs, including the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the soon-to-be-expanded Physician Compare website (www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx), and the Physician Feedback Program.

“These agendas are part of a continuum, and of equal importance, in the evolution toward physician value-based purchasing,” says Patrick J. Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Performance Measurement and Reporting Committee, and director of hospital medicine at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La.

PQRS began as a voluntary “pay for reporting” system that gave physicians a modest financial bonus (currently 0.5% of allowable Medicare charges) for submitting quality data (left). The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has since authorized CMS to penalize physicians who do not participate—1.5% of allowable Medicare charges beginning in 2015, and 2% in 2016.

The Physician Compare website, launched at the end of 2010, currently contains such rudimentary information as education, gender, and whether a physician is enrolled in Medicare and satisfactorily reports data to the PQRS. But as of January, the site will begin reporting some PQRS data, as well as other metrics.

CMS’ Physician Feedback Program provides quality and cost information to physicians in an effort to encourage them to improve the care they provide and its efficiency. CMS recently combined the program with its value-based payment modifier program as it moves toward physician reimbursement that it says will reward “value rather than volume.” The program, currently being piloted in Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas, and Missouri, issues to physicians confidential quality and resource use reports (QRURs) that compare their performance to peer groups in similar specialties by tracking PQRS results, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures, and per-capita cost data and preventable hospital admission rates for various medical conditions. CMS will roll out the program nationwide next year.

Metrics Lack Relevance

Developing performance measures that capture the most relevant activities of physicians across many different specialties with equal validity is notoriously difficult—something that CMS acknowledges.1

Assigning the right patient to the right physician (i.e. figuring out who contributed what care, in what proportion, to which patient) also is fraught with complications, especially in the inpatient care setting, where a patient is likely to see many different physicians during a hospitalization.

SHM president Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM, highlighted these challenges in a letter sent in May to acting CMS administrator Marilyn B. Tavenner in which he pointed to dramatic data deficiencies in the initial round of QRURs sent to Physician Feedback Program participants that included hospitalists in Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas and Missouri. Because hospitalists were categorized as general internal-medicine physicians in the reports, their per-capita cost of care was dramatically higher (73% higher, in one case study) than the average cost of all internal-medicine physicians. No allowance was made for distinguishing the outpatient-oriented practice of a general internist from the inherently more expensive inpatient-focused hospitalist practice.

In the case study reviewed by SHM, the hospitalist’s patients saw, on average, 28 different physicians over the course of a year, during which the hospitalist contributed to the care of many patients but did not direct the care of any one of them—facts that clearly highlight the difficulty of assigning responsibility and accountability for a patient’s care when comparing physician performance.

“Based on the measurement used in the QRUR, it seems likely that a hospitalist would be severely disadvantaged with the introduction of a value-based modifier based on the present QRUR methodology,” Dr. Frost wrote.

SHM is similarly critical of the PQRS measures, which Dr. Torcson says lack relevance to hospitalist practices. “We want to be defined as HM physicians with our own unique measures of quality and cost,” he says. “Our results will look very different from those of an internist with a primarily outpatient practice.”

Dr. Torcson notes that SHM is an active participant in providing feedback during CMS rule proposals and has offered to work with the CMS on further refining the measures. For example, SHM proposed adding additional measures related to care transitions, given their particular relevance to hospitalist practices.

Rule-Changing Reform

The disruptive innovation of CMS’ healthcare reform agenda might wind up being a game-changer that dramatically affects the contours of all provider performance reporting and incentive systems, redefining the issues of physician accountability and patient assignment.

“We’re going to need to figure out how to restructure our measurement systems to match our evolving healthcare delivery and payment systems,” says Thomas B. Valuck, MD, JD, senior vice president of strategic partnerships for the National Quality Forum and former CMS adviser to the VBP program. Healthcare quality reporting should focus more on measures that cut across care contexts and assess whether the care provided truly made a difference for patients—metrics such as health improvement, return to functional status, level of patient involvement in the management of their care, provider team coordination, and other patient needs and preferences, Dr. Valuck believes.

“We need to be focused more on measures that encourage joint responsibility and cooperation among providers, and are important to patients across hospital, post-acute, and ambulatory settings, rather than those that are compartmentalized to one setting or relevant only to specific diseases or subspecialties,” Dr. Valuck says.

Such measure sets, while still retaining some disease- and physician-specific metrics, ideally would be complementary with families of related measures at the community, state, and national levels, Dr. Valuck says. “Such a multidimensional framework can begin to tell a meaningful story about what’s happening to the patient, and how well our system is delivering the right care,” he adds.

Dr. Torcson says HM has a pioneering role to play in this evolution, and he notes that SHM has proposed that CMS harmonize measures that align hospital-based physician activities (e.g. hospital medicine, emergency medicine, anesthesia, radiology) with hospital-level performance agendas so that physicians practicing together in the hospital setting can report on measures that are relevant to both.

Christopher Guadagnino is a freelance medical writer in Philadelphia.

Reference

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Physician Quality Reporting System Town Hall Meeting. Available at: http://www.usqualitymeasures.org/shared/content/C4M_PQRS_transcript.pdf. Accessed July 3, 2012.

Know Surgical Package Requirements before Billing Postoperative Care

Hospitalists often are involved in the postoperative care of the surgical patient. However, HM is emerging in the admitting/attending role for procedural patients. Confusion can arise as to the nature of the hospitalist service, and whether it is deemed billable. Knowing the surgical package requirements can help hospitalists consider the issues.

Global Surgical Package Period1

Surgical procedures, categorized as major or minor surgery, are reimbursed for pre-, intra-, and postoperative care. Postoperative care varies according to the procedure’s assigned global period, which designates zero, 10, or 90 postoperative days. (Physicians can review the global period for any given CPT code in the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, available at www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/search/search-criteria.aspx.)

Services classified with “XXX” do not have the global period concept. “ZZZ” services denote an “add-on” procedure code that must always be reported with a primary procedure code and assumes the global period assigned to the primary procedure performed.

Major surgery allocates a 90-day global period in which the surgeon is responsible for all related surgical care one day before surgery through 90 postoperative days with no additional charge. Minor surgery, including endoscopy, appoints a zero-day or 10-day postoperative period. The zero-day global period encompasses only services provided on the surgical day, whereas 10-day global periods include services on the surgical day through 10 postoperative days.

Global Surgical Package Components2

The global surgical package comprises a host of responsibilities that include standard facility requirements of filling out all necessary paperwork involved in surgical cases (e.g. preoperative H&P, operative consent forms, preoperative orders). Additionally, the surgeon’s packaged payment includes (at no extra charge):

- Preoperative visits after making the decision for surgery beginning one day prior to surgery;

- All additional postoperative medical or surgical services provided by the surgeon related to complications but not requiring additional trips to the operating room;

- Postoperative visits by the surgeon related to recovery from surgery, including but not limited to dressing changes; local incisional care; removal of cutaneous sutures and staples; line removals; changes and removal of tracheostomy tubes; and discharge services; and

- Postoperative pain management provided by the surgeon.

- Examples of services that are not included in the global surgical package, (i.e. are separately billable and may require an appropriate modifier) are:

- The initial consultation or evaluation of the problem by the surgeon to determine the need for surgery;

- Services of other physicians except where the other physicians are providing coverage for the surgeon or agree on a transfer of care (i.e. a formal agreement in the form of a letter or an annotation in the discharge summary, hospital record, or ASC record);

- Postoperative visits by the surgeon unrelated to the diagnosis for which the surgical procedure is performed, unless the visits occur due to complications of the surgery;

- Diagnostic tests and procedures, including diagnostic radiological procedures;

- Clearly distinct surgical procedures during the postoperative period that do not result in repeat operations or treatment for complications;

- Treatment for postoperative complications that requires a return trip to the operating room (OR), catheterization lab or endoscopy suite;

- Immunosuppressive therapy for organ transplants; and

- Critical-care services (CPT codes 99291 and 99292) unrelated to the surgery where a seriously injured or burned patient is critically ill and requires constant attendance of the surgeon.

Classification of “Surgeon”

For billing purposes, the “surgeon” is a qualified physician who can perform “surgical” services within their scope of practice. All physicians with the same specialty designation in the same group practice as the “surgeon” (i.e. reporting services under the same tax identification number) are considered a single entity and must adhere to the global period billing rules initiated by the “surgeon.”

Alternately, physicians with different specialty designations in the same group practice (e.g. a hospitalist and a cardiologist in a multispecialty group who report services under the same tax identification number) or different group practices can perform and separately report medically necessary services during the surgeon’s global period, as long as a formal (mutually agreed-upon) transfer of care did not occur.

Medical Necessity

With the growth of HM programs and the admission/attending role expansion, involvement in surgical cases comes under scrutiny for medical necessity. Admitting a patient who has active medical conditions (e.g. hypertension, diabetes, emphysema) is reasonable and necessary because the patient has a well-defined need for medical management by the hospitalist. Participation in the care of these patients is separately billable from the surgeon’s global period package.

Alternatively, a hospitalist might be required to admit and follow surgical patients who have no other identifiable chronic or acute conditions aside from the surgical problem. In these cases, hospitalist involvement may satisfy facility policy (quality of care, risk reduction, etc.) and administrative functions (discharge services or coordination of care) rather than active clinical management. This “medical management” will not be considered “medically necessary” by the payor, and may be denied as incidental to the surgeon’s perioperative services. Erroneous payment can occur, which will result in refund requests, as payors do not want to pay twice for duplicate services. Hospitalists can attempt to negotiate other terms with facilities to account for the unpaid time and effort directed toward these types of cases.

Consider the Case

A patient with numerous medical comorbidities is admitted to the hospitalist service for stabilization prior to surgery, which will occur the next day. The hospitalist can report the appropriate admission code (99221-99223) without need for modifiers because the hospitalist is the attending of record and in a different specialty group. If a private insurer denies the claim as inclusive to the surgical service, the hospitalist can appeal with notes and a cover letter, along with the Medicare guidelines for global surgical package. The hospitalist may continue to provide postoperative daily care, as needed, to manage the patient’s chronic conditions, and report each service as subsequent hospital care (99231-99233) without modifier until the day of discharge (99238-99239). Again, if a payor issues a denial (inclusive to surgery), appealing with notes might be necessary.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 40. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. ICD-10: HHS proposes one-year delay of ICD-10 compliance date. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/ICD10/index.html?redirect=/ICD10. Accessed May 5, 2012.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Anderson C, Boudreau A, Connelly J. Current Procedural Terminology 2012 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011.

Hospitalists often are involved in the postoperative care of the surgical patient. However, HM is emerging in the admitting/attending role for procedural patients. Confusion can arise as to the nature of the hospitalist service, and whether it is deemed billable. Knowing the surgical package requirements can help hospitalists consider the issues.

Global Surgical Package Period1

Surgical procedures, categorized as major or minor surgery, are reimbursed for pre-, intra-, and postoperative care. Postoperative care varies according to the procedure’s assigned global period, which designates zero, 10, or 90 postoperative days. (Physicians can review the global period for any given CPT code in the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, available at www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/search/search-criteria.aspx.)

Services classified with “XXX” do not have the global period concept. “ZZZ” services denote an “add-on” procedure code that must always be reported with a primary procedure code and assumes the global period assigned to the primary procedure performed.

Major surgery allocates a 90-day global period in which the surgeon is responsible for all related surgical care one day before surgery through 90 postoperative days with no additional charge. Minor surgery, including endoscopy, appoints a zero-day or 10-day postoperative period. The zero-day global period encompasses only services provided on the surgical day, whereas 10-day global periods include services on the surgical day through 10 postoperative days.

Global Surgical Package Components2

The global surgical package comprises a host of responsibilities that include standard facility requirements of filling out all necessary paperwork involved in surgical cases (e.g. preoperative H&P, operative consent forms, preoperative orders). Additionally, the surgeon’s packaged payment includes (at no extra charge):

- Preoperative visits after making the decision for surgery beginning one day prior to surgery;

- All additional postoperative medical or surgical services provided by the surgeon related to complications but not requiring additional trips to the operating room;

- Postoperative visits by the surgeon related to recovery from surgery, including but not limited to dressing changes; local incisional care; removal of cutaneous sutures and staples; line removals; changes and removal of tracheostomy tubes; and discharge services; and

- Postoperative pain management provided by the surgeon.

- Examples of services that are not included in the global surgical package, (i.e. are separately billable and may require an appropriate modifier) are:

- The initial consultation or evaluation of the problem by the surgeon to determine the need for surgery;

- Services of other physicians except where the other physicians are providing coverage for the surgeon or agree on a transfer of care (i.e. a formal agreement in the form of a letter or an annotation in the discharge summary, hospital record, or ASC record);

- Postoperative visits by the surgeon unrelated to the diagnosis for which the surgical procedure is performed, unless the visits occur due to complications of the surgery;

- Diagnostic tests and procedures, including diagnostic radiological procedures;

- Clearly distinct surgical procedures during the postoperative period that do not result in repeat operations or treatment for complications;

- Treatment for postoperative complications that requires a return trip to the operating room (OR), catheterization lab or endoscopy suite;

- Immunosuppressive therapy for organ transplants; and

- Critical-care services (CPT codes 99291 and 99292) unrelated to the surgery where a seriously injured or burned patient is critically ill and requires constant attendance of the surgeon.

Classification of “Surgeon”

For billing purposes, the “surgeon” is a qualified physician who can perform “surgical” services within their scope of practice. All physicians with the same specialty designation in the same group practice as the “surgeon” (i.e. reporting services under the same tax identification number) are considered a single entity and must adhere to the global period billing rules initiated by the “surgeon.”

Alternately, physicians with different specialty designations in the same group practice (e.g. a hospitalist and a cardiologist in a multispecialty group who report services under the same tax identification number) or different group practices can perform and separately report medically necessary services during the surgeon’s global period, as long as a formal (mutually agreed-upon) transfer of care did not occur.

Medical Necessity

With the growth of HM programs and the admission/attending role expansion, involvement in surgical cases comes under scrutiny for medical necessity. Admitting a patient who has active medical conditions (e.g. hypertension, diabetes, emphysema) is reasonable and necessary because the patient has a well-defined need for medical management by the hospitalist. Participation in the care of these patients is separately billable from the surgeon’s global period package.

Alternatively, a hospitalist might be required to admit and follow surgical patients who have no other identifiable chronic or acute conditions aside from the surgical problem. In these cases, hospitalist involvement may satisfy facility policy (quality of care, risk reduction, etc.) and administrative functions (discharge services or coordination of care) rather than active clinical management. This “medical management” will not be considered “medically necessary” by the payor, and may be denied as incidental to the surgeon’s perioperative services. Erroneous payment can occur, which will result in refund requests, as payors do not want to pay twice for duplicate services. Hospitalists can attempt to negotiate other terms with facilities to account for the unpaid time and effort directed toward these types of cases.

Consider the Case